Apple Инк.

Логотип Apple с 1998 года. | |

| |

| Formerly |

|

|---|---|

| Company type | Public |

| ISIN | US0378331005 |

| Industry | |

| Founded | April 1, 1976, in Los Altos, California |

| Founders | |

| Headquarters | 1 Apple Park Way, , United States |

Number of locations | 530 retail stores (2024) |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | |

| Products | |

| Services | |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | 161,000 (2023) |

| Subsidiaries | |

| ASN | |

| Website | apple.com |

| Footnotes / references [1][2][3][4][5] | |

Apple Inc. — американская транснациональная корпорация и технологическая компания со штаб-квартирой в Купертино, Калифорния , в Силиконовой долине . Она наиболее известна своей бытовой электроникой , программным обеспечением и услугами . Apple В линейку продуктов входят iPhone , iPad , Mac , Apple Watch , Vision Pro и Apple TV ; а также такое программное обеспечение, как iOS , iPadOS , macOS , watchOS , tvOS и VisionOS ; и такие сервисы, как Apple Card , Apple Pay , iCloud , Apple Music и Apple TV+ .

С 2011 года Apple является крупнейшей компанией в мире по рыночной капитализации, за исключением периода, когда Microsoft удерживала эту позицию в период с января по июнь 2024 года. [6] [7] [8] В 2022 году Apple стала крупнейшей технологической компанией по выручке с доходом в 394,3 миллиарда долларов США . [9] [ не удалось пройти проверку ] По состоянию на 2023 год [update]Apple была четвертым по величине поставщиком персональных компьютеров по объему продаж . [10] крупнейшая производственная компания по выручке и крупнейший поставщик мобильных телефонов в мире. [11] Это одна из «большой пятерки» американских в области информационных технологий компаний , наряду с Alphabet (материнская компания Google ), Amazon , Meta (материнская компания Facebook ) и Microsoft .

Apple was founded as Apple Computer Company on April 1, 1976, to produce and market Steve Wozniak's Apple I personal computer. The company was incorporated by Wozniak and Steve Jobs in 1977. Its second computer, the Apple II, became a best seller as one of the first mass-produced microcomputers. Apple introduced the Lisa in 1983 and the Macintosh in 1984, as some of the first computers to use a graphical user interface and a mouse. By 1985, the company's internal problems included the high cost of its products and power struggles between executives. That year Jobs left Apple to form NeXT, Inc., and Wozniak withdrew to other ventures. The market for personal computers expanded and evolved throughout the 1990s, and Apple lost considerable market share to the lower-priced Wintel duopoly of the Microsoft Windows operating system on Intel-powered PC clones.

In 1997, Apple was weeks away from bankruptcy. To resolve its failed operating system strategy and entice Jobs's return, it bought NeXT. Over the next decade, Jobs guided Apple back to profitability through several tactics including introducing the iMac, iPod, iPhone, and iPad to critical acclaim, launching the "Think different" campaign and other memorable advertising campaigns, opening the Apple Store retail chain, and acquiring numerous companies to broaden its product portfolio. Jobs resigned in 2011 for health reasons, and died two months later. He was succeeded as CEO by Tim Cook.

Apple has received criticism regarding its contractors' labor practices, its environmental practices, and its business ethics, including anti-competitive practices and materials sourcing. Nevertheless, it has a large following and a high level of brand loyalty. It has been consistently ranked as one of the world's most valuable brands.

Apple became the first publicly traded U.S. company to be valued at over $1 trillion in August 2018, $2 trillion in August 2020, and at $3 trillion in January 2022. As of June 2024[update], it was valued at just over $3.2 trillion.[8]

History

1976–1980: Founding and incorporation

Apple Computer Company was founded on April 1, 1976, by Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, and Ronald Wayne as a partnership.[12][15] The company's first product is the Apple I, a computer designed and hand-built entirely by Wozniak.[16] To finance its creation, Jobs sold his Volkswagen Bus, and Wozniak sold his HP-65 calculator.[17]: 57 Neither received the full selling price but in total earned $1,300 (equivalent to $7,000 in 2023). Wozniak debuted the first prototype Apple I at the Homebrew Computer Club in July 1976.[18] The Apple I was sold as a motherboard with CPU, RAM, and basic textual-video chips—a base kit concept which was not yet marketed as a complete personal computer.[19] It was priced soon after debut for $666.66 (equivalent to $3,600 in 2023).[20][21]: 180 Wozniak later said he was unaware of the coincidental mark of the beast in the number 666, and that he came up with the price because he liked "repeating digits".[22]

Apple Computer, Inc. was incorporated on January 3, 1977,[23][24] without Wayne, who had left and sold his share of the company back to Jobs and Wozniak for $800 only twelve days after having co-founded it.[25] Multimillionaire Mike Markkula provided essential business expertise and funding of $250,000 (equivalent to $1,257,000 in 2023) to Jobs and Wozniak during the incorporation of Apple.[26] During the first five years of operations, revenues grew exponentially, doubling about every four months. Between September 1977 and September 1980, yearly sales grew from $775,000 to US$118 million, an average annual growth rate of 533%.[27]

The Apple II, also designed by Wozniak, was introduced on April 16, 1977, at the first West Coast Computer Faire.[28] It differs from its major rivals, the TRS-80 and Commodore PET, because of its character cell-based color graphics and open architecture. The Apple I and early Apple II models use ordinary audio cassette tapes as storage devices, which were superseded by the 5+1⁄4-inch floppy disk drive and interface called the Disk II in 1978.[29][30]

The Apple II was chosen to be the desktop platform for the first killer application of the business world: VisiCalc, a spreadsheet program released in 1979.[29] VisiCalc created a business market for the Apple II and gave home users an additional reason to buy an Apple II: compatibility with the office,[29] but Apple II market share remained behind home computers made by competitors such as Atari, Commodore, and Tandy.[31][32]

On December 12, 1980, Apple (ticker symbol "AAPL") went public selling 4.6 million shares at $22 per share ($.10 per share when adjusting for stock splits as of September 3, 2022[update]),[24] generating over $100 million, which was more capital than any IPO since Ford Motor Company in 1956.[33] By the end of the day, 300 millionaires were created, including Jobs and Wozniak, from a stock price of $29 per share[34] and a market cap of $1.778 billion.[33][34]

1980–1990: Success with Macintosh

In December 1979, Steve Jobs and Apple employees, including Jef Raskin, visited Xerox PARC, where they observed the Xerox Alto, featuring a graphical user interface (GUI). Apple subsequently negotiated access to PARC's technology, leading to Apple's option to buy shares at a preferential rate. This visit influenced Jobs to implement a GUI in Apple's products, starting with the Apple Lisa. Despite being pioneering as a mass-marketed GUI computer, the Lisa suffered from high costs and limited software options, leading to commercial failure.

Jobs, angered by being pushed off the Lisa team, took over the company's Macintosh division. Wozniak and Raskin had envisioned the Macintosh as a low-cost computer with a text-based interface like the Apple II, but a plane crash in 1981 forced Wozniak to step back from the project. Jobs quickly redefined the Macintosh as a graphical system that would be cheaper than the Lisa, undercutting his former division.[35] Jobs was also hostile to the Apple II division, which at the time, generated most of the company's revenue.[36]

In 1984, Apple launched the Macintosh, the first personal computer without a bundled programming language.[37] Its debut was signified by "1984", a US$1.5 million television advertisement directed by Ridley Scott that aired during the third quarter of Super Bowl XVIII on January 22, 1984.[38] This was hailed as a watershed event for Apple's success[39] and was called a "masterpiece" by CNN[40] and one of the greatest TV advertisements of all time by TV Guide.[41]

The advertisement created great interest in Macintosh, and sales were initially good, but began to taper off dramatically after the first three months as reviews started to come in. Jobs had required 128 kilobytes of RAM, which limited its speed and software in favor of aspiring for a projected price point of $1,000 (equivalent to $2,900 in 2023). The Macintosh shipped for $2,495 (equivalent to $7,300 in 2023), a price panned by critics due to its slow performance.[42]: 195 In early 1985, this sales slump triggered a power struggle between Steve Jobs and CEO John Sculley, who had been hired away from Pepsi two years earlier by Jobs[43] saying, "Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life or come with me and change the world?"[44] Sculley removed Jobs as the head of the Macintosh division, with unanimous support from the Apple board of directors.[45]

