Сопротивление во время Второй мировой войны

| Хронология Второй мировой войны |

|---|

| хронологический |

| Прелюдия |

| По теме |

| По театру |

| Часть серии о |

| Антифашизм |

|---|

|

Во время мировой войны Второй движения сопротивления действовали в оккупированной немцами Европе различными способами: от отказа от сотрудничества до пропаганды, сокрытия разбившихся пилотов и даже до открытой войны и возвращения городов. Во многих странах движения сопротивления иногда также называли «Подпольем» .

Движения сопротивления во Второй мировой войне можно разделить на два основных политически поляризованных лагеря:

- интернационалистическое сопротивление , и обычно Коммунистической партией возглавляемое антифашистское существовавшее почти во всех странах мира; и

- различные националистические группы в Германией или Советским Союзом странах, оккупированных , таких как Республика Польша , которые выступали как против нацистской Германии, так и против коммунистов.

Хотя историки и правительства некоторых европейских стран пытались представить сопротивление нацистской оккупации широко распространенным среди их населения, [ 1 ] лишь небольшое меньшинство людей участвовало в организованном сопротивлении, которое оценивается в один-три процента населения стран Западной Европы. В Восточной Европе, где нацистское правление было более репрессивным, больший процент людей был в организованных движениях сопротивления, например, примерно 10-15 процентов населения Польши. Пассивное сопротивление путем отказа от сотрудничества с оккупантами было гораздо более распространенным явлением. [2]

Summary of resistance movements by territory

[edit]Among the most notable resistance movements were:

Europe

[edit]- the Albanian resistance

- the Belgian Resistance

- the Czech resistance

- the Danish Resistance

- the Dutch Resistance (especially the "LO" (national hiding organisation))

- the French Resistance

- the Greek Resistance

- the Italian Resistenza (led mainly by the Italian CLN)

- the Jewish Resistance in various German-occupied territories

- the Norwegian Resistance

- the Polish Resistance (including the Polish Home Army, that started the Warsaw Uprising on August 1, 1944, Leśni, and the greater Polish Underground State);

- Soviet partisans[a]

- Yugoslav Partisans

And the politically persecuted opposition in Germany itself (there were 16 main resistance groups and at least 27 failed attempts to assassinate Hitler with many more planned).

Far East

[edit]- the Chinese resistance

- the Korean Resistance in the Japan Occupied Korea and the Chinese Zone

Many countries had resistance movements dedicated to fighting or undermining the Axis invaders, and Nazi Germany itself also had an anti-Nazi movement. Although Britain was not occupied during the war, the British made complex preparations for a British resistance movement. The main organisation was created by the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS, aka MI6) and is now known as Section VII.[3] In addition there was a short-term secret commando force called the Auxiliary Units.[4] Various organizations were also formed to establish foreign resistance cells or support existing resistance movements, like the British Special Operations Executive and the American Office of Strategic Services (the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency). There were also resistance movements fighting against Allied invaders. In Italian East Africa, after the Italians were defeated during the East African Campaign, some Italian soldiers and settlers participated in a guerrilla war against the Allies from 1941 to 1943. Though the Werwolf Nazi German resistance movement never amounted to much, the German Volkssturm played an extensive role in the Battle of Berlin. The "Forest Brothers" of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania included many fighters who operated against the Soviet occupation of the Baltic States into the 1960s. During or after the war, similar anti-Soviet resistance rose up in places like Romania, Poland, Bulgaria, Ukraine, and Chechnya.

Organization

[edit]After the first shock following the Blitzkrieg, people slowly started organizing, both locally and on a larger scale, especially when Jews and other groups began to be deported and used as Arbeitseinsatz (forced labor for the Germans). Organization was dangerous, so most resistance actions was performed by individuals. The possibilities depended much on the terrain; where there were large tracts of uninhabited land, especially hills and forests, resistance could more easily organise undetected; this favoured in particular Soviet partisans in Eastern Europe. In the more densely populated countries such as the Netherlands, the Biesbosch wilderness was used. In northern Italy, both the Alps and the Apennines offered shelter to partisan brigades, though many groups operated directly inside the major cities.

There were many different types of groups, ranging in activity from humanitarian aid to armed resistance, and sometimes cooperated in varying degrees. Resistance usually arose spontaneously, but was encouraged and helped from London and Moscow.

Size

[edit]Greece, Yugoslavia, Poland, and Ukraine had large numbers of resistors to the German occupation. In western Europe, where the German hand was less oppressive, the resistors were fewer. However, in the west, according to historian Tony Judt, the "myth of resistance mattered most."[5]

A number of sources note that the Polish Home Army was the largest resistance movement in Nazi-occupied Europe. Norman Davies writes that the "Armia Krajowa (Home Army), the AK,... could fairly claim to be the largest of European resistance [organizations]."[6] Gregor Dallas writes that the "Home Army (Armia Krajowa or AK) in late 1943 numbered around 400,000, making it the largest resistance organization in Europe."[7] Mark Wyman writes that the "Armia Krajowa was considered the largest underground resistance unit in wartime Europe."[8] However, the numbers of Soviet partisans were very similar to those of the Polish resistance,[9] as were the numbers of Yugoslav Partisans.[citation needed] For the French Resistance, François Marcot ventured an estimate of 200,000 activists and a further 300,000 with substantial involvement in Resistance operations.[10] For the Resistance in Italy, Giovanni di Capua estimates that, by August 1944, the number of partisans reached around 100,000, and it escalated to more than 250,000 with the final insurrection in April 1945.[11]

Forms of resistance

[edit]Various forms of resistance were:

- Non-violent

- Sabotage – the Arbeitseinsatz ("Work Contribution") forced locals to work for the Germans, but work was often done slowly or intentionally badly

- Strikes and demonstrations

- Based on existing organizations, such as the churches, students, communists and doctors (professional resistance)

- Armed

- raids on distribution offices to get food coupons or various documents such as Ausweise or on birth registry offices to get rid of information about Jews and others to whom the Nazis paid special attention

- temporary liberation of areas, such as in Yugoslavia, Paris, and northern Italy, occasionally in cooperation with the Allied forces

- uprisings such as in Warsaw in 1943 and 1944, and in extermination camps such as in Sobibor in 1943 and Auschwitz in 1944

- continuing battle and guerrilla warfare, such as the partisans in the USSR and Yugoslavia and the Maquis in France

- Espionage, including sending reports of military importance (e.g. troop movements, weather reports etc.)

- Illegal press to counter Nazi propaganda

- Anti-Nazi propaganda including movies for example anti-Nazi color film Calling Mr. Smith (1943) about current Nazi crimes in German-occupied Poland.

- Covert listening to BBC broadcasts for news bulletins and coded messages

- Political resistance to prepare for the reorganization after the war

- Helping people to go into hiding (e.g., to escape the Arbeitseinsatz or deportation)—this was one of the main activities in the Netherlands, due to the large number of Jews and the high level of administration, which made it easy for the Germans to identify Jews.

- Escape and evasion lines to help Allied military personnel caught behind Axis lines

- Helping POWs with illegal supplies, breakouts, communication, etc.

- Forgery of documents

Resistance operations

[edit]1939–1940

[edit]

On 15 September 1939, a member of the Czech resistance movement, Ctibor Novák, planted explosive devices in Berlin. His first bomb detonated in front of the Ministry of Aeronautics, and the second detonated in front of police headquarters. Both buildings were damaged and many Germans were injured.

On 28 October 1939 (the anniversary of the establishment of Czechoslovakia in 1918) there were large demonstrations against Nazi occupation in Prague, with about 100,000 Czechs. Demonstrators crowded the streets in the city. German police had to disperse the demonstrators, and began shooting in the evening. The first victim was baker Václav Sedláček, who was shot dead. The second victim was student Jan Opletal, who was critically injured, and died on 11 November. Another 15 people were badly injured and hundreds of people sustained minor injuries. About 400 people were arrested.

