Вроцлав

Вроцлав | |

|---|---|

| Motto(s): | |

| Coordinates: 51°06′36″N 17°01′57″E / 51.11000°N 17.03250°E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | |

| County | city county |

| Established | 10th century |

| City rights | 1214 |

| Government | |

| • City mayor | Jacek Sutryk (Ind.) |

| Area | |

| • City | 292.81 km2 (113.05 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 3,627 km2 (1,400 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 155 m (509 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 105 m (344 ft) |

| Population (30 June 2023) | |

| • City | 674,132 (3rd)[1] |

| • Density | 2,302/km2 (5,960/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,250,000 |

| • Metro density | 340/km2 (890/sq mi) |

| • Demonym |

|

| GDP | |

| • Metro | €15.222 billion (2020) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 50-041 to 54–612 |

| Area code | +48 71 |

| Car plates | DW, DX |

| Primary airport | Wrocław Airport |

| Website | www |

Вроцлав ( Польское произношение: [ˈvrɔt͡swaf] ; Великобритания : / ˈ v r ɒ t s w ɑː f / ROT -swahf , [3] США : / ˈ v r ɔː t s w ɑː f , - s l ɑː f / VRAWT -сваф, -слахф . [4] [5] Немецкий : Бреслау , [ˈbʁɛslaʊ] , также известен под другими названиями ) — город на юго-западе Польши и крупнейший город исторической области Силезия . Он расположен на берегу Одера в Силезской низменности Центральной Европы , примерно в 40 километрах (25 миль) от Судетских гор на юге. По состоянию на 2023 год [update]Официальное население Вроцлава составляет 674 132 человека, что делает его третьим по величине городом в Польше. Население Вроцлавской агломерации составляет около 1,25 миллиона человек.

Вроцлав – историческая столица Силезии и Нижней Силезии . Сегодня это столица Нижнесилезского воеводства . История города насчитывает более 1000 лет; [6] в разное время он был частью Королевства Польского , Королевства Богемия , Королевства Венгерского , Габсбургской монархии Австрии, Королевства Пруссии и Германии , пока он снова не стал частью Польши в 1945 году в результате территориальные изменения Польши сразу после Второй мировой войны .

Wrocław is a university city with a student population of over 130,000, making it one of the most youth-oriented cities in the country.[7] Since the beginning of the 20th century, the University of Wrocław, previously the German Breslau University, has produced nine Nobel Prize laureates and is renowned for its high quality of teaching.[8][9] Wrocław also possesses numerous historical landmarks, including the Main Market Square, Cathedral Island, Wrocław Opera, the National Museum and the Centennial Hall, which is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The city is also home to the Wrocław Zoo, the oldest zoological garden in Poland.

Wrocław is classified as a Gamma global city by GaWC.[10] It is often featured in lists of the most livable places in the world,[11][12] and was ranked 1st among all medium and small cities by fDi Intelligence in 2021.[13] In 1989, 1995 and 2019 Wrocław hosted the European Youth Meetings of the Taizé Community, the Eucharistic Congress in 1997, and the 2012 European Football Championship. In 2016, the city was a European Capital of Culture and the World Book Capital.[14] Also in that year, Wrocław hosted the Theatre Olympics, World Bridge Games and the European Film Awards. In 2017, the city was host to the IFLA Annual Conference and the World Games. In 2019, it was named a UNESCO City of Literature.

Etymology[edit]

The origin of the city's name is disputed. The city was believed to be named after Duke Vratislav I of Bohemia from the Czech Přemyslid dynasty, who supposedly ruled the region between 915 and 921.[15] However, modern scholars and historians dispute this theory; recent archeological studies prove that even if Vratislav once ruled over the area, the city was not founded until at least 20 years after his death. They suggest that the founder of the city might have simply been a local prince who only shared the popular West Slavic name with the Bohemian Duke. [citation needed] Further evidence against Czech origin is that the oldest surviving documents containing the recorded name, such as the chronicle of Thietmar of Merseburg from the early 11th century, records the city's name as Wrotizlava and Wrotizlaensem, characteristic of Old Polish -ro-, unlike Old Czech -ra-.[16] In the Polish language, the city's name Wrocław derives from the given name Wrocisław, which is the Polish equivalent of the Czech Vratislav. Also, the earliest variations of this name in the Old Polish language would have used the letter l instead of the modern Polish ł.

The Old Czech language version of the name was used in Latin documents, as Vratislavia or Wratislavia. The city's first municipal seal was inscribed with Sigillum civitatis Wratislavie.[17] By the 15th century, the Early New High German variations of the name, Breslau, first began to be used. Despite the noticeable differences in spelling, the numerous German forms were still based on the original West Slavic name of the city, with the -Vr- sound being replaced over time by -Br-,[18] and the suffix -slav- replaced with -slau-. These variations included Wrotizla, Vratizlau, Wratislau, Wrezlau, Breßlau or Bresslau among others.[19] A Prussian description from 1819 mentions two names of the city – Polish and German – stating "Breslau (polnisch Wraclaw)”.[20]

In other languages, the city's name is: German: Breslau, [ˈbʁɛslaʊ] , modern Czech: Vratislav, Hungarian: Boroszló, Hebrew: ורוצלב (Vrotsláv), Yiddish: ברעסלוי (Bresloi), Silesian: Wrocław, Silesian German: Brassel and Latin: Wratislavia, Vratislavia.[21]

People born or resident in the city are known as "Wrocławians" or "Vratislavians" (Polish: wrocławianie). The now little-used German equivalent is "Breslauer."

History[edit]

In ancient times, there was a place called Budorigum at or near the site of Wrocław. It was already mapped on Claudius Ptolemy's map of AD 142–147.[22] Settlements in the area existed from the 6th century onward during the migration period. The Ślężans, a West Slavic tribe, settled on the Oder river and erected a fortified gord on Ostrów Tumski.

Wrocław originated at the intersection of two trade routes, the Via Regia and the Amber Road. Archeological research conducted in the city indicates that it was founded around 940.[23] In 985, Duke Mieszko I of Poland conquered Silesia, and constructed new fortifcations on Ostrów.[24] The town was mentioned by Thietmar explicitly in the year 1000 AD in connection with its promotion to an episcopal see during the Congress of Gniezno.[25]

Middle Ages[edit]

During Wrocław's early history, control over it changed hands between the Duchy of Bohemia (1038–1054), the Duchy of Poland and the Kingdom of Poland (985–1038 and 1054–1320). Following the fragmentation of the Kingdom of Poland, the Piast dynasty ruled the Duchy of Silesia. One of the most important events during this period was the foundation of the Diocese of Wrocław in 1000. Along with the Bishoprics of Kraków and Kołobrzeg, Wrocław was placed under the Archbishopric of Gniezno in Greater Poland, founded by Pope Sylvester II through the intercession of Polish duke (and later king) Bolesław I the Brave and Emperor Otto III, during the Gniezno Congress.[26] In the years 1034–1038 the city was affected by the pagan reaction in Poland.[27]

The city became a commercial centre and expanded to Wyspa Piasek (Sand Island), and then onto the left bank of the River Oder. Around 1000, the town had about 1,000 inhabitants.[28] In 1109 during the Polish-German war, Prince Bolesław III Wrymouth defeated the King of Germany Henry V at the Battle of Hundsfeld, stopping the German advance into Poland. The medieval chronicle, Gesta principum Polonorum (1112–1116) by Gallus Anonymus, named Wrocław, along with Kraków and Sandomierz, as one of three capitals of the Polish Kingdom. Also, the Tabula Rogeriana, a book written by the Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi in 1154, describes Wrocław as one of the Polish cities, alongside Kraków, Gniezno, Sieradz, Łęczyca and Santok.[29]

By 1139, a settlement belonging to Governor Piotr Włostowic (also known as Piotr Włast Dunin) was built, and another on the left bank of the River Oder, near the present site of the university. While the city was largely Polish, it also had communities of Bohemians (Czechs), Germans, Walloons and Jews.[30][27][31]

In the 13th century, Wrocław was the political centre of the divided Polish kingdom.[32] In April 1241, during the first Mongol invasion of Poland, the city was abandoned by its inhabitants and burnt down for strategic reasons. During the battles with the Mongols Wrocław Castle was successfully defended by Henry II the Pious.[33]

In 1245, in Wrocław, Franciscan friar Benedict of Poland, considered one of the first Polish explorers, joined Italian diplomat Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, on his journey to the seat of the Mongol Khan near Karakorum, the capital of the Mongol Empire, in what is considered the first such journey by Europeans.[34]

After the Mongol invasion the town was partly populated by German settlers who, in the ensuing centuries, gradually became its dominant population.[35] The city, however, retained its multi-ethnic character, a reflection of its importance as a trading post on the junction of the Via Regia and the Amber Road.[36]

With the influx of settlers, the town expanded and in 1242 came under German town law. The city council used both Latin and German, and the early forms of the name Breslau, the German name of the city, appeared for the first time in its written records.[35] Polish gradually ceased to be used in the town books, while it survived in the courts until 1337, when it was banned by the new rulers, the German-speaking House of Luxembourg.[31] The enlarged town covered around 60 hectares (150 acres), and the new main market square, surrounded by timber-frame houses, became the trade centre of the town. The original foundation, Ostrów Tumski, became its religious centre. The city gained Magdeburg rights in 1261. While the Polish Piast dynasty remained in control of the region, the city council's ability to govern independently had increased.[37] In 1274 prince Henry IV Probus gave the city its staple right. In the 13th century, two Polish monarchs were buried in Wrocław churches founded by them, Henry II the Pious in the St. Vincent church[38] and Henryk IV Probus in the Holy Cross church.[39]

Wrocław, which for 350 years had been mostly under Polish hegemony, fell in 1335, after the death of Henry VI the Good, to John of Luxembourg. His son Emperor Charles IV in 1348 formally incorporated the city into the Holy Roman Empire. Between 1342 and 1344, two fires destroyed large parts of the city. In 1387 the city joined the Hanseatic League. On 5 June 1443, the city was rocked by an earthquake, estimated at magnitude 6, which destroyed or seriously damaged many of its buildings.

