Судан

Республика Судан | |

|---|---|

| Девиз: Победа за нами ан-Наср Лана «Победа за нами» | |

| Гимн: Мы солдаты Бога, солдаты нации. Нахну Джунд Аллах, Джунд аль-Ватан «Мы солдаты Бога, солдаты Родины» | |

Sudan displayed in dark green colour, claimed territories not administered in light green | |

| Capital and largest city | Khartoum |

| Capital-in-exile | Port Sudan[a] |

| Official languages | |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Religion (2020)[14] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Sudanese |

| Government | Federal republic under a military junta[15][16] |

| |

| |

| Legislature | Vacant |

| Formation | |

| 2500 BC | |

| 1070 BC | |

| c. 350 | |

| c. 1500 | |

| 1820 | |

| 1885 | |

| 1899 | |

| 1 January 1956 | |

| 25 May 1969 | |

| 6 April 1985 | |

• Secession of South Sudan | 9 July 2011 |

| 19 December 2018 | |

• 2019 Draft Constitutional Declaration effective | 20 August 2019 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,886,068 km2 (728,215 sq mi) (15th) |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 50,467,278[17] (30th) |

• Density | 21.3/km2 (55.2/sq mi) (202nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2014) | medium |

| HDI (2022) | low (170th) |

| Currency | Sudanese pound (SDG) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +249 |

| ISO 3166 code | SD |

| Internet TLD | .sd سودان. |

Судан , [с] официально Республика Судан , [д] — страна в Северо-Восточной Африке . Он граничит с Центральноафриканской Республикой на юго-западе, Чадом на западе, Египтом на севере, Эритреей на северо-востоке, Эфиопией на юго-востоке, Ливией на северо-западе, Южным Суданом на юге и Красным морем на востоке. По состоянию на 2024 год население Судана составляет почти 50 миллионов человек. [21] Африки и занимает 1 886 068 квадратных километров (728 215 квадратных миль), что делает его третьей по величине страной по площади и третьей по величине страной в Лиге арабских государств . Это была самая большая по площади страна в Африке и Лиге арабских государств до отделения Южного Судана в 2011 году ; [22] с тех пор оба титула принадлежат Алжиру . Столица Судана и самый густонаселенный город – Хартум .

На территории нынешнего Судана произошла эпоха Хормусана (ок. 40 000–16 000 до н. э.). [23] Халфанская культура (ок. 20500–17000 до н.э.), [24] [25] Себилиан (ок. 13000–10000 до н.э.), [26] Qadan culture (c. 15000–5000 BC),[27] the war of Jebel Sahaba, the earliest known war in the world, around 11500 BC,[28][29] A-Group culture[30] (ок. 3800 г. до н.э. – 3100 г. до н.э.), Королевство Керма ( ок. 2500–1500 до н.э.), Новое египетское царство ( ок. 1500 г. до н.э. – 1070 г. до н.э.) и Королевство Куш ( ок. 785 г. до н.э. – 350 г. н.э.) . После падения Куша нубийцы образовали три христианских королевства: Нобатия , Макурия и Алодия .

Between the 14th and 15th centuries, most of Sudan was gradually settled by Arab nomads. From the 16th to the 19th centuries, central and eastern Sudan were dominated by the Funj sultanate, while Darfur ruled the west and the Ottomans the east. In 1811, Mamluks established a state at Dunqulah as a base for their slave trading. Under Turco-Egyptian rule of Sudan after the 1820s, the practice of trading slaves was entrenched along a north–south axis, with slave raids taking place in southern parts of the country and slaves being transported to Egypt and the Ottoman empire.[31]

From the 19th century, the entirety of Sudan was conquered by the Egyptians under the Muhammad Ali dynasty. Religious-nationalist fervour erupted in the Mahdist Uprising in which Mahdist forces were eventually defeated by a joint Egyptian-British military force. In 1899, under British pressure, Egypt agreed to share sovereignty over Sudan with the United Kingdom as a condominium. In effect, Sudan was governed as a British possession.[32]

The Egyptian revolution of 1952 toppled the monarchy and demanded the withdrawal of British forces from all of Egypt and Sudan. Muhammad Naguib, one of the two co-leaders of the revolution and Egypt's first President, was half-Sudanese and had been raised in Sudan. He made securing Sudanese independence a priority of the revolutionary government. The following year, under Egyptian and Sudanese pressure, the British agreed to Egypt's demand for both governments to terminate their shared sovereignty over Sudan and to grant Sudan independence. On 1 January 1956, Sudan was duly declared an independent state.

After Sudan became independent, the Gaafar Nimeiry regime began Islamist rule.[33] This exacerbated the rift between the Islamic North, the seat of the government, and the Animists and Christians in the South. Differences in language, religion, and political power erupted in a civil war between government forces, influenced by the National Islamic Front (NIF), and the southern rebels, whose most influential faction was the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), which eventually led to the independence of South Sudan in 2011.[34] Between 1989 and 2019, a 30-year-long military dictatorship led by Omar al-Bashir ruled Sudan and committed widespread human rights abuses, including torture, persecution of minorities, alleged sponsorship of global terrorism, and ethnic genocide in Darfur from 2003–2020. Overall, the regime killed an estimated 300,000 to 400,000 people. Protests erupted in 2018, demanding Bashir's resignation, which resulted in a coup d'état on 11 April 2019 and Bashir's imprisonment.[35] Sudan is currently embroiled in a civil war between two rival factions, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

Islam was Sudan's state religion and Islamic laws were applied from 1983 until 2020 when the country became a secular state.[33] Sudan is a least developed country and ranks 172nd on the Human Development Index as of 2022. It is one of the poorest countries in Africa;[36] its economy largely relies on agriculture due to international sanctions and isolation, as well as a history of internal instability and factional violence. The large majority of Sudan is dry and over 60% of Sudan's population lives in poverty. Sudan is a member of the United Nations, Arab League, African Union, COMESA, Non-Aligned Movement and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation.

Etymology

[edit]The country's name Sudan is a name given historically to the large Sahel region of West Africa to the immediate west of modern-day Sudan. Historically, Sudan referred to both the geographical region, stretching from Senegal on the Atlantic Coast to Northeast Africa and the modern Sudan.

The name derives from the Arabic bilād as-sūdān (بلاد السودان), or "The Land of the Blacks".[37] The name is one of various toponyms sharing similar etymologies, in reference to the very dark skin of the indigenous people. Prior to this, Sudan was known as Nubia and Ta Nehesi or Ta Seti by Ancient Egyptians named for the Nubian and Medjay archers or bowmen.

Since 2011, Sudan is also sometimes referred to as North Sudan to distinguish it from South Sudan.[38]

History

[edit]Prehistoric Sudan (before c. 8000 BC)

[edit]

Affad 23 is an archaeological site located in the Affad region of southern Dongola Reach in northern Sudan,[39] which hosts "the well-preserved remains of prehistoric camps (relics of the oldest open-air hut in the world) and diverse hunting and gathering loci some 50,000 years old".[40][41][42]

By the eighth millennium BC, people of a Neolithic culture had settled into a sedentary way of life there in fortified mudbrick villages, where they supplemented hunting and fishing on the Nile with grain gathering and cattle herding.[43] Neolithic peoples created cemeteries such as R12. During the fifth millennium BC, migrations from the drying Sahara brought neolithic people into the Nile Valley along with agriculture.

The population that resulted from this cultural and genetic mixing developed a social hierarchy over the next centuries which became the Kingdom of Kush (with the capital at Kerma) at 1700 BC. Anthropological and archaeological research indicates that during the predynastic period Nubia and Nagadan Upper Egypt were ethnically and culturally nearly identical, and thus, simultaneously evolved systems of pharaonic kingship by 3300 BC.[44]

Kingdom of Kush (c. 1070 BC–350 AD)

[edit]

The Kingdom of Kush was an ancient Nubian state centred on the confluences of the Blue Nile and White Nile, and the Atbarah River and the Nile River. It was established after the Bronze Age collapse and the disintegration of the New Kingdom of Egypt; it was centred at Napata in its early phase.[45]

After King Kashta ("the Kushite") invaded Egypt in the eighth century BC, the Kushite kings ruled as pharaohs of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt for nearly a century before being defeated and driven out by the Assyrians.[46] At the height of their glory, the Kushites conquered an empire that stretched from what is now known as South Kordofan to the Sinai. Pharaoh Piye attempted to expand the empire into the Near East but was thwarted by the Assyrian king Sargon II.

