Международные санкции во время вторжения России в Украину

После полного объявления о вторжении России в Украину , которое началось 24 февраля 2022 года, такие институты, как США, Европейский Союз, [1] и другие западные страны [2] введены или существенно расширены санкции, распространяющиеся на президента России Владимира Путина , других членов правительства [3] и граждане России в целом. Некоторым российским банкам запретили использовать международную платежную систему SWIFT . [4] Санкции и бойкоты России и Белоруссии по-разному повлияли на российскую экономику .

Предыстория и история санкций и их последствий

История санкций

Западные и другие страны ввели санкции против России после того, как она признала независимость своих оккупированных территорий, так называемых Донецкой и Луганской Народных Республик , 21 февраля 2022 года в выступлении Владимира Путина. С началом атак 24 февраля 2022 года большое количество других стран начали применять санкции с целью разрушить российскую экономику. [5] The sanctions were wide-ranging, targeting individuals, banks, businesses, monetary exchanges, bank transfers, exports, and imports.[6][7][8] The sanctions included cutting off major Russian banks from SWIFT, the global messaging network for international payments, although there would still be limited accessibility to ensure the continued ability to pay for gas shipments.[9] Sanctions also included asset freezes on the Russian Central Bank, which holds $630 billion in foreign-exchange reserves,[10] to prevent it from offsetting the impact of sanctions[11][12][13] By 1 March, the total amount of Russian assets frozen by sanctions amounted to $1 trillion.[14]

Major multinational companies including Apple, IKEA, ExxonMobil, and General Motors, have individually decided to apply sanctions to Russia.[15][16] Ukrainian along with U.S. and EU governments have explicitly urged the global private sector to help uphold sanctions, and the EU, UK and Australia have also called on global digital platforms to remove Russian-based web sites.[15] Some multinational companies have disengaged from Russia to comply with sanctions and trade restrictions imposed by home states, but also on their own accord, beyond what was required by law, to avoid the economic and reputational risks associated with maintaining commercial ties with Russia.[15][16]

Several countries that are historically neutral, such as Switzerland and Singapore,[17][18] have agreed to partial sanctions.[19][20] Some countries also applied sanctions to Belarusian organisations and individuals, such as President Alexander Lukashenko, because of Belarus' involvement in the invasion.[21]

In response to the invasion, Germany's chancellor, Olaf Scholz, suspended the Nord Stream 2 pipeline and announced a new policy of energy independence from Russia. In addition, Germany provided arms shipments to Ukraine, the first time that it provided arms to a country at war since the end of World War II. Germany also created a €100 billion fund for additional defence expenditures.[22] German industry shifted from reliance on Russian natural gas to producing more energy from renewable sources, importing gas and more coal to provide power and heating while new power generation facilities could be built.[23][24]

Upon his arrival for the NATO extraordinary summit in Brussels on 24 March, U.S. President Joe Biden indicated that further economic sanctions would be placed against Russia, including restrictions on the Russian Central Bank's use of gold in transactions and a new round of sanctions that targeted defense companies, the head of Russia's largest bank, and more than 300 members of the Russian State Duma.[25]

On 27 February 2022, Putin responded to the sanctions, and to what he called "aggressive statements" by Western governments, by ordering the country's "deterrence forces"—generally understood to include its nuclear forces—to be put on a "special regime of combat duty". This novel term provoked some confusion as to what exactly was changing, but US officials declared it generally "escalatory".[26] Following sanctions and criticisms of their relations with Russian business, a boycott movement began and many companies and organisations chose to exit Russian or Belarusian markets voluntarily.[27] The boycotts impacted many consumer goods, entertainment, education, technology, and sporting organisations.[28]

The US instituted export controls, a novel sanction focused on restricting Russian access to high-tech components, both hardware and software, made with any parts or intellectual property from the US. The sanction required that any person or company that wanted to sell technology, semiconductors, encryption software, lasers, or sensors to Russia request a license, which by default was denied. The enforcement mechanism involved sanctions against the person or company, with the sanctions focused on the shipbuilding, aerospace, and defence industries.[29]

During a speech at the UN General Assembly in New York City on 20 September 2022, French president Emmanuel Macron asked, "who here can defend the idea that the invasion of Ukraine justifies no sanctions?" He purported neutral states to be "indifferent" towards the conflict.[30]

On 9 December 2022, Canada imposed new sanctions on Russia, alleging human rights violations. The decision includes sanctions against 33 current or former senior Russian officials and six entities involved in alleged "systematic human rights violations" against Russian citizens who protested against Russia's invasion of Ukraine.[31]

On 16 December 2022, The EU introduced a ninth package of sanctions against the Russian economy. A spokesperson for the Belgian government said, "It is becoming increasingly difficult to impose sanctions that hit Russia hard enough, without excessive collateral damage to the EU."[32]

Since 2014, the European Union has applied eleven rounds of sanctions against the Russian Federation. The last 11th round of sanctions in June 2023 focused on dual-use items such as computer chips and as well as an attempt to limit ship-to-ship transactions of sanctioned goods. More suspensions of Russian broadcasting licenses in Europe were also announced.[33]

Sanctions

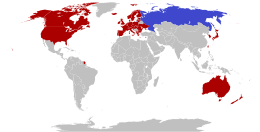

Countries on Russia's "Unfriendly Countries List". Countries and territories on the list have imposed or joined sanctions against Russia.[34]

Western countries and others began imposing limited sanctions on Russia when it recognised the independence of self-declared Donbass republics. With the commencement of attacks on 24 February, a large number of other countries began applying sanctions with the aim of devastating the Russian economy. The sanctions were wide-ranging, targeting individuals, banks, businesses, monetary exchanges, bank transfers, exports, and imports.[1][2][35]

After Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022, two governments that had not previously taken part in sanctions, namely South Korea[36] and non-UN member state Taiwan,[37] engaged in sanctions against Russia. On 28 February 2022, Singapore announced that it will impose banking sanctions against Russia for Ukraine invasion, thus making them the first country in Southeast Asia to impose sanctions upon Russia.[38]

The sanctions also included materials that could be used for weapons against Ukraine, as well as electronics, technology devices and related equipment, which were listed in a detailed statement on 5 March.[39][40]

On 25 February and 1 March 2022, Serbia, Mexico and Brazil announced that they would not be participating in any economic sanctions against Russia.[41][42][43][44]

On 28 February 2022, the Central Bank of Russia was blocked from accessing more than $400 billion in foreign-exchange reserves held abroad[45][46] and the EU imposed sanctions on several Russian oligarchs and politicians.[47] On the same day US Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) prohibited United States persons from engaging in transactions with Central Bank of Russia, Russian Direct Investment Fund (including its predecessor, JSC RDIF, sanctioned previously), the Russian Venture Company, and Kirill Dmitriev, an ally of Vladimir Putin, personally.[48][49][50]

Sergei Aleksashenko, the former Russian deputy finance minister, said: "This is a kind of financial nuclear bomb that is falling on Russia."[51] On 1 March 2022, the French finance minister Bruno Le Maire predicted that the West would freeze "almost 1,000 billion dollars" of Russian assets, which would cause a collapse of the Russian economy.[52][53] By July 2023, Russian assets frozen by the G7 countries and the EU were estimated at $335 billion (€300 billion).[54] On 20 April 2022 the Yermak-McFaul Expert Group on Russian Sanctions arranged by Zelensky published an "Action Plan for Strengthening Sanctions against the Russian Federation". The document contains recommendations for the international democratic community regarding further sanctions and economic measures, designed to force the Russian leadership in the shortest possible time to end the war in Ukraine and to punish those who committed war crimes.[27][55]

In a March 2022 interview with 60 Minutes correspondent Sharyn Alfonsi, Daleep Singh, then the U.S. Deputy National Security Advisor, who previously crafted U.S. sanctions in 2014 in response to Russian annexation of Crimea, described the sanctions as the "most severe economic sanctions ever levied on Russia", called them "Putin's sanctions", said further sanctions could target "the commanding heights" of Russia's economy, and claimed the country's economy was in "free-fall" as a result of sanctions. He added that the U.S. was not "pressing buttons to destroy an economy" and said that the sanctions should have "the power to impose overwhelming costs on your target".[56]

