Никарагуа

Республика Никарагуа Республика Никарагуа ( испанский ) | |

|---|---|

| Девиз: Мы верим в Бога ( исп .) « Мы верим в Бога » [а] | |

| Гимн: Salve a ti, Никарагуа (испанский). «Слава Тебе, Никарагуа» | |

| |

| Капитал и крупнейший город | Манагуа 12 ° 6' с.ш. 86 ° 14' з.д. / 12,100 ° с.ш. 86,233 ° з.д. |

| Официальные языки | испанский |

| Признанные региональные языки | |

| Этнические группы (2023 [2] ) |

|

| Религия |

|

| Демон(ы) |

|

| Правительство | Унитарная президентская республика в условиях авторитарной диктатуры [5] [6] [7] |

| Дэниел Ортега | |

| Розарио Мурильо | |

| Законодательная власть | Национальное собрание |

| Независимость из Испании , Мексики и Федеративной Республики Центральной Америки | |

• Заявлено | 15 сентября 1821 г. |

• Признанный | 25 июля 1850 г. |

| 1 июля 1823 г. | |

| 31 мая 1838 г. | |

• Революция | 19 июля 1979 г. |

• Действующая конституция | 9 января 1987 г. [8] |

| Область | |

• Общий | 130 375 км 2 (50 338 квадратных миль) ( 96-е место ) |

• Вода (%) | 7.14 |

| Население | |

• Оценка на 2023 год | 6,359,689 [9] ( 110-е ) |

• Плотность | 51/км 2 (132,1/кв. миль) ( 155-е место ) |

| ВВП ( ГЧП ) | оценка на 2023 год |

• Общий | |

• На душу населения | |

| ВВП (номинальный) | оценка на 2023 год |

• Общий | |

• На душу населения | |

| Джини (2014) | 46.2 [11] высокий |

| ИЧР (2022) | средний ( 130-й ) |

| Валюта | Кордова ( NIO ) |

| Часовой пояс | UTC −6 ( центральное стандартное время ) |

| Ведущая сторона | верно |

| Код вызова | +505 |

| Код ISO 3166 | В |

| Интернет-ДВУ | .в |

Никарагуа , [б] официально Республика Никарагуа , [с] Географически крупнейшая страна Центральной Америки , занимающая 130 370 км². 2 (50 340 квадратных миль). С населением 6 850 540 человек по состоянию на 2021 год это третья по численности населения страна в Центральной Америке после Гватемалы и Гондураса . Никарагуа граничит с Гондурасом на севере, Карибским морем на востоке, Коста-Рикой на юге и Тихим океаном , а также имеет общие морские границы с Сальвадором на западе и Колумбией на востоке. Крупнейшим городом страны и национальной столицей является Манагуа , четвертый по величине город в Центральной Америке с населением 1 055 247 человек по состоянию на 2020 год. Многоэтническое население Никарагуа включает людей метисов, коренных народов, европейского и африканского происхождения. Самым распространенным языком в стране является испанский , хотя коренные племена на Берегу Москитов говорят на своих языках и английском .

Первоначально этот регион с древних времен был населен различными коренными культурами, но он был завоеван Испанской империей в 16 веке . Никарагуа получила независимость от Испании в 1821 году. Берег Москитов пошел другим историческим путем: в 17 веке он был колонизирован англичанами, а затем перешел под британское правление. Она стала автономной территорией Никарагуа в 1860 году, а ее самая северная часть была передана Гондурасу в 1960 году. С момента обретения независимости Никарагуа пережила периоды политических волнений, диктатуры, оккупации и финансового кризиса, включая Никарагуанскую революцию 1960-х и 1970-х годов и Контра война [ сломанный якорь ] 1980-х годов.

Смешение культурных традиций привело к существенному разнообразию фольклора, кухни, музыки и литературы, включая вклад никарагуанских поэтов и писателей, таких как Рубен Дарио . Известная как «страна озер и вулканов», [13] [14] Никарагуа также является домом для биосферного заповедника Босавас , второго по величине тропического леса Америки. [15] Биологическое разнообразие, теплый тропический климат и действующие вулканы делают Никарагуа все более популярным туристическим направлением . [16] [17] Никарагуа стала соучредителем Организации Объединенных Наций [18] а также является членом Движения неприсоединения , [19] Боливарианский альянс народов нашей Америки , [20] и Сообщество государств Латинской Америки и Карибского бассейна . [21]

Этимология

[ редактировать ]Есть две преобладающие теории о том, как название Никарагуа появилось . Во-первых, это название было придумано испанскими колонистами на основе названия Никарао . [22] который был вождем или касиком могущественного местного племени, с которым столкнулся испанский конкистадор Хиль Гонсалес Давила во время его вторжения на юго-запад Никарагуа в 1522 году. Эта теория утверждает, что название Никарагуа образовалось от слов Никарао и агуа (по-испански «вода»), чтобы ссылаются на тот факт, что на территории страны есть два больших озера и несколько других водоемов. [23] Однако по состоянию на 2002 год было установлено, что настоящее имя касика было Макуилмикистли , что на языке науатль означало «Пять смертей» , а не Никарао. [24] [25] [26] [27]

Вторая теория заключается в том, что название страны происходит от любого из следующих слов на науатле: nic-anahuac , что означает « Анауак зашел так далеко», или « Науа зашли так далеко», или «те, кто пришел из Анауака, зашли так далеко». ; никан-науа , что означало «здесь науа»; или nic-atl-nahuac , что означало «здесь, у воды» или «окруженный водой». [22] [23] [28] [29]

История

[ редактировать ]Доколумбовая история

[ редактировать ]

Палеоиндейцы впервые заселили территорию, которая сейчас известна как Никарагуа, еще в 12 000 году до нашей эры. [30] В более поздние доколумбовые Никарагуа времена коренные жители были частью Промежуточной зоны . [31] : 33 между мезоамериканским и андским культурными регионами и под влиянием Истмо-Колумбийской зоны . Центральный регион Никарагуа и его Карибское побережье были населены этническими группами, говорящими на макро-чибчанском языке, такими как мискито , рама , майангна и матагальпас . [31] : 20 Они объединились в Центральной Америке и мигрировали как в современную северную Колумбию, так и из близлежащих районов. [32] Их пища добывалась в основном за счет охоты и собирательства, а также рыболовства и подсечного земледелия. [31] : 33 [33] [34] : 65

В конце 15 века западную Никарагуа населяли несколько коренных народов, родственных по культуре с мезоамериканскими цивилизациями ацтеков и майя , а по языку — с мезоамериканской языковой ареалом . [35] Чоротега были этническими группами , говорящими на языке манге , которые прибыли в Никарагуа из нынешнего мексиканского штата Чьяпас где-то около 800 года нашей эры. [28] [34] : 26–33 Народ Никарао был ветвью науа , говорившей на диалекте нават и также пришедшей из Чьяпаса около 1200 г. н.э. [36] До этого никарао были связаны с цивилизацией тольтеков . [34] : 26–33 [36] [37] [38] [39] И Чоротегас, и Никараос возникли в мексиканской Чолула . долине [36] и мигрировал на юг. [34] : 26–33 Третья группа, субтиаба , представляла собой ото-мангский народ, мигрировавший из мексиканского штата Герреро около 1200 г. н. э. [40] : 159 Кроме того, начиная с 14 века в Никарагуа ацтеки основали торговые колонии. [34] : 26–33

Испанская эпоха (1523–1821)

[ редактировать ]

В 1502 году во время своего четвертого путешествия Христофор Колумб стал первым известным европейцем, достигшим территории нынешней Никарагуа, направляясь на юго-восток к Панамскому перешейку . [31] : 193 [34] : 92 Колумб исследовал Берег Москитов на атлантической стороне Никарагуа. [41] но не встретил ни одного коренного населения. Спустя 20 лет испанцы вернулись в Никарагуа, на этот раз в ее юго-западную часть. Первую попытку завоевать Никарагуа предпринял конкистадор Хиль Гонсалес Давила . [42] который прибыл в Панаму в январе 1520 года. В 1522 году Гонсалес Давила отправился в район, который позже стал департаментом Ривас в Никарагуа. [31] : 35 [34] : 92 Там он столкнулся с коренным племенем науа во главе с вождём Макуильмикистли, имя которого иногда ошибочно называют « Никарао » или «Никарагуа». Столицей племени была Кваукаполька. [27] [43] [44] Гонсалес Давила беседовал с Макуильмикистли благодаря двум переводчикам из числа коренных народов, выучившим испанский язык, которых он привел с собой. [26] После исследования и сбора золота [27] [31] : 35 [34] : 55 в плодородных западных долинах Гонсалес Давила и его люди были атакованы и изгнаны Чоротегой во главе с вождём Дириангеном . [27] [45] Испанцы пытались обратить племена в христианство; Племя Макуильмикистли крестилось, [27] [34] : 86 но Дирианген был открыто враждебен испанцам. Западная Никарагуа, расположенная на тихоокеанском побережье, стала портом и судостроительным заводом для галеонов, курсирующих по водам между Манилой (Филиппины) и Акапулько (Мексика). [46]

