Боинг 777

| Боинг 777 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Первый построенный Боинг 777, эксплуатируемый компанией Cathay Pacific в июле 2011 года. Боинг 777 представляет собой двухдвигательный низкоплан ; оригинальный -200 - самый короткий вариант. | |

| Роль | Широкофюзеляжный реактивный авиалайнер |

| Национальное происхождение | Соединенные Штаты |

| Производитель | Коммерческие самолеты Боинг |

| Первый полет | 12 июня 1994 г |

| Introduction | June 7, 1995 with United Airlines |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Emirates United Airlines Qatar Airways Air France |

| Produced | 1993–present |

| Number built | 1,734 as of June 2024[update] based on deliveries[1][2][3] |

| Variants | Boeing 777X |

Boeing 777 , обычно называемый Triple Seven , — американский дальнемагистральный широкофюзеляжный авиалайнер, разработанный и производимый компанией Boeing Commercial Airplanes . Боинг 777 — самый большой в мире двухдвигательный реактивный самолет и самый массовый широкофюзеляжный авиалайнер.Лайнер был разработан , чтобы заполнить пробел между другими широкофюзеляжными самолетами Boeing, двухмоторным 767 и четырехмоторным 747 , а также заменить устаревшие DC-10 и L-1011 трехдвигательные самолеты . Программа 777, разработанная в консультации с восемью крупными авиакомпаниями, была запущена в октябре 1990 года по заказу United Airlines . Прототип был выпущен в апреле 1994 года и совершил первый полет в июне. Боинг 777 поступил на вооружение стартового оператора United Airlines в июне 1995 года. Варианты с большей дальностью полета были запущены в эксплуатацию в 2000 году и впервые доставлены в 2004 году.

Боинг 777 может вместить десять сидений в ряд и имеет типичную вместимость 3-го класса от 301 до 368 пассажиров с дальностью полета от 5 240 до 8 555 морских миль [нми] (от 9 700 до 15 840 км; от 6 030 до 9 840 миль). Лайнер узнаваем по турбовентиляторным двигателям большого диаметра, шести колесам на каждом основном шасси , полностью круглому поперечному сечению фюзеляжа и лопастному хвостовому обтекателю. Боинг 777 стал первым авиалайнером Boeing, который использовал электродистанционное управление и применил конструкцию из углеродного композита в хвостовом оперении .

The original 777 with a maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) of 545,000–660,000 lb (247–299 t) was produced in two fuselage lengths: the initial 777-200 was followed by the extended-range -200ER in 1997; and the 33.25 ft (10.13 m) longer 777-300 in 1998. These 777 Classics were powered by 77,200–98,000 lbf (343–436 kN) General Electric GE90, Pratt & Whitney PW4000, or Rolls-Royce Trent 800 engines. The extended-range 777-300ER, with a MTOW of 700,000–775,000 lb (318–352 t), entered service in 2004, the longer-range 777-200LR in 2006, and the 777F freighter in 2009. These longer-haul variants use 110,000–115,300 lbf (489–513 kN) GE90 engines and have extended raked wingtips. In November 2013, Boeing announced the 777X development with the -8 and -9 variants, both featuring composite wings with folding wingtips and General Electric GE9X engines.

As of 2018[update], Emirates was the largest operator with a fleet of 163 aircraft. As of June 2024[update], more than 60 customers have placed orders for 2,279 Triple Sevens across all variants, of which 1,734 have been delivered. This makes the 777 the best-selling wide-body airliner, while its best-selling variant is the 777-300ER with 837 aircraft ordered and 832 delivered. The airliner initially competed with the Airbus A340 and McDonnell Douglas MD-11; since 2015 it has mainly competed with the Airbus A350 and later also with the A330-900. As of May 2024[update], the 777 has been involved in 31 aviation accidents and incidents, including five hull loss accidents out of eight total hull losses with 542 fatalities including one ground casualty.

Development

[edit]Background

[edit]

In the early 1970s, the Boeing 747, McDonnell Douglas DC-10, and the Lockheed L-1011 TriStar became the first generation of wide-body passenger airliners to enter service.[4] In 1978, Boeing unveiled three new models: the twin-engine or twinjet Boeing 757 to replace its 727, the twinjet 767 to challenge the Airbus A300, and a trijet 777 concept to compete with the DC-10 and L-1011.[5][6][7] The mid-size 757 and 767 launched to market success, due in part to 1980s' extended-range twin-engine operational performance standards (ETOPS) regulations governing transoceanic twinjet operations.[8] These regulations allowed twin-engine airliners to make ocean crossings at up to three hours' distance from emergency diversionary airports.[9] Under ETOPS rules, airlines began operating the 767 on long-distance overseas routes that did not require the capacity of larger airliners.[8] The trijet 777 was later dropped, following marketing studies that favored the 757 and 767 variants.[10] Boeing was left with a size and range gap in its product line between the 767-300ER and the 747-400.[11]

By the late 1980s, DC-10 and L-1011 models were expected to be retired in the next decade, prompting manufacturers to develop replacement designs.[12] McDonnell Douglas was working on the MD-11, a stretched successor of the DC-10,[12] while Airbus was developing its A330 and A340 series.[12] In 1986, Boeing unveiled proposals for an enlarged 767, tentatively named 767-X,[13] to target the replacement market for first-generation wide-bodies such as the DC-10,[9] and to complement existing 767 and 747 models in the company lineup.[14] The initial proposal featured a longer fuselage and larger wings than the existing 767,[13] along with winglets.[15] Later plans expanded the fuselage cross-section but retained the existing 767 flight deck, nose, and other elements.[13] However, airline customers were uninterested in the 767-X proposals, and instead wanted an even wider fuselage cross-section, fully flexible interior configurations, short- to intercontinental-range capability, and an operating cost lower than that of any 767 stretch.[9]

Airline planners' requirements for larger aircraft had become increasingly specific, adding to the heightened competition among aircraft manufacturers.[12] By 1988, Boeing realized that the only answer was a clean-sheet design, which became the twinjet 777.[16] The company opted for the twin-engine configuration given past design successes, projected engine developments, and reduced-cost benefits.[17] On December 8, 1989, Boeing began issuing offers to airlines for the 777.[13]

Design effort

[edit]

Alan Mulally served as the Boeing 777 program's director of engineering, and then was promoted in September 1992 to lead it as vice-president and general manager.[18][19] The design phase of the all-new twinjet was different from Boeing's previous jetliners, in which eight major airlines (All Nippon Airways, American Airlines, British Airways, Cathay Pacific, Delta Air Lines, Japan Airlines, Qantas, and United Airlines) played a role in the development.[20] This was a departure from industry practice, where manufacturers typically designed aircraft with minimal customer input.[21] The eight airlines that contributed to the design process became known within Boeing as the "Working Together" group.[20] At the group's first meeting in January 1990, a 23-page questionnaire was distributed to the airlines, asking what each wanted in the design.[9] By March 1990, the group had decided upon a baseline configuration: a cabin cross-section close to the 747's, capacity up to 325 passengers, flexible interiors, a glass cockpit, fly-by-wire controls, and 10 percent better seat-mile costs than the A330 and MD-11.[9]

The development phase of the 777 coincided with United Airlines's replacement program for its aging DC-10s.[22] On October 14, 1990, United became the launch customer with an order for 34 Pratt & Whitney-powered 777s valued at US$11 billion (~$22.7 billion in 2023) and options for 34 more.[23][24] The airline required that the new aircraft be capable of flying three different routes: Chicago to Hawaii, Chicago to Europe, and non-stop from Denver, a hot and high airport, to Hawaii.[22] ETOPS certification was also a priority for United,[25] given the overwater portion of United's Hawaii routes.[23] In late 1991, Boeing selected its Everett factory in Washington, home of 747 production, as the 777's final assembly line (FAL).[26] In January 1993, a team of United developers joined other airline teams and Boeing designers at the Everett factory.[27] The 240 design teams, with up to 40 members each, addressed almost 1,500 design issues with individual aircraft components.[28] The fuselage diameter was increased to suit Cathay Pacific, the baseline model grew longer for All Nippon Airways, and British Airways' input led to added built-in testing and interior flexibility,[9] along with higher operating weight options.[29]

The 777 was the first commercial aircraft to be developed using an entirely computer-aided design (CAD) process.[14][23][30] Each design drawing was created on a three-dimensional CAD software system known as CATIA, sourced from Dassault Systemes and IBM.[31] This allowed engineers to virtually assemble the 777 aircraft on a computer system to check for interference and verify that the thousands of parts fit properly before the actual assembly process—thus reducing costly rework.[32] Boeing developed its high-performance visualization system, FlyThru, later called IVT (Integrated Visualization Tool) to support large-scale collaborative engineering design reviews, production illustrations, and other uses of the CAD data outside of engineering.[33] Boeing was initially not convinced of CATIA's abilities and built a physical mock-up of the nose section to verify its results. The test was so successful that additional mock-ups were canceled.[34] The 777 was completed with such precision that it was the first Boeing jetliner that didn't require the details to be worked out on an expensive physical aircraft mock-up,[35] helping the program cost just US$5 billion.[36]

Testing and certification

[edit]

