Конфедеративные Штаты Америки

Эта статья может оказаться слишком длинной для удобного чтения и навигации . Когда этот тег был добавлен, его читаемый размер составлял 18 000 слов. ( декабрь 2023 г. ) |

Конфедеративные Штаты Америки | |

|---|---|

| 1861–1865 | |

| Девиз: Бог-мститель Под Богом, нашим Защитником | |

| Гимн: Боже, храни Юг (неофициальный) Дикси (популярное, неофициальное) Март: Голубой флаг Бонни | |

| |

| Статус | Непризнанное государство [ 1 ] |

| Капитал |

|

| Крупнейший город | Новый Орлеан (до 1 мая 1862 г. ) |

| Общие языки | английский ( де-факто ) второстепенные языки: французский ( Луизиана ), языки коренных народов ( территория Индии ) |

| Демон(ы) | Конфедерация Южный |

| Правительство |

|

| Президент | |

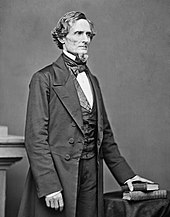

• 1861–1865 | Джефферсон Дэвис |

| вице-президент | |

• 1861–1865 | Александр Х. Стивенс |

| Законодательная власть | Конгресс |

| Сенат | |

| Палата представителей | |

| Историческая эпоха | Гражданская война в США |

| 8 февраля 1861 г. | |

| 12 апреля 1861 г. | |

| 22 февраля 1862 г. | |

| 9 апреля 1865 г. | |

| 26 апреля 1865 г. | |

| 5 мая 1865 г. | |

| Население | |

• 1860 [ а ] | 9,103,332 |

• Рабы [ б ] | 3,521,110 |

| Валюта | |

| Сегодня часть | Соединенные Штаты |

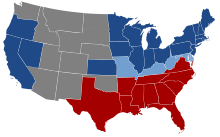

Конфедеративные Штаты Америки ( КША ), обычно называемые Конфедеративными Штатами ( КС ), Конфедерацией или Югом , были непризнанным отколовшимся государством. [ 1 ] Республика на юге США , существовавшая с 8 февраля 1861 года по 9 мая 1865 года. [ 8 ] Конфедерация состояла из одиннадцати штатов США , которые объявили о своем отделении и воевали против Соединенных Штатов во время Гражданской войны в США . [ 8 ] [ 9 ] В число штатов входили Южная Каролина , Миссисипи , Флорида , Алабама , Джорджия , Луизиана , Техас , Вирджиния , Арканзас , Теннесси и Северная Каролина .

Когда Авраам Линкольн был избран президентом Соединенных Штатов в 1860 году, южные штаты были убеждены, что их плантационная экономика , основанная на рабстве, находится под угрозой, и начали отделяться от Соединенных Штатов . [ 1 ] [ 10 ] [ 11 ] Конфедерация была образована 8 февраля 1861 года Южной Каролиной, Миссисипи, Флоридой, Алабамой, Джорджией, Луизианой и Техасом. Эти государства отделились в ходе первой из двух волн отделения. [ 12 ] [ 13 ] [ 14 ] Они приняли новую конституцию, устанавливающую правительство конфедерации «суверенных и независимых государств». [ 15 ] [ 16 ] [ 17 ] Некоторые северяне отреагировали словами: «Пусть Конфедерация уходит с миром!», в то время как некоторые южане хотели сохранить свою лояльность Союзу. Федеральное правительство в Вашингтоне и штатах, находящихся под его контролем, было известно как Союз . [ 9 ] [ 12 ] [ 18 ]

Гражданская война началась 12 апреля 1861 года, когда ополчение Южной Каролины атаковало форт Самтер . Четыре рабовладельческих штата Верхнего Юга — Вирджиния , Арканзас , Теннесси и Северная Каролина — затем отделились во время второй волны отделения и присоединились к Конфедерации. 22 февраля 1862 года лидеры армии Конфедеративных Штатов восстановили федеральное правительство в Ричмонде, штат Вирджиния , и 16 апреля 1862 года приняли первый проект Конфедерации . К 1865 году федеральное правительство Конфедерации растворилось в хаосе, и Конгресс Конфедеративных Штатов объявил перерыв. , фактически прекративший свое существование в качестве законодательного органа 18 марта. После четырех лет тяжелого В ходе боевых действий почти все сухопутные и военно-морские силы Конфедерации либо сдались, либо иным образом прекратили боевые действия к маю 1865 года. [ 19 ] [ 20 ] Самой значительной капитуляцией стала капитуляция генерала Конфедерации Роберта Э. Ли 9 апреля, после которой любые сомнения относительно исхода войны или выживания Конфедерации исчезли. Администрация президента Конфедерации Дэвиса объявила о роспуске Конфедерации 5 мая. [ 21 ] [ 22 ] [ 23 ]

После войны, в эпоху Реконструкции , штаты Конфедерации были вновь приняты в Конгресс после того, как каждый из них ратифицировал 13-ю поправку к Конституции США, запрещающую рабство. Мифология «Проигранного дела» , идеализированный взгляд на Конфедерацию, доблестно сражающуюся за правое дело, возникла в течение десятилетий после войны среди бывших генералов и политиков Конфедерации, а также в таких организациях, как « Объединенные дочери Конфедерации» и « Сыны ветеранов Конфедерации» . На рубеже 20-го века и во время движения за гражданские права 1950-х и 1960-х годов в ответ на растущую поддержку расового равенства развивались интенсивные периоды деятельности «Утраченного дела» . Защитники стремились гарантировать, что будущие поколения белых южан будут продолжать поддерживать политику превосходства белой расы, такую как законы Джима Кроу, посредством таких действий, как строительство памятников Конфедерации и влияние на авторов учебников . [ 24 ] Современное отображение боевого флага Конфедерации в первую очередь началось во время президентских выборов 1948 года , когда боевой флаг использовался диксикратами . Во время права движения за гражданские сторонники расовой сегрегации использовали его для демонстраций. [ 25 ] [ 26 ]

Объем контроля

22 февраля 1862 года Конституция Конфедеративных Штатов семи подписавших штатов — Миссисипи , Южной Каролины , Флориды , Алабамы , Джорджии , Луизианы и Техаса — заменила Временную конституцию от 8 февраля 1861 года, в преамбуле которой говорилось о желании «постоянное федеральное правительство». До замены временной конституции еще четыре южных рабовладельческих штата — Вирджиния , Арканзас , Теннесси и Северная Каролина — объявили о своем отделении и присоединились к Конфедерации в соответствии с временной конституцией после падения форта Самтер . Эти штаты оставались в составе Конфедерации, пока подписывалась новая официальная конституция. [ 27 ]

Миссури и Кентукки были представлены партизанскими группировками, принявшими формы правительств штатов в правительстве Конфедерации Миссури и правительстве Конфедерации Кентукки , а Конфедерация контролировала более половины Кентукки и южную часть Миссури в начале войны. В любом случае после 1862 года правительства Конфедерации ни одного штата не контролировали какую-либо значительную территорию или население. Довоенные правительства штатов в обоих сохранили свое представительство в Союзе . За Конфедерацию также сражались два из « пяти цивилизованных племен » — чокто и чикасо — на территории Индии , а также новая, но неконтролируемая территория Конфедерации в Аризоне . Усилия некоторых группировок в Мэриленде по отделению были остановлены федеральным введением военного положения ; Делавэр , хотя и придерживался разделенной лояльности, не пытался этого сделать. В Вирджинии было сформировано юнионистское правительство в оппозиции сепаратистскому правительству штата в Ричмонде, которое управляло западными частями штата, оккупированными федеральными войсками. Восстановленное правительство Вирджинии позже признало новый штат Западная Вирджиния , который был принят в Союз 20 июня 1863 года и переехал в Александрию до конца войны. [ 27 ]

Контроль Конфедерации над заявленной территорией и населением в округах Конгресса неуклонно сокращался с трех четвертей до трети во время Гражданской войны в США из-за успешных сухопутных кампаний Союза, его контроля над внутренними водными путями на юг и блокады южного побережья. [ 28 ] Прокламацией об освобождении рабов от 1 января 1863 года Союз сделал отмену рабства целью войны (помимо воссоединения). Когда силы Союза двинулись на юг, большое количество рабов на плантациях было освобождено. Многие присоединились к линии Союза, поступив на службу в качестве солдат, возчиков и рабочих. » Шермана Самым заметным достижением стал « Марш к морю в конце 1864 года. Большая часть инфраструктуры Конфедерации была разрушена, включая телеграфы, железные дороги и мосты. Плантации на пути войск Шермана были серьезно повреждены. Внутреннее передвижение внутри Конфедерации становилось все более затрудненным, что ослабляло ее экономику и ограничивало мобильность армии. [ 29 ]

Эти потери создали непреодолимый недостаток в людях, технике и финансах. Общественная поддержка администрации президента Конфедерации Джефферсона Дэвиса со временем ослабла из-за неоднократных военных неудач, экономических трудностей и обвинений в автократическом правительстве. После четырех лет кампании Ричмонд был захвачен войсками Союза в апреле 1865 года. Несколько дней спустя генерал Роберт Э. Ли сдался генералу Союза Улиссу С. Гранту , что фактически сигнализировало о крахе Конфедерации. Президент Дэвис был схвачен 10 мая 1865 года и заключен в тюрьму за государственную измену, но суд так и не состоялся. [ 30 ]

