Kingston upon Hull

Kingston upon Hull, usually shortened to Hull, is a port city and unitary authority area in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England.[2] It lies upon the River Hull at its confluence with the Humber Estuary, 25 miles (40 km) inland from the North Sea and 37 miles (60 km) south-east of York, the historic county town.[2] With a population of 268,852 (2022), it is the fourth-largest city in the Yorkshire and the Humber region after Leeds, Sheffield and Bradford.

The town of Wyke on Hull was founded late in the 12th century by the monks of Meaux Abbey as a port from which to export their wool. Renamed Kings-town upon Hull in 1299, Hull had been a market town,[3] military supply port,[4] trading centre,[5] fishing and whaling centre and industrial metropolis.[4]Hull was an early theatre of battle in the English Civil Wars.[5] Its 18th-century Member of Parliament, William Wilberforce, took a prominent part in the abolition of the slave trade in Britain.[6]

More than 95% of the city was damaged or destroyed in the blitz and suffered a period of post-industrial decline (social deprivation, education and policing).[7] The destroyed areas of the city were rebuilt in the post–Second World War period.[8] In the early 21st century spending boom before the late 2000s recession the city saw large amounts of new retail, commercial, housing and public service construction spending.

In 2017, it was the UK City of Culture and hosted the Turner Prize at the city's Ferens Art Gallery.[9] Other notable landmarks in the city are the Minster, the tidal surge barrier, the Paragon Interchange and The Deep aquarium. Areas of the town centre include the old town (including its museum quarter) and the marina. Hull University was founded in 1927 and had over 16,000 students in 2022.[10] Rugby league football teams include clubs Hull F.C. and Hull Kingston Rovers. The city's association football club is Hull City (EFL Championship). Hull RUFC and Hull Ionians both play in the National League 2 North of rugby union.

History[edit]

Wyke and wool trade[edit]

Kingston upon Hull stands on the north bank of the Humber Estuary at the mouth of its tributary, the River Hull. The valley of the River Hull has been inhabited since the early Neolithic period but there is little evidence of a substantial settlement in the area of the present city.[11] The area was attractive to people because it gave access to a prosperous hinterland and navigable rivers but the site was poor, being remote, low-lying and with no fresh water. It was originally an outlying part of the hamlet of Myton, named Wyke. The name is thought to originate either from a Scandinavian word Vik meaning inlet or from the Saxon Wic meaning dwelling place or refuge.[12][13]

The River Hull was a good haven for shipping, whose trade included the export of wool from Meaux Abbey, which owned Myton. In 1293, the town of Wyke was acquired from the abbey by King Edward I, who, on 1 April 1299, granted it a royal charter that renamed the settlement King's town upon Hull or Kingston upon Hull. The charter is preserved in the archives of the Guildhall.[5]

In 1440, a further charter incorporated the town and instituted local government consisting of a mayor, a sheriff and twelve aldermen.[5]

In his Guide to Hull (1817), J. C. Craggs provides a colourful background to Edward's acquisition and naming of the town. He writes that the King and a hunting party started a hare which "led them along the delightful banks of the River Hull to the hamlet of Wyke … [Edward], charmed with the scene before him, viewed with delight the advantageous situation of this hitherto neglected and obscure corner. He foresaw it might become subservient both to render the kingdom more secure against foreign invasion, and at the same time greatly to enforce its commerce". Pursuant to these thoughts, Craggs continues, Edward purchased the land from the Abbot of Meaux, had a manor hall built for himself, issued proclamations encouraging development within the town, and bestowed upon it the royal appellation, King's Town.[15]

Prospering port[edit]

The port served as a base for Edward I during the First War of Scottish Independence and later developed into the foremost port on the east coast of England. It prospered by exporting wool and woollen cloth, and importing wine and timber. Hull also established a flourishing commerce with the Baltic ports of the Hanseatic League.[16]

From its medieval beginnings, Hull's main trading links were with Scotland and northern Europe. Scandinavia, the Baltic and the Low Countries were all key trading areas for Hull's merchants. In addition, there was trade with France, Spain and Portugal.[citation needed]

Sir William de la Pole was the town's first mayor.[17] A prosperous merchant, de la Pole founded a family that became prominent in government.[5] Another successful son of a Hull trading family was bishop John Alcock, who founded Jesus College, Cambridge and was a patron of the grammar school in Hull.[5] The increase in trade after the discovery of the Americas and the town's maritime connections are thought to have played a part in the introduction of a virulent strain of syphilis through Hull and on into Europe from the New World.[18]

The town prospered during the 16th and early 17th centuries,[5] and Hull's affluence at this time is preserved in the form of several well-maintained buildings from the period, including Wilberforce House, now a museum documenting the life of William Wilberforce.[5]

During the English Civil War, Hull became strategically important because of the large arsenal located there. Very early in the war, on 11 January 1642, the king named the Earl of Newcastle governor of Hull while Parliament nominated Sir John Hotham and asked his son, Captain John Hotham, to secure the town at once.[5] Sir John Hotham and Hull corporation declared support for Parliament and denied Charles I entry into the town.[5] Charles I responded to these events by besieging the town.[5] This siege helped precipitate open conflict between the forces of Parliament and those of the Royalists.[5]

After the Civil War, docks were built along the route of the town walls, which were demolished. The first dock (1778, renamed Queen's Dock in 1854) was built in the area occupied by Beverley and North gates, and the intermediate walls, which were demolished, a second dock (Humber Dock, 1809) was built on the land between Hessle and Myton gates, and a third dock between the two was opened 1829 as Junction Dock (later Prince's Dock).[19]

Whaling played a major role in the town's fortunes until the mid-19th century.[5] As sail power gave way to steam, Hull's trading links extended throughout the world. Docks were opened to serve the frozen meat trade of Australia, New Zealand and South America. Hull was also the centre of a thriving inland and coastal trading network, serving the whole of the United Kingdom.[20]

City status[edit]

Throughout the second half of the 19th century and leading up to the First World War, the Port of Hull played a major role in the emigration of Northern European settlers to the New World, with thousands of emigrants sailing to Hull and stopping for administrative purposes before travelling on to Liverpool and then North America.[21]

Parallel to this growth in passenger shipping was the emergence of the Wilson Line of Hull (which had been founded in 1825 by Thomas Wilson). By the early 20th century, the company had grown – largely through its monopolisation of North Sea passenger routes and later mergers and acquisitions – to be the largest privately owned shipping company in the world, with over 100 ships sailing to different parts of the globe. The Wilson Line was sold to the Ellerman Lines – which itself was owned by Hull-born magnate (and the richest man in Britain at the time) Sir John Ellerman.[22]

Hull's prosperity peaked in the decades just before the First World War; it was during this time, in 1897, that city status was granted.[4] Many of the suburban areas on the western side of Hull were built in the 1930s, particularly Willerby Road and Anlaby Park, as well as most of Willerby itself. This was part of the biggest British housing boom of the 20th century (possibly ever).[citation needed]

Bombed and battered[edit]

The city's port and industrial facilities, coupled with its proximity to mainland Europe and ease of location being on a major estuary, led to extremely widespread damage by bombing raids during the Second World War; much of the city centre was destroyed.[5] Hull had 95% of its houses damaged or destroyed, making it the most severely bombed British city or town in terms of number of damaged or destroyed buildings, apart from London, during the Second World War.[23] More than 1,200 people died in air raids on the city and some 3,000 others were injured.[24]

The worst of the bombing occurred in 1941. Little was known about this destruction by the rest of the country at the time, since most of the radio and newspaper reports did not reveal Hull by name but referred to it as "a North-East town" or "a northern coastal town".[25] Most of the city centre was rebuilt in the years following the war. As recently as 2006 researchers found documents in the local archives that suggested a non-exploded wartime bomb might be buried beneath a major new redevelopment, the Boom, in Hull.[26][27]

After the decline of the whaling industry post the Second World War, emphasis shifted to deep-sea trawling until the Anglo-Icelandic Cod War of 1975–1976. The conditions set at the end of this dispute started Hull's economic decline.[5]

City of Culture[edit]

In 2017 Hull was awarded the title of 'City of Culture'[28] by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. Within the city there was a series of festivals in public spaces to promote the city and its newly given title. At the start of the year there was a huge firework display attracting a crowd of 25,000.

