Алабама

Алабама | |

|---|---|

| Прозвища : Штат Йеллохаммер , Сердце Дикси , Хлопковый штат | |

| Девиз(ы) : | |

| Гимн: « Алабама ». | |

Map of the United States with Alabama highlighted | |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Alabama Territory |

| Admitted to the Union | December 14, 1819 (22nd) |

| Capital | Montgomery |

| Largest city | Huntsville |

| Largest county or equivalent | Jefferson |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Greater Birmingham |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Kay Ivey (R) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Will Ainsworth (R) |

| Legislature | Alabama Legislature |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| Judiciary | Supreme Court of Alabama |

| U.S. senators | Tommy Tuberville (R) Katie Britt (R) |

| U.S. House delegation | 6 Republicans 1 Democrat (list) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 52,419 sq mi (135,765 km2) |

| • Land | 50,744 sq mi (131,426 km2) |

| • Water | 1,675 sq mi (4,338 km2) 3.2% |

| • Rank | 30th |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 330 mi (531 km) |

| • Width | 190 mi (305 km) |

| Elevation | 500 ft (150 m) |

| Highest elevation | 2,413 ft (735.5 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 5,024,279[3] |

| • Rank | 24th |

| • Density | 99.2/sq mi (38.3/km2) |

| • Rank | 27th |

| • Median household income | $52,000[4] |

| • Income rank | 46th[5] |

| Demonym(s) | Alabamian,[6] Alabaman[7] |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English |

| • Spoken language | As of 2010[update][8]

|

| Time zones | |

| Entire state (legally) | UTC– 06:00 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC– 05:00 (CDT) |

| Phenix City area (unofficially) | UTC– 05:00 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC– 04:00 (EDT) |

| USPS abbreviation | AL |

| ISO 3166 code | US-AL |

| Traditional abbreviation | Ala. |

| Latitude | 30°11' N to 35° N |

| Longitude | 84°53' W to 88°28' W |

| Website | alabama |

| List of state symbols | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

| Slogan | Share The Wonder, Alabama the beautiful, Where America finds its voice, Sweet Home Alabama |

| Living insignia | |

| Amphibian | Red Hills salamander |

| Bird | Yellowhammer, wild turkey |

| Butterfly | Eastern tiger swallowtail |

| Fish | Largemouth bass, fighting tarpon |

| Flower | Camellia, oak-leaf hydrangea |

| Horse breed | Racking horse |

| Insect | Monarch butterfly |

| Mammal | American black bear |

| Reptile | Alabama red-bellied turtle |

| Tree | Longleaf pine |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Beverage | Conecuh Ridge Whiskey |

| Color(s) | Red, white |

| Dance | Square dance |

| Food | Pecan, blackberry, peach |

| Fossil | Basilosaurus |

| Gemstone | Star blue quartz |

| Mineral | Hematite |

| Rock | Marble |

| Shell | Johnstone's junonia |

| Soil | Bama |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

Released in 2003 | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

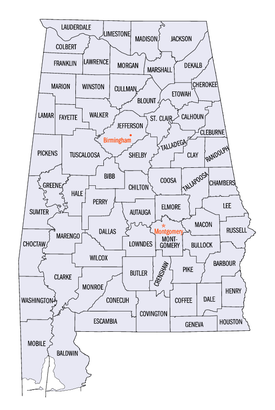

Алабама ( / ˌ æ l ə ˈ b æ m ə / AL -ə- BAM -ə ) [ 9 ] — штат в юго-восточном регионе США . Он граничит с Теннесси на севере, с Джорджией на востоке, с Флоридой и Мексиканским заливом на юге и с Миссисипи на западе. Алабама занимает 30-е место по площади. [ 10 ] и 24-й по численности населения из 50 штатов США . [ 11 ]

Алабаму называют Йеллохаммер штатом , в честь птицы штата . Алабама также известна как «Сердце Дикси » и «Хлопковый штат». География штата разнообразна: на севере преобладает гористая долина Теннесси , а на юге - залив Мобил , исторически значимый порт. Столица Алабамы — Монтгомери , а крупнейший по численности населения и площади город — Хантсвилл . [ 12 ] Старейший город — Мобил , основанный французскими колонистами ( креолами Алабамы ) в 1702 году как столица французской Луизианы . [ 13 ] [ 14 ] Большой Бирмингем — крупнейший мегаполис Алабамы и ее экономический центр. [ 15 ] В политическом отношении, как часть Глубокого Юга , Алабама является преимущественно консервативным штатом и известна своей южной культурой . В Алабаме американский футбол , особенно на уровне колледжей , играет важную роль в культуре штата.

Originally home to many native tribes, present-day Alabama was a Spanish territory beginning in the sixteenth century until the French acquired it in the early eighteenth century. The British won the territory in 1763 until losing it in the American Revolutionary War. Spain held Mobile as part of Spanish West Florida until 1813. In December 1819, Alabama was recognized as a state. During the antebellum period, Alabama was a major producer of cotton, and widely used African American slave labor. In 1861, the state seceded from the United States to become part of the Confederate States of America, with Montgomery acting as its first capital, and rejoined the Union in 1868. Following the American Civil War, Alabama would suffer decades of economic hardship, in part due to agriculture and a few cash crops being the main driver of the state's economy. Similar to other former slave states, Alabamian legislators employed Jim Crow laws from the late 19th century up until the 1960s. High-profile events such as the Selma to Montgomery marches made the state a major focal point of the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

During and after World War II, Alabama grew as the state's economy diversified with new industries. In 1960, the establishment of NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville helped boost Alabama's economic growth by developing a local aerospace industry. Alabama's economy in the 21st century is based on automotive, finance, tourism, manufacturing, aerospace, mineral extraction, healthcare, education, retail, and technology.[16]

Etymology

The name of the Alabama River and state is derived from the Alabama people, a Muskogean-speaking tribe whose members lived just below the confluence of the Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers on the upper reaches of the river.[17] In the Alabama language, the word for a person of Alabama lineage is Albaamo (or variously Albaama or Albàamo in different dialects; the plural form is Albaamaha).[18] The word's spelling varies significantly among historical sources.[19] The first usage appears in three accounts of the Hernando de Soto expedition of 1540: Garcilaso de la Vega used Alibamo, while the Knight of Elvas and Rodrigo Ranjel wrote Alibamu and Limamu, respectively, in transliterations of the term.[19] As early as 1702, the French called the tribe the Alibamon, with French maps identifying the river as Rivière des Alibamons.[17] Other spellings of the name have included Alibamu, Alabamo, Albama, Alebamon, Alibama, Alibamou, Alabamu, and Allibamou.[19][20][21] The use of state names derived from Native American languages is common in the U.S.; an estimated 26 states have names of Native American origin.[22]

Sources disagree on the word's meaning. Some scholars suggest the word comes from the Choctaw alba (meaning 'plants' or 'weeds') and amo (meaning 'to cut', 'to trim', or 'to gather').[19][23][24] The meaning may have been 'clearers of the thicket'[23] or 'herb gatherers',[24][25] referring to clearing land for cultivation[20] or collecting medicinal plants.[25] The state has numerous place names of Native American origin.[26][27]

An 1842 article in the Jacksonville Republican proposed it meant 'Here We Rest'.[19] This notion was popularized in the 1850s through the writings of Alexander Beaufort Meek.[19] Experts in the Muskogean languages have not found any evidence to support such a translation.[17][19]

History

Pre-European settlement

Indigenous peoples of varying cultures lived in the area for thousands of years before the advent of European colonization. Trade with the northeastern tribes by the Ohio River began during the Burial Mound Period (1000 BCE – 700 CE) and continued until European contact.[28]

The agrarian Mississippian culture covered most of the state from 1000 to 1600 CE, with one of its major centers built at what is now the Moundville Archaeological Site in Moundville, Alabama.[29][30] This is the second-largest complex of the classic Middle Mississippian era, after Cahokia in present-day Illinois, which was the center of the culture. Analysis of artifacts from archaeological excavations at Moundville were the basis of scholars' formulating the characteristics of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (SECC).[31] Contrary to popular belief, the SECC appears to have no direct links to Mesoamerican culture but developed independently. The Ceremonial Complex represents a major component of the religion of the Mississippian peoples; it is one of the primary means by which their religion is understood.[32]

Among the historical tribes of Native American people living in present-day Alabama at the time of European contact were the Cherokee, an Iroquoian language people; and the Muskogean-speaking Alabama (Alibamu), Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Koasati.[33] While part of the same large language family, the Muskogee tribes developed distinct cultures and languages.