Major assembly of the first aircraft began on January 4, 1993.[37] On April 9, 1994, the first 777, number WA001, was rolled out in a series of 15 ceremonies held during the day to accommodate the 100,000 invited guests.[38] The first flight took place on June 12, 1994,[39] under the command of chief test pilot John E. Cashman.[40] This marked the start of an 11-month flight test program that was more extensive than testing for any previous Boeing model.[41] Nine aircraft fitted with General Electric, Pratt & Whitney, and Rolls-Royce engines[39] were flight tested at locations ranging from the desert airfield at Edwards Air Force Base in California[42] to frigid conditions in Alaska, mainly Fairbanks International Airport.[43] To satisfy ETOPS requirements, eight 180-minute single-engine test flights were performed.[44] The first aircraft built was used by Boeing's nondestructive testing campaign from 1994 to 1996, and provided data for the -200ER and -300 programs.[45]

At the successful conclusion of flight testing, the 777 was awarded simultaneous airworthiness certification by the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and European Joint Aviation Authorities (JAA) on April 19, 1995.[39]

Entry into service

[edit]

Boeing delivered the first Triple Seven to United Airlines on May 15, 1995.[46][47] The FAA awarded 180-minute ETOPS clearance ("ETOPS-180") for the Pratt & Whitney PW4084-engined aircraft on May 30, 1995, making it the first airliner to carry an ETOPS-180 rating at its entry into service.[48] The first commercial flight took place on June 7, 1995, from London Heathrow Airport to Dulles International Airport near Washington, D.C.[49] Longer ETOPS clearance of 207 minutes was approved in October 1996.[a]

On November 12, 1995, Boeing delivered the first model with General Electric GE90-77B engines to British Airways,[50] which entered service five days later.[51] Initial service was affected by gearbox bearing wear issues, which caused British Airways to temporarily withdraw its 777 fleet from transatlantic service in 1997,[51] returning to full service later that year.[42] General Electric subsequently announced engine upgrades.[42]

The first Rolls-Royce Trent 877-powered aircraft was delivered to Thai Airways International on March 31, 1996,[50] completing the introduction of the three powerplants initially developed for the airliner.[52] Each engine-aircraft combination had secured ETOPS-180 certification from the point of entry into service.[53] By June 1997, orders for the 777 numbered 323 from 25 airlines, including satisfied launch customers that had ordered additional aircraft.[39] Operations performance data established the consistent capabilities of the twinjet over long-haul transoceanic routes, leading to additional sales.[54] By 1998, the 777 fleet had approached 900,000 flight hours.[55] Boeing states that the 777 fleet has a dispatch reliability (rate of departure from the gate with no more than 15 minutes delay due to technical issues) above 99 percent.[56][57][58][59]

Improvement and stretching: -200ER/-300

[edit]

After the baseline model, the 777-200, Boeing developed an increased gross weight variant with greater range and payload capability.[60] Initially named 777-200IGW,[61] the 777-200ER first flew on October 7, 1996,[62] received FAA and JAA certification on January 17, 1997,[63] and entered service with British Airways on February 9, 1997.[63] Offering greater long-haul performance, the variant became the most widely ordered version of the aircraft through the early 2000s.[60] On April 2, 1997, a Malaysia Airlines -200ER named "Super Ranger" broke the great circle "distance without landing" record for an airliner by flying eastward from Boeing Field, Seattle to Kuala Lumpur, a distance of 10,823 nautical miles (20,044 km; 12,455 mi), in 21 hours and 23 minutes.[55]

Following the introduction of the -200ER, Boeing turned its attention to a stretched version of the baseline model. On October 16, 1997, the 777-300 made its first flight.[62] At 242.4 ft (73.9 m) in length, the -300 became the longest airliner yet produced (until the A340-600), and had a 20 percent greater overall capacity than the standard length model.[64] The -300 was awarded type certification simultaneously from the FAA and JAA on May 4, 1998,[65] and entered service with launch customer Cathay Pacific on May 27, 1998.[62][66]

The first generation of Boeing 777 models, the -200, -200ER, and -300 have since been known collectively as Boeing 777 Classics.[67] These three early 777 variants had three engine options ranging from 77,200 to 98,000 lbf (343 to 436 kN): General Electric GE90, Pratt & Whitney PW4000, or Rolls-Royce Trent 800.[67]

Production

[edit]The production process included substantial international content, an unprecedented level of global subcontracting for a Boeing jetliner,[68] later exceeded by the 787.[69] International contributors included Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Kawasaki Heavy Industries (fuselage panels),[70] Fuji Heavy Industries, Ltd. (center wing section),[70] Hawker de Havilland (elevators), and Aerospace Technologies of Australia (rudder).[71] An agreement between Boeing and the Japan Aircraft Development Corporation, representing Japanese aerospace contractors, made the latter risk-sharing partners for 20 percent of the entire development program.[68]

To accommodate production of its new airliner, Boeing doubled the size of the Everett factory at the cost of nearly US$1.5 billion (~$2.86 billion in 2023)[23] to provide space for two new assembly lines.[22] New production methods were developed, including a turn machine that could rotate fuselage subassemblies 180 degrees, giving workers access to upper body sections.[31] By the start of production 1993, the program had amassed 118 firm orders, with options for 95 more from 10 airlines.[72] Total investment in the program was estimated at over US$4 billion from Boeing, with an additional US$2 billion from suppliers.[73]

Initially second to the 747 as Boeing's most profitable jetliner,[74] the 777 became the company's most lucrative model in the 2000s.[75] An analyst established the 777 program, assuming Boeing has fully recouped the plane's development costs, may account for US$400 million of the company's pretax earnings in 2000, US$50 million more than the 747.[74] By 2004, the airliner accounted for the bulk of wide-body revenues for Boeing Commercial Airplanes.[76] In 2007, orders for second-generation 777 models approached 350 aircraft,[77] and in November of that year, Boeing announced that all production slots were sold out to 2012.[78] The program backlog of 356 orders was valued at US$95 billion at list prices in 2008.[79]

In 2010, Boeing announced plans to increase production from 5 aircraft per month to 7 aircraft per month by mid-2011, and 8.3 per month by early 2013.[80] In November 2011, assembly of the 1,000th 777, a -300ER, began when it took 49 days to fully assemble each of these variants.[81] The aircraft in question was built for Emirates airline,[81] and rolled out of the production facility in March 2012.[82] By the mid-2010s, the 777 had become prevalent on the longest flights internationally and had become the most widely used airliner for transpacific routes, with variants of the type operating over half of all scheduled flights and with the majority of transpacific carriers.[83][84] By April 2014, with cumulative sales surpassing those of the 747, the 777 became the best-selling wide-body airliner; at existing production rates, the aircraft was on track to become the most-delivered wide-body airliner by mid-2016.[85]

By February 2015, the backlog of undelivered 777s totaled 278 aircraft, equivalent to nearly three years at the then production rate of 8.3 aircraft per month,[86] causing Boeing to ponder the 2018–2020 time frame. In January 2016, Boeing confirmed plans to reduce the production rate of the 777 family from 8.3 per month to 7 per month in 2017 to help close the production gap between the 777 and 777X due to a lack of new orders.[87] In August 2017, Boeing was scheduled to drop 777 production again to five per month.[88] In 2018, assembling test 777-9 aircraft was expected to lower output to an effective rate of 5.5 per month.[89] In March 2018, as previously predicted, the 777 overtook the 747 as the world's most produced wide body aircraft.[90] Due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on aviation, demand for new jets fell in 2020 and Boeing further reduced monthly 777 production from five to two aircraft.[91]

Second generation (777-X): -300ER/-200LR/F

[edit]

From the program's start, Boeing had considered building ultra-long-range variants.[92] Early plans centered on a 777-100X proposal,[93] a shortened variant of the -200 with reduced weight and increased range,[93] similar to the 747SP.[94] However, the -100X would have carried fewer passengers than the -200 while having similar operating costs, leading to a higher cost per seat.[93][94] By the late 1990s, design plans shifted to longer-range versions of existing models.[93]

In March 1997, the Boeing board approved the 777-200X/300X specifications: 298 passengers in three classes over 8,600 nmi (15,900 km; 9,900 mi) for the 200X and 6,600 nmi (12,200 km; 7,600 mi) with 355 passengers in a tri-class layout for the 300X, with design freeze planned in May 1998, 200X certification in August 2000, and introduction in September and in January 2001 for the 300X.[95] The 4.5 ft (1.37 m) wider wing was to be strengthened and the fuel capacity enlarged, and it was to be powered by simple derivatives with similar fans.[95] GE was proposing a 102,000 lbf (454 kN) GE90-102B, while P&W offered its 98,000 lbf (436 kN) PW4098 and R-R was proposing a 98,000 lbf (437 kN) Trent 8100.[95] Rolls-Royce was also studying a Trent 8102 over 100,000 lbf (445 kN).[96]Boeing was studying a semi-levered, articulated main gear to help the take-off rotation of the proposed -300X, with its higher 715,600 lb (324,600 kg) MTOW.[97]By January 1999, its MTOW grew to 750,700 lb (340,500 kg), and thrust requirements increased to 110,000–114,000 lbf (490–510 kN).[98]

A more powerful engine in the thrust class of 100,000 lbf (440 kN) was required, leading to talks between Boeing and engine manufacturers. General Electric offered to develop the GE90-115B engine,[99] while Rolls-Royce proposed developing the Trent 8104 engine.[100] In 1999, Boeing announced an agreement with General Electric, beating out rival proposals.[99] Under the deal with General Electric, Boeing agreed to only offer GE90 engines on new 777 versions.[99]

