Редкоземельный элемент

Редкоземельные элементы ( РЗЭ ), также называемые редкоземельными металлами или редкоземельными элементами или, в контексте, редкоземельными оксидами , а иногда и лантаноиды (хотя обычно сюда включают скандий и иттрий , не принадлежащие к этому ряду). как редкоземельные элементы), [1] представляют собой набор из 17 почти неразличимых блестящих серебристо-белых мягких тяжелых металлов . Соединения, содержащие редкоземельные элементы, находят разнообразное применение в электрических и электронных компонентах, лазерах, стекле, магнитных материалах и промышленных процессах.

Скандий и иттрий считаются редкоземельными элементами, поскольку они, как правило, встречаются в тех же рудных месторождениях, что и лантаноиды, и обладают сходными химическими свойствами, но имеют разные электрические и магнитные свойства . [2] [3] Термин «редкоземельные элементы» является неправильным, поскольку на самом деле они не являются дефицитными, хотя исторически на их выделение ушло много времени. [4] [5]

These metals tarnish slowly in air at room temperature and react slowly with cold water to form hydroxides, liberating hydrogen. They react with steam to form oxides and ignite spontaneously at a temperature of 400 °C (752 °F). These elements and their compounds have no biological function other than in several specialized enzymes, such as in lanthanide-dependent methanol dehydrogenases in bacteria.[6] The water-soluble compounds are mildly to moderately toxic, but the insoluble ones are not.[7] Все изотопы прометия радиоактивны, и он не встречается в природе в земной коре, за исключением незначительного количества, образующегося в результате спонтанного деления урана -238 . Они часто встречаются в минералах с торием , реже с ураном .

Though rare-earth elements are technically relatively plentiful in the entire Earth's crust (cerium being the 25th-most-abundant element at 68 parts per million, more abundant than copper), in practice this is spread thin across trace impurities, so to obtain rare earths at usable purity requires processing enormous amounts of raw ore at great expense, thus the name "rare" earths.

Because of their geochemical properties, rare-earth elements are typically dispersed and not often found concentrated in rare-earth minerals. Consequently, economically exploitable ore deposits are sparse.[8] The first rare-earth mineral discovered (1787) was gadolinite, a black mineral composed of cerium, yttrium, iron, silicon, and other elements. This mineral was extracted from a mine in the village of Ytterby in Sweden; four of the rare-earth elements bear names derived from this single location.

Minerals[edit]

A table listing the 17 rare-earth elements, their atomic number and symbol, the etymology of their names, and their main uses (see also Applications of lanthanides) is provided here. Some of the rare-earth elements are named after the scientists who discovered them, or elucidated their elemental properties, and some after the geographical locations where discovered.

| Z | Symbol | Name | Etymology | Selected applications | Abundance[9][10] (ppm[a]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | Sc | Scandium | from Latin Scandia (Scandinavia). | Light aluminium-scandium alloys for aerospace components, additive in metal-halide lamps and mercury-vapor lamps,[11] radioactive tracing agent in oil refineries | 22 |

| 39 | Y | Yttrium | after the village of Ytterby, Sweden, where the first rare-earth ore was discovered. | Yttrium aluminium garnet (YAG) laser, yttrium vanadate (YVO4) as host for europium in television red phosphor, YBCO high-temperature superconductors, yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) (used in tooth crowns; as refractory material - in metal alloys used in jet engines, and coatings of engines and industrial gas turbines; electroceramics - for measuring oxygen and pH of hot water solutions, i.e. in fuel cells; ceramic electrolyte - used in solid oxide fuel cell; jewelry - for its hardness and optical properties; do-it-yourself high temperature ceramics and cements based on water), yttrium iron garnet (YIG) microwave filters,[11] energy-efficient light bulbs (part of triphosphor white phosphor coating in fluorescent tubes, CFLs and CCFLs, and yellow phosphor coating in white LEDs),[12] spark plugs, gas mantles, additive to steel, aluminium and magnesium alloys, cancer treatments, camera and refractive telescope lenses (due to high refractive index and very low thermal expansion), battery cathodes (LYP) | 33 |

| 57 | La | Lanthanum | from the Greek "lanthanein", meaning to be hidden. | High refractive index and alkali-resistant glass, flint, hydrogen storage, battery-electrodes, camera and refractive telescope lenses, fluid catalytic cracking catalyst for oil refineries | 39 |

| 58 | Ce | Cerium | after the dwarf planet Ceres, named after the Roman goddess of agriculture. | Chemical oxidizing agent, polishing powder, yellow colors in glass and ceramics, catalyst for self-cleaning ovens, fluid catalytic cracking catalyst for oil refineries, ferrocerium flints for lighters, robust intrinsically hydrophobic coatings for turbine blades[13] | 66.5 |

| 59 | Pr | Praseodymium | from the Greek "prasios", meaning leek-green, and "didymos", meaning twin. | Rare-earth magnets, lasers, core material for carbon arc lighting, colorant in glasses and enamels, additive in didymium glass used in welding goggles,[11] ferrocerium firesteel (flint) products, single-mode fiber optical amplifiers (as a dopant of fluoride glass) | 9.2 |

| 60 | Nd | Neodymium | from the Greek "neos", meaning new, and "didymos", meaning twin. | Rare-earth magnets, lasers, violet colors in glass and ceramics, didymium glass, ceramic capacitors, electric motors in electric automobiles | 41.5 |

| 61 | Pm | Promethium | after the Titan Prometheus, who brought fire to mortals. | Nuclear batteries, luminous paint | 1×10−15[14][b] |

| 62 | Sm | Samarium | after mine official, Vasili Samarsky-Bykhovets. | Rare-earth magnets, lasers, neutron capture, masers, control rods of nuclear reactors | 7.05 |

| 63 | Eu | Europium | after the continent of Europe. | Red and blue phosphors, lasers, mercury-vapor lamps, fluorescent lamps, NMR relaxation agent | 2 |

| 64 | Gd | Gadolinium | after Johan Gadolin (1760–1852), to honor his investigation of rare earths. | High refractive index glass or garnets, lasers, X-ray tubes, computer bubble memories, neutron capture, MRI contrast agent, NMR relaxation agent, steel and chromium alloys additive, magnetic refrigeration (using significant magnetocaloric effect), positron emission tomography scintillator detectors, a substrate for magneto-optical films, high performance high-temperature superconductors, ceramic electrolyte used in solid oxide fuel cells, oxygen detectors, possibly in catalytic conversion of automobile fumes. | 6.2 |

| 65 | Tb | Terbium | after the village of Ytterby, Sweden. | Additive in neodymium based magnets, green phosphors, lasers, fluorescent lamps (as part of the white triband phosphor coating), magnetostrictive alloys such as terfenol-D, naval sonar systems, stabilizer of fuel cells | 1.2 |

| 66 | Dy | Dysprosium | from the Greek "dysprositos", meaning hard to get. | Additive in neodymium based magnets, lasers, magnetostrictive alloys such as terfenol-D, hard disk drives | 5.2 |

| 67 | Ho | Holmium | after Stockholm (in Latin, "Holmia"), the native city of one of its discoverers. | Lasers, wavelength calibration standards for optical spectrophotometers, magnets | 1.3 |

| 68 | Er | Erbium | after the village of Ytterby, Sweden. | Infrared lasers, vanadium steel, fiber-optic technology | 3.5 |

| 69 | Tm | Thulium | after the mythological northern land of Thule. | Portable X-ray machines, metal-halide lamps, lasers | 0.52 |

| 70 | Yb | Ytterbium | after the village of Ytterby, Sweden. | Infrared lasers, chemical reducing agent, decoy flares, stainless steel, strain gauges, nuclear medicine, earthquake monitoring | 3.2 |

| 71 | Lu | Lutetium | after Lutetia, the city that later became Paris. | Positron emission tomography – PET scan detectors, high-refractive-index glass, lutetium tantalate hosts for phosphors, catalyst used in refineries, LED light bulb | 0.8 |

- ^ Parts per million in Earth's crust, e.g. Pb=13 ppm

- ^ Promethium has no stable isotopes or primordial radioisotopes; trace quantities occur in nature as fission products.

A mnemonic for the names of the sixth-row elements in order is "Lately college parties never produce sexy European girls that drink heavily even though you look".[15]

Discovery and early history[edit]

Rare earths were mainly discovered as components of minerals. Ytterbium was found in the "ytterbite" (renamed to gadolinite in 1800) discovered by Lieutenant Carl Axel Arrhenius in 1787 at a quarry in the village of Ytterby, Sweden[16] and termed "rare" because it had never yet been seen.[17] Arrhenius's "ytterbite" reached Johan Gadolin, a Royal Academy of Turku professor, and his analysis yielded an unknown oxide ("earth" in the geological parlance of the day[17]), which he called yttria. Anders Gustav Ekeberg isolated beryllium from the gadolinite but failed to recognize other elements in the ore. After this discovery in 1794, a mineral from Bastnäs near Riddarhyttan, Sweden, which was believed to be an iron–tungsten mineral, was re-examined by Jöns Jacob Berzelius and Wilhelm Hisinger. In 1803 they obtained a white oxide and called it ceria. Martin Heinrich Klaproth independently discovered the same oxide and called it ochroia. It took another 30 years for researchers to determine that other elements were contained in the two ores ceria and yttria (the similarity of the rare-earth metals' chemical properties made their separation difficult).