Первые постоянные поселения в Испании были основаны в 1524 году. [42] В том же году завоеватель Франсиско Эрнандес де Кордова основал два главных города Никарагуа: Гранаду на озере Никарагуа , а затем Леон , к западу от озера Манагуа . [31] : 35, 193 [34] : 92 Кордова вскоре построила оборону городов и боролась с вторжениями других конкистадоров. [34] : 92 Позже Кордова был публично обезглавлен за то, что бросил вызов своему начальнику Педро Ариасу Давиле . [31] : 35 Могила и останки Кордовы были обнаружены в 2000 году среди руин Леон-Вьехо . [47]

Столкновения между испанскими войсками не помешали уничтожению коренного населения и его культуры. Серия сражений стала известна как «Война капитанов». [48] Победителем стал Педро Ариас Давила; [31] : 35 хотя он потерял контроль над Панамой, он переехал в Никарагуа и основал свою базу в Леоне. [49] В 1527 году Леон стал столицей колонии. [34] : 93 [49] Благодаря дипломатии Ариас Давила стал первым губернатором колонии. [47]

Без женщин в своих партиях, [34] : 123 испанские завоеватели взяли в жены и партнеров науа и чоротегу, положив начало многоэтнической смеси коренного и европейского происхождения, ныне известной как « метисы », которая составляет подавляющее большинство населения западной Никарагуа. [35] Многие коренные жители погибли от европейских инфекционных болезней , что усугублялось пренебрежением со стороны испанцев, которые контролировали их существование. [42] Многие другие коренные народы были захвачены в плен и отправлены в рабство в Панаму и Перу между 1526 и 1540 годами. [31] : 193 [34] : 104–105

В 1610 году произошло извержение вулкана Момотомбо , уничтожившее город Леон. [50] Город был перестроен к северо-западу от первоначального. [49] [50] который сейчас известен как руины Леон-Вьехо . Во время американской войны за независимость Центральная Америка была предметом конфликта между Великобританией и Испанией. Адмирал британского флота Горацио Нельсон возглавлял экспедиции в битве при Сан-Фернандо-де-Омоа в 1779 году и на реке Сан-Хуан в 1780 году , последняя из которых имела временный успех, прежде чем была прекращена из-за болезни.

Независимая Никарагуа с 1821 по 1909 год.

[ редактировать ]

The Act of Independence of Central America dissolved the Captaincy General of Guatemala in September 1821, and Nicaragua soon became part of the First Mexican Empire. In July 1823, after the overthrow of the Mexican monarchy in March of the same year, Nicaragua joined the newly formed United Provinces of Central America, a country later known as the Federal Republic of Central America. Nicaragua definitively became an independent republic in 1838.[51]

The early years of independence were characterized by rivalry between the Liberal elite of León and the Conservative elite of Granada, which often degenerated into civil war, particularly during the 1840s and 1850s. Managua rose to undisputed preeminence as the nation's capital in 1852 to allay the rivalry between the two feuding cities.[52][53] Following the start of the California Gold Rush in 1848, Nicaragua provided a route for travelers from the eastern United States to journey to California by sea, via the San Juan River and Lake Nicaragua.[31]: 81 Invited by the Liberals in 1855 to join their struggle against the Conservatives, the American adventurer and filibuster William Walker set himself up as President of Nicaragua after conducting a farcical election in 1856; his presidency lasted less than a year.[54] Military forces from Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua itself united to drive Walker out of Nicaragua in 1857,[55][56][57] bringing three decades of Conservative rule.

Great Britain, which had claimed the Mosquito Coast as a protectorate since 1655, delegated the area to Honduras in 1859 before transferring it to Nicaragua in 1860. The Mosquito Coast remained an autonomous area until 1894. José Santos Zelaya, President of Nicaragua from 1893 to 1909, negotiated the integration of the Mosquito Coast into Nicaragua. In his honor, the region became "Zelaya Department".

Throughout the late 19th-century, the United States and several European powers considered various schemes to link the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic by building a canal across Nicaragua.[58]

United States occupation (1909–1933)

[edit]In 1909, the United States supported the forces rebelling against President Zelaya. U.S. motives included differences over the proposed Nicaragua Canal, Nicaragua's potential to destabilize the region, and Zelaya's attempts to regulate foreign access to Nicaraguan natural resources. On November 18, 1909, U.S. warships were sent to the area after 500 revolutionaries (including two Americans) were executed by order of Zelaya. The U.S. justified the intervention by claiming to protect U.S. lives and property. Zelaya resigned later that year.

In August 1912, the President of Nicaragua, Adolfo Díaz, requested the secretary of war, General Luis Mena, to resign for fear he was leading an insurrection. Mena fled Managua with his brother, the chief of police of Managua, to start an insurrection. After Mena's troops captured steam boats of an American company, the U.S. delegation asked President Díaz to ensure the safety of American citizens and property during the insurrection. He replied he could not, and asked the U.S. to intervene in the conflict.[59][60]

U.S. Marines occupied Nicaragua from 1912 to 1933,[31]: 111, 197 [61] except for a nine-month period beginning in 1925. In 1914, the Bryan–Chamorro Treaty was signed, giving the U.S. control over a proposed canal through Nicaragua, as well as leases for potential canal defenses.[62] After the U.S. Marines left, another violent conflict between Liberals and Conservatives in 1926 resulted in the return of U.S. Marines.[63]

From 1927 to 1933, rebel general Augusto César Sandino led a sustained guerrilla war against the regime and then against the U.S. Marines, whom he fought for over five years.[64] When the Americans left in 1933, they set up the Guardia Nacional (national guard),[65] a combined military and police force trained and equipped by the Americans and designed to be loyal to U.S. interests.

After the U.S. Marines withdrew from Nicaragua in January 1933, Sandino and the newly elected administration of President Juan Bautista Sacasa reached an agreement that Sandino would cease his guerrilla activities in return for amnesty, a land grant for an agricultural colony, and retention of an armed band of 100 men for a year.[66] However, due to a growing hostility between Sandino and National Guard director Anastasio Somoza García and a fear of armed opposition from Sandino, Somoza García ordered his assassination.[65][67][68] Sacasa invited Sandino for dinner and to sign a peace treaty at the Presidential House on the night of February 21, 1934. After leaving the Presidential House, Sandino's car was stopped by National Guard soldiers and they kidnapped him. Later that night, Sandino was assassinated by National Guard soldiers. Later, hundreds of men, women, and children from Sandino's agricultural colony were murdered.[69]

Somoza dynasty (1927–1979)

[edit]

Nicaragua has experienced several military dictatorships, the longest being the hereditary dictatorship of the Somoza family, who ruled for 43 nonconsecutive years during the 20th century.[70] The Somoza family came to power as part of a U.S.-engineered pact in 1927 that stipulated the formation of the Guardia Nacional to replace the marines who had long reigned in the country.[71] Somoza García slowly eliminated officers in the national guard who might have stood in his way, and then deposed Sacasa and became president on January 1, 1937, in a rigged election.[65]

In 1941, during the Second World War, Nicaragua declared war on Japan (8 December), Germany (11 December), Italy (11 December), Bulgaria (19 December), Hungary (19 December) and Romania (19 December). Only Romania reciprocated, declaring war on Nicaragua on the same day (19 December 1941).[72] No soldiers were sent to the war, but Somoza García confiscated properties held by German Nicaraguan residents.[73] In 1945, Nicaragua was among the first countries to ratify the United Nations Charter.[74]

On September 29, 1956,[75] Somoza García was shot to death by Rigoberto López Pérez, a 27-year-old Liberal Nicaraguan poet. Luis Somoza Debayle, the eldest son of the late president, was appointed president by the congress and officially took charge of the country.[65] He is remembered by some as moderate, but after only a few years in power died of a heart attack. His successor as president was René Schick Gutiérrez, whom most Nicaraguans viewed "as nothing more than a puppet of the Somozas".[76] Somoza García's youngest son, Anastasio Somoza Debayle, often referred to simply as "Somoza", became president in 1967.