The board of directors instructed Sculley to contain Jobs and his ability to launch expensive forays into untested products. Rather than submit to Sculley's direction, Jobs attempted to oust him from leadership.[46] Jean-Louis Gassée informed Sculley that Jobs had been attempting to organize a boardroom coup and called an emergency meeting at which Apple's executive staff sided with Sculley and stripped Jobs of all operational duties.[46] Jobs resigned from Apple in September 1985 and took several Apple employees with him to found NeXT.[47] Wozniak had also quit his active employment at Apple earlier in 1985 to pursue other ventures, expressing his frustration with Apple's treatment of the Apple II division and stating that the company had "been going in the wrong direction for the last five years".[36][48][49] Wozniak remained employed by Apple as a representative,[48] receiving a stipend estimated to be $120,000 per year.[21] Jobs and Wozniak remained Apple shareholders following their departures.[50]

After the departures of Jobs and Wozniak in 1985, Sculley launched the Macintosh 512K that year with quadruple the RAM, and introduced the LaserWriter, the first reasonably priced PostScript laser printer. PageMaker, an early desktop publishing application taking advantage of the PostScript language, was also released by Aldus Corporation in July 1985.[51] It has been suggested that the combination of Macintosh, LaserWriter, and PageMaker was responsible for the creation of the desktop publishing market.[52]

This dominant position in the desktop publishing market[53] allowed the company to focus on higher price points, the so-called "high-right policy" named for the position on a chart of price vs. profits. Newer models selling at higher price points offered higher profit margin, and appeared to have no effect on total sales as power users snapped up every increase in speed. Although some worried about pricing themselves out of the market, the high-right policy was in full force by the mid-1980s, due to Jean-Louis Gassée's slogan of "fifty-five or die", referring to the 55% profit margins of the Macintosh II.[54]: 79–80

This policy began to backfire late in the decade as desktop publishing programs appeared on IBM PC compatibles with some of the same functionality of the Macintosh at far lower price points. The company lost its dominant position in the desktop publishing market and estranged many of its original consumer customer base who could no longer afford Apple products. The Christmas season of 1989 was the first in the company's history to have declining sales, which led to a 20% drop in Apple's stock price.[54]: 117–129 During this period, the relationship between Sculley and Gassée deteriorated, leading Sculley to effectively demote Gassée in January 1990 by appointing Michael Spindler as the chief operating officer.[55] Gassée left the company later that year.[56]

1990–1997: Decline and restructuring

The company pivoted strategy and in October 1990 introduced three lower-cost models, the Macintosh Classic, the Macintosh LC, and the Macintosh IIsi, all of which saw significant sales due to pent-up demand.[57] In 1991, Apple introduced the hugely successful PowerBook with a design that set the current shape for almost all modern laptops. The same year, Apple introduced System 7, a major upgrade to the Macintosh operating system, adding color to the interface and introducing new networking capabilities.

The success of the lower-cost Macs and PowerBook brought increasing revenue.[58] For some time, Apple was doing very well, introducing fresh new products at increasing profits. The magazine MacAddict named the period between 1989 and 1991 as the "first golden age" of the Macintosh.[59]

The success of lower-cost consumer Macs, especially the LC, cannibalized higher-priced machines. To address this, management introduced several new brands, selling largely identical machines at different price points, for different markets: the high-end Quadra series, the mid-range Centris series, and the consumer-marketed Performa series. This led to significant consumer confusion between so many models.[61]

In 1993, the Apple II series was discontinued. It was expensive to produce, and the company decided it was still absorbing sales from lower-cost Macintosh models. After the launch of the LC, Apple encouraged developers to create applications for Macintosh rather than Apple II, and authorized salespersons to redirect consumers from Apple II and toward Macintosh.[62] The Apple IIe was discontinued in 1993.[63]

Apple experimented with several other unsuccessful consumer targeted products during the 1990s, including QuickTake digital cameras, PowerCD portable CD audio players, speakers, the Pippin video game console, the eWorld online service, and Apple Interactive Television Box. Enormous resources were invested in the problematic Newton tablet division, based on John Sculley's unrealistic market forecasts.[64]

Throughout this period, Microsoft continued to gain market share with Windows by focusing on delivering software to inexpensive personal computers, while Apple was delivering a richly engineered but expensive experience.[65] Apple relied on high profit margins and never developed a clear response; it sued Microsoft for making a GUI similar to the Lisa in Apple Computer, Inc. v. Microsoft Corp.[66] The lawsuit dragged on for years and was finally dismissed.

The major product flops and the rapid loss of market share to Windows sullied Apple's reputation, and in 1993 Sculley was replaced as CEO by Michael Spindler.[67]

Under Spindler, Apple, IBM, and Motorola formed the AIM alliance in 1994 to create a new computing platform (the PowerPC Reference Platform or PReP), with IBM and Motorola hardware coupled with Apple software. The AIM alliance hoped that PReP's performance and Apple's software would leave the PC far behind and thus counter the dominance of Windows. That year, Apple introduced the Power Macintosh, the first of many computers with Motorola's PowerPC processor.[68]

In the wake of the alliance, Apple opened up to the idea of allowing Motorola and other companies to build Macintosh clones. Over the next two years, 75 distinct Macintosh clone models were introduced. However, by 1996, Apple executives were worried that the clones were cannibalizing sales of its own high-end computers, where profit margins were highest.[69]

In 1996, Spindler was replaced by Gil Amelio as CEO, who was hired for his reputation as a corporate rehabilitator. Amelio made deep changes, including extensive layoffs and cost-cutting.[70]

This period was also marked by numerous failed attempts to modernize the Macintosh operating system (MacOS). The original Macintosh operating system (System 1) was not built for multitasking (running several applications at once). The company attempted to correct this by introducing cooperative multitasking in System 5, but still decided it needed a more modern approach.[71] This led to the Pink project in 1988, A/UX that year, Copland in 1994, and evaluated the purchase of BeOS in 1996. Talks with Be stalled when the CEO, former Apple executive Jean-Louis Gassée, demanded $300 million instead of Apple's $125 million offer.[72]

Only weeks away from bankruptcy,[73] Apple's board preferred NeXTSTEP and purchased NeXT in late 1996 for $400 million, and retained Steve Jobs.[74]

1997–2007: Return to profitability

The NeXT acquisition was finalized on February 9, 1997,[75] and the board brought Jobs back to Apple as an advisor. On July 9, 1997, Jobs staged a boardroom coup that resulted in Amelio's resignation after overseeing a three-year record-low stock price and crippling financial losses.

The board named Jobs as interim CEO and he immediately reviewed the product lineup. Jobs canceled 70% of models, ending 3,000 jobs and paring to the core of its computer offerings.[76] The next month, in August 1997, Steve Jobs convinced Microsoft to make a $150 million investment in Apple and a commitment to continue developing Mac software.[77] This was seen as an "antitrust insurance policy" for Microsoft which had recently settled with the Department of Justice over anti-competitive practices in the United States v. Microsoft Corp. case.[78] Around then, Jobs donated Apple's internal library and archives to Stanford University, to focus more on the present and the future rather than the past.[79][80] He ended the Mac clone deals and in September 1997, purchased the largest clone maker, Power Computing.[81] On November 10, 1997, the Apple Store website launched, which was tied to a new build-to-order manufacturing model similar to PC manufacturer Dell's success.[82]

The moves paid off for Jobs; at the end of his first year as CEO, the company had a $309 million profit.[76]

On May 6, 1998, Apple introduced a new all-in-one computer reminiscent of the original Macintosh: the iMac. The iMac was a huge success with 800,000 units sold in its first five months[83] and ushered in major shifts in the industry by abandoning legacy technologies like the 3+1⁄2-inch diskette, being an early adopter of the USB connector, and coming pre-installed with Internet connectivity (the "i" in iMac)[84] via Ethernet and a dial-up modem. Its striking teardrop shape and translucent materials were designed by Jonathan Ive, who had been hired by Amelio, and who collaborated with Jobs for more than a decade to reshape Apple's product design.[85][86]

A little more than a year later on July 21, 1999, Apple introduced the iBook consumer laptop. It culminated Jobs's strategy to produce only four products: refined versions of the Power Macintosh G3 desktop and PowerBook G3 laptop for professionals, and the iMac desktop and iBook laptop for consumers. Jobs said the small product line allowed for a greater focus on quality and innovation.[87]

Around then, Apple also completed numerous acquisitions to create a portfolio of digital media production software for both professionals and consumers. Apple acquired Macromedia's Key Grip digital video editing software project which was launched as Final Cut Pro in April 1999.[88] Key Grip's development also led to Apple's release of the consumer video-editing product iMovie in October 1999.[89] Apple acquired the German company Astarte in April 2000, which had developed the DVD authoring software DVDirector, which Apple repackaged as the professional-oriented DVD Studio Pro, and reused its technology to create iDVD for the consumer market.[89] In 2000, Apple purchased the SoundJam MP audio player software from Casady & Greene. Apple renamed the program iTunes, and simplified the user interface and added CD burning.[90]

In 2001, Apple changed course with three announcements.

