Собака

| Собака Временной диапазон: Поздний плейстоцен по настоящее время [ 1 ]

| |

|---|---|

Domesticated

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | C. familiaris

|

| Binomial name | |

| Canis familiaris | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

|

List | |

Собака Canis ( familis или lupus familis ) — одомашненный потомок волка . Canis Также называемая домашней собакой , она была одомашнена из вымершей популяции волков во время позднего плейстоцена , более 14 000 лет назад, охотниками-собирателями , до развития сельского хозяйства . Собака была первым видом , одомашненным человеком . По оценкам экспертов, благодаря длительному общению с людьми собаки превратились в большое количество домашних особей и приобрели способность жить на богатой крахмалом диете, которая была бы неадекватна другим псовым . [ 4 ]

Собаку селекционно разводили на протяжении тысячелетий по различному поведению, сенсорным способностям и физическим качествам. [ 5 ] Породы собак сильно различаются по форме, размеру и окрасу. Они выполняют множество функций для людей, таких как охота , выпас скота , перетаскивание грузов , защита , помощь полиции и военным , общение , терапия и помощь инвалидам . За тысячелетия собаки уникально адаптировались к человеческому поведению, а связь между человеком и собакой стала темой частых исследований. Это влияние на человеческое общество дало им прозвище « лучших друзей человека ».

Taxonomy

| Canine phylogeny with ages of divergence | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cladogram and divergence of the gray wolf (including the domestic dog) among its closest extant relatives[6] |

In 1758, the Swedish botanist and zoologist Carl Linnaeus published in his Systema Naturae, the two-word naming of species (binomial nomenclature). Canis is the Latin word meaning "dog",[7] and under this genus, he listed the domestic dog, the wolf, and the golden jackal. He classified the domestic dog as Canis familiaris and, on the next page, classified the grey wolf as Canis lupus.[2] Linnaeus considered the dog to be a separate species from the wolf because of its upturning tail (cauda recurvata in Latin term), which is not found in any other canid.[8]

In 1999, a study of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) indicated that the domestic dog may have originated from the grey wolf, with the dingo and New Guinea singing dog breeds having developed at a time when human communities were more isolated from each other.[9] In the third edition of Mammal Species of the World published in 2005, the mammalogist W. Christopher Wozencraft listed under the wolf Canis lupus its wild subspecies and proposed two additional subspecies, which formed the domestic dog clade: familiaris, as named by Linnaeus in 1758, and dingo, named by Meyer in 1793. Wozencraft included hallstromi (the New Guinea singing dog) as another name (junior synonym) for the dingo. Wozencraft referred to the mtDNA study as one of the guides informing his decision.[3] Mammalogists have noted the inclusion of familiaris and dingo together under the "domestic dog" clade[10] with some debating it.[11]

In 2019, a workshop hosted by the IUCN/Species Survival Commission's Canid Specialist Group considered the dingo and the New Guinea singing dog to be feral Canis familiaris and therefore did not assess them for the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.[12]

Evolution

Domestication

The earliest remains generally accepted to be those of a domesticated dog were discovered in Bonn-Oberkassel, Germany. Contextual, isotopic, genetic, and morphological evidence shows that this dog was not a local wolf.[13] The dog was dated to 14,223 years ago and was found buried along with a man and a woman, all three having been sprayed with red hematite powder and buried under large, thick basalt blocks. The dog had died of canine distemper.[14] Earlier remains dating back to 30,000 years ago have been described as Paleolithic dogs, but their status as dogs or wolves remains debated[15] because considerable morphological diversity existed among wolves during the Late Pleistocene.[1]

This timing indicates that the dog was the first species to be domesticated[16][17] in the time of hunter-gatherers,[18] which predates agriculture.[1] DNA sequences show that all ancient and modern dogs share a common ancestry and descended from an ancient, extinct wolf population that was distinct from any modern wolf lineage. Some studies have posited that all living wolves are more closely related to each other than to dogs,[19][18] while others have suggested that dogs are more closely related to modern Eurasian wolves than to American wolves.[20]

The dog is a classic example of a domestic animal that likely travelled a commensal pathway into domestication.[15][21] The questions of when and where dogs were first domesticated have taxed geneticists and archaeologists for decades.[16] Genetic studies suggest a domestication process commencing over 25,000 years ago, in one or several wolf populations in either Europe, the high Arctic, or eastern Asia.[22] In 2021, a literature review of the current evidence infers that the dog was domesticated in Siberia 23,000 years ago by ancient North Siberians, then later dispersed eastward into the Americas and westward across Eurasia,[13] with dogs likely accompanying the first humans to inhabit the Americas.[13] Some studies have suggested that the extinct Japanese wolf is closely related to the ancestor of domestic dogs.[23]

Breeds

Dogs are the most variable mammal on earth, with around 450 globally recognized dog breeds.[22][24] In the Victorian era, directed human selection developed the modern dog breeds, which resulted in a vast range of phenotypes.[17] Most breeds were derived from small numbers of founders within the last 200 years.[17][22] Since then, dogs have undergone rapid phenotypic change and have been subjected to artificial selection by humans. The skull, body, and limb proportions between breeds display more phenotypic diversity than can be found within the entire order of carnivores. These breeds possess distinct traits related to morphology, which include body size, skull shape, tail phenotype, fur type, and colour.[17] Their behavioural traits include guarding, herding, hunting,[17] retrieving, and scent detection. Their personality traits include hypersocial behavior, boldness, and aggression.[17] Present-day dogs are dispersed around the world.[22] An example of this dispersal is the numerous modern breeds of European lineage during the Victorian era.[18]

-

Morphological variation in six dogs

-

Phenotypic variation in four dogs

Anatomy and physiology

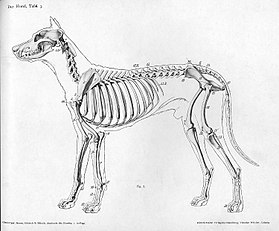

Size and skeleton

Dogs are extremely variable in size, ranging from one of the largest breeds, the great dane, at 50 to 79 kg (110 to 174 lb) and 71 to 81 cm (28 to 32 in), to one of the smallest, the chihuahua, at 0.5 to 3 kg (1.1 to 6.6 lb) and 13 to 20 cm (5.1 to 7.9 in).[25][26] All healthy dogs, regardless of their size and type, have an identical skeletal structure with the exception of the number of bones in the tail, although there is significant skeletal variation between dogs of different types.[27][28] The dog's skeleton is well adapted for running; the vertebrae on the neck and back have extensions for back muscles, consisting of epaxial muscles and hypaxial muscles, to connect to; the long ribs provide room for the heart and lungs; and the shoulders are unattached to the skeleton, allowing for flexibility.[27][28][29]

Compared to the dog's wolf-like ancestors, selective breeding since domestication has seen the dog's skeleton larger in size for larger types such as mastiffs and miniaturised for smaller types such as terriers; dwarfism has been selectively used for some types where short legs are advantageous, such as dachshunds and corgis.[28] Most dogs naturally have 26 vertebrae in their tails, but some with naturally short tails have as few as three.[27]

The dog's skull has identical components regardless of breed type, but there is significant divergence in terms of skull shape between types.[28][30] The three basic skull shapes are the elongated dolichocephalic type as seen in sighthounds, the intermediate mesocephalic or mesaticephalic type, and the very short and broad brachycephalic type exemplified by mastiff type skulls.[28][30] The jaw contains around 42 teeth, and is designed for the consumption of flesh. Dogs use their carnassial teeth to cut food into bite-sized chunks, more especially meat.[31]

Senses

Dogs' senses include vision, hearing, smell, taste, touch, and magnetoreception. One study suggests that dogs can feel small variations in Earth's magnetic field.[32] Dogs prefer to defecate with their spines aligned in a north-south position in calm magnetic field conditions.[33]

Dogs' vision is dichromatic; the dog's visual world consists of yellows, blues, and grays. They have difficulty differentiating between red and green. The divergence of the eye axis of dogs ranges from 12–25°, depending on the breed. Dogs' eyes of different breeds can have different retina configurations. The fovea centralis area of dogs' eyes, which is attached to a nerve fiber, is the most sensitive to photons.[34]

While the human brain is dominated by a large visual cortex, the dog brain is dominated by a large olfactory cortex. Dogs have roughly forty times more smell-sensitive receptors than humans, ranging from about 125 million to nearly 300 million in some dog breeds, such as bloodhounds.[35] This sense of smell is the most prominent sense of the species; it detects chemical changes in the environment, allowing dogs to pinpoint the location of the scent of mating partners, potential stressors, resources, etc.[36] Dogs also have an acute sense of hearing up to 4 times greater than that of humans. They can pick up the slightest sounds from about 400 m (1,300 ft) compared to 90 m (300 ft) for humans.[37]

Dogs have specialized whiskers known as vibrissae, sensing organs present above the dog's eyes, below their jaw, and on their muzzle. Vibrissae are more rigid, embedded much more deeply in the skin than other hairs, and have a greater number of receptor cells at their base. They can detect air currents, subtle vibrations, and objects in the dark. They provide an early warning system for objects that might strike the face or eyes, and probably help direct food and objects towards the mouth.[38]

Coat

The coats of domestic dogs are of two varieties: "double" being familiar with dogs (as well as wolves) originating from colder climates, made up of a coarse guard hair and a soft down hair, or "single", with the topcoat only. Breeds may have an occasional "blaze", stripe, or "star" of white fur on their chest or underside.[39] Premature graying can occur in dogs as early as one year of age; this is associated with impulsive behaviors, anxiety behaviors, and fear of unfamiliar noise, people, or animals.[40] Some dog breeds are hairless, while others have a very thick corded coat. The coats of certain breeds are often groomed to a characteristic style, for example, the Yorkshire terrier's "show cut".[31]