An earthquake in 1972 destroyed nearly 90% of Managua, including much of its infrastructure.[77] Instead of helping to rebuild the city, Somoza siphoned off relief money. The mishandling of relief money also prompted Pittsburgh Pirates star Roberto Clemente to personally fly to Managua on December 31, 1972, but he died en route in an airplane accident.[78][79] Even the economic elite were reluctant to support Somoza, as he had acquired monopolies in industries that were key to rebuilding the nation.[80]

The Somoza family was among a few families or groups of influential firms which reaped most of the benefits of the country's growth from the 1950s to the 1970s. When Somoza was deposed by the Sandinistas in 1979, the family's worth was estimated to be between $500 million and $1.5 billion.[81]

Nicaraguan Revolution (1960s–1990)

[edit]

In 1961, Carlos Fonseca looked back to the historical figure of Sandino, and along with two other people, one of whom was believed to be Casimiro Sotelo, who was later assassinated, founded the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN).[65] After the 1972 earthquake and Somoza's apparent corruption, the ranks of the Sandinistas were flooded with young disaffected Nicaraguans who no longer had anything to lose.[82]

In December 1974, a group of the FSLN, in an attempt to kidnap U.S. ambassador Turner Shelton, held some Managuan partygoers hostage after killing the party's host, former agriculture minister Jose Maria Castillo, until the Somoza government met their demands for a large ransom and free transport to Cuba. Somoza granted the demand, and then subsequently sent his national guard out into the countryside to look for the kidnappers, who were described by opponents as terrorists.[83]

On January 10, 1978, Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, the editor of the national newspaper La Prensa and ardent opponent of Somoza, was assassinated.[84] It is alleged that the planners and perpetrators of the murder were at the highest echelons of the Somoza regime.[84]

The Sandinistas forcefully took power in July 1979, ousting Somoza, and prompting the exodus of the majority of Nicaragua's middle class, wealthy landowners, and professionals, many of whom settled in the United States.[85][86][87] The Carter administration decided to work with the new government, while attaching a provision for aid forfeiture if it was found to be assisting insurgencies in neighboring countries.[88] Somoza fled the country, and eventually ended up in Paraguay, where he was assassinated in September 1980, allegedly by members of the Argentinian Revolutionary Workers' Party.[89]

In 1980, the Carter administration provided $60 million in aid to Nicaragua under the Sandinistas, but the aid was suspended when the administration obtained evidence of Nicaraguan shipment of arms to El Salvadoran rebels.[90] Most people sided with Nicaragua against the Sandinistas.[clarify][91]

Contras

[edit]In response to the Sandinistas, various rebel groups collectively known as the "Contras" were formed to oppose the new government. The Reagan administration ultimately authorized the CIA to help the Contra rebels with funding, weapons, and training.[92] The Contras operated from camps in the neighboring countries of Honduras to the north and Costa Rica to the south.[92]

They engaged in a systematic campaign of terror among rural Nicaraguans to disrupt the social reform projects of the Sandinistas. Several historians have criticized the Contra campaign and the Reagan administration's support for the Contras, citing the brutality and numerous human rights violations of the Contras, alleging that health centers, schools, and cooperatives were destroyed by rebels,[93] and that murder, rape, and torture occurred on a large scale in Contra-dominated areas.[94] The U.S. also carried out a campaign of economic sabotage, and disrupted shipping by planting underwater mines in Nicaragua's port of Corinto,[95] an action condemned by the International Court of Justice as illegal.[96] The court also found that the U.S. encouraged acts contrary to humanitarian law by producing the manual Psychological Operations in Guerrilla Warfare and disseminating it to the Contras.[97] The manual, among other things, advised on how to rationalize killings of civilians.[98] The U.S. also sought to place economic pressure on the Sandinistas, and the Reagan administration imposed a full trade embargo.[99]

The Sandinistas were also accused of human rights abuses including torture, disappearances and mass executions.[100][101] The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights investigated abuses by Sandinista forces, including an execution of 35 to 40 Miskitos in December 1981,[102] and an execution of 75 people in November 1984.[103]

In the Nicaraguan general elections of 1984, which were judged by at least one visiting 30-person delegation of NGO representatives to have been free and fair,[104] the Sandinistas won the parliamentary election and their leader Daniel Ortega won the presidential election.[105] The Reagan administration criticized the elections as a "sham" based on the claim that Arturo Cruz, the candidate nominated by the Coordinadora Democrática Nicaragüense, comprising three right wing political parties, did not participate in the elections. However, the administration privately argued against Cruz's participation for fear that his involvement would legitimize the elections, and thus weaken the case for American aid to the Contras.[106]

In 1983 the U.S. Congress prohibited federal funding of the Contras, but the Reagan administration illegally continued to back them by covertly selling arms to Iran and channeling the proceeds to the Contras in the Iran–Contra affair, for which several members of the Reagan administration were convicted of felonies.[107] The International Court of Justice, in regard to the case of Nicaragua v. United States in 1986, found, "the United States of America was under an obligation to make reparation to the Republic of Nicaragua for all injury caused to Nicaragua by certain breaches of obligations under customary international law and treaty-law committed by the United States of America".[108] During the war between the Contras and the Sandinistas, 30,000 people were killed.[109]

Post-war (1990–2018)

[edit]

In the 1990 Nicaraguan general election, a coalition of anti-Sandinista parties from both the left and right of the political spectrum led by Violeta Chamorro, the widow of Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, defeated the Sandinistas. The defeat shocked the Sandinistas, who had expected to win.[110]

Exit polls of Nicaraguans reported Chamorro's victory over Ortega was achieved with a 55% majority.[111] Chamorro was the first woman president of Nicaragua. Ortega vowed he would govern desde abajo (from below).[112] Chamorro came to office with an economy in ruins, primarily because of the financial and social costs of the Contra War with the Sandinista-led government.[113] In the 1996 general election, Daniel Ortega and the Sandinistas of the FSLN lost again, this time to Arnoldo Alemán of the Constitutional Liberal Party (PLC).

In the 2001 elections, the PLC again defeated the FSLN, with Alemán's Vice President Enrique Bolaños succeeding him as president. However, Alemán was convicted and sentenced in 2003 to 20 years in prison for embezzlement, money laundering, and corruption;[114] liberal and Sandinista parliament members combined to strip the presidential powers of President Bolaños and his ministers, calling for his resignation and threatening impeachment. The Sandinistas said they no longer supported Bolaños after U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell told Bolaños to distance from the FSLN.[115] This "slow motion coup d'état" was averted partially by pressure from the Central American presidents, who vowed not to recognize any movement that removed Bolaños; the U.S., the OAS, and the European Union also opposed the action.[116]

Nicaragua briefly participated in the Iraq War in 2004 as part of the Plus Ultra Brigade, a military contingent of mixed personnel.[117]

Before the general elections on November 5, 2006, the National Assembly passed a bill further restricting abortion in Nicaragua.[118] As a result, Nicaragua is one of five countries in the world where abortion is illegal with no exceptions.[119] Legislative and presidential elections took place on November 5, 2006. Ortega returned to the presidency with 37.99% of the vote. This percentage was enough to win the presidency outright, because of a change in electoral law which lowered the percentage requiring a runoff election from 45% to 35% (with a 5% margin of victory).[120] Nicaragua's 2011 general election resulted in the re-election of Ortega, with a landslide 62.46% of the vote. In 2014 the National Assembly approved changes to the constitution allowing Ortega to run for a third successive term.[121]

In November 2016, Ortega was elected for his third consecutive term (his fourth overall). International monitoring of the elections was initially prohibited, and as a result the validity of the elections has been disputed, but observation by the OAS was announced in October.[122][123] Ortega was reported by Nicaraguan election officials as having received 72% of the vote. However, the Broad Front for Democracy (FAD), having promoted boycotts of the elections, claimed that 70% of voters had abstained (while election officials claimed 65.8% participation).[124]

In April 2018, demonstrations were held to oppose a decree increasing taxes and reducing benefits in the country's pension system. Local independent press organizations had documented at least 19 dead and over 100 missing in the ensuing conflict.[125] A reporter from NPR spoke to protestors who explained that while the initial issue was the pension reforms, the uprisings that spread across the country reflected many grievances about the government's time in office, and that the fight is for President Ortega and his vice president, his wife, to step down.[126] April 24, 2018 marked the day of the greatest march in opposition of the Sandinista party. On May 2, 2018, university-student leaders made a public announcement giving the government seven days to set a date and time for a dialogue that was promised to the people due to the recent events of repression. The students also scheduled another peaceful protest march on that same day. As of May 2018, estimates of the death toll were as high as 63, many of them student protesters, and the wounded totalled more than 400.[127] Following a working visit from May 17 to 21, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights adopted precautionary measures aimed at protecting members of the student movement and their families after testimonies indicated the majority of them had suffered acts of violence and death threats for their participation.[128] In the last week of May, thousands who accuse Mr. Ortega and his wife of acting like dictators joined in resuming anti-government rallies after attempted peace talks have remained unresolved.[129] Open suppression of political dissent and more militarized policing began in April 2018, but the onset of repression was gradual.[130]

Geography and climate

[edit]

Nicaragua occupies a landmass of 130,967 km2 (50,567 sq mi), which makes it slightly larger than England. Nicaragua has three distinct geographical regions: the Pacific lowlands – fertile valleys which the Spanish colonists settled, the Amerrisque Mountains (North-central highlands), and the Mosquito Coast (Atlantic lowlands/Caribbean lowlands).