In March 1940, a partisan unit of the first guerilla organization of the Second World War in Europe, the Detached Unit of the Polish Army, led by Major Henryk Dobrzański (Hubal), defeated a battalion of German infantry in a skirmish near the Polish village of Hucisko. A few days later in an ambush near the village of Szałasy it inflicted heavy casualties upon another German unit. As time progressed, resistance forces grew in size and number. To counter this threat, the German authorities formed a special 1,000 man-strong anti-partisan unit of combined SS-Wehrmacht forces, including a Panzer group. Although Dobrzański's unit never exceeded 300 men, the Germans fielded at least 8,000 men in the area to secure it.[12][13]

In 1940, Witold Pilecki, of the Polish resistance, presented to his superiors a plan to enter Germany's Auschwitz concentration camp, gather intelligence on the camp from the inside, and organize inmate resistance.[14] The Home Army approved this plan and provided him with a false identity card, and on 19 September 1940 he deliberately went out during a street roundup in Warsaw-łapanka, and was caught by the Germans along with other civilians and sent to Auschwitz. In the camp he organized the underground organization Związek Organizacji Wojskowej (ZOW).[15] From October 1940, ZOW sent the first reports about the camp and its genocide to Home Army Headquarters in Warsaw through the resistance network organized in Auschwitz.[16]

On the night of January 21–22, 1940, in the Soviet-occupied Podolian town of Czortków, the Czortków Uprising started. It was the first Polish uprising and the first anti-Soviet uprising of World War II. Anti-Soviet Poles, most of them teenagers from local high schools, stormed the local Red Army barracks and a prison, in order to release Polish soldiers kept there.

1940 was the year of establishing the Warsaw Ghetto and the infamous Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp by the German Nazis in occupied Poland. Among the many activities of Polish resistance and Polish people was helping endangered Jews. Polish citizens have the world's highest count of individuals who have been recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem as non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews from extermination during the Holocaust.[17]

One of the events that helped the growth of the French Resistance was the targeting of the French Jews, Communists, Romani, homosexuals, Catholics, and others, forcing many into hiding. This in turn gave the French Resistance new people to incorporate into their political structures.

Around May 1940, a resistance group formed around the Austrian priest Heinrich Maier, who until 1944 very successfully passed on the plans and production locations for V-2 rockets, Tiger tanks and airplanes (Messerschmitt Bf 109, Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet, etc.) to the Allies, so that they could target these important factories for destruction and on the other hand, for the after the war Central European states planned.[clarification needed] Very early on they passed on information about the mass murder of the Jews to the Allies.[18][19][20]

The Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a British World War II organisation. With Cabinet approval, it was officially formed by Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton on 22 July 1940, to develop a spirit of resistance in the occupied countries and to prepare a fifth column of resistance fighters to engage in open opposition to the occupiers when the United Kingdom was able to return to the continent.[21] To aid in the transport of agents and the supply of the resistance fighters, a Royal Air Force Special Duty Service was developed. Whereas the SIS was primarily involved in espionage, the SOE and the resistance fighters were geared toward reconnaissance of German defenses and sabotage. In England the SOE was also involved in the formation of the Auxiliary Units, a top secret stay-behind resistance organisation which would have been activated in the event of a German invasion of Britain. The SOE operated in all countries or former countries occupied by or attacked by the Axis forces, except where demarcation lines were agreed with Britain's principal allies (the Soviet Union and the United States).

The organisation was officially dissolved on 15 January 1946.

1941

[edit]

In February 1941, the Dutch Communist Party organized a general strike in Amsterdam and surrounding cities, known as the February strike, in protest against anti-Jewish measures by the Nazi occupying force and violence by fascist street fighters against Jews. Several hundreds of thousands of people participated in the strike. The strike was put down by the Nazis and some participants were executed.

In April 1941, the Liberation Front of the Slovene Nation was established in the Province of Ljubljana. Its armed wing were the Slovene Partisans. It represented both the working class and the Slovene ethnicity.[22]

From April 1941, Bureau of Information and Propaganda of the Union for Armed Struggle started in Poland Operation N headed by Tadeusz Żenczykowski. Action was complex of sabotage, subversion and black-propaganda activities carried out by the Polish resistance against Nazi German occupation forces during World War II[23]

Beginning in March 1941, Witold Pilecki's reports were being forwarded via the Polish resistance to the Polish government in exile and through it, to the British government in London and other Allied governments. These reports were the first information about the Holocaust and the principal source of intelligence on Auschwitz for the Western Allies.[24]

In May 1941, the Resistance Team "Elevtheria" (Freedom) was established in Thessaloniki by politicians Paraskevas Barbas, Apostolos Tzanis, Ioannis Passalidis, Simos Kerasidis, Athanasios Fidas, Ioannis Evthimiadis and military officer Dimitrios Psarros. Its armed wing comprised two armed forces; Athanasios Diakos led by Christodoulos Moschos (captain "Petros"), operating in Kroussia; and Odysseas Androutsos led by Athanasios Genios (captain "Lassanis"), operating in Visaltia.[25][26][27]

The first anti-soviet uprising during World War II began on June 22, 1941 (the start-date of Operation Barbarossa) in Lithuania. On the same day, the Sisak People's Liberation Partisan Detachment was formed in Croatia, near the town of Sisak. It was the first armed partisan unit in Croatia.

Communist-initiated uprising against Axis started in German-occupied Serbia on July 7, 1941, and six days later in Montenegro. The Republic of Užice (Ужичка република) was a short-lived liberated Yugoslav territory, the first part of occupied Europe to be liberated. Organized as a military mini-state it existed throughout the autumn of 1941 in the western part of Serbia. The Republic was established by the Partisan resistance movement and its administrative center was in the town of Užice. The government was made of "people's councils" (odbors), and the Communists opened schools and published a newspaper, Borba (meaning "Struggle"). They even managed to run a postal system and around 145 km (90 mi) of railway and operated an ammunition factory from the vaults beneath the bank in Užice.

In July 1941 Mieczysław Słowikowski (using the codename "Rygor"—Polish for "Rigor") set up "Agency Africa," one of World War II's most successful intelligence organizations.[28] His Polish allies in these endeavors included Lt. Col. Gwido Langer and Major Maksymilian Ciężki. The information gathered by the Agency was used by the Americans and British in planning the amphibious November 1942 Operation Torch[29][30] landings in North Africa.

On 13 July 1941, in Italian-occupied Montenegro, Montenegrin separatist Sekula Drljević proclaimed an independent Kingdom of Montenegro as an Italian governorate, upon which a nationwide rebellion escalated raised by Partisans, Yugoslav Royal officers and various other armed personnel. It was the first organized armed uprising in then occupied Europe, and involved 32,000 people. Most of Montenegro was quickly liberated, except major cities where Italian forces were well fortified. On 12 August — after a major Italian offensive involving 5 divisions and 30,000 soldiers — the uprising collapsed as units were disintegrating; poor leadership occurred as well as collaboration. The final toll of July 13 uprising in Montenegro was 735 dead, 1120 wounded and 2070 captured Italians and 72 dead and 53 wounded Montenegrins.[citation needed]

In the Battle of Loznica, 31 August 1941, Chetniks attacked and freed the town of Loznica in German-occupied Serbia from the Germans. Several Germans were killed and wounded; 93 were captured.

On 11 October 1941, in Bulgarian-occupied Prilep, Macedonians attacked post of the Bulgarian occupation police, which was the start of Macedonian resistance against the fascists who occupied Macedonia: Germans, Italians, Bulgarians and Albanians. The resistance finished successfully in August–November 1944 when the independent Macedonian state was formed, which was later added to the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia.

At the time Hitler gave his anti-resistance Nacht und Nebel decree – the very day of the Attack on Pearl Harbor in the Pacific – the planning for Britain's Operation Anthropoid was underway, as a resistance move to assassinate Reinhard Heydrich, the Deputy Protector of Bohemia and Moravia and the chief of the Final Solution, by the Czech resistance in Prague. Over fifteen thousand Czechs were killed in reprisals, with the most infamous incidents being the complete destruction of the towns of Lidice and Ležáky.

