Судан

Республика Судан | |

|---|---|

| Девиз: Победа за нами ан-Наср Лана «Победа за нами» | |

| Гимн: Мы солдаты Бога, солдаты нации. Нахну Джунд Аллах, Джунд аль-Ватан «Мы солдаты Бога, солдаты Родины» | |

Судан показан темно-зеленым цветом, заявленные территории, не находящиеся под управлением, - светло-зеленым. | |

| Капитал и крупнейший город | Хартум |

| Капитал в изгнании | Порт-Судан [ а ] |

| Официальные языки | |

| Этнические группы | |

| Религия (2020) [ 13 ] |

|

| Демон(ы) | Суданский |

| Правительство | Федеративная республика под властью военной хунты [ 15 ] [ 16 ] |

| |

| |

| Законодательная власть | Вакантный |

| Формирование | |

| 2500 г. до н.э. | |

| 1070 г. до н.э. | |

| в. 350 | |

| в. 1500 | |

| 1820 | |

| 1885 | |

| 1899 | |

| 1 января 1956 г. | |

| 25 мая 1969 г. | |

| 6 апреля 1985 г. | |

• Отделение Южного Судана | 9 июля 2011 г. |

| 19 декабря 2018 г. | |

• Проект Конституционной декларации 2019 г. вступил в силу | 20 августа 2019 г. |

| Область | |

• Общий | 1 886 068 км 2 (728 215 квадратных миль) ( 15-е место ) |

| Население | |

• Оценка на 2024 год | 50,467,278 [ 17 ] ( 30-е ) |

• Плотность | 21,3/км 2 (55,2/кв. миль) ( 202-й ) |

| ВВП ( ГЧП ) | оценка на 2023 год |

• Общий | |

• На душу населения | |

| ВВП (номинальный) | оценка на 2023 год |

• Общий | |

• На душу населения | |

| Джини (2014) | среднее неравенство |

| ИЧР (2022) | низкий ( 170-й ) |

| Валюта | Суданский фунт ( SDG ) |

| Часовой пояс | UTC +2 ( КАТ ) |

| Формат даты | дд/мм/гггг |

| Едет дальше | верно |

| Код вызова | +249 |

| Код ISO 3166 | СД |

| Интернет-ДВУ | .sd Судан. |

Судан , [ с ] официально Республика Судан , [ д ] — страна в Северо-Восточной Африке . Он граничит с Центральноафриканской Республикой на юго-западе, Чадом на западе, Ливией на северо-западе, Египтом на севере, Красным морем на востоке, Эритреей и Эфиопией на юго-востоке и Южным Суданом на юге. По состоянию на 2024 год население Судана составляет почти 50 миллионов человек. [ 21 ] Африки и занимает 1 886 068 квадратных километров (728 215 квадратных миль), что делает его третьей по величине страной по площади и третьей по величине страной в Лиге арабских государств . Это была самая большая по площади страна в Африке и Лиге арабских государств до отделения Южного Судана в 2011 году ; [ 22 ] с тех пор оба титула принадлежат Алжиру . Столица Судана и самый густонаселенный город – Хартум .

На территории нынешнего Судана произошла эпоха Хормусана (ок. 40 000–16 000 до н. э.). [ 23 ] Халфанская культура (ок. 20500–17000 до н.э.), [ 24 ] [ 25 ] Себилиан (ок. 13000–10000 до н.э.), [ 26 ] Каданская культура (ок. 15000–5000 до н. э.), [ 27 ] война Джебель-Сахаба , самая ранняя известная война в мире, около 11500 г. до н.э., [ 28 ] [ 29 ] Культура группы А [ 30 ] (ок. 3800 г. до н.э. – 3100 г. до н.э.), Королевство Керма ( ок. 2500–1500 до н.э.), Новое египетское царство ( ок. 1500 г. до н.э. – 1070 г. до н.э.) и Королевство Куш ( ок. 785 г. до н.э. – 350 г. н.э.) . После падения Куша нубийцы образовали три христианских королевства: Нобатия , Макурия и Алодия .

Между 14 и 15 веками большая часть Судана постепенно была заселена арабскими кочевниками . С 16 по 19 века в центральном и восточном Судане доминировал султанат Фундж , в то время как Дарфур правил западом, а османы – востоком. В 1811 году мамлюки основали государство в Дункуле как базу для своей работорговли . Во время турецко-египетского правления в Судане после 1820-х годов практика торговли рабами укоренилась по оси север-юг: набеги рабов происходили в южных частях страны, а рабов перевозили в Египет и Османскую империю . [ 31 ]

С 19 века весь Судан был завоеван египтянами при династии Мухаммеда Али . Религиозно-националистический пыл вспыхнул в восстании махдистов , в котором силы махдистов в конечном итоге потерпели поражение от совместных египетско-британских вооруженных сил. В 1899 году под давлением Великобритании Египет согласился разделить суверенитет над Суданом с Соединенным Королевством в качестве кондоминиума . Фактически Судан управлялся как британское владение. [ 32 ]

Египетская революция 1952 года свергла монархию и потребовала вывода британских войск со всего Египта и Судана. Мухаммад Нагиб , один из двух соруководителей революции и первый президент Египта, был наполовину суданцем и вырос в Судане. Он сделал обеспечение независимости Судана приоритетом революционного правительства. В следующем году под давлением Египта и Судана британцы согласились на требование Египта о том, чтобы оба правительства прекратили свой общий суверенитет над Суданом и предоставили Судану независимость. 1 января 1956 года Судан был официально провозглашен независимым государством.

После того как Судан стал независимым, режим Гаафара Нимейри к власти пришел исламистский . [ 33 ] Это усугубило раскол между исламским Севером, резиденцией правительства, и анимистами и христианами на Юге. Различия в языке, религии и политической власти вылились в гражданскую войну между правительственными силами, находившимися под влиянием Национального исламского фронта (НИФ), и южными повстанцами, наиболее влиятельной группировкой которых была Народно-освободительная армия Судана (НОАС), которая в конечном итоге возглавила до независимости Южного Судана в 2011 году. [ 34 ] В период с 1989 по 2019 год 30-летняя военная диктатура во главе с Омаром аль-Баширом управляла Суданом и совершала массовые нарушения прав человека , включая пытки, преследование меньшинств, предполагаемую поддержку глобального терроризма и этнический геноцид в Дарфуре в 2003–2020 годах. . В целом режим убил примерно от 300 000 до 400 000 человек. В 2018 году вспыхнули протесты с требованиями отставки Башира, что привело к государственному перевороту 11 апреля 2019 года и тюремному заключению Башира. [ 35 ] Судан в настоящее время втянут в гражданскую войну между двумя конкурирующими группировками — Суданскими вооруженными силами (СВС) и военизированными силами быстрой поддержки (РСБ).

Ислам был государственной религией Судана, и исламские законы применялись с 1983 по 2020 год, когда страна стала светским государством . [ 33 ] Судан является наименее развитой страной и занимает 172-е место в Индексе человеческого развития по состоянию на 2022 год. Это одна из самых бедных стран Африки; [ 36 ] ее экономика в значительной степени зависит от сельского хозяйства из-за международных санкций и изоляции, а также истории внутренней нестабильности и фракционного насилия. Большая часть Судана засушлива, и более 60% населения Судана живет в бедности. Судан является членом Организации Объединенных Наций , Лиги арабских государств , Африканского союза , КОМЕСА , Движения неприсоединения и Организации исламского сотрудничества .

Этимология

[ редактировать ]Название страны Судан — это исторически сложившееся название большого региона Сахель в Западной Африке, расположенного непосредственно на западе современного Судана. Исторически Суданом называли как географический регион , простирающийся от Сенегала на Атлантическом побережье до Северо-Восточной Африки, так и современный Судан.

Название происходит от арабского билад ас-судан ( بلاد السودان ), что означает «Земля черных » . [ 37 ] Это имя является одним из различных топонимов, имеющих схожую этимологию , что связано с очень темной кожей коренного населения. До этого Судан был известен Нубия и Та Нехеси или Та Сети, как древним египтянам названные в честь нубийских и меджайских лучников или лучников.

С 2011 года Судан также иногда называют Северным Суданом, чтобы отличить его от Южного Судана . [ 38 ]

История

[ редактировать ]Доисторический Судан (до 8000 г. до н.э.)

[ редактировать ]

Аффад 23 — археологический памятник , расположенный в регионе Аффад на юге Донголы на севере Судана. [ 39 ] где находятся «хорошо сохранившиеся остатки доисторических лагерей (реликвии самой старой под открытым небом хижины в мире) и разнообразные места охоты и собирательства возрастом около 50 000 лет». [ 40 ] [ 41 ] [ 42 ]

К восьмому тысячелетию до нашей эры люди неолитической культуры освоили здесь оседлый образ жизни в укрепленных деревнях из сырцового кирпича , дополняя охоту и рыбалку на Ниле сбором зерна и выпасом скота. [ 43 ] Неолитические народы создавали кладбища типа R12 . В пятом тысячелетии до нашей эры миграции из высыхающей Сахары привели в долину Нила людей неолита вместе с сельским хозяйством.

Популяция, возникшая в результате этого культурного и генетического смешения, в течение следующих столетий развила социальную иерархию, которая в 1700 году до нашей эры стала Королевством Куш (со столицей в Керме). Антропологические и археологические исследования показывают, что в додинастический период Нубия и Нагадан Верхнего Египта были почти идентичны в этническом и культурном отношении и, таким образом, к 3300 году до нашей эры одновременно развивались системы правления фараонов. [ 44 ]

Королевство Куш (ок. 1070 г. до н.э. – 350 г. н.э.)