Dewclaw

A dog's dewclaw is the five digits in its forelimb and hind legs. Dewclaws on the forelimbs are attached by bone and ligament, while the dewclaws on the hind legs are attached only by skin. Most dogs aren't born with dewclaws in their hind legs, and some are without them in their forelimbs. Dogs' dewclaws consist of the proximal phalanges and distal phalanges. Some publications thought that dewclaws in wolves, who usually do not have dewclaws, were a sign of hybridization with dogs.[41][42]

Tail

A dog's tail is the terminal appendage of the vertebral column, which is made up of a string of 5 to 23 vertebrae enclosed in muscles and skin that support the dog's back extensor muscles. One of the primary functions of a dog's tail is to communicate their emotional state.[43] The tail also helps the dog maintain balance by putting its weight on the opposite side of the dog's tilt, and it can also help the dog spread its anal gland's scent through the tail's position and movement.[44] Dogs can have a violet gland (or supracaudal gland) characterized by sebaceous glands on the dorsal surface of their tails; in some breeds, it may be vestigial or absent. The enlargement of the violet gland in the tail, which can create a bald spot from hair loss, can be caused by Cushing's disease or an excess of sebum from androgens in the sebaceous glands.[45]

A study suggests that dogs show asymmetric tail-wagging responses to different emotive stimuli. "Stimuli that could be expected to elicit approach tendencies seem to be associated with [a] higher amplitude of tail-wagging movements to the right side".[46][47]

Dogs can injure themselves by wagging their tails forcefully; this condition is called kennel tail, happy tail, bleeding tail, or splitting tail.[48] In some hunting dogs, the tail is traditionally docked to avoid injuries. Some dogs can be born without tails because of a DNA variant in the T gene, which can also result in a congenitally short (bobtail) tail.[49] Tail docking is opposed by many veterinary and animal welfare organistions such as the American Veterinary Medical Association[50] and the British Veterinary Association.[51] Evidence from veterinary practices and questionnaires showed that around 500 dogs would need to have their tail docked to prevent one injury.[52]

Health

Some breeds of dogs are prone to specific genetic ailments such as elbow and hip dysplasia, blindness, deafness, pulmonic stenosis, a cleft palate, and trick knees. Two severe medical conditions significantly affecting dogs are pyometra, affecting unspayed females of all breeds and ages, and gastric dilatation volvulus (bloat), which affects larger breeds or deep-chested dogs. Both of these are acute conditions and can kill rapidly. Dogs are also susceptible to parasites such as fleas, ticks, mites, hookworms, tapeworms, roundworms, and heartworms that can live in their hearts.[53] In addition, they may suffer from canine distemper virus (CDV). This morbillivirus can infect caniforms and feliforms, such as canines, felines, and bears. As the dog population grows, cases of CDV in wildlife will spread accordingly.[54] Rabies is another pathogen dogs may catch, particularly those who have not been sanitized or given vaccines.[55]

Several human foods and household ingestibles are toxic to dogs, including chocolate, causing theobromine poisoning, onions and garlic, causing thiosulfate, sulfoxide, or disulfide poisoning, grapes and raisins, macadamia nuts, and xylitol.[56] The nicotine in tobacco can also be dangerous to dogs. Signs of ingestion can include copious vomiting (e.g., from eating cigar butts) or diarrhea. The symptoms of hydrocarbon mixture indigestion can be abdominal pain, aspiration pneumonia, oral ulcers, vomiting, or death.[57][58] The most common deaths among dogs were neoplasia and heart disease, followed by toxicosis and gastrointestinal disease.[59][60][61] A 20-year-record study found that respiratory disease was the most common cause of death in Bulldogs.[62] Puppies were more likely to die from infection or congenital disease.[63]

Dogs can also have some of the same health conditions as humans, including diabetes, dental and heart disease, epilepsy, cancer, hypothyroidism, and arthritis. Type 1 diabetes mellitus, resembling human diabetes, is the type of diabetes seen most often in dogs.[64] Their pathology is similar to that of humans, as is their response to treatment and their outcomes. The genes involved in canine obsessive-compulsive disorders led to the detection of four genes in humans' related pathways.[22]

Dogs regulate their body temperature through evaporation of saliva and lung moisture by panting.[65] Dogs are a source of zoonotic infections and are known to transmit several diseases to humans by infected saliva, aerosols, feces, and direct contact.[66] Pets, including dogs, can catch COVID-19. As with humans, infected pets may exhibit a variety of symptoms or no symptoms at all.[67]

Lifespan

The typical lifespan of dogs varies widely among breeds, but the median longevity (the age at which half the dogs in a population have died and half are still alive) is approximately 12.7 years.[68][69] Obesity correlates negatively with longevity with one study finding obese dogs have a life expectancy approximately a year and a half less than dogs with a healthy weight.[68]

Reproduction

In domestic dogs, sexual maturity happens around six months to one year for both males and females, although this can be delayed until up to two years of age for some large breeds. This is the time at which female dogs will have their first estrous cycle, characterized by their vulvas swelling and producing discharges, usually lasting between 4 and 20 days.[70] They will experience subsequent estrous cycles semiannually, during which the body prepares for pregnancy. At the peak of the cycle, females will become estrous, mentally and physically receptive to copulation. Because the ova survive and can be fertilized for a week after ovulation, more than one male can sire the same litter.[5] Fertilization typically occurs two to five days after ovulation. After ejaculation, the dogs are coitally tied for around 5–30 minutes because of the male's bulbus glandis swelling and the female's constrictor vestibuli contracting; the male will continue ejaculating until they untie naturally due to muscle relaxation.[71] 14–16 days after ovulation, the embryo attaches to the uterus, and after seven to eight more days, a heartbeat is detectable.[72][73] Dogs bear their litters roughly 58 to 68 days after fertilization,[5][74] with an average of 63 days, although the length of gestation can vary. An average litter consists of about six puppies.[75]

Neutering

Neutering is the sterilization of animals, usually by removing the male's testicles or the female's ovaries and uterus, to eliminate the ability to procreate and reduce sex drive. Because of dogs' overpopulation in some countries, many animal control agencies, such as the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), advise that dogs not intended for further breeding should be neutered, so that they do not have undesired puppies that may later be euthanized.[76] According to the Humane Society of the United States, three to four million dogs and cats are euthanized each year.[77] Many more are confined to cages in shelters. Spaying or castrating dogs is considered a major factor in keeping overpopulation down.[78]

Neutering reduces problems caused by hypersexuality, especially in male dogs.[79] Spayed female dogs are less likely to develop cancers affecting the mammary glands, ovaries, and other reproductive organs.[80] However, neutering increases the risk of urinary incontinence in female dogs,[81] prostate cancer in males,[82] and osteosarcoma, hemangiosarcoma, cruciate ligament rupture, pyometra, obesity, and diabetes mellitus in either sex.[83]

Inbreeding depression

A common breeding practice for pet dogs is to mate them between close relatives (e.g., between half- and full-siblings).[84] Inbreeding depression is considered to be due mainly to the expression of homozygous deleterious recessive mutations.[85] Outcrossing between unrelated individuals, including dogs of different breeds, results in the beneficial masking of deleterious recessive mutations in progeny.[86]

In a study of seven dog breeds (the Bernese Mountain Dog, Basset Hound, Cairn Terrier, Brittany, German Shepherd Dog, Leonberger, and West Highland White Terrier), it was found that inbreeding decreases litter size and survival.[87] Another analysis of data on 42,855 Dachshund litters found that as the inbreeding coefficient increased, litter size decreased and the percentage of stillborn puppies increased, thus indicating inbreeding depression.[88] In a study of Boxer litters, 22% of puppies died before reaching 7 weeks of age. Stillbirth was the most frequent cause of death, followed by infection. Mortality due to infection increased significantly with increases in inbreeding.[89]

Behavior

Dog behavior is the internally coordinated responses (actions or inactions) of the domestic dog (individuals or groups) to internal and external stimuli.[90] Dogs' minds have been shaped by millennia of contact with humans. They have acquired the ability to understand and communicate with humans and are uniquely attuned to human behaviors.[91] Behavioral scientists thought that a set of social-cognitive abilities in domestic dogs that are not possessed by the dog's canine relatives or other highly intelligent mammals, such as great apes, are parallel to children's social-cognitive skills.[92]

Unlike other domestic species selected for production-related traits, dogs were initially selected for their behaviors.[93][94] In 2016, a study found that only 11 fixed genes showed variation between wolves and dogs.[95] These gene variations were unlikely to have been the result of natural evolution and indicate selection on both morphology and behavior during dog domestication. These genes have been shown to affect the catecholamine synthesis pathway, with the majority of the genes affecting the fight-or-flight response[94][96] (i.e., selection for tameness) and emotional processing.[94] Dogs generally show reduced fear and aggression compared with wolves, though some of these genes have been associated with aggression in certain dog breeds.[97][94] Traits of high sociability and lack of fear in dogs may include genetic modifications related to Williams-Beuren syndrome in humans, which cause hypersociability at the expense of problem-solving ability.[98] In a 2023 study of 58 dogs, some dogs classified as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder-like showed lower serotonin and dopamine concentrations.[99] A similar study claims that hyperactivity is more common in male and young dogs.[100] A dog can become aggressive because of trauma or abuse, fear or anxiety, territorial protection, or protecting an item it considers valuable.[101] Acute stress reactions from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) seen in dogs can evolve into chronic stress.[102] Police dogs with PTSD can often refuse to work.[103]