On February 29, 2000, Boeing launched its next-generation twinjet program,[101] initially called 777-X,[92] and began issuing offers to airlines.[60] Development was slowed by an industry downturn during the early 2000s.[62] The first model to emerge from the program, the 777-300ER, was launched with an order for ten aircraft from Air France,[102] along with additional commitments.[60] On February 24, 2003, the -300ER made its first flight, and the FAA and EASA (European Aviation Safety Agency, successor to the JAA) certified the model on March 16, 2004.[103] The first delivery to Air France took place on April 29, 2004.[62] The -300ER, which combined the -300's added capacity with the -200ER's range, became the top-selling 777 variant in the late 2000s,[104] benefitting as airlines replaced comparable four-engine models with twinjets for their lower operating costs.[78]

The second long-range model, the 777-200LR, rolled out on February 15, 2005, and completed its first flight on March 8, 2005.[62] The -200LR was certified by both the FAA and EASA on February 2, 2006,[105] and the first delivery to Pakistan International Airlines occurred on February 26, 2006.[106] On November 10, 2005, the first -200LR set a record for the longest non-stop flight of a passenger airliner by flying 11,664 nautical miles (21,602 km; 13,423 mi) eastward from Hong Kong to London.[107] Lasting 22 hours and 42 minutes, the flight surpassed the -200LR's standard design range and was logged in the Guinness World Records.[108]

The production freighter model, the 777F, rolled out on May 23, 2008.[109] The maiden flight of the 777F, which used the structural design and engine specifications of the -200LR[110] along with fuel tanks derived from the -300ER, occurred on July 14, 2008.[111] FAA and EASA type certification for the freighter was received on February 6, 2009,[112] and the first delivery to launch customer Air France took place on February 19, 2009.[113][114]

By the late 2000s, the 777 was facing increased potential competition from Airbus' planned A350 XWB and internally from proposed 787 series,[77] both airliners that offer fuel efficiency improvements. As a consequence, the 777-300ER received engine and aerodynamics improvement packages for reduced drag and weight.[115] In 2010, the variant further received a 5,000 lb (2,300 kg) maximum zero-fuel weight increase, equivalent to a higher payload of 20–25 passengers; its GE90-115B1 engines received a 1–2.5 percent thrust enhancement for increased takeoff weights at higher-altitude airports.[115] Through these improvements, the 777 remains the largest twin-engine jetliner in the world.[116][117]

In 2011, the 787 Dreamliner entered service, the completed first stage a.k.a. the Yellowstone-2 (Y2) of a replacement aircraft initiative called the Boeing Yellowstone Project,[118] which would replace large variants of the 767 (300/300ER/400) but also small variants of the 777 (-200/200ER/200LR). While the larger variants of the 777 (-300/300ER) as well as the 747 could eventually be replaced by a new generation aircraft, the Yellowstone-3 (Y3), which would draw upon technologies from the 787 Dreamliner (Y2).[77] More changes were targeted for late 2012, including possible extension of the wingspan,[115] along with other major changes, including a composite wing, a new generation engine, and different fuselage lengths.[115][119][120] Emirates was reportedly working closely with Boeing on the project, in conjunction with being a potential launch customer for the new 777 generation.[121] Among customers for the aircraft during this period, China Airlines ordered ten 777-300ER aircraft to replace 747-400s on long-haul transpacific routes (with the first of those aircraft entering service in 2015), noting that the 777-300ER's per seat cost is about 20% lower than the 747's costs (varying due to fuel prices).[122]

Improvement packages

[edit]In tandem with the development of the third generation Boeing 777X, Boeing worked with General Electric to offer a 2% improvement in fuel efficiency to in-production 777-300ER aircraft. General Electric improved the fan module and the high-pressure compressor stage-1 blisk in the GE-90-115 turbofan, as well as reduced clearances between the tips of the turbine blades and the shroud during cruise. These improvements, of which the latter is the most important and was derived from work to develop the 787, were stated by GE to lower fuel burn by 0.5%. Boeing's wing modifications were intended to deliver the remainder. Boeing stated that every 1% improvement in the 777-300ER's fuel burn translates into being able to fly the aircraft another 75 nmi (139 km; 86 mi) on the same load of fuel, or add ten passengers or 2,400 lb (1,100 kg) of cargo to a "load limited" flight.[123]

In March 2015, additional details of the improvement package were unveiled. The 777-300ER was to shed 1,800 lb (820 kg) by replacing the fuselage crown with tie rods and composite integration panels, similar to those used on the 787. The new flight control software was to eliminate the need for the tail skid by keeping the tail off the runway surface regardless of the extent to which pilots command the elevators. Boeing was also redesigning the inboard flap fairings to reduce drag by reducing pressure on the underside of the wing. The outboard raked wingtip was to have a divergent trailing edge, described as a "poor man's airfoil" by Boeing; this was originally developed for the McDonnell Douglas MD-12 project. Another change involved elevator trim bias. These changes were to increase fuel efficiency and allow airlines to add 14 additional seats to the airplane, increasing per seat fuel efficiency by 5%.[124]

Mindful of the long time required to bring the 777X to the market, Boeing continued to develop improvement packages which improve fuel efficiency, as well as lower prices for the existing product. In January 2015, United Airlines ordered ten 777-300ERs, normally costing around US$150 million each but paid around US$130 million, a discount to bridge the production gap to the 777X.[125] In 2019, the -200ER unit cost was US$306.6 million, the -200LR: US$346.9 million, the -300ER: US$375.5 million and the 777F US$352.3 million.[126] The -200ER is the only Classic variant listed.

Third generation (777X): -8/-8F/-9

[edit]

In November 2013, with orders and commitments totaling 259 aircraft from Lufthansa, Emirates, Qatar Airways, and Etihad Airways, Boeing formally launched the 777X program, the third generation of the 777, with two models: the 777-8 and 777-9.[127] The 777-9 is a further stretched variant with a capacity of over 400 passengers and a range of over 8,200 nmi (15,200 km; 9,400 mi), whereas the 777-8 is slated to seat approximately 350 passengers and have a range of over 9,300 nmi (17,200 km; 10,700 mi).[127] Both models are to be equipped with new generation GE9X engines and feature new composite wings with folding wingtips. The first member of the 777X family was projected to enter service in 2020 at the time of the program announcement. The roll-out of the prototype 777X, a 777-9 model, occurred on March 13, 2019.[128] The 777-9 first flew on January 25, 2020, with deliveries initially forecast for 2022 or 2023[129] and later delayed to 2025.[130]

Design

[edit]

Boeing introduced a number of advanced technologies with the 777 design, including fully digital fly-by-wire controls,[131] fully software-configurable avionics, Honeywell LCD glass cockpit flight displays,[132] and the first use of a fiber optic avionics network on a commercial airliner.[133] Boeing made use of work done on the cancelled Boeing 7J7 regional jet,[134] which utilized similar versions of the chosen technologies.[134] In 2003, Boeing began offering the option of cockpit electronic flight bag computer displays.[135] In 2013, Boeing announced that the upgraded 777X models would incorporate airframe, systems, and interior technologies from the 787.[136]

Fly-by-wire

[edit]In designing the 777 as its first fly-by-wire commercial aircraft, Boeing decided to retain conventional control yokes rather than change to sidestick controllers as used in many fly-by-wire fighter aircraft and in many Airbus airliners.[131] Along with traditional yoke and rudder controls, the cockpit features a simplified layout that retains similarities to previous Boeing models.[137] The fly-by-wire system also incorporates flight envelope protection, a system that guides pilot inputs within a computer-calculated framework of operating parameters, acting to prevent stalls, overspeeds, and excessively stressful maneuvers.[131] This system can be overridden by the pilot if deemed necessary.[131] The fly-by-wire system is supplemented by mechanical backup.[138]

Airframe and systems

[edit]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

The airframe incorporates the use of composite materials, accounting for nine percent of the original structural weight, while the third-generation models, the 777-8 and 777-9, feature more composite parts.[139] Composite components include the cabin floor and rudder, with the 777 being the first Boeing airliner to use composite materials for both the horizontal and vertical stabilizers (empennage).[140] The main fuselage cross-section is fully circular,[141][142] and tapers rearward into a blade-shaped tail cone with a port-facing auxiliary power unit.[143]

The wings on the 777 feature a supercritical airfoil design that is swept back at 31.6 degrees and optimized for cruising at Mach 0.83 (revised after flight tests up to Mach 0.84).[144] The wings are designed with increased thickness and a longer span than previous airliners, resulting in greater payload and range, improved takeoff performance, and a higher cruising altitude.[39] The wings also serve as fuel storage, with longer-range models able to carry up to 47,890 US gallons (181,300 L) of fuel.[145] This capacity allows the 777-200LR to operate ultra-long-distance, trans-polar routes such as Toronto to Hong Kong.[146] In 2013, a new wing made of composite materials was introduced for the upgraded 777X, with a wider span and design features based on the 787's wings.[136]

Folding wingtips, 21 feet (6.40 m) long, were offered when the 777 was first launched, to appeal to airlines who might use gates made to accommodate smaller aircraft, but no airline purchased this option.[147] Folding wingtips reemerged as a design feature at the announcement of the upgraded 777X in 2013. Smaller folding wingtips of 11 feet (3.35 m) in length will allow 777X models to use the same airport gates and taxiways as earlier 777s.[136] These smaller folding wingtips are less complex than those proposed for earlier 777s, and internally only affect the wiring needed for wingtip lights.[136]

