Недоедание

| Недоедание | |

|---|---|

| |

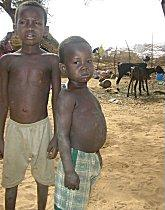

| Недокормленный ребенок в Доло Адо , Эфиопия , в MSF лечебной палатке | |

| Специальность | Медицина интенсивной терапии |

| Симптомы | Problems with physical or mental development; poor energy levels; hair loss; swollen legs and abdomen[1][2] |

| Causes | Paxton Eating a diet with too few or too many nutrients; malabsorption[3][4] |

| Risk factors | Lack of breastfeeding; gastroenteritis; pneumonia; malaria; measles; poverty; homelessness[5] |

| Prevention | Improving agricultural practices; reducing poverty; improving sanitation; education |

| Treatment | Improved nutrition; supplementation; ready-to-use therapeutic foods; treating the underlying cause[6][7][8] |

| Medication | Eating food with enough nutrients on a near daily basis |

| Frequency | 821 million undernourished / 11% of the population (2017)[9] |

| Deaths | 406,000 from nutritional deficiencies (2015)[10] |

Недоедание возникает, когда организм получает слишком мало или слишком много питательных веществ , что приводит к проблемам со здоровьем. [ 11 ] [ 12 ] В частности, это дефицит , избыток или дисбаланс энергии, белка и других питательных веществ и форму организма , что отрицательно влияет на ткани . [ 13 ]

Недоедание – это категория заболеваний, включающая недостаточное и избыточное питание . [ 14 ] Недостаточное питание – это недостаток питательных веществ, который может привести к задержке роста , истощению и недостаточному весу . [ 15 ] Избыток питательных веществ вызывает переедание, что может привести к ожирению . В некоторых развивающихся странах избыточное питание в форме ожирения начинает проявляться в тех же сообществах, что и недостаточное питание. [ 16 ]

В большинстве клинических исследований термин «недоедание» используется для обозначения недостаточного питания. Однако использование термина «недоедание» вместо «недоедание» делает невозможным различие между недоеданием и избыточным питанием, менее признанной формой недоедания. [ 13 ] [ 17 ] Accordingly, a 2019 report by The Lancet Commission suggested expanding the definition of malnutrition to include "all its forms, including obesity, undernutrition, and other dietary risks."[18] The World Health Organization[19] and The Lancet Commission have also identified "[t]he double burden of malnutrition", which occurs from "the coexistence of overnutrition (overweight and obesity) alongside undernutrition (stunted growth and wasting)."[20][21]

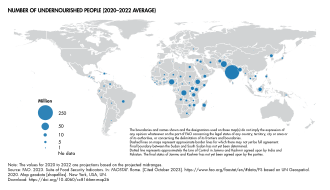

Prevalence

[edit]

It is estimated that nearly one in three persons globally has at least one form of malnutrition: wasting, stunting, vitamin or mineral deficiency, overweight, obesity, or diet-related noncommunicable diseases.[22] Undernutrition is more common in developing countries.[23] Stunting is more prevalent in urban slums than in rural areas.[24] Studies on malnutrition have the population categorised into different groups including infants, under-five children, children, adolescents, pregnant women, adults and the elderly population. The use of different growth references in different studies leads to variances in the undernutrition prevalence reported in different studies. Some of the growth references used in studies include the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) growth charts, WHO reference 2007, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) growth charts, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), WHO reference 1995, Obesity Task Force (IOTF) criteria and Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP) growth charts.[25]

In children

[edit]The prevalence of undernutrition is highest among children under five.[24] In 2021, 148.1 million children under five years old were stunted, 45 million were wasted, and 37 million were overweight or obese.[26] The same year, an estimated 45% of deaths in children were linked to undernutrition.[26][5] As of 2020[update], the prevalence of wasting among children under five in South Asia was reported to be 16% moderately or severely wasted.[24] As of 2022[update], UNICEF reported this prevalence as having slightly improved, but still being at 14.8%.[27] In Asia, India has one of the highest burden of wasting with over 20% wasted children.[28] However, the burden of undernutrition among under-five children in African countries is much higher. A pooled analysis of the prevalence of chronic undernutrition among under-five children in East Africa was identified to be 33.3%. This prevalence of undernutrition among under-five children ranged from 21.9% in Kenya to 53% in Burundi.[29] In Tanzania, the prevalence of stunting, among children under five varied from 41% in lowland and 64.5% in highland areas. Undernutrition by underweight and wasting was 11.5% and 2.5% in lowland and 22.% and 1.4% in the highland areas of Tanzania respectively.[30] In South Sudan, the prevalence of undernutrition explained by stunting, underweight and wasting in under-five children were 23.8%, 4.8% and 2.3% respectively.[31] In 28 countries, at least 30% of children were still affected by stunting in 2022.[32]

Vitamin A deficiency affects one third of children under age 5 around the world,[33] leading to 670,000 deaths and 250,000–500,000 cases of blindness.[34] Vitamin A supplementation has been shown to reduce all-cause mortality by 12 to 24%.[35]

In adults

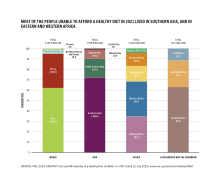

[edit]As of June 2021, 1.9 billion adults were overweight or obese, and 462 million adults were underweight.[26] Globally, two billion people had iodine deficiency in 2017.[36] In 2020, 900 million women and children had anemia, which is often caused by iron deficiency.[37] More than 3.1 billion people in the world – 42% – were unable to afford a healthy diet in 2021.[38]

Certain groups have higher rates of undernutrition, including elderly people and women (in particular while pregnant or breastfeeding children under five years of age). Undernutrition is an increasing health problem in people aged over 65 years, even in developed countries, especially among nursing home residents and in acute care hospitals.[39] In the elderly, undernutrition is more commonly due to physical, psychological, and social factors, not a lack of food.[40] Age-related reduced dietary intake due to chewing and swallowing problems, sensory decline, depression, imbalanced gut microbiome, poverty and loneliness are major contributors to undernutrition in the elderly population. Malnutrition is also attributed due to wrong diet plan adopted by people who aim to reduce their weight without medical practitioners or nutritionist advice.[41]

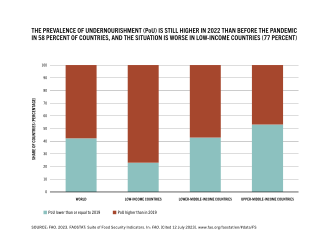

Increase in 2020

[edit]

There has been a global increase in food insecurity and hunger between 2011 and 2020. In 2015, 795 million people (about one in ten people on earth) had undernutrition.[9][42] It is estimated that between 691 and 783 million people in the world faced hunger in 2022.[43] According to UNICEF, 2.4 billion people were moderately or severely food insecure in 2022, 391 million more than in 2019.[44]

These increases are partially related to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which continues to highlight the weaknesses of current food and health systems. It has contributed to food insecurity, increasing hunger worldwide; meanwhile, lower physical activity during lockdowns has contributed to increases in overweight and obesity.[45] In 2020, experts estimated that by the end of the year, the pandemic could have double the number of people at risk of suffering acute hunger.[46] Similarly, experts estimated that the prevalence of moderate and severe wasting could increase by 14% due to COVID-19; coupled with reductions in nutrition and health services coverage, this could result in over 128,000 additional deaths among children under 5 in 2020 alone.[45] Although COVID-19 is less severe in children than in adults, the risk of severe disease increases with undernutrition.[47]

Other major causes of hunger include manmade conflicts, climate changes, and economic downturns.[48]

Type

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

Undernutrition

[edit]

Undernutrition can occur either due to protein-energy wasting or as a result of micronutrient deficiencies.[2][49][26][1][3][50][51] It adversely affects physical and mental functioning, and causes changes in body composition and body cell mass.[52][53] Undernutrition is a major health problem, causing the highest mortality rate in children, particularly in those under 5 years, and is responsible for long-lasting physiologic effects.[54] It is a barrier to the complete physical and mental development of children.[51]

Undernutrition can manifest as stunting, wasting, and underweight. If undernutrition occurs during pregnancy, or before two years of age, it may result in permanent problems with physical and mental development.[1][50] Extreme undernutrition can cause starvation, chronic hunger, Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM), and/or Moderate Acute Malnutrition (MAM).

