Св. Луи

Эта статья нуждается в дополнительных цитатах для проверки . ( июль 2024 г. ) |

Св. Луи | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Nickname(s): | |

Interactive map of St. Louis | |

| Coordinates: 38°37′38″N 90°11′52″W / 38.62722°N 90.19778°W | |

| Country | United States |

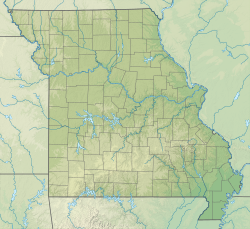

| State | Missouri |

| CSA | St. Louis–St. Charles–Farmington, MO–IL |

| Metro | St. Louis, MO-IL |

| Founded | February 14, 1764 |

| Incorporated | 1822 |

| Named for | Louis IX of France |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Body | Board of Aldermen |

| • Mayor | Tishaura Jones (D) |

| • President, Board of Aldermen | Megan Green (D) |

| • Treasurer | Adam Layne |

| • Comptroller | Darlene Green (D) |

| • Congressional representative | Cori Bush (D) |

| Area | |

| • Independent city | 66.17 sq mi (171.39 km2) |

| • Land | 61.72 sq mi (159.85 km2) |

| • Water | 4.45 sq mi (11.53 km2) |

| • Urban | 910.4 sq mi (2,357.8 km2) |

| • Metro | 8,458 sq mi (21,910 km2) |

| Elevation | 466 ft (142 m) |

| Highest elevation | 614 ft (187 m) |

| Population | |

| • Independent city | 301,578 |

| • Estimate (2021)[9] | 293,310 |

| • Rank | US: 76th Midwest: 13th Missouri: 2nd |

| • Density | 4,886.23/sq mi (1,886.59/km2) |

| • Urban | 2,156,323 (US: 22nd) |

| • Urban density | 2,368.6/sq mi (914.5/km2) |

| • Metro | 2,809,299 (US: 21st) |

| • CSA | 2,914,230 (US: 20th) |

| Demonym(s) | St. Louisan; Saint Louisan |

| GDP | |

| • Greater St. Louis | $209.9 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | List |

| Area code | 314/557 |

| FIPS code | 29-65000 |

| Website | stlouis-mo |

Св. Луи ( / s t eɪ n ˈ l uː ɪ s , s ən t - / saynt LOO -iss, sənt- ) [ 11 ] — независимый город в штате Миссури американском . Он расположен недалеко от рек слияния Миссисипи и Миссури . В 2020 году население города составляло 301 578 человек. [ 8 ] в то время как в его агломерации , которая простирается до штата Иллинойс , население, по оценкам, превышает 2,8 миллиона человек. Это крупнейший мегаполис в Миссури и второй по величине в Иллинойсе. города Объединенная статистическая площадь является 20-й по величине в Соединенных Штатах. [ 12 ]

The land that became St. Louis had been occupied by Native American cultures for thousands of years before European settlement. The city was founded on February 14, 1764, by French fur traders Gilbert Antoine de St. Maxent, Pierre Laclède, and Auguste Chouteau.[13] They named it for King Louis IX of France, and it quickly became the regional center of the French Illinois Country. In 1804, the United States acquired St. Louis as part of the Louisiana Purchase. In the 19th century, St. Louis developed as a major port on the Mississippi River; from 1870 until the 1920 census, it was the fourth-largest city in the country. It separated from St. Louis County in 1877, becoming an independent city and limiting its political boundaries. In 1904, it hosted the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, also known as the St. Louis World's Fair, and the Summer Olympics.[14][15]

St. Louis is designated as one of 173 global cities by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network.[16] The GDP of Greater St. Louis was $209.9 billion in 2022.[17] St. Louis has a diverse economy with strengths in the service, manufacturing, trade, transportation, and aviation industries.[18] It is home to fifteen Fortune 1000 companies, seven of which are also Fortune 500 companies.[19] Federal agencies headquartered in the city or with significant operations there include the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.

Major research universities in Greater St. Louis include Washington University in St. Louis, Saint Louis University, and the University of Missouri–St. Louis. The Washington University Medical Center in the Central West End neighborhood hosts an agglomeration of medical and pharmaceutical institutions, including Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

St. Louis has four professional sports teams: the St. Louis Cardinals of Major League Baseball, the St. Louis Blues of the National Hockey League, St. Louis City SC of Major League Soccer, and the St. Louis BattleHawks of the United Football League. The city's attractions include the 630-foot (192 m) Gateway Arch in Downtown St. Louis, the St. Louis Zoo, the Missouri Botanical Garden, the St. Louis Art Museum, and Bellefontaine Cemetery.[20][21]

History

Mississippian culture and European exploration

Kingdom of France 1690s–1763

Kingdom of Spain 1763–1800

French First Republic 1800–1803

United States 1803–present

The area that became St. Louis was a center of the Native American Mississippian culture, which built numerous temple and residential earthwork mounds on both sides of the Mississippi River. Their major regional center was at Cahokia Mounds, active from 900 to 1500. Due to numerous major earthworks within St. Louis boundaries, the city was nicknamed as the "Mound City". These mounds were mostly demolished during the city's development. Historic Native American tribes in the area encountered by early Europeans included the Siouan-speaking Osage people, whose territory extended west, and the Illiniwek.

European exploration of the area was first recorded in 1673, when French explorers Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette traveled through the Mississippi River valley. Five years later, La Salle claimed the region for France as part of La Louisiane, also known as Louisiana. The earliest European settlements in the Illinois Country (also known as Upper Louisiana) were built by the French during the 1690s and early 1700s at Cahokia, Kaskaskia, and Fort de Chartres. Migrants from the French villages on the east side of the Mississippi River, such as Kaskaskia, also founded Ste. Genevieve in the 1730s.

In 1764, after France lost the Seven Years' War, Pierre Laclède and his stepson Auguste Chouteau founded what was to become the city of St. Louis.[22] (French lands east of the Mississippi had been ceded to Great Britain and the lands west of the Mississippi to Spain; Catholic France and Spain were 18th-century allies. Louis XV of France and Charles III of Spain were cousins, both from the House of Bourbon.[23][circular reference]) The French families built the city's economy on the fur trade with the Osage, and with more distant tribes along the Missouri River. The Chouteau brothers gained a monopoly from Spain on the fur trade with Santa Fe. French colonists used African slaves as domestic servants and workers in the city.

During the negotiations for the 1763 Treaty of Paris, French negotiators agreed to transfer France's colonial territories west of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers to New Spain to compensate for Spanish territorial losses during the war. These areas remained under Spanish control until 1803, when they were transferred to the French First Republic. During the American Revolutionary War, St. Louis was unsuccessfully attacked by British-allied Native Americans in the 1780 Battle of St. Louis.[24]

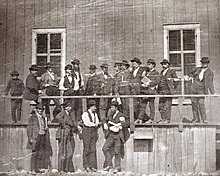

Founding

The founding of St. Louis was preceded by a trading business between Gilbert Antoine de St. Maxent and Pierre Laclède (Liguest) in late 1763. St. Maxent invested in a Mississippi River expedition led by Laclède, who searched for a location to base the company's fur trading operations. Though Ste. Genevieve was already established as a trading center, he sought a place less prone to flooding. He found an elevated area overlooking the flood plain of the Mississippi River, not far south from its confluence with the Missouri and Illinois rivers. In addition to having an advantageous natural drainage system, there were nearby forested areas to supply timber and grasslands which could easily be converted for agricultural purposes. Laclède declared that this place "might become, hereafter, one of the finest cities in America". He dispatched his 14-year-old stepson, Auguste Chouteau, to the site, with the support of 30 settlers in February 1764.[25]

Laclède arrived at the future town site two months later and produced a plan for St. Louis based on the New Orleans street plan. The default block size was 240 by 300 feet, with just three long avenues running parallel to the west bank of the Mississippi. He established a public corridor of 300 feet fronting the river, but later this area was released for private development.[25]

For the city's first few years, it was not recognized by any governments. Although the settlement was thought to be under the control of the Spanish government, no one asserted any authority over it, and thus St. Louis had no local government. This vacuum led Laclède to assume civil control, and all problems were disposed in public settings, such as communal meetings. In addition, Laclède granted new settlers lots in town and the surrounding countryside. In hindsight, many of these original settlers thought of these first few years as "the golden age of St. Louis".[26] In 1763, the Native Americans in the region around St. Louis began expressing dissatisfaction with the victorious British, objecting to their refusal to continue to the French tradition of supplying gifts to Natives. Odawa chieftain Pontiac began forming a pan-tribal alliance to counter British control over the region but received little support from the indigenous residents of St. Louis. By 1765, the city began receiving visits from representatives of the British, French, and Spanish governments.

