Кувейт

Государство Кувейт | |

|---|---|

| Гимн: Государственный гимн Аль-Нашид аль-Ватани "Государственный гимн" | |

Location of Kuwait (green) | |

| Capital and largest city | Kuwait City |

| Official languages | Arabic[1] |

| Other languages | English (lingua franca) • Tagalog • Gulf Pidgin Arabic (lingua franca) • Hindi • Persian • Bengali • Urdu • French • Malayalam • Pashto • Turkish • Armenian • Kurdish • Other minority languages spoken[2][3] |

| Ethnic groups (2018)[4] | |

| Religion (2013)[4] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Kuwaiti |

| Government | Unitary constitutional elective monarchy[5][6] |

• Emir | Mishal Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah |

| Sabah Al-Khalid Al-Sabah | |

| Ahmad Al-Abdullah Al-Sabah | |

| Legislature | The National Assembly[7] Emergency clauses invoked; suspended temporarily[8] |

| Establishment | |

| 1752 | |

| 23 January 1899 | |

| 29 July 1913 | |

• End of treaties with the United Kingdom | 19 June 1961 |

| 14 May 1963 | |

| 11 November 1962 | |

| 28 August 1990 | |

| 28 February 1991 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 17,818 km2 (6,880 sq mi) (152nd) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 3,138,355[9] (137th) |

• Density | 200.2/km2 (518.5/sq mi) (62nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| HDI (2022) | very high (49th) |

| Currency | Kuwaiti dinar |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (AST) |

| ISO 3166 code | KW |

| Internet TLD | .kw |

Website www.e.gov.kw | |

| |

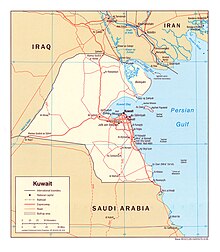

Кувейт , [ а ] официально Государство Кувейт , [ б ] это страна в Западной Азии . Он расположен на северной окраине Восточной Аравии , на оконечности Персидского залива , граничит с Ираком на севере и Саудовской Аравией на юге . [ 14 ] Имея береговую линию длиной около 500 км (311 миль), Кувейт также имеет морскую границу с Ираном . [ 15 ] Большая часть населения страны проживает в городской агломерации Эль - Кувейт , столице и крупнейшем городе. [ 16 ] По состоянию на 2023 год [update]Население Кувейта составляет 4,82 миллиона человек, из которых 1,53 миллиона являются гражданами Кувейта , а остальные 3,29 миллиона являются иностранными гражданами из более чем 100 стран. [ 17 ]

Исторически большая часть современного Кувейта была частью древней Месопотамии . [ 18 ] [ 19 ] [ 20 ] До открытия запасов нефти в 1938 году страна была региональным торговым портом; [ 21 ] [ 22 ] с 1946 по 1982 год в стране прошла масштабная модернизация, во многом основанная на доходах от добычи нефти . В 1980-х годах Кувейт пережил период геополитической нестабильности и экономического кризиса, последовавшего за крахом фондового рынка . В 1990 году Кувейт был захвачен и впоследствии аннексирован Ираком из- за под руководством Саддама Хусейна споров по поводу добычи нефти. [23] Иракская оккупация Кувейта закончилась 26 февраля 1991 года после того, как США , Великобритании , Франции , Саудовской Аравии и Египта под руководством международная коалиция завершилась изгнанием иракских войск .

Like most other Arab states in the Persian Gulf, Kuwait is an emirate; the emir is the head of state and the ruling Al Sabah family dominates the country's political system. Kuwait's official state religion is Islam, specifically the Maliki school of Sunni Islam. Kuwait is a high-income economy, backed by the world's sixth largest oil reserves. Kuwaiti popular culture, in the form of theatre, radio, music, and television soap opera, is exported to neighboring Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states.[24] Kuwait is a founding member of the GCC and is also a member of the UN, AL, OPEC and the OIC.

Etymology

[edit]The name "Kuwait" is from the Mesopotamian Arabic diminutive form of كوت (Kut or Kout), meaning "fortress built near water". The country's official name has been the "State of Kuwait" since 1961.

History

[edit]Antiquity

[edit]Following the post-glacial flooding of the Persian Gulf basin, debris from the Tigris–Euphrates river formed a substantial delta, creating most of the land in present-day Kuwait and establishing the present coastlines.[25] One of the earliest evidence of human habitation in Kuwait dates back to 8000 BC where Mesolithic tools were found in Burgan.[26] Historically, most of present-day Kuwait was part of ancient Mesopotamia.[18][19][20]

During the Ubaid period (6500 BC), Kuwait was the central site of interaction between the peoples of Mesopotamia and Neolithic Eastern Arabia,[27][28][29][30][31] including Bahra 1 and site H3 in Subiya.[27][32][33][34] The Neolithic inhabitants of Kuwait were among the world's earliest maritime traders.[35] One of the world's earliest reed-boats was discovered at site H3 dating back to the Ubaid period.[36] Other Neolithic sites in Kuwait are located in Khiran and Sulaibikhat.[27]

Mesopotamians first settled in the Kuwaiti island of Failaka in 2000 BC[37][38] Traders from the Sumerian city of Ur inhabited Failaka and ran a mercantile business.[37][38] The island had many Mesopotamian-style buildings typical of those found in Iraq dating from around 2000 BC[38][37] In 4000 BC until 2000 BC, Kuwait was home to the Dilmun civilization.[39][40][41][42][26] Dilmun included Al-Shadadiya,[26] Akkaz,[39] Umm an Namil,[39][43] and Failaka.[39][42] At its peak in 2000 BC, Dilmun controlled the Persian Gulf trading routes.[44]

During the Dilmun era (from ca. 3000 BC), Failaka was known as "Agarum", the land of Enzak, a great god in the Dilmun civilization according to Sumerian cuneiform texts found on the island.[45] As part of Dilmun, Failaka became a hub for the civilization from the end of the 3rd to the middle of the 1st millennium BC.[45][46] After the Dilmun civilization, Failaka was inhabited by the Kassites of Mesopotamia,[47] and was formally under the control of the Kassite dynasty of Babylon.[47] Studies indicate traces of human settlement can be found on Failaka dating back to as early as the end of the 3rd millennium BC, and extending until the 20th century AD.[45] Many of the artifacts found in Falaika are linked to Mesopotamian civilizations and seem to show that Failaka was gradually drawn toward the civilization based in Antioch.[48]

Under Nebuchadnezzar II, the bay of Kuwait was under Babylonian control.[49] Cuneiform documents found in Failaka indicate the presence of Babylonians in the island's population.[50] Babylonian Kings were present in Failaka during the Neo-Babylonian Empire period, Nabonidus had a governor in Failaka and Nebuchadnezzar II had a palace and temple in Falaika.[51][52] Failaka also contained temples dedicated to the worship of Shamash, the Mesopotamian sun god in the Babylonian pantheon.[52]

Following the Fall of Babylon, the bay of Kuwait came under the control of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550‒330 BC) as the bay was repopulated after seven centuries of abandonment.[53] Failaka was under the control of the Achaemenid Empire as evidenced by the archaeological discovery of Achaemenid strata.[51][54] There are Aramaic inscriptions that testify Achaemenid presence.[54]

In fourth century BC, the ancient Greeks colonized the bay of Kuwait under Alexander the Great. The ancient Greeks named mainland Kuwait Larissa and Failaka was named Ikaros.[55][56][57][58] The bay of Kuwait was named Hieros Kolpos.[59] According to Strabo and Arrian, Alexander the Great named Failaka Ikaros because it resembled the Aegean Island of that name in size and shape. Elements of Greek mythology were mixed with the local cults.[60] "Ikaros" was also the name of a prominent city situated in Failaka.[61] Large Hellenistic forts and Greek temples were uncovered.[62] Archaeological remains of Greek colonization were also discovered in Akkaz, Umm an Namil, and Subiya.[26]

At the time of Alexander the Great, the mouth of the Euphrates River was located in northern Kuwait.[63][64] The Euphrates river flowed directly into the Persian Gulf via Khor Subiya which was a river channel at the time.[63][64] Failaka was located 15 kilometers from the mouth of the Euphrates river.[63][64] By the first century BC, the Khor Subiya river channel dried out completely.[63][64]

In 127 BC, Kuwait was part of the Parthian Empire and the kingdom of Characene was established around Teredon in present-day Kuwait.[65][66][67] Characene was centered in the region encompassing southern Mesopotamia,[68] Characene coins were discovered in Akkaz, Umm an Namil, and Failaka.[69][70] A busy Parthian commercial station was situated in Kuwait.[71]

In 224 AD, Kuwait became part of the Sassanid Empire. At the time of the Sassanid Empire, Kuwait was known as Meshan,[72] which was an alternative name of the kingdom of Characene.[73][74] Akkaz was a Partho-Sassanian site;[75] the Sassanid religion's tower of silence was discovered in northern Akkaz.[75][76][77] Late Sassanian settlements were discovered in Failaka.[78] In Bubiyan, there is archaeological evidence of Sassanian to early Islamic periods of human presence as evidenced by the recent discovery of torpedo-jar pottery shards on several prominent beach ridges.[79]

