Движение за гражданские права

| Движение за гражданские права | |

|---|---|

1963 года Участники и лидеры Марша на Вашингтон маршируют от памятника Вашингтону к мемориалу Линкольна. | |

| Дата | 17 мая 1954 г. - 11 апреля 1968 г. [а] |

| Расположение | Соединенные Штаты |

| Вызвано | |

| Методы | |

| В результате |

|

Движение за гражданские права [б] — общественное движение и кампания, проводившаяся с 1954 по 1968 год в США с целью отмены легализованной расовой сегрегации , дискриминации и лишения избирательных прав в стране. Движение зародилось в эпоху Реконструкции в конце 19 века, а современные корни уходят в 1940-е годы. [1] успехов движение добилось хотя наибольших законодательных в 1960-х годах после многих лет прямых действий и массовых протестов. общественного движения Крупные кампании ненасильственного сопротивления и гражданского неповиновения в конечном итоге обеспечили в федеральном законе новую защиту гражданских прав всех американцев .

После Гражданской войны в США и последующей отмены рабства в 1860-х годах Реконструкционные поправки к Конституции США предоставили эмансипацию и конституционные права гражданства всем афроамериканцам , большинство из которых недавно были порабощены. В течение короткого периода времени афроамериканцы голосовали и занимали политические посты, но со временем чернокожие все больше лишались гражданских прав , часто в соответствии с расистскими законами Джима Кроу , а афроамериканцы подвергались дискриминации и постоянному насилию со стороны белых. сторонники превосходства на Юге. В течение следующего столетия афроамериканцы предпринимали различные усилия для защиты своих законных и гражданских прав, такие как движение за гражданские права (1865–1896) и движение за гражданские права (1896–1954) . Движение характеризовалось ненасильственными массовыми протестами и гражданским неповиновением после получивших широкую огласку событий, таких как линчевание Эммета Тилля . В их число входили бойкоты, такие как бойкот автобусов в Монтгомери , « сидячие забастовки». " в Гринсборо и Нэшвилле , серия протестов во время предвыборной кампании в Бирмингеме и марш от Сельмы до Монтгомери . [2] [3]

Кульминацией правовой стратегии, проводимой афроамериканцами, в 1954 году Верховный суд отменил основы законов, которые позволяли расовой сегрегации и дискриминации быть законными в Соединенных Штатах, как неконституционные. [4] [5] [6] [7] Суд Уоррена вынес ряд знаковых решений против расистской дискриминации, включая отдельную, но равную доктрину , например, Браун против Совета по образованию (1954 г.), Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. против Соединенных Штатов (1964 г.) и Ловинг против Вирджиния (1967 г.), которая запретила сегрегацию в государственных школах и общественных местах и отменила все законы штата, запрещающие межрасовые браки . [8] [9] [10] Постановления сыграли решающую роль в прекращении сегрегационных законов Джима Кроу, распространенных в южных штатах. [11] В 1960-х годах умеренные участники движения работали с Конгрессом США, чтобы добиться принятия нескольких важных федеральных законов, разрешающих надзор и обеспечение соблюдения законов о гражданских правах. Закон о гражданских правах 1964 года. [12] прямо запретил любую дискриминацию по расовому признаку, включая расовую сегрегацию в школах, на предприятиях и в общественных местах . Закон об избирательных правах 1965 года восстановил и защитил избирательные права, разрешив федеральный надзор за регистрацией и выборами в районах, где исторически сложилось недостаточное представительство избирателей из числа меньшинств. Закон о справедливом жилищном обеспечении 1968 года запретил дискриминацию при продаже или аренде жилья.

Афроамериканцы вновь вошли в политику на Юге, и молодые люди по всей стране начали действовать. С 1964 по 1970 год волна беспорядков и протестов в чернокожих общинах ослабила поддержку со стороны белого среднего класса, но увеличила поддержку со стороны частных фондов . [13] [ нужны разъяснения ] Появление движения «Власть черных» , которое продолжалось с 1965 по 1975 год, бросило вызов черным лидерам движения за их готовность к сотрудничеству и приверженность законничеству и ненасилию . Ее лидеры требовали не только юридического равенства, но и экономической самодостаточности общества. Поддержка движения «Власть черных» исходила от афроамериканцев, которые не увидели существенных существенных улучшений с момента пика движения за гражданские права в середине 1960-х годов и все еще сталкивались с дискриминацией в сфере работы, жилья, образования и политики.

Многие популярные представления о движении за гражданские права основаны на харизматическом лидерстве и философии Мартина Лютера Кинга-младшего , получившего Нобелевскую премию мира 1964 года за борьбу с расовым неравенством посредством ненасильственного сопротивления. Однако некоторые ученые отмечают, что это движение было слишком разнообразным, чтобы его можно было приписать какому-то конкретному человеку, организации или стратегии. [14]

Фон

Эпоха гражданской войны и реконструкции в США

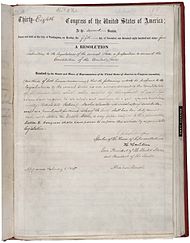

До Гражданской войны в США восемь действующих президентов владели рабами , почти четыре миллиона чернокожих людей оставались порабощенными на Юге , как правило, голосовать могли только белые мужчины, имеющие собственность, а Закон о натурализации 1790 года ограничивал гражданство США только белыми . [15] [16] [17] После Гражданской войны были приняты три поправки к конституции, в том числе 13-я поправка (1865 г.), положившая конец рабству; 14- я поправка (1869 г.), которая предоставила чернокожим гражданство, добавив их общее количество для распределения Конгрессом ; и 15-я поправка (1870 г.), которая дала чернокожим мужчинам право голоса (в то время в США голосовали только мужчины). [18] С 1865 по 1877 год Соединенные Штаты пережили бурную эпоху Реконструкции , во время которой федеральное правительство пыталось установить свободный труд и гражданские права вольноотпущенников на Юге после окончания рабства. Многие белые сопротивлялись социальным изменениям, что привело к формированию повстанческих движений, таких как Ку-клукс-клан (ККК), члены которого нападали на черных и белых республиканцев , чтобы сохранить превосходство белых . В 1871 году президент Улисс С. Грант , армия США и генеральный прокурор США Амос Т. Акерман инициировали кампанию по подавлению ККК в соответствии с Законами о правоприменении . [19] Некоторые штаты не хотели обеспечивать соблюдение федеральных мер закона. Кроме того, к началу 1870-х годов возникли другие военизированные группы сторонников превосходства белой расы и повстанцев, которые яростно выступали против юридического равенства и избирательного права афроамериканцев, запугивая и подавляя чернокожих избирателей и убивая чиновников-республиканцев. [20] [21] Однако, если штаты не выполнили эти законы, законы позволяли федеральному правительству . вмешаться [21] Многие губернаторы-республиканцы боялись отправлять чернокожих ополченцев для борьбы с кланом, опасаясь войны. [21]

Лишение избирательных прав после реконструкции

После спорных выборов 1876 года, которые привели к окончанию Реконструкции и выводу федеральных войск, белые на Юге восстановили политический контроль над законодательными собраниями штатов региона. Они продолжали запугивать и жестоко нападать на чернокожих до и во время выборов, чтобы подавить их голосование, но последние афроамериканцы были избраны в Конгресс от Юга до того, как штаты всего региона лишили чернокожих избирательных прав, как описано ниже.

С 1890 по 1908 год южные штаты приняли новые конституции и законы, лишавшие избирательных прав афроамериканцев и многих белых бедняков , создавая препятствия для регистрации избирателей; списки избирателей резко сократились, поскольку чернокожие и белые бедняки были вытеснены из избирательной политики. После знаменательного Верховного суда дела Смит против Олрайта (1944 г.), которое запретило праймериз белых , был достигнут прогресс в увеличении участия чернокожих в политической жизни на юге Рима и в Акадиане , хотя почти полностью в городских районах. [22] и несколько сельских местностей, где большинство чернокожих работали за пределами плантаций. [23] Статус -кво исключения афроамериканцев из политической системы сохранялся на остальной территории Юга, особенно в Северной Луизиане , Миссисипи и Алабаме, пока в середине 1960-х годов не было принято национальное законодательство о гражданских правах, обеспечивающее федеральное обеспечение соблюдения конституционных избирательных прав. На протяжении более шестидесяти лет чернокожие на Юге были по сути исключены из политики, не имея возможности выбирать кого-либо, кто представлял бы их интересы в Конгрессе или местных органах власти. [21] Поскольку они не могли голосовать, они не могли входить в состав местных присяжных.

