Экономическая история Китая до 1912 года.

Экономическая история Китая охватывает тысячи лет, и регион переживал чередующиеся циклы процветания и упадка. Китай на протяжении последних двух тысячелетий был одной из крупнейших и наиболее развитых экономик мира. [1] [2] [3] Историки экономики обычно делят историю Китая на три периода: доимперскую эпоху до прихода к власти Цинь ; ранняя имперская эпоха от Цинь до расцвета Сун ( 221 г. до н.э. – 960 г. н.э.); имперская эпоха, от Сун до падения Цин . и поздняя

Неолитическое сельское хозяйство развилось в Китае примерно к 8000 году до нашей эры. Стратифицированные культуры бронзового века , такие как Эрлитоу , возникли к третьему тысячелетию до нашей эры. При Шане (16–11 вв. до н. э.) и Западном Чжоу (11–8 вв. до н. э.) зависимая [ нужны разъяснения ] рабочая сила работала на крупных литейных заводах и мастерских по производству бронзы и шелка для элиты. Излишки сельского хозяйства, производимые поместной экономикой, поддерживали эти ранние ремесленные отрасли, а также городские центры и значительные армии. Эта система начала распадаться после краха Западной Чжоу в 771 г. до н.э., в результате чего Китай оказался фрагментированным в эпоху Весны и Осени (8–5 вв. до н.э.) и воюющих царств (5–3 вв. до н.э.).

As the feudal system collapsed, most legislative power transferred from the nobility to local kings. Increased trade during the Warring States period produced a stronger merchant class. The new kings established an elaborate bureaucracy, using it to wage wars, build large temples, and enact public-works projects. This meritocratic system rewarded talent over birthright. Greater use of iron tools from 500 BC revolutionized agriculture and led to a large population increase during this period. In 221 BCE, the king of the Qin declared himself the First Emperor, uniting China into a single empire, its various state walls into the Great Wall, and its various peoples and traditions into a single system of government.[4] Although their initial implementation led to its overthrow in 206 BCE, the Qin's institutions survived. During the Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), China became a strong, unified, and centralized empire of self-sufficient farmers and artisans, with limited local autonomy.

The Song period (960–1279 AD/CE) brought additional economic reforms. Paper money, the compass, and other technological advances facilitated communication on a large scale and the widespread circulation of books. The state's control of the economy diminished, allowing private merchants to prosper and a large increase in investment and profit. Despite disruptions during the Mongol conquest of 1279, the Black Plague in the 14th century, and the large-scale rebellions that followed it, China's population was buoyed by the Columbian Exchange and increased greatly under the Ming (1368–1644 AD/CE). The economy was remonetised by Japanese and South American silver brought through foreign trade, despite generally isolationist policies. The relative economic status of Europe and China during most of the Qing (1644–1912 AD/CE) remains a matter of debate,[n 1] but a Great Divergence was apparent in the 19th century,[7] pushed by the Industrial and Technological Revolutions.[8]

Pre-imperial era[edit]

By Neolithic times, the tribes living in what is now the Yellow River valley were practising agriculture. By the third millennium BCE, stratified Bronze Age societies had emerged, most notably the Erlitou culture. The Erlitou dominated northern China and are identified with the Xia dynasty, the first dynasty in traditional Chinese historiography. Erlitou was followed by the Shang and Zhou dynasties, which developed a manorial economy similar to that of medieval Western Europe.[n 2] By the end of the Spring and Autumn period, this system began to collapse and was replaced by a prosperous economy of self-sufficient farmers and artisans during the Warring States period. This transformation was completed when the state of Qin unified China in 221 BCE, initiating the imperial era of Chinese history.[11][12]

Neolithic and early Bronze Ages[edit]

Agriculture began almost 10,000 years ago in several regions of modern-day China.[13] The earliest domesticated crops were millet in the north and rice in the south.[14][15] Some Neolithic cultures produced textiles with hand-operated spindle-whorls as early as 5000 BCE.[16] The earliest discovered silk remains date to the early third millennium BCE.[17] By Northern China's Longshan culture (3rd millennium BCE), a large number of communities with stratified social structures had emerged.[18]

The Erlitou culture (c. 1900-1350 BCE), named after its type site in modern Henan, dominated northern China in the early second millennium BCE,[19][20] when urban societies and bronze casting first appeared in the area.[21] The cowries, tin, jade, and turquoise that were buried at Erlitou suggest that they traded with many neighbours.[22] A considerable labour force would be required to build the rammed-earth foundations of their buildings.[22] Although the highly stratified[23] Erlitou society has left no writing, some historians have identified it as the legendary Xia dynasty mentioned in traditional Chinese accounts as preceding the Shang.[24][19]

Only a strong centralised state led by rich elites could have produced the bronzes of the Erligang culture (c. 15th–14th centuries BCE).[23] Their state, which Bagley has called "the first great civilization of East Asia",[25] interacted with neighbouring states, which imported bronzes or the artisans who could cast them.[26] These exchanges allowed the technique of bronze metallurgy to spread.[23] Some historians have identified Erligang as a Shang site because it corresponds with the area where traditional sources say the Shang were active, but no written source from the time exists to confirm this identification.[27]

Shang dynasty (c. 1600 – c. 1045 BCE)[edit]

The first site unequivocally identified with the Shang dynasty by contemporaneous inscriptions is Anyang, a Shang capital that became a major settlement around 1300 BCE.[26] The staple crop of the Shang, a predominantly agricultural society, was millet,[28] but rice and wheat were also cultivated[citation needed] in fields owned by the royal aristocracy. Agricultural surpluses produced by royal fields supported the Shang royal family and ruling elite, advanced handicraft industries (bronze, silk, &c.), and large armies.[29] Large royal pastures provided animals for sacrifices and meat consumption.[30] Other agricultural produce supported the population of Shang, estimated to be about 5.5 to 8 million people.[31]

Since land was only cultivated for a few years before being left fallow, new lands constantly needed to be opened[32] by drainage of low-lying fields or by clearing scrubland or forests.[33] These tasks were performed by forced labour under state supervision,[32] often in the context of hunting expeditions.[34]

Like their Neolithic predecessors, the Shang used spindle-wheels to make textiles, but the Shang labour force was more formally organised.[35] By Shang times, controlled workers produced silk in workshops for the aristocracy.[36] Fields and workshops were manned by labour of varying degrees of servitude.[37] Some historians have called these dependent workers "slaves" and labelled the Shang a "slave society," but others reject such labels as too vague because we know too little about the nature of this labour force.[38]

Western Zhou dynasty (c. 1045 – 771 BCE)[edit]

By traditional dating, the Zhou dynasty defeated the Shang around 1045 BCE and took control of the Wei and Yellow River valleys that the Shang had dominated. Land continued to belong to the royal family, which redistributed it among its dependants in a system that many historians have (dubiously)[9] likened to the feudal organisation of medieval Europe. Epigraphic evidence shows that as early as the late 10th century BCE land was being traded, though it was not yet considered private property.[39][40] Shaughnessy hypothesises that this increase in the land exchanges resulted from the division of elite lineages into branches, increasing demand for land while its supply was diminishing.[41]

The 4th-century Mencius claims that the early Zhou developed the well-field system,[n 3] a pattern of land occupation in which eight peasant families cultivated fields around a central plot that they farmed for a lord.[43] Modern historians have generally doubted the existence of this idealised system,[44][45] but some maintain that it may have existed informally in the early Zhou, when dependent tenants working on manorial estates paid corvée to their landlords instead of rent, as they would later.[46] Many Chinese historians continue to describe it as historical.[47]

Handicraft industries developed during the Shang, such as textiles, bronze, and the production of weapons, were continued during the Zhou but became completely state-controlled. The Zhou government also controlled most commerce and exchange through appointing jia, officials whose title was later used to mean any merchant.[48]

Spring and Autumn period (771–475 BCE)[edit]

The collapse of the Zhou initiated the Spring and Autumn period, named after Confucius' Spring and Autumn Annals. It was a time of war between states, when the earlier semi-feudal system fell into decline and trade began to flourish. Competition between states led to rapid technological advancement. Iron tools became available, producing agricultural surpluses that ended whatever had once existed of the well-field system. Towards the end of this era, the introduction of iron technology caused the complete collapse of the feudal system and ushered in a new era of development.[49] Chinese developments in this era included the first isolation of elemental sulphur in the sixth century BCE.[50]

During the Spring and Autumn period, many cities grew in size and population. Linzi, the prosperous capital of Qi, had a population estimated at over 200,000 in 650 BCE, making it one of the largest cities in the world.[citation needed] Alongside other large cities, Linzi served as a centre of administration, trade, and economic activity. Most of the cities' people engaged in husbandry and were thus self-sufficient. The growth of these cities was an important development for the ancient Chinese economy.[51]

Large-scale trade began in the Spring and Autumn period as merchants transported goods between states. Large amounts of currency were issued to accommodate commerce. Although some states restricted trade, others encouraged it. Zheng in central China promised not to regulate merchants. Zheng merchants became powerful throughout China, from Yan in the north to Chu in the south.[52]

Large feudal estates were broken up, a process hastened when Lu changed its taxation system in 594 BCE. Under the new laws, grain producers were taxed by the amount of land under cultivation rather than an equal amount being levied upon every noble. Other states followed their example.[53] Free peasants became the majority of the population and provided a tax base for the centralising states.