In 1839 Carl Gustav Mosander, an assistant of Berzelius, separated ceria by heating the nitrate and dissolving the product in nitric acid. He called the oxide of the soluble salt lanthana. It took him three more years to separate the lanthana further into didymia and pure lanthana. Didymia, although not further separable by Mosander's techniques, was in fact still a mixture of oxides.

In 1842 Mosander also separated the yttria into three oxides: pure yttria, terbia, and erbia (all the names are derived from the town name "Ytterby"). The earth giving pink salts he called terbium; the one that yielded yellow peroxide he called erbium.

In 1842 the number of known rare-earth elements had reached six: yttrium, cerium, lanthanum, didymium, erbium, and terbium.

Nils Johan Berlin and Marc Delafontaine tried also to separate the crude yttria and found the same substances that Mosander obtained, but Berlin named (1860) the substance giving pink salts erbium, and Delafontaine named the substance with the yellow peroxide terbium. This confusion led to several false claims of new elements, such as the mosandrium of J. Lawrence Smith, or the philippium and decipium of Delafontaine. Due to the difficulty in separating the metals (and determining the separation is complete), the total number of false discoveries was dozens,[18][19] with some putting the total number of discoveries at over a hundred.[20]

Spectroscopic identification[edit]

There were no further discoveries for 30 years, and the element didymium was listed in the periodic table of elements with a molecular mass of 138. In 1879, Delafontaine used the new physical process of optical flame spectroscopy and found several new spectral lines in didymia. Also in 1879, Paul Émile Lecoq de Boisbaudran isolated the new element samarium from the mineral samarskite.

The samaria earth was further separated by Lecoq de Boisbaudran in 1886, and a similar result was obtained by Jean Charles Galissard de Marignac by direct isolation from samarskite. They named the element gadolinium after Johan Gadolin, and its oxide was named "gadolinia".

Further spectroscopic analysis between 1886 and 1901 of samaria, yttria, and samarskite by William Crookes, Lecoq de Boisbaudran and Eugène-Anatole Demarçay yielded several new spectral lines that indicated the existence of an unknown element. The fractional crystallization of the oxides then yielded europium in 1901.

In 1839 the third source for rare earths became available. This is a mineral similar to gadolinite called uranotantalum (now called "samarskite") an oxide of a mixture of elements such as yttrium, ytterbium, iron, uranium, thorium, calcium, niobium, and tantalum. This mineral from Miass in the southern Ural Mountains was documented by Gustav Rose. The Russian chemist R. Harmann proposed that a new element he called "ilmenium" should be present in this mineral, but later, Christian Wilhelm Blomstrand, Galissard de Marignac, and Heinrich Rose found only tantalum and niobium (columbium) in it.

The exact number of rare-earth elements that existed was highly unclear, and a maximum number of 25 was estimated. The use of X-ray spectra (obtained by X-ray crystallography) by Henry Gwyn Jeffreys Moseley made it possible to assign atomic numbers to the elements. Moseley found that the exact number of lanthanides had to be 15, but that element 61 had not yet been discovered. (This is promethium, a radioactive element whose most stable isotope has a half-life of just 18 years.)

Using these facts about atomic numbers from X-ray crystallography, Moseley also showed that hafnium (element 72) would not be a rare-earth element. Moseley was killed in World War I in 1915, years before hafnium was discovered. Hence, the claim of Georges Urbain that he had discovered element 72 was untrue. Hafnium is an element that lies in the periodic table immediately below zirconium, and hafnium and zirconium have very similar chemical and physical properties.

Sources and purification[edit]

During the 1940s, Frank Spedding and others in the United States (during the Manhattan Project) developed chemical ion-exchange procedures for separating and purifying rare-earth elements. This method was first applied to the actinides for separating plutonium-239 and neptunium from uranium, thorium, actinium, and the other actinides in the materials produced in nuclear reactors. Plutonium-239 was very desirable because it is a fissile material.

The principal sources of rare-earth elements are the minerals bastnäsite (RCO3F, where R is a mixture of rare-earth elements), monazite (XPO4, where X is a mixture of rare-earth elements and sometimes thorium), and loparite ((Ce,Na,Ca)(Ti,Nb)O3), and the lateritic ion-adsorption clays. Despite their high relative abundance, rare-earth minerals are more difficult to mine and extract than equivalent sources of transition metals (due in part to their similar chemical properties), making the rare-earth elements relatively expensive. Their industrial use was very limited until efficient separation techniques were developed, such as ion exchange, fractional crystallization, and liquid–liquid extraction during the late 1950s and early 1960s.[21]

Some ilmenite concentrates contain small amounts of scandium and other rare-earth elements, which could be analysed by X-ray fluorescence (XRF).[22]

Classification[edit]

Before the time that ion exchange methods and elution were available, the separation of the rare earths was primarily achieved by repeated precipitation or crystallization. In those days, the first separation was into two main groups, the cerium earths (lanthanum, cerium, praseodymium, neodymium, and samarium) and the yttrium earths (scandium, yttrium, dysprosium, holmium, erbium, thulium, ytterbium, and lutetium). Europium, gadolinium, and terbium were either considered as a separate group of rare-earth elements (the terbium group), or europium was included in the cerium group, and gadolinium and terbium were included in the yttrium group. In the latter case, the f-block elements are split into half: the first half (La–Eu) form the cerium group, and the second half (Gd–Yb) together with group 3 (Sc, Y, Lu) form the yttrium group.[23] The reason for this division arose from the difference in solubility of rare-earth double sulfates with sodium and potassium. The sodium double sulfates of the cerium group are poorly soluble, those of the terbium group slightly, and those of the yttrium group are very soluble.[24] Sometimes, the yttrium group was further split into the erbium group (dysprosium, holmium, erbium, and thulium) and the ytterbium group (ytterbium and lutetium), but today the main grouping is between the cerium and the yttrium groups.[25] Today, the rare-earth elements are classified as light or heavy rare-earth elements, rather than in cerium and yttrium groups.

Light versus heavy classification[edit]

The classification of rare-earth elements is inconsistent between authors.[26] The most common distinction between rare-earth elements is made by atomic numbers; those with low atomic numbers are referred to as light rare-earth elements (LREE), those with high atomic numbers are the heavy rare-earth elements (HREE), and those that fall in between are typically referred to as the middle rare-earth elements (MREE).[27] Commonly, rare-earth elements with atomic numbers 57 to 61 (lanthanum to promethium) are classified as light and those with atomic numbers 62 and greater are classified as heavy rare-earth elements.[28] Increasing atomic numbers between light and heavy rare-earth elements and decreasing atomic radii throughout the series causes chemical variations.[28] Europium is exempt of this classification as it has two valence states: Eu2+ and Eu3+.[28] Yttrium is grouped as heavy rare-earth element due to chemical similarities.[29] The break between the two groups is sometimes put elsewhere, such as between elements 63 (europium) and 64 (gadolinium).[30] The actual metallic densities of these two groups overlap, with the "light" group having densities from 6.145 (lanthanum) to 7.26 (promethium) or 7.52 (samarium) g/cc, and the "heavy" group from 6.965 (ytterbium) to 9.32 (thulium), as well as including yttrium at 4.47. Europium has a density of 5.24.

Origin[edit]

Rare-earth elements, except scandium, are heavier than iron and thus are produced by supernova nucleosynthesis or by the s-process in asymptotic giant branch stars. In nature, spontaneous fission of uranium-238 produces trace amounts of radioactive promethium, but most promethium is synthetically produced in nuclear reactors.

Due to their chemical similarity, the concentrations of rare earths in rocks are only slowly changed by geochemical processes, making their proportions useful for geochronology and dating fossils.

Compounds[edit]

Rare-earth elements occur in nature in combination with phosphate (monazite), carbonate-fluoride (bastnäsite), and oxygen anions.

