Шейх Муджибур Рахман

Отец нации Бангабандху Шейх Муджибур Рахман | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Шейх Муджибур Рахман | |||

Portrait, c. 1950 | |||

| President of Bangladesh | |||

| In office 25 January 1975 – 15 August 1975 | |||

| Prime Minister | Muhammad Mansur Ali | ||

| Preceded by | Mohammad Mohammadullah | ||

| Succeeded by | Khondaker Mostaq Ahmad (usurper)[a] | ||

| In office 17 April 1971 – 12 January 1972 | |||

| Prime Minister | Tajuddin Ahmed | ||

| Preceded by | Position established | ||

| Succeeded by | Abu Sayeed Chowdhury | ||

| Member of the Bangladesh Parliament for Dhaka-12 | |||

| In office 7 March 1972 – 15 August 1975 | |||

| Preceded by | Constituency established | ||

| Succeeded by | Jahangir Mohammad Adel | ||

| Prime Minister of Bangladesh | |||

| In office 12 January 1972 – 24 January 1975 | |||

| President |

| ||

| Preceded by | Tajuddin Ahmad | ||

| Succeeded by | Muhammad Mansur Ali | ||

| President of Bangladesh Awami League | |||

| In office 26 March 1971 – 18 January 1974 | |||

| General Secretary |

| ||

| Preceded by | Abdur Rashid Tarkabagish | ||

| Succeeded by | A. H. M Qamaruzzaman | ||

| |||

| Personal details | |||

| Born | 17 March 1920 Tungipara, Bengal Presidency, British India | ||

| Died | 15 August 1975 (aged 55) Dacca, Bangladesh | ||

| Manner of death | Assassination | ||

| Resting place | Mausoleum of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman | ||

| Nationality |

| ||

| Political party | Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (1975) | ||

| Other political affiliations |

| ||

| Spouse | Begum Fazilatunnesa | ||

| Children | |||

| Parents |

| ||

| Relatives | Tungipara Sheikh family | ||

| Residence | 10/32 Dhanmondi, Dhaka | ||

| Alma mater | |||

| Occupation |

| ||

| Awards | Joliot-Curie Medal of Peace Gandhi Peace Prize SAARC Literary Award | ||

| Signature | |||

| Nickname | Khoka | ||

| Independence of Bangladesh |

|---|

|

| Events |

| Organisations |

| Key persons |

| Related |

Шейх Муджибур Рахман [с] (17 марта 1920 - 15 августа 1975), широко известный под почетным префиксом Бангабандху. [д] ( букв. « Друг Бенгалии » ) — бангладешский политик, революционер, государственный деятель, активист и автор дневников . Как политик Муджиб постоянно занимал посты либо президента Бангладеш , либо премьер-министра с апреля 1971 года до своего убийства в августе 1975 года. [и] Муджиб успешно возглавил движение за независимость Бангладеш и восстановил суверенитет Бенгалии спустя более двух столетий после битвы при Плесси в 1757 году, за что в Бангладеш его почитают как « Отца нации ». [8] В 2011 году пятнадцатая поправка к конституции Бангладеш назвала шейха Муджиба отцом нации, провозгласившей независимость ; эти ссылки были закреплены в пятом, шестом и седьмом приложениях конституции. [9] Его бенгальскую националистическую идеологию, социально-политические теории и политические доктрины иногда называют муджибизмом .

Mujib emerged as a student activist in the province of Bengal during the final years of the British Raj. He was a member of the All India Muslim League. In 1949, Mujib was part of a liberal, secular and leftwing faction which later became the Awami League. In the 1950s, Mujib was elected to Pakistan's parliament where he defended the rights of East Bengal; wore suits and bowties; and was described as urbane and charming. By the 1960s, Mujib was transformed into the nationalist leader of East Pakistan, with his trademark Mujib coat and forceful oratory. He became popular for opposing political, ethnic and institutional discrimination; leading the 6-point autonomy movement; and challenging the regime of Field Marshal Ayub Khan. In 1970, Mujib led the Awami League to win Pakistan's first general election. When the Pakistani military junta refused to transfer power, he gave the 7th March speech and announced an independence movement. During the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, Mujib declared Bangladesh's independence. Bengali nationalists declared Mujib as the head of the Provisional Government of Bangladesh, while he was confined in a jail in West Pakistan. He returned to Bangladesh in January 1972 as a hero.

A populist of the 20th century, Sheikh Mujib was one of the most charismatic leaders of the Third World in the early 1970s. Mujib served more than 12 and a half years of his political life in prison during the British Raj and Pakistani rule.[10][11] He succeeded in normalizing diplomatic ties with most of the world, with a policy of friendship to all and malice to none. He signed a friendship treaty with India, joined the Commonwealth, NAM and the OIC, opposed apartheid and dispatched an army medical unit during the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. Mujib's legacies include the secularist Constitution of Bangladesh and the transformation of East Pakistan's state apparatus, bureaucracy, armed forces, and judiciary into an independent Bangladeshi state. He gave the first Bengali speech to the UN General Assembly in 1974. Mujib's five-year regime was also the only socialist period in Bangladesh's history. In 1975, Mujib installed a one party state which lasted for seven months until his assassination.

Mujib's legacy remains divisive among Bangladeshis due to his economic mismanagement, the Bangladesh famine of 1974, human rights violations, and authoritarianism. The Awami League has been accused of promoting a personality cult around Mujib. But most Bangladeshis credit Mujib for leading the country to independence in 1971.[12] In a 2004 BBC opinion poll, Mujib was voted as the Greatest Bengali of all time and ranked first on the list followed by Asia's first Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore (2nd) and Bangladeshi national poet Kazi Nazrul Islam (3rd).[13] Mujib's 7 March speech in 1971 is recognized by UNESCO for its historic value, and enshrined in the Memory of the World Register – Asia and the Pacific.[14] His diaries and travelogues were published many years after his death and have been translated into several languages.

