Алеппо

Алеппо

Держать | |

|---|---|

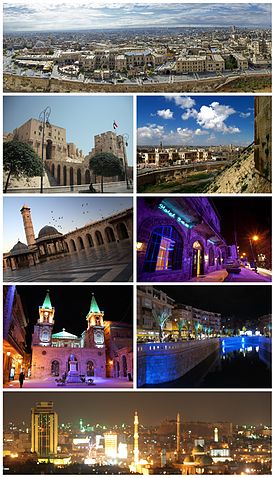

Ancient City of Aleppo Aleppo Citadel • The entrance to al-Madina Souq Great Mosque of Aleppo • Baron Hotel Saint Elijah Cathedral • Queiq River Panorama of Aleppo at night | |

| Nickname(s): | |

| Coordinates: 36°12′N 37°10′E / 36.20°N 37.16°E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Aleppo |

| District | Mount Simeon (Jabal Semaan) |

| Subdistrict | Mount Simeon (Jabal Semaan) |

| First settled | c. 5000 BC |

| First city council | 1868 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council government |

| • Governor | Ahmad Hussein Diab |

| • Mayor | Muhammad Hijazi |

| Area | |

| • Total | 190 km2 (70 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 379 m (1,243 ft) |

| Population (2021 est.) | |

| • Total | 2,098,210 |

| • Rank | 2nd in Syria 18th in the Arab World |

| • Density | 11,000/km2 (29,000/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Arabic: حلبي Ḥalabi English: Aleppine[2] |

| Time zone | UTC+3 |

| Area code(s) | Country code: 963 City code: 21 |

| Geocode | C1007 |

| Climate | BSk |

| International airport | Aleppo International Airport |

| Sources: Aleppo city area[3] Sources: City population[4][5][6][7] | |

| Official name | Ancient City of Aleppo |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv |

| Designated | 1986 (10th session) |

| Reference no. | 21 |

| Region | Arab States |

Алеппо ( / a l ɛ p oʊ ; / a -lep -Oh : арабский , حلب , -lc : ḥalab ala IPA: [ˈħalab] ) - это город в Сирии , который служит столицей мухафазной Алеппо , самой густонаселенной мухафазной в Сирии . [ 8 ] С оценкой населения 2 098 000 жителей по состоянию на 2021 год, [update][ 9 ] в Сирии, Это был крупнейший город пока его население не превзошло Дамаск , столицей Сирии, крупнейшей в северных губернаторах Сирии , а также одним из крупнейших городов в регионе Леванта . [ 10 ] [ 11 ]

Алеппо является одним из старейших постоянно населенных городов мира ; Возможно, он был заселен с шестого тысячелетия до н.э. [ 12 ] [ 13 ] [ 14 ] [ 15 ] [ 16 ] Раскопки в «Tell as-sawda» и «Al-Ansari», к югу от старого города Алеппо , показывают, что этот район был занят аморитами последней частью третьего тысячелетия до нашей эры. [ 17 ] Это также время, когда «Алеппо» впервые упоминается в клинописных таблетках, обнаруженных в EBLA и Mesopotamia , которые говорят о нем как в рамках аморитного штата Ямхад , и отмечают его коммерческое и военное значение. [18] Such a long history is attributed to its strategic location as a trading center between the Mediterranean Sea and Mesopotamia. For centuries, Aleppo was the largest city in the Syrian region, and the Ottoman Empire's third-largest after Constantinople (now Istanbul) and Cairo.[19][20][21] Значение города в истории было его расположением на одном конце шелковой дороги , которая проходила через Центральную Азию и Месопотамию . Когда Суэцкий канал был открыт в 1869 году, много торговли было перемещено в море, и Алеппо начал медленный снижение.

At the fall of the Ottoman Empire after World War I, Aleppo lost its northern hinterland to modern Turkey, as well as the important Baghdad Railway connecting it to Mosul. In the 1940s, it lost its main access to the sea, by Antakya and İskenderun, also to Turkey. The growth in importance of Damascus in the past few decades further exacerbated the situation. This decline may have helped to preserve the old city of Aleppo, its medieval architecture and traditional heritage. It won the title of the Islamic Capital of Culture 2006 and has had a wave of successful restorations of its historic landmarks. The battle of Aleppo occurred in the city during the Syrian Civil War, and many parts of the city had suffered massive destruction.[22][23] Affected parts of the city are currently undergoing reconstruction.[24][25] An estimated 31,000 people were killed in Aleppo during the conflict.[26]

Etymology

[edit]

| ||||||

| ḫrb3 in hieroglyphs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC) | ||||||

Modern-day English-speakers commonly refer to the city as Aleppo. It was known in antiquity as Khalpe, Khalibon, and to the Greeks and Romans as Beroea (Βέροια).[27] During the Crusades, and again during the Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon of 1923–1946, the name Alep was used. Aleppo represents the Italianised version of this.

The original ancient name, Ḥalab, has survived as the current Arabic name of the city. It is of obscure origin. Some have proposed that Ḥalab means "iron" or "copper" in the Amorite language since the area served as a major source of these metals in antiquity.[28] Another possibility is that Ḥalab means 'white', as this is the word for 'white' in Aramaic.[citation needed] This may explain how Ḥalab became the Hebrew word for 'milk' or vice versa, as well as offering a possible explanation for the modern-day Arabic nickname of the city, al-Shahbāʾ (Arabic: الشهباء), which means "the white-colored mixed with black" and allegedly derives from the white marble found at Aleppo.[29]

According to a folk etymology related by the twelfth century CE Rabbi Pethahiah of Regensburg and the traveler Ibn Battuta, the name derives from Hebrew: חלב, lit. 'milk' or Arabic: ḥaleb, lit. 'milk' because Abraham milked his sheep there to feed the poor.[30]

From the 11th century, it was common Rabbinic usage to apply the term "Aram-Zobah" to the area of Aleppo, and many Syrian Jews continue to do so.

History

[edit]Pre-history and pre-classical era

[edit]

Aleppo has scarcely been touched by archaeologists, since the modern city occupies its ancient site. The earliest occupation of the site was around 8,000 BC, as shown by excavations in Tallet Alsauda.[31]

Aleppo appears in historical records as an important city much earlier than Damascus. The first record of Aleppo comes from the third millennium BC, in the Ebla tablets when Aleppo was referred to as Ha-lam (𒄩𒇴).[32] Some historians, such as Wayne Horowitz, identify Aleppo with the capital of an independent kingdom closely related to Ebla, known as Armi,[33] although this identification is contested. The main temple of the storm god Hadad was located on the citadel hill in the center of the city,[34] when the city was known as the city of Hadad.[35]

Naram-Sin of Akkad mentioned his destruction of Ebla and Armanum,[36] in the 23rd century BC.[37][38] However, the identification of Armani in the inscription of Naram-Sim as Armi in the Eblaite tablets is heavily debated,[39] as there was no Akkadian annexation of Ebla or northern Syria.[39]

In the Old Babylonian and Old Assyrian Empire period, Aleppo's name appears in its original form as Ḥalab (Ḥalba) for the first time.[38] Aleppo was the capital of the important Amorite dynasty of Yamḥad. The kingdom of Yamḥad (c. 1800–1525 BC), alternatively known as the 'land of Ḥalab,' was one of the most powerful in the Near East during the reign of Yarim-Lim I, who formed an alliance with Hammurabi of Babylonia against Shamshi-Adad I of Assyria.[40]

Hittite period

[edit]Yamḥad was devastated by the Hittites under Mursili I in the 16th century BC. However, it soon resumed its leading role in the Levant when the Hittite power in the region waned due to internal strife.[38]

Taking advantage of the power vacuum in the region, Baratarna, king of the Hurrian kingdom of Mitanni instigated a rebellion that ended the life of Yamhad's last king Ilim-Ilimma I in c. 1525 BC,[41] Subsequently, Parshatatar conquered Aleppo and the city found itself on the frontline in the struggle between the Mitanni, the Hittites and Egypt.[38] Niqmepa of Alalakh who descends from the old Yamhadite kings controlled the city as a vassal to Mitanni and was attacked by Tudhaliya I of the Hittites as a retaliation for his alliance to Mitanni.[42] Later the Hittite king Suppiluliumas I permanently defeated Mitanni, and conquered Aleppo in the 14th century BC. Suppiluliumas installed his son Telepinus as king and a dynasty of Suppiluliumas descendants ruled Aleppo until the Late Bronze Age collapse.[43] However, Talmi-Šarruma, grandson of Suppiluliumas I, who was the king of Aleppo, had fought on the Hittite side, along with king Muwatalli II during the Battle of Kadesh against the Egyptian army led by Ramesses II.[note 2]

Aleppo had cultic importance to the Hittites as the center of worship of the Storm-God.[38] This religious importance continued after the collapse of the Hittite empire at the hands of the Assyrians and Phrygians in the 12th century BC, when Aleppo became part of the Middle Assyrian Empire,[45] whose king renovated the temple of Hadad which was discovered in 2003.[46]

