Тринадцатая поправка к Конституции США

| Эта статья является частью серии статей о |

| Конституция Соединенных Штатов |

|---|

|

| Преамбула и статьи |

| Поправки к Конституции |

Unratified Amendments: |

| History |

| Full text |

Тринадцатая поправка ( Поправка XIII ) к Конституции США отменила рабство и принудительное подневольное состояние , за исключением случаев наказания за преступление . Поправка была принята Сенатом 8 апреля 1864 года, Палатой представителей 31 января 1865 года, ратифицирована необходимыми 27 из тогдашних 36 штатов 6 декабря 1865 года и провозглашена 18 декабря. первая из трех поправок к реконструкции, принятых после Гражданской войны в США .

президента Авраама Линкольна об Прокламация освобождении , вступившая в силу 1 января 1863 года, провозгласила, что порабощенные на территориях, контролируемых Конфедерацией (и, следовательно, почти все рабы), свободны. Когда они бежали к границам Союза или федеральные силы (включая теперь уже бывших рабов) продвигались на юг, освобождение происходило без какой-либо компенсации бывшим владельцам. было объявлено о приведении в исполнение прокламации Техас был последней территорией Конфедерации, находившейся в рабстве, где 19 июня 1865 года . В рабовладельческих районах, контролируемых войсками Союза 1 января 1863 года, государственные меры были использованы для отмены рабства. Исключением были Кентукки и Делавэр и, в ограниченной степени, Нью-Джерси , где рабство движимого имущества и подневольное состояние были окончательно прекращены Тринадцатой поправкой в декабре 1865 года.

In contrast to the other Reconstruction Amendments, the Thirteenth Amendment has rarely been cited in case law, but it has been used to strike down peonage and some race-based discrimination as "badges and incidents of slavery". The Thirteenth Amendment has also been invoked to empower Congress to make laws against modern forms of slavery, such as sex trafficking.

From its inception in 1776, the United States was divided into states that allowed slavery and states that prohibited it. Slavery was implicitly recognized in the original Constitution in provisions such as the Three-fifths Compromise (Article I, Section 2, Clause 3), which provided that three-fifths of each state's enslaved population ("other persons") was to be added to its free population for the purposes of apportioning seats in the United States House of Representatives, its number of Electoral votes, and direct taxes among the states. The Fugitive Slave Clause (Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3) provided that slaves held under the laws of one state who escaped to another state did not become free, but remained slaves.

Though three million Confederate slaves were eventually freed as a result of Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, their postwar status was uncertain. To ensure that abolition was beyond legal challenge, an amendment to the Constitution to that effect was drafted. On April 8, 1864, the Senate passed an amendment to abolish slavery. After one unsuccessful vote and extensive legislative maneuvering by the Lincoln administration, the House followed suit on January 31, 1865. The measure was swiftly ratified by nearly all Northern states, along with a sufficient number of border states up to the assassination of President Lincoln. However, the approval came via his successor, President Andrew Johnson, who encouraged the "reconstructed" Southern states of Alabama, North Carolina, and Georgia to agree, which brought the count to 27 states, leading to its adoption before the end of 1865.

Though the Amendment abolished slavery throughout the United States, some black Americans, particularly in the South, were subjected to other forms of involuntary labor, such as under the Black Codes, white supremacist violence, and selective enforcement of statutes, as well as other disabilities.

Text

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.[1]

Slavery in the United States

Slavery existed and was legal in the United States of America upon its founding in 1776. It was established by European colonization in all of the original thirteen American colonies of British America. Prior to the Thirteenth Amendment, the United States Constitution did not expressly use the words slave or slavery but included several provisions about unfree persons. The Three-Fifths Compromise, Article I, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution, allocated Congressional representation based "on the whole Number of free Persons" and "three-fifths of all other Persons". This clause was a compromise between Southern politicians who wished for enslaved African-Americans to be counted as 'persons' for congressional representation and Northern politicians rejecting these out of concern of too much power for the South, because representation in the new Congress would be based on population in contrast to the one-vote-for-one-state principle in the earlier Continental Congress.[3] Under the Fugitive Slave Clause, Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3, "No person held to Service or Labour in one State" would be freed by escaping to another. Article I, Section 9, Clause 1 allowed Congress to pass legislation outlawing the "Importation of Persons", which would not be passed until 1808. However, for purposes of the Fifth Amendment—which states that "No person shall ... be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law"—slaves were understood as property.[4] Although abolitionists used the Fifth Amendment to argue against slavery, it became part of the legal basis in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) for treating slaves as property.[5]

Stimulated by the philosophy of the Declaration of Independence, between 1777 and 1804 every Northern state provided for the immediate or gradual abolition of slavery. (Slavery was never legal in Vermont; it was prohibited in the 1777 constitution creating Vermont, to become the fourteenth state.) Most of the slaves who were emancipated by such legislation were household servants. No Southern state did so, and the enslaved population of the South continued to grow, peaking at almost four million in 1861. An abolitionist movement, headed by such figures as William Lloyd Garrison, Theodore Dwight Weld, and Angelina Grimké, grew in strength in the North, calling for the immediate end of slavery nationwide and exacerbating tensions between North and South. The American Colonization Society, an alliance between abolitionists who felt the "races" should be kept separated and slaveholders who feared the presence of freed blacks would encourage slave rebellions, called for the emigration of both free blacks and slaves to Africa, where they would establish independent colonies. Its views were endorsed by politicians such as Henry Clay, who feared that the American abolitionist movement would provoke a civil war.[6] Proposals to eliminate slavery by constitutional amendment were introduced by Representative Arthur Livermore in 1818 and by John Quincy Adams in 1839, but failed to gain significant traction.[7]

As the country continued to expand, the issue of slavery in its new territories became the dominant national issue. The senatorial votes of new states could break the deadlock in the Senate over slavery. The Southern position was that slaves were property and therefore could be moved to the territories like all other forms of property.[8] The 1820 Missouri Compromise provided for the admission of Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, preserving the Senate's equality between the regions. In 1846, the Wilmot Proviso was introduced to a war appropriations bill to ban slavery in all territories acquired in the Mexican–American War; the Proviso repeatedly passed the House, but not the Senate.[8] The Compromise of 1850 temporarily defused the issue by admitting California as a free state, instituting a stronger Fugitive Slave Act, banning the slave trade in Washington, D.C., and allowing New Mexico and Utah self-determination on the slavery issue.[9]

Despite the compromise, tensions between North and South continued to rise over the subsequent decade, inflamed by, among other things, the publication of the 1852 anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin; fighting between pro-slavery and abolitionist forces in Kansas, beginning in 1854; the 1857 Dred Scott decision, which struck down provisions of the Compromise of 1850; abolitionist John Brown's 1859 attempt to start a slave revolt at Harpers Ferry, and the 1860 election of slavery critic Abraham Lincoln to the presidency. The Southern states seceded from the Union in the months following Lincoln's election, forming the Confederate States of America, and beginning the American Civil War.[10]

Proposal and ratification

Crafting the amendment

Acting under presidential war powers, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, with effect on January 1, 1863, which proclaimed the freedom of slaves in the ten states that were still in rebellion.[11] In his State of the Union message to Congress on December 1, 1862, Lincoln also presented a plan for "gradual emancipation and deportation" of slaves. This plan envisioned three amendments to the Constitution. The first would have required the states to abolish slavery by January 1, 1900.[12] Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation then proceeded immediately freeing slaves in January 1863 but did not affect the status of slaves in the border states that had remained loyal to the Union.[13] By December 1863, Lincoln again used his war powers and issued a "Proclamation for Amnesty and Reconstruction", which offered Southern states a chance to peacefully rejoin the Union if they immediately abolished slavery and collected loyalty oaths from 10% of their voting population.[14] Southern states did not readily accept the deal, and the status of slavery remained uncertain.

In the final years of the Civil War, Union lawmakers debated various proposals for Reconstruction.[15] Some of these called for a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery nationally and permanently. On December 14, 1863, a bill proposing such an amendment was introduced by Representative James Mitchell Ashley of Ohio.[16][17] Representative James F. Wilson of Iowa soon followed with a similar proposal. On January 11, 1864, Senator John B. Henderson of Missouri submitted a joint resolution for a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. The Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired by Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, became involved in merging different proposals for an amendment.

