Джозеф Листер

Господь Листер | |

|---|---|

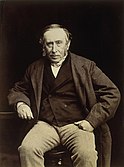

Листер в 1902 году | |

| 37 -й президент Королевского общества | |

| В офисе 1895–1900 | |

| Предшествует | Господь Кельвин |

| Преуспевает | Сэр Уильям Хаггинс |

| Личные данные | |

| Рожденный | 5 апреля 1827 г. Аптон Хаус , Вест Хэм, Англия |

| Умер | 10 февраля 1912 года (в возрасте 84 лет) Уолмер , Кент, Англия |

| Место отдыха | Хэмпстедское кладбище , Лондон |

| Супруг | |

| Родители |

|

| Подпись | |

| Образование | Университетский колледж Лондон |

| Известен для | Хирургические стерильные методы |

| Награды |

|

| Научная карьера | |

| Поля | Лекарство |

| Учреждения | |

Джозеф Листер, 1 -й барон Листер , Ом , ПК , FRS , FRCSE , FRCPGLAS , FRCS (5 апреля 1827 г. - 10 февраля 1912 г. [ 1 ] ) был британским хирургом , ученым -медиком, экспериментальным патологом и пионером антисептической хирургии [ 2 ] и профилактическое здравоохранение . [ 1 ] Джозеф Листер произвел революцию в ремесле хирургии так же, как Джон Хантер произвел революцию в науке хирургии. [ 3 ]

С технической точки зрения, Листер не был исключительным хирургом, [ 2 ] Но его исследование бактериологии и инфекции в ранах подняло его оперативную технику на новую плоскость, где его наблюдения, вычеты и практики произвели революцию в операции во всем мире. [ 4 ]

Вклад Листера был в четыре раза. Во-первых, как хирург в Королевском лазарете Глазго , он ввел карболевую кислоту (современный фенол ) в качестве стерилизера для хирургических инструментов, шкуры пациентов, швов , рук хирургов и палат, способствующих принципу антисептики . Во -вторых, он исследовал роль воспаления и перфузии тканей в заживлении ран. В -третьих, он продвинул диагностическую науку, анализируя образцы с использованием микроскопов. В -четвертых, он разработал стратегии для увеличения шансов на выживание после операции. Однако его наиболее важным вкладом было признание того, что гниение в ранах вызвано микробы, в связи с Луи Пастера тогдашней теорией зародышей зародышей . [ А ] [ 6 ]

Работа Листера привела к снижению послеоперационных инфекций и сделала операцию более безопасной для пациентов, что привело к тому, что он будет отличаться как «отец современной хирургии». [ 7 ]

Ранний период жизни

[ редактировать ]Листер родился в процветающей, образованной семье квакеров в деревне Аптон , затем рядом, но теперь в Лондоне , [ 8 ] Англия. Он был четвертым ребенком и вторым сыном четырех сыновей и трех дочерей [ 9 ] Родился у джентльмена -ученый и вином торговец Джозеф Джексон Листер и помощник школы Изабелла Листер Ней Харрис. [ 10 ] [ 11 ] 14 июля 1818 года пара вышла замуж на церемонии в Акворте, Западный Йоркшир . [ 12 ]

Прапрадед Листера от отцовской линии Томас Листер был последним из нескольких поколений фермеров, которые жили в Бингли в Западном Йоркшире . [ 13 ] Листер вступил в общество друзей в молодости и передал свои убеждения своему сыну Джозефу Листеру. [ 13 ] Он переехал в Лондон в 1720 году, чтобы открыть табаккона [ 13 ] на улице Олдерсгейт в лондонском городе . [ 14 ] Его сын, Джон Листер, родился там. Дедушка Листера был ученик для часовщика, Исаака Роджерса, [ 15 ] в 1752 году и последовал за этой торговлей на своем собственном аккаунте в Белл -переулке, Ломбард -стрит с 1759 по 1766 год. Затем он взял на себя табачный бизнес своего отца, [ 13 ] Но в 1769 году отказался от работы в бизнесе своего тестя Стивена Джексона в качестве вина в № 28 старых винных и бренди на улице Лотбери , напротив токенхаусного двора. [ 16 ]

Его отец был пионером в дизайне ахроматических объективов для использования в составных микроскопах [ 8 ] Он провел 30 лет, совершенствовая микроскоп и в процессе обнаружил закон апланатических фокусов , [ 17 ] Создание микроскопа, где точка изображения одного объектива совпала с фокусной точкой другой. [ 8 ] До этого момента лучшие линзы с более высоким увеличением создавали чрезмерную вторичную аберрацию, известную как кома , которая мешала нормальному использованию. [ 8 ] Это считалось серьезным прогрессом, который повышал гистологию в независимую науку. [ 18 ] К 1832 году работа Листера создала репутацию, достаточную для того, чтобы он был избран в Королевское общество . [ 19 ] [ 20 ] Его мать, Изабелла, была младшей дочерью мастера -моряка Энтони Харриса. [ 21 ] Изабелла работала в школе Ackworth , в школе квакеров для бедных, помогая своей овдовевшей матери, суперинтенданту школы. [ 21 ]

Старшей дочерью пары была Мэри Листер. 21 августа 1851 года она вышла замуж за адвоката Рикмана Годли [ 22 ] Линкольна Инн и Среднего Храма , который принадлежал Дому собрания друзей в Плейстоу . [ 23 ] У пары было шестеро детей. Их вторым ребенком был Рикман Годли , нейрохирург для того, кто стал профессором клинической хирургии в больнице Университетского колледжа [ 22 ] и хирург королевы Виктории . Он стал биографом Листера в 1917 году. [ 22 ] Старшим сыном Джозефа и Изабеллы Листер был Джон Листер, который умер от болезненной опухоли головного мозга. [ 24 ] С смертью Джона Джозеф стал наследником семьи. [ 24 ] Второй дочерью пары была Изабелла Софи Листер, которая вышла замуж за ирландского квакера Томаса Пим [ 25 ] в 1848 году. Другой брат Листера Уильям Генри Листер умер после длительной болезни. [ 9 ] Младшим сыном был Артур Листер , торговец вином, ботаник и квакер на протяжении всей жизни, который изучал Mycetozoa . Он работал вместе со своей дочерью Гулильмой Листер, чтобы произвести стандартную монографию о Мисетозои. К 1898 году работа Листера создала репутацию, достаточную для того, чтобы обеспечить его выборы в Королевское общество . [ 26 ] Гулильма Листер, талантливый художник, позже обновил стандартную монографию с цветовыми рисунками. Ее работа построила репутацию, достаточную для избрания члена Линниского общества в 1904 году. Она стала его вице-президентом в 1929 году. [ 27 ] Последним ребенком пары была Джейн Листер; Она вышла замуж за вдовца Смита Харрисона, оптового торговца чаем. [ 28 ]

После их брака Listers жили в 5 Tokenhouse Yard в центре Лондона в течение трех лет до 1822 года, где они управляли винным бизнесом в партнерстве с Томасом Бартоном Беком. [ 29 ] Бек был дедушкой профессора хирургии и сторонник теории болезней зародышей , Маркус Бек , [ 30 ] кто позже будет продвигать открытия Листера в своей борьбе за представление антисептиков. [ 31 ] В 1822 году семья Листера переехала в Стоук Ньюингтон. [ 32 ] В 1826 году семья переехала в Хаус Аптон , длинную низко в стиле Анны -королеву -особняк [ 32 ] Это пришло с 69 акрами земли. [ 33 ] Он был восстановлен в 1731 году, чтобы соответствовать стилю периода. [ 34 ]

Образование

[ редактировать ]Школа

[ редактировать ]В детстве у Листера был заикание, и, возможно, именно поэтому он получил образование дома, пока ему не исполнилось одиннадцать. [ 35 ] Затем Листер посетил Академию Исаака Брауна и Бенджамина Эбботта, частного [ 36 ] Квакерская школа в Хитчине , Хартфордшир . [ 37 ] Когда Листеру было тринадцать лет, [ 35 ] Он посещал школу Grove House в Тоттенхэме , также частной школе квакеров [ 37 ] Изучить математику, естественную науку и языки. Его отец настаивал на том, что Листер получил хорошее обоснование на французском и немецком языке, зная, что он будет изучать латынь в школе. [ 38 ] С раннего возраста Листер был сильно воодушевлен его отцом [ 8 ] и говорил о большом влиянии своего отца в более позднем возрасте, особенно в том, чтобы поощрять его в его изучении естественной истории. [ 35 ] Интерес Листера к естественной истории заставил его изучать кости и собирать и рассеять мелких животных и рыбы, которые были исследованы с использованием микроскопа его отца [ 19 ] а затем нарисован с использованием техники камеры Lucida , которую ему объяснил его отец, [ 30 ] или наброски. [ 37 ] Интересы его отца в микроскопических исследованиях развились в Листере решимость стать хирургом [ 19 ] и подготовил его к жизни научных исследований. [ 8 ] Ни один из родственников Листера не был в медицинской профессии. Согласно Годли, решение стать врачом, казалось, было совершенно спонтанным решением. [ 39 ]