First, on March 24, 2001, Apple announced the release of a new modern operating system, Mac OS X. This was after numerous failed attempts in the early 1990s, and several years of development. Mac OS X is based on NeXTSTEP, OpenStep, and BSD Unix, to combine the stability, reliability, and security of Unix with the ease of use of an overhauled user interface

Second, in May 2001, the first two Apple Store retail locations opened in Virginia and California, offering an improved presentation of the company's products.[91][92][93] At the time, many speculated that the stores would fail, but they became highly successful, and the first of more than 500 stores around the world.[94][95]

Third, on October 23, 2001, the iPod portable digital audio player debuted. The product was first sold on November 10, 2001, and was phenomenally successful with over 100 million units sold within six years.[96]

In 2003, the iTunes Store was introduced with music downloads for 99¢ a song and iPod integration. It quickly became the market leader in online music services, with over five billion downloads by June 19, 2008.[97] Two years later, the iTunes Store was the world's largest music retailer.[98]

In 2002, Apple purchased Nothing Real for its advanced digital compositing application Shake,[99] and Emagic for the music productivity application Logic. The purchase of Emagic made Apple the first computer manufacturer to own a music software company. The acquisition was followed by the development of Apple's consumer-level GarageBand application.[100] The release of iPhoto that year completed the iLife suite.[101]

At the Worldwide Developers Conference keynote address on June 6, 2005, Jobs announced that Apple would move away from PowerPC processors, and the Mac would transition to Intel processors in 2006.[102] On January 10, 2006, the new MacBook Pro and iMac became the first Apple computers to use Intel's Core Duo CPU. By August 7, 2006, Apple made the transition to Intel chips for the entire Mac product line—over one year sooner than announced.[102] The Power Mac, iBook, and PowerBook brands were retired during the transition; the Mac Pro, MacBook, and MacBook Pro became their respective successors.[103] Apple also introduced Boot Camp in 2006 to help users install Windows XP or Windows Vista on their Intel Macs alongside Mac OS X.[104]

Apple's success during this period was evident in its stock price. Between early 2003 and 2006, the price of Apple's stock increased more than tenfold, from around $6 per share (split-adjusted) to over $80.[105] When Apple surpassed Dell's market cap in January 2006,[106] Jobs sent an email to Apple employees saying Dell's CEO Michael Dell should eat his words.[107] Nine years prior, Dell had said that if he ran Apple he would "shut it down and give the money back to the shareholders".[108]

2007–2011: Success with mobile devices

During his keynote speech at the Macworld Expo on January 9, 2007, Jobs announced the renaming of Apple Computer, Inc. to Apple Inc., because the company had broadened its focus from computers to consumer electronics.[109] This event also saw the announcement of the iPhone[110] and the Apple TV.[111] The company sold 270,000 iPhone devices during the first 30 hours of sales,[112] and the device was called "a game changer for the industry".[113]

In an article posted on Apple's website on February 6, 2007, Jobs wrote that Apple would be willing to sell music on the iTunes Store without digital rights management, thereby allowing tracks to be played on third-party players if record labels would agree to drop the technology.[114] On April 2, 2007, Apple and EMI jointly announced the removal of DRM technology from EMI's catalog in the iTunes Store, effective in May 2007.[115] Other record labels eventually followed suit and Apple published a press release in January 2009 to announce that all songs on the iTunes Store are available without their FairPlay DRM.[116]

In July 2008, Apple launched the App Store to sell third-party applications for the iPhone and iPod Touch.[117] Within a month, the store sold 60 million applications and registered an average daily revenue of $1 million, with Jobs speculating in August 2008 that the App Store could become a billion-dollar business for Apple.[118] By October 2008, Apple was the third-largest mobile handset supplier in the world due to the popularity of the iPhone.[119]

On January 14, 2009, Jobs announced in an internal memo that he would be taking a six-month medical leave of absence from Apple until the end of June 2009 and would spend the time focusing on his health. In the email, Jobs stated that "the curiosity over my personal health continues to be a distraction not only for me and my family, but everyone else at Apple as well", and explained that the break would allow the company "to focus on delivering extraordinary products".[120] Though Jobs was absent, Apple recorded its best non-holiday quarter (Q1 FY 2009) during the recession with revenue of $8.16 billion and profit of $1.21 billion.[121]

After years of speculation and multiple rumored "leaks", Apple unveiled a large screen, tablet-like media device known as the iPad on January 27, 2010. The iPad ran the same touch-based operating system as the iPhone, and all iPhone apps were compatible with the iPad. This gave the iPad a large app catalog on launch, though having very little development time before the release. Later that year on April 3, 2010, the iPad was launched in the U.S. It sold more than 300,000 units on its first day, and 500,000 by the end of the first week.[122] In May 2010, Apple's market cap exceeded that of competitor Microsoft for the first time since 1989.[123]

In June 2010, Apple released the iPhone 4,[124] which introduced video calling using FaceTime, multitasking, and a new design with an exposed stainless steel frame as the phone's antenna system. Later that year, Apple again refreshed the iPod line by introducing a multi-touch iPod Nano, an iPod Touch with FaceTime, and an iPod Shuffle that brought back the clickwheel buttons of earlier generations.[125] It also introduced the smaller, cheaper second generation Apple TV which allowed renting of movies and shows.[126]

On January 17, 2011, Jobs announced in an internal Apple memo that he would take another medical leave of absence for an indefinite period to allow him to focus on his health. Chief operating officer Tim Cook assumed Jobs's day-to-day operations at Apple, although Jobs would still remain "involved in major strategic decisions".[127] Apple became the most valuable consumer-facing brand in the world.[128] In June 2011, Jobs surprisingly took the stage and unveiled iCloud, an online storage and syncing service for music, photos, files, and software which replaced MobileMe, Apple's previous attempt at content syncing.[129] This would be the last product launch Jobs would attend before his death.

On August 24, 2011, Jobs resigned his position as CEO of Apple.[130] He was replaced by Cook and Jobs became Apple's chairman. Apple did not have a chairman at the time[131] and instead had two co-lead directors, Andrea Jung and Arthur D. Levinson,[132] who continued with those titles until Levinson replaced Jobs as chairman of the board in November after Jobs's death.[133]

2011–present: Post-Jobs era, Tim Cook

On October 5, 2011, Steve Jobs died, marking the end of an era for Apple.[134] The next major product announcement by Apple was on January 19, 2012, when Apple's Phil Schiller introduced iBook's Textbooks for iOS and iBook Author for Mac OS X in New York City.[135] Jobs stated in the biography "Steve Jobs" that he wanted to reinvent the textbook industry and education.[136]

From 2011 to 2012, Apple released the iPhone 4S[137] and iPhone 5,[138] which featured improved cameras, an intelligent software assistant named Siri, and cloud-synced data with iCloud; the third- and fourth-generation iPads, which featured Retina displays;[139][140] and the iPad Mini, which featured a 7.9-inch screen in contrast to the iPad's 9.7-inch screen.[141] These launches were successful, with the iPhone 5 (released September 21, 2012) becoming Apple's biggest iPhone launch with over two million pre-orders[142] and sales of three million iPads in three days following the launch of the iPad Mini and fourth-generation iPad (released November 3, 2012).[143] Apple also released a third-generation 13-inch MacBook Pro with a Retina display and new iMac and Mac Mini computers.[140][141][144]

On August 20, 2012, Apple's rising stock price increased the company's market capitalization to a then-record $624 billion. This beat the non-inflation-adjusted record for market capitalization previously set by Microsoft in 1999.[145] On August 24, 2012, a US jury ruled that Samsung should pay Apple $1.05 billion (£665m) in damages in an intellectual property lawsuit.[146] Samsung appealed the damages award, which was reduced by $450 million[147] and further granted Samsung's request for a new trial.[147] On November 10, 2012, Apple confirmed a global settlement that dismissed all existing lawsuits between Apple and HTC up to that date, in favor of a ten-year license agreement for current and future patents between the two companies.[148] It is predicted that Apple will make US$280 million per year from this deal with HTC.[149]

In May 2014, Apple confirmed its intent to acquire Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine's audio company Beats Electronics—producer of the "Beats by Dr. Dre" line of headphones and speaker products, and operator of the music streaming service Beats Music—for US$3 billion, and to sell their products through Apple's retail outlets and resellers. Iovine believed that Beats had always "belonged" with Apple, as the company modeled itself after Apple's "unmatched ability to marry culture and technology." The acquisition was the largest purchase in Apple's history.[150]

During a press event on September 9, 2014, Apple introduced a smartwatch called the Apple Watch.[151] Initially, Apple marketed the device as a fashion accessory[152] and a complement to the iPhone, that would allow people to look at their smartphones less.[153] Over time, the company has focused on developing health and fitness-oriented features on the watch, in an effort to compete with dedicated activity trackers.