Early life and background

Family and parents

Mujib was born on 17 March 1920 into the Bengali Muslim aristocratic Sheikh family of the village of Tungipara in Gopalganj sub-division of Faridpur district in the province of Bengal in British India.[15][16] His father Sheikh Lutfur Rahman was a sheristadar (law clerk) in the courthouse of Gopalganj; Mujib's mother Sheikh Sayera Khatun was a housewife. Mujib's father Sheikh Lutfur Rahman was a Taluqdar in Tungipara, owning landed property, around 100 Bighas of cultivable land.[17] His clan's ancestors were Zamindars of Faridpur Mahakumar, however due to successive turns in the family fortune over generations had turned them middle class.[18][19] The Sheikh clan of Tungipara were of Iraqi Arab descent, being descended from Sheikh Abdul Awal Darwish of Baghdad, who had come to preach Islam in the Mughal era.[20] His lineage is; Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, son of Sheikh Lutfar Rahman, son of Sheikh Abdul Hamid, son of Sheikh Mohammad Zakir, son of Sheikh Ekramullah, son of Sheikh Borhanuddin, son of Sheikh Jan Mahmud, son of Sheikh Zahiruddin, son of Sheikh Abdul Awal Darwish.[21] Mujib was the eldest son and third child in the family of four daughters (Fatima, Achia, Helen, Laili) and two sons (Mujib, Naser).[15] His parents nicknamed him "Khoka".[22]

Childhood

As a child, Mujib was described as "compassionate and very energetic". Either playing or roaming around. Feding birds, monkeys and dogs.[23] In his autobiography, Mujib mentions, "I used to play football, volleyball and hockey. Although I was not a very good player but still had a good position in the school team. At this time I was not interested in politics."[23] Once the farmers in his village lost their crops and faced a near-famine situation, which had a great impact on Mujib. During these days, he usually used to distribute rice among the poor farmers and students from his own or collecting from others.[23]

Mujib was enrolled in Gimadanga Primary School in 1927.[24] In 1929, he entered the third grade of Gopalganj Public School. His parents transferred him to Madaripur Islamia High School after two years.[25] Mujib withdrew from school in 1934 to undergo eye surgery. He returned to formal education after 4 years owing to the severity of the surgery and slow recovery.[26] Mujib was eighteen years old when he was married to eight years old Fazilatunnesa, widely known in Bangladesh as Begum Mujib, in an arranged marriage, according to the custom of the region at that time. They are second cousins.[27][28][29][30]

Mujib began showing signs of political leadership around this time. At the Gopalganj Missionary School, Mujib's political passion was noticed by Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, who was visiting the area along with A. K. Fazlul Huq. Mujib passed out from the Gopalganj Missionary School in 1942.[6]

United Bengal politics (1943–1947)

Mujib moved to Calcutta for higher education. At the time, Calcutta was the capital of British Bengal and the largest city in undivided India. He studied liberal arts, including political science,[6] at the erstwhile Islamia College of Calcutta and lived in Baker Hostel.[31][32] Islamia College was one of the leading educational institutions for the Muslims of Bengal. He obtained his bachelor's degree from the college in 1947.[15]

Muslim League activism

During his time in Calcutta, Sheikh Mujib became involved in the politics of the Bengal Provincial Muslim League, the All India Muslim Students Federation, the Indian independence movement and the Pakistan movement. In 1943, he was elected as a councillor of the Muslim League. In 1944, he was elected as secretary of the Faridpur District Association, a Calcutta-based association of residents from Faridpur. In 1946, at the height of the Pakistan movement, Mujib was elected as General Secretary of the Islamia College Students Union in Calcutta.[33] His political mentor Suhrawardy led the center-left faction of the Muslim League. Suhrawardy was responsible for creating 36 trade unions in Bengal, including unions for sailors, railway workers, jute and cotton mills workers, rickshaw pullers, cart drivers and other working class groups.[34] Mujib assisted Suhrawardy in these efforts and also worked to ensure protection for Muslim families during the violent days in the run up to partition.

United Bengal Movement

In 1947, Sheikh Mujib also joined the "United Bengal Movement" which was organized under the leadership of Suhrawardy, Abul Hashim, Sarat Chandra Bose and others to form an undivided independent Bengal outside the jurisdiction of India and Pakistan.[35] Later, when the creation of the states of India and Pakistan was confirmed, a referendum was held to decide the fate of the Bengali Muslim-dominated Sylhet District of Assam Province. Sheikh Mujib worked as an organizer and campaigner for inclusion in Pakistan in the Sylhet referendum. He went to Sylhet from Kolkata with about 500 workers. In his autobiography, he expressed his displeasure about the non-adherence of Karimganj to Pakistan despite winning the referendum and the various geographical inadequacies of East Pakistan during the demarcation of the partition.[36]

Student of law

After the partition of India, Mujib was admitted into the Law Department of the University of Dhaka. The university was created in 1921 as a residential university modelled on Oxford and Cambridge where students would be affiliated with colleges; but its residential character was dramatically changed after partition and students became affiliated with departments.[37][38] Mujib suffered repeated bouts of police detention due to his ability to instigate opposition protests against the Pakistani government. His political activities were targeted by the government and police. In 1949, Mujib was expelled from Dhaka University on charges of inciting employees against the university. After 61 years, in 2010, the university withdrew its famously politically motivated expulsion order.[15][39][40]