В 1843 году его отец решил отправить его в университет. Поскольку Листер не смог посетить ни Университет Оксфордского университета , либо в Кембриджском университете из -за религиозных испытаний , которые фактически запретили его, [ 8 ] не сетанского Лондонского колледжа Он решил подать заявку в медицинскую школу университета (UCL), один из нескольких учреждений в Великобритании, которые в то время приняли квакеров. [ 40 ] Листер сдал общественный экзамен в младшем классе ботаники, который позволил бы ему поступить. [ 41 ] Листер покинул школу весной 1844 года, когда ему было семнадцать. [ 37 ]

Университет

[ редактировать ]В 1844 году, незадолго до семнадцатого дня рождения Листера, он переехал в квартиру на 28 London Road, которую он поделился с Эдвардом Палмером, также квакером. [ 42 ] Между 1844 и 1845 годами Листер продолжил свои исследования до применения в греческой, латинской и естественной философии . [ 43 ] На латинских и греческих классах он выиграл «Сертификат чести». [ 44 ] Для экспериментального класса естественной философии Листер выиграл первый приз и был награжден копией «воссозданий Чарльза Хаттона в математике и естественной философии». [ 43 ]

Хотя его отец хотел, чтобы он продолжил свое общее образование, [ 45 ] Университет потребовал с 1837 года, чтобы каждый студент получил степень бакалавра гуманитарных наук (BA) до начала медицинской подготовки. [ 46 ] Листер поступил в августе 1845 года, первоначально обучаясь на степень бакалавра в классике . [ 47 ] В период с 1845 по 1846 год Листер изучал математику естественной философии, математики и греческого, зарабатывающего «сертификат чести» в каждом классе. [ 44 ] Между 1846 и 1847 годами Листер изучал как анатомию , так и атомную теорию (химию) и получил приз за эссе. [ 44 ] 21 декабря 1846 года Листер и Палмер приняли участие в Роберта Листона знаменитой операции , где Эфир был применен одноклассником Листера Уильямом Сквайром, чтобы анестетизировать пациента. впервые [ 48 ] [ 49 ] 23 декабря 1847 года Листер и Палмер переехали на 2 Бедфорд -Плейс и присоединились к Джон Ходжкин, племянник Томаса Ходжкина , который обнаружил лимфому Ходжкина . [ 50 ] Листер и Ходжкин были школьными друзьями. [ 47 ]

В декабре 1847 года Листер окончил степень бакалавра искусств 1 -й дивизии с отличием в классике и ботанике. [ 8 ] Пока он учился, Листер страдал от легкого прихода оспы , через год после того, как его старший брат умер от этой болезни. [ 8 ] Утрата в сочетании со стрессом его классов привела к нервному срыву в марте 1848 года. [ 51 ] [ 52 ] Племянник Листера Годли использовал этот термин для описания ситуации и, возможно, указывает на то, что в 1847 году подростковый возраст был таким же трудным, как и сейчас. [ 8 ] Листер решил пройти долгий отпуск [ 36 ] выздоравливать, и это задержало начало его исследований. [ 36 ] В конце апреля 1848 года Листер посетил остров Мэн с Ходжкином, а к 7 июня 1848 года он посещал Ильфракомб . [ 53 ] В конце июня Листер принял приглашение остаться в доме Томана Пим, дублинского квакера. Используя его в качестве своей базы, Листер путешествовал по всей Ирландии. [ 54 ] 1 июля 1848 года Листер получил письмо, полное тепла и любви от своего отца, где его последняя встреча была «... солнечный свет после освежающего душа, после того, как облако» и посоветовал ему «дорожать благочестивым веселым духом, открытым Чтобы увидеть и наслаждаться наградами, и красоты распространились вокруг нас: - не уступить место, чтобы повернуть свои мысли на себя или даже в настоящее время, чтобы долго остановиться на серьезных вещах ». [ 36 ] С 22 июля 1848 года, в течение почти года, рекорд пуст. [ 55 ]

Студент -медик

[ редактировать ]Листер зарегистрировался в качестве студента -медика зимой 1849 года. [ 47 ] Во время обучения Листер был активным в университетском обществе и в больничном медицинском обществе. [ 30 ] Осенью 1849 года он вернулся в колледж, неся подарок микроскопа от своего отца. [ 49 ] После завершения курсов по анатомии, физиологии и хирургии он был награжден «сертификатом почестей», выиграв серебряную медаль по анатомии и физиологии и золотую медаль в ботанике. [ 41 ]

Его главными лекторами были Джона Линдли профессор ботаники , Томаса Грэма профессор химии , Роберта Эдмонда профессор сравнительной анатомии , Джорджа Винера Эллиса профессор анатомии и Уильяма Бенджамина профессора медицинской юриспруденции . [ 36 ] Хотя Листер часто высоко говорил о Линдли и Грэме в своих трудах, и хирургии Уортона Джонса профессор офтальмологической медицины , и Уильяма Шарпи профессор физиологии оказывал наибольшее влияние на Листер. [ 36 ] Будучи студентом, Листер был очень привлекал лекции доктора Шарпи, которые вдохновили его любовь к экспериментальной физиологии и гистологии, которые никогда не покидали его. [ 56 ]

Уортон Джонс был высоко оценил Томас Генри Хаксли за метод и качество его физиологических лекций. [ 36 ] Будучи клиническим ученым, работающим в физиологических науках, он был главным в количестве открытий, которые он сделал. [ 36 ] Его также считали блестящим офтальмо -хирургом, его главным полем. [ 36 ] Он провел исследование кровообращения крови и явлений воспаления, которое проводилось в сети лягушке и крыло летучей мыши, и, несомненно, предположил, что этот метод исследования Листеру. [ 36 ] Шарпи назывался отцом современной физиологии, так как он был первым, кто прочитал серию лекций по этому вопросу. [ 36 ] До этого поле считалось частью анатомии. [ 36 ] Шарпи учился в Эдинбургском университете, а затем отправился в Париж, чтобы изучить клиническую операцию под руководством французского анатомиста Гийом Дюпютрен и оперативной хирургии под руководством Жака Лисфранта де Мартина . Именно в Париже Шарпи познакомился с Саймами и стал друзьями на всю жизнь. [ 36 ] Переехав в Эдинбург, он преподавал анатомию с Алленом Томсоном в качестве своего физиологического коллеги. Он покинул Эдинбург в 1836 году, чтобы стать первым профессором физиологии в Университетском колледже, Лондон [ 36 ]

Клиническая инструкция

[ редактировать ]

Прежде чем он получил право на получение степени, Листер должен был пройти два года клинического обучения, [ 46 ] Начало его проживания в больнице Университетского колледжа в октябре 1850 года. [ 58 ] Он начал как стажер, а затем дома врача Уолтера Хейла Уолше . [ 30 ] Профессор патологической анатомии и автор исследования 1846 года, природа и лечение рака . [ 59 ] Листер продолжил свой академический превосходство в 1850 году, получив «Сертификаты почестей» и выиграв две золотые медали в анатомии и серебряных медалях в хирургии и медицине. [ 41 ]

Затем, на втором курсе 1851 года, Листер стал первым комодом в январе 1851 года. [ 60 ] Затем в мае 1851 года домашний хирург Джона Эрика Эриксена . [ 49 ] Эрихсен был профессором хирургии [ 7 ] и автор науки и искусства хирургии 1853 года [ 61 ] Описано как один из самых знаменитых учебников по хирургии на английском языке. [ 60 ] Книга прошла через многие издания, из которых Маркус Бек отредактировал восьмые и девятые издания, добавив антисептические методы Листера и Пастера и Роберта Коха теорию зародышей . [ 62 ] Его первые заметки о деле были записаны 5 февраля 1851 года. Как комод, его непосредственным боссом был Генри Томпсон , который вспомнил «... застенчивый квакер ... Я помню, что у него был лучший микроскоп, чем любой человек в колледже». [ 58 ]

Листер только начал работать в роли комода в Эрихсен в январе 1851 года, когда была эпидемия эрисипелы . в мужской палате [ 63 ] Зараженный пациент, который приехал из рабочего дома Ислингтона, остался в хирургическом отделении Эрихсена на два часа. [ 63 ] Больница была свободна от инфекции, но в течение нескольких дней было двенадцать случаев инфекции и четыре смерти. [ 63 ] В своей записной книжке Листер заявил, что болезнь была формой хирургической лихорадки, и особенно отметил, что недавние хирургические пациенты инфицировали худшие, но пациенты с более старыми операциями с гневающими ранами, «в основном сбежали». [ 63 ] В то время как Листер работал на Эрихсена, его интерес к исцелению ран начался. [ 7 ] Эрихсен был миазмом , который думал, что раны были заражены от миасмы , которые были получены от самой раны и вызвали вредную форму «плохого воздуха», которая распространилась на других пациентов в палате. [ 7 ] Эриксен полагал, что 7 пациентов с инфицированной раной привели к насыщению палата «плохой воздух», которые распространились, чтобы вызвать гангрену. [ 7 ] Тем не менее, Листер принял более рациональный подход, увидев, что некоторые раны, когда они были сброшены и очищены, иногда заживают. Он верил, что что -то в самой ране было виноват. [ 7 ]

