Фейсбук

Логотип используется с 2023 года. | |

Скриншот | |

Тип сайта | Служба социальных сетей |

|---|---|

| Доступно в | 112 языков [1] |

Список языков | |

| Основан | 4 февраля 2004 г в Кембридже, Массачусетс , США |

| Обслуживаемая территория | По всему миру, кроме блокирующих стран |

| Owner | Meta Platforms |

| Founder(s) | |

| CEO | Mark Zuckerberg |

| URL | facebook |

| Registration | Required (to do any activity) |

| Users | |

| Launched | February 4, 2004 |

| Current status | Active |

| Written in | C++, Hack (as HHVM) and PHP |

| [3][4][5] | |

| This article is part of a series about |

| Meta Platforms |

|---|

|

| Products and services |

| People |

| Business |

Facebook — социальная сеть и служба социальных сетей, принадлежащая американскому технологическому конгломерату Meta . Созданная в 2004 году Марком Цукербергом вместе с четырьмя другими студентами Гарвардского колледжа и соседями по комнате Эдуардо Саверином , Эндрю МакКоллумом , Дастином Московицем и Крисом Хьюзом , ее название происходит от каталогов Facebook, которые часто дают студентам американских университетов. Первоначально членство было ограничено студентами Гарварда, но постепенно оно распространилось и на другие университеты Северной Америки. С 2006 года Facebook позволяет регистрироваться каждому с 13 лет, за исключением нескольких стран, где возрастной предел составляет 14 лет. [6] По состоянию на декабрь 2022 г. [update]Facebook заявил о почти 3 миллиардах активных пользователей в месяц. [7] По состоянию на октябрь 2023 года Facebook занимал третье место по посещаемости веб-сайта в мире , при этом 22,56% трафика приходилось из США. [8] [9] Это было самое загружаемое мобильное приложение 2010-х годов. [10]

Facebook can be accessed from devices with Internet connectivity, such as personal computers, tablets and smartphones. After registering, users can create a profile revealing information about themselves. They can post text, photos and multimedia which are shared with any other users who have agreed to be their friend or, with different privacy settings, publicly. Users can also communicate directly with each other with Messenger, join common-interest groups, and receive notifications on the activities of their Facebook friends and the pages they follow.

The subject of numerous controversies, Facebook has often been criticized over issues such as user privacy (as with the Cambridge Analytica data scandal), political manipulation (as with the 2016 U.S. elections) and mass surveillance.[11] Facebook has also been subject to criticism over psychological effects such as addiction and low self-esteem, and various controversies over content such as fake news, conspiracy theories, copyright infringement, and hate speech.[12] Commentators have accused Facebook of willingly facilitating the spread of such content, as well as exaggerating its number of users to appeal to advertisers.[13]

History

2003–2006: Thefacebook, Thiel investment, and name change

Zuckerberg built a website called "Facemash" in 2003 while attending Harvard University. The site was comparable to Hot or Not and used "photos compiled from the online face books of nine Houses, placing two next to each other at a time and asking users to choose the 'hotter' person".[15] Facemash attracted 450 visitors and 22,000 photo-views in its first four hours.[16] The site was sent to several campus group listservs, but was shut down a few days later by Harvard administration. Zuckerberg faced expulsion and was charged with breaching security, violating copyrights and violating individual privacy. Ultimately, the charges were dropped.[15] Zuckerberg expanded on this project that semester by creating a social study tool. He uploaded art images, each accompanied by a comments section, to a website he shared with his classmates.[17]

A "face book" is a student directory featuring photos and personal information.[16] In 2003, Harvard had only a paper version[18] along with private online directories.[15][19] Zuckerberg told The Harvard Crimson, "Everyone's been talking a lot about a universal face book within Harvard. ... I think it's kind of silly that it would take the University a couple of years to get around to it. I can do it better than they can, and I can do it in a week."[19] In January 2004, Zuckerberg coded a new website, known as "TheFacebook", inspired by a Crimson editorial about Facemash, stating, "It is clear that the technology needed to create a centralized Website is readily available ... the benefits are many." Zuckerberg met with Harvard student Eduardo Saverin, and each of them agreed to invest $1,000 ($1,613 in 2023 dollars[20]) in the site.[21] On February 4, 2004, Zuckerberg launched "TheFacebook", originally located at thefacebook.com.[22]

Six days after the site launched, Harvard seniors Cameron Winklevoss, Tyler Winklevoss, and Divya Narendra accused Zuckerberg of intentionally misleading them into believing that he would help them build a social network called HarvardConnection.com. They claimed that he was instead using their ideas to build a competing product.[23] The three complained to the Crimson and the newspaper began an investigation. They later sued Zuckerberg, settling in 2008[24] for 1.2 million shares (worth $300 million at Facebook's IPO, or $398 million in 2023 dollars[20]).[25]

Membership was initially restricted to students of Harvard College. Within a month, more than half the undergraduates had registered.[26] Dustin Moskovitz, Andrew McCollum, and Chris Hughes joined Zuckerberg to help manage the growth of the website.[27] In March 2004, Facebook expanded to Columbia, Stanford and Yale.[28] It then became available to all Ivy League colleges, Boston University, NYU, MIT, and successively most universities in the United States and Canada.[29][30]

In mid-2004, Napster co-founder and entrepreneur Sean Parker—an informal advisor to Zuckerberg—became company president.[31] In June 2004, the company moved to Palo Alto, California.[32] Sean Parker called Reid Hoffman to fund Facebook. However, Reid Hoffman was too busy launching LinkedIn so he set Facebook up with PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel, who gave Facebook its first investment later that month.[33][34] In 2005, the company dropped "the" from its name after purchasing the domain name Facebook.com for US$200,000 ($312,012 in 2023 dollars[20]).[35] The domain had belonged to AboutFace Corporation.

In May 2005, Accel Partners invested $12.7 million ($19.8 million in 2023 dollars[20]) in Facebook, and Jim Breyer[36] added $1 million ($1.56 million in 2023 dollars[20]) of his own money. A high-school version of the site launched in September 2005.[37] Eligibility expanded to include employees of several companies, including Apple Inc. and Microsoft.[38]

2006–2012: Public access, Microsoft alliance, and rapid growth

In May 2006, Facebook hired its first intern, Julie Zhuo.[39] After a month, Zhuo was hired as a full-time engineer.[39] On September 26, 2006, Facebook opened to everyone at least 13 years old with a valid email address.[40][41][42] By late 2007, Facebook had 100,000 pages on which companies promoted themselves.[43] Organization pages began rolling out in May 2009.[44] On October 24, 2007, Microsoft announced that it had purchased a 1.6% share of Facebook for $240 million ($353 million in 2023 dollars[20]), giving Facebook a total implied value of around $15 billion ($22 billion in 2023 dollars[20]). Microsoft's purchase included rights to place international advertisements.[45][46]

In May 2007, at the first f8 developers conference, Facebook announced the launch of the Facebook Developer Platform, providing a framework for software developers to create applications that interact with core Facebook features. By the second annual f8 developers conference on July 23, 2008, the number of applications on the platform had grown to 33,000, and the number of registered developers had exceeded 400,000.[47]

The website won awards such as placement into the "Top 100 Classic Websites" by PC Magazine in 2007,[48] and winning the "People's Voice Award" from the Webby Awards in 2008.[49] In early 2008, Facebook became EBITDA profitable, but was not cash flow positive yet.[50]

On July 20, 2008, Facebook introduced "Facebook Beta", a significant redesign of its user interface on selected networks. The Mini-Feed and Wall were consolidated, profiles were separated into tabbed sections, and an effort was made to create a cleaner look.[51] Facebook began migrating users to the new version in September 2008.[52] In July 2008, Facebook sued StudiVZ, a German social network that was alleged to be visually and functionally similar to Facebook.[53][54]

In October 2008, Facebook announced that its international headquarters would locate in Dublin, Ireland.[55] A January 2009 Compete.com study ranked Facebook the most used social networking service by worldwide monthly active users.[56][better source needed] China blocked Facebook in 2009 following the Ürümqi riots.[57]