Struggle for Bengali rights (1948–1971)

Mujib emerged as a major opposition figure in Pakistani politics between 1948 and 1971. He represented the Bengali grassroots. He had an uncanny ability to remember people by their first name regardless of whether they were political leaders, workers, or ordinary citizens. Mujib founded the Muslim Students League on 4 January 1948 as the student wing of the Muslim League in East Bengal. This organisation later transformed into the Bangladesh Chhatra League. During the visit of Governor General Muhammad Ali Jinnah to Dhaka, it was declared that Urdu will be the sole national language of Pakistan. This sparked the Bengali Language Movement. Mujib became embroiled in the language movement, as well as left-wing trade unionism among Bengali factions of the Muslim League. Bengali factions eventually split away and formed the Awami Muslim League in 1949.

Mujib was arrested many times. His movements were tracked by spies of the Pakistani government. He was accused of being a secessionist and an agent of India. East Pakistan's Intelligence Branch compiled many secret reports on his movements and political activities. The secret documents have been declassified by the Bangladeshi government. The formerly classified reports have also been published.[41]

Founding of the Awami League

The All Pakistan Awami Muslim League was founded on 23 June 1949 at the Rose Garden mansion on K. M. Das Lane in Old Dhaka.[42] Sheikh Mujib was elected as one of its joint secretaries.[42] The term "Muslim" was later dropped from the party's nomenclature. The Awami League sought to represent both Muslims and Pakistan's religious minorities, including Bengali Hindus and Pakistani Christians. Hence, it dropped "Muslim" from its name to appeal to the minority votebanks. Suhrawardy joined the party within a few years and became its main leader. He relied on Sheikh Mujib to organise his political activities in East Bengal. Mujib became Suhrawardy's political protégé. Prior to partition, Suhrawardy mooted the idea of an independent United Bengal. But in Pakistan, Suhrawardy reportedly preferred to preserve the unity of Pakistan in a federal framework; while Mujib supported autonomy and was open to the idea of East Bengali independence. Mujib reportedly remarked that "[t]he Bengalis had initially failed to appreciate a leader of Mr. Suhrawardy's stature. By the time they learned to value him, they had run out of time".[43] At the federal level, the Awami League was led by Suhrawardy. At the provincial level, the League was led by Sheikh Mujib who was given a free rein over the party's activities by Suhrawardy. Mujib consolidated his control of the party. The Awami League veered away from the left-wing extremism of its founding president Maulana Bhashani. Under Suhrawardy and Mujib, the Awami League emerged as a centre-left party.

Language Movement

The Awami League strongly backed the Bengali Language Movement. Bengalis argued that the Bengali language deserved to be a federal language on par with Urdu because Bengalis formed the largest ethnic group in Pakistan. The movement appealed to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan to declare both Urdu and Bengali as national languages, in addition to English. During a conference in Fazlul Huq Muslim Hall, Sheikh Mujib was instrumental in establishing the All-Party State Language Action Committee.[44] He was repeatedly arrested during the movement. When he was released from jail in 1948, he was greeted by a rally of the State Language Struggle Committee.[45] Mujib announced a nationwide student strike on 17 March 1948.[46][47]

In early January 1950, the Awami League held an anti-famine rally in Dhaka during the visit of Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan. Mujib was arrested for instigating the protests. On 26 January 1952, Pakistan's then Bengali Prime Minister Khawaja Nazimuddin reiterated that Urdu will be the only state language. Despite his imprisonment, Mujib played a key role in organising protests by issuing instructions from jail to students and protestors. He played a key role in declaring 21 February 1952 as a strike day. Mujib went on hunger strike from 14 February 1952 in the prelude to the strike day. His own hunger strike lasted 13 days. On 26 February, he was released from jail amid the public outrage over police killings of protestors on 21 February, including Salam, Rafiq, Barkat, and Jabbar.[46][48][15][49][50][51]

United Front

The League teamed up with other parties like the Krishak Praja Party of A. K. Fazlul Huq to form the United Front coalition. During the East Bengali legislative election, 1954, Mujib was elected to public office for the first time. He became a member of the East Bengal Legislative Assembly. This was the first election in East Bengal since the partition of India in 1947. The Awami League-led United Front secured a landslide victory of 223 seats in the 237 seats of the provincial assembly. Mujib himself won by a margin of 13,000 votes against his Muslim League rival Wahiduzzaman in Gopalganj.[52] A. K. Fazlul Huq became Chief Minister and inducted Mujib into his cabinet. Mujib's initial portfolios were agriculture and forestry.[52] After taking oath on 15 May 1954, Chief Minister Huq travelled with ministers to India and West Pakistan. The coalition government was dismissed on 30 May 1954. Mujib was arrested upon his return to Dhaka from Karachi. He was released on 23 December 1954. Governor's rule was imposed in East Bengal.[53] The elected government was eventually restored in 1955.

On 5 June 1955, Mujib was elected to a newly reconstituted second Constituent Assembly of Pakistan. The Awami League organised a huge public meeting at Paltan Maidan in Dhaka on 17 June 1955 which outlined 21 points demanding autonomy for Pakistan's provinces. Mujib was a forceful orator at the assembly in Karachi. He opposed the government's plan to rename East Bengal as East Pakistan as part of the One Unit scheme. On 25 August 1955, he delivered the following speech.