In their oxides, most rare-earth elements only have a valence of 3 and form sesquioxides (cerium forms CeO2). Five different crystal structures are known, depending on the element and the temperature. The X-phase and the H-phase are only stable above 2000 K. At lower temperatures, there are the hexagonal A-phase, the monoclinic B-phase, and the cubic C-phase, which is the stable form at room temperature for most of the elements. The C-phase was once thought to be in space group I213 (no. 199),[31] but is now known to be in space group Ia3 (no. 206). The structure is similar to that of fluorite or cerium dioxide (in which the cations form a face-centred cubic lattice and the anions sit inside the tetrahedra of cations), except that one-quarter of the anions (oxygen) are missing. The unit cell of these sesquioxides corresponds to eight unit cells of fluorite or cerium dioxide, with 32 cations instead of 4. This is called the bixbyite structure, as it occurs in a mineral of that name ((Mn,Fe)2O3).[32]

Geological distribution[edit]

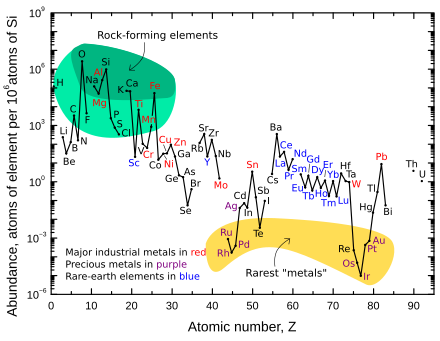

As seen in the chart, rare-earth elements are found on Earth at similar concentrations to many common transition metals. The most abundant rare-earth element is cerium, which is actually the 25th most abundant element in Earth's crust, having 68 parts per million (about as common as copper). The exception is the highly unstable and radioactive promethium "rare earth" is quite scarce. The longest-lived isotope of promethium has a half-life of 17.7 years, so the element exists in nature in only negligible amounts (approximately 572 g in the entire Earth's crust).[33] Promethium is one of the two elements that do not have stable (non-radioactive) isotopes and are followed by (i.e. with higher atomic number) stable elements (the other being technetium).

The rare-earth elements are often found together. During the sequential accretion of the Earth, the dense rare-earth elements were incorporated into the deeper portions of the planet. Early differentiation of molten material largely incorporated the rare earths into mantle rocks.[34] The high field strength[clarification needed] and large ionic radii of rare earths make them incompatible with the crystal lattices of most rock-forming minerals, so REE will undergo strong partitioning into a melt phase if one is present.[34] REE are chemically very similar and have always been difficult to separate, but the gradual decrease in ionic radius from light REE (LREE) to heavy REE (HREE), called the lanthanide contraction, can produce a broad separation between light and heavy REE. The larger ionic radii of LREE make them generally more incompatible than HREE in rock-forming minerals, and will partition more strongly into a melt phase, while HREE may prefer to remain in the crystalline residue, particularly if it contains HREE-compatible minerals like garnet.[34][35] The result is that all magma formed from partial melting will always have greater concentrations of LREE than HREE, and individual minerals may be dominated by either HREE or LREE, depending on which range of ionic radii best fits the crystal lattice.[34]

Among the anhydrous rare-earth phosphates, it is the tetragonal mineral xenotime that incorporates yttrium and the HREE, whereas the monoclinic monazite phase incorporates cerium and the LREE preferentially. The smaller size of the HREE allows greater solid solubility in the rock-forming minerals that make up Earth's mantle, and thus yttrium and the HREE show less enrichment in Earth's crust relative to chondritic abundance than does cerium and the LREE. This has economic consequences: large ore bodies of LREE are known around the world and are being exploited. Ore bodies for HREE are more rare, smaller, and less concentrated. Most of the current supply of HREE originates in the "ion-absorption clay" ores of Southern China. Some versions provide concentrates containing about 65% yttrium oxide, with the HREE being present in ratios reflecting the Oddo–Harkins rule: even-numbered REE at abundances of about 5% each, and odd-numbered REE at abundances of about 1% each. Similar compositions are found in xenotime or gadolinite.[36]

Well-known minerals containing yttrium, and other HREE, include gadolinite, xenotime, samarskite, euxenite, fergusonite, yttrotantalite, yttrotungstite, yttrofluorite (a variety of fluorite), thalenite, and yttrialite. Small amounts occur in zircon, which derives its typical yellow fluorescence from some of the accompanying HREE. The zirconium mineral eudialyte, such as is found in southern Greenland, contains small but potentially useful amounts of yttrium. Of the above yttrium minerals, most played a part in providing research quantities of lanthanides during the discovery days. Xenotime is occasionally recovered as a byproduct of heavy-sand processing, but is not as abundant as the similarly recovered monazite (which typically contains a few percent of yttrium). Uranium ores from Ontario have occasionally yielded yttrium as a byproduct.[36]

Well-known minerals containing cerium, and other LREE, include bastnäsite, monazite, allanite, loparite, ancylite, parisite, lanthanite, chevkinite, cerite, stillwellite, britholite, fluocerite, and cerianite. Monazite (marine sands from Brazil, India, or Australia; rock from South Africa), bastnäsite (from Mountain Pass rare earth mine, or several localities in China), and loparite (Kola Peninsula, Russia) have been the principal ores of cerium and the light lanthanides.[36]

Enriched deposits of rare-earth elements at the surface of the Earth, carbonatites and pegmatites, are related to alkaline plutonism, an uncommon kind of magmatism that occurs in tectonic settings where there is rifting or that are near subduction zones.[35] In a rift setting, the alkaline magma is produced by very small degrees of partial melting (<1%) of garnet peridotite in the upper mantle (200 to 600 km depth).[35] This melt becomes enriched in incompatible elements, like the rare-earth elements, by leaching them out of the crystalline residue. The resultant magma rises as a diapir, or diatreme, along pre-existing fractures, and can be emplaced deep in the crust, or erupted at the surface. Typical REE enriched deposits types forming in rift settings are carbonatites, and A- and M-Type granitoids.[34][35] Near subduction zones, partial melting of the subducting plate within the asthenosphere (80 to 200 km depth) produces a volatile-rich magma (high concentrations of CO2 and water), with high concentrations of alkaline elements, and high element mobility that the rare earths are strongly partitioned into.[34] This melt may also rise along pre-existing fractures, and be emplaced in the crust above the subducting slab or erupted at the surface. REE-enriched deposits forming from these melts are typically S-Type granitoids.[34][35]

Alkaline magmas enriched with rare-earth elements include carbonatites, peralkaline granites (pegmatites), and nepheline syenite. Carbonatites crystallize from CO2-rich fluids, which can be produced by partial melting of hydrous-carbonated lherzolite to produce a CO2-rich primary magma, by fractional crystallization of an alkaline primary magma, or by separation of a CO2-rich immiscible liquid from.[34][35] These liquids are most commonly forming in association with very deep Precambrian cratons, like the ones found in Africa and the Canadian Shield.[34] Ferrocarbonatites are the most common type of carbonatite to be enriched in REE, and are often emplaced as late-stage, brecciated pipes at the core of igneous complexes; they consist of fine-grained calcite and hematite, sometimes with significant concentrations of ankerite and minor concentrations of siderite.[34][35] Large carbonatite deposits enriched in rare-earth elements include Mount Weld in Australia, Thor Lake in Canada, Zandkopsdrift in South Africa, and Mountain Pass in the USA.[35] Peralkaline granites (A-Type granitoids) have very high concentrations of alkaline elements and very low concentrations of phosphorus; they are deposited at moderate depths in extensional zones, often as igneous ring complexes, or as pipes, massive bodies, and lenses.[34][35] These fluids have very low viscosities and high element mobility, which allows for the crystallization of large grains, despite a relatively short crystallization time upon emplacement; their large grain size is why these deposits are commonly referred to as pegmatites.[35] Economically viable pegmatites are divided into Lithium-Cesium-Tantalum (LCT) and Niobium-Yttrium-Fluorine (NYF) types; NYF types are enriched in rare-earth minerals. Examples of rare-earth pegmatite deposits include Strange Lake in Canada and Khaladean-Buregtey in Mongolia.[35] Nepheline syenite (M-Type granitoids) deposits are 90% feldspar and feldspathoid minerals. They are deposited in small, circular massifs and contain high concentrations of rare-earth-bearing accessory minerals.[34][35] For the most part, these deposits are small but important examples include Illimaussaq-Kvanefeld in Greenland, and Lovozera in Russia.[35]

Rare-earth elements can also be enriched in deposits by secondary alteration either by interactions with hydrothermal fluids or meteoric water or by erosion and transport of resistate REE-bearing minerals. Argillization of primary minerals enriches insoluble elements by leaching out silica and other soluble elements, recrystallizing feldspar into clay minerals such kaolinite, halloysite, and montmorillonite. In tropical regions where precipitation is high, weathering forms a thick argillized regolith, this process is called supergene enrichment and produces laterite deposits; heavy rare-earth elements are incorporated into the residual clay by absorption. This kind of deposit is only mined for REE in Southern China, where the majority of global heavy rare-earth element production occurs. REE-laterites do form elsewhere, including over the carbonatite at Mount Weld in Australia. REE may also be extracted from placer deposits if the sedimentary parent lithology contains REE-bearing, heavy resistate minerals.[35]

