Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh (/ˌʊtər prəˈdɛʃ/ UUT-ər prə-DESH,[13] Hindi: [ˈʊtːəɾ pɾəˈdeːʃ]; lit. 'North Province') is a state in northern India. With over 241 million inhabitants, it is the most populated state in India as well as the most populous country subdivision in the world – more populous than all but four other countries outside of India[14] – and accounting for 16.5 per cent of the population of India or around 3 per cent of the total world population. The state is bordered by Rajasthan to the west, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh and Delhi to the northwest, Uttarakhand and Nepal to the north, Bihar to the east, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand to the south. It is the fourth-largest Indian state by area covering 243,286 km2 (93,933 sq mi), equal to 7.3 per cent of the total area of India. Lucknow serves as the state capital, with Prayagraj being the judicial capital. It is divided into 18 divisions and 75 districts. On 9 November 2000, a new state, Uttaranchal (now Uttarakhand), was created from Uttar Pradesh's western Himalayan hill region. The two major rivers of the state, the Ganges and its tributary Yamuna, meet at the Triveni Sangam in Prayagraj, a Hindu pilgrimage site. Other notable rivers are Gomti and Saryu. The forest cover in the state is 6.1 per cent of the state's geographical area. The cultivable area is 82 per cent of the total geographical area, and the net area sown is 68.5 per cent of the cultivable area.[15]

Uttar Pradesh was established in 1950 after India had become a republic. It is a successor to the United Provinces, established in 1935 by renaming the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, in turn established in 1902 from the North-Western Provinces and the Oudh Province. Though long known for sugar production, the state's economy is now dominated by the services industry. The service sector comprises travel and tourism, hotel industry, real estate, insurance and financial consultancies. The economy of Uttar Pradesh is the third-largest state economy in India, with ₹18.63 lakh crore (US$220 billion) in gross domestic product and a per capita GSDP of ₹68,810 (US$820).[9] The High Court of the state is located in Prayagraj. The state contributes 80 seats to the lower house Lok Sabha and 31 seats and the upper house Rajya Sabha.

Inhabitants of the state are called Awadhi, Bagheli, Bhojpuriya, Braji, Bundeli, Kannauji or Rohilkhandi depending upon their region of origin. Hinduism is practised by more than three-fourths of the population, with Islam being the next-largest religious group. Hindi is the most widely spoken language and is also the official language of the state, along with Urdu. Uttar Pradesh was home to most of the mainstream political entities that existed in ancient and medieval India including the Maurya Empire, Harsha Empire, Gupta Empire, Pala Empire, Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire as well as many other empires. At the time of the Indian independence movement in the early 20th century, there were three major princely states in Uttar Pradesh – Ramgadi, Rampur and Benares. The state houses several holy Hindu temples and pilgrimage centres. Along with several historical, natural and religious tourist destinations, including Agra, Aligarh, Ayodhya, Bareilly, Gorakhpur, Kanpur, Kushinagar, Lucknow, Mathura, Meerut, Prayagraj, Varanasi, and Vrindavan, Uttar Pradesh is also home to three World Heritage sites.

History

Prehistory

Modern human hunter-gatherers have been in Uttar Pradesh[16][17][18] since between around[19] 85,000 and 72,000 years ago. There have also been prehistorical finds in the state from the Middle and Upper Paleolithic dated to 21,000–31,000 years old[20] and Mesolithic/Microlithic hunter-gatherer settlement, near Pratapgarh, from around 10550–9550 BCE. Villages with domesticated cattle, sheep, and goats and evidence of agriculture began as early as 6000 BCE, and gradually developed between c. 4000 and 1500 BCE beginning with the Indus Valley Civilisation and Harappa culture to the Vedic period and extending into the Iron Age.[21][22][23]

Ancient and classical period

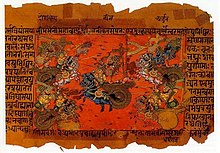

Out of the sixteen mahajanapadas (lit. 'great realms') or oligarchic republics that existed in ancient India, seven fell entirely within the present-day boundaries of the state.[24] The kingdom of Kosala, in the Mahajanapada era, was also located within the regional boundaries of modern-day Uttar Pradesh.[25] According to Hinduism, the divine King Rama of the Ramayana epic reigned in Ayodhya, the capital of Kosala.[26] Krishna, another divine king of Hindu legend, who plays a key role in the Mahabharata epic and is revered as the eighth reincarnation (Avatar) of the Hindu god Vishnu, is said to have been born in the city of Mathura.[25] The aftermath of the Kurukshetra War is believed to have taken place in the area between the Upper Doab and Delhi, (in what was Kuru Mahajanapada), during the reign of the Pandava King Yudhishthira. The kingdom of the Kurus corresponds to the Black and Red Ware and Painted Gray Ware culture and the beginning of the Iron Age in northwest India, around 1000 BCE.[25]

Control over Gangetic plains region was of vital importance to the power and stability of all of India's major empires, including the Maurya (320–200 BCE), Kushan (100–250 CE), Gupta (350–600), and Gurjara-Pratihara (650–1036) empires.[27] Following the Huns' invasions that broke the Gupta empire, the Ganges-Yamuna Doab saw the rise of Kannauj.[28] During the reign of Harshavardhana (590–647), the Kannauj empire reached its zenith.[28] It spanned from Punjab in the north and Gujarat in the west to Bengal in the east and Odisha in the south.[25] It included parts of central India, north of the Narmada River and it encompassed the entire Indo-Gangetic Plain.[29] Many communities in various parts of India claim descent from the migrants of Kannauj.[30] Soon after Harshavardhana's death, his empire disintegrated into many kingdoms, which were invaded and ruled by the Gurjara-Pratihara empire, which challenged Bengal's Pala Empire for control of the region.[29] Kannauj was several times invaded by the South Indian Rashtrakuta dynasty, from the 8th century to the 10th century.[31][32] After the fall of the Pala empire, the Chero dynasty ruled from the 12th century to the 18th century.[33]

Delhi Sultanate

Uttar Pradesh was partially or entirely ruled by the Delhi Sultanate for 320 years (1206–1526). Five dynasties ruled over the Delhi Sultanate sequentially: the Mamluk dynasty (1206–90), the Khalji dynasty (1290–1320), the Tughlaq dynasty (1320–1414), the Sayyid dynasty (1414–51), and the Lodi dynasty (1451–1526).[34][35]

The first Sultan of Delhi, Qutb ud-Din Aibak, conquered some parts of Uttar Pradesh, including Meerut, Aligarh, and Etawah. His successor, Iltutmish, expanded the Sultanate's rule over Uttar Pradesh by defeating the King of Kannauj. During the reign of Sultan Balban, the Mamluk dynasty faced numerous rebellions in the state, but he was able to suppress them and establish his authority. Alauddin Khilji, extended his conquests to various regions in the state, including Varanasi and Prayagraj. Apart from the rulers, the Delhi Sultanate era also saw the growth of Sufism in Uttar Pradesh. Sufi saints, such as Nizamuddin Auliya and Qutbuddin Bakhtiar Kaki, lived during this period and their teachings had a significant impact on the people of the region. Sultanat era in the state also witnessed the construction of mosques and tombs, including the Atala Masjid in Jaunpur, the Jama Masjid in Fatehpur Sikri, and the Ghiyath al-Din Tughluq's Tomb in Tughlaqabad.[36][37]

Medieval and early modern period

In the 16th century, Babur, a Timurid descendant of Timur and Genghis Khan from Fergana Valley (modern-day Uzbekistan), swept across the Khyber Pass and founded the Mughal Empire, covering India, along with modern-day Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh.[38] The Mughals were descended from Persianised Central Asian Turks (with significant Mongol admixture). In the Mughal era, Uttar Pradesh became the heartland of the empire.[30] Mughal emperors Babur and Humayun ruled from Delhi.[39][40] In 1540 an Afghan, Sher Shah Suri, took over the reins of Uttar Pradesh after defeating the Mughal King Humanyun.[41] Sher Shah and his son Islam Shah ruled Uttar Pradesh from their capital at Gwalior.[42] After the death of Islam Shah Suri, his prime minister Hemu became the de facto ruler of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and the western parts of Bengal. He was bestowed the title of Hemchandra Vikramaditya (title of Vikramāditya adopted from Vedic period) at his formal coronation took place at Purana Qila in Delhi on 7 October 1556. A month later, Hemu died in the Second Battle of Panipat, and Uttar Pradesh came under Emperor Akbar's rule.[43] Akbar ruled from Agra and Fatehpur Sikri.[44]

In the 18th century, after the fall of Mughal authority, the power vacuum was filled by the Maratha Empire, in the mid-18th century, the Maratha army invaded the Uttar Pradesh region, which resulted in Rohillas losing control of Rohilkhand to the Maratha forces led by Raghunath Rao and Malha Rao Holkar. The conflict between Rohillas and Marathas came to an end on 18 December 1788 with the arrest of Ghulam Qadir, the grandson of Najeeb-ud-Daula, who was defeated by the Maratha general Mahadaji Scindia. In 1803–04, following the Second Anglo-Maratha War, when the British East India Company defeated the Maratha Empire, much of the region came under British suzerainty.[45]

