Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–1950)

German expellees, 1946 | |

| Date | 1944–1950 |

|---|---|

| Location | Eastern Europe |

| Deaths | 500,000 – 2.5 million |

| Displaced | 12–14.6 million |

|

| Flight and expulsion of Germans during and after World War II |

|---|

| (demographic estimates) |

| Background |

| Wartime flight and evacuation |

| Post-war flight and expulsion |

| Later emigration |

| Other themes |

| History of Germany |

|---|

|

During the later stages of World War II and the post-war period, Germans and Volksdeutsche fled and were expelled from various Eastern and Central European countries, including Czechoslovakia, and from the former German provinces of Lower and Upper Silesia, East Prussia, and the eastern parts of Brandenburg (Neumark) and Pomerania (Hinterpommern), which were annexed by Poland and the Soviet Union.

The idea to expel the Germans from the annexed territories had been proposed by Winston Churchill, in conjunction with the Polish and Czechoslovak exile governments in London at least since 1942.[1][2] Tomasz Arciszewski, the Polish prime minister in-exile, supported the annexation of German territory but opposed the idea of expulsion, wanting instead to naturalize the Germans as Polish citizens and to assimilate them.[3] Joseph Stalin, in concert with other Communist leaders, planned to expel all ethnic Germans from east of the Oder and from lands which from May 1945 fell inside the Soviet occupation zones.[4] In 1941, his government had already transported Germans from Crimea to Central Asia.

Between 1944 and 1948, millions of people, including ethnic Germans (Volksdeutsche) and German citizens (Reichsdeutsche), were permanently or temporarily moved from Central and Eastern Europe. By 1950, a total of about 12 million[5] Germans had fled or been expelled from east-central Europe into Allied-occupied Germany and Austria. The West German government put the total at 14.6 million,[6] including a million ethnic Germans who had settled in territories conquered by Nazi Germany during World War II, ethnic German migrants to Germany after 1950, and the children born to expelled parents. The largest numbers came from former eastern territories of Germany ceded to the People's Republic of Poland and the Soviet Union (about seven million),[7][8] and from Czechoslovakia (about three million).

The areas affected included the former eastern territories of Germany, which were annexed by Poland,[9][10] as well as the Soviet Union after the war and Germans who were living within the borders of the pre-war Second Polish Republic, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia, and the Baltic states. The Nazis had made plans—only partially completed before the Nazi defeat—to remove Jews and many Slavic people from Eastern Europe and settle the area with Germans.[11][12] The death toll attributable to the flight and expulsions is disputed, with estimates ranging from 500,000[13][14] up to 2.5 million according to the German government.[15][16][17]

The removals occurred in three overlapping phases, the first of which was the organized evacuation of ethnic Germans by the Nazi government in the face of the advancing Red Army, from mid-1944 to early 1945.[18] The second phase was the disorganised fleeing of ethnic Germans immediately following the Wehrmacht's surrender. The third phase was a more organised expulsion following the Allied leaders' Potsdam Agreement,[18] which redefined the Central European borders and approved expulsions of ethnic Germans from the former German territories transferred to Poland, Russia and Czechoslovakia.[19] Many German civilians were sent to internment and labour camps where they were used as forced labour as part of German reparations to countries in Eastern Europe.[20] The major expulsions were completed in 1950.[18] Estimates for the total number of people of German ancestry still living in Central and Eastern Europe in 1950 ranged from 700,000 to 2.7 million.

Background

[edit]

Before World War II, East-Central Europe generally lacked clearly delineated ethnic settlement areas. There were some ethnic-majority areas, but there were also vast mixed areas and abundant smaller pockets settled by various ethnicities. Within these areas of diversity, including the major cities of Central and Eastern Europe, people in various ethnic groups had interacted every day for centuries, while not always harmoniously, on every civic and economic level.[21]

With the rise of nationalism in the 19th century, the ethnicity of citizens became an issue[21] in territorial claims, the self-perception/identity of states, and claims of ethnic superiority. The German Empire introduced the idea of ethnicity-based settlement in an attempt to ensure its territorial integrity. It was also the first modern European state to propose population transfers as a means of solving "nationality conflicts", intending the removal of Poles and Jews from the projected post–World War I "Polish Border Strip" and its resettlement with Christian ethnic Germans.[22]

Following the collapse of Austria-Hungary, the Russian Empire, and the German Empire at the end of World War I, the Treaty of Versailles pronounced the formation of several independent states in Central and Eastern Europe, in territories previously controlled by these imperial powers. None of the new states were ethnically homogeneous.[23] After 1919, many ethnic Germans emigrated from the former imperial lands back to the Weimar Republic and the First Austrian Republic after losing their privileged status in those foreign lands, where they had maintained minority communities. In 1919 ethnic Germans became national minorities in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Yugoslavia, and Romania. In the following years, the Nazi ideology encouraged them to demand local autonomy. In Germany during the 1930s, Nazi propaganda claimed that Germans elsewhere were subject to persecution. Nazi supporters throughout eastern Europe (Czechoslovakia's Konrad Henlein, Poland's Deutscher Volksverband and Jungdeutsche Partei, Hungary's Volksbund der Deutschen in Ungarn) formed local Nazi political parties sponsored financially by the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs, e.g. by the Hauptamt Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle. However, by 1939 more than half of Polish Germans lived outside of the formerly German territories of Poland due to improving economic opportunities.[24]

Population movements

[edit]| Geographical region | West German estimate for 1939 | National Census data 1930–31 | Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poland (1939 borders) | 1,371,000[25] | 741,000[26] | 630,000 |

| Czechoslovakia | 3,477,000[25] | 3,232,000[27] | 245,000 |

| Romania | 786,000[25] | 745,000[28] | 41,000 |

| Yugoslavia | 536,800[25] | 500,000[29] | 36,800 |

| Hungary | 623,000[25] | 478,000[30] | 145,000 |

| Netherlands | 3,691[31] | 3,691[32] | 3,500 |

Notes:

- According to the national census figures the percentage of ethnic Germans in the total population was: Poland 2.3%; Czechoslovakia 22.3%; Hungary 5.5%; Romania 4.1% and Yugoslavia 3.6%.[33]

- The West German figures are the base used to estimate losses in the expulsions.[25]

- The West German figure for Poland is broken out as 939,000 monolingual German and 432,000 bi-lingual Polish/German.[34]

- The West German figure for Poland includes 60,000 in Trans-Olza which was annexed by Poland in 1938. In the 1930 census, this region was included in the Czechoslovak population.[34]

- A West German analysis of the wartime Deutsche Volksliste by Alfred Bohmann (de) put the number of Polish nationals in the Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany who identified themselves as German at 709,500 plus 1,846,000 Poles who were considered candidates for Germanisation. In addition, there were 63,000 Volksdeutsch in the General Government.[35] Martin Broszat cited a document with different Volksliste figures 1,001,000 were identified as Germans and 1,761,000 candidates for Germanisation.[36] The figures for the Deutsche Volksliste exclude ethnic Germans resettled in Poland during the war.

- The national census figures for Germans include German-speaking Jews. Poland (7,000)[37] Czech territory not including Slovakia (75,000)[38] Hungary 10,000,[39] Yugoslavia (10,000)[40]

During the Nazi German occupation, many citizens of German descent in Poland registered with the Deutsche Volksliste. Some were given important positions in the hierarchy of the Nazi administration, and some participated in Nazi atrocities, causing resentment towards German speakers in general. These facts were later used by the Allied politicians as one of the justifications for the expulsion of the Germans.[41] The contemporary position of the German government is that, while the Nazi-era war crimes resulted in the expulsion of the Germans, the deaths due to the expulsions were an injustice.[42]

During the German occupation of Czechoslovakia, especially after the reprisals for the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, most of the Czech resistance groups demanded that the "German problem" be solved by transfer/expulsion. These demands were adopted by the Czechoslovak government-in-exile, which sought the support of the Allies for this proposal, beginning in 1943.[43] The final agreement for the transfer of the Germans was not reached until the Potsdam Conference.