In 2011, Yasuhiro Kato, a geologist at the University of Tokyo who led a study of Pacific Ocean seabed mud, published results indicating the mud could hold rich concentrations of rare-earth minerals. The deposits, studied at 78 sites, came from "[h]ot plumes from hydrothermal vents pull[ing] these materials out of seawater and deposit[ing] them on the seafloor, bit by bit, over tens of millions of years. One square patch of metal-rich mud 2.3 kilometers wide might contain enough rare earths to meet most of the global demand for a year, Japanese geologists report in Nature Geoscience." "I believe that rare[-]earth resources undersea are much more promising than on-land resources," said Kato. "[C]oncentrations of rare earths were comparable to those found in clays mined in China. Some deposits contained twice as much heavy rare earths such as dysprosium, a component of magnets in hybrid car motors."[36][37]

The global demand for rare-earth elements (REEs) is expected to increase more than fivefold by 2030.[38][39]

Geochemistry[edit]

The REE geochemical classification is usually done on the basis of their atomic weight. One of the most common classifications divides REE into 3 groups: light rare earths (LREE - from 57La to 60Nd), intermediate (MREE - from 62Sm to 67Ho) and heavy (HREE - from 68Er to 71Lu). REE usually appear as trivalent ions, except for Ce and Eu which can take the form of Ce4+ and Eu2+ depending on the redox conditions of the system. Consequentially, REE are characterized by a substantial identity in their chemical reactivity, which results in a serial behaviour during geochemical processes rather than being characteristic of a single element of the series. Sc, Y, and Lu can be electronically distinguished from the other rare earths because they do not have f valence electrons, whereas the others do, but the chemical behaviour is almost the same.

A distinguishing factor in the geochemical behaviour of the REE is linked to the so-called "lanthanide contraction" which represents a higher-than-expected decrease in the atomic/ionic radius of the elements along the series. This is determined by the variation of the shielding effect towards the nuclear charge due to the progressive filling of the 4f orbital which acts against the electrons of the 6s and 5d orbitals. The lanthanide contraction has a direct effect on the geochemistry of the lanthanides, which show a different behaviour depending on the systems and processes in which they are involved. The effect of the lanthanide contraction can be observed in the REE behaviour both in a CHARAC-type geochemical system (CHArge-and-RAdius-Controlled[40]) where elements with similar charge and radius should show coherent geochemical behaviour, and in non-CHARAC systems, such as aqueous solutions, where the electron structure is also an important parameter to consider as the lanthanide contraction affects the ionic potential. A direct consequence is that, during the formation of coordination bonds, the REE behaviour gradually changes along the series. Furthermore, the lanthanide contraction causes the ionic radius of Ho3+ (0.901 Å) to be almost identical to that of Y3+ (0.9 Å), justifying the inclusion of the latter among the REE.

Applications[edit]

The application of rare-earth elements to geology is important to understanding the petrological processes of igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic rock formation. In geochemistry, rare-earth elements can be used to infer the petrological mechanisms that have affected a rock due to the subtle atomic size differences between the elements, which causes preferential fractionation of some rare earths relative to others depending on the processes at work.

The geochemical study of the REE is not carried out on absolute concentrations – as it is usually done with other chemical elements – but on normalized concentrations in order to observe their serial behaviour. In geochemistry, rare-earth elements are typically presented in normalized "spider" diagrams, in which concentration of rare-earth elements are normalized to a reference standard and are then expressed as the logarithm to the base 10 of the value.

Commonly, the rare-earth elements are normalized to chondritic meteorites, as these are believed to be the closest representation of unfractionated Solar System material. However, other normalizing standards can be applied depending on the purpose of the study. Normalization to a standard reference value, especially of a material believed to be unfractionated, allows the observed abundances to be compared to the initial abundances of the element. Normalization also removes the pronounced 'zig-zag' pattern caused by the differences in abundance between even and odd atomic numbers. Normalization is carried out by dividing the analytical concentrations of each element of the series by the concentration of the same element in a given standard, according to the equation:

where n indicates the normalized concentration, the analytical concentration of the element measured in the sample, and the concentration of the same element in the reference material.[41]

It is possible to observe the serial trend of the REE by reporting their normalized concentrations against the atomic number. The trends that are observed in "spider" diagrams are typically referred to as "patterns", which may be diagnostic of petrological processes that have affected the material of interest.[27]

According to the general shape of the patterns or thanks to the presence (or absence) of so-called "anomalies", information regarding the system under examination and the occurring geochemical processes can be obtained. The anomalies represent enrichment (positive anomalies) or depletion (negative anomalies) of specific elements along the series and are graphically recognizable as positive or negative "peaks" along the REE patterns. The anomalies can be numerically quantified as the ratio between the normalized concentration of the element showing the anomaly and the predictable one based on the average of the normalized concentrations of the two elements in the previous and next position in the series, according to the equation:

where is the normalized concentration of the element whose anomaly has to be calculated, and the normalized concentrations of the respectively previous and next elements along the series.

The rare-earth elements patterns observed in igneous rocks are primarily a function of the chemistry of the source where the rock came from, as well as the fractionation history the rock has undergone.[27] Fractionation is in turn a function of the partition coefficients of each element. Partition coefficients are responsible for the fractionation of trace elements (including rare-earth elements) into the liquid phase (the melt/magma) into the solid phase (the mineral). If an element preferentially remains in the solid phase it is termed 'compatible', and if it preferentially partitions into the melt phase it is described as 'incompatible'.[27] Each element has a different partition coefficient, and therefore fractionates into solid and liquid phases distinctly. These concepts are also applicable to metamorphic and sedimentary petrology.

In igneous rocks, particularly in felsic melts, the following observations apply: anomalies in europium are dominated by the crystallization of feldspars. Hornblende, controls the enrichment of MREE compared to LREE and HREE. Depletion of LREE relative to HREE may be due to the crystallization of olivine, orthopyroxene, and clinopyroxene. On the other hand, the depletion of HREE relative to LREE may be due to the presence of garnet, as garnet preferentially incorporates HREE into its crystal structure. The presence of zircon may also cause a similar effect.[27]

In sedimentary rocks, rare-earth elements in clastic sediments are a representation of provenance. The rare-earth element concentrations are not typically affected by sea and river waters, as rare-earth elements are insoluble and thus have very low concentrations in these fluids. As a result, when sediment is transported, rare-earth element concentrations are unaffected by the fluid and instead the rock retains the rare-earth element concentration from its source.[27]

Sea and river waters typically have low rare-earth element concentrations. However, aqueous geochemistry is still very important. In oceans, rare-earth elements reflect input from rivers, hydrothermal vents, and aeolian sources;[27] this is important in the investigation of ocean mixing and circulation.[29]

Rare-earth elements are also useful for dating rocks, as some radioactive isotopes display long half-lives. Of particular interest are the 138La-138Ce, 147Sm-143Nd, and 176Lu-176Hf systems.[29]

Production[edit]

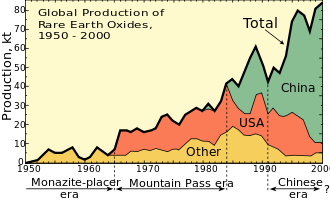

Until 1948, most of the world's rare earths were sourced from placer sand deposits in India and Brazil. Through the 1950s, South Africa was the world's rare earth source, from a monazite-rich reef at the Steenkampskraal mine in Western Cape province.[42] Through the 1960s until the 1980s, the Mountain Pass rare earth mine in California made the United States the leading producer. Today, the Indian and South African deposits still produce some rare-earth concentrates, but they were dwarfed by the scale of Chinese production. In 2017, China produced 81% of the world's rare-earth supply, mostly in Inner Mongolia,[8][43] although it had only 36.7% of reserves. Australia was the second and only other major producer with 15% of world production.[44] All of the world's heavy rare earths (such as dysprosium) come from Chinese rare-earth sources such as the polymetallic Bayan Obo deposit.[43][45] The Browns Range mine, located 160 km south east of Halls Creek in northern Western Australia, was under development in 2018 and is positioned to become the first significant dysprosium producer outside of China.[46]

Increased demand has strained supply, and there is growing concern that the world may soon face a shortage of the rare earths.[47] In several years from 2009 worldwide demand for rare-earth elements is expected to exceed supply by 40,000 tonnes annually unless major new sources are developed.[48] In 2013, it was stated that the demand for REEs would increase due to the dependence of the EU on these elements, the fact that rare-earth elements cannot be substituted by other elements and that REEs have a low recycling rate. Furthermore, due to the increased demand and low supply, future prices are expected to increase and there is a chance that countries other than China will open REE mines.[49] REE is increasing in demand due to the fact that they are essential for new and innovative technology that is being created. These new products that need REEs to be produced are high-technology equipment such as smart phones, digital cameras, computer parts, semiconductors, etc. In addition, these elements are more prevalent in the following industries: renewable energy technology, military equipment, glass making, and metallurgy.[50]