В этот период Демократическая партия, в которой доминировали белые , сохраняла политический контроль над Югом. Поскольку белые контролировали все места, представляющие все население Юга, у них был мощный избирательный блок в Конгрессе. Республиканская партия — «партия Линкольна» и партия, к которой принадлежало большинство чернокожих — отошла на второй план, за исключением отдаленных юнионистских районов Аппалачей и Озаркса , поскольку регистрация чернокожих избирателей была подавлена. Республиканское движение белых лилий также набрало силу за счет исключения чернокожих. До 1965 года « Сплошной Юг » представлял собой однопартийную систему под руководством белых демократов. За исключением ранее отмеченных исторических оплотов юнионистов, выдвижение кандидатуры Демократической партии было равносильно выборам на государственные и местные должности. [24] В 1901 году президент Теодор Рузвельт пригласил Букера Т. Вашингтона , президента Института Таскиги , пообедать в Белом доме , что сделало его первым афроамериканцем, присутствовавшим на официальном ужине там. «Приглашение подверглось резкой критике со стороны южных политиков и газет». [25] Вашингтон убедил президента назначать больше чернокожих на федеральные посты на Юге и попытаться повысить лидерство афроамериканцев в республиканских организациях штатов. Однако эти действия встретили сопротивление как белых демократов, так и белых республиканцев как нежелательного федерального вторжения в политику штата. [25]

В то же время, когда афроамериканцы были лишены избирательных прав, белые южане ввели расовую сегрегацию по закону. произошли многочисленные линчевания Насилие в отношении чернокожих возросло, на рубеже веков . Система расовой дискриминации и угнетения, санкционированная де-юре государством, возникшая на Юге после Реконструкции, стала известна как система « Джима Кроу ». Верховный суд Соединенных Штатов, почти полностью состоящий из северян, подтвердил конституционность тех законов штатов, которые требовали расовой сегрегации в общественных учреждениях, в своем решении 1896 года «Плесси против Фергюсона» , узаконив их посредством доктрины « отдельного, но равного ». [27] Сегрегация, начавшаяся с рабства, продолжилась законами Джима Кроу с знаками, показывающими чернокожим, где они могут законно ходить, разговаривать, пить, отдыхать или есть. [28] В тех заведениях, где смешанные расы, небелым приходилось ждать, пока сначала обслужат всех белых клиентов. [28] Избранный в 1912 году президент Вудро Вильсон уступил требованиям членов своего кабинета с Юга и приказал провести сегрегацию рабочих мест во всем федеральном правительстве. [29]

Начало 20 века — период, который часто называют « надиром американских расовых отношений », когда количество линчеваний было самым высоким. Хотя напряженность и нарушения гражданских прав были наиболее интенсивными на Юге, социальная дискриминация затронула афроамериканцев и в других регионах. [30] На национальном уровне Южный блок контролировал важные комитеты Конгресса, воспрепятствовал принятию федеральных законов против линчевания и обладал значительной властью, превосходящей число белых на Юге.

Характеристики постреконструкционного периода:

- Расовая сегрегация . По закону общественные учреждения и государственные услуги, такие как образование, были разделены на отдельные «белые» и «цветные» сферы. [31] Характерно, что программы для цветных имели недостаточное финансирование и были низкого качества.

- Лишение избирательных прав . Когда белые демократы вернулись к власти, они приняли законы, которые сделали регистрацию избирателей более ограничительной, по сути вытеснив чернокожих избирателей из списков для голосования. Число избирателей-афроамериканцев резко сократилось, и они больше не могли выбирать представителей. С 1890 по 1908 год южные штаты бывшей Конфедерации создали конституции, положения которых лишили избирательных прав десятки тысяч афроамериканцев, а такие штаты США, как Алабама, также лишили гражданских прав белых бедняков.

- Эксплуатация . Усиление экономического притеснения чернокожих через систему аренды заключенных , латиноамериканцев и азиатов . [ нужны разъяснения ] отказ в экономических возможностях и широко распространенная дискриминация в сфере занятости.

- Насилие. Индивидуальное, полицейское, военизированное, организационное и групповое расовое насилие против чернокожих (и латиноамериканцев на Юго-Западе , и азиатов на Западном побережье ).

Афроамериканцы и другие этнические меньшинства отвергли этот режим. Они сопротивлялись этому разными способами и искали лучших возможностей посредством судебных исков, новых организаций, политического восстановления и профсоюзных организаций (см. Движение за гражданские права (1896–1954) ). Национальная ассоциация содействия прогрессу цветного населения (NAACP) была основана в 1909 году. Она боролась за прекращение расовой дискриминации посредством судебных разбирательств , образования и лоббирования . Его главным достижением стала юридическая победа в решении Верховного суда « Браун против Совета по образованию» (1954 г.), когда суд Уоррена постановил, что сегрегация государственных школ в США является неконституционной и, как следствие, отменил доктрину « отдельных, но равных ». установлено в деле Плесси против Фергюсона в 1896 году. [8] [32] После единогласного решения Верховного суда многие штаты начали постепенно интегрировать свои школы, но некоторые районы Юга воспротивились и вообще закрыли государственные школы. [8] [32]

Интеграция публичных библиотек Юга последовала за демонстрациями и протестами, в которых использовались методы, используемые в других элементах более широкого движения за гражданские права. [33] Это включало сидячие забастовки, избиения и сопротивление белых. [33] Например, в 1963 году в городе Аннистон, штат Алабама , два чернокожих министра были жестоко избиты за попытку интегрировать публичную библиотеку. [33] Несмотря на сопротивление и насилие, интеграция библиотек в целом происходила быстрее, чем интеграция других государственных учреждений. [33]

Национальные вопросы

Ситуация для чернокожих за пределами Юга была несколько лучше (в большинстве штатов они могли голосовать и давать образование своим детям, хотя они все еще сталкивались с дискриминацией в сфере жилья и работы). В 1900 году преподобный Мэтью Андерсон, выступая на ежегодной Хэмптонской негритянской конференции в Вирджинии, сказал, что «...линии вдоль большинства путей получения заработной платы более жестко прочерчены на Севере, чем на Юге. очевидные усилия по всему Северу, особенно в городах, лишить цветных рабочих всех возможностей более высокооплачиваемого труда, что затрудняет улучшение его экономического положения даже, чем на Юге». [34] С 1910 по 1970 год чернокожие искали лучшей жизни, мигрируя с Юга на север и запад. В общей сложности почти семь миллионов чернокожих покинули Юг в результате так называемой Великой миграции , большинство из которых во время и после Второй мировой войны. Так много людей мигрировали, что демография некоторых штатов, где раньше было черное большинство, изменилась на белое большинство (в сочетании с другими событиями). Быстрый приток чернокожих изменил демографию северных и западных городов; Происходя в период расширения иммиграции из Европы, Латинской Америки и Азии, это усилило социальную конкуренцию и напряженность, когда новые мигранты и иммигранты боролись за место на работе и жилье.

Отражая социальную напряженность после Первой мировой войны, когда ветераны изо всех сил пытались вернуться на работу, а профсоюзы организовывались, Красное лето 1919 года было отмечено сотнями смертей и еще большим количеством жертв по всей территории США в результате бунтов белой расы против чернокожих, которые охватили место в более чем трех десятках городов, например, расовые беспорядки в Чикаго в 1919 году и расовые беспорядки в Омахе в 1919 году . В городских проблемах, таких как преступность и болезни, обвиняли большой приток чернокожих южан в города на севере и западе, основываясь на стереотипах о сельских южных афроамериканцах. В целом чернокожие в городах Севера и Запада подвергались системной дискриминации во многих аспектах жизни. В сфере занятости экономические возможности для чернокожих были сведены к самому низкому статусу и ограничили потенциальную мобильность. На рынке жилья в связи с притоком жилья применялись более строгие дискриминационные меры, что приводило к сочетанию «целенаправленного насилия, ограничительных соглашений , красных черт и расового регулирования». ". [35] Великая миграция привела к тому, что многие афроамериканцы стали урбанизированными, и они начали переходить от Республиканской к Демократической партии, особенно из-за возможностей, предоставляемых « Новым курсом» администрации Франклина Д. Рузвельта во время Великой депрессии 1930-х годов. [36] Существенно под давлением афроамериканских сторонников, начавших движение «Марш против Вашингтона» , президент Рузвельт издал первый федеральный указ, запрещающий дискриминацию, и создал Комитет по справедливой практике трудоустройства . После обеих мировых войн чернокожие ветераны вооруженных сил настаивали на полных гражданских правах и часто возглавляли активистские движения. В 1948 году президент Гарри Трумэн издал Указ № 9981 , положивший конец сегрегации в армии . [37]

Жилищная сегрегация стала общенациональной проблемой после Великой миграции чернокожих людей с Юга. Расовые соглашения использовались многими застройщиками для «защиты» целых подразделений с основной целью сохранить « белые » районы «белыми». Девяносто процентов жилищных проектов, построенных в годы после Второй мировой войны, были ограничены такими соглашениями на расовой почве. [38] Города, известные своим широким использованием расовых соглашений, включают Чикаго , Балтимор , Детройт , Милуоки , [39] Лос-Анджелес , Сиэтл и Сент-Луис . [40]

Указанные помещения не могут сдаваться в аренду, передаваться или заниматься кем-либо, кроме белой или европеоидной расы.

