Ala (demon)

To farmers of eastern Europe, the ala was a demon who led hail and thunderstorms over their fields, ruining their crops. | |

| Grouping | Legendary creature |

|---|---|

| Similar entities | Demon |

| Other name(s) | Aletina, Alina, Alosija, Alčina, Hala |

| Country | Serbia, North Macedonia, Bulgaria |

| Details | Found in the sky, clouds, storms |

An ala or hala (plural: ale or hali) is a female mythological creature recorded in the folklore of Bulgarians, Macedonians, and Serbs. Ale are considered demons of bad weather whose main purpose is to lead hail-producing thunderclouds in the direction of fields, vineyards, or orchards to destroy the crops, or loot and take them away. Extremely voracious, ale particularly like to eat children, though their gluttony is not limited to Earth. It is believed they sometimes try devouring the Sun or the Moon, causing eclipses, and that it would mean the end of the world should they succeed. When people encounter an ala, their mental or physical health, or even life, are in peril; however, her favor can be gained by approaching her with respect and trust. Being in a good relationship with an ala is very beneficial, because she makes her favorites rich and saves their lives in times of trouble.

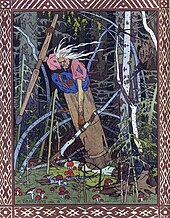

The appearance of an ala is diversely and often vaguely described in folklore. A given ala may look like a black wind, a gigantic creature of indistinct form, a huge-mouthed, humanlike, or snakelike monster, a female dragon, or a raven. An ala may also assume various human or animal shapes, and can even possess a person's body. It is believed that the diversity of appearances described is due to the ala's being a synthesis of a Slavic demon of bad weather and a similar demon of the central Balkans pre-Slavic population.[1] In folk tales with a humanlike ala, her personality is similar to that of the Russian Baba Yaga. Ale are said to live in the clouds, or in a lake, spring, hidden remote place, forest, inhospitable mountain, cave, or gigantic tree.[2] While ale are usually hostile towards humans, they do have other powerful enemies that can defeat them, like dragons. In Christianized tales, St. Elijah takes the dragons' role, but in some cases the saint and the dragons fight ale together. Eagles are also regarded as defenders against ale, chasing them away from fields and thus preventing them from bringing hail clouds overhead.

Origin

[edit]While some mythological beings are common to all Slavic ethnic groups, ale seem to be exclusive to Bulgarian, Macedonian and Serb folklore. Even so, other Slavic groups also had demons of bad weather. Among East Slavs, this witch was called Baba Yaga, and was imagined as a woman of gigantic stature with a big nose, iron teeth, and protruding chin; it was believed that she ate children, and her presence brought thunderstorms and cold weather. The term baba is present in customs, beliefs, and toponyms of all Slavic groups, usually as a personification of wind, darkness, and rain. This leads some scholars to believe there was a proto-Slavic divinity or demon called Baba, associated with bad weather.[1]

Traces of beliefs in that demon are preserved among South Slavs in expressions for the bad weather common in early spring (baba Marta, babini jarci, babine huke, etc.). Brought to the Balkans from the ancient homeland, these beliefs combined with those of the native populations, eventually developing into the personage of the ala. The pre-Slavic Balkan source of the ala is related to the vlva, female demons of bad weather of the Romanians of the Timok Valley, who, like ale, led hail clouds over crops to ruin them, and uprooted trees. A Greek female demon Lamia might also have contributed in the development of the ala. Just like ale, she eats children, and is called gluttonous. In southern Serbia and North Macedonia, lamnja, a word derived from lamia, is also a synonym for ala.[1] The Bulgarian lamya has remained a creature distinct from the ala, but shares many similarities with her.[2] The numerous variations in form of ale, ranging from the animal and half-animal to the humanlike concepts, tell us that beliefs in these demons were not uniform.[1]

Etymology

[edit]| Singular and plural forms of the demon's name, with pronunciations transcribed in the IPA (see help:IPA): | ||||||

| Language | Singular | Plural | ||||

| C. | R. | IPA | C. | R. | IPA | |

| Serbian | ала | ala | [ˈala] | але | ale | [ˈalɛ̝] |

| Bulgarian | хала | hala | [ˈxala] | хали | hali | [ˈxali] |

| Macedonian | ала | ala | [ˈala] | али | ali | [ˈali] |

| C. – Cyrillic script; R. – Serbian Latin alphabet, Romanization of Bulgarian or Romanization of Macedonian. (Note: the Serbian forms have different endings in the grammatical cases other than the nominative, which is given here.) | ||||||

