Ереван

Эта статья может оказаться слишком длинной для удобного чтения и навигации . ( март 2023 г. ) |

Эта статья нуждается в дополнительных цитатах для проверки . ( июнь 2023 г. ) |

Ереван Ереван | |

|---|---|

Yerevan skyline with Mount Ararat | |

| Nickname(s): | |

| Coordinates: 40°10′53″N 44°30′52″E / 40.18139°N 44.51444°E | |

| Country | |

| Settled (Shengavit)[11] | c. 3300 BC[12] |

| Founded as Erebuni by Argishti I of Urartu | 782 BC |

| City status by Alexander II | 1 October 1879[13][14] |

| Capital of Armenia | 19 July 1918 (de facto)[15][16] |

| Administrative Districts | 12 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–Council |

| • Body | City Council |

| • Mayor | Tigran Avinyan |

| Area | |

| • Capital city | 223 km2 (86 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,390 m (4,560 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 865 m (2,838 ft) |

| Population (2011 census)[17] | |

| • Capital city | 1,060,138 |

| • Estimate (2022[18]) | 1,092,800 |

| • Density | 4,824/km2 (12,490/sq mi) |

| • Metro (2001 estimate)[19] | 1,420,000 |

| Demonym(s) | Yerevantsi(s),[20][21] Yerevanite(s)[22][23] |

| Time zone | UTC+04:00 (AMT) |

| Area code | +374 10 |

| International airport | Zvartnots International Airport |

| HDI (2021) | 0.794[24] high · 1st |

| Website | www |

Ереван ( Великобритания : / ˌ j ɛr ə ˈ v æ n / , YERR -ə- VAN ; НАС : /- ˈ v ɑː n / , - ВАХН ; Армянский : Ереван [с] [jɾɛˈvɑn] ; иногда пишется Ереван ) [д] Столица и крупнейший город Армении мира , а также один из старейших постоянно населенных городов . [28] Расположенный вдоль реки Раздан , Ереван является административным, культурным и промышленным центром страны, а также ее главным городом . Это столица с 1918 года, четырнадцатая в истории Армении и седьмая, расположенная на Араратской равнине или вокруг нее . Город также служит резиденцией Араратской Папской епархии , которая является крупнейшей епархией Армянской Апостольской церкви и одной из старейших епархий в мире. [29]

The history of Yerevan dates back to the 8th century BC, with the founding of the fortress of Erebuni in 782 BC by King Argishti I of Urartu at the western extreme of the Ararat Plain.[30] Erebuni was "designed as a great administrative and religious centre, a fully royal capital."[31] By the late ancient Armenian Kingdom, new capital cities were established and Yerevan declined in importance. The city was mostly depopulated by the Great Surgun of 1603–05, when the Safavid Empire forcibly deported hundreds of thousands of Armenians to Iran. In 1679, the city was mostly destroyed by an earthquake, and then rebuilt on a smaller scale. In 1828, Yerevan became part of the Russian Empire, which led to the repatriation of Armenians whose ancestors had been forcibly relocated in the 17th century. After World War I, Yerevan became the capital of the First Republic of Armenia as thousands of survivors of the Armenian genocide in the Ottoman Empire arrived in the area.[32] The city expanded rapidly during the 20th century while Armenia was a part of the Soviet Union. In a few decades, Yerevan was transformed from a provincial town within the Russian Empire to Armenia's principal cultural, artistic, and industrial center, as well as becoming the seat of national government.

With the growth of the Armenian economy, Yerevan has undergone major transformation. Much construction has been done throughout the city since the early 2000s, and retail outlets such as restaurants, shops, and street cafés, which were rare during Soviet times, have multiplied. As of 2011[update], the population of Yerevan was 1,060,138, just over 35% of Armenia's total population. According to the official estimate of 2022, the current population of the city is 1,092,800.[18] Yerevan was named the 2012 World Book Capital by UNESCO.[33] Yerevan is an associate member of Eurocities.[34]

Of the notable landmarks of Yerevan, Erebuni Fortress is considered to be the birthplace of the city, the Katoghike Tsiranavor church is the oldest surviving church of Yerevan, and Saint Gregory Cathedral is the largest Armenian cathedral in the world. Tsitsernakaberd is the official memorial to the victims of the Armenian genocide. The city is home to several opera houses, theatres, museums, libraries, and other cultural institutions. Yerevan Opera Theatre is the main spectacle hall of the Armenian capital, the National Gallery of Armenia is the largest art museum in Armenia and shares a building with the History Museum of Armenia, and the Matenadaran contains one of the largest depositories of ancient books and manuscripts in the world.

Etymology

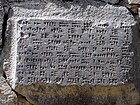

The exact origin of the name is unknown. One theory regarding the origin of Yerevan's name is the city was named after the Armenian king, Yervand (Orontes) IV, the last ruler of Armenia from the Orontid dynasty, and founder of the city of Yervandashat.[36] However, it is likely that the city's name is derived from the Urartian military fortress of Erebuni, which was founded on the territory of modern-day Yerevan in 782 BC by Argishti I.[36] "Erebuni" may derive from the Urartian word for "to take" or "to capture," meaning that the fortress's name could be interpreted as "capture," "conquest," or "victory."[37] As elements of the Urartian language blended with that of the Armenian one, the name eventually evolved into Yerevan (Erebuni = Erevani = Erevan = Yerevan). Scholar Margarit Israelyan notes these changes when comparing inscriptions found on two cuneiform tablets at Erebuni:

The transcription of the second cuneiform bu [original emphasis] of the word was very essential in our interpretation as it is the Urartaean b that has been shifted to the Armenian v (b > v). The original writing of the inscription read «er-bu-ni»; therefore the prominent Armenianologist-orientalist Prof. G. A. Ghapantsian justly objected, remarking that the Urartu b changed to v at the beginning of the word (Biani > Van) or between two vowels (ebani > avan, Zabaha > Javakhk)....In other words b was placed between two vowels. The true pronunciation of the fortress-city was apparently Erebuny.[38]

Early Christian Armenian chroniclers connected the origin of the city's name to the legend of Noah's Ark. After the ark had landed on Mount Ararat and the flood waters had receded, Noah, while looking in the direction of Yerevan, is said to have exclaimed "Yerevats!" ("it appeared!" in Armenian), from which originated the name Yerevan.[36]

In the late medieval and early modern periods, when Yerevan was under Turkic and later Persian rule, the city was known in Persian as Iravân (Persian: ایروان).[39][40] The city was officially known as Erivan (Russian: Эривань) under Russian rule during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The city was renamed back to Yerevan (Ереван) in 1936.[41] Up until the mid-1970s the city's name was spelled Erevan more often than Yerevan in English sources.[42][43]

Symbols

The principal symbol of Yerevan is Mount Ararat, which is visible from any area in the capital. The seal of the city is a crowned lion on a pedestal with a shield that has a depiction of Mount Ararat on the upper part and half of an Armenian eternity sign on the bottom part. The emblem is a rectangular shield with a blue border.[46]

On 27 September 2004, Yerevan adopted an anthem, "Erebuni-Yerevan", using lyrics written by Paruyr Sevak and set to music composed by Edgar Hovhannisyan. It was selected in a competition for a new anthem and new flag that would best represent the city. The chosen flag has a white background with the city's seal in the middle, surrounded by twelve small red triangles that symbolize the twelve historic capitals of Armenia. The flag includes the three colours of the Armenian National flag. The lion is portrayed on the orange background with blue edging.[47]

History

Pre-history and pre-classical era

The territory of Yerevan has been inhabited since approximately the 2nd half of the 4th millennium BC. The southern part of the city currently known as Shengavit has been populated since at least 3200 BC, during the period of Kura–Araxes culture of the early Bronze Age. The first excavations at the Shengavit historical site was conducted between 1936 and 1938 under the guidance of archaeologist Yevgeny Bayburdyan. After two decades, archaeologist Sandro Sardarian resumed the excavations starting from 1958 until 1983.[48] The 3rd phase of the excavations started in 2000, under the guidance of archaeologist Hakob Simonyan. In 2009, Simonyan was joined by Mitchell S. Rothman from the Widener University of Pennsylvania. Together they conducted three series of excavations in 2009, 2010, and 2012 respectively.[citation needed] During the process, a full stratigraphic column to bedrock was reached, showing there to be 8 or 9 distinct stratigraphic levels. These levels cover a time between 3200 BC and 2500 BC. Evidences of later use of the site, possibly until 2200 BC, were also found. The excavation process revealed a series of large round buildings with square adjoining rooms and minor round buildings. A series of ritual installations was discovered in 2010 and 2012.[citation needed]

Erebuni

The ancient kingdom of Urartu was formed in the 9th century BC by King Arame in the basin of Lake Van of the Armenian Highland, including the territory of modern-day Yerevan.[49] Archaeological evidence, such as a cuneiform inscription,[50] indicates that the Urartian military fortress of Erebuni was founded in 782 BC by the orders of King Argishti I at the site of modern-day Yerevan, to serve as a fort and citadel guarding against attacks from the north Caucasus.[36] The cuneiform inscription found at Erebuni Fortress reads:

By the greatness of the God Khaldi, Argishti, son of Menua, built this mighty stronghold and proclaimed it Erebuni for the glory of Biainili [Urartu] and to instill fear among the king's enemies. Argishti says, "The land was a desert, before the great works I accomplished upon it. By the greatness of Khaldi, Argishti, son of Menua, is a mighty king, king of Biainili, and ruler of Tushpa."[Van].[51]

During the height of the Urartian power, irrigation canals and artificial reservoirs were built in Erebuni and its surrounding territories.

