Бахрейн

Королевство Бахрейн | |

|---|---|

| Гимн: Наш Бахрейн В Бахрайнуне Наш Бахрейн | |

Расположение Бахрейна (зеленым цветом) | |

| Капитал и крупнейший город | Манама 26 ° 13' с.ш., 50 ° 35' в.д. / 26,217 ° с.ш., 50,583 ° в.д. |

| Официальный язык и национальный язык | арабский [1] |

| Этнические группы (2020) [2] | |

| Религия |

|

| Demonym(s) | Бахрейн |

| Правительство | Унитарная исламская парламентская полуконституционная монархия |

• Король | Хамад бин Иса Аль Халифа |

| Салман бин Хамад Аль Халифа | |

| Законодательная власть | Национальное собрание |

| Консультативный совет | |

| Совет представителей | |

| Учреждение | |

| 1783 | |

• Провозглашенная независимость [5] | 14 августа 1971 г. |

• Независимость от Соединенного Королевства [6] | 15 августа 1971 г. |

| 21 сентября 1971 г. | |

| 14 февраля 2002 г. | |

| Область | |

• Общий | 786.5 [7] км 2 (303,7 квадратных миль) ( 173-е место ) |

• Вода (%) | незначительный |

| Население | |

• Оценка на 2021 год | 1,463,265 [8] [9] ( 149-е ) |

• Перепись 2020 года | 1,501,635 [2] |

• Density | 1,864/km2 (4,827.7/sq mi) (6th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| HDI (2022) | very high (34th) |

| Currency | Bahraini dinar (BHD) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (AST) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +973 |

| ISO 3166 code | BH |

| Internet TLD | .bh |

Website bahrain | |

| |

Бахрейн ( / b ɑː ˈ r eɪ n / бах- РЭЙН , / b æ x ˈ r eɪ n / ; Арабский : Бахрейн , латинизированный : аль-Бахрейн , букв. «Два моря », локально [æl bɑħˈreːn] ), официально Королевство Бахрейн , [а] — островное государство в Западной Азии . Он расположен в Персидском заливе и включает в себя небольшой архипелаг , состоящий из 50 естественных островов и еще 33 искусственных островов , с центром на острове Бахрейн , который составляет около 83 процентов территории страны. Бахрейн расположен между Катаром и северо-восточным побережьем Саудовской Аравии , с которым он соединен Дорогой короля Фахда . По данным Организации Объединенных Наций, население Бахрейна по состоянию на 14 мая 2023 года составляет 1 501 635 человек, из которых 712 362 человека являются гражданами Бахрейна. [2] Бахрейн занимает площадь около 760 квадратных километров (290 квадратных миль). [13] и является третьей по величине страной в Азии после Мальдив и Сингапура . [14] Столица и крупнейший город — Манама .

Бахрейн является местом древней цивилизации Дилмун . [15] С древности он славился ловлей жемчуга , который до 19 века считался лучшим в мире. [16] Бахрейн был одной из первых территорий, на которые оказало влияние ислам , при жизни Мухаммеда в 628 году нашей эры. После периода арабского правления Бахрейн находился под властью Португальской империи с 1521 по 1602 год, когда они были изгнаны шахом Аббасом Великим из Сефевидского Ирана . В 1783 году Бани Утба и союзные племена захватили Бахрейн у Насра аль-Мадхкура , и с тех пор им управляет королевская семья Аль Халифа с Ахмедом аль Фатехом Бахрейна в качестве первого хакима .

В конце 1800-х годов, после последовательных договоров с Великобританией , Бахрейн стал протекторатом Соединенного Королевства. [17] В 1971 году оно провозгласило независимость . Бывший эмират , Бахрейн был объявлен полуконституционной монархией в 2002 году, а статья 2 недавно принятой конституции сделала шариат основным источником законодательства.

Бахрейн создал первую постнефтяную экономику в Персидском заливе . [18] результат десятилетий инвестиций в банковский и туристический секторы; [19] многие крупнейшие финансовые учреждения мира присутствуют в столице страны. Она признана Всемирным банком страной с высоким уровнем дохода . Бахрейн является членом Организации Объединенных Наций , Движения неприсоединения , Лиги арабских государств , Организации исламского сотрудничества и Совета сотрудничества стран Персидского залива . [20] Бахрейн является партнером по диалогу Шанхайской организации сотрудничества . [21] [22]

Этимология

[ редактировать ]Бахрейн — это двойная форма арабского море слова Бахр (буквально означающего « первоначально »), поэтому аль-Бахрейн означает буквально «два моря ». Однако это имя было лексикализовано как имя собственное женского рода и не соответствует грамматическим правилам для двойственных чисел; таким образом, его форма всегда Бахрейн и никогда Бахран , ожидаемая форма именительного падежа. Окончания добавляются к слову без изменений, как в названии государственного гимна Bahraynunā («наш Бахрейн») или демонима Bahraynī . Средневековый грамматист аль-Джавахари прокомментировал это, заявив, что более формально правильный термин Бахри (букв. «принадлежащий морю») был бы неправильно понят и поэтому не использовался. [23]

Остается спорным, название Бахрейн . к каким «двум морям» первоначально относится [24] Этот термин встречается в Коране пять раз , но не относится к современному острову, первоначально известному арабам как Аваль . [24]

Сегодня под «двумя морями» Бахрейна обычно понимают залив к востоку и западу от острова. [25] моря к северу и югу от острова, [26] или соленая и пресная вода, присутствующая над и под землей. Помимо колодцев, к северу от Бахрейна есть участки моря, где пресная вода пузырится посреди соленой воды, как отмечали посетители еще с древности. [27] Альтернативную теорию относительно топонимии Бахрейна предлагает регион Аль-Ахса, которая предполагает, что двумя морями были Большой Зеленый океан (Персидский залив) и мирное озеро на материковой части Аравии .

Until the late Middle Ages, "Bahrain" referred to the region of Eastern Arabia that included Southern Iraq, Kuwait, Al-Hasa, Qatif, and Bahrain. The region stretched from Basra in Iraq to the Strait of Hormuz in Oman. This was Iqlīm al-Bahrayn's "Bahrayn Province." The exact date at which the term "Bahrain" began to refer solely to the Awal archipelago is unknown.[28] The entire coastal strip of Eastern Arabia was known as "Bahrain" for a millennium.[29] The island and kingdom were also commonly spelled Bahrein[16][30] into the 1950s.

History

[edit]Antiquity

[edit]Bahrain was home to Dilmun, an important Bronze Age trade centre linking Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley.[31] Bahrain was later ruled by the Assyrians and Babylonians.[32]

From the sixth to third century BC, Bahrain was part of the Achaemenid Empire. By about 250 BC, Parthia brought the Persian Gulf under its control and extended its influence as far as Oman. The Parthians established garrisons along the southern coast of the Persian Gulf to control trade routes.[33]

During the classical era, Bahrain was referred to by the ancient Greeks as Tylos, the centre of pearl trading, when the Greek admiral Nearchus serving under Alexander the Great landed on Bahrain.[34] Nearchus is believed to have been the first of Alexander's commanders to visit the island, and he found a verdant land that was part of a wide trading network; he recorded: "That on the island of Tylos, situated in the Persian Gulf, are large plantations of cotton trees, from which are manufactured clothes called sindones, of strongly differing degrees of value, some being costly, others less expensive. The use of these is not confined to India, but extends to Arabia."[35] The Greek historian Theophrastus states that much of Bahrain was covered by these cotton trees and that Bahrain was famous for exporting walking canes engraved with emblems that were customarily carried in Babylon.[36]Alexander had planned to settle Greek colonists in Bahrain, and although it is not clear that this happened on the scale he envisaged, Bahrain became very much part of the Hellenised world: the language of the upper classes was Greek (although Aramaic was in everyday use). Local coinage shows a seated Zeus, who may have been worshipped there as a syncretised form of the Arabian sun-god Shams.[37] Tylos was also the site of Greek athletic contests.[38]

The Greek historian Strabo believed the Phoenicians originated from Bahrain.[39] Herodotus also believed that the homeland of the Phoenicians was Bahrain.[40][41] This theory was accepted by the 19th-century German classicist Arnold Heeren who said that: "In the Greek geographers, for instance, we read of two islands, named Tyrus or Tylos, and Aradus, which boasted that they were the mother country of the Phoenicians, and exhibited relics of Phoenician temples."[42] The people of Tyre, in particular, have long maintained Persian Gulf origins, and the similarity in the words "Tylos" and "Tyre" has been commented upon.[43] However, there is little evidence of any human settlement at all on Bahrain during the time when such migration had supposedly taken place.[44]