История

Этот раздел может быть слишком длинным для удобного чтения и навигации . Когда этот тег был добавлен, его читаемый размер составлял 11 000 слов. ( май 2024 г. ) |

Конфедерация была основана Конфедерацией Монтгомери в феврале 1861 года семью штатами ( Южная Каролина , Миссисипи , Алабама , Флорида , Джорджия , Луизиана , добавив Техас в марте перед инаугурацией Линкольна), расширилась в мае-июле 1861 года (вместе с Вирджинией , Арканзасом , Теннесси). , Северная Каролина ) и распалась в апреле–мае 1865 года. сформированный делегациями семи рабовладельческих штатов Нижнего Юга , провозгласивших свое отделение. После того, как в апреле начались боевые действия, еще четыре рабовладельческих штата отделились и были приняты. Позже два рабовладельческих штата ( Миссури и Кентукки ) и две территории получили места в Конгрессе Конфедерации. [ 31 ]

Его создание вытекало из южного национализма и углубляло его. [ 32 ] который готовил людей к борьбе за «Южное дело». [ 33 ] Это «Дело» включало поддержку прав штатов , тарифную политику и внутренние улучшения, но, прежде всего, культурную и финансовую зависимость от экономики Юга, основанной на рабстве. Сближение расы и рабства, политики и экономики подняло политические вопросы, связанные с Югом, до статуса моральных вопросов, образа жизни, слияния любви к Южному и ненависти к Северному. По мере приближения войны политические партии разделились, а национальные церкви и межгосударственные семьи разделились по фракционным линиям. [ 34 ] По словам историка Джона М. Коски:

Государственные деятели, возглавлявшие движение за отделение, не стеснялись открыто называть защиту рабства своим главным мотивом ... Признание центральной роли рабства для Конфедерации имеет важное значение для понимания Конфедерации. [ 35 ]

Южные демократы выбрали Джона Брекинриджа своим кандидатом во время президентских выборов 1860 года, но ни в одном южном штате его поддержка не была единогласной, поскольку они зафиксировали по крайней мере некоторое количество голосов избирателей, по крайней мере, за одного из трех других кандидатов (Авраама Линкольна, Стивена А. Дуглас и Джон Белл ). Поддержка этих троих в совокупности варьировалась от значительного до абсолютного большинства: от 25% в Техасе до 81% в Миссури. [ 36 ] Повсюду существовали взгляды меньшинства, особенно в горных и плато Юга, особенно сконцентрированных в западной Вирджинии и восточном Теннесси. Первые шесть подписавших государств, создавших Конфедерацию, насчитывали около четверти ее населения. За пропрофсоюзных кандидатов они проголосовали 43%. В четырех штатах, вошедших в состав после нападения на форт Самтер, проживало почти половина населения Конфедерации, и 53% проголосовали за пропрофсоюзных кандидатов. Три штата с большой явкой проголосовали за крайние позиции; Техас, где проживает 5% населения, проголосовал 20% за пропрофсоюзных кандидатов; Кентукки и Миссури, где проживает четверть населения Конфедерации, 68% проголосовали за Союз.

После единогласного голосования за отделение Южной Каролины в 1860 году ни один другой южный штат не рассматривал этот вопрос до 1861 года; когда они это сделали, ни один из них не проголосовал единогласно. Во всех из них были жители, которые отдали значительное количество голосов юнионистов. Голосование за то, чтобы остаться в Союзе, не обязательно означало, что отдельные люди сочувствовали Северу. Когда начались боевые действия, многие из тех, кто проголосовал за то, чтобы остаться в Союзе, приняли решение большинства и поддержали Конфедерацию. [ 37 ] Многие писатели оценили войну как американскую трагедию - «Братьевскую войну», в которой «брат против брата, отец против сына, родственники против родственников всех степеней». [ 38 ] [ 39 ]

Происхождение

Конфедерация как государственная власть была создана сепаратистами в южных рабовладельческих штатах, которые считали, что федеральное правительство делает их гражданами второго сорта. [ 40 ] Они считали, что агентами перемен являются аболиционисты и элементы, выступающие против рабства в Республиканской партии , которые, по их мнению, использовали оскорбления и оскорбления, чтобы подвергнуть их невыносимому «унижению и деградации». [ 40 ] «Черные республиканцы» (как их называли южане) и их союзники вскоре стали доминировать в Палате представителей, Сенате и президентстве США. В Верховном суде председателю Верховного суда Роджеру Б. Тейни (предполагаемому стороннику рабства) было 83 года, и он был болен.

Во время выборов 1860 года некоторые сепаратисты угрожали разъединением, если Линкольн (который выступал против расширения рабства на территории ) будет избран, включая Уильяма Л. Янси . Янси совершил поездку по Северу, призывая к отделению, в то время как Стивен А. Дуглас совершил поездку по Югу, призывая к союзу, если Линкольн будет избран. [ 41 ] Для сепаратистов намерения республиканцев были ясны: сдержать рабство в его нынешних границах и, в конечном итоге, полностью его ликвидировать. Победа Линкольна поставила их перед выбором: «Союз без рабства или рабство без Союза». [ 42 ]

Причины отделения

Новая Конституция [Конфедерации] навсегда положила конец всем волнующим вопросам, касающимся наших особых институтов — африканского рабства, существующего среди нас, — надлежащего статуса негра в нашей форме цивилизации. Это было непосредственной причиной позднего разрыва и нынешней революции. Джефферсон в своем прогнозе предвидел это как «скалу, на которой расколется старый Союз». Он был прав. То, что было для него предположением, теперь стало осознанным фактом. Но можно сомневаться в том, что он полностью постиг великую истину, на которой стояла и стоит эта скала.

Преобладающие идеи, которых придерживались он и большинство ведущих государственных деятелей во время формирования старой Конституции, заключались в том, что порабощение африканцев нарушало законы природы; что это неправильно в принципе, социально, морально и политически. Это было зло, с которым они плохо знали, как бороться; но общее мнение людей того времени заключалось в том, что так или иначе, по воле Провидения, этот институт исчезнет и исчезнет... Однако эти идеи были в корне неправильными. Они основывались на предположении равенства рас. Это была ошибка. Это был песчаный фундамент , и на нем строилась идея правительства — когда «пришла буря и подул ветер, оно упало».

Наше новое правительство основано на прямо противоположных идеях; ее фундамент заложен, ее краеугольный камень покоится на великой истине о том, что негр не равен белому человеку ; что рабство , подчинение высшей расе — его естественное и нормальное состояние. Это наше новое правительство является первым в мировой истории, основанным на этой великой физической, философской и моральной истине.

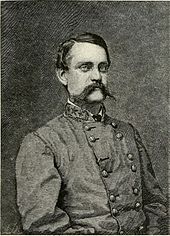

Александр Х. Стивенс , выступление перед Театром Саванны . (21 марта 1861 г.)

Непосредственным катализатором отделения стала победа Республиканской партии и избрание Линкольна. Для южан самой зловещей особенностью побед республиканцев на выборах в Конгресс и президентских выборах была масштабность: республиканцы получили более 60% голосов северян и 75% делегаций в Конгрессе. [ 43 ] Южная пресса писала, что такие республиканцы представляют часть Севера, выступающую против рабства, «партию, основанную на одном чувстве… ненависти к африканскому рабству», а теперь контролирующую силу в национальных делах. «Черная республиканская партия» может подорвать статус превосходства белой расы на Юге. Дельта Нового Орлеана заявила о республиканцах: «Фактически это, по сути, революционная партия», призванная свергнуть рабство. [ 44 ] К 1860 году разногласия между Севером и Югом касались в первую очередь статуса рабства в Соединенных Штатах. Конкретный вопрос заключался в том, будет ли разрешено рабству распространяться на западные территории, что приведет к образованию большего количества рабовладельческих государств , или его можно будет предотвратить, что, как широко считалось, поставит рабство на путь исчезновения. Историк Дрю Гилпин Фауст заметил, что «лидеры сепаратистского движения на Юге назвали рабство наиболее убедительной причиной независимости Юга». [ 45 ] Хотя большинство белых южан не владели рабами, большинство из них поддерживали институт рабства и косвенно получали выгоду от рабовладельческого общества. Для борющихся йоменов и натуральных фермеров это предоставило большой класс людей, ранг которых был ниже их самих. [ 46 ] Вторичные различия касались свободы слова, беглых рабов, экспансии на Кубу и прав штатов .