Fossil fuels and other commodities

On 28 February 2022, Canada banned imports of Russian crude oil.[57][58] On 8 June, Canada banned services to the Russian oil, mining, gas, and chemical industries.[59]

On 8 March 2022, US President Joe Biden ordered a ban on imports of oil, gas and coal from Russia to the United States.[60]

Also on 8 March 2022, Shell announced its intention to withdraw from the Russian hydrocarbons industry.[61][62]

Switzerland is a major hub for commodities trading globally. As such, about 80% of Russia's commodity trading goes through Geneva and there are an estimated 40 commodities companies linked to Russia in Zug.[63] Glencore, Gunvor, Vitol, Trafigura and Lukoil Litasco SA are oil and commodities trading firms with stakes in Rosneft and Lukoil, two major Russian oil companies.[64][65][66] Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Works (MMK), a Russian-based company in Lugano, is also a major player in commodities/steel trading with Eastern Europe.[67]

In May 2022, the European Commission proposed a ban on oil imports from Russia.[68] The proposal was reduced to a ban on oil imports by sea to appease Hungary, whose prime minister, Viktor Orbán, has befriended Putin and which gets 60% of its oil from Russia via pipelines.[69] European imports of oil supplied by pipeline from Russia are estimated at 800,000 barrels a day and are exempted from the sanctions, with oil transit insurance bans being phased in over several months. Germany and Poland have vowed to end pipeline deliveries.[70] The embargo on crude oil began in December 2022 and oil products in February 2023

In response to the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, the European Commission and International Energy Agency presented joint plans to reduce reliance on Russian energy, reduce gas imports from Russia by two thirds within a year, and completely by 2030.[71][72][24] In April 2022, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said "the era of Russian fossil fuels in Europe will come to an end".[73] On 18 May 2022, the European Union published plans to end its reliance on Russian oil, natural gas and coal by 2027.[74]

On 2 September 2022, the G7 group of nations agreed to cap the price of Russian oil in order to reduce Russia's ability to finance its war with Ukraine without further increasing inflation.[75] This was followed by the European Union on 6 October, which in its 8th round of sanctions agreed to put a price cap on Russian oil imports (for Europe and third countries) with a price maximum to be set on 5 December 2022.[76][77] Several countries, including Hungary and Serbia gained major exemptions from the agreement.[78][79] According to a US Treasury report published in May 2023 the sanctions were successful in achieving oil supply stability and reducing Russian tax revenue.[80] In August 2023 the price of Russian oil exceeded the cap and reached $73.57 per barrel.[81]

The detrimental effects on European countries from economic sanctions against Russia had been initially valued as insignificant compared to the impact these measures have on the Russian economy. However, after 2022, a number of economists have pointed out that Eastern European countries with more intense economic relations with Russia (and Ukraine) before the conflict, would experience more disruptions to their economies. These 'asymmetric effects' might be considerable, particularly for smaller countries with domestic production, as these international sanctions not only affected the energy industry but also agriculture and manufacturing.[82] After the onset of the armed conflict in 2022, energy prices had skyrocketed, contributing to the 2021/2022 energy crisis. While those energy prices had fallen again in 2023 and shortages, particularly for LNG, had eased, other factors came into play, such as the serious disruption of grain exports through the Black Sea corridor, thus causing a glut of grain in Eastern Europe, depressing prices seriously and endangering the livelihood of local farmers in Poland, Hungary as well as Bulgaria.[83]

In 2022, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said that Turkey could not join sanctions on Russia because of import dependency.[84] Turkey imported almost half of its gas from Russia.[85] Erdoğan and Russian President Vladimir Putin planned for Turkey to become an energy hub for all of Europe.[86] According to Aura Săbăduș, a senior energy journalist focusing on the Black Sea region, "Turkey would accumulate gas from various producers — Russia, Iran and Azerbaijan, [liquefied natural gas] and its own Black Sea gas — and then whitewash it and relabel it as Turkish. European buyers wouldn't know the origin of the gas."[87] For Turkey, the re-sale of Russian gas had been limited as it is practically impossible to re-configure gas flows with the European Union. Furthermore, gas supplies to Turkey are constrained as the TurkStream pipeline was running well below its 31.5 billion cubic meters (bcm) of annual capacity. China, however, has been a more likely candidate for such maneuvers. The PRC overtook Japan as the largest importer of LNG and already practiced such techniques of re-labelling Russian-sourced gas for export.[88]

In March 2023, when the EU adopted new sanctions against Russia, Russian diamond exports to Europe and other nations remained unaffected. While calls from Ukrainian nationals and EU officials to strictly apply sanctions to Russian-sourced diamonds had been referred to the G7, such measures had only experienced weak support from European capitals. In June 2023, EU sanctions against Russian-based diamond exporters were announced, however, their efficacy remained doubtful. Similar to the export routes of other Russian commodities, evading such sanctions through diamond traders in India and other countries that do not impose direct sanction, are very likely.[89]

According to experts, a "refining loophole" allows Russian oil to be transported to refineries in third countries (such as Turkey for example) to be turned into other products like diesel or petrol and re-rexported to Europe.[90]

In July 2023, Ukraine again stated that it would likely not renew the gas transit deal for Gazprom, which delivers natural gas directly to Western Europe across Ukraine. That deal ending in 2024 provides Kyiv about $7 billion per year for 40 billion cubic meters (bpm) of gas. Such a shut-off would force Central European countries (including Austria, Slovakia, and partly Hungary) to seek gas resource elsewhere. At the same time, Gazprom chief Alexei Miller warned Naftogaz that Russia would do the same as a retribution for seizures of Russian state assets in Ukraine. Russian gas supplies to Europe would drop to 10-16bcm p.a.[91]

In October 2023, the Treasury Department's Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) sanctioned two shipping companies for violating price cap sanctions on Russian crude exports as the start of a process to sanction crude oil sanction breakers.[92]

In combination with the transition to renewable energy in Europe, European sanctions against Russian coal forced Russia to accelerate the shift of its coal exports to Asia.[24] However, the limited capacity of the Trans-Siberian Railway remained a bottleneck for Russia's eastern reorientation.[24]

Banking

In a 22 February 2022 speech,[93] US president Joe Biden announced restrictions against four Russian banks, including V.E.B., as well as on corrupt billionaires close to Putin.[94][95] UK prime minister Boris Johnson announced that all major Russian banks would have their assets frozen and be excluded from the UK financial system, and that some export licences to Russia would be suspended.[96] He also introduced a deposit limit for Russian citizens in UK bank accounts, and froze the assets of over 100 additional individuals and entities.[97]

Days later, and after substantial negotiation between European nations, an agreement was made to expel many Russian banks from the SWIFT international banking network.[9]

On 26 February, two Chinese state banks—the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, which is the largest bank in the world, and the Bank of China, which is the country's biggest currency trader—were limiting financing to purchase Russian raw materials, which was limiting Russian access to foreign currency.[99] On 28 February, Switzerland froze a number of Russian assets and joined EU sanctions. According to Ignazio Cassis, the president of the Swiss Confederation, the decision was unprecedented but consistent with Swiss neutrality.[100] The same day, Monaco adopted economic sanctions and procedures for freezing funds identical to those taken by most European states.[101] Singapore became the first Southeast Asian country to impose sanctions on Russia by restricting banks and transactions linked to Russia;[102] the move was described by the South China Morning Post as being "almost unprecedented".[103] South Korea announced it would participate in the SWIFT ban against Russia, as well as announcing an export ban on strategic materials covered by the "Big 4" treaties to which Korea belongs—the Nuclear Suppliers Group, the Wassenaar Arrangement, the Australia Group, and the Missile Technology Control Regime; in addition, 57 non-strategic materials, including semiconductors, IT equipment, sensors, lasers, maritime equipment, and aerospace equipment, were planned to be included in the export ban "soon".[104]

