Синд

| Part of a series on |

| Sindhis |

|---|

|

Sindh portal |

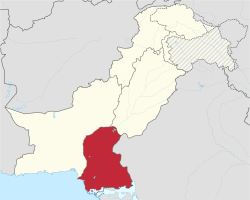

Sindh ( / ˈ s ɪ n d / ae Sindhi; Сунна ; Урду : Сенда , произносится [sɪndʱə] ; Аббр SD , исторически романизированный как Синд является провинцией Пакистан ) , . Расположенный в юго-восточном регионе страны, Синд является третьей по величине провинцией Пакистана по суше и второй по величине провинцией по населению после Пенджаба . Он граничит с провинциями Белуджистана пакистанскими на западе и северо-западе и Пенджабом на севере. Он разделяет международную границу с штатами Гуджарат индийскими и Раджастханом на востоке; Он также ограничен Аравийским морем на юге. Пейзаж Синда состоит в основном из аллювиальных равнин, фланкирующих реку Инд , пустыню Тар Синд в восточной части провинции вдоль международной границы с Индией , и горы Киртар в западной части провинции.

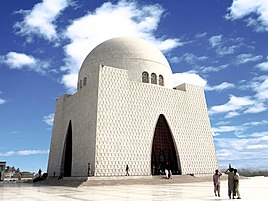

The economy of Sindh is the second largest in Pakistan after the province of Punjab; its provincial capital of Karachi is the most populous city in the country as well as its main financial hub. Sindh is home to a large portion of Pakistan's industrial sector and contains two of the country's busiest commercial seaports: Port Qasim and the Port of Karachi. The remainder of Sindh consists of an agriculture-based economy and produces fruits, consumer items and vegetables for other parts of the country.[7][8][9]

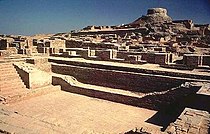

Sindh is sometimes referred to as the Bab-ul Islam (transl. 'Gateway of Islam'), as it was one of the first regions of the Indian subcontinent to fall under Islamic rule.[10][11] The province is well known for its distinct culture, which is strongly influenced by Sufist Islam, an important marker of Sindhi identity for both Hindus and Muslims.[12] Sindh is prominent for its history during the Bronze Age under the Indus Valley civilization, and is home to two UNESCO-designated World Heritage Sites: the Makli Necropolis and Mohenjo-daro.[13]

Etymology

The Greeks who conquered Sindh in 325 BCE under the command of Alexander the Great referred to the Indus River as Indós, hence the modern Indus. The ancient Iranians referred to everything east of the river Indus as hind.[14][15] The word Sindh is a Persian derivative of the Sanskrit term Sindhu, meaning "river," a reference to the Indus River.[16]

Southworth suggests that the name Sindhu is in turn derived from Cintu, a Dravidian word for date palm, a tree commonly found in Sindh.[17][18]

The previous spelling Sind (from the Perso-Arabic سند) was discontinued in 1988 by an amendment passed in the Sindh Assembly.[19]

History

Ancient era

Sindh and surrounding areas contain the ruins of the Indus Valley Civilization. There are remnants of thousand-year-old cities and structures, with a notable example in Sindh being that of Mohenjo Daro. Built around 2500 BCE, it was one of the largest settlements of the ancient Indus civilization, with features such as standardized bricks, street grids, and covered sewerage systems.[20][21] It was one of the world's earliest major cities, contemporaneous with the civilizations of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Minoan Crete, and Caral-Supe. Mohenjo-daro was abandoned in the 19th century BCE as the Indus Valley Civilization declined, and the site was not rediscovered until the 1920s. Significant excavation has since been conducted at the site of the city, which was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980.[22] The site is currently threatened by erosion and improper restoration.[23] A gradual drying of the region during the 3rd millennium BCE may have been the initial stimulus for its urbanisation.[24] Eventually it also reduced the water supply enough to cause the civilisation's demise and to disperse its population to the east.[c]

During the Bronze Age, the territory of Sindh was known as Sindhu-Sauvīra, covering the lower Indus Valley,[25] with its southern border being the Indian Ocean and its northern border being the Pañjāb around Multān.[26] The capital of Sindhu-Sauvīra was named Roruka and Vītabhaya or Vītībhaya, and corresponds to the mediaeval Arohṛ and the modern-day Rohṛī.[26][27][28] The Achaemenids conquered the region and established the satrapy of Hindush. The territory may have corresponded to the area covering the lower and central Indus basin (present day Sindh and the southern Punjab regions of Pakistan).[29] Alternatively, some authors consider that Hindush may have been located in the Punjab area.[30] These areas remained under Persian control until the invasion by Alexander.[31]

Alexander conquered parts of Sindh after Punjab for few years and appointed his general Peithon as governor. He constructed a harbour at the city of Patala in Sindh.[32][33] Chandragupta Maurya fought Alexander's successor in the east, Seleucus I Nicator, when the latter invaded. In a peace treaty, Seleucus ceded all territories west of the Indus River and offered a marriage, including a portion of Bactria, while Chandragupta granted Seleucus 500 elephants.[34]

Following a century of Mauryan rule which ended by 180 BCE, the region came under the Indo-Greeks, followed by the Indo Scythians, who ruled with their capital at Minnagara.[35] Later on, Sasanian rulers from the reign of Shapur I claimed control of the Sindh area in their inscriptions, known as Hind.[36][37]

The local Rai dynasty emerged from Sindh and reigned for a period of 144 years, concurrent with the Huna invasions of North India.[38] Aror was noted to be the capital.[38][39] The Brahmin dynasty of Sindh succeeded the Rai dynasty.[40][41][42][43] Most of the information about its existence comes from the Chach Nama, a historical account of the Chach-Brahmin dynasty.[44] After the empire's fall in 712, though the empire had ended, its dynasty's members administered parts of Sindh under the Umayyad Caliphate's Caliphal province of Sind.[45]

Medieval era

After the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, the Arab expansion towards the east reached the Sindh region beyond Persia.[46] The connection between the Sindh and Islam was established by the initial Muslim invasions during the Rashidun Caliphate. Al-Hakim ibn Jabalah al-Abdi, who attacked Makran in the year 649 CE, was an early partisan of Ali ibn Abu Talib.[47] During the caliphate of Ali, many Jats of Sindh had come under the influence of Shi'ism[48] and some even participated in the Battle of Camel and died fighting for Ali.[47] Under the Umayyads (661–750 CE), many Shias sought asylum in the region of Sindh, to live in relative peace in the remote area. Ziyad Hindi is one of those refugees.[49] The first clash with the Hindu kings of Sindh took place in 636 (15 A.H.) under Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab with the governor of Bahrain, Uthman ibn Abu-al-Aas, dispatching naval expeditions against Thane and Bharuch and Debal.[50] Al-Baladhuri states they were victorious at Debal but doesn't mention the results of other two raids. However, the Chach Nama states that the raid of Debal was defeated and its governor killed the leader of the raids.[51] These raids were thought to be triggered by a later pirate attack on Umayyad ships.[52] Baladhuri adds that this stopped any more incursions until the reign of Uthman.[53]

In 712, Mohammed Bin Qasim defeated the Brahmin dynasty and annexed it to the Umayyad Caliphate. This marked the beginning of Islam in the Indian subcontinent. The Habbari dynasty ruled much of Greater Sindh, as a semi-independent emirate from 854 to 1024. Beginning with the rule of 'Umar bin Abdul Aziz al-Habbari in 854 CE, the region became semi-independent from the Abbasid Caliphate in 861, while continuing to nominally pledge allegiance to the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad.[54][55] The Habbaris ruled Sindh until they were defeated by Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi in 1026, who then went on to destroy the old Habbari capital of Mansura, and annex the region to the Ghaznavid Empire, thereby ending Arab rule of Sindh.[56][57]

The Soomra dynasty was a local Sindhi Muslim dynasty that ruled between early 11th century and the 14th century.[58][59][60] Later chroniclers like Ali ibn al-Athir (c. late 12th c.) and Ibn Khaldun (c. late 14th c.) attributed the fall of Habbarids to Mahmud of Ghazni, lending credence to the argument of Hafif being the last Habbarid.[61] The Soomras appear to have established themselves as a regional power in this power vacuum.[61][62] The Ghurids and Ghaznavids continued to rule parts of Sindh, across the eleventh and early twelfth century, alongside Soomrus.[61] The precise delineations are not yet known but Sommrus were probably centered in lower Sindh.[61] Some of them were adherents of Isma'ilism.[62] One of their kings Shimuddin Chamisar had submitted to Iltutmish, the Sultan of Delhi, and was allowed to continue on as a vassal.[63]

The Sammas overthrew the Soomras soon after 1335 and established the Sindh Sultanate. The last Soomra ruler took shelter with the governor of Gujarat, under the protection of Muhammad bin Tughluq, the sultan of Delhi.[65][66][67] Mohammad bin Tughlaq made an expedition against Sindh in 1351 and died at Sondha, possibly in an attempt to restore the Soomras. With this, the Sammas became independent. The next sultan, Firuz Shah Tughlaq attacked Sindh in 1365 and 1367, unsuccessfully, but with reinforcements from Delhi he later obtained Banbhiniyo's surrender. For a period the Sammas were therefore subject to Delhi again. Later, as the Sultanate of Delhi collapsed they became fully independent.[68] Jam Unar was the founder of Samma dynasty mentioned by Ibn Battuta.[68] The Samma civilization contributed significantly to the evolution of the Indo-Islamic architectural style. Thatta is famous for its necropolis, which covers 10 square km on the Makli Hill.[69] It has left its mark in Sindh with magnificent structures including the Makli Necropolis of its royals in Thatta.[70][71] They were later overthrown by the Turkic Arghuns in the late 15th century.[72][73]

Modern era

In the late 16th century, Sindh was brought into the Mughal Empire by Akbar, himself born in the Rajputana kingdom in Umerkot in Sindh.[74][75] Mughal rule from their provincial capital of Thatta was to last in lower Sindh until the early 18th century, while upper Sindh was ruled by the indigenous Kalhora dynasty holding power, consolidating their rule from their capital of Khudabad, before shifting to Hyderabad from 1768 onwards.[76][77][78]

The Talpurs succeeded the Kalhoras and four branches of the dynasty were established.[79] One ruled lower Sindh from the city of Hyderabad, another ruled over upper Sindh from the city of Khairpur, a third ruled around the eastern city of Mirpur Khas, and a fourth was based in Tando Muhammad Khan. They were ethnically Baloch,[80] and for most of their rule, they were subordinate to the Durrani Empire and were forced to pay tribute to them.[81][82]

They ruled from 1783, until 1843, when they were in turn defeated by the British at the Battle of Miani and Battle of Dubbo.[83] The northern Khairpur branch of the Talpur dynasty, however, continued to maintain a degree of sovereignty during British rule as the princely state of Khairpur,[80] whose ruler elected to join the new Dominion of Pakistan in October 1947 as an autonomous region, before being fully amalgamated into West Pakistan in 1955.