Sir [President of the Constituent Assembly], you will see that they want to use the phrase 'East Pakistan' instead of 'East Bengal'. We have demanded many times that you should use Bengal instead of Pakistan. The word Bengal has a history and tradition of its own. You can change it only after the people have been consulted. If you want to change, we have to go back to Bengal and ask them whether they are ready to accept it. So far as the question of one unit is concerned it can be incorporated in the constitution. Why do you want it to be taken up right now? What about the state language, Bengali? We are prepared to consider one unit with all these things. So, I appeal to my friends on the other side to allow the people to give their verdict in any way, in the form of referendum or in the form of plebiscite.[54]

Mujib was often a vocal defender of human rights. Speaking on freedom of assembly and freedom of speech, he told Pakistan's parliament the following on 29 November 1955:-

For whom are you going to frame the Constitution? Are you going to give freedom of speech, freedom of action to the people of Pakistan? When you do not have any other law under which you can arrest a person, you haul him under this so-called Public Safety Act. This is the blackest Act on the statute book of Pakistan. I do not know how long such an Act will continue. I want to warn you. Sir, that you must do justice to all people without fear or favour. If justice fails, equity fails, fair-play fails, then we will see how the matter is decided.[55]

Mujib often called for increased recruitment and affirmative action in East Pakistan. Bengalis were under-represented in the civil and military services despite making up the largest ethnic group in the federation.[56] Mujib felt that Bengalis were being relegated to provincial jobs instead of federal jobs because most Bengalis could not afford to travel outside the province in spite of holding master's degrees and bachelor's degrees. A similar situation also prevailed under British rule when Bengali degree holders were employed mostly in the Bengal Civil Service instead of the pan-Indian civil service. In parliament, Mujib spoke about parity between East and West Pakistan on 4 February 1956 and said the following.

It was stated that at the time of partition there was only one I.C.S. officer in East Bengal and there were no Engineers. I say that Bengal with 16 per cent literacy has only such a meagre representation in the service. Sir, this fact must be realised that it costs an individual Rs. 200 to come from East Bengal to this place. If you recruit in East Bengal and give a job you will find a large number of people from East Bengal coming forward. There are such a large number of M.As. and B. As....... (Interruptions)....... Sir, my time has been spoiled.[55]

Mujib later became provincial minister of commerce and industries in the cabinet of Ataur Rahman Khan. These portfolios allowed Mujib to consolidate his popularity among the working class. The Awami League's demand for Bengali as a federal language was successfully implemented in the 1956 constitution, which declared Urdu, Bengali and English as national languages. East Bengal, however, was renamed East Pakistan. In 1957, Mujib visited the People's Republic of China. In 1958, he toured the United States as part of the State Department's International Visitor Leadership Program.[57][58] Mujib resigned from the provincial cabinet to work full time for the Awami League as a party organiser.[59]

Suhrawardy premiership

Between 1956 and 1957, Mujib's mentor Suhrawardy served as the 5th Prime Minister of Pakistan. Suhrawardy strengthened Pakistan's relations with the United States and China. Suhrawardy was a strong supporter of Pakistan's membership in SEATO and CENTO.[60] Suhrawardy's pro-Western foreign policy caused Maulana Bhashani to break away from the Awami League to form the National Awami Party, though Mujib remained loyal to Suhrawardy.

Mujib joined the Alpha Insurance Company in 1960. He continued to work in the insurance industry for many years.[61][62][63]

The 1958 Pakistani military coup ended Pakistan's first era of parliamentary democracy as Muhammad Ayub Khan, the commander-in-chief of the Pakistan Army, overthrew the Bengali president Iskandar Ali Mirza and abolished the 1956 constitution. Many politicians were imprisoned and disqualified from holding public office, including Mujib's mentor Suhrawardy.[64] A new constitution was introduced by Ayub Khan which curtailed universal suffrage and empowered electoral colleges to elect the country's parliament.[65][66]

Six point movement

Following Suhrawardy's death in 1963, Mujib became General Secretary of the All Pakistan Awami League with Nawabzada Nasrullah Khan as its titular president.[67][68] The 1962 constitution introduced a presidential republic.[69] Mujib was one of the key leaders to rally opposition to president Ayub Khan who enacted a system of electoral colleges to elect the country's parliament and president under a system known as "Basic Democracy".[70][65][71] Universal suffrage was curtailed as part of the Basic Democracy scheme.

Mujib supported opposition candidate Fatima Jinnah against Ayub Khan in the 1965 presidential election.[72] Fatima Jinnah, the sister of Pakistan's founder Muhammad Ali Jinnah, drew huge crowds in East Pakistan during her presidential campaign which was supported by the Combined Opposition Party, including the Awami League.[73] East Pakistan was the hotbed of opposition to the presidency of Ayub Khan.[74] Mujib became popular for voicing the grievances of the Bengali population, including under-representation in the military and central bureaucracy.[75] Despite generating most of Pakistan's export earnings and customs tax revenue, East Pakistan received a smaller budget allocation than West Pakistan.[76]

The 1965 war between India and Pakistan ended in stalemate. The Tashkent Declaration was domestically seen as giving away Pakistan's gains to India. Ayub Khan's foreign minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto resigned from the government,[77] formed the Pakistan Peoples Party, and exploited public discontent against the regime.