In January 2016, Apple announced that over one billion Apple devices were in active use worldwide.[154]

On June 6, 2016, Fortune released Fortune 500, its list of companies ranked on revenue generation. In the trailing fiscal year of 2015, Apple was listed as the top tech company.[155] It ranked third, overall, with US$233 billion in revenue.[155] This represents a movement upward of two spots from the previous year's list.[155]

In June 2017, Apple announced the HomePod, its smart speaker aimed to compete against Sonos, Google Home, and Amazon Echo.[156] Toward the end of the year, TechCrunch reported that Apple was acquiring Shazam, a company that introduced its products at WWDC and specializing in music, TV, film and advertising recognition.[157] The acquisition was confirmed a few days later, reportedly costing Apple US$400 million, with media reports that the purchase looked like a move to acquire data and tools bolstering the Apple Music streaming service.[158] The purchase was approved by the European Union in September 2018.[159]

Also in June 2017, Apple appointed Jamie Erlicht and Zack Van Amburg to head the newly formed worldwide video unit. In November 2017, Apple announced it was branching out into original scripted programming: a drama series starring Jennifer Aniston and Reese Witherspoon, and a reboot of the anthology series Amazing Stories with Steven Spielberg.[160] In June 2018, Apple signed the Writers Guild of America's minimum basic agreement and Oprah Winfrey to a multi-year content partnership.[161] Additional partnerships for original series include Sesame Workshop and DHX Media and its subsidiary Peanuts Worldwide, and a partnership with A24 to create original films.[162]

During the Apple Special Event in September 2017, the AirPower wireless charger was announced alongside the iPhone X, iPhone 8, and Watch Series 3. The AirPower was intended to wirelessly charge multiple devices, simultaneously. Though initially set to release in early 2018, the AirPower would be canceled in March 2019, marking the first cancellation of a device under Cook's leadership.[163]

On August 19, 2020, Apple's share price briefly topped $467.77, making it the first US company with a market capitalization of US$2 trillion.[164]

During its annual WWDC keynote speech on June 22, 2020, Apple announced it would move away from Intel processors, and the Mac would transition to processors developed in-house.[165] The announcement was expected by industry analysts, and it has been noted that Macs featuring Apple's processors would allow for big increases in performance over current Intel-based models.[166] On November 10, 2020, the MacBook Air, MacBook Pro, and the Mac Mini became the first Mac devices powered by an Apple-designed processor, the Apple M1.[167]

In April 2022, it was reported that Samsung Electro-Mechanics would be collaborating with Apple on its M2 chip instead of LG Innotek.[168] Developer logs showed that at least nine Mac models with four different M2 chips were being tested.[169]

The Wall Street Journal reported that Apple's effort to develop its own chips left it better prepared to deal with the semiconductor shortage that emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to increased profitability, with sales of M1-based Mac computers rising sharply in 2020 and 2021. It also inspired other companies like Tesla, Amazon, and Meta Platforms to pursue a similar path.[170]

In April 2022, Apple opened an online store that allowed anyone in the US to view repair manuals and order replacement parts for specific recent iPhones, although the difference in cost between this method and official repair is anticipated to be minimal.[171]

In May 2022, a trademark was filed for RealityOS, an operating system reportedly intended for virtual and augmented reality headsets, first mentioned in 2017. According to Bloomberg, the headset may come out in 2023.[172] Further insider reports state that the device uses iris scanning for payment confirmation and signing into accounts.[173]

On June 18, 2022, the Apple Store in Towson, Maryland became the first to unionize in the U.S., with the employees voting to join the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers.[174]

On July 7, 2022, Apple added Lockdown Mode to macOS 13 and iOS 16, as a response to the earlier Pegasus revelations; the mode increases security protections for high-risk users against targeted zero-day malware.[175]

Apple launched a buy now, pay later service called 'Apple Pay Later' for its Apple Wallet users in March 2023. The program allows its users to apply for loans between $50 and $1,000 to make online or in-app purchases and then repaying them through four installments spread over six weeks without any interest or fees.[176][177]

In November 2023, Apple agreed to a $25 million settlement in a U.S. Department of Justice case that alleged Apple was discriminating against U.S. citizens in hiring. Apple created jobs that were not listed online and required paper submission to apply for, while advertising these jobs to foreign workers as part of recruitment for PERM.[178]

In January 2024, Apple announced compliance with the European Union's competition law, with major changes to the App Store and other services, effective March 7. This enables iOS users in the 27-nation bloc to use alternative app stores, and alternative payment methods within apps. This adds a menu in Safari for downloading alternative browsers, such as Chrome or Firefox.[179]

In June 2024, Apple introduced Apple Intelligence to incorporate on-device artificial intelligence capabilities.[180]

Products

Mac

Macintosh, commonly known as Mac, is Apple's line of personal computers that use the company's proprietary macOS operating system. Personal computers were Apple's original business line, but as of the end of 2023[update] they account for only about eight percent of the company's revenue.[1]

There are six Macintosh computer families in production:

- iMac: Consumer all-in-one desktop computer, introduced in 1998.

- Mac Mini: Consumer sub-desktop computer, introduced in 2005.

- MacBook Pro: Professional notebook, introduced in 2006.

- Mac Pro: Professional workstation, introduced in 2006.

- MacBook Air: Consumer ultra-thin notebook, introduced in 2008.

- Mac Studio: Professional small form-factor workstation, introduced in 2022.

Often described as a walled garden, Macs use Apple silicon chips, run the macOS operating system, and include Apple software like the Safari web browser, iMovie for home movie editing, GarageBand for music creation, and the iWork productivity suite. Apple also sells pro apps: Final Cut Pro for video production, Logic Pro for musicians and producers, and Xcode for software developers.

Apple also sells a variety of accessories for Macs, including the Pro Display XDR, Apple Studio Display, Magic Mouse, Magic Trackpad, and Magic Keyboard.

iPhone

The iPhone is Apple's line of smartphones, which run the iOS operating system. The first iPhone was unveiled by Steve Jobs on January 9, 2007. Since then, new models have been released every year. When it was introduced, its multi-touch screen was described as "revolutionary" and a "game-changer" for the mobile phone industry. The device has been credited with creating the app economy.

iOS is one of the two largest smartphone platforms in the world alongside Android. The iPhone has generated large profits for the company, and is credited with helping to make Apple one of the world's most valuable publicly traded companies.[181] As of the end of 2023[update], the iPhone accounts for more than half of the company's revenue.[1]

iPad

The iPad is Apple's line of tablets which run iPadOS. The first-generation iPad was announced on January 27, 2010. The iPad is mainly marketed for consuming multimedia, creating art, working on documents, videoconferencing, and playing games. The iPad lineup consists of several base iPad models, and the smaller iPad Mini, upgraded iPad Air, and high-end iPad Pro. Apple has consistently improved the iPad's performance, with the iPad Pro adopting the same M1 and M2 chips as the Mac; but the iPad still receives criticism for its limited OS.[182][183]

As of September 2020,[update] Apple has sold more than 500 million iPads, though sales peaked in 2013.[184] The iPad still remains the most popular tablet computer by sales as of the second quarter of 2020[update],[185] and accounted for seven percent of the company's revenue as of the end of 2023[update].[1]

Apple sells several iPad accessories, including the Apple Pencil, Smart Keyboard, Smart Keyboard Folio, Magic Keyboard, and several adapters.

