Неметалл

| Отрывок из таблицы Менделеева с выделением неметаллов. |

|

| всегда/обычно считаются неметаллами [1] [2] [3] |

| металлоиды, иногда считающиеся неметаллами [а] |

| status as nonmetal or metal unconfirmed[5] |

| Part of a series on the |

| Periodic table |

|---|

В контексте таблицы Менделеева неметалл — это химический элемент , который в большинстве случаев не обладает характерными металлическими свойствами. Они варьируются от бесцветных газов, таких как водород, до блестящих кристаллов, таких как йод . Физически они обычно легче (менее плотны), чем элементы, образующие металлы, и часто являются плохими проводниками тепла и электричества . С химической точки зрения неметаллы имеют относительно высокую электроотрицательность или обычно притягивают электроны в химической связи с другим элементом, а их оксиды имеют тенденцию быть кислотными .

Семнадцать элементов широко признаны неметаллами. Кроме того, некоторые или все из шести пограничных элементов ( металлоидов ) иногда считаются неметаллами.

The two lightest nonmetals, hydrogen and helium, together make up about 98% of the mass of the observable universe. Five nonmetallic elements—hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and silicon—make up the bulk of Earth's atmosphere, biosphere, crust and oceans.

Industrial uses of nonmetals include in electronics, energy storage, agriculture, and chemical production.

Most nonmetallic elements were identified in the 18th and 19th centuries. While a distinction between metals and other minerals had existed since antiquity, a basic classification of chemical elements as metallic or nonmetallic emerged only in the late 18th century. Since then over thirty properties have been suggested as criteria for distinguishing nonmetals from metals.

Definition and applicable elements

[edit]- Unless otherwise noted, this article describes the stable form of an element at standard temperature and pressure (STP).[b]

Nonmetallic chemical elements are often described as lacking properties common to metals, namely shininess, pliability, good thermal and electrical conductivity, and a general capacity to form basic oxides.[8][9] There is no widely-accepted precise definition;[10] any list of nonmetals is open to debate and revision.[1] The elements included depend on the properties regarded as most representative of nonmetallic or metallic character.

Fourteen elements are almost always recognized as nonmetals:[1][2]

Three more are commonly classed as nonmetals, but some sources list them as "metalloids",[3] a term which refers to elements regarded as intermediate between metals and nonmetals:[11]

One or more of the six elements most commonly recognized as metalloids are sometimes instead counted as nonmetals:

About 15–20% of the 118 known elements[12] are thus classified as nonmetals.[c]

General properties

[edit]Physical

[edit]of some nonmetallic elements

Nonmetals vary greatly in appearance, being colorless, colored or shiny.For the colorless nonmetals (hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, and the noble gases), no absorption of light happens in the visible part of the spectrum, and all visible light is transmitted.[15]The colored nonmetals (sulfur, fluorine, chlorine, bromine) absorb some colors (wavelengths) and transmit the complementary or opposite colors. For example, chlorine's "familiar yellow-green colour ... is due to a broad region of absorption in the violet and blue regions of the spectrum".[16][d] The shininess of boron, graphite (carbon), silicon, black phosphorus, germanium, arsenic, selenium, antimony, tellurium, and iodine[e] is a result of varying degrees of metallic conduction where the electrons can reflect incoming visible light.[19]

About half of nonmetallic elements are gases under standard temperature and pressure; most of the rest are solids. Bromine, the only liquid, is usually topped by a layer of its reddish-brown fumes. The gaseous and liquid nonmetals have very low densities, melting and boiling points, and are poor conductors of heat and electricity.[20] The solid nonmetals have low densities and low mechanical strength (often being brittle or crumbly),[21] and a wide range of electrical conductivity.[f]

This diversity in form stems from variability in internal structures and bonding arrangements. Covalent nonmetals existing as discrete atoms like xenon, or as small molecules, such as oxygen, sulfur, and bromine, have low melting and boiling points; many are gases at room temperature, as they are held together by weak London dispersion forces acting between their atoms or molecules, although the molecules themselves have strong covalent bonds.[25] In contrast, nonmetals that form extended structures, such as chains of up to 1,000 selenium atoms,[26] sheets of carbon atoms in graphite,[27] or three-dimensional lattices of silicon atoms[28] have higher melting and boiling points, and are all solids, as it takes more energy to overcome their stronger bonding.[29] Nonmetals closer to the left or bottom of the periodic table (and so closer to the metals) often have metallic interactions between their molecules, chains, or layers; this occurs in boron,[30] carbon,[31] phosphorus,[32] arsenic,[33] selenium,[34] antimony,[35] tellurium[36] and iodine.[37]

| Aspect | Metals | Nonmetals |

|---|---|---|

| Appearance and form | Shiny if freshly prepared or fractured; few colored;[38] all but one solid[39] | Shiny, colored or transparent;[40] all but one solid or gaseous[39] |

| Density | Often higher | Often lower |

| Plasticity | Mostly malleable and ductile | Often brittle solids |

| Electrical conductivity[41] | Good | Poor to good |

| Electronic structure[42] | Metal or semimetalic | Semimetal, semiconductor, or insulator |

Covalently bonded nonmetals often share only the electrons required to achieve a noble gas electron configuration.[43] For example, nitrogen forms diatomic molecules featuring a triple bonds between each atom, both of which thereby attain the configuration of the noble gas neon. Antimony's larger atomic size prevents triple bonding, resulting in buckled layers in which each antimony atom is singly bonded with three other nearby atoms.[44]

Good electrical conductivity occurs when there is metallic bonding,[45] however the electrons in nonmetals are often not metallic.[46] Good electrical and thermal conductivity associated with metallic electrons is seen in carbon (as graphite, along its planes), arsenic, and antimony.[g] Good thermal conductivity occurs in boron, silicon, phosphorus, and germanium;[22] such conductivity is transmitted though vibrations of the crystalline lattices of these elements.[47] Moderate electrical conductivity is observed in the semiconductors[48] boron, silicon, phosphorus, germanium, selenium, tellurium, and iodine.

Many of the nonmetallic elements are brittle, where dislocation cannot readily move so they tend to undergo brittle fracture rather than deforming.[49] Some do deform such as white phosphorus (soft as wax, pliable and can be cut with a knife, at room temperature),[50] in plastic sulfur,[51] and in selenium which can be drawn into wires from its molten state.[52] Graphite is a standard solid lubricant where dislocations move very easily in the basal planes.[53]

Allotropes

[edit]Over half of the nonmetallic elements exhibit a range of less stable allotropic forms, each with distinct physical properties.[54] For example, carbon, the most stable form of which is graphite, can manifest as diamond, buckminsterfullerene,[55] amorphous[56] and paracrystalline[57] variations. Allotropes also occur for nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, sulfur, selenium, the six metalloids, and iodine.[58]

Chemical

[edit]| Aspect | Metals | Nonmetals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactivity[59] | Wide range: very reactive to noble | ||

| Oxides | lower | Basic | Acidic; never basic[60] |

| higher | Increasingly acidic | ||

| Compounds with metals[61] | Alloys | Ionic compounds | |

| Ionization energy[62] | Low to high | Moderate to very high | |

| Electronegativity[63] | Low to high | Moderate to very high | |

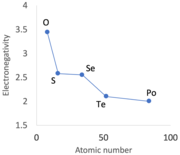

Nonmetals have relatively high values of electronegativity, and their oxides are usually acidic. Exceptions may occur if a nonmetal is not very electronegative, or if its oxidation state is low, or both. These non-acidic oxides of nonmetals may be amphoteric (like water, H2O[64]) or neutral (like nitrous oxide, N2O[65][h]), but never basic.

Nonmetals tend to gain electrons during chemical reactions, in contrast to metals which tend to donate electrons. This behavior is related to the stability of electron configurations in the noble gases, which have complete outer shells as summarized by the duet and octet rules of thumb.[68]

They typically exhibit higher ionization energies, electron affinities, and standard electrode potentials than metals. Generally, the higher these values are (including electronegativity) the more nonmetallic the element tends to be.[69] For example, the chemically very active nonmetals fluorine, chlorine, bromine, and iodine have an average electronegativity of 3.19—a figure[i] higher than that of any metallic element.

The chemical distinctions between metals and nonmetals is connected to the attractive force between the positive nuclear charge of an individual atom and its negatively charged outer electrons. From left to right across each period of the periodic table, the nuclear charge (number of protons in the atomic nucleus) increases.[70] There is a corresponding reduction in atomic radius[71] as the increased nuclear charge draws the outer electrons closer to the nuclear core.[72] In chemical bonding, nonmetals tend to gain electrons due to their higher nuclear charge, resulting in negatively charged ions.[73]

The number of compounds formed by nonmetals is vast.[74] The first 10 places in a "top 20" table of elements most frequently encountered in 895,501,834 compounds, as listed in the Chemical Abstracts Service register for November 2, 2021, were occupied by nonmetals. Hydrogen, carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen collectively appeared in most (80%) of compounds. Silicon, a metalloid, ranked 11th. The highest-rated metal, with an occurrence frequency of 0.14%, was iron, in 12th place.[75] A few examples of nonmetal compounds are: boric acid (H

3BO

3), used in ceramic glazes;[76] selenocysteine (C

3H

7NO

2Se), the 21st amino acid of life;[77] phosphorus sesquisulfide (P4S3), found in strike anywhere matches;[78] and teflon ((C

2F

4)n), used to create non-stick coatings for pans and other cookware.[79]

Complications

[edit]Adding complexity to the chemistry of the nonmetals are anomalies occurring in the first row of each periodic table block; non-uniform periodic trends; higher oxidation states; multiple bond formation; and property overlaps with metals.