In 2009, Yuri Milner's DST (which later split into DST Global and Mail.ru Group), alongside Uzbek Russian metals magnate Alisher Usmanov, invested $200 million in Facebook when it was valued at $10 billion.[58][59][60] A separate stake was also acquired by Usmanov's USM Holdings on another occasion.[61][58] According to the New York Times in 2013, "Mr. Usmanov and other Russian investors at one point owned nearly 10 percent of Facebook, though precise details of their ownership stakes are difficult to assess."[61] It was later revealed in 2017 by the Paradise Papers that lending by Russian state-backed VTB Bank and Gazprom's investment vehicle partially financed these 2009 investments, although Milner was reportedly unaware at the time.[62][63]

In May 2009, Zuckerberg said of the $200 million Russian investment, "This investment is purely buffer for us. It is not something we needed to get to cash flow positive."[64] In September 2009, Facebook became cash flow positive ahead of schedule[65][66] after closing a roughly $200 million gap in operating profitability.[66]

In 2010, Facebook won the Crunchie "Best Overall Startup Or Product" award[67] for the third year in a row.[68]

The company announced 500 million users in July 2010.[69] Half of the site's membership used Facebook daily, for an average of 34 minutes, while 150 million users accessed the site from mobile devices. A company representative called the milestone a "quiet revolution".[70] In October 2010 groups were introduced.[71] In November 2010, based on SecondMarket Inc. (an exchange for privately held companies' shares), Facebook's value was $41 billion ($57.3 billion in 2023 dollars[20]). The company had slightly surpassed eBay to become the third largest American web company after Google and Amazon.com.[72][73]

On November 15, 2010, Facebook announced it had acquired the domain name fb.com from the American Farm Bureau Federation for an undisclosed amount. On January 11, 2011, the Farm Bureau disclosed $8.5 million ($11.5 million in 2023 dollars[20]) in "domain sales income", making the acquisition of FB.com one of the ten highest domain sales in history.[74]

In February 2011, Facebook announced plans to move its headquarters to the former Sun Microsystems campus in Menlo Park, California.[75][76] In March 2011, it was reported that Facebook was removing about 20,000 profiles daily for violations such as spam, graphic content and underage use, as part of its efforts to boost cyber security.[77] Statistics showed that Facebook reached one trillion page views in the month of June 2011, making it the most visited website tracked by DoubleClick.[78][79] According to a Nielsen study, Facebook had in 2011 become the second-most accessed website in the U.S. behind Google.[80][81]

2012–2013: IPO, lawsuits, and one billion active users

In March 2012, Facebook announced App Center, a store selling applications that operate via the website. The store was to be available on iPhones, Android devices, and for mobile web users.[82]

Facebook's initial public offering came on May 17, 2012, at a share price of US$38 ($50.00 in 2023 dollars[20]). The company was valued at $104 billion ($138 billion in 2023 dollars[20]), the largest valuation to that date.[83][84][85] The IPO raised $16 billion ($21.2 billion in 2023 dollars[20]), the third-largest in U.S. history, after Visa Inc. in 2008 and AT&T Wireless in 2000.[86][87] Based on its 2012 income of $5 billion ($6.64 billion in 2023 dollars[20]), Facebook joined the Fortune 500 list for the first time in May 2013, ranked 462.[88] The shares set a first-day record for trading volume of an IPO (460 million shares).[89] The IPO was controversial given the immediate price declines that followed,[90][91][92][93] and was the subject of lawsuits,[94] while SEC and FINRA both launched investigations.[95]

Zuckerberg announced at the start of October 2012 that Facebook had one billion monthly active users,[96] including 600 million mobile users, 219 billion photo uploads and 140 billion friend connections.[97]

On October 1, 2012, Zuckerberg visited Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev in Moscow to stimulate social media innovation in Russia and to boost Facebook's position in the Russian market.[98][99]

2013–2014: Site developments, A4AI, and 10th anniversary

On January 15, 2013, Facebook announced Facebook Graph Search, which provides users with a "precise answer", rather than a link to an answer by leveraging data present on its site.[100] Facebook emphasized that the feature would be "privacy-aware", returning results only from content already shared with the user.[101] On April 3, 2013, Facebook unveiled Facebook Home, a user-interface layer for Android devices offering greater integration with the site. HTC announced HTC First, a phone with Home pre-loaded.[102]

On April 15, 2013, Facebook announced an alliance across 19 states with the National Association of Attorneys General, to provide teenagers and parents with information on tools to manage social networking profiles.[103] On April 19 Facebook modified its logo to remove the faint blue line at the bottom of the "F" icon. The letter F moved closer to the edge of the box.[104]

Following a campaign by 100 advocacy groups, Facebook agreed to update its policy on hate speech. The campaign highlighted content promoting domestic violence and sexual violence against women and led 15 advertisers to withdraw, including Nissan UK, House of Burlesque, and Nationwide UK. The company initially stated, "while it may be vulgar and offensive, distasteful content on its own does not violate our policies".[105] It took action on May 29.[106]

On June 12, Facebook announced that it was introducing clickable hashtags to help users follow trending discussions, or search what others are talking about on a topic.[107] San Mateo County, California, became the top wage-earning county in the country after the fourth quarter of 2012 because of Facebook. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the average salary was 107% higher than the previous year, at $168,000 a year ($222,961 in 2023 dollars[20]), more than 50% higher than the next-highest county, New York County (better known as Manhattan), at roughly $110,000 a year ($145,986 in 2023 dollars[20]).[108]

Facebook joined Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4AI) in October, as it launched. The A4AI is a coalition of public and private organizations that includes Google, Intel and Microsoft. Led by Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the A4AI seeks to make Internet access more affordable to ease access in the developing world.[109]

The company celebrated its 10th anniversary during the week of February 3, 2014.[110] In January 2014, over one billion users connected via a mobile device.[111] As of June, mobile accounted for 62% of advertising revenue, an increase of 21% from the previous year.[112] By September Facebook's market capitalization had exceeded $200 billion ($257 billion in 2023 dollars[20]).[113][114][115]

Zuckerberg participated in a Q&A session at Tsinghua University in Beijing, China, on October 23, where he attempted to converse in Mandarin. Zuckerberg hosted visiting Chinese politician Lu Wei, known as the "Internet czar" for his influence in China's online policy, on December 8.[116][117][118]

2015–2020: Algorithm revision; fake news

As of 2015[update], Facebook's algorithm was revised in an attempt to filter out false or misleading content, such as fake news stories and hoaxes. It relied on users who flag a story accordingly. Facebook maintained that satirical content should not be intercepted.[119] The algorithm was accused of maintaining a "filter bubble", where material the user disagrees with[120] and posts with few likes would be deprioritized.[121] In November, Facebook extended paternity leave from 4 weeks to 4 months.[122]

On April 12, 2016, Zuckerberg outlined his 10-year vision, which rested on three main pillars: artificial intelligence, increased global connectivity, and virtual and augmented reality.[123] In July, a US$1 billion suit was filed against the company alleging that it permitted Hamas to use it to perform assaults that cost the lives of four people.[124] Facebook released its blueprints of Surround 360 camera on GitHub under an open-source license.[125] In September, it won an Emmy for its animated short "Henry".[126] In October, Facebook announced a fee-based communications tool called Workplace that aims to "connect everyone" at work. Users can create profiles, see updates from co-workers on their news feed, stream live videos and participate in secure group chats.[127]

Following the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Facebook announced that it would combat fake news by using fact checkers from sites like FactCheck.org and Associated Press (AP), making reporting hoaxes easier through crowdsourcing, and disrupting financial incentives for abusers.[128]