The expulsion policy was part of a geopolitical and ethnic reconfiguration of postwar Europe. In part, it was retribution for Nazi Germany's initiation of the war and subsequent atrocities and ethnic cleansing in Nazi-occupied Europe.[44][45] Allied leaders Franklin D. Roosevelt of the United States, Winston Churchill of the United Kingdom, and Joseph Stalin of the USSR, had agreed in principle before the end of the war that the border of Poland's territory would be moved west (though how far was not specified) and that the remaining ethnic German population were subject to expulsion. They assured the leaders of the émigré governments of Poland and Czechoslovakia, both occupied by Nazi Germany, of their support on this issue.[46][47][48][49]

Reasons and justifications for the expulsions

[edit]

Given the complex history of the affected regions and the divergent interests of the victorious Allied powers, it is difficult to ascribe a definitive set of motives to the expulsions. The respective paragraph of the Potsdam Agreement only states vaguely: "The Three Governments, having considered the question in all its aspects, recognize that the transfer to Germany of German populations, or elements thereof, remaining in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, will have to be undertaken. They agreed that any transfers that take place should be effected in an orderly and humane manner." The major motivations revealed were:

- A desire to create ethnically homogeneous nation-states: This is presented by several authors as a key issue that motivated the expulsions.[51][52][53][54][55][56]

- View of a German minority as potentially troublesome: From the Soviet perspective, shared by the communist administrations installed in Soviet-occupied Europe, the remaining large German populations outside postwar Germany were seen as a potentially troublesome 'fifth column' that would, because of its social structure, interfere with the envisioned Sovietisation of the respective countries.[57] The Western allies also saw the threat of a potential German 'fifth column', especially in Poland after the agreed-to compensation with former German territory.[51] In general, the Western allies hoped to secure a more lasting peace by eliminating the German minorities, which they thought could be done in a humane manner.[51][58] The proposals from the Polish and Czech governments-in-exile to expel ethnic Germans after the war received support from Winston Churchill[1] and Anthony Eden.[2]

- Another motivation was to punish the Germans:[51][53][56][59] the Allies declared them collectively guilty of German war crimes.[58][60][61][62]

- Soviet political considerations: Stalin saw the expulsions as a means of creating antagonism between Germany and its Eastern neighbors, who would thus need Soviet protection.[63] The expulsions served several practical purposes as well.

Ethnically homogeneous nation-state

[edit]

The creation of ethnically homogeneous nation states in Central and Eastern Europe[52] was presented as the key reason for the official decisions of the Potsdam and previous Allied conferences as well as the resulting expulsions.[53] The principle of every nation inhabiting its own nation state gave rise to a series of expulsions and resettlements of Germans, Poles, Ukrainians and others who after the war found themselves outside their supposed home states.[64][54] The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey lent legitimacy to the concept. Churchill cited the operation as a success in a speech discussing the German expulsions.[65][66]

In view of the desire for ethnically homogeneous nation-states, it did not make sense to draw borders through regions that were already inhabited homogeneously by Germans without any minorities. As early as 9 September 1944, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and Polish communist Edward Osóbka-Morawski of the Polish Committee of National Liberation signed a treaty in Lublin on population exchanges of Ukrainians and Poles living on the "wrong" side of the Curzon Line.[64][54] Many of the 2.1 million Poles expelled from the Soviet-annexed Kresy, so-called 'repatriants', were resettled to former German territories, then dubbed 'Recovered Territories'.[62] Czech Edvard Beneš, in his decree of 19 May 1945, termed ethnic Hungarians and Germans "unreliable for the state", clearing a way for confiscations and expulsions.[67]

View of German minorities as potential fifth columns

[edit]Distrust and enmity

[edit]

One of the reasons given for the population transfer of Germans from the former eastern territories of Germany was the claim that these areas had been a stronghold of the Nazi movement.[68] Neither Stalin nor the other influential advocates of this argument required that expellees be checked for their political attitudes or their activities. Even in the few cases when this happened and expellees were proven to have been bystanders, opponents or even victims of the Nazi regime, they were rarely spared from expulsion.[69] Polish Communist propaganda used and manipulated hatred of the Nazis to intensify the expulsions.[55]

With German communities living within the pre-war borders of Poland, there was an expressed fear of disloyalty of Germans in Eastern Upper Silesia and Pomerelia, based on wartime Nazi activities.[70] Created on order of Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, a Nazi ethnic German organisation called Selbstschutz carried out executions during Intelligenzaktion alongside operational groups of German military and police, in addition to such activities as identifying Poles for execution and illegally detaining them.[71]

To Poles, expulsion of Germans was seen as an effort to avoid such events in the future. As a result, Polish exile authorities proposed a population transfer of Germans as early as 1941.[71] The Czechoslovak government-in-exile worked with the Polish government-in-exile towards this end during the war.[72]

Preventing ethnic violence

[edit]The participants at the Potsdam Conference asserted that expulsions were the only way to prevent ethnic violence. As Winston Churchill expounded in the House of Commons in 1944, "Expulsion is the method which, insofar as we have been able to see, will be the most satisfactory and lasting. There will be no mixture of populations to cause endless trouble... A clean sweep will be made. I am not alarmed by the prospect of disentanglement of populations, not even of these large transferences, which are more possible in modern conditions than they have ever been before".[73]

Polish resistance fighter, statesman and courier Jan Karski warned President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1943 of the possibility of Polish reprisals, describing them as "unavoidable" and "an encouragement for all the Germans in Poland to go west, to Germany proper, where they belong."[74]

Punishment for Nazi crimes

[edit]

The expulsions were also driven by a desire for retribution, given the brutal way German occupiers treated non-German civilians in the German-occupied territories during the war. Thus, the expulsions were at least partly motivated by the animus engendered by the war crimes and atrocities perpetrated by the German belligerents and their proxies and supporters.[53][59] Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš, in the National Congress, justified the expulsions on 28 October 1945 by stating that the majority of Germans had acted in full support of Hitler; during a ceremony in remembrance of the Lidice massacre, he blamed all Germans as responsible for the actions of the German state.[60] In Poland and Czechoslovakia, newspapers,[75] leaflets and politicians across the political spectrum,[75][76] which narrowed during the post-war Communist take-over,[76] asked for retribution for wartime German activities.[75][76] Responsibility of the German population for the crimes committed in its name was also asserted by commanders of the late and post-war Polish military.[75]

Karol Świerczewski, commander of the Second Polish Army, briefed his soldiers to "exact on the Germans what they enacted on us, so they will flee on their own and thank God they saved their lives."[75]

In Poland, which had suffered the loss of six million citizens, including its elite and almost its entire Jewish population due to Lebensraum and the Holocaust, most Germans were seen as Nazi-perpetrators who could now finally be collectively punished for their past deeds.[62]

Soviet political considerations

[edit]Stalin, who had earlier directed several population transfers in the Soviet Union, strongly supported the expulsions, which worked to the Soviet Union's advantage in several ways. The satellite states would now feel the need to be protected by the Soviets from German anger over the expulsions.[63] The assets left by expellees in Poland and Czechoslovakia were successfully used to reward cooperation with the new governments, and support for the Communists was especially strong in areas that had seen significant expulsions. Settlers in these territories welcomed the opportunities presented by their fertile soils and vacated homes and enterprises, increasing their loyalty.[77]

Movements in the later stages of the war

[edit]Evacuation and flight to areas within Germany

[edit]

Late in the war, as the Red Army advanced westward, many Germans were apprehensive about the impending Soviet occupation.[78] Most were aware of the Soviet reprisals against German civilians.[79] Soviet soldiers committed numerous rapes and other crimes.[78][79][80] News of atrocities such as the Nemmersdorf massacre[78][79] were exaggerated and disseminated by the Nazi propaganda machine.[81]

Plans to evacuate the ethnic German population westward into Germany, from Poland and the eastern territories of Germany, were prepared by various Nazi authorities toward the end of the war. In most cases, implementation was delayed until Soviet and Allied forces had defeated the German forces and advanced into the areas to be evacuated. The abandonment of millions of ethnic Germans in these vulnerable areas until combat conditions overwhelmed them can be attributed directly to the measures taken by the Nazis against anyone suspected of 'defeatist' attitudes (as evacuation was considered) and the fanaticism of many Nazi functionaries in their execution of Hitler's 'no retreat' orders.[78][80][82]