In 1965, Pakistan banned the works of Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore in state media.[78][79][80] Censorship in state media spurred Bengali civil society groups like Chhayanaut to preserve Bengali culture. When Ayub Khan compared Bengalis to beasts, the poet Sufia Kamal retorted that "If the people are beasts then as the President of the Republic, you are the king of the beasts".[81] The Daily Ittefaq led by Tofazzal Hossain voiced growing aspirations for democracy, autonomy, and nationalism. Economists in Dhaka University pointed to the massive reallocation of revenue to West Pakistan despite East Pakistan's role in generating most of Pakistan's export income. Rehman Sobhan paraphrased the two-nation theory into the two economies theory.[82][83][84][85] He argued that East and West Pakistan had two fundamentally distinct economies within one country.In 1966, Mujib put forward a 6-point plan at a national conference of opposition parties in Lahore.[15] The city of Lahore was chosen because of its symbolism as the place where the Lahore Resolution was adopted by the Muslim League in 1940. The six points called for abolishing the Basic Democracy scheme, restoring universal suffrage, devolving federal power to the provinces of East and West Pakistan, separate fiscal, monetary and trade policies for East and West Pakistan, and increased security spending for East Pakistan.[86]

- The constitution should provide for a Federation of Pakistan in its true sense based on the Lahore Resolution and the parliamentary form of government with supremacy of a legislature directly elected on the basis of universal adult franchise.

- The federal government should deal with only two subjects: defence and foreign affairs, and all other residuary subjects shall be vested in the federating states.

- Two separate, but freely convertible currencies for two wings should be introduced; or if this is not feasible, there should be one currency for the whole country, but effective constitutional provisions should be introduced to stop the flight of capital from East to West Pakistan. Furthermore, a separate banking reserve should be established and a separate fiscal and monetary policy be adopted for East Pakistan.

- The power of taxation and revenue collection shall be vested in the federating units and the federal center will have no such power. The Federation will be entitled to a share in the state taxes to meet its expenditures.

- There should be two separate accounts for the foreign exchange earnings of the two wings; the foreign exchange requirements of the federal government should be met by the two wings equally or in a ratio to be fixed; indigenous products should move free of duty between the two wings, and the constitution should empower the units to establish trade links with foreign countries.

- East Pakistan should have its own security force.

Mujib's points catalysed public support across East Pakistan, launching what historians have termed the six point movement – recognised as the turning point towards East and West Pakistan becoming two nations.[87][88] Mujib insisted on a federal democracy and obtained broad support from the Bengali population.[89][90] In 1966, Mujib was elected as President of the Awami League. Tajuddin Ahmad succeeded him as General Secretary.

Agartala Conspiracy Case

Mujib was arrested by the Pakistan Army and after two years in jail, an official sedition trial in a military court opened. During his imprisonment between 1967 and 1969, Mujib began to write his autobiography.[91] In what is widely known as the Agartala Conspiracy Case, Mujib and 34 Bengali military officers were accused by the government of colluding with Indian government agents in a scheme to divide Pakistan and threaten its unity, order and national security. The plot was alleged to have been planned in the city of Agartala in the bordering Indian state of Tripura.[15] The outcry and unrest over Mujib's arrest and the charge of sedition against him destabilised East Pakistan amidst large protests and strikes. Various Bengali political and student groups added demands to address the issues of students, workers and the poor, forming a larger "11-point plan". The government caved to the mounting pressure, dropped the charges on 22 February 1969 and unconditionally released Mujib the following day. He returned to East Pakistan as a public hero.[92] He was given a mass reception on 23 February, at the Ramna Race Course and conferred with the popular honorary title of Bangabandhu by Tofail Ahmed.[93] The term Bangabandhu means Friend of the Bengal in the Bengali language.[92] Several of Bengal's historic leaders were given similar honorary titles, including Sher-e-Bangla (Lion of Bengal) for A. K. Fazlul Huq, Deshbandhu (Friend of the Nation) for Chittaranjan Das, and Netaji (The Leader) for Subhash Chandra Bose.

1969 uprising and Round Table Conference

In 1969, President Ayub Khan convened a Round Table Conference with opposition parties to find a way out of the prevailing political impasse. A few days after his release from prison, Mujib flew to Rawalpindi to attend the Round Table Conference.[94] Mujib sought to bargain for East Pakistan's autonomy. Mujib was the most powerful opposition leader at the Round Table Conference. Ayub Khan shook hands with Mujib, whom Khan previously had imprisoned. Talking to British media, Mujib said "East Pakistan must get full regional autonomy. It must be self-sufficient in all respects. It must get its due share and legitimate share in the central administration. The West Pakistani people support [East Pakistani demands]. Only the vested interests want to divide the people of East and West Pakistan".[94] When asked about the prospect of East Pakistan ruling West Pakistan if the Awami League gained power, Mujib replied that majority rule is important in a democracy but the people of East Pakistan had no intention to discriminate against West Pakistan, and that West Pakistani parties would continue to play an important role.[94] Mujib toured West Pakistani cities by train after the Round Table Conference. West Pakistani crowds received him with chants of "Sheikh Saheb Zindabad!" (meaning Long Live the Sheikh!).[95] He was received by huge crowds in Quetta, Baluchistan. He spoke to West Pakistani crowds in a heavily Bengali accent of Urdu, talking about chhey nukati (six points) and hum chhoy dofa mangta sab ke liye.[95]

Mujib demanded that Pakistan accept his six-point plan for federal democracy. He wasn't satisfied by Ayub Khan's pledges. When he returned to Dhaka, he declared that East Pakistan should be known as Bangladesh. On 5 December 1969 Mujib made a declaration at a public meeting, held to observe the death anniversary of his mentor Suhrawardy, that henceforth East Pakistan would be called "Bangladesh":

There was a time when all efforts were made to erase the word "Bangla" from this land and its map. The existence of the word "Bangla" was found nowhere except in the term Bay of Bengal. I on behalf of Pakistan announce today that this land will be called "Bangladesh" instead of East Pakistan.[51]

Mujib's fiery rhetoric ignited Bengali nationalism and pro-independence aspirations among the masses, students, professionals, and intellectuals of East Pakistan. Many observers believed that Bengali nationalism was a rejection of Pakistan's founding two-nation theory but Mujib never phrased his rhetoric in these terms.[96] Mujib was able to galvanise support throughout East Pakistan, which was home to the majority of Pakistan's population. He became one of the most powerful political figures in the Indian subcontinent. Bengalis increasingly referred to him as Bangabandhu.