On 28 February, Japan announced that its central bank would join sanctions by limiting transactions with Russia's central bank, and would impose sanctions on Belarusian organisations and individuals, including President Aleksandr Lukashenko, because of Belarus' "evident involvement in the invasion" of Ukraine.[105]

Sanctions against Russia already had a significant impact on global banks. Since the invasion in 2022, the value of EU imports from Russia fell by half to about 10 billion euros ($10.85bn) in December 2022. As a result, particularly European banks experienced a serious downturn that could be felt worldwide. As Russia slashed pipeline deliveries to Europe since the invasion, balance books of European financial entities were also affected. As other commodities imported from Russia, were also the target of sanctions, including diamonds, gold, and potash fertilizers, the impact of sanctions was again magnified. Additionally other imports from Russia that are subject to secondary sanctions did already decline before 2023, such as fuel for nuclear plants, before direct measures were implemented. According to the American Bankers Association, sanctions against Russia had increased operational risks for lenders worldwide, and will require additional changes to lower financial risks, according to the source.[106][107][108]

From late December 2023 the United States, empowered with a Presidential Order amending E.O. 14024, may issue secondary sanctions against financial institutions that are providing financial support to Russia's defence industry, which could see banks based anywhere in the world having their assets blocked or being disconnected from the US financial system if they continue the practice of providing services to companies involved in Russia's military-industrial base.[109]

Russian frozen central bank assets

Within days of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 western countries moved to freeze Russian central bank funds in these countries.[110][a] In March 2023 (prior to the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam) a joint assessment was released by the Government of Ukraine, the World Bank, the European Commission, and the United Nations, estimating the total cost of reconstruction and recovery in Ukraine to be US$411 billion (€383 billion).[112][113] This could eventually exceed $1 trillion (€911 billion), depending on the course of the war.[114] The Kyiv School of Economics has a project and website dedicated to detailing the damages the war has caused to Ukraine.[115] The G7 countries plus the European Union announced in May 2023 that the approximately $300 billion (€275 billion) in Russian central bank assets that had been frozen in these countries would remain frozen "until Russia pays for the damage it has caused to Ukraine,"[113][116] and this was reaffirmed after the G7 meeting in December, 2023.[117] This constituted about half of the $612 billion (€560 billion) total foreign currency and gold reserves held at that time by the Russian central bank.[111] By late July 2023, the amount of frozen Russian assets held in these countries was estimated at $335 billion (€300 billion).[54] Most frozen assets, by far, reside in Europe ($217 billion (€201 billion)[117] to $230 billion (€210 billion)),[118] with the United States holding just a small portion ($5 billion (€4.5 billion))[118] and Japan also holding some.[119] Josep Borrell, EU's foreign affairs chief, said he wants EU countries to confiscate the frozen assets to cover the costs of rebuilding Ukraine after the war. Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Alexander Grushko remarked that Borrell's initiative amounted to "complete lawlessness" and said it would hurt Europe if adopted.[120][121] Russia has threatened to retaliate by confiscating assets owned by the EU.[122] Austrian Foreign Minister Alexander Schallenberg warned that confiscation of Russian assets that does not have a "watertight" justification would be an "enormous setback, and basically a disgrace" for the EU.[123]

There is a legal distinction between private assets, such as the yacht of a Russian oligarch, and state assets. Private assets are relatively easy to freeze — for example if it is suggested that the individual has been 'obtaining a benefit from or supporting the government of Russia'.[124] However, it is much more difficult to seize (confiscate) such assets. Ordinarily, it must first be proven that they constitute the proceeds of crime. Sanctions evasion is such a crime but only the portion of the assets involved in the evasion can be seized.[124][125] With respect to confiscation of frozen Russian state assets, the difficult problem is how to do it without violating international treaties concerning the protection of cross-border investments,[126] and without violating the principle that laws and regulations cannot be retroactive.[127] Russia's rights also include those under "sovereign immunity", which forbids one state from seizing another's property. It is cautioned that doing so could create dangerous precedents.[128] Risks also include aggravating the suspicions of the Global South,[119] to whom it may seem that double standards sometimes apply when the interests of Western countries are at stake,[129][130][b] and substantiating the view that the West is turning the international financial system into a weapon of war.[119]

Euroclear

The Euroclear depository, in Belgium, holds frozen Russian assets variously estimated at €125 billion ($137 billion),[131] €180 billion ($197 billion),[132] and €190 billion ($208 billion).[133][134] Euroclear generated €3 billion ($3.28 billion) in profits from these assets in the first nine months of 2023.[132][135] Belgium anticipates 2023 tax revenues of €625 million ($684 million) on the income generated by frozen Russian assets and €1.7 billion ($1.86 billion) in 2024.[131] According to Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo, 100% of this tax revenue should go directly to Ukraine.[131] This level of taxation falls far short of the level contemplated by the European Commission and others,[136] which are said to involve distributing to Ukraine some portion of the profits generated by the frozen assets.[122] Another European clearinghouse holding frozen Russian assets, Clearstream, is in Luxembourg. Both Belgium and Luxembourg have asked for assurance that they will not be required to bear all the risks that may attend European action against these assets.[132] The argument has been made that using Euroclear to seize Russian assets fuels financial fragmentation by encouraging non-G7 countries to switch to non-Western alternatives to Euroclear, such as China Securities Depository and Clearing Corporation, in order to protect their assets, making it harder to police sanctions on Russia, as well as harder to track financial transactions of groups involved in activities such as terrorism or nuclear proliferation.[129][137]

Legality of confiscation of state assets

In September 2023, the Renew Democracy Initiative (RDI) released a report (lead author Laurence Tribe) which concluded that Russia's arguments against confiscating its frozen state assets and transferring them to Ukraine have no validity, either practically or under U.S. or international law. According to Tribe, "There is simply no basis for saying Russia can violate Ukraine's sovereignty while invoking its own sovereignty as an inviolable shield."[138][139][140] The report argues that confiscation of Russian assets would be permissible under the international doctrine of "countermeasure", according to which an action (such as confiscation) that would ordinarily violate international law is permissible if it is undertaken with the aim of inducing another state to resume compliance with international law and is conducted in accordance with the requirements of the Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts (ARSIWA),[141] which "are considered by courts and commentators to be in whole or in large part an accurate codification of the customary international law of state responsibility".[142][143] According to the report, since a strong showing can be made that Russia has violated fundamental international laws, confiscation is an appropriate countermeasure to induce it to comply with its international obligations.[144]

On 12 January 2024 Russia was said to be close to initiating legal proceedings to challenge in court the freezing of its frozen central bank assets. Russians believe that such litigation "could last for decades", and in the interim would block any transfer of the assets to Ukraine.[145]

Countermeasures must be temporary and reversible

An article in Foreign Policy disagrees that confiscating Russian frozen assets and delivering them to Ukraine would constitute a valid countermeasure. It points out that the purpose of a legitimate countermeasure is to induce compliance with international law and not to act as punishment for violations. As such, it must be temporary and capable of being reversed if the violating country resumes its compliance with international law.[129] Confiscation, however, is aimed not at inducing Russia to stop its aggression but at compensating for the injury it has caused.[146][147] Once Russian assets have been transferred to Ukraine they can no longer be returned to Russia, rendering the countermeasure permanent, and its purpose punitive.[129][148] This is the prevailing view[149] and it has much support.[147][150][151][152]

Others assert that this errs in its assumption that the sole function of countermeasures is to induce compliance with international law, insisting that this is contradicted by Comment 1 to Article 22 of ARSIWA, which says, 'In certain circumstances, the commission by one State of an internationally wrongful act may justify another State injured by that act in taking non-forcible countermeasures in order to procure its cessation and to achieve reparation for the injury...' (emphasis added).[153] Therefore, according to this argument, the correct dichotomy is not between inducing compliance and achieving reparations, but is between countermeasures that make the injured state whole and those that impose punishment. Consequently, the ARSIWA requirement that countermeasures be reversible 'as far as possible' means that after Russia complies with its obligation to compensate Ukraine for the damage it caused it should no longer face countermeasures. Reversibility does not require that after Russia's compliance its compliance must be undone (by reversing its reparation to Ukraine), according to this argument.[153]