European settlement

The Spanish were the first Europeans to reach Alabama during their exploration of North America in the 16th century. The expedition of Hernando de Soto passed through Mabila and other parts of the state in 1540. More than 160 years later, the French founded the region's first European settlement at Old Mobile in 1702.[34] The city was moved to the current site of Mobile in 1711. This area was claimed by the French from 1702 to 1763 as part of La Louisiane.[35]

After the French lost to the British in the Seven Years' War, it became part of British West Florida from 1763 to 1783. After the U.S. victory in the American Revolutionary War, the territory was divided between the United States and Spain. The latter retained control of this western territory from 1783 until the surrender of the Spanish garrison at Mobile to U.S. forces on April 13, 1813.[35][36]

Thomas Bassett, a loyalist to the British monarchy during the Revolutionary era, was one of the earliest white settlers in the state outside Mobile. He settled in the Tombigbee District during the early 1770s.[37] The district's boundaries were roughly limited to the area within a few miles of the Tombigbee River and included portions of what is today southern Clarke County, northernmost Mobile County, and most of Washington County.[38][39]

What are now Baldwin and Mobile counties became part of Spanish West Florida in 1783, part of the independent Republic of West Florida in 1810, and finally part of the Mississippi Territory in 1812. Most of what is now the northern two-thirds of Alabama was known as the Yazoo lands beginning during the British colonial period. It was claimed by the Province of Georgia from 1767 onwards. Following the Revolutionary War, it remained a part of Georgia, although heavily disputed.[40][41]

With the exception of the area around Mobile and the Yazoo lands, what is now the lower one-third of Alabama was made part of the Mississippi Territory when it was organized in 1798. The Yazoo lands were added to the territory in 1804, following the Yazoo land scandal.[41][42] Spain kept a claim on its former Spanish West Florida territory in what would become the coastal counties until the Adams–Onís Treaty officially ceded it to the U.S. in 1819.[36]

19th century

Before Mississippi's admission to statehood on December 10, 1817, the more sparsely settled eastern half of the territory was separated and named the Alabama Territory. The United States Congress created the Alabama Territory on March 3, 1817. St. Stephens, now abandoned, served as the territorial capital from 1817 to 1819.[43]

Alabama was admitted as the 22nd state on December 14, 1819, with Congress selecting Huntsville as the site for the first Constitutional Convention. From July 5 to August 2, 1819, delegates met to prepare the new state constitution. Huntsville served as temporary capital from 1819 to 1820, when the seat of government moved to Cahaba in Dallas County.[44]

Cahaba, now a ghost town, was the first permanent state capital from 1820 to 1825.[45] The Alabama Fever land rush was underway when the state was admitted to the Union, with settlers and land speculators pouring into the state to take advantage of fertile land suitable for cotton cultivation.[46][47] Part of the frontier in the 1820s and 1830s, its constitution provided for universal suffrage for white men.[48]

Southeastern planters and traders from the Upper South brought slaves with them as the cotton plantations in Alabama expanded. The economy of the central Black Belt (named for its dark, productive soil) was built around large cotton plantations whose owners' wealth grew mainly from slave labor.[48] The area also drew many poor, disenfranchised people who became subsistence farmers. Alabama had an estimated population of under 10,000 people in 1810, but it increased to more than 300,000 people by 1830.[46] Most Native American tribes were completely removed from the state within a few years of the passage of the Indian Removal Act by Congress in 1830.[49]

From 1826 to 1846, Tuscaloosa served as Alabama's capital. On January 30, 1846, the Alabama legislature announced it had voted to move the capital city from Tuscaloosa to Montgomery. The first legislative session in the new capital met in December 1847.[50] A new capitol building was erected under the direction of Stephen Decatur Button of Philadelphia. The first structure burned down in 1849, but was rebuilt on the same site in 1851. This second capitol building in Montgomery remains to the present day. It was designed by Barachias Holt of Exeter, Maine.[51][52]

Civil War and Reconstruction

By 1860, the population had increased to 964,201 people, of which nearly half, 435,080, were enslaved African Americans, and 2,690 were free people of color.[53] On January 11, 1861, Alabama declared its secession from the Union. After remaining an independent republic for a few days, it joined the Confederate States of America. The Confederacy's capital was initially at Montgomery. Alabama was heavily involved in the American Civil War. Although comparatively few battles were fought in the state, Alabama contributed about 120,000 soldiers to the war effort.

A company of cavalry soldiers from Huntsville, Alabama, joined Nathan Bedford Forrest's battalion in Hopkinsville, Kentucky. The company wore new uniforms with yellow trim on the sleeves, collar and coattails. This led to them being greeted with "Yellowhammer", and the name later was applied to all Alabama troops in the Confederate Army.[54]

Alabama's slaves were freed by the 13th Amendment in 1865.[55] Alabama was under military rule from the end of the war in May 1865 until its official restoration to the Union in 1868. From 1867 to 1874, with most white citizens barred temporarily from voting and freedmen enfranchised, many African Americans emerged as political leaders in the state. Alabama was represented in Congress during this period by three African-American congressmen: Jeremiah Haralson, Benjamin S. Turner, and James T. Rapier.[56]

Following the war, the state remained chiefly agricultural, with an economy tied to cotton. During Reconstruction, state legislators ratified a new state constitution in 1868 which created the state's first public school system and expanded women's rights. Legislators funded numerous public road and railroad projects, although these were plagued with allegations of fraud and misappropriation.[56] Organized insurgent, resistance groups tried to suppress the freedmen and Republicans. These groups included The Ku Klux Klan, the Pale Faces, Knights of the White Camellia, Red Shirts, and the White League.[56]

Reconstruction in Alabama ended in 1874, when the Democrats regained control of the legislature and governor's office through an election dominated by fraud and violence. They wrote another constitution in 1875,[56] and the legislature passed the Blaine Amendment, prohibiting public money from being used to finance religious-affiliated schools.[57] The same year, legislation was approved that called for racially segregated schools.[58] Railroad passenger cars were segregated in 1891.[58]

20th century

The new 1901 Constitution of Alabama included provisions for voter registration that effectively disenfranchised large portions of the population, including nearly all African Americans and Native Americans, and tens of thousands of poor European Americans, through making voter registration difficult, requiring a poll tax and literacy test.[59] The 1901 constitution required racial segregation of public schools. By 1903 only 2,980 African Americans were registered in Alabama, although at least 74,000 were literate. This compared to more than 181,000 African Americans eligible to vote in 1900. The numbers dropped even more in later decades.[60] The state legislature passed additional racial segregation laws related to public facilities into the 1950s: jails were segregated in 1911; hospitals in 1915; toilets, hotels, and restaurants in 1928; and bus stop waiting rooms in 1945.[58]

While the planter class had persuaded poor whites to vote for this legislative effort to suppress black voting, the new restrictions resulted in their disenfranchisement as well, due mostly to the imposition of a cumulative poll tax.[60] By 1941, whites constituted a slight majority of those disenfranchised by these laws: 600,000 whites vs. 520,000 African Americans.[60] Nearly all Blacks had lost the ability to vote. Despite numerous legal challenges which succeeded in overturning certain provisions, the state legislature would create new ones to maintain disenfranchisement. The exclusion of blacks from the political system persisted until after passage of federal civil rights legislation in 1965 to enforce their constitutional rights as citizens.[61]

The rural-dominated Alabama legislature consistently underfunded schools and services for the disenfranchised African Americans, but it did not relieve them of paying taxes.[48] Partially as a response to chronic underfunding of education for African Americans in the South, the Rosenwald Fund began funding the construction of what came to be known as Rosenwald Schools. In Alabama, these schools were designed, and the construction partially financed with Rosenwald funds, which paid one-third of the construction costs. The fund required the local community and state to raise matching funds to pay the rest. Black residents effectively taxed themselves twice, by raising additional monies to supply matching funds for such schools, which were built in many rural areas. They often donated land and labor as well.[62]

Beginning in 1913, the first 80 Rosenwald Schools were built in Alabama for African American children. A total of 387 schools, seven teachers' houses, and several vocational buildings were completed by 1937 in the state. Several of the surviving school buildings in the state are now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[62]

Continued racial discrimination and lynchings, agricultural depression, and the failure of the cotton crops due to boll weevil infestation led tens of thousands of African Americans from rural Alabama and other states to seek opportunities in northern and midwestern cities during the early decades of the 20th century as part of the Great Migration out of the South.[63][64] Reflecting this emigration, the population growth rate in Alabama (see "historical populations" table below) dropped by nearly half from 1910 to 1920.[65]