First row anomaly

[edit]| Condensed periodic table highlighting the first row of each block: s p d and f | |||||||||||||

| Period | s-block | ||||||||||||

| 1 | H 1 | He 2 | p-block | ||||||||||

| 2 | Li 3 | Be 4 | B 5 | C 6 | N 7 | O 8 | F 9 | Ne 10 | |||||

| 3 | Na 11 | Mg 12 | d-block | Al 13 | Si 14 | P 15 | S 16 | Cl 17 | Ar 18 | ||||

| 4 | K 19 | Ca 20 | Sc-Zn 21-30 | Ga 31 | Ge 32 | As 33 | Se 34 | Br 35 | Kr 36 | ||||

| 5 | Rb 37 | Sr 38 | f-block | Y-Cd 39-48 | In 49 | Sn 50 | Sb 51 | Te 52 | I 53 | Xe 54 | |||

| 6 | Cs 55 | Ba 56 | La-Yb 57-70 | Lu-Hg 71-80 | Tl 81 | Pb 82 | Bi 83 | Po 84 | At 85 | Rn 86 | |||

| 7 | Fr 87 | Ra 88 | Ac-No 89-102 | Lr-Cn 103-112 | Nh 113 | Fl 114 | Mc 115 | Lv 116 | Ts 117 | Og 118 | |||

| Group | (1) | (2) | (3-12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | (17) | (18) | ||||

| The first-row anomaly strength by block is s >> p > d > f.[80][j] | |||||||||||||

Starting with hydrogen, the first row anomaly primarily arises from the electron configurations of the elements concerned. Hydrogen is notable for its diverse bonding behaviors. It most commonly forms covalent bonds, but it can also lose its single electron in an aqueous solution, leaving behind a bare proton with tremendous polarizing power.[81] Consequently, this proton can attach itself to the lone electron pair of an oxygen atom in a water molecule, laying the foundation for acid-base chemistry.[82] Moreover, a hydrogen atom in a molecule can form a second, albeit weaker, bond with an atom or group of atoms in another molecule. Such bonding, "helps give snowflakes their hexagonal symmetry, binds DNA into a double helix; shapes the three-dimensional forms of proteins; and even raises water's boiling point high enough to make a decent cup of tea."[83]

Hydrogen and helium, as well as boron through neon, have unusually small atomic radii. This phenomenon arises because the 1s and 2p subshells lack inner analogues (meaning there is no zero shell and no 1p subshell), and they therefore experience less electron-electron exchange interactions, unlike the 3p, 4p, and 5p subshells of heavier elements.[84][dubious – discuss] As a result, ionization energies and electronegativities among these elements are higher than the periodic trends would otherwise suggest. The compact atomic radii of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen facilitate the formation of double or triple bonds.[85]

While it would normally be expected, on electron configuration consistency grounds, that hydrogen and helium would be placed atop the s-block elements, the significant first row anomaly shown by these two elements justifies alternative placements. Hydrogen is occasionally positioned above fluorine, in group 17, rather than above lithium in group 1. Helium is almost always placed above neon, in group 18, rather than above beryllium in group 2.[86]

Secondary periodicity

[edit]

An alternation in certain periodic trends, sometimes referred to as secondary periodicity, becomes evident when descending groups 13 to 15, and to a lesser extent, groups 16 and 17.[87][k] Immediately after the first row of d-block metals, from scandium to zinc, the 3d electrons in the p-block elements—specifically, gallium (a metal), germanium, arsenic, selenium, and bromine—prove less effective at shielding the increasing positive nuclear charge.

The Soviet chemist Shchukarev gives two more tangible examples:[89]

- "The toxicity of some arsenic compounds, and the absence of this property in analogous compounds of phosphorus [P] and antimony [Sb]; and the ability of selenic acid [H2SeO4] to bring metallic gold [Au] into solution, and the absence of this property in sulfuric [H2SO4] and [H2TeO4] acids."

Higher oxidation states

[edit]- Roman numerals such as III, V and VIII denote oxidation states

Some nonmetallic elements exhibit oxidation states that deviate from those predicted by the octet rule, which typically results in a valency of –3 in group 15, –2 in group 16, –1 in group 17, and 0 in group 18. Examples include ammonia N(III)H3, hydrogen sulfide(II) H2S, hydrogen fluoride(I) HF, and elemental xenon(0) Xe. Meanwhile, the maximum possible oxidation state increases from +5 in group 15, to +8 in group 18. The +5 oxidation state is observable from period 2 onward, in compounds such as nitric acid HN(V)O3 and phosphorus pentafluoride PCl5.[l] Higher oxidation states in later groups emerge from period 3 onwards, as seen in sulfur hexafluoride SF6, iodine heptafluoride IF7, and xenon(VIII) tetroxide XeO4. For heavier nonmetals, their larger atomic radii and lower electronegativity values enable the formation of compounds with higher oxidation numbers, supporting higher bulk coordination numbers.[90]

Multiple bond formation

[edit]

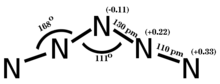

Period 2 nonmetals, particularly carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen, show a propensity to form multiple bonds. The compounds formed by these elements often exhibit unique stoichiometries and structures, as seen in the various nitrogen oxides,[90] which are not commonly found in elements from later periods.

Property overlaps

[edit]While certain elements have traditionally been classified as nonmetals and others as metals, some overlapping of properties occurs. Writing early in the twentieth century, by which time the era of modern chemistry had been well-established,[92] Humphrey[93] observed that:

- ... these two groups, however, are not marked off perfectly sharply from each other; some nonmetals resemble metals in certain of their properties, and some metals approximate in some ways to the non-metals.

Examples of metal-like properties occurring in nonmetallic elements include:

- Silicon has an electronegativity (1.9) comparable with metals such as cobalt (1.88), copper (1.9), nickel (1.91) and silver (1.93);[63]

- The electrical conductivity of graphite exceeds that of some metals;[n]

- Selenium can be drawn into a wire;[52]

- Radon is the most metallic of the noble gases and begins to show some cationic behavior, which is unusual for a nonmetal;[97] and

- In extreme conditions, just over half of nonmetallic elements can form homopolyatomic cations.[o]

Examples of nonmetal-like properties occurring in metals are:

- Tungsten displays some nonmetallic properties, sometimes being brittle, having a high electronegativity, and forming only anions in aqueous solution,[99] and predominately acidic oxides.[9][100]

- Gold, the "king of metals" has the highest electrode potential among metals, suggesting a preference for gaining rather than losing electrons. Gold's ionization energy is one of the highest among metals, and its electron affinity and electronegativity are high, with the latter exceeding that of some nonmetals. It forms the Au– auride anion and exhibits a tendency to bond to itself, behaviors which are unexpected for metals. In aurides (MAu, where M = Li–Cs), gold's behavior is similar to that of a halogen.[101] Gold has a large enough nuclear potential that the electrons have to be considered with relativistic effects included which changes some of the properties.[102]

A relatively recent development involves certain compounds of heavier p-block elements, such as silicon, phosphorus, germanium, arsenic and antimony, exhibiting behaviors typically associated with transition metal complexes. This is linked to a small energy gap between their filled and empty molecular orbitals, which are the regions in a molecule where electrons reside and where they can be available for chemical reactions. In such compounds, this allows for unusual reactivity with small molecules like hydrogen (H2), ammonia (NH3), and ethylene (C2H4), a characteristic previously observed primarily in transition metal compounds. These reactions may open new avenues in catalytic applications.[103]

Types

[edit]Nonmetal classification schemes vary widely, with some accommodating as few as two subtypes and others identifying up to seven. For example, the periodic table in the Encyclopaedia Britannica recognizes noble gases, halogens, and other nonmetals, and splits the elements commonly recognized as metalloids between "other metals" and "other nonmetals".[104] On the other hand, seven of twelve color categories on the Royal Society of Chemistry periodic table include nonmetals.[105][p]

| Group (1, 13−18) | Period | ||||||

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 1/17 | 18 | (1−6) | |

| H | He | 1 | |||||

| B | C | N | O | F | Ne | 2 | |

| Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | 3 | ||

| Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | 4 | ||

| Sb | Te | I | Xe | 5 | |||

| Rn | 6 | ||||||

Starting on the right side of the periodic table, three types of nonmetals can be recognized:

The elements in a fourth set are sometimes recognized as nonmetals:

While many of the early workers attempted to classify elements none of their classifications were satisfactory. They were divided into metals and nonmetals, but some were soon found to have properties of both. These were called metalloids. This only added to the confusion by making two indistinct divisions where one existed before.[126]

Whiteford & Coffin 1939, Essentials of College Chemistry

The boundaries between these types are not sharp.[u] Carbon, phosphorus, selenium, and iodine border the metalloids and show some metallic character, as does hydrogen.

The greatest discrepancy between authors occurs in metalloid "frontier territory".[128] Some consider metalloids distinct from both metals and nonmetals, while others classify them as nonmetals.[4] Some categorize certain metalloids as metals (e.g., arsenic and antimony due to their similarities to heavy metals).[129][v] Metalloids resemble the elements universally considered "nonmetals" in having relatively low densities, high electronegativity, and similar chemical behavior.[125][w]

Noble gases

[edit]

Six nonmetals are classified as noble gases: helium, neon, argon, krypton, xenon, and the radioactive radon. In conventional periodic tables they occupy the rightmost column. They are called noble gases due to their exceptionally low chemical reactivity.[106]

These elements exhibit similar properties, characterized by their colorlessness, odorlessness, and nonflammability. Due to their closed outer electron shells, noble gases possess weak interatomic forces of attraction, leading to exceptionally low melting and boiling points.[130] As a consequence, they all exist as gases under standard conditions, even those with atomic masses surpassing many typically solid elements.[131]

Chemically, the noble gases exhibit relatively high ionization energies, negligible or negative electron affinities, and high to very high electronegativities. The number of compounds formed by noble gases is in the hundreds and continues to expand,[132] with most of these compounds involving the combination of oxygen or fluorine with either krypton, xenon, or radon.[133]

Halogen nonmetals

[edit]While the halogen nonmetals are notably reactive and corrosive elements, they can also be found in everyday compounds like toothpaste (NaF); common table salt (NaCl); swimming pool disinfectant (NaBr); and food supplements (KI). The term "halogen" itself means "salt former".[134]

