Сэнди Куфакс

| Сэнди Куфакс | |

|---|---|

Рекламный кадр Куфакса, ок. 1965 год | |

| Кувшин | |

| Родился: 30 декабря 1935 г. Бруклин, Нью-Йорк , США | |

Отбит: Верно Бросок: слева | |

| Дебют в МЛБ | |

| 24 июня 1955 года за «Бруклин Доджерс». | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| October 2, 1966, for the Los Angeles Dodgers | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Win–loss record | 165–87 |

| Earned run average | 2.76 |

| Strikeouts | 2,396 |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1972 |

| Vote | 86.9% (first ballot) |

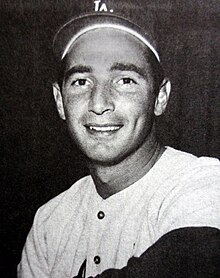

Сэнфорд Куфакс ( / ˈ k oʊ f æ k s / ; урожденный Браун ; родился 30 декабря 1935), по прозвищу « Левая рука Бога », американский бывший бейсбольный питчер, сыгравший 12 сезонов в Высшей бейсбольной лиге за команду «Бруклин ». Лос-Анджелес Доджерс с 1955 по 1966 год. Широко известный как один из величайших питчеров в истории бейсбола, а также первая крупная спортивная звезда на Западном побережье , Куфакс был первым трехкратным обладателем Премии Сая Янга , каждый раз выигрывая единогласно и единственный питчер, сделавший это, когда для обеих лиг была вручена одна награда; он также был назван самым ценным игроком Национальной лиги в 1963 году. Выйдя на пенсию в возрасте 30 лет из-за хронической боли в подающем локте, Куфакс был избран в Зал славы бейсбола в первый год своего участия в отборе в 1972 году в возрасте 36 лет. , самый молодой игрок, когда-либо избранный.

Куфакс родился в Бруклине, штат Нью-Йорк , в юности в основном играл в баскетбол и сыграл всего несколько игр, прежде чем подписать контракт с « Бруклин Доджерс» в 19 лет. Из-за бонусного правила, под которым он подписался, Куфакс никогда не выступал в низших лигах . Отсутствие у него опыта подачи заставило менеджера Уолтера Олстона не доверять Куфаксу, который в течение своих первых шести сезонов видел нестабильное игровое время. В результате, хотя Куфакс часто проявлял блестящие способности, на раннем этапе у него были проблемы. Разочарованный тем, как им управляли «Доджерс», он чуть не ушел после сезона 1960 года. После внесения корректировок перед сезоном 1961 года Куфакс быстро стал самым доминирующим питчером в высшей лиге. Он участвовал в Матче всех звезд в каждом из своих последних шести сезонов, лидируя в Национальной лиге (НЛ) по среднему заработку каждый из последних пяти лет, по аутам четыре раза, а по победам и локаутам по три раза каждый. Он был первым питчером в эпоху живого мяча, показавшим средний заработанный результат ниже 2,00 в трех разных квалификационных сезонах, и первым в истории, трижды зафиксировавшим в сезоне 300 аутов.

Koufax won the Major League Triple Crown three times, leading the Dodgers to a pennant in each of those years. He was the first major league pitcher to throw four no-hitters, including a perfect game in 1965. He was named the World Series MVP twice, leading the weak-hitting Dodgers to titles in 1963 and 1965. Despite his comparatively short career, his 2,396 career strikeouts ranked seventh in major league history at the time, trailing only Warren Spahn (2,583) among left-handers; his 40 shutouts were tied for ninth in modern NL history. He was the first pitcher in history to average more than nine strikeouts per nine innings pitched, and the first to allow fewer than seven hits per nine innings pitched. Koufax, along with teammate Don Drysdale, became a pivotal figure in baseball's labor movement when the two staged a joint holdout and demanded a fairer contract from the Dodgers before in 1966 season. Koufax is also considered one of the greatest Jewish athletes in history; his decision to sit out Game 1 of the 1965 World Series because it coincided with the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur garnered national attention and made him an iconic figure within the American Jewish community.

Since retiring, Koufax has kept a low profile and makes public appearances on rare occasions. In December 1966, he signed a 10-year contract to work as a broadcaster for NBC; uncomfortable in front of cameras and with public speaking, he resigned after six years. In 1979, Koufax returned to work as a pitching coach in the Dodgers' farm system; he resigned from the position in 1990 but continues to make informal appearances during spring training. From 2013 to 2015, Koufax worked in an executive position for the Dodgers, as special advisor to chairman Mark Walter. In 1999, he was named to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team. His number 32 was retired by the Dodgers in 1972 and he was honored with a statue outside the centerfield plaza of Dodger Stadium in 2022. That same year, Koufax became the first player to mark the 50th anniversary of his election to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Early life[edit]

Koufax was born Sanford Braun to a Jewish family on December 30, 1935, in Borough Park, Brooklyn.[1] His parents, Evelyn (née Lichtenstein) and Jack Braun, divorced when he was three years old. The son of a single working parent, he spent most of his childhood with his maternal grandparents and spent his summers at Camp Chi-Wan-Da, a Jewish summer camp in Ulster Park, New York, where his mother worked as a bookkeeper.[2]

Evelyn, an accountant, eventually remarried when her son was nine years old to Irving Koufax, an attorney whose name Sandy took. Koufax also gained a stepsister, Edie, Irving's daughter from a previous marriage.[3] Shortly afterwards, the family moved to the Long Island suburb of Rockville Centre. They moved back to Brooklyn in June 1949, the day after Koufax graduated from ninth grade, settling in the neighborhood of Bensonhurst.[4]

As a youth, Koufax was better known for basketball than for baseball. He had started playing it at the Edith and Carl Marks Jewish Community House of Bensonhurst, winning a few local titles with the community center team. Attending Lafayette High School, Koufax would become the basketball team's captain in his senior year. That year, he ranked second in his division in scoring, averaging 16.5 points per game.[3] He made newspaper headlines for the first time when, during a preseason exhibition game between the Lafayette basketball team and the New York Knicks, he dunked twice and showed up Knicks star Harry Gallatin.[5][6]

In 1951, Koufax joined a local youth baseball league known as the "Ice Cream League", playing for the Tomahawks. He started out as a left-handed catcher before moving to first base. He joined Lafayette's baseball team as a first baseman in his senior year at the urging of his friend Fred Wilpon.[7] While with the high school team, he was spotted by Milt Laurie, a newspaper deliveryman and baseball coach who was the father of two Lafayette baseball players. Laurie noticed Koufax's strong throwing arm and recruited him to pitch for the Coney Island Sports League's Parkviews.[8]

Koufax chose to attend the University of Cincinnati after becoming a walk-on for their freshman basketball team. Playing under coach Ed Jucker, he averaged 9.7 points per game.[3] As a student, he was enrolled in a liberal arts major with the intention of transfering to the architectural school,[9] and was a member of Pi Lambda Phi, a historically Jewish fraternity.[10][11]

One day, Koufax overheard Jucker, who also coached the college baseball team, planning a last-minute road trip in his office which started in New Orleans. Eager to visit the city, he told Jucker, "I'm a pitcher" and made the team in a subsequent tryout.[12] For the season, Koufax went 3–1 with a 2.81 earned run average, 51 strikeouts and 30 walks in 32 innings pitched.[13]

Major League tryouts[edit]

While with the college baseball team, Koufax began to attract the attention of baseball scouts. Bill Zinser, a scout for the Brooklyn Dodgers, sent the team a glowing report that was seemingly filed away and forgotten.[14] Gene Bonnibeau, a scout for the New York Giants, learned of Koufax through a Cincinnati newspaper and invited him to try out at the Polo Grounds after his freshman year. The workout did not go well for the nervous Koufax who threw wildly over the catcher's head; he never heard back from the Giants afterwards.[15]

That summer, Koufax began pitching regularly for the Parkviews. In September, Ed McCarrick, a scout for the Pittsburgh Pirates, was highly impressed with Koufax after seeing him in a few sandlot games.[16] At McCarrick's behest, Branch Rickey, general manager of the Pirates, sent scout Clyde Sukeforth to see Koufax. Sukeforth subsequently invited him to Forbes Field for a tryout before the Pirates' front office. Upon seeing Koufax pitch in person, Rickey remarked, "This is the greatest arm I've ever seen."[17] The Pirates, however, failed to offer Koufax a contract until after he was already committed to the Dodgers.[18]

Al Campanis, a Dodgers scout, heard about Koufax from sportswriter Jimmy Murphy of the Brooklyn Eagle who covered sandlot teams in Brooklyn and had seen him pitch a few times.[19][20] He was also urged by Pat Auletta, the owner of a sporting goods store and founder of the Coney Island Sports League, to come and see Koufax pitch. Auletta arranged a workout at the Lafayette High baseball field; after watching Koufax throw, Campanis arranged a tryout for him at Ebbets Field.[21] With Dodgers manager Walter Alston and scouting director Fresco Thompson watching, Campanis assumed the hitter's stance while Koufax started throwing; he later said, "There are two times in my life the hair on my arms has stood up: The first time I saw the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and the second time, I saw Sandy Koufax throw a fastball."[22][23]

After the tryout, Koufax's father negotiated the contract with the Dodgers, asking for a bonus which would allow his son to finish college if his baseball career failed.[3] They agreed on a $20,000 contract ($227,000 today) – $6,000 then-league minimum salary, with a $14,000 signing bonus – and not to officially sign until after the season ended, with Irving Koufax and owner Walter O'Malley making a handshake commitment.[24]