In the mid-7th century BC, the city of Teishebaini was built by Rusa II of Urartu, around 7 kilometres (4.3 miles) west of Erebuni Fortress.[52] It was fortified on a hill -currently known as Karmir Blur within Shengavit District of Yerevan- to protect the eastern borders of Urartu from the barbaric Cimmerians and Scythians. During excavations, the remains of a governors palace that contained a hundred and twenty rooms spreading across more than 40,000 m2 (10 acres) was found, along with a citadel dedicated to the Urartian god Teisheba. The construction of the city of Teishebaini, as well as the palace and the citadel was completed by the end of the 7th century BC, during the reign of Rusa III. However, Teishebaini was destroyed by an alliance of Medes and the Scythians in 585 BC.

Median and Achaemenid rules

In 590 BC, following the fall of the Kingdom of Urartu at the hands of the Iranian Medes, Erebuni along with the Armenian Highlands became part of the Median Empire.

However, in 550 BC, the Median Empire was conquered by Cyrus the Great, and Erebuni became part of the Achaemenid Empire. Between 522 BC and 331 BC, Erebuni was one of the main centers of the Satrapy of Armenia, a region controlled by the Orontid dynasty as one of the satrapies of the Achaemenid Empire. The Satrapy of Armenia was divided into two parts: the northern part and the southern part, with the cities of Erebuni (Yerevan) and Tushpa (Van) as their centres, respectively.

Coins issued in 478 BC, along with many other items found in the Erebuni Fortress, reveal the importance of Erebuni as a major centre for trade under Achaemenid rule.

Ancient Kingdom of Armenia

After Alexander the Great's victory over the Achaemenid Empire, the Orontid rulers of the Armenian satrapy achieved independence as a result of the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BC, founding the Kingdom of Armenia. With the establishment of new cities such as Armavir, Zarehavan, Bagaran and Yervandashat, the importance of Erebuni gradually declined.

With the rise of the Artaxiad dynasty of Armenia who seized power in 189 BC, the Kingdom of Armenia greatly expanded to include major territories of Asia Minor, Atropatene, Iberia, Phoenicia and Syria. The Artaxiads considered Erebuni and Tushpa as cities of Persian heritage. Consequently, new cities and commercial centres were built by Kings Artaxias I, Artavasdes I and Tigranes the Great. Thus, with the dominance of cities such as Artaxata and Tigranocerta, Erebuni significantly lost its importance as a central city.

Under the rule of the Arsacid dynasty of Armenia (54–428 AD), many other cities around Erebuni including Vagharshapat and Dvin flourished. Consequently, Erebuni was completely neutralized, losing its role as an economic and strategic centre of Armenia. During the period of the Arsacid kings, Erebuni was only recorded in a Manichaean text of the 3rd century, where it is mentioned that one of the disciples of the prophet Mani founded a Manichaean community near the Christian community in Erebuni.

According to the medieval Armenian geography Ashkharhatsuyts, Erebuni was part of the canton (gawaṙ) of Kotayk (not to be confused with the current Kotayk Province) of the province of Ayrarat, within Armenia Major.

Armenia became a Christian nation in the early 4th century AD, during the reign of the Arsacid king Tiridates III.

Sasanian and Roman periods

Following the partition of Armenia by the Byzantine and Sasanian empires in 387 and in 428, Erebuni and the entire territory of Eastern Armenia came under the rule of Sasanian Persia.[53] The Armenian territories formed the province of Persian Armenia within the Sasanian Empire.

Due to the diminished role of Erebuni, as well as the absence of proper historical data, much of the city's history under the Sasanian rule is unknown.[citation needed]

In 587, during the reign of emperor Maurice, Yerevan and much of Armenia came under Roman administration after the Romans defeated the Sassanid Persian Empire at the battle of the Blarathon.[citation needed] Soon after, Katoghike Tsiranavor Church in Avan was built between 595 and 602. Despite being partly damaged during the 1679 earthquake), it is the oldest surviving church within modern Yerevan city limits.[citation needed]

The province of Persian Armenia (also known as Persarmenia) lasted until 646, when the province was dissolved with the Muslim conquest of Persia.

Arab Islamic invasion

In 658 AD, at the height of the Arab Islamic invasions, Erebuni-Yerevan was conquered during the Muslim conquest of Persia, as it was part of Persian-ruled Armenia. The city became part of the Emirate of Armenia under the Umayyad Caliphate. The city of Dvin was the centre of the newly created emirate. Starting from this period, as a result of the developing trade activities with the Arabs, the Armenian territories had gained strategic importance as a crossroads for the Arab caravan routes passing between Europe and India through the Arab-controlled Ararat Plain of Armenia. Most probably, "Erebuni" has become known as "Yerevan" since at least the 7th century AD.

Bagratid Armenia

After two centuries of Islamic rule over Armenia, the Bagratid prince Ashot I of Armenia led the revolution against the Abbasid Caliphate. Ashot I liberated Yerevan in 850, and was recognized as the Prince of Princes of Armenia by the Abbasid Caliph al-Musta'in in 862. Ashot was later crowned King of Armenia through the consent of Caliph al-Mu'tamid in 885. During the rule of the Bagratuni dynasty of Armenia between 885 and 1045, Yerevan was relatively a secure part of the Kingdom before falling to the Byzantines.

However, Yerevan did not have any strategic role during the reign of the Bagratids, who developed many other cities of Ayrarat, such as Shirakavan, Dvin, and Ani.

Seljuk period, Zakarid Armenia and Mongol rule

After a brief Byzantine rule over Armenia between 1045 and 1064, the invading Seljuks—led by Tughril and later by his successor Alp Arslan—ruled over the entire region, including Yerevan. However, with the establishment of the Zakarid Principality of Armenia in 1201 under the Georgian protectorate, the Armenian territories of Yerevan and Lori had significantly grown. After the Mongols captured Ani in 1236, Armenia turned into a Mongol protectorate as part of the Ilkhanate, and the Zakarids became vassals to the Mongols. After the fall of the Ilkhanate in the mid-14th century, the Zakarid princes ruled over Lori, Shirak and the Ararat Plain until 1360 when they fell to the invading Turkic tribes.

Aq Qoyunlu and Kara Koyunlu tribes

During the last quarter of the 14th century, the Aq Qoyunlu Sunni Oghuz Turkic tribe took over Armenia, including Yerevan. In 1400, Timur invaded Armenia and Georgia, and captured more than 60,000 of the survived local people as slaves. Many districts including Yerevan were depopulated.[54]

In 1410, Armenia fell under the control of the Kara Koyunlu Shia Oghuz Turkic tribe. According to the Armenian historian Thomas of Metsoph, although the Kara Koyunlu levied heavy taxes against the Armenians, the early years of their rule were relatively peaceful and some reconstruction of towns took place.[55] The Kara Koyunlus made Yerevan the centre of the newly formed Chukhur Saad administrative territory. The territory was named after a Turkic leader known as Emir Saad.

However, this peaceful period was shattered with the rise of Qara Iskander between 1420 and 1436, who reportedly made Armenia a "desert" and subjected it to "devastation and plunder, to slaughter, and captivity".[56] The wars of Iskander and his eventual defeat against the Timurids, invited further destruction in Armenia, as many more Armenians were taken captive and sold into slavery and the land was subjected to outright pillaging, forcing many of them to leave the region.[57]

Following the fall of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia in 1375, the seat of the Armenian Church was transferred from Sis back to Vagharshapat near Yerevan in 1441. Thus, Yerevan became the main economic, cultural and administrative centre in Armenia.