British India era

| Timeline of reorganisation and name changes of UP[46] | |

|---|---|

| 1807 | Ceded and Conquered Provinces |

| 14 November 1834 | Presidency of Agra |

| 1 January 1836 | North-Western Provinces |

| 3 April 1858 | Oudh taken under British control, Delhi taken away from NWP and merged into Punjab |

| 1 April 1871 | Ajmer, Merwara & Kekri made separate commissioner-ship |

| 15 February 1877 | Oudh added to North-Western Provinces |

| 22 March 1902 | Renamed United Provinces of Agra and Oudh |

| 3 January 1921 | Renamed United Provinces of British India |

| 1 April 1937 | Renamed United Provinces |

| 1 April 1946 | Self rule granted |

| 15 August 1947 | Part of independent India |

| 24 January 1950 | Renamed Uttar Pradesh |

| 9 November 2000 | Uttaranchal state, now known as Uttarakhand, created from part of Uttar Pradesh |

Starting from Bengal in the second half of the 18th century, a series of battles for north Indian lands finally gave the British East India Company accession over the state's territories.[47] Ajmer and Jaipur kingdoms were also included in this northern territory, which was named the "North-Western Provinces" (of Agra). Although UP later became the fifth-largest state of India, NWPA was one of the smallest states of the British Indian empire.[48] Its capital shifted twice between Agra and Allahabad.[49]

Due to dissatisfaction with British rule, a serious rebellion erupted in various parts of North India, which became known as the Indian Rebellion of 1857; Bengal regiment's sepoy stationed at Meerut cantonment, Mangal Pandey, is widely considered as its starting point.[50] After the revolt failed, the British divided the most rebellious regions by reorganising their administrative boundaries, splitting the Delhi region from 'NWFP of Agra' and merging it with Punjab Province, while the Ajmer–Marwar region was merged with Rajputana and Oudh was incorporated into the state. The new state was called the North Western Provinces of Agra and Oudh, which in 1902 was renamed as the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh.[51] It was commonly referred to as the United Provinces or its acronym UP.[52][53]

In 1920, the capital of the province was shifted from Allahabad to Lucknow.[54] The high court continued to be at Allahabad, but a bench was established at Lucknow.[55] Allahabad continues to be an important administrative base of today's Uttar Pradesh and has several administrative headquarters.[56] Uttar Pradesh continued to be central to Indian politics and was especially important in modern Indian history as a hotbed of the Indian independence movement. The state hosted modern educational institutions such as the Aligarh Muslim University, Banaras Hindu University and Darul Uloom Deoband. Nationally known figures such as Ram Prasad Bismil and Chandra Shekhar Azad were among the leaders of the movement in Uttar Pradesh, and Motilal Nehru, Jawaharlal Nehru, Madan Mohan Malaviya and Govind Ballabh Pant were important national leaders of the Indian National Congress. The All India Kisan Sabha was formed at the Lucknow session of the Congress on 11 April 1936, with the famous nationalist Sahajanand Saraswati elected as its first president,[57] to address the longstanding grievances of the peasantry and mobilise them against the zamindari landlords attacks on their occupancy rights, thus sparking the Farmers movements in India.[58] During the Quit India Movement of 1942, Ballia district overthrew the colonial authority and installed an independent administration under Chittu Pandey. Ballia became known as "Baghi Ballia" (Rebel Ballia) for this significant role in India's independence movement.[59]

Post-independence

After India's independence, the United Provinces were renamed "Uttar Pradesh" (lit. 'northern province'), preserving UP as the acronym,[60][61] with the change coming into effect on 24 January 1950.[1] The new state was formed after the merger of several princely states and territories, including the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, and the Delhi territory. The state has provided nine of India's prime ministers which is more than any other state and is the source of the largest number of seats in the Lok Sabha. Despite its political influence since ancient times, its poor record in economic development and administration, poor governance, organised crime and corruption have kept it among India's backward states. The state has been affected by repeated episodes of caste-related and communal violence.[62] In December 1992 the disputed Babri Mosque located in Ayodhya was demolished by Hindu activists, leading to widespread violence across India.[63] In 2000, northern districts of the state were separated to form the state of Uttarakhand.[64]

Geography

Uttar Pradesh, with a total area of 240,928 square kilometres (93,023 sq mi), is India's fourth-largest state in terms of land area and is roughly of same size as United Kingdom. It is situated on the northern spout of India and shares an international boundary with Nepal. The Himalayas border the state on the north,[65] but the plains that cover most of the state are distinctly different from those high mountains.[66] The larger Gangetic Plain region is in the north; it includes the Ganges-Yamuna Doab, the Ghaghra plains, the Ganges plains and the Terai.[67] The smaller Vindhya Range and plateau region are in the south.[68] It is characterised by hard rock strata and a varied topography of hills, plains, valleys and plateaus. The Bhabhar tract gives place to the terai area which is covered with tall elephant grass and thick forests interspersed with marshes and swamps.[69][70] The sluggish rivers of the bhabhar deepen in this area, their course running through a tangled mass of thick undergrowth. The terai runs parallel to the bhabhar in a thin strip. The entire alluvial plain is divided into three sub-regions.[71] The first in the eastern tract consisting of 14 districts which are subject to periodical floods and droughts and have been classified as scarcity areas. These districts have the highest density of population which gives the lowest per capita land. The other two regions, the central and the western, are comparatively better with a well-developed irrigation system.[72] They suffer from waterlogging and large-scale user tracts.[73] In addition, the area is fairly arid. The state has more than 32 large and small rivers; of them, the Ganga, Yamuna, Saraswati, Sarayu, Betwa, and Ghaghara are larger and of religious importance in Hinduism.[74]

Cultivation is intensive in the state.[75] Uttar Pradesh falls under three agro-climatic zones viz. Middle Gangetic Plains region (Zone–IV), Upper Gangetic Plains region (Zone–V) and Central Plateau and Hills region (Zone–VIII).[76] The valley areas have fertile and rich soil. There is intensive cultivation on terraced hill slopes, but irrigation facilities are deficient.[77] The Siwalik Range which forms the southern foothills of the Himalayas, slopes down into a boulder bed called 'bhabhar'.[78] The transitional belt running along the entire length of the state is called the terai and bhabhar area. It has rich forests, cutting across it are innumerable streams which swell into raging torrents during the monsoon.[79]

Climate

Uttar Pradesh has a humid subtropical climate and experiences four seasons.[80] The winter in January and February is followed by summer between March and May and the monsoon season between June and September.[81] Summers are extreme with temperatures fluctuating anywhere between 0–50 °C (32–122 °F) in parts of the state coupled with dry hot winds called the Loo.[82] The Gangetic plain varies from semiarid to sub-humid.[81] The mean annual rainfall ranges from 650 mm (26 inches) in the southwest corner of the state to 1,000 mm (39 inches) in the eastern and south eastern parts of the state.[83] Primarily a summer phenomenon, the Bay of Bengal branch of the Indian monsoon is the major bearer of rain in most parts of state. After summer it is the southwest monsoon which brings most of the rain here, while in winters rain due to the western disturbances and north-east monsoon also contribute small quantities towards the overall precipitation of the state.[80][84]

| Climate data for Uttar Pradesh | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 29.9 (85.8) |

31.9 (89.4) |

35.4 (95.7) |

37.7 (99.9) |

36.9 (98.4) |

31.7 (89.1) |

28.4 (83.1) |

27.4 (81.3) |

29.4 (84.9) |

31.4 (88.5) |

30.1 (86.2) |

28.9 (84.0) |

31.6 (88.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 11.0 (51.8) |

12.1 (53.8) |

15.8 (60.4) |

19.9 (67.8) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.9 (73.2) |

22.2 (72.0) |

21.6 (70.9) |

20.8 (69.4) |

18.5 (65.3) |

14.4 (57.9) |

11.5 (52.7) |

17.8 (64.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0 (0) |

3 (0.1) |

2 (0.1) |

11 (0.4) |

40 (1.6) |

138 (5.4) |

163 (6.4) |

129 (5.1) |

155 (6.1) |

68 (2.7) |

28 (1.1) |

4 (0.2) |

741 (29.2) |

| Average precipitation days | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 3.3 | 10.9 | 17.0 | 16.2 | 10.9 | 5.0 | 2.4 | 0.3 | 67.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 291.4 | 282.8 | 300.7 | 303.0 | 316.2 | 186.0 | 120.9 | 111.6 | 177.0 | 248.44 | 270.0 | 288.3 | 2,896.34 |

| Source: [85] | |||||||||||||

The rain in Uttar Pradesh can vary from an annual average of 170 cm (67 inches) in hilly areas to 84 cm (33 inches) in Western Uttar Pradesh.[80] Given the concentration of most of this rainfall in the four months of the monsoon, excess rain can lead to floods and shortage to droughts. As such, these two phenomena, floods and droughts, commonly recur in the state. The climate of the Vindhya Range and plateau is subtropical with a mean annual rainfall between 1,000 and 1,200 mm (39 and 47 inches), most of which comes during the monsoon.[81] Typical summer months are from March to June, with maximum temperatures ranging from 30–38 °C (86–100 °F). There is a low relative humidity of around 20% and dust-laden winds blow throughout the season. In summer, hot winds called loo blow all across Uttar Pradesh.[80]