Warring States period (475–221 BCE)[edit]

The Warring States period saw rapid technological advances and philosophical developments. As rulers competed to take control of one another's lands, they implemented various reforms, greatly changing China's economic system. Common-born landowners and merchants prospered and the remaining aristocracy lost influence. Some merchants, such as Lü Buwei, may have been as wealthy as minor states.[54]

State-sponsored foundries made iron tools ubiquitous;[citation needed] the iron plough, draft oxen, row cultivation, and intensive hoeing were introduced.[55] Cast iron was invented in China during the 4th century BCE.[citation needed] Governments, which controlled the largest ironworks, developed a monopoly on military equipment, strengthening the states at the expense of the feudal lords. Iron agricultural tools allowed a massive increase in surplus farm goods.[56]

After Shang Yang's reforms in the 3rd century BCE, land could be bought and sold, stimulating economic progress in agriculture and an increase in productivity.[57] The newly powerful states undertook large-scale irrigation projects, such as the Zhengguo Canal and the Dujiangyan Irrigation System. Large amounts of previously desolate land were cultivated and integrated into the Qin economy. The agricultural boom allowed larger armies.

In this era, the growing power of the state strengthened the monarchy, allowing it to undertake reforms to strengthen the monarch's authority. The most extensive of these reforms was carried out in Qin by Shang Yang, including the abolition of the feudal nobility, redistribution of nobles' land based on military merit, and allowing private ownership of land. He encouraged the cultivation of unsettled lands, gave noble ranks to soldiers who performed well in battle, and established an efficient and strict legal code. Absolute monarchy persisted in China until its gradual weakening under the Song and Ming dynasties.[58]

Early imperial era[edit]

The early imperial era was marked by a strong, unified and centralised monarchy, though local officials still maintained limited autonomy. During the early imperial era, self-sufficient peasant farmers and artisans dominated the economy and largely operated independently of the overall market. Commerce was relatively frequent, increasing after the Han Dynasty with the development of the silk road The Wu Hu uprising crippled the economy,[59] which did not recover until the Tang, under which it transformed into the mercantile economy of the Song and Ming Dynasties.

Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE)[edit]

In 221 BCE, the State of Qin conquered the remaining states in China, becoming what scholars consider the first unified Chinese state.[4] It quickly expanded, extending the Southern frontier from the Yangtze to modern Vietnam, and the northern frontier to modern Mongolia. While the early Xia, Shang, and Zhou Dynasties had nominal authority over all of China, the feudal system gave most regions a large degree of autonomy. Under the Qin, however, a centralised state was established,[4] and the entire empire had uniform standards and currency to facilitate trade. In addition, the Qin government undertook many public works projects, like the Great Wall of China. The Qin initiated what is considered the "first Chinese empire", which lasted until the Wu Hu uprising.

The Qin emperor unified standards of writing, weight measurement, and wheel length, while abolishing the old currencies, which varied between states. He also issued a uniform code of laws throughout the empire, which made trade easier. Defensive walls between states were demolished because of their disruptive influence upon trade. The Qin Empire did not return to the old feudal system, but set up a system of 36 commandries, each governing a number of counties.[4] Other Qin policies including heavy taxation of salt and iron manufactures, and forced migration of many Chinese towards new territories in the south and west.

The Qin government undertook many public works projects, the workers often being conscripted by the state in order to repay a tax debt. The most famous of these projects is the Great Wall of China, built to defend the state against Xiongnu incursions. Other Qin projects include the Lingqu Canal, which linked subsidiaries of the Yangtze and Pearl rivers and made possible the Qin's southern conquests,[60] as well as an extensive road system estimated at 4,250 mi (6,840 km).[61]

However, Qin's legalist laws and the heavy burden of its taxes and corvee were not easily accepted by the rest of the empire. Unlike the other states, Qin specifically enacted laws to exile merchants and expropriate their wealth, as well as imposing monopolies on salt, iron, forests and other natural resources. Scholars note that the list of prominent merchants during the Warring States compiled in Sima Qian's Shiji (Grand History) during the Han dynasty does not include a single merchant from Qin.[62] Rebellions occurred soon after the death of the first Qin emperor, and by 206 BCE, the Qin had collapsed.[60]

Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE)[edit]

The Han dynasty is remembered as the first of China's Golden Ages. The Han reached its peak size under Emperor Wu (141-87 BC), who subdued the Xiongnu and took control of the Hexi Corridor, opening up the Silk Road in 121 BC. The country's economy boomed, and the registered population was 58 million. Large-scale enterprises emerged, some which were later temporarily nationalised during the Western Han. Technological innovations, such as the wheelbarrow, paper and a seismograph, were invented during this period.[63]

Western Han dynasty[edit]

The reigns of the Emperors Wen (180-157 BC) and Jing (157-141 BC) were a period of peace and prosperity. During their reigns, state control of the economy was minimal, following the Taoist principle of Wu wei (無為), meaning "actionless action".[64] As part of their laissez-faire policy,[dubious – discuss] agricultural taxes were reduced from 1/15 of agricultural output to 1/30 and for a brief period, abolished entirely. In addition, the labour corvée required of peasants was reduced from 1 month every year to one month every three years.[65][66] The minting of coins was privatised.[67]

Both the private and public sectors flourished during this period. Under Emperor Jing,

... the ropes used to hang the bags of coins were breaking apart due to the weight, and bags of grain which had been stored for several years were rotting because they had been neglected and not eaten.[68]

Severe criminal punishments, such as cutting off the nose of an offender, were abolished.[66]

The Han taxation system was based on two taxes; a land property tax and a poll tax. The average individual's tax burden consisted of one-thirtieth of the output on land, and a poll tax of 20 coins paid for every person between 7 and 14, with another poll tax for those above 14. Late in the Han dynasty, the taxation rate for agriculture was reduced to one-hundredth, the lost revenue being made up with increased poll taxes.[69] Merchants were charged at double the individual's rate. Another important component of the taxation system was Corvee labour. Every able-bodied man, defined as a man in good health above 20, was eligible for two years of military service or one month of military service and one year of corvee labour (later those above 56 were exempt from any military or corvee labour service).[70]

Emperor Wu, on the other hand, sparked debate when he intervened into the economy to pay for his wars. His interventions were hotly debated between the Reformists, who were composed mainly of Confucian scholars favoring laissez-faire policies, and the Modernists, a group of government officials who supported the state monopolies on salt and iron and high taxation policies that Emperor Wu had pioneered.[71] These debates were recorded in the book Discourses on Salt and Iron, an important document showing ancient Chinese economic thought. Although the Modernist policies were followed through most of the Western Han after Emperor Wu, the Reformists repealed these policies in Eastern Han, save for the government monopoly on minting coins.[72]

Han industry[edit]