Other products

Apple makes several other products that it categorizes as "Wearables, Home and Accessories".[186] These products include the AirPods line of wireless headphones, Apple TV digital media players, Apple Watch smartwatches, Beats headphones, HomePod smart speakers, and the Vision Pro mixed reality headset.

As of the end of 2023[update], this broad line of products comprises about ten percent of the company's revenues.[1]

Services

Apple offers a broad line of services, including advertising in the App Store and Apple News app, the AppleCare+ extended warranty plan, the iCloud+ cloud-based data storage service, payment services through the Apple Card credit card and the Apple Pay processing platform, digital content services including Apple Books, Apple Fitness+, Apple Music, Apple News+, Apple TV+, and the iTunes Store.

As of the end of 2023[update], services comprise about 22% of the company's revenue.[1] In 2019, Apple announced it would be making a concerted effort to expand its service revenues.[187]

Marketing

This section should include a better summary of, or be better summarized in Marketing of Apple Inc.. (January 2023) |

Branding

According to Steve Jobs, the company's name was inspired by his visit to an apple farm while on a fruitarian diet. Jobs thought the name "Apple" was "fun, spirited and not intimidating".[189] Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak were fans of the Beatles,[190] but Apple Inc. had name and logo trademark issues with Apple Corps Ltd., a multimedia company started by the Beatles in 1968. This resulted in a series of lawsuits and tension between the two companies. These issues ended when they settled their lawsuit in 2007.[191]

Apple's first logo, designed by Ron Wayne, depicts Sir Isaac Newton sitting under an apple tree. It was almost immediately replaced by Rob Janoff's "rainbow Apple", the now-familiar rainbow-colored silhouette of an apple with a bite taken out of it.[192] On August 27, 1999,[193] Apple officially dropped the rainbow scheme and began to use monochromatic logos nearly identical in shape to the previous rainbow incarnation.[194]

Apple evangelists were actively engaged by the company at one time, but this was after the phenomenon had already been firmly established. Apple evangelist Guy Kawasaki has called the brand fanaticism "something that was stumbled upon,"[195] while Ive claimed in 2014 that "people have an incredibly personal relationship" with Apple's products.[85]

Fortune magazine named Apple the most admired company in the United States in 2008, and in the world from 2008 to 2012.[196] On September 30, 2013, Apple surpassed Coca-Cola to become the world's most valuable brand in the Omnicom Group's "Best Global Brands" report.[197] Boston Consulting Group has ranked Apple as the world's most innovative brand every year as of 2005[update].[198]

As of January 2021,[update] 1.65 billion Apple products were in active use.[199][200] In February 2023, that number exceeded 2 billion devices.[201][202]

Advertising

Apple's first slogan, "Byte into an Apple", was coined in the late 1970s.[203] From 1997 to 2002, the slogan "Think different" was used in advertising campaigns, and is still closely associated with Apple.[204] Apple also has slogans for specific product lines—for example, "iThink, therefore iMac" was used in 1998 to promote the iMac,[205] and "Say hello to iPhone" has been used in iPhone advertisements.[206] "Hello" was also used to introduce the original Macintosh, Newton, iMac ("hello (again)"), and iPod.[207]

From the introduction of the Macintosh in 1984, with the 1984 Super Bowl advertisement to the more modern Get a Mac adverts, Apple has been recognized for its efforts toward effective advertising and marketing for its products. However, claims made by later campaigns were criticized,[208] particularly the 2005 Power Mac ads.[209] Apple's product advertisements gained significant attention as a result of their eye-popping graphics and catchy tunes.[210] Musicians who benefited from an improved profile as a result of their songs being included on Apple advertisements include Canadian singer Feist with the song "1234" and Yael Naïm with the song "New Soul".[210]

Stores

The first Apple Stores were originally opened as two locations in May 2001 by then-CEO Steve Jobs,[92] after years of attempting but failing store-within-a-store concepts.[93] Seeing a need for improved retail presentation of the company's products, he began an effort in 1997 to revamp the retail program to get an improved relationship to consumers, and hired Ron Johnson in 2000.[93] Jobs relaunched Apple's online store in 1997,[211] and opened the first two physical stores in 2001.[92] The media initially speculated that Apple would fail,[94] but its stores were highly successful, bypassing the sales numbers of competing nearby stores and within three years reached US$1 billion in annual sales, becoming the fastest retailer in history to do so.[94]

Over the years, Apple has expanded the number of retail locations and its geographical coverage, with 499 stores across 22 countries worldwide as of December 2017[update].[95] Strong product sales have placed Apple among the top-tier retail stores, with sales over $16 billion globally in 2011.[212] Apple Stores underwent a period of significant redesign, beginning in May 2016. This redesign included physical changes to the Apple Stores, such as open spaces and re-branded rooms, and changes in function to facilitate interaction between consumers and professionals.[213]

Many Apple Stores are located inside shopping malls, but Apple has built several stand-alone "flagship" stores in high-profile locations.[93] It has been granted design patents and received architectural awards for its stores' designs and construction, specifically for its use of glass staircases and cubes.[214] The success of Apple Stores have had significant influence over other consumer electronics retailers, who have lost traffic, control and profits due to a perceived higher quality of service and products at Apple Stores.[215] Due to the popularity of the brand, Apple receives a large number of job applications, many of which come from young workers.[212] Although Apple Store employees receive above-average pay, are offered money toward education and health care, and receive product discounts,[212] there are limited or no paths of career advancement.[212]

Market power

On March 16, 2020, France fined Apple €1.1 billion for colluding with two wholesalers to stifle competition and keep prices high by handicapping independent resellers. The arrangement created aligned prices for Apple products such as iPads and personal computers for about half the French retail market. According to the French regulators, the abuses occurred between 2005 and 2017 but were first discovered after a complaint by an independent reseller, eBizcuss, in 2012.[216]

On August 13, 2020, Epic Games, the maker of the popular game Fortnite, sued both Apple and Google after Fortnite was removed from Apple's and Google's app stores. The lawsuits came after Apple and Google blocked the game after it introduced a direct payment system that bypassed the fees that Apple and Google had imposed.[217] In September 2020, Epic Games founded the Coalition for App Fairness together with thirteen other companies, which aims for better conditions for the inclusion of apps in the app stores.[218] Later, in December 2020, Facebook agreed to assist Epic in their legal game against Apple, planning to support the company by providing materials and documents to Epic. Facebook had, however, stated that the company would not participate directly with the lawsuit, although did commit to helping with the discovery of evidence relating to the trial of 2021. In the months prior to their agreement, Facebook had been dealing with feuds against Apple relating to the prices of paid apps and privacy rule changes.[219] Head of ad products for Facebook Dan Levy commented, saying that "this is not really about privacy for them, this is about an attack on personalized ads and the consequences it's going to have on small-business owners," commenting on the full-page ads placed by Facebook in various newspapers in December 2020.[220]

Privacy

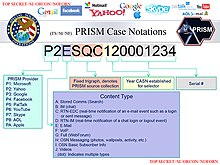

Apple has publicly taken a pro-privacy stance, actively making privacy-conscious features and settings part of its conferences, promotional campaigns, and public image.[222] With its iOS 8 mobile operating system in 2014, the company started encrypting all contents of iOS devices through users' passcodes, making it impossible at the time for the company to provide customer data to law enforcement requests seeking such information.[223] With the popularity rise of cloud storage solutions, Apple began a technique in 2016 to do deep learning scans for facial data in photos on the user's local device and encrypting the content before uploading it to Apple's iCloud storage system.[224] It also introduced "differential privacy", a way to collect crowdsourced data from many users, while keeping individual users anonymous, in a system that Wired described as "trying to learn as much as possible about a group while learning as little as possible about any individual in it".[225] Users are explicitly asked if they want to participate, and can actively opt-in or opt-out.[226]

However, Apple has aided law enforcement in criminal investigations by providing iCloud backups of users' devices,[227] and the company's commitment to privacy has been questioned by its efforts to promote biometric authentication technology in its newer iPhone models, which do not have the same level of constitutional privacy as a passcode in the United States.[228]

With Apple's release of an update to iOS 14, Apple required all developers of iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch applications to directly ask iPhone users permission to track them. The feature, called "App Tracking Transparency", received heavy criticism from Facebook, whose primary business model revolves around the tracking of users' data and sharing such data with advertisers so users can see more relevant ads, a technique commonly known as targeted advertising. After Facebook's measures, including purchasing full-page newspaper advertisements protesting App Tracking Transparency, Apple released the update in early 2021. A study by Verizon subsidiary Flurry Analytics reported only 4% of iOS users in the United States and 12% worldwide have opted into tracking.[229]

