Влияние табака на здоровье

Табачные изделия, особенно при курении или пероральном употреблении, оказывают серьезное негативное воздействие на здоровье человека. [ 1 ] [ 2 ] Курение и употребление бездымного табака являются крупнейшей причиной предотвратимой смертности во всем мире. [ 3 ] Около половины людей, курящих табак или употребляющих его перорально, умирают от осложнений, связанных с таким употреблением. [ 4 ] По оценкам, каждый год в общей сложности около 6 миллионов человек умирают от причин, связанных с табакокурением (около 10% всех смертей), причем 600 000 из них происходят среди некурящих из-за пассивного курения . [ 4 ] [ 5 ] По оценкам, в 20 веке от него погибло 100 миллионов человек. [ 4 ]

Табачный дым содержит более 70 химических веществ , вызывающих рак . [ 4 ] [ 6 ] Он также содержит никотин , , вызывающий сильную зависимость психоактивный наркотик . При курении табака содержащийся в нем никотин вызывает физическую и психологическую зависимость . Сигареты, продаваемые в слаборазвитых странах, имеют более высокое содержание смол. Они с меньшей вероятностью будут фильтроваться, что повышает уязвимость к заболеваниям, связанным с курением табака, в этих регионах. [7]

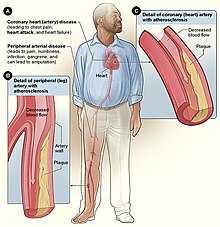

Tobacco use most commonly leads to diseases affecting the heart, liver and lungs. Smoking is a major risk factor for several conditions, namely pneumonia, heart attacks, strokes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (including emphysema and chronic bronchitis), and multiple cancers (particularly lung cancer, cancers of the larynx and mouth, bladder cancer, and pancreatic cancer). It is also responsible for peripheral arterial disease and high blood pressure. The effects vary, depending on how frequently and for how many years a person smokes. Smoking earlier in life and smoking cigarettes higher in tar increase the risk of these diseases. Additionally, environmental tobacco smoke, or second-hand smoke, has manifested harmful health effects in people of all ages.[8] Tobacco use is also a significant factor in miscarriages among pregnant smokers. It contributes to a number of other health problems of the fetus such as premature birth, low birth weight, and increases the chance of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) by 1.4 to 3 times.[9] Incidence of erectile dysfunction is approximately 85 percent higher in male smokers compared to non-smokers.[10][11]

Many countries have taken measures to control the consumption of tobacco (smoking) by restricting its usage and sales. On top of that, they have printed warning messages on packaging. Moreover, smoke-free laws that ban smoking in public places like workplaces, theaters, bars, and restaurants have been enacted to reduce exposure to second-hand smoke.[4] Tobacco taxes inflating the price of tobacco products have also been imposed.[4]

In the late 1700s and the 1800s, the idea that tobacco use caused certain diseases, including mouth cancers, was initially accepted by the medical community.[12] In the 1880s, automation dramatically reduced the cost of cigarettes, cigarette companies greatly increased their marketing, and use expanded.[13][14] From the 1890s onwards, associations of tobacco use with cancers and vascular disease were regularly reported. By the 1930s multiple researchers concluded that tobacco use caused cancer and tobacco users lived substantially shorter lives.[15][16] Further studies were published in Nazi Germany in 1939 and 1943, and one in the Netherlands in 1948. However, the widespread attention was first drawn in 1950 by researchers from the US and UK but their research were widely criticized. Follow-up studies in the early 1950s found that smokers died faster and were more likely to die of lung cancer and cardiovascular disease.[12] These results were accepted in the medical community and publicized among the general public in the mid-1960s.[12]

| Part of a series on |

| Tobacco |

|---|

|

Health effects of smoking

[edit]

(See also: Multiple infarct dementia, Vascular Diseases)

Smoking most commonly leads to diseases affecting the heart and lungs and will commonly affect areas such as hands or feet. First signs of smoking-related health issues often show up as numbness in the extremities, with smoking being a major risk factor for heart attacks, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema, and cancer, particularly lung cancer, cancers of the larynx and mouth, and pancreatic cancer.[18] Overall life expectancy is also reduced in long term smokers, with estimates ranging from 10[19] to 17.9[20] years fewer than nonsmokers.[21] About one half of long term male smokers will die of illness due to smoking.[22]

The association of smoking with lung cancer and COPD are among strongest, both in the public perception and etiologically. Among male smokers, the lifetime risk of developing lung cancer is 17.2%; among female smokers, the risk is 11.6%. This risk is significantly lower in nonsmokers: 1.3% in men and 1.4% in women.[23] For COPD, the 25 year incidence of moderate and severe COPD is at least 20.7% for continuous smokers and 3.6% for nonsmokers, with no difference being reported between men and women.[24]

A person's increased risk of contracting disease is related to the length of time that a person continues to smoke as well as the amount smoked. However, even smoking one cigarette a day raises the risk of coronary heart disease by about 50% or more, and for stroke by about 30%. Smoking 20 cigarettes a day entails a higher risk, but not proportionately.[25][26]

If someone stops smoking, then these chances gradually decrease as the damage to their body is repaired. A year after quitting, the risk of contracting heart disease is half that of a continuing smoker.[27] The health risks of smoking are not uniform across all smokers. Risks vary according to the amount of tobacco smoked, with those who smoke more at greater risk. Smoking so-called "light" cigarettes does not reduce the risk.[28]

Mortality

[edit]Smoking is the cause of about 5 million deaths per year.[29] This makes it the most common cause of preventable early death.[30] One study found that male and female smokers lose an average of 13.2 and 14.5 years of life, respectively.[31] Another measured a loss of life of 6.8 years.[32] Each cigarette that is smoked is estimated to shorten life by an average of 11 minutes, though this may vary slightly on the contents and brand.[33][34][35] At least half of all lifelong smokers die early as a result of smoking.[19] Smokers are three times more likely to die before the age of 60 or 70 than non-smokers.[19][36][37]

In the United States, cigarette smoking and exposure to tobacco smoke accounts for roughly one in five,[38] or at least 443,000 premature deaths annually.[39] To put this into context, ABC's Peter Jennings (who would later die at 67 from complications of lung cancer caused by life-long smoking) famously reported that in the US alone, smoking tobacco kills the equivalent of three jumbo jets full of people crashing every day, with no survivors.[40] On a worldwide basis, this equates to a single jumbo jet every hour.[41]

A 2015 study found that about 17% of mortality due to cigarette smoking in the United States is due to diseases outside of those commonly linked with smoking, and that official estimates may therefore be significantly underestimating the number of deaths currently being attributed to smoking.[42]

It is estimated that there are between 1 and 1.4 deaths per million cigarettes smoked. In fact, cigarette factories are the most deadly factories in the history of the world.[43][44] See the below chart detailing the highest-producing cigarette factories, and their estimated deaths caused annually due to the health detriments of cigarettes.[43]

According to WHO, 27137 annual deaths are attributed to tobacco use in Nepal.[45]

-

Share of deaths from smoking, 2017[46]

-

The number of deaths attributed to smoking per 100,000 people in 2017[47]

Cancer

[edit]

The primary risks of tobacco usage include many forms of cancer, particularly lung cancer,[49] kidney cancer,[50] cancer of the larynx[51] and head and neck,[52] bladder cancer,[53] cancer of the esophagus,[54] cancer of the pancreas,[55] stomach cancer,[56] and penile cancer.[57] Tobacco smoke can increase the risk of cervical cancer in women.[58] There may be a small increased risk of myeloid leukemia,[59] squamous cell sinonasal cancer, liver cancer, colorectal cancer, cancers of the gallbladder, the adrenal gland, the small intestine, and various childhood cancers.[56] The possible connection between breast cancer and tobacco is still uncertain.[60][61]

Lung cancer

[edit]The risk of lung cancer risk is highly influenced by smoking, with up to 90% of diagnoses being attributed to tobacco smoking.[62] The risk of developing lung cancer increases with the number of years smoking and number of cigarettes smoked per day.[63] Smoking can be linked to all subtypes of lung cancer. Small-cell carcinoma (SCLC) is the most closely associated with almost 100% of cases occurring in smokers.[64] This form of cancer has been identified with autocrine growth loops, proto-oncogene activation and inhibition of tumour suppressor genes. SCLC may originate from neuroendocrine cells located in the bronchus called Feyrter cells.[65]