Когда он стал домашним хирургом, Листер заставил пациентов встать на его ответственность. [ 60 ] Впервые он вступил в контакт лицом к лицу с различными формами заболеваний, занимающихся крови, такими как Пимемия [ 64 ] и больница гангрена, которая гниет живую ткань с замечательной быстротой. [ 60 ] [ 65 ] Изучая удаление локтя маленького мальчика во время вскрытия , который умер от Пимемии густая желтая гнойная геня присутствовала , Листер заметил, что на сиденье плечевой кости , и это расширило плечевые и подмышечные вены . [ 66 ] Он также заметил, что гной продвигался в обратном направлении вдоль вен, обходив клапаны в жилах. [ 66 ] Он также обнаружил нанесение на колено и множественные абсцессы в легких. [ 66 ] Листер знал, что Чарльз-Эммануэль Седиллот обнаружил, что множественные абсцессы в легких были вызваны введением гной в вены животного, но в то время не могли объяснить факты, но полагал, что гной в органах имел метастатическое происхождение. [ 66 ] 2 октября 1900 года во время лекции Хаксли Листер рассказал, как его интерес к теории зародышей болезней и как теория применялась к хирургии, начался с исследования смерти маленького мальчика. [ 67 ]

Во время его хирурга была эпидемия гангрены. чтобы хлороформ пациента, соскребайте мягкую шлепа Метод для восстановления состоял в том , [ 60 ] Иногда лечение было бы успешным, но если на краю раны появилась серая пленка, то оно представляло смерть. [ 60 ] У одного пациента лечение повторялось несколько раз из -за того, что оно не удалось, что приводит к тому, что Эрихсен ампутирует конечность, которая заживала нормально. [ 68 ] Доказательства того, что Листер признал, заключалось в том, что болезнь была «местным ядом» и, вероятно, паразитарным по своей природе. [ 68 ] Он исследовал больные ткани под своим микроскопом. Он видел своеобразные объекты, которые он не мог идентифицировать, так как у него не было никакой структуры, чтобы сделать выводы из наблюдений. [ 60 ] В своей записной книжке он записал:

Я предполагал, что они могут быть Матери Морби в форме какого -то гриба. [ B ]

Листер написал две статьи об эпидемиях; Оба были потеряны. Первая статья была на больнице гангрены [ 49 ] и второй был при использовании микроскопа . Они были прочитаны Студенческому медицинскому обществу в UCL. [ 49 ]

Первая операция Листера

[ редактировать ]26 июня 2013 года медицинский историк Рут Ричардсон и ортопедический хирург Брайан Роудс опубликовали статью, в которой они описали свое открытие первой операции Листера, сделанную, когда оба изучали его карьеру. [ 49 ] В 13:00 27 июня 1851 года, Листер, студент второго курса, работающий в отделении пострадавшего на Гауэр-стрит, провела свою первую операцию на Джулии Салливан, мать восьми взрослых детей, которые были зарезаны в живот ее мужем, Пьяный и не-до-до-холд, который был взят под стражу. [ 69 ] 15 сентября 1851 года Листер был вызван в качестве свидетеля его судебного разбирательства в Олд Бейли . [ 69 ] Его показания помогли осудить мужа, которого транспортировали в Австралию в течение 20 лет. [ 69 ]

Листер нашел женщину с примерно двором тонкой кишки примерно восьми дюймов поперек, поврежденную в двух местах, выступая из ее нижней части живота . Сам живот содержал три открытых рана. [ 49 ] После очистки кишечника с помощью кровавой воды водой, Листер не смог поместить их обратно в тело, поэтому он принял решение продлить срез. [ 49 ] Затем они были помещены обратно в тело, раны закрыли, а живот зашила . [ 49 ] Пациенту вводили опиум , чтобы вызвать запор , чтобы позволить кишечнику восстанавливаться. Суливан восстановила свое здоровье. [ 49 ] Прошло целое десятилетие до его первой публичной операции в лазарете Глазго. [ 49 ]

Эта операция была пропущена историками. [ 49 ] Хирург -консультант Ливерпуля Джон Шепард в своем эссе о Листере, Джозефе Листере и хирургии живота , написанном в 1968 году, [ 70 ] Не упомянул операцию, вместо этого начал свои даты с 1860 -х годов. Очевидно, он не знал о том, чего совершил Листер. [ 49 ]

Микроскоп Эксперименты 1852

[ редактировать ]Наблюдения за сократительной тканью радужной оболочки

[ редактировать ]Листер написал свою первую статью [ 71 ] Пока он еще был в университете. Это считалось достаточно хорошим [ 72 ] быть опубликованным в ежеквартальном журнале микроскопических наук в 1853 году. [ 73 ]

11 августа 1852 года Листер был представлен с кусочком свежей радужной оболочки Человека Уортона Джонса в больнице Университетского колледжа. Листер присутствовал на операции, проведенной Джонсом [ 74 ] и воспользовался редкой возможностью, чтобы изучать радужную оболочку. [ 71 ] Листер рассмотрел существующее исследование, а также изучая ткани у лошади, кошки, кролика и морской свинки, а также взял шесть хирургических образцов от пациентов, которые перенесли хирургическую операцию на глазах. [ 75 ] Листер не смог завершить исследование до его удовлетворения, из -за необходимости сдать свой финальный экзамен. Он принес извинения в газете:

Мои обязательства не позволяют мне нести, расследование в настоящее время; и мои извинения за предложение результатов неполного расследования заключается в том, что взнос, склонной, в малой степени, расширить наше знакомство с таким важным органом, как глаз, или проверить наблюдения, которые можно считать сомнительными, может быть, может быть из Интерес для физиолога. [ 72 ]

Документ выдвинул работу швейцарского физиолога Альберта фон Келликера , демонстрируя существование двух различных мышц, дилататора и сфинктера в радужной оболочке , [ 19 ] Это исправило убеждения предыдущих исследователей в том, что не было мышц дилататора. [ 75 ]

Наблюдения на мышечной ткани кожи

[ редактировать ]Его следующей статьей стало расследование гуся [ 76 ] [ 77 ] Это было опубликовано 1 июня 1853 года, в том же журнале. [ 78 ] Листер смог подтвердить экспериментальные исследования Келликера, что у людей волокна гладких мышц ответственны за выделение волос из кожи, в отличие от других млекопитающих, в которых крупные тактильные волосы связаны со сшитой мышцей . [ 75 ] Листер продемонстрировал новый метод создания гистологических срезов из ткани кожи головы. [ 79 ]

Навыки микроскопии Листера были настолько продвинутыми, что он смог исправить наблюдения немецкого гистолога Фридриха Густава Хенла , который принял небольшие кровеносные сосуды за мышечные волокна . [ 80 ] В каждой из бумаг он создавал камеру чертежей Lucida, которые были настолько точными, что их можно было использовать для масштабирования и измерения наблюдений. [ 78 ]

Обе работы привлекли значительное внимание как в Британии, так и за рубежом. [ 81 ] Натуралист Ричард Оуэн , который был старым другом отца Листера, был особенно впечатлен обеими документами. [ 81 ] Оуэн размышлял о наборе Листера для своего отделения и направил ему благодарственное письмо 2 августа 1853 года. [ 81 ] Келликер был особенно доволен анализом, который сформулировал Листер. Келликер, который совершил много поездок в Великобританию, в конечном итоге встретится с Листером и станет друзьями на всю жизнь. [ 81 ] Их близкая дружба была описана в письме Келликера 17 ноября 1897 года, что Рикман Годли решил использовать для иллюстрации их отношений. [ 82 ] Келликер послал письмо Листеру, когда он был президентом Королевского общества , поздравляя Листера с получением медаль Копли и с любовью вспомнил своих старых друзей, которые умерли и отпраздновали свое время в Шотландии, когда с Саймами и Листером. Келликеру было 80 лет в то время. [ 82 ]

Выпускной

[ редактировать ]Листер получил степень бакалавра медицины с отличием , осенью 1852 года. [ 73 ] В течение своего последнего года Листер получил несколько престижных наград, которые были в значительной степени оспорены среди студентов лондонских учебных больниц. [ 83 ] Он выиграл приз Лонгриджа

За наибольшее мастерство, проявленное в течение трех лет, непосредственно предшествующих, на сессионных экзаменах по наградам на классах медицинского факультета колледжа; и для заслуги в должности в больнице в больнице

Это включало стипендию в 40 фунтов стерлингов. [ 83 ] Он также был награжден золотой медалью в структурной и физиологической ботанике. [ 83 ] [ 44 ] Листер получил две из четырех доступных золотых медалей в области анатомии и физиологии, а также хирургию, которая составляла стипендию медали в размере 50 фунтов стерлингов в год, в течение двух лет для своего второго обследования в области медицины. [ 83 ] В том же году Листер сдал экзамен на стипендию Королевского колледжа хирургов , [ 73 ] Получение до конца девять лет образования. [ 73 ]