Radical Republicans led by Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner and Pennsylvania Representative Thaddeus Stevens sought a more expansive version of the amendment.[18] On February 8, 1864, Sumner submitted a constitutional amendment stating:

All persons are equal before the law, so that no person can hold another as a slave; and the Congress shall have power to make all laws necessary and proper to carry this declaration into effect everywhere in the United States.[19][20]

Sumner tried to have his amendment sent to his committee, rather than the Trumbull-controlled Judiciary Committee, but the Senate refused.[21] On February 10, the Senate Judiciary Committee presented the Senate with an amendment proposal based on drafts of Ashley, Wilson and Henderson.[22][23]

The committee's version used text from the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which stipulates, "There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted."[24][25]: 1786 Though using Henderson's proposed amendment as the basis for its new draft, the Judiciary Committee removed language that would have allowed a constitutional amendment to be adopted with only a majority vote in each House of Congress and ratification by two-thirds of the states (instead of two-thirds and three-fourths, respectively).[26]

Passage by Congress

The Senate passed the amendment on April 8, 1864, by a vote of 38 to 6; two Democrats, Oregon Senators Benjamin F Harding and James Nesmith voted for the amendment.[27] However, just over two months later on June 15, the House failed to do so, with 93 in favor and 65 against, thirteen votes short of the two-thirds vote needed for passage; the vote split largely along party lines, with Republicans supporting and Democrats opposing.[28] In the 1864 presidential race, former Free Soil Party candidate John C. Frémont threatened a third-party run opposing Lincoln, this time on a platform endorsing an anti-slavery amendment. The Republican Party platform had, as yet, failed to include a similar plank, though Lincoln endorsed the amendment in a letter accepting his nomination.[29][30] Frémont withdrew from the race on September 22, 1864, and endorsed Lincoln.[31]

With no Southern states represented, few members of Congress pushed moral and religious arguments in favor of slavery. Democrats who opposed the amendment generally made arguments based on federalism and states' rights.[32] Some argued that the proposed change so violated the spirit of the Constitution it would not be a valid "amendment" but would instead constitute "revolution".[33] Representative Chilton A. White, among other opponents, warned that the amendment would lead to full citizenship for blacks.[34]

Republicans portrayed slavery as uncivilized and argued for abolition as a necessary step in national progress.[35] Amendment supporters also argued that the slave system had negative effects on white people. These included the lower wages resulting from competition with forced labor, as well as repression of abolitionist whites in the South. Advocates said ending slavery would restore the First Amendment and other constitutional rights violated by censorship and intimidation in slave states.[34][36]

White, Northern Republicans and some Democrats became excited about an abolition amendment, holding meetings and issuing resolutions.[37] Many blacks though, particularly in the South, focused more on land ownership and education as the key to liberation.[38] As slavery began to seem politically untenable, an array of Northern Democrats successively announced their support for the amendment, including Representative James Brooks,[39] Senator Reverdy Johnson,[40] and the powerful New York political machine known as Tammany Hall.[41]

President Lincoln had had concerns that the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 might be reversed or found invalid by the judiciary after the war.[42] He saw constitutional amendment as a more permanent solution.[43][44] He had remained outwardly neutral on the amendment because he considered it politically too dangerous.[45] Nonetheless, Lincoln's 1864 election platform resolved to abolish slavery by constitutional amendment.[46][47] After winning reelection in the election of 1864, Lincoln made the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment his top legislative priority. He began with his efforts in Congress during its "lame duck" session, in which many members of Congress had already seen their successors elected; most would be concerned about unemployment and lack of income, and none needed to fear the electoral consequences of cooperation.[48][49] Popular support for the amendment mounted and Lincoln urged Congress on in his December 6, 1864 State of the Union Address: "there is only a question of time as to when the proposed amendment will go to the States for their action. And as it is to so go, at all events, may we not agree that the sooner the better?"[50]

Lincoln instructed Secretary of State William H. Seward, Representative John B. Alley and others to procure votes by any means necessary, and they promised government posts and campaign contributions to outgoing Democrats willing to switch sides.[51][52] Seward had a large fund for direct bribes. Ashley, who reintroduced the measure into the House, also lobbied several Democrats to vote in favor of the measure.[53] Representative Thaddeus Stevens later commented that "the greatest measure of the nineteenth century was passed by corruption aided and abetted by the purest man in America"; however, Lincoln's precise role in making deals for votes remains unknown.[54]

Republicans in Congress claimed a mandate for abolition, having gained in the elections for Senate and House.[55] The 1864 Democratic vice-presidential nominee, Representative George H. Pendleton, led opposition to the measure.[56] Republicans toned down their language of radical equality in order to broaden the amendment's coalition of supporters.[57] In order to reassure critics worried that the amendment would tear apart the social fabric, some Republicans explicitly promised the amendment would leave broader American society's patriarchal traditions intact.[58]

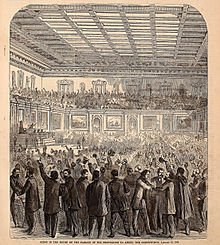

In mid-January 1865, Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax estimated the amendment to be five votes short of passage. Ashley postponed the vote.[59] At this point, Lincoln intensified his push for the amendment, making direct emotional appeals to particular members of Congress.[60] On January 31, 1865, the House called another vote on the amendment, with neither side being certain of the outcome. With a total of 183 House members (one seat was vacant after Reuben Fenton was elected governor), 122 would have to vote "aye" to secure passage of the resolution; however, eight Democrats abstained, reducing the number to 117. Every Republican (84), Independent Republican (2), and Unconditional Unionist (16) supported the measure, as well as fourteen Democrats, almost all of them lame ducks, and three Unionists. The amendment finally passed by a vote of 119 to 56,[61] narrowly reaching the required two-thirds majority.[62] The House exploded into celebration, with some members openly weeping.[63] Black onlookers, who had only been allowed to attend Congressional sessions since the previous year, cheered from the galleries.[64]

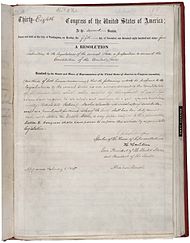

While the Constitution does not provide the President any formal role in the amendment process, the joint resolution was sent to Lincoln for his signature.[65] Under the usual signatures of the Speaker of the House and the President of the Senate, President Lincoln wrote the word "Approved" and added his signature to the joint resolution on February 1, 1865.[66] On February 7, Congress passed a resolution affirming that the Presidential signature was unnecessary.[67] The Thirteenth Amendment is the only ratified amendment signed by a President, although James Buchanan had signed the Corwin Amendment that the 36th Congress had adopted and sent to the states in March 1861.[68][69]

Ratification by the states

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

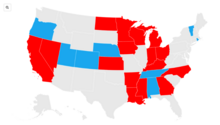

On February 1, 1865, when the proposed amendment was submitted to the states for ratification, there were 36 states in the U.S., including those that had been in rebellion; at least 27 states had to ratify the amendment for it to come into force. By the end of February, 18 states had ratified the amendment. Among them were the ex-Confederate states of Virginia and Louisiana, where ratifications were submitted by Reconstruction governments. These, along with subsequent ratifications from Arkansas and Tennessee raised the issues of how many seceded states had legally valid legislatures; and if there were fewer legislatures than states, if Article V required ratification by three-fourths of the states or three-fourths of the legally valid state legislatures.[70] President Lincoln in his last speech, on April 11, 1865, called the question about whether the Southern states were in or out of the Union a "pernicious abstraction". He declared they were not "in their proper practical relation with the Union"; whence everyone's object should be to restore that relation.[71] Lincoln was assassinated three days later.

With Congress out of session, the new president, Andrew Johnson, began a period known as "Presidential Reconstruction", in which he personally oversaw the creation of new state governments throughout the South. He oversaw the convening of state political conventions populated by delegates whom he deemed to be loyal. Three leading issues came before the conventions: secession itself, the abolition of slavery, and the Confederate war debt. Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, and South Carolina held conventions in 1865, while Texas' convention did not organize until March 1866.[72][73][74] Johnson hoped to prevent deliberation over whether to re-admit the Southern states by accomplishing full ratification before Congress reconvened in December. He believed he could silence those who wished to deny the Southern states their place in the Union by pointing to how essential their assent had been to the successful ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment.[75]

Direct negotiations between state governments and the Johnson administration ensued. As the summer wore on, administration officials began giving assurances of the measure's limited scope with their demands for ratification. Johnson himself suggested directly to the governors of Mississippi and North Carolina that they could proactively control the allocation of rights to freedmen. Though Johnson obviously expected the freed people to enjoy at least some civil rights, including, as he specified, the right to testify in court, he wanted state lawmakers to know that the power to confer such rights would remain with the states.[76] When South Carolina provisional governor Benjamin Franklin Perry objected to the scope of the amendment's enforcement clause, Secretary of State Seward responded by telegraph that in fact the second clause "is really restraining in its effect, instead of enlarging the powers of Congress".[76] Politicians throughout the South were concerned that Congress might cite the amendment's enforcement powers as a way to authorize black suffrage.[77]

When South Carolina ratified the Amendment in November 1865, it issued its own interpretive declaration that "any attempt by Congress toward legislating upon the political status of former slaves, or their civil relations, would be contrary to the Constitution of the United States."[25]: 1786–1787 [78] Alabama and Louisiana also declared that their ratification did not imply federal power to legislate on the status of former slaves.[25]: 1787 [79] During the first week of December, North Carolina and Georgia gave the amendment the final votes needed for it to become part of the Constitution.