The signs and symptoms of micronutrient deficiencies depend on which micronutrient is lacking.[2] However, undernourished people are often thin and short, with very poor energy levels; and swelling in the legs and abdomen is also common.[1][2][50] People who are undernourished often get infections and frequently feel cold.[2]

Micronutrient undernutrition

[edit]Micronutrient undernutrition results from insufficient intake of vitamins and minerals.[26] Worldwide, deficiencies in iodine, Vitamin A, and iron are the most common. Children and pregnant women in low-income countries are at especially high risk for micronutrient deficiencies.[26][50]

Anemia is most commonly caused by iron deficiency, but can also result from other micronutrient deficiencies and diseases. This condition can have major health consequences.[55]

It is possible to have overnutrition simultaneously with micronutrient deficiencies; this condition is termed the double burden of malnutrition.

Protein-energy malnutrition

[edit]'Undernutrition' sometimes refers specifically to protein–energy malnutrition (PEM).[2][56] This condition involves both micronutrient deficiencies and an imbalance of protein intake and energy expenditure.[49] It differs from calorie restriction in that calorie restriction may not result in negative health effects. Hypoalimentation (underfeeding) is one cause of undernutrition.[57]

Two forms of PEM are kwashiorkor and marasmus; both commonly coexist.[11]

Kwashiorkor is primarily caused by inadequate protein intake.[11] Its symptoms include edema, wasting, liver enlargement, hypoalbuminaemia, and steatosis; the condition may also cause depigmentation of skin and hair.[11] The disorder is further identified by a characteristic swelling of the belly, and extremities which disguises the patient's undernourished condition.[58] 'Kwashiorkor' means 'displaced child' and is derived from the Ga language of coastal Ghana in West Africa. It means "the sickness the baby gets when the next baby is born," as it often occurs when the older child is deprived of breastfeeding and weaned to a diet composed largely of carbohydrates.[59]

Marasmus (meaning 'to waste away') can result from a sustained diet that is deficient in both protein and energy. This causes their metabolism to adapt to prolong survival.[11] The primary symptoms are severe wasting, leaving little or no edema; minimal subcutaneous fat; and abnormal serum albumin levels.[11] It is traditionally seen in cases of famine, significant food restriction, or severe anorexia.[11] Conditions are characterized by extreme wasting of the muscles and a gaunt expression.[58]

Overnutrition

[edit]Excessive consumption of energy-dense foods and drinks and limited physical activity causes overnutrition.[60] It causes overweight, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of 25 or more, and can lead to obesity (a BMI of 30 or more).[26][2] Obesity has become a major health issue worldwide.[61] Overnutrition is linked to chronic non-communicable diseases like diabetes, certain cancers, and cardiovascular diseases. Hence identifying and addressing the immediate risk factors has become a major health priority.[62] The recent evidence on the impact of diet-induced obesity in fathers and mothers around the time of conception is identified to negatively program the health outcomes of multiple generations.[63]

According to UNICEF, at least 1 in every 10 children under five is overweight in 33 countries.[64]

Classifying malnutrition

[edit]Definition by Gomez and Galvan

[edit]In 1956, Gómez and Galvan studied factors associated with death in a group of undernourished children in a hospital in Mexico City, Mexico. They defined three categories of malnutrition: first, second, and third degree.[65] The degree of malnutrition is calculated based on a child's body size compared to the median weight for their age.[66] The risk of death increases with increasing degrees of malnutrition.[65]

An adaptation of Gomez's original classification is still used today. While it provides a way to compare malnutrition within and between populations, this classification system has been criticized for being "arbitrary" and for not considering overweight as a form of malnutrition. Also, height alone may not be the best indicator of malnutrition; children who are born prematurely may be considered short for their age even if they have good nutrition.[67]

| Degree of PEM | % of desired body weight for age and sex | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 90–100% | ||||||||||||||

| Mild: Grade I (1st degree) | 75–89% | ||||||||||||||

| Moderate: Grade II (2nd degree) | 60–74% | ||||||||||||||

| Severe: Grade III (3rd degree) | <60% | ||||||||||||||

| SOURCE:"Serum Total Protein and Albumin Levels in Different Grades of Protein Energy Malnutrition"[58] | |||||||||||||||

Definition by Waterlow

[edit]In the 1970s, John Conrad Waterlow established a new classification system for malnutrition.[68] Instead of using just weight for age measurements, Waterlow's system combines weight-for-height (indicating acute episodes of malnutrition) with height-for-age to show the stunting that results from chronic malnutrition.[69] One advantage of the Waterlow classification is that weight for height can be calculated even if a child's age is unknown.[68]

| Degree of PEM | Stunting (%) Height for age | Wasting (%) Weight for height | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal: Grade 0 | >95% | >90% | |||||||||||||

| Mild: Grade I | 87.5–95% | 80–90% | |||||||||||||

| Moderate: Grade II | 80–87.5% | 70–80% | |||||||||||||

| Severe: Grade III | <80% | <70% | |||||||||||||

| SOURCE: "Classification and definition of protein-calorie malnutrition." by Waterlow, 1972[68] | |||||||||||||||

The World Health Organization frequently uses these classifications of malnutrition, with some modifications.[66]

Effects

[edit]

Undernutrition weakens every part of the immune system.[70] Protein and energy undernutrition increases susceptibility to infection; so do deficiencies of specific micronutrients (including iron, zinc, and vitamins).[70] In communities or areas that lack access to safe drinking water, these additional health risks present a critical problem.[citation needed]

Undernutrition plays a major role in the onset of active tuberculosis.[71] It also raises the risk of HIV transmission from mother to child, and increases replication of the virus.[70] Undernutrition can cause vitamin-deficiency-related diseases like scurvy and rickets. As undernutrition worsens, those affected have less energy and experience impairment in brain functions. This can make it difficult (or impossible) for them to perform the tasks needed to acquire food, earn an income, or gain an education.[citation needed]

Undernutrition can also cause acute problems, like hypoglycemia (low blood sugar). This condition can cause lethargy, limpness, seizures, and loss of consciousness. Children are particularly at risk and can become hypoglycemic after 4 to 6 hours without food. Dehydration can also occur in malnourished people, and can be life-threatening, especially in babies and small children.[citation needed]

Signs

[edit]There are many different signs of dehydration in undernourished people. These can include sunken eyes; a very dry mouth; decreased urine output and/or dark urine; increased heart rate with decreasing blood pressure; and altered mental status.

| Site | Sign | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Face | Moon face (in kwashiorkor); shrunken, monkey-like face (in marasmus) | ||||||||||||||

| Eye | Dry eyes; pale conjunctiva; periorbital edema; Bitot's spots (in vitamin A deficiency) | ||||||||||||||

| Mouth | Angular stomatitis; cheilitis; glossitis; parotid enlargement; spongy, bleeding gums (in vitamin C and B12 deficiencies) | ||||||||||||||

| Teeth | Enamel mottling; delayed eruption | ||||||||||||||

| Hair | Dull, sparse, brittle hair, with thinning of the hair follicles; hypopigmentation; flag sign (alternating bands of light and normal color); broomstick eyelashes; alopecia | ||||||||||||||

| Skin | Dry skin; follicular hyperkeratosis; patchy hyper- and hypopigmentation; erosions; poor wound healing; loose and wrinkled skin (in marasmus); shiny and edematous skin (in kwashiorkor) | ||||||||||||||

| Nail | Koilonychia; thin and soft nail plates; fissures or ridges | ||||||||||||||

| Musculature | Muscle wasting, particularly in the buttocks and thighs | ||||||||||||||

| Skeletal | Deformities, usually resulting from deficiencies in calcium, vitamin D, or vitamin C | ||||||||||||||

| Abdomen | Distended; hepatomegaly with fatty liver; possible ascites | ||||||||||||||

| Cardiovascular | Bradycardia; hypotension; reduced cardiac output; small vessel vasculopathy | ||||||||||||||

| Neurologic | Global developmental delay; loss of knee and ankle reflexes; poor memory, often resulting from deficiencies in vitamin B12 and other B vitamins | ||||||||||||||

| Hematological | Pallor; petechiae; bleeding diathesis | ||||||||||||||

| Behavior | Lethargic; apathetic; anxious | ||||||||||||||

| Source: "Protein Energy Malnutrition"[66] | |||||||||||||||

Cognitive development

[edit]Protein-calorie malnutrition can cause cognitive impairments. This most commonly occurs in people who were malnourished during a "critical period ... from the final third of gestation to the first 2 years of life".[72] For example, in children under two years of age, iron deficiency anemia is likely to affect brain function acutely, and probably also chronically. Similarly, folate deficiency has been linked to neural tube defects.[73]