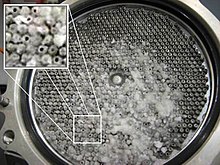

The aircraft features the largest landing gear and the biggest tires ever used in a commercial jetliner.[148] The six-wheel bogies are designed to spread the load of the aircraft over a wide area without requiring an additional centerline gear. This helps reduce weight and simplifies the aircraft's braking and hydraulic systems. Each tire of a 777-300ER six-wheel main landing gear can carry a load of 59,490 lb (26,980 kg), which is heavier than other wide-bodies such as the 747-400.[149] The aircraft has triple redundant hydraulic systems with only one system required for landing.[150] A ram air turbine—a small retractable device which can provide emergency power—is also fitted in the wing root fairing.[151]

Interior

[edit]

The original 777 interior, also known as the Boeing Signature Interior, features curved panels, larger overhead bins, and indirect lighting.[51] Seating options range from four[152] to six–abreast in first class up to ten–abreast in economy.[153] The 777's windows were the largest of any current commercial airliner until the 787, and measure 15 by 10 inches (380 by 250 mm) for all models outside the 777-8 and -9.[154] The cabin also features "Flexibility Zones", which entails deliberate placement of water, electrical, pneumatic, and other connection points throughout the interior space, allowing airlines to move seats, galleys, and lavatories quickly and more easily when adjusting cabin arrangements.[153] Several aircraft have also been fitted with VIP interiors for non-airline use.[155] Boeing designed a hydraulically damped toilet seat cover hinge that closes slowly.[156]

In February 2003, Boeing introduced overhead crew rests as an option on the 777.[157] Located above the main cabin and connected via staircases, the forward flight crew rest contains two seats and two bunks, while the aft cabin crew rest features multiple bunks.[157] The Signature Interior has since been adapted for other Boeing wide-body and narrow-body aircraft, including 737NG, 747-400, 757-300, and newer 767 models, including all 767-400ER models.[158][159] The 747-8 and 767-400ER have also adopted the larger, more rounded windows of the original 777.

In July 2011, Flight International reported that Boeing was considering replacing the Signature Interior on the 777 with a new interior similar to that on the 787, as part of a move towards a "common cabin experience" across all Boeing platforms.[160] With the launch of the 777X in 2013, Boeing confirmed that the aircraft would be receiving a new interior featuring 787 cabin elements and larger windows.[136] Further details released in 2014 included re-sculpted cabin sidewalls for greater interior room, noise-damping technology, and higher cabin humidity.[161]

Air France has a 777-300ER sub-fleet with 472 seats each, more than any other international 777, to achieve a cost per available seat kilometer (CASK) around €.05, similar to Level's 314-seat Airbus A330-200, its benchmark for low-cost, long-haul.[162] Competing on similar French overseas departments destinations, Air Caraïbes has 389 seats on the A350-900 and 429 on the -1000.[162] French Bee's is even more dense with its 411 seats A350-900, due to 10-abreast economy seating, reaching a €.04 CASK according to Air France, and lower again with its 480 seats on the -1000.[162]

Engines

[edit]The initial 777-200 model was launched with propulsion options from three manufacturers, General Electric, Pratt & Whitney, and Rolls-Royce,[163] giving the airlines their choice of engines from competing firms.[99] Each manufacturer agreed to develop an engine in the 77,000 lbf (340 kN) and higher thrust class (a measure of jet engine output) for the world's largest twinjet.[163]

Variants

[edit]Boeing uses two characteristics – fuselage length and range – to define its 777 models.[11][164] Passengers and cargo capacity varies by fuselage length: the 777-300 has a stretched fuselage compared to the base 777-200. Three range categories were defined: the A-market would cover domestic and regional operations, the B-market would cover routes from Europe to the US West coast and the C-market the longest transpacific routes.[165] The A-market would be covered by a 4,200 nmi (7,800 km; 4,800 mi) range, 516,000 lb (234 t) MTOW aircraft for 353 to 374 passengers powered by 71,000 lbf (316 kN) engines, followed by a 6,600 nmi (12,200 km; 7,600 mi) B-market range for 286 passengers in three-class, with 82,000 lbf (365 kN) unit thrust and 580,000 lb (263 t) of MTOW, an A340 competitor, basis of an A-market 409 to 434 passengers stretch, and eventually a 7,600 nmi (14,000 km; 8,700 mi) C-market with 90,000 lbf (400 kN) engines.[166]

When referring to different variants, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) code collapses the 777 model designator and the -200 or -300 variant designator to "772" or "773".[167] The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) aircraft type designator system adds a preceding manufacturer letter, in this case "B" for Boeing, hence "B772" or "B773".[168] Designations may append a range identifier like "B77W" for the 777-300ER by the ICAO,[168] "77W" for the IATA,[167] though the -200ER is a company marketing designation and not certificated as such. Other notations include "773ER"[169] and "773B" for the -300ER.[170]

777-200

[edit]The initial 777-200 made its maiden flight on June 12, 1994, and was first delivered to United Airlines on May 15, 1995.[62] With a 545,000 lb (247 t) MTOW and 77,000 lbf (340 kN) engines, it has a range of 5,240 nautical miles (9,700 km; 6,030 mi) with 305 passengers in a three-class configuration.[171] The -200 was primarily aimed at US domestic airlines,[11] although several Asian carriers and British Airways have also operated the type. Nine different -200 customers have taken delivery of 88 aircraft,[2] with 55 in airline service as of 2018[update].[172] The competing Airbus aircraft was the A330-300.[173]

In March 2016, United Airlines shifted operations with all 19 of its -200s to exclusively domestic US routes, including flights to and from Hawaii, and added more economy class seats by shifting to a ten-abreast configuration (a pattern that matched American Airlines' reconfiguration of the type).[174][175] As of 2019[update], Boeing no longer markets the -200, as indicated by its removal from the manufacturer's price listings for 777 variants.[126]

777-200ER

[edit]

The B-market 777-200ER ("ER" for Extended Range), originally known as the 777-200IGW (increased gross weight), has additional fuel capacity and an increased MTOW enabling transoceanic routes.[61] With a 658,000 lb (298 t) MTOW and 93,700 lbf (417 kN) engines, it has a 7,065 nmi (13,084 km; 8,130 mi) range.[176] It was delivered first to British Airways on February 6, 1997.[62] Thirty-three customers received 422 deliveries, with no unfilled orders as of 2019[update].[2]

As of 2018[update], 338 examples of the -200ER are in airline service.[172] It competed with the A340-300.[177] Boeing proposes the 787-10 to replace it.[178] The value of a new -200ER rose from US$110 million at service entry to US$130 million in 2007; a 2007 model 777 was selling for US$30 million ten years later, while the oldest ones had a value around US$5–6 million, depending on the remaining engine time.[179]

The engine can be delivered de-rated with reduced engine thrust for shorter routes to lower the MTOW, reduce purchase price and landing fees (as 777-200 specifications) but can be re-rated to full standard.[180] Singapore Airlines ordered over half of its -200ERs de-rated.[180][181]

777-200LR

[edit]

The 777-200LR ("LR" for Long Range), the C-market model, entered service in 2006 as one of the longest-range commercial airliners.[182][183] Boeing nicknamed it Worldliner as it can connect almost any two airports in the world,[107] although it is still subject to ETOPS restrictions.[184] It holds the world record for the longest nonstop flight by a commercial airliner.[107] It has a maximum design range of 8,555 nautical miles (15,844 km; 9,845 mi) as of 2017[update].[176] The -200LR was intended for ultra long-haul routes such as Los Angeles to Singapore.[92]

Developed alongside the -300ER, the -200LR features an increased MTOW and three optional auxiliary fuel tanks in the rear cargo hold.[182] Other new features include extended raked wingtips, redesigned main landing gear, and additional structural strengthening.[182] As with the -300ER and 777F, the -200LR is equipped with wingtip extensions of 12.8 ft (3.90 m).[182] The -200LR is powered by GE90-110B1 or GE90-115B turbofans.[185] The first -200LR was delivered to Pakistan International Airlines on February 26, 2006.[106][186] Twelve different -200LR customers took delivery of 61 aircraft.[187] Airlines operated 50 of the -200LR variant as of 2018[update].[172] Emirates is the largest operator of the LR variant with 10 aircraft.[188] The closest competing aircraft from Airbus are the discontinued A340-500HGW[182] and the current A350-900ULR.[189]

777-300

[edit]

Launched at the Paris Air Show on June 26, 1995, its major assembly started in March 1997 and its body was joined on July 21, it was rolled-out on September 8 and made its first flight on October 16.[190] The 777 was designed to be stretched by 20%: 60 extra seats to almost 370 in tri-class, 75 more to 451 in two classes, or up to 550 in all-economy like the 747SR. The 33 ft (10.1 m) stretch is done with 17 ft (5.3 m) in ten frames forward and 16 ft (4.8 m) in nine frames aft for a 242 ft (73.8 m) length, 11 ft (3.4 m) longer than the 747-400. It uses the -200ER 45,200 US gal (171,200 L) fuel capacity and 84,000–98,000 lbf (374–436 kN) engines with a 580,000 to 661,000 lb (263.3 to 299.6 t) MTOW.[190]

It has ground maneuvering cameras for taxiing and a tailskid to rotate, while the proposed 716,000 lb (324.6 t) MTOW -300X would have needed a semi-levered main gear. Its overwing fuselage section 44 was strengthened, with its skin thickness going from the -200's 0.25 to 0.45 in (6.3 to 11.4 mm), and received a new evacuation door pair. Its operating empty weight with Rolls-Royce engines in typical tri-class layout is 343,300 lb (155.72 t) compared to 307,300 lb (139.38 t) for a similarly configured -200.[190] Boeing wanted to deliver 170 -300s by 2006 and to produce 28 per year by 2002, to replace early Boeing 747s, burning one-third less fuel with 40% lower maintenance costs.[190]