[ редактировать ]

Королевство Куш было древним нубийским государством, сосредоточенным в месте слияния Голубого и Белого Нила , а также рек Атбара и Нил . Он был основан после краха бронзового века и распада Нового Египетского царства ; На начальном этапе его центр был сосредоточен в Напате. [ 45 ]

После того, как царь Кашта («Кушит») вторгся в Египет в восьмом веке до нашей эры, кушитские цари правили как фараоны Двадцать пятой династии Египта в течение почти столетия, прежде чем были побеждены и изгнаны ассирийцами . [ 46 ] На пике своей славы кушиты завоевали империю, простиравшуюся от нынешнего Южного Кордофана до Синая. Фараон Пийе попытался расширить империю на Ближний Восток, но ему помешал ассирийский царь Саргон II .

Между 800 г. до н. э. и 100 г. н. э. были построены нубийские пирамиды , среди них можно назвать Эль-Курру , Кашта , Пийе , Тантамани , Шабака , пирамиды Гебель Баркала , пирамиды Мероэ (Бегаравия) , пирамиды Седейнги и пирамиды Нури . [ 47 ]

Царство Куш упоминается в Библии как спасшее израильтян от гнева ассирийцев, хотя болезнь среди осаждающих могла быть одной из причин неудачи в взятии города. [ 48 ] [ нужна страница ] Война, которая произошла между фараоном Тахаркой и ассирийским царем Сеннахиримом, в своих попытках закрепиться на Ближнем Востоке стала решающим событием в западной истории: нубийцы потерпели поражение от Ассирии . Преемник Сеннахирима Асархаддон пошел еще дальше и вторгся в сам Египет, чтобы обеспечить себе контроль над Левантом. Это удалось, поскольку ему удалось изгнать Тахарку из Нижнего Египта. Тахарка бежал обратно в Верхний Египет и Нубию, где умер два года спустя. Нижний Египет попал под вассальную зависимость от Ассирии, но оказался неуправляемым и безуспешно восстал против ассирийцев. Затем царь Тантамани , преемник Тахарки, предпринял последнюю решительную попытку вернуть себе Нижний Египет у недавно восстановленного в должности ассирийского вассала Нехо I. Ему удалось вернуть Мемфис, убив при этом Нечо, и осадить города в дельте Нила. Ашшурбанипал , сменивший Асархаддона, послал в Египет большую армию, чтобы восстановить контроль. Он разгромил Тантамани возле Мемфиса и, преследуя его, разграбил Фивы . Хотя после этих событий ассирийцы сразу же покинули Верхний Египет, ослабев, Фивы мирно подчинились сыну Нехо. Псамтик I менее десяти лет спустя. Это положило конец всем надеждам на возрождение Нубийской империи, которая скорее продолжалась в форме меньшего королевства с центром в Напате . На город совершили набег египетские ок. 590 г. до н. э., а вскоре после этого, в конце III века до н. э., кушиты переселились в Мероэ . [ 46 ] [ 49 ] [ 50 ]

Средневековые христианские нубийские королевства (ок. 350–1500)

[ редактировать ]

На рубеже V века блемми основали недолговечное государство в Верхнем Египте и Нижней Нубии, вероятно, с центром вокруг Талмиса ( Калабша ), но уже к 450 г. они были изгнаны из долины Нила нобатийцами. Последние в конечном итоге основали собственное королевство, Нобатию . [ 52 ] К шестому веку всего существовало три нубийских королевства: Нобатия на севере со столицей в Пахорасе ( Фарас ); центральное королевство, Макурия, с центром в Тунгуле ( Старая Донгола ), примерно в 13 километрах (8 милях) к югу от современной Донголы ; и Алодия , в самом сердце старого Кушитского королевства, столица которого находилась в Собе (ныне пригород современного Хартума). [ 53 ] Еще в шестом веке они обратились в христианство. [ 54 ] В седьмом веке, вероятно, где-то между 628 и 642 годами, Нобатия была включена в состав Мукурии. [ 55 ]

Между 639 и 641 годами арабы-мусульмане из халифата Рашидун завоевали Византийский Египет. В 641 или 642 и снова в 652 году они вторглись в Нубию, но были отбиты, что сделало нубийцев одними из немногих, кому удалось победить арабов во время исламской экспансии . После этого царь Мукурии и арабы заключили уникальный пакт о ненападении, который также включал ежегодный обмен подарками , тем самым признавая независимость Мукурии. [ 56 ] Хотя арабам не удалось завоевать Нубию, они начали селиться к востоку от Нила, где в конечном итоге основали несколько портовых городов. [ 57 ] и вступил в брак с местным беджа . [ 58 ]

С середины восьмого до середины одиннадцатого века политическая мощь и культурное развитие христианской Нубии достигли своего пика. [ 59 ] В 747 году Мукурия вторглась в Египет, принадлежавший в это время приходящим в упадок Омейядам . [ 60 ] и это произошло снова в начале 960-х годов, когда оно продвинулось на север до Ахмима . [ 61 ] Мукурия поддерживал тесные династические связи с Алодией, что, возможно, привело к временному объединению двух королевств в одно государство. [ 62 ] Культуру средневековых нубийцев называют « афро-византийской ». [ 63 ] но также находился под все большим влиянием арабской культуры. [ 64 ] Государственная организация была чрезвычайно централизована, [ 65 ] основанная на византийской бюрократии шестого и седьмого веков. [ 66 ] Искусство процветало в виде керамических картин. [ 67 ] и особенно настенные росписи. [ 68 ] Нубийцы разработали алфавит для своего языка, Старый Нобиин , взяв за основу коптский алфавит , а также используя греческий , коптский и арабский языки . [ 69 ] Женщины имели высокий социальный статус: они имели доступ к образованию, могли владеть, покупать и продавать землю и часто использовали свое богатство для пожертвования церквей и церковных картин. [ 70 ] Даже королевская преемственность была по материнской линии , законным наследником был сын сестры короля. [ 71 ]

С конца 11-12 веков столица Макурии Донгола находилась в упадке, а столица Алодии также пришла в упадок в 12 веке. [ 72 ] В XIV и XV веках бедуинские племена захватили большую часть Судана. [ 73 ] мигрируя в Бутану , Гезиру , Кордофан и Дарфур . [ 74 ] В 1365 году гражданская война вынудила мукурский двор бежать в Гебель-Адду в Нижней Нубии , а Донгола была разрушена и отдана арабам. Впоследствии Мукурия продолжала существовать лишь как мелкое королевство. [ 75 ] После процветающего [ 76 ] правление короля Иоиля ( эт. 1463–1484) Мукурия рухнуло. [ 77 ] Прибрежные районы от южного Судана до портового города Суакин перешли к султанату Адал . в пятнадцатом веке [ 78 ] [ 79 ] На юге королевство Алодия перешло либо к арабам под командованием вождя племени Абдаллаху Джамме , либо к Фунджу , африканскому народу, происходящему с юга. [ 80 ] Датировки варьируются от 9 века после Хиджры ( ок. 1396–1494 гг.). [ 81 ] конец 15 века, [ 82 ] 1504 [ 83 ] до 1509. [ 84 ] Алодийское государство могло сохраниться в виде королевства Фазугли , просуществовавшего до 1685 года. [ 85 ]

Исламские королевства Сеннар и Дарфур (ок. 1500–1821 гг.)

[ редактировать ]

Сообщается, что в 1504 году Фунджи основали Королевство Сеннар , в состав которого вошло царство Абдаллы Джаммы. [ 87 ] К 1523 году, когда еврейский путешественник Давид Рубени посетил Судан, государство Фундж уже простиралось на север до Донголы. [ 88 ] Тем временем ислам начали проповедовать на Ниле суфийские святые, поселившиеся там в XV-XVI веках. [ 89 ] а после визита Давида Рубени король Амара Дункас , ранее язычник или номинальный христианин, был записан как мусульманин. [ 90 ] Однако Фундж сохранял неисламские обычаи, такие как божественное царствование или употребление алкоголя, до 18 века. [ 91 ] Суданский народный ислам до недавнего прошлого сохранил многие ритуалы, восходящие к христианским традициям. [ 92 ]

Вскоре Фундж вступил в конфликт с османами , оккупировавшими Суакин ок. 1526 [ 93 ] и в конечном итоге двинулся на юг вдоль Нила, достигнув третьего района порогов Нила в 1583/1584 году. Последующая попытка Османской империи захватить Донголу была отражена Фунджем в 1585 году. [ 94 ] Впоследствии Ханник , расположенный к югу от третьего порога, станет границей между двумя государствами. [ 95 ] Последствием османского вторжения стала попытка узурпации Аджиба , второстепенного короля северной Нубии. Хотя Фундж в конечном итоге убил его в 1611/1612 году, его преемникам, Абдаллабам , было предоставлено право управлять всем к северу от слияния Голубого и Белого Нила со значительной автономией. [ 96 ]

В 17 веке государство Фундж достигло своего наибольшего распространения. [ 97 ] но в следующем столетии оно начало приходить в упадок. [ 98 ] Переворот 1718 года привел к династической смене. [ 99 ] а еще один в 1761–1762 гг. [ 100 ] привело к созданию Регентства Хамадж , где Хамадж (народ из приграничных районов Эфиопии) эффективно правил, в то время как султаны Фунджа были их простыми марионетками. [ 101 ] Вскоре после этого султанат начал распадаться; [ 102 ] к началу 19 века он был практически ограничен Гезирой. [ 103 ]