Between 1469 and 1490, Wrocław was part of the Kingdom of Hungary, and king Matthias Corvinus was said to have had a Vratislavian mistress who bore him a son.[40] In 1474, after almost a century, the city left the Hanseatic League. Also in 1474, the city was besieged by combined Polish-Czech forces. However, in November 1474, Kings Casimir IV of Poland, his son Vladislaus II of Bohemia, and Matthias Corvinus of Hungary met in the nearby village of Muchobór Wielki (present-day a district of Wrocław), and in December 1474 a ceasefire was signed according to which the city remained under Hungarian rule.[41] The following year was marked by the publication in Wrocław of the Statuta Synodalia Episcoporum Wratislaviensium (1475) by Kasper Elyan, the first ever Incunable in Polish, containing the proceedings and prayers of the Wrocław bishops.[42]

Renaissance and the Reformation[edit]

In the 16th century, the Breslauer Schöps beer style was created in Breslau.[43]

The Protestant Reformation reached the city in 1518 and it converted to the new rite. However, starting in 1526 Silesia was ruled by the Catholic House of Habsburg. In 1618, it supported the Bohemian Revolt out of fear of losing the right to religious freedom. During the ensuing Thirty Years' War, the city was occupied by Saxon and Swedish troops and lost thousands of inhabitants to the plague.[44]

The Emperor brought in the Counter-Reformation by encouraging Catholic orders to settle in the city, starting in 1610 with the Franciscans, followed by the Jesuits, then Capuchins, and finally Ursuline nuns in 1687.[15] These orders erected buildings that shaped the city's appearance until 1945. At the end of the Thirty Years' War, however, it was one of only a few Silesian cities to stay Protestant.

The Polish Municipal school opened in 1666 and lasted until 1766. Precise record-keeping of births and deaths by the city fathers led to the use of their data for analysis of mortality, first by John Graunt and then, based on data provided to him by Breslau professor Caspar Neumann, by Edmond Halley.[45] Halley's tables and analysis, published in 1693, are considered to be the first true actuarial tables, and thus the foundation of modern actuarial science. During the Counter-Reformation, the intellectual life of the city flourished, as the Protestant bourgeoisie lost some of its dominance to the Catholic orders as patrons of the arts.

Enlightenment period[edit]

One of two main routes connecting Warsaw and Dresden ran through the city in the 18th century and Kings Augustus II the Strong and Augustus III of Poland often traveled that route.[46] The city became the centre of German Baroque literature and was home to the First and Second Silesian school of poets.[47] In 1742, the Schlesische Zeitung was founded in Breslau. In the 1740s the Kingdom of Prussia annexed the city and most of Silesia during the War of the Austrian Succession. Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa ceded most of the territory in the Treaty of Breslau in 1742 to Prussia. Austria attempted to recover Silesia during the Seven Years' War at the Battle of Breslau, but they were unsuccessful. The Venetian Italian adventurer, Giacomo Casanova, stayed in Breslau in 1766.[48]

Napoleonic Wars[edit]

During the Napoleonic Wars, it was occupied by the Confederation of the Rhine army. The fortifications of the city were levelled, and monasteries and cloisters were seized.[15] The Protestant Viadrina European University at Frankfurt an der Oder was relocated to Breslau in 1811, and united with the local Jesuit University to create the new Silesian Frederick-William University (German: Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelm-Universität, now the University of Wrocław). The city became a centre of the German Liberation movement against Napoleon, and a gathering place for volunteers from all over Germany. The city was the centre of Prussian mobilisation for the campaign which ended at the Battle of Leipzig.[49]

Industrial age[edit]

The Confederation of the Rhine had increased prosperity in Silesia and in the city. The removal of fortifications opened room for the city to expand beyond its former limits. Breslau became an important railway hub and industrial centre, notably for linen and cotton manufacture and the metal industry. The reconstructed university served as a major centre of science; Johannes Brahms later wrote his Academic Festival Overture to thank the university for an honorary doctorate awarded in 1879.[50]

In 1821, the (Arch)Diocese of Breslau withdrew from dependence on the Polish archbishopric of Gniezno, and Breslau became an exempt see. In 1822, the Prussian police discovered the Polonia Polish youth resistance organization and carried out arrests of its members and searches of their homes.[51] In 1848, many local Polish students joined the Greater Poland uprising against Prussia.[52] On 5 May 1848, a convention of Polish activists from the Prussian and Austrian partitions of Poland was held in the city.[53] On 10 October 1854, the Jewish Theological Seminary opened. The institution was the first modern rabbinical seminary in Central Europe. In 1863 the brothers Karl and Louis Stangen founded the travel agency Stangen, the second travel agency in the world.[54]

The city was an important centre of the Polish secret resistance movement and the seat of a Polish uprising committee before and during the January Uprising of 1863–1864 in the Russian Partition of Poland.[55] Local Poles took part in Polish national mourning after the Russian massacre of Polish protesters in Warsaw in February 1861, and also organized several patriotic Polish church services throughout 1861.[56] Secret Polish correspondence, weapons, and insurgents were transported through the city.[57] After the outbreak of the uprising in 1863, the Prussian police carried out mass searches of Polish homes, especially those of Poles who had recently come to the city.[58] The city's inhabitants, both Poles and Germans, excluding the German aristocracy, largely sympathized with the uprising, and some Germans even joined local Poles in their secret activities.[59] In June 1863 the city was officially confirmed as the seat of secret Polish insurgent authorities.[60] In January 1864, the Prussian police arrested a number of members of the Polish insurgent movement.[61]

The Unification of Germany in 1871 turned Breslau into the sixth-largest city in the German Empire. Its population more than tripled to over half a million between 1860 and 1910. The 1900 census listed 422,709 residents.[62]

In 1890, construction began of Breslau Fortress as the city's defenses. Important landmarks were inaugurated in 1910, the Kaiser bridge (today Grunwald Bridge) and the Technical University, which now houses the Wrocław University of Technology.The 1900 census listed 98% of the population as German-speakers, with 5,363 Polish-speakers (1.3%), and 3,103 (0.7%) as bilingual in German and Polish.[63] The population was 58% Protestant, 37% Catholic (including at least 2% Polish)[64] and 5% Jewish (totaling 20,536 in the 1905 census).[63] The Jewish community of Breslau was among the most important in Germany, producing several distinguished artists and scientists.[65]

From 1912, the head of the university's Department of Psychiatry and director of the Clinic of Psychiatry (Königlich Psychiatrischen und Nervenklinik) was Alois Alzheimer and, that same year, professor William Stern introduced the concept of IQ.[66]

In 1913, the newly built Centennial Hall housed an exhibition commemorating the 100th anniversary of the historical German Wars of Liberation against Napoleon and the first award of the Iron Cross.[67] The Centennial Hall was built by Max Berg (1870–1947), since 2006 it is part of the world heritage of UNESCO.[68] The central station (by Wilhelm Grapow, 1857) was one of the biggest in Germany and one of the first stations with electrified railway services.[69] Since 1900 modern department stores like Barasch (today "Feniks") or Petersdorff (built by architect Erich Mendelsohn) were erected.

During World War I, in 1914, a branch of the Organizacja Pomocy Legionom ("Legion Assistance Organization") operated in the city with the goal of gaining support and recruiting volunteers for the Polish Legion, but three Legions' envoys were arrested by the Germans in November 1914 and deported to Austria, and the organization soon ended its activities in the city.[70] During the war, the Germans operated seven forced labour camps for Allied prisoners of war in the city.[71]

Following the war, Breslau became the capital of the newly created Prussian Province of Lower Silesia of the Weimar Republic in 1919. After the war the Polish community began holding masses in Polish at the Church of Saint Anne, and, as of 1921, at St. Martin's and a Polish School was founded by Helena Adamczewska.[72] In 1920 a Polish consulate was opened on the Main Square.