Chemically, the halogen nonmetals exhibit high ionization energies, electron affinities, and electronegativity values, and are mostly relatively strong oxidizing agents.[135] These characteristics contribute to their corrosive nature.[136] All four elements tend to form primarily ionic compounds with metals,[137] in contrast to the remaining nonmetals (except for oxygen) which tend to form primarily covalent compounds with metals.[x] The highly reactive and strongly electronegative nature of the halogen nonmetals epitomizes nonmetallic character.[141]

Unclassified nonmetals

[edit]

Hydrogen behaves in some respects like a metallic element and in others like a nonmetal.[143] Like a metallic element it can, for example, form a solvated cation in aqueous solution;[144] it can substitute for alkali metals in compounds such as the chlorides (NaCl cf. HCl) and nitrates (KNO3 cf. HNO3), and in certain alkali metal complexes[145][146] as a nonmetal.[147] It attains this configuration by forming a covalent or ionic bond[148] or, if it has initially given up its electron, by attaching itself to a lone pair of electrons.[149]

Some or all of these nonmetals share several properties. Being generally less reactive than the halogens,[150] most of them can occur naturally in the environment.[151] They have significant roles in biology[152] and geochemistry.[153] Collectively, their physical and chemical characteristics can be described as "moderately non-metallic".[153] Sometimes they have corrosive aspects. Carbon corrosion can occur in fuel cells.[154] Untreated selenium in soils can lead to the formation of corrosive hydrogen selenide gas.[155] Very different, when combined with metals, the unclassified nonmetals can form interstitial or refractory compounds[156] due to their relatively small atomic radii and sufficiently low ionization energies.[153] They also exhibit a tendency to bond to themselves, particularly in solid compounds.[157] Additionally, diagonal periodic table relationships among these nonmetals mirror similar relationships among the metalloids.[158]

Abundance, extraction, and use

[edit]Abundance

[edit]| Universe[159] | 75% hydrogen | 23% helium | 1% oxygen |

| Atmosphere[160] | 78% nitrogen | 21% oxygen | 0.5% argon |

| Hydrosphere[161] | 86% oxygen | 11% hydrogen | 2% chlorine |

| Biomass[162] | 63% oxygen | 20% carbon | 10% hydrogen |

| Crust[161] | 46% oxygen | 27% silicon | 8% aluminium |

The abundance of elements in the universe results from nuclear physics processes like nucleosynthesis and radioactive decay.

The volatile noble gas nonmetal elements are less abundant in the atmosphere than expected based their overall abundance due to cosmic nucleosynthesis. Mechanisms to explain this difference is an important aspect of planetary science.[163] Even within that challenge, the nonmetal element Xe is unexpectedly depleted. A possible explanation comes from theoretical models of the high pressures in the Earth's core suggest there may be around 1013 tons of xenon, in the form of stable XeFe3 and XeNi3 intermetallic compounds.[164]

Five nonmetals—hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and silicon—form the bulk of the directly observable structure of the Earth: about 73% of the crust, 93% of the biomass, 96% of the hydrosphere, and over 99% of the atmosphere, as shown in the accompanying table. Silicon and oxygen form highly stable tetrahedral structures, known as silicates. Here, "the powerful bond that unites the oxygen and silicon ions is the cement that holds the Earth's crust together."[165]

In the biomass, the relative abundance of the first four nonmetals (and phosphorus, sulfur, and selenium marginally) is attributed to a combination of relatively small atomic size, and sufficient spare electrons. These two properties enable them to bind to one another and "some other elements, to produce a molecular soup sufficient to build a self-replicating system."[166]

Extraction

[edit]Nine of the 23 nonmetallic elements are gases, or form compounds that are gases, and are extracted from natural gas or liquid air. These elements include hydrogen, helium, nitrogen, oxygen, neon, sulfur, argon, krypton, and xenon. For example, nitrogen and oxygen are extracted from air through fractional distillation of liquid air. This method capitalizes on their different boiling points to separate them efficiently.[167] Sulfur was extracted using the Frasch process, which involved injecting superheated water into underground deposits to melt the sulfur, which is then pumped to the surface. This technique leveraged sulfur's low melting point relative to other geological materials. It is now obtained by reacting the hydrogen sulfide in natural gas, with oxygen. Water is formed, leaving the sulfur behind.[168]

Nonmetallic elements are extracted from the following sources:[151]

| Group (1, 13−18) | Period | ||||||

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 1/17 | 18 | (1−6) | |

| H | He | 1 | |||||

| B | C | N | O | F | Ne | 2 | |

| Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | 3 | ||

| Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | 4 | ||

| Sb | Te | I | Xe | 5 | |||

| Rn | 6 | ||||||

Uses

[edit]Uses of nonmetals and non-metallic elements are broadly categorized as domestic, industrial, attenuative (lubricative, retarding, insulating or cooling), and agricultural

Many have domestic and industrial applications in household accoutrements;[170][z] medicine and pharmaceuticals;[172] and lasers and lighting.[173] They are components of mineral acids;[174] and prevalent in plug-in hybrid vehicles;[175] and smartphones.[176]

A significant number have attenuative and agricultural applications. They are used in lubricants;[177] and flame retardants and fire extinguishers.[178] They can serve as inert air replacements;[179] and are used in cryogenics and refrigerants.[180] Their significance extends to agriculture, through their use in fertilizers.[181]

Additionally, a smaller number of nonmetals or nonmetallic elements find specialized uses in explosives;[182] and welding gases.[183]

- Nitric acid (here colored due to the presence of nitrogen dioxide) is often used in the explosives industry[184]

- A high-voltage circuit-breaker employing sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) as its inert (air replacement) interrupting medium[185]

- A COIL (chemical oxygen iodine laser) system mounted on a Boeing 747 variant known as the YAL-1 Airborne Laser

- Cylinders containing argon gas for use in extinguishing fire without damaging computer server equipment

Taxonomical history

[edit]Background

[edit]

Around 340 BCE, in Book III of his treatise Meteorology, the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle categorized substances found within the Earth into metals and "fossiles".[aa] The latter category included various minerals such as realgar, ochre, ruddle, sulfur, cinnabar, and other substances that he referred to as "stones which cannot be melted".[186]

Until the Middle Ages the classification of minerals remained largely unchanged, albeit with varying terminology. In the fourteenth century, the English alchemist Richardus Anglicus expanded upon the classification of minerals in his work Correctorium Alchemiae. In this text, he proposed the existence of two primary types of minerals. The first category, which he referred to as "major minerals", included well-known metals such as gold, silver, copper, tin, lead, and iron. The second category, labeled "minor minerals", encompassed substances like salts, atramenta (iron sulfate), alums, vitriol, arsenic, orpiment, sulfur, and similar substances that were not metallic bodies.[187]

The term "nonmetallic" dates back to at least the 16th century. In his 1566 medical treatise, French physician Loys de L'Aunay distinguished substances from plant sources based on whether they originated from metallic or non-metallic soils.[188]

Later, the French chemist Nicolas Lémery discussed metallic and nonmetallic minerals in his work Universal Treatise on Simple Drugs, Arranged Alphabetically published in 1699. In his writings, he contemplated whether the substance "cadmia" belonged to either the first category, akin to cobaltum (cobaltite), or the second category, exemplified by what was then known as calamine—a mixed ore containing zinc carbonate and silicate.[189]

Origin and use of the term

[edit]Just as the ancients distinguished metals from other minerals, a similar dichotomy developed as the modern idea of chemical elements emerged in the late 1700s. French chemist Antoine Lavoisier published the first modern list of chemical elements in his revolutionary[191] 1789 Traité élémentaire de chimie. The elements were categorized into distinct groups, including gases, metallic substances, nonmetallic substances, and earths (heat-resistant oxides).[192] Lavoisier's work gained widespread recognition and was republished in twenty-three editions across six languages within its first seventeen years, significantly advancing the understanding of chemistry in Europe and America.[193]

The widespread adoption of the term "nonmetal" followed a complex process spanning nearly nine decades. In 1811, the Swedish chemist Berzelius introduced the term "metalloids"[194] to describe nonmetallic elements, noting their ability to form negatively charged ions with oxygen in aqueous solutions.[195][196] While Berzelius' terminology gained significant acceptance,[197] it later faced criticism from some who found it counterintuitive,[196] misapplied,[198] or even invalid.[199][200] In 1864, reports indicated that the term "metalloids" was still endorsed by leading authorities,[201] but there were reservations about its appropriateness. The idea of designating elements like arsenic as metalloids had been considered.[201] By as early as 1866, some authors began preferring the term "nonmetal" over "metalloid" to describe nonmetallic elements.[202] In 1875, Kemshead[203] observed that elements were categorized into two groups: non-metals (or metalloids) and metals. He noted that the term "non-metal", despite its compound nature, was more precise and had become universally accepted as the nomenclature of choice.

Suggested distinguishing criteria

[edit]From the mid-1700s, a variety of physical, chemical, and atomic properties have been suggested for distinguishing metals from nonmetals (or other bodies), as listed in the accompanying table. Some of the earliest recorded properties are the (high) density and (good) electrical conductivity of metals.

In 1809, the British chemist and inventor Humphry Davy made a groundbreaking discovery that reshaped the understanding of metals and nonmetals.[232] When he isolated sodium and potassium, their low densities (floating on water!) contrasted with their metallic appearance, challenging the stereotype of metals as dense substances.[233][ai] Nevertheless, their classification as metals was firmly established by their distinct chemical properties.[235]

One of the most commonly recognized properties used in this context is the temperature coefficient of resistivity, the effect of heating on electrical resistance and conductivity. As temperature rises, the conductivity of metals decreases while that of nonmetals increases.[223] However, plutonium, carbon, arsenic, and antimony defy the norm. When plutonium (a metal) is heated within a temperature range of −175 to +125 °C its conductivity increases.[236] Similarly, despite its common classification as a nonmetal, when carbon (as graphite) is heated it experiences a decrease in electrical conductivity.[237] Arsenic and antimony, which are occasionally classified as nonmetals, show behavior similar to carbon, highlighting the complexity of the distinction between metals and nonmetals.[238]

Kneen and colleagues[239] proposed that the classification of nonmetals can be achieved by establishing a single criterion for metallicity. They acknowledged that various plausible classifications exist and emphasized that while these classifications may differ to some extent, they would generally agree on the categorization of nonmetals.