Returning to university, Koufax also had a tryout with the Milwaukee Braves after which general manager John Quinn made him a $30,000 offer. Having already committed to signing with the Dodgers, Koufax turned down the Braves' offer. He also turned down a belated offer from the Pirates, promising him $5,000 more than what the Dodgers did.[25] Koufax officially signed with his hometown team on December 14.[26]

Professional career[edit]

At the time of Koufax's signing, the bonus rule implemented by Major League Baseball was still in effect, stipulating that if a major league team signed a player to a contract with a signing bonus in excess of $4,000 ($55,000 today), they were required to keep them on their 25-man active roster for two full seasons.[27] In compliance with the rule, the Dodgers placed Koufax on their major league roster. As it subsequently turned out, Koufax never played in the minor leagues.[28]

During his first spring training, Koufax struggled with his new training regime and suffered from a sore arm most of the time.[29] Having pitched less than twenty games in the sandlots and in college combined, he did not know a lot about pitching such as how to properly field a ball, how to hold a runner on base, or even pitching signs, later saying, "The only signs I knew were one finger for fastball and two for a curve, and here there were five or six signs." His lack of minor league experience meant Koufax never fully mastered all aspects of the game and took a lot longer to develop as a pitcher.[30]

Early years (1955–1960)[edit]

Having injured his ankle in the last week of spring training, Koufax was placed on the disabled list for 30 days; he would be activated by the Dodgers on June 8. To make room for him, they optioned their future Hall of Fame manager, Tommy Lasorda, to their Triple-A affiliate, the Montreal Royals. Lasorda would later joke that it took "one of the greatest left-handers in history" to keep him off the Dodgers major league roster.[31]

Koufax made his major league debut on June 24, 1955, against the Milwaukee Braves, with the Dodgers trailing 7–1 in the fifth inning. Johnny Logan, the first batter Koufax faced, hit a bloop single. Eddie Mathews bunted back to the mound, and Koufax threw the ball into center field. He then walked Henry Aaron on four pitches to load the bases before striking out Bobby Thomson on a 3–2 fastball for his first career strikeout.[32] Koufax ended up pitching two scoreless innings, inducing a double play to end the bases-loaded threat and picking up another strikeout in a perfect sixth.[33]

Koufax's first start was on July 6, the second game of a doubleheader against the Pittsburgh Pirates. He lasted only 4.2 innings, giving up eight walks.[34] He did not start again for almost two months.[35]

On August 27, Koufax threw a two-hit, 7–0 complete game shutout against the Cincinnati Redlegs for his first major league win. He struck out 14 batters and allowed only two hits.[36][37] His only other win in 1955 was also a shutout, a five-hitter against the Pirates on September 3.[38]

In his rookie year, Koufax threw 41.2 innings in 12 appearances, striking out 30 batters and walking 28, with a record of 2–2 and 3.02 earned run average.[39] The Dodgers went on to win the National League pennant and the 1955 World Series over the New York Yankees, the first title in franchise history; however, Koufax did not appear in the series. During the fall, he had enrolled in the Columbia University School of General Studies, which offered night classes in architecture; after the final out of Game 7, Koufax went straight to Columbia to attend class.[40]

The 1956 season was not very different from 1955 for Koufax. Despite the blazing speed of his fastball, Koufax continued to struggle with his control. He saw little work, pitching only 58.2 innings with a 4.91 earned run average, 29 walks and 30 strikeouts.[41] When Koufax allowed baserunners, he was rarely permitted to finish the inning. Teammate Joe Pignatano remarked, years later, that as soon as Koufax threw a couple of balls in a row, Alston would signal for a replacement to start warming up in the bullpen.[42]

Notably, teammates Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella both clashed with Alston on Koufax's usage, noting the young pitcher's talent and objecting to him being benched for weeks at a time. Pitcher Don Newcombe stated years later that Koufax faced antisemitism as a young pitcher from white players on the team who shunned him and used antisemitic slurs when referring to him. This led to black teammates rallying to Koufax's defense and supporting him during his early years.[43]

To prepare him for the 1957 season, the Dodgers sent Koufax to Puerto Rico to play winter ball for the Criollos de Caguas.[44] For the Criollos, Koufax compiled a record of 3–6 with a 4.35 earned run average and 76 strikeouts in 64.2 innings pitched.[45] Two of his wins were shutouts, including a one-hitter and a two-hitter, with Roberto Clemente getting both hits against him in the latter, his last game in Puerto Rico before being released. Besides the Dodgers, the Criollos were the only other team Koufax pitched for in his career.[46]

On May 15, the restriction on sending Koufax down to the minors was lifted. Alston gave him a chance to justify his place on the major league roster by giving him the next day's start. Facing the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field, Koufax struck out 13 while pitching his first complete game in almost two years. For the first time in his career, he was in the starting rotation, but only for two weeks. Despite winning three of his next five with a 2.90 earned run average, Koufax did not get another start for 45 days. In that start, he struck out 11 in seven innings, but got no decision. On September 29, he became the last man to pitch for the Brooklyn Dodgers before their move to Los Angeles, throwing an inning of relief in the final game of the season.[47]

Koufax and fellow Dodgers pitcher Don Drysdale served six months in the United States Army Reserve in Fort Dix, New Jersey and Van Nuys, California after the 1957 season and before spring training in 1958.[48]

Koufax began the 1958 season 7–3, but sprained his ankle in a collision at first base on July 5 against the Chicago Cubs, resulting in a long layoff. Throughout the season, he was also plagued with back pain which was the result of a benign tumor on his rib cage, necessitating him to undergo surgery in the offseason to have the growth removed.[30] As a result, he finished the season at 11–11 and leading the majors in wild pitches.[49]

In 1959, on June 22, he set the record for a night game with 16 strikeouts against Philadelphia Phillies.[50][51] On August 31, against the Giants, he set the NL single-game record and tied Bob Feller's modern Major League record of 18 strikeouts, and also scored on Wally Moon's walk-off home run for a 5–2 win.[52][53][54]

That season, the Dodgers won a tight pennant race against the Giants and the Milwaukee Braves. They faced the Chicago White Sox in the World Series. In his first World Series appearance, Koufax pitched two perfect relief innings in Game 1, though they came after the Dodgers were already behind 11–0. Alston gave Koufax the start in Game 5, at the Los Angeles Coliseum. In what would have been the series-clincher, Koufax allowed only one run in seven innings but lost the game 1–0 when Nellie Fox scored on a double play and the Dodgers failed to score a run in support. Returning to Chicago, the Dodgers won Game 6 and their first championship in Los Angeles.[55][56]

In early 1960, Koufax asked Dodgers general manager Buzzie Bavasi to trade him because he believed he was not getting enough playing time, a request that was denied. On May 23, he pitched a one-hit shutout against the Pirates, allowing only a second-inning single by pitcher Bennie Daniels and striking out 10 batters in the process.[57] However, the game was a highlight in an otherwise bad year for Koufax in which he went 8–13 with a 3.97 earned run average.[39]

After the last game of the season, frustrated with his lack of progress as well as resentment towards Dodger management, Koufax threw his equipment into the trash, having decided to quit baseball and devote himself to an electronics business in which he had invested.[58] In his first six seasons, he had posted a record of 36–40 with a 4.10 earned run average. Nobe Kawano, the clubhouse supervisor, retrieved the equipment in case Koufax decided to return the following year.[59]

Domination (1961–1964)[edit]

Koufax came to regret his decision to quit, having found working in the offseason boring. He decided to give baseball another try, remarking years later, "I decided I was really going to find out how good I can be."[60] During the offseason, Koufax underwent tonsillectomy due to recurring throat issues and, as a result, reported to spring training thirty pounds under his normal playing weight. Koufax later stated that it forced him to regain the lost muscle mass and weight through exercise and nutrition, allowing him to get into the "best shape" of his life. From then on, he made it a point to report to spring training under his playing weight.[3][61]

During spring training, Dodger scout Kenny Myers discovered a hitch in Koufax's windup, where he would rear back so far he would lose sight of the target.[62] As a result, Koufax tightened up his mechanics, believing that not only would it help better his control but would also help him disguise his pitches better.[a][64] Additionally, Dodgers statistician Allan Roth helped Koufax tweak his game in the early 1960s, particularly regarding the importance of first-pitch strikes and the benefits of breaking pitches.[3][65]

On March 23, Koufax was chosen to pitch in a B-squad game against the Minnesota Twins in Orlando, Florida, by teammate Gil Hodges who was acting manager for the day. As teammate Ed Palmquist had missed the flight, leaving the team short one pitcher, Hodges told Koufax he needed to pitch at least seven innings. Prior to the game, catcher Norm Sherry told him: "If you get behind the hitters, don't try to throw so hard." This was due to Koufax's tendency to lose his temper and throw hard and wildly whenever he got into trouble.[3]

The strategy worked initially before Koufax temporarily reverted to throwing hard and walked the bases loaded with no out in the fifth. Sherry reminded Koufax of their discussion, advising him to settle down and throw to his glove. The advice worked; Koufax struck out the side, finishing the game with seven no-hit innings. He went on to have a strong spring training.[66][67]

1961 season[edit]

All the improvements and changes made in the offseason and during spring training resulted in 1961 becoming Koufax's breakout season. He posted an 18–13 record and led the majors with 269 strikeouts, breaking Christy Mathewson's 58-year-old NL mark of 267, and doing so in 110 innings fewer than Mathewson had.[68]

