Сваминараян Сампрадая

Сваминараян , основатель Сваминараян-сампрадаи | |

| Общая численность населения | |

|---|---|

| 5,000,000 [1] | |

| Основатель | |

| Сваминараян | |

| Регионы со значительной численностью населения | |

| Гуджарат | |

| Религии | |

| индуизм | |

| Священные Писания | |

| Языки | |

| Часть серии о |

| Вайшнавизм |

|---|

|

| Часть серии о | |

| Индуистская философия | |

|---|---|

| |

| православный | |

| неортодоксальный | |

Сваминараян -сампрадая , также известная как сваминараянский индуизм и сваминараянское движение , — это индуистская вайшнавская сампрадая, уходящая корнями в Рамануджи » «Вишиштадвайту . [примечание 1] [примечание 2] характеризуется поклонением своему харизматическому [3] основатель Сахаджананд Свами, более известный как Сваминараян (1781–1830), как аватар Кришны . [4] [5] [6] или как высшее проявление Пурушоттама . , верховного Бога [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] Согласно преданию, и религиозная группа, и Сахаджананд Свами стали известны как Сваминараян в честь Сваминараянской мантры, которая представляет собой соединение двух санскритских слов, свами («господин, господин»). [Интернет 1] [Интернет 2] ) и Нараян (верховный Бог, Вишну). [10] [примечание 3]

В течение своей жизни Сваминараян институционализировал свою харизму и убеждения. различными способами [3] Он построил шесть мандиров, чтобы облегчить последователям преданное поклонение Богу. [11] [12] [13] и поощрял создание библейской традиции . [14] [15] [3] В 1826 году в юридическом документе под названием Лех Сваминараян создал две епархии: Лакшми Нараян Дев Гади (Вадтал Гади) и Нар Нараян Дев Гади (Ахмадабад Гади) с наследственным руководством ачарьев и их жен. [Интернет 3] которым было разрешено устанавливать в храмах статуи божеств и посвящать аскетов. [3]

Сваминараяна В сотериологии конечная цель жизни — стать Брахмарупой . [16] достижение формы ( рупа ) Акшарбрахмана , в которой джива освобождается от майи . и самсары (цикла рождений и смертей) и наслаждается вечным блаженством, предлагая садхья-бхакти , постоянную и чистую преданность Богу [16] [17]

Будучи укорененным в «Вишиштадвайте» Рамануджи, [примечание 1] к которому он заявил о своей близости, [примечание 4] и включение религиозных элементов Валлабхи Пуштимарга , [18] [19] [примечание 5] Сахаджананд Сваминараян дал свою собственную интерпретацию классических индуистских текстов. [примечание 1] Как и в Вишиштадвайте, Бог и джива всегда различны, но также проводится различие между Парабрахманом ( Пурушоттам , Нараяна ) и Акшарбрахманом как двумя отдельными вечными реальностями. [20] [Интернет 4] Это различие подчеркивается БАПС -свами как определяющая характеристика. [20] [21] [22] и называется Акшар-Пурушоттам Даршаном, чтобы отличить Сваминараян Даршана , взгляды или учения Сваминараяна, от других традиций Веданты. [Интернет 5] [20] [22]

В ХХ веке из-за «разных интерпретаций подлинного преемства» [23] различные конфессии отделились от епархий. [24] Все группы считают Сваминараяна Богом, но различаются по своей теологии и религиозному руководству, которое они принимают. [10] [21] [25] [26] [10] [27] BAPS , , отделившаяся в 1907 году от Вадтала Гади, почитает «линию акшарагуру или живых гуру, [которая] задним числом восходит к Гунатитананду Свами ». [24]

В социальном плане Сваминараян принял дискриминацию по кастовому признаку внутри религиозного сообщества, но вдохновил последователей участвовать в гуманитарной деятельности, что привело к тому, что различные конфессии Сваминараян-сампрадаи в настоящее время оказывают гуманитарную помощь по всему миру.

Ранняя история

Происхождение

Сваминараян-сампрадая развилась из сампрадаи Рамананда Свами Уддхав- . [28] [29] [Интернет 6] Учитель Гуджарата из шри-вайшнавизма основанный на Рамануджи Вишиштадвайте , . [30] Он получил свое название от преемника Рамананда Сахаджананда Свами. [9] [8] кто был харизматичным лидером [31] и получил известность как Сваминараян. [9] [8] Различные ветви традиции Сваминараяна связывают свое происхождение с Сахаджанандом Свами. [24] но точное «современное историческое описание» его жизни невозможно восстановить, учитывая агиографический характер рассказов, сохранившихся среди его последователей. [24] [32]

Сахаджананд Свами

Сахаджананд Свами родился 3 апреля 1781 года в деревне Чхапайя в современном Уттар-Прадеше, Индия , и получил имя Гансьям. [9] [33] [34] После смерти родителей он покинул свой дом в возрасте 11 лет и в качестве ребенка- йога путешествовал по Индии в течение 7 лет , взяв имя Нилкантх, прежде чем поселиться в обители Рамананда Свами, религиозного лидера вайшнавов в современном Гуджарате. . [9] [35] [36] Рамананд Свами инициировал его как вайшнавского аскета 28 октября 1800 года, дав ему имя Сахаджананд Свами. [24] [28] Согласно традиции Сваминараяна, Рамананд назначил Сахаджананда своим преемником и лидером сампрадаи в 1801 году, незадолго до своей смерти. [37] [36] [38]

Рамананд Свами умер 17 декабря 1801 года. [39] и Сахаджананд Свами стал новым лидером остатков Уддхав Сампрадея, несмотря на «значительную оппозицию». [37] [Интернет 6] Несколько членов покинули группу или были изгнаны Сахаджанандом Свами, а одна группа основала новую группу вместе с одним из четырех храмов Рамананда. [28] Хотя иконография Кришны в первоначальных храмах, а также Вачанамритам и Шикшапатри отражают веру в Кришну как Пурушоттама, [24] еще в 1804 году самого Сахаджананда Свами описывали как проявление Бога, [28] и на протяжении всей его жизни тысячи последователей будут поклоняться ему как Богу. [40] [41] Тем не менее, по словам Кима, в первоначальной сампрадае Сахаджананд Свами «не обязательно» считается Пурушоттамом. [6] [примечание 6]

Со временем и лидер, и группа стали известны под именем «Сваминараян». [8] Согласно «повествованию о сваминараянском происхождении», [24] вскоре после своего преемства Сахаджананд Свами приказал преданным повторять новую мантру «Сваминараян» ( Сваминараяна ), [28] [10] соединение двух санскритских слов: Свами ( Свами ) и Нараян ( Нараяна ), [10] то есть Вишну как Пурушоттам . [10] Согласно традиции Сваминараяна, Нараяна также было вторым именем, данным Нахараджанду, когда он был посвящен в аскеты. [24] [28] [примечание 3]

Рост и противостояние

Сампрадая быстро росла за 30 лет под руководством Сваминараяна, и, по оценкам британских источников, к 1820-м годам в ней насчитывалось не менее 100 000 последователей. [46] [9] [36] Он был харизматической личностью, [3] и в ранний период движения Сваминараян последователи часто погружались в состояние визионерского транса, интерпретируемое как самадхи , либо путем прямого контакта со Сваминараяном, либо путем пения сваминараянской мантры, в которой у них были видения своего «избранного божества» ( истадевата ). . [47] [48] [49] Сваминараяна критиковали за то, что он получил большие подарки от своих последователей после того, как отрекся от мира и принял на себя руководство сообществом. [50] Сваминараян ответил, что он принимает подарки, потому что «человеку было уместно дарить» и чтобы удовлетворить преданность своих последователей, но он не ищет их из личного желания. [51]

В первые пятнадцать лет его руководства, до прибытия британских колонизаторов в Гуджарат, министерство Сваминараяна «сталкивалось с сильным сопротивлением». [52] Сообщается о ряде покушений на его жизнь, «как со стороны религиозных, так и светских властей». [52] Сваминараян принимал людей всех каст, подрывая кастовую дискриминацию, которая приводит к критике и противодействию со стороны индуистов из высших каст. [53] Хотя этические реформы Сахаджананда рассматривались как протест против аморальных практик пуштимаргов, [54] На самом деле Сахаджананд находился под влиянием Валлабхи и других вайшнавских традиций и положительно относился к ним. [55] и он включил элементы Пуштимарга Валлабхи , [18] [55] популярный в Гуджарате, [ нужна ссылка ] чтобы получить признание. [18] [примечание 5] Его реформы, возможно, были в первую очередь направлены против тантриков и против практик, «связанных с деревенскими и племенными божествами». [55]

По словам Дэвида Хардимана, низшие классы были привлечены в сообщество Сваминараяна, потому что они стремились к такому же успеху и коммерческой идеологии. Он вырос, утверждает Хардиман, в эпоху британского колониального правления, когда налоги на землю были подняты до беспрецедентных высот, земли «отобрались у деревенских общин» и распространилась бедность. [56] По словам Хардимана, пацифистский подход Сахаджананда к реорганизации общества и работе с низшими классами своего времени нашел поддержку британских правителей, но также способствовал их эксплуатации со стороны британцев, местных ростовщиков и более богатых фермеров. [56]

За время своего руководства Сваминараян рукоположил 3000 свами. [10] [9] с 500 из них в высшую степень аскетизма как парамахансы , что позволяет им приостановить все отличительные практики, такие как нанесение священных знаков. [52] [57] [примечание 7] Сваминараян призывал своих свами служить другим. Например, во время опустошительного голода 1813–1814 годов в Катхиаваре свами собирали милостыню в незатронутых регионах Гуджарата, чтобы раздать ее пострадавшим. [58] [59] Как учителя и проповедники, они сыграли важную роль в распространении учения Сваминараяна по всему Гуджарату, что способствовало быстрому росту сампрадаи. [59] [24] и они создали «священную литературу» сампрадаи, написание комментариев к Священным Писаниям и сочинение стихов о бхакти . [59] [60] [61] [62]

Храмы

К концу своей жизни Сваминараян узаконил свою харизму различными способами: строительством храмов для облегчения поклонения; написание священных текстов; и создание религиозной организации для посвящения в аскезу. [3] Он основал традицию мандира в сампрадае, чтобы предоставить последователям место для преданного поклонения (упасана, упасана ) Богу. [11] [12] Он построил шесть мандиров в следующих местах, в которых разместились изображения Кришны. [63] которые его последователи считают изображениями Сваминараяна: [63]

- Храм Сваминараян, Ахмадабад, посвященный Нару Нараяну (1822 г.)

