Вторая мировая война в Югославии

| Вторая мировая война в Югославии | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Часть европейского театра Второй мировой войны. | ||||||||

По часовой стрелке сверху слева: Анте Павелич посещает Адольфа Гитлера в Бергхофе ; Степан Филипович повешен оккупационными войсками; Дража Михайлович совещается со своими войсками; группа четников с немецкими солдатами в деревне в Сербии; Иосип Броз Тито с членами британской миссии | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Воюющие стороны | ||||||||

|

Апрель 1941 года : |

Апрель 1941 года: | |||||||

| 1941 – сентябрь 1943 : | 1941–43: |

1941–43:

| ||||||

Сентябрь 1943–1945 гг.:

|

1943–45:

| |||||||

| Strength | ||||||||

|

130,000 (1945)[5] |

(400,000 ill-prepared)[10] |

800,000 (1945)[14] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

|

19,235-103,693 killed 14,805 missing[16] 9,065 killed 15,160 wounded 6,306 missing 99,000 killed |

245,549 killed 399,880 wounded 31,200 died from wounds 28,925 missing | |||||||

|

Total Yugoslav casualties: ≈850,000[21]–1,200,000 a ^ Axis puppet regime established on occupied Yugoslav territory | ||||||||

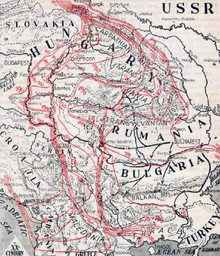

Вторая мировая война в Королевстве Югославия началась 6 апреля 1941 года, когда страна была захвачена и быстро завоевана силами Оси и разделена между Германией , Италией , Венгрией , Болгарией и их сателлитскими режимами . Вскоре после нападения Германии на СССР 22 июня 1941 г. [ 25 ] республиканские возглавляемые коммунистами югославские партизаны приказу Москвы по [ 25 ] развернул партизанскую освободительную войну против сил Оси и их местных марионеточных режимов , включая союзное с Осью Независимое Государство Хорватия (NDH) и Правительство национального спасения на оккупированной немцами территории Сербии . это было названо Национально-освободительной войной и Социалистической революцией В послевоенной югославской коммунистической историографии многосторонняя гражданская война . Одновременно велась между югославскими коммунистическими партизанами, сербскими роялистами- четниками , союзными Оси хорватскими усташами и ополчением , сербским добровольческим корпусом и государственной гвардией , словенским ополчением , а также союзными нацистам российскими защитными силами. корпуса . Войска [ 26 ]

Both the Yugoslav Partisans and the Chetnik movement initially resisted the Axis invasion. However, after 1941, Chetniks extensively and systematically collaborated with the Italian occupation forces until the Italian capitulation, and thereon also with German and Ustaše forces.[26][27] Страны Оси предприняли серию наступлений, направленных на уничтожение партизан, и были близки к этому в битвах при Неретве и Сутьеске весной и летом 1943 года.

Despite the setbacks, the Partisans remained a credible fighting force, with their organisation gaining recognition from the Western Allies at the Tehran Conference and laying the foundations for the post-war Yugoslav socialist state. With support in logistics and air power from the Western Allies, and Soviet ground troops in the Belgrade offensive, the Partisans eventually gained control of the entire country and of the border regions of Trieste and Carinthia. The victorious Partisans established the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

The conflict in Yugoslavia had one of the highest death tolls by population in the war, and is usually estimated at around one million, about half of whom were civilians. Genocide and ethnic cleansing was carried out by the Axis forces (particularly the Wehrmacht) and their collaborators (particularly the Ustaše and Chetniks), and reprisal actions from the Partisans became more frequent towards the end of the war, and continued after it.

Background

[edit]Prior to the outbreak of war, the government of Milan Stojadinović (1935–1939) tried to navigate between the Axis powers and the imperial powers by seeking neutral status, signing a non-aggression treaty with Italy and extending its treaty of friendship with France. At the same time, the country was destabilized by internal tensions, as Croatian leaders demanded a greater level of autonomy. Stojadinović was sacked by the regent Prince Paul in 1939 and replaced by Dragiša Cvetković, who negotiated a compromise with Croatian leader Vladko Maček in 1939, resulting in the formation of the Banovina of Croatia.

However, rather than reducing tensions, the agreement only reinforced the crisis in the country's governance.[28] Groups from both sides of the political spectrum were not satisfied: the pro-fascist Ustaše sought an independent Croatia allied with the Axis; Serbian public and military circles preferred alliance with the Western European empires, while the then-banned Communist Party of Yugoslavia saw the Soviet Union as a natural ally.

Following the fall of France in May 1940, Yugoslavia's Regent Prince Paul and his government saw no way of saving the Kingdom of Yugoslavia except through accommodation with the Axis powers. Although Germany's Adolf Hitler was not particularly interested in creating another front in the Balkans, and Yugoslavia itself remained at peace during the first year of the war, Benito Mussolini's Italy had invaded Albania in April 1939 and launched the rather unsuccessful Italo-Greek War in October 1940. These events resulted in Yugoslavia's geographical isolation from potential Allied support. The government tried to negotiate with the Axis on cooperation with as few concessions as possible, while attempting secret negotiations with the Allies and the Soviet Union, but these moves failed to keep the country out of the war.[29] A secret mission to the U.S., led by the influential Serbian-Jewish Captain David Albala, with the purpose of obtaining funding to buy arms for the expected invasion went nowhere,[citation needed] while the Soviet Union's Joseph Stalin expelled Yugoslav ambassador Milan Gavrilović just one month after agreeing a treaty of friendship with Yugoslavia[30] (prior to 22 June 1941, Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia adhered to the non-aggression pact the parties had signed in August 1939 and in the autumn 1940, Germany and the Soviet Union had been in talks on the USSR's potential accession to the Tripartite Pact).

1941

[edit]Having steadily fallen within the orbit of the Axis during 1940 after events such as the Second Vienna Award, Yugoslavia followed Bulgaria and formally joined the Tripartite Pact on 25 March 1941. Senior Serbian air force officers opposed to the move staged a coup d'état and took over in the following days.

Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia

[edit]

On 6 April 1941 the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was invaded from all sides — by Germany, Italy, and their ally Hungary. Belgrade was bombed by the German air force (Luftwaffe). The war, known in the post-Yugoslavia states as the April War, lasted little more than ten days, ending with the unconditional surrender of the Royal Yugoslav Army on 17 April. Not only hopelessly ill-equipped compared to the German Army (Heer), the Yugoslav army attempted to defend all of its borders, thinly spreading its scarce resources. Additionally, much of the population refused to fight, instead welcoming the Germans as liberators from government oppression. As this meant that each individual ethnic group would turn to movements opposed to the unity promoted by the South Slavic state, two different concepts of anti-Axis resistance emerged: the royalist Chetniks, and the communist-led Partisans.[31]

Two of the principal constituent national groups, Slovenes and Croats, were not prepared to fight in defense of a Yugoslav state with a continued Serb monarchy. The only effective opposition to the invasion was from units wholly from Serbia itself.[32] The Serbian General Staff was united on the question of Yugoslavia as a "Greater Serbia" ruled, in one way or another, by Serbia. On the eve of the invasion, there were 165 generals on the Yugoslav active list. Of these, all but four were Serbs.[33]

The terms of the surrender were extremely severe, as the Axis proceeded to dismember Yugoslavia. Germany annexed northern Slovenia, while retaining direct occupation over a rump Serbian state. Germany also exercised considerable influence over the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) proclaimed on 10 April, which extended over much of today's Croatia and contained all of modern Bosnia and Herzegovina, despite the fact that the Treaties of Rome concluded between the NDH and Italy on 18 May envisioned the NDH becoming an effective protectorate of Italy.[34] Mussolini's Italy gained the remainder of Slovenia, Kosovo, coastal and inland areas of the Croatian Littoral and large chunks of the coastal Dalmatia region (along with nearly all of the Adriatic islands and the Bay of Kotor). It also gained control over the Italian governorate of Montenegro, and was granted the kingship in the Independent State of Croatia, though wielding little real power within it; although it did (alongside Germany) maintain a de facto zone of influence within the borders of the NDH. Hungary dispatched the Hungarian Third Army to occupy Vojvodina in northern Serbia, and later forcibly annexed sections of Baranja, Bačka, Međimurje, and Prekmurje.[35]

The Bulgarian army moved in on 19 April 1941, occupying nearly all of modern-day North Macedonia and some districts of eastern Serbia which, with Greek western Thrace and eastern Macedonia (the Aegean Province), were annexed by Bulgaria on 14 May.[36]

The government in exile was now only recognized by the Allied powers.[37] The Axis had recognized the territorial acquisitions of their allied states.[38][39]

Early resistance

[edit]From the start, the Yugoslav resistance forces consisted of two factions: the Partisans, a communist-led movement propagating pan-Yugoslav tolerance ("brotherhood and unity") and incorporating republican, left-wing and liberal elements of Yugoslav politics, on one hand, and the Chetniks, a conservative royalist and nationalist force, enjoying support almost exclusively from the Serbian population in occupied Yugoslavia, on the other hand. From the start and until 1943, the Chetniks, who fought in the name of the London-based King Peter II's Yugoslav government-in-exile, enjoyed recognition and support from the Western Allies, while the Partisans were supported by the Soviet Union.

