Воинская повинность

| Part of a series on |

| War (outline) |

|---|

|

Призыв — это государственный призыв людей на национальную службу , преимущественно военную службу . [ 1 ] Призыв на военную службу восходит к древности и продолжается в некоторых странах по сей день под разными названиями. Современная система почти всеобщей национальной воинской повинности для молодых людей восходит к Французской революции 1790-х годов, когда она стала основой очень большой и мощной армии . Большинство европейских стран позже скопировали эту систему в мирное время, так что мужчины в определенном возрасте служили на действительной военной службе от 1 до 8 лет , а затем переводились в резерв .

Conscription is controversial for a range of reasons, including conscientious objection to military engagements on religious or philosophical grounds; political objection, for example to service for a disliked government or unpopular war; sexism, in that historically men have been subject to the draft in the most cases; and ideological objection, for example, to a perceived violation of individual rights. Those conscripted may evade service, sometimes by leaving the country,[2] и ищет убежища в другой стране. Некоторые системы отбора учитывают это отношение, предоставляя альтернативную службу за пределами боевых действий или даже за пределами армии, например, siviilipalvelus (альтернативная государственная служба) в Финляндии и Zivildienst (обязательные общественные работы) в Австрии и Швейцарии. Некоторые страны призывают солдат-мужчин не только в вооруженные силы, но и в военизированные формирования, которые предназначены для выполнения полицейской службы , внутренних например войск , пограничной службы или небоевых спасательных операций, таких как гражданская оборона .

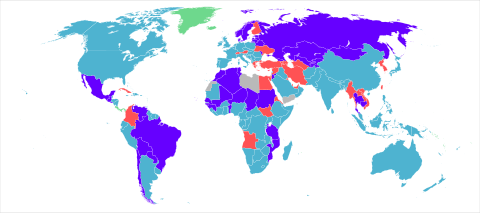

As of 2023, many states no longer conscript their citizens, relying instead upon professional militaries with volunteers. The ability to rely on such an arrangement, however, presupposes some degree of predictability with regard to both war-fighting requirements and the scope of hostilities. Many states that have abolished conscription still, therefore, reserve the power to resume conscription during wartime or times of crisis.[3] States involved in wars or interstate rivalries are most likely to implement conscription, and democracies are less likely than autocracies to implement conscription.[4] With a few exceptions, such as Singapore and Egypt, former British colonies are less likely to have conscription, as they are influenced by British anti-conscription norms that can be traced back to the English Civil War; the United Kingdom abolished conscription in 1960.[4]

History

[edit]In pre-modern times

[edit]Ilkum

[edit]Around the reign of Hammurabi (1791–1750 BC), the Babylonian Empire used a system of conscription called Ilkum. Under that system those eligible were required to serve in the royal army in time of war. During times of peace they were instead required to provide labour for other activities of the state. In return for this service, people subject to it gained the right to hold land. It is possible that this right was not to hold land per se but specific land supplied by the state.[5]

Various forms of avoiding military service are recorded. While it was outlawed by the Code of Hammurabi, the hiring of substitutes appears to have been practiced both before and after the creation of the code. Later records show that Ilkum commitments could become regularly traded. In other places, people simply left their towns to avoid their Ilkum service. Another option was to sell Ilkum lands and the commitments along with them. With the exception of a few exempted classes, this was forbidden by the Code of Hammurabi.[6]

Medieval period

[edit]Medieval levies

[edit]Under the feudal laws on the European continent, landowners in the medieval period enforced a system whereby all peasants, freemen commoners and noblemen aged 15 to 60 living in the countryside or in urban centers, were summoned for military duty when required by either the king or the local lord, bringing along the weapons and armor according to their wealth. These levies fought as footmen, sergeants, and men at arms under local superiors appointed by the king or the local lord such as the arrière-ban in France. Arrière-ban denoted a general levy, where all able-bodied males age 15 to 60 living in the Kingdom of France were summoned to go to war by the King (or the constable and the marshals). Men were summoned by the bailiff (or the sénéchal in the south). Bailiffs were military and political administrators installed by the King to steward and govern a specific area of a province following the king's commands and orders. The men summoned in this way were then summoned by the lieutenant who was the King's representative and military governor over an entire province comprising many bailiwicks, seneschalties and castellanies. All men from the richest noble to the poorest commoner were summoned under the arrière-ban and they were supposed to present themselves to the King or his officials.[7][8][9][10]

In medieval Scandinavia the leiðangr (Old Norse), leidang (Norwegian), leding, (Danish), ledung (Swedish), lichting (Dutch), expeditio (Latin) or sometimes leþing (Old English), was a levy of free farmers conscripted into coastal fleets for seasonal excursions and in defence of the realm.[11]

The bulk of the Anglo-Saxon English army, called the fyrd, was composed of part-time English soldiers drawn from the freemen of each county. In the 690s laws of Ine of Wessex, three levels of fines are imposed on different social classes for neglecting military service.[12]

Some modern writers claim military service in Europe was restricted to the landowning minor nobility. These thegns were the land-holding aristocracy of the time and were required to serve with their own armour and weapons for a certain number of days each year. The historian David Sturdy has cautioned about regarding the fyrd as a precursor to a modern national army composed of all ranks of society, describing it as a "ridiculous fantasy":

The persistent old belief that peasants and small farmers gathered to form a national army or fyrd is a strange delusion dreamt up by antiquarians in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries to justify universal military conscription.[13]

In feudal Japan the shogun decree of 1393 exempted money lenders from religious or military levies, in return for a yearly tax. The Ōnin War weakened the shogun and levies were imposed again on money lenders. This overlordism was arbitrary and unpredictable for commoners. While the money lenders were not poor, several overlords tapped them for income. Levies became necessary for the survival of the overlord, allowing the lord to impose taxes at will. These levies included tansen tax on agricultural land for ceremonial expenses. Yakubu takumai tax was raised on all land to rebuild the Ise Grand Shrine, and munabechisen tax was imposed on all houses. At the time, land in Kyoto was acquired by commoners through usury and in 1422 the shogun threatened to repossess the land of those commoners who failed to pay their levies.[14]

Military slavery

[edit]

The system of military slaves was widely used in the Middle East, beginning with the creation of the corps of Turkic slave-soldiers (ghulams or mamluks) by the Abbasid caliph al-Mu'tasim in the 820s and 830s. The Turkic troops soon came to dominate the government, establishing a pattern throughout the Islamic world of a ruling military class, often separated by ethnicity, culture and even religion[citation needed] by the mass of the population, a paradigm that found its apogee in the Mamluks of Egypt and the Janissary corps of the Ottoman Empire, institutions that survived until the early 19th century.

In the middle of the 14th century, Ottoman Sultan Murad I developed personal troops to be loyal to him, with a slave army called the Kapıkulu. The new force was built by taking Christian children from newly conquered lands, especially from the far areas of his empire, in a system known as the devşirme (translated "gathering" or "converting"). The captive children were forced to convert to Islam. The Sultans had the young boys trained over several years. Those who showed special promise in fighting skills were trained in advanced warrior skills, put into the sultan's personal service, and turned into the Janissaries, the elite branch of the Kapıkulu. A number of distinguished military commanders of the Ottomans, and most of the imperial administrators and upper-level officials of the Empire, such as Pargalı İbrahim Pasha and Sokollu Mehmet Paşa, were recruited in this way.[15] By 1609, the Sultan's Kapıkulu forces increased to about 100,000.[16]

In later years, Sultans turned to the Barbary Pirates to supply their Jannissaries corps. Their attacks on ships off the coast of Africa or in the Mediterranean, and subsequent capture of able-bodied men for ransom or sale provided some captives for the Sultan's system. Starting in the 17th century, Christian families living under the Ottoman rule began to submit their sons into the Kapikulu system willingly, as they saw this as a potentially invaluable career opportunity for their children. Eventually the Sultan turned to foreign volunteers from the warrior clans of Circassians in southern Russia to fill his Janissary armies. As a whole the system began to break down, the loyalty of the Jannissaries became increasingly suspect. Mahmud II forcibly disbanded the Janissary corps in 1826.[17]

Similar to the Janissaries in origin and means of development were the Mamluks of Egypt in the Middle Ages. The Mamluks were usually captive non-Muslim Iranian and Turkic children who had been kidnapped or bought as slaves from the Barbary coasts. The Egyptians assimilated and trained the boys and young men to become Islamic soldiers who served the Muslim caliphs and the Ayyubid sultans during the Middle Ages. The first mamluks served the Abbasid caliphs in 9th-century Baghdad. Over time they became a powerful military caste. On more than one occasion, they seized power, for example, ruling Egypt from 1250 to 1517.