Iodine deficiency is "the most common preventable cause of mental impairment worldwide."[74][75] "Even moderate [iodine] deficiency, especially in pregnant women and infants, lowers intelligence by 10 to 15 I.Q. points, shaving incalculable potential off a nation's development."[74] Among those affected, very few people experience the most visible and severe effects: disabling goiters, cretinism and dwarfism. These effects occur most commonly in mountain villages. However, 16 percent of the world's people have at least mild goiter (a swollen thyroid gland in the neck)."[74][76]

Causes and risk factors

[edit]

Social and political

[edit]

Social conditions have a significant influence on the health of people.[77] The social determinants of undernutrition mainly include poor education, poverty, disease burden and lack of women's empowerment.[78] Identifying and addressing these determinants can eliminate undernutrition in the long term.[78] Identification of the social conditions that causes malnutrition in children under five has received significant research attention as it is a major public health problem.[citation needed]

Undernutrition most commonly results from a lack of access to high-quality, nutritious food.[5] The household income is a socio-economic variable that influences the access to nutritious food and the probability of under and overnutrition in a community.[79] In the study by Ghattas et al. (2020), the probability of overnutrition is significantly higher in higher-income families than in disadvantaged families.[21] High food prices is a major factor preventing low income households from getting nutritious food[1][5] For example, Khan and Kraemer (2009) found that in Bangladesh, low socioeconomic status was associated with chronic malnutrition since it inhibited purchase of nutritious foods (like milk, meat, poultry, and fruits).[80] Food shortages may also contribute to malnutritions in countries which lack technology. However, in the developing world, eighty percent of malnourished children live in countries that produce food surpluses, according to estimates from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).[81] The economist Amartya Sen observes that, in recent decades, famine has always been a problem of food distribution, purchasing power, and/or poverty, since there has always been enough food for everyone in the world.[82]

There are also sociopolitical causes of malnutrition. For example, the population of a community might be at increased risk for malnutrition if government is poor and the area lacks health-related services. On a smaller scale, certain households or individuals may be at an even higher risk due to differences in income levels, access to land, or levels of education.[83] Community plays a crucial role in addressing the social causes of malnutrition.[84] For example, communities with high social support and knowledge sharing about social protection programs can enable better public service demands.[85] Better public service demands and social protection programs minimise the risk of malnutrition in these communities.

It is argued that commodity speculators are increasing the cost of food. As the real-estate bubble in the United States was collapsing, it is said that trillions of dollars moved to invest in food and primary commodities, causing the 2007–2008 food price crisis.[86]

The use of biofuels as a replacement for traditional fuels raises the price of food.[87] The United Nations special rapporteur on the right to food, Jean Ziegler proposes that agricultural waste, such as corn cobs and banana leaves, should be used as fuel instead of crops.[88]

In some developing countries, overnutrition (in the form of obesity) is beginning to appear in the same communities where malnutrition occurs.[89] Overnutrition increases with urbanisation, food commercialisation and technological developments and increases physical inactivity.[90] Variations in the health status of individuals in the same society are associated with the societal structure and an individual's socioeconomic status which leads to income inequality, racism, educational differences and lack of opportunities.[91]

Diseases and conditions

[edit]Infectious diseases which increase nutrient requirements, such as gastroenteritis,[92] pneumonia, malaria, and measles, can cause malnutrition.[5] So can some chronic illnesses, especially HIV/AIDS.[93][94]

Malnutrition can also result from abnormal nutrient loss due to diarrhea or chronic small bowel illnesses, like Crohn's disease or untreated coeliac disease.[4][8][95] "Secondary malnutrition" can result from increased energy expenditure.[66][96]

In infants, a lack of breastfeeding may contribute to undernourishment.[66][96] Anorexia nervosa and bariatric surgery can also cause malnutrition.[97][98]

Dietary practices

[edit]Undernutrition

[edit]Undernutrition due to lack of adequate breastfeeding is associated with the deaths of an estimated one million children annually. Illegal advertising of breast-milk substitutes contributed to malnutrition and continued three decades after its 1981 prohibition under the WHO International Code of Marketing Breast Milk Substitutes.[99]

Maternal malnutrition can also factor into the poor health or death of a baby. Over 800,000 neonatal deaths have occurred because of deficient growth of the fetus in the mother's womb.[100]

Deriving too much of one's diet from a single source, such as eating almost exclusively potato, maize or rice, can cause malnutrition. This may either be from a lack of education about proper nutrition, only having access to a single food source, or from poor healthcare access and unhealthy environments.[101][102]

It is not just the total amount of calories that matters but specific nutritional deficiencies such as vitamin A deficiency, iron deficiency or zinc deficiency can also increase risk of death.[103]

Overnutrition

[edit]

Overnutrition caused by overeating is also a form of malnutrition. In the United States, more than half of all adults are now overweight—a condition that, like hunger, increases susceptibility to disease and disability, reduces worker productivity, and lowers life expectancy.[81] Overeating is much more common in the United States, since most people have adequate access to food. Many parts of the world have access to a surplus of non-nutritious food. Increased sedentary lifestyles also contribute to overnutrition. Yale University psychologist Kelly Brownell calls this a "toxic food environment", where fat- and sugar-laden foods have taken precedence over healthy nutritious foods.[81]

In these developed countries, overnutrition can be prevented by choosing the right kind of food. More fast food is consumed per capita in the United States than in any other country. This mass consumption of fast food results from its affordability and accessibility. Fast food, which is low in cost and nutrition, is high in calories. Due to increasing urbanization and automation, people are living more sedentary lifestyles. These factors combine to make weight gain difficult to avoid.[104]

Overnutrition also occurs in developing countries. It has appeared in parts of developing countries where income is on the rise.[81] It is also a problem in countries where hunger and poverty persist. Economic development, rapid urbanisation and shifting dietary patterns have increased the burden of overnutrition in the cities of low and middle-income countries.[105] In China, consumption of high-fat foods has increased, while consumption of rice and other goods has decreased.[81] Overeating leads to many diseases, such as heart disease and diabetes, that may be fatal.

Agricultural productivity

[edit]

Local food shortages can be caused by a lack of arable land, adverse weather, and/or poorer farming skills (like inadequate crop rotation). They can also occur in areas which lack the technology or resources needed for the higher yields found in modern agriculture. These resources include fertilizers, pesticides, irrigation, machinery, and storage facilities. As a result of widespread poverty, farmers and governments cannot provide enough of these resources to improve local yields.[citation needed]

Additionally, the World Bank and some wealthy donor countries have pressured developing countries to use free market policies. Even as the United States and Europe extensively subsidized their own farmers, they urged developing countries to cut or eliminate subsidized agricultural inputs, like fertilizer.[106][107] Without subsidies, few (if any) farmers in developing countries can afford fertilizer at market prices. This leads to low agricultural production, low wages, and high, unaffordable food prices.[106] Fertilizer is also increasingly unavailable because Western environmental groups have fought to end its use due to environmental concerns. The Green Revolution pioneers Norman Borlaug and Keith Rosenberg cited as the obstacle to feeding Africa by .[108]

Future threats

[edit]In the future, variety of factors could potentially disrupt global food supply and cause widespread malnutrition. According to UNICEF's projections, it is projected that almost 600 million people will be chronically undernourished in 2030.[109]

Global warming is of importance to food security. Almost all malnourished people (95%) live in the tropics and subtropics, where the climate is relatively stable. According to the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports, temperature increases in these regions are "very likely."[110] Even small changes in temperatures can make extreme weather conditions occur more frequently.[110] Extreme weather events, like drought, have a major impact on agricultural production, and hence nutrition. For example, the 1998–2001 Central Asian drought killed about 80 percent of livestock in Iran and caused a 50% reduction in wheat and barley crops there.[111] Other central Asian nations experienced similar losses. An increase in extreme weather such as drought in regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa would have even greater consequences in terms of malnutrition. Even without an increase of extreme weather events, a simple increase in temperature reduces the productivity of many crop species, and decreases food security in these regions.[110][112]

Another threat is colony collapse disorder, a phenomenon where bees die in large numbers.[113] Since many agricultural crops worldwide are pollinated by bees, colony collapse disorder represents a threat to the global food supply.[114]

Prevention

[edit]

Reducing malnutrition is key part of the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG2), "Zero Hunger", which aims to reduce malnutrition, undernutrition, and stunted child growth.[115] Managing severe acute undernutrition in a community setting has received significant research attention.[78][51]

Food security

[edit]In the 1950s and 1960s, the Green Revolution aimed to bring modern Western agricultural techniques (like nitrogen fertilizers and pesticides) to Asia. Investments in agriculture, such as fund fertilizers and seeds, increased food harvests and thus food production. Consequently, food prices and malnutrition decreased (as they had earlier in Western nations).[106][116]

The Green Revolution was possible in Asia because of existing infrastructure and institutions, such as a system of roads and public seed companies that made seeds available.[117] These resources were in short supply in Africa, decreasing the Green Revolution's impact on the continent.