In 636 AD, the Battle of Chains between the Sassanid Empire and Rashidun Caliphate was fought in Kuwait.[80][81] As a result of Rashidun victory in 636 AD, the bay of Kuwait was home to the city of Kazma (also known as "Kadhima" or "Kāzimah") in the early Islamic era.[81][82][83][84][85][86][87]

1752–1945: Pre-oil

[edit]

In the early to mid 1700s, Kuwait City was as a small fishing village. Administratively, it was a sheikhdom, ruled by local sheikhs from Bani Khalid clan.[88] Sometime in the mid 1700s, the Bani Utbah settled in Kuwait City.[89][90] Sometime after the death of the Bani Khalid's leader Barak bin Abdul Mohsen and the fall of the Bani Khalid Emirate, the Utub were able to wrest control of Kuwait as a result of successive matrimonial alliances.[90]

In the latter half of the eighteenth century, Kuwait began establishing itself as a maritime port and gradually became a principal commercial center for the transit of goods between Baghdad, India, Persia, Muscat, and the Arabian Peninsula.[91][92] By the late-1700s, Kuwait had established itself as a trading route from the Persian Gulf to Aleppo.[93] During the Persian siege of Basra in 1775–79, Iraqi merchants took refuge in Kuwait and were partly instrumental in the expansion of Kuwait's boat-building and trading activities.[94] As a result, Kuwait's maritime commerce boomed,[94] as the Indian trade routes with Baghdad, Aleppo, Smyrna and Constantinople were diverted to Kuwait during this time.[93][95][96] The East India Company was diverted to Kuwait in 1792.[97] The East India Company secured the sea routes between Kuwait, India and the east coasts of Africa.[97] After the Persians withdrew from Basra in 1779, Kuwait continued to attract trade away from Basra.[98] The flight of many of Basra's leading merchants to Kuwait continued to play a significant role in Basra's commercial stagnation well into the 1850s.[98]

The instability in Basra helped foster economic prosperity in Kuwait.[99][100] In the late 18th century, Kuwait was a haven for Basra merchants fleeing Ottoman persecution.[101] Kuwait was the center of boat building in the Persian Gulf,[102] its ships renowned throughout the Indian Ocean.[103][104] Its sailors developed a positive reputation in the Persian Gulf.[91][105][106] In the 19th century, Kuwait became significant in the horse trade,[107] with regular shipments in sailing vessels.[107] In the mid 19th century, it was estimated that Kuwait exported an average of 800 horses to India annually.[99]

In 1899, ruler Sheikh Mubarak Al Sabah signed an agreement with the British government in India (subsequently known as the Anglo-Kuwaiti Agreement of 1899) making Kuwait a British protectorate. This gave Britain exclusive access and trade with Kuwait, while denying Ottoman provinces to the north a port on the Persian Gulf. The Sheikhdom of Kuwait remained a British protectorate until 1961.[88]

After the Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1913, Kuwait was established as an autonomous kaza, or district, of the Ottoman Empire and a de facto protectorate of Great Britain.

During World War I, the British Empire imposed a trade blockade against Kuwait because Kuwait's ruler at the time, Salim Al-Mubarak Al-Sabah, supported the Ottoman Empire.[109][110][111] The British economic blockade heavily damaged Kuwait's economy.[111]

In 1919, Sheikh Salim Al-Mubarak Al-Sabah intended to build a commercial city in the south of Kuwait. This caused a diplomatic crisis with Najd, but Britain intervened, discouraging Sheikh Salim. In 1920, an attempt by the Ikhwan to build a stronghold in southern Kuwait led to the Battle of Hamdh. The Battle of Hamdh involved 2,000 Ikhwan fighters against 100 Kuwaiti cavalrymen and 200 Kuwaiti infantrymen. The battle lasted for six days and resulted in heavy but unknown casualties on both sides resulting in the victory of the Ikhwan forces and leading to the battle of Jahra around the Kuwait Red Fort. The Battle of Jahra happened as the result of the Battle of Hamdh. A force of three to four thousand Ikhwan, led by Faisal Al-Dawish, attacked the Red Fort at Al-Jahra, defended by fifteen hundred men. The fort was besieged and the Kuwaiti position precarious[112] The Ikhwan attack repulsed for the while, negotiations began between Salim and Al-Dawish; the latter threatened another attack if the Kuwaiti forces did not surrender. The local merchant class convinced Salim to call in help from British troops, who showed up with airplanes and three warships, ending the attacks.[112] After the Battle of Jahra, Ibn Saud's warriors, the Ikhwan, demanded that Kuwait follows five rules: evict all the Shias, adopt the Ikhwan doctrine, label the Turks "heretics", abolish smoking, munkar and prostitution, and destroy the American missionary hospital.[113]

The Kuwait–Najd War of 1919–20 erupted in the aftermath of World War I. The war occurred because Ibn Saud of Najd wanted to annex Kuwait.[109][114] The sharpened conflict between Kuwait and Najd led to the death of hundreds of Kuwaitis. The war resulted in sporadic border clashes throughout 1919–1920.

When Percy Cox was informed of the border clashes in Kuwait, he sent a letter to the Ruler of Arabistan Sheikh Khazʽal Ibn Jabir offering the Kuwaiti throne to either him or one of his heirs. Khaz'al refused.[115] He then asked:

...even so, do you think that you have come to me with something new? Al Mubarak's position as ruler of Kuwait means that I am the true ruler of Kuwait. So there is no difference between myself and them, for they are like the dearest of my children and you are aware of this. Had someone else come to me with this offer, I would have complained about them to you. So how do you come to me with this offer when you are well aware that myself and Al Mubarak are one soul and one house, what affects them affects me, whether good or evil.[115]

Following the Kuwait–Najd War in 1919–20, Ibn Saud imposed a trade blockade against Kuwait from the years 1923 until 1937.[116] The goal of the Saudi economic and military attacks on Kuwait was to annex as much of Kuwait's territory as possible. At the Uqair conference in 1922, the boundaries of Kuwait and Najd were set; as a result of British interference, Kuwait had no representative at the Uqair conference. After the Uqair conference, Kuwait was still subjected to a Saudi economic blockade and intermittent Saudi raiding.

Kuwait immensely declined in regional economic importance,[104] due to the trade blockades and the world economic depression.[109] Before Mary Bruins Allison visited Kuwait in 1934, Kuwait had already lost its prominence in long-distance trade.[104]

The Great Depression harmed Kuwait's economy, starting in the late 1920s.[116] International trading was one of Kuwait's main sources of income before oil.[116] Kuwait's merchants were mostly intermediary merchants.[116] As a result of the decline of European demand for goods from India and Africa, Kuwait's economy suffered. The decline in international trade resulted in an increase in gold smuggling by Kuwait's ships to India.[116] Some local merchant families became rich from this smuggling.[117] Kuwait's pearl industry also collapsed as a result of the worldwide economic depression.[117] At its height, Kuwait's pearl industry had led the world's luxury market, regularly sending out between 750 and 800 ships to meet the European elite's desire for pearls.[117] During the economic depression, luxuries like pearls were in little demand.[117] The Japanese invention of cultured pearls also contributed to the collapse of Kuwait's pearl industry.[117]

Freya Stark wrote about the extent of poverty in Kuwait at the time:[116]

Poverty has settled in Kuwait more heavily since my last visit five years ago, both by sea, where the pearl trade continues to decline, and by land, where the blockade established by Saudi Arabia now harms the merchants.

On 22 February 1938, oil was first discovered in the Burgan field.

1946–1980: State-building

[edit]Between 1946 and 1980, Kuwait experienced a period of prosperity driven by oil and its liberal cultural atmosphere; this period is called the "golden era of Kuwait".[118][119][120][121] In 1946, crude oil was exported for the first time. In 1950, a major public-work programme began to enable Kuwaiti citizens to enjoy a luxurious standard of living.

By 1952, the country became the largest oil exporter in the Persian Gulf region. This massive growth attracted many foreign workers, especially from Palestine, Iran, India, and Egypt – with the latter being particularly political within the context of the Arab Cold War.[122] It was also in 1952 that the first masterplan of Kuwait was designed by the British planning firm of Minoprio, Spenceley, and Macfarlane. In 1958, Al-Arabi magazine was first published.[123] Many foreign writers moved to Kuwait because they enjoyed greater freedom of expression than elsewhere in the Middle East.[124][125] Kuwait's press was described as one of the freest in the world.[126] Kuwait was the pioneer in the literary renaissance in the Middle East.[123]

In June 1961, Kuwait became independent with the end of the British protectorate and the Sheikh Abdullah Al-Salim Al-Sabah became Emir of Kuwait. Kuwait's national day, however, is celebrated on 25 February, the anniversary of the coronation of Sheikh Abdullah (it was originally celebrated on 19 June, the date of independence, but concerns over the summer heat caused the government to move it).[127]

At the time, Kuwait was considered the most developed country in the region.[128][129][130] Kuwait was the pioneer in the Middle East in diversifying its earnings away from oil exports.[131] The Kuwait Investment Authority is the world's first sovereign wealth fund.