In the early Western Han, the wealthiest men in the empire were merchants who produced and distributed salt and iron[73] and gained wealth that rivalled the annual tax revenues collected by the imperial court.[73] These merchants invested in land, becoming great landowners and employing large numbers of peasants.[73] A salt or iron industrialist could employ over one thousand peasants to extract either liquid brine, sea salt, rock salt, or iron ore.[73] Advanced drilling techniques that allowed drilling up to 4800 feet/1440 metres were developed, allowing Chinese to extract salt and even natural gas for use in fuel and lighting.[citation needed]

Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87 BCE) viewed such large-scale private industries as a threat to the state, as they drew the peasants' loyalties away from farming and towards the industrialists.[73] Nationalising the salt and iron trades eliminated this threat and produced large profits for the state.[73] This policy was in line with Emperor Wu's expansionary goals of challenging the nomadic Xiongnu Confederation while colonising the Hexi Corridor and what is now Xinjiang of Central Asia, Northern Vietnam, Yunnan, and North Korea.[74] Historian Donald Wagner estimates that the production of the Han iron monopoly was roughly around 5,000 tons (assuming 100 tons per iron office).[75]

Although many industrialists were bankrupted by this action, the government drafted former merchants like Sang Hongyang (d. 80 BCE) to administer the national monopolies.[73] Although a political faction in the court succeeded in having the central government monopolies abolished from 44 to 41 BCE, the monopolies resumed until the end of Wang Mang's (r. 9–23 CE) regime.[76] After his overthrow, the central government relinquished control of these industries to private businessmen.[73][76]

Liquor, another profitable commodity, was also nationalised by the government for a brief period between 98 and 81 BCE. After its return to private ownership, the government imposed heavy taxes on alcohol merchants.[77][78]

In addition to the state's short-lived monopolies, the government operated a separate sector of handicraft industries intended to supply the needs of the court and army,[79] a practice that was continued throughout Chinese history, though the importance of this sector decreased after the Tang dynasty.

Light industries such as textiles and pottery also developed substantially during this period. In particular, hand-made pottery was made in large quantities; its price dropped substantially, allowing it to replace the bronze vessels that had been used during the Zhou. Porcelain also emerged during this period.[80]

Han agriculture[edit]

Widespread use of iron tools that had begun under the Warring States period allowed Chinese agriculture to increase its efficiency. These include the "two-teeth" plough and an early sickle. The use of cattle-pulled ploughs improved with the introduction of three-cattle plough which required two operators and the two-cattle plough requiring one.[81] Another important invention was the invention of the horse collar harness, in contrast with the earlier throat harness. This innovation, along with the wheelbarrow, integrated the Chinese economy by drastically decreasing transportation costs and allowing long-distance trade.

The seed drill was also developed during this period, allowing farmers to drill seeds in precise rows, instead of casting them out randomly. During the reign of Emperor Wu of Han, The 'Dai Tian Fa', an early form of crop rotation was introduced. Farmers divided their land into two portions, one of which would be planted, the other being left fallow.[81]

Han trade and currency[edit]

Sources of revenue used to fund Emperor Wu's military campaigns and colonisation efforts included seizures of lands from nobles, the sale of offices and titles, increased commercial taxes, and the issuing of government minting of coins.[82] The central government had previously attempted – and failed – to monopolise coin minting, taking power from the private commandery-level and kingdom-level mints.[83] In 119 BCE the central government introduced the wushu (五銖) coin weighing 3.2 g (0.11 oz), and by 113 BCE this became the only legally accepted coin in the empire, the government having outlawed private mints.[72] Wang Mang's regime introduced a variety of new, lightweight currencies, including archaic knife money, which devalued coinage. The wushu coin was reinstated in 40 CE by the founder of Eastern Han, Emperor Guangwu, and remained the standard coin of China until the Tang dynasty.[72][84][85]

Trade with foreign nations on a large scale began during the reign of Emperor Wu, when he sent the explorer Zhang Qian to contact nations west of China in search of allies to fight the Xiongnu. After the defeat of the Xiongnu, however, Chinese armies established themselves in Central Asia and the Western Regions, starting the famed Silk Road, which became a major avenue of international trade.[86]

Xin dynasty[edit]

In 8 CE, the Han chancellor Wang Mang usurped the throne of the Han emperors and established his own dynasty, the Xin. Wang Mang wanted to restore the Han to what he believed to be the "idyllic" condition of the early Zhou. He outlawed the trading of land and slaves, and instituted numerous state monopolies. These ultra-modernist policies proved highly unpopular with the population, who overthrew and executed him in 25 CE and restored the Han dynasty.[87]

Eastern Han dynasty[edit]

Under the Eastern Han dynasty, which followed Wang Mang's overthrow, earlier laissez-faire policies were reinstated, and the government abolis–hed conscription and withdrew from managing the economy. A new period of prosperity and intellectual thought, called the Rule of Ming and Zhang, began. This period saw the birth of the great scientist, Zhang Heng, and the invention of paper.[88] However, by the end of the 2nd century, Han society began to disintegrate. In 184, a peasant preacher started a rebellion called the Yellow Turban Rebellion, which ended the Han dynasty in all but name.[59]

Wei and Western Jin (220–304)[edit]

Also known as the Three kingdoms period, the Wei and Jin eras, which followed the collapse of the Han Dynasty, saw large-scale warfare envelop China for the first time in more than 150 years. The death toll and subsequent economic damage were significant. Powerful aristocratic landowners offered shelter to displaced peasants, using their increased authority to reclaim privileges abolished during the Qin and Han. These refugees were no longer taxable by the state. During the Jin, the taxable population was 20 million; during the Han it had been 57 million. Most of North China was unified by Cao Cao, who founded the Wei Dynasty (220–265), and the Jin reunified the remainder of China in 280. The centralised state weakened after losing the tax revenue of those under the protection of large landowners.[59] Nevertheless, the economy recovered slightly under the policies of Cao Cao, who nationalised abandoned land and ordered peasants to work on them,[89] as well as re-instituting the hated iron monopoly, which would continue under Jin and the Southern Dynasties. Later, the War of the Eight Princes, which coupled with the Jin policy of moving the barbarian Wu Hu into China to alleviate labour shortages caused the eventual collapse of unified rule in China for a time.[90]

Sixteen Kingdoms and Eastern Jin (304–439)[edit]

The War of the Eight Princes (291–306) during the Western Jin dynasty led to widespread discontent among the people against the ruling government. In 304, the Xiongnu, led by Liu Yuan, revolted and declared their independence from Jin. Several other groups within China subsequently revolted, including the Jie, Qiang, Di, and Xianbei, and they became collectively known as the "Five Barbarians". The collapse of the Western Jin quickly followed these revolts.[90] The rebellions caused large-scale depopulation and the market economy that developed during the Qin, Han, Wei and Jin to decline rapidly, allowing the feudal manorial economy returned to prominence. Large manorial estates were self-sufficient and isolated from the wider market. These estates were self-contained economies that practised agriculture, herding, forestry, fishing, and the production of handicraft goods. Exchange was no longer carried out through money, but barter. Following the economic revival after the unification of the Sui, the manorial economy again declined.[91]

A brief economic recovery occurred in the North under Fú Jiān, the Di ruler of Former Qin, who reunified North China. Fu Jian repaired irrigation projects constructed under Han and Jin, and set up hotels and stations for traders every 20 kilometres. Under Fu Jian's rule, trade and agriculture were significantly revived, and many nations again sent tribute to Fu Jian's court.[92] This recovery ended when Fu Jian was defeated at the Battle of Fei River by Jin forces, causing his empire to collapse into a series of small states.[93]

Meanwhile, the legitimate Jin dynasty had fled to the south, then an undeveloped periphery of the Chinese Empire. Jin rulers attempted to develop this region as a centre of rule and as a base for the reconquest of their homeland.[94] Jin rulers granted large tracts of land in the south to Chinese immigrants and landowners fleeing barbarian rule, who preserved the system of government that was in place before the uprising. The migration of northern people stimulated the southern economy, allowing it to rival the northern economy. Improved agricultural techniques introduced to the south increased production and a market economy survived as Jin rulers enforced laws. The improvement of the southern economy can be seen later when it financed Liu Yu's expeditions to recover Sichuan and most of the Chinese heartland from the barbarian states of the north.[94]

Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–581)[edit]

The Northern and Southern Dynasties largely recovered from the constant war of the 4th century and early-5th century. The early part of the era saw the greater part of China reunified by the native Liu Song dynasty, whose northern border extended to the Yellow River. The Eastern Jin general and Liu Song founder, Liu Yu, reclaimed much of China's heartland through his northern expeditions. Under his son, China witnessed a brief period of prosperity during the Yuanjia era. However, an invasion by the Xianbei-led Northern Wei once more confined the Chinese dynasties to the territories south of the Huai River.[95] Northern Wei conquered the last of the Sixteen Kingdoms by 439, thereby unifying all of northern China. Henceforth, China was divided into the Northern and Southern dynasties, which developed separately; the north prospering under a new equal-field system, while the southern economy continued to develop in the fashion of Wei and Jin. In 589, the Sui dynasty restored native rule to northern China and reunified the country.