British Raj

The British conquered Sindh in 1843. General Charles Napier is said to have reported victory to the Governor General with a one-word telegram, namely "Peccavi" – or "I have sinned" (Latin).[84] The British had two objectives in their rule of Sindh: the consolidation of British rule and the use of Sindh as a market for British products and a source of revenue and raw materials. With the appropriate infrastructure in place, the British hoped to utilise Sindh for its economic potential.[85] The British incorporated Sindh, some years later after annexing it, into the Bombay Presidency. Distance from the provincial capital, Bombay, led to grievances that Sindh was neglected in contrast to other parts of the Presidency. The merger of Sindh into Punjab province was considered from time to time but was turned down because of British disagreement and Sindhi opposition, both from Muslims and Hindus, to being annexed to Punjab.[85]

Later, desire for a separate administrative status for Sindh grew. At the annual session of the Indian National Congress in 1913, a Sindhi Hindu put forward the demand for Sindh's separation from the Bombay Presidency on the grounds of Sindh's unique cultural character. This reflected the desire of Sindh's predominantly Hindu commercial class to free itself from competing with the more powerful Bombay's business interests.[85] Meanwhile, Sindhi politics was characterised in the 1920s by the growing importance of Karachi and the Khilafat Movement.[86] A number of Sindhi pirs, descendants of Sufi saints who had proselytised in Sindh, joined the Khilafat Movement, which propagated the protection of the Ottoman Caliphate, and those pirs who did not join the movement found a decline in their following.[87] The pirs generated huge support for the Khilafat cause in Sindh.[88] Sindh came to be at the forefront of the Khilafat Movement.[89]

Although Sindh had a cleaner record of communal harmony than other parts of India, the province's Muslim elite and emerging Muslim middle class demanded separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency as a safeguard for their own interests. In this campaign, local Sindhi Muslims identified 'Hindu' with Bombay instead of Sindh. Sindhi Hindus were seen as representing the interests of Bombay instead of the majority of Sindhi Muslims. Sindhi Hindus, for the most part, opposed the separation of Sindh from Bombay.[85] Although Sindh had a culture of religious syncretism, communal harmony and tolerance due to Sindh's strong Sufi culture in which both Sindhi Muslims and Sindhi Hindus partook,[90] both the Muslim landed elite, waderas, and the Hindu commercial elements, banias, collaborated in oppressing the predominantly Muslim peasantry of Sindh who were economically exploited.[91] Sindhi Muslims eventually demanded the separation of Sindh from the Bombay Presidency, a move opposed by Sindhi Hindus.[88][92][93]

In Sindh's first provincial election after its separation from Bombay in 1936, economic interests were an essential factor of politics informed by religious and cultural issues.[94] Due to British policies, much land in Sindh was transferred from Muslim to Hindu hands over the decades.[95] Religious tensions rose in Sindh over the Sukkur Manzilgah issue where Muslims and Hindus disputed over an abandoned mosque in proximity to an area sacred to Hindus. The Sindh Muslim League exploited the issue and agitated for the return of the mosque to Muslims. Consequentially, a thousand members of the Muslim League were imprisoned. Eventually, due to panic the government restored the mosque to Muslims.[94] The separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency triggered Sindhi Muslim nationalists to support the Pakistan Movement. Even while the Punjab and North-West Frontier Province were ruled by parties hostile to the Muslim League, Sindh remained loyal to Jinnah.[96] Although the prominent Sindhi Muslim nationalist G.M. Syed left the All India Muslim League in the mid-1940s and his relationship with Jinnah never improved, the overwhelming majority of Sindhi Muslims supported the creation of Pakistan, seeing in it their deliverance.[86] Sindhi support for the Pakistan Movement arose from the desire of the Sindhi Muslim business class to drive out their Hindu competitors.[97] The Muslim League's rise to becoming the party with the strongest support in Sindh was in large part linked to its winning over of the religious pir families.[98] Although the Muslim League had previously fared poorly in the 1937 elections in Sindh, when local Sindhi Muslim parties won more seats,[98] the Muslim League's cultivation of support from local pirs in 1946 helped it gain a foothold in the province,[99] it didn't take long for the overwhelming majority of Sindhi Muslims to campaign for the creation of Pakistan.[100][101]

Partition (1947)

In 1947, violence did not constitute a major part of the Sindhi partition experience, unlike in Punjab. There were very few incidents of violence on Sindh, in part due to the Sufi-influenced culture of religious tolerance and in part that Sindh was not divided and was instead made part of Pakistan in its entirety. Sindhi Hindus who left generally did so out of a fear of persecution, rather than persecution itself, because of the arrival of Muslim refugees from India. Sindhi Hindus differentiated between the local Sindhi Muslims and the migrant Muslims from India. A large number of Sindhi Hindus travelled to India by sea, to the ports of Bombay, Porbandar, Veraval and Okha.[102]

Demographics

| Demographic Indicators | |

|---|---|

| Urban population | 53.97% |

| Rural population | 46.03% |

| Population growth rate | 2.57% |

| Gender ratio (male per 100 female) | 108.76[103] |

| Economically active population | 22.75% (Old Data) |

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1891 | 2,875,100 | — |

| 1901 | 3,410,223 | +18.6% |

| 1911 | 3,737,223 | +9.6% |

| 1921 | 3,472,508 | −7.1% |

| 1931 | 4,114,253 | +18.5% |

| 1941 | 4,840,795 | +17.7% |

| 1951 | 6,047,748 | +24.9% |

| 1961 | 8,367,065 | +38.4% |

| 1972 | 14,155,909 | +69.2% |

| 1981 | 19,028,666 | +34.4% |

| 1998 | 29,991,161 | +57.6% |

| 2017 | 47,854,510 | +59.6% |

| 2023 | 55,696,147 | +16.4% |

| Source: Census in Pakistan, Census of British Raj[104]: 7 [d][e][f][g][h] | ||

Sindh has the second highest Human Development Index out of all of Pakistan's provinces at 0.628.[109] The 2023 Census of Pakistan indicated a population of 55.7 million.

Religion

Religion in Sindh according to 2023 census

Islam in Sindh has a long history, starting with the capture of Sindh by Muhammad Bin Qasim in 712 CE. Over time, the majority of the population in Sindh converted to Islam, especially in rural areas. Today, Muslims make up 90% of the population, and are more dominant in urban than rural areas. Islam in Sindh has a strong Sufi ethos with numerous Muslim saints and mystics, such as the Sufi poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, having lived in Sindh historically. One popular legend which highlights the strong Sufi presence in Sindh is that 125,000 Sufi saints and mystics are buried on Makli Hill near Thatta.[110] The development of Sufism in Sindh was similar to the development of Sufism in other parts of the Muslim world. In the 16th century two Sufi tareeqat (orders) – Qadria and Naqshbandia – were introduced in Sindh.[111] Sufism continues to play an important role in the daily lives of Sindhis.[112]

In 1941, the last census conducted prior to the partition of India, the total population of Sindh was 4,840,795 out of which 3,462,015 (71.5%) were Muslims, 1,279,530 (26.4%) were Hindus and the remaining were Tribals, Sikhs, Christians, Parsis, Jains, Jews, and Buddhists.[104]: 28 [113]

Sindh also has Pakistan's highest percentage of Hindus overall, accounting for 8.8% of the population, roughly around 4.9 million people,[114] and 13.3% of the province's rural population as per 2023 Pakistani census report. These numbers also include the scheduled caste population, which stands at 1.7% of the total in Sindh (or 3.1% in rural areas),[115] and is believed to have been under-reported, with some community members instead counted under the main Hindu category.[116] Although, Pakistan Hindu Council claimed that there are 6,842,526 Hindus living in Sindh Province covering around 14.29% of the region's population.[117] Umerkot district in the Thar Desert is Pakistan's only Hindu-majority district. The Shri Ramapir Temple in Tandoallahyar whose annual festival is the second largest Hindu pilgrimage in Pakistan is in Sindh.[118] Sindh is also the only province in Pakistan to have a separate law for governing Hindu marriages.[119]

Per community estimates, there are approximately 10,000 Sikhs in Sindh.[120]

| Religious group |

1901[108][h] | 1911[107][g] | 1921[106][f] | 1931[105][e] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Islam |

2,609,337 | 76.52% | 2,822,756 | 75.53% | 2,562,700 | 73.8% | 3,017,377 | 73.34% |

| Hinduism |

787,683 | 23.1% | 877,313 | 23.47% | 876,629 | 25.24% | 1,055,119 | 25.65% |

| Christianity |

7,825 | 0.23% | 10,917 | 0.29% | 11,734 | 0.34% | 15,152 | 0.37% |

| Zoroastrianism |

2,000 | 0.06% | 2,411 | 0.06% | 2,913 | 0.08% | 3,537 | 0.09% |

| Jainism |

921 | 0.03% | 1,349 | 0.04% | 1,534 | 0.04% | 1,144 | 0.03% |

| Judaism |

428 | 0.01% | 595 | 0.02% | 671 | 0.02% | 985 | 0.02% |

| Buddhism |

0 | 0% | 21 | 0.001% | 41 | 0.001% | 53 | 0.001% |

| Sikhism |

— | — | 12,339 | 0.33% | 8,036 | 0.23% | 19,172 | 0.47% |

| Tribal[i] | — | — | 9,224 | 0.25% | 8,186 | 0.24% | 204 | 0% |

| Others | 2,029 | 0.06% | 298 | 0.01% | 64 | 0.002% | 1,510 | 0.04% |

| Total Population | 3,410,223 | 100% | 3,737,223 | 100% | 3,472,508 | 100% | 4,114,253 | 100% |

| Religious group |

1941[104]: 28 [d] | 1951[121]: 22–26 [j] | 1998[122] | 2017[123][114] | 2023[124][125] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Islam |