Flora and fauna

| State animal | Swamp deer (Rucervus duvaucelii) | |

| State bird | Sarus crane (Antigone antigone) |

|

| State tree | Ashoka (Saraca asoca) | |

| State flower | Palash (Butea monosperma) | |

| State dance | Kathak |

|

| State sport | Field hockey |

Uttar Pradesh has an abundance of natural resources.[88] In 2011, the recorded forest area in the state was 16,583 km2 (6,403 sq mi) which is about 6.9% of the state's geographical area.[89] In spite of rapid deforestation and poaching of wildlife, a diverse flora and fauna continue to exist in the state. Uttar Pradesh is a habitat for 4.2% of all species of Algae recorded in India, 6.4% of Fungi, 6.0% of Lichens, 2.9% of Bryophytes, 3.3% of Pteridophytes, 8.7% of Gymnosperms, 8.1% of Angiosperms.[90] Several species of trees, large and small mammals, reptiles, and insects are found in the belt of temperate upper mountainous forests. Medicinal plants are found in the wild[91] and are also grown in plantations. The Terai–Duar savanna and grasslands support cattle. Moist deciduous trees grow in the upper Gangetic plain, especially along its riverbanks. This plain supports a wide variety of plants and animals. The Ganges and its tributaries are the habitat of large and small reptiles, amphibians, fresh-water fish, and crabs. Scrubland trees such as the Babool (Vachellia nilotica) and animals such as the Chinkara (Gazella bennettii) are found in the arid Vindhyas.[92][93] Tropical dry deciduous forests are found in all parts of the plains. Since much sunlight reaches the ground, shrubs and grasses are also abundant.[94] Large tracts of these forests have been cleared for cultivation. Tropical thorny forests, consisting of widely scattered thorny trees, mainly babool are mostly found in the southwestern parts of the state.[95]

Uttar Pradesh is known for its extensive avifauna.[96] The most common birds which are found in the state are doves, peafowl, junglefowl, black partridges, house sparrows, songbirds, blue jays, parakeets, quails, bulbuls, comb ducks, kingfishers, woodpeckers, snipes, and parrots. Bird sanctuaries in the state include Bakhira Sanctuary, National Chambal Sanctuary, Chandra Prabha Wildlife Sanctuary, Hastinapur Wildlife Sanctuary, Kaimoor Wildlife Sanctuary, and Okhla Sanctuary.[97][98][99][100][101][102]

Other animals in the state include reptiles such as lizards, cobras, kraits, and gharials. Among the wide variety of fishes, the most common ones are mahaseer and trout. Some animal species have gone extinct in recent years, while others, like the lion from the Gangetic Plain, the rhinoceros from the Terai region, Ganges river dolphin primarily found in the Ganges have become endangered.[103] Many species are vulnerable to poaching despite regulation by the government.[104]

-

Anandabodhi tree (Ficus religiosa) in Jetavana Monastery, Sravasti

-

A hybrid nasturtium (Tropaeolum majus) showing nectar spur, found mainly in Hardoi district

-

An endangered Ganges river dolphin (Platanista gangetica) lives in the Ganges river

-

View of the Terai region

-

The threatened Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) is a large fish-eating crocodilian found in the Ganges River

Divisions, districts and cities

Uttar Pradesh is divided into 75 districts under these 18 divisions:[105]

The following is a list of top districts from state of Uttar Pradesh by population, ranked in respect of all India.[106]

| Rank (in India) | District | Population | Growth Rate (%) | Sex Ratio (Females per 1000 Males) | Literacy Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | Prayagraj | 5,954,391 | 20.63 | 901 | 72.32 |

| 26 | Moradabad | 4,772,006 | 25.22 | 906 | 56.77 |

| 27 | Ghaziabad | 4,681,645 | 42.27 | 881 | 78.07 |

| 30 | Azamgarh | 4,613,913 | 17.11 | 1019 | 70.93 |

| 31 | Lucknow | 4,589,838 | 25.82 | 917 | 77.29 |

| 32 | Kanpur Nagar | 4,581,268 | 9.92 | 862 | 79.65 |

| 41 | Agra | 4,418,797 | 22.05 | 868 | 71.58 |

| 50 | Bareilly | 4,448,359 | 22.93% | 887 | 58.5 |

Each district is governed by a District Magistrate, who is an Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer appointed Government of Uttar Pradesh and reports to Divisional Commissioner of the division in which his district falls.[107] The Divisional Commissioner is an IAS officer of high seniority. Each district is divided into subdivisions, governed by a Sub-Divisional Magistrate, and again into Blocks. Blocks consists of panchayats (village councils) and town municipalities.[108] These blocks consists of urban units viz. census towns and rural units called gram panchayat.[107]

Uttar Pradesh has more metropolitan cities than any other state in India.[109][110] The absolute urban population of the state is 44.4 million, which constitutes 11.8% of the total urban population of India, the second-highest of any state.[111] According to the 2011 census, there are 15 urban agglomerations with a population greater than 500,000.[112] Uttar Pradesh has a complex system of municipalities. Nagar Nigam (Municipal Corporation) are urban local bodies in large cities such as Lucknow, Kanpur, Varanasi and cities having population more than 4 million.[113] These governed by a mayor and councilors elected from wards. Nagar Palika Parishad or Municipal Council, serves medium-sized towns like Bela Pratapgarh, Jalaun, or Bisalpur and are governed by a chairperson and councilors.[114] Nagar Panchayat which operate in smaller towns and semi-urban areas like Badlapur, Jaunpur, Bikapur, or Chilkana Sultanpur, are governed by a chairman and councilors.[114] There are 14 Municipal Corporations,[115][116] while Noida and Greater Noida in Gautam Budha Nagar district are specially administered by statutory authorities under the Uttar Pradesh Industrial Development Act, 1976.[117][118]

In 2011, state's cabinet ministers headed by the then Chief Minister Mayawati announced the separation of Uttar Pradesh into four different states of Purvanchal, Bundelkhand, Avadh Pradesh and Paschim Pradesh with twenty-eight, seven, twenty-three and seventeen districts, respectively, later the proposal was turned down when the Akhilesh Yadav–lead Samajwadi Party came to power in the 2012 election.[119]

Demographics

Uttar Pradesh has a very large population and a high population growth rate. From 1991 to 2001 its population increased by over 26 per cent.[122] It is the most populous state in India, with 199,581,477 people on 1 March 2011.[123] The state contributes to 16.2 per cent of India's population. As of 2021, the estimated population of the state is around 240 million people.[124] The population density is 828 people per square kilometre, making it one of the most densely populated states in the country.[125] It has the largest scheduled caste population whereas scheduled tribes are less than 1 per cent of the total population.[126][127]

The sex ratio in 2011, at 912 women to 1000 men, was lower than the national figure of 943.[11] The low sex ratio in Uttar Pradesh, is a result of various factors, such as sex-selective abortion, female infanticide, and discrimination against girls and women.[128][129] The state's 2001–2011 decennial growth rate (including Uttrakhand) was 20.1 per cent, higher than the national rate of 17.64 per cent.[130][131] It has a large number of people living below the poverty line.[132] As per a World Bank document released in 2016, the pace of poverty reduction in the state has been slower than the rest of the country.[133] Estimates released by the Reserve Bank of India for the year 2011–12 revealed that the state had 59 million (59819,000) people below the poverty line, the most for any state in India.[132][134] The central and eastern districts in particular have very high levels of poverty. The state is also experiencing widening consumption inequality. As per the report of the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation released in 2020, the state per capita income is below ₹80,000 (US$960) per annum.[135]

As per 2011 census, Uttar Pradesh, the most populous state in India, is home to the highest numbers of both Hindus and Muslims.[136] The literacy rate of the state at the 2011 census was 67.7 per cent, which was below the national average of 74 per cent.[137][138] The literacy rate for men is 79 per cent and for women 59 per cent. In 2001 the literacy rate in the state stood at 56 per cent overall, 67 per cent for men and 43 per cent for women.[139] A report based on a National Statistical Office (NSO) survey[a] revealed that Uttar Pradesh's literacy rate is 73 per cent, less than the national average of 77.7 per cent. According to the report, in the rural region, the literacy rate among men is 80.5 per cent and women is 60.4 per cent, while in urban areas, the literacy rate among men is 86.8 per cent and women is 74.9 per cent.[140]

Hindi is the primary official language and is spoken by the majority of the population.[8] Bhojpuri is the second most spoken language of the state,[141] it is spoken by almost 11 per cent of the population. Most people speak regional languages classified as dialects of Hindi in the census. These include Awadhi spoken in Awadh in central Uttar Pradesh, Bhojpuri spoken in Purvanchal in eastern Uttar Pradesh, and Braj Bhasha spoken in the Braj region in Western Uttar Pradesh. These languages have also been recognised by the state government for official use in their respective regions. Urdu is given the status of a second official language, spoken by 5.4 per cent of the population.[8][142] English is used as a means of communication for education, commerce, and governance. It is commonly spoken and employed as a language of instruction in educational institutions, as well as for conducting business transactions and managing administrative affairs. Other notable languages spoken in the state include Punjabi (0.3 per cent) and Bengali (0.1 per cent).[142]

Governance and administration

The state is governed by a parliamentary system of representative democracy. Uttar Pradesh is one of the seven states in India, where the state legislature is bicameral, comprising two houses: the Vidhan Sabha (Legislative Assembly) and the Vidhan Parishad (Legislative Council).[143][144] The Legislative Assembly consists of 404 members who are elected for five-year terms. The Legislative Council is a permanent body of 100 members with one-third (33 members) retiring every two years. The state sends the largest number of legislators to the national Parliament.[145] The state contributes 80 seats to Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian Parliament, and 31 seats to Rajya Sabha, the upper house.[146][147]