Southern Dynasties[edit]

The Yuanjia era, inaugurated by Liu Yu and his son, Emperor Wen, was a period of prosperous rule and economic growth, despite ongoing war. Emperor Wen was known for his frugal administration and his concern with the welfare of the people. Although he lacked the martial power of his father, he was an excellent economic manager. He reduced taxes and levies on peasants and encouraged them to settle in areas that had been reconquered by his father. He reduced the power of wealthy landowners and increased the taxable population. He also enacted a system of reviewing the performance of civil servants. As a result of his policies, China experienced an era of prosperity and economic recovery.[96]

During the Yuanjia era, the Chinese developed the co-fusion process of steel manufacturing, which involved melting cast iron and wrought iron together to create steel, increasing the quality and production volume of Chinese iron.[citation needed]

Towards the end of Emperor Wen's reign, the Xianbei state of Northern Wei began to strengthen, and decisively defeated an attempt by Emperor Wen to destroy it. Following this victory, Wei launched repeated incursions into the northern provinces, finally capturing them in 468.[95]

The economic prosperity of southern China continued after Liu Song's fall and was greatest during the succeeding Liang dynasty, which briefly reconquered the North with 7,000 troops under the command of general Chen Qingzhi. The Liang emperor, Emperor Wu, gave a grant of 400 million coins to Buddhist monasteries, indicating the amount of wealth present in the south. It was recorded that during his reign, the city of Nanjing had a population of up to 1.4 million, exceeding that of Han-era Luoyang.[97] The Southern Dynasties' economy eventually declined after the disastrous sacking of Nanjing by the barbarian general Hou Jing.[98]

Northern Dynasties[edit]

After the Tuoba conquest of Northern China, it experienced an economic recovery under the Northern Wei that was even greater than the prosperous era of Yuanjia. This came mostly under the rule of Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei, who introduced several reforms designed to further sinify Northern Wei, which included banning the Xianbei language and customs and promoting Chinese law, language and surnames. A new agricultural system was introduced; in the equal-field system, the state rented land to the peasant laborers for life, reclaiming it after the tenant's death. Peasants also received smaller, private plots that could be inherited. Cattle and farm tools were also rented or sold to peasants.

The state also introduced the Fubing system, where soldiers would farm as well as undergoing military training. This military system was used until the Tang dynasty, and empowered Han Chinese, who comprised the majority of the army. In addition, Xiaowen strengthened the state's control over the provinces by appointing local officials rather than relying on local landowners, and paying officials with regular salaries. The capital was moved to Luoyang, in the centre of the North China Plain, which revitalised the city and the surrounding provinces.[99] Xiaowen's reforms were very successful and lead to prosperity for north China. Under Emperor Xiaowen, the taxable population was an estimated 30 million, which surpassed that under the Jin.[99]

After Xiaowen's rule, Northern Wei's economy began to deteriorate, and famines and droughts undermined Wei rule. From 523 onwards, conservative Xianbei noblemen dominated the north and reversed much of Xiaowen's reforms, setting up their own regimes and warring against each other. It was not until 577 that North China was again reunited by Northern Zhou, which was soon usurped by Han Chinese Yang Jian, who restored native rule over North China.[100]

Sui dynasty (581–618)[edit]

The Sui dynasty replaced the Northern Zhou, whose throne was usurped by Yang Jian in 581. Yang Jian quickly enacted a series of policies to restore China's economy. His reunification of China marked the creation of what some historians call the 'Second Chinese Empire', spanning the Sui, Tang and Northern Song dynasties. Despite its brevity, the Sui reunified China, and its laws and administration formed the basis of the later Tang, Song and Ming dynasties. Sui dynasty China had a population of about 46 million at its peak.[101]

One of Yang Jian's first priorities was the reunification of China. Chen, which ruled the south, was weak compared to Sui and its ruler was incompetent and pleasure-loving. South China also had a smaller population than the north. After eight years of preparation, Sui armies marched on and defeated Chen in 589, reunifying China and prompting a recovery in the Chinese economy.[102] The registered population increased by fifty percent from 30 to 46 million in twenty years.[103]To encourage economic growth, the Sui government issued a new currency to replace those issued by its predecessors, Northern Zhou and Chen.[104] They also encouraged foreign merchants to travel to China and import goods, and built numerous hotels to house them.[105]

The Sui continued to use the equal-field system introduced by Northern Wei. Every able-bodied male received 40 mou of freehold land and a lifetime lease of 80 mou of land, which was returned to the state when the recipient died. Even women could receive a lifetime lease of 40 mou of land which was returned to the state upon her death. The Sui government charged three "Shi" of grain each year. Peasants were required to perform 20 days of labour for the state per year, but those over 50 could instead pay a small fee.[106]

In 604, Emperor Wen was most likely assassinated by his son Yang Guang, who became Emperor Yang of Sui. Emperor Yang was an ambitious ruler who immediately undertook many projects, including the building of the Grand Canal and the reconstruction of the Great Wall. Thousands of forced labourers died while building the projects, and eventually women were required to labour in the absence of men. He also launched a series of unsuccessful campaigns against Goguryeo. These campaigns negatively impacted the image of the dynasty, while his policies drove the people to revolt. Agrarian uprisings and raids by the Gokturks became common. In 618, the Emperor was assassinated and the Sui dynasty ended.[107]

Tang dynasty (618–907)[edit]

The Tang dynasty was another golden age, beginning in the ruins of the Sui. By 630, the Tang had conquered the powerful Gokturk Khagnate, preventing threats to China's borders for more than a century. A series of strong and efficient rulers, beginning with the founder and including a woman, expanded the Tang Empire to the point that it rivalled the later Yuan, Ming and Qing. The Tang was a period of rapid economic growth and prosperity, seeing the beginnings of woodblock printing. Tang rulers issued large amounts of currency to facilitate trade and distributed land under the equal-field system. The population recovered to and then surpassed Han levels, reaching an estimated 90 million.[citation needed] Although the state weakened after the disastrous An Shi Rebellion, and withdrew from managing the economy in the 9th century, this withdrawal encouraged economic growth and helped China's economy to develop into the mercantile economy of the Song and Ming Dynasties.[101]

Before the An Shi Rebellion[edit]

Emperor Taizong of Tang, the second ruler of the dynasty, is regarded as one of the greatest rulers in Chinese history. Under his rule, China progressed rapidly from the ruins of a civil war to a prosperous and powerful nation. His reign is called the Reign of Zhenguan. Taizong reduced conscript labour requirements and lowered taxes; in addition, he was careful to avoid undertaking projects that might deplete the treasury and exhaust the strength of the population. Under his reign, a legal code called the Code of Tang was introduced, moderating the laws of the Sui.[108]

During Taizong's reign and until the An Shi Rebellion, the Chinese Empire went through a relatively peaceful period of economic development. Taizong and his son's conquest of the Gokturk, Xueyantue, Goguryeo and other enemy empires ensured relative peace for China. Control over the western provinces of China reopened the Silk Road, allowing trade between China and the regions to its west to flourish. Tang armies repeatedly intervened in the western regions to preserve this state of peace and prosperity.[109]

The equal-field system did not allow large land transactions and thus during the early Tang estates remained small. The Tang government managed the economy through the bureaucratic regulation of markets, limiting the times where they could exchange goods, setting standards for product quality, and regulating prices of produce.[110]

During the Tang, the taxation system was based on the equal-field system, which equalised wealth among the farmers. The tax burden of peasants was based on population per household, rather than the value of property. The standard tax amounted to 2 tan (about 100 litres) of grain, as well as 2 Zhang (around 3 1/3 meters) and 5 Chi (about 1/3 of a meter) of cloth. The peasant was eligible for 20 days' conscripted labour; if he defaulted he was obliged to pay 3 Chi of cloth per day missed.[111] Assuming each farmer had 30 mou of land which produced 1 tan of grain a year, the tax rate amounted to 25% of the farmer's income.[112] Commercial taxes were lighter, at 3.3% of income.