3,462,015 | 71.52% | 5,535,645 | 91.53% | 27,796,814 | 91.32% | 43,234,107 | 90.34% | 50,126,428 | 90.09% |

| Hinduism |

1,279,530 | 26.43% | 482,560 | 7.98% | 2,280,842 | 7.49% | 4,176,986 | 8.73% | 4,901,407 | 8.81% |

| Tribal | 37,598 | 0.78% | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Sikhism |

32,627 | 0.67% | — | — | — | — | — | — | 5,182 | 0.01% |

| Christianity |

20,304 | 0.42% | 22,601 | 0.37% | 294,885 | 0.97% | 408,301 | 0.85% | 546,968 | 0.98% |

| Zoroastrianism |

3,841 | 0.08% | 5,046 | 0.08% | — | — | — | — | 1,763 | 0.003% |

| Jainism |

3,687 | 0.08% | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Judaism |

1,082 | 0.02% | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Buddhism |

111 | 0.002% | 670 | 0.01% | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ahmadiyya |

— | — | — | — | 43,524 | 0.14% | 21,661 | 0.05% | 18,266 | 0.03% |

| Others | 0 | 0% | 1,226 | 0.02% | 23,828 | 0.08% | 13,455 | 0.03% | 38,395 | 0.07% |

| Total Population | 4,840,795 | 100% | 6,047,748 | 100% | 30,439,893 | 100% | 47,854,510 | 100% | 55,638,409 | 100% |

Languages

According to the 2023 census, the most widely spoken language in the province is Sindhi, the first language of 60% of the population. It is followed by Urdu (22%), Pashto (5.3%), Punjabi (4.1%), Balochi (2.2%), Saraiki (1.6%), and Hindko (1.5).[126]

Other minority languages include Kutchi, Gujarati,[127] Aer, Bagri, Bhaya, Brahui, Dhatki, Ghera, Goaria, Gurgula, Jadgali, Jandavra, Jogi, Kabutra, Kachi Koli, Parkari Koli, Wadiyari Koli, Loarki, Marwari, Sansi, and Vaghri.[128]

Karachi city is Sindh's most multiethnic city which hosts most of the province's Urdu-speaking population who form a plurality, along many other groups.[129]

Geography and nature

Sindh is in the western corner of South Asia, bordering the Iranian plateau in the west. Geographically it is the third largest province of Pakistan, stretching about 579 kilometres (360 mi) from north to south and 442 kilometres (275 mi) (extreme) or 281 kilometres (175 mi) (average) from east to west, with an area of 140,915 square kilometres (54,408 sq mi) of Pakistani territory. Sindh is bounded by the Thar Desert to the east, the Kirthar Mountains to the west and the Arabian Sea and Rann of Kutch to the south. In the centre is a fertile plain along the Indus River.

Sindh is divided into three main geographical regions: Siro ("upper country"), aka Upper Sindh, which is above Sehwan; Vicholo ("middle country"), or Middle Sindh, from Sehwan to Hyderabad; and Lāṟu ("sloping, descending country"), or Lower Sindh, mostly consisting of the Indus Delta below Hyderabad.[130]

Flora

The province is mostly arid with scant vegetation except for the irrigated Indus Valley. The dwarf palm, Acacia Rupestris (kher), and Tecomella undulata (lohirro) trees are typical of the western hill region. In the Indus valley, the Acacia nilotica (babul) (babbur) is the most dominant and occurs in thick forests along the Indus banks. The Azadirachta indica (neem) (nim), Zizyphys vulgaris (bir) (ber), Tamarix orientalis (jujuba lai) and Capparis aphylla (kirir) are among the more common trees.

Mango, date palms and the more recently introduced banana, guava, orange and chiku are the typical fruit-bearing trees. The coastal strip and the creeks abound in semi-aquatic and aquatic plants and the inshore Indus delta islands have forests of Avicennia tomentosa (timmer) and Ceriops candolleana (chaunir) trees. Water lilies grow in abundance in the numerous lake and ponds, particularly in the lower Sindh region.[citation needed]

Fauna

Among the wild animals, the Sindh ibex (sareh), blackbuck, wild sheep (Urial or gadh) and wild bear are found in the western rocky range. The leopard is now rare and the Asiatic cheetah extinct. The Pirrang (large tiger cat or fishing cat) of the eastern desert region is also disappearing. Deer occur in the lower rocky plains and in the eastern region, as do the Striped hyena (charakh), jackal, fox, porcupine, common gray mongoose and hedgehog. The Sindhi phekari, red lynx or Caracal cat, is found in some areas. Phartho (hog deer) and wild bear occur, particularly in the central inundation belt. There are bats, lizards and reptiles, including the cobra, lundi (viper) and the mysterious Sindh krait of the Thar region, which is supposed to suck the victim's breath in his sleep. Some unusual sightings of Asian cheetah occurred in 2003 near the Balochistan border in Kirthar Mountains. The rare houbara bustard find Sindh's warm climate suitable to rest and mate. Unfortunately, it is hunted by locals and foreigners.

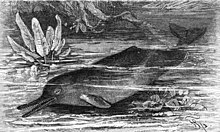

Crocodiles are rare and inhabit only the backwaters of the Indus, eastern Nara channel and Karachi backwater. Besides a large variety of marine fish, the plumbeous dolphin, the beaked dolphin, rorqual or blue whale and skates frequent the seas along the Sindh coast. The Pallo (Sable fish), a marine fish, ascends the Indus annually from February to April to spawn. The Indus river dolphin is among the most endangered species in Pakistan and is found in the part of the Indus river in northern Sindh. Hog deer and wild bear occur, particularly in the central inundation belt.

Although Sindh has a semi arid climate, through its coastal and riverine forests, its huge fresh water lakes and mountains and deserts, Sindh supports a large amount of varied wildlife. Due to the semi-arid climate of Sindh the left out forests support an average population of jackals and snakes. The national parks established by the Government of Pakistan in collaboration with many organizations such as World Wide Fund for Nature and Sindh Wildlife Department support a huge variety of animals and birds. The Kirthar National Park in the Kirthar range spreads over more than 3000 km2 of desert, stunted tree forests and a lake. The KNP supports Sindh ibex, wild sheep (urial) and black bear along with the rare leopard. There are also occasional sightings of The Sindhi phekari, ped lynx or Caracal cat. There is a project to introduce tigers and Asian elephants too in KNP near the huge Hub Dam Lake. Between July and November when the monsoon winds blow onshore from the ocean, giant olive ridley turtles lay their eggs along the seaward side. The turtles are protected species. After the mothers lay and leave them buried under the sands the SWD and WWF officials take the eggs and protect them until they are hatched to keep them from predators.

Climate

Sindh lies in a tropical to subtropical region; it is hot in the summer and mild to warm in winter. Temperatures frequently rise above 46 °C (115 °F) between May and August, and the minimum average temperature of 2 °C (36 °F) occurs during December and January in the northern and higher elevated regions. The annual rainfall averages about seven inches, falling mainly during July and August. The southwest monsoon wind begins in mid-February and continues until the end of September, whereas the cool northerly wind blows during the winter months from October to January.

Sindh lies between the two monsoons—the southwest monsoon from the Indian Ocean and the northeast or retreating monsoon, deflected towards it by the Himalayan mountains—and escapes the influence of both. The region's scarcity of rainfall is compensated by the inundation of the Indus twice a year, caused by the spring and summer melting of Himalayan snow and by rainfall in the monsoon season.

Sindh is divided into three climatic regions: Siro (the upper region, centred on Jacobabad), Wicholo (the middle region, centred on Hyderabad), and Lar (the lower region, centred on Karachi). The thermal equator passes through upper Sindh, where the air is generally very dry. Central Sindh's temperatures are generally lower than those of upper Sindh but higher than those of lower Sindh. Dry hot days and cool nights are typical during the summer. Central Sindh's maximum temperature typically reaches 43–44 °C (109–111 °F). Lower Sindh has a damper and humid maritime climate affected by the southwestern winds in summer and northeastern winds in winter, with lower rainfall than Central Sindh. Lower Sindh's maximum temperature reaches about 35–38 °C (95–100 °F). In the Kirthar range at 1,800 m (5,900 ft) and higher at Gorakh Hill and other peaks in Dadu District, temperatures near freezing have been recorded and brief snowfall is received in the winters.

Major cities

| List of major cities in Sindh | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | City | District(s) | Population | Image |

| 1 | Karachi | Nazimabad, Orangi, Gulshan, Korangi, Malir, Keamari, Karachi | 21,910,352[132] |

|

| 2 | Hyderabad | Hyderabad | 1,732,693 |

|

| 3 | Sukkur | Sukkur | 499,900 |

|

| 4 | Larkana | Larkana | 490,508 |

|

| 5 | Benazirabad[132] | Shaheed Benazirabad | 279,689 |

|

| 6 | Kotri | Jamshoro | 259,358 |

|

| 7 | Mirpur Khas | Mirpur Khas | 233,916 |

|

| 8 | Shikarpur | Shikarpur | 195,437 |  |

| 9 | Jacobabad | Jacobabad | 191,076 |

|

| 10 | Khairpur | Khairpur | 183,181 |

|

| Source: Pakistan Census 2017[133] | ||||

| This is a list of city proper populations and does not indicate metro populations. | ||||

Government

Sindh province

| Provincial animal | Sindh ibex |  |

|---|---|---|

| Provincial bird | Black partridge |  |

| Provincial tree | Neem Tree |  |

The Provincial Assembly of Sindh is a unicameral and consists of 168 seats, of which 5% are reserved for non-Muslims and 17% for women. The provincial capital of Sindh is Karachi. The provincial government is led by Chief Minister who is directly elected by the popular and landslide votes; the Governor serves as a ceremonial representative nominated and appointed by the President of Pakistan. The administrative boss of the province who is in charge of the bureaucracy is the Chief Secretary Sindh, who is appointed by the Prime Minister of Pakistan. Most of the influential Sindhi tribes in the province are involved in Pakistan's politics.