The Government of Uttar Pradesh is a democratically elected body in India with the governor as its constitutional head and is appointed by the president of India for a five-year term.[148] The leader of the party or coalition with a majority in the Legislative Assembly is appointed as the chief minister by the governor, and the council of ministers is appointed by the governor on the advice of the chief minister. The governor remains a ceremonial head of the state, while the chief minister and his council are responsible for day-to-day government functions. The Council of Ministers consists of Cabinet Ministers and Ministers of State (MoS). The Secretariat headed by the Chief Secretary assists the council of ministers. The Chief Secretary is also the administrative head of the government. Each government department is headed by a minister, who is assisted by an Additional Chief Secretary or a Principal Secretary, who is usually an officer of Indian Administrative Service (IAS), the Additional Chief Secretary/Principal Secretary serves as the administrative head of the department they are assigned to. Each department also has officers of the rank of Secretary, Special Secretary, Joint Secretary etc. assisting the Minister and the Additional Chief Secretary/Principal Secretary.[149][150]

For administration, the state is divided into 18 divisions and 75 districts. Divisional Commissioner, an IAS officer is the head of administration on the divisional level.[149][151][152] The administration in each district is headed by a District Magistrate, who is also an IAS officer, and is assisted by several officers belonging to state services.[149][153] District Magistrate being the head of the district administration, is responsible for maintaining law and order and providing public services in the district. At the block level, the Block Development Officer (BDO) is responsible for the overall development of the block. The Uttar Pradesh Police is headed by an IPS officer of the rank of Director general of police. A Superintendent of Police, an IPS officer assisted by the officers of the Uttar Pradesh Police Service, is entrusted with the responsibility of maintaining law and order and related issues in each district. The Divisional Forest Officer, an officer belonging to the Indian Forest Service manages the forests, environment, and wildlife of the district, assisted by the officers of Provincial Forest Service and Uttar Pradesh Forest Subordinate Service.[154]

The judiciary in the state consists of the Allahabad High Court in Prayagraj, the Lucknow Bench of Allahabad High Court, district courts and session courts in each district or Sessions Division, and lower courts at the tehsil level.[149][155] The president of India appoints the chief justice of the High Court of the Uttar Pradesh judiciary on the advice of the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of India as well as the governor of Uttar Pradesh.[149][156] Subordinate Judicial Service, categorised into two divisions viz. Uttar Pradesh civil judicial services and Uttar Pradesh higher judicial service are another vital part of the judiciary of Uttar Pradesh.[149][157] While the Uttar Pradesh civil judicial services comprise the Civil Judges (Junior Division)/Judicial Magistrates and civil judges (Senior Division)/Chief Judicial Magistrate, the Uttar Pradesh higher judicial service comprises civil and sessions judges.[149] The Subordinate judicial service (viz. The district court of Etawah and the district court of Kanpur Dehat) of the judiciary at Uttar Pradesh is controlled by the District Judge.[149][157][158]

Politics in Uttar Pradesh has been dominated by four political parties – the Samajwadi Party, the Bahujan Samaj Party, the Bharatiya Janata Party, and the Indian National Congress. Uttar Pradesh has provided India with eight Prime Ministers.[159]

Crime and accidents

According to the National Human Rights Commission of India (NHRC), Uttar Pradesh tops the list of states of encounter killings and custodial deaths.[160] In 2014, the state recorded 365 judicial deaths out of a total 1,530 deaths recorded in the country.[161] NHRC further said, of the over 30,000 murders registered in the country in 2016, Uttar Pradesh had 4,889 cases.[162] A data from Minister of Home Affairs (MHA) avers, Bareilly recorded the highest number of custodial death at 25, followed by Agra (21), Allahabad (19) and Varanasi (9). National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data from 2011 says, the state has the highest number of crimes among any state in India, but due to its high population, the actual per capita crime rate is low.[163] The state also continues to top the list of states with maximum communal violence incidents. An analysis of Ministers of State of Home Affairs states (2014), 23% of all incidents of communal violence in India took place in the state.[164][165] According to a research assembled by State Bank of India, Uttar Pradesh failed to improve its Human Development Index (HDI) ranking over a period of 27 years (1990–2017).[166] Based on sub-national human development index data for Indian states from 1990 to 2017, the report also stated that the value of human development index has steadily increased over time from 0.39 in 1990 to 0.59 in 2017.[167][168][169] The Uttar Pradesh Police, governed by the Department of Home and Confidential, is the largest police force in the world.[170][171][172]

Uttar Pradesh also reported the highest number of deaths – 23,219 – due to road and rail accidents in 2015, according to NCRB data.[173][174] This included 8,109 deaths due to careless driving.[175] Between 2006 and 2010, the state has been hit with three terrorist attacks, including explosions in a landmark holy place, a court and a temple. The 2006 Varanasi bombings were a series of bombings that occurred across the Hindu holy city of Varanasi on 7 March 2006. At least 28 people were killed and as many as 101 others were injured.[176][177]

In the afternoon of 23 November 2007, within a span of 25 minutes, six consecutive serial blasts occurred in the Lucknow, Varanasi, and Faizabad courts, in which 28 people were killed.[178][179][180] Another blast occurred on 7 December 2010, the blast occurred at Sheetla Ghat in Varanasi in which more than 38 people were killed.[181][182] In February 2016, a series of bomb blasts occurred at the Jhakarkati Bus Station in Kanpur, killing 2 people and injuring more than 30.[183]

Economy

| Net State Domestic Product at Factor Cost at Current Prices (2011–12 Base)

figures in crores of Indian rupees | |

| Year | Net State Domestic Product[184] |

|---|---|

| 2011–12 | 532,218 |

| 2015–16 | 1,137,808 |

| 2016–17 | 1,288,700 |

| 2017–18 | 1,446,000[185] (est.) |

In terms of net state domestic product (NSDP), Uttar Pradesh is the fourth-largest economy in India, with an estimated gross state domestic product of ₹14.89 lakh crore (US$180 billion),[185] contributing 8.4% of India's gross domestic product.[186] According to the report generated by India Brand Equity Foundation (IBEF), in 2014–15, Uttar Pradesh has accounted for 19% share in the country's total food grain output.[187] About 70% of India's sugar comes from Uttar Pradesh. Sugarcane is the most important cash crop as the state is country's largest producer of sugar.[187] As per the report generated by Indian Sugar Mills Association (ISMA), total sugarcane production in India was estimated to be 28.3 million tonnes in the fiscal ending September 2015 which includes 10.47 million tonnes from Maharashtra and 7.35 million tonnes from Uttar Pradesh.[188]

With 359 manufacturing clusters, cement is the top sector of SMEs in Uttar Pradesh.[189] The Uttar Pradesh Financial Corporation (UPFC) was established in 1954 under the SFCs Act of 1951 mainly to develop small- and medium-scale industries in the state.[190] The UPFC also provides working capital to existing units with a soundtrack record and to new units under a single window scheme.[191] In July 2012, due to financial constraints and directions from the state government, lending activities were suspended except for State Government Schemes.[192] The state has reported total private investment worth over Rs. 25,081 crores during the years of 2012 and 2016.[193] According to a recent report of the World Bank on Ease of Doing Business in India, Uttar Pradesh was ranked among the top 10 states and first among Northern states.[194]

According to the Uttar Pradesh Budget Documents (2019–20), Uttar Pradesh's debt burden is 29.8 per cent of the GSDP.[195] The state's total financial debt stood at ₹2.09 lakh crore (US$25 billion) in 2011.[196] Uttar Pradesh has not been able to witness double-digit economic growth despite consistent attempts over the years.[195] The GSDP is estimated to have grown 7 per cent in 2017–18 and 6.5 per cent in 2018–19 which is about 10 per cent of India's GDP. According to a survey conducted by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), Uttar Pradesh's unemployment rate increased 11.4 percentage points, rising to 21.5 per cent in April 2020.[197] Uttar Pradesh has the largest number of net migrants migrating out of the state.[198] The 2011 census data on migration shows that nearly 14.4 million (14.7%) people had migrated out of Uttar Pradesh.[199] Marriage was cited as the predominant reason for migration among females. Among males, the most important reason for migration was work and employment.[200] Uttar Pradesh continues to have regional disparities, particularly with the western districts of the state showing higher development indicators such as per capita district development product (PCDDP) and gross district development product (GDDP) compared to other regions.[201] Due to inadequate infrastructure and a dense population, Eastern Uttar Pradesh (Purvanchal) faces notable socio-economic disparities.[202] For 2021-22 the GDDP for Purvanchal it is ₹5.37 lakh crore, while for Western Uttar Pradesh it is ₹9.44 lakh crore. For the Bundelkhand and Central Uttar Pradesh regions, the GDDP remained ₹99,029.34 crore and ₹3.36 lakh crore, respectively. As of 2021-22, the per capita annual income in eastern districts is about one-fourth of the national average at Rs 12,741 while the state's average stood at Rs 17,349.[203]