1942

[edit]On February 16, 1942, the Greek Communist Party (KKE)-led National Liberation Front gave permission to a communist veteran, Athanasios (Thanasis) Klaras (later known as Aris Velouchiotis) to examine the possibilities of an armed resistance movement, which led to the formation of the Greek People's Liberation Army (ELAS). ELAS initiated actions against the German and Italian forces of occupation in Greece on 7 June 1942. The ELAS grew to become the largest resistance movement against the fascists in Greece.

The Luxembourgish general strike of 1942 was a passive resistance movement organised within a short time period to protest against a directive that incorporated the Luxembourg youth into the Wehrmacht. A national general strike, originating mainly in Wiltz, paralysed the country and forced the occupying German authorities to respond violently by sentencing 21 strikers to death.

On 27 May 1942 Operation Anthropoid took place. Two armed Czechoslovak members of the army in exile (Jan Kubiš and Jozef Gabčík) attempted to assassinate the SS-obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich. Heydrich was not killed on the spot but died later at the hospital from his wounds. He is the highest ranked Nazi to have been assassinated during the war.

In September 1942, the Council to Aid Jews (Żegota) was founded by Zofia Kossak-Szczucka and Wanda Krahelska-Filipowicz ("Alinka") and made up of Polish Democrats as well as other Catholic activists. Poland was the only country in occupied Europe where there existed such a dedicated secret organization. Half of the Jews who survived the war (thus over 50,000) were aided in some shape or form by Żegota.[31] The most known activist of Żegota was Irena Sendler head of the children's division who saved 2,500 Jewish children by smuggling them out of the Warsaw Ghetto, providing them false documents, and sheltering them in individual and group children's homes outside the ghetto.[32]

On the night of 7–8 October 1942, Operation Wieniec started. It targeted rail infrastructure near Warsaw. Similar operations aimed at disrupting German transport and communication in occupied Poland occurred in the coming months and years. It targeted railroads, bridges and supply depots, primarily near transport hubs such as Warsaw and Lublin.

On 25 November, Greek guerrillas with the help of twelve British saboteurs[33] carried out a successful operation which disrupted the German ammunition transportation to the German Africa Corps under Rommel—the destruction of Gorgopotamos bridge (Operation Harling).[34][35]

On 20 June 1942, the most spectacular escape from Auschwitz concentration camp took place. Four Poles, Eugeniusz Bendera,[36] Kazimierz Piechowski, Stanisław Gustaw Jaster and Józef Lempart made a daring escape.[37] The escapees were dressed as members of the SS-Totenkopfverbände, fully armed and in an SS staff car. They drove out the main gate in a stolen Rudolf Hoss automobile Steyr 220 with a smuggled report from Witold Pilecki about the Holocaust. The Germans never recaptured any of them.[38]

The Zamość Uprising was an armed uprising of Armia Krajowa and Bataliony Chłopskie against the forced expulsion of Poles from the Zamość region (Zamość Lands, Zamojszczyzna) under the Nazi Generalplan Ost. Nazi Germans attempting to remove the local Poles from the Greater Zamosc area (through forced removal, transfer to forced labor camps, or, in rare cases, mass murder) to get it ready for German colonization. It lasted from 1942 to 1944, and despite heavy casualties suffered by the Underground, the Germans failed.

1943

[edit]By the middle of 1943 partisan resistance to the Germans and their allies had grown from the dimensions of a mere nuisance to those of a major factor in the general situation. In many parts of occupied Europe Germany was suffering losses at the hands of partisans that he could ill afford. Nowhere were these losses heavier than in Yugoslavia.[39]

In early January 1943, the 20,000 strong main operational group of the Yugoslav Partisans, stationed in western Bosnia, came under ferocious attack by over 150,000 German and Axis troops, supported by about 200 Luftwaffe aircraft in what became known as the Battle of the Neretva (the German codename was "Fall Weiss" or "Case White").[40] The Axis rallied eleven divisions, six German, three Italian, and two divisions of the Independent State of Croatia (supported by Ustaše formations) as well as a number of Chetnik brigades.[41] The goal was to destroy the Partisan HQ and main field hospital (all Partisan wounded and prisoners faced certain execution), but this was thwarted by the diversion and retreat across the Neretva river, planned by the Partisan supreme command led by Marshal Josip Broz Tito. The main Partisan force escaped into Serbia.

On 19 April 1943, three members of the Belgian resistance movement were able to stop the Twentieth convoy, which was the 20th prisoner transport in Belgium organised by the Germans during World War II. The exceptional action by members of the Belgian resistance occurred to free Jewish and Romani ("Gypsy") civilians who were being transported by train from the Dossin army base located in Mechelen, Belgium to the concentration camp Auschwitz. The 20th train convoy transported 1,631 Jews (men, women and children). Some of the prisoners were able to escape and marked this particular kind of liberation action by the Belgian resistance movement as unique in the European history of the Holocaust.

One of the bravest and most significant displays of public defiance against the Nazis is the rescue of the Danish Jews in October 1943. Nearly all of the Danish Jews were saved from concentration camps by the Danish resistance. However, the action was largely due to the personal intervention of German diplomat Georg Ferdinand Duckwitz, who both leaked news of the intended round up of the Jews to both the Danish opposition and Jewish groups and negotiated with the Swedes to ensure Danish Jews would be accepted in Sweden.

The Battle of Sutjeska from 15 May – 16 June 1943 was a joint attack of the Axis forces that once again attempted to destroy the main Yugoslav Partisan force, near the Sutjeska river in southeastern Bosnia. The Axis rallied 127,000 troops for the offensive, including German, Italian, NDH, Bulgarian and Cossack units, as well as over 300 airplanes (under German operational command), against 18,000 soldiers of the primary Yugoslav Partisans operational group organised in 16 brigades. Facing almost exclusively German troops in the final encirclement, the Yugoslav Partisans finally succeeded in breaking out across the Sutjeska river through the lines of the German 118th Jäger Division, 104th Jäger Division and 369th (Croatian) Infantry Division in the northwestern direction, towards eastern Bosnia. Three brigades and the central hospital with over 2,000 wounded remained surrounded and, following Hitler's instructions, German commander-in-chief General Alexander Löhr ordered and carried out their annihilation, including the wounded and unarmed medical personnel. In addition, Partisan troops suffered from a severe lack of food and medical supplies, and many were struck down by typhoid. However, the failure of the offensive marked a turning point for Yugoslavia during World War II.

Operation Heads started—an action of serial assassinations of the Nazi personnel sentenced to death by the Underground court for crimes against Polish citizens in occupied Poland. The Resistance fighters of Polish Home Army's unit Agat killed Franz Bürkl during Operation Bürkl. Bürkl was a high-ranking Nazi German SS and secret police officer responsible for the murder and brutal interrogation of thousands of Polish Jews and Polish resistance fighters and supporters.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising by the Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto lasted from 19 April-16 May, and cost the Nazi forces 17 dead and 93 wounded by their own count, though some Jewish resistance figures claimed that German casualties were far higher.

On 30 September the German forces occupying the Italian city of Naples were forced out by the townsfolk and the Italian Resistance before the arrival of the first Allied forces in the city on 1 October. This popular uprising is known as the Four days of Naples.[42]

On October 9, 1943, the Kinabalu guerillas launched the Jesselton Revolt against the Japanese occupation of British Borneo.

From November 1943, Operation Most III started. The Armia Krajowa provided the Allies with crucial intelligence on the German V-2 rocket. In effect, some 50 kg (110 lb) of the most important parts of the captured V-2, as well as the final report, analyses, sketches and photos, were transported to Brindisi by a Royal Air Force Douglas Dakota aircraft. In late July 1944, the V-2 parts were delivered to London.[43]

1944

[edit]

On 1 February 1944, the Resistance fighters of the Polish Home Army's unit Agat executed Franz Kutschera, SS and Reich's Police Chief in Warsaw in an action known as Operation Kutschera.[44][45]

In the spring of 1944, a plan was laid out by the Allies to kidnap General Müller, whose harsh repressive measures had earned him the nickname "the Butcher of Crete". The operation was led by Major Patrick Leigh Fermor, together with Captain W. Stanley Moss, Greek SOE agents and Cretan resistance fighters. However, Müller left the island before the plan could be carried out. Undeterred, Fermor decided to abduct General Heinrich Kreipe instead.