In 2003, a statue of a king named Taita bearing inscriptions in Luwian was discovered during excavations conducted by German archeologist Kay Kohlmeyer in the Citadel of Aleppo.[47] The new readings of Anatolian hieroglyphic signs proposed by the Hittitologists Elisabeth Rieken and Ilya Yakubovich were conducive to the conclusion that the country ruled by Taita was called Palistin.[48] This country extended in the 11th-10th centuries BC from the Amouq Valley in the west to Aleppo in the east down to Maharda and Shaizar in the south.[49] Due to the similarity between Palistin and Philistines, Hittitologist John David Hawkins (who translated the Aleppo inscriptions) hypothesizes a connection between the Syro-Hittite states Palistin and the Philistines, as do archaeologists Benjamin Sass and Kay Kohlmeyer.[50] Gershon Galil suggests that King David halted the Arameans' expansion into the Land of Israel on account of his alliance with the southern Philistine kings, as well as with Toi, king of Ḥamath, who is identified with Tai(ta) II, king of Palistin (the northern Sea Peoples).[51]

State of Bit Agusi

[edit]During the early years of the 1st millennium BC, Aleppo was incorporated into the Aramean realm of Bit Agusi, which held its capital at Arpad.[52] Bit Agusi along with Aleppo and the entirety of the Levant was conquered by the Assyrians in the 8th century BC and became part of the Neo-Assyrian Empire during the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III until the late 7th century BC,[53] before passing through the hands of the Neo-Babylonians and the Achaemenid Persians.[54] The region remained known as Aramea and Eber Nari throughout these periods.

Classical antiquity (Beroea)

[edit]

Alexander the Great took over the city in 333 BC. Seleucus Nicator established a Hellenic settlement in the site between 301 and 286 BC. He called it Beroea (Βέροια), after Beroea in Macedon; it is sometimes spelled as Beroia. Beroea is mentioned in 1 Macc. 9:4.

Northern Syria was the center of gravity of the Hellenistic colonizing activity, and therefore of Hellenistic culture in the Seleucid Empire. As did other Hellenized cities of the Seleucid kingdom, Beroea probably enjoyed a measure of local autonomy, with a local civic assembly or boulē composed of free Hellenes.[55]

Beroea remained under Seleucid rule until 88 BC when Syria was conquered by the Armenian king Tigranes the Great and Beroea became part of the Kingdom of Armenia.[56] After the Roman victory over Tigranes, Syria was handed over to Pompey in 64 BC, at which time they became a Roman province. Rome's presence afforded relative stability in northern Syria for over three centuries. Although the province was administered by a legate from Rome, Rome did not impose its administrative organization on the Greek-speaking ruling class or Aramaic speaking populace.[55]

The Roman era saw an increase in the population of northern Syria that accelerated under the Byzantines well into the 5th century. In Late Antiquity, Beroea was the second largest Syrian city after Antioch, the capital of Roman Syria and the third largest city in the Roman world. Archaeological evidence indicates a high population density for settlements between Antioch and Beroea right up to the 6th century. This agrarian landscape still holds the remains of large estate houses and churches such as the Church of Saint Simeon Stylites.[55]

Ecclesiastical history

[edit]

The names of several bishops of the episcopal see of Beroea, which was in the Roman province of Syria Prima, are recorded in extant documents. The first whose name survives is that of Saint Eustathius of Antioch, who, after being bishop of Beroea, was transferred to the important metropolitan see of Antioch shortly before the 325 First Council of Nicaea. His successor in Beroea Cyrus was for his fidelity to the Nicene faith sent into exile by the Roman Emperor Constantius II. After the Council of Seleucia of 359, called by Constantius, Meletius of Antioch was transferred from Sebastea to Beroea but in the following year was promoted to Antioch. His successor in Beroea, Anatolius, was at a council in Antioch in 363. Under the persecuting Emperor Valens, the bishop of Beroea was Theodotus, a friend of Basil the Great. He was succeeded by Acacius of Beroea, who governed the see for over 50 years and was at the First Council of Constantinople in 381 and the Council of Ephesus in 431. In 438, he was succeeded by Theoctistus, who participated in the Council of Chalcedon in 451 and was a signatory of the joint letter that the bishops of the province of Syria Prima sent in 458 to Emperor Leo I the Thracian about the murder of Proterius of Alexandria. In 518, Emperor Justin I exiled the bishop of Beroea Antoninus for rejecting the Council of Chalcedon. The last known bishop of the see is Megas, who was at a synod called by Patriarch Menas of Constantinople in 536.[57][58] After the Arab conquest, Beroea ceased to be a residential bishopric, and is today listed by the Roman Catholic Church as a titular see.[59]

Very few physical remains have been found from the Roman and Byzantine periods in the Citadel of Aleppo. The two mosques inside the Citadel are known to have been converted by the Mirdasids during the 11th century from churches originally built by the Byzantines.[60]

Medieval period

[edit]

Early Islamic Arab period

[edit]The Sasanian Persians led by King Khosrow I pillaged and burned Aleppo in 540,[61][62] then they invaded and controlled Syria briefly in the early 7th century. Soon after Aleppo was taken by the Muslims under Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah in 637. It later became part of Jund Qinnasrin under the Umayyad Caliphate. In 944, it became the seat of an independent Emirate under the Hamdanid prince Sayf al-Dawla, and enjoyed a period of great prosperity, being home to the great poet al-Mutanabbi and the philosopher and polymath al-Farabi.[63] In 962, the city was sacked by the Byzantine general Nicophorus Phocas.[64] Subsequently, the city and its Emirate became a temporary vassal of the Byzantine Empire. For the next few decades, the city was disputed by the Fatimid Caliphate and Byzantine Empire, with the nominally independent Hamdanids in between, eventually falling to the Fatimids in 1017.[65] In 1024, Salih ibn Mirdas launched an attack on Fatimid Aleppo, and after a few months was invited into the city by its population.[66]

Seljuq and Ayyubid periods

[edit]In late 1077, Seljuk emir Tutush I launched a campaign to capture Aleppo during the reign of Sabiq ibn Mahmud of the Mirdasid dynasty, which lasted until 1080, when his reinforcements were ambushed and routed by a coalition of Arab tribesmen led by Kilabi chief Abu Za'ida at Wadi Butnan.[67] After the death of Sharaf al-Dawla of the Uqaylid dynasty in June 1085, the headman in Aleppo Sharif Hassan ibn Hibat Allah Al-Hutayti promised to surrender the city to Sultan Malik-Shah I. When the latter delayed his arrival, Hassan contacted the Sultan's brother Tutush. However, after Tutush defeated Suleiman ibn Qutulmish, who had intended to take Aleppo for himself, in the battle of Ain Salm, Hassan went back on his commitment. In response, Tutush attacked the city and managed to get hold of parts of the walls and towers in July 1086, but he left in September, either due to the advance of Malik-Shah or because the Fatimids were besieging Damascus.[68][69] In 1087, Aq Sunqur al-Hajib became the Seljuk governor of Aleppo under Sultan Malik Shah I.[70] During his bid for the Seljuk throne, Tutush had Aq Sunqur executed and after Tutush died in battle, the town was ruled by his son Ridwan.[71][72]

The city was besieged by Crusaders led by the King of Jerusalem Baldwin II in 1124–1125, but was not conquered after receiving protection by forces of Aqsunqur al Bursuqi arriving from Mosul in January 1125.[73]

In 1128, Aleppo became capital of the expanding Zengid dynasty, which ultimately conquered Damascus in 1154. In 1138, Byzantine emperor John II Komnenos led a campaign, which main objective was to capture the city of Aleppo. On 20 April 1138, the Christian army including Crusaders from Antioch and Edessa launched an attack on the city but found it too strongly defended, hence John II moved the army southward to take nearby fortresses.[74] On 11 October 1138, a deadly earthquake ravaged the city and the surrounding area. Although estimates from this time are very unreliable, it is believed that 230,000 people died, making it the seventh deadliest earthquake in recorded history.