In 2009–10, the tertiary sector of the economy (service industries) was the largest contributor to the gross domestic product of the state, contributing 44.8 per cent of the state domestic product compared to 44 per cent from the primary sector (agriculture, forestry, and tourism) and 11.2 per cent from the secondary sector (industrial and manufacturing).[205][206] Noida, Meerut, and Agra rank as the top 3 districts with the highest per capita income, whereas Lucknow and Kanpur rank 7th and 9th in per capita income.[207] During the 11th five-year plan (2007–2012), the average gross state domestic product (GSDP) growth rate was 7.3 per cent, lower than 15.5 per cent, the average for all states of the country.[208][209] The state's per capita GSDP was ₹29,417 (US$350), lower than the national per capita GSDP of ₹60,972 (US$730).[210] Labor efficiency is higher at an index of 26 than the national average of 25. Textiles and sugar refining, both long-standing industries in Uttar Pradesh, employ a significant proportion of the state's total factory labour. The economy also benefits from the state's tourism industry.[211]

Transportation

The state has the largest railway network in the country but in relative terms has only sixth-highest railway density despite its plain topography and largest population. As of 2015[update], there were 9,077 km (5,640 mi) of rail in the state.[212][213] The railway network in the state is controlled by two divisions of the Indian Railways viz. North Central Railway and North Eastern Railway. Allahabad is the headquarters of the North Central Railway[214] and Gorakhpur is the headquarters of the North Eastern Railway.[215][216] Lucknow and Moradabad serve as divisional Headquarters of the Northern Railway Division. Lucknow Swarna Shatabdi Express, the second fastest Shatabdi Express train, connects the Indian capital of New Delhi to Lucknow while Kanpur Shatabdi Express, connects New Delhi to Kanpur Central. This was the first train in India to get the new German LHB coaches.[217] The railway stations of Prayagraj Junction, Agra Cantonment, Lucknow Charbagh, Gorakhpur Junction, Kanpur Central, Mathura Junction and Varanasi Junction are included in the Indian Railways list of 50 world-class railway stations.[218] The Lucknow Metro, along with the Kanpur Metro (Orange line), are rapid transit systems that serve Lucknow and Kanpur, respectively.

The state has a large, multimodal transportation system with the largest road network in the country.[219] It has 42 national highways, with a total length of 4,942 km (3,071 miles) comprising 8.9 per cent of the total national highways length in India.[220] The Uttar Pradesh State Road Transport Corporation was established in 1972 to provide transportation in the state with connecting services to adjoining states.[221] All cities are connected to state highways, and all district headquarters are being connected with four lane roads which carry traffic between major centres within the state. One of them is Agra–Lucknow Expressway, which is a 302 km (188 miles) controlled-access highway constructed by UPEIDA.[222] Uttar Pradesh has the highest road density in India – 1,027 km (638 miles) per 1,000 km2 (390 square miles) – and the largest surfaced urban-road network in the country – 50,721 km (31,517 miles).[223]

By passenger traffic in India, Chaudhary Charan Singh International Airport in Lucknow and Lal Bahadur Shastri Airport in Varanasi, are the major international airports and the main gateway to the state.[224] Another international airport has been built at Kushinagar. However, since its inauguration, Kushinagar International Airport has not yet seen any outbound flights to international destinations.[225][226] Uttar Pradesh has six domestic airports located at Agra, Allahabad, Bareilly, Ghaziabad, Gorakhpur and Kanpur.[227][228] The state has also proposed creating the Noida International Airport near Jewar in Gautam Buddha Nagar district.[229][230] [231]

Sports

Traditional sports, now played mostly as a pastime, include wrestling, swimming, kabaddi, and track-sports or water-sports played according to local traditional rules and without modern equipment. Some sports are designed to display martial skills such as using a sword or 'Pata' (stick).[232] Due to a lack of organised patronage and requisite facilities, these sports survive mostly as individuals' hobbies or local competitive events. Among modern sports, field hockey is popular and Uttar Pradesh has produced top-level players in India, such as Nitin Kumar. and Lalit Kumar Upadhyay.[233]

Recently, cricket has become more popular than field hockey.[234] Uttar Pradesh won its first Ranji Trophy tournament in February 2006, beating Bengal in the final.[235] Shaheed Vijay Singh Pathik Sports Complex is a newly built international cricket stadium with a capacity of around 20,000 spectators.[236] Wrestling has deep roots in Uttar Pradesh, with many akharas (traditional wrestling schools) spread across the state.[237]

The Uttar Pradesh football team (UPFS) serves as the governing body for football in Uttar Pradesh. It holds authority over the Uttar Pradesh football team and is officially affiliated with the All India Football Federation.[238] The UPFS participates in sending state teams to compete in all National Football Championships organised by the All India Football Federation.[239] Additionally, the UPFS oversees two Mandal Football Associations: the Aligarh Football Association and the Kanpur Football Association.[240] The Uttar Pradesh Badminton Association is a sports body affiliated to Badminton Association of India responsible for overseeing players representing Uttar Pradesh at the national level.[241]

The Buddh International Circuit hosted India's inaugural F1 Grand Prix race on 30 October 2011.[242] Races were only held three times before being cancelled due to falling attendance and lack of government support. The government of Uttar Pradesh considered Formula One to be entertainment and not a sport, and thus imposed taxes on the event and participants.[243]

Education

Uttar Pradesh has a prolonged tradition of education, although historically it was primarily confined to the elite class and religious schools.[244] Sanskrit-based learning formed the major part of education from the Vedic to the Gupta periods. As cultures travelled through the region they brought their bodies of knowledge with them, adding Pali, Persian and Arabic scholarship to the community. These formed the core of Hindu-Buddhist-Muslim education until the rise of British colonialism. The present schools-to-university system of education owes its inception and development in the state (as in the rest of the country) to foreign Christian missionaries and the British colonial administration.[245] Schools in the state are either managed by the government or by private trusts. Hindi is used as a medium of instruction in most of the schools except those affiliated to the CBSE or the council for ICSE boards.[246] Under the 10+2+3 plan, after completing secondary school, students typically enroll for two years in a junior college, also known as pre-university, or in schools with a higher secondary facility affiliated with the Uttar Pradesh Board of High School and Intermediate Education (commonly referred to as U.P. Board) or a central board. Students choose from one of three streams, namely liberal arts, commerce, or science. Upon completing the required coursework, students may enrol in general or professional degree programs. In a study done by Child Rights and You (CRY) and the Centre for Budgets, Governance, and Accountability (CBGA), Uttar Pradesh spent ₹9,167 per pupil, which is below the national average of ₹12,768.[247] The pupil/teacher ratio is 39:1[b], lower than the national average of 23:1.[248] According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the state reported the second-highest teacher absenteeism (31 percent) in rural public schools among 19 surveyed states.[249] According to an answer given by the Union Education Minister in 2020 in the Lok Sabha, about 17.1 percent of all elementary teacher posts in government schools in Uttar Pradesh are vacant. In terms of absolute numbers, the figure stands at 210,000.[250] In February 2024, the Uttar Pradesh government informed legislative assembly that, 85,152 posts of headmasters and assistant teachers are vacant in the state.[251]

Uttar Pradesh has more than 45 universities,[252] including six central universities, twenty eight state universities, eight deemed universities, two IITs in Varanasi and Kanpur, AIIMS Gorakhpur and AIIMS Rae Bareli, an IIM in Lucknow[253][254] Founded in 1845, La Martinière Girls' College in Lucknow, stands as one of the oldest schools in India.[255] Located in Amethi, Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Petroleum Technology (RGIPT), provides education and training in STEM fields, particularly emphasizing the petroleum industry. With deemed university status, the RGIPT awards degrees in its own right. King George's Medical University (KGMU), located in Lucknow, is an institution for medical education, research, and healthcare services. The Integral University, a state level institution, was established by the Uttar Pradesh Government to provide education in different technical, applied science, and other disciplines.[256] The Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies was founded as an autonomous organisation by the national ministry of culture. Jagadguru Rambhadracharya Handicapped University is the only university established exclusively for the disabled in the world.[257]

As of 2023, the state has 573 public libraries.[258][259] Established in 1875, Maulana Azad Library is one of the oldest and is the largest university library in Asia. Rampur Raza Library is a repository of Indo-Islamic cultural heritage established in the last decades of the 18th century.[259] It was established in 1774 by nawab Faizullah Khan and now an autonomous body under the Ministry of Culture.[260] Thornhill Mayne Memorial also known as Allahabad Public Library, has an approximate collection of 125,000 books, 40 types of magazines, and 28 different newspapers in Hindi, English, Urdu and Bangla and it also contains 21 Arabic manuscripts.[261] A large number of Indian scholars are educated at different universities in Uttar Pradesh. Notable scholars who were born, worked or studied in the geographic area of the state include Harivansh Rai Bachchan, Motilal Nehru, Harish Chandra and Indira Gandhi.[262]

Tourism

Uttar Pradesh ranks first in domestic tourist arrivals among all states of India.[263][264] Some 44,000 foreign tourists arrived in the state in 2021, and almost 110 million domestic tourists.[265] The Taj Mahal attracts some 7 million people a year, earning almost ₹78 crore (US$9.3 million) in ticket sales in 2018–19.[266] The state is home to three World Heritage Sites: the Taj Mahal,[267] Agra Fort,[268] and the nearby Fatehpur Sikri.[269]

