Мемориальный стадион Роберта Ф. Кеннеди

РФК | |

| |

RFK Stadium with the U.S. Capitol and the Washington Monument visible in the background in 1988 | |

| |

| Former names | District of Columbia Stadium (1961–1969) |

|---|---|

| Address | 2400 East Capitol Street SE |

| Location | Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Coordinates | 38°53′24″N 76°58′19″W / 38.890°N 76.972°W |

| Public transit | |

| Owner | District of Columbia |

| Operator | Events DC |

| Capacity | Baseball: 43,500 (1961) 45,016 (1971) 45,596 (2005) Football or soccer: 56,692 (1961) 45,596 (2005–2019) 20,000 (2012–2017, MLS) |

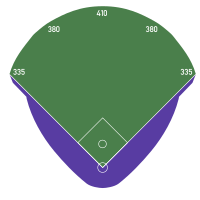

| Field size | Football: 120 yd × 53.333 yd (110 m × 49 m) Soccer: 110 yd × 72 yd (101 m × 66 m) Baseball: Left field: 335 ft (102 m) Left-center: 380 ft (116 m) Center field: 410 ft (125 m) Right-center: 380 ft (116 m) Right field: 335 ft (102 m) Backstop: 54 ft (16 m)  |

| Surface | TifGrand Bermuda grass[1] |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | July 8, 1960[2] |

| Opened | October 1, 1961 |

| Closed | September 15, 2019 |

| Demolished | 2023–present |

| Construction cost | $24 million ($245 million in 2023 dollars[3]) |

| Architect | George Leighton Dahl, Architects and Engineers, Inc. |

| Structural engineer | Osborn Engineering Company |

| Services engineer | Ewin Engineering Associates |

| General contractor | McCloskey and Co. |

| Tenants | |

| Washington Redskins (NFL) 1961–1996 George Washington Colonials (NCAA) 1961–1966 Washington Senators (MLB) 1962–1971 Washington Whips (USA / NASL) 1967–1968 Howard Bison (NCAA) 1974–1976 Washington Diplomats (NASL) 1974, 1977–1981 Team America (NASL) 1983 Washington Federals (USFL) 1983–1984 Washington Diplomats (ASL/APSL) 1988–1990 D.C. United (MLS) 1996–2017 Washington Freedom (WUSA) 2001–2003 Washington Nationals (MLB) 2005–2007 Military Bowl (NCAA) 2008–2012 | |

| Website | |

| eventsdc | |

Мемориальный стадион Роберта Ф. Кеннеди , широко известный как стадион RFK и первоначально известный как стадион округа Колумбия , — несуществующий многоцелевой стадион в Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия. Он расположен примерно в двух милях (3 км) к востоку от здания Капитолия США . недалеко от западного берега реки Анакостия и рядом с Оружейной палатой округа Колумбия . он принадлежал федеральному правительству . Открытый в 1961 году, до 1986 года [ 4 ]

Стадион РФК был домом для команды Национальной футбольной лиги (НФЛ), двух команд Высшей бейсбольной лиги (MLB), пяти профессиональных футбольных команд, двух команд колледжа по футболу , игры в чашу и команды USFL . Здесь состоялось пять игр чемпионата NFC , две игры всех звезд MLB , мужские и женские матчи чемпионата мира , девять мужских и женских футбольных игр первого раунда Олимпийских игр 1996 года , три Кубка MLS матча , две игры всех звезд MLS и многочисленные американские матчи. Товарищеские матчи и отборочные матчи чемпионата мира. Здесь проходили студенческий футбол, студенческий футбол, показательные выступления по бейсболу, боксерские матчи, велогонка , американской серии Ле-Ман автогонка , марафоны и десятки крупных концертов и других мероприятий.

RFK was one of the first major stadiums designed to host both baseball and football. Although other stadiums already served this purpose, such as Cleveland Stadium (1931) and Baltimore's Memorial Stadium (1950), RFK was one of the first to employ what became known as the circular "cookie-cutter" design.

It is owned and operated by Events DC, the successor agency to the DC Armory Board, a quasi-public organization affiliated with the city government, under a lease that runs until 2038 from the National Park Service, which owns the land.[5]

In September 2019, Events DC officials announced plans to demolish the stadium due to maintenance costs.[6] In September 2020, the cost was estimated at $20 million.[7] Demolition of the surrounding area began in 2023, however, demolition of the stadium itself has not begun as of 2024.[8][9]

As of February 2024, there is an active bill in the U.S. Congress[10] to extend the lease by 99 years.[11] This bill passed the House on February 28, 2024, and is pending before the Senate.[12]

On May 2, 2024 it was announced that the stadium was set to be demolished.[13]

History

[edit]Planning

[edit]The idea of a stadium at this location originated in 1930 when plans were developed by the "Allied Architects of Washington, in cooperation with the Fine Arts and National Capital Park and Planning Commissions and the Board of Trade."[14] Plans were further developed in 1932 when the Roosevelt Memorial Association (RMA) proposed a National Stadium for the site[15] and Allied Architects, a group of local architects organized in 1925 to secure large-scale projects from the government, made designs for it.[16] A "National Stadium" in Washington was an idea that had been pursued since 1916, when Congressman George Hulbert of New York proposed the construction of a 50,000-seat stadium at East Potomac Park for the purpose of attracting the 1920 Olympics. It was thought that such a stadium could attract Davis Cup tennis matches, polo tournaments and the annual Army-Navy football game. A later effort by DC Director of Public Buildings and Parks Ulysses S. Grant III and Congressman Hamilton Fish of New York sought to turn the National Stadium into a 100,000-seat memorial to Theodore Roosevelt, suitable for hosting inaugurations, possibly on the National Mall or Theodore Roosevelt Island. This attracted the attention of the RMA, which suggested the East Capital location. This would allow the Lincoln Memorial, then under construction west of the Capitol, and the Roosevelt memorial to become bookend monuments to the two great Republican presidents. The effort lost steam when Congress chose not to fund the stadium in time to move the 1932 Olympics from Los Angeles.[17]

The idea of a stadium gained support in 1938, when Senator Robert Reynolds of North Carolina pushed for the creation of a municipal outdoor stadium within the District, citing the "fact that America is the only major country not possessing a stadium with facilities to accommodate the Olympic Games". The following year a model of the proposed stadium, to be located near the current site of RFK Stadium, was presented to the public. By 1941, the National Capital Planning Commission had begun buying property for a stadium, purchasing the land between East Capitol, C, 19th and 21st NE.[18] A few years later, on December 20, 1944, Congress created a nine-man National Memorial Stadium Commission to study the idea.[19] They intended the stadium to be a memorial to the veterans of the World Wars. The commission wrote a report recommending that a 100,000-seat stadium be built near the site of RFK in time for the 1948 Olympics, but it failed to get funding.[20]

Ignored in the early 1950s, a new stadium again drew interest in 1954. Congressman Charles R. Howell of New Jersey proposed legislation to build a stadium, again with hopes of attracting the Olympics. He pushed for a report, completed in 1956 by the National Capital Planning Commission entitled "Preliminary Report on Sites for National Memorial Stadium", which identified the "East Capitol Site" to be used for the stadium. In September 1957, "The District of Columbia Stadium Act" was introduced and authorized a 50,000-seat stadium to be used by the Senators and Redskins at the Armory site. It was signed into law by President Eisenhower on July 29, 1958, with an estimated cost of $7.5 to $8.6 million.[19] The lease for the stadium was signed by the D.C. Armory Board and the Department of the Interior on December 12, 1958. The stadium, the first major multisport facility built for both football and baseball, was designed by George Dahl, Ewin Engineering Associates (since 1954 part of what became Volkert, Inc.) and Osborn Engineering. Groundbreaking for the $24 million venue was in 1960 on July 8, and construction proceeded over the following 14 months.[21] The existing venue for baseball (and football) in Washington was Griffith Stadium, about four miles (6 km) northwest.