The RDI report responds to the charge that confiscating Russian assets is not reversible by asserting that the countermeasure being taken is a suspension of the sovereign immunity that Russia normally enjoys and insists that the requirement of reversibility does not apply to the frozen assets but to the suspension of immunity, which can be reversed when Russia comes into compliance with its international obligations. Others have agreed,[154][155] adding that confiscating Russian state assets is analogous to the asset transfers that were done with respect to Iran in 1981, Iraq in 1992, and Afghanistan in 2022.[156] A Stanford Law Review article calls this "...too clever by half. The reversibility requirement cannot be circumvented so easily." Since transferring the assets to Ukraine is not reversible the countermeasure does not serve to induce compliance, undercutting "the very raison d'être of countermeasures doctrine." Reversibility is a key requirement, the article insists, without which there is likely to be a rapidly proliferating unlawfulness bringing many undesirable consequences.[142]

The RDI report claims that even if reversibility referred to the economic effects of the suspension rather than to the suspension itself, the transfer of frozen assets to Russia would still satisfy reversibility since Russia will be placed in the same economic condition it would have been in if no countermeasures had been applied. Let's assume that the frozen assets amount to €300 billion and that by invading Ukraine Russia became obligated under international law to pay reparations to Ukraine for the damage caused, amounting to €800 billion.[c] If there had been no freezing of assets, Russia's balance sheet (so to speak) would show a €300 billion asset and an €800 billion liability, with a net economic result of a €500 billion liability. On the other hand, if the frozen assets are transferred to Ukraine, Russia's liability to Ukraine would be reduced by that amount, resulting in the same net €500 billion liability on its balance sheet. Since Russia would thereby be placed in the same economic condition it would have occupied if no countermeasures had been applied this must be seen as consonant with the reversibility requirement, according to the RDI report[158] and others.[159] Looked at in a different way, freezing the €300 billion until Russia has complied with its reparation obligation to Ukraine has the same impact on Russia as transferring the €300 billion directly to Ukraine.[153] According to this line of thinking, if there is a right to hold onto the €300 billion until Russia agrees to give it to Ukraine then it is absurd to say that the doctrine of reversibility is violated if it is transferred directly to Ukraine but it is not violated if the countermeasure is "reversed" and the money is transferred to Russia but under conditions that offset it against an amount that Russia would be required to pay Ukraine, as in one European Commission proposal.[146]

The RDI report adds that countermeasures must be reversible "as far as possible", and that this is not an absolute and inflexible requirement. "Accordingly, even if transfer of Russia's sovereign assets did not fully comport with the reversibility principle, this would be a prime example in which the expectation of reversibility must yield to the more pressing need to pursue a countermeasure that would effectively induce Russia's compliance with international law."[158] However, the Stanford Law Review article claims that the comments to the ARSIWA show that the term "as far as possible" "does not create a loophole" to justify irreversible measures, but requires a state having a choice as to which countermeasure to implement, to choose one that is reversible.[142] On the other hand, it is pointed out that according to James Crawford, former Special Rapporteur of the International Law Commission for the topic State Responsibility, reversibility "needs to be viewed broadly".[160] Others add that while the ARSIWA may have some flexibility on reversibility, it has no flexibility on the requirement that countermeasures be temporary, and confiscation is not temporary.[147]

Another analyst points out that since customary international law can change over time,[d] it might be interpreted to already recognize the confiscation of central bank assets under the current circumstances as a legitimate countermeasure or act of collective self-defense. This analyst also suggests that resolutions of the UN General Assembly could be taken as evidence that such an action is already a recognized state practice.[161][162] The RDI report agrees with this, adding that "norms of accepted state practice arise suddenly during moments at which the system is under great stress" and that U.N. General Assembly resolutions can "crystallize emerging customs" and serve as "evidence of a new rule of customary international law", citing Michael Scharf.[163][164]

Legality of third party countermeasures

Another argument against the RDI analysis concerns the right in international law of third party states, such as EU countries, to apply countermeasures at all. As a result of significant risks of abuse associated with the use of third-party countermeasures, and strong opposition in the International Law Commission during the drafting of the ARSIWA, "The ARSIWA do not directly address whether non-injured states invoking the responsibility of a breaching state...can take countermeasures."[142][165][e] However, though this is disputed by some,[167] it is widely believed that even if it is not expressly sanctioned in the ARSIWA, a rule has emerged under customary international law[d]entitling third party states to apply countermeasures to enforce compliance with erga omnes ("owed to the international community as a whole") obligations.[170][165] Once such a rule emerges, a war of aggression would violate an erga omnes obligation, giving third party states such rights.[154][171][f]

Some analysts believe that since Russia defied the International Court of Justice (ICJ) order that the "Russian Federation shall immediately suspend the military operations that it commenced on 24 February 2022 in the territory of Ukraine," and also defied a U.N. General Assembly emergency resolution condemning its invasion and demanding immediate withdrawal, therefore third-party states are entitled for those reasons to take countermeasures in order to bring Russia into international compliance.[143] Others respond that neither of these is an authoritative and conclusive determination. The ICJ ruling, it is argued, was preliminary. Furthermore, if General Assembly resolutions can substitute for Security Council decisions does that mean that the many General Assembly resolutions declaring Israel to be an international outlaw are sufficient to authorize states to ignore Israel's rights with impunity under international law?[174][175]

Legality of countermeasures to enforce obligation to pay reparations

The obligation to pay reparations is not,[171] or may not be,[176] an erga omnes obligation, rendering dubious the legitimacy of countermeasures by third party states to enforce an obligation to pay reparations. In addition, the leading treatise on the question of third-party countermeasures concluded that, with one possible exception, "third-party countermeasures have simply not been adopted to obtain any form of reparation".[147] Other legal analysts have presented arguments in favor of the legitimacy of countermeasures by third party states "aimed at stopping the ongoing failure to meet the obligation to make reparations" (but without confiscation).[142][g]

Legality of confiscation of income of frozen assets

The EU has concluded that it "can't legally confiscate outright frozen Russian assets",[128][h] but the annual profits from the investment of those assets is expected to be around €3 billion[177] (US$3.4 billion)[178] and a "windfall profits tax" on those profits is being investigated.[179] European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said on 22 June 2023 that before mid-July they would come up with a proposal on how to use these frozen assets to benefit Ukraine,[180][181] but this was later postponed until September,[54] and then until year-end.[132] On 12 December the European Commission announced that it had agreed on a legal way to use the interest and profits of the frozen assets to benefit Ukraine, but did not immediately disclose its contents. It could potentially make up to €3 billion ($3.25 billion) per year available to Ukraine. Such a plan must be approved by the European Parliament as well as all 27 member states and is expected to receive opposition from some states, such as France, Germany, Italy and Hungary.[117] The G7 has also backed the idea of finding a way to access the frozen assets to benefit Ukraine.[132][182]

Those arguing that it is an illegitimate countermeasure to confiscate Russian assets and deliver them to Ukraine for purposes of reparations also argue that the same principle governs investing the frozen assets and turning over investment gains to Ukraine,[147] with one analyst saying "...the European Commission's proposed extraction of investment returns from frozen assets—investing the frozen assets and seizing their earnings—is fundamentally confiscatory. ...The prime international legal barrier these proposals fail to overcome is the customary international legal principle of sovereign immunity,"[142] since it does not qualify as a valid countermeasure or as any of the other "circumstances precluding wrongfulness" provided in the ARSIWA.[147][i] Some analysts claim that confiscating just the income or interest on the frozen funds would not violate the requirement that countermeasures be reversible.[183] The proposal announced 12 December 2023 by the European Commission to use the interest and profits to benefit Ukraine was said to take the position that these revenues "do not constitute sovereign assets and do not have to be made available to the Central Bank of Russia under applicable rules",[117] and therefore delivering them to Ukraine would not violate the reversibility requirement.

