Триглав (мифология)

| Триглав | |

|---|---|

Бог | |

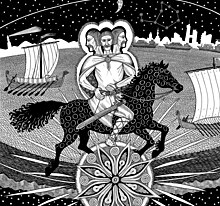

Триглав от Марека Хапона 2014 | |

| Почитаемый в | Померанская религия |

| Основной культовый центр | Щецин |

| Артефакты | Золотая и серебряная седло |

| Животные | Черная лошадь |

| Область | Померания |

Триглав ( горит. "Трехголовый" [ 1 ] ) был главным богом Померанского и , вероятно, некоторых из полабианских славян , поклоняемых в Zczecin , Wolin и, вероятно, Бренне (ныне Бранденбург ). Его культ засвидеживается в нескольких биографиях епископа Св. Отто Бамберга в те годы, непосредственно предшествующие его подавлению в 1127 году.

Источники и история

[ редактировать ]В Latin Records этот теним отмечен как Triglau , Trigelaw , Trigelau , Triglou , Triglaff , Trigeloff . [ 2 ]

Информация о Триглаве поступает из трех источников, самого старейшего из - жизнь Святого Отто, епископ Бамберга ( латынь : vita prieflingensis ) анонимного монаха из аббатства Пюфенинг , написанного к 1146 году, [ 3 ] Вторым источником является жизнь Святого Отто 1151 года, епископ Бамберга, от Монаха Эбо , третий- диалог о жизни Святого Отто Бамберга от Монаха Герборд , написанного около 1158-1159. [ А ] [ 3 ] [ 5 ] Эти источники являются биографиями Святого Отто из Бамберга и описывают его христианские миссии среди балтийских славян. [ 6 ]

Первая миссия

[ редактировать ]Отто, получив разрешение от Папы Каллистуса II , отправляется в Померанию для христианизации . [ 7 ] Епископ впервые прибывает в Волин (согласно Anonymous 4 августа, [ 8 ] По словам Эбо 13 августа, [ 9 ] 1124). Аноним описывает местный культ « копья Юлия Цезаря ». [ 10 ] Тем не менее, Волиняне отказываются принять новую религию и заставлять Отто покинуть город; Он идет в Szczecin . [ 11 ] Херборд сообщает, что Отто, после периодического прятаться в городе, начал христианизация 1 ноября после получения гарантий безопасности от Болеслава III . [ 12 ] Анонимный монах кратко представляет культ Триглава и разрушение его храма и статуи: в городе должны были быть два богато украшенных храма ( латинские : контине ) Триглав поклонялся. Один из храмов держал позолоченное и серебренное седло, принадлежащее Богу, а также хорошо построенную лошадь, которая использовалась во время пророчества: на земле было распространено несколько копьев, а лошадь велась между ними-если лошадь , управляемый Богом, не касался какого -либо копья ногой, это означало удачу и хороший прогноз для предстоящей битвы или путешествия. В конце концов, по приказу Отто, храмы были уничтожены, а предложения распространялись на жителей. Епископ в одиночку уничтожил деревянную статую Триглава, взяв только три деревянные головы серебристого цвета из статуи, которую он отправил Папе в качестве доказательства того, что жители были крещены. [ 13 ] По словам Херборда, в Zczecin было четыре храма, в том числе один, богато украшенный картинами людей и животных, посвященных триглаву. Золотые и серебряные " Kraters ", рога Булла, украшенные драгоценными камнями, которые были пьяны или использовались в качестве инструментов, а также мечи, ножи и мебель были посвящены Богу. Лошадь, используемая во время гадания, была черной по цвету . [ 14 ]

Затем Эбо описывает, как священники Волина убрали золотую статую Триглава, чтобы спасти ее от разрушения: [ 15 ]