Religious tourism plays a significant role in the state's economy. Varanasi is a major religious hub and one of the seven sacred cities (Sapta Puri) in Hinduism and Jainism.[270][271][272] Vrindavan is considered to be a holy place for Vaishnavism.[273][274] Sravasti generally considered as revered sites in Buddhism, believed to be where the Buddha taught many of his Suttas (sermons).[275] Owing to the belief as to the birthplace of Rama, Ayodhya (Awadh) has been regarded as one of the seven most important pilgrimage sites.[276][277][278] Millions gather at Prayagraj to take part in the Magh Mela festival on the banks of the Ganges.[279] This festival is organised on a larger scale every 12th year and is called the Kumbh Mela, where over 10 million Hindu pilgrims congregate in one of the largest gatherings of people in the world.[280]

Buddhist attractions in Uttar Pradesh include stupas and monasteries. The historically important towns of Sarnath where Gautama Buddha gave his first sermon after his enlightenment and died at Kushinagar; both of which are important pilgrimage sites for Buddhists.[281] Also at Sarnath are the Pillars of Ashoka and the Lion Capital of Ashoka, both important archaeological artefacts with national significance. At a distance of 80 km (50 miles) from Varanasi, Ghazipur is famous not only for its Ghats on the Ganges but also for the tomb of Lord Cornwallis, the 18th-century Governor of East India Company ruled Bengal Presidency. The tomb is maintained by the Archaeological Survey of India.[282] Jhansi Fort, located in the city of Jhansi, is closely associated with the "First War of Indian Independence", also known as the "Great Rebellion" or the Indian Rebellion of 1857.[283] The fort is constructed in accordance with medieval Indian military architecture, featuring thick walls, bastions, and various structures within its complex. The architecture reflects a blend of Hindu and Islamic styles.[284]

Healthcare

Uttar Pradesh has a mix of public as well as private healthcare infrastructure. Public healthcare in Uttar Pradesh is provided through a grid of primary health centers, community health centers, district hospitals, and medical colleges. Although an extensive network of public and private sector healthcare providers has been built, the available health infrastructure is inadequate to meet the demand for health services in the state.[285] In 15 years to 2012–13, the population increased by more than 25 per cent. The public health centres, which are the frontline of the government's health care system, decreased by 8 per cent.[286] Smaller sub-centres, the first point of public contact, increased by no more than 2 per cent over the 25 years to 2015, a period when the population grew by more than 51 per cent.[286] The state is also facing challenges such as a shortage of healthcare professionals, increasing cost of healthcare, a lack of essential medicines and equipment, the mushrooming of private healthcare and a lack of planning.[287] The number of doctors registered with State Medical Councils or the Medical Council of India in Uttar Pradesh was 77,549.[288] As of 2019[update], the number of government hospital in rural and urban areas of Uttar Pradesh stood at 4,442 with 39,104 beds and 193 with 37,156 beds respectively. The average population served per government hospital stands at 47,782 individuals.[289] As of December 2023[update], Out-of-pocket expenditures in Uttar Pradesh is ₹60,883 crore (US$7.3 billion), highest in India.[290]

A newborn in Uttar Pradesh is expected to live four years fewer than in the neighbouring state of Bihar, five years fewer than in Haryana and seven years fewer than in Himachal Pradesh. The state contributed to the largest share of almost all communicable and noncommunicable disease deaths, including 48 per cent of all typhoid deaths (2014); 17 per cent of cancer deaths and 18 per cent of tuberculosis deaths (2015).[286] Its maternal mortality ratio is higher than the national average at 285 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births (2021), with 64.2 per cent of pregnant women unable to access minimum ante-natal care.[291][292][293] Around 42 per cent of pregnant women, more than 1.5 million, deliver babies at home. About two-thirds (61 per cent) of childbirths at home in the state are unsafe.[294] It has the highest child mortality indicators,[295] from the neonatal mortality rate to the under-five mortality rate of 64 children who die per 1,000 live births before five years of age, 35 die within a month of birth, and 50 do not complete a year of life.[296]

Culture

Language and literature

Several texts and hymns of the Vedic literature were composed in Uttar Pradesh. Renowned Indian writers who have resided in Uttar Pradesh were Kabir, Ravidas, and Tulsidas, who wrote much of his Ram Charit Manas in Varanasi. The festival of Guru Purnima is dedicated to Sage Vyasa, and also known as Vyasa Purnima as it is the day which is believed to be his birthday and also the day he divided the Vedas.[297]

Hindi became the language of state administration with the Uttar Pradesh Official Language Act of 1951.[298] A 1989 amendment to the act added Urdu, as an additional language of the state.[299] Linguistically, the state spreads across the Central, East-Central, and Eastern zones of the Indo Aryan languages. The major Hindi languages of the state are Awadhi, Bagheli, Bundeli, Braj Bhasha, Kannauji, and Hindustani.[300] Bhojpuri, an Eastern Indo Aryan language, is also spoken in the state.[301]

Music and dance

With each district of Uttar Pradesh having its unique music and tradition, traditional folk music in Uttar Pradesh has been categorised in three different ways including music transmitted orally, music with unknown composers and music performed by custom. During the medieval period, two distinct types of music began to emerge in Uttar Pradesh. One was the courtly music, which received support from cities like Agra, Fatehpur Sikri, Lucknow, Jaunpur, Varanasi, and Banda. The other was the religious music stemming from the Bhakti Cult, which thrived in places like Mathura, Vrindavan, and Ayodhya.[302] The popular folk music of Uttar Pradesh includes sohar, which is sung to celebrate the birth of a child. Evolved into the form of semi-classical singing, Kajari sung during the rainy season, and its singing style is closely associated the Benares gharana.[303] Ghazal, Thumri and Qawwali which is a form of Sufi poetry is popular in the Awadh region, Rasiya (especially popular in Braj), which celebrate the divine love of Radha and Krishna. Khayal is a form of semi-classical singing which comes from the courts of Awadh. Other forms of music are Biraha, Chaiti, Chowtal, Alha, and Sawani.[302]

Kathak, a classical dance form, owes its origin to the state of Uttar Pradesh.[304] Ramlila is one of the oldest dramatic folk dances; it depicts the life of the Hindu deity Rama and is performed during festivals such as Vijayadashami.[305] Nautanki is a traditional form of folk theatre that originated in Uttar Pradesh. It typically portrays a variety of themes ranging from historical and mythological tales to social and political commentary.[306] In the gharana dance form, both the Lucknow and the Benares gharanas are situated in the state.[307] Charkula is popular dance of the Braj region.[308]

Fairs and festivals

Chhath Puja is the biggest festival of eastern Uttar Pradesh.[309] The Kumbh Mela, organised in the month of Maagha (February—March), is a major festival held every twelve years in rotation at Prayagraj on the river Ganges.[310] Латмар Холи — местное празднование индуистского фестиваля Холи . Это происходит задолго до настоящего Холи в городе Барсана недалеко от Матхуры. [ 311 ] Тадж-Махотсав , ежегодно проводимый в Агре, представляет собой красочную демонстрацию культуры региона Врадж. [ 312 ] Ганга Махотсав , праздник Картик Пурнима , отмечается через пятнадцать дней после Дивали. [ 313 ]

Кухня

Муглайская кухня — это стиль приготовления пищи, разработанный на Индийском субконтиненте кухнями императорскими Империи Великих Моголов . Он представляет стили кулинарии, используемые в Северной Индии , особенно в Уттар-Прадеше, и находился под сильным влиянием среднеазиатской кухни . Кухня авадхи из города Лакхнау состоит как из вегетарианских, так и из невегетарианских блюд. На него большое влияние оказала кухня Муглай. [ 314 ]

Кухня бходжпури — это стиль приготовления пищи, распространенный в районах, расположенных недалеко от границы с Бихаром. Бходжпури в основном мягкие и менее острые с точки зрения используемых специй. Кухня состоит как из овощных, так и из мясных блюд. [ 315 ]

См. также

Пояснительные примечания

Ссылки

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Объединенная провинция, UP была уведомлена в газете Union 24 января 1950 года» . Новый Индийский экспресс . 2 мая 2017 года. Архивировано из оригинала 8 мая 2017 года . Проверено 4 мая 2017 г.

- ^ «Район Уттар-Прадеш» . up.gov.in. Правительство штата Уттар-Прадеш. Архивировано из оригинала 15 апреля 2017 года . Проверено 12 апреля 2017 г.

- ^ «Список районов Уттар-Прадеша» . archive.india.gov.in . Правительство Индии. Архивировано из оригинала 26 апреля 2017 года . Проверено 12 апреля 2017 г.

- ^ ПТИ (20 июля 2019 г.). «Анандибен Патель назначила губернатором UP Лал Джи Тандона вместо нее в Мадхья-Прадеше» . Индия сегодня . Архивировано из оригинала 20 июля 2019 года . Проверено 20 июля 2019 г.

- ^ «Губернатор штата Уттар-Прадеш» . uplegisassembly.gov.in . Законодательное собрание штата Уттар-Прадеш. Архивировано из оригинала 3 мая 2017 года . Проверено 12 апреля 2017 г.

- ^ «Уттар-Прадеш | История, правительство, карта и население | Британника» . Британская энциклопедия . Архивировано из оригинала 1 апреля 2020 года . Проверено 24 марта 2023 г.

- ^ «Список высочайших горных вершин в штате» . Wordpandit . 29 июля 2017 года. Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2023 года . Проверено 24 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Отчет комиссара по делам языковых меньшинств: 52-й отчет (июль 2014 г. – июнь 2015 г.)» (PDF) . Комиссар по делам языковых меньшинств Министерства по делам меньшинств правительства Индии. стр. 49–53. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 15 ноября 2016 года . Проверено 16 февраля 2016 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Справочник по статистике индийских штатов на 2021–2022 годы» (PDF) . Резервный банк Индии . стр. 37–42. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 29 января 2022 года . Проверено 11 февраля 2022 г.