In August 1920, during the Polish Silesian Uprising in Upper Silesia, the Polish Consulate and School were destroyed, while the Polish Library was burned down by a mob. The number of Poles as a percentage of the total population fell to just 0.5% after the re-emergence of Poland as a state in 1918, when many moved to Poland.[64] Antisemitic riots occurred in 1923.[73]

The city boundaries were expanded between 1925 and 1930 to include an area of 175 km2 (68 sq mi) with a population of 600,000. In 1929, the Werkbund opened WuWa (German: Wohnungs- und Werkraumausstellung) in Breslau-Scheitnig, an international showcase of modern architecture by architects of the Silesian branch of the Werkbund. In June 1930, Breslau hosted the Deutsche Kampfspiele, a sporting event for German athletes after Germany was excluded from the Olympic Games after World War I. The number of Jews remaining in Breslau fell from 23,240 in 1925 to 10,659 in 1933.[74] Up to the beginning of World War II, Breslau was the largest city in Germany east of Berlin.[75]

Known as a stronghold of left wing liberalism during the German Empire, Breslau eventually became one of the strongest support bases of the Nazi Party, which in the 1932 elections received 44% of the city's vote, their third-highest total in all Germany.[76][77]

KZ Dürrgoy, one of the first concentration camps in Nazi Germany, was set up in the city in 1933.[78]

After Hitler's appointment as German Chancellor in 1933, political enemies of the Nazis were persecuted, and their institutions closed or destroyed. The Gestapo began actions against Polish and Jewish students (see: Jewish Theological Seminary of Breslau), Communists, Social Democrats, and trade unionists. Arrests were made for speaking Polish in public, and in 1938 the Nazi-controlled police destroyed the Polish cultural centre.[79][80] In June 1939, Polish students were expelled from the university.[81] Also many other people seen as "undesirable" by Nazi Germany were sent to concentration camps.[79] A network of concentration camps and forced labour camps was established around Breslau to serve industrial concerns, including FAMO, Junkers, and Krupp. Tens of thousands of forced laborers were imprisoned there.[82]

The last big event organized by the National Socialist League of the Reich for Physical Exercise, called Deutsches Turn-und-Sportfest (Gym and Sports Festivities), took place in Breslau from 26 to 31 July 1938. The Sportsfest was held to commemorate the 125th anniversary of the German Wars of Liberation against Napoleon's invasion.[83]

Second World War[edit]

During the invasion of Poland, which started World War II, in September 1939, the Germans carried out mass arrests of local Polish activists and banned Polish organizations,[81] and the city was made the headquarters of the southern district of the Selbstschutz, whose task was to persecute Poles.[84] For most of the war, the fighting did not affect the city. During the war, the Germans opened the graves of medieval Polish monarchs and local dukes to carry out anthropological research for propaganda purposes, wanting to demonstrate German "racial purity."[38] The remains were transported to other places by the Germans, and they have not been found to this day.[38] In 1941 the remnants of the pre-war Polish minority in the city, as well as Polish slave labourers, organised a resistance group called Olimp. The organisation gathered intelligence, carrying out sabotage and organising aid for Polish slave workers. In September 1941 the city's 10,000 Jews were expelled from their homes and soon deported to concentration camps. Few survived the Holocaust.[85] As the war continued, refugees from bombed-out German cities, and later refugees from farther east, swelled the population to nearly one million,[86] including 51,000 forced labourers in 1944, and 9,876 Allied PoWs. At the end of 1944 an additional 30,000–60,000 Poles were moved into the city after the Germans crushed the Warsaw Uprising.[87]

During the war the Germans operated four subcamps of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp in the city.[88] Approximately 3,400–3,800 men were imprisoned in three subcamps, among them Poles, Russians, Italians, Frenchmen, Ukrainians, Czechs, Belgians, Yugoslavs, and about 1,500 Jewish women were imprisoned in the fourth camp.[88] Many prisoners died, and the remaining were evacuated to the main camp of Gross-Rosen in January 1945.[88] There were also three subcamps of the Stalag VIII-B/344 prisoner-of-war camp,[89] and two Nazi prisons in the city, including a youth prison, with multiple forced labour subcamps.[90][91]

In 1945, the city became part of the front lines and was the site of the brutal Siege of Breslau.[92] Adolf Hitler had in 1944 declared Breslau to be a fortress (Festung), to be held at all costs. An attempted evacuation of the city took place in January 1945, with 18,000 people freezing to death in icy snowstorms of −20 °C (−4 °F) weather. In February 1945, the Soviet Army approached the city and the German Luftwaffe began an airlift to the besieged garrison. A large area of the city centre was demolished and turned into an airfield by the defenders.[93] By the end of the three-month siege in May 1945, half the city had been destroyed. Breslau was the last major city in Germany to surrender, capitulating only two days before the end of the war in Europe.[94] Civilian deaths amounted to as many as 80,000. In August the Soviets placed the city under the control of German communists.[95]

Following the Yalta Conference held in February 1945, where the new geopolitics of Central Europe were decided, the terms of the Potsdam Conference decreed that along with almost all of Lower Silesia, the city would again become part of Poland[95] in exchange for Poland's loss of the city of Lwów along with the massive territory of Kresy in the east, which was annexed by the Soviet Union.[96] The Polish name of Wrocław was declared official. There had been discussion among the Western Allies to place the southern Polish-German boundary on the Eastern Neisse, which meant post-war Germany would have been allowed to retain approximately half of Silesia, including those parts of Breslau that lay on the west bank of the Oder. However, the Soviet government insisted the border be drawn at the Lusatian Neisse farther west.[96]

1945–present[edit]

The city's German inhabitants who had not fled, or who had returned to their home city after the war had ended, were expelled between 1945 and 1949 in accordance to the Potsdam Agreement and were settled in the Soviet occupation zone or in the Allied Occupation Zones in the remainder of Germany. The city's last pre-war German school was closed in 1963.[97]

The Polish population was dramatically increased by the resettlement of Poles, partly due to postwar population transfers during the forced deportations from Polish lands annexed by the Soviet Union in the east region, some of whom came from Lviv (Lwów), Volhynia, and the Vilnius Region. However, despite the prime role given to re-settlers from the Kresy, in 1949, only 20% of the new Polish population actually were refugees themselves.[98] A small German minority (about 1,000 people, or 2% of the population) remains in the city, so that today the relation of Polish to German population is the reverse of what it was a hundred years ago.[99] Traces of the German past, such as inscriptions and signs, were removed.[100] In 1948, Wrocław organized the Recovered Territories Exhibition and the World Congress of Intellectuals in Defense of Peace. Picasso's lithograph, La Colombe (The Dove), a traditional, realistic picture of a pigeon, without an olive branch, was created on a napkin at the Monopol Hotel in Wrocław during the World Congress of Intellectuals in Defense of Peace.[101]

In 1963, Wrocław was declared a closed city because of a smallpox epidemic.[102]

In 1982, during martial law in Poland, the anti-communist underground organizations Fighting Solidarity and Orange Alternative were founded in Wrocław. Wrocław's dwarves, made of bronze, famously grew out of and commemorate Orange Alternative.[103]

In 1983 and 1997, Pope John Paul II visited the city.[104]

PTV Echo, the first non-state television station in Poland and in the post-communist countries, began to broadcast in Wrocław on 6 February 1990.[105]

In May 1997, Wrocław hosted the 46th International Eucharistic Congress.[106]

In July 1997, the city was heavily affected by the Millennium Flood, the worst flooding in post-war Poland, Germany, and the Czech Republic. About one-third of the area of the city was flooded.[107] The smaller Widawa River also flooded the city simultaneously, worsening the damage. An earlier, equally devastating flood of the Oder river had taken place in 1903.[108]A small part of the city was also flooded during the flood of 2010. From 2012 to 2015, the Wrocław water node was renovated and redeveloped to prevent further flooding.[109]

Municipal Stadium in Wrocław, opened in 2011, hosted three matches in Group A of the UEFA Euro 2012 championship.[110]

In 2016, Wrocław was declared the European Capital of Culture.[111]

In 2017, Wrocław hosted the 2017 World Games.[112]

Wrocław won the European Best Destination title in 2018.[113]

Wrocław is now a unique European city of mixed heritage, with architecture influenced by Polish, Bohemian, Austrian, Saxon, and Prussian traditions, such as Silesian Gothic and its Baroque style of court builders of Habsburg Austria (Fischer von Erlach). Wrocław has a number of notable buildings by German modernist architects including the famous Centennial Hall (1911–1913) designed by Max Berg.

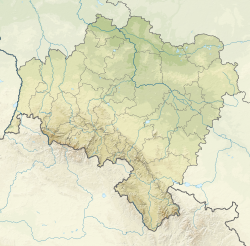

Geography[edit]

Wrocław is located in the three mesoregions of the Silesian Lowlands (Wrocław Plain, Wrocław Valley, Oleśnica Plain) at an elevation of around 105–156 metres (Gajowe Hill and Maślickie Hill) above sea level.[114] The city lies on the Oder River and its four tributaries, which supply it within the city limits – Bystrzyca, Oława, Ślęza and Widawa.[115] In addition, the Dobra River and many streams flow through the city. The city has a sewage treatment plant on the Janówek estate.[116]

Flora and fauna[edit]

There are 44 city parks and public green spaces covering around 800 hectares. The most notable are Szczytnicki Park, Park Południowy (South Park) and Anders Park. In addition, Wrocław University runs an historical Botanical garden (founded in 1811), with a salient Alpine garden, a lake and a valley.[117]

In Wrocław, the presence of over 200 species of birds has been registered, of which over 100 have nesting places there.[118] As in other large Polish cities, the most numerous are pigeons. Other common species are the sparrow, tree sparrow, siskin, rook, crow, jackdaw, magpie, swift, martin, swallow, kestrel, mute swan, mallard, coot, merganser, black-headed gull, great tit, blue tit, long-tailed tit, greenfinch, hawfinch, collared dove, common wood pigeon, fieldfare, redwing, common starling, grey heron, white stork, common chaffinch, blackbird, jay, nuthatch, bullfinch, cuckoo, waxwing, lesser spotted woodpecker, great spotted woodpecker, white-backed woodpecker, white wagtail, blackcap, black redstart, old world flycatcher, emberizidae, goldfinch, western marsh harrier, little bittern, common moorhen, reed bunting, remiz, great reed warbler, little crake, little ringed plover and white-tailed eagle.[119]

In addition, the city is periodically plagued by the brown rat, especially in the Market Square and in the vicinity of eateries. Otherwise, due to the proximity of wooded areas, there are hedgehogs, foxes, wild boar, bats, martens, squirrels, deer, hares, beavers, polecats, otters, badgers, weasels, stoats and raccoon dogs. There are also occasional sightings of escaped muskrat, american mink and raccoon.[119][120]

Climate[edit]