The name Tylos is thought to be a Hellenisation of the Semitic Tilmun (from Dilmun).[45] The term Tylos was commonly used for the islands until Ptolemy's Geographia when the inhabitants are referred to as Thilouanoi.[46] Some place names in Bahrain go back to the Tylos era; for instance the name of Arad, a residential suburb of Muharraq, is believed to originate from "Arados", the ancient Greek name for Muharraq.[34]

In the 3rd century, Ardashir I, the first ruler of the Sassanid dynasty, marched on Oman and Bahrain, where he defeated Sanatruq the ruler of Bahrain.[47]

Bahrain was also the site of worship of an ox deity called Awal (Arabic: اوال) Worshipers built a large statue to Awal in Muharraq, although it has now been lost. For many centuries after Tylos, Bahrain was known as Awal. By the 5th century, Bahrain became a centre for Nestorian Christianity, with the village Samahij[48] as the seat of bishops. In 410, according to the Oriental Syriac Church synodal records, a bishop named Batai was excommunicated from the church in Bahrain.[49] As a sect, the Nestorians were often persecuted as heretics by the Byzantine Empire, but Bahrain was outside the Empire's control, offering some safety. The names of several Muharraq villages today reflect Bahrain's Christian legacy, with Al Dair meaning "the monastery".

Bahrain's pre-Islamic population consisted of Christian Arabs (mostly Abd al-Qays), Persians (Zoroastrians), Jews,[50] and Aramaic-speaking agriculturalists.[51][52][53] According to Robert Bertram Serjeant, the Baharna may be the Arabised "descendants of converts from the original population of Christians (Aramaeans), Jews and Persians inhabiting the island and cultivated coastal provinces of Eastern Arabia at the time of the Muslim conquest".[51][54] The sedentary people of pre-Islamic Bahrain were Aramaic speakers and to some degree Persian speakers, while Syriac functioned as a liturgical language.[52]

Arrival of Islam

[edit]

Muhammad's first interaction with the people of Bahrain was the Al Kudr Invasion. Muhammad ordered a surprise attack on the Banu Salim tribe for plotting to attack Medina. He had received news that some tribes were assembling an army in Bahrain and preparing to attack the mainland, but the tribesmen retreated when they learned Muhammad was leading an army to do battle with them.[55][56]

Traditional Islamic accounts state that Al-Ala'a Al-Hadrami was sent as an envoy during the Expedition of Zayd ibn Harithah (Hisma)[57][58] to the Bahrain region by Muhammad in AD 628 and that Munzir ibn Sawa Al Tamimi, the local ruler, responded to his mission and converted the entire area.[59][60]

Middle Ages

[edit]In the year 899, the Qarmatians, a millenarian Ismaili Muslim sect, seized Bahrain, seeking to create a utopian society based on reason and redistribution of property among initiates. Thereafter, the Qarmatians demanded tribute from the caliph in Baghdad, and in 930 sacked Mecca, bringing the sacred Black Stone back to their base in Ahsa, in medieval Bahrain, for ransom. According to historian Al-Juwayni, the stone was returned 22 years later in 951 under mysterious circumstances. Wrapped in a sack, it was thrown into the Great Mosque of Kufa in Iraq, accompanied by a note saying "By command we took it, and by command, we have brought it back." The theft and removal of the Black Stone caused it to break into seven pieces.[61][62][63]

Following their defeat in the year 976 by the Abbasids,[64] the Qarmatians were overthrown by the Arab Uyunid dynasty of al-Hasa, who took over the entire Bahrain region in 1076.[65] The Uyunids controlled Bahrain until 1235, when the archipelago was briefly occupied by the Persian ruler of Fars. In 1253, the Bedouin Usfurids brought down the Uyunid dynasty, thereby gaining control over eastern Arabia, including the islands of Bahrain. In 1330, the archipelago became a tributary state of the rulers of Hormuz,[28] though locally the islands were controlled by the Shi'ite Jarwanid dynasty of Qatif.[66]In the mid-15th century, the archipelago came under the rule of the Jabrids, a Bedouin dynasty also based in Al-Ahsa that ruled most of eastern Arabia.[67]

Portuguese and early modern era

[edit]

In 1521, the Portuguese Empire allied with Hormuz and seized Bahrain from the Jabrid ruler Muqrin ibn Zamil, who was killed during the takeover. Portuguese rule lasted for around 80 years, during which time they depended mainly on Sunni Persian governors.[28] The Portuguese were expelled from the islands in 1602 by Abbas I of the Safavid Iran,[68] which gave impetus to Shia Islam.[69] For the next two centuries, Persian rulers retained control of the archipelago, interrupted by the 1717 and 1738 invasions of the Ibadis of Oman.[70] During most of this period, they resorted to governing Bahrain indirectly, either through the city of Bushehr or through immigrant Sunni Arab clans. The latter were tribes returning to the Arabian side of the Persian Gulf from Persian territories in the north who were known as Huwala.[28][71][72] In 1753, the Huwala clan of Nasr Al-Madhkur invaded Bahrain on behalf of the Iranian Zand leader Karim Khan Zand and restored direct Iranian rule.[72]

In 1783, Al-Madhkur lost the islands of Bahrain following his defeat by the Bani Utbah clan and allied tribes at the 1782 Battle of Zubarah. Bahrain was not new territory to the Bani Utbah; they had been a presence there since the 17th century.[73] During that time, they started purchasing date palm gardens in Bahrain; a document shows that 81 years before the arrival of the Al Khalifa, one of the sheikhs of the Al Bin Ali tribe (an offshoot of the Bani Utbah) had bought a palm garden from Mariam bint Ahmed Al Sanadi in Sitra island.[74]

The Al Bin Ali were the dominant group controlling the town of Zubarah on the Qatar peninsula,[75][76] originally the centre of power of the Bani Utbah. After the Bani Utbah gained control of Bahrain, the Al Bin Ali had a practically independent status there as a self-governing tribe. They used a flag with four red and three white stripes, called the Al-Sulami flag[77] in Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, and the Eastern province of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Later, different Arab family clans and tribes from Qatar moved to Bahrain to settle after the fall of Nasr Al-Madhkur of Bushehr. These families included the House of Khalifa, Al-Ma'awdah, Al-Buainain, Al-Fadhil, Al-Kuwari, Al-Mannai, Al-Noaimi, Al-Rumaihi, Al-Sulaiti, Al-Sadah, Al-Thawadi and other families and tribes.[78]

The House of Khalifa moved from Qatar to Bahrain in 1799. Originally, their ancestors were expelled from Umm Qasr in central Arabia by the Ottomans due to their predatory habits of preying on caravans in Basra and trading ships in Shatt al-Arab waterway until Turks expelled them to Kuwait in 1716, where they remained until 1766.[79]

Around the 1760s, the Al Jalahma and House of Khalifa, both belonging to the Utub Federation, migrated to Zubarah in modern-day Qatar, leaving Al Sabah as the sole proprietors of Kuwait.[80]

19th century and later

[edit]In the early 19th century, Bahrain was invaded by both the Omanis and the Al Sauds. In 1802 it was governed by a 12-year-old child, when the Omani ruler Sayyid Sultan installed his son, Salim, as governor in the Arad Fort.[81] In 1816, the British political resident in the Persian Gulf, William Bruce, received a letter from the Sheikh of Bahrain who was concerned about a rumour that Britain would support an attack on the island by the Imam of Muscat. He sailed to Bahrain to reassure the Sheikh that this was not the case and drew up an informal agreement assuring the Sheikh that Britain would remain a neutral party.[82]

In 1820, the Al Khalifa tribe were recognised by the United Kingdom as the rulers ("Al-Hakim" in Arabic) of Bahrain after signing a treaty relationship.[83] However, ten years later they were forced to pay yearly tributes to Egypt despite seeking Persian and British protection.[84]

In 1860, the Al Khalifas used the same tactic when the British tried to overpower Bahrain. Writing letters to the Persians and Ottomans, Al Khalifas agreed to place Bahrain under the latter's protection in March due to offering better conditions. Eventually, the Government of British India overpowered Bahrain when the Persians refused to protect it. Colonel Pelly signed a new treaty with Al Khalifas placing Bahrain under British rule and protection.[84]

Following the Qatari–Bahraini War in 1868, British representatives signed another agreement with the Al Khalifas. It specified that the ruler could not dispose of any of his territories except to the United Kingdom and could not enter into relationships with any foreign government without British consent.[85][86] In return the British promised to protect Bahrain from all aggression by sea and to lend support in case of land attack.[86] More importantly the British promised to support the rule of the Al Khalifa in Bahrain, securing its unstable position as rulers of the country. Other agreements in 1880 and 1892 sealed the protectorate status of Bahrain to the British.[86]