Governance[edit]

Municipal[edit]

| County | Borough/ district | Notes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Type | Type | Dependent on county | From | Until | |

| Yorkshire | Ancient | Borough | 1299 | 1440 | Town status from 1299 | |

| County-at-large | County Corporate | 1440 | 1835 | |||

| Historic | Municipal borough | 1835 | 1889 | |||

| East Riding of Yorkshire | Geographic | County borough | 1889 | 1974 | City status from 1897 | |

| Humberside | Non-metropolitan | Shire district | 1974 | 1996 | ||

| East Riding of Yorkshire | Ceremonial | Unitary authority | 1996 | Current | ||

Following the Local Government Act 1888, Hull became a county borough, a local government district independent of the East Riding of Yorkshire. This district was dissolved under the Local Government Act 1972, on 1 April 1974 when it became a non-metropolitan district of the newly created shire county of Humberside. Humberside (and its county council) was abolished on 1 April 1996 and Hull was made a unitary authority area.[5][29]

The single-tier local authority of the city is now Hull City Council (officially Kingston upon Hull City Council), headquartered in the Guildhall in the city centre.[30] The council was designated as the UK's worst performing authority in both 2004 and 2005, but in 2006 was rated as a two star 'improving adequate' council and in 2007 it retained its two stars with an 'improving well' status.[31][32][33][34] In the 2008 corporate performance assessment the city retained its "improving well" status but was upgraded to a three star rating.[35]

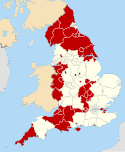

The Liberal Democrats won overall control of the City Council in the 2007 local elections, ending several years in which no single party had a majority.[36] They retained control in the 2008 local elections by an increased majority[37] and in the 2010 local elections.[38] Following the UK's local elections of 2011, the Labour Party gained control of the council,[39] increasing their majority in the 2012[40] and retained this following the 2014 local elections.[41] They increased their majority by one in the 2015 local elections,[42] but lost it in the 2016 local elections.[43] In the 2018 local elections all of the council was up for election following boundary changes that reduced the number of seats by 2.[44] Labour retained control of the council but with a much reduced majority, while in the 2019 local elections there was no change to the make-up of the council.[45] In the 2021 local elections the Liberal Democrats gained a couple of seats but Labour retained control by just three seats.[46] On 3 March 2022, Labour councillor Julia Conner defected to the Liberal Democrats, reducing the Labour majority to one.[47] The Liberal Democrats won overall control of the City Council in the 2022 local elections to end ten years of Labour rule,[48] increasing their majority in the 2023 local elections.[49]

Parliament[edit]

The city returned three members of parliament to the House of Commons and at the last general election, in 2019, elected three Labour MPs: Emma Hardy,[50] Diana Johnson[51] and Karl Turner.[52]

William Wilberforce is the most celebrated of Hull's former MPs. He was a native of the city and the member for Hull from 1780 to 1784 when he was elected as an Independent member for Yorkshire.[53][54]

Geography[edit]

| Place | Distance | Direction | Relation |

|---|---|---|---|

| London | 155 miles (249 km)[55] | South | Capital city |

| Lincoln | 37 miles (60 km)[56] | South | Nearby city |

| Doncaster | 36 miles (58 km)[57] | South-west | Nearby city |

| York | 34 miles (55 km)[58] | North-west | Historic county town |

| Beverley | 8 miles (13 km)[59] | North | County town |

| Brough | 12 miles (19 km) | West | Town |

Kingston upon Hull is on the northern bank of the Humber Estuary.[2] The city centre is west of the River Hull and close to the Humber.[2] The city is built upon alluvial and glacial deposits which overlie chalk rocks but the underlying chalk has no influence on the topography. The land within the city is generally very flat and is only 2 to 4 metres (6.5 to 13 ft) above sea level. Because of the relative flatness of the site there are few physical constraints upon building and many open areas are the subject of pressures to build.[60]

The parishes of Drypool, Marfleet, Sculcoates, and most of Sutton parish, were absorbed within the borough of Hull in the 19th and 20th centuries. Much of their area has been built over, and socially and economically they have long been inseparable from the city. Only Sutton retained a recognisable village centre in the late 20th century, but on the south and east the advancing suburbs had already reached it. The four villages were, nevertheless, distinct communities, of a largely rural character, until their absorption in the borough—Drypool and Sculcoates in 1837, Marfleet in 1882, and Sutton in 1929.[61] The current boundaries of the city are tightly drawn and exclude many of the metropolitan area's nearby villages, of which Cottingham is the largest.[62] The city is surrounded by the rural East Riding of Yorkshire.

Some areas of Hull lie on reclaimed land at or below sea level. The Hull Tidal Surge Barrier is at the point where the River Hull joins the Humber Estuary and is lowered at times when unusually high tides are expected. It is used between 8 and 12 times per year and protects the homes of approximately 10,000 people from flooding.[63] Due to its low level, Hull is expected to be at increasing levels of risk from flooding due to global warming.[64]

Historically, Hull has been affected by tidal and storm flooding from the Humber;[65] the last serious floods were in the 1950s, in 1953, 1954 and the winter of 1959.[66]

Many areas of Hull were flooded during the June 2007 United Kingdom floods,[67] with 8,600 homes and 1,300 businesses affected.[68]

Further flooding occurred in 2013, resulting in a new flood defence scheme to protect homes and businesses, stretching 4 miles (6.4 km) from St Andrews Quay Retail Park to Victoria Dock, linking to other defences at Paull and Hessle. Started in 2016, it was completed in early 2021.[69][70] The scheme was officially opened on 3 March 2022, by Rebecca Pow.[71]

At around 00:56 GMT on 27 February 2008, Hull was 30 miles (48 km) north of the epicentre of an earthquake measuring 5.3 on the Richter Scale which lasted for nearly 10 seconds. This was an unusually large earthquake for this part of the world.[72] Another notable quake occurred early in the morning of 10 June 2018.[73]

Climate[edit]

Located in Northern England, Hull has a temperate maritime climate which is dominated by the passage of mid-latitude depressions. The weather is very changeable from day to day and the warming influence of the Gulf Stream makes the region mild for its latitude. Locally, the area is sunnier than most areas this far north in the British Isles, and also considerably drier, due to the rain shadowing effect of the Pennines. It is somewhat warmer than west coast areas at a similar latitude such as Liverpool in summer due to stronger shielding from maritime air but also colder in winter and North Sea breezes keep the city cooler than inland areas during summer. It is also one of the most northerly areas where the July average maximum temperature exceeds 21.5 °C (70.7 °F), although this appears to be very localised around the city. Flooding in June 2007 caused significant damage to areas of the city. Droughts and heatwaves also occur such as in 2003, 2006 and recently in 2018.[74]

The absolute maximum temperature recorded is 36.9 °C (98.4 °F),[75] set in July 2022. Typically, the warmest day should reach 28.8 °C (83.8 °F),[76] though slightly over 10 days[77] should achieve a temperature of 25.1 °C (77.2 °F) or more in an "average" year. All averages refer to the 1981–2010 period.[citation needed]

The absolute minimum temperature is −11.1 °C (12.0 °F),[78] recorded during January 1982. Winters are generally mild for the latitude with snow only occurring a couple of times a year on average and mostly only staying for a day or two before melting. It is frequently cloudy and the North Sea winds make it feel colder than it actually is. An average of 32.5 nights should report an air frost. Heavy snowfalls do occasionally occur such as in 2010.[citation needed]

On 23 November 1981, during the record-breaking nationwide tornado outbreak, Hull was struck by two tornadoes. The first, rated as a very weak F0/T0 tornado, touched down in the Port of Hull shortly before 13:30 local time. This was followed several minutes later by a much stronger F1/T2 tornado, which passed through and caused damage to residential buildings across the north-eastern suburbs of Hull.[79][failed verification]

| Climate data for Hull, elevation: 2 m (7 ft), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1905–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.6 (60.1) | 18.3 (64.9) | 23.3 (73.9) | 27.3 (81.1) | 30.1 (86.2) | 32.8 (91.0) | 36.9 (98.4) | 34.4 (93.9) | 30.6 (87.1) | 27.9 (82.2) | 18.5 (65.3) | 15.9 (60.6) | 36.9 (98.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.7 (45.9) | 8.6 (47.5) | 10.9 (51.6) | 13.7 (56.7) | 16.6 (61.9) | 19.6 (67.3) | 22.0 (71.6) | 21.8 (71.2) | 18.9 (66.0) | 14.8 (58.6) | 10.7 (51.3) | 7.9 (46.2) | 14.5 (58.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.0 (41.0) | 5.4 (41.7) | 7.1 (44.8) | 9.4 (48.9) | 12.2 (54.0) | 15.0 (59.0) | 17.4 (63.3) | 17.2 (63.0) | 14.7 (58.5) | 11.2 (52.2) | 7.7 (45.9) | 5.2 (41.4) | 10.7 (51.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) | 2.2 (36.0) | 3.4 (38.1) | 5.1 (41.2) | 7.7 (45.9) | 10.5 (50.9) | 12.8 (55.0) | 12.6 (54.7) | 10.5 (50.9) | 7.8 (46.0) | 4.6 (40.3) | 2.4 (36.3) | 6.9 (44.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −11.1 (12.0) | −10.0 (14.0) | −10.0 (14.0) | −8.3 (17.1) | −2.5 (27.5) | 1.7 (35.1) | 4.4 (39.9) | 2.8 (37.0) | 0.6 (33.1) | −3.3 (26.1) | −5.1 (22.8) | −11.1 (12.0) | −11.1 (12.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 54.3 (2.14) | 47.7 (1.88) | 43.3 (1.70) | 47.5 (1.87) | 48.4 (1.91) | 69.7 (2.74) | 61.4 (2.42) | 64.7 (2.55) | 61.4 (2.42) | 66.4 (2.61) | 68.3 (2.69) | 60.5 (2.38) | 693.5 (27.30) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 11.7 | 10.4 | 9.8 | 9.5 | 9.3 | 9.8 | 9.7 | 10.1 | 9.1 | 11.2 | 12.6 | 11.6 | 124.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 55.5 | 79.0 | 117.7 | 159.1 | 200.2 | 189.4 | 197.1 | 183.2 | 147.4 | 109.2 | 65.7 | 55.3 | 1,558.8 |