The first 27 states to ratify the Amendment were:[80]

- Illinois: February 1, 1865

- Rhode Island: February 2, 1865

- Michigan: February 3, 1865

- Maryland: February 3, 1865

- New York: February 3, 1865

- Pennsylvania: February 3, 1865

- West Virginia: February 3, 1865

- Missouri: February 6, 1865

- Maine: February 7, 1865

- Kansas: February 7, 1865

- Massachusetts: February 7, 1865

- Virginia: February 9, 1865

- Ohio: February 10, 1865

- Indiana: February 13, 1865

- Nevada: February 16, 1865

- Louisiana: February 17, 1865

- Minnesota: February 23, 1865

- Wisconsin: February 24, 1865

- Vermont: March 9, 1865

- Tennessee: April 7, 1865

- Arkansas: April 14, 1865

- Connecticut: May 4, 1865

- New Hampshire: July 1, 1865

- South Carolina: November 13, 1865

- Alabama: December 2, 1865

- North Carolina: December 4, 1865

- Georgia: December 6, 1865

Having been ratified by the legislatures of three-fourths of the states (27 of the 36 states, including those that had been in rebellion), Secretary of State Seward, on December 18, 1865, certified that the Thirteenth Amendment had become valid, to all intents and purposes, as a part of the Constitution.[81] Included on the enrolled list of ratifying states were the three ex-Confederate states that had given their assent, but with strings attached. Seward accepted their affirmative votes and brushed aside their interpretive declarations without comment, challenge or acknowledgment.[82]

The Thirteenth Amendment was subsequently ratified by the other states, as follows:[80]: 30

- Oregon: December 8, 1865

- California: December 19, 1865

- Florida: December 28, 1865 (reaffirmed June 9, 1868)

- Iowa: January 15, 1866

- New Jersey: January 23, 1866 (after rejection March 16, 1865)

- Texas: February 18, 1870

- Delaware: February 12, 1901 (after rejection February 8, 1865)

- Kentucky: March 18, 1976[83] (after rejection February 24, 1865)

- Mississippi: March 16, 1995 (after rejection December 5, 1865; not certified until February 7, 2013)[84]

With the ratification by Mississippi in 1995, and certification thereof in 2013, the amendment was finally ratified by all states having existed at the time of its adoption in 1865.

Effects

Freeing slaves

The immediate impact of the amendment was to make the entire pre-war system of chattel slavery in the U.S. illegal.[85] The impact of the abolition of slavery was felt quickly. When the Thirteenth Amendment became operational, the scope of Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation was widened to include the entire nation. Although the majority of Kentucky's slaves had been emancipated, 65,000–100,000 people remained to be legally freed when the amendment went into effect on December 18.[86][87] In Delaware, where a large number of slaves had escaped during the war, nine hundred people became legally free.[87][88]With slavery abolished, the Fugitive Slave Clause remained in place but became largely moot.

Native American territory

Despite being rendered unconstitutional, slavery continued in areas under the jurisdiction of Native American tribes beyond ratification. The federal government negotiated new treaties with the "Five Civilized Tribes" in 1866, in which they agreed to end slavery.[89]

Electoral changes

The Three-Fifths Compromise in the original Constitution counted, for purposes of allocating taxes and seats in the House of Representatives, all "free persons", three-fifths of "other persons" (i.e., slaves) and excluded untaxed Native Americans. The freeing of all slaves made the three-fifths clause moot. Compared to the pre-war system, it also had the effect of increasing the political power of former slave-holding states by increasing their share of seats in the House of Representatives, and consequently their share in the Electoral College (where the number of a state's electoral votes, under Article II of the United States Constitution, is tied to the size of its congressional delegation).[90][91]

Even as the Thirteenth Amendment was working its way through the ratification process, Republicans in Congress grew increasingly concerned about the potential for there to be a large increase in the congressional representation of the Democratic-dominated Southern states. Because the full population of freed slaves would be counted rather than three-fifths, the Southern states would dramatically increase their power in the population-based House of Representatives.[92] Republicans hoped to offset this advantage by attracting and protecting votes of the newly enfranchised black population.[92][93] They would eventually attempt to address this issue in section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Political and economic change in the South

Southern culture remained deeply racist, and those blacks who remained faced a dangerous situation. J. J. Gries reported to the Joint Committee on Reconstruction: "There is a kind of innate feeling, a lingering hope among many in the South that slavery will be regalvanized in some shape or other. They tried by their laws to make a worse slavery than there was before, for the freedman has not the protection which the master from interest gave him before."[94] W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in 1935:

Slavery was not abolished even after the Thirteenth Amendment. There were four million freedmen and most of them on the same plantation, doing the same work they did before emancipation, except as their work had been interrupted and changed by the upheaval of war. Moreover, they were getting about the same wages and apparently were going to be subject to slave codes modified only in name. There were among them thousands of fugitives in the camps of the soldiers or on the streets of the cities, homeless, sick, and impoverished. They had been freed practically with no land nor money, and, save in exceptional cases, without legal status, and without protection.[95][96]

Official emancipation did not substantially alter the economic situation of most blacks who remained in the south.[97]

As the amendment still permitted labor as punishment for convicted criminals, Southern states responded with what historian Douglas A. Blackmon called "an array of interlocking laws essentially intended to criminalize black life".[98] These laws, passed or updated after emancipation, were known as Black Codes.[99] Mississippi was the first state to pass such codes, with an 1865 law titled "An Act to confer Civil Rights on Freedmen".[100] The Mississippi law required black workers to contract with white farmers by January 1 of each year or face punishment for vagrancy.[98] Blacks could be sentenced to forced labor for crimes including petty theft, using obscene language, or selling cotton after sunset.[101] States passed new, strict vagrancy laws that were selectively enforced against blacks without white protectors.[98][102] The labor of these convicts was then sold to farms, factories, lumber camps, quarries, and mines.[103]

After its ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in November 1865, the South Carolina legislature immediately began to legislate Black Codes.[104] The Black Codes created a separate set of laws, punishments, and acceptable behaviors for anyone with more than one black great-grandparent. Under these Codes, Blacks could only work as farmers or servants and had few Constitutional rights.[105] Restrictions on black land ownership threatened to make economic subservience permanent.[38]

Some states mandated indefinitely long periods of child "apprenticeship".[106] Some laws did not target blacks specifically, but instead affected farm workers, most of whom were black. At the same time, many states passed laws to actively prevent blacks from acquiring property.[107]

Congressional and executive enforcement

As its first enforcement legislation, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, guaranteeing black Americans citizenship and equal protection of the law, though not the right to vote. The amendment was also used as authorizing several Freedmen's Bureau bills. President Andrew Johnson vetoed these bills, but Congress overrode his vetoes to pass the Civil Rights Act and the Second Freedmen's Bureau Bill.[108][109]

Proponents of the Act, including Trumbull and Wilson, argued that Section 2 of the Thirteenth Amendment authorized the federal government to legislate civil rights for the States. Others disagreed, maintaining that inequality conditions were distinct from slavery.[25]: 1788–1790 Seeking more substantial justification, and fearing that future opponents would again seek to overturn the legislation, Congress and the states added additional protections to the Constitution: the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) defining citizenship and mandating equal protection under the law, and the Fifteenth Amendment (1870) banning racial voting restrictions.[110]

The Freedmen's Bureau enforced the amendment locally, providing a degree of support for people subject to the Black Codes.[111] Reciprocally, the Thirteenth Amendment established the Bureau's legal basis to operate in Kentucky.[112] The Civil Rights Act circumvented racism in local jurisdictions by allowing blacks access to the federal courts. The Enforcement Acts of 1870–1871 and the Civil Rights Act of 1875, in combating the violence and intimidation of white supremacy, were also part of the effort to end slave conditions for Southern blacks.[113] However, the effect of these laws waned as political will diminished and the federal government lost authority in the South, particularly after the Compromise of 1877 ended Reconstruction in exchange for a Republican presidency.[114]