Unrest amongst the people of Bahrain began when Britain officially established complete dominance over the territory in 1892. The first revolt and widespread uprising took place in March 1895 against Sheikh Issa bin Ali, then ruler of Bahrain.[87] Sheikh Issa was the first of the Al Khalifa to rule without Persian relations. Sir Arnold Wilson, Britain's representative in the Persian Gulf and author of The Persian Gulf, arrived in Bahrain from Muscat at this time.[87] The uprising developed further with some protesters killed by British forces.[87]

Before the development of the petroleum industry, the island was largely devoted to pearl fisheries and, as late as the 19th century, was considered to be the finest in the world.[16] In 1903, German explorer Hermann Burchardt visited Bahrain and took many photographs of historical sites, including the old Qaṣr es-Sheikh, photos now stored at the Ethnological Museum of Berlin.[88] Before the First World War, there were about 400 vessels hunting pearls and an annual export of more than £30,000.[30]

In 1911, a group of Bahraini merchants demanded restrictions on the British influence in the country. The group's leaders were subsequently arrested and exiled to India. In 1923, the British introduced administrative reforms and replaced Sheikh Issa bin Ali with his son. Some clerical opponents and families, such as Al Dosari, left or were exiled to Saudi Arabia.[89] Three years later the British placed the country under the de facto rule of Charles Belgrave who operated as an adviser to the ruler until 1957.[90][91] Belgrave brought a number of reforms such as establishment of the country's first modern school in 1919 and the abolition of slavery in 1937.[92] At the same time, the pearl diving industry developed at a rapid pace.

In 1927, Rezā Shāh, then Shah of Iran, demanded sovereignty over Bahrain in a letter to the League of Nations, a move that prompted Belgrave to undertake harsh measures including encouraging conflicts between Shia and Sunni Muslims to bring down the uprisings and limit the Iranian influence.[93] Belgrave even went further by suggesting to rename the Persian Gulf to the "Arabian Gulf"; however, the proposal was refused by the British government.[90] Britain's interest in Bahrain's development was motivated by concerns over Saudi and Iranian ambitions in the region.

The Bahrain Petroleum Company (Bapco), a subsidiary of the Standard Oil Company of California (Socal),[94] discovered oil in 1932.[95]

In the early 1930s, Bahrain Airport was developed. Imperial Airways flew there, including the Handley Page HP42 aircraft. Later in the same decade, the Bahrain Maritime Airport was established, for flying boats and seaplanes.[96]

Bahrain participated in the Second World War on the Allied side, joining on 10 September 1939. On 19 October 1940, four Italian SM.82s bombers bombed Bahrain alongside Dhahran oilfields in Saudi Arabia,[97] targeting Allied-operated oil refineries.[98] Although minimal damage was caused in both locations, the attack forced the Allies to upgrade Bahrain's defences, an action which further stretched Allied military resources.[98]

After World War II, increasing anti-British sentiment spread throughout the Arab World and led to riots in Bahrain. The riots focused on the Jewish community.[99] In 1948, following rising hostilities and looting,[100] most members of Bahrain's Jewish community abandoned their properties and evacuated to Bombay, later settling in Israel (Pardes Hanna-Karkur) and the United Kingdom. As of 2008[update], 37 Jews remained in the country.[100] In the 1950s, the National Union Committee, formed by reformists following sectarian clashes, demanded an elected popular assembly, removal of Belgrave and carried out a number of protests and general strikes. In 1965 a month-long uprising broke out after hundreds of workers at the Bahrain Petroleum Company were laid off.[101]

Independence

[edit]

On 15 August 1971,[102][103] though the Shah of Iran was claiming historical sovereignty over Bahrain, he accepted a referendum held by the United Nations and eventually Bahrain declared independence and signed a new treaty of friendship with the United Kingdom. Bahrain joined the United Nations and the Arab League later in the year.[104] The oil boom of the 1970s benefited Bahrain greatly, although the subsequent downturn hurt the economy. The country had already begun diversification of its economy and benefited further from the Lebanese Civil War in the 1970s and 1980s, when Bahrain replaced Beirut as the Middle East's financial hub after Lebanon's large banking sector was driven out of the country by the war.[105]

In 1981, following the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran, the Bahraini Shia population orchestrated a failed coup attempt under the auspices of a front organisation, the Islamic Front for the Liberation of Bahrain. The coup would have installed a Shia cleric exiled in Iran, Hujjatu l-Islām Hādī al-Mudarrisī, as supreme leader heading a theocratic government.[106] In December 1994, a group of youths threw stones at female runners for running bare-legged during an international marathon. The resulting clash with police soon grew into civil unrest.[107][108]

A popular uprising occurred between 1994 and 2000 in which leftists, liberals and Islamists joined forces.[109] The event resulted in approximately forty deaths and ended after Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa became the Emir of Bahrain in 1999.[110] He instituted elections for parliament, gave women the right to vote, and released all political prisoners.[111] A referendum on 14–15 February 2001 massively supported the National Action Charter.[112] As part of the adoption of the National Action Charter on 14 February 2002, Bahrain changed its formal name from the State (dawla) of Bahrain to the Kingdom of Bahrain.[113] At the same time, the title of the Head of State, Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa, was changed from Emir to King.[114]

After the September 11 attacks, the country participated in military action against the Taliban in October 2001 by deploying a frigate in the Arabian Sea for rescue and humanitarian operations.[115] As a result, in November of that year, US president George W. Bush's administration designated Bahrain as a "major non-NATO ally".[115] Bahrain opposed the invasion of Iraq and had offered Saddam Hussein asylum in the days before the invasion.[115] Relations improved with neighbouring Qatar after the border dispute over the Hawar Islands was resolved by the International Court of Justice in The Hague in 2001.[116] Following the political liberalisation of the country, Bahrain negotiated a free trade agreement with the United States in 2004.[117]

In 2005, Qal'at al-Bahrain, a fort and archaeological complex was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

2011 Bahraini protests

[edit]Inspired by the regional Arab Spring, Bahrain's Shia majority started large protests against its Sunni rulers in early 2011.[118][119] The government initially allowed protests following a pre-dawn raid on protesters camped in Pearl Roundabout.[120] A month later it requested security assistance from Saudi Arabia and other Gulf Cooperation Council countries and declared a three-month state of emergency.[121] The government then launched a crackdown on the opposition that included conducting thousands of arrests and systematic torture.[122][123][124] Almost daily clashes between protesters and security forces led to dozens of deaths.[125] Protests, sometimes staged by opposition parties, were ongoing.[126][127][128] More than 80 civilians and 13 policemen have been killed as of March 2014[update].[129]According to Physicians for Human Rights, 34 of these deaths were related to government usage of tear gas originally manufactured by U.S.-based Federal Laboratories.[130][131] The lack of coverage by Arab media in the Persian Gulf,[132] as compared to other Arab Spring uprisings, has sparked several controversies. Iran is alleged by United States and others to have a hand in the arming of Bahraini militants.[133]

Post-Arab Spring years

[edit]The Saudi-led Intervention of Bahrain issued swift suppression of widespread government protests through military assistance from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

The 2011 Bahraini uprising, inspired by the Arab Spring, ended in a bloody crackdown against the mainly Shiite demonstrators who had demanded an elected government, threatening the Sunni monarchy's grip on power.

In 2012, the Bahrain Pearling Trail, consisting of three oyster beds, was designated as a World Heritage Site, inscribing it as "Pearling, Testimony of an Island Economy".

On 9 April 2020, Bahrain launched a committee to paying private-sector employees for a three-month period in order to ease the financial pain caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bahrain assailed the movement as an Iranian plot, and banned opposition parties, put civilians in front of military courts and jailed dozens of peaceful political opponents, eliciting harsh international criticism.[134]

"Ten years after Bahrain's popular uprising, systemic injustice has intensified and political repression targeting dissidents, human rights defenders, clerics and independent civil society have effectively shut any space for the peaceful exercise of the right to freedom of expression or peaceful activism", Amnesty International said in a statement.[135]

Bahrain remains militarily and financially dependent on Saudi Arabia and the UAE,[134] though this is changing with the economic reforms being implemented by the government.[136]

Geography

[edit]

Bahrain is a generally flat and arid archipelago in the Persian Gulf. It consists of a low desert plain rising gently to a low central escarpment with the highest point the 134 m (440 ft) Mountain of Smoke (Jabal ad Dukhan).[137][138] Bahrain had a total area of 665 km2 (257 sq mi) but due to land reclamation, the area increased to 780 km2 (300 sq mi), which is slightly larger than Anglesey.[138]

Often described as an archipelago of 33 islands,[139] extensive land reclamation projects have changed this; by August 2008 the number of islands and island groups had increased to 84.[140] Bahrain does not share a land boundary with another country but does have a 161 km (100 mi) coastline. The country also claims a further 22 km (12 nmi) of territorial sea and a 44 km (24 nmi) contiguous zone. Bahrain's largest islands are Bahrain Island, the Hawar Islands, Muharraq Island, Umm an Nasan, and Sitra. Bahrain has mild winters and very hot, humid summers. The country's natural resources include large quantities of oil and natural gas as well as fish in the offshore waters. Arable land constitutes only 2.82%[6] of the total area.