The low plains of the Atlantic Coast are 97 km (60 mi) wide in areas. They have long been exploited for their natural resources.

On the Pacific side of Nicaragua are the two largest freshwater lakes in Central America—Lake Managua and Lake Nicaragua. Surrounding these lakes and extending to their northwest along the rift valley of the Gulf of Fonseca are fertile lowland plains, with soil highly enriched by ash from nearby volcanoes of the central highlands. Nicaragua's abundance of biologically significant and unique ecosystems contribute to Mesoamerica's designation as a biodiversity hotspot. Nicaragua has made efforts to become less dependent on fossil fuels, and it expects to acquire 90% of its energy from renewable resources by 2020.[131][132] Nicaragua was one of the few countries that did not enter an INDC at COP21.[133][134] Nicaragua initially chose not to join the Paris Climate Accord because it felt that "much more action is required" by individual countries on restricting global temperature rise.[131] However, in October 2017, Nicaragua made the decision to join the agreement.[135][136][137] It ratified this agreement on November 22, 2017.[138]

Nearly one fifth of Nicaragua is designated as protected areas like national parks, nature reserves, and biological reserves. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 3.63/10, ranking it 146th globally out of 172 countries.[139] Geophysically, Nicaragua is surrounded by the Caribbean Plate, an oceanic tectonic plate underlying Central America, and the Cocos Plate. Since Central America is a major subduction zone, Nicaragua hosts most of the Central American Volcanic Arc. On 9 June 2021, Nicaragua launched a new volcanic supersite research in strengthening the monitoring and surveillance of the country's 21 active volcanoes.

Pacific lowlands

[edit]

In the west of the country, these lowlands consist of a broad, hot, fertile plain. Punctuating this plain are several large volcanoes of the Cordillera Los Maribios mountain range, including Mombacho just outside Granada, and Momotombo near León. The lowland area runs from the Gulf of Fonseca to Nicaragua's Pacific border with Costa Rica south of Lake Nicaragua. Lake Nicaragua is the largest freshwater lake in Central America (20th largest in the world),[140] and is home to some of the world's rare freshwater sharks (Nicaraguan shark).[141] The Pacific lowlands region is the most populous, with over half of the nation's population.

The eruptions of western Nicaragua's 40 volcanoes, many of which are still active, have sometimes devastated settlements but also have enriched the land with layers of fertile ash. The geologic activity that produces vulcanism also breeds powerful earthquakes. Tremors occur regularly throughout the Pacific zone, and earthquakes have nearly destroyed the capital city, Managua, more than once.[142]

Most of the Pacific zone is tierra caliente, the "hot land" of tropical Spanish America at elevations under 610 metres (2,000 ft). Temperatures remain virtually constant throughout the year, with highs ranging between 29.4 and 32.2 °C (85 and 90 °F). After a dry season lasting from November to April, rains begin in May and continue to October, giving the Pacific lowlands 1,016 to 1,524 millimetres (40 to 60 in) of precipitation. Good soils and a favourable climate combine to make western Nicaragua the country's economic and demographic centre. The southwestern shore of Lake Nicaragua lies within 24 kilometres (15 mi) of the Pacific Ocean. Thus the lake and the San Juan River were often proposed in the 19th century as the longest part of a canal route across the Central American isthmus. Canal proposals were periodically revived in the 20th and 21st centuries.[142][143] Roughly a century after the opening of the Panama Canal, the prospect of a Nicaraguan ecocanal remains a topic of interest.[144][145][146][147]

In addition to its beach and resort communities, the Pacific lowlands contains most of Nicaragua's Spanish colonial architecture and artifacts. Cities such as León and Granada abound in colonial architecture; founded in 1524, Granada is the oldest colonial city in the Americas.[148][needs update]

North central highlands

[edit]

Northern Nicaragua is the most diversified region producing coffee, cattle, milk products, vegetables, wood, gold, and flowers. Its extensive forests, rivers and geography are suited for ecotourism.

The central highlands are a significantly less populated and economically developed area in the north, between Lake Nicaragua and the Caribbean. Forming the country's tierra templada, or "temperate land", at elevations between 610 and 1,524 metres (2,000 and 5,000 ft), the highlands enjoy mild temperatures with daily highs of 23.9 to 26.7 °C (75 to 80 °F). This region has a longer, wetter rainy season than the Pacific lowlands, making erosion a problem on its steep slopes. Rugged terrain, poor soils, and low population density characterize the area as a whole, but the northwestern valleys are fertile and well settled.[142]

The area has a cooler climate than the Pacific lowlands. About a quarter of the country's agriculture takes place in this region, with coffee grown on the higher slopes. Oaks, pines, moss, ferns and orchids are abundant in the cloud forests of the region.

Bird life in the forests of the central region includes resplendent quetzals, goldfinches, hummingbirds, jays and toucanets.

Caribbean lowlands

[edit]This large rainforest region is irrigated by several large rivers and is sparsely populated. The area has 57% of the territory of the nation and most of its mineral resources. It has been heavily exploited, but much natural diversity remains. The Rio Coco is the largest river in Central America; it forms the border with Honduras. The Caribbean coastline is much more sinuous than its generally straight Pacific counterpart; lagoons and deltas make it very irregular.[citation needed]

Nicaragua's Bosawás Biosphere Reserve is in the Atlantic lowlands, part of which is located in the municipality of Siuna; it protects 7,300 square kilometres (1,800,000 acres) of La Mosquitia forest – almost 7% of the country's area – making it the largest rainforest north of the Amazon in Brazil.[149]

The municipalities of Siuna, Rosita, and Bonanza, known as the "Mining Triangle", are located in the region known as the North Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region, in the Caribbean lowlands. Bonanza still contains an active gold mine owned by HEMCO. Siuna and Rosita do not have active mines but panning for gold is still very common in the region.[citation needed]

Nicaragua's tropical east coast is very different from the rest of the country. The climate is predominantly tropical, with high temperature and high humidity. Around the area's principal city of Bluefields, English is widely spoken along with the official Spanish. The population more closely resembles that found in many typical Caribbean ports than the rest of Nicaragua.[150]

A great variety of birds can be observed including eagles, toucans, parakeets and macaws. Other animal life in the area includes different species of monkeys, anteaters, white-tailed deer and tapirs.[151]

Flora and fauna

[edit]

Nicaragua is home to a rich variety of plants and animals. Nicaragua is located in the middle of the Americas and this privileged location has enabled the country to serve as host to a great biodiversity. This factor, along with the weather and light altitudinal variations, allows the country to harbor 248 species of amphibians and reptiles, 183 species of mammals, 705 bird species, 640 fish species, and about 5,796 species of plants.

The region of great forests is located on the eastern side of the country. Rainforests are found in the Río San Juan Department and in the autonomous regions of RAAN and RAAS. This biome groups together the greatest biodiversity in the country and is largely protected by the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve in the south and the Bosawás Biosphere Reserve in the north. The Nicaraguan jungles, which represent about 9,700 square kilometres (2.4 million acres), are considered the lungs of Central America and comprise the second largest-sized rainforest of the Americas.[152][153]

There are currently 78 protected areas in Nicaragua, covering more than 22,000 square kilometres (8,500 sq mi), or about 17% of its landmass. These include wildlife refuges and nature reserves that shelter a wide range of ecosystems. There are more than 1,400 animal species classified thus far in Nicaragua. Some 12,000 species of plants have been classified thus far in Nicaragua, with an estimated 5,000 species not yet classified.[154]

The bull shark is a species of shark that can survive for an extended period of time in fresh water. It can be found in Lake Nicaragua and the San Juan River, where it is often referred to as the "Nicaragua shark".[155] Nicaragua has recently banned freshwater fishing of the Nicaragua shark and the sawfish in response to the declining populations of these animals.[156]

Government

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2017) |

Politics of Nicaragua takes place in a framework of a presidential representative democratic republic, whereby the President of Nicaragua is both head of state and head of government, and of a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the national assembly. The judiciary makes up the third branch of government.