On January 17, 2017, Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg planned to open Station F, a startup incubator campus in Paris, France.[130] On a six-month cycle, Facebook committed to work with ten to 15 data-driven startups there.[131] On April 18, Facebook announced the beta launch of Facebook Spaces at its annual F8 developer conference.[132] Facebook Spaces is a virtual reality version of Facebook for Oculus VR goggles. In a virtual and shared space, users can access a curated selection of 360-degree photos and videos using their avatar, with the support of the controller. Users can access their own photos and videos, along with media shared on their newsfeed.[133] In September, Facebook announced it would spend up to US$1 billion on original shows for its Facebook Watch platform.[134] On October 16, it acquired the anonymous compliment app tbh, announcing its intention to leave the app independent.[135][136][137][138]

In October 2017, Facebook expanded its work with Definers Public Affairs, a PR firm that had originally been hired to monitor press coverage of the company to address concerns primarily regarding Russian meddling, then mishandling of user data by Cambridge Analytica, hate speech on Facebook, and calls for regulation.[139] Company spokesman Tim Miller stated that a goal for tech firms should be to "have positive content pushed out about your company and negative content that's being pushed out about your competitor". Definers claimed that George Soros was the force behind what appeared to be a broad anti-Facebook movement, and created other negative media, along with America Rising, that was picked up by larger media organisations like Breitbart News.[139][140] Facebook cut ties with the agency in late 2018, following public outcry over their association.[141] Posts originating from the Facebook page of Breitbart News, a media organization previously affiliated with Cambridge Analytica,[142] were among the most widely shared political content on Facebook.[143][144][145][146][excessive citations]

In May 2018 at F8, the company announced it would offer its own dating service. Shares in competitor Match Group fell by 22%.[147] Facebook Dating includes privacy features and friends are unable to view their friends' dating profile.[148] In July, Facebook was charged £500,000 by UK watchdogs for failing to respond to data erasure requests.[149] On July 18, Facebook established a subsidiary named Lianshu Science & Technology in Hangzhou City, China, with $30 million ($36.4 million in 2023 dollars[20]) of capital. All its shares are held by Facebook Hong.[150] Approval of the registration of the subsidiary was then withdrawn, due to a disagreement between officials in Zhejiang province and the Cyberspace Administration of China.[151] On July 26, Facebook became the first company to lose over $100 billion ($121 billion in 2023 dollars[20]) worth of market capitalization in one day, dropping from nearly $630 billion to $510 billion after disappointing sales reports.[152][153] On July 31, Facebook said that the company had deleted 17 accounts related to the 2018 U.S. midterm elections. On September 19, Facebook announced that, for news distribution outside the United States, it would work with U.S. funded democracy promotion organizations, International Republican Institute and the National Democratic Institute, which are loosely affiliated with the Republican and Democratic parties.[154] Through the Digital Forensic Research Lab Facebook partners with the Atlantic Council, a NATO-affiliated think tank.[154] In November, Facebook launched smart displays branded Portal and Portal Plus (Portal+). They support Amazon's Alexa (intelligent personal assistant service). The devices include video chat function with Facebook Messenger.[155][156]

In August 2018, a lawsuit was filed in Oakland, California claiming that Facebook created fake accounts in order to inflate its user data and appeal to advertisers in the process.[13]

In January 2019, the 10-year challenge was started[157] asking users to post a photograph of themselves from 10 years ago (2009) and a more recent photo.[158]

Criticized for its role in vaccine hesitancy, Facebook announced in March 2019 that it would provide users with "authoritative information" on the topic of vaccines.[159]A study published in the journal Vaccine of advertisements posted in the three months prior to that found that 54% of the anti-vaccine advertisements on Facebook were placed by just two organisations funded by well-known anti-vaccination activists.[160][161] The Children's Health Defense / World Mercury Project chaired by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Stop Mandatory Vaccination, run by campaigner Larry Cook, posted 54% of the advertisements. The ads often linked to commercial products, such as natural remedies and books.

On March 14, the Huffington Post reported that Facebook's PR agency had paid someone to tweak Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg's Wikipedia page, as well as adding a page for the global head of PR, Caryn Marooney.[162]

In March 2019, the perpetrator of the Christchurch mosque shootings in New Zealand used Facebook to stream live footage of the attack as it unfolded. Facebook took 29 minutes to detect the livestreamed video, which was eight minutes longer than it took police to arrest the gunman. About 1.3m copies of the video were blocked from Facebook but 300,000 copies were published and shared. Facebook has promised changes to its platform; spokesman Simon Dilner told Radio New Zealand that it could have done a better job. Several companies, including the ANZ and ASB banks, have stopped advertising on Facebook after the company was widely condemned by the public.[163] Following the attack, Facebook began blocking white nationalist, white supremacist, and white separatist content, saying that they could not be meaningfully separated. Previously, Facebook had only blocked overtly supremacist content. The older policy had been condemned by civil rights groups, who described these movements as functionally indistinct.[164][165] Further bans were made in mid-April 2019, banning several British far-right organizations and associated individuals from Facebook, and also banning praise or support for them.[166][167]

NTJ's member Moulavi Zahran Hashim, a radical Islamist imam believed to be the mastermind behind the 2019 Sri Lanka Easter bombings, preached on a pro-ISIL Facebook account, known as "Al-Ghuraba" media.[168][169]

On May 2, 2019, at F8, the company announced its new vision with the tagline "the future is private".[170] A redesign of the website and mobile app was introduced, dubbed as "FB5".[171] The event also featured plans for improving groups,[172] a dating platform,[173] end-to-end encryption on its platforms,[174] and allowing users on Messenger to communicate directly with WhatsApp and Instagram users.[175][176]

On July 31, 2019, Facebook announced a partnership with University of California, San Francisco to build a non-invasive, wearable device that lets people type by simply imagining themselves talking.[177]

On August 13, 2019, it was revealed that Facebook had enlisted hundreds of contractors to create and obtain transcripts of the audio messages of users.[178][179][180] This was especially common of Facebook Messenger, where the contractors frequently listened to and transcribed voice messages of users.[180] After this was first reported on by Bloomberg News, Facebook released a statement confirming the report to be true,[179] but also stated that the monitoring program was now suspended.[179]

On September 5, 2019, Facebook launched Facebook Dating in the United States. This new application allows users to integrate their Instagram posts in their dating profile.[181]

Facebook News, which features selected stories from news organizations, was launched on October 25.[182] Facebook's decision to include far-right website Breitbart News as a "trusted source" was negatively received.[183][184]

On November 17, 2019, the banking data for 29,000 Facebook employees was stolen from a payroll worker's car. The data was stored on unencrypted hard drives and included bank account numbers, employee names, the last four digits of their social security numbers, salaries, bonuses, and equity details. The company did not realize the hard drives were missing until November 20. Facebook confirmed that the drives contained employee information on November 29. Employees were not notified of the break-in until December 13, 2019.[185]

On March 10, 2020, Facebook appointed two new directors Tracey Travis and Nancy Killefer to their board of members.[186]

In June 2020, several major companies including Adidas, Aviva, Coca-Cola, Ford, HP, InterContinental Hotels Group, Mars, Starbucks, Target, and Unilever, announced they would pause adverts on Facebook for July in support of the Stop Hate For Profit campaign which claimed the company was not doing enough to remove hateful content.[187] The BBC noted that this was unlikely to affect the company as most of Facebook's advertising revenue comes from small- to medium-sized businesses.[188]

On August 14, 2020, Facebook started integrating the direct messaging service of Instagram with its own Messenger for both iOS and Android devices. After the update, an update screen is said to pop up on Instagram's mobile app with the following message, "There's a New Way to Message on Instagram" with a list of additional features. As part of the update, the regular DM icon on the top right corner of Instagram will be replaced by the Facebook Messenger logo.[189]

On September 15, 2020, Facebook launched a climate science information centre to promote authoritative voices on climate change and provide access of "factual and up-to-date" information on climate science. It featured facts, figures and data from organizations, including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Met Office, UN Environment Programme (UNEP), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and World Meteorological Organization (WMO), with relevant news posts.[190]

After the 2020 U.S. presidential election, Facebook temporarily increased the weight of ecosystem quality in its news feed algorithm.[191]