About 92% of Bahrain is desert with periodic droughts and dust storms, the main natural hazards for Bahrainis.[141] Environmental issues facing Bahrain include desertification resulting from the degradation of limited arable land, coastal degradation (damage to coastlines, coral reefs, and sea vegetation) resulting from oil spills and other discharges from large tankers, oil refineries, distribution stations, and illegal land reclamation at places such as Tubli Bay. The agricultural and domestic sectors' over-utilisation of the Dammam Aquifer, the principal aquifer in Bahrain, has led to its salinisation by adjacent brackish and saline water bodies. A hydrochemical study identified the locations of the sources of aquifer salinisation and delineated their areas of influence. The investigation indicates that the aquifer water quality is significantly modified as groundwater flows from the northwestern parts of Bahrain, where the aquifer receives its water by lateral underflow from eastern Saudi Arabia to the southern and southeastern parts. Four types of salinisation of the aquifer are identified: brackish-water up-flow from the underlying brackish-water zones in north-central, western, and eastern regions; seawater intrusion in the eastern region; intrusion of sabkha water in the southwestern region; and irrigation return flow in a local area in the western region. Four alternatives for the management of groundwater quality that are available to the water authorities in Bahrain are discussed and their priority areas are proposed, based on the type and extent of each salinisation source, in addition to groundwater use in that area.[142]

Climate

[edit]

The Zagros Mountains across the Persian Gulf in Iran cause low-level winds to be directed toward Bahrain. Dust storms from Iraq and Saudi Arabia transported by northwesterly winds, locally called shamal wind, cause reduced visibility in the months of June and July.[143]

Summers are very hot. The seas around Bahrain are very shallow, heating up quickly in the summer to produce very high humidity, especially at night. Summer temperatures may reach up to 40 °C (104 °F) under the right conditions.[144] Rainfall in Bahrain is minimal and irregular. Precipitation mostly occurs in winter, with an average of 70.8 millimetres or 2.8 inches of rainfall recorded annually. The country experienced widespread flooding in April 2024 after heavy rainfall affected the Gulf region.

Biodiversity

[edit]

More than 330 species of birds were recorded in the Bahrain archipelago, 26 species of which breed in the country. Millions of migratory birds pass through the Persian Gulf region in the winter and autumn months.[145] One globally endangered species, Chlamydotis undulata, is a regular migrant in the autumn.[145] The many islands and shallow seas of Bahrain are globally important for the breeding of the Socotra cormorant; up to 100,000 pairs of these birds were recorded over the Hawar Islands.[145] Bahrain's national bird is the bulbul while its national animal is the Arabian oryx. And the national flower of Bahrain is the beloved Deena.

Only 18 species of mammals are found in Bahrain, animals such as gazelles, desert rabbits and hedgehogs are common in the wild but the Arabian oryx was hunted to extinction on the island.[145] Twenty-five species of amphibians and reptiles were recorded as well as 21 species of butterflies and 307 species of flora.[145] The marine biotopes are diverse and include extensive sea grass beds and mudflats, patchy coral reefs as well as offshore islands. Sea grass beds are important foraging grounds for some threatened species such as dugongs and the green turtle.[146] In 2003, Bahrain banned the capture of sea cows, marine turtles and dolphins within its territorial waters.[145]

The Hawar Islands Protected Area provides valuable feeding and breeding grounds for a variety of migratory seabirds, it is an internationally recognised site for bird migration. The breeding colony of Socotra cormorant on Hawar Islands is the largest in the world, and the dugongs foraging around the archipelago form the second-largest dugong aggregation after Australia.[146]

Bahrain has five designated protected areas, four of which are marine environments.[145] They are:

- Hawar Islands

- Mashtan Island, off the coast of Bahrain.

- Arad bay, in Muharraq.

- Tubli Bay

- Al Areen Wildlife Park, which is a zoo and a breeding centre for endangered animals, is the only protected area on land and also the only protected area which is managed on a day-to-day basis.[145]

Bahrain emits a lot of carbon dioxide per person compared to other countries, primarily due to it just being a small country.[147]

Government and politics

[edit]

Bahrain under the Al Khalifa is a semi-constitutional monarchy headed by the king, Shaikh Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa. King Hamad enjoys wide executive powers which include appointing the prime minister and his ministers, commanding the army, chairing the Higher Judicial Council, appointing the parliament's upper house and dissolving its elected lower house.[148] The head of government is the prime minister. In 2010, about half of the cabinet was composed of the Al Khalifa family.[149]

Bahrain has a bicameral National Assembly (al-Majlis al-Watani) consisting of the Shura Council (Majlis Al-Shura) with 40 seats and the Council of Representatives (Majlis Al-Nuwab) with 40 seats. The forty members of the Shura are appointed by the king. In the Council of Representatives, 40 members are elected by absolute majority vote in single-member constituencies to serve four-year terms.[150] The appointed council "exercises a de facto veto" over the elected, because draft acts must be approved so they may pass into law. After approval, the king may ratify and issue the act or return it within six months to the National Assembly where it may only pass into law if approved by two-thirds of both councils.[148]

In 1973, the country held its first parliamentary elections; however, two years later, the late emir dissolved the parliament and suspended the constitution after parliament rejected the State Security Law.[101] The period between 2002 and 2010 saw three parliamentary elections. The first, held in 2002 was boycotted by the opposition, Al Wefaq, which won a majority in the second in 2006 and third in 2010.[151] A 2011 by-election was held to replace 18 members of Al Wefaq who resigned in protest against government crackdown.[152][153] According to the V-Dem Democracy indices Bahrain is 2023 the 4th least electoral democratic country in the Middle East.[154]

The opening up of politics saw big gains for both Shīa and Sunnī Islamists in elections, which gave them a parliamentary platform to pursue their policies.[155] It gave a new prominence to clerics within the political system, with the most senior Shia religious leader, Sheikh Isa Qassim, playing a vital role.[156] This was especially evident when in 2005 the government called off the Shia branch of the "Family law" after over 100,000 Shia took to the streets. Islamists opposed the law because "neither elected MPs nor the government has the authority to change the law because these institutions could misinterpret the word of God". The law was supported by women activists who said they were "suffering in silence". They managed to organise a rally attended by 500 participants.[157][158][159] Ghada Jamsheer, a leading woman activist[160] said the government was using the law as a "bargaining tool with opposition Islamic groups".[161]

Analysts of democratisation in the Middle East cite the Islamists' references to respect human rights in their justification for these programmes as evidence that these groups can serve as a progressive force in the region.[162] Some Islamist parties have been particularly critical of the government's readiness to sign international treaties such as the United Nations' International Convention on Civil and Political Rights. At a parliamentary session in June 2006 to discuss ratification of the convention, Sheikh Adel Mouwda, the former leader of a salafist party, Asalah, explained the party's objections: "The convention has been tailored by our enemies, God kill them all, to serve their needs and protect their interests rather than ours. This why we have eyes from the American Embassy watching us during our sessions, to ensure things are swinging their way".[163]

Military

[edit]The kingdom has a small but professional and well-equipped military called the Bahrain Defence Force (BDF), numbering around 8,200 personnel, including 6,000 in the Royal Bahraini Army, 700 in the Royal Bahraini Naval Force, and 1,500 in the Royal Bahraini Air Force. The BDF command structure also includes the Bahrain Royal Guard, which is the size of one battalion and has its own armored vehicles and artillery. The Bahrain National Guard is separate from the BDF, though it is tasked with assisting it in defense from external threats, and it has about 2,000 personnel.[164][165] The supreme commander of the Bahraini military is King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa and the deputy supreme commander is the Crown Prince, Salman bin Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa.[166][167] The Commander-in-Chief of the BDF has been Field Marshal Khalid bin Ahmed Al Khalifa since 2008.[168]