Закончив его медицинское образование, Шарпи посоветовал Листеру провести месяц на медицинской практике своего друга на протяжении всей жизни Джеймса Сайма в Эдинбурге, а затем посетить медицинские школы в Европе для более длительного периода обучения. [ 84 ] Сам Шарпи был преподан первым в Эдинбурге, а затем в Париже. Шарпи встретил Сайма, учителя клинической хирургии, которого широко считались лучшим хирургом в Великобритании [ 85 ] Пока он был в Париже. [ 86 ] Шарпи отправился на север в Эдинбург в 1818 году, [ 87 ] наряду со многими другими хирургами с тех пор, из -за влияния Джона Хантера . [ 85 ] Охотник научил Эдварда Дженнера , которого считают первым хирургом, который принял научный подход к изучению медицины, который был известен как охотничий метод [ 88 ] Охотник был ранним сторонником тщательного расследования и экспериментов, [ 89 ] Использование методов патологии и физиологии, чтобы дать себе лучшее понимание исцеления, чем многие его коллеги. [ 85 ] Например, его бумага 1794 года, трактат о крови, воспалении и выстрелах с оружием [ 89 ] было первым систематическим исследованием отек , [ 85 ] Обнаружение, что воспаление было общим для всех болезней. [ 90 ] Из -за Охотника операция была поднята с работы, затем практиковалась любителями или любителями в настоящую научную профессию. [ 85 ] Поскольку шотландские университеты преподавали медицину и хирургию с научной точки зрения, хирурги, которые хотели подражать этим методам, путешествовали на север для обучения. [ 91 ] У шотландских университетов было несколько других особенностей, которые отличали их от медицинских университетов на юге. [ 92 ] Они были недорогими и не требовали религиозных тестов на прием, привлекая наиболее научно прогрессивных студентов в Великобритании. [ 92 ] Самым важным отличием было то, что медицинские школы в Шотландии развивались из научной традиции, где английские медицинские школы опирались на больницы и практику. [ 92 ] В экспериментальной науке не было практиков в английских медицинских школах, и, хотя в то время медицинская школа Эдинбургского университета была большой и активной, южные медицинские школы, как правило, были умирают, их лабораторные помещения и учебные материалы были неадекватными. [ 92 ] Английские медицинские школы, как правило, рассматривали хирургию как ручной труд, а не респектабельный призыв к академическому джентльмену. [ 92 ]

Хирургическая профессия 1854

[ редактировать ]Перед исследованием хирургии Листера многие люди считали, что химическое повреждение от воздействия «плохой воздух» или миазма отвечал за инфекции в ранах. [ 93 ] Больничные палаты иногда выходили в эфир в полдень в качестве меры предосторожности против распространения инфекции через миасму, но учреждения для мытья рук или раны пациента не были доступны. Хирург не должен был вымыть руки, прежде чем увидеть пациента; В отсутствие какой -либо теории бактериальной инфекции такие практики не считались необходимыми. Несмотря на работу Игназа Семмельвейса и Оливера Уэнделла Холмса -старшего , больницы практиковали операцию в антисанитарных условиях. Хирурги того времени упомянули о «старом добром хирургическом вонюте» и гордились пятнами на своих немытых операционных платьях как демонстрацию своего опыта. [ 94 ]

Эдинбург 1853–1860

[ редактировать ]Джеймс Сайм

[ редактировать ]Сайм был хорошо известным клиническим лектором в Эдинбургском университете более двух десятилетий, прежде чем он встретил Листера [ 95 ] и считался самым смелым и самым оригинальным хирургом, чем живет в Великобритании. [ 96 ] Он стал хирургическим пионером во время своей карьеры, предпочитая более простые хирургические процедуры, поскольку он ненавидел сложность, [ 95 ] в эпоху, которая немедленно предшествовала введению анестезии. [ 97 ]

В сентябре 1823 года, в возрасте 24 лет, Сайм сделал себе имя, впервые выполнив ампутацию в хип-штрафе , [ 97 ] [ 98 ] В первый раз в Шотландии. Считается самой кровавой операцией в хирургии, Сайм завершил его менее чем за минуту, [ 95 ] [ 97 ] как скорость была важна в то время до анестезии . Сайм стал широко известным и признанным за его развитие хирургической операции, которая стала известной как ампутация Syme , ампутация на уровне сустава лодыжки , где нога удаляется и консервирована на пятке. [ 99 ] Сайм считался научным хирургом, о чем свидетельствует его статья о силе периостеума сформировать новую кость , [ 97 ] и стал одним из первых сторонников антисептиков.

Прибытие в Эдинбург

[ редактировать ]В сентябре 1853 года Листер прибыл в Эдинбург с введением из Шарпи в Сайм. [ 100 ] Листер беспокоился о своем первом назначении, но решил поселиться в Эдинбурге после встречи с Саймом, который обнял его с распростертыми объятиями, пригласил его на ужин и предложил ему возможность помочь в его частных операциях. [ 84 ]

Листер был приглашен в дом Сайма, Миллбэнк , в Морнингсайде (ныне часть больницы Эшеми Эйнсли ), [ 101 ] Там, где он встретил, среди прочего, Агнес Сайм , дочь Симэ другим браком и внучкой врача Роберта Уиллиса . [ 102 ] [ 103 ] В то время как Листер думал, что Агнес не был традиционно красивым, он восхищался ее быстротой ума, ее знакомством с медицинской практикой и ее теплом. [ 103 ] Листер стал частым посетителем Millbank и встречал гораздо более широкую группу выдающихся людей, чем в Лондоне. [ 104 ]

В том же месяце Листер начал работать в качестве помощника Syme в Эдинбургском университете [ 84 ] В письме своему отцу Листер был удивлен размером с лазарета и рассказал о своих впечатлениях о Сайме »,« больше, чем я ожидал найти его; есть 200 хирургических слоев и большое количество в других отделениях. В больнице Университетского колледжа было только около 60 хирургических коек, поэтому, по -видимому, перспектива открывает очень выгодный пребывание. Разговор такого человека имеет наибольшее возможное преимущество ». [ 105 ] К октябрю 1853 года Листер решил провести зиму в Эдинбурге. Сайм был настолько впечатлен Листером, что через месяц Листер стал хирургом сверхскоростного дома Сайма в Королевском лазарете Эдинбурга [ 106 ] и его помощник в его частной больнице в Минто Хаус на Чемберс -стрит. [ 101 ] Как домашний хирург, он помогал Syme во время каждой операции, делая заметки. [ 106 ] Это была очень приколевающая позиция [ 30 ] и дал Листеру возможность выбрать, какой из обычных случаев он посетит. [ 19 ] В течение этого периода Листер представил статью в Королевском Эдинбургском медицинском обществе по структуре губчатых экзостозов, которые были удалены Симэ, демонстрируя, что метод оссьми этих ростов был таким же, как и в эпифизарском хит-няне . [ 107 ]

В сентябре 1854 года была закончена назначение House House House Hirgeoncy. [ 108 ] С перспективой быть без работы, он поговорил со своим отцом о поиске должности в Королевской бесплатной больнице в Лондоне. [ 108 ] Тем не менее, Шарпи написал Симе, предупредив его, что маловероятно, что Листер будет приветствовать в Royal Free, так как он, вероятно, затмил Томаса Х. Уокли, чей отец держал значительное влияние в больнице. [ 109 ] Затем Листер планировал совершить поездку по Европе на год. [ 110 ] Тем не менее, возможность появилась, когда известный хирург лазарета и хирургический лектор в Эдинбургской медицинской школе Ричард Джеймс Маккензи умер. [ 111 ] Маккензи был замечен как преемник Syme [ 111 ] но заключил контракт с холерой в Бальбеке в Скутари , Стамбул , в то время как на четырехмесячном творческом отпуске в качестве полевого хирурга 79-го горца во время Крымской войны . [ 30 ] Листер воспользовался ситуацией и предложил Сайме, что он занял положение Маккензи, чтобы стать помощником хирурга в Саме. [ 110 ] Симэ первоначально отверг эту идею, поскольку Листер не имел лицензии на работу в Шотландии, а позже согрел эту идею. [ 110 ] В октябре 1854 года Листер был назначен лектором [ 112 ] Листер успешно перенес арендную аренду Маккензи в своей лекционной комнате на 4 школьных ярдах. 21 апреля 1855 года Листер был избран членом Королевского колледжа хирургов Эдинбурга [ 113 ] и два дня спустя, арендовал дом на площади 3 Ратленда для жизни. [ 30 ] В июне 1855 года Листер совершил поспешную поездку в Париж, чтобы пройти курс по оперативной операции на мертвом теле и вернулся в июне. [ 113 ]

За исключением лекций

[ редактировать ]

7 ноября 1855 года Листер прочитал свою первую внешнюю лекцию о «принципах и практике хирургии», в театре лекций на 4 старших классах [ 114 ] известный как Старый Иерусалим и непосредственно расположен напротив лазарета. [ 115 ] Его первая лекция была прочитана со 21 страницы дурака Фолио . [ 116 ] Первые лекции Листера были основаны на заметках, либо читали, либо сказали, но со временем он использовал их все меньше и меньше [ 115 ] Становясь в его речи, медленно и намеренно формируя свой аргумент, когда он пошел вместе. [ 117 ] С этим преднамеренным способом выступления ему удалось преодолеть небольшой, случайный заикание, которое в первые годы было более выраженным. [ 117 ]

Его первым учеником был Джон Бэтти Тук , [ 115 ] В классе из девяти или десяти, в основном состоит из комодов. [ 116 ] В течение недели присоединились двадцать три человека. [ 116 ] В следующем году появилось только восемь людей. Летом 1858 года у Листера был позорный опыт читать свою лекцию одному студенту, который прибыл на десять минут поздно. Еще семь студентов прибыли позже. [ 118 ]