2020–present: FTC lawsuit, corporate re-branding, shut down of facial recognition technology, ease of policy

Facebook was sued by the Federal Trade Commission as well as a coalition of several states for illegal monopolization and antitrust. The FTC and states sought the courts to force Facebook to sell its subsidiaries WhatsApp and Instagram.[192][193] The suits were dismissed by a federal judge on June 28, 2021, who stated that there was not enough evidence brought in the suit to determine Facebook to be a monopoly at this point, though allowed the FTC to amend its case to include additional evidence.[194] In its amended filings in August 2021, the FTC asserted that Facebook had been a monopoly in the area of personal social networks since 2011, distinguishing Facebook's activities from social media services like TikTok that broadcast content without necessarily limiting that message to intended recipients.[195]

In response to the proposed bill in the Australian Parliament for a News Media Bargaining Code, on February 17, 2021, Facebook blocked Australian users from sharing or viewing news content on its platform, as well as pages of some government, community, union, charity, political, and emergency services.[196] The Australian government strongly criticised the move, saying it demonstrated the "immense market power of these digital social giants".[197]

On February 22, Facebook said it reached an agreement with the Australian government that would see news returning to Australian users in the coming days. As part of this agreement, Facebook and Google can avoid the News Media Bargaining Code adopted on February 25 if they "reach a commercial bargain with a news business outside the Code".[198][199][200]

Facebook has been accused of removing and shadow banning content that spoke either in favor of protesting Indian farmers or against Narendra Modi's government.[201][202][203] India-based employees of Facebook are at risk of arrest.[204]

On February 27, 2021, Facebook announced Facebook BARS app for rappers.[205]

On June 29, 2021, Facebook announced Bulletin, a platform for independent writers.[206][207] Unlike competitors such as Substack, Facebook would not take a cut of subscription fees of writers using that platform upon its launch, like Malcolm Gladwell and Mitch Albom. According to The Washington Post technology writer Will Oremus, the move was criticized by those who viewed it as an tactic intended by Facebook to force those competitors out of business.[208]

In October 2021, owner Facebook, Inc. changed its company name to Meta Platforms, Inc., or simply "Meta", as it shifts its focus to building the "metaverse". This change does not affect the name of the Facebook social networking service itself, instead being similar to the creation of Alphabet as Google's parent company in 2015.[209]

In November 2021, Facebook stated it would stop targeting ads based on data related to health, race, ethnicity, political beliefs, religion and sexual orientation. The change will occur in January and will affect all apps owned by Meta Platforms.[210]

In February 2022, Facebook's daily active users dropped for the first time in its 18-year history. According to Facebook's parent Meta, DAUs dropped to 1.929 billion in the three months ending in December, down from 1.930 billion the previous quarter. Furthermore, the company warned that revenue growth would slow due to competition from TikTok and YouTube, as well as advertisers cutting back on spending.[211]

On March 10, 2022, Facebook announced that it will temporarily ease rules to allow violent speech against 'Russian invaders'.[212] Russia then banned all Meta services, including Instagram.[213]

In September 2022, Jonathan Vanian, a Technology Reporter for CNBC, wrote a piece on CNBC.com about the recent struggles Facebook was experiencing, writing "Users are jumping ship and advertisers are reducing their spending, leaving Meta poised to report its second straight drop in quarterly revenue." He also cited poor leadership decisions devoting resources to the metaverse, writing "CEO Mark Zuckerberg spends much of his time proselytizing the metaverse, which may be the company's future but accounts for virtually none of its near-term revenue and is costing billions of dollars a year to build." He also detailed accounts from analysts predicting a "death spiral" for Facebook stock as users leave, ad impressions increase, and the company chases revenue.[214]

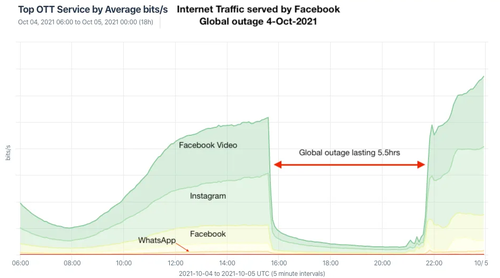

October 4, 2021, global service outage

On October 4, 2021, Facebook had its worst outage since 2008. The outage was global in scope, and took down all Facebook properties, including Instagram and WhatsApp, from approximately 15:39 UTC to 22:05 UTC, and affected roughly three billion users.[215][216][217] Security experts identified the problem as a BGP withdrawal of all of the IP routes to their Domain Name (DNS) servers which were all self-hosted at the time.[218][219] The outage also affected all internal communications systems used by Facebook employees, which disrupted restoration efforts.[219]

The outage cut off Facebook's internal communications, preventing employees from sending or receiving external emails, accessing the corporate directory, and authenticating to some Google Docs and Zoom services.[220][221] The outage had a major impact on people in the developing world, who depend on Facebook's "Free Basics" program, affecting communication, business and humanitarian work.[222][223][224]

Facebook's chief technology officer, Mike Schroepfer, wrote an apology after the downtime had extended to several hours,[225][226] saying, "Teams are working as fast as possible to debug and restore as fast as possible."[227]

Shutdown of facial recognition

On November 2, 2021, Facebook announced it would shut down its facial recognition technology and delete the data on over a billion users.[228] Meta later announced plans to implement the technology as well as other biometric systems in its future products, such as the metaverse.[229]

The shutdown of the technology will reportedly also stop Facebook's automated alt text system, used to transcribe media on the platform for visually impaired users.[229]

In February 2023, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg announced that Meta would start selling blue "verified" badges on Instagram and Facebook.[230]

Features

Facebook posts can have an unlimited number of characters. They can also have images and videos.

Users can "friend" users, both sides must agree to being friends. Post can be changed to be seen by everyone (public), friends, people in a certain group (group) or by selected friends (private).

Users can also join groups. Groups are composed of persons with shared interests. For example, they might go to the same sporting club, live in the same suburb, have the same breed of pet or share a hobby. Posts posted in a group can be seen only by those in a group, unless set to public.

Users can also buy, sell or swap things on Facebook Marketplace or in a Buy, Swap and Sell group.

Facebook users can also advertise events on Facebook. Events advertised can be offline, on a website other than Facebook or on Facebook.

Website

Technical aspects

The site's primary color is blue as Zuckerberg is red–green colorblind, a realization that occurred after a test taken around 2007.[231][232] Facebook was initially built using PHP, a popular scripting language designed for web development.[233] PHP was used to create dynamic content and manage data on the server side of the Facebook application. Zuckerberg and co-founders chose PHP for its simplicity and ease of use, which allowed them to quickly develop and deploy the initial version of Facebook. As Facebook grew in user base and functionality, the company encountered scalability and performance challenges with PHP. In response, Facebook engineers developed tools and technologies to optimize PHP performance. One of the most significant was the creation of the HipHop Virtual Machine (HHVM). This significantly improved the performance and efficiency of PHP code execution on Facebook's servers.