The first exodus of German civilians from the eastern territories was composed of both spontaneous flight and organized evacuation, starting in mid-1944 and continuing until early 1945. Conditions turned chaotic during the winter when kilometers-long queues of refugees pushed their carts through the snow trying to stay ahead of the advancing Red Army.[18][83]

Refugee treks which came within reach of the advancing Soviets suffered casualties when targeted by low-flying aircraft, and some people were crushed by tanks.[79] The German Federal Archive has estimated that 100–120,000 civilians (1% of the total population) were killed during the flight and evacuations.[84] Polish historians Witold Sienkiewicz and Grzegorz Hryciuk maintain that civilian deaths in the flight and evacuation were "between 600,000 and 1.2 million. The main causes of death were cold, stress, and bombing."[85] The mobilized Strength Through Joy liner Wilhelm Gustloff was sunk in January 1945 by Soviet Navy submarine S-13, killing about 9,000 civilians and military personnel escaping East Prussia in the largest loss of life in a single ship sinking in history. Many refugees tried to return home when the fighting ended. Before 1 June 1945, 400,000 people crossed back over the Oder and Neisse rivers eastward, before Soviet and Polish communist authorities closed the river crossings; another 800,000 entered Silesia through Czechoslovakia.[86]

In accordance with the Potsdam Agreement, at the end of 1945—wrote Hahn & Hahn—4.5 million Germans who had fled or been expelled were under the control of the Allied governments. From 1946 to 1950 around 4.5 million people were brought to Germany in organized mass transports from Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary. An additional 2.6 million released POWs were listed as expellees.[87]

Evacuation and flight to Denmark

[edit]From the Baltic coast, many soldiers and civilians were evacuated by ship in the course of Operation Hannibal.[79][83]

Between 23 January and 5 May 1945, up to 250,000 Germans, primarily from East Prussia, Pomerania, and the Baltic states, were evacuated to Nazi-occupied Denmark,[88][89] based on an order issued by Hitler on 4 February 1945.[90] When the war ended, the German refugee population in Denmark amounted to 5% of the total Danish population. The evacuation focused on women, the elderly and children—a third of whom were under the age of fifteen.[89]

After the war, the Germans were interned in several hundred refugee camps throughout Denmark, the largest of which was the Oksbøl Refugee Camp with 37,000 inmates. The camps were guarded by Danish Defence units.[89] The situation eased after 60 Danish clergymen spoke in defence of the refugees in an open letter,[91] and Social Democrat Johannes Kjærbøl took over the administration of the refugees on 6 September 1945.[92] On 9 May 1945, the Red Army occupied the island of Bornholm; between 9 May and 1 June 1945, the Soviets shipped 3,000 refugees and 17,000 Wehrmacht soldiers from there to Kolberg.[93] In 1945, 13,492 German refugees died, among them 7,000 children[89] under five years of age.[94]

According to Danish physician and historian Kirsten Lylloff, these deaths were partially due to denial of medical care by Danish medical staff, as both the Danish Association of Doctors and the Danish Red Cross began refusing medical treatment to German refugees starting in March 1945.[89] The last refugees left Denmark on 15 February 1949.[95] In the Treaty of London, signed 26 February 1953, West Germany and Denmark agreed on compensation payments of 160 million Danish kroner for its extended care of the refugees, which West Germany paid between 1953 and 1958.[96]

Following Germany's defeat

[edit]The Second World War ended in Europe with Germany's defeat in May 1945. By this time, all of Eastern and much of Central Europe was under Soviet occupation. This included most of the historical German settlement areas, as well as the Soviet occupation zone in eastern Germany.

The Allies settled on the terms of occupation, the territorial truncation of Germany, and the expulsion of ethnic Germans from post-war Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary to the Allied Occupation Zones in the Potsdam Agreement,[97][98] drafted during the Potsdam Conference between 17 July and 2 August 1945. Article XII of the agreement is concerned with the expulsions to post-war Germany and reads:

The Three Governments, having considered the question in all its aspects, recognize that the transfer to Germany of German populations, or elements thereof, remaining in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary, will have to be undertaken. They agree that any transfers that take place should be effected in an orderly and humane manner.[99]

The agreement further called for equal distribution of the transferred Germans for resettlement among American, British, French and Soviet occupation zones comprising post–World War II Germany.[100]

Expulsions that took place before the Allies agreed on the terms at Potsdam are referred to as "irregular" expulsions (Wilde Vertreibungen). They were conducted by military and civilian authorities in Soviet-occupied post-war Poland and Czechoslovakia in the first half of 1945.[98][101]

In Yugoslavia, the remaining Germans were not expelled; ethnic German villages were turned into internment camps where over 50,000 perished from deliberate starvation and direct murders by Yugoslav guards.[100][102]

In late 1945 the Allies requested a temporary halt to the expulsions, due to the refugee problems created by the expulsion of Germans.[98] While expulsions from Czechoslovakia were temporarily slowed, this was not true in Poland and the former eastern territories of Germany.[100] Sir Geoffrey Harrison, one of the drafters of the cited Potsdam article, stated that the "purpose of this article was not to encourage or legalize the expulsions, but rather to provide a basis for approaching the expelling states and requesting them to co-ordinate transfers with the Occupying Powers in Germany."[100]

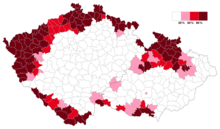

After Potsdam, a series of expulsions of ethnic Germans occurred throughout the Soviet-controlled Eastern European countries.[103][104] Property and materiel in the affected territory that had belonged to Germany or to Germans was confiscated; it was either transferred to the Soviet Union, nationalised, or redistributed among the citizens. Of the many post-war forced migrations, the largest was the expulsion of ethnic Germans from Central and Eastern Europe, primarily from the territory of 1937 Czechoslovakia (which included the historically German-speaking area in the Sudeten mountains along the German-Czech-Polish border (Sudetenland)), and the territory that became post-war Poland. Poland's post-war borders were moved west to the Oder-Neisse line, deep into former German territory and within 80 kilometers of Berlin.[98]

Polish refugees expelled from the Soviet Union were resettled in the former German territories that were awarded to Poland after the war. During and after the war, 2,208,000 Poles fled or were expelled from the former eastern Polish regions that were merged to the USSR after the 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland; 1,652,000 of these refugees were resettled in the former German territories.[105]

Czechoslovakia

[edit]The final agreement for the transfer of the Germans was reached at the Potsdam Conference.

According to the West German Schieder commission, there were 4.5 million German civilians present in Bohemia-Moravia in May 1945, including 100,000 from Slovakia and 1.6 million refugees from Poland.[107]

Between 700,000 and 800,000 Germans were affected by irregular expulsions between May and August 1945.[108] The expulsions were encouraged by Czechoslovak politicians and were generally executed by order of local authorities, mostly by groups of armed volunteers and the army.[109]

Transfers of population under the Potsdam agreements lasted from January until October 1946. 1.9 million ethnic Germans were expelled to the American zone, part of what would become West Germany. More than 1 million were expelled to the Soviet zone, which later became East Germany.[110]

About 250,000 ethnic Germans were allowed to remain in Czechoslovakia.[111] According to the West German Schieder commission 250,000 persons who had declared German nationality in the 1939 Nazi census remained in Czechoslovakia; however the Czechs counted 165,790 Germans remaining in December 1955.[112]Male Germans with Czech wives were expelled, often with their spouses, while ethnic German women with Czech husbands were allowed to stay.[113] According to the Schieder commission, Sudeten Germans considered essential to the economy were held as forced labourers.[114]

The West German government estimated the expulsion death toll at 273,000 civilians,[115] and this figure is cited in historical literature.[116] However, in 1995, research by a joint German and Czech commission of historians found that the previous demographic estimates of 220,000 to 270,000 deaths to be overstated and based on faulty information. They concluded that the death toll was between 15,000 and 30,000 dead, assuming that not all deaths were reported.[117][118][119][120]

The German Red Cross Search Service (Suchdienst) confirmed the deaths of 18,889 people during the expulsions from Czechoslovakia. (Violent deaths 5,556; Suicides 3,411; Deported 705; In camps 6,615; During the wartime flight 629; After wartime flight 1,481; Cause undetermined 379; Other misc. 73.)[121]

Hungary

[edit]