Dogs have a natural instinct called prey drive (the term is chiefly used to describe training dogs' habits) which can be influenced by breeding. These instincts can drive dogs to consider objects or other animals to be prey or drive possessive behavior. These traits have been enhanced in some breeds so that they may be used to hunt and kill vermin or other pests.[104] Puppies or dogs sometimes bury food underground. One study found that wolves outperformed dogs in finding food caches, likely due to a "difference in motivation" between wolves and dogs.[105] Some puppies and dogs engage in coprophagy out of habit, stress, for attention, or boredom; most of them will not do it later in life. A study hypothesizes that the behavior was inherited from wolves, a behavior likely evolved to lessen the presence of intestinal parasites in dens.[106]

Most dogs can swim. In a study of 412 dogs, around 36.5% of the dogs could not swim; the other 63.5% were able to swim without a trainer in a swimming pool.[107] A study of 55 dogs found a correlation between swimming and 'improvement' of the hip osteoarthritis joint.[108]

Nursing

The female dog may produce colostrum 1–7 days before giving birth, lasting for around three months.[109][110] Colostrum peak production was around 3 weeks postpartum and increased with litter size.[110] The dog can sometimes vomit and refuse food during child contractions.[111] In the later stages of the dog's pregnancy, nesting behaviour may occur.[112] Puppies are born with a protective fetal membrane that the mother usually removes shortly after birth. Dogs can have the maternal instincts to start grooming their puppies, consume their puppies' feces, and protect their puppies, likely due to their hormonal state.[113][114] While male-parent dogs can show more disinterested behaviour toward their own puppies,[115] most can play with the young pups as they would with other dogs or humans.[116] A female dog may abandon or attack her puppies or her male partner dog if she is stressed or in pain.[117]

Intelligence

Researchers have tested dogs' ability to perceive information, retain it as knowledge, and apply it to solve problems. Studies of two dogs suggest that dogs can learn by inference. A study with Rico, a Border Collie, showed that he knew the labels of over 200 different items. He inferred the names of novel things by exclusion learning and correctly retrieved those new items after four weeks of the initial exposure. A study of another Border Collie, Chaser, documented that he had learned the names and could associate them by verbal command with over 1,000 words.[118]

One study of canine cognitive abilities found that dogs' capabilities are similar to those of horses, chimpanzees, or cats.[119] One study of 18 household dogs found that the dogs could not distinguish food bowls at specific locations without distinguishing cues; the study stated that this indicates a lack of spatial memory.[120] A study stated that dogs have a visual sense for number. The dogs showed a ratio-dependent activation both for numerical values from 1–3 to larger than four.[121]

Dogs demonstrate a theory of mind by engaging in deception.[122] Another experimental study showed evidence that Australian dingos can outperform domestic dogs in non-social problem-solving, indicating that domestic dogs may have lost much of their original problem-solving abilities once they joined humans.[123] Another study showed that after undergoing training to solve a simple manipulation task, dogs faced with an unsolvable version of the same problem look at humans, while socialized wolves do not.[124]

Communication

Dog communication is how dogs convey information to other dogs, understand messages from humans, and translate the information that dogs are transmitting.[125] Communication behaviors of dogs include eye gaze, facial expression,[126][127] vocalization, body posture (including movements of bodies and limbs), and gustatory communication (scents, pheromones, and taste). Dogs mark their territories by urinating on them, which is more likely when entering a new environment.[128][129] Both sexes of dogs may also urinate to communicate anxiety or frustration, submissiveness, or when in exciting or relaxing situations.[130] Aroused dogs can be a result of the dogs' higher cortisol levels.[131] Between 3 and 8 weeks of age, dogs tend to focus on other dogs for social interaction, and between 5 and 12 weeks of age, they shift their focus to people.[132] Belly exposure in dogs can be a defensive behavior that can lead to a bite or to seek comfort.[133]

Humans communicate with dogs by using vocalization, hand signals, and body posture. With their acute sense of hearing, dogs rely on the auditory aspect of communication for understanding and responding to various cues, including the distinctive barking patterns that convey different messages. A study using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has shown that dogs respond to both vocal and nonvocal voices using the brain's region towards the temporal pole, similar to that of humans' brains. Most dogs also looked significantly longer at the face whose expression matched the valence of vocalization.[134][135][136] A study of caudate responses shows that dogs tend to respond more positively to social rewards than to food rewards.[137]

Ecology

Population

The dog is probably the most widely abundant large carnivoran living in the human environment.[138][139] In 2013, the estimated global dog population was between 700 million[140] and 987 million.[141] About 20% of dogs live as pets in developed countries.[142] In the developing world, it is estimated that three-quarters of the world's dog population lives in the developing world as feral, village, or community dogs.[143] Most of these dogs live as scavengers and have never been owned by humans, with one study showing that village dogs' most common response when approached by strangers is to run away (52%) or respond aggressively (11%).[144]

Competitors

Feral and free-ranging dogs' potential to compete with other large carnivores is limited by their strong association with humans.[138] Although wolves are known to kill dogs, they tend to live in pairs in areas where they are highly persecuted, giving them a disadvantage when facing large dog groups.[145][146] In some instances, wolves have displayed an uncharacteristic fearlessness of humans and buildings when attacking dogs, to the extent that they have to be beaten off or killed.[147] Although the numbers of dogs killed each year are relatively low, it induces a fear of wolves entering villages and farmyards to take dogs, and losses of dogs to wolves have led to demands for more liberal wolf hunting regulations.[145]

Coyotes and big cats have also been known to attack dogs. In particular, leopards are known to have a preference for dogs and have been recorded to kill and consume them, no matter their size.[148] Siberian tigers in the Amur River region have killed dogs in the middle of villages. Amur tigers will not tolerate wolves as competitors within their territories, and the tigers could be considering dogs in the same way.[149] Striped hyenas are known to kill dogs in their range.[150]

Dogs as introduced predator mammals have affected the ecology of New Zealand, which lacked indigenous land-based mammals before human settlement.[151] Dogs have made 11 vertebrate species extinct and are identified as a 'potential threat' to at least 188 threatened species worldwide;[152] another figure is that dogs have also been linked to the extinction of 156 animal species.[153] Dogs have been documented to have killed a few birds of the endangered species, the kagu, in New Caledonia.[154]

Diet

Dogs are typically described as omnivores.[5][155][156] Compared to wolves, dogs from agricultural societies have extra copies of amylase and other genes involved in starch digestion that contribute to an increased ability to thrive on a starch-rich diet.[4] Similar to humans, some dog breeds produce amylase in their saliva and are classified as having a high-starch diet.[157] However, more like cats and less like other omnivores, dogs can only produce bile acid with taurine, and they cannot produce vitamin D, which they obtain from animal flesh.

Of the twenty-one amino acids common to all life forms (including selenocysteine), dogs cannot synthesize ten: arginine, histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine.[158][159][160] Like cats, dogs require arginine to maintain nitrogen balance. These nutritional requirements place dogs halfway between carnivores and omnivores.[161]

Range

As a domesticated or semi-domesticated animal, the dog has notable exceptions of presence in:

- The Aboriginal Tasmanians, who were separated from Australia before the arrival of dingos on that continent

- The Andamanese peoples, who were isolated when rising sea levels covered the land bridge to Myanmar

- The Fuegians, who instead domesticated the Fuegian dog, an already extinct different canid species

- Individual Pacific islands whose maritime settlers did not bring dogs or where the dogs died out after original settlement, notably the Mariana Islands,[162] Palau[163] and most of the Caroline Islands with exceptions such as Fais Island and Nukuoro,[164] the Marshall Islands,[165] the Gilbert Islands,[165] New Caledonia,[166] Vanuatu,[166][167] Tonga,[167] Marquesas,[167] Mangaia in the Cook Islands, Rapa Iti in French Polynesia, Easter Island,[167] the Chatham Islands,[168] and Pitcairn Island (settled by the Bounty mutineers, who killed off their dogs to escape discovery by passing ships).[169]

Dogs were introduced to Antarctica as sled dogs. Starting practice in December 1993, dogs were later outlawed by the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty international agreement due to the possible risk of spreading infections.[170]

Dogs shall not be introduced onto land, ice shelves or sea ice.

— Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, signed in 1991 in Madrid, amended version of Annex II, Article 4 (number two)

Roles with humans

The domesticated dog apparently originated as a predator and scavenger.[171][172] Domestic dogs inherited complex behaviors, such as bite inhibition, from their wolf ancestors, which would have been pack hunters with complex body language. These sophisticated forms of social cognition and communication may account for dogs' trainability, playfulness, and ability to fit into human households and social situations,[173] and probably also their co-existence with early human hunter-gatherers.[174][175]

Dogs perform many roles for people, such as hunting, herding, pulling loads, protection, assisting police and the military, companionship, and aiding disabled individuals. These roles in human society have earned them the nickname "man's best friend" in the Western world. In some cultures, however, dogs are also a source of meat.[176][177]

Pets

The keeping of dogs as companions, particularly by elites, has a long history.[178] Pet-dog populations grew significantly after World War II as suburbanization increased.[178] In the 1980s, there have been changes in the pet dog's functions, such as the increased role of dogs in the emotional support of their human guardians.[179][180][181] Within the second half of the 20th century, the first dogs' social status major shift has been "commodification", allowing it to conform to social expectations of personality and behavior.[181] The second has been the broadening of the concepts of family and the home to include dogs-as-dogs within everyday routines and practices.[181]

A vast range of commodity forms aim to transform a pet dog into an ideal companion.[182] The list of goods and services available for dogs, such as dog-training books, classes, and television programs, has increased.[183][182] The majority of contemporary dog-owners describe their pet as part of the family, although some state that it is an ambivalent relationship.[181] Some dog-trainers have promoted a dominance model of dog-human relationships. However, the idea of the "alpha dog" trying to be dominant is based on a controversial theory about wolf packs.[184][185] It has been disputed that "trying to achieve status" is characteristic of dog-human interactions.[186] Human family members have increased participation in activities in which the dog is an integral partner, such as dog dancing and dog yoga.[182]