St. Louis was transferred to the French First Republic in 1800 (although all of the colonial lands continued to be administered by Spanish officials), then sold by the French to the U.S. in 1803 as part of the Louisiana Purchase. St. Louis became the capital of, and gateway to, the new territory. Shortly after the official transfer of authority was made, the Lewis and Clark Expedition was commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson. The expedition departed from St. Louis in May 1804 along the Missouri River to explore the vast territory. There were hopes of finding a water route to the Pacific Ocean, but the party had to go overland in the Upper West. They reached the Pacific Ocean via the Columbia River in summer 1805. They returned, reaching St. Louis on September 23, 1806. Both Lewis and Clark lived in St. Louis after the expedition. Many other explorers, settlers, and trappers (such as Ashley's Hundred) would later take a similar route to the West.

19th century

The city elected its first municipal legislators (called trustees) in 1808. Steamboats first arrived in St. Louis in 1817, improving connections with New Orleans and eastern markets. Missouri was admitted as a state in 1821. St. Louis was incorporated as a city in 1822, and continued to develop largely due to its busy port and trade connections.

Immigrants from Ireland and Germany arrived in St. Louis in significant numbers starting in the 1840s, and the population of St. Louis grew from less than 20,000 inhabitants in 1840, to 77,860 in 1850, to more than 160,000 by 1860. By the mid-1800s, St. Louis had a greater population than New Orleans.

Settled by many Southerners in a slave state, the city was split in political sympathies and became polarized during the American Civil War. In 1861, 28 civilians were killed in a clash with Union troops. The war hurt St. Louis economically, due to the Union blockade of river traffic to the south on the Mississippi River. The St. Louis Arsenal constructed ironclads for the Union Navy.

Slaves worked in many jobs on the waterfront and on the riverboats. Given the city's location close to the free state of Illinois and others, some slaves escaped to freedom. Others, especially women with children, sued in court in freedom suits, and several prominent local attorneys aided slaves in these suits. About half the slaves achieved freedom in hundreds of suits before the American Civil War. The printing press of abolitionist Elijah Parish Lovejoy was destroyed for the third time by townsfolk. He was murdered the next year in nearby Alton, Illinois.

After the war, St. Louis profited via trade with the West, aided by the 1874 completion of the Eads Bridge, named for its design engineer. Industrial developments on both banks of the river were linked by the bridge, the second in the Midwest over the Mississippi River after the Hennepin Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis. The bridge connects St. Louis, Missouri to East St. Louis, Illinois. The Eads Bridge became a symbolic image of the city of St. Louis, from the time of its erection until 1965 when the Gateway Arch Bridge was constructed. The bridge crosses the St. Louis riverfront between Laclede's Landing, to the north, and the grounds of the Gateway Arch, to the south. Today the road deck has been restored, allowing vehicular and pedestrian traffic to cross the river. The St. Louis MetroLink light rail system has used the rail deck since 1993. An estimated 8,500 vehicles pass through it daily.

On August 22, 1876, the city of St. Louis voted to secede from St. Louis County and become an independent city, and, following a recount of the votes in November, officially did so in March 1877.[27] The 1877 St. Louis general strike caused significant upheaval, in a fight for the eight-hour day and the banning of child labor.[28][page needed]

Industrial production continued to increase during the late 19th century. Major corporations such as the Anheuser-Busch brewery, Ralston Purina company and Desloge Consolidated Lead Company were established at St. Louis which was also home to several brass era automobile companies, including the Success Automobile Manufacturing Company;[29] St. Louis is the site of the Wainwright Building, a skyscraper designed in 1892 by architect Louis Sullivan.

20th century

In 1900, the entire streetcar system was shut down by a several months-long strike, with significant unrest occurring in the city & violence against the striking workers.[30]

In 1904, the city hosted the World's Fair and the Olympics, becoming the first non-European city to host the games.[31] The formal name for the 1904 World's Fair was the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. Permanent facilities and structures remaining from the fair are located in Forest Park, and other notable structures within the park's boundaries include the St. Louis Art Museum, the St. Louis Zoo and the Missouri History Museum, and Tower Grove Park and the Botanical Gardens.

After the Civil War, social and racial discrimination in housing and employment were common in St. Louis. In 1916, during the Jim Crow Era, St. Louis passed a residential segregation ordinance[32] saying that if 75% of the residents of a neighborhood were of a certain race, no one from a different race was allowed to move in.[33] That ordinance was struck down in a court challenge, by the NAACP,[34] after which racial covenants were used to prevent the sale of houses in certain neighborhoods to "persons not of Caucasian race".[clarification needed] Again, St. Louisans offered a lawsuit in challenge, and such covenants were ruled unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1948 in Shelley v. Kraemer.[35]

In 1926, Douglass University, a historically black university was founded by B. F. Bowles in St. Louis, and at the time no other college in St. Louis County admitted black students.[36]

In the first half of the 20th century, St. Louis was a destination in the Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South seeking better opportunities.[citation needed] During World War II, the NAACP campaigned to integrate war factories. In 1964, civil rights activists protested at the construction of the Gateway Arch to publicize their effort to gain entry for African Americans into the skilled trade unions, where they were underrepresented. The Department of Justice filed the first suit against the unions under the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[citation needed]

Between 1900 and 1929, St. Louis, had about 220 automakers, close to 10 percent of all American carmakers, about half of which built cars exclusively in St. Louis. Notable names include Dorris, Gardner and Moon.[37]

In the first part of the century, St. Louis had some of the worst air pollution in the United States. In April 1940, the city banned the use of soft coal mined in nearby states. The city hired inspectors to ensure that only anthracite was burned. By 1946, the city had reduced air pollution by about 75%.[38]

De jure educational segregation continued into the 1950s, and de facto segregation continued into the 1970s, leading to a court challenge and interdistrict desegregation agreement. Students have been bused mostly from the city to county school districts to have opportunities for integrated classes, although the city has created magnet schools to attract students.[39]

St. Louis, like many Midwestern cities, expanded in the early 20th century due to industrialization, which provided jobs to new generations of immigrants and migrants from the South. It reached its peak population of 856,796 at the 1950 census.[40] Suburbanization from the 1950s through the 1990s dramatically reduced the city's population, as did restructuring of industry and loss of jobs.[citation needed] The effects of suburbanization were exacerbated by the small geographical size of St. Louis due to its earlier decision to become an independent city, and it lost much of its tax base. During the 19th and 20th century, most major cities aggressively annexed surrounding areas as residential development occurred away from the central city; however, St. Louis was unable to do so.[citation needed]

Several urban renewal projects were built in the 1950s, as the city worked to replace old and substandard housing. Some of these were poorly designed and resulted in problems. One prominent example, Pruitt–Igoe, became a symbol of failure in public housing, and was torn down less than two decades after it was built.

Since the 1980s, several revitalization efforts have focused on Downtown St. Louis.

21st century

The urban revitalization projects that started in the 1980s continued into the new century. The city's old garment district, centered on Washington Avenue in the Downtown and Downtown West neighborhoods, experienced major development starting in the late 1990s as many of the old factory and warehouse buildings were converted into lofts. The American Planning Association designated Washington Avenue as one of 10 Great Streets for 2011.[41] The Cortex Innovation Community, located within the city's Central West End neighborhood, was founded in 2002 and has become a multi-billion dollar economic engine for the region, with companies such as Microsoft and Boeing currently leasing office space.[42][43] The Forest Park Southeast neighborhood in the central corridor has seen major investment starting in the early 2010s. Between 2013 and 2018, over $50 million worth of residential construction has been built in the neighborhood.[44] The population of the neighborhood has increased by 19% from the 2010 to 2020 Census.[45]

The St. Louis Rams of the National Football League controversially returned to Los Angeles in 2016. The city of St. Louis sued the NFL in 2017, alleging the league breached its own relocation guidelines to profit at the expense of the city. In 2021, the NFL and Rams owner Stan Kroenke agreed to settle out of court with the city for $790 million.[46][47]

Geography

Landmarks

| Name | Description | Photo |

|---|---|---|

| Gateway Arch | At 630 feet (190 m), the Gateway Arch is the world's tallest arch and tallest human-made monument in the Western Hemisphere.[48] Built as a monument to the westward expansion of the United States, it is the centerpiece of Gateway Arch National Park which was known as Jefferson National Expansion Memorial until 2018. |

|

| St. Louis Art Museum | Built for the 1904 World's Fair, with a building designed by Cass Gilbert, the museum houses paintings, sculptures, and cultural objects. The museum is located in Forest Park, and admission is free. |

|

| Missouri Botanical Garden | Founded in 1859, the Missouri Botanical Garden is one of the oldest botanical institutions in the United States and a National Historic Landmark. It spans 79 acres in the Shaw neighborhood, including a 14-acre (5.7-hectare) Japanese garden and the Climatron geodesic dome conservatory. |

|

| Cathedral Basilica of St. Louis | Dedicated in 1914, it is the mother church of the Archdiocese of St. Louis and the seat of its archbishop. The church is known for its large mosaic installation (which is one of the largest in the Western Hemisphere with 41.5 million pieces), burial crypts, and its outdoor sculpture. |

|

| City Hall | Located in Downtown West, City Hall was designed by Harvey Ellis in 1892 in the Renaissance Revival style. It is reminiscent of the Hôtel de Ville, Paris. |