Переворот 1718 года положил начало политике принятия более ортодоксального ислама, что, в свою очередь, способствовало арабизации государства. [ 104 ] Чтобы узаконить свое правление над своими арабскими подданными, Фунджи начали пропагандировать происхождение Омейядов . [ 105 ] К северу от слияния Голубого и Белого Нила, вплоть до Аль-Даббы , нубийцы приняли племенную идентичность арабских Джаалинов . [ 106 ] До XIX века арабскому языку удавалось стать доминирующим языком в центральном речном Судане. [ 107 ] [ 108 ] [ 109 ] и большая часть Кордофана. [ 110 ]

К западу от Нила, в Дарфуре , в исламский период сначала возникло королевство Тунджур , которое заменило старое королевство Даджу в 15 веке. [ 111 ] и простирался на запад до Вадаи . [ 112 ] Народ Тунджур , вероятно, был арабизированными берберами и, по крайней мере, их правящая элита, мусульманами. [ 113 ] В 17 веке Тунджур был отстранен от власти султанатом Фур -Кейра . [ 112 ] Государство Кейра, номинально мусульманское со времен правления Сулеймана Солонга (ок . 1660–1680), [ 114 ] изначально было небольшим королевством на севере Джебель-Марры . [ 115 ] но расширился на запад и север в начале 18 века. [ 116 ] и на восток под властью Мухаммада Тайраба (годы правления 1751–1786), [ 117 ] достигнув пика при завоевании Кордофана в 1785 году. [ 118 ] Апогей этой империи, ныне размером примерно с современную Нигерию , [ 118 ] продлится до 1821 года. [ 117 ]

Турция и Махдистский Судан (1821–1899)

[ редактировать ]

В 1821 году османский правитель Египта Мухаммед Али вторгся и завоевал северный Судан. Хотя формально Мухаммед Али был вали Египта в составе Османской империи , он называл себя хедивом практически независимого Египта. Стремясь присоединить Судан к своим владениям, он послал своего третьего сына Исмаила (не путать с Исмаилом-пашой, упомянутым позже) завоевать страну и впоследствии включить ее в состав Египта. За исключением Шайкии и султаната Дарфур в Кордофане, он встретил без сопротивления. Завоевательная политика Египта была расширена и усилена сыном Ибрагима -паши Исмаилом, под властью которого была завоевана большая часть остальной территории современного Судана.

Египетские власти существенно улучшили суданскую инфраструктуру (в основном на севере), особенно в отношении ирригации и производства хлопка. В 1879 году великие державы добились смещения Исмаила и поставили его сына Тевфик-пашу на его место . Коррупция и бесхозяйственность Тевфика привели к восстанию Ураби , которое поставило под угрозу выживание хедива. Тевфик обратился за помощью к британцам, которые впоследствии оккупировали Египет в 1882 году. Судан остался в руках правительства Хедивиала, а также бесхозяйственности и коррупции его чиновников. [ 119 ] [ 120 ]

В период Хедивиала инакомыслие распространилось из-за высоких налогов, взимаемых на большинство видов деятельности. Налоги на ирригационные колодцы и сельскохозяйственные земли были настолько высокими, что фермеры бросили свои фермы и домашний скот. В 1870-х годах европейские инициативы против работорговли оказали негативное влияние на экономику северного Судана, ускорив подъем сил махдистов . [ 121 ] Мухаммад Ахмад ибн Абдаллах , Махди (Путеводный), предложил ансарам ( своим последователям) и тем, кто сдался ему, выбор между принятием ислама или быть убитым. Махдия (режим махдистов) ввела традиционные исламские законы шариата . произошел инцидент 12 августа 1881 года на острове Аба , вызвавший вспышку того, что впоследствии стало Махдистской войной .

С момента провозглашения Махдии в июне 1881 года до падения Хартума в январе 1885 года Мухаммад Ахмад вел успешную военную кампанию против турецко-египетского правительства Судана, известного как Туркия . Мухаммад Ахмад умер 22 июня 1885 года, всего через шесть месяцев после завоевания Хартума. После борьбы за власть среди своих заместителей Абдаллахи ибн Мухаммад , в первую очередь с помощью Баггара западного Судана, преодолел сопротивление остальных и стал бесспорным лидером Махдии. Укрепив свою власть, Абдаллахи ибн Мухаммад принял титул халифа (преемника) Махди, учредил администрацию и назначил ансаров (которые обычно были Баггара ) эмирами каждой из нескольких провинций.

Региональные отношения оставались напряженными на протяжении большей части периода правления Махдии, в основном из-за жестоких методов халифа по распространению своего правления на всю страну. В 1887 году 60-тысячная армия ансаров вторглась в Эфиопию , проникнув до Гондэра . В марте 1889 года король Йоханнес IV Эфиопии двинулся на Метемму ; однако после того, как Йоханнес пал в бою, эфиопские войска отступили. Абд ар-Рахман ан-Нуджуми, генерал халифа, предпринял попытку вторжения в Египет в 1889 году, но египетские войска под руководством британцев разгромили ансаров при Тушке. Провал египетского вторжения разрушил чары непобедимости ансаров. Бельгийцы Агордат помешали людям Махди завоевать Экваторию , а в 1893 году итальянцы отразили нападение ансаров на ( в Эритрее ) и вынудили ансаров уйти из Эфиопии.

В 1890-х годах британцы попытались восстановить свой контроль над Суданом, еще раз официально от имени египетского хедива, но на самом деле рассматривая страну как британскую колонию. К началу 1890-х годов претензии Великобритании, Франции и Бельгии сошлись в верховьях Нила . Великобритания опасалась, что другие державы воспользуются нестабильностью Судана для приобретения территорий, ранее аннексированных Египтом. Помимо этих политических соображений, Великобритания хотела установить контроль над Нилом, чтобы защитить планируемую ирригационную плотину в Асуане . Герберт Китченер возглавлял военные кампании против махдистского Судана с 1896 по 1898 год. Кампании Китченера завершились решающей победой в битве при Омдурмане 2 сентября 1898 года. Год спустя битва при Умм-Дивайкарате 25 ноября 1899 года привела к гибели Абдаллахи. ибн Мухаммада , впоследствии положившего конец Махдистской войне.

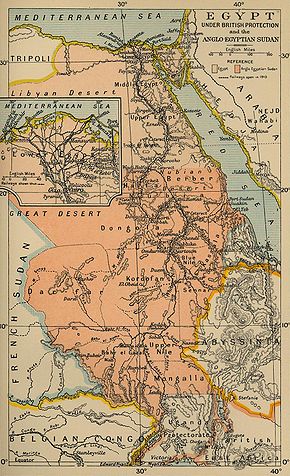

Англо-египетский Судан (1899–1956)

[ редактировать ]

В 1899 году Великобритания и Египет достигли соглашения, согласно которому Суданом управлял генерал-губернатор, назначаемый Египтом с согласия Великобритании. [ 122 ] В действительности Судан фактически управлялся как колония Короны . Британцы стремились повернуть вспять процесс под руководством Египта, начатый при Мухаммеде Али-паше объединения долины Нила , и стремились сорвать все усилия, направленные на дальнейшее объединение двух стран. [ нужна ссылка ]

В рамках делимитации граница Судана с Абиссинией оспаривалась в результате набегов соплеменников, торгующих рабами, что нарушало границы закона. В 1905 году местный вождь султан Ямбио, сопротивлявшийся до конца, отказался от борьбы с британскими войсками, оккупировавшими регион Кордофан , окончательно положив конец беззаконию. Постановления, изданные Великобританией, ввели в действие систему налогообложения. Это было следствием прецедента, созданного Халифом. Были признаны основные налоги. Эти налоги взимались с земли, скота и финиковых пальм. [ 123 ] Продолжающееся британское управление Суданом вызвало все более резкую националистическую реакцию: египетские националистические лидеры были полны решимости заставить Великобританию признать единый независимый союз Египта и Судана. После официального прекращения османского правления в 1914 году сэр Реджинальд Вингейт был отправлен в декабре того же года оккупировать Судан в качестве нового военного губернатора. Хусейн Камель был объявлен султаном Египта и Судана , как и его брат и преемник Фуад I. Они продолжали настаивать на создании единого египетско-суданского государства даже тогда, когда Султанат Египет был переименован в Королевство Египет и Судан , но именно Саад Заглул продолжал разочаровываться в своих амбициях до своей смерти в 1927 году. [ 124 ]

С 1924 года до обретения независимости в 1956 году британцы проводили политику управления Суданом как двумя, по сути, отдельными территориями; север и юг. убийство генерал-губернатора англо-египетского Судана в Каире Причинным фактором стало ; он принес требования недавно избранному правительству Вафда со стороны колониальных сил. Постоянная база из двух батальонов в Хартуме была переименована в Силы обороны Судана, действовавшие под руководством правительства, заменив бывший гарнизон солдат египетской армии, который впоследствии принял участие в боевых действиях во время инцидента в Валвале . [ 125 ] Парламентское большинство вафдистов отклонило план Сарват-паши по размещению с Остином Чемберленом в Лондоне; однако Каиру все еще нужны были деньги. Доходы правительства Судана достигли пика в 1928 году и составили 6,6 миллиона фунтов стерлингов, после этого из-за беспорядков вафдистов и вторжений на итальянскую границу из Сомалиленда Лондон решил сократить расходы во время Великой депрессии. Экспорт хлопка и жевательной резинки был затмевался необходимостью импортировать почти все из Великобритании, что привело к дефициту платежного баланса в Хартуме. [ 126 ]