Emsley[240] pointed out the complexity of this task, asserting that no single property alone can unequivocally assign elements to either the metal or nonmetal category. Furthermore, Jones[241] emphasized that classification systems typically rely on more than two attributes to define distinct types.

Johnson[242] distinguished between metals and nonmetals on the basis of their physical states, electrical conductivity, mechanical properties, and the acid-base nature of their oxides:

- gaseous elements are nonmetals (hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, fluorine, chlorine and the noble gases);

- liquids (mercury, bromine) are either metallic or nonmetallic: mercury, as a good conductor, is a metal; bromine, with its poor conductivity, is a nonmetal;

- solids are either ductile and malleable, hard and brittle, or soft and crumbly:

- a. ductile and malleable elements are metals;

- b. hard and brittle elements include boron, silicon and germanium, which are semiconductors and therefore not metals; and

- c. soft and crumbly elements include carbon, phosphorus, sulfur, arsenic, antimony,[aj] tellurium and iodine, which have acidic oxides indicative of nonmetallic character.[ak]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Several authors[247] have noted that nonmetals generally have low densities and high electronegativity. The accompanying table, using a threshold of 7 g/cm3 for density and 1.9 for electronegativity (revised Pauling), shows that all nonmetals have low density and high electronegativity. In contrast, all metals have either high density or low electronegativity (or both). Goldwhite and Spielman[248] added that, "... lighter elements tend to be more electronegative than heavier ones." The average electronegativity for the elements in the table with densities less than 7 gm/cm3 (metals and nonmetals) is 1.97 compared to 1.66 for the metals having densities of more than 7 gm/cm3.

Some authors divide elements into metals, metalloids, and nonmetals, but Oderberg[249] disagrees, arguing that by the principles of categorization, anything not classified as a metal should be considered a nonmetal.

Development of types

[edit]

In 1844, Alphonse Dupasquier, a French doctor, pharmacist, and chemist,[250] established a basic taxonomy of nonmetals to aid in their study. He wrote:[251]

- They will be divided into four groups or sections, as in the following:

- Organogens—oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, carbon

- Sulphuroids—sulfur, selenium, phosphorus

- Chloroides—fluorine, chlorine, bromine, iodine

- Boroids—boron, silicon.

Dupasquier's quartet parallels the modern nonmetal types. The organogens and sulphuroids are akin to the unclassified nonmetals. The chloroides were later called halogens.[252] The boroids eventually evolved into the metalloids, with this classification beginning from as early as 1864.[201] The then unknown noble gases were recognized as a distinct nonmetal group after being discovered in the late 1800s.[253]

His taxonomy was noted for its natural basis.[254][am] That said, it was a significant departure from other contemporary classifications, since it grouped together oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, and carbon.[256]

In 1828 and 1859, the French chemist Dumas classified nonmetals as (1) hydrogen; (2) fluorine to iodine; (3) oxygen to sulfur; (4) nitrogen to arsenic; and (5) carbon, boron and silicon,[257] thereby anticipating the vertical groupings of Mendeleev's 1871 periodic table. Dumas' five classes fall into modern groups 1, 17, 16, 15, and 14 to13 respectively.

Comparison of selected properties

[edit]The two tables in this section list some of the properties of five types of elements (noble gases, halogen nonmetals, unclassified nonmetals, metalloids and, for comparison, metals) based on their most stable forms at standard temperature and pressure. The dashed lines around the columns for metalloids signify that the treatment of these elements as a distinct type can vary depending on the author, or classification scheme in use.

Physical properties by element type

[edit]Physical properties are listed in loose order of ease of their determination.

| Property | Element type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metals | Metalloids | Unc. nonmetals | Halogen nonmetals | Noble gases | |

| General physical appearance | lustrous[20] | lustrous[258] | colorless[263] | ||

| Form and density[264] | solid (Hg liquid) | solid | solid or gas | solid or gas (bromine liquid) | gas |

| often high density such as iron, lead, tungsten | low to moderately high density | low density | low density | low density | |

| some light metals including beryllium, magnesium, aluminium | all lighter than iron | hydrogen, nitrogen lighter than air[265] | helium, neon lighter than air[266] | ||

| Plasticity | mostly malleable and ductile[20] | often brittle[258] | phosphorus, sulfur, selenium, brittle[an] | iodine brittle[270] | not applicable |

| Electrical conductivity | good[ao] |

|

|

| poor[as] |

| Electronic structure[42] | metal (beryllium, strontium, α-tin, ytterbium, bismuth are semimetals) | semimetal (arsenic, antimony) or semiconductor |

| semiconductor (I) or insulator | insulator |

Chemical properties by element type

[edit]Chemical properties are listed from general characteristics to more specific details.

| Property | Element type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metals | Metalloids | Unc. nonmetals | Halogen nonmetals | Noble gases | |

| General chemical behavior |

| weakly nonmetallic[at] | moderately nonmetallic[276] | strongly nonmetallic[277] | |

| Oxides | basic; some amphoteric or acidic[9] | amphoteric or weakly acidic[280][au] | acidic[av] or neutral[aw] | acidic[ax] | metastable XeO3 is acidic;[287] stable XeO4 strongly so[288] |

| few glass formers[ay] | all glass formers[290] | some glass formers[az] | no glass formers reported | no glass formers reported | |

| ionic, polymeric, layer, chain, and molecular structures[292] | polymeric in structure[293] |

| |||

| Compounds with metals | alloys[20] or intermetallic compounds[296] | tend to form alloys or intermetallic compounds[297] | mainly ionic[137] | simple compounds at STP not known[ba] | |

| Ionization energy (kJ mol−1)[62] ‡ | low to high | moderate | moderate to high | high | high to very high |

| 376 to 1,007 | 762 to 947 | 941 to 1,402 | 1,008 to 1,681 | 1,037 to 2,372 | |

| average 643 | average 833 | average 1,152 | average 1,270 | average 1,589 | |

| Electronegativity (Pauling)[bb][63] ‡ | low to high | moderate | moderate to high | high | high (radon) to very high |

| 0.7 to 2.54 | 1.9 to 2.18 | 2.19 to 3.44 | 2.66 to 3.98 | ca. 2.43 to 4.7 | |

| average 1.5 | average 2.05 | average 2.65 | average 3.19 | average 3.3 | |

† Hydrogen can also form alloy-like hydrides[146]

‡ The labels low, moderate, high, and very high are arbitrarily based on the value spans listed in the table

See also

[edit]- CHON (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen)

- List of nonmetal monographs

- Metallization pressure

- Nonmetal (astrophysics)

- Period 1 elements (hydrogen, helium)

- Properties of nonmetals (and metalloids) by group

Notes

[edit]- ^ These six (boron, silicon, germanium, arsenic, antimony, and tellurium) are the elements commonly recognized as "metalloids",[3] a category sometimes counted as a subcategory of nonmetals and sometimes as a category separate from both metals and nonmetals.[4]

- ^ The most stable forms are: diatomic hydrogen H2; β-rhombohedral boron; graphite for carbon; diatomic nitrogen N2; diatomic oxygen O2; tetrahedral silicon; black phosphorus; orthorhombic sulfur S8; α-germanium; gray arsenic; gray selenium; gray antimony; gray tellurium; and diatomic iodine I2. All other nonmetallic elements have only one stable form at STP.[6]

- ^ At higher temperatures and pressures the numbers of nonmetals can be called into question. For example, when germanium melts it changes from a semiconducting metalloid to a metallic conductor with an electrical conductivity similar to that of liquid mercury.[13] At a high enough pressure, sodium (a metal) becomes a non-conducting insulator.[14]

- ^ The absorbed light may be converted to heat or re-emitted in all directions so that the emission spectrum is thousands of times weaker than the incident light radiation.[17]

- ^ Solid iodine has a silvery metallic appearance under white light at room temperature. At ordinary and higher temperatures it sublimes from the solid phase directly into a violet-colored vapor.[18]

- ^ The solid nonmetals have electrical conductivity values ranging from 10−18 S•cm−1 for sulfur[22] to 3 × 104 in graphite[23] or 3.9 × 104 for arsenic;[24] cf. 0.69 × 104 for manganese to 63 × 104 for silver, both metals.[22] The conductivity of graphite (a nonmetal) and arsenic (a metalloid nonmetal) exceeds that of manganese. Such overlaps show that it can be difficult to draw a clear line between metals and nonmetals.

- ^ Thermal conductivity values for metals range from 6.3 W m−1 K−1 for neptunium to 429 for silver; cf. antimony 24.3, arsenic 50, and carbon 2000.[22] Electrical conductivity values of metals range from 0.69 S•cm−1 × 104 for manganese to 63 × 104 for silver; cf. carbon 3 × 104,[23] arsenic 3.9 × 104 and antimony 2.3 × 104.[22]

- ^ While CO and NO are commonly referred to as being neutral, CO is a slightly acidic oxide, reacting with bases to produce formates (CO + OH− → HCOO−);[66] and in water, NO reacts with oxygen to form nitrous acid HNO2 (4NO + O2 + 2H2O → 4HNO2).[67]

- ^ Electronegativity values of fluorine to iodine are: 3.98 + 3.16 + 2.96 + 2.66 = 12.76/4 3.19.

- ^ Helium is shown above beryllium for electron configuration consistency purposes; as a noble gas it is usually placed above neon, in group 18.