1970 election

In March 1969, Ayub Khan resigned and Yahya Khan became president. Prior to the scheduled general election for 1970, one of the most powerful cyclones on record devastated East Pakistan, leaving half a million people dead and millions displaced. President Yahya Khan, who was flying back from China after the cyclone, viewed the devastation from the air. The ruling military junta was slow to respond with relief efforts. Newspapers in East Pakistan accused the federal government of "gross neglect, callous inattention, and bitter indifference".[97] Mujib remarked that "We have a large army but it is left to the British Marines to bury our dead".[97] International aid had to pour in due to the slow response of the Pakistani military regime. Bengalis were outraged at what was widely considered to be the weak and ineffective response of the federal government to the disaster.[98][99] Public opinion and political parties in East Pakistan blamed the ruling military junta for the lack of relief efforts. The dissatisfaction led to divisions between East Pakistanis and West Pakistanis within the civil services, police and Pakistani Armed Forces.[98][100]

In the Pakistani general elections held on 7 December 1970, the Awami League won 167 out of 169 seats belonging to East Pakistan in the National Assembly of Pakistan, as well as a landslide in the East Pakistan Provincial Assembly.[101][15][102] The Awami League emerged as the single largest party in the federal parliament of Pakistan. With 167 seats, it was past the halfway mark of 150 seats in the 300 member national assembly and had the right to form a government of its own. Sheikh Mujib was widely considered to be the Prime Minister-elect, including by President Yahya Khan. The Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) came in second with 86 seats. The new parliament was scheduled to hold its first sitting in Dhaka, Pakistan's legislative capital under the 1962 constitution. The political crisis emerged when PPP leader Zulfikar Ali Bhutto declared that his party would boycott parliament if Mujib formed the next government. Bhutto threatened to break the legs of any West Pakistani MP-elect who accepted Mujib's mandate.[103][104][105][106][107][108] However, Khan Abdul Wali Khan of the Awami National Party from North West Frontier Province was open to accepting an Awami League government and travelled to Dhaka to meet with Mujib.[109] Many in Pakistan's establishment were opposed to Mujib becoming Pakistan's prime minister. At the time neither Mujib nor the Awami League had explicitly advocated political independence for East Pakistan, but smaller nationalist groups were demanding independence for Bangladesh.[110] After the election victory, Mujib was ornamented as "Sher-e-Pakistan" (Lion of Pakistan) on a newspaper ad published on The Daily Ittefaq on 3 January 1971.[111]

Both Bhutto and Yahya Khan travelled to Dhaka for negotiations with the Awami League. Mujib's delegation included the notable lawyer and constitutional expert Kamal Hossain. The Bengali negotiating position is extensively discussed in Kamal Hossain's autobiography Bangladesh: Quest for Freedom and Justice.[112] The Pakistani government was represented by former chief justice Alvin Robert Cornelius. At the InterContinental Dhaka, Bengali chefs refused to cook food for Yahya Khan.[112] Governor Sahabzada Yaqub Khan requested the Awami League to end the strike of the chefs at the InterContinental Hotel.[112]

Bhutto feared civil war, and sent a secret message to Mujib and his inner circle to arrange a meeting with them.[113][114] Mubashir Hassan met with Mujib and persuaded him to form a coalition government with Bhutto. They decided that Bhutto would serve as president, with Mujib as Prime Minister. These developments took place secretly and no Pakistan Armed Forces personnel were kept informed. Meanwhile, Bhutto increased the pressure on Yahya Khan to take a stand on dissolving the government.[115]

Establishment of Bangladesh

Civil disobedience

The National Assembly was scheduled to meet in Dhaka on 3 March 1971. President Yahya Khan indefinitely postponed the assembly's first sitting, which triggered an uprising in East Pakistan. The cities of Dhaka, Chittagong, Rajshahi, Rangpur, and Khulna were engulfed with protests. Amid signs of an impending crackdown, Mujib addressed the people of East Pakistan on 7 March 1971 at the Ramna Race Course Maidan.[116][117][118][119] In his speech, Mujib laid out the political history of Pakistan since partition and told the crowd that "[w]e gave blood in 1952; we won a mandate in 1954; but we were still not allowed to take up the reigns of this country".[120] While Mujib stopped short of declaring outright independence, he stated that the goal of the Awami League from then on would be eventual independence. He declared that the Awami League would collect taxes and form committees in every neighbourhood to organise resistance. He called on the people "to turn every house into a fortress".[120] His most famous words from the speech were the following.

This time the struggle is for our liberation! This time the struggle is for our independence![117][119][121]

(For more info, see: 7 March Speech of Bangabandhu)[122]

Following the speech, 17 days of civil disobedience known as the non-cooperation movement took place across East Pakistan.[116][117][118][119] The Awami League began to collect taxes while all monetary transfers to West Pakistan were suspended. East Pakistan came under the de facto control of the Awami League. On 23 March 1971, Bangladeshi flags were flown throughout East Pakistan on Pakistan's Republic Day as a show of resistance. The Awami League and the Pakistani military leadership continued negotiations over the transfer of power. However, West Pakistani troops were being flown into the eastern wing through PIA flights while arms were being unloaded from Pakistan Navy ships in Chittagong harbour.[123][124] The Pakistani military was preparing for a crackdown.