Between 800 BCE and 100 AD were built the Nubian pyramids, among them can be named El-Kurru, Kashta, Piye, Tantamani, Shabaka, Pyramids of Gebel Barkal, Pyramids of Meroe (Begarawiyah), the Sedeinga pyramids, and Pyramids of Nuri.[47]

The Kingdom of Kush is mentioned in the Bible as having saved the Israelites from the wrath of the Assyrians, although disease among the besiegers might have been one of the reasons for the failure to take the city.[48][page needed]The war that took place between Pharaoh Taharqa and the Assyrian king Sennacherib was a decisive event in western history, with the Nubians being defeated in their attempts to gain a foothold in the Near East by Assyria. Sennacherib's successor Esarhaddon went further and invaded Egypt itself to secure his control of the Levant. This succeeded, as he managed to expel Taharqa from Lower Egypt. Taharqa fled back to Upper Egypt and Nubia, where he died two years later. Lower Egypt came under Assyrian vassalage but proved unruly, unsuccessfully rebelling against the Assyrians. Then, the king Tantamani, a successor of Taharqa, made a final determined attempt to regain Lower Egypt from the newly reinstated Assyrian vassal Necho I. He managed to retake Memphis killing Necho in the process and besieged cities in the Nile Delta. Ashurbanipal, who had succeeded Esarhaddon, sent a large army in Egypt to regain control. He routed Tantamani near Memphis and, pursuing him, sacked Thebes. Although the Assyrians immediately departed Upper Egypt after these events, weakened, Thebes peacefully submitted itself to Necho's son Psamtik I less than a decade later. This ended all hopes of a revival of the Nubian Empire, which rather continued in the form of a smaller kingdom centred on Napata. The city was raided by the Egyptian c. 590 BC, and sometime soon after to the late-3rd century BC, the Kushite resettled in Meroë.[46][49][50]

Medieval Christian Nubian kingdoms (c. 350–1500)

[edit]

On the turn of the fifth century the Blemmyes established a short-lived state in Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia, probably centred around Talmis (Kalabsha), but before 450 they were already driven out of the Nile Valley by the Nobatians. The latter eventually founded a kingdom on their own, Nobatia.[52]By the sixth century there were in total three Nubian kingdoms: Nobatia in the north, which had its capital at Pachoras (Faras); the central kingdom, Makuria centred at Tungul (Old Dongola), about 13 kilometres (8 miles) south of modern Dongola; and Alodia, in the heartland of the old Kushitic kingdom, which had its capital at Soba (now a suburb of modern-day Khartoum).[53] Still in the sixth century they converted to Christianity.[54] In the seventh century, probably at some point between 628 and 642, Nobatia was incorporated into Makuria.[55]

Between 639 and 641 the Muslim Arabs of the Rashidun Caliphate conquered Byzantine Egypt. In 641 or 642 and again in 652 they invaded Nubia but were repelled, making the Nubians one of the few who managed to defeat the Arabs during the Islamic expansion. Afterward the Makurian king and the Arabs agreed on a unique non-aggression pact that also included an annual exchange of gifts, thus acknowledging Makuria's independence.[56] While the Arabs failed to conquer Nubia they began to settle east of the Nile, where they eventually founded several port towns[57] and intermarried with the local Beja.[58]

From the mid eighth to mid eleventh century the political power and cultural development of Christian Nubia peaked.[59] In 747 Makuria invaded Egypt, which at this time belonged to the declining Umayyads,[60] and it did so again in the early 960s, when it pushed as far north as Akhmim.[61] Makuria maintained close dynastic ties with Alodia, perhaps resulting in the temporary unification of the two kingdoms into one state.[62] The culture of the medieval Nubians has been described as "Afro-Byzantine",[63] but was also increasingly influenced by Arab culture.[64] The state organisation was extremely centralised,[65] being based on the Byzantine bureaucracy of the sixth and seventh centuries.[66] Arts flourished in the form of pottery paintings[67] and especially wall paintings.[68] The Nubians developed an alphabet for their language, Old Nobiin, basing it on the Coptic alphabet, while also using Greek, Coptic and Arabic.[69] Women enjoyed high social status: they had access to education, could own, buy and sell land and often used their wealth to endow churches and church paintings.[70] Even the royal succession was matrilineal, with the son of the king's sister being the rightful heir.[71]

From the late 11th/12th century, Makuria's capital Dongola was in decline, and Alodia's capital declined in the 12th century as well.[72] In the 14th and 15th centuries Bedouin tribes overran most of Sudan,[73] migrating to the Butana, the Gezira, Kordofan and Darfur.[74] In 1365 a civil war forced the Makurian court to flee to Gebel Adda in Lower Nubia, while Dongola was destroyed and left to the Arabs. Afterwards Makuria continued to exist only as a petty kingdom.[75] After the prosperous[76] reign of king Joel (fl. 1463–1484) Makuria collapsed.[77] Coastal areas from southern Sudan up to the port city of Suakin was succeeded by the Adal Sultanate in the fifteenth century.[78][79] To the south, the kingdom of Alodia fell to either the Arabs, commanded by tribal leader Abdallah Jamma, or the Funj, an African people originating from the south.[80] Datings range from the 9th century after the Hijra (c. 1396–1494),[81] the late 15th century,[82] 1504[83] to 1509.[84] An alodian rump state might have survived in the form of the kingdom of Fazughli, lasting until 1685.[85]

Islamic kingdoms of Sennar and Darfur (c. 1500–1821)

[edit]

In 1504 the Funj are recorded to have founded the Kingdom of Sennar, in which Abdallah Jamma's realm was incorporated.[87] By 1523, when Jewish traveller David Reubeni visited Sudan, the Funj state already extended as far north as Dongola.[88] Meanwhile, Islam began to be preached on the Nile by Sufi holy men who settled there in the 15th and 16th centuries[89] and by David Reubeni's visit king Amara Dunqas, previously a Pagan or nominal Christian, was recorded to be Muslim.[90] However, the Funj would retain un-Islamic customs like the divine kingship or the consumption of alcohol until the 18th century.[91] Sudanese folk Islam preserved many rituals stemming from Christian traditions until the recent past.[92]

Soon the Funj came in conflict with the Ottomans, who had occupied Suakin c. 1526[93] and eventually pushed south along the Nile, reaching the third Nile cataract area in 1583/1584. A subsequent Ottoman attempt to capture Dongola was repelled by the Funj in 1585.[94] Afterwards, Hannik, located just south of the third cataract, would mark the border between the two states.[95] The aftermath of the Ottoman invasion saw the attempted usurpation of Ajib, a minor king of northern Nubia. While the Funj eventually killed him in 1611/1612 his successors, the Abdallab, were granted to govern everything north of the confluence of Blue and White Niles with considerable autonomy.[96]

During the 17th century the Funj state reached its widest extent,[97] but in the following century it began to decline.[98] A coup in 1718 brought a dynastic change,[99] while another one in 1761–1762[100] resulted in the Hamaj Regency, where the Hamaj (a people from the Ethiopian borderlands) effectively ruled while the Funj sultans were their mere puppets.[101] Shortly afterwards the sultanate began to fragment;[102] by the early 19th century it was essentially restricted to the Gezira.[103]

The coup of 1718 kicked off a policy of pursuing a more orthodox Islam, which in turn promoted the Arabisation of the state.[104] To legitimise their rule over their Arab subjects the Funj began to propagate an Umayyad descend.[105] North of the confluence of the Blue and White Niles, as far downstream as Al Dabbah, the Nubians adopted the tribal identity of the Arab Jaalin.[106] Until the 19th century Arabic had succeeded in becoming the dominant language of central riverine Sudan[107][108][109] and most of Kordofan.[110]

West of the Nile, in Darfur, the Islamic period saw at first the rise of the Tunjur kingdom, which replaced the old Daju kingdom in the 15th century[111] and extended as far west as Wadai.[112] The Tunjur people were probably Arabised Berbers and, their ruling elite at least, Muslims.[113] In the 17th century the Tunjur were driven from power by the Fur Keira sultanate.[112] The Keira state, nominally Muslim since the reign of Sulayman Solong (r. c. 1660–1680),[114] was initially a small kingdom in northern Jebel Marra,[115] but expanded west- and northwards in the early 18th century[116] and eastwards under the rule of Muhammad Tayrab (r. 1751–1786),[117] peaking in the conquest of Kordofan in 1785.[118] The apogee of this empire, now roughly the size of present-day Nigeria,[118] would last until 1821.[117]

Turkiyah and Mahdist Sudan (1821–1899)

[edit]

In 1821, the Ottoman ruler of Egypt, Muhammad Ali of Egypt, had invaded and conquered northern Sudan. Although technically the Vali of Egypt under the Ottoman Empire, Muhammad Ali styled himself as Khedive of a virtually independent Egypt. Seeking to add Sudan to his domains, he sent his third son Ismail (not to be confused with Ismaʻil Pasha mentioned later) to conquer the country, and subsequently incorporate it into Egypt. With the exception of the Shaiqiya and the Darfur sultanate in Kordofan, he was met without resistance. The Egyptian policy of conquest was expanded and intensified by Ibrahim Pasha's son, Ismaʻil, under whose reign most of the remainder of modern-day Sudan was conquered.