- ^ «Субнациональный ИЧР – база данных территорий» . Лаборатория глобальных данных . Институт исследований менеджмента Университета Радбауд. Архивировано из оригинала 23 сентября 2018 года . Проверено 25 сентября 2018 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Перепись 2011 г. (Окончательные данные) – Демографические данные, грамотное население (всего, сельское и городское)» (PDF) . Planningcommission.gov.in . Комиссия по планированию правительства Индии. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 27 января 2018 года . Проверено 3 октября 2018 г.

- ^ «Соотношение полов в штатах и союзных территориях Индии по данным Национального обследования здравоохранения (2019–2021 гг.)» . Министерство здравоохранения и благополучия семьи, Индия . Архивировано из оригинала 8 января 2023 года . Проверено 8 января 2023 г.

- ^ «Уттар-Прадеш» . Lexico Британский словарь английского языка . Издательство Оксфордского университета . Архивировано из оригинала 26 апреля 2022 года.

- ^ Копф, Дэн; Варатан, Прити (11 октября 2017 г.). «Если бы Уттар-Прадеш был страной» . Кварц Индия . Архивировано из оригинала 22 июня 2019 года . Проверено 20 мая 2019 г.

- ^ «Сельское хозяйство» (PDF) . niti.gov.in. НИТИ Аайог . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 7 октября 2021 года . Проверено 19 октября 2021 г.

- ^ Вирендра Н. Мисра, Питер Беллвуд (1985). Последние достижения в предыстории Индо-Тихоокеанского региона: материалы международного симпозиума, состоявшегося в Пуне . БРИЛЛ. п. 69. ИСБН 9004075127 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 марта 2018 года . Проверено 23 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Бриджит Олчин, Фрэнк Рэймонд Олчин (1982). Подъем цивилизации в Индии и Пакистане . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 58. ИСБН 052128550X . Архивировано из оригинала 25 марта 2017 года . Проверено 23 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Хасмукхлал Дхираджлал Санкалиа; Шантарам Бхалчандра Део; Мадукар Кешав Дхаваликар (1985). Исследования по индийской археологии: Том поздравлений профессора Х.Д. Санкалии . Популярные публикации. п. 96.ISBN 978-0861320882 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2017 года.

- ^ Доверительные пределы возраста: 85 (±11) и 72 (±8) тысяч лет назад.

- ^ Гиблинг, Синха; Синха, Рой; Рой, Тандон; Тандон, Джайн; Джайн, М (2008). «Четвертичные речные и эоловые отложения на реке Белан, Индия: палеоклиматическая обстановка археологических памятников эпохи палеолита и неолита за последние 85 000 лет». Четвертичные научные обзоры . 27 (3–4): 391. Бибкод : 2008QSRv...27..391G . doi : 10.1016/j.quascirev.2007.11.001 . ISSN 0277-3791 . S2CID 129392697 .

- ^ Кеннет А.Р. Кеннеди (2000). Богообезьяны и ископаемые люди . Издательство Мичиганского университета. п. 263. ИСБН 0472110136 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2017 года . Проверено 23 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Бриджит Олчин, Фрэнк Рэймонд Олчин (1982). Подъем цивилизации в Индии и Пакистане . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 119. ИСБН 052128550X . Архивировано из оригинала 3 марта 2018 года . Проверено 23 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Мисра, В.Н. (ноябрь 2001 г.). «Доисторическая человеческая колонизация Индии» . Журнал биологических наук . 26 (4 прил.). Индийская академия наук : 491–531. дои : 10.1007/bf02704749 . ПМИД 11779962 . S2CID 26248907 . Архивировано из оригинала 7 октября 2017 года . Проверено 19 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ «Уттар-Прадеш – История» . Британская энциклопедия . Архивировано из оригинала 1 апреля 2020 года . Проверено 12 января 2020 г.

Систематическая история Индии и территории Уттар-Прадеша восходит к концу VII века до нашей эры, когда 16 махаджанапад (великих штатов) на севере Индии боролись за превосходство. Из них семь полностью находились в пределах современных границ Уттар-Прадеша.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Сайлендра Нат Сен (1999). Древняя индийская история и цивилизация . Нью Эйдж Интернэшнл. стр. 105–106. ISBN 978-8122411980 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2013 года . Проверено 1 октября 2012 года .

- ^ Уильям Бак (2000). Рамаяна . Мотилал Банарсидасс. ISBN 978-8120817203 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 июня 2013 года . Проверено 1 октября 2012 года .

- ^ Ричард Уайт (2010). Золотая середина: индейцы, империи и республики в районе Великих озер, 1650–1815 гг . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-1107005624 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2013 года . Проверено 1 октября 2012 года .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Корпорация Маршалла Кавендиша (2007 г.). Мир и его народы: Восточная и Южная Азия . Маршалл Кавендиш. стр. 331–335. ISBN 978-0761476313 . Архивировано из оригинала 5 июня 2013 года . Проверено 1 октября 2012 года .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пран Натх Чопра (2003). Всеобъемлющая история Древней Индии . Стерлинг Паблишерс Пвт. ООО с. 196. ИСБН 978-8120725034 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2013 года . Проверено 1 октября 2012 года .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Джон Стюарт Боуман (2000). Колумбийские хронологии азиатской истории и культуры . Издательство Колумбийского университета. п. 273 . ISBN 978-0231110044 . Проверено 2 августа 2012 г.

- ^ История Индии Кеннета Плетчера с. 102

- ^ Город в Южной Азии Джеймса Хейцмана с. 37

- ^ Сингх, Прадьюман (19 января 2021 г.). Дайджест общих знаний Бихара . Прабхат Пракашан. ISBN 978-9352667697 .

- ^ * Шривастава, Аширвади Лал (1929). Султанат Дели 711–1526 гг . Шива Лал Агарвала и компания. Архивировано из оригинала 8 апреля 2016 года . Проверено 29 апреля 2018 г.

- ^ Ислам; Босворт (1998). История цивилизаций Центральной Азии . ЮНЕСКО. стр. 269–291. ISBN 978-9231034671 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 марта 2024 года . Проверено 21 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Атала Масджид» . Район Джаунпур, правительство Уттар-Прадеша . 20 июня 2017 г. Проверено 6 мая 2024 г.

- ^ Датта, Ранган (22 июля 2022 г.). «Могила Гиясуддина Туглака» . Телеграф Индии . Проверено 6 мая 2024 г.

- ^ «Исламский мир до 1600 года: Расцвет великих исламских империй (Империя Великих Моголов)» . Архивировано из оригинала 27 сентября 2011 года.

- ^ Аннемари Шиммель (2004). Империя Великих Моголов: история, искусство и культура . Книги реакции. ISBN 978-1861891853 . Проверено 1 октября 2012 года .

- ^ Бабур (Император Индостана); Дилип Хиро (2006). Бабур Нама: Журнал императора Бабура . Книги Пингвинов Индия. ISBN 978-0144001491 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2013 года . Проверено 1 октября 2012 года .

- ^ Карлос Рамирес-Фариа (2007). Краткая энциклопедия всемирной истории . Atlantic Publishers & Dist. п. 171. ИСБН 978-8126907755 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2013 года . Проверено 2 августа 2012 г.

- ^ Стронг, Сьюзен (2012). Индостан Великих Моголов известен своим богатством . Лондон: Искусство сикхских королевств. п. 255. ИСБН 9788174366962 . Архивировано из оригинала 16 февраля 2017 года . Проверено 23 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Ашвини Агравал (1983). Исследования по истории Великих Моголов . Мотилал Банарсидасс. стр. 30–46. ISBN 978-8120823266 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2013 года . Проверено 27 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Фергус Николл, Шах Джахан: Взлет и падение императора Великих Моголов (2009)

- ^ Маярам, Шаил (2003). Против истории, против государства: маргинальные контрперспективы Культуры истории . Издательство Колумбийского университета. ISBN 978-0231127318 .

- ^ «День Уттар-Прадеша: как зародился штат 67 лет назад» . 3 мая 2017 года. Архивировано из оригинала 3 мая 2017 года . Проверено 3 мая 2017 г.

- ^ Гьянеш Кудайся (1994). Регион, нация, «центр»: Уттар-Прадеш в теле-политике Индии . ЛИТ Верлаг Мюнстер. стр. 126–376. ISBN 978-3825820978 .

- ^ К. Шиварамакришнан (1999). Современные леса: государственное устройство и экологические изменения в колониальной Восточной Индии . Издательство Стэнфордского университета. стр. 240–276. ISBN 978-0804745567 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2013 года . Проверено 26 июля 2012 года .

- ^ Ашутош Джоши (2008). Градостроительное возрождение городов . Издательство Новой Индии. п. 237. ИСБН 978-8189422820 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 марта 2018 года.

- ^ Рудрангшу Мукерджи (2005). Мангал Пандей: храбрый мученик или случайный герой? . Книги о пингвинах. ISBN 978-0143032564 . Архивировано из оригинала 5 июня 2013 года . Проверено 1 октября 2012 года .