В ночь на 26 апреля генерал Крайпе покинул свой штаб в Арханесе и без сопровождения направился в свою хорошо охраняемую резиденцию «Вилла Ариадни», примерно в 25 км от Ираклиона . Майор Фермор и капитан Мосс, одетые как немецкие военные полицейские, ждали его за 1 км (0,62 мили) до его дома. Они попросили водителя остановиться и потребовали документы. Как только машина остановилась, Фермор быстро открыл дверь Крайпе, ворвался и угрожал ему оружием, а Мосс занял место водителя. Проехав некоторое расстояние, британцы вышли из машины, подложив подходящие приманки, которые предполагали, что побег с острова был совершен на подводной лодке , и вместе с генералом начали марш по пересеченной местности. Преследуемая немецкими патрулями, группа двинулась через горы, чтобы достичь южной стороны острова, где британский моторный катер ( ML 842 их должен был подобрать , которым командовал Брайан Коулман). В конце концов, 14 мая 1944 года их забрали (на пляже Перистер возле Родакино) и переправили в Египет.

В апреле-мае 1944 года СС предприняло дерзкий воздушно-десантный рейд на Дрвар с целью захватить маршала Иосипа Броз Тито , главнокомандующего югославских партизан , а также разрушить их руководство и структуру управления. штаб партизан находился на холмах недалеко от в Дрвара Боснии В то время представители союзников , британец Рэндольф Черчилль и Ивлин Во . На мероприятии также присутствовали . Элитные немецкие парашютно-десантные подразделения СС пробились к штаб-квартире Тито в пещере и вступили в перестрелку, что привело к многочисленным жертвам с обеих сторон. [ 46 ] Четники под командованием Дражи Михайловича также стекались в перестрелку, пытаясь захватить Тито. Однако к тому времени, когда немецкие войска проникли в пещеру, Тито уже скрылся с места происшествия. Его ждал поезд, который отвез его в город Яйце . Судя по всему, Тито и его штаб были хорошо подготовлены к чрезвычайным ситуациям. Коммандос смогли забрать только форму маршала Тито, которая позже была выставлена в Вене . После ожесточенных боев на деревенском кладбище и вокруг него немцам удалось соединиться с горными войсками. К тому времени Тито, его британских гостей и выживших партизан чествовали на борту Королевского флота эсминца HMS Blackmore и ее капитана лейтенанта Карсона, RN.

во Франции была начата сложная серия операций сопротивления Перед и во время операции «Оверлорд» . 5 июня 1944 года BBC передала серию необычных предложений, которые, как знали немцы, были кодовыми словами — возможно, для вторжения в Нормандию. Би-би-си регулярно передавала сотни личных сообщений, из которых лишь немногие были действительно значимыми. За несколько дней до дня «Д» командиры Сопротивления услышали первую строчку стихотворения Верлена « Осенний шанс », «Les sanglots longs des violons de l’automne» ( Долгие рыдания осенних скрипок ), что означало, что «день» был неизбежен. Когда прозвучала вторая строчка «Blessent mon cœur d'une langueur monotone» ( ранила мое сердце монотонной томностью ), Сопротивление знало, что вторжение произойдет в течение следующих 48 часов. Затем они поняли, что пришло время приступить к выполнению заранее назначенных миссий. По всей Франции были скоординированы группы сопротивления, и различные группы по всей стране усилили свой саботаж. Коммуникации были прерваны, поезда сошли с рельсов, дороги, водонапорные башни и склады боеприпасов были разрушены, а немецкие гарнизоны подверглись нападениям. Незадолго до 6 июня некоторые передали по радио информацию о немецких оборонительных позициях на пляжах Нормандии американскому и британскому командованию. Победа далась нелегко; в июне и июле в г. На плато Веркор недавно усиленная группа маки сражалась с более чем 10 000 немецких солдат (не Ваффен-СС) под командованием генерала Карла Пфлаума и потерпела поражение, потеряв 840 человек (639 бойцов и 201 мирное лицо). После убийств в Тюле уничтожила деревню Орадур-сюр-Глан рота Ваффен-СС майора Отто Дикмана 10 июня . Сопротивление также способствовало более позднему вторжению союзников на юг Франции ( операция «Драгун» ). Они начали восстания в таких городах, как Париж , когда союзные войска подошли близко.

Операция Halyard , проходившая с августа по декабрь 1944 года. [ 47 ] — операция союзников по воздушной переброске в тыл врага во время Второй мировой войны, проводившаяся четниками в оккупированной Югославии. В июле 1944 года Управление стратегических служб (УСС) разработало план отправки в четники группы под командованием генерала Дража Михайловича на немцами оккупированной территории военного командующего в Сербии с целью эвакуации летчиков союзников, сбитых над этим районом. . [ 48 ] Этой командой, известной как группа Фала, командовал лейтенант Георгий Мусулин вместе с старшим сержантом Майклом Раячичем и специалистом Артуром Джибилианом, радистом. Группа была прикомандирована к США Пятнадцатым воздушным силам и обозначена как 1-е подразделение спасения экипажей. [ 49 ] Это была крупнейшая операция по спасению американских летчиков в истории. [ 50 ] По словам историка профессора Йозо Томасевича , отчет, представленный в УСС, показал, что 417 [ 51 ] Летчики союзников, сбитые над оккупированной Югославией, были спасены четниками Михайловича. [ 52 ] и переброшен по воздуху Пятнадцатой воздушной армией. [ 48 ] По словам лейтенанта-коммандера. Ричард М. Келли (УСС) в общей сложности 432 военнослужащих США и 80 военнослужащих союзников были переброшены по воздуху во время миссии Халярда. [ 53 ]

Операция «Буря», начатая в Польше в 1944 году, привела к нескольким крупным действиям Армии Крайовой , наиболее заметными из которых было Варшавское восстание , которое произошло между 1 августа и 2 октября и провалилось из-за отказа Советского Союза из-за различий в идеологии. помочь; [ нужна ссылка ] еще одной была операция «Остра Брама» : Армия Крайова или Армия Крайова направила оружие, данное им нацистскими немцами (в надежде, что они будут сражаться с наступающими Советами) против нацистских немцев - в конце концов, Армия Крайова вместе с советскими войсками. территорию Большого Вильнюса к ужасу литовцев захватил .

25 июня 1944 года началась битва при Осухах — одно из крупнейших сражений между польским сопротивлением и нацистской Германией в оккупированной Польше во время Второй мировой войны , по сути являющееся продолжением Замосцкого восстания . [ 54 ] Во время операции «Мост III» в 1944 году Польская Армия Крайова ( Армия Крайова) предоставила британцам части ракеты Фау-2 .

Норвежские диверсии немецкой ядерной программы завершились через три года, 20 февраля 1944 года, диверсантской бомбардировкой парома SF Hydro . Паром должен был перевозить железнодорожные вагоны с бочками с тяжелой водой с гидроэлектростанции Веморк , где они производились, через озеро Тинн для отправки в Германию. Его затопление фактически положило конец ядерным амбициям нацистов. Серия рейдов на завод была позднее названа британским ГП самым успешным актом саботажа за всю Вторую мировую войну и легла в основу американского военного фильма « Герои Телемарка» .

В качестве начала своего восстания словацкие повстанцы вошли в Банска-Бистрицу утром 30 августа 1944 года, на второй день восстания, и сделали его своим штабом. К 10 сентября повстанцы взяли под свой контроль большие территории центральной и восточной Словакии. В том числе два захваченных аэродрома. В результате двухнедельного мятежа советские ВВС смогли начать переброску техники словацким и советским партизанам.