In contrast to expulsions from other nations or states, the expulsion of the Germans from Hungary was dictated from outside Hungary.[122] It began on 22 December 1944 when the Soviet Red Army Commander-in-Chief ordered the expulsions. In February 1945 the Soviet-dominated Allied Control Commission ordered the Hungarian Ministry of Interior to compile lists of all ethnic Germans living in the country. Initially the Census Bureau refused to divulge information on Hungarians who had registered as Volksdeutsche, but acceded under pressure from the Hungarian State Protection Authority.[123] Three percent of the German pre-war population (about 20,000 people) had been evacuated by the Volksbund before that. They went to Austria, but many had returned. Overall, 60,000 ethnic Germans had fled.[103]

According to the West German Schieder commission report of 1956, in early 1945 between 30 and 35,000 ethnic German civilians and 30,000 military POW were arrested and transported from Hungary to the Soviet Union as forced labourers. In some villages, the entire adult population was taken to labor camps in the Donbas. 6,000 died there as a result of hardships and ill-treatment.[124]

Data from the Russian archives, which were based on an actual enumeration, put the number of ethnic Germans registered by the Soviets in Hungary at 50,292 civilians, of whom 31,923 were deported to the USSR for reparation labor implementing Order 7161. 9% (2,819) were documented as having died.[125]

In 1945, official Hungarian figures showed 477,000 German speakers in Hungary, including German-speaking Jews, 303,000 of whom had declared German nationality. Of the German nationals, 33% were children younger than 12 or elderly people over 60; 51% were women.[126] On 29 December 1945, the postwar Hungarian Government, obeying the directions of the Potsdam Conference agreements, ordered the expulsion of anyone identified as German in the 1941 census, or who had been a member of the Volksbund, the SS, or any other armed German organisation. Accordingly, mass expulsions began.[103] The rural population was affected more than the urban population or those ethnic Germans determined to have needed skills, such as miners.[127][128] Germans married to Hungarians were not expelled, regardless of sex.[113] The first 5,788 expellees departed from Wudersch on 19 January 1946.[127]

About 180,000 German-speaking Hungarian citizens were stripped of their citizenship and possessions, and expelled to the Western zones of Germany.[129] By July 1948, 35,000 others had been expelled to the Soviet occupation zone of Germany.[129] Most of the expellees found new homes in the south-west German province of Baden-Württemberg,[130] but many others settled in Bavaria and Hesse. Other research indicates that, between 1945 and 1950, 150,000 were expelled to western Germany, 103,000 to Austria, and none to eastern Germany.[111] During the expulsions, numerous organized protest demonstrations by the Hungarian population took place.[131]

Acquisition of land for distribution to Hungarian refugees and nationals was one of the main reasons stated by the government for the expulsion of the ethnic Germans from Hungary.[128] The botched organization of the redistribution led to social tensions.[128]

22,445 people were identified as German in the 1949 census. An order of 15 June 1948 halted the expulsions. A governmental decree of 25 March 1950 declared all expulsion orders void, allowing the expellees to return if they so wished.[128] After the fall of Communism in the early 1990s, German victims of expulsion and Soviet forced labor were rehabilitated.[130] Post-Communist laws allowed expellees to be compensated, to return, and to buy property.[132] There were reportedly no tensions between Germany and Hungary regarding expellees.[132]

In 1958, the West German government estimated, based on a demographic analysis, that by 1950, 270,000 Germans remained in Hungary; 60,000 had been assimilated into the Hungarian population, and there were 57,000 "unresolved cases" that remained to be clarified.[133] The editor for the section of the 1958 report for Hungary was Wilfried Krallert, a scholar dealing with Balkan affairs since the 1930s when he was a Nazi Party member. During the war, he was an officer in the SS and was directly implicated in the plundering of cultural artifacts in eastern Europe. After the war, he was chosen to author the sections of the demographic report on the expulsions from Hungary, Romania, and Yugoslavia. The figure of 57,000 "unresolved cases" in Hungary is included in the figure of 2 million dead expellees, which is often cited in official German and historical literature.[116]

Netherlands

[edit]After World War II, the Dutch government decided to expel the German expatriates (25,000) living in the Netherlands.[134] Germans, including those with Dutch spouses and children, were labelled as "hostile subjects" ("vijandelijke onderdanen").[134]

The operation began on 10 September 1946 in Amsterdam, when German expatriates and their families were arrested at their homes in the middle of the night and given one hour to pack 50 kg (110 lb) of luggage. They were only allowed to take 100 guilders with them. The remainder of their possessions were seized by the state. They were taken to internment camps near the German border, the largest of which was Mariënbosch concentration camp, near Nijmegen. About 3,691 Germans (less than 15% of the total number of German expatriates in the Netherlands) were expelled. The Allied forces occupying the Western zone of Germany opposed this operation, fearing that other nations might follow suit.

Poland, including former German territories

[edit]

Throughout 1944 until May 1945, as the Red Army advanced through Eastern Europe and the provinces of eastern Germany, some German civilians were killed in the fighting. While many had already fled ahead of the advancing Soviet Army, frightened by rumors of Soviet atrocities, which in some cases were exaggerated and exploited by Nazi Germany's propaganda,[135] millions still remained.[136] A 2005 study by the Polish Academy of Sciences estimated that during the final months of the war, 4 to 5 million German civilians fled with the retreating German forces, and in mid-1945, 4.5 to 4.6 million Germans remained in the territories under Polish control. By 1950, 3,155,000 had been transported to Germany, 1,043,550 were naturalized as Polish citizens and 170,000 Germans still remained in Poland.[137]

According to the West German Schieder commission of 1953, 5,650,000 Germans remained in what would become Poland's new borders in mid-1945, 3,500,000 had been expelled and 910,000 remained in Poland by 1950.[138] According to the Schieder commission, the civilian death toll was 2 million;[139] in 1974, the German Federal Archives estimated the death toll at about 400,000.[140] (The controversy regarding the casualty figures is covered below in the section on casualties.)

During the 1945 military campaign, most of the male German population remaining east of the Oder–Neisse line were considered potential combatants and held by Soviet military in detention camps subject to verification by the NKVD. Members of Nazi party organizations and government officials were segregated and sent to the USSR for forced labour as reparations.[125][141]

In mid-1945, the eastern territories of pre-war Germany were turned over to the Soviet-controlled Polish military forces. Early expulsions were undertaken by the Polish Communist military authorities[142] even before the Potsdam Conference placed them under temporary Polish administration pending the final Peace Treaty,[143] in an effort to ensure later territorial integration into an ethnically homogeneous Poland.[144] The Polish Communists wrote: "We must expel all the Germans because countries are built on national lines and not on multinational ones."[145][146] The Polish government defined Germans as either Reichsdeutsche, people enlisted in first or second Volksliste groups; or those who held German citizenship. Around 1,165,000[147][148][149] German citizens of Slavic descent were "verified" as "autochthonous" Poles.[150] Of these, most were not expelled; but many[151][152] chose to migrate to Germany between 1951 and 1982,[153] including most of the Masurians of East Prussia.[154][155]

At the Potsdam Conference (17 July – 2 August 1945), the territory to the east of the Oder–Neisse line was assigned to Polish and Soviet Union administration pending the final peace treaty. All Germans had their property confiscated and were placed under restrictive jurisdiction.[150][156] The Silesian voivode Aleksander Zawadzki in part had already expropriated the property of the German Silesians on 26 January 1945, another decree of 2 March expropriated that of all Germans east of the Oder and Neisse, and a subsequent decree of 6 May declared all "abandoned" property as belonging to the Polish state.[157] Germans were also not permitted to hold Polish currency, the only legal currency since July, other than earnings from work assigned to them.[158] The remaining population faced theft and looting, and also in some instances rape and murder by the criminal elements, crimes that were rarely prevented nor prosecuted by the Polish Militia Forces and newly installed communist judiciary.[159]

In mid-1945, 4.5 to 4.6 million Germans resided in territory east of the Oder–Neisse Line. By early 1946, 550,000 Germans had already been expelled from there, and 932,000 had been verified as having Polish nationality. In the February 1946 census, 2,288,000 people were classified as Germans and subject to expulsion, and 417,400 were subject to verification action, to determine nationality.[137]: 312, 452–66 The negatively verified people, who did not succeed in demonstrating their "Polish nationality", were directed for resettlement.[105]