— Расовый договор о доме в Беверли-Хиллз, Калифорния. [41]

В то время как многие белые защищали свое пространство насилием, запугиванием или юридической тактикой по отношению к чернокожим, многие другие белые мигрировали в более однородные в расовом отношении пригородные или пригородные регионы - процесс, известный как бегство белых . [42] С 1930-х по 1960-е годы Национальная ассоциация советов по недвижимости (NAREB) издавала руководящие принципы, в которых указывалось, что риэлтор «никогда не должен играть важную роль в представлении в районе какого-либо персонажа, собственности или места проживания, представителей какой-либо расы или национальности или любого другого лица». человек, чье присутствие явно нанесет ущерб стоимости собственности в районе». Результатом стало появление гетто, состоящих исключительно из чернокожих , на Севере и Западе, где большая часть жилья была старше, а также на Юге. [43]

Первый закон против смешанных браков был принят Генеральной ассамблеей Мэриленда в 1691 году и устанавливал уголовную ответственность за межрасовые браки . [44] В речи в Чарльстоне, штат Иллинойс , в 1858 году Авраам Линкольн заявил: «Я не сторонник и никогда не был сторонником того, чтобы избирателями или присяжными были негры, или чтобы они имели право занимать должности, или вступали в брак с белыми людьми». [45] К концу 1800-х годов в 38 штатах США были приняты законы, запрещающие смешанные браки. [44] К 1924 году запрет на межрасовые браки все еще действовал в 29 штатах. [44] Хотя межрасовые браки были законны в Калифорнии с 1948 года, в 1957 году актер Сэмми Дэвис-младший столкнулся с негативной реакцией за свою связь с белой актрисой Ким Новак . [46] Дэвис ненадолго женился на чернокожей танцовщице в 1958 году, чтобы защитить себя от насилия со стороны толпы. [46] В 1958 году офицеры в Вирджинии вошли в дом Милдред и Ричарда Ловингов и вытащили их из постели за то, что они жили вместе как межрасовая пара, на том основании, что «любой белый человек вступает в брак с цветным человеком» — или наоборот — каждая сторона». будет признан виновным в совершении тяжкого преступления» и ему грозит тюремное заключение сроком на пять лет. [44]

Воодушевленные победой Брауна и разочарованные отсутствием немедленного практического эффекта, частные граждане все чаще отвергали постепенные, легалистические подходы как основной инструмент достижения десегрегации . они столкнулись с « массовым сопротивлением На Юге » со стороны сторонников расовой сегрегации и подавления избирателей . Вопреки этому, афроамериканские активисты приняли комбинированную стратегию прямых действий , ненасилия , ненасильственного сопротивления и многих событий, описанных как гражданское неповиновение , что привело к движению за гражданские права в 1954–1968 годах.

А. Филип Рэндольф планировал марш на Вашингтон, округ Колумбия, в 1941 году в поддержку требований ликвидации дискриминации при приеме на работу в оборонной промышленности ; он отменил марш, когда администрация Рузвельта удовлетворила это требование, издав указ № 8802 , который запрещал расовую дискриминацию и создавал агентство для надзора за соблюдением указа. [47]

Протесты начинаются

Стратегия государственного просвещения, законодательного лоббирования и судебных разбирательств, которая характеризовала движение за гражданские права в первой половине 20-го века, после Брауна расширилась до стратегии, которая делала упор на « прямые действия »: бойкоты, сидячие забастовки , марши свободы , марши и т. д. прогулки и подобная тактика, основанная на массовой мобилизации, ненасильственном сопротивлении, стоянии в очереди и, иногда, гражданском неповиновении. [48]

Церкви, местные массовые организации, братские общества и предприятия, принадлежащие чернокожим, мобилизовали добровольцев для участия в широкомасштабных акциях. Это был более прямой и потенциально более быстрый способ добиться перемен, чем традиционный подход к судебным разбирательствам, используемый NAACP и другими.

В 1952 году Региональный совет негритянских лидеров (RCNL), возглавляемый Т. Р. М. Ховардом , чернокожим хирургом, предпринимателем и плантатором, организовал успешный бойкот заправочных станций в Миссисипи, которые отказывались предоставлять туалеты для чернокожих. Через RCNL Ховард руководил кампаниями по разоблачению жестокости дорожного патруля штата Миссисипи и по поощрению чернокожих делать вклады в принадлежащем чернокожим банке Tri-State Bank of Nashville, который, в свою очередь, выдавал кредиты борцам за гражданские права, ставшим жертвами «кредитное сжатие» со стороны Советов белых граждан . [49]

После того, как Клодетт Колвин была арестована за то, что не уступила свое место в автобусе в Монтгомери, штат Алабама , в марте 1955 года, вопрос о бойкоте автобуса был рассмотрен и отклонен. Но когда Розу Паркс в декабре арестовали , Джо Энн Гибсон Робинсон из Женского политического совета Монтгомери положила начало протесту против бойкота автобусов. Поздно вечером она, Джон Кэннон (заведующий кафедрой бизнеса Университета штата Алабама ) и другие напечатали на мимеографе и распространили тысячи листовок с призывом к бойкоту. [50] [51] Конечный успех бойкота сделал его представителя Мартина Лютера Кинга-младшего общенационально известной фигурой. Это также вдохновило на другие бойкоты автобусов, такие как успешный бойкот в Таллахасси, Флорида, в 1956–57 годах. [52] Это движение также спровоцировало беспорядки в «Сахарной чаше» 1956 года в Атланте, которая позже стала крупным организационным центром движения за гражданские права, во главе с Мартином Лютером Кингом-младшим. [53] [54]

В 1957 году Кинг и Ральф Абернати , лидеры Ассоциации улучшения Монтгомери, присоединились к другим церковным лидерам, которые возглавили аналогичные усилия по бойкоту, таким как К. К. Стил из Таллахасси и Т. Дж. Джемисон из Батон-Руж, а также другие активисты, такие как Фред Шаттлсворт , Элла Бейкер , А. Филип Рэндольф , Баярд Растин и Стэнли Левисон , чтобы сформировать Конференцию христианских лидеров Юга (SCLC). SCLC со штаб-квартирой в Атланте , штат Джорджия , не пытался создать сеть отделений, как это сделала NAACP. Он предлагал обучение и помощь в руководстве местными усилиями по борьбе с сегрегацией. Для поддержки таких кампаний штаб-квартира собирала средства, в основном из северных источников. Оно сделало ненасилие своим центральным принципом и основным методом борьбы с расизмом.

В 1959 году Септима Кларк , Бернис Робинсон и Исау Дженкинс с помощью Хортона Майлса народной школы горцев в Теннесси открыли первые школы гражданства на Южной Каролины морских островах . Они обучали грамоте, чтобы чернокожие могли пройти избирательные тесты. Программа имела огромный успех и утроила число чернокожих избирателей на острове Джонс . SCLC взял на себя программу и продублировал ее результаты в других местах.

История

Браун против Совета по образованию , 1954 г.

Весной 1951 года чернокожие студенты Вирджинии протестовали против своего неравного статуса в сегрегированной образовательной системе штата. Учащиеся средней школы Мотона протестовали против переполненности и неудовлетворительного состояния помещений. [55] Некоторые местные лидеры NAACP пытались убедить учеников отказаться от протеста против законов Джима Кроу о школьной сегрегации. Когда ученики не сдвинулись с места, NAACP присоединилась к их борьбе против школьной сегрегации. NAACP рассмотрела пять дел, бросающих вызов школьной системе; Позже они были объединены в одно дело, известное сегодня как «Браун против Совета по образованию» . [55] Под руководством Уолтера Ройтера Объединение работников автомобильной промышленности пожертвовало 75 000 долларов на оплату усилий NAACP в Верховном суде. [56]

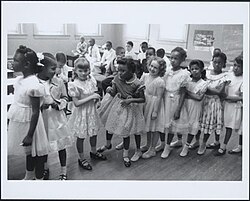

17 мая 1954 года Верховный суд США под руководством главного судьи Эрла Уоррена единогласно постановил в деле Браун против Совета по образованию Топики, штат Канзас , что требование или даже разрешение разделения государственных школ по расовому признаку является неконституционным . [8] Главный судья Уоррен написал в заключении большинства суда, что [8] [32]

Сегрегация белых и цветных детей в государственных школах оказывает пагубное воздействие на цветных детей. Воздействие сильнее, когда оно санкционировано законом; поскольку политика разделения рас обычно интерпретируется как обозначение неполноценности негритянской группы. [57]

Юристам NAACP пришлось собрать правдоподобные доказательства, чтобы выиграть дело Браун против Совета по образованию . Их метод решения проблемы школьной сегрегации заключался в перечислении нескольких аргументов. Один из них касался межрасовых контактов в школьной среде. Утверждалось, что межрасовые контакты, в свою очередь, помогут подготовить детей к тому, чтобы жить с давлением, которое общество оказывает в отношении расы, и тем самым дадут им больше шансов жить в условиях демократии. Кроме того, другой аргумент подчеркивал, что «образование охватывает весь процесс развития и тренировки умственных, физических и моральных сил и способностей человека». [58]

Риса Голубофф написала, что целью NAACP было показать судам, что афроамериканские дети стали жертвами школьной сегрегации и их будущее находится под угрозой. Суд постановил, что как Плесси против Фергюсона (1896 г.), которое установило «отдельный, но равный» стандарт в целом, так и Камминг против Совета по образованию округа Ричмонд (1899 г.), которое применило этот стандарт к школам, были неконституционными.