At the very beginning, the Partisan forces were relatively small, poorly armed, and without any infrastructure. But they had two major advantages over other military and paramilitary formations in former Yugoslavia: the first and most immediate advantage was a small but valuable cadre of Spanish Civil War veterans. Unlike some of the other military and paramilitary formations, these veterans had experience with a modern war fought in circumstances quite similar to those found in World War II Yugoslavia. In Slovenia, the Partisans likewise drew on the experienced TIGR members to train troops.

Their other major advantage, which became more apparent in the later stages of the War, was in the Partisans being founded on a communist ideology rather than ethnicity. Therefore, they won support that crossed national lines, meaning they could expect at least some levels of support in almost any corner of the country, unlike other paramilitary formations limited to territories with Croat or Serb majority. This allowed their units to be more mobile and fill their ranks with a larger pool of potential recruits.

While the activity of the Macedonian and Slovene Partisans was part of the Yugoslav People's Liberation War, the specific conditions in Macedonia and Slovenia, due to the strong autonomist tendencies of the local communists, led to the creation of separate sub-armies called the People's Liberation Army of Macedonia, and the Slovene Partisans led by the Liberation Front of the Slovene People, respectively.

The most numerous local force, apart from the four second-line German Wehrmacht infantry divisions assigned to occupation duties, was the Croatian Home Guard (Hrvatsko domobranstvo) founded in April 1941, a few days after the founding of the NDH. The force was formed with the authorisation of German authorities. The task of the new Croatian armed forces was to defend the new state against both foreign and domestic enemies.[41] The Croatian Home Guard was originally limited to 16 infantry battalions and 2 cavalry squadrons – 16,000 men in total. The original 16 battalions were soon enlarged to 15 infantry regiments of two battalions each between May and June 1941, organised into five divisional commands, some 55,000 enlisted men.[42] Support units included 35 light tanks supplied by Italy,[43] 10 artillery battalions (equipped with captured Royal Yugoslav Army weapons of Czech origin), a cavalry regiment in Zagreb and an independent cavalry battalion at Sarajevo. Two independent motorized infantry battalions were based at Zagreb and Sarajevo respectively.[44] Several regiments of Ustaše militia were also formed at this time, which operated under a separate command structure to, and independently from, the Croatian Home Guard, until late 1944.[45] The Home Guard crushed the Serb revolt in Eastern Herzegovina in June 1941, and in July they fought in Eastern and Western Bosnia. They fought in Eastern Herzegovina again, when Croatian-Dalmatian and Slavonian battalions reinforced local units.[44]

The Italian High Command assigned 24 divisions and three coastal brigades to occupation duties in Yugoslavia from 1941. These units were located from Slovenia, Croatia and Dalmatia through to Montenegro and Kosovo.[46]

From 1931 to 1939, the Soviet Union had prepared communists for a guerrilla war in Yugoslavia. On the eve of the war, hundreds of future prominent Yugoslav communist leaders completed special "partisan courses" organised by the Soviet military intelligence in the Soviet Union and Spain.[47]

On the day Germany attacked the Soviet Union, on 22 June 1941, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (CPY) received orders from Moscow-based Comintern to come to the Soviet Union's aid.[25] On the same day, Croatian communists set up the 1st Sisak Partisan Detachment, the first armed anti-fascist resistance unit formed by a resistance movement in occupied Yugoslavia during World War II.[48] The detachment began resistance activities the day after its creation;[49] launching sabotage and diversionary attacks on nearby railway lines, destroying telegraph poles, attacking municipal buildings in surrounding villages, seizing arms and ammunition and creating a Communist propaganda network in Sisak and nearby villages.[49][50] At the same time, the CPY's Provincial Committee for Serbia made its decision to launch an armed uprising in Serbia and put together its Supreme Staff of the National Liberation Partisan Units of Yugoslavia to be chaired by Josip Broz Tito.[25] On 4 July, a formal order to begin the uprising was issued.[25] On 7 July, the Bela Crkva incident happened, which would later be considered the beginning of the uprising in Serbia. On 10 August 1941 in Stanulović, a mountain village, the Partisans formed the Kopaonik Partisan Detachment Headquarters. Their liberated area, consisting of nearby villages and called the "Miners Republic", was the first in Yugoslavia, and lasted 42 days. The resistance fighters formally joined the ranks of the Partisans later on.

The Chetnik movement (officially the Yugoslav Army in the Fatherland, JVUO) was organised following the surrender of the Royal Yugoslav Army by some of the remaining Yugoslav soldiers. This force was organised in the Ravna Gora district of western Serbia under Colonel Draža Mihailović in mid-May 1941. However, unlike the Partisans, Mihailović's forces were almost entirely ethnic Serbs. The Partisans and Chetniks attempted to cooperate early during the conflict and Chetniks were active in the uprising in Serbia, but this fell apart thereafter.

In September 1941, Partisans organised sabotage at the General Post Office in Zagreb. As the levels of resistance to its occupation grew, the Axis Powers responded with numerous minor offensives. There were also seven major Axis operations specifically aimed at eliminating all or most Yugoslav Partisan resistance. These major offensives were typically combined efforts by the German Wehrmacht and SS, Italy, Chetniks, the Independent State of Croatia, the Serbian collaborationist government, Bulgaria, and Hungary.

The First Anti-Partisan Offensive was the attack conducted by the Axis in autumn of 1941 against the "Republic of Užice", a liberated territory the Partisans established in western Serbia. In November 1941, German troops attacked and reoccupied this territory, with the majority of Partisan forces escaping towards Bosnia. It was during this offensive that tenuous collaboration between the Partisans and the royalist Chetnik movement broke down and turned into open hostility.

After fruitless negotiations, the Chetnik leader, General Mihailović, turned against the Partisans as his main enemy. According to him, the reason was humanitarian: the prevention of German reprisals against Serbs.[51] This however, did not stop the activities of the Partisan resistance, and Chetnik units attacked the Partisans in November 1941, while increasingly receiving supplies and cooperating with the Germans and Italians in this. The British liaison to Mihailović advised London to stop supplying the Chetniks after the Užice attack (see First Anti-Partisan Offensive), but Britain continued to do so.[52]

On 22 December 1941 the Partisans formed the 1st Proletarian Assault Brigade (1. Proleterska Udarna Brigada) – the first regular Partisan military unit capable of operating outside its local area. 22 December became the "Day of the Yugoslav People's Army".

1942

[edit]This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (December 2015) |

On 15 January 1942, the Bulgarian 1st Army, with three infantry divisions, transferred to south-eastern Serbia. Headquartered at Niš, it replaced German divisions needed in Croatia and the Soviet Union.[53]

The Chetniks initially enjoyed the support of the Western Allies (up to the Tehran Conference in December 1943). In 1942, Time Magazine featured an article which praised the "success" of Mihailović's Chetniks and heralded him as the sole defender of freedom in Nazi-occupied Europe.

Tito's Partisans fought the Germans more actively during this time. Tito and Mihailović had a bounty of 100,000 Reichsmarks offered by Germans for their heads. While "officially" remaining mortal enemies of the Germans and the Ustaše, the Chetniks were known for making clandestine deals with the Italians. The Second Enemy Offensive was a coordinated Axis attack conducted in January 1942 against Partisan forces in eastern Bosnia. The Partisan troops once again avoided encirclement and were forced to retreat over the Igman mountain near Sarajevo.

The Third Enemy Offensive, an offensive against Partisan forces in eastern Bosnia, Montenegro, Sandžak and Herzegovina which took place in the spring of 1942, was known as Operation TRIO by the Germans, and again ended with a timely Partisan escape. Over the course of the summer, they conducted the so-called Partisan Long March westwards through Bosnia and Herzegovina, while at the same time the Axis conducted the Kozara Offensive in northwestern Bosnia.

The Partisans fought an increasingly successful guerrilla campaign against the Axis occupiers and their local collaborators, including the Chetniks (which they also considered collaborators). They enjoyed gradually increased levels of success and support of the general populace, and succeeded in controlling large chunks of Yugoslav territory. People's committees were organised to act as civilian governments in areas of the country liberated by the Partisans. In places, even limited arms industries were set up.

To gather intelligence, agents of the Western Allies were infiltrated into both the Partisans and the Chetniks. The intelligence gathered by liaisons to the resistance groups was crucial to the success of supply missions and was the primary influence on Allied strategy in the Yugoslavia. The search for intelligence ultimately resulted in the decline of the Chetniks and their eclipse by Tito's Partisans. In 1942, though supplies were limited, token support was sent equally to each. In November 1942, Partisan detachments were officially merged into the People's Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia (NOV i POJ).

1943

[edit]Critical Axis offensives

[edit]In the first half of 1943 two Axis offensives came close to defeating the Partisans. They are known by their German code names Fall Weiss (Case White) and Fall Schwarz (Case Black), as the Battle of Neretva and the Battle of Sutjeska after the rivers in the areas they were fought, or the Fourth and Fifth Enemy Offensive, respectively, according to former Yugoslav historiography.

On 7 January 1943, the Bulgarian 1st Army also occupied south-west Serbia. Savage pacification measures reduced Partisan activity appreciably. Bulgarian infantry divisions in the Fifth anti-Partisan Offensive blocked the Partisan escape-route from Montenegro into Serbia and also participated in the Sixth anti-Partisan Offensive in Eastern Bosnia.[53]

Negotiations between Germans and Partisans started on 11 March 1943 in Gornji Vakuf, Bosnia. Tito's key officers Vladimir Velebit, Koča Popović and Milovan Đilas brought three proposals, first about an exchange of prisoners, second about the implementation of international law on treatment of prisoners and third about political questions.[54] The delegation expressed concerns about Italian involvement in supplying the Chetnik army and stated that the National Liberation Movement was an independent movement, with no aid from the Soviet Union or the UK.[55] Somewhat later, Đilas and Velebit were brought to Zagreb to continue the negotiations.[56]

In the Fourth Enemy Offensive, also known as the Battle of the Neretva or Fall Weiss (Case White), Axis forces pushed Partisan troops to retreat from western Bosnia to northern Herzegovina, culminating in the Partisan retreat over the Neretva river. This took place from January to April, 1943.