While Redskins' owner George Preston Marshall was pleased with the stadium, Senators' owner Calvin Griffith was not. It wasn't where he wanted it to be (he had preferred to play at a site in Washington's Northwest Quadrant) and he'd have to pay rent and let others run the parking and concessions. The Senators' attendance figures had suffered after the arrival of the Baltimore Orioles in 1954 and Griffith then grew to prefer the less racially-defined demographics and profit potential of the Minnesota market.[22] In 1960, when the American League granted the city of Minneapolis an expansion team, Griffith proposed that he be allowed to move his team to Minneapolis-Saint Paul and give the expansion team to Washington. Upon league approval, the team moved to Minnesota after the 1960 season and Washington fielded a "new Senators" team, entering the junior circuit in 1961 with the Los Angeles Angels.[19]

Opening

[edit]

The stadium opened in autumn 1961 as District of Columbia Stadium, often shortened to D.C. Stadium. The new venue opened for football even though construction was not completed until the following spring.[23]

Its first official event was an NFL regular season game on October 1, ten days after the final MLB baseball game at Griffith Stadium. The Redskins lost that game to the New York Giants 24–21 before 36,767 fans, including President John F. Kennedy.[24] This was slightly more than the attendance record at Griffith Stadium of 36,591 on October 26, 1947 (in a game vs the Bears).[19][24]

At a college football game labeled the "Dedication Game," the stadium was dedicated on October 7. George Washington University became the first home team to win at the stadium with a 30–6 defeat of VMI.[21][25]

Its first sell-out came on November 23, 1961, for the first of what were to be annual Thanksgiving Day high-school football games between the D.C. public school champion and the D.C. Catholic school champion: Eastern defeated St. John's 34–14.[26][27]

The first Major League Baseball game was played on April 9, 1962, after two exhibition games against the Pirates had been cancelled. President John F. Kennedy threw out the ceremonial first pitch in front of 44,383 fans, who watched the Senators defeat the Detroit Tigers 4–1 and Senators shortstop Bob Johnson hit the first home run.[28][29] The previous Washington baseball attendance record was 38,701 at Griffith Stadium on October 11, 1925, at the fourth game of the World Series, and was the largest ever for a professional sports event in Washington.[30] The previous largest baseball opening day figure had been 31,728 (on April 19, 1948).[19]

When it opened, D.C. Stadium hosted the Redskins, the Senators, and the GWU Colonials football team, all of whom had previously used Griffith Stadium: the GWU Colonials shut down their football team at the end of the 1966 season, while the Senators moved to Dallas-Fort Worth at the end of the 1971 season, and became the Texas Rangers, playing in Arlington Stadium.

Early years

[edit]In 1961, Washington Redskins owner George Preston Marshall refused to integrate his team with black players, but President Kennedy forced his hand by refusing to allow the team to play in the stadium, which was on Federal land, unless he desegregated the organization. In 1962, Marshall relented and selected Ernie Davis first overall in the 1962 draft. However, Davis refused to play for the team and was traded for Bobby Mitchell, with Marshall later signing four other black players for the season as the last NFL owner to integrate.[31]

In 1961 and 1962, D.C. Stadium hosted the annual city title game, matching the D.C. Public Schools champion and the titleholder for the Washington Catholic Athletic Conference, played before capacity crowds on Thanksgiving Day. The November 22, 1962, game between St. John's, a predominantly white school in Northwest D.C., and Eastern, a majority-black school just blocks from the stadium, ended in a racially motivated riot.[32][33]

In 1964, the stadium emerged as an element in the Bobby Baker bribery scandal. Don B. Reynolds, a Maryland insurance businessman, made a statement in August 1964 which he claimed that Matthew McCloskey, a former Democratic National Committee chairman and Kennedy's ambassador to Ireland, paid a $25,000 kickback through Reynolds and at the instruction of Baker to the Kennedy-Johnson campaign as payback for the stadium construction contract.[34] Baker later went to jail for tax fraud, and the FBI investigated the awarding of the stadium contract, although McCloskey was never charged.[35]

Renaming the stadium

[edit]The stadium was renamed in January 1969 for U.S. Senator and presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy,[36] who had been assassinated in Los Angeles seven months earlier. The announcement was made by Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall on January 18, in the last days of the Johnson Administration.[37][38] The dedication ceremony at the stadium was held several months later on June 7.[38][39]

Senators depart

[edit]The Senators' final game was at RFK on Thursday night, September 30, 1971,[40] with less than 15,000 in attendance.[41] Rains from Hurricane Ginger threatened the event,[40] but the game proceeded. Fan favorite Frank "Hondo" Howard hit a home run (RFK's last until 2005) in the sixth inning to spark a four-run rally to tie the game; the Senators scored two more in the eighth to go up 7–5, but the game was forfeited (9–0) to the Yankees after unruly fans stormed the field with two outs in the top of the ninth.[19][40] Subsequent efforts to bring baseball back to RFK, including an attempt to attract the San Diego Padres in 1973,[42][43][44] and a plan to have the nearby Baltimore Orioles play eleven home games there in 1976, all failed.[45] The former was derailed by lease issues with the city in San Diego,[44] and the latter was shot down by commissioner Bowie Kuhn, who had planned to expand the league with four teams (aiming for Seattle, New Orleans, Toronto and Washington that would see an 14-team NL and AL).[46][47] The expansion for 1977 was later reduced to two teams to be placed in the American League with Toronto and Seattle, and the next wasn't until 1993 (speculation for expansion had started as early as 1989 with Washington as a city in mind, but it proved fruitless). In the mid-1990s RFK was planned to be the home of the yet-to-be-named Washington team, a charter franchise of the United League (UL) which was planned to be a third league of Major League Baseball (MLB).

For much of the 1970s and 1980s, RFK was primarily known as the home of the Redskins, where they played during their three Super Bowl championship seasons. It also hosted several short-lived professional soccer teams and in 1983–1984 the Washington Federals of the USFL. In 1980, it hosted the Soccer Bowl, the championship game of the NASL.

D.C. United moves in, Redskins move out, Nationals come and go

[edit]Major changes to the stadium came in 1996. Following the success of hosting matches in the 1994 World Cup and 1996 Summer Olympics, RFK became home to one of the charter teams of the new Major League Soccer. On April 20, 1996, it played host to the first home match of D.C. United, a 2–1 loss to the LA Galaxy.

However, later that year the stadium hosted the Redskins' final home game in Washington, D.C. After nearly a decade of negotiating for a new stadium with Mayors Sharon Pratt Kelly and Marion Barry, abandoning them in 1992 and 1993 in search of a suburban site and then having a 1994 agreement collapse in the face of neighborhood complaints, environmental concerns and a dispute in Congress (over what some members viewed as the team's racially insensitive name and the use of federal land for private profit), Jack Kent Cooke decided to move his team to Maryland.[48][49][50] On December 22, 1996, the Redskins won their last game at RFK Stadium 37–10 over the Dallas Cowboys, reprising their first win there in 1961, before 56,454, the largest football crowd in stadium history. The Redskins then moved east to FedExField in 1997, leaving D.C. United as the stadium's only major tenant for much of the next decade, though from 2001 to 2003 they were joined by the Washington Freedom of the short-lived Women's United Soccer Association.

After hosting 16 exhibition games after the Senators' departure, baseball returned to RFK temporarily in 2005.[51] That year the National League's newly renamed Washington Nationals made it their home while a new permanent home, Nationals Park, was constructed. On April 14, 2005, before a crowd of 45,496 including President Bush and MLB Commissioner Bud Selig, the Nationals beat the Arizona Diamondbacks 5–3 victory in their first game at RFK. President George W. Bush, formerly a part-owner of the Texas Rangers (the former Senators), threw out the first pitch becoming the last president, and the first since Richard Nixon, to do so in RFK Stadium.[21] Bush threw a ball saved by former Senators pitcher Joe Grzenda from that teams ill-fated final home game—the ball Grzenda would have pitched to Yankee second baseman Horace Clarke when fans rioted and forced the forfeit. The last MLB game at RFK, a 5–3 Nationals win over the Phillies, was played on September 23, 2007, and in 2008 the Nationals moved to their new stadium.

The last team leaves

[edit]In 2008, RFK was once again primarily the host of D.C. United, though it also hosted a college football bowl game, the Military Bowl, from 2008 to 2012, before it moved in 2013 to Navy–Marine Corps Memorial Stadium in Annapolis, Maryland.[52] On July 25, 2013, the District of Columbia and D.C. United announced a tentative deal to build a $300 million, 20,000–25,000-seat stadium at Buzzard Point.[53][54] Groundbreaking on the new soccer stadium, Audi Field, occurred in February 2017, and on October 22, 2017, RFK hosted its last MLS match, a 2–1 D.C. United loss to the New York Red Bulls.[55]

Demolition

[edit]On September 5, 2019, Events DC announced plans to demolish the stadium by 2021. Officials said the decision would save $2 million a year on maintenance and $1.5 million a year on utilities.[6] One year later, they hired a contractor to oversee the demolition, which was expected to begin in 2022 and cost $20 million.[7] In July 2022, Events DC announced that the removal of hazardous materials had begun and would "take several months," and that demolition would "be completed by the end of 2023."[56] In the same month, several fires occurred inside the stadium. The District of Columbia Fire and Emergency Medical Services Department firefighters and emergency workers responded and extinguished them. They indicated that the fires were in "below grade levels". No injuries were reported, and cause of the fires is currently unknown.[57][58] In November 2022, a sale of stadium seats was announced ahead of the 2023 demolition.[59][60] As of October 2023[update], crews have begun gutting areas of the site, though structural demolition has not begun.[61][8][9] On May 2, 2024 the NPS announced that it had determined the stadium could be demolished with no significant impacts to the natural, cultural and human environment, meaning they could issue a permit to the District to demolish the stadium.[62]

Name

[edit]The stadium opened in October 1961 named the District of Columbia Stadium, but the media quickly shortened that to D.C. Stadium and sometimes, in the early days, as "Washington Stadium".[63] On January 18, 1969, in the last days of the Johnson Administration, Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall announced that the stadium would be renamed Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium, in Kennedy's honor.[38][36] The official renaming ceremony was held on June 7,[38][39] but by then many had already been referring to it as "RFK Stadium" or simply "RFK".[19] Coincidentally, following the death of John F. Kennedy in 1963, the Armory Board had directed that the stadium be renamed for him,[64] but the plan faltered when a few weeks later the Philadelphia city council passed a bill renaming Philadelphia Stadium as "John F. Kennedy Stadium".[65]

Robert Kennedy was not without connection to the stadium; as attorney general in the early 1960s, his Justice Department played a role in the Redskins' racial integration.[66] Along with Udall, Kennedy threatened to revoke the team's lease at the federally owned stadium until it promised to sign African American players.[66][67] His brother John attended the first event there and threw out the first pitch. In 2008, a nearby bridge was renamed for Ethel Kennedy, Robert Kennedy's wife.