- Сваминараян Мандир, Бхудж, посвященный Нар Нараяну (1823 г.)

- Сваминараян Мандир, Вадтал, посвященный Радхе Кришне и Лакшми Нараяну (1824 г.)

- Шри Сваминараян Мандир, Дхолера, посвященный Радхе Мадан Мохану (1826 г.)

- Шри Сваминараян Мандир, Джунагад, посвященный Ранчходраю и Радхе Рамандеву (1827 г.)

- Сваминараян Мандир, Гадхада, посвященный Радхе Гопинатху (1828 г.). [64]

Сваминараян установил в храмах мурти различных проявлений Кришны. Например, идол Вишну был установлен вместе с его супругой Лакшми , а идол Кришны был установлен с его супругой Радхой , чтобы подчеркнуть представление Бога и его идеального преданного в центральных святынях каждого из этих храмов. [65] Он также установил свое изображение в образе Харикришны в боковом святилище мандира в Вадтале. [63] [66] [67] [68] БАПС положил начало традиции установки мурти Бога (Сваминараяна) и его идеального преданного, чтобы облегчить его последователям стремление к мокше. [69]

Вадтал Гади и Ахмедабад Гади

В первые годы существования сампрадаи Сваминараян лично руководил духовными и административными обязанностями. [70] Позже Сваминараян делегировал обязанности свами, домохозяевам и членам своей семьи. [70] Перед своей смертью Сваминараян основал две епархии: Лакшми Нараян Дев Гади (Вадтал Гади) и Нар Нараян Дев Гади (Ахмадабад Гади), как записано в Лехе , [71] [24] [72] [10] на основе мандиров Вадталь и Ахмедабад соответственно.

Ачарьи

21 ноября 1825 года он назначил двух своих племянников ачарьями для управления двумя гади, или епархиями, усыновив их как своих собственных сыновей и установив наследственную линию преемственности. [10] Эти ачарьи происходили из его ближайших родственников после того, как они отправили своих представителей разыскивать их в Уттар-Прадеше . [73] Им было разрешено «управлять имуществом его храма». [10] которые распределены между ними. [71] [72] Айодхьяпрасадджи, сын его старшего брата Рампратапа, стал ачарьей Нар Нараян Дев Гади (Ахмедабадская епархия), а Рагхувирджи, сын его младшего брата Иччарама, стал ачарьей Лакшми Нараян Дев Гади (епархия Вадталь). [74] [71] [примечание 8] Сиддхант Пакш считает, что Аджендрапрасад является нынешним ачарьей Вадтала Гади. [ нужна ссылка ] Благодаря посвящению Сваминараяна в Уддхав-сампрадаю, ветви Вадтал и Ахмадабад возводят власть своих ачарьев к гуру-парампаре Рамануджи. [80]

Смерть Сваминараяна

Сваминараян умер 1 июня 1830 года, но сампрадая продолжала расти: к 1872 году британские официальные лица насчитали 287 687 последователей. [81] [82] К 2001 году число участников выросло примерно до 5 миллионов последователей. [1]

Расколы

На данный момент существуют следующие филиалы:

- Лакшми Нараян Дев Гади (Вадтал Гади) (1825 г., основан Сваминараяном)

- - Международный Сваминараян Сатсанг Мандал (ISSM)(дочернее отделение, США)

- - Лакшминараян Дев Ювак Мандал (LNDYM)(молодежное крыло)

- - Шри Сваминараян Агина Упасана Сатсанг Мандал (SSAUSM)(дочерняя ветвь, США)

- Бочасанваси Акшар Пурушоттам Сваминараян Санстха (BAPS) (отделение от Вадтала Гади в 1907 году, основанное Шастриджи Махараджем)

- Гунатит Самадж (Божественное общество йогов (YDS), отделившееся от BAPS в 1966 году. Несколько крыльев: YDS, Миссия Анупам и Гунатит Джйот.

- Сваминараян Гурукул (образовательное учреждение, основанное в 1947 году Дхармадживандасджи Свами с целью распространения садвидьи среди студентов по всему миру) [83]

- Нар Нараян Дев Гади (Ахмедабад Гади) (1825 г., основан Сваминараяном)

- - Международная организация Сваминараян Сатсанг (ISSO) (дочернее отделение, США)

- - ИССО Сева (2001, благотворительная организация)

- - Нарнараян Дев Ювак Мандал (NNDYM) (молодежная организация)

- Сваминараян Гади (Манинагар) (отколовшийся от Ахмедабада Гади в 1940-х годах)

- Сваминараян Мандир Васна Санстха (SMVS) (отделение от Сваминараян Гади в 1987 году)

- - Международная организация Сваминараян Сатсанг (ISSO) (дочернее отделение, США)

Различные интерпретации преемственности

В ХХ веке из-за «разных интерпретаций подлинного преемства» [23] от епархии отделились различные ветви, [84] крупнейшим из которых является БАПС . [24] Все группы считают Сваминараян проявлением Бога, но различаются по своей теологии и религиозному руководству, которое они принимают. [10] [25]

Вадтал Гади и Ахмадабад Гади являются первоначальными институтами с наследственным руководством в форме ачарьев. Наследование было установлено в Лехе , юридическом документе, автором которого является Сваминараян. [71] За ним следуют ветви Нар-Нараян (Ахмадабад) и Лакшми-Нараян (Вадтал), но «преуменьшают [редактируют] или игнорируют» другие ветви, которые «подчеркивают власть садху над ачарьей». [85] [примечание 9]

Уильямс отмечает, что «эта важная функция ачарьи как религиозного специалиста подчеркивается во всех сваминараянских писаниях, включая Деш Вибхаг Лекх . В стихе 62 «Шикшапатри»: «Мои последователи должны поклоняться только тем изображениям Господа, которые даны ачарьей или Установленный им в Вачанамрут Вадтал I-18.4 и в других писаниях Сваминараян указывает на важность Дхармакула (семьи Дхармадева, отца Сваминараяна) и заявляет, что те, кто знает его как свое божество и желает мокши, должны следовать только Сваминараян-сампрадаю. под руководством назначенных им ачарьев и их преемников.

Согласно ветви Вадтала, «Гопалананд Свами был главным учеником-аскетом Саджахананда», и «ачарьи имеют единоличное право инициировать садху и устанавливать изображения в храмах». [86] По данным BAPS, крупнейшего ответвления Сваминараи, Гунатитананд Свами был назначен преемником Саджахананда, и «главным аскетам были даны полномочия выполнять основные ритуалы группы, включая посвящение садху», и «эти полномочия не имели был отозван, когда были назначены ачарьи». [87] Кроме того, они утверждают, что те, кто живет строго добродетельной жизнью, достойны наследства. По словам Уильямса, «[т] он делает упор на духовную линию, а не на наследственную линию, и утверждает, что тот, кто соблюдает правила, должен быть ачарьей». [88]

Согласно BAPS , Сваминараян установил два режима преемственности: наследственный административный режим через Леха ; и духовный режим, установленный в Вачанамруте , в котором Сваминараян передал свои богословские доктрины. [89] Согласно BAPS, Сваминараян описал духовный способ преемственности, цель которого чисто сотериологическая : [89] отражая его принцип, согласно которому стремящимся достичь мокши (освобождения) необходима форма Бога, живущая «перед глазами». [90] Они почитают «линию акшарагуру , или живых гуру, [которая] задним числом восходит к Гунатитананду Свами ». [24] Согласно BAPS, Сваминараян назвал Гунатитананда Свами первым преемником в этой линии. [10] Для садху епархии Вадталь идея о том, что Сваминараян назначил Гунатитананда своим духовным преемником, была еретическим учением, и они «отказывались поклоняться тому, что считали человеком». [91]

Бочасанваси Акшар Пурушоттам Сваминараян Санстха

Бочасанваси Акшар Пурушоттам Сваминараян Санстха (БАПС) был основан в 1907 году Шастриджи Махараджем (Шастри Ягнапурушдасом) . [92] [93] Он отделился от епархии Вадталь и создал БАПС согласно своей интерпретации Акшара (Акшарбрахмы) и Пурушоттама. [92] [94] [95] Как сформулировано в BAPS-теологии Акшара-Пурушоттама Упасаны , [сайт 11] Приверженцы BAPS , вслед за Шастриджи Махараджем, полагают, что Сваминараян представил Гунатитананда Свами как своего идеального преданного, от которого началась духовная линия гуру. [96] [24] [10] отражая идею Шастриджи Махараджа о том, что форма Бога, который живет «перед глазами», которому следует поклоняться, необходима стремящимся для достижения мокши (освобождения). [90] [примечание 10]