The demon’s name in the standard Serbian, ala, comes from dialects which lost the velar fricative, while hala is recorded in a Serbian dialect which has retained this sound and in Bulgarian. For this reason, it is believed that the original name had an initial h-sound, a fact that has led Serbian scholar Ljubinko Radenković to reject the etymology given by several dictionaries, including that of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, by which the demon’s name comes from the Turkish word ‘ala’ (snake) as that word lacks the h-sound.[3] The name may instead stem from the Greek word for hail, χάλαζα (pronounced [ˈxalaza]; transliterated chalaza or khalaza). This etymology is proposed by Bulgarian scholar Ivanichka Georgieva,[4] and supported by Bulgarian scholar Rachko Popov[5] and Serbian scholars Slobodan Zečević,[1] and Sreten Petrović.[6] According to Serbian scholar Marta Bjeletić, ala and hala stem from the noun *xala in Proto-South-Slavic, the dialect of Proto-Slavic from which South Slavic languages emerged (x in xala represents the voiceless velar fricative). That noun was derived from the Proto-Slavic root *xal-, denoting the fury of the elements.[7] A possible cognate in Kashubian language might be hała - "a large creature or thing".[8]

Appearance

[edit]Dragon or serpent like demon connected with the wind, and thunderstorm and hail clouds. It was believed in the Gruža region of central Serbia that the ala is invisible, but that she can be heard — her powerful hissing resonated in front of the dark hail clouds.[1]

In Bulgaria, farmers saw a horrible ala with huge wings and sword-like thick tail in the contours of a dark cloud. When an ala–cloud overtook the village, villagers peered into the sky hoping to see an imperial eagle emerging there. They believed that the mighty bird with a cross on its back could banish the ala–cloud from the fields.[9] In eastern Bulgaria, ala appeared not in clouds, but in gales and whirlwinds.[10] In other regions of Bulgaria, the ala was seen either as a "bull with huge horns, a black cloud, dark fog or a snake-like monster with six wings and twelve tails". The ala is thought to inhabit remote mountain areas or caves, in which she keeps bad weather. In Bulgarian tradition, thunderstorms and hail clouds were interpreted as a battle between the good dragon or eagle and the evil ala.[5]

Serbs in Kosovo believed that the ala lowers her tail to the ground and hides her head in the clouds. Anyone who saw her head became instantly insane. In a high relief carved above a window of the Visoki Dečani monastery’s church, an eagle clutches a snakelike ala while an eaglet looks on.[11] According to a description from eastern Serbia, the ala is a very large creature with a snake’s body and a horse’s head. A very common opinion is that the ala is the sister of the dragon, and looks more or less like him.[2] In a spell from eastern Serbia, the ala is described as a three-headed snake:[12]

|

У једна уста носи виле и ветрови, |

By a description recorded in the Boljevac region, the ala is a black and horrible creature in the form of wind. Similarly, in the Homolje region of eastern Serbia, the people imagine the ala as a black wind moving over the land. Wherever she goes, a whirlwind blows, turning like a drill, and those who get exposed to the whirlwind go mad. In Bulgaria too, the ala is a violent wind that sweeps up everything in its way and brings havoc:[13]

|

Излезнаха до три люти хали, |

|

A belief from the Leskovac region states the ala is a monster with an enormous mouth who holds in her hand a big wooden spoon, with which she grabs and devours everything that gets in her way. One story has it that a man kept such an ala in his barn; she drank thirty liters of milk every day. Another warns that ale in the form of twelve ravens used to take the crops from vineyards.[3]

In eastern Serbia it was believed that ale who interact with people can metamorphose into humans or animals, after which their true selves can be seen only by so-called šestaci – men with six fingers on both hands and six toes on both feet – though human-looking ale cause houses to shake when they enter.[14] By a belief recorded in the Homolje region, ale that charge to the Moon also display shapeshifting abilities: they repeatedly shift from their basic shape of two-headed snakes to six-fingered men who hold iron pitchforks, black young bulls, big boars, or black wolves, and back.[3]

Effect on humans

[edit]