For example, almost five million of the 13 million people in Malawi used to need emergency food aid. However, in the early 2000s, the Malawian government changed its agricultural policies, and implemented subsidies for fertilizer and seed introduced against World Bank strictures. By 2007, farmers were producing record-breaking corn harvests. Corn production leaped to 3.4 million in 2007 compared to 1.2 million in 2005, making Malawi a major food exporter.[106] Consequently, food prices lowered and wages for farmworkers rose.[106] Such investments in agriculture are still needed in other African countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Despite the country's great agricultural potential, the prevalence of malnutrition in the DRC is among the highest in the world.[118] Proponents for investing in agriculture include Jeffrey Sachs, who argues that wealthy countries should invest in fertilizer and seed for Africa's farmers.[106][119]

Imported Ready to Use Therapeutic Food (RUTF) has been used to treat malnutrition in northern Nigeria. Some Nigerians also use soy kunu, a locally sourced and prepared blend consisting of peanut, millet and soybeans.[120]

New technology in agricultural production has great potential to combat undernutrition. It makes farming easier, thus improving agricultural yields.[121] By increasing farmers' incomes, this could reduce poverty. It would also open up area which farmers could use to diversify crops for household use.

The World Bank claims to be part of the solution to malnutrition, asserting that countries can best break the cycle of poverty and malnutrition by building export-led economies, which give them the financial means to buy foodstuffs on the world market.

Economics

[edit]Many aid groups have found that giving cash assistance (or cash vouchers) is more effective than donating food. Particularly in areas where food is available but unaffordable, giving cash assistance is a cheaper, faster, and more efficient way to deliver help to the hungry.[122] In 2008, the UN's World Food Program, the biggest non-governmental distributor of food, announced that it would begin distributing cash and vouchers instead of food in some areas, which Josette Sheeran, the WFP's executive director, described as a "revolution" in food aid.[122][123] The aid agency Concern Worldwide piloted a method of giving cash assistance using a mobile phone operator, Safaricom, which runs a money transfer program that allows cash to be sent from one part of a country to another.[122]

However, during a drought, delivering food might be the most appropriate way to help people, especially those who live far from markets and thus have limited access to them.[122] Fred Cuny stated that "the chances of saving lives at the outset of a relief operation are greatly reduced when food is imported. By the time it arrives in the country and gets to people, many will have died."[124] U.S. law requires food aid to be purchased at home rather than in the countries where the hungry live; this is inefficient because approximately half of the money spent goes for transport.[125] Cuny further pointed out that "studies of every recent famine have shown that food was available in-country—though not always in the immediate food deficit area" and "even though by local standards the prices are too high for the poor to purchase it, it would usually be cheaper for a donor to buy the hoarded food at the inflated price than to import it from abroad."[126]

Food banks and soup kitchens address malnutrition in places where people lack money to buy food. A basic income has been proposed as a way to ensure that everyone has enough money to buy food and other basic needs. This is a form of social security in which all citizens or residents of a country regularly receive an unconditional sum of money, either from a government or some other public institution, in addition to any income received from elsewhere.[127]

Successful initiatives

[edit]Ethiopia pioneered a program that later became part of the World Bank's prescribed method for coping with a food crisis. Through the country's main food assistance program, the Productive Safety Net Program, Ethiopia provided rural residents who were chronically short of food a chance to work for food or cash. Foreign aid organizations like the World Food Program were then able to buy food locally from surplus areas to distribute in areas with a shortage of food.[128] Aid organizations now view the Ethiopian program as a model of how to best help hungry nations.[citation needed]

Successful initiatives also include Brazil's recycling program for organic waste, which benefits farmers, the urban poor, and the city in general. City residents separate organic waste from their garbage, bag it, and then exchange it for fresh fruit and vegetables from local farmers. This reduces the country's waste while giving the urban poor a steady supply of nutritious food.[104]

World population

[edit]Restricting population size is a proposed solution to malnutrition. Thomas Malthus argues that population growth can be controlled by natural disasters and by voluntary limits through "moral restraint."[129] Robert Chapman suggests that government policies are a necessary ingredient for curtailing global population growth.[130] The United Nations recognizes that poverty and malnutrition (as well as the environment) are interdependent and complementary with population growth.[131] According to the World Health Organization, "Family planning is key to slowing unsustainable population growth and the resulting negative impacts on the economy, environment, and national and regional development efforts".[132] However, more than 200 million women worldwide lack adequate access to family planning services.

There are different theories about what causes famine. Some theorists, like the Indian economist Amartya Sen, believe that the world has more than enough resources to sustain its population. In this view, malnutrition is caused by unequal distribution of resources and under- or unused arable land.[133][134] For example, Sen argues that "no matter how a famine is caused, methods of breaking it call for a large supply of food in the Public Distribution System. This applies not only to organizing rationing and control, but also to undertaking work programmes and other methods of increasing purchasing power for those hit by shifts in exchange entitlements in a general inflationary situation."[82]

Food sovereignty

[edit]Food sovereignty is one suggested policy framework to resolve access issues. In this framework, people (rather than international market forces) have the right to define their own food, agricultural, livestock, and fishery systems. Food First is one of the primary think tanks working to build support for food sovereignty. Neoliberals advocate for an increasing role of the free market.[citation needed]

Health facilities

[edit]Another possible long-term solution to malnutrition is to increase access to health facilities in rural parts of the world. These facilities could monitor undernourished children, act as supplemental food distribution centers, and provide education on dietary needs. Similar facilities have already proven very successful in countries such as Peru and Ghana.[135][136]

Breastfeeding

[edit]In 2016, estimates suggested that more widespread breastfeeding could prevent about 823,000 deaths annually of children under age 5.[137] In addition to reducing infant deaths, breast milk provides an important source of micronutrients - which are clinically proven to bolster children's immune systems – and provides long-term defenses against non-communicable and allergic diseases.[138] Breastfeeding may improve cognitive abilities in children, and correlates strongly with individual educational achievements.[138][139] As previously noted, lack of proper breastfeeding is a major factor in child mortality rates, and is a primary determinant of disease development for children. The medical community recommends exclusively breastfeeding infants for 6 months, with nutritional whole food supplementation and continued breastfeeding up to 2 years or older for overall optimal health outcomes.[139][140][141] Exclusive breastfeeding is defined as giving an infant only breast milk for six months as a source of food and nutrition.[139][141] This means no other liquids, including water or semi-solid foods.[141]

Barriers to breastfeeding

[edit]Breastfeeding is noted as one of the most cost-effective medical interventions benefiting child health.[140] While there are considerable differences among developed and developing countries, there are universal determinants of whether a mother breastfeeds or uses formula; these include income, employment, social norms, and access to healthcare.[139][140] Many newly made mothers face financial barriers; community-based healthcare workers have helped to alleviate these barriers, while also providing a viable alternative to traditional and expensive hospital-based medical care.[139] Recent studies, based upon surveys conducted from 1995 to 2010, show that exclusive breastfeeding rates have risen globally, from 33% to 39%.[141] Despite the growth rates, medical professionals acknowledge the need for improvement given the importance of exclusive breastfeeding.[141]

21st century global initiatives

[edit]Starting around 2009, there was renewed international media and political attention focused on malnutrition. This resulted in part from spikes in food prices and the 2008 financial crisis. Additionally, there was an emerging consensus that combating malnutrition is one of the most cost-effective ways to contribute to development. This led to the 2010 launch of the UN's Scaling up Nutrition movement (SUN).[142]