In 1183, Aleppo came under the control of Saladin and then the Ayyubid dynasty. When the Ayyubids were toppled in Egypt by the Mamluks, the Ayyubid emir of Aleppo An-Nasir Yusuf became sultan of the remaining part of the Ayyubid Empire. He ruled Syria from his seat in Aleppo until, on 24 January 1260,[75] the city was taken by the Mongols under Hulagu in alliance with their vassals the Frankish knights of the ruler of Antioch Bohemond VI and his father-in-law the Armenian ruler Hethum I.[76] The city was poorly defended by Turanshah, and as a result the walls fell after six days of siege, and the citadel fell four weeks later. The Muslim population was massacred and many Jews were also killed.[77] The Christian population was spared. Turanshah was shown unusual respect by the Mongols, and was allowed to live because of his age and bravery. The city was then given to the former Emir of Homs, al-Ashraf, and a Mongol garrison was established in the city. Some of the spoils were also given to Hethum I for his assistance in the attack. The Mongol Army then continued on to Damascus, which surrendered, and the Mongols entered the city on 1 March 1260.[78]

Mamluk period

[edit]

In September 1260, the Egyptian Mamluks negotiated for a treaty with the Franks of Acre which allowed them to pass through Crusader territory unmolested, and engaged the Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jalut on 3 September 1260. The Mamluks won a decisive victory, killing the Mongols' Nestorian Christian general Kitbuqa, and five days later they had retaken Damascus. Aleppo was recovered by the Muslims within a month, and a Mamluk governor placed to govern the city. Hulagu sent troops to try to recover Aleppo in December. They were able to massacre a large number of Muslims in retaliation for the death of Kitbuqa, but after a fortnight could make no other progress and had to retreat.[79]

The Mamluk governor of the city became insubordinate to the central Mamluk authority in Cairo, and in Autumn 1261 the Mamluk leader Baibars sent an army to reclaim the city. In October 1271, the Mongols led by general Samagar took the city again, attacking with 10,000 horsemen from Anatolia, and defeating the Turcoman troops who were defending Aleppo. The Mamluk garrisons fled to Hama, until Baibars came north again with his main army, and the Mongols retreated.[80]

On 20 October 1280, the Mongols took the city again, pillaging the markets and burning the mosques.[81] The Muslim inhabitants fled for Damascus, where the Mamluk leader Qalawun assembled his forces. When his army advanced following the Second Battle of Homs in October 1281, the Mongols again retreated, back across the Euphrates. In October 1299, Ghazan captured the city, joined by his vassal Armenian King Hethum II, whose forces included some Templars and Hospitallers.[82]

In 1400, the Mongol-Turkic leader Tamerlane captured the city again from the Mamluks.[83] He massacred many of the inhabitants, ordering the building of a tower of 20,000 skulls outside the city.[84] After the withdrawal of the Mongols, all the Muslim population returned to Aleppo. On the other hand, Christians who left the city during the Mongol invasion, were unable to resettle back in their own quarter in the old town, a fact that led them to establish a new neighbourhood in 1420, built at the northern suburbs of Aleppo outside the city walls, to become known as al-Jdeydeh quarter ("new district" Arabic: جديدة).

Ottoman era

[edit]

Aleppo became part of the Ottoman Empire in 1516 as part of the vast expansion of the Ottoman borders during the reign of Selim I. The city then had around 50,000 inhabitants, or 11,224 households according to an Ottoman census.[85] In 1517, Selim I obtained a fatwa from Sunnite religious leaders and unleashed violence on the Alawites, killing 9,400 men, which is known as the Massacre of the Telal.[86] It was the centre of the Aleppo Eyalet; the rest of what later became Syria was part of either the eyalets of Damascus, Tripoli, Sidon or Raqqa. Following the Ottoman provincial reform of 1864 Aleppo became the centre of the newly constituted Vilayet of Aleppo in 1866.

Aleppo's agriculture was well-developed in the Ottoman period. Archaeological excavations revealed water mills in its river basin.[87][88] Contemporary Chinese source also suggests Aleppo in the Ottoman period had well-developed animal husbandry.[88]

During his travels to the Levant in the 17th century, French traveler Jacques Goujon recounted how the Maronite community in Aleppo, facing financial difficulties and considering conversion to Islam due to their inability to pay the jizya tax, was aided by the Franciscans who bought their church, enabling them to meet their tax obligations.[89]

Moreover, thanks to its strategic geographic location on the trade route between Anatolia and the east, Aleppo rose to high prominence in the Ottoman era, at one point being second only to Constantinople in the empire. By the middle of the 16th century, Aleppo had displaced Damascus as the principal market for goods coming to the Mediterranean region from the east. This is reflected by the fact that the Levant Company of London, a joint-trading company founded in 1581 to monopolize England's trade with the Ottoman Empire, never attempted to settle a factor, or agent, in Damascus, despite having had permission to do so. Aleppo served as the company's headquarters until the late 18th century.[90]

As a result of the economic development, many European states had opened consulates in Aleppo during the 16th and the 17th centuries, such as the consulate of the Republic of Venice in 1548, the consulate of France in 1562, the consulate of England in 1583 and the consulate of the Netherlands in 1613.[91] The Armenian community of Aleppo also rose to prominence in this period as they moved into the city to take up trade and developed the new quarter of Judayda.[92] The most outstanding among Aleppine Armenian merchants during the late 16th and early 17th centuries were Khwaja Petik Chelebi, the richest merchant in the city, and his brother Khwaja Sanos Chelebi, who monopolized Aleppine silk trade and were important patrons of the Armenians.[93][94]

However, the prosperity Aleppo experienced in the 16th and 17th century started to fade as silk production in Iran went into decline with the fall of the Safavid dynasty in 1722. By mid-century, caravans were no longer bringing silk from Iran to Aleppo, and local Syrian production was insufficient for Europe's demand. European merchants left Aleppo and the city went into an economic decline that was not reversed until the mid-19th century when locally produced cotton and tobacco became the principal commodities of interest to the Europeans.[90] According to Halil İnalcık, "Aleppo ... underwent its worst catastrophe with the wholesale destruction of its villages by Bedouin raiding in the later years of the century, creating a long-running famine which by 1798 killed half of its inhabitants."[95]

The economy of Aleppo was badly hit by the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. This, in addition to political instability that followed the implementation of significant reforms in 1841 by the central government, contributed to Aleppo's decline and the rise of Damascus as a serious economic and political competitor with Aleppo.[90] The city nevertheless continued to play an important economic role and shifted its commercial focus from long-distance caravan trade to more regional trade in wool and agricultural products. This period also saw the immigration of numerous "Levantine" (European-origin) families who dominated international trade. Aleppo's mixed commercial tribunal (ticaret mahkamesi), one of the first in the Ottoman Empire, was set up around 1855.[96]

Reference is made to the city in 1606 in William Shakespeare's Macbeth. The witches torment the captain of the ship the Tiger, which was headed to Aleppo from England and endured a 567-day voyage before returning unsuccessfully to port. Reference is also made to the city in Shakespeare's Othello when Othello speaks his final words (ACT V, ii, 349f.): "Set you down this/And say besides that in Aleppo once,/Where a malignant and a turbanned Turk/Beat a Venetian and traduced the state,/I took by th' throat the circumcised dog/And smote him—thus!" (Arden Shakespeare Edition, 2004). The English naval chaplain Henry Teonge describes in his diary a visit he paid to the city in 1675, when there was a colony of Western European merchants living there.

The city remained Ottoman until the empire's collapse, but was occasionally riven with internal feuds as well as attacks of cholera from 1823. Around 20–25 percent of the population died of plague in 1827.[97] In 1850, a Muslim mob attacked Christian neighbourhoods, tens of Christians were killed and several churches looted. Though this event has been portrayed as driven by pure sectarian principles, Bruce Masters argues that such analysis of this period of violence is too shallow and neglects the tensions that existed among the population due to the commercial favor afforded to certain Christian minorities by the Tanzimat Reforms during this time which played a large role in creating antagonism between previously cooperative groups of Muslim and Christians in the eastern quarters of the city.[98] By 1901, the city's population was around 110,000.

In October 1918, Aleppo was captured by Prince Feisal's Sherifial Forces and the 5th Cavalry Division of the Allied forces from the Ottoman Empire during the World War I. At the end of war, the Treaty of Sèvres made most of the Province of Aleppo part of the newly established nation of Syria, while Cilicia was promised by France to become an Armenian state. However, Kemal Atatürk annexed most of the Province of Aleppo as well as Cilicia to Turkey in his War of Independence. The Arab residents in the province (as well as the Kurds) supported the Turks in this war against the French, including the leader of the Hananu Revolt, Ibrahim Hananu, who directly coordinated with Atatürk and received weaponry from him. The outcome, however, was disastrous for Aleppo, because as per the Treaty of Lausanne, most of the Province of Aleppo was made part of Turkey with the exception of Aleppo and Alexandretta;[99] thus, Aleppo was cut from its northern satellites and from the Anatolian cities beyond on which Aleppo depended heavily in commerce. Moreover, the Sykes-Picot division of the Near East separated Aleppo from most of Mesopotamia, which also harmed the economy of Aleppo.

French mandate

[edit]

The State of Aleppo was declared by French General Henri Gouraud in September 1920 as part of a French plan to make Syria easier to administer by dividing it into several smaller states. France became more concerned about the idea of a united Syria after the Battle of Maysaloun.

By separating Aleppo from Damascus, Gouraud wanted to capitalize on a traditional state of competition between the two cities and turn it into political division. The people in Aleppo were unhappy with the fact that Damascus was chosen as capital for the new nation of Syria. Gouraud sensed this sentiment and tried to address it by making Aleppo the capital of a large and wealthier state with which it would have been hard for Damascus to compete. The State of Aleppo as drawn by France contained most of the fertile area of Syria: the fertile countryside of Aleppo in addition to the entire fertile basin of river Euphrates. The state also had access to sea via the autonomous Sanjak of Alexandretta. On the other hand, Damascus, which is basically an oasis on the fringes of the Syrian Desert, had neither enough fertile land nor access to sea. Basically, Gouraud wanted to satisfy Aleppo by giving it control over most of the agricultural and mineral wealth of Syria so that it would never want to unite with Damascus again.[100][101]

The limited economic resources of the Syrian states made the option of completely independent states undesirable for France, because it threatened an opposite result: the states collapsing and being forced back into unity. This was why France proposed the idea of a Syrian federation that was realized in 1923. Initially, Gouraud envisioned the federation as encompassing all the states, even Lebanon. In the end however, only three states participated: Aleppo, Damascus, and the Alawite State. The capital of the federation was Aleppo at first, but it was relocated to Damascus. The president of the federation was Subhi Barakat, an Antioch-born politician from Aleppo.