According to statistics published by the American Pet Products Manufacturers Association in the National Pet Owner Survey in 2009–2010, an estimated 77.5 million people in the United States have pet dogs.[187] The source shows that nearly 40% of American households own at least one dog, of which 67% own just one dog, 25% own two dogs, and nearly 9% own more than two dogs. The data also shows an equal number of male and female pet dogs; less than one-fifth of the owned dogs come from shelters.[188]

Workers

In addition to dogs' role as companion animals, dogs such as collies and sheepdogs have been bred for herding livestock; for hunting; for rodent control (such as terriers); as search and rescue dogs;[189] as detection dogs (such as those trained to detect illicit drugs or chemical weapons);[190][191] as homeguard dogs; as police dogs ("K-9"); as welfare-purpose dogs; as dogs who assist fishermen retrieve their nets; and as dogs that pull loads (such as sled dogs).[5] In 1957, the dog Laika became one of the first animals to be launched into Earth orbit aboard the Soviets's Sputnik 2; she provided evidence that mammals could survive in space, but died during the flight from overheating.[192][193]

Various kinds of service dogs and assistance dogs, including guide dogs, hearing dogs, mobility assistance dogs, and psychiatric service dogs, assist individuals with disabilities.[194][195] A study of 29 dogs found that 9 dogs owned by people with epilepsy were reported to exhibit attention-getting behavior to their handler 30 seconds to 45 minutes prior to an impending seizure; there was no significant correlation between the patients' demographics, health, or attitude towards their pets.[196]

Shows and sports

There are breed-conformation shows and dog sports (including racing, sledding, and agility competitions) for dogs to participate in with their guardians. In dog shows, also referred to as "breed shows", a judge familiar with the specific dog breed evaluates individual purebred dogs for conformity with their established breed type as described in a breed standard.[197] Weight pulling, a dog sport involving pulling weight, has been criticized for promoting doping and for its risk of injury.[198]

Dogs as food

Meat from dogs is consumed in some East Asian countries, including China,[176] Vietnam,[177] Korea,[199] Indonesia,[200] and the Philippines;[201] such traditions date back to antiquity.[202] It is estimated that 30 million dogs are killed and consumed in Asia every year. Han Chinese traditionally ate dog meat.[203] China is the world's largest consumer of dogs, with an estimated 10 to 20 million dogs killed every year for human consumption—a figure derived from extrapolating industry reports on meat tonnage.[204] Switzerland, Polynesia, and pre-Columbian Mexico historically consumed dog meat.[205][206][207] In some parts of Poland[208][209] and Central Asia,[210][211] dog fat is reportedly believed to be beneficial for the lungs.[212]

Eating dog meat is a social taboo in most parts of the world; debates have ensued over banning the consumption of dog meat.[213] Emperors of the Sui dynasty (581–618) in China attempted to outlaw dog-meat consumption, with the Tang dynasty (618–907) partially prohibiting dog meat consumption at events.[214] Proponents of eating dog meat have argued that placing a distinction between livestock and dogs is Western hypocrisy and that there is no difference in eating different animals' meat.[215][216][217][218] In some countries, selling or slaughtering dogs for human consumption is prohibited, though some still consume it in modern times.[219][220]

In Korea

The most popular Korean dog dish, bosintang, a spicy stew, aims to balance the body's heat during the summer months. Some followers of the custom claim this is done to ensure good health by balancing one's gi, or the body's 'vital energy'. Dogs are not as widely consumed as beef, pork, and chicken.[221]

The primary dog breed raised for meat in South Korea is the Nureongi, which is a breed that has not been recognized by international bodies.[222] In 2018, the South Korean government passed a bill banning restaurants that sell dog meat from doing so during that year's Winter Olympics.[223] On 9 January 2024, the South Korean parliament passed a law banning the distribution and sale of dog meat, to take effect in 2027.[224]

Health risks

In 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that 59,000 people died globally from rabies, with 59.6% of the deaths in Asia and 36.4% in Africa. Rabies is a disease for which dogs are the most significant vector.[225] Dog bites affect tens of millions of people globally each year. Children in mid-to-late childhood are the largest group bitten by dogs, with a greater risk of injury to the head and neck. They are more likely to need medical treatment and have the highest death-rate.[226] Sharp claws can lacerate flesh, which can lead to serious infections.[227] In the United States, cats and dogs are a factor in more than 86,000 falls each year.[228] It has been estimated that around 2% of dog-related injuries treated in U.K. hospitals are domestic accidents. The same study concluded that dog-associated road accidents involving injuries more commonly involve two-wheeled vehicles.[229]

Toxocara canis (dog roundworm) eggs in dog feces can cause toxocariasis. In the United States, about 10,000 cases of Toxocara infection are reported in humans each year, and almost 14% of the U.S. population is infected.[230] Untreated toxocariasis can cause retinal damage and decreased vision.[231] Dog feces can also contain hookworms that cause cutaneous larva migrans in humans.[232][233]

Health benefits

The scientific evidence is mixed as to whether a dog's companionship can enhance human physical and psychological well-being.[234] Studies suggest that there are benefits to physical health and psychological well-being, but they have been criticized for being "poorly controlled".[235][236] One study states that "the health of elderly people is related to their health habits and social supports but not to their ownership of, or attachment to, a companion animal".[237] Earlier studies have shown that pet-dog or -cat guardians make fewer hospital visits and are less likely to be on medication for heart problems and sleeping difficulties than non-guardians.[237] People with pet dogs took considerably more physical exercise than those with cats or those without pets; these effects are relatively long-term.[238] Pet guardianship has also been associated with increased survival in cases of coronary artery disease. Human guardians are significantly less likely to die within one year of an acute myocardial infarction than those who do not own dogs.[239] Studies have found a small to moderate correlation between dog-ownership and increased adult physical-activity levels.[240]

A 2005 paper states:[234]

recent research has failed to support earlier findings that pet ownership is associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, a reduced use of general practitioner services, or any psychological or physical benefits on health for community dwelling older people. Research has, however, pointed to significantly less absenteeism from school through sickness among children who live with pets.

Health benefits of dogs can result from contact with dogs in general, not solely from having dogs as pets. For example, when in a pet dog's presence, people show reductions in cardiovascular, behavioral, and psychological indicators of anxiety,[241] and are exposed to immune-stimulating microorganisms, which can protect against allergies and autoimmune diseases (according to the hygiene hypothesis). Other benefits include dogs as social support.[242]

One study indicated that wheelchair-users experience more positive social interactions with strangers when accompanied by a dog than when they are not.[243] In 2015, a study found that pet owners were significantly more likely to get to know people in their neighborhood than non-pet owners.[244] In one study, new guardians reported a significant reduction in minor health problems during the first month following pet acquisition, which was sustained through the 10-month study.[238]

Using dogs and other animals as a part of therapy dates back to the late-18th century, when animals were introduced into mental institutions to help socialize patients with mental disorders.[245] Animal-assisted intervention research has shown that animal-assisted therapy with a dog can increase smiling and laughing among people with Alzheimer's disease.[246] One study demonstrated that children with ADHD and conduct disorders who participated in an education program with dogs and other animals showed increased attendance, knowledge, and skill-objectives and decreased antisocial and violent behavior compared with those not in an animal-assisted program.[247]

Cultural importance

Artworks have depicted dogs as symbols of guidance, protection, loyalty, fidelity, faithfulness, alertness, and love.[248] In ancient Mesopotamia, from the Old Babylonian period until the Neo-Babylonian period, dogs were the symbol of Ninisina, the goddess of healing and medicine,[249] and her worshippers frequently dedicated small models of seated dogs to her.[249] In the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian periods, dogs served as emblems of magical protection.[249] In China, Korea, and Japan, dogs are viewed as kind protectors.[250]

In mythology, dogs often appear as pets or as watchdogs.[250] Stories of dogs guarding the gates of the underworld recur throughout Indo-European mythologies[251][252] and may originate from Proto-Indo-European traditions.[251][252] In Greek mythology, Cerberus is a three-headed, dragon-tailed watchdog who guards the gates of Hades.[250] Dogs also feature in association with the Greek goddess Hecate.[253] In Norse mythology, a dog called Garmr guards Hel, a realm of the dead.[250] In Persian mythology, two four-eyed dogs guard the Chinvat Bridge.[250] In Welsh mythology, Cŵn Annwn guards Annwn.[250] In Hindu mythology, Yama, the god of death, owns two watchdogs named Shyama and Sharvara, which each have four eyes—they are said to watch over the gates of Naraka.[254] A black dog is considered to be the vahana (vehicle) of Bhairava (an incarnation of Shiva).[255]

In Christianity, dogs represent faithfulness.[250] Within the Roman Catholic denomination specifically, the iconography of Saint Dominic includes a dog, after the saint's mother dreamt of a dog springing from her womb and became pregnant shortly after that.[256] As such, the Dominican Order (Ecclesiastical Latin: Domini canis) means "dog of the Lord" or "hound of the Lord".[256] In Christian folklore, a church grim often takes the form of a black dog to guard Christian churches and their churchyards from sacrilege.[257] Jewish law does not prohibit keeping dogs and other pets, but requires Jews to feed dogs (and other animals that they own) before themselves and to make arrangements for feeding them before obtaining them.[258][259] The view on dogs in Islam is mixed, with some schools of thought viewing them as unclean,[250] although Khaled Abou El Fadl states that this view is based on "pre-Islamic Arab mythology" and "a tradition [...] falsely attributed to the Prophet".[260] The Sunni Maliki school jurists disagree with the idea that dogs are unclean.[261]

Терминология

- Собака – вид (или подвид) в целом, а также любой представитель мужского пола. [ 262 ]