With a 660,000 lb (299 t) MTOW and 90,000 lbf (400 kN) engines, it has a range of 6,005 nautical miles (11,121 km; 6,910 mi) with 368 passengers in three-class.[171] Eight different customers have taken delivery of 60 aircraft of the variant, of which 18 were powered by the PW4000 and 42 by the RR Trent 800 (none were ordered with the GE90, which was never certified on this variant[191]),[2] with 48 in airline service as of 2018[update].[172] The last -300 was delivered in 2006 while the longer-range -300ER started deliveries in 2004.[2]

777-300ER

[edit]

The 777-300ER ("ER" for Extended Range) is the B-market version of the -300. Its higher MTOW and increased fuel capacity permits a maximum range of 7,370 nautical miles (13,650 km; 8,480 mi) with 396 passengers in a two-class seating arrangement.[176] The 777-300ER features extended raked wingtips, a strengthened fuselage and wings and a modified main landing gear.[192] Its wings have an aspect ratio of 9.0.[193] It is powered by the GE90-115B turbofan, the world's most powerful jet engine with a maximum thrust of 115,300 lbf (513 kN).[194]

Following flight testing, aerodynamic refinements have reduced fuel burn by an additional 1.4%.[104][195]At Mach 0.839 (495 kn; 916 km/h), FL300, -59 °C and at a 513,400 lb (232.9 t) weight, it burns 17,300 lb (7.8 t) of fuel per hour. Its operating empty weight is 371,600 lb (168.6 t).[196]The projected operational empty weight is 371,610 lb (168,560 kg) in airline configuration, at a weight of 477,010 lb (216,370 kg) and FL350, total fuel flow is 15,000 lb/h (6,790 kg/h) at Mach 0.84 (495 kn; 917 km/h), rising to 19,600 lb/h (8,890 kg/h) at Mach 0.87 (513 kn; 950 km/h).[197]

Since its launch, the -300ER has been a primary driver of the twinjet's sales past the rival A330/340 series.[198] Its direct competitors have included the Airbus A340-600 and the A350-1000.[77] Using two engines produces a typical operating cost advantage of around 8–9% for the -300ER over the A340-600.[199] Several airlines have acquired the -300ER as a 747-400 replacement amid rising fuel prices given its 20% fuel burn advantage.[78] The -300ER has an operating cost of US$44 per seat hour, compared to an Airbus A380's roughly US$50 per seat hour (hourly cost is about US$26,000), and US$90 per seat hour for a Boeing 747-400 as of 2015[update].[200]

The first 777-300ER was delivered to Air France on April 29, 2004.[201] The -300ER is the best-selling 777 variant, having surpassed the -200ER in orders in 2010 and deliveries in 2013.[2] As of 2018[update], 784 units of the -300ER variant were in service,[172] and as of 2020[update], the best-seller had a total of 837 orders and 832 deliveries.[2]

777 Freighter

[edit]

The 777 Freighter (777F) is an all-cargo version of the twinjet, and shares features with the -200LR; these include its airframe, engines,[202] and fuel capacity.[145] With a maximum payload of 228,700 lb (103,700 kg) (similar to the 243,000 lb (110,000 kg) of the Boeing 747-200F), it has a maximum range of 9,750 nmi (18,057 km; 11,220 mi)) or 4,970 nmi (9,200 km; 5,720 mi)) at its max structural payload.[203]

The 777F also features a new supernumerary area, which includes four business-class seats forward of the rigid cargo barrier, full main deck access, bunks, and a galley.[204] As the aircraft promises improved operating economics compared to older freighters,[78] airlines have viewed the 777F as a replacement for freighters such as the Boeing 747-200F, McDonnell Douglas DC-10, and McDonnell Douglas MD-11F.[110][205]

The first 777F was delivered to Air France on February 19, 2009.[113] As of April 2021[update], 247 freighters have been ordered by 25 different customers with 45 unfilled orders.[2] Operators had 202 of the 777F in service as of 2018[update].[172]

In the 2000s, Boeing began studying the conversion of 777-200ER and -200 passenger airliners into freighters, under the name 777 BCF (Boeing Converted Freighter).[206] The company has been in discussion with several airline customers, including FedEx Express, UPS Airlines, and GE Capital Aviation Services, to provide launch orders for a 777 BCF program.[207]

777-300ER Special Freighter (SF)

[edit]In July 2018, Boeing was studying a 777-300ER freighter conversion, targeted for the volumetric market instead of the density market served by the 777F.[208] After having considered a -200ER P2F program, Boeing was hoping to conclude its study by the Fall as the 777X replacing aging -300ERs from 2020 will generate feedstock.[208] New-build 777-300ER may maintain the delivery rate at five per month, to bridge the production gap until the 777X is delivered.[209]Within the 811 777-300ERs delivered and 33 to be delivered by October 2019, GE Capital Aviation Services (GECAS) anticipates up to 150-175 orders through 2030, the four to five months conversion costing around $35m.[210]

In October 2019, Boeing and Israeli Aerospace Industries (IAI) launched the 777-300ERSF passenger to freighter conversion program with GECAS ordering 15 aircraft and 15 options, the first aftermarket 777 freighter conversion program.[210]In June 2020, IAI received the first 777-300ER to be converted, from GECAS.[211] In October 2020, GECAS announced the launch operator from 2023: Michigan-based Kalitta Air, already operating 24 747-400Fs, nine 767-300ERFs and three 777-200LRFs.[211]IAI should receive the first aircraft in December 2020 while certification and service entry was scheduled for late 2022.[210]

The converted aircraft has a maximum payload of 224,000 lb (101.6 t), a range of 4,500 nmi (8,300 km; 5,200 mi) and shares the door aperture and aft position of the 777F.[210]It has a cargo volume capacity of 28,900 cu ft (819 m3), 5,800 cu ft (164 m3) greater than the 777F (or 25% more) and can hold 47 standard 96 x 125 in pallet (P6P) positions, 10 more positions than a 777-200LRF or eight more than a 747-400F.[210] With windows plugged, passenger doors deactivated, fuselage and floor reinforced, and a main-deck cargo door installed, the 777-300ERSF has 15% more volume than a 747-400BCF.[211] By March 2023, IAI had completed the 777-300ER first flight, converted for AerCap, as it had a backlog over 60 orders.[212]

777X

[edit]

The 777X is to feature new GE9X engines and new composite wings with folding wingtips.[127] It was launched in November 2013 with two variants: the 777-8 and the 777-9.[127] The 777-8 provides seating for 384 passengers and has a range of 8,730 nmi (16,168 km; 10,046 mi), while the 777-9 has seating for 426 passengers and a range of over 7,285 nmi (13,492 km; 8,383 mi).[213] A longer 777-10X, 777X Freighter, and 777X BBJ variants have also been proposed.[214]

Government and corporate

[edit]

Versions of the 777 have been acquired by government and private customers. The main purpose has been for VIP transport, including as an air transport for heads of state, although the aircraft has also been proposed for other military applications.

- 777 Business Jet (777 VIP) – the Boeing Business Jet version of the 777 that is sold to corporate customers. Boeing has received orders for 777 VIP aircraft based on the 777-200LR and 777-300ER passenger models.[215][216] The aircraft are fitted with private jet cabins by third party contractors,[215] and completion may take 3 years.[217]

- KC-777 – this was a proposed tanker version of the 777. In September 2006, Boeing announced that it would produce the KC-777 if the United States Air Force (USAF) required a larger tanker than the KC-767, able to transport more cargo or personnel.[218][219][220] In April 2007, Boeing offered its 767-based KC-767 Advanced Tanker instead of the KC-777 to replace the smaller Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker under the USAF's KC-X program.[221] Boeing officials have described the KC-777 as suitable for the related KC-Z program to replace the wide-body McDonnell Douglas KC-10 Extender.[222]

- In 2014, the Japanese government chose to procure two 777-300ERs to serve as the official air transport for the Emperor of Japan and Prime Minister of Japan.[223] The aircraft, operated by the Japan Air Self-Defense Force under the callsign Japanese Air Force One, entered service in 2019 and replaced two 747-400s - the 777-300ER was specifically selected by the Ministry of Defense owing to its similar capabilities to the preceding 747 pair.[224] Besides VIP transport, the 777s are also intended for use in emergency relief missions.[223]

- 777s are serving or have served as official government transports for nations including Gabon (VIP-configured 777-200ER),[225] Turkmenistan (VIP-configured 777-200LR)[226] and the United Arab Emirates (VIP-configured 777-200ER and 777-300ER operated by Abu Dhabi Amiri Flight).[216] Prior to returning to power as Prime Minister of Lebanon, Rafic Hariri acquired a 777-200ER as an official transport.[227] The Indian government purchased two Air India 777-300ERs and converted them for VVIP transport operated by the Indian Air Force under the callsign Air India One; they entered service in 2021 replacing the Air India-owned 747s.[228][229]

- In 2014, the USAF examined the possibility of adopting modified 777-300ERs or 777-9Xs to replace the Boeing 747-200 aircraft used as Air Force One.[230] Although the USAF had preferred a four-engine aircraft, this was mainly due to precedent (existing aircraft were purchased when the 767 was just beginning to prove itself with ETOPS; decades later, the 777 and other twin jets established a comparable level of performance to quad-jet aircraft).[230] Ultimately, the air force decided against the 777, and selected the Boeing 747-8 to become the next presidential aircraft.[231]