At the same time, many rural people migrated to the city of Birmingham to work in new industrial jobs. Birmingham experienced such rapid growth it was called the "Magic City".[66] By 1920, Birmingham was the 36th-largest city in the United States.[67] Heavy industry and mining were the basis of its economy. Its residents were under-represented for decades in the state legislature, which refused to redistrict after each decennial census according to population changes, as it was required by the state constitution. This did not change until the late 1960s following a lawsuit and court order.[68]

Beginning in the 1940s, when the courts started taking the first steps to recognize the voting rights of black voters, the Alabama legislature took several counter-steps designed to disfranchise black voters. The legislature passed, and the voters ratified [as these were mostly white voters], a state constitutional amendment that gave local registrars greater latitude to disqualify voter registration applicants. Black citizens in Mobile successfully challenged this amendment as a violation of the Fifteenth Amendment. The legislature also changed the boundaries of Tuskegee to a 28-sided figure designed to fence out blacks from the city limits. The Supreme Court unanimously held that this racial "gerrymandering" violated the Constitution. In 1961, ... the Alabama legislature also intentionally diluted the effect of the black vote by instituting numbered place requirements for local elections.[69]

Industrial development related to the demands of World War II brought a level of prosperity to the state not seen since before the civil war.[48] Rural workers poured into the largest cities in the state for better jobs and a higher standard of living. One example of this massive influx of workers occurred in Mobile. Between 1940 and 1943, more than 89,000 people moved into the city to work for war-related industries.[70] Cotton and other cash crops faded in importance as the state developed a manufacturing and service base.

Despite massive population changes in the state from 1901 to 1961, the rural-dominated legislature refused to reapportion House and Senate seats based on population, as required by the state constitution to follow the results of decennial censuses. They held on to old representation to maintain political and economic power in agricultural areas. One result was that Jefferson County, containing Birmingham's industrial and economic powerhouse, contributed more than one-third of all tax revenue to the state, but did not receive a proportional amount in services. Urban interests were consistently underrepresented in the legislature. A 1960 study noted that because of rural domination, "a minority of about 25% of the total state population is in majority control of the Alabama legislature."[68][71]

In the United States Supreme Court cases of Baker v. Carr (1962) and Reynolds v. Sims (1964), the court ruled that the principle of "one man, one vote" needed to be the basis of both houses of state legislatures, and that their districts had to be based on population rather than geographic counties.[72][73]

African Americans continued to press in the 1950s and 1960s to end disenfranchisement and segregation in the state through the civil rights movement, including legal challenges. In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that public schools had to be desegregated, but Alabama was slow to comply. During the 1960s, under Governor George Wallace, Alabama resisted compliance with federal demands for desegregation.[74][75] The civil rights movement had notable events in Alabama, including the Montgomery bus boycott (1955–1956), Freedom Rides in 1961, and 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches.[76] These contributed to Congressional passage and enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 by the U.S. Congress.[77][78]

Legal segregation ended in the states in 1964, but Jim Crow customs often continued until specifically challenged in court.[79] According to The New York Times, by 2017, many of Alabama's African Americans were living in Alabama's cities such as Birmingham and Montgomery. Also, the Black Belt region across central Alabama "is home to largely poor counties that are predominantly African-American. These counties include Dallas, Lowndes, Marengo and Perry."[80]

In 1972, for the first time since 1901, the legislature completed the congressional redistricting based on the decennial census. This benefited the urban areas that had developed, as well as all in the population who had been underrepresented for more than sixty years.[71] Other changes were made to implement representative state house and senate districts.

Alabama has made some changes since the late 20th century and has used new types of voting to increase representation. In the 1980s, an omnibus redistricting case, Dillard v. Crenshaw County, challenged the at-large voting for representative seats of 180 Alabama jurisdictions, including counties and school boards. At-large voting had diluted the votes of any minority in a county, as the majority tended to take all seats. Despite African Americans making up a significant minority in the state, they had been unable to elect any representatives in most of the at-large jurisdictions.[69]

As part of settlement of this case, five Alabama cities and counties, including Chilton County, adopted a system of cumulative voting for election of representatives in multi-seat jurisdictions. This has resulted in more proportional representation for voters. In another form of proportional representation, 23 jurisdictions use limited voting, as in Conecuh County. In 1982, limited voting was first tested in Conecuh County. Together use of these systems has increased the number of African Americans and women being elected to local offices, resulting in governments that are more representative of their citizens.[81]

Beginning in the 1960s, the state's economy shifted away from its traditional lumber, steel, and textile industries because of increased foreign competition. Steel jobs, for instance, declined from 46,314 in 1950 to 14,185 in 2011.[82] However, the state, particularly Huntsville, benefited from the opening of the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center in 1960, a major facility in the development of the Saturn rocket program and the space shuttle. Technology and manufacturing industries, such as automobile assembly, replaced some the state's older industries in the late twentieth century, but the state's economy and growth lagged behind other states in the area, such as Georgia and Florida.[83]

21st century

In 2001, Alabama Supreme Court chief justice Roy Moore installed a statue of the Ten Commandments in the capitol in Montgomery. In 2002, the 11th US Circuit Court ordered the statue removed, but Moore refused to follow the court order, which led to protests around the capitol in favor of keeping the monument. The monument was removed in August 2003.[84]

A few natural disasters have occurred in the state in the twenty-first century. In 2004, Hurricane Ivan, a category 3 storm upon landfall, struck the state and caused over $18 billion of damage. It was among the most destructive storms to strike the state in its modern history.[85] A super outbreak of 62 tornadoes hit the state in April 2011 and killed 238 people, devastating many communities.[86]

Geography

Alabama is the thirtieth-largest state in the United States with 52,419 square miles (135,760 km2) of total area: 3.2% of the area is water, making Alabama 23rd in the amount of surface water, also giving it the second-largest inland waterway system in the United States.[87] About three-fifths of the land area is part of the Gulf Coastal Plain, a gentle plain with a general descent towards the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. The North Alabama region is mostly mountainous, with the Tennessee River cutting a large valley and creating numerous creeks, streams, rivers, mountains, and lakes.[88]

Alabama is bordered by the states of Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama has coastline at the Gulf of Mexico, in the extreme southern edge of the state.[88] The state ranges in elevation from sea level[89] at Mobile Bay to more than 2,000 feet (610 m) in the northeast, to Mount Cheaha[88] at 2,413 ft (735 m).[90]

Alabama's land consists of 22 million acres (89,000 km2) of forest or 67% of the state's total land area.[91] Suburban Baldwin County, along the Gulf Coast, is the largest county in the state in both land area and water area.[92]

Areas in Alabama administered by the National Park Service include Horseshoe Bend National Military Park near Alexander City; Little River Canyon National Preserve near Fort Payne; Russell Cave National Monument in Bridgeport; Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site in Tuskegee; and Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site near Tuskegee.[93] Additionally, Alabama has four National Forests: Conecuh, Talladega, Tuskegee, and William B. Bankhead.[94] Alabama also contains the Natchez Trace Parkway, the Selma To Montgomery National Historic Trail, and the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail.

Natural wonders include the "Natural Bridge" rock, the longest natural bridge east of the Rockies, just south of Haleyville; Cathedral Caverns, in Marshall County, named for its cathedral-like appearance, which features one of the largest cave entrances and one of the largest stalagmites in the world; Ecor Rouge, in Fairhope, the highest coastline point between Maine and Mexico;[95] DeSoto Caverns, in Childersburg, the first officially recorded cave in the United States;[96] Noccalula Falls, in Gadsden, which has a 90-foot waterfall; Dismals Canyon, near Phil Campbell, which is home to two waterfalls and six natural bridges and is said to have been a hideout of Jesse James;[97] Stephens Gap Cave, in Jackson County, which has a 143-foot pit and two waterfalls and is one of the most photographed wild cave scenes in America;[98] Little River Canyon, near Fort Payne, one of the nation's longest mountaintop rivers; Rickwood Caverns, near Warrior, which has an underground pool, blind cave-fish, and 260-million-year-old limestone formations; and the Walls of Jericho canyon, on the Alabama–Tennessee border.