Kuwaiti society embraced liberal and non-traditional attitudes throughout the 1960s and 1970s.[132][133] For example, most Kuwaiti women did not wear the hijab in the 1960s and 70s.[134][135]

Although Kuwait formally gained independence in 1961, Iraq initially refused to recognize the country's independence by maintaining that Kuwait is part of Iraq, albeit Iraq later briefly backed down following a show of force by Britain and Arab League support of Kuwait's independence.[136][137][138]

The short-lived Operation Vantage crisis evolved in July 1961, as the Iraqi government threatened to invade Kuwait and the invasion was finally averted following plans by the Arab League to form an international Arab force against the potential Iraqi invasion of Kuwait.[139][140] As a result of Operation Vantage, the Arab League took over the border security of Kuwait and the British had withdrawn their forces by 19 October.[136] Iraqi prime minister Abd al-Karim Qasim was killed in a coup in 1963 but, although Iraq recognised Kuwaiti independence and the military threat was perceived to be reduced, Britain continued to monitor the situation and kept forces available to protect Kuwait until 1971. There had been no Iraqi military action against Kuwait at the time: this was attributed to the political and military situation within Iraq which continued to be unstable.[14]

A treaty of friendship between Iraq and Kuwait was signed in 1963 by which Iraq recognised the 1932 border of Kuwait.[141] Under the terms of the newly drafted Constitution, Kuwait held its first parliamentary elections in 1963.

Kuwait University was established in 1966.[130] Kuwait's theatre industry became well known throughout the region.[118][130] After the 1967 Six Day War, Kuwait along with other Arabic speaking countries voted the three no's of the Khartoum Resolution: no peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, and no negotiations with Israel. From the 1970s onward, Kuwait scored highest of all Arab countries on the Human Development Index.[130] The Iraqi poet Ahmed Matar left Iraq in the 1970s to take refuge in the more liberal environment of Kuwait.

The Kuwait-Iraq 1973 Samita border skirmish evolved on 20 March 1973, when Iraqi army units occupied El-Samitah near the Kuwaiti border, which evoked an international crisis.[142]

On 6 February 1974, Palestinian militants occupied the Japanese embassy in Kuwait, taking the ambassador and ten others hostage. The militants' motive was to support the Japanese Red Army members and Palestinian militants who were holding hostages on a Singaporean ferry in what is known as the Laju incident. Ultimately, the hostages were released, and the guerrillas allowed to fly to Aden. This was the first time Palestinian guerrillas struck in Kuwait as the Al Sabah ruling family, headed by Sheikh Sabah Al-Salim Al-Sabah, funded the Palestinian resistance movement. Kuwait had been a regular endpoint for Palestinian plane hijacking in the past and had considered itself safe.

Kuwait International Airport was opened in 1979 by the Al Hani Construction with a joint venture of Ballast Nedam.

1981–1991: Wars and terrorism

[edit]The Al Sabah strongly advocated Islamism throughout the 1980s.[143] At that time, the most serious threat to the continuity of Al Sabah came from home-grown democrats,[143] who were protesting the 1976 suspension of the parliament.[143] The Al Sabah were attracted to Islamists preaching the virtues of a hierarchical order that included loyalty to the Kuwaiti monarchy.[143] In 1981, the Kuwaiti government gerrymandered electoral districts in favour of the Islamists.[144][143] Islamists were the government's main allies, hence Islamists were able to dominate state agencies, such as the government ministries.[143]

During the Iran–Iraq War, Kuwait ardently supported Iraq. As a result, there were various pro-Iran terror attacks across Kuwait, including the 1983 bombings, the attempted assassination of Emir Jaber in May 1985, the 1985 Kuwait City bombings, and the hijacking of several Kuwait Airways planes. Kuwait's economy and scientific research sector significantly suffered due to the pro-Iran terror attacks.[145]

Simultaneously, Kuwait experienced a major economic crisis after the Souk Al-Manakh stock market crash and decrease in oil price.[146][147][148][149]

After the Iran–Iraq War ended, Kuwait declined an Iraqi request to forgive its US$65 billion debt.[150] An economic rivalry between the two countries ensued after Kuwait increased its oil production by 40 percent.[151] Tensions between the two countries increased further in July 1990, after Iraq complained to OPEC claiming that Kuwait was stealing its oil from a field near the border by slant drilling of the Rumaila field.[151]

In August 1990, Iraqi forces invaded and annexed Kuwait without any warning. After a series of failed diplomatic negotiations, the United States led a coalition to remove the Iraqi forces from Kuwait, in what became known as the Gulf War. On 26 February 1991, in phase of code-named Operation Desert Storm, the coalition succeeded in driving out the Iraqi forces. As they retreated, Iraqi forces carried out a scorched earth policy by setting oil wells on fire.[152]

During the Iraqi occupation, nearly 1,000 civilians were killed in Kuwait. In addition, 600 people went missing during Iraq's occupation;[153] remains of approximately 375 were found in mass graves in Iraq. Kuwait celebrates February 26 as Liberation Day. The event marked the country as the centre of the last major war in the 20th century.

1992–present: Present era

[edit]In the early 1990s, Kuwait deported nearly 400,000 Palestinians.[154] Kuwait's policy was a response to alignment of the PLO with Saddam Hussein. It was a form of collective punishment. Kuwait also deported thousands of Iraqis and Yemenis after the Gulf War.[155][156]

In addition, hundreds of thousands of stateless Bedoon were expelled from Kuwait in the early-to-mid 1990s.[157][158][155][159][156] At the House of Commons of the United Kingdom in 1995, it was revealed that the Al Sabah ruling family deported 150,000 stateless Bedoon to refugee camps in the Kuwaiti desert near the Iraqi border with minimal water, insufficient food, and no basic shelter.[160][158] Many of the stateless Bedoon fled to Iraq where they still remain stateless people even today.[161][162]

In March 2003, Kuwait became the springboard for the US-led invasion of Iraq. In 2005, women won the right to vote and run in elections. Upon the death of the Emir Jaber in January 2006, Sheikh Saad Al-Sabah succeeded him but was removed nine days later due to his failing health. As a result, Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah was sworn in as Emir. From that point onwards, Kuwait suffered from chronic political deadlock between the government and parliament which resulted in multiple cabinet reshuffles and dissolutions.[163] This significantly hampered investment and economic reforms in Kuwait, making the country's economy much more dependent on oil.[163]

Despite the political instability, Kuwait had the highest Human Development Index ranking in the Arab world from 2006 to 2009.[164][165][166][167][168][169] China awarded Kuwait Investment Authority an additional $700 million quota on top of $300 million awarded in March 2012.[170] The quota is the highest to be granted by China to foreign investment entities.[170]

In March 2014, David S. Cohen, who was then Secretary of the Treasury for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence, accused Kuwait of funding terrorism.[171] Accusations of Kuwait funding terrorism have been very common and come from a wide variety of sources including intelligence reports, Western government officials, scholarly research, and renowned journalists.[172][173][174][175][176][177][178][179][180][171] In 2014 and 2015, Kuwait was frequently described as the world's biggest source of terrorism funding, particularly for ISIS and Al-Qaeda.[172][173][174][180][171][178][175][176]

On 26 June 2015, a suicide bombing took place at a Shia Muslim mosque in Kuwait. The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant claimed responsibility for the attack. Twenty-seven people were killed and 227 people were wounded. It was the largest terror attack in Kuwait's history. In the aftermath, a lawsuit was filed accusing the Kuwaiti government of negligence and direct responsibility for the terror attack.[181][182]

Due to declining oil prices in the mid-to-late 2010s, Kuwait faced one of the worst economic crunches in its history.[183] Sabah Al Ahmad Sea City was inaugurated in mid-2016.[184][185][186][187][188] Simultaneously, Kuwait invested significantly in its economic relations with China.[189] China has been Kuwait's largest trade partner since 2016.[190][191][192][193][194]

Under the Belt and Road Initiative, Kuwait and China have various cooperation projects including South al-Mutlaa which is currently under construction in northern Kuwait.[195][196][197][198][199] The Sheikh Jaber Al-Ahmad Al-Sabah Causeway is part of the first phase of the Silk City project.[200] The causeway was inaugurated in May 2019 as part of Kuwait Vision 2035,[201][202] it connects Kuwait City to northern Kuwait.[201][200]

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated Kuwait's economic crisis.[203][204][205][206] Kuwait's economy faced a budget deficit of $46 billion in 2020.[207][208][163] It was Kuwait's first fiscal deficit since 1995.[209][210] In September 2020, Kuwait's Crown Prince Sheikh Nawaf Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah became the 16th Emir of Kuwait and the successor to Emir Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, who died at the age of 91.[211] In October 2020, Sheikh Mishal Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah was appointed as the Crown Prince.[212][213][214][215] In December 2023, Kuwait’s Emir Sheikh Nawaf al-Ahmad al-Jaber al-Sabah died and was replaced by Mishal Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah.[216]

Kuwait currently has the largest US military presence in the entire Middle East region.[217] There are over 14,000 US military personnel stationed in the country.[217] Camp Arifjan is the largest US military base in Kuwait. The US uses bases in Kuwait as staging hubs, training ranges, and logistical support for its Middle East operations.[217]

In recent years, Kuwait's infrastructure projects market has regularly underperformed due to political deadlock between the government and parliament.[218][163] Kuwait is now the region's most oil-dependent country with the lowest share of economic diversification.[163][204] According to the World Economic Forum, Kuwait has the weakest infrastructure quality in the GCC region.[219]

Geography

[edit]

Located at the head of the Persian Gulf in the north-east corner of the Arabian Peninsula, Kuwait is one of the smallest countries in the world in terms of land area. Kuwait lies between latitudes 28° and 31° N, and longitudes 46° and 49° E. Kuwait is generally low-lying, with the highest point being 306 m (1,004 ft) above sea level.[14] Mutla Ridge is the highest point in Kuwait.

