Йельский университет

| |

| Латынь : Университет Яленсиса. | |

Прежние имена | Университетская школа (1701–1718) Йельский колледж (1718–1887) |

|---|---|

| Девиз | Свет и истина ( лат .) Урим и Тамим ( иврит ) |

Девиз на английском языке | «Свет и истина» |

| Тип | Частный исследовательский университет |

| Учредил | 9 октября 1701 г |

| Аккредитация | СКОЛЬКО |

Академическая принадлежность | |

| Пожертвование | 40,7 млрд долларов (2023 г.) [1] |

| Президент | Питер Саловей [2] |

| Провост | Скотт Стробел [3] |

Академический состав | 5499 (осень 2023 г.) [4] |

| Студенты | 15 081 (осень 2023 г.) [5] |

| Студенты | 6749 (осень 2023 г.) [5] |

| Аспиранты | 8263 (осень 2023 г.) [5] |

| Расположение | , , Соединенные Штаты 41 ° 18'59 "N 72 ° 55'20" W / 41,31639 ° N 72,92222 ° W |

| Кампус | Город среднего размера , 1015 акров (411 га) |

| Газета | Йель Дейли Ньюс |

| Цвета | Йельский синий [6] |

| Псевдоним | Бульдоги |

Спортивная принадлежность | |

| Талисман | Красавчик Дэн |

| Веб-сайт | Йельский университет |

Йельский университет — частный Лиги плюща исследовательский университет в Нью-Хейвене, штат Коннектикут . Основанный в 1701 году, Йельский университет является третьим старейшим высшим учебным заведением в Соединенных Штатах и одним из девяти колониальных колледжей, созданных до американской революции . [7]

Йельский университет был основан как университетская школа в 1701 году конгрегационалистским духовенством колонии Коннектикут . Первоначально ограниченная обучением служителей богословию и священным языкам учебная программа школы расширилась, включив в нее гуманитарные и естественные науки , ко времени Американской революции . В 19 веке колледж расширился до аспирантуры и профессионального обучения, присвоив первую докторскую степень в Соединенных Штатах в 1861 году и превратившись в университет в 1887 году. После 1890 года количество преподавателей и студентов Йельского университета быстро росло из-за расширения физического кампуса и свои научно-исследовательские программы.

Йельский университет состоит из четырнадцати школ, включая первоначальный бакалавриат , Йельскую высшую школу искусств и наук и Йельскую юридическую школу . [8] Хотя университетом управляет Йельская корпорация каждой школы , преподаватели курируют его учебную программу и программы получения степени. Помимо центрального кампуса в центре Нью-Хейвена , университет владеет спортивными сооружениями в западной части Нью-Хейвена, кампусом в Вест-Хейвене , а также лесами и природными заповедниками по всей Новой Англии . По состоянию на 2023 год [update] оценивались Пожертвования университета в 40,7 миллиардов долларов, что является третьим по величине среди всех учебных заведений . [1] Библиотека Йельского университета , обслуживающая все входящие в ее состав школы, насчитывает более 15 миллионов томов и является третьей по величине академической библиотекой в Соединенных Штатах. [9] [10] Студенты-спортсмены соревнуются в межвузовских видах спорта под названием «Йельские бульдоги» на конференции NCAA Division I Лиги плюща .

По состоянию на октябрь 2020 г. [update] 65 нобелевских лауреатов, пять медалистов Филдса , четыре лауреата Абеля и три лауреата премии Тьюринга С Йельским университетом связаны . Кроме того, Йельский университет выпустил множество выдающихся выпускников , в том числе пять президентов США , 10 отцов-основателей , 19 судей Верховного суда США , 31 ныне живущего миллиардера , [11] 54 основателя и президента колледжей , многие главы государств , кабинета министров члены и губернаторы . Сотни членов Конгресса и многие американские дипломаты , 78 стипендиатов Макартура , 263 стипендиата Родса , 123 стипендиата Маршалла , 81 стипендиат Гейтса из Кембриджа , 102 стипендиата Гуггенхайма и девять стипендиатов Митчелла были связаны с университетом. В настоящее время в состав профессорско-преподавательского состава Йельского университета входят 67 членов Национальной академии наук . [12] 55 членов Национальной медицинской академии , [13] 8 членов Национальной инженерной академии , [14] и 187 членов Американской академии искусств и наук . [15]

История [ править ]

Йельского история Ранняя колледжа

Происхождение [ править ]

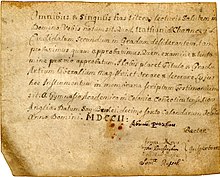

Йельский университет берет свое начало с «Закона о свободе строительства университетской школы», будущей хартии, принятой в Нью-Хейвене Генеральным судом колонии Коннектикут 9 октября 1701 года. Закон был попыткой создать учреждение обучать служителей и светских лидеров. Вскоре после этого группа из десяти Конгрегации служителей Сэмюэл Эндрю , Томас Бэкингем, Исраэль Чонси, Сэмюэл Мэзер (племянник Инкриза Мэзера ), преподобный Джеймс Нойес II (сын Джеймса Нойеса ), Джеймс Пирпонт , Авраам Пирсон , Ноадия Рассел , Джозеф Уэбб и Тимоти Вудбридж , Гарварда выпускники , встретились в кабинете преподобного Сэмюэля Рассела в Брэнфорде , чтобы пожертвовать книги для формирования школьной библиотеки. [16] Группа, возглавляемая Джеймсом Пирпонтом , теперь известна как «Основатели». [17]

Это учебное заведение, известное по своему происхождению как «Университетская школа», открылось в доме своего первого ректора Авраама Пирсона, который считается первым президентом Йельского университета. Пирсон жил в Киллингворте . Школа переехала в Сэйбрук в 1703 году, когда первый казначей Йельского университета Натаниэль Линд пожертвовал землю и здание. В 1716 году он переехал в Нью-Хейвен.

Тем временем в Гарварде образовался раскол между шестым президентом Инкрисом Мэзером и остальным духовенством Гарварда, которого Мэзер считал все более либеральным, церковно-расслабленным и чрезмерно широким в церковной политике . Вражда заставила Мазерсов выступить в защиту Университетской школы в надежде, что она сохранит пуританскую религиозную ортодоксальность, чего не удалось сделать Гарварду. [18] Преподобный Джейсон Хейвен , служитель Первой церкви и прихода в Дедхэме , штат Массачусетс, рассматривался на пост президента из-за его ортодоксального богословия и «аккуратности, достоинства и чистоты стиля, [которые] превосходят все, что было упомянуто». но его обошли вниманием из-за его «очень ветхого и слабого состояния здоровья». [19]

и Именование развитие

В 1718 году по указанию ректора Сэмюэля Эндрю или губернатора колонии Гердона Солтонстолла Коттон Мэзер связался с уроженцем Бостона бизнесменом Элиху Йелем , чтобы попросить денег на строительство нового здания для колледжа. По уговорам Джереми Даммера , Йельский университет, который заработал состояние в Мадрасе , работая в Ост-Индской компании в качестве первого президента форта Сент-Джордж , пожертвовал девять тюков товаров, которые были проданы на сумму более 560 фунтов стерлингов, что является значительной суммой. сумма денег. Коттон Мэзер предложил школе сменить название на «Йельский колледж». [20] Название Йель — это англизированное написание валлийского имени Иал , которое использовалось для названия семейного поместья в Плас-ин-Иал, недалеко от Лландеглы , Уэльс.

Тем временем выпускник Гарварда, работавший в Англии, убедил 180 выдающихся интеллектуалов пожертвовать книги Йельскому университету. Партия из 500 книг 1714 года представляла собой лучшее из современной английской литературы, науки, философии и теологии. [21] Это оказало глубокое влияние на интеллектуалов Йельского университета. Студент Джонатан Эдвардс открыл для себя Джона Локка работы и развил свою « новую божественность ». В 1722 году ректор и шестеро друзей, у которых была группа по изучению новых идей, объявили, что они отказались от кальвинизма , стали арминианами и присоединились к англиканской церкви . Они были рукоположены в Англии и вернулись в колонии в качестве миссионеров англиканской веры. Томас Клэпп стал президентом в 1745 году и, хотя он пытался вернуть колледж в кальвинистскую ортодоксальность, не закрыл библиотеку. Другие студенты нашли Деиста . в библиотеке книги [22]

Учебный план [ править ]

Студенты Йельского колледжа обучаются по программе гуманитарных наук по факультетским специальностям и организованы в социальную систему колледжей-интернатов .