According to the Köppen climate classification, Wrocław has an oceanic climate (Cfb), bordering on a humid continental climate (Dfb) using the 0 °C (32 °F) isotherm. The position of Wrocław in the Silesian Lowlands, which are themselves located just north of the Sudetes and to the southwest of the Trzebnickie Hills, creates a favourable environment for accumulation of heat in the Oder river valley between Wrocław and Opole.[121] Wrocław is therefore the warmest city in Poland, among those tracked by the Institute of Meteorology and Water Management (IMGW), with the mean annual temperature of 9.7 °C (49 °F).[122]

The city experiences relatively mild and dry winters, but with the skies frequently overcast; summers are warm and generally sunny, however, that is the period when most precipitation occurs, which often falls during thunderstorms. The city also sometimes experiences foehn-like conditions, particularly when the wind blows from the south or the south-west.[121] In addition to that, the temperatures in the city centre often tend to be higher than on the outskirts due to the urban heat island effect.[123][121] Snow may fall in any month from October to May but normally does so in winter; the snow cover of at least 1 cm (0.39 in) stays on the ground for an average of 27.5 days per year – one of the lowest in Poland.[122] The highest temperature in Wrocław recognised by IMGW was noted on 8 August 2015 (37.9 °C (100 °F)),[122] though thermometers at the meteorological station managed by the University of Wrocław indicated 38.9 °C (102 °F) on that day.[124] The lowest temperature was recorded on 11 February 1956 (−32 °C (−26 °F)).

| Climate data for Wrocław (Wrocław Airport), elevation: 120 m, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1951–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.0 (64.4) | 20.6 (69.1) | 25.2 (77.4) | 30.0 (86.0) | 32.4 (90.3) | 36.9 (98.4) | 37.4 (99.3) | 38.9 (102.0) | 35.3 (95.5) | 28.1 (82.6) | 20.9 (69.6) | 16.4 (61.5) | 38.9 (102.0) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 10.8 (51.4) | 12.7 (54.9) | 18.2 (64.8) | 24.3 (75.7) | 27.8 (82.0) | 31.5 (88.7) | 32.8 (91.0) | 32.5 (90.5) | 27.6 (81.7) | 22.8 (73.0) | 16.2 (61.2) | 11.4 (52.5) | 34.3 (93.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.0 (37.4) | 4.7 (40.5) | 9.0 (48.2) | 15.3 (59.5) | 20.0 (68.0) | 23.4 (74.1) | 25.6 (78.1) | 25.4 (77.7) | 20.0 (68.0) | 14.3 (57.7) | 8.3 (46.9) | 4.1 (39.4) | 14.4 (57.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) | 1.1 (34.0) | 4.3 (39.7) | 9.7 (49.5) | 14.3 (57.7) | 17.7 (63.9) | 19.7 (67.5) | 19.3 (66.7) | 14.5 (58.1) | 9.6 (49.3) | 4.8 (40.6) | 1.1 (34.0) | 9.7 (49.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.3 (26.1) | −2.5 (27.5) | 0.0 (32.0) | 3.8 (38.8) | 8.3 (46.9) | 12.0 (53.6) | 13.9 (57.0) | 13.4 (56.1) | 9.4 (48.9) | 5.2 (41.4) | 1.3 (34.3) | −2.1 (28.2) | 5.0 (41.0) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −14.6 (5.7) | −11.4 (11.5) | −7.3 (18.9) | −3.5 (25.7) | 1.9 (35.4) | 6.0 (42.8) | 8.7 (47.7) | 7.0 (44.6) | 2.4 (36.3) | −2.8 (27.0) | −6.4 (20.5) | −11.5 (11.3) | −16.8 (1.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −30.0 (−22.0) | −32.0 (−25.6) | −23.8 (−10.8) | −8.1 (17.4) | −4.0 (24.8) | 0.2 (32.4) | 3.6 (38.5) | 2.1 (35.8) | −3.0 (26.6) | −9.3 (15.3) | −18.2 (−0.8) | −24.4 (−11.9) | −32.0 (−25.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 28.3 (1.11) | 25.6 (1.01) | 35.0 (1.38) | 31.2 (1.23) | 59.6 (2.35) | 65.4 (2.57) | 91.4 (3.60) | 59.5 (2.34) | 48.4 (1.91) | 37.6 (1.48) | 31.4 (1.24) | 27.9 (1.10) | 541.1 (21.30) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 4.6 (1.8) | 4.5 (1.8) | 2.7 (1.1) | 0.4 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.1) | 1.5 (0.6) | 3.0 (1.2) | 4.6 (1.8) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 15.50 | 12.99 | 13.50 | 10.90 | 13.03 | 12.97 | 14.00 | 11.80 | 11.30 | 12.27 | 13.17 | 14.77 | 156.19 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.0 cm) | 12.4 | 9.1 | 4.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 2.4 | 6.4 | 34.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83.7 | 80.1 | 75.3 | 68.0 | 69.8 | 69.8 | 69.9 | 70.5 | 76.8 | 81.6 | 85.5 | 84.9 | 76.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 58.8 | 82.2 | 129.2 | 202.6 | 245.5 | 247.6 | 257.4 | 250.8 | 170.1 | 118.5 | 66.9 | 52.8 | 1,882.5 |

| Source 1: IMGW (normals, except humidity)[122] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteomodel.pl (humidity and extremes)[125][126][127] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Wrocław (Wrocław Airport), elevation: 120 m, 1961–1990 normals |

|---|

Government and politics[edit]

Wrocław is the capital city of Lower Silesian Voivodeship, a province (voivodeship) created in 1999. It was previously the capital of Wrocław Voivodeship.[129] The city is a separate urban gmina and city-county. It is also the seat of Wrocław County, which adjoins but does not include the city.[130]

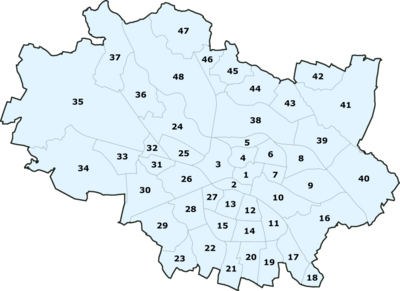

Districts[edit]

Wrocław was previously subdivided into five boroughs (Polish: dzielnice): Old Town, Downtown, Krzyki, Fabryczna, and Psie Pole. Although they were abolished in 1991 and have not existed as public administration units since then, areas of borders and names similar/identical to the former districts still exist in the practice of operation of various types of authorities and administrations (e.g. as divisions of territorial competencies of courts, prosecutors' offices, tax offices, etc.).

The present Wrocław districts (Polish: osiedla) were all created on 21 March 1991, and are a type of local government district.

Municipal government[edit]

Wrocław is currently governed by the city's mayor and a municipal legislature known as the city council. The city council is made up of 39 councilors and is directly elected by the city's inhabitants. The remit of the council and president extends to all areas of municipal policy and development planning, up to and including development of local infrastructure, transport and planning permission. However, it is not able to draw taxation directly from its citizens, and instead receives its budget from the Polish national government whose seat is in Warsaw.

The city's current mayor is Jacek Sutryk, who has served in this position since 2018. The first mayor of Wrocław after the war was Bolesław Drobner, appointed to the position on 14 March 1945, even before the surrender of Festung Breslau.

Economy[edit]

Wrocław is the second-wealthiest of the large cities in Poland after Warsaw.[131] The city is also home to the largest number of leasing and debt collection companies in the country, including the largest European Leasing Fund as well as numerous banks. Due to the proximity of the borders with Germany and the Czech Republic, Wrocław and the region of Lower Silesia is a large import and export partner with these countries.

Wrocław is one of the most innovative cities in Poland with the largest number of R&D centers, due to the cooperation between the municipality, business sector and numerous universities.[132] Currently, in Wrocław there are many organizations that are dealing with innovation–research institutions and technology transfer offices, incubators, technology and business parks, business support organizations, companies, start-ups and co-working spaces. The complex and varied infrastructure available in Wrocław facilitates the creation of innovative products and services and enables conducting research projects. The city has the biggest number of R&D centers in Poland, with many co-working spaces and business incubators offering great support to start a project fast and without high costs or too much paperwork.

Wrocław's industry manufactures buses, railroad cars, home appliances, chemicals, and electronics. The city houses factories and development centres of many foreign and domestic corporations, such as WAGO Kontakttechnik, Siemens, Bosch, Whirlpool Corporation, Nokia Networks, Volvo, HP, IBM, Google, Opera Software, Bombardier Transportation, WABCO and others. Wrocław is also the location of offices for large Polish companies including Getin Holding, AmRest, Polmos, and MCI Management SA. Additionally, Kaufland Poland has its main headquarters in the city.[133]

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the city has had a developing high-tech sector.Many high-tech companies are located in the Wrocław Technology Park, such as Baluff, CIT Engineering, Caisson Elektronik, ContiTech, Ericsson, Innovative Software Technologies, IBM, IT-MED, IT Sector, LiveChat Software, Mitsubishi Electric, Maas, PGS Software, Technology Transfer Agency Techtra and Vratis. In Biskupice Podgórne (Community Kobierzyce) there are factories of LG (LG Display, LG Electronics, LG Chem, LG Innotek), Dong Seo Display, Dong Yang Electronics, Toshiba, and many other companies, mainly from the electronics and home appliances sectors, while the Nowa Wieś Wrocławska factory and distribution centre of Nestlé Purina and factories a few other enterprises.