| Source 1: Met Office[80] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: KNMI[81] | |||||||||||||

Demography[edit]

| Population growth in Kingston upon Hull since 1801 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Population | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1801 | 21,280 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1811 | 28,040 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1821 | 33,393 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1831 | 40,902 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1841 | 57,342 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1851 | 57,484 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1861 | 93,955 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1871 | 130,426 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1881 | 166,896 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1891 | 199,134 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1901 | 236,722 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1911 | 281,525 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1921 | 295,017 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1931 | 309,158 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1941 | 302,074[a] | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1951 | 295,172 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1961 | 289,716 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1971 | 284,365 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1981 | 266,751 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1991 | 254,117[82] | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2001 | 243,595[c][d] | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2011 | 256,406 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Vision of Britain Through Time and Hull Daily Mail[83][84] | ||||||||||||||||||||

According to the 2001 UK census, Hull had a population of 243,589 living in 104,288 households. The population density was 34.1 per hectare.[85] Of the total number of homes 47.85% were rented compared with a national figure of 31.38% rented.[86] The population had declined by 7.5% since the 1991 UK census,[85] and has been officially estimated as 256,200 in July 2006.[87]

In 2001, approximately 53,000 people were aged under 16, 174,000 were aged 16–74, and 17,000 aged 75 and over.[85] Of the total population 97.7% were white and the largest minority ethnic group was of 749 people who considered themselves to be ethnically Chinese. There were 3% of people living in Hull who were born outside the United Kingdom.[85][88] In 2006, the largest minority ethnic grouping was Iraqi Kurds who were estimated at 3,000. Most of these people were placed in the city by the Home Office while their applications for asylum were being processed.[89] In 2001, the city was 71.7% Christian. A further 18% of the population indicated they were of no religion while 8.4% did not specify any religious affiliation.[85]

Historically, minorities of many faiths and nationalities have lived around the docks, Old Town and City Centre, coming in from European ports like Hamburg, aided by continental railways and steam-ships from the mid-1800s.[90] Over 2 million passed through Hull between 1850 and 1914, on the way to a new life in America and elsewhere, but some planned or decided to stay. Dutch, Jews, Germans, Scandinavians and others were sometimes prominently involved in the life of the port city. They found opportunity but endured discrimination at times, such that these communities have now largely dispersed.[90]

Also in 2001, the city had a high proportion, at 6.2%, of people of working age who were unemployed, ranking 354th out of 376 local and unitary authorities within England and Wales.[85] The distance travelled to work was less than 3 miles (4.8 km) for 64,578 out of 95,957 employed people. A further 18,031 travelled between 3.1 and 6.2 miles (5 and 10 km) to their place of employment. The number of people using public transport to get to work was 12,915 while the number travelling by car was 53,443.[85]

Men in the University ward had the fourth lowest life expectancy at birth, 69.4 years, of any ward in England and Wales in 2016.[91]

Ethnicity[edit]

| Ethnic Group | Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991[92] | 2001[93] | 2011[94] | 2021[95] | |||||

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Total | 254,117 | 100% | 243,589 | 100% | 256,406 | 100% | 267,013 | 100% |

Industry[edit]

The traditional industries of Hull are seafaring (whaling and later seafishing) and later heavy industry which both have since declined in the city. Companies BP and Reckitt Benckiser, have facilities in Hull.[96] The city is part of the Humber Enterprise Zone.[97][98]

Port[edit]

Although the fishing industry, including oilseed production, declined in the 1970s due to the Cod Wars, the city remains a busy port, handling 13 million tonnes of cargo per year.[99] The port operations run by Associated British Ports and other companies in the port employ 5,000 people. A further 18,000 are employed as a direct result of the port's activities.[100] The port freight railway line, the Hull Docks Branch, operates 22 trains per day.[101][102]

Energy[edit]

In January 2011 Siemens Wind Power and Associated British Ports signed a memorandum of understanding concerning the construction of a wind turbine blade manufacturing plant at Alexander Dock. The plan would require some modification of the dock to allow the ships, used for transporting the wind turbine blades, to dock and be loaded.[103] Planning applications for the plant were submitted in December 2011,[104] and affirmed in 2014, concerning 75-metre (246 ft) blades for the 6 MW offshore model.[105][106]A 12.5-acre (5.1 ha) site waste-to-energy centre costing in the region of £150 million is also planned to be built by the Spencer Group. Announced in mid-2011, and named 'Energy Works',[107] the proposed plant would process up to 200,000 tonnes of organic material per year, with energy produced via a waste gasification process.[107][108]

Other[edit]

Hull Marina was from the old Humber and Railway docks in the centre of the city. It was repurposed and opened in 1983, it has 270 berths for yachts and small sailing craft.[citation needed]

In July 2014, the former Fruit Market was demolished with a technology hub C4DI (Centre for Digital Innovation) built in December 2015.[109][110]

The city has chemical and health care sectors, Smith & Nephew's founder Thomas James Smith being from the city. The health care sector has research facilities provided by the University of Hull through the Institute of Woundcare and the Hull York Medical School partnerships.[111]

Ferry services started after the decline in fishing by the introduction of Roll-on Roll-off ferry services to the continent of Europe. These ferries handle over a million passengers each year.[112]

Commerce[edit]

Trade[edit]

Merchant's houses such as Blaydes House and some warehouses survive in the Old Town, where trade was centred on the River Hull, later shifting to the Humber docks.

Humber Quays incorporates the World Trade Centre Hull & Humber and offices for The Spencer Group, RBS, and Jonathan Oliver Lee.The quays was a late 2000s development costing £165 million[113] with office buildings, housing, a 200-bedroom hotel and a restaurant.[114][115]

Retail[edit]

In March 2017, the Old Town area was designated as one of 10 Heritage Action Zones by Historic England with the benefit that the area would get a share of £6 million.[116]Retailers such as Heron Foods, and Jacksons began their operations in Hull.[citation needed] The former electrical retailer Comet Group was founded in the city as Comet Battery Stores Limited in 1933; the company's first superstore was opened in Hull in 1968.[117]

Hull has many shopping streets, both inside and outside the city centre. The main non-city-centre shopping streets are Hessle Road, Holderness Road, Chanterlands Avenue, Beverley Road, Princes Avenue, and Newland Avenue.[118]

Additionally, two covered shopping arcades, Paragon and Hepworth. The latter was modernised and renovated in the late 2000s.[119][120] The city also has the Trinity Market Hall, a grade II listed building Edwardian era indoor hall with 50 stalls, it was last renovated in 2016.[121]

The city centre has three shopping centres, St Stephen's, Princes Quay, and the Prospect Centre. The Prospect Centre on Prospect Street is the smaller and older shopping centre which benefits from large footfall; having chain stores, banks, fashion retailers and the city's main post office.[122][123][124]

Princes Quay Shopping Centre was built in 1991 on stilts over the closed Prince's Dock. It has a mixture chain stores and food outlets. It was built with four retail floors, known as "decks", with the uppermost deck converted to a cinema from December 2007.[125]

The St Stephen's shopping centre development on Ferensway adjacent to Hull Paragon Interchange is a 560,000-square-foot (52,000 m2) scheme, that opened in 2007. It is anchored by a superstore and provides many shop units, food outlets, a hotel, and a 7-screen cinema. Since its opening, shopping patterns within the city centre have shifted to the centre from around Princes Quay.[126]