Ale primarily destroy crops in fields, vineyards, and orchards by leading hail storm clouds overhead, usually during the first half of the summer when grain crops ripen. Ale are also believed to “drink the crops”, or seize the crops of a village and transport them to another place in their huge ears, thereby making some villages poor, and others rich. This was held as the reason why the Aleksandrovac region in central Serbia was so fruitful: it was where ale transported their loot. The people of Kopaonik mountain believed the local ala defended the crops of the area from other ale. If hail destroyed the crops, it was thought that an ala from another area had defeated the local ala and “drunk the crops”. Ale can also spread themselves over fields and thwart the ripening of the crops, or worse, consume the field's fertility, and drink the milk from sheep, especially when it thunders. Ale also possess great strength; when a storm uprooted trees, the people believed that an ala had done it.[1][3] This resulted in a saying for a very strong man: jak kao ala, "as strong as an ala".

At the sight of hail and thunderstorm clouds, i.e. the ala that leads them, people did not just sit and wait – they resorted to magic. In the Pomoravlje region, this magic was assisted by ala’s herbs, picked in levees and the places on a field where a plow turns around during plowing. These locations were considered unclean because ale visited them. In folk spells of eastern Serbia, a particular ala could be addressed by a female personal name: Smiljana, Kalina, Magdalena, Dobrica, Dragija, Zagorka, etc. An expression for addressing an ala – Maate paletinke – is of uncertain meaning. One of the spells that was used upon sighting hail clouds, and which explicitly mentioned an ala, was shouted in the direction of the clouds:[14]

|

Alo, ne ovamo, putuj na Tatar planinu! |

|

Another spell was spoken by a vračara, a woman versed in magic, while she performed a suitable ritual:[15]

|

Не, ало, овамо, |

As several other supernatural entities were also held responsible for bringing hail and torrential rains, when the entity is not explicitly named, it is often impossible to conclude to which the magical measures apply. There was, for example, a custom used when the approach of a thunderstorm was perceived: to bring a table in front of the house, and to put bread, salt, a knife with a black sheath, and an axe with its edge directed skywards on the table. By another custom, a fireplace trivet with its legs directed skywards, knives, forks, and the stub of the Slava candle were put on the table.[15]

Another characteristic attributed to the ala is extreme voracity; in the Leskovac region, she was imagined as a monster with a huge mouth and a wooden spoon in her hand, with which she grabbed and devoured whatever came her way. According to a widely spread tradition, ale used to seize children and devour them in her dwelling, which was full of children’s bones and spilt blood. Less often, they attacked and ate adults; they were able to find a hidden human by smell.[1][3]

People in eastern and southern Serbia believed that ale, in their voracity, attacked the Sun and the Moon. They gradually ate more and more of those celestial bodies, thereby causing an eclipse. During an eclipse, the Sun turned red because it was covered with its own blood as a result of the ale’s bites; when it shone brightly again, that meant it had defeated the ale. The spots on the Moon were seen as scars from the ale’s bites. While ale devoured the Sun or the Moon, many elderly people became depressed and even wept in fear. If ale succeeded in devouring the Sun, the world would end. To prevent that, men shot their guns toward the eclipse or rang bells, and women cast spells incessantly. There was a notion in the Homolje region that, if ale succeeded in devouring the Moon, the Sun would die from sorrow, and darkness would overwhelm the world.[3][14]

Ale were believed to be able to make men insane; in eastern Serbia there is a special term for such a man: alosan. When people encountered an ala on a road or field, they could get dangerous diseases from her.[3] Ale are also responsible for dogs’ rabies, although indirectly: a skylark that reaches the clouds and encounters an ala there goes mad (alosan), plunges to the ground, and so kills itself; a dog that finds and eats the bird goes mad too.[14]

Traversing a crossroads at night was considered dangerous because it was the place and time of the ala’s supper; the unfortunate person who stepped on an “ala’s table” could become blind, deaf, or lame.[6] Ale gather at night on the eves of greater holidays, divert men from their ways into gullies, and torture them there by riding them like horses.[14]

Ala can “sneak” into humans, gaining a human form while retaining their own properties. A tradition has it that an ala sneaked into St. Simeon, which made him voracious,[B] but St. Sava took her out of him. In a tale recorded in eastern Serbia and Bulgaria, a farmer killed an ala who possessed a skinny man living in a distant village, because the ala destroyed his vineyard. In another story, an ala gets into a deceased princess and devours the soldiers on watch.[3]