Историк Эмори Томас оценил самооценку Конфедерации, изучив корреспонденцию, отправленную правительством Конфедерации в 1861–1862 годах иностранным правительствам. Он обнаружил, что дипломатия Конфедерации создавала множество противоречивых представлений о себе:

Южная нация поочередно представляла собой бесхитростный народ, атакованный ненасытным соседом, «устоявшуюся» нацию, испытывающую временные трудности, скопление деревенских аристократов, выступавших в романтическом духе против банальностей промышленной демократии , клику коммерческих фермеров, стремившихся создать пешка короля Коттона , апофеоз национализма и революционного либерализма девятнадцатого века, или окончательное утверждение социальной и экономической реакции. [ 47 ]

Краеугольная речь часто цитируется в анализе идеологии Конфедерации. [ 48 ] В нем вице-президент Конфедерации Александр Х. Стивенс заявил, что «краеугольный камень» нового правительства «покоится [ред] на великой истине о том, что негр не равен белому человеку». Он заявил, что разногласия по поводу порабощения африканцев Американцы были «непосредственной причиной» отделения , и конституция Конфедерации разрешила такие проблемы. [ 49 ] Стивенс утверждал, что достижения науки доказали, что точка зрения Декларации независимости о том, что « все люди созданы равными », была ошибочной, заявляя при этом, что Конфедерация была первой страной, основанной на принципе превосходства белых , и что рабство движимого имущества совпадало с Учение Библии . После поражения Конфедерации в гражданской войне и отмены рабства он попытался задним числом опровергнуть и отказаться от высказанных в речи мнений, утверждая, что война коренится в конституционных различиях; [ 50 ] [ 51 ] это объяснение Стивенса широко отвергается историками. [ 48 ] [ 52 ]

Четыре из отделившихся штатов, штаты Глубокого Юга Южной Каролины, [ 53 ] Миссисипи, [ 54 ] Грузия, [ 55 ] и Техас, [ 56 ] опубликовали официальные заявления о причинах своего решения; каждый указал на угрозу правам рабовладельцев. Грузия также заявила о проведении федеральной политики, отдающей предпочтение экономическим интересам Севера над экономическими интересами Юга. Техас упомянул рабство 21 раз, но также перечислил неспособность федерального правительства выполнить свои обязательства по первоначальному соглашению об аннексии по защите поселенцев вдоль открытой западной границы. В резолюциях Техаса говорилось, что правительства штатов и нации были созданы «исключительно белой расой для себя и своего потомства». Они заявили, что, хотя равные гражданские и политические права распространяются на всех белых людей, они не распространяются на представителей «африканской расы», а также полагают, что конец расового порабощения «принесет неизбежные бедствия для обеих [рас] и опустошение для всех остальных». пятнадцать рабовладельческих государств». [ 56 ]

Алабама не представила отдельного заявления о причинах. Вместо этого в постановлении говорилось

избрание Авраама Линкольна... секционной партией, явно враждебной внутренним институтам, а также миру и безопасности народа штата Алабама, чему предшествовали многочисленные и опасные нарушения Конституции Соединенных Штатов многими из против штатов и жителей северной части, является политическим преступлением настолько оскорбительного и угрожающего характера, что оправдывает принятие народом штата Алабама быстрых и решительных мер для их будущего мира и безопасности. [ 57 ]

В постановлениях об отделении оставшихся двух штатов, Флориды и Луизианы, просто было объявлено о разрыве связей с Союзом, без указания причин. [ 58 ] [ 59 ] После этого съезд отделения Флориды сформировал комитет для разработки декларации о причинах, но комитет был распущен до завершения. [ 60 ] Остался только недатированный и безымянный черновик. [ 61 ]

Четыре штата Верхнего Юга (Вирджиния, Арканзас, Теннесси и Северная Каролина) отвергли отделение до тех пор, пока не произошло столкновение в Самтере. [ 62 ] [ 63 ] [ 64 ] Постановление Вирджинии заявляло о родстве с рабовладельческими штатами Нижнего Юга, но не называло сам институт в качестве основной причины. [ 65 ] Постановление об отделении Арканзаса включало в себя возражение против использования военной силы для сохранения Союза в качестве мотивирующей причины. [ 66 ] Перед войной Арканзасский съезд 20 марта принял первую резолюцию:

Народы северных штатов организовали политическую партию, чисто секционную по своему характеру, центральной и доминирующей идеей которой является враждебность к институту африканского рабства, существующему в южных штатах; и эта партия избрала президента... пообещала управлять правительством на принципах, несовместимых с правами и подрывающих интересы южных штатов. [ 67 ]

Северная Каролина и Теннесси ограничили свои постановления простым выходом, хотя Теннесси ясно дал понять, что не желает комментировать «абстрактную доктрину отделения». Однако политики и военные лидеры обоих штатов выразили разочарование в выступлениях по поводу взглядов Республиканской партии на рабство и призыва Линкольна ввести 75 000 солдат после падения форта Самтер . [ 68 ] [ 69 ] Выступая перед Конгрессом Конфедерации 29 апреля 1861 года, Джефферсон Дэвис привел как тарифы, так и тарифы. [ 70 ] и рабство ради отделения Юга. [ 71 ]

Сепаратисты и конвенции

Группе южных демократов « Пожиратели огня », выступающей за рабство и призывающей к немедленному отделению, противостояли две фракции. « Кооператоры » на Глубоком Юге будут откладывать отделение до тех пор, пока несколько штатов не выйдут из союза, возможно, на Южном съезде. Под влиянием таких людей, как губернатор Техаса Сэм Хьюстон , отсрочка имела бы эффект сохранения Союза. [ 72 ] «Юнионисты», особенно на приграничном юге, часто бывшие виги , апеллировали к сентиментальной привязанности к Соединенным Штатам. Любимым кандидатом в президенты южных юнионистов был Джон Белл из Теннесси, иногда баллотировавшийся под лозунгом «Оппозиционной партии». [ 72 ]

-

Уильям Л. Янси , Пожиратель огня из Алабамы, «Оратор отделения»

-

Уильям Генри Гист , губернатор Южной Каролины, созвал сепаратистский съезд.

Многие сепаратисты вели политическую активность. Губернатор Уильям Генри Гист тайно переписывался с другими губернаторами Глубокого Юга, и большинство южных губернаторов обменивались тайными комиссарами. Южной Каролины [ 73 ] Сепаратистская «Ассоциация 1860 года» Чарльстона опубликовала более 200 000 брошюр, чтобы убедить молодежь Юга. Самыми влиятельными были: «Гибель рабства» и «Только Юг должен управлять Югом», оба написаны Джоном Таунсендом из Южной Каролины; и Джеймса Д.Б. Де Боу . «Интерес рабства южных нерабовладельцев» [ 74 ]

События в Южной Каролине положили начало цепочке событий. Председатель присяжных отверг легитимность федеральных судов, поэтому федеральный судья Эндрю Маграт постановил, что судебная власть США в Южной Каролине освобождена. Массовый митинг в Чарльстоне, посвященный железной дороге Чарльстона и Саванны и сотрудничеству штатов, привел к тому, что законодательный орган Южной Каролины призвал к созыву съезда об отделении. [ 75 ]

выборы на съезды сепаратистов были накалены до «почти безумного напряжения, никто не осмелился выразить несогласие». По словам историка Уильяма В. Фрилинга , Даже некогда уважаемые голоса, в том числе главный судья Южной Каролины Джон Белтон О'Нил , проиграли выборы на Конвенцию о сецессии из-за кооперации. По всему Югу банды изгоняли янки, а в Техасе казнили американцев немецкого происхождения, подозреваемых в лояльности Соединенным Штатам. [ 76 ] Как правило, съезды отделения не требовали референдума, хотя второй съезд Техаса, Арканзаса, Теннесси и Вирджинии требовал его. Кентукки объявил нейтралитет, в то время как в Миссури шла гражданская война, пока юнионисты не пришли к власти и не изгнали законодателей Конфедерации из штата. [ 77 ]

Попытки помешать отделению

В феврале 1861 года ведущие политики северных штатов и приграничных штатов, которые еще не отделились, встретились в Вашингтоне на Мирную конференцию 1861 года . Участники отвергли Криттенденский компромисс и другие предложения. Он предложил поправку Корвина Конгрессу , чтобы вернуть отделившиеся штаты и убедить приграничные рабовладельческие штаты остаться. [ 78 ] Это была поправка к Конституции Соединенных Штатов, предложенная конгрессменом Огайо Томасом Корвином , которая защитила бы «внутренние институты» [например, рабство] штатов от процесса внесения поправок в конституцию, а также от отмены или вмешательства Конгресса. [ 79 ] [ 80 ]

Он был принят 36-м Конгрессом 2 марта 1861 года. Палата представителей одобрила его 133 голосами против 65, а Сенат Соединенных Штатов принял его без изменений 24 голосами против 12. Затем он был представлен на рассмотрение Конгресса США. законодательными собраниями штатов для ратификации. [ 81 ] В своей инаугурационной речи Линкольн одобрил предложенную поправку.

Текст был следующий:

Никакая поправка не может быть внесена в Конституцию, которая уполномочит или предоставит Конгрессу право упразднять или вмешиваться в деятельность внутри любого штата его внутренних институтов, включая институты лиц, привлекаемых к труду или службе по законам этого штата.