On April 14, 2005, just before the Nationals' home opener, the D.C. Sports and Entertainment Commission announced an agreement with the Department of Defense under which the military would pay the city about $6 million for naming rights and the right to place recruiting kiosks and signage in the stadium. In return, the stadium would be dubbed "Armed Forces Field at RFK Stadium".[68] This plan was dropped within days, however, after several prominent members of Congress questioned the use of public funds for a stadium sponsorship.[69]

Similar proposals to sell the naming rights to the National Guard,[68] ProFunds (a Bethesda, Maryland investment company),[69] and Sony[70] were formed and discarded in 2005 and 2006.

Tenants

[edit]George Washington Colonials (1961–1966)

[edit]The other team to move from Griffith to D.C. Stadium was the George Washington University Colonials college football team. The stadium was dedicated during the October 7, 1961, game against VMI, the first college football game there, which GWU won 30–6. The Colonials were forced to play their first three games on the road to allow the stadium to be completed. In the following years, because the Senators had priority, GWU waited until October (when baseball season was over) to schedule games. From 1961 to 1964 they played road games in September, and in 1965 and 1966 they played at high school stadiums in Arlington and Alexandria, Virginia.[25][21][71][72]

The Colonials had no real success at D.C. Stadium. GWU was 22–35 (.386) during its D.C. Stadium years and never posted a winning record. The Colonials weren't much better at D.C. Stadium where their record was 11–13 (.458), facing off against Army twice and against a Liberty Bowl-bound West Virginia in 1964 (all losses).[73] Perhaps their biggest win was the 1964 upset of Villanova, which came to Washington with a 6–1 record. Sophomore quarterback Garry Lyle, the school's last NFL draftee, led the Colonials to a 13–6 win.[74]

The final George Washington football game to date, and the last at D.C. Stadium, came on Thanksgiving Day, November 24, 1966, when the team lost to Villanova, 16–7.[75]

After the season was over, GW President Dr. Lloyd H. Elliott chose to reevaluate GW's football program.[76] On December 19, 1966, head coach Jim Camp, conference coach of the year, resigned citing the uncertainty. The next day, a member of the Board of Trustees announced that the school would drop football.[77] On January 19, 1967, the decision became official.[78] GW decided to use the football program's funding to eventually build the Charles E. Smith Center for the basketball team.[78] Poor game attendance and the expense, estimated at $254,000 during the 1966 season, contributed to the decision. Former GW player Harry Ledford believed that most people were unwilling to drive on Friday nights to D.C. Stadium, which was perceived as an unsafe area and lacked rail transit. Maryland and Virginia were nationally competitive teams that drew potential suburban spectators away from GW.[79]

Washington Redskins (1961–1996)

[edit]RFK Stadium was home to the Washington Redskins for 36 seasons, from 1961 through 1996. The football field was aligned northwest to southeast, along the first baseline.

The Redskins' first game in D.C. Stadium was its first event, a 24–21 loss to the New York Giants on October 1, 1961. The first win in the stadium came at the end of the season on December 17, over its future archrival, the struggling second-year Dallas Cowboys. The Redskins played 266 regular-season games at RFK, compiling a 173–102–3 (.628) record, including an impressive 11–1 record in the playoffs.[80]

In its twelfth season, RFK hosted its first professional football playoff game on Christmas Eve 1972, a 16–3 Redskins' win over the Green Bay Packers. It was the city's first postseason game in three decades, following the NFL championship game victory in 1942. The stadium hosted the NFC Championship Game five times (1972, 1982, 1983, 1987, and 1991), 2nd only to Candlestick Park, and the Redskins won them all. They are the only team to win five NFC titles at the same stadium. In the subsequent Super Bowls, Washington won three (XVII, XXII, XXVI).

The Redskins' last game at the stadium was a victory, as 56,454 saw a 37–10 win over the division champion Cowboys on December 22, 1996.[81][82]

Washington Senators (1962–1971)

[edit]

The Washington Senators of the American League played at RFK Stadium from 1962 through 1971. They played their first season in 1961 at Griffith Stadium.

In its ten seasons as the Senators' home field, RFK Stadium was known as a hitters' park, aided by the stagnant heat (and humidity) of Washington summers. Slugger Frank Howard, (6 ft 7 in (2.01 m), 255 lb (116 kg)), hit a number of "tape-measure" home runs, a few of which landed in the center field area of the upper deck. The seats he hit with his home runs are painted white, rather than the gold of the rest of the upper deck. Howard came to the Senators from the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1965. He hit the Senators' final RFK homer, in the sixth inning on September 30, 1971. With two outs in the top of the ninth,[83] a fan riot turned a 7–5 Senators lead over the New York Yankees into a 9–0 forfeit loss, the first in the majors in 17 years.[84][85]

These Senators' only winning season came in 1969 at 86–76 (.531); they never made the postseason. They had a home record at RFK of 363–441 (.451), representing the most games, wins, and losses by any team at RFK in any sport. The stadium hosted the All-Star Game twice, in 1962 (first of two) and 1969, both won by the visiting National League. Presidents Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon all attended games there. President Johnson was scheduled to throw out the first pitch in 1968, but the opening game was delayed following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., so Vice President Hubert Humphrey got the privilege.[86] President Nixon was to throw out the first ball at the 1969 game to celebrate baseball's centennial, but it was postponed due to rain and so Nixon chose instead to greet the Apollo 11 astronauts. Vice President Spiro Agnew filled in.[87]

Washington Whips (1967–68)

[edit]In 1967, D.C. Stadium became the home of its first professional soccer team, the Washington Whips. They played 23 regular-season games at D.C. Stadium over 16 months, putting together a 13–5–5 (.674) home record as well as losing an exhibition against Pelé and his standout Brazilian club Santos FC, for a total RFK record of 13–6–5 (.646).[88] 20,189 fans attended the Santos exhibition, more than three times as large as a typical Whips match, making it the most heavily attended soccer game in DC history at the time. The game was heavily promoted in the local press and the Whips, who were struggling to attract fans to their regular matches, provided additional incentive through a "Meet Pelé" contest.[89]

RFK served as the venue for the inaugural match of the United Soccer Association (USA), a May 26, 1967, match between the Whips and the Cleveland Stokers, won by the Stokers.[89]

In their first season, the Whips were one of the league's top teams and they were staffed by the Aberdeen Football Club of the Scottish Football League or the Aberdeen Dons. They finished 5–2–5, good enough to win the Eastern Division and play for the USA Championship against the Los Angeles Wolves.

The owners estimated that they needed to attract 16,000 fans per game, but they never broke 10,000 and averaged only 6,200. Towards the end of the 1967 season, the Whips resorted to organizing British Isles sporting contests such as cricket, hurling, and rugby before games in hopes of luring expatriates.[89]

In 1968, to stay viable, they negotiated a reduction in the lease payment and reduced admission prices by one-third; among other discounts. The USA merged with the National Professional Soccer League to form the new North American Soccer League. Despite problems on and off the field, the team found itself in a battle for a playoff spot and towards the end of the season crowds swelled to as much as 14,227 in what proved to be the deciding match for the NASL Atlantic Division title. This September 7, 1968, match against the Atlanta Chiefs was the last for the Whips at D.C. Stadium. That season, the team went 15–10–7 drawing an average of 6,586 fans. After a tour of Europe, the Whips folded in October 1968.[89]

Howard Bison (1970–2016)

[edit]No team has a longer history with RFK Stadium than the Howard Bison football team, who played there 42 times over nearly 46 years (the Detroit Tigers are 2nd by ~8 months, having played their first game there April 9, 1962, and their last on June 20, 2007). Between their first game in 1970 and last, in 2016, they earned a 22–17–3 (.560) record, winning more games at RFK than any other college football program.

Looking to play on a bigger stage than Howard Stadium, they began scheduling games at RFK. Howard's first RFK game was a 24–7 victory over Fisk on October 24, 1970.[90] From 1974 to 1976, Howard played all but one of their home games at RFK and in 1977 they played half their home games there.[91] After the 1977 season they returned to Howard Stadium, but continued to play their annual homecoming game at RFK through 1985. After the 1985 season, Howard Stadium was refurbished and renamed, and for the next 7 years, Howard played all of their home games there.