Those Polish citizens who had collaborated or were believed to have collaborated with the Nazis, were considered "traitors of the nation" and sentenced to forced labor prior to being expelled.[84] By 1950, 3,155,000 German civilians had been expelled and 1,043,550 were naturalized as Polish citizens. 170,000[105] Germans considered "indispensable" for the Polish economy were retained until 1956,[156] although almost all had left by 1960.[154] 200,000 Germans in Poland were employed as forced labor in communist-administered camps prior to being expelled from Poland.[137]: 312 These included Central Labour Camp Jaworzno, Central Labour Camp Potulice, Łambinowice and Zgoda labour camp. Besides these large camps, numerous other forced labor, punitive and internment camps, urban ghettos and detention centers, sometimes consisting only of a small cellar, were set up.[156]

The German Federal Archives estimated in 1974 that more than 200,000 German civilians were interned in Polish camps; they put the death rate at 20–50% and estimated that over 60,000 probably died.[160] Polish historians Witold Sienkiewicz and Grzegorz Hryciuk maintain that the internment:

resulted in numerous deaths, which cannot be accurately determined because of lack of statistics or falsification. At certain periods, they could be in the tens of percent of the inmate numbers. Those interned are estimated at 200–250,000 German nationals and the indigenous population and deaths might range from 15,000 to 60,000 persons."[161]

Note: The indigenous population were former German citizens who declared Polish ethnicity.[162] Historian R. M. Douglas describes a chaotic and lawless regime in the former German territories in the immediate postwar era. The local population was victimized by criminal elements who arbitrarily seized German property for personal gain. Bilingual people who were on the Volksliste during the war were declared Germans by Polish officials who then seized their property for personal gain.[163]

The Federal Statistical Office of Germany estimated that in mid-1945, 250,000 Germans remained in the northern part of the former East Prussia, which became the Kaliningrad Oblast. They also estimated that more than 100,000 people surviving the Soviet occupation were evacuated to Germany beginning in 1947.[164]

German civilians were held as "reparation labor" by the USSR. Data from the Russian archives, newly published in 2001 and based on an actual enumeration, put the number of German civilians deported from Poland to the USSR in early 1945 for reparation labor at 155,262; 37% (57,586) died in the USSR.[125] The West German Red Cross had estimated in 1964 that 233,000 German civilians were deported to the USSR from Poland as forced laborers and that 45% (105,000) were dead or missing.[165] The West German Red Cross estimated at that time that 110,000 German civilians were held as forced labor in the Kaliningrad Oblast, where 50,000 were dead or missing.[165] The Soviets deported 7,448 Poles of the Armia Krajowa from Poland. Soviet records indicated that 506 Poles died in captivity.[125] Tomasz Kamusella maintains that in early 1945, 165,000 Germans were transported to the Soviet Union.[166] According to Gerhardt Reichling, an official in the German Finance office, 520,000 German civilians from the Oder–Neisse region were conscripted for forced labor by both the USSR and Poland; he maintains that 206,000 perished.[167]

The attitudes of surviving Poles varied. Many had suffered brutalities and atrocities by the Germans, surpassed only by the German policies against Jews, during the Nazi occupation. The Germans had recently expelled more than a million Poles from territories they annexed during the war.[79] Some Poles engaged in looting and various crimes, including murders, beatings, and rapes against Germans. On the other hand, in many instances Poles, including some who had been made slave laborers by the Germans during the war, protected Germans, for instance by disguising them as Poles.[79] Moreover, in the Opole (Oppeln) region of Upper Silesia, citizens who claimed Polish ethnicity were allowed to remain, even though some, not all, had uncertain nationality, or identified as ethnic Germans. Their status as a national minority was accepted in 1955, along with state subsidies, with regard to economic assistance and education.[168]

The attitude of Soviet soldiers was ambiguous. Many committed atrocities, most notably rape and murder,[80] and did not always distinguish between Poles and Germans, mistreating them equally.[169] Other Soviets were taken aback by the brutal treatment of the German civilians and tried to protect them.[170]

Richard Overy cites an approximate total of 7.5 million Germans evacuated, migrated, or expelled from Poland between 1944 and 1950.[171] Tomasz Kamusella cites estimates of 7 million expelled in total during both the "wild" and "legal" expulsions from the recovered territories from 1945 to 1948, plus an additional 700,000 from areas of pre-war Poland.[156]

Romania

[edit]The ethnic German population of Romania in 1939 was estimated at 786,000.[172][173] In 1940, Bessarabia and Bukovina were occupied by the USSR, and the ethnic German population of 130,000 was deported to German-held territory during the Nazi–Soviet population transfers, as well as 80,000 from Romania. 140,000 of these Germans were resettled in German-occupied Poland; in 1945, they were caught up in the flight and expulsion from Poland.[174] Most of the ethnic Germans in Romania resided in Transylvania, the northern part of which was annexed by Hungary during World War II. The pro-German Hungarian government, as well as the pro-German Romanian government of Ion Antonescu, allowed Germany to enlist the German population in Nazi-sponsored organizations. During the war, 54,000 of the male population was conscripted by Nazi Germany, many into the Waffen-SS.[175] In mid-1944, roughly 100,000 Germans fled from Romania with the retreating German forces.[176] According to the West German Schieder commission report of 1957, 75,000 German civilians were deported to the USSR as forced labour and 15% (approximately 10,000) did not return.[177] Data from the Russian archives which were based on an actual enumeration put the number of ethnic Germans registered by the Soviets in Romania at 421,846 civilians, of whom 67,332 were deported to the USSR for reparation labour, where 9% (6,260) died.[125]

The roughly 400,000 ethnic Germans who remained in Romania were treated as guilty of collaboration with Nazi Germany [citation needed] and were deprived of their civil liberties and property.[citation needed] Many were impressed into forced labour and deported from their homes to other regions of Romania.[citation needed] In 1948, Romania began a gradual rehabilitation of the ethnic Germans: they were not expelled, and the communist regime gave them the status of a national minority, the only Eastern Bloc country to do so.[178]

In 1958, the West German government estimated, based on a demographic analysis, that by 1950, 253,000 were counted as expellees in Germany or the West, 400,000 Germans still remained in Romania, 32,000 had been assimilated into the Romanian population, and that there were 101,000 "unresolved cases" that remained to be clarified.[179] The figure of 101,000 "unresolved cases" in Romania is included in the total German expulsion dead of 2 million which is often cited in historical literature.[116] 355,000 Germans remained in Romania in 1977. During the 1980s, many began to leave, with over 160,000 leaving in 1989 alone. By 2002, the number of ethnic Germans in Romania was 60,000.[103][111]

Soviet Union and annexed territories

[edit]

The Baltic, Bessarabian and ethnic Germans in areas that became Soviet-controlled following the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 were resettled to Nazi Germany, including annexed areas like Warthegau, during the Nazi-Soviet population exchange. Only a few returned to their former homes when Germany invaded the Soviet Union and temporarily gained control of those areas. These returnees were employed by the Nazi occupation forces to establish a link between the German administration and the local population. Those resettled elsewhere shared the fate of the other Germans in their resettlement area.[180]

The ethnic German minority in the USSR was considered a security risk by the Soviet government, and they were deported during the war in order to prevent their possible collaboration with the Nazi invaders. In August 1941 the Soviet government ordered ethnic Germans to be deported from the European USSR, by early 1942, 1,031,300 Germans were interned in "special settlements" in Central Asia and Siberia.[181] Life in the special settlements was harsh and severe, food was limited, and the deported population was governed by strict regulations. Shortages of food plagued the whole Soviet Union and especially the special settlements. According to data from the Soviet archives, by October 1945, 687,300 Germans remained alive in the special settlements;[182] an additional 316,600 Soviet Germans served as labour conscripts during World War II. Soviet Germans were not accepted in the regular armed forces but were employed instead as conscript labour. The labor army members were arranged into worker battalions that followed camp-like regulations and received Gulag rations.[183] In 1945 the USSR deported to the special settlements 203,796 Soviet ethnic Germans who had been previously resettled by Germany in Poland.[184] These post-war deportees increased the German population in the special settlements to 1,035,701 by 1949.[185]