Если бы он был ратифицирован необходимым числом штатов до 1865 года, на первый взгляд он сделал бы узаконенное рабство невосприимчивым к конституционным поправкам и вмешательству Конгресса. [ 82 ] [ 83 ]

Инаугурация и ответ

Первые съезды штатов, отделившихся от Глубокого Юга, направили своих представителей на съезд Монтгомери в Алабаме 4 февраля 1861 года. Были обнародованы основные правительственные документы, было создано временное правительство и собрался представительный Конгресс от Конфедеративных Штатов Америки. [ 84 ]

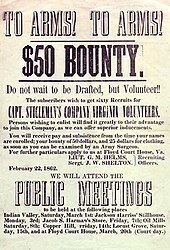

Новый временный президент Конфедерации Джефферсон Дэвис призвал 100 000 человек из ополчений штатов защитить недавно сформированную Конфедерацию. [ 84 ] Вся федеральная собственность была конфискована, а также золотые слитки и штампы для монет на монетных дворах США в Шарлотте , Северная Каролина; Далонега , Джорджия; и Новый Орлеан . [ 84 ] Столица Конфедерации была перенесена из Монтгомери в Ричмонд, штат Вирджиния, в мае 1861 года. 22 февраля 1862 года Дэвис вступил в должность президента сроком на шесть лет. [ 85 ]

Администрация Конфедерации проводила политику национальной территориальной целостности, продолжая предыдущие усилия государства в 1860–1861 годах по устранению присутствия правительства США. Это включало захват американских судов, таможен, почтовых отделений и, прежде всего, арсеналов и фортов. Но после нападения Конфедерации и захвата форта Самтер в апреле 1861 года Линкольн призвал 75 000 ополченцев штата для сбора под своим командованием. Заявленная цель состояла в том, чтобы повторно оккупировать американскую собственность на юге, поскольку Конгресс США не санкционировал ее оставление. Сопротивление в форте Самтер сигнализировало об изменении его политики по сравнению с политикой администрации Бьюкенена. Ответ Линкольна вызвал бурю эмоций. Народы как Севера, так и Юга требовали войны, и сотни тысяч солдат спешили под их знамена. [ 84 ]

Сецессия

Сепаратисты утверждали, что Конституция Соединенных Штатов представляет собой договор между суверенными штатами, от которого можно отказаться без консультаций, и что каждый штат имеет право на отделение. После интенсивных дебатов и голосований по всему штату семь хлопковых штатов Глубинного Юга к февралю 1861 года приняли постановления об отделении, в то время как в других восьми рабовладельческих штатах усилия по отделению потерпели неудачу. Разговоры юнионистов о воссоединении провалились, и Дэвис начал собирать 100-тысячную армию. [ 86 ]

Штаты

Первоначально некоторые сепаратисты надеялись на мирный уход. Умеренные в Конституционном съезде Конфедерации включили положение, запрещающее ввоз рабов из Африки для обращения к Верхнему Югу. Нерабовладельческие штаты могли бы присоединиться, но радикалы добились того, чтобы в обеих палатах Конгресса их приняли две трети голосов. [ 87 ]

Семь штатов заявили о своем выходе из Соединенных Штатов до того, как Линкольн вступил в должность 4 марта 1861 года. После нападения Конфедерации на форт Самтер 12 апреля 1861 года и последующего призыва Линкольна к войскам еще четыре штата заявили о своем отделении.

Кентукки объявил нейтралитет, но после того, как войска Конфедерации вошли, законодательный орган штата попросил войска Союза изгнать их. Делегаты из 68 округов Кентукки были отправлены на съезд в Расселвилле, который подписал Постановление об отделении. Кентукки был принят в состав Конфедерации 10 декабря 1861 года, а его первой столицей стал Боулинг-Грин. В начале войны Конфедерация контролировала более половины Кентукки, но в значительной степени потеряла контроль в 1862 году. Отколовшееся правительство Конфедерации Кентукки переехало, чтобы сопровождать западные армии Конфедерации, и никогда не контролировало население штата после 1862 года. К концу войны 90 000 жителей Кентукки сражались за Союз, по сравнению с 35 000 за Конфедерацию. [ 88 ]

В Миссури и было одобрено конституционное собрание избраны делегаты. Съезд отклонил отделение 89–1 19 марта 1861 года. [ 89 ] Губернатор предпринял маневр, чтобы взять под свой контроль арсенал Сент-Луиса и ограничить передвижения федеральных сил. Это привело к конфронтации, и в июне федеральные силы изгнали его и Генеральную Ассамблею из Джефферсон-Сити. Исполнительный комитет съезда созвал членов в июле, объявил должности в штатах вакантными и назначил временное правительство штата из числа юнионистов. [ 90 ] Ссыльный губернатор созвал итоговую сессию бывшей Генеральной ассамблеи в Неошо , и 31 октября 1861 года она приняла постановление об отделении . [ 91 ] [ 92 ] Правительство штата Конфедерация не смогло контролировать значительную часть территории Миссури, фактически контролируя только южный штат Миссури в начале войны. Его столица находилась в Неошо, затем в Кассвилле , прежде чем он был изгнан из штата. До конца войны оно действовало как правительство в изгнании в Маршалле, штат Техас . [ 93 ]

Не отделившись, ни Кентукки, ни Миссури не были объявлены восставшими в Прокламации Линкольна об освобождении рабов . Конфедерация признала проконфедеративных претендентов в Кентукки (10 декабря 1861 г.) и Миссури (28 ноября 1861 г.) и предъявила права на эти штаты, предоставив им представительство в Конгрессе и добавив две звезды к флагу Конфедерации. Голосовали за представителей в основном солдаты Конфедерации из Кентукки и Миссури. [ 94 ]

Некоторые южные профсоюзные деятели обвинили призыв Линкольна к вводу войск как событие, ускорившее вторую волну отделений. Историк Джеймс Макферсон утверждает, что такие утверждения носят «корыстный характер», и считает их вводящими в заблуждение:

Пока по телеграфу распространялись сообщения о нападении на Самтер 12 апреля и его капитуляции на следующий день, огромные толпы людей вышли на улицы Ричмонда, Роли, Нэшвилла и других городов Верхнего Юга, чтобы отпраздновать эту победу над янки. Эти толпы размахивали флагами Конфедерации и приветствовали славное дело независимости Юга. Они потребовали, чтобы их собственные государства присоединились к этому делу. С 12 по 14 апреля прошли десятки демонстраций, прежде чем Линкольн призвал войска. Многие условные юнионисты были захвачены мощной волной южного национализма; другие были запуганы и молчали. [ 95 ]

Историк Дэниел Крофтс не согласен с Макферсоном:

Бомбардировка форта Самтер сама по себе не уничтожила юнионистское большинство на верхнем Юге. Поскольку до того, как Линкольн издал прокламацию, прошло всего три дня, эти два события, если смотреть ретроспективно, кажутся почти одновременными. Тем не менее внимательное изучение современных свидетельств... показывает, что это провозглашение имело гораздо более решающее воздействие. [ 96 ] ...Многие пришли к выводу... что Линкольн сознательно решил «изгнать все рабовладельческие государства, чтобы начать с ними войну и уничтожить рабство». [ 97 ]

Порядок резолюций об отделении и даты:

- 1. Южная Каролина (20 декабря 1860 г.) [ 98 ]

- 2. Миссисипи (9 января 1861 г.) [ 99 ]

- 3. Флорида (10 января) [ 100 ]

- 4. Алабама (11 января) [ 101 ]

- 5. Грузия (19 января) [ 102 ]

- 6. Луизиана (26 января) [ 103 ]

- 7. Техас (1 февраля; референдум 23 февраля) [ 104 ]

- Инаугурация президента Линкольна , 4 марта.

- Бомбардировка форта Самтер (12 апреля) и призыв президента Линкольна (15 апреля) [ 105 ]

- 8. Вирджиния (17 апреля; референдум 23 мая 1861 г.) [ 106 ]

- 9. Арканзас (6 мая) [ 107 ]

- 10. Теннесси (7 мая; референдум 8 июня) [ 108 ]

- 11. Северная Каролина (20 мая) [ 109 ]

В Вирджинии густонаселенные округа вдоль границ Огайо и Пенсильвании отвергли Конфедерацию. Юнионисты провели съезд в Уилинге в июне 1861 года, установив «восстановленное правительство» с оставшимся законодательным органом , но настроения в регионе оставались глубоко разделенными. В 50 округах, которые войдут в состав штата Западная Вирджиния , избиратели из 24 округов проголосовали за разъединение на референдуме 23 мая в Вирджинии по поводу постановления об отделении. [ 110 ] На выборах 1860 года «конституционный демократ» Брекенридж опередил «конституционного юниониста» Белла в 50 округах на 1900 голосов, с 44% против 42%. [ 111 ] Округа одновременно предоставили каждой стороне конфликта более 20 000 солдат. [ 112 ] [ 113 ] Представители большинства округов заседали в законодательных собраниях обоих штатов в Уилинге и Ричмонде на время войны. [ 114 ]

Попытки выхода из состава Конфедерации округов Восточного Теннесси были пресечены введением военного положения. [ 115 ] Хотя рабовладельческие Делавэр и Мэриленд не отделились, граждане продемонстрировали разделенную лояльность. Полки жителей Мэриленда сражались в армии Ли Северной Вирджинии . [ 116 ] В целом к силам Конфедерации присоединились 24 000 мужчин из Мэриленда по сравнению с 63 000, которые присоединились к силам Союза. [ 88 ] Делавэр никогда не создавал полного полка для Конфедерации, но и не освобождал рабов, как это делали Миссури и Западная Вирджиния. Граждане округа Колумбия не предпринимали попыток отделения, и во время войны референдумы, спонсируемые Линкольном, одобрили компенсируемое освобождение и конфискацию рабов у «нелояльных граждан». [ 117 ]