The North Point Shopping Centre (also known by as Bransholme Shopping Centre which is the area of the city it's in) contains a similar range of popular chain and budget retailers including Boyes and Heron Foods. There are also other outer centres for shopping and retail parks, including St Andrews Quay retail park on the Humber bank and Kingswood retail park (Kingswood).[citation needed]

Nightlife, bars and pubs[edit]

The main drinking area in the city centre is the Old Town. One pub has Hull's smallest window (The George Hotel).[127]

Spiders, which opened in 1979, is an alternative rock nightclub on Cleveland Street, situated in a building that was once The Hope and Anchor pub.[128][129][130]

'ATIK' nightclub [131] (formerly The Sugarmill) is situated adjacent to Princes Quay shopping centre and the historic Princes Dock which dated back to 1829.[132][133]

Culture[edit]

Hull has several museums of national importance. The city has a theatrical tradition with some famous actors and writers having been born and lived in Hull. The city's arts and heritage have played a role in attracting visitors and encouraging tourism in recent efforts at regeneration.[citation needed] Hull has a diverse range of architecture and this is complemented by parks and squares and a number of statues and modern sculptures. The city has inspired author Val Wood who has set many of her best-selling novels in the city.[134] The Wilberforce Lecture and award of the Wilberforce Medallion, which has taken place annually since 1995, celebrates the historic role of Hull and William Wilberforce in combating the abuse of human rights.[135][136]

In April 2013 Hull put forward a bid to be the UK City of Culture in 2017,[137] reaching the shortlist of four in June 2013 along with Dundee, Leicester and Swansea Bay.[138] On 20 November 2013, Maria Miller, the Culture Secretary, announced that Hull had won the award to become the UK City of Culture 2017.[139]

Monopoly have released a version focusing on Hull, with attractions such as the Deep and St Stephens included.[140]

Museums[edit]

The Museums Quarter is a development on the High Street in the heart of the Old Town. It combines four museums around a leisure garden. The work cost £5.1 million and was carried out from 1998 to 2003, being formally opened by the Duke of Gloucester.[141][142][143]

The Museums are Wilberforce House, the birthplace of William Wilberforce (1759–1833), the British politician, abolitionist and social reformer; the Arctic Corsair, a deep-sea trawler that was converted to a museum ship in 1999, on the adjacent River Hull; the Hull and East Riding Museum, showing the archaeology and history of the region; and the Streetlife Museum of Transport, which includes a sizeable collection of vintage cars, preserved public transport vehicles and horse-drawn carriages.[142]

Other museums include the Hull Maritime Museum in Victoria Square, the Spurn Lightship,[144] and The Deep, a public aquarium.[145]

Art and galleries[edit]

The civic art gallery is the Ferens Art Gallery on Queen Victoria Square, a Grade II listed building.[146] It is named after Thomas Ferens who provided the funds for it.[147] Other galleries include the three-storey Humber Street Gallery, in the former Fruit Market building which was opened in 2017 as part of Hull City of Culture.[148] There are other smaller exhibition spaces.[149]

Creations[edit]

Marine painter John Ward (1798–1849) was born, worked and died in Hull and a leading ship artist of his day.[150]Artist and Royal Academician David Remfry (born 1942) grew up in Hull and studied at the Hull College of Art (now part of Lincoln University) from 1959 to 1964. His tutor, Gerald T Harding, trained at the Royal College of Art, London and was awarded the Abbey Minor Travelling Scholarship in 1957 by the British School in Rome.[151] Remfry has had two solo exhibitions at the Ferens Art Gallery in 1975 and 2005.[151]

Hull has a number of historical statues such as the Wilberforce Memorial in Queen's Gardens and the gilded King William III statue on Market Place (known locally as "King Billy"). There is a statue of Hull-born Amy Johnson in Prospect Street[152] and Hull's Paragon Interchange has a statue of Philip Larkin, the latter unveiled on 2 December 2010.[153]

In 2010 a public art event in Hull city centre entitled Larkin with Toads displayed 40 individually decorated giant toad models as the centrepiece of the Larkin 25 festival. Most of these sculptures have since been sold off for charity and transported to their new owners.[154][155]

In recent years a number of modern art sculptures and heritage trails have been installed around Hull. These include a figure looking out to the Humber called 'Voyage' which has a twin in Iceland. In July 2011, this artwork was reported stolen.[156][157] There is a shark sculpture outside The Deep and a fountain and installation called 'Tower of Light' outside Britannia House on the corner of Spring Bank.[citation needed]

The Seven Seas Fish Trail marks Hull's fishing heritage, leading its followers through old and new sections of the city, following a wide variety of sealife engraved in the pavement.[158] Running along Spring Bank there is also an elephant trail, with stone pavers carved by a local artist to the designs of members of the community. This trail commemorates the Victorian Zoological Gardens and the route taken daily by the elephant as it walked from its house down Spring Bank to the zoo and back, stopping for gingerbread at a shop on the way. The animals are further represented on the Albany Street 'Home Zone' a project involving local residents and resulting in sculptures of a hippo ('Water Horse') at the bottom of Albany Street; an elephant balancing on its trunk on an island in the middle; and two bears climbing poles and reaching out to each other to form an open archway across the entrance to Albany Street from Spring Bank. Other sculptural details of animals along the street represent the participation of street residents, either through workshops with artists and makers, or through independent work of their own.[159]

In 2019 a series of blue plaques appeared around Hull as part of the Alternative Heritage project.[160]The art project was designed to celebrate the little known and quirky facts that make Hull the city it is. A variety of tongue in cheek and humorous blue plaques appeared over night celebrating everything from Chip Spice[161] to The Beautiful South. New plaques continue to appear on a regular basis and their content has occasionally divided opinion in the city.[162][163]

The "Dead Bod", a graffito originally painted on the Alexandria Dock, became a local landmark.[164] It is now located in the Humber Street Gallery.[164]

Three Ships mural[edit]

The mural is on a curved screen attached to the end-wall of the old city centre Co-operative store building sited at the intersection where Jameson Street meets King Edward Street, now a mainly pedestrianised area created for the City of Culture 2017.[165][166]

Built by 1963 and later home to BHS, the building closed in 2016 with the collapse of BHS retail stores and was scheduled for demolition due to asbestos content. The building was listed as Grade II after lobbying by local pressure group Hull Heritage Action Group, potentially preventing demolition of the mural-wall. Specialist spraying to seal the building's internal structure has enabled moves to determine the actual level of asbestos in the mural-wall itself and provided a possible solution to incorporate the wall into a new development.[167]

Theatres[edit]

The city has two main theatres. Hull New Theatre, which opened in 1939,[168] with a £16 million refurbishment in 2016–17, is the largest venue which features musicals, opera, ballet, drama, children's shows and pantomime.[169][170]The Hull Truck Theatre is a smaller independent theatre, established in 1971,[171]that regularly features plays, notably those written by John Godber.[172]Since April 2009, the Hull Truck Theatre has had a new £14.5 million, 440 seat venue in the St Stephen's Hull development.[173][174][175] This replaced the former home of the Hull Truck Theatre on Spring Street, a complex of buildings demolished in 2011.[176] The playwright Alan Plater was brought up in Hull and was associated with Hull Truck Theatre.

Hull has produced several veteran stage and TV actors. Sir Tom Courtenay, Ian Carmichael and Maureen Lipman were born and brought up in Hull. Younger actors Reece Shearsmith, Debra Stephenson, Liam Gerrard and Liam Garrigan were also born in Hull.[citation needed]

In 1914, there were 29 cinemas in Hull but most of these have now closed. The first purpose-built cinema was the Prince's Hall in George Street which was opened in 1910 by Hull's theatre magnate, William Morton.[177] It was subsequently renamed the Curzon.[178]

On 25 July 2018, a new 3,000 seat arena was opened to the public in the centre of the city.[179] It was officially opened on 20 August 2018, with a Van Morrison concert.[180]

Festivals[edit]

The Humber Mouth literature festival is an annual event and the 2012 season featured artists such as John Cooper Clarke, Kevin MacNeil and Miriam Margolyes.[181] The annual Hull Jazz Festival takes place around the Marina area for a week at the beginning of August.[182]

From 2008 Hull has also held its Freedom Festival, an annual free arts and live music event that celebrates freedom in all its forms.[183] Performers have included Pixie Lott, JLS and Martha Reeves and The Vandellas, Public Service Broadcasting and The 1975 as well as featuring a torchlight procession, local bands like The Talks and Happy Endings from Fruit Trade Music label and a Ziggy Stardust photo exhibition including photos of the late-Hull-born Mick Ronson who worked with David Bowie.[184] Former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan was awarded the Wilberforce Medallion at the 2017 festival.[136]

Early October sees the arrival of Hull Fair which is one of Europe's largest travelling funfairs and takes place on land adjacent to the MKM Stadium.[185]