Prior to the release of iOS 15, Apple announced new efforts at combating child sexual abuse material on iOS and Mac platforms. Parents of minor iMessage users can now be alerted if their child sends or receives nude photographs. Additionally, on-device hashing would take place on media destined for upload to iCloud, and hashes would be compared to a list of known abusive images provided by law enforcement; if enough matches were found, Apple would be alerted and authorities informed. The new features received praise from law enforcement and victims rights advocates, however privacy advocates, including the Electronic Frontier Foundation, condemned the new features as invasive and highly prone to abuse by authoritarian governments.[230]

Ireland's Data Protection Commission launched a privacy investigation to examine whether Apple complied with the EU's GDPR law following an investigation into how the company processes personal data with targeted ads on its platform.[231]

In December 2019, security researcher Brian Krebs discovered that the iPhone 11 Pro would still show the arrow indicator –signifying location services are being used– at the top of the screen while the main location services toggle is enabled, despite all individual location services being disabled. Krebs was unable to replicate this behavior on older models and when asking Apple for comment, he was told by Apple that "It is expected behavior that the Location Services icon appears in the status bar when Location Services is enabled. The icon appears for system services that do not have a switch in Settings."[232]Apple later further clarified that this behavior was to ensure compliance with ultra-wideband regulations in specific countries, a technology Apple started implementing in iPhones starting with iPhone 11 Pro, and emphasized that "the management of ultra wideband compliance and its use of location data is done entirely on the device and Apple is not collecting user location data." Will Strafach, an executive at security firm Guardian Firewall, confirmed the lack of evidence that location data was sent off to a remote server. Apple promised to add a new toggle for this feature and in later iOS revisions Apple provided users with the option to tap on the location services indicator in Control Center to see which specific service is using the device's location.[233][234]

According to published reports by Bloomberg News on March 30, 2022, Apple turned over data such as phone numbers, physical addresses, and IP addresses to hackers posing as law enforcement officials using forged documents. The law enforcement requests sometimes included forged signatures of real or fictional officials. When asked about the allegations, an Apple representative referred the reporter to a section of the company policy for law enforcement guidelines, which stated, "We review every data request for legal sufficiency and use advanced systems and processes to validate law enforcement requests and detect abuse."[235]

Corporate affairs

Business trends

The key trends for Apple are, as of each financial year ending September 24:[236][237]

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue figures | |||||||||||||

| Total revenue[a] (US$ b) | 108 | 156 | 170 | 182 | 233 | 215 | 229 | 265 | 260 | 274 | 365 | 394 | 383 |

| - iPhone revenue (US$ b) | 45.9 | 78.6 | 91.2 | 101 | 155 | 136 | 139 | 164 | 142 | 137 | 191 | 205 | 200 |

| - Mac revenue (US$ b) | 21.7 | 23.2 | 21.4 | 24.0 | 25.4 | 22.8 | 25.5 | 25.1 | 25.7 | 28.6 | 35.1 | 40.1 | 29.3 |

| - iPad revenue (US$ b) | 19.1 | 30.9 | 31.9 | 30.2 | 23.2 | 20.6 | 18.8 | 18.3 | 21.2 | 23.7 | 31.8 | 29.2 | 28.3 |

| - Wearables, Home, and Accessories revenue (US$ b) | 11.9 | 10.7 | 10.1 | 8.3 | 10.0 | 11.1 | 12.8 | 17.3 | 24.4 | 30.6 | 38.3 | 41.2 | 39.8 |

| - Services revenue (US$ b) | 9.3 | 12.8 | 16.0 | 18.0 | 19.9 | 24.3 | 32.7 | 39.7 | 46.2 | 53.7 | 68.4 | 78.1 | 85.2 |

| Non-revenue figures | |||||||||||||

| Net profit[b] (US$ b) | 25.9 | 41.7 | 37.0 | 39.5 | 53.3 | 45.6 | 48.3 | 59.3 | 55.2 | 57.4 | 94.6 | 99.8 | 96.9 |

| Number of employees (k, FTE) | 60.4 | 72.8 | 80.3 | 92.6 | 110 | 116 | 123 | 132 | 137 | 147 | 154 | 164 | 161 |

| References | [238] | [239] | [240] | [241] | [242] | [243] | [244] | [245] | [246] | [247] | [248] | [249] | [250] |

Leadership

Senior management

As of March 16, 2021[update], the management of Apple Inc. includes:[251]

- Tim Cook (chief executive officer)

- Jeff Williams (chief operating officer)

- Luca Maestri (senior vice president and chief financial officer)

- Katherine L. Adams (senior vice president and general counsel)

- Eddy Cue (senior vice president – Internet Software and Services)

- Craig Federighi (senior vice president – Software Engineering)

- John Giannandrea (senior vice president – Machine Learning and AI Strategy)

- Deirdre O'Brien (senior vice president – Retail + People)

- John Ternus (senior vice president – Hardware Engineering)

- Greg Josiwak (senior vice president – Worldwide Marketing)

- Johny Srouji (senior vice president – Hardware Technologies)

- Sabih Khan (senior vice president – Operations)

Board of directors

As of January 20, 2023[update], the board of directors of Apple Inc. includes:[251]

- Arthur D. Levinson (chairman)

- Tim Cook (executive director and CEO)

- James A. Bell

- Al Gore

- Alex Gorsky

- Andrea Jung

- Monica Lozano

- Ronald Sugar

- Susan Wagner

Previous CEOs

- Michael Scott (1977–1981)

- Mike Markkula (1981–1983)

- John Sculley (1983–1993)

- Michael Spindler (1993–1996)

- Gil Amelio (1996–1997)

- Steve Jobs (1997–2011)

Ownership

As of December 30, 2023[update], the largest shareholders of Apple were:[252]

- The Vanguard Group (1,317,966,471 shares, 8.54%)

- BlackRock (1,042,391,808 shares, 6.75%)

- Berkshire Hathaway (905,560,000 shares, 5.86%)

- State Street Corporation (586,052,057 shares, 3.80%)

- Geode Capital Management (300,822,623 shares, 1.95%)

- Fidelity Investments (299,871,352 shares, 1.94%)

- Morgan Stanley (217,961,227 shares, 1.41%)

- T. Rowe Price (210,827,097 shares, 1.37%)

- Norges Bank (176,141,203 shares, 1.14%)

- Northern Trust (162,115,200 shares, 1.05%)

Corporate culture

Apple is one of several highly successful companies founded in the 1970s that bucked the traditional notions of corporate culture. Jobs often walked around the office barefoot even after Apple became a Fortune 500 company. By the time of the "1984" television advertisement, Apple's informal culture had become a key trait that differentiated it from its competitors.[253] According to a 2011 report in Fortune, this has resulted in a corporate culture more akin to a startup rather than a multinational corporation.[254] In a 2017 interview, Wozniak credited watching Star Trek and attending Star Trek conventions in his youth as inspiration for co-founding Apple.[255]

As the company has grown and been led by a series of differently opinionated chief executives, it has arguably lost some of its original character. Nonetheless, it has maintained a reputation for fostering individuality and excellence that reliably attracts talented workers, particularly after Jobs returned. Numerous Apple employees have stated that projects without Jobs's involvement often took longer than others.[256]

The Apple Fellows program awards employees for extraordinary technical or leadership contributions to personal computing. Recipients include Bill Atkinson,[257] Steve Capps,[258] Rod Holt,[257] Alan Kay,[259][260] Guy Kawasaki,[259][261] Al Alcorn,[262] Don Norman,[259] Rich Page,[257] Steve Wozniak,[257] and Phil Schiller.[263]

At Apple, employees are intended to be specialists who are not exposed to functions outside their area of expertise.[needs update] Jobs saw this as a means of having "best-in-class" employees in every role. For instance, Ron Johnson—Senior Vice President of Retail Operations until November 1, 2011—was responsible for site selection, in-store service, and store layout, yet had no control of the inventory in his stores. This was done by Tim Cook, who had a background in supply-chain management.[264] Apple is known for strictly enforcing accountability. Each project has a "directly responsible individual" or "DRI" in Apple jargon.[254][265] As an example, when iOS senior vice president Scott Forstall refused to sign Apple's official apology for numerous errors in the redesigned Maps app, he was forced to resign.[266] Unlike other major U.S. companies, Apple provides a relatively simple compensation policy for executives that does not include perks enjoyed by other CEOs like country club fees or private use of company aircraft. The company typically grants stock options to executives every other year.[267]