|

| Central Library | Completed in 1912, the Central Library building was designed by Cass Gilbert. It serves as the main location for the St. Louis Public Library. |

|

| City Museum | City Museum is a play house museum, consisting largely of repurposed architectural and industrial objects, housed in the former International Shoe building in the Washington Avenue Loft District. |

|

| Old Courthouse | Built in the 19th century, it served as a federal and state courthouse. The Scott v. Sandford case (resulting in the Dred Scott decision) was tried at the courthouse in 1846. |

|

| St. Louis Science Center | Founded in 1963, it includes a science museum and a planetarium, and is situated in Forest Park. Admission is free. It is one of two science centers in the United States which offers free general admission. |

|

| St. Louis Symphony | Founded in 1880, the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra is the second oldest symphony orchestra in the United States, preceded by the New York Philharmonic. Its principal concert venue is Powell Symphony Hall. |

|

| Union Station | Built in 1888, it was the city's main passenger intercity train terminal. Once the world's largest and busiest train station, it was converted in the 1980s into a hotel, shopping center, and entertainment complex. Today, it also continues to serve local rail (MetroLink) transit passengers, with Amtrak service nearby. On December 25, 2019, the St. Louis Aquarium opened inside Union Station. The St. Louis Wheel, a 200 ft 42 gondola ferris wheel, is also located at Union Station. |

|

| St. Louis Zoo | Built for the 1904 World's Fair, it is recognized as a leading zoo in animal management, research, conservation, and education. It is located in Forest Park, and admission is free. |

|

Architecture

The architecture of St. Louis exhibits a variety of commercial, residential, and monumental architecture. St. Louis is known for the Gateway Arch, the tallest monument constructed in the United States at 630 feet (190 m).[49] The Arch pays homage to Thomas Jefferson and St. Louis's position as the gateway to the West. Architectural influences reflected in the area include French Colonial, German, early American, and modern architectural styles.

Several examples of religious structures are extant from the pre-Civil War period, and most reflect the common residential styles of the time. Among the earliest is the Basilica of St. Louis, King of France (referred to as the Old Cathedral). The Basilica was built between 1831 and 1834 in the Federal style. Other religious buildings from the period include SS. Cyril and Methodius Church (1857) in the Romanesque Revival style and Christ Church Cathedral (completed in 1867, designed in 1859) in the Gothic Revival style.

A few civic buildings were constructed during the early 19th century. The original St. Louis courthouse was built in 1826 and featured a Federal style stone facade with a rounded portico. However, this courthouse was replaced during renovation and expansion of the building in the 1850s. The Old St. Louis County Courthouse (known as the Old Courthouse) was completed in 1864 and was notable for having a cast iron dome and for being the tallest structure in Missouri until 1894. Finally, a customs house was constructed in the Greek Revival style in 1852, but was demolished and replaced in 1873 by the U.S. Customhouse and Post Office.

Because much of the city's commercial and industrial development was centered along the riverfront, many pre-Civil War buildings were demolished during construction of the Gateway Arch. The city's remaining architectural heritage of the era includes a multi-block district of cobblestone streets and brick and cast-iron warehouses called Laclede's Landing. Now popular for its restaurants and nightclubs, the district is located north of Gateway Arch along the riverfront. Other industrial buildings from the era include some portions of the Anheuser-Busch Brewery, which date to the 1860s.

St. Louis saw a vast expansion in variety and number of religious buildings during the late 19th century and early 20th century. The largest and most ornate of these is the Cathedral Basilica of St. Louis, designed by Thomas P. Barnett and constructed between 1907 and 1914 in the Neo-Byzantine style. The St. Louis Cathedral, as it is known, has one of the largest mosaic collections in the world. Another landmark in religious architecture of St. Louis is the St. Stanislaus Kostka, which is an example of the Polish Cathedral style. Among the other major designs of the period were St. Alphonsus Liguori (known as The Rock Church) (1867) in the Gothic Revival and Second Presbyterian Church of St. Louis (1900) in Richardsonian Romanesque.

By the 1900 census, St. Louis was the fourth largest city in the country. In 1904, the city hosted a world's fair at Forest Park called the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. Its architectural legacy is somewhat scattered. Among the fair-related cultural institutions in the park are the St. Louis Art Museum designed by Cass Gilbert, part of the remaining lagoon at the foot of Art Hill, and the Flight Cage at the St. Louis Zoo. The Missouri History Museum was built afterward, with the profit from the fair. But 1904 left other assets to the city, like Theodore Link's 1894 St. Louis Union Station, and an improved Forest Park.

One US Bank Plaza, the local headquarters for US Bancorp, was constructed in 1976 in the structural expressionist style. Several notable postmodern commercial skyscrapers were built downtown in the 1970s and 1980s, including the former AT&T building at 909 Chestnut Street (1986), and One Metropolitan Square (1989), which is the tallest building in St. Louis.

During the 1990s, St. Louis saw the construction of the largest United States courthouse by area, the Thomas F. Eagleton United States Courthouse(2000). The Eagleton Courthouse is home to the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri and the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. The most recent high-rise buildings in St. Louis include two residential towers: One Hundred in the Central West End neighborhood and One Cardinal Way in the Downtown neighborhood.

Neighborhoods

The city is divided into 79 officially-recognized neighborhoods.[50]

Topography

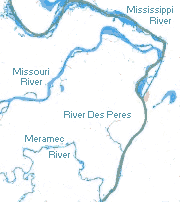

According to the United States Census Bureau, St. Louis has a total area of 66 square miles (170 km2), of which 62 square miles (160 km2) is land and 4.1 square miles (11 km2) (6.2%) is water.[51] The city is built on bluffs and terraces that rise 100–200 feet above the western banks of the Mississippi River, in the Midwestern United States just south of the Missouri-Mississippi confluence. Much of the area is a fertile and gently rolling prairie that features low hills and broad, shallow valleys. Both the Mississippi River and the Missouri River have cut large valleys with wide flood plains.

Limestone and dolomite of the Mississippian epoch underlie the area, and parts of the city are karst in nature. This is particularly true of the area south of downtown, which has numerous sinkholes and caves. Most of the caves in the city have been sealed, but many springs are visible along the riverfront. Coal, brick clay, and millerite ore were once mined in the city. The predominant surface rock, known as St. Louis limestone, is used as dimension stone and rubble for construction.

Near the southern boundary of the city of St. Louis (separating it from St. Louis County) is the River des Peres, practically the only river or stream within the city limits that is not entirely underground.[52] Most of River des Peres was confined to a channel or put underground in the 1920s and early 1930s. The lower section of the river was the site of some of the worst flooding of the Great Flood of 1993.

The city's eastern boundary is the Mississippi River, which separates Missouri from Illinois. The Missouri River forms the northern line of St. Louis County, except for a few areas where the river has changed its course. The Meramec River forms most of its southern line.

Climate

The urban area of St. Louis has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen: Cfa); however, its metropolitan region even to the south may present a hot-summer humid continental climate (Dfa), which shows the effect of the urban heat island in the city. The city experiences hot, humid summers and chilly to cold winters. It is subject to both cold Arctic air and hot, humid tropical air from the Gulf of Mexico. The average annual temperature recorded at nearby Lambert–St. Louis International Airport, is 57.4 °F (14.1 °C). 100 and 0 °F (38 and −18 °C) temperatures can be seen on an average 3 and 1 days per year, respectively. Precipitation averages 41.70 inches (1,100 mm), but has ranged from 20.59 in (523 mm) in 1953 to 61.24 in (1,555 mm) in 2015. The highest recorded temperature in St. Louis was 115 °F (46 °C) on July 14, 1954, and the lowest was −22 °F (−30 °C) on January 5, 1884.

St. Louis experiences thunderstorms 48 days a year on average.[53] Especially in the spring, these storms can often be severe, with high winds, large hail and tornadoes. Lying within the hotbed of Tornado Alley, St. Louis is one of the most frequently tornado-struck metropolitan areas in the U.S. and has an extensive history of damaging tornadoes. Severe flooding, such as the Great Flood of 1993, may occur in spring and summer; the (often rapid) melting of thick snow cover upstream on the Missouri or Mississippi Rivers can contribute to springtime flooding.

| Climate data for St. Louis, Missouri (Lambert–St. Louis Int'l), 1991−2020 normals,[a] extremes 1874−present[b] |

|---|

Flora and fauna

Before the founding of the city, the area was mostly prairie and open forest. Native Americans maintained this environment, good for hunting, by burning underbrush. Trees are mainly oak, maple, and hickory, similar to the forests of the nearby Ozarks; common understory trees include eastern redbud, serviceberry, and flowering dogwood. Riparian areas are forested with mainly American sycamore.

Most of the residential areas of the city are planted with large native shade trees. The largest native forest area is found in Forest Park. In autumn, the changing color of the trees is notable. Most species here are typical of the eastern woodland, although numerous decorative non-native species are found. The most notable invasive species is Japanese honeysuckle, which officials are trying to manage because of its damage to native trees. It is removed from some parks.