- ^ Соединенные провинции Агра и Ауд (Индия); Д. Л. Дрейк-Брокман (1934). Окружные справочники объединенных провинций Агра и Ауд: supp.D.Pilibhit District . Supdt., Government Press, Соединенные провинции. Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2013 года . Проверено 1 октября 2012 года .

- ^ Дилип К. Чакрабарти (1997). Колониальная индология: социополитика древнеиндийского прошлого . Мичиган: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. ООО ООО п. 257. ИСБН 978-8121507509 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2013 года . Проверено 26 июля 2012 года .

- ^ Бернард С. Кон (1996). Колониализм и его формы познания: британцы в Индии . Издательство Принстонского университета. п. 189. ИСБН 978-0691000435 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2013 года . Проверено 26 июля 2012 года .

- ^ Клэр М. Уилкинсон-Вебер (1999). Вышивание жизни: женский труд и мастерство в вышивальной промышленности Лакхнау . СУНИ Пресс. п. 18. ISBN 978-0791440872 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 марта 2024 года . Проверено 24 мая 2020 г.

- ^ Матур, Пракаш Нараин. «История коллегии Высокого суда Лакхнау» (PDF) . Высокий суд Аллахабада. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 24 февраля 2021 года . Проверено 24 мая 2020 г.

- ^ К. Баласанкаран Наир (2004). Закон о неуважении к суду в Индии Atlantic Publishers & Dist. п. 320. ИСБН 978-8126903597 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2013 года . Проверено 26 июля 2012 года .

- ^ Шекхара, Бандиопадхьяя (2004). От Плесси до раздела: история современной Индии . Ориент Лонгман . п. 407. ИСБН 978-8125025962 .

- ^ Бандиопадхьяя, Шекхара (2004). От Плесси до раздела: история современной Индии . Ориент Лонгман . п. 406. ИСБН 978-8125025962 .

- ^ Банким Чандра Чаттерджи (2006). Анандаматх . Восточные книги в мягкой обложке. п. 168. ИСБН 978-8122201307 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2013 года . Проверено 26 июля 2012 года .

- ^ «Уттар-Прадеш – штаты и союзные территории» . Познай Индию: Национальный портал Индии . Архивировано из оригинала 15 июля 2015 года . Проверено 14 июля 2015 г.

- ^ «Уттар-Прадеш» . Что такое Индия. 22 августа 2007 г. Архивировано из оригинала 12 октября 2016 г. Проверено 8 октября 2016 г.

- ^ «Коммунальное насилие» . Бизнес-стандарт . Издательство Ананда . Котак Махиндра Банк . 6 августа 2014 года. Архивировано из оригинала 26 августа 2014 года . Проверено 25 августа 2014 г.

- ^ межобщинное насилие в штате Уттар-Прадеш. «Коммунальные конфликты в государстве» . Техалка . Архивировано из оригинала 12 января 2014 года . Проверено 12 января 2014 г.

- ^ Дж. К. Аггарвал; СП Агравал (1995). Уттаракханд: прошлое, настоящее и будущее . Концептуальная издательская компания Индии. п. 391. ИСБН 978-8170225720 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2017 года.

- ^ «Наиболее важные факторы» . Департамент климата штата Уттар-Прадеш. Архивировано из оригинала 15 декабря 2012 года . Проверено 22 июля 2012 г.

- ^ «География Уттар-Прадеша» . Профиль штата Уттар-Прадеш. Архивировано из оригинала 23 июля 2012 года . Проверено 22 июля 2012 г.

- ^ «Большая Гангская равнина» (PDF) . Гекафы. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 26 декабря 2013 года . Проверено 22 июля 2012 г.

- ^ «Гангские равнины, холмы и плато Виндхья» . Зи новости . Архивировано из оригинала 6 апреля 2012 года . Проверено 22 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Анвар, Шакил (16 августа 2018 г.). «Список основных каналов и плотин в Уттар-Прадеше» . Дайник Ягран . Джагран Пракашан Лимитед. Архивировано из оригинала 22 июня 2020 года . Проверено 21 июня 2020 г.

- ^ «Индо-африканский журнал по управлению ресурсами» (PDF) . Индо-африканский журнал по управлению ресурсами и планированию. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 1 апреля 2022 года . Проверено 21 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Анвар, Шакил. «Великие равнины Индии» . Джагран Джош . Дайник Ягран. Джагран Пракашан Прайвет Лимитед. Архивировано из оригинала 21 ноября 2017 года . Проверено 19 мая 2020 г.

- ^ Клифт, Чарльз (1977). «Прогресс ирригации в Уттар-Прадеше: различия между Востоком и Западом» . Экономический и политический еженедельник . 12 (39). JSTOR : A83–A90. JSTOR 4365953 . Архивировано из оригинала 30 октября 2021 года . Проверено 19 октября 2021 г.

- ^ РП Мина. Ежегодник текущих событий Уттар-Прадеша за 2020 год . Публикация Новой Эры. п. 6. GGKEY:XTXLJ8SQZFE. Архивировано из оригинала 28 марта 2024 года . Проверено 19 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Реки Уттар-Прадеша» . Экономические времена . Архивировано из оригинала 7 мая 2013 года . Проверено 22 июля 2012 г.

- ^ «Глоссарий метеорологии» . Allen Press Inc. Архивировано из оригинала 5 октября 2012 года . Проверено 23 июля 2012 г.

- ^ «Руководство по механизации сельского хозяйства для Уттар-Прадеша» . Министерство сельского хозяйства, правительство Индии. Архивировано из оригинала 16 мая 2021 года . Проверено 16 мая 2021 г.

- ^ «Потенциальное создание и использование» . Департамент ирригации UP Архивировано из оригинала 13 февраля 2012 года . Проверено 22 июля 2012 г.

- ^ «Предполагается дать определение каждому важному метеорологическому термину, который может быть найден в современной литературе» . Allen Press, Inc. Архивировано из оригинала 12 июля 2012 года . Проверено 22 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Вир Сингх (1998). Горные экосистемы: сценарий неустойчивости . Индус Паблишинг. стр. 102–264. ISBN 978-8173870811 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2013 года . Проверено 27 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Упкар Пракашан – редакционная коллегия (2008). Общие сведения об Уттар-Прадеше . Публикации Упкара. стр. 26-. ISBN 978-8174824080 . Архивировано из оригинала 5 июня 2013 года . Проверено 9 марта 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Последствия изменения климата» . Департамент климата штата Уттар-Прадеш. Архивировано из оригинала 15 ноября 2012 года . Проверено 22 июля 2012 г.

- ^ SVS Rana (2007), Основы экологии и наук об окружающей среде , Прентис-Холл, Индия, ISBN 978-81-203-3300-0

- ^ Правительство Уттар-Прадеша, Лакхнау, Департамент ирригации Уттар-Прадеша. «Средний режим осадков в Уттар-Прадеше» . Департамент ирригации штата Уттар-Прадеш. Архивировано из оригинала 24 августа 2012 года . Проверено 22 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Сети, Нитин (13 февраля 2007 г.). «Метрополитен винит в этом «беспорядки на Западе» » . Таймс оф Индия . Архивировано из оригинала 11 августа 2011 года . Проверено 9 марта 2011 г.

- ^ «Местная сводка погоды» . Местный отдел сводок погоды и прогнозов. 21 мая 2012 года. Архивировано из оригинала 1 мая 2012 года . Проверено 18 июля 2012 г.

- ^ «Государство животное, птица, дерево и цветок» . Панна тигровый заповедник . Архивировано из оригинала 13 октября 2014 года . Проверено 29 августа 2014 г.

- ^ «Музыка и танец» . uptourism.gov.in . Туризм Уттар-Прадеша. Архивировано из оригинала 23 января 2017 года . Проверено 3 марта 2017 г.

- ^ «Лесная корпорация Уттар-Прадеш» . Лесной департамент штата Уттар-Прадеш. Архивировано из оригинала 20 января 2013 года . Проверено 23 июля 2012 г.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: неподходящий URL ( ссылка ) - ^ «Лесные и древесные ресурсы в штатах и союзных территориях: Уттар-Прадеш» (PDF) . Отчет о состоянии лесов Индии за 2009 год . Лесное обследование Индии, Министерство окружающей среды и лесов, правительство Индии. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 7 ноября 2013 года . Проверено 4 марта 2012 г.

- ^ «Цветочное и фаунистическое разнообразие Уттар-Прадеша» . Совет по биоразнообразию штата Уттар-Прадеш. Архивировано из оригинала 5 июля 2019 года . Проверено 22 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Египтика» . Bsienvis.nic.in. Архивировано из оригинала 6 мая 2009 года . Проверено 21 сентября 2009 г.

- ^ «Птичий заповедник» . УП туризм. Архивировано из оригинала 4 июля 2012 года . Проверено 23 июля 2012 г.

- ^ «Санкчуари-Парк в УП» . УП туризм. Архивировано из оригинала 18 июля 2012 года . Проверено 23 июля 2012 г.

- ^ «Несколько участков естественного леса» . Правительство штата Уттар-Прадеш. Архивировано из оригинала 20 мая 2012 года . Проверено 22 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Леса и биоразнообразие в ЮП важны во многих отношениях. «Разная статистика» . Министерство окружающей среды и лесов. Архивировано из оригинала 15 ноября 2012 года . Проверено 22 июля 2012 г.

- ^ «Сохранение орнитофауны» (PDF) . Национальный парк Дудхва . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 22 июля 2012 года . Проверено 20 июля 2012 г.