The federation ended in December 1924, when France merged Aleppo and Damascus into a single Syrian State and separated the Alawite State again. This action came after the federation decided to merge the three federated states into one and to take steps encouraging Syria's financial independence, steps which France viewed as too much.[100][101]

When the Syrian Revolt erupted in southern Syria in 1925, the French held in Aleppo State new elections that were supposed to lead to the breaking of the union with Damascus and restore the independence of Aleppo State. The French were driven to believe by pro-French Aleppine politicians that the people in Aleppo were supportive of such a scheme. After the new council was elected, however, it surprisingly voted to keep the union with Damascus. Syrian nationalists had waged a massive anti-secession public campaign that vigorously mobilized the people against the secession plan, thus leaving the pro-French politicians no choice but to support the union. The result was a big embarrassment for France, which wanted the secession of Aleppo to be a punitive measure against Damascus, which had participated in the Syrian Revolt, however, the result was respected. This was the last time that independence was proposed for Aleppo.[102]

Bad economic situation of the city after the separation of the northern countryside was exacerbated further in 1939 when Alexandretta was annexed to Turkey as Hatay State,[103][104][105] thus depriving Aleppo of its main port of Iskenderun and leaving it in total isolation within Syria.[106]

Post-independence

[edit]

The increasing disagreements between Aleppo and Damascus led eventually to the split of the National Block into two factions: the National Party, established in Damascus in 1946, and the People's Party, established in Aleppo in 1948 by Rushdi al-Kikhya, Nazim Qudsi and Mustafa Bey Barmada.[107] An underlying cause of the disagreement, in addition to the union with Iraq, was Aleppo's intention to relocate the capital from Damascus. The issue of the capital became an open debate matter in 1950 when the Popular Party presented a constitution draft that called Damascus a "temporary capital."[108]

The first coup d'état in modern Syrian history was carried out in March 1949 by an army officer from Aleppo, Hussni Zaim. However, lured by the absolute power he enjoyed as a dictator, Zaim soon developed a pro-Egyptian, pro-Western orientation and abandoned the cause of union with Iraq. This incited a second coup only four months after his.[109] The second coup, led by Sami Hinnawi (also officer from Aleppo), empowered the Popular Party and actively sought to realize the union with Iraq. The news of an imminent union with Iraq incited a third coup the same year: in December 1949, Adib Shishakly led a coup preempting a union with Iraq that was about to be declared.[110]

Soon after Shishakly's domination ended in 1954, a union with Egypt under Gamal Abdul Nasser was implemented in 1958. The union, however, collapsed three and a half years later when a junta of young Damascene officers carried out a separatist coup. Aleppo resisted the separatist coup, but eventually it had no choice but to recognize the new government.[111]

In March 1963 a coalition of Baathists, Nasserists, and Socialists launched a new coup whose declared objective was to restore the union with Egypt. However, the new government only restored the flag of the union. Soon thereafter disagreement between the Baathists and the Nasserists over the restoration of the union became a crisis, and the Baathists ousted the Nasserists from power. The Nasserists, most of whom were from the Aleppine middle class, responded with an insurgency in Aleppo in July 1963.

Again, the Ba'ath government tried to absorb the dissent of the Syrian middle class (whose center of political activism was Aleppo) by putting to the front Amin al-Hafiz, a Baathist military officer from Aleppo.[112]

President Hafez al-Assad, who came to power in 1970, relied on support from the business class in Damascus.[113] This gave Damascus further advantage over Aleppo, and hence Damascus came to dominate the Syrian economy. The strict centralization of the Syrian state, the intentional direction of resources towards Damascus, and the hegemony Damascus enjoys over the Syrian economy made it increasingly hard for Aleppo to compete. Despite this, Aleppo remained a nationally important economic and cultural center.[114]

On 16 June 1979 thirty-two military cadets were massacred by antigovernmental Islamist rebel group Muslim Brotherhood.[115][116] In the subsequent violence around fifty people were killed.[117] On 10 July a further twenty-two Syrian soldiers were killed.[118] Both terrorist attacks were part of the Islamist uprising in Syria.[119] In 1980, events escalated into the a large-scale military operation in Aleppo, where Syrian government responded with military and security forces, sending in tens of thousands of troops backed by tanks, armored vehicles and helicopters.[120] Several hundred rebels were killed in and around city and eight thousand were arrested. By February 1981, the Islamist uprising in the city of Aleppo was suppressed.[121]

Since the late 1990s, Aleppo has become one of the fastest growing cities in the Levant and the Middle East.[122] The opening of the industrial city of Shaykh Najjar and the influx of new investments and flow of the new industries after 2004 also contributed to the development of the city.[123] In 2006, Aleppo was named by the Islamic Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (ISESCO) as the capital of Islamic culture.[124]

Syrian Civil War

[edit]

On 12 August 2011, some months after protests had begun elsewhere in Syria, anti-government protests were held in several districts of Aleppo, including the city's Sakhour district. During this demonstration, which included tens of thousands of protesters, security forces shot and killed at least twelve people.[125] Two months later, a pro-government demonstration was held in Saadallah Al-Jabiri Square, in the heart of the city. According to the New York Times, the 11 October 2011 rally in support of Bashar al-Assad was attended by large crowds,[126] while state and local media claimed more than 1.5 million attended and stated that it was one of the largest rallies ever held in Syria.[127]

In early 2012, rebels began bombing Aleppo after the spread of anti-government protests. On 10 February 2012, suicide car bombs exploded outside two security compounds — the Military Intelligence Directorate's local headquarters, and a Syrian Internal Security Forces barracks[128] — reportedly killing 28 (four civilians, thirteen military personnel and eleven security personnel)[128] and wounding 235.[129] On 18 March 2012, another car bomb blast in a residential neighbourhood reportedly killed two security personnel and one female civilian, and wounded 30 residents.[130][131]

In late July 2012, the conflict reached Aleppo in earnest when rebels in the city’s surrounding countryside mounted their first offensive there,[132] apparently trying to capitalise on momentum gained during the Damascus assault.[133] Then, some of the civil war's "most devastating bombing and fiercest fighting" took place in Aleppo, often in residential areas.[132] In the summer, autumn and winter of 2012 house-to-house fighting between armed opposition and government forces continued, and by the spring 2013 the Syrian Army had entrenched itself in the western part of Aleppo (government loyalist forces were operating from a military base in the southern part of the city) and the Free Syrian Army in the eastern part with a no man's land between them.[132] One estimate of casualties by an international humanitarian organization is that by this time 13,500 had been killed in the fighting — 1,500 under 5 years of age — and that another 23,000 had been injured.[132] Local police stations in the city, used as bases of government forces and hated and feared by residents, were a focus of much of the conflict.[134][135]

As a result of the severe battle, many sections in Al-Madina Souq (part of the Old City of Aleppo World Heritage Site), including parts of the Great Mosque of Aleppo and other medieval buildings in the ancient city, were destroyed and ruined or burnt in late summer 2012 as the armed groups of the Syrian Arab Army and the Free Syrian Army fought for control of the city.[136][137][23] By March 2013, a majority of Aleppo’s factory owners transferred their goods to Turkey with the full knowledge and facilitation of the Turkish government.[138]

A stalemate that had been in place for four years ended in July 2016, when Syrian Army troops closed the last supply line of the rebels into Aleppo with the support of Russian airstrikes. In response, rebel forces launched unsuccessful counter-offensives in September and October that failed to break the siege; in November, government forces embarked on a decisive campaign. The rebels agreed to evacuate from their remaining areas in December 2016.[140] Syrian government victory with Russian aerial bombardment was widely seen as a potential turning point in Syria's civil war.[141][142]

On 22 December, the evacuation was completed with the Syrian Army declaring it had taken complete control of the city.[143] Red Cross later confirmed that the evacuation of all civilians and rebels was complete.[144]

When the battle ended, 500,000 refugees and internally displaced persons returned to Aleppo,[24] and Syrian state media said that hundreds of factories returned to production as electricity supply greatly increased.[145] Many parts of the city that were affected are undergoing reconstruction.[24] On 15 April 2017, a convoy of buses carrying evacuees was attacked by a suicide bomber in Aleppo, killing more than 126 people, including at least 80 children.[146] Syrian state media reported that the Aleppo shopping festival took place on 17 November 2017 to promote industry in the city.[147] A YPG commander stated in February 2018 that Kurdish fighters had shifted to Afrin to help repel the Turkish assault. As a result, he said the pro-Syrian government forces had regained control of the districts previously controlled by them.[148] In February 2020, government forces achieved a major breakthrough when they captured the last remaining rebel-held areas in Aleppo's western periphery, thus decisively ending the clashes that began with the Battle of Aleppo over eight years prior.[149][150]

The city received some damages due to the 2023 Turkey-Syria earthquake.