Outbreak of war

Talks broke down on 25 March 1971 when Yahya Khan left Dhaka, declared martial law, banned the Awami League and ordered the Pakistan Army to arrest Mujib and other Bengali leaders and activists.[117] The Pakistan Army launched Operation Searchlight. Mujib sent telegrams to Chittagong where M. A. Hannan from the Awami League and Major Ziaur Rahman from the East Bengal Regiment announced the Bangladeshi declaration of independence on Mujib's behalf. The text of Mujib's telegram sent at midnight on 26 March 1971 stated the following:

This may be my last message, from today Bangladesh is independent. I call upon the people of Bangladesh wherever you might be and with whatever you have, to resist the army of occupation to the last. Your fight must go on until the last soldier of the Pakistan occupation army is expelled from the soil of Bangladesh and final victory is achieved.[9]

Shortly after having declared the independence of Bangladesh,[125] Mujib was arrested without charges and flown to prison in West Pakistan after midnight. Mujib was moved to West Pakistan and kept under heavy guard in a jail near Faisalabad.[121] Sheikh Mujib was later moved to Central Jail Mianwali where he remained in solitary confinement for the entirety of the war.[126][127] Kamal Hossain was also arrested and flown to West Pakistan while many other League leaders escaped to India.[128] Pakistani general Rahimuddin Khan was appointed to preside over Mujib's court-martial trial, the proceedings of which have never been made public.[129] Mujib was sentenced to death but his execution was deferred on three occasions.[126]

The Pakistan Army's operations in East Pakistan were widely labelled as genocide.[130][131] The Pakistan Army carried out atrocities against Bengali civilians. With help from Jamaat militias like the Razakars, Al-Badr and Al-Shams, the army targeted Bengali intellectuals, professionals, politicians, students, and other ordinary civilians. Many Bengali women suffered rape. Due to the deteriorating situation, large numbers of Hindus fled across the border to the neighbouring Indian states of West Bengal, Assam and Tripura.[132] Bengali army and police regiments soon revolted and League leaders formed the Provisional Government of Bangladesh. A major insurgency led by the Mukti Bahini arose across East Pakistan. Despite international pressure, the Pakistani government refused to release Mujib and negotiate with him. Mujib's family was kept under house arrest during this period. General Osmani was the key military commanding officer in the Mukti Bahini. Following Indian intervention in December, the Pakistan Army surrendered to the allied forces of Bangladesh and India.[133][134]

Homecoming

Upon assuming the presidency after Yahya Khan's resignation, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto responded to international pressure and released Mujib on 8 January 1972.[135] Kamal Hossain was also released. Bhutto and Aziz Ahmed secretly met Mujib and Kamal Hossain in Rawalpindi.[136] Bhutto proposed a last minute attempt at mediation through the Shah of Iran, who was scheduled to arrive the next day.[112][137] Mujib declined the offer after consulting with Kamal Hossain. Mujib requested a flight to London.[112][137][138] Both Mujib and Hossain were then flown to London. En route to London, their plane made a stopover in Cyprus for refuelling.[139] In London, Mujib was welcomed by British officials and a policeman remarked "Sir, we have been praying for you".[140] Mujib was lodged at Claridge's Hotel and later met with British Prime Minister Edward Heath at 10 Downing Street. Heath and Mujib discussed Bangladesh's membership of the Commonwealth. Crowds of Bengalis converged on Claridge's Hotel to get a glimpse of Mujib.[141]Mujib held his first press conference in 9 months and addressed the international media at Claridge's Hotel. He made the following remarks at the press conference.

I am free to share the unbounded joy of freedom with my fellow countrymen. We have won our freedom in an epic liberation struggle.[142]

Mujib was provided an RAF plane by the British government to take him back to newly independent Bangladesh. He was accompanied on the flight by members of the Provisional Government of Bangladesh, as well as an emissary of India's premier Indira Gandhi. The emissary was Indian Bengali diplomat Shashank Banerjee, who recounted Mujib smoking his trademark smoking pipe with Erinmore tobacco.[143] During the flight, both men agreed that Bangladesh would adopt the Westminster style of parliamentary government. On Indira Gandhi's hopes for Bangladesh, Banerjee told Mujib that "on India's eastern flank, she wished to have a friendly power, a prosperous economy, and a secular democracy, with a parliamentary system of government".[144] Regarding the presence of Indian troops in Bangladesh, Mujib requested Banerjee to convey to the Indian government that Indian troops should be withdrawn as early as possible.[143] The RAF de Havilland Comet made a stopover in the Middle East en route to Dhaka.[143]

The RAF plane then made a stopover in New Delhi. Mujib was received by Indian President V. V. Giri and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, as well as the entire Indian cabinet and chiefs of armed forces. Delhi was given a festive look as Mujib and Gandhi addressed a huge crowd where he publicly expressed his gratitude to Gandhi and the Indian public.[145]