The Fifth Enemy Offensive, also known as the Battle of the Sutjeska or Fall Schwarz (Case Black), immediately followed the Fourth Offensive and included a complete encirclement of Partisan forces in southeastern Bosnia and northern Montenegro in May and June 1943.

In that August of my arrival [1943] there were over 30 enemy divisions on the territory of Jugoslavia, as well as a large number of satellite and police formations of Ustashe and Domobrani (military formations of the puppet Croat State), German Sicherheitsdienst, chetniks, Neditch militia, Ljotitch militia, and others. The partisan movement may have counted up to 150,000 fighting men and women (perhaps five per cent women) in close and inextricable co-operation with several million peasants, the people of the country. Partisan numbers were liable to increase rapidly.[57]

The Croatian Home Guard reached its maximum size at the end of 1943, when it had 130,000 men. It also included an air force, the Air Force of the Independent State of Croatia (Zrakoplovstvo Nezavisne Države Hrvatske, or ZNDH), the backbone of which was provided by 500 former Royal Yugoslav Air Force officers and 1,600 NCOs with 125 aircraft.[58] By 1943 the ZNDH was 9,775 strong and equipped with 295 aircraft.[45]

Italian capitulation and Allied support for the Partisans

[edit]

On 8 September 1943, the Italians concluded an armistice with the Allies, leaving 17 divisions stranded in Yugoslavia. All divisional commanders refused to join the Germans. Two Italian infantry divisions joined the Montenegrin Partisans as complete units, while another joined the Albanian Partisans. Other units surrendered to the Germans to face imprisonment in Germany or summary execution. Others surrendered themselves and their arms, ammunition and equipment to Croatian forces or to the Partisans, simply disintegrated, or reached Italy on foot via Trieste or by ship across the Adriatic.[42] The Italian Governorship of Dalmatia was disestablished and the country's possessions were subsequently divided between Germany, which established its Operational Zone of the Adriatic Littoral, and the Independent State of Croatia, which established the new district of Sidraga-Ravni Kotari. The former Italian kingdoms of Albania and of Montenegro were placed under German occupation.

On 25 September 1943, the German High Command launched Operation "Istrien", and on October 21 the military operation "Wolkenbruch" with the aim of destroying Partisan units in the Slovene-populated lands, Istria and the Littoral. In that operation 2,500 Istrians were killed among whom were Partisans and civilians including women, children, and elderly. Partisan units which did not withdraw from Istria in time were completely destroyed. German troops, including the SS division "Prinz Eugen", on September 25 began to carry out a plan for the complete destruction of the Partisans in Primorska and Istria.[59][unreliable source?]

Events in 1943 brought about a change in the attitude of the Allies. The Germans were executing Fall Schwarz (Battle of Sutjeska, the Fifth anti-Partisan offensive), one of a series of offensives aimed at the resistance fighters, when F.W.D. Deakin was sent by the British to gather information. His reports contained two important observations. The first was that the Partisans were courageous and aggressive in battling the German 1st Mountain and 104th Light Division, had suffered significant casualties, and required support. The second observation was that the entire German 1st Mountain Division had transited from the Soviet Union on rail lines through Chetnik-controlled territory. British intercepts (ULTRA) of German message traffic confirmed Chetnik timidity. Even though today many circumstances, facts, and motivations remain unclear, intelligence reports resulted in increased Allied interest in Yugoslavia air operations and shifted policy.

The Sixth Enemy Offensive was a series of operations undertaken by the Wehrmacht and the Ustaše after the capitulation of Italy in an attempt to secure the Adriatic coast. It took place in the autumn and winter of 1943/1944.

At this point the Partisans were able to win the moral, as well as limited material support of the Western Allies, who until then had supported Mihailović's Chetnik Forces, but were finally convinced of their collaboration by many intelligence-gathering missions dispatched to both sides during the course of the war.

In September 1943, at Churchill's request, Brigadier General Fitzroy Maclean was parachuted to Tito's headquarters near Drvar to serve as a permanent, formal liaison to the Partisans. While the Chetniks were still occasionally supplied, the Partisans received the bulk of all future support.[60]

When the AVNOJ (the Partisan wartime council in Yugoslavia) was eventually recognized by the Allies, by late 1943, the official recognition of the Partisan Democratic Federal Yugoslavia soon followed. The National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia was recognized by the major Allied powers at the Tehran Conference, when United States agreed to the position of other Allies.[61] The newly recognized Yugoslav government, headed by Prime Minister Tito, was a joint body formed of AVNOJ members and the members of the former government-in-exile in London. The resolution of a fundamental question, whether the new state would remained a monarchy or become a republic, was postponed until the end of the war, as was the status of King Peter II.

Subsequent to switching their support to the Partisans, the Allies set up the RAF Balkan Air Force (at the suggestion of Maclean) with the aim to provide increased supplies and tactical air support for Marshal Tito's Partisan forces.

1944

[edit]Last Axis offensive

[edit]In January 1944, Tito's forces unsuccessfully attacked Banja Luka. But, while Tito was forced to withdraw, Mihajlović and his forces were also noted by the Western press for their lack of activity.[62]

The Seventh Enemy Offensive was the final Axis attack in western Bosnia in the spring of 1944, which included Operation Rösselsprung (Knight's Leap), an unsuccessful attempt to eliminate Josip Broz Tito personally and annihilate the leadership of the Partisan movement.

Partisan growth to domination

[edit]Allied aircraft specifically started targeting ZNDH (Air Force of the Independent State of Croatia) and Luftwaffe bases and aircraft for the first time as a result of the Seventh Offensive, including Operation Rösselsprung in late May 1944. Up until then Axis aircraft could fly inland almost at will, as long as they remained at low altitude. Partisan units on the ground frequently complained about enemy aircraft attacking them while hundreds of Allied aircraft flew above at higher altitude. This changed during Rösselsprung as Allied fighter-bombers went low en-masse for the first time, establishing full aerial superiority. Consequently, both the ZNDH and Luftwaffe were forced to limit their operations in clear weather to early morning and late afternoon hours.[63]

The Yugoslav Partisan movement grew to become the largest resistance force in occupied Europe, with 800,000 men organised in 4 field armies. Eventually the Partisans prevailed against all of their opponents as the official army of the newly founded Democratic Federal Yugoslavia (later Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia).

In 1944, the Macedonian and Serbian commands made contact in southern Serbia and formed a joint command, which consequently placed the Macedonian Partisans under the direct command of Marshal Tito.[64] The Slovene Partisans also merged with Tito's forces in 1944.[65][66]

On 16 June 1944, the Tito-Šubašić agreement between the Partisans and the Yugoslav Government in exile of Peter II was signed on the island of Vis. This agreement was an attempt to form a new Yugoslav government which would include both the communists and the royalists. It called for a merge of the Partisan Anti-Fascist Council of National Liberation of Yugoslavia (Antifašističko V(ij)eće Narodnog Oslobođenja Jugoslavije, AVNOJ) and the Government in exile. The Tito-Šubašić agreement also called on all Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs to join the Partisans. The Partisans were recognized by the Royal Government as Yugoslavia's regular army. Mihajlović and many Chetniks refused to answer the call. The Chetniks were, however, praised for saving 500 downed Allied pilots in 1944; United States President Harry S. Truman posthumously awarded Mihailović the Legion of Merit for his contribution to the Allied victory.[67]

Allied advances in Romania and Bulgaria

[edit]

In August 1944 after the Jassy-Kishinev Offensive overwhelmed the front line of Germany's Army Group South Ukraine, King Michael I of Romania staged a coup, Romania quit the war, and the Romanian army was placed under the command of the Red Army. Romanian forces, fighting against Germany, participated in the Prague Offensive. Bulgaria quit as well and, on 10 September, declared war on Germany and its remaining allies. The weak divisions sent by the Axis powers to invade Bulgaria were easily driven back.

In Macedonia, the Germans swiftly disarmed the 1st Occupation Corps of 5 divisions and the 5th Army, despite short-lived resistance by the latter. Survivors fought their way back to the old borders of Bulgaria.

After the occupation of Bulgaria by the Soviet army, negotiations between Tito and the Bulgarian communist leaders were organised which ultimately resulted in a military alliance between the two.

In late September 1944, three Bulgarian armies, some 455,000 strong in total led by General Georgi Marinov Mandjev, entered Yugoslavia with the strategic task of blocking the German forces withdrawing from Greece.

The new Bulgarian People's Army and the Red Army 3rd Ukrainian Front troops were concentrated at the old Bulgarian-Yugoslav border. At the dawn of October 8, they entered Yugoslavia from the south. The First and Fourth Bulgarian Armies invaded Vardar Macedonia, and the Second Army south-eastern Serbia. The First Army then swung north with the Soviet 3rd Ukrainian Front, through eastern Yugoslavia and south-western Hungary, before linking up with the British 8th Army in Austria in May 1945.[68]

Liberation of Belgrade and eastern Yugoslavia

[edit]

Concurrently, with Allied air support and assistance from the Red Army, the Partisans turned their attention to Central Serbia. The chief objective was to disrupt railroad communications in the valleys of the Vardar and Morava rivers, and prevent Germans from withdrawing their 300,000+ forces from Greece.