Федеральное правительство представило в суд записку по этому делу, призывая судей принять во внимание влияние сегрегации на имидж Америки во время холодной войны . слова госсекретаря Дина Ачесона В докладе цитировались , в котором говорится, что «Соединенные Штаты находятся под постоянными нападками в иностранной прессе, по зарубежному радио и в таких международных организациях, как Организация Объединенных Наций, из-за различных видов дискриминации в этой стране». [59] [60]

В следующем году по делу, известному как «Браун II» , суд постановил постепенно сокращать сегрегацию «со всей сознательной скоростью». [61] Дело Браун против Совета по образованию Топики, штат Канзас (1954 г.) не отменило дело Плесси против Фергюсона (1896 г.). Дело Плесси против Фергюсона касалось сегрегации в видах транспорта. Дело Браун против Совета по образованию касалось сегрегации в сфере образования. Дело «Браун против Совета по образованию» положило начало будущему отмене принципа «отдельные, но равные».

18 мая 1954 года Гринсборо, штат Северная Каролина Верховного суда по делу Браун против Совета по образованию , стал первым городом на Юге, публично объявившим, что он будет соблюдать решение . «Немыслимо, — заметил суперинтендант школьного совета Бенджамин Смит, — что мы попытаемся обойти законы Соединенных Штатов». [62] Этот положительный прием Брауна, а также назначение афроамериканца Дэвида Джонса в школьный совет в 1953 году убедили многих белых и чернокожих граждан в том, что Гринсборо движется в прогрессивном направлении. Интеграция в Гринсборо прошла довольно мирно по сравнению с процессом в южных штатах, таких как Алабама, Арканзас и Вирджиния, где « массовое сопротивление » практиковалось высшими чиновниками и во всех штатах. В Вирджинии некоторые округа вместо того, чтобы интегрироваться, закрыли свои государственные школы, и многие частные школы для белых христиан были основаны для приема учащихся, которые раньше ходили в государственные школы. Даже в Гринсборо продолжалось активное сопротивление десегрегации на местном уровне, и в 1969 году федеральное правительство обнаружило, что город не соблюдает Закон о гражданских правах 1964 года. Переход к полностью интегрированной школьной системе начался только в 1971 году. [62]

Во многих северных городах де-факто проводилась политика сегрегации , что привело к огромному разрыву в образовательных ресурсах между черными и белыми сообществами. В Гарлеме , штат Нью-Йорк, например, с начала века не было построено ни одной новой школы и не существовало ни одного детского сада – даже несмотря на то, что Вторая Великая миграция вызывала перенаселенность. Существующие школы, как правило, были ветхими и укомплектованы неопытными учителями. Браун помог стимулировать активность среди Нью-Йорка, родителей таких как Мэй Мэллори , которая при поддержке NAACP инициировала успешный иск против города и штата на Брауна принципах . Мэллори и тысячи других родителей усилили давление иска бойкотом школ в 1959 году. Во время бойкота были созданы некоторые из первых свободных школ того периода. Город отреагировал на кампанию, разрешив более открытый перевод в высококачественные школы, исторически сложившиеся для белых. (Афро-американское сообщество Нью-Йорка и активисты северной десегрегации в целом столкнулись с проблемой белый полет , однако.) [63] [64]

Убийство Эммета Тилля, 1955 год.

Эммет Тилль , 14-летний афроамериканец из Чикаго, навестил своих родственников в Мани, штат Миссисипи летом . Утверждается, что он вступил в контакт с белой женщиной Кэролайн Брайант в небольшом продуктовом магазине, что нарушило нормы культуры штата Миссисипи, а муж Брайанта Рой и его сводный брат Дж. В. Милам жестоко убили молодого Эммета Тилла. Они избили и изувечили его, а затем выстрелили ему в голову и утопили тело в реке Таллахатчи . Три дня спустя тело Тилля было обнаружено и извлечено из реки. В честь матери Эммета, Мейми Тилль , [65] Придя опознать останки своего сына, она решила, что хочет «дать людям увидеть то, что видела я». [66] Затем мать Тилля отвезла его тело обратно в Чикаго, где она выставила его в открытом гробу во время панихиды, куда прибыли многие тысячи посетителей, чтобы выразить свое почтение. [66] Более поздняя публикация изображения на похоронах в журнале Jet считается решающим моментом в эпоху гражданских прав, поскольку в ярких деталях продемонстрирован жестокий расизм, направленный против чернокожих людей в Америке. [67] [66] В колонке для The Atlantic Ванн Р. Ньюкирк написал: «Суд над его убийцами стал зрелищем, освещающим тиранию превосходства белой расы ». [2] В штате Миссисипи судили двух обвиняемых, но они были быстро оправданы присяжными, состоявшими исключительно из белых . [68]

«Убийство Эммета, — пишет историк Тим Тайсон, — никогда не стало бы переломным историческим моментом, если бы Мейми не нашла в себе силы сделать свое личное горе достоянием общественности». [69] Интуитивная реакция на решение его матери устроить похороны в открытом гробу мобилизовала чернокожее сообщество по всей территории США. [2] Убийство и последовавший за ним суд заметно повлияли на взгляды нескольких молодых чернокожих активистов. [69] Джойс Ладнер называла таких активистов «поколением Эммета Тилля». [69] Через сто дней после убийства Эммета Тилля Роза Паркс отказалась уступить место в автобусе в Монтгомери, штат Алабама. [70] Позже Паркс сообщила матери Тилля, что ее решение остаться на своем месте было основано на образе изуродованных останков Тилля, который она до сих пор отчетливо помнит. [70] Гроб со стеклянной крышкой, который использовался на похоронах Тилля в Чикаго, был найден в гараже кладбища в 2009 году. Тилль был перезахоронен в другом гробу после эксгумации в 2005 году. [71] Семья Тилля решила подарить оригинальную шкатулку Смитсоновскому национальному музею афроамериканской культуры и истории, где она сейчас выставлена. [72] В 2007 году Брайант заявила, что самую сенсационную часть своей истории она сфабриковала в 1955 году. [67] [73]

Роза Паркс и бойкот автобусов в Монтгомери, 1955–1956 гг.

1 декабря 1955 года, через девять месяцев после того, как 15-летняя ученица средней школы Клодетт Колвин отказалась уступить место белому пассажиру общественного автобуса в Монтгомери, штат Алабама, и была арестована, Роза Паркс сделала то же самое. вещь. Вскоре Паркс стал символом бойкота автобусов в Монтгомери и получил общенациональную огласку. Позже ее провозгласили «матерью движения за гражданские права». [74]

Паркс был секретарем отделения NAACP в Монтгомери и недавно вернулся со встречи в Народной школе горцев и другие преподавали ненасилие как стратегию в Теннесси, где Майлз Хортон . После ареста Паркса афроамериканцы собрались и организовали бойкот автобусов в Монтгомери, чтобы потребовать создания автобусной системы, в которой с пассажирами будут обращаться одинаково. [75] Организацию возглавила Джо Энн Робинсон, член Женского политического совета, которая ждала возможности бойкотировать автобусную систему. После ареста Розы Паркс Джо Энн Робинсон напечатала на мимеографе 52 500 листовок с призывами к бойкоту. Они были распространены по городу и помогли привлечь внимание лидеров гражданских прав. После того, как город отверг многие из предложенных реформ, NAACP во главе с Э.Д. Никсоном выступила за полную десегрегацию общественных автобусов. При поддержке большинства из 50 000 афроамериканцев Монтгомери бойкот длился 381 день, пока не было отменено местное постановление, разделяющее афроамериканцев и белых в общественных автобусах. Девяносто процентов афроамериканцев в Монтгомери приняли участие в бойкоте, что значительно снизило доходы от автобусов, поскольку они составляли большинство пассажиров. Это движение также спровоцировало беспорядки, приведшие к « Сахарной чаше» 1956 года . [76] В ноябре 1956 года Верховный суд США оставил в силе решение окружного суда по делу Браудер против Гейла и приказал отменить сегрегацию в автобусах Монтгомери, положив конец бойкоту. [75]

Местные лидеры создали Ассоциацию улучшения Монтгомери, чтобы сосредоточить свои усилия. Мартин Лютер Кинг-младший был избран президентом этой организации. Длительный протест привлек внимание всей страны к нему и городу. Его красноречивые призывы к христианскому братству и американскому идеализму произвели положительное впечатление на людей как внутри Юга, так и за его пределами. [51]

Литл-Рок-девять, 1957 год.