According to J. Otto Pohl, 65,599 Germans perished in the special settlements. He believes that an additional 176,352 unaccounted for people "probably died in the labor army".[186] Under Stalin, Soviet Germans continued to be confined to the special settlements under strict supervision, in 1955 they were rehabilitated but were not allowed to return to the European USSR.[187] The Soviet-German population grew despite deportations and forced labor during the war; in the 1939 Soviet census the German population was 1.427 million. By 1959 it had increased to 1.619 million.[188]

The calculations of the West German researcher Gerhard Reichling do not agree to the figures from the Soviet archives. According to Reichling a total of 980,000 Soviet ethnic Germans were deported during the war; he estimated that 310,000 died in forced labour.[189] During the early months of the invasion of the USSR in 1941 the Germans occupied the western regions of the USSR that had German settlements. A total of 370,000 ethnic Germans from the USSR were deported to Poland by Germany during the war. In 1945 the Soviets found 280,000 of these resettlers in Soviet-held territory and returned them to the USSR; 90,000 became refugees in Germany after the war.[189]

Those ethnic Germans who remained in the 1939 borders of the Soviet Union occupied by Nazi Germany in 1941 remained where they were until 1943, when the Red Army liberated Soviet territory and the Wehrmacht withdrew westward.[190] From January 1943, most of these ethnic Germans moved in treks to the Warthegau or to Silesia, where they were to settle.[191] Between 250,000 and 320,000 had reached Nazi Germany by the end of 1944.[192] On their arrival, they were placed in camps and underwent 'racial evaluation' by the Nazi authorities, who dispersed those deemed 'racially valuable' as farm workers in the annexed provinces, while those deemed to be of "questionable racial value" were sent to work in Germany.[192] The Red Army captured these areas in early 1945, and 200,000 Soviet Germans had not yet been evacuated by the Nazi authorities,[191] who were still occupied with their 'racial evaluation'.[192] They were regarded by the USSR as Soviet citizens and repatriated to camps and special settlements in the Soviet Union. 70,000 to 80,000 who found themselves in the Soviet occupation zone after the war were also returned to the USSR, based on an agreement with the Western Allies. The death toll during their capture and transportation was estimated at 15–30%, and many families were torn apart.[191] The special "German settlements" in the post-war Soviet Union were controlled by the Internal Affairs Commissioner, and the inhabitants had to perform forced labor until the end of 1955. They were released from the special settlements by an amnesty decree of 13 September 1955,[191] and the Nazi collaboration charge was revoked by a decree of 23 August 1964.[193] They were not allowed to return to their former homes and remained in the eastern regions of the USSR, and no individual's former property was restored.[191][193] Since the 1980s, the Soviet and Russian governments have allowed ethnic Germans to emigrate to Germany.

Different situations emerged in northern East Prussia regarding Königsberg (renamed Kaliningrad) and the adjacent Memel territory around Memel (Klaipėda). The Königsberg area of East Prussia was annexed by the Soviet Union, becoming an exclave of the Russian Soviet Republic. Memel was integrated into the Lithuanian Soviet Republic. Many Germans were evacuated from East Prussia and the Memel territory by Nazi authorities during Operation Hannibal or fled in panic as the Red Army approached. The remaining Germans were conscripted for forced labor. Ethnic Russians and the families of military staff were settled in the area. In June 1946, 114,070 Germans and 41,029 Soviet citizens were registered as living in the Kaliningrad Oblast, with an unknown number of unregistered Germans ignored. Between June 1945 and 1947, roughly half a million Germans were expelled.[194] Between 24 August and 26 October 1948, 21 transports with a total of 42,094 Germans left the Kaliningrad Oblast for the Soviet Occupation Zone. The last remaining Germans were expelled between November 1949[103] (1,401 people) and January 1950 (7).[195] Thousands of German children, called the "wolf children", had been left orphaned and unattended or died with their parents during the harsh winter without food. Between 1945 and 1947, around 600,000 Soviet citizens settled in the oblast.[194]

Yugoslavia

[edit]Before World War II, roughly 500,000 German-speaking people (mostly Danube Swabians) lived in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.[103][196] Most fled during the war or emigrated after 1950 thanks to the Displaced Persons Act of 1948; some were able to emigrate to the United States. During the final months of World War II a majority of the ethnic Germans fled Yugoslavia with the retreating Nazi forces.[196]

After the liberation, Yugoslav Partisans exacted revenge on ethnic Germans for the wartime atrocities of Nazi Germany, in which many ethnic Germans had participated, especially in the Banat area of the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia. The approximately 200,000 ethnic Germans remaining in Yugoslavia suffered persecution and sustained personal and economic losses. About 7,000 were killed as local populations and partisans took revenge for German wartime atrocities.[103][197] From 1945 to 1948 ethnic Germans were held in labour camps where about 50,000 perished.[197] Those surviving were allowed to emigrate to Germany after 1948.[197]

According to West German figures in late 1944 the Soviets transported 27,000 to 30,000 ethnic Germans, a majority of whom were women aged 18 to 35, to Ukraine and the Donbas for forced labour; about 20% (5,683) were reported dead or missing.[103][197][198] Data from Russian archives published in 2001, based on an actual enumeration, put the number of German civilians deported from Yugoslavia to the USSR in early 1945 for reparation labour at 12,579, where 16% (1,994) died.[199] After March 1945, a second phase began in which ethnic Germans were massed into villages such as Gakowa and Kruševlje that were converted into labour camps. All furniture was removed, straw placed on the floor, and the expellees housed like animals under military guard, with minimal food and rampant, untreated disease. Families were divided into the unfit women, old, and children, and those fit for slave labour. A total of 166,970 ethnic Germans were interned, and 48,447 (29%) perished.[102] The camp system was shut down in March 1948.[200]

In Slovenia, the ethnic German population at the end of World War II was concentrated in Slovenian Styria, more precisely in Maribor, Celje, and a few other smaller towns (like Ptuj and Dravograd), and in the rural area around Apače on the Austrian border. The second-largest ethnic German community in Slovenia was the predominantly rural Gottschee County around Kočevje in Lower Carniola, south of Ljubljana. Smaller numbers of ethnic Germans also lived in Ljubljana and in some western villages in the Prekmurje region. In 1931, the total number of ethnic Germans in Slovenia was around 28,000: around half of them lived in Styria and in Prekmurje, while the other half lived in the Gottschee County and in Ljubljana. In April 1941, southern Slovenia was occupied by Italian troops. By early 1942, ethnic Germans from Gottschee/Kočevje were forcefully transferred to German-occupied Styria by the new German authorities. Most resettled to the Posavje region (a territory along the Sava river between the towns of Brežice and Litija), from where around 50,000 Slovenes had been expelled. Gottschee Germans were generally unhappy about their forced transfer from their historical home region. One reason was that the agricultural value of their new area of settlement was perceived as much lower than the Gottschee area. As German forces retreated before the Yugoslav Partisans, most ethnic Germans fled with them in fear of reprisals. By May 1945, only a few Germans remained, mostly in the Styrian towns of Maribor and Celje. The Liberation Front of the Slovenian People expelled most of the remainder after it seized complete control in the region in May 1945.[200]

The Yugoslavs set up internment camps at Sterntal and Teharje. The government nationalized their property on a "decision on the transition of enemy property into state ownership, on state administration over the property of absent people, and on sequestration of property forcibly appropriated by occupation authorities" of 21 November 1944 by the Presidency of the Anti-Fascist Council for the People's Liberation of Yugoslavia.[200][201]

After March 1945, ethnic Germans were placed in so-called "village camps".[202] Separate camps existed for those able to work and for those who were not. In the latter camps, containing mainly children and the elderly, the mortality rate was about 50%. Most of the children under 14 were then placed in state-run homes, where conditions were better, though the German language was banned. These children were later given to Yugoslav families, and not all German parents seeking to reclaim their children in the 1950s were successful.[200]