Гунати Самадж

Божественное общество йогов (YDS) было основано в 1966 году Дадубхаем Пателем и его братом Бабубхаем после того, как Йогиджи Махарадж отлучил их от BAPS. Братья были исключены после того, как было обнаружено, что Дадубхай незаконно собирал и присваивал средства и, ложно утверждая, что он действовал от имени организации, побудил ряд молодых женщин отказаться от своих семей и присоединиться к его ашраму под его руководством. [97] После смерти Дадубхая в 1986 году аскет по имени Харипрасад Свами стал лидером Божественного общества йогов. Божественное общество йогов стало известно как Гунатит Самадж и состоит из нескольких крыльев: YDS, Миссии Анупам и Гунатит Джйот. [98]

Сваминараян Гади (Манинагар)

Сваминараян Гади (Манинагар) был основан в 1940-х годах Муктадживандасом Свами после того, как он покинул Ахмедабадскую епархию с верой, что Гопаланан Свами , парамханса времен Сваминараяна, был духовным преемником Сваминараяна. [99] Нынешний духовный лидер - Джитендраприядасджи Свами. Кроме того, Сваминараян Гади почитает Ниргундасджи Свами, Ишварчарандасджи Свами и Пурушоттамприю Свами. [100] [сайт 12] [сайт 13] [примечание 11]

Последователи Сваминараян Гади принимают «Рахасьартх Прадипика Тика», пятитомный труд, написанный Абджи Бапой , как подлинное толкование Вачанамрута . [101]

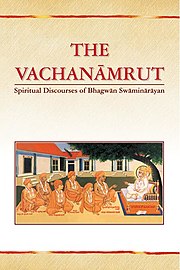

Верования и практики

Взгляды Сваминараяна можно найти в Вачанамруте ( Вачанамрита ), основном богословском тексте Сваминараян-сампрадаи. [102] Поскольку последователи считают Сваминараяна проявлением Парабрахмана или Пурушоттамы , его взгляды считаются прямым откровением Бога. [103] В «Вачанамруте» Сваминараян описывает, что конечной целью жизни является мокша ( мокша ), духовное состояние окончательного освобождения от цикла рождений и смертей, характеризующееся вечным блаженством и преданностью Богу. [104] [105]

Фон

Сваминаярана Сиддханта («воззрение», «доктрина») возникла в традиции Веданты, особенно в традиции вайшнавов, сформулированной Рамануджей, Мадхвой, Валлабхой и Чайтаньей. [106] [107] Интерпретация Сваминараяна классических индуистских текстов имеет сходство с «Вишистадвайтой» Рамануджи . [108] [107] [109] [24] [примечание 1] к которому он заявил о своей близости. [примечание 4] Он также включил элементы Валлабхи Пуштимарга , принадлежащего Шуддхадвайте , чтобы добиться признания. [18] [примечание 5] Тем не менее, между учениями Сваминараяна и Рамануджи существуют также метафизические и философские расхождения, в первую очередь различие между Пурушоттамом и Акшарбрахманом. [110] [19] [примечание 1] упоминается БАПС-свами как Акшар-Пурушоттам Даршан (философия) и используется для отделения учения Сваминараяна от других традиций Веданты. [111] Хотя Вадтал Мандир утверждает, что «Сваминараян пропагандировал философию под названием Вишистадвайта», [Интернет 6] ряд БАПС-свами утверждают, что учение Сваминараяна представляет собой отдельную систему в рамках традиции Веданты. [112] [22]

Сотериология - Брахмаруп

Сваминараяна В сотериологии конечная цель жизни — стать Брахмарупом . [16] обретение формы ( рупа ) Акшарбрахмана , [сайт 15] в котором джива освобождается от ( майи и самсары цикла рождений и смертей) и в котором джива предлагает садхья-бхакти , непрерывную и чистую преданность Богу. [16] [17] В то время как отождествление с Пурушоттамом невозможно, отождествление с Брахмарупой с Акшрабрахманом возможно и поощряется. [113] хотя джива или Ишвар остается отличным от Акшарбрахмана. [114] [115]

Чтобы стать Брахмарупом , человек должен преодолеть невежество майи, которое Сваминараян описывает как самоотождествление с физическим телом, личными талантами и материальным имуществом. [116] [примечание 12] Сваминараян объясняет в «Вачанамруте» , что экантик дхарма — это средство заслужить милость Бога и достичь освобождения. [117] [118] [119] [примечание 13] Экантик дхарма ( ekāntik dharma ) состоит из дхармы ( дхарма ; религиозные и моральные обязанности), гнан ( гьяна ; реализация атмана и Параматмана), вайрагья ( вайрагья ; бесстрастие к мирским объектам) и бхакти (признание Сваминараяна Пурушоттамом и преданность его в сочетании с пониманием величия Бога). [24] [120] [118] [119] [примечание 13]

Различные ветви Сваминараян-сампрадаи расходятся во взглядах на то, как достичь мокши. Нарнараянские и Лакшминараянские Гади верят, что мокша достигается путем поклонения священным изображениям Сваминараяна, установленным ачарьями. [121] При чтении BAPS Вачанамрута и других писаний [120] джива становится брахмарупом , или подобным Акшарбрахману, под руководством проявленной формы Бога. [122] [123] [124] [примечание 14] Сваминараян Гади (Манинагар) считает, что мокши можно достичь через линию гуру, начиная с Гопалананда Свами. [99]

уединенная религия

Экантик дхарма ( ekāntik dharma ) — важный элемент Сваминараян-сампрадаи, и его создание — одна из причин, по которой, как полагают, воплотился Сваминараян. [125] Экантик дхарма состоит из дхармы, гнан, вайрагьи и бхакти. [126] [118] [119] [примечание 15]

Дхарма

Дхарма состоит из религиозных и моральных обязанностей в соответствии с обязанностями и ситуацией. [127] Все сваминараянские индуисты, являющиеся домохозяевами, соблюдают пять основных обетов: воздержание от воровства, азартных игр, прелюбодеяния, мяса и одурманивающих веществ, таких как алкоголь. [128] [129] В рамках своей дхармы свами дополнительно стремятся совершенствовать пять добродетелей: отсутствие вожделения (нишкам/ нишкама ), отсутствие жадности (нирлобх/ нирлобха ), непривязанность (ниснех/ ниснеха ), отсутствие вкуса (нисвад/ нисвада ). и не-эго (нирман/ нирмана ). [130] [131] Другим аспектом практики дхармы является сваминараянская диета, разновидность вегетарианства, подобная той, которую обычно практикуют вайшнавские сампрадаи, которая предполагает воздержание от мяса животных, яиц, лука и чеснока. [128]

Гнан (джняна)

Гнан – это знание Парабрахмана и осознание себя как атмана. Основные практики гнан включают ежедневное изучение писаний, таких как Вачанамрут и Шикшапатри , и еженедельное участие в коллективных богослужениях (сабха/ сабха ) в мандире (храме), в которых происходят библейские беседы, направленные на личностный и духовный рост. [132] Согласно BAPS, в «Вачанамруте» Сваминараян объясняет, что следование командам Акшарбрахмана Гуру соизмеримо с совершенным воплощением гнана, то есть осознанием себя как атмана. [133] [примечание 16]

Вайрагья

Вайрагья – это бесстрастие к мирским объектам. Сваминараянские индуисты культивируют вайрагью с помощью таких практик, как пост в дни экадаши, два из которых происходят каждый месяц, и соблюдение дополнительных постов во время священных месяцев Чатурмас (четырехмесячный период с июля по октябрь). [134] Вайрагья реализуется путем соблюдения кодексов поведения, включая эти практики, физического служения другим преданным, слушания бесед и занятия преданностью. [135] [примечание 17]

Бхакти

Бхакти предполагает преданность Богу, понимание величия Бога и отождествление своего внутреннего ядра — атмана — с Акшарбрахманом. [136] [примечание 18] Приверженцы верят, что они могут достичь мокши , или свободы от цикла рождений и смертей, став акшаррупом (или брахмарупом), то есть достигнув качеств, подобных Акшару (или Акшарбрахману), и поклоняясь Пурушоттаму (или Парабрахману; высшему живому существу). ; Бог). [137] Важные ритуалы бхакти для сваминараянских индуистов включают пуджу ( пуджа ; личное поклонение Богу), арти ( арти ; ритуальное размахивание зажженными фитилями вокруг мурти или изображений), тхал ( тал ; подношение еды мурти Бога) и чешта. ( чешта ; пение религиозных песен, прославляющих божественные деяния и форму Сваминараяна). [138]

Во время пуджи приверженцы ритуально поклоняются Сваминараяну, а в БАПС и некоторых других конфессиях - также линии гуру Акшарбрахмана, через которую, как полагают, проявляется Сваминараян. [139] [140] [141] В начале ритуала пуджи мужчины наносят на лоб символ, известный как тилак чандло, а женщины — чандло. [142] Тилак, представляющий собой U-образный символ шафранового цвета, сделанный из сандалового дерева, символизирует стопы Бога. Чандло — красный символ, сделанный из кумкума, символизирующий Лакшми , богиню удачи и процветания. В совокупности эти двое символизируют Лакшми, живущую в самом сердце Сваминараяна. [142] [сайт 16]

Поклонение Сваминараяну является важным элементом религии Сваминараяна. В епархии Ахмадабад и Вадталь Сваминараян присутствует в своих изображениях и в своих священных писаниях. [143] Для БАПС Нараяна , который есть Пурушоттам, можно достичь только через контакт с Пурушоттамом в форме гуру, обители бога. [143] По мнению БАПС, общаясь с гуру Акшарбрахмана, которого также называют Сатпурушем, Экантик Бхактой или Экантик Сантом, и понимая его, духовные искатели могут преодолеть влияние майи и достичь духовного совершенства. [144]