Experimental

[edit]

Boeing has used 777 aircraft in two research and development programs. The first program, the Quiet Technology Demonstrator (QTD) was run in collaboration with Rolls-Royce and General Electric to develop and validate engine intake and exhaust modifications, including the chevrons subsequently used in the 737 MAX, 747-8 and 787 series. The tests were flown in 2001 and 2005.[232]

A further program, the ecoDemonstrator series, is intended to test and develop technologies and techniques to reduce aviation's environmental impact. The program started in 2011, with the first ecoDemonstrator aircraft flying in 2012. Various airframes have been used since to test a wide variety of technologies in collaboration with a range of industrial partners. 777s have been used on three occasions as of 2023. The first of these, a 777F in 2018, performed the world's first commercial airliner flights using 100% sustainable aviation fuel (SAF).[233] In 2022-3, the testbed is a 777-200ER which is to operate in the role until 2024.[234]

Operators

[edit]

Boeing customers that have received the most 777s are Emirates, Singapore Airlines, United Airlines, ILFC, and American Airlines.[2] Emirates is the largest airline operator as of 2018[update],[172] and is the only customer to have operated all 777 variants produced, including the -200, -200ER, -200LR, -300, -300ER, and 777F.[2][235] The 1,000th 777 off the production line, a -300ER set to be Emirates' 102nd 777, was unveiled at a factory ceremony in March 2012.[82]

A total of 1,416 aircraft (all variants) were in airline service as of 2018[update], with Emirates (163), United Airlines (91), Air France (70), Cathay Pacific (69), American Airlines (67), Qatar Airways (67), British Airways (58), Korean Air (53), All Nippon Airways (50), Singapore Airlines (46), and other operators with fewer aircraft of the type.[172]

In 2017, 777 Classics are reaching the end of their mainline service: with a -200 age ranging from three to 22 years, 43 Classic 777s or 7.5% of the fleet have been retired. Values of 777-200ERs have declined by 45% since January 2014, faster than Airbus A330s and Boeing 767s with 30%, due to the lack of a major secondary market but only a few budget, air charters and ACMI operators. In 2015, Richard H. Anderson, then Delta Air Lines' chairman and chief executive, said he had been offered 777-200s for less than US$10 million.[67] To keep them cost-efficient, operators densify their 777s for about US$10 million each, like Scoot with 402 seats in its dual-class -200s, or Cathay Pacific which switched the 3–3–3 economy layout of 777-300s to 3–4–3 to seat 396 on regional services.[67]

Orders and deliveries

[edit]The 777 surpassed 2,000 orders by the end of 2018.[236]

| Total orders | Total deliveries | Unfilled | |

| 777-200 | 88 | 88 | – |

| 777-200ER | 422 | 422 | – |

| 777-200LR | 61 | 61 | – |

| 777-300 | 60 | 60 | – |

| 777-300ER | 837 | 832 | 5 |

| 777F | 330 | 271 | 59 |

| 777X | 481 | – | 481 |

| Total | 2,279 | 1,734 | 545 |

Orders and deliveries through June 2024[1][2]

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total | ||

| Orders | 58 | 23 | 53 | 51 | -3 | 10 | 53 | 68 | 100 | 38 | 2,279 | |

| Deliveries | −200 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 88 |

| −200ER | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 422 | |

| −200LR | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | 1 | – | – | – | 61 | |

| −300 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 60 | |

| −300ER | 79 | 88 | 65 | 32 | 19 | 4 | 7 | 3 | – | – | 832 | |

| 777F | 19 | 11 | 9 | 16 | 25 | 22 | 16 | 21 | 26 | 7 | 271 | |

| 777X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| All | 98 | 99 | 74 | 48 | 45 | 26 | 24 | 24 | 26 | 7 | 1,734 | |

| 90−94 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | ||

| Orders | 112 | 101 | 68 | 54 | 68 | 35 | 116 | 30 | 32 | 13 | 42 | 153 | 76 | 110 | 39 | 30 | 75 | 194 | 75 | 121 | 277 | |

| Deliveries | −200 | – | 13 | 32 | 11 | 10 | 3 | 9 | 3 | – | 1 | 2 | 3 | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| −200ER | – | – | – | 48 | 50 | 63 | 42 | 55 | 41 | 29 | 22 | 13 | 23 | 19 | 3 | 4 | 3 | – | 3 | 4 | – | |

| −200LR | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 10 | 11 | 16 | 9 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| −300 | – | – | – | – | 14 | 17 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| −300ER | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10 | 20 | 39 | 53 | 47 | 52 | 40 | 52 | 60 | 79 | 83 | |

| 777F | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 16 | 22 | 15 | 19 | 14 | 13 | |

| 777X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| All | – | 13 | 32 | 59 | 74 | 83 | 55 | 61 | 47 | 39 | 36 | 40 | 65 | 83 | 61 | 88 | 74 | 73 | 83 | 98 | 99 | |

Orders through June 30, 2024[1][2] and deliveries[3]

Boeing 777 orders and deliveries (cumulative, by year):

Orders

Deliveries

Orders[1][2] and deliveries[3] through June 30, 2024

Accidents and incidents

[edit]

As of May 2024[update], the 777 had been involved in 31 aviation accidents and incidents,[239] including a total of eight hull losses (five in-flight accidents), resulting in 542 (including one fatality due to ground casualties) fatalities along with three hijackings.[240][241] The first fatality involving the twinjet occurred in a fire while an aircraft was being refueled at Denver International Airport in the United States on September 5, 2001, during which a ground worker sustained fatal burns.[242] The aircraft, operated by British Airways, sustained fire damage to the lower wing panels and engine housing; it was later repaired and returned to service.[242][243]

The first hull loss occurred on January 17, 2008, when a 777-200ER with Rolls-Royce Trent 895 engines, flying from Beijing to London as British Airways Flight 38, crash-landed approximately 1,000 feet (300 m) short of Heathrow Airport's runway 27L and slid onto the runway's threshold. There were 47 injuries and no fatalities. The impact severely damaged the landing gear, wing roots and engines.[244][245] The accident was attributed to ice crystals suspended in the aircraft's fuel clogging the fuel-oil heat exchanger (FOHE).[238][246] Two other minor momentary losses of thrust with Trent 895 engines occurred later in 2008.[247][237] Investigators found these were also caused by ice in the fuel clogging the FOHE. As a result, the heat exchanger was redesigned.[238][248]

The second hull loss occurred on July 29, 2011, when a 777-200ER scheduled to operate as EgyptAir Flight 667 suffered a cockpit fire while parked at the gate at Cairo International Airport before its departure.[249] The aircraft was evacuated with no injuries,[249] and airport fire teams extinguished the fire.[250] The aircraft sustained structural, heat and smoke damage, and was written off.[249][250] Investigators focused on a possible short circuit between an electrical cable and a supply hose in the cockpit crew oxygen system.[249]

The third hull loss occurred on July 6, 2013, when a 777-200ER, operating as Asiana Airlines Flight 214, crashed while landing at San Francisco International Airport after touching down short of the runway. The 307 surviving passengers and crew on board evacuated before fire destroyed the aircraft. Two passengers, who had not been wearing their seatbelts, were ejected from the aircraft during the crash and were killed.[251] A third passenger died six days later as a result of injuries sustained during the crash.[252] These were the first fatalities in a crash involving a 777 since its entry into service in 1995.[253][252][254] The official accident investigation concluded in June 2014 that the pilots committed 20 to 30 minor to significant errors in their final approach. Deficiencies in Asiana Airlines' pilot training and in Boeing's documentation of complex flight control systems were also cited as contributory factors.[255][256][257]

The fourth hull loss occurred on March 8, 2014, when a 777-200ER carrying 227 passengers and 12 crew, en route from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing as Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, was reported missing. Air Traffic Control's last reported coordinates for the aircraft were over the South China Sea.[258][259] After the search for the aircraft began, Malaysia's prime minister announced on March 24, 2014, that after analysis of new satellite data it was now to be assumed "beyond reasonable doubt" that the aircraft had crashed in the Indian Ocean and there were no survivors.[260][261] The cause remains unknown, but the Malaysian Government in January 2015, declared it an accident.[262][263] US officials believe the most likely explanation to be that someone in the cockpit of Flight 370 re-programmed the aircraft's autopilot to travel south across the Indian Ocean.[264][265] On July 29, 2015, an item later identified as a flaperon from the still missing aircraft[266] was found on the island of Réunion in the western Indian Ocean, consistent with having drifted from the main search area.[267]

The fifth hull loss occurred on July 17, 2014, when a 777-200ER, bound for Kuala Lumpur from Amsterdam as Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 (MH17), was shot down by an anti-aircraft missile while flying over eastern Ukraine.[268] All 298 people (283 passengers and 15 crew) on board were killed, making this the deadliest crash involving the Boeing 777.[269] The incident was linked to the ongoing War in Donbas.[270][271] On the basis of the Dutch Safety Board and the Joint Investigation Team official conclusions of May 2018, the governments of the Netherlands and Australia hold Russia responsible for the deployment of the Buk missile system used in shooting down the airliner from territory held by pro-Russian separatists.[272]

The sixth hull loss occurred on August 3, 2016, when a 777-300 crashed while landing and caught fire at Dubai Airport at the end of its flight as Emirates Flight 521.[273] The preliminary investigation indicated that the aircraft was attempting a landing during active wind shear conditions. The pilots initiated a go-around procedure shortly after the wheels touched-down onto the runway, however, the aircraft settled back onto the ground apparently due to late throttle application. As the undercarriage was in the process of being retracted, the aircraft landed on its rear underbody and engine nacelles, resulting in the separation of one engine, loss of control and subsequent crash.[274] There were no passenger casualties of the 300 people on board, however, one airport fireman was killed fighting the fire. The aircraft's fuselage and right wing were irreparably damaged by the fire.[273][275]