- ^ The net result is an even-odd difference between periods (except in the s-block): elements in even periods have smaller atomic radii and prefer to lose fewer electrons, while elements in odd periods (except the first) differ in the opposite direction. Many properties in the p-block then show a zigzag rather than a smooth trend along the group. For example, phosphorus and antimony in odd periods of group 15 readily reach the +5 oxidation state, whereas nitrogen, arsenic, and bismuth in even periods prefer to stay at +3.[88]

- ^ Oxidation states, which denote hypothetical charges for conceptualizing electron distribution in chemical bonding, do not necessarily reflect the net charge of molecules or ions. This concept is illustrated by anions such as NO3−, where the nitrogen atom is considered to have an oxidation state of +5 due to the distribution of electrons. However, the net charge of the ion remains −1. Such observations underscore the role of oxidation states in describing electron loss or gain within bonding contexts, distinct from indicating the actual electrical charge, particularly in covalently bonded molecules.

- ^ Greenwood[94] commented that: "The extent to which metallic elements mimic boron (in having fewer electrons than orbitals available for bonding) has been a fruitful cohering concept in the development of metalloborane chemistry ... Indeed, metals have been referred to as "honorary boron atoms" or even as "flexiboron atoms". The converse of this relationship is clearly also valid."

- ^ For example, the conductivity of graphite is 3 × 104 S•cm−1.[95] whereas that of manganese is 6.9 × 103 S•cm−1.[96]

- ^ A homopolyatomic cation consists of two or more atoms of the same element bonded together and carrying a positive charge, for example, N5+, O2+ and Cl4+. This is unusual behavior for nonmetals since cation formation is normally associated with metals, and nonmetals are normally associated with anion formation. Homopolyatomic cations are further known for carbon, phosphorus, antimony, sulfur, selenium, tellurium, bromine, iodine and xenon.[98]

- ^ Of the twelve categories in the Royal Society periodic table, five only show up with the metal filter, three only with the nonmetal filter, and four with both filters. Interestingly, the six elements marked as metalloids (boron, silicon, germanium, arsenic, antimony, and tellurium) show under both filters. Six other elements (113–118: nihonium, flerovium, moscovium, livermorium, tennessine, and oganesson), whose status is unknown, also show up under both filters but are not included in any of the twelve color categories.

- ^ The quote marks are not found in the source; they are used here to make it clear that the source employs the word non-metals as a formal term for the subset of chemical elements in question, rather than applying to nonmetals generally.

- ^ Varying configurations of these nonmetals have been referred to as, for example, basic nonmetals,[108] bioelements,[109] central nonmetals,[110] CHNOPS,[111] essential elements,[112] "non-metals",[113][q] orphan nonmetals,[114] or redox nonmetals.[115]

- ^ Arsenic is stable in dry air. Extended exposure in moist air results in the formation of a black surface coating. "Arsenic is not readily attacked by water, alkaline solutions or non-oxidizing acids".[120] It can occasionally be found in nature in an uncombined form.[121] It has a positive standard reduction potential (As → As3+ + 3e = +0.30 V), corresponding to a classification of semi-noble metal.[122]

- ^ "Crystalline boron is relatively inert."[116] Silicon "is generally highly unreactive."[117] "Germanium is a relatively inert semimetal."[118] "Pure arsenic is also relatively inert."[119][s] "Metallic antimony is … inert at room temperature."[123] "Compared to S and Se, Te has relatively low chemical reactivity."[124]

- ^ Boundary fuzziness and overlaps often occur in classification schemes.[127]

- ^ Jones takes a philosophical or pragmatic view to these questions. He writes: "Though classification is an essential feature of all branches of science, there are always hard cases at the boundaries. The boundary of a class is rarely sharp ... Scientists should not lose sleep over the hard cases. As long as a classification system is beneficial to economy of description, to structuring knowledge and to our understanding, and hard cases constitute a small minority, then keep it. If the system becomes less than useful, then scrap it and replace it with a system based on different shared characteristics."[127]

- ^ For a related comparison of the properties of metals, metalloids, and nonmetals, see Rudakiya & Patel (2021), p. 36.

- ^ Metal oxides are usually somewhat ionic, depending upon the metal element electropositivity.[138] On the other hand, oxides of metals with high oxidation states are often either polymeric or covalent.[139] A polymeric oxide has a linked structure composed of multiple repeating units.[140]

- ^ Exceptionally, a study reported in 2012 noted the presence of 0.04% native fluorine (F

2) by weight in antozonite, attributing these inclusions to radiation from tiny amounts of uranium.[169] - ^ Radon sometimes occurs as potentially hazardous indoor pollutant[171]

- ^ The term "fossile" is not to be confused with the modern usage of fossil to refer to the preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing.

- ^ "... [metals'] specific gravity is greater than that of any other bodies yet discovered; they are better conductors of electricity, than any other body."

- ^ The Goldhammer-Herzfeld ratio is roughly equal to the cube of the atomic radius divided by the molar volume.[209] More specifically, it is the ratio of the force holding an individual atom's outer electrons in place with the forces on the same electrons from interactions between the atoms in the solid or liquid element. When the interatomic forces are greater than, or equal to, the atomic force, outer electron itinerancy is indicated and metallic behavior is predicted. Otherwise nonmetallic behavior is anticipated.

- ^ Sonorousness is making a ringing sound when struck.

- ^ Liquid range is the difference between melting point and boiling point.

- ^ Configuration energy is the average energy of the valence electrons in a free atom.

- ^ Atomic conductance is the electrical conductivity of one mole of a substance. It is equal to electrical conductivity divided by molar volume.

- ^ The Mott parameter is N 1/3ɑ*H where N the number of atoms per unit volume, and ɑ*H "is their effective size, usually taken as the effective Bohr radius of the maximum in the outermost (valence) electron probability distribution." In ambient conditions, a value of 0.45 is given for the value for the dividing line between metals and nonmetals.

- ^ It was subsequently proposed, by Erman and Simon,[234] to refer to sodium and potassium as metalloids, meaning "resembling metals in form or appearance". Their suggestion was ignored; the two new elements were admitted to the metal club in cognizance of their physical properties (opacity, luster, malleability, conductivity) and "their qualities of chemical combination".Hare and Bache[232] observed that the line of demarcation between metals and nonmetals had been "annihilated" by the discovery of alkaline metals having a density less than that of water:

- "Peculiar brilliance and opacity were in the next place appealed to as a means of discrimination; and likewise that superiority in the power of conducting heat and electricity ... Yet so difficult has it been to draw the line between metallic…and non-metallic ... that bodies which are by some authors placed in one class, are by others included in the other. Thus selenium, silicon, and zirconion [sic] have by some chemists been comprised among the metals, by others among non-metallic bodies."

- ^ While antimony trioxide is usually listed as being amphoteric its very weak acid properties dominate over those of a very weak base.[243]

- ^ Johnson counted boron as a nonmetal and silicon, germanium, arsenic, antimony, tellurium, polonium and astatine as "semimetals" i.e. metalloids.

- ^ (a) The table includes elements up to einsteinium (99) except for astatine (85) and francium (87), with densities and most electronegativities from Aylward and Findlay;[244] Electronegativities of noble gases are from Rahm, Zeng and Hoffmann.[245]

(b) A survey of definitions of the term "heavy metal" reported density criteria ranging from above 3.5 g/cm3 to above 7 g/cm3;[246]

(c) Vernon specified a minimum electronegativity of 1.9 for the metalloids, on the revised Pauling scale;[3] - ^ A natural classification was based on "all the characters of the substances to be classified as opposed to the 'artificial classifications' based on one single character" such as the affinity of metals for oxygen. "A natural classification in chemistry would consider the most numerous and most essential analogies."[255]

- ^ All four have less stable non-brittle forms: carbon as exfoliated (expanded) graphite,[267][268] and as carbon nanotube wire;[269] phosphorus as white phosphorus (soft as wax, pliable and can be cut with a knife, at room temperature);[50] sulfur as plastic sulfur;[51] and selenium as selenium wires.[52]

- ^ Metals have electrical conductivity values of from 6.9×103 S•cm−1 for manganese to 6.3×105 for silver.[271]

- ^ Metalloids have electrical conductivity values of from 1.5×10−6 S•cm−1 for boron to 3.9×104 for arsenic.[272]

- ^ Unclassified nonmetals have electrical conductivity values of from ca. 1×10−18 S•cm−1 for the elemental gases to 3×104 in graphite.[95]

- ^ Halogen nonmetals have electrical conductivity values of from ca. 1×10−18 S•cm−1 for F and Cl to 1.7×10−8 S•cm−1 for iodine.[95][273]

- ^ Elemental gases have electrical conductivity values of ca. 1×10−18 S•cm−1.[95]

- ^ Metalloids always give "compounds less acidic in character than the corresponding compounds of the [typical] nonmetals."[258]

- ^ Arsenic trioxide reacts with sulfur trioxide, forming arsenic "sulfate" As2(SO4)3.[281] This substance is covalent in nature rather than ionic;[282] it is also given as As2O3·3SO3.[283]

- ^ NO

2, N

2O

5, SO

3, SeO

3 are strongly acidic.[284] - ^ H2O, CO, NO, N2O are neutral oxides; CO and N2O are "formally the anhydrides of formic and hyponitrous acid, respectively viz. CO + H2O → H2CO2 (HCOOH, formic acid); N2O + H2O → H2N2O2 (hyponitrous acid)."[285]

- ^ ClO

2, Cl

2O

7, I

2O

5 are strongly acidic.[286] - ^ Metals that form glasses are: vanadium; molybdenum, tungsten; alumnium, indium, thallium; tin, lead; and bismuth.[289]

- ^ Unclassified nonmetals that form glasses are phosphorus, sulfur, selenium;[289] CO2 forms a glass at 40 GPa.[291]

- ^ Disodium helide (Na2He) is a compound of helium and sodium that is stable at high pressures above 113 GPa. Argon forms an alloy with nickel, at 140 GPa and close to 1,500 K, however at this pressure argon is no longer a noble gas.[299]