Йельский университет был охвачен великими интеллектуальными движениями того периода — Великим Пробуждением и Просвещением — благодаря религиозным и научным интересам президентов Томаса Клэпа и Эзры Стайлза . Они сыграли важную роль в разработке научной учебной программы, одновременно имея дело с войнами, студенческими волнениями, граффити, «неуместностью» учебных программ, отчаянной потребностью в пожертвованиях и разногласиями с законодательным органом Коннектикута . [23] [24] [ нужна страница ]

Серьезные американские исследователи теологии и богословия, особенно в Новой Англии, считали иврит классическим языком , наряду с греческим и латынью , и необходимым для изучения Ветхого Завета в оригинале. Преподобный Стайлз, президент с 1778 по 1795 год, принес с собой свой интерес к ивриту как средству изучения древних библейских текстов на языке оригинала, требуя от всех первокурсников изучать иврит (в отличие от Гарварда, где его должны были изучать только старшеклассники). и отвечает за еврейскую фразу אורים ותמים ( Урим и Туммим ) на печати Йельского университета. Выпускник Йельского университета 1746 года, Стайлз поступил в колледж с опытом работы в сфере образования, сыграв важную роль в основании Университета Брауна . [25] Самая большая проблема Стайлза возникла в 1779 году, когда британские войска оккупировали Нью-Хейвен и пригрозили снести колледж. Однако вмешался выпускник Йельского университета Эдмунд Фаннинг , секретарь британского генерала, командующего оккупацией, и колледж был спасен. В 1803 году Фэннингу была присвоена почетная степень доктора юридических наук. . [26]

Студенты [ править ]

Будучи единственным колледжем в Коннектикуте с 1701 по 1823 год, Йельский университет обучал сыновей элиты. [27] Наказуемые правонарушения включали игру в карты , посещение таверн, разрушение имущества колледжа и акты неповиновения. Гарвард отличался стабильностью и зрелостью своего преподавательского состава, тогда как Йельский университет отличался молодостью и рвением. [28]

Акцент на классике привел к появлению частных студенческих обществ, открытых только по приглашению, которые возникли как форумы для дискуссий о науке, литературе и политике. Первыми были дискуссионные общества: «Кротония» в 1738 г., «Линония» в 1753 г. и «Братья в единстве» в 1768 г. Линония и «Братья в единстве» продолжают существовать; в память о них можно найти имена, присвоенные структурам кампуса, например, «Братья во дворе единства» в Брэнфордском колледже.

19 век [ править ]

Йельский отчет 1828 года представлял собой догматическую защиту учебной программы по латыни и греческому языку от критиков, которые хотели большего количества курсов по современным языкам, математике и естественным наукам. В отличие от высшего образования в Европе не существовало национальной учебной программы , в колледжах и университетах США . В борьбе за студентов и финансовую поддержку руководители колледжей стремились идти в ногу с требованиями инноваций. В то же время они поняли, что значительная часть студентов и будущих студентов требует классического образования. Отчет означал, что от классики не будут отказываться. В этот период учебные заведения экспериментировали с изменениями в учебной программе, что часто приводило к созданию двойной учебной программы. В децентрализованной среде высшего образования США баланс между изменениями и традициями был общей проблемой. [29] [30] A group of professors at Yale and New Haven Congregationalist ministers articulated a conservative response to the changes brought by Victorian culture. They concentrated on developing a person possessed of religious values strong enough to sufficiently resist temptations from within, yet flexible enough to adjust to the 'isms' (professionalism, materialism, individualism, and consumerism) tempting them from without.[31][page needed] William Graham Sumner, professor from 1872 to 1909, taught in the emerging disciplines of economics and sociology to overflowing classrooms. Sumner bested President Noah Porter, who disliked the social sciences and wanted Yale to lock into its traditions of classical education. Porter objected to Sumner's use of a textbook by Herbert Spencer that espoused agnostic materialism because it might harm students.[32]

Until 1887, the legal name of the university was "The President and Fellows of Yale College, in New Haven." In 1887, under an act passed by the Connecticut General Assembly, Yale was renamed "Yale University".[33]

Sports and debate[edit]

The Revolutionary War soldier Nathan Hale (Yale 1773) was the archetype of the Yale ideal in the early 19th century: a manly yet aristocratic scholar, well-versed in knowledge and sports, and a patriot who "regretted" that he "had but one life to lose" for his country. Western painter Frederic Remington (Yale 1900) was an artist whose heroes gloried in the combat and tests of strength in the Wild West. The fictional, turn-of-the-20th-century Yale man Frank Merriwell embodied this same heroic ideal without racial prejudice, and his fictional successor Dink Stover in the novel Stover at Yale (1912) questioned the business mentality that had become prevalent at the school. Increasingly students turned to athletic stars as their heroes, especially since winning the big game became the goal of the student body, the alumni, and the team itself.[34]

Along with Harvard and Princeton, Yale students rejected British concepts about 'amateurism' and constructed athletic programs that were uniquely American.[35] The Harvard–Yale football rivalry began in 1875. Between 1892, when Harvard and Yale met in one of the first intercollegiate debates,[36] and in 1909 (year of the first Triangular Debate of Harvard/Yale/Princeton) the rhetoric, symbolism, and metaphors used in athletics were used to frame these debates. Debates were covered on front pages of college newspapers and emphasized in yearbooks, and team members received the equivalent of athletic letters for their jackets. There were rallies to send off teams to matches, but they never attained the broad appeal athletics enjoyed. One reason may be that debates do not have a clear winner, because scoring is subjective. With late 19th-century concerns about the impact of modern life on the body, athletics offered hope that neither the individual nor society was coming apart.[37]

In 1909–10, football faced a crisis resulting from the failure of the reforms of 1905–06, which sought to solve the problem of serious injuries. There was a mood of alarm and mistrust, and, while the crisis was developing, the presidents of Harvard, Yale, and Princeton developed a project to reform the sport and forestall possible radical changes forced by government. Presidents Arthur Hadley of Yale, A. Lawrence Lowell of Harvard, and Woodrow Wilson of Princeton worked to develop moderate reforms to reduce injuries. Their attempts, however, were reduced by rebellion against the rules committee and formation of the Intercollegiate Athletic Association. While the big three had attempted to operate independently of the majority, the changes pushed did reduce injuries.[38]

Expansion[edit]

Starting with the addition of the Yale School of Medicine in 1810, the college expanded gradually, establishing the Yale Divinity School in 1822, Yale Law School in 1822, the Yale Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in 1847, the now-defunct Sheffield Scientific School in 1847,[a] and the Yale School of Fine Arts in 1869. In 1887, under the presidency of Timothy Dwight V, Yale College was renamed to Yale University, and the former name was applied only to the undergraduate college. The university would continue to expand into the 20th and 21st centuries, adding the Yale School of Music in 1894, the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies in 1900, the Yale School of Public Health in 1915, the Yale School of Architecture in 1916, the Yale School of Nursing 1923, the Yale School of Drama in 1955, the Yale School of Management in 1976, and the Jackson School of Global Affairs in 2022.[39] The Sheffield Scientific School would also reorganize its relationship with the university to teach only undergraduate courses.

Expansion caused controversy about Yale's new roles. Noah Porter, a moral philosopher, was president from 1871 to 1886. During an age of expansion in higher education, Porter resisted the rise of the new research university, claiming an eager embrace of its ideals would corrupt undergraduate education. Historian George Levesque argues Porter was not a simple-minded reactionary, uncritically committed to tradition, but a principled and selective conservative.[40][page needed] Levesque says he did not endorse everything old or reject everything new; rather, he sought to apply long-established ethical and pedagogical principles to a changing culture. Levesque concludes, noting he may have misunderstood some of the challenges, but he correctly anticipated the enduring tensions that have accompanied the emergence of the modern university.