Between 2007 and 2009, Nicaragua's major political parties discussed the possibility of going from a presidential system to a parliamentary system. Their reason: there would be a clear differentiation between the head of government (prime minister) and the head of state (president). Nevertheless, it was argued that the true reason for this proposal was to find a legal way for President Ortega to stay in power after January 2012, when his second and last government period was expected to end. Ortega was reelected to a third term in November 2016, and a fourth in 2021; both elections were tainted by credible reports of large-scale fraud, voter intimidation, and politically motivated arrests of opposition party leaders. Independent observers were barred from the polls. The OAS, United States, and European Union all described the 2021 election as a "sham" due to these issues.[157][158]

Since Daniel Ortega's election in 2006, liberal democratic norms and individual rights in practice have deteriorated. Parties other than the ruling FSLN have been repressed through arbitrary arrest and detention of opposition candidates and activists. Most government jobs de facto require membership in the FSLN. Opposition media has been repressed through arrests of journalists and seizure of broadcasting and printing materials.[159]

Foreign relations

[edit]Nicaragua pursues an independent foreign policy. Nicaragua is in territorial disputes with Colombia over the Archipelago de San Andrés y Providencia and Quita Sueño Bank and with Costa Rica over a boundary dispute involving the San Juan River.

On 12 October 2022, Nicaragua voted against condemning Russia for its invasion of Ukraine.[160]

Since 2019, human rights in Nicaragua have been rated not free.

Military

[edit]The Nicaraguan Armed Forces consist of various military contingents. Nicaragua has an army, navy and an air force. There are roughly 14,000 active duty personnel, which is much less compared to the numbers seen during the Nicaraguan Revolution. Although the army has had a rough military history, a portion of its forces, which were known as the national guard, became integrated with what is now the National Police of Nicaragua. In essence, the police became a gendarmerie. The National Police of Nicaragua are rarely, if ever, labeled as a gendarmerie. The other elements and manpower that were not devoted to the national police were sent over to cultivate the new Army of Nicaragua.

The age to serve in the armed forces is 17 and conscription is not imminent. As of 2006[update], the military budget was roughly 0.7% of Nicaragua's expenditures.

In 2017, Nicaragua signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[161]

Law enforcement

[edit]

The National Police of Nicaragua Force (in Spanish: La Policía Nacional Nicaragüense) is the national police of Nicaragua. The force is in charge of regular police functions and, at times, works in conjunction with the Nicaraguan military, making it an indirect and rather subtle version of a gendarmerie.[citation needed] However, the Nicaraguan National Police work separately and have a different established set of norms than the nation's military.[citation needed] According to a recent US Department of State report, corruption is endemic, especially within law enforcement and the judiciary, and arbitrary arrests, torture, and harsh prison conditions are the norm.[162]

Nicaragua has one of the lowest intentional homicide rates in Central America, according to the United Nations Development Program, with a homicide rate of 11 per 100,000 inhabitants as of 2021.[163]

Administrative divisions

[edit]Nicaragua is a unitary republic. For administrative purposes it is divided into 15 departments (departamentos) and two self-governing regions (autonomous communities) based on the Spanish model. The departments are then subdivided into 153 municipios (municipalities). The two autonomous regions are the North Caribbean Coast Autonomous Regionand South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region, often referred to as RACCN and RACCS, respectively.[164]

Economy

[edit]

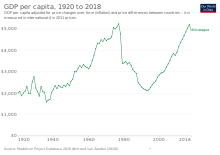

Nicaragua is one of poorest countries in the Americas.[165][166][167] Its gross domestic product (GDP) in purchasing power parity (PPP) in 2008 was estimated at US$17.37 billion.[8] Agriculture represents 15.5% of GDP, the highest percentage in Central America.[168] Remittances account for over 15% of the Nicaraguan GDP. Close to one billion dollars are sent to the country by Nicaraguans living abroad.[169] The economy grew at a rate of about 4% in 2011.[8] By 2019, given restrictive taxes and a civil conflict, it recorded a negative growth of - 3.9%; the International Monetary Fund forecast for 2020 is a further decline of 6% due to COVID-19.[170]

The restrictive tax measures put in place in 2019 and a political crisis over social security negatively affected the country's weak public spending and investor confidence in sovereign debt. According to the update IMF forecasts from 14 April 2020, due to the COVID-19 outbreak, GDP growth is expected to fall to -6% in 2020.[citation needed][needs update]

According to the United Nations Development Programme, 48% of the population of Nicaragua live below the poverty line,[171] 79.9% of the population live with less than $2 per day,[172] According to UN figures, 80% of the indigenous people (who make up 5% of the population) live on less than $1 per day.[173]

According to the World Bank, Nicaragua ranked as the 123rd out of 190 best economy for starting a business.[174] In 2007, Nicaragua's economy was labelled "62.7% free" by the conservative think tank Heritage Foundation, with high levels of fiscal, government, labor, investment, financial, and trade freedom.[175] It ranked as the 61st freest economy, and 14th (of 29) in the Americas. Nicaragua was ranked 115th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[176]

In March 2007, Poland and Nicaragua signed an agreement to write off 30.6 million dollars, which was borrowed by the Nicaraguan government in the 1980s.[177] Inflation reduced from 33,500% in 1988 to 9.45% in 2006, and the foreign debt was cut in half.[178]

Nicaragua is primarily an agricultural country; agriculture constitutes 60% of its total exports which annually yield approximately US$300 million.[179] Nearly two-thirds of the coffee crop comes from the northern part of the central highlands, in the area north and east of the town of Estelí.[142] Tobacco, grown in the same northern highlands region as coffee, has become an increasingly important cash crop since the 1990s, with annual exports of leaf and cigars in the neighborhood of $200 million per year.[180] Soil erosion and pollution from the heavy use of pesticides have become serious concerns in the cotton district. Yields and exports have both been declining since 1985.[142] Today most of Nicaragua's bananas are grown in the northwestern part of the country near the port of Corinto; sugarcane is also grown in the same district.[142] Cassava, a root crop somewhat similar to the potato, is an important food in tropical regions. Cassava is also the main ingredient in tapioca pudding.[142] Nicaragua's agricultural sector has benefited because of the country's strong ties to Venezuela. It is estimated that Venezuela will import approximately $200 million in agricultural goods.[181] In the 1990s, the government initiated efforts to diversify agriculture. Some of the new export-oriented crops were peanuts, sesame, melons, and onions.[142]

Fishing boats on the Caribbean side bring shrimp as well as lobsters into processing plants at Puerto Cabezas, Bluefields, and Laguna de Perlas.[142] A turtle fishery thrived on the Caribbean coast before it collapsed from overexploitation.[142]

Mining is becoming a major industry in Nicaragua,[182] contributing less than 1% of gross domestic product (GDP). Restrictions are being placed on lumbering due to increased environmental concerns about destruction of the rain forests. But lumbering continues despite these obstacles; indeed, a single hardwood tree may be worth thousands of dollars.[142]

During the war between the US-backed Contras and the government of the Sandinistas in the 1980s, much of the country's infrastructure was damaged or destroyed.[183] Transportation throughout the nation is often inadequate. For example, it was until recently impossible to travel all the way by highway from Managua to the Caribbean coast. A new road between Nueva Guinea and Bluefields was completed in 2019 and allows regular bus service to the capital.[184] The Centroamérica power plant on the Tuma River in the Central highlands has been expanded, and other hydroelectric projects have been undertaken to help provide electricity to the nation's newer industries.[142] Nicaragua has long been considered as a possible site for a new canal that could supplement the Panama Canal, connecting the Caribbean Sea (and therefore the Atlantic Ocean) with the Pacific Ocean.

Nicaragua's minimum wage is among the lowest in the Americas and in the world.[185][186][187][188] Remittances are equivalent to roughly 15% of the country's gross domestic product.[8] Growth in the maquila sector slowed in the first decade of the 21st century with rising competition from Asian markets, particularly China.[142] Land is the traditional basis of wealth in Nicaragua, with great fortunes coming from the export of staples such as coffee, cotton, beef, and sugar. Almost all of the upper class and nearly a quarter of the middle class are substantial landowners.

A 1985 government study classified 69.4 percent of the population as poor on the basis that they were unable to satisfy one or more of their basic needs in housing, sanitary services (water, sewage, and garbage collection), education, and employment. The defining standards for this study were very low; housing was considered substandard if it was constructed of discarded materials with dirt floors or if it was occupied by more than four persons per room.