A 5-mile (8 km)-wide meteorite impact crater is located in Elmore County, just north of Montgomery. This is the Wetumpka crater, the site of "Alabama's greatest natural disaster". A 1,000-foot (300 m)-wide meteorite hit the area about 80 million years ago.[99] The hills just east of downtown Wetumpka showcase the eroded remains of the impact crater that was blasted into the bedrock, with the area labeled the Wetumpka crater or astrobleme ("star-wound") because of the concentric rings of fractures and zones of shattered rock that can be found beneath the surface.[100] In 2002, Christian Koeberl with the Institute of Geochemistry University of Vienna published evidence and established the site as the 157th recognized impact crater on Earth.[101]

Climate

The state is classified as humid subtropical (Cfa) under the Koppen Climate Classification.[102] The average annual temperature is 64 °F (18 °C). Temperatures tend to be warmer in the southern part of the state with its proximity to the Gulf of Mexico, while the northern parts of the state, especially in the Appalachian Mountains in the northeast, tend to be slightly cooler.[103] Generally, Alabama has very hot summers and mild winters with copious precipitation throughout the year. Alabama receives an average of 56 inches (1,400 mm) of rainfall annually and enjoys a lengthy growing season of up to 300 days in the southern part of the state.[103]

Summers in Alabama are among the hottest in the U.S., with high temperatures averaging over 90 °F (32 °C) throughout the summer in some parts of the state. Alabama is also prone to tropical storms and hurricanes. Areas of the state far away from the Gulf are not immune to the effects of the storms, which often dump tremendous amounts of rain as they move inland and weaken.

South Alabama reports many thunderstorms. The Gulf Coast, around Mobile Bay, averages between 70 and 80 days per year with thunder reported. This activity decreases somewhat further north in the state, but even the far north of the state reports thunder on about 60 days per year. Occasionally, thunderstorms are severe with frequent lightning and large hail; the central and northern parts of the state are most vulnerable to this type of storm. Alabama ranks ninth in the number of deaths from lightning and tenth in the number of deaths from lightning strikes per capita.[104]

Alabama, along with Oklahoma and Iowa, has the most confirmed F5 and EF5 tornadoes of any state, according to statistics from the National Climatic Data Center for the period January 1, 1950, to June 2013.[105] Several long-tracked F5/EF5 tornadoes have contributed to Alabama reporting more tornado fatalities since 1950 than any other state. The state was affected by the 1974 Super Outbreak and was devastated tremendously by the 2011 Super Outbreak. The 2011 Super Outbreak produced a record amount of tornadoes in the state. The tally reached 62.[106]

The peak season for tornadoes varies from the northern to southern parts of the state. Alabama is one of the few places in the world that has a secondary tornado season in November and December besides the typically severe spring. The northern part—along the Tennessee River Valley—is most vulnerable. The area of Alabama and Mississippi most affected by tornadoes is sometimes referred to as Dixie Alley, as distinct from the Tornado Alley of the Southern Plains.

Winters are generally mild in Alabama, as they are throughout most of the Southeastern United States, with average January low temperatures around 40 °F (4 °C) in Mobile and around 32 °F (0 °C) in Birmingham. Although snow is a rare event in much of Alabama, areas of the state north of Montgomery may receive a dusting of snow a few times every winter, with an occasional moderately heavy snowfall every few years. Historic snowfall events include New Year's Eve 1963 snowstorm and the 1993 Storm of the Century. The annual average snowfall for the Birmingham area is 2 inches (51 mm) per year. In the southern Gulf coast, snowfall is less frequent, sometimes going several years without any snowfall.

Alabama's highest temperature of 112 °F (44 °C) was recorded on September 5, 1925, in the unincorporated community of Centerville. The record low of −27 °F (−33 °C) occurred on January 30, 1966, in New Market.[107]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huntsville[108] | Average high | 48.9 (9.4) |

54.6 (12.6) |

63.4 (17.4) |

72.3 (22.4) |

79.6 (26.4) |

86.5 (30.3) |

89.4 (31.9) |

89.0 (31.7) |

83.0 (28.3) |

72.9 (22.7) |

61.6 (16.4) |

52.4 (11.3) |

71.1 (21.7) | |

| Average low | 30.7 (-0.7) |

34.0 (1.1) |

41.2 (5.1) |

48.4 (9.1) |

57.5 (14.2) |

65.4 (18.6) |

69.5 (20.8) |

68.1 (20.1) |

61.7 (16.5) |

49.6 (9.8) |

40.7 (4.8) |

33.8 (1.0) |

50.1 (10.1) | ||

| Birmingham[109] | Average high | 52.8 (11.6) |

58.3 (14.6) |

66.5 (19.2) |

74.1 (23.4) |

81.0 (27.2) |

87.5 (30.8) |

90.6 (32.6) |

90.2 (32.3) |

84.6 (29.2) |

74.9 (23.8) |

64.5 (18.1) |

56.0 (13.3) |

73.4 (23.0) | |

| Average low | 32.3 (0.2) |

35.4 (1.9) |

42.4 (5.8) |

48.4 (9.1) |

57.6 (14.2) |

65.4 (18.6) |

69.7 (20.9) |

68.9 (20.5) |

63.0 (17.2) |

50.9 (10.5) |

41.8 (5.4) |

35.2 (1.8) |

50.9 (10.5) | ||

| Montgomery [110] | Average high | 57.6 (14.2) |

62.4 (16.9) |

70.5 (21.4) |

77.5 (25.3) |

84.6 (29.2) |

90.6 (32.6) |

92.7 (33.7) |

92.2 (33.4) |

87.7 (30.9) |

78.7 (25.9) |

68.7 (20.4) |

60.3 (15.7) |

77.0 (25.0) | |

| Average low | 35.5 (1.9) |

38.6 (3.7) |

45.4 (7.4) |

52.1 (11.2) |

60.1 (15.6) |

67.3 (19.6) |

70.9 (21.6) |

70.1 (21.2) |

64.9 (18.3) |

52.2 (11.2) |

43.5 (6.4) |

37.6 (3.1) |

53.2 (11.8) | ||

| Mobile[111] | Average high | 60.7 (15.9) |

64.5 (18.1) |

71.2 (21.8) |

77.4 (25.2) |

84.2 (29.0) |

89.4 (31.9) |

91.2 (32.9) |

90.8 (32.7) |

86.8 (30.4) |

79.2 (26.2) |

70.1 (21.2) |

62.9 (17.2) |

77.4 (25.2) | |

| Average low | 39.5 (4.2) |

42.4 (5.8) |

49.2 (9.6) |

54.8 (12.7) |

62.8 (17.1) |

69.2 (20.7) |

71.8 (22.1) |

71.7 (22.0) |

67.6 (19.8) |

56.3 (13.5) |

47.8 (8.8) |

41.6 (5.3) |

56.2 (13.4) | ||

Flora and fauna

Alabama is home to a diverse array of flora and fauna in habitats that range from the Tennessee Valley, Appalachian Plateau, and Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians of the north to the Piedmont, Canebrake, and Black Belt of the central region to the Gulf Coastal Plain and beaches along the Gulf of Mexico in the south. The state is usually ranked among the top in nation for its range of overall biodiversity.[112][113]

Alabama is in the subtropical coniferous forest biome and once boasted huge expanses of pine forest, which still form the largest proportion of forests in the state.[112] It currently ranks fifth in the nation for the diversity of its flora. It is home to nearly 4,000 pteridophyte and spermatophyte plant species.[114]

Indigenous animal species in the state include 62 mammal species,[115] 93 reptile species,[116] 73 amphibian species,[117] roughly 307 native freshwater fish species,[112] and 420 bird species that spend at least part of their year within the state.[118] Invertebrates include 97 crayfish species and 383 mollusk species. 113 of these mollusk species have never been collected outside the state.[119][120]