20th century[edit]

Medicine[edit]

Milton Winternitz led the Yale School of Medicine as its dean from 1920 to 1935. Dedicated to the new scientific medicine established in Germany, he was equally fervent about "social medicine" and the study of humans in their environment. He established the "Yale System" of teaching, with few lectures and fewer exams, and strengthened the full-time faculty system; he created the graduate-level Yale School of Nursing and the psychiatry department and built new buildings. Progress toward his plans for an Institute of Human Relations, envisioned as a refuge where social scientists would collaborate with biological scientists in a holistic study of humankind, lasted only a few years before resentful antisemitic colleagues drove him to resign.[41]

Faculty[edit]

Before World War II, most elite university faculties counted among their numbers few, if any, Jews, blacks, women, or other minorities; Yale was no exception. By 1980, this condition had been altered dramatically, as numerous members of those groups held faculty positions.[42] Almost all members of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences—and some members of other faculties—teach undergraduate courses, more than 2,000 of which are offered annually.[43]

Women[edit]

In 1793, Lucinda Foote passed the entrance exams for Yale College, but was rejected by the president on the basis of her gender.[44] Women studied at Yale from 1892, in graduate-level programs at the Yale Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.[45] The first seven women to earn PhDs received their degrees in 1894: Elizabeth Deering Hanscom, Cornelia H. B. Rogers, Sara Bulkley Rogers, Margaretta Palmer, Mary Augusta Scott, Laura Johnson Wylie, and Charlotte Fitch Roberts. There is a portrait of them in Sterling Memorial Library, painted by Brenda Zlamany.[46]

In 1966, Yale began discussions with its sister school Vassar College about merging to foster coeducation at the undergraduate level. Vassar, then all-female and part of the Seven Sisters—elite higher education schools that served as sister institutions to the Ivy League when Ivy League institutions still only admitted men—tentatively accepted, but then declined the invitation. Both schools introduced coeducation independently in 1969.[47] Amy Solomon was the first woman to register as a Yale undergraduate;[48] she was the first woman at Yale to join an undergraduate society, St. Anthony Hall. The undergraduate class of 1973 was the first to have women starting from freshman year;[49] all undergraduate women were housed in Vanderbilt Hall.[50]

A decade into co-education, student assault and harassment by faculty became the impetus for the trailblazing lawsuit Alexander v. Yale. In the 1970s, a group of students and a faculty member sued Yale for its failure to curtail sexual harassment, especially by male faculty. The case was partly built from a 1977 report authored by plaintiff Ann Olivarius, "A report to the Yale Corporation from the Yale Undergraduate Women's Caucus."[51] This case was the first to use Title IX to argue and establish that sexual harassment of female students can be considered illegal sex discrimination. The plaintiffs were Olivarius, Ronni Alexander, Margery Reifler, Pamela Price[52], and Lisa E. Stone. They were joined by Yale classics professor John "Jack" J. Winkler. The lawsuit, brought partly by Catharine MacKinnon, alleged rape, fondling, and offers of higher grades for sex by faculty, including Keith Brion, professor of flute and director of bands, political science professor Raymond Duvall,[53] English professor Michael Cooke, and coach of the field hockey team, Richard Kentwell. While unsuccessful in the courts, the legal reasoning changed the landscape of sex discrimination law and resulted in the establishment of Yale's Grievance Board and Women's Center.[54] In 2011 a Title IX complaint was filed against Yale by students and graduates, including editors of Yale's feminist magazine Broad Recognition, alleging the university had a hostile sexual climate.[55] In response, the university formed a Title IX steering committee to address complaints of sexual misconduct.[56] Afterwards, universities and colleges throughout the US also established sexual harassment grievance procedures.

Class[edit]

Yale instituted policies in the early 20th century designed to maintain the proportion of white Protestants from notable families in the student body (see numerus clausus) and eliminated such preferences, beginning with the class of 1970.[57]

21st century[edit]

In 2006, Yale and Peking University (PKU) established a Joint Undergraduate Program in Beijing, an exchange program allowing Yale students to spend a semester living and studying with PKU honor students.[58] In July 2012, the Yale University-PKU Program ended due to weak participation.[58]

In 2007 outgoing Yale President Rick Levin characterized Yale's institutional priorities: "First, among the nation's finest research universities, Yale is distinctively committed to excellence in undergraduate education. Second, in our graduate and professional schools, as well as in Yale College, we are committed to the education of leaders."[59]

In 2009, former British Prime Minister Tony Blair picked Yale as one location – the others being Britain's Durham University and Universiti Teknologi Mara – for the Tony Blair Faith Foundation's United States Faith and Globalization Initiative.[60] As of 2009, former Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo is the director of the Yale Center for the Study of Globalization and teaches an undergraduate seminar, "Debating Globalization".[61] As of 2009, former presidential candidate and DNC chair Howard Dean teaches a residential college seminar, "Understanding Politics and Politicians".[62] Also in 2009, an alliance was formed among Yale, University College London, and both schools' affiliated hospital complexes to conduct research focused on the direct improvement of patient care—a field known as translational medicine. President Richard Levin noted that Yale has hundreds of other partnerships across the world, but "no existing collaboration matches the scale of the new partnership with UCL".[63] In August 2013, a new partnership with the National University of Singapore led to the opening of Yale-NUS College in Singapore, a joint effort to create a new liberal arts college in Asia featuring a curriculum including Western and Asian traditions.[64]

In 2017, having been suggested for decades,[65] Yale University renamed Calhoun College, named for slave owner, anti-abolitionist, and white supremacist Vice President John C. Calhoun. It is now Hopper College, after Grace Hopper.[66][67]

In 2020, in the wake of the George Floyd protests, the #CancelYale tag was used on social media to demand that Elihu Yale's name be removed from Yale University. Much of the support originated from right-wing pundits such as Mike Cernovich and Ann Coulter, who intended to satirize what they perceived as the excesses of cancel culture.[68] Yale spent most of his professional career in the employ of the East India Company (EIC), serving as the governor of the Presidency of Fort St. George in modern-day Chennai. The EIC, including Yale himself, was involved in the Indian Ocean slave trade, though the extent of Yale's involvement in slavery remains debated.[69]His singularly large donation led critics to argue Yale University relied on money derived from slavery for its first scholarships and endowments.[70][71][72][73]

In 2020, the US Justice Department sued Yale for alleged discrimination against Asian and white candidates, through affirmative action admission policies.[74] In 2021, under the new Biden administration, the Justice Department withdrew the lawsuit. The group, Students for Fair Admissions, later won a similar lawsuit against Harvard.[75]

Alumni in politics[edit]

The Boston Globe wrote in 2002 that "if there's one school that can lay claim to educating the nation's top national leaders over the past three decades, it's Yale".[76] Yale alumni were represented on the Democratic or Republican ticket in every U.S. presidential election between 1972 and 2004.[77] Yale-educated presidents since the end of the Vietnam War include Gerald Ford, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush, and major-party nominees include Hillary Clinton (2016), John Kerry (2004), Joseph Lieberman (vice president, 2000), and Sargent Shriver (vice president, 1972). Other alumni who have made serious bids for the presidency include Amy Klobuchar (2020), Tom Steyer (2020), Ben Carson (2016), Howard Dean (2004), Gary Hart (1984 and 1988), Paul Tsongas (1992), Pat Robertson (1988) and Jerry Brown (1976, 1980, 1992).

Several explanations have been offered for Yale's representation since the end of the Vietnam War. Sources note the spirit of campus activism that has existed at Yale since the 1960s, and the intellectual influence of Reverend William Sloane Coffin on future candidates.[78] Yale President Levin attributes the run to Yale's focus on creating "a laboratory for future leaders", an institutional priority that began during the tenure of Yale Presidents Alfred Whitney Griswold and Kingman Brewster.[78] Richard H. Brodhead, former dean of Yale College and now president of Duke University, stated: "We do give very significant attention to orientation to the community in our admissions, and there is a very strong tradition of volunteerism at Yale."[76] Yale historian Gaddis Smith notes "an ethos of organized activity" at Yale during the 20th century that led Kerry to lead the Yale Political Union's Liberal Party, George Pataki the Conservative Party, and Lieberman to manage the Yale Daily News.[79] Camille Paglia points to a history of networking and elitism: "It has to do with a web of friendships and affiliations built up in school."[80] CNN suggests that George W. Bush benefited from preferential admissions policies for the "son and grandson of alumni", and for a "member of a politically influential family".[81] Elisabeth Bumiller and James Fallows credit the culture of community that exists between students, faculty, and administration, which downplays self-interest and reinforces commitment to others.[82]

During the 1988 presidential election, George H. W. Bush (Yale '48) derided Michael Dukakis for having "foreign-policy views born in Harvard Yard's boutique". When challenged on the distinction between Dukakis's Harvard connection and his Yale background, he said that, unlike Harvard, Yale's reputation was "so diffuse, there isn't a symbol, I don't think, in the Yale situation, any symbolism in it" and said Yale did not share Harvard's reputation for "liberalism and elitism".[83] In 2004 Howard Dean stated, "In some ways, I consider myself separate from the other three (Yale) candidates of 2004. Yale changed so much between the class of '68 and the class of '71. My class was the first class to have women in it; it was the first class to have a significant effort to recruit African Americans. It was an extraordinary time, and in that span of time is the change of an entire generation".[82]

Administration and organization[edit]

Leadership[edit]

The President and Fellows of Yale College, also known as the Yale Corporation, or board of trustees, is the governing body of the university and consists of thirteen standing committees with separate responsibilities outlined in the by-laws. The corporation has 19 members: three ex officio members, ten successor trustees, and six elected alumni fellows.[84] The university has three major academic components: Yale College (the undergraduate program), the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and the twelve professional schools.[85]