- Сука – любая самка вида (или подвида). [ 263 ]

- Щенок или щенок – молодой представитель вида (или подвида) в возрасте до 12 месяцев. [ 264 ]

- Отец – родитель-самец помета. [ 264 ]

- Мать – родительница помета. [ 264 ]

- Помет – все щенки, рожденные от одного щенения. [ 264 ]

- Щенение – рождение суки. [ 264 ]

- Щенки – щенки, все еще зависящие от матери. [ 264 ]

Ссылки

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Тельманн О, Перри А.Р. (2018). «Палеогеномные выводы о приручении собак». В Линдквист С., Раджора О. (ред.). Палеогеномика . Популяционная геномика. Спрингер, Чам. стр. 273–306. дои : 10.1007/13836_2018_27 . ISBN 978-3-030-04752-8 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Линней С (1758 г.). Система природы по трем царствам природы, по классам, отрядам, родам, видам, с признаками, различиями, синонимами, местами. Томус I (на латыни) (10-е изд.). Холмии (Стокгольм): Лаврентий Сальвий. стр. 38–40. Архивировано из оригинала 8 ноября 2012 года . Проверено 11 февраля 2017 г. .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Wozencraft WC (2005). «Орден Хищников» . В Wilson DE , Reeder DM (ред.). Виды млекопитающих мира: таксономический и географический справочник (3-е изд.). Издательство Университета Джонса Хопкинса. стр. 575–577. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0 . OCLC 62265494 . (через Google Книги). Архивировано 14 марта 2024 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Аксельссон Э., Ратнакумар А., Арендт М.Л., Макбул К., Вебстер М.Т., Перлоски М. и др. (март 2013 г.). «Геномная характеристика приручения собаки свидетельствует об адаптации к диете, богатой крахмалом». Природа . 495 (7441): 360–364. Бибкод : 2013Natur.495..360A . дои : 10.1038/nature11837 . ISSN 0028-0836 . ПМИД 23354050 . S2CID 4415412 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Дьюи, Т. и С. Бхагат. 2002. « Canis lupus familis ». Архивировано 26 мая 2022 года в Wayback Machine , Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ Кепфли К.П., Поллинджер Дж., Годиньо Р., Робинсон Дж., Леа А., Хендрикс С. и др. (август 2015 г.). «Общегеномные данные показывают, что африканские и евразийские золотые шакалы являются разными видами» . Современная биология . 25 (16): 2158–2165. Бибкод : 2015CBio...25.2158K . дои : 10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.060 . ПМИД 26234211 .

- ^ Ван и Тедфорд 2008 , с. 58.

- ^ Клаттон-Брок Дж (1995). «2-Происхождение собаки» . В Серпелле Дж. (ред.). Домашняя собака: ее эволюция, поведение и взаимодействие с людьми . Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. 7–20 . ISBN 978-0-521-41529-3 .

- ^ Уэйн Р.К., Острандер Э.А. (29 марта 1999 г.). «Происхождение, генетическое разнообразие и структура генома домашней собаки». Биоэссе . 21 (3): 247–257. doi : 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199903)21:3<247::AID-BIES9>3.0.CO;2-Z . ПМИД 10333734 . S2CID 5547543 .

- ^ Джексон С.М., Гроувс С.П., Флеминг П.Дж., Аплин К.П., Элдридж М.Д., Гонсалес А. и др. (4 сентября 2017 г.). «Своенравная собака: аборигенная австралийская собака или динго — это отдельный вид?» . Зоотакса . 4317 (2). дои : 10.11646/zootaxa.4317.2.1 . hdl : 1885/186590 .

- ↑ Смит, 2015 , стр. xi–24. Глава 1 – Брэдли Смит.

- ^ Альварес Ф., Богданович В., Кэмпбелл Л.А., Годиньо Р., Хатлауф Дж., Джала Ю.В. и др. (2019). «Виды Old World Canis с таксономической неопределенностью: выводы и рекомендации семинара. CIBIO. Вайран, Португалия, 28–30 мая 2019 г.» (PDF) . Группа специалистов МСОП/SSC по псовым . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 12 февраля 2020 года . Проверено 6 марта 2020 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Перри А.Р., Фейерборн Т.Р., Франц Л.А., Ларсон Г., Малхи Р.С., Мельцер Д.Д. и др. (9 февраля 2021 г.). «Приручение собак и двойное расселение людей и собак по Америке» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 118 (6). Бибкод : 2021PNAS..11810083P . дои : 10.1073/pnas.2010083118 . ПМК 8017920 . ПМИД 33495362 .

- ^ Янссенс Л., Гимш Л., Шмитц Р., Стрит М., Ван Донген С., Кромбе П. (апрель 2018 г.). «Новый взгляд на старую собаку: пересмотр Бонн-Оберкасселя» . Журнал археологической науки . 92 : 126–138. Бибкод : 2018JArSc..92..126J . дои : 10.1016/j.jas.2018.01.004 . hdl : 1854/LU-8550758 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 февраля 2021 года . Проверено 27 марта 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ирвинг-Пис Э.К., Райан Х., Джеймисон А., Димопулос Э.А., Ларсон Г., Франц Л.А. (2018). «Палеогеномика приручения животных» . Палеогеномика . Популяционная геномика. стр. 225–272. дои : 10.1007/13836_2018_55 . ISBN 978-3-030-04752-8 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 14 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ларсон Дж., Брэдли Д.Г. (16 января 2014 г.). «Сколько это в собачьих годах? Появление геномики собачьей популяции» . ПЛОС Генетика . 10 (1): e1004093. дои : 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004093 . ПМЦ 3894154 . ПМИД 24453989 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Фридман А.Х., Уэйн Р.К. (2017). «Расшифровка происхождения собак: от окаменелостей к геномам» . Ежегодный обзор биологических наук о животных . 5 : 281–307. doi : 10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-110937 . ПМИД 27912242 . S2CID 26721918 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Франц Л.А., Брэдли Д.Г., Ларсон Дж., Орландо Л. (август 2020 г.). «Одомашнивание животных в эпоху древней геномики» (PDF) . Обзоры природы Генетика . 21 (8): 449–460. дои : 10.1038/s41576-020-0225-0 . ПМИД 32265525 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 29 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 2 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Бергстрем А., Франц Л., Шмидт Р., Эрсмарк Э., Лебрассер О., Гирдланд-Флинк Л. и др. (2020). «Происхождение и генетическое наследие доисторических собак» . Наука . 370 (6516): 557–564. дои : 10.1126/science.aba9572 . ПМК 7116352 . ПМИД 33122379 . S2CID 225956269 .

- ^ Годобори Дж., Аракава Н., Сяокаити Х., Мацумото Ю., Мацумура С., Хонго Х. и др. (23 февраля 2024 г.). «Японские волки наиболее тесно связаны с собаками и имеют общую ДНК с восточно-евразийскими собаками» . Природные коммуникации . 15 (1): 1680. Бибкод : 2024NatCo..15.1680G . дои : 10.1038/s41467-024-46124-y . ПМЦ 10891106 . ПМИД 38396028 .

- ^ Ларсон Дж. (2012). «Переосмысление приручения собак путем интеграции генетики, археологии и биогеографии» . ПНАС . 109 (23): 8878–8883. Бибкод : 2012PNAS..109.8878L . дои : 10.1073/pnas.1203005109 . ПМЦ 3384140 . ПМИД 22615366 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Острандер Э.А., Ван Г.Д., Ларсон Г., фон Холдт Б.М., Дэвис Б.В., Джаганнатан В. и др. (1 июля 2019 г.). «Dog10K: международная попытка секвенирования для дальнейшего изучения приручения, фенотипов и здоровья собак» . Национальный научный обзор . 6 (4): 810–824. дои : 10.1093/nsr/nwz049 . ПМК 6776107 . ПМИД 31598383 .

- ^ Годобори Дж., Аракава Н., Сяокаити Х., Мацумото Ю., Мацумура С., Хонго Х. и др. (23 февраля 2024 г.). «Японские волки наиболее тесно связаны с собаками и имеют общую ДНК с восточно-евразийскими собаками» . Природные коммуникации . 15 (1): 1680. Бибкод : 2024NatCo..15.1680G . дои : 10.1038/s41467-024-46124-y . ПМЦ 10891106 . ПМИД 38396028 .

- ^ Паркер Х.Г., Дрегер Д.Л., Рембо М., Дэвис Б.В., Маллен А.Б., Карпинтеро-Рамирес Г. и др. (2017). «Геномный анализ показывает влияние географического происхождения, миграции и гибридизации на развитие современных пород собак» . Отчеты по ячейкам . 19 (4): 697–708. дои : 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.079 . ПМЦ 5492993 . ПМИД 28445722 .

- ^ «Немецкий дог | Описание, темперамент, продолжительность жизни и факты | Британника» . www.britanica.com . 14 июня 2024 г. Проверено 15 июня 2024 г.

- ^ «Собака чихуахуа | Описание, темперамент, изображения и факты | Британника» . www.britanica.com . 29 мая 2024 г. Проверено 15 июня 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Канлифф (2004) , с. 12.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Фогл (2009) , стр. 38–39.

- ^ «Боль в спине» . Элвудский ветеринар . Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2024 года . Проверено 24 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Джонс и Гамильтон (1971) , с. 27.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б ДК (6 июля 2023 г.). Энциклопедия собак: полное наглядное руководство . Дорлинг Киндерсли Лимитед. стр. 15–19. ISBN 978-0-241-63310-6 .

- ^ Ниснер С., Денцау С., Малкемпер Е.П. , Гросс Дж.К., Бурда Х., Винкльхофер М. и др. (2016). «Криптохром 1 в фоторецепторах колбочек сетчатки предполагает новую функциональную роль у млекопитающих» . Научные отчеты . 6 : 21848. Бибкод : 2016NatSR...621848N . дои : 10.1038/srep21848 . ПМЦ 4761878 . ПМИД 26898837 .