The risk of dying from lung cancer before age 85 is 22.1% for a male smoker and 11.9% for a female smoker, in the absence of competing causes of death. The corresponding estimates for lifelong nonsmokers are a 1.1% probability of dying from lung cancer before age 85 for a man of European descent, and a 0.8% probability for a woman.[66]

Head and neck cancer

[edit]Tobacco smoking is one of the main risk factors for head and neck cancer. Cigarette smokers have a lifetime increased risk for head and neck cancer that is 5 to 25 times higher than the general population.[67] The ex-smoker's risk of developing head and neck cancer begins to approach the risk in the general population 15 years after smoking cessation.[68] In addition, people who smoke have a worse prognosis than those who have never smoked.[69] Furthermore, people who continue to smoke after diagnosis of head and neck cancer have the highest probability of dying compared to those who have never smoked.[70][71] This effect is seen in patients with HPV-positive head and neck cancer as well.[72][73][74] Passive smoking, both at work and at home, also increases the risk of head and neck cancer.[75]

Using tobacco together with alcohol is an especially high risk factor for head and neck cancer causing 72% of all cases.[76] This rises to 89% when looking specifically at laryngeal cancer.[77] Smokeless tobacco (including products where tobacco is chewed) is also a cause of oral cancer.[78][79][80] Cigar and pipe smoking are also important risk factors for oral cancer.[81] They have a dose dependent relationship with more consumption leading to higher chances of developing cancer.[82] The use of electronic cigarettes may also lead to the development of head and neck cancers due to the substances like propylene glycol, glycerol, nitrosamines, and metals contained therein, which can cause damage to the airways.[83][78]

Pulmonary

[edit]

In smoking, long term exposure to compounds found in the smoke (e.g., carbon monoxide and cyanide) are believed to be responsible for pulmonary damage and for loss of elasticity in the alveoli, leading to emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).[84] COPD caused by smoking is a permanent, incurable (often terminal) reduction of pulmonary capacity characterised by shortness of breath, wheezing, persistent cough with sputum, and damage to the lungs, including emphysema and chronic bronchitis.[85] The carcinogen acrolein and its derivatives also contribute to the chronic inflammation present in COPD.[86]

Cardiovascular disease

[edit]

Inhalation of tobacco smoke causes several immediate responses within the heart and blood vessels. Within one minute the heart rate begins to rise, increasing by as much as 30 percent during the first 10 minutes of smoking. Carbon monoxide in tobacco smoke exerts negative effects by reducing the blood's ability to carry oxygen.[87]

Smoking also increases the chance of heart disease, stroke, atherosclerosis, and peripheral vascular disease.[88][89] Several ingredients of tobacco lead to the narrowing of blood vessels, increasing the likelihood of a blockage, and thus a heart attack or stroke. According to a study by an international team of researchers, people under 40 are five times more likely to have a heart attack if they are smokers.[90][91]

Exposure to tobacco smoke is known to increase oxidative stress in the body by various mechanisms, including depletion of plasma antioxidants such as vitamin C.[92]

Research by American biologists has shown that cigarette smoke also influences the process of cell division in the cardiac muscle and changes the heart's shape.[93]

Smoking tobacco has also been linked to Buerger's disease (thromboangiitis obliterans), the acute inflammation and thrombosis (clotting) of arteries and veins of the hands and feet.[94]

Although cigarette smoking causes a greater increase in the risk of cancer than cigar smoking, cigar smokers still have an increased risk for many health problems, including cancer, when compared to non-smokers.[95][96] As for second-hand smoke, the NIH study points to the large amount of smoke generated by one cigar, saying "cigars can contribute substantial amounts of tobacco smoke to the indoor environment; and, when large numbers of cigar smokers congregate in a cigar smoking event, the amount of ETS (i.e. second-hand smoke) produced is sufficient to be a health concern for those regularly required to work in those environments."[97]

Smoking also tends to increase blood cholesterol levels. Furthermore, the ratio of high-density lipoprotein (HDL, also known as the "good" cholesterol) to low-density lipoprotein (LDL, also known as the "bad" cholesterol) tends to be lower in smokers compared to non-smokers. Smoking also raises the levels of fibrinogen and increases platelet production (both involved in blood clotting) which makes the blood thicker and more likely to clot. Carbon monoxide binds to hemoglobin (the oxygen-carrying component in red blood cells), resulting in a much stabler complex than hemoglobin bound with oxygen or carbon dioxide—the result is permanent loss of blood cell functionality. Blood cells are naturally recycled after a certain period of time, allowing for the creation of new, functional red blood cells. However, if carbon monoxide exposure reaches a certain point before they can be recycled, hypoxia (and later death) occurs. All these factors make smokers more at risk of developing various forms of arteriosclerosis (hardening of the arteries). As the arteriosclerosis progresses, blood flows less easily through rigid and narrowed blood vessels, making the blood more likely to form a thrombosis (clot). Sudden blockage of a blood vessel may lead to an infarction (stroke or heart attack). However, the effects of smoking on the heart may be more subtle. These conditions may develop gradually given the smoking-healing cycle (the human body heals itself between periods of smoking), and therefore a smoker may develop less significant disorders such as worsening or maintenance of unpleasant dermatological conditions, e.g. eczema, due to reduced blood supply. Smoking also increases blood pressure and weakens blood vessels.[98]

Renal

[edit]In addition to increasing the risk of kidney cancer, smoking can also contribute to additional renal damage. Smokers are at a significantly increased risk for chronic kidney disease than non-smokers.[99] A history of smoking encourages the progression of diabetic nephropathy.[100]

Influenza

[edit]A study of an outbreak of an (H1N1) influenza in an Israeli military unit of 336 healthy young men to determine the relation of cigarette smoking to the incidence of clinically apparent influenza, revealed that, of 168 smokers, 68.5 percent had influenza, as compared with 47.2 percent of nonsmokers. Influenza was also more severe in the smokers; 50.6 percent of them lost work days or required bed rest, or both, as compared with 30.1 percent of the nonsmokers.[101]

According to a study of 1,900 male cadets after the 1968 Hong Kong A2 influenza epidemic at a South Carolina military academy, compared with nonsmokers, heavy smokers (more than 20 cigarettes per day) had 21% more illnesses and 20% more bed rest, light smokers (20 cigarettes or fewer per day) had 10% more illnesses and 7% more bed rest.[102]

The effect of cigarette smoking upon epidemic influenza was studied prospectively among 1,811 male college students. Clinical influenza incidence among those who daily smoked 21 or more cigarettes was 21% higher than that of non-smokers. Influenza incidence among smokers of 1 to 20 cigarettes daily was intermediate between non-smokers and heavy cigarette smokers.[102]

Surveillance of a 1979 influenza outbreak at a military base for women in Israel revealed that influenza symptoms developed in 60.0% of the current smokers vs. 41.6% of the nonsmokers.[103]

Smoking seems to cause a higher relative influenza-risk in older populations than in younger populations. In a prospective study of community-dwelling people 60–90 years of age, during 1993, of unimmunized people 23% of smokers had clinical influenza as compared with 6% of non-smokers.[104]

Smoking may substantially contribute to the growth of influenza epidemics affecting the entire population.[101] However, the proportion of influenza cases in the general non-smoking population attributable to smokers has not yet been calculated.[citation needed]

Mouth

[edit]

Perhaps the most serious oral condition caused by smoking (including pipe smoking) is oral cancer.[97][105][106] However, smoking also increases the risk for various other oral diseases, some almost completely exclusive to tobacco users. Roughly half of periodontitis or inflammation around the teeth cases are attributed to current or former smoking. Smokeless tobacco causes gingival recession and white mucosal lesions. Up to 90% of periodontitis patients who are not helped by common modes of treatment are smokers. Smokers have significantly greater loss of bone height than nonsmokers, and the trend can be extended to pipe smokers to have more bone loss than nonsmokers.[107]

Smoking has been proven to be an important factor in the staining of teeth.[108][109] Halitosis or bad breath is common among tobacco smokers.[110] Tooth loss has been shown to be 2[111] to 3 times[112] higher in smokers than in non-smokers.[113] In addition, complications may further include leukoplakia, the adherent white plaques or patches on the mucous membranes of the oral cavity, including the tongue.[114]