Geography

[edit]

Aleppo lies about 120 km (75 mi) inland from the Mediterranean Sea, on a plateau 380 m (1,250 ft) above sea level, 45 km (28 mi) east of the Syrian-Turkish border checkpoint of Bab al-Hawa. The city is surrounded by farmlands from the north and the west, widely cultivated with olive and pistachio trees. To the east, Aleppo approaches the dry areas of the Syrian Desert.

The city was founded a few kilometres south of the location of the current old city, on the right bank of Queiq River which arises from the Aintab plateau in the north and runs through Aleppo southward to the fertile country of Qinnasrin. The old city of Aleppo lies on the left bank of the Queiq. It was surrounded by a circle of eight hills surrounding a prominent central hill on which the castle (originally a temple dating to the 2nd millennium BC) was erected. The radius of the circle is about 10 km (6.2 mi). The hills are Tell as-Sawda, Tell ʕāysha, Tell as-Sett, Tell al-Yāsmīn (Al-ʕaqaba), Tell al-Ansāri (Yārūqiyya), ʕan at-Tall, al-Jallūm, Baḥsīta.[151] The old city was enclosed within an ancient wall that was last rebuilt by the Mamluks. The wall has since disappeared. It had nine gates and was surrounded by a broad deep ditch.[151]

Occupying an area of more than 190 km2 (73 sq mi), Aleppo is one of the fastest-growing cities in the Middle East. According to the new major plan of the city adopted in 2001, it is envisaged to increase the total area of Aleppo up to 420 km2 (160 sq mi) by the end of 2015.[3][152]

Climate

[edit]Aleppo has a cool steppe climate (Köppen: BSk). The mountain series that run along the Mediterranean coast, namely the Alawiyin Mountains and the Nur Mountains, largely block the effects of the Mediterranean on climate (rain shadow effect). The average high and low temperature throughout the year is 23.8 and 11.1 °C (74.8 and 52.0 °F). The average precipitation is 329.4 mm (12.97 in). More than 80% of precipitation occurs between October and March. It snows once or twice every winter. Average humidity is 55.7%.[153]

| Climate data for Aleppo (Aleppo International Airport), 393 m (1,289 ft) above sea level, 1991–2020 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.5 (68.9) |

25.4 (77.7) |

29.8 (85.6) |

38.6 (101.5) |

41.0 (105.8) |

44.0 (111.2) |

45.7 (114.3) |

44.3 (111.7) |

44.0 (111.2) |

39.0 (102.2) |

29.7 (85.5) |

24.5 (76.1) |

45.7 (114.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 10.7 (51.3) |

12.9 (55.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

23.1 (73.6) |

29.4 (84.9) |

34.2 (93.6) |

36.8 (98.2) |

36.8 (98.2) |

33.5 (92.3) |

27.6 (81.7) |

18.8 (65.8) |

12.2 (54.0) |

24.5 (76.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.4 (36.3) |

3.2 (37.8) |

6.1 (43.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

19.8 (67.6) |

22.8 (73.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

7.3 (45.1) |

3.7 (38.7) |

12.2 (54.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −11.3 (11.7) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

5.0 (41.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

12.0 (53.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

6.0 (42.8) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

−10.8 (12.6) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 57.5 (2.26) |

47.8 (1.88) |

42.4 (1.67) |

27.8 (1.09) |

16.0 (0.63) |

1.7 (0.07) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.00) |

3.5 (0.14) |

23.0 (0.91) |

35.6 (1.40) |

58.3 (2.30) |

313.7 (12.35) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 9.0 | 7.6 | 6.8 | 4.3 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 3.4 | 4.9 | 8.0 | 47.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84 | 79 | 68 | 65 | 50 | 42 | 42 | 45 | 46 | 55 | 66 | 80 | 60 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 120.9 | 140.0 | 198.4 | 243.0 | 319.3 | 366.0 | 387.5 | 365.8 | 303.0 | 244.9 | 186.0 | 127.1 | 3,001.9 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 3.9 | 5.0 | 6.4 | 8.1 | 10.3 | 12.2 | 12.5 | 11.8 | 10.1 | 7.9 | 6.2 | 4.1 | 8.2 |

| Source 1: NOAA (sun 1961–1990)[154][155] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (humidity 1960–1967, extremes 1951–1978)[153] | |||||||||||||

Architecture

[edit]

Aleppo is characterized with mixed architectural styles, having been ruled by, among others, Romans, Byzantines, Seljuqs, Mamluks and Ottomans.[156]

Various types of 13th and 14th centuries constructions, such as caravanserais, caeserias, Quranic schools, hammams and religious buildings are found in the old city. The quarters of al-Jdayde district are home to numerous 16th and 17th-century houses of the Aleppine bourgeoisie, featuring stone engravings. Baroque architecture of the 19th and early 20th centuries is common in al-Azizyah district, including the Villa Rose. The new Shahbaa district is a mixture of several styles, such as Neo-classic, Norman, Oriental and even Chinese architecture.[157]

Since the old city is characterized with its large mansions, narrow alleys and covered souqs, the modern city's architecture has replenished the town with wide roads and large squares such as the Saadallah Al-Jabiri Square, the Liberty Square, the President's Square and Sabaa Bahrat Square

There is a relatively clear division between old and new Aleppo. The older portions of the city, with an approximate area of 160 ha (0.6 sq mi) are contained within a wall, 5 km (3.1 mi) in circuit with nine gates. The huge medieval castle in the city — known as the Citadel of Aleppo — occupies the center of the ancient part, in the shape of an acropolis.

Being subjected to constant invasions and political instability, the inhabitants of the city were forced to build cell-like quarters and districts that were socially and economically independent. Each district was characterized by the religious and ethnic characteristics of its inhabitants.

The mainly white-stoned old town was built within the historical walls of the city, pierced by the nine historical gates, while the newer quarters of the old city were first built by the Christians during the early 15th century in the northern suburbs of the ancient city, after the Mongol withdrawal from Aleppo. The new quarter known as al-Jdayde is one of the finest examples of a cell-like quarter in Aleppo. After Tamerlane invaded Aleppo in 1400 and destroyed it, the Christians migrated out of the city walls and established their own cell in 1420, at the northwestern suburbs of the city, thus founding the quarters of al-Jdayde. The inhabitants of the new quarters were mainly brokers who facilitated trade between foreign traders and local merchants. As a result of the economic development, many other quarters were established outside the walls of the ancient city during the 15th and 16th centuries.

Thus, the Old City of Aleppo — composed of the ancient city within the walls and the old cell-like quarters outside the walls — has an approximate area of 350 ha (1.4 sq mi) housing more than 120,000 residents.[158]

Demographics

[edit]History

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1883 | 99,179 | — |

| 1901 | 108,143 | +9.0% |

| 1922 | 156,748 | +44.9% |

| 1925 | 210,000 | +34.0% |

| 1934 | 249,921 | +19.0% |

| 1944 | 325,000 | +30.0% |

| 1950 | 362,500 | +11.5% |

| 1960 | 425,467 | +17.4% |

| 1965 | 500,000 | +17.5% |

| 1983 | 639,000 | +27.8% |

| 1990 | 1,216,000 | +90.3% |

| 1995 | 1,500,000 | +23.4% |

| 2000 | 1,937,858 | +29.2% |

| 2004 | 2,132,100 | +10.0% |

| 2005 | 2,301,570 | +7.9% |

| 2016 | 1,800,000 | −21.8% |

| 2021 | 2,098,210 | +16.6% |

| Source[4][159][7] | ||

According to the Aleppine historian Sheikh Kamel Al-Ghazzi (1853–1933), the population of Aleppo was around 400,000 before the disastrous earthquake of 1822. Followed by cholera and plague attacks in 1823 and 1827 respectively, the population of the city declined to 110,000 by the end of the 19th century.[160] In 1901, the total population of Aleppo was 108,143 of which Muslims were 76,329 (70.58%), Christians — mostly Catholics — 24,508 (22.66%) and Jews 7,306 (6.76%).[161]

Aleppo's large Christian population swelled with the influx of Armenian and Assyrian Christian refugees during the early 20th-century and after the Armenian and Assyrian genocides of 1915. After the arrival of the first groups of Armenian refugees (1915–1922) the population of Aleppo in 1922 counted 156,748 of which Muslims were 97,600 (62.26%), native Christians — mostly Catholics — 22,117 (14.11%), Jews 6,580 (4.20%), Europeans 2,652 (1.70%), Armenian refugees 20,007 (12.76%) and others 7,792 (4.97%).[162][163] However, even though a large majority of the Armenians arrived during the period, the city has had an Armenian community since at least the 1100s, when a considerable number of Armenian families and merchants from the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia settled in the city. The oldest Armenian church in the city is from 1491 as well, which indicates that they have been there long before.