The seventh hull loss occurred on November 29, 2017, when a Singapore Airlines 777-200ER experienced a fire while being towed at Singapore Changi Airport. An aircraft technician was the only occupant on board and evacuated safely. The aircraft sustained heat damage and was written off.[276] Another fire occurred on July 22, 2020 to an Ethiopian Airlines 777F while at the cargo area of Shanghai Pudong International Airport. The aircraft sustained heat damage and was written off as the eighth hull loss.[277]

On February 20, 2021, a 777-200 operating as United Airlines Flight 328 suffered a failure of its starboard engine. The cowling and other engine parts fell over a Denver suburb. The captain declared an emergency and returned to land at the Denver airport.[278] An immediate examination, before any formal investigation, found that two fan blades had broken off. One blade had suffered metal fatigue and may have chipped another blade, which also broke off.[279] Boeing recommended suspending flights of all 128 operational 777s equipped with Pratt & Whitney PW4000 engines until they had been inspected. Several countries also restricted flights of PW4000-equipped 777s in their territory.[279] In 2018, there had been a similar issue on United Airlines Flight 1175 from San Francisco to Hawaii, involving another 777-200 equipped with the same engine type.[280]

On May 21, 2024, Singapore Airlines Flight 321, a Boeing 777-300ER encountered severe turbulence over the Andaman Sea that injured 104 passengers[281] and lead to the death of one passenger (who died of a suspected heart attack).[282]

Самолет на выставке

[ редактировать ]

- Первый прототип Боинг 777-200, B-HNL [283] (например, N7771), был выведен из эксплуатации в середине 2018 года на фоне сообщений в прессе о том, что он должен был быть выставлен в Музее авиации в Сиэтле, хотя впоследствии музей опроверг эти сообщения. [284] 18 сентября 2018 года Cathay Pacific и Boeing объявили, что B-HNL будет передан в дар Музею авиации и космонавтики Пима недалеко от Тусона, штат Аризона, где он будет размещен в постоянной экспозиции. [285] Этот самолет, который ранее регулярно использовался Cathay Pacific в период с 2000 по 2018 год, был произведен в 1994 году и был доставлен авиакомпании после шести лет работы в Boeing. [286] [287]

- Носовая часть фюзеляжа и кабина бывшего самолета Boeing 777-200ER компании Korean Air, HL7531. [288] был установлен в Институте науки и технологий Тонвон в качестве учебного заведения для студентов, обучающихся в аэрокосмических областях. Кабина экипажа и части кают первого и экономического классов были сохранены, а передний грузовой отсек преобразован в зону встреч. Монтаж завершился в октябре 2022 года. [289]

Технические характеристики

[ редактировать ]| Варианты | Исходный [185] | дальнобойный [145] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Модель | 777-200/200ЭР | 777-300 | 777-300ЭР | 777-200LR/777F | ||

| Экипаж кабины | Два | |||||

| 3-классные места [171] | 305 (24F/54J/227Y) | 368 (30F/84J/254Y) | 365 (22F/70J/273Y) | 301 (16F/58J/227Y) [б] | ||

| 2-классные места [176] | 313 | 396 | 317 | |||

| Лимит выхода [191] | 440 | 550 | 440 [с] | |||

| Длина | 209 футов 1 дюйм (63,73 м) | 242 фута 4 дюйма (73,86 м) | 209 футов 1 дюйм (63,73 м) | |||

| Размах крыльев | 199 футов 11 дюймов (60,93 м), стреловидность крыла 31,6 ° [290] | 212 футов 7 дюймов (64,80 м), стреловидность крыла 31,6 ° [290] | ||||

| Площадь крыла | 4605 кв. футов (427,8 м 2 ), [290] 8,68 АР | 4702 квадратных футов (436,8 м ) 2 ), [291] 9.61 АР | ||||

| Высота хвоста [176] | 60 футов 9 дюймов (18,5 м) | 60 футов 8 дюймов (18,5 м) | 61 фут 1 дюйм (18,6 м) | |||

| Ширина фюзеляжа | 20 футов 4 дюйма (6,20 м) | |||||

| Ширина кабины | 19 футов 3 дюйма (5,86 м), [292] Сиденья: 18,5 дюймов (47 см) по 9 человек в ряд, 17 дюймов (43 см) по 10 человек в ряд | |||||

| Объем груза [176] | 5330 куб футов (150,9 м 3 ) | 7120 куб футов (201,6 м 3 ) [д] | 5330 куб футов (150,9 м 3 ) [и] | |||

| МВВ | 545 000 фунтов (247 200 кг) 200ER: 656 000 фунтов (297 550 кг) | 660 000 фунтов (299 370 кг) | 775 000 фунтов (351 533 кг) | 766 000 фунтов (347 452 кг) 777F: 766 800 фунтов (347 815 кг) | ||

| ОЙ | 299 550 фунтов (135 850 кг) 200ER: 304 500 фунтов (138 100 кг) | 353 800 фунтов (160 530 кг) | 370 000 фунтов (167 829 кг) 300ERSF: 336 000 фунтов (152 000 кг) [293] | 320 000 фунтов (145 150 кг) 777F: 318 300 фунтов (144 379 кг) | ||

| Запас топлива | 31 000 галлонов США (117 340 л) / 207 700 фунтов (94 240 кг) 200ER/300: 45 220 галлонов США (171 171 л) / 302 270 фунтов (137 460 кг) | 47 890 галлонов США (181 283 л) / 320 863 фунтов (145 538 кг) | ||||

| Потолок [191] | 43 100 футов (13 100 м) | |||||

| Скорость | Макс. 0,87 Маха – 0,89 Маха (499–511 узлов; 924–945 км/ч; 574–587 миль в час), [191] Крейсерский Маха 0,84 (482 узла; 892 км / ч; 554 миль в час) | |||||

| Диапазон [176] | 5240 миль (9700 км; 6030 миль) [ф] [171] 200ER: 7065 миль (13080 км; 8130 миль) [г] | 6030 миль (11165 км; 6940 миль) [час] [171] | 7370 миль (13649 км; 8480 миль) [я] 300ERSF: 4650 миль (8610 км; 5350 миль) [293] | 8555 миль (15843 км; 9845 миль) [Дж] 777F: 4970 миль (9200 км; 5720 миль) [к] | ||

| Снимать [л] | 8000 футов (2440 м) 200ER: 11 100 футов (3380 м) | 10 600 футов (3230 м) | 10 000 футов (3050 м) | 9200 футов (2800 м) 777F: 9300 футов (2830 м) | ||

| Двигатель (2 ×) | PW4000 / Трент 800 / GE90 | PW4000 / Трент 800 [191] | ГЭ90-115Б [294] | ГЭ90-110Б /-115Б [294] | ||

| Максимальная тяга (2×) | 77 200 фунтов силы (343 кН) 200ER: 93700 фунтов силы (417 кН) | 98000 фунтов силы (440 кН) | 115 300 фунтов силы (513 кН) | 110 000–115 300 фунтов силы (489–513 кН) | ||

| ИКАО Обозначение [168] | Б772 | Б773 | B77W | Б77Л | ||

См. также

[ редактировать ]Самолеты сопоставимой роли, конфигурации и эпохи

- Airbus A330 - широкофюзеляжный двухмоторный реактивный авиалайнер.

- Airbus A340 — страницы самолетов

- Airbus A350 XWB - семейство дальнемагистральных широкофюзеляжных реактивных авиалайнеров.

- Boeing 787 Dreamliner - широкофюзеляжный реактивный авиалайнер Boeing, представленный в 2011 году.

- Ильюшин Ил-96 — российский дальнемагистральный широкофюзеляжный авиалайнер.

- McDonnell Douglas MD-11 - широкофюзеляжные авиалайнеры, разработанные на базе DC-10.

Связанные списки

- Список операторов Боинга 777

- Список заказов и поставок Boeing 777

- Список заказов и поставок Boeing 777X

- Список кодов клиентов Boeing

- Список коммерческих реактивных авиалайнеров

- Список гражданских самолетов

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Сноски

[ редактировать ]- ^ 180-минутное одобрение ETOPS было предоставлено модели 777 с двигателем General Electric GE90 3 октября 1996 года и модели 777 с двигателем Rolls-Royce Trent 800 10 октября 1996 года.

- ^ 777F: 228 700 фунтов / 103 737 кг

- ^ 777F: 11

- ^ 300ERSF: 28 900 куб футов (819 м 3 ) [293]

- ^ 777F: 23 051 куб футов (652,7 м 3 )

- ^ 305 пассажиров, Трентс

- ^ 313 пассажиров

- ^ 368 пассажиров, GE90

- ^ 396 пассажиров

- ^ 317 пассажиров

- ^ Полезная нагрузка 102 т

- ^ МВМ, уровень моря, ISA

Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д «Boeing: Заказы и поставки (обновляется ежемесячно)» . Компания Боинг . 30 июня 2024 г. . Проверено 9 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот «Боинг 777: Заказы и поставки (обновляется ежемесячно)» . Компания Боинг . 31 июля 2020 года. Архивировано из оригинала 31 октября 2015 года . Проверено 11 августа 2020 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д «Ежегодные заказы и поставки Boeing» . Компания Боинг . 30 апреля 2019 года . Проверено 14 мая 2019 г.