In 2015, Apple had 110,000 full-time employees. This increased to 116,000 full-time employees the next year, a notable hiring decrease, largely due to its first revenue decline. Apple does not specify how many of its employees work in retail, though its 2014 SEC filing put the number at approximately half of its employee base.[268] In September 2017, Apple announced that it had over 123,000 full-time employees.[269]

Apple has a strong culture of corporate secrecy, and has an anti-leak Global Security team that recruits from the National Security Agency, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the United States Secret Service.[270]

In December 2017, Glassdoor said Apple was the 48th best place to work, having originally entered at rank 19 in 2009, peaking at rank 10 in 2012, and falling down the ranks in subsequent years.[271]

In 2023, Bloomberg's Mark Gurman revealed the existence of Apple's Exploratory Design Group (XDG), which was working to add glucose monitoring to the Apple Watch. Gurman compared XDG to Alphabet's X "moonshot factory".[272]

Offices

Apple Inc.'s world corporate headquarters are located in Cupertino, in the middle of California's Silicon Valley, at Apple Park, a massive circular groundscraper building with a circumference of one mile (1.6 km). The building opened in April 2017 and houses more than 12,000 employees. Apple co-founder Steve Jobs wanted Apple Park to look less like a business park and more like a nature refuge, and personally appeared before the Cupertino City Council in June 2011 to make the proposal, in his final public appearance before his death.

Apple also operates from the Apple Campus (also known by its address, 1 Infinite Loop), a grouping of six buildings in Cupertino that total 850,000 square feet (79,000 m2) located about 1 mile (1.6 km) to the west of Apple Park.[273] The Apple Campus was the company's headquarters from its opening in 1993, until the opening of Apple Park in 2017. The buildings, located at 1–6 Infinite Loop, are arranged in a circular pattern around a central green space, in a design that has been compared to that of a university.

In addition to Apple Park and the Apple Campus, Apple occupies an additional thirty office buildings scattered throughout the city of Cupertino, including three buildings as prior headquarters: Stephens Creek Three from 1977 to 1978, Bandley One from 1978 to 1982, and Mariani One from 1982 to 1993.[274] In total, Apple occupies almost 40% of the available office space in the city.[275]

Apple's headquarters for Europe, the Middle East and Africa (EMEA) are located in Cork in the south of Ireland, called the Hollyhill campus.[276] The facility, which opened in 1980, houses 5,500 people and was Apple's first location outside of the United States.[277] Apple's international sales and distribution arms operate out of the campus in Cork.[278]

Apple has two campuses near Austin, Texas: a 216,000-square-foot (20,100 m2) campus opened in 2014 houses 500 engineers who work on Apple silicon[279] and a 1.1-million-square-foot (100,000 m2) campus opened in 2021 where 6,000 people work in technical support, supply chain management, online store curation, and Apple Maps data management.

The company also has several other locations in Boulder, Colorado; Culver City, California; Herzliya (Israel), London, New York, Pittsburgh, San Diego, and Seattle that each employ hundreds of people.[280]

Litigation

Apple has been a participant in various legal proceedings and claims since it began operation.[281] In particular, Apple is known for and promotes itself as actively and aggressively enforcing its intellectual property interests. Some litigation examples include Apple v. Samsung, Apple v. Microsoft, Motorola Mobility v. Apple Inc., and Apple Corps v. Apple Computer. Apple has also had to defend itself against charges on numerous occasions of violating intellectual property rights. Most have been dismissed in the courts as shell companies known as patent trolls, with no evidence of actual use of patents in question.[282] On December 21, 2016, Nokia announced that in the U.S. and Germany, it has filed a suit against Apple, claiming that the latter's products infringe on Nokia's patents.[283] Most recently, in November 2017, the United States International Trade Commission announced an investigation into allegations of patent infringement in regards to Apple's remote desktop technology; Aqua Connect, a company that builds remote desktop software, has claimed that Apple infringed on two of its patents.[284] In January 2022, Ericsson sued Apple over payment of royalty of 5G technology.[285]

On June 24, 2024, the European Commission accused Apple of violating the Digital Markets Act by preventing "app developers from freely steering consumers to alternative channels for offers and content".[286]

Finances

Apple is the world's largest technology company by revenue, the world's largest technology company by total assets,[287] and the world's second-largest mobile phone manufacturer after Samsung.[288]

In its fiscal year ending in September 2011, Apple Inc. reported a total of $108 billion in annual revenues—a significant increase from its 2010 revenues of $65 billion—and nearly $82 billion in cash reserves.[289] On March 19, 2012, Apple announced plans for a $2.65-per-share dividend beginning in fourth quarter of 2012, per approval by their board of directors.[290]

The company's worldwide annual revenue in 2013 totaled $170 billion.[291] In May 2013, Apple entered the top ten of the Fortune 500 list of companies for the first time, rising 11 places above its 2012 ranking to take the sixth position.[292] As of 2016[update], Apple has around US$234 billion of cash and marketable securities, of which 90% is located outside the United States for tax purposes.[293]

Apple amassed 65% of all profits made by the eight largest worldwide smartphone manufacturers in quarter one of 2014, according to a report by Canaccord Genuity. In the first quarter of 2015, the company garnered 92% of all earnings.[294]

On April 30, 2017, The Wall Street Journal reported that Apple had cash reserves of $250 billion,[295] officially confirmed by Apple as specifically $256.8 billion a few days later.[296]

As of August 3, 2018[update], Apple was the largest publicly traded corporation in the world by market capitalization. On August 2, 2018, Apple became the first publicly traded U.S. company to reach a $1 trillion market value.[297][298] Apple was ranked No. 4 on the 2018 Fortune 500 rankings of the largest United States corporations by total revenue.[299]

In July 2022, Apple reported an 11% decline in Q3 profits compared to 2021. Its revenue in the same period rose 2% year-on-year to $83 billion, though this figure was also lower than in 2021, where the increase was at 36%. The general downturn is reportedly caused by the slowing global economy and supply chain disruptions in China.[300]

In 2022, Apple was one of the largest corporate spenders on research and development worldwide, with R&D expenditure amounting to $27 billion.[301]

In May 2023, Apple reported a decline in its sales for the first quarter of 2023. Compared to that of 2022, revenue for 2023 fell by 3%. This is Apple's second consecutive quarter of sales decline. This fall is attributed to the slowing economy and consumers putting off purchases of iPads and computers due to increased pricing. However, iPhone sales held up with a year-on-year increase of 1.5%. According to Apple, demands for such devices were strong, particularly in Latin America and South Asia.[302]

Taxes

Apple has created subsidiaries in low-tax places such as Ireland, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and the British Virgin Islands to cut the taxes it pays around the world. According to The New York Times, in the 1980s Apple was among the first tech companies to designate overseas salespeople in high-tax countries in a manner that allowed the company to sell on behalf of low-tax subsidiaries on other continents, sidestepping income taxes. In the late 1980s, Apple was a pioneer of an accounting technique known as the "Double Irish with a Dutch sandwich", which reduces taxes by routing profits through Irish subsidiaries and the Netherlands and then to the Caribbean.[303][304]

British Conservative Party Member of Parliament Charlie Elphicke published research on October 30, 2012,[305] which showed that some multinational companies, including Apple Inc., were making billions of pounds of profit in the UK, but were paying an effective tax rate to the UK Treasury of only 3 percent, well below standard corporate tax rates. He followed this research by calling on the Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne to force these multinationals, which also included Google and The Coca-Cola Company, to state the effective rate of tax they pay on their UK revenues. Elphicke also said that government contracts should be withheld from multinationals who do not pay their fair share of UK tax.[306]

According to a US Senate report on the company's offshore tax structure concluded in May 2013, Apple has held billions of dollars in profits in Irish subsidiaries to pay little or no taxes to any government by using an unusual global tax structure.[307] The main subsidiary, a holding company that includes Apple's retail stores throughout Europe, has not paid any corporate income tax in the last five years. "Apple has exploited a difference between Irish and U.S. tax residency rules", the report said.[308]

On May 21, 2013, Apple CEO Tim Cook defended his company's tax tactics at a Senate hearing.[309]