The Allied air forces sent 1,973 aircraft (mostly from the US 15th Air Force) over Yugoslavia, which discharged over 3,000 tons of bombs. On 17 August 1944, Tito offered an amnesty to all collaborators. On 12 September, Peter II broadcast a message from London, calling upon all Serbs, Croats and Slovenes to "join the National Liberation Army under the leadership of Marshal Tito". The message reportedly had a devastating effect on the morale of the Chetniks, many of which later defected to the Partisans. They were followed by a substantial number of former Croatian Home Guard and Slovene Home Guard troops.

In September under the leadership of the new Bulgarian pro-Soviet government, four Bulgarian armies, 455,000 strong in total, were mobilized. By the end of September, the Red Army (3rd Ukrainian Front) troops were concentrated at the Bulgarian-Yugoslav border. In the early October 1944 three Bulgarian armies, consisting of around 340,000 men,[69] together with the Red Army, reentered occupied Yugoslavia and moved from Sofia to Niš, Skopje and Pristina to block the German forces withdrawing from Greece.[70][71] The Red Army organised the Belgrade Offensive, and took the city on 20 October.

The partisans meanwhile attempted to stem the German withdrawal as the German Army Group E abandoned Greece and Albania via Yugoslavia and withdraw to defence lines further north. In September 1944, the allies launched Operation Ratweek, aiming to frustrate German movements through Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia. The British also sent a powerful combat unit launching Operation Floxo (known as 'Floydforce') composing of artillery and engineers which the Partisans were lacking. The Partisans with British artillery were able to stem the Germans and liberated Risan and Podgorica between October and December. By this time the Partisans effectively controlled the entire eastern half of Yugoslavia—Serbia, Macedonia, Montenegro—as well as most of the Dalmatian coast. The Wehrmacht and the forces of the Ustaše-controlled Independent State of Croatia fortified a front in Syrmia that held through the winter of 1944–45 in order to aid the evacuation of Army Group E from the Balkans.

To raise the number of Partisan troops Tito again offered the amnesty on 21 November 1944. In November 1944, the units of the Ustaše militia and the Croatian Home Guard were reorganised and combined to form the Army of the Independent State of Croatia.[45]

1945

[edit]"Every German unit which could safely evacuate from Yugoslavia might count itself lucky."[72]

The Germans continued their retreat. Having lost the easier withdrawal route through Serbia, they fought to hold the Syrmian front in order to secure the more difficult passage through Kosovo, Sandzak and Bosnia. They even scored a series of temporary successes against the People's Liberation Army. They left Mostar on 12 February 1945. They did not leave Sarajevo until 15 April. Sarajevo had assumed a last-moment strategic position as the only remaining withdrawal route and was held at substantial cost. In early March the Germans moved troops from southern Bosnia to support an unsuccessful counter-offensive in Hungary, which enabled the NOV to score some successes by attacking the Germans' weakened positions. Although strengthened by Allied aid, a secure rear and mass conscription in areas under their control, the one-time partisans found it difficult to switch to conventional warfare, particularly in the open country west of Belgrade, where the Germans held their own until mid-April in spite of all of the raw and untrained conscripts the NOV hurled in a bloody war of attrition against the Syrmian Front.[73]

On 8 March 1945, a coalition Yugoslav government was formed in Belgrade with Tito as Premier and Ivan Šubašić as Foreign Minister.

Partisan general offensive

[edit]

On 20 March 1945, the Partisans launched a general offensive in the Mostar-Višegrad-Drina sector. With large swaths of Bosnian, Croatian and Slovenian countryside already under Partisan guerrilla control, the final operations consisted in connecting these territories and capturing major cities and roads. For the general offensive Marshal Josip Broz Tito commanded a Partisan force of about 800,000 men organised into four armies: the

- 1st Army commanded by Peko Dapčević,

- 2nd Army commanded by Koča Popović,

- 3rd Army commanded by Kosta Nađ,

- 4th Army commanded by Petar Drapšin.

In addition, the Yugoslav Partisans had eight independent army corps (the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, 9th, and the 10th).

Set against the Yugoslav Partisans was German General Alexander Löhr of Army Group E (Heeresgruppe E). This Army Group had seven army corps :

- XV Mountain Corps,

- XV Cossack Corps,

- XXI Mountain Corps,

- XXXIV Infantry Corps,

- LXIX Infantry Corps,

- LXXXXVII Infantry Corps.

These corps included seventeen weakened divisions (1st Cossack, 2nd Cossack, 7th SS, 11th Luftwaffe Field Division, 22nd, 41st, 104th, 117th, 138th, 181st, 188th, 237th, 297th, 369th Croat, 373rd Croat, 392nd Croat and the 14th SS Ukrainian Division). In addition to the seven corps, the Axis had remnant naval and Luftwaffe forces, under constant attack by the British Royal Navy, Royal Air Force and United States Air Force.[74]

The army of the Independent State of Croatia was at the time composed of eighteen divisions: 13 infantry, two mountain, two assault and one replacement Croatian Divisions, each with its own organic artillery and other support units. There were also several armoured units. From early 1945, the Croatian Divisions were allocated to various German corps and by March 1945 were holding the Southern Front.[45] Securing the rear areas were some 32,000 men of the Croatian gendarmerie (Hrvatsko Oružništvo), organised into 5 Police Volunteer Regiments plus 15 independent battalions, equipped with standard light infantry weapons, including mortars.[75]

The Air Force of the Independent State of Croatia (Zrakoplovstvo Nezavisne Države Hrvatske, or ZNDH) and the units of the Croatian Air Force Legion (Hrvatska Zrakoplovna Legija, or HZL), returned from service on the Eastern Front provided some level of air support (attack, fighter and transport) right up until May 1945, encountering and sometimes defeating opposing aircraft from the British Royal Air Force, United States Air Force and the Soviet Air Force. Although 1944 had been a catastrophic year for the ZNDH, with aircraft losses amounting to 234, primarily on the ground, it entered 1945 with 196 machines. Further deliveries of new aircraft from Germany continued in the early months of 1945 to replace losses. By 10 March, the ZNDH had 23 Messerschmitt Bf 109 G&Ks, three Morane-Saulnier M.S.406, six Fiat G.50 Freccia, and two Messerschmitt Bf 110 G fighters. The final deliveries of up-to-date German Messerschmitt Bf 109 G and K fighter aircraft were still taking place in March 1945.[76] and the ZNDH still had 176 aircraft on its strength in April 1945.[77]

Between 30 March and 8 April 1945, General Mihailović's Chetniks mounted a final attempt to establish themselves as a credible force fighting the Axis in Yugoslavia. The Chetniks under Lieutenant Colonel Pavle Đurišić fought a combination of Ustaša and Croatian Home Guard forces in the Battle on Lijevča field. In late March 1945 elite NDH Army units were withdrawn from the Syrmian front to destroy Djurisic's Chetniks trying to make their way across the northern NDH.[78] The battle was fought near Banja Luka in what was then the Independent State of Croatia and ended in a decisive victory for the Independent State of Croatia forces.

Serbian units included the remnants of the Serbian State Guard and the Serbian Volunteer Corps from the Serbian Military Administration. There were even some units of the Slovene Home Guard (Slovensko domobranstvo, SD) still intact in Slovenia.[79]

By the end of March, 1945, it was obvious to the Croatian Army Command that, although the front remained intact, they would eventually be defeated by sheer lack of ammunition. For this reason, the decision was made to retreat into Austria, in order to surrender to the British forces advancing north from Italy.[80] The German Army was in the process of disintegration and the supply system lay in ruins.[81]

Bihać was liberated by the Partisans the same day that the general offensive was launched. The 4th Army, under the command of Petar Drapšin, broke through the defences of the XVth SS Cossack Cavalry Corps. By 20 April, Drapšin liberated Lika and the Croatian Littoral, including the islands, and reached the old Yugoslav border with Italy. On 1 May, after capturing the Italian territories of Rijeka and Istria from the German LXXXXVII Corps, the Yugoslav 4th Army beat the western Allies to Trieste by one day.

The Yugoslav 2nd Army, under the command of Koča Popović, forced a crossing of the Bosna River on 5 April, capturing Doboj, and reached the Una River. On 6 April, the 2nd, 3rd, and 5th Corps of the Yugoslav Partisans took Sarajevo from the German XXI Corps. On 12 April, the Yugoslav 3rd Army, under the command of Kosta Nađ, forced a crossing of the Drava river. The 3rd Army then fanned out through Podravina, reached a point north of Zagreb, and crossed the old Austrian border with Yugoslavia in the Dravograd sector. The 3rd Army closed the ring around the enemy forces when its advanced motorized detachments linked up with detachments of the 4th Army in Carinthia.

Also, on 12 April, the Yugoslav 1st Army, under the command of Peko Dapčević penetrated the fortified front of the German XXXIV Corps in Syrmia. By 22 April, the 1st Army had smashed the fortifications and was advancing towards Zagreb.

The long-drawn out liberation of western Yugoslavia caused more victims among the population. The breakthrough of the Syrmian front on 12 April was, in Milovan Đilas's words, "the greatest and bloodiest battle our army had ever fought", and it would not have been possible had it not been for Soviet instructors and arms.[82] By the time Dapčević's NOV units had reached Zagreb, on 9 May 1945, they had perhaps lost as many as 36,000 dead. There were by then over 400,000 refugees in Zagreb.[83] After entering Zagreb with the Yugoslav 2nd Army, both armies advanced in Slovenia.