Kuwait has ten islands.[220] With an area of 860 km2 (330 sq mi), the Bubiyan is the largest island in Kuwait and is connected to the rest of the country by a 2,380-metre-long (7,808 ft) bridge.[221] 0.6% of Kuwaiti land area is considered arable[14] with sparse vegetation found along its 499-kilometre-long (310 mi) coastline.[14] Kuwait City is located on Kuwait Bay, a natural deep-water harbor.

Kuwait's Burgan field has a total capacity of approximately 70 billion barrels (11 billion cubic metres) of proven oil reserves. During the 1991 Kuwaiti oil fires, more than 500 oil lakes were created covering a combined surface area of about 35.7 km2 (13+3⁄4 sq mi).[222] The resulting soil contamination due to oil and soot accumulation had made eastern and south-eastern parts of Kuwait uninhabitable. Sand and oil residue had reduced large parts of the Kuwaiti desert to semi-asphalt surfaces.[223] The oil spills during the Gulf War also drastically affected Kuwait's marine resources.[224]

Climate

[edit]Due to Kuwait's proximity to Iraq and Iran, the winter season in Kuwait is colder than other coastal countries in the region (especially UAE, Qatar, and Bahrain).[225] Kuwait is also less humid than other coastal countries in the region. The spring season in March is warm with occasional thunderstorms. The frequent winds from the northwest are cold in winter and hot in summer. Southeasterly damp winds spring up between July and October. Hot and dry south winds prevail in spring and early summer. The shamal, a northwesterly wind common during June and July, causes dramatic sandstorms.[226] Summers in Kuwait are some of the hottest on earth. The highest recorded temperature was 54.0 °C (129.2 °F) at Mitribah on 21 July 2016, which is the highest temperature recorded in Asia.[227][228]

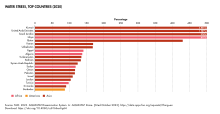

Kuwait emits a lot of carbon dioxide per person compared to most other countries.[229] In recent years, Kuwait has been regularly ranked among the world's highest countries in term of CO2 per capita emissions.[230][231][232]

Nature reserves

[edit]At present, there are five protected areas in Kuwait recognized by the IUCN. In response to Kuwait becoming the 169th signatory of the Ramsar Convention, Bubiyan Island's Mubarak al-Kabeer reserve was designated as the country's first Wetland of International Importance.[233] The 50,948 ha reserve consists of small lagoons and shallow salt marshes and is important as a stop-over for migrating birds on two migration routes.[233] The reserve is home to the world's largest breeding colony of crab-plover.[233]

Biodiversity

[edit]Currently, 444 species of birds have been recorded in Kuwait, 18 species of which breed in the country.[234] The arfaj is the national flower of Kuwait.[235] Due to its location at the head of the Persian Gulf near the mouth of the Tigris–Euphrates river, Kuwait is situated at the crossroads of many major bird migration routes and between two and three million birds pass each year.[236] Kuwait's marine and littoral ecosystems contain the bulk of the country's biodiversity heritage.[236] The marshes in northern Kuwait and Jahra have become increasingly important as a refuge for passage migrants.[236]

Twenty eight species of mammal are found in Kuwait; animals such as gerboa, desert rabbits and hedgehogs are common in the desert.[236] Large carnivores, such as the wolf, caracal and jackal, are no longer present.[236] Among the endangered mammalian species are the red fox and wild cat.[236] Forty reptile species have been recorded although none are endemic to Kuwait.[236]

Kuwait, Oman and Yemen are the only locations where the endangered smoothtooth blacktip shark is confirmed as occurring.[237]

Kuwaiti islands are important breeding areas for four species of tern and the socotra cormorant.[236] Kubbar Island has been recognised an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because it supports a breeding colony of white-cheeked terns.[238]

Water and sanitation

[edit]

Kuwait is part of the Tigris–Euphrates river system basin.[239][240][241][242][243][244] Several Tigris–Euphrates confluences form parts of the Kuwait–Iraq border.[245] Bubiyan Island is part of the Shatt al-Arab delta.[79] Kuwait is partially part of the Mesopotamian Marshes.[246][247][248] Kuwait does not currently have any permanent rivers within its territory. However, Kuwait does have several wadis, the most notable of which is Wadi al-Batin which forms the border between Kuwait and Iraq.[249] Kuwait also has several river-like marine channels around Bubiyan Island, most notably Khawr Abd Allah which is now an estuary, but once was the point where the Shatt al-Arab emptied into the Persian Gulf. Khawr Abd Allah is located in southern Iraq and northern Kuwait, the Iraq-Kuwait border divides the lower portion of the estuary, but adjacent to the port of Umm Qasr the estuary becomes wholly Iraqi. It forms the northeast coastline of Bubiyan Island and the north coastline of Warbah Island.[250]

Kuwait relies on water desalination as a primary source of fresh water for drinking and domestic purposes.[251][252] There are currently more than six desalination plants.[252] Kuwait was the first country in the world to use desalination to supply water for large-scale domestic use. The history of desalination in Kuwait dates back to 1951 when the first distillation plant was commissioned.[251]

In 1965, the Kuwaiti government commissioned the Swedish engineering company of VBB (Sweco) to develop and implement a plan for a modern water-supply system for Kuwait City. The company built five groups of water towers, thirty-one towers total, designed by its chief architect Sune Lindström, called "the mushroom towers". For a sixth site, the Emir of Kuwait, Sheikh Jaber Al-Ahmed, wanted a more spectacular design. This last group, known as Kuwait Towers, consists of three towers, two of which also serve as water towers.[253] Water from the desalination facility is pumped up to the tower. The thirty-three towers have a standard capacity of 102,000 cubic meters of water. "The Water Towers" (Kuwait Tower and the Kuwait Water Towers) were awarded the Aga Khan Award for Architecture (1980 Cycle).[254]

Kuwait's fresh water resources are limited to groundwater, desalinated seawater, and treated wastewater effluents.[251] There are three major municipal wastewater treatment plants.[251] Most water demand is currently satisfied through seawater desalination plants.[251][252] Sewage disposal is handled by a national sewage network that covers 98% of facilities in the country.[255]

Government and politics

[edit]Political system

[edit]Kuwait is an emirate,[5] which is sometimes described as "anocratic".[256] The Polity data series[259] and Economist Democracy Index[260] both categorize Kuwait as an autocracy (dictatorship). Freedom House previously rated the country as "partly free" in the Freedom in the World survey.[261] The Emir is the head of state, he belongs to the Al Sabah ruling family. The political system consists of an appointed government and judiciary. The Constitution of Kuwait was promulgated in 1962.[262]

Executive power is exercised by the government. The Emir appoints the prime minister, who in turn chooses the cabinet of ministers comprising the government. In recent decades, numerous policies of the Kuwaiti government have been characterized as "demographic engineering", especially in relation to Kuwait's stateless Bedoon crisis and the history of naturalization in Kuwait.