Движения Сопротивления во время Второй мировой войны

[ редактировать ]- Албанское движение сопротивления

- Национально-освободительное движение

- Балли Комбетар (антиитальянские, а затем антикоммунистические и антиюгославские движения сопротивления)

- Движение за легальность

- Австрийское движение сопротивления (например, O5)

- Белорусские националистические движения сопротивления:

- Антисоветское сопротивление в Белоруссии (1944–1950-е годы)

- Белорусские народные партизаны , антисоветские и антинацистские [ 55 ]

- Бельгийское сопротивление

- Воссозданная бельгийская армия (ABR)

- Секретная армия (АС)

- Линия кометы

- Комитет защиты евреев (CDJ, Еврейское сопротивление)

- Фронт независимости (FI)

- Группа G

- Кемпен Легион (КЛ)

- Бельгийский легион

- Патриотические ополчения (МП-ПМ)

- Бельгийское национальное движение (МНБ)

- Национальное роялистское движение (МНР-НКБ)

- Бельгийская военная организация сопротивления (OMBR)

- Вооруженные партизаны (AP)

- Сервис Д

- Бригада Витте

- Движение сопротивления Борнео

- Британские движения сопротивления [ 4 ] [ 56 ]

- Раздел D и Раздел VII СИС (планируемые организации Сопротивления)

- Вспомогательные подразделения (планируемые скрытые отряды коммандос, которые будут действовать во время военной кампании против вторжения)

- Сопротивление немецкой оккупации Нормандских островов

- Болгарские движения сопротивления

- Болгарское движение сопротивления

- Горьяни (антикоммунистическое сопротивление с 1944 г.)

- Бирманские движения сопротивления:

- Армия независимости Бирмы (антибританская)

- Антифашистская Лига народной свободы

- Чеченское движение сопротивления (антисоветское)

- Китайские движения сопротивления

- Антияпонская армия спасения страны

- Китайская народная армия национального спасения

- Исцеление Кианга Армия национального спасения

- Армия самообороны Цзилинь

- Северо-восточная антияпонская армия национального спасения

- Северо-Восточная антияпонская объединенная армия

- Северо-восточная народная антияпонская добровольческая армия

- Северо-восточная верная и храбрая армия

- Северо-Восточная народно-революционная армия

- Северо-восточные добровольцы, праведные и храбрые бойцы

- Движения сопротивления Гонконга

- Ганцзю дадуй ( бригада Гонконг-Коулун )

- Колонна Ист-Ривер (партизаны Дунцзян, организация Южного Китая и Гонконга)

- Исламское движение сопротивления против Японии

- Мусульманский отряд (Хуйминь Чжидуй)

- Мусульманский корпус

- Чешское движение сопротивления

- Датское движение сопротивления

- Голландское движение сопротивления

- Внутренние Вооруженные Силы

- Группа Стейкель — голландское движение сопротивления, действовавшее в основном в районе С-Гравенхаге.

- Валкенбургское сопротивление

- Эстонское движение сопротивления

- Эфиопское движение сопротивления

- Прогерманское движение сопротивления в Финляндии

- Французское движение сопротивления

- Немецкие антинацистские движения сопротивления

- Группа Бэстлейн-Якоб-Абшаген

- Черный оркестр

- Исповедующая церковь

- Пираты Эдельвейса

- Группа Эренфельд

- Евросоюз

- Левый круг

- Национальный комитет за свободную Германию

- Начать сначала

- Красный оркестр

- Роберт Уриг Групп

- Организация Саефкова-Якоба-Бестлейна

- Сольф Круг

- Группы из четырех человек в Гамбурге, Мюнхене и Вене

- Белая Роза

- Немецкое пронацистское сопротивление на оккупированных союзниками территориях

- Фольксштурм - немецкая группа сопротивления и ополчение, созданное НСДАП в конце Второй мировой войны.

- Вервольф - движение сопротивления нацистской Германии против союзной оккупации.

- Греческое сопротивление

- Список организаций греческого сопротивления

- Критское сопротивление

- Фронт национального освобождения (EAM) и Греческая народно-освободительная армия (ELAS), партизанские силы EAM.

- Национальная республиканская греческая лига (EDES)

- Национальное и социальное освобождение (ЕККА)

- Венгерское движение сопротивления , антифашистское антиосевое движение против режима Хорти и правительства национального единства.

- Индийские движения сопротивления :

- Движение «Выход из Индии»

- Азад Хинд

- Индийская национальная армия — вооруженная сила, которая боролась за независимость Индии вместе с Японией, сражаясь против союзных войск (в основном против Британии ) в Юго-Восточной Азии и вдоль самых восточных границ Индии.

- Индонезийские движения сопротивления

- Итальянское движение сопротивления

- Ардити дель Пополо

- Сеть Ассизи

- Бригады Зеленого Пламени

- Комитет национального освобождения

- Итальянская антифашистская концентрация

- я делаю это

- Христианская демократия

- Четыре дня Неаполя

- Справедливость и свобода

- Гражданская война в Италии

- Итальянская воюющая армия , военно-морской флот и военно-воздушные силы

- Коммунистическая партия Италии (ИКП)

- Итальянские партизанские республики

- Итальянская социалистическая партия (PSI)

- Лейбористская демократическая партия (PDL)

- Коммунистическое движение Италии

- Комитет национального освобождения Северной Италии

- Вечеринка действий

- Искра

- Итальянское сопротивление союзникам

- Японское антиимперское сопротивление

- Японское проимперское сопротивление

- Еврейское сопротивление в оккупированной немцами Европе (транснациональное)

- Корейское движение сопротивления

- Литовское , латвийское и эстонское антисоветское Лесные движение сопротивления (« братья »)

- Латвийское движение сопротивления

- Ливийское движение сопротивления

- Литовское сопротивление во время Второй мировой войны

- Люксембургское сопротивление во время Второй мировой войны

- Малайское движение сопротивления

- Молдавское сопротивление во время Второй мировой войны

- Норвежское движение сопротивления

- Милорг

- Нортрашип

- Норвежская независимая компания 1 (Компания Линге)

- Освальд Групп

- СЮ

- Филиппинское движение сопротивления

- Союзные партизаны (состоящие из несдавшихся войск USAFFE, включая филиппинских гражданских лиц). [ 57 ]

- Мусульманское движение сопротивления моро

- Хукбалахап

- Польское движение сопротивления

- Польское подпольное государство во главе с польским правительством в изгнании.

- Польские вооруженные силы на Западе

- Армия Крайовой (Армия Крайова — основное направление: авторитарная/западная демократия)

- Gwardia Ludowa WRN (Народная гвардия, свобода, равенство, независимость - подпольная, прогрессивная, антинацистская и антисоветская партия Польской социалистической партии)

- Национальные вооруженные силы - антинацистские, антикоммунистические

- Проклятые солдаты (Антикоммунист)

- Лесни (разные «лесные люди»)

- Bataliony Chłopskie (Крестьянские батальоны - мейнстрим, аполитичный, упор на частную собственность)

- Польский комитет национального освобождения при поддержке СССР

- Польская рабочая партия и Союз польских патриотов

- армия Народная

- гвардия Народная

- Польские вооруженные силы на Востоке

- Еврейские организации

- Еврейская боевая организация (ЖОБ в Польше )

- Еврейский боевой союз в Польше (ZZW)

- Польское подпольное государство во главе с польским правительством в изгнании.

- Румынское антифашистское антиосевое сопротивление и политическая оппозиция

- « Республика Россония », образованная группой советских партизан, описывалась как «ни за Советы, ни за немцев». [ 58 ]

- Так называемое « Русское освободительное движение » попыталось создать независимую (либо в союзе с Германией, либо противостоящую обеим сторонам) российскую антикоммунистическую силу посредством сотрудничества с нацистами. [ 59 ]

- Комитет освобождения народов России и Русская освободительная армия в составе Вермахта, официально освобожденные от немецкого командования в январе 1945 года, перешли на другую сторону в мае 1945 года.