В июле 1936 года лидера либеральной конституционной партии Мухаммеда Махмуда убедили привезти делегатов Вафда в Лондон для подписания англо-египетского договора, «начала нового этапа в англо-египетских отношениях», писал Энтони Иден . [ 127 ] Британской армии разрешили вернуться в Судан для защиты зоны канала. Им удалось найти тренировочные базы, и ВВС Великобритании смогли свободно летать над территорией Египта. Однако это не решило проблему Судана: суданская интеллигенция агитировала за возвращение к метрополии, вступая в сговор с агентами Германии. [ 128 ]

Итальянский фашистский лидер Бенито Муссолини ясно дал понять, что он не может вторгнуться в Абиссинию, не завоевав сначала Египет и Судан; они намеревались объединить итальянскую Ливию с итальянской Восточной Африкой . Британский имперский генеральный штаб готовился к военной защите региона, который был немногочисленным. [ 129 ] Британский посол заблокировал попытки Италии заключить договор о ненападении с Египтом и Суданом. Но Махмуд был сторонником Великого муфтия Иерусалима ; регион оказался между усилиями Империи по спасению евреев и призывами умеренных арабов остановить миграцию. [ 130 ]

Суданское правительство принимало непосредственное военное участие в Восточноафриканской кампании . Сформированные в 1925 году Силы обороны Судана играли активную роль в реагировании на вторжения в начале Второй мировой войны. Итальянские войска оккупировали Кассалу и другие приграничные районы итальянского Сомалиленда в 1940 году. В 1942 году СДС также сыграли роль во вторжении в итальянскую колонию сил Великобритании и Содружества. Последним британским генерал-губернатором был Роберт Джордж Хоу .

Египетская революция 1952 года наконец ознаменовала начало марша к независимости Судана. Отменив монархию в 1953 году, новые лидеры Египта Мохаммед Нагиб , чья мать была суданкой, а затем Гамаль Абдель Насер , полагали, что единственный способ положить конец британскому господству в Судане — это официальный отказ Египта от своих претензий на суверенитет. Кроме того, Насер знал, что Египту будет трудно управлять обедневшим Суданом после обретения им независимости. Британцы, с другой стороны, продолжали оказывать политическую и финансовую поддержку преемнику-махдисту Абд ар-Рахману аль-Махди , который, как считалось, будет сопротивляться давлению Египта с требованием независимости Судана. Абд аль-Рахман был способен на это, но его режим страдал от политической некомпетентности, что привело к колоссальной потере поддержки в северном и центральном Судане. И Египет, и Великобритания почувствовали нарастающую большую нестабильность и поэтому решили позволить обоим суданским регионам, северу и югу, иметь свободное голосование по поводу того, желают ли они независимости или вывода британских войск.

Независимость (1956 – настоящее время)

[ редактировать ]В этом разделе отсутствует информация об истории Судана с 1956 по 1969 год и с 1977 по 1989 год. ( январь 2016 г. ) |

В результате голосования был определен состав демократического парламента, и Исмаил аль-Ажари был избран первым премьер-министром и возглавил первое современное суданское правительство. [ 131 ] 1 января 1956 года на специальной церемонии, состоявшейся в Народном дворце, премьер-министр Исмаил аль- Ажари был спущен египетский и британский флаги, а вместо них был поднят новый суданский флаг, состоящий из зеленых, синих и желтых полос. .

Недовольство достигло кульминации в государственном перевороте 25 мая 1969 года. Лидер переворота полковник Гаафар Нимейри стал премьер-министром, а новый режим упразднил парламент и объявил вне закона все политические партии. Споры между марксистскими и немарксистскими элементами внутри правящей военной коалиции привели к кратковременному успешному перевороту в июле 1971 года , возглавляемому Коммунистической партией Судана . Несколько дней спустя антикоммунистические военные элементы вернули Нимейри к власти.

В 1972 году Аддис-Абебское соглашение привело к прекращению гражданской войны между севером и югом и установлению определенного самоуправления. Это привело к десятилетнему перерыву в гражданской войне, но положило конец американским инвестициям в проект канала Джонглей . Это считалось абсолютно необходимым для орошения региона Верхнего Нила и предотвращения экологической катастрофы и широкомасштабного голода среди местных племен, особенно динка. В последовавшей за этим гражданской войне их родину подвергали набегам, грабежам, разграблениям и сожжениям. Многие представители племени были убиты в ходе кровавой гражданской войны, которая бушевала более 20 лет.

До начала 1970-х годов сельскохозяйственная продукция Судана в основном предназначалась для внутреннего потребления. В 1972 году суданское правительство стало более прозападным и планировало экспортировать продукты питания и товарные культуры . Однако цены на сырьевые товары падали на протяжении 1970-х годов, что вызвало экономические проблемы для Судана. В то же время затраты на обслуживание долга, связанные с деньгами, потраченными на механизацию сельского хозяйства, выросли. В 1978 году МВФ согласовал программу структурной перестройки с правительством . Это еще больше способствовало развитию механизированного экспортного сельскохозяйственного сектора. Это причинило большие трудности скотоводам Судана. В 1976 году Ансары предприняли кровавую, но безуспешную попытку государственного переворота. Но в июле 1977 года президент Нимейри встретился с лидером Ансара Садиком аль-Махди , открыв путь к возможному примирению. Сотни политзаключенных были освобождены, а в августе была объявлена всеобщая амнистия для всех оппозиционеров.

Эпоха Башира (1989–2019)

[ редактировать ]

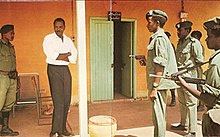

30 июня 1989 года полковник Омар аль-Башир возглавил бескровный военный переворот . [ 132 ] Новое военное правительство приостановило деятельность политических партий и ввело исламский правовой кодекс на национальном уровне. [ 133 ] Позже аль-Башир провел чистки и казни в высших рядах армии, запрет ассоциаций, политических партий и независимых газет, а также заключение под стражу ведущих политических деятелей и журналистов. [ 134 ] 16 октября 1993 года аль-Башир назначил себя « президентом » и распустил Совет революционного командования. Исполнительную и законодательную власть совета взял на себя аль-Башир. [ 135 ]

На всеобщих выборах 1996 года он был единственным кандидатом по закону, баллотировавшимся на выборах. [ 136 ] Судан стал однопартийным государством под руководством Партии Национальный конгресс (ПНК). [ 137 ] В 1990-е годы Хасан аль-Тураби , тогдашний спикер Национальной ассамблеи, обратился к исламским фундаменталистским группам и пригласил Усаму бен Ладена в страну. [ 138 ] Впоследствии Соединенные Штаты включили Судан в список стран-спонсоров терроризма . [ 139 ] После взрыва Аль-Каидой посольств США в Кении и Танзании США начали операцию «Бесконечный охват» и нанесли удар по фармацевтическому заводу Аль-Шифа , который, как ошибочно полагало правительство США, производил химическое оружие для террористической группировки. Влияние Аль-Тураби начало ослабевать, и другие сторонники более прагматичного руководства попытались изменить международную изоляцию Судана . [ 140 ] Страна старалась успокоить своих критиков, изгоняя членов Египетского исламского джихада и поощряя бен Ладена уйти. [ 141 ]

Перед президентскими выборами 2000 года аль-Тураби внес законопроект об ограничении полномочий президента, что побудило аль-Башира отдать приказ о роспуске и объявить чрезвычайное положение . Когда аль-Тураби призвал бойкотировать кампанию по переизбранию президента, подписывающую соглашение с Народно-освободительной армией Судана , аль-Башир заподозрил, что они готовят заговор с целью свержения правительства. [ 142 ] Позже в том же году Хасан аль-Тураби был заключен в тюрьму. [ 143 ]

В феврале 2003 года группы Суданского освободительного движения/армии (ОДС/А) и Движения за справедливость и равенство (ДСР) в Дарфуре взяли в руки оружие, обвинив суданское правительство в притеснении суданцев неарабского происхождения в пользу суданских арабов , что спровоцировало войну в Судане. Дарфур . Конфликт с тех пор был назван геноцидом . [ 144 ] а Международный уголовный суд (МУС) в Гааге выдал два ордера на арест аль-Башира. [ 145 ] [ 146 ] Арабоязычные кочевые ополченцы, известные как « Джанджавид», обвиняются во многих злодеяниях.

9 января 2005 года правительство подписало Найробийское Всеобъемлющее мирное соглашение с Народно-освободительным движением Судана (НОДС) с целью положить конец Второй гражданской войне в Судане . Миссия Организации Объединенных Наций в Судане (МООНВС) была создана в соответствии с резолюцией 1590 Совета Безопасности ООН для поддержки ее реализации. Мирное соглашение было предпосылкой референдума 2011 года : результатом стало единогласное голосование в пользу отделения Южного Судана ; регион Абьей проведет собственный референдум В будущем .