The Emir appoints the judges. The Constitutional Court is charged with ruling on the conformity of laws and decrees with the constitution. Kuwait has an active public sphere and civil society with political and social organizations.[263][264] Professional groups like the Chamber of Commerce, which represents the interests of Kuwaiti businesses and industries, maintain their autonomy from the government.[263][264]

Legislative power is exercised by the Emir. It was formerly exercised by the National Assembly. As per article 107 of the Kuwait constitution, the Emir has the power to dissolve the assembly and elections for a new assembly should be held within two months.[265] The Emir has suspended various articles of the constitution thrice: 29 August 1976 under Sheikh Sabah Al-Salim Al-Sabah, 3 July 1986 under Sheikh Jaber Al-Ahmed Al-Sabah, and 10 May 2024 under Sheikh Mishal Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah.[5]

Kuwait's political instability has significantly hampered the country's economic development and infrastructure.[266][163][204] Kuwait is regularly characterized as being a "rentier state" in which the ruling family uses oil revenues to buy the political acquiescence of the citizenry; more than 70% of government spending consists of public sector salaries and subsidies.[267] Kuwait has the highest public sector wage bill in the GCC region as public sector wages account for 12.4% of GDP.[207]

Kuwaiti women are considered among the most emancipated women in the Middle East. In 2014 and 2015, Kuwait was ranked first among Arab countries in the Global Gender Gap Report.[268][269][270] In 2013, 53% of Kuwaiti women participated in the labor force,[271] where they outnumber working Kuwaiti men,[272] giving Kuwait the highest female citizen participation in the workforce of any GCC country.[272][271][273] According to the Social Progress Index, Kuwait ranks first in social progress in the Arab world and Muslim world and second highest in the Middle East after Israel.[274] However, women's political participation in Kuwait has been limited.[275] Despite multiple prior attempts at granting Kuwaiti women suffrage, they were not permanently enfranchised until 2005.[276]

Kuwait ranks among the world's top countries by life expectancy,[277] women's workforce participation,[272][271] global food security,[278] and school order and safety.[279]

Al Sabah dynasty

[edit]The Al Sabah ruling family adhere to the Maliki school of Sunni Islam. Article 4 of the Kuwait constitution stipulates that Kuwait is a hereditary emirate whose emir must be an heir of Mubarak Al-Sabah.[265] Mubarak had four sons, but an informal pattern of alternation between the descendants of his sons Jabir and Salem emerged since his death in 1915.[280] This pattern of succession had one exception before 2006, when Sheikh Sabah Al-Salim, a son of Salem, was named crown prince to succeed his half-brother Sheikh Abdullah Al-Salem as a consequence of infighting and lack of consensus within the ruling family council.[280] The alternating system was resumed when Sheikh Sabah Al-Salim named Sheikh Jaber Al-Ahmed of the Jabir branch as his crown prince, eventually ruling as Emir for 29 years from 1977 to 2006.[280] On January 15, 2006, Emir Sheikh Jaber Al-Ahmed died and his crown prince, Sheikh Saad Al-Abdullah of the Salem branch was named Emir.[281] On January 23, 2006, the National Assembly unanimously voted in favor of Sheikh Saad Al-Abdullah abdicating in favor of Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmed, citing his illness with a form of dementia.[280] Instead of naming a successor from the Salem branch as per convention, Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmed named his half-brother Sheikh Nawaf Al-Ahmed as crown prince and his nephew Sheikh Nasser Al-Mohammed as prime minister.[280] On December 16, 2023, Sheikh Nawaf Al-Ahmed Passed away, And Sheikh Mishal Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber would be the successor.

Theoretically, Article 4 of the constitution stipulates that the incoming Emir's choice of crown prince needs to be approved by an absolute majority of the National Assembly.[265] If this approval is not achieved, the emir is constitutionally required to submit three alternative candidates for crown prince to the National Assembly.[265] This process previously caused contenders for power to engage in alliance-building in the political scene, which had taken historically private feuding within the ruling family to the "public arena and the political realm".[280]

Foreign relations

[edit]

The foreign affairs of Kuwait are handled at the level of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The first foreign affairs department bureau was established in 1961. Kuwait became the 111th member state of the United Nations in May 1963. It is a long-standing member of the Arab League and Gulf Cooperation Council.

Before the Gulf War, Kuwait was the only "pro-Soviet" state in the Persian Gulf region.[282] Kuwait acted as a conduit for the Soviets to the other Arab states of the Persian Gulf, and Kuwait was used to demonstrate the benefits of a pro-Soviet stance.[282] In July 1987, Kuwait refused to allow U.S. military bases in its territory.[283] As a result of the Gulf War, Kuwait's relations with the U.S. have improved (major non-NATO ally). Kuwait is also a major ally of ASEAN and enjoys a close economic relationship with China while working to establish a model of cooperation in numerous fields.[284][285]

Kuwait is a major non-NATO ally to the United States and currently has the largest US military presence in the entire Middle East region.[217] The United States government utilizes Kuwait-based military bases as staging hubs, training ranges, and logistical support for regional and international military operations.[217] The bases include Camp Arifjan, Camp Buehring, Ali Al Salem Air Field, and the naval base Camp Patriot.[217] Kuwait also has strong economic ties to China and ASEAN.[286][287]

Under the Belt and Road Initiative,[288][200] Kuwait and China have many important cooperation projects including South al-Mutlaa and Mubarak Al Kabeer Port.[195][196][197][289][200]

Military

[edit]

The Kuwaiti armed forces consist of the Land Forces, the Air Force (including the Air Defense Force), the Navy (including the Coast Guard), the National Guard, and the Emiri Guard, with a total of 17,500 active personnel and 23,700 reservists. The Emiri Guard is tasked with the protection of the Emir of Kuwait. The National Guard remains independent of the regular armed forces command structure, subordinated directly to the Emir and the prime minister, and is involved in both internal security and external defense. The Coast Guard is part of the Ministry of Interior while all of the other branches are part of the Ministry of Defense, and the National Guard provides assistance to both agencies. Since 1991 the United States has been the country's main security partner, carrying out training exercises with its military, and Kuwait is also a participant in the Gulf Cooperation Council's Peninsula Shield Force. The Kuwaiti military uses American, Russian, and western European equipment.[290][291]

In 2017 Kuwait reintroduced mandatory military service for its male citizens, consisting of four months of training and eight months of service. Conscription was previously in effect from 1961 to 2001, though it was not fully enforced at that time.[292][293] Kuwait was the only Gulf country to have had military conscription until 2014, when Qatar also implemented the policy.[294]

When Saudi Arabia began its intervention in the Yemeni civil war in early 2015, Kuwait joined the Saudi-led coalition. Kuwaiti forces provided an artillery battalion and 15 fighter jets, though their contribution to the operations in Yemen was limited.[295][296]

Legal system

[edit]Kuwait follows the civil law system modeled after the French legal system;[297][298][299] Kuwait's legal system is largely secular.[300][301][302][303] Sharia law governs only family law for Muslim residents,[301][304] while non-Muslims in Kuwait have a secular family law. For the application of family law, there are three separate court sections: Sunni (Maliki), Shia, and non-Muslim. According to the United Nations, Kuwait's legal system is a mix of English common law, French civil law, Egyptian civil law and Islamic law.[305]

The court system in Kuwait is secular.[306][307] Unlike other Arab states of the Persian Gulf, Kuwait does not have Sharia courts.[307] Sections of the civil court system administer family law.[307] Kuwait has the most secular commercial law in the Persian Gulf region.[308] The parliament criminalized alcohol consumption in 1983.[309] Kuwait's Code of Personal Status was promulgated in 1984.[310]

Administrative divisions

[edit]Kuwait is divided into six governorates: Al Asimah Governorate (or Capital Governorate); Hawalli Governorate; Farwaniya Governorate; Mubarak Al-Kabeer Governorate; Ahmadi Governorate; and Jahra Governorate. The governorates are further subdivided into areas.

Human rights and corruption

[edit]Human rights in Kuwait has been the subject of significant criticism, particularly regarding the Bedoon (stateless people).[159][157][311][155] The Kuwaiti government's handling of the stateless Bedoon crisis has come under criticism from many human rights organisations and even the United Nations.[312] According to Human Rights Watch in 1995, Kuwait has produced 300,000 stateless Bedoon.[313] Kuwait has the largest number of stateless people in the entire region.[157][314] Since 1986, the Kuwaiti government has refused to grant any form of documentation to the Bedoon including birth certificates, death certificates, identity cards, marriage certificates, and driving licences.[314][315] The Kuwaiti Bedoon crisis resembles the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar (Burma).[316] According to several human rights organizations, Kuwait is committing ethnic cleansing and genocide against the stateless Bedoon.[159][157][314] Additionally, LGBT people in Kuwait have few legal protections.[317]

On the other hand, human rights organizations have criticized Kuwait for the human rights abuses toward foreign nationals. Foreign nationals account for 70% of Kuwait's total population. The kafala system leaves foreign nationals prone to exploitation. Administrative deportation is very common in Kuwait for minor offenses, including minor traffic violations. Kuwait is one of the world's worst offenders in human trafficking. Hundreds of thousands of foreign nationals are subjected to numerous human rights abuses including involuntary servitude. They are subjected to physical and sexual abuse, non-payment of wages, poor work conditions, threats, confinement to the home, and withholding of passports to restrict their freedom of movement.[318][319] Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic vaccination rollout, Kuwait has been regularly accused of implementing a xenophobic vaccine policy toward foreign nationals.[320]