Other bhakti rituals included in Swaminarayan religious practice are abhishek (abhiśeka), the bathing of a murti of God,[145] mahapuja (māhāpūjā), a collective worship of God usually performed on auspicious days or festivals,[146] and mansi (mānsi) puja, worship of God offered mentally.[147]

In general, Swaminarayan was positive about "other Vaishnava and Krishnite traditions,"[55] and Swaminarayan "adopted three aspects of Vallabhacharya practice," namely "the pattern of temple worship, fasts, and observances of festivals."[55] Shruti Patel argues that such a consistency with existing practices, notably the Pushtimarg, would have aided in "sanctioning [the] novelty" of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya.[148][note 5]

Manifestation of God

Swaminarayan's view on god was theanthropic, the idea that "the most extalted of the manifestations of god are in a divine form in human shape,"[149] teaching that "god's divine form has a human-shaped form."[150] Most followers believe that Swaminarayan was the 'manifest' form of this supreme God.[151] By 'manifest', it is understood that the very same transcendent entity who possesses a divine form in his abode assumes a human form that is still "totally divine," but "accessible" to his human devotees.[152]

Three stances regarding the ontological position of Sahajanand Swami, c.q. Swaminarayan, can be found in the tradition and its history: as guru, as an avatar of Krishna, or as a manifestation of God c.q. Purushottam, the highest Godhead, himself.[153][5][6]

According to Williams, "Some followers hold the position that Sahajanand taught that Krishna was the highest maifestation of Parabrahman or Purushottam and that he was the only appropriate object of devotion and meditation."[154] According to Kim, in the original sampradaya "Sahajanand Swami is not necessarily seen to occupy the space of ultimate reality," purna purushottam,[6] and the Krishna-iconography in the original temples, as well as the Vachanamritam and the Shikshapatri, reflect a belief in Krishna as Purushottam.[24]

According to Williams another, more accepted idea, is that "Sahajanand was a manifestation of Krishna,"[155] an understanding reflected in the Ahmedabad and Vadtal mandirs, where statues of NarNarayan and Lakshmi Narayan are enshrined, but where Swaminarayan's uniqueness is also emphasized.[156]

Most followers, including the BAPS,[5][6] take a third stance, that "Swaminarayan is the single, complete manifestation of Purushottam, the supreme god, superior to [...] all other manifestations of god, including Rama and Krishna."[157] He was thus "not a manifestation of Krishna, as some believed,"[157] but "the full manifestation of Purushottam, the supreme person himself."[157] These other manifestations of God, of which Rama and Krishna are two examples, are known as avatars, and according to Paramtattvadas Purushottam (or God) is believed to be "metaphysically different"[152] from them and their cause, the avatarin,[152] whom Swaminarayan revealed as himself.[152]

Akshar-Purushottam Darsana

The BAPS puts a strong emphasis on the distinction between Akshar and Purushottam, which it sees as a defining difference between Ramanuja's Vishistadvaita and other systems of Vedanta, and Swaminarayan's teachings.[20][21][22] While his preference for Ramanuja's theology is stated in the sacred text, the Shikshapatri (Śikṣāpatrī),[note 4] in his discourses collected in the Vachanamrut Swaminarayan gave a somewhat different explanation of the classical Hindu texts. In Ramanuja's understanding, there are three entities: Parabrahman, maya (māyā), and jiva (jīva).[158][159][160][161] Throughout the Vachanamrut, Swaminarayan identifies five eternal and distinct entities: Parabrahman, Aksharbrahman (Akṣarabrahman, also Akshara, Akṣara, or Brahman), maya, ishwar (īśvara), and jiva.[162][163][164][165][note 19] This distinction between Akshar and Purushottam is referred to by the BAPS as Akshar-Purushottam Darshan or Aksarabrahma-Parabrahma-Darsanam,[20] (darśana, philosophy)[note 20] and used as an alternate name for Swaminarayan Darshana,[20][22][web 5] Swaminarayan's views or teachings. This emphasis on the distinction between Akshar and Purushottam is also reflected in its name[69] and the prominent position of Akshar as the living guru.[24][168]

BAPS-theologian Paramtattvadas (2017) and others further elaborate on these five eternal realities:

God is Parabrahman, the all-doer (kartā, "omniagent"), possessing an eternal and divine form (sākār,) but transcending all entities (sarvoparī, ), and forever manifests on Earth to liberate spiritual seekers (pragat).[169][note 21]

Aksharbrahman, from akshar (अक्षर, "imperishable," "unalterable"), and Brahman, is the second highest entity and has four forms: 1) Parabrahman's divine abode; 2) the ideal devotee of Parabrahman, eternally residing in that divine abode; 3) the sentient substratum pervading and supporting the cosmos (chidakash, cidākāśa); and 4) the Aksharbrahman Guru, who serves as the manifest form of God on earth. In the BAPS, the gurus is the ideal devotee and Aksharbrahman Guru through whom God guides aspirants to moksha.[170][171][172] This further interpretation of Akshar is one of the features that distinguishes Swaminarayan's theology from others.[173][174][175][110][note 22]

Maya refers to the universal material source used by Parabrahman to create the world.[177][note 23] Maya has three gunas (guṇas, qualities) which are found to varying degrees in everything formed of it: serenity (sattva), passion (rajas), and darkness (tamas).[178][note 24] Maya also refers to the ignorance which enshrouds both ishwars and jivas, which results in their bondage to the cycle of births and deaths (transmigration) and subsequently suffering.[179][180][181][note 25]

Ishwars are sentient beings responsible for the creation, sustenance, and dissolution of the cosmos, at the behest of Parabrahman.[178][179][note 26] While they are metaphysically higher than jivas, they too are bound by maya and must transcend it to attain moksha.[182][183][181][note 27]

Jivas, also known as atmans, are distinct, eternal entities, composed of consciousness that can reside in bodies, animating them. The jiva is inherently pure and flawless, though under the influence of maya, jivas falsely believe themselves to be the bodies they inhabit and remain bound to the cycle of transmigration.[184][185][181][note 28]

Mandir tradition

The Swaminarayan Sampradaya is well known for its mandirs, or Hindu places of worship.[186] From Swaminarayan's time through the present, mandirs functioned as centers of worship and gathering as well as hubs for cultural and theological education.[187][188] They can vary in consecration rituals and architecture, which can be adapted to the means of the local congregation.[189]

Murti puja

The Swaminarayan Sampradaya is a bhakti tradition that believes God possesses an eternal, divine, human-like, transcendent form.[190] Thus, Swaminarayan mandirs facilitate devotion to God by housing murtis which are believed to resemble God's divine form.[191] The murtis are consecrated through the prana pratishta (prāṅa pratiṣṭha) ceremony, after which God is believed to reside in the murtis. Consequently, the worship practiced in Swaminarayan mandirs is believed to directly reach God.[191]

After the consecration of a mandir, various rituals are regularly performed in it. Arti is a ritual which involves singing a devotional song of praise, while waving a flame before the murtis. Arti is performed five times per day in shikharbaddha mandirs and twice per day in hari mandirs. Thal, a ritual offering of food to God accompanied by devotional songs, is also regularly offered three times per day to the murtis in Swaminarayan mandirs. The sanctified food is distributed to devotees after the ritual.[192]

In all major Swaminarayan temples, usually Radha Krishna, Lakshmi Narayan, Nar Narayan and Swaminarayan idols are worshipped.[193][page needed]

Devotees also engage with the murtis in a Swaminarayan mandir through other worship rituals, including darshan, dandvat, and pradakshina. Darshan is the devotional act of viewing the murtis, which are adorned with elegant clothing and ornaments.[194] Dandvats (daṇdavat), or prostrations, before the murtis symbolize surrendering to God.[195] Pradakshina (pradakṣiṇā), or circumambulations around the murtis, express the desire to keep God at the center of the devotees' lives.[196]

Community building and worship

Swaminarayan mandirs also serve as hubs for congregational worship and theological and cultural education.[197][198] Singing devotional songs, delivering katha (sermons), and performing rituals such as arti all occur daily in Swaminarayan mandirs. In addition, devotees from the surrounding community gather at least once per week, often on a weekend, to perform these activities congregationally.[199]

Cultural and theological instruction is also delivered on this day of weekly congregation. Cultural instruction may include Gujarati language instruction; training in music and dance; and preparation for festival performances.[188] Theological instruction includes classes on the tradition's history and doctrines, and the life and work of the tradition's gurus.[200]

Types of Swaminarayan temples

Swaminarayan followers conduct their worship in various types of mandirs. The homes of Swaminarayan devotees contain ghar mandirs, or home shrines, which serve as spaces for the daily performance of worship and ritual activities such as arti, thal, and reading sermons or scripture.[201]

The majority of freestanding public Swaminarayan mandirs are hari mandirs, whose architectural style and consecration rituals are adopted to the means available to the local congregation.[186]

As a means of expressing their devotion to Swaminarayan and their guru, some congregations elect to construct stone, shikharbaddha mandirs following Hindu architectural scriptures.[202] In addition to being an expression of devotion, congregants strengthen their sense of community by cooperatively volunteering to construct these mandirs.[203]

A fourth type of mandir, called a mahamandiram (mahāmandiram) can be found in India and the United States, in New Delhi, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, and Robbinsville, NJ.[204][205][206] These mahamandirs are the largest type of mandir constructed and they contain exhibits which present the life of Swaminarayan and the history of Hinduism in various formats with the goal of inspiring introspection and self-improvement.[207]

Scriptural tradition

In addition to Swaminarayan's acceptance of perennial Hindu texts such as the four Vedas, Vedanta-sutras, and the Bhagavad Gita, Swaminarayan encouraged the creation of a scriptural tradition specific to the Swaminarayan Sampradaya,[14][15] as part of the institutionalization of his charisma.[3] Along with theological texts with revelatory status, the genres of textual production in the Swaminarayan Sampradaya include sacred biographies, ethical precepts, commentaries, and philosophical treatises.[208][209]