In 1992, they returned to RFK for a game against Bowie State that was marked by taunting and a game-ending scuffle.[92] From 1993 to 1999 Howard played at least one game a year at RFK including the Greater Washington Urban League Classic, at one point called the Hampton-Howard Classic, against Hampton from 1994 to 1999. In 2000 that game moved to Giants Stadium and Howard spent more than a decade away from RFK.

Starting in 2011 and through the 2016 season, Howard played in the Nation's Football Classic at RFK, matching up against Morehouse at first and then Hampton again.[93] In 2017, Events DC announced that they would discontinue the Classic and thus the last Bison game at RFK Stadium was a 34–7 loss to Hampton on September 16, 2016.[94][95]

Washington Diplomats (1974–1981 and 1988–1990)

[edit]Between 1974 and 1990, three soccer teams played at RFK under the name Washington Diplomats. In 1974, two Maryland businessmen purchased the rights to the Baltimore Bays of the semi-professional American Soccer League, moved the team to the District and renamed it the Washington Diplomats. They signed a lease calculating that an average of 12,000 spectators would allow them to break even. Despite white flight, owners thought that recent completion of the Beltway, the stadium's 12,000 parking spaces and future completion of a Metro station would facilitate attendance. Games were scheduled for Saturday and prices were set low. The Diplomats inaugural game was on May 4 with an attendance of 10,175; Mayor Walter Washington ceremonially kicked off the game, but the Dips lost 5–1 to the defending NASL champion Philadelphia Atoms. Attendance dropped throughout the season.[89]

In 1975, the Diplomats were informed that the recently installed natural turf at RFK would not be ready for opening day, so they scheduled their first two home games that season for W.T. Woodson High School in Fairfax, Virginia. After the games attracted more than 10,000 fans each, the Diplomats moved most of their home games to Woodson, but then moved the last five back to RFK once soccer superstar Pelé was added to the roster of the New York Cosmos. Pelé was so popular that the 1975 Cosmos-Diplomats match broke the NASL attendance record at 35,620.[96] Even with the success of the Cosmos game, attendance declined again and before the 1976 season the Diplomats announced that they had scheduled every home game, except the one against the Cosmos, at Woodson. During the season, they moved that game to Woodson.[89]

After averaging 5,963 at Woodson, the Diplomats decided to ramp up their marketing and move back to RFK in 1977. The team changed everything from the uniforms to the cheerleaders, but the team's disappointing on-the-field performance hurt attendance (a ~31,000 fan game against Pelé and the Cosmos notwithstanding). In 1978, attendance continued to fall, even though the Dips made the playoffs. Success on the field during the 1978 and 1979 seasons (including a franchise-best 19 wins in '79) did not translate to ticket sales and even with a negligible amount of revenue from "indoor Dips" games at the D.C. Armory during the offseason, the franchise continued to lose money.[89]

In 1980, they signed Dutch international superstar Johan Cruyff, the Pelé of the Potomac, from the Los Angeles Aztecs. Needing 20,000 fans per game to break even, they managed to attract 24,000 for the opener and a District record 53,351 for the game against the Pelé-less Cosmos (the fifth-largest soccer crowd at RFK ever), but the team failed to break-even financially. After racking up debts of $5 million, the first incarnation of the Dips folded.[89]

Three months later, the Detroit Express announced a move to D.C. for 1981, and that they would also be the Diplomats. They had trouble attracting fans; and soon folded.

The Diplomats of the NASL, racked up an impressive 60–29 (.674) record at RFK, the best winning percentage of any RFK home team, and were 1–1 in the playoffs.[97][89]

In 1987, a new soccer team also called the Washington Diplomats, was formed. They played at RFK, and sometimes at the RFK auxiliary field, for three seasons as part of the ASL and then the APSL. They won the ASL Championship in 1988 but often drew fewer than 1000 fans. In 1990 they finished last in the Southern Division of the APSL East, were unable to pay the rent and folded in October 1990.[98][99] Over the course of 4 seasons they were 18–15 (.545) at RFK, and 2–0 at the RFK auxiliary field.

Team America (1983)

[edit]Team America was a professional version of the United States men's national soccer team which played like a franchise in the North American Soccer League (NASL) during the 1983 season. The team played its home games at RFK Stadium and was intended by the NASL and the United States Soccer Federation to build fan support for the league and create a cohesive and internationally competitive national team. However, the team finished in last place drawing 12,000 fans per game.

Team America played 19 games at RFK. In those games they went 5–10 in NASL matches and tied three friendlies against Watford F.C. (from the United Kingdom), FC Dinamo Minsk (from the Soviet Union), and Juventus FC (from Italy) for a final record of 5–10–3 (.361).

The team's attendance averaged 19,952 through the first seven home matches,[100] including the 50,108 who attended a match vs. Fort Lauderdale that featured a free Beach Boys concert. Losses led to declining attendance as the season wore on. Attendance averaged 13,002 for the entire 1983 season, having played only a single season.[101]

Washington Federals (1983–1984)

[edit]Washington's only USFL team, the Washington Federals, played two seasons at RFK and during that time, they had the league's worst record each season, and, in 1984, the lowest per-game attendance. For the opening game, 38,000 fans showed up to see the return of former Redskins coach George Allen, the coach of the Chicago Blitz, in a game the Federals lost, 28–7. But attendance quickly dropped off, with as few as 7,303 showing up for a late-season game against the Boston Breakers. The team went 4–14 in 1983 and 3–15 in 1984, averaging 7,700 fans.

With six games remaining in the 1984 season, owner Berl Bernhard sold the team to Florida real estate developer Woody Weiser. In the off-season, that deal fell through. Donald Dizney bought the team, moved it to Orlando and renamed it the Renegades.

After going 7–29 (.194) overall, and 5–18 (.217) at RFK, the Federals ended their run with a 20–17 win over the New Orleans Breakers on June 24, 1984.

D.C. United (1996–2017)

[edit]

D.C. United of Major League Soccer played over 400 matches at RFK Stadium from the team's debut in 1996 until 2017, when they moved to a new stadium. During that time, RFK hosted three MLS Cup finals, including the 1997 match won by D.C. United. At RFK, they compiled a 228–113–75 (.638) record, winning more games at RFK than any team other than the Senators.

With its new stadium, Audi Field, opening in 2018, D.C. United played its final game at RFK on October 22, 2017, completing 22 seasons at the stadium, during which the team won four league titles.[102][103] At the time, RFK Stadium was the longest-used stadium in MLS and the only one left from the league's debut season. When they shared the stadium with the Nationals from 2005 to 2007, the playing surface and the dimensions of the field that resulted from baseball use drew criticism. D.C. United's departure left RFK with no professional sports tenant; however, after moving to Audi Field, D.C. United continued to use the outer practice fields at RFK for training and leased locker room and basement space there.[80]

Washington Freedom (2001–2003)

[edit]For three seasons, RFK was home to the Women's United Soccer Association team, the Washington Freedom. On April 14, 2001, the Freedom defeated the Bay Area CyberRays 1–0 in WUSA's inaugural match before 34,198 fans, the largest crowd in WUSA history and the largest crowd to watch a women's professional sports event in DC history (the largest crowd for a women's sporting event was 45,946 for the 1996 women's Olympic soccer tournament, also at RFK). Over three years, the Freedom racked up a 15–9–6 record at RFK and finished as one of the league's top teams. They came in 2nd in 2002 and won the league's Founder's Cup in 2003. They played all of their home games at RFK, except for one in 2001 at Navy-Marine Corps Memorial Stadium in Annapolis to avoid the Washington Grand Prix. Their last game at RFK as part of WUSA was on August 2, 2003, when they defeated the San Jose Cyber Rays. They won the final Founder's Cup in August 2003 and returned to RFK a few days later – minus the players who were playing in the 2003 Women's World Cup – for a victory celebration with the fans, which would be their final WUSA event at RFK. WUSA suspended operation the next month. Their victory in the Founders Cup means that the Freedom won both the first and last games in WUSA history. For a time, their championship banner hung in RFK, but when the Nationals moved in, the banner was moved to the Maryland Soccerplex.

The Freedom continued, first as an exhibition team called the Washington Freedom Soccer Club, and then as a member of the W-League and the Women's Professional Soccer league in 2006. Their home stadium was the Maryland Soccerplex, but they continued to play a few games at RFK. In 2004 they played an exhibition against Nottingham Forest, which they won 8–0.[104] They returned on June 22, 2008, in a W-League match, which they won 5–0, against the Richmond Kickers Destiny that was part of a doubleheader with DC United.[105] In 2009, the Freedom moved to the WPS and while they continued to play most of their home games in Maryland, they played 3 of 10 home games at RFK in 2009 and one game there in 2010.[106][107] In the years after WUSA suspended operations, the Freedom went 5–0–1 at RFK, bringing their combined RFK total to 20–9–7 (.653). After the 2010 season, the Freedom's owners had had enough and sold the team to Dan Borislow, owner of the phone service MagicJack. He moved them to Boca Raton, Florida for the team's last season. The Freedom's final game at RFK was a 3–1 victory over Saint Louis Athletica on May 1, 2010.