Other concerns

Confiscation could weaken currencies

Christine Lagarde, president of the European Central Bank, which takes a view opposite that of the European Commission concerning the risks of using these profits for the benefit of Ukraine,[184] warned the European Union that taking action against frozen Russian assets could endanger the eurozone's financial stability and weaken the standing of the euro as a reserve currency, arguing that the negative consequences to the EU could exceed the amount generated for Ukraine.[132][185][186] Many international law experts believe that Ukraine's best chance against Russian assets lies in a favorable end to the war with Russia, after which it's claim for reparations under international law would be clear.[125]

The RDI report argues that the claim that such an action could weaken a particular national currency has no force if all the major currencies take the same action. "The idea is to do this multilaterally. ...If others didn't, there might be a flight from the dollar. But if it is done by all the major currencies, where are people going to move their money?"[138] According to other financial analysts, if non-western governments were going to pull their currency reserves out of the west they would have done so (a) when the west blocked Russia's access to its foreign exchange reserves, and (b) when the G7 announced that the block will remain in force until Russia pays reparation to Ukraine.[110][187] The reality is that Russia's ability to access the frozen funds is forever gone, and it is unclear why delivering the funds to Ukraine would damage the international financial world in ways that haven't already materialized.[188] Data from the European Central Bank and the U.S. Federal Reserve since the freezing of Russia's assets show that there has been no meaningful move away from the dollar.[129] In the second quarter of 2023, 89.2% of all currency reserves were held in U.S., EU, Japanese and British currencies.[189][190]

Confiscation would set a dangerous precedent

The RDI report claims that "any concern that confiscating Russia's assets will set a dangerous precedent if similar circumstances arise in the future rests on an assumption that conduct analogous to Russia's has occurred with frequency in the modern era or will in fact recur. On the contrary, Russia's war in Ukraine may well be unprecedented since the Second World War."[191] Others ask how, once Russia's assets have been seized, Western democracies will be able to convince China or India, sometime in the future, that they have no right to confiscate whatever assets they wish.[129]

A conclusion similar to that of the RDI report was reached by Lawrence Summers, who believes that the G7 should be moving collectively to use Russian state assets to finance the ongoing expenses in Ukraine made necessary by Russia's aggressive war. According to Summers, that is what the Russians did with respect to the Germans and the Japanese after World War II, it's what the U.S. did with respect to Saddam Hussein during the Iraq war, and there is ample legal precedent.[192] He said that it would set a "healthy precedent" if countries committing aggression against their neighbors stand to lose state assets.[193]

Others have maintained that it must not be forgotten that Russia is guilty of using a war of aggression to destroy Ukraine, its people and its culture, and to erase it from the map, and that since 1945 there have been few, if any, breaches of international law as serious as this.[194] To argue that under these circumstances seizing Russia's sovereign assets would undermine the international financial system is to argue that foreign reserves must be safe from seizure no matter what, and is like arguing that if real estate in London that represents the proceeds of crime is not free from the threat of seizure by the government, then all real estate in London has lost its security.[188]

Russia will retaliate

The RDI report argues that a Russian threat to retaliate against the assets of any state announcing an intention to seize Russian assets overlooks the fact that because Russia is not a financial center and the ruble is not a reserve currency, Russia does not hold the sovereign funds of other countries. It would have to resort to seizing private assets of European and U.S. companies but most such companies fled from Russia after its invasion of Ukraine and Russia has already seized their assets.[195] Tribe argues that given that the Russian assets have already been frozen and Vladimir Putin declared a war criminal, it's inconceivable that the assets will ever be unfrozen except to fund Ukraine's reconstruction, so we might as well get on with it.[138]

It has also been argued that the value of foreign assets in Russia that are subject to retaliation would have already been reduced as a result of the risks of being in Russia to begin with. Furthermore, it is asked to what extent essential foreign policy interests should give way in order to protect the value of assets whose owners have not taken advantage of the two years they have had to remove their assets from Russia.[188]

Competing claims against the frozen assets

The strength of Ukraine's claim against the frozen assets would be diminished if Russia and Ukraine were to negotiate an end to hostilities that did not include reparations for Ukraine, or included an amount less than the value of the frozen Russian assets.[196] In that case, Russia would have a claim for their return. Furthermore, there may be judgment creditors of Russia with claims that would have a higher priority than those of Ukraine, or who could at least delay reparations to Ukraine until the conclusion of litigation. Therefore, it has been suggested that the frozen funds should be transferred to an international entity that would be as insulated as possible from all claims except those of Ukraine.[196] The RDI report suggests that the frozen assets be transferred to an international fund analogous to the United Nations Compensation Commission (UNCC) that was set up to handle the transfer of Iraqi state funds to Kuwait after Iraq's unprovoked 1990 invasion.[197][198][j]

Use to which confiscated assets would be put

The justification for confiscating Russian central bank assets is found in Article 31 of the ARSIWA which says, "The responsible State is under an obligation to make full reparation for the injury caused by the internationally wrongful act." However, if confiscated Russian assets are used not to repair any injury suffered but instead to fund arms supplies to Ukraine, then Russia and its sympathizers could maintain that the confiscation did not constitute reparations but was instead a penalty, which does not qualify as a legitimate countermeasure under ARSIWA, entitling Russia to reparations under Article 31 for the amount unjustly confiscated.[196]

EU sanctions

On the morning of 24 February 2022, Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, announced "massive" EU sanctions to be adopted by the union. The sanctions targeted technological transfers, Russian banks, and Russian assets.[202] Josep Borrell, the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, stated that Russia would face "unprecedented isolation" as the EU would impose the "harshest package of sanctions [which the union has] ever implemented". He also said that "these are among the darkest hours of Europe since the Second World War".[203] President of the European Parliament Roberta Metsola called for "immediate, quick, solid and swift action" and convened an extraordinary session of Parliament for 1 March.[204][205]

Since February 2022, the European Union has sanctioned exports to the Russian Federation at a total value of €43.9 billion and imports to the EU worth €91.2 billion, including financial and legal services.[206]

In February 2024, the European Union proposed sanctions that would target Chinese companies aiding Russia's war effort in Ukraine.[207]

Restrictions on purchase and transfer of goods

The EU banned cars with Russian license plates from entering the EU, except for vehicles owned by EU citizens or their immediate family members.[208][209] The ban on vehicles and some other goods was imposed shortly after the invasion; however, the enforcement was not uniform and some Russian citizens had their cars confiscated after they already were in the EU.[210] The Russian Foreign Ministry claimed that this policy was motivated by "racism pure and simple" against Russians.[211]

European impoundment of yachts

A 5 April 2022 article by Insider claims the total cost of yachts impounded throughout Europe to be over $2 billion. This amount includes the motoryacht Tango, seized pursuant to United States sanctions with Spanish assistance.[212]

- France

On 26 February, the French Navy intercepted Russian cargo ship Baltic Leader in the English Channel. The ship was suspected of belonging to a company targeted by the sanctions. The ship was escorted to the port of Boulogne-sur-Mer and was being investigated.[213]

On 2 March 2022, French customs officials seized the yacht Amore Vero at a shipyard in La Ciotat. The Amore Vero is believed to be owned by the sanctioned oligarch Igor Sechin.[214]

Two yachts belonging to Alexei Kuzmichev of Alfa Bank were seized by France on 24 March.[215]

- Germany

On 2 March 2022, German authorities immobilized the Dilbar, owned by Alisher Usmanov.[216][217] She is reported to have cost $800 million, employ 84 full-time crew members, and contain the largest indoor swimming pool installed on a superyacht at 180 cubic metres.[218]

- Italy

On 4 March 2022, Italian police impounded the yacht Lady M. Authorities believe the ship is owned by Alexei Mordashov.[219] The same day, Italian police seized the yacht of Gennady Timchenko, the Lena, in the port city of Sanremo.[220] The yacht was also placed on a United States sanctions list.[221] On 12 March 2022, Italian authorities in the port of Trieste seized the sailing yacht A, known to be owned by Andrey Melnichenko. A spokesperson for Melnichenko vowed to contest the seizure.[222]