Территории

Граждане Месильи и Тусона в южной части территории Нью-Мексико сформировали съезд отделения, который проголосовал за присоединение к Конфедерации 16 марта 1861 года и назначил доктора Льюиса С. Оуингса новым губернатором территории. Они выиграли битву при Месилье и создали территориальное правительство, столицей которого стала Месилья. [ 118 ] Конфедерация провозгласила Конфедеративную территорию Аризоны 14 февраля 1862 года к северу от 34-й параллели . Маркус Х. МакВилли работал на обоих Конгрессах Конфедерации в качестве делегата от Аризоны. В 1862 году кампания Конфедерации Нью-Мексико по захвату северной половины территории США провалилась, и территориальное правительство Конфедерации в изгнании переехало в Сан-Антонио, штат Техас. [ 119 ]

Сторонники Конфедерации на западе за Миссисипи заявили свои права на части Индийской территории после того, как США эвакуировали федеральные форты и объекты. Более половины индейских войск, участвовавших в войне с территории Индии, поддержали Конфедерацию. 12 июля 1861 года правительство Конфедерации подписало договор с индейскими народами чокто и чикасо . После нескольких сражений армии Союза взяли под свой контроль территорию. [ 120 ]

Индийская территория никогда официально не присоединялась к Конфедерации, но получила представительство в Конгрессе. Многие индейцы с территории были интегрированы в регулярные подразделения армии Конфедерации. После 1863 года правительства племен направили своих представителей в Конгресс Конфедерации : Элиаса Корнелиуса Будино, представлявшего чероки , и Сэмюэля Бентона Каллахана, представлявшего семинолов и криков . Нация чероки присоединилась к Конфедерации. Они практиковали и поддерживали рабство, выступали против его отмены и боялись, что их земли будут конфискованы Союзом. После войны территория индейцев была упразднена, их черные рабы были освобождены, а племена потеряли часть своих земель. [ 121 ]

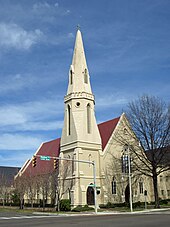

Столицы

Монтгомери, штат Алабама , служил столицей Конфедеративных Штатов с 4 февраля по 29 мая 1861 года в Капитолии штата Алабама . Шесть штатов создали здесь Конфедерацию 8 февраля 1861 года. В то время заседала делегация Техаса, поэтому она считается «первоначальными семью» штатами Конфедерации; у него не было поименного голосования до тех пор, пока референдум не сделал отделение «действующим». [ 122 ] [ 123 ] Постоянная конституция была принята там 12 марта 1861 года. [ 124 ]

Постоянная столица, предусмотренная Конституцией Конфедерации, предусматривала уступку штата района площадью 100 квадратных миль центральному правительству. Атланта, которая еще не заменила Милледжвилль , штат Джорджия, в качестве столицы штата, подала заявку, отметив свое центральное расположение и железнодорожное сообщение, как и Опелика, штат Алабама , отметив его стратегическое внутреннее положение, железнодорожное сообщение и залежи угля и железа. [ 125 ]

Ричмонд, штат Вирджиния , был выбран временной столицей – Капитолием штата Вирджиния . Этот шаг был использован вице-президентом Стивенсом и другими, чтобы побудить другие приграничные штаты последовать за Вирджинией в Конфедерацию. В политическом моменте это была демонстрация «вызова и силы». Война за независимость Юга, несомненно, должна была вестись в Вирджинии, но там также проживало самое большое белое население Юга призывного возраста с инфраструктурой, ресурсами и припасами. Политика администрации Дэвиса заключалась в том, что «его необходимо удерживать любой опасностью». [ 126 ]

Название Ричмонда новой столицей состоялось 30 мая 1861 года, и там прошли две последние сессии Временного конгресса. [ 127 ] По мере того как война затягивалась, Ричмонд стал переполнен учебными и транспортными службами, материально-техническим снабжением и больницами. Цены резко выросли, несмотря на усилия правительства по регулированию цен. Движение в Конгрессе выступало за перенос столицы из Ричмонда. С приближением федеральных армий в середине 1862 года правительственные архивы были готовы к вывозу. По мере продвижения кампании за дикую природу Конгресс уполномочил Дэвиса удалить исполнительный департамент и созвать Конгресс на сессию в другом месте в 1864 году и снова в 1865 году. Незадолго до окончания войны правительство Конфедерации эвакуировало Ричмонд, планируя переехать дальше на юг. До капитуляции Ли из этих планов мало что вышло. [ 128 ] Дэвис и большая часть его кабинета бежали в Данвилл, штат Вирджиния , который служил их штаб-квартирой в течение восьми дней.

Дипломатия

За четыре года своего существования Конфедерация отстояла свою независимость и назначила десятки дипломатических агентов за рубежом. Ни один из них не был признан иностранным правительством. Правительство США считало, что южные штаты находятся в состоянии восстания или восстания, и поэтому отказалось от какого-либо формального признания их статуса.

Правительство США никогда не объявляло войну этим «сородичам и соотечественникам» в Конфедерации, но начало свою военную деятельность, начиная с президентской прокламации, изданной 15 апреля 1861 года. [ 129 ] Он призывал войска отбить форты и подавить то, что Линкольн позже назвал «восстанием и восстанием». [ 130 ] Переговоры между двумя сторонами в середине войны проходили без официального политического признания, хотя законы войны преимущественно регулировали военные отношения с обеих сторон военного конфликта. [ 131 ]

Когда началась война с Соединенными Штатами, Конфедерация возлагала надежды на выживание на военное вмешательство Великобритании или Франции . Правительство Конфедерации отправило Джеймса М. Мэйсона в Лондон и Джона Слайделла в Париж. По пути в 1861 году ВМС США перехватили их корабль « Трент» и доставили в Бостон. Это международный эпизод, известный как « Трента» Дело . В конце концов дипломаты были освобождены и продолжили свое путешествие. [ 132 ] Однако их миссия не увенчалась успехом; историки оценивают их дипломатию как плохую. [ 133 ] [ нужна страница ] Ни один из них не обеспечил дипломатического признания Конфедерации , не говоря уже о военной помощи.

Конфедераты, которые считали, что « хлопок — король », то есть что Британия должна поддерживать Конфедерацию, чтобы получить хлопок, оказались ошибочными. У британцев было запасов, которых хватило бы на год, и они разрабатывали альтернативные источники. [ 134 ] Соединенное Королевство гордилось тем, что положило конец трансатлантическому порабощению африканцев; к 1833 году Королевский флот патрулировал воды среднего прохода, чтобы не допустить попадания дополнительных рабовладельческих кораблей в Западное полушарие. первый Всемирный съезд против рабства. Именно в Лондоне в 1840 году был проведен зависимый", [ 135 ] и «не равен белому человеку... высшей расе». Фредерик Дуглас , Генри Хайленд Гарнет , Сара Паркер Ремонд , ее брат Чарльз Ленокс Ремонд , Джеймс У. К. Пеннингтон , Мартин Делани , Сэмюэл Рингголд Уорд и Уильям Г. Аллен — все они провели годы в Британии, где беглые рабы были в безопасности и, как сказал Аллен, наблюдалось «отсутствие предубеждений против цвета кожи. Здесь цветной человек чувствует себя среди друзей, а не среди врагов». [ 136 ] Большая часть британского общественного мнения была против этой практики, а Ливерпуль считался основной базой поддержки Юга. [ 137 ]

В первые годы войны министр иностранных дел Великобритании лорд Джон Рассел , император Наполеон III Франции и, в меньшей степени, премьер-министр Великобритании лорд Пальмерстон проявляли интерес к признанию Конфедерации или, по крайней мере, к посредничеству в войне. Канцлер казначейства Уильям Гладстон безуспешно пытался убедить Пальмерстона вмешаться. [ 138 ] К сентябрю 1862 года победа Союза в битве при Антиетаме Линкольна , предварительная Прокламация об освобождении и оппозиция аболиционистов в Великобритании положили конец этим возможностям. [ 139 ] Цена войны с США для Великобритании была бы высокой: немедленная потеря американских поставок зерна, прекращение британского экспорта в США и конфискация миллиардов фунтов, вложенных в американские ценные бумаги. Война означала бы повышение налогов в Великобритании, новое вторжение в Канаду и нападения на британский торговый флот. В середине 1862 года опасения расовой войны (например, Гаитянской революции 1791–1804 годов) привели к тому, что британцы рассматривали возможность вмешательства по гуманитарным причинам. [ 140 ]

Джону Слайделлу, эмиссару Конфедеративных Штатов во Франции, удалось договориться о кредите в размере 15 миллионов долларов от Эрлангера и других французских капиталистов на броненосные военные корабли и военные поставки. [ 141 ] Британское правительство действительно разрешило строительство блокадников в Великобритании; ими владели и управляли британские финансисты и судовладельцы; некоторые из них принадлежали и управлялись Конфедерацией. Целью британских инвесторов было приобретение высокодоходного хлопка. [ 142 ]