Yale's former president Richard C. Levin was, at the time, one of the highest paid university presidents in the United States with a 2008 salary of $1.5 million.[86] Yale's succeeding president Peter Salovey ranks 40th with a 2020 salary of $1.16 million.[87]

The Yale Provost's Office and similar executive positions have launched several women into prominent university executive positions. In 1977, Provost Hanna Holborn Gray was appointed interim president of Yale and later went on to become president of the University of Chicago, being the first woman to hold either position at each respective school.[88][89] In 1994, Provost Judith Rodin became the first permanent female president of an Ivy League institution at the University of Pennsylvania.[90] In 2002, Provost Alison Richard became the vice-chancellor of the University of Cambridge.[91] In 2003, the dean of the Divinity School, Rebecca Chopp, was appointed president of Colgate University and later went on to serve as the president of Swarthmore College in 2009, and then the first female chancellor of the University of Denver in 2014.[92] In 2004, Provost Dr. Susan Hockfield became the president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[93] In 2004, Dean of the Nursing school, Catherine Gilliss, was appointed the dean of Duke University's School of Nursing and vice chancellor for nursing affairs.[94] In 2007, Deputy Provost H. Kim Bottomly was named president of Wellesley College.[95]

Similar examples for men who have served in Yale leadership positions can also be found. In 2004, Dean of Yale College Richard H. Brodhead was appointed as the president of Duke University.[96] In 2008, Provost Andrew Hamilton was confirmed to be the vice chancellor of the University of Oxford.[97]

Staff and labor unions[edit]

Yale University staff are represented by several different unions. Clerical and technical workers are represented by Local 34, and service and maintenance workers are represented by Local 35, both of the same union affiliate UNITE HERE.[98] Unlike similar institutions, Yale has consistently refused to recognize its graduate student union, Local 33 (another affiliate of UNITE HERE), citing claims that the union's elections were undemocratic and how graduate students are not employees;[99][100] the move to not recognize the union has been criticized by the American Federation of Teachers.[101] In addition, officers of the Yale University Police Department are represented by the Yale Police Benevolent Association, which affiliated in 2005 with the Connecticut Organization for Public Safety Employees.[98][102] Yale security officers joined the International Union of Security, Police and Fire Professionals of America in late 2010,[103] even though the Yale administration contested the election.[104] In October 2014, after deliberation,[105] Yale security decided to form a new union, the Yale University Security Officers Association, which has since represented the campus security officers.[98][106]

Yale has a history of difficult and prolonged labor negotiations, often culminating in strikes.[107][page needed] There have been at least eight strikes since 1968, and The New York Times wrote that Yale has a reputation as having the worst record of labor tension of any university in the U.S.[108] Moreover, Yale has been accused by the AFL–CIO of failing to treat workers with respect,[109] as well as not renewing contracts with professors over involvement in campus labor issues.[110] Yale has responded to strikes with claims over mediocre union participation and the benefits of their contracts.[111]

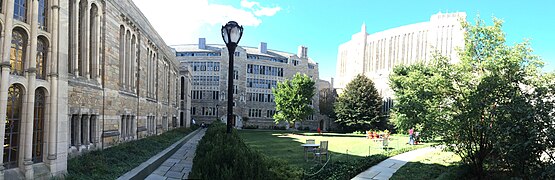

Campus[edit]

Yale's central campus in downtown New Haven covers 260 acres (1.1 km2) and comprises its main, historic campus and a medical campus adjacent to the Yale–New Haven Hospital. In western New Haven, the university holds 500 acres (2.0 km2) of athletic facilities, including the Yale Golf Course.[112] In 2008, Yale purchased the 17-building, 136-acre (0.55 km2) former Bayer HealthCare complex in West Haven, Connecticut,[113] the buildings of which are now used as laboratory and research space.[114] Yale also owns seven forests in Connecticut, Vermont, and New Hampshire—the largest of which is the 7,840-acre (31.7 km2) Yale-Myers Forest in Connecticut's Quiet Corner—and nature preserves including Horse Island.[115]

Yale is noted for its largely Collegiate Gothic campus[116] as well as several iconic modern buildings commonly discussed in architectural history survey courses: Louis Kahn's Yale Art Gallery[117] and Center for British Art, Eero Saarinen's Ingalls Rink and Ezra Stiles and Morse Colleges, and Paul Rudolph's Art & Architecture Building. Yale also owns and has restored many noteworthy 19th-century mansions along Hillhouse Avenue, which was considered the most beautiful street in America by Charles Dickens when he visited the United States in the 1840s.[118] In 2011, Travel + Leisure listed the Yale campus as one of the most beautiful in the United States.[119]

Many of Yale's buildings were constructed in the Collegiate Gothic architecture style from 1917 to 1931, financed largely by Edward S. Harkness, including the Yale Drama School.[120][121] Stone sculpture built into the walls of the buildings portray contemporary college personalities, such as a writer, an athlete, a tea-drinking socialite, and a student who has fallen asleep while reading. Similarly, the decorative friezes on the buildings depict contemporary scenes, like a policemen chasing a robber and arresting a prostitute (on the wall of the Law School), or a student relaxing with a mug of beer and a cigarette. The architect, James Gamble Rogers, faux-aged these buildings by splashing the walls with acid,[122] deliberately breaking their leaded glass windows and repairing them in the style of the Middle Ages, and creating niches for decorative statuary but leaving them empty to simulate loss or theft over the ages. In fact, the buildings merely simulate Middle Ages architecture, for though they appear to be constructed of solid stone blocks in the authentic manner, most actually have steel framing as was commonly used in 1930. One exception is Harkness Tower, 216 feet (66 m) tall, which was originally a free-standing stone structure. It was reinforced in 1964 to allow the installation of the Yale Memorial Carillon.

Other examples of the Gothic style are on the Old Campus by architects like Henry Austin, Charles C. Haight and Russell Sturgis. Several are associated with members of the Vanderbilt family, including Vanderbilt Hall,[123] Phelps Hall,[124] St. Anthony Hall (a commission for member Frederick William Vanderbilt), the Mason, Sloane and Osborn laboratories, dormitories for the Sheffield Scientific School (the engineering and sciences school at Yale until 1956) and elements of Silliman College, the largest residential college.[125]

The oldest building on campus, Connecticut Hall (built in 1750), is in the Georgian style. Georgian-style buildings erected from 1929 to 1933 include Timothy Dwight College, Pierson College, and Davenport College, except the latter's east, York Street façade, which was constructed in the Gothic style to coordinate with adjacent structures.

The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, designed by Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, is one of the largest buildings in the world reserved exclusively for the preservation of rare books and manuscripts. The library includes a six-story above-ground tower of book stacks, filled with 180,000 volumes, that is surrounded by large translucent Vermont marble panels and a steel and granite truss. The panels act as windows and subdue direct sunlight while also diffusing the light in warm hues throughout the interior.[126] Near the library is a sunken courtyard with sculptures by Isamu Noguchi that are said to represent time (the pyramid), the sun (the circle), and chance (the cube).[127] The library is located near the center of the university in Hewitt Quadrangle, which is now more commonly referred to as "Beinecke Plaza".

Alumnus Eero Saarinen, Finnish-American architect of such notable structures as the Gateway Arch in St. Louis, Washington Dulles International Airport main terminal, Bell Labs Holmdel Complex and the CBS Building in Manhattan, designed Ingalls Rink, dedicated in 1959,[128] as well as the residential colleges Ezra Stiles and Morse.[129] These latter were modeled after the medieval Italian hill town of San Gimignano – a prototype chosen for the town's pedestrian-friendly milieu and fortress-like stone towers.[130] These tower forms at Yale act in counterpoint to the college's many Gothic spires and Georgian cupolas.[131]

The athletic field complex is partially in New Haven, and partially in West Haven.[132]

Notable nonresidential campus buildings[edit]

Notable nonresidential campus buildings and landmarks include Battell Chapel, Beinecke Rare Book Library, Harkness Tower, Humanities Quadrangle, Ingalls Rink, Kline Biology Tower, Osborne Memorial Laboratories, Payne Whitney Gymnasium, Peabody Museum of Natural History, Sterling Hall of Medicine, Sterling Law Buildings, Sterling Memorial Library, Woolsey Hall, Yale Center for British Art, Yale University Art Gallery, Yale Art & Architecture Building, and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art in London.