Vachanamrut

The Vachanamrut, literally the 'immortalizing ambrosia in the form of words', is the fundamental text for the Swaminarayan Sampradaya, containing Swaminarayan's interpretations of the classical Hindu texts.[103][210] The text is a compilation of 273 discourses, with each discourse within the collection also called a Vachanamrut.[211] Swaminarayan delivered these discourses in Gujarati between the years of 1819–1829, and his senior disciples noted his teachings while they were delivered and compiled them during Swaminarayan's lifetime.[212] In this scripture, Swaminarayan gives his interpretation of the classical Hindu texts, which includes five eternal entities: jiva, ishwar, maya, Aksharbrahman, Parabrahman.[213][163] He also describes the ultimate goal of life, moksha (mokṣa), a spiritual state of ultimate liberation from the cycle of births and deaths and characterized by eternal bliss and devotion to God.[214][105] To attain this state, Swaminarayan states that the jiva needs to follow the four-fold practice of ekantik dharma[note 29] to transcend maya[215][note 30] and become brahmarup[118] and reside in the service of God.[216][217]

As followers believe Swaminarayan to be God, the Vachanamrut is considered a direct revelation of God and thus the most precise interpretation of the Upanishads, Bhagavad Gita, and other important Hindu scriptures.[103][210] This scripture is read by followers regularly and discourses are conducted daily in Swaminarayan temples around the world.[218]

Shikshapatri

The Shikshapatri is a composition of 212 Sanskrit verses believed to be authored by Swaminarayan and completed in 1826.[36][15] As an 'epistle of precepts,' the verses primarily communicate the Swaminarayan Sampradaya's moral injunctions for devotees which should be read daily.[219][220][note 31] Swaminarayan states that the Shikshapatri is not merely his words but his personified form and merits worship in its own right.[221][222]

Sacred biographies

The Swaminarayan Sampradaya has produced voluminous biographical literature on Swaminarayan. The Satsangi Jivan, a five volume Sanskrit sacred biography of Swaminarayan, consists of 17,627 verses written by Shatananda Muni that also incorporates some of Swaminarayan's teachings.[223] The Bhaktachintamani is a sacred biography of Swaminarayan composed by Nishkulanand Swami. Consisting of 8,536 couplets, this biography serves as a record of Swaminarayan's life and teachings.[224] The Harililamrut is a longer biographical text in verse written by Dalpatram and published in 1907.[225] The Harilila Kalpataru a 33,000-verse Sanskrit biographical text, was written by Achintyanand Brahmachari, at the suggestion of Gunatitanand Swami.[223][226] These and many other sacred biographies complement the theological texts, insofar as their incidents serve as practical applications of the theology.[14]

Swamini Vato

The Swamini Vato is a compilation of teachings delivered by Gunatitanand Swami over the course of his forty-year ministry,[219] which is valued by the BAPS.[85] He was one of Swaminarayan's foremost disciple,[227][219] and according to the BAPS and some denominations of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya, he was the first manifestation of Swaminarayan in a lineage of Aksharbrahman Gurus.[228][96] Similarly to the Vachanamrut, Gunatitanand Swami's followers recorded his teachings, which were compiled in his lifetime and reviewed by Gunatitanand Swami himself.[219] These teachings were first published by Balmukund Swami in 5 chapters and then 7 chapters by Krishnaji Ada.[web 17] The text consists of approximately 1,478 excerpts taken from Gunatitanand Swami's sermons.[229] In his teachings, he reflects on the nature of human experience and offers thoughts on how one ought to frame the intentions with which they act in this world, while also elaborating on Swaminarayan's supremacy, the importance of the sadhu, and the means for attaining liberation.[230] Often, Gunatitanand Swami elaborates upon topics or passages from the Vachanamrut, which lends the text to be considered a 'natural commentary' on the Vachanamrut within the Swaminarayan Sampradaya. In addition, he often made references to other Hindu texts, parables, and occurrences in daily life in order not only to explain spiritual concepts, but also to provide guidance on how to live them.[231]

Vedanta commentaries

Early commentaries

From its early history, the Swaminarayan Sampradaya has also been involved in the practice of producing Sanskrit commentarial work as a way of engaging with the broader scholastic community. The classical Vedanta school of philosophy and theology is of particular import for the Swaminarayan Sampradaya, which has produced exegetical work on the three canonical Vedanta texts—the Upanishads, Brahmasutras, and the Bhagavad Gita.[232] While Swaminarayan himself did not author a commentary on these texts, he engaged with them and their interpretations in the Vachanamrut. The earliest Vedanta commentarial literature in the Swaminarayan Sampradaya reflects a heavy dependence on the Vedanta systems of Ramanuja and Vallabha. Although authorship of these nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century texts[233] are attributed to two of Swaminarayan's eminent disciples, Muktanand Swami and Gopalanand Swami,[62]

Swaminarayan Bhashyam

The most comprehensive commentarial work on Vedanta in the Swaminarayan Sampradaya is the Swaminarayan Bhashyam authored by Bhadreshdas Swami, an ordained monk of BAPS. It is a five-volume work written in Sanskrit and published between 2009 and 2012. The format and style of exegesis and argument conform with the classical tradition of Vedanta commentarial writing. In more than two thousand pages, the commentator Bhadreshdas Swami, offers detailed interpretations of the principal ten Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, and the Brahmasutras (Vedanta Sutras) that articulate Swaminarayan's ideas and interpretations.[234]

The Swaminarayan Bhashyam has led to some recognition for Swaminarayan's Akshar-Purushottam distinction as a distinct view within Vedanta. The Shri Kashi Vidvat Parishad, an authoritative council of scholars of Vedic dharma and philosophy throughout India, stated in a meeting in Varanasi on 31 July 2017 that it is "appropriate to identify Sri Svāminārāyaṇa's Vedānta by the title: Akṣarapuruṣottama Darśana,"[note 32] and that his siddhanta ("view," "doctrine") on the Akshar-Purushottam distinction is "distinct from Advaita, Viśiṣṭādvaita, and all other doctrines."[web 5][web 18] Swaminarayan's Akshar-Purushottam darshan was also acclaimed as a distinct view within Vedanta in 2018 by professor Ashok Aklujkar, at the 17th World Sanskrit Conference, stating that the Swaminarayan Bhashyam "very clearly and effectively explains that Akshar is distinct from Purushottam."[web 4][note 33][235]

Influence on society

Humanitarian Service

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2022) |

In addition to his efforts in social reform, Swaminarayan was instrumental in providing humanitarian aid to the people of Gujarat during turbulent times of famine.[236] When given the opportunity to receive two boons from his guru, Swaminarayan asked to receive any miseries destined for followers and to bear any scarcities of food or clothing in place of any followers.[237] In the initial years of the sampradaya, Swaminaryan maintained almshouses throughout Gujarat and directed swamis to maintain the almshouses even under the threat of physical injury by opponents.[238] During a particularly harsh famine in 1813–14, Swaminarayan himself collected and distributed grains to those who were suffering, and he had step wells and water reservoirs dug in various villages.[236] He codified devotees' engagement with humanitarian service in the Shikshapatri, instructing followers to help the poor and those in need during natural disasters, to establish schools, and to serve the ill, according to their ability.[239]

Consequently, various denominations of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya currently engage in humanitarian service at a global scale. ISSO Seva, a subsidiary of the Ahmedabad diocese, is involved in disaster relief, food and blood donation drives in the United States and providing accessible healthcare in Africa.[web 19][better source needed] BAPS Charities, a humanitarian services wing of the Baps, engages in medical, educational, and disaster relief efforts.[240][241] The Gunatit Samaj also hosts medical camps, provides educational services, healthcare, and other social services in India.[web 20] The Swaminarayan Gadi (Maninagar) diocese primarily hosts health camps and other social services in the UK, Africa and North America.[web 21] SVG Charity, a subsidiary of the Laxmi Narayan Dev Gadi, is involved in disaster relief, food and medicine donations, blood drives, and organ donation registration drives across the United States, Europe, Canada, and India.[web 22][web 23]

Caste

During Swaminarayan's time, the oppressive nature of caste-based customs, like endogamy, dress codes, and commensality, pervaded many aspects of society.[242] Religious groups and other institutions often regulated membership based on caste,[243] and Swaminarayan too supported the caste system.[244] According to Williams, caste distinctions and inconsistencies between caste theory and practice still exist within the Swaminarayan sampraday.[245]

Dalits or the former untouchables were banned from Swaminarayan temples from the beginning of certain sects. There was however one case a separate temple being built at Chhani near Vadodra for the dalits.[246] After the Indian Independence in 1947, in order to be exempted from the Bombay Harijan Temple Entry Act of November 1947, which made it illegal for any temple to bar its doors to the previously outcaste communities, the Nar Narayan diocese went to court to claim that they were not 'Hindus', but members of an entirely different religion. Since the sect was not "Hindu", they argued that the Temple Entry Act did not apply to them. The sect did win the case in 1951, which was later overturned by the Indian Supreme court.[247][web 24]

Swaminarayan demanded a vow from his followers that they would not accept food from members of lower castes,[244] and explicated this in the Shikshapatri, in which Swaminarayan states that his followers should follow rules of the caste system when consuming food and water:[248][249]

None shall receive food and water, which are unacceptable at the hands of some people under scruples of caste system, may the same happen to the sanctified portions of the Shri Krishna, except at Jagannath Puri."[250][251]

BAPS-member Parikh attributes this statement to "deep-rooted rigidities of age-old varna-stratied society," and speculates that "Possibly, Swaminarayan sought to subtly subvert and thereby undermine the traditional social order instead of negating it outright through such prescriptions."[252]

BAPS-sadhu Mangalnidhidas acknowledges that Swaminarayan accepted the caste system, which according to Mangalnidhidas may have been "a strategic accommodation to the entrenched traditions of the various elements in Hindu society,"[253] but acknowledging that this may have had "unintended negative consequences such as the reinforcement of caste identities."[254] Mangalnidhidas states that, in the early years of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya, high-caste Hindus criticized Swaminarayan for his teachings, inclusiveness, and practices that undermined caste-based discrimination,[53][note 34] and argues that, overall, Swaminarayan's followers, practices and teachings helped reduce the oppressive nature of caste-based customs prevalent in that era and drew individuals of lower strata towards the Swaminarayan sampraday.[249]

See also

Notes

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e relation with Vishistadvaita:

- Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Vadtal: "Swaminarayan propagated a philosophy called Vishistadvaita."[web 6]

- Brahmbhatt 2016b: "Sahajanand explicitly states that his school of Vedanta is Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita," while "he also states that his system of devotional praxis is based on the Vallabha tradition."