China[edit]

These concerns have intensified due to the actions of China, the predominant supplier.[51] Specifically, China has announced regulations on exports and a crackdown on smuggling.[52] On September 1, 2009, China announced plans to reduce its export quota to 35,000 tons per year in 2010–2015 to conserve scarce resources and protect the environment.[53] On October 19, 2010, China Daily, citing an unnamed Ministry of Commerce official, reported that China will "further reduce quotas for rare-earth exports by 30 percent at most next year to protect the precious metals from over-exploitation."[54] The government in Beijing further increased its control by forcing smaller, independent miners to merge into state-owned corporations or face closure. At the end of 2010, China announced that the first round of export quotas in 2011 for rare earths would be 14,446 tons, which was a 35% decrease from the previous first round of quotas in 2010.[55] China announced further export quotas on 14 July 2011 for the second half of the year with total allocation at 30,184 tons with total production capped at 93,800 tonnes.[56] In September 2011, China announced the halt in production of three of its eight major rare-earth mines, responsible for almost 40% of China's total rare-earth production.[57] In March 2012, the US, EU, and Japan confronted China at WTO about these export and production restrictions. China responded with claims that the restrictions had environmental protection in mind.[58][59] In August 2012, China announced a further 20% reduction in production.[60]The United States, Japan, and the European Union filed a joint lawsuit with the World Trade Organization in 2012 against China, arguing that China should not be able to deny such important exports.[59]

In response to the opening of new mines in other countries (Lynas in Australia and Molycorp in the United States), prices of rare earths dropped.[61]The price of dysprosium oxide was US$994/kg in 2011, but dropped to US$265/kg by 2014.[62]

On August 29, 2014, the WTO ruled that China had broken free-trade agreements, and the WTO said in the summary of key findings that "the overall effect of the foreign and domestic restrictions is to encourage domestic extraction and secure preferential use of those materials by Chinese manufacturers." China declared that it would implement the ruling on September 26, 2014, but would need some time to do so. By January 5, 2015, China had lifted all quotas from the export of rare earths, but export licenses will still be required.[63]

In 2019, China supplied between 85% and 95% of the global demand for the 17 rare-earth powders, half of them sourced from Myanmar.[64] [dubious – discuss] After the 2021 military coup in that country, future supplies of critical ores were possibly constrained. Additionally, it was speculated that the PRC could again reduce rare-earth exports to counter-act economic sanctions imposed by the US and EU countries. Rare-earth metals serve as crucial materials for electric vehicle manufacturing and high-tech military applications.[65]

Myanmar (Burma)[edit]

Kachin State in Myanmar is the world's largest source of rare earths.[66] In 2021, China imported US$200 million of rare earths from Myanmar in December 2021, exceeding 20,000 tonnes.[67] Rare earths were discovered near Pangwa in Chipwi Township along the China–Myanmar border in the late 2010s.[68] As China has shut down domestic mines due to the detrimental environmental impact, it has largely outsourced rare-earth mining to Kachin State.[67] Chinese companies and miners illegally set up operations in Kachin State without government permits, and instead circumvent the central government by working with a Border Guard Force militia under the Tatmadaw, formerly known as the New Democratic Army – Kachin, which has profited from this extractive industry.[67][69] As of March 2022[update], 2,700 mining collection pools scattered across 300 separate locations were found in Kachin State, encompassing the area of Singapore, and an exponential increase from 2016.[67] Land has also been seized from locals to conduct mining operations.[67]

Other countries[edit]

As a result of the increased demand and tightening restrictions on exports of the metals from China, some countries are stockpiling rare-earth resources.[70] Searches for alternative sources in Australia, Brazil, Canada, South Africa, Tanzania, Greenland, and the United States are ongoing.[71] Mines in these countries were closed when China undercut world prices in the 1990s, and it will take a few years to restart production as there are many barriers to entry.[52][72] Significant sites under development outside China include Steenkampskraal in South Africa, the world's highest grade rare earths and thorium mine, closed in 1963, but has been gearing to go back into production.[73] Over 80% of the infrastructure is already complete.[74] Other mines include the Nolans Project in Central Australia, the Bokan Mountain project in Alaska, the remote Hoidas Lake project in northern Canada,[75] and the Mount Weld project in Australia.[43][72][76] The Hoidas Lake project has the potential to supply about 10% of the $1 billion of REE consumption that occurs in North America every year.[77] Vietnam signed an agreement in October 2010 to supply Japan with rare earths[78] from its northwestern Lai Châu Province,[79] however the deal was never realized due to disagreements.[80]

The largest rare-earth deposit in the U.S. is at Mountain Pass, California, sixty miles south of Las Vegas. Originally opened by Molycorp, the deposit has been mined, off and on, since 1951.[43][81] A second large deposit of REEs at Elk Creek in southeast Nebraska[82] is under consideration by NioCorp Development Ltd [83] who hopes to open a niobium, scandium, and titanium mine there.[84] That mine may be able to produce as much as 7200 tonnes of ferro niobium and 95 tonnes of scandium trioxide annually,[85] although, as of 2022, financing is still in the works.[82]

In the UK, Pensana has begun construction of their US$195 million rare-earth processing plant which secured funding from the UK government's Automotive Transformation Fund. The plant will process ore from the Longonjo mine in Angola and other sources as they become available.[86][87] The company are targeting production in late 2023, before ramping up to full capacity in 2024. Pensana aim to produce 12,500 metric tons of separated rare earths, including 4,500 tons of magnet metal rare earths.[88][89]

Also under consideration for mining are sites such as Thor Lake in the Northwest Territories, and various locations in Vietnam.[43][48][90] Additionally, in 2010, a large deposit of rare-earth minerals was discovered in Kvanefjeld in southern Greenland.[91] Pre-feasibility drilling at this site has confirmed significant quantities of black lujavrite, which contains about 1% rare-earth oxides (REO).[92] The European Union has urged Greenland to restrict Chinese development of rare-earth projects there, but as of early 2013, the government of Greenland has said that it has no plans to impose such restrictions.[93] Many Danish politicians have expressed concerns that other nations, including China, could gain influence in thinly populated Greenland, given the number of foreign workers and investment that could come from Chinese companies in the near future because of the law passed December 2012.[94]

In central Spain, Ciudad Real Province, the proposed rare-earth mining project 'Matamulas' may provide, according to its developers, up to 2,100 Tn/year (33% of the annual UE demand). However, this project has been suspended by regional authorities due to social and environmental concerns.[95]

Adding to potential mine sites, ASX listed Peak Resources announced in February 2012, that their Tanzanian-based Ngualla project contained not only the 6th largest deposit by tonnage outside of China but also the highest grade of rare-earth elements of the 6.[96]

North Korea has been reported to have exported rare-earth ore to China, about US$1.88 million worth during May and June 2014.[97][98]

In May 2012, researchers from two universities in Japan announced that they had discovered rare earths in Ehime Prefecture, Japan.[99]

On 12 January 2023, Swedish state-owned mining company LKAB announced that it had discovered a deposit of over 1 million tonnes of rare earths in the country's Kiruna area, which would make it the largest such deposit in Europe.[100]

China processes about 90% of the world's REEs and 60% of the world's lithium. As a result, the European Union imports practically all of its rare earth elements from China. The EU Critical Raw Materials Act of 2023 has set in action the required policy adjustments for Europe to start producing two-thirds of the lithium-ion batteries required for electric vehicles and energy storage.[39][101][102]

In 2024 American Rare Earths Inc. disclosed that its reserves near Wheatland Wyoming totaled 2.34 billion metric tons, possibly the world's largest and larger than a separate 1.2 million metric ton deposit in northeastern Wyoming.[103]

In June 2024, Rare Earths Norway found a rare-earth oxide deposit of 8.8 million metric tons in Telemark, Norway, making it Europe's largest known rare-earth element deposit. The mining firm predicted that it would finish developing the first stage of mining in 2030.[104]

Malaysian refining plans[edit]