Iranian rule

In 1501–02, most of the Eastern Armenian territories including Yerevan were swiftly conquered by the emerging Safavid dynasty of Iran led by Shah Ismail I.[58] Soon after in 1502, Yerevan became the centre of the Erivan Province, a new administrative territory of Iran formed by the Safavids. For the following 3 centuries, it remained, with brief intermissions, under the Iranian rule. Due to its strategic significance, Yerevan was initially often fought over, and passed back and forth, between the dominion of the rivaling Iranian and Ottoman Empire, until it permanently became controlled by the Safavids. In 1555, Iran had secured its legitimate possession over Yerevan with the Ottomans through the Treaty of Amasya.[59]

In 1582–1583, the Ottomans led by Serdar Ferhad Pasha took brief control over Yerevan. Ferhad Pasha managed to build the Erivan Fortress on the ruins of one thousand-years old ancient Armenian fortress, on the shores of Hrazdan river.[60] However, Ottoman control ended in 1604 when the Persians regained Yerevan as a result of first Ottoman-Safavid War.[citation needed]

Shah Abbas I of Persia who ruled between 1588 and 1629, ordered the deportation of hundreds of thousands of Armenians including citizens from Yerevan to mainland Persia. As a consequence, Yerevan significantly lost its Armenian population who had declined to 20%, while Muslims including Persians, Turks, Kurds and Tatars gained dominance with around 80% of the city's population. Muslims were either sedentary, semi-sedentary, or nomadic. Armenians mainly occupied the Kond neighbourhood of Yerevan and the rural suburbs around the city. However, the Armenians dominated over various professions and trade in the area and were of great economic significance to the Persian administration.[61]

During the second Ottoman-Safavid War, Ottoman troops under the command of Sultan Murad IV conquered the city on 8 August 1635. Returning in triumph to Constantinople, he opened the "Yerevan Kiosk" (Revan Köşkü) in Topkapı Palace in 1636. However, Iranian troops commanded by Shah Safi retook Yerevan on 1 April 1636. As a result of the Treaty of Zuhab in 1639, the Iranians reconfirmed their control over Eastern Armenia, including Yerevan. On 7 June 1679, a devastating earthquake razed the city to the ground.

In 1724, the Erivan Fortress was besieged by the Ottoman army.[citation needed] After a period of resistance, the fortress fell to the Turks. As a result of the Ottoman invasion, the Erivan Province of the Safavids was dissolved.[citation needed]

Following a brief period of Ottoman rule over Eastern Armenia between 1724 and 1736, and as a result of the fall of the Safavid dynasty in 1736, Yerevan along with the adjacent territories became part of the newly formed administrative territory of Erivan Khanate under the Afsharid dynasty of Iran, which encompassed an area of 15,000 square kilometres (5,800 square miles). The Afsharids controlled Eastern Armenia from the mid-1730s until the 1790s. Following the fall of the Afsharids, the Qajar dynasty of Iran took control of Eastern Armenia until 1828, when the region was conquered by the Russian Empire after their victory over the Qajars that resulted in the Treaty of Turkmenchay of 1828.[62]

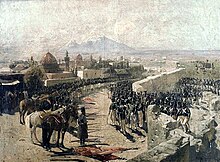

Russian rule

During the second Russo-Persian War of the 19th century, the Russo-Persian War of 1826–28, Yerevan was captured by Russian troops under general Ivan Paskevich on 1 October 1827.[36][63][64] It was formally ceded by the Iranians in 1828, following the Treaty of Turkmenchay.[65] After 3 centuries of Iranian occupation, Yereven along with the rest of Eastern Armenia designated as the "Armenian Oblast", became part of the Russian Empire, a period that would last until the collapse of the Empire in 1917.

Although not mentioned specifically by name, article XV of the Turkmenchay treaty was intended solely for the repatriation of those Armenians whose ancestors had been forcibly relocated to Iran in the early 17th century during the Safavid period. The Russians sponsored the resettlement process of the Armenian population from Persia and Turkey and spread announcements in Armenian villages.[66] Due to the resettlement, the percentage of the Armenian population of Yerevan increased from 28% to 53.8%. The resettlement was intended to create Russian power bridgehead in the Middle East.[67] In 1829, Armenian repatriates from Persia were resettled in the city and a new quarter was built.

Yerevan served as the seat of the newly formed Armenian Oblast between 1828 and 1840. By the time of Nicholas I's visit in 1837, Yerevan had become an uezd ("county"). In 1840, the Armenian Oblast was dissolved and its territory incorporated into a new larger province; the Georgia-Imeretia Governorate. In 1850 the territory of the former oblast was reorganized into the Erivan Governorate, covering an area of 28,000 square kilometres (11,000 square miles). Yerevan was the centre of the newly established governorate.

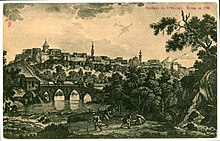

At that period, Yerevan was a small town with narrow roads and alleys, including the central quarter of Shahar, the Ghantar commercial centre, and the residential neighbourhoods of Kond, Dzoragyugh, Nork and Shentagh. During the 1840s and the 1850s, many schools were opened in the city. However, the first major plan of Yerevan was adopted in 1856, during which, Saint Hripsime and Saint Gayane women's colleges were founded and the English Park was opened. In 1863, the Astafyan Street was redeveloped and opened. In 1874, Zacharia Gevorkian opened Yerevan's first printing house, while the first theatre opened its doors in 1879.

On 1 October 1879, Yerevan was granted the status of a city through a decree issued by Alexander II of Russia. In 1881, The Yerevan Teachers' Seminary and the Yerevan Brewery were opened, followed by the Tairyan's wine and brandy factory in 1887. Other factories for alcoholic beverages and mineral water were opened during the 1890s. The monumental church of Saint Gregory the Illuminator was opened in 1900. Electricity and telephone lines were introduced to the city in 1907 and 1913 respectively. When British traveller H. F. B. Lynch visited Yerevan in 1893–1894, he considered it an Oriental city.[68] However, this started to change in the first decade of the 20th century, in the penultimate decade of Imperial Russian rule, when the city grew and altered dramatically.[68] In general, Yerevan rapidly grew under Russian rule, both economically and politically. Old buildings were torn down and new buildings of European style were erected.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Yerevan city's population was over 29,000.[69] In 1902, a railway line linked Yerevan with Alexandropol, Tiflis and Julfa. In the same year, Yerevan's first public library was opened. In 1905, the grandnephew of Napoleon I; prince Louis Joseph Jérôme Napoléon (1864–1932) was appointed as governor of Yerevan province.[70] In 1913, for the first time in the city, a telephone line with eighty subscribers became operational.

Yerevan served as the centre of the governorate until 1917, when Erivan governorate was dissolved with the collapse of the Russian Empire.

Brief independence

At the beginning of the 20th century, Yerevan was a small city with a population of 30,000.[71] In 1917, the Russian Empire ended with the October Revolution. In the aftermath, Armenian, Georgian and Muslim leaders of Transcaucasia united to form the Transcaucasian Federation and proclaimed Transcaucasia's secession.

The Federation, however, was short-lived. After gaining control over Alexandropol, the Turkish army was advancing towards the south and east to eliminate the center of Armenian resistance based in Yerevan. On 21 May 1918, the Turks started their campaign moving towards Yerevan via Sardarabad. Catholicos Gevorg V ordered that church bells peal for 6 days as Armenians from all walks of life – peasants, poets, blacksmiths, and even the clergymen – rallied to form organized military units.[72] Civilians, including children, aided in the effort as well, as "Carts drawn by oxen, water buffalo, and cows jammed the roads bringing food, provisions, ammunition, and volunteers from the vicinity" of Yerevan.[73]

By the end of May 1918, Armenians were able to defeat the Turkish army in the battles of Sardarabad, Abaran and Karakilisa. Thus, on 28 May 1918, the Dashnak leader Aram Manukian declared the independence of Armenia. Subsequently, Yerevan became the capital and the center of the newly founded Republic of Armenia, although the members of the Armenian National Council were yet to stay in Tiflis until their arrival in Yerevan to form the government in the summer of the same year.[74] Armenia became a parliamentary republic with four administrative divisions. The capital Yerevan was part of the Araratian Province. At the time, Yerevan received more than 75,000 refugees from Western Armenia, who escaped the massacres perpetrated by the Ottoman Turks during the Armenian genocide.

On 26 May 1919, the government passed a law to open the Yerevan State University, which was located on the main Astafyan (now Abovyan) street of Yerevan.[citation needed]

After the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, Armenia was granted formal international recognition. The United States, as well as many South American countries, officially opened diplomatic channels with the government of independent Armenia. Yerevan had also opened representatives in Great Britain, Italy, Germany, Serbia, Greece, Iran and Japan.[citation needed]

However, after the short period of independence, Yerevan fell to the Bolsheviks, and Armenia was incorporated into Soviet Russia on 2 December 1920. Although nationalist forces managed to retake the city in February 1921 and successfully released all the imprisoned political and military figures, the city's nationalist elite were once again defeated by the Soviet forces on 2 April 1921.[citation needed]

Soviet rule

The Red Soviet Army invaded Armenia on 29 November 1920 from the northeast. On 2 December 1920, Yerevan along with the other territories of the Republic of Armenia, became part of Soviet Russia, known as the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic. However, the Armenian SSR formed the Transcaucasian SFSR (TSFSR) together with the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic and the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic, between 1922 and 1936.

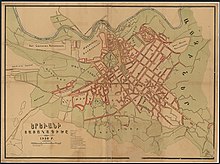

Under the Soviet rule, Yerevan became the first among the cities in the Soviet Union for which a general plan was developed. The "General Plan of Yerevan" developed by the academician Alexander Tamanian, was approved in 1924. It was initially designed for a population of 150,000.[citation needed] The city was quickly transformed into a modern industrial metropolis of over one million people.[citation needed] New educational, scientific and cultural institutions were founded as well.