The site started switching from HTTP to HTTPS in January 2011.[234]

2012 architecture

Facebook is developed as one monolithic application. According to an interview in 2012 with Facebook build engineer Chuck Rossi, Facebook compiles into a 1.5 GB binary blob which is then distributed to the servers using a custom BitTorrent-based release system. Rossi stated that it takes about 15 minutes to build and 15 minutes to release to the servers. The build and release process has zero downtime. Changes to Facebook are rolled out daily.[235]

Facebook used a combination platform based on HBase to store data across distributed machines. Using a tailing architecture, events are stored in log files, and the logs are tailed. The system rolls these events up and writes them to storage. The user interface then pulls the data out and displays it to users. Facebook handles requests as AJAX behavior. These requests are written to a log file using Scribe (developed by Facebook).[236]

Data is read from these log files using Ptail, an internally built tool to aggregate data from multiple Scribe stores. It tails the log files and pulls data out. Ptail data are separated into three streams and sent to clusters in different data centers (Plugin impression, News feed impressions, Actions (plugin + news feed)). Puma is used to manage periods of high data flow (Input/Output or IO). Data is processed in batches to lessen the number of times needed to read and write under high demand periods. (A hot article generates many impressions and news feed impressions that cause huge data skews.) Batches are taken every 1.5 seconds, limited by memory used when creating a hash table.[236]

Data is then output in PHP format. The backend is written in Java. Thrift is used as the messaging format so PHP programs can query Java services. Caching solutions display pages more quickly. The data is then sent to MapReduce servers where it is queried via Hive. This serves as a backup as the data can be recovered from Hive.[236]

Content delivery network (CDN)

Facebook uses its own content delivery network or "edge network" under the domain fbcdn.net for serving static data.[237][238] Until the mid-2010s, Facebook also relied on Akamai for CDN services.[239][240][241]

Hack programming language

On March 20, 2014, Facebook announced a new open-source programming language called Hack. Before public release, a large portion of Facebook was already running and "battle tested" using the new language.[242]

User profile/personal timeline

Each registered user on Facebook has a personal profile that shows their posts and content.[243] The format of individual user pages was revamped in September 2011 and became known as "Timeline", a chronological feed of a user's stories,[244][245] including status updates, photos, interactions with apps and events.[246] The layout let users add a "cover photo".[246] Users were given more privacy settings.[246] In 2007, Facebook launched Facebook Pages for brands and celebrities to interact with their fanbases.[247][248] 100,000 Pages[further explanation needed] launched in November.[249] In June 2009, Facebook introduced a "Usernames" feature, allowing users to choose a unique nickname used in the URL for their personal profile, for easier sharing.[250][251]

In February 2014, Facebook expanded the gender setting, adding a custom input field that allows users to choose from a wide range of gender identities. Users can also set which set of gender-specific pronoun should be used in reference to them throughout the site.[252][253][254] In May 2014, Facebook introduced a feature to allow users to ask for information not disclosed by other users on their profiles. If a user does not provide key information, such as location, hometown, or relationship status, other users can use a new "ask" button to send a message asking about that item to the user in a single click.[255][256]

News Feed

News Feed appears on every user's homepage and highlights information including profile changes, upcoming events and friends' birthdays.[257] This enabled spammers and other users to manipulate these features by creating illegitimate events or posting fake birthdays to attract attention to their profile or cause.[258] Initially, the News Feed caused dissatisfaction among Facebook users; some complained it was too cluttered and full of undesired information, others were concerned that it made it too easy for others to track individual activities (such as relationship status changes, events, and conversations with other users).[259] Zuckerberg apologized for the site's failure to include appropriate privacy features. Users then gained control over what types of information are shared automatically with friends. Users are now able to prevent user-set categories of friends from seeing updates about certain types of activities, including profile changes, Wall posts and newly added friends.[260]

On February 23, 2010, Facebook was granted a patent[261] on certain aspects of its News Feed. The patent covers News Feeds in which links are provided so that one user can participate in the activity of another user.[262] The sorting and display of stories in a user's News Feed is governed by the EdgeRank algorithm.[263]

The Photos application allows users to upload albums and photos.[264] Each album can contain 200 photos.[265] Privacy settings apply to individual albums. Users can "tag", or label, friends in a photo. The friend receives a notification about the tag with a link to the photo.[266] This photo tagging feature was developed by Aaron Sittig, now a Design Strategy Lead at Facebook, and former Facebook engineer Scott Marlette back in 2006 and was only granted a patent in 2011.[267][268]

On June 7, 2012, Facebook launched its App Center to help users find games and other applications.[269]

On May 13, 2015, Facebook in association with major news portals launched "Instant Articles" to provide news on the Facebook news feed without leaving the site.[270][271]

In January 2017, Facebook launched Facebook Stories for iOS and Android in Ireland. The feature, following the format of Snapchat and Instagram stories, allows users to upload photos and videos that appear above friends' and followers' News Feeds and disappear after 24 hours.[272]

On October 11, 2017, Facebook introduced the 3D Posts feature to allow for uploading interactive 3D assets.[273] On January 11, 2018, Facebook announced that it would change News Feed to prioritize friends/family content and de-emphasize content from media companies.[274]

In February 2020, Facebook announced it would spend $1 billion ($1.18 billion in 2023 dollars[20]) to license news material from publishers for the next three years; a pledge coming as the company falls under scrutiny from governments across the globe over not paying for news content appearing on the platform. The pledge would be in addition to the $600 million ($706 million in 2023 dollars[20]) paid since 2018 through deals with news companies such as The Guardian and Financial Times.[275][276][277]

In March and April 2021, in response to Apple announcing changes to its iOS device's Identifier for Advertisers policy, which included requiring app developers to directly request to users the ability to track on an opt-in basis, Facebook purchased full-page newspaper advertisements attempting to convince users to allow tracking, highlighting the effects targeted ads have on small businesses.[278] Facebook's efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, as Apple released iOS 14.5 in late April 2021, containing the feature for users in what has been deemed "App Tracking Transparency". Moreover, statistics from Verizon Communications subsidiary Flurry Analytics show 96% of all iOS users in the United States are not permitting tracking at all, and only 12% of worldwide iOS users are allowing tracking, which some news outlets deem "Facebook's nightmare", among similar terms.[279][280][281][282] Despite the news, Facebook has stated that the new policy and software update would be "manageable".[283]

Like button

The "like" button, stylized as a "thumbs up" icon, was first enabled on February 9, 2009,[284] and enables users to easily interact with status updates, comments, photos and videos, links shared by friends, and advertisements. Once clicked by a user, the designated content is more likely to appear in friends' News Feeds.[285][286] The button displays the number of other users who have liked the content.[287] The like button was extended to comments in June 2010.[288] In February 2016, Facebook expanded Like into "Reactions", choosing among five pre-defined emotions, including "Love", "Haha", "Wow", "Sad", or "Angry".[289][290][291][292] In late April 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a new "Care" reaction was added.[293]

Instant messaging

Facebook Messenger is an instant messaging service and software application. It began as Facebook Chat in 2008,[294] was revamped in 2010[295] and eventually became a standalone mobile app in August 2011, while remaining part of the user page on browsers.[296]

Complementing regular conversations, Messenger lets users make one-to-one[297] and group[298] voice[299] and video calls.[300] Its Android app has integrated support for SMS[301] and "Chat Heads", which are round profile photo icons appearing on-screen regardless of what app is open,[302] while both apps support multiple accounts,[303] conversations with optional end-to-end encryption[304] and "Instant Games".[305] Some features, including sending money[306] and requesting transportation,[307] are limited to the United States.[306] In 2017, Facebook added "Messenger Day", a feature that lets users share photos and videos in a story-format with all their friends with the content disappearing after 24 hours;[308] Reactions, which lets users tap and hold a message to add a reaction through an emoji;[309] and Mentions, which lets users in group conversations type @ to give a particular user a notification.[309]

In April 2020, Facebook began rolling out a new feature called Messenger Rooms, a video chat feature that allows users to chat with up to 50 people at a time.[310] In July 2020, Facebook added a new feature in Messenger that lets iOS users to use Face ID or Touch ID to lock their chats. The feature is called App Lock and is a part of several changes in Messenger regarding privacy and security.[311][312] On October 13, 2020, the Messenger application introduced cross-app messaging with Instagram, which was launched in September 2021.[313] In addition to the integrated messaging, the application announced the introduction of a new logo, which will be an amalgamation of the Messenger and Instagram logo.[314]

Businesses and users can interact through Messenger with features such as tracking purchases and receiving notifications, and interacting with customer service representatives. Third-party developers can integrate apps into Messenger, letting users enter an app while inside Messenger and optionally share details from the app into a chat.[315] Developers can build chatbots into Messenger, for uses such as news publishers building bots to distribute news.[316] The M virtual assistant (U.S.) scans chats for keywords and suggests relevant actions, such as its payments system for users mentioning money.[317][318] Group chatbots appear in Messenger as "Chat Extensions". A "Discovery" tab allows finding bots, and enabling special, branded QR codes that, when scanned, take the user to a specific bot.[319]

Privacy policy

Facebook's data policy outlines its policies for collecting, storing, and sharing user's data.[320] Facebook enables users to control access to individual posts and their profile[321] through privacy settings.[322] The user's name and profile picture (if applicable) are public.