The second period of Armenian flow towards Aleppo marked with the withdrawal of the French troops from Cilicia in 1923.[164] After the arrival of more than 40,000 Armenian refugees between 1923 and 1925, the population of the city reached up to 210,000 by the end of 1925, of which more than a quarter were Armenians.[165]

According to the historical data presented by Al-Ghazzi, the vast majority of the Aleppine Christians were Catholics until the latter days of the Ottoman rule. The growth of the Oriental Orthodox Christians is related with the arrival of the Assyrian survivors from Cilicia and Southern Turkey, while on the other hand, large numbers of Eastern Orthodox Christians from the Sanjak of Alexandretta arrived in Aleppo, after the annexation of the Sanjak in 1939 in favour of Turkey.

In 1944, Aleppo's population was around 325,000, with 112,110 (34.5%) Christians among which Armenians numbered 60,200. Armenians formed more than half of the Christian community in Aleppo until 1947, when many groups of them left for Soviet Armenia within the frames of the Armenian Repatriation Process (1946–1967).

Pre-civil war status

[edit]

Aleppo was the most populous city in Syria, with a population of 2,132,100 as indicated in the latest official census in 2004 by the Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). Its subdistrict (nahiya) consisted of 23 localities with a collective population of 2,181,061 in 2004.[166] According to the official estimate announced by the Aleppo City Council, the population of the city was 2,301,570 by the end of 2005. As a result of the Syrian Civil War, however, the city eastern half's population under the control of the opposition had plummeted to an estimated 40,000 by 2015.[167]

Muslims

[edit]More than 80% of Aleppo's inhabitants are Sunni Muslims.[citation needed] They are mainly Syrian Arabs, followed by Turkmens and Kurds. Other Muslim groups include small numbers of ethnic Circassians, Chechens, Albanians, Bosniaks, Greeks and Bulgarians.

Christians

[edit]

Until the beginning of the Battle of Aleppo in 2012, the city contained one of the largest Christian communities in the Middle East. There were many Oriental Orthodox Christian congregations, mainly Armenians and Assyrians (locally known as Syriacs). Historically, the city was the main centre of French Catholic missionaries in Syria.[168]

The Christian population of Aleppo was slightly more than 250,000 before the Syrian Civil War, representing about 12% of the total population of the city. However, as a consequence of the war, the Christian population of the city decreased to less than 100,000 as of the beginning of 2017, of whom around 30% were ethnic Armenians.[169]

A significant number of the Assyrians in Aleppo speak Aramaic, hailing from the city of Urfa in Turkey. The large community of Oriental Orthodox Christians belongs to the Armenian Apostolic and Syriac Orthodox churches. However, there is a significant presence of the Eastern Orthodox Church of Antioch as well.

There is also a large number Eastern Catholic Christians in the city, including Melkite Greeks, Maronites, Chaldeans, Syrian Catholics and the followers of the Latin Church. Evangelical Christians of different denominations are a minority in the city.[citation needed]

Several districts of the city have a Christian and Armenian majority, such as the old Christian quarter of al-Jdayde.[170] Around 50 churches are operated in the city by the above-mentioned congregations. However, according to the Deputy Chairman of the commission for UNESCO of the Russian Federation, Alexander Dzasokhov, around 20 churches suffered great destruction during the battles in Aleppo,[171][172][173][174] with the most notable being the National Evangelical Church,[139] as well as the surrounding historic churches of al-Jdayde district.[175][176][177] On 25 December 2016, following the government victory, Christmas was publicly celebrated in Aleppo for the first time in four years.[178]

Jews

[edit]

The city was home to a significant Jewish population from ancient times. The Great Synagogue, built in the 5th century, housed the Aleppo Codex.[179] The Jews of Aleppo were known for their religious commitment, Rabbinic leadership, and their liturgy, consisting of Pizmonim and Baqashot. After the Spanish Inquisition, the city of Aleppo received many Sephardic Jewish immigrants, who eventually joined with the native Aleppo Jewish community. Peaceful relations existed between the Jews and surrounding population. In the early 20th century, the town's Jews lived mainly in Al-Jamiliyah, Bab Al-Faraj and the neighbourhoods around the Great Synagogue. Unrest in Palestine in the years preceding the establishment of Israel in 1948 resulted in growing hostility towards Jews living in Arab countries, culminating in the Jewish exodus from Arab lands. In December 1947, after the UN decided the partition of Palestine, an Arab mob[180] attacked the Jewish quarter. Homes, schools and shops were badly damaged.[181] Soon after, many of the town's remaining 6,000 Jews emigrated.[182] In 1968, there were an estimated 700 Jews still remaining in Aleppo.[183]

The houses and other properties of the Jewish families which were not sold after the migration, remain uninhabited under the protection of the Syrian Government. Most of these properties are in Al-Jamiliyah and Bab Al-Faraj areas, and the neighbourhoods around the Central Synagogue of Aleppo. In 1992, the Syrian government lifted the travel ban on its 4,500 Jewish citizens.[184] Most traveled to the United States, where a sizable number of Syrian Jews currently live in Brooklyn, New York. The last Jews of Aleppo, the Halabi family, were evacuated from the city in October 2016 by the Free Syrian Army and now live in Israel.[185]

The Jews from Aleppo referred to their city as "Aram Tzova" (ארם צובא) after the ancient Aramean city of Aram-Zobah mentioned in the Hebrew Bible.

Spoken languages

[edit]The Arabic dialect of Aleppo is a type of Syrian Arabic, which is of the North Levantine Arabic variety. Much of its vocabulary is derived from the Syriac language. The Kurdish language is the second most spoken language in the city, after Arabic.[186] Kurds in Aleppo speak the Northern Kurdish (also known as Kurmanji). Syrian Turkmen population of Aleppo speak the Kilis and Antep dialect of the Turkish language. Most Armenians speak the Western form of the Armenian language. The Syriac language is rarely spoken by the Syriac community during daily life, but commonly used as the liturgical language of the Syriac Church. The members of the small Greco-Syrian community in Aleppo speak Arabic, but the Koine Greek dialect of the Greek language is used during church service by the Orthodox and Catholic Greek churches of Antioch. English and French are also spoken.

Culture

[edit]Art

[edit]

Aleppo is considered one of the main centres of Arabic traditional and classic music with the Aleppine Muwashshahs, Qudud Halabiya and Maqams (religious, secular and folk poetic-musical genres). In December 2021, the Qudud Halabiya was included into the UNESCO's intangible cultural heritage list as Intangible cultural heritage.[187]

Aleppines in general are fond of Arab classical music, the Tarab, and it is not a surprise that many artists from Aleppo are considered pioneers among the Arabs in classic and traditional music. The most prominent figures in this field are Sabri Mdallal, Sabah Fakhri,[188] Shadi Jamil, Abed Azrie and Nour Mhanna. Many iconic artists of the Arab music like Sayed Darwish and Mohammed Abdel Wahab were visiting Aleppo to recognize the legacy of Aleppine art and learn from its cultural heritage.

Aleppo is also known for its knowledgeable and cultivated listeners, known as sammi'a or "connoisseur listeners".[189] Aleppine musicians often claim that no major Arab artist achieved fame without first earning the approval of the Aleppine sammi'a.[190]

Aleppo hosts many music shows and festivals every year at the citadel amphitheatre, such as the "Syrian Song Festival", the "Silk Road Festival" and "Khan al-Harir Festival".

Al-Adeyat Archaeological Society founded in 1924 in Aleppo, is a cultural and social organization to preserve the tangible and intangible heritage of Aleppo and Syria in general. The society has branches in other governorates as well.[191]

Museums

[edit]

- National Museum of Aleppo.

- Museum of the popular traditions known as the Aleppine House at Beit Achiqbash in al-Jdayde.

- Aleppo Citadel Museum.

- Museum of medicine and science at Bimaristan Arghun al-Kamili.

- Aleppo Memory Museum at Beit Ghazaleh in al-Jdayde.

- Zarehian Treasury of the Armenian Apostolic Church at the old Armenian church of the Holy Mother of God, Al-Jdeydeh.

Cuisine

[edit]

Aleppo is surrounded by olive, nut and fruit orchards, and its cuisine is the product of its fertile land and location along the Silk Road.[122] The International Academy of Gastronomy in France awarded Aleppo its culinary prize in 2007.[122] The city has a wide selection of different types of dishes, such as kebab, kibbeh, dolma, hummus, ful halabi, za'atar halabi , muhshi. Ful halabi is a typical Aleppine breakfast meal: fava bean soup with a splash of olive oil, lemon juice, garlic and Aleppo's red peppers. The za'atar of Aleppo (thyme) is a kind of oregano which is popular in the regional cuisines.

The kibbeh is one of the favourite foods of the locals, and the Aleppines have created more than 17 types of kibbeh dishes, which is considered a form of art for them. These include kibbeh prepared with sumac (kәbbe sәmmāʔiyye), yogurt (kәbbe labaniyye), quince (kәbbe safarjaliyye), lemon juice (kәbbe ḥāmḍa), pomegranate sauce and cherry sauce. Other varieties include the "disk" kibbeh (kәbbe ʔrāṣ), the "plate" kibbeh (kәbbe bәṣfīḥa or kәbbe bṣēniyye) and the raw kibbeh (kәbbe nayye). Kebab Halabi – influenced by Armenian and Turkish tastes – has around 26 variants[192] including: kebab prepared with cherry (kebab karaz), eggplant (kebab banjan), chili pepper with parsley and pine nut (kebab khashkhash), truffle (kebab kamayeh), tomato paste (kebab hindi), cheese and mushroom (kebab ma'juʔa), etc.[193] The favourite drink is Arak, which is usually consumed along with meze, Aleppine kebabs and kibbehs. Al-Shark beer – a product of Aleppo – is also among the favourite drinks. Local wines and brandies are consumed as well.