- ^ Уэллс и Родригес 2004 , с. 146

- ^ «Поколение 1980-х» . Время . 14 августа 1978 года. Архивировано из оригинала 18 ноября 2007 года . Проверено 19 июля 2008 г.

- ^ Иден 2008 , стр. 98, 102–103.

- ^ «Боинг 767 и 777» . Рейс Интернешнл . 13 мая 1978 года. Архивировано из оригинала 6 ноября 2018 года . Проверено 10 сентября 2018 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Иден 2008 , стр. 99–104.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Норрис и Вагнер 1999 , с. 128

- ^ Йенн 2002 , с. 33

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Иден 2008 , с. 112

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Норрис и Вагнер 1999 , с. 126

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Норрис и Вагнер 1999 , с. 127

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Иден 2008 , с. 106

- ^ Норрис и Вагнер 2001 , с. 11

- ^ Норрис и Вагнер 1996 , стр. 9–14.

- ^ Норрис и Вагнер 1999 , с. 129

- ^ «Исполнительные биографии: Алан Малалли» . Боинг. Май 2006. Архивировано из оригинала 31 августа 2006 года . Проверено 5 сентября 2006 г.

- ^ Чжан, Бенджамин. «Славная история лучшего самолета, который когда-либо создавал Boeing» . Бизнес-инсайдер . Архивировано из оригинала 22 сентября 2019 года . Проверено 22 сентября 2019 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бертлз 1998 , стр. 13–16.

- ^ Вайнер, Эрик (19 декабря 1990 г.). «Новый авиалайнер Boeing, созданный авиакомпаниями» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 11 декабря 2011 года . Проверено 8 мая 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Норрис и Вагнер 1996 , с. 14

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Норрис и Вагнер 1999 , с. 132

- ^ «Деловые заметки: Самолеты» . Время . 29 октября 1990 года. Архивировано из оригинала 18 ноября 2007 года . Проверено 19 июля 2008 г.

- ^ Норрис и Вагнер 1996 , с. 13

- ^ Лейн, Полли (1 декабря 1991 г.). «Аэрокосмическая компания, возможно, переосмысливает свою деятельность в районе Пьюджет-Саунд» . Сиэтл Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 11 августа 2011 года . Проверено 15 октября 2009 г.

- ^ Норрис и Вагнер 1996 , с. 15

- ^ Норрис и Вагнер 1996 , с. 20

- ^ «BA получает новую модель 777» . Сиэтлский пост-разведчик . 10 февраля 1997 года. Архивировано из оригинала 5 ноября 2012 года . Проверено 4 июля 2015 г.

- ^ Введение в машиностроение . Кл-Инжиниринг. Январь 2012. с. 19. ISBN 978-1-111-57680-6 .

Например, Боинг 777 был первым коммерческим авиалайнером, разработанным с помощью безбумажного автоматизированного процесса проектирования.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Норрис и Вагнер 1999 , с. 133

- ^ Норрис и Вагнер 1999 , стр. 133–134.

- ^ Абарбанель и Макнили 1996 , с. 124 Примечание. В 2010 году система IVT все еще работала в компании Boeing и имела более 29 000 пользователей.

- ^ Норрис и Вагнер 1996 , с. 21

- ^ Ткачик, Морин (18 сентября 2019 г.). «Ускоренный курс» . Новая Республика . Архивировано из оригинала 19 сентября 2019 года . Проверено 22 сентября 2019 г.

- ^ AW&ST 26 апреля 1999 г., с. 39

- ^ Саббах 1995 , стр. 168–169

- ^ Саббах 1995 , стр. 256–259

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Иден 2008 , с. 107

- ^ Бертлз 1998 , с. 25

- ^ Андерсен, Ларс (16 августа 1993 г.). «Boeing 777 будет лучшим, когда дело доходит до ETOPS» . Сиэтл Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 11 августа 2011 года . Проверено 20 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Норрис и Вагнер 1999 , с. 144

- ^ Бертлз 1998 , с. 40

- ^ Бертлз 1998 , с. 20

- ^ Бертлз 1999 , с. 34

- ^ Бертлз 1998 , с. 69

- ^ «Первая поставка Boeing 777 поступила в United Airlines» . Деловой провод . 15 мая 1995 года. Архивировано из оригинала 20 августа 2011 года . Проверено 4 июля 2015 г.

- ^ Норрис и Вагнер 1999 , с. 139

- ^ Бертлз 1998 , с. 80

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Иден 2004, с. 115.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Норрис и Вагнер 1999 , с. 143

- ^ Норрис и Вагнер 1999 , с. 147

- ^ Норрис и Вагнер 1999 , стр. 146–147.

- ^ «Боинг рвется вперед» . БизнесУик . 6 ноября 2005 года. Архивировано из оригинала 2 марта 2009 года . Проверено 1 декабря 2008 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Норрис и Вагнер 1999 , с. 148

- ^ «Данные о надежности 777» (PDF) . Боинг. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 2 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ «Боинг признает, что надежность Dreamliner с проблемами только на 98%» . Боинг

- ^ «777» . boeing.com . Архивировано из оригинала 30 марта 2015 года . Проверено 1 апреля 2015 г.

- ^ Виндхэм, Дэвид (октябрь 2012 г.). «Надежность самолетов» . AvBuyer . World Aviation Communication Ltd. Архивировано из оригинала 21 февраля 2014 года . Проверено 23 января 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Иден 2008 , с. 113

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Иден 2008 , стр. 112–113.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час «Предыстория программы Boeing 777» . Боинг . Архивировано из оригинала 8 июня 2009 года . Проверено 6 июня 2009 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хенгги, Майкл. «777 Революция тройной семерки». Боинг широкофюзеляжные . Сент-Пол, Миннесота: MBI, 2003. ISBN 0-7603-0842-X .

- ^ Норрис и Вагнер 1999 , с. 151

- ^ Норрис и Вагнер 2001 , с. 125

- ^ Норрис и Вагнер 1999 , стр. 151–157.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Эллис Тейлор (1 сентября 2017 г.). «777 Classics вступают в свои закатные годы» . Флайтглобал . Архивировано из оригинала 11 сентября 2017 года . Проверено 11 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Иден 2008 , с. 108

- ^ Хайс, Федра (9 июля 2007 г.). «Сила, лежащая в основе Boeing 787 Dreamliner» . Си-Эн-Эн. Архивировано из оригинала 24 декабря 2009 года . Проверено 15 октября 2009 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ричардсон, Майкл (23 февраля 1994 г.). «Ожидается, что спрос на авиалайнеры резко возрастет: рынок высококлассных самолетов Азии» . Интернэшнл Геральд Трибьюн . Архивировано из оригинала 14 июля 2011 года . Проверено 20 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Саббах 1995 , стр. 112–114

- ^ Норрис, Гай (31 марта 1993 г.). «Boeing готовится к растянутому запуску 777» . Рейс Интернешнл . Архивировано из оригинала 24 июля 2012 года . Проверено 8 мая 2011 г.

- ^ Норрис и Вагнер 1996 , с. 7

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сон, Кён (4 июня 2000 г.). «Кто делает лучший широкофюзеляжный?» . Сиэтл Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 11 августа 2011 года . Проверено 29 октября 2009 г.

- ^ Рэй, Сюзанна (21 апреля 2009 г.). «Прибыль Boeing снизилась из-за спада производства 777» . Блумберг. Архивировано из оригинала 19 ноября 2018 года . Проверено 29 октября 2009 г.

- ^ Гейтс, Доминик (16 ноября 2004 г.). «Грузовая версия лайнера 777 в разработке» . Сиэтл Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 11 августа 2011 года . Проверено 29 октября 2009 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д «Airbus A350 XWB оказывает давление на Boeing 777» . рейсглобальный. 26 ноября 2007 года. Архивировано из оригинала 8 марта 2016 года . Проверено 25 февраля 2016 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Томас, Джеффри (13 июня 2008 г.). «Boeing находится под давлением из-за роста спроса на экономичный 777» . Австралиец . Архивировано из оригинала 30 апреля 2014 года . Проверено 20 июня 2008 г.

- ^ Хефер, Тим (8 сентября 2008 г.). «Оценка портфолио самолетов Boeing» . Рейтер . Архивировано из оригинала 24 июня 2011 года . Проверено 3 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Рэнсон, Лори (20 декабря 2010 г.). «Boeing объявляет об очередном увеличении производства Boeing 777» . Разведка воздушного транспорта через Flightglobal.com . Архивировано из оригинала 23 декабря 2010 года . Проверено 2 января 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Boeing начинает работу над тысячным Боингом 777» . Боинг . 7 ноября 2011 года. Архивировано из оригинала 13 ноября 2011 года . Проверено 8 ноября 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Авиакомпания Emirates получила тысячный Боинг 777» . Новости Персидского залива . 3 марта 2012. Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2012 года . Проверено 3 марта 2012 г.

- ^ Рид, Тед (11 февраля 2017 г.). «Boeing 777 летает по семи из десяти самых длинных маршрутов в мире» . Форбс . Архивировано из оригинала 29 июня 2019 года . Проверено 29 июня 2019 г.

- ^ Брэндон, Грейвер; Дэниел, Резерфорд (январь 2018 г.). «Рейтинг топливной эффективности авиакомпаний Транстихоокеанского региона, 2016 г.» (PDF) . Международный совет чистого транспорта . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 19 августа 2019 г. Проверено 29 июня 2019 г.