Facebook's revenue depends on targeted advertising, which involves analyzing user data to decide which ads to show each user. Facebook buys data from third parties, gathered from both online and offline sources, to supplement its own data on users. Facebook maintains that it does not share data used for targeted advertising with the advertisers themselves.[323] The company states:

"We provide advertisers with reports about the kinds of people seeing their ads and how their ads are performing, but we don't share information that personally identifies you (information such as your name or email address that by itself can be used to contact you or identifies who you are) unless you give us permission. For example, we provide general demographic and interest information to advertisers (for example, that an ad was seen by a woman between the ages of 25 and 34 who lives in Madrid and likes software engineering) to help them better understand their audience. We also confirm which Facebook ads led you to make a purchase or take an action with an advertiser."[320]

As of October 2021[update], Facebook claims it uses the following policy for sharing user data with third parties:

Apps, websites, and third-party integrations on or using our Products.

When you choose to use third-party apps, websites, or other services that use, or are integrated with, our Products, they can receive information about what you post or share. For example, when you play a game with your Facebook friends or use a Facebook Comment or Share button on a website, the game developer or website can receive information about your activities in the game or receive a comment or link that you share from the website on Facebook. Also, when you download or use such third-party services, they can access your public profile on Facebook, and any information that you share with them. Apps and websites you use may receive your list of Facebook friends if you choose to share it with them. But apps and websites you use will not be able to receive any other information about your Facebook friends from you, or information about any of your Instagram followers (although your friends and followers may, of course, choose to share this information themselves). Information collected by these third-party services is subject to their own terms and policies, not this one.

Devices and operating systems providing native versions of Facebook and Instagram (i.e. where we have not developed our own first-party apps) will have access to all information you choose to share with them, including information your friends share with you, so they can provide our core functionality to you.

Note: We are in the process of restricting developers' data access even further to help prevent abuse. For example, we will remove developers' access to your Facebook and Instagram data if you haven't used their app in 3 months, and we are changing Login, so that in the next version, we will reduce the data that an app can request without app review to include only name, Instagram username and bio, profile photo and email address. Requesting any other data will require our approval.[320]

Facebook will also share data with law enforcement if needed to.[320]

Facebook's policies have changed repeatedly since the service's debut, amid a series of controversies covering everything from how well it secures user data, to what extent it allows users to control access, to the kinds of access given to third parties, including businesses, political campaigns and governments. These facilities vary according to country, as some nations require the company to make data available (and limit access to services), while the European Union's GDPR regulation mandates additional privacy protections.[324]

Bug Bounty Program

On July 29, 2011, Facebook announced its Bug Bounty Program that paid security researchers a minimum of $500 ($677.00 in 2023 dollars[20]) for reporting security holes. The company promised not to pursue "white hat" hackers who identified such problems.[325][326] This led researchers in many countries to participate, particularly in India and Russia.[327]

Reception

Userbase

Facebook's rapid growth began as soon as it became available and continued through 2018, before beginning to decline.

Facebook passed 100 million registered users in 2008,[328] and 500 million in July 2010.[69] According to the company's data at the July 2010 announcement, half of the site's membership used Facebook daily, for an average of 34 minutes, while 150 million users accessed the site by mobile.[70]

In October 2012, Facebook's monthly active users passed one billion,[96][329] with 600 million mobile users, 219 billion photo uploads, and 140 billion friend connections.[97] The 2 billion user mark was crossed in June 2017.[330][331]

In November 2015, after skepticism about the accuracy of its "monthly active users" measurement, Facebook changed its definition to a logged-in member who visits the Facebook site through the web browser or mobile app, or uses the Facebook Messenger app, in the 30-day period prior to the measurement. This excluded the use of third-party services with Facebook integration, which was previously counted.[332]

From 2017 to 2019, the percentage of the U.S. population over the age of 12 who use Facebook has declined, from 67% to 61% (a decline of some 15 million U.S. users), with a higher drop-off among younger Americans (a decrease in the percentage of U.S. 12- to 34-year-olds who are users from 58% in 2015 to 29% in 2019).[333][334] The decline coincided with an increase in the popularity of Instagram, which is also owned by Meta.[333][334]

The number of daily active users experienced a quarterly decline for the first time in the last quarter of 2021, down to 1.929 billion from 1.930 billion,[335] but increased again the next quarter despite being banned in Russia.[336]

Historically, commentators have offered predictions of Facebook's decline or end, based on causes such as a declining user base;[337] the legal difficulties of being a closed platform, inability to generate revenue, inability to offer user privacy, inability to adapt to mobile platforms, or Facebook ending itself to present a next generation replacement;[338] or Facebook's role in Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections.[339]

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

in 2004 to 2.8 billion in 2020.[324]

Demographics

The highest number of Facebook users as of April 2023 are from India and the United States, followed by Indonesia, Brazil, Mexico and the Philippines.[341] Region-wise, the highest number of users in 2018 are from Asia-Pacific (947 million) followed by Europe (381 million) and US-Canada (242 million). The rest of the world has 750 million users.[342]

Over the 2008–2018 period, the percentage of users under 34 declined to less than half of the total.[324]

Censorship

In many countries the social networking sites and mobile apps have been blocked temporarily or permanently, including China,[343] Iran,[344] Vietnam,[345] Pakistan,[346] Syria,[347] and North Korea. In May 2018, the government of Papua New Guinea announced that it would ban Facebook for a month while it considered the impact of the website on the country, though no ban has since occurred.[348] In 2019, Facebook announced it would start enforcing its ban on users, including influencers, promoting any vape, tobacco products, or weapons on its platforms.[349]

Criticisms and controversies

"I'm here today because I believe Facebook's products harm children, stoke division, and weaken our democracy. The company's leadership knows how to make Facebook and Instagram safer, but won't make the necessary changes because they have put their astronomical profits before people."

—Frances Haugen, condemning lack of transparency around Facebook at a US congressional hearing (2021).[350]

"I don't believe private companies should make all of the decisions on their own. That's why we have advocated for updated internet regulations for several years now. I have testified in Congress multiple times and asked them to update these regulations. I've written op-eds outlining the areas of regulation we think are most important related to elections, harmful content, privacy, and competition."

—Mark Zuckerberg, responding to Frances Haugen's revelations (2021).[351]

Facebook's importance and scale has led to criticisms in many domains. Issues include Internet privacy, excessive retention of user information,[352] its facial recognition software, DeepFace[353][354] its addictive quality[355] and its role in the workplace, including employer access to employee accounts.[356]

Facebook has been criticized for electricity usage,[357] tax avoidance,[358] real-name user requirement policies,[359] censorship[360][361] and its involvement in the United States PRISM surveillance program.[362] According to The Express Tribune, Facebook "avoided billions of dollars in tax using offshore companies".[363]

Facebook is alleged to have harmful psychological effects on its users, including feelings of jealousy[364][365] and stress,[366][367] a lack of attention[368] and social media addiction.[369][370] According to Kaufmann et al., mothers' motivations for using social media are often related to their social and mental health.[371] European antitrust regulator Margrethe Vestager stated that Facebook's terms of service relating to private data were "unbalanced".[372]

Facebook has been criticized for allowing users to publish illegal or offensive material. Specifics include copyright and intellectual property infringement,[373] hate speech,[374][375] incitement of rape[376] and terrorism,[377][378] fake news,[379][380][381] and crimes, murders, and livestreaming violent incidents.[382][383][384] Commentators have accused Facebook of willingly facilitating the spread of such content.[385][386][387] Sri Lanka blocked both Facebook and WhatsApp in May 2019 after anti-Muslim riots, the worst in the country since the Easter Sunday bombing in the same year as a temporary measure to maintain peace in Sri Lanka.[388][389]Facebook removed 3 billion fake accounts only during the last quarter of 2018 and the first quarter of 2019;[390] in comparison, the social network reports 2.39 billion monthly active users.[390]