From 1250 Egypt had been ruled by the Bahri dynasty of Kipchak origin. Slaves from the Caucasus served in the army and formed an elite corps of troops. They eventually revolted in Egypt to form the Burgi dynasty. The Mamluks' excellent fighting abilities, massed Islamic armies, and overwhelming numbers succeeded in overcoming the Christian Crusader fortresses in the Holy Land. The Mamluks were the most successful defence against the Mongol Ilkhanate of Persia and Iraq from entering Egypt.[18]

On the western coast of Africa, Berber Muslims captured non-Muslims to put to work as laborers. They generally converted the younger people to Islam and many became quite assimilated. In Morocco, the Berber looked south rather than north. The Moroccan Sultan Moulay Ismail, called "the Bloodthirsty" (1672–1727), employed a corps of 150,000 black slaves, called his Black Guard. He used them to coerce the country into submission.[19]

In modern times

[edit]

Modern conscription, the massed military enlistment of national citizens (levée en masse), was devised during the French Revolution, to enable the Republic to defend itself from the attacks of European monarchies. Deputy Jean-Baptiste Jourdan gave its name to the 5 September 1798 Act, whose first article stated: "Any Frenchman is a soldier and owes himself to the defense of the nation." It enabled the creation of the Grande Armée, what Napoleon Bonaparte called "the nation in arms", which overwhelmed European professional armies that often numbered only into the low tens of thousands. More than 2.6 million men were inducted into the French military in this way between the years 1800 and 1813.[20]

The defeat of the Prussian Army in particular shocked the Prussian establishment, which had believed it was invincible after the victories of Frederick the Great. The Prussians were used to relying on superior organization and tactical factors such as order of battle to focus superior troops against inferior ones. Given approximately equivalent forces, as was generally the case with professional armies, these factors showed considerable importance. However, they became considerably less important when the Prussian armies faced Napoleon's forces that outnumbered their own in some cases by more than ten to one. Scharnhorst advocated adopting the levée en masse, the military conscription used by France. The Krümpersystem was the beginning of short-term compulsory service in Prussia, as opposed to the long-term conscription previously used.[21]

In the Russian Empire, the military service time "owed" by serfs was 25 years at the beginning of the 19th century. In 1834 it was decreased to 20 years. The recruits were to be not younger than 17 and not older than 35.[22] In 1874 Russia introduced universal conscription in the modern pattern, an innovation only made possible by the abolition of serfdom in 1861. New military law decreed that all male Russian subjects, when they reached the age of 20, were eligible to serve in the military for six years.[23]

In the decades prior to World War I universal conscription along broadly Prussian lines became the norm for European armies, and those modeled on them. By 1914 the only substantial armies still completely dependent on voluntary enlistment were those of Britain and the United States. Some colonial powers such as France reserved their conscript armies for home service while maintaining professional units for overseas duties.[24]

World Wars

[edit]

The range of eligible ages for conscripting was expanded to meet national demand during the World Wars. In the United States, the Selective Service System drafted men for World War I initially in an age range from 21 to 30 but expanded its eligibility in 1918 to an age range of 18 to 45.[25] In the case of a widespread mobilization of forces where service includes homefront defense, ages of conscripts may range much higher, with the oldest conscripts serving in roles requiring lesser mobility.[citation needed]

Expanded-age conscription was common during the Second World War: in Britain, it was commonly known as "call-up" and extended to age 51. Nazi Germany termed it Volkssturm ("People's Storm") and included boys as young as 16 and men as old as 60.[26] During the Second World War, both Britain and the Soviet Union conscripted women. The United States was on the verge of drafting women into the Nurse Corps because it anticipated it would need the extra personnel for its planned invasion of Japan. However, the Japanese surrendered and the idea was abandoned.[27]

During the Great Patriotic War, the Red Army conscripted nearly 30 million men.[28]

Arguments against conscription

[edit]Sexism

[edit]Men's rights activists,[29][30] feminists,[31][32][33] and opponents of discrimination against men[34][35]: 102 have criticized military conscription, or compulsory military service, as sexist. The National Coalition for Men, a men's rights group, sued the US Selective Service System in 2019, leading to it being declared unconstitutional by a US Federal Judge.[36][37] The federal district judge's opinion was unanimously overturned on appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit.[38] In September 2021, the House of Representatives passed the annual Defense Authorization Act, which included an amendment that states that "all Americans between the ages of 18 and 25 must register for selective service." This amendment omitted the word "male", which would have extended a potential draft to women; however, the amendment was removed before the National Defense Authorization Act was passed.[39][40][41]

Feminists have argued, first, that military conscription is sexist because wars serve the interests of what they view as the patriarchy; second, that the military is a sexist institution and that conscripts are therefore indoctrinated into sexism; and third, that conscription of men normalizes violence by men as socially acceptable.[42][43] Feminists have been organizers and participants in resistance to conscription in several countries.[44][45][46][47]

Conscription has also been criticized on the ground that, historically, only men have been subjected to conscription.[35][48][49][50][51] Men who opt out or are deemed unfit for military service must often perform alternative service, such as Zivildienst in Austria, Germany and Switzerland, or pay extra taxes,[52] whereas women do not have these obligations. In the US, men who do not register with the Selective Service cannot apply for citizenship, receive federal financial aid, grants or loans, be employed by the federal government, be admitted to public colleges or universities, or, in some states, obtain a driver's license.[53][54]

Involuntary servitude

[edit]

Many American libertarians oppose conscription and call for the abolition of the Selective Service System, arguing that impressment of individuals into the armed forces amounts to involuntary servitude.[55] For example, Ron Paul, a former U.S. Libertarian Party presidential nominee, has said that conscription "is wrongly associated with patriotism, when it really represents slavery and involuntary servitude".[56] The philosopher Ayn Rand opposed conscription, opining that "of all the statist violations of individual rights in a mixed economy, the military draft is the worst. It is an abrogation of rights. It negates man's fundamental right—the right to life—and establishes the fundamental principle of statism: that a man's life belongs to the state, and the state may claim it by compelling him to sacrifice it in battle."[57]

In 1917, a number of radicals[who?] and anarchists, including Emma Goldman, challenged the new draft law in federal court, arguing that it was a violation of the Thirteenth Amendment's prohibition against slavery and involuntary servitude. However, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld the constitutionality of the draft act in the case of Arver v. United States on 7 January 1918, on the ground that the Constitution gives Congress the power to declare war and to raise and support armies. The Court also relied on the principle of the reciprocal rights and duties of citizens. "It may not be doubted that the very conception of a just government in its duty to the citizen includes the reciprocal obligation of the citizen to render military service in case of need and the right to compel."[58]

Economic

[edit]It can be argued that in a cost-to-benefit ratio, conscription during peacetime is not worthwhile.[59] Months or years of service performed by the most fit and capable subtract from the productivity of the economy; add to this the cost of training them, and in some countries paying them. Compared to these extensive costs, some would argue there is very little benefit; if there ever was a war then conscription and basic training could be completed quickly, and in any case there is little threat of a war in most countries with conscription. In the United States, every male resident is required by law to register with the Selective Service System within 30 days following his 18th birthday and be available for a draft; this is often accomplished automatically by a motor vehicle department during licensing or by voter registration.[60]

According to Milton Friedman the cost of conscription can be related to the parable of the broken window in anti-draft arguments. The cost of the work, military service, does not disappear even if no salary is paid. The work effort of the conscripts is effectively wasted, as an unwilling workforce is extremely inefficient. The impact is especially severe in wartime, when civilian professionals are forced to fight as amateur soldiers. Not only is the work effort of the conscripts wasted and productivity lost, but professionally skilled conscripts are also difficult to replace in the civilian workforce. Every soldier conscripted in the army is taken away from his civilian work, and away from contributing to the economy which funds the military. This may be less a problem in an agrarian or pre-industrialized state where the level of education is generally low, and where a worker is easily replaced by another. However, this is potentially more costly in a post-industrial society where educational levels are high and where the workforce is sophisticated and a replacement for a conscripted specialist is difficult to find. Even more dire economic consequences result if the professional conscripted as an amateur soldier is killed or maimed for life; his work effort and productivity are lost.[61]

Arguments for conscription

[edit]Political and moral motives

[edit]