- ^ Values for the noble gases are from Rahm, Zeng and Hoffmann.[245]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c Larrañaga, Lewis & Lewis 2016, p. 988

- ^ Jump up to: a b Steudel 2020, p. 43: Steudel's monograph is an updated translation of the fifth German edition of 2013, incorporating the literature up to Spring 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Vernon 2013

- ^ Jump up to: a b Goodrich 1844, p. 264; The Chemical News 1897, p. 189; Hampel & Hawley 1976, pp. 174, 191; Lewis 1993, p. 835; Hérold 2006, pp. 149–50

- ^ At: Restrepo et al. 2006, p. 411; Thornton & Burdette 2010, p. 86; Hermann, Hoffmann & Ashcroft 2013, pp. 11604‒1‒11604‒5; Cn: Mewes et al. 2019; Fl: Florez et al. 2022; Og: Smits et al. 2020

- ^ Wismer 1997, p. 72: H, He, C, N, O, F, Ne, S, Cl, Ar, As, Se, Br, Kr, Sb, I, Xe; Powell 1974, pp. 174, 182: P, Te; Greenwood & Earnshaw 2002, p. 143: B; Field 1979, p. 403: Si, Ge; Addison 1964, p. 120: Rn

- ^ Pascoe 1982, p. 3[broken anchor]

- ^ Malone & Dolter 2010, pp. 110–111

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Porterfield 1993, p. 336

- ^ Godovikov & Nenasheva 2020, p. 4; Sanderson 1957, p. 229; Morely & Muir 1892, p. 241

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vernon 2020, p. 220; Rochow 1966, p. 4

- ^ IUPAC Periodic Table of the Elements

- ^ Berger 1997, pp. 71–72

- ^ Gatti, Tokatly & Rubio 2010

- ^ Wibaut 1951, p. 33: "Many substances ...are colourless and therefore show no selective absorption in the visible part of the spectrum."

- ^ Elliot 1929, p. 629

- ^ Fox 2010, p. 31

- ^ Tidy 1887, pp. 107–108; Koenig 1962, p. 108

- ^ Wiberg 2001, p. 416; Wiberg is here referring to iodine.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Kneen, Rogers & Simpson 1972, pp. 261–264

- ^ Phillips 1973, p. 7

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Aylward & Findlay 2008, pp. 6–12

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jenkins & Kawamura 1976, p. 88

- ^ Carapella 1968, p. 30

- ^ Zumdahl & DeCoste 2010, pp. 455, 456, 469, A40; Earl & Wilford 2021, p. 3-24

- ^ Still 2016, p. 120

- ^ Wiberg 2001, pp. 780

- ^ Wiberg 2001, pp. 824, 785

- ^ Earl & Wilford 2021, p. 3-24

- ^ Siekierski & Burgess 2002, p. 86

- ^ Charlier, Gonze & Michenaud 1994

- ^ Taniguchi et al. 1984, p. 867: "... black phosphorus ... [is] characterized by the wide valence bands with rather delocalized nature."; Carmalt & Norman 1998, p. 7: "Phosphorus ... should therefore be expected to have some metalloid properties."; Du et al. 2010: Interlayer interactions in black phosphorus, which are attributed to van der Waals-Keesom forces, are thought to contribute to the smaller band gap of the bulk material (calculated 0.19 eV; observed 0.3 eV) as opposed to the larger band gap of a single layer (calculated ~0.75 eV).

- ^ Wiberg 2001, pp. 742

- ^ Evans 1966, pp. 124–25

- ^ Wiberg 2001, pp. 758

- ^ Stuke 1974, p. 178; Donohue 1982, pp. 386–87; Cotton et al. 1999, p. 501

- ^ Steudel 2020, p. 601: "... Considerable orbital overlap can be expected. Apparently, intermolecular multicenter bonds exist in crystalline iodine that extend throughout the layer and lead to the delocalization of electrons akin to that in metals. This explains certain physical properties of iodine: the dark color, the luster and a weak electric conductivity, which is 3400 times stronger within the layers then perpendicular to them. Crystalline iodine is thus a two-dimensional semiconductor."; Segal 1989, p. 481: "Iodine exhibits some metallic properties ..."

- ^ Тейлор 1960, с. 207 ; Сгорел 1919, с. 34

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Грин 2012, с. 14

- ^ Спенсер, Боднер и Рикард 2012, стр. 178

- ^ Redmer, Hensel & Holst 2010, предисловие

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Килер и Уотерс 2013, с. 293

- ^ ДеКок и Грей 1989, стр. 423, 426–427.

- ^ Боресков 2003, с. 45

- ^ Эшкрофт и Мермин

- ^ Эшкрофт и Мермин

- ^ Ян 2004, с. 9

- ^ Wiberg 2001, стр. 416, 574, 681, 824, 895, 930 ; Секерский и Берджесс 2002, с. 129

- ^ Вертман, Йоханнес; Вертман, Джулия Р. (1992). Элементарная теория дислокаций . Нью-Йорк: Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-506900-6 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фарадей 1853, с. 42 ; Холдернесс и Берри 1979, с. 255

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Партингтон 1944, с. 405

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Реньо 1853, с. 208

- ^ Шарф, ТВ; Прасад, С.В. (январь 2013 г.). «Твердые смазочные материалы: обзор» . Журнал материаловедения . 48 (2): 511–531. Бибкод : 2013JMatS..48..511S . дои : 10.1007/s10853-012-7038-2 . ISSN 0022-2461 .

- ^ Бартон 2021, с. 200

- ^ Виберг 2001, стр. 796.

- ^ Шан и др. 2021 г.

- ^ Тан и др. 2021 год

- ^ Штойдель, 2020, проходящее ; Карраско и др. 2023 ; Шанабрук, Ланнин и Хисацунэ 1981, стр. 130–133.

- ^ Веллер и др. 2018, предисловие

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Эбботт 1966, с. 18

- ^ Гангули 2012, с. 1-1

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Эйлуорд и Финдли 2008, с. 132

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Эйлуорд и Финдли 2008, с. 126

- ^ Иглсон 1994, 1169.

- ^ Муди 1991, с. 365

- ^ Дом 2013, с. 427

- ^ Льюис и Дин 1994, с. 568

- ^ Смит 1990, стр. 177–189.

- ^ Йодер, Суйдам и Снавли 1975, стр. 58

- ^ Янг и др. 2018, с. 753

- ^ Браун и др. 2014, с. 227

- ^ Секиерски и Берджесс 2002, стр. 21, 133, 177

- ^ Мур 2016 ; Берфорд, Пассмор и Сандерс 1989, с. 54

- ^ Брэди и Сенезе 2009, с. 69

- ^ Служба химических рефератов, 2021 г.

- ^ Эмсли 2011, стр. 81.

- ^ Кокелл 2019, с. 210

- ^ Скотт 2014, с. 3

- ^ Эмсли 2011, с. 184

- ^ Дженсен 1986, стр. 506.

- ^ Ли 1996, с. 240

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 2002, с. 43

- ^ Кресси 2010

- ^ Секиерски и Берджесс 2002, стр. 24–25

- ^ Секиерски и Берджесс 2002, стр. 23.

- ^ Петрушевский и Цветкович 2018 ; Грочала 2018

- ^ Книн, Роджерс и Симпсон 1972, стр. 226, 360 ; Секерский и Берджесс 2002, стр. 52, 101, 111, 124, 194.

- ^ Шерри 2020, стр. 407–420

- ^ Shchukarev 1977, p. 229

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кокс 2004, с. 146

- ^ Видж и др. 2001 г.

- ^ Дорси 2023, стр. 12–13.

- ^ Хамфри 1908 г.

- ^ Гринвуд 2001, с. 2057

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Bogoroditskii & Pasynkov 1967, p. 77 ; Jenkins & Kawamura 1976, p. 88

- ^ Десаи, Джеймс и Хо 1984, стр. 1160

- ^ Штейн 1983, с. 165

- ^ Энгессер и Кроссинг 2013, с. 947

- ^ Швейцер и Пестерфилд 2010, с. 305

- ^ Рик 1967, с. 97 : Триоксид вольфрама растворяется в плавиковой кислоте с образованием оксифторидного комплекса .

- ^ Виберг 2001, стр. 1279.

- ^ Пайпер, Северная Каролина (18 сентября 2020 г.). «Относительность и таблица Менделеева» . Философские труды Королевского общества A: Математические, физические и технические науки . 378 (2180): 20190305. Бибкод : 2020RSPTA.37890305P . дои : 10.1098/rsta.2019.0305 . ISSN 1364-503X . ПМИД 32811360 .

- ^ Мощность 2010 ; Ворона 2013 [ сломанный якорь ] ; Ветман и Иноуэ 2018

- ^ Британская энциклопедия 2021 г.

- ^ Королевское химическое общество 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Мэтсон и Орбек 2013, с. 203

- ^ Кернион и Маскетта 2019, с. 191 ; Цао и др. 2021, стр. 20–21 ; Хусейн и др. 2023 ; также называемые «неметаллическими галогенами»: Chambers & Holliday 1982, стр. 273–274 ; Больманн 1992, с. 213 ; Йентч и Матиле, 2015, с. 247 или «стабильные галогены»: Василакис, Калемос и Мавридис 2014, стр. 1 ; Хэнли и Кога, 2018, с. 24 ; Кайхо 2017, гл. 2, с. 1

- ^ Уильямс 2007, стр. 1550–1561: H , C , N , P , O , S

- ^ Waechtershäuser 2014, с. 5: Ч , С , Н , П , О , С , Се

- ^ Хенгевелд и Федонкин 2007, стр. 181–226: С , Н , П , О , С

- ^ Уэйкман 1899, с. 562

- ^ Фрапс 1913, с. 11: H , C , Si , N , P , O , S , Cl

- ^ Парамесваран и др. 2020, с. 210: Ч , С , Н , П , О , С , Се

- ^ Найт 2002, с. 148: Ч , Ц , Н , П , О , С , Се

- ^ Фраусто да Силва и Уильямс 2001, с. 500: Ч , С , Н , О , С , Се

- ^ Чжу и др. 2022 г.