- ^ Харт В., Новакова П., Малкемпер Е.П., Бегалл С., Ханзал В., Ежек М. и др. (декабрь 2013 г.). «Собаки чувствительны к небольшим изменениям магнитного поля Земли» . Границы в зоологии . 10 (1): 80. дои : 10.1186/1742-9994-10-80 . ПМЦ 3882779 . ПМИД 24370002 .

- ^ «Структура и функции глаз у собак – владельцы собак» . Ветеринарное руководство MSD . Архивировано из оригинала 22 февраля 2024 года . Проверено 5 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Корен С. (2004). Как думают собаки: понимание собачьего разума . Интернет-архив. Нью-Йорк: Свободная пресса. стр. 50–81. ISBN 978-0-7432-2232-7 .

- ^ Кокоциньска-Кусяк А, Вощило М, Зыбала М, Мацёха Ю, Барловска К, Дзенцол М (август 2021 г.). «Обоняние собак: физиология, поведение и возможности практического применения» . Животные . 11 (8): 2463. дои : 10.3390/ani11082463 . ISSN 2076-2615 . ПМЦ 8388720 . ПМИД 34438920 .

- ^ Барбер А.Л., Уилкинсон А., Монтеалегре-З.Ф., Рэтклифф В.Ф., Го К., Миллс Д.С. (2020). «Сравнение слуха и слухового функционирования собак и людей» . Сравнительные обзоры познания и поведения . 15 : 45–94. дои : 10.3819/CCBR.2020.150007 .

- ^ «Чувства собаки — осязание собаки по сравнению с человеческим | Уход за щенками и собаками» . 24 июня 2015 года. Архивировано из оригинала 24 июня 2015 года . Проверено 18 августа 2024 г.

- ^ Канлифф (2004) , стр. 22–23.

- ^ Кинг С., Смит Т.Дж., Грандин Т., Борчелт П. (2016). «Тревожность и импульсивность: факторы, связанные с преждевременным поседением молодых собак» . Прикладная наука о поведении животных . 185 : 78–85. дои : 10.1016/j.applanim.2016.09.013 .

- ^ Чиуччи П., Луккини В., Бойтани Л., Рэнди Э. (декабрь 2003 г.). «Прибылые пальцы у волков как свидетельство смешанного происхождения с собаками». Канадский журнал зоологии . 81 (12): 2077–2081. дои : 10.1139/z03-183 .

- ^ Амичи Ф, Меаччи С, Кэрай Э, Она Л, Либал К, Чиуччи П (2024). «Первое исследовательское сравнение поведения волков (Canis lupus) и гибридов волка и собаки в неволе» . Познание животных . 27 (1): 9. дои : 10.1007/s10071-024-01849-7 . ПМЦ 10907477 . ПМИД 38429445 .

- ^ «Исследование раскрывает тайну того, почему собаки виляют хвостами» . Земля.com . Архивировано из оригинала 4 февраля 2024 года . Проверено 13 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Какова цель собачьего хвоста?» . Далласский зверь Чиро . 15 октября 2019 года. Архивировано из оригинала 30 марта 2024 года . Проверено 30 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Гиперплазия хвостовой железы у собак» . Больницы для животных VCA . Архивировано из оригинала 30 марта 2024 года . Проверено 30 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Синискальчи М., Лусито Р., Валлортигара Г., Куаранта А. (31 октября 2013 г.). «Наблюдение за асимметричным вилянием хвостом влево или вправо вызывает у собак разные эмоциональные реакции» . Современная биология . 23 (22). Cell Press : 2279–2282. Бибкод : 2013CBio...23.2279S . дои : 10.1016/j.cub.2013.09.027 . ПМИД 24184108 .

- ^ Артель К.А., Дюмулен Л.К., Раймхен Т.Е. (19 января 2010 г.). «Поведенческие реакции собак на асимметричное виляние хвостом точной копии роботизированной собаки». Латеральность: асимметрия тела, мозга и познания . 16 (2). При финансовой поддержке Совета естественных наук и инженерных исследований Канады : 129–135. дои : 10.1080/13576500903386700 . ПМИД 20087813 .

- ^ «Что такое синдром счастливого хвоста у собак?» . www.thewildest.com . Архивировано из оригинала 29 марта 2024 года . Проверено 29 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Генетика отпечатков лап — T-локус (натуральный бобтейл) у пуделя» . www.pawprintgenetics.com . Архивировано из оригинала 29 марта 2024 года . Проверено 29 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Купирование ушей и купирование хвоста у собак» . Американская ветеринарная медицинская ассоциация . Проверено 29 июня 2024 г.

- ^ «Купирование хвоста у собак» . Британская ветеринарная ассоциация . Проверено 29 июня 2024 г.

- ^ Дизель Г., Пфайффер Д., Криспин С., Бродбелт Д. (26 июня 2010 г.). «Факторы риска травм хвоста у собак в Великобритании» . Ветеринарный учет . 166 (26): 812–817. дои : 10.1136/vr.b4880 . ISSN 0042-4900 . ПМИД 20581358 .

- ^ «Не пускайте червей в сердце вашего питомца! Факты о болезни сердечного червя» . Управление по санитарному надзору за качеством пищевых продуктов и медикаментов США . 22 декабря 2022 года. Архивировано из оригинала 30 марта 2024 года . Проверено 30 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Капил С., Годи Т.Дж. (ноябрь 2011 г.). «Распространение собачьей чумы у домашних собак из городской дикой природы» . Ветеринарные клиники Северной Америки: практика мелких животных . 41 (6): 1069–1086. дои : 10.1016/j.cvsm.2011.08.005 . ПМЦ 7132517 . ПМИД 22041204 .

- ^ Ванделер А.И., Материя ХК, Каппелер А., Бадде А. (март 1993 г.). «Экология собак и собачье бешенство: выборочный обзор». Revue Scientifique et Technique (Международное бюро эпизоотий) . 12 (1): 51–71. дои : 10.20506/rst.12.1.663 . ПМИД 8518447 .

- ^ Мерфи Л., Коулман А. (2012). «Ксилитовый токсикоз у собак». Ветеринарные клиники Северной Америки: практика мелких животных . 42 (№ 2): 307–312. дои : 10.1016/j.cvsm.2011.12.003 . ПМИД 22381181 .

- ^ «Отравление животных нефтепродуктами – токсикология» . Ветеринарное руководство MSD . Архивировано из оригинала 30 марта 2024 года . Проверено 30 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Фогл Б. (1974). Уход за вашей собакой . п. 423.

- ^ «Рак у домашних животных | Американская ветеринарная медицинская ассоциация» . www.avma.org . Архивировано из оригинала 29 марта 2024 года . Проверено 29 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Когда к домашнему животному приходит внезапная смерть | Американская ветеринарная медицинская ассоциация» . www.avma.org . 4 марта 2022 года. Архивировано из оригинала 29 марта 2024 года . Проверено 29 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Эйхельберг Х., Сена Р. (август 1996 г.). «Продолжительность жизни и причины смертности собак - I. О положении помесей и разных пород» [Продолжительность жизни и причины смертности собак. I. Ситуация в метисах и различных породах собак. Берлинский и Мюнхенский ветеринарный еженедельник (на немецком языке). 109 (8): 292–303. ПМИД 9005839 .

- ^ «Исследование изучает причины смерти собак | Американская ветеринарная медицинская ассоциация» . www.avma.org . 31 мая 2011 г. Архивировано из оригинала 28 ноября 2023 г. . Проверено 29 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Штраус М. (18 мая 2011 г.). «Исследование породных причин смерти собак» . Весь собачий журнал . Архивировано из оригинала 29 марта 2024 года . Проверено 29 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Нельсон Р.В., Ройш CE (сентябрь 2014 г.). «ЖИВОТНЫЕ МОДЕЛИ БОЛЕЗНЕЙ: Классификация и этиология диабета у собак и кошек». Журнал эндокринологии . 222 (3): Т1–Т9. дои : 10.1530/JOE-14-0202 . ПМИД 24982466 .

- ^ «Опасность волн тепла для собак» . Британская организация Bluecross по защите домашних животных . Проверено 17 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Гасемзаде И., Намази С. (2015). «Обзор бактериальных и вирусных зоонозных инфекций, передающихся собаками» . Журнал медицины и жизни . 8 (Спецвыпуск 4): 1–5. ПМЦ 5319273 . ПМИД 28316698 .

- ^ «Домашние животные» . Центр США по контролю заболеваний . 24 мая 2024 г. Проверено 19 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Монтойя М., Моррисон Дж.А., Арриньон Ф., Споффорд Н., Чарльз Х., Хоурс М.А. и др. (21 февраля 2023 г.). «Таблицы продолжительности жизни собак и кошек, составленные на основе клинических данных» . Границы ветеринарной науки . 10 . дои : 10.3389/fvets.2023.1082102 . ПМК 9989186 . ПМИД 36896289 .

- ^ Макмиллан К.М., Билби Дж., Уильямс К.Л., Апджон М.М., Кейси Р.А., Кристли Р.М. (февраль 2024 г.). «Долголетие пород собак-компаньонов: те, кто подвержен риску ранней смерти» . Научные отчеты . 14 (1): 531. Бибкод : 2024НатСР..14..531М . doi : 10.1038/s41598-023-50458-w . ПМЦ 10834484 . ПМИД 38302530 .