The city's Pride in Hull festival is one of the largest free-to-attend LGBT+ Pride events in the UK, attracting in excess of 50,000 attendees.[186] Headline performers have included Adore Delano, Louise Redknapp, Marc Almond, Nadine Coyle of Girls Aloud, Alaska Thunderfuck and B*Witched.[citation needed]

The Hull Global Food Festival held its third annual event in the city's Queen Victoria Square for three days – 4–6 September 2009.[187] According to officials, the event in 2007 attracted 125,000 visitors and brought some £5 million in revenue to the area.[188]In 2007 the Hull Metalfest began in the Welly Club,[189] it featured major label bands from the United States, Canada and Italy, as well as the UK.The first Hull Comedy Festival, which included performers such as Stewart Lee and Russell Howard was held in 2007.[190]

In 2010, Hull marked the 25th anniversary of the death of the poet Philip Larkin with the Larkin 25 Festival. This included the popular Larkin with Toads public art event.[191] The 40 Larkin toads were displayed around Hull and later sold off in a charity auction. A charity appeal raised funds to cast a life-size bronze statue of Philip Larkin, to a design by Martin Jennings, at Hull Paragon Interchange. The statue was unveiled at a ceremony attended by the Lord Mayor of Hull on 2 December 2010, the 25th anniversary of Larkin's death.[153] It bears an inscription drawn from the first line of Larkin's poem, 'The Whitsun Weddings'.[192]

In 2013, from 29 April to 5 May, Hull Fashion Week took place with various events happening in venues in and around Hull's City centre. It finished with a finale on 5 May at Hull Paragon Interchange, when recently reformed pop group Atomic Kitten appeared in a celebrity fashion show.[193]

on 24 June 2017, The first Yellow Day Hull event, organised by Hull-born Preston Likely, was staged. Likely invited everybody in the city to participate in the event, encouraging all participants to either wear, carry or make something yellow in order to celebrate the city's history and culture.[194]

On 3 August 2013, the second Humber Street Sesh Festival took place celebrating local music talent and arts, with several stages showcasing bands and artists from the Fruit Trade Music Label, Humber Street Sesh and Purple Worm Records.[195] The festival has taken place yearly, with the exception of 2021 where the festival took place in September being renamed 'Inner City Sesh' and taking place in Queens Gardens.

In 2018, the 16th Pride in Hull festival saw attendees take part in the annual celebration of LGBT+ culture.[186]

Charity[edit]

Kingston is home to the charity group The Society of M.I.C.E., modeled after the Grand Order of Water Rats. MICE stands for Men In Charitable Endeavour.

Cultural references[edit]

Poetry[edit]

Hull has attracted the attention of poets to the extent that Australian author Peter Porter described it as "the most poetic city in England".[196]

Philip Larkin set many of his poems in Hull, including "The Whitsun Weddings", "Toads", and "Here".[197] Scottish-born Douglas Dunn's Terry Street, a portrait of working-class Hull life, is one of the outstanding poetry collections of the 1970s.[198]Dunn forged close associations with such Hull poets as Peter Didsbury and Sean O'Brien. The works of some of these writers appear in the 1982 Bloodaxe anthology A Rumoured City, which Dunn edited.[199] Andrew Motion, past Poet Laureate, lectured at the University of Hull between 1976 and 1981,[200] and Roger McGough studied there. Both poets spoke at the Humber Mouth Festival in 2010.[201] Contemporary poets associated with Hull are Maggie Hannan,[202] David Wheatley,[203] and Caitriona O'Reilly.[204]

17th-century metaphysical poet and parliamentarian Andrew Marvell was born nearby, and grew up and received his education in the city.[205][206] There is a statue in his honour in the Market Square (Trinity Square), set against the backdrop of his alma mater Hull Grammar School.[citation needed]

Music[edit]

Classical[edit]

In the field of classical music, Hull is home to Sinfonia UK Collective (formerly Hull Sinfonietta, founded in 2004), a national and international touring group that serves Hull and its surrounding regions in its role as Ensemble in Residence at University of Hull,[207] and also the Hull Philharmonic Orchestra, one of the oldest amateur orchestras in the country.[208] and formerly The Hull Philharmonic Youth Orchestra, established in 1952,[209]the Hull Choral Union, the Hull Bach Choir – which specialises in the performance of 17th- and 18th-century choral music – the Hull Male Voice Choir, the Arterian Singers and two Gilbert & Sullivan Societies: the Dagger Lane Operatic Society and the Hull Savoyards are also based in Hull. There are two brass bands, the East Yorkshire Motor Services Band, who are the current North of England Area Brass Band Champions,[210][211] and East Riding of Yorkshire Band who are the 2014 North of England Regional Champions within their section.[212]

Hull City Hall annually plays host to major British and European symphony Orchestras with its 'International Masters' orchestral concert season.[213] During the 2009–10 season visiting orchestras included the St Petersburg Symphony Orchestra and the Czech National Symphony Orchestra.[214] Internationally renowned touring pop, rock, and comedy acts also regularly play the City Hall.[213]

In September 2013 a five-year partnership with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra was announced by the City Council.[215]

Rock, pop and folk[edit]

On the popular music scene, in the 1960s, Mick Ronson of the Hull band Rats worked closely with David Bowie and was heavily involved in production of the album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.[citation needed] Ronson later went on to record with Lou Reed, Bob Dylan, Morrissey and the Wildhearts.[citation needed] There is a Mick Ronson Memorial Stage in Queen's Gardens in Hull.[216] The 1960s were also notable for the revival of English folk music, of which the Hull-based quartet, the Watersons were prominent exponents. The Who performed and recorded a concert, at the Hull City Hall, on 15 February 1970.[217]

In the 1980s, Hull groups such as the Red Guitars, the Housemartins and Everything but the Girl found mainstream success, followed by Kingmaker in the 1990s.[218] Paul Heaton, former member of the Housemartins went on to front the Beautiful South.[219] Another former member of the Housemartins, Norman Cook, now performs as Fatboy Slim.[220] In 1982, Hull-born Paul Anthony Cook, Stuart Matthewman and Paul Spencer Denman formed the group Sade. In 1984, the singer Helen Adu signed to CBS Records and the group released the album Diamond Life. The album had sales of four million copies.[221]

The pioneering industrial band Throbbing Gristle formed in Hull; Genesis P-Orridge (Neil Megson) attended Hull University between 1968 and 1969, where he met Cosey Fanni Tutti (Christine Newby), who was born in the city, and first became part of the Hull performance art group COUM Transmissions in 1970.[222][223][224]

The record label Pork Recordings started in Hull in the mid-1990s, and has released music by Fila Brazillia.[225]

The New Adelphi is a popular local venue for alternative live music in the city, and has achieved notability outside Hull, having hosted such bands as the Stone Roses, Radiohead, Green Day, and Oasis in its history,[226] while the Springhead caters to a variety of bands and has been recognised nationally as a 'Live Music Pub of the Year'.[227]

In the 2000s, Hull indie rock band the Paddingtons saw mainstream success with two UK Top 40 singles in 2005,[228] later reforming in 2014 and performing at the Humber Street Sesh with notable bands such as Sulu Babylon and Street Parade.[citation needed]

In the 1990s, the duo Scarlet from Hull had two Top 40 hits with "Independent Love Song" and "I Wanna Be Free (To Be With Him)" in 1995.[229]

The Humber Street Sesh night has released four DIY compilations featuring the cream of Hull's live music scene, and there are currently a few labels emerging in the city, including Purple Worm Records based at Hull College, with bands such as The Blackbirds showing a promising future.[230]

Religion[edit]

| Religion | 2001[231] | 2011[232] | 2021[233][full citation needed] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Total population | 243,589 | 100.0 | 256,406 | 100.0 | 267,013 | 100.0 |

Unlike many other English cities, Hull has no cathedral. Since 13 May 2017, the Holy Trinity Church (dating back to 1300) became a Minster, known as Hull Minster.[234][235] It is a part of the Anglican Diocese of York and has a suffragan bishop.[236]

Hull forms part of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Middlesbrough's southern vicariate.[237] St Charles Borromeo is the oldest post-Reformation Roman Catholic church in the city.[238]

There are several seamen's missions and churches in Hull. The Mission to Seafarers has a centre at West King George Dock[239] and the St Nikolaj Danish Seamen's Church is located in Osborne Street.[240]

Parks and green spaces[edit]