Его первая лекция была сосредоточена на концепции хирургии, указав определение заболевания, которое связало ее с клятвой Гиппократа . [ 119 ] Затем он объяснил, что операция может иметь больше преимуществ, чем лекарства, которые в лучшем случае могли бы утешить пациента. Затем он объяснил атрибуты, которые должен продемонстрировать хороший хирург, прежде чем закончить лекцию, рекомендованной книгой Сайма «Принципы хирургии». Листер завершил 114 лекций, которые последовали за стандартной программой. Лекция VII описала свой самый ранний эксперимент по воспалению, когда он положил горчицу на руку и наблюдал за результатами. Лекции IV для IX имели дело с кровообращением. Воспаление обсуждалось в лекциях x до xiii. Вторая половина курса касалась клинической хирургии. В течение последних 4 дней он прочитал 2 лекции в день, чтобы завершить мероприятие до его брака, а первый курс закончился 18 апреля 1856 года. [ 120 ] Летом 1858 года Листер начал второй, совершенно отдельный курс, где он читал лекции по хирургической патологии и оперативной хирургии. [ 121 ]

Свадьба

[ редактировать ]К середине лета 1854 года Листер понял, что его привлекает Агнес Сайм [ 122 ] И он начал удручать ей. Листер написал своему отцу и матери о своей любви, но оба его родителя были обеспокоены профсоюзом, особенно в отношении того факта, что он был квакером, и Агнес не имел никаких признаков того, что она собирается изменить свою деноминацию. [ 123 ] За это время, когда квакер вышла замуж за человека с другой деноминацией , это будет считаться выходом из общества . [ 112 ] Листер был полон решимости выйти замуж за Агнес и послал дальнейшее письмо своему отцу, спрашивая его отца, будет ли его финансовая поддержка, если Листер и Агнес выйдут замуж. Отец Листера ответил, что Агнес, не находящийся в обществе друзей, не повлияет на его материальные меры. [ 124 ] Джозеф Джексон предложил своему сыну дополнительные деньги, чтобы купить мебель, и предложил Саймам предложить приданое и что он будет вести переговоры с Саймом напрямую на нем. [ 124 ] Его отец предложил Листеру добровольно уйти в отставку из общества друзей. [ 124 ] Листер решил и впоследствии оставил квакеров стать протестантом , позже присоединившись к собранию епископальной церкви Святого Павла на улице Джеффри, Эдинбург. [ 125 ] В августе 1855 года Листер обручился с Агнес Симэ . [ 30 ] 23 апреля 1856 года Листер женился на Агнес Саме в гостиной Миллбэнк, дома Сайма в Морнингсайде . [ 126 ] Сестра Агнес заявила, что это было из -за каких -либо квакерских отношений. [ 124 ] Присутствовали только семья Сайма. [ 127 ] Шотландский врач и друг семьи Джон Браун поджарил пару после приема. [ 124 ]

На медовом месяце пара провела месяц в Аптоне и в районе озера , [ 126 ] За последующим три месяца в экскурсии по ведущим медицинским институтам во Франции, Германии, Швейцарии и Италии. [ 128 ] Пара вернулась в октябре 1856 года. [ 129 ] К этому времени Агнес была очарована медицинскими исследованиями и стала партнером Листера в лаборатории до конца своей жизни. [ 127 ] Когда они вернулись в Эдинбург, пара переехала в арендованный дом на 11 Ратленд -стрит в Эдинбурге. [ 129 ] Дом был расположен на трех этажах с исследованием на первом этаже, который был превращен в консалтинговую комнату для пациентов и комнату с горячими и холодными кранами на втором этаже, которая стала его лабораторией. [ 124 ] Шотландский хирург Уотсон Чейн , который был почти суррогатным сыном Листеру, заявил после его смерти, что Агнес из всего сердца вступила в свою работу, был его единственным секретарем, и что они обсуждали его работу на почти равной основе . [ 63 ]

Книги Листера полны осторожного почерка Агнес. [ 63 ] Агнес будет взять диктовку от Листера, взявшего в часы на протяжении всего часа. Пространства будут оставлены пустыми среди потертостей почерка Агнес для небольших диаграмм, которые Листер создаст с помощью камеры техника Люсида, а Агнес позже встанет. [ 63 ]

Помощник хирурга

[ редактировать ]13 октября 1856 года он был единогласно избран на должность помощника хирурга в Королевском лазарете в Эдинбурге . [ 129 ] В 1856 году он также был избран членом Харвейского общества Эдинбурга . [ 130 ] [ 131 ]

Вклад в физиологию и патологию 1853–1859 гг.

[ редактировать ]В то время как он был в Эдинбурге, Листер провел серию физиологических и патологических экспериментов между 1853 и 1859 годами. [ 132 ] Его подход был строгим и дотошным как в измерении, так и в описании. [ 132 ] Листер четко знал о последних достижениях в области физиологических исследований во Франции, Германии и других европейских странах [ 8 ] и сохранил постоянное обсуждение своих наблюдений и результатов с другими ведущими врачами в его группе сверстников , включая Альберта фон Келликера , Вильгельма фон Виттича , Теодора Шванна и Рудольфа Вирчова [ 132 ] и гарантировал, что он правильно процитировал их работу.

Основным инструментом исследований Листера был его микроскоп, а его основным исследовательским материалом были лягушки. Перед своим медовым месяцем пара посетила дом его дяди в Кинросс . [ 133 ] Листер взял свой микроскоп и захватил несколько лягушек, намереваясь использовать их при изучении воспаления, но они сбежали. [ 133 ] Когда он вернулся из своего медового месяца, он использовал лягушек, запечатленных из Duddingston Loch в его экспериментах. [ 134 ] Листер провел свои эксперименты в своей лаборатории и в ветеринарном колледже скотоби на животных, которые были либо мертвы, либо когда они были хлороформированы . Если Листер использовал лягушку, они были отбиты , чтобы лишить их ощущения. [ 135 ] Он также использовал летучих мышей, овец, кошек, кроликов, волов и лошадей в своих экспериментах. [ 135 ] Листер был неутомим в своем стремлении к знаниям, и это иллюстрируется Томасом Аннандейлом , его помощником, который заявил:

Признаюсь, что в течение нескольких раз, наше терпение было немного испытано долгими часами, и, в частности, часа ужина было много часов, но никто не мог работать с мистером Листером, не впитывая некоторые из его энтузиазма [ 136 ]

Эти эксперименты привели к публикации одиннадцати документов между 1857 и 1859 годами. [ 132 ] Они включали изучение нервного контроля артерий, самые ранние стадии воспаления, ранние стадии коагуляции, структуру нервных волокон и изучение нервного контроля кишечника со ссылкой на симпатические нервы. [ 132 ] Он продолжил эксперименты в течение трех лет, пока не был назначен на должность в Университете Глазго . [ 137 ]

1855 Начало исследования воспаления

[ редактировать ]В письме от 16 сентября 1855 года Листер записал начало своего исследования воспаления, за шесть недель до начала его лекций. [ 138 ] Воспаление было предметом, который заинтересовал его на всю оставшуюся жизнь. [ 139 ] Позже Листер заявил, что считал, что свое исследование о природе воспаления является «важной предварительной» для его концепции антисептического принципа и настаивал на том, что эти ранние результаты будут включены в любой поминальный объем его работы. [ 140 ] В 1905 году, когда ему было семьдесят восемь лет, он написал

Если мои работы будут прочитаны, когда я уйду, это будет самым очень широко распространенным [ 141 ]

Воспаление определяется четырьмя симптомами: тепло, покраснение, отек и боль. [ 139 ] Для хирургов до Листера это означало прибытие наглучения или гниения, что означает локальную или общую инфекцию. [ 142 ] Поскольку зародышевая теория заболевания не была обнаружена, инфекция как концепция не существовала. [ 142 ] Однако Листер знал, что явления замедления крови через капилляры, по -видимому, предшествовали воспалению. [ 142 ] Джозеф Джексон Листер написал статью с Томасом Ходжкином , в которой описывались клетки крови до сгустка , т.е. конкретно, как вогнутые клетки объединились в стеки. [ 142 ] Листер знал, что для наблюдения за следующим шагом было важно, чтобы ткань оставалась живой, чтобы через микроскоп наблюдался кровеносные сосуды. [ 142 ]

В сентябре 1855 года первый эксперимент Листера был на артерии лягушки, просмотренной под его микроскопом, который подвергался капельке воды с различными температурами, чтобы определить раннюю стадию воспаления . [ 143 ] [ 144 ] Первоначально он применил каплю воды при 80 ° F (27 ° C), что заставило артерию сокращаться на секунду, а поток прекратился, затем расширилась, а область покраснела, а поток крови увеличился. [ 145 ] Он постепенно повышал температуру до 200 ° F (93 ° C). Кровь замедлилась, а затем коагулировала. [ 145 ] Он продолжил эксперимент на крыле хлороформированной летучей мыши, чтобы расширить свое исследование. [ 146 ] Листер пришел к выводу, что сокращение сосудов привело к исключению клеток крови из капилляров, а не их арест и сыворотка крови продолжали течь. Это было его первое независимое открытие. [ 119 ]