Infection

[edit]Smoking is also linked to susceptibility to infectious diseases, particularly in the lungs (pneumonia). Smoking more than 20 cigarettes a day increases the risk of tuberculosis by two to four times,[115][116] and being a current smoker has been linked to a fourfold increase in the risk of invasive disease caused by the pathogenic bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae.[117] It is believed that smoking increases the risk of these and other pulmonary and respiratory tract infections both through structural damage and through effects on the immune system. The effects on the immune system include an increase in CD4+ cell production attributable to nicotine, which has tentatively been linked to increased HIV susceptibility.[118]

Smoking increases the risk of Kaposi's sarcoma in people without HIV infection.[119] One study found this only with the male population and could not draw any conclusions for the female participants in the study.[120]

Impotence

[edit]The incidence of impotence (difficulty achieving and maintaining penile erection) is approximately 85 percent higher in male smokers compared to non-smokers.[121] Smoking is a key cause of erectile dysfunction (ED).[10][121] It causes impotence because it promotes arterial narrowing and damages cells lining the inside of the arteries, thus leading to reduce penile blood flow.[122]

Female infertility

[edit]Smoking is harmful to the ovaries, potentially causing female infertility, and the degree of damage is dependent upon the amount and length of time a woman smokes. Nicotine and other harmful chemicals in cigarettes interfere with the body's ability to create estrogen, a hormone that regulates folliculogenesis and ovulation. Also, cigarette smoking interferes with folliculogenesis, embryo transport, endometrial receptivity, endometrial angiogenesis, uterine blood flow and the uterine myometrium.[123] Some damage is irreversible, but stopping smoking can prevent further damage.[124][125] Smokers are 60% more likely to be infertile than non-smokers.[126] Smoking reduces the chances of in vitro fertilization (IVF) producing a live birth by 34% and increases the risk of an IVF pregnancy miscarrying by 30%.[126]

Psychological

[edit]American Psychologist stated, "Smokers often report that cigarettes help relieve feelings of stress. However, the stress levels of adult smokers are slightly higher than those of nonsmokers, adolescent smokers report increasing levels of stress as they develop regular patterns of smoking, and smoking cessation leads to reduced stress. Far from acting as an aid for mood control, nicotine dependency seems to exacerbate stress. This is confirmed in the daily mood patterns described by smokers, with normal moods during smoking and worsening moods between cigarettes. Thus, the apparent relaxant effect of smoking only reflects the reversal of the tension and irritability that develop during nicotine depletion. Dependent smokers need nicotine to remain feeling normal."[127]

Immediate effects

[edit]Users report feelings of relaxation, sharpness, calmness, and alertness.[128] Those new to smoking may experience nausea, dizziness,[129] increased blood pressure,[citation needed] narrowed arteries,[citation needed] rapid heart beat,[citation needed] coughing and a bad taste in the mouth.[129] Generally, the unpleasant symptoms will eventually vanish over time, with repeated use, as the body builds a tolerance to the chemicals in the cigarettes, such as nicotine.[130]

Stress

[edit]Smokers report higher levels of everyday stress.[131] Several studies have monitored feelings of stress over time and found reduced stress after quitting.[132][133]

The deleterious mood effects of everyday between-cigarette nicotine withdrawal symptoms explain why people who smoke experience more daily stress than non-smokers, and become less stressed when they quit smoking. Deprivation reversal also explains much of the arousal data, with deprived smokers being less vigilant and less alert than non-deprived smokers or non-smokers.[131]

Recent studies have shown a positive relationship between psychological distress and salivary cotinine levels in smoking and non-smoking adults, indicating that both firsthand and second-hand smoke exposure may lead to higher levels of mental stress.[134]

Social and behavioral

[edit]Medical researchers have found that smoking is a predictor of divorce.[135] Smokers have a 53% greater chance of divorce than nonsmokers.[136]

Cognitive function, AD and PD

[edit]The usage of tobacco can also create cognitive dysfunction. There seems to be an increased risk of Alzheimer's disease (AD), although "case–control and cohort studies produce conflicting results as to the direction of the association between smoking and AD".[137] Smoking has been found to contribute to dementia and cognitive decline,[138] reduced memory and cognitive abilities in adolescents,[139] and brain shrinkage (cerebral atrophy).[140][141]

Most notably, some studies have found that patients with Alzheimer's disease are more likely not to have smoked than the general population, which has been interpreted to suggest that smoking offers some protection against Alzheimer's. However, the research in this area is limited and the results are conflicting; some studies show that smoking increases the risk of Alzheimer's disease.[142] A recent review of the available scientific literature concluded that the apparent decrease in Alzheimer's risk may be simply because smokers tend to die before reaching the age at which Alzheimer's normally occurs. "Differential mortality is always likely to be a problem where there is a need to investigate the effects of smoking in a disorder with very low incidence rates before age 75 years, which is the case of Alzheimer's disease," it stated, noting that smokers are only half as likely as non-smokers to survive to the age of 80.[137]

Some older analyses have claimed that non-smokers are up to twice as likely as smokers to develop Alzheimer's disease.[143] However, a more current analysis found that most of the studies, which showed a preventing effect, had a close affiliation to the tobacco industry. Researchers without tobacco lobby influence have concluded the complete opposite: Smokers are almost twice as likely as nonsmokers to develop Alzheimer's disease.[144]

Former and current smokers have a lower incidence of Parkinson's disease compared to people who have never smoked,[145][146] although the authors stated that it was more likely that the movement disorders which are part of Parkinson's disease prevented people from being able to smoke than that smoking itself was protective. Another study considered a possible role of nicotine in reducing Parkinson's risk: nicotine stimulates the dopaminergic system of the brain, which is damaged in Parkinson's disease, while other compounds in tobacco smoke inhibit MAO-B, an enzyme which produces oxidative radicals by breaking down dopamine.[147]

In many respects, nicotine acts on the nervous system in a similar way to caffeine. Some writings have stated that smoking can also increase mental concentration; one study documents a significantly better performance on the normed Advanced Raven Progressive Matrices test after smoking.[148]

Most smokers, when denied access to nicotine, exhibit withdrawal symptoms such as irritability, jitteriness, dry mouth, and rapid heart beat.[149] The onset of these symptoms is very fast, nicotine's half-life being only two hours.[150] The psychological dependence may linger for months or even many years. Unlike some recreational drugs, nicotine does not measurably alter a smoker's motor skills, judgement, or language abilities while under the influence of the drug. Nicotine withdrawal has been shown to cause clinically significant distress.[151]

This article or section appears to contradict itself on schizophrenia; the following para contradicts the history of claimed benefits section. (October 2022) |

A very large percentage of schizophrenics smoke tobacco as a form of self-medication.[152][153][154][155] The high rate of smoking tobacco by the mentally ill is a major factor in their decreased life expectancy, which is about 25 years shorter than the general population.[156] Following the observation that smoking improves condition of people with schizophrenia, in particular working memory deficit, nicotine patches had been proposed as a way to treat schizophrenia.[157] Some studies suggest that a link exists between smoking and mental illness, citing the high incidence of smoking amongst those with schizophrenia[158] and the possibility that smoking may alleviate some of the symptoms of mental illness,[159] but these have not been conclusive. In 2015, a meta-analysis found that smokers were at greater risk of developing psychotic illness.[160]

Recent studies have linked smoking to anxiety disorders, suggesting the correlation (and possibly mechanism) may be related to the broad class of anxiety disorders, and not limited to just depression. Current and ongoing research attempt to explore the addiction-anxiety relationship. Data from multiple studies suggest that anxiety disorders and depression play a role in cigarette smoking.[161] A history of regular smoking was observed more frequently among individuals who had experienced a major depressive disorder at some time in their lives than among individuals who had never experienced major depression or among individuals with no psychiatric diagnosis.[162] People with major depression are also much less likely to quit due to the increased risk of experiencing mild to severe states of depression, including a major depressive episode.[163] Depressed smokers appear to experience more withdrawal symptoms on quitting, are less likely to be successful at quitting, and are more likely to relapse.[164]

Pregnancy

[edit]A number of studies have shown that tobacco use is a significant factor in miscarriages among pregnant smokers,[165] and that it contributes to a number of other threats to the health of the fetus such as low birth weight and pre-term birth.[166] It slightly increases the risk of neural tube defects.[167]

Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and maternal smoking during pregnancy have been shown to cause lower infant birth weights.[168]

Studies have shown an association between prenatal exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and conduct disorder in children.[medical citation needed] As well, post-natal tobacco smoke exposure may cause similar behavioral problems in children.[medical citation needed]

Drug interactions

[edit]Smoking is known to increase levels of liver enzymes that break down drugs and toxins. That means that drugs cleared by these enzymes are cleared more quickly in smokers, which may result in the drugs not working. Specifically, levels of CYP1A2 and CYP2A6 are induced:[169][170] substrates for 1A2 include caffeine and tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline; substrates for 2A6 include the anticonvulsant valproic acid.