And when the pious Otto destroyed the temples and the images of the idols, the pagan priests stole the golden image of Triglav, which they worshipped as the most important, smuggled it out of the province and delivered it to the safekeeping of a widow who lived on a modest farm, where there was no danger that anybody would come in search of it. Once they had taken this gift to her, she looked after it as if it were the apple of her eye and guarded that pagan idol in the following manner: after making a hole in the trunk of a large tree, she placed the image of Triglav therein, wrapped in a blanket and nobody was allowed to see it, much less touch it; only a small hole was left open in the trunk through which to insert the sacrifice and nobody entered that house unless it was to perform the rituals of the pagan sacrifices [...] And thus, Hermann bought himself a cap and a tunic in the Slavic style and, after many dangers along a difficult road, when he reached the house of that widow, declared that he had not long since succeeded in escaping from the tempestuous jaws of the sea thanks to the invocation of his god Triglav, and that he therefore wished to offer him the sacrifice promised for his salvation and that he had arrived there, led by him, following a miraculous order through unknown stretches of the road. And she says: “If you have been sent by him, I have here the altar which contains our god, enclosed in the hole made in an oak. You may not see him nor touch him, but rather, prostrating yourself before the trunk, take note from a prudent distance of the small hole where you must place the sacrifice you wish to make. And after offering it, once the orifice is reverently closed, go and, if you value your life, do not reveal this conversation to anybody”. He entered joyfully in that place and threw a silver drachma into the hole, so that it would appear, from the sound of the metal, that he had offered a sacrifice. But after throwing it in, he took back out what he had thrown and, by way of homage to Triglav, he offered him a humiliation, specifically, a large gob of spit as a sacrifice. Afterwards, he looked carefully to see if there was any possibility of carrying out the mission for which he had been sent there and he realised that the image of Triglav had been placed in the trunk so carefully and firmly that it could not be taken out or even moved. Whereby, afflicted by no small sorrow, he asked himself anxiously what he should do, saying to himself: “Woe! Why have I travelled so fruitlessly such a long journey by sea! What shall I say to my lord or who will believe that I was here, if I return empty-handed?” And looking around him, he saw Triglav’s saddle hanging nearby on the wall: this was extremely old and now served no purpose and, immediately rushing towards it, he tears the hapless trophy off the wall, hides it and, leaving in the early evening, he hurries to meet up with his lord and his men, tells them what he had done and shows Triglav’s saddle as proof of his loyalty. And thus, the Apostle of the Pomeranians, after holding council with his companions, came to the conclusion that that they should desist in their undertaking, unless it should appear that they were driven less by a zeal for justice than by a greed for gold. After summoning and gathering the tribal chieftains and the elders, they demanded, by means of a solemn oath, that they abandon their cult to Triglav and that, once the image was broken, all of its gold would be used to redeem captives.[16]

– Ebo, Life of Saint Otto, Bishop of Bamberg

Otto then demanded that the inhabitants abandon the cult of Triglav. Then Otto established two Wolin churches: one in the city, dedicated to St. Adalbert and St. Wenceslas, and the other outside the city, large and beautiful, St. Peter's Temple.[b] On March 28, 1125, Otto returns to his Archdiocese of Bamberg.[17]

Second mission

[edit]Soon afterwards, some Wolinians and Stettinians returned to their native faith,[17] as Ebo describes: In Wolin, the inhabitants, after burning idols during the first Christianization mission, began to create new statues decorated with gold and silver, and celebrated the feast of deities. For this, the Christian God was to punish them with fire from heaven.[18] He further states:

Stettin, a big city, larger than Wollin, had three hills in its jurisdiction; the middle one of these, which was also the highest, was dedicated to Triglav, the most important god of the pagans. Its statue had three heads and its eyes and lips were covered with a golden bandage. About the idols, the priests said that their most important god had three heads because it ruled three kingdoms, namely, heaven, earth, and hell, and that its face was covered with a bandage so that it might ignore the sins of men as it did not see them and was silent.[19]

– Ebo, Life of Saint Otto, Bishop of Bamberg

There was once an epidemic in the city, which the priests believed was sent by the gods as punishment for abandoning their faith, and that they should start offering sacrifices to the gods if they wanted to survive. Since then, pagan rituals and sacrifices began to be performed again in Szczecin, and Christian temples began to decline.[18]