Hull has a large number of parks and green spaces. These include East Park, Pearson Park, Pickering Park, Peter Pan Park (Costello Playing fields), and West Park. West Park is home to Hull's MKM Stadium. Pearson Park contains a lake and a 'Victorian Conservatory' housing birds and reptiles. East Park has a large boating lake and a collection of birds and animals.[241] East Park and Pearson Park are registered Grade II listed sites by Historic England.[242][243]The city centre has the large Queen's Gardens parkland at its heart. This was originally built as formal ornamental gardens used to fill in the former Queen's Dock. It is now a more flexible grassed and landscaped area used for concerts and festivals, but retains a large ornamental flower circus and fountain at its western end.[citation needed]

The streets of Hull's suburban areas also lined with large numbers of trees, particularly the Avenues area around Princes Avenue, and Boulevard to the west. Many of the old trees in the Avenues district have been felled in recent years with the stumps carved into a variety of 'living sculptures'.[244] Other green areas include the University area and parts of Beverley Road to the north.[citation needed]

West Hull has a district known as 'Botanic'. This recalls the short-lived Botanic Garden that once existed on the site now occupied by Hymers College. Elephants once lived nearby in the former Zoological Gardens on Spring Bank and were paraded in the local streets.[245] The land has since been redeveloped. There was also a former Botanic Garden between Hessle Road and the Anlaby Road commemorated by Linnaeus Street.[246]

Media[edit]

Hull's only local daily newspaper is the longstanding Hull Daily Mail, whose circulation area covers much of the East Riding of Yorkshire too. A free paper, The Hull Advertiser, used to be issued weekly by the same publisher.The city was once served by three competing daily newspapers, all operating from the Whitefriargate area Eastern Morning News, Hull News and Hull and East Yorkshire Times. On 17 April 1930 the last edition of Evening News was published after the paper was taken over by its longstanding rival the Hull Daily Mail.[citation needed]

Local listings and what's-on guides include Tenfoot City Magazine and Sandman Magazine (combined into single volume covering all of England, print version then made defunct in favour of online site). The BBC has its Yorkshire and Lincolnshire regional headquarters at Queen's Gardens,[247] from which the regional news programme Look North is broadcast.[citation needed]

Radio services broadcasting from the city are community radio stations, Hull Kingston Radio, 106.9 West Hull FM (formerly WHCR FM) and hospital radio station Kingstown Radio. The BBC's regional station BBC Radio Humberside is also based in Hull and broadcasts to East Yorkshire & Northern Lincolnshire. Commercial stations for the city Viking FM and Nation Radio East Yorkshire (formerly KCFM) broadcast from outside of Hull and are now part of a national network like Capital Yorkshire which has a base over 60 miles (100 km) away in Leeds.[248]The Hull University Union's student radio station Jam 1575, stopped broadcasting on MW.[249]

On 24 November 2013, a RSL (Restricted Service Licence) was given to new station "Hull Community Radio" broadcasting on 87.9 FM.[citation needed]

Sport[edit]

Sports in the city include professional football, rugby league, rugby union, golf, darts, athletics, and watersports.[250]

The city's professional football club, Hull City A.F.C., play in the Championship, the second tier of the English football league system, after promotion, as champions, from League One, at the first time of asking, in the 2020–21 season.[251] The team play at the MKM Stadium. There are also two non-league clubs based in the city, Hall Road Rangers, and Hull United, who play at Haworth Park. The latter play in the Humber Premier League.[252]

A popular sport in Hull is rugby league, with the city supplying two teams in to the Super League competition. The first is Hull FC, who were founded in 1865, and are one of the founding clubs of rugby league. They play at the MKM Stadium.[253] Also in Super League are Hull Kingston Rovers, who play at Sewell Group Craven Park Stadium in East Hull, following promotion from the Championship in 2017.[254]There are also several lower league teams in the city, such as East Hull, West Hull, Hull Dockers and Hull Isberg, who all play in the National Conference League.[255]

Rugby union is catered for by Hull Ionians who play at Brantingham Park.[256] and Hull RUFC who are based in the city.[257] From the 2023–04 season, both clubs will play in the National League 2 North.[258]

The city has two athletics clubs based at the Costello Stadium in the west of the city – Kingston upon Hull Athletics Club[259] and Hull Achilles Athletics Club.[citation needed]

Hull Cycle Speedway Club is at the Hessle raceway near the Humber bridge. The side race in the sports Northern league and won both the league titles in 2008. Other cycling clubs also operate including Hull Thursday, the area's road racing group.[citation needed]

Hull Arena,[260] is an ice rink and concert venue, which is home to the Hull Seahawks ice hockey team who play in the NIHL National Division for the 2022–23 season.[261] It is also home to the Kingston Kestrels ice sledge hockey team.[262] In August 2010, Hull Daily Mail reported that Hull Stingrays was facing closure, following a financial crisis.[263] The club was subsequently saved from closure following a takeover by Coventry Blaze.[264] But on 24 June 2015, the club announced on its official website that it has been placed into liquidation.[265][266]

The Hull Hornets American football existed from 2005 until 2011. The club, which acquired full member status in the British American Football League on 5 November 2006, played in the BAFL Division 2 Central league for 5 years. The Humber Warhawks formed in 2013 became Hull's American football team. Greyhound racing returned to the city on 25 October 2007 when The Boulevard stadium re-opened as a venue for the sport.[267]In mid-2006 Hull was home to the professional wrestling company One Pro Wrestling, which held the Devils Due event on 27 July in the Gemtec Arena.[268] From 16 May 2008, Hull gained its own homegrown wrestling company based at the Eastmount Recreation Centre—New Generation Wrestling—that have featured El Ligero, Kris Travis, and Alex Shane.[269]

Hull Lacrosse Club was formed in 2008 and was in 2012 playing in the Premier 3 division of the North of England Men's Lacrosse Association.[270]

The city played host to the Clipper Round the World Yacht Race for the 2009–10 35,000 miles (56,000 km) race around the globe, which started on 13 September 2009 and finished on 17 July 2010.[271][272][273] The locally named yacht, Hull and Humber, captained by Danny Watson, achieved second place in the 2007–2008 race.[274]

The city hosted The British Open Squash Championships at the KC Stadium in 2013 and 2014,[275] before moving to the adjacent Airco Arena in 2015, as part of a three-year deal.[276]

Swimming is hosted at Beverley Road Baths, Woodford Leisure Centre, the Ennerdale Centre, and Albert Avenue Baths.[277] Albert Avenue pools were established in 1933, with an outdoor pool which shut to swimmers in 1995, but has been used for canoe training.[278] A major refurbishment to upgrade the complex and return outdoor swimming was announced in 2021. Included are a fitness studio, gym and general upgrades.[279][280]

Transport[edit]

Hull Paragon Interchange, opened on 16 September 2007,[281]is the city's transport hub, combining the existing main bus and rail termini in an integrated complex. In 2009, it was expected to have 24,000 people passing through the complex each day.[282]

Railway[edit]

Hull Paragon Exchange is served by four train operating companies:

- Hull Trains operates regular express services to London King's Cross[283]

- London North Eastern Railway runs one service per day to London King's Cross in each direction[284]

- TransPennine Express operates a route to Manchester Piccadilly via Leeds[285]

- Northern Trains operates regular local stopping trains to Halifax via Selby, Leeds and Bradford Interchange; to York via Brough and Selby; to Sheffield via Doncaster; and to Scarborough via Beverley and Bridlington.[286]

In the 1960s, Hull and Hornsea Railway and Hull and Holderness Railway branch lines closed, with all goods traffic transferred to the high-level line that circles the city.[287]

Buses[edit]

Bus services in and around the city are provided by East Yorkshire, a Go-Ahead Group company which was previously known as East Yorkshire Motor Services, and by Stagecoach in Hull.[288]

To provide greater travel flexibility, bus users can obtain a Hull Card which can be used on services run by either operator.[289]

Bridges[edit]

Hull is close to the Humber Bridge, which provides links to south of the river Humber. It was built between 1972 and 1981; at the time, was the longest single-span suspension bridge in the world. It is now[when?] eighth on the list.[citation needed] Before the bridge was built, those wishing to cross the Humber had to either take a Humber Ferry or travel inland as far as Goole.[290]

In March 2021, a new footbridge was opened connecting the city to Princes Quay waterfront, marina and fruit market over Castle Street, a dual carriageway road also designated A63. Named Murdoch's Connection after Hull's first female doctor, GP Mary Murdoch, the name was nominated by pupils from Newland School for Girls in Newland, Hull. Works began in autumn 2018 but progress was delayed due to the coronavirus pandemic. There was no opening ceremony due to distancing restrictions; instead, videos were compiled.[291][292] Members of the public have been requested not to attach love locks.[293]

Ports[edit]

P&O Ferries provide daily overnight ferry services from King George Dock in Hull to Zeebrugge and Rotterdam.[294][295]Services to Rotterdam are worked by ferries MS Pride of Rotterdam and MS Pride of Hull. Services to Zeebrugge are worked by ferries MS Pride of Bruges and MS Pride of York (previously named MS Norsea). Both Pride of Rotterdam and Pride of Hull are too wide to pass through the lock at Hull. Associated British Ports built a new terminal at Hull to accommodate the passengers using these two ferries. The Rotterdam Terminal at the Port of Hull, was built at a cost of £14,300,000.[citation needed]

Airports[edit]

The nearest airport is Humberside Airport, 20 miles (32 km) away in Lincolnshire, which provides a few charter flights but also has high-frequency flights to Amsterdam with KLM and Aberdeen with Eastern Airways each day.