In April 2012, a number of countries signed the Food Assistance Convention, the world's first legally binding international agreement on food aid. The following month, the Copenhagen Consensus recommended that politicians and private sector philanthropists should prioritize interventions against hunger and malnutrition to maximize the effectiveness of aid spending. The Consensus recommended prioritizing these interventions ahead of any others, including the fights against malaria and AIDS.[143]

In June 2015, the European Union and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation launched a partnership to combat undernutrition, especially in children. The program was first implemented in Bangladesh, Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya, Laos and Niger. It aimed to help these countries improve information and analysis about nutrition, enabling them to develop effective national nutrition policies.[144]

Also in 2015, the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization created a partnership aimed at ending hunger in Africa by 2025. The African Union's Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) provided the framework for the partnership. It includes a variety of interventions, including support for improved food production, a strengthening of social protection, and integration of the right to food into national legislation.[145]

The EndingHunger campaign is an online communication campaign whose goal is to raise awareness about hunger. The campaign has created viral videos depicting celebrities voicing their anger about the large number of hungry people in the world.[citation needed]

After the Millennium Development Goals expired in 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals became the main global policy focus to reduce hunger and poverty. In particular, Goal 2: Zero Hunger sets globally agreed-upon targets to wipe out hunger, end all forms of malnutrition, and make agriculture sustainable.[146] The partnership Compact2025 develops and disseminates evidence-based advice to politicians and other decision-makers, with the goal of ending hunger and undernutrition by 2025.[147][148][149] The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) led the partnership, with the involvement of UN organisations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and private foundations.

Treatment

[edit]

Improving nutrition

[edit]Efforts such as infant and young child feeding practices to improve nutrition are some of the common forms of development aid.[6][150] Interventions often promote breastfeeding to reduce rates of malnutrition and death in children.[1] Some of these interventions have been successful.[7] For example, interventions with commodities such as ready to use therapeutic foods, ready to use supplementary foods, micronutrient intervention and vitamin supplementation were identified to significantly improve nutrition, reduce stunting and prevent diseases in communities with severe acute malnutrition.[78] In young children, outcomes improve when children between six months and two years of age receive complementary food (in addition to breast milk).[7] There is also good evidence that supports giving supplemental micronutrients to pregnant women and young children in the developing world.[7]

The United Nations has reported on the importance of nutritional counselling and support, for example in the care of HIV-infected persons, especially in "resource-constrained settings where malnutrition and food insecurity are endemic".[151] UNICEF provides nutritional counselling services for malnourished children in Afghanistan.[152]

Sending food and money is a common form of development aid, aimed at feeding hungry people. Some strategies help people buy food within local markets.[6][153] Simply feeding students at school is insufficient.[6]

Longer-term measures include improving agricultural practices,[154] reducing poverty, and improving sanitation.

Identifying malnourishment

[edit]Measuring children is crucial to identifying malnourishment. In 2000, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) established the International Micronutrient Malnutrition Prevention and Control (IMMPaCt) program. It tested children for malnutrition by conducting a three-dimensional scan, using an iPad or a tablet. Its objective was to help doctors provide more efficient treatments.[155] There may be some chance of error when using this method.[155] The Screening Tool for the Assessment of Malnutrition in Paediatrics (STAMPa) is another method for the identification and evaluation of malnutrition in young children.[156] The assessment tool has fair to medium reliability in the identification of children at risk of malnutrition.[156]

A systematic review of 42 studies found that many approaches to mitigating acute malnutrition are equally effective; thus, intervention decisions can be based on cost-related factors. Overall, evidence for the effectiveness of acute malnutrition interventions is not robust. The limited evidence related to cost indicates that community and outpatient management of children with uncomplicated malnutrition may be the most cost-effective strategy.[157]

Regularly measuring and charting children's growth and including activities to promote health (an intervention called growth monitoring and promotion, also known as GPM) is often considered by policy makers and is recommended by the World Health Organization.[158] This program is often performed at the same time as a child has their regular immunizations.[159] Despite widespread use of this type of program, further studies are needed to understand the impact of these programs on overall child health and how to better address faltering growth in a child and improve practices related to feeding children in lower to middle income countries.[159]

Medical management

[edit]It is often possible to manage severe malnutrition within a person's home, using ready-to-use therapeutic foods.[7] In people with severe malnutrition complicated by other health problems, treatment in a hospital setting is recommended.[7] In-hospital treatment often involves managing low blood sugar, maintaining adequate body temperature, addressing dehydration, and gradual feeding.[7][160]

Routine antibiotics are usually recommended because malnutrition weakens the immune system, causing a high risk of infection.[160] Additionally, broad spectrum antibiotics are recommended in all severely undernourished children with diarrhea requiring admission to hospital.[161]

A severely malnourished child who appears to have dehydration, but has not had diarrhea, should be treated as if they have an infection.[161]

Among malnourished people who are hospitalized, nutritional support improves protein intake, calorie intake, and weight.[162]

Bangladeshi model

[edit]

In response to child malnutrition, the Bangladeshi government recommends ten steps for treating severe malnutrition:[163]

- Prevent or treat dehydration

- Prevent or treat low blood sugar

- Prevent or treat low body temperature

- Prevent or treat infection;

- Correct electrolyte imbalances

- Correct micronutrient deficiencies

- Start feeding cautiously

- Achieve catch-up growth

- Provide psychological support

- Prepare for discharge and follow-up after recovery

Therapeutic foods

[edit]Due in part to limited research on supplementary feeding, there is little evidence that this strategy is beneficial.[164] A 2015 systematic review of 32 studies found that there are limited benefits when children under 5 receive supplementary feeding, especially among younger, poorer, and more undernourished children.[165]

However, specially formulated foods do appear to be useful in treating moderate acute malnutrition in the developing world.[166] These foods may have additional benefits in humanitarian emergencies, since they can be stored for years, can be eaten directly from the packet, and do not have to be mixed with clean water or refrigerated.[167] In young children with severe acute malnutrition, it is unclear if ready-to-use therapeutic food differs from a normal diet.[168]

Severely malnourished individuals can experience refeeding syndrome if fed too quickly.[169] Refeeding syndrome can result regardless of whether food is taken orally, enterally or parenterally.[169] It can present several days after eating with potentially fatal heart failure, dysrhythmias, and confusion.[169][170]

Some manufacturers have fortified everyday foods with micronutrients before selling them to consumers. For example, flour has been fortified with iron, zinc, folic acid, and other B vitamins like thiamine, riboflavin, niacin and vitamin B12.[103] Baladi bread (Egyptian flatbread) is made with fortified wheat flour. Other fortified products include fish sauce in Vietnam and iodized salt.[167]

Micronutrient supplementation

[edit]According to the World Bank, treating malnutrition – mostly by fortifying foods with micronutrients – improves lives more quickly than other forms of aid, and at a lower cost.[171] After reviewing a variety of development proposals, The Copenhagen Consensus, a group of economists who reviewed a variety of development proposals, ranked micronutrient supplementation as its number-one treatment strategy.[172][125]

In malnourished people with diarrhea, zinc supplementation is recommended following an initial four-hour rehydration period. Daily zinc supplementation can help reduce the severity and duration of the diarrhea. Additionally, continuing daily zinc supplementation for ten to fourteen days makes diarrhea less likely to recur in the next two to three months.[173]

Malnourished children also need both potassium and magnesium.[163] Within two to three hours of starting rehydration, children should be encouraged to take food, particularly foods rich in potassium[163][173] like bananas, green coconut water, and unsweetened fresh fruit juice.[173] Along with continued eating, many homemade products can also help restore normal electrolyte levels. For example, early during the course of a child's diarrhea, it can be beneficial to provide cereal water (salted or unsalted) or vegetable broth (salted or unsalted).[173] If available, vitamin A, potassium, magnesium, and zinc supplements should be added, along with other vitamins and minerals.[163]

Giving base (as in Ringer's lactate) to treat acidosis without simultaneously supplementing potassium worsens low blood potassium.[173]

Treating diarrhea

[edit]Preventing dehydration

[edit]Food and drink can help prevent dehydration in malnourished people with diarrhea. Eating (or breastfeeding, among infants) should resume as soon as possible.[161] Sugary beverages like soft drinks, fruit juices, and sweetened teas are not recommended as they may worsen diarrhea.[174]

Malnourished people with diarrhea (especially children) should be encouraged to drink fluids; the best choices are fluids with modest amounts of sugar and salt, like vegetable broth or salted rice water. If clean water is available, they should be encouraged to drink that too. Malnourished people should be allowed to drink as much as they want, unless signs of swelling emerge.