- Операция ГУЛАГ

- Русская Народно-Освободительная Армия , пронацистское ополчение Локотской автономии , позже включенное в состав Ваффен-СС, после войны преобразованное в антисоветское партизанское движение.

- Сингапурское движение сопротивления

- Словацкое движение сопротивления

- Советское партизанское движение

- Тайское движение сопротивления

- Тыграянское движение сопротивления (антиэфиопское)

- Украинские движения сопротивления:

- Украинская повстанческая армия (антинемецкое, антисоветское и антипольское движение сопротивления)

- Украинская народно-революционная армия (антинемецкое, антисоветское и антипольское движение сопротивления)

- Усташи - хорватское националистическое и фашистское движение сопротивления против Королевства Югославия / четников и югославских коммунистов.

- Крестоносцы - хорватское партизанское движение усташей , борющееся против югославских коммунистических сил.

- Вьетминь (вьетнамская организация сопротивления, которая боролась с Вишистской Францией и японцами, а затем против попытки французов повторно оккупировать Вьетнам)

- Югославское движение сопротивления

- Югославские партизаны (Народно-освободительная армия — просоветское югославское коммунистическое антифашистское антиосевое движение и антиюгославское роялистское против четников движение сопротивления )

- Четники (югославская армия на родине — югославские роялисты , антиоси , антифашистские немцы , антихорватские усташи , антиалбанское и антиюгославское коммунистическое партизанское движение сопротивления) [ 60 ]

- Синяя гвардия – словенские четники

- ТИГР (Словенское и хорватское антиитальянское движение сопротивления, действовавшее между 1927 и 1941 годами. На протяжении Второй мировой войны постепенно поглощалось югославскими партизанами.) [ 61 ] [ 62 ]

Известные личности

[ редактировать ]- Иосип Броз Тито

- Шарль Де Голль

- Коча Попович

- Сава Ковачевич

- Джорджио Амендола

- Тувия Бельски

- Мордехай Анелевич

- Дэвид Апфельбаум

- Ицхак Арад

- Уолтер Аудизио

- Жорж Бидо

- Александровская книга

- Дитрих Бонхеффер

- Тадеуш Бор-Коморовский

- Петр Брайко

- Пьер Броссолетт

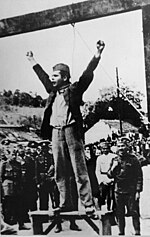

- Masha Bruskina

- Тарас Бульба-Боровец

- Alexander Chekalin

- Даниэль Казанова

- Марек Эдельман

- Анри Оноре д'Этьен д'Орв

- Д'Арси Осборн, 12-й герцог Лидс

- Поль Элюар

- Oleksiy Fedorov

- Манолис Глезос

- Марианна Гольц

- Стефан Грот-Ровецкий

- Йенс Кристиан Хауге

- Арис Велучиотис

- Энвер Ходжа

- Хасан Исраилов

- Ян Карски

- Станислав Аронсон

- Vassili Kononov

- Oleg Koshevoy

- Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya

- Sydir Kovpak

- Николай Кузнецов

- Альберт Квок

- Ганс Литтен

- Отец Пьер

- Мартин Линге

- Луиджи Лонго

- Зивия Любеткин

- Юозас Лукша

- Pavel Luspekayev

- Макс Манус

- Pyotr Masherov

- Хо Ши Мин

- Ким Ку

- Ли Бон Чан

- Это Бонг Гиль

- Мустафа бин Харун

- 马Benzhai Ма Бенжай ( zh: )

- Мисак Манушян

- Жан Мулен

- Омар Мухтар

- Отомарс Ошкалнс

- Ферруччо Парри

- Александр Печерский

- Мотеюс Печюленис ( lt )

- Салипада Пендатун

- Чин Пэн

- Сандро Пертини

- Гамбей Пианг

- Витольд Пилецкий

- Кристиан Пино

- Пантелеймон Пономаренко

- Zinaida Portnova

- Красивый Радич

- Адольфас Раманаускас

- Семен Руднев

- Alexander Saburov

- Ханни Шафт

- Пьер Шунк

- Софи Шолль

- Барон Жан де Селис Лонгшам

- Роман Шухевич

- Хенк Снивлит

- Артурс Спрогис

- Ilya Starinov

- Клаус фон Штауффенберг

- Имантс Судмалис

- Рамон Магсайсай

- Гуннар Сонстеби

- Луис Тарук

- Пальмиро Тольятти

- Арис Велучиотис

- Pyotr Vershigora

- Нэнси Уэйк

- Наполеон Зервас

- Анри Жиро

- Ромен Гэри

- Simcha Zorin

- Йонас Жемайтис

- Кадзи Ватару

- Сандзо определяет

- Гийс ван Холл

- Вальравен ван Холл

- Эрик Хазелхофф Рулфзема

- Велимир Джурич

- Ицхак Цукерман

Документальные фильмы

[ редактировать ]- Путаница была их делом из сериала BBC « Секреты Второй мировой войны» - документального фильма о SOE (руководитель специальных операций) и его операциях.

- «Настоящие герои Телемарка» — книга и документальный фильм эксперта по выживанию Рэя Мирса о норвежском саботаже немецкой ядерной программы ( норвежский саботаж тяжелой воды ).

- Делая выбор: Голландское сопротивление во время Второй мировой войны (2005 г.) Этот удостоенный наград часовой документальный фильм рассказывает истории четырех участников голландского сопротивления и чудеса, которые спасли их от верной смерти от рук нацистов.

Драматизации

[ редактировать ]- 'Алло' Алло! (1982–1992) комедия ситуаций о французском движении сопротивления (пародия на «Секретную армию» ).

- L'Armée des ombres (1969) внутренние и внешние сражения французского сопротивления. Режиссер Жан-Пьер Мельвиль

- Битва при Неретве (фильм) (1969) — фильм, изображающий события, произошедшие во время Четвёртого антипартизанского наступления ( Фолл Вайс ), также известного как Битва за раненых.

- Черная книга (фильм) (2006) изображает двойные и тройные кресты голландского Сопротивления.

- «Бонхёффер» (премьера 2004 года в театре «Акация») — пьеса о Дитрихе Бонхёффере , пасторе Исповедующей церкви , казнённом за участие в немецком сопротивлении.

- Бошко Буха (1978) рассказывает историю мальчика, который в возрасте 15 лет обманом проник в партизанские ряды и прославился своим талантом разрушать вражеские бункеры.

- Шарлотта Грей (2001) – предположительно основана на Нэнси Уэйк

- Четники! «Боевые партизаны» (1943) - военный фильм о лидере сербских четников Дразе Михайловиче и его антинацистской борьбе в Югославии, снятый Twentieth Century Fox .

- Иди и смотри (1985) - фильм советского производства о партизанах в Беларуси, а также о военных преступлениях, совершенных различными группировками войны.

- «Вызов» (2008) рассказывает историю партизан Бельских , группы бойцов еврейского сопротивления, действующей в Белоруссии .

- «Пламя и цитрон» (2008) — фильм, основанный на двух датских бойцах сопротивления, входивших в Holger Danske (группу сопротивления) .

- «Четыре дня Неаполя» (1962) — фильм, основанный на народном восстании против немецких войск, оккупировавших итальянский город Неаполь .

- Поколение (1955) (польский) двое молодых людей, участвовавших в сопротивлении GL

- «Герои Телемарка» (1965) во многом основаны на норвежском саботаже немецкой ядерной программы (более поздние « Настоящие герои Телемарка» более точны).

- Девушка с рыжими волосами (1982) (голландский) рассказывает о голландском борце сопротивления Ханни Шафт.

- Канал (1956) (польский) первый фильм, когда-либо изображающий Варшавское восстание.

- В «Самый длинный день» (1962) представлены сцены операций сопротивления во время операции «Оверлорд».

- Резня в Риме (1973) основана на реальной истории о возмездии нацистов после нападения сопротивления в Риме.