Yale's secret society buildings (some of which are called "tombs") were built to be private yet unmistakable. A diversity of architectural styles is represented: Berzelius, Donn Barber in an austere cube with classical detailing (erected in 1908 or 1910); Book and Snake, Louis R. Metcalfe in a Greek Ionic style (erected in 1901); Elihu, architect unknown but built in a Colonial style (constructed on an early 17th-century foundation although the building is from the 18th century); Mace and Chain, in a late colonial, early Victorian style (built in 1823). (Interior moulding is said to have belonged to Benedict Arnold); Manuscript Society, King-lui Wu with Dan Kiley responsible for landscaping and Josef Albers for the brickwork intaglio mural. Building constructed in a mid-century modern style; Scroll and Key, Richard Morris Hunt in a Moorish- or Islamic-inspired Beaux-Arts style (erected 1869–70); Skull and Bones, possibly Alexander Jackson Davis or Henry Austin in an Egypto-Doric style utilizing Brownstone (in 1856 the first wing was completed, in 1903 the second wing, 1911 the Neo-Gothic towers in rear garden were completed); St. Elmo, (former tomb) Kenneth M. Murchison, 1912, designs inspired by Elizabethan manor. Current location, brick colonial; and Wolf's Head, Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, erected 1923–1924, Collegiate Gothic.

Sustainability[edit]

Yale's Office of Sustainability develops and implements sustainability practices at Yale.[133] Yale is committed to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions 10% below 1990 levels by 2020. As part of this commitment, the university allocates renewable energy credits to offset some of the energy used by residential colleges.[134] Eleven campus buildings are candidates for LEED design and certification.[135] Yale Sustainable Food Project initiated the introduction of local, organic vegetables, fruits, and beef to all residential college dining halls.[136] Yale was listed as a Campus Sustainability Leader on the Sustainable Endowments Institute's College Sustainability Report Card 2008, and received a "B+" grade overall.[137] Yale is a member of the Ivy Plus Sustainability Consortium, through which it has committed to best-practice sharing and the ongoing exchange of campus sustainability solutions along with other member institutions.[138]

Relationship with New Haven[edit]

Yale is the largest taxpayer and employer in the City of New Haven,[139] and has often buoyed the city's economy and communities. Yale, however, has consistently opposed paying a tax on its academic property.[140] Yale's Art Galleries, along with many other university resources, are free and openly accessible. Yale also funds the New Haven Promise program, paying full tuition for eligible students from New Haven public schools.[141]

Town–gown relations[edit]

Yale has a complicated relationship with its home city; for example, thousands of students volunteer every year in myriad community organizations, but city officials, who decry Yale's exemption from local property taxes, have long pressed the university to do more to help. Under President Levin, Yale has financially supported many of New Haven's efforts to reinvigorate the city. Evidence suggests that the town and gown relationships are mutually beneficial. Still, the economic power of the university increased dramatically with its financial success amid a decline in the local economy.[142]

Campus safety[edit]

Several campus safety strategies have been pioneered at Yale. The first campus police force was founded at Yale in 1894, when the university contracted city police officers to exclusively cover the campus.[143][144] Later hired by the university, the officers were originally brought in to quell unrest between students and city residents and curb destructive student behavior.[145][146] In addition to the Yale Police Department, a variety of safety services are available including blue phones, a safety escort, and 24-hour shuttle service.

In the 1970s and 1980s, poverty and violent crime rose in New Haven, dampening Yale's student and faculty recruiting efforts.[147] Between 1990 and 2006, New Haven's crime rate fell by half, helped by a community policing strategy by the New Haven Police and Yale's campus became the safest among peer schools.[148]

In 2004, the national non-profit watchdog group Security on Campus filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Education, accusing Yale of under-reporting rape and sexual assaults.[149][150]

In April 2021, Yale announced that it will require students to receive a COVID-19 vaccine as a condition of being on campus during the fall 2021 term.[151]

Academics[edit]

Admissions[edit]

Undergraduate admission to Yale College is considered "most selective" by U.S. News.[152][153] In 2022, Yale accepted 2,234 students to the Class of 2026 out of 50,015 applicants, for an acceptance rate of 4.46%.[154] 98% of students graduate within six years.[155]

Through its program of need-based financial aid, Yale commits to meet the full demonstrated financial need of all applicants, and the university is need-blind for both domestic and international applicants.[156] Most financial aid is in the form of grants and scholarships that do not need to be paid back to the university, and the average need-based aid grant for the Class of 2017 was $46,395.[157] 15% of Yale College students are expected to have no parental contribution, and about 50% receive some form of financial aid.[155][158][159] About 16% of the Class of 2013 had some form of student loan debt at graduation, with an average debt of $13,000 among borrowers.[155] For 2019, Yale ranked second in enrollment of recipients of the National Merit $2,500 Scholarship (140 scholars).[160]

Half of all Yale undergraduates are women, more than 39% are ethnic minority U.S. citizens (19% are underrepresented minorities), and 10.5% are international students.[157] 55% attended public schools and 45% attended private, religious, or international schools, and 97% of students were in the top 10% of their high school class.[155] Every year, Yale College also admits a small group of non-traditional students through the Eli Whitney Students Program.

Collections[edit]

Yale University Library, which holds over 15 million volumes, is the third-largest university collection in the United States.[9][161] The main library, Sterling Memorial Library, contains about 4 million volumes, and other holdings are dispersed at subject and location libraries.

Rare books are found in several Yale collections. The Beinecke Rare Book Library has a large collection of rare books and manuscripts. The Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library includes important historical medical texts, including an impressive collection of rare books, as well as historical medical instruments. The Lewis Walpole Library contains the largest collection of 18th‑century British literary works. The Elizabethan Club, technically a private organization, makes its Elizabethan folios and first editions available to qualified researchers through Yale.

Yale's museum collections are also of international stature. The Yale University Art Gallery, the country's first university-affiliated art museum, contains more than 200,000 works, including Old Masters and important collections of modern art, in the Swartwout and Kahn buildings. The latter, Louis Kahn's first large-scale American work (1953), was renovated and reopened in December 2006. The Yale Center for British Art, the largest collection of British art outside of the UK, grew from a gift of Paul Mellon and is housed in another Kahn-designed building.

The Peabody Museum of Natural History in New Haven is used by school children and contains research collections in anthropology, archaeology, and the natural environment.

The Yale University Collection of Musical Instruments, affiliated with the Yale School of Music, is perhaps the least-known of Yale's collections because its hours of opening are restricted.

The museums once housed the artifacts brought to the United States from Peru by Yale history professor Hiram Bingham in his Yale-financed expedition to Machu Picchu in 1912 – when the removal of such artifacts was legal. The artifacts were restored to Peru in 2012.[162]

| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| ARWU[163] | 9 |

| Forbes[164] | 2 |

| U.S. News & World Report[165] | 5 |

| Washington Monthly[166] | 8 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[167] | 3 |

| Global | |

| ARWU[168] | 11 |

| QS[169] | 23 |

| THE[170] | 10 |

| U.S. News & World Report[171] | 10 |

Rankings[edit]

The U.S. News & World Report ranked Yale third among U.S. national universities for 2016,[152] as it had for each of the previous sixteen years. Yale University is accredited by the New England Commission of Higher Education.[172]

Internationally, Yale was ranked 11th in the 2016 Academic Ranking of World Universities, tenth in the 2016–17 Nature Index[173] for quality of scientific research output, and tenth in the 2016 CWUR World University Rankings.[174] The university was also ranked sixth in the 2016 Times Higher Education (THE) Global University Employability Rankings[175] and eighth in the Academic World Reputation Rankings.[176] In 2019, it ranked 27th among the universities around the world by SCImago Institutions Rankings.[177]

Faculty, research, and intellectual traditions[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2021) |

Yale is a member of the Association of American Universities (AAU) and is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity".[178] The National Science Foundation ranked Yale 15th among American universities for research and development expenditures in 2021 with $1.16 billion.[179][180]

Yale's current faculty include 67 members of the National Academy of Sciences,[12] 55 members of the National Academy of Medicine,[13] 8 members of the National Academy of Engineering,[14] and 187 members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[15] The college is, after normalization for institution size, the tenth-largest baccalaureate source of doctoral degree recipients in the United States, and the largest such source within the Ivy League.[181] It also is a top 10 (ranked seventh) baccalaureate source (after normalization for the number of graduates) of some of the most notable scientists (Nobel, Fields, Turing prizes, or membership in National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, or National Academy of Medicine).[182]

Yale's English and Comparative Literature departments were part of the New Criticism movement. Of the New Critics, Robert Penn Warren, W.K. Wimsatt, and Cleanth Brooks were all Yale faculty. Later, the Yale Comparative literature department became a center of American deconstruction. Jacques Derrida, the father of deconstruction, taught at the department of comparative literature from the late 1970s to mid-1980s. Several other Yale faculty members were also associated with deconstruction, forming the so-called "Yale School". These included Paul de Man who taught in the Departments of Comparative Literature and French, J. Hillis Miller, Geoffrey Hartman (both taught in the Departments of English and Comparative Literature), and Harold Bloom (English), whose theoretical position was always somewhat specific, and who ultimately took a very different path from the rest of this group. Yale's history department has also originated important intellectual trends. Historians C. Vann Woodward and David Brion Davis are credited with beginning in the 1960s and 1970s an important stream of southern historians; likewise, David Montgomery, a labor historian, advised many of the current generation of labor historians in the country. Yale's Music School and department fostered the growth of Music Theory in the latter half of the 20th century. The Journal of Music Theory was founded there in 1957; Allen Forte and David Lewin were influential teachers and scholars.