- Lithuania

On 20 April 2023, Lithuanian parliament Seimas finalised and approved sanctions to all Russian and Belarusian citizens as a response to Russian invasion of Ukraine. From 1 May 2023, citizens of both countries are ineligible to obtain Lithuanian visas, e-resident status or exchange Ukrainian hryvnia. In addition, Russian citizens are also ineligible to submit request for permanent stay in Lithuania or purchase property within Lithuanian territory.[223]

- Spain

In March 2022, the Spanish Ministry of Development (known by its acronym "MITMA") detained three yachts pending investigation into whether their true owners are individuals sanctioned by the European Union. The Valerie is detained in the Port of Barcelona; Lady Anastasia in Port Adriano in Calvià, Mallorca; and the Crescent in the Port of Tarragona.[224][225][226]

- United Kingdom

On 29 March 2022, Grant Shapps, the British secretary of state for transport, announced the National Crime Agency's seizure of the PHI. The yacht was docked at Canary Wharf and was about to leave.[227][228]

- Netherlands

On 6 April 2022, Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs Wopke Hoekstra sent a letter on the subject of sanctions addressed to the House of Representatives. In it, he reported that while no Russian superyachts were at anchor in the Netherlands, twelve yachts under construction across five shipyards were immobilized to ascertain ownership, including possible beneficial ownership.[229]

In September 2023, the Dutch shipyard Damen Group has initiated a lawsuit against the government of the Netherlands for losses inflicted by these measures. The cancellation of contracts from Russian clients had significantly impacted the business environment for many shipbuilders. The financial setbacks for that industry stems from the severance of ties with its Russian engineering branch, according to the statement.[230]

Aviation

The EU sanctions introduced on 25 February 2022 included a ban on the sale of aircraft and spare parts,[231] and also required lessors to terminate the leases on aircraft placed with Russian airlines by the end of March.[232]

Services and spare parts

On 2 March 2022, Airbus and Boeing both suspended maintenance support for Russian airlines.[233]On 11 March, China blocked the supply of aircraft parts to Russia.[234]Business jet manufacturer Bombardier Aviation announced that, in addition to suspending after-sales service activities, it had cancelled all outstanding orders placed by Russian individuals or companies.[235]As of April 2022, spare part and repair difficulties for the Safran/Saturn SaM146 engines used on the Sukhoi Superjet 100 were expected to force Russian airlines to ground the type.[citation needed]The lack of approved spare parts also affected foreign aircraft flying into Russian airports.[236]

In June 2022, the Russian government advised its airlines to use some aircraft for parts.[237] That same month, Patrick Ky, executive director of the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), expressed concern about the safety of Western-made aircraft flying in Russia without proper access to spare parts or maintenance. He highlighted that risks increase over time and cited reports that Russia will be forced to cannibalise aircraft.[238] In August 2022, Reuters reported confirmation from "four industry sources" that Russia had stripped parts from Airbus A320s and A350s, a Boeing 737 and a Sukhoi Superjet in order to perform maintenance on other aircraft. Around 15% of Aeroflot's fleet appeared to be grounded.[237]

In April 2023, Aeroflot started sending its aircraft to Iran for maintenance, benefitting from Iran's experience in performing maintenance under sanctions.[239] In May 2023, it was reported that Aeroflot flight attendants had been instructed not to log maintenance issues that would normally require aircraft to be grounded for repairs.[240] In August 2023, it emerged that the airline was operating some of its fleet with disabled brakes, instead telling pilots to rely solely on reverse thrusters.[241]

Leased aircraft

On 10 March 2022, Russia passed legislation outlining conditions to impede the return of leased aircraft to foreign lessors, including the need for approval from a government committee and payment of settlements in Roubles.[242]

Many aircraft operated by Russian airlines had been registered with the Bermuda registry, which suspended airworthiness approvals on 14 March.[243] The same day, Russia implemented a law allowing aircraft operated by Russian airlines to be re-registered with the Russian registry, effectively confiscating them from their overseas owners. Some 515 commercial aircraft, valued at approximately $10 billion, were leased by Russian airlines from foreign lessors prior to the sanctions.[244] Lessors moved swiftly to repossess those few aircraft "stranded" outside Russia[245] and reassigned some new aircraft due to be placed with Russian airlines, particularly Boeing 737 MAX that are now unlikely to be recertified by Russia.[246]

By 22 March, 78 foreign-owned aircraft had been reclaimed, amid speculation that some Russian airlines were cooperating with lessors in order to avoid jeopardising future relations.[247] Rossiya Airlines, a subsidiary of Aeroflot, had reregistered all its fleet with the Russian registry by 29 March.[248]

By 30 March, Irish lessor AerCap had repossessed 22 of the 135 aircraft it had leased to Russian airlines, and 3 of the 14 engines on lease. It filed insurance claims totalling $3.5 billion for the remaining aircraft, many of which were "now being flown illegally by [its] former airline customers".[249] Singapore-based lessor BOC Aviation had 18 aircraft worth $935 million on lease to Russian companies; it repossessed from Hong Kong one Boeing 747-8F leased to AirBridgeCargo but two other freighters were flown back to Russia contrary to explicit instructions, despite their insurance coverage and airworthiness certificates having been revoked.[250]

On 31 March, Russian Deputy Prime Minister Yury Borisov declared that all leased aircraft still in Russia had been re-registered and would remain in Russia, a total of over 400 aircraft.[251] However, re-registration of aircraft without their owners' consent is a breach of ICAO standards. These aircraft may be confiscated and repossessed upon landing in any airport outside of Russia.[252]

Aeroflot gradually resumed international flights to "friendly" countries: to Kyrgyzstan from 14 March, Azerbaijan on 21 March, Armenia from 22 March, Iran from 2 April, Sri Lanka from 8 April,[253] and Turkey and India from 6 May.[254] On 2 June, an Aeroflot A330 belonging to an Irish lessor was temporarily impounded by a commercial court in Sri Lanka, though the aircraft was subsequently allowed to return to Russia on 5 June.[255]

On 13 May, Aeroflot announced that it had purchased 8 A330s from foreign leasing companies, under an exemption that allows the execution of a lease solely to obtain repayments.[256]On 1 June, it emerged that five Russian airlines had kept a total of 31 aircraft outside Russia and returned them to lessors. Other airlines including Aeroflot have deposited money in special Rouble accounts to enable lessors to claim the amounts once sanctions are lifted.[257]In August, S7 Airlines was given special permission to "export" its two 737 MAX aircraft to Turkey in order to return them to their lessor.[258]

Airspace

On 24 February 2022, Ukrainian airspace was closed to civilian aircraft a few hours before the Russian invasion started, on the basis of a notification from the Russian Ministry of Defence. The European regulator EASA issued a Conflict Zone Information Bulletin (CZIB) warning that civilian aircraft could be misidentified or even directly targeted.[citation needed]

On 25 February, the UK announced the closure of its airspace to Russian airlines.[259] On 27 February, the EU and Canada closed their airspace to all Russian aircraft, including both commercial and private aircraft.[260] Russia issued a reciprocal ban, forcing many airlines to reroute or cancel flights to Asian destinations.[261] The US issued a similar ban on 1 March.[262]On 8 March, Aeroflot suspended all its remaining flights to international destinations (except for Minsk, Belarus) due to airspace restrictions[263] and to counter the "risk" of aircraft being repossessed by lessors.[264]On 9 March, to avoid Russian airspace, Finnair started routing its flights to Asia over the North Pole, the first time a polar route has been used for commercial flights in nearly 30 years.[265]An analysis of routes between Europe and Asia showed increased travel distances of between 1200 and 4000 km; the frequency of flights to some destinations has been reduced and other routes have been dropped.[266]

By 29 March 2022, the following countries and territories had completely closed their airspace to all Russian airlines and Russian-registered private jets:[267][268][269][270]

Albania

Albania Anguilla[271]

Anguilla[271] Aruba[272]

Aruba[272] Bermuda[273]

Bermuda[273] Bonaire[274]

Bonaire[274] British Virgin Islands[275]

British Virgin Islands[275] Canada

Canada Cayman Islands[276]