Apple says that it is the single largest taxpayer in the U.S., with an effective tax rate of approximately of 26% as of Q2 FY2016.[310] In an interview with the German newspaper FAZ in October 2017, Tim Cook stated that Apple was the biggest taxpayer worldwide.[311]

In 2016, after a two-year investigation, the European Commission claimed that Apple's use of a hybrid Double Irish tax arrangement constituted "illegal state aid" from Ireland, and ordered Apple to pay 13 billion euros ($14.5 billion) in unpaid taxes, the largest corporate tax fine in history. This was later annulled, after the European General Court ruled that the commission had provided insufficient evidence.[312][313] In 2018, Apple repatriated $285 billion to America, resulting in a $38 billion tax payment spread over the following eight years.[314]

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 | 30 | 25 | 26 | 28 | 26 | 29 | 30 | 30 | 31.8 | 24.4 | 24.2 | 25.2 | 26.2 | 26.1 | 26.4 | 25.6 | 24.6 | 18.3 | 15.9 |

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | ||||||||||||||||

| 14.4 | 13.3 | 16.2 | 14.7 | ||||||||||||||||

Charity

Apple is a partner of Product Red, a fundraising campaign for AIDS charity. In November 2014, Apple arranged for all App Store revenue in a two-week period to go to the fundraiser,[315] generating more than US$20 million,[316] and in March 2017, it released an iPhone 7 with a red color finish.[317]

Apple contributes financially to fundraisers in times of natural disasters. In November 2012, it donated $2.5 million to the American Red Cross to aid relief efforts after Hurricane Sandy,[318] and in 2017 it donated $5 million to relief efforts for both Hurricane Irma and Hurricane Harvey,[319] and for the 2017 Central Mexico earthquake.[320] The company has used its iTunes platform to encourage donations in the wake of environmental disasters and humanitarian crises, such as the 2010 Haiti earthquake,[321] the 2011 Japan earthquake,[322] Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines in November 2013,[323] and the 2015 European migrant crisis.[324] Apple emphasizes that it does not incur any processing or other fees for iTunes donations, sending 100% of the payments directly to relief efforts, though it also acknowledges that the Red Cross does not receive any personal information on the users donating and that the payments may not be tax deductible.[325]

On April 14, 2016, Apple and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) announced that they have engaged in a partnership to, "help protect life on our planet." Apple released a special page in the iTunes App Store, Apps for Earth. In the arrangement, Apple has committed that through April 24, WWF will receive 100% of the proceeds from the applications participating in the App Store via both the purchases of any paid apps and the In-App Purchases. Apple and WWF's Apps for Earth campaign raised more than $8 million in total proceeds to support WWF's conservation work. WWF announced the results at WWDC 2016 in San Francisco.[326]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Apple's CEO Cook announced that the company will be donating "millions" of masks to health workers in the United States and Europe.[327]

On January 13, 2021, Apple announced a $100 million Racial Equity and Justice Initiative to help combat institutional racism worldwide after the 2020 murder of George Floyd.[328][329][330] In June 2023, Apple announced doubling this and then distributed more than $200 million to support organizations focused on education, economic growth, and criminal justice. Half is philanthropic grants and half is centered on equity.[328]

Environment

This section should include a better summary of, or be better summarized in Environmental impact of Apple. (January 2023) |

Apple Energy

Apple Energy, LLC is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Apple Inc. that sells solar energy. As of June 6, 2016[update], Apple's solar farms in California and Nevada have been declared to provide 217.9 megawatts of solar generation capacity.[331] Apple has received regulatory approval to construct a landfill gas energy plant in North Carolina to use the methane emissions to generate electricity.[332] Apple's North Carolina data center is already powered entirely by renewable sources.[333]

Energy and resources

In 2010, Climate Counts, a nonprofit organization dedicated to directing consumers toward the greenest companies, gave Apple a score of 52 points out of a possible 100, which puts Apple in their top category "Striding".[334] This was an increase from May 2008, when Climate Counts only gave Apple 11 points out of 100, which placed the company last among electronics companies, at which time Climate Counts also labeled Apple with a "stuck icon", adding that Apple at the time was "a choice to avoid for the climate-conscious consumer".[335]

Following a Greenpeace protest, Apple released a statement on April 17, 2012, committing to ending its use of coal and shifting to 100% renewable clean energy.[336][337] By 2013, Apple was using 100% renewable energy to power their data centers. Overall, 75% of the company's power came from clean renewable sources.[338]

In May 2015, Greenpeace evaluated the state of the Green Internet and commended Apple on their environmental practices saying, "Apple's commitment to renewable energy has helped set a new bar for the industry, illustrating in very concrete terms that a 100% renewable Internet is within its reach, and providing several models of intervention for other companies that want to build a sustainable Internet."[339]

As of 2016[update], Apple states that 100% of its U.S. operations run on renewable energy, 100% of Apple's data centers run on renewable energy and 93% of Apple's global operations run on renewable energy.[340] However, the facilities are connected to the local grid which usually contains a mix of fossil and renewable sources, so Apple carbon offsets its electricity use.[341] The Electronic Product Environmental Assessment Tool (EPEAT) allows consumers to see the effect a product has on the environment. Each product receives a Gold, Silver, or Bronze rank depending on its efficiency and sustainability. Every Apple tablet, notebook, desktop computer, and display that EPEAT ranks achieves a Gold rating, the highest possible. Although Apple's data centers recycle water 35 times,[342] the increased activity in retail, corporate and data centers also increase the amount of water use to 573 million US gal (2.2 million m3) in 2015.[343]

During an event on March 21, 2016, Apple provided a status update on its environmental initiative to be 100% renewable in all of its worldwide operations. Lisa P. Jackson, Apple's vice president of Environment, Policy and Social Initiatives who reports directly to CEO, Tim Cook, announced that as of March 2016[update], 93% of Apple's worldwide operations are powered with renewable energy. Also featured was the company's efforts to use sustainable paper in their product packaging; 99% of all paper used by Apple in the product packaging comes from post-consumer recycled paper or sustainably managed forests, as the company continues its move to all paper packaging for all of its products.[344] Apple working in partnership with The Conservation Fund, have preserved 36,000 acres of working forests in Maine and North Carolina. Another partnership announced is with the World Wildlife Fund to preserve up to 1,000,000 acres (4,000 km2) of forests in China. Featured was the company's installation of a 40 MW solar power plant in the Sichuan province of China that was tailor-made to coexist with the indigenous yaks that eat hay produced on the land, by raising the panels to be several feet off of the ground so the yaks and their feed would be unharmed grazing beneath the array. This installation alone compensates for more than all of the energy used in Apple's Stores and Offices in the whole of China, negating the company's energy carbon footprint in the country. In Singapore, Apple has worked with the Singaporean government to cover the rooftops of 800 buildings in the city-state with solar panels allowing Apple's Singapore operations to be run on 100% renewable energy. Liam was introduced to the world, an advanced robotic disassembler and sorter designed by Apple Engineers in California specifically for recycling outdated or broken iPhones. Reuses and recycles parts from traded in products.[345]

Apple announced on August 16, 2016, that Lens Technology, one of its major suppliers in China, has committed to power all its glass production for Apple with 100 percent renewable energy by 2018. The commitment is a large step in Apple's efforts to help manufacturers lower their carbon footprint in China.[346] Apple also announced that all 14 of its final assembly sites in China are now compliant with UL's Zero Waste to Landfill validation. The standard, which started in January 2015, certifies that all manufacturing waste is reused, recycled, composted, or converted into energy (when necessary). Since the program began, nearly 140,000 metric tons of waste have been diverted from landfills.[347]

On July 21, 2020, Apple announced its plan to become carbon neutral across its entire business, manufacturing supply chain, and product life cycle by 2030. In the next 10 years, Apple will try to lower emissions with a series of innovative actions, including: low carbon product design, expanding energy efficiency, renewable energy, process and material innovations, and carbon removal.[348]

In April 2021, Apple said that it had started a $200 million fund in order to combat climate change by removing 1 million metric tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere each year.[349]

In February 2022, the NewClimate Institute, a German environmental policy think tank, published a survey evaluating the transparency and progress of the climate strategies and carbon neutrality pledges announced by 25 major companies in the United States that found that Apple's carbon neutrality pledge and climate strategy was unsubstantiated and misleading.[350][351]

In Russia, in 2022, the company's revenue amounted to 85 billion rubles.[7]