That season also marked the first time in his career that Koufax started at least 30 games (35) and pitched at least 200 innings (255.2). He lowered his walks allowed per nine innings from 5.1 in 1960 to 3.4 in 1961, led the NL with a strikeout-to-walk ratio of 2.80, and led the majors with a fielding independent pitching mark (FIP) of 3.00.[39]

On September 20 when Koufax won a 13-inning contest against the Chicago Cubs for his 18th win of the year. He pitched a complete game, throwing 205 pitches, striking out fifteen batters.[69]

1962 season[edit]

In 1962, the Dodgers moved from the Los Angeles Coliseum – a football stadium which had a 250-foot (75 m) left-field line, an enormous disadvantage to left-handed pitchers – to Dodger Stadium. The new park was pitcher-friendly, with a large foul territory and a relatively poor hitting background. Koufax was an immediate beneficiary of the move, lowering his earned run average at home from 4.22 to 1.75.[70] Subsequently, he recorded what would be his first great season, leading the NL in ERA and the majors in hits per nine innings, strikeouts per nine innings, and FIP.[39]

On April 24, Koufax tied his own record of 18 strikeouts in a 10–2 win over the Chicago Cubs in Wrigley Field.[71] On June 13, against the Braves at Milwaukee County Stadium, he hit his first career home run off future Hall of Famer Warren Spahn, providing the winning margin in a 2–1 victory.[72]

On June 30, Koufax threw his first career no-hitter against the expansion New York Mets; it was also the first Dodgers no-hitter since their move to Los Angeles. In the first inning, he threw an immaculate inning, becoming the sixth NL pitcher and the 11th overall to throw one; he remains the only one to do so in a no-hitter.[73][74] His no-hitter, along with a 4–2 record, 73 strikeouts and a 1.23 ERA, earned him the Player of the Month Award for June. It was the only time in his career he earned this distinction.[75]

Throughout the first half of the season, Koufax dealt with an injured pitching hand.[30] In April, while at bat, he had been jammed by a pitch. A numbness soon developed in his left index finger and it slowly turned cold and pale. Due to his strong performance, Koufax ignored the condition, hoping it would clear up in due time. The condition worsened, however, with his whole hand turning numb by July. During a start against Cincinnati, his finger split open.[76] A vascular specialist determined that Koufax had a crushed artery in his palm. Ten days of experimental medicine successfully reopened the artery, preventing the possibility of amputation.[77]

Koufax was finally able to pitch again in September, when the team was locked in a tight pennant race with the Giants.[78] However, after the long layoff, he was rusty and ineffective in three appearances and, by the end of the regular season and in part due to Koufax's absence from the Dodgers rotation, the Giants caught up with the Dodgers and forced a three-game playoff.[79]

With an overworked pitching staff, manager Alston asked Koufax if he could start the first game. Koufax obliged but, still rusty from the long layoff, was knocked out in the second inning, after giving up home runs to Willie Mays and Jim Davenport. After winning the second game of the series, the Dodgers blew a 4–2 lead in the ninth inning of the deciding third game, losing the pennant.[80]

1963 season[edit]

In 1963, Major League Baseball expanded the strike zone to combat what they perceived as too much offense.[81] Compared to the previous season, walks in the NL fell 13%, strikeouts increased 6%, the league batting average fell from .261 to .245, and runs scored declined 15%.[82] Koufax, who had reduced his walks allowed per nine innings to 3.4 in 1961 and 2.8 in 1962, reduced it further to 1.7 in 1963, which ranked fifth in the league.[39]

On April 19, Koufax threw his second immaculate inning, this time in a two-hit shutout win against the Houston Colt .45s, becoming the first NL pitcher and the second pitcher ever (after Lefty Grove) to throw two immaculate innings.[74] However, on April 23, he left a game against the Braves after throwing seven scoreless innings due to injuring the posterior capsule of his left shoulder. Koufax subsequently missed two weeks, returning on May 7 against the Cardinals.[83]

Koufax threw his second career no-hitter against the San Francisco Giants on May 11, besting Giants ace Juan Marichal – himself a no-hit pitcher on June 15. Koufax carried a perfect game into the eighth inning against the powerful Giants lineup which included future Hall of Famers Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, and Orlando Cepeda. The perfect game ended when he walked catcher Ed Bailey on a 3-and-2 pitch. He closed out the game after walking pinch-hitter McCovey on four pitches with two out in the ninth.[84][85]

From July 3 to 16, he pitched 33 consecutive scoreless innings, pitching three shutouts to lower his earned run average to 1.65. On July 20, he hit the second and last home run of his career, coincidentally again in Milwaukee. He hit a three-run shot off Braves pitcher Denny Lemaster to propel the team to a 5–4 win; it was his only game with three runs batted in.[39]

In 1963, Koufax won the first of three pitching Triple Crowns, leading the league in wins (25), strikeouts (306), and earned run average (1.88).[86] He threw 11 shutouts, eclipsing Carl Hubbell's 30-year, post-1900 mark for a left-handed pitcher of 10 and setting a record that stands to this day. Only Bob Gibson, with 13 shutouts in his iconic 1968 season (known as "the year of the pitcher"), has thrown more since.[87]

Koufax won the National League Most Valuable Player Award,[88] and was the first unanimous selection for the Cy Young Award, winning at a time when only one was awarded for both leagues.[b][89] He was also named the Associated Press Male Athlete of the Year for the first time, and was awarded the Hickok Belt as the athlete of the year.[90]

Clinching the pennant on September 27, the Dodgers faced the New York Yankees in the 1963 World Series who were heavily favored to win. In Game 1, Koufax beat Whitey Ford 5–2. He struck out the first five batters and 15 overall, breaking Carl Erskine's decade-old record of 14. The Dodgers won Games 2 and 3 behind the pitching of Johnny Podres, Ron Perranoski, and Don Drysdale. Koufax completed the Dodgers' series sweep in Game 4 with a 2–1 victory over Ford; the only run he allowed was a home run by Mickey Mantle.[91][92]

During the series, Koufax struck out 23 batters in 18 innings, a record for a four-game World Series, and had a 2–0 record with an earned run average of 1.50; for his performance, he was awarded the World Series Most Valuable Player Award.[93][94][95]

Salary dispute[edit]

After his successful 1963 season, Koufax asked the Dodgers for a salary raise to $75,000, later writing in his autobiography: "I felt I was entitled to a healthy raise. Like double of the $35,000 I had received the year before, plus another $5,000 for good measure, good conduct, and good luck. They could hardly say I didn't deserve it."[96] However, during his meeting with Dodgers general manager Buzzie Bavasi, the latter stated Koufax had not earned such a big raise, using numerous excuses to justify his stance, including that he had not pitched enough innings the year before. Bavasi instead offered him $65,000.[97]

Angered at Bavasi's reasonings, Koufax held his ground. After tense negotiations, the pair finally agreed to $70,000 and Koufax signed just before the team was about to leave for spring training.[98] Soon after his signing, however, the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner published a story which incorrectly stated that Koufax had threatened to retire if he did not get a salary of $90,000. Angered and shocked that the story painted him as greedy, Koufax responded in an interview with Frank Finch of the Los Angeles Times that he did neither of those things, saying: "I've been hurt by people I thought were my friends."[99]

The story continued into spring training, with the usually quiet and reserved Koufax telling his side of the negotiations to sportswriters. He strongly suspected that somebody in the front office leaked the story. It took both Bavasi and Dodgers owner Walter O'Malley meeting with Koufax separately that finally led to him to drop the matter. However, due to the bitter negotiations and what he felt was disrespect from the front office, Koufax's relationship with both men never fully recovered.[100]

1964 season[edit]

On April 14, Koufax made the only Opening Day start of his career, pitching a 4–0 shutout against the St. Louis Cardinals.[101] In his next start, he struck out three batters on nine pitches in the third inning of a 3–0 loss to the Cincinnati Reds, becoming the first pitcher in Major League history to throw three immaculate innings.[74] On April 22, in St. Louis, however, Koufax "felt something let go" in his arm during the first inning, resulting in three cortisone shots in his left elbow and three missed starts.[102]

On June 4, against the Philadelphia Phillies in Connie Mack Stadium, Koufax threw his third career no-hitter, tying Bob Feller as the only modern-era pitchers to hurl three no-hitters. He only needed 97 pitches and faced the minimum 27 batters while striking out 12. The only full-count he allowed was to Dick Allen in the fourth inning; Allen walked and was thrown out trying to steal second base; he was the Phillies' only baserunner that day.[103][104]

On August 8, during a game against the Milwaukee Braves, Koufax jammed his pitching arm while diving back to second base to beat a pick-off throw by Tony Cloninger. He managed to pitch and win two more games. However, the morning after his 19th win, a shutout in which he struck out 13 batters, Koufax woke up to find his elbow "as big as his knee" and that he could no longer straighten his arm. He was diagnosed by Dodgers team physician Robert Kerlan with traumatic arthritis.[c][106] With the Dodgers out of the pennant race, Koufax did not pitch again that season, finishing with a 19–5 win-loss record and leading the National League with a 1.74 ERA and seven shutouts, the majors with a 2.08 FIP.[39]

Playing in pain (1965–66)[edit]

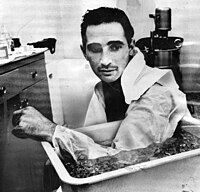

After resting during the off-season, Koufax returned to spring training in 1965 and initially had no problems from pitching. On March 30, however, he woke up the morning after pitching a complete game against the Chicago White Sox to find his entire left arm swollen and black and blue from hemorrhaging. He returned to Los Angeles to consult with Kerlan who warned him that he would eventually lose the full use of his arm if he continued to pitch.[107]