Wildlife includes urbanized coyotes, white-tailed deer, eastern gray squirrel, cottontail rabbit, and the nocturnal Virginia opossum. Large bird species are abundant in parks and include Canada goose, mallard duck, and shorebirds, including the great egret and great blue heron. Gulls are common along the Mississippi River; these species follow barge traffic.

Winter populations of bald eagles are along the Mississippi River around the Chain of Rocks Bridge. The city is on the Mississippi Flyway, used by migrating birds, and has a large variety of small bird species, common to the eastern U.S. The Eurasian tree sparrow, an introduced species, is limited in North America to the counties surrounding St. Louis. The city has special sites for birdwatching of migratory species, including Tower Grove Park.

Common frog species include the American toad and species of chorus frogs called spring peepers, which are found in nearly every pond. Some years have outbreaks of cicadas or ladybugs. Mosquitoes, no-see-ums, and houseflies are common insect nuisances, especially in July and August; because of this, windows are almost always fitted with screens. Invasive populations of honeybees have declined in recent years. Numerous native species of pollinator insects have recovered to fill their ecological niche, and armadillos are throughout the St. Louis area.[59]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1810 | 1,600 | — | |

| 1830 | 4,977 | — | |

| 1840 | 16,469 | 230.9% | |

| 1850 | 77,860 | 372.8% | |

| 1860 | 160,773 | 106.5% | |

| 1870 | 310,864 | 93.4% | |

| 1880 | 350,518 | 12.8% | |

| 1890 | 451,770 | 28.9% | |

| 1900 | 575,238 | 27.3% | |

| 1910 | 687,029 | 19.4% | |

| 1920 | 772,897 | 12.5% | |

| 1930 | 821,960 | 6.3% | |

| 1940 | 816,048 | −0.7% | |

| 1950 | 856,796 | 5.0% | |

| 1960 | 750,026 | −12.5% | |

| 1970 | 622,236 | −17.0% | |

| 1980 | 453,805 | −27.1% | |

| 1990 | 396,685 | −12.6% | |

| 2000 | 348,189 | −12.2% | |

| 2010 | 319,294 | −8.3% | |

| 2020 | 301,578 | −5.5% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 281,754 | [9] | −6.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[60] 2020 Census[8] | |||

St. Louis grew slowly until the American Civil War, when industrialization and immigration sparked a boom. Mid-19th century immigrants included many Irish and Germans; later there were immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. In the early 20th century, African American and white migrants came from the South; the former as part of the Great Migration out of rural areas of the Deep South. Many came from Mississippi and Arkansas. Italians, Serbians, Lebanese, Syrians, and Greeks settled in St. Louis by the late 19th-Century.[61]

After years of immigration, migration, and expansion, the city reached its peak population in 1950. That year, the Census Bureau reported St. Louis's population as 82% White and 17.9% African American.[62] After World War II, St. Louis began losing population to the suburbs, first because of increased demand for new housing, unhappiness with city services, ease of commuting by highways, and later, white flight.[63] St. Louis's population decline has resulted in a significant increase of abandoned residential housing units and vacant lots throughout the city proper; this blight has attracted much wildlife (such as deer and coyotes) to the many abandoned overgrown lots.

St. Louis has lost 64.0% of its population since the 1950 United States census. Detroit, Michigan, and Youngstown, Ohio, are the only other cities that have had population declines of at least 60% in the same time frame. The population of the city of St. Louis has been in decline since the 1950 census; during this period the population of the St. Louis Metropolitan Area, which includes more than one county, has grown every year and continues to do so. A big factor in the decline has been the rapid increase in suburbanization.

According to the 2010 United States census, St. Louis had 319,294 people living in 142,057 households, of which 67,488 households were families. The population density was 5,158.2 people per square mile (1,991.6 people/km2). About 24% of the population was 19 or younger, 9% were 20 to 24, 31% were 25 to 44, 25% were 45 to 64, and 11% were 65 or older. The median age was about 34 years.

The African-American population is concentrated in the north side of the city (the area north of Delmar Boulevard is 94.0% black, compared with 35.0% in the central corridor and 26.0% in the south side of St. Louis[64]). Among the Asian-American population in the city, the largest ethnic group is Vietnamese (0.9%), followed by Chinese (0.6%) and Indians (0.5%). The Vietnamese community has concentrated in the Dutchtown neighborhood of south St. Louis; Chinese are concentrated in the Central West End.[65] People of Mexican descent are the largest Latino group, and make up 2.2% of St. Louis's population. They have the highest concentration in the Dutchtown, Benton Park West (Cherokee Street), and Gravois Park neighborhoods.[66] People of Italian descent are concentrated in The Hill.

In 2000, the median income for a household in the city was $29,156, and the median income for a family was $32,585. Males had a median income of $31,106; females, $26,987. Per capita income was $18,108.

Some 19% of the city's housing units were vacant, and slightly less than half of these were vacant structures not for sale or rent.

In 2010, St. Louis's per-capita rates of online charitable donations and volunteerism were among the highest among major U.S. cities.[67]

As of 2010[update], 91.05% (270,934) of St. Louis city residents age 5 and older spoke English at home as a primary language, while 2.86% (8,516) spoke Spanish, 0.91% (2,713) Serbo-Croatian, 0.74% (2,200) Vietnamese, 0.50% (1,495) African languages, 0.50% (1,481) Chinese, and French was spoken as a main language by 0.45% (1,341) of the population over the age of five. In total, 8.95% (26,628) of St. Louis's population age 5 and older spoke a mother language other than English.[68]

| Historical racial composition | 2020[69] | 2010[70] | 2000[71] | 1990[62] | 1970[62] | 1940[62] |

|---|

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[74] | Pop 2010[75] | Pop 2020[76] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 142,329 | 134,702 | 129,368 | 42.89% | 42.19% | 42.90% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 177,446 | 156,389 | 128,993 | 50.96% | 48.98% | 42.77% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 862 | 684 | 614 | 0.25% | 0.21% | 0.20% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 6,820 | 9,233 | 12,205 | 1.96% | 2.89% | 4.05% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 83 | 62 | 88 | 0.02% | 0.02% | 0.03% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 647 | 478 | 1,773 | 0.19% | 0.15% | 0.59% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 5,980 | 6,616 | 13,132 | 1.72% | 2.07% | 4.35% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 7,022 | 11,130 | 15,405 | 2.02% | 3.49% | 5.11% |

| Total | 348,189 | 319,294 | 301,578 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Bosnian population

About fifteen families from Bosnia settled in St. Louis between 1960 and 1970. After the Bosnian War started in 1992, more Bosnian refugees began arriving and by 2000, tens of thousands of Bosnian refugees settled in St. Louis with the help of Catholic aid societies. Many of them were professionals and skilled workers who had to take any job opportunity to be able to support their families. Most Bosnian refugees are Muslim, ethnically Bosniaks (87%); they have settled primarily in south St. Louis[77] and South County. Bosnian-Americans are well integrated into the city, developing many businesses and ethnic/cultural organizations.[78]

An estimated 70,000 Bosnians live in the metro area, which is tied with Chicago for largest population of Bosnians in the United States and the largest Bosnian population outside their homeland. The highest concentration of Bosnians is in the neighborhood of Bevo Mill and in Affton, Mehlville, and Oakville of south St. Louis County.[79][80]

Bosnian Muslim Romani people have also settled in St. Louis.[81]

Crime

Since 2014 the city of St. Louis has had, as of April 2017[update], one of the highest murder rates, per capita, in the United States,[82] with 188 homicides in 2015 (59.3 homicides per 100,000)[83][84] and ranks No. 13 of the most dangerous cities in the world by homicide rate. Detroit, Flint, Memphis, Birmingham, and Baltimore have higher overall violent crime rates than St. Louis, when comparing other crimes such as rape, robbery, and aggravated assault.[83][85] These crime rates are high relative to other American cities, but St. Louis index crime rates have declined almost every year since the peak in 1993 (16,648), to the 2014 level of 7,931 (which is the sum of violent crimes and property crimes) per 100,000. In 2015, the index crime rate reversed the 2005–2014 decline to a level of 8,204. Between 2005 and 2014, violent crime has declined by 20%, although rates of violent crime remains 6 times higher than the United States national average and property crime in the city remains 2 1⁄2 times the national average.[86] St. Louis has a higher homicide rate than the rest of the U.S. for both whites and blacks and a higher proportion committed by males. As of October 2016[update], 7 of the homicide suspects were white, 95 black, 0 Hispanic, 0 Asian and 1 female out of the 102 suspects. In 2016, St. Louis was the most dangerous city in the United States with populations of 100,000 or more, ranking 1st in violent crime and 2nd in property crime. It was also ranked 6th of the most dangerous of all establishments in the United States, and East St. Louis, a suburb of the city itself, was ranked 1st.[87][88] The St. Louis Police Department at the end of 2016 reported a total of 188 murders for the year, the same number of homicides that had occurred in the city in 2015.[89] According to the STLP At the end of 2017, St. Louis had 205 murders but the city recorded only 159 inside St. Louis city limits.[90][91] The new Chief of Police, John Hayden said two-thirds (67%) of all the murders and one-half of all the assaults are concentrated in a triangular area in the North part of the city.[90]