The nearest airport with intercontinental flights is Leeds Bradford Airport is 70 miles (110 km) away.[296][297]

Cycling[edit]

According to the 2001 census data cycling in the city is well above the national average of 2%, with a 12% share of the travel to work traffic.[298] A report by the University of East London in 2011 ranked Hull as the fourth-best cycling city in the United Kingdom.[299]

Roads[edit]

The main road into and out of Hull is the M62 motorway/A63 road, one of the main east–west routes in Northern England. It provides a link to the cities of Leeds, Manchester and Liverpool, as well as the rest of the country via the UK motorway network. The motorway itself ends some distance from the city; the rest of the route is along the A63 dual carriageway. This east–west route forms a small part of the European road route E20.[300]

Road transport in Hull suffers from delays caused both by the many bridges over the navigable River Hull, which bisects the city and can cause disruption at busy times.

The city has three railway level crossings in the city; it formerly had more with bridges built to go over the tracks on Hessle Road in 1962 and Anlaby Road in 1964.[citation needed] A nearby road was renamed from Garrison Road to Roger Millward Way in 2018, after rugby player Roger Millward who played for Hull Kingston Rovers. The developments are part of a wider improvement and redevelopment scheme.[301][302]

Infrastructure[edit]

Telephone system[edit]

Hull is the only city in the UK with its own independent telephone network company, KCOM, formerly KC and Kingston Communications, a subsidiary of KCOM Group. Its distinctive cream telephone boxes can be seen across the city. KCOM produces its own 'White Pages' telephone directory for Hull and the wider KC area. Colour Pages is KCOM's business directory, the counterpart to Yellow Pages. The company was formed in 1902 as a municipal department by the City Council and is an early example of municipal enterprise. It remains the only locally operated telephone company in the UK, although it is now privatised. KCOM's Internet brands are Karoo Broadband (ISP serving Hull) and Eclipse (national ISP).[303]Initially Hull City Council retained a 44.9 per cent interest in the company and used the proceeds from the sale of shares to fund the city's sports venue, the MKM Stadium, among other things.[304] On 24 May 2007 it sold its remaining stake in the company for over £107 million.[305]

KCOM (Kingston Communications) was one of the first telecoms operators in Europe to offer ADSL to business users, and the first in the world to run an interactive television service using ADSL, known as Kingston Interactive TV (KiT), which has since been discontinued due to financial problems.[306] In the last decade, the KCOM Group has expanded beyond Hull and diversified its service portfolio to become a nationwide provider of telephone, television, and Internet access services, having close to 180,000 customers projected for 2007.[307] After its ambitious programme of expansion, KCOM has struggled in recent years and now has partnerships with other telecommunications firms such as BT who are contracted to manage its national infrastructure.[308] Telephone House, on Carr Lane, the firm's 1960s-built headquarters, in stark modernist style, is a local landmark.

In October 2019, Hull became the first UK city to have full fibre broadband available for all residents.[309]

Hydraulic power[edit]

The first public hydraulic power network, supplying many companies, was constructed in Hull. The Hull Hydraulic Power Company began operation in 1877, with Edward B. Ellington as its engineer and the main pumping station (now a Grade II listed building) in Catherine Street.[310] Ellington was involved in most British networks, including those in London, Liverpool, Birmingham, Manchester and Glasgow, but the advent of electrical power combined with wartime damage meant the Hull company was wound up in 1947.[citation needed]

Public services[edit]

Policing in Kingston upon Hull is provided by Humberside Police. In October 2006 the force was named (jointly with Northamptonshire Police) as the worst-performing police force in the United Kingdom, based on data released from the Home Office.[311] However, after a year of "major improvements", the Home Office list released in October 2007 shows the force rising several places (although still among the bottom six of 43 forces rated). Humberside Police received ratings of "good" or "fair" in most categories.[312]

HM Prison Hull is located in the city and is operated by HM Prison Service. It caters for up to 1,000 Category B/C adult male prisoners.[313]

Statutory emergency fire and rescue service is provided by the Humberside Fire and Rescue Service, which has its headquarters near Hessle and five fire stations in Hull. This service was formed in 1974 following local government reorganisation from the amalgamation of the East Riding of Yorkshire County Fire Service, Grimsby Borough Fire and Rescue Service, Kingston Upon Hull City Fire Brigade and part of the Lincoln (Lindsey) Fire Brigade and a small part of the West Riding of Yorkshire County Fire and Rescue Service.[314]

Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust provides healthcare from three sites, Hull Royal Infirmary, Castle Hill Hospital and, until 2008, Princess Royal Hospital[315] and there are several private hospitals including ones run by BUPA and Nuffield Hospitals.[316] The Yorkshire Ambulance Service provides emergency patient transport.[317] NHS primary health care services are commissioned by the Hull Clinical Commissioning Group and are provided at several smaller clinics and general practitioner surgeries across the city.[318] NHS Mental health services in Hull are provided by Humber NHS Foundation Trust. It runs a memory clinic in Coltman Street, west Hull designed to help older people with early onset dementia.[319]

Waste management is co-ordinated by the local authority. The Waste Recycling Group is a company which works in partnership with the Hull City and East Riding of Yorkshire councils to deal with the waste produced by residents.[320] The company plans to build an energy from waste plant at Salt End to deal with 240,000 tonnes of rubbish and put waste to a productive use by providing power for the equivalent of 20,000 houses. Hull's distribution network operator for electricity is CE Electric UK (YEDL); there are no power stations in the city. Yorkshire Water manages Hull's drinking and waste water. Drinking water is provided by boreholes and aquifers in the East Riding of Yorkshire, and it is abstracted from the River Hull at Tophill Low, near Hutton Cranswick. Should either supply experience difficulty meeting demand, water abstracted from the River Derwent[321] at both Elvington and Loftsome Bridge can be moved to Hull via the Yorkshire water grid. There are many reservoirs in the area for storage of potable and non-potable water. Waste water and sewage has to be transported in a wholly pumped system because of the flat nature of the terrain to a sewage treatment works at Salt End. The treatment works is partly powered by both a wind turbine[322] and a biogas CHP engine.[citation needed]

Education[edit]

Higher education[edit]

University of Hull[edit]

Kingston upon Hull is home to the University of Hull, which was founded in 1927[323] and received its Royal Charter in 1954. It now has a total student population of around 20,000 across its main campuses in Hull and Scarborough.[324] The main University campus is in North Hull, on Cottingham Road. Notable alumni include former Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott, social scientist Lord Anthony Giddens, Woman's Hour presenter and writer Jenni Murray, and the dramatist Anthony Minghella. The University of Hull is a partner in the new University Centre of the Grimsby Institute of Further and Higher Education (GIFE) being built in Grimsby, North Lincolnshire.[325]

University of Lincoln[edit]

The University of Lincoln grew out of the University of Humberside, a former polytechnic based in Hull. In the 1990s the focus of the institution moved to nearby Lincoln and the administrative headquarters and management moved in 2001.[326] The University of Lincoln has retained a campus in George Street in Hull city centre whilst Hull University purchased the adjacent University of Lincoln campus site on Cottingham Road.[327]

Specialist[edit]

Hull York Medical School is a joint venture between the University of Hull and the University of York. It first admitted students in 2003 as a part of the British government's attempts to train more doctors.[328]

The Northern Academy of Performing Arts and Northern Theatre School[329] both provide education in musical theatre, performance and dance.[citation needed]

The Hull School of Art, founded in 1861, is regarded nationally and internationally for its excellence as a specialist creative centre for higher education.[330]

Colleges[edit]

There is a further education college, Hull College,[331] and two large sixth form colleges, Wyke College[332] and Wilberforce College.[333] East Riding College operates a small adult education campus in the city,[334] and Endeavour Learning and Skills Centre is an adult education provision operated by Hull Training & Adult Education.[335]

Schools[edit]