Jean Jacques Rousseau argued vehemently against professional armies since he believed that it was the right and privilege of every citizen to participate to the defense of the whole society and that it was a mark of moral decline to leave the business to professionals. He based his belief upon the development of the Roman Republic, which came to an end at the same time as the Roman Army changed from a conscript to a professional force.[62] Similarly, Aristotle linked the division of armed service among the populace intimately with the political order of the state.[63] Niccolò Machiavelli argued strongly for conscription[64] and saw the professional armies, made up of mercenary units, as the cause of the failure of societal unity in Italy.[65]

Other proponents, such as William James, consider both mandatory military and national service as ways of instilling maturity in young adults.[66] Some proponents, such as Jonathan Alter and Mickey Kaus, support a draft in order to reinforce social equality, create social consciousness, break down class divisions and allow young adults to immerse themselves in public enterprise.[67][68][69] Charles Rangel called for the reinstatement of the draft during the Iraq War not because he seriously expected it to be adopted but to stress how the socioeconomic restratification meant that very few children of upper-class Americans served in the all-volunteer American armed forces.[70]

Economic and resource efficiency

[edit]It is estimated by the British military that in a professional military, a company deployed for active duty in peacekeeping corresponds to three inactive companies at home. Salaries for each are paid from the military budget. In contrast, volunteers from a trained reserve are in their civilian jobs when they are not deployed.[71]

It was more financially beneficial for less-educated young Portuguese men born in 1967 to participate in conscription than to participate in the highly competitive job market with men of the same age who continued to higher education.[72]

Drafting of women

[edit]

Throughout history, women have only been conscripted to join armed forces in a few countries, in contrast to the universal practice of conscription from among the male population. The traditional view has been that military service is a test of manhood and a rite of passage from boyhood into manhood.[73][74] In recent years, this position has been challenged on the basis that it violates gender equality, and some countries, especially in Europe, have extended conscription obligations to women.

Nations that in present-day actively draft women into military service are Eritrea,[75][76][77] Israel,[75][76][78] Mozambique,[79] Norway,[80] North Korea,[81] Myanmar,[82] and Sweden.[83]

Norway introduced female conscription in 2015, making it the first NATO member to have a legally compulsory national service for both men and women.[80] In practice only motivated volunteers are selected to join the army in Norway.[84]

Sweden introduced female conscription in 2010, but it was not activated until 2017. This made Sweden the second nation in Europe to draft women, and the second in the world to draft women on the same formal terms as men.[83]

Israel has universal female conscription, although it is possible to avoid service by claiming a religious exemption and over a third of Israeli women do so.[75][76][85]

Finland introduced voluntary female conscription in 1995, giving women between the ages of 18 and 29 an option to complete their military service alongside men.[86][87]

Denmark will extend conscription to women from 2027.[88][89][90]

Sudanese law allows for conscription of women, but this is not implemented in practice.[91]

In the United Kingdom during World War II, beginning in 1941, women were brought into the scope of conscription but, as all women with dependent children were exempt and many women were informally left in occupations such as nursing or teaching, the number conscripted was relatively few.[92]

In the Soviet Union, there was never conscription of women for the armed forces, but the severe disruption of normal life and the high proportion of civilians affected by World War II after the German invasion attracted many volunteers for "The Great Patriotic War".[93] Medical doctors of both sexes could and would be conscripted (as officers). Also, the Soviet university education system required Department of Chemistry students of both sexes to complete an ROTC course in NBC defense, and such female reservist officers could be conscripted in times of war.

The United States came close to drafting women into the Nurse Corps in preparation for a planned invasion of Japan.[94][95]

In 1981 in the United States, several men filed lawsuit in the case Rostker v. Goldberg, alleging that the Selective Service Act of 1948 violates the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment by requiring that only men register with the Selective Service System (SSS). The Supreme Court eventually upheld the Act, stating that "the argument for registering women was based on considerations of equity, but Congress was entitled, in the exercise of its constitutional powers, to focus on the question of military need, rather than 'equity.'"[96] In 2013, Judge Gray H. Miller of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas ruled that the Service's men-only requirement was unconstitutional, as while at the time Rostker was decided, women were banned from serving in combat, the situation had since changed with the 2013 and 2015 restriction removals.[97] Miller's opinion was reversed by the Fifth Circuit, stating that only the Supreme Court could overturn the Supreme Court precedence from Rostker. The Supreme Court considered but declined to review the Fifth Circuit's ruling in June 2021.[98] In an opinion authored by Justice Sonia Sotomayor and joined by Justices Stephen Breyer and Brett Kavanaugh, the three justices agreed that the male-only draft was likely unconstitutional given the changes in the military's stance on the roles, but because Congress had been reviewing and evaluating legislation to eliminate its male-only draft requirement via the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service (NCMNPS) since 2016, it would have been inappropriate for the Court to act at that time.[99]

On 1 October 1999, in Taiwan, the Judicial Yuan of the Republic of China in its Interpretation 490 considered that the physical differences between males and females and the derived role differentiation in their respective social functions and lives would not make drafting only males a violation of the Constitution of the Republic of China.[100][(see discussion) verification needed] Though women are not conscripted in Taiwan, transsexual persons are exempt.[101]

In 2018, the Netherlands started including women in its draft registration system, although conscription is not currently enforced for either sex.[102] France and Portugal, where conscription was abolished, extended their symbolic, mandatory day of information on the armed forces for young people - called Defence and Citizenship Day in France and Day of National Defence in Portugal – to women in 1997 and 2008, respectively; at the same time, the military registry of both countries and obligation of military service in case of war was extended to women.[103][104]

Conscientious objection

[edit]A conscientious objector is an individual whose personal beliefs are incompatible with military service, or, more often, with any role in the armed forces.[105][106] In some countries, conscientious objectors have special legal status, which augments their conscription duties. For example, Sweden allows conscientious objectors to choose a service in the weapons-free civil defense.[107][108]

The reasons for refusing to serve in the military are varied. Some people are conscientious objectors for religious reasons. In particular, the members of the historic peace churches are pacifist by doctrine, and Jehovah's Witnesses, while not strictly pacifists, refuse to participate in the armed forces on the ground that they believe that Christians should be neutral in international conflicts.[109]

By country

[edit]| Country | Conscription[110] | Sex |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | N/A | |

| No (abolished in 2010)[111] | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No. Voluntary; conscription may be required for specified reasons per Article 19 of Public Law No.24.429 promulgated on 5 January 1995.[112] | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No (abolished by parliament in 1972)[113] | N/A | |

| Yes (alternative service available)[114] | Male | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (but can volunteer for service in Bangladesh Ansar) | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No (suspended in 1992; service not required of draftees inducted for 1994 military classes or any thereafter)[115] | N/A | |

| No. Laws allow for conscription only if volunteers are insufficient, but conscription has never been implemented.[116] | N/A | |

| Yes | Male and female | |

| No[116] | N/A | |

| Yes (whenever annual number of volunteers falls short of government's goal)[117] | Male and Female | |

| No (abolished on 1 January 2006)[118] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes, but almost all recruits have been volunteers in recent years.[119] (Alternative service is cited in Brazilian law,[120] but a system has not been implemented.)[119] | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (abolished by law on 1 January 2008)[121] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No. Legislative provision making all men of military age a Reserve Militia member was removed in 1904.[122] Conscription into a full-time military service took place in both world wars, with 1945 being the last year conscription was practice.[123] | N/A | |

| Yes (selective compulsory military service) | Male and Female | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No, however Male citizens 18 years of age and over are required to register for military service in People's Liberation Army recruiting offices (registration exempted for residents of Hong Kong and Macao special administrative regions).[124][125][126][127] | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (ended in 1969) | N/A | |

| Yes (conscription is reportedly not enforced) | Male and Female | |

| No. Abolished by law in 2008 but it will be reintroduced on 1 January 2025.[128] | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| Yes (alternative service available) | Male | |

| No (abolished in 2005)[129] | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| Yes (alternative service available)[130][131] | Male until 2026; male and female from 2026.[132] | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (suspended in 2008) | N/A | |

| Yes (alternative service available) | Male | |

| No. Legal, not practiced. | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| Yes (18 months by law, but often extended indefinitely) | Male and female | |

| Yes (alternative service available) | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No, but the military can conduct callups when necessary. | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes (alternative service available) | Male | |

| No (suspended during peacetime in 2001).[133] A voluntary national service (Service national universel, with the option of military or civil service for men and women) was instituted in 2021. | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes[134] | Male | |

| No (suspended during peacetime by the federal legislature from 1 July 2011)[135] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes (alternative service available) | Male | |

| Yes[136][137] | Male | |

| Yes | Male | |

| Yes | Male and Female | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (peacetime conscription abolished in 2004)[138] | N/A

| |

| No | N/A | |

| No. But has a similar system called PKRS (Pertahanan Keamanan Rakyat Semesta, or Universal People's Defense and Security). In the event of war, the government will draft all men and women.[139] | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No (abolished in 2003) | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male and female Jews, male Druze and Circassians | |

| No (suspended during peacetime in 2005)[140] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (abolished in 1945)[141][142] | N/A | |

| Yes (ended in 1992, reinstated in September 2020 for unemployed men) [143] | Male | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes[144] | Male | |

| Yes | Male | |

| Yes | Male | |

| Yes[145] (abolished in 2007, reintroduced on January 1, 2024)[146] | Male | |

| No (abolished in 2007)[147] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| Yes[148] About 3,000–4,000 conscripts each year must be selected, of whom up to 10% serve involuntarily.[149]) | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No.[150] Malaysian National Service was suspended from January 2015 due to government budget cuts.[151] It resumed in 2016, then was abolished in 2018. However, in 2023 the government announced its revival pending approval. | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male and Female | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (there is a compulsory two-year military service law, but the law has never been enforced in practice.) | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| Yes[152] | Male

| |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes (reintroduced in 2018)[153] | Male and female | |

| Yes[154] | Male and female | |

| Yes, enforced as of February 2024[update].[82][155] | Male and female | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