- Brahmbhatt 2016b: "Certain portions of Swaminarayan Vedanta commentaries indicate an affinity for Vishishtadvaita's interpretation of canonical texts; others indicate overlap with Shuddhadvaita School, and yet others are altogether unique interpretations."

- Williams (2018, p. 38): "They are not Shrivaishnavas, but they do propagate a theology that developed in relation to the modified nondualism of Ramanuja and they follow the devotional path within Vaishnavism"

- Kim 2005: "The philosophical foundation for Swaminarayan devotionalism is the viśiṣṭādvaita, or qualified non-dualism, of Rāmānuja (1017–1137 ce)."

- Dwyer 2018, p. 186: "The sect's origin in Vishistadvaita"

- Beckerlegge 2008: "Swaminarayan theology is largely dependent on Ramanuja's theistic Vedanta and the Vishishtadvaita tradition"

- Herman 2010, p. 153: "Most certainly, the sect is directly tied to traditional Vishishtadvaita as expounded by Ramanuja in the 12th century.

- Roshen Dalal (2020), Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide, Penguin Books India:[258] "Swaminarayan's philosophy is said to be similar to Vishistadvaita, with some minor differences."

- Williams (2018, p. 91): "Ramanuja allowed for some distinction within the ultimate reality, and Sahajanand elaborated on this duality by indicating that two entities, Purushottam and Akshar, are eternal and free from the illusion of maya."

- Yogi Trivedi (2016), p. 134: "...there were many who followed [after Shankara]: Ramanuja (eleventh–twelfth centuries), Madhva (thirteenth century), Vallabha, and those in Chaitanya's tradition (both fifteenth–sixteenth centuries), to mention four of the most prominent. It is within the Vedantic tradition, particularly as expressed in the thinking of these four bhakti ācāryas (acharyas), that Swaminarayan's doctrine emerged. Swaminarayan was keen to engage with this Vedanta commentarial tradition by presenting his own theological system."

- Dwyer 2018, p. 185: "While vishistadvaita forms the theological and philosophical basis of the Swamiyaranam sect, there are several significant differences."

- ^ The sect has in the past claimed not to belong to Hinduism in order to deny entry to the marginalized or Dalit groups[2]

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Swaminarayan mantra is a compound of two Sanskrit words, swami (an initiated ascetic[43][web 7] but here "master, lord"[web 1][web 2]) and Narayan (supreme God, Vishnu).[10] Originally, the name refers to one entity, namely Lord Narayan.[web 6][web 2] Some later branches, including the BAPS, believe that Swami denotes Aksharbrahman (God's ideal devotee), namely Gunatitanand Swami, as identified by Sahajanand Swami, and Narayan denotes Parabrahman (God), a reference to Sahajanand Swami himself.[44][8] The latter interpretation recalls an earlier Vaishnava tradition of the divine companionship between the perfect devotee and God (for example, Radha and Krishna or Lakshmi and Vishnu).[45]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Brahmbhatt (2016): "Sahajanand explicitly states that his school of Vedanta is Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita."

See Shikshapatri Shlok 121: "Vishishtadvaita is accepted as the Lord's philosophy. From the various philosophies - Advaita, Kevaladvaita, Shuddhadvaita, Vishishtadvaita etc. the Lord accepts Ramanuja's philosophy of Vishishtadvaita (special theory of non-dualism) as accurate."[web 14] - ^ Jump up to: a b c d Shruti Patel (2017): "it is probable that Sahajanand did not possess the means by which to initiate his views and have them or him be seamlessly accepted in western India at the outset of the century. For this reason, first incorporating common and observable aspects of Vaishava culture would have mitigated his appearing unknown, made Sahajanand's aims seem less drastic, and contributed to advancing his local influence in with an aura of rootedness. By identifying with the widely-recognised Pustimarg in the course of worshipping Krsna the Svaminarayan foundation could be related to an identifiable, solidified ethos. Particularly, assimilation would be achieved more effortlessly with the adoption of select Pustimarg symbols. And yet, this would not require the sacrifice of core ideas or independence."[148]

- ^ Several years after the establishment of the sampradaya, the 19th-century Hindu reformer Dayananda Saraswati questioned the acceptance of Sahajanand Swami as a manifestation of God in the sect. According to Dayananda, Sahajananda decked himself out as Narayan to gain disciples.[42]

- ^ His followers, particularly his ascetics, also faced harassment.[52][49] Swaminarayan's ascetics, who were easily identifiable, had to refrain from retaliation and angry responses. To help them escape such harassment, at 30 June 1807 Swaminarayan ordained 500 swamis into the highest state of asceticism as paramhansas, thereby allowing them to suspend all distinguishing practices, like applying sacred marks.[52][57][10]

- ^ Their descendants continue the hereditary line of succession.[10] He formally adopted a son from each of his brothers and appointed him to the office of acharya. Swaminarayan decreed that the office should be hereditary so that acharyas would maintain a direct line of blood descent from his family.[75] Swaminarayan stated to all the devotees and saints to obey both the Acharyas and Gopalanand Swami who was considered as the main pillar and chief ascetic[76] for the sampradaya.[77] Their respective wives, known as the ‘Gadiwala’, are the initiator of all female Satsangis.[78]The current acharya of the Nar Narayan Dev Gadi is Koshalendraprasad Pande, while there is currently an active case regarding the leadership of Vadtal Gadi between Dev paksh, the faction led by Rakeshprasad Pande, and Siddhant paksh, which is led by Ajendraprasad Pande.[web 8] Gujarat high court has stayed the Nadiad court order removing Ajendraprasad until a final verdict is reached. He is restrained from enjoying the rights of acharya during the proceedings.[web 9] Dev paksh, governing the Vadtal temple trust, has appointed Rakeshprasad to act and officiate as acharya.[web 10][79]

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 208: "The original Ahmedabad and Vadtal dioceses value the Lekh, where as those groups that emphasis the authority of the sadhus over the acharya and different lineages of gurus downplay or ignore the lekh as simply an administrative document for temporary application and not as sacred scripture. Baps emphasizes the Swamini Vato, which contains the sayings of Gunatitanand."

- ^ The lineage of gurus for BAPS begin with Gunatitanand Swami, followed by Bhagatji Maharaj, Shastriji Maharaj, Yogiji Maharaj, Pramukh Swami Maharaj, and presently Mahant Swami.

- ^ Swaminarayan Gadi (Maninagar) lineage of gurus begin with Gopalanand Swami, Nirgundas Swami, Abji Bapa, Ishwarcharandas Swami, Muktajivandas Swami, Purushottampriyadasji Maharaj Swami

- ^ See Sahajānanda 2015: Gadhada II.50, Gadhada III.39, Kariyani 12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b See Sahajānanda 2015: Gadhada II.21, Gadhada III.21, Sarangpur 11

- ^ See Sahajānanda 2015: Gadhada I.21, Gadhada II.28, Gadhada II.45, Gadhada II.66, Gadhada III.2, Gadhada III.7, Gadhada III.10, Sarangpur 9.

- ^ See Sahajānanda 2015: Sarangpur 11, Gadhada II.21, and Gadhada III.21.

- ^ See Sahajānanda 2015: Gadhada II.51.

- ^ See Sahajānanda 2015: Gadhada III.34.

- ^ See Sahajānanda 2015: Panchala 9.

- ^ See Sahajānanda 2015: Gadhada I.7, Gadhada I.39, Gadhada I.42, Gadhada III.10.

- ^ Another meaning is the sight of the image of God,[70] a holy person,[166] or the guru as the abode of God.[167]

- ^ See Sahajānanda 2015: Gadhada I.71, Loya 4, Kariyani 10, Vartal 19.

- ^ In Vachanamrut Gadhada I-63, Swaminarayan emphasizes the need to understand Akshar in order to understand God (Parabrahman) perfectly and completely.[176]

- ^ See Sahajānanda 2015: Gadhada I.13, Gadhada III.10, Loya 17.

- ^ See Sahajānanda 2015: Loya 10.

- ^ See Sahajānanda 2015: Gadhada I.13, Gadhada I.1, Gadhada II.36, Gadhada III.39.

- ^ See Sahajānanda 2015: Gadhada II.31, Gadhada II.66, Gadhada III.38, Sarangpur 1, Panchala 4 .

- ^ See Sahajānanda 2015: Gadhada II.31, Kariyani 12, Sarangpur 5, Panchala 2.

- ^ See Sahajānanda 2015: Gadhada I.21, Gadhada I.44, Gadhada III.22, Gadhada III.39, Jetalpur 2.