Rural workers are dependent on agricultural wage labor, especially in coffee and cotton. Only a small fraction hold permanent jobs. Most are migrants who follow crops during the harvest period and find other work during the off-season. The "lower" peasants are typically smallholders without sufficient land to sustain a family; they also join the harvest labor force. The "upper" peasants have sufficient resources to be economically independent. They produce enough surplus, beyond their personal needs, to allow them to participate in the national and world markets.

The urban lower class is characterized by the informal sector of the economy. The informal sector consists of small-scale enterprises that utilize traditional technologies and operate outside the legal regime of labor protections and taxation. Workers in the informal sector are self-employed, unsalaried family workers or employees of small-enterprises, and they are generally poor.

Nicaragua's informal sector workers include tinsmiths, mattress makers, seamstresses, bakers, shoemakers, and carpenters; people who take in laundry and ironing or prepare food for sale in the streets; and thousands of peddlers, owners of small businesses (often operating out of their own homes), and market stall operators. Some work alone, but others labor in the small talleres (workshops/factories) that are responsible for a large share of the country's industrial production. Because informal sector earnings are generally very low, few families can subsist on one income.[189] Like most Latin American nations Nicaragua is also characterized by a very small upper-class, roughly 2% of the population, that is very wealthy and wields the political and economic power in the country that is not in the hands of foreign corporations and private industries. These families are oligarchical in nature and have ruled Nicaragua for generations and their wealth is politically and economically horizontally and vertically integrated.

Nicaragua is currently a member of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas, also known as ALBA. ALBA has proposed creating a new currency, the Sucre, for use among its members. In essence, this means that the Nicaraguan córdoba will be replaced with the Sucre. Other nations that will follow a similar pattern include: Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Honduras, Cuba, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Dominica and Antigua and Barbuda.[190]

Nicaragua is considering construction of a canal linking the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean, which President Daniel Ortega has said will give Nicaragua its "economic independence".[191] Scientists have raised concerns about environmental impacts, but the government has maintained that the canal will benefit the country by creating new jobs and potentially increasing its annual growth to an average of 8% per year.[192] The project was scheduled to begin construction in December 2014,[193] however the Nicaragua Canal has yet to be started.[194]

Tourism

[edit]

By 2006, tourism became the second-largest industry in Nicaragua.[195] Previously, tourism had grown about 70% nationwide during a period of 7 years, with rates of 10%–16% annually.[196] The increase and growth led to the income from tourism to rise more than 300% over a period of 10 years.[197] The growth in tourism has also positively affected the agricultural, commercial, and finance industries, as well as the construction industry. President Daniel Ortega has stated his intention to use tourism to combat poverty throughout the country.[198] The results for Nicaragua's tourism-driven economy have been significant, with the nation welcoming one million tourists in a calendar year for the first time in its history in 2010.[199]

Every year about 60,000 U.S. citizens visit Nicaragua, primarily business people, tourists, and those visiting relatives.[200] Some 5,300 people from the U.S. reside in Nicaragua. The majority of tourists who visit Nicaragua are from the U.S., Central or South America, and Europe. According to the Ministry of Tourism of Nicaragua (INTUR),[201] the colonial cities of León and Granada are the preferred spots for tourists. Also, the cities of Masaya, Rivas and the likes of San Juan del Sur, El Ostional, the Fortress of the Immaculate Conception, Ometepe Island, the Mombacho volcano, and the Corn Islands among other locations are the main tourist attractions. In addition, ecotourism, sport fishing and surfing attract many tourists to Nicaragua.

According to the TV Noticias news program, the main attractions in Nicaragua for tourists are the beaches, the scenic routes, the architecture of cities such as León and Granada, ecotourism, and agritourism particularly in northern Nicaragua.[196] As a result of increased tourism, Nicaragua has seen its foreign direct investment increase by 79.1% from 2007 to 2009.[202]

Nicaragua is referred to as "the land of lakes and volcanoes" due to the number of lagoons and lakes, and the chain of volcanoes that runs from the north to the south along the country's Pacific side.[13][14][203] Today, only 7 of the 50 volcanoes in Nicaragua are considered active. Many of these volcanoes offer some great possibilities for tourists with activities such as hiking, climbing, camping, and swimming in crater lakes.

The Apoyo Lagoon Natural Reserve was created by the eruption of the Apoyo Volcano about 23,000 years ago, which left a huge 7 km-wide crater that gradually filled with water. It is surrounded by the old crater wall.[204] The rim of the lagoon is lined with restaurants, many of which have kayaks available. Besides exploring the forest around it, many water sports are practiced in the lagoon, most notably kayaking.[205]

Sand skiing has become a popular attraction at the Cerro Negro volcano in León. Both dormant and active volcanoes can be climbed. Some of the most visited volcanoes include the Masaya Volcano, Momotombo, Mombacho, Cosigüina and Ometepe's Maderas and Concepción.

Ecotourism aims to be ecologically and socially conscious; it focuses on local culture, wilderness, and adventure. Nicaragua's ecotourism is growing with every passing year.[206] It boasts a number of ecotourist tours and perfect places for adventurers. Nicaragua has three eco-regions (the Pacific, Central, and Atlantic) which contain volcanoes, tropical rainforests, and agricultural land.[207] The majority of the eco-lodges and other environmentally-focused touristic destinations are found on Ometepe Island,[208] located in the middle of Lake Nicaragua just an hour's boat ride from Granada. While some are foreign-owned, others are owned by local families.

Demographics

[edit]| Population[209][210] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Million | ||

| 1950 | 1.3 | ||

| 2000 | 5.0 | ||

| 2021 | 6.9 | ||

According to a 2014 research published in the journal Genetics and Molecular Biology, European ancestry predominates in 69% of Nicaraguans, followed by African ancestry in 20%, and lastly indigenous ancestry in 11%.[211] A Japanese research of "Genomic Components in America's demography" demonstrated that, on average, the ancestry of Nicaraguans is 58–62% European, 28% Native American, and 14% African, with a very small Near Eastern contribution.[212] Non-genetic data from the CIA World Factbook establish that from Nicaragua's 2016 population of 5,966,798, around 69% are mestizo, 17% white, 5% Native American, and 9% black and other races.[8] This fluctuates with changes in migration patterns. The population is 58% urban as of 2013[update].[213]

The capital Managua is the biggest city, with an estimated population of 1,042,641 in 2016.[214] In 2005, over 5 million people lived in the Pacific, Central and North regions, and 700,000 in the Caribbean region.[215]

There is a growing expatriate community,[216] the majority of whom move for business, investment or retirement from across the world, such as from the US, Canada, Taiwan, and European countries; the majority have settled in Managua, Granada and San Juan del Sur.

Many Nicaraguans live abroad, particularly in Costa Rica, the United States, Spain, Canada, and other Central American countries.[217][failed verification]

Nicaragua has a population growth rate of 1.5% as of 2013[update].[218] This is the result of one of the highest birth rates in the Western Hemisphere:[citation needed] 17.7 per 1,000 as of 2017.[219] The death rate was 4.7 per 1,000 during the same period according to the United Nations.[220]

Ethnic groups

[edit]

The majority of the Nicaraguan population is composed of mestizos, roughly 69%, while 17% of Nicaragua's population is white,[221] with the majority of them being of Spanish descent, while others are of German, Italian, English, Turkish, Danish or French ancestry.

Black Creoles

[edit]About 9% of Nicaragua's population is black and mainly resides on the country's Caribbean (or Atlantic) coast. The black population is mostly composed of black English-speaking Creoles who are the descendants of escaped or shipwrecked slaves; many carry the name of Scottish settlers who brought slaves with them, such as Campbell, Gordon, Downs, and Hodgson. Although many Creoles supported Somoza because of his close association with the United States, they rallied to the Sandinista cause in July 1979, only to reject the revolution soon afterwards in response to a new phase of "westernization" and imposition of central rule from Managua.[222] There is a smaller number of Garifuna, a people of mixed West African, Carib and Arawak descent. In the mid-1980s, the government divided the Zelaya Department – consisting of the eastern half of the country – into two autonomous regions and granted the black and indigenous people of this region limited self-rule within the republic.