Peonage law

Southern business owners sought to reproduce the profitable arrangement of slavery with a system called peonage, in which disproportionately black workers were entrapped by loans and compelled to work indefinitely due to the resulting debt.[115][116] Peonage continued well through Reconstruction and ensnared a large proportion of black workers in the South.[117] These workers remained destitute and persecuted, forced to work dangerous jobs and further confined legally by the racist Jim Crow laws that governed the South.[116] Peonage differed from chattel slavery because it was not strictly hereditary and did not allow the sale of people in exactly the same fashion. However, a person's debt—and by extension a person—could still be sold, and the system resembled antebellum slavery in many ways.[118]

Slavery in New Mexico also continued de facto in the form of peonage, which became a Spanish colonial tradition to work around the prohibition of hereditary slavery by the New Laws of 1542. Though this practice was rendered unconstitutional by the Thirteenth Amendment, enforcement was lax. The Peonage Act of 1867 specifically mentioned New Mexico and increased enforcement by banning nationwide "the holding of any person to service or labor under the system known as peonage",[119] specifically banning "the voluntary or involuntary service or labor of any persons as peons, in liquidation of any debt or obligation, or otherwise."[120]

In 1939, the United States Department of Justice created the Civil Rights Section, which focused primarily on First Amendment and labor rights.[121] The increasing scrutiny of totalitarianism in the lead-up to World War II brought increased attention to issues of slavery and involuntary servitude, abroad and at home.[122] The U.S. sought to counter foreign propaganda and increase its credibility on the race issue by combatting the Southern peonage system.[123] Under the leadership of Attorney General Francis Biddle, the Civil Rights Section invoked the constitutional amendments and legislation of the Reconstruction Era as the basis for its actions.[124]

In 1947, the DOJ successfully prosecuted Elizabeth Ingalls for keeping domestic servant Dora L. Jones in conditions of slavery. The court found that Jones "was a person wholly subject to the will of defendant; that she was one who had no freedom of action and whose person and services were wholly under the control of defendant and who was in a state of enforced compulsory service to the defendant."[125] The Thirteenth Amendment enjoyed a swell of attention during this period, but from Brown v. Board of Education (1954) until Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co. (1968) it was again eclipsed by the Fourteenth Amendment.[126]

Penal labor exemption

The Thirteenth Amendment exempts penal labor from its prohibition of forced labor. This allows prisoners who have been convicted of crimes (not those merely awaiting trial) to be required to perform labor or else face punishment while in custody.[127]

Few records of the committee's deliberations during the drafting of the Thirteenth Amendment survive, and the debate that followed both in Congress and in the state legislatures featured almost no discussion of this provision. It was apparently considered noncontroversial at the time, or at least legislators gave it little thought.[127] The drafters based the amendment's phrasing on the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which features an identical exception.[127] Thomas Jefferson authored an early version of that ordinance's anti-slavery clause, including the exception of punishment for a crime, and also sought to prohibit slavery in general after 1800. Jefferson was an admirer of the works of Italian criminologist Cesare Beccaria.[127] Beccaria's On Crimes and Punishments suggested that the death penalty should be abolished and replaced with a lifetime of enslavement for the worst criminals; Jefferson likely included the clause due to his agreement with Beccaria. Beccaria, while attempting to reduce "legal barbarism" of the 1700s, considered forced labor one of the few harsh punishments acceptable; for example, he advocated slave labor as a just punishment for robbery, so that the thief's labor could be used to pay recompense to their victims and to society.[129] Penal "hard labor" has ancient origins, and was adopted early in American history (as in Europe) often as a substitute for capital or corporal punishment.[130]

Various commentators have accused states of abusing this provision to re-establish systems similar to slavery,[131] or of otherwise exploiting such labor in a manner unfair to local labor. The Black Codes in the South criminalized "vagrancy", which was largely enforced against freed slaves. Later, convict lease programs in the South allowed local plantations to rent inexpensive prisoner labor.[132] While many of these programs have been phased out (leasing of convicts was forbidden by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1941), prison labor continues in the U.S. under a variety of justifications. Prison labor programs vary widely; some are uncompensated prison maintenance tasks, some are for local government maintenance tasks, some are for local businesses, and others are closer to internships. Modern rationales for prison labor programs often include reduction of recidivism and re-acclimation to society; the idea is that such labor programs will make it easier for the prisoner upon release to find gainful employment rather than relapse to criminality. However, this topic is not well-studied, and much of the work offered is so menial as to be unlikely to improve employment prospects.[133] As of 2017, most prison labor programs do compensate prisoners, but generally with very low wages. What wages they do earn are often heavily garnished, with as much as 80% of a prisoner's paycheck withheld in the harshest cases.[134]

In 2018, artist and entertainer Kanye West advocated for repealing the Thirteenth Amendment's exception for penal labor in a meeting with President Donald Trump, calling the exception a "trap door".[135] In late 2020, Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR) and Representative William Lacy Clay (D-MO) introduced a resolution to create a new amendment to close this loophole.[136][137]

Judicial interpretation

In contrast to the other "Reconstruction Amendments", the Thirteenth Amendment was rarely cited in later case law. As historian Amy Dru Stanley summarizes, "beyond a handful of landmark rulings striking down debt peonage, flagrant involuntary servitude, and some instances of race-based violence and discrimination, the Thirteenth Amendment has never been a potent source of rights claims."[138][139]

Black slaves and their descendants

United States v. Rhodes (1866),[140] one of the first Thirteenth Amendment cases, tested the constitutionality of provisions in the Civil Rights Act of 1866 that granted blacks redress in the federal courts. Kentucky law prohibited blacks from testifying against whites—an arrangement which compromised the ability of Nancy Talbot ("a citizen of the United States of the African race") to reach justice against a white person accused of robbing her. After Talbot attempted to try the case in federal court, the Kentucky Supreme Court ruled this federal option unconstitutional. Noah Swayne (a Supreme Court justice sitting on the Kentucky Circuit Court) overturned the Kentucky decision, holding that without the material enforcement provided by the Civil Rights Act, slavery would not truly be abolished.[141][142] With In Re Turner (1867), Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase ordered freedom for Elizabeth Turner, a former slave in Maryland who became indentured to her former master.[143]

In Blyew v. United States, (1872)[144] the Supreme Court heard another Civil Rights Act case relating to federal courts in Kentucky. John Blyew and George Kennard were white men visiting the cabin of a black family, the Fosters. Blyew apparently became angry with sixteen-year-old Richard Foster and hit him twice in the head with an ax. Blyew and Kennard killed Richard's parents, Sallie and Jack Foster, and his blind grandmother, Lucy Armstrong. They severely wounded the Fosters' two young daughters. Kentucky courts would not allow the Foster children to testify against Blyew and Kennard. Federal courts, authorized by the Civil Rights Act, found Blyew and Kennard guilty of murder. The Supreme Court ruled that the Foster children did not have standing in federal courts because only living people could take advantage of the Act. In doing so, the Courts effectively ruled that the Thirteenth Amendment did not permit a federal remedy in murder cases. Swayne and Joseph P. Bradley dissented, maintaining that in order to have meaningful effects, the Thirteenth Amendment would have to address systemic racial oppression.[145]

The Blyew case set a precedent in state and federal courts that led to the erosion of Congress's Thirteenth Amendment powers. The Supreme Court continued along this path in the Slaughter-House Cases (1873), which upheld a state-sanctioned monopoly of white butchers. In United States v. Cruikshank (1876), the Court ignored Thirteenth Amendment dicta from a circuit court decision to exonerate perpetrators of the Colfax massacre and invalidate the Enforcement Act of 1870.[113]

The Thirteenth Amendment is not solely a ban on chattel slavery; it also covers a much broader array of labor arrangements and social deprivations.[147][148] As the U.S. Supreme Court explicated in the Slaughter-House Cases with respect to the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendment, and the Thirteenth Amendment in particular:

Undoubtedly while negro slavery alone was in the mind of the Congress which proposed the thirteenth article, it forbids any other kind of slavery, now or hereafter. If Mexican peonage or the Chinese coolie labor system shall develop slavery of the Mexican or Chinese race within our territory, this amendment may safely be trusted to make it void. And so if other rights are assailed by the States which properly and necessarily fall within the protection of these articles, that protection will apply, though the party interested may not be of African descent. But what we do say, and what we wish to be understood is, that in any fair and just construction of any section or phrase of these amendments, it is necessary to look to the purpose which we have said was the pervading spirit of them all, the evil which they were designed to remedy, and the process of continued addition to the Constitution, until that purpose was supposed to be accomplished, as far as constitutional law can accomplish it.[149]