A human going into an ala’s house, which is frequently deep in a forest, but may also be in the clouds, in a lake, spring, cave, gigantic tree, or other hidden remote place, or on an inhospitable mountain,[2] can have varied consequences. If he approaches the ala with an appeal, and does not mention the differences between her and humans, he will be rewarded. Otherwise, he will be cruelly punished. According to one story, a stepdaughter, driven away from home by her stepmother, comes to an ala’s house; addresses her with the word mother; picks lice from the ala’s hair full of worms; and feeds the ala’s “livestock” of owls, wolves, badgers, and other wild animals; behaving and talking as if these things are quite normal to her, and is rewarded by the ala with a chest filled with gold. When the stepmother’s daughter comes to the ala’s house, she does the opposite, and the ala punishes her and her mother by sending them a chest of snakes, which blind them. In another example, when a prince asks an ala for her daughter’s hand, she saves him from other ale, and helps him get married. But when a girl to whom an ala is the godmother visits the ala with her mother, the ala eats them both because the mother talked about the strange things in her house.[3]

That even a dead ala is bad is seen in the legend explaining the origin of the Golubatz fly (Simulium colombaschense),[16] a species of bloodsucking black fly (of the genus Simulium) that can be lethal to livestock. The legend, recorded in the Požarevac District in the 19th century by Vuk Karadžić, tells how a Serbian man, after a chase, caught and wounded an ala, but she broke away and fled into a cave near Golubac (a town in the district), where she died of the wounds. Ever since, her body has bred the Golubatz flies, and in late spring, they fly out of the cave in a big swarm, spreading as far as Šumadija. People walled up the cave’s opening once, but when the time came for the flies to swarm, the wall shattered.[17]

Aloviti men

[edit]

In Serbia, men believed to possess properties of an ala were called aloviti (ala-like) men, and they were given several explanations. An ala may have sneaked into them; these were recognized by their voracity, because the ala, in order to satisfy her excessive hunger, drove them to eat incessantly. They may also have survived an ala blowing on them – an ala’s breath is usually lethal to humans. These people would then become exceptionally strong. Alternatively, they could be the offspring of an ala and a woman, or could have been born covered with the caul. It was believed that aloviti men could not be killed with a gun or arrow, unless gold or silver was used.[18]

Like ale, aloviti men led hail-producing and thunderstorm clouds: when the skies darkened, such a man would fall into a trance, and his spirit would fly out of his body toward the clouds as if his spirit were an ala herself. There was, however, a significant difference – he never led the clouds over the fields of his own village; the damage was done to the neighboring villages.[18] In this respect, aloviti men are equivalent to zduhaći. Besides leading clouds away, an aloviti man could also fight against ale to protect his village.[3] Children, too, could be aloviti, and they fought ale using plough beams. In these fights they were helped by the Aesculapian snake (smuk in Serbian), and for this reason people would not hurt these snakes.[7]

There is a story about an aloviti man, who is described as unusually tall, thin, bony-faced, and with a long beard and moustache. When the weather was nice, he worked and behaved like the other people in his village, but as soon as the dark clouds covered the sky, he used to close himself in his house, put blinds on the windows, and remain alone and in a trance as long as the bad weather and thunder lasted.[18] Historical persons believed to be aloviti men are Stefan Nemanja,[18] and Stefan Dečanski.[6]

In modern Serbian adjective ''alav'' still signifies voracious appetite.[19]

Adversaries

[edit]

Ale have several adversaries, including dragons, zmajeviti (dragon-like) men, eagles, St. Elijah, and St. Sava. The principal enemy of the ala is the dragon; he is able to defeat her and eliminate her harmful effects. Dragons are thus seen as guardians of the fields and harvest, and as protectors against bad weather. When an ala threatens by bringing hail clouds, a dragon comes out to fight with her and drive her away. His main weapon is lightning; thunder represents a fight between ale and dragons (during which ale hide in tall trees). An instance of a more abundant crop at a particular point is explained in the Pčinja region as a result of a dragon having struck an ala with lightning just over that place, making her drop the looted grains she had been carrying in her huge ears. If an ala finds a dragon in a hollow tree, however, she can destroy him by burning the tree.[1][3][9]

Ale can be defeated by zmajeviti men, who have a human mother, but a dragon father. They look like ordinary people except for little wings beneath their armpits; such men are always born at night after a twelve-month term.[20] Much like a zduhać, a zmajeviti man lives like everybody else when the weather is nice, but when an ala leads threatening clouds into sight, he falls into a trance and his spirit comes out of his body and flies up to the clouds to fight with the ala, just like a dragon would do. A story from Banat, which was held as true until the 1950s, says that before World War I, an exhausted ala in the form of a giant snake fell from the clouds onto a road. The explanation of the event was that the ala was defeated in her fight with a zmajeviti man; people gave her milk to help her recover.[1][3]