Cayman Islands[276] Faroe Islands[277]

Faroe Islands[277] Gibraltar[278]

Gibraltar[278] Greenland[279]

Greenland[279] Iceland

Iceland Kosovo

Kosovo Moldova

Moldova Montenegro

Montenegro Montserrat[280]

Montserrat[280] North Macedonia

North Macedonia Norway

Norway Saba[281]

Saba[281] Saint Helena[282]

Saint Helena[282] Sint Eustatius[283]

Sint Eustatius[283] Sint Maarten[284]

Sint Maarten[284] Switzerland (with exceptions for diplomats and United Nations representatives)[285]

Switzerland (with exceptions for diplomats and United Nations representatives)[285] Turks and Caicos Islands[286]

Turks and Caicos Islands[286] Ukraine (since 2015)

Ukraine (since 2015) United Kingdom

United Kingdom United States

United States

![]() European Union (EU27)

European Union (EU27)

In addition to airspace closure under sanctions, on 11 April EASA blacklisted 21 Russian airlines on safety grounds, given that aircraft are being operated without airworthiness certificates, in breach of the Chicago Convention and international safety standards.[287] EASA clarified that the Russian air transport regulator, Rosaviatsia, had failed to provide evidence that it has the capacity to perform the oversight activities required to ensure air safety.[288]The US Federal Aviation Administration also downgraded Russia's safety rating, meaning that no new services to the US and no codeshares with US carriers are authorised.[289]

In May 2022, the UK announced that Russian airlines would be prohibited from selling their landing slots at UK airports, valued at approximately £50 million.[290] The slots were subsequently reallocated to other airlines.[291]

At the end of May 2022, the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) closed its airspace to aircraft that have been re-registered with the Russian registry in breach of ICAO regulations and for which the airlines are thus unable to provide proper documentation.[292]

Russian aircraft manufacturing industry

EASA revoked the type certificates of the Sukhoi Superjet 100, Tupolev Tu-204 and four other Russian aircraft types on 14 March, as well as approvals of maintenance organisations and third-country authorisations for Russian airlines. EASA also suspended all work on new certification applications, including the Irkut MC-21 airliner.[293] Due to the need to source all aircraft components domestically, notably the Pratt & Whitney PW1400G engines which will be replaced by Russian-built Aviadvigatel PD-14 units, production of the MC-21 is expected to be delayed by 2 years. In the meantime, production of older and less fuel-efficient Russian-built aircraft such as the Tupolev Tu-214 and Ilyushin Il-96-400 will be stepped up, and a fuel subsidy introduced.[294]The Sino-Russian CR929 wide-body aircraft programme, which was already in difficulty due to the diverging expectations of the two parties, is also expected to suffer significant delays or even cancellation.[295]

On 29 June, the US government expanded its sanctions to cover United Aircraft Corporation (UAC) (the parent company of Irkut, United Engine, Tupolev, Ilyushin and others), with an exemption allowing UAC to export parts and services for civil aircraft not registered in Russia if necessary for aviation safety.[296]

Aviation industry organisations and alliances

On 15 March, Aeroflot CEO Mikhail Poluboyarinov, who is targeted with EU sanctions, was removed from the IATA board of governors.[297]

In April, the two Russian airlines that were members of global airline alliances both saw their memberships suspended: S7 Airlines from Oneworld and Aeroflot from SkyTeam.[298]

U.S. "freeze and seize" policy

The main United States sanctions law, IEEPA, blocks the designated person or entity's assets, and also prohibits any United States person from transacting business with the designated person or entity. Specifically, 50 U.S.C. § 1705 criminalizes activities that "violate, attempt to violate, conspire to violate, or cause a violation of any license, order, regulation, or prohibition", and allows for fines up to $1,000,000, imprisonment up to 20 years, or both. Additionally, United States asset forfeiture laws allow for the seizure of assets considered to be the proceeds of criminal activity.

On 3 February 2022, John "Jack" Hanick was arrested in London for violating the sanctions against Konstantin Malofeev, owner of Tsargrad TV. Malofeev is targeted with sanctions by the European Union and United States for material and financial support to Donbass separatists.[299][300][301][302][303][304][k] Hanick was the first person criminally indicted for violating United States sanctions during the War in Ukraine.[306]

According to court records, Hanick has been under sealed indictment in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York since November 2021. The indictment was unsealed 3 March 2022. Hanick awaits extradition from the United Kingdom to the United States.[307][308]

In the 1 March 2022 State of the Union Address, American President Joe Biden announced an effort to target the wealth of Russian oligarchs.

Tonight, I say to the Russian oligarchs and the corrupt leaders who've bilked billions of dollars off this violent regime: No more.

The United States — I mean it. The United States Department of Justice is assembling a dedicated task force to go after the crimes of the Russian oligarchs.

We're joining with European Allies to find and seize their yachts, their luxury apartments, their private jets. We're coming for your ill-begotten gains.[309]

On 2 March 2022, U.S. Attorney General Merrick B. Garland announced the formation of Task Force KleptoCapture, an inter-agency effort.[310]

On 11 March 2022, United States President Joseph R. Biden signed Executive Order 14068, "Prohibiting Certain Imports, Exports, and New Investment With Respect to Continued Russian Federation Aggression," an order of economic sanctions under the United States International Emergency Economic Powers Act against several oligarchs. The order targeted two properties of Viktor Vekselberg worth an estimated $180 million: an Airbus A319-115 jet and the motoryacht Tango.[311] Estimates of the value of the Tango range from $90 million (U.S. Department of Justice estimate) to $120 million (from the website Superyachtfan.com).

On 4 April 2022, the yacht was seized by Civil Guard of Spain and U.S. federal agents in Mallorca. A United States Department of Justice press release states that the seizure of the Tango was by request of Task Force KleptoCapture, an interagency task force operated through the U.S. Deputy Attorney General.[312][313][314]

The matter is pending in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia. The affidavit for the seizure warrant states that the yacht is seized on probable cause to suspect violations of 18 U.S.C. § 1349 (conspiracy to commit bank fraud), 50 U.S.C. § 1705 (International Emergency Economic Powers Act), and 18 U.S.C. § 1956 (money laundering), and as authorized by American statutes on civil and criminal asset forfeiture.[315]

The increased US sanctions against Russia, aimed at the companies and individuals based in Turkey, China and the UAE for supplying the military purposes goods to Moscow. On 2 November 2023, the US Treasury Department said new sanctions include more restrictions on Russia energy and mining industry. The US sanctioned the UAE's ARX Financial Engineering and four of its employees for assisting transfer of Russian assets to the Emirates and for providing alternatives to sanctioned-hit Russian bank VTB in converting roubles into US dollars.[316]

Science

Shortly after the invasion, the European Commission,[317] followed by the United States,[318] decided to suspend cooperation with Russian entities in research, science and innovation. With the adoption of the fifth package of sanctions against Russia on 8 April 2022, the participations of all Russian public bodies or public-related entities in ongoing Horizon Europe projects were terminated, though the science community remains divided over the justification for science sanctions.[319] Russian scientists are impacted by the sanctions —irrespective of the individual scientists' attitudes towards the war.[320] Among other effects, the sanctions hinder scientific cooperation in the Arctic.[321][322] More generally, the sanctions have had stark effects on Russian participation in global scientific exchange and collaboration,[323][324] a concern pointed out by the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics and researchers in international particle physics community in particular.[325][326][327]

Other entities

On 9 March 2022, the New Zealand Parliament passed the Russia Sanctions Act 2022, which allows for sanctions to be placed on individuals connected to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine and targets their assets including funds, ships, and planes. New Zealand also created a blacklist targeting senior Russian officials and oligarchs.[328][329] On 6 April, New Zealand also imposed a 35% tariff on Russian products while restricting industrial exports to Russia.[330][331]

The Bahamas, Antigua and Barbuda and Saint Kitts and Nevis also joined the list of imposing sanctions on Russia.[332][333][334]