Kerlan and Koufax established a schedule which he followed for the last two seasons of his career. Koufax initially agreed to stop throwing between starts but, as it had been a part of his routine for a long time, he soon resumed it. Instead, he stopped throwing sidearm pitches (which he often did against left-handed batters) and removed his rarely-used slider from his repertoire.[108]

Before each start, Koufax had capsaicin-based Capsolin ointment – nicknamed the "Atomic Balm" by players – rubbed onto his shoulder and arm. Afterwards, he soaked his arm in a tub of ice to prevent swelling; during the ice treatments, he often wore a rubber sleeve fashioned from an inner tube to prevent frostbite. If his elbow swelled up after a game, the fluid would be drained with a syringe and he would be given a cortisone shot in the joint. For the pain, Koufax took Empirin with codeine every night and occasionally during a game. He also took Butazolidin, a drug used to treat inflammation caused by arthritis which was eventually taken off the market due to its toxic side effects.[109]

1965 season[edit]

Despite the constant pain in his pitching elbow, Koufax pitched a major league-leading 335.2 innings and 27 complete games, leading the Dodgers to another pennant. He won his second pitching Triple Crown, leading the Majors in wins (26), earned run average (2.04), and strikeouts (382).[86] Koufax captured his second unanimous Cy Young Award,[89] and was runner-up for the National League MVP Award, behind Willie Mays.[88]

Koufax's 382 strikeouts broke Bob Feller's modern record of 348 strikeouts in 1946, and was the highest modern-day total at the time.[d] He walked only 71 batters, the first time a pitcher struck out 300 more batters than he walked (311). Additionally, he held batters to 5.79 hits per nine innings, and allowed the fewest baserunners per nine innings in any season ever: 7.83, breaking his own record (set two years earlier) of 7.96.[39]

Koufax was the pitcher for the Dodgers during the game on August 22, when Giants pitcher Juan Marichal clubbed Dodgers catcher John Roseboro in the head with a bat.[111] The game, which came in the middle of a heated pennant race, had been tense since it began, with Marichal brushing back Dodgers outfielder Ron Fairly and shortstop Maury Wills, and Koufax retaliating by throwing over the head of Willie Mays. After Koufax's retaliation, both benches were warned by umpire Shag Crawford; despite this, he asked Roseboro, "Who do you want me to get?" Not wanting Koufax ejected in the middle of a crucial game, Roseboro replied, "I'll handle it."[112]

After the clubbing occurred, Koufax rushed from the mound and attempted to grab the bat from Marichal. A fourteen-minute brawl ensued in which he and Mays attempted to restore peace, with Mays dragging the injured Roseboro away from the fight.[113] After the game resumed, a shaken Koufax walked two batters before giving up a three-run home run to Mays. While he eventually settled down and pitched a complete game without allowing more runs, the Dodgers lost the game 4–3.[114]

Perfection[edit]

On September 9, 1965, Koufax became the sixth pitcher of the modern era, and eighth overall, to throw a perfect game. The game, pitched against the Chicago Cubs, was Koufax's fourth no-hitter, setting a then-major league record, and the first by a left-hander in the modern era. He struck out 14 batters, the most recorded in a perfect game, and at least one batter in each inning in the 1–0 win.[115]

The game also set a record for the fewest hits in a major league contest as Cubs pitcher Bob Hendley pitched a one-hitter and allowed only two batters to reach base.[116] Both pitchers had no-hitters intact until the seventh inning. The winning run was unearned, scored in the fifth inning without a hit when Dodgers left fielder Lou Johnson walked, reached second on a sacrifice, stole third, and scored on a throwing error by Cubs catcher Chris Krug. The only hit was a bloop double by Johnson to shallow right in the seventh inning.[117]

World Series and Yom Kippur decision[edit]

The Dodgers won the NL pennant on the second-to-last game of the season, against the Milwaukee Braves. Koufax started the game on two days' rest and pitched a complete game 3–1 win, striking out 13, to clinch the pennant for the Dodgers.[e][119]

Koufax garnered national attention when he declined to start Game 1 of the 1965 World Series as it clashed with Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar.[120] Instead, Drysdale pitched the opener, but was hit hard by the Minnesota Twins. When Dodgers manager Walter Alston came out to remove Drysdale from the game, the latter quipped: "I bet right now you wish I was Jewish, too."[121]

In Game 2, Koufax pitched six innings, giving up two runs (one unearned); the Twins won 5–1 to take an early 2–0 lead in the series. The Dodgers fought back in Games 3 and 4, with wins by Claude Osteen and Drysdale. With the Series tied at 2–2, Koufax pitched a four-hit shutout in Game 5, striking out 10 batters, for a 3–2 Dodgers lead.

The Series returned to Metropolitan Stadium for Game 6, which the Twins' Jim Grant won to force a seventh, decisive game. For the series clincher, Alston decided to start Koufax on two days' rest over the fully-rested Drysdale against the Twins' Jim Kaat. Pitching through fatigue and chronic pain, he threw a three-hit shutout with 10 strikeouts, despite the fact he did not have his curveball and relied almost entirely on his fastball.[122][123]

For his performance, Koufax won the World Series MVP Award, the first player to be awarded it multiple times. Koufax also won the Hickok Belt for a second time, also the first time anyone won the belt more than once.[90] That year, he was named the Sportsman of the Year by Sports Illustrated and Associated Press Male Athlete of the Year for a second time.[124]

Holdout[edit]

In the offseason, prior to the 1966 season, Koufax and Drysdale met separately with general manager Buzzie Bavasi to negotiate their contracts for the upcoming season. Koufax still harbored ill feelings towards Bavasi stemming from his contract dispute before the 1964 season.[125] After his meeting, he met Drysdale and his wife Ginger for dinner, irritated that Bavasi was using his own teammate against him in the salary negotiations. Drysdale responded that Bavasi had done the same thing with him. After comparing notes, they realized that Bavasi had played each pitcher against the other.[126]

Ginger Drysdale, who had worked as a model and actress and was once a member of the Screen Actors Guild, suggested the pair negotiate together to get what they wanted. Hence, in January 1966, Koufax and Drysdale informed the Dodgers of their decision to hold out together.[127][128]

In a highly unusual move for the time, they were represented by entertainment lawyer J. William Hayes, Koufax's business manager. Also unusual was their demand of $1 million ($9.4 million today), divided equally over the next three years, or $167,000 ($1.57 million today) each for each of the next three seasons. They told Bavasi they would negotiate their contracts as one unit through their agent. The Dodgers refused to do so, stating it was against their policy, and a stalemate ensued. The front office began to wage a public relations campaign against the pair.[128]

Koufax and Drysdale did not report to spring training in February 1966. Instead, both signed to appear in the movie Warning Shot. Additionally, Koufax had signed a book deal to write his autobiography, Koufax, with author Ed Linn.[128] Meanwhile, Hayes unearthed a state law, the result of the De Havilland v. Warner Bros. Pictures case, that made it illegal to extend personal service contracts in California beyond seven years; he began to prepare a lawsuit which to challenge the reserve clause. When Dodgers owner Walter O'Malley found out about this, the team's front office softened their stance towards the pair.[128]

Actor and former baseball player Chuck Connors helped arrange a meeting between Bavasi and the two pitchers. Koufax gave Drysdale the go-ahead to negotiate new deals on behalf of both of them. At the end of the thirty-two day holdout, Koufax signed for $125,000 ($1.17 million today) and Drysdale for $110,000 ($1.03 million today).[128] The deal made Koufax the highest paid player in Major League Baseball for 1966.[129]

The holdout was the first significant event in baseball's labor movement and the first time major league players challenged the absolute stronghold the owners held in baseball at the time. That same year, trade unionist Marvin Miller used the Koufax–Drysdale holdout as an argument for collective bargaining while campaigning for players' votes during spring training; he would soon be elected by the players as first executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association.[130]

1966 season[edit]

In April 1966, Kerlan told Koufax it was time to retire and that his arm could not take another season. By this time, Koufax could no longer straighten his arm and it occasionally went numb, causing him to drop anything he was holding. Koufax kept Kerlan's advice to himself, having decided the year before to make 1966 his last season. He went out to pitch every fourth day, accumulating 323 innings and not missing a start.[131]

He posted a 27–9 win-loss record, with 317 strikeouts and a 1.73 earned run average, and won his third pitching Triple Crown.[86] Koufax won his third unanimous Cy Young Award, the first pitcher ever to win three,[89] and was again runner-up for the National League MVP Award, finishing behind Roberto Clemente of the Pirates.[f][88]

On September 25, the day after Yom Kippur, Koufax matched up with Ken Holtzman of the Chicago Cubs, a fellow Jewish southpaw.[132] At Wrigley Field, Koufax allowed only two runs (one unearned), both in the first inning, but lost by a 2–1 score. Holtzman carried a no-hitter into the 9th, allowing only one run and one hit. It was Koufax's last regular season loss.[133]

In the final game of the regular season, the Dodgers had to beat the Phillies to win the pennant. In the second game of a doubleheader, Koufax faced Jim Bunning for the second time that season.[134] On two days' rest, Koufax pitched a 6–3 complete-game victory to clinch the pennant, the final win of his career.[135]