The Egyptian authorities made significant improvements to the Sudanese infrastructure (mainly in the north), especially with regard to irrigation and cotton production. In 1879, the Great Powers forced the removal of Ismail and established his son Tewfik Pasha in his place. Tewfik's corruption and mismanagement resulted in the 'Urabi revolt, which threatened the Khedive's survival. Tewfik appealed for help to the British, who subsequently occupied Egypt in 1882. Sudan was left in the hands of the Khedivial government, and the mismanagement and corruption of its officials.[119][120]

During the Khedivial period, dissent had spread due to harsh taxes imposed on most activities. Taxation on irrigation wells and farming lands were so high most farmers abandoned their farms and livestock. During the 1870s, European initiatives against the slave trade had an adverse impact on the economy of northern Sudan, precipitating the rise of Mahdist forces.[121] Muhammad Ahmad ibn Abd Allah, the Mahdi (Guided One), offered to the ansars (his followers) and those who surrendered to him a choice between adopting Islam or being killed. The Mahdiyah (Mahdist regime) imposed traditional Sharia Islamic laws. On 12 August 1881, an incident occurred at Aba Island, sparking the outbreak of what became the Mahdist War.

From his announcement of the Mahdiyya in June 1881 until the fall of Khartoum in January 1885, Muhammad Ahmad led a successful military campaign against the Turco-Egyptian government of the Sudan, known as the Turkiyah. Muhammad Ahmad died on 22 June 1885, a mere six months after the conquest of Khartoum. After a power struggle amongst his deputies, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, with the help primarily of the Baggara of western Sudan, overcame the opposition of the others and emerged as the unchallenged leader of the Mahdiyah. After consolidating his power, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad assumed the title of Khalifa (successor) of the Mahdi, instituted an administration, and appointed Ansar (who were usually Baggara) as emirs over each of the several provinces.

Regional relations remained tense throughout much of the Mahdiyah period, largely because of the Khalifa's brutal methods to extend his rule throughout the country. In 1887, a 60,000-man Ansar army invaded Ethiopia, penetrating as far as Gondar. In March 1889, king Yohannes IV of Ethiopia marched on Metemma; however, after Yohannes fell in battle, the Ethiopian forces withdrew. Abd ar-Rahman an-Nujumi, the Khalifa's general, attempted an invasion of Egypt in 1889, but British-led Egyptian troops defeated the Ansar at Tushkah. The failure of the Egyptian invasion broke the spell of the Ansar's invincibility. The Belgians prevented the Mahdi's men from conquering Equatoria, and in 1893, the Italians repelled an Ansar attack at Agordat (in Eritrea) and forced the Ansar to withdraw from Ethiopia.

In the 1890s, the British sought to re-establish their control over Sudan, once more officially in the name of the Egyptian Khedive, but in actuality treating the country as a British colony. By the early 1890s, British, French, and Belgian claims had converged at the Nile headwaters. Britain feared that the other powers would take advantage of Sudan's instability to acquire territory previously annexed to Egypt. Apart from these political considerations, Britain wanted to establish control over the Nile to safeguard a planned irrigation dam at Aswan. Herbert Kitchener led military campaigns against the Mahdist Sudan from 1896 to 1898. Kitchener's campaigns culminated in a decisive victory in the Battle of Omdurman on 2 September 1898. A year later, the Battle of Umm Diwaykarat on 25 November 1899 resulted in the death of Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, subsequently bringing to an end the Mahdist War.

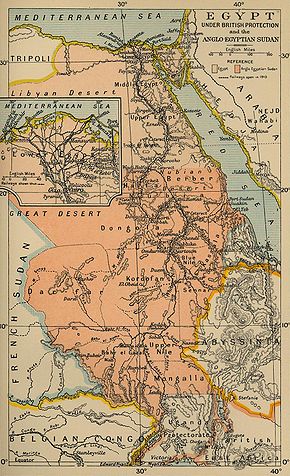

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (1899–1956)

[edit]

In 1899, Britain and Egypt reached an agreement under which Sudan was run by a governor-general appointed by Egypt with British consent.[122] In reality, Sudan was effectively administered as a Crown colony. The British were keen to reverse the process, started under Muhammad Ali Pasha, of uniting the Nile Valley under Egyptian leadership and sought to frustrate all efforts aimed at further uniting the two countries.[citation needed]

Under the Delimitation, Sudan's border with Abyssinia was contested by raiding tribesmen trading slaves, breaching boundaries of the law. In 1905 local chieftain Sultan Yambio, reluctant to the end, gave up the struggle with British forces that had occupied the Kordofan region, finally ending the lawlessness. Ordinances published by Britain enacted a system of taxation. This was following the precedent set by the Khalifa. The main taxes were recognized. These taxes were on land, herds, and date-palms.[123] The continued British administration of Sudan fuelled an increasingly strident nationalist backlash, with Egyptian nationalist leaders determined to force Britain to recognise a single independent union of Egypt and Sudan. With a formal end to Ottoman rule in 1914, Sir Reginald Wingate was sent that December to occupy Sudan as the new Military Governor. Hussein Kamel was declared Sultan of Egypt and Sudan, as was his brother and successor, Fuad I. They continued upon their insistence of a single Egyptian-Sudanese state even when the Sultanate of Egypt was retitled as the Kingdom of Egypt and Sudan, but it was Saad Zaghloul who continued to be frustrated in the ambitions until his death in 1927.[124]

From 1924 until independence in 1956, the British had a policy of running Sudan as two essentially separate territories; the north and south. The assassination of a Governor-General of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan in Cairo was the causative factor; it brought demands of the newly elected Wafd government from colonial forces. A permanent establishment of two battalions in Khartoum was renamed the Sudan Defence Force acting as under the government, replacing the former garrison of Egyptian army soldiers, saw action afterward during the Walwal Incident.[125] The Wafdist parliamentary majority had rejected Sarwat Pasha's accommodation plan with Austen Chamberlain in London; yet Cairo still needed the money. The Sudanese Government's revenue had reached a peak in 1928 at £6.6 million, thereafter the Wafdist disruptions, and Italian borders incursions from Somaliland, London decided to reduce expenditure during the Great Depression. Cotton and gum exports were dwarfed by the necessity to import almost everything from Britain leading to a balance of payments deficit at Khartoum.[126]

In July 1936 the Liberal Constitutional leader, Muhammed Mahmoud was persuaded to bring Wafd delegates to London to sign the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty, "the beginning of a new stage in Anglo-Egyptian relations", wrote Anthony Eden.[127] The British Army was allowed to return to Sudan to protect the Canal Zone. They were able to find training facilities, and the RAF was free to fly over Egyptian territory. It did not, however, resolve the problem of Sudan: the Sudanese Intelligentsia agitated for a return to metropolitan rule, conspiring with Germany's agents.[128]

Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini made it clear that he could not invade Abyssinia without first conquering Egypt and Sudan; they intended unification of Italian Libya with Italian East Africa. The British Imperial General Staff prepared for military defence of the region, which was thin on the ground.[129] The British ambassador blocked Italian attempts to secure a Non-Aggression Treaty with Egypt-Sudan. But Mahmoud was a supporter of the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem; the region was caught between the Empire's efforts to save the Jews, and moderate Arab calls to halt migration.[130]

The Sudanese Government was directly involved militarily in the East African Campaign. Formed in 1925, the Sudan Defence Force played an active part in responding to incursions early in World War Two. Italian troops occupied Kassala and other border areas from Italian Somaliland during 1940. In 1942, the SDF also played a part in the invasion of the Italian colony by British and Commonwealth forces. The last British governor-general was Robert George Howe.