Babies can be given small amounts of fluids via an eyedropper or a syringe without the needle. Children under two should receive a teaspoon of fluid every one to two minutes; older children and adults should take frequent sips of fluids directly from a cup.[173] After the first two hours, fluids and foods should be alternated, rehydration should be continued at the same rate or more slowly, depending on how much fluid the child wants and whether they are having ongoing diarrhea.[163]

If vomiting occurs, fluids can be paused for 5–10 minutes and then restarted more slowly. Vomiting rarely prevents rehydration, since fluids are still absorbed and vomiting is usually short-term.[174]

Oral rehydration therapy

[edit]If prevention has failed and dehydration develops, the preferred treatment is rehydration through oral rehydration therapy (ORT). In severely undernourished children with diarrhea, rehydration should be done slowly, according to the World Health Organization.

Oral rehydration solutions consist of clean water mixed with small amounts of sugars and salts. These solutions help restore normal electrolyte levels, provide a source of carbohydrates, and help with fluid replacement.[175]

Reduced-osmolarity ORS is the current standard of care for oral rehydration therapy, with reasonably wide availability.[176][177] Introduced in 2003 by WHO and UNICEF, reduced-osmolarity solutions contain lower concentrations of sodium and glucose than original ORS preparations. Reduced-osmolarity ORS has the added benefit of reducing stool volume and vomiting while simultaneously preventing dehydration. Packets of reduced-osmolarity ORS include glucose, table salt, potassium chloride, and trisodium citrate. For general use, each packet should be mixed with a liter of water. However, for malnourished children, experts recommend adding a packet of ORS to two liters of water, along with an extra 50 grams of sucrose and some stock potassium solution.[178]

People who have no access to commercially available ORS can make a homemade version using water, sugar, and table salt. Experts agree that homemade ORS preparations should include one liter (34 oz.) of clean water and 6 teaspoons of sugar; however, they disagree about whether they should contain half a teaspoon of table salt or a full teaspoon. Most sources recommend using half a teaspoon of salt per liter of water.[173][179][180][181] However, people with malnutrition have an excess of body sodium.[163] To avoid worsening this symptom, ORS for people with severe undernutrition should contain half the usual amount of sodium and more potassium.

Patients who do not drink may require fluids by nasogastric tube. Intravenous fluids are recommended only in those who have significant dehydration due to their potential complications, including congestive heart failure.[161]

Low blood sugar

[edit]Hypoglycemia, whether known or suspected, can be treated with a mixture of sugar and water. If the patient is conscious, the initial dose of sugar and water can be given by mouth.[182] Otherwise, they should receive glucose by intravenous or nasogastric tube. If seizures occur (and continue after glucose is given), rectal diazepam may be helpful. Blood sugar levels should be re-checked on two-hour intervals.[163]

Hypothermia

[edit]Hypothermia (dangerously low core body temperature) can occur in malnutrition, particularly in children. Mild hypothermia causes confusion, trembling, and clumsiness; more severe cases can be fatal. Keeping malnourished children warm can prevent or treat hypothermia. Covering the child (including their head) in blankets is one method. Another method is to warm the child through direct skin-to-skin contact with their mother or father, then covering both parent and child.

Warming methods are usually most important at night.[163] Prolonged bathing or prolonged medical exams can further lower body temperature and are not recommended for malnourished children at high risk of hypothermia.

Epidemiology

[edit]

| no data <200 200–400 400–600 600–800 800–1000 1000–1200 | 1200–1400 1400–1600 1600–1800 1800–2000 2000–2200 >2200 |

The figures provided in this section on epidemiology all refer to undernutrition even if the term malnutrition is used which, by definition, could also apply to too much nutrition.

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is a multidimensional statistical tool used to describe the state of countries' hunger situation. The GHI measures progress and failures in the global fight against hunger.[184] The GHI is updated once a year. The data from the 2015 report shows that Hunger levels have dropped 27% since 2000. Fifty two countries remain at serious or alarming levels. In addition to the latest statistics on Hunger and Food Security, the GHI also features different special topics each year. The 2015 report include an article on conflict and food security.[185]

People affected

[edit]The United Nations estimated that there were 821 million undernourished people in the world in 2017. This is using the UN's definition of 'undernourishment', where it refers to insufficient consumption of raw calories, and so does not necessarily include people who lack micro nutrients.[9] The undernourishment occurred despite the world's farmers producing enough food to feed around 12 billion people—almost double the current world population.[186]

Malnutrition, as of 2010, was the cause of 1.4% of all disability adjusted life years.[187]

| Year | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number in millions[9] | 945 | 911 | 877 | 855 | 840 | 821 | 813 | 806 | 795 | 784 | 784 | 804 |

| Percentage[9] | 14.5% | 13.8% | 13.1% | 12.6% | 12.2% | 11.8% | 11.5% | 11.3% | 11.0% | 10.7% | 10.6% | 10.8% |

| Year | 1969–71 | 1979–81 | 1990–92 | 1995–97 | 2001–03 | 2003–05 | 2005–07 | 2010–12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number in millions[188][189][190] | 875 | 841 | 820 | 790 | 825 | 848 | 927 | 805 |

| Percentage[188][189][190] | 37% | 28% | 20% | 18% | 17% | 16% | 17% | 14% |

Mortality

[edit]

Mortality due to malnutrition accounted for 58 percent of the total mortality in 2006: "In the world, approximately 62 million people, all causes of death combined, die each year. One in twelve people worldwide is malnourished and according to the Save the Children 2012 report, one in four of the world's children are chronically malnourished.[191] In 2006, more than 36 million died of hunger or diseases due to deficiencies in micronutrients".[192]

In 2010 protein-energy malnutrition resulted in 600,000 deaths down from 883,000 deaths in 1990.[193] Other nutritional deficiencies, which include iodine deficiency and iron deficiency anemia, result in another 84,000 deaths.[193] In 2010 malnutrition caused about 1.5 million deaths in women and children.[194]

According to the World Health Organization, malnutrition is the biggest contributor to child mortality, present in half of all cases.[195] Six million children die of hunger every year.[196] Underweight births and intrauterine growth restrictions cause 2.2 million child deaths a year. Poor or non-existent breastfeeding causes another 1.4 million. Other deficiencies, such as lack of vitamin A or zinc, for example, account for 1 million. Malnutrition in the first two years is irreversible. Malnourished children grow up with worse health and lower education achievement. Their own children tend to be smaller. Malnutrition was previously[when?] seen as something that exacerbates the problems of diseases such as measles, pneumonia and diarrhea, but malnutrition actually causes diseases, and can be fatal in its own right.[195]

History

[edit]Hunger has been a perennial human problem. However, until the early 20th century, there was relatively little awareness of the qualitative aspects of malnutrition.

Throughout history, various peoples have known the importance of eating certain foods to prevent symptoms now associated with malnutrition. Yet such knowledge appears to have been repeatedly lost and then re-discovered. For example, the ancient Egyptians reportedly knew the symptoms of scurvy. Much later, in the 14th century, Crusaders sometimes used anti-scurvy measures – for example, ensuring that citrus fruits were planted on Mediterranean islands, for use on sea journeys. However, for several centuries, Europeans appear to have forgotten the importance of these measures. They rediscovered this knowledge in the 18th century, and by the early 19th century, the Royal Navy was issuing frequent rations of lemon juice to every crewman on their ships. This massively reduced scurvy deaths among British sailors, which in turn gave the British a significant advantage in the Napoleonic Wars. Later on in the 19th century, the Royal Navy replaced lemons with limes (unaware at the time that lemons are far more effective at preventing scurvy).[197][198]

According to historian Michael Worboys, malnutrition was essentially discovered, and the science of nutrition established, between World War I and World War II. Advances built on prior works like Casimir Funk's 1912 formulisation of the concept of vitamins. Scientific study of malnutrition increased in the 1920s and 1930s, and grew even more common after World War II.