During the fifth inning, Koufax injured his back while pitching to Gary Sutherland who was pinch-hitting for Bunning. After the inning, he went to the trainer's room where the injury was diagnosed as a slipped disc. Dodger trainers Bill Buehler and Wayne Anderson applied Capsolin on his back and, along with former Dodger Don Newcombe, pulled Koufax in opposite directions until the disc slipped back into place.[136]

The Dodgers went on to face the Baltimore Orioles in the 1966 World Series. As Koufax had pitched the pennant clincher just three days earlier, Walter Alston was reluctant to start him in Game 1 for what would have been two consecutive starts on two days' rest. Instead, Drysdale started in Koufax's place; he proved to be ineffective, however, recording only six outs and losing 5–2.[137]

In Game 2, his third start in eight days, Koufax shut out the Orioles for the first four innings. However, three errors by Dodgers centerfielder Willie Davis in the fifth inning produced three unearned runs. The only earned run allowed by Koufax was the result of Davis losing a fly ball hit by Frank Robinson which fell for a triple; Robinson subsequently scored on a single by Boog Powell. Koufax did not receive any run support either; Baltimore's 20-year-old future Hall of Famer Jim Palmer pitched a four-hit shutout, and the Orioles won 6–0.[138]

Alston lifted Koufax at the end of the sixth inning with the idea of getting him extra rest before a potential fifth game. Instead, the Dodgers were swept in four games. Claude Osteen and Drysdale both lost by a score of 1–0 in Games 3 and 4 respectively, with the offense failing to score a single run after having scored just two in Game 1.[139]

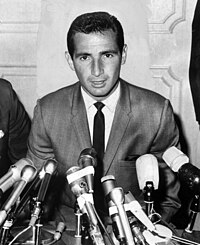

Retirement[edit]

On November 18, 1966, Koufax announced his retirement from baseball in a press conference at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel.[140][141] He cited the treatments that were required to make it possible for him pitch regularly and the possibility of losing the use of his arm as the reasons for retiring at age 30:

I've got a lot of years to live after baseball and I would like to live them with the complete use of my body. I don't regret one minute of the last twelve years, but I think I would regret one year that was too many.[142]

With the Dodgers touring Japan at the time, nobody from the team's front office was present at the press conference. Koufax, who told Buzzie Bavasi of his decision a few days before the conference, refused his request to delay his retirement until after the winter meetings in order to facilitate a few deals in the Dodgers' favor or to wait until owner Walter O'Malley returned from Japan, having already once delayed it and feeling he was being deceitful to sportswriters asking him about his future plans. In turn, Bavasi refused to attend the conference.[143]

The announcement of his retirement came as a shock, particularly to his teammates. Soon afterwards, Koufax told an incredulous Dick Tracewski, his old Dodger roommate, that he could have continued to pitch but would have risked disability if he did so: "My arm still hurts. I can't go on doing this medication thing and pitching. It's going to kill me... Lots of bad things could happen. I just gotta retire." Years later, Koufax stated that he never regretted retiring when he did but did regret having to make the decision to retire.[144]

Koufax's retirement ended a five-year run in which he went 111–34 with a 1.95 earned run average and 1,444 strikeouts. During that run, he led the Dodgers to three National League pennants and two World Series titles, in both of which he was named the series MVP. He won Cy Young Awards in each of the pennant-winning years and also won the NL Most Valuable Player Award in 1963.[39]

Career overall[edit]

Statistics and achievements[edit]

In his 12-season major league career, Koufax had a 165–87 record with a 2.76 earned run average, 2,396 strikeouts, 137 complete games, and 40 shutouts.[39] He was the first pitcher to average fewer than seven hits allowed per nine innings pitched (6.79) and to strike out more than nine batters (9.28) per nine innings pitched, retiring with more career strikeouts than innings pitched.[145][146]

Koufax was the first pitcher to win three Cy Young Awards, an especially impressive feat as it was during the era when only one was given out for both major leagues. He was also the first pitcher to win the award by a unanimous vote, a distinction which he received twice more.[89]

He became the first pitcher in baseball history to have two games with 18 or more strikeouts, and the first to have eight games with at least 15 strikeouts (now fourth-most all-time). He also set a then-record of 97 games with at least 10 strikeouts (now sixth-most all-time).[147] In his last ten seasons, from 1957 to 1966, batters hit .203 against him, with a .271 on-base percentage and a .315 slugging average.[39] His run of five consecutive ERA titles is a Major League record.[148] He also led the majors in WHIP four consecutive times and FIP six consecutive times, both also records.[149][150]

Since the start of the live-ball era, Koufax is one of only nine pitchers to record multiple 10+ WAR seasons. He is also the only one to record an ERA under 1.90 in three different qualifying seasons. In each of his last ten seasons, from 1957 to 1966, Koufax finished top ten in strikeouts, including top three finishes in seven; this was despite him being a part-time starter in three of those seasons and suffering a season-shortening injury in two.[151]

Koufax is considered one of the greatest big game pitchers in baseball history. Sabermetrician Bill James described Koufax as having a bigger impact on pennant races than any other pitcher in the 20th and 21st centuries,[152] and though his record across four World Series is 4–3, his 0.95 ERA and two World Series MVP Awards testify to how well he actually pitched.[153][154] In his three losses, Koufax only gave up one earned run in each; the Dodgers scored only one run in support across the three games, getting shut out twice.[39]

He was selected as an All-Star for six consecutive seasons and made seven out of eight possible All-Star Game appearances those seasons.[g] Koufax pitched six innings across four All-Star games; he was the winning pitcher in the 1965 All-Star Game, and was the starting pitcher in the 1966 All-Star Game, throwing three innings of one-run ball on two days' rest.[156]

| Category | W | L | ERA | G | GS | CG | SHO | SV | IP | H | R | ER | HR | BB | IBB | SO | HBP | ERA+ | FIP | WHIP | H/9 | SO/9 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 165 | 87 | 2.76 | 397 | 314 | 137 | 40 | 9 | 2,324.1 | 1,754 | 806 | 713 | 204 | 817 | 48 | 2,396 | 18 | 131 | 2.69 | 1.106 | 6.8 | 9.3 | [39] |

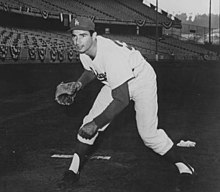

Pitching style and repertoire[edit]

Koufax was a power pitcher and threw with a pronounced straight-over-the-top arm action. Most of his velocity came from his strong legs and back, combined with a high leg kick during his wind-up and long forward extension on his release point toward home plate. His unusually large hands also allowed him to put heavy spin on his pitches and control the direction in which they would break.[157]

Though reserved and shy by nature, Koufax was a fierce competitor on the mound, once pushing back on his "gentle competitor" image: "It sure as hell isn't 'gentle', especially playing the game."[158] Though not a headhunter like teammate Don Drysdale, contrary to belief, he did not hesitate to pitch inside or brush back an opponent, once remarking: "The art of pitching is instilling fear."[159]

Throughout his career, Koufax relied heavily on two pitches.[160] His four-seam fastball gave batters the impression of rising as it approached them, due to heavy backspin he created by pulling on the seams.[161] His overhand curveball, spun with the middle finger, dropped vertically 12 to 24 inches due to his arm action; it is considered by many as being the best curve of all time.[162]

Хотя у него была замена , Куфакс почти никогда ее не бросал; в конце концов он заменил его вилочным мячом , который более регулярно использовал в качестве третьей подачи. [163] Shortstop Roy McMillan described its movement as being not unlike that of a spitball.[164] В свои последние сезоны Куфакс также начал бросать каттер , чтобы компенсировать потерю скорости. [165]

Действия после игры [ править ]

Вскоре после выхода на пенсию Куфакс подписал 10-летний контракт с NBC на сумму 1 миллион долларов (9,1 миллиона долларов на сегодняшний день) на роль ведущего субботней игры недели . [166] Во время своего пребывания в должности он также работал цветным комментатором Матча всех звезд и аналитиком перед игрой Мировой серии .

Застенчивый человек, Куфакс никогда не чувствовал себя комфортно в эфире; ему было трудно разговаривать о бейсболе с людьми, которые не играли в эту игру профессионально. Ему также было сложно описывать питчеров, чей репертуар и стиль подачи отличался от его, а также критиковать игроков, с которыми он играл и против которых он играл. В результате он ушел через шесть лет, и его контракт с NBC был расторгнут по обоюдному согласию перед сезоном 1973 года. [167] [168]

В 1979 году Куфакс был нанят «Доджерс» в качестве тренера по подаче низшей лиги в их фермерской системе. [169] За время своего пребывания в должности он работал с рядом питчеров, в том числе с Орлом Хершайзером , Дэйвом Стюартом , Джоном Франко , Бобом Уэлчем и другими членами Зала славы Доном Саттоном и Педро Мартинесом . [170] [171] Куфакс с помощью бывшего товарища по команде Роджера Крейга научился бросать фастбол с разделенными пальцами , популярную подачу в 1980-х годах, чтобы иметь возможность обучать этому питчеров в системе низшей лиги «Доджерс». [172]

Он ушел со своей должности в 1990 году, заявив, что не зарабатывает на жизнь, поскольку Доджерс сократили его рабочую нагрузку; большинство наблюдателей, однако, винили в этом его непростые отношения с менеджером Томми Ласордой , который, как сообщается, возмущался работой Куфакса со своими питчерами. Несмотря на это, Куфакс продолжал неофициально посещать весенние тренировки. [173]

В это время Куфакс также начал посещать весенние тренировки с другими командами, особенно с « Нью-Йорк Метс» , которые тогда принадлежали его другу детства Фреду Уилпону . [174] Примечательно, что питчер Mets Эл Лейтер выразил благодарность Куфаксу за то, что он помог ему стать лучшим питчером. [175] [176]