In April 1127, Otto returns to Pomerania to continue his Christianization mission.[19] In May and June, he carries out Christianization in Wolgast and Gützkow,[20] and on July 31 he returns to Szczecin.[21] Further, Ebo and Herbord report that pagan places of worship were destroyed, and that Christianization continued.[22]

Other potential sources

[edit]It is possible that the cult Triglav was mentioned by the 13th-century writer Henry of Antwerp, who was well informed about the battles for Brenna in the mid-12th century, according to whom a three-headed deity was worshipped in the stronghold, but he does not give its name.[23][24][25][26]

Some authors believe that Adam of Bremen's information about "Neptune"[c] worshipped in Wolin may refer to the Triglav.[25]

Legacy

[edit]

Scholars have tried to find any references to the Triglav beyond the Polabia and Pomerania.[28] In this context, Mount Triglav in Slovenia[29][30][31] and the legend associated with it are often mentioned: "the first to appear from the water was the high mountain Triglav",[30] although Marko Snoj, for example, found the mountain's connection to a god unlikely.[32] Aleksander Gieysztor, following Josip Mal, cites the Triglav stone near Ptuj, whose name was mentioned in 1322.[d][29]

There is a village Trzygłów in Poland, but it is within the range of the Szczecinian cult.[29] In northwestern Poland, folklorists have collected a number of local legends, according to which the statue of Triglav taken from Wolin was supposed to be hidden in the village of Gryfice, in Świętoujść on Wolin, in Tychowo under the erratic boulder Trygław, or in Jezioro Trzygłowskie ("Trzygłów's Lake").[33]

In archaeology

[edit]The Hill on which Szczecin's temple to Triglav was located was most likely identical to Castle Hill. At the top of the Hill there was supposed to be a circle surrounded by a ditch, which was originally a sacred circle (from the 8th century), later a temple of Triglav was built there, and later a Christian temple.[34]

Brandenburg's Mound of Triglav is located about 0.5 kilometers from the fortress located on the island. A bronze horse, iron and decorative objects, including a lot of pottery, were discovered in the stronghold, indicating its importance and that an extensive religious cult may have been associated with it.[35]

Interpretations

[edit]

The chthonic God

[edit]According to Aleksander Gieysztor, it should be considered that Triglav was a tribal god, separate from Perun, as indicated by Herbord's information that in Szczecin, in addition to temples, the place of worship included an oak tree and a spring,[e] which are attributes of the thunder god.[36] Gieysztor recognizes that Triglav was a god close to the chthonic Veles. According to him, this interpretation is supported by the fact that a black horse was sacrificed to Triglav, while Svetovit, interpreted by him as a Polabian hypostasis of Perun, was sacrificed to a white horse.[37]

Andrzej Szyjewski also recognizes Triglav as a chthonic god.[26] He mentions the opinions of some researchers that the names Volos (Veles), Vologost, Volyn and Wolin are related to each other, and Herbord's information that "Pluto" – the Greek god of death – was worshipped in Wolin.[38]

Trinity

[edit]

According to Jiří Dynda, Triglav may have been a three-headed god who combined the three gods responsible for Earth, Heaven, Underworld. In doing so, he cites the pass of "Neptune"[c] worshipped in Wolin and links this to Slovenian traditions regarding Mount Triglav, a three-leveled idol from Zbruch, a Wolin's sacred spear attached to a pole, and an oak tree with a spring which,[e] according to Dynda, corresponds to the Norse Yggdrasil and the wells beneath it, and the hiding of the god's statue in the tree all of which are said to be connected to the Axis mundi. Dynda proposes the following interpretations:[31]

- Relationship to Heaven: Triglav has his mouth and eyes covered to "not see or hear the sins of men." In Indo-European mythologies, "dark" gods have a vision problem: Odin, Velnias, Varuna, Lugh. However, the blindfolds on the eyes of Triglav can be linked to the Sun in the context of "paradoxical mutilation" – a principle concerning some Indo-European deities proposed by Georges Dumézil – the Greek sun god Helios is called "[he], who sees everything and hears everything"; the Vedic Surya is called "all-seeing" or "men-watching."