Эксперименты прекратились в период с октября 1855 года и продолжались в сентябре 1856 года, когда пара переехала на площадь Ратленд. [ 147 ] Листер начал с горчицы в качестве раздражителя, затем кротонового масла , уксусной кислоты , масла кантаридина и хлороформа и многих других. [ 147 ] Они привели к производству трех статей. Его первая статья вышла из -за необходимости подготовиться к этим внешним лекциям и началась годом ранее, продолжая развиваться в течение шести недель после того, как он переехал на улицу Ратленд. [ 148 ] Ранняя статья под названием «На ранних стадиях воспаления, как наблюдалось в подноже лягушки», была прочитана Королевскому колледжу хирургов Эдинбурга 5 декабря 1856 года. Последняя треть была зачитана Extempore . [ 148 ]

1856 г. Начало исследования коагуляции

[ редактировать ]Исследование Листера в процессе коагуляции было второй основной областью расследования, которую он провели в течение этого периода. [ 149 ] Во время воспаления он наблюдал во время воспаления в некоторых случаях сепсиса , что это влияло на кровеносные сосуды, ведущие к внутрисосудистому свертыванию крови , [ 150 ] Это привело к гниению и вторичному кровоизлиянию в ранах. [ 151 ] Начиная с простого эксперимента в декабре 1856 года, который был описан в примечании Агнесом, где он уколол свой палец, чтобы наблюдать за процессом коагуляции, [ 149 ] Это привело к пяти физиологическим документам о коагуляции между 1858 году [ 121 ] и последний в 1863 году. [ 67 ]

Было несколько конкурирующих теорий, которые объясняли возникновение сгустка крови, и, хотя теории были в значительной степени заброшены, все еще считалось, что в кровке содержалась ликвидирующий агент, [ 152 ] т.е. фибрин удерживается в растворе аммиака [ 153 ] Это стало известно как «теория аммиака». [ 151 ]

В 1824 году Чарльз Скадамор предложил углекислоту в качестве раствора . [ 154 ] Преобладающая теория была от Бенджамина Уорда Ричардсона , который выиграл триенневую премию Эсттли Купер 1857 года за его эссе, где он постулировал, что кровь остается жидкостью из -за наличия аммиака . В том же году Эрнст Вильгельм фон Брюке предположил, что жизненно важные действия сосудов ингибировали естественную тенденцию крови к коагуляции. [ 155 ]

1856 на мельчайшей структуре непроизвольного мышечного волокна

[ редактировать ]Третья статья Листера [ 156 ] [ 157 ] был опубликован в 1858 году в том же журнале и был прочитал перед Королевским обществом Эдинбурга 1 декабря 1856 года. [ 156 ] Это было исследование гистологии и функции мельчайших структур непроизвольных мышечных волокон . [ 75 ] Эксперимент проводился осенью 1856 года, [ 158 ] и был разработан для подтверждения наблюдений Келликера о структуре отдельных мышечных волокон. [ 75 ] Описание Келликера подвергалось критике, поскольку он использовал иглы для разделения ткани, чтобы наблюдать за отдельными клетками, поэтому его критики заявили, что он наблюдал артефакты для эксперимента, а не реальных мышечных клеток. [148] Lister proved conclusively that the muscle fibres of blood vessels, described by Lister as slightly flattened elongated elements,[156] were similar to those found by Kölliker in pig intestine, but were wrapped spirally and individually, around the innermost membrane.[158] He stated that the different variations in shape, from long tubular bodies with pointed ends and elongated nuclei to short "spindles" with squat nuclei, were due to different phases of the contraction.[158] During "The Huxley Lecture" he stated he could not imagine a more efficient mechanism being used to constrict these vessels.[159]

1857 On the flow of the lacteal fluid in the mesentery of the mouse

[edit]His next paper[160] was a short report based on observations that he made in 1853.[161] This first experiment by Lister, as opposed to purely microscope work, was to prove two goals:[82] firstly to determine the nature of the flow of chyle in the lymphatics and secondly,[82] to determine if the lacteals in the gastrointestinal wall could absorb solid matter, in the form of granules, from the lumen.[82] For the first experiment, a mouse that was fed beforehand on bread and milk was chloroformed and then had its abdomen opened and a length of intestine placed on glass under a microscope.[82] Lister repeated the experiment several times and each time saw mesenteric lymph flowing in a steady stream, without visible contractions of the lacteals. For the second experiment, Lister dyed some bread with indigo dye and fed it to a mouse, with the result that no indigo particles were ever seen in the chyle.[162] Lister delivered the paper to the 27th meeting of the British Medical Association, that was held in Dublin between 26 August to 2 September 1857.[122] The paper was formally published in 1858 in the Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science.[160]

Seven papers on the origin and mechanism of inflammation

[edit]In 1858, Lister published seven papers on physiological experiments he conducted on the origin and mechanism of inflammation.[163] Two of these papers were research into the neural control by the nervous system of blood vessels, "An Inquiry Regarding the Parts of the Nervous System Which Regulate the Contractions of the Arteries" and "On the Cutaneous Pigmentary System of the Frog", while the third and the principal paper in the series was titled: "On the Early Stages of Inflammation", which extended the research by Wharton Jones.[163] The three papers were read to the Royal Society of London on 18 June 1857.[164] They had originally been written as one paper and had been sent to Sharpey, John Goodsir and the English pathologist James Paget for review.[165] However, Paget and Goodsir both recommended that it should be published as three separate papers.[165][166]

1858 An Inquiry Regarding the Parts of the Nervous System Which Regulate the Contractions of the Arteries

[edit]The first of these series of experiments[167] was designed to satisfy a contemporary dispute between physiologists, concerning the origin of the influence exercised over blood vessel diameter (calibre) by the sympathetic nervous system.[150] The dispute began when Albrecht von Haller formulated a new theory known as Sensibility and Irritability in his 1752 thesis De partibus corporis humani sensibilibus et irritabilibus. The dispute had been debated since the middle of the 18th century. Haller put forward the view that contractability was a power inherent in the tissues which possessed it, and was fundamental fact of physiology.[168] It concerned the property of irratability, the supposed automatic response of muscular tissue, especially visceral tissue, to external stimulus, that caused them to contract when stimulated.[168] Even as late as 1853, highly respected textbooks, for example William Benjamin Carpenter Principles of Human Physiology stated the doctrine of 'irritability' was a fact beyond dispute,[169] and was still considered contentious when John Hughes Bennett created the Physiology article for the 8th edition of Encyclopædia Britannica in 1859.[168]

In his experiments that he started in the autumn of 1856, Lister used a microscope fitted with ocular micrometer to measure the diameter of blood vessels in a frogs web.[c] In a before and after experiment, he ablated parts of the central nervous system[170] and also before and after, with the splitting of the sciatic nerve.[171][163] Lister concluded that blood vessel tone[d] was controlled by the medulla oblongata and the spinal cord.[173] This refuted Wharton's conclusions, in his paper Observations on the State of the Blood and the Blood-Vessels in Inflammation.[174] who was not able to confirm that the control of blood vessels of the hind legs was dependent upon spinal centres.[175]

1858 On the Cutaneous Pigmentary System of the Frog

[edit]The second part of the original paper[176] was an experiment into the nature and behaviour of pigment.[177] It had been known for some years that the skin of the frog is capable of varying in colour under different circumstances.[178] The first account of this mechanism and how it is affected had been first described by Ernst Wilhelm von Brücke of Vienna in 1832[178] and later investigated further by Wilhelm von Wittich in 1854[176] and Emile Harless in 1947.[179]

Lister had seen how the beginning of inflammation was always accompanied by a change of colour in the frog's web.[178] He determined that the pigments consisted of "very minute pigment-granules" that are contained in a network of stellate cells, the branches of which, subdividing minutely and anastomosing freely with one another and with those of neighbouring cells, constitute a delicate network in the substance of the true skin.[178] It had been supposed that the concentration and diffusion of the pigment depended upon the contraction and extension of the branches of the star-shaped cells in which it was contained; and that only these movements of the cells were under the influence of the nervous system. At the time, there was no cell theory of matter nor was there any dyes or fixatives that could used to enhance experimental discovery.[177] Indeed, Lister wrote of this, stating "The extreme delicacy of the cell wall makes it very difficult to trace it among the surrounding tissue".[177] Lister observed that it was the pigment granules themselves and not the cells that moved, and that this movement is not merely brought about by the control of the nervous system, but that it may be caused by the direct action of irritants on the tissues themselves.[178] He believed that pigment reflected the activity of blood vessels, though it was the slowing of blood flow that initiated the process of inflammation.[177]

1858 On the early stages of inflammation

[edit]The focal study[180] was the longest paper of the three and the last to be published.[165] Like many of his colleagues, Lister was aware that inflammation was the first stage of many postoperative conditions[181] and that excessive inflammation often preceded the onset of a septic condition.[182] Once that happened, the patient would develop a fever.[182] Lister had come to the conclusion that accurate knowledge of the functioning of inflammation could not be obtained by researching the more advanced stages that were subject to secondary processes.[183] He therefore started, in quite a different way from that of almost all his predecessors by directing his enquiry to the very first deviations from health, hoping to find in them "the essential character of the morbid state most unequivocally stamped".[183] Essentially, Lister performed these experiments to discover the causes of erythrocyte adhesiveness. As well as experimenting on frogs' web and bats wing,[183] Lister used blood that he had obtained from the end of his own finger that was inflamed and compared it against blood from one of his other fingers.[163] He discovered that after something irritating had been applied to living tissues which did not kill them outright firstly the blood vessels contracted and their lumen became very small; the part became pale. Secondly, the vessels after an interval, dilated and the part became red. Thirdly, some of the blood in the most injured blood vessels slowed down in its flow and coagulated. Redness occurred which, being solid, could not be pressed away. Lastly, the fluid of the blood passed through the vessel walls and formed a "blister" about the seat of injury.[135] He found that each tiny artery was surrounded by a muscle, which enables it to contract and dilate. He found further that this contraction and dilation was not an individual act on its part, but was an act dictated to it by the nervous cells in the spinal cord.[184]

The paper was divided into four sections:

- The aggregation of red blood cells when removed from the body, i.e., which occurs during coagulation.