Несколько европейских стран сохранили дипломатов, которые были назначены в США, но ни одна страна не назначила ни одного дипломата в Конфедерацию. Эти страны признали стороны Союза и Конфедерации воюющими сторонами . В 1863 году Конфедерация выслала европейские дипломатические миссии за то, что они посоветовали своим постоянным подданным отказаться от службы в армии Конфедерации. [ 143 ] Агентам Конфедерации и Союза было разрешено открыто работать на британских территориях. [ 144 ] Конфедерация назначила Эмброуза Дадли Манна специальным агентом Святого Престола в сентябре 1863 года, но Святой Престол так и не опубликовал заявления в поддержку или признание Конфедерации. В ноябре 1863 года Манн встретился с Папой Пием IX и получил письмо, предположительно адресованное «прославленному и достопочтенному Джефферсону Дэвису, президенту Конфедеративных Штатов Америки»; Манн неправильно перевел адрес. В своем докладе Ричмонду Манн заявил о своем большом дипломатическом достижении, но госсекретарь Конфедерации Джуда П. Бенджамин сказал Манну, что это «просто умозрительное признание, не связанное с политическими действиями или регулярным установлением дипломатических отношений», и, таким образом, не сделал этого. придать ему вес формального признания. [145][146]

Nevertheless, the Confederacy was seen internationally as a serious attempt at nationhood, and European governments sent military observers to assess whether there had been a de facto establishment of independence. These observers included Arthur Lyon Fremantle of the British Coldstream Guards, who entered the Confederacy via Mexico, Fitzgerald Ross of the Austrian Hussars, and Justus Scheibert of the Prussian Army.[147] European travelers visited and wrote accounts for publication. Importantly in 1862, the Frenchman Charles Girard's Seven months in the rebel states during the North American War testified "this government ... is no longer a trial government ... but really a normal government, the expression of popular will".[148] Fremantle went on to write in his book Three Months in the Southern States that he had:

...not attempted to conceal any of the peculiarities or defects of the Southern people. Many persons will doubtless highly disapprove of some of their customs and habits in the wilder portion of the country; but I think no generous man, whatever may be his political opinions, can do otherwise than admire the courage, energy, and patriotism of the whole population, and the skill of its leaders, in this struggle against great odds. And I am also of opinion that many will agree with me in thinking that a people in which all ranks and both sexes display a unanimity and a heroism which can never have been surpassed in the history of the world, is destined, sooner or later, to become a great and independent nation.[149]

French Emperor Napoleon III assured Confederate diplomat John Slidell that he would make "direct proposition" to Britain for joint recognition. The Emperor made the same assurance to British Members of Parliament John A. Roebuck and John A. Lindsay. Roebuck in turn publicly prepared a bill to submit to Parliament supporting joint Anglo-French recognition of the Confederacy. "Southerners had a right to be optimistic, or at least hopeful, that their revolution would prevail, or at least endure." Following the disasters at Vicksburg and Gettysburg in July 1863, the Confederates "suffered a severe loss of confidence in themselves" and withdrew into an interior defensive position.[150] By December 1864, Davis considered sacrificing slavery in order to enlist recognition and aid from Paris and London; he secretly sent Duncan F. Kenner to Europe with a message that the war was fought solely for "the vindication of our rights to self-government and independence" and that "no sacrifice is too great, save that of honor". The message stated that if the French or British governments made their recognition conditional on anything at all, the Confederacy would consent to such terms.[151] European leaders all saw that the Confederacy was on the verge of defeat.[152]

The Confederacy's biggest foreign policy successes were with Brazil and Cuba. Militarily this meant little. Brazil represented the "peoples most identical to us in Institutions",[153] in which slavery remained legal until the 1880s and the abolitionist movement was small. Confederate ships were welcome in Brazilian ports.[154] After the war, Brazil was the primary destination of those Southerners who wanted to continue living in a slave society, where, as one immigrant remarked, Confederado slaves were cheap. The Captain–General of Cuba declared in writing that Confederate ships were welcome, and would be protected in Cuban ports.[153] Historians speculate that if the Confederacy had achieved independence, it probably would have tried to acquire Cuba as a base of expansion.[155]

Confederacy at war

Motivations of soldiers

Most soldiers who joined Confederate national or state military units joined voluntarily. Perman (2010) says historians are of two minds on why millions of soldiers seemed so eager to fight, suffer and die over four years:

Some historians emphasize that Civil War soldiers were driven by political ideology, holding firm beliefs about the importance of liberty, Union, or state rights, or about the need to protect or to destroy slavery. Others point to less overtly political reasons to fight, such as the defense of one's home and family, or the honor and brotherhood to be preserved when fighting alongside other men. Most historians agree that, no matter what he thought about when he went into the war, the experience of combat affected him profoundly and sometimes affected his reasons for continuing to fight.[156][157]

Military strategy

Civil War historian E. Merton Coulter wrote that for those who would secure its independence, "The Confederacy was unfortunate in its failure to work out a general strategy for the whole war". Aggressive strategy called for offensive force concentration. Defensive strategy sought dispersal to meet demands of locally minded governors. The controlling philosophy evolved into a combination "dispersal with a defensive concentration around Richmond". The Davis administration considered the war purely defensive, a "simple demand that the people of the United States would cease to war upon us".[158] Historian James M. McPherson is a critic of Lee's offensive strategy: "Lee pursued a faulty military strategy that ensured Confederate defeat".[159]

As the Confederate government lost control of territory in campaign after campaign, it was said that "the vast size of the Confederacy would make its conquest impossible". The enemy would be struck down by the same elements which so often debilitated or destroyed visitors and transplants in the South. Heat exhaustion, sunstroke, endemic diseases such as malaria and typhoid would match the destructive effectiveness of the Moscow winter on the invading armies of Napoleon.[160]

Early in the war, both sides believed that one great battle would decide the conflict; the Confederates won a surprise victory at the First Battle of Bull Run, also known as First Manassas (the name used by Confederate forces). It drove the Confederate people "insane with joy"; the public demanded a forward movement to capture Washington, relocate the Confederate capital there, and admit Maryland to the Confederacy.[161] A council of war by the victorious Confederate generals decided not to advance against larger numbers of fresh Federal troops in defensive positions. Davis did not countermand it. Following the Confederate incursion into Maryland halted at the Battle of Antietam in October 1862, generals proposed concentrating forces from state commands to re-invade the north. Nothing came of it.[162] Again in mid-1863 at his incursion into Pennsylvania, Lee requested of Davis that Beauregard simultaneously attack Washington with troops taken from the Carolinas. But the troops there remained in place during the Gettysburg Campaign.

The eleven states of the Confederacy were outnumbered by the North about four-to-one in military manpower. It was overmatched far more in military equipment, industrial facilities, railroads for transport, and wagons supplying the front.

Confederates slowed the Yankee invaders, at heavy cost to the Southern infrastructure. The Confederates burned bridges, laid land mines in the roads, and made harbors inlets and inland waterways unusable with sunken mines (called "torpedoes" at the time). Coulter reports:

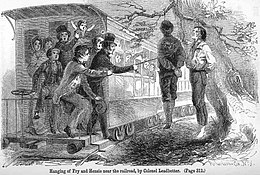

Rangers in twenty to fifty-man units were awarded 50% valuation for property destroyed behind Union lines, regardless of location or loyalty. As Federals occupied the South, objections by loyal Confederate concerning Ranger horse-stealing and indiscriminate scorched earth tactics behind Union lines led to Congress abolishing the Ranger service two years later.[163]

The Confederacy relied on external sources for war materials. The first came from trade with the enemy. "Vast amounts of war supplies" came through Kentucky, and thereafter, western armies were "to a very considerable extent" provisioned with illicit trade via Federal agents and northern private traders.[164] But that trade was interrupted in the first year of war by Admiral Porter's river gunboats as they gained dominance along navigable rivers north–south and east–west.[165] Overseas blockade running then came to be of "outstanding importance".[166] On April 17, President Davis called on privateer raiders, the "militia of the sea", to wage war on U.S. seaborne commerce.[167] Despite noteworthy effort, over the course of the war the Confederacy was found unable to match the Union in ships and seamanship, materials and marine construction.[168]

An inescapable obstacle to success in the warfare of mass armies was the Confederacy's lack of manpower, and sufficient numbers of disciplined, equipped troops in the field at the point of contact with the enemy. During the winter of 1862–63, Lee observed that none of his famous victories had resulted in the destruction of the opposing army. He lacked reserve troops to exploit an advantage on the battlefield as Napoleon had done. Lee explained, "More than once have most promising opportunities been lost for want of men to take advantage of them, and victory itself had been made to put on the appearance of defeat, because our diminished and exhausted troops have been unable to renew a successful struggle against fresh numbers of the enemy."[169]

Armed forces

The military armed forces of the Confederacy comprised three branches: Army, Navy and Marine Corps.

The Confederate military leadership included many veterans from the United States Army and United States Navy who had resigned their Federal commissions and were appointed to senior positions. Many had served in the Mexican–American War (including Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis), but some such as Leonidas Polk (who graduated from West Point but did not serve in the Army) had little or no experience.

-

Battle Flag – square

The Confederate officer corps consisted of men from both slave-owning and non-slave-owning families. The Confederacy appointed junior and field grade officers by election from the enlisted ranks. Although no Army service academy was established for the Confederacy, some colleges (such as The Citadel and Virginia Military Institute) maintained cadet corps that trained Confederate military leadership. A naval academy was established at Drewry's Bluff, Virginia[170] in 1863, but no midshipmen graduated before the Confederacy's end.