In addition, Sindh's politics leans towards the left-wing and its political culture serves as a dominant place for the left-wing spectrum in the country.[137] The province's trend towards the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and away from the Pakistan Muslim League (N) can be seen in nationwide general elections, in which Sindh is a stronghold of the PPP.[137] The PML(N) has a limited support due to its centre-right agenda.[138]

In metropolitan cities such as Karachi and Hyderabad, the MQM (another party of the left with the support of Muhajirs) has a considerable vote bank and support.[137] Minor leftist parties such as the People's Movement also found support in rural areas of the province.[139]

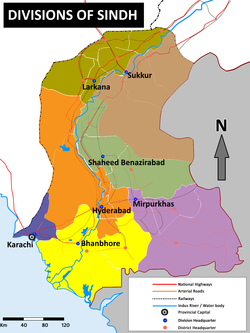

Divisions

In 2008, after the public elections, the new government decided to restore the structure of Divisions of all provinces.[140] In Sindh after the lapse of the Local Governments Bodies term in 2010 the Divisional Commissioners system was to be restored.[141][142][143]

In July 2011, following excessive violence in the city of Karachi and after the political split between the ruling PPP and the majority party in Sindh, the MQM and after the resignation of the MQM Governor of Sindh, PPP and the Government of Sindh decided to restore the commissionerate system in the province. As a consequence, the five divisions of Sindh were restored – namely Karachi, Hyderabad, Sukkur, Mirpurkhas and Larkana with their respective districts. Subsequently, a new division was added in Sindh, the Nawab Shah/Shaheed Benazirabad division.[144]

Karachi district has been de-merged into its five original constituent districts: Karachi East, Karachi West, Karachi Central, Karachi South and Malir. Recently Korangi has been upgraded to the status of the sixth district of Karachi. These six districts form the Karachi Division now.[145] In 2020, the Kemari District was created after splitting Karachi West District.[146] Currently the Sindh government is planning to divide the Tharparkar district into Tharparkar and Chhachro district.[147]

Districts

| Sr. No. | District | Headquarters | Area (km2) |

Population (in 2017) |

Density (people/km2) |

Division |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Badin | Badin | 6,470 | 1,804,516 | 279 | Hyderabad |

| 2 | Dadu | Dadu | 8,034 | 1,550,266 | 193 | Hyderabad |

| 3 | Ghotki | Ghotki | 6,506 | 1,647,239 | 253 | Sukkur |

| 4 | Hyderabad | Hyderabad | 1,022 | 2,201,079 | 2,155 | Hyderabad |

| 5 | Jacobabad | Jacobabad | 2,771 | 1,006,297 | 363 | Larkana |

| 6 | Jamshoro | Jamshoro | 11,250 | 993,142 | 88 | Hyderabad |

| 7 | Karachi Central | Karachi | 62 | 2,972,639 | 48,336 | Karachi |

| 8 | Kashmore (formerly Kandhkot) | Kashmore | 2,551 | 1,089,169 | 427 | Larkana |

| 9 | Khairpur | Khairpur | 15,925 | 2,405,523 | 151 | Sukkur |

| 10 | Larkana | Larkana | 1,906 | 1,524,391 | 800 | Larkana |

| 11 | Matiari | Matiari | 1,459 | 769,349 | 527 | Hyderabad |

| 12 | Mirpur Khas | Mirpur Khas | 3,319 | 1,505,876 | 454 | Mirpur Khas |

| 13 | Naushahro Feroze | Naushahro Feroze | 2,027 | 1,612,373 | 369 | Shaheed Benazir Abad |

| 14 | Shaheed Benazirabad (formerly Nawabshah) | Nawabshah | 4,618 | 1,612,847 | 349 | Shaheed Benazir Abad |

| 15 | Qambar Shahdadkot | Qambar | 5,599 | 1,341,042 | 240 | Larkana |

| 16 | Sanghar | Sanghar | 10,259 | 2,057,057 | 200 | Shaheed Benazir Abad |

| 17 | Shikarpur | Shikarpur | 2,577 | 1,231,481 | 478 | Larkana |

| 18 | Sukkur | Sukkur | 5,216 | 1,487,903 | 285 | Sukkur |

| 19 | Tando Allahyar | Tando Allahyar | 1,573 | 836,887 | 532 | Hyderabad |

| 20 | Tando Muhammad Khan | Tando Muhammad Khan | 1,814 | 677,228 | 373 | Hyderabad |

| 21 | Tharparkar | Mithi | 19,808 | 1,649,661 | 83 | Mirpur Khas |

| 22 | Thatta | Thatta | 7,705 | 979,817 | 127 | Hyderabad |

| 23 | Umerkot | Umerkot | 5,503 | 1,073,146 | 195 | Mirpur Khas |

| 24 (22) | Sujawal | Sujawal | 8,699 | 781,967 | 90 | Hyderabad |

| 25 (7) | Karachi East | Karachi | 165 | 2,909,921 | 17,625 | Karachi |

| 26 (7) | Karachi South | Karachi | 85 | 1,791,751 | 21,079 | Karachi |

| 27 (7) | Karachi West | Karachi | 630 | 3,914,757 | 6,212 | Karachi |

| 28 (7) | Korangi | Korangi Town | 95 | 2,457,019 | 25,918 | Karachi |

| 29 (7) | Malir | Malir Town | 2,635 | 2,008,901 | 762 | Karachi |

| 30 (7) | Kemari | Karachi | N/A | Karachi |

Lower-level subdivisions

В Синде талуки эквивалентны техсилам, используемым в других местах страны, надзорные тапас соответствуют кругам канунго, используемым в других местах, тапас соответствует кругам патвар, используемым в других провинциях, а DEH эквивалентны музам, используемым в других местах. [148]

Города и деревни

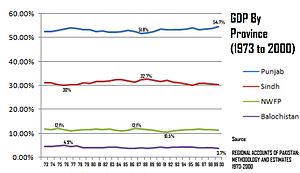

Экономика

Экономика Синда является вторым по величине из всех провинций в Пакистане . Большая часть экономики Синда влияет на экономику Карачи , крупнейшего города и экономического столица страны. Исторически вклад Синда в ВВП Пакистана составлял от 30% до 32,7%. Его доля в секторе услуг варьировалась от 21% до 27,8% и в сельскохозяйственном секторе от 21,4% до 27,7%. С точки зрения производительности, его лучшим сектором является производственный сектор, где его доля варьировалась от 36,7% до 46,5%. [ 149 ] С 1972 года ВВП Синда расширился на 3,6 раза. [ 150 ]

Синд, наделенный прибрежным доступом, является основным центром экономической деятельности в Пакистане и обладает высоко диверсифицированной экономикой, начиная от тяжелой промышленности и финансов, сосредоточенных на Карачи и его окрестностях до значительной сельскохозяйственной базы вдоль Инда . Производство включает в себя машинные продукты, цемент, пластмассы и различные другие товары.

Сельское хозяйство играет важную роль в синде с хлопком , рисом , пшеницей , сахарным тростником , бананами и манго в качестве наиболее важных культур. Самое большое и более тонкое качество риса производится в районе Ларкано . [ 151 ] [ 152 ]

Синд является самой богатой провинцией природных ресурсов газа, бензина и угля. Mari Gas Field является крупнейшим производителем природного газа в стране, с такими компаниями, как Mari Petroleum . [ 153 ] Thar Coalfield также включает в себя большой лигнитный месторождение. [ 153 ]

Образование

| Год | Уровень грамотности |

|---|---|

| 1972 | 60.77 |

| 1981 | 37.5% |

| 1998 | 45.29% |

| 2017 | 54.57% [ 154 ] |

Ниже приведена график рынка образования Синда, оцененный правительством в 1998 году: [ 155 ]

| Квалификация | Городской | Деревенский | Общий | Коэффициент зачисления (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | 14,839,862 | 15,600,031 | 30,439,893 | — |

| Ниже первичного | 1,984,089 | 3,332,166 | 5,316,255 | 100.00 |

| Начальный | 3,503,691 | 5,687,771 | 9,191,462 | 82.53 |

| Середина | 3,073,335 | 2,369,644 | 5,442,979 | 52.33 |

| Поступок | 2,847,769 | 2,227,684 | 5,075,453 | 34.45 |

| Средний | 1,473,598 | 1,018,682 | 2,492,280 | 17.78 |

| Диплом, сертификат ... | 1,320,747 | 552,241 | 1,872,988 | 9.59 |

| BA, BSC ... градусы | 440,743 | 280,800 | 721,543 | 9.07 |

| MA, MSC ... градусы | 106,847 | 53,040 | 159,887 | 2.91 |

| Другие квалификации | 89,043 | 78,003 | 167,046 | 0.54 |

Крупные государственные и частные образовательные институты в Синде включают:

- Правительственный научный колледж Адамджи

- Университет Ага Хан

- Апит

- Исследовательский центр прикладной экономики

- Бахрия Университет

- Бакайский медицинский университет

- Чанка Медицинский колледж Ларкана

- Кадетский колледж Петаро

- Колледж цифровых наук

- Колледж врачей и хирургов Пакистан

- Институт бизнеса и развивающиеся науки

- DJ Science College

- Университет и технологии Давуда

- Колледж управления обороны для мужчин

- Dow International Medical College

- Dow University of Health Sciences

- Фатима Джинна стоматологический колледж

- Федеральный университет урду

- GBELS DOORAI MAHAR TALUKA DAUR DISTT: Шахид Беназирабад

- Гулам Мухаммед Махар Медицинский колледж Суккур

- Государственный колледж для мужчин Назимабад

- Государственный колледж Хайдарабад

- Государственный коммерческий колледж Торговый

- Государственный технологический колледж, Карачи

- Группический колледж Матиари

- Государственная средняя школа Ранипур

- Правительство Исламское научное колледж Суккур

- Государственный мусульманский научный колледж Хайдарабад

- Правительственный национальный колледж (Карачи)

- Гринвичский университет (Карачи)

- Хамдардский университет

- Исследовательский институт химии Хуссейна Эбрагима Джамала

- Имперский научный колледж Навабшах

- Институт искусств и архитектуры долины Инда

- Институт делового администрирования, Карачи

- Институт делового администрирования, Суккар

- Институт управления бизнесом

- Институт промышленной электроники инженерии

- Институт синдхологии

- Университет Икра

- Исламский научный колледж (Карачи)