Washington Nationals (2005–2007)

[edit]After playing as the Montreal Expos from 1969 to 2004, the Expos franchise moved to Washington, D.C., to become the Washington Nationals for the 2005 season. The Nationals played their first three seasons (2005–2007) at RFK, then moved to Nationals Park in 2008. While the Nationals played at RFK, it was the fourth-oldest active stadium in the majors, behind Fenway Park, Wrigley Field and Yankee Stadium.[108]

During the Nationals' three seasons there, RFK then became known as a pitchers' park. While Frank Howard hit at least 44 home runs for three straight seasons at RFK for the second Washington Senators franchise from 1968 through 1970, the 2005 Nationals had only one hitter with more than 15 home runs, José Guillén with 24. However, in his lone season with the team in 2006, Alfonso Soriano hit 46 home runs.

During their three seasons at RFK, the Nationals failed to make the playoffs or post a winning record. They went 41–40 at home in 2005 and 2006 and 40–41 in 2007 to finish with a 122–121 (.502) record at RFK.

Design

[edit]The stadium's design was circular, attempting to facilitate both football and baseball. It was the first to use the so-called "cookie-cutter" concept, an approach also used in Philadelphia, New York, Houston, Atlanta, St. Louis, San Diego, Cincinnati, Oakland, and Pittsburgh.

While the perimeter of the stadium is circular, the front edge of the upper and lower decks form a "V" shape in deference to the baseball configuration. The rows of seating in the upper and lower decks follow the "V" layout, and the discrepancy between the shapes of the inner and outer rings permits more rows of seats to be inserted along the foul lines than at home plate and in the outfield. As a result, the height of the outside wall rises and falls in waves, and this is echoed in the roof, resulting in a "butterfly" appearance when seen at ground level from the west. This feature is unique among the circular stadiums of the 1960s, and it was reused by the Kingdome and Tropicana Field for their seating layouts.

The upper deck is cantilevered so that there are no columns from the lower deck obstructing views there.[109] Such a design is less compatible with the later demand for luxury boxes, due to weight; in contrast, FedExField has columns that obstruct views.[110] The design at RFK allowed the upper deck to shake when fans stomped in unison.[111]

In 1961, the stadium represented a new level of luxury. It offered 50,000 seats, each 22 inches (56 cm) wide (at a time when the typical seat was only 15–16 in (38–41 cm)), air-conditioned locker rooms and a lounge for player's wives. It had a machine-operated tarpaulin to cover the field, yard-wide aisles, and ramps that made it possible to empty the stadium in just 15 minutes. The ticket office was connected to the ticket windows by pneumatic tubes. The press boxes could be enclosed and expanded for big events. The stadium had a holding cell for drunks and brawlers. It had 12,000 parking spaces and was served by 300 buses. It had lighting that was twice as bright as Griffith Stadium.[23]

It was not ideal for either sport, due to the different geometries of the playing fields. As the playing field dimensions for football and baseball vary greatly, seating had to accommodate the larger playing surface. This would prove to be the case at nearly every multi-purpose/cookie-cutter stadium.

As a baseball park, RFK was a target of scorn from baseball purists, largely because it was one of the few stadiums with no lower-deck seats in the outfield. The only outfield seats were in the upper deck, above a high wall. According to Sporting News publications in the 1960s, over 27,000 seats—roughly 60% of the listed capacity of 45,000 for baseball—were in the upper tier or mezzanine levels. The lower-to-upper proportion improved for the Redskins with end-zone seats. The first ten rows of the football configuration were nearly at the field level, making it difficult to see over the players. The baseball diamond was aligned due east (home plate to center field), and the football field ran along the first baseline (northwest to southeast).

A complex conversion was necessary, at a cost of $40,000 each time, to change the stadium from a football configuration to baseball and back again; in its final form, this included rolling the third-base lower-level seats into the outfield along a buried rail, dropping the hydraulic pitcher's mound 3 feet (0.9 m) into the ground, and laying sod over the infield dirt. Later facilities were designed so the seating configuration could be changed more quickly and at a lower cost. The conversion was required several times per year during the Senators' joint tenancy with the Redskins (1962–71) but became much more frequent during the Nationals/D.C. United era; in 2005, the conversion was made over twenty times.

Originally the seats located behind the stadium's third-base dugout were removed for baseball games and put back in place when the stadium was converted to the football (and later soccer) configuration. When these sections were in place, RFK seated approximately 56,000. With the Nationals' arrival in 2005, this particular segment of the stands was permanently removed to facilitate the switch between the baseball and soccer configurations. These seats were not restored following the Nationals' move to Nationals Park, leaving the stadium's seating capacity at approximately 46,000. The majority of the upper-deck seats normally were not made available for D.C. United matches, so the stadium's reduced capacity normally was not problematic for the club.

During the years when the stadium was without baseball (1972–2004), the rotating seats remained in the football configuration. If an exhibition baseball game was scheduled, the left-field wall was only 250 feet (76 m) from home plate, and a large screen was erected in left field for some games.

Some of RFK's quirks endear the venue to fans and players.[citation needed] The large rolling bleacher section is less stable than other seating, allowing fans to jump in rhythm to cause the whole area to bounce. Also, despite its small size (it never seated more than 58,000), because of the stadium's design and the proximity of the fans to the field when configured for football, the stadium was extremely loud when the usual sell-out Redskins crowds became vocal. Legend has it that Redskins head coach George Allen would order a large rolling door in the side of the stadium to be opened when visiting teams were attempting field goals at critical moments in games so that a swirling wind from off the Potomac and Anacostia rivers might interfere with the flight of the kicked ball.

Since the stadium is on a direct sightline with the Washington Monument and the U.S. Capitol, light towers were not allowed; instead, arc lights were placed on its curved, dipping roof.

Events D.C.—the city agency which operates RFK Stadium—began a strategic planning process in November 2013 to study options for the future of the stadium, its 80 acres (32 ha) campus and the nonmilitary portions of the adjacent D.C. Armory. Events D.C. said one option to be studied was demolition within a decade, while another would be the status quo. The strategic planning process also included the design and development of options. The agency said that RFK Stadium has generated $4 million to $5 million a year in revenues since 1997, which did not cover operating expenses.[112] In August 2014, Events D.C. chose the consulting firm of Brailsford & Dunlavey to create the master plan.[113]

Seating capacity

[edit]

|

|

|

|

Dimensions

[edit]

The dimensions of the baseball field were 335 feet (102 m) down the foul lines, 380 feet (116 m) to the power alleys and 408 feet (124 m) to center field during the Senators' time. The official distances when the Nationals arrived were identical, except for two additional feet to center field. After complaints from Nationals hitters it was discovered in July 2005 that the fence had actually been put in place incorrectly, and it was 394.74 feet (120.3 m) to the power alleys in left; 395 feet (120 m) to the right-field power alley; and 407.83 feet (124.3 m) to center field. The section of wall containing the 380-foot (116 m) sign was moved closer to the foul lines to more accurately represent the distance shown on the signs but no changes were made to the actual dimensions.

The approximate elevation of the playing field is 10 feet (3.0 m) above sea level.

Sports events

[edit]Baseball

[edit]

Two major league teams called RFK home, the Senators (1962–71) and the Nationals (2005–07). In between, the stadium hosted an assortment of exhibition games, old-timer games, and at least one college baseball exhibition game. In addition, from 1988 to 1991 the RFK auxiliary field served as the home stadium of the George Washington Colonials college baseball team, and hosted some Howard University and Interhigh League and D.C. Interscholastic Athletic Association championship baseball games.

- April 9, 1962: The Washington Senators defeated the Detroit Tigers 4–1 in the first baseball game played at D.C. Stadium. President John F. Kennedy – the brother of the stadium's future namesake, then-United States Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy – threw out the ceremonial first pitch.

- July 10, 1962: With 45,480 in attendance, D.C. Stadium hosted its first All-Star Game, the first of two during the 1962 season. President Kennedy threw out the first pitch and the National League won 3–1.

- June 12, 1967: The Senators defeated the Chicago White Sox 6–5 in the longest night game to date in major league history.[129] The 22-inning game lasted 6 hours and 38 minutes and ended at 2:43 a.m. EDT.[130]

- April 7, 1969: With President Richard Nixon and about 45,000 on hand on Monday afternoon, rookie manager Ted Williams made his debut with the Senators, an 8–4 loss to the New York Yankees.[131][132][133]

- June 7, 1969: The stadium was renamed for Robert Kennedy on January 18; while the Senators were away at Minnesota, the rededication ceremony was held.[38][39]

- July 23, 1969: The stadium hosted its second and last All-Star Game, a National League 9–3 victory before 45,259. Postponed by a rainout the night before, the game was on Wednesday afternoon,[134][135] the final MLB All-Star Game to conclude during daylight. President Nixon was scheduled to throw out the first pitch the evening before;[136] because of the postponement, he missed the game to personally greet the returning Apollo 11 crew aboard the USS Hornet.[137] Vice President Spiro Agnew threw out the first pitch.[138]

- September 30, 1971: In the Senators' final game (on a Thursday night), they led the New York Yankees 7–5 with two outs in the top of the ninth. After an obese teenager ran onto the field, picked up first base, and ran off, fans stormed the field and tore up bases, grass patches, and anything else for souvenirs. Washington forfeited the game, 9–0,[41][139] the first forfeit in the majors in seventeen years.[41] It was the last MLB home game at RFK until 2005.