West German government figures from 1958 put the death toll at 135,800 civilians.[203] A recent study published by the ethnic Germans of Yugoslavia based on an actual enumeration has revised the death toll down to about 58,000. A total of 48,447 people had died in the camps; 7,199 were shot by partisans, and another 1,994 perished in Soviet labour camps.[204] Those Germans still considered Yugoslav citizens were employed in industry or the military, but could buy themselves free of Yugoslav citizenship for the equivalent of three months' salary. By 1950, 150,000 of the Germans from Yugoslavia were classified as "expelled" in Germany, another 150,000 in Austria, 10,000 in the United States, and 3,000 in France.[200] According to West German figures 82,000 ethnic Germans remained in Yugoslavia in 1950.[111] After 1950, most emigrated to Germany or were assimilated into the local population.[189]

Kehl, Germany

[edit]The population of Kehl (12,000 people), on the east bank of the Rhine opposite Strasbourg, fled and was evacuated in the course of the Liberation of France, on 23 November 1944.[205] The French Army occupied the town in March 1945 and prevented the inhabitants from returning until 1953.[205][206]

Latin America

[edit]Fearing a Nazi Fifth Column, between 1941 and 1945 the US government facilitated the expulsion of 4,058 German citizens from 15 Latin American countries to internment camps in Texas and Louisiana. Subsequent investigations showed many of the internees to be harmless, and three-quarters of them were returned to Germany during the war in exchange for citizens of the Americas, while the remainder returned to their homes in Latin America.[207]

Palestine

[edit]At the start of World War II, colonists with German citizenship were rounded up by the British authorities and sent to internment camps in Bethlehem in Galilee. 661 Templers were deported to Australia via Egypt on 31 July 1941, leaving 345 in Palestine. Internment continued in Tatura, Victoria, Australia, until 1946–47. In 1962 the State of Israel paid 54 million Deutsche Marks in compensation to property owners whose assets were nationalized.[208]

Human losses

[edit]Estimates of total deaths of German civilians in the flight and expulsions, including forced labour of Germans in the Soviet Union, range from 500,000 to a maximum of 3 million people.[209] Although the German government's official estimate of deaths has stood at 2 million since the 1960s, the publication in 1987–89 of previously classified West German studies has led some historians to the conclusion that the actual number was much lower—in the range of 500,000–600,000. English-language sources have put the death toll at 2–3 million based on West German government figures from the 1960s.[210][211][212][213][214][215][216][217][218][219]

West German government estimates of the death toll

[edit]- In 1950 the West German Government made a preliminary estimate of 3.0 million missing people (1.5 million in prewar Germany and 1.5 million in Eastern Europe) whose fate needed to be clarified.[220] These figures were superseded by the publication of the 1958 study by the Statistisches Bundesamt.

- In 1953 the West German government ordered a survey by the Suchdienst (search service) of the German churches to trace the fate of 16.2 million people in the area of the expulsions; the survey was completed in 1964 but kept secret until 1987. The search service was able to confirm 473,013 civilian deaths; there were an additional 1,905,991 cases of persons whose fate could not be determined.[221]

- From 1954 to 1961 the Schieder commission issued five reports on the flight and expulsions. The head of the commission Theodor Schieder was a rehabilitated former Nazi party member who was involved in the preparation of the Nazi Generalplan Ost to colonize eastern Europe. The commission estimated a total death toll of about 2.3 million civilians including 2 million east of the Oder Neisse line.[222]

- The figures of the Schieder commission were superseded by the publication in 1958 of the study by the West German government Statistisches Bundesamt, Die deutschen Vertreibungsverluste (The German Expulsion Casualties). The authors of the report included former Nazi party members, de:Wilfried Krallert, Walter Kuhn and de:Alfred Bohmann. The Statistisches Bundesamt put losses at 2,225,000 (1.339 million in prewar Germany and 886,000 in Eastern Europe).[223] In 1961 the West German government published slightly revised figures that put losses at 2,111,000 (1,225,000 in prewar Germany and 886,000 in Eastern Europe)[224]

- In 1969, the federal West German government ordered a further study to be conducted by the German Federal Archives, which was finished in 1974 and kept secret until 1989. The study was commissioned to survey crimes against humanity such as deliberate killings, which according to the report included deaths caused by military activity in the 1944–45 campaign, forced labor in the USSR and civilians kept in post-war internment camps. The authors maintained that the figures included only those deaths caused by violent acts and inhumanities (Unmenschlichkeiten) and do not include post-war deaths due to malnutrition and disease. Also not included are those who were raped or suffered mistreatment and did not die immediately. They estimated 600,000 deaths (150,000 during flight and evacuations, 200,000 as forced labour in the USSR and 250,000 in post-war internment camps. By region 400,000 east of the Oder Neisse line, 130,000 in Czechoslovakia and 80,000 in Yugoslavia). No figures were given for Romania and Hungary.[225]

- A 1986 study by Gerhard Reichling "Die deutschen Vertriebenen in Zahlen" (the German expellees in figures) concluded 2,020,000 ethnic Germans perished after the war including 1,440,000 as a result of the expulsions and 580,000 deaths due to deportation as forced labourers in the Soviet Union. Reichling was an employee of the Federal Statistical Office who was involved in the study of German expulsion statistics since 1953.[226] The Reichling study is cited by the German government to support their estimate of 2 million expulsion deaths[17]

Discourse

[edit]The West German figure of 2 million deaths in the flight and expulsions was widely accepted by historians in the West prior to the fall of communism in Eastern Europe and the end of the Cold War.[210][211][212][213][214][219][227][216][228][229] The recent disclosure of the German Federal Archives study and the Search Service figures have caused some scholars in Germany and Poland to question the validity of the figure of 2 million deaths; they estimate the actual total at 500–600,000.[230][231][232]

The German government continues to maintain that the figure of 2 million deaths is correct.[233] The issue of the "expellees" has been a contentious one in German politics, with the Federation of Expellees staunchly defending the higher figure.[234]

Analysis by Rüdiger Overmans

[edit]In 2000 the German historian Rüdiger Overmans published a study of German military casualties; his research project did not investigate civilian expulsion deaths.[235] In 1994, Overmans provided a critical analysis of the previous studies by the German government which he believes are unreliable. Overmans maintains that the studies of expulsion deaths by the German government lack adequate support; he maintains that there are more arguments for the lower figures than for the higher figures. ("Letztlich sprechen also mehr Argumente für die niedrigere als für die höhere Zahl.")[209]

In a 2006 interview, Overmans maintained that new research is needed to clarify the fate of those reported as missing.[236] He found the 1965 figures of the Search Service to be unreliable because they include non-Germans; the figures according to Overmans include military deaths; the numbers of surviving people, natural deaths and births after the war in Eastern Europe are unreliable because the Communist governments in Eastern Europe did not extend full cooperation to West German efforts to trace people in Eastern Europe; the reports given by eyewitnesses surveyed are not reliable in all cases. In particular, Overmans maintains that the figure of 1.9 million missing people was based on incomplete information and is unreliable.[237] Overmans found the 1958 demographic study to be unreliable because it inflated the figures of ethnic German deaths by including missing people of doubtful German ethnic identity who survived the war in Eastern Europe; the figures of military deaths is understated; the numbers of surviving people, natural deaths and births after the war in Eastern Europe are unreliable because the Communist governments in Eastern Europe did not extend full cooperation to West German efforts to trace people in Eastern Europe.[209]

Overmans maintains that the 600,000 deaths found by the German Federal Archives in 1974 is only a rough estimate of those killed, not a definitive figure. He pointed out that some deaths were not reported because there were no surviving eyewitnesses of the events; also there was no estimate of losses in Hungary, Romania and the USSR.[238]

Overmans conducted a research project that studied the casualties of the German military during the war and found that the previous estimate of 4.3 million dead and missing, especially in the final stages of the war, was about one million short of the actual toll. In his study Overmans researched only military deaths; his project did not investigate civilian expulsion deaths; he merely noted the difference between the 2.2 million dead estimated in the 1958 demographic study, of which 500,000 have so far have been verified.[239] He found that German military deaths from areas in Eastern Europe were about 1.444 million, and thus 334,000 higher than the 1.1 million figure in the 1958 demographic study, lacking documents available today included the figures with civilian deaths. Overmans believes this will reduce the number of civilian deaths in the expulsions. Overmans further pointed out that the 2.225 million number estimated by the 1958 study would imply that the casualty rate among the expellees was equal to or higher than that of the military, which he found implausible.[240]