Hull has over 100 local schools; of these, Hull City Council supports 14 secondary and 71 primary schools.[336] The highest achieving state school in Hull is Malet Lambert School,[337] Schools which are independent of the City Council include Hymers College[338] and Tranby School. The latter, which is run by the United Church Schools Trust, was formed by the merging of Hull Grammar School and Hull High School.[339] Hull Trinity House Academy has been offering pre-sea training to prospective mariners since 1787.[340] There are only two single-sex schools in Hull: Trinity House Academy, which teaches only boys, and Newland School for Girls.[citation needed]

The city has had a poor examination success rate for many years and is often at the bottom of government GCSE league tables.[341][342]In 2007 the city moved off the bottom of these tables for pupils who achieve five A* to C grades, including English and Maths, at General Certificate of Secondary Education by just one place when it came 149th out of 150 local education authorities. However, the improvement rate of 4.1 per cent, from 25.9 per cent in 2006 to 30 per cent in summer 2007, was among the best in the country.[343]They returned to the bottom of the table in 2008 when 29.3 per cent achieved five A* to C grades which is well below the national average of 47.2 per cent.[344] There are insufficient places in referral units for school children with special needs or challenging behaviour due to squeezed budgets and cuts to children's services.[345]

Dialect and accent[edit]

The local accent is quite distinctive and noticeably different from the rest of the East Riding; however it is still categorised among Yorkshire accents. The most notable feature of the accent is the strong I-mutation[346] in words like goat, which is [ˈɡəʊt] in standard English and [ˈɡoːt] across most of Yorkshire, becomes [ˈɡɵːʔt̚ ] ("gert") in and around parts of Hull (cf. similar refined pronunciations in Leeds/York), although there is variation across areas and generations.[347]In common with much of England (outside of the far north), another feature is dropping the H from the start of words, for example Hull is more often pronounced 'Ull in the city. The vowel in "Hull" is pronounced the same way as in northern English, however, and not as the very short /ʊ/ that exists in Lincolnshire. Though the rhythm of the accent is more like that of northern Lincolnshire than that of the rural East Riding, which is perhaps due to migration from Lincolnshire to the city during its industrial growth, one feature that it does share with the surrounding rural area is that an /aɪ/ sound in the middle of a word often becomes an /ɑː/: for example, "five" may sound like "fahve", "time" like "tahme".[348]

The SQUARE–NURSE merger is a feature of Hull's dialect.[349][350] The vowel sound in words such as burnt, nurse, first is pronounced with an /ɛ/ sound, as is also heard in Middlesbrough and in areas of Liverpool yet this sound is very uncommon in most of Yorkshire. The word pairs spur/spare and fur/fair illustrate this.[351]The generational and/or geographic variation can be heard in word pairs like pork/poke or cork/coke, or hall/hole, which some people pronounce almost identically, sounding to non-locals like they are using the second of the two variations – while others make more of a vocal distinction; anyone called "Paul" (for example) soon becomes aware of this (pall/pole).[347][352]

Notable people[edit]

- Most of the notable people associated with the city can be found in the People from Kingston upon Hull and People associated with the University of Hull categories.

People from Hull are called "Hullensians"[353] and the city has been the birthplace and home to many notable people. Amongst those of historic significance with a connection to Hull are former city MP William Wilberforce who was instrumental in the abolition of slavery[53]and Amy Johnson, aviator who was the first woman to fly solo from England to Australia.[354]

Entertainers from the city include; Dorothy Mackaill, 1950s singer David Whitfield, sports commentator Tony Green, actors Sir Tom Courtenay, Ian Carmichael, John Alderton,[355] actress Maureen Lipman[356] and Reece Shearsmith.Playwrights Richard Bean, John Godber and Alan Plater have close connections with Hull.[172][357][358]

Musicians associated with Hull include Paul Heaton of The Housemartins and The Beautiful South,[219]guitarist Mick Ronson and bassist Trevor Bolder, who worked with David Bowie, and more recently 2000s indie band The Paddingtons.[citation needed]

The astrophysicist Edward Arthur Milne and logician John Venn both hailed from Hull. The poet Philip Larkin lived in Hull for 30 years and wrote much of his mature work in the city. An earlier poet, Andrew Marvell represented the city in Parliament during the 17th century.[359] Artist David Remfry RA studied at Hull College of Art before moving to London and New York.[360]

Chemist George Gray, who had a 45-year career at the university, developed the first stable liquid crystals that became an immediate success for the screens of all sorts of electronic gadgets.

Notable sportspeople include Ebenezer Cobb Morley (16 August 1831 – 20 November 1924), an English sportsman who is regarded as the father of the Football Association and modern football.[361] Clive Sullivan, rugby league player, who played for both of Hull's professional rugby league teams, was the first black Briton to captain any national representative team.[362] The main A63 road into the city from the Humber Bridge is named after him (Clive Sullivan Way). Nick Barmby played for Tottenham Hotspur, Middlesbrough, Everton, Liverpool, and Leeds United before returning to play for his hometown club Hull City. He also won 23 England caps and played in the famous 5–1 victory over Germany in 2001. Another footballer is Dean Windass, who had two spells with Hull City.[363]

On accepting a peerage, Welsh-born Baron Prescott of Kingston-upon-Hull (former MP and Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott) took his title from his adopted home city of Hull.[364]

International relations[edit]

Hull has formal twinning arrangements with[365][366]

- Chișinău, Moldova

- Freetown, Sierra Leone

- Fengtai, Beijing, China

- Niigata, Japan

- Raleigh, North Carolina, United States

- Reykjavík, Iceland

- Rotterdam, Netherlands

- Szczecin, Poland[367]

The following cities are named directly after Hull:

- Hull, Massachusetts, United States[368]

- Hull, Quebec, Canada[369]

Freedom of the City[edit]

The following people and military units have received the Freedom of the City of Kingston upon Hull.

Individuals[edit]

- Desmond Tutu: 2 July 1987.

- Helen Suzman: 2 July 1987.

- Nelson Mandela: 2 July 1987.

- John Prescott: 1 August 1996.

- Kevin McNamara: 16 January 1997.

- Jean Bishop – "Bee Lady": 23 November 2017.[370]

- Sir Thomas Courtenay: 18 January 2018.[371][372]

- Yvonne Blenkinsop: 15 November 2018.[373]

- Carol Thomas: 22 September 2022.[374]

- Patrick Doyle: 17 November 2022.[375][376]

Military units[edit]

- The East Yorkshire Regiment: 1 June 1944.

- The Prince of Wales's Own Regiment of Yorkshire: 5 June 1958.

- The Yorkshire Regiment: 16 November 2006.

- The Royal Dragoon Guards

- 440 (Humber) light Anti-Aircraft Regiment Royal Artillery (TA): 28 June 1960.

- 440 (Humber) light Anti-Aircraft Regiment Royal Artillery (Territorials): 3 August 1967.

- RAF Patrington: 16 May 1970.

- 150(N) Transport Regiment Royal Corps of Transport (Volunteers): 1 February 1990.

- RRH Staxton Wold: 3 March 1994.

- 150-й (Йоркширский) транспортный полк Королевского логистического корпуса ( добровольцы ): 3 марта 1994 г.

- HMS Iron Duke , RN : 3 марта 1994 г. [377]

- 250-я полевая машина скорой помощи (добровольческий отряд): 15 июля 1999 г.

- Корпусная часть морского кадетского корпуса : 27 февраля 2014 г. [378] [372]

- Хамберсайда и Южного Йоркшира Кадетский корпус армии : 21 марта 2024 г.

- (город Халл) 152-я эскадрилья авиационного учебного корпуса : 21 марта 2024 г.

См. также [ править ]

- Церкви I степени внесены в список в Восточном райдинге Йоркшира.

- История евреев в Халле

- Трагедия тройного траулера «Халл» (1968 г.)

- Земля зеленого имбиря

- Список евреев из Кингстона-апон-Халла

- ТОО «Роллитс»

- Электростанция Скулкоатес

- Трамваи в Кингстон-апон-Халле

- Троллейбусы в Кингстон-апон-Халле

Примечания [ править ]

- а В 1941 году переписи населения не проводилось: данные взяты из Национального реестра. Великобритания и остров Мэн. Статистика населения на 29 сентября 1939 года по полу, возрасту и семейному состоянию.

- б В статье Hull Daily Mail указывается, что в 1991 году население составляло 254 117 человек.

- с Существует расхождение в 6 баллов между данными Управления национальной статистики (цитировавшимися ранее) и данными на веб-сайте Vision of Britain (цитируемыми здесь).

- д В статье Hull Daily Mail указывается, что в 2001 году население составляло 246 355 человек.

Ссылки [ править ]

- ^ Перепись Великобритании (2011 г.). «Отчет о местности – Кингстон-апон-Халл, местные власти (1946157109)» . Номис . Управление национальной статистики . Проверено 1 марта 2018 г.