Since the late 1960s, Yale produces social sciences and policy research through its Yale Institution for Social and Policy Studies (ISPS).

In addition to eminent faculty members, Yale research relies heavily on the presence of roughly 1200 Postdocs from various national and international origin working in the multiple laboratories in the sciences, social sciences, humanities, and professional schools of the university. The university progressively recognized this working force with the recent creation of the Office for Postdoctoral Affairs and the Yale Postdoctoral Association.

Campus life[edit]

| Race and ethnicity[183] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 35% | ||

| Asian | 24% | ||

| Hispanic | 15% | ||

| Foreign national | 10% | ||

| Black | 9% | ||

| Other[b] | 6% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[c] | 20% | ||

| Affluent[d] | 80% | ||

Yale is a research university, with the majority of its students in the graduate and professional schools. Undergraduates, or Yale College students, come from a variety of ethnic, national, socioeconomic, and personal backgrounds. Of the 2010–2011 freshman class, 10% are non‑U.S. citizens, while 54% went to public high schools.[184] The median family income of Yale students is $192,600, with 57% of students coming from the top 10% highest-earning families and 16% from the bottom 60%.[185]

Residential colleges[edit]

Yale's residential college system was established in 1933 by Edward S. Harkness, who admired the social intimacy of Oxford and Cambridge and donated significant funds to found similar colleges at Yale and Harvard. Though Yale's colleges resemble their English precursors organizationally and architecturally, they are dependent entities of Yale College and have limited autonomy. The colleges are led by a head and an academic dean, who reside in the college, and university faculty and affiliates constitute each college's fellowship. Colleges offer their own seminars, social events, and speaking engagements known as "Master's Teas", but do not contain programs of study or academic departments. All other undergraduate courses are taught by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and are open to members of any college.

All undergraduates are members of a college, to which they are assigned before their freshman year, and 85 percent live in the college quadrangle or a college-affiliated dormitory.[186] While the majority of upperclassman live in the colleges, most on-campus freshmen live on the Old Campus, the university's oldest precinct.

While Harkness' original colleges were Georgian Revival or Collegiate Gothic in style, two colleges constructed in the 1960s, Morse and Ezra Stiles Colleges, have modernist designs. All twelve college quadrangles are organized around a courtyard, and each has a dining hall, courtyard, library, common room, and a range of student facilities. The twelve colleges are named for important alumni or significant places in university history. In 2017, the university opened two new colleges near Science Hill.[187]

- Jonathan Edwards College courtyard

- Branford College courtyard

- Saybrook College's Killingworth Courtyard

- Hopper College courtyard

- Berkeley College buildings

- Trumbull College courtyard

- Davenport College courtyard

- Pierson College courtyard

- Silliman College courtyard

- Timothy Dwight College courtyard

- Morse College courtyard

- Ezra Stiles College courtyard

- Benjamin Franklin College courtyard

- Pauli Murray College courtyard

Calhoun College[edit]

Since the 1960s, John C. Calhoun's white supremacist beliefs and pro-slavery leadership[188][189][190][191] had prompted calls to rename the college or remove its tributes to Calhoun. The racially motivated church shooting in Charleston, South Carolina, led to renewed calls in the summer of 2015 for Calhoun College, one of 12 residential colleges at the time, to be renamed. In July 2015 students signed a petition calling for the name change.[189] They argued in the petition that—while Calhoun was respected in the 19th century as an "extraordinary American statesman"—he was "one of the most prolific defenders of slavery and white supremacy" in the history of the United States.[189][190] In August 2015, Yale President Peter Salovey addressed the Freshman Class of 2019 in which he responded to the racial tensions but explained why the college would not be renamed.[191] He described Calhoun as "a notable political theorist, a vice president to two different U.S. presidents, a secretary of war and of state, and a congressman and senator representing South Carolina".[191] He acknowledged that Calhoun also "believed that the highest forms of civilization depend on involuntary servitude. Not only that, but he also believed that the races he thought to be inferior, black people in particular, ought to be subjected to it for the sake of their own best interests."[188] Student activism about this issue increased in the fall of 2015, and included further protests sparked by controversy surrounding an administrator's comments on the potential positive and negative implications of students who wear Halloween costumes that are culturally sensitive.[192] Campus-wide discussions expanded to include critical discussion of the experiences of women of color on campus, and the realities of racism in undergraduate life.[193] The protests were sensationalized by the media and led to the labelling of some students as being members of Generation Snowflake.[194]

In April 2016, Salovey announced that "despite decades of vigorous alumni and student protests", Calhoun's name will remain on the Yale residential college[195] explaining that it is preferable for Yale students to live in Calhoun's "shadow" so they will be "better prepared to rise to the challenges of the present and the future". He claimed that if they removed Calhoun's name, it would "obscure" his "legacy of slavery rather than addressing it".[195] "Yale is part of that history" and "We cannot erase American history, but we can confront it, teach it and learn from it." One change that will be issued is the title of "master" for faculty members who serve as residential college leaders will be renamed to "head of college" due to its connotation of slavery.[196]

Despite this apparently conclusive reasoning, Salovey announced that Calhoun College would be renamed for groundbreaking computer scientist Grace Hopper in February 2017.[197] This renaming decision received a range of responses from Yale students and alumni.[198][199][200] In his 2019 book Assault on American Excellence, former Dean of Yale Law School Anthony T. Kronman criticized the title and name changes and the lack of support from Salovey for the Christakises, who were targeted by the student activists. Other members of the university community disagreed with Kronman's positions.[201]

Student organizations[edit]

In 2024, Yale had 526 registered undergraduate student organizations, plus hundreds of others for graduate students.[202]

The university hosts a variety of student journals, magazines, and newspapers. The Yale Literary Magazine, founded in February 1836, is the oldest student literary magazine in the United States.[203] Established in 1872, The Yale Record is the world's oldest college humor magazine. Newspapers include the Yale Daily News, which was first published in 1878, and the weekly Yale Herald, which was first published in 1986. The Yale Journal of Medicine & Law is a biannual magazine that explores the intersection of law and medicine.

Dwight Hall, an independent, non-profit community service organization, oversees more than 2,000 Yale undergraduates working on more than 70 community service initiatives in New Haven. The Yale College Council runs several agencies that oversee campus wide activities and student services. The Yale Dramatic Association and Bulldog Productions cater to the theater and film communities, respectively. In addition, the Yale Drama Coalition[204] serves to coordinate between and provide resources for the various Sudler Fund sponsored theater productions which run each weekend. WYBC Yale Radio[205] is the campus's radio station, owned and operated by students. While students used to broadcast on AM and FM frequencies, they now have an Internet-only stream.

The Yale College Council (YCC) serves as the campus's undergraduate student government. All registered student organizations are regulated and funded by a subsidiary organization of the YCC, known as the Undergraduate Organizations Funding Committee (UOFC).[206] The Graduate and Professional Student Senate (GPSS) serves as Yale's graduate and professional student government.

The Yale Political Union (YPU) is a debate society founded in 1934 to host student discussions on a wide variety of topics. It is advised by alumni political leaders such as John Kerry and George Pataki.

The Yale International Relations Association (YIRA) functions as the umbrella organization for the university's top-ranked Model UN team. YIRA also has a Europe-based offshoot, Yale Model Government Europe, other Model UN conferences such as YMUN, YMUN Korea, YMUN Taiwan and Yale Model African Union (YMAU), and educational programs such as the Yale Review of International Studies (YRIS), Yale International Relations Leadership Institute, and Hemispheres.

The campus includes several fraternities and sororities. The campus features at least 18 a cappella groups, the most famous of which is The Whiffenpoofs, which from its founding in 1909 until 2018 was made up solely of senior men.

The Elizabethan Club, a social club, has a membership of undergraduates, graduates, faculty and staff with literary or artistic interests. Membership is by invitation. Members and their guests may enter the "Lizzie's" premises for conversation and tea. The club owns first editions of a Shakespeare Folio, several Shakespeare Quartos, and a first edition of Milton's Paradise Lost, among other important literary texts.