In early 2011, Australian mining company Lynas was reported to be "hurrying to finish" a US$230 million rare-earth refinery on the eastern coast of Peninsular Malaysia's industrial port of Kuantan. The plant would refine ore — lanthanides concentrate from the Mount Weld mine in Australia. The ore would be trucked to Fremantle and transported by container ship to Kuantan. Within two years, Lynas was said to expect the refinery to be able to meet nearly a third of the world's demand for rare-earth materials, not counting China.[105] The Kuantan development brought renewed attention to the Malaysian town of Bukit Merah in Perak, where a rare-earth mine operated by a Mitsubishi Chemical subsidiary, Asian Rare Earth, closed in 1994 and left continuing environmental and health concerns.[106][107] In mid-2011, after protests, Malaysian government restrictions on the Lynas plant were announced. At that time, citing subscription-only Dow Jones Newswire reports, a Barrons report said the Lynas investment was $730 million, and the projected share of the global market it would fill put at "about a sixth."[108] An independent review initiated by the Malaysian Government, and conducted by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in 2011 to address concerns of radioactive hazards, found no non-compliance with international radiation safety standards.[109]

However, the Malaysian authorities confirmed that as of October 2011, Lynas was not given any permit to import any rare-earth ore into Malaysia. On February 2, 2012, the Malaysian AELB (Atomic Energy Licensing Board) recommended that Lynas be issued a temporary operating license subject to meeting a number of conditions. On 2 September 2014, Lynas was issued a 2-year full operating stage license by the AELB.[110]

Other sources[edit]

Mine tailings[edit]

Significant quantities of rare-earth oxides are found in tailings accumulated from 50 years of uranium ore, shale, and loparite mining at Sillamäe, Estonia.[111] Due to the rising prices of rare earths, extraction of these oxides has become economically viable. The country currently exports around 3,000 tonnes per year, representing around 2% of world production.[112] Similar resources are suspected in the western United States, where gold rush-era mines are believed to have discarded large amounts of rare earths, because they had no value at the time.[113]

Ocean mining[edit]

In January 2013 a Japanese deep-sea research vessel obtained seven deep-sea mud core samples from the Pacific Ocean seafloor at 5,600 to 5,800 meters depth, approximately 250 kilometres (160 mi) south of the island of Minami-Tori-Shima.[114] The research team found a mud layer 2 to 4 meters beneath the seabed with concentrations of up to 0.66% rare-earth oxides. A potential deposit might compare in grade with the ion-absorption-type deposits in southern China that provide the bulk of Chinese REO mine production, which grade in the range of 0.05% to 0.5% REO.[115][116]

Waste and recycling[edit]

Another recently developed source of rare earths is electronic waste and other wastes that have significant rare-earth components.[117] Advances in recycling technology have made the extraction of rare earths from these materials less expensive.[118] Recycling plants operate in Japan, where an estimated 300,000 tons of rare earths are found in unused electronics.[119] In France, the Rhodia group is setting up two factories, in La Rochelle and Saint-Fons, that will produce 200 tons of rare earths a year from used fluorescent lamps, magnets, and batteries.[120][121] Coal[122] and coal by-products, such as ash and sludge, are a potential source of critical elements including rare-earth elements (REE) with estimated amounts in the range of 50 million metric tons.[123]

Methods[edit]

One study mixed fly ash with carbon black and then sent a 1-second current pulse through the mixture, heating it to 3,000 °C (5,430 °F). The fly ash contains microscopic bits of glass that encapsulate the metals. The heat shatters the glass, exposing the rare earths. Flash heating also converts phosphates into oxides, which are more soluble and extractable. Using hydrochloric acid at concentrations less than 1% of conventional methods, the process extracted twice as much material.[124]

Properties[edit]

According to chemistry professor Andrea Sella, rare-earth elements differ from other elements, in that when looked at analytically, they are virtually inseparable, having almost the same chemical properties. However, in terms of their electronic and magnetic properties, each one occupies a unique technological niche that nothing else can.[2] For example, "the rare-earth elements praseodymium (Pr) and neodymium (Nd) can both be embedded inside glass and they completely cut out the glare from the flame when one is doing glass-blowing."[2]

Uses[edit]

US consumption of REE, 2018[126]

The uses, applications, and demand for rare-earth elements have expanded over the years. Globally, most REEs are used for catalysts and magnets.[125] In the US, more than half of REEs are used for catalysts; ceramics, glass, and polishing are also main uses.[126]

Other important uses of rare-earth elements are applicable to the production of high-performance magnets, alloys, glasses, and electronics. Ce and La are important as catalysts, and are used for petroleum refining and as diesel additives. Nd is important in magnet production in traditional and low-carbon technologies. Rare-earth elements in this category are used in the electric motors of hybrid and electric vehicles, generators in some wind turbines, hard disc drives, portable electronics, microphones, and speakers.[citation needed]

Ce, La, and Nd are important in alloy making, and in the production of fuel cells and nickel-metal hydride batteries. Ce, Ga, and Nd are important in electronics and are used in the production of LCD and plasma screens, fiber optics, and lasers,[127] and in medical imaging. Additional uses for rare-earth elements are as tracers in medical applications, fertilizers, and in water treatment.[29]

REEs have been used in agriculture to increase plant growth, productivity, and stress resistance seemingly without negative effects for human and animal consumption. REEs are used in agriculture through REE-enriched fertilizers which is a widely used practice in China.[128] In addition, REEs are feed additives for livestock which has resulted in increased production such as larger animals and a higher production of eggs and dairy products. However, this practice has resulted in REE bioaccumulation within livestock and has impacted vegetation and algae growth in these agricultural areas.[129] Additionally while no ill effects have been observed at current low concentrations the effects over the long term and with accumulation over time are unknown prompting some calls for more research into their possible effects.[128][130]

Environmental considerations[edit]

REEs are naturally found in very low concentrations in the environment. Mines are often in countries where environmental and social standards are very low, leading to human rights violations, deforestation, and contamination of land and water.[131][132] Generally, it is estimated that extracting 1 tonne of rare earth element creates around 2,000 tonnes of waste, partly toxic, including 1 ton of radioactive waste. The largest mining site of REEs, Bayan Obo in China produced more than 70,000 tons of radioactive waste, that contaminated ground water.[133]

Near mining and industrial sites, the concentrations of REEs can rise to many times the normal background levels. Once in the environment, REEs can leach into the soil where their transport is determined by numerous factors such as erosion, weathering, pH, precipitation, groundwater, etc. Acting much like metals, they can speciate depending on the soil condition being either motile or adsorbed to soil particles. Depending on their bio-availability, REEs can be absorbed into plants and later consumed by humans and animals. The mining of REEs, use of REE-enriched fertilizers, and the production of phosphorus fertilizers all contribute to REE contamination.[134] Furthermore, strong acids are used during the extraction process of REEs, which can then leach out into the environment and be transported through water bodies and result in the acidification of aquatic environments. Another additive of REE mining that contributes to REE environmental contamination is cerium oxide (CeO

2), which is produced during the combustion of diesel and released as exhaust, contributing heavily to soil and water contamination.[129]

Mining, refining, and recycling of rare earths have serious environmental consequences if not properly managed. Low-level radioactive tailings resulting from the occurrence of thorium and uranium in rare-earth ores present a potential hazard[135][136] and improper handling of these substances can result in extensive environmental damage. In May 2010, China announced a major, five-month crackdown on illegal mining in order to protect the environment and its resources. This campaign is expected to be concentrated in the South,[137] where mines – commonly small, rural, and illegal operations – are particularly prone to releasing toxic waste into the general water supply.[43][138] However, even the major operation in Baotou, in Inner Mongolia, where much of the world's rare-earth supply is refined, has caused major environmental damage.[139] China's Ministry of Industry and Information Technology estimated that cleanup costs in Jiangxi province at $5.5 billion.[132]

It is, however, possible to filter out and recover any rare-earth elements that flow out with the wastewater from mining facilities. However, such filtering and recovery equipment may not always be present on the outlets carrying the wastewater.[140][141][142]

Recycling and reusing REEs[edit]

This section is missing information about processes to recycle/REEs that are established, demonstrated experimentally or under development as well as related policies. (March 2022) |

Potential methods[edit]

The rare-earth elements (REEs) are vital to modern technologies and society and are amongst the most critical elements. Despite this, typically only around 1% of REEs are recycled from end-products, with the rest deporting to waste and being removed from the materials cycle.[143] Recycling and reusing REEs play an important role in high technology fields and manufacturing environmentally friendly products all around the world.[144]

В последние годы все больше внимания уделяется переработке и повторному использованию РЗЭ. Основные проблемы включают загрязнение окружающей среды при переработке РЗЭ и повышение эффективности переработки. Литература, опубликованная в 2004 году, предполагает, что, наряду с ранее установленными мерами по снижению загрязнения, более замкнутая цепочка поставок поможет смягчить часть загрязнения в точке добычи. Это означает переработку и повторное использование РЗЭ, которые уже используются или достигли конца своего жизненного цикла. [130] A study published in 2014 suggests a method to recycle REEs from waste nickel-metal hydride batteries, demonstrating a recovery rate of 95.16%.[145] Rare-earth elements could also be recovered from industrial wastes with practical potential to reduce environmental and health impacts from mining, waste generation, and imports if known and experimental processes are scaled up.[146][147] A study suggests that "fulfillment of the circular economy approach could reduce up to 200 times the impact in the climate change category and up to 70 times the cost due to the REE mining."[148] В большинстве опубликованных исследований, рассмотренных в научном обзоре , «вторичные отходы подвергаются химическому или биологическому выщелачиванию с последующими процессами экстракции растворителем для чистого разделения РЗЭ». [149]