Yet another factor when comparing the murder rates of St. Louis and other cities is the manner of drawing municipal boundaries. While many other municipalities have annexed many suburbs, St. Louis has not annexed as much suburban area as most American cities. According to a 2018 estimate, the St. Louis metro area included about 3 million residents and the city included about 300,000 residents. Therefore, the city contains about ten percent of the metro population, a low ratio indicating that the municipal boundaries include only a small part of the metro population.[92]

Economy

The gross domestic product of Greater St. Louis was $209.9 billion in 2022, up from $192.9 billion the previous year.[17] Greater St. Louis had a GDP per capita of $68,574 in 2021, up 10% from the previous year.[93][94] In 2007, manufacturing in the city conducted nearly $11 billion in business, followed by the health care and social service industry with $3.5 billion; professional or technical services with $3.1 billion; and the retail trade with $2.5 billion. The health care sector was the area's biggest employer with 34,000 workers, followed by administrative and support jobs, 24,000; manufacturing, 21,000, and food service, 20,000.[95]

Major companies and institutions

As of 2022, the St. Louis Metropolitan Area is home to seven Fortune 500 companies. They include Centene, Emerson Electric, Reinsurance Group of America, Edward Jones, Olin, Graybar Electric, and Ameren.[96]

Other corporations headquartered in the region include Arch Coal, Bunge Limited, Wells Fargo Advisors (formerly A.G. Edwards), Energizer Holdings, Patriot Coal, Post Foods, United Van Lines, and Mayflower Transit, Post Holdings, Olin, Enterprise Holdings (a parent company of several car rental companies). Notable corporations with operations in St. Louis include Cassidy Turley, Kerry Group, Mastercard, TD Ameritrade, BMO Harris Bank, and World Wide Technology.

Health care and biotechnology institutions with operations in St. Louis include Pfizer, the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center, the Solae Company, Sigma-Aldrich, and Multidata Systems International. General Motors manufactures automobiles in Wentzville, while an earlier plant, known as the St. Louis Truck Assembly, built GMC automobiles from 1920 until 1987. Chrysler closed its St. Louis Assembly production facility in nearby Fenton, Missouri and Ford closed the St. Louis Assembly Plant in Hazelwood.

Several once-independent pillars of the local economy have been purchased by other corporations. Among them are Anheuser-Busch, purchased by Belgium-based InBev; Missouri Pacific Railroad, which was headquartered in St. Louis, merged with the Omaha, Nebraska-based Union Pacific Railroad in 1982;[97] McDonnell Douglas, whose operations are now part of Boeing Defense, Space & Security;[98] Trans World Airlines, which was headquartered in the city for its last decade of existence, prior to being acquired by American Airlines; Mallinckrodt, purchased by Tyco International; and Ralston Purina, now a wholly owned subsidiary of Nestlé.[99] The May Department Stores Company (which owned Famous-Barr and Marshall Field's stores) was purchased by Federated Department Stores, which has its regional headquarters in the area. The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis in downtown is one of two federal reserve banks in Missouri.[100] Most of the assets of Furniture Brands International were sold to Heritage Home Group in 2013, which moved to North Carolina.[101][102]

St. Louis is a center of medicine and biotechnology.[103] The Washington University School of Medicine is affiliated with Barnes-Jewish Hospital, the fifth largest hospital in the world. Both institutions operate the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center.[104] The School of Medicine also is affiliated with St. Louis Children's Hospital, one of the country's top pediatric hospitals.[105] Both hospitals are owned by BJC HealthCare. The McDonnell Genome Institute at Washington University played a major role in the Human Genome Project.[106] Saint Louis University Medical School is affiliated with SSM Health's Cardinal Glennon Children's Hospital and Saint Louis University Hospital. It also has a cancer center, vaccine research center, geriatric center, and a bioethics institute. Several different organizations operate hospitals in the area, including BJC HealthCare, Mercy, SSM Health Care, and Tenet.

Cortex Innovation Community in Midtown neighborhood is the largest innovation hub in the midwest. Cortex is home to offices of Square, Microsoft, Aon, Boeing, and Centene. Cortex has generated 3,800 tech jobs in 14 years. Once built out, projections are for it to make $2 billion in development and create 13,000 jobs for the region.[107]

Boeing has nearly 15,000 employees in its north St. Louis campus, headquarters to its defense unit. In 2013, the company said it would move about 600 jobs from Seattle, where labor costs have risen, to a new IT center in St. Louis.[108][109] Other companies, such as LaunchCode and LockerDome, think the city could become the next major tech hub.[110] Programs such as Arch Grants are attracting new startups to the region.[111]

According to the St. Louis Business Journal, the top employers in the St. Louis metropolitan area as of 1 April 2021[update], are:[112]

| # | Employer | # of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | BJC Health Care | 29,595 |

| 2 | Washington University | 18,805 |

| 3 | Mercy | 15,410 |

| 4 | Boeing Defense, Space & Security | 14,865 |

| 5 | SSM Health | 14,600 |

According to St. Louis's 2022 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report (June 30),[113] the top employers in the city only are (representing 82,481 people, or 18.74% of the city's total employment of 440,000):

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Washington University | 19,380 |

| 2 | Barnes Jewish Hospital | 18,920 |

| 3 | Saint Louis University | 9,152 |

| 4 | City of St. Louis | 7,033 |

| 5 | Defense Finance and Accounting Service | 6,051 |

| 6 | Wells Fargo Advisors | 5,801 |

| 7 | US Postal Service | 4,960 |

| 8 | St. Louis Board of Education | 4,131 |

| 9 | SSM SLUH | 3,983 |

| 9 | State of Missouri | 3,259 |

Arts and culture

The same year as the 1904 World's Fair, the Strassberger Music Conservatory Building was constructed at 2300 Grand. Otto Wilhelmi was the architect. In 1911, the conservatory had over 1,100 students.[114] The building is presently in the National Register of Historic Places.[115] A well known graduate was Alfonso D'Artega.[116]

With its French past and waves of Catholic immigrants in the 19th and 20th centuries, from Ireland, Germany and Italy, St. Louis is a major center of Roman Catholicism in the United States. St. Louis also boasts the largest Ethical Culture Society in the United States and is one of the most generous cities in the United States, ranking ninth in 2013.[117] Several places of worship in the city are noteworthy, such as the Cathedral Basilica of St. Louis, home of the world's largest mosaic installation.[118]

Other churches include the Basilica of St. Louis, King of France, the oldest Roman Catholic cathedral west of the Mississippi River and the oldest church in St. Louis; the St. Louis Abbey, whose distinctive architectural style garnered multiple awards at the time of its completion in 1962; and St. Francis de Sales Oratory, a neo-Gothic church completed in 1908 in South St. Louis and the second largest church in the city.

The city is identified with music and the performing arts, especially blues, jazz, and ragtime. The St. Louis Symphony is the second oldest symphony orchestra in the United States. Until 2010, it was also home to KFUO-FM, one of the oldest classical music FM radio stations west of the Mississippi River.[119] Opera Theatre of St. Louis has been called "one of America's best summer festivals" by the Washington Post. Former general director Timothy O'Leary was known for drawing the community into discussions of challenging operas. John Adams's "The Death of Klinghoffer", which touched off protests and controversy when performed by the Metropolitan Opera in 2014, had no such problems in St. Louis three years before, because the company fostered a citywide discussion, with interfaith dialogues addressing the tough issues of terrorism, religion and the nature of evil that the opera brings up. St. Louis's Jewish Community Relations Council gave O'Leary an award. Under O'Leary, the company—always known for innovative work—gave second chances to other major American operas, such as John Corigliano's "The Ghosts of Versailles", presented in 2009 in a smaller-scale version.[120]

The Gateway Arch anchors downtown St. Louis and a historic center that includes: the Federal courthouse where the Dred Scott case was first argued, an expanded public library, major churches and businesses, and retail. An increasing downtown residential population has taken to adapted office buildings and other historic structures. In nearby University City is the Delmar Loop, ranked by the American Planning Association as a "great American street" for its variety of shops and restaurants, and the Tivoli Theater, all within walking distance.

Unique city and regional cuisine reflecting various immigrant groups include toasted ravioli, gooey butter cake, provel cheese, the slinger, the Gerber sandwich, and the St. Paul sandwich. Some St. Louis chefs have begun emphasizing use of local produce, meats and fish, and neighborhood farmers' markets have become more popular. Artisan bakeries, salumeria, and chocolatiers also operate in the city.