Multigenerational effects

[edit]Other harm

[edit]

Studies suggest that smoking decreases appetite, but did not conclude that overweight people should smoke or that their health would improve by smoking. This is also a cause of heart diseases.[171][172] Smoking also decreases weight by overexpressing the gene AZGP1, which stimulates lipolysis.[173]

Smoking causes about 10% of the global burden of fire deaths,[174] and smokers are placed at an increased risk of injury-related deaths in general, partly due to also experiencing an increased risk of dying in a motor vehicle crash.[175]

Smoking increases the risk of symptoms associated with Crohn's disease (a dose-dependent effect with use of greater than 15 cigarettes per day).[176][177][178][179] There is some evidence for decreased rates of endometriosis in infertile smoking women,[180] although other studies have found that smoking increases the risk in infertile women.[181] There is little or no evidence of a protective effect in fertile women. Some preliminary data from 1996 suggested a reduced incidence of uterine fibroids,[182] but overall the evidence is unconvincing.[183]

Current research shows that tobacco smokers who are exposed to residential radon are twice as likely to develop lung cancer as non-smokers.[184] As well, the risk of developing lung cancer from asbestos exposure is twice as likely for smokers than for non-smokers.[185]

New research has found that women who smoke are at significantly increased risk of developing an abdominal aortic aneurysm, a condition in which a weak area of the abdominal aorta expands or bulges, and is the most common form of aortic aneurysm.[186]

Smoking leads to an increased risk of bone fractures, especially hip fractures.[187] It also leads to slower wound healing after surgery, and an increased rate of postoperative healing complication.[188]

Tobacco smokers are 30-40% more likely to develop type 2 diabetes than non-smokers, and the risk increases with the number of cigarettes smoked. Furthermore, diabetic smokers have worse outcomes than diabetic non-smokers.[189][190]

Claimed benefits

[edit]Against the background of the overwhelmingly negative effects of smoking on health, some observational studies have suggested that smoking might have specific beneficial effects, including in the field of cardiovascular disease.[191][192] Interest in this epidemiological phenomenon has also been aroused by COVID-19.[192] Systematic review of reports that suggested smokers respond better to treatment for ischemic stroke provided no support for such claims.[191]

Claims of surprising benefits of smoking, based on observational data, have also been made for Parkinson's disease,[192] as well as a variety of other conditions, including basal-cell carcinoma,[193] malignant melanoma,[193] acute mountain sickness,[194] pemphigus,[195] celiac disease,[196] and ulcerative colitis,[197] among others.[198]

Tobacco smoke has many bioactive substances, including nicotine, that are capable of exerting a variety of systemic effects.[192] Surprising correlations may also stem from non-biological factors such as residual confounding (that is to say, the methodological difficulties in completely adjusting for every confounding factor that can affect outcomes in observational studies).[192]

In Parkinson's disease

[edit]In the case of Parkinson's disease, a series of observational studies that consistently suggest a possibly substantial reduction in risk among smokers (and other consumers of tobacco products) has led to longstanding interest among epidemiologists.[199][200][201][202] Non-biological factors that may contribute to such observations include reverse causality (whereby prodromal symptoms of Parkinson's disease may lead some smokers to quit before diagnosis), and personality considerations (people predisposed to Parkinson's disease tend to be relatively risk-averse, and may be less likely to have a history of smoking).[199] Possible existence of a biological effect is supported by a few studies that involved low levels of exposure to nicotine without any active smoking.[199] A data-driven hypothesis that long-term administration of very low doses of nicotine (for example, in an ordinary diet) might provide a degree of neurological protection against Parkinson's disease remains open as a potential preventive strategy.[199][203][204][205]

History of claimed benefits

[edit]In 1888, an article appeared in Scientific American discussing potential germicidal activity of tobacco smoke providing immunity against yellow fever epidemic of Florida inspiring research in the lab of Vincenzo Tassinari at the Hygienic Institute of the University of Pisa, who explored the antimicrobial activity against pathogens including Bacillus anthracis, Tubercle bacillus, Bacillus prodigiosus, Staphylococcus aureus, and others.[206] Carbon monoxide is a bioactive component tobacco smoke that has been explored for its antimicrobial properties against many of these pathogens.[207]

On epidemiological grounds, unexpected correlations between smoking and favorable outcomes initially emerged in the context of cardiovascular disease, where they were described as a smoker's paradox (or smoking paradox).[192][191] The term smoker's paradox was coined in 1995 in relation to reports that smokers appeared to have unexpectedly good short-term outcomes following acute coronary syndrome or stroke.[192] One of the first reports of an apparent smoker's paradox was published in 1968 based on an observation of relatively decreased mortality in smokers one month after experiencing acute myocardial infarction.[208] In the same year, a case–control study first suggested a possible protective role in Parkinson's disease.[199][209]

Historical claims of possible benefits in schizophrenia, whereby smoking was thought to ameliorate cognitive symptoms, are not supported by current evidence.[210][211]

Mechanism

[edit]Chemical carcinogens

[edit]Smoke, or any partially burnt organic matter, contains carcinogens (cancer-causing agents). The potential effects of smoking, such as lung cancer, can take up to 20 years to manifest themselves. Historically, women began smoking en masse later than men, so an increased death rate caused by smoking amongst women did not appear until later. The male lung cancer death rate decreased in 1975—roughly 20 years after the initial decline in cigarette consumption in men. A fall in consumption in women also began in 1975[213] but by 1991 had not manifested in a decrease in lung cancer–related mortalities amongst women.[214]

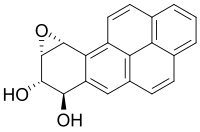

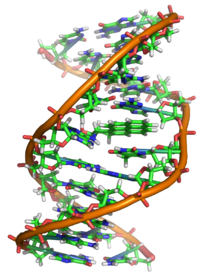

Smoke contains several carcinogenic pyrolytic products that bind to DNA and cause genetic mutations. Particularly potent carcinogens are polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), which are toxicated to mutagenic epoxides. The first PAH to be identified as a carcinogen in tobacco smoke was benzopyrene, which has been shown to toxicate into an epoxide that irreversibly attaches to a cell's nuclear DNA, which may either kill the cell or cause a genetic mutation. If the mutation inhibits programmed cell death, the cell can survive to become a cancer cell. Similarly, acrolein, which is abundant in tobacco smoke, also irreversibly binds to DNA, causes mutations and thus also cancer. However, it needs no activation to become carcinogenic.[215]

There are over 19 known carcinogens in cigarette smoke.[216] The following are some of the most potent carcinogens:

- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are tar components produced by pyrolysis in smoldering organic matter and emitted into smoke. Several of these PAH's are already toxic in their normal form, however, many of then can become more toxic to the liver. Due to the hydrophobic nature of PAH's they do not dissolve in water and are hard to expel from the body. In order to make the PAH more soluble in water, the liver creates an enzyme called Cytochrome P450 which adds an additional oxygen to the PAH, turning it into a mutagenic epoxides, which is more soluble, but also more reactive.[217] The first PAH to be identified as a carcinogen in tobacco smoke was benzopyrene, which been shown to toxicate into a diol epoxide and then permanently attach to nuclear DNA, which may either kill the cell or cause a genetic mutation. The DNA contains the information on how the cell function; in practice, it contains the recipes for protein synthesis. If the mutation inhibits programmed cell death, the cell can survive to become a cancer, a cell that does not function like a normal cell. The carcinogenicity is radiomimetic, i.e. similar to that produced by ionizing nuclear radiation. Tobacco manufacturers have experimented with combustion less vaporizer technology to allow cigarettes to be consumed without the formation of carcinogenic benzopyrenes.[218] Although such products have become increasingly popular, they still represent a very small fraction of the market, and no conclusive evidence has shown to prove or disprove the positive health claims.[citation needed]