- Университет Исры Хайдарабад

- Медицинский и стоматологический колледж Джинна

- Джинна Политехнический институт

- Джинна после аспирантуры медицинский центр

- Университет женщин Джинны

- Канупп Институт ядерной энергетической инженерии

- Институт экономики и технологий Карачи

- Карачи Школа бизнеса и лидерства

- Университет медицинских и медицинских наук Liaquat

- Мехранский инженерный университет и технологии

- Университет Мухаммеда Али Джинна

- Национальная академия исполнительских искусств

- Национальный университет компьютерного университета и развивающихся наук

- Национальный университет современных языков

- Национальный университет наук и технологий

- Инженерный университет Нед

- Институт грудной клетки Ойха

- Институт авиационных технологий PAF

- Государственная школа TES, Даур

- Пакистанский военно -морской инженерный колледж

- Пакистанский корабельный колледж

- Пакистанский стальной кадетский колледж

- Медицинский колледж народов для девочек Навабшах

- PIA Training Center Karachi

- Провинциальный институт учителей Образование Навабшах

- Государственная школа Хайдарабад

- Университет, науки и техники Quaid-e-Awam , Навабшах

- Rana Liaquat Ali Khan Государственный колледж домов экономика

- Колледж Святого Патрика, Карачи

- Шах Абдул Латиф Бхитайский университет

- Шахид Беназир Бхутто Медицинский колледж

- Шахид Зульфикар Али Бхутто Институт науки и техники

- Синд Сельскохозяйственный университет

- Синд Медицинский колледж

- Верхний колледж науки Хайдарабад

- Синд мусульманский юридический колледж

- Сэр Сайед Правительственный колледж девочек

- Инженерный университет и технологии сэра Сайеда

- Колледж Святого Иосифа

- Суккурский институт науки и техники

- Текстильный институт Пакистана

- Университет Карачи

- Университет Синда

- Усманский технологический институт

- Зиауддин Медицинский университет

Культура

Богатая культура, искусство и архитектурный ландшафт Синда очаровали историков. Культура, народные сказки, искусство и музыка Синда образуют мозаику истории человечества. [ 156 ]

Культурное наследие

Работа ремесленников Синди была продана на древних рынках Дамаска, Багдада, Басры, Стамбула, Каира и Самарканда. Ссылаясь на лаковую работу над деревом, известная как Джанди, Т. Постен (английский путешественник, который посетил Синд в начале 19 -го века) утверждал, что статьи Халы можно сравнить с изысканными образцами Китая. Технологические улучшения, такие как прядильное колесо ( Charkha ) и педаль (pai-chah) в ткацком станке, были постепенно введены, а процессы проектирования, окрашивания и печать с помощью блока были уточнены. Рафинированные, легкие, красочные, стираемые ткани из Hala стали роскошью для людей, используемых для Woollens и постельного белья эпохи. [ 157 ]

Неправительственные организации (НПО), такие как Всемирный фонд дикой природы, Пакистан, играют важную роль в продвижении культуры Синда. Они обеспечивают обучение женщин -ремесленников в Синде, чтобы получить источник дохода. Они продвигают свои продукты под названием «ремесла навсегда». Многие женщины в сельской местности Синд квалифицированы в производстве кепок. Кэпки Sindhi производятся в коммерческих целях в небольших масштабах в New Saeedabad и Hala New. Народ Синди начал праздновать День Синди Топи 6 декабря 2009 года, чтобы сохранить историческую культуру Синдха, надев Аджрак и Синди Топи. [ 158 ]

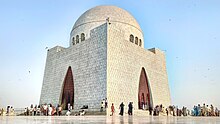

Туризм

Синд - провинция в Пакистане .

Провинция включает в себя ряд важных исторических мест. Цивилизация долины Инда (IVC) была бронзового века цивилизацией (зрелый период 2600–1900 гг. До н.э.), которая была сосредоточена в основном в Синде. [ 159 ] У Синда есть многочисленные туристические сайты с самыми выдающимися руинами Мохенджо-Даро недалеко от города Ларкана . [ 159 ] Исламская архитектура довольно заметна, а также колониальные и пост-стационарные места. Кроме того, природные места, такие как озеро Манчар, все чаще стали источником устойчивого туризма в провинции. [ 160 ]-

Gorakh Hill Station , Dadu

-

Файз Махал , Хайрпур

-

Форт Раникот , один из крупнейших фортов в мире Тана Була Хан, Джамшоро

-

Гробницы , Карачи

-

Остатки джайнского храма 9 -го века в Бходезаре, недалеко от Нагарпаркар

-

Раскопанные руины Мохенджо-даро

-

Карачи пляж

-

Наш форт , остров Манора Каричи

-

Кот Диджи , Хайрпур

-

Бакри Варо озеро, Хайрпур

-

Национальный музей Пакистана , Карачи

-

Национальный парк Киртхар , Тано Була Хан, Джамшоро

-

Карунджхарские горы , Торпоркар

-

Гробница Шах Абдул Латиф Бхиттай , Матири

-

Лал Шахбаз Каландар , Сехван Шариф, Джамшоро

-

Гробница Миана Мухаммеда, Беназирабад

Смотрите также

- Являются арабскими

- Багх

- Брахма из Мирпур-Хас

- Дебал

- Институт синдхологии

- Список городов в Синде по населению

- Список сайтов культурного наследия в Синде

- Список медицинских школ в Синде

- Список районов Пакистана

- Список людей синдхи

- Список племен синдхи

- Мансура, Синд

- Мохенджо-Даро

- Провинциальные дороги Синда

- Являются разделением

- Sindh Cricket Team

- Синди одежда

- Синдху Королевство

- Суфизм в Синде

- Гробницы картины Синда

Примечания

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Вклад Синда в национальную экономику составил 23,7%или 345 миллиардов долларов (ГЧП) и 86 миллиардов долларов (номинальный) в 2022 году. [ 2 ] [ 3 ]

- ^ Английский и урду также используются в качестве официальных языков, но их статус гарантируется национальной конституцией , а не каким -либо законодательством Синда

- ^ Брук (2014) , с. 296. «История в Хараппанской Индии была несколько иначе (см. Рисунок 111.3). Деревня бронзовых веков и городские общества долины Инда, некоторые аномалии, в том, что археологи обнаружили мало признаков местной обороны и региональной войны. Казалось бы, что обильные муссонные дожди в начале до середины холоцена создали условия изобилия для всех, и что конкурентные энергии были направлены в коммерцию, а не конфликт. Общества, которые появились из неолитических деревень около 2600 года. Азия была первоначальной реакцией народов долины Инда на начало позднего голоцена. и долина Ганг .... 17 (сноска):

(а) Giosan et al. (2012) ;

(б) Понтон и соавт. (2012) ;

(C) Rashid et al. (2011) ;

(D) Madella & Fuller (2006) ;

Сравните с совершенно разными интерпретациями в

(E) Possehl (2002) , с. 237–245

(F) Dustwater et al. (2003) - ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный 1941 Цифра, взятая из данных переписи, путем объединения общей численности населения всех районов ( Даду , Хайдарабад , Карачи , Ларкана , Навабшах , Суккур , Тарпаркар , Верхняя Синд -Фронта ) и одно принципы ( Хайрпур ), в провинции Синдх, Британская Индия. См. Данные переписи 1941 года здесь: [ 104 ]

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный 1931 Цифра, взятая из данных переписи путем объединения общей численности населения всех районов ( Хайдарабад , Карачи , Ларкана , Навабшах , Суккур , Тарпаркар , Верхний Синд -Фронт ) и одно княжеское государство ( Хайрпур ), в провинции Синд, Британская Индия. См. Данные переписи 1931 года здесь: [ 105 ]

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный 1921 Цифра, взятая из данных переписи путем объединения общей численности населения всех районов ( Хайдарабад , Карачи , Ларкана , Навабшах , Суккур , Тарпаркар , Верхний Синд -Фронт ) и одно княжеское государство ( Хайрпур ), в провинции Синд, Британская Индия. См. Данные переписи 1921 года здесь: [ 106 ]

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Цифра 1911 года, взятая из данных переписи , путем объединения общей численности населения всех районов ( Хайдарабад , Карачи , Ларкана , Суккур , Тарпаркар , Верхний Синд -Фронт ) и одно принцип Принцли ( Хайрпур ), в провинции Синд, Британская Индия. См. Данные переписи 1911 здесь: [ 107 ]

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный 1901 Цифр, взятый из данных переписи путем объединения общей численности населения всех районов ( Карачи , Хайдарабад , Шикарпур , Тарпаркар , Верхняя Синд -Фронта ) и одно княжеское государство ( Хайрпур ), в провинции Синд, Британская Индия. См. Данные переписи 1901 года здесь: [ 108 ]

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Перепись 1901 года: перечислен как индусы.

- ^ Включая федеральную столичную территорию (Карачи)

Ссылки

- ^ «Объявление о результатах 7-го численного и жилищного переписи-2023 (провинция Синд)» (PDF) . Пакистанское бюро статистики (www.pbs.gov.pk) . 5 августа 2023 года . Получено 25 ноября 2023 года .

- ^ «ВВП районов Хайбер Пухтунхва» (PDF) . kpbos.gov.pk .

- ^ «Отчет для отдельных стран и субъектов» .

- ^ «Субнациональный HDI - субнациональный HDI - глобальная лаборатория данных» . Globaldatalab.org . Получено 5 июня 2022 года .

- ^ «Добро пожаловать на сайт провинциальной Ассамблеи Синда» . www.pas.gov.pk. Архивировано из оригинала 14 декабря 2014 года . Получено 24 июля 2009 г.

- ^ «Lgdsindh - блог новостей» . Lgdsindh . Архивировано из оригинала 16 июня 2019 года . Получено 5 сентября 2006 года .

- ^ Штатный репортер (9 марта 2014 г.). «Синд должен использовать потенциал для производства фруктов» . Нация, 2014. Нация . Получено 29 мая 2015 года .

- ^ Маркханд, Гулам Сарвар; Сауд, Адила А. "Даты в Синде" . Материалы Международного семинара . Salu Press . Получено 29 мая 2015 года .