(see details) |

No. Active conscription suspended in 1997 (except in Curaçao and Aruba).[citation needed][156] | Male and female |

| No (abolished in December 1972) | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes (selective compulsory military service for unmarried men and women) | Male and Female | |

| No. However, under Nigeria's National Youths Service Corps Act, graduates from tertiary institutions are required to undertake national service for a year. The service begins with a 3-week military training. | ||

| Yes[157] | Male and female | |

| No (abolished in 2006)[158] | N/A | |

| Yes by law, but in practice people are not forced to serve against their will.[84] Conscientious objectors have not been prosecuted since 2011; they are simply exempted from service.[159] | Male and female | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No (abolished in 1999) | N/A | |

| No (abolished in 2016)[160][161][163] | N/A | |

| No. Ended in 2009, but selective registration is still required.[164][165] | N/A | |

| No. Peacetime conscription abolished in 2004, but there remains a symbolic military obligation for all 18-year-olds, of both sexes: National Defense Day (Dia da Defesa Nacional).[166] | Male and female | |

| Yes[167] | Male | |

| No (stopped in January 2007) | N/A | |

| Yes (alternative service available) | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male and female | |

| No (abolished on January 1, 2011) | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No (abolished on January 1, 2006)[168] | N/A | |

| No[169] | N/A | |

| No (conscription of men aged 18-40 and women aged 18-30 is authorized, but not currently used) | N/A | |

| No (ended in 1994)[170] | N/A | |

| Yes (alternative service available). The military service law was established in 1948.[171] | Male | |

| Yes | Male and female | |

| No (abolished by law on 31 December 2001)[172] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes. Sudanese law allows for conscription of women, but this is not implemented in practice.[91] | Male and female | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes. Abolished in 2010 but reintroduced in 2017 (alternative service available)[173] | Male and female | |

| Yes (alternative service available)[174] | Male | |

| Yes | Male | |

| Yes (alternative service available).[175] According to the Defence Minister, from 2018 there will be no compulsory enlistment for military service;[176] however, all men born after 1995 will be subject to four months of compulsory military training, increasing to one full year after 2024 (for men born after 2005).[177] |

Male | |

| Yes | Male | |

| Yes (selective conscription for 2 years of public service) | Male and Female | |

| Yes, but can be exempted if three years of Territorial Defense Student training are completed. Students who start but do not complete a Ror Dor course in high school are still permitted to continue coursework for two more years at a university. Otherwise, they face training or must draw a conscription lottery "black card". The government intends to abolish these rules in 2027. [178] | Male | |

| Yes (authorized in 2020) | Male and Female | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male and Female | |

| Yes[179] | Male | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes (abolished in 2013, reinstated in 2014 due to the Russo-Ukrainian War)[180] | Male | |

| Yes (alternative service available). Implemented in 2014, compulsory for all male citizens aged 18–30.[181] | Male | |

| No. Required from 1916 until 1920 and from 1939 until 31 December 1960 (except for the Bermuda Regiment, abolished in 2018).[182] | N/A | |

| No. Ended in 1973, but registration is still required of all men aged 18–25.[183] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| Yes[184][185] | Male and female | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No (abolished in 2001) | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A |

Austria

[edit]Every male citizen of the Republic of Austria from the age of 17 up to 50, specialists up to 65 years is liable to military service. However, besides mobilization, conscription calls to a six-month long basic military training in the Bundesheer can be done up to the age of 35. For men refusing to undergo this training, a nine-month lasting community service is mandatory.

Belgium

[edit]Belgium abolished the conscription in 1994. The last conscripts left active service in February 1995. To this day (2019), a small minority of the Belgian citizens supports the idea of reintroducing military conscription, for both men and women.

Bulgaria

[edit]Bulgaria had mandatory military service for males above 18 until conscription was ended in 2008.[186] Due to a shortfall in the army of some 5500 soldiers,[187] parts of the former ruling coalition have expressed their support for the return of mandatory military service, most notably Krasimir Karakachanov. Opposition towards this idea from the main coalition partner, GERB, saw a compromise in 2018, where instead of mandatory military service, Bulgaria could have possibly introduced a voluntary military service by 2019 where young citizens can volunteer for a period of 6 to 9 months, receiving a basic wage. However this has not gone forward.[188]

Cambodia

[edit]Since the signing of the Peace Accord in 1993, there has been no official conscription in Cambodia. Also the National Assembly has repeatedly rejected to reintroduce it due to popular resentment.[189] However, in November 2006, it was reintroduced. Although mandatory for all males between the ages of 18 and 30 (with some sources stating up to age 35), less than 20% of those in the age group are recruited amidst a downsizing of the armed forces.[190]

Canada

[edit]Compulsory service in a sedentary militia was practiced in Canada as early as 1669. In peacetime, compulsory service was typically limited to attending an annual muster, although the Canadian militia was mobilized for longer periods during wartime. Compulsory service in the sedentary militia continued until the early 1880s when Canada's sedentary Reserve Militia system fell into disuse. The legislative provision that formally made every male inhabitant aged 16 to 60 member of the Reserve Militia was removed in 1904, replaced with provisions that made them theoretically "liable to serve in the militia".[191]

Conscription into a full-time military service had only been instituted twice by the government of Canada, during both world wars. Conscription into the Canadian Expeditionary Force was practiced in the last year of the First World War in 1918. During the Second World War, conscription for home defence was introduced in 1940 and for overseas service in 1944. Conscription has not been practiced in Canada since the end of the Second World War in 1945.[192]

China

[edit]

Universal conscription in China dates back to the State of Qin, which eventually became the Qin Empire of 221 BC. Following unification, historical records show that a total of 300,000 conscript soldiers and 500,000 conscript labourers constructed the Great Wall of China.[193] In the following dynasties, universal conscription was abolished and reintroduced on numerous occasions.

As of 2011[update],[194] universal military conscription is theoretically mandatory in China, and reinforced by law. However, due to the large population of China and large pool of candidates available for recruitment, the People's Liberation Army has always had sufficient volunteers, so conscription has not been required in practice.[195][125][126][196]

Cuba

[edit]Cyprus

[edit]Military service in Cyprus has a deep rooted history entangled with the Cyprus problem.[197] Military service in the Cypriot National Guard is mandatory for all male citizens of the Republic of Cyprus, as well as any male non-citizens born of a parent of Greek Cypriot descent, lasting from the 1 January of the year in which they turn 18 years of age to 31 December, of the year in which they turn 50.[198][199] All male residents of Cyprus who are of military age (16 and over) are required to obtain an exit visa from the Ministry of Defense.[200] Currently, military conscription in Cyprus lasts up to 14 months.

Denmark

[edit]

Conscription is known in Denmark since the Viking Age, where one man out of every 10 had to serve the king. Frederick IV of Denmark changed the law in 1710 to every 4th man. The men were chosen by the landowner and it was seen as a penalty.