St. Louis-style pizza has thin crust, provel cheese, and is cut in small squares.[121] Frozen-custard purveyor Ted Drewes offers its "Concrete": frozen custard blended with any combination of dozens of ingredients into a mixture so thick that a spoon inserted into the custard does not fall if the cup is inverted.[122]

Sports

St. Louis hosts the St. Louis Cardinals of Major League Baseball and the St. Louis Blues of the National Hockey League. In 2019, it became the eighth North American city to have won titles in all four major leagues (MLB, NBA, NFL, and NHL) when the Blues won the Stanley Cup championship. It has collegiate-level soccer teams and is one of three American cities to have hosted the Summer Olympic Games. A third major team, the St. Louis City SC of Major League Soccer, began play in 2023.

Professional sports

Pro teams in the St. Louis area include:

The St. Louis Cardinals are one of the most successful franchises in Major League Baseball.[123] The Cardinals have won 19 National League (NL) titles (the most pennants for the league franchise in one city) and 11 World Series titles (second to the New York Yankees and the most by any NL franchise), recently in 2011.[124] They play at Busch Stadium. Previously, the St. Louis Browns played in the American League (AL) from 1902 to 1953, before moving to Baltimore, Maryland to become the current incarnation of the Orioles. The 1944 World Series was an all-St. Louis World Series, matching up the St. Louis Cardinals and St. Louis Browns at Sportsman's Park, won by the Cardinals in six games. It was the third and final time that the teams shared a home field. St. Louis also was home to the St. Louis Stars (baseball), also known as the St. Louis Giants from 1906 to 1921, who played in the Negro league baseball from 1920 to 1931 and won championships in 1928, 1930, and 1931, and the St. Louis Maroons who played in the Union Association in 1884 and in the National League from 1885 to 1889. In 1884, The St. Louis Maroons won the Union Association pennant and started the season with 20 straight wins, a feat that was not surpassed by any major professional sports team in the United States until the 2015-16 Golden State Warriors season when they started their NBA season with 24 straight wins.

The St. Louis Blues of the National Hockey League (NHL) play at the Enterprise Center. They were one of the six teams added to the NHL in the 1967 expansion. The Blues went to the Stanley Cup finals in their first three years, but got swept every time. Although they were the first 1967 expansion team to make the Stanley Cup Finals, they were also the last of the 1967 expansion teams to win the Stanley Cup. They finally won their first Stanley Cup in 2019 after beating the Boston Bruins in the final. This championship made St. Louis the eighth city to win a championship in each of the four major U.S. sports. Prior to the Blues, the city was home to the St. Louis Eagles. The team played in the 1934–35 season.

St. Louis has been home to four National Football League (NFL) teams. The St. Louis All-Stars played in the city in 1923, the St. Louis Gunners in 1934, the St. Louis Cardinals from 1960 to 1987, and the St. Louis Rams from 1995 to 2015. The football Cardinals advanced to the NFL playoffs four times (1964, 1974, 1975 and 1982), never hosting in any appearance. They did, however, win the 1964 Playoff Bowl for third place against the Green Bay Packers by a score of 24–17. The Cardinals moved to Phoenix, Arizona, in 1988. The Rams played at the Edward Jones Dome from 1995 to 2015 and won Super Bowl XXXIV in 2000. They also went to Super Bowl XXXVI but lost to the New England Patriots. The Rams then returned to Los Angeles in 2016.

The St. Louis Hawks of the National Basketball Association (NBA) played at Kiel Auditorium from 1955 to 1968. They won the NBA championship in 1958 and played in three other NBA Finals: 1957, 1960, and 1961. In 1968 the Hawks moved to Atlanta. St. Louis was also the home to the St. Louis Bombers of the Basketball Association of America from 1946 to 1949 and the National Basketball Association from 1949 to 1950 and the Spirits of St. Louis of the American Basketball Association from 1974 to 1976 when the ABA and NBA merged.

Major League Soccer's St. Louis City SC began play in 2023 at CityPark. Their MLS Next Pro affiliate is St. Louis City SC 2, which began play in 2022 and also plays at CityPark. Formerly, USL Championship's Saint Louis FC played in the area from 2015 to 2020 at World Wide Technology Soccer Park.

The St. Louis BattleHawks of the XFL began play in 2020, using The Dome at America's Center as their home field. After a two-year hiatus of the league, the Battlehawks returned in 2023, when the XFL resumed play.

St. Louis hosts several minor league sports teams. The Gateway Grizzlies of the independent Frontier League play in the area in Sauget, IL. The St. Louis Trotters of the Independent Basketball Association play at Matthews-Dickey Boys and Girls Club. The St. Louis Ambush indoor soccer team plays in nearby St. Charles at the Family Arena as a part of the Major Arena Soccer League. The St. Louis Slam play in the Women's Football Alliance at Harlen C. Hunter Stadium.

The region hosts INDYCAR, NHRA drag racing, and NASCAR events at World Wide Technology Raceway at Gateway in Madison, Illinois. Thoroughbred flat racing events are hosted at Fairmount Park Racetrack near Collinsville, Illinois.

Amateur sports

St. Louis has hosted the Final Four of both the women's and men's college basketball NCAA Division I championship tournaments, and the Frozen Four collegiate ice hockey tournament. Saint Louis University has won 10 NCAA men's soccer championships, and the city has hosted the College Cup several times. In addition to collegiate soccer, many St. Louisans have played for the United States men's national soccer team, and 20 St. Louisans have been elected into the National Soccer Hall of Fame. St. Louis also is the origin of the sport of corkball, a type of baseball in which there is no base running.

Although the area does not have a National Basketball Association team, it hosts the St. Louis Phoenix, an American Basketball Association team.

Club Atletico Saint Louis, a semi-professional soccer team, competes within the National Premier Soccer League and plays out of St. Louis University High School Soccer Stadium.

Chess

St. Louis is home to the Saint Louis Chess Club where the U.S. Chess Championship is held. St. Louisan Rex Sinquefield founded the Chess Club and Scholastic Center of St. Louis (which was renamed as St. Louis Chess Club later) and moved the World Chess Hall of Fame to St. Louis in 2011. The Sinquefield Cup Tournament started at St. Louis in 2013. In 2014 the Sinquefield Cup was the highest-rated chess tournament of all time. Former U.S. Chess Champions Fabiano Caruana and Hikaru Nakamura have lived in St. Louis. Former women's chess champion Susan Polgar also resides in St. Louis.

Parks and recreation

The city operates more than 100 parks, with amenities that include sports facilities, playgrounds, concert areas, picnic areas, and lakes. Forest Park, located on the western edge of city, is the largest, occupying 1,400 acres of land, making it almost twice as large as Central Park in New York City.[49] The park is home to five major institutions, including the St. Louis Art Museum, the St. Louis Zoo, the St. Louis Science Center, the Missouri History Museum, and the Muny amphitheatre.[49] Another significant park in the city is Gateway Arch National Park, which was known as Jefferson National Expansion Memorial until 2018 and is located on the riverfront in downtown St. Louis. The centerpiece of the park is the 630-foot (192 m) tall Gateway Arch, a National Memorial designed by noted architect Eero Saarinen and completed on October 28, 1965. Also part of the historic park is the Old Courthouse, where the first two trials of Dred Scott v. Sandford were held in 1847 and 1850.

Other parks include the Missouri Botanical Garden, Tower Grove Park, Carondelet Park, and Citygarden. The Missouri Botanical Garden, a private garden and botanical research facility, is a National Historic Landmark and one of the oldest botanical gardens in the United States.[49] The Garden features 79 acres of horticultural displays from around the world. This includes a Japanese strolling garden, Henry Shaw's original 1850 estate home and a geodesic dome called the Climatron.[49] Immediately south of the Missouri Botanical Garden is Tower Grove Park, a gift to the city by Henry Shaw. Citygarden is an urban sculpture park located in downtown St. Louis, with art from Fernand Léger, Aristide Maillol, Julian Opie, Tom Otterness, Niki de Saint Phalle, and Mark di Suvero.[125][126] The park is divided into three sections, each of which represent a different theme: river bluffs; flood plains; and urban gardens. Another downtown sculpture park is the Serra Sculpture Park, with the 1982 Richard Serra sculpture Twain.[127]

Government

St. Louis is one of the 41 independent cities in the U.S. that does not legally belong to any county.[128] St. Louis has a strong mayor–council government with legislative authority and oversight vested in the Board of Aldermen and with executive authority in the mayor and six other elected officials.[129] The Board of Aldermen is made up of 28 members (one elected from each of the city's wards) plus a board president who is elected citywide.[130] The 2014 fiscal year budget topped $1 billion for the first time, a 1.9% increase over the $985.2 million budget in 2013.[131] 238,253 registered voters lived in the city in 2012,[132] down from 239,247 in 2010, and 257,442 in 2008.[133]

Structure

| Citywide office[134][135] | Elected official |

|---|---|

| Mayor of St. Louis | Tishaura Jones |

| President of the Board of Aldermen | Megan Green |

| City Comptroller | Darlene Green |

| Recorder of Deeds | Michael Butler |

| Collector of Revenue | Gregory F.X. Daly |

| License Collector | Mavis T. Thompson |

| Treasurer | Adam Layne |

| Circuit Attorney | Gabe Gore |

| Шериф города Сент-Луис | Вернон Беттс |

Мэр является главным исполнительным директором города и отвечает за назначение глав городских департаментов, в том числе; директор общественной безопасности, директор улиц и дорожного движения, директор здравоохранения, директор социальных служб, директор аэропорта, директор парков и зон отдыха, директор по развитию рабочей силы, директор Агентства общественного развития , директор экономического развития, директор коммунального хозяйства, директор Агентства по защите гражданских прав, регистратор и оценщик, а также другие должности на уровне департамента или высшие административные должности. Президент Совета старейшин - второй по рангу чиновник в городе. Президент является председателем Совета старейшин, который является законодательной ветвью власти города.