В настоящее время люди принимают во внимание два важных ресурса для безопасного снабжения РЗЭ: один – извлечение РЗЭ из первичных ресурсов, таких как шахты, содержащие руды, содержащие РЗЭ, глинистые месторождения, содержащие реголит, [150] донные осадки океана, летучая зола угля, [151] и т. д. В работе была разработана «зеленая» система извлечения РЗЭ из угольной золы с использованием цитрата и оксалата, которые являются сильными органическими лигандами и способны образовывать комплексы или осаждаться с РЗЭ. [152] Другой – из вторичных ресурсов, таких как электронные, промышленные и городские отходы. Электронные отходы содержат значительную концентрацию РЗЭ и поэтому в настоящее время являются основным вариантом переработки РЗЭ. [ когда? ] . Согласно исследованию, ежегодно около 50 миллионов тонн электронных отходов выбрасывается на свалки по всему миру. Несмотря на то, что электронные отходы содержат значительное количество редкоземельных элементов (РЗЭ), в настоящее время перерабатывается только 12,5% электронных отходов на все металлы. [153] [144]

Проблемы [ править ]

На данный момент существуют некоторые препятствия при переработке и повторном использовании РЗЭ. Одной из больших проблем является химическое разделение РЗЭ. В частности, процесс выделения и очистки отдельных редкоземельных элементов (РЗЭ) представляет трудность из-за их схожих химических свойств. Чтобы уменьшить загрязнение окружающей среды, выделяющееся при выделении РЗЭ, а также диверсифицировать их источники, существует очевидная необходимость разработки новых технологий разделения, которые могут снизить стоимость крупномасштабного разделения и переработки РЗЭ. [154] В таких условиях Институт критических материалов (CMI) при Министерстве энергетики разработал метод, который предполагает использование бактерий Gluconobacter для метаболизма сахаров и производства кислот, которые могут растворять и отделять редкоземельные элементы (РЗЭ) из измельченных электронных отходов. [155]

загрязнения РЗЭ Влияние

О растительности [ править ]

Добыча РЗЭ привела к загрязнению почвы и воды вокруг производственных площадей, что повлияло на растительность на этих территориях за счет снижения производства хлорофилла , что влияет на фотосинтез и подавляет рост растений. [129] Однако влияние загрязнения РЗЭ на растительность зависит от растений, присутствующих в загрязненной среде: не все растения сохраняют и поглощают РЗЭ. Кроме того, способность растительности поглощать РЗЭ зависит от типа РЗЭ, присутствующего в почве, поэтому существует множество факторов, влияющих на этот процесс. [156] Сельскохозяйственные растения являются основным типом растительности, на которую влияет загрязнение окружающей среды РЗЭ, причем двумя растениями с более высокой вероятностью поглощения и хранения РЗЭ являются яблоки и свекла. [134] Кроме того, существует вероятность того, что РЗЭ могут выщелачиваться в водную среду и поглощаться водной растительностью, которая затем может биоаккумулироваться и потенциально попасть в пищевую цепь человека, если домашний скот или люди захотят съесть эту растительность. Примером такой ситуации является случай с водным гиацинтом ( Eichhornia crassipes) в Китае, где вода была загрязнена из-за использования удобрений, обогащенных РЗЭ, в близлежащем сельскохозяйственном районе. Водная среда была загрязнена церием , в результате чего концентрация церия в водном гиацинте стала в три раза выше, чем в окружающей его воде. [156]

О здоровье человека [ править ]

РЗЭ представляют собой большую группу с множеством различных свойств и уровней в окружающей среде. Из-за этого, а также из-за ограниченности исследований было трудно определить безопасные уровни воздействия для человека. [157] Ряд исследований был сосредоточен на оценке риска на основе путей воздействия и отклонения от фоновых уровней, связанных с близлежащим сельским хозяйством, горнодобывающей промышленностью и промышленностью. [158] [159] Было продемонстрировано, что многие РЗЭ обладают токсичными свойствами и присутствуют в окружающей среде или на рабочих местах. Воздействие этих веществ может привести к широкому спектру негативных последствий для здоровья, таких как рак, проблемы с дыханием , потеря зубов и даже смерть. [49] Однако РЗЭ многочисленны и присутствуют во многих различных формах и с разными уровнями токсичности, что затрудняет предоставление общих предупреждений о риске рака и токсичности, поскольку некоторые из них безвредны, а другие представляют риск. [157] [159] [158]

Токсичность проявляется при очень высоких уровнях воздействия при употреблении в пищу загрязненных продуктов питания и воды, при вдыхании частиц пыли/дыма либо в качестве профессионального риска, либо из-за близости к загрязненным объектам, таким как шахты и города. Таким образом, основные проблемы, с которыми могут столкнуться эти жители, — это биоаккумуляция РЗЭ и воздействие на их дыхательную систему, но в целом могут быть и другие возможные краткосрочные и долгосрочные последствия для здоровья. [160] [129] Было обнаружено, что у людей, живущих рядом с шахтами в Китае, уровень РЗЭ в крови, моче, костях и волосах во много раз выше, чем у людей, живущих вдали от мест добычи полезных ископаемых. Этот более высокий уровень был связан с высоким содержанием РЗЭ в выращиваемых ими овощах, почве и воде из колодцев, что указывает на то, что высокие уровни были вызваны близлежащей шахтой. [158] [159] Хотя уровни РЗЭ различались у мужчин и женщин, группой наибольшего риска были дети, поскольку РЗЭ могут влиять на неврологическое развитие детей, влияя на их IQ и потенциально вызывая потерю памяти. [161]

В процессе добычи и плавки редкоземельных металлов может выделяться переносимый по воздуху фторид, который будет связываться с общим количеством взвешенных частиц (TSP) с образованием аэрозолей, которые могут попасть в дыхательные системы человека и вызвать повреждения и респираторные заболевания. Исследования, проведенные в Баотоу, Китай, показывают, что концентрация фторида в воздухе возле шахт по добыче РЗЭ превышает предельное значение ВОЗ, что может повлиять на окружающую среду и стать риском для тех, кто живет или работает поблизости. [162]

Жители обвинили завод по переработке редкоземельных металлов в Букит Мерах в врожденных дефектах и восьми случаях лейкемии за пять лет в сообществе с населением 11 000 человек после многих лет отсутствия случаев лейкемии. Семь жертв лейкемии умерли. Осаму Симидзу, директор Asian Rare Earth, сказал, что «компания могла бы продать несколько мешков кальций-фосфатных удобрений на пробной основе, поскольку она стремилась продавать побочные продукты; фосфат кальция не является радиоактивным или опасным», в ответ бывшему жителю Букит Мера, который сказал: «Все коровы, которые ели траву [выращенную с помощью удобрений], умерли». [163] Верховный суд Малайзии 23 декабря 1993 года постановил, что нет никаких доказательств того, что местное совместное химическое предприятие Asian Rare Earth загрязняло местную окружающую среду. [164]

О здоровье животных [ править ]

Эксперименты по воздействию на крыс различных соединений церия показали его накопление преимущественно в легких и печени. Это привело к различным негативным последствиям для здоровья, связанным с этими органами. [165] РЗЭ добавляют в корм скоту для увеличения его массы тела и увеличения надоев молока. [165] Их чаще всего используют для увеличения массы тела свиней, и было обнаружено, что РЗЭ повышают усвояемость и использование питательных веществ пищеварительной системой свиней. [165] Исследования указывают на зависимость от дозы при рассмотрении токсичности в сравнении с положительными эффектами. Хотя небольшие дозы из окружающей среды или при правильном применении, по-видимому, не оказывают вредного воздействия, было показано, что более высокие дозы оказывают негативное воздействие именно на органы, где они накапливаются. [165] Процесс добычи РЗЭ в Китае привел к загрязнению почвы и воды в определенных районах, которые при транспортировке в водные объекты потенциально могут биоаккумулироваться в водной биоте. Кроме того, в некоторых случаях у животных, живущих на территориях, загрязненных РЗЭ, диагностировались проблемы с органами или системами. [129] РЗЭ используются в пресноводном рыбоводстве, поскольку они защищают рыбу от возможных заболеваний. [165] Одна из основных причин, почему их активно используют в кормлении скота, заключается в том, что они дают лучшие результаты, чем неорганические усилители кормов для скота. [166]