The BDF is primarily equipped with United States-made-equipment, such as the F-16 Fighting Falcon, F-5 Freedom Fighter, UH-60 Blackhawk, M60A3 tanks, and the ex-USS Jack Williams, an Oliver Hazard Perry class frigate renamed the RBNS Sabha.[165][169][170] On 7 August 2020, it was announced in a ceremony held at the HMNB Portsmouth Naval Base in the UK, that HMS Clyde had been transferred to the Royal Bahrain Naval Force, with the ship renamed as RBNS Al-Zubara.[171][172] On 18 January 2024 the Bahraini Navy received a second Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigate, the former USS Robert G. Bradley, which was renamed RBNS Khalid bin Ali.[173][174] Bahrain was the first country in the Gulf to operate the F-16. Sometime in 2024 the Royal Bahraini Air Force expects to receive 16 aircraft of the modernized F-16 Block 70 variant,[175] in addition to its current 20 F-16C/D and 12 F-5E/F fighters. The Royal Bahraini Army has 180 M60A3 main battle tanks, with 100 in active service and 80 in storage.[165]

The Government of Bahrain has close relations with the United States, having signed a cooperative agreement with the United States Military and has provided the United States a base in Juffair since the early 1990s, although a US naval presence existed since 1948.[176] This is the home of the headquarters for Commander, United States Naval Forces Central Command (COMUSNAVCENT) / United States Fifth Fleet (COMFIFTHFLT),[177] and around 6,000 United States military personnel.[178]

Bahrain participates in the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen against the Shia Houthis and forces loyal to former President Ali Abdullah Saleh,[179] who was deposed in the 2011 Arab Spring uprising.[180]

The permanent British Royal Navy base at Mina Salman, HMS Jufair, was officially opened in April 2018.[181]

Foreign relations

[edit]

Bahrain has established bilateral relations with 190 countries worldwide.[182] As of 2012[update], Bahrain maintains a network of 25 embassies, three consulates and four permanent missions to the Arab League, United Nations and European Union respectively.[183] Bahrain also hosts 36 embassies. The United States designated Bahrain a major non-NATO ally in 2001.[184] Bahrain plays a modest, moderating role in regional politics and adheres to the views of the Arab League on Middle East peace and Palestinian rights by supporting the two state solution.[185] Bahrain is also one of the founding members of the Gulf Cooperation Council.[186] Relations with Iran tend to be tense as a result of a failed coup in 1981 which Bahrain blames Iran for and occasional claims of Iranian sovereignty over Bahrain by ultra-conservative elements in the Iranian public.[187][188] In 2016, following the storming of the Saudi embassy in Tehran, both Saudi Arabia and Bahrain cut diplomatic relations with Iran. Bahrain and Israel established bilateral relations in 2020 under the Bahrain–Israel normalization agreement.[189]

Human rights

[edit]

The period between 1975 and 1999 known as the “State Security Law Era”, saw wide range of human rights violations including arbitrary arrests, detention without trial, torture and forced exile.[190][191] After Emir (now King) Hamad Al Khalifa succeeded his father Isa Al Khalifa in 1999, he introduced wide reforms and human rights improved significantly.[192] These moves were described by Amnesty International as representing a "historic period of human rights".[111]

Consensual male and female homosexual relations between adults over the age of 21 are legal in Bahrain and the only Muslim Gulf country where it is legal since 1976.[193]

Human rights conditions started to decline by 2007 when torture began to be employed again.[194] In 2011, Human Rights Watch described the country's human rights situation as "dismal".[195] Due to this, Bahrain lost some of the high International rankings it had gained before.[196][197][198][199][200]

In 2011, Bahrain was criticised for its crackdown on the Arab spring uprising. In September, a government-appointed commission confirmed reports of grave human rights violations, including systematic torture. The government promised to introduce reforms and avoid repeating the "painful events".[201] However, reports by human rights organisations Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch issued in April 2012 said the same violations were still happening.[202][203]

Amnesty International's 2015 report on the country points to the continued suppression of dissent, restricted freedom of expression, unjust imprisonment, and frequent torture and other ill-treatment of its citizens.[204] As of October 2014[update], Bahrain is ruled by an "authoritarian regime" and is rated as "Not Free" by the U.S.-based non-governmental Freedom House.[205] Freedom House continues to label Bahrain as "not free" in its 2021 report.[206] On 7 July 2016, the European Parliament adopted, with a large majority, a resolution condemning human rights abuses performed by Bahraini authorities, and strongly called for an end to the ongoing repression against the country's human rights defenders, political opposition and civil society.[207]

In August 2017, United States Secretary of State Rex Tillerson spoke against the discrimination of Shias in Bahrain, saying, "Members of the Shia community there continue to report ongoing discrimination in government employment, education, and the justice system," and that "Bahrain must stop discriminating against the Shia communities." He also stated that "In Bahrain, the government continue to question, detain and arrest Shia clerics, community members and opposition politicians."[208][209] However, in September 2017, the U.S. State Department has approved arms sales packages worth more than $3.8 billion to Bahrain including F-16 jets, upgrades, missiles and patrol boats.[210][211] In its latest report the Amnesty International accused both, US and the UK governments, of turning a blind eye to horrific abuses of human rights by the ruling Bahraini regime.[212] On 31 January 2018, Amnesty International reported that the Bahraini government expelled four of its citizens after having revoked their nationality in 2012; turning them into stateless people.[213] On 21 February 2018, human rights activist Nabeel Rajab was sentenced to a further five years in jail for tweets and documentation of human rights violations.[214] On behalf of the ruling family, Bahraini police have received training on how to deal with public protests from the British government.[215][unreliable source?][216]

Women's rights

[edit]Women in Bahrain acquired voting rights and the right to stand in national elections in the 2002 election.[217] However, no women were elected to office in that year's polls.[218] In response to the failure of women candidates, six were appointed to the Shura Council, which also includes representatives of the Kingdom's indigenous Jewish and Christian communities.[219] Nada Haffadh became the country's first female cabinet minister on her appointment as Minister of Health in 2004. The quasi-governmental women's group, the Supreme Council for Women, trained female candidates to take part in the 2006 general election. When Bahrain was elected to head the United Nations General Assembly in 2006 it appointed lawyer and women's rights activist Haya bint Rashid Al Khalifa President of the United Nations General Assembly, only the third woman in history to head the world body.[220] Female activist Ghada Jamsheer said "The government used women's rights as a decorative tool on the international level." She referred to the reforms as "artificial and marginal" and accused the government of "hinder[ing] non-governmental women societies".[161]

In 2006, Lateefa Al Gaood became the first female MP after winning by default.[221] The number rose to four after the 2011 by-elections.[222] In 2008, Houda Nonoo was appointed ambassador to the United States making her the first Jewish ambassador of any Arab country.[223] In 2011, Alice Samaan, a Christian woman, was appointed ambassador to the United Kingdom.[224]

Media

[edit]The predominant forms of media in Bahrain consists of weekly and daily newspapers, television, and radio.

Newspapers are widely available in multiple languages such as Arabic, English, Malayalam, etc. to support the varied population. Akhbar Al Khaleej (أخبار الخليج) and Al Ayam (الأيام) are examples of major Arabic newspapers published daily. Gulf Daily News and Daily Tribune publish daily newspapers in English. Gulf Madhyamam is a newspaper published in Malayalam.

The country's television network operates five networks, all of which are by the Information Affairs Authority. Radio, much like the television network, is mostly state-run and usually in Arabic. Radio Bahrain is a long-running English language radio station, and Your FM is a radio station serving the large expatriate population from the Indian subcontinent living in the country.