- This section deals with the aggregation of the cells of the blood, which occurs during the process of clotting. It shows that when blood is removed from the body this aggregation depends on their possessing a certain degree of mutual adhesiveness, which is much greater in the white blood cells than in the red blood cells. This property, though apparently not depending upon vitality, is capable of remarkable variations, in consequence of very slight chemical changes in the blood plasma.[183]

- The structure and function of blood vessels.

- This section shows that the arteries regulate, by their contractility, the amount of blood transmitted in a given time through the capillaries, but that neither full dilatation, extreme contraction, nor any intermediate state of the arteries, is capable per se of producing accumulation of blood cells in the capillaries.[185]

- The effects of irritants on blood vessels, e.g., hot water.

- This section details how the effects are two-fold

- firstly, a dilatation of the arteries (commonly preceded by a brief period of contraction), which is developed through the nervous system and is not confined to the part brought into actual contact with the irritant, but implicates a surrounding area of greater or less extent; and

- secondly, an alteration in the tissues upon which the irritant directly acts, which makes them influence the blood in the same manner as does ordinary solid matter. This imparts adhesiveness to both the red and the white blood cells, making them prone to stick to one another and to the walls of the vessels, and so gives rise, if the damage to the tissues be severe, to stagnation of the blood flow and ultimately to obstruction.[185]

- This section details how the effects are two-fold

- The effects of irritants on tissue.[185]

- The fourth section describes the effects of irritants upon the tissues. It proves that those which destroy the tissues when they act powerfully, produce by their gentler action only a condition bordering on loss of vitality, i.e. a condition in which the tissues are incapacitated, but from which they may recover, provided the irritation has not been too severe or protracted.[185]

Lister's paper was able to show that capillary action is governed by the constriction and dilation of the arteries. The action is affected by trauma,[e] irritation or reflex action through the central nervous system.[163] He noticed that although the capillary walls lack muscle fibres, they are very elastic and are subject to significant capacity variations that are influenced by arterial blood flow into the circulatory system.[163] Drawings made with a camera lucida were used to depict the experimental reactions.[163] They displayed vascular stasis and congestion in the early stages of the body's reaction to damage. According to Lister, vascular alterations that were initially brought on by reflexes occurring within the nervous system were followed by changes that were brought on by local tissue damage. In the conclusions of the paper, Lister linked his experimental observations to physical clinical conditions, for example skin damage resulting from boiling water and trauma occurring after a surgical incision.[163]

After the paper was read to the Royal Society in June 1857, it was very well received and his name became known outside Edinburgh.[137]

On a Case of Spontaneous Gangrene from Arteritis, and on the Causes of Coagulation of the Blood in Diseases of the Blood-Vessels

[edit]Lister's first paper is an account of a case of spontaneous gangrene in a child.[186] The paper on coagulation[187] was read before the Medico-Chirugical Society of Edinburgh on 18 March 1858.[152] In an account written by Agnes, she states that there was no one at the medical school meeting who was capable of appreciating it, and the remarks made upon it were very poor. There were suggestions for improvement which Lister threw out. There was lots of cheering, proclaiming it a great success. The paper was written up at 7pm, with Lister dictating and Agnes writing it during a 50-minute session, followed by the exposition to the society at George Street hall at 8pm.[188]

Lister first used the amputated legs from sheep and discovered that blood remained liquid in the blood vessels for up to six days and still underwent coagulation, albeit more slowly when the vessel was opened. He also noticed that if vessels remained fresh, the blood would remain fluid.[189] In later experiments he moved to cats.[152] He tried to emulate an inflamed blood vessel by exposing the jugular vein of the animal and applying irritants then constricting and opening the flow, to measure the effect. He noticed that in the damaged vessel the blood would coagulate[187][150] He eventually came to the conclusion that if there was ammonia in the blood, it was much less important than the condition of the vessel in stopping coagulation.[152] He tested his hypothesis on three cadavers by examining the condition of various veins and arteries and found he was correct.[190] He also concluded that the Ammonia theory did not apply to vessels in the body, but it could apply to blood outside the body. While that was incorrect, his other conclusions were accurate.[152] Specifically that inflammation in the blood vessel lining, results in coagulation occurring.[67] Lister realised that vascular occlusion increased the pressure through the network of small vessels, leading to the formation of "liquor sanguinis"[f] that lead to further localised damaged perfusion.[67] Certainly, Lister had no knowledge of the coagulation cascade but his experiments contributed to the current understanding of clotting,[150] the final product of coagulation.

Lister continued experimenting in April, examining vessels and blood from a horse. This resulted in another communication to the society on 7 April.[152] His work in coagulation continued until the end of the year. Lister's second article on coagulation was published in August 1958, and was one of two case histories he published in the Edinburgh Medical Journal in 1858.[191] Titled: "Case of Ligature of the Brachial Artery, Illustrating the Persistent Vitality of the Tissues".[192] The history described saving a patient's arm from being amputated which had been constricted by a tourniquet for thirty hours.[186] The second history was titled "Example of mixed Aortic Aneurysm" and published in December 1858.[193]

1858 Preliminary account of an inquiry into the functions of the visceral nerves

[edit]Lister continual interest in the nervous control of blood vessels led him to conduct a series of experiments during June and July 1858, where he researched the nervous control of the gut.[191] The research was published in the form of three letters sent to Sharpey. The first two letters were sent on 28 June and 7 July 1858[194] The last letter was published as the "Preliminary Account of an Inquiry into the Functions of the Visceral Nerves, with special reference to the so-called Inhibitory System.".[195]

He had been studying the work of Claude Bernard, LJ Budge and Augustus Waller and had become interested in what was known as "sympathetic action", where inflammation appeared in a different area from the source of irritation.[196] This led him to study Pflüger's 1857 paper titled "About the inhibitory nervous system for the peristaltic movements of the intestines",[197] proposed that the splanchnic nerves instead of exciting the intestine muscle layer that they are connected to, inhibit their movement.[191] The German physiologist Eduard Weber made the same claim.[191] Pflüger had named these inhibitory nerves "Hemmungs-Nervensystem", a name that Syme, at Lister's request thought they should be translated as inhibitory nervous system.[198] Lister dismissed Pflüger's idea of inhibitory nerves as not only implausible but not supported by observation,[199] as a mild stimulus caused increased muscle activity which changed to a decreased muscle activity as the incoming stimulus became stronger.[199] Lister believed that it was questionable whether the motions of the heart or the intestines are ever checked by the spinal system, except for very brief periods.[199]

Lister conducted a series of experiments using mechanical irritation and galvanism to stimulate the nerves and spinal cord in rabbits and frogs.[199] and due to rabbits active gut movement, he considered them ideal for the experiment.[200] To ensure their gut reflexes were not impaired, the rabbits were not anaesthetised.[150] Lister conducted three experiments. In the first experiment, an incision was made in the rabbit's side and a section of intestine was pulled through the skin. Lister then connected a magnetic coil battery to the splanchnic nerves in the spinal cord. When the current was applied, the gut completely relaxed but when the current was applied locally, a small localised contraction occurred that did not spread to the bowel.[150] Lister stated that "this observation is of fundamental importance, since it proves that the inhibitory influence does not operate directly upon the muscular tissue, but upon the nervous apparatus by which its contractions are, under ordinary circumstances, elicited".[195] In the second experiment, Lister examined the reaction in a section of the bowel, when he restricted the blood supply by tying the vessels and found that there was an increase in peristalsis. When he applied current the gut relaxed. He concluded that activity in the gut was under the control of bowel wall nerves and had been stimulated due to loss of blood.[195] In the third experiment he removed the nerves from a section of the bowel while ensuring to maintain a good blood supply. This time, stimulation of the section had no effect except when the section would spontaneously contract.