Non-governmental organizations and United Nations agencies began to devote considerable energy to alleviating malnutrition around the world. The exact methods and priorities for doing this tended to fluctuate over the years, with varying levels of focus on different types of malnutrition like Kwashiorkor or Marasmus; varying levels of concern on protein deficiency compared to vitamins, minerals and lack of raw calories; and varying priorities given to the problem of malnutrition in general compared to other health and development concerns. The green Revolution of the 1950s and 1960s saw considerable improvement in capability to prevent malnutrition.[198][197][199]

One of the first official global documents addressing Food security and global malnutrition was the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights(UDHR). Within this document it stated that access to food was part of an adequate right to a standard of living.[200] The Right to food was asserted in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, a treaty adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 16, 1966. The Right to food is a human right for people to feed themselves in dignity, be free from hunger, food insecurity, and malnutrition.[201] As of 2018, the treaty has been signed by 166 countries, by signing states agreed to take steps to the maximum of their available resources to achieve the right to adequate food.

However, after the 1966 International Covenant the global concern for the access to sufficient food only became more present, leading to the first ever World Food Conference that was held in 1974 in Rome, Italy. The Universal Declaration on the Eradication of Hunger and Malnutrition was a UN resolution adopted November 16, 1974 by all 135 countries that attended the 1974 World Food Conference.[202] This non-legally binding document set forth certain aspirations for countries to follow to sufficiently take action on the global food problem. Ultimately this document outline and provided guidance as to how the international community as one could work towards fighting and solving the growing global issue of malnutrition and hunger.

Принятие права на питание было включено в Дополнительный протокол к Американской конвенции о правах человека в области экономических, социальных и культурных прав . Этот документ 1978 года был принят многими странами Америки. Цель документа: «укрепить в этом полушарии, в рамках демократических институтов, систему личной свободы и социальной справедливости, основанную на уважении основных прав человека». [ 203 ]

Более поздним документом в рамках глобальных инициатив по борьбе с недоеданием стала Римская декларация 1996 года о всемирной продовольственной безопасности , организованная Продовольственной и сельскохозяйственной организацией . В этом документе подтверждено право каждого на доступ к безопасной и питательной пище, также принимая во внимание, что каждый получает достаточное количество еды, и поставлены цели для всех стран по улучшению их приверженности продовольственной безопасности путем сокращения вдвое числа недоедающих людей к 2015 году. [ 204 ] В 2004 году Продовольственная и сельскохозяйственная организация приняла « Руководящие принципы права на питание », которые предложили государствам основу для расширения права на питание на национальном уровне.

Особые группы населения

[ редактировать ]недостаточное питание является важным фактором, определяющим здоровье матери и ребенка: на него приходится более трети детской смертности и более 10 процентов от общего глобального бремени болезней . По данным исследований 2008 года, [ 205 ]

Дети

[ редактировать ]

Недостаточное питание отрицательно влияет на когнитивное развитие детей, способствуя снижению трудоспособности и бедности во взрослом возрасте. [ 206 ] Развитие недостаточного питания у детей совпадает с введением прикорма при прикорме, в котором обычно наблюдается дефицит питательных веществ. [ 207 ] По оценкам Всемирной организации здравоохранения, недоедание является причиной 54 процентов детской смертности во всем мире. [ 56 ] около 1 миллиона детей. [ 208 ] Существует тесная связь между недоеданием и детской смертностью. [ 209 ] Другая оценка, также проведенная ВОЗ, гласит, что недостаточный вес детей является причиной около 35% всех смертей детей в возрасте до пяти лет во всем мире. [ 210 ] Более 90% детей в возрасте до пяти лет с задержкой роста проживают в странах Африки к югу от Сахары и Южной Центральной Азии. [ 78 ] Хотя доступ к достаточному питанию и улучшение потребления питательных веществ являются очевидным решением проблемы недостаточного питания детей, прогресс в сокращении недостаточного питания среди детей разочаровывает. [ 211 ]

Женщины

[ редактировать ]

Согласно докладу ЮНИСЕФ за 2023 год «Недоедание и недоедание: глобальный кризис питания среди девочек и женщин-подростков», в 2022 году более 1 миллиарда девочек и женщин-подростков страдали от недостаточного питания. [ 212 ] Гендерный разрыв в плане отсутствия продовольственной безопасности увеличился более чем вдвое в период с 2019 (49 миллионов) по 2021 год (126 миллионов). В докладе показано, что во всем мире 30% женщин в возрасте 15–49 лет страдают анемией, а 10 процентов женщин в возрасте 20–49 лет страдают от недостаточного веса. В Южной Азии, Западной и Центральной Африке, а также в Восточной и Южной Африке проживает 60% женщин с анемией и 65% женщин с недостаточным весом. Напротив, от избыточного веса страдают более 35% женщин в возрасте 20–49 лет, из которых 13% страдают ожирением. [ 212 ] На Ближнем Востоке и в Северной Африке самая высокая распространенность избыточного веса – 61%. Северная Америка следует за ней с показателем 60%. [ 212 ] В Судане (10%), Бурунди (12%), Буркина-Фасо (17%) и Афганистане (26%) менее 1 из 3 девочек-подростков и женщин имеют рацион, соответствующий минимальному разнообразию рациона питания. [ 212 ] В Нигере процент женщин, получающих минимально разнообразный рацион питания, упал с 53% до 37% в период с 2020 по 2022 год. [ 212 ]

Исследователи из Центра мировых продовольственных исследований в 2003 году обнаружили, что разрыв между уровнями недоедания среди мужчин и женщин, как правило, невелик, но этот разрыв варьируется от региона к региону и от страны к стране. [ 213 ] Эти мелкомасштабные исследования показали, что показатели распространенности недостаточного питания среди женщин превышают показатели распространенности недостаточного питания среди мужчин в Южной/Юго-Восточной Азии и Латинской Америке и были ниже в странах Африки к югу от Сахары. [ 213 ] Наборы данных по Эфиопии и Зимбабве показали, что уровень недоедания у мужчин в 1,5–2 раза выше, чем у женщин; однако в Индии и Пакистане показатели недоедания среди женщин были в 1,5–2 раза выше, чем среди мужчин. Также наблюдаются различия внутри страны, при этом часто наблюдаются большие различия между региональными показателями недоедания. [ 213 ] Гендерное неравенство в питании в некоторых странах, таких как Индия, присутствует на всех этапах жизни. [ 214 ]

Исследования питания, касающиеся гендерных предубеждений в домохозяйствах, изучают модели распределения продуктов питания, а одно исследование 2003 года показало, что женщины часто получают меньшую долю необходимых продуктов питания, чем мужчины. [ 213 ] Гендерная дискриминация, гендерные роли и социальные нормы, влияющие на женщин, могут привести к ранним бракам и деторождению, близкому интервалу между родами и недостаточному питанию, и все это способствует недоеданию матерей. [ 80 ]

Внутри домохозяйства могут существовать различия в уровне недоедания между мужчинами и женщинами, и было показано, что эти различия значительно различаются от одного региона к другому, при этом в проблемных областях наблюдается относительная депривация женщин. [ 213 ] Выборки 1000 женщин в Индии в 2008 году показали, что недоедание у женщин связано с бедностью, отсутствием развития и осведомленности, а также неграмотностью. [ 214 ] То же исследование показало, что гендерная дискриминация в домохозяйствах может препятствовать доступу женщин к достаточному питанию и медицинскому обслуживанию. [ 214 ] Как социализация влияет на здоровье женщин в Бангладеш, объясняет Наджма Ривзи в статье об исследовательской программе по этой теме. [ 215 ] В некоторых случаях, например, в некоторых частях Кении в 2006 году, уровень недоедания среди беременных женщин был даже выше, чем среди детей. [ 216 ]

В некоторых обществах женщинам традиционно дают меньше еды, чем мужчинам, поскольку считается, что у мужчин более тяжелая рабочая нагрузка. [ 217 ] Домашняя работа и сельскохозяйственные работы на самом деле могут быть очень трудными и требовать дополнительной энергии и питательных веществ; однако физическую активность, которая во многом определяет энергетические потребности, оценить сложно. [ 213 ]

Физиология

[ редактировать ]Женщины имеют уникальные потребности в питании, и в некоторых случаях им требуется больше питательных веществ, чем мужчинам; например, женщинам нужно в два раза больше кальция, чем мужчинам. [ 217 ]