( Народно-освободительная армия Судана НОАС) была основным членом Восточного фронта , коалиции повстанческих группировок, действовавших в восточном Судане. После мирного соглашения их место заняли в феврале 2004 года после слияния более крупной организации «Фулани и Конгресс беджа» с меньшей организацией « Свободные львы Рашайды» . [ 147 ] Мирное соглашение между правительством Судана и Восточным фронтом было подписано 14 октября 2006 года в Асмэре. 5 мая 2006 года было подписано Мирное соглашение по Дарфуру , направленное на прекращение конфликта, который до этого момента продолжался три года. [ 148 ] Конфликт между Чадом и Суданом (2005–2007 гг.) Вспыхнул после того, как битва при Адре спровоцировала объявление Чадом войны. [ 149 ] Лидеры Судана и Чада подписали в Саудовской Аравии 3 мая 2007 года соглашение о прекращении боевых действий из-за конфликта в Дарфуре , распространяющегося вдоль границы их стран протяженностью 1000 километров (600 миль). [ 150 ]

В июле 2007 года страну поразило разрушительное наводнение . [ 151 ] непосредственно пострадали более 400 000 человек. [ 152 ] С 2009 года серия продолжающихся конфликтов между соперничающими кочевым племенами в Судане и Южном Судане привела к большому количеству жертв среди гражданского населения.

Раздел и реабилитация

[ редактировать ]Суданский конфликт в Южном Кордофане и Голубом Ниле в начале 2010-х годов между Армией Судана и Суданским революционным фронтом начался как спор по поводу богатого нефтью региона Абьей в несколько месяцев, предшествовавших независимости Южного Судана в 2011 году, хотя также связано с гражданской войной в Дарфуре, которая номинально разрешена. Год спустя, в 2012 году, во время кризиса Хеглига, Судан одержал победу над Южным Суданом, войной за богатые нефтью регионы между штатами Юнити Южного Судана и суданскими штатами Южный Кордофан . Эти события позже будут известны как Суданская интифада , которая закончится только в 2013 году после того, как аль-Башир пообещал, что не будет добиваться переизбрания в 2015 году. оппозиция, которая считала, что выборы не будут свободными и честными. Явка избирателей была на низком уровне – 46%. [ 153 ]

13 января 2017 года президент США Барак Обама подписал указ, отменяющий многие санкции, введенные против Судана и активов его правительства, находящихся за рубежом. 6 октября 2017 года следующий президент США Дональд Трамп снял большую часть оставшихся санкций против страны и ее нефтяной, экспортно-импортной и имущественной отраслей. [ 154 ]

Суданская революция 2019 года и переходное правительство

[ редактировать ]

19 декабря 2018 года массовые протесты начались после решения правительства утроить цены на товары в то время, когда страна страдала от острой нехватки иностранной валюты и инфляции в 70 процентов. [ 155 ] Кроме того, президент аль-Башир, находившийся у власти более 30 лет, отказался уйти в отставку, что привело к сближению оппозиционных группировок в единую коалицию. В ответ правительство арестовало более 800 деятелей оппозиции и протестующих, что, по данным Human Rights Watch, привело к гибели около 40 человек. [ 156 ] хотя, согласно местным и гражданским сообщениям, это число было намного выше. Протесты продолжились после свержения его правительства 11 апреля 2019 года после массовой сидячей забастовки перед главным штабом Суданских вооруженных сил , после которой начальники штабов решили вмешаться, приказали арестовать президента аль-Башира и объявили трехмесячное чрезвычайное положение. [ 157 ] [ 158 ] [ 159 ] Более 100 человек погибли 3 июня после того, как силы безопасности разогнали сидячую забастовку, применив слезоточивый газ и боевые патроны в так называемой Хартумской резне . [ 160 ] [ 161 ] что привело к исключению Судана из Африканского союза. [ 162 ] Сообщается, что молодежь Судана является движущей силой протестов. [ 163 ] Протесты закончились, когда « Силы за свободу и перемены» (альянс групп, организующих протесты) и Переходный военный совет (правящее военное правительство) подписали Политическое соглашение от июля 2019 года и проект конституционной декларации от августа 2019 года. [ 164 ] [ 165 ]

Переходные институты и процедуры включали создание совместного военно-гражданского суверенного совета Судана в качестве главы государства, нового главного судьи Судана в качестве главы судебной ветви власти Немата Абдуллы Хайра и нового премьер-министра. Бывший премьер-министр Абдалла Хамдок , 61-летний экономист, ранее работавший в Экономической комиссии ООН для Африки , был приведен к присяге 21 августа 2019 года. [ 166 ] Он инициировал переговоры с МВФ и Всемирным банком, направленные на стабилизацию экономики, которая находилась в тяжелом положении из-за нехватки продовольствия, топлива и твердой валюты. Хамдок подсчитал, что 10 миллиардов долларов США в течение двух лет будет достаточно, чтобы остановить панику, и сказал, что более 70% бюджета 2018 года было потрачено на меры, связанные с гражданской войной. Правительства Саудовской Аравии и Объединенных Арабских Эмиратов вложили значительные суммы в поддержку военного совета после свержения Башира. [ 167 ] 3 сентября Хамдок назначил 14 гражданских министров, в том числе первую женщину-министра иностранных дел и первую коптскую христианку, тоже женщину. [ 168 ] [ 169 ] По состоянию на август 2021 года страной совместно руководили председатель Переходного суверенного совета Абдель Фаттах аль-Бурхан и премьер-министр Абдалла Хамдок. [ 170 ]

Переворот 2021 года и режим аль-Бурхана

[ редактировать ]21 сентября 2021 года правительство Судана объявило о неудавшейся попытке военного государственного переворота , в результате которой были арестованы 40 офицеров. [ 171 ] [ 172 ]

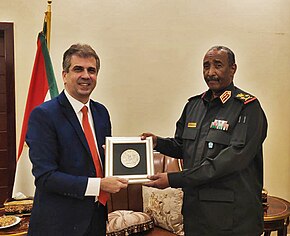

Через месяц после попытки государственного переворота 25 октября 2021 года произошел еще один военный переворот, в результате которого было свергнуто гражданское правительство, включая бывшего премьер-министра Абдаллу Хамдока. Переворот возглавил генерал Абдель Фаттах аль-Бурхан, который впоследствии объявил чрезвычайное положение. [ 173 ] [ 174 ] [ 175 ] [ 176 ] Бурхан вступил в должность фактического главы государства Судан и 11 ноября 2021 года сформировал новое правительство, поддерживаемое армией. [ 177 ]

21 ноября 2021 года Хамдок был восстановлен в должности премьер-министра после того, как Бурхан подписал политическое соглашение о восстановлении перехода к гражданскому правлению (хотя Бурхан сохранил контроль). Соглашение из 14 пунктов призывало к освобождению всех политических заключенных, задержанных во время переворота, и предусматривало, что конституционная декларация 2019 года продолжает оставаться основой для политического перехода. [ 178 ] Хамдок уволил начальника полиции Халеда Махди Ибрагима аль-Эмама и его заместителя Али Ибрагима. [ 179 ]

2 января 2022 года Хамдок объявил о своей отставке с поста премьер-министра после одного из самых смертоносных протестов на сегодняшний день. [ 180 ] Его преемником стал Осман Хусейн . [ 181 ] [ 182 ] К марту 2022 года за сопротивление перевороту было задержано более 1000 человек, в том числе 148 детей, было зарегистрировано 25 обвинений в изнасиловании. [ 183 ] и 87 человек были убиты [ 184 ] в том числе 11 детей. [ 183 ]

2023 – настоящее время: Внутренний конфликт.

[ редактировать ]

В апреле 2023 года, когда обсуждался при посредничестве международного сообщества план перехода к гражданскому правлению, обострилась борьба за власть между командующим армией (и де-факто национальным лидером) Абдель Фаттахом аль-Бурханом и его заместителем Хемедти , главой хорошо вооруженного военизированного формирования «Рапид». Силы поддержки (RSF), сформированные из ополчения Джанджавид . [ 185 ] [ 186 ]

15 апреля 2023 года их конфликт перерос в гражданскую войну, начавшуюся с боев на улицах Хартума между армией и RSF – с участием войск, танков и самолетов. , к третьему дню 400 человек были убиты и не менее 3500 получили ранения По данным ООН . [ 187 ] Среди погибших были трое сотрудников Всемирной продовольственной программы , что привело к приостановке работы организации в Судане, несмотря на продолжающийся голод, поразивший большую часть страны. [ 188 ] Суданский генерал Ясир аль-Атта заявил, что ОАЭ поставляют RSF припасы, которые использовались в войне. [ 189 ]

И Суданские вооруженные силы, и Силы оперативной поддержки обвиняются в совершении военных преступлений . [ 190 ] [ 191 ] По состоянию на 29 декабря 2023 года более 5,8 миллиона человек были внутренне перемещенными лицами и более 1,5 миллиона человек покинули страну в качестве беженцев. [ 192 ] Сообщается , что многие гражданские лица в Дарфуре погибли в результате массовых убийств в Масалите . [ 193 ] В городе Генейна погибло до 15 000 человек . [ 194 ]

В результате войны Всемирная продовольственная программа опубликовала 22 февраля 2024 года отчет, в котором говорится, что более 95% населения Судана не могут позволить себе еду в день. [ 195 ] По состоянию на апрель 2024 года Организация Объединенных Наций сообщила, что более 8,6 миллиона человек были вынуждены покинуть свои дома, а 18 миллионов страдают от сильного голода, пять миллионов из них находятся на чрезвычайном уровне. [ 196 ] В мае 2024 года официальные лица правительства США подсчитали, что только за последний год в войне погибло не менее 150 000 человек. [ 197 ] Очевидные нападения RSF на общины чернокожих коренных народов, особенно вокруг города Эль-Фашир, побудили международных чиновников предупредить о риске повторения истории с новым геноцидом в регионе Дарфур. [ 197 ]

созвала конференцию в Палате представителей 31 мая 2024 года конгрессмен США Элеонора Холмс Нортон по решению гуманитарного кризиса в Судане. Доклад Государственного департамента об участии ОАЭ в Судане, включая военные преступления и экспорт оружия, был в центре внимания конференции. Спикер дискуссии, член совета Мохамед Зайфельдейн, призвал положить конец участию ОАЭ в Судане, заявив, что роль ОАЭ в использовании RSF в Судане, а также в гражданской войне в Йемене «необходимо прекратить». Зайфельдейн вместе с другим участником дискуссии Хагиром С. Эльшейхом призвали международное сообщество прекратить всякую поддержку RSF, указав на разрушительную роль группировки боевиков в Судане. Эльшейх также рекомендовал использовать социальные сети для повышения осведомленности о суданской войне и оказать давление на выборных должностных лиц США, чтобы они прекратили продажу оружия ОАЭ. [ 198 ]

География

[ редактировать ]

Судан расположен в Северной Африке, его береговая линия длиной 853 км (530 миль) граничит с Красным морем . [ 199 ] Имеет сухопутные границы с Египтом , Эритреей , Эфиопией , Южным Суданом , Центральноафриканской Республикой , Чадом и Ливией . Площадью 1 886 068 км². 2 (728 215 квадратных миль), это третья по величине страна на континенте (после Алжира и Демократической Республики Конго ) и пятнадцатая по величине в мире.