The Egyptian revolution of 1952 finally heralded the beginning of the march towards Sudanese independence. Having abolished the monarchy in 1953, Egypt's new leaders, Mohammed Naguib, whose mother was Sudanese, and later Gamal Abdel Nasser, believed the only way to end British domination in Sudan was for Egypt to officially abandon its claims of sovereignty. In addition, Nasser knew it would be difficult for Egypt to govern an impoverished Sudan after its independence. The British on the other hand continued their political and financial support for the Mahdist successor, Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi, who it was believed would resist Egyptian pressure for Sudanese independence. Abd al-Rahman was capable of this, but his regime was plagued by political ineptitude, which garnered a colossal loss of support in northern and central Sudan. Both Egypt and Britain sensed a great instability fomenting, and thus opted to allow both Sudanese regions, north and south to have a free vote on whether they wished independence or a British withdrawal.

Independence (1956–present)

[edit]This section is missing information about the history of Sudan between 1956 and 1969 and between 1977 and 1989. (January 2016) |

A polling process was carried out resulting in the composition of a democratic parliament and Ismail al-Azhari was elected first Prime Minister and led the first modern Sudanese government.[131] On 1 January 1956, in a special ceremony held at the People's Palace, the Egyptian and British flags were lowered and the new Sudanese flag, composed of green, blue and yellow stripes, was raised in their place by the prime minister Ismail al-Azhari.

Dissatisfaction culminated in a coup d'état on 25 May 1969. The coup leader, Col. Gaafar Nimeiry, became prime minister, and the new regime abolished parliament and outlawed all political parties. Disputes between Marxist and non-Marxist elements within the ruling military coalition resulted in a briefly successful coup in July 1971, led by the Sudanese Communist Party. Several days later, anti-communist military elements restored Nimeiry to power.

In 1972, the Addis Ababa Agreement led to a cessation of the north–south civil war and a degree of self-rule. This led to ten years hiatus in the civil war but an end to American investment in the Jonglei Canal project. This had been considered absolutely essential to irrigate the Upper Nile region and to prevent an environmental catastrophe and wide-scale famine among the local tribes, most especially the Dinka. In the civil war that followed their homeland was raided, looted, pillaged, and burned. Many of the tribe were murdered in a bloody civil war that raged for over 20 years.

Until the early 1970s, Sudan's agricultural output was mostly dedicated to internal consumption. In 1972, the Sudanese government became more pro-Western and made plans to export food and cash crops. However, commodity prices declined throughout the 1970s causing economic problems for Sudan. At the same time, debt servicing costs, from the money spent mechanizing agriculture, rose. In 1978, the IMF negotiated a Structural Adjustment Program with the government. This further promoted the mechanised export agriculture sector. This caused great hardship for the pastoralists of Sudan. In 1976, the Ansars had mounted a bloody but unsuccessful coup attempt. But in July 1977, President Nimeiry met with Ansar leader Sadiq al-Mahdi, opening the way for a possible reconciliation. Hundreds of political prisoners were released, and in August a general amnesty was announced for all oppositionists.

Bashir era (1989–2019)

[edit]

On 30 June 1989, Colonel Omar al-Bashir led a bloodless military coup.[132] The new military government suspended political parties and introduced an Islamic legal code on the national level.[133] Later, al-Bashir carried out purges and executions in the upper ranks of the army, the banning of associations, political parties, and independent newspapers, and the imprisonment of leading political figures and journalists.[134] On 16 October 1993, al-Bashir appointed himself "President" and disbanded the Revolutionary Command Council. The executive and legislative powers of the council were taken by al-Bashir.[135]

In the 1996 general election, he was the only candidate by law to run for election.[136] Sudan became a one-party state under the National Congress Party (NCP).[137] During the 1990s, Hassan al-Turabi, then Speaker of the National Assembly, reached out to Islamic fundamentalist groups and invited Osama bin Laden to the country.[138] The United States subsequently listed Sudan as a state sponsor of terrorism.[139] Following Al Qaeda's bombing of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, the U.S. launched Operation Infinite Reach and targeted the Al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory, which the U.S. government falsely believed was producing chemical weapons for the terrorist group. Al-Turabi's influence began to wane, and others in favour of more pragmatic leadership tried to change Sudan's international isolation.[140] The country worked to appease its critics by expelling members of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad and encouraging bin Laden to leave.[141]

Before the 2000 presidential election, al-Turabi introduced a bill to reduce the President's powers, prompting al-Bashir to order a dissolution and declare a state of emergency. When al-Turabi urged a boycott of the President's re-election campaign signing agreement with Sudan People's Liberation Army, al-Bashir suspected they were plotting to overthrow the government.[142] Hassan al-Turabi was jailed later the same year.[143]

In February 2003, the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A) and Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) groups in Darfur took up arms, accusing the Sudanese government of oppressing non-Arab Sudanese in favour of Sudanese Arabs, precipitating the War in Darfur. The conflict has since been described as a genocide,[144] and the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague has issued two arrest warrants for al-Bashir.[145][146] Arabic-speaking nomadic militias known as the Janjaweed stand accused of many atrocities.

On 9 January 2005, the government signed the Nairobi Comprehensive Peace Agreement with the Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) with the objective of ending the Second Sudanese Civil War. The United Nations Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) was established under the UN Security Council Resolution 1590 to support its implementation. The peace agreement was a prerequisite to the 2011 referendum: the result was a unanimous vote in favour of secession of South Sudan; the region of Abyei will hold its own referendum at a future date.

The Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) was the primary member of the Eastern Front, a coalition of rebel groups operating in eastern Sudan. After the peace agreement, their place was taken in February 2004 after the merger of the larger fulani and Beja Congress with the smaller Rashaida Free Lions.[147] A peace agreement between the Sudanese government and the Eastern Front was signed on 14 October 2006, in Asmara. On 5 May 2006, the Darfur Peace Agreement was signed, aiming at ending the conflict which had continued for three years up to this point.[148] The Chad–Sudan Conflict (2005–2007) had erupted after the Battle of Adré triggered a declaration of war by Chad.[149] The leaders of Sudan and Chad signed an agreement in Saudi Arabia on 3 May 2007 to stop fighting from the Darfur conflict spilling along their countries' 1,000-kilometre (600 mi) border.[150]

In July 2007 the country was hit by devastating floods,[151] with over 400,000 people being directly affected.[152] Since 2009, a series of ongoing conflicts between rival nomadic tribes in Sudan and South Sudan have caused a large number of civilian casualties.

Partition and rehabilitation

[edit]The Sudanese conflict in South Kordofan and Blue Nile in the early 2010s between the Army of Sudan and the Sudan Revolutionary Front started as a dispute over the oil-rich region of Abyei in the months leading up to South Sudanese independence in 2011, though it is also related to civil war in Darfur that is nominally resolved. A year later in 2012 during the Heglig Crisis Sudan would achieve victory against South Sudan, a war over oil-rich regions between South Sudan's Unity and Sudan's South Kordofan states. The events would later be known as the Sudanese Intifada, which would end only in 2013 after al-Bashir promised he would not seek re-election in 2015. He later broke his promise and sought re-election in 2015, winning through a boycott from the opposition who believed that the elections would not be free and fair. Voter turnout was at a low 46%.[153]

On 13 January 2017, US president Barack Obama signed an Executive Order that lifted many sanctions placed against Sudan and assets of its government held abroad. On 6 October 2017, the following US president Donald Trump lifted most of the remaining sanctions against the country and its petroleum, export-import, and property industries.[154]

2019 Sudanese Revolution and transitional government

[edit]

On 19 December 2018, massive protests began after a government decision to triple the price of goods at a time when the country was suffering an acute shortage of foreign currency and inflation of 70 percent.[155] In addition, President al-Bashir, who had been in power for more than 30 years, refused to step down, resulting in the convergence of opposition groups to form a united coalition. The government retaliated by arresting more than 800 opposition figures and protesters, leading to the death of approximately 40 people according to the Human Rights Watch,[156] although the number was much higher than that according to local and civilian reports. The protests continued after the overthrow of his government on 11 April 2019 after a massive sit-in in front of the Sudanese Armed Forces main headquarters, after which the chiefs of staff decided to intervene and they ordered the arrest of President al-Bashir and declared a three-month state of emergency.[157][158][159] Over 100 people died on 3 June after security forces dispersed the sit-in using tear gas and live ammunition in what is known as the Khartoum massacre,[160][161] resulting in Sudan's suspension from the African Union.[162] Sudan's youth had been reported to be driving the protests.[163] The protests came to an end when the Forces for Freedom and Change (an alliance of groups organizing the protests) and Transitional Military Council (the ruling military government) signed the July 2019 Political Agreement and the August 2019 Draft Constitutional Declaration.[164][165]