- Моя оппозиция: дневники Фридриха Келлнера (2007) - канадский фильм об инспекторе юстиции Фридрихе Келлнере из Лаубаха , который бросил вызов нацистам до и во время войны.

- Сопротивление (2003): фильм по одноименной книге Аниты Шрив 1995 года . Сюжет вращается вокруг сбитого американского пилота, которого прикрывает бельгийское сопротивление.

- Секретная армия (1977) телесериал о бельгийском движении сопротивления, основанный на реальных событиях.

- Море крови (1971), северокорейская опера, изображающая антияпонское сопротивление.

- Soldaat van Oranje (1977) (голландский) рассказывает о некоторых голландских студентах, которые вступают в сопротивление в сотрудничестве с Англией.

- Софи Шолль – Die letzten Tage (2005) рассказывает о последних днях жизни Софи Шолль.

- Stärker als die Nacht (1954) (Восточная Германия) рассказывает историю группы немецких борцов коммунистического сопротивления.

- «Битва при Сутьеске» (1973) — фильм, основанный на событиях, произошедших во время Пятого антипартизанского наступления ( Падение Шварца ).

- Зима во время войны (фильм) , адаптация 2008 года романа Яна Терлоу 1972 года о голландском юноше, чья благосклонность к членам голландского Сопротивления последней зимой Второй мировой войны оказала разрушительное влияние на его семью.

- Банкир Сопротивления Bankier van het verzet (фильм) — голландский драматический фильм 2018 года, снятый Йорамом Люрсеном во время Второй мировой войны. Фильм основан на жизни банкира Вальравена ван Холла, который финансировал голландское сопротивление во время Второй мировой войны.

См. также

[ редактировать ]Примечания

[ редактировать ]а ^ Источники различаются относительно того, какое движение сопротивления было крупнейшим во время Второй мировой войны. Путаница часто возникает из-за того, что по мере развития войны некоторые движения сопротивления становились все больше, а другие уменьшались. В частности, польские и советские территории были в основном освобождены от контроля нацистской Германии в 1944–1945 годах, что устранило необходимость в соответствующих (антинацистских) партизанских отрядах (в Польше проклятые солдаты продолжали воевать против Советов). Однако бои в Югославии, в которых югославские партизаны сражались с немецкими частями, продолжались до конца войны . Численность каждого из этих трех движений можно приблизительно оценить как приближающуюся к 100 000 в 1941 году и 200 000 в 1942 году, при этом численность польских и советских партизан достигла пика примерно в 1944 году и составила 350 000–400 000, а югославских партизан росла до самого конца, пока не достигла 800 000. . [ 63 ] [ 64 ]

Некоторые источники отмечают, что польская Армия Крайова была крупнейшим движением сопротивления в оккупированной нацистами Европе . Например, Норман Дэвис написал: «Армия Крайова (Армия Крайова), АК, которая по праву может претендовать на звание крупнейшего европейского сопротивления»; [ 65 ] Грегор Даллас писал: «Армия Крайова (Армия Крайова или АК) в конце 1943 года насчитывала около 400 000 человек, что делало ее крупнейшей организацией сопротивления в Европе»; [ 7 ] Марк Вайман писал: «Армия Крайова считалась крупнейшим подпольным отрядом сопротивления в Европе военного времени». [ 66 ] Конечно, польское сопротивление было крупнейшим сопротивлением до вторжения Германии в Югославию и вторжения в Советский Союз в 1941 году.

После этого число советских и югославских партизан начало быстро расти. Численность советских партизан быстро сравнялась с численностью польского сопротивления (график также доступен здесь ). [ 63 ] [ 67 ]

Численность югославских партизан Тито была примерно такой же, как и численность польских и советских партизан в первые годы войны (1941–1942), но в последние годы быстро росла, превосходя численность польских и советских партизан в 2:1 или более. (по оценкам, численность югославских войск составляла около 800 000 человек в 1945 году, а численность польских и советских войск - 400 000 человек в 1944 году). [ 63 ] [ 64 ] Некоторые авторы также называют его крупнейшим движением сопротивления в оккупированной нацистами Европе, например, Кэтлин Мэлли-Моррисон писала: «Югославская партизанская партизанская кампания, которая переросла в крупнейшую армию сопротивления в оккупированной Западной и Центральной Европе...». [ 68 ]

Численность французского сопротивления была меньше: около 10 000 в 1942 году, а к 1944 году увеличилась до 200 000. [ 69 ]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Росботтом, Рональд К. (2014), Когда Париж погрузился во тьму, Нью-Йорк: Little, Brown and Company, стр. 198-199.

- ^ Вевиорка, Оливье и Тебинка, Яцек, «Сопротивляющиеся: от повседневной жизни к контргосударству», в книге « Выжить Гитлера и Муссолини» (2006), ред.: Роберт Гильдеа, Оливье Вевиорка и Анетт Уорринг, Оксфорд: Берг, стр. 153

- ^ Аткин, Малькольм (2015). Борьба с нацистской оккупацией: британское сопротивление 1939-1945 гг . Барнсли: Перо и меч. стр. Глава 11. ISBN 978-1-47383-377-7 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Архив Британского Сопротивления - Вспомогательные подразделения Черчилля - обширный онлайн-ресурс» . www.coleshillhouse.com .

- ^ Джадт, Тони (2005). Послевоенное: История Европы с 1945 года . Нью-Йорк: Книги Пингвина. стр. 41–42. ISBN 0143037757 .

- ^ Норман Дэвис (28 февраля 2005 г.). Божья площадка: с 1795 года по настоящее время . Издательство Колумбийского университета. п. 344 . ISBN 978-0-231-12819-3 . Проверено 30 мая 2012 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Грегор Даллас, 1945: Война, которая никогда не заканчивалась , издательство Йельского университета, 2005, ISBN 0-300-10980-6 , Google Print, стр. 79.

- ^ Марк Вайман, DP: Перемещенные лица Европы, 1945–1951 , Cornell University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-8014-8542-8 , Google Print, стр. 34

- ^ См., например, Леонид Д. Гренкевич, Советское партизанское движение, 1941–44: критический историографический анализ , с. 229, и Уолтер Лакер , «Партизанский читатель: историческая антология» , Нью-Йорк, Сыновья Чарльза Скрибнера, 1990, стр. 229. 233.

- ^ Лаффон, Роберт (2006). Исторический словарь Сопротивления . Париж: Книги. п. 339. ИСБН 978-2-221-09997-1 .

- ^ Сопротивление против сопротивления

- ^ Марек Шимански: Подразделение майора Хубала , Варшава, 1999 г., ISBN 978-83-912237-0-3

- ^ Александра Циолковска-Бём : польский герой Роман Родзевич Судьба солдата Хубала в Освенциме, Бухенвальде и послевоенной Англии , Lexington Books, 2013, ISBN 978-0-7391-8535-3

- ^ Юзеф Гарлински, Борьба с Освенцимом: движение сопротивления в концентрационном лагере, Фосетт, 1975, ISBN 978-0-449-22599-8 , перепечатано Time Life Education, 1993. ISBN 978-0-8094-8925-1

- ^ Гершель Эдельхейт, История Холокоста: справочник и словарь , Westview Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0-8133-2240-7 , Google Print, стр. 413. [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Адам Сайра , волонтер Освенцима - Витольд Пилецкий 1901–1948 [«Доброволец Освенцима»], Освенцим, 2000. ISBN 978-83-912000-3-2

- ^ «Имена праведников по странам» . www.yadvashem.org . Архивировано из оригинала 16 ноября 2017 г. Проверено 14 февраля 2017 г.

- ^ Элизабет Бекл-Клампер, Томас Манг, Вольфганг Нойгебауэр: Центр управления гестапо Вена 1938–1945. Вена 2018, ISBN 978-3-902494-83-2 , стр. 299–305.

- ^ Петер Броучек «Австрийская идентичность в сопротивлении 1938–1945» (2008), стр. 163.