- Acrolein is a pyrolysis product that is abundant in cigarette smoke. It gives smoke an acrid smell and an irritating, tear causing effect and is a major contributor to its carcinogenicity. Like PAH metabolites, acrolein is also an electrophilic alkylating agent and permanently binds to the DNA base guanine, by a conjugate addition followed by cyclization into a hemiaminal. The acrolein-guanine adduct induces mutations during DNA copying and thus causes cancers in a manner similar to PAHs. However, acrolein is 1000 times more abundant than PAHs in cigarette smoke and is able to react as is, without metabolic activation. Acrolein has been shown to be a mutagen and carcinogen in human cells. The carcinogenicity of acrolein has been difficult to study by animal experimentation, because it has such a toxicity that it tends to kill the animals before they develop cancer.[215] Generally, compounds able to react by conjugate addition as electrophiles (so-called Michael acceptors after Michael reaction) are toxic and carcinogenic, because they can permanently alkylate DNA, similarly to mustard gas or aflatoxin. Acrolein is only one of them present in cigarette smoke; for example, crotonaldehyde has been found in cigarette smoke.[219] Michael acceptors also contribute to the chronic inflammation present in diseases brought about by smoking.[86]

- Nitrosamines are a group of carcinogenic compounds found in cigarette smoke but not in uncured tobacco leaves. Nitrosamines form on flue-cured tobacco leaves during the curing process through a chemical reaction between nicotine and other compounds contained in the uncured leaf and various oxides of nitrogen found in all combustion gasses. Switching to Indirect fire curing has been shown to reduce nitrosamine levels to less than 0.1 parts per million.[220][221]

Sidestream tobacco smoke, or exhaled mainstream smoke, is particularly harmful. Because exhaled smoke exists at lower temperatures than inhaled smoke, chemical compounds undergo changes which can cause them to become more dangerous. As well, smoke undergoes changes as it ages, which causes the transformation of the compound NO into the more toxic NO2. Further, volatilization causes smoke particles to become smaller, and thus more easily embedded deep into the lung of anyone who later breathes the air.[222]

Radioactive carcinogens

[edit]In addition to chemical, nonradioactive carcinogens, chewing tobacco and tobacco smoke contain small amounts of lead-210 (210Pb) and polonium-210 (210Po), both of which are radioactive carcinogens. The presence of polonium-210 in mainstream cigarette smoke has been experimentally measured at levels of 0.0263–0.036 pCi (0.97–1.33 mBq),[223][224] which is equivalent to about 0.1 pCi per milligram of smoke (4 mBq/mg); or about 0.81 pCi of lead-210 per gram of dry condensed smoke (30 Bq/kg).

Research by NCAR radiochemist Ed Martell suggested that radioactive compounds in cigarette smoke are deposited in "hot spots" where bronchial tubes branch, that tar from cigarette smoke is resistant to dissolving in lung fluid and that radioactive compounds have a great deal of time to undergo radioactive decay before being cleared by natural processes. Indoors, these radioactive compounds can linger in second-hand smoke, and greater exposure would occur when these radioactive compounds are inhaled during normal breathing, which is deeper and longer than when inhaling cigarettes. Damage to the protective epithelial tissue from smoking only increases the prolonged retention of insoluble polonium-210 compounds produced from burning tobacco. Martell estimated that a carcinogenic radiation dose of 80–100 rads is delivered to the lung tissue of most smokers who die of lung cancer.[225][226][227]

Smoking an average of 1.5 packs per day gives a radiation dose of 60-160 mSv/year,[228][229] compared with living near a nuclear power station (0.0001 mSv/year)[230][231] or the 3.0 mSv/year average dose for Americans.[231][232] Some of the mineral apatite in Florida used to produce phosphate for US tobacco crops contains uranium, radium, lead-210 and polonium-210 and radon.[233][234] The radioactive smoke from tobacco fertilized this way is deposited in lungs and releases radiation even if a smoker quits the habit. The combination of carcinogenic tar and radiation in a sensitive organ such as lungs increases the risk of cancer.[citation needed]

In contrast, a 1999 review of tobacco smoke carcinogens published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute states that "levels of polonium-210 in tobacco smoke are not believed to be great enough to significantly impact lung cancer in smokers."[217] In 2011 Hecht has also stated that the "levels of 210Po in cigarette smoke are probably too low to be involved in lung cancer induction".[235]

Oxidation and inflammation

[edit]Free radicals and pro-oxidants in cigarettes damage blood vessels and oxidize LDL cholesterol.[236] Only oxidized LDL cholesterol is taken-up by macrophages, which become foam cells, leading to atherosclerotic plaques.[236] Cigarette smoke increases proinflammatory cytokines in the bloodstream, causing atherosclerosis.[236] The pro-oxidative state also leads to endothelial dysfunction,[236] which is another important cause of atherosclerosis.[237]

Nicotine

[edit]

Nicotine, which is contained in cigarettes and other smoked tobacco products, is a stimulant and is one of the main factors leading to continued tobacco smoking. Nicotine is a highly addictive psychoactive chemical. When tobacco is smoked, most of the nicotine is pyrolyzed; a dose sufficient to cause mild somatic dependency and mild to strong psychological dependency remains. The amount of nicotine absorbed by the body from smoking depends on many factors, including the type of tobacco, whether the smoke is inhaled, and whether a filter is used. There is also a formation of harmane (a MAO inhibitor) from the acetaldehyde in cigarette smoke, which seems to play an important role in nicotine addiction[238] probably by facilitating dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens in response to nicotine stimuli. According to studies by Henningfield and Benowitz, nicotine is more addictive than cannabis, caffeine, alcohol, cocaine, and heroin when considering both somatic and psychological dependence. However, due to the stronger withdrawal effects of alcohol, cocaine and heroin, nicotine may have a lower potential for somatic dependence than these substances.[239][240] About half of Canadians who currently smoke have tried to quit.[241] McGill University health professor Jennifer O'Loughlin stated that nicotine addiction can occur as soon as five months after the start of smoking.[242]

Ingesting a compound by smoking is one of the most rapid and efficient methods of introducing it into the bloodstream, second only to injection, which allows for the rapid feedback which supports the smokers' ability to titrate their dosage. On average it takes about ten seconds for the substance to reach the brain. As a result of the efficiency of this delivery system, many smokers feel as though they are unable to cease. Of those who attempt cessation and last three months without succumbing to nicotine, most are able to remain smoke-free for the rest of their lives.[243][failed verification] There exists a possibility of depression in some who attempt cessation, as with other psychoactive substances. Depression is also common in teenage smokers; teens who smoke are four times as likely to develop depressive symptoms as their nonsmoking peers.[244]

Although nicotine does play a role in acute episodes of some diseases (including stroke, impotence, and heart disease) by its stimulation of adrenaline release, which raises blood pressure,[98] heart and respiration rate, and free fatty acids, the most serious longer term effects are more the result of the products of the smoldering combustion process. This has led to the development of various nicotine delivery systems, such as the nicotine patch or nicotine gum, that can satisfy the addictive craving by delivering nicotine without the harmful combustion by-products. This can help the heavily dependent smoker to quit gradually while discontinuing further damage to health.[citation needed]

Recent evidence has shown that smoking tobacco increases the release of dopamine in the brain, specifically in the mesolimbic pathway, the same neuro-reward circuit activated by addictive substances such as heroin and cocaine. This suggests nicotine use has a pleasurable effect that triggers positive reinforcement.[245] One study found that smokers exhibit better reaction-time and memory performance compared to non-smokers, which is consistent with increased activation of dopamine receptors.[246] Neurologically, rodent studies have found that nicotine self-administration causes lowering of reward thresholds—a finding opposite that of most other addictive substances (e.g. cocaine and heroin).

The carcinogenity of tobacco smoke is not explained by nicotine per se, which is not carcinogenic or mutagenic, although it is a metabolic precursor for several compounds which are.[citation needed] In addition, it inhibits apoptosis, therefore accelerating existing cancers.[247] Also, NNK, a nicotine derivative converted from nicotine, can be carcinogenic.