Census-designated and metropolitan areas

| Rank | Combined statistical area | Population (2021 estimate) | Population (2020 census) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Birmingham–Hoover–Talladega | 1,350,646 | 1,290,744 |

| 2 | Chattanooga–Cleveland–Dalton[CSA 1] | 1,000,303 | 951,434 |

| 3 | Mobile–Daphne–Fairhope | 661,964 | 612,838 |

| 4 | Huntsville–Decatur–Albertville | 648,217 | 571,422 |

| 5 | Columbus–Auburn–Opelika[CSA 2] | 503,124 | 448,035 |

| 6 | Dothan–Enterprise–Ozark | 200,333 | 195,890 |

| Rank | Metropolitan area | Population (2021 estimate) | Population (2020 census) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Birmingham–Hoover | 1,114,262 | 1,115,289 |

| 2 | Huntsville | 502,728 | 491,723 |

| 3 | Mobile | 429,536 | 430,573 |

| 4 | Montgomery | 385,798 | 386,047 |

| 5 | Tuscaloosa | 268,191 | 268,674 |

| 6 | Daphne–Fairhope–Foley | 239,294 | 231,767 |

| 7 | Auburn–Opelika | 177,218 | 174,241 |

| 8 | Decatur | 156,758 | 156,494 |

| 9 | Dothan | 151,618 | 151,007 |

| 10 | Florence–Muscle Shoals | 147,970 | 147,137 |

| 11 | Anniston–Oxford–Jacksonville | 115,972 | 116,441 |

| 12 | Gadsden | 103,162 | 103,436 |

Cities

| Rank | City | Population (2020 census) |

County(ies) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Huntsville | 221,933 | Madison, Limestone, Morgan |

| 2 | Montgomery | 196,986 | Montgomery |

| 3 | Birmingham | 196,910 | Jefferson, Shelby |

| 4 | Mobile | 183,289 | Mobile |

| 5 | Tuscaloosa | 110,602 | Tuscaloosa |

| 6 | Hoover | 92,435 | Jefferson, Shelby |

| 7 | Auburn | 80,006 | Lee |

| 8 | Dothan | 71,235 | Houston, Dale, Henry |

| 9 | Madison | 59,785 | Madison, Limestone |

| 10 | Decatur | 57,922 | Morgan, Limestone |

| 11 | Florence | 41,690 | Lauderdale |

| 12 | Prattville | 38,776 | Autauga, Elmore |

| 13 | Vestavia Hills | 38,292 | Jefferson, Shelby |

| 14 | Phenix City | 38,267 | Russell |

| 15 | Alabaster | 33,945 | Shelby |

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 1,250 | — | |

| 1810 | 9,046 | 623.7% | |

| 1820 | 144,317 | [122] | 1,495.4% |

| 1830 | 309,527 | 114.5% | |

| 1840 | 590,756 | 90.9% | |

| 1850 | 771,623 | 30.6% | |

| 1860 | 964,201 | 25.0% | |

| 1870 | 996,992 | 3.4% | |

| 1880 | 1,262,505 | 26.6% | |

| 1890 | 1,513,401 | 19.9% | |

| 1900 | 1,828,697 | 20.8% | |

| 1910 | 2,138,093 | 16.9% | |

| 1920 | 2,348,174 | 9.8% | |

| 1930 | 2,646,248 | 12.7% | |

| 1940 | 2,832,961 | 7.1% | |

| 1950 | 3,061,743 | 8.1% | |

| 1960 | 3,266,740 | 6.7% | |

| 1970 | 3,444,165 | 5.4% | |

| 1980 | 3,893,888 | 13.1% | |

| 1990 | 4,040,587 | 3.8% | |

| 2000 | 4,447,100 | 10.1% | |

| 2010 | 4,779,736 | 7.5% | |

| 2020 | 5,024,279 | 5.1% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 5,108,468 | 1.7% | |

| Sources: 1910–2020[123] | |||

According to the 2020 United States census the population of Alabama was 5,024,279 on April 1, 2020, which represents an increase of 244,543 or 5.12%, since the 2010 census.[124] This includes a natural increase since the last census of 121,054 (502,457 births minus 381,403 deaths) and an increase due to net migration of 104,991 into the state.[125]

Immigration from outside the U.S. resulted in a net increase of 31,180 people, and migration within the country produced a net gain of 73,811 people.[125] The state had 108,000 foreign-born (2.4% of the state population), of which an estimated 22.2% were undocumented (24,000). The top countries of origin for immigrants were Mexico, China, India, Germany and Guatemala in 2018.[126]

The center of population of Alabama is located in Chilton County, outside the town of Jemison.[127]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 3,752 homeless people in Alabama.[128][129]

Ancestry

Those citing "American" ancestry in Alabama are of overwhelmingly English extraction. Demographers estimate that a minimum of 20–23% of people in Alabama are of predominantly English ancestry and state that the figure is probably much higher. In the 1980 census 1,139,976 people in Alabama cited that they were of English ancestry out of a total state population of 2,824,719 making them 41% of the state at the time and the largest ethnic group.[135][136][137]

Alabama has the 5th highest African American population among US states at 25.8% as of 2020.[138] In 2011, 46.6% of Alabama's population younger than age 1 were minorities.[139] The largest reported ancestry groups in Alabama are American (13.4%), Irish (10.5%), English (10.2%), German (7.9%), and Scots-Irish (2.5%) based on 2006–2008 Census data.[140]

The Scots-Irish were the largest non-English immigrant group from the British Isles before the American Revolution, and many settled in the South, later moving into the Deep South as it was developed.[141]

In 1984, under the Davis–Strong Act, the state legislature established the Alabama Indian Affairs Commission.[142] Native American groups within the state had increasingly been demanding recognition as ethnic groups and seeking an end to discrimination. Given the long history of slavery and associated racial segregation, the Native American peoples, who have sometimes been of mixed race, have insisted on having their cultural identification respected. In the past, their self-identification was often overlooked as the state tried to impose a binary breakdown of society into white and black. The state has officially recognized nine American Indian tribes in the state, descended mostly from the Five Civilized Tribes of the American Southeast. These are the following.[143]

- Poarch Band of Creek Indians (who also have federal recognition)

- MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians

- Star Clan of Muscogee Creeks

- Echota Cherokee Tribe of Alabama

- Cherokee Tribe of Northeast Alabama

- Cher-O-Creek Intra Tribal Indians

- Ma-Chis Lower Creek Indian Tribe

- Piqua Shawnee Tribe

- Ani-Yun-Wiya Nation

The state government has promoted recognition of Native American contributions to the state, including the designation in 2000 for Columbus Day to be jointly celebrated as American Indian Heritage Day.[144]

Language

Most Alabama residents (95.1% of those five and older) spoke only English at home in 2010, a minor decrease from 96.1% in 2000.

| Language | Percentage of population (as of 2010[update])[citation needed] |

|---|---|

| Spanish | 2.2% |

| German | 0.4% |

| French (incl. Patois, Cajun) | 0.3% |

| Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean, Arabic, African languages, Japanese, and Italian (tied) | 0.1% |

Religion

In the 2008 American Religious Identification Survey, 86% of Alabama respondents reported their religion as Christian, including 6% Catholic, with 11% as having no religion.[145] The composition of other traditions is 0.5% Mormon, 0.5% Jewish, 0.5% Muslim, 0.5% Buddhist, and 0.5% Hindu.[146]

| Affiliation | % of population | |

|---|---|---|

| Christian | 86 | |

| Protestant | 78 | |

| Evangelical Protestant | 49 | |

| Mainline Protestant | 13 | |

| Black church | 16 | |

| Catholic | 7 | |

| Mormon | 1 | |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 0.1 | |

| Eastern Orthodox | 0.1 | |

| Other Christian | 0.1 | |

| Unaffiliated | 12 | |

| Nothing in particular | 9 | |

| Agnostic | 1 | |

| Atheist | 1 | |

| Non-Christian faiths | 1 | |

| Jewish | 0.2 | |

| Muslim | 0.2 | |

| Buddhist | 0.2 | |

| Hindu | 0.2 | |

| Other Non-Christian faiths | 0.2 | |

| Don't know/refused answer | 1 | |

| Total | 100 | |

Alabama is located in the middle of the Bible Belt, a region of numerous Protestant Christians. Alabama has been identified as one of the most religious states in the United States, with about 58% of the population attending church regularly.[148] A majority of people in the state identify as Evangelical Protestant. As of 2010[update], the three largest denominational groups in Alabama are the Southern Baptist Convention, The United Methodist Church, and non-denominational Evangelical Protestant.[149]

In Alabama, the Southern Baptist Convention has the highest number of adherents with 1,380,121; this is followed by the United Methodist Church with 327,734 adherents, non-denominational Evangelical Protestant with 220,938 adherents, and the Catholic Church with 150,647 adherents. Many Baptist and Methodist congregations became established in the Great Awakening of the early 19th century, when preachers proselytized across the South. The Assemblies of God had almost 60,000 members, the Churches of Christ had nearly 120,000 members. The Presbyterian churches, strongly associated with Scots-Irish immigrants of the 18th century and their descendants, had a combined membership around 75,000 (PCA—28,009 members in 108 congregations, PC(USA)—26,247 members in 147 congregations,[150] the Cumberland Presbyterian Church—6,000 members in 59 congregations, the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in America—5,000 members and fifty congregations plus the EPC and Associate Reformed Presbyterians with 230 members and nine congregations).[151]

In a 2007 survey, nearly 70% of respondents could name all four of the Christian Gospels. Of those who indicated a religious preference, 59% said they possessed a "full understanding" of their faith and needed no further learning.[152] In a 2007 poll, 92% of Alabamians reported having at least some confidence in churches in the state.[153][154]