В 2002 году газета New York Post опубликовала ложную историю о Куфаксе в связи с биографией о нем спортивным обозревателем Джейн Ливи , написанной под названием «Сэнди Куфакс: Наследие левши» , ошибочно намекая, что он согласился на биографию только потому, что Ливи угрожал выдать его за гея. если он не будет сотрудничать. [177] Куфакс разорвал связи с Доджерс, поскольку и команда, и газета в то время принадлежали Руперта Мердока , News Corp и он не хотел способствовать продвижению какой-либо из их дочерних компаний . [178] Он воссоединился с организацией в 2004 году, когда News Corp продала Доджерс Фрэнку МакКорту . [179]

Перед сезоном 2013 года «Доджерс» снова наняли Куфакса, на этот раз в качестве специального советника председателя команды Марка Уолтера , для работы с питчерами во время весенних тренировок и консультирования в течение сезона. [180] [181] Куфакс ушел с должности фронт-офиса перед сезоном 2016 года. [182]

С момента своего основания Koufax принимал активное участие в деятельности Baseball Assistance Team (BAT), некоммерческой организации, призванной помогать бывшим бейсболистам преодолевать финансовые и медицинские трудности. Он был членом его консультативного совета, [183] и был постоянным участником ежегодного ужина BAT. [184]

Почести и признание [ править ]

Куфакс был избран в Зал славы бейсбола в 1972 году , в первый год его участия. В 36 лет и 20 дней он стал самым молодым человеком, когда-либо избранным, на пять месяцев моложе, чем Лу Гериг был на момент его внеочередных выборов в декабре 1939 года. [час] [186] Он также был вторым еврейским игроком, избранным в Зал славы, после Хэнка Гринберга, избранного в 1956 году .

4 июня 1972 года «Доджерс» удалили форму Куфакса под номером 32 вместе с формами Роя Кампанеллы (39) и Джеки Робинсона (42). [187] 18 июня 2022 года статуя Куфакса была открыта на стадионе «Доджер» , рядом со статуей Робинсона, его бывшего товарища по команде «Бруклин Доджер» . [188] [189]

В 1999 году издание Sporting News поместило Куфакса на 26-е место в своем списке «100 величайших игроков бейсбола». [190] В том же году он был также назван одним из 30 игроков в команде всех веков Высшей лиги бейсбола . [191] В 2020 году издание The Athletic поставило Куфакса на 70-е место в своем списке «100 бейсболистов», составленном спортивным обозревателем Джо Познански . [192]

назвали Куфакса одним из четырех величайших ныне живущих игроков Фанаты Высшей бейсбольной лиги вместе с Уилли Мэйсом , Генри Аароном и Джонни Бенчем в рамках голосования «Четвертая франшиза» сезона 2015 года. [193] Перед Матчем всех звезд 2015 года в Цинциннати он бросил церемониальную первую подачу на скамейку запасных перед основанием насыпи. [194]

В 2022 году в рамках своего проекта SN Rushmore издание Sporting News включило Куфакса в список «Спортивная гора Лос-Анджелеса Рашмор» вместе с «Лос-Анджелес Лейкерс» баскетболистами Мэджиком Джонсоном , Каримом Абдул-Джаббаром и Коби Брайантом . Спортивный обозреватель Скотт Миллер описал его как «первую икону бейсбола Лос-Анджелеса», добавив: «Даже не пытаясь, он стал воплощением калифорнийского крутого человека. Для него это естественно». [195] В том же году авторы MLB.com назвали Куфакса величайшим игроком в истории франшизы «Доджерс», опередив Джеки Робинсона:

Величайшие из великих игроков расширяют свое доминирование на поле и определяют наследие своей команды. И Робинсон, и Куфакс выступили за «Доджерс». Оба почитаемы за их влияние на спорт, но Джеки был социальной иконой, а Сэнди был образцом питчерского наследия своей франшизы. Робинсон преуспел, несмотря на непостижимое бремя разрушения расовых барьеров. Куфакс собрал недосягаемую статистику, которая скрывает стойкость и бескорыстие, необходимые для того, чтобы испытывать постоянную боль. В фотофинише это Куфакс. [196]

еврейской Наследие общины

Важность Куфакса в еврейской общине объяснялась его атлетизмом; Еврейских мужчин считали слабыми и неспортивными, и Куфакс, ставший звездным спортсменом через шестнадцать лет после Холокоста , помог разрушить этот имидж. Его пропуск первой игры Мировой серии 1965 года из-за того, что она пришлась на Йом Кипур, помог укрепить его статус иконы для американских евреев. Раввин Ребекка Альперт объяснила значение своего решения в 2014 году:

Когда вы разговариваете с поколением еврейских мужчин, выросших в тот период, [его решение] имело большое значение. Евреев, в частности, считали в то время не очень мужественными, слабыми фигурами... И Куфакс страдал от этого. Куфакса высмеивали, потому что он предпочитал читать книгу. С ним обращались как с отшельником, и с ним было что-то не так, потому что он не стремился к славе. Представьте себе, что вы играете в Лос-Анджелесе и не заинтересованы в заголовках! Но его мужественность была поставлена под сомнение, и опять же отчасти из-за скрытого антисемитизма — или, по крайней мере, стереотипного представления о еврейских мужчинах как о не мускулистых. Так что Куфакс тоже был важным примером для подражания и настоящим героем. [197]

Раввин Брюс Люстиг рассказал биографу Джейн Ливи , что Куфакс изменил восприятие евреев: «Подумайте о стереотипе еврея в литературе. Уродливая скупость Шейлока . Он сломал так много из них. Вот был красивый еврей, левша, очень сильный на холме; идеальный игрок, загадка, человек, не стремившийся к славе или деньгам. Он расширил представление о том, что такое еврей». [198]

Куфакс был занесен в Международный зал еврейской спортивной славы в 1979 году. [199] и в Национальном зале еврейской спортивной славы в 1993 году. [200] В 1990 году он был введен в первый класс Зала еврейской спортивной славы Южной Калифорнии . [201]

Изображение Куфакса является частью фрески возле Canter's Deli в Фэрфаксе, Лос-Анджелес , которая увековечивает историю еврейской общины в городе. [202]

27 мая 2010 года Куфакс был среди группы выдающихся американских евреев, удостоенных чести на приеме в Белом доме в честь Месяца еврейско-американского наследия . [203] В своем вступительном слове президент Барак Обама прямо признал высокое уважение, которым пользуется Куфакс в еврейской общине: «Это довольно... выдающаяся группа. У нас есть сенаторы и представители. У нас есть судьи Верховного суда и успешные предприниматели, ученые-раввины, олимпийские спортсмены – и Сэнди Куфакс». Упоминание имени Куфакса вызвало в зале самые громкие аплодисменты. [204]

В том же году он был одним из двух главных героев фильма «Евреи и бейсбол: американская история любви» вместе с членом Зала славы Хэнком Гринбергом из « Детройт Тайгерс» . Куфакс согласился дать редкое интервью, заметив Ире Беркоу , сценаристу фильма: «Это не имеет смысла, если это «Евреи и бейсбол», а я в нем не участвую». [205]

С самого начала своей карьеры Куфакс считался союзником игроков меньшинства как товарищами по команде, так и противниками. Мори Уиллс напомнил, что они оба просматривали почту фанатов друг друга и разбирали расистские и антисемитские письма. [206] Питчер Джо Блэк , который был наставником Куфакса во время его первой весенней тренировки, отметил: «Если бы он был в ресторане, он бы никогда не уклонился от того, чтобы посидеть с цветными парнями». Чизи Кавано, жена менеджера клуба Нобе , которая помогала на стадионе Доджер со стиркой игроков, отметила, что Куфакс был единственным игроком в команде, который знал ее имя и спрашивал о ней. Его репутация человека, относящегося ко всем с одинаковым уважением, побудила кэтчера Эрла Бэтти , соперника Мировой серии, сказать о нем: «Я обвинил его в том, что он черный. Я сказал ему, что он слишком крут, чтобы быть белым». [207]

Ливи заявил, что Куфакс отождествлял себя с меньшинствами, потому что сам был одним из них. Один из немногих еврейских игроков в бейсболе, он боролся с антисемитизмом как внутри своей команды, так и со стороны спортивных обозревателей: «Многие из его афроамериканских коллег объясняли прямоту и сдержанность Куфакса тем, что он был меньшинством... Если бы Куфакс был Белого англосаксонского протестанта , который играл чисто и держал нос в чистоте, его можно было бы провозгласить вторым пришествием Джека Армстронга . Лу Джонсон отметил, что они придерживаются более высоких стандартов, как и любое другое меньшинство. Другими словами, он «идентифицировал себя с [ними] настолько же, насколько они идентифицировали себя с ним». [208]

В медиакультуре [ править ]

Выступления на телевидении [ править ]

За свою игровую карьеру Куфакс несколько раз появлялся в телевизионных программах. В 1959 году он появился в роли персонажа по имени Бен Кэссиди в вестерне « Shotgun Slade» . В следующем году у него были короткие эпизодические роли в трех телесериалах: в «Сансет-Стрип, 77» в роли полицейского, в «Бурбон-стрит Бит» в роли швейцара и в «Кольте .45» в роли персонажа по имени Джонни. [209]

Дважды Куфакс появлялся в телесериалах в роли самого себя. В 1962 году он появился в сериале «Деннис-Угроза » в эпизоде « Деннис и Плут », в котором он тренировал команду небольшой лиги. В 1963 году у него была молчаливая роль в роли мистера Эда в эпизоде «Лео Дюрошер встречает мистера Эда», в котором он отказался от хоумрана внутри парка главному герою, говорящей лошади. [209]

После Мировой серии 1963 года Куфакс вместе с товарищами по команде Доном Дрисдейлом и Томми Дэвисом появился на шоу Боба Хоупа , где все трое выступили в скетче с комиком Бобом Хоупом перед тем, как исполнить танцевальную программу. [210] [211] После совместного противостояния в 1966 году Куфакс и Дрисдейл появились в «Голливудском дворце » с ведущим Джином Барри и комиком Милтоном Берлом . [212]

ссылки Культурные

В 1965 году в рамках The Sound of the Dodgers альбома , посвященного команде, комик и певец Джимми Дюранте записал песню о Куфаксе под названием «Dandy Sandy». [213]

Куфакс, наряду с Уайти Фордом , — одна из центральных фигур поэмы Роберта Пински « Ночная игра ». [214] Хотя имя Пински и не названо явно, в последней строфе он сослался на Куфакса как на «решение» проблемы Форда, которого он называет в стихотворении «аристократическим» и «язычником»:

В другой раз,

Я придумал левшу

Еще более одаренный

Чем Уайти Форд: Плут.