Муниципальные выборы в Сент-Луисе проводятся в нечетные годы: первичные выборы в марте, а всеобщие выборы в апреле. Мэр избирается через нечетные годы после президентских выборов в США с использованием первичного голосования по одобрению двух лучших кандидатов . [ 136 ] Олдермены, представляющие округа с нечетными номерами, могут быть избраны одновременно с мэром. Председатель совета олдерменов и олдермены четных округов избираются в нерабочие годы. Демократическая партия доминировала в городской политике Сент-Луиса на протяжении десятилетий. В городе не было мэра -республиканца с 1949 года, а последний раз республиканец избирался на другую общегородскую должность в 1970-х годах. По состоянию на 2015 год [update], все 28 городских олдерменов являются демократами. [ 137 ]

Пост мэра Сент-Луиса занимало сорок семь человек, четверо из которых — Уильям Карр Лейн , Джон Флетчер Дарби , Джон Уаймер и Джон Хау — избирались на срок непоследовательно. Наибольшее количество сроков мэра занимал Лейн, который отбыл 8 полных сроков плюс неистёкший срок Дарби. Нынешним мэром является Тишаура Джонс , вступившая в должность 20 апреля 2021 года и являющаяся первой афроамериканкой, занявшей этот пост. Она сменила Лиду Крюсон , первую женщину-мэра города, вышедшую на пенсию в 2021 году, прослужив на посту четыре года. Дольше всех прослужил мэром Фрэнсис Слэй , который вступил в должность 17 апреля 2001 года и покинул свой пост 18 апреля 2017 года, в общей сложности 16 лет и шесть дней за четыре срока пребывания в должности. Мэром, проработавшим меньше всего времени, был Артур Баррет , который умер через 11 дней после вступления в должность.

Хотя Сент-Луис отделился от округа Сент-Луис в 1876 году, были созданы некоторые механизмы для совместного управления финансированием и финансирования региональных активов. Район зоопарка-музея Сент-Луиса собирает налоги на недвижимость с жителей города и округа Сент-Луис, а средства используются для поддержки культурных учреждений, включая зоопарк Сент-Луиса , Художественный музей Сент-Луиса и Ботанический сад Миссури . Точно так же столичный канализационный округ обеспечивает услуги санитарной и ливневой канализации городу и большей части округа Сент-Луис. Агентство развития двух штатов (теперь известное как Metro) управляет региональной MetroLink системой легкорельсового транспорта и автобусной системой .

| Департамент шерифа города Сент-Луис | |

|---|---|

| |

| Аббревиатура | СТЛ-СО |

| Девиз | Профессионализм, честность, порядочность и смелость |

| Обзор агентства | |

| Сформированный | 1876 |

| Сотрудники | 216 |

| Годовой бюджет | 9 690 784 долларов США [2021 финансовый год] [ 138 ] |

| Юрисдикционная структура | |

| Юридическая юрисдикция | Сент-Луис, Миссури |

| Руководящий орган | 22-й судебный округ |

| Операционная структура | |

| Штаб-квартира | Здание гражданских судов , 10 N Tucker Blvd, 8-й этаж, Сент-Луис, Миссури, 63101 |

| Депутаты | 165 |

| руководитель агентства |

|

| Материнское агентство | Комитет общественной безопасности Совета старейшин , 22-й судебный округ |

| Подразделения | 5 |

| Удобства | |

| Центры правосудия | Центр правосудия города Сент-Луиса, бульвар С. Такер, 200, Сент-Луис, Миссури |

| Маркированные и немаркированные | Транспортные фургоны Ford, Транспортные фургоны Chevrolet, Полицейский перехватчик Ford |

| Самолеты | 0 |

Офис шерифа города Сент-Луис (STLSO или STLCSO) в первую очередь предоставляет услуги безопасности в залах суда, обслуживает судебные документы и выдает разрешения на ношение оружия. В 2022 году оно получило возможность производить аресты и остановки движения. [ 139 ]

Правительство штата и федеральное правительство

| Год | республиканец | Демократический | Третья сторона(а) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Нет. | % | Нет. | % | Нет. | % | |

| 2020 | 21,474 | 15.98% | 110,089 | 81.93% | 2,809 | 2.09% |

| 2016 | 20,832 | 15.72% | 104,235 | 78.68% | 7,420 | 5.60% |

| 2012 | 22,943 | 15.93% | 118,780 | 82.45% | 2,343 | 1.63% |

| 2008 | 24,662 | 15.50% | 132,925 | 83.55% | 1,517 | 0.95% |

| 2004 | 27,793 | 19.22% | 116,133 | 80.29% | 712 | 0.49% |

| 2000 | 24,799 | 19.88% | 96,557 | 77.40% | 3,396 | 2.72% |

| 1996 | 22,121 | 18.13% | 91,233 | 74.78% | 8,649 | 7.09% |

| 1992 | 25,441 | 17.26% | 102,356 | 69.44% | 19,607 | 13.30% |

| 1988 | 40,906 | 26.96% | 110,076 | 72.55% | 732 | 0.48% |

| 1984 | 61,020 | 35.20% | 112,318 | 64.80% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1980 | 50,333 | 29.48% | 113,697 | 66.59% | 6,721 | 3.94% |

| 1976 | 58,367 | 32.47% | 118,703 | 66.03% | 2,714 | 1.51% |

| 1972 | 72,402 | 37.67% | 119,817 | 62.33% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1968 | 58,252 | 26.37% | 143,010 | 64.74% | 19,652 | 8.90% |

| 1964 | 59,604 | 22.28% | 207,958 | 77.72% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 101,331 | 33.37% | 202,319 | 66.63% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1956 | 130,045 | 39.14% | 202,210 | 60.86% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1952 | 144,828 | 38.00% | 235,893 | 61.89% | 427 | 0.11% |

| 1948 | 120,656 | 35.10% | 220,654 | 64.19% | 2,460 | 0.72% |

| 1944 | 134,411 | 39.54% | 204,687 | 60.22% | 821 | 0.24% |

| 1940 | 168,165 | 41.79% | 233,338 | 57.98% | 948 | 0.24% |

| 1936 | 127,887 | 32.23% | 260,063 | 65.54% | 8,880 | 2.24% |

| 1932 | 123,448 | 34.57% | 226,338 | 63.38% | 7,319 | 2.05% |

| 1928 | 161,701 | 47.67% | 176,428 | 52.01% | 1,065 | 0.31% |

| 1924 | 139,433 | 52.70% | 95,888 | 36.24% | 29,276 | 11.06% |

| 1920 | 163,280 | 57.77% | 106,047 | 37.52% | 13,325 | 4.71% |

| 1916 | 83,798 | 51.72% | 74,059 | 45.71% | 4,175 | 2.58% |

| 1912 | 46,509 | 33.14% | 58,845 | 41.93% | 34,973 | 24.92% |

| 1908 | 74,160 | 52.76% | 60,917 | 43.34% | 5,473 | 3.89% |

| 1904 | 57,547 | 49.70% | 51,858 | 44.79% | 6,387 | 5.52% |

| 1900 | 60,597 | 48.64% | 59,931 | 48.11% | 4,046 | 3.25% |

| 1896 | 65,708 | 56.16% | 50,091 | 42.81% | 1,197 | 1.02% |

| 1892 | 35,528 | 49.94% | 34,669 | 48.73% | 942 | 1.32% |

| 1888 | 33,656 | 53.40% | 27,401 | 43.48% | 1,969 | 3.12% |

Сент-Луис разделен на 8 округов Палаты представителей штата Миссури : 76-й, 77-й, 78-й, 79-й, 80-й, 81-й, 82-й и 84-й округа. [ 141 ] 5-й округ Сената штата Миссури полностью находится в пределах города, а 4-й - совместно с округом Сент-Луис. [ 142 ]

На федеральном уровне Сент-Луис является центром 1-го избирательного округа штата Миссури , который также включает часть северного округа Сент-Луис. [ 143 ] Республиканец не представлял значительную часть Сент-Луиса в Палате представителей США с 1953 года. С 1928 года город перешел от голосования республиканцев к оплоту демократов на президентском уровне. Джордж Буш- старший в 1988 году был последним республиканцем, выигравшим хотя бы четверть голосов города на президентских выборах.