The Tang government operated a huge handicraft industry, separate from the private handicraft industry that served the majority of the population. The public handicraft industry provided the Tang government, army and nobility with various products. The government's handicraft industries retarded the growth of the private sector which did not develop rapidly until after the Anshi Rebellion, when the Tang government's interference in the economy (and the size of its government handicraft industries) drastically decreased.[113] Despite this, a large number of households worked in private industry; scholars have estimated that 10% of Tang China's population lived in cities.[112]

The height of Tang prosperity came during the Kaiyuan Era of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang, who expanded Tang influence westward to the Aral Sea.[114] Emperor Xuan was a capable administrator, and his Kaiyuan Era is often compared with the earlier Zhenkuan era in efficiency of administration. After this era, the Tang dynasty went into decline.

After the An Shi Rebellion[edit]

Emperor Xuanzong's reign ended with the Arab victory at Talas and the An Shi Rebellion, the first war inside China in over 120 years, led by a Sogdian general named An Lushan who used a large number of foreign troops.[115] The Tang economy was devastated as the northern regions, the mainstay of economic activity, were destroyed. The once populous cities of Luoyang and Chang'an were reduced to ruins. After the war, the Tang central government never recovered its former power, and local generals gradually became independent of Tang rule. These generals wielded enormous power, passed on their titles by heredity, collected taxes, and raised their own armies.[115] Although most of these jiedushi were quelled by the early 9th century, the jiedushi of Hebei, many of them former officers of An Lushan, retained their independence.

The weakened Tang government was forced to abolish many of its regulations and interventions after the rebellion; this unintentionally stimulated trade and commerce in Tang China, which reached an apogee in the early 9th century.[116] The economic centre of China shifted southwards because the north had been devastated.[117]

The equal-field system, which had formed the basis of agriculture for the past two and a half centuries, began to collapse after the An Shi Rebellion. The equal-field system had relied on the state having large amounts of land, but state landholdings had decreased as they were privatised or granted to peasants. Landowners perpetually enlarging their estates exacerbated the collapse. The Fubing system, in which soldiers served the army and farmed on equal-field land was abolished and replaced with the Mubing system, which relied on a volunteer and standing army. In 780, the Tang government discontinued the equal field system and reorganised the tax system, collecting taxes based on property value twice a year, in spring and autumn.[118]

Woodblock printing began to develop during the 8th and 9th centuries. This grew out of the huge paper industry that had emerged since the Han. Woodblock printing allowed the rapid production of many books, and increased the speed at which knowledge spread. The first book to be printed in this manner, with a production date, was the Jin Gang Jin, a Buddhist text printed in 868,[117] but the hand-copying of manuscripts still remained much more important for centuries to come.[119] During the later years of the Tang dynasty, overseas trade also began with East Africa, India, and the Middle East.[citation needed]

Although the economy recovered during the 9th century, the central government was weakened. The most pressing issue was the government's salt monopoly, which raised revenue after the equal-field system collapsed and the government could no longer collect land tax effectively. After the An Shi Rebellion, the Tang government monopolised salt to raise revenue; it soon accounted for over half the central government's revenues. During the reign of emperors Shi and Yi, private salt traders were executed, and the price of salt was so high that many people could not afford it. Eventually, private salt traders allied and rebelled against the Tang army.[120] This rebellion, known as the Huang Chao Rebellion,[121] lasted ten years and destroyed the countryside from Guangzhou to Chang'an.[122] Following the rebellion, two generals, the Shatuo Li Keqiang and the former rebel Zhu Wen, dominated the Tang court.[122] Civil war broke out again in the early 10th century, ending with Zhu Wen's victory.[122] Following his victory, Zhu Wen forced the Tang emperor to abdicate, and the Tang empire disintegrated into a group of states known as the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms.[122]

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907–960)[edit]

The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms was a period of warfare and disruption. After 907, the Tang government effectively disintegrated into several small states in the south, while the north saw a series of short-lived dynasties and barbarian invasions. A key event of the era was the conquest of North China by the Shatuo Turks. During their rule, the Shatuo gave the vital Sixteen Prefectures area, containing the natural geographical defences of North China and the eastern section of the Great Wall, to the Khitan, another barbarian people. This effectively left Northern China defenceless against incursions from the north, a major factor in the later fall of the Song dynasty. The Shatuo and Khitan invasions severely disrupted economic activity in the north and displaced economic activity southwards, and native Chinese rule was not restored until the Later Zhou dynasty, the Song's precursor.[123]

The southern provinces remained relatively unaffected by the collapse. The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period was largely one of continued prosperity in these regions.[124]

Late imperial era[edit]

In 960, Zhao Kuangyin led a coup and established the Song dynasty, which would go on to reunite China by 976. Song China.[125] The Late Imperial Era, encouraged by technological advancement, saw the beginnings of large-scale enterprise, waged labour and the issuing of paper money. The economy underwent large increases in manufacturing output. Overseas trade flourished during the late Ming dynasty, when it relaxed the ban on maritime trade in 1567 (although the trade was restricted to only one port at Yuegang).[126] Investment, capital, and commerce were liberalized as technology advanced and the central state weakened. Government manufacturing industries were privatised. The emergence of rural and urban markets, where production was geared towards consumption, was a key development in this era. China's growing wealth in this era lead to the loss of martial vigour; the era involved two periods of native rule, each followed by periods of alien rule. By the mid-Qing dynasty era in the 18th century China was possibly the most commercialized country in the world. The total amount of the empire's trade increased along with the expansion of overseas trade by the 19th century, and even more so during the Opium Wars when Western mercantile influence spread to inland cities.[127]

The food production grew thanks to more lands being cultivated and to the increasing yields. The production of iron and salt and other commodities also grew in this period. According to the GDP estimates by Broadberry et al., the per capita GDP was stable during the Song and Ming dynasties before going down during the Qing dynasty when the population increase outstripped the GDP growth. Thus Song China was the richest country in the world by GDP per capita at the turn of the millennium, by the 14th century parts of Europe caught up with it and the significant gap between China and Europe appeared by the middle of the 18th century.[128]

Song dynasty (960–1279)[edit]

In 960, the Later Zhou general Zhao Kuangyi overthrew his imperial master and established the Song dynasty. Nineteen years later, he had reunified most of China. During the northern Song dynasty, China was the wealthiest country in the world as measured by GDP per capita.[129]: 21 According to economist David Daokui Li, however, per capita income began declining to in 980 (and continued to decline until 1840).[130]: 32 Li writes that a rapidly increasing population outpaced the growth of arable land and capital.[130]: 32

Unlike its predecessors, the monarchy and aristocracy weakened under the Song, allowing a class of non-aristocratic gentry to gain power. The central government withdrew from managing the economy (except during Wang Anshi's chancellorship and the Southern Song), provoking drastic economic changes. Technological advances encouraged growth; three of the so-called Four Great Inventions: gunpowder, woodblock printing, and the compass, were invented or perfected during this era. The population rose to more than 100 million during the Song period. However, the Song eventually became the first unified Chinese dynasty to be completely conquered by invaders.[131]

Song industry[edit]

During the 11th century, China developed sophisticated technologies to extract and use coal for energy, leading to soaring iron production.[132] Iron production rose fivefold from 800 to 1078, to about 125,000 English tons (114,000 metric tons), not counting unregistered iron production.[133][citation needed] Initially, the government restricted the iron industry, but the restrictions on private smelting was lifted after the prominent official Bao Qingtian's (999-1062) petition to the government[134] Production of other metals also soared; officially registered Song production of silver, bronze, tin, and lead increased to 3, 23, 54, and 49 times that of Tang levels.[135] Officially registered Salt production also rose at least 57%.[136]