Люди были поражены им.

Однажды, когда он был молод,

Он отказался участвовать в Йом Кипуре.

В фильме 1975 года « Пролетая над гнездом кукушки» , после того как ему не разрешили смотреть его по телевидению, Джека Николсона персонаж Рэндл Макмерфи рассказывает воображаемый отчет о Мировой серии 1963 года , в котором Куфакс выбывает из игры после того, как сдался дабл и два хоумрана Бобби Ричардсону , Тому Трешу и Микки Мэнтлу соответственно. [215]

В фильме 1998 года «Большой Лебовски » персонаж Джона Гудмана Уолтер Собчак упоминает Куфакса в ответ на то, что ему сказали, что он «живет в гребаном прошлом»: «Три тысячи лет прекрасной традиции от Моисея до Сэнди Куфакса... ты чертовски прав, я живу в гребаном прошлом!" [216]

Куфакс косвенно упоминается в эпизоде телешоу « Умерь свой энтузиазм » «Палестинская курица» (S8 E3), когда Ларри Дэвида персонаж недоверчиво спрашивает Марти Фанкхаузера, которого играет Боб Эйнштейн : «Вы нас куфаксируете?» после того, как Марти решает не участвовать в турнире по гольфу, поскольку он совпадает с Шабатом . [217]

Личная жизнь [ править ]

Куфакс вырос в светской еврейской семье и не имел бар-мицвы . Биограф Джейн Ливи описала его как «очень еврейского человека», который был «очень еврейским в своем мышлении». [218] Его дед Макс Лихтенштейн, иммигрант с социалистическими взглядами, прививал еврейские ценности внуку и культуру, часто водил Куфакса в идишский театр и на концерты . [219]

Его отказ участвовать в еврейских праздниках на протяжении всей своей карьеры был вызван уважением к его культуре, а не религиозной преданностью. [я] [221] По словам друзей, Куфакс позже стал заядлым читателем еврейской литературы и литературы о Холокосте . [222]

Несмотря на то, что за свою карьеру Куфакс был одной из крупнейших звезд Америки, после выхода на пенсию он вел себя сдержанно, редко давая интервью и скупо появляясь на публике. Даже во время своей карьеры он был известен своей застенчивостью и сдержанностью, в результате чего сложилось впечатление, что Куфакс был затворником и отстраненным человеком. [223] [224] По словам Ливи, Куфакс просто чувствовал себя некомфортно среди знаменитостей и отказывался «поедать себя ради прибыли». Сам Куфакс опроверг это мнение, однажды заметив: «Мои друзья не думают, что я отшельник». [225]

Курильщик во время игр, Куфакс отказывался пропагандировать табак или фотографироваться с курением, считая, что это пошлет неправильный сигнал детям, которые уважают его. Он также отказался рекламировать алкогольную продукцию. [226] [227]

Куфакс был женат трижды. В 1969 году он женился на Анне Видмарк, дочери актера Ричарда Видмарка ; они развелись в 1982 году. Его второй брак с личным тренером Кимберли Фрэнсис продлился с 1985 по 1998 год. [228] Он женился на своей третьей жене, Джейн Кларк (урожденная Пурукер), в 2008 году. У Куфакса нет биологических детей, но он является отчимом дочери Кларка от ее предыдущего брака с художником Джоном Клемом Кларком и имеет двух приемных внуков. [229]

Получив награду за заслуги перед жизнью от Фонда Гарольда Пампа в 2012 году, Куфакс во время своей благодарственной речи сообщил, что в 2010 году у него был диагностирован рак : «Двадцать шесть месяцев назад я был так называемой жертвой рака. Сегодня я» Я выживший». [230]

В 2009 году Куфакс числился среди клиентов, инвестировавших финансиста Берни Мэдоффа , и стал одной из жертв его схемы Понци . [231] Его близкий друг, Mets владелец Фред Уилпон порекомендовал Куфаксу инвестировать в Мэдоффа. [232] Несмотря на это, Куфакс поддержал Уилпона и предложил дать показания от имени владельца Mets, прежде чем мировое соглашение предотвратило гражданский судебный процесс. [233] [234]

В 2014 году во время весенней тренировки на ранчо Кэмелбэк Куфакс получил удар по голове от случайного поводка, в результате чего он получил порез на голове. [235] [236] Он прошел профилактическую компьютерную томографию , которая показала чистоту, и на следующий день он вернулся на место, где его ударили. [237]

В настоящее время он проживает в Веро-Бич, Флорида . [238]

В свои сорок и пятьдесят лет Куфакс стал энтузиастом физических упражнений. Чтобы оставаться в форме, он начал заниматься бегом , принимая участие в марафонах как дома, так и за рубежом. [239] [240] Всю жизнь играя в гольф, он часто участвовал в любительских чемпионатах по гольфу и участвовал в благотворительных турнирах для профессионалов и до сих пор продолжает активно заниматься этим видом спорта. Куфакс также является фанатом баскетбола в колледже и регулярно посещает чемпионаты NCAA «Финал четырех» . [241]

См. также [ править ]

- Лидеры титулов Высшей лиги бейсбола

- Тройная корона Высшей лиги бейсбола

- Список игроков еврейской Высшей бейсбольной лиги

- Список ежегодных лидеров ERA Высшей лиги бейсбола

- Список лидеров ежегодных аутов Высшей лиги бейсбола

- Список лидеров ежегодных побед Высшей лиги бейсбола

- Список лидеров ежегодного локаута Высшей лиги бейсбола

- Список лидеров аута в карьере Высшей лиги бейсбола

- Список лидеров WHIP карьеры Высшей лиги бейсбола

- Список лидеров карьеры ERA Высшей лиги бейсбола

- Список лидеров локаут-карьеры Высшей лиги бейсбола

- Список индивидуальных серий Высшей лиги бейсбола

- Список не нападающих Высшей лиги бейсбола

- Список идеальных игр Высшей лиги бейсбола

- Список лидеров аута в одиночной игре Высшей лиги бейсбола

- Список питчеров Высшей лиги бейсбола, проведших безупречный иннинг

- Список игроков Высшей лиги бейсбола, которые всю свою карьеру провели в одной франшизе

- Список вышедших на пенсию номеров Высшей лиги бейсбола

- Список бейсболистов, которые попали непосредственно в Высшую лигу бейсбола

- Список стартовых питчеров Мировой серии

Примечания [ править ]

- ↑ На протяжении всей своей карьеры Куфакс боролся со склонностью к «опрокидыванию» подачи, которую он так и не преодолел полностью; в лиге было хорошо известно, когда он бросал фастбол или делал поворот. Несмотря на это, такие игроки, как Уилли Мэйс и Джои Амальфитано, считали, что это не имеет большого значения, поскольку нападающие «все еще не могли поразить его» из-за эффективности его подачи. [63]

- ↑ Отдельные награды Сая Янга для каждой лиги начали вручаться в 1967 году, через год после того, как Куфакс ушел в отставку.

- ↑ Доктор Фрэнк Джоб , изобретатель операции Томми Джона , позже не согласился с диагнозом Куфакса. Он считал, что Куфакс получил разрыв локтевой коллатеральной связки , но заявил, что не было средств для диагностики или лечения такой травмы, когда Куфакс был активным игроком. [105]

- ^ Рекорд был побит Ноланом Райаном , забившим 383 аута в 1973 году, но он остается высшим показателем для питчеров и левшей Национальной лиги. [110]

- ↑ За свою карьеру Куфакс провел девять игр с двухдневным отдыхом, стартовав восемь раз. Он никогда не продержался меньше семи подач, выиграв семь из этих игр и шесть раз проведя полную игру. [118]

- ↑ Хотя Куфакс получил больше голосов за первое место, чем Клементе в гонке за MVP 1966 года, последний имел более высокую долю голосов, опередив Куфакса на 78% против 74%.

- ↑ Высшая бейсбольная лига провела два Матча всех звезд с 1959 по 1962 год. [155]

- ↑ В 2022 году Куфакс стал первым человеком, отметившим 50-летие своего избрания в Зал славы бейсбола. [185]

- ↑ Помимо Йом Кипура , другие еврейские праздники, на которые Куфакс не претендовал, включали в себя первую ночь Песаха и Рош ха-Шана , в частности, он не посещал тренировки перед четвертой игрой Мировой серии 1959 года . [220]

Ссылки [ править ]

- ^ «Сэнди Куфакс (Биопроект SABR)» . Общество исследований американского бейсбола .