- ^ Могилы 2022 г.

- ^ Розенберг 2013, с. 847

- ^ Obodovskiy 2015, p. 151

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 2002, с. 552

- ^ Иглсон 1994, с. 91

- ^ Хуан 2018, стр. 30, 32

- ^ Орисакве 2012, с. 000

- ^ Инь и др. 2018, с. 2

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Мёллер и др. 1989, с. 742

- ^ Уайтфорд и Гроб 1939, с. 239

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Джонс 2010, стр. 169–71.

- ^ Рассел и Ли 2005, с. 419

- ^ Тайлер 1948, с. 105 ; Рейли 2002, стр. 5–6.

- ^ Веселый 1966, с. 20

- ^ Клагстон и Флемминг 2000, стр. 100–101, 104–105, 302.

- ^ Маошэн 2020, стр. 962.

- ^ Май 2020 г.

- ^ Виберг 2001, стр. 402.

- ^ Рудольф 1973, с. 133 : «Кислород и особенно галогены ... поэтому являются сильными окислителями».

- ^ Дэниел и Рэпп 1976, с. 55

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Коттон и др. 1999, с. 554

- ^ Вудворд и др. 1999, стр. 133–194.

- ^ Филлипс и Уильямс 1965, стр. 478–479.

- ^ Мёллер и др. 1989, с. 314

- ^ Лэнфорд 1959, с. 176

- ^ Эмсли 2011, с. 478

- ^ Seese & Daub 1985, стр. 65

- ^ Маккей, Маккей и Хендерсон 2002, стр. 209, 211.

- ^ Казинс, Дэвидсон и Гарсиа-Виво 2013, стр. 11809–11811

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Цао и др. 2021, с. 4

- ^ Liptrot 1983, p. 161; Malone & Dolter 2008, p. 255

- ^ Wiberg 2001, pp. 255–257

- ^ Scott & Kanda 1962, p. 153

- ^ Taylor 1960, p. 316

- ^ Jump up to: a b Emsley 2011, passim

- ^ Crawford 1968, p. 540; Benner, Ricardo & Carrigan 2018, pp. 167–168: "The stability of the carbon-carbon bond ... has made it the first choice element to scaffold biomolecules. Hydrogen is needed for many reasons; at the very least, it terminates C-C chains. Heteroatoms (atoms that are neither carbon nor hydrogen) determine the reactivity of carbon-scaffolded biomolecules. In ... life, these are oxygen, nitrogen and, to a lesser extent, sulfur, phosphorus, selenium, and an occasional halogen."

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Cao et al. 2021, p. 20

- ^ Zhao, Tu & Chan 2021

- ^ Wasewar 2021, pp. 322–323

- ^ Messler 2011, p. 10

- ^ King 1994, p. 1344; Powell & Tims 1974, pp. 189–191; Cao et al. 2021, pp. 20–21

- ^ Vernon 2020, pp. 221–223; Rayner-Canham 2020, p. 216

- ^ Chandra X-ray Center 2018

- ^ Chapin, Matson & Vitousek 2011, p. 27

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fortescue 1980, p. 56

- ^ Georgievskii 1982, p. 58

- ^ Pepin, R. O.; Porcelli, D. (2002-01-01). "Origin of Noble Gases in the Terrestrial Planets". Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 47 (1): 191–246. Bibcode:2002RvMG...47..191P. doi:10.2138/rmg.2002.47.7. ISSN 1529-6466.

- ^ Zhu et al. 2014, pp. 644–648

- ^ Klein & Dutrow 2007, p. 435[broken anchor]

- ^ Cockell 2019, p. 212, 208–211

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 363, 379

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 516

- ^ Schmedt, Mangstl & Kraus 2012, p. 7847‒7849

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 39, 44, 80–81, 85, 199, 248, 263, 367, 478, 531, 610; Smulders 2011, pp. 416–421; Chen 1990, part 17.2.1; Hall 2021, p. 143: H (primary constituent of water); He (party balloons); B (in detergents); C (in pencils, as graphite); N (beer widgets); O (as peroxide, in detergents); F (as fluoride, in toothpaste); Ne (lighting); Si (in glassware); P (matches); S (garden treatments); Cl (bleach constituent); Ar (insulated windows); Ge (in wide-angle camera lenses); Se (glass; solar cells); Br (as bromide, for purification of spa water); Kr (energy saving fluorescent lamps); Sb (in batteries); Te (in ceramics, solar panels, rewrite-able DVDs); I (in antiseptic solutions); Xe (in plasma TV display cells, a technology subsequently made redundant by low cost LED and OLED displays.

- ^ Maroni 1995, pp. 108–123

- ^ Imbertierti 2020: H, He, B, C, N, O, F, Si, P, S, Cl, Ar, As, Se, Br, Kr, Sb, Te, I, Xe and Rn

- ^ Csele 2016; Winstel 2000; Davis et al. 2006, p. 431–432; Grondzik et al. 2010, p. 561: Cl, Ar, Ge, As, Se, Br, Kr, Te, I and Xe

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary; Eagleson 1994 (all bar germanic acid); Wiberg 2001, p. 897, germanic acid: H, B, C, N, O, F, Si, P, S, Cl, Ge, As, Sb, Br, Te, I and Xe

- ^ Бхувалка и др. 2021, стр. 10097–10107 : H, He, B, C, N, O, F, Si, P, S, Cl, Ar, Br, Sb, Te и I.

- ^ Король 2019, с. 408 : H, He, B, C, N, O, F, Si, P, S, Cl, Ge, As, Se, Br, Sb.

- ^ Эмсли 2011, стр. 98, 117, 331, 487 ; Грешам и др. 2015, стр. 25, 55, 60, 63 : H, He, B, C, N, O, F, Si, P, S, Cl, Ar, Se, Sb.

- ^ Бирд и др. 2021 ; Слай 2008 : H, B, C (включая графит), N, O, F, Si, P, S, Cl, Ar, Br и Sb.

- ^ Рейнхардт и др. 2015 ; Иглсон 1994, с. 1053 : H, He, C, N, O, F, P, S и Ar.

- ^ Windmeier & Barron 2013 : H, He, N, O, F, Ne, S, Cl и Ar

- ^ Кииски и др. 2016 : Ч, Б, С, Н, О, Си, П, С

- ^ Эмсли 2011, стр. 113, 231, 327, 362, 377, 393, 515:: H, C, N, O, P, S, Cl.

- ^ Брандт и Вейлер 2000 : H, He, C, N, O, Ar

- ^ Харбисон, Буржуа и Джонсон 2015, с. 364

- ^ Болин 2017, с. 2-1 [ сломанный якорь ]

- ^ Иордания, 2016 г.

- ^ Стиллман 1924, с. 213

- ^ де Л'Оне 1566, с. 7

- ^ Лемери 1699, с. 118 ; Дежонге 1998, с. 329

- ^ Лавуазье 1790, с. 175

- ^ Стратерн 2000, с. 239

- ^ Крисвелл 2007, с. 1140

- ^ Зальцберг 1991, с. 204

- ^ Берцелиус 1811, стр. 258.

- ^ Партингтон 1964, с. 168

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Баше 1832, с. 250

- ^ Голдсмит 1982, с. 526

- ^ Роско и Шормлеммер 1894, с. 4

- ^ Глинка 1960, с. 76

- ^ Герольд 2006, стр. 149–150

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Химические новости и журнал физических наук 1864 г.

- ^ Оксфордский словарь английского языка, 1989 г.

- ^ Кемсхед 1875, с. 13

- ^ Чемберс 1743, «Металл» : «То, что отличает металлы от всех других тел… это их тяжесть…»

- ^ Харрис 1803, с. 274

- ^ Бранде 1821, стр. 5.

- ^ Смит 1906, стр. 646–647.

- ^ Пляж 1911 г.

- ^ Эдвардс и Сиенко 1983, с. 693

- ^ Херцфельд 1927 ; Эдвардс 2000, стр. 100–103.

- ^ Кубашевский 1949, стр. 931–940.

- ^ Реми 1956, с. 9

- ^ Стотт 1956, стр. 100–102.

- ^ Сандерсон 1957, с. 229

- ^ Уайт 1962, с. 106

- ^ Джонсон 1966, стр. 3–4.

- ^ Мартин 1969, с. 6

- ^ Хорват 1973, стр. 335–336.

- ^ Приход 1977, с. 178

- ^ Майерс 1979, с. 712

- ^ Рао и Гангули, 1986 г.

- ^ Смит и Дуайер 1991, стр. 65

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Герман 1999, с. 702

- ^ Скотт 2001, с. 1781 г.

- ^ Манн и др. 2000, с. 5136.

- ^ Суреш и Кога 2001, стр. 5940–5944.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Эдвардс 2010, стр. 941–965.

- ^ Повх и Розин 2017, с. 131

- ^ Хилл, Холман и Халм 2017, стр. 182

- ^ Яо Б., Кузнецов В.Л., Сяо Т. и др. (2020). «Металлы и неметаллы в таблице Менделеева» . Философские труды Королевского общества A: Математические, физические и технические науки . 378 (2180): 1–21. Бибкод : 2020RSPTA.37800213Y . дои : 10.1098/rsta.2020.0213 . ПМЦ 7435143 . ПМИД 32811363 .

- ^ Бенжен и др. 2020, стр. 13.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Заяц и Бач 1836, с. 310

- ^ Чемберс 1743 г. [ сломанный якорь ] : "То, что отличает металлы от всех других тел... - это их тяжесть..."

- ^ Эрман и Саймон 1808 г.

- ^ Эдвардс 2000, с. 85

- ^ Рассел и Ли 2005, с. 466

- ^ Аткинс и др. 2006, стр. 320–21.

- ^ Жигальский и Джонс 2003, с. 66

- ^ Книн, Роджерс и Симпсон 1972, стр. 218–219.