после загрязнения Восстановление

Этот раздел необходимо обновить . ( май 2019 г. ) |

После радиоактивного загрязнения Букит Мера в 1982 году шахта в Малайзии стала объектом очистки стоимостью 100 миллионов долларов США, которая продолжается в 2011 году. После завершения захоронения на вершине холма 11 000 грузовиков с радиоактивно загрязненным материалом, ожидается, что летом , 2011 г., вывоз «более 80 000 стальных бочек с радиоактивными отходами в хранилище на вершине холма». [107]

В мае 2011 года, после ядерной катастрофы на Фукусиме , в Куантане прошли массовые протесты по поводу нефтеперерабатывающего завода Линас и радиоактивных отходов с него. Руда, которую предстоит перерабатывать, содержит очень низкий уровень тория, и основатель и исполнительный директор Lynas Николас Кертис заявил: «Нет абсолютно никакого риска для здоровья населения». Т. Джаябалан, врач, который говорит, что он наблюдает и лечит пациентов, пострадавших от завода Mitsubishi, «настороженно относится к заверениям Линаса. Аргумент о том, что низкие уровни тория в руде делают ее более безопасной, не имеет смысла, говорит он, потому что радиационное воздействие является кумулятивным». [163] Строительство объекта было остановлено до завершения независимого ООН расследования группы МАГАТЭ , которое ожидается к концу июня 2011 года. [167] О новых ограничениях правительство Малайзии объявило в конце июня. [108]

Расследование комиссии МАГАТЭ было завершено, и строительство не было остановлено. Проект Lynas соответствует бюджету и графику начала производства в 2011 году. В отчете, опубликованном в июне 2011 года, МАГАТЭ пришло к выводу, что оно не обнаружило в проекте ни одного случая «какого-либо несоответствия международным стандартам радиационной безопасности». [168]

Если соблюдаются надлежащие стандарты безопасности, добыча РЗЭ оказывает относительно небольшое воздействие. Molycorp (до банкротства) часто превышала экологические нормы, чтобы улучшить свой имидж в обществе. [169]

В Гренландии ведется серьезный спор о том, следует ли начинать новый рудник по добыче редкоземельных металлов в Кванефьельде из-за экологических проблем. [170]

соображения Геополитические

Китай официально назвал истощение ресурсов и экологические проблемы причинами общенационального подавления своего сектора добычи редкоземельных минералов. [57] Однако политике Китая в отношении редкоземельных элементов также приписывают и неэкологические мотивы. [139] По мнению журнала The Economist , «сокращение экспорта редкоземельных металлов… направлено на продвижение китайских производителей вверх по цепочке поставок, чтобы они могли продавать миру ценную готовую продукцию, а не дешевое сырье». [171] Более того, Китай в настоящее время обладает эффективной монополией в мировой цепочке создания стоимости РЗЭ. [172] (Все нефтеперерабатывающие и перерабатывающие заводы, которые преобразуют сырую руду в ценные элементы. [173] ) По словам Дэн Сяопина, китайского политика конца 1970-х - конца 1980-х годов, «На Ближнем Востоке есть нефть; у нас есть редкоземельные металлы... это имеет чрезвычайно важное стратегическое значение; мы должны обязательно обращаться с редкими должным образом решать проблему земли и максимально полно использовать преимущества нашей страны в редкоземельных ресурсах». [174]

Одним из возможных примеров контроля над рынком является подразделение General Motors, занимающееся исследованиями миниатюрных магнитов, которое закрыло свой офис в США и перевело весь свой персонал в Китай в 2006 году. [175] (Экспортная квота Китая распространяется только на металл, но не на изделия из этих металлов, такие как магниты).

Сообщалось, [176] но официально опровергнуто, [177] что Китай ввел запрет на экспорт поставок оксидов редкоземельных элементов (но не сплавов) в Японию 22 сентября 2010 года в ответ на капитана китайского рыболовного судна задержание японской береговой охраной . [178] [59] 2 сентября 2010 г., за несколько дней до инцидента с рыбацким судном, The Economist сообщил, что «Китай... в июле объявил о последнем из серии ежегодных сокращений экспорта, на этот раз на 40%, ровно до 30 258 тонн». [179] [59]

Министерство энергетики США в своем отчете о стратегии в отношении критических материалов за 2010 год определило диспрозий как элемент, который имеет наиболее важное значение с точки зрения зависимости от импорта. [180]

В докладе «Редкоземельная промышленность Китая» за 2011 год, опубликованном Геологической службой США и Министерством внутренних дел США, обрисовываются отраслевые тенденции в Китае и анализируется национальная политика, которая может определять будущее производства страны. В докладе отмечается, что лидерство Китая в производстве редкоземельных минералов ускорилось за последние два десятилетия. В 1990 году на долю Китая приходилось лишь 27% таких полезных ископаемых. В 2009 году мировое производство составило 132 000 метрических тонн; Китай произвел 129 000 из этих тонн. Согласно отчету, последние тенденции позволяют предположить, что Китай замедлит экспорт таких материалов в мир: «Из-за увеличения внутреннего спроса правительство постепенно сокращало экспортную квоту в течение последних нескольких лет». В 2006 году Китай разрешил экспортировать 47 отечественным производителям и торговцам редкоземельными элементами и 12 китайско-иностранным производителям редкоземельных элементов. С тех пор контроль ежегодно ужесточается; к 2011 году разрешение получили только 22 отечественных производителя и торговца редкоземельными элементами и 9 китайско-иностранных производителей редкоземельных элементов. Будущая политика правительства, скорее всего, сохранит строгий контроль: «Согласно проекту китайского плана развития редкоземельных металлов, ежегодное производство редкоземельных металлов может быть ограничено от 130 000 до 140 000 [метрических тонн] в период с 2009 по 2015 год. Экспорт квота на редкоземельные продукты может составлять около 35 000 [метрических тонн], и правительство может разрешить 20 отечественным производителям и торговцам редкоземельными элементами экспортировать редкоземельные элементы». [181]

Геологическая служба США активно исследует южный Афганистан на предмет месторождений редкоземельных металлов, находящихся под защитой вооруженных сил США. С 2009 года Геологическая служба США проводит исследования дистанционного зондирования, а также полевые работы для проверки советских заявлений о том, что вулканические породы, содержащие редкоземельные металлы, существуют в провинции Гильменд недалеко от деревни Ханашин . Исследовательская группа Геологической службы США обнаружила в центре потухшего вулкана значительную площадь горных пород, содержащих легкие редкоземельные элементы, включая церий и неодим. Он нанес на карту 1,3 миллиона тонн желательной породы, или около десяти лет поставок при нынешнем уровне спроса. Пентагон оценил его стоимость примерно в 7,4 миллиарда долларов. [182]

Утверждалось, что геополитическое значение редких земель преувеличено в литературе по геополитике возобновляемых источников энергии, что недооценивает силу экономических стимулов для расширения производства. [183] [184] Особенно это касается неодима. Из-за его роли в постоянных магнитах, используемых в ветряных турбинах, утверждалось, что неодим станет одним из основных объектов геополитической конкуренции в мире, работающем на возобновляемых источниках энергии. Но эта точка зрения подверглась критике за неспособность признать, что большинство ветряных турбин имеют шестерни и не используют постоянные магниты. [184]

В популярной культуре [ править ]

Сюжет Эрика Эмблера ставшего классикой международного криминального триллера 1967 года «Грязная история» (также известного как « Этот пистолет по найму» , но не путать с фильмом «Этот пистолет по найму» (1942)) представляет собой борьбу между двумя конкурирующими горнодобывающими картелями за контроль над участок земли в вымышленной африканской стране, содержащий богатые залежи редкоземельных руд, пригодных для добычи полезных ископаемых. [185]

Цены [ править ]

Эта статья содержит контент, написанный как реклама . ( Август 2023 г. ) |

Институт редкоземельных элементов и стратегических металлов представляет собой неформальную сеть на международном рынке сырья . [ нужна ссылка ] Основной интерес клиентов института вызывает база данных, доступная по подписке с ежедневно обновляемыми ценами: помимо одноименных редкоземельных элементов , там числятся 900 чистых металлов и 4500 других металлических изделий. Штаб-квартира компании находится в Люцерне , Швейцария.

См. также [ править ]

- Драгоценный металл

- Список элементов, испытывающих дефицит

- Паспорт материала : список использованных материалов в изделиях.

- Пенсана Солт Энд

- Редкоземельный магнит

- Редкоземельный минерал

Ссылки [ править ]

- ^ 1985 года «Красная книга» Международного союза теоретической и прикладной химии (стр. 45) рекомендует лантаноиды использовать , а не лантаноиды . Окончание «-ide» обычно указывает на отрицательный ион. Однако из-за широкого использования в настоящее время «лантанид» все еще разрешен и примерно аналогичен редкоземельному элементу.