Since 12 February 1849, every physically fit man must do military service. According to §81 in the Constitution of Denmark, which was promulgated in 1849:

Every male person able to carry arms shall be liable with his person to contribute to the defence of his country under such rules as are laid down by Statute. — Constitution of Denmark[201]

The legislation about compulsory military service is articulated in the Danish Law of Conscription.[202] National service takes 4–12 months.[203] It is possible to postpone the duty when one is still in full-time education.[204] Every male turning 18 will be drafted to the 'Day of Defence', where they will be introduced to the Danish military and their health will be tested.[205] Physically unfit persons are not required to do military service.[203][206] It is only compulsory for men, while women are free to choose to join the Danish army.[207] Almost all of the men have been volunteers in recent years,[208] 96.9% of the total number of recruits having been volunteers in the 2015 draft.[209]

After lottery,[210] one can become a conscientious objector.[211] Total objection (refusal from alternative civilian service) results in up to 4 months jailtime according to the law.[212] However, in 2014 a Danish man, who signed up for the service and objected later, got only 14 days of home arrest.[213] In many countries the act of desertion (objection after signing up) is punished harder than objecting the compulsory service.

Eritrea

[edit]Estonia

[edit]Estonia adopted a policy of ajateenistus (literally "time service") in late 1991, having inherited the concept from Soviet legislature. According to §124 of the 1992 constitution, "Estonian citizens have a duty to participate in national defence on the bases and pursuant to a procedure provided by a law",[219] which in practice means that men aged 18–27 are subject to the draft.[220]

In the formative years, conscripts had to serve an 18-month term. An amendment passed in 1994 shortened this to 12 months. Further revisions in 2003 established an eleven-month term for draftees trained as NCOs and drivers, and an eight-month term for rank & file. Under the current system, the yearly draft is divided into three "waves" - separate batches of eleven-month conscripts start their service in January and July while those selected for an eight-month term are brought in on October.[221] An estimated 3200 people go through conscript service every year.

Conscripts serve in all branches of the Estonian Defence Forces except the air force which only relies on paid professionals due to its highly technical nature and security concerns. Historically, draftees could also be assigned to the border guard (before it switched to an all-volunteer model in 2000), a special rapid response unit of the police force (disbanded in 1997) or three militarized rescue companies within the Estonian Rescue Board (disbanded in 2004).

Finland

[edit]

Conscription in Finland is part of a general compulsion for national military service for all adult males (Finnish: maanpuolustusvelvollisuus; Swedish: totalförsvarsplikt) defined in the 127§ of the Constitution of Finland.

Conscription can take the form of military or of civilian service. According to 2021 data, 65%[222] of Finnish males entered and finished the military service. The number of female volunteers to annually enter armed service had stabilised at approximately 300.[223] The service period is 165, 255 or 347 days for the rank and file conscripts and 347 days for conscripts trained as NCOs or reserve officers. The length of civilian service is always twelve months. Those electing to serve unarmed in duties where unarmed service is possible serve either nine or twelve months, depending on their training.[224][225]

Any Finnish male citizen who refuses to perform both military and civilian service faces a penalty of 173 days in prison, minus any served days. Such sentences are usually served fully in prison, with no parole.[226][227] Jehovah's Witnesses are no longer exempted from service as of 27 February 2019.[228] The inhabitants of demilitarized Åland are exempt from military service. By the Conscription Act of 1951, they are, however, required to serve a time at a local institution, like the coast guard. However, until such service has been arranged, they are freed from service obligation. The non-military service of Åland has not been arranged since the introduction of the act, and there are no plans to institute it. The inhabitants of Åland can also volunteer for military service on the mainland. As of 1995, women are permitted to serve on a voluntary basis and pursue careers in the military after their initial voluntary military service.

The military service takes place in Finnish Defence Forces or in the Finnish Border Guard. All services of the Finnish Defence Forces train conscripts. However, the Border Guard trains conscripts only in land-based units, not in coast guard detachments or in the Border Guard Air Wing. Civilian service may take place in the Civilian Service Center in Lapinjärvi or in an accepted non-profit organization of educational, social or medical nature.

Germany

[edit]Between 1956 and 2011 conscription was mandatory for all male citizens in the German federal armed forces (German: Bundeswehr), as well as for the Federal Border Guard (Bundesgrenzschutz) in the 1970s (see Border Guard Service). With the end of the Cold War the German government drastically reduced the size of its armed forces. The low demand for conscripts led to the suspension of compulsory conscription in 2011. Since then, only volunteer professionals serve in the Bundeswehr.

Greece

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (March 2017) |

Since 1914 Greece has been enforcing mandatory military service, currently lasting 12 months (but historically up to 36 months) for all adult men. Citizens discharged from active service are normally placed in the reserve and are subject to periodic recalls of 1–10 days at irregular intervals.[229]

Universal conscription was introduced in Greece during the military reforms of 1909, although various forms of selective conscription had been in place earlier. In more recent years, conscription was associated with the state of general mobilisation declared on 20 July 1974, due to the crisis in Cyprus (the mobilisation was formally ended on 18 December 2002).

The duration of military service has historically ranged between 9 and 36 months depending on various factors either particular to the conscript or the political situation in the Eastern Mediterranean. Although women are employed by the Greek army as officers and soldiers, they are not obliged to enlist. Soldiers receive no health insurance, but they are provided with medical support during their army service, including hospitalization costs.

Greece enforces conscription for all male citizens aged between 19 and 45. In August 2009, duration of the mandatory service was reduced from 12 months as it was before to 9 months for the army, but remained at 12 months for the navy and the air force. The number of conscripts allocated to the latter two has been greatly reduced aiming at full professionalization. Nevertheless, mandatory military service at the army was once again raised to 12 months in March 2021, unless served in units in Evros or the North Aegean islands where duration was kept at 9 months. Although full professionalization is under consideration, severe financial difficulties and mismanagement, including delays and reduced rates in the hiring of professional soldiers, as well as widespread abuse of the deferment process, has resulted in the postponement of such a plan.

Iran

[edit]

In Iran, all men who reach the age of 18 must do about two years of compulsory military service in the IR police department or Iranian army or Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.[230] Before the 1979 revolution, women could serve in the military.[231] However, after the establishment of the Islamic Republic, some Ayatollahs considered women's military service to be disrespectful to women by the Pahlavi government and banned women's military service in Iran.[232] Therefore, Iranian women and girls were completely exempted from military service, which caused Iranian men and boys to oppose.[233]

In Iran, men who refuse to go to military service are deprived of their citizenship rights, such as employment, health insurance,[234] continuing their education at university,[235] finding a job, going abroad, opening a bank account,[236] etc.[237] Iranian men have so far opposed mandatory military service and demanded that military service in Iran become a job like in other countries, but the Islamic Republic is opposed to this demand.[230] Some Iranian military commanders consider the elimination of conscription or improving the condition of soldiers as a security issue and one of Ali Khamenei's powers as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces,[230][238] so they treat it with caution.[239] In Iran, usually wealthy people are exempted from conscription.[240][241] Some other men can be exempted from conscription due to their fathers serving in the Iran-Iraq war.[242][243]

Israel

[edit]There is a mandatory military service for all men and women in Israel who are fit and 18 years old. Men must serve 32 months while women serve 24 months, with the vast majority of conscripts being Jewish.

Some Israeli citizens are exempt from mandatory service:

- Non-Jewish Arab citizens

- Permanent residents (non-civilian) such as the Druze of the Golan Heights

- Male Ultra-Orthodox Jews can apply for deferment to study in Yeshiva and the deferment tends to become an exemption, although some do opt to serve in the military

- Female religious Jews, as long as they declare they are unable to serve due to religious grounds. Most of whom opt for the alternative of volunteering in the national service Sherut Leumi

All of the exempt above are eligible to volunteer to the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), as long as they declare so.

Male Druze and male Circassian Israeli citizens are liable for conscription, in accordance with agreement set by their community leaders (their community leaders however signed a clause in which all female Druze and female Circassian are exempt from service).

A few male Bedouin Israeli citizens choose to enlist to the Israeli military in every draft (despite their Muslim-Arab background that exempt them from conscription).

Lithuania

[edit]Lithuania abolished its conscription in 2008.[244] In May 2015, the Lithuanian parliament voted to reintroduce conscription and the conscripts started their training in August 2015.[245] From 2015 to 2017 there were enough volunteers to avoid drafting civilians.[246]

Luxembourg

[edit]Luxembourg practiced military conscription from 1948 until 1967.

Moldova

[edit]Moldova has a 12-month conscription for all males between 18 and 27 years. However, a citizen who completed a military training course at a military department is exempted from conscription.[247]

Netherlands

[edit]назывался «Служебная обязанность» ( голландский : dienstplicht Призыв, который в Нидерландах ) , впервые был введен в действие в 1810 году французскими оккупационными войсками. Луи Брат Наполеона Бонапарт , который был королем Голландии с 1806 по 1810 год, несколькими годами ранее безуспешно пытался ввести воинскую повинность. В армию должен был записаться каждый мужчина в возрасте 20 лет и старше. Путем жеребьевки решалось, кто должен поступить на службу во французскую армию. Возможна замена за оплату.