- ^ Редакционная статья (3 сентября 2007 г.). «Как выращивать бананы» . Dawn News, 2007. Dawn News . Получено 29 мая 2015 года .

- ^ Куддус, Сайед Абдул (1992). Синд, земля Инда цивилизации . Королевская книжная компания. ISBN 978-969-407-131-2 .

- ^ Отчет JPRS: Ближнец и Южная Азия . Информационная служба иностранного вещания. 1992.

- ^ Джуди Вакабаяши; Рита Котари (2009). Учебные исследования перевода: Индия и за его пределами . Джон Бенджаминс издательство. С. 132–. ISBN 978-90-272-2430-9 .

- ^ «Свойства, вписанные в Список всемирного наследия (Пакистан)» . ЮНЕСКО . Получено 14 июля 2016 года .

- ^ Чоудхари Рахмат Али (28 января 1933 г.). "Сейчас или никогда. Мы должны жить или погибать навсегда?" Полем

- ^ SM Ikram (1 января 1995 г.). Индийские мусульмане и раздел Индии . Atlantic Publishers & Dist. С. 177 -. ISBN 978-81-7156-374-6 Полем Получено 23 декабря 2011 года .

- ^ Phiroze Vasunia 2013 , с. 6

- ^ Саутворт, Франклин. Реконструкция доисторического южноазиатского языка контакта (1990) с. 228

- ^ Burrow, T. Dravidian Etymology Arackary Arackived 1 марта 2021 года на машине Wayback p. 227

- ^ «Синд, не Синд» . Express Tribune . Веб -столовая. 12 февраля 2013 года . Получено 16 октября 2015 года .

- ^ Саньял, Санджив (10 июля 2013 г.). Земля Семь рек: краткая история географии Индии . Книги пингвинов. ISBN 978-0-14-342093-4 Полем OCLC 855957425 .

- ^ «Археологические руины в Moanjodaro» . Сайт Организации Объединенных Наций по образовательной, научной и культурной организации (ЮНЕСКО) . Получено 6 сентября 2014 года .

- ^ «Мохенджо-даро: древний мегаполис долины Инда» .

- ^ "Мохенджо Даро: Может ли этот древний город быть потерян навсегда?" Полем BBC News . 26 июня 2012 года . Получено 22 августа 2022 года .

- ^ Эдвин Брайант (2001). Стремление к происхождению ведической культуры. С. 159–60.

- ^ Raychauudhuri, Hemchandra (1953). Политическая история древней Индии: от вступления Paricsit до расширения династии Гупта Университет Калькутты П. 197

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Jain 1974 , p. 209 - 210 .

- FFAL Calalerer 1964 , P. 501-5

- ^ HC Raychaudhuri (1923). Политическая история древней Индии: от вступления Парикшита до исчезновения династии Гупта . Университет Калькутты. ISBN 978-1-4400-5272-9 .

- ^ MA Дандамаев. «Политическая история империи Ахеменидов», стр. 147. Брилл, 1989 ISBN 978-9004091726

- ^ « Хидус может быть районами Синда, или Таксила и Западного Пенджаба». в Кембридж Древняя история . Издательство Кембриджского университета. 2002. с. 204. ISBN 9780521228046 .

- ^ Рафи У. Самад, величие Гандхары: древняя цивилизация долины Сват, Пешавар, Кабул и Инда. Algora Publishing, 2011, с. 33 ISBN 0875868592

- ^ Дани 1981 , с.

- ^ Eggermont 1975 , p. 13

- ^ Thorpe 2009 , p. 33.

- ^ Rawlinson, HG (2001). Общение между Индией и западным миром: с самых ранних времен падения Рима . Азиатские образовательные услуги. п. 114. ISBN 978-81-206-1549-6 .

- ^ Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Сасанианская Персия: подъем и падение империи . Ib tauris. п. 17. ISBN 9780857716668 .

- ^ Шиндель, Николаус; Алрам, Майкл; Дарей, Туадж; Пендлтон, Элизабет (2016). Парфянскую и раннюю сасанискую империи: адаптация и расширение . Книги Oxbow. С. 126–129. ISBN 9781785702105 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Wink 1996 , pp. 133, 152–153.

- ^ ASIF 2016 , с. 65, 81–82, 131–134.

- ^ Wink 1996 , p. 151.

- ^ P. 505 История Индии, как рассказал его собственные историки Генри Миерс Эллиот, Джон Доусон

- ^ Николас Ф. Гиер, от монголов до моголов: религиозное насилие в Индии 9-18 веков , представленное на Тихоокеанском северо-западном региональном собрании Американской академии религии, Университет Гонзага, май 2006 г. [1] . Получено 11 декабря 2006 года.

- ^ Найк, CD (2010). Буддизм и далиты: социальная философия и традиции . Дели: Калпаз Публикации. п. 32. ISBN 978-81-7835-792-8 .

- ^ P. 164 Заметки о религиозном, моральном и политическом государстве Индии до вторжения Магомеда, в основном основанной на путешествиях китайского буддийского священника Фай Хан в Индии, 399 г. н. Burnouf, лейтенант-подполковник Wh Sykes , Sykes, полковник;

- ^ Wink 1991 , pp. 152–153.

- ^ Эль Хареир, Идрис; Mbaye, Ragane (2012), распространение ислама через мир , ЮНЕСКО, П. 602, ISBN 978-92-3-104153-2

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Маклин, Деррил Н. (1989), Религия и общество в арабском Синде, с. 126, Брилл, ISBN 90-04-08551-3

- SAA Rizvi, « Социально -интеллектуальная история шиитов индийская», Воло. 1, стр .. 138, Канберра (1986).

- ^ Сан Резави, «Мусульмане -шииты», в истории науки, философии и культуры в индийской цивилизации, вып. 2, часть. 2: «Религиозные движения и учреждения в средневековой Индии», глава 13, издательство Оксфордского университета (2006).

- ^ Эль Хареир, Идрис; Mbaye, Ragane (2012), распространение ислама через мир , ЮНЕСКО, с. 601–602, ISBN 978-92-3-104153-2

- ^ Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1976), Чтения в политической истории Индии, древнего, средневекового и современного , BR Pub. Корпорация, от имени Индийского общества доисторических и четвертичных исследований, с. 216

- ^ Трипати 1967 , с. 337.

- ^ ASIF 2016 , с.

- ^ PM (Нагендра Кумар Сингх), мусульманское царство в Индии , Anmol Publications, 1999, ISBN 81-261-0436-8 , ISBN 978-81-261-0436-9 PG 43-45.

- ^ PM (Деррил Н. Маклин), религия и общество в арабском Синде , опубликованная Брилл, 1989, ISBN 90-04-08551-3 , ISBN 978-90-04-08551-0 PG 140-143.

- ^ Абдулла, Ахмед (1987). Наблюдение: перспектива Пакистана . Издатели Tanzeem.

- ^ Хабиб, Ирфан (2011). Экономическая история средневековой Индии, 1200-1500 . Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-2791-1 .

- ^ Сиддики, Хабибулла. «Soomras of Sindh: их происхождение, основные характеристики и правило - обзор (общий обзор) (1025–1351 CE)» (PDF) . Литературная конференция по периоду Сумры в Синде .

- ^ «Арабское завоевание». Международный журнал дравидийской лингвистики . 36 (1): 91. 2007.

Считается, что Soomras - это Пармар Раджпуты, найденные даже сегодня в Раджастхане, Саураштре, Кутч и Синд. Кембриджская история Индии называет Сумры «династией Раджпут, более поздние члены которого приняли ислам» (стр. 54).

- ^ Дэн, Ахмад Хасан (2007). Heyan Pakistan: Paxeran Then Escorts Постоянная публикация. п. 218. ISBN 978-969-35-2020-0 Полем

Но так же, как многие короли династии носили индуистские имена, почти наверняка, что Soomras были местного происхождения. Иногда они связаны с Парамара Раджпутами, но этого нет определенного доказательства.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Collinet, Annabelle (2008). «Хронология Сехван Шариф через керамику (исламский период)». В Бойвине, Мишель (ред.). Синд через историю и представления: французский вклад в исследования Синдхи . Карачи: издательство Оксфордского университета. С. 9, 11, 113 (примечание 43). ISBN 978-0-19-547503-6 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Boivin, Michel (2008). «Культы Shivaite и суфийские центры: переоценка средневекового наследия в Синде». В Бойвине, Мишель (ред.). Синд через историю и представления: французский вклад в исследования Синдхи . Карачи: издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 30. ISBN 978-0-19-547503-6 .

- ^ Анируддха Рэй (4 марта 2019 г.). Султанат Дели (1206-1526): государство, экономика, общество и культура . Тейлор и Фрэнсис. С. 43–. ISBN 978-1-00-000729-9 .

- ^ «Исторические памятники в Макли, Тейта» .

- ^ Организация переписи (Пакистан); Абдул Латиф (1976). Перепись населения Пакистана, 1972: Ларкана . Менеджер публикаций.

- ^ Рапсон, Эдвард Джеймс; Хейг, сэр Уолсели; Берн, сэр Ричард; Додвелл, Генри (1965). Кембриджская история Индии: турки и афганцы, под редакцией У. Хейга . Чанд. п. 518.

- ^ Ум Чокши; Мистер Триведи (1989). Гуджарат Государственный газетер . Директор правительственной печати, канцелярские товары и публикации, штат Гуджарат. п. 274.

Это было завоевание Кутча племенем Синди Сама Раджпутов, которое ознаменовало появление Кутча как отдельного королевства в 14 -м веке.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный «Направления в истории и археологии Синда от MH Panhwar» . Архивировано из оригинала 25 декабря 2018 года . Получено 12 января 2023 года .

- ^ Archnet.org: Tathtah Archived 2012-06-06 на The Wayback Machine

- ^ Организация переписи (Пакистан); Абдул Латиф (1976). Перепись населения Пакистана, 1972: Ларкана . Менеджер публикаций.

- ^ Перепись населения Пакистана, 1972: Якобабад

- ^ Путешествия Марко Поло - Комплекс (Mobi Classics) от Marco Polo, Rustichello Pisa, Генри Юле (переводчик)

- ^ Босворт, «Новые исламские династии», с. 329

- ^ Тарлинг, Николас (1999). Кембриджская история Юго -Восточной Азии от Николаса Тарлинг с.39 . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 9780521663700 .