Nicotine, although frequently implicated in producing tobacco addiction, is not significantly addictive when administered alone.[248][non-primary source needed] The addictive potential manifests itself after co-administration of an MAOI, which specifically causes sensitization of the locomotor response in rats, a measure of addictive potential.[249]

Forms of exposure

[edit]Second-hand smoke

[edit]

Second-hand smoke is a mixture of smoke from the burning end of a cigarette, pipe or cigar, and the smoke exhaled from the lungs of smokers. It is involuntarily inhaled, lingers in the air hours after cigarettes have been extinguished, and may cause a wide range of adverse health effects, including cancer, respiratory infections, and asthma.[250]

Studies have shown that exposure to second-hand smoke causes harmful effects on the cardiovascular system and is associated with prevalent heart failure among non-smokers.[251] Non-smokers who are exposed to second-hand smoke at home or work are thought, due to a wide variety of statistical studies, to increase their heart disease risk by 25–30% and their lung cancer risk by 20–30%. According to the World Health Organization, second-hand smoke is reported to kill about 1 million people per year and causes numerous diseases including cancer and heart diseases. [252]

The current US Surgeon General's Report concludes that there is no established risk-free level of exposure to second-hand smoke. Short exposures to second-hand smoke are believed to cause blood platelets to become stickier, damage the lining of blood vessels, decrease coronary flow velocity reserves, and reduce heart rate variability, potentially increasing the mortality of heart attacks.[253] New research indicates that private research conducted by cigarette company Philip Morris in the 1980s showed that second-hand smoke was toxic, yet the company suppressed the finding during the next two decades.[250]

Chewing tobacco

[edit]Chewing tobacco has been known to cause cancer, particularly of the mouth and throat.[254] According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer, "Some health scientists have suggested that smokeless tobacco should be used in smoking cessation programmes and have made implicit or explicit claims that its use would partly reduce the exposure of smokers to carcinogens and the risk for cancer. These claims, however, are not supported by the available evidence."[254] Oral and spit tobacco increase the risk for leukoplakia and erythroplakia a precursor to oral cancer.[255][256]

Cigars

[edit]Like other forms of smoking, cigar smoking poses a significant health risk depending on dosage: risks are greater for those who inhale more when they smoke, smoke more cigars, or smoke them longer.[96] The risk of dying from any cause is significantly greater for cigar smokers, with the risk particularly higher for smokers less than 65 years old, and with risk for moderate and deep inhalers reaching levels similar to cigarette smokers.[257] The increased risk for those smoking 1–2 cigars per day is too small to be statistically significant,[258] and the health risks of the 3/4 of cigar smokers who smoke less than daily are not known[259] and are hard to measure. Although it has been claimed that people who smoke few cigars have no increased risk, a more accurate statement is that their risks are proportionate to their exposure.[95] Health risks are similar to cigarette smoking in nicotine addiction, periodontal health, tooth loss, and many types of cancer, including cancers of the mouth, throat, and esophagus.[260][261][unreliable medical source?] Cigar smoking also can cause cancers of the lung, and larynx, where the increased risk is less than that of cigarettes. Many of these cancers have extremely low cure rates. Cigar smoking also increases the risk of lung and heart diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).[96][262][263][unreliable medical source?][264][unreliable medical source?]

Hookahs

[edit]

A common belief among users is that the smoke of a hookah (waterpipe, narghile) is significantly less dangerous than that from cigarettes.[265] The water moisture induced by the hookah makes the smoke less irritating and may give a false sense of security and reduce concerns about true health effects.[266] Doctors at institutions including the Mayo Clinic have stated that use of hookah can be as detrimental to a person's health as smoking cigarettes,[267][268] and a study by the World Health Organization also confirmed these findings.[269] Although the smoking effects are similar to a cigarettes, due to the manner in which a hookah is utilized, smoking hookah may potentially absorb a higher amount of toxic substances, compared to cigarette smokers. [270]

Each hookah session typically lasts more than 40 minutes, and consists of 50 to 200 inhalations that each range from 0.15 to 0.50 liters of smoke.[271][272] In an hour-long smoking session of hookah, users consume about 100 to 200 times the smoke of a single cigarette;[271][273] A study in the Journal of Periodontology found that water pipe smokers were marginally more likely than regular smokers to show signs of gum disease, showing rates 5-fold higher than non-smokers rather than the 3.8-fold risk that regular smokers show.[274] According to USA Today, people who smoked water pipes had five times the risk of lung cancer of non-smokers.[275][better source needed]

A study on hookah smoking and cancer in Pakistan was published in 2008. Its objective was "to find serum CEA levels in ever/exclusive hookah smokers, i.e. those who smoked only hookah (no cigarettes, bidis, etc.), prepared between 1 and 4 times a day with a quantity of up to 120 g of a tobacco-molasses mixture each (i.e. the tobacco weight equivalent of up to 60 cigarettes of 1 g each) and consumed in 1 to 8 sessions". Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is a marker found in several forms of cancer. Levels in exclusive hookah smokers were lower compared to cigarette smokers although the difference was not as statistically significant as that between a hookah smoker and a non-smoker. Also, the study concluded that heavy hookah smoking (2–4 daily preparations; 3–8 sessions a day; >2 hrs to ≤ 6 hours) substantially raises CEA levels.[276] Hookah smokers were nearly 6 times more likely to develop lung cancer than healthy non-smokers in Kashmir.[277]

Dipping tobacco

[edit]Dipping tobacco, often referred to as dip in the United States; is placed in the mouth, between the cheek and gum.[278] Dipping tobacco does not need to be chewed for the nicotine to be absorbed. First-time users of these products often become nauseated and dizzy. Long-term effects include bad breath, yellowed teeth, and an increased risk of oral cancer.[citation needed]

Users of dipping tobacco are believed to face less risk of some cancers than are smokers, but are still at greater risk than people who do not use any tobacco products.[279] Smokeless tobacco has been linked with oral cancer, hypertension, and heart disease.[280] They also have an equal risk of other health problems directly linked to nicotine, such as increased rate of atherosclerosis.[citation needed]

Prevention

[edit]Education and counselling by physicians of children and adolescents have been found to be effective in decreasing tobacco use.[281] The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 5.6 billion people, or 71% of the world's population, are protected by at least one tobacco prevention policy.[282]

-

Average price of a pack of 20 cigarettes, measured in international dollars in 2014[283]

-

Taxes as a share of cigarette price, 2014[284]

-

Types of bans on tobacco advertising, 2014[285]

-

Support to help quit tobacco use, 2014[286]

Usage

[edit]Though tobacco may be consumed by either smoking or other smokeless methods such as chewing, the World Health Organization (WHO) only collects data on smoked tobacco.[1] Smoking has therefore been studied more extensively than any other form of tobacco consumption.[2]

In 2000, smoking was practiced by 1.22 billion people, predicted to rise to 1.45 billion people in 2010 and 1.5 to 1.9 billion by 2025. If prevalence had decreased by 2% a year since 2000 this figure would have been 1.3 billion in 2010 and 2025.[287] Despite dropping by 0.4 percent from 2009 to 2010, the United States still reports an average of 17.9 percent usage.[38]

As of 2002, about twenty percent of young teens (13–15) smoked worldwide, with 80,000 to 100,000 children taking up the addiction every day, roughly half of whom live in Asia. Half of those who begin smoking in adolescent years are projected to go on to smoke for 15 to 20 years.[288]

Teens are more likely to use e-cigarettes than cigarettes. About 31% of teenagers who use e-cigs started smoking within six months, compared to 8% of non-smokers. Manufacturers do not have to report what is in e-cigs, and most teens either say e-cigs contain only flavoring, or that they do not know what they contain.[289][290]

The WHO states that "Much of the disease burden and premature mortality attributable to tobacco use disproportionately affect the poor". Of the 1.22 billion smokers, 1 billion live in developing or transitional nations. Rates of smoking have leveled off or declined in the developed world.[291] In the developing world, however, smoking rates were rising by 3.4% per year as of 2002.[288]

The WHO in 2004 projected 58.8 million deaths to occur globally,[292]: 8 from which 5.4 million are smoking-attributed,[292]: 23 and 4.9 million as of 2007.[293] As of 2002, 70% of the deaths are in developing countries.[293]

The shift in prevalence of tobacco smoking to a younger demographic, mainly in the developing world, can be attributed to several factors. The tobacco industry spends up to $12.5 billion annually on advertising, which is increasingly geared towards adolescents in the developing world because they are a vulnerable audience for the marketing campaigns. Adolescents have more difficulty understanding the long-term health risks that are associated with smoking and are also more easily influenced by "images of romance, success, sophistication, popularity, and adventure which advertising suggests they could achieve through the consumption of cigarettes". This shift in marketing towards adolescents and even children in the tobacco industry is debilitating to organizations' and countries' efforts to improve child health and mortality in the developing world. It reverses or halts the effects of the work that has been done to improve health care in these countries, and although smoking is deemed as a "voluntary" health risk, the marketing of tobacco towards very impressionable adolescents in the developing world makes it less of a voluntary action and more of an inevitable shift.[7]