Final operations

[edit]

2 мая столица Германии Берлин пала под натиском Красной Армии. 8 мая 1945 года немцы безоговорочно капитулировали , и война в Европе официально закончилась . Итальянцы вышли из войны в 1943 году, болгары - в 1944 году, а венгры - ранее в 1945 году. Однако, несмотря на капитуляцию Германии, спорадические боевые действия в Югославии все еще происходили. 7 мая Загреб был эвакуирован, 9 мая Марибор и Любляна были захвачены партизанами, а Лёр, главнокомандующий группой армий «Е», был вынужден подписать акт о полной капитуляции войск, находящихся под его командованием, в Топольшице, недалеко от Веленье , Словения, среда, 9 мая 1945 года. Остались только хорватские и другие антипартизанские силы.

С 10 по 15 мая югославские партизаны продолжали сталкиваться с сопротивлением хорватских и других антипартизанских сил на остальной территории Хорватии и Словении. Битва при Поляне началась 14 мая и закончилась 15 мая 1945 года в Поляне, недалеко от Превалье в Словении. Это была кульминация и последнее из серии сражений между югославскими партизанами и большой (свыше 30 000) смешанной колонной солдат немецкой армии вместе с хорватскими усташами, хорватским ополчением, словенским ополчением и другими антипартизанскими силами, которые были пытаясь отступить в Австрию. Битва при Оджаке была последней битвой Второй мировой войны в Европе. [ 84 ] Бой начался 19 апреля 1945 г. и продолжался до 25 мая 1945 г. [ 85 ] 17 дней после окончания войны в Европе .

Последствия

[ редактировать ]| Часть серии о |

| Последствия Вторая мировая война в Югославии |

|---|

| Основные события |

| Резня |

| Лагеря |

5 мая в городе Пальманова (50 км к северо-западу от Триеста) англичанам сдались от 2400 до 2800 членов Сербского добровольческого корпуса. [ 86 ] 12 мая еще около 2500 членов сербского добровольческого корпуса сдались британцам в Унтербергене на реке Драва. [ 86 ] 11 и 12 мая британские войска в Клагенфурте , Австрия, подверглись нападению со стороны прибывших сил югославских партизан. [ почему? ] В Белграде посол Великобритании в югославском коалиционном правительстве вручил Тито ноту с требованием вывести югославские войска из Австрии.

15 мая 1945 года большая колонна хорватского ополчения, усташей, XV казачьего кавалерийского корпуса СС, остатков сербской государственной гвардии и сербского добровольческого корпуса прибыла к южной австрийской границе возле города Блайбург . Представители Независимого государства Хорватия попытались договориться о капитуляции перед британцами в соответствии с условиями Женевской конвенции , к которой они присоединились в 1943 году, и были признаны ею «воюющей стороной», но были проигнорированы. [ 80 ] Большинство людей в колонне были переданы югославскому правительству в рамках так называемой операции «Килхаул» . После репатриации партизаны приступили к жестокому обращению с военнопленными . Действия партизан были частично совершены из мести, а также для подавления потенциального продолжения вооруженной борьбы внутри Югославии. [ 87 ]

15 мая Тито поставил партизанские силы в Австрии под контроль союзников. Через несколько дней он согласился их отозвать. К 20 мая югославские войска из Австрии начали вывод. 8 июня США, Великобритания и Югославия договорились о контроле над Триестом. 11 ноября парламентские выборы . в Югославии прошли [ 88 ] На этих выборах коммунисты имели важное преимущество, поскольку они контролировали полицию, судебную систему и средства массовой информации. По этой причине оппозиция не захотела участвовать в выборах. [ 89 ] 29 ноября, в соответствии с результатами выборов, Петр II был свергнут Учредительным собранием Югославии, в котором доминировали коммунисты. [ 90 ] В тот же день была создана Союзная Народная Республика Югославия как социалистическое государство на первом заседании югославского парламента в Белграде . Тито был назначен премьер-министром. Автономистское крыло Коммунистической партии Македонии , доминировавшее во время Второй мировой войны, было окончательно оттеснено в 1945 году после Второй ассамблеи АСНОМ .

13 марта 1946 года Михайлович был схвачен агентами Югославского департамента национальной безопасности ( Odsjek Zaštite Naroda или ОЗНА). [ 91 ] [ 92 ] С 10 июня по 15 июля того же года его судили за государственную измену и военные преступления . 15 июля он был признан виновным и приговорен к смертной казни через расстрел. [ 93 ]

16 июля прошение о помиловании было отклонено Президиумом Национального собрания. Рано утром 18 июля Михайлович вместе с девятью другими офицерами Четника и Недича был казнен в Лисичи-Потоке . [ 94 ] Эта казнь, по сути, положила конец гражданской войне времен Второй мировой войны между коммунистическими партизанами и четниками-роялистами. [ 95 ]

Военные преступления и зверства

[ редактировать ]Военные преступления и зверства против гражданского населения были широко распространены. населения страны Небоевые жертвы включали в себя большинство еврейского , многие из которых погибли в концентрационных лагерях и лагерях смерти (например, Ясеновац , Стара Градишка , Баница , Саймиште и т. д.), управляемых клиентскими режимами или самими оккупационными силами.

Режим усташей в Хорватии (в основном хорваты, но также мусульмане и другие) совершил геноцид против сербов , евреев , цыган и хорватов -антифашистов . Четники (в основном сербы, но также черногорцы и другие) занимались геноцидом. [ 96 ] [ 97 ] против мусульман, хорватов и пропартизанских сербов, а итальянские оккупационные власти спровоцировали этническую чистку ( итальянизацию ) против словенцев и хорватов. Вермахт проводил массовые казни мирных жителей в отместку за деятельность сопротивления (например, резня в Крагуеваце и резня в Кралево ). Дивизия СС «Принц Ойген» уничтожила большое количество мирных жителей и военнопленных. [ 98 ] Венгерские оккупационные войска устроили резню мирных жителей (в основном сербов и евреев) во время крупного рейда на юге Бачки под предлогом подавления деятельности сопротивления.

Во время и после заключительных этапов войны югославские коммунистические власти и партизанские войска проводили репрессии против тех, кто был связан с странами Оси.

усташи

[ редактировать ]Усташи, хорватское ультранационалистическое и фашистское движение, которое действовало с 1929 по 1945 год и возглавлялось Анте Павеличем , получило контроль над недавно сформированным Независимым государством Хорватия (NDH), которое было создано немцами после вторжения в Югославию. [ 99 ] Усташи стремились к созданию этнически чистого хорватского государства, истребляя сербов , евреев и цыган . с его территории [ 100 ] Их основным направлением были сербы, которых было около двух миллионов. [ 101 ] Стратегия достижения их цели предположительно заключалась в том, чтобы убить одну треть сербов, изгнать одну треть и насильственно обратить в другую веру оставшуюся треть. [ 102 ] Первая резня сербов произошла 28 апреля 1941 года в деревне Гудовац , где было собрано и казнено около 200 сербов . Это событие положило начало волне насилия усташей против сербов, которая пришла в последующие недели и месяцы, когда в деревнях по всей территории NDH произошли массовые убийства. [ 103 ] особенно в Бании , Кордуне , Лике, на северо-западе Боснии и восточной Герцеговине. [ 104 ] Сербов в сельских деревнях зарубали различными инструментами, бросали живыми в ямы и овраги, а в некоторых случаях запирали в церквях, которые впоследствии поджигали . [ 105 ] Отряды усташской милиции разрушали целые деревни, часто пытая мужчин и насилуя женщин. [ 106 ] Примерно каждый шестой серб, проживающий в NDH, стал жертвой резни, а это означает, что почти у каждого серба из этого региона был член семьи, убитый на войне, в основном усташами. [ 107 ]

Усташи также разбили лагеря по всей территории NDH. Некоторые из них использовались для содержания политических оппонентов и лиц, считавшихся врагами государства, некоторые представляли собой транзитные лагеря и лагеря для переселения для депортации и перемещения населения, а другие использовались с целью массовых убийств. Самым крупным лагерем был концентрационный лагерь Ясеновац, который представлял собой комплекс из пяти подлагерей, расположенный примерно в 100 км к юго-востоку от Загреба. [ 106 ] Лагерь был известен своей варварской и жестокой практикой убийств, о чем свидетельствуют показания свидетелей. [ 108 ] К концу 1941 года, наряду с сербами и цыганами, власти NDH заключили большинство евреев страны в лагеря, включая Ядовно , Крушчицу , Лоборград , Джаково , Тенью и Ясеновац. Почти все цыганское население NDH также было убито усташами. [ 106 ]

Четники

[ редактировать ]Четники, сербское роялистское и националистическое движение, которое первоначально сопротивлялось Оси. [ 109 ] но постепенно вступил в сотрудничество с итальянскими, немецкими и частями сил усташей, стремился к созданию Великой Сербии путем очищения несербов, в основном мусульман и хорватов, от территорий, которые будут включены в их послевоенное государство. [ 110 ] Четники систематически убивали мусульман в захваченных ими деревнях. [ 111 ] Они произошли в основном в восточной Боснии, в таких городах и муниципалитетах, как Горажде , Фоча , Сребреница и Вишеград. [ 111 ] Позже «зачистки» против мусульман прошли в уездах Санджака. [ 112 ] Действия против хорватов были меньшими по масштабу, но схожими по действию. [ 113 ] Хорваты были убиты в Боснии, Герцеговине, северной Далмации и Лике. [ 104 ]

Немецкие войска

[ редактировать ]В Сербии, чтобы подавить сопротивление, отомстить оппозиции и терроризировать население, немцы разработали формулу, согласно которой за каждого убитого немецкого солдата будет расстреляно 100 заложников, а за каждого раненого немецкого солдата будет расстреляно 50 заложников. [ 114 ] [ а ] В первую очередь казнили евреев и сербских коммунистов. [ 115 ] Наиболее яркими примерами были массовые убийства в деревнях Кралево и Крагуевац в октябре 1941 года. [ 114 ] Немцы также создали концентрационные лагеря, и Недича Милана марионеточное правительство и другие коллаборационистские силы помогали им в преследовании евреев.