Kuwait's mistreatment of foreign workers has resulted in various high-profile diplomatic crises. In 2018, there was a diplomatic crisis between Kuwait and the Philippines due to the mistreatment of Filipino workers in Kuwait. Approximately 60% of Filipinos in Kuwait are employed as domestic workers. In July 2018, Kuwaiti fashionista Sondos Alqattan released a controversial video criticizing domestic workers from the Philippines.[321] In 2020, there was a diplomatic crisis between Kuwait and Egypt due to the mistreatment of Egyptian workers in Kuwait.[322]

Various Kuwaitis have been jailed after they criticized the Al Sabah ruling family.[323] In 2010, the U.S. State Department said it had concerns about the case of Kuwaiti blogger and journalist Mohammad Abdul-Kader al-Jassem who was on trial for allegedly criticizing the ruling al-Sabah family, and faced up to 18 years in prison if convicted.[324] He was detained after a complaint against him was issued by the office of Kuwait's Emir Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad al-Sabah.[324]

Extensive corruption among Kuwait's high-level government officials is a serious problem resulting in tensions between the government and the public.[325] In the Corruption Perceptions Index 2007, Kuwait was ranked 60th out of 179 countries for corruption (least corrupt countries are at the top of the list). On a scale of 0 to 10 with 0 the most corrupt and 10 the most transparent, Transparency International rated Kuwait 4.3.[326]

In 2009, 20% of the youth in juvenile centres had dyslexia, as compared to the 6% of the general population.[327] Data from a 1993 study found that there is a higher rate of psychiatric morbidity in Kuwaiti prisons than in the general population.[328]

Economy

[edit]

Kuwait has a wealthy petroleum-based economy.[329] Kuwait is one of the richest countries in the world.[330][331][332][333] The Kuwaiti dinar is the highest-valued unit of currency in the world.[334] According to the World Bank, Kuwait is the fifth richest country in the world by gross national income per capita, and one of five nations with a GNI per capita above $70,000.[330]

Kuwait is currently the GCC region's most oil-dependent country with the weakest infrastructure and lowest share of economic diversification.[163][204][219]

In 2019, Iraq was Kuwait's leading export market and food/agricultural products accounted for 94.2% of total export commodities.[335] Globally, Kuwait's main export products were mineral fuels including oil (89.1% of total exports), aircraft and spacecraft (4.3%), organic chemicals (3.2%), plastics (1.2%), iron and steel (0.2%), gems and precious metals (0.1%), machinery including computers (0.1%), aluminum (0.1%), copper (0.1%), and salt, sulphur, stone and cement (0.1%).[336] Kuwait was the world's biggest exporter of sulfonated, nitrated and nitrosated hydrocarbons in 2019.[337] Kuwait was ranked 63rd out of 157 countries in the 2019 Economic Complexity Index (ECI).[337]

In recent decades, Kuwait has enacted certain measures to regulate foreign labor due to security concerns. For instance, workers from Georgia are subject to heightened scrutiny when applying for entry visas, and an outright ban was imposed on the entry of domestic workers from Guinea-Bissau and Vietnam.[338] Workers from Bangladesh are also banned.[339] In April 2019, Kuwait added Ethiopia, Burkina Faso, Bhutan, Guinea and Guinea-Bissau to the list of banned countries bringing the total to 20. According to Migrant Rights, the bans are put in place mainly due to the fact that these countries lack embassies and labour corporations in Kuwait.[340]

Petroleum and natural gas

[edit]Despite its relatively small territory, Kuwait has proven crude oil reserves of 104 billion barrels, estimated to be 10% of the world's reserves. Kuwait also has substantial natural gas reserves. All natural resources in the country are state property.

As part of Kuwait Vision 2035, Kuwait aims to position itself as a global hub for the petrochemical industry.[341] Al Zour Refinery is the largest refinery in the Middle East.[342][343][344] It is Kuwait's largest environmentally friendly oil refinery,[345][341] where this refers to the effect on the local environment as opposed to the global environmental impact of burning the resulting oil. This Al Zour Refinery is a Kuwait-China cooperation project under the Belt and Road Initiative.[346] Al Zour LNG Terminal is the Middle East's largest import terminal for liquefied natural gas.[347][348][349] It is the world's largest capacity LNG storage and regasification green field project.[350][351] The project has attracted investments worth US$3 billion.[352][353] Other megaprojects include biofuel and clean fuels.[354][355]

Steel manufacturing

[edit]The biggest non-oil industry is steel manufacturing.[356][357][358][359][360] United Steel Industrial Company (KWT Steel) is Kuwait's main steel manufacturing company, which caters to all of Kuwait's domestic market demands (particularly construction).[357][356][358][359] Kuwait is self-sufficient in steel.[357][356][358][359]

Agriculture

[edit]In 2016, Kuwait's food self-sufficiency ratio was 49.5% in vegetables, 38.7% in meat, 12.4% in dairy, 24.9% in fruits, and 0.4% in cereals.[361] 8.5% of Kuwait's entire territory consists of agricultural land, although arable land constitutes 0.6% of Kuwait's entire territory.[362][363] Historically, Jahra was a predominantly agricultural area. There are currently various farms in Jahra.[364]

Finance

[edit]The Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA) is Kuwait's largest sovereign wealth fund specializing in foreign investment. The KIA is the world's oldest sovereign wealth fund. Since 1953, the Kuwaiti government has directed investments into Europe, United States and Asia Pacific. In 2021, the holdings were valued at around $700 billion in assets.[365][366] It is the 3rd largest sovereign wealth fund in the world.[365][366]

Kuwait has a leading position in the financial industry in the GCC.[367] The Emir has promoted the idea that Kuwait should focus its energies, in terms of economic development, on the financial industry.[367] The historical preeminence of Kuwait (among the GCC monarchies) in finance dates back to the founding of the National Bank of Kuwait in 1952.[367] The bank was the first local publicly traded corporation in the GCC region.[367] In the late 1970s and early 1980s, an alternative stock market, trading in shares of GCC companies, emerged in Kuwait, the Souk Al-Manakh.[367] At its peak, its market capitalization was the third highest in the world, behind only the United States and Japan, and ahead of the United Kingdom and France.[367]

Kuwait has a large wealth-management industry.[367] Kuwaiti investment companies administer more assets than those of any other GCC country, save the much larger Saudi Arabia.[367] The Kuwait Financial Centre, in a rough calculation, estimated that Kuwaiti firms accounted for over one-third of the total assets under management in the GCC.[367]

The relative strength of Kuwait in the financial industry extends to its stock market.[367] For many years, the total valuation of all companies listed on the Kuwait Stock Exchange far exceeded the value of those on any other GCC bourse, except Saudi Arabia.[367] In 2011, financial and banking companies made up more than half of the market capitalization of the Kuwaiti bourse; among all the GCC states, the market capitalization of Kuwaiti financial-sector firms was, in total, behind only that of Saudi Arabia.[367] In recent years, Kuwaiti investment companies have invested large percentages of their assets abroad, and their foreign assets have become substantially larger than their domestic assets.[367]

Kuwait is a major source of foreign economic assistance to other states through the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development, an autonomous state institution created in 1961 on the pattern of international development agencies. In 1974, the fund's lending mandate was expanded to include all developing countries in the world.

In the past five years, there has been a rise in entrepreneurship and small business start-ups in Kuwait.[368][369] The informal sector is also on the rise,[370] mainly due to the popularity of Instagram businesses.[371][372][373] In 2020, Kuwait ranked fourth in the MENA region in startup funding after the UAE, Egypt and Saudi Arabia.[374]

Health

[edit]Kuwait has a state-funded healthcare system, which provides treatment without charge to Kuwaiti nationals. There are outpatient clinics in every residential area in Kuwait. A public insurance scheme exists to provide reduced cost healthcare to expatriates. Private healthcare providers also run medical facilities in the country, available to members of their insurance schemes. As part of Kuwait Vision 2035, many new hospitals recently opened.[375][376][377] In the years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic, Kuwait invested in its health care system at a rate that was proportionally higher than most other GCC countries.[378] Under the Kuwait Vision 2035 healthcare strategy, the public hospital sector significantly increased its capacity.[376][375][377] Many new hospitals recently opened, Kuwait currently has 20 public hospitals.[379][376][375][377] The new Sheikh Jaber Al-Ahmad Hospital is the largest hospital in the Middle East.[380] Kuwait also has 16 private hospitals.[375]

Private sector hospitals in Kuwait offer multiple specialities. This trend is likely to grow further, especially in tapping opportunities to reduce treatments performed overseas and develop inbound medical tourism market by developing high end speciality hospitals.[381]

Science and technology

[edit]Kuwait was ranked 64th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[382][383] According to the United States Patent and Trademark Office, Kuwait registered 448 patents as of 31 December 2015.[384][385][386][387] In the early to mid 2010s, Kuwait produced the largest number of scientific publications and patents per capita in the region and registered the highest growth regionally.[388][389][390][391][392][386]

Kuwait was the first country in the region to implement 5G technology.[393] Kuwait is among the world's leading markets in 5G penetration.[393][394]