Tamanian incorporated national traditions with contemporary urban construction. His design presented a radial-circular arrangement that overlaid the existing city and incorporated much of its existing street plan. As a result, many historic buildings were demolished, including churches, mosques, the Erivan Fortress, baths, bazaars and caravanserais. Many of the districts around central Yerevan were named after former Armenian communities that were destroyed by the Ottoman Turks during the Armenian genocide. The districts of Arabkir, Malatia-Sebastia and Nork Marash, for example, were named after the towns Arabkir, Malatya, Sebastia, and Marash, respectively. After the end of World War II, German POWs were used to help in the construction of new buildings and structures, such as the Kievyan Bridge.[citation needed]

Within the years, the central Kentron district has become the most developed area in Yerevan, something that created a significant gap compared with other districts in the city. Most of the educational, cultural and scientific institutions were centred in the Kentron district.

In 1965, during the commemorations of the fiftieth anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, Yerevan was the location of a demonstration, the first such demonstration in the Soviet Union, to demand recognition of the Genocide by the Soviet authorities.[75] In 1968, the city's 2,750th anniversary was commemorated.

Yerevan played a key role in the Armenian national democratic movement that emerged during the Gorbachev era of the 1980s. The reforms of Glasnost and Perestroika opened questions on issues such as the status of Nagorno-Karabakh, the environment, Russification, corruption, democracy, and eventually independence. At the beginning of 1988, nearly one million Armenians from several regions of Armenia engaged in demonstrations concerning these subjects, centered in the city's Theater Square (currently Freedom Square).[76]

Post-independence

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Yerevan became the capital of Armenia on 21 September 1991.[77] Maintaining supplies of gas and electricity proved difficult; constant electricity was not restored until 1996 amidst the chaos of the badly instigated and planned transition to a market-based economy.

Since 2000, central Yerevan has been transformed into a vast construction site, with cranes erected all over the Kentron district. Officially, the scores of multi-storied buildings are part of large-scale urban planning projects. Roughly $1.8 billion was spent on such construction in 2006, according to the national statistical service.[citation needed] Prices for downtown apartments have increased by about ten times during the first decade of the 21st century.[citation needed] Many new streets and avenues were opened, such as the Argishti street, Italy street, Saralanj Avenue, Monte Melkonian Avenue, and the Northern Avenue.

However, as a result of this construction boom, the majority of the historic buildings located on the central Aram Street, were either entirely destroyed or transformed into modern residential buildings through the construction of additional floors. Only a few structures were preserved, mainly in the portion that extends between Abovyan Street and Mashtots Avenue.

The first major post-independence protest in Yerevan took place in September 1996, after the announcement of incumbent Levon Ter-Petrosyan's victory in the presidential election. Major opposition parties of the time, consolidated around the former Karabakh Committee member and former Prime Minister Vazgen Manukyan, organized mass demonstrations between 23 and 25 September, claiming electoral fraud by Ter-Petrosyan.[78] An estimated of 200,000 people gathered in the Freedom Square to protest the election results.[79] After a series of riot and violent protests around the Parliament building on 25 September, the government sent tanks and troops to Yerevan to enforce the ban on rallies and demonstrations on the following day.[80] Prime Minister Vazgen Sargsyan and Minister of National Security Serzh Sargsyan announced on the Public Television of Armenia that their respective agencies have prevented an attempted coup d'état.[81]

In February 2008, unrest in the capital between the authorities and opposition demonstrators led by ex-President Levon Ter-Petrosyan took place after the 2008 Armenian presidential election. The events resulted in 10 deaths[82] and a subsequent 20-day state of emergency declared by President Robert Kocharyan.[83]

In July 2016, a group of armed men calling themselves the Daredevils of Sassoun (Armenian: Սասնա Ծռեր Sasna Tsrrer) stormed a police station in Erebuni District of Yerevan, taking several hostages, demanding the release of opposition leader Jirair Sefilian and the resignation of President Serzh Sargsyan. 3 policeman were killed as a result of the attack.[84] Many anti-government protestors held rallies in solidarity with the gunmen.[85] However, after 2 weeks of negotiations, the crisis ended and the gunmen surrendered.

Geography

Topography and cityscape

Yerevan has an average height of 990 m (3,248.03 ft), with a minimum of 865 m (2,837.93 ft) and a maximum of 1,390 m (4,560.37 ft) above sea level in its southwestern and northeastern sections, respectively.[86] It is among the fifty highest cities in the world with over 1 million inhabitants.[87]

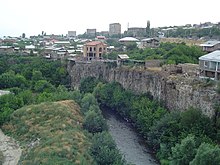

Yerevan is located on the banks of the Hrazdan River, northeast of the Ararat Plain, in the central-western part of the country. The upper part of the city is surrounded with mountains on three sides while it descends to the banks of the river Hrazdan at the south. The Hrazdan divides Yerevan into two parts through a picturesque canyon.

The city is situated at the heart of the Armenian Highland.[88] Historically, Yerevan was located in the Kotayk canton (Armenian: Կոտայք գավառ Kotayk gavar, not to be confused with the current Kotayk Province) of the Ayrarat province of historic Armenia Major.

According to the current administrative division of Armenia, Yerevan is not part of any marz ("province") and has special administrative status as the country's capital. It is bordered by Kotayk Province to the north and the east, Ararat Province to the south and the south-west, Armavir Province to the west and Aragatsotn Province to the north-west.

The Erebuni State Reserve, formed in 1981, is located around 8 km southeast of the city centre within the Erebuni District of the city. At a height between 1300 and 1450 meters above sea level, the reserve occupies an area of 120 hectares, mainly consisting of semi-deserted mountain-steppes.[89]

Climate

Yerevan features a continental influenced steppe climate (Köppen climate classification: BSk or "cold semi-arid climate"), with long, hot, dry summers and short, but cold and snowy winters. This is attributed to Yerevan being on a plain surrounded by mountains and to its distance from the sea and its moderating effects. The summers are usually very hot with the temperature in August reaching up to 40 °C (104 °F), and winters generally carry snowfall and freezing temperatures with January often being as cold as −15 °C (5 °F) and lower. The amount of precipitation is small, amounting annually to about 318 millimetres (12.5 in). Yerevan experiences an average of 2,700 sunshine hours per year.[86] On 12 July 2018, Yerevan recorded a temperature of 43.7 °C (110.7 °F), which is the joint highest temperature to have ever been recorded in Armenia.[90]

| Climate data for Yerevan (1991–2020, extremes 1885–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.5 (67.1) | 19.6 (67.3) | 27.6 (81.7) | 35.0 (95.0) | 36.1 (97.0) | 41.1 (106.0) | 43.7 (110.7) | 42.0 (107.6) | 40.0 (104.0) | 34.1 (93.4) | 26.0 (78.8) | 21.0 (69.8) | 43.7 (110.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 1.7 (35.1) | 6.3 (43.3) | 13.7 (56.7) | 19.8 (67.6) | 25.1 (77.2) | 30.9 (87.6) | 34.5 (94.1) | 34.4 (93.9) | 29.2 (84.6) | 21.6 (70.9) | 12.8 (55.0) | 4.2 (39.6) | 19.5 (67.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −3.5 (25.7) | 0.0 (32.0) | 7.0 (44.6) | 12.9 (55.2) | 17.7 (63.9) | 23.1 (73.6) | 26.8 (80.2) | 26.7 (80.1) | 21.4 (70.5) | 14.0 (57.2) | 5.8 (42.4) | −0.8 (30.6) | 12.6 (54.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −7.8 (18.0) | −5.4 (22.3) | 0.9 (33.6) | 6.4 (43.5) | 10.8 (51.4) | 15.1 (59.2) | 19.1 (66.4) | 18.9 (66.0) | 13.2 (55.8) | 7.1 (44.8) | 0.1 (32.2) | −4.9 (23.2) | 6.1 (43.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.6 (−17.7) | −26 (−15) | −19.1 (−2.4) | −10.9 (12.4) | −0.6 (30.9) | 3.7 (38.7) | 7.5 (45.5) | 7.9 (46.2) | 0.1 (32.2) | −6.5 (20.3) | −14.7 (5.5) | −28.3 (−18.9) | −28.3 (−18.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 21 (0.8) | 21 (0.8) | 60 (2.4) | 56 (2.2) | 47 (1.9) | 24 (0.9) | 17 (0.7) | 10 (0.4) | 10 (0.4) | 51 (2.0) | 25 (1.0) | 21 (0.8) | 363 (14.3) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 5 (2.0) | 3 (1.2) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 5 (2.0) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 4.9 | 4.3 | 6.2 | 8.2 | 9.3 | 5.7 | 3 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 5.1 | 4.4 | 5 | 60.9 |

| Average rainy days | 2 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 78 |

| Average snowy days | 7 | 7 | 2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 1 | 5 | 22 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75.0 | 67.6 | 58.3 | 55.5 | 54.6 | 46.0 | 42.9 | 41.1 | 45.7 | 57.8 | 68.6 | 77.0 | 57.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 104.5 | 136.8 | 186.5 | 206.5 | 267.1 | 326.6 | 353.9 | 333.7 | 291.5 | 217.0 | 159.9 | 91.0 | 2,675 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net[91] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun, humidity and precipitation days)[92], [90] | |||||||||||||

Architecture

The Yerevan TV Tower is the tallest structure in the city and one of the tallest structures in the South Caucasus.