- July 19, 1982: At the first Cracker Jack Old Timers Baseball Classic exhibition game, attended by nearly thirty thousand, 75-year-old Hall of Famer Luke Appling hit a home run against the National League's Warren Spahn.[140][141][142][143] Although he had a .310 lifetime batting average, Appling only hit 45 home runs in 20 seasons. However, because the stadium had not been fully reconfigured, it was just 260 feet (79 m) to the left-field foul pole, far shorter than normal, and Spahn applauded him as he rounded the bases. Five more Cracker Jack All Star games were hosted at RFK,[144] until summer construction at RFK in 1988 moved it north to Buffalo.[145][146] During that time, Hall of Famers and stars such as Joe Dimaggio, Bob Feller, Stan Musial, Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Sandy Koufax, Roger Maris, Whitey Ford, and Washington favorite Frank Howard would take the field. There was even a conversation about allowing then-Vice President George H. W. Bush, who'd captained Yale's College World Series team, to play one year.[147]

- April 5, 1987: RFK Stadium hosted an exhibition game between the Philadelphia Phillies and the New York Mets, the first MLB game played in Washington, D.C., since a pair of exhibition games in 1972. The game was a sell-out, with 45,614 tickets sold, and a crowd of 38,437 actually attended on a cold, rainy afternoon. Mets pitcher Sid Fernandez threw a one-hitter, and the Mets won, 1–0.[148][149]

- April 3, 1988: The Mets and Orioles met at RFK for an exhibition game watched by 36,123 as the Mets won 10–7 off a three-run homer by Darryl Strawberry.[150]

- April 2, 1989: The Cardinals and Orioles met at RFK for an exhibition game watched by 37,204 as the Orioles won 7–6 in the 10th inning.[151]

- May 6, 1989: George Washington University defeated the Soviet national baseball team 20–1.[152]

- April 7, 1990: The Cardinals and Orioles met at RFK for an exhibition game watched by 21,298 as the Orioles won 11–10.[153]

- April 6–7, 1991: The Red Sox and Orioles played a pair of exhibition games at RFK. The first was watched by 37,458 as the Orioles won 4–1. The Stadium was in its baseball configuration for the first time since September 30, 1971.[154] 43,624 watched the Orioles lose the 2nd game 6–5, and Vice President Dan Quayle threw out the first pitch.[155]

- April 4–5, 1992: The Red Sox and Orioles met at RFK for an exhibition game watched by 20,551 as the Sox won 4–3. The next day the Red Sox played the Phllies at RFK in a game watched by 16,823.[156][157]

- April 3, 1998: The Orioles and Mets met for an exhibition game.[158]

- April 2 and 4, 1999: Montreal Expos and St. Louis Cardinals met in a pair of exhibition games. The stadium was restored to its full baseball configuration for the first time since the 1991 exhibition. Rumors already swirled then that the Expos could soon call RFK home, a possibility that came to pass after the 2004 season.[159]

- April 3, 2005: The Washington Nationals (formerly the Montreal Expos) lost to the Mets 4–3 in an exhibition game before a paid crowd of 25,453 in their first game in Washington. It was the first MLB home game at RFK since 1971. Mayor Anthony Williams threw out the first pitch.[160]

- April 14, 2005: The Washington Nationals defeated the Arizona Diamondbacks 5–3 before a crowd of 45,596 in their first regular season game in Washington.[161][162] President George W. Bush threw out the first pitch,[161][163] and Washington swept the three-game series to improve to 8–4.[164] It is the largest baseball crowd at RFK ever, and the largest ever home crowd for the Nationals.

- June 18, 2006: Nationals third baseman Ryan Zimmerman, who became known as "Mr. Walk-Off" for his penchant for hitting game-ending home runs, hit his first walk-off home run off New York Yankees pitcher Chien-Ming Wang in the bottom of the ninth inning for a 3–2 Nats victory.[165]

- September 16, 2006: The Nationals' Alfonso Soriano stole second base in the first inning against the Milwaukee Brewers and became the fourth player to hit 40 home runs and steal 40 bases in a season.[166]

- September 23, 2007: The Nationals defeated the Philadelphia Phillies 5–3 before 40,519 in the final major league game (and final baseball game) played at RFK Stadium.[167] The win gave the Nationals an overall home record of 122–121 (.502) in three seasons at the stadium.

The last winning pitcher in any baseball game at RFK was Luis Ayala of the Nationals, the last runner to score was Chase Utley of the Phillies and the last home run was also hit by Chase Utley the day before off Tim Redding.[citation needed]

Football

[edit]RFK was the home of two professional football teams, two college football teams, a bowl game and more than one college all-star game. It hosted neutral-site college football games, various HBCU games, and high school regular season and championship games.[168]

Professional football

[edit]- November 27, 1966: The Washington Redskins beat the New York Giants 72–41. The 113 combined points are the most ever scored in an NFL game.

- December 14, 1969: The Redskins defeat the New Orleans Saints 17–14 in what would be Vince Lombardi's last victory. The Redskins would lose the next week at Dallas, and Lombardi would die just before the start of the 1970 season.

- November 20, 1972: RFK Stadium hosts its first Monday Night Football game. The Washington Redskins defeat the Atlanta Falcons 24–13.

- December 31, 1972, the Redskins defeat the Dallas Cowboys 26–3 in the NFC Championship Game to earn a trip to Super Bowl VII.

- October 8, 1973: In a Monday Night Football game, Redskins safety Ken Houston stops Cowboys' running back Walt Garrison at the goal line as time expired to secure a win.

- December 17, 1977: The Redskins defeat the Los Angeles Rams 17–14 in what would be head coach George Allen's final game with the team.

- October 25, 1981: The Redskins narrowly beat the New England Patriots 24–22 to earn head coach Joe Gibbs his first win at RFK Stadium.

- October 17, 1982: First NFLPA's all-star games during the 1982 NFL strike[169]

- January 22, 1983: The stadium physically shakes as a capacity crowd of 54,000 chants "We Want Dallas" taunting the hated Cowboys in the NFC Championship Game. The Redskins go on to defeat the Cowboys 31–17 to earn a trip to Super Bowl XVII where they beat the Miami Dolphins 27–17 to claim the franchise's first Super Bowl win.

- March 6, 1983: The Washington Federals of the United States Football League play their first game, losing to the Chicago Blitz 28-7 before 38,007 fans at RFK stadium in the USFL's first nationally televised game.[170] The Federals never draw more than 15,000 fans again.[170]

- September 5, 1983: Redskins' rookie cornerback Darrell Green chases down Cowboys' running back Tony Dorsett from behind to prevent him from scoring. However, the Redskins ended up losing late in the fourth quarter.

- May 6, 1984: The Washington Federals play their final game, losing in overtime to the Memphis Showboats at RFK Stadium before 4,432 fans, the smallest crowd in USFL history.[170]

- November 18, 1985: Giants' linebacker Lawrence Taylor sacks Redskins' quarterback Joe Theismann, severely breaking his leg and ending his NFL career. Backup quarterback Jay Schroeder comes in and leads the Redskins to a 23–21 victory on Monday Night Football.

- January 17, 1988: Cornerback Darrell Green knocks down a Wade Wilson pass at the goal line to clinch a victory over the Minnesota Vikings in the NFC Championship game. The Redskins go on to defeat the Denver Broncos 42–10 in Super Bowl XXII.

- January 4, 1992: In pouring rain, the Redskins beat the Atlanta Falcons 24–7 in the Divisional round of the playoffs. After a touchdown scored by Redskins fullback Gerald Riggs with 6:32 remaining in the fourth quarter, the fans shower the field with the free yellow seat cushions given to them when they entered the stadium.

- January 12, 1992: The Redskins beat the Detroit Lions 41–10 in the NFC Championship Game earning a trip to Super Bowl XXVI where they beat the Buffalo Bills 37–24. This was the last time the RFK held a post-season game.

- December 13, 1992: Redskins' head coach Joe Gibbs coaches what would be his last win at RFK Stadium. The Redskins defeat the Cowboys 20–17.

- September 6, 1993: RFK Stadium hosts its last Monday Night Football game as the Redskins open their season by defeating the Dallas Cowboys 35–16.

- December 22, 1996: The Redskins won their last game in the stadium, defeating their arch-rivals, the Dallas Cowboys, 37–10. A capacity crowd of 56,454 fans watched the game, tying the football record set against the Detroit Lions in 1995. It was the last professional football game played at RFK. In a halftime ceremony, several past Redskins greats were introduced, wearing replicas of the jerseys of their time. After the game, fans storm the field and rip up chunks of grass as souvenirs. In the parking lot, fans are seen walking away with the stadium's burgundy and gold seats.