В дальнейшем призыв стали применять для всех мужчин старше 18 лет. Отсрочка была возможна, например, в связи с учебой. Лица, отказывающиеся от военной службы по соображениям совести, могли проходить альтернативную гражданскую службу вместо военной. По разным причинам эта принудительная военная служба подверглась критике в конце ХХ века. Поскольку холодная война закончилась, исчезла и прямая угроза войны. Вместо этого голландская армия участвовала во все большем количестве миротворческих операций. Сложность и опасность этих миссий сделали использование призывников спорным. Более того, система призыва считалась несправедливой, поскольку призывались только мужчины.

В европейской части Нидерландов обязательное посещение официально приостановлено с 1 мая 1997 года. [ 248 ] В период с 1991 по 1996 год голландские вооруженные силы постепенно сократили свой призывной персонал и превратились в полностью профессиональные силы. Последние призывники были призваны в 1995 году и демобилизованы в 1996 году. [ 248 ] Приостановление означает, что граждан больше не принуждают служить в вооруженных силах, если это не требуется для безопасности страны. С тех пор голландская армия стала полностью профессиональной силой. Однако по сей день каждый мужчина, а с января 2020 года и женщина [ 249 ] Гражданин в возрасте 17 лет получает письмо, в котором ему сообщается, что он поставлен на учет, но не обязан являться на службу. [ 250 ]

Норвегия

[ редактировать ]Призыв был конституционно установлен 12 апреля 1907 года в соответствии с § 119 Kongeriket Norges Grunnlov . [ 251 ] По состоянию на март 2016 г. [update] действует В настоящее время в Норвегии слабая форма обязательной военной службы для мужчин и женщин. На практике новобранцев не принуждают служить, вместо этого отбираются только те, кто мотивирован. [ 252 ] Ежегодно призываются на военную службу около 60 000 норвежцев, но призываются только от 8 000 до 10 000 человек. [ 253 ] С 1985 года женщины получили возможность поступать на добровольную службу в качестве обычных призывников. 14 июня 2013 года парламент Норвегии проголосовал за распространение воинской повинности на женщин, в результате чего с 2015 года вступит в силу всеобщая воинская повинность. [ 80 ] Это сделало Норвегию первым членом НАТО и первой европейской страной, которая сделала национальную службу обязательной для обоих полов. [ 254 ] Раньше, по крайней мере, до начала 2000-х годов, все мужчины в возрасте от 19 до 44 лет подлежали обязательной службе, при этом требовались веские причины, чтобы избежать призыва в армию. Существует право на отказ от военной службы по соображениям совести . По состоянию на 2020 год Норвегия не добилась гендерного равенства при призыве на военную службу: только 33% всех призывников составляют женщины. [ 255 ]

Помимо военной службы, норвежское правительство призывает в общей сложности 8000 человек. [ 256 ] мужчины и женщины в возрасте от 18 до 55 лет на невоенную службу в гражданской обороне . [ 257 ] (Не путать с альтернативной гражданской службой .) Бывшая военная служба не исключает возможности последующего призыва в гражданскую оборону, но применяется верхний предел общей продолжительности службы в 19 месяцев. [ 258 ] Игнорирование приказов о мобилизации, учений и реальных происшествий может привести к наложению штрафа. [ 259 ]

Россия

[ редактировать ]Российские Вооруженные Силы комплектуют личный состав из различных источников. Помимо призывников , российская мобилизация 2022 года в рамках Специальной военной операции выявила российские иррегулярные части на Украине и российские штрафные воинские части в качестве источников живой силы . Сюда добавляются БАРС (Россия) , Национальная гвардия России и российские добровольческие батальоны .

Сербия

[ редактировать ]По состоянию на 1 января 2011 г. [update], Сербия больше не практикует обязательную военную службу. До этого обязательная военная служба для мужчин длилась 6 месяцев. Однако лица, отказывающиеся от военной службы по соображениям совести, могли вместо этого выбрать 9 месяцев государственной службы .

15 декабря 2010 года парламент Сербии проголосовал за приостановку обязательной военной службы. Решение полностью вступило в силу 1 января 2011 года. [ 260 ]

ЮАР

[ редактировать ]в 1994 году в Южной Африке существовал обязательный военный призыв для всех белых мужчин С 1968 года до конца апартеида . [ 261 ] Согласно закону Южной Африки об обороне, молодые белые мужчины должны были пройти двухлетнюю непрерывную военную подготовку после окончания школы, после чего они должны были отслужить 720 дней на случайной военной службе в течение следующих 12 лет. [ 262 ] Кампания по прекращению призыва на военную службу началась в 1983 году вопреки этому требованию. В том же году правительство Национальной партии объявило о планах распространить призыв на военную службу на белых иммигрантов в стране. [ 262 ]

Южная Корея

[ редактировать ]Швеция

[ редактировать ]

В Швеции существовал призыв на военную службу ( швед . värnplikt ) для мужчин в период с 1901 по 2010 год. В течение последних нескольких десятилетий он был выборочным. [ 263 ] С 1980 года женщинам разрешено записываться по выбору и, если они сдадут экзамены, проходить военную подготовку вместе с призывниками-мужчинами. С 1989 года женщинам разрешено служить на всех воинских должностях и частях, включая боевые. [ 83 ]

В 2010 году призыв стал гендерно-нейтральным, то есть и женщины, и мужчины будут призываться на равные условия. Одновременно в мирное время была деактивирована система призыва. [ 83 ] Семь лет спустя, ссылаясь на возросшую военную угрозу, шведское правительство возобновило призыв на военную службу. С 2018 года призываются как мужчины, так и женщины. [ 83 ]

Тайвань

[ редактировать ]Тайвань , официально Китайская Республика (КР), поддерживает активную систему воинской повинности. Все квалифицированные граждане мужского пола призывного возраста теперь обязаны пройти 4-месячную военную подготовку. В декабре 2022 года президент Цай Инвэнь возглавила правительство, чтобы объявить о восстановлении обязательной годичной военной службы с января 2024 года. [ 264 ]

Великобритания

[ редактировать ]Соединенное Королевство впервые ввело призыв на постоянную военную службу в январе 1916 года (восемнадцатый месяц Первой мировой войны ) и отменило его в 1920 году. Ирландия , тогда входившая в состав Соединенного Королевства, была освобождена от первоначальной военной службы 1916 года. законодательство, и хотя дальнейшее законодательство 1918 года давало право на распространение воинской повинности на Ирландию, это право так и не было введено в действие.

Призыв был вновь введен в 1939 году, в преддверии Второй мировой войны , и продолжал действовать до 1963 года . Северная Ирландия была освобождена от законодательства о воинской повинности на протяжении всего периода.

Всего во время обеих мировых войн было призвано восемь миллионов мужчин, а также несколько сотен тысяч молодых одиноких женщин. [ 265 ] Введение воинской повинности в мае 1939 года, до начала войны, отчасти произошло из-за давления со стороны французов, которые подчеркивали необходимость наличия крупной британской армии для противостояния немцам. [ 266 ] С начала 1942 года были призваны незамужние женщины в возрасте 20–30 лет (исключались незамужние женщины, имевшие на иждивении детей в возрасте 14 лет и младше, в том числе имевшие внебрачных детей или вдовы с детьми). Большинство призывавшихся женщин отправляли на заводы, но они могли добровольно работать во Вспомогательной территориальной службе (ВТС) и других женских службах. Некоторые женщины служили в Женской Сухопутной армии : первоначально добровольцами, но позже была введена воинская повинность. Однако женщинам, которые уже работали на квалифицированной работе, которую считали полезной для военных действий, например, телефонистками Главпочтамта , было приказано продолжать работать, как и раньше. Никто не был назначен на боевые роли, если только она не вызвалась добровольцем. К 1943 году женщины до 51 года были обязаны выполнять ту или иную работу по указанию. Во время Второй мировой войны 1,4 миллиона британских мужчин пошли добровольцами на службу и 3,2 миллиона были призваны на военную службу. Призывники составляли 50% Королевских ВВС , 60% Королевского флота и 80% британской армии . [ 267 ]

Об отмене воинской повинности в Великобритании было объявлено 4 апреля 1957 года новым премьер-министром Гарольдом Макмилланом , а последние призывники были набраны три года спустя. [ 268 ]