Space and satellite programmes

[edit]

Kuwait has an emerging space industry which is largely driven by private sector initiatives.[395] Seven years after the launch of the world's first communications satellite, Telstar 1, Kuwait in October 1969 inaugurated the first satellite ground station in the Middle East, "Um Alaish".[396] The Um Alaish satellite station complex housed several satellite ground stations including Um Alaish 1 (1969), Um Alaish 2 (1977), and Um Alaish 3 (1981). It provided satellite communication services in Kuwait until 1990 when it was destroyed by the Iraqi armed forces during the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait.[397] In 2019, Kuwait's Orbital Space established an amateur satellite ground station to provide free access to signals from satellites in orbit passing over Kuwait. The station was named Um Alaish 4 to continue the legacy of "Um Alaish" satellite station.[398] Um Alaish 4 is a member of FUNcube distributed ground station network[399] and the Satellite Networked Open Ground Station project (SatNOGS).[400]

Kuwait's Orbital Space in collaboration with the Space Challenges Program[401] and EnduroSat[402] introduced an international initiative called "Code in Space". The initiative allows students from around the world to send and execute their own code in space.[403] The code is transmitted from a satellite ground station to a cubesat (nanosatellite) orbiting earth 500 km (310 mi) above sea level. The code is then executed by the satellite's onboard computer and tested under real space environment conditions. The nanosatellite is called "QMR-KWT" (Arabic: قمر الكويت) which means "Moon of Kuwait", translated from Arabic.[404] QMR-KWT launched to space on 30 June 2021[405] on SpaceX Falcon 9 Block 5 rocket and was part of the payload of a satellite carrier called ION SCV Dauntless David by D-Orbit.[406] It was deployed into its final orbit (Sun-synchronous orbit) on 16 July 2021.[407] QMR-KWT is Kuwait's first satellite.[405][408][404]

The Kuwait Space Rocket (KSR) is a Kuwaiti project to build and launch the first suborbital liquid bi-propellant rocket in Arabia.[409] The project is divided into two phases with two separate vehicles: an initial testing phase with KSR-1 as a test vehicle capable of reaching an altitude of 8 km (5.0 mi) and a more expansive suborbital test phase with the KSR-2 planned to fly to an altitude of 100 km (62 mi).[410]

Kuwait's Orbital Space in collaboration with the Kuwait Scientific Center (TSCK) introduced for the first time in Kuwait the opportunity for students to send a science experiment to space. The objectives of this initiative was to allow students to learn about (a) how science space missions are done; (b) microgravity (weightlessness) environment; (c) how to do science like a real scientist. This opportunity was made possible through Orbital Space agreement with DreamUp PBC and Nanoracks LLC, which are collaborating with NASA under a Space Act Agreement.[411] The students' experiment was named "Kuwait's Experiment: E.coli Consuming Carbon Dioxide to Combat Climate Change".[412][413] The experiment was launched on SpaceX CRS-21 (SpX-21) spaceflight to the International Space Station (ISS) on 6 December 2020. Astronaut Shannon Walker (member of the ISS Expedition 64) conducted the experiment on behalf of the students. In July 2021, Kuwait University announced that it is launching a national satellite project as part of state-led efforts to pioneer the country's sustainable space sector.[414][415]

Education

[edit]

Kuwait had the highest literacy rate in the Arab world in 2010.[416] The general education system consists of four levels: kindergarten (lasting for 2 years), primary (lasting for 5 years), intermediate (lasting for 4 years) and secondary (lasting for 3 years).[417] Schooling at primary and intermediate level is compulsory for all students aged 6 – 14. All the levels of state education, including higher education, are free.[418] The public education system is undergoing a revamp due to a project in conjunction with the World Bank.[419][420] There are two public universities and 14 private universities.

Tourism

[edit]Tourism in Kuwait still remains very limited due to poor infrastructure and the alcohol ban. The annual "Hala Febrayer" festival somewhat attracts tourists from neighboring GCC countries,[421] and includes a variety of events including music concerts, parades, and carnivals.[421][422][423] The festival is a month-long commemoration of the liberation of Kuwait, and runs from 1 to 28 February. Liberation Day itself is celebrated on 26 February.[424]

In 2020, Kuwait's domestic travel and tourism spending was $6.1 billion.[425] The WTTC named Kuwait as one of the world's fastest-growing countries in travel and tourism GDP in 2019, with 11.6% year-on-year growth.[425] In 2016, the tourism industry generated nearly $500 million in revenue.[426] In 2015, tourism accounted for 1.5 percent of the GDP.[427][428] Sabah Al Ahmad Sea City is one of Kuwait's biggest attractions.

The Amiri Diwan recently inaugurated the new Kuwait National Cultural District (KNCD), which comprises Sheikh Abdullah Al Salem Cultural Centre, Sheikh Jaber Al Ahmad Cultural Centre, Al Shaheed Park, and Al Salam Palace.[429][430][431][432] With a capital cost of more than US$1 billion, the project is one of the largest cultural investments in the world.[430] The Kuwait National Cultural District is a member of the Global Cultural Districts Network.[433] Al Shaheed Park is the largest green roof project ever undertaken in the Arab world.[434]

Transport

[edit]Kuwait has a modern network of highways. Roadways extended 5,749 km (3,572 mi), of which 4,887 km (3,037 mi) is paved. There are more than two million passenger cars, and 500,000 commercial taxis, buses, and trucks in use. On major highways the maximum speed is 120 km/h (75 mph). Since there is no railway system in the country, most people travel by automobiles.

The country's public transportation network consists almost entirely of bus routes. The state owned Kuwait Public Transportation Company was established in 1962. It runs local bus routes across Kuwait as well as longer distance services to other Gulf states. The main private bus company is CityBus, which operates about 20 routes across the country. Another private bus company, Kuwait Gulf Link Public Transport Services, was started in 2006. It runs local bus routes across Kuwait and longer distance services to neighbouring Arab countries.

There are two airports in Kuwait. Kuwait International Airport serves as the principal hub for international air travel. State-owned Kuwait Airways is the largest airline in the country. A portion of the airport complex is designated as Al Mubarak Air Base, which contains the headquarters of the Kuwait Air Force, as well as the Kuwait Air Force Museum. In 2004, the first private airline of Kuwait, Jazeera Airways, was launched. In 2005, the second private airline, Wataniya Airways was founded.

Kuwait has one of the largest shipping industries in the region. The Kuwait Ports Public Authority manages and operates ports across Kuwait. The country's principal commercial seaports are Shuwaikh and Shuaiba, which handled combined cargo of 753,334 TEU in 2006.[435] Mina Al-Ahmadi is the largest port in the country. Mubarak Al Kabeer Port in Bubiyan Island is currently under construction. The port is expected to handle 2 million TEU when operations start.

Demographics

[edit]

Kuwait's 2023 population was 4.82 million people, of which 1.53 million were Kuwaitis and 3.29 million expatriates.[17]

Ethnic groups

[edit]Expatriates in Kuwait account for around 60% of Kuwait's total population. At the end of December 2018, 57.65% of Kuwait's total population were Arabs (including Arab expats).[436] Indians and Egyptians are the largest expat communities respectively.[437][17]

Religion

[edit]

Kuwait's official state religion is Maliki Sunni Islam. The Al Sabah ruling family adhere to the Maliki school of Sunni Islam. Most Kuwaiti citizens are Muslim; there is no official national census but it is estimated that 60%–70% are Sunni and 30%–40% are Shia.[438][439] Kuwait also has a large community of expatriate Christians, Hindus, Buddhists, and Sikhs.[440] As of 2020, there are an estimated 837,585 Christians, comprising 17.93% of the population — the second largest religious group.[436] Most Christians in Kuwait are from Kerala in India, namely Malankara Orthodox, Mar Thoma, and Roman Catholic. The first Malankara Orthodox parish was St. Thomas Indian Orthodox Pazhayapally Ahmadi, established in 1934.[441] Kuwait includes a native Christian community, estimated to be composed of between 259 and 400 Kuwaiti citizens.[442] Kuwait is the only GCC country besides Bahrain to have a local Christian population who hold citizenship. A small number of Kuwaiti citizens follow the Baháʼí Faith.[440][443]

Languages

[edit]Kuwait's official language is Modern Standard Arabic, but its everyday usage is limited to journalism and education. Kuwaiti Arabic is the variant of Arabic used in everyday life.[444] English is widely understood and often used as a business language. Besides English, French is taught as a third language for the students of the humanities at schools, but for two years only. Kuwaiti Arabic is a variant of Gulf Arabic, sharing similarities with the dialects of neighboring coastal areas in Eastern Arabia.[445] Due to immigration during its pre-oil history as well as trade, Kuwaiti Arabic borrowed a lot of words from Persian, Indian languages, Balochi language, Turkish, English and Italian.[446]