Although in much smaller numbers, many other religious faiths are represented in the state as well, including Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, the Baháʼí Faith, and Unitarian Universalism.[151]

Jews have been present in what is now Alabama since 1763, during the colonial era of Mobile, when Sephardic Jews immigrated from London.[155] The oldest Jewish congregation in the state is Congregation Sha'arai Shomayim in Mobile. It was formally recognized by the state legislature on January 25, 1844.[155] Later immigrants in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries tended to be Ashkenazi Jews from eastern Europe. Jewish denominations in the state include two Orthodox, four Conservative, ten Reform, and one Humanistic synagogue.[156]

Muslims have been increasing in Alabama, with 31 mosques built by 2011, many by African-American converts.[157]

Several Hindu temples and cultural centers in the state have been founded by Indian immigrants and their descendants, the best-known being the Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in Birmingham, the Hindu Temple and Cultural Center of Birmingham in Pelham, the Hindu Cultural Center of North Alabama in Capshaw, and the Hindu Mandir and Cultural Center in Tuscaloosa.[158][159]

There are six Dharma centers and organizations for Theravada Buddhists.[160] Most monastic Buddhist temples are concentrated in southern Mobile County, near Bayou La Batre. This area has attracted an influx of refugees from Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam during the 1970s and thereafter.[161] The four temples within a ten-mile radius of Bayou La Batre, include Chua Chanh Giac, Wat Buddharaksa, and Wat Lao Phoutthavihan.[162][163][164]

The first community of adherents of the Baháʼí Faith in Alabama was founded in 1896 by Paul K. Dealy, who moved from Chicago to Fairhope. Baháʼí centers in Alabama exist in Birmingham, Huntsville, and Florence.[165]

Health

In 2018, life expectancy in Alabama was 75.1 years, below the national average of 78.7 years and is the third lowest life expectancy in the country. Factors that can cause lower life expectancy are maternal mortality, suicide, and gun crimes.[166]

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study in 2008 showed that obesity in Alabama is a problem, with most counties having more than 29% of adults obese, except for ten which had a rate between 26% and 29%.[167] Residents of the state, along with those in five other states, were least likely in the nation to be physically active during leisure time.[168] Alabama, and the southeastern U.S. in general, has one of the highest incidences of adult onset diabetes in the country, exceeding 10% of adults.[169][170]

Economy

The state has invested in aerospace, education, health care, banking, and various heavy industries, including automobile manufacturing, mineral extraction, steel production and fabrication. By 2006, crop and animal production in Alabama was valued at $1.5 billion. In contrast to the primarily agricultural economy of the previous century, this was only about one percent of the state's gross domestic product. The number of private farms has declined at a steady rate since the 1960s, as land has been sold to developers, timber companies, and large farming conglomerates.[171]

Non-agricultural employment in 2008 was 121,800 in management occupations; 71,750 in business and financial operations; 36,790 in computer-related and mathematical occupation; 44,200 in architecture and engineering; 12,410 in life, physical, and social sciences; 32,260 in community and social services; 12,770 in legal occupations; 116,250 in education, training, and library services; 27,840 in art, design and media occupations; 121,110 in healthcare; 44,750 in fire fighting, law enforcement, and security; 154,040 in food preparation and serving; 76,650 in building and grounds cleaning and maintenance; 53,230 in personal care and services; 244,510 in sales; 338,760 in office and administration support; 20,510 in farming, fishing, and forestry; 120,155 in construction and mining, gas, and oil extraction; 106,280 in installation, maintenance, and repair; 224,110 in production; and 167,160 in transportation and material moving.[16]

According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, the 2008 total gross state product was $170 billion, or $29,411 per capita. Alabama's 2012 GDP increased 1.2% from the previous year. The single largest increase came in the area of information.[172] In 2010, per capita income for the state was $22,984.[173]

The state's seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was 5.8% in April 2015.[174] This compared to a nationwide seasonally adjusted rate of 5.4%.[175]

Alabama has no minimum wage and in February 2016 passed legislation preventing municipalities from setting one. (A Birmingham city ordinance would have raised theirs to $10.10.)[176]

As of 2018[update], Alabama has the sixth highest poverty rate among states in the U.S.[177] In 2017, United Nations Special Rapporteur Philip Alston toured parts of rural Alabama and observed environmental conditions he said were poorer than anywhere he had seen in the developed world.[178]

Largest employers

The five employers that employed the most employees in Alabama in April 2011 were:[179]

| Employer | Employees |

|---|---|

| Redstone Arsenal | 25,373 |

| University of Alabama at Birmingham (includes UAB Hospital) | 18,750 |

| Maxwell Air Force Base | 12,280 |

| State of Alabama | 9,500 |

| Mobile County Public School System | 8,100 |

The next twenty largest employers, as of 2011[update], included:[180]

| Employer | Location |

|---|---|

| Anniston Army Depot | Anniston |

| AT&T | Multiple |

| Auburn University | Auburn |

| Baptist Medical Center South | Montgomery |

| Birmingham City Schools | Birmingham |

| City of Birmingham | Birmingham |

| DCH Health System | Tuscaloosa |

| Huntsville City Schools | Huntsville |

| Huntsville Hospital System | Huntsville |

| Hyundai Motor Manufacturing Alabama | Montgomery |

| Infirmary Health System | Mobile |

| Jefferson County Board of Education | Birmingham |

| Marshall Space Flight Center | Huntsville |

| Mercedes-Benz U.S. International | Vance |

| Montgomery Public Schools | Montgomery |

| Regions Financial Corporation | Multiple |

| Boeing | Multiple |

| University of Alabama | Tuscaloosa |

| University of South Alabama | Mobile |

| Walmart | Multiple |

Agriculture

Alabama's agricultural outputs include poultry and eggs, cattle, fish, plant nursery items, peanuts, cotton, grains such as corn and sorghum, vegetables, milk, soybeans, and peaches. Although known as "The Cotton State", Alabama ranks between eighth and tenth in national cotton production, according to various reports,[181][182] with Texas, Georgia and Mississippi comprising the top three.

Aquaculture

Aquaculture is a large part of the economy of Alabama.[183] Alabamians began to practice aquaculture in the early 1960s.[184] U.S. farm-raised catfish is the 8th most popular seafood product in America.[185] By 2008, approximately 4,000 people in Alabama were employed by the catfish industry and Alabama produced 132 million pounds of catfish.[183] In 2020, Alabama produced 1⁄3 of the United States' farm-raised catfish.[185] The total 2020 sales of catfish raised in Alabama equaled $307 million but by 2020 the total employment of Alabamians fell to 2,442.[185]

From the early 2000s to 2020, the Alabamian catfish industry has declined from 250 farms and 4 processors to 66 farms and 2 processors.[185] Reasons for this decline include increased feed prices, catfish alternatives, COVID-19's impact on restaurant sales, disease, and fish size.[185]

Industry

Alabama's industrial outputs include iron and steel products (including cast-iron and steel pipe); paper, lumber, and wood products; mining (mostly coal); plastic products; cars and trucks; and apparel. In addition, Alabama produces aerospace and electronic products, mostly in the Huntsville area, the location of NASA's George C. Marshall Space Flight Center and the U.S. Army Materiel Command, headquartered at Redstone Arsenal.

A great deal of Alabama's economic growth since the 1990s has been due to the state's expanding automotive manufacturing industry. Located in the state are Honda Manufacturing of Alabama, Hyundai Motor Manufacturing Alabama, Mercedes-Benz U.S. International, and Toyota Motor Manufacturing Alabama, as well as their various suppliers. Since 1993, the automobile industry has generated more than 67,800 new jobs in the state. Alabama currently ranks 4th in the nation for vehicle exports.[186]

Automakers accounted for approximately a third of the industrial expansion in the state in 2012.[187] The eight models produced at the state's auto factories totaled combined sales of 74,335 vehicles for 2012. The strongest model sales during this period were the Hyundai Elantra compact car, the Mercedes-Benz GL-Class sport utility vehicle and the Honda Ridgeline sport utility truck.[188]

Steel producers Outokumpu, Nucor, SSAB, ThyssenKrupp, and U.S. Steel have facilities in Alabama and employ more than 10,000 people. In May 2007, German steelmaker ThyssenKrupp selected Calvert in Mobile County for a 4.65 billion combined stainless and carbon steel processing facility.[189] ThyssenKrupp's stainless steel division, Inoxum, including the stainless portion of the Calvert plant, was sold to Finnish stainless steel company Outokumpu in 2012.[190] The remaining portion of the ThyssenKrupp plant had final bids submitted by ArcelorMittal and Nippon Steel for $1.6 billion in March 2013. Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional submitted a combined bid for the mill at Calvert, plus a majority stake in the ThyssenKrupp mill in Brazil, for $3.8 billion.[191] In July 2013, the plant was sold to ArcelorMittal and Nippon Steel.[192]

The Hunt Refining Company, a subsidiary of Hunt Consolidated, Inc., is based in Tuscaloosa and operates a refinery there. The company also operates terminals in Mobile, Melvin, and Moundville.[193] JVC America, Inc. operates an optical disc replication and packaging plant in Tuscaloosa.[194]

The Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company operates a large plant in Gadsden which employs about 1,400 people. It has been in operation since 1929.