Secret societies[edit]

Yale's secret societies include Skull and Bones, Scroll and Key, Wolf's Head, Book and Snake, Elihu, Berzelius, St. Elmo, Manuscript, Brothers in Unity, Linonia, St. Anthony Hall, Shabtai, Myth and Sword, Daughters of Sovereign Government (DSG), Mace and Chain, ISO, Spade and Grave, and Sage and Chalice, among others. The two oldest existing honor societies are the Aurelian (1910) and the Torch Honor Society (1916).[207]

These are akin to Harvard finals clubs, Princeton eating clubs, and senior societies at University of Pennsylvania.

Traditions[edit]

Yale seniors at graduation smash clay pipes underfoot to symbolize passage from their "bright college years", though in recent history the pipes have been replaced with "bubble pipes".[208][209] ("Bright College Years", the university's alma mater, was penned in 1881 by Henry Durand, Class of 1881, to the tune of Die Wacht am Rhein.) Yale's student tour guides tell visitors that students consider it good luck to rub the toe of the statue of Theodore Dwight Woolsey on Old Campus; however, actual students rarely do so.[210] In the second half of the 20th century Bladderball, a campus-wide game played with a large inflatable ball, became a popular tradition but was banned by administration due to safety concerns. In spite of administration opposition, students revived the game in 2009, 2011, and 2014.[211][212][213]

Athletics[edit]

Yale supports 35 varsity athletic teams that compete in the Ivy League Conference, the Eastern College Athletic Conference, and the New England Intercollegiate Sailing Association. Yale athletic teams compete intercollegiately at the NCAA Division I level. Like other members of the Ivy League, Yale does not offer athletic scholarships.

Yale has numerous athletic facilities, including the Yale Bowl (the nation's first natural "bowl" stadium, and prototype for such stadiums as the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and the Rose Bowl), located at The Walter Camp Field athletic complex, and the Payne Whitney Gymnasium, the second-largest indoor athletic complex in the world.[214]

In 1970 the NCAA banned Yale from participating in all NCAA sports for two years, in reaction to Yale – against the wishes of the NCAA – playing its Jewish center Jack Langer in college games after Langer had played for Team United States at the 1969 Maccabiah Games in Israel with the approval of Yale President Kingman Brewster.[215][216][217][218] The decision impacted 300 Yale students, every Yale student on its sports teams, over the next two years.[219]

In 2016, the men's basketball team won the Ivy League Championship title for the first time in 54 years, earning a spot in the NCAA Division I men's basketball tournament. In the first round of the tournament, the Bulldogs beat the Baylor Bears 79–75 in the school's first-ever tournament win.[220]

In May 2018, the men's lacrosse team defeated the Duke Blue Devils to claim their first-ever NCAA Division I Men's Lacrosse Championship,[221] and were the first Ivy League school to win the title since the Princeton Tigers in 2001.[222]

Yale crew is the oldest collegiate athletic team in America, and won Olympic Games Gold Medal for men's eights in 1924 and 1956. The Yale Corinthian Yacht Club, founded in 1881, is the oldest collegiate sailing club in the world. October 21, 2000, marked the dedication of Yale's fourth new boathouse in 157 years of collegiate rowing. The Gilder Boathouse is named to honor former Olympic rower Virginia Gilder '79 and her father Richard Gilder '54, who gave $4 million towards the $7.5 million project. Yale also maintains the Gales Ferry site where the heavyweight men's team trains for the Yale-Harvard Boat Race.

In 1896, Yale and Johns Hopkins played the first known ice hockey game in the United States. Since 2006, the school's ice hockey clubs have played a commemorative game.[223]

Yale students claim to have invented Frisbee, by tossing empty Frisbie Pie Company tins.[224][225]

Yale athletics are supported by the Yale Precision Marching Band. "Precision" is used here ironically; the band is a scatter-style band that runs wildly between formations rather than actually marching.[226] The band attends every home football game and many away, as well as most hockey and basketball games throughout the winter.

Yale intramural sports are also a significant aspect of student life. Students compete for their respective residential colleges, fostering a friendly rivalry. The year is divided into fall, winter, and spring seasons, each of which includes about 10 different sports. About half the sports are coeducational. At the end of the year, the residential college with the most points (not all sports count equally) wins the Tyng Cup.

Song[edit]

Notable among the songs commonly played and sung at events such as commencement, convocation, alumni gatherings, and athletic games are the alma mater, "Bright College Years". Despite its popularity, "Boola Boola" is not the official fight song, albeit being the origin of the university's unofficial motto. The official Yale fight song, "Bulldog" was written by Cole Porter during his undergraduate days and is sung after touchdowns during a football game.[227] Additionally, two other songs, "Down the Field" by C.W. O'Conner, and "Bingo Eli Yale", also by Cole Porter, are still sung at football games. According to College Fight Songs: An Annotated Anthology published in 1998, "Down the Field" ranks as the fourth-greatest fight song of all time.[228]

Mascot[edit]

The school mascot is "Handsome Dan", the Yale bulldog, and the Yale fight song contains the refrain, "Bulldog, bulldog, bow wow wow." The school color, since 1894, is Yale Blue.[229] Yale's Handsome Dan is believed to be the first college mascot in America, having been established in 1889.[230]

Mental health[edit]

Yale has faced significant criticism for its handling of student mental health on campus.[231][232][233][234] Suicidal and depressed students say that Yale forced them to medically withdraw rather than provide them with academic accommodations under the Americans with Disabilities Act, and in 2018 the Ruderman Family Foundation ranked Yale as having the worst mental health policies in the Ivy League.[235][236][233]

Dear Yale, I loved being here. I only wish I could've had some time. I needed time to work things out and to wait for new medication to kick in, but I couldn't do it in school, and I couldn't bear the thought of having to leave for a full year, or of leaving and never being readmitted. Love, Luchang.

Luchang Wang, posted on Facebook in 2015 shortly before her death[231][234][237][238][239]

Students at Yale say that the university's policies force them to hide their depression and avoid seeking help, for fear of being forced to leave.[231][235][234] One prominent case was the suicide of Luchang Wang in 2015, who died by suicide after making a Facebook post saying that she needed time to deal with her mental health issues, but could not deal with being forced to medically withdraw for an entire year with an uncertain chance of being readmitted.[237][234][239] Wang had previously withdrawn from school due to mental health issues, and was afraid of being forced to withdraw again, as a second readmission attempt would be considerably more difficult for her.[237][234] A friend of Wang said that she routinely lied to her university therapist to avoid being kicked out,[237] and another student said that many at Yale lie to their counselors as "there's no clear standard established that says exactly what students will get involuntarily hospitalized or withdrawn for".[234] In response, the university convened a commission to evaluate their readmission policies after a mental health withdrawal, renaming the process to "reinstatement" as well as eliminating the $50 reapplication fee.[231]

For students that do seek help, waitlists for therapy can be months long, with individual counselling sessions only 30 minutes in length.[231] In 2022, after a Washington Post article about their medical withdrawal policies, the school increased the number of mental health clinicians on campus from 51 to 60 as well as promised further changes.[232] In 2023, after a lawsuit was filed against the school for what the plaintiffs described as discrimination, the university changed the name of a "medical withdrawal" to a "medical leave of absence" saying that the "leave of absence" terminology would allow students to remain on Yale's insurance while away from the school.[240] The new policy also allowed for students on a leave of absence to participate in extracurricular clubs and visit campus,[240] something a student on medical withdrawal was banned from doing.[231] A representative of Yale also said that the criticism of their policies "misrepresents our efforts and unwavering commitment to supporting our students, whose well-being and success are our primary focus" and that "the mental health of our students is a very, very high priority".[232]

After the death of undergraduate student Rachael Shaw Rosenbaum by suicide, an organization called Elis for Rachael was formed, advocating for mental health-related reforms. The group has sued Yale, demanding changes.[241]

Notable people[edit]

Benefactors[edit]

Yale has had many financial supporters, but some stand out by the magnitude or timeliness of their contributions. Among those who have made large donations commemorated at the university are: Elihu Yale, Jeremiah Dummer, the Vanderbilt family, the Harkness family (Edward, Anna, and William), the Beinecke family (Edwin, Frederick, and Walter), John William Sterling, Payne Whitney, Joseph Earl Sheffield, Paul Mellon, Charles B. G. Murphy, Joseph Tsai, William K. Lanman, and Stephen Schwarzman. The Yale Class of 1954, led by Richard Gilder, donated $70 million in commemoration of their 50th reunion.[242] Charles B. Johnson, a 1954 graduate of Yale College, pledged a $250 million gift in 2013 to support the construction of two new residential colleges.[243] The colleges have been named respectively in honor of Pauli Murray and Benjamin Franklin. A $100 million contribution[244] by Stephen Adams enabled the Yale School of Music to become tuition-free and the Adams Center for Musical Arts to be built, while a $150 million contribution[245] by David Geffen enabled the Yale School of Drama (renamed the David Geffen School of Drama at Yale) to become tuition-free as well.