The city is the seat of Wrocław Research Centre EIT+, which contains, inter alia, geological research laboratories to the unconventional and Lower Silesian Cluster of Nanotechnology.[134] The logistics centres DHL, FedEx and UPS are based in Wrocław.[135] Furthermore, it is a major centre for the pharmaceutical industry (U.S. Pharmacia, Hasco-Lek, Galena, Avec Pharma, 3M, Labor, S-Lab, Herbapol, and Cezal).

Wrocław is home to Poland's largest shopping mall – Bielany Avenue (pl. Aleja Bielany) and Bielany Trade Center, located in Bielany Wrocławskie where stores such as Auchan, Decathlon, Leroy Merlin, Makro, IKEA, Jula, OBI, Castorama, Black Red White, Poco, E. Wedel, Cargill, Prologis and Panattoni can be found.[136]

In February 2013, Qatar Airways launched its Wrocław European Customer Service.[137]

Major corporations[edit]

- 3M

- Akwawit–Polmos S.A. – Wratislavia vodka plant

- The Bank of New York Mellon

- Bombardier Transportation Poland

- BSH – Bosch und Siemens Hausgeräte

- CD Projekt

- CH Robinson Worldwide

- Crédit Agricole Poland

- Credit Suisse[138]

- Deichmann

- DeLaval Operations Poland

- DHL

- Dolby Labs

- Ernst & Young

- Fantasy Expo – owner CD-Action

- Gigaset Communications

- Hewlett-Packard

- IBM[139]

- Kaufland Poland

- KGHM Polska Miedź

- LiveChat Software

- LG Electronics

- McKinsey & Company

- Microsoft[140]

- National Bank of Poland

- Nokia Networks

- Olympus Business Services Europe

- Opera Software

- Parker Hannifin

- PZ Cussons Poland

- PZU

- QAD

- Qatar Airways

- Qiagen

- Robert Bosch GmbH

- SAP Poland

- Santander Consumer Bank

- Siemens

- Südzucker

- Techland

- Tieto

- UBS

- UPS

- United Technologies Corporation

- Viessmann

- Volvo Poland

- WABCO Poland

- Whirlpool Poland

Shopping malls[edit]

- Wroclavia

- Galeria Dominikańska

- Arkady Wrocławskie

- Galeria Handlowa Sky Tower

- Pasaż Grunwaldzki

- Centrum Handlowe Borek

- Tarasy Grabiszyńskie

- Magnolia Park

- Wrocław Fashion Outlet

- Factoria Park

- Centrum Handlowe Korona

- Renoma, a 1930s department store of architectural interest over and above its shopping value

- Feniks

- Wrocław Market Hall

- Marino

- Park Handlowy Młyn

- Family Point

- Ferio Gaj

- Aleja Bielany in Bielany Wrocławskie (suburb of Wrocław) – the largest shopping mall in Poland

Transport[edit]

Wrocław is a major transport hub, situated at the crossroad of many routes linking Western and Central Europe with the rest of Poland.[141] The city is skirted on the south by the A4 highway, which is part of the European route E40, extending from the Polish-German to the Polish-Ukrainian border across southern Poland. The 672-kilometre highway beginning at Jędrzychowice connects Lower Silesia with Opole and the industrial Upper Silesian metropolis, Kraków, Tarnów and Rzeszów. It also provides easy access to German cities such as Dresden, Leipzig, Magdeburg and with the A18 highway Berlin, Hamburg.[141]

The toll-free A8 bypass (Wrocław ring road) around the west and north of the city connects the A4 highway with three major routes – S5 expressway leading to Poznań, Bydgoszcz; the S8 express road towards Oleśnica, Łódź, Warsaw, Białystok; and the National Road 8 to Prague, Brno and other townships in the Czech Republic.

Traffic congestion is a significant issue in Wrocław as in most Polish cities; in early 2020 it was ranked as the fifth-most congested city in Poland, and 41st in the world.[142] On average, a car driver in Wrocław annually spends seven days and two hours in a traffic jam.[143] Roadblocks, gridlocks and narrow cobblestone streets around the Old Town are considerable obstacles for drivers. The lack of parking space is also a major setback; private lots or on-street pay bays are the most common means of parking.[144] A study in 2019 has revealed that there are approximately 130 vehicles per each parking spot, and the search for an unoccupied bay takes on average eight minutes.[145]

Aviation[edit]

The city is served by Wrocław Airport (IATA:WRO ICAO:EPWR) situated around 10 kilometres southwest from the city centre. The airport handles passenger flights with LOT Polish Airlines, Buzz, Ryanair, Wizz Air, Lufthansa, Eurowings, Air France, KLM, Scandinavian Airlines, Swiss International Air Lines and air cargo connections. In 2019 over a 3.5 million passengers passed through the airport, placing it fifth on the list of busiest airports in Poland.[146][147] Among the permanent and traditional destinations are Warsaw, Amsterdam, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt am Main, Zürich and Budapest.[148] Low-cost flights are common among British, Italian, Spanish and Ukrainian travellers, based on the number of destinations.[148] Seasonal charter flights are primarily targeted at Polish holidaymakers travelling to Southern Europe and North Africa.[148]

Rail and bus[edit]

The main rail station is Wrocław Główny, which is the largest railway station in Poland by the number of passengers served (21,2 million passengers a year), and perhaps the most important railroad junction alongside Warsaw Central station.[149] The station is supported by PKP Intercity, Polregio, Koleje Dolnośląskie and Leo Express. There are direct connections to Szczecin, Poznań, and to Warsaw Central through Łódź Fabryczna station. There is also a regular connection to Berlin Hauptbahnhof and Wien Hauptbahnhof (Vienna), as well as indirect to Praha hlavní nádraží (Prague) and Budapest-Nyugati with one transfer depending on the carrier.

Adjacent to the railway station, is a central bus station located in the basement of the shopping mall Wroclavia, with services offered by PKS, Neobus, Flixbus, Sindbad, and others.[150][151]

Public transport[edit]

The public transport in Wrocław comprises 99 bus lines and a well-developed network of 23 tram lines (with a length over 200 kilometres) operated by the Municipal Transport Company MPK (Miejskie Przedsiębiorstwo Komunikacyjne).[152][153] Rides are paid for, tickets can be purchased in vending machines, which are located at bus stops, as well as in the vending machines located in the vehicle (payment contactless payment card, the ticket is saved on the card). The tickets are available for purchase in the electronic form via mobile app: mPay, Apple Pay, SkyCash, Mobill, Google Pay. Tickets are one-ride or temporary (0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 24, 48, 72, or 168 hours).

All buses and big part of trams is low-floor.

Over a dozen traditional taxicab firms operate in the city as well as Uber, iTaxi, Bolt and Free Now.

Other[edit]

There are 1200 km of cycling paths including about 100 km paths on flood embankments. Wrocław has a bike rental network called the City Bike (Wrocławski Rower Miejski). It has 2000 bicycles and 200 self-service stations.[154] In addition to regular bicycles, tandem, cargo, electric, folding, tricycles, children's, and handbikes are available, operating every year from 1 March to 30 November. During winter (December – February) 200 bikes are available in the system.

Wrocław possesses a scooter-sharing system of Lime, Bird, Bolt and Hive Free Now – motorized scooter rental is available using a mobile application.

Electronic car rental systems include Traficar, Panek CarSharing (hybrid cars),[155][156] GoScooter and hop.city electric scooters using the mobile application.

A gondola lift over the Oder called Polinka began operation in 2013.[157] Wrocław also has a river port on the Oder and several marinas.

Demographics[edit]

In December 2020, the population of Wrocław was estimated at 641,928 individuals, of which 342,215 were women and 299,713 were men.[158] Since 2011, the population has been steadily rising, with a 0.142% increase between 2019 and 2020, and a 2.167% increase in the years 2011–2020.[159] In 2018, the crude birth rate stood at 11.8 and the mortality rate at 11.1 per 1,000 residents.[160] The median age in 2018 was 43 years.[161] The city's population is aging significantly; between 2013 and 2018, the number of seniors (per Statistics Poland – men aged 65 or above and women aged 60 or above) surged from 21.5% to 24.2%.[160]

Historically, the city's population grew rapidly throughout the 19th and 20th centuries; in the year 1900 approximately 422,709 people were registered as residents and by 1933 the population was already 625,000.[162] The strongest growth was recorded from 1900 to 1910, with almost 100,000 new residents within the city limits. Although the city was overwhelmingly German-speaking, the ethnic composition based on heritage or place of birth was mixed.[163][164] According to a statistical report from 2000, around 43% of all inhabitants in 1910 were born outside Silesia and migrated into the city, mostly from the contemporary regions of Greater Poland (then the Prussian Partition of Poland) or Pomerania.[163] Poles and Jews were among the most prominent active minorities. Simultaneously, the city's territorial expansion and incorporation of surrounding townships further strengthened population growth.[163]

Following the end of the Second World War and post-1945 expulsions of the pre-war population, Wrocław became again predominantly Polish-speaking. New incomers were primarily resettled from areas in the east which Poland lost (Vilnius and Lviv), or from other provinces, notably the regions of Greater Poland, Lublin, Białystok and Rzeszów.[163] At the end of 1947, the city's population was estimated at 225,000 individuals, most of whom were migrants.[163] German nationals who stayed were either resettled in the late 1940s and 1950s, or assimilated,[165] though a cultural society now exists to promote German culture in the still-existing German minority.[166]

Contemporary Wrocław has one of the highest concentration of foreigners in Poland alongside Warsaw and Poznań; a significant majority are migrant workers from Ukraine; others came from Italy, Spain, South Korea, India, Russia and Turkey.[167][168] No exact statistic exists on the number of temporary residents from abroad. Many are students studying at Wrocław's schools and institutions of higher learning.