- ^ «Испания [периодические публикации]. Том 74, номер 3, сентябрь 1991 г.» . Виртуальная библиотека Мигель де Сервантес . Архивировано с оригинала 24 сентября 2015 года . Получено 27 января 2016 года .

- ^ Брохи, Али Ахмад (1998). Храм Солнца Бога: Реликвии прошлого . Sangam Publications. п. 175.

Калхорас Местное племя синдхи происхождения Чанны ...

- ^ Бертон, Ричард Фрэнсис (1851). Синд и расы, которые населяют долину Инда . Wh Allen. п. 410.

Калхоры ... изначально были Чанна Синдхис и, следовательно, обращенные индусы.

- ^ Парус, Оскар (2004). Мигранты и боевики: веселье и насилие в городе в Пакистане . ПРИЗНАЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТА ПРИСЕТА. стр. 94 , 99. ISBN 978-0-69111-709-6 Полем

Площадь индуистского особняка Пакка Цила была построена в 1768 году Королями Калхоры, местной династией арабского происхождения, которая управляла Синдом независимо от распадающейся империи Моголь, начиная с середины восемнадцатого века.

- ^ «История Хайрпура и Королевских Талпурс Синда» . Ежедневно . 21 апреля 2018 года . Получено 6 марта 2020 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Соломон, RV; Бонд, JW (2006). Индийские штаты: биографическое, историческое и административное обследование . Азиатские образовательные услуги. ISBN 978-81-206-1965-4 .

- ^ Белудж, Инаугуилья (1987). : Штайнер Верлаг из Уэзадена. п. 121. ISBN 9783515049993 .

- ^ Ziad, Waleed (2021). Скрытый кальфаат: суфийские святые за оксом и Индом Гарвардский университет издательство. П. 53. ISBN 9780674248816 .

- ^ «Королевские талпуры Синда - исторический фон» . www.talpur.org . 24 июля 2002 г. Получено 23 февраля 2020 года .

- ^ Генерал Нейпир Апокрифально сообщил о своем завоевании провинции своим начальникам с одним словом « Пеккави» , каламбуром школьницы, записанного в Punch (журнал), полагаясь на значение латинского слова, «я грешил», гомофонный, чтобы «у меня есть синдх» Полем Евгений Эрлих , Nil Desperandum: словарь латинских тегов и полезных фраз [Оригинальное название: AMO, AMA, AMAT и другие ], BCA 1992 [1985], с. 175.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Роджер Д. Лонг; Гурхарпал Сингх; Юнас Самад; Ян Тэлбот (8 октября 2015 г.), государственное и национальное строительство в Пакистане: за пределами ислама и безопасности , Routledge, с. 102–, ISBN 978-1-317-44820-4

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный И. Малик (3 июня 1999 г.), Ислам, национализм и Запад: проблемы идентичности в Пакистане , Palgrave Macmillan UK, стр. 56–, ISBN 978-0-230-37539-0

- ^ Гейл Мино (1982), Движение Хилафата: религиозная символика и политическая мобилизация в Индии , издательство Колумбийского университета, с. 105–, ISBN 978-0-231-05072-2

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Ансари 1992 , с. 77

- ^ Пакистанское историческое общество (2007), Журнал Пакистанского исторического общества , Пакистанское историческое общество., С. 245

- ^ Прия Кумар и Рита Котари (2016) Синд, 1947 и за его пределами, Южная Азия: Журнал исследований Южной Азии , 39: 4, 775, doi : 10.1080/00856401.2016.1244752

- ^ Айеша Джалал (4 января 2002 г.). Сам само собой и суверенитет: индивидуальный и общинный в Южной Азии ислам с 1850 года . Routledge. С. 415–. ISBN 978-1-134-59937-0 .

- ^ Роджер Д. Лонг; Гурхарпал Сингх; Юнас Самад; Ян Тэлбот (8 октября 2015 г.). Государственное и национальное строительство в Пакистане: за пределами ислама и безопасности . Routledge. С. 102–. ISBN 978-1-317-44820-4 .

- ^ Пакистанское историческое общество (2007). Журнал Пакистанского исторического общества . Пакистанское историческое общество. п. 245

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Jalal 2002 , p. 415

- ^ Амритджит Сингх; Налини Айер; Рахул К. Гайрола (15 июня 2016 г.), пересмотр раздела Индии: новые очерки о памяти, культуре и политике , Lexington Books, стр. 127–, ISBN 978-1-4985-3105-4

- ^ Халед Ахмед (18 августа 2016 г.), лунатичный, чтобы сдаться: дело с терроризмом в Пакистане , Penguin Books Limited, стр. 230–, ISBN 978-93-86057-62-4

- ^ Veena Kukreja (24 февраля 2003 г.), современный Пакистан: политические процессы, конфликты и кризисы , Sage Publications, с. 138–, ISBN 978-0-7619-9683-5

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Ансари 1992 , с. 115.

- ^ Ансари 1992 , с. 122

- ^ И. Малик (3 июня 1999 г.). Ислам, национализм и Запад: проблемы идентичности в Пакистане . Palgrave Macmillan UK. С. 56–. ISBN 978-0-230-37539-0 .

- ^ Вина Кукрейя (24 февраля 2003 г.). Современный Пакистан: политические процессы, конфликты и кризисы . SAGE Publications. с. 138–. ISBN 978-0-7619-9683-5 .

- ^ Прия Кумар и Рита Котари (2016) Синдх, 1947 и за его пределами, Южная Азия: Журнал исследований Южной Азии , 39: 4, 776–777, doi: 10.1080/00856401.2016.1244752

- ^ «Перепись населения 2023» .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Комиссар по переписи Индии (1941). «Перепись Индии, 1941. Том 12, Синд» . Jstor Saoa.crl.28215545 . Архивировано из оригинала 29 января 2023 года . Получено 5 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Комиссар по переписи Индии (1931). «Перепись Индии, 1931. Том 8, Бомбей. Pt. 2, Статистические таблицы» . Jstor Saoa.crl.25797128 . Получено 5 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Комиссар по переписи Индии (1921). «Перепись Индии, 1921. Том 8, Бомбейский президентство. Pt. 2, Таблицы: Имперский и провинциальный» . Jstor Saoa.crl.25394131 . Получено 6 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Комиссар по переписи Индии (1911). «Перепись Индии, 1911. Том 7, Бомбей. Pt. 2, Императорские таблицы» . Jstor Saoa.crl.25393770 . Получено 12 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Комиссар по переписи Индии (1901). «Перепись Индии, 1901. Vols. 9-11, Bombay» . Jstor Saoa.crl.25366895 . Получено 12 мая 2024 года .

- ^ "Центр социальной политики и развития |" (PDF) . www.spdc.org.pk. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 21 мая 2009 года.

- ^ Annemarie Schimmel, жемчуг из Инда Джамшоро, Синд, Пакистан: Синди Адаби Совет (1986). Смотрите с. 150.

- ^ «История суфизма в Синде обсуждала» . Dawn.com . 25 сентября 2013 года . Получено 30 марта 2017 года .

- ^ "Может ли суфизм спасти Синд?" Полем Dawn.com . 2 февраля 2015 года . Получено 30 марта 2017 года .

- ^ Рахимдад Хан Молай Шедай; Джанет Уль Синд; 3 -е издание, 1993; Синди Адби Совет, Джамшоро; Страница №: 2.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный «Религиозная демография Пакистана 2023» (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 29 августа 2021 года . Получено 20 мая 2021 года .

- ^ «Религия в Пакистане (перепись 2017 года)» (PDF) . Пакистанское бюро статистики. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 29 марта 2020 года . Получено 28 марта 2018 года .

- ^ «Запланированные касты имеют отдельную коробку для них, но только если кто -то знал» . Получено 19 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ «Индуистская популяция (PK)» . Pakistanhinducouncil.org.pk. Архивировано из оригинала 15 августа 2020 года . Получено 24 июня 2022 года .

- ^ «Индус сходится в Рамапир Мела возле Карачи, стремясь к божественной помощи для их безопасности» . The Times of India . 26 сентября 2012 года . Получено 13 октября 2020 года .

- ^ Шахид Джатои (8 июня 2017 г.). "Синдх индуистский брак акт - релик или сдержанность?" Полем Express Tribune . Получено 10 ноября 2020 года .

- ^ Тунио, Хафиз (31 мая 2020 г.). «Сикхи Шикарпура служат человечеству за пределами религии» . Express Tribune . Пакистан . Получено 2 июля 2020 года .

- ^ «Cpopulation в соответствии с религией, таблицы -6, Пакистан - перепись 1951 года» . Получено 21 июля 2024 года .

- ^ «Распределение населения по религии, перепись 1998 года» (PDF) . Получено 23 января 2023 года .

- ^ «Таблица 9 - Население по полу, религии и сельской местности/город» (PDF) . Получено 23 января 2023 года .

- ^ «Таблица 9: Население по полу, религии и сельской местности/городской, перепись - 2023» (PDF) .

- ^ «7 -я население и жилищная перепись - подробные результаты Таблица 9 Население по полу, религии и сельской/городской» . Пакистанское бюро статистики . Получено 6 августа 2024 года .

- ^ https://www.pbs.gov.pk/sites/default/files/population/2023/tables/sindh/dcr/table_11.pdf [ только URL PDF ]

- ^ Рехман, Зия Ур (18 августа 2015 г.). «С горсткой подборов две газеты едва ли поддерживают гуджарати в Карачи» . News International . Получено 13 января 2017 года .

В Пакистане большинство, говорящих на гуджарати, находятся в Карачи, в том числе Давуоуди Бохры, Исмаили Ходжас, Мемонс, Катиавари, Катчхи, Парзис (Зороастрийцы) и индуистские индусы, сказал Гул Хасан Калмати, исследователь, который написал «Карачи, Синдх-джи» Книга, обсуждающая город и его коренные общины. Хотя официальной статистики нет, лидеры сообщества утверждают, что в Карачи есть три миллиона спикеров гуджарати-примерно около 15 процентов всего населения города.