Итальянские войска

[ редактировать ]В апреле 1941 года Италия вторглась в Югославию, аннексировав или оккупировав значительную часть Словении, Хорватии, Герцеговины, Черногории, Сербии и Македонии, одновременно присоединив к Италии провинцию Любляна , Горский Котар и губернию Далмации , а также большинство хорватских островов . Чтобы подавить растущее сопротивление словенских и хорватских партизан, итальянцы применили тактику «субъектных казней, захвата заложников, репрессий, интернирований и сожжения домов и деревень». [ 116 ] Это особенно имело место в провинции Любляна, где итальянские власти терроризировали словенское гражданское население и депортировали его в концентрационные лагеря с целью итальянизации региона. [ 117 ] [ 118 ]

Венгерские войска

[ редактировать ]Тысячи сербов и евреев были убиты венгерскими войсками в районе Бачки , территории, оккупированной и аннексированной Венгрией с 1941 года. В этих злодеяниях были замешаны несколько высокопоставленных военных чиновников. [ 119 ]

Партизаны

[ редактировать ]Партизаны участвовали в массовых убийствах мирного населения во время и после войны. [ 120 ] Ряд партизанских отрядов и местное население в некоторых районах сразу после войны участвовали в массовых убийствах военнопленных и других предполагаемых сторонников Оси, коллаборационистов и / или фашистов, а также их родственников. были проведены форсированные марши и казни десятков тысяч пленных солдат и гражданских лиц (преимущественно хорватов, связанных с NDH, но также словенцев и других), спасавшихся от их наступления В ходе репатриации в Блайбурге . Зверства также включали резню в Кочевском Роге , зверства против итальянского населения в Истрии ( резня в Фойбе ) и чистки против сербов, венгров и немцев, связанных с силами оси, во время коммунистических чисток в Сербии в 1944–45 . Также с изгнанием немецкого населения , которое произошло после войны. [ 121 ]

Потери

[ редактировать ]Югославские потери

[ редактировать ]| Национальность | список 1964 года | Кочович [ 122 ] | Жерьявич [ 20 ] |

|---|---|---|---|

| сербы | 346,740 | 487,000 | 530,000 |

| хорваты | 83,257 | 207,000 | 192,000 |

| Словенцы | 42,027 | 32,000 | 42,000 |

| Черногорцы | 16,276 | 50,000 | 20,000 |

| македонцы | 6,724 | 7,000 | 6,000 |

| мусульмане | 32,300 | 86,000 | 103,000 |

| Другие славяне | – | 12,000 | 7,000 |

| албанцы | 3,241 | 6,000 | 18,000 |

| евреи | 45,000 | 60,000 | 57,000 |

| Цыгане | – | 27,000 | 18,000 |

| немцы | – | 26,000 | 28,000 |

| Венгры | 2,680 | – | – |

| словаки | 1,160 | – | – |

| турки | 686 | – | – |

| Другие | – | 14,000 | 6,000 |

| Неизвестный | 16,202 | – | – |

| Общий | 597,323 | 1,014,000 | 1,027,000 |

| Расположение | Число погибших | Выжил |

|---|---|---|

| Босния и Герцеговина | 177,045 | 49,242 |

| Хорватия | 194,749 | 106,220 |

| Македония | 19,076 | 32,374 |

| Черногория | 16,903 | 14,136 |

| Словения | 40,791 | 101,929 |

| Сербия (справа) | 97,728 | 123,818 |

| АП Косово (Сербия) | 7,927 | 13,960 |

| АП Воеводина (Сербия) | 41,370 | 65,957 |

| Неизвестный | 1,744 | 2,213 |

| Общий | 597,323 | 509,849 |

Правительство Югославии оценило число жертв в 1 704 000 человек и представило эту цифру в Международную комиссию по репарациям в 1946 году без какой-либо документации. [ 123 ] Оценка 1,7 миллиона смертей, связанных с войной, была позже представлена Союзному комитету по репарациям в 1948 году, несмотря на то, что это была оценка общих демографических потерь, охватывающих ожидаемое население, если война не разразится, количество нерожденных детей и потери от эмиграции. и болезнь. [ 124 ] После того, как Германия запросила поддающиеся проверке данные, Федеральное статистическое бюро Югославии в 1964 году провело общенациональное исследование. [ 124 ] Общее число убитых составило 597 323 человека. [ 125 ] [ 126 ] Список оставался государственной тайной до 1989 года, когда он был опубликован впервые. [ 20 ]

Бюро переписи населения США опубликовало в 1954 году отчет, в котором пришел к выводу, что в результате войны в Югославии погибло 1 067 000 человек. Бюро переписи населения США отметило, что официальная цифра правительства Югославии в 1,7 миллиона погибших на войне была завышена, поскольку она «была опубликована вскоре после войны и была оценена без учета послевоенной переписи населения». [ 127 ] Исследование Владимира Жерьявича оценивает общее количество смертей, связанных с войной, в 1 027 000 человек. Военные потери оцениваются в 237 000 югославских партизан и 209 000 коллаборационистов, а потери среди гражданского населения - в 581 000 человек, включая 57 000 евреев. Потери югославских республик составили Босния - 316 000 человек; Сербия 273 000; Хорватия 271 000; Словения 33 000; Черногория 27 000; Македония 17 000; и убили за границей 80 000 человек. [ 20 ] Статистик Боголюб Кочович подсчитал, что фактические военные потери составили 1 014 000 человек. [ 20 ] Покойный Йозо Томасевич , почетный профессор экономики Государственного университета Сан-Франциско, считает, что расчеты Кочовича и Жерьявича «кажется свободными от предвзятости, мы можем принять их как надежные». [ 128 ] Степан Мештрович подсчитал, что на войне погибло около 850 000 человек. [ 21 ] Vego приводит цифры от 900 000 до 1 000 000 погибших. [ 129 ] По оценкам Стивена Р. А'Барроу, в результате войны погибло 446 000 солдат и 514 000 мирных жителей, или в общей сложности 960 000 человек среди югославского населения из 15 миллионов. [ 19 ]

Исследование Кочовича человеческих потерь в Югославии во время Второй мировой войны считалось первым объективным исследованием проблемы. [ 130 ] Вскоре после того, как Кочович опубликовал свои выводы в книге «Жертвы Второй мировой войны в Югославии» , Владета Вучкович, профессор американского колледжа, заявила в лондонском эмигрантском журнале, что он участвовал в подсчете числа жертв в Югославии в 1947 году. [ 131 ] Вучкович утверждал, что цифра в 1 700 000 принадлежит ему, пояснив, что, как сотруднику Федерального статистического управления Югославии, ему было приказано оценить количество жертв, понесенных Югославией во время войны, с использованием соответствующих статистических инструментов. [ 132 ] Он пришел к выводу, что демографические (не реальные) потери населения составят 1,7 миллиона человек. [ 132 ] Он не намеревался использовать свою оценку для расчета фактических потерь. [ 133 ] Однако министр иностранных дел Эдвард Кардель воспринял эту цифру как реальную потерю на переговорах с Межсоюзническим агентством по репарациям. [ 132 ] Эту цифру уже использовал маршал Тито в мае 1945 года, а цифру в 1 685 000 использовал Митар Бакич , генеральный секретарь президиума югославского правительства, в обращении к иностранным корреспондентам в августе 1945 года. Югославская комиссия по репарациям также использовала эту цифру. уже сообщил цифру в 1 706 000 Межсоюзническому агентству по репарациям в Париже в конце 1945 год. [ 132 ] Цифра Тито в 1,7 миллиона была направлена как на максимизацию военной компенсации от Германии, так и на демонстрацию миру, что героизм и страдания югославов во время Второй мировой войны превзошли героизм и страдания всех других народов, за исключением только народов СССР и, возможно, Польши. [ 134 ]

Причины высоких человеческих жертв в Югославии заключались в следующем:

- Военные действия пяти основных армий (немцев, итальянцев, усташей , югославских партизан и четников ). [ 135 ]

- Немецкие войска по прямому приказу Гитлера с особой яростью боролись против сербов, которых считали унтерменами . [ 135 ] Одним из самых страшных кровавых событий во время немецкой военной оккупации Сербии была резня в Крагуеваце .

- Все комбатанты совершали преднамеренные акты репрессий против целевых групп населения. Все стороны широко практиковали расстрел заложников. В конце войны многие усташи-коллаборационисты были убиты в маршах смерти в Блайбурге . [ 136 ]

- Систематическое истребление большого количества людей по политическим, религиозным или расовым мотивам. Самыми многочисленными жертвами стали сербы, убитые усташами. Хорваты и мусульмане также были убиты четниками.