Records

[edit]- Most passing yards and passing TDs at RFK, career – Sonny Jurgenson, 12,985 yards, 108 TDs

- Most rushing yards and rushing TDs at RFK, career – John Riggins, 3448 yards, 32 TDs

- Most receiving yards at RFK, career – Art Monk, 6329 yards

- Most receiving TDs at RFK, career – Charley Taylor, 42 TDs

- Most passing yards, game – Boomer Esiason, 522 yards, October 11, 1996

- Most passing TDs, game – Mark Rypien, 6 TDs, October 11, 1991

- Most rushing yards, career – Gerald Riggs, 3448 yards, 32 TDs

- Most rushing TDs, game – tie Earnest Byner, Dick James, Terry Allen, Joe Morris, John Riggins, Duane Thomas; 3

- Most receiving yards, game – Anthony Allen, 255 yards, 1987

- Most receiving TDs, game – tie Anthony Allen, Gary Clark, Michael Irvin, Keith Jackson, Del Shofner; 3

Bowl games

[edit]- December 20, 2008: Wake Forest defeats Navy 29–19 in the inaugural EagleBank Bowl before a crowd of 28,777 in the first bowl game to be played in Washington, D.C.

- December 29, 2009: UCLA defeats Temple 30–21 before a crowd of 23,072 in the second annual EagleBank Bowl.

- December 29, 2010: Maryland defeats East Carolina 51–20 before a crowd of 38,062 in the 2010 Military Bowl, formerly the EagleBank Bowl. Great fan turnout from both universities set a bowl attendance record in Maryland coach Ralph Friedgen's final game.

- December 28, 2011: Toledo defeats Air Force 42–41 before a crowd of 25,042 in the 2011 Military Bowl.

- December 27, 2012: In the last Military Bowl hosted at RFK Stadium, San Jose State defeats Bowling Green 29–20 in the 2012 Military Bowl before a crowd of 17,835, the lowest bowl attendance figure since the 2005 Hawaii Bowl had only 16,134 attendees.[171] Beginning in 2013, Navy–Marine Corps Memorial Stadium in Annapolis, Maryland, replaced RFK Stadium as the site of the Military Bowl.

HBCU games

[edit]- October 24, 1970 – First Howard University game at RFK, a 24–7 victory over Fisk.

- September 30, 1972 – Grambling beat Prairie View, 38–12.

- Timmie Football Classic (1974–1975) Grambling vs. Morgan State[172]

- November 4, 1978 – Tennessee State vs North Carolina-Central faced off in an attempted reboot of the Capitol Classic, though renamed "A Touch of Greatness".[173]

- Nation's Capital Football Classic (1991) – Delaware State defeated Jackson State 37–34[174]

- September 16, 2016 – The last Howard University game at RFK, a 34–7 loss to Hampton.

College All-Star Games

[edit]- U.S. Bowl (1962) – A college all-star game that lasted only one season. Galen Hall was the game's only MVP.[175]

- Freedom Bowl All-Star Classic (1986)[176]

- All-America Classic (1993)[177]

Neutral site games for local colleges

[edit]- October 17, 1965: Navy beat Pitt, 12–0.[178]

- October 17, 1970: In their 4th ever meeting, Air Force beat Navy 26–3.[179]

- November 4, 1972: Kentucky State defeated Federal City 26–8, in the only football game by a UDC school.[180]

- October 4, 1975: Navy beat Air Force, 17–0.[181]

- November 11, 1995: Virginia Tech clinched a share of the Big East title with a win over Temple.[182]

- November 11, 2000: Salisbury defeated Frostburg State, 18–8 to win the 2nd Regents Cup.[183]

- November 10, 2001: In the only college football game at RFK to go into overtime, Frostburg State beat Salisbury 30–24 to win the 3rd Regents Cup.[184]

- September 30, 2017: Harvard defeated Georgetown, 41–2 in the last college football game at RFK.[185]

High schools

[edit]RFK has occasionally hosted high school football games, but never has done so regularly.[186] On August 14, 2018, DC Events announced the DC Events Kickoff Classic, a football tripleheader featuring six Washington, D.C., high schools, with games between Dunbar and Maret, Archbishop Carroll and Woodrow Wilson, and Friendship Collegiate Academy and H. D. Woodson.[186] The first Classic was held on September 15, 2018, and the second, only a double-header, was the following year.[186][187][188] The 2019 Classic represented the last official event in the stadium, coming days after the announcement that the stadium would be razed and months before the coronavirus pandemic.[citation needed] On September 14, 2019 the final game of any sport at RFK Stadium saw Friendship Collegiate defeat H.D. Woodson, 34–6 to win the Clash of Ward 7 Titans trophy. The last touchdown scored at RFK was on a pass from Collegiate's Dyson Smith to Taron Riddick.[189]

Soccer

[edit]

Although not designed for soccer, RFK Stadium, starting in the mid-1970s, became a center of American soccer, rivaled only by the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, California, in terms of its history as a soccer venue.[80] It is the only facility in the world to have hosted the FIFA World Cup (in 1994), the FIFA Women's World Cup (in 2003), Olympic group stages for men and women (in 1996), the MLS Cup (in 1997, 2000, and 2007), the North American Soccer League's Soccer Bowl (in 1980) and CONCACAF Champions' Cup matches (in 1988 and 1998).[80] The United States men's national soccer team played more of its matches at RFK stadium than at any other site,[80] and D.C. United played 347 regular-season matches there.

In addition to being the home stadium of DC United, the Diplomats, the Freedom, the Whips and Team America, RFK also hosted three friendly Washington Darts games in 1970.[190]

Notable soccer dates at the stadium include:

- May 26, 1967: Professional soccer's debut game at D.C. Stadium is also the inaugural game of the new United Soccer Association. 9,403 fans show up to watch the Washington Whips lose 2–1 to the Cleveland Stokers.[191]

- July 14, 1968: Pelé's D.C. Stadium debut, before a District record soccer crowd of 20,189 fans. Pelé's and the Santos FC squad defeated the Washington Whips 3 to 1.

- September 7, 1968: In a de facto Atlantic Division championship game, the Whips lost to the Atlanta Chiefs before 14,227 fans, the largest, non-exhibition home crowd in Whips history. It would be the last Whips game at D.C. Stadium.

- September 19, 1970: In what would be the largest crowd to ever watch a Washington Darts match, 13,878 fans come to RFK to watch them take on Pelé and his Santos squad. They lost 7–4. The Darts also lost their two other RFK matches, against Hertha Berlin and Coventry City the prior May.[192]

- May 4, 1974: The Washington Diplomats play their first game at RFK, a 5–1 loss to the Philadelphia Atoms. 10,145 fans attend.

- June 29, 1975: A District record 35,620 fans show up to see Pelé in his first game in DC with the New York Cosmos as they take on the Washington Diplomats. Cosmos wins 9–2.

- August 6, 1977: Playing for the New York Cosmos, Pelé plays his final regular-season game in the North American Soccer League, facing the Washington Diplomats at RFK Stadium. He scores the Cosmos' only goal, but the Diplomats upset the Cosmos 2-1 before 31,283 fans.[193]

- October 6, 1977: The United States men's national soccer team plays its first match at the stadium versus China.

- August 19, 1979: The Diplomats drop their first-ever home playoff game to the Los Angeles Aztecs 4–1.

- June 1, 1980: In a nationally televised game, before a then District record crowd of 53,351 – the largest ever for NASL game in DC – the Diplomats lose a controversial game to the Cosmos, 2–1.[194][195]

- August 27, 1980: The Diplomats top the Los Angeles Aztecs 1–0 in the only home playoff victory in the franchise's NASL history.

- September 21, 1980: In the Soccer Bowl '80, before a crowd of 50,768, the New York Cosmos defeat the Fort Lauderdale Strikers, 3–0.

- August 16, 1981: The Washington Diplomats of the NASL play their last game at RFK, a 5–1 victory over the Toronto Blizzard.

- April 23, 1983: Team America, a Washington, D.C.-based NASL franchise, plays its first game, defeating the Seattle Sounders 1–0 at RFK Stadium.[196]

- June 14: 1983: 50,108 fans come to watch Team America play Fort Lauderdale followed a Beach Boys concert. The largest NASL crowd in RFK history saw Team America win 2–1 after a shootout.

- September 3, 1983: Team America plays its last game, a 2–0 loss to the Fort Lauderdale Strikers at RFK Stadium. The team folds after a single season, leaving Washington, D.C., without a professional soccer franchise until 1988.[196]

- June 7, 1987: In the final game of the US Ambassador Cup tournament, the newly formed Washington Diplomats tie Honduras National Team to win the cup in front of 5,117 fans.[197]

- April 17, 1988: In the first professional soccer game in DC in over 4 years, the new Washington Diplomats lost 2–1 to the New Jersey Eagles in front of a crowd of just 2,451.[198]

- June 28, 1988: The Washington Diplomats lose to Monarcas Morelia 2–1 in the first of a two-game second-round series between the teams as part of the CONCACAF Champions' Cup. The second game, two days later, would also result in a 2–1 loss.[199]

- August 13, 1988: In their first-ever home playoff game in the ASL, the Diplomats top the New Jersey Eagles, 4–1.