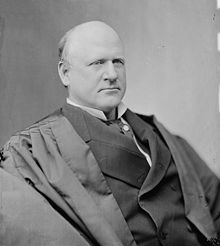

In the Civil Rights Cases (1883),[150] the Supreme Court reviewed five consolidated cases dealing with the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which outlawed racial discrimination at "inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement". The Court ruled that the Thirteenth Amendment did not ban most forms of racial discrimination by non-government actors.[151] In the majority decision, Bradley wrote (again in non-binding dicta) that the Thirteenth Amendment empowered Congress to attack "badges and incidents of slavery". However, he distinguished between "fundamental rights" of citizenship, protected by the Thirteenth Amendment, and the "social rights of men and races in the community".[152] The majority opinion held that "it would be running the slavery argument into the ground to make it apply to every act of discrimination which a person may see fit to make as to guests he will entertain, or as to the people he will take into his coach or cab or car; or admit to his concert or theatre, or deal with in other matters of intercourse or business."[153] In his solitary dissent, John Marshall Harlan (a Kentucky lawyer who changed his mind about civil rights law after witnessing organized racist violence) argued that "such discrimination practiced by corporations and individuals in the exercise of their public or quasi-public functions is a badge of servitude, the imposition of which congress may prevent under its power."[154]

The Court in the Civil Rights Cases also held that appropriate legislation under the amendment could go beyond nullifying state laws establishing or upholding slavery, because the amendment "has a reflex character also, establishing and decreeing universal civil and political freedom throughout the United States" and thus Congress was empowered "to pass all laws necessary and proper for abolishing all badges and incidents of slavery in the United States."[150] The Court stated about the amendment's scope:

This amendment, as well as the Fourteenth, is undoubtedly self-executing, without any ancillary legislation, so far as its terms are applicable to any existing state of circumstances. By its own unaided force and effect, it abolished slavery and established universal freedom. Still, legislation may be necessary and proper to meet all the various cases and circumstances to be affected by it, and to prescribe proper modes of redress for its violation in letter or spirit. And such legislation may be primary and direct in its character, for the amendment is not a mere prohibition of State laws establishing or upholding slavery, but an absolute declaration that slavery or involuntary servitude shall not exist in any part of the United States.[150]

Attorneys in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)[155] argued that racial segregation involved "observances of a servile character coincident with the incidents of slavery", in violation of the Thirteenth Amendment. In their brief to the Supreme Court, Plessy's lawyers wrote that "distinction of race and caste" was inherently unconstitutional.[156] The Supreme Court rejected this reasoning and upheld state laws enforcing segregation under the "separate but equal" doctrine. In the (7–1) majority decision, the Court found that "a statute which implies merely a legal distinction between the white and colored races—a distinction which is founded on the color of the two races and which must always exist so long as white men are distinguished from the other race by color—has no tendency to destroy the legal equality of the two races, or reestablish a state of involuntary servitude."[157] Harlan dissented, writing: "The thin disguise of 'equal' accommodations for passengers in railroad coaches will not mislead anyone, nor, atone for the wrong this day done."[158]

In Robertson v. Baldwin, 165 U.S. 275 (1897) the Court laid out the scope and exceptions of the Thirteenth Amendment:

The prohibition of slavery in the Thirteenth Amendment is well known to have been adopted with reference to a state of affairs which had existed in certain states of the Union since the foundation of the government, while the addition of the words "involuntary servitude" were said, in the Slaughter-House Cases, 16 Wall. 36, to have been intended to cover the system of Mexican peonage and the Chinese coolie trade, the practical operation of which might have been a revival of the institution of slavery under a different and less offensive name. It is clear, however, that the amendment was not intended to introduce any novel doctrine with respect to certain descriptions of service which have always been treated as exceptional, such as military and naval enlistments, or to disturb the right of parents and guardians to the custody of their minor children or wards. The amendment, however, makes no distinction between a public and a private service. To say that persons engaged in a public service are not within the amendment is to admit that there are exceptions to its general language, and the further question is at once presented, where shall the line be drawn? We know of no better answer to make than to say that services which have from time immemorial been treated as exceptional shall not be regarded as within its purview.[159]

In Hodges v. United States (1906),[160] the Court struck down a federal statute providing for the punishment of two or more people who "conspire to injure, oppress, threaten or intimidate any citizen in the free exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege secured to him by the Constitution or laws of the United States". A group of white men in Arkansas conspired to violently prevent eight black workers from performing their jobs at a lumber mill; the group was convicted by a federal grand jury. The Supreme Court ruled that the federal statute, which outlawed conspiracies to deprive citizens of their liberty, was not authorized by the Thirteenth Amendment. It held that "no mere personal assault or trespass or appropriation operates to reduce the individual to a condition of slavery." Harlan dissented, maintaining his opinion that the Thirteenth Amendment should protect freedom beyond "physical restraint".[161] Corrigan v. Buckley (1922) reaffirmed the interpretation from Hodges, finding that the amendment does not apply to restrictive covenants.

Enforcement of federal civil rights law in the South created numerous peonage cases, which slowly traveled up through the judiciary. The Supreme Court ruled in Clyatt v. United States (1905) that peonage was involuntary servitude. It held that although employers sometimes described their workers' entry into contract as voluntary, the servitude of peonage was always (by definition) involuntary.[162]

In Bailey v. Alabama the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed its holding that the Thirteenth Amendment is not solely a ban on chattel slavery, it also covers a much broader array of labor arrangements and social deprivations.[147][148] In addition to the aforesaid the Court also ruled on Congress enforcement power under the Thirteenth Amendment. The Court said:

The plain intention [of the amendment] was to abolish slavery of whatever name and form and all its badges and incidents; to render impossible any state of bondage; to make labor free, by prohibiting that control by which the personal service of one man is disposed of or coerced for another's benefit, which is the essence of involuntary servitude. While the Amendment was self-executing, so far as its terms were applicable to any existing condition, Congress was authorized to secure its complete enforcement by appropriate legislation.[163]

Jones and beyond

Legal histories cite Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co. (1968) as a turning point of Thirteen Amendment jurisprudence.[164][165] The Supreme Court confirmed in Jones that Congress may act "rationally" to prevent private actors from imposing "badges and incidents of servitude".[164][166] The Joneses were a black couple in St. Louis County, Missouri, who sued a real estate company for refusing to sell them a house. The Court held:

Congress has the power under the Thirteenth Amendment rationally to determine what are the badges and the incidents of slavery, and the authority to translate that determination into effective legislation. ... this Court recognized long ago that, whatever else they may have encompassed, the badges and incidents of slavery—its "burdens and disabilities"—included restraints upon "those fundamental rights which are the essence of civil freedom, namely, the same right ... to inherit, purchase, lease, sell and convey property, as is enjoyed by white citizens." Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 109 U. S. 22.[167]

Just as the Black Codes, enacted after the Civil War to restrict the free exercise of those rights, were substitutes for the slave system, so the exclusion of Negroes from white communities became a substitute for the Black Codes. And when racial discrimination herds men into ghettos and makes their ability to buy property turn on the color of their skin, then it too is a relic of slavery.

Negro citizens, North and South, who saw in the Thirteenth Amendment a promise of freedom—freedom to "go and come at pleasure" and to "buy and sell when they please"—would be left with "a mere paper guarantee" if Congress were powerless to assure that a dollar in the hands of a Negro will purchase the same thing as a dollar in the hands of a white man. At the very least, the freedom that Congress is empowered to secure under the Thirteenth Amendment includes the freedom to buy whatever a white man can buy, the right to live wherever a white man can live. If Congress cannot say that being a free man means at least this much, then the Thirteenth Amendment made a promise the Nation cannot keep.[168]

The Court in Jones reopened the issue of linking racism in contemporary society to the history of slavery in the United States.[169]

Прецедент Джонса использовался для оправдания действий Конгресса по защите рабочих-мигрантов и борьбе с торговлей людьми в целях сексуальной эксплуатации. [170] The direct enforcement power found in the Thirteenth Amendment contrasts with that of the Fourteenth, which allows only responses to institutional discrimination of state actors.[171] Верховный суд в деле Джонса заявил в отношении действия Тринадцатой поправки: «Тринадцатая поправка» — это не просто запрет законов штата, устанавливающих или поддерживающих рабство, но абсолютное заявление о том, что рабство или принудительное подневольное состояние не должны существовать ни в какой части территории. , Дела о гражданских правах 109 US 3, 109 US 20. Поэтому никогда не подвергалось сомнению, что «полномочия, предоставленные Конгрессу для обеспечения соблюдения этой статьи посредством соответствующего законодательства», там же , включают в себя полномочия принимать законы. «прямое и первичное, действующее на действия отдельных лиц, независимо от того, санкционированы ли они законодательством штата или нет, в 109 США, 23» . [172]