Aleppo is the origin of different types of sweets and pastries. The Aleppine sweets, such as mabrumeh, siwar es-sett, balloriyyeh, etc., are characterized by containing high rates of ghee butter and sugar. Other sweets include mamuniyeh, shuaibiyyat, mushabbak, zilebiyeh, ghazel al-banat etc. Most pastries contain the renowned Aleppine pistachios and other types of nuts.

Leisure and entertainment

[edit]

Until the break-out of the Battle of Aleppo in July 2012, the city was known for its vibrant nightlife.[194] Several night-clubs, bars and cabarets operated at the centre of the city as well as at the northern suburbs. The historic quarter of al-Jdayde was known for its pubs and boutique hotels, situated within ancient oriental mansions, providing special treats from the Aleppine flavour and cuisine, along with local music.[195][196]

Club d'Alep, opened in 1945, is a unique social club known for bridge games and other nightlife activities, located in a 19th-century mansion in the Aziziyah district of central Aleppo.[197]

The Aleppo Public Park, opened in 1949, is one of the largest planted parks in Syria, located near in the Aziziyah district, where Queiq River breaks through the green park.[198]

The Blue Lagoon water park – heavily damaged during the battles – was one of the favourite places among the locals, as it was the first water park in Syria. Aleppo's Shahba Mall – one of the largest shopping centres in Syria – was also among the most visited locations for the locals. It has received major damages during the civil war.

Historical sites

[edit]Souqs and khans

[edit]

The city's strategic trading position attracted settlers of all races and beliefs who wished to take advantage of the commercial roads that met in Aleppo from as far as China and Mesopotamia to the east, Europe to the west, and the Fertile Crescent and Egypt to the south. The largest covered souq-market in the world is in Aleppo, with an approximate length of 13 km (8.1 mi).[199][200]

Al-Madina Souq, as it is locally known, is an active trade centre for imported luxury goods, such as raw silk from Iran, spices and dyes from India, and coffee from Damascus. Souq al-Madina is also home to local products such as wool, agricultural products and soap. Most of the souqs date back to the 14th century and are named after various professions and crafts, hence the wool souq, the copper souq, and so on. Aside from trading, the souq accommodated the traders and their goods in khans (caravanserais) and scattered in the souq. Other types of small market-places were called caeserias (ﻗﻴﺴﺎﺭﻳﺎﺕ). Caeserias are smaller than khans in their sizes and functioned as workshops for craftsmen. Most of the khans took their names after their location in the souq and function, and are characterized by their façades, entrances and fortified wooden doors.

Gates of Aleppo and other historic buildings

[edit]

The old part of the city is surrounded with 5 km-long (3.1 mi), thick walls, pierced by the nine historical gates (many of them are well-preserved) of the old town. These are, clockwise from the north-east of the citadel:

- Bab al-Hadid, Bab al-Ahmar, Bab al-Nairab, Bab al-Maqam, Bab Qinnasrin, Bab Antakeya, Bāb Jnēn, Bab al-Faraj and Bab al-Nasr.

The most significant historic buildings of the ancient city include:

- The Citadel, a large fortress built atop a huge, partially artificial mound rising 50 m (160 ft) above the city, dates back to the first millennium BC. Recent excavations unearthed a temple and 25 statues dating back to the first millennium BC.[201] Many of the current structures date from the 13th century. The Citadel had been extensively damaged by earthquakes, notably in 1822.

- Al-Shibani building, al-Halawiyah Madrasa, al-Muqaddamiyah Madrasa, al-Zahiriyah Madrasa, al-Sultaniyah Madrasa, al-Firdaws Madrasa, Bimaristan Arghun al-Kamili, Beit Junblatt, Bab al-Faraj Clock Tower, etc.

The following are among the important historic mansions of al-Jdayde Christian quarter:[202]

- Beit Wakil, an Aleppine mansion built in 1603, with unique wooden decorations. One of its decorations was taken to Berlin and exhibited in the Museum of Islamic Art, known as the Aleppo Room.

- Beit Achiqbash, an old Aleppine house built in 1757. The building is home to the Popular Traditions Museum since 1975, showing fine decorations of the Aleppine art.

- Beit Ghazaleh, an old 17th-century mansion characterized with fine decorations, carved by the Armenian sculptor Khachadur Bali in 1691. It was used as an Armenian elementary school during the 20th century.

Places of worship

[edit]

- Great Mosque of Aleppo (Jāmi' Bani Omayya al-Kabīr), founded c. 715 by Umayyad caliph Walid I and most likely completed by his successor Sulayman. The building contains a tomb associated with Zachary, father of John the Baptist. Construction of the present structure for Nur al-Din commenced in 1158. However, it was damaged during the Mongol invasion of 1260 and was rebuilt. The 45 m-high (148 ft) tower (described as "the principal monument of medieval Syria")[203] was erected in 1090–1092 under the first Seljuk sultan, Tutush I. It had four façades with different styles. The tower was completely destroyed during the Syrian civil war in March 2013 (reported on 24 March 2013).

- Al-Nuqtah Mosque ("Mosque of the drop [of blood]"), a Shī'ah mosque, which contains a stone said to be marked by a drop of Husayn's blood. The site is believed to have previously been a monastery, which was converted into a mosque in 944.

- Al-Shuaibiyah Mosque, Al-Qaiqan Mosque, Mahmandar Mosque, Altun Bogha Mosque, Al-Sahibiyah Mosque, Bahsita Mosque, Al-Tawashi Mosque, Al-Otrush Mosque, Al-Saffahiyah Mosque, Khusruwiyah Mosque, Al-Adiliyah Mosque, Bahramiyah Mosque, etc.

- Churches of al-Jdayde quarter: the Forty Martyrs Armenian Apostolic Cathedral, the Dormition of Our Lady Greek Orthodox church, Mar Assia al-Hakim Syrian Catholic church, the Maronite Cathedral of Saint Elijah, the Armenian Catholic Cathedral of Our Mother of Reliefs and the Melkite Greek Catholic Cathedral of Virgin Mary.

- Central Synagogue of Aleppo or al-Bandara synagogue, dating to the 9th century. The synagogue was destroyed during an anti-Jewish pogrom in 1947.[204] In the 1980s, the building was restored, but destroyed again during the civil war.[205]

Hammams

[edit]

Aleppo was home to 177 hammams during the medieval period until the Mongol invasion, when many of the prominent structures of the city were destroyed. Before the civil war, 18 hammams were operating in the old city, including:

- Hammam al-Nahhasin built during the 12th century near khan al-Nahhaseen.

- Hammam al-Sultan built in 1211 by Az-Zahir Ghazi.

- Hammam al-Bayadah of the Mamluk era built in 1450.

- Hammam Yalbugha built in 1491 by the Emir of Aleppo Saif ad-Din Yalbugha al-Naseri.[206]

- Hammam al-Jawhary, hammam Azdemir, hammam Bahram Pasha, hammam Bab al-Ahmar, etc.

Nearby attractions and the Dead Cities

[edit]

Aleppo's western suburbs are home to a group of historical sites and villages which are commonly known as the Dead Cities. Around 700 abandoned settlements in the northwestern parts of Syria before the 5th century, contain remains of Christian Byzantine architecture. Many hundreds of those settlements are in Mount Simeon (Jabal Semaan) and Jabal Halaqa regions at the western suburbs of Aleppo, within the range of Limestone Massif.[207] Dead Cities were inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2011, under the name of "Ancient Villages of Northern Syria".[208]

The most notable Dead cities and archaeological sites in Mount Simeon and Mount Kurd near Aleppo include: Kalota Castle and churches northwest of Aleppo, Kharab Shams Byzantine basilica of the 4th century,[209] the half-ruined Roman basilica in Fafertin village dating back to 372 AD, the old Byzantine settlement of Surqanya village at the northwest of Aleppo, the 4th-century Basilica of Sinhar settlement, the Mushabbak Basilica dating back to the second half of the 5th century, the 9th-century BC Assyrian settlement of Kafr Nabu, Brad village and the Saint Julianus Maronite monastery (399–402 AD) where the shrine of Saint Maron is located, the 5th-century Kimar settlement of the Roman and Byzantine eras, the Church of Saint Simeon Stylites of the 5th century, the Syro-Hittite Ain Dara temple of the Iron Age dating back to the 10th and 8th centuries BC, the ancient city of Cyrrhus with the old Roman amphitheatre and two historic bridges, etc.