- Сокращение поставок продовольствия вызвало голод и болезни. [ 137 ]

- Бомбардировки союзниками немецких линий снабжения привели к жертвам среди гражданского населения. Больше всего пострадали Подгорица , Лесковац , Задар и Белград . [ 138 ]

- Демографические потери из-за сокращения рождаемости на 335 000 и эмиграции около 660 000 не включены в военные потери. [ 138 ]

Словения

[ редактировать ]В Словении Институт современной истории в Любляне начал комплексное исследование точного числа жертв Второй мировой войны в Словении в 1995 году. [ 139 ] После более чем десятилетних исследований в 2005 году был опубликован окончательный отчет, включающий список имен. Число жертв было установлено на уровне 89 404 человек. [ 140 ] В эту цифру также включены жертвы суммарных убийств, совершенных коммунистическим режимом сразу после войны (около 13 500 человек). Результаты исследования стали шоком для общественности, поскольку фактические цифры оказались более чем на 30% выше самых высоких оценок югославского периода. [ 141 ] Даже если считать только количество смертей до мая 1945 года (исключая, таким образом, военнопленных, убитых югославской армией в период с мая по июль 1945 года), это число остается значительно выше самых высоких предыдущих оценок (около 75 000 смертей против предыдущей оценки в 60 000). .

Причин такой разницы несколько. Новое комплексное исследование также включало словенцев, погибших в результате партизанского сопротивления, как в бою (члены коллаборационистских и антикоммунистических отрядов), так и мирных жителей (около 4000 человек в период с 1941 по 1945 год). Кроме того, в новые оценки включены все словенцы из аннексированной нацистами Словении, которые были призваны в Вермахт и погибли либо в боях, либо в лагерях для военнопленных во время войны. В эту цифру также входят словенцы из Юлианского марша , погибшие в итальянской армии (1940–43), жители Прекмурья , погибшие в венгерской армии, а также те, кто сражался и погиб в различных частях союзников (в основном британских). В цифру не включены жертвы из венецианской Словении (кроме тех, кто присоединился к словенским партизанским отрядам), а также не включены жертвы среди каринтийских словенцев (опять же за исключением тех, кто сражался в партизанских отрядах) и венгерских словенцев . 47% жертв во время войны составили партизаны, 33% - гражданские лица (из которых 82% были убиты державами Оси или словенским ополчением), а 20% - членами словенского ополчения. [ 142 ]

Территория НДХ

[ редактировать ]Согласно исследованию Жерьявича о потерях сербов в NDH, 82 000 человек погибли как члены югославских партизан и 23 000 как четники и сотрудники Оси. Из числа жертв среди гражданского населения 78 000 человек были убиты усташами в результате прямого террора и в лагерях, 45 000 - немецкими войсками, 15 000 - итальянскими войсками, 34 000 - в боях между усташами, четниками и партизанами, а 25 000 умерли от тифа. Еще 20 000 человек погибли в концентрационном лагере Саймиште . [ 20 ] По словам Иво Гольдштейна , на территории NDH 45 000 хорватов убиты как партизаны, а 19 000 погибли в тюрьмах или лагерях. [ 143 ]

Жерьявич оценил структуру реальных военных и послевоенных потерь хорватов и боснийцев. Согласно его исследованию, 69–71 000 хорватов погибли в составе вооруженных сил NDH, 43–46 000 в составе югославских партизан и 60–64 000 в качестве гражданских лиц в результате прямого террора и в лагерях. [ 144 ] За пределами NDH еще 14 000 хорватов погибли за границей; 4000 партизан и 10 000 гражданских лиц, ставших жертвами террора или в лагерях. Что касается боснийцев, включая мусульман Хорватии , он подсчитал, что 29 000 человек погибли в составе вооруженных сил NDH, 11 000 - в составе югославских партизан, 37 000 были гражданскими лицами и еще 3 000 боснийцев были убиты за границей; 1000 партизан и 2000 мирных жителей. Из общего числа жертв среди хорватов и боснийцев в NDH его исследование показало, что 41 000 смертей среди гражданского населения (18 000+ хорватов и 20 000+ боснийцев) были вызваны четниками, 24 000 - усташами (17 000 хорватов и 7 000 боснийцев), 16 000 - партизанами. (14 000 хорватов и 2 000 боснийцев), 11 000 немецких войск (7 000 хорватов и 4 000 боснийцев), 8 000 итальянских войск (5 000 хорватов и 3 000 боснийцев), а 12 000 погибли за границей (10 000 хорватов и 2 000 боснийцев). [ 145 ]

Отдельные исследователи, утверждающие неизбежность использования идентификации пострадавших и погибших по отдельным именам, выдвинули серьезные возражения против подсчетов/оценок человеческих потерь, сделанных Жерьявичем путем использования стандартных статистических методов и консолидации данных из различных источников, указывая, что такой подход недостаточен и ненадежны в определении количества и характера жертв и погибших, а также принадлежности исполнителей преступлений. [ 146 ]

В Хорватии Комиссия по идентификации военных и послевоенных жертв Второй мировой войны действовала с 1991 года до тех пор, пока Седьмое правительство республики под руководством премьер-министра Ивицы Рачана не прекратило работу комиссии в 2002 году. [ 147 ] В 2000-х годах в Словении и Сербии были созданы комиссии по скрытым массовым захоронениям для документирования и раскопок массовых захоронений времен Второй мировой войны.

Немецкие потери

[ редактировать ]Согласно спискам немецких потерь, цитируемым The Times от 30 июля 1945 года, из документов, найденных среди личных вещей генерала Германа Райнеке , главы отдела по связям с общественностью немецкого верховного командования, общие потери немцев на Балканах составили 24 000 убитыми и 12 000 человек. пропал без вести, число раненых не упоминается. Большая часть этих потерь, понесенных на Балканах, была нанесена в Югославии. [ 148 ] По данным немецкого исследователя Рюдигера Оверманса , немецкие потери на Балканах были более чем в три раза выше — 103 693 человека в ходе войны и около 11 000 человек погибли в качестве югославских военнопленных. [ 149 ]

Итальянские потери

[ редактировать ]За время оккупации Югославии итальянцы потеряли 30 531 человека (9 065 убитых, 15 160 раненых, 6 306 пропавших без вести). Соотношение убитых/пропавших без вести мужчин и раненых было необычайно высоким, поскольку югославские партизаны часто убивали пленных. [ нужна ссылка ] Самые высокие потери были в Боснии и Герцеговине: 12 394 человека. В Хорватии их общее число составило 10 472, а в Черногории - 4 999. Далмация была менее воинственной: 1773 человека. Самым тихим регионом оказалась Словения, где итальянцы потеряли 893 человека. [ 150 ] Еще 10 090 итальянцев погибли после перемирия либо убитыми во время операции «Ахсе» , либо после присоединения к югославским партизанам.

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Адриатическая кампания Второй мировой войны

- Бомбардировка союзниками Югославии во Второй мировой войне

- Музей 4 июля

- Фронт освобождения словенского народа

- Восстание в Сербии (1941 г.)

- Семь антипартизанских наступлений

- Воздушная война на Югославском фронте

- Югославия и союзники

- Национально-освободительная война Македонии

- Словенские земли во Второй мировой войне

- Резня в Бейсфьорде , перевод пленных из Югославии, приведший к крупнейшей резне в Норвегии.

- Русский охранный корпус — подразделение Вермахта, состоящее из белых русских эмигрантов из Сербии.

- Югославские памятники и мемориалы времен Второй мировой войны

Примечания

[ редактировать ]Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Д'Амико, Ф. и Дж. Валентини. Regia Aeronautica Vol. 2: Иллюстрированная история Aeronautica Nazionale Repubblicana и итальянских военно-воздушных сил, 1943–1945 гг . Кэрроллтон, Техас: Squadron/Signal Publications, Inc., 1986.

- ^ Митровски, Глишич и Ристовски 1971 , с. 211.

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , с. 255.

- ^ Елич Бутич 1977 , с. 270.

- ^ Колич 1977 , стр. 61–79.

- ^ Митровски, Глишич и Ристовски 1971 , с. 49.

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , с. 167.

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , с. 183.

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , с. 771.

- ^ Томасевич 1975 , с. 64.

- ^ Микрокопия № Т314, рулон 566, кадры 778 – 785.

- ^ Боркович , с. 9.

- ^ Сборник документов Института военной истории: том XII - Документы частей, командований и учреждений Германского рейха - книга 3, стр.619

- ^ Перика 2004 , с. 96.

- ^ Зорге, Мартин К. (1986). Другая цена гитлеровской войны: немецкие военные и гражданские потери в результате Второй мировой войны . Издательская группа Гринвуд. стр. 62–63. ISBN 978-0-313-25293-8 .

- ^ Оверманс, Рюдигер (2000). Военные потери Германии во Второй мировой войне. П:336

- ^ Гейгер 2011 , стр. 743–744.

- ^ Гейгер 2011 , стр. 701.

- ^ Jump up to: а б А'Барроу 2016 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г Жерьявич 1993 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мештрович 2013 , с. 129.

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , с. 226.

- ^ Рамет 2006 , с. 147.

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , с. 308.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Рамет 2006 , с. 142.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Рамет 2006 , стр. 145–155.

- ^ Томасевич 1975 , с. 246.

- ^ Трбович 2008 , стр. 131–132.

- ^ Лампе 2000 , стр. 198.

- ^ Городецкий 2002 , с. 130– .

- ^ Робертс 1973 , с. 26.

- ^ Шоу 1973 , с. 92.

- ^ Шоу 1973 , с. 89.

- ^ Деган, Владимир Джуро (2008). Правовые аспекты и политические последствия Римских договоров от 18 мая 1941 г. (PDF) . Юридический факультет в Сплите.