Беременность и кормление грудью

[ редактировать ]Во время беременности и кормления грудью женщины должны получать достаточное количество питательных веществ для себя и своего ребенка, поэтому в эти периоды им требуется значительно больше белка и калорий, а также больше витаминов и минералов (особенно железа, йода, кальция, фолиевой кислоты и витаминов А, С и К). [ 217 ] В 2001 году ФАО ООН сообщила, что дефицит железа затронул 43 процента женщин в развивающихся странах и увеличил риск смерти во время родов. [ 217 ] По оценкам обзора мер, проведенного в 2008 году, универсальный прием добавок кальция, железа и фолиевой кислоты во время беременности может предотвратить 105 000 материнских смертей (23,6 процента всех материнских смертей). [ 218 ] Было обнаружено, что от недоедания страдают три четверти британских женщин в возрасте 16–49 лет, у которых уровень фолиевой кислоты ниже рекомендованного ВОЗ. [ 219 ]

Частые беременности с короткими интервалами между ними и длительные периоды грудного вскармливания создают дополнительную пищевую нагрузку. [ 213 ]

Обучение детей

[ редактировать ]« Действие для здоровых детей » разработало несколько методов обучения детей правильному питанию. Они знакомят с двумя разными темами: самосознание, которое учит детей заботиться о своем здоровье, и социальная осведомленность, то есть то, как кулинарное искусство варьируется от культуры к культуре. А также его важность в питании. Они включают в себя электронные книги, советы, кулинарные клубы. включая факты об овощах и фруктах. [ 220 ]

Компания Team Nutrition создала « MyPlate eBooks », в которую входят 8 различных электронных книг, которые можно загрузить бесплатно. Эти электронные книги содержат раскрашенные рисунки, аудиозапись и большое количество символов, что делает уроки питания интересными для детей. [ 221 ]

По данным ФАО, женщины часто несут ответственность за приготовление пищи и имеют возможность обучать своих детей полезным привычкам питания и здоровья, давая матерям еще один шанс улучшить питание своих детей. [ 217 ]

Пожилые

[ редактировать ]

Недоедание и недостаточный вес чаще встречаются у пожилых людей, чем у взрослых других возрастов. [ 222 ] Если пожилые люди здоровы и активны, процесс старения сам по себе обычно не приводит к недостаточности питания. [ 223 ] Однако изменения в составе тела, функциях органов, адекватном потреблении энергии и способности есть или получать доступ к пище связаны со старением и могут способствовать недостаточному питанию. [ 224 ] Грусть или депрессия могут сыграть свою роль, вызывая изменения аппетита, пищеварения, уровня энергии, веса и самочувствия. [ 223 ] Исследование связи между недоеданием и другими состояниями у пожилых людей показало, что недоедание у пожилых людей может быть результатом расстройств желудочно-кишечного тракта и эндокринной системы, потери вкуса и обоняния, снижения аппетита и недостаточного потребления пищи. [ 224 ] Плохое состояние зубов, плохо подогнанные зубные протезы или проблемы с жеванием и глотанием могут затруднить прием пищи. [ 223 ] В результате действия этих факторов недоедание легче развивается у пожилых людей. [ 225 ]

Уровень недоедания имеет тенденцию увеличиваться с возрастом: менее 10 процентов «молодых» пожилых людей (до 75 лет) недоедают, в то время как от 30 до 65 процентов пожилых людей, находящихся на дому, в учреждениях длительного ухода или в больницах неотложной помощи, недоедают. . [ 226 ] Многим пожилым людям требуется помощь в приеме пищи, что может способствовать недоеданию. [ 225 ] Однако уровень смертности из-за недоедания может быть снижен. [ 227 ] В связи с этим одним из основных требований ухода за пожилыми людьми является обеспечение адекватного питания и всех необходимых питательных веществ . [ 228 ] Обеспечение различными питательными веществами, такими как белок и энергия, позволяет поддерживать даже небольшой, но постоянный прирост веса. [ 227 ] Госпитализация из-за недоедания в Соединенном Королевстве связана с недостаточной социальной помощью, когда уязвимым людям дома или в домах престарелых не помогают есть. [ 229 ]

В Австралии недоедание или риск недоедания наблюдаются у 80 процентов пожилых людей, поступающих в больницы для госпитализации. [ 230 ] Недоедание и потеря веса могут способствовать саркопении с потерей мышечной массы и мышечной функции. [ 222 ] Абдоминальное ожирение или потеря веса в сочетании с саркопенией приводят к обездвиженности, нарушениям скелета, инсулинорезистентности, гипертонии, атеросклерозу и метаболическим нарушениям . [ 224 ] В статье, опубликованной в журнале Американской диетической ассоциации, отмечается, что регулярные проверки питания представляют собой один из способов выявления и, следовательно, снижения распространенности недоедания среди пожилых людей. [ 223 ]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Действия против голода

- Место за столом

- Агробиоразнообразие

- Здоровье и питание детей в Африке

- Детское ожирение

- Общественная терапевтическая помощь

- Дефицит (лекарства)

- Расстройство пищевого поведения

- Экономические вопросы

- Масштабы голода

- Фоме Зеро (Нулевой голод)

- Соединение для пожертвований еды

- Бездомность

- Голод в Соединенном Королевстве

- Голод в США

- Голодные марши

- Проект «Голод»

- Неравенство доходов

- Классификация этапов интегрированной продовольственной безопасности

- Список глобальных проблем

- Недоедание в Индии

- Недоедание в Южной Африке

- Недоедание в Перу

- Недоедание в Зимбабве

- ПитаниеДень

- Международное питание и образование

- Мусельманн

- Меморандум 200 об исследовании национальной безопасности (1974 г.)

- Оксфам

- Ловушка бедности

- Проект «Открытая рука»

- Социальные программы

- Ответ на голодание

- Устойчивое рыболовство

- Декларация тысячелетия Организации Объединенных Наций

- Дефицит витаминов

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Факты из жизни (PDF) (4-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: Детский фонд ООН. 2010. стр. 61 и 75. ISBN. 978-92-806-4466-1 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 12 декабря 2018 года . Проверено 19 марта 2012 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Молодой ЭМ (2012). Еда и развитие . Абингдон, Оксон: Рутледж. стр. 36–38. ISBN 978-1-135-99941-4 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «недоедание» в Медицинском словаре Дорланда

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пападиа С., Ди Сабатино А., Корацца Г.Р., Forbes А. (февраль 2014 г.). «Диагностика мальабсорбции тонкой кишки: обзор». Внутренняя и неотложная медицина (обзор). 9 (1): 3–8. дои : 10.1007/s11739-012-0877-7 . ПМИД 23179329 . S2CID 33775071 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и «Здоровье матерей, новорожденных, детей и подростков» . ВОЗ . Архивировано из оригинала 10 марта 2012 года . Проверено 4 июля 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д «Обновление книги «Забытый кризис недостаточного питания: доказательства к действию» » (PDF) . www.gov.uk. Департамент международного развития. Октябрь 2012 года . Проверено 5 июля 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Бхутта З.А., Дас Дж.К., Ризви А., Гаффи М.Ф., Уокер Н., Хортон С. и др. (август 2013 г.). «Научно обоснованные меры по улучшению питания матери и ребенка: что можно сделать и какой ценой?». Ланцет . 382 (9890): 452–477. дои : 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60996-4 . ПМИД 23746776 . S2CID 11748341 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кастин Д.А., Бухман А.Л. (ноябрь 2002 г.). «Недоедание и желудочно-кишечные заболевания». Текущее мнение о клиническом питании и метаболической помощи (обзор). 5 (6): 699–706. дои : 10.1097/00075197-200211000-00014 . ПМИД 12394647 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Состояние отсутствия продовольственной безопасности в мире в 2018 году . Продовольственная и сельскохозяйственная организация Объединенных Наций. 2020. номер документа : 10.4060/CA9692EN . ISBN 978-92-5-132901-6 . S2CID 239729231 . Проверено 11 января 2019 г.

- ^ Ван, Хайдун; Нагави, Мохсен; Аллен, Кристина; Барбер, Райан М.; и др. (GBD 2015 Смертность и причины смерти, сотрудники) (8 октября 2016 г.). «Глобальная, региональная и национальная продолжительность жизни, смертность от всех причин и смертность от конкретных причин по 249 причинам смерти, 1980–2015 гг.: систематический анализ для исследования глобального бремени болезней, 2015 г.» . Ланцет . 388 (10053): 1459–1544. дои : 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1 . ПМЦ 5388903 . ПМИД 27733281 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Кациламброс Н (2011). Клиническое питание на практике . Джон Уайли и сыновья. п. 37. ИСБН 978-1-4443-4777-7 .

- ^ «Недоедание» . www.who.int . Проверено 3 мая 2024 г.