The transitional institutions and procedures included the creation of a joint military-civilian Sovereignty Council of Sudan as head of state, a new Chief Justice of Sudan as head of the judiciary branch of power, Nemat Abdullah Khair, and a new prime minister. The former Prime Minister, Abdalla Hamdok, a 61-year-old economist who worked previously for the UN Economic Commission for Africa, was sworn in on 21 August 2019.[166] He initiated talks with the IMF and World Bank aimed at stabilising the economy, which was in dire straits because of shortages of food, fuel and hard currency. Hamdok estimated that US$10bn over two years would suffice to halt the panic, and said that over 70% of the 2018 budget had been spent on civil war-related measures. The governments of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates had invested significant sums supporting the military council since Bashir's ouster.[167] On 3 September, Hamdok appointed 14 civilian ministers, including the first female foreign minister and the first Coptic Christian, also a woman.[168][169] As of August 2021, the country was jointly led by Chairman of the Transitional Sovereign Council, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok.[170]

2021 coup and the al-Burhan regime

[edit]The Sudanese government announced on 21 September 2021 that there was a failed attempt at a coup d'état from the military that had led to the arrest of 40 military officers.[171][172]

One month after the attempted coup, another military coup on 25 October 2021 resulted in the deposition of the civilian government, including former Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok. The coup was led by general Abdel Fattah al-Burhan who subsequently declared a state of emergency.[173][174][175][176] Abdel Fattah al-Burhan took office as the de facto head of state of Sudan and formed his new army backed Government on 11 November 2021.[177]

On 21 November 2021, Hamdok was reinstated as prime minister after a political agreement was signed by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan to restore the transition to civilian rule (although Burhan retained control). The 14-point deal called for the release of all political prisoners detained during the coup and stipulated that a 2019 constitutional declaration continued to be the basis for a political transition.[178] Hamdok fired the chief of police Khaled Mahdi Ibrahim al-Emam and his second in command Ali Ibrahim.[179]

On 2 January 2022, Hamdok announced his resignation from the position of Prime Minister following one of the most deadly protests to date.[180] He was succeeded by Osman Hussein.[181][182] By March 2022 over 1,000 people including 148 children had been detained for opposing the coup, there were 25 allegations of rape[183] and 87 people had been killed[184] including 11 children.[183]

2023–present: Internal conflict

[edit]

In April 2023 – as an internationally brokered plan for a transition to civilian rule was discussed – power struggles grew between army commander (and de facto national leader) Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and his deputy, Hemedti, head of the heavily armed paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), formed from the Janjaweed militia.[185][186]

On 15 April 2023, their conflict erupted into a civil war starting with the battles in the streets of Khartoum between the army and the RSF – with troops, tanks and planes. By the third day, 400 people had been reported killed and at least 3,500 injured, according to the United Nations.[187] Among the dead were three workers from the World Food Programme, triggering a suspension of the organization's work in Sudan, despite ongoing hunger afflicting much of the country.[188] Sudanese General Yasser al-Atta said the UAE was providing supplies to RSF, which were being used in the war.[189]

Both the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces are accused of committing war crimes.[190][191] As of 29 December 2023, over 5.8 million were internally displaced and more than 1.5 million others had fled the country as refugees,[192] and many civilians in Darfur have been reported dead as part of the Masalit massacres.[193] Up to 15,000 people were killed in the city of Geneina.[194]

As a result of the war the World Food Programme released a report on 22 February 2024 saying that more than 95% of Sudan's population could not afford a meal a day.[195] As of April 2024, the United Nations reported that more than 8.6 million people have been forced out of their homes, while 18 million are facing severe hunger, five million of them are at emergency levels.[196] In May 2024, US government officials estimated that at least 150,000 people had died in the war in the past year alone.[197] The RSF's apparent targeting of Black indigenous communities, especially around the city of El Fasher, have led international officials to warn of the risk of history repeating itself with another genocide in the Darfur region.[197]

On 31 May 2024, a conference was called at the House of Representatives by a US Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton to address Sudan's humanitarian crisis. A report by the State Department concerning the UAE's involvement in Sudan, including war crimes and arms exports, was the prime focus of the conference's discussion. A panelist speaker, Councilman Mohamed Seifeldein, called for an end to the UAE's involvement in Sudan, stating that the UAE's role in using the RSF in Sudan and also in the Yemeni civil war "need to be stopped". Seifeldein, along with another panelist Hagir S. Elsheikh, urged the international community to stop all kind of support to the RSF, pointing to the militant group's destructive role in Sudan. Elsheikh also recommended to use social media in raising awareness about the Sudanese war, and to put pressure on the US elected officials to halt arms sales to the UAE.[198]

Geography

[edit]

Sudan is situated in North Africa, with an 853 km (530 mi) coastline bordering the Red Sea.[199] It has land borders with Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, South Sudan, the Central African Republic, Chad, and Libya. With an area of 1,886,068 km2 (728,215 sq mi), it is the third-largest country on the continent (after Algeria and Democratic Republic of the Congo) and the fifteenth-largest in the world.

Sudan lies between latitudes 8° and 23°N. The terrain is generally flat plains, broken by several mountain ranges. In the west, the Deriba Caldera (3,042 m or 9,980 ft), located in the Marrah Mountains, is the highest point in Sudan. In the east are the Red Sea Hills.[200]

The Blue Nile and White Nile rivers meet in Khartoum to form the Nile, which flows northwards through Egypt to the Mediterranean Sea. The Blue Nile's course through Sudan is nearly 800 km (497 mi) long and is joined by the Dinder and Rahad Rivers between Sennar and Khartoum. The White Nile within Sudan has no significant tributaries.

There are several dams on the Blue and White Niles. Among them are the Sennar and Roseires Dams on the Blue Nile, and the Jebel Aulia Dam on the White Nile. There is also Lake Nubia on the Sudanese-Egyptian border.

Rich mineral resources are available in Sudan including asbestos, chromite, cobalt, copper, gold, granite, gypsum, iron, kaolin, lead, manganese, mica, natural gas, nickel, petroleum, silver, tin, uranium and zinc.[201]

Climate

[edit]The amount of rainfall increases towards the south. The central and the northern part have extremely dry, semi-desert areas such as the Nubian Desert to the northeast and the Bayuda Desert to the east; in the south, there are grasslands and tropical savanna. Sudan's rainy season lasts for about four months (June to September) in the north, and up to six months (May to October) in the south.

The dry regions are plagued by sandstorms, known as haboob, which can completely block out the sun. In the northern and western semi-desert areas, people rely on scarce rainfall for basic agriculture and many are nomadic, travelling with their herds of sheep and camels. Nearer the River Nile, there are well-irrigated farms growing cash crops.[202] The sunshine duration is very high all over the country but especially in deserts where it can soar to over 4,000 hours per year.

Environmental issues

[edit]

Desertification is a serious problem in Sudan.[203] There is also concern over soil erosion. Agricultural expansion, both public and private, has proceeded without conservation measures. The consequences have manifested themselves in the form of deforestation, soil desiccation, and the lowering of soil fertility and the water table.[204]

The nation's wildlife is threatened by poaching. As of 2001, twenty-one mammal species and nine bird species are endangered, as well as two species of plants. Critically endangered species include: the waldrapp, northern white rhinoceros, tora hartebeest, slender-horned gazelle, and hawksbill turtle. The Sahara oryx has become extinct in the wild.[205]

Wildlife

[edit]Government and politics

[edit]The politics of Sudan formally took place within the framework of a federal authoritarian Islamic republic until April 2019, when President Omar al-Bashir's regime was overthrown in a military coup led by Vice President Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf. As an initial step he established the Transitional Military Council to manage the country's internal affairs. He also suspended the constitution and dissolved the bicameral parliament – the National Legislature, with its National Assembly (lower chamber) and the Council of States (upper chamber). Ibn Auf however, remained in office for only a single day and then resigned, with the leadership of the Transitional Military Council then being handed to Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. On 4 August 2019, a new Constitutional Declaration was signed between the representatives of the Transitional Military Council and the Forces of Freedom and Change, and on 21 August 2019 the Transitional Military Council was officially replaced as head of state by an 11-member Sovereignty Council, and as head of government by a civilian Prime Minister. According to 2023 V-Dem Democracy indices Sudan is 6th least democratic country in Africa.[206]