«Литл-Рокская девятка» — группа из девяти студентов, посещавших отдельные средние школы для чернокожих в Литл-Роке , столице штата Арканзас. Каждый из них вызвался добровольцем, когда в сентябре 1957 года NAACP и национальное движение за гражданские права получили постановление федерального суда об объединении престижной Центральной средней школы Литл-Рока . «Девять» столкнулись с сильными преследованиями и угрозами насилия со стороны белых родителей и учеников, а также организованных белых группы превосходства. Разъяренная оппозиция подчеркивала смешанные браки как угрозу белому обществу. Губернатор Арканзаса , Орвал Фаубус заявивший, что его единственной целью было сохранение мира, задействовал Национальную гвардию Арканзаса, чтобы не допустить проникновения чернокожих учеников в школу. Фаубус проигнорировал постановления федерального суда, после чего вмешался президент Дуайт Д. Эйзенхауэр. Он федерализовал Национальную гвардию Арканзаса и отправил ее домой. Затем он послал элитное армейское подразделение, чтобы сопровождать учеников в школу и защищать их между уроками в течение 1957–58 учебного года. Однако в классе Девять каждый день дразнили и высмеивали. В городе все усилия по достижению компромисса потерпели неудачу, и политическая напряженность продолжала нарастать. Год спустя, в сентябре 1958 года, Верховный суд постановил, что все средние школы города должны быть немедленно объединены. Губернатор Фобус и законодательный орган в ответ немедленно закрыли все государственные средние школы города на весь 1958–1959 учебный год, несмотря на вред, который это причинило всем учащимся. Решение объединить школу стало знаковым событием в движении за гражданские права, а храбрость и решимость учащихся перед лицом жестокой оппозиции запомнились как ключевой момент в американской истории. Город и штат на протяжении десятилетий были вовлечены в очень дорогостоящие юридические споры, имея при этом репутацию места ненависти и обструкции. [77] [78]

Метод ненасилия и обучения ненасилию

В период времени, который считается эрой «афроамериканских гражданских прав», преобладающее использование протеста было ненасильственным или мирным. [79] Метод ненасилия, который часто называют пацифизмом, считается попыткой положительно повлиять на общество. Хотя акты расовой дискриминации исторически происходили на всей территории Соединенных Штатов, возможно, самые жестокие регионы были в бывших штатах Конфедерации. В 1950-х и 1960-х годах ненасильственные протесты движения за гражданские права вызвали определенную напряженность, которая привлекла внимание всей страны.

Чтобы подготовиться к протестам физически и психологически, демонстранты прошли обучение ненасилию. По словам бывшего борца за гражданские права Брюса Хартфорда, обучение ненасилию состоит из двух основных компонентов. Есть философский метод, который предполагает понимание метода ненасилия и того, почему он считается полезным, и есть тактический метод, который в конечном итоге учит демонстрантов, «как быть протестующим – как сидеть, как пикетировать, как защищайтесь от нападений, обучая тому, как сохранять хладнокровие, когда люди выкрикивают вам в лицо расистские оскорбления, обливают вас всякой всячиной и бьют» (Архив Движения за гражданские права). Философская основа практики ненасилия в американском движении за гражданские права во многом была вдохновлена Махатмы Ганди во политикой «отказа от сотрудничества» время его участия в движении за независимость Индии , которая была призвана привлечь внимание, чтобы общественность либо « вмешаться заранее» или «оказать общественное давление в поддержку действий, которые необходимо предпринять» (Эриксон, 415). Как объясняет Хартфорд, философское обучение ненасилию направлено на «формирование отношения и психической реакции отдельного человека на кризисы и насилие» (Архив Движения за гражданские права). Хартфорд и подобные ему активисты, обучавшиеся тактическому ненасилию, считали это необходимым для того, чтобы обеспечить физическую безопасность, привить дисциплину, научить демонстрантов проводить демонстрации и сформировать взаимное доверие среди демонстрантов (Архив Движения за гражданские права). [79] [80]

Для многих концепция ненасильственного протеста была образом жизни, культурой. Однако не все согласились с этим мнением. Джеймс Форман, бывший член SNCC (а позже «Черной пантеры») и тренер по ненасилию, был среди тех, кто этого не сделал. В своей автобиографии «Становление черных революционеров » Форман раскрыл свой взгляд на метод ненасилия как «исключительно тактику, а не образ жизни без ограничений». Точно так же Боб Мозес , который также был активным членом SNCC , считал, что метод ненасилия практичен. В интервью писателю Роберту Пенну Уоррену Мозес сказал: «Нет сомнений в том, что он ( Мартин Лютер Кинг-младший ) имел большое влияние на массы. Но я не думаю, что это в направлении любви. Это в практическом плане. направление … ." (Кто говорит за негров? Уоррен). [81] [82]

Согласно исследованию 2020 года, опубликованному в журнале American Political Science Review , ненасильственные протесты за гражданские права увеличили долю голосов за Демократическую партию на президентских выборах в близлежащих округах, но насильственные протесты существенно увеличили поддержку республиканцев со стороны белых в округах, близких к местам насильственных протестов. [83]

Сидячие забастовки, 1958–1960 гг.

В июле 1958 года Молодежный совет NAACP спонсировал сидячие забастовки у обеденной стойки аптеки Dockum в центре Уичито, штат Канзас . Через три недели движение успешно убедило магазин изменить политику разделения мест, и вскоре после этого все магазины Dockum в Канзасе были десегрегированы. За этим движением в том же году вскоре последовала сидячая студенческая забастовка в аптеке Кац в Оклахома-Сити, которую возглавила Клара Лупер , которая также имела успех. [84]

В основном чернокожие студенты местных колледжей возглавили сидячую забастовку у магазина Woolworth 's в Гринсборо, Северная Каролина . [85] 1 февраля 1960 года четверо студентов, Эзелл А. Блер-младший , Дэвид Ричмонд, Джозеф Макнил и Франклин Маккейн из сельскохозяйственно-технического колледжа Северной Каролины , колледжа, в котором обучались исключительно чернокожие, сели за отдельную обеденную стойку в знак протеста против политики Вулворта. запретить афроамериканцам получать там еду. [86] Четверо студентов купили мелкие товары в других частях магазина и сохранили чеки, затем сели за обеденную стойку и попросили, чтобы их обслужили. Получив отказ в обслуживании, они предъявили чеки и спросили, почему их деньги хороши везде в магазине, но не у обеденной стойки. [87]

Протестующим было предложено одеться профессионально, сидеть тихо и занимать все остальные стулья, чтобы к ним могли присоединиться потенциальные сторонники белых. За сидячей забастовкой в Гринсборо быстро последовали другие сидячие забастовки в Ричмонде, штат Вирджиния ; [88] [89] Нэшвилл, Теннесси ; и Атланта, Джорджия. [90] [91] Самый эффектный из них был в Нэшвилле, где сотни хорошо организованных и дисциплинированных студентов колледжей провели сидячие забастовки в рамках кампании бойкота. [92] [93] Когда студенты на юге страны начали «сидеть» за обеденными стойками местных магазинов, полиция и другие официальные лица иногда применяли жестокую силу, чтобы физически выпроводить демонстрантов из обеденных залов.

Техника «сидячей забастовки» не была новой: еще в 1939 году афроамериканский адвокат Сэмюэл Уилберт Такер организовал сидячую забастовку в тогда еще изолированной библиотеке Александрии, штат Вирджиния . [94] В 1960 году этой технике удалось привлечь к движению внимание всей страны. [95] 9 марта 1960 года Университетского центра Атланты группа студентов опубликовала «Призыв к правам человека» в виде полностраничной рекламы в газетах, включая « Атланта Конститушн» , «Атланта Джорнал» и «Атланта Дейли Уорлд» . [96] Известная как Апелляционный комитет по правам человека (COAHR), группа инициировала Студенческое движение Атланты и начала проводить сидячие забастовки, начиная с 15 марта 1960 года. [91] [97] К концу 1960 года процесс сидячих забастовок распространился на все южные и пограничные штаты и даже на учреждения в Неваде , Иллинойсе и Огайо , которые дискриминировали чернокожих.

Демонстранты сосредоточили внимание не только на обеденных стойках, но и на парках, пляжах, библиотеках, театрах, музеях и других общественных объектах. В апреле 1960 года активисты, возглавлявшие эти сидячие забастовки, были приглашены активисткой SCLC Эллой Бейкер провести конференцию в Университете Шоу , исторически сложившемся университете для чернокожих в Роли, Северная Каролина . Эта конференция привела к созданию Студенческого координационного комитета ненасильственных действий (SNCC). [98] SNCC развила эту тактику ненасильственной конфронтации и организовала «поездки за свободу». Поскольку конституция защищала торговлю между штатами, они решили бросить вызов сегрегации в автобусах между штатами и в общественных автобусах, разместив в них межрасовые команды, которые будут путешествовать с Севера через сегрегированный Юг. [99]

Поездки свободы, 1961 год.