Construction of an Airbus A320 family aircraft assembly plant in Mobile was formally announced by Airbus CEO Fabrice Brégier from the Mobile Convention Center on July 2, 2012. The plans include a $600 million factory at the Brookley Aeroplex for the assembly of the A319, A320 and A321 aircraft. Construction began in 2013, with plans for it to become operable by 2015 and produce up to 50 aircraft per year by 2017.b[195][196] The assembly plant is the company's first factory to be built within the United States.[197] It was announced on February 1, 2013, that Airbus had hired Alabama-based Hoar Construction to oversee construction of the facility.[198] The factory officially opened on September 14, 2015, covering one million square feet on 53 acres of flat grassland.[199]

Tourism and entertainment

According to Business Insider, Alabama ranked 14th in most popular states to visit in 2014.[200] An estimated 26 million tourists visited the state in 2017 and spent $14.3 billion, providing directly or indirectly 186,900 jobs in the state,[201] which includes 362,000 International tourists spending $589 million.[202]

The state is home to various attractions, natural features, parks and events that attract visitors from around the globe, notably the annual Hangout Music Festival, held on the public beaches of Gulf Shores; the Alabama Shakespeare Festival, one of the ten largest Shakespeare festivals in the world;[203] the Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail, a collection of championship caliber golf courses distributed across the state; casinos such as Victoryland; amusement parks such as Alabama Splash Adventure; the Riverchase Galleria, one of the largest shopping centers in the southeast; Guntersville Lake, voted the best lake in Alabama by Southern Living Magazine readers;[204] and the Alabama Museum of Natural History, the oldest museum in the state.[205]

Mobile is known for having the oldest organized Mardi Gras celebration in the United States, beginning in 1703.[206] It was also host to the first formally organized Mardi Gras parade in the U.S. in 1830, a tradition that continues to this day.[206] Mardi Gras is an official state holiday in Mobile and Baldwin counties.[207]

In 2018, Mobile's Mardi Gras parade was the state's top event, producing the most tourists with an attendance of 892,811. The top attraction was the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville with an attendance of 849,981, followed by the Birmingham Zoo with 543,090. Of the parks and natural destinations, Alabama's Gulf Coast topped the list with 6,700,000 visitors.[208]

Alabama has historically been a popular region for film shoots due to its diverse landscapes and contrast of environments.[209] Movies filmed in Alabama include Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Get Out, 42, Selma, Big Fish, The Final Destination, Due Date, and Need for Speed.[210]

Healthcare

UAB Hospital, USA Health University Hospital, Huntsville Hospital, and Children's Hospital of Alabama are the only Level I trauma centers in Alabama.[211] UAB is the largest state government employer in Alabama, with a workforce of about 18,000.[212] A 2017 study found that Alabama had the least competitive health insurance market in the country, with Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama having a market share of 84% followed by UnitedHealth Group at 7%.[213]

Banking

Regions Financial Corporation is the largest bank headquartered in or operating in Alabama. PNC Financial Services and Wells Fargo also have a major presence in Alabama.[214]

Wells Fargo has a regional headquarters, an operations center campus, and a $400 million data center in Birmingham. Many smaller banks are also headquartered in the Birmingham area, including ServisFirst and New South Federal Savings Bank. Birmingham also serves as the headquarters for several large investment management companies, including Harbert Management Corporation.

Electronics and communications

Telecommunications provider AT&T, formerly BellSouth, has a major presence in Alabama with several large offices in Birmingham.

Many technology companies are headquartered in Huntsville, such as ADTRAN, a network access company; Intergraph, a computer graphics company; and Avocent, an IT infrastructure company.

Construction

Brasfield & Gorrie, BE&K, Hoar Construction, and B.L. Harbert International, based in Alabama and subsidiaries of URS Corporation, are all routinely are included in the Engineering News-Record lists of top design, international construction, and engineering firms.

Law and government

State government

The foundational document for Alabama's government is the Alabama Constitution, the current one having been adopted in 2022.[clarification needed] The Alabama constitution adopted in 1901 was, with over 850 amendments and almost 87,000 words, by some accounts the world's longest constitution and roughly forty times the length of the United States Constitution.[215][216][217][218]

There has been a significant movement to rewrite and modernize Alabama's constitution.[219] Critics have argued that Alabama's constitution maintains highly centralized power with the state legislature, leaving practically no power in local hands. Most counties do not have home rule. Any policy changes proposed in different areas of the state must be approved by the entire Alabama legislature and, frequently, by state referendum. The former constitution was particularly criticized for its complexity and length intentionally codifying segregation and racism.

Alabama's government is divided into three coequal branches. The legislative branch is the Alabama Legislature, a bicameral assembly composed of the Alabama House of Representatives, with 105 members, and the Alabama Senate, with 35 members. The Legislature is responsible for writing, debating, passing, or defeating state legislation. The Republican Party currently holds a majority in both houses of the Legislature. The Legislature has the power to override a gubernatorial veto by a simple majority (most state Legislatures require a two-thirds majority to override a veto).

Until 1964, the state elected state senators on a geographic basis by county, with one per county. It had not redistricted congressional districts since passage of its constitution in 1901; as a result, urbanized areas were grossly underrepresented. It had not changed legislative districts to reflect the decennial censuses, either. In Reynolds v. Sims (1964), the U.S. Supreme Court implemented the principle of "one man, one vote", ruling that congressional districts had to be reapportioned based on censuses (as the state already included in its constitution but had not implemented.) Further, the court ruled that both houses of bicameral state legislatures had to be apportioned by population, as there was no constitutional basis for states to have geographically based systems.

At that time, Alabama and many other states had to change their legislative districting, as many across the country had systems that underrepresented urban areas and districts. This had caused decades of underinvestment in such areas. For instance, Birmingham and Jefferson County taxes had supplied one-third of the state budget, but Jefferson County received only 1/67th of state services in funding. Through the legislative delegations, the Alabama legislature kept control of county governments.

The executive branch is responsible for the execution and oversight of laws. It is headed by the governor of Alabama. Other members of the executive branch include the cabinet, the lieutenant governor of Alabama, the Attorney General of Alabama, the Alabama Secretary of State, the Alabama State Treasurer, and the State Auditor of Alabama. The current governor is Republican Kay Ivey.

The members of the Legislature take office immediately after the November elections. Statewide officials, such as the governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, and other constitutional officers, take office the following January.[220]

The judiciary is responsible for interpreting the Constitution of Alabama and applying the law in state criminal and civil cases. The state's highest court is the Supreme Court of Alabama. Alabama uses partisan elections to select judges. Since the 1980s judicial campaigns have become increasingly politicized.[221] The current chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court is Republican Tom Parker. All sitting justices on the Alabama Supreme Court are members of the Republican Party. There are two intermediate appellate courts, the Court of Civil Appeals and the Court of Criminal Appeals, and four trial courts: the circuit court (trial court of general jurisdiction), and the district, probate, and municipal courts.[221]

Alabama has the death penalty with authorized methods of execution that include the electric chair and the gas chamber.[222] Some critics believe the election of judges has contributed to an exceedingly high rate of executions.[223] Alabama has the highest per capita death penalty rate in the country. In some years, it imposes more death sentences than does Texas, a state which has a population five times larger.[224] However, executions per capita are significantly higher in Texas.[225] Some of its cases have been highly controversial; the U.S. Supreme Court has overturned[226] 24 convictions in death penalty cases.[citation needed] It was the only state to allow judges to override jury decisions in whether or not to use a death sentence; in 10 cases judges overturned sentences of life imprisonment without parole that were voted unanimously by juries.[224] This judicial authority was removed in April 2017.[227]

On May 14, 2019, Alabama passed the Human Life Protection Act, banning abortion at any stage of pregnancy unless there is a "serious health risk", with no exceptions for rape and incest. The law subjects doctors who perform abortions with 10 to 99 years imprisonment.[228] The law was originally supposed to take effect the following November, but on October 29, 2019, U.S. District Judge Myron Thompson blocked the law from taking effect due to it being in conflict with the 1973 U.S. Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade.[229] On June 24, 2022, after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, Judge Thompson lifted the injunction, allowing the law to go into effect.[230]

Alabama is one of the very few states that does not allow the creation of state lotteries.[231]

Taxes

Taxes are collected by the Alabama Department of Revenue.[232] Alabama levies a 2%, 4%, or 5% personal income tax, depending on the amount earned and filing status.[233] Taxpayers are allowed to deduct their federal income tax from their Alabama state tax, even if taking the standard deduction; those who itemize can also deduct FICA (the Social Security and Medicare tax).[234]

The state's general sales tax rate is 4%.[235] Sales tax rates for cities and counties are also added to purchases.[236] For example, the total sales tax rate in Mobile County, Alabama is 10% and there is an additional restaurant tax of 1%, which means a diner in Mobile County, Alabama would pay an 11% tax on a meal.