Судан расположен между 8° и 23° северной широты . Рельеф в основном представляет собой плоские равнины, разбитые несколькими горными хребтами. На западе кальдера Дериба (3042 м или 9980 футов), расположенная в горах Марра , является самой высокой точкой Судана. На востоке расположены холмы Красного моря . [ 200 ]

Реки Голубой и Белый Нил встречаются в Хартуме и образуют Нил , который течет на север через Египет в Средиземное море. Длина Голубого Нила через Судан составляет почти 800 км (497 миль), к нему присоединяются реки Диндер и Рахад между Сеннаром и Хартумом . Белый Нил в Судане не имеет значительных притоков.

На Голубом и Белом Ниле имеется несколько плотин. Среди них плотины Сеннар и Розейрес на Голубом Ниле и плотина Джебель-Аулия на Белом Ниле. также есть озеро Нубия На границе Судана и Египта .

В Судане имеются богатые минеральные ресурсы, включая асбест , хромит , кобальт , медь, золото, гранит , гипс , железо, каолин , свинец, , марганец слюду , природный газ, никель , нефть, серебро, олово , уран и цинк . [ 201 ]

Климат

[ редактировать ]The amount of rainfall increases towards the south. The central and the northern part have extremely dry, semi-desert areas such as the Nubian Desert to the northeast and the Bayuda Desert to the east; in the south, there are grasslands and tropical savanna. Sudan's rainy season lasts for about four months (June to September) in the north, and up to six months (May to October) in the south.

The dry regions are plagued by sandstorms, known as haboob, which can completely block out the sun. In the northern and western semi-desert areas, people rely on scarce rainfall for basic agriculture and many are nomadic, travelling with their herds of sheep and camels. Nearer the River Nile, there are well-irrigated farms growing cash crops.[202] The sunshine duration is very high all over the country but especially in deserts where it can soar to over 4,000 hours per year.

Environmental issues

[edit]

Desertification is a serious problem in Sudan.[203] There is also concern over soil erosion. Agricultural expansion, both public and private, has proceeded without conservation measures. The consequences have manifested themselves in the form of deforestation, soil desiccation, and the lowering of soil fertility and the water table.[204]

The nation's wildlife is threatened by poaching. As of 2001, twenty-one mammal species and nine bird species are endangered, as well as two species of plants. Critically endangered species include: the waldrapp, northern white rhinoceros, tora hartebeest, slender-horned gazelle, and hawksbill turtle. The Sahara oryx has become extinct in the wild.[205]

Wildlife

[edit]Government and politics

[edit]The politics of Sudan formally took place within the framework of a federal authoritarian Islamic republic until April 2019, when President Omar al-Bashir's regime was overthrown in a military coup led by Vice President Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf. As an initial step he established the Transitional Military Council to manage the country's internal affairs. He also suspended the constitution and dissolved the bicameral parliament – the National Legislature, with its National Assembly (lower chamber) and the Council of States (upper chamber). Ibn Auf however, remained in office for only a single day and then resigned, with the leadership of the Transitional Military Council then being handed to Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. On 4 August 2019, a new Constitutional Declaration was signed between the representatives of the Transitional Military Council and the Forces of Freedom and Change, and on 21 August 2019 the Transitional Military Council was officially replaced as head of state by an 11-member Sovereignty Council, and as head of government by a civilian Prime Minister. According to 2023 V-Dem Democracy indices Sudan is 6th least democratic country in Africa.[206]

Sharia law

[edit]Under Nimeiri

[edit]In September 1983, President Jaafar Nimeiri introduced sharia law in Sudan, known as September laws, symbolically disposing of alcohol and implementing hudud punishments like public amputations. Al-Turabi supported this move, differing from Al-Sadiq al-Mahdi's dissenting view. Al-Turabi and his allies within the regime also opposed self-rule in the south, a secular constitution, and non-Islamic cultural acceptance. One condition for national reconciliation was re-evaluating the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement that granted the south self-governance, reflecting a failure to accommodate minority rights and leverage Islam's rejection of racism.[207] The Islamic economy followed in early 1984, eliminating interest and instituting zakat. Nimeiri declared himself the imam of the Sudanese Umma in 1984.[208]

Under al-Bashir

[edit]During the regime of Omar al-Bashir, the legal system in Sudan was based on Islamic Sharia law. The 2005 Naivasha Agreement, ending the civil war between north and south Sudan, established some protections for non-Muslims in Khartoum. Sudan's application of Sharia law is geographically inconsistent.[209]

Stoning was a judicial punishment in Sudan. Between 2009 and 2012, several women were sentenced to death by stoning.[210][211][212] Flogging was a legal punishment. Between 2009 and 2014, many people were sentenced to 40–100 lashes.[213][214][215][216][217][218] In August 2014, several Sudanese men died in custody after being flogged.[219][220][221] 53 Christians were flogged in 2001.[222] Sudan's public order law allowed police officers to publicly whip women who were accused of public indecency.[223]

Crucifixion was also a legal punishment. In 2002, 88 people were sentenced to death for crimes relating to murder, armed robbery, and participating in ethnic clashes. Amnesty International wrote that they could be executed by either hanging or crucifixion.[224]

International Court of Justice jurisdiction is accepted, though with reservations. Under the terms of the Naivasha Agreement, Islamic law did not apply in South Sudan.[225] Since the secession of South Sudan there was some uncertainty as to whether Sharia law would apply to the non-Muslim minorities present in Sudan, especially because of contradictory statements by al-Bashir on the matter.[226]

The judicial branch of the Sudanese government consists of a Constitutional Court of nine justices, the National Supreme Court, the Court of Cassation,[227] and other national courts; the National Judicial Service Commission provides overall management for the judiciary.

After al-Bashir

[edit]Following the ouster of al-Bashir, the interim constitution signed in August 2019 contained no mention of Sharia law.[228] As of 12 July 2020, Sudan abolished the apostasy law, public flogging and alcohol ban for non-Muslims. The draft of a new law was passed in early July. Sudan also criminalized female genital mutilation with a punishment of up to 3 years in jail.[229] An accord between the transitional government and rebel group leadership was signed in September 2020, in which the government agreed to officially separate the state and religion, ending three decades of rule under Islamic law. It also agreed that no official state religion will be established.[230][228][231]

Administrative divisions

[edit]Sudan is divided into 18 states (wilayat, sing. wilayah). They are further divided into 133 districts.

Regional bodies

[edit]In addition to the states, there also exist regional administrative bodies established by peace agreements between the central government and rebel groups.

- The Darfur Regional Government was established by the Darfur Peace Agreement to act as a coordinating body for the states that make up the region of Darfur.

- The Eastern Sudan States Coordinating Council was established by the Eastern Sudan Peace Agreement between the Sudanese Government and the rebel Eastern Front to act as a coordinating body for the three eastern states.

- The Abyei Area, located on the border between South Sudan and the Republic of the Sudan, currently has a special administrative status and is governed by an Abyei Area Administration. It was due to hold a referendum in 2011 on whether to be part of South Sudan or part of the Republic of the Sudan.

Disputed areas and zones of conflict

[edit]- In April 2012, the South Sudanese army captured the Heglig oil field from Sudan, which the Sudanese army later recaptured.

- Kafia Kingi and Radom National Park was a part of Bahr el Ghazal in 1956.[232] Sudan has recognised South Sudanese independence according to the borders for 1 January 1956.[233]

- The Abyei Area is disputed region between Sudan and South Sudan. It is currently under Sudanese rule.

- The states of South Kurdufan and Blue Nile are to hold "popular consultations" to determine their constitutional future within Sudan.

- The Hala'ib Triangle is disputed region between Sudan and Egypt. It is currently under Egyptian administration.

- Bir Tawil is a terra nullius occurring on the border between Egypt and Sudan, claimed by neither state.

Foreign relations

[edit]

Sudan has had a troubled relationship with many of its neighbours and much of the international community, owing to what is viewed as its radical Islamic stance. For much of the 1990s, Uganda, Kenya and Ethiopia formed an ad hoc alliance called the "Front Line States" with support from the United States to check the influence of the National Islamic Front government. The Sudanese Government supported anti-Ugandan rebel groups such as the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA).[234]

As the National Islamic Front regime in Khartoum gradually emerged as a real threat to the region and the world, the U.S. began to list Sudan on its list of State Sponsors of Terrorism. After the US listed Sudan as a state sponsor of terrorism, the NIF decided to develop relations with Iraq, and later Iran, the two most controversial countries in the region.