The government regulated several other industries. Sulphur, an ingredient in gunpowder – a crucial new weapon introduced during the Tang – became a growth industry, and in 1076 was placed under government control.[137] In Sichuan province, revenue from the Song government's monopoly on tea was used to purchase horses for the Song's cavalry forces.[138] Chancellor Wang Anshi instated monopolies in several industries, sparking controversy.[139]

In order to supply the boom in the iron and other industries, the output of mines increased massively. Near Bianjing, the Song capital, according to one estimate over one million households were using coal for heating, an indication of the magnitude of coal use.[140] Light industries also began to prosper during the Song, including porcelain – which replaced pottery – shipbuilding and textiles.[140] Compared with the Tang, textile production increased 55%.[141] The historian Xie Qia estimates that over 100,000 households were working in textile production by Song times, an indicator of the magnitude of the Song textile industry.[112] The urbanisation rate of the Song increased to 12%, compared with 10% during the Tang.[112]

Song agriculture[edit]

Agriculture advanced greatly under the Song. The Song government started a series of irrigation projects that increased cultivatable land, and encouraged peasants to cultivate more land. The total area of cultivated land was greatly increased to 720 million mou, a figure unsurpassed by later dynasties.[142] A variety of crops were cultivated, unlike the monocultures of previous dynasties. Specialised crops like oranges and sugar cane were regularly planted alongside rice.[143] Unlike the earlier self-sufficient peasantry of the Han and Tang eras, rural families produced a surplus which could be sold. The income allowed families to afford not only food, but charcoal, tea, oil, and wine. Many Song peasants supplemented their incomes with handicraft work.[144][145]

New tools, like the Water Wheel, greatly enhanced productivity. Although most peasants in China were still primarily rice farmers, some farmers specialised in certain crops. For example, Luoyang was known for its flower cultivation; flower prices reached such exorbitant prices that one bulb reached the price of 10,000 coins.[146] An important new crop introduced during the Song was Champa rice, a new breed which had superior yields to earlier forms of rice and greatly increased rice production.[147] The practice of multiple cropping, which increased yields by allowed farmers to harvest rice twice a year, was a key innovation of the Song era.[147] Per-mou agricultural output doubled for South China, while increasing only slightly in the north. Scholars offer "conservative estimates" which suggest that agricultural yields rose at least 20% during the Song.[148] Other scholars note that although taxable land rose only 5% during the Song, the actual amount of grain revenues taken in increased by 46%.[148]

Agricultural organisation also changed. Unlike the Han and Tang, in which agriculture was dominated by self-sufficient farmers, or the pre-Warring States period and era of division (period between Han and Tang), which was dominated by aristocratic landowners, during the Song agriculture was dominated by non-aristocratic landowners. The majority of farmers no longer owned their land; they became tenants of these landowners, who developed the rural economy through investment. This system of agriculture was to continue until the establishment of the People's Republic of China under Mao.[149]

Song commerce[edit]

During the Song dynasty, the merchant class became more sophisticated, well-respected, and organised. The accumulated wealth of the merchant class often rivalled that of the scholar-officials who administered the affairs of government. For their organisational skills, Ebrey, Walthall, and Palais state that Song dynasty merchants:

... set up partnerships and joint stock companies, with a separation of owners (shareholders) and managers. In large cities, merchants were organised into guilds according to the type of product sold; they periodically set prices and arranged sales from wholesalers to shop owners. When the government requisitioned goods or assessed taxes, it dealt with the guild heads.[150]

Unfortunately, like their counterparts in Europe, these guilds restricted economic growth through collaboration with government to restrict competition.[151]

Large privately owned enterprises dominated the market system of urban Song China. There was a large black market, which grew after the Jur'chen conquest of North China in 1127. Around 1160, black marketeers smuggled some 70 to 80 thousand cattle.[152]

There were many successful small kilns and pottery shops owned by local families, along with oil presses, wine-making shops, and paper-making businesses.[153] The "... inn keeper, the petty diviner, the drug seller, the cloth trader," also experienced increased economic success.[154]

Song abolition of trade restrictions greatly aided the economy. Commerce increased in frequency and could be conducted anywhere, in contrast to earlier periods where trade was restricted to the 'Fang' and 'Shi' areas. In all the major cities of the Song dynasty, many shops opened. Often, shops selling the same product were concentrated into one urban area. For example, all the rice shops would occupy one street, and all the fish shops another.[155] Unlike the later Ming dynasty, most businesses during the Song dynasty were producers and retailers, selling the products they produced, thus creating a mixture of handicraft and commerce. Although the Song dynasty saw some large enterprises, the majority of enterprises were small.[156]

Overseas commerce also prospered with the invention of the compass and the encouragement of Song rulers.[157] Developments in shipping and navigation technologies allowed trade and investment on a large scale. The Song-era Chinese could conduct large amounts of overseas trade, bringing some merchants great fortune.[158] Song-era commercial enterprises became very complex. The accumulated wealth of merchants often rivalled that of the scholar-officials who administered the affairs of government.

Song currency[edit]

The prosperous Song economy resulted in an increase in the minting of currency. By 1085, the output of copper currency reached 6 billion coins a year, compared to 5.86 billion in 1080. 327 million coins were minted annually in the Tang dynasty's prosperous Tianbao period of 742–755, and only 220 million coins minted annually from 118 BCE to 5 CE during the Han dynasty.[159]

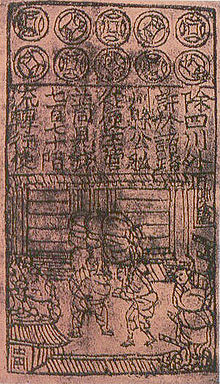

Paper receipts of deposit first appeared in the 10th century, but the first officially sponsored bills were introduced in Sichuan Province,[160] where the currency was metallic and extremely heavy. Although businesses began to issue private bills of exchange, by the mid-11th century the central government introduced its paper money, produced using woodblock printing and backed by bronze coins. The Song government had also been amassing large amounts of paper tribute. Each year before 1101, the prefecture of Xinan (modern Xi-xian, Anhui) alone sent 1,500,000 sheets of paper in seven different varieties to the capital at Kaifeng.[161] In the Southern Song, standard currency bearing a marked face value, was used. However, a lack of standards caused face values to wildly fluctuate. A nationwide standard paper currency was not produced until 1274, two years before the Southern Song's fall.[162]

Song fiscal administration[edit]

The Song government instituted a taxation system on agriculture in which a property value tax was collected twice every year, amounting to roughly 10% of income.[112] However, the actual level was higher due to numerous surcharges. Commercial taxes were around 2%.[112] In an important change from Tang practices, however, the Song did not attempt to regulate prices and markets, with the exception of the time of Wang Anshi, though it also instituted an indirect monopoly in salt, in which merchants had to deliver grain to the state before being allowed to sell salt.[112][163]

In 1069, Wang Anshi, whose ideas were similar to the modern welfare state, became chancellor. Believing that the state must provide for the people, and pressed by the need for revenues to wage an irredentist war against the Xi Xia and Liao, he initiated a series of reforms. These reforms included nationalising industries such as tea, salt and liquor, and adopting a policy of directly transporting goods in abundance in one region to another, which Wang believed would eliminate the need for merchants. Other policies included a rural credit program for peasants, the replacement of corvee labour with a tax, lending peasants military horses for use in peacetime, compulsory military training for civilians, and a "market exchange bureau" to set prices. These policies were extremely controversial, especially to Orthodox Confucians who favoured laissez faire, and were largely repealed after Wang Anshi's death, except during the reign of Emperor Huizong.[164]

A second, more serious attempt to intervene in the economy occurred in the late 13th century, when the Song dynasty suffered from fiscal problems while trying to defend themselves against Mongol invasions. The Song chancellor Jia Sidao attempted to solve the problem through land nationalisation, a policy that was heavily opposed and later withdrawn.[165]

Song collapse[edit]