Most soldiers were white males aged between 16 and 28. The median year of birth was 1838, so half the soldiers were 23 or older by 1861.[171] The Confederate Army was permitted to disband for two months in early 1862 after its short-term enlistments expired. The majority of those in uniform would not re-enlist after their one-year commitment, thus on April 16, 1862, the Confederate Congress imposed the first mass conscription on North American territory. (A year later, on March 3, 1863, the United States Congress passed the Enrollment Act.) Rather than a universal draft, the first program was a selective one with physical, religious, professional, and industrial exemptions. These became narrower as the battle progressed. Initially substitutes were permitted, but by December 1863 these were disallowed. In September 1862 the age limit was increased from 35 to 45 and by February 1864, all men under 18 and over 45 were conscripted to form a reserve for state defense inside state borders. By March 1864, the Superintendent of Conscription reported that all across the Confederacy, every officer in constituted authority, man and woman, "engaged in opposing the enrolling officer in the execution of his duties".[172] Although challenged in the state courts, the Confederate State Supreme Courts routinely rejected legal challenges to conscription.[173]

Many thousands of slaves served as personal servants to their owner, or were hired as laborers, cooks, and pioneers.[174] Some freed blacks and men of color served in local state militia units of the Confederacy, primarily in Louisiana and South Carolina, but their officers deployed them for "local defense, not combat".[175] Depleted by casualties and desertions, the military suffered chronic manpower shortages. In early 1865, the Confederate Congress, influenced by the public support by General Lee, approved the recruitment of black infantry units. Contrary to Lee's and Davis's recommendations, the Congress refused "to guarantee the freedom of black volunteers". No more than two hundred black combat troops were ever raised.[176]

Raising troops

The immediate onset of war meant that it was fought by the "Provisional" or "Volunteer Army". State governors resisted concentrating a national effort. Several wanted a strong state army for self-defense. Others feared large "Provisional" armies answering only to Davis.[177] When filling the Confederate government's call for 100,000 men, another 200,000 were turned away by accepting only those enlisted "for the duration" or twelve-month volunteers who brought their own arms or horses.[178]

It was important to raise troops; it was just as important to provide capable officers to command them. With few exceptions the Confederacy secured excellent general officers. Efficiency in the lower officers was "greater than could have been reasonably expected". As with the Federals, political appointees could be indifferent. Otherwise, the officer corps was governor-appointed or elected by unit enlisted. Promotion to fill vacancies was made internally regardless of merit, even if better officers were immediately available.[179]

Anticipating the need for more "duration" men, in January 1862 Congress provided for company level recruiters to return home for two months, but their efforts met little success on the heels of Confederate battlefield defeats in February.[180] Congress allowed for Davis to require numbers of recruits from each governor to supply the volunteer shortfall. States responded by passing their own draft laws.[181]

The veteran Confederate army of early 1862 was mostly twelve-month volunteers with terms about to expire. Enlisted reorganization elections disintegrated the army for two months. Officers pleaded with the ranks to re-enlist, but a majority did not. Those remaining elected majors and colonels whose performance led to officer review boards in October. The boards caused a "rapid and widespread" thinning out of 1,700 incompetent officers. Troops thereafter would elect only second lieutenants.[182]

In early 1862, the popular press suggested the Confederacy required a million men under arms. But veteran soldiers were not re-enlisting, and earlier secessionist volunteers did not reappear to serve in war. One Macon, Georgia, newspaper asked how two million brave fighting men of the South were about to be overcome by four million northerners who were said to be cowards.[183]

Conscription

The Confederacy passed the first American law of national conscription on April 16, 1862. The white males of the Confederate States from 18 to 35 were declared members of the Confederate army for three years, and all men then enlisted were extended to a three-year term. They would serve only in units and under officers of their state. Those under 18 and over 35 could substitute for conscripts, in September those from 35 to 45 became conscripts.[184] The cry of "rich man's war and a poor man's fight" led Congress to abolish the substitute system altogether in December 1863. All principals benefiting earlier were made eligible for service. By February 1864, the age bracket was made 17 to 50, those under eighteen and over forty-five to be limited to in-state duty.[185]

Confederate conscription was not universal; it was a selective service. The First Conscription Act of April 1862 exempted occupations related to transportation, communication, industry, ministers, teaching and physical fitness. The Second Conscription Act of October 1862 expanded exemptions in industry, agriculture and conscientious objection. Exemption fraud proliferated in medical examinations, army furloughs, churches, schools, apothecaries and newspapers.[186]

Rich men's sons were appointed to the socially outcast "overseer" occupation, but the measure was received in the country with "universal odium". The legislative vehicle was the controversial Twenty Negro Law that specifically exempted one white overseer or owner for every plantation with at least 20 slaves. Backpedaling six months later, Congress provided overseers under 45 could be exempted only if they held the occupation before the first Conscription Act.[187] The number of officials under state exemptions appointed by state Governor patronage expanded significantly.[188]

-

Gen. Gabriel J. Rains, Conscription Bureau chief, April 1862 – May 1863

-

Gen. Gideon J. Pillow, military recruiter under Bragg, then J.E. Johnston[189]

The Conscription Act of February 1864 "radically changed the whole system" of selection. It abolished industrial exemptions, placing detail authority in President Davis. As the shame of conscription was greater than a felony conviction, the system brought in "about as many volunteers as it did conscripts." Many men in otherwise "bombproof" positions were enlisted in one way or another, nearly 160,000 additional volunteers and conscripts in uniform. Still there was shirking.[190] To administer the draft, a Bureau of Conscription was set up to use state officers, as state Governors would allow. It had a checkered career of "contention, opposition and futility". Armies appointed alternative military "recruiters" to bring in the out-of-uniform 17–50-year-old conscripts and deserters. Nearly 3,000 officers were tasked with the job. By late 1864, Lee was calling for more troops. "Our ranks are constantly diminishing by battle and disease, and few recruits are received; the consequences are inevitable." By March 1865 conscription was to be administered by generals of the state reserves calling out men over 45 and under 18 years old. All exemptions were abolished. These regiments were assigned to recruit conscripts ages 17–50, recover deserters, and repel enemy cavalry raids. The service retained men who had lost but one arm or a leg in home guards. Ultimately, conscription was a failure, and its main value was in goading men to volunteer.[191]

The survival of the Confederacy depended on a strong base of civilians and soldiers devoted to victory. The soldiers performed well, though increasing numbers deserted in the last year of fighting, and the Confederacy never succeeded in replacing casualties as the Union could. The civilians, although enthusiastic in 1861–62, seem to have lost faith in the future of the Confederacy by 1864, and instead looked to protect their homes and communities. As Rable explains, "This contraction of civic vision was more than a crabbed libertarianism; it represented an increasingly widespread disillusionment with the Confederate experiment."[192]

Victories: 1861

The American Civil War broke out in April 1861 with a Confederate victory at the Battle of Fort Sumter in Charleston.

In January, President James Buchanan had attempted to resupply the garrison with the steamship, Star of the West, but Confederate artillery drove it away. In March, President Lincoln notified South Carolina Governor Pickens that without Confederate resistance to the resupply there would be no military reinforcement without further notice, but Lincoln prepared to force resupply if it were not allowed. Confederate President Davis, in cabinet, decided to seize Fort Sumter before the relief fleet arrived, and on April 12, 1861, General Beauregard forced its surrender.[194]

Following Sumter, Lincoln directed states to provide 75,000 troops for three months to recapture the Charleston Harbor forts and all other federal property.[195] This emboldened secessionists in Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee and North Carolina to secede rather than provide troops to march into neighboring Southern states. In May, Federal troops crossed into Confederate territory along the entire border from the Chesapeake Bay to New Mexico. The first battles were Confederate victories at Big Bethel (Bethel Church, Virginia), First Bull Run (First Manassas) in Virginia July and in August, Wilson's Creek (Oak Hills) in Missouri. At all three, Confederate forces could not follow up their victory due to inadequate supply and shortages of fresh troops to exploit their successes. Following each battle, Federals maintained a military presence and occupied Washington, DC; Fort Monroe, Virginia; and Springfield, Missouri. Both North and South began training up armies for major fighting the next year.[196] Union General George B. McClellan's forces gained possession of much of northwestern Virginia in mid-1861, concentrating on towns and roads; the interior was too large to control and became the center of guerrilla activity.[197][198] General Robert E. Lee was defeated at Cheat Mountain in September and no serious Confederate advance in western Virginia occurred until the next year.

Meanwhile, the Union Navy seized control of much of the Confederate coastline from Virginia to South Carolina. It took over plantations and the abandoned slaves. Federals there began a war-long policy of burning grain supplies up rivers into the interior wherever they could not occupy.[199] The Union Navy began a blockade of the major southern ports and prepared an invasion of Louisiana to capture New Orleans in early 1862.

Incursions: 1862

The victories of 1861 were followed by a series of defeats east and west in early 1862. To restore the Union by military force, the Federal strategy was to (1) secure the Mississippi River, (2) seize or close Confederate ports, and (3) march on Richmond. To secure independence, the Confederate intent was to (1) repel the invader on all fronts, costing him blood and treasure, and (2) carry the war into the North by two offensives in time to affect the mid-term elections.