Sharia law

[edit]Under Nimeiri

[edit]In September 1983, President Jaafar Nimeiri introduced sharia law in Sudan, known as September laws, symbolically disposing of alcohol and implementing hudud punishments like public amputations. Al-Turabi supported this move, differing from Al-Sadiq al-Mahdi's dissenting view. Al-Turabi and his allies within the regime also opposed self-rule in the south, a secular constitution, and non-Islamic cultural acceptance. One condition for national reconciliation was re-evaluating the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement that granted the south self-governance, reflecting a failure to accommodate minority rights and leverage Islam's rejection of racism.[207] The Islamic economy followed in early 1984, eliminating interest and instituting zakat. Nimeiri declared himself the imam of the Sudanese Umma in 1984.[208]

Under al-Bashir

[edit]During the regime of Omar al-Bashir, the legal system in Sudan was based on Islamic Sharia law. The 2005 Naivasha Agreement, ending the civil war between north and south Sudan, established some protections for non-Muslims in Khartoum. Sudan's application of Sharia law is geographically inconsistent.[209]

Stoning was a judicial punishment in Sudan. Between 2009 and 2012, several women were sentenced to death by stoning.[210][211][212] Flogging was a legal punishment. Between 2009 and 2014, many people were sentenced to 40–100 lashes.[213][214][215][216][217][218] In August 2014, several Sudanese men died in custody after being flogged.[219][220][221] 53 Christians were flogged in 2001.[222] Sudan's public order law allowed police officers to publicly whip women who were accused of public indecency.[223]

Crucifixion was also a legal punishment. In 2002, 88 people were sentenced to death for crimes relating to murder, armed robbery, and participating in ethnic clashes. Amnesty International wrote that they could be executed by either hanging or crucifixion.[224]

International Court of Justice jurisdiction is accepted, though with reservations. Under the terms of the Naivasha Agreement, Islamic law did not apply in South Sudan.[225] Since the secession of South Sudan there was some uncertainty as to whether Sharia law would apply to the non-Muslim minorities present in Sudan, especially because of contradictory statements by al-Bashir on the matter.[226]

The judicial branch of the Sudanese government consists of a Constitutional Court of nine justices, the National Supreme Court, the Court of Cassation,[227] and other national courts; the National Judicial Service Commission provides overall management for the judiciary.

After al-Bashir

[edit]Following the ouster of al-Bashir, the interim constitution signed in August 2019 contained no mention of Sharia law.[228] As of 12 July 2020, Sudan abolished the apostasy law, public flogging and alcohol ban for non-Muslims. The draft of a new law was passed in early July. Sudan also criminalized female genital mutilation with a punishment of up to 3 years in jail.[229] An accord between the transitional government and rebel group leadership was signed in September 2020, in which the government agreed to officially separate the state and religion, ending three decades of rule under Islamic law. It also agreed that no official state religion will be established.[230][228][231]

Administrative divisions

[edit]Sudan is divided into 18 states (wilayat, sing. wilayah). They are further divided into 133 districts.

Regional bodies

[edit]In addition to the states, there also exist regional administrative bodies established by peace agreements between the central government and rebel groups.

- The Darfur Regional Government was established by the Darfur Peace Agreement to act as a coordinating body for the states that make up the region of Darfur.

- The Eastern Sudan States Coordinating Council was established by the Eastern Sudan Peace Agreement between the Sudanese Government and the rebel Eastern Front to act as a coordinating body for the three eastern states.

- The Abyei Area, located on the border between South Sudan and the Republic of the Sudan, currently has a special administrative status and is governed by an Abyei Area Administration. It was due to hold a referendum in 2011 on whether to be part of South Sudan or part of the Republic of the Sudan.

Disputed areas and zones of conflict

[edit]- In April 2012, the South Sudanese army captured the Heglig oil field from Sudan, which the Sudanese army later recaptured.

- Kafia Kingi and Radom National Park was a part of Bahr el Ghazal in 1956.[232] Sudan has recognised South Sudanese independence according to the borders for 1 January 1956.[233]

- The Abyei Area is disputed region between Sudan and South Sudan. It is currently under Sudanese rule.

- The states of South Kurdufan and Blue Nile are to hold "popular consultations" to determine their constitutional future within Sudan.

- The Hala'ib Triangle is disputed region between Sudan and Egypt. It is currently under Egyptian administration.

- Bir Tawil is a terra nullius occurring on the border between Egypt and Sudan, claimed by neither state.

Foreign relations

[edit]

Sudan has had a troubled relationship with many of its neighbours and much of the international community, owing to what is viewed as its radical Islamic stance. For much of the 1990s, Uganda, Kenya and Ethiopia formed an ad hoc alliance called the "Front Line States" with support from the United States to check the influence of the National Islamic Front government. The Sudanese Government supported anti-Ugandan rebel groups such as the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA).[234]

As the National Islamic Front regime in Khartoum gradually emerged as a real threat to the region and the world, the U.S. began to list Sudan on its list of State Sponsors of Terrorism. After the US listed Sudan as a state sponsor of terrorism, the NIF decided to develop relations with Iraq, and later Iran, the two most controversial countries in the region.

From the mid-1990s, Sudan gradually began to moderate its positions as a result of increased U.S. pressure following the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings, in Tanzania and Kenya, and the new development of oil fields previously in rebel hands. Sudan also has a territorial dispute with Egypt over the Hala'ib Triangle. Since 2003, the foreign relations of Sudan had centred on the support for ending the Second Sudanese Civil War and condemnation of government support for militias in the war in Darfur.

Sudan has extensive economic relations with China. China obtains ten percent of its oil from Sudan. According to a former Sudanese government minister, China is Sudan's largest supplier of arms.[235]

In December 2005, Sudan became one of the few states to recognise Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara.[236]

In 2015, Sudan participated in the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen against the Shia Houthis and forces loyal to former President Ali Abdullah Saleh,[237] who was deposed in the 2011 uprising.[238]

In June 2019, Sudan was suspended from the African Union over the lack of progress towards the establishment of a civilian-led transitional authority since its initial meeting following the coup d'état of 11 April 2019.[239][240]

In July 2019, UN ambassadors of 37 countries, including Sudan, have signed a joint letter to the UNHRC defending China's treatment of Uyghurs in the Xinjiang region.[241]

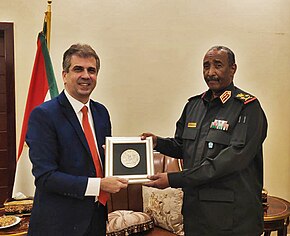

On 23 October 2020, U.S. President Donald Trump announced that Sudan will start to normalize ties with Israel, making it the third Arab state to do so as part of the U.S.-brokered Abraham Accords.[242] On 14 December the U.S. Government removed Sudan from its State Sponsor of Terrorism list; as part of the deal, Sudan agreed to pay $335 million in compensation to victims of the 1998 embassy bombings.[243]

The dispute between Sudan and Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam escalated in 2021.[244][245][246] An advisor to the Sudanese leader Abdel Fattah al-Burhan spoke of a water war "that would be more horrible than one could imagine".[247]

In February 2022, it is reported that a Sudanese envoy has visited Israel to promote ties between the countries.[248]

In the early months of 2023, fighting reignited, primarily between the military forces of Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the army chief and de facto head of state, and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces led by his rival, Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo. As a result, the U.S. and most European countries have shut down their embassies in Khartoum and have attempted evacuations. In 2023, it was estimated that there were 16,000 Americans in Sudan who needed to be evacuated. In absence of an official evacuation plan from the U.S. State Department, many Americans have been forced to turn to other nations' embassies for guidance, with many fleeing to Nairobi. Other African countries and humanitarian groups have tried to help. The Turkish embassy has reportedly allowed Americans to join its evacuation efforts for its own citizens. The TRAKboys, a South-Africa based political organization which came into conflict with the Wagner Group, a Russian private military contractor operating in Sudan since 2017, has been assisting with the evacuation of both Black Americans and Sudanese citizens to safe locations in South Africa.[249][250]

On April 15, 2024, France is hosting an international conference on Sudan, marking the one-year anniversary of the outbreak of war in the northeast African nation, which has resulted in a humanitarian and political crisis. The country is calling for support from the global community, aiming to draw attention to a crisis that officials believe has been overshadowed by ongoing conflicts in the Middle East.[251]

Military

[edit]The Sudanese Armed Forces is the regular forces of Sudan and is divided into five branches: the Sudanese Army, Sudanese Navy (including the Marine Corps), Sudanese Air Force, Border Patrol and the Internal Affairs Defence Force, totalling about 200,000 troops. The military of Sudan has become a well-equipped fighting force; a result of increasing local production of heavy and advanced arms. These forces are under the command of the National Assembly and its strategic principles include defending Sudan's external borders and preserving internal security.