From the mid-1990s, Sudan gradually began to moderate its positions as a result of increased U.S. pressure following the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings, in Tanzania and Kenya, and the new development of oil fields previously in rebel hands. Sudan also has a territorial dispute with Egypt over the Hala'ib Triangle. Since 2003, the foreign relations of Sudan had centred on the support for ending the Second Sudanese Civil War and condemnation of government support for militias in the war in Darfur.

Sudan has extensive economic relations with China. China obtains ten percent of its oil from Sudan. According to a former Sudanese government minister, China is Sudan's largest supplier of arms.[235]

In December 2005, Sudan became one of the few states to recognise Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara.[236]

In 2015, Sudan participated in the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen against the Shia Houthis and forces loyal to former President Ali Abdullah Saleh,[237] who was deposed in the 2011 uprising.[238]

In June 2019, Sudan was suspended from the African Union over the lack of progress towards the establishment of a civilian-led transitional authority since its initial meeting following the coup d'état of 11 April 2019.[239][240]

In July 2019, UN ambassadors of 37 countries, including Sudan, have signed a joint letter to the UNHRC defending China's treatment of Uyghurs in the Xinjiang region.[241]

On 23 October 2020, U.S. President Donald Trump announced that Sudan will start to normalize ties with Israel, making it the third Arab state to do so as part of the U.S.-brokered Abraham Accords.[242] On 14 December the U.S. Government removed Sudan from its State Sponsor of Terrorism list; as part of the deal, Sudan agreed to pay $335 million in compensation to victims of the 1998 embassy bombings.[243]

The dispute between Sudan and Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam escalated in 2021.[244][245][246] An advisor to the Sudanese leader Abdel Fattah al-Burhan spoke of a water war "that would be more horrible than one could imagine".[247]

In February 2022, it is reported that a Sudanese envoy has visited Israel to promote ties between the countries.[248]

In the early months of 2023, fighting reignited, primarily between the military forces of Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the army chief and de facto head of state, and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces led by his rival, Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo. As a result, the U.S. and most European countries have shut down their embassies in Khartoum and have attempted evacuations. In 2023, it was estimated that there were 16,000 Americans in Sudan who needed to be evacuated. In absence of an official evacuation plan from the U.S. State Department, many Americans have been forced to turn to other nations' embassies for guidance, with many fleeing to Nairobi. Other African countries and humanitarian groups have tried to help. The Turkish embassy has reportedly allowed Americans to join its evacuation efforts for its own citizens. The TRAKboys, a South-Africa based political organization which came into conflict with the Wagner Group, a Russian private military contractor operating in Sudan since 2017, has been assisting with the evacuation of both Black Americans and Sudanese citizens to safe locations in South Africa.[249][250]

On April 15, 2024, France is hosting an international conference on Sudan, marking the one-year anniversary of the outbreak of war in the northeast African nation, which has resulted in a humanitarian and political crisis. The country is calling for support from the global community, aiming to draw attention to a crisis that officials believe has been overshadowed by ongoing conflicts in the Middle East.[251]

Military

[edit]The Sudanese Armed Forces is the regular forces of Sudan and is divided into five branches: the Sudanese Army, Sudanese Navy (including the Marine Corps), Sudanese Air Force, Border Patrol and the Internal Affairs Defence Force, totalling about 200,000 troops. The military of Sudan has become a well-equipped fighting force; a result of increasing local production of heavy and advanced arms. These forces are under the command of the National Assembly and its strategic principles include defending Sudan's external borders and preserving internal security.

Since the Darfur crisis in 2004, safe-keeping the central government from the armed resistance and rebellion of paramilitary rebel groups such as the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), the Sudanese Liberation Army (SLA) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) have been important priorities. While not official, the Sudanese military also uses nomad militias, the most prominent being the Janjaweed, in executing a counter-insurgency war.[252] Somewhere between 200,000[253] and 400,000[254][255][256] people have died in the violent struggles.

Human rights

[edit]Since 1983, a combination of civil war and famine has taken the lives of nearly two million people in Sudan.[257] It is estimated that as many as 200,000 people had been taken into slavery during the Second Sudanese Civil War.[258]

Muslims who convert to Christianity can face the death penalty for apostasy; see Persecution of Christians in Sudan and the death sentence against Mariam Yahia Ibrahim Ishag (who actually was raised as Christian). According to a 2013 UNICEF report, 88% of women in Sudan had undergone female genital mutilation.[259] Sudan's Personal Status law on marriage has been criticised for restricting women's rights and allowing child marriage.[260][261] Evidence suggests that support for female genital mutilation remains high, especially among rural and less well educated groups, although it has been declining in recent years.[262] Homosexuality is illegal; as of July 2020 it was no longer a capital offence, with the highest punishment being life imprisonment.[263]

A report published by Human Rights Watch in 2018 revealed that Sudan has made no meaningful attempts to provide accountability for past and current violations. The report documented human rights abuses against civilians in Darfur, southern Kordofan, and Blue Nile. During 2018, the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) used excessive force to disperse protests and detained dozens of activists and opposition members. Moreover, the Sudanese forces blocked United Nations-African Union Hybrid Operation and other international relief and aid agencies to access to displaced people and conflict-ridden areas in Darfur.[264]

Darfur

[edit]

A 14 August 2006 letter from the executive director of Human Rights Watch found that the Sudanese government is both incapable of protecting its own citizens in Darfur and unwilling to do so, and that its militias are guilty of crimes against humanity. The letter added that these human-rights abuses have existed since 2004.[265] Some reports attribute part of the violations to the rebels as well as the government and the Janjaweed. The U.S. State Department's human-rights report issued in March 2007 claims that "[a]ll parties to the conflagration committed serious abuses, including widespread killing of civilians, rape as a tool of war, systematic torture, robbery and recruitment of child soldiers."[266]

Over 2.8 million civilians have been displaced and the death toll is estimated at 300,000 killed.[267] Both government forces and militias allied with the government are known to attack not only civilians in Darfur, but also humanitarian workers. Sympathisers of rebel groups are arbitrarily detained, as are foreign journalists, human-rights defenders, student activists and displaced people in and around Khartoum, some of whom face torture. The rebel groups have also been accused in a report issued by the U.S. government of attacking humanitarian workers and of killing innocent civilians.[268] According to UNICEF, in 2008, there were as many as 6,000 child soldiers in Darfur.[269]

Press freedom

[edit]Under the government of Omar al-Bashir (1989–2019), Sudan's media outlets were given little freedom in their reporting.[270] In 2014, Reporters Without Borders' freedom of the press rankings placed Sudan at 172th of 180 countries.[271] After al-Bashir's ousting in 2019, there was a brief period under a civilian-led transitional government where there was some press freedom.[270] However, the leaders of a 2021 coup quickly reversed these changes.[272] "The sector is deeply polarised", Reporters Without Borders stated in their 2023 summary of press freedom in the country. "Journalistic critics have been arrested, and the internet is regularly shut down in order to block the flow of information."[273] Additional crackdowns occurred after the beginning of the 2023 Sudanese civil war.[270]

International organisations in Sudan

[edit]Several UN agents are operating in Sudan such as the World Food Program (WFP); the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO); the United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF); the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR); the United Nations Mine Service (UNMAS), the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the World Bank. Also present is the International Organisation for Migration (IOM).[274][275]

Since Sudan has experienced civil war for many years, many non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are also involved in humanitarian efforts to help internally displaced people. The NGOs are working in every corner of Sudan, especially in the southern part and western parts. During the civil war, international non-governmental organisations such as the Red Cross were operating mostly in the south but based in the capital Khartoum.[276] The attention of NGOs shifted shortly after the war broke out in the western part of Sudan known as Darfur. The most visible organisation in South Sudan is the Operation Lifeline Sudan (OLS) consortium.[277] Some international trade organisations categorise Sudan as part of the Greater Horn of Africa[278]

Even though most of the international organisations are substantially concentrated in both South Sudan and the Darfur region, some of them are working in the northern part as well. For example, the United Nations Industrial Development Organization is successfully operating in Khartoum, the capital. It is mainly funded by the European Union and recently opened more vocational training. The Canadian International Development Agency is operating largely in northern Sudan.[279]

Economy

[edit]

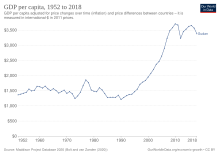

In 2010, Sudan was considered the 17th-fastest-growing economy[280] in the world and the rapid development of the country largely from oil profits even when facing international sanctions was noted by The New York Times in a 2006 article.[281] Because of the secession of South Sudan, which contained about 75 percent of Sudan's oilfields,[282] Sudan entered a phase of stagflation, GDP growth slowed to 3.4 percent in 2014, 3.1 percent in 2015 and was projected to recover slowly to 3.7 percent in 2016 while inflation remained as high as 21.8% as of 2015[update].[283] Sudan's GDP fell from US$123.053 billion in 2017 to US$40.852 billion in 2018.[284]