- Relationship to Earth: a description of the difficult journey to find the god's statue and his "rulership of three kingdoms." This may correspond to Hermes, the god of roads and paths, who is sometimes described as "three-formed" or "three-headed," and the three-headed Hecate who is the protector of the crossroads and who was given a piece of sea, land and sky to rule equally from Zeus.

- The connection to the Underworld: the comparison of the Triglav to Neptune. This is supposed to correspond to Indo-European beliefs that the afterlife is beyond the Sea; in a Slavic context, this may correspond to a Czech text in which a man wishes his malicious dead wife to turn into a goose and "fly somewhere beyond the sea to Veles" with Veles being usually interpreted as god of death.

Alleged influence of Christianity

[edit]

According to Henryk Lowmianski, the Triglav originated in Christianity – in the Middle Ages the Holy Trinity was depicted with three faces, which was later taken over by pagans in the form of a three-headed deity. However, this view cannot be accepted, since the depiction of the Holy Trinity with three faces is attested only from the 14th century, and the official condemnation by the Pope from 1628. The depiction of the Holy Trinity with three faces itself may be of pagan origin (Balkans).[28]

According to Stanislaw Rosik, Christianity may have influenced the development of the Triglav cult in its declining phase. The significance may have been that for the Slavs the Christian God was a "German god," associated with a different ethnic group, but known from neighborly contacts and the later coexistence of the cult of Jesus and the Triglav (the so-called "doublefaith"). As pagans understood it, they linked the power of the deity to the military-political strength of the tribe in question, so the Pomeranians reckoned with a new deity, and the monolatrous (or henotheistic) worship of Triglav may have fostered his identification with Jesus on the basis of interpretatio Slavica. Such an alignment of religiosity fostered a later highlighting of the separateness of Jesus and Triglav, in accordance with Christian theology, and further demonization of Triglav after the final christianisation of Pomerania, which perhaps finds an outlet in the 15th-century Liber sancti Jacobi, where Triglav is referred to as "the enemy of mankind" and "the god or rather the devil."[39]

In culture

[edit]- Manuscript by Bronislaw Trentowski: With the word Halu Jessa created the world and all that existed in it. Therefore Triglav, having heard it, tore off his three heads, and from the blood that flowed from them arose hosts of three successive deities.[40]

- It is possible that the Triglav was already depicted in 12th-century French epic, along with Muhammad, as a pagan enemy of Christianity (in Old French: Mahomet et Tervagnan).[28] However, it's also possible that this name was derived from Hermes Trismegistus,[41] or from an "occitanization" of a vulgar Latin present participle from terrificans ("terrifying").[42]

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ Researchers do not completely agree on the dating of the sources – some believe that Herbord's source is older than Ebon's; some believe that the anonymous source is the youngest.[4]

- ^ Perhaps on the site of an earlier pagan temple.[17]

- ^ Jump up to: a b There one sees a Neptune of three-fold nature: for the island is bathed by three straits of which it is said that one is of an intense green colour, another whitish and the third rages furiously in perpetual tempests.[27]

- ^ Latin: curia una prope lapidem Triglav

- ^ Jump up to: a b There was also there a large and leafy holm oak tree with a delightful fountain underneath, which the simple-minded people regarded as rendered sacred by the presence of a certain god, and treated with great veneration. After the destruction of the continas, when the bishop wished to cut it down, the people begged him not to, because they promised that they would never again venerate in the name of religion either that tree or that place, but that only due to its shade and the agreeableness of the place, which were not in themselves sinful, they desired to save it rather than be saved by it.

- References

- ^ Urbańczyk 1991, p. 129.