In late July 2019, the company announced it was under antitrust investigation by the Federal Trade Commission.[391]

The consumer advocacy group, Which?, claims that individuals are still utilizing Facebook to set up fraudulent five-star ratings for various products. The group has identified 14 communities that exchange reviews for either money or complimentary items such as watches, earbuds, and sprinklers.[392]

Privacy

Facebook has experienced a steady stream of controversies over how it handles user privacy, repeatedly adjusting its privacy settings and policies.[393]

Since 2009, Facebook has been participating in the PRISM secret program, sharing with the US National Security Agency audio, video, photographs, e-mails, documents and connection logs from user profiles, among other social media services.[394][395]

On November 29, 2011, Facebook settled Federal Trade Commission charges that it deceived consumers by failing to keep privacy promises.[396] In August 2013 High-Tech Bridge published a study showing that links included in Facebook messaging service messages were being accessed by Facebook.[397] In January 2014 two users filed a lawsuit against Facebook alleging that their privacy had been violated by this practice.[398]

On June 7, 2018, Facebook announced that a bug had resulted in about 14 million Facebook users having their default sharing setting for all new posts set to "public".[399]

On April 4, 2019, half a billion records of Facebook users were found exposed on Amazon cloud servers, containing information about users' friends, likes, groups, and checked-in locations, as well as names, passwords and email addresses.[400]

The phone numbers of at least 200 million Facebook users were found to be exposed on an open online database in September 2019. They included 133 million US users, 18 million from the UK, and 50 million from users in Vietnam. After removing duplicates, the 419 million records have been reduced to 219 million. The database went offline after TechCrunch contacted the web host. It is thought the records were amassed using a tool that Facebook disabled in April 2018 after the Cambridge Analytica controversy. A Facebook spokeswoman said in a statement: "The dataset is old and appears to have information obtained before we made changes last year...There is no evidence that Facebook accounts were compromised."[401]

Facebook's privacy problems resulted in companies like Viber Media and Mozilla discontinuing advertising on Facebook's platforms.[402][403]

A January 2024 study by Consumer Reports found that among a self-selected group of volunteer participants, each user is monitored or tracked by over two thousand companies on average. LiveRamp, a San Francisco-based data broker, is responsible for 96 per cent of the data. Other companies such as Home Depot, Macy's, and Walmart are involved as well.[404]

In March 2024, a court in California released documents detailing Facebook's 2016 "Project Ghostbusters". The project was aimed at helping Facebook compete with Snapchat and involved Facebook trying to develop decryption tools to collect, decrypt, and analyze traffic that users generated when visiting Snapchat and, eventually, YouTube and Amazon. The company eventually used its tool Onavo to initiate man-in-the-middle attacks and read users' traffic before it was encrypted.[405]

Racial bias

Facebook was accused of committing "systemic" racial bias by EEOC based on the complaints of three rejected candidates and a current employee of the company. The three rejected employees along with the Operational Manager at Facebook as of March 2021 accused the firm of discriminating against Black people. The EEOC has initiated an investigation into the case.[406]

Shadow profiles

A "shadow profile" refers to the data Facebook collects about individuals without their explicit permission. For example, the "like" button that appears on third-party websites allows the company to collect information about an individual's internet browsing habits, even if the individual is not a Facebook user.[407][408] Data can also be collected by other users. For example, a Facebook user can link their email account to their Facebook to find friends on the site, allowing the company to collect the email addresses of users and non-users alike.[409] Over time, countless data points about an individual are collected; any single data point perhaps cannot identify an individual, but together allows the company to form a unique "profile".

This practice has been criticized by those who believe people should be able to opt-out of involuntary data collection. Additionally, while Facebook users have the ability to download and inspect the data they provide to the site, data from the user's "shadow profile" is not included, and non-users of Facebook do not have access to this tool regardless. The company has also been unclear whether or not it is possible for a person to revoke Facebook's access to their "shadow profile".[407]

Cambridge Analytica

Facebook customer Global Science Research sold information on over 87 million Facebook users to Cambridge Analytica, a political data analysis firm led by Alexander Nix.[410] While approximately 270,000 people used the app, Facebook's API permitted data collection from their friends without their knowledge.[411] At first Facebook downplayed the significance of the breach, and suggested that Cambridge Analytica no longer had access. Facebook then issued a statement expressing alarm and suspended Cambridge Analytica. Review of documents and interviews with former Facebook employees suggested that Cambridge Analytica still possessed the data.[412] This was a violation of Facebook's consent decree with the Federal Trade Commission. This violation potentially carried a penalty of $40,000 ($48,534 in 2023 dollars[20]) per occurrence, totalling trillions of dollars.[413]

According to The Guardian, both Facebook and Cambridge Analytica threatened to sue the newspaper if it published the story. After publication, Facebook claimed that it had been "lied to". On March 23, 2018, The English High Court granted an application by the Information Commissioner's Office for a warrant to search Cambridge Analytica's London offices, ending a standoff between Facebook and the Information Commissioner over responsibility.[414]

On March 25, Facebook published a statement by Zuckerberg in major UK and US newspapers apologizing over a "breach of trust".[415]

You may have heard about a quiz app built by a university researcher that leaked Facebook data of millions of people in 2014. This was a breach of trust, and I'm sorry we didn't do more at the time. We're now taking steps to make sure this doesn't happen again.

We've already stopped apps like this from getting so much information. Now we're limiting the data apps get when you sign in using Facebook.

We're also investigating every single app that had access to large amounts of data before we fixed this. We expect there are others. And when we find them, we will ban them and tell everyone affected.

Finally, we'll remind you which apps you've given access to your information – so you can shut off the ones you don't want anymore.

Thank you for believing in this community. I promise to do better for you.

On March 26, the Federal Trade Commission opened an investigation into the matter.[416] The controversy led Facebook to end its partnerships with data brokers who aid advertisers in targeting users.[393]

On April 24, 2019, Facebook said it could face a fine between $3 billion ($3.58 billion in 2023 dollars[20]) to $5 billion ($5.96 billion in 2023 dollars[20]) as the result of an investigation by the Federal Trade Commission.[417] On July 24, 2019, the FTC fined Facebook $5 billion, the largest penalty ever imposed on a company for violating consumer privacy. Additionally, Facebook had to implement a new privacy structure, follow a 20-year settlement order, and allow the FTC to monitor Facebook.[418] Cambridge Analytica's CEO and a developer faced restrictions on future business dealings and were ordered to destroy any personal information they collected. Cambridge Analytica filed for bankruptcy.[419]

Facebook also implemented additional privacy controls and settings[420] in part to comply with the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which took effect in May.[421] Facebook also ended its active opposition to the California Consumer Privacy Act.[422]

Some, such as Meghan McCain have drawn an equivalence between the use of data by Cambridge Analytica and the Barack Obama's 2012 campaign, which, according to Investor's Business Daily, "encouraged supporters to download an Obama 2012 Facebook app that, when activated, let the campaign collect Facebook data both on users and their friends."[423][424][425] Carol Davidsen, the Obama for America (OFA) former director of integration and media analytics, wrote that "Facebook was surprised we were able to suck out the whole social graph, but they didn't stop us once they realised that was what we were doing".[424][425] PolitiFact has rated McCain's statements "Half-True", on the basis that "in Obama's case, direct users knew they were handing over their data to a political campaign" whereas with Cambridge Analytica, users thought they were only taking a personality quiz for academic purposes, and while the Obama campaign only used the data "to have their supporters contact their most persuadable friends", Cambridge Analytica "targeted users, friends and lookalikes directly with digital ads."[426]

DataSpii

In July 2019, cybersecurity researcher Sam Jadali exposed a catastrophic data leak known as DataSpii involving data provider DDMR and marketing intelligence company Nacho Analytics (NA).[427][428] Branding itself as the "God mode for the internet," NA through DDMR, provided its members access to private Facebook photos and Facebook Messenger attachments including tax returns.[429] DataSpii harvested data from millions of Chrome and Firefox users through compromised browser extensions.[430] The NA website stated it collected data from millions of opt-in users. Jadali, along with journalists from Ars Technica and The Washington Post, interviewed impacted users, including a Washington Post staff member. According to the interviews, the impacted users did not consent to such collection.