«Поездки свободы» - это поездки борцов за гражданские права на междуштатных автобусах в сегрегированные южные районы Соединенных Штатов с целью проверки решения Верховного суда США «Бойнтон против Вирджинии» (1960 г.), которое постановило, что сегрегация является неконституционной для пассажиров, совершающих поездки между штатами. Организованная CORE , первая поездка свободы 1960-х годов покинула Вашингтон, округ Колумбия, 4 мая 1961 года и должна была прибыть в Новый Орлеан 17 мая. [100]

During the first and subsequent Freedom Rides, activists traveled through the Deep South to integrate seating patterns on buses and desegregate bus terminals, including restrooms and water fountains. That proved to be a dangerous mission. In Anniston, Alabama, one bus was firebombed, forcing its passengers to flee for their lives.[101]

In Birmingham, Alabama, an FBI informant reported that Public Safety Commissioner Eugene "Bull" Connor gave Ku Klux Klan members fifteen minutes to attack an incoming group of freedom riders before having police "protect" them. The riders were severely beaten "until it looked like a bulldog had got a hold of them." James Peck, a white activist, was beaten so badly that he required fifty stitches to his head.[101]

In a similar occurrence in Montgomery, Alabama, the Freedom Riders followed in the footsteps of Rosa Parks and rode an integrated Greyhound bus from Birmingham. Although they were protesting interstate bus segregation in peace, they were met with violence in Montgomery as a large, white mob attacked them for their activism. They caused an enormous, 2-hour long riot which resulted in 22 injuries, five of whom were hospitalized.[102]

Mob violence in Anniston and Birmingham temporarily halted the rides. SNCC activists from Nashville brought in new riders to continue the journey from Birmingham to New Orleans. In Montgomery, Alabama, at the Greyhound Bus Station, a mob charged another busload of riders, knocking John Lewis[103] unconscious with a crate and smashing Life photographer Don Urbrock in the face with his own camera. A dozen men surrounded James Zwerg,[104] a white student from Fisk University, and beat him in the face with a suitcase, knocking out his teeth.[101]

On May 24, 1961, the freedom riders continued their rides into Jackson, Mississippi, where they were arrested for "breaching the peace" by using "white only" facilities. New Freedom Rides were organized by many different organizations and continued to flow into the South. As riders arrived in Jackson, they were arrested. By the end of summer, more than 300 had been jailed in Mississippi.[100]

… When the weary Riders arrive in Jackson and attempt to use "white only" restrooms and lunch counters they are immediately arrested for Breach of Peace and Refusal to Obey an Officer. Says Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett in defense of segregation: "The Negro is different because God made him different to punish him." From lockup, the Riders announce "Jail No Bail"—they will not pay fines for unconstitutional arrests and illegal convictions—and by staying in jail they keep the issue alive. Each prisoner will remain in jail for 39 days, the maximum time they can serve without losing their right to appeal the unconstitutionality of their arrests, trials, and convictions. After 39 days, they file an appeal and post bond...[105]

The jailed freedom riders were treated harshly, crammed into tiny, filthy cells and sporadically beaten. In Jackson, some male prisoners were forced to do hard labor in 100 °F (38 °C) heat. Others were transferred to the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, where they were treated to harsh conditions. Sometimes the men were suspended by "wrist breakers" from the walls. Typically, the windows of their cells were shut tight on hot days, making it hard for them to breathe.

Public sympathy and support for the freedom riders led John F. Kennedy's administration to order the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to issue a new desegregation order. When the new ICC rule took effect on November 1, 1961, passengers were permitted to sit wherever they chose on the bus; "white" and "colored" signs came down in the terminals; separate drinking fountains, toilets, and waiting rooms were consolidated; and lunch counters began serving people regardless of skin color.

The student movement involved such celebrated figures as John Lewis, a single-minded activist; James Lawson,[106] the revered "guru" of nonviolent theory and tactics; Diane Nash,[107] an articulate and intrepid public champion of justice; Bob Moses, pioneer of voting registration in Mississippi; and James Bevel, a fiery preacher and charismatic organizer, strategist, and facilitator. Other prominent student activists included Dion Diamond,[108] Charles McDew, Bernard Lafayette,[109] Charles Jones, Lonnie King, Julian Bond,[110] Hosea Williams, and Stokely Carmichael.

Voter registration organizing

After the Freedom Rides, local black leaders in Mississippi such as Amzie Moore, Aaron Henry, Medgar Evers, and others asked SNCC to help register black voters and to build community organizations that could win a share of political power in the state. Since Mississippi ratified its new constitution in 1890 with provisions such as poll taxes, residency requirements, and literacy tests, it made registration more complicated and stripped blacks from voter rolls and voting. Also, violence at the time of elections had earlier suppressed black voting.

By the mid-20th century, preventing blacks from voting had become an essential part of the culture of white supremacy. In June and July 1959, members of the black community in Fayette County, TN formed the Fayette County Civic and Welfare League to spur voting. At the time, there were 16,927 blacks in the county, yet only 17 of them had voted in the previous seven years. Within a year, some 1,400 blacks had registered, and the white community responded with harsh economic reprisals. Using registration rolls, the White Citizens Council circulated a blacklist of all registered black voters, allowing banks, local stores, and gas stations to conspire to deny registered black voters essential services. What's more, sharecropping blacks who registered to vote were getting evicted from their homes. All in all, the number of evictions came to 257 families, many of whom were forced to live in a makeshift Tent City for well over a year. Finally, in December 1960, the Justice Department invoked its powers authorized by the Civil Rights Act of 1957 to file a suit against seventy parties accused of violating the civil rights of black Fayette County citizens.[111] In the following year the first voter registration project in McComb and the surrounding counties in the Southwest corner of the state. Their efforts were met with violent repression from state and local lawmen, the White Citizens' Council, and the Ku Klux Klan. Activists were beaten, there were hundreds of arrests of local citizens, and the voting activist Herbert Lee was murdered.[112]

White opposition to black voter registration was so intense in Mississippi that Freedom Movement activists concluded that all of the state's civil rights organizations had to unite in a coordinated effort to have any chance of success. In February 1962, representatives of SNCC, CORE, and the NAACP formed the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO). At a subsequent meeting in August, SCLC became part of COFO.[113]

In the Spring of 1962, with funds from the Voter Education Project, SNCC/COFO began voter registration organizing in the Mississippi Delta area around Greenwood, and the areas surrounding Hattiesburg, Laurel, and Holly Springs. As in McComb, their efforts were met with fierce opposition—arrests, beatings, shootings, arson, and murder. Registrars used the literacy test to keep blacks off the voting roles by creating standards that even highly educated people could not meet. In addition, employers fired blacks who tried to register, and landlords evicted them from their rental homes.[114] Despite these actions, over the following years, the black voter registration campaign spread across the state.

Similar voter registration campaigns—with similar responses—were begun by SNCC, CORE, and SCLC in Louisiana, Alabama, southwest Georgia, and South Carolina. By 1963, voter registration campaigns in the South were as integral to the Freedom Movement as desegregation efforts. After the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,[12] protecting and facilitating voter registration despite state barriers became the main effort of the movement. It resulted in the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which had provisions to enforce the constitutional right to vote for all citizens.

Integration of Mississippi universities, 1956–1965

Beginning in 1956, Clyde Kennard, a black Korean War-veteran, wanted to enroll at Mississippi Southern College (now the University of Southern Mississippi) at Hattiesburg under the G.I. Bill. William David McCain, the college president, used the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, in order to prevent his enrollment by appealing to local black leaders and the segregationist state political establishment.[115]

The state-funded organization tried to counter the civil rights movement by positively portraying segregationist policies. More significantly, it collected data on activists, harassed them legally, and used economic boycotts against them by threatening their jobs (or causing them to lose their jobs) to try to suppress their work.

Kennard was twice arrested on trumped-up charges, and eventually convicted and sentenced to seven years in the state prison.[116] After three years at hard labor, Kennard was paroled by Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett. Journalists had investigated his case and publicized the state's mistreatment of his colon cancer.[116]

McCain's role in Kennard's arrests and convictions is unknown.[117][118][119][120] While trying to prevent Kennard's enrollment, McCain made a speech in Chicago, with his travel sponsored by the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission. He described the blacks' seeking to desegregate Southern schools as "imports" from the North. (Kennard was a native and resident of Hattiesburg.) McCain said:

We insist that educationally and socially, we maintain a segregated society...In all fairness, I admit that we are not encouraging Negro voting...The Negroes prefer that control of the government remain in the white man's hands.[117][119][120]

Note: Mississippi had passed a new constitution in 1890 that effectively disfranchised most blacks by changing electoral and voter registration requirements; although it deprived them of constitutional rights authorized under post-Civil War amendments, it survived U.S. Supreme Court challenges at the time. It was not until after the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that most blacks in Mississippi and other southern states gained federal protection to enforce the constitutional right of citizens to vote.