The Republic Square, the Yerevan Opera Theatre, and the Yerevan Cascade are among the main landmarks at the centre of Yerevan, mainly developed based on the original design of architect Alexander Tamanian, and the revised plan of architect Jim Torosyan.

A major redevelopment process has been launched in Yerevan since 2000. As a result, many historic structures have been demolished and replaced with new buildings. This urban renewal plan has been met with opposition[93] and criticism from some residents, as the projects destroy historic buildings dating back to the period of the Russian Empire, and often leave residents homeless.[94][95][96] Downtown houses deemed too small are increasingly demolished and replaced by high-rise buildings.

The Saint Gregory Cathedral, the new building of Yerevan City Council, the new section of Matenadaran institute, the new terminal of Zvartnots International Airport, the Cafesjian Center for the Arts at the Cascade, the Northern Avenue, and the new government complex of ministries are among the major construction projects fulfilled during the first two decades of the 21st century.

Aram Street of old Yerevan and the newly built Northern Avenue are respectively among the notable examples featuring the traditional and modern architectural characteristics of Yerevan.

As of May 2017, Yerevan is home to 4,883 residential apartment buildings, and 65,199 street lamps installed on 39,799 street light posts, covering a total length of 1,514 km. The city has 1,080 streets with a total length of 750 km.[97]

Parks

Yerevan is a densely built city but still offers several public parks throughout its districts, graced with mid-sized green gardens. The public park of Erebuni District along with its artificial lake is the oldest garden in the city. Occupying an area of 17 hectares, the origins of the park and the artificial lake date back to the period of king Argishti I of Urartu during the 8th century BCE. In 2011, the garden was entirely remodelled and named as Lyon Park, to become a symbol of the partnership between the cities of Lyon and Yerevan.[98]

The Lovers' Park on Marshal Baghramyan Avenue and the English Park at the centre of the city, dating back to the 18th and 19th centuries respectively, are among the most popular parks in Yerevan. The Yerevan Botanical Garden (opened in 1935), the Victory Park (opened in the 1950s) and the Circular Park are among the largest green spaces of the city.

Opened in the 1960s, the Yerevan Opera Theatre Park along with its artificial Swan Lake is also among the favourite green spaces of the city. In 2019 some of the public space of the park leased to restaurants was reclaimed allowing for improved landscape design.[99] A public ice-skating arena is operated in the park's lake area during winters.

The Yerevan Lake is an artificial reservoir opened in 1967 on Hrazdan riverbed at the south of the city centre, with a surface of 0.65 km2 (0.25 sq mi).

Each administrative district of Yerevan has its own public park, such as the Buenos Aires Park and Tumanyan Park in Ajapnyak, Komitas Park in Shengavit, Vahan Zatikian Park in Malatia-Sebastia, David Anhaght Park in Kanaker-Zeytun, the Family Park in Avan, and Fridtjof Nansen Park in Nor Nork.

Politics and government

Capital

Yerevan has been the capital of Armenia since the independence of the First Republic in 1918. Situated in the Ararat Plain, the historic lands of Armenia, it served as the best logical choice for capital of the young republic at the time.

When Armenia became a republic of the Soviet Union, Yerevan remained as capital and accommodated all the political and diplomatic institutions in the republic. In 1991 with the independence of Armenia, Yerevan continued with its status as the political and cultural centre of the country, being home to all the national institutions: the Government House, the National Assembly, the Presidential Palace, the Central Bank, the Constitutional Court, all ministries, judicial bodies and other government organizations.

Municipality

Yerevan received the status of a city on 1 October 1879, upon a decree issued by Tsar Alexander II of Russia. The first city council formed was headed by Hovhannes Ghorghanyan, who became the first mayor of Yerevan.

The Constitution of the Republic of Armenia adopted on 5 July 1995, granted Yerevan the status of a marz (մարզ, province).[100] Therefore, Yerevan functions similarly to the provinces of Armenia with a few specifications.[101]The administrative authority of Yerevan is thus represented by:

- the mayor, appointed by the President (who can remove him at any moment) upon the recommendation of the Prime Minister,[100] alongside a group of four deputy mayors heading eleven ministries (of which financial, transport, urban development etc.),[102]

- the Yerevan City Council, regrouping the Heads of community districts under the authority of the mayor,[103]

- twelve "community districts", with each having its own leader and their elected councils.[104] Yerevan has a principal city hall and twelve deputy mayors of districts.

In the modified Constitution of 27 November 2005, Yerevan city was turned into a "community" (համայնք, hamaynk); since, the Constitution declares that this community has to be led by a mayor, elected directly or indirectly, and that the city needs to be governed by a specific law.[105] The first election of the Yerevan City Council took place in 2009 and won by the ruling Republican Party of Armenia.[106][107]

In addition to the national police and road police, Yerevan has its own municipal police. All three bodies cooperate to maintain law in the city.

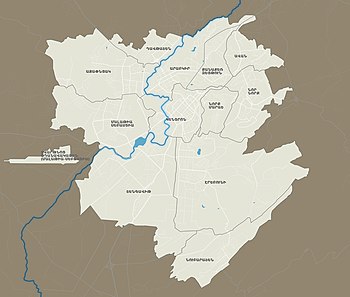

Administrative districts

Yerevan is divided into twelve "administrative districts" (վարչական շրջան, varčakan šrĵan)[108] each with an elected leader. The total area of the 12 districts of Yerevan is 223 square kilometres (86 square miles).[109][110][111]

| District | Armenian | Population (2011 census) | Population (2016 estimate) | Area (km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ajapnyak | Աջափնյակ | 108,282 | 109,100 | 25.82 |

| Arabkir | Արաբկիր | 117,704 | 115,800 | 13.29 |

| Avan | Ավան | 53,231 | 53,100 | 7.26 |

| Davtashen | Դավթաշեն | 42,380 | 42,500 | 6.47 |

| Erebuni | Էրեբունի | 123,092 | 126,500 | 47.49 |

| Kanaker-Zeytun | Քանաքեր-Զեյթուն | 73,886 | 74,100 | 7.73 |

| Kentron | Կենտրոն | 125,453 | 125,700 | 13.35 |

| Malatia-Sebastia | Մալաթիա-Սեբաստիա | 132,900 | 135,900 | 25.16 |

| Nork-Marash | Նորք-Մարաշ | 12,049 | 11,800 | 4.76 |

| Nor Nork | Նոր Նորք | 126,065 | 130,300 | 14.11 |

| Nubarashen | Նուբարաշեն | 9,561 | 9,800 | 17.24 |

| Shengavit | Շենգավիթ | 135,535 | 139,100 | 40.6 |

Demographics

| Year | Armenians | Azerbaijanisa | Russians | Others | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1650[112] | absolute majority | — | — | — | — | ||||

| c. 1725[113] | absolute majority | — | — | — | 20,000 | ||||

| 1830[114] | 4,132 | 35.7% | 7,331 | 64.3% | 195 | 1.7% | 11,463 | ||

| 1831[115] | 4,484 | 37.6% | 7,331 | 61.5% | 105 | 0.9% | 11,920 | ||

| 1873[116] | 5,900 | 50.1% | 5,800 | 48.7% | 150 | 1.3% | 24 | 0.2% | 11,938 |

| 1886[115] | 7,142 | 48.5% | 7,228 | 49.0% | 368 | 2.5% | 14,738 | ||

| 1897[117] | 12,523 | 43.2% | 12,359 | 42.6% | 2,765 | 9.5% | 1,359 | 4.7% | 29,006 |

| 1908[115] | 30,670 | ||||||||

| 1914[118] | 15,531 | 52.9% | 11,496 | 39.1% | 1,628 | 5.5% | 711 | 2.4% | 29,366[e] |

| 1916[119] | 37,223 | 72.6% | 12,557 | 24.5% | 1,059 | 2.1% | 447 | 0.9% | 51,286 |

| 1919[115] | 48,000 | ||||||||

| 1922[115] | 40,396 | 86.6% | 5,124 | 11.0% | 1,122 | 2.4% | 46,642 | ||

| 1926[120] | 59,838 | 89.2% | 5,216 | 7.8% | 1,401 | 2.1% | 666 | 1% | 67,121 |

| 1931[115] | 80,327 | 90.4% | 5,620 | 6.3% | 2,957 | 3.3% | 88,904 | ||

| 1939[120] | 174,484 | 87.1% | 6,569 | 3.3% | 15,043 | 7.5% | 4,300 | 2.1% | 200,396 |

| 1959[120] | 473,742 | 93.0% | 3,413 | 0.7% | 22,572 | 4.4% | 9,613 | 1.9% | 509,340 |

| 1970[121] | 738,045 | 95.2% | 2,721 | 0.4% | 21,802 | 2.8% | 12,460 | 1.6% | 775,028 |

| 1979[120] | 974,126 | 95.8% | 2,341 | 0.2% | 26,141 | 2.6% | 14,681 | 1.4% | 1,017,289 |

| 1989[122][123] | 1,100,372 | 96.5% | 897 | 0.0% | 22,216 | 2.0% | 17,507 | 1.5% | 1,201,539 |

| 2001[124] | 1,088,389 | 98.6% | — | 6,684 | 0.61% | 8,415 | 0.76% | 1,103,488 | |

| 2011[125] | 1,048,940 | 98.9% | — | 4,940 | 0.5% | 6,258 | 0.6% | 1,060,138 | |

| ^a Called Tatars prior to 1918 | |||||||||

Originally a small town, Yerevan became the capital of Armenia and a large city with over one million inhabitants.[citation needed] Until the fall of the Soviet Union, the majority of the population of Yerevan were Armenians with minorities of Russians, Kurds, Azerbaijanis and Iranians present as well. However, with the breakout of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War from 1988 to 1994, the Azerbaijani minority diminished in the country in what was part of population exchanges between Armenia and Azerbaijan. A big part of the Russian minority also fled the country during the 1990s economic crisis in the country.[citation needed] Today, the population of Yerevan is overwhelmingly Armenian.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, due to economic crises, thousands fled Armenia, mostly to Russia, North America and Europe. The population of Yerevan fell from 1,250,000 in 1989[86] to 1,103,488 in 2001[126] and to 1,091,235 in 2003.[127] However, the population of Yerevan has been increasing since. In 2007, the capital had 1,107,800 inhabitants.