Другие случаи принудительного рабства

Верховный суд особенно узко относится к искам о принудительном рабстве, предъявляемым людьми, не происходящими от черных (африканских) рабов. В деле Робертсон против Болдуина (1897 г.) группа моряков торгового флота оспорила федеральные законы, которые устанавливали уголовную ответственность за неисполнение моряком контрактного срока службы. Суд постановил, что контракты моряков с незапамятных времен считались уникальными и что «поправка не имела целью введение какой-либо новой доктрины в отношении определенных видов службы, которые всегда считались исключительными». В этом случае, как и во многих случаях «значков и инцидентов», судья Харлан выразил несогласие в пользу более широкой защиты Тринадцатой поправкой. [173]

В делах, посвященных выборочным законопроектам , [174] Верховный суд постановил, что призыв в армию не является «принудительным рабством». В деле Соединенные Штаты против Козьминского , [175] Верховный суд постановил, что Тринадцатая поправка не запрещает принуждение к подневольному труду посредством психологического принуждения. [176] [177] Козьминский определил принудительное подневольное состояние для целей уголовного преследования как «состояние подневольного труда, при котором жертву принуждают работать на обвиняемого путем применения или угрозы физического сдерживания или телесных повреждений, либо путем применения или угрозы принуждения посредством закона или правовых норм». Это определение охватывает дела, в которых обвиняемый удерживает жертву в рабстве, подвергая ее или ее страху перед таким физическим ограничением, нанесением телесных повреждений или юридическим принуждением». [175]

по Апелляционные суды США делам Иммедиато против школьного округа Рай-Нек , Херндон против Чапел-Хилл и Штайрер против школьного округа Вифлеема постановили, что использование общественных работ в качестве требования для окончания средней школы не нарушает Тринадцатую поправку. [178]

Предыдущие предложенные Тринадцатые поправки

В течение шести десятилетий после ратификации Двенадцатой поправки в 1804 году два предложения о внесении поправок в Конституцию были приняты Конгрессом и отправлены штатам на ратификацию. Ни один из них не был ратифицирован количеством штатов, необходимым для того, чтобы стать частью Конституции. каждая из них упоминается как Статья Тринадцатая , как и успешная Тринадцатая поправка В совместной резолюции, принятой Конгрессом, .

- ( Поправка о дворянских титулах находящаяся на рассмотрении штатов с 1 мая 1810 года) в случае ратификации лишит гражданства титул любого гражданина Соединенных Штатов, который примет дворянский или почетный титул из иностранного государства без согласия Конгресса. [179]

- Поправка Корвина (находящаяся на рассмотрении штатов со 2 марта 1861 г.) в случае ратификации защитит «внутренние институты» штатов (в 1861 г. это был обычный эвфемизм для обозначения рабства) от процесса внесения поправок в конституцию , а также от отмены или вмешательства Конгресса. . [180] [181]

См. также

- Криттенденский компромисс

- Конец рабства в США

- История несвободного труда в США

- История рабства в США по штатам

- Список поправок к Конституции США

- Брак порабощенных людей (США)

- День национальной свободы

- Законы о работорговле

- Закон об отмене рабства 1833 года в Соединенном Королевстве

- Трудовое право США

Фильмы

Ссылки

Цитаты

- ^ «13-я поправка» . Институт правовой информации . Юридический факультет Корнеллского университета. 20 ноября 2012 года . Проверено 30 ноября 2012 г.

- ^ Кеннет М. Стэмпп (1980). Союз под угрозой: Очерки на фоне гражданской войны . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 85. ИСБН 9780199878529 .

- ^ Аллен, 2012 , стр. 116-117

- ^ Аллен, 2012 , стр. 119-120

- ^ Цесис, Тринадцатая поправка и американская свобода (2004), с. 14.

- ^ Фонер, 2010 , стр. 20–22.

- ^ Вайл, Джон Р., изд. (2003). «Тринадцатая поправка». Энциклопедия конституционных поправок, предлагаемых поправок и вопросов внесения поправок: 1789–2002 гг . АВС-КЛИО. стр. 449–52.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гудвин, 2005 , с. 123

- ^ Фонер, 2010 , с. 59

- ^ «Надвигающаяся буря: кризис отделения» . Американский фонд поля боя . 4 апреля 2017 года . Проверено 4 июля 2020 г.

- ^ «Прокламация об освобождении» . Национальное управление архивов и документации . Проверено 27 июня 2013 г.

- ^ Линд, Майкл, Во что верил Линкольн. Ценности и убеждения величайшего президента Америки (2004 г.). Anchor Books, подразделение Random House, Inc., Нью-Йорк. ISBN 1-4000-3073-0 , 978-1-4000-3073-6 . Глава шестая. Раса и восстановление , стр. 205-212.

- ^ Макферсон, 1988 , с. 558

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), с. 47.

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), с. 48–51.

- ^ Леонард Л. Ричардс, Кто освободил рабов?: борьбы за Тринадцатую поправку (2015) Отрывок из

- ^ «Джеймс Эшли» . Центральный исторический центр Огайо . Историческое общество Огайо.

- ^ Цесис, Тринадцатая поправка и американская свобода (2004), (2001), стр. 38–42.

- ^ Стэнли, «Вместо ожидания тринадцатой поправки» (2010), стр. 741–742.

- ^ Историческое общество штата Мичиган (1901). Исторические сборники . Мичиганская историческая комиссия. п. 582 . Проверено 5 декабря 2012 г.

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), стр. 52–53. «Самнер более ясно выразил свои намерения 8 февраля, когда он представил свою поправку к конституции Сенату и попросил передать ее в его новый комитет. Он настолько отчаянно пытался сделать свою поправку окончательной версией, что бросил вызов общепризнанному обычаю отправив предложенные поправки в Судебный комитет, его коллеги-республиканцы ничего об этом не услышали.

- ^ «Предложения Конгресса и принятие Сената». Архивировано 7 ноября 2006 г., в Wayback Machine , Harpers Weekly , The Creation of 13th Amendment , Проверено 15 февраля 2007 г.

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), с. 53. «Это не совпадение, что заявление Трамбулла прозвучало всего через два дня после того, как Самнер предложил свою поправку, делающую всех людей «равными перед законом». Сенатор Массачусетса подтолкнул комитет к окончательным действиям».

- ^ «Северо-Западный указ от 13 июля 1787 г.» . Проект Авалон . Юридическая библиотека Лилиан Голдман, Йельская школа права . Проверено 17 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д МакАрвард, Дженнифер Мейсон (ноябрь 2012 г.). « Маккаллох и Тринадцатая поправка» . Обзор права Колумбии . 112 (7). Юридическая школа Колумбийского университета : 1769–1809 гг. JSTOR 41708164 . Архивировано из оригинала 17 ноября 2015 г. PDF.

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), с. 54. «Хотя поправка Хендерсона стала основой окончательной поправки, комитет отклонил статью в версии Хендерсона, которая позволяла принять поправку путем одобрения всего лишь простого большинства в Конгрессе и ратификации только двумя третями голосов. государства».

- ^ «Просмотр голосования | Голосование по сюжету: 38-й Конгресс > Сенат > 134» . вотвотвью.com . Проверено 7 января 2023 г.

- ^ Гудвин, 2005 , с. 686

- ^ Гудвин, 2005 , стр. 624–25.

- ^ Фонер, 2010 , с. 299

- ^ Гудвин, 2005 , с. 639

- ^ Бенедикт, «Конституционная политика, конституционное право и Тринадцатая поправка» (2012), стр. 179.

- ^ Бенедикт, «Конституционная политика, конституционное право и Тринадцатая поправка» (2012), стр. 179–180. Бенедикт цитирует сенатора Гаррета Дэвиса : «Существует граница между властью революции и властью внесения поправок, которую последняя, как это установлено в нашей Конституции, не может перейти; и что, если предлагаемое изменение является революционным, оно будет недействительным». несмотря на это, оно может быть официально принято». Полный текст речи Дэвиса с комментариями других опубликован в книге «Великие дебаты в американской истории» (1918), изд. Мэрион Миллс Миллер.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кольбер, «Освобождение Тринадцатой поправки» (1995), стр. 10–11.

- ^ Бенедикт, «Конституционная политика, конституционное право и Тринадцатая поправка» (2012), стр. 182.