During the histological study of the bowel wall, Lister discovered a plexus of neurons[200] the myenteric plexus, that confirmed the observations made by Georg Meissner in 1857.[201][202]

Lister concluded, "...it appears that the intestines possess an intrinsic ganglionic apparatus which is in all cases essential to the peristaltic movements, and, while capable of independent action, is liable to be stimulated or checked by other parts of the nervous system".[199]

Although Lister did not believe in the inhibitory system, he did conclude that extrinsic nerves controlled the intestinal motor function indirectly through their effect on the plexus. It was not until 1964 that this was proven by Karl‐Axel Norberg.[203]

Notice of further researches on the coagulation of the blood

[edit]Lister's third paper on coagulation[204] was a short article in the form of a communication consisting of five pages that were read before the Medico-Chirugical Society of Edinburgh on 16 November 1859. In the paper, Lister found that the coagulation of blood was not solely dependent on the presence of ammonia, but may also be influenced by other factors. In a demonstration before the society, Lister had a sample of horse's blood that had been shed twenty-nine hours earlier and added acetic acid to it. The blood remained fluid despite being acidified, but it eventually coagulated after being left to stand for 15 minutes. Lister demonstrated that the Ammonia theory was incorrect as the coagulation of the blood was not dependent on the presence of ammonia. He concluded that other factors may influence blood coagulation in addition to or instead of ammonia, and that the Ammonia theory was fallacious.[204]

Glasgow appointment

[edit]On 1 August 1859, Lister wrote to his father to inform him of the ill-health of James Adair Lawrie, Regius Professor of Surgery at the University of Glasgow, believing he was close to death.[205] The anatomist Allen Thomson had written to Syme to inform him of Lawrie's condition and that it was his opinion that Lister was the most suitable person for the position.[206] Lister stated that Syme believed he should become a candidate for the position.[205] He went on to discuss the merits of the post; a higher salary, being able to undertake more surgery and being able to create a bigger private practice.[205] Lawrie died on 23 November 1859.[207] In the following month, Lister received a private communication, although baseless, that confirmed he had received the appointment.[208] However, it was clear the matter was not settled when a letter appeared in the Glasgow Herald on 18 January 1860 that discussed a rumour that the decision had been handed over to the Lord Advocate and officials in Edinburgh.[209][208] The letter annoyed the members of the governing body of Glasgow University, the Senatus Academicus. The matter was referred to the Vice-Chancellor Thomas Barclay who tipped the decision in favour of Lister.[210] On 28 January 1860, Lister's appointment was confirmed.[30]

Glasgow 1860–1869

[edit]

University life

[edit]To be formally inducted into the academic staff, Lister had to deliver a Latin oration before the senatus academicus.[211] In a letter to his father, he described how surprised he was when a letter arrived from Allen Thomson informing him that the thesis had to be presented the next day on 9 March. Lister unable to start the paper until 2 am the next night, had only prepared around two-thirds of it, when he arrived in Glasgow. The rest was written at Thomson's house. In the letter, he described the dread he felt being admitted into the room prior to presenting the oration. After the thesis was read and Lister was inducted to the senate, he signed a statement not to act contrary to the wishes of the Church of Scotland.[212] While the contents of his thesis have been lost, the title is known, "De Arte Chirurgica Recte Erudienda" ("On the proper way of teaching the art of surgery").[213]

In early May 1860, the couple made the journey to Glasgow to move into their new house at 17 Woodside Place, at the time on the western edge of the city.[214] In 1860, university life in Glasgow was lived in the grimy quadrangles of the small college on Glasgow High Street, a mile east of the city centre next to Glasgow Royal Infirmary (GRI) and the Cathedral and surrounded by the most squalid part of the old medieval city.[215] The Scottish poet and novelist Andrew Lang wrote of his student days at the college, that while Coleridge could smell 75 different stenches during his student days in Cologne, Lang counted more.[215] The city was so polluted the grass did not grow.

The position of Professor of Surgery at Glasgow was peculiar, as it did not carry with it an appointment as surgeon to the Royal Infirmary, as the university was separate from the hospital. The allotment of surgical wards to the care of the Professor of Surgery depended upon the goodwill of the directors of the infirmary.[216] His predecessor Lawrie never held any hospital appointments at all.[217] Having no patients to care for, Lister immediately began a summer lecture course. He discovered that college classrooms were considered too small and had low ceilings for the number of students, which made them unpleasant to be in when filled to overcrowding.[215] Before his first lecture, the couple cleaned and painted the dingy lecture room assigned to them, at their own expense.[215] He inherited a large class of students from his predecessor that grew rapidly.[215]

After his first session, he wrote favourably of Glasgow:

The facilities I have here for prosecuting this course as compared to the difficulties I laboured under in Edinburgh are quite delightful – museums, abundant material and a good library all at my disposal and my colleague Allen Thompson co-operating in the kindest and most valuable manner[218]

In August 1860, Lister was visited by his parents, who took a "saloon" carriage on the Great Northern Railway.[219] In September 1860, Marcus Beck came to live with the Listers and their two servants, while he studied medicine at the university.[219] In the closing weeks of the summer, the Listers along with Beck, Lucy Syme and Ramsay went on a short holiday to Balloch, Loch Lomond. While the group was visiting Tarbet, Argyll, the men rowed across the loch and ascended Ben Lomond.[220]

Election to surgeoncy

[edit]In August 1860, Lister had been rejected for a post at the Royal Infirmary by David Smith, a shoemaker who was the chairman of the hospital board.[221] When Lister put his case to Smith explaining the need for anatomical demonstrations so the students could understand the practice of surgery, Smith stated his belief that "the infirmary was a curative institution, not an educational one".[220] The rejection both annoyed and surprised Lister as he had been promised by Thomson that the position was assured.[220] Indeed, he had informed his father of the fact that the post was guaranteed in his letter to his father.[221]

In November 1860, the winter lecture course began. In total 182 students registered for the lectures[222] and according to Godlee it was likely the "largest class of systematic surgery in Great Britain, if not in Europe".[222] The class consisting of mostly 4th year students with some 3rd and 2nd year students, was so enthused, that they decided to make Lister the Honorary President of their Medical Society.[220] When the time approached for the election to the surgeoncy in 1861, 161 students signed a petition on parchment supporting his claim for election.[222] Lister was not elected until 5 August 1861, in what was described by Beck as a "troublesome canvas".[223] Lister was put in charge of wards XXIV (24) and XXV (25) in October 1861.[224] It wasn't until November 1861 that he performed his first public operation.[225] Soon after Lister arrived at the GRI, a new surgical block was built and it was here that he conducted many of his trials of antisepsis.[226]

Holmes System of Surgery

[edit]During this period between the end of his winter lecture course and his appointment, Lister's correspondence contained little of scientific interest. Finally, a letter to his father dated 2 August 1861 explained the reason.[227] He had halted his experiments on coagulation to work on writing two chapters, "Amputation" and "On Æsthetics" (On anaesthetics) for the medical reference work System of Surgery by Timothy Holmes, published in four volumes in 1862.[228] Chloroform was Lister's preferred anaesthetic.[229] He wrote three papers for Holmes in 1861, 1870 and 1882 chapters.[230][231] The science of anaesthesia was in its infancy[232] when Lister had first recommended chloroform to Syme in 1855 and had continued to use it until the 1880s.[223] His sister Isabella Sophie had first described its use to him in 1848 when she had a tooth pulled. He had further clinical experience using it on three patients who had tumours of the jaw, without complications in 1854.[229] He had classed it along with alcohol and opium as a "specific irritant" in "On the early stages of imflammation".[229] Lister preferred it, as it was safer to use in artificial light than ether, it protected the heart and blood vessels and as Lister believed gave the patient "mental tranquility" as it was the safest.[223] In the 1871 edition, he reported there had been no deaths in Edinburgh or Glasgow infirmaries from chloroform, during the period between 1861 and 1870.[223] Lister described how his assistant applied the chloroform onto a simple handkerchief, as a mask while he watched the patient's breathing. In 1870, he updated the chapter to state that he felt apprehension about using chloroform on the "aged and infirm".[223] In the same edition he recommended nitrous oxide for tooth extraction and the use of ether to avoid vomiting after abdominal surgery. In the winter of 1873, the English medical journals reported that sulphuric ether should be used instead but Watson Cheyne stated there had been no deaths from chloroform during the winter of 1873. In 1880, the British Medical Association recommended the synthetic gas ethidene dichloride for clinical trials. On 14 November 1881, Paul Bert published the dose-response curve of chloroform but Lister believed that smaller doses would be sufficient to anaesthetize the patient.[233] Starting in April 1882, Lister first conducted clinical research using ether and from July to November, lab experiments on chaffinches and then on himself and Agnes, to determine the correct dose.[234] The 1882 chapter continued to recommend chloroform.[234]

The chapter on amputation was much more technical than the anaesthesia chapter, for example describing the ways of cutting the skin to produce flaps to close over the wound.[g][234][235] In the first edition, Lister examined the history of amputation from Hippocrates to Thomas Pridgin Teale, William Hey, François Chopart, Nikolay Pirogov and Dominique Jean Larrey[236] and the discovery of the tourniquet by Etienne Morel.[122] In the first edition, Lister devoted 7 pages to dressings, but by the third edition only a single sentence to recommend a dry dressing[237] as opposed to the more common water dressing, where it was thought that water excluded the air.[238] By the third edition, Lister focused on describing three innovative surgical techniques. The first was a method for amputation through the thigh that he developed between 1858 and 1860 that was a modification of Henry Douglas Carden's technique for knee amputation.[234] The thigh amputation was through the femoral condyles, in a circular fashion with a small posterior flap that enabled a neat scar.[239]

The second technique was an aortic tourniquet for controlling blood flow in the abdominal aorta.[236] The vessels of the aorta were too tough to close properly and ligatures either damaged the artery walls or caused premature death if left in too long.[234] The third technique was a method of bloodless operation that he created in 1863–1864 by elevating a limb and quickly applying an india rubber tourniquet to stop limb circulation[240] but it became unnecessary with the use of the Esmarch bandage.[122] In 1859, he advocated for the use of silver wire sutures that had been invented by J. Marion Sims, but their use fell out of favour with the introduction of antiseptics.[236]

Croonian Lecture