Сэнди Куфакс родился как Сэнфорд Браун 30 декабря 1935 года. Его родителями были Эвелин (урожденная Лихтенштейн) и Джек Браун, евреи-сефарды венгерского происхождения.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 16, 38; Ливи , стр. 28–29, 51–52.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Орфалея, Григорий (6 октября 2016 г.). «Несравненная карьера Сэнди Куфакса» . Атлантика .

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 19–22; Ливи , с. 29.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 22–28; Ливи , стр. 37–40.

- ^ Сандомир, Ричард (14 августа 2012 г.). «Рундбол Куфакса однажды превзошел его фастбол» . Нью-Йорк Таймс .

- ^ «Сэнди Куфакс (Биопроект SABR)» . Общество исследований американского бейсбола .

По настоянию друзей Куфакс все же пошел играть в бейсбол на последнем курсе школы «Лафайет». Он играл на первой базе. Капитаном команды был Фред Уилпон, левша с «хрустящим» крученым мячом, который десятилетия спустя стал владельцем «Нью-Йорк Метс».

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 32–39.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , с. 30.

- ^ Ливи , с. 48.

- ^ «Знаменитые пиламы» . Пи Ламдба Фи .

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 43–44.

- ^ Дайер, Майк (4 мая 2014 г.). «Вспомнился сезон Сэнди Куфакса в UC Bearcats» . Цинциннати Инкуайрер .

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 44–45; Ливи , с. 50.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 46–48; Ливи , с. 52.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 50–53.

- ^ Ливи , стр. 53–54.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 70–74.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , с. 61.

- ^ Мерфи, Джимми (17 августа 1954 г.). «Пользуется большим спросом» . Бруклин Дейли Игл .

- ^ Ливи , стр. 54–55

- ^ Ливи , с. 55.

- ^ Андерсон, Дэйв (28 января 1979 г.). «Сэнди Куфакс и Сикстинская капелла» . Нью-Йорк Таймс .

- ^ Ливи , стр. 56–57.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 67–69; Ливи , с. 57–58.

- ^ «Куфакс, Звезда Боро-Сэндлот, Новейший Доджер» . Бруклин Дейли Игл . 15 декабря 1954 года . Проверено 29 июня 2024 г.

- ^ «Бонус MLB для малышей» . Бейсбольный альманах .

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 73–74.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 75–94.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Куфакс, Сэнди; Гросс, Милтон (31 декабря 1963 г.). «Я всего лишь человек» . Смотреть .

- ^ Ливи , стр. 63–64.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 95–97.

- ^ «Бруклин Доджерс — Милуоки Брэйвс, счет бокса: 24 июня 1955 года» . Baseball-Reference.com .

- ^ Бидерман, Лестер Дж. (16 мая 1966 г.). «Куфакс вспоминает свой дикий старт на поле Forbes» . Питтсбург Пресс . п. 18. Архивировано из оригинала 11 сентября 2023 года.

- ^ Ливи , с. 74.

- ^ «Цинциннати Редлегс - Бруклин Доджерс, счет бокса: 27 августа 1955 года» . Baseball-Reference.com .

- ^ Макгоуэн, Роско (28 августа 1955 г.). «Куфакс, Доджерс, Топс Редлегс, 7–0» . The New York Times – через TimesMachine.

- ^ «Питтсбург Пайрэтс» против «Бруклин Доджерс», счет на боксе: 3 сентября 1955 года» . Baseball-Reference.com .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м «Карьерная статистика Сэнди Куфакса» . Baseball-Reference.com .

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 3, 105–107; Ливи , стр. XX, 75–76.

- ^ «Сэнди Куфакс (Биопроект SABR)» . Общество исследований американского бейсбола .

За свои первые два года в качестве Доджера Куфакс приобрел мало опыта - всего 28 матчей (15 стартов) и всего 100 подач. Он был расстроен и поспешил обвинить в своей дикости и неустойчивости отсутствие регулярной работы. Это был порочный круг. Он не мог подавать, пока его контроль не улучшился, но чем меньше он подавал, тем хуже становился его контроль.

- ^ Ливи , стр. 84–86.

- ^ Кашатус, Уильям К. (2014). Джеки и Кэмпи: нерассказанная история их непростых отношений и нарушения цветовой линии бейсбола . Издательство Университета Небраски. стр. 164–165. ISBN 978-0803246331 .

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 117–199.

- ^ «Статистика Сэнди Куфакса в Пуэрто-Рико» . Бейсбол 101 . Профессиональная бейсбольная лига Пуэрто-Рико.

- ^ «Сэнди Куфакс (Биопроект SABR)» . Общество исследований американского бейсбола .

В межсезонье 1956–57 Куфакс получил возможность попрактиковаться в том, чему его учили на зимнем мяче. «Доджерс» организовали для него подачу в Пуэрто-Рико с «Кагуас Криоллос». 16 декабря локаут. Великий Роберто Клементе нанес единственные удары от Куфакса в последней игре, последней для Сэнди в Пуэрто-Рико. Кагуасу пришлось отпустить его, потому что постановление лиги запрещало командам иметь более трех импортированных игроков с опытом работы в высшей лиге.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 117–124; Ливи , стр. 87–90.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 107, 126.; Ливи , с. 203.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 130–132.

- ^ «Счет на боксе «Филадельфия Филлис» против «Лос-Анджелес Доджерс»: 22 июня 1959 года» . Baseball-Reference.com .

- ^ Даун, Фред (23 июня 1959 г.). «Куфакс Уиффс 16 Phils, один не дотягивает до рекорда NL» . Сакраменто Би .

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 125–138; Ливи , стр. 90–92.

- ^ «Сан-Франциско Джайентс — Лос-Анджелес Доджерс, счет в боксе: 31 августа 1959 года» . Baseball-Reference.com .

- ^ Даун, Фред (1 сентября 1959 г.). «Куфакс связывает 18-й результат в победе в Лос-Анджелесе» . Сакраменто Би .

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 139–141.

- ^ Шор , стр. 262–265.

- ^ «Лос-Анджелес Доджерс» против «Питтсбург Пайрэтс», счет в боксе: 23 мая 1960 года» . Baseball-Reference.com .

- ^ «Елисейские поля Бруклина: плац» . Общество исследований американского бейсбола .

Сочетание негодования со стороны игроков-ветеранов, отсутствия подготовки в низшей лиге, нерегулярности работы и давления, которое он чувствовал со стороны антисемитской фракции, способствовало разочарованию молодого питчера, и какое-то время он подумывал о том, чтобы бросить все это.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 142–147; Ливи , стр. 93–95.

- ^ Ливи , с. 101.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 147–148.

- ^ Ливи , с. 102.

- ^ Ливи , с. 24.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , с. 153.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 148–152.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 153–155; Ливи , стр. 102–103.

- ^ Уитмарш, Эл (24 марта 1961 г.). «Куфакс считает, что отсутствие Hitless связано с зависимостью от Fastball» . Орландо Сентинел .

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 157–159; Ливи , стр. 115–116.

- ^ «Чикаго Кабс» против «Лос-Анджелес Доджерс», счет на боксе: 20 сентября 1961 года . Baseball-Reference.com .

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 127–128; Ливи , с. 116.

- ^ «Лос-Анджелес Доджерс против Чикаго Кабс, счет бокса: 24 апреля 1962 года» . Baseball-Reference.com .

- ^ Ливи , с. 116.

- ^ Аарон, Марк. «30 июня 1962 года: Сэнди Куфакс впервые в карьере забивает «Мец» без нападающих . Общество исследований американского бейсбола .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с «Безупречные подачи» . Бейсбольный альманах .

- ^ «Бейсболисты месяца Высшей лиги» . Baseball-Reference.com .

- ^ Финч, Фрэнк (18 июля 1962 г.). «Куфакс возвращается на лечение» . Лос-Анджелес Таймс .

- ^ Кример, Роберт (4 марта 1963 г.). «Срочное дело одного указательного пальца» . Иллюстрированный спорт .

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 165–176; Ливи , стр. 120–121.

- ^ Плаут, Дэвид (1994). В погоне за октябрем: Гонка за вымпел «Джайентс-Доджерс» 1962 года . Алмазные коммуникации. стр. 84–87. ISBN 978-0912083698 .

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 176–177; Лихи , стр. 54–59.

- ^ «Зона удара: история официальных правил зоны удара» . Бейсбольный альманах .

- ^ «Средние показатели по результативности Высшей лиги за год» . Baseball-Reference.com .

- ^ «Сэнди Куфакс (Биопроект SABR)» . Общество исследований американского бейсбола .

В преддверии сезона 1963 года оставались некоторые сомнения относительно состояния Куфакса. Он пропустил три старта в конце апреля и начале мая из-за боли в плече. Его первой игрой в ответ стала победа над Кардиналами.

- ^ Куфакс и Линн , стр. 181–183; Ливи , стр. 122–123.

- ^ Аарон, Марк. «11 мая 1963 года: Сэнди Куфакс бросает второй ноу-хиттер и побеждает Маришаля, Джайентс» . Общество исследований американского бейсбола .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с «Тройная корона качки» . Бейсбольный альманах .

- ^ «Лидеры одного сезона и рекорды по аутам» . Baseball-Reference.com .