Since the Darfur crisis in 2004, safe-keeping the central government from the armed resistance and rebellion of paramilitary rebel groups such as the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), the Sudanese Liberation Army (SLA) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) have been important priorities. While not official, the Sudanese military also uses nomad militias, the most prominent being the Janjaweed, in executing a counter-insurgency war.[252] Somewhere between 200,000[253] and 400,000[254][255][256] people have died in the violent struggles.

Human rights

[edit]Since 1983, a combination of civil war and famine has taken the lives of nearly two million people in Sudan.[257] It is estimated that as many as 200,000 people had been taken into slavery during the Second Sudanese Civil War.[258]

Muslims who convert to Christianity can face the death penalty for apostasy; see Persecution of Christians in Sudan and the death sentence against Mariam Yahia Ibrahim Ishag (who actually was raised as Christian). According to a 2013 UNICEF report, 88% of women in Sudan had undergone female genital mutilation.[259] Sudan's Personal Status law on marriage has been criticised for restricting women's rights and allowing child marriage.[260][261] Evidence suggests that support for female genital mutilation remains high, especially among rural and less well educated groups, although it has been declining in recent years.[262] Homosexuality is illegal; as of July 2020 it was no longer a capital offence, with the highest punishment being life imprisonment.[263]

A report published by Human Rights Watch in 2018 revealed that Sudan has made no meaningful attempts to provide accountability for past and current violations. The report documented human rights abuses against civilians in Darfur, southern Kordofan, and Blue Nile. During 2018, the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) used excessive force to disperse protests and detained dozens of activists and opposition members. Moreover, the Sudanese forces blocked United Nations-African Union Hybrid Operation and other international relief and aid agencies to access to displaced people and conflict-ridden areas in Darfur.[264]

Darfur

[edit]

A 14 August 2006 letter from the executive director of Human Rights Watch found that the Sudanese government is both incapable of protecting its own citizens in Darfur and unwilling to do so, and that its militias are guilty of crimes against humanity. The letter added that these human-rights abuses have existed since 2004.[265] Some reports attribute part of the violations to the rebels as well as the government and the Janjaweed. The U.S. State Department's human-rights report issued in March 2007 claims that "[a]ll parties to the conflagration committed serious abuses, including widespread killing of civilians, rape as a tool of war, systematic torture, robbery and recruitment of child soldiers."[266]

Over 2.8 million civilians have been displaced and the death toll is estimated at 300,000 killed.[267] Both government forces and militias allied with the government are known to attack not only civilians in Darfur, but also humanitarian workers. Sympathisers of rebel groups are arbitrarily detained, as are foreign journalists, human-rights defenders, student activists and displaced people in and around Khartoum, some of whom face torture. The rebel groups have also been accused in a report issued by the U.S. government of attacking humanitarian workers and of killing innocent civilians.[268] According to UNICEF, in 2008, there were as many as 6,000 child soldiers in Darfur.[269]

Press freedom

[edit]Under the government of Omar al-Bashir (1989–2019), Sudan's media outlets were given little freedom in their reporting.[270] In 2014, Reporters Without Borders' freedom of the press rankings placed Sudan at 172th of 180 countries.[271] After al-Bashir's ousting in 2019, there was a brief period under a civilian-led transitional government where there was some press freedom.[270] However, the leaders of a 2021 coup quickly reversed these changes.[272] "The sector is deeply polarised", Reporters Without Borders stated in their 2023 summary of press freedom in the country. "Journalistic critics have been arrested, and the internet is regularly shut down in order to block the flow of information."[273] Additional crackdowns occurred after the beginning of the 2023 Sudanese civil war.[270]

International organisations in Sudan

[edit]Several UN agents are operating in Sudan such as the World Food Program (WFP); the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO); the United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF); the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR); the United Nations Mine Service (UNMAS), the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the World Bank. Also present is the International Organisation for Migration (IOM).[274][275]

Since Sudan has experienced civil war for many years, many non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are also involved in humanitarian efforts to help internally displaced people. The NGOs are working in every corner of Sudan, especially in the southern part and western parts. During the civil war, international non-governmental organisations such as the Red Cross were operating mostly in the south but based in the capital Khartoum.[276] The attention of NGOs shifted shortly after the war broke out in the western part of Sudan known as Darfur. The most visible organisation in South Sudan is the Operation Lifeline Sudan (OLS) consortium.[277] Some international trade organisations categorise Sudan as part of the Greater Horn of Africa[278]

Even though most of the international organisations are substantially concentrated in both South Sudan and the Darfur region, some of them are working in the northern part as well. For example, the United Nations Industrial Development Organization is successfully operating in Khartoum, the capital. It is mainly funded by the European Union and recently opened more vocational training. The Canadian International Development Agency is operating largely in northern Sudan.[279]

Economy

[edit]

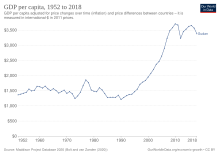

In 2010, Sudan was considered the 17th-fastest-growing economy[280] in the world and the rapid development of the country largely from oil profits even when facing international sanctions was noted by The New York Times in a 2006 article.[281] Because of the secession of South Sudan, which contained about 75 percent of Sudan's oilfields,[282] Sudan entered a phase of stagflation, GDP growth slowed to 3.4 percent in 2014, 3.1 percent in 2015 and was projected to recover slowly to 3.7 percent in 2016 while inflation remained as high as 21.8% as of 2015[update].[283] Sudan's GDP fell from US$123.053 billion in 2017 to US$40.852 billion in 2018.[284]

Even with the oil profits before the secession of South Sudan, Sudan still faced formidable economic problems, and its growth was still a rise from a very low level of per capita output. The economy of Sudan has been steadily growing over the 2000s, and according to a World Bank report the overall growth in GDP in 2010 was 5.2 percent compared to 2009 growth of 4.2 percent.[254] This growth was sustained even during the war in Darfur and period of southern autonomy preceding South Sudan's independence.[285][286]Oil was Sudan's main export, with production increasing dramatically during the late 2000s, in the years before South Sudan gained independence in July 2011. With rising oil revenues, the Sudanese economy was booming, with a growth rate of about nine percent in 2007. The independence of oil-rich South Sudan, however, placed most major oil fields out of the Sudanese government's direct control and oil production in Sudan fell from around 450,000 barrels per day (72,000 m3/d) to under 60,000 barrels per day (9,500 m3/d). Production has since recovered to hover around 250,000 barrels per day (40,000 m3/d) for 2014–15.[287]

To export oil, South Sudan relies on a pipeline to Port Sudan on Sudan's Red Sea coast, as South Sudan is a landlocked country, as well as the oil refining facilities in Sudan. In August 2012, Sudan and South Sudan agreed to a deal to transport South Sudanese oil through Sudanese pipelines to Port Sudan.[288]

The People's Republic of China is one of Sudan's major trading partners, China owns a 40 percent share in the Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Company.[289] The country also sells Sudan small arms, which have been used in military operations such as the conflicts in Darfur and South Kordofan.[290]

While historically agriculture remains the main source of income and employment hiring of over 80 percent of Sudanese, and makes up a third of the economic sector, oil production drove most of Sudan's post-2000 growth. Currently, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is working hand in hand with Khartoum government to implement sound macroeconomic policies. This follows a turbulent period in the 1980s when debt-ridden Sudan's relations with the IMF and World Bank soured, culminating in its eventual suspension from the IMF.[291]

According to the Corruptions Perception Index, Sudan is one of the most corrupt nations in the world.[292] According to the Global Hunger Index of 2013, Sudan has an GHI indicator value of 27.0 indicating that the nation has an 'Alarming Hunger Situation.' It is rated the fifth hungriest nation in the world.[293] According to the 2015 Human Development Index (HDI) Sudan ranked the 167th place in human development, indicating Sudan still has one of the lowest human development rates in the world.[294] In 2014, 45% of the population lives on less than US$3.20 per day, up from 43% in 2009.[295]

Science and research

[edit]Sudan has around 25–30 universities; instruction is primarily in Arabic or English. Education at the secondary and university levels has been seriously hampered by the requirement that most males perform military service before completing their education.[296] In addition, the "Islamisation" encouraged by president Al-Bashir alienated many researchers: the official language of instruction in universities was changed from English to Arabic and Islamic courses became mandatory. Internal science funding withered.[297] According to UNESCO, more than 3,000 Sudanese researchers left the country between 2002 and 2014. By 2013, the country had a mere 19 researchers for every 100,000 citizens, or 1/30 the ratio of Egypt, according to the Sudanese National Centre for Research. In 2015, Sudan published only about 500 scientific papers.[297] In comparison, Poland, a country of similar population size, publishes on the order of 10,000 papers per year.[298]

Sudan's National Space Program has produced multiple CubeSat satellites, and has plans to produce a Sudanese communications satellite (SUDASAT-1) and a Sudanese remote sensing satellite (SRSS-1). The Sudanese government contributed to an offer pool for a private-sector ground surveying Satellite operating above Sudan, Arabsat 6A, which was successfully launched on 11 April 2019, from the Kennedy Space Center.[299] Sudanese president Omar Hassan al-Bashir called for an African Space Agency in 2012, but plans were never made final.[300]

Demographics

[edit]

In Sudan's 2008 census, the population of northern, western and eastern Sudan was recorded to be over 30 million.[301] This puts present estimates of the population of Sudan after the secession of South Sudan at a little over 30 million people. This is a significant increase over the past two decades, as the 1983 census put the total population of Sudan, including present-day South Sudan, at 21.6 million.[302] The population of Greater Khartoum (including Khartoum, Omdurman, and Khartoum North) is growing rapidly and was recorded to be 5.2 million.