Notable alumni[edit]

Yale has produced many distinguished alumni in various fields, from the public to private sector. According to 2020 data, around 71% of undergraduates join the workforce, while 17% attend graduate or professional schools.[246] Yale graduates have been recipients of 263 Rhodes Scholarships,[247] 123 Marshall Scholarships,[248] 67 Truman Scholarships,[249] 21 Churchill Scholarships,[250] and 9 Mitchell Scholarships.[251] The university is the 2nd largest producer of Fulbright Scholars, with 1,244 in its history[252] and 89 MacArthur Fellows.[253] The U.S. Department of State Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs ranked Yale fifth among research institutions producing the most 2020–2021 Fulbright Scholars.[254] 31 living billionaires are alumni.[11]

One of the most popular undergraduate majors is political science, with many going on to serve in government and politics.[255] Former presidents who attended for undergrad include William Howard Taft, George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush while former presidents Gerald Ford and Bill Clinton attended Yale Law School.[256] Former vice-president and influential antebellum era politician John C. Calhoun[257] also graduated from Yale. Former world leaders include Italian prime minister Mario Monti,[258] Turkish prime minister Tansu Çiller,[259] Mexican president Ernesto Zedillo,[260] German president Karl Carstens,[261] Philippine president José Paciano Laurel,[262] Latvian president Valdis Zatlers,[263] Taiwanese premier Jiang Yi-huah,[264] and Malawian president Peter Mutharika,[265] among others. Prominent royals who graduated are Crown Princess Victoria of Sweden,[266] and Olympia Bonaparte, Princess Napoléon.[267]

Alumni have had considerable presence in U.S. government in all three branches. On the U.S. Supreme Court, 19 justices have been alumni, including current Associate Justices Sonia Sotomayor,[268] Samuel Alito,[269] Clarence Thomas,[269] and Brett Kavanaugh.[270] Alumni have been U.S. Senators, including current senators Michael Bennet,[271] Richard Blumenthal,[272] Cory Booker,[273] Sherrod Brown,[274] Chris Coons,[275] Amy Klobuchar,[276] Sheldon Whitehouse,[277] and J. D. Vance.[278] Current and former cabinet members include Secretaries of State John Kerry,[279] Hillary Clinton,[280] Cyrus Vance,[281] and Dean Acheson;[282] U.S. Secretaries of the Treasury Oliver Wolcott,[283] Robert Rubin,[284] Nicholas F. Brady,[285] Steven Mnuchin,[286] and Janet Yellen;[287] U.S. Attorneys General Nicholas Katzenbach,[288] Edwin Meese, John Ashcroft,[289] and Edward H. Levi;[290] and many others. Peace Corps founder and American diplomat Sargent Shriver[291] and public official and urban planner Robert Moses[292] are Yale alumni.

Yale has produced numerous award-winning authors and influential writers,[293] like Nobel Prize in Literature laureate Sinclair Lewis[294] and Pulitzer Prize winners Stephen Vincent Benét,[295] Thornton Wilder,[296] Doug Wright,[297] and David McCullough.[298] Academy Award winning actors, actresses, and directors include Jodie Foster,[299] Paul Newman,[300] Meryl Streep,[301] Elia Kazan,[302] George Roy Hill,[303] Lupita Nyong'o,[304] Oliver Stone,[305] and Frances McDormand.[306] Alumni from Yale have also made notable contributions to both music and the arts. Leading American composer from the 20th century Charles Ives,[307] Broadway composer Cole Porter,[308] Grammy award winner David Lang,[309] multi-Tony Award winner Composer and Musicologist Maury Yeston,[310] and award-winning jazz pianist and composer Vijay Iyer[311] all hail from Yale. Hugo Boss Prize winner Matthew Barney,[312] famed American sculptor Richard Serra,[313] President Barack Obama presidential portrait painter Kehinde Wiley,[314] MacArthur Fellows and contemporary artists Tschabalala Self,[315] Titus Kaphar, Richard Whitten, and Sarah Sze,[316] Pulitzer Prize winning cartoonist Garry Trudeau,[317] and National Medal of Arts photorealist painter Chuck Close[318] all graduated from Yale. Additional alumni include architect and Presidential Medal of Freedom winner Maya Lin,[319] Pritzker Prize winner Norman Foster,[320] and Gateway Arch designer Eero Saarinen.[321] Journalists and pundits include Dick Cavett,[322] Chris Cuomo,[323] Anderson Cooper,[324] William F. Buckley Jr.,[325] Blake Hounshell,[326] and Fareed Zakaria.[327]

In business, Yale has had numerous alumni and former students go on to become founders of influential business, like William Boeing[328] (Boeing, United Airlines), Briton Hadden[329] and Henry Luce[330] (Time Magazine), Stephen A. Schwarzman[331] (Blackstone Group), Frederick W. Smith[332] (FedEx), Juan Trippe[333] (Pan Am), Harold Stanley[334] (Morgan Stanley), Bing Gordon[335] (Electronic Arts), and Ben Silbermann[336] (Pinterest). Other business people from Yale include former chairman and CEO of Sears Holdings Edward Lampert,[337] former Time Warner president Jeffrey Bewkes,[338] former PepsiCo chairperson and CEO Indra Nooyi,[339] sports agent Donald Dell,[340] and investor/philanthropist Sir John Templeton,[341]

Alumni distinguished in academia include literary critic and historian Henry Louis Gates,[342] economists Irving Fischer,[343] Mahbub ul Haq,[344] and Nobel Prize laureate Paul Krugman;[345] Nobel Prize in Physics laureates Ernest Lawrence[346] and Murray Gell-Mann;[347] Fields Medalist John G. Thompson;[348] Human Genome Project leader and National Institutes of Health director Francis S. Collins;[349] brain surgery pioneer Harvey Cushing;[350] pioneering computer scientist Grace Hopper;[351] influential mathematician and chemist Josiah Willard Gibbs;[352] National Women's Hall of Fame inductee and biochemist Florence B. Seibert;[353] Turing Award recipient Ron Rivest;[354] inventors Samuel F.B. Morse[355] and Eli Whitney;[356] Nobel Prize in Chemistry laureate John B. Goodenough;[357] lexicographer Noah Webster;[358] and theologians Jonathan Edwards[359] and Reinhold Niebuhr.[360]

In the sporting arena, alumni include baseball players Ron Darling[361] and Craig Breslow who in the major leagues played with fellow Yale alum Ryan Lavarnway[362] and baseball executives Theo Epstein[363] and George Weiss;[364] football players Calvin Hill,[365] Gary Fenick,[366] Amos Alonzo Stagg,[367] and "the Father of American Football" Walter Camp;[368] ice hockey players Chris Higgins[369] and Olympian Helen Resor;[370] Olympic figure skaters Sarah Hughes[371] and Nathan Chen;[372] nine-time U.S. Squash men's champion Julian Illingworth;[373] Olympic swimmer Don Schollander;[374] Olympic rowers Josh West[375] and Rusty Wailes;[376] Olympic sailor Stuart McNay;[377] Olympic runner Frank Shorter;[378] and others.

- Notable Yale alumni include:

- 7th Vice President of the United States John C. Calhoun (College, 1806)

- 27th President of the United States and Chief Justice William Howard Taft (BA, 1878)

- 38th President of the United States Gerald Ford (LLB, 1941)

- 41st President of the United States George H. W. Bush (BA, 1948)

- 42nd President of the United States Bill Clinton (JD, 1973)

- 43rd President of the United States George W. Bush (BA, 1968)

- Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States Clarence Thomas (JD, 1974)

- Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States Samuel Alito (JD, 1975)

- Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States Sonia Sotomayor (JD, 1979)

- Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States Brett Kavanaugh (BA, 1987; JD, 1990)

- 67th United States Secretary of State and Former US Senator of New York Hillary Clinton (JD, 1973)

- Senator of Minnesota Amy Klobuchar (BA, 1982)

- Senator of New Jersey Cory Booker (JD, 1997)

- Governor of Connecticut Ned Lamont (MBA, 1980)

- Governor of Florida Ron DeSantis (BA, 2001)

- Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig (JD, 1989)

- Former Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz (LLB, 1962)

- Literary critic and historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. (BA, 1973)