Соединенные Штаты

[ редактировать ]Призыв в США закончился в 1973 году, но мужчины в возрасте от 18 до 25 лет должны зарегистрироваться в системе выборочной службы , чтобы при необходимости можно было вновь ввести призыв на военную службу. Президент Джеральд Форд приостановил обязательную регистрацию призывников в 1975 году, но президент Джимми Картер восстановил это требование, когда пять лет спустя Советский Союз вторгся в Афганистан . Следовательно, регистрация в избирательной службе по-прежнему требуется почти от всех молодых людей. [ 269 ] С 1986 года уголовных дел за нарушение проекта закона о регистрации не было. [ 270 ] Мужчины в возрасте от 17 до 45 лет и женщины – члены Национальной гвардии США могут быть призваны на службу в федеральную милицию в соответствии с § 246 Кодекса США 10 и милиции о статьями Конституции США . [ 271 ]

В феврале 2019 года Окружной суд США Южного округа Техаса постановил, что регистрация на военную службу только для мужчин нарушает положение о равной защите Четырнадцатой поправки. В деле «Национальная коалиция мужчин против системы выборочной службы» , возбужденном некоммерческой организацией по защите прав мужчин « Национальная коалиция мужчин» против системы выборочной службы в США, судья Грей Х. Миллер вынес декларативное решение о том, что требование регистрации только для мужчин является недействительным. неконституционным, хотя и не уточнил, какие действия должно предпринять правительство. [ 272 ] Это решение было отменено Пятым округом. В июне 2021 года Верховный суд США отказался пересматривать решение Апелляционного суда.

Другие страны

[ редактировать ]- Призыв в Австралии

- Призыв в Египте

- Призыв во Франции

- Призыв в Гибралтаре

- Призыв в Малайзии

- Призыв в Мексике

- Призыв в Мьянме

- Призыв в Новой Зеландии

- Призыв в Северную Корею

- Призыв в России

- Призыв в Сингапуре

- Призыв в Южной Корее

- Призыв в Швейцарии

- Призыв в Турции

- Призыв в Украине

- Воинская повинность в Османской империи

- Воинская повинность в Российской Империи

- Призыв во Вьетнаме

- Призыв в Грузии

- Призыв в Мозамбике

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Гражданская воинская повинность

- Гражданская государственная служба

- рутинная работа

- Контрвербовка

- Уклонение от призыва

- Экономическая воинская повинность

- Тыл во время Первой мировой войны

- Тыл во время Второй мировой войны

- Список стран по количеству военного и военизированного персонала

- Мужской расходный материал

- Военный набор

- Народное восстание , массовая мобилизация в Польше

- Система квот

- Хронология участия женщин в войне

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ «Призыв» . Мерриам-Вебстер Онлайн . 13 сентября 2023 г.

- ^ «В поисках убежища: уклоняющиеся от призыва» . Цифровые архивы CBC .

- ^ «Вторая мировая война» . Канадская энциклопедия . Торонто: Историка Канады. 15 июля 2015 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Асаль, Виктор; Конрад, Джастин; Торонто, Натан (01 августа 2017 г.). «Я хочу тебя! Определяющие факторы призыва в армию». Журнал разрешения конфликтов . 61 (7): 1456–1481. дои : 10.1177/0022002715606217 . ISSN 0022-0027 . S2CID 9019768 .

- ^ Постгейт, Дж. Н. (1992). Общество и экономика Ранней Месопотамии на заре истории . Рутледж. п. 242 . ISBN 0-415-11032-7 .

- ^ Постгейт, Дж. Н. (1992). Общество и экономика Ранней Месопотамии на заре истории . Рутледж. п. 243 . ISBN 0-415-11032-7 .

- ^ «запрет на доставку» . Бесплатный словарь . Проверено 17 сентября 2012 г.

- ^ Николь, Д. (2000). Французские армии Столетней войны (т. 337). Издательство Оспри.

- ^ Николь, Д. (2004). Пуатье 1356: Пленение короля (Том 138). Издательство Оспри.

- ^ Карри, А. (2002). Основные истории – Столетняя война. Нова-Йорк, Оспри.

- ^ Уильямс, DGE (1 января 1997 г.). «Датировка норвежской системы лейдангр: филологический подход» . НОВЭЛЕ. Эволюция языков Северо-Западной Европы . 30 (1): 21–25. doi : 10.1075/nowele.30.02wil . ISSN 0108-8416 .

- ^ Аттенборо, Флорида (1922). Законы древнейших английских королей . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 9780404565459 .

- ^ Крепкий, Дэвид Альфред Великий констебль (1995), с. 153

- ^ Гей, Сюзанна (2001). Ростовщики позднесредневекового Киото . Издательство Гавайского университета. п. 111. ИСБН 9780824864880 .

- ^ Льюис, Бернард. «Раса и рабство на Ближнем Востоке» . Чтение глав для занятий в Фордхэмском университете. Архивировано из оригинала 1 апреля 2001 г. Проверено 24 марта 2008 г.

- ^ Инальчик, Халил (1979). «Рабльский труд в Османской империи» . В А. Ашер, Б. К. Кирали; Т. Халаси-Кун (ред.). Взаимные эффекты исламского и иудео-христианского миров: восточноевропейский образец . Бруклинский колледж. сек. На государственной и военной службе. Архивировано из оригинала 4 мая 2017 года.

- ^ «Янычарский корпус, или Янычары, или Еничери (турецкие военные)» . Британская онлайн-энциклопедия .

- ^ «Династия мамлюков (рабов) (хронология)» . Сунна онлайн . Архивировано из оригинала 16 июля 2011 г. Проверено 24 марта 2008 г.

- ^ Льюис (1994). «Раса и рабство на Ближнем Востоке» . Издательство Оксфордского университета. Архивировано из оригинала 1 апреля 2001 г. Проверено 24 марта 2008 г.

- ^ «Призыв» . Энкарта . Майкрософт. Архивировано из оригинала 28 октября 2009 г.

- ^ Дирк Уолтер. Реформы прусской армии 1807–1870 гг.: Военные инновации и миф о «рунской реформе» . 2003, в Ситино, с. 130

- ^ «Военная служба в Российской империи» . roots-saknes.lv. Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2016 г.

- ^ «Призыв и сопротивление: исторический контекст, заархивированный из оригинала» . 3 июня 2008 г. Архивировано из оригинала 3 июня 2008 г. Проверено 24 марта 2008 г.

- ^ Славин, Дэвид Генри (2001). Колониальное кино и имперская Франция, 1919–1939: белые слепые пятна, мужские фантазии, мифы поселенцев . Джу Пресс. п. 140. ИСБН 978-0-8018-6616-6 .

Призывники охраняли тыл, а европейских специалистов отправляли за границу

- ^ «Записи системы выборочной службы (Первая мировая война)» . 15 августа 2016 г .; см. также Закон о выборной службе 1917 года и Закон о выборной подготовке и службе 1940 года .

- ^ «Немецкий фольксштурм из разведывательного бюллетеня» . LoneSentry.com . Февраль 1945 года.

- ^ «CBC News InГлубокий: Международные вооруженные силы» . Новости ЦБК . Архивировано из оригинала 18 мая 2013 года.

- ^ Кривошеев, ГФ [Krivosheev, GF], Россия и СССР в войнах XX века: потери вооруженных сил. Статистическое исследование [ Russia and the USSR in the wars of the 20th century: losses of the Armed Forces. A Statistical Study ] (in Russian)

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: несколько имен: список авторов ( ссылка ) . - ^ Месснер, Майкл А. (20 марта 1997 г.). Политика мужественности: мужчины в движениях . Роуман и Литтлфилд. стр. 41–48. ISBN 978-0-8039-5577-6 .

- ^ Стивен Блейк Бойд; У. Мерл Лонгвуд; Марк Уильям Мюссе, ред. (1996). Искупление мужчин: религия и мужественность . Вестминстер Джон Нокс Пресс. п. 17. ISBN 978-0-664-25544-2 .

Однако, в отличие от профеминизма, подход к правам мужчин рассматривает конкретные правовые и культурные факторы, которые ставят мужчин в невыгодное положение. Движение состоит из множества формальных и неформальных групп, которые различаются своими подходами и проблемами; Защитники прав мужчин, например, выступают против призыва на военную службу по признаку пола и судебной практики, которая дискриминирует мужчин в делах об опеке над детьми.

- ^ Стивен, Линн (1981). «Сделать законопроект женской проблемой» . Женщины: Журнал освобождения . 8 (1) . Проверено 28 марта 2016 г.