Due to historical immigration, Kuwaiti Persian is used among Ajam Kuwaitis.[447][448] The Iranian sub-dialects of Larestani, Khonji, Bastaki and Gerashi also influenced the vocabulary of Kuwaiti Arabic.[449] Most Shia Kuwaiti citizens are of Iranian ancestry.[450][451][452][453][454][455]

Culture

[edit]Kuwaiti popular culture, in the form of theatre, radio, music, and television soap opera, flourishes and is even exported to neighboring states.[24][456] Within the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, the culture of Kuwait is the closest to the culture of Bahrain; this is evident in the close association between the two states in theatrical productions and soap operas.[457]

Performing arts

[edit]

Kuwait has the oldest performing arts industry in the Arabian Peninsula.[458] Kuwait's television drama industry is the largest and most active Gulf Arab drama industry and annually produces a minimum of fifteen serials.[459][460][461] Kuwait is the main production centre of the Gulf television drama and comedy scene.[460] Most Gulf television drama and comedy productions are filmed in Kuwait.[460][462][463] Kuwaiti soap operas are the most-watched soap operas from the Gulf region.[459][464][465] Soap operas are most popular during the time of Ramadan, when families gather to break their fast.[466] Although usually performed in the Kuwaiti dialect, they have been shown with success as far away as Tunisia.[467] Kuwait is frequently dubbed the "Hollywood of the Gulf" due to the popularity of its television soap operas and theatre.[468][469]

Kuwait is the main centre of scenographic and performing arts education in the GCC region.[470][471] Many famous Middle Eastern actors and singers attribute their success to training in Kuwait.[472] The Higher Institute of Theatrical Arts (HIDA) provides higher education in theatrical arts.[471] The institute has several divisions and attracts theatrical students from all over the GCC region. Many actors have graduated from the institute, such as Souad Abdullah, Mohammed Khalifa, Mansour Al-Mansour, along with a number of prominent critics such as Ismail Fahd Ismail.

Kuwait is known for its home-grown tradition of theatre.[473][474][475] Kuwait is the only country in the Gulf Arab region with a theatrical tradition.[473] The theatrical movement in Kuwait constitutes a major part of the country's cultural life.[476] Theatrical activities in Kuwait date back to the 1920s when the first spoken dramas were released.[477] Theatre activities are still popular today.[476]

Theatre in Kuwait is subsidized by the government, previously by the Ministry of Social Affairs and now by the National Council for Culture, Arts, and Letters (NCCAL).[478] Every urban district has a public theatre.[479] The public theatre in Salmiya is named after actor Abdulhussain Abdulredha. The annual Kuwait Theater Festival is the largest theatrical arts festival in Kuwait.

Kuwait is the birthplace of various popular musical genres, such as sawt and fijiri.[480][481] Traditional Kuwaiti music is a reflection of the country's seafaring heritage,[482] which was influenced by many diverse cultures.[483][484][480] Kuwait is widely considered the centre of traditional music in the GCC region.[480] Kuwaiti music has considerably influenced the music culture in other GCC countries.[485][481] Kuwait pioneered contemporary Khaliji music.[486][487][488] Kuwaitis were the first commercial recording artists in the Gulf region.[486][487][488] The first known Kuwaiti recordings were made between 1912 and 1915.[489] Saleh and Daoud Al-Kuwaity pioneered the Kuwaiti sawt music genre and wrote over 650 songs, many of which are considered traditional and still played daily on radio stations both in Kuwait and the rest of the Arab world.[481][490][491][492][493][494]

Kuwait is home to various music festivals, including the International Music Festival hosted by the National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters (NCCAL).[495][496] The Sheikh Jaber Al-Ahmad Cultural Centre contains the largest opera house in the Middle East.[497] Kuwait has several academic institutions specializing in university-level music education.[498][499] The Higher Institute of Musical Arts was established by the government to provide bachelor's degrees in music.[500][498][499] In addition, the College of Basic Education offers bachelor's degrees in music education.[500][498][499] The Institute of Musical Studies offers music education qualifications equivalent to secondary school.[500][499][498]

Kuwait has a reputation for being the central music influence of the GCC countries.[501] Over the last decade of satellite television stations, many Kuwaiti musicians have become household names in other Arab countries. For example, Bashar Al Shatty became famous due to Star Academy. Contemporary Kuwaiti music is popular throughout the Arab world. Nawal El Kuwaiti, Nabeel Shoail and Abdallah Al Rowaished are the most popular contemporary performers.[502]

Visual arts

[edit]

Kuwait has the oldest modern arts movement in the Arabian Peninsula.[503][504][505] Beginning in 1936, Kuwait was the first Gulf Arab country to grant scholarships in the arts.[503] The Kuwaiti artist Mojeb al-Dousari was the earliest recognized visual artist in the Gulf Arab region.[506] He is regarded as the founder of portrait art in the region.[507] The Sultan Gallery was the first professional Arab art gallery in the Gulf.[508][509]

Kuwait is home to more than 30 art galleries.[510][511] In recent years, Kuwait's contemporary art scene has boomed.[512][513][514] Khalifa Al-Qattan was the first artist to hold a solo exhibition in Kuwait. He founded a new art theory in the early 1960s known as "circulism".[515][516] Other notable Kuwaiti artists include Sami Mohammad, Thuraya Al-Baqsami and Suzan Bushnaq.

The government organizes various arts festivals, including the Al Qurain Cultural Festival and Formative Arts Festival.[517][518][519] The Kuwait International Biennial was inaugurated in 1967,[520] more than 20 Arab and foreign countries have participated in the biennial.[520] Prominent participants include Layla Al-Attar. In 2004, the Al Kharafi Biennial for Contemporary Arab Art was inaugurated.

Cuisine

[edit]Kuwaiti cuisine is a fusion of Arabian, Iranian, and Mesopotamian cuisines. Kuwaiti cuisine is part of the Eastern Arabian cuisine. A prominent dish in Kuwaiti cuisine is machboos, a rice-based dish usually prepared with basmati rice seasoned with spices, and chicken or mutton.

Seafood is a significant part of the Kuwaiti diet, especially fish.[521] Mutabbaq samak is a national dish in Kuwait. Other local favourites are hamour (grouper), which is typically served grilled, fried, or with biryani rice because of its texture and taste; safi (rabbitfish); maid (mulletfish); and sobaity (sea bream).

Kuwait's traditional flatbread is called Iranian khubz. It is a large flatbread baked in a special oven and it is often topped with sesame seeds. Numerous local bakeries dot the country; the bakers are mainly Iranians (hence the name of the bread, "Iranian khubuz"). Bread is often served with mahyawa fish sauce.

Museums

[edit]

The new Kuwait National Cultural District (KNCD) consists of various cultural venues including Sheikh Abdullah Al Salem Cultural Centre, Sheikh Jaber Al Ahmad Cultural Centre, Al Shaheed Park, and Al Salam Palace.[430][429] With a capital cost of more than US$1 billion, it is one of the largest cultural districts in the world.[430] The Abdullah Salem Cultural Centre is the largest museum complex in the Middle East.[523][524] The Kuwait National Cultural District is a member of the Global Cultural Districts Network.[433]

Sadu House is among Kuwait's most important cultural institutions. Bait Al-Othman is the largest museum specializing in Kuwait's history. The Scientific Center is one of the largest science museums in the Middle East. The Museum of Modern Art showcases the history of modern art in Kuwait and the region.[525] The Kuwait Maritime Museum presents the country's maritime heritage in the pre-oil era. Several traditional Kuwaiti dhow ships are open to the public, such as Fateh Al-Khayr and Al-Hashemi-II which entered the Guinness Book of World Records as the largest wooden dhow ever built.[526][527] The Historical, Vintage, and Classical Cars Museum displays vintage cars from Kuwait's motoring heritage. The National Museum, established in 1983, has been described as "underused and overlooked".[528]

Several Kuwaiti museums are devoted to Islamic art, most notably the Tareq Rajab Museums and Dar al Athar al Islamiyyah cultural centres.[522][529][530][531] The Dar al Athar al Islamiyyah cultural centres include education wings, conservation labs, and research libraries.[531][532] There are several art libraries in Kuwait.[533][531][534][532] Khalifa Al-Qattan's Mirror House is the most popular art museum in Kuwait.[535] Many museums in Kuwait are private enterprises.[536][529] In contrast to the top-down approach in other Gulf states, museum development in Kuwait reflects a greater sense of civic identity and demonstrates the strength of civil society in Kuwait, which has produced many independent cultural enterprises.[537][529][536]

Society

[edit]Urban Kuwaiti society is more open than other Gulf Arab societies.[538] Kuwaiti citizens are ethnically diverse, consisting of both Arabs and Persians ('Ajam).[539][540][541] Kuwait stands out in the region as the most liberal in empowering women in the public sphere.[542][543][544] Kuwaiti women outnumber men in the workforce.[272] Kuwaiti political scientist Ghanim Alnajjar sees these qualities as a manifestation of Kuwaiti society as a whole, whereby in the Gulf Arab region it is "the least strict about traditions".[545]

Media