On 2 May, Finnish consortium Fennovoima announced that it had terminated its contract with Russia's state-owned nuclear power supplier Rosatom for the delivery of a planned nuclear power plant in Finland.[335]

Shifting of safe havens and sanctions evasion

Andorra

On 24 March 2022, sanctions imposed by Andorra on banking transactions carried out by individuals and legal entities from Russia and Belarus came into force. In total, 1,150 were blocked, the purchase, sale and negotiation of certain financial issues were prohibited, as well as Andorran nationals from borrowing from the central banks and public entities of these two countries; trade with Russia and Belarus was prohibited with public funds, and Russian nations were prohibited from making new deposits in Andorra for values greater than €100,000. In general, Andorra aligned itself with the sanctions imposed by the European Union.[336] The Andorran government extended the list of persons sanctioned by decree on 4 May 2022.[337]

Switzerland

Switzerland follows the EU sanctions and in response was put on the list of "unfriendly nations" by Russia.[338] According to the Swiss Embassy in Moscow, Switzerland has long been "the most important destination worldwide for rich Russians to manage their wealth".[339] The Bank for International Settlements estimates that Russian nationals have only $11 billion deposited in Swiss bank accounts, though other estimates are much higher: for example the Neue Zürcher Zeitung estimates the amount deposited to be CHF 150 billion[340] and the Swiss Bankers Association states even between CHF 150 and 200 billion (between US$160 and 214 billion).[341] As of July 2022, CHF 6.7 billion had been frozen by the Swiss authorities, according to Swiss authorities more than any other country has.[342][343][344] The sanctions target at least 1156 people and 98 companies which were identified by the EU.[344]

Leading Russian opposition figures, including British financier Bill Browder, have criticised Switzerland by saying the country is not doing nearly enough, while granting Russia too many loopholes in commodities trading, real estate investing or banking sector.[345][346][347] According to U.S. Ambassador to Switzerland Scott Miller in 2023, "Switzerland could block an additional CHF 50-100 billion" of the Russian assets.[348]

In May 2022, the Helsinki Commission of the U.S. Congress accused Switzerland to be "a leading enabler of Russian dictator Vladimir Putin and his cronies" – a claim that was strongly rejected by the Swiss government stating that "the country implements all sanctions that were decided by the EU and the Federal Council".[349] The Federal Council of Switzerland called the allegations of the Helsinki Commission "politically unacceptable" and the President of the Swiss Confederation complained in a phone call with the US secretary of state Antony Blinken about the accusations.[350][351] Switzerland hosted an international conference in Lugano on 5 July 2022 to finance the rebuilding of war-torn Ukraine. In August 2022, Switzerland adopted new EU sanctions to ban all Russian gold imports. At the same time, new exemptions with respect to financial transactions related to agricultural products and oil supplies to third countries were also made public.[352][353][354] In September, Switzerland stopped sharing tax information with Russia; Russia therefore no longer receives information about financial accounts Russian citizens have in Switzerland.[355] According to Swiss NGO Public Eye in 2023: "The war in Ukraine has put a spotlight on all the Swiss shortcomings in the fight against corruption, money laundering, and the implementation of sanctions".[356][357]

On 24 July 2023, a meeting between the U.S. Treasury and the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) was held in Geneva, Switzerland to further pressure Swiss commodity traders to reduce their exposure to Russian-based energy imports to Europe. The U.S. embassy in Bern was also present. A number of issues were discussed, including the impact of sanctions against Russia on the global energy market and food security. Swiss interests were represented by Suissenégoce, composed of trading companies, transporters, banks, insurance companies and specialist service providers. Swiss companies had been seriously affected by the war in Ukraine, and resulting economic sanctions. By the end of July 2023, as a result of additional sanctions imposed by the EU, Ukraine and the U.S., crude oil prices were again rising by as much as 8%, and concurrently the price for discounted Russian Urals crude was also increasing. Despite the sanctions, particularly Urals crude was trading again above US$60 per barrel. Against the backdrop of these new developments, U.S. and EU interests to sanction Russian oil exports were at the center of these critical talks in Geneva, but without accusing Swiss commodity traders to have directly evaded economic sanctions.

The top four traders Vitol, Cargill, Glencore and Trafigura, made a combined $50 billion in profits in 2022, five times more than in the previous decade, also because traders were producing additional profits from buying cheaper and sanctioned oil cargoes and selling them at a hefty profit. Henceforth, the main concern for the U.S. and European allies is that adherence to sanctions is a matter of self-verification without any independent or directed supervision. The talks in Switzerland between external U.S. interests and representatives from Swiss companies were described as "useful for all parties". The United States Department of the Treasury is conducting such meetings not only in Switzerland but in a number of other European countries to discuss the technical aspects of sanctions imposed on the Russia energy economy.[358][359]

On 27 September 2023, shares of the Swiss bank UBS were under considerable pressure and the Swiss Stock Exchange had to temporarily halt trading activities as the stock price retreated by as much as 8%. Bloomberg reported that the US Department of Justice (DOJ) had started an investigation into the dealings of Credit Suisse with Russia before Switzerland's second ranking bank was acquired by UBS in June 2023. Share values of UBS increased considerably in late summer of 2023 before the DOJ probe again brought uncertainty to the largest Swiss bank. The DOJ had suspected that Credit Suisse, traditionally a substantial holder of Russian assets, had violated economic sanctions before it was acquired by UBS. Switzerland complied with all E.U. financial sanctions against Russia in 2022 and 2023, but the recent probe was not included in the latest quarterly report by UBS, and is a result of previous dealings by CS with sanctioned Russian entities. Since the take-over of Credit Suisse, UBS has built up a large buffer of 9 billion CHF (US$10.3 billion) to cover potential losses of Credit Suisse assets.[360]

United Arab Emirates

Lured by the United Arab Emirates' flexible visa program, many wealthy Russians moved their money to the UAE. Property purchases in Dubai by Russians surged by 67% in the first three months of 2022. Around 200,000 Russians were estimated to have left the country in the first 10 days of the war.[362] Investigations revealed that private jets and yachts belonging to sanctioned Russian oligarchs and billionaires were found in places like Dubai and the Maldives. A number of private jets belonging to sanctioned Russians were also tracked flying back and forth between Moscow and Tel Aviv, and between Russia and Dubai.[363][364] Some Russians also began to utilize the UAE's "golden visa" program, which could allow these oligarchs to live, work, and study in the UAE with full ownership of their business.[365][366]

In May 2022, European Parliament members suggested that the UAE should be blacklisted for allowing sanctioned Russian oligarchs and other officials to invest in properties and businesses in Dubai.[367]

A Russian oligarch, Andrey Melnichenko was sanctioned by the European Union in March 2022, after claims that he attended a meeting with Putin on the day of the invasion. Following the sanctions, Italian authorities seized Melnichenko's $600 million Sailing Yacht A. Another yacht belonging to him, the $300 million Motor Yacht A was identified parked in a port in Ras al-Khaimah in the UAE.[368] A $350 million Boeing 787 Dreamliner private jet belonging to Roman Abramovich was also grounded in Dubai. The US Department of Justice has an order from a US federal judge to seize the jet.[369] Politicians and campaigners, including Danish MEP Kira Marie Peter-Hansen and campaigner Bill Browder, called for the UAE to be blacklisted for allowing the flow of "dirty money" and acting as a refuge for sanctioned Russians.[370][371]

On 23 June 2022, the Madame Gu superyacht, owned by sanctioned billionaire Andrey Skoch, was reported to have been docked at Port Rashid in Dubai since 25 March. It was designated as sanctioned property by the US.[372] In June 2022, Russia's wealthiest oligarch, Vladimir Potanin moved his $300 million superyacht, Nirvana, to Dubai. Potanin was not sanctioned at the time, and the move to shift the luxury superyacht to Dubai's Port Rashid was a precautionary measure.[373][374]

The United Arab Emirates defends its stance on sanctions targeting Russian individuals by stating that it remains neutral and has not imposed sanctions.[376] The UAE stated that its state policy complies with the international rights norms, stipulated by the United Nations Organization, which has not imposed any sanctions.[377]