- ^ Линдси, Карен (1982). «Женщины и призыв» . В Макалистере, Пэм (ред.). Переплетая паутину жизни: феминизм и ненасилие . Издатели Нового общества. ISBN 0865710163 .

- ^ Левертов, Дениз (1982). «Речь: на митинге против призыва, округ Колумбия, 22 марта 1980 г.» . Свечи в Вавилоне . Новые направления Пресса. ISBN 9780811208314 .

- ^ Берлацкий, Ной (29 мая 2013 г.). «Когда мужчины испытывают сексизм» . Атлантика . Архивировано из оригинала 5 января 2015 года . Проверено 26 апреля 2015 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бенатар, Дэвид (15 мая 2012 г.). Второй сексизм: дискриминация мужчин и мальчиков . Джон Уайли и сыновья . ISBN 978-0-470-67451-2 . Проверено 26 апреля 2015 г.

- ^ Пейджер, Тайлер (24 февраля 2019 г.). «Призыв в армию только мужчин является неконституционным, - постановил судья» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Проверено 13 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Пейджер, Тайлер (24 февраля 2019 г.). «Призыв в армию только мужчин является неконституционным, - постановил судья» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Проверено 5 августа 2020 г.

- ^ «Федеральный апелляционный суд: проект, предназначенный только для мужчин, является конституционным» . Новости АВС .

- ^ «Палата представителей принимает законопроект об обороне с комиссией по расследованию неудач в Афганистане, предписывает женщинам регистрироваться для призыва в армию» . Вашингтон Пост . ISSN 0190-8286 . Проверено 28 октября 2021 г.

- ^ Тернер, Триш (24 июля 2021 г.). «Новое законодательство потребует от женщин, как и от мужчин, подписаться на потенциальный военный призыв» . ABC7 Чикаго . Проверено 28 октября 2021 г.

- ^ Берманн, Саванна (8 декабря 2021 г.). «Законодатели отвергают меру, которая требовала бы от женщин регистрации на выборной службе» . США сегодня . Проверено 22 января 2022 г.

- ^ Михаловски, Хелен (май 1982 г.). «Пять феминистских принципов и проект». Новости Сопротивления (8): 2.

- ^ Нойдель, Мариан Энрикес (июль 1983 г.). «Феминизм и призыв». Новости Сопротивления (13): 7.

- ^ «Письма женщин призывного возраста о том, почему они не идут на призыв». Новости Сопротивления . № 2. 1 марта 1980 г. с. 6.

- ^ «Гестация: женщины и сопротивление призыву». Новости Сопротивления . № 11. Ноябрь 1982 г.

- ^ «Женщины и движение сопротивления». Новости Сопротивления . № 21. 8 июня 1986 г.

- ^ «Нет равенству в милитаризме! (Заявление феминистского коллектива TO MOV, подписанное Ассоциацией греческих отказников от военной службы по убеждениям)» . Противодействие милитаризации молодежи . Интернационал сопротивления войне . Проверено 28 марта 2016 г.

- ^ Гольдштейн, Джошуа С. (2003). «Война и гендер: роли мужчин в войне – детство и взросление» . В Эмбере, Кэрол Р.; Эмбер, Мелвин Энциклопедия пола и гендера: мужчины и женщины в мировых культурах . Том 1. Спрингер . п. 108. ISBN 978-0-306-47770-6 . Проверено 25 апреля 2015 г.

- ↑ Кронселл, Аника (29 июня 2006 г.). «Методы изучения молчания: «молчание» шведского призыва» . В Акерли, Брук А.; Стерн, Мария; Верно, Жаки «Феминистские методологии международных отношений» . Издательство Кембриджского университета . п. 113. ISBN 978-1-139-45873-3 . Проверено 25 апреля 2015 г.

- ^ Селмески, Брайан Р. (2007). Мультикультурные граждане, монокультурные мужчины: самобытность, мужественность и воинская повинность в Эквадоре . Сиракузский университет . п. 149. ИСБН 978-0-549-40315-9 . Проверено 25 апреля 2015 г.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: отсутствует местоположение издателя ( ссылка ) - ^ Йоэнниеми, Пертти (2006). Меняющееся лицо европейской воинской повинности . Издательство Эшгейт . стр. 142–49. ISBN 978-0-754-64410-1 . Проверено 25 апреля 2015 г.

- ^ «RS 661.1 Постановление от 30 августа 1995 года об обязанности по уплате освобожденного от уплаты налога (OTEO)» . www.admin.ch . Проверено 13 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Корте, Грегори. «Для миллиона американцев отказ от регистрации на призыв имеет серьезные, долгосрочные последствия» . США сегодня . Проверено 13 июня 2020 г.

- ^ «Выборочная служба | USAGov» . www.usa.gov . Проверено 13 июня 2020 г.

- ^ «Призыв и армия» . Либертарианская партия . www.dehnbase.org.

- ↑ Представитель США Рон Пол «Призыв на военную службу — это рабство» , antiwar.com, 14 января 2003 г.

- ^ "Черновик" . aynrandlexicon.com . Проверено 15 октября 2016 г.

- ^ Джон Уайтклей Чемберс II, Чтобы собрать армию: призыв приходит в современную Америку (1987), стр. 219–20

- ^ Хендерсон, Дэвид Р. « Роль экономистов в завершении проекта » (август 2005 г.).

- ^ Сиго, Лаура (2009). «Автоматическая регистрация в США: пример выборочной услуги» (PDF) . Центр юстиции Бреннана .

- ^ Фридман, Милтон (1967). «Почему не Добровольческая армия?» . Новый индивидуалистический обзор . Проверено 11 сентября 2008 г.

- ^ Руссо, Дж.Дж. Социальный контракт. Глава «Римские выборы»

- ^ Аристотель, Политика, Книга 6 , Глава VII и Книга 4, Глава XIII.

- ^ Харрис, Фил; Лок, Эндрю; Рис, Патрисия (2002). Макиавелли, Маркетинг и менеджмент . Рутледж. п. 10. ISBN 9781134605682 .

- ^ Долман, Эверетт Карл (1995). «Обязательства и гражданин-солдат: макиавеллистская добродетель против гоббсовского порядка». Журнал политической и военной социологии . 23 (2): 195. ISSN 0047-2697 . JSTOR 45294067 .

- ^ Джеймс, Уильям (1906). «Моральный эквивалент войны» . Архивировано из оригинала 26 мая 2020 г. Проверено 17 октября 2008 г.

- ^ Альтер, Джонатан. «Полицейский на уроке» . Newsweek .

- ^ «Интервью с Микки Каусом» . Realclearpolitics.com.

- ^ Пострел, Вирджиния (октябрь 1995 г.). «Преодоление заслуг» .

- ^ «Рангель: пришло время военного налога и восстановления призыва» . Время . Проверено 30 сентября 2021 г.

- ^ Хэгглунд, Густав (2006). Лев и голубь (на финском языке). Большая Медведица. ISBN 951-1-21161-7 .

- ^ Кард, Дэвид; Кардосо, Ана Руте (октябрь 2012 г.). «Может ли обязательная военная служба повысить заработную плату гражданским лицам? Свидетельства призыва в мирное время в Португалии» (PDF) . Американский экономический журнал: Прикладная экономика . 4 (4): 57–93. дои : 10.1257/app.4.4.57 . hdl : 10261/113437 . S2CID 55247633 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 10 октября 2022 г.

- ^ Шепард, Бен (2003). Война нервов: солдаты и психиатры в двадцатом веке . Издательство Гарвардского университета. п. 18 . ISBN 978-0-674-01119-9 .

- ^ Эмбер, Кэрол Р.; Эмбер, Мелвин (2003). Энциклопедия пола и гендера: мужчины и женщины в мировых культурах . Том. 2. Спрингер. стр. 108–109 . ISBN 978-0-306-47770-6 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Женщины в армии – интернационал» . CBC News Подробно: Международные вооруженные силы . 30 мая 2006 г. Архивировано из оригинала 13 сентября 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Экономические издержки и политическая привлекательность воинской повинности» (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 24 июня 2008 г. Проверено 7 июня 2008 г. (см. сноску 3)

- ^ «Эритрея» . Всемирная книга фактов (изд. 2024 г.). Центральное разведывательное управление . 8 ноября 2021 г. (Архивировано издание за 2021 г.)

- ^ «Израиль» . Всемирная книга фактов (изд. 2024 г.). Центральное разведывательное управление . 5 ноября 2021 г. (Архивировано за 2021 г.).

- ^ «Мозамбик» . Всемирная книга фактов (изд. 2024 г.). Центральное разведывательное управление . 5 ноября 2021 г. (Архивировано за 2021 г.).