Religion[edit]

Wrocław's population is predominantly Roman Catholic, like the rest of Poland. The diocese was founded in the city as early as 1000, it was one of the first dioceses in the country at that time. Now the city is the seat of a Catholic Archdiocese.

Prior to World War II, Breslau was mostly inhabited by Protestants, followed by a large Roman Catholic and a significant Jewish minority. In 1939, of 620,976 inhabitants 368,464 were Protestants (United Protestants; mostly Lutherans and minority Reformed; in the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union), 193,805 Catholics, 2,135 other Christians and 10,659 Jews. Wrocław had the third largest Jewish population of all cities in Germany before the war.[170] Its White Stork Synagogue was completed in 1840,[170] and rededicated in 2010.[170] Four years later, in 2014, it celebrated its first ordination of four rabbis and three cantors since the Holocaust.[170] The Polish authorities together with the German Foreign Minister attended the official ceremony.[170]

Post-war resettlements from Poland's ethnically and religiously more diverse former eastern territories (known in Polish as Kresy) and the eastern parts of post-1945 Poland (see Operation Vistula) account for a comparatively large portion of Greek Catholics and Orthodox Christians of mostly Ukrainian and Lemko descent. Wrocław is also unique for its "Dzielnica Czterech Świątyń" (Borough of Four Temples) — a part of Stare Miasto (Old Town) where a synagogue, a Lutheran church, a Roman Catholic church and an Eastern Orthodox church stand near each other. Other Christian denominations present in Wrocław include Seventh Day Adventists, Baptists, Free Christians, Reformed (Clavinist), Methodists, Pentecostals, Jehovah's Witnesses and members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Non-christian congregations include Buddhists. There are also minor associations practicing and promoting Rodnovery neopaganism.[171][172]

In 2007, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Wrocław established the Pastoral Centre for English Speakers, which offers Mass on Sundays and Holy Days of Obligation, as well as other sacraments, fellowship, retreats, catechesis and pastoral care for all English-speaking Catholics and non-Catholics interested in the Catholic Church. The Pastoral Centre is under the care of Order of Friars Minor, Conventual (Franciscans) of the Kraków Province in the parish of St Charles Borromeo (Św Karol Boromeusz).[173]

Education[edit]

Wrocław is the third largest educational centre of Poland, with 135,000 students in 30 colleges which employ some 7,400 staff.[174]The city is home to ten public colleges and universities: University of Wrocław (Uniwersytet Wrocławski):[175] over 47,000 students, ranked fourth among public universities in Poland by the Wprost weekly ranking in 2007;[176] Wrocław University of Technology (Politechnika Wrocławska):[177] over 40,000 students, the best university of technology in Poland by the Wprost weekly ranking in 2007;[178] Wrocław Medical University (Uniwersytet Medyczny we Wrocławiu);[179] University School of Physical Education in Wrocław;[180] Wrocław University of Economics (Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny we Wrocławiu)[181] over 18,000 students, ranked fifth best among public economic universities in Poland by the Wprost weekly ranking in 2007;[182] Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences (Uniwersytet Przyrodniczy we Wrocławiu):[183] over 13,000 students, ranked third best among public agricultural universities in Poland by the Wprost weekly ranking in 2007;[184] Academy of Fine Arts in Wrocław (Akademia Sztuk Pięknych we Wrocławiu);[185] Karol Lipiński University of Music (Akademia Muzyczna im. Karola Lipińskiego we Wrocławiu);[186] Ludwik Solski Academy for the Dramatic Arts, Wrocław Campus (Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Teatralna w Krakowie filia we Wrocławiu);[187] and the Tadeusz Kościuszko Land Forces Military Academy (Wyższa Szkoła Oficerska Wojsk Lądowych).[188]

Private universities in the city include Wyższa Szkoła Bankowa (University of Business in Wrocław); University of Social Sciences and Humanities (SWPS Uniwersytet Humanistycznospołeczny); University of Law (Wyższa Szkoła Prawa);[189] and Coventry University Wrocław[190] (Branch campus of the Coventry University, UK). Other cultural institutions based in Wrocław are Alliance Française in Wrocław; Austrian Institute in Wrocław; British Council in Wrocław; Dante Alighieri Society in Wrocław and Grotowski Institute in Wrocław.

Culture and landmarks[edit]

Old Town[edit]

The Old Town of Wrocław is listed in the Registry of Objects of Cultural Heritage and is, since 1994, on Poland's prestigious list of National Monuments.[191] Several architectural landmarks and edifices are one of the best examples of Brick Gothic and Baroque architecture in the country.[192] Fine examples of Neoclassicism, Gründerzeit and Historicism are also scattered across the city's central precinct. The Wrocław Opera House, Monopol Hotel, University Library, Ossolineum, the National Museum and the castle-like District Court are among some of the grandest and most recognizable historic structures. There are several examples of Art Nouveau and Modernism in pre-war retail establishments such as the Barasch-Feniks, Petersdorff-Kameleon and Renoma department stores.[193]

The Ostrów Tumski (Cathedral Island) is the oldest section of the city; it was once an isolated islet between the branches of the Oder River. The Wrocław Cathedral, one of the tallest churches in Poland, was erected in the mid 10th century and later expanded over the next hundreds of years. The island is also home to five other Christian temples and churches, the Archbishop's Palace, the Archdiocese Museum, a 9.5-metre 18th-century monument dedicated to Saint John of Nepomuk, historic tenements and the steel Tumski Bridge from 1889.[194][195] A notable attraction are 102 original gas lanterns which are manually lit each evening by a cloaked lamplighter.[196]

The early 13th-century Main Market Square (Rynek) is the oldest medieval public square in Poland, and also one of the largest (the area of the main square together with the auxiliary square is 48,500 m²).[197] It features the ornate Gothic Old Town Hall, the oldest of its kind in the country.[197] In the north-west corner of the square is St. Elisabeth's Church (Bazylika Św. Elżbiety) with its 91.5-metre-high tower and an observation deck at an altitude of 75 metres. Beneath the basilica are two small medieval houses connected by an arched gate that once led into a churchyard; these were reshaped into their current form in the 1700s. Today, the two connected buildings are known to the city's residents as "Jaś i Małgosia," named after the children's fairy tale characters from Hansel and Gretel.[198] North of the church are so-called "shambles" (Polish: jatki), a former meat market with a Monument of Remembrance for Slaughtered Animals.[199] The Salt Square (now a flower market) opened in 1242 is located at the south-western corner of the Market Square – close to the square, between Szewska and Łaciarska streets, is the domeless 13th-century St. Mary Magdalene Church, which during the Reformation (1523) was converted into Wrocław's first Protestant temple.[200]

The Cathedral of St. Vincent and St. James and the Holy Cross and St. Bartholomew's Collegiate Church are burial sites of Polish monarchs, Henry II the Pious and Henry IV Probus, respectively.[201]

The Pan Tadeusz Museum, open since May 2016, is located in the "House under the Golden Sun" at 6 Market Square. The manuscript of the national epos, Pan Tadeusz, is housed there as part of the Ossolineum National Institute, with multimedia and interactive educational opportunities.[202]

Tourism and places of interest[edit]

The Tourist Information Centre (Polish: Centrum Informacji Turystycznej) is situated on the Main Market Square (Rynek) in building no 14. In 2011, Wrocław was visited by about 3 million tourists, and in 2016 about 5 million.[203] Free wireless Internet (Wi-Fi) is available at a number of places around town.[204]

Wrocław is a major attraction for both domestic and international tourists. Noteworthy landmarks include the Multimedia Fountain, Szczytnicki Park with its Japanese Garden, miniature park and dinosaur park, the Botanical Garden founded in 1811, Poland's largest railway model Kolejkowo, Hydropolis Centre for Ecological Education, University of Wrocław with Mathematical Tower, Church of the Name of Jesus, Wrocław water tower, the Royal Palace, ropes course on the Opatowicka Island, White Stork Synagogue, the Old Jewish Cemetery and the Cemetery of Italian Soldiers. An interesting way to explore the city is seeking out Wrocław's dwarfs – over 800 small bronze figurines can be found across the city, on pavements, walls and lampposts.[205] They first appeared in 2005.[206]

The Racławice Panorama is a monumental cycloramic painting, done by Jan Styka and Wojciech Kossak, depicting the Battle of Racławice during the Kościuszko Uprising in 1794. The 15×114 meter panorama was originally located in Lwów and following the end of World War II it was brought to Wrocław.[207]

Wrocław Zoo is home to the Africarium – the only space devoted solely to exhibiting the fauna of Africa with an oceanarium. It is the oldest zoological garden in Poland established in 1865. It is also the third-largest zoo in the world in terms of the number of animal species on display.[208]

Small passenger vessels on the Oder offer river tours, as do historic trams or the converted open-topped historic buses Jelcz 043.[209] In 2021, the Odra Centrum has opened, an educational centre on the river which is offering workshops, a library and kayak rentals.[210]

The Centennial Hall (Hala Stulecia, German: Jahrhunderthalle), designed by Max Berg in 1911–1913, is a World Heritage Site listed by UNESCO in 2006.[211]

Entertainment[edit]

The city is well known for its large number of nightclubs and pubs. Many are in or near the Market Square, and in the Niepolda passage, the railway wharf on the Bogusławskiego street. The basement of the old City Hall houses one of the oldest restaurants in Europe—Piwnica Świdnicka (operating since around 1273),[212] while the basement of the new City Hall contains the brewpub Spiż. There are also 3 other brewpubs – Browar Stu Mostów, Browar Staromiejski Złoty Pies, Browar Rodzinny Prost. Every year on the second weekend of June the Festival of Good Beer takes place.[213] It is the biggest beer festival in Poland.[213]

Each year in November and December the Christmas market is held at the Main Market Square.[214]

Museums[edit]

The National Museum at Powstańców Warszawy Square, one of Poland's main branches of the National Museum system, holds one of the largest collections of contemporary art in the country.[215]

Ossolineum is a National Institute and Library incorporating the Lubomirski Museum (pl), partially salvaged from the formerly Polish city of Lwów (now Lviv in Ukraine), containing items of international and national significance. It has a history of major World War II theft of collections after the invasion and takeover of Lwów by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.