- ↑ Хансякоб Штеле «Die Spione aus dem Pfarrhaus (нем.: Шпион из дома приходского священника)» В: Die Zeit, 5 января 1996 г.

- ^ Фут, MRD (2004) [1966]. SOE во Франции: отчет о работе британского управления специальных операций во Франции, 1940–1944 гг . Нью-Йорк: Фрэнк Касс. п. 14. ISBN 978-0-7146-5528-4 .

- ^ Хрибар, Тина (2004). Euroslovendom [ Европейское словенство ] (на словенском языке). Словацкая матрица. ISBN 961-213-129-5 .

- ^ Халина Аудерска, Зигмунт Зиолек, Действие Н. Мемуары 1939–1945 ) , Wydawnictwo Czytelnik, Варшава, 1972 (на польском языке

- ^ Норман Дэвис , Европа: История , Oxford University Presse, 1996, ISBN

- ↑ газета Αυγή (Авги), статья: 68 лет со дня освобождения Салоников от нацистов.

- ^ газета Πρώτη Σελίδα (Проти Селида), статья: 11-е воссоединение кикисиотов, Афинские кикисиоты почтили память Холокоста Крусии. Архивировано 3 июня 2013 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ Газета Ризоспастис, статья: Убийство членов македонского бюро Коммунистической партии Греции.

- ^ Тесса Стирлинг и др. , Разведывательное сотрудничество между Польшей и Великобританией во время Второй мировой войны , вып. I: Отчет англо-польского исторического комитета , Лондон, Валлентайн Митчелл, 2005 г.

- ^ Черчилль, Уинстон Спенсер (1951). Вторая мировая война: замыкание кольца . Компания Houghton Mifflin, Бостон. п. 643.

- ^ Генерал-майор Рыгор Словиковский, «В секретной службе - Молния факела», The Windrush Press, Лондон, 1988, с. 285

- ^ Тадеуш Пиотровский (1997). «Помощь евреям» . Польский Холокост . МакФарланд и компания. п. 118. ИСБН 978-0-7864-0371-4 .

- ^ Бачинска, Габриэла; ДжонБойл (12 мая 2008 г.). «Умер Сендлер, спаситель детей Варшавского гетто» . Вашингтон Пост . Проверено 12 мая 2008 г. [ мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Кристофер М. Вудхаус, «Борьба за Грецию, 1941–1949», Харт-Дэвис Мак-Гиббон, 1977, Google print, стр.37

- ^ Ричард Клогг, «Краткая история современной Греции», Cambridge University Press, 1979, Google print, стр. 142–143.

- ^ Прокопис Папастратис, «Британская политика в отношении Греции во время Второй мировой войны, 1941–1944», Cambridge University Press, 1984 Google print, стр.129

- ^ Войцех Завадский (2012), Евгениуш Бендера (1906-после 1970). Биографический словарь Пшедборжа, Интернет-архив.

- ^ «Я был номером: Свидетельства из Освенцима» Казимежа Пеховского, Евгении Божены Кодецкой-Качинской, Михала Зиоковского, твердый переплет, Wydawn. Сестры Лорето, ISBN 83-7257-122-8

- ↑ En.auschwitz.org. Архивировано 22 мая 2011 г., в Wayback Machine.

- ^ «Бэзил Дэвидсон: ПАРТИЗАНСКАЯ КАРТИНА» . www.znaci.net .

- ^ Операция WEISS - Битва при Неретве

- ^ Сражения и кампании во время Второй мировой войны в Югославии.

- ^ Барбагалло, Коррадо, Неаполь против нацистского террора . Маоне, Неаполь.

- ^ Ордуэй, Фредерик I., III. Ракетная команда . Apogee Books Space Series 36 (стр. 158, 173)

- ^ Петр Стахневич, "Akcja" "Kutschera", Głos i Wiedza, Варшава 1982,

- ^ Иоахим Лилла (ред.): Заместители гауляйтеров и представительство гауляйтеров НСДАП в «Третьем рейхе» , Кобленц, 2003, стр. 52-3 (материалы Федерального архива, выпуск 13) ISBN 978-3-86509-020-1

- ^ стр. 343-376, Эйр

- ^ Миодраг Д. Пешич (2004). Миссия Хальярда: спасение пилотов союзников Четником Дражой Михайловичем во время Второй мировой войны . Просмотры. ISBN 9788682235408 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Лири (1995) , с. 30

- ^ Форд (1992) , с. 100

- ^ «США чтят поддержку Сербии во время Второй мировой войны» . 21 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Томасевич (1975) , с. 378

- ^ Лири (1995) , с. 32

- ^ Келли (1946) , с. 62

- ^ Мартин Гилберт, Полная история Второй мировой войны , книги Холта в мягкой обложке, 2004 г., ISBN 978-0-8050-7623-3 , Google Print, стр. 542.

- ^ https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/130845/3/Pomiecko_Aleksandra_201811_PhD_thesis.pdf [ только URL-адрес PDF ]

- ^ Аткин, Малькольм (2015). Борьба с нацистской оккупацией: британское сопротивление 1939–1945 гг . Барнсли: Перо и меч. стр. Главы 4 и 11. ISBN. 978-1-47383-377-7 .

- ^ «Гипервойна: Армия США во Второй мировой войне: Триумф на Филиппинах [Глава 33]» . www.ibiblio.org .

- ^ Народные мстители: советские партизаны, сталинское общество и политика сопротивления, 1941-1944 гг . Мичиганский университет. 1994.

- ^ Екатерина Андреева. Власов и Русское освободительное движение.

- ^ «Четник» . Британская энциклопедия . Проверено 20 мая 2020 г.

- ^ Милиция Кацин Вохинц , Первый антифашизм в Европе. Приморская 1925-1935 (Копер: Липа, 1990)

- ^ Веб-сайт Общества ТИГР.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Велимир Вукшич (23 июля 2003 г.). Партизаны Тито 1941-45 гг . Издательство Оспри. стр. 11–. ISBN 978-1-84176-675-1 . Проверено 1 марта 2011 г. [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Jump up to: а б Анна М. Чиенчала, Начало войны и Восточная Европа во Второй мировой войне. , История 557 Конспект лекций

- ^ Норман Дэвис , Божья площадка: История Польши , Колумбийский университет Пресс, 2005, ISBN 0-231-12819-3 , Google Print стр. 344

- ^ Марк Вайман, DP: Перемещенные лица Европы, 1945-1951 , Cornell University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-8014-8542-8 , Google Print, стр. 34.

- ^ См., например: Леонид Д. Гренкевич в книге «Советское партизанское движение, 1941-44: критический историографический анализ», стр. 229 или Уолтер Лакер в книге «Партизанский читатель: историческая антология» (Нью-Йорк, Чарльз Скрибинер, 1990, стр. 233.

- ^ Кэтлин Мэлли-Моррисон (30 октября 2009 г.). Государственное насилие и право на мир: Западная Европа и Северная Америка . АВС-КЛИО. стр. 1–. ISBN 978-0-275-99651-2 . Проверено 1 марта 2011 г.

- ^ Жан-Бенуа Надо; Джули Барлоу (2003). Шестьдесят миллионов французов не могут ошибаться: почему мы любим Францию, а не французов . Справочники, Inc., стр. 89 –. ISBN 978-1-4022-0045-8 . Проверено 6 марта 2011 г.

Внешние ссылки

[ редактировать ]- Еврейское вооруженное сопротивление и восстания на Яд Вашем сайте

- Дом британского движения сопротивления

- Европейский архив сопротивления

- Интервью из «Подполья» рассказывают очевидцы о еврейском сопротивлении России во время Второй мировой войны; сайт и документальный фильм.

- Серии и разные публикации о подпольном движении в Европе во время Второй мировой войны, 1936-1945 гг. Из Отдела редких книг и специальных коллекций Библиотеки Конгресса.

- Коллекция подпольного движения из Отдела редких книг и специальных коллекций Библиотеки Конгресса.

- «Британское сопротивление во Второй мировой войне» . 2015.