- ^ ТенБрук, Якобус (июнь 1951 г.). «Тринадцатая поправка к Конституции Соединенных Штатов: путь к отмене и ключ к четырнадцатой поправке» . Обзор законодательства Калифорнии . 39 (2): 180. дои : 10.2307/3478033 . JSTOR 3478033 .

Это позволило бы белым гражданам реализовать свое конституционное право в соответствии с пунктом о вежливости проживать в южных штатах независимо от их мнения. Он осуществит конституционную декларацию, «что каждый гражданин Соединенных Штатов должен иметь равные привилегии в любом другом штате». Он защитит права граждан в соответствии с Первой поправкой и пунктом о вежливости в отношении свободы слова, свободы прессы, свободы религии и свободы собраний

. - ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), с. 61.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Трелиз, Белый террор (1971), с. XVIII. «Негры хотели той же свободы, которой пользовались белые люди, с равными прерогативами и возможностями. Образованное черное меньшинство подчеркивало гражданские и политические права больше, чем массы, которые больше всего требовали земли и школ. из них знали, что землевладение ассоциируется со свободой, респектабельностью и хорошей жизнью. Чернокожие южане почти повсеместно желали этого, как и безземельные крестьяне во всем мире. «Дайте нам нашу землю, и мы сможем позаботиться о себе», — сказал один из них. группа негров из Южной Каролины северному журналисту в 1865 году: без земли старые хозяева могут нанять нас или морить голодом, как им заблагорассудится».

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), с. 73. «Первым заметным новообращенным был представитель Нью-Йорка Джеймс Брукс, который, выступая в Конгрессе 18 февраля 1864 года, заявил, что рабство умирает, если не уже умерло, и что его партия должна прекратить защищать этот институт».

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), с. 74. «Однако поправка против рабства привлекла внимание Джонсона, поскольку она предлагала неоспоримое конституционное решение проблемы рабства».

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), с. 203.

- ^ «Репутация Авраама Линкольна» . C-SPAN.org .

- ^ Фонер, 2010 , стр. 312–14.

- ^ Дональд, 1996 , с. 396

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), с. 48. «Президент беспокоился, что поправка об отмене смертной казни может засорить политическую воду. Поправки, которые он рекомендовал в декабре 1862 года, ни к чему не привели, главным образом потому, что они отражали устаревшую программу постепенной эмансипации, которая включала компенсацию и колонизацию. Более того, Линкольн знал, что ему не нужно было предлагать поправки, потому что это сделали бы другие, более приверженные отмене смертной казни, особенно если бы он указывал на уязвимость существующего законодательства об эмансипации. Он также был обеспокоен негативной реакцией со стороны консерваторов, особенно потенциальных новых рекрутов от демократов».

- ^ Уиллис, Джон К. «Платформа Республиканской партии, 1864 год» . Университет Юга. Архивировано из оригинала 29 марта 2013 года . Проверено 28 июня 2013 г.

Решено, что, поскольку рабство было причиной и теперь составляет силу этого Восстания, и поскольку оно должно быть всегда и везде враждебно принципам республиканского правительства, справедливость и национальная безопасность требуют его полного и полного искоренения на земле. Республики; и что, хотя мы поддерживаем и поддерживаем акты и прокламации, которыми правительство в свою защиту нанесло смертельный удар этому гигантскому злу, мы, кроме того, выступаем за такую поправку к Конституции, которая должна быть сделана народа в соответствии с его положениями, а также положить конец и навсегда запретить существование рабства в пределах юрисдикции Соединенных Штатов.

- ^ «1864: Выборы во время гражданской войны» . Выйдите из голосования . Корнелльский университет. 2004 . Проверено 28 июня 2013 г.

Несмотря на внутрипартийные конфликты, республиканцы сплотились вокруг платформы, поддерживающей восстановление Союза и отмену рабства.

- ^ Гудвин, 2005 , стр. 686–87.

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), с. 176–177, 180.

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), с. 178.

- ^ Фонер, 2010 , стр. 312–13.

- ^ Гудвин, 2005 , с. 687

- ^ Гудвин, 2005 , стр. 687–689.

- ^ Дональд, 1996 , с. 554

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), с. 187. «Но самым явным признаком голоса народа против рабства, утверждали сторонники поправки, были недавние выборы. Следуя примеру Линкольна, представители республиканцев, такие как Годлав С. Орт из Индианы, заявили, что голосование представляет собой «народный вердикт … в безошибочном виде». языка» в пользу поправки».

- ^ Гудвин, 2005 , с. 688

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), с. 191. «Необходимость поддерживать достаточно широкую поддержку поправки, чтобы обеспечить ее принятие, создала странную ситуацию. Поправка, касающаяся исключительно свободы афроамериканцев, таким образом, придала свободе в соответствии с поправкой против рабства расплывчатую концепцию: свобода была чем-то большим, чем отсутствие рабства движимого имущества, но меньшим, чем абсолютное равенство».

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), стр. 191–192. «Одним из наиболее эффективных методов, используемых сторонниками поправки, чтобы передать консервативный характер меры, было провозглашение постоянства патриархальной власти внутри американской семьи перед лицом этого или любого текстуального изменения Конституции. В ответ демократам, которые утверждали, что борьба с рабством была лишь первым шагом в республиканском замысле разрушить все основы общества, включая иерархическую структуру семьи. Республиканец из Айовы Джон А. Кассон отрицал любое желание вмешиваться в «права мужа на жену» или «права мужа на жену». право отца на своего ребенка».

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), стр. 197–198.

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), с. 198. «Именно в этот момент президент начал действовать в защиту поправки [...] Теперь он стал более решительным. Одному представителю, чей брат погиб на войне, Линкольн сказал: «Твой брат умер, чтобы спасти Республику от гибели в результате восстания рабовладельцев. Я бы хотел, чтобы вы считали своим долгом проголосовать за поправку к Конституции, прекращающую рабство . »

- ^ «ПРОДАТЬ SJ РЕЗ. 16. (Стр. 531-2)» . GovTrack.us .

- ^ Фонер, 2010 , с. 313

- ^ Фонер, 2010 , с. 314

- ^ Макферсон, 1988 , с. 840

- ^ Харрисон, «Законность поправок о реконструкции» (2001), стр. 389. «По причинам, которые никогда не были до конца ясны, поправка была представлена Президенту в соответствии с разделом 7 статьи I Конституции и подписана.

- ^ «Совместная резолюция о внесении 13-й поправки в Штаты; подписана Авраамом Линкольном и Конгрессом» . Документы Авраама Линкольна в Библиотеке Конгресса . Серия 3. Общая переписка. 1837–1897. 1 февраля 1865 года. Архивировано из оригинала 8 февраля 2022 года.

- ^ Торп, Конституционная история (1901), стр. 154. «Но многие считали, что подпись президента не является существенной для акта такого рода, и четвертого февраля сенатор Трамбалл предложил резолюцию, которая была согласована три дня спустя, о том, что одобрение не требуется Конституция; «что это противоречило ранее принятому решению Сената и Верховного суда и что отрицание президента, применимое только к обычным законодательным случаям, не имело ничего общего с предложениями о внесении поправок в Конституцию » » .

- ^ Торп, Конституционная история (1901), стр. 154. «Президент подписал совместную резолюцию первого февраля. Несколько любопытно, что подписание имеет только один прецедент, и это было по духу и цели полной противоположностью настоящему закону. Президент Бьюкенен подписал предложенную поправку 1861 года, которая сделало бы рабство национальным и вечным».

- ↑ Борьба Линкольна за проведение поправки через Конгресс и одновременное прекращение войны изображена в «Линкольне» .

- ^ Харрисон (2001), Законность поправок о реконструкции , стр. 390.

- ^ Сэмюэл Элиот Морисон (1965). Оксфордская история американского народа . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 710 .

- ^ Харрисон, «Законность поправок о реконструкции» (2001), стр. 394–397.

- ^ Эрик Л. Маккитрик (1960). Эндрю Джонсон и реконструкция . У. Чикаго Пресс. п. 178. ИСБН 9780195057072 .

- ^ Клара Милдред Томпсон (1915). Реконструкция в Грузии: экономическая, социальная, политическая, 1865–1872 гг . Издательство Колумбийского университета. п. 156 .

- ^ Воренберг (2001), Последняя свобода , стр. 227–228.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Воренберг (2001), Последняя свобода , с. 229.

- ^ Дюбуа (1935), Черная реконструкция , с. 208.

- ^ Торп (1901), Конституционная история , стр. 210.