- ^ See Sahajānanda 2015: Sarangpur 11.

- ^ See Sahajānanda 2015: Gadhada III-39.

- ^ See Sahajānanda 2015: Gadhada III I-14

- ^ "Within philosophy, just as Śrī Śaṅkara's Vedānta is identified as the Advaita Darśana, Śrī Rāmānuja's Vedānta is identified as the Viśiṣṭādvaita Darśana, Śrī Madhva's Vedānta is identified as the Dvaita Darśana, Śrī Vallabha's Vedānta is identified as the Śuddhādvaita Darśana, and others are respectively known; it is in every way appropriate to identify Sri Svāminārāyaṇa's Vedānta by the title: Akṣara-Puruṣottama Darśana."[web 5]

- ^ "Professor Ashok Aklujkar said [...] Just as the Kashi Vidvat Parishad acknowledged Swaminarayan Bhagwan's Akshar-Purushottam Darshan as a distinct darshan in the Vedanta tradition, we are honored to do the same from the platform of the World Sanskrit Conference [...] Professor George Cardona [said] "This is a very important classical Sanskrit commentary that very clearly and effectively explains that Akshar is distinct from Purushottam."[web 4]

- ^ According to Kishorelal Mashruwala, a Gandhian scholar cited by Mangalnidhidas, "Swaminarayan was the first to bring about religious advancement of Shudras in Gujarat and Kathiawad region [...] And that became the main reason for many to oppose the Sampraday."[253][255] Mangalnidhidas further refers to an 1823 memorandum from a British official in the Asiatic Journal notes that the native upper classes "regret (as Hindus) the levelling nature of [Swaminarayan's] system," accepting people from all castes into the sampradaya, and also Muslims and tribal peoples, resulting in their violent opposition to and frequent merciless beatings of Swaminarayan's disciples.[253][256] Additionally, various historical sources indicate that Swaminarayan himself often ignored caste rules and urged his followers to do the same.[53][252] Numerous historical accounts show that in practice Swaminarayan himself and his followers shared food and openly interacted with everyone without discrimination.[257]

References

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rinehart 2004, p. 215.

- ^ Hardiman, D. (1988). Class Base of Swaminarayan Sect. Economic and Political Weekly, 23(37), 1907–1912. JSTOR.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Schreiner 2001.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 80–90.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kim 2014, p. 243.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Kim 2010, p. 362.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 18, 85.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e I.Patel 2018, p. 1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p I.Patel 2018, p. 2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b S.Patel 2017, p. 65.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Trivedi 2015, p. 353.

- ^ Hatcher 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 64.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Williams 2018, p. 200.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kim 2014, p. 240.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Changela n.d., p. 19.6 Concept of Moksha.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d S.Patel 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brahmbhatt 2016b.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Bhadreshdas & Aksharananddas 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Paramtattvadas 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Paramtattvadas 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b I.Patel 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Kim 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Warrier 2012, p. 172.

- ^ A.Patel 2018, p. 55, 58.

- ^ Mamtora 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Williams 2018, p. 18.

- ^ Burman 2005, p. 17.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 16.

- ^ Schreiner 2001, p. 155,158.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 13.

- ^ Williams 1984, p. 8-9.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 13-14.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 15–16.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Brahmbhatt 2016, p. 101.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Williams 2018, p. 17.

- ^ Trivedi 2015, p. 126.

- ^ Dave 2004, p. 386.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, pp. 8, 13–14.

- ^ Williams 2016, p. xvii.

- ^ Narayan 1992, p. 141–143.

- ^ Brewer 2009, p. "Swami" entry.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 55, 93.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 92.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 22.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 23-24.

- ^ Schreiner 2001, p. 159-161.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Paramtattvadas & Williams 2016, p. 65.

- ^ Williams 2001, p. 81.

- ^ Williams 2001, p. 19.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Williams 2018, p. 24-25.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mangalnidhidas 2016, p. 122-126.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 29.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Williams 2018, p. 30.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hardiman 1988.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Trivedi 2015, p. 207.

- ^ Williams 1984, p. 17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Williams 2018, p. 26.

- ^ Trivedi 2016, p. 198-214.

- ^ Rajpurohit 2016, p. 218-230.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brahmbhatt 2016b, p. 142-143.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Williams 2018, p. 103.

- ^ Vasavada 2016, p. 263-264.

- ^ Vasavada 2016, p. 264.

- ^ Packert 2019, p. 198.

- ^ Packert 2016, p. 253.

- ^ Trivedi 2015, p. 370.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kim 2010, p. 363.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Williams 2018, p. 36.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Cush 2008, p. 536.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tripathy 2010, p. 107-108.

- ^ Williams, Raymond Brady (2001). An Introduction to Swaminarayan Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 173. ISBN 9780521654227.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 37-38.

- ^ Williams 2001, p. 35

- ^ Williams 2001, pp. 59

- ^ Dave, Ramesh (1978). Sahajanand charitra. University of California: BAPS. pp. 199–200. ISBN 978-8175261525.

- ^ Williams 2019, p. 261.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 51.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 38.

- ^ Brahmbhatt 2016, p. 102.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 23.

- ^ Sansthan, Shree Swaminarayan Gurukul Rajkot. "History". Rajkot Gurukul. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 49-51.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Williams 2018, p. 208.

- ^ Williams 2001, p. 59.

- ^ Williams 2001, p. 59-60.

- ^ Williams 2001, p. 60.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 132-156.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 134.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 93.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Williams 2018, p. 60-61.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 22.

- ^ Kim 2012, p. 419.

- ^ Gadhia 2016, p. 157.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Williams 2018, p. 61.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 72.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 72-73,127.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Williams 2018, p. 58.

- ^ Sansthan, Maninagar Shree Swaminarayan Gadi. "Maninagar Shree Swaminarayan Gadi Sansthan". swaminarayangadi.com. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 205.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 13-4, 45.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 272-284.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bhadreshdas & Aksharananddas 2016, p. 13, 173.

- ^ Trivedi 2016b, p. 134, 135.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gadhia 2016.

- ^ Trivedi 2016b, p. 134.

- ^ Bhadreshdas & Aksharananddas 2016, p. 186.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Williams 2018, p. 91.

- ^ Bhadreshdas 2018, p. 53.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 319.

- ^ Bhadreshdas & Aksharananddas 2016, p. "a similar goal".

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 277, 303-4.

- ^ Kim 2014, p. 246-247.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 273-4.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 287-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kim 2014, p. 247.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mangalnidhidas 2016, p. 126.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 287-288.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 308.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 74-84, 303-304.

- ^ Kim 2014, p. 239-40.

- ^ Gadhia 2016, p. 166-169.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 150.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 287.

- ^ Lagassé 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Williams 2018, p. 174.

- ^ Vivekjivandas 2016, p. 344.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 165-174.

- ^ Gadhia 2016, p. 166.

- ^ Kurien 2007, p. 107.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 62.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 169-170.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 61-62.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 151.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 275.

- ^ Williams 1998, p. 861.

- ^ Kim 2013, p. 132.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 308-310.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. Ch.2, 48.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mosher 2006, p. 44.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Williams 2018, p. 100.

- ^ Kim 2016.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 140.

- ^ Williams 1998, p. 852.

- ^ Bhatt 2016, p. 91.

- ^ Jump up to: a b S.Patel 2017, p. 53.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 78.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 79.

- ^ Williams 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 154.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 80-90.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 80.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 82.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 89-90.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Williams 2018, p. 85.

- ^ Brahmbhatt 2016b, p. 141-142.

- ^ Gadhia 2016, p. 157-60.

- ^ Bhadreshdas & Aksharananddas 2016, p. 183–4.

- ^ Trivedi 2016, p. 211.

- ^ Kim 2001, p. 319.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kim 2014, p. 244.

- ^ Brahmbhatt 2016.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 69-71.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 261.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 183.

- ^ Kim 2014, p. 362-363.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 71,75,109.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 158, 200-1.

- ^ Gadhia 2016, p. 156, 165-9.

- ^ Kim 2013, p. 131.

- ^ Gadhia 2016, p. 169.

- ^ Kim 2014, p. 245.

- ^ Bhadreshdas & Aksharananddas 2016, p. 172–90.

- ^ Gadhia 2016, p. 162.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 71-3, 245.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 71, 246.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kim 2001, p. 320.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 245, 249-50.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kim 2016, p. 388–9.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 234-5.

- ^ Trivedi 2016, p. 215.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 211-18.

- ^ Kim 2001, p. 320-321.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kim 2007, p. 64.

- ^ Vasavada 2016, p. 263.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kim 2010, p. 377.

- ^ Kim 2010, p. 367.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 124-130.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Trivedi 2016b, p. 236.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 148-149.

- ^ Williams 2019.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 133.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 138.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 137.

- ^ Kim 2007, p. 65–66.

- ^ Kim 2012.

- ^ Vivekjivandas 2016, p. 341, 344–345.

- ^ Kim 2007, p. 66.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 145-147.

- ^ Kim 2010, p. 366-367.

- ^ Kim 2010, p. 370.

- ^ Kim 2007, p. 68.

- ^ Kim 2016, p. 384.

- ^ Kim 2011, p. 46.

- ^ Kim 2016, p. 392–398.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 47.

- ^ Trivedi 2016b, p. 133.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bhadreshdas & Aksharananddas 2016, p. 173.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 13.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 333.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 69.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 272-84.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 273.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 303-4.

- ^ Kim 2014, p. 246.

- ^ Brear 1996, p. 217.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 16.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 200-202.

- ^ Hatcher 2020, p. 156.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. 41.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Williams 2018, p. 203.

- ^ Mangalnidhidas 2016, p. 118.