Transportation

[edit]Highways and roads

[edit]The main highway leading to and within the city is the M4 Highway, which runs in the eastern side of the city from south to north along the Queiq River.[210] Driving south on M4 Highway gives access to M5 Highway leading to Homs, Hama, and Damascus. The northern bypass of the city called Castello Road leads through Azaz to the border with Turkey and further to the city of Gaziantep.[211] Driving east on M4 Highway gives access to the coastal road leading to Latakia and Tartus. Within the city, main routes include Al Jalaa Street, Shukri Al-Quwatly Street, King Faisal Street, Bab Antakya Street, Ibrahim Hanano Street and Tishreen Boulevard.

Public transport

[edit]

The city of Aleppo is a major transportation hub, served by a comprehensive public transport network of buses and minibuses. New modern buses are used to connect the city with Damascus and the other Syrian cities to the east and the south of Aleppo. The city is also served by local and inter-city share taxis.

Railway

[edit]

Aleppo was one of the major stations of Syria that was connected to the Baghdad Railway in 1912, within the Ottoman Empire. The connections to Turkey and onwards to Ankara still exist today, with a twice weekly train from Damascus. It is perhaps for this historical reason that Aleppo is the headquarters of Syria national railway network, Chemins de Fer Syriens. As the railway is relatively slow, much of the passenger traffic to the port of Latakia had moved to road-based air-conditioned coaches. But this has reversed in recent years with the 2005 introduction of South Korean built DMUs providing a regular bi-hourly express service to both Latakia and Damascus, which miss intermediate stations.

However, after the break-out of the civil war in 2011, the Syrian railway network has suffered major damage and is partially out of use. Reconstruction of the Damascus-Aleppo railway line was started in 2020, after its completion and securing rail transport will be resumed.[212]

The opening scene in Agatha Christie's Murder on the Orient Express takes place on the railway station in Aleppo: "It was five o'clock on a winter's morning in Syria. Alongside the platform at Aleppo stood the train grandly designated in railway guides as the Taurus Express."

Airport

[edit]

Aleppo International Airport (IATA: ALP, ICAO: OSAP) is the international airport serving the city. The airport serves as a secondary hub for Syrian Arab Airlines. The history of the airport dates back to the beginning of the 20th century. It was upgraded and developed in the years to 1999 when the new current terminal was opened.[213]

The airport was closed since the beginning of 2013 as a result of the military operations in the area. However, following the Syrian government's recapture of eastern Aleppo during the Battle of Aleppo, an airplane conducted its first flight from the airport in four years.[214]

Economy

[edit]Trade and industry

[edit]

The main role of the city was as a trading place throughout the history, as it sat at the crossroads of two trade routes and mediated the trade from India, the Tigris and Euphrates regions and the route coming from Damascus in the South, which traced the base of the mountains rather than the rugged seacoast. Although trade was often directed away from the city for political reasons [why?], it continued to thrive until the Europeans began to use the Cape route to India and later to utilize the route through Egypt to the Red Sea.

The commercial traditions in Aleppo have deep roots in the history. The Aleppo Chamber of commerce founded in 1885, is one of the oldest chambers in the Middle East and the Arab world. According to many historians, Aleppo was the most developed commercial and industrial city in the Ottoman Empire after Constantinople and Cairo.[19]

As the largest urban area in pre-civil war Syria, Aleppo was considered the capital of Syrian industry.[215] The economy of the city was mainly driven by textiles, chemicals, pharmaceutics, agro-processing industries, electrical commodities, alcoholic beverages, engineering and tourism. It occupied a dominant position in the country's manufacturing output, with a share of more than 50% of manufacturing employment, and an even greater export share.[216]

Possessing the most developed commercial and industrial plants in Syria, Aleppo is a major centre for manufacturing precious metals and stones.[217] The annual amount of the processed gold produced in Aleppo is around 8.5 tonnes, making up to 40% of the entire manufactured gold in Syria.[218]

The industrial city of Aleppo in Sheikh Najjar district is one of the largest in Syria and the region. Occupying an area of 4,412 ha (10,900 acres) in the north-eastern suburbs of Aleppo, the total investments in the city counted more than US$3.4 billion during 2010.[219] Still under development, it is envisaged to open hotels, exhibition centres and other facilities within the industrial city.

In July 2022, the Aleppo Thermal Power Plant, which generates 200 megawatts of electricity for the city and its surroundings, was put into partial operation after restoration.[220]

Старые традиционные поделки хорошо сохранились в старой части города. Знаменитое лавревое мыло Алеппо считается первым в мире твердым мылом. [ 221 ]

Строительство

[ редактировать ]

В 2000-х годах Алеппо был одним из самых быстрорастущих городов в Сирии и на Ближнем Востоке. [ 222 ] Многие жители и жители других сирийских районов мигрируют в Алеппо, чтобы найти лучшие возможности трудоустройства, что всегда повышает давление населения, с растущим спросом на новые жилые возможности. Новые районы и жилые сообщества были построены в пригороде Алеппо, многие из них все еще были в стадии строительства с 2010 года [update].

Два основных строительных проекта запланированы в Алеппо: проект «Возрождение старого города» и «Восстановление русла ручья реки Кейк»:

- Проект Возрождения Старого города завершил свой первый этап к концу 2008 года, а второй этап начался в начале 2010 года. Целью проекта является сохранение старого города Алеппо с его суксами и ханами, а также восстановление узких переулков старого города и дорог вокруг Цитадели.

- Восстановление реки Кейк направлено на возрождение потока реки, разрушая как искусственное покров ручь, так и подкрепление берегов ручья вдоль реки в центре города. Поток реки был заблокирован в 1960 -х годах турками, превратив реку в крошечный канал сточных вод, что привело к тому, что власти покрывают ручей в течение 1970 -х годов. В 2008 году поток чистой воды был восстановлен благодаря усилиям сирийского правительства, предоставив новую жизнь реке Куэйк. [ 223 ]

Как и в других крупных сирийских городах, Алеппо страдает от рассеяния неформальных поселений : по оценкам, почти половина его населения (около 1,2 миллиона) будет жить в 22 неформальных поселениях различных типов. [ 224 ]

Образование

[ редактировать ]

Будучи основным экономическим центром Сирии, Алеппо имеет большое количество образовательных учреждений. По данным UNICEF, в Алеппо насчитывается около 1280 школ и его пригородов, которые приветствовали 485 000 новых учеников по состоянию на сентябрь 2018 года, [ 225 ] и около 25 000 студентов возобновили свое обучение по состоянию на декабрь 2021 года. [ 226 ]

Не говоря уже о некоторых колледжах. В дополнение к Университету Алеппо , есть государственные колледжи и частные университеты, которые привлекают большое количество студентов из других регионов Сирии и арабских стран. Число студентов в университете Алеппо составляет более 60 000. [ 227 ] Университет имеет 18 факультетов и 8 технических колледжей в городе Алеппо.

В настоящее время в городе действуют два частных университета: Университет Аль-Шахбы (SU) и Университет науки и техники Мамуна (обязательно). Филиалы государственной консерватории и школы изобразительных искусств также работают в городе.

Алеппо является домом для нескольких христианских школ, таких как христианская школа Святой Мариам (главная христианская школа города) и Армянские частные школы, а также две международные школы: Международная школа Алеппо и Лиси Франсайс д'Алеп .

Спорт

[ редактировать ]

Город Алеппо считается важным центром командных видов спорта , когда футбол является самым популярным в городе. Пять крупных спортивных клубов города- «Аль-Иттхад С.К.» , «Аль-Хуррия» , «Аль-Ярмук» , Jalaa SC и Ouroube SC . [ 228 ] Многие другие спортивные клубы расположены в нескольких районах города, в том числе Al-Herafyeen SC , Shorta Aleppo SC , Ommal Alepopo SC , Nayrab SC, Al-Shahbaa SC, Al-Qala'a SC и Aleppo Railways SC.

Баскетбол также играется в городе. Все 5 крупных спортивных клубов Алеппина участвуют в высшем жене и женской женской дивизии сирийской баскетбольной лиги , в котором как Jalaa SC , так и Al-Ittihad SC последовательно доминировали в победе в лиге с 1956 по 1993 год. [ 229 ] [ 230 ]

В июле 2022 года в Алеппо впервые с начала конфликта были сыграны международные квалификационные матчи. На арене Хамадании , команда Сирии встретила команды Ирана и Бахрейна в рамках квалификации на чемпионат мира . [ 231 ] [ 232 ]

Другие виды спорта, практикуемые крупными клубами в городе, включают теннис , гандбол , волейбол , легкую атлетику , настольный теннис и плавание .

С мощностью 53 200 мест, международный стадион Алеппо является крупнейшим спортивным центром в Сирии. [ 233 ] Другие крупные спортивные площадки в городе включают в себя спортивную арену аль-Хамадании , плавательный комплекс Бассель аль-Асад и Олимпийский и дайвинг-комплекс Аль-Хамадании .

29 января 2017 года Алеппо организовал первое спортивное мероприятие с 2012 года, [ 234 ] Когда местные конкуренты по футболу Al-Ettihad SC и Al-Hurriya SC сыграли на стадионе Ri'ayet Al-Shabab , в рамках Сирийской Премьер-лиги 2016–17 годов . [ 235 ]

Муниципалитет

[ редактировать ]