Much of northwestern Virginia was under Federal control.[201] In February and March, most of Missouri and Kentucky were Union "occupied, consolidated, and used as staging areas for advances further South". Following the repulse of a Confederate counterattack at the Battle of Shiloh, Tennessee, permanent Federal occupation expanded west, south and east.[202] Confederate forces repositioned south along the Mississippi River to Memphis, Tennessee, where at the naval Battle of Memphis, its River Defense Fleet was sunk. Confederates withdrew from northern Mississippi and northern Alabama. New Orleans was captured on April 29 by a combined Army-Navy force under U.S. Admiral David Farragut, and the Confederacy lost control of the mouth of the Mississippi River. It had to concede extensive agricultural resources that had supported the Union's sea-supplied logistics base.[203]

Although Confederates had suffered major reverses everywhere, as of the end of April the Confederacy still controlled territory holding 72% of its population.[204] Federal forces disrupted Missouri and Arkansas; they had broken through in western Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee and Louisiana. Along the Confederacy's shores, Union forces had closed ports and made garrisoned lodgments on every coastal Confederate state except Alabama and Texas.[205] Although scholars sometimes assess the Union blockade as ineffectual under international law until the last few months of the war, from the first months it disrupted Confederate privateers, making it "almost impossible to bring their prizes into Confederate ports".[206] British firms developed small fleets of blockade running companies, such as John Fraser and Company and S. Isaac, Campbell & Company while the Ordnance Department secured its own blockade runners for dedicated munitions cargoes.[207]

During the Civil War fleets of armored warships were deployed for the first time in sustained blockades at sea. After some success against the Union blockade, in March the ironclad CSS Virginia was forced into port and burned by Confederates at their retreat. Despite several attempts mounted from their port cities, CSA naval forces were unable to break the Union blockade. Attempts were made by Commodore Josiah Tattnall III's ironclads from Savannah in 1862 with the CSS Atlanta.[208] Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory placed his hopes in a European-built ironclad fleet, but they were never realized. On the other hand, four new English-built commerce raiders served the Confederacy, and several fast blockade runners were sold in Confederate ports. They were converted into commerce-raiding cruisers, and manned by their British crews.[209]

In the east, Union forces could not close on Richmond. General McClellan landed his army on the Lower Peninsula of Virginia. Lee subsequently ended that threat from the east, then Union General John Pope attacked overland from the north only to be repulsed at Second Bull Run (Second Manassas). Lee's strike north was turned back at Antietam MD, then Union Major General Ambrose Burnside's offensive was disastrously ended at Fredericksburg VA in December. Both armies then turned to winter quarters to recruit and train for the coming spring.[210]

In an attempt to seize the initiative, reprove, protect farms in mid-growing season and influence U.S. Congressional elections, two major Confederate incursions into Union territory had been launched in August and September 1862. Both Braxton Bragg's invasion of Kentucky and Lee's invasion of Maryland were decisively repulsed, leaving Confederates in control of but 63% of its population.[204] Civil War scholar Allan Nevins argues that 1862 was the strategic high-water mark of the Confederacy.[211] The failures of the two invasions were attributed to the same irrecoverable shortcomings: lack of manpower at the front, lack of supplies including serviceable shoes, and exhaustion after long marches without adequate food.[212] Also in September Confederate General William W. Loring pushed Federal forces from Charleston, Virginia, and the Kanawha Valley in western Virginia, but lacking reinforcements Loring abandoned his position and by November the region was back in Federal control.[213][214]

Anaconda: 1863–1864

The failed Middle Tennessee campaign was ended January 2, 1863, at the inconclusive Battle of Stones River (Murfreesboro), both sides losing the largest percentage of casualties suffered during the war. It was followed by another strategic withdrawal by Confederate forces.[215] The Confederacy won a significant victory April 1863, repulsing the Federal advance on Richmond at Chancellorsville, but the Union consolidated positions along the Virginia coast and the Chesapeake Bay.

Without an effective answer to Federal gunboats, river transport and supply, the Confederacy lost the Mississippi River following the capture of Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Port Hudson in July, ending Southern access to the trans-Mississippi West. July brought short-lived counters, Morgan's Raid into Ohio and the New York City draft riots. Robert E. Lee's strike into Pennsylvania was repulsed at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania despite Pickett's famous charge and other acts of valor. Southern newspapers assessed the campaign as "The Confederates did not gain a victory, neither did the enemy."

September and November left Confederates yielding Chattanooga, Tennessee, the gateway to the lower south.[216] For the remainder of the war fighting was restricted inside the South, resulting in a slow but continuous loss of territory. In early 1864, the Confederacy still controlled 53% of its population, but it withdrew further to reestablish defensive positions. Union offensives continued with Sherman's March to the Sea to take Savannah and Grant's Wilderness Campaign to encircle Richmond and besiege Lee's army at Petersburg.[203]

In April 1863, the C.S. Congress authorized a uniformed Volunteer Navy, many of whom were British.[217] The Confederacy had altogether eighteen commerce-destroying cruisers, which seriously disrupted Federal commerce at sea and increased shipping insurance rates 900%.[218] Commodore Tattnall again unsuccessfully attempted to break the Union blockade on the Savannah River in Georgia with an ironclad in 1863.[219] Beginning in April 1864 the ironclad CSS Albemarle engaged Union gunboats for six months on the Roanoke River in North Carolina.[220] The Federals closed Mobile Bay by sea-based amphibious assault in August, ending Gulf coast trade east of the Mississippi River. In December, the Battle of Nashville ended Confederate operations in the western theater.

Large numbers of families relocated to safer places, usually remote rural areas, bringing along household slaves if they had any. Mary Massey argues these elite exiles introduced an element of defeatism into the southern outlook.[221]

Collapse: 1865

The first three months of 1865 saw the Federal Carolinas Campaign, devastating a wide swath of the remaining Confederate heartland. The "breadbasket of the Confederacy" in the Great Valley of Virginia was occupied by Philip Sheridan. The Union Blockade captured Fort Fisher in North Carolina, and Sherman finally took Charleston, South Carolina, by land attack.[203]

The Confederacy controlled no ports, harbors or navigable rivers. Railroads were captured or had ceased operating. Its major food-producing regions had been war-ravaged or occupied. Its administration survived in only three pockets of territory holding only one-third of its population. Its armies were defeated or disbanding. At the February 1865 Hampton Roads Conference with Lincoln, senior Confederate officials rejected his invitation to restore the Union with compensation for emancipated slaves.[203] The three pockets of unoccupied Confederacy were southern Virginia—North Carolina, central Alabama—Florida, and Texas, the latter two areas less from any notion of resistance than from the disinterest of Federal forces to occupy them.[222] The Davis policy was independence or nothing, while Lee's army was wracked by disease and desertion, barely holding the trenches defending Jefferson Davis' capital.

The Confederacy's last remaining blockade-running port, Wilmington, North Carolina, was lost. When the Union broke through Lee's lines at Petersburg, Richmond fell immediately. Lee surrendered a remnant of 50,000 from the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9, 1865.[223] "The Surrender" marked the end of the Confederacy.[224] The CSS Stonewall sailed from Europe to break the Union blockade in March; on making Havana, Cuba, it surrendered. Some high officials escaped to Europe, but President Davis was captured May 10; all remaining Confederate land forces surrendered by June 1865. The U.S. Army took control of the Confederate areas without post-surrender insurgency or guerrilla warfare against them, but peace was subsequently marred by a great deal of local violence, feuding and revenge killings.[225] The last confederate military unit, the commerce raider CSS Shenandoah, surrendered on November 6, 1865, in Liverpool.[226]

Historian Gary Gallagher concluded that the Confederacy capitulated in early 1865 because northern armies crushed "organized southern military resistance". The Confederacy's population, soldier and civilian, had suffered material hardship and social disruption.[227] Jefferson Davis' assessment in 1890 determined, "With the capture of the capital, the dispersion of the civil authorities, the surrender of the armies in the field, and the arrest of the President, the Confederate States of America disappeared ... their history henceforth became a part of the history of the United States."[228]

Legacy and assessment

Amnesty and treason issue

When the war ended over 14,000 Confederates petitioned President Johnson for a pardon; he was generous in giving them out.[229] He issued a general amnesty to all Confederate participants in the "late Civil War" in 1868.[230] Congress passed additional Amnesty Acts in May 1866 with restrictions on office holding, and the Amnesty Act in May 1872 lifting those restrictions. There was a great deal of discussion in 1865 about bringing treason trials, especially against Jefferson Davis. There was no consensus in President Johnson's cabinet, and no one was charged with treason. An acquittal of Davis would have been humiliating for the government.[231]

Davis was indicted for treason but never tried; he was released from prison on bail in May 1867. The amnesty of December 25, 1868, by President Johnson eliminated any possibility of Jefferson Davis (or anyone else associated with the Confederacy) standing trial for treason.[232][233][234]

Henry Wirz, the commandant of a notorious prisoner-of-war camp near Andersonville, Georgia, was tried and convicted by a military court, and executed on November 10, 1865. The charges against him involved conspiracy and cruelty, not treason.

The U.S. government began a decade-long process known as Reconstruction which attempted to resolve the political and constitutional issues of the Civil War. The priorities were: to guarantee that Confederate nationalism and slavery were ended, to ratify and enforce the Thirteenth Amendment which outlawed slavery; the Fourteenth which guaranteed dual U.S. and state citizenship to all native-born residents, regardless of race; the Fifteenth, which made it illegal to deny the right to vote because of race; and repeal each state's ordinance of secession.[235]