Indigenous population

[edit]The remaining 5% of Nicaraguans are indigenous, the descendants of the country's original inhabitants. Nicaragua's pre-Columbian population consisted of many indigenous groups. In the western region, the Nahuas (Nicarao people) were present along with other groups such as the Chorotega people and the Subtiabas (also known as Maribios or Hokan Xiu). The central region and the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua were inhabited by indigenous peoples who were Macro-Chibchan language groups that had migrated to and from South America in ancient times, primarily what is now Colombia and Venezuela.[223][224] These groups include the present-day Matagalpas, Miskitos, Ramas, as well as Mayangnas and Ulwas who are also known as Sumos.[225][31]: 20 In the 19th century, there was a substantial indigenous minority, but this group was largely assimilated culturally into the mestizo majority. The Garifuna are also present, mainly on the Caribbean Coast. They are a people of mixed African and Indigenous descent.[226]

Languages

[edit]

Nicaraguan Spanish has many indigenous influences and several distinguishing characteristics. For example, some Nicaraguans have a tendency to replace /s/ with /h/ when speaking. Although Spanish is spoken throughout, the country has great variety: vocabulary, accents and colloquial language can vary between towns and departments.[227] Nicaraguan Sign Language emerged in the 1970s and 1980s among deaf children as the first special education schools brought them together, and its emergence became of particular interest to linguists as an opportunity to directly observe the creation of a language.[228][229][230]

On the Caribbean coast, indigenous languages, English-based creoles, and Spanish are spoken. The Miskito language, spoken by the Miskito people as a first language and some other indigenous and Afro-descendants people as a second, third, or fourth language, is the most commonly spoken indigenous language. The indigenous Misumalpan languages of Mayangna and Ulwa are spoken by the respective peoples of the same names. Many Miskito, Mayangna, and Sumo people also speak Miskito Coast Creole, and a large majority also speak Spanish. Fewer than three dozen of nearly 2,000 Rama people speak their Chibchan language fluently, with nearly all Ramas speaking Rama Cay Creole and the vast majority speaking Spanish. Linguists have attempted to document and revitalize the language over the past three decades.[231]

The Garifuna people, descendants of indigenous and Afro-descendant people who came to Nicaragua from Honduras in the early twentieth century, have recently attempted to revitalize their Arawakan language. The majority speak Miskito Coast Creole as their first language and Spanish as their second. The Creole or Kriol people, descendants of enslaved Africans brought to the Mosquito Coast during the British colonial period and European, Chinese, Arab, and British West Indian immigrants, also speak Miskito Coast Creole as their first language and Spanish as their second.[232]

Largest cities

[edit]| Rank | Name | Department | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

León | 1 | Managua | Managua | 1,042,641 |  Masaya  Matagalpa | ||||

| 2 | León | León | 206,264 | ||||||

| 3 | Masaya | Masaya | 176,344 | ||||||

| 4 | Matagalpa | Matagalpa | 158,095 | ||||||

| 5 | Tipitapa | Managua | 140,569 | ||||||

| 6 | Chinandega | Chinandega | 135,154 | ||||||

| 7 | Jinotega | Jinotega | 133,705 | ||||||

| 8 | Granada | Granada | 127,892 | ||||||

| 9 | Estelí | Estelí | 126,290 | ||||||

| 10 | Puerto Cabezas | RACCN | 113,534 | ||||||

Religion

[edit]

Religion plays a significant role in Nicaraguan culture and is afforded special protections in its constitution. Religious freedom (which has been guaranteed since 1939) and religious tolerance are officially promoted by the government, but, in recent years, the Catholic Church and the regime led by Daniel Ortega have been in open conflict. The latter has been accused of using the police to harass clergy (including bishops),[233] closing down Catholic media outlets, and arresting members of the clergy (including Bishop Rolando Alvarez of the Diocese of Matagalpa).

Nicaragua has no official state religion. Catholic bishops are expected to lend their authority to important state occasions, and their pronouncements on national issues are closely followed. They can be called upon to mediate between contending parties at moments of political crisis.[234] In 1979, Miguel D'Escoto Brockman, a priest who had embraced Liberation Theology, served in the government as foreign minister when the Sandinistas came to power. The largest denomination, and traditionally the religion of the majority, is the Roman Catholic Church. It came to Nicaragua in the 16th century with the Spanish conquest and remained, until 1939, the established faith.

The number of practicing Roman Catholics has been declining, while membership of evangelical Protestant groups and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) has been growing rapidly since the 1990s. There is a significant LDS missionary effort in Nicaragua. There are two missions and 95,768 members of the LDS Church (1.54% of the population).[235] There are also strong Anglican and Moravian communities on the Caribbean coast in what once constituted the sparsely populated Mosquito Coast colony. It was under British influence for nearly three centuries. Protestantism was brought to the Mosquito Coast mainly by British and German colonists in forms of Anglicanism and the Moravian Church. Other kinds of Protestant and other Christian denominations were introduced to the rest of Nicaragua during the 19th century.

Popular religion revolves around the saints, who are perceived as intercessors between human beings and God. Most localities, from the capital of Managua to small rural communities, honor patron saints, selected from the Roman Catholic calendar, with annual fiestas. In many communities, a rich lore has grown up around the celebrations of patron saints, such as Managua's Saint Dominic (Santo Domingo), honored in August with two colorful, often riotous, day-long processions through the city. The high point of Nicaragua's religious calendar for the masses is neither Christmas nor Easter, but La Purísima, a week of festivities in early December dedicated to the Immaculate Conception, during which elaborate altars to the Virgin Mary are constructed in homes and workplaces.[234]

Buddhism has increased with a steady influx of immigration.[236]

Although Jews have been living in Nicaragua since the 18th century, the Jewish population is small, numbering less than 200 people in 2017. Of these, 112 were recent converts who claimed Sephardic Jewish ancestry.[237]

As of 2007, approximately 1,200 to 1,500 Nicaraguan residents practiced Islam, most of them Sunnis who are resident aliens or naturalized citizens from Palestine, Libya, and Iran or natural-born Nicaraguan descendants of the two groups.[238]

Immigration

[edit]Relative to its population, Nicaragua has not experienced large waves of immigration. The number of immigrants in Nicaragua, from other Latin American countries or other countries, never surpassed 1% of its total population before 1995. The 2005 census showed the foreign-born population at 1.2%, having risen a mere 0.06% in 10 years.[215]

In the 19th century, Nicaragua experienced modest waves of immigration from Europe. In particular, families from Germany, Italy, Spain, France and Belgium immigrated to Nicaragua, particularly the departments in the Central and Pacific region.

Also present is a small Middle Eastern-Nicaraguan community of Syrians, Armenians, Jewish Nicaraguans, and Lebanese people in Nicaragua. This community numbers about 30,000. There is an East Asian community mostly consisting of Chinese. The Chinese Nicaraguan population is estimated at 12,000.[239] The Chinese arrived in the late 19th century but were unsubstantiated until the 1920s.

Diaspora

[edit]The Civil War forced many Nicaraguans to start lives outside of their country. Many people emigrated during the 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century due to the lack of employment opportunities and poverty. The majority of the Nicaraguan Diaspora migrated to the United States and Costa Rica. Today one in six Nicaraguans live in these two countries.[240]

The diaspora has seen Nicaraguans settling around in smaller communities in other parts of the world, particularly Western Europe. Small communities of Nicaraguans are found in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Communities also exist in Australia and New Zealand. Canada, Brazil and Argentina host small groups of these communities. In Asia, Japan hosts a small Nicaraguan community.

Due to extreme poverty at home, many Nicaraguans are now living and working in neighboring El Salvador, a country that has the US dollar as its currency.[241][242]

Healthcare

[edit]Although Nicaragua's health outcomes have improved over the past few decades with the efficient utilization of resources relative to other Central American nations, healthcare in Nicaragua still confronts challenges responding to its populations' diverse healthcare needs.[243]

The Nicaraguan government guarantees universal free health care for its citizens.[244] However, limitations of current delivery models and unequal distribution of resources and medical personnel contribute to the persistent lack of quality care in more remote areas of Nicaragua, especially among rural communities in the Central and Atlantic region.[243] To respond to the dynamic needs of localities, the government has adopted a decentralized model that emphasizes community-based preventive and primary medical care.[245]

Education

[edit]The adult literacy rate in 2005 was 78.0%, the lowest literacy rate in Central America.[246]

Primary education is free in Nicaragua. A system of private schools exists, many of which are religiously affiliated and often have more robust English programs.[247] As of 1979, the educational system was one of the poorest in Latin America.[248] One of the first acts of the newly elected Sandinista government in 1980 was an extensive and successful literacy campaign, using secondary school students, university students and teachers as volunteer teachers: it reduced the overall illiteracy rate from 50.3% to 12.9% within only five months.[249] This was one of a number of large-scale programs which received international recognition for their gains in literacy, health care, education, childcare, unions, and land reform.[250][251] The Sandinistas also added a leftist ideological content to the curriculum, which was removed after 1990.[142] In September 1980, UNESCO awarded Nicaragua the Soviet Union sponsored Nadezhda Krupskaya award for the literacy campaign.[252]