Presently, approximately 8 million individuals succumb to tobacco-related diseases annually, resulting in a significant economic burden of $1.4 trillion on the global scale each year.[294]

In the US smoking is considered to be the most common preventable deaths. About 480,000 individuals die annually due to smoking in the US alone. [295] Currently, the number of premature deaths in the US from tobacco use per year exceeds the number of employees in the tobacco industry by 4 to 1.[296] It has been estimated that tobacco smoking will kill about 1 billion people in the 21st century if current smoking patterns continue, half of them before the age of 70.[297]

China has the largest tobacco smoking population, followed by India. India has the highest tobacco chewing population in the world. 154 people die every hour in India because of chewing and smoking tobacco.[298][299]

Many government regulations have been passed to protect citizens from harm caused by public environmental tobacco smoke. In the United States, the "Pro-Children's Act of 2001" prohibits smoking within any facility that provides health care, day care, library services, or elementary and secondary education to children.[300] On May 23, 2011, New York City enforced a smoking ban for all parks, beaches, and pedestrian malls in an attempt to eliminate threats posed to civilians by environmental tobacco smoke.[301]

History

[edit]Pre-cigarette

[edit]Texts on the harmful effects of smoking tobacco were recorded in the Timbuktu manuscripts.[302]

James I wrote a book that denounced tobacco smoking as: "...loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, dangerous to the lungs..."[303]

Pipe smoking gradually became generally accepted as a cause of mouth cancers following work done in the 1700s. "An association between a variety of cancers and tobacco use was repeatedly observed from the late 1800s into the early 1920s."[304]

Gideon Lincecum, an American naturalist and practitioner of botanical medicine, wrote in the early 19th century on tobacco: "This poisonous plant has been used a great deal as a medicine by the old school faculty, and thousands have been slain by it. ... It is a very dangerous article, and use it as you will, it always diminishes the vital energies in exact proportion to the quantity used – it may be slowly, but it is very sure."[305]

The 1880s invention of automated cigarette-making machinery in the American South made it possible to mass-produce cigarettes at low cost, and smoking became common. This led to a backlash and a tobacco prohibition movement, which challenged tobacco use as harmful and brought about some bans on tobacco sale and use.[13] In 1912, American Dr. Isaac Adler was the first to strongly suggest that lung cancer is related to smoking.[306] In 1924, economist Irving Fisher wrote an anti-smoking article for Reader's Digest which said "...tobacco lowers the whole tone of the body and decreases its vital power and resistance ... tobacco acts like a narcotic poison, like opium, and like alcohol, though usually in a less degree".[307] In December 1952, the Reader's Digest reprinted an article titled Cancer by the Carton which outlined the research links between smoking and lung cancer.

Prior to World War I, lung cancer was considered to be a rare disease, which most physicians would never see during their career.[308][309] With the postwar rise in popularity of cigarette smoking, however, came an epidemic of lung cancer.[310][311] For instance, it is estimated that "35 to 79 percent of excess veteran deaths due to heart disease and lung cancer are attributable to military-induced smoking"[312]

Early observational studies

[edit]From the 1890s onwards, associations of tobacco use with cancers and vascular disease were regularly reported.[12] In 1930, Fritz Lickint of Dresden, Germany, published[16][15] a meta-analysis citing 167 other works to link tobacco use to lung cancer.[15] Lickint showed that people with lung cancer were likely to be smokers. He also argued that smoking tobacco was the best way to explain the fact that lung cancer struck men four or five times more often than women (since women smoked much less),[16] and discussed the causal effect of smoking on cancers of the liver and bladder.[15]

It may be suggested that the chief reason that the subject has received so little attention from members of the medical profession is that the majority of them as of the general community practice smoking in one form of another, and do not wish to inquire too closely into a habit in defense of which so much can be said from the hedonistic but so little from the hygienic standpoint

Rolleston JD (July 1932). "The Cigarette Habit". Addiction. 30 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1932.tb04849.x. S2CID 72586449.

More observational evidence was published throughout the 1930s, and in 1938, Science published a paper showing that tobacco smokers live substantially shorter lives. It built a survival curve from family history records kept at the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health. This result was ignored or incorrectly explained away.[12]

An association between smoking tobacco and heart attacks was first mentioned in 1930; a large case–control study found a significant association in 1940, but avoided saying anything about cause, on the grounds that such a conclusion would cause controversy and doctors were not yet ready for it.[12]

Official hostility to tobacco use was widespread in Nazi Germany where case-control studies were published in 1939 and 1943. Another was published in the Netherlands in 1948. A case-control study on lung cancer and smoking, done in 1939 by Franz Hermann Müller, had serious weaknesses in its methodology, but study design problems were better addressed in subsequent studies.[12] The association of anti-tobacco smoking research and public health measures with the Nazi leadership may have contributed to the lack of attention paid to these studies.[16] They were also published in German and Dutch. These studies were widely ignored.[313] In 1947 the British Medical Council held a conference to discuss the reason for the rise in lung cancer deaths; unaware of the German studies, they planned and started their own.[12]

Five case-control studies published in 1950 by researchers from the US and UK did draw widespread attention.[314] The strongest results were found by "Smoking and carcinoma of the lung. Preliminary report", by Richard Doll and Austin Bradford Hill,[315][12] and the 1950 Wynder and Graham Study, entitled "Tobacco Smoking as a Possible Etiologic Factor in Bronchiogenic Carcinoma: A Study of Six Hundred and Eighty-Four Proved Cases". These two studies were the largest, and the only ones to carefully exclude ex-smokers from their nonsmokers group. The other three studies also reported that, to quote one, "smoking was powerfully implicated in the causation of lung cancer".[314] The Doll and Hill paper reported that "heavy smokers were fifty times as likely as non-smokers to contract lung cancer".[315][314]

Causality

[edit]Early case-control studies clearly showed a close association between smoking and lung cancer, but contemporary doctors and scientists did not feel evidence existed for causality.[12] Follow-up large prospective cohort studies in the early 1950s showed clearly that smokers died faster, and were more likely to die of lung cancer, cardiovascular disease, and a list of other diseases which lengthened as the studies continued[12]

The British Doctors Study, a longitudinal study of some 40,000 doctors, began in 1951.[19] By 1954 it had evidence from three years of doctors' deaths, based on which the government issued advice that smoking and lung cancer rates were related[316][19] (the British Doctors Study last reported in 2001,[19] by which time there were approximately 40 linked diseases).[12] The British Doctors Study demonstrated that about half of the persistent cigarette smokers born in 1900–1909 were eventually killed by their addiction.[317]

Public awareness

[edit]In 1953, scientists at the Sloan-Kettering Institute in New York City demonstrated that cigarette tar painted on the skin of mice caused fatal cancers.[313] This work attracted much media attention; the New York Times and Life both covered the issue. The Reader's Digest published an article entitled "Cancer by the Carton".[313]: 14

On January 11, 1964, the United States Surgeon General's Report on Smoking and Health was published; this led millions of American smokers to quit, the banning of certain types of advertising, and the requirement of warning labels on tobacco products.[318][319]

These results were first widely accepted in the medical community, and publicized among the general public, in the mid-1960s.[12] The medical community's resistance to the idea that smoking tobacco caused disease has been attributed to bias from nicotine-dependent doctors, the novelty of the adaptations needed to apply epidemiological techniques and heuristics to non-infectious diseases, and cigarette industry pressure.[12]

The harmful health effects of smoking have been significant for the development of the science of epidemiology. As the mechanism of carcinogenicity is radiomimetic or radiological, the effects are stochastic. Definite statements can be made only on the relative increased or decreased probabilities of contracting a given disease. For a particular individual, it is impossible to definitively prove a direct causal link between exposure to a radiomimetic poison such as tobacco smoke and the cancer that follows; such statements can only be made at the aggregate population level. Cigarette companies have capitalized on this philosophical objection and exploited the doubts of clinicians, who consider only individual cases, on the causal link in the stochastic expression of the toxicity as actual disease.[320]

There have been multiple court cases against tobacco companies for having researched the health effects of smoking, but having then suppressed the findings or formatted them to imply lessened or no hazard.[320]

After a ban on smoking in all enclosed public places was introduced in Scotland in March 2006, there was a 17 percent reduction[when?] in hospital admissions for acute coronary syndrome. 67% of the decrease occurred in non-smokers.[321]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b "Prevalence of current tobacco use among adults aged=15 years (percentage)". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2008-12-11. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Mayo report on addressing the worldwide tobacco epidemic through effective, evidence-based treatment". World Health Organization. p. 2. Archived from the original on May 12, 2004. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ Jump up to: a b WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2008 : The MPOWER Package (PDF). World Health Organization. 2008. pp. 6, 8, 20. ISBN 9789240683112. OCLC 476167599. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Tobacco Fact sheet N°339". May 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ "The top 10 causes of death". Archived from the original on March 14, 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ "Harmful Chemicals in Tobacco Products". www.cancer.org. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nichter M, Cartwright E (1991). "Saving the Children for the Tobacco Industry". Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 5 (3): 236–56. doi:10.1525/maq.1991.5.3.02a00040. JSTOR 648675.