Yerevantsis in general use the Yerevan dialect, an Eastern Armenian dialect most probably formed during the 13th century. It is currently spoken in and around Yerevan, including the towns of Vagharshapat and Ashtarak. Classical Armenian (Grabar) words compose a significant part of the dialect's vocabulary.[128] Throughout the history, it was influenced by several languages, especially Russian and Persian and loan words have significant presence in it today. It is currently the most widespread Armenian dialect.[129]

Ethnic groups

Yerevan was inhabited first by Armenians and remained homogeneous until the 15th century.[112][113][130][better source needed] The population of the Erivan Fortress, founded in the 1580s, was mainly composed of Muslim soldiers, estimated two to three thousand.[112] The city itself was mainly populated by Armenians. French traveler Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, who visited Yerevan possibly up to six times between 1631 and 1668, states that the city is exclusively populated by Armenians.[131] Although much of the Armenian population of the city was deported during the 17th century,[61] the city remained Armenian-majority during the Ottoman–Hotaki War (1722–1727).[113] The demographics of the region changed because of a series of wars between the Ottoman Empire, Iran and Russia. In the early 19th century Yerevan had a Muslim majority, mainly with an Armenian and "Caucasian Tatar" population.[132][133] According to the traveler H. F. B. Lynch, the city was about 50% Armenian and 50% Muslim (Azerbaijanis and Persians) in the early 1890s [134]

After the Armenian genocide, many refugees from what Armenians call Western Armenia (nowadays Turkey, then Ottoman Empire) escaped to Eastern Armenia. In 1919, about 75,000 Armenian refugees from the Ottoman Empire arrived in Yerevan, mostly from the Vaspurakan region (city of Van and surroundings). A significant part of these refugees died of typhus and other diseases.[135]

From 1921 to 1936, about 42,000 ethnic Armenians from Iraq, Turkey, Iran, Greece, Syria, France, Bulgaria etc. went to Soviet Armenia, with most of them settling in Yerevan. The second wave of repatriation occurred from 1946 to 1948, when about 100,000 ethnic Armenians from Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, Cyprus, Palestine, Iraq, Egypt, France, United States etc. moved to Soviet Armenia, again most of whom settled in Yerevan. Thus, the ethnic makeup of Yerevan became more monoethnic during the first 3 decades in the Soviet Union. The Azerbaijani population of Yerevan, who made up 43% of the population of the city prior to the October Revolution, dropped to 0.7% by 1959 and further to 0.1% by 1989, during the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.[136]

There is an Indian population in Armenia, with over 22,000 residents recorded in the country. Much of this population resides in Yerevan, where a large proportion run businesses, Indian restaurants, and study in Yerevan universities.[137][138]

Religion

Armenian Apostolic Church

Armenian Apostolic Christianity is the predominant religion in Armenia. The 5th-century Saint Paul and Peter Church demolished in November 1930 by the Soviets, was among the earliest churches ever built in Erebuni-Yerevan. Many of the ancient Armenian and medieval churches of the city were destroyed by the Soviets in the 1930s during the Great Purge.

The regulating body of the Armenian Church in Yerevan is the Araratian Pontifical Diocese, with the Surp Sarkis Cathedral being the seat of the diocese. It is the largest diocese of the Armenian Church and one of the oldest dioceses in the world, covering the city of Yerevan and the Ararat Province of Armenia.[29]

Yerevan is currently home to the largest Armenian church in the world, the Cathedral of Saint Gregory the Illuminator. It was consecrated in 2001, during the 1700th anniversary of the establishment of the Armenian Church and the adoption of Christianity as the national religion in Armenia.

As of 2017, Yerevan has 17 active Armenian churches as well as four chapels.

Russian Orthodox Church

After the capture of Yerevan by the Russians as a result of the Russo-Persian War of 1826–28, many Russian Orthodox churches were built in the city under the orders of the Russian commander General Ivan Paskevich. The Saint Nikolai Cathedral opened during the second half of the 19th century, was the largest Russian church in the city. The Church of the Intercession of the Holy Mother of God was opened in 1916 in Kanaker-Zeytun.[139]

However, most of the churches were either closed or demolished by the Soviets during the 1930s. The Saint Nikolai Cathedral was entirely destroyed in 1931, while the Church of the Intercession of the Holy Mother of God was closed and converted first into a warehouse and later into a club for the military personnel. Religious services resumed in the church in 1991, and in 2004 a cupola and a belfry were added to the building.[140] In 2010, the groundbreaking ceremony of the new Holy Cross Russian Orthodox church took place with the presence of Patriarch Kirill I of Moscow. The church was eventually consecrated on 7 October 2017, with the presence of Catholicos Karekin II, Russian bishops and the church benefactor Ara Abramyan.

Other religions

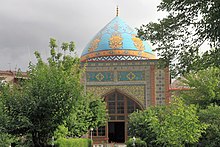

According to Ivan Chopin, there were eight mosques in Yerevan in the middle of the 19th century.[141][142] The 18th-century Blue Mosque of Yerevan was restored and reopened in the 1990s, with Iranian funding,[143] and is currently the only active mosque in Armenia, mainly serving Iranian Shia visitors.

Yerevan is home to tiny Yezidi, Molokan, Neopagan, Baháʼí and Jewish communities, with the Jewish community being represented by the Jewish Council of Armenia. A variety of nontrinitarian communities, considered dangerous sects by the Armenian Apostolic Church,[144] are also found in the city, including Jehovah's Witnesses, Mormons, Seventh-day Adventists and Word of Life.[145]

Health and medical care

Yerevan is a major healthcare and medical service centre in the region. Several hospitals of Yerevan, refurbished with modern technologies, provide healthcare and conduct medical research, such as Shengavit Medical Center, Erebouni Medical Center, Izmirlian Medical Center, Saint Gregory the Illuminator Medical Center, Nork-Marash Medical Center, Armenia Republican Medical Center, Astghik Medical Center, Armenian American Wellness Center, and Mkhitar Heratsi Hospital Complex of the Yerevan State Medical University. The municipality runs 39 polyclinics/medical centers throughout the city.

The Research Center of Maternal and Child Health Protection has operated in Yerevan since 1937, while the Armenicum Clinical Center was opened in 1999,[146] where research is conducted mainly related to infectious diseases, including HIV, immunodeficiency disorders and hepatitis.

The Liqvor Pharmaceuticals Factory, operating in Yerevan since 1991, is currently the largest medicine manufacturer of Armenia.[147]

Culture

Yerevan is Armenia's principal cultural, artistic, and industrial center, with a large number of museums, important monuments and the national public library. It also hosts Vardavar, the most widely celebrated festival among Armenians, and is one of the historic centres of traditional Armenian carpet weaving.

Museums

Yerevan is home to a large number of museums, art galleries and libraries. The most prominent of these are the National Gallery of Armenia, the History Museum of Armenia, the Cafesjian Museum of Art, the Matenadaran library of ancient manuscripts, and the Armenian Genocide Museum at the Tsitsernakaberd Armenian Genocide Memorial Complex.

Founded in 1921, the National Gallery of Armenia and the History Museum of Armenia are the principal museums of the city. In addition to having a permanent exposition of works by Armenian painters, the gallery houses a collection of paintings, drawings and sculptures by German, American, Austrian, Belgian, Spanish, French, Hungarian, Italian, Dutch, Russian and Swiss artists.[148] It usually hosts temporary expositions.

The Armenian Genocide Museum is located at the foot of the Tsitsernakaberd Armenian Genocide Memorial Complex and features numerous eyewitness accounts, texts and photographs from the time. It comprises a memorial stone made of three parts, the latter of which is dedicated to the intellectual and political figures who, as the museum's site says, "raised their protest against the Genocide committed against the Armenians by the Turks," such as Armin T. Wegner, Hedvig Büll, Henry Morgenthau Sr., Franz Werfel, Johannes Lepsius, James Bryce, Anatole France, Giacomo Gorrini, Benedict XV, Fridtjof Nansen, and others.