Gender equality

[edit]Nicaragua's gender equality ranks high among countries in Latin America.[253] When it came to global rankings regarding gender equality, the World Economic Forum ranked Nicaragua at number twelve in 2015,[253] and in its 2020 report Nicaragua ranked number five, behind only northern European countries.[254]

Nicaragua was among the many countries in Latin America and the Caribbean to ratify the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, which aimed to promote women's rights.[255]

In 2009, a Special Ombudsman for Sexual Diversity position was created within its Office of the Human Rights Ombudsman. And, in 2014, the Health Ministry in 2014 banned discrimination based on gender identity and sexual orientation.[256] Nevertheless, discrimination against LGBTQ individuals is common, particularly in housing, education, and the workplace.[162]

The Human Development Report ranked Nicaragua 106 out of 160 countries in the Gender Inequality Index (GII) in 2017. It reflects gender-based inequalities in three dimensions - reproductive health, empowerment, and economic activity.[257]

Culture

[edit]

Nicaraguan culture has strong folklore, music and religious traditions, deeply influenced by European culture but also including Native American sounds and flavors. Nicaraguan culture can further be defined in several distinct strands. The Pacific coast has strong folklore, music and religious traditions, deeply influenced by Europeans. It was colonized by Spain and has a similar culture to other Spanish-speaking Latin American countries. The indigenous groups that historically inhabited the Pacific coast have largely been assimilated into the mestizo culture.

The Caribbean coast of Nicaragua was once a British protectorate. English is still predominant in this region and spoken domestically along with Spanish and indigenous languages. Its culture is similar to that of Caribbean nations that were or are British possessions, such as Jamaica, Belize, the Cayman Islands, etc. Unlike on the west coast, the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean coast have maintained distinct identities, and some still speak their native languages as first languages.

Music

[edit]

Nicaraguan music is a mixture of indigenous and Spanish influences. Musical instruments include the marimba and others common across Central America. The marimba of Nicaragua is played by a sitting performer holding the instrument on his knees. He is usually accompanied by a bass fiddle, guitar and guitarrilla (a small guitar like a mandolin). This music is played at social functions as a sort of background music.

The marimba is made with hardwood plates placed over bamboo or metal tubes of varying lengths. It is played with two or four hammers. The Caribbean coast of Nicaragua is known for a lively, sensual form of dance music called Palo de Mayo which is popular throughout the country. It is especially loud and celebrated during the Palo de Mayo festival in May. The Garifuna community (Afro-Native American) is known for its popular music called Punta.

Nicaragua has international influence in music. Bachata, Merengue, Salsa and Cumbia have gained prominence in cultural centres such as Managua, Leon and Granada. Cumbia dancing has grown popular with the introduction of Nicaraguan artists, including Gustavo Leyton, on Ometepe Island and in Managua. Salsa dancing has become extremely popular in Managua's nightclubs. With various influences, the form of salsa dancing varies in Nicaragua. New York style and Cuban Salsa (Salsa Casino) elements have gained popularity across the country.

Dance

[edit]Dance in Nicaragua varies depending upon the region. Rural areas tend to have a stronger focus on movement of the hips and turns. The dance style in cities focuses primarily on more sophisticated footwork in addition to movement and turns. Combinations of styles from the Dominican Republic and the United States can be found throughout Nicaragua. Bachata dancing is popular in Nicaragua. A considerable amount of Bachata dancing influence comes from Nicaraguans living abroad, in cities that include Miami, Los Angeles and, to a much lesser extent, New York City. Tango has also surfaced recently in cultural cities and ballroom dance occasions.

Literature

[edit]

The origin of Nicaraguan literature can arguably be traced to pre-Columbian times. The myths and oral literature formed the cosmogenic view of the world of the indigenous people. Some of these stories are still known in Nicaragua. Like many Latin American countries, the Spanish conquerors have had the most effect on both the culture and the literature. Nicaraguan literature has historically been an important source of poetry in the Spanish-speaking world, with internationally renowned contributors such as Rubén Darío who is regarded as the most important literary figure in Nicaragua. He is called the "Father of Modernism" for leading the modernismo literary movement at the end of the 19th century.[259] Other literary figures include Carlos Martinez Rivas, Pablo Antonio Cuadra, Alberto Cuadra Mejia, Manolo Cuadra, Pablo Alberto Cuadra Arguello, Orlando Cuadra Downing, Alfredo Alegría Rosales, Sergio Ramirez Mercado, Ernesto Cardenal, Gioconda Belli, Claribel Alegría and José Coronel Urtecho, among others.[260]

The satirical drama El Güegüense was the first literary work of post-Columbian Nicaragua. It was written in both Nicarao and Spanish.[40]: 21 It's regarded as one of Latin America's most distinctive colonial-era expressions and as Nicaragua's signature folkloric masterpiece. El Güegüense is a work of resistance to Spanish colonialism that combined music, dance and theatre.[259] The theatrical play was written by an anonymous author in the 16th century, making it one of the oldest indigenous theatrical/dance works of the Western Hemisphere. In 2005 it was recognized by UNESCO as "a patrimony of humanity".[261] After centuries of popular performance, the play was first published in a book in 1942.[262]

Cuisine

[edit]

Nicaraguan cuisine is a mixture of Spanish food and dishes of a pre-Columbian origin.[263] Traditional cuisine changes from the Pacific to the Caribbean coast. The Pacific coast's main staple revolves around local fruits and corn, the Caribbean coast cuisine makes use of seafood and the coconut.

Как и во многих других странах Латинской Америки, кукуруза является основным продуктом питания и используется во многих широко потребляемых блюдах, таких как накатамал , гуирила и индио-вьехо . Кукуруза также является ингредиентом таких напитков, как пинолило и чича, а также сладостей и десертов. Помимо кукурузы очень часто едят рис и фасоль.

Галло пинто Никарагуа , национальное блюдо , готовится из белого риса и маленькой красной фасоли, которые готовятся по отдельности, а затем обжариваются вместе. Блюдо имеет несколько вариаций, включая добавление кокосового молока или тертого кокоса на Карибском побережье. Большинство никарагуанцев начинают свой день с галло пинто. Галло пинто чаще всего подают с карне асада , салатом, жареным сыром, бананами или мадуро.

Многие блюда Никарагуа включают местные фрукты и овощи, такие как жокоте , манго , папайя , тамариндо , пипиан, банан, авокадо , юка , а также травы, такие как кинза , орегано и ачиоте . [263]

Традиционные закуски уличной еды, которые можно найти в Никарагуа, включают « кесильо », толстую лепешку с мягким сыром и сливками, «тахадас» (обжаренные во фритюре чипсы из подорожника), «мадурос» (обжаренный спелый подорожник) и «фреско» (свежие соки, такие как как гибискус и тамаринд обычно подают в пластиковом пакете с соломинкой). [264]

Известно, что никарагуанцы едят морских свинок . [265] известный как куй . Тапиров, игуан, черепашьих яиц, броненосцев и удавов также иногда едят, но из-за угрозы исчезновения этих диких существ предпринимаются попытки обуздать этот обычай. [263]

СМИ

[ редактировать ]Для большинства никарагуанцев радио и телевидение являются основными источниками новостей. Есть более 100 радиостанций и несколько телевизионных сетей. Кабельное телевидение доступно в большинстве городских районов. [266]

Печатные СМИ Никарагуа разнообразны и партийны, представляют проправительственные и антиправительственные позиции. Публикации включают La Prensa , El Nuevo Diario , Confidencial , Hoy и Mercurio. Интернет-издания включают Confidencial и The Nicaragua Dispatch .

Спорт

[ редактировать ]

Бейсбол — самый популярный вид спорта в Никарагуа. Хотя некоторые профессиональные бейсбольные команды Никарагуа недавно закрылись, в стране по-прежнему сохраняются сильные традиции бейсбола в американском стиле.

Бейсбол появился в Никарагуа в 19 веке. На побережье Карибского моря жителей Блуфилдса в 1888 году научил играть в бейсбол Альберт Аддлсберг, торговец из США. [267] Бейсбол не прижился на тихоокеанском побережье до 1891 года, когда группа, состоящая в основном из студентов колледжей из Соединенных Штатов, сформировала «La Sociedad de Recreo» (Общество отдыха), где они занимались различными видами спорта, самым популярным из которых был бейсбол. [267]