- ^ Paramtattvadas & Williams 2016, p. 86.

- ^ Dave 2018, p. 133.

- ^ Mangalnidhidas 2016, p. 119.

- ^ Williams 2016, p. xviii.

- ^ Mamtora 2019, p. 16.

- ^ Mamtora 2019, p. 123.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 17.

- ^ Brahmbhatt 2016b, p. 138-140.

- ^ Brahmbhatt 2018, p. 120.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 19.

- ^ Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 40.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brahmbhatt 2016, p. 105.

- ^ Beckerlegge 2006, p. 192.

- ^ Dani 1980, p. 11–12.

- ^ Parekh 1936.

- ^ Brahmbhatt 2016, p. 112-114.

- ^ Brahmbhatt 2016, p. 117.

- ^ Mangalnidhidas 2016, p. 121.

- ^ Mangalnidhidas 2016, p. 117.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hardiman 1988, p. 1907.

- ^ Williams 2019, p. 185.

- ^ Hardiman, D. (1988). Class Base of Swaminarayan Sect. Economic and Political Weekly, 23(37), 1907–1912. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4379024

- ^ Hardiman, D. (1988). Class Base of Swaminarayan Sect. Economic and Political Weekly, 23(37), 1907–1912. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4379024

- ^ Parikh 2016, p. 106–107.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mangalnidhidas 2016.

- ^ Williams & 2018b.

- ^ Parikh 2016, p. 143.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Parikh 2016, p. 105–107.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mangalnidhidas 2016, p. 122.

- ^ Mangalnidhidas 2016, p. 116.

- ^ Mashruwala 1940, p. 63–64.

- ^ N.A. 1823, p. 348–349.

- ^ Mangalnidhidas 2016, p. 122–124.

- ^ p.403

Sources

- Printed sources

- Beckerlegge, Gwilym (2006). Swami Vivekananda's Legacy of Service: A Study of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-567388-3.

- Beckerlegge, Gwilym (2008), Colonialism, Modernity, and Religious Identities: Religious Reform Movements in South Asia, Oxford University Press

- Bhadreshdas, Sadhu; Aksharananddas, Sadhu (1 April 2016), "Swaminarayan's Brahmajnana as Aksarabrahma-Parabrahma-Darsanam", Swaminarayan Hinduism, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199463749.003.0011, ISBN 978-0-19-946374-9

- Bhadreshdas, Sadhu (2018). "Parabrahman Swaminarayan's Akshara-Purushottama Darshana". Journal of the BAPS Swaminarayan Research Institute. 1.

- Bhatt, Kalpesh (2016). "Daily pūjā: moralizing dharma in the BAPS Swaminarayan Hindu tradition". Nidan: International Journal for Indian Studies: 88–109.

- Brahmbhatt, Arun (2016). "BAPS Swaminarayan community: Hinduism". In Cherry, Stephen M.; Ebaugh, Helen Rose (eds.). Global religious movements across borders: sacred service. Burlington: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-4094-5689-6. OCLC 872618204.

- Brahmbhatt, Arun (2016b). "The Swaminarayan commentarial tradition". In Williams, Raymond Brady; Trivedi, Yogi (eds.). Swaminarayan Hinduism: tradition, adaptation and identity (1st ed.). New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-908657-3. OCLC 948338914.

- Brahmbhatt, Arun (2018), Scholastic Publics: Sanskrit textual practices in Gujarat, 1800-Present. PhD diss., University of Toronto (PDF)

- Brear, Douglas (1996). Williams, Raymond Brady (ed.). Transmission of a Swaminarayan Hindu scripture in the British East Midlands (Columbia University Press ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-10779-X. OCLC 34984234.

- Brewer, E. Cobham (2009). Rockwood, Camilla (ed.). Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. London: Chambers Harrap. "Swami" entry. ISBN 9780550104113. OL 2527037W.

- Burman, J. J. Roy (2005). Gujarat Unknown. Mittal Publications. ISBN 9788183240529. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- Changela, Hitesh (n.d.), The Supreme Godhead Bhagawan Swaminarayan: Bhagawan Swaminarayan Jivan Darshan, Shree Swaminarayan Gurukul Rajkot Sansthan

- Dani, Gunvant (1980). Bhagwan Swaminarayan, a social reformer. Bochasanwasi Shri Aksharpurushottam Sanstha. OCLC 500188660.

- Dave, Harshad (2004). Bhagwan Shri Swaminarayan - Part 1. Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpith. ISBN 81-7526-211-7.

- Dave, Jyotindra (2018). "The tradition of education within the Swaminarayan Sampraday". Journal of the BAPS Swaminarayan Research Institute. 1.

- Dwyer, Rachel (2018), "The Swaminarayan Movement", in Jacobsen, Knut A.; Kumar, Pratap (eds.), South Asians in the Diaspora: Histories and Religious Traditions, BRILL, ISBN 9789047401407

- Cush, Denise (2008). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Robinson, Catherine A., York, Michael. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7007-1267-0. OCLC 62133001.

- Gadhia, Smit (2016). "Akshara and its four forms in Swaminarayan's doctrine". In Williams, Raymond Brady; Trivedi, Yogi (eds.). Swaminarayan Hinduism: tradition, adaptation and identity (1st ed.). New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-908657-3. OCLC 948338914.

- Hardiman, David (1988). "Class Base of Swaminarayan Sect". Economic and Political Weekly. 23 (37): 1907–1912. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 4379024.

- Hatcher, Brian (2020). Hinduism before reform. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-24713-0. OCLC 1138500516.

- Heber, Reginald (1828). Narrative Of A Journey Through The Upper Provinces Oof India, From Calcutta To Bombay, 1824-1825, (With Notes Upon Ceylon) : An Account Of A Journey Tto Madras And The Southern Provinces, 1826, And Letters Written In India; In Three Volumes. Gilbert. OCLC 554124407.

- Herman, Phyllis K. (2010), "Seeing the divine through windows: online puja and virtual religious experience", Online: Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet, 4 (1)

- Jones, Constance A.; Ryan, James D. (2007). "Swaminarayan movement". Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Encyclopedia of World Religions. J. Gordon Melton, Series Editor. New York: Facts On File. pp. 429–431. ISBN 978-0-8160-5458-9. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020.

- Kim, Hanna Hea-Sun (2001). Being Swaminarayan: the ontology and significance of belief in the construction of a Gujarati diaspora (PhD thesis, Columbia University). Ann Arbor, Mi: UMI Dissertation Services. OCLC 452027310.

- Kim, Hanna H. (2005), "Swaminarayan Movement", in Jones, Lindsay (ed.), Encyclopedia of Religion: 15-Volume Set, vol. 13 (2nd ed.), Detroit, Mi: MacMillan Reference USA, ISBN 0-02-865735-7, archived from the original on 29 December 2020 – via Encyclopedia.com

- Kim, Hanna (2007). "Edifice complex: Swaminarayan bodies and buildings in the diaspora". Gujaratis in the West: evolving identities in contemporary society. Mukadam, Anjoom A., Mawani, Sharmina. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Pub. ISBN 978-1-84718-368-2. OCLC 233491089.

- Kim, Hanna H. (2010), Public Engagement and Personal Desires: BAPS Swaminarayan Temples and their Contribution to the Discourses on Religion, Anthropology Faculty Publications

- Kim, Hanna (2011). "Steeples and spires: exploring the materiality of built and unbuilt temples". Nidan: International Journal for the Study of Hinduism. 23.

- Kim, Hanna (2012). "Chapter 30. The BAPS Swaminarayan Temple Organisation and Its Publics". In Zavos, John; et al. (eds.). Public Hinduisms. New Delhi: SAGE Publ. India. ISBN 978-81-321-1696-7.

- Kim, Hanna (2013). "Devotional expressions in the Swaminarayan community". In Kumar, P. Pratap (ed.). Contemporary Hinduism. Durham, UK: Acumen. ISBN 978-1-84465-690-5. OCLC 824353503.

- Kim, Hanna (2014). "Svāminārāyaṇa: Bhaktiyoga and the Akṣarabrahman Guru". In Singleton, Mark; Goldberg, Ellen (eds.). Gurus of modern yoga. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-993871-1. OCLC 861692270.

- Kim, Hanna (2016). "Thinking through Akshardham and the making of the Swaminarayan self". In Williams, Raymond Brady; Trivedi, Yogi (eds.). Swaminarayan Hinduism: tradition, adaptation and identity (1st ed.). New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-908657-3. OCLC 948338914.

- Kurien, Prerna (2007). A place at the multicultural table: the development of an American Hinduism. Piscataway: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-4161-7. OCLC 476118265.

- Lagassé, Paul (2013). "Dharma". The Columbia encyclopedia (6th ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-7876-5015-5. OCLC 43599122.

- Mamtora, Bhakti (2018), "BAPS: Pramukh Swami", in Jacobsen, Knut A.; et al. (eds.), Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism Online, retrieved 6 June 2021

- Mamtora, Bhakti (2019), The making of a modern scripture: Svāmīnī Vāto and the formation of religious subjectivities in Gujarat. PhD diss., University of Florida

- Mangalnidhidas, Sadhu (2016). "Sahajanand Swami's approach to caste". In Williams, Raymond Brady; Trivedi, Yogi (eds.). Swaminarayan Hinduism: tradition, adaptation and identity (1st ed.). New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-908657-3. OCLC 948338914.

- Mashruwala, Kishore (1940). Sahajanand Swami and Swaminarayan Sampradaya (2 ed.). Ahmedabad: Navajivan Publishing House.

- Mosher, Lucinda Allen. (2006). Praying. New York, N.Y.: Seabury Books. ISBN 1-59627-016-0. OCLC 63048497.