Cafesjian Museum of Art within the Yerevan Cascade is an art centre opened on 7 November 2009. It showcases a massive collection of glass artwork, particularly the works of the Czech artists Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtová. The front gardens showcase sculptures from Gerard L. Cafesjian's collection.

The Erebuni Museum founded in 1968, is an archaeological museum housing Urartian artifacts found during excavations at the Erebuni Fortress. The Yerevan History Museum and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation History Museum are among the prominent museums that feature the history of Yerevan and the First Republic of Armenia respectively. The Military Museum within the Mother Armenia complex is about the participation of Armenian soldiers in World War II and the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

The city is also home to a large number of art museums. Sergei Parajanov Museum opened in 1988 is dedicated to Sergei Parajanov's art works in cinema and painting.[149] Komitas Museum opened in 2015, is a musical art museum devoted to the renowned Armenian composer Komitas. Charents Museum of Literature and Arts opened in 1921, Modern Art Museum of Yerevan opened in 1972, and the Middle East Art Museum opened in 1993, are also among the notable art museums of the city.[150]

Biographical museums are also common in Yerevan. Many renowned Armenian poets, painters and musicians are honored with house-museums in their memory, such as poet Hovhannes Tumanyan, composer Aram Khachaturian, painter Martiros Saryan, novelist Khachatur Abovian, and French-Armenian singer Charles Aznavour.

Many museums of science and technology have opened in Yerevan, such as the Museum of Armenian Medicine (1999), the Space Museum of Yerevan (2001), Museum of Science and Technology (2008), Museum of Communications (2012) and the Little Einstein Interactive Science Museum (2016).

Libraries

The National Library of Armenia located on Teryan Street is the chief public library of the city and the entire republic. It was founded in 1832 and is operating in its current building since 1939. Another national library of Yerevan is the Khnko Aper Children's Library, founded in 1933. Other major public libraries include the Avetik Isahakyan Central Library founded in 1935, the Republican Library of Medical Sciences founded in 1939, the Library of Science and Technology founded in 1957, and the Musical Library founded in 1965. In addition, each administrative district of Yerevan has its own public library (usually more than one library).

The Matenadaran is a library-museum and a research centre, regrouping 17,000 ancient manuscripts and several bibles from the Middle Ages. Its archives hold a rich collection of valuable ancient Armenian, Ancient Greek, Aramaic, Assyrian, Hebrew, Latin, Middle and Modern Persian manuscripts. It is located on Mashtots Avenue at central Yerevan.

On 6 June 2010, Yerevan was named as the 2012 World Book Capital by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The Armenian capital was chosen for the quality and variety of the programme it presented to the selection committee, which met at UNESCO's headquarters in Paris on 2 July 2010.

The National Archives of Armenia founded in 1923, is a scientific research centre and depositary, with a collection of around 3.5 million units of valuable documents.

Art

Yerevan is one of the historic centres of traditional Armenian carpet. Various rug fragments have been excavated in areas around Yerevan dating back to the 7th century BC or earlier. The tradition was further developed from the 16th century when Yerevan became the central city of Persian Armenia. However, carpet manufacturing in the city was greatly enriched with the flock of Western Armenian migrants from the Ottoman Empire throughout the 19th century, and the arrival of Armenian refugees escaping the genocide in the early 20th century. Currently, the city is home to the Arm Carpet factory opened in 1924, as well as the Tufenkian handmade carpets (since 1994), and Megerian handmade carpets (since 2000).

The Yerevan Vernissage open-air exhibition-market formed in the late 1980s on Aram Street, features a large collection of different types of traditional Armenian hand-made art works, especially woodwork sculptures, rugs and carpets. On the other hand, the Saryan park located near the opera house, is famous for being a permanent venue where artists exhibit their paintings.

The Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art founded in 1992 in Yerevan,[151] is a creativity centre helping to exchange experience between professional artists in an appropriate atmosphere.[152]

Music

Jazz, classical, folk and traditional music are among several genres that are popular in the city of Yerevan. A large number of ensembles, orchestras and choirs of different types of Armenian and international music are active in the city.

The Armenian Philharmonic Orchestra founded in 1925, is one of the oldest musical groups in Yerevan and modern Armenia. The Armenian National Radio Chamber Choir founded in 1929, won the First Prize of the Soviet Union in the 1931 competition of choirs among the republics of the Soviet Union. Folk and classical music of Armenia was taught in state-sponsored conservatoires during the Soviet days. The Sayat-Nova Armenian Folk Song Ensemble was founded in Yerevan in 1938. Currently directed by Tovmas Poghosyan, the ensemble performs the works of prominent Armenian gusans such as Sayat-Nova, Jivani, and Sheram.

In 1939, the Armenian National Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet was opened. It is home to the Aram Khatchaturian concert hall and the Alexander Spendiarian auditorium of the National Theatre of Opera and Ballet.

The Komitas Chamber Music House opened in 1977, is the home of chamber music performers and lovers in Armenia. In 1983, the Karen Demirchyan Sports and Concerts Complex was opened. It is currently the largest indoor venue in Armenia.

The National Chamber Orchestra of Armenia (founded in 1961), Yerevan State Brass Band (1964), Folk Instruments Orchestra of Armenia (1977), Gusan and Folk Song Ensemble of Armenia (1983), Hover Chamber Choir (1992), Shoghaken Folk Ensemble (1995), Yerevan State Chamber Choir (1996), State Orchestra of Armenian National Instruments (2004), and the Youth State Orchestra of Armenia (2005), are also among the famous musical ensembles of the city of Yerevan. The Ars lunga piano-cello duo achieved international fame since its foundation in 2009 in Yerevan.[citation needed]

Armenian religious music remained liturgical until Komitas introduced polyphony by the end of the 19th century. Starting from the late 1950s, religious music became widely spread when Armenian chants (also known as sharakans) were performed by the soprano Lusine Zakaryan.[citation needed]The state-run Tagharan Ensemble of Yerevan founded in 1981 and currently directed by Sedrak Yerkanian, also performs ritual and ancient Armenian music.[citation needed]

Jazz is also among the popular genres in Yerevan. The first jazz band in Yerevan was founded in 1936. Currently, many jazz and ethno jazz bands are active in Yerevan such as Time Report, Art Voices, and Nuance Jazz Band. The Malkhas jazz club founded by renowned artist Levon Malkhasian, is among the most popular clubs in the city. The Yerevan Jazz Fest is an annual jazz festival taking place every autumn since 2015, organized by the Armenian Jazz Association with the support of the Yerevan Municipality.[153]

Armenian rock has been originated in Yerevan in the mid-1960s, mainly through Arthur Meschian and his band Arakyalner (Disciples). In the early 1970s, there were a range of professional bands in Yerevan strong enough to compete with their Soviet counterparts. In post-Soviet Armenia, an Armenian progressive rock scene has been developed in Yerevan, mainly through Vahan Artsruni, the Oaksenham rock band, and the Dorians band. The Armenian Navy Band founded by Arto Tunçboyacıyan in 1998 is also famous for jazz, avant-garde and folk music. Reggae is also becoming popular in Yerevan mainly through the Reincarnation musical band.

The Cafesjian Center for the Arts is known for its regularly programmed events including the "Cafesjian Classical Music Series" on the first Wednesday of each month, and the "Music Cascade" series of jazz, pop and rock music live concerts performed every Friday and Saturday.

Open-air concerts are frequently held in curtain location in Yerevan during summer, such as the Cafesjian Sculpture Garden on Tamanyan Street, the Freedom Square near the Opera House, the Republic Square, etc. The famous KOHAR Symphony Orchestra and Choir occasionally performs open-air concerts in the city.

Dance

Traditional dancing is very popular among Armenians. During the cool summertime of the Yerevan city, it is very common to find people dancing in groups at the Northern Avenue or the Tamanyan Street near the cascade.

Professional dance groups were formed in Yerevan during the Soviet days. The first group was the Armenian Folk Music and Dance Ensemble founded in 1938 by Tatul Altunyan. It was followed by the State Dance Ensemble of Armenia in 1958. In 1963, the Berd Dance Ensemble was formed. The Barekamutyun State Dance Ensemble of Armenia was founded in 1987 by Norayr Mehrabyan.

The Karin Traditional Song and Dance Ensemble founded in 2001 by Gagik Ginosyan is known for revitalizing and performing the ancient Armenian dances of the historical regions of the Armenian Highlands,[154] such as Hamshen, Mush, Sasun, Karin, etc.

Theatre

Yerevan is home to many theatre groups, mainly operating under the support of the ministry of culture. Theatre halls in the city organize several shows and performances throughout the year. Most prominent state-run theatres of Yerevan are the Sundukyan State Academic Theatre, Paronyan Musical Comedy Theatre, Stanislavski Russian Theatre, Hrachya Ghaplanyan Drama Theatre, and the Sos Sargsyan Hamazgayin State Theatre. The Edgar Elbakyan Theatre of Drama and Comedy is among the prominent theatres run by the private sector.