DataSpii demonstrated how a compromised user exposed the data of others, including the private photos and Messenger attachments belonging to a Facebook user's network of friends.[429]

DataSpii exploited Facebook's practice of making private photos and Messenger attachments publicly accessible via unique URLs. To bolster security in this regard, Facebook appends query strings in the URLs so as to limit the period of accessibility.[429] Nevertheless, NA provided real-time access to these unique URLs, which were intended to be secure. This allowed NA members to access the private content within the restricted time frame designated by Facebook.

The Washington Post's Geoffrey Fowler, in collaboration with Jadali, opened Fowler's private Facebook photo in a browser with a compromised browser extension.[427] Within minutes, they anonymously retrieved the "private" photo. To validate this proof-of-concept, they searched for Fowler's name using NA, which yielded his photo as a search result. In addition, Jadali discovered Fowler's Washington Post colleague, Nick Mourtoupalas, was directly impacted by DataSpii.

Jadali's investigation elucidated how DataSpii disseminated private data to additional third-parties, including foreign entities, within minutes of the data being acquired. In doing so, he identified the third-parties who were scraping, storing, and potentially enabling the facial-recognition of individuals in photos being furnished by DataSpii.[431]

Breaches

On September 28, 2018, Facebook experienced a major breach in its security, exposing the data of 50 million users. The data breach started in July 2017 and was discovered on September 16.[432] Facebook notified users affected by the exploit and logged them out of their accounts.[433][434]

In March 2019, Facebook confirmed a password compromise of millions of Facebook lite application users also affected millions of Instagram users. The reason cited was the storage of password as plain text instead of encryption which could be read by its employees.[435]

On December 19, 2019, security researcher Bob Diachenko discovered a database containing more than 267 million Facebook user IDs, phone numbers, and names that were left exposed on the web for anyone to access without a password or any other authentication.[436]

In February 2020, Facebook encountered a major security breach in which its official Twitter account was hacked by a Saudi Arabia-based group called "OurMine". The group has a history of actively exposing high-profile social media profiles' vulnerabilities.[437]

In April 2021, The Guardian reported approximately half a billion users' data had been stolen including birthdates and phone numbers. Facebook alleged it was "old data" from a problem fixed in August 2019 despite the data's having been released a year and a half later only in 2021; it declined to speak with journalists, had apparently not notified regulators, called the problem "unfixable", and said it would not be advising users.[438]

Phone data and activity

After acquiring Onavo in 2013, Facebook used its Onavo Protect virtual private network (VPN) app to collect information on users' web traffic and app usage. This allowed Facebook to monitor its competitors' performance, and motivated Facebook to acquire WhatsApp in 2014.[439][440][441] Media outlets classified Onavo Protect as spyware.[442][443][444] In August 2018, Facebook removed the app in response to pressure from Apple, who asserted that it violated their guidelines.[445][446] The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission sued Facebook on December 16, 2020, for "false, misleading or deceptive conduct" in response to the company's use of personal data obtained from Onavo for business purposes in contrast to Onavo's privacy-oriented marketing.[447][448]

In 2016, Facebook Research launched Project Atlas, offering some users between the ages of 13 and 35 up to $20 per month ($25.00 in 2023 dollars[20]) in exchange for their personal data, including their app usage, web browsing history, web search history, location history, personal messages, photos, videos, emails and Amazon order history.[449][450] In January 2019, TechCrunch reported on the project. This led Apple to temporarily revoke Facebook's Enterprise Developer Program certificates for one day, preventing Facebook Research from operating on iOS devices and disabling Facebook's internal iOS apps.[450][451][452]

Ars Technica reported in April 2018 that the Facebook Android app had been harvesting user data, including phone calls and text messages, since 2015.[453][454][455] In May 2018, several Android users filed a class action lawsuit against Facebook for invading their privacy.[456][457]

In January 2020, Facebook launched the Off-Facebook Activity page, which allows users to see information collected by Facebook about their non-Facebook activities.[458] The Washington Post columnist Geoffrey A. Fowler found that this included what other apps he used on his phone, even while the Facebook app was closed, what other web sites he visited on his phone, and what in-store purchases he made from affiliated businesses, even while his phone was completely off.[459]

In November 2021, a report was published by Fairplay, Global Action Plan and Reset Australia detailing accusations that Facebook was continuing to manage their ad targeting system with data collected from teen users.[460] The accusations follow announcements by Facebook in July 2021 that they would cease ad targeting children.[461][462]

Public apologies

The company first apologized for its privacy abuses in 2009.[463]

Facebook apologies have appeared in newspapers, television, blog posts and on Facebook.[464] On March 25, 2018, leading US and UK newspapers published full-page ads with a personal apology from Zuckerberg. Zuckerberg issued a verbal apology on CNN.[465] In May 2010, he apologized for discrepancies in privacy settings.[464]

Previously, Facebook had its privacy settings spread out over 20 pages, and has now put all of its privacy settings on one page, which makes it more difficult for third-party apps to access the user's personal information.[393] In addition to publicly apologizing, Facebook has said that it will be reviewing and auditing thousands of apps that display "suspicious activities" in an effort to ensure that this breach of privacy does not happen again.[466] In a 2010 report regarding privacy, a research project stated that not a lot of information is available regarding the consequences of what people disclose online so often what is available are just reports made available through popular media.[467] In 2017, a former Facebook executive went on the record to discuss how social media platforms have contributed to the unraveling of the "fabric of society".[468]

Content disputes and moderation

Facebook relies on its users to generate the content that bonds its users to the service. The company has come under criticism both for allowing objectionable content, including conspiracy theories and fringe discourse,[469] and for prohibiting other content that it deems inappropriate.

Misinformation and fake news

Facebook has been criticized as a vector for fake news, and has been accused of bearing responsibility for the conspiracy theory that the United States created ISIS,[470] false anti-Rohingya posts being used by Myanmar's military to fuel genocide and ethnic cleansing,[471][472] enabling climate change denial[473][474][475] and Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting conspiracy theorists,[476] and anti-refugee attacks in Germany.[477][478][479] The government of the Philippines has also used Facebook as a tool to attack its critics.[480]

In 2017, Facebook partnered with fact checkers from the Poynter Institute's International Fact-Checking Network to identify and mark false content, though most ads from political candidates are exempt from this program.[481][482] As of 2018, Facebook had over 40 fact-checking partners across the world, including The Weekly Standard.[483] Critics of the program have accused Facebook of not doing enough to remove false information from its website.[483][484]

Facebook has repeatedly amended its content policies. In July 2018, it stated that it would "downrank" articles that its fact-checkers determined to be false, and remove misinformation that incited violence.[485] Facebook stated that content that receives "false" ratings from its fact-checkers can be demonetized and suffer dramatically reduced distribution. Specific posts and videos that violate community standards can be removed on Facebook.[486]

In May 2019, Facebook banned a number of "dangerous" commentators from its platform, including Alex Jones, Louis Farrakhan, Milo Yiannopoulos, Paul Joseph Watson, Paul Nehlen, David Duke, and Laura Loomer, for allegedly engaging in "violence and hate".[487][488]

In May 2020, Facebook agreed to a preliminary settlement of $52 million ($61.2 million in 2023 dollars[20]) to compensate U.S.-based Facebook content moderators for their psychological trauma suffered on the job.[489][490] Other legal actions around the world, including in Ireland, await settlement.[491]

In September 2020, the Government of Thailand utilized the Computer Crime Act for the first time to take action against Facebook and Twitter for ignoring requests to take down content and not complying with court orders.[492]