Апелляционный суд восьмого округа США и Окружной суд США Восточного округа штата Миссури расположены в здании суда США Томаса Ф. Иглтона в центре Сент-Луиса. В Сент-Луисе также находится филиал Федеральной резервной системы — Федеральный резервный банк Сент-Луиса . Национальное агентство геопространственной разведки (NGA) также поддерживает основные объекты в районе Сент-Луиса. [ 144 ]

Центр учета военного персонала (NPRC-MPR), расположенный по адресу 9700 Пейдж-авеню в Сент-Луисе, является филиалом Национального центра учета личного состава и хранилищем более 56 миллионов записей о военнослужащих и медицинских записей, касающихся пенсионеров, уволенных и военнослужащих. умершие ветераны вооруженных сил США. [ 145 ]

Образование

Колледжи и университеты

В городе расположены три национальных исследовательских университета: Вашингтонский университет в Сент-Луисе и Университет Сент-Луиса , входящие в Классификацию высших учебных заведений Карнеги . Медицинский факультет Вашингтонского университета в Сент-Луисе входит в десятку лучших медицинских школ страны по версии US News & World Report на протяжении всего времени, пока этот список публикуется, и занимает второе место в 2003 и 2004 годах . & World Report также включил бакалавриат и другие аспирантуры, такие как юридический факультет Вашингтонского университета , в двадцатку лучших в стране. [ 49 ] [ 146 ]

В столичном регионе Сент-Луиса находится Общественный колледж Сент-Луиса . Здесь также находится несколько других четырехлетних колледжей и университетов, в том числе Государственный университет Харриса-Стоу , исторически черный государственный университет , Университет Фонбонна, Университет Вебстера, Баптистский университет Миссури, Университет медицинских наук и фармации (бывший Колледж Сент-Луиса). Фармацевтика), Университет Южного Иллинойса в Эдвардсвилле (SIUE) и Университет Линденвуда.

Помимо католических богословских учреждений, таких как семинария Кенрика-Гленнона и теологический институт Аквинского , спонсируемых Орденом проповедников , в Сент-Луисе расположены три протестантские семинарии: Иденская теологическая семинария Объединенной церкви Христа , теологическая семинария Завета . Пресвитерианская Церковь в Америке и семинария Конкордия Лютеранской церкви в Сент-Луисе – Синод штата Миссури .

Начальные и средние школы

Государственные школы Сент-Луиса (SLPS), охватывающие весь город, [ 147 ] действуют более 75 школ, в которых обучаются более 25 000 учащихся, в том числе несколько магнитных школ . SLPS действует согласно предварительной аккредитации штата Миссури и находится под управлением назначенного государством школьного совета , называемого Специальным административным советом, хотя местный совет продолжает существовать без юридических полномочий над округом. С 2000 года чартерные школы в городе Сент-Луис действуют с разрешения законодательства штата Миссури. Эти школы спонсируются местными учреждениями или корпорациями и принимают учащихся от детского сада до средней школы. [ 148 ] Кроме того, в городе существует несколько частных школ, а Архиепископия Сент-Луиса управляет десятками приходских школ в городе, включая приходские средние школы. В городе также есть несколько частных средних школ, в том числе светские, Монтессори , католические и лютеранские школы . Средняя школа Университета Сент-Луиса — иезуитская подготовительная средняя школа, основанная в 1818 году, — старейшее среднее учебное заведение в США к западу от реки Миссисипи. [ 149 ] Государственная школа-интернат K-12 Missouri School for the Blind находится в Сент-Луисе.

СМИ

Большой Сент-Луис занимает 19-е место по величине медиа-рынка в Соединенных Штатах, и его положение практически не меняется уже более десяти лет. [ 150 ] Все основные телевизионные сети США имеют филиалы в Сент-Луисе, в том числе KTVI 2 ( Fox ), KMOV 4 ( CBS , с MyNetworkTV на DT2), KSDK 5 ( NBC ), KETC 9 ( PBS ), KPLR-TV 11 ( The CW ), KNLC 24 ( MeTV ), KDNL 30 ( ABC ), WRBU 46 ( Ion ) и WPXS 51 Daystar Television Network . Среди самых популярных радиостанций региона - KMOX (спортивные и ток-шоу AM, известная как давняя ведущая радиостанция для трансляций турнира St. Louis Cardinals), KLOU (старые FM-радио), WIL-FM (кантри-FM), WARH (хиты FM для взрослых), и KSLZ (мейнстрим FM Top 40). [ 151 ] Сент-Луис также поддерживает общественное радио KWMU , филиал NPR , и общественное радио KDHX . общеспортивные станции, такие как KFNS 590 AM «The Fan» и WXOS Также популярны «101.1 ESPN». KSHE 95 FM "Real Rock Radio" транслирует рок-музыку с ноября 1967 года - дольше, чем любая другая радиостанция в США.

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch - крупнейшая газета региона. Другие в регионе включают Suburban Journals , которые обслуживают некоторые части округа Сент-Луис, а основной альтернативной газетой является Riverfront Times . Афроамериканскому сообществу служат три еженедельника: St. Louis Argus , St. Louis American и St. Louis Sentinel . Журнал St. Louis Magazine , ежемесячный журнал, освещает такие темы, как местная история, кухня и образ жизни, а еженедельный журнал St. Louis Business Journal освещает региональные деловые новости. Сент-Луис обслуживался онлайн-газетой St. Louis Beacon , но в 2013 году это издание объединилось с KWMU . [ 152 ]

О Сент-Луисе написано множество книг и фильмов. Некоторые из наиболее влиятельных и выдающихся фильмов — « Встретимся в Сент-Луисе» и «Американские флаеры» . [ 153 ] и романы включают «Смертельный танец» , «Встретимся в Сент-Луисе» , «Сбежавшая душа» , «Роза старого Сент-Луиса » и «Цирк проклятых» .

Поскольку Сент-Луис был отличным местом для переезда иммигрантов, большая часть ранних социальных работ, изображающих жизнь иммигрантов, была основана на Сент-Луисе, например, в книге « Иммигрант в Сент-Луисе» .

Транспорт

Автомобильный , железнодорожный , морской и воздушный транспорт соединяют город с окружающими населенными пунктами Большого Сент-Луиса , национальными транспортными сетями и международными точками. Сент-Луис также поддерживает сеть общественного транспорта , включающую автобусы и легкорельсовый транспорт.

Дороги и шоссе

Четыре автомагистрали между штатами соединяют город с более крупной региональной системой автомагистралей. Межштатная автомагистраль 70 , шоссе с востока на запад, проходит от северо-западного угла города до центра Сент-Луиса . с севера на юг Межштатная автомагистраль 55 входит в город на юге, недалеко от района Каронделет , и идет к центру города, а межштатные автомагистрали 64 и 44 входят в город на западе, идя параллельно востоку. Две из четырех межштатных автомагистралей (межштатные автомагистрали 55 и 64) сливаются к югу от национального парка Гейтвей-Арк и покидают город по мосту на Поплар-стрит в Иллинойс, а межштатная автомагистраль 44 заканчивается на межштатной автомагистрали 70 на новой развязке возле N Бродвея и Касс-авеню. Небольшой Часть внешней автострады межштатной автомагистрали 270 проходит через северную часть города.

длиной 563 мили Авеню Святых связывает Сент-Луис с Сент-Полом, штат Миннесота .

Основные дороги включают Мемориал-драйв с севера на юг , расположенный на западной окраине национального парка Гейтвей-Арк и параллельно межштатной автомагистрали 70, улицы Гранд-Бульвара и Джефферсон-авеню с севера на юг , обе из которых проходят по всей длине города, и Гравуа. Дорога , которая проходит от юго-восточной части города до центра города и раньше обозначалась как US Route 66 . Дорога с востока на запад, которая соединяет город с окружающими населенными пунктами, - это улица Мартина Лютера Кинга-младшего , по которой осуществляется движение транспорта от западной окраины города к центру города.

Метро легкорельсового транспорта и метро

Столичный регион Сент-Луиса обслуживается компанией MetroLink (известной как Metro) и является 11-й по величине системой легкорельсового транспорта в стране с двухпутным легкорельсовым транспортом длиной 46 миль (74 км) . Красная и синяя ветка обслуживают все станции в центре города и разветвляются в разные пункты назначения за пределами пригородов. Обе линии входят в город к северу от Форест-парка на западной окраине города или по мосту Идс в центре Сент-Луиса до Иллинойса. Все пути системы имеют независимую полосу отвода: как наземные, так и подземные пути метро в городе. Все станции имеют отдельный вход, а все платформы находятся на одном уровне с поездами. Железнодорожное сообщение обеспечивается Агентством развития двух штатов (также известным как Metro), которое финансируется за счет налогов с продаж, взимаемых в городе и других округах региона. [ 154 ] действует Мультимодальный транспортный центр Gateway как узловая станция в городе Сент-Луис, соединяя городскую систему легкорельсового транспорта, местную автобусную систему, пассажирское железнодорожное сообщение и национальное автобусное сообщение. Он расположен к востоку от исторического величественного вокзала Сент-Луис Юнион .

Аэропорты