In September 1962, James Meredith won a lawsuit to secure admission to the previously segregated University of Mississippi. He attempted to enter campus on September 20, on September 25, and again on September 26. He was blocked by Governor Ross Barnett, who said, "[N]o school will be integrated in Mississippi while I am your Governor." The Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals held Barnett and Lieutenant Governor Paul B. Johnson Jr. in contempt, ordering them arrested and fined more than $10,000 for each day they refused to allow Meredith to enroll.

Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy sent in a force of U.S. Marshals and deputized U.S. Border Patrol agents and Federal Bureau of Prisons officers. On September 30, 1962, Meredith entered the campus under their escort. Students and other whites began rioting that evening, throwing rocks and firing on the federal agents guarding Meredith at Lyceum Hall. Rioters ended up killing two civilians, including a French journalist; 28 federal agents suffered gunshot wounds, and 160 others were injured. President John F. Kennedy sent U.S. Army and federalized Mississippi National Guard forces to the campus to quell the riot. Meredith began classes the day after the troops arrived.[121]

Kennard and other activists continued to work on public university desegregation. In 1965 Raylawni Branch and Gwendolyn Elaine Armstrong became the first African-American students to attend the University of Southern Mississippi. By that time, McCain helped ensure they had a peaceful entry.[122] In 2006, Judge Robert Helfrich ruled that Kennard was factually innocent of all charges for which he had been convicted in the 1950s.[116]

Albany Movement, 1961–1962

The SCLC, which had been criticized by some student activists for its failure to participate more fully in the freedom rides, committed much of its prestige and resources to a desegregation campaign in Albany, Georgia, in November 1961. King, who had been criticized personally by some SNCC activists for his distance from the dangers that local organizers faced—and given the derisive nickname "De Lawd" as a result—intervened personally to assist the campaign led by both SNCC organizers and local leaders.

The campaign was a failure because of the canny tactics of Laurie Pritchett, the local police chief, and divisions within the black community. The goals may not have been specific enough. Pritchett contained the marchers without violent attacks on demonstrators that inflamed national opinion. He also arranged for arrested demonstrators to be taken to jails in surrounding communities, allowing plenty of room to remain in his jail. Pritchett also foresaw King's presence as a danger and forced his release to avoid King's rallying the black community. King left in 1962 without having achieved any dramatic victories. The local movement, however, continued the struggle, and it obtained significant gains in the next few years.[123]

Birmingham campaign, 1963

The Albany movement was shown to be an important education for the SCLC, however, when it undertook the Birmingham campaign in 1963. Executive Director Wyatt Tee Walker carefully planned the early strategy and tactics for the campaign. It focused on one goal—the desegregation of Birmingham's downtown merchants, rather than total desegregation, as in Albany.

The movement's efforts were helped by the brutal response of local authorities, in particular Eugene "Bull" Connor, the Commissioner of Public Safety. He had long held much political power but had lost a recent election for mayor to a less rabidly segregationist candidate. Refusing to accept the new mayor's authority, Connor intended to stay in office.

The campaign used a variety of nonviolent methods of confrontation, including sit-ins, kneel-ins at local churches, and a march to the county building to mark the beginning of a drive to register voters. The city, however, obtained an injunction barring all such protests. Convinced that the order was unconstitutional, the campaign defied it and prepared for mass arrests of its supporters. King elected to be among those arrested on April 12, 1963.[124]

While in jail, King wrote his famous "Letter from Birmingham Jail"[125] on the margins of a newspaper, since he had not been allowed any writing paper while held in solitary confinement.[126] Supporters appealed to the Kennedy administration, which intervened to obtain King's release. Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers, arranged for $160,000 to bail out King and his fellow protestors.[127] King was allowed to call his wife, who was recuperating at home after the birth of their fourth child and was released early on April 19.

The campaign, however, faltered as it ran out of demonstrators willing to risk arrest. James Bevel, SCLC's Director of Direct Action and Director of Nonviolent Education, then came up with a bold and controversial alternative: to train high school students to take part in the demonstrations. As a result, in what would be called the Children's Crusade, more than one thousand students skipped school on May 2 to meet at the 16th Street Baptist Church to join the demonstrations. More than six hundred marched out of the church fifty at a time in an attempt to walk to City Hall to speak to Birmingham's mayor about segregation. They were arrested and put into jail. In this first encounter, the police acted with restraint. On the next day, however, another one thousand students gathered at the church. When Bevel started them marching fifty at a time, Bull Connor finally unleashed police dogs on them and then turned the city's fire hoses water streams on the children. National television networks broadcast the scenes of the dogs attacking demonstrators and the water from the fire hoses knocking down the schoolchildren.[128]

Widespread public outrage led the Kennedy administration to intervene more forcefully in negotiations between the white business community and the SCLC. On May 10, the parties announced an agreement to desegregate the lunch counters and other public accommodations downtown, to create a committee to eliminate discriminatory hiring practices, to arrange for the release of jailed protesters, and to establish regular means of communication between black and white leaders.

Not everyone in the black community approved of the agreement—Fred Shuttlesworth was particularly critical, since he was skeptical about the good faith of Birmingham's power structure from his experience in dealing with them. Parts of the white community reacted violently. They bombed the Gaston Motel, which housed the SCLC's unofficial headquarters, and the home of King's brother, the Reverend A. D. King. In response, thousands of blacks rioted, burning numerous buildings and one of them stabbed and wounded a police officer.[129]

Kennedy prepared to federalize the Alabama National Guard if the need arose. Four months later, on September 15, a conspiracy of Ku Klux Klan members bombed the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, killing four young girls.

"Rising tide of discontent" and Kennedy's response, 1963

Birmingham was only one of over a hundred cities rocked by the chaotic protest that spring and summer, some of them in the North but mainly in the South. During the March on Washington, Martin Luther King Jr. would refer to such protests as "the whirlwinds of revolt." In Chicago, blacks rioted through the South Side in late May after a white police officer shot a fourteen-year-old black boy who was fleeing the scene of a robbery.[130] Violent clashes between black activists and white workers took place in both Philadelphia and Harlem in successful efforts to integrate state construction projects.[131][132] On June 6, over a thousand whites attacked a sit-in in Lexington, North Carolina; blacks fought back and one white man was killed.[133][134] Edwin C. Berry of the National Urban League warned of a complete breakdown in race relations: "My message from the beer gardens and the barbershops all indicate the fact that the Negro is ready for war."[130]

In Cambridge, Maryland, a working‐class city on the Eastern Shore, Gloria Richardson of SNCC led a movement that pressed for desegregation but also demanded low‐rent public housing, job‐training, public and private jobs, and an end to police brutality.[135] On June 11, struggles between blacks and whites escalated into violent rioting, leading Maryland Governor J. Millard Tawes to declare martial law. When negotiations between Richardson and Maryland officials faltered, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy directly intervened to negotiate a desegregation agreement.[136] Richardson felt that the increasing participation of poor and working-class blacks was expanding both the power and parameters of the movement, asserting that "the people as a whole really do have more intelligence than a few of their leaders.ʺ[135]

In their deliberations during this wave of protests, the Kennedy administration privately felt that militant demonstrations were ʺbad for the countryʺ and that "Negroes are going to push this thing too far."[137] On May 24, Robert Kennedy had a meeting with prominent black intellectuals to discuss the racial situation. The black delegation criticized Kennedy harshly for vacillating on civil rights and said that the African-American community's thoughts were increasingly turning to violence. The meeting ended with ill will on all sides.[138][139][140] Nonetheless, the Kennedys ultimately decided that new legislation for equal public accommodations was essential to drive activists "into the courts and out of the streets."[137][141]

On June 11, 1963, George Wallace, Governor of Alabama, tried to block[142] the integration of the University of Alabama. President John F. Kennedy sent a military force to make Governor Wallace step aside, allowing the enrollment of Vivian Malone Jones and James Hood. That evening, President Kennedy addressed the nation on TV and radio with his historic civil rights speech, where he lamented "a rising tide of discontent that threatens the public safety." He called on Congress to pass new civil rights legislation, and urged the country to embrace civil rights as "a moral issue...in our daily lives."[143] In the early hours of June 12, Medgar Evers, field secretary of the Mississippi NAACP, was assassinated by a member of the Klan.[144][145] The next week, as promised, on June 19, 1963, President Kennedy submitted his Civil Rights bill to Congress.[146]

March on Washington, 1963

Randolph and Bayard Rustin were the chief planners of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which they proposed in 1962. In 1963, the Kennedy administration initially opposed the march out of concern it would negatively impact the drive for passage of civil rights legislation. However, Randolph and King were firm that the march would proceed.[147] With the march going forward, the Kennedys decided it was important to work to ensure its success. Concerned about the turnout, President Kennedy enlisted the aid of white church leaders and Walter Reuther, president of the UAW, to help mobilize white supporters for the march.[148][149]

The march was held on August 28, 1963. Unlike the planned 1941 march, for which Randolph included only black-led organizations in the planning, the 1963 march was a collaborative effort of all of the major civil rights organizations, the more progressive wing of the labor movement, and other liberal organizations. The march had six official goals:

- meaningful civil rights laws

- a massive federal works program

- full and fair employment

- decent housing

- the right to vote

- adequate integrated education.