The prosperity of the Song was interrupted by the invasion of Jur'chen Jin in 1127. After a successful alliance with the Jin in which the Song destroyed its old enemy the Khitan, the Jin attacked the Song and sacked its capital in Kaifeng.[166] The invasion preceded 15 years of constant warfare which ended when the Song court surrendered territory north of the Huai River in exchange for peace, despite victories by the Song general Yue Fei, who had almost defeated the Jur'chens.[167] The southern Chinese provinces became the center of commerce. Millions of Chinese fled Jur'chen rule to the South, which the Song dynasty still held.[168]

Due to the new military pressure of the Jur'chens, the Southern Song massively increased the tax burden to several times of that of the Northern Song. The Southern Song maintained an uneasy truce with the Jin until the rise of the Mongols, with whom Song allied to destroy the Jin in 1234.[169] Taking advantage of this, the Song army briefly recaptured their lost territory south of the Yellow River as the Mongols withdrew. However, a flood of the Yellow River, coupled with Mongol attacks, eventually forced the Song to withdraw.[170]

Seeking to conquer China, the Mongol Empire launched a series of attacks on the Song.[171] By the 1270s, the Song economy had collapsed from the burden of taxes and inflation which the Song government used to finance its war against the Mongols.[172] In 1275, the Mongols defeated the Song army near Xiangyang and captured Hangzhou,[173] the Song capital, the following year. Song resistance ended at the Battle of Yamen, in which the last Song emperor drowned with the remnants of his navy.[174] The destruction caused by the barbarian invasions in the later half of the Song represented a major setback in China's development.[175]

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)[edit]

The Mongol Yuan dynasty was the first foreign dynasty to rule the whole of China. As the largest khanate in the Mongol Empire, the emperors of Yuan had nominal authority over the other three Mongol Empires. This period of Pax Mongolica stimulated trade. However, millions of Chinese died because of the Mongol conquest.[176] Under Mongol rule, approximately 65 million people were registered in 1290; in 1215, the dynasties of Jur'chen Jin and Song had registered populations of between 110 and 120 million.[177] In addition, the Mongol government later imposed high taxes and extensively nationalised major sectors of the economy, greatly damaging what was left of China's economic development.

In their conquest of China, particularly the north under Jur'chen Jin, the Mongols resorted to scorched earth policies, destroying entire provinces. Mongol forces carried out massacres in cities they captured, and one Khan proposed that all Chinese under Mongol rule be killed and their lands turned to pasture,[176] but was persuaded against this by his minister Yelu Chucai, who proposed that taxing the region's inhabitants was more advantageous than killing them.[178]

Kublai Khan, after becoming ruler of China, extended the Grand Canal, connecting the Yellow and Yangtze rivers, to the capital, Beijing. This eased transportation between the south, now the hub of economic activity, and Beijing. This enhanced Beijing's status, it having formerly been a peripheral city, and was important to later regimes' decisions to have it remain the capital.[179]

The Yuan Government revolutionised the economy by introducing paper currency as the predominant circulating medium.[180] Initially, the currency was pegged to silver but persistent fiscal constraints gradually compelled Yuan rulers to abandon silver convertibility.[180] The silver standard was abandoned in 1310.[180] According to a 2024 study, "inflation remained moderate, except during the dynasty's early years, and again during its final two decades."[180] This monetary system was ultimately abandoned due to insufficient state capacity to manage the system.[180]

The founder of the Yuan dynasty, Kublai Khan, issued paper money known as Chao in his reign. Chinese paper money was guaranteed by the State and not by the private merchant or private banker. The concept of banknotes was not brought up in the world ever since until during the 13th century in Europe, with proper banknotes appearing in the 17th century. The original notes during the Yuan dynasty were restricted in area and duration as in the Song dynasty, but in the later course of the dynasty, facing massive shortages of specie to fund their ruling in China, began printing paper money without restrictions on duration. Chinese paper money was therefore guaranteed by the State and not by the private merchant or private banker.

Kublai and his fellow rulers encouraged trade between China and other Khanates of the Mongol Empire. During this era, trade between China and the Middle East increased, and many Arabs, Persians, and other foreigners entered China, some permanently immigrating. It was during this period that Marco Polo visited China.[181] Although Kublai Khan wished to identify with his Chinese subjects, Mongol rule was strict and foreign to the Chinese. Civil service examinations, the traditional way that Chinese elites entered the government, was ended, and most government positions were held by non-Chinese, especially the financial administration of the state.[182]

Over-spending by Kublai and his successor caused them to resort to high taxes and extensive state monopolization of major sectors of the economy to fund their extravagant spending and military campaigns, which became a major burden on the Chinese economy.[183] State monopolies were instituted in salt, iron, sugar, porcelain, tea, vinegar, alcohol and other industries. The most controversial of Kublai's policies, however, was opening the tombs of the Song emperors to gain treasure for the treasury,[184] and issuing large amounts of notes which caused hyperinflation. These policies greatly conflicted with Confucian ideals of frugal government and light taxation.[185] As a result of Kublai's policies, and the discrimination of the Mongols towards the Chinese,[186] South China was beset by violent insurrections against Mongol rule. Many Chinese refused to serve or associate themselves with the Yuan administration, who they viewed as barbarian despots.[187]

During the 1340s, frequent famines, droughts, and plagues encouraged unrest among the Chinese. In 1351, a peasant rebel leader, who claimed he was the descendant of the Song Emperor Huizong, sought to restore the Song by driving out the Mongols. By 1360, much of South China was free of Mongol rule and had been divided into regional states, such as Zhu Yuanzhang's Ming, Zhang Shichen's Wu and Chen Yolian's Han. On the other hand, North China became divided between regional warlords who were only nominally loyal to the Yuan.[188] In 1368, after reunifying South China, the Ming dynasty advanced northward and captured Beijing, ending the Yuan.[189]

Ming dynasty (1368–1644)[edit]

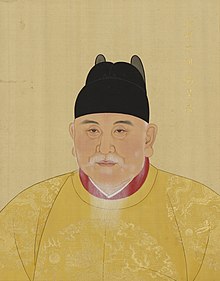

Following the unrest in the late Yuan dynasty, the peasant Zhu Yuanzhang led a rebellion against Mongol rule.[190] He founded the Ming dynasty, whose reign is considered one of China's Golden Ages.[191] Private industries replaced those managed by the state. Vibrant foreign trade allowed contact to become established between East and West. Cash crops were more frequently grown, specialised industries were founded, and the economic growth caused by privatisation of state industries resulted in one of the most prosperous periods in Chinese history, exceeding that of the earlier Song dynasty.

The Ming was also a period of technological progress, though less so than the earlier Song.[192] It is estimated that Ming China had a population of almost 200 million in 1600.[citation needed]

Early Ming[edit]

Zhu Yuanzhang, also called the Hongwu Emperor, was born of a peasant family and was sympathetic towards peasants. Zhu enacted a series of policies designed to favour agriculture at the expense of other industries. The state gave aid to farmers, providing land and agricultural equipment and revising the taxation system.[192] The state also repaired many long-neglected canals and dikes that had aided agriculture. In addition, the Ming dynasty reinstated the examination system.[193]

Hongwu's successor and grandson, the Jianwen Emperor, was overthrown by his uncle, Zhu Di, called the Yongle Emperor, in a bloody civil war that lasted three years. Zhu Di was more liberally-minded than his father and he repealed many of the controls on gentry and merchants.[194] Thus, his reign is sometimes regarded as a 'second founding' of the Ming dynasty. The expeditions of his eunuch Zheng He created new trade routes. Under Yongle's rule, Ming armies enjoyed continued victories against the Mongols, who were forced to acknowledge him as their ruler.[195] He also moved the capital to Beijing.[196] By Yongle's reign, China had recovered the territories of Eastern Xinjiang, Manchuria, Tibet, and those lost during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Era.

Ming fiscal administration[edit]

The Ming government has been described as "... one of the greatest achievements of Chinese civilization".[197] Although it began as a despotic regime, the Ming government evolved into a system of power-sharing between the emperor and the civil service.