Yerevan is also home to several specialized theatres such as the Tumanyan Puppet Theatre, Yerevan State Pantomime Theatre, and the Yerevan State Marionettes Theatre.

Cinema

Cinema in Armenia was born on 16 April 1923, when the Armenian State Committee of Cinema was established upon a decree issued by the Soviet Armenian government.

In March 1924, the first Armenian film studio; Armenfilm (Armenian: Հայֆիլմ "Hayfilm", Russian: Арменкино "Armenkino") was opened in Yerevan, starting with a documentary film called Soviet Armenia. Namus was the first Armenian silent black and white film, directed by Hamo Beknazarian in 1925, based on a play of Alexander Shirvanzade, describing the ill fate of two lovers, who were engaged by their families to each other since childhood, but because of violations of namus (a tradition of honor), the girl was married by her father to another person. The first produced sound film was Pepo directed by Hamo Beknazarian in 1935.

Yerevan is home to many movie theatres including the Moscow Cinema, Nairi Cinema, Hayastan Cinema, Cinema Star multiplex cinemas of the Dalma Garden Mall, and the KinoPark multiplex cinemas of Yerevan Mall. The city also hosts a number of film festivals:

- The Golden Apricot Yerevan International Film Festival has been hosted by the Moscow Cinema annually since 2004.[155]

- The ReAnimania International Animation Film & Comics Art Festival of Yerevan launched in 2005, is also among the popular annual events in the city.[156]

- The Sose International Film Festival has been held annually by the Zis Center of Culture since 2014.[157]

Festivals

In addition to the film and other arts festivals, the city organizes many public celebrations that greatly attract the locals as well as the visitors. Vardavar is the most widely celebrated festival among Armenians, having it roots back to the pagan history of Armenia. It is celebrated 98 days (14 weeks) after Easter. During the day of Vardavar, people from a wide array of ages are allowed to douse strangers with water. It is common to see people pouring buckets of water from balconies on unsuspecting people walking below them. The Swan Lake of the Yerevan Opera is the most popular venue for the Vardavar celebrations.

In August 2015, Teryan Cultural Centre supported by the Yerevan Municipality has launched its first Armenian traditional clothing festival known as the Yerevan Taraz Fest.[158]

As one of the ancient winemaking regions, many wine festivals are celebrated in Armenia. Yerevan launched its first annual wine festivals known as the Yerevan Wine Days in May 2016.[159] The Watermelon Fest launched in 2013 is also becoming a popular event in the city. The Yerevan Beer Fest is held annually during the month of August. It was first organized in 2014.[160]

Media

Many public and private TV and radio channels operate in Yerevan. The Public TV of Armenia has been in service since 1956. It became a satellite television in 1996. Other satellite TVs include the Armenia TV owned by the Pan-Armenian Media Group, Kentron TV owned by Gagik Tsarukyan, Shant TV and Shant TV premium. On the other hand, Yerkir Media, Armenia 2, Shoghakat TV, Yerevan TV, 21TV and the TV channels of the Pan-Armenian Media Group are among the most notable local televisions of Yerevan.

Notable newspapers published in Yerevan include the daily newspapers of Aravot, Azg, Golos Armenii and Hayastani Hanrapetutyun.

Monuments

Historic

Many of the structures of Yerevan had been destroyed either during foreign invasions or as a result of the devastating earthquake in 1679. However, some structures have remained moderately intact and were renovated during the following years.

Erebuni Fortress, also known as Arin Berd, is the hill where the city of Yerevan was founded in 782 BC by King Argishti I. The remains of other structures from earlier periods are also found in Shengavit.

The 4th-century chapel of the Holy Mother of God and the 6th-century Tsiranavor Church both located in Avan District at the north of Yerevan, are among the oldest surviving Christian structures of the city. Originally a suburb at the north of Yerevan, Avan was eventually absorbed by the city's gradual expansion. The district is also home to the remains of Surp Hovhannes Chapel dating back to the 12–13th centuries.

Katoghike Church; a medieval chapel (a section of once much larger basilica) in the centre of Yerevan, built in 1264, is one of the best preserved churches of the city.[161] Zoravor Surp Astvatsatsin Church is also among the best surviving churches of Yerevan, built 1693–94 right after the devastating earthquake, on the ruins of a medieval church. Saint Sarkis Cathedral rebuilt in 1835–42, is the seat of Araratian Pontifical Diocese of the Armenian Apostolic Church.

The Blue Mosque or "Gök Jami", built between 1764 and 1768 at the centre of the city, is currently the only operating mosque in Armenia.

The Red Bridge of Hrazdan River is a 17th-century structure, built after the 1679 earthquake and later reconstructed in 1830.

Contemporary

Yerevan Opera Theater or the Armenian National Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre opened in 1933, is a major landmark in the city along with the Mesrop Mashtots Matenadaran opened in 1959, and Tsitsernakaberd monument of the Armenian genocide opened in 1967.

Moscow Cinema, opened in 1937 on the site of Saint Paul and Peter Church of the 5th century, is an important example of the Soviet-era architecture. In 1959, a monument was erected near the Yerevan Railway Station dedicated to the legendary Armenian hero David of Sassoun. The monumental statue of Mother Armenia is a female personification of the Armenian nation, erected in 1967, replacing the huge statue of Joseph Stalin in the Victory park.

Komitas Pantheon is a cemetery opened in 1936 where many famous Armenians are buried, while the Yerablur Pantheon, is a military cemetery where over 1,000 Armenian martyrs of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict are buried since 1990.

Many new notable buildings were constructed after the independence of Armenia such as the Yerevan Cascade, and the Saint Gregory Cathedral opened in 2001 to commemorate the 1700th anniversary of Christianity in Armenia. In May 2016, a monumental statue of the prominent Armenian statesman and military leader Garegin Nzhdeh was erected at the centre of Yerevan.

Transportation

Air

Yerevan is served by the Zvartnots International Airport, located 12 kilometres (7 miles) west of the city center.

A second airport, Erebuni Airport, is located just south of the city. Since the independence, "Erebuni" is mainly used for military or private flights. The Armenian Air Force has equally installed its base there and there are several MiG-29s stationed on Erebuni's tarmac.

City buses, public vans and trolleybuses

This section needs to be updated. (May 2024) |

Public transport in Yerevan is heavily privatized and mostly handled by around 60 private operators. As of May 2017, 39 city bus lines are being operated throughout Yerevan.[162] These lines mostly consist of about 425 Bogdan, Higer City Bus and Hyundai County buses. However, the market share these buses in public transit is only about 39.1%.

But the 50.4% of public transit is still served by "public vans", locally known as marshrutka. These are about 1210 Russian-made GAZelle vans with 13 seats, that operate same way as buses, having 79 different lines with certain routes and same stops. According to Yerevan Municipality office, in future, marshrutkas should be replaced by ordinary larger buses. Despite having about 13 seats, the limit of passengers is not controlled, so usually these vans carry many more people who stand inside.

The Yerevan trolleybus system has been operating since 1949. Some old Soviet-era trolleybuses have been replaced with comparably new ones. As of May 2017, only 5 trolleybus lines are in operation (2.6% share), with around 45 units in service. The trolleybus system is owned and operated by the municipality.

The tram network that operated in Yerevan since 1906 was decommissioned in January 2004. Its operation had a cost 2.4 times higher than the generated profits, which pushed the municipality to shut down the network,[163] despite a last-ditch effort to save it towards the end of 2003. Since the closure, the rails have been dismantled and sold.

Due to being dispersed among dozens of private operators, the transportation is barely regulated, with only trip fee is being a subject of regulation. Thus, the quality of vehicles is often inadequate, with no certain regulations for safety. Unlike the majority of world capitals, there is no established ticketing system in Yerevan's public transportation. Passengers need to pay the money directly to the driver when getting out of the vehicle. The fare -being one of the few things that is regulated- is fixed and controlled by authorities.

The central station in Nor Kilikia neighbourhood serves as bus terminal for inter-city transport, serving outbound routes towards practically all the cities of Armenia as well as abroad, notably Tbilisi and Tabriz.

Underground

The Yerevan Metro named after Karen Demirchyan, (Armenian: Կարեն Դեմիրճյանի անվան Երեւանի մետրոպոլիտեն կայարան (Karen Dyemirchyani anvan Yerevani metropoliten kayaran)) is a rapid transit system that serves the capital city since 1981. It has a single line of 12.1 km (7.5 mi) length with 10 active stations and 45 units in service. The interiors of the stations resemble that of the former western Soviet nations, with chandeliers hanging from the corridors. The metro stations had most of their names changed after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the independence of the Republic of Armenia.

A northeastern extension of the line with two new stations is currently being developed. The construction of the first station (Ajapnyak) and of the one-kilometre (0.62-mile) tunnel linking it to the rest of the network will cost US$18 million.[164] The time of the end of the project has not yet been defined. Another long-term project is the construction of two new lines, but these have been suspended due to lack of finance.

The system transports more than 60,000 people on a daily basis.[citation needed]

Railway