By June 2012, Bahrain had 961,000 internet users.[225] The platform "provides a welcome free space for journalists, although one that is increasingly monitored", according to Reporters Without Borders. Rigorous filtering targets political, human rights, religious material and content deemed obscene. Bloggers and other netizens were among those detained during protests in 2011.[226]

Bahraini journalists risk prosecution for offences that include "undermining" the government and religion. Self-censorship is widespread. Journalists were targeted by officials during anti-government protests in 2011. Three editors from the opposition daily Al-Wasat were sacked and later fined for publishing "false" news. Several foreign correspondents were expelled.[226] An independent commission, set up to look into the unrest, found that state media coverage was at times inflammatory. It said opposition groups suffered from lack of access to mainstream media and recommended that the government "consider relaxing censorship". Assessments by Reporters sans frontières have consistently found Bahrain to be one of the most world's most restrictive regimes.[227]

Governorates

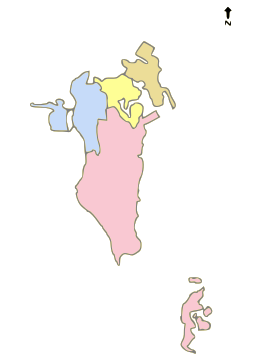

[edit]Bahrain is divided into four governorates:[228]

| Map | Current Governorates |

|---|---|

| 1 – Capital Governorate |

| 2 – Muharraq Governorate | |

| 3 – Northern Governorate | |

| 4 – Southern Governorate |

Economy

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (November 2020) |

According to a January 2006 report by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, Bahrain has the fastest-growing economy in the Arab world.[229] Bahrain also has the freest economy in the Middle East and is twelfth-freest overall in the world based on the 2011 Index of Economic Freedom, published by The Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal.[230]

In 2008, Bahrain was named the world's fastest-growing financial centre by the City of London's Global Financial Centres Index.[231][232] Bahrain's banking and financial services sector, particularly Islamic banking, have benefited from the regional boom driven by demand for oil.[233] Petroleum production and processing is Bahrain's most exported product, accounting for 60% of export receipts, 70% of government revenues, and 11% of GDP.[6] Aluminium production is the second-most exported product, followed by finance and construction materials.[6]

Economic conditions have fluctuated with the changing price of oil since 1985, for example during and following the Persian Gulf crisis of 1990–91. With its highly developed communication and transport facilities, Bahrain is home to a number of multinational firms and construction proceeds on several major industrial projects. A large share of exports consists of petroleum products made from imported crude oil, which accounted for 51% of the country's imports in 2007.[141] In October 2008, the Bahraini government introduced a long-term economic vision for Bahrain known as 'Vision 2030' which aims to transform Bahrain into a diversified and sustainable economy.

In recent years, the government has undertaken several economic reforms in order to improve its financial dependency and also to boost its image as an island tourist destination that is compact, has short travel times and provides a much more authentic Arab experience than the regional economic and tourism powerhouse of Dubai.[234] The Avenues is one such example of the recent developments. It is a waterfront facing shopping mall that was opened in October 2019.[235] Bahrain depends heavily on food imports to feed its growing population; it relies heavily on meat imports from Australia and also imports 75% of its total fruit consumption needs.[236][237]

Since only 2.9% of the country's land is arable, agriculture contributes to 0.5% of Bahrain's GDP.[237] In 2004, Bahrain signed the Bahrain–US Free Trade Agreement, which will reduce certain trade barriers between the two nations.[238] In 2011, due to the combination of the Great Recession and the 2011 Bahraini uprising, its GDP growth rate decreased to 1.3%, which was the lowest growth rate since 1994.[239] The country's public debt in 2020 is $44.5 billion, or 130% of GDP. It is expected to rise to 155 per cent of GDP in 2026, according to IMF estimates. The military expenditure is the main reason for this increase in debt.[240]

Access to biocapacity in Bahrain is much lower than the world average. In 2016, Bahrain had 0.52 global hectares [241] of biocapacity per person within its territory, much less than the world average of 1.6 global hectares per person.[242]

In 2016, Bahrain used 8.6 global hectares of biocapacity per person – their ecological footprint of consumption. This means they use 16.5 times as much biocapacity as Bahrain contains. As a result, Bahrain is running a biocapacity deficit.[241]

Unemployment, especially among the young, and the depletion of both oil and underground water resources are major long-term economic problems. In 2008, the jobless figure was at 4%,[243] with women overrepresented at 85% of the total.[244] In 2007 Bahrain became the first Arab country to institute unemployment benefits as part of a series of labour reforms instigated under Minister of Labour, Majeed Al Alawi.[245]

As of Q4 2022, total employment in Bahrain[246] stood at 746,145 workers. This included both Bahraini and Non-Bahraini workers. These employment levels represented a full recovery of employment since the downturn caused by the COVID pandemic.[247]

Tourism

[edit]

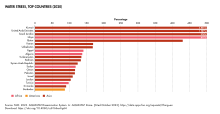

As a tourist destination, Bahrain received over eleven million visitors in 2019.[248] Most of these are from the surrounding Arab states, although an increasing number hail from outside the region due to growing awareness of the kingdom's heritage and partly due to its higher profile as a result of the Bahrain Grand Prix.

The kingdom combines modern Arab culture and the archaeological legacy of five thousand years of civilisation. The island is home to forts including Qalat Al Bahrain which has been listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. The Bahrain National Museum has artefacts from the country's history dating back to the island's first human inhabitants some 9000 years ago and the Beit Al Quran (Arabic: بيت القرآن, meaning: the House of Qur'an) is a museum that holds Islamic artefacts of the Qur'an. Some of the popular historical tourist attractions in the kingdom are the Al Khamis Mosque, which is one of the oldest mosques in the region, the Arad fort in Muharraq, Barbar temple, which is an ancient temple from the Dilmunite period of Bahrain, as well as the A'ali Burial Mounds and the Saar temple.[249] The Tree of Life, a 400-year-old tree that grows in the Sakhir desert with no nearby water, is also a popular tourist attraction.[250]

Bird watching (primarily in the Hawar Islands), scuba diving, and horse riding are popular tourist activities in Bahrain. Many tourists from nearby Saudi Arabia and across the region visit Manama primarily for the shopping malls in the capital Manama, such as the Bahrain City Centre and Seef Mall in the Seef district of Manama. The Manama Souq and Gold Souq in the old district of Manama are also popular with tourists.[251]

In January 2019 the state-run Bahrain News Agency announced the summer 2019 opening of an underwater theme park covering about 100,000 square meters with a sunken Boeing 747 as the site's centrepiece. The project is a partnership between the Supreme Council for Environment, Bahrain Tourism and Exhibitions Authority (BTEA), and private investors. Bahrain hopes scuba divers from around the world will visit the underwater park, which will also include artificial coral reefs, a copy of a Bahraini pearl merchant's house, and sculptures.[252] The park is intended to become the world's largest eco-friendly underwater theme park.[253]

Since 2005, Bahrain hosts an annual festival in March, titled Spring of Culture, which features internationally renowned musicians and artists performing in concerts.[254] Manama was named the Arab Capital of Culture for 2012 and Capital of Arab Tourism for 2013 by the Arab League and Asian Tourism for 2014 with the Gulf Capital of Tourism for 2016 by The Gulf Cooperation Council. The 2012 festival featured concerts starring Andrea Bocelli, Julio Iglesias and other musicians.[255]

Value Added Tax (VAT)

[edit]The Kingdom of Bahrain introduced the Value Added Tax with effect from 1 January 2019.[256] This is a multipoint tax on the sale of goods and services in Kingdom of Bahrain. This has been managed by the government through the national bureau of revenue. The ultimate burden of this tax is passed on the consumer. To start with the maximum rate of VAT was 5% which is increased to 10% with effect from 1 January 2022.[257] The government of Bahrain is assuring compliance through high penalties on defaults and tighter audits. This first of its kind VAT has invited qualified chartered accounting firms mainly from India to advise on VAT matters. Firms like KPMG, KeyPoint, Assure Consulting and APMH have set up offices looking at the need for consulting in this domain of VAT.

Infrastructure

[edit]

Bahrain has one main international airport, the Bahrain International Airport (BAH) which is located on the island of Muharraq, in the north-east. The airport handled almost 100,000 flights and more than 9.5 million passengers in 2019.[258] On January 28, 2021, Bahrain opened its new airport terminal as part of its economic vision 2030.[259] The new airport terminal is capable of handling 14 million passengers and is a big boost to the country's aviation sector.[259] Bahrain's national carrier, Gulf Air operates and bases itself in the BIA.

Bahrain has a well-developed road network, particularly in Manama. The discovery of oil in the early 1930s accelerated the creation of multiple roads and highways in Bahrain, connecting several isolated villages, such as Budaiya, to Manama.[260]

To the east, a bridge connected Manama to Muharraq since 1929, a new causeway was built in 1941 which replaced the old wooden bridge.[260] Currently there are three modern bridges connecting the two locations.[261] Transits between the two islands peaked after the construction of the Bahrain International Airport in 1932.[260] Ring roads and highways were later built to connect Manama to the villages of the Northern Governorate and towards towns in central and southern Bahrain.