Analysis by historian Ingo Haar

[edit]In 2006, Haar called into question the validity of the official government figure of 2 million expulsion deaths in an article in the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung.[241] Since then Haar has published three articles in academic journals that covered the background of the research by the West German government on the expulsions.[242][243][244][245]

Haar maintains that all reasonable estimates of deaths from expulsions lie between around 500,000 and 600,000, based on the information of Red Cross Search Service and German Federal Archives. Harr pointed out that some members of the Schieder commission and officials of the Statistisches Bundesamt involved in the study of the expulsions were involved in the Nazi plan to colonize Eastern Europe. Haar posits that figures have been inflated in Germany due to the Cold War and domestic German politics, and he maintains that the 2.225 million number relies on improper statistical methodology and incomplete data, particularly in regard to the expellees who arrived in East Germany. Haar questions the validity of population balances in general. He maintains that 27,000 German Jews who were Nazi victims are included in the West German figures. He rejects the statement by the German government that the figure of 500–600,000 deaths omitted those people who died of disease and hunger, and has stated that this is a "mistaken interpretation" of the data. He maintains that deaths due to disease, hunger and other conditions are already included in the lower numbers. According to Haar the numbers were set too high for decades, for postwar political reasons.[245][246][247][248]

Studies in Poland

[edit]In 2001, Polish researcher Bernadetta Nitschke puts total losses for Poland at 400,000 (the same figure as the German Federal Archive study). She noted that historians in Poland have maintained that most of the deaths occurred during the flight and evacuation during the war, the deportations to the USSR for forced labour and, after the resettlement, due to the harsh conditions in the Soviet occupation zone in postwar Germany.[249] Polish demographer Piotr Eberhardt found that, "Generally speaking, the German estimates... are not only highly arbitrary, but also clearly tendentious in presentation of the German losses." He maintains that the German government figures from 1958 overstated the total number of the ethnic Germans living in Poland prior to the war as well as the total civilian deaths due to the expulsions. For example, Eberhardt points out that "the total number of Germans in Poland is given as equal to 1,371,000. According to the Polish census of 1931, there were altogether only 741,000 Germans in the entire territory of Poland."[8]

Study by Hans Henning Hahn and Eva Hahn

[edit]German historians Hans Henning Hahn and Eva Hahn published a detailed study of the flight and expulsions that is sharply critical of German accounts of the Cold War era. The Hahns regard the official German figure of 2 million deaths as an historical myth, lacking foundation. They place the ultimate blame for the mass flight and expulsion on the wartime policy of the Nazis in Eastern Europe. The Hahns maintain that most of the reported 473,013 deaths occurred during the Nazi organized flight and evacuation during the war, and the forced labor of Germans in the Soviet Union; they point out that there are 80,522 confirmed deaths in the postwar internment camps. They put the postwar losses in eastern Europe at a fraction of the total losses: Poland- 15,000 deaths from 1945 to 1949 in internment camps; Czechoslovakia- 15,000–30,000 dead, including 4,000–5,000 in internment camps and ca. 15,000 in the Prague uprising; Yugoslavia- 5,777 deliberate killings and 48,027 deaths in internment camps; Denmark- 17,209 dead in internment camps; Hungary and Romania - no postwar losses reported. The Hahns point out that the official 1958 figure of 273,000 deaths for Czechoslovakia was prepared by Alfred Bohmann, a former Nazi Party member who had served in the wartime SS. Bohmann was a journalist for an ultra-nationalist Sudeten-Deutsch newspaper in postwar West Germany. The Hahns believe the population figures of ethnic Germans for eastern Europe include German-speaking Jews killed in the Holocaust.[250] They believe that the fate of German-speaking Jews in Eastern Europe deserves the attention of German historians. ("Deutsche Vertreibungshistoriker haben sich mit der Geschichte der jüdischen Angehörigen der deutschen Minderheiten kaum beschäftigt.")[250]

German and Czech commission of historians

[edit]In 1995, research by a joint German and Czech commission of historians found that the previous demographic estimates of 220,000 to 270,000 deaths in Czechoslovakia to be overstated and based on faulty information. They concluded that the death toll was at least 15,000 people and that it could range up to a maximum of 30,000 dead, assuming that not all deaths were reported.[117]

Rebuttal by the German government

[edit]The German government maintains that the figure of 2–2.5 million expulsion deaths is correct. In 2005 the German Red Cross Search Service put the death toll at 2,251,500 but did not provide details for this estimate.[251]

On 29 November 2006, State Secretary in the German Federal Ministry of the Interior, Christoph Bergner, outlined the stance of the respective governmental institutions on Deutschlandfunk (a public-broadcasting radio station in Germany) saying that the numbers presented by the German government and others are not contradictory to the numbers cited by Haar and that the below 600,000 estimate comprises the deaths directly caused by atrocities during the expulsion measures and thus only includes people who were raped, beaten, or else killed on the spot, while the above two million estimate includes people who on their way to postwar Germany died of epidemics, hunger, cold, air raids and the like.[252]

Schwarzbuch der Vertreibung by Heinz Nawratil

[edit]A German lawyer, Heinz Nawratil, published a study of the expulsions entitled Schwarzbuch der Vertreibung ("Black Book of Expulsion").[253] Nawratil claimed the death toll was 2.8 million: he includes the losses of 2.2 million listed in the 1958 West German study, and an estimated 250,000 deaths of Germans resettled in Poland during the war, plus 350,000 ethnic Germans in the USSR. In 1987, German historian Martin Broszat (former head of the Institute of Contemporary History in Munich) described Nawratil's writings as "polemics with a nationalist-rightist point of view and exaggerates in an absurd manner the scale of 'expulsion crimes'." Broszat found Nawratil's book to have "factual errors taken out of context."[254][255] German historian Thomas E. Fischer calls the book "problematic".[256] James Bjork (Department of History, King's College London) has criticized German educational DVDs based on Nawratil's book.[257]

Condition of the expellees after arriving in post-war Germany

[edit]

Those who arrived were in bad condition—particularly during the harsh winter of 1945–46, when arriving trains carried "the dead and dying in each carriage (other dead had been thrown from the train along the way)".[258] After experiencing Red Army atrocities, Germans in the expulsion areas were subject to harsh punitive measures by Yugoslav partisans and in post-war Poland and Czechoslovakia.[259] Beatings, rapes and murders accompanied the expulsions.[258][259] Some had experienced massacres, such as the Ústí (Aussig) massacre, in which 80–100 ethnic Germans died, or Postoloprty massacre, or conditions like those in the Upper Silesian Camp Łambinowice (Lamsdorf), where interned Germans were exposed to sadistic practices and at least 1,000 died.[259] Many expellees had experienced hunger and disease, separation from family members, loss of civil rights and familiar environment, and sometimes internment and forced labour.[259]

Once they arrived, they found themselves in a country devastated by war. Housing shortages lasted until the 1960s, which along with other shortages led to conflicts with the local population.[260][261] The situation eased only with the West German economic boom in the 1950s that drove unemployment rates close to zero.[262]

France did not participate in the Potsdam Conference, so it felt free to approve some of the Potsdam Agreements and dismiss others. France maintained the position that it had not approved the expulsions and therefore was not responsible for accommodating and nourishing the destitute expellees in its zone of occupation. While the French military government provided for the few refugees who arrived before July 1945 in the area that became the French zone, it succeeded in preventing entrance by later-arriving ethnic Germans deported from the East.[263]

Britain and the US protested against the actions of the French military government but had no means to force France to bear the consequences of the expulsion policy agreed upon by American, British and Soviet leaders in Potsdam. France persevered with its argument to clearly differentiate between war-related refugees and post-war expellees. In December 1946 it absorbed into its zone German refugees from Denmark,[263] where 250,000 Germans had traveled by sea between February and May 1945 to take refuge from the Soviets. These were refugees from the eastern parts of Germany, not expellees; Danes of German ethnicity remained untouched and Denmark did not expel them. With this humanitarian act the French saved many lives, due to the high death toll German refugees faced in Denmark.[264][265][266]

Until mid-1945, the Allies had not reached an agreement on how to deal with the expellees. France suggested immigration to South America and Australia and the settlement of 'productive elements' in France, while the Soviets' SMAD suggested a resettlement of millions of expellees in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.[267]