In a Christianized version, the duel involves the Christian St. Elijah and the ala, but there is a belief that the saint and the dragons in fact cooperate: as soon as St. Elijah spots an ala, he summons the dragons, either takes them aboard his chariot or harnesses them to it, and they jointly shoot the ala with lightning. Arrow-shaped stones, like belemnites or stone-age arrowheads, are regarded as materialized lightning bolts imbued with a beneficial magical power, and finding one is a good omen.[20]

In a more Christianized version, St. Elijah shoots lightning at the devils who lead the hail clouds; the devils in this case are obviously ale. As shown by these examples, beliefs with various degrees of Christianization, from none to almost complete, can exist side by side.[1]

An eagle’s appearance in the sky when thunderclouds threatened was greeted with joy and hope by people who trusted in their power to defeat an ala; after defeating the ala, the eagle led the clouds away from the fields. An explanation for this, recorded in eastern Serbia, is that the eagles which nest in the vicinity of a village want thunderstorms and hail as far as possible from their nestlings, so coincidentally protect the village’s fields as well. The role of eagles, however, was controversial, because in the same region there was a belief that an eagle flying in front of thunderstorm clouds was a manifestation of an ala, leading the clouds toward the crops, rather than driving them away.[1]

Connection with Baba Yaga

[edit]

Comparing folk tales, there are similarities between the ala and the Russian Baba Yaga. The aforementioned motif of a stepdaughter coming to an ala’s house in a forest is recorded among Russians too – there a stepdaughter comes to Baba Yaga’s house and feeds her “livestock”. Similar are also the motifs of an ala (by Serbs) and Baba Yaga (by Russians) becoming godmothers to children whom they later eat because the children discover their secret. In the Serbian example, the mother of an ala’s godchild speaks with the ala, and in the Russian, the godchild speaks with Baba Yaga.[3]

- Serbian tale

-

- (...) Yesterday, the woman went to the ala’s house with her child, the ala’s godchild. Upon entering the first room, she saw a poker and a broom fighting; in the second room, she saw human legs; in the third, she saw human arms; in the fourth – human flesh; in the fifth – blood; in the sixth – she saw that the ala had taken off her head and was delousing it, while wearing a horse’s head in its place. After that, the ala brought lunch and said to the woman, “Eat, kuma.”[C] “How can I eat after I saw a poker and a broom fighting in the first room?” “Eat, kuma, eat. Those are my maids: they fight about which one should take the broom and sweep.” “How can I eat after I saw human arms and legs in the second and third rooms?” And the ala told her, “Eat, kuma, eat. That is my food.” “How can I eat, kuma, after I saw the sixth room full of blood?” “Eat, kuma, eat. That is the wine that I drink.” “How can I eat after I saw that you had taken your head off and were delousing it, having fixed a horse’s head on yourself?” The ala, after hearing that, ate both the woman and her child.

- Russian tale

-

- (...) On her name day, the girl goes to her godmother’s house with cakes to treat her. She comes to the gate – the gate is closed with a human leg; she goes into the yard – there a barrel full of blood; she goes up the stairs – there dead children; the porch is closed with an arm; on the floor – arms, legs; the door is closed with a finger. Baba Yaga comes to meet her at the door and asks her, “Have you seen anything, my dear, on your way to my house?” “I saw,” the girl answers, “the gate closed with a leg.” “That is my iron latch.” “I saw a barrel in the yard full of blood.” “That is my wine, my darling.” “I saw children lying on the stairs.” “Those are my pigs.” “The porch is closed with an arm.” “That is my latch, my golden one.” “I saw in the house a hairy head.” “That is my broom, my curly one,” said Baba Yaga, then got angry with her prying goddaughter and ate her.

The two examples witness the chthonic nature of these mythological creatures: a hero can enter the chthonic space and discover the secret of that world, but he is not allowed to relate that secret to other humans. Both the ala and Baba Yaga can be traced back to an older concept of a female demonic divinity: the snakelike mistress of the underworld.[3]

Annotations

[edit]- ^ The mountain represents a wild, bleak, inhuman space, where demons dwell, and into which they are expelled by means of incantations, from the human space. See Trebješanin, Žarko. "Sorcery practise as the key to the understanding of the mytho-magical world image" (PDF). University of Niš. p. 2. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ One of the Serbian words for "voracious" is alav, literally: "who has an ala in himself".