Of these, the march's major focus was on passage of the civil rights law that the Kennedy administration had proposed after the upheavals in Birmingham.

National media attention also greatly contributed to the march's national exposure and probable impact. In the essay "The March on Washington and Television News",[150] historian William Thomas notes: "Over five hundred cameramen, technicians, and correspondents from the major networks were set to cover the event. More cameras would be set up than had filmed the last presidential inauguration. One camera was positioned high in the Washington Monument, to give dramatic vistas of the marchers". By carrying the organizers' speeches and offering their own commentary, television stations framed the way their local audiences saw and understood the event.[150]

The march was a success, although not without controversy. An estimated 200,000 to 300,000 demonstrators gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial, where King delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech. While many speakers applauded the Kennedy administration for the efforts it had made toward obtaining new, more effective civil rights legislation protecting the right to vote and outlawing segregation, John Lewis of SNCC took the administration to task for not doing more to protect southern blacks and civil rights workers under attack in the Deep South.

After the march, King and other civil rights leaders met with President Kennedy at the White House. While the Kennedy administration appeared sincerely committed to passing the bill, it was not clear that it had enough votes in Congress to do so. However, when President Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963,[146] the new President Lyndon Johnson decided to use his influence in Congress to bring about much of Kennedy's legislative agenda.

Malcolm X joins the movement, 1964–1965

In March 1964, Malcolm X (el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz), national representative of the Nation of Islam, formally broke with that organization, and made a public offer to collaborate with any civil rights organization that accepted the right to self-defense and the philosophy of Black nationalism (which Malcolm said no longer required Black separatism). Gloria Richardson, head of the Cambridge, Maryland, chapter of SNCC, and leader of the Cambridge rebellion,[151] an honored guest at The March on Washington, immediately embraced Malcolm's offer. Mrs. Richardson, "the nation's most prominent woman [civil rights] leader,"[152] told The Baltimore Afro-American that "Malcolm is being very practical...The federal government has moved into conflict situations only when matters approach the level of insurrection. Self-defense may force Washington to intervene sooner."[152] Earlier, in May 1963, writer and activist James Baldwin had stated publicly that "the Black Muslim movement is the only one in the country we can call grassroots, I hate to say it...Malcolm articulates for Negroes, their suffering...he corroborates their reality..."[153] On the local level, Malcolm and the NOI had been allied with the Harlem chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) since at least 1962.[154]

On March 26, 1964, as the Civil Rights Act was facing stiff opposition in Congress, Malcolm had a public meeting with Martin Luther King Jr. at the Capitol. Malcolm had tried to begin a dialog with King as early as 1957, but King had rebuffed him. Malcolm had responded by calling King an "Uncle Tom", saying he had turned his back on black militancy in order to appease the white power structure. But the two men were on good terms at their face-to-face meeting.[155] There is evidence that King was preparing to support Malcolm's plan to formally bring the U.S. government before the United Nations on charges of human rights violations against African Americans.[156] Malcolm now encouraged Black nationalists to get involved in voter registration drives and other forms of community organizing to redefine and expand the movement.[157]

Civil rights activists became increasingly combative in the 1963 to 1964 period, seeking to defy such events as the thwarting of the Albany campaign, police repression and Ku Klux Klan terrorism in Birmingham, and the assassination of Medgar Evers. The latter's brother Charles Evers, who took over as Mississippi NAACP Field Director, told a public NAACP conference on February 15, 1964, that "non-violence won't work in Mississippi...we made up our minds...that if a white man shoots at a Negro in Mississippi, we will shoot back."[158] The repression of sit-ins in Jacksonville, Florida, provoked a riot in which black youth threw Molotov cocktails at police on March 24, 1964.[159] Malcolm X gave numerous speeches in this period warning that such militant activity would escalate further if African Americans' rights were not fully recognized. In his landmark April 1964 speech "The Ballot or the Bullet", Malcolm presented an ultimatum to white America: "There's new strategy coming in. It'll be Molotov cocktails this month, hand grenades next month, and something else next month. It'll be ballots, or it'll be bullets."[160]

As noted in the PBS documentary Eyes on the Prize, "Malcolm X had a far-reaching effect on the civil rights movement. In the South, there had been a long tradition of self-reliance. Malcolm X's ideas now touched that tradition".[161] Self-reliance was becoming paramount in light of the 1964 Democratic National Convention's decision to refuse seating to the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) and instead to seat the regular state delegation, which had been elected in violation of the party's own rules, and by Jim Crow law instead.[162] SNCC moved in an increasingly militant direction and worked with Malcolm X on two Harlem MFDP fundraisers in December 1964.

When Fannie Lou Hamer spoke to Harlemites about the Jim Crow violence that she'd suffered in Mississippi, she linked it directly to the Northern police brutality against blacks that Malcolm protested against;[163] When Malcolm asserted that African Americans should emulate the Mau Mau army of Kenya in efforts to gain their independence, many in SNCC applauded.[164]

During the Selma campaign for voting rights in 1965, Malcolm made it known that he'd heard reports of increased threats of lynching around Selma. In late January he sent an open telegram to George Lincoln Rockwell, the head of the American Nazi Party, stating:

"if your present racist agitation against our people there in Alabama causes physical harm to Reverend King or any other black Americans...you and your KKK friends will be met with maximum physical retaliation from those of us who are not handcuffed by the disarming philosophy of nonviolence."[165]

The following month, the Selma chapter of SNCC invited Malcolm to speak to a mass meeting there. On the day of Malcolm's appearance, President Johnson made his first public statement in support of the Selma campaign.[166] Paul Ryan Haygood, a co-director of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, credits Malcolm with a role in gaining support by the federal government. Haygood noted that "shortly after Malcolm's visit to Selma, a federal judge, responding to a suit brought by the Department of Justice, required Dallas County, Alabama, registrars to process at least 100 Black applications each day their offices were open."[167]

St. Augustine, Florida, 1963–1964

St. Augustine was famous as the "Nation's Oldest City", founded by the Spanish in 1565. It became the stage for a great drama leading up to the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964. A local movement, led by Robert B. Hayling, a black dentist and Air Force veteran affiliated with the NAACP, had been picketing segregated local institutions since 1963. In the fall of 1964, Hayling and three companions were brutally beaten at a Ku Klux Klan rally.

Nightriders shot into black homes, and teenagers Audrey Nell Edwards, JoeAnn Anderson, Samuel White, and Willie Carl Singleton (who came to be known as "The St. Augustine Four") sat in at a local Woolworth's lunch counter, seeking to get served. They were arrested and convicted of trespassing, and sentenced to six months in jail and reform school. It took a special act of the governor and cabinet of Florida to release them after national protests by the Pittsburgh Courier, Jackie Robinson, and others.

In response to the repression, the St. Augustine movement practiced armed self-defense in addition to nonviolent direct action. In June 1963, Hayling publicly stated that "I and the others have armed. We will shoot first and answer questions later. We are not going to die like Medgar Evers." The comment made national headlines.[168] When Klan nightriders terrorized black neighborhoods in St. Augustine, Hayling's NAACP members often drove them off with gunfire. In October 1963, a Klansman was killed.[169]

In 1964, Hayling and other activists urged the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to come to St. Augustine. Four prominent Massachusetts women—Mary Parkman Peabody, Esther Burgess, Hester Campbell (all of whose husbands were Episcopal bishops), and Florence Rowe (whose husband was vice president of an insurance company)—also came to lend their support. The arrest of Peabody, the 72-year-old mother of the governor of Massachusetts, for attempting to eat at the segregated Ponce de Leon Motor Lodge in an integrated group, made front-page news across the country and brought the movement in St. Augustine to the attention of the world.[170]

Widely publicized activities continued in the ensuing months. When King was arrested, he sent a "Letter from the St. Augustine Jail" to a northern supporter, Rabbi Israel S. Dresner. A week later, in the largest mass arrest of rabbis in American history took place, while they were conducting a pray-in at the segregated Monson Motel. A well-known photograph taken in St. Augustine shows the manager of the Monson Motel pouring hydrochloric acid in the swimming pool while blacks and whites are swimming in it. As he did so he yelled that he was "cleaning the pool", a presumed reference to it now being, in his eyes, racially contaminated.[171] The photograph was run on the front page of a Washington newspaper the day the Senate was to vote on passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Chester school protests, Spring 1964

From November 1963 through April 1964, the Chester school protests were a series of civil rights protests led by George Raymond of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored Persons (NAACP) and Stanley Branche of the Committee for Freedom Now (CFFN) that made Chester, Pennsylvania one of the key battlegrounds of the civil rights movement. James Farmer, the national director of the Congress of Racial Equality called Chester "the Birmingham of the North".[172]