- August 21, 1988: In the first game of the 1988 American Soccer League finals, the Washington Diplomats defeat the Fort Lauderdale Strikers 5-3 before 5,745 fans at RFK Stadium. The Diplomats will defeat the Strikers again at Fort Lauderdale, Florida, for a surprising American Soccer League championship in the league's first season.

- June 29, 1989: The Diplomats host the ASL All-Star game, losing to the All-Stars 2–1 in front of a crowd of 4,375.[200]

- June 24, 1990: In their last game at RFK Stadium, the Diplomats lose to the Maryland Bays 4–2. Because of conflicts with concerts, they played their last two home games at RFK Stadium's auxiliary field, losing their last one 4–0 to the Miami Freedom on July 22, 1990.[98] Professional soccer would not return to RFK Stadium for more than five years.

- June 13, 1993: a record-setting crowd of 54,118 show up to watch England tie Brazil 1–1 in the US Cup.[195]

- August 21, 1993: A.C. Milan defeats Torino F.C. 1–0 to win their second consecutive Supercoppa Italiana.

- June 28, 1994: 53,186 fans show up to watch Italy and Mexico during the World Cup in what becomes the 6th highest attendance soccer match in RFK history.[195]

- June 29, 1994: Saeed Al-Owairan of the Saudi Arabia national football team sprints the length of the field and weaves through a maze of Belgium national football team players to score a stunning individual goal, giving Saudi Arabia a 1–0 upset victory over Belgium in Group F of the FIFA 1994 World Cup. The goal later is voted the sixth-greatest FIFA World Cup goal of the 20th century. The win helps Saudi Arabia to advance to the second round of the FIFA World Cup for the first time.[201][202]

- July 2, 1994: The 1994 FIFA World Cup concludes its play in RFK as Spain defeats Switzerland 3–0 in the Round of Sixteen (RFK had earlier hosted four group-play games).

- June 18, 1995: In the U.S. Cup the United States defeats Mexico 4–0, with goals by Roy Wegerle (3' min), Thomas Dooley (25th min), John Harkes (36' min) and Claudio Reyna (67' min).

- April 20, 1996: D.C. United plays its first game at RFK Stadium, losing 2–1 to the LA Galaxy.

- July 21, 1996: 45,946 fans show up to watch a group play match between Norway and Brazil in the 1996 Olympics Women's Soccer tournament. It is the largest crowd for women's sports in Washington history. Two other women's Olympic matches were played in RFK as part of the Atlanta Olympics.

- July 24, 1996: RFK hosted the final match for the US men's side in the 1996 Olympics Men's Soccer tournament. 58,012 spectators, the largest crowd in RFK history, watched the men tie Portugal 1–1, which was not enough to advance as they needed a win. Five other men's Olympic matches were played in RFK as part of the Atlanta Olympics.[203][195][204]

- October 30, 1996: Ten days after winning the first Major League Soccer title, D.C. United defeats the Rochester Raging Rhinos 3–1 in the U.S. Open Cup final, achieving the first "double" in the modern American soccer era.

- October 26, 1997: D.C. United defeats the Colorado Rapids 2–1 to win their second consecutive MLS Cup. 57,431 fans attend, the 2nd largest soccer crowd in DC history, and the largest for a professional league match.[195]

- August 16, 1998: D.C. United defeats CD Toluca of Mexico 1–0 to win the CONCACAF Champions' Cup, becoming the first American team to do so and marking their first victory in an international tournament.

- October 15, 2000: The Kansas City Wizards defeat the Chicago Fire 1–0 to win their first MLS Cup.

- April 11, 2001: D.C. United defeats Arnett Gardens 2–1 in the second leg of the CONCACAF Giants Cup quarterfinals.

- April 14, 2001: The Washington Freedom defeats the Bay Area CyberRays 1–0 in the inaugural match of the Women's United Soccer Association.

- September 1, 2001: 54,282 people, the largest ever for a world cup qualifier at RFK, show up to watch the USA men vs. Honduras.[195]

- August 3, 2002: In the MLS All-Star Game, a team of MLS players defeat the U.S. Men's National Team 3–2. D.C. United midfielder Marco Etcheverry is named MVP.

- July 30, 2003: Ronaldinho makes his debut for FC Barcelona against A.C. Milan in a pre-season tour of the United States. Ronaldinho had a goal and an assist as Barcelona defeated defending European champion Milan 2–0 in an exhibition game that drew 45,864 to RFK Stadium.[205][206]

- August 2, 2003: The Washington Freedom defeat the San Jose Cyber Rays in their last game at RFK as part of WUSA. The win clinches them a playoff spot and the Freedom go on to win the last Founder's Cup, which is awarded to the winner of the post-season playoff.

- September 21, 2003: RFK hosts the 2003 FIFA Women's World Cup opening ceremonies and first match. RFK would host six matches during the tournament.

- April 3, 2004: Freddy Adu debuts with D.C. United at RFK with a capacity soccer crowd of 24,603.[207] At age 14, Adu was, and still is, the youngest player to play in MLS.

- November 6, 2004: D.C. United win the Eastern Conference final by tying the New England Revolution 3–3 and advancing on penalty kicks in what is generally regarded as one of the greatest games in MLS history. They would go on to defeat the Kansas City Wizards 3–2 in the MLS Cup.

- July 31, 2004: RFK Stadium hosts its second and last MLS All-Star Game. The East beats the West 3–2.

- August 9, 2007: David Beckham debuts for the MLS Los Angeles Galaxy, losing to home team D.C. United before a sellout crowd of 46,686 fans, the fourth largest to watch MLS at RFK Stadium.

- September 2, 2009: Seattle Sounders FC defeats D.C. United 2–1 in the 2009 Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup Final. This marked the first of Seattle's record-tying three consecutive Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup titles.

- October 23, 2010: Jaime Moreno scores on a penalty kick in his final game as a D.C. United player to retire as the all-time leading scorer in MLS history. United would lose the match, 3–2, to Toronto FC.

- May 1, 2010: The Washington Freedom's last game at RFK, a 3–1 victory over Saint Louis Athletica

- June 19, 2011: Quarterfinal of 2011 CONCACAF Gold Cup, USA vs. Jamaica. US defeats Jamaica 2–0 and moves onto the semi-final. In the second game of the double header El Salvador played Panama to a 1–1 tie. Panama won in a shoot out in front of 46,000 people.

- June 2, 2013: The United States defeated No. 2 ranked Germany 4–3 in a friendly commemorating the 100th anniversary of the U.S. Soccer Federation.[208]

- September 3, 2014: RFK hosts a triple-header on the first day of the group stage of the Central American Cup USA 2014[209]

- October 20, 2014: The United States women's national soccer team defeats the Haiti women's national football team 6–0 in the 2014 CONCACAF Women's Championship, which also acts as a qualifying tournament for the 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup.

- March 1, 2016: Querétaro eliminated D.C. United from the CONCACAF Champions League with a 1–1 tie, the last of four Champions League matches at RFK during the 2015–2016 season.[210]

- October 22, 2017: In front of 41,418 fans (the highest attendance at the stadium since David Beckham's debut game), the New York Red Bulls beat D.C. United 2–1 in United's last match at RFK Stadium.[103]

- June 10, 2018: Alianza del El Salvador defeated Olimpia de Honduras 3–1 in a friendly

- March 25, 2019: El Salvador defeated Peru 2–0 in a friendly.[211]

- June 2, 2019: El Salvador defeated Haiti 1–0 in a pre-Gold Cup friendly and the last ever soccer game at RFK.[212]

College soccer

[edit]RFK hosted at least two college soccer games, once when Maryland moved their game there due to wet field conditions at Ludwig Field and again for a scheduled game following their national championship season. It has hosted several other Maryland games at the auxiliary field.

- November 8, 1997: Maryland Terps defeated Ohio State 2–1[213]

- April 20, 2009: Maryland lost to Wake Forest 3–1.[214]

United States men's national team matches

[edit]The United States men's national soccer team has played more games at RFK Stadium than any other stadium.[215] At times it was suggested that due to the nature of RFK and its quirkiness that it would be a suitable national stadium if US Soccer were ever to seek one out.[216][217] Several prominent members of the national team have scored at RFK, including Brian McBride, Cobi Jones, Eric Wynalda, Joe-Max Moore, Clint Dempsey, Michael Bradley, and Landon Donovan. Winners are listed first.

| Date | Competition | Team | Score | Team | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| October 6, 1977 | Friendly | 1–1 | Unknown | ||

| May 12, 1990 | 1–1 | 18,245 | |||

| October 19, 1991 | 2–1 | 16,351 | |||

| May 30, 1992 | 1992 U.S. Cup | 3–1 | 35,696 | ||