Основные музеи также включают Городской музей Вроцлава (pl) , Музей буржуазного искусства в Старой ратуше , Музей архитектуры , Археологический музей (pl) , Музей естественной истории при Вроцлавском университете , Музей современного искусства во Вроцлаве, Архиепархия. Музей (пл) , Галерея Авангарда , Арсенал , Аптечный музей (пл) , Музей почты и телекоммуникаций (пл) , Геологический музей (пл) , Минералогический музей (пл) , Этнографический музей (пл) . Недавними открытиями музеев стали Исторический центр Заездня (открытие в 2016 году), Галерея OP ENHEIM (открытие в 2018 году) и Музей иллюзий (открытие в 2021 году). [216]

В литературе [ править ]

История Вроцлава подробно описана в монографии «Микрокосм: портрет центральноевропейского города» Нормана Дэвиса и Роджера Мурхауса . [217] После Второй мировой войны о Вроцлаве было написано несколько книг.

Вроцлавский филолог и писатель Марек Краевский написал серию криминальных романов о сыщике Эберхарде Моке , вымышленном персонаже из города Бреслау. [218] Соответственно, Михал Качмарек опубликовал «Вроцлав по Эберхарду Мок – Путеводитель» по книгам Марека Краевского . В 2011 году появился 1104-страничный «Лексикон архитектуры Вроцлава», а в 2013 году — 960-страничный «Лексикон о зелени Вроцлава». В марте 2015 года Вроцлав подал заявку на статус ЮНЕСКО. литературного города [219] и получил его в 2019 году. Вроцлав был признан Всемирной столицей книги в 2016 году ЮНЕСКО . [220]

Кино, музыка и театр [ править ]

Во Вроцлаве находятся Центр аудиовизуальных технологий (ранее Wytwórnia Filmów Fabularnych), Школа каскадеров кино, ATM Grupa, Grupa 13 и Tako Media. [221]

Кинорежиссеры Анджей Вайда , Кшиштоф Кеслёвский , Сильвестр Хенчинский и другие дебютировали во Вроцлаве. В городе снято множество фильмов, в том числе «Пепел и бриллианты» , «Рукопись Сарагосы» , «Сами свой» , «Лалка» , «Одинокая женщина» , «Персонаж» , «Эме и Ягуар» , «Авалон» , «Женщина в Берлине» , «Комната самоубийц» , «Победитель» , «80 миллионов» , «Беги, мальчик, беги» , Мост шпионов и преодоление границ . [222]

Во Вроцлаве также снимались многочисленные польские сериалы, в частности «Свят для Кепских» , «Первая любовь », «Белфер» , «Четыре танкиста и собака» .

Есть несколько театров и театральных коллективов, в том числе Польский театр (Teatr Polski) с тремя сценами и Современный театр (Wrocławski Teatr Współczesny). Международный театральный фестиваль «Диалог-Вроцлав» проводится раз в два года. [223]

Оперные традиции Вроцлава восходят к первой половине семнадцатого века и поддерживаются Вроцлавской оперой , построенной между 1839 и 1841 годами. Вроцлавская филармония, основанная в 1954 году Войцехом Дзедушицким, также важна для любителей музыки. Национальный музыкальный форум был открыт в 2015 году и является известной достопримечательностью, спроектированной польской архитектурной фирмой Kurylowicz & Associates . [224]

Спорт [ править ]

Район Вроцлава является домом для многих популярных профессиональных спортивных команд; Самый популярный вид спорта - футбол ( клуб «Сленск Вроцлав» - чемпион Польши в 1977 и 2012 годах), за ним следует баскетбол ( баскетбольный клуб «Сленск Вроцлав» - отмеченная наградами мужская баскетбольная команда и 17-кратный чемпион Польши). [225]

Матчи группы А Евро-2012 прошли во Вроцлаве на Муниципальном стадионе . матчи Евробаскета 1963 и Евробаскета 2009 , а также чемпионата Европы по волейболу среди женщин 2009 года , чемпионата мира по волейболу среди мужчин 2014 года и чемпионата Европы по гандболу среди мужчин 2016 года Во Вроцлаве также прошли . Вроцлав был местом проведения чемпионата мира по тяжелой атлетике 2013 года , а также примет чемпионат мира 2016 года по дублирующему мосту и Всемирные игры 2017 года, соревнования по 37 неолимпийским спортивным дисциплинам.

Олимпийский стадион во Вроцлаве принимает Гран-при Польши по спидвею . Это также домашняя арена популярного мотоспидвей- клуба WTS Sparta Wrocław , пятикратного чемпиона Польши .

Марафон . проходит во Вроцлаве каждый год в сентябре [226] Вроцлав также принимает Wrocław Open , профессиональный теннисный турнир, который является частью ATP Challenger Tour .

Мужской спорт [ править ]

- Слёнск Вроцлав : мужская футбольная команда, Чемпионат Польши по футболу 1977, 2012; Обладатель Кубка Польши 1976, 1987 годов; Обладатель Суперкубка Польши 1987, 2012 годов; Обладатель Кубка Польской Лиги 2009. Сейчас в Экстракласе (Польская Премьер-лига).

- WTS Sparta Wrocław : команда по мотоспорту , пятикратный чемпион Польши.

- Слёнск Вроцлав : мужская баскетбольная команда, 18-кратный чемпион Польши, шесть раз занявший второе место , 15-кратное третье место; 12-кратный обладатель Кубка Польши.

- Сленск Вроцлав : мужская гандбольная команда, 15-кратный чемпион Польши.

- Гвардия Вроцлав : волейбольная команда, трехкратный чемпион Польши.

- KS Rugby Wrocław: сборная союза регби .

- Пантеры Вроцлав : команда по американскому футболу. «Пантеры» присоединились к Европейской лиге футбола (ELF), которая представляет собой профессиональную лигу из восьми команд, первую лигу в Европе после упадка Национальной футбольной лиги Европы . [227] Матчи против команд Германии и Испании «Пантеры» начнут проводить в июне 2021 года. [228]

Женский спорт [ править ]

- Сленза Вроцлав : женская баскетбольная команда, двукратная чемпионка Польши.

- WKS Śląsk Wrocław (ранее KŚ AZS Wrocław ): женская футбольная команда.

- AZS AWF Вроцлав: женская гандбольная команда.

- AZS AE Вроцлав: женская сборная по настольному теннису .

Люди [ править ]

- Алоис Альцгеймер , психиатр и невропатолог

- Адольф Андерсен , мастер по шахматам

- Джордже Андреевич-Кун , художник

- Наталья Авелон , актриса

- Макс Берг , архитектор

- Макс Бильшовский , невропатолог

- Дитрих Бонхёффер , теолог, антинацистский диссидент

- Эдмунд Бояновский , благословенный католической церкви.

- Макс Борн , физик-теоретик и математик, лауреат Нобелевской премии

- Лешек Чарнецкий , бизнесмен

- Славомир Добжаньский , пианист и музыковед.

- Герман фон Эйххорн , прусский фельдмаршал

- Артур Экерт , физик

- Герман Фернау , юрист

- Хайнц Френкель-Конрат , биохимик и вирусолог

- Владислав Фрасынюк , политик

- Иоланта Фрашиньска , актриса

- Ганс Фриман , биохимик

- Генрих Гульбинович , архиепископ

- Ежи Гротовский , театральный режиссёр

- Клара Иммервар , химик [229]

- Клаудия Ячира , политик и комик

- Зигмунт Хаас , ученый-компьютерщик

- Фриц Габер , химик, лауреат Нобелевской премии

- Ян Хартман , философ

- Феликс Хаусдорф , математик

- Мирослав Гермашевский , космонавт.

- Хуберт Гуркач , теннисист [230]

- Лех Янерка , музыкант

- Карл Готхард Ланганс , архитектор

- Альфред Керр , немецко-еврейский критик

- Хедвиг Кон , выдающаяся женщина-физик

- Август Копиш , поэт

- Артур Корн , физик, математик и изобретатель

- Уршула Козел , поэт

- Генрих Герхард Кун , физик

- Марек Краевский , писатель и лингвист [231]

- Войцех Куртика , альпинист

- Aleksandra Kurzak , operatic soprano [232]

- Фердинанд Лассаль , инициатор социал-демократического движения в Германии

- Олаф Любасенко , актер и кинорежиссер

- Хьюго Люблинер , драматург

- Мата , рэпер

- Аарон Мор , израильский государственный служащий польского происхождения.

- Матеуш Моравецкий , политик, премьер-министр Польши [233]

- Александр Мошковский , сатирик, писатель и философ.

- Мориц Мошковский , композитор, пианист и педагог.

- Рут Нойдек , руководитель немецких лагерей смерти СС и военный преступник

- Рафал Омелько , спортсмен

- Генрих Пик (1882-1947), юрист

- Зепп Пионтек , футбольный менеджер

- Петр Пониковский , кардиолог

- Маргарет Поспих , писательница, кинорежиссер

- Майкл Озер Рабин , математик и ученый-компьютерщик

- Манфред фон Рихтгофен , летчик-истребитель

- Тадеуш Ружевич , поэт и драматург

- Ванда Руткевич , альпинистка [234]

- Огюст Шмидт , педагог и феминистка

- Марлен Шмидт , Мисс Германия 1961, Мисс Вселенная 1961.