The four main islands and all the towns and villages are linked by well-constructed roads. There were 3,164 km (1,966 mi) of roadways in 2002, of which 2,433 km (1,512 mi) were paved. A causeway stretching over 2.8 km (2 mi), connect Manama with Muharraq Island, and another bridge joins Sitra to the main island. The King Fahd Causeway, measuring 24 km (15 mi), links Bahrain with the Saudi Arabian mainland via the island of Umm an-Nasan. It was completed in December 1986, and financed by Saudi Arabia. In 2008, there were 17,743,495 passengers transiting through the causeway.[262] A second causeway, which will have both road and rail connection, between Bahrain and Saudi Arabia called 'King Hamad Causeway' is currently being discussed and is in the planning phase.[263]

Bahrain's port of Mina Salman is the main seaport of the country and consists of 15 berths.[264] In 2001, Bahrain had a merchant fleet of eight ships of 1,000 GT or over, totaling 270,784 GT.[265] Private vehicles and taxis are the primary means of transportation in the city.[266] A nationwide metro system is currently under construction and is due to be operational by 2025.

Telecommunications

[edit]The telecommunications sector in Bahrain officially started in 1981 with the establishment of Bahrain's first telecommunications company, Batelco and until 2004, it monopolised the sector. In 1981, there were more than 45,000 telephones in use in the country. By 1999, Batelco had more than 100,000 mobile contracts.[267] In 2002, under pressure from international bodies, Bahrain implemented its telecommunications law which included the establishment of an independent Telecommunications Regulatory Authority (TRA).[267] In 2004, Zain (a rebranded version of MTC Vodafone) started operations in Bahrain and in 2010 VIVA (owned by STC Group) became the third company to provide mobile services.[268]

Bahrain has been connected to the internet since 1995 with the country's domain suffix is '.bh'. The country's connectivity score (a statistic which measures both Internet access and fixed and mobile telephone lines) is 210.4 per cent per person, while the regional average in Arab States of the Persian Gulf is 135.37 per cent.[269] The number of Bahraini internet users has risen from 40,000 in 2000[270] to 250,000 in 2008,[271] or from 5.95 to 33 per cent of the population. As of August 2013[update], the TRA has licensed 22 Internet Service Providers.[272]

Science and technology

[edit]Policy framework

[edit]The Bahraini Economic Vision 2030 published in 2008 does not indicate how the stated goal of shifting from an economy built on oil wealth to a productive, globally competitive economy will be attained. Bahrain has already diversified its exports to some extent, out of necessity. It has the smallest hydrocarbon reserves of any Persian Gulf state, producing 48,000 barrels per day from its one onshore field.[273] The bulk of the country's revenue comes from its share in the offshore field administered by Saudi Arabia. The gas reserve in Bahrain is expected to last for less than 27 years, leaving the country with few sources of capital to pursue the development of new industries. Investment in research and development remained very low in 2013.[274]

Apart from the Ministry of Education and the Higher Education Council, the two main hives of activity in science, technology, and innovation are the University of Bahrain (established in 1986) and the Bahrain Centre for Strategic, International, and Energy Studies. The latter was founded in 2009 to undertake research with a focus on strategic security and energy issues to encourage new thinking and influence policymaking.[274]

New infrastructure for science and education

[edit]Bahrain hopes to build a science culture within the kingdom and to encourage technological innovation, among other goals. In 2013, the Bahrain Science Centre was launched as an interactive educational facility targeting 6- to 18-year-olds. The topics covered by current exhibitions include junior engineering, human health, the five senses, Earth sciences and biodiversity.[274]

In April 2014, Bahrain launched its National Space Science Agency. The agency has been working to ratify international space-related agreements such as the Outer Space Treaty, the Rescue Agreement, the Space Liability Convention, the Registration Convention and the Moon Agreement. The agency plans to establish infrastructure for the observation of both outer space and the Earth.[274]

In November 2008, an agreement was signed to establish a Regional Centre for Information and Communication Technology in Manama under the auspices of UNESCO. The aim is to establish a knowledge hub for the six-member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council. In March 2012, the centre hosted two high-level workshops on ICTs and education. In 2013, Bahrain topped the Arab world for internet penetration (90% of the population), trailed by the United Arab Emirates (86%) and Qatar (85%). Just half of Bahrainis and Qataris (53%) and two-thirds of those in the United Arab Emirates (64%) had access in 2009.[274]

Investment in education and research

[edit]In 2012, the government devoted 2.6% of GDP to education, one of the lowest ratios in the Arab world. This ratio was on a par with investment in education in Lebanon and higher only than that in Qatar (2.4% in 2008) and Sudan (2.2% in 2009).[274] Bahrain was ranked 67th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[275]

Bahrain invests little in research and development. In 2009 and 2013, this investment reportedly amounted to 0.04% of GDP, although the data were incomplete, covering only the higher education sector. The lack of comprehensive data on research and development poses a challenge for policymakers, as data inform evidence-based policymaking.[274]

The available data for researchers in 2013 cover only the higher education sector. Here, the number of researchers is equivalent to 50 per million inhabitants, compared to a global average for all employment sectors of 1,083 per million.[274]

The University of Bahrain had over 20,000 students in 2014, 65% of whom are women, and around 900 faculty members, 40% of whom are women. From 1986 to 2014, university staff published 5,500 papers and books. The university spent about US$11 million per year on research in 2014, which was conducted by a contingent of 172 men and 128 women. Women thus made up 43% of researchers at the University of Bahrain in 2014.[274]

Bahrain was one of 11 Arab states which counted a majority of female university graduates in science and engineering in 2014. Women accounted for 66% of graduates in natural sciences, 28% of those in engineering and 77% of those in health and welfare. It is harder to judge the contribution of women to research, as the data for 2013 only cover the higher education sector.[274]

Trends in research output

[edit]In 2014, Bahraini scientists published 155 articles in internationally catalogued journals, according to Thomson Reuters' Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded). This corresponds to 15 articles per million inhabitants, compared to a global average of 176 per million inhabitants in 2013. Scientific output has risen slowly from 93 articles in 2005 and remains modest. By 2014, only Mauritania and Palestine had a smaller output in this database among Arab states.[276][274]

Between 2008 and 2014, Bahraini scientists collaborated most with their peers from Saudi Arabia (137 articles), followed by Egypt (101), the United Kingdom (93), the United States (89) and Tunisia (75).[274]

Demographics

[edit]

In 2010, Bahrain's population grew to 1.2 million, of which 568,399 were Bahraini and 666,172 were non-nationals.[277] It had risen from 1.05 million (517,368 non-nationals) in 2007, the year when Bahrain's population crossed the one million mark.[278] Though a majority of the population is Middle Eastern, a sizeable number of people from South Asia live in the country. In 2008, approximately 290,000 Indian nationals lived in Bahrain, making them the single largest expatriate community in the country, the majority of which hail from the south Indian state of Kerala.[279][280] Bahrain is the fourth most densely populated sovereign state in the world with a population density of 1,646 people per km2 in 2010.[277] The only sovereign states with larger population densities are city states. Much of this population is concentrated in the north of the country with the Southern Governorate being the least densely populated part.[277] The north of the country is so urbanized that it is considered by some to be one large metropolitan area.[281]

Ethnic groups

[edit]Bahraini people are ethnically diverse. Shia Bahrainis are divided into two main ethnic groups: Baharna and Ajam. The Shia Bahrainis are Baharna (Arab), and the Ajam are Persian Shias. Shia Persians form large communities in Manama and Muharraq. A small minority of Shia Bahrainis are ethnic Hasawis from Al-Hasa.

Sunni Bahrainis are mainly divided into two main ethnic groups: Arabs (al Arab) and Huwala. Sunni Arabs are the most influential ethnic group in Bahrain. They hold most government positions and the Bahraini monarchy are Sunni Arabs. Sunni Arabs have traditionally lived in areas such as Zallaq, Muharraq, Riffa and Hawar islands. The Huwala are descendants of Sunni Iranians; some of them are Sunni Persians,[282][283] while others Sunni Arabs.[284][285] There are also Sunnis of Baloch origin. Most African Bahrainis come from East Africa and have traditionally lived in Muharraq Island and Riffa.[286]

Religion

[edit]The state religion of Bahrain is Islam and most Bahrainis are Muslim. The majority of Bahraini Muslims are Shia Muslims according to official data as of 2021.[287] It is one of three countries in the Middle East in which Shiites were the majority, the other two nations being Iraq and Iran.[288] Public surveys are rare in Bahrain, but the US department of state's report on religious freedom in Bahrain estimated that Shias constituted approximately 55% of Bahrain's citizen population in 2018.[289] The royal family and most Bahrani elites are Sunni.[290] The country's two Muslim communities are united on some issues, but disagree sharply on others.[290] Shia have often complained of being politically repressed and economically marginalized in Bahrain; as a result, most of the protestors in the Bahraini uprising of 2011 were Shia.[291][292][293]