- ^ Цесис (2004), Тринадцатая поправка и американская свобода , с. 48.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Типография правительства США, 112-й Конгресс, 2-я сессия, ДОКУМЕНТ СЕНАТА № 112–9 (2013 г.). «Анализ и интерпретация Конституции Соединенных Штатов Америки, промежуточное издание столетия столетия: анализ дел, решенных Верховным судом Соединенных Штатов до 26 июня 2013 года» (PDF) . п. 30 . Проверено 17 февраля 2014 г.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: несколько имен: список авторов ( ссылка ) CS1 maint: числовые имена: список авторов ( ссылка ) - ↑ Свидетельство Сьюарда, провозглашающее Тринадцатую поправку принятой как часть Конституции 6 декабря 1865 года.

- ^ Воренберг (2001), Последняя свобода , с. 232.

- ^ Кочер, Грег (23 февраля 2013 г.). «Кентукки поддержал усилия Линкольна по отмене рабства – с опозданием на 111 лет» . Лексингтон Геральд-Лидер . Архивировано из оригинала 20 февраля 2014 года . Проверено 17 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ Бен Уолдрон (18 февраля 2013 г.). «Миссисипи официально отменяет рабство и ратифицирует 13-ю поправку» . Новости Эй-Би-Си. Архивировано из оригинала 27 июня 2013 года . Проверено 23 апреля 2013 г.

- ^ Грин, Джамал; Мейсон МакАрвард, Дженнифер. «Конституционный закон. Тринадцатая поправка» . Национальный конституционный центр . 55 . дои : 10.2307/1071811 . JSTOR 1071811 . Проверено 4 июля 2020 г.

- ^ Лоуэлл Харрисон и Джеймс К. Клоттер, Новая история Кентукки , Университетское издательство Кентукки, 1997; п. 180 ; ISBN 9780813126210

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Форхенд, «Поразительное сходство» (1996), с. 82.

- ^ Хорнсби, Алан, изд. (2011). «Делавэр» . Черная Америка: Историческая энциклопедия по штатам . АВС-КЛИО. п. 139. ИСБН 9781573569767 .

- ^ Нил П. Шатлен (10 июля 2018 г.). «После 13-й поправки: прекращение рабства на территории Индии» .

- ^ Цесис, Тринадцатая поправка и американская свобода (2004), стр. 17 и 34.

- ^ «Тринадцатая поправка» , Основные документы по американской истории , Библиотека Конгресса. Проверено 15 февраля 2007 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Голдстоун 2011 , с. 22.

- ^ Нельсон, Уильям Э. (1988). Четырнадцатая поправка: от политического принципа к судебной доктрине . Издательство Гарвардского университета. п. 47. ИСБН 9780674041424 . Проверено 6 июня 2013 г.

- ^ Дж. Дж. Грис в Объединенном комитете по реконструкции , цитируется в Du Bois, Black Reconstruction (1935), p. 140.

- ^ Дюбуа, Черная реконструкция (1935), с. 188.

- ^ Цитируется по Воренбергу, Final Freedom (2001), с. 244.

- ^ Трелиз, Белый террор (1971), с. XVIII. «Правда, похоже, состоит в том, что после краткого восторга идеей свободы негры поняли, что их положение почти не изменилось; они продолжали жить и работать так же, как и раньше».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Блэкмон 2008 , с. 53.

- ^ Стромберг, «Простая народная перспектива» (2002), с. 111.

- ^ Новак, Колесо рабства (1978), с. 2.

- ^ Блэкмон 2008 , с. 100.

- ^ Цесис, Тринадцатая поправка и американская свобода (2004), стр. 51–52.

- ^ Блэкмон 2008 , с. 6.

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), стр. 230–231. «Черные кодексы были нарушением свободы договоров, одного из гражданских прав, которое республиканцы ожидали вытекать из поправки. Поскольку Южная Каролина и другие штаты ожидали, что республиканцы в Конгрессе попытаются использовать Тринадцатую поправку, чтобы объявить кодексы вне закона, они сделали упреждающий удар, заявивший в своих резолюциях о ратификации, что Конгресс не может использовать второй пункт поправки для принятия законов о гражданских правах освобожденных людей».

- ^ Бенджамин Гинзберг, Моисей из Южной Каролины: еврей-скалаваг во время радикальной реконструкции ; Джонс Хопкинс Пресс, 2010; стр. 44–46 .

- ^ Цесис, Тринадцатая поправка и американская свобода (2004), с. 50.

- ^ Цесис, Тринадцатая поправка и американская свобода (2004), с. 51.

- ^ Воренберг, Последняя свобода (2001), стр. 233–234.

- ^ WEB Дюбуа , « Бюро вольноотпущенников », The Atlantic , март 1901 г.

- ^ Голдстоун 2011 , стр. 23–24.

- ^ Цесис, Тринадцатая поправка и американская свобода (2004), стр. 50–51. «Чернокожие обращались к местным маршалам и в Бюро вольноотпущенников за помощью в борьбе с похищениями детей, особенно в тех случаях, когда детей забирали у живых родителей. Джек Принс просил помощи, когда женщина связала его племянницу по материнской линии. Салли Хантер просила помощи, чтобы добиться освобождения. из двух ее племянниц чиновники Бюро наконец положили конец системе контрактов в 1867 году».

- ^ Форхенд, «Поразительное сходство» (1996), с. 99–100, 105.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Цесис, Тринадцатая поправка и американская свобода (2004), с. 66–67.

- ^ Цесис, Тринадцатая поправка и американская свобода (2004), стр. 56–57, 60–61. «Если бы республиканцы надеялись постепенно использовать раздел 2 Тринадцатой поправки для принятия закона о реконструкции, они вскоре узнали бы, что президент Джонсон, используя свое право вето, будет все более затруднять принятие любой меры, увеличивающей власть национального правительства. Более того, со временем даже ведущие республиканцы, выступающие против рабства, станут менее непреклонными и более склонными к примирению с Югом, чем к защите прав недавно освобожденных. Это стало ясно к тому времени, когда Хорас Грили принял кандидатуру Демократической партии на пост президента в 1872 году и даже больше. когда президент Резерфорд Б. Хейс заключил Компромисс 1877 года, согласившись вывести федеральные войска с Юга».

- ^ Тобиас Баррингтон Вольф (май 2002 г.). «Тринадцатая поправка и рабство в мировой экономике» . Обзор права Колумбии . 102 (4). п. 981 в 973-1050 гг. дои : 10.2307/1123649 . JSTOR 1123649 . S2CID 155279033 .

Пеонаж был системой принудительного труда, которая зависела от задолженности рабочего, а не от фактического права собственности на раба, как средства принуждения к работе. Потенциальный работодатель предлагал работнику «ссуду» или «аванс» на его заработную плату, обычно в качестве условия трудоустройства, а затем использовал вновь созданный долг, чтобы заставить работника оставаться на работе столько, сколько пожелает работодатель.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вольф (2002). «Тринадцатая поправка и рабство в мировой экономике» . Обзор права Колумбии . 102 (4). п. 982(?). дои : 10.2307/1123649 . JSTOR 1123649 . S2CID 155279033 .

Неудивительно, что работодатели использовали систему рабства преимущественно в отраслях, связанных с вредными условиями труда и очень низкой оплатой труда. Хотя чернокожие рабочие не были единственными жертвами рабских отношений в Америке, они пострадали под его ярмом в непропорционально больших количествах. Наряду с законами Джима Кроу, которые разделяли транспорт и общественные учреждения, эти законы помогли ограничить передвижение освобожденных чернокожих рабочих и тем самым держать их в состоянии бедности и уязвимости.

- ^ Вольф (май 2002 г.). «Тринадцатая поправка и рабство в мировой экономике» . Обзор права Колумбии . 102 (4). п. 982. дои : 10.2307/1123649 . JSTOR 1123649 . S2CID 155279033 .

Юридически санкционированные механизмы рабства расцвели на Юге после Гражданской войны и продолжались и в двадцатом веке. По словам профессора Жаклин Джонс, «возможно, около одной трети всех [фермеров-издольщиков] в Алабаме, Миссисипи и Джорджии в 1900 году удерживались против их воли.

- ^ Вольф, «Тринадцатая поправка и рабство в глобальной экономике» (май 2002 г.), стр. 982. «Оно не признавало права собственности за человеком (пеон не мог быть продан на манер раба); и условие пеонажа не производило «растления крови» и проезда к детям рабочего Короче говоря, рабство не было рабством движимого имущества, однако эта практика, несомненно, воспроизводила многие из непосредственных практических реалий рабства — огромный низший класс рабочих, удерживаемых на своей работе силой закона и угрозой тюремного заключения, с небольшими возможностями для этого. побег."

- ^ Голубофф, «Утраченные истоки гражданских прав» (2001), с. 1638.