- ^ Kuma is a name for either one’s godmother, one’s child’s godmother, or one’s godchild’s mother, depending on the context.

References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Zečević, Slobodan (1981). "Ала". Митска бића српских предања (in Serbian). Belgrade: "Vuk Karadžić": Etnografski muzej. ISBN 978-0-585-04345-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Беновска-Събкова, Милена. "Хала и Ламя" (in Bulgarian). Детски танцов ансамбъл “Зорница”. Archived from the original on 2018-06-17. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Radenković 1996

- ^ Георгиева, Иваничка (1993). Българска народна митология (in Bulgarian). Sofia: Наука и изкуство. p. 119.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Стойнев, Анани; Димитър Попов; Маргарита Василева; Рачко Попов (2006). "Хала". Българска митология. Енциклопедичен речник (in Bulgarian). изд. Захари Стоянов. p. 347. ISBN 978-954-739-682-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Petrović 2000, ch. "aždaja-ala"

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bjeletić, Marta (2004). Јужнословенска лексика у балканском контексту. Лексичка породица именице хала (PDF). Balcanica (in Serbian) (34): 143–146. ISSN 0350-7653. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "ала²". Етимолошки речник српског језика. Vol. 1:А. Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. 2003. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-86-82873-04-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Панайотова, Румяна (21 September 2006). "Тъмен се облак задава" (in Bulgarian). Българско Национално Радио. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-06-24.

- ^ MacDermott, Mercia (1998). Bulgarian folk customs. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-85302-485-6.

- ^ Janićijević, Jovan (1995). U znaku Moloha: antropološki ogled o žrtvovanju (in Serbian). Belgrade: Idea. p. 8. ISBN 978-86-7547-037-3.

- ^ Radenković, Ljubinko (1982). Народне басме и бајања (in Serbian). Niš: Gradina. p. 97.

- ^ Маринов, Димитьр (1994). Народна вяра и религиозни народни обичаи (in Bulgarian). Sofia: БАН. p. 70.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Kulišić, Petrović & Pantelić 1970, Ала

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vuković, Milan T. (2004). Narodni običaji, verovanja i poslovice kod Srba: Sa kratkim pogledom u njihovu prošlost Народни обичаји, веровања и пословице код Срба (in Serbian). Belgrade: Sazvežđa. p. 220. ISBN 978-86-83699-08-7.

- ^ Ramel, Gordon John Larkman (4 March 2007). "The Nematocera". Earth-Life Web Productions. Archived from the original on 6 August 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-21. (Beside biological data, the page mentions a legend on black flies from the Carpathians.)

- ^ Karadžić, Vuk Stefanović (2005). Живот и обичаји народа српскога (in Serbian). Belgrade: Politika : Narodna knjiga. p. 276. ISBN 978-86-331-1946-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kulišić, Petrović & Pantelić 1970, Аловити људи

- ^ "а̏лав". Речник српскохрватскога књижевног језика. Vol. 1 А-Е. Novi Sad: Matica Srpska. 1967. p. 63.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Беновска-Събкова, Милена. "Змей" (in Bulgarian). Детски танцов ансамбъл “Зорница”. Archived from the original on 2018-06-17. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

Sources

[edit]- Bandić, Dušan (2004). Narodna religija Srba u 100 pojmova Народна религија Срба у 100 појмова (in Serbian) (2 ed.). Belgrade: Nolit. ISBN 978-86-19-02328-3.

- Kulišić, Špiro; Petrović, Petar Ž.; Pantelić, Nikola (1970). Српски митолошки речник (in Serbian). Belgrade: Nolit.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Petrović, Sreten (2000). Srpska mitologija: Sistem Srpske mitologije. Prosveta. ISBN 9788674554159.

- Radenković, Ljubinko (1996). "Митска бића српског народа: (Х)АЛА". Archived from the original on 2014-04-11. Retrieved 2007-06-21.. First appeared in the academic journal Liceum, issue no. 2 (1996, Kragujevac, Serbia), pages 11–16; the online version published by Project Rastko. (in Serbian)

- Zečević, Slobodan (1981). Митска бића српских предања (in Serbian). Belgrade: "Vuk Karadžić": Etnografski muzej.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)