- ^ Łuczyński 2020, p. 176.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Urbańczyk 1991, p. 97.

- ^ Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 113–114, 147.

- ^ Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 113, 132, 147.

- ^ Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 113–114, 132, 147.

- ^ Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 116–119.

- ^ Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 147.

- ^ Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 116.

- ^ Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 148.

- ^ Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 116–117, 149.

- ^ Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 133.

- ^ Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 149–151.

- ^ Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 137–138.

- ^ Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 117, 119.

- ^ Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 117-120.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 120–121.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 122–123.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 123.

- ^ Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 125, 127.

- ^ Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 129–130.

- ^ Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 129–131, 142–147.

- ^ Gieysztor 2006, p. 148.

- ^ Urbańczyk 1991, p. 195.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dynda 2014, p. 57, 59.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Szyjewski 2003, p. 121.

- ^ Alvarez-Pedroza 2021, p. 83.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gieysztor 2006, p. 152.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gieysztor 2006, p. 152–153.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Szyjewski 2003, p. 70.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dynda 2014.

- ^ Snoj 2009, p. 439.

- ^ Kajkowski & Szczepanik 2013, p. 210.

- ^ Szczepanik 2020, p. 310.

- ^ Szczepanik 2020, p. 295.

- ^ Gieysztor 2006, p. 151.

- ^ Gieysztor 2006, p. 151, 125.

- ^ Szyjewski 2003, p. 56–57.

- ^ Rosik 2019, p. 56–57.

- ^ Szyjewski 2003, p. 100.

- ^ Joseph T. Shipley, Dictionary of Word Origins. Edition: 2nd, Philosophical Library, New York, 1945, p.354

- ^ Leo Spitzer, "Tervagant", Romania 70.279 (1948): 39–408.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gieysztor, Aleksander (2006). Mitologia Słowian (in Polish). Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego. ISBN 978-83-235-0234-0.

- Szyjewski, Andrzej (2003). Religia Słowian (in Polish). Kraków: Wydawnictwo WAM. ISBN 83-7318-205-5.

- Urbańczyk, Stanisław (1991). Dawni Słowianie. Wiara i kult (in Polish). Wrocław: Ossolineum.

- Alvarez-Pedroza, Juan Antonio (2021). Sources of Slavic Pre-Christian Religion. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-44138-5.

- Rosik, Stanisław (2019). "Kult Trzygława w Szczecinie lat 20. XII stulecia. Między monolatrią a "dwuwiarą"". Slavia Antiqua. 60 (60): 95–106. doi:10.14746/sa.2019.60.5. ISSN 2545-0212.

- Dynda, Jiři (2014). "The Three-Headed One at the Crossroad: A Comparative Study of the Slavic God Triglav". Studia mythologica Slavica. 17: 57–82. doi:10.3986/sms.v17i0.1495. ISSN 1581-128X.

- Kajkowski, Kamil; Szczepanik, Paweł (2013). "Drobna plastyka figuralna wczesnośredniowiecznych Pomorzan". Materiały Zachodniopomorskie. 9: 207–247. ISSN 1581-128X.

- Łowmiański, Henryk (1979). Religia Słowian i jej upadek, w. VI-XII. Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. ISBN 83-01-00033-3.

- Snoj, Marko (2009). Etimološki slovar slovenskih zemljepisnih imen. Lublana: Modrijan. ISBN 978-9612413606.

- Łuczyński, Michał (2020). Bogowie dawnych Słowian. Studium onomastyczne. Kielce: Kieleckie Towarzystwo Naukowe. ISBN 978-83-60777-83-1.

- Szczepanik, Paweł (2020). Rzeczywistość mityczna Słowian północno-zachodnich i jej materialne wyobrażenia. Toruń: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika. ISBN 978-83-231-4349-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Trkanjec, Luka. 2013. “Chthonic Aspects of the Pomeranian Deity Triglav and Other Tricephalic Characters in Slavic Mythology". Studia Mythologica Slavica 16 (October). Ljubljana, Slovenija, 9-25. https://doi.org/10.3986/sms.v16i0.1526.