- ^ Перейра К. «Жара у домашних собак и кошек, цикл эструса и ложная беременность – DawgieBowl» . Архивировано из оригинала 29 марта 2024 года . Проверено 29 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Течка и спаривание у собак» . Больницы для животных VCA . Архивировано из оригинала 7 февраля 2024 года . Проверено 1 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Конкэннон П., Цуцуи Т., Шилле В. (2001). «Развитие эмбриона, гормональные потребности и материнские реакции во время беременности у собак». Журнал репродукции и фертильности. Добавка . 57 : 169–179. ПМИД 11787146 .

- ^ «Развитие собак – Эмбриология» . Php.med.unsw.edu.au. 16 июня 2013 года. Архивировано из оригинала 2 декабря 2013 года . Проверено 20 мая 2021 г.

- ^ «Гестация у собак» . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июня 2013 года . Проверено 24 марта 2013 г.

- ^ «Оценки перенаселения домашних животных HSUS» . Гуманное общество США. Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2013 года . Проверено 22 октября 2008 г.

- ^ «10 главных причин стерилизовать/кастрировать вашего питомца» . Американское общество по предотвращению жестокого обращения с животными. Архивировано из оригинала 1 февраля 2009 года . Проверено 16 мая 2007 г.

- ^ «Домашние животные в цифрах» . Гуманное общество США . Архивировано из оригинала 22 февраля 2021 года . Проверено 3 марта 2021 г.

- ^ Махлоу Дж. К. (1999). «Оценка доли собак и кошек, стерилизованных хирургическим путем». Журнал Американской ветеринарной медицинской ассоциации . 215 (№5): 640–643. дои : 10.2460/javma.1999.215.05.640 . ПМИД 10476708 .

Хотя причина перенаселения домашних животных многогранна, основным фактором, способствующим этому, является относительное отсутствие владельцев, решивших стерилизовать или кастрировать своих животных.

- ^ Хайденбергер Э., Уншелм Дж. (февраль 1990 г.). «Изменения в поведении собак после кастрации». Ветеринарная практика (на немецком языке). 18 (1): 69–75. ПМИД 2326799 .

- ^ Моррисон, Уоллес Б. (1998). Рак у собак и кошек (1-е изд.). Уильямс и Уилкинс. п. 583. ИСБН 978-0-683-06105-5 .

- ^ Арнольд С. (1997). «Недержание мочи у кастрированных сук. Часть 1: Значение, клиника и этиопатогенез» [Недержание мочи у кастрированных сук. Часть 1: Значение, клинические аспекты и этиопатогенез. Швейцарский архив ветеринарной медицины (на немецком языке). 139 (6): 271–276. ПМИД 9411733 .

- ^ Джонстон С., Камолпатана К., Рут-Кустриц М., Джонстон Г. (июль 2000 г.). «Расстройства простаты у собак». Наука о воспроизводстве животных . 60–61: 405–415. дои : 10.1016/s0378-4320(00)00101-9 . ПМИД 10844211 .

- ^ Кустриц М.В. (декабрь 2007 г.). «Определение оптимального возраста для гонадэктомии собак и кошек» . Журнал Американской ветеринарной медицинской ассоциации . 231 (11): 1665–1675. дои : 10.2460/javma.231.11.1665 . ПМИД 18052800 .

- ^ Лерой Дж. (2011). «Генетическое разнообразие, инбридинг и практика разведения собак: результаты анализа родословных». Ветеринар. Дж . 189 (2): 177–182. дои : 10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.06.016 . ПМИД 21737321 .

- ^ Чарльзворт Д., Уиллис Дж. Х. (2009). «Генетика инбредной депрессии». Нат. Преподобный Жене . 10 (11): 783–796. дои : 10.1038/nrg2664 . ПМИД 19834483 . S2CID 771357 .

- ^ Бернштейн Х., Хопф Ф.А., Мишод Р.Э. (1987). «Молекулярная основа эволюции пола». Молекулярная генетика развития . Достижения генетики. Том. 24 (опубликовано 2 марта 2008 г.). стр. 323–370. дои : 10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60012-7 . ISBN 978-0-12-017624-3 . ПМИД 3324702 .

- ^ Лерой Дж., Фокас Ф., Хедан Б., Верье Э., Роньон Х. (январь 2015 г.). «Влияние инбридинга на размер помета и выживаемость некоторых пород собак» (PDF) . Ветеринарный журнал . 203 (1): 74–78. дои : 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.11.008 . ПМИД 25475165 .

- ^ Грески С., Хаманн Х., Distl O (2005). «Влияние инбридинга на размер помета и долю мертворожденных щенков у такс». Берлинский и Мюнхенский ветеринарный еженедельник (на немецком языке). 118 (3–4): 134–139. ПМИД 15803761 .

- ^ ван дер Бик С., Нилен А.Л., Шуккен Ю.Х., Браскамп Э.В. (сентябрь 1999 г.). «Оценка генетического, общего и внутрипометного влияния на смертность перед отъемом в когорте щенков при рождении». Американский журнал ветеринарных исследований . 60 (9): 1106–1110. дои : 10.2460/ajvr.1999.60.09.1106 . ПМИД 10490080 .

- ^ Левитис Д.А., Лидикер В.З., Фройнд Г. (июль 2009 г.). «Поведенческие биологи не пришли к единому мнению относительно того, что представляет собой поведение» . Поведение животных . 78 (1): 103–110. дои : 10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.03.018 . ПМК 2760923 . ПМИД 20160973 .

- ^ Бернс Г., Брукс А., Спивак М. (2012). Нойхаусс СК (ред.). «Функциональная МРТ у бодрствующих безудержных собак» . ПЛОС ОДИН . 7 (5): e38027. Бибкод : 2012PLoSO...738027B . дои : 10.1371/journal.pone.0038027 . ПМК 3350478 . ПМИД 22606363 .

- ^ Томаселло М., Камински Дж. (4 сентября 2009 г.). «Как младенец, как собака». Наука . 325 (5945): 1213–1214. дои : 10.1126/science.1179670 . ПМИД 19729645 . S2CID 206522649 .

- ^ Серпелл Дж. А., Даффи Д. Л. (2014). «Породы собак и их поведение». Познание и поведение домашней собаки . стр. 31–57. дои : 10.1007/978-3-642-53994-7_2 . ISBN 978-3-642-53993-0 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Кейган А., Бласс Т. (декабрь 2016 г.). «Идентификация геномных вариантов, предположительно являющихся целью отбора во время приручения собаки» . Эволюционная биология BMC . 16 (1): 10. Бибкод : 2016BMCEE..16...10C . дои : 10.1186/s12862-015-0579-7 . ПМК 4710014 . ПМИД 26754411 .

- ^ Кейган А., Бласс Т. (2016). «Идентификация геномных вариантов, предположительно являющихся целью отбора во время приручения собаки» . Эволюционная биология BMC . 16 (1): 10. Бибкод : 2016BMCEE..16...10C . дои : 10.1186/s12862-015-0579-7 . ПМК 4710014 . ПМИД 26754411 .

- ^ Алмада RC, Коимбра, Северная Каролина (июнь 2015 г.). «Рекрутирование стриатонигральных растормаживающих и нигротектальных тормозных ГАМКергических путей при организации защитного поведения мышей в опасной среде с ядовитой змеей Bothrops alternatus ( Reptilia , Viperidae )». Синапс . 69 (6): 299–313. дои : 10.1002/syn.21814 . ПМИД 25727065 .

- ^ Лорд К., Шнайдер Р.А., Коппингер Р. (2016). «Эволюция служебных собак». В Серпелле Дж. (ред.). Домашняя собака: ее эволюция, поведение и взаимодействие с людьми . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. 42–66. дои : 10.1017/9781139161800 . ISBN 978-1-107-02414-4 .

- ^ фон Холдт Б.М., Шульдинер Э., Кох И.Дж., Карцинель Р.Ю., Хоган А., Брубейкер Л. и др. (7 июля 2017 г.). «Структурные варианты генов, связанных с синдромом Вильямса-Бойрена, лежат в основе стереотипной гиперсоциальности у домашних собак» . Достижения науки . 3 (7): e1700398. Бибкод : 2017SciA....3E0398V . дои : 10.1126/sciadv.1700398 . ПМК 5517105 . ПМИД 28776031 .

- ^ Гонсалес-Мартинес А, Муньис де Мигель С, Гранья Н, Костас Х, Дьегес ФХ (13 марта 2023 г.). «Уровни серотонина и дофамина в крови у собак с СДВГ» . Животные . 13 (6): 1037. дои : 10.3390/ani13061037 . ПМЦ 10044280 . ПМИД 36978578 .

- ^ Сулкама С., Пуурунен Дж., Салонен М., Миккола С., Хаканен Е., Араухо С. и др. (октябрь 2021 г.). «Гиперактивность, импульсивность и невнимательность собак имеют схожие демографические факторы риска и поведенческие сопутствующие заболевания, что и СДВГ у людей» . Трансляционная психиатрия . 11 (1): 501. doi : 10.1038/s41398-021-01626-x . ПМЦ 8486809 . ПМИД 34599148 .

- ^ «Как справиться с агрессией между собаками (агрессивное поведение между собаками)» . www.petmd.com . Архивировано из оригинала 29 марта 2024 года . Проверено 29 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Фань З, Бянь З, Хуан Х, Лю Т, Рен Р, Чен Икс и др. (21 февраля 2023 г.). «Диетические стратегии снятия стресса у домашних собак и кошек» . Антиоксиданты . 12 (3): 545. doi : 10.3390/antiox12030545 . ПМЦ 10045725 . ПМИД 36978793 .

- ^ «Собаки и посттравматическое стрессовое расстройство (ПТСР)» . Американский кинологический клуб . Сотрудники Американского кинологического клуба. 22 мая 2018 г. Архивировано из оригинала 30 марта 2024 г. . Проверено 30 марта 2024 г.