- ^ Эберхард, Дэвид М.; Саймонс, Гэри Ф.; Фенниг, Чарльз Д., ред. (2019). "Пакистан - языки" . Этнолог (22 -е изд.).

- ^ «Политические и этнические сражения превращают Карачи в Бейрут из Южной Азии« Полумесяц » . Merinews.com. Архивировано с оригинала 30 ноября 2012 года . Получено 24 ноября 2012 года .

- ^ Хейг, Малкольм Роберт (1894). Страна Инда Дельта: мемуары, главным образом по ее древней географии и истории . Лондон: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. 1 Получено 29 января 2022 года .

- ^ Менон, Сунита. «Королева манго: Синдхри из Пакистана сейчас в ОАЭ» . Khaleej Times . Получено 22 сентября 2019 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Хан, Мохаммад Хуссейн (20 декабря 2021 г.). «Сказка о Беназирабаде» . Dawn.com . Получено 19 февраля 2024 года .

- ^ «Пакистанское бюро статистики - 6 -е население и перепись жилья» . www.pbscensus.gov.pk . Архивировано с оригинала 15 октября 2017 года . Получено 3 сентября 2017 года .

- ^ Ильюс, Файза (10 июля 2012 г.). «Провинциальное млекопитающее, птица уведомлен» . Рассвет . Получено 3 ноября 2016 года .

- ^ «Правительство объявляет Ним« провинциальное дерево » . Рассвет . 15 апреля 2010 года . Получено 6 сентября 2014 года .

- ^ Амар Гуриро (14 декабря 2011 г.). "Наши символы Sindhi - IBX, черная куропатка " Пакистан сегодня . Получено 6 сентября

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Шейх, Ясир (5 ноября 2012 г.). «Области политического влияния в Пакистане: правое против левого крыла» . Карачи, Синд: коричневые пандиты, Ясир. Архивировано из оригинала 30 мая 2015 года . Получено 29 мая 2015 года .

- ^ Рехман, Зия Ур (26 мая 2015 г.). «PML-N Хранил безмолвное восстание в лидерах Синда и Карачи» . News International . Архивировано из оригинала 29 мая 2015 года . Получено 29 мая 2015 года .

- ^ Содхар, Мухаммед Касим. «Поверните направо: Синди национализм и избирательная политика» . Танкед, Содхар. Архивировано из оригинала 30 мая 2015 года . Получено 29 мая 2015 года .

- ^ «Комиссионная система восстановлена» . 26 октября 2008 года. Архивировано с оригинала 9 января 2010 года.

- ^ "502 Неверный шлюз" . www.emoiz.com . Архивировано с оригинала 26 декабря 2018 года . Получено 6 марта 2017 года .

- ^ «Система комиссара скоро будет восстановлена: Дуррани» . Архивировано из оригинала 31 июля 2012 года.

- ^ «Синдх: Система комиссаров может быть возрождена сегодня» . Архивировано с оригинала 24 ноября 2010 года . Получено 25 апреля 2016 года .

- ^ Чандио, Рамзан (12 июля 2011 г.). «Комиссары, DCS размещены в Синде» . Нация . Архивировано из оригинала 13 июля 2011 года.

- ^ «Синд возвращается к 5 подразделениям через 11 лет» . Пакистан сегодня .

- ^ Абдулла Зафар (21 августа 2020 г.). «Кабинет Sindh утверждает отдел Карачи на семь районов» . Nation.com.pk . Получено 25 мая 2021 года .

- ^ «Синд, правительство разделить Тарпаркар в двух районах» . Получено 7 июня 2021 года .

- ^ Хан, Тарик Шафик (2009). Пакистан 2008 МУЗА СТАТИСТИКА (PDF) . Правительство Пакистана: Отдел статистики - сельскохозяйственная организация переписи. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 12 июня 2021 года . Получено 15 мая 2021 года .

- ^ «Провинциальные отчеты Пакистана: методология и оценки 1973-2000» (PDF) . [ Постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ http://siteresources.worldbank.org/pakistanextn/resources/293051-1241610364594/6097548-12574441952102/balochistaneconomicReportvol2.pdf

- ^ Gazetteer провинции Синд … Правительство в «Меркантильной» паровой прессе. 1907.

- ^ "О Синде" . Генеральное консульство Китайской Народной Республики в Карачи . Получено 15 декабря 2016 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный «Пакистан: добыча полезных ископаемых, минералы и топливные ресурсы» . Azomining.com . 15 сентября 2012 года . Получено 4 октября 2021 года .

- ^ «Высокие особенности конечных результатов переписи 2017 года» (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 19 мая 2021 года . Получено 14 июня 2021 года .

- ^ «Население по уровню образования и сельской/городской» . Отдел статистики: Министерство экономических дел и статистики. Правительство Пакистана. Архивировано из оригинала 20 июля 2009 года . Получено 19 августа 2009 года .

- ^ «Spotlighting: Sindh выставка дает взгляд на богатую культуру провинции - Express Tribune» . Express Tribune . 28 сентября 2013 года . Получено 30 марта 2017 года .

- ^ «Культурное наследие» . WishWebDesign.com = . Архивировано с оригинала 5 ноября 2013 года . Получено 6 сентября 2014 года .

- ^ «Синд празднует первый в истории« День Синди Топи » . Архивировано из оригинала 8 декабря 2009 года . Получено 6 декабря 2009 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный «Туризм в Синде - Экспресс Трибуна» . 22 ноября 2013 года.

- ^ Манган, Техмина; Брауэр, Рой; Лохано, Хеман Дас; Nangraj, Ghulam Mustafa (1 апреля 2013 г.). «Оценка рекреационной стоимости крупнейшего пресноводного озера Пакистана для поддержки устойчивого управления туризмом с использованием модели затрат на поездки» . Журнал устойчивого туризма . 21 (3): 473–486. doi : 10.1080/09669582.2012.708040 . ISSN 0966-9582 .

Библиография

- Ансари, Сара Ф.Д. (1992). Суфийские святые и государственная власть: Пиры Синда, 1843–1947 . Тол. 50. Кембридж: издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 9780511563201 .

- Асиф, Манан Ахмед (2016), книга Завоевания , издательство Гарвардского университета, ISBN 978-0-674-66011-3

- Брук, Джон Л. (2014). Изменение климата и курс глобальной истории: грубое путешествие . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-521-87164-8 .

- Почти, ах (1981). "Синдху - Совира: Совис: В Хухро, страна (ред.). Международный семинар был предоставлен к 1975 году Карачи: издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 35–42. ISBN 978-0-19-577250-0 .

- Эггермонт, Пьер Герман Леонард (1975). Кампании Александра в Синде и Белуджистане и осада города брахмана Хармателия . Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-6186-037-2 .

- Giosan L, Clift PD, Macklin MG, Fuller DQ, et al. (2012). «Речные ландшафты хараппской цивилизации» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 109 (26): E1688 - E1694. BIBCODE : 2012PNAS..109E1688G . doi : 10.1073/pnas.1112743109 . ISSN 0027-8424 . PMC 3387054 . PMID 22645375 .

- Джайн, Кайлаш Чанд (1974). Господь Махавира и Его время . Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-0-8426-0738-4 .

- Джалал, Айеша (4 января 2002 г.), «Я и суверенитет»: индивидуальный и общинный в Южно -Азиатском исламе с 1850 года , Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-59937-0

- Маделла, Марко; Fuller, Dorian Q. (2006). «Палеоэкология и хараппская цивилизация Южной Азии: пересмотр». Кватернарные науки обзоры . 25 (11–12): 1283–1301. Bibcode : 2006qsrv ... 25.1283m . doi : 10.1016/j.quascirev.2005.10.012 . ISSN 0277-3791 .

- Малкани, Кевал Рам (1984). Синдская история . Союзные издатели.

- Фироз Васуния (16 мая 2013 г.). Классика и колониальная Индия . Издательство Оксфордского университета . ISBN 978-01-9920-323-9 .

- Понтон, Камило; Giosan, Liviu; Эглинтон, Тим I.; Фуллер, Дориан Q.; и др. (2012). «Голоценовая аридификация Индии» (PDF) . Геофизические исследования . 39 (3). L03704. Bibcode : 2012georl..39.3704p . doi : 10.1029/2011GL050722 . HDL : 1912/5100 . ISSN 0094-8276 .

- Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). Цивилизация Инда: современная перспектива . Роуман Альтамира. ISBN 978-0-7591-1642-9 .

- Рашид, Харунур; Англия, Эмили; Томпсон, Лонни; Поляк, Леонид (2011). «Поздние ледниковые до голоценовых индийских летних муссонов изменчиво, основанная на записях осадков, взятых из Бенгальского залива» (PDF) . Наземные, атмосферные и океанические науки . 22 (2): 215–228. Bibcode : 2011taos ... 22..215r . doi : 10.3319/tao.2010.09.17.02 (TIBXS) . ISSN 1017-0839 .

- Sikdar, Jogendra Chandra (1964). Исследования в Бхагаватисутре . Музаффарпур, Бихар, Индия: Научно -исследовательский институт пракрит, джайнология и ахимса. Стр. 388-464.

- Staubwasser, M.; Sirocko, F.; Grootes, PM; Segl, M. (2003). «Изменение климата при увольнении 4,2 кА байна цивилизации долины Инда и голоцена в южноазиатских муссонах». Геофизические исследования . 30 (8): 1425. Bibcode : 2003georl..30.1425S . doi : 10.1029/2002gl016822 . ISSN 0094-8276 . S2CID 129178112 .

- Thorpe, Shisick Thorpe Edgar (2009), Руководство по общим исследованиям Пирсона 2009, 1/E , Pearson Education India, ISBN 978-81-317-2133-9

- Tripathi, Rama Shankar (1967), История древней Индии , Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0018-2

- Винк, Андре (1991). Аль-Хинд: рабовладельцы и исламское завоевание. 2 Брилль ISBN 9004095098 .

- Винк, Андре (1996). Аль Хинд: создание индоисламского мира . Брилль ISBN 90-04-09249-8 .

Внешние ссылки

- Официальный сайт департамента транспорта Синда

- Правительство Синда архивировано 31 мая 2013 года на машине Wayback

- Руководство Синда Архивировано 5 апреля 2012 года на машине Wayback

- Карта районов Синда

- Синд в Керли