In 2020, sales and excise taxes in Alabama accounted for 38% of all state and local revenue.[237] Only Alabama, Mississippi, and South Dakota tax groceries at the full state sales tax rate.[238]

The corporate income tax rate in Alabama is 6.5%. The overall federal, state, and local tax burden in Alabama ranks the state as the second least tax-burdened state in the country.[239] Property taxes of .40% of assessed value per year, are the second-lowest in the U.S., after Hawaii.[240] The state constitution currently requires a voter referendum to raise property taxes.

County and local governments

Alabama has 67 counties. Each county has its own elected legislative branch, usually called the county commission. It also has limited executive authority in the county. Because of the constraints of the Alabama Constitution, which centralizes power in the state legislature, only seven counties (Jefferson, Lee, Mobile, Madison, Montgomery, Shelby, and Tuscaloosa) in the state have limited home rule. Instead, most counties in the state must lobby the Local Legislation Committee of the state legislature to get simple local policies approved, ranging from waste disposal to land use zoning.

The state legislature has retained power over local governments by refusing to pass a constitutional amendment establishing home rule for counties, as recommended by the 1973 Alabama Constitutional Commission.[241] Legislative delegations retain certain powers over each county. United States Supreme Court decisions in Baker v. Carr (1964) required that both houses have districts established on the basis of population, and redistricted after each census, to implement the principle of "one man, one vote". Before that, each county was represented by one state senator, leading to under-representation in the state senate for more urbanized, populous counties. The rural bias of the state legislature, which had also failed to redistrict seats in the state house, affected politics well into the 20th century, failing to recognize the rise of industrial cities and urbanized areas.

"The lack of home rule for counties in Alabama has resulted in the proliferation of local legislation permitting counties to do things not authorized by the state constitution. Alabama's constitution has been amended more than 700 times, and almost one-third of the amendments are local in nature, applying to only one county or city. A significant part of each legislative session is spent on local legislation, taking away time and attention of legislators from issues of statewide importance."[241]

Alabama is an alcoholic beverage control state, meaning the state government holds a monopoly on the sale of alcohol. The Alabama Alcoholic Beverage Control Board controls the sale and distribution of alcoholic beverages in the state. A total of 25 of the 67 counties are "dry counties" which ban the sale of alcohol, and there are many dry municipalities in counties which permit alcohol sales.[242]

| Rank | County | Population (2019 Estimate) |

Population (2010 Census) |

Seat | Largest city |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jefferson | 658,573 | 658,158 | Birmingham | Birmingham |

| 2 | Mobile | 413,210 | 412,992 | Mobile | Mobile |

| 3 | Madison | 372,909 | 334,811 | Huntsville | Huntsville |

| 4 | Montgomery | 226,486 | 229,363 | Montgomery | Montgomery |

| 5 | Shelby | 217,702 | 195,085 | Columbiana | Hoover (part) Alabaster |

| 6 | Baldwin | 223,234 | 182,265 | Bay Minette | Daphne |

| 7 | Tuscaloosa | 209,355 | 194,656 | Tuscaloosa | Tuscaloosa |

| 8 | Lee | 164,542 | 140,247 | Opelika | Auburn |

| 9 | Morgan | 119,679 | 119,490 | Decatur | Decatur |

| 10 | Calhoun | 113,605 | 118,572 | Anniston | Anniston |

| 11 | Houston | 105,882 | 101,547 | Dothan | Dothan |

| 12 | Etowah | 102,268 | 104,303 | Gadsden | Gadsden |

| 13 | Limestone | 98,915 | 82,782 | Athens | Athens |

| 14 | Marshall | 96,774 | 93,019 | Guntersville | Albertville |

| 15 | Lauderdale | 92,729 | 92,709 | Florence | Florence |

Politics

During Reconstruction following the American Civil War, Alabama was occupied by federal troops of the Third Military District under General John Pope. In 1874, the political coalition of white Democrats known as the Redeemers took control of the state government from the Republicans, in part by suppressing the black vote through violence, fraud, and intimidation. After 1890, a coalition of White Democratic politicians passed laws to segregate and disenfranchise African American residents, a process completed in provisions of the 1901 constitution. Provisions which disenfranchised blacks resulted in excluding many poor Whites. By 1941 more Whites than Blacks had been disenfranchised: 600,000 to 520,000. The total effects were greater on the black community, as almost all its citizens were disfranchised and relegated to separate and unequal treatment under the law.

From 1901 through the 1960s, the state did not redraw election districts as population grew and shifted within the state during urbanization and industrialization of certain areas. As counties were the basis of election districts, the result was a rural minority that dominated state politics through nearly three-quarters of the century, until a series of federal court cases required redistricting in 1972 to meet equal representation. Alabama state politics gained nationwide and international attention in the 1950s and 1960s during the civil rights movement, when whites bureaucratically, and at times violently, resisted protests for electoral and social reform. Governor George Wallace, the state's only four-term governor, was a controversial figure who vowed to maintain segregation. Only after passage of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964[77] and Voting Rights Act of 1965 did African Americans regain the ability to exercise suffrage, among other civil rights. In many jurisdictions, they continued to be excluded from representation by at-large electoral systems, which allowed the majority of the population to dominate elections. Some changes at the county level have occurred following court challenges to establish single-member districts that enable a more diverse representation among county boards.

In 2007, the Alabama Legislature passed, and Republican governor Bob Riley signed a resolution expressing "profound regret" over slavery and its lingering impact. In a symbolic ceremony, the bill was signed in the Alabama State Capitol, which housed Congress of the Confederate States of America.[243] In 2010, Republicans won control of both houses of the legislature for the first time in 136 years.[244]

As of February 2023[update], there are a total of 3,707,233 registered voters, with 3,318,679 active, and the others inactive in the state.[245]

The 2023 American Values Atlas by Public Religion Research Institute found that a majority of Alabama residents support same-sex marriage.[246]

Elections

State elections

With the disfranchisement of Blacks in 1901, the state became part of the "Solid South", a system in which the Democratic Party operated as effectively the only viable political party in every Southern state. For nearly a hundred years local and state elections in Alabama were decided in the Democratic Party primary, with generally only token Republican challengers running in the general election. Since the mid- to late 20th century, however, white conservatives started shifting to the Republican Party. In Alabama, majority-white districts are now expected to regularly elect Republican candidates to federal, state and local office.

Members of the nine seats on the Supreme Court of Alabama[247] and all ten seats on the state appellate courts are elected to office. Until 1994, no Republicans held any of the court seats. In that general election, the then-incumbent chief justice, Ernest C. Hornsby, refused to leave office after losing the election by approximately 3,000 votes to Republican Perry O. Hooper Sr.[248] Hornsby sued Alabama and defiantly remained in office for nearly a year before finally giving up the seat after losing in court.[249] The Democrats lost the last of the nineteen court seats in August 2011 with the resignation of the last Democrat on the bench.

In the early 21st century, Republicans hold all seven of the statewide elected executive branch offices. Republicans hold six of the eight elected seats on the Alabama State Board of Education. In 2010, Republicans took large majorities of both chambers of the state legislature, giving them control of that body for the first time in 136 years. The last remaining statewide Democrat, who served on the Alabama Public Service Commission, was defeated in 2012.[250][251][252]

Only three Republican lieutenant governors have been elected since the end of Reconstruction, when Republicans generally represented Reconstruction government, including the newly emancipated freedmen who had gained the franchise. The three GOP lieutenant governors are Steve Windom (1999–2003), Kay Ivey (2011–2017), and Will Ainsworth (2019–present).

Local elections