- ^ NutriSource (19 октября 2022 г.). «Какие естественные инстинкты есть у собак?» . Корма для домашних животных NutriSource . Архивировано из оригинала 2 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 2 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Веттер С.Г., Рангхард Л., Шайдл Л., Котршаль К., Рейндж Ф (13 сентября 2023 г.). «Наблюдательная пространственная память у волков и собак» . ПЛОС ОДИН . 18 (9): e0290547. Бибкод : 2023PLoSO..1890547V . дои : 10.1371/journal.pone.0290547 . ПМЦ 10499247 . ПМИД 37703235 .

- ^ Харт Б.Л., Харт Л.А., Тигпен А.П., Тран А., Бейн М.Дж. (май 2018 г.). «Парадокс конспецифической копрофагии собак» . Ветеринария и наука . 4 (2): 106–114. дои : 10.1002/vms3.92 . ПМК 5980124 . ПМИД 29851313 .

- ^ Нганвонгпанит К., Яно Т. (сентябрь 2012 г.). «Побочные эффекты у 412 собак от плавания в хлорированном бассейне». Тайский журнал ветеринарной медицины . 42 (3): 281–286. дои : 10.56808/2985-1130.2398 .

- ^ Нганвонгпанит К., Танвисут С., Яно Т., Конгтавелерт П. (9 января 2014 г.). «Влияние плавания на клинические функциональные параметры и биомаркеры сыворотки крови у здоровых собак и собак с остеоартритом» . ISRN Ветеринария . 2014 : 459809. doi : 10.1155/2014/459809 . ПМК 4060742 . ПМИД 24977044 .

- ^ Росси Л., Вальдес Лумбрерас А.Е., Вани С., Делл'Анно М., Бонтемпо В. (15 ноября 2021 г.). «Пищевые и функциональные свойства молозива у щенков и котят» . Животные . 11 (11): 3260. дои : 10.3390/ani11113260 . ПМЦ 8614261 . ПМИД 34827992 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Частант С (14 июня 2023 г.). «Лактация домашних хищников» . Animal Frontiers: Обзорный журнал животноводства . 13 (3): 78–83. дои : 10.1093/af/vfad027 . ПМЦ 10266749 . ПМИД 37324213 .

- ^ «Беременность, роды и послеродовой уход у собак: полное руководство» . www.petmd.com . Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2024 года . Проверено 24 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Родится ваш первый помет» (PDF) . Эбби Ветс . Февраль 2022.

- ^ Бивер Б.В. (2009 г.). «Социальное поведение собак». Поведение собак . стр. 133–192. дои : 10.1016/B978-1-4160-5419-1.00004-3 . ISBN 978-1-4160-5419-1 .

- ^ Додман Н. «Копрофагия | Поведение собак» . www.tendercareanimalhospital.net . Архивировано из оригинала 31 марта 2024 года . Проверено 31 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Как кобель отреагирует на новорожденных щенков? | Милашка» . Милота.com . Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2024 года . Проверено 24 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Есть ли у кобелей отцовский инстинкт?» . Панель Мудрости™ . 16 июня 2019 года. Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2024 года . Проверено 24 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Что делать, если ваша собака отказывается от щенков» . PBS Pet Travel . 17 декабря 2018 года. Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2024 года . Проверено 24 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Пилли, Джон (2013). Чейзер: Раскрытие гениальности собаки, которая знает тысячу слов . Хоутон Миффлин Харкорт . ISBN 978-0-544-10257-6 .

- ^ Леа С.Е., Остхаус Б (2018). «В каком смысле собаки особенные? Собачье мышление в сравнительном контексте» . Обучение и поведение . 46 (4): 335–363. дои : 10.3758/s13420-018-0349-7 . ПМК 6276074 . ПМИД 30251104 .

- ^ Слука С.М., Станко К., Кэмпбелл А., Касерес Дж., Паноз-Браун Д., Уилер А. и др. (2018). «Случайная пространственная память у домашней собаки ( Canis familis )» . Обучение и поведение . 46 (4): 513–521. дои : 10.3758/s13420-018-0327-0 . ПМИД 29845456 .

- ^ Аулет Л.С., Чиу В.К., Причард А., Спивак М., Лоуренко С.Ф., Бернс Г.С. (декабрь 2019 г.). «Собачье чувство количества: свидетельства активации, зависящей от числового соотношения, в теменно-височной коре» . Издательство Королевского общества . 15 (12) (опубликовано 18 декабря 2019). дои : 10.1098/rsbl.2019.0666 . ПМК 6936025 . ПМИД 31847744 .

- ^ Пиотти П., Камински Дж. (10 августа 2016 г.). «Полезно ли собаки предоставляют информацию?» . ПЛОС ОДИН . 11 (8): e0159797. Бибкод : 2016PLoSO..1159797P . дои : 10.1371/journal.pone.0159797 . ПМК 4980001 . ПМИД 27508932 .

- ^ Смит Б., Личфилд С. (2010). «Насколько хорошо динго ( Canis dingo ) справляются с задачей объезда». Поведение животных . 80 : 155–162. дои : 10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.04.017 . S2CID 53153703 .

- ^ Миклоши А., Кубиньи Э., Топал Дж., Гачи М., Вираньи З., Чаньи В. (апрель 2003 г.). «Простая причина большой разницы: волки не оглядываются на людей, а собаки оглядываются» . Курр Биол . 13 (9): 763–766. Бибкод : 2003CBio...13..763M . дои : 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00263-X . ПМИД 12725735 . S2CID 10200094 .

- ^ Корен С (2001). Как говорить с собакой: освоение искусства общения между собакой и человеком . Саймон и Шустер. п. xii. ISBN 978-0-7432-0297-8 .

- ^ Камински Дж., Хайндс Дж., Моррис П., Уоллер Б.М. (2017). «Человеческое внимание влияет на мимику домашних собак» . Научные отчеты . 7 (1): 12914. Бибкод : 2017НатСР...712914К . дои : 10.1038/s41598-017-12781-x . ПМК 5648750 . ПМИД 29051517 .

- ^ Камински Дж., Уоллер Б.М., Диого Р., Хартстон-Роуз А., Берроуз А.М. (2019). «Эволюция анатомии лицевых мышц у собак» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 116 (29): 14677–14681. Бибкод : 2019PNAS..11614677K . дои : 10.1073/pnas.1820653116 . ПМК 6642381 . ПМИД 31209036 .

- ^ Линделл Э., Фейресильде М., Хорвиц Д., Ландсберг Г. «Проблемы поведения собак: поведение при маркировке» . Больницы для животных VCA . Архивировано из оригинала 21 января 2024 года . Проверено 13 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Решение проблемы маркировки собак» . Американский кинологический клуб . Архивировано из оригинала 29 сентября 2023 года . Проверено 13 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Почему собаки писают, когда они взволнованы или напуганы?» . Еловые питомцы . Архивировано из оригинала 30 марта 2024 года . Проверено 30 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Что такое перевозбуждение у собак? | FOTP» . Передняя часть стаи . 26 мая 2023 года. Архивировано из оригинала 30 марта 2024 года . Проверено 30 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Нормальное социальное поведение собак – владельцы собак» . Ветеринарное руководство MSD . Архивировано из оригинала 29 марта 2024 года . Проверено 29 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Тами Дж., Галлахер А. (сентябрь 2009 г.). «Описание поведения домашней собаки (Canis familiaris) опытными и неопытными людьми». Прикладная наука о поведении животных . 120 (3–4): 159–169. дои : 10.1016/j.applanim.2009.06.009 .

- ^ Андикс А., Гачи М., Фараго Т., Киш А., Миклоши А. (2014). «Регионы, чувствительные к голосу в мозгу собаки и человека, выявлены с помощью сравнительной фМРТ» (PDF) . Современная биология . 24 (5): 574–578. Бибкод : 2014CBio...24..574A . дои : 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.058 . ПМИД 24560578 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 6 октября 2022 года . Проверено 2 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Нагасава М., Мурай К., Моги К., Кикусуи Т. (2011). «Собаки могут отличить улыбающиеся лица людей от пустых выражений». Познание животных . 14 (4): 525–533. дои : 10.1007/s10071-011-0386-5 . ПМИД 21359654 . S2CID 12354384 .

- ^ Альбукерке Н., Го К., Уилкинсон А., Савалли С., Отта Е., Миллс Д. (2016). «Собаки распознают собачьи и человеческие эмоции» . Письма по биологии . 12 (1): 20150883. doi : 10.1098/rsbl.2015.0883 . ПМЦ 4785927 . ПМИД 26763220 .

- ^ Кук П.Ф., Причард А., Спивак М., Бернс Г.С. (12 августа 2016 г.). «ФМРТ собак в бодрствовании предсказывает их предпочтение похвале, а не еде» . Социальная когнитивная и аффективная нейронаука . 11 (12): 1853–1862. дои : 10.1093/скан/nsw102 . ПМК 5141954 . ПМИД 27521302 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Янг Дж.К., Олсон К.А., Ридинг Р.П., Амгаланбаатар С., Бергер Дж. (февраль 2011 г.). «Дикая природа переходит к собакам? Влияние одичавших и свободно бродящих собак на популяции диких животных» . Бионаука . 61 (2): 125–132. дои : 10.1525/bio.2011.61.2.7 .

- ^ Дэниэлс Т.Дж., Бекофф М. (27 ноября 1989 г.). «Популяция и социальная биология собак, гуляющих на свободном выгуле, Canis familis» . Журнал маммологии . 70 (4): 754–762. дои : 10.2307/1381709 . JSTOR 1381709 .

- ^ Хьюз Дж., Макдональд Д.В. (январь 2013 г.). «Обзор взаимодействия между свободно бродящими домашними собаками и дикой природой». Биологическая консервация . 157 : 341–351. Бибкод : 2013BCons.157..341H . doi : 10.1016/j.biocon.2012.07.005 .