The Ming government collected far less revenue than the Song dynasty. Regional tax quotas set up by the Emperor Hongwu would be collected, though in practice Ming revenues were markedly lower than the quotas declared. The gentry class won concessions from the government and resisted tax increases. Throughout the Ming dynasty, the state was constantly underfunded.[198] Unlike earlier dynasties such as the Tang and Song, and later dynasties such as the Qing, the Ming did not regulate the economy, but had a laissez-faire policy similar to that of the Han dynasty.[199] The Cambridge history of China volume on the Ming Dynasty stated that:

Ming government allowed those Chinese people who could attain more than mere subsistence to employ their resources mostly for the uses freely chosen by them, for it was a government that, by comparison with others throughout the world then and later, taxed the people at very low levels and left most of the wealth generated by its productive people in theregions where that wealth was produced.[200]

Key Ming taxes included the land tax (21 million taels),[201] the service levy (direct requisitioning of labour services and goods from civilians, valued at about 10 million taels), and the revenue from the Ming salt monopoly (2 million taels).[202] Other miscellaneous sources of revenue included the inland customs duty (343,729 taels), sale of rank (500,000 taels), licensing fees for monks (200,000 taels), and fines (300,000 taels) and others, which all added up to about 4 million taels. The overall Ming tax rate was very low, at around 3 to 4%.[203] However, by the end of the dynasty, this situation had changed dramatically. Zhang Juzheng instituted the single whip law, in which the arbitrary service levy was merged into the land tax. The Ming government's salt monopoly was undermined by private sellers, and had collapsed completely by the 15th century; government officials estimated that three-quarters of salt produced was being sold privately.[204]

Ming commerce and currency[edit]

Zhu Yuanzhang had promoted foreign trade as a source of revenue while he was a rebel, but sharply curtailed this with a series of sea bans (haijin) once in power.[206] These proclaimed the death penalty for private foreign traders and exile for their family and relatives in 1371;[207] the foreign ports of Guangzhou, Quanzhou, and Ningbo were closed in 1384.[208]After the ´voyages to the western oceans´ between 1405 and 1433, which had shown China to be technically ahead shipbuilding, a restrictive closed-door policy towards long-distance trade was adopted.[209]Legal trade was restricted to tribute delegations sent to or by official representatives of foreign governments,[210] although this took on an epic scale under the Yongle Emperor with Zheng He's treasure voyages to Southeast Asia, India, and eastern Africa.[199] The policies exacerbated "Japanese" piracy along the coasts, with many Chinese merchants joining their ranks in an illegal trade network the Ming were unable to curtail. The sea bans were finally ended in 1567,[199] with trade only prohibited to states at war with the throne. Needham estimated the trade between the end of the ban and the end of the dynasty (1567–1644) at about 300 million taels.

In addition to small base-metal coins, the Ming issued fiat paper currency as the standard currency from the beginning of the reign until 1450, by which point – like its predecessors – it was suffering from hyperinflation and rampant counterfeiting. (In 1425, Ming notes were trading at about 0.014% of its original value under the Hongwu Emperor.)[211] Monetary needs were initially met by bullion trading in silver sycee, but a shortage of silver in the mid-15th century caused a severe monetary contraction and forced a great deal of trade to be conducted by barter.[212] After the single whip law substituted silver instead of rice as the means of paying taxes, China, which had not been much interested in European or Japanese goods, found that the silver of Iwami Ginzan and Potosí was too profitable and important to restrict.[213][214] Inflows of Japanese (imported via Macau by the Portuguese) and Spanish silver (brought by the Manila galleons) monetized China's economy, and Spanish dollars became a common medium of exchange.[215]China was part of the global silver trade.

The size of the late Ming economy is a matter of conjecture, with Twitchett claiming it to be the largest and wealthiest nation on earth[198] and Maddison estimating its per capita GDP as average within Asia and lower than Europe's.[216]

Ming industry[edit]

After 1400, Ming China's economic recovery led to high economic growth and the revival of heavy industries such as coal and iron. Industrial output reached new heights surpassing that of the Song. Unlike the Song, however, the new industrial centres were located in the south, rather than in North China, and did not have ready access to coal, a factor that may have contributed to the Great Divergence.[217] Iron output increased to triple Song levels, at well over 300,000 tons.[218] Further innovations helped improve industrial capability to above Song levels.[132] Many Ming-era innovations were recorded in the Tiangong Kaiwu, an encyclopaedia compiled in 1637.

Ming agriculture[edit]

Under the Ming, some rural areas were reserved exclusively for the production of cash crops. Agricultural tools and carts, some water-powered, allowed the production of a sizable agricultural surplus, which formed the basis of the rural economy. Alongside other crops, rice was grown on a large scale.[219] The population growth and the decrease in fertile land made it necessary that farmers produce cash crops to earn a living.[220] Landed, managed estates grew substantially; while in 1379 only 14,241 households had over 700 mou, by the end of the Ming some large landowners had over 70,000 mou.[221] Increasing commercialisation caused huge advances in productivity during the Ming dynasty, allowing a greater population.[222]

Many markets, with three main types, were established in the countryside. In the simplest markets, goods were exchanged or bartered.[220] In 'urban-rural' markets, rural goods were sold to urban dwellers; landlords residing in cities used income from rural landholdings to facilitate exchange in the cities. Merchants bought rural goods in large quantities and sold them in these markets.[220] The 'national market' developed during the Song dynasty became more important during the Ming. In addition to the merchants and barter, this type of market involved products produced directly for the market. Many Ming peasants no longer relied upon subsistence farming; they produced products for the market, which they sold for a profit.[220] The Cambridge history states about the Ming that:

"The commercialisation of Ming society within the context of expanding communications may be regarded as a distinguishing aspect of the history of this dynasty. In the matter of commodity production and circulation, the Ming marked a turning point in Chinese history, both in the scale at which goods were being produced for the market, and in the nature of the economicrelations that governed commercial exchange.[223]"

Ming collapse[edit]

At the end of the Ming dynasty, the Little Ice Age severely curtailed Chinese agriculture in the northern provinces. From 1626, famine, drought, and other disasters befell northern China, bringing peasant revolts. The Ming government's inability to collect taxes resulted in troops frequently not being paid. Many troops joined the rebels, worsening the situation. In 1644, the rebels under Li Zicheng took Beijing, ending Ming rule in the north.[224] Regimes loyal to the Ming throne (collectively called the Southern Ming) continued to reign in southern China until 1662.[224] Recent historians have debated the validity of the theory that silver shortages caused the downfall of the Ming dynasty.[225][226]

Qing dynasty (1644–1912)[edit]

China's last imperial dynasty, the Qing dynasty, was founded by the Jurchens, later called the Manchus, who had been subjects of the Ming and had earlier founded the Jurchen Jin dynasty.[227] In 1616, under Nurhaci, the Manchus established the Later Jin dynasty and attacked the Ming. In 1644 Beijing was sacked by Li Zicheng's rebel forces and the Chongzhen Emperor committed suicide when the city fell. The Manchu Qing dynasty then allied with former Ming general Wu Sangui and seized control of Beijing and quickly overthrew Li's short-lived Shun dynasty. It was only after a few decades until 1683 that the Qing took control of the whole of China.[228] By the end of the century the Chinese economy had recovered from the devastation caused by the previous wars, and the resulting breakdown of order. Although the Qing economy significantly developed and markets continued to expand during the 18th century, it failed to keep pace with the economies of European countries in the Industrial Revolution,[229] which gradually became colonial empires since the 16th century and also gained lead over other powers and civilizations around the world including the Islamic gunpowder empires.

Early Qing[edit]

Although the Qing dynasty established by the Manchus had quickly seized Beijing in 1644, hostile regimes still existed in other parts of China, and it would take the Qing a few decades to take control of all of China. During this period, especially in the 1640s and 1650s, people died of starvation and disease, which resulted in a decline in population. In 1661, facing attacks by overseas Ming loyalist forces, the Qing government adopted a policy of clearing the shore line, which ordered all people residing along the coast of Zhejiang to the border with Vietnam to move 25 kilometres (16 mi) inland and guards were positioned on the coast to prevent anyone from living there. Thus, until 1685 few people engaged in coastal and foreign trade. During these decades, although grain harvests improved, few participated in the market because the economy had contracted and local prices hit bottom. Tang Zhen, a retired Chinese scholar and failed merchant described a dismal picture of the market economy of the preceding decades in his writing in the early 1690s.[n 4]