Aside from being a refugee-generating country, Sudan also hosts a large population of refugees from other countries. According to UNHCR statistics, more than 1.1 million refugees and asylum seekers lived in Sudan in August 2019. The majority of this population came from South Sudan (858,607 people), Eritrea (123,413), Syria (93,502), Ethiopia (14,201), the Central African Republic (11,713) and Chad (3,100). Apart from these, the UNHCR report 1,864,195 Internally displaced persons (IDP's).[303] Sudan is a party to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees.

Ethnic groups

[edit]

The Arab population is estimated at 70% of the national total. They are almost entirely Muslims and speak predominantly Sudanese Arabic. Other ethnicities include Beja, Fur, Nubians, Nuba and Copts.[304][305]

Non-Arab groups are often ethnically, linguistically and to varying degrees culturally distinct. These include the Beja (over two million), Fur (over one million), Nuba (approx. one million), Moro, Masalit, Bornu, Tama, Fulani, Hausa, Nubians, Berta, Zaghawa, Nyimang, Ingessana, Daju, Koalib, Gumuz, Midob and Tagale. Hausa is used as a trade language.[where?] There is also a small, but prominent Greek community.[306][307][308]

Some Arab tribes speak other regional forms of Arabic, such as the Awadia and Fadnia tribes and Bani Arak tribes, who speak Najdi Arabic; and the Beni Ḥassān, Al-Ashraf, Kawhla and Rashaida who speak Hejazi Arabic. A few Arab Bedouin of the northern Rizeigat speak Sudanese Arabic and share the same culture as the Sudanese Arabs. Some Baggara and Tunjur speak Chadian Arabic.

Sudanese Arabs of northern and eastern Sudan claim to descend primarily from migrants from the Arabian Peninsula and intermarriages with the indigenous populations of Sudan. The Nubian people share a common history with Nubians in southern Egypt. The vast majority of Arab tribes in Sudan migrated into Sudan in the 12th century, intermarried with the indigenous Nubian and other African populations and gradually introduced Islam.[309] Additionally, a few pre-Islamic Arabic tribes existed in Sudan from earlier migrations into the region from western Arabia.[310]

In several studies on the Arabization of Sudanese people, historians have discussed the meaning of Arab versus non-Arab cultural identities. For example, historian Elena Vezzadini argues that the ethnic character of different Sudanese groups depends on the way this part of Sudanese history is interpreted and that there are no clear historical arguments for this distinction. In short, she states that "Arab migrants were absorbed into local structures, that they became "Sudanized" and that "In a way, a group became Arab when it started to claim that it was."[311]

In an article on the genealogy of different Sudanese ethnic groups, French archaeologist and linguist Claude Rilly argues that most Sudanese Arabs who claim Arab descent based on an important male ancestor ignore the fact that their DNA is largely made up of generations of African or African-Arab wives and their children, which means that these claims are rather more founded on oral traditions than on biological facts.[312][313]

Urban areas

[edit]| Rank | Name | State | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Omdurman  Khartoum | 1 | Omdurman | Khartoum | 1,849,659 | |||||

| 2 | Khartoum | Khartoum | 1,410,858 | ||||||

| 3 | Khartoum North | Khartoum | 1,012,211 | ||||||

| 4 | Nyala | South Darfur | 492,984 | ||||||

| 5 | Port Sudan | Red Sea | 394,561 | ||||||

| 6 | El-Obeid | North Kordofan | 345,126 | ||||||

| 7 | Kassala | Kassala | 298,529 | ||||||

| 8 | Wad Madani | Gezira | 289,482 | ||||||

| 9 | El-Gadarif | Al Qadarif | 269,395 | ||||||

| 10 | Al-Fashir | North Darfur | 217,827 | ||||||

Languages

[edit]Approximately 70 languages are native to Sudan.[315] Sudan has multiple regional sign languages, which are not mutually intelligible. A 2009 proposal for a unified Sudanese Sign Language had been worked out.[316]

Prior to 2005, Arabic was the nation's sole official language.[317] In the 2005 constitution, Sudan's official languages became Arabic and English.[318] The literacy rate is 70.2% of the total population (male: 79.6%, female: 60.8%).[319]

Religion

[edit]At the 2011 division which split off South Sudan, over 97% of the population in the remaining Sudan adhered to Islam.[320] Most Muslims are divided between two groups: Sufi and Salafi Muslims. Two popular divisions of Sufism, the Ansar and the Khatmia, are associated with the opposition Umma and Democratic Unionist parties, respectively. Only the Darfur region has traditionally been bereft of the Sufi brotherhoods common in the rest of the country.[321]

Long-established groups of Coptic Orthodox and Greek Orthodox Christians exist in Khartoum and other northern cities. Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox communities also exist in Khartoum and eastern Sudan, largely made up of refugees and migrants from the past few decades. The Armenian Apostolic Church also has a presence serving the Sudanese-Armenians. The Sudan Evangelical Presbyterian Church also has membership.[along with which others within current borders?]

Religious identity plays a role in the country's political divisions. Northern and western Muslims have dominated the country's political and economic system since independence. The NCP draws much of its support from Islamists, Salafis/Wahhabis and other conservative Arab-Muslims in the north. The Umma Party has traditionally attracted Arab followers of the Ansar sect of Sufism as well as non-Arab Muslims from Darfur and Kordofan. The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) includes both Arab and non-Arab Muslims in the north and east, especially those in the Khatmia Sufi sect.[citation needed]

Health

[edit]Sudan has a life expectancy of 65.1 years according to the latest data for the year 2019 from macrotrends.net[322] Infant mortality in 2016 was 44.8 per 1,000.[323]

UNICEF estimates that 87% of Sudanese females between the ages of 15 and 49 have had female genital mutilation performed on them.[324]

Education

[edit]

Education in Sudan is free and compulsory for children aged 6 to 13 years, although more than 40% of children do not go to schools due to the economic situation. Environmental and social factors also increase the difficulty of getting to school, especially for girls.[325] Primary education consists of eight years, followed by three years of secondary education. The former educational ladder 6 + 3 + 3 was changed in 1990. The primary language at all levels is Arabic. Schools are concentrated in urban areas; many in the west have been damaged or destroyed by years of civil war. In 2001 the World Bank estimated that primary enrollment was 46 percent of eligible pupils and 21 percent of secondary students. Enrollment varies widely, falling below 20 percent in some provinces. The literacy rate is 70.2% of total population, male: 79.6%, female: 60.8%.[254]

Culture

[edit]Sudanese culture melds the behaviours, practices, and beliefs of about 578 ethnic groups, communicating in numerous different dialects and languages, in a region microcosmic of Africa, with geographic extremes varying from sandy desert to tropical forest. Recent evidence suggests that while most citizens of the country identify strongly with both Sudan and their religion, Arab and African supranational identities are much more polarising and contested.[326]

Media

[edit]Music

[edit]

Sudan has a rich and unique musical culture that has been through chronic instability and repression during the modern history of Sudan. Beginning with the imposition of strict Salafi interpretation of sharia law in 1983, many of the country's most prominent poets and artists, like Mahjoub Sharif, were imprisoned while others, like Mohammed el Amin (returned to Sudan in the mid-1990s) and Mohammed Wardi (returned to Sudan 2003), fled to Cairo. Traditional music suffered too, with traditional Zār ceremonies being interrupted and drums confiscated [1].