- Ева Зиверт , журналистка и активистка-лесбиянка

- Ангелус Силезиус (Иоганн Шеффлер), перешедший из протестантизма в католицизм, мистик и религиозный поэт.

- Макс Саймон , офицер Ваффен-СС

- Карл Слотта , биохимик

- Аньес Сорма , актриса

- Дэниел Спир , автор, композитор

- Ева Стачняк , писатель

- Эдит Штайн , философ и римско-католическая мученица

- Чарльз Протеус Стейнмец , инженер-электрик

- Фриц Штерн , историк

- Юлиус Штерн , композитор

- Уильям Стерн , психолог

- Август Толак , теолог

- Ольга Токарчук , писательница, лауреат Нобелевской премии по литературе [235]

- Ян Томашевски , футболист

- Дагмара Возняк (1988 г.р.), польско-американская олимпийская саблистка США

- Людвиг фон Зант (1796–1857), архитектор.

Международные отношения [ править ]

Дипломатические миссии [ править ]

Во Вроцлаве 3 генеральных консульства – Германии , Венгрии и Украины , и 23 почетных консульства – Австрии , Болгарии , Чехии , Чили , Дании , Грузии , Эстонии , Франции , Финляндии , Испании , Индии , Казахстана , Кореи , Литвы , Люксембурга , Латвия , Мальта , Мексика , Норвегия , Словакия , Швеция , Турция , Италия .

Города-побратимы – города-побратимы [ править ]

Вроцлав является побратимом : [236] [237]

Батуми , Грузия (2019)

Батуми , Грузия (2019)  Бреда , Нидерланды (1991)

Бреда , Нидерланды (1991)  Шарлотта , США (1991)

Шарлотта , США (1991)  Чхонджу , Южная Корея (2023 г.)

Чхонджу , Южная Корея (2023 г.)  Дрезден , Германия (1991)

Дрезден , Германия (1991)  Гвадалахара , Мексика (1995)

Гвадалахара , Мексика (1995)  Градец-Кралове , Чехия (2003)

Градец-Кралове , Чехия (2003)  Каунас , Литва (2003)

Каунас , Литва (2003)  Лилль , Франция (2013)

Лилль , Франция (2013)  Львов , Украина (2002)

Львов , Украина (2002)  Оксфорд , Великобритания (2018)

Оксфорд , Великобритания (2018)  Рамат-Ган , Израиль (1997)

Рамат-Ган , Израиль (1997)  Рейкьявик , Исландия (2017)

Рейкьявик , Исландия (2017)  Вена , Франция (1990)

Вена , Франция (1990)  Висбаден , Германия (1987)

Висбаден , Германия (1987)

См. также [ править ]

- 2003 Футбольный бунт во Вроцлаве

- Ян (епископ Вроцлавский)

- Глобальный форум Вроцлава

- Микрокосм: портрет центральноевропейского города

- Бреслау, Онтарио - бывшая деревня (поселение в 1806 г., почтовая деревня в 1857 г.), а ныне община имени Вроцлава.

Примечания [ править ]

Ссылки [ править ]

- ^ [1] Архивировано 1 февраля 2023 г. в Wayback Machine (на польском языке).

- ^ «Валовой внутренний продукт (ВВП) в текущих рыночных ценах по мегаполисам» . ec.europa.eu . Архивировано из оригинала 15 февраля 2023 года.

- ^ «Вроцлав» . Lexico Британский словарь английского языка . Издательство Оксфордского университета . Архивировано из оригинала 12 сентября 2021 года.

- ^ «Вроцлав» . Словарь английского языка американского наследия (5-е изд.). ХарперКоллинз . Проверено 18 августа 2023 г.

- ^ «Вроцлав» . Словарь Merriam-Webster.com . Проверено 13 мая 2019 г.

- ^ «Вроцлав-инфо – официальный туристический информационный сайт Вроцлава» . Вроцлав-info.pl . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2017 года . Проверено 17 апреля 2017 г.

- ^ Администратор. «Вроцлав – Темный туризм – путеводитель по темным и странным местам мира» . Дарк-туризм.com . Архивировано из оригинала 18 апреля 2017 года . Проверено 19 мая 2017 г.

- ^ «Вроцлавские лауреаты Нобелевской премии» . Вроцлав.пл . Архивировано из оригинала 7 апреля 2022 года . Проверено 1 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ «Российские университеты возглавили рейтинг 2016 года в регионе ВЕЦА» . Topuniversities.com . 10 июня 2016 года. Архивировано из оригинала 17 августа 2019 года . Проверено 17 апреля 2017 г.

- ^ «GaWC – Мир по версии GaWC 2020» . www.lboro.ac.uk . Архивировано из оригинала 24 августа 2020 года . Проверено 3 сентября 2020 г.

- ^ «Опрос качества жизни 2019» . UK.mercer.com . Архивировано из оригинала 18 апреля 2018 года . Проверено 17 сентября 2019 г.

- ^ «Индекс движения городов IESE 2019» (PDF) . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 3 июня 2019 года . Проверено 3 июня 2019 г.

- ^ Балаевич, Конрад (16 февраля 2021 г.). «Вроцлав занимает очень высокое место в рейтинге городов будущего. Что оценивали?» . Газета Вроцлавская . Архивировано из оригинала 19 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 16 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Минихейн, Джо. «20 прекрасных европейских городов, в которых практически нет туристов» . CNN . Архивировано из оригинала 16 сентября 2019 года . Проверено 13 января 2020 г. .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Исторический обзор Вроцлава – Вроцлав в вашем кармане» . Inyourpocket.com . Архивировано из оригинала 5 апреля 2016 года . Проверено 17 апреля 2017 г.

- ^ Самсонович, Хенрик, изд. (2000). «Силезия между Гнезно и Прагой» [в:] «Польские земли в X веке и их значение в формировании новой карты Европы . Краков: Университеты. стр. 187. ISBN. 83-7052-710-8 . OCLC 45809955 .

- ^ «Корпус польского языка PWN» . sjp.pwn.pl. Архивировано из оригинала 26 сентября 2021 года . Проверено 7 декабря 2020 г.

- ^ Станислав Роспонд, «Бывший Вроцлав и его окрестности в свете имен», Соботка, 1970.

- ^ Пол Хеффтнер: Муниципальная протестантская средняя школа I, происхождение и значение топонимов в районе Бреслау, 1909, стр. 9 и далее.

- ^ Г. Хассель: Полное и новейшее земное описание Прусской монархии. Веймар: Веймарский географический институт, 1819 г.

- ^ Грассе, JGT (1861 г.). Orbis latinus или справочник латинских названий самых известных городов и т. д., морей, озер, гор и рек во всех частях света, вместе с немецко-латинским регистром того же языка . Дрезден: Книжный магазин Г. Шенфельда (CA Werner). п. 40 .

- ^ «Отдел карт – История коллекции» . www.bu.uni.wroc.pl. 6 октября 2009 г. Архивировано из оригинала 7 апреля 2022 г. Проверено 7 декабря 2020 г.

- ^ К. Яворский, П. Ржежник (1998). Остров Тумский во Вроцлаве в раннем средневековье», [в:] «Civitates Principales, Избранные центры власти в раннесредневековой Польше (Каталог выставки)» . Гнезно. стр. 88–94.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: отсутствует местоположение издателя ( ссылка ) - ↑ Spis treści. Архивировано 31 августа 2021 года в Wayback Machine (на польском языке).

- ^ «Собор Иоанна Предтечи» . ПосетитеWroclaw.eu . Архивировано из оригинала 31 декабря 2020 года . Проверено 7 декабря 2020 г.

- ^ «Новый год – Папа сражается с драконом» . ВашаИстория.pl . 31 декабря 2019 года. Архивировано из оригинала 22 января 2021 года . Проверено 7 декабря 2020 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Норман Дэвис «Микрокосмос», стр. 110–115.

- ^ Везерка, стр. 39.

- ^ Тадеуш Левицкий, Польша и соседние страны в свете «Книги Роджера» арабского географа XII века Аль Индриси, часть I, Польская академия наук. Восточный комитет, PWN, Краков, 1945 г.

- ^ Везерка, стр. 41.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кулак, Тереза (21 августа 2011 г.). «Вроцлав в истории и памяти поляков» . enrs.eu. Европейская сеть памяти и солидарности . Архивировано из оригинала 4 февраля 2021 года . Проверено 9 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Бенедикт Зентара (1997). Генрих Бородатый и его время (на польском языке). Варшава: Трио. стр. 317–320. ISBN 978-83-85660-46-0 .

- ^ Норман Дэвис "Микрокосмос" с. 114

- ^ Адам Максимович. «Необычайная экспедиция Бенедикта Поляка» . Niedziela.pl (на польском языке) . Проверено 16 мая 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Тум, с. 316

- ^ Норман Дэвис "Микрокосмос" с. 110

- ^ Петр Гурецкий (2007). Местное общество в переходный период: Книга Генрикова и связанные с ней документы . Папский институт средневековых исследований. стр. 27, 62. ISBN. 978-0-88844-155-3 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Роман Томчак (6 июля 2017 г.). «Где безголовый скелет?» . Госьч Легницкий (на польском языке). Архивировано из оригинала 16 января 2021 года . Проверено 26 апреля 2020 г.