Even with the oil profits before the secession of South Sudan, Sudan still faced formidable economic problems, and its growth was still a rise from a very low level of per capita output. The economy of Sudan has been steadily growing over the 2000s, and according to a World Bank report the overall growth in GDP in 2010 was 5.2 percent compared to 2009 growth of 4.2 percent.[254] This growth was sustained even during the war in Darfur and period of southern autonomy preceding South Sudan's independence.[285][286] Oil was Sudan's main export, with production increasing dramatically during the late 2000s, in the years before South Sudan gained independence in July 2011. With rising oil revenues, the Sudanese economy was booming, with a growth rate of about nine percent in 2007. The independence of oil-rich South Sudan, however, placed most major oil fields out of the Sudanese government's direct control and oil production in Sudan fell from around 450,000 barrels per day (72,000 m3/d) to under 60,000 barrels per day (9,500 m3/d). Production has since recovered to hover around 250,000 barrels per day (40,000 m3/d) for 2014–15.[287]

To export oil, South Sudan relies on a pipeline to Port Sudan on Sudan's Red Sea coast, as South Sudan is a landlocked country, as well as the oil refining facilities in Sudan. In August 2012, Sudan and South Sudan agreed to a deal to transport South Sudanese oil through Sudanese pipelines to Port Sudan.[288]

The People's Republic of China is one of Sudan's major trading partners, China owns a 40 percent share in the Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Company.[289] The country also sells Sudan small arms, which have been used in military operations such as the conflicts in Darfur and South Kordofan.[290]

While historically agriculture remains the main source of income and employment hiring of over 80 percent of Sudanese, and makes up a third of the economic sector, oil production drove most of Sudan's post-2000 growth. Currently, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is working hand in hand with Khartoum government to implement sound macroeconomic policies. This follows a turbulent period in the 1980s when debt-ridden Sudan's relations with the IMF and World Bank soured, culminating in its eventual suspension from the IMF.[291]

According to the Corruptions Perception Index, Sudan is one of the most corrupt nations in the world.[292] According to the Global Hunger Index of 2013, Sudan has an GHI indicator value of 27.0 indicating that the nation has an 'Alarming Hunger Situation.' It is rated the fifth hungriest nation in the world.[293] According to the 2015 Human Development Index (HDI) Sudan ranked the 167th place in human development, indicating Sudan still has one of the lowest human development rates in the world.[294] In 2014, 45% of the population lives on less than US$3.20 per day, up from 43% in 2009.[295]

Science and research

[edit]Sudan has around 25–30 universities; instruction is primarily in Arabic or English. Education at the secondary and university levels has been seriously hampered by the requirement that most males perform military service before completing their education.[296] In addition, the "Islamisation" encouraged by president Al-Bashir alienated many researchers: the official language of instruction in universities was changed from English to Arabic and Islamic courses became mandatory. Internal science funding withered.[297] According to UNESCO, more than 3,000 Sudanese researchers left the country between 2002 and 2014. By 2013, the country had a mere 19 researchers for every 100,000 citizens, or 1/30 the ratio of Egypt, according to the Sudanese National Centre for Research. In 2015, Sudan published only about 500 scientific papers.[297] In comparison, Poland, a country of similar population size, publishes on the order of 10,000 papers per year.[298]

Sudan's National Space Program has produced multiple CubeSat satellites, and has plans to produce a Sudanese communications satellite (SUDASAT-1) and a Sudanese remote sensing satellite (SRSS-1). The Sudanese government contributed to an offer pool for a private-sector ground surveying Satellite operating above Sudan, Arabsat 6A, which was successfully launched on 11 April 2019, from the Kennedy Space Center.[299] Sudanese president Omar Hassan al-Bashir called for an African Space Agency in 2012, but plans were never made final.[300]

Demographics

[edit]

In Sudan's 2008 census, the population of northern, western and eastern Sudan was recorded to be over 30 million.[301] This puts present estimates of the population of Sudan after the secession of South Sudan at a little over 30 million people. This is a significant increase over the past two decades, as the 1983 census put the total population of Sudan, including present-day South Sudan, at 21.6 million.[302] The population of Greater Khartoum (including Khartoum, Omdurman, and Khartoum North) is growing rapidly and was recorded to be 5.2 million.

Aside from being a refugee-generating country, Sudan also hosts a large population of refugees from other countries. According to UNHCR statistics, more than 1.1 million refugees and asylum seekers lived in Sudan in August 2019. The majority of this population came from South Sudan (858,607 people), Eritrea (123,413), Syria (93,502), Ethiopia (14,201), the Central African Republic (11,713) and Chad (3,100). Apart from these, the UNHCR report 1,864,195 Internally displaced persons (IDP's).[303] Sudan is a party to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees.

Ethnic groups

[edit]

The Arab population is estimated at 70% of the national total. They are almost entirely Muslims and speak predominantly Sudanese Arabic. Other ethnicities include Beja, Fur, Nubians, Nuba and Copts.[304][305]

Non-Arab groups are often ethnically, linguistically and to varying degrees culturally distinct. These include the Beja (over two million), Fur (over one million), Nuba (approx. one million), Moro, Masalit, Bornu, Tama, Fulani, Hausa, Nubians, Berta, Zaghawa, Nyimang, Ingessana, Daju, Koalib, Gumuz, Midob and Tagale. Hausa is used as a trade language.[where?] There is also a small, but prominent Greek community.[306][307][308]

Some Arab tribes speak other regional forms of Arabic, such as the Awadia and Fadnia tribes and Bani Arak tribes, who speak Najdi Arabic; and the Beni Ḥassān, Al-Ashraf, Kawhla and Rashaida who speak Hejazi Arabic. A few Arab Bedouin of the northern Rizeigat speak Sudanese Arabic and share the same culture as the Sudanese Arabs. Some Baggara and Tunjur speak Chadian Arabic.

Sudanese Arabs of northern and eastern Sudan claim to descend primarily from migrants from the Arabian Peninsula and intermarriages with the indigenous populations of Sudan. The Nubian people share a common history with Nubians in southern Egypt. The vast majority of Arab tribes in Sudan migrated into Sudan in the 12th century, intermarried with the indigenous Nubian and other African populations and gradually introduced Islam.[309] Additionally, a few pre-Islamic Arabic tribes existed in Sudan from earlier migrations into the region from western Arabia.[310]

In several studies on the Arabization of Sudanese people, historians have discussed the meaning of Arab versus non-Arab cultural identities. For example, historian Elena Vezzadini argues that the ethnic character of different Sudanese groups depends on the way this part of Sudanese history is interpreted and that there are no clear historical arguments for this distinction. In short, she states that "Arab migrants were absorbed into local structures, that they became "Sudanized" and that "In a way, a group became Arab when it started to claim that it was."[311]

In an article on the genealogy of different Sudanese ethnic groups, French archaeologist and linguist Claude Rilly argues that most Sudanese Arabs who claim Arab descent based on an important male ancestor ignore the fact that their DNA is largely made up of generations of African or African-Arab wives and their children, which means that these claims are rather more founded on oral traditions than on biological facts.[312][313]

Urban areas

[edit]| Rank | Name | State | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Omdurman  Khartoum |

1 | Omdurman | Khartoum | 1,849,659 | |||||

| 2 | Khartoum | Khartoum | 1,410,858 | ||||||

| 3 | Khartoum North | Khartoum | 1,012,211 | ||||||

| 4 | Nyala | South Darfur | 492,984 | ||||||

| 5 | Port Sudan | Red Sea | 394,561 | ||||||

| 6 | El-Obeid | North Kordofan | 345,126 | ||||||

| 7 | Kassala | Kassala | 298,529 | ||||||

| 8 | Wad Madani | Gezira | 289,482 | ||||||

| 9 | El-Gadarif | Al Qadarif | 269,395 | ||||||

| 10 | Al-Fashir | North Darfur | 217,827 | ||||||

Languages

[edit]Approximately 70 languages are native to Sudan.[315] Sudan has multiple regional sign languages, which are not mutually intelligible. A 2009 proposal for a unified Sudanese Sign Language had been worked out.[316]

Prior to 2005, Arabic was the nation's sole official language.[317] In the 2005 constitution, Sudan's official languages became Arabic and English.[318] The literacy rate is 70.2% of the total population (male: 79.6%, female: 60.8%).[319]

Religion

[edit]At the 2011 division which split off South Sudan, over 97% of the population in the remaining Sudan adhered to Islam.[320] Most Muslims are divided between two groups: Sufi and Salafi Muslims. Two popular divisions of Sufism, the Ansar and the Khatmia, are associated with the opposition Umma and Democratic Unionist parties, respectively. Only the Darfur region has traditionally been bereft of the Sufi brotherhoods common in the rest of the country.[321]

Long-established groups of Coptic Orthodox and Greek Orthodox Christians exist in Khartoum and other northern cities. Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox communities also exist in Khartoum and eastern Sudan, largely made up of refugees and migrants from the past few decades. The Armenian Apostolic Church also has a presence serving the Sudanese-Armenians. The Sudan Evangelical Presbyterian Church also has membership.[along with which others within current borders?]

Religious identity plays a role in the country's political divisions. Northern and western Muslims have dominated the country's political and economic system since independence. The NCP draws much of its support from Islamists, Salafis/Wahhabis and other conservative Arab-Muslims in the north. The Umma Party has traditionally attracted Arab followers of the Ansar sect of Sufism as well as non-Arab Muslims from Darfur and Kordofan. The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) includes both Arab and non-Arab Muslims in the north and east, especially those in the Khatmia Sufi sect.[citation needed]

Health

[edit]Sudan has a life expectancy of 65.1 years according to the latest data for the year 2019 from macrotrends.net[322] Infant mortality in 2016 was 44.8 per 1,000.[323]

UNICEF estimates that 87% of Sudanese females between the ages of 15 and 49 have had female genital mutilation performed on them.[324]

Education

[edit]