- ^ Vainio H (June 1987). "Is passive smoking increasing cancer risk?". Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 13 (3): 193–6. doi:10.5271/sjweh.2066. PMID 3303311.

- ^ "The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the Surgeon General" (PDF). Atlanta, U.S.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. 2006. p. 93. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Peate I (2005). "The effects of smoking on the reproductive health of men". British Journal of Nursing. 14 (7): 362–6. doi:10.12968/bjon.2005.14.7.17939. PMID 15924009.

- ^ Korenman SG (2004). "Epidemiology of erectile dysfunction". Endocrine. 23 (2–3): 87–91. doi:10.1385/ENDO:23:2-3:087. PMID 15146084. S2CID 29133230.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Doll R (June 1998). "Uncovering the effects of smoking: historical perspective" (PDF). Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 7 (2): 87–117. doi:10.1177/096228029800700202. PMID 9654637. S2CID 154707. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-10-01. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Alston LJ, Dupré R, Nonnenmacher T (2002). "Social reformers and regulation: the prohibition of cigarettes in the United States and Canada". Explorations in Economic History. 39 (4): 425–445. doi:10.1016/S0014-4983(02)00005-0.

- ^ James R (2009-06-15). "A Brief History Of Cigarette Advertising". TIME. Archived from the original on September 21, 2011. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Haustein KO (2004). "Fritz Lickint (1898–1960) – Ein Leben als Aufklärer über die Gefahren des Tabaks". Suchtmed (in German). 6 (3): 249–255. Archived from the original on November 5, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Proctor RN (February 2001). "Commentary: Schairer and Schöniger's forgotten tobacco epidemiology and the Nazi quest for racial purity". International Journal of Epidemiology. 30 (1): 31–4. doi:10.1093/ije/30.1.31. PMID 11171846.

- ^ Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C (March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–53. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831. S2CID 5903121.

- ^ ASPA. "Health Effects of Tobacco". Archived from the original on 2014-09-20. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I (June 2004). "Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors". BMJ. 328 (7455): 1519. doi:10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. PMC 437139. PMID 15213107.

- ^ "Life Expectancy at Age 30: Nonsmoking Versus Smoking Men". Tobacco Documents Online. Archived from the original on 2012-04-19. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ^ Ferrucci L, Izmirlian G, Leveille S, Phillips CL, Corti MC, Brock DB, Guralnik JM (April 1999). "Smoking, physical activity, and active life expectancy". American Journal of Epidemiology. 149 (7): 645–53. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009865. PMID 10192312.

- ^ Doll R, Peto R, Wheatley K, Gray R, Sutherland I (October 1994). "Mortality in relation to smoking: 40 years' observations on male British doctors". BMJ. 309 (6959): 901–11. doi:10.1136/bmj.309.6959.901. PMC 2541142. PMID 7755693.

- ^ Villeneuve PJ, Mao Y (1994). "Lifetime probability of developing lung cancer, by smoking status, Canada". Canadian Journal of Public Health. 85 (6): 385–8. PMID 7895211.

- ^ Løkke A, Lange P, Scharling H, Fabricius P, Vestbo J (November 2006). "Developing COPD: a 25 year follow up study of the general population". Thorax. 61 (11): 935–9. doi:10.1136/thx.2006.062802. PMC 2121175. PMID 17071833.

- ^ Johnson K (Jan 24, 2018). "Just one cigarette a day seriously elevates cardiovascular risk". British Medical Journal. 360: k167. doi:10.1136/bmj.k167. PMID 29367307. S2CID 46825572.

- ^ "Just one cigarette a day can cause serious heart problems". New Scientist. Feb 3, 2020.

- ^ "Benefits of Quitting – American Lung Association". Stop Smoking. American Lung Association. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ^ "Light Cigarettes and Cancer Risk". National Cancer Institute. 2005-08-18. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ Rizzuto D, Fratiglioni L (2014). "Lifestyle factors related to mortality and survival: a mini-review". Gerontology. 60 (4): 327–35. doi:10.1159/000356771. PMID 24557026.

- ^ Samet JM (May 2013). "Tobacco smoking: the leading cause of preventable disease worldwide". Thoracic Surgery Clinics. 23 (2): 103–12. doi:10.1016/j.thorsurg.2013.01.009. PMID 23566962.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (April 2002). "Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs—United States, 1995–1999". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 51 (14): 300–3. PMID 12002168.

- ^ Streppel MT, Boshuizen HC, Ocké MC, Kok FJ, Kromhout D (April 2007). "Mortality and life expectancy in relation to long-term cigarette, cigar and pipe smoking: the Zutphen Study". Tobacco Control. 16 (2): 107–13. doi:10.1136/tc.2006.017715. PMC 2598467. PMID 17400948.

- ^ "Treating Nicotine Addiction" (PDF). The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-29. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- ^ "HEALTH | Cigarettes 'cut life by 11 minutes'". BBC News. 1999-12-31. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ^ Shaw M (2000). "Time for a smoke? One cigarette reduces your life by 11 minutes". BMJ. 320 (7226): 53. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7226.53. PMC 1117323. PMID 10617536.

- ^ Mamun AA, Peeters A, Barendregt J, Willekens F, Nusselder W, Bonneux L (March 2004). "Smoking decreases the duration of life lived with and without cardiovascular disease: a life course analysis of the Framingham Heart Study". European Heart Journal. 25 (5): 409–15. doi:10.1016/j.ehj.2003.12.015. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30081703. PMID 15033253.

- ^ Thun MJ, Day-Lally CA, Calle EE, Flanders WD, Heath CW (September 1995). "Excess mortality among cigarette smokers: changes in a 20-year interval". American Journal of Public Health. 85 (9): 1223–30. doi:10.2105/AJPH.85.9.1223. PMC 1615570. PMID 7661229.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "America's Health Rankings – 2011" (PDF). United Health Foundation. December 2011. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-18. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (November 2008). "Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses—United States, 2000–2004". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 57 (45): 1226–8. PMID 19008791.

- ^ Never Say Die, an ABC News special by Peter Jennings 6/27/1996

- ^ "21st Century Could See a Billion Tobacco Victims" (PDF). Tobacco News Flash. 3 (12): 1. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ^ Carter BD, Abnet CC, Feskanich D, Freedman ND, Hartge P, Lewis CE, Ockene JK, Prentice RL, Speizer FE, Thun MJ, Jacobs EJ (February 2015). "Smoking and mortality—beyond established causes". The New England Journal of Medicine. 372 (7): 631–40. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1407211. PMID 25671255. S2CID 34821377.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Proctor RN (2012-02-16). "The history of the discovery of the cigarette–lung cancer link: evidentiary traditions, corporate denial, global toll: Table 1". Tobacco Control. 21 (2): 87–91. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050338. ISSN 0964-4563. PMID 22345227.

- ^ Cohen BL (September 1991). "Catalog of Risks Extended and Updated". Health Physics. 61 (3): 317–335. doi:10.1097/00004032-199109000-00002. ISSN 0017-9078. PMID 1880022.

- ^ "The Kathmandu Post | Read online latest news and articles from Nepal". kathmandupost.com. Retrieved 2024-02-24.

- ^ "Share of deaths from smoking". Our World in Data. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ "Death rate from smoking". Our World in Data. Retrieved 5 March 2020.