Christians in Bahrain make up about 14.5% of the population.[277] There is a native Christian community in Bahrain. Non-Muslim Bahraini residents numbered 367,683 per the 2010 census, most of whom are Christians.[294] Expatriate Christians make up the majority of Christians in Bahrain, while native Christian Bahrainis (who hold Bahraini citizenship) make up a smaller community. Native Christians who hold Bahraini citizenship number approximately 1,000 persons.[294] Alees Samaan, a former Bahraini ambassador to the United Kingdom is a native Christian. Bahrain also has a native Jewish community numbering thirty-seven Bahraini citizens.[295] Various sources cite Bahrain's native Jewish community as being from 36 to 50 people.[296] According to Bahraini writer Nancy Khedouri, the Jewish community of Bahrain is one of the youngest in the world, having its origins in the migration of a few families to the island from then-Iraq and then-Iran in the late 1880s.[297] Houda Nonoo, former ambassador to the United States, is Jewish. There is also a Hindu community on the island. They constitute the third largest religious group. The Shrinathji temple located in old Manama is the oldest Hindu temple in the GCC and the Arab world. It is over 200 years old and was built by the Thattai Hindu community in 1817.[298]

According to the 2001 census, 81.2% of Bahrain's population was Muslim, 10% were Christian, and 9.8% practised Hinduism or other religions.[6] The 2010 census records that the Muslim proportion had fallen to 70.2% (the 2010 census did not differentiate between the non-Muslim religions).[277]

Languages

[edit]Arabic is the official language of Bahrain, though English is widely used.[299] Bahrani Arabic is the most widely spoken dialect of the Arabic language, though it differs widely from standard Arabic, like all Arabic dialects. Arabic plays an important role in political life, as, according to article 57 (c) of Bahrain's constitution, an MP must be fluent in Arabic to stand for parliament.[300] In addition, Balochi is the second largest and widely spoken language in Bahrain. The Baloch are fluent in Arabic and Balochi. Among the Bahraini and non-Bahraini population, many people speak Persian, the official language of Iran, or Urdu, an official language in Pakistan and a regional language in India.[299] Nepali is also widely spoken in the Nepalese workers and Gurkha Soldiers community. Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu, Bangla and Hindi are spoken among significant Indian communities.[299] All commercial institutions and road signs are bilingual, displaying both English and Arabic.[301]

Education

[edit]

Education is compulsory for children between the ages of 6 and 14.[302] Education is free for Bahraini citizens in public schools, with the Bahraini Ministry of Education providing free textbooks. Coeducation is not used in public schools, with boys and girls segregated into separate schools.[303]

At the beginning of the 20th century, Qur'anic schools (Kuttab) were the only form of education in Bahrain.[304] They were traditional schools aimed at teaching children and youth the reading of the Qur'an. After World War I, Bahrain became open to western influences, and a demand for modern educational institutions appeared. 1919 marked the beginning of modern public school system in Bahrain when the Al-Hidaya Al-Khalifia School for boys opened in Muharraq.[304] In 1926, the Education Committee opened the second public school for boys in Manama, and in 1928 the first public school for girls was opened in Muharraq.[304] As of 2011[update], there are a total of 126,981 students studying in public schools.[305]

In 2004, King Hamad ibn Isa Al Khalifa introduced the "King Hamad Schools of Future" project that uses Information Communication Technology to support K–12 education in Bahrain.[306] The project's objective is to connect all schools within the kingdom with the Internet.[307] In addition to British intermediate schools, the island is served by the Bahrain School (BS). The BS is a United States Department of Defense school that provides a K-12 curriculum including International Baccalaureate offerings. There are also private schools that offer either the IB Diploma Programme or United Kingdom's A-Levels.

Bahrain also encourages institutions of higher learning, drawing on expatriate talent and the increasing pool of Bahrain nationals returning from abroad with advanced degrees. The University of Bahrain was established for standard undergraduate and graduate study, and the King Abdulaziz University College of Health Sciences, operating under the direction of the Ministry of Health, trains physicians, nurses, pharmacists and paramedics. The 2001 National Action Charter paved the way for the formation of private universities such as the Ahlia University in Manama and University College of Bahrain in Saar. The Royal University for Women (RUW), established in 2005, was the first private, purpose-built, international university in Bahrain dedicated solely to educating women. The University of London External has appointed MCG (Management Consultancy Group) as the regional representative office in Bahrain for distance learning programmes.[308] MCG is one of the oldest private institutes in the country. Institutes have also opened which educate South Asian students, such as the Pakistan Urdu School, Bahrain and the Indian School, Bahrain. A few prominent institutions are the American University of Bahrain established in 2019,[309] the Bahrain Institute of Banking and Finance, the Ernst & Young Training Institute, and the Birla Institute of Technology International Centre. In 2004, the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) set up a constituent medical university in the country. In addition to the Arabian Gulf University, AMA International University and the College of Health Sciences, these are the only medical schools in Bahrain.

Health

[edit]

Bahrain has a universal health care system, dating back to 1960.[310] Government-provided health care is free to Bahraini citizens and heavily subsidised for non-Bahrainis. Healthcare expenditure accounted for 4.5% of Bahrain's GDP, according to the World Health Organization. Bahraini physicians and nurses form a majority of the country's workforce in the health sector, unlike neighbouring Gulf states.[311] The first hospital in Bahrain was the American Mission Hospital, which opened in 1893 as a dispensary.[312] The first public hospital, and also tertiary hospital, to open in Bahrain was the Salmaniya Medical Complex, in the Salmaniya district of Manama, in 1957.[313] Private hospitals are also present throughout the country, such as the International Hospital of Bahrain.

The life expectancy in Bahrain is 73 for males and 76 for females. Compared to many countries in the region, the prevalence of AIDS and HIV is relatively low.[314] Malaria and tuberculosis (TB) do not constitute major problems in Bahrain as neither disease is indigenous to the country. As a result, cases of malaria and TB have declined in recent decades with cases of contractions amongst Bahraini nationals becoming rare.[314] The Ministry of Health sponsors regular vaccination campaigns against TB and other diseases such as hepatitis B.[314][315]

Currently, Bahrain has an obesity epidemic as 28.9% of all males and 38.2% of all females are classified as obese.[316] Bahrain also has one of the highest prevalence of diabetes in the world (5th place). More than 15% of the Bahraini population are affected by the disease, and they account for 5% of deaths in the country.[317] Cardiovascular diseases account for 32% of all deaths in Bahrain, being the number one cause of death in the country (the second being cancer).[318] Sickle-cell anaemia and thalassaemia are prevalent in the country, with a study concluding that 18% of Bahrainis are carriers of sickle-cell anaemia while 24% are carriers of thalassaemia.[319]

Culture

[edit]

Islam is the main religion, and Bahrainis are known for their tolerance towards the practice of other faiths.[320] Intermarriages between Bahrainis and expatriates are not uncommon—there are many Filipino Bahrainis like Filipino child actress Mona Marbella Al-Alawi.[321]

Rules regarding female attire are generally relaxed compared to regional neighbours; the traditional attire of women usually include the hijab or the abaya.[138] Although the traditional male attire is the thobe, which also includes traditional headdresses such as the keffiyeh, ghutra and agal, Western clothing is common in the country.[138]

Although Bahrain legalized homosexuality in 1976, many homosexuals have since been arrested, often for violating broadly written laws against public immorality and public indecency.[322][323][324]

Art

[edit]

The modern art movement in the country officially emerged in the 1950s, culminating in the establishment of an art society. Expressionism and surrealism, as well as calligraphic art are the popular forms of art in the country. Abstract expressionism has gained popularity in recent decades.[325] Pottery-making and textile-weaving are also popular products that were widely made in Bahraini villages.[325] Arabic calligraphy grew in popularity as the Bahraini government was an active patron in Islamic art, culminating in the establishment of an Islamic museum, Beit Al Quran.[325] The Bahrain national museum houses a permanent contemporary art exhibition.[326] The annual Spring of Culture [327] festival run by the Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities[328] has become a popular event promoting performance arts in the Kingdom. The architecture of Bahrain is similar to that of its neighbours in the Persian Gulf. The wind tower, which generates natural ventilation in a house, is a common sight on old buildings, particularly in the old districts of Manama and Muharraq.[329]

Literature

[edit]

Literature retains a strong tradition in the country; most traditional writers and poets write in the classical Arabic style. In recent years, the number of younger poets influenced by western literature are rising, most writing in free verse and often including political or personal content.[330] Ali Al Shargawi, a decorated longtime poet, was described in 2011 by Al Shorfa as the literary icon of Bahrain.[331]

In literature, Bahrain was the site of the ancient land of Dilmun mentioned in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Legend also states that it was the location of the Garden of Eden.[332][333]

Media

[edit]Music