- ^ Эмсли 1971, с. 1

- ^ Джонс 2010, с. 169

- ^ Джонсон 1966, стр. 3–6, 15.

- ^ Shkol'nikov 2010, p. 2127

- ^ Эйлуорд и Финдли, 2008, стр. 6–13; 126

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Рам, Зенг и Хоффманн, 2019, стр. 345

- ^ Даффус 2002, с. 798

- ^ Hein & Arena 2011, стр. 228, 523 ; Тимберлейк 1996, стр. 88, 142 ; Книн, Роджерс и Симпсон 1972, с. 263 ; Бейкер 1962, стр. 21, 194 ; Меллер 1958, стр. 11, 178.

- ^ Голдуайт и Спилман 1984, с. 130

- ^ Одерберг 2007, с. 97

- ^ Бертомеу-Санчес и др. 2002, стр. 248–249

- ^ Дюпаскье 1844, стр. 66–67.

- ^ Баче 1832, стр. 248–276.

- ^ Ренуф 1901, стр. 268.

- ^ Бертомеу-Санчес и др. 2002, с. 248

- ^ Бертомеу-Санчес и др. 2002, с. 236

- ^ Хофер 1845, с. 85

- ^ Дюма 1828 ; Дюма 1859 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Рохов 1966, с. 4

- ^ Виберг 2001, с. 780 ; Эмсли 2011, с. 397 ; Рохов 1966, стр. 23, 84.

- ^ Книн, Роджерс и Симпсон 1972, с. 439

- ^ Книн, Роджерс и Симпсон 1972, стр. 321, 404, 436.

- ^ Книн, Роджерс и Симпсон 1972, с. 465

- ^ Книн, Роджерс и Симпсон 1972, с. 308

- ^ Трегартен 2003, с. 10

- ^ Льюис 1993, стр. 28, 827.

- ^ Льюис 1993, стр. 28, 813.

- ^ Чунг 1987

- ^ Godfrin & Lauter 1995, pp. 216‒218

- ^ Янас, Кабреро-Вилатела и Балмер, 2013 г.

- ^ Виберг 2001, стр. 416.

- ^ Десаи, Джеймс и Хо 1984, стр. 1160 ; Матула 1979, с. 1260

- ^ Шефер 1968, с. 76 ; Карапелла 1968, стр. 29‒32

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 2002, с. 804

- ^ Книн, Роджерс и Симпсон 1972, с. 264

- ^ Рейнер-Кэнхэм 2018, стр. 203

- ^ Уэлчер 2009, с. 3–32 : «Элементы изменяются от … металлоидов до умеренно активных неметаллов, очень активных неметаллов и благородного газа».

- ^ Маккин 2014, с. 80

- ^ Джонсон 1966, стр. 105–108.

- ^ Штейн 1969, стр. 5396–5397 ; Питцер 1975, стр. 760–761.

- ^ Рохов 1966, с. 4 ; Аткинс и др. 2006, стр. 8, 122–123.

- ^ Виберг 2001, стр. 750 .

- ^ Дуглас и Мерсье 1982, стр. 723

- ^ Гиллеспи и Робинсон 1959, с. 418

- ^ Сандерсон 1967, с. 172 ; Мингос 2019, с. 27

- ^ Дом 2008, с. 441

- ^ Мингос 2019, с. 27 ; Сандерсон 1967, с. 172

- ^ Виберг 2001, стр. 399.

- ^ Кленинг и Аппельман 1988, с. 3760

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Рао 2002, стр. 22.

- ^ Sidorov 1960, pp. 599–603

- ^ Макмиллан 2006, с. 823

- ^ Уэллс 1984, с. 534

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Паддефатт и Монаган 1989, с. 59

- ^ Кинг 1995, с. 182

- ^ Риттер 2011, с. 10

- ^ Ямагути и Шираи 1996, стр. 3.

- ^ Вернон 2020, с. 223

- ^ Вудворд и др. 1999, с. 134

- ^ Далтон 2019

Библиография

[ редактировать ]- Эбботт Д. 1966, Введение в периодическую таблицу , JM Dent & Sons, Лондон.

- Аддисон WE 1964, Аллотропия элементов , Oldbourne Press, Лондон

- Аткинс П.А. и др. 2006, Неорганическая химия Шрайвера и Аткинса , 4-е изд., Oxford University Press, Оксфорд, ISBN 978-0-7167-4878-6

- Эйлуорд Г. и Финдли Т. 2008, SI Chemical Data , 6-е изд., John Wiley & Sons Australia, Милтон, ISBN 978-0-470-81638-7

- Бах нашей эры, 1832 г., «Очерк химической номенклатуры перед трактатом по химии Дж. Дж. Берцелиуса» , American Journal of Science , vol. 22, стр. 248–277.

- Бейкер и др. PS 1962, Химия и вы , Лайонс и Карнахан, Чикаго

- Barton AFM 2021, Состояния материи, состояния разума , CRC Press, Бока-Ратон, ISBN 978-0-7503-0418-4

- Бич ФК (редактор) 1911, Американа: универсальная справочная библиотека , том. XIII, Мел-Нью, Металлоид, Отдел сбора данных Scientific American, Нью-Йорк

- Берд А., Баттенберг, К. и Саткер Б.Дж. 2021, «Антипирены», в Энциклопедии промышленной химии Ульмана, два : 10.1002/14356007.a11_123.pub2

- Бейзер А., 1987, Концепции современной физики , 4-е изд., МакГроу-Хилл, Нью-Йорк, ISBN 978-0-07-004473-9

- Беннер С.А., Рикардо А. и Кэрриган М.А. 2018, «Существует ли общая химическая модель жизни во Вселенной?», в Клеланде К.Э. и Бедо М.А. (ред.), Природа жизни: классические и современные перспективы философии и науки , Издательство Кембриджского университета, Кембридж, ISBN 978-1-108-72206-3

- Бенжен и др. 2020, Металлы и неметаллы в периодической таблице, Философские труды Королевского общества A , том. 378, 20200213

- Бергер Л.И., 1997, Полупроводниковые материалы , CRC Press, Бока-Ратон, ISBN 978-0-8493-8912-2

- Бертомеу-Санчес-младший, Гарсия-Бельмар А. и Бенсоде-Винсент Б. 2002, «В поисках порядка вещей: учебники и химические классификации во Франции девятнадцатого века», Ambix , vol. 49, нет. 3, дои : 10.1179/amb.2002.49.3.227

- Берцелиус Дж. Дж. 1811, «Очерк химической номенклатуры», Журнал физики, химии, естественной истории , том. LXXIII, с. 253‒286

- Бхувалка и др. 2021, «Характеристика изменений в использовании материалов в связи с электрификацией транспортных средств», Environmental Science & Technology vol. 55, нет. 14, doi : 10.1021/acs.est.1c00970

- Богородицкий Н.П. и Пасынков В.В. 1967, Радио и электронные материалы , Iliffe Books, Лондон.

- Больманн Р. 1992, «Синтез галогенидов», в Винтерфельдте Э. (ред.), Манипулирование гетероатомами , Pergamon Press, Оксфорд, ISBN 978-0-08-091249-3

- Боресков Г.К. 2003, Гетерогенный катализ , Nova Science, Нью-Йорк, ISBN 978-1-59033-864-3

- Брэди Дж. Э. и Сенезе Ф. 2009, Химия: исследование материи и ее изменений , 5-е изд., John Wiley & Sons, Нью-Йорк, ISBN 978-0-470-57642-7

- Бранде WT 1821, Руководство по химии , вып. II, Джон Мюррей, Лондон

- Брандт Х.Г. и Вейлер Х., 2000, «Сварка и резка», в Энциклопедии промышленной химии Ульмана, два : 10.1002/14356007.a28_203

- Брант WT 1919, Справочник приемок и процессов для металлистов , HC Baird & Company, Филадельфия

- Браун Т.Л. и др. 2014, Химия: Центральная наука , 3-е изд., Pearson Australia: Сидней, ISBN 978-1-4425-5460-3

- Берфорд Н., Пассмор Дж. и Сандерс JCP 1989, «Приготовление, структура и энергетика гомополиатомных катионов групп 16 (халькогены) и 17 (галогены)», в книге Либмана Дж. Ф. и Гринберга А. (ред.), От атомов к полимеры: изоэлектронные аналогии , ВЧ, Нью-Йорк, ISBN 978-0-89573-711-3

- Байнум В.Ф., Браун Дж. и Портер Р. 1981 (ред.), Словарь истории науки , Princeton University Press, Принстон, ISBN 978-0-691-08287-5

- Кан Р.В. и Хаасен П., Физическая металлургия: Том. 1 , 4-е изд., Elsevier Science, Амстердам, ISBN 978-0-444-89875-3

- Цао С и др. 2021, «Понимание периодической и непериодической химии в периодических таблицах», Frontiers in Chemistry , vol. 8, нет. 813, два : 10.3389/fchem.2020.00813

- Carapella SC 1968, «Мышьяк» в Хампеле, Калифорния (ред.), Энциклопедия химических элементов , Рейнхольд, Нью-Йорк.

- Кармалт CJ и Норман NC 1998, «Мышьяк, сурьма и висмут: некоторые общие свойства и аспекты периодичности», в Norman NC (ред.), Химия мышьяка, сурьмы и висмута , Blackie Academic & Professional, Лондон, стр. 1– 38, ISBN 0-7514-0389-X

- Карраско и др. 2023, «Антимонен: настраиваемый постграфеновый материал для перспективных применений в оптоэлектронике, катализе, энергетике и биомедицине», Chemical Society Reviews , vol. 52, нет. 4, с. 1288–1330, дои : 10.1039/d2cs00570k

- Чаллонер Дж. 2014, Элементы: Новое руководство по строительным блокам нашей Вселенной , Carlton Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-233-00436-5

- Чемберс E 1743, в «Металл» , Циклопедия: Или Универсальный словарь искусств и наук (и т. д.) , том. 2, D Midwinter, Лондон