- ^ «Венгрия» . Архив визуальной истории Института Фонда Шоа . Архивировано из оригинала 3 февраля 2007 года . Проверено 4 декабря 2015 г.

- ^ Томас и Микулан 1995 , с. 24.

- ^ Талмон 1998 , с. 294.

- ^ Томас и Микулан 1995 , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Лемкин 2008 , стр. 241–64.

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , с. 85.

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , с. 419.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Томас и Микулан 1995 , с. 12.

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , с. 420.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Томас и Микулан 1995 , с. 13.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Томас и Микулан 1995 , с. 17.

- ^ Томас и Микулан 1995 , с. 10.

- ^ Тимофеев 2011 .

- ^ Павличевич 2007 , стр. 441–442.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Гольдштейн, Иво (1999). Хорватия: История . Монреаль, Квебек: Издательство Университета Макгилла-Куина . п. 141 . ISBN 978-0-7735-2017-2 .

- ^ Никола Анич (2005), Антифашистская Хорватия: Национально-освободительная армия и партизанские отряды Хорватии 1941-1945. (на немецком языке), Загреб: Мультиграф-маркетинговый Союз борцов-антифашистов и антифашистов Республики Хорватия, стр. 34, ISBN. 953-7254-00-3 ,

Первый партизанский отряд, который был сформирован в Хорватии, т. е. в оккупированной Югославии, был сформирован 22 июня 1941 года в лесу Жабно близ Сисака. […] Это был не первый партизанский отряд в оккупированной Европе и не первый антифашистский партизанский отряд в Европе, как уже давно говорилось. Первые вооруженные партизанские отряды в оккупированной Европе появились еще в 1939 году, в оккупированной Польше, затем в Норвегии, Франции, странах Бенилюкса, Греции и др. Отряд Сисакской НОП был первым антифашистским партизанским отрядом в оккупированной Югославии, в Хорватии. .

- ^ Бэйли 1980 , с. 80.

- ^ LCWeb2.loc.gov

- ^ Jump up to: а б Томас и Микулан 1995 , с. 32.

- ^ Лекович 1985 , с. 83.

- ^ Лекович 1985 , с. 86,87.

- ^ Томасевич 1975 , с. 245.

- ^ Дэвидсон , Контакт.

- ^ Савич и Циглич 2002 , стр. 60.

- ^ Редактор Гашпер Митанс; (2017) Поджог в воспоминаниях стр. 11-12; Истрийское историческое общество – Società storica istriana ISBN 978-953-59439-0-7 [1]

- ^ Мартин 1946 , с. 34.

- ^ Рендулич, Златко. Avioni domaće konstrukcije posle Drugog svetskog Rata (Отечественное авиастроение после Второй мировой войны), Институт Лолы, Белград, 1996, стр. 10. «На Тегеранской конференции с 28 ноября по 1 декабря 1943 года NOVJ признана союзной армией, на этот раз всеми тремя союзными сторонами и впервые Соединенными Штатами».

- ^ «Пока Тито сражается» . Журнал «Тайм» . 17 января 1944 года. Архивировано из оригинала 17 октября 2007 года . Проверено 14 сентября 2007 г.

- ^ Чиглич и Савич 2007 , стр. 113.

- ^ Национально-освободительная армия Югославии. Белград. в 1982 году

- ^ Стюарт, Джеймс (2006). Линда МакКуин (ред.). Словения . Издательство Нью Холланд. п. 15. ISBN 978-1-86011-336-9 . [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Клеменчич и Жагар 2004 , стр. 167–168.

- ^ «Посол в Югославии (Кэннон) госсекретарю» . Офис историка Института дипломатической службы Государственного департамента США.

- ^ Томас и Микулан 1995 , с. 33.

- ^ Оксфордский спутник Второй мировой войны , Ян Дир, Майкл Ричард Дэниэл Фут, Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-19-860446-7 , с. 134 .

- ^ Силы Оси в Югославии 1941–45 , Найджел Томас, К. Микулан, Дарко Павлович, Osprey Publishing, 1995, ISBN 1-85532-473-3 , с. 33 [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ] .

- ^ Вторая мировая война: Средиземноморье 1940–1945, Вторая мировая война: Основные истории , Пол Коллиер, Роберт О'Нил, The Rosen Publishing Group, 2010, ISBN 1-4358-9132-5 , с. 77.

- ^ Дэвидсон , Правила и причины.

- ^ Павлович 2008 , с. 258.

- ^ Томас и Микулан 1995 , с. 9.

- ^ Томас и Микулан 1995 , с. 30.

- ^ Савич и Циглич 2002 , с. 70.

- ^ Чиглич и Савич 2007 , с. 150.

- ^ Павлович 2008 , с. 256.

- ^ Томас и Микулан 1995 , с. 22.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Шоу 1973 , с. 101.

- ^ Эмброуз, С. (1998). Победители – участники Второй мировой войны . Лондон: Саймон и Шустер. п. 335 . ISBN 978-0-684-85629-2 .

- ^ Жилас 1977 , с. 440.

- ^ Павлович 2008 , с. 259.

- ^ Бушич и Ласич 1983 , с. 277.

- ^ Чорич 1996 , с. 169.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Томасевич 1975 , стр. 451–452.

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , с. 766.

- ^ Хаммонд, Эндрю (2017). Балканы и Запад: построение европейского Другого, 1945–2003 гг . Рутледж. п. 22. ISBN 978-1-351-89422-7 .

- ^ Клеменчич и Жагар 2004 , стр. 197.

- ^ Джон Абромейт; Йорк Норман; Гэри Маротта; Бриджит Мария Честертон (19 ноября 2015 г.). Трансформации популизма в Европе и Америке: история и последние тенденции . Издательство Блумсбери. стр. 60–. ISBN 978-1-4742-2522-9 .

- ^ Джуреинович, Елена (2019). Политика памяти о Второй мировой войне в современной Сербии: сотрудничество, сопротивление и возмездие . Рутледж. п. 24. ISBN 978-1-000-75438-4 .

- ^ Рамет 2006 , с. 166.

- ↑ «Too Tired» , time.com, 24 июня 1946 г.

- ^ Бюиссон, Жан-Кристоф (1999). Генерал Михайлович: герой, преданный союзниками 1893–1946 гг . Перрен. п. 272. ИСБН 978-2-262-01393-6 .

- ^ Драгнич, Алекс Н. (1995). Распад Югославии и борьба за правду . Восточноевропейские монографии. п. 65. ИСБН 978-0-880-33333-7 .

- ^ Сэмюэл Тоттен; Уильям С. Парсонс (1997). Век геноцида: критические очерки и свидетельства очевидцев . Рутледж. п. 430. ИСБН 978-0-203-89043-1 . Проверено 11 января 2011 г.

- ^ Реджич, Энвер (2005). Босния и Герцеговина во Второй мировой войне . Нью-Йорк: Тайлор и Фрэнсис. п. 84. ИСБН 978-0714656250 .

- ^ Томасевич 2001 , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Зандер, Патрик Г. (2020). Фашизм через историю: культура, идеология и повседневная жизнь [2 тома] . АВС-КЛИО. п. 498. ИСБН 978-1-440-86194-9 .

- ^ Реджич, Энвер; Дония, Роберт (2004). Босния и Герцеговина во Второй мировой войне . Рутледж. п. 11. ISBN 978-1-135-76736-5 .

- ^ Вахтель, Эндрю (1998). Создание нации, разрушение нации: литература и культурная политика в Югославии . Издательство Стэнфордского университета. п. 128. ИСБН 978-0-804-73181-2 .

- ^ Црнобрня, Михаил (1996). Югославская драма . Издательство Университета Макгилла-Куина. стр. 65. ISBN 978-0-773-51429-4 .

- ^ Байфорд, Йован (2020). Изображение геноцида в Независимом государстве Хорватия: образы зверств и спорные воспоминания о Второй мировой войне на Балканах . Издательство Блумсбери. п. 25. ISBN 978-1-350-01598-2 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Томасевич 2001 , с. 747.

- ^ Йоманс, Рори (2012). Видения уничтожения: режим усташей и культурная политика фашизма, 1941-1945 гг . Издательство Питтсбургского университета. п. 17. ISBN 978-0822977933 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Мегарджи, Джеффри П.; Уайт, Джозеф Р. (2018). Энциклопедия лагерей и гетто Мемориального музея Холокоста США, 1933–1945, том III: Лагеря и гетто при европейских режимах, связанных с нацистской Германией . Издательство Университета Индианы. стр. 47–49. ISBN 978-0-253-02386-5 .

- ^ Павкович, Александр (1996). Фрагментация Югославии: национализм в многонациональном государстве . Спрингер. п. 43. ИСБН 978-0-23037-567-3 .

- ^ Кроу, Дэвид М. (2018). Холокост: корни, история и последствия . Рутледж. п. 488. ИСБН 978-0-429-97606-3 .

- ^ Кеннеди, Шон (2011). Шок войны: гражданский опыт, 1937-1945 гг . Университет Торонто Пресс. п. 57. ИСБН 978-1-442-69469-9 .

- ^ Рамет 2006 , с. 145.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Хоар, Марко Аттила (2006). Геноцид и сопротивление в гитлеровской Боснии: партизаны и четники, 1941-1943 гг . Издательство Оксфордского университета/Британская академия. стр. 143–147. ISBN 978-0-197-26380-8 .

- ^ Томасевич 1975 , стр. 258–259.

- ^ Томасевич 1975 , с. 259.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Томасевич 2001 , с. 745.