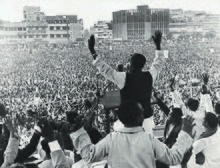

After a few hours in Delhi, the RAF plane flew Mujib to Dhaka in independent Bangladesh. Before the plane landed, it circled the city to view the million people who converged on Tejgaon Airport to greet Mujib.[146] In Dhaka, Mujib's homecoming was described as "one of the most emotional outbursts in that emotional part of the world".[147] Crowds overwhelmed the airport tarmac and breached the security cordon as cabinet ministers went inside the plane to bring Mujib out. Mujib was given a guard of honour by members of the nascent Bangladesh Army, Bangladesh Navy, and Bangladesh Air Force.[147] Mujib was driven in an open truck through the dense crowds for a speech at the Ramna Race Course, where ten months earlier he had announced the liberation movement.[147][148][149][150][151] Mujib's emotional speech to the million-strong crowd was caught on camera by Marilyn Silverstone and Rashid Talukdar; the photos of his homecoming day have become iconic in Bangladeshi political and popular culture.[152]

Governing Bangladesh (1972–1975)

Mujib briefly assumed the provisional presidency and later took office as the prime minister. In January 1972 Time magazine reported that "[i]n the aftermath of the Pakistani army's rampage last March, a special team of inspectors from the World Bank observed that some cities looked "like the morning after a nuclear attack". Since then, the destruction has only been magnified. An estimated 6,000,000 homes have been destroyed, and nearly 1,400,000 farm families have been left without tools or animals to work their lands. Transportation and communications systems are totally disrupted. Roads are damaged, bridges out and inland waterways blocked. The rape of the country continued right up until the Pakistani army surrendered a month ago. In the last days of the war, West Pakistani-owned businesses—which included nearly every commercial enterprise in the country—remitted virtually all their funds to the West. Pakistan International Airlines left exactly 117 rupees ($16) in its account at the port city of Chittagong. The army also destroyed bank notes and coins, so that many areas now suffer from a severe shortage of ready cash. Private cars were picked up off the streets or confiscated from auto dealers and shipped to the West before the ports were closed.[153][154]

The new government of Bangladesh quickly converted East Pakistan's state apparatus into the machinery of an independent Bangladeshi state. For example, a presidential decree transformed the High Court of East Pakistan into the Supreme Court of Bangladesh.[155] The Awami League successfully reorganised the bureaucracy, framed a written constitution, and rehabilitated war victims and survivors. In January 1972, Mujib introduced a parliamentary republic through a presidential decree.[155] The emerging state structure was influenced by the Westminster model in which the Prime Minister was the most powerful leader while the President acted on the government's advice. MPs elected during the 1970 general election became members of the Constituent Assembly of Bangladesh. The Constitution Drafting Committee led by Dr. Kamal Hossain produced a draft constitution which was adopted on 4 November 1972 and came into force on 16 December 1972. In comparison to the prolonged constitution-making process in Pakistan during the 1950s, the Awami League was credited for swiftly enacting the Constitution of Bangladesh within just one year of independence. However, the League is criticised for this swift enactment because the Constituent Assembly was largely made up of members from the League itself; the few opposition lawmakers included Manabendra Narayan Larma, who demanded the term "Bangladeshi" to describe the new country's citizens instead of "Bengali" since not all Bangladeshis were Bengalis.[156] Critics argued that in reality "the Awami League sought to rule by Mujib's charisma and build a political process by dicta".[157]

Mujib introduced a quota for backward regions to get access to public sector jobs.[155] Bangladesh also faced a gun control problem because many of its guerrilla fighters from the Liberation War were roaming the country with guns. Mujib successfully called on former guerrillas to surrender their arms through public ceremonies which affirmed their status as freedom fighters during the Liberation War.[155] The President's Relief and Welfare Fund was created to rehabilitate an estimated 10 million displaced Bangladeshis. Mujib established 11,000 new primary schools and nationalised 40,000 primary schools.[158]

Withdrawal of Indian troops

One of Mujib's first priorities was the withdrawal of Indian troops from Bangladesh. Mujib requested the Indian government to ensure a swift withdrawal of Indian military forces from Bangladeshi territory. A timeline was drawn up for rapid withdrawal. The withdrawal took place within three months of the surrender of Pakistan to the allied forces of Bangladesh and India. A formal ceremony was held in Dhaka Stadium on 12 March 1972 in which Mujib inspected a guard of honour from the 1st Rajput Regiment.[159] The withdrawal of Indian forces was completed by 15 March.[160] Many countries established diplomatic relations with Bangladesh soon after the withdrawal of Indian troops.[161] India's intervention and subsequent withdrawal has been cited as a successful case of humanitarian intervention in international law.[161]

War criminals

In 1972, Mujib told David Frost that he was a strong man but he had tears in his eyes when he saw pictures of the 1971 Bangladesh genocide.[162] He told Frost that "I am a very generous man. I always believe in forgive and forget but this is impossible on my part to forgive and forget. This was cold blooded murder in a planned way; genocide to kill my people. These people must be punished".[162] Speaking about a potential war crimes trial, Mujib said "the world powers arranged the Nuremberg trials against the war criminals of fascist Germany. I think they should come forward and there should be another trial or inquiry under the United Nations".[162] Mujib pledged to hold a trial for those accused in wartime atrocities. An estimated 11,000 local collaborators of the Pakistan Army were arrested.[163] Their cases were heard by the Collaborators Tribunal.[164] In 1973, the government introduced the International Crimes (Tribunal) Act to prosecute 195 Pakistani PoWs under Indian custody.[165] In response, Pakistan filed a case against India at the International Court of Justice.[166] The Delhi Agreement struck a compromise between India, Pakistan and Bangladesh after the three countries agreed to transfer PoWs to Pakistani custody. However, the foreign minister of Bangladesh stated that "the excesses and manifold crimes committed by those prisoners of war constituted, according to the relevant provisions of the UN General Assembly resolutions and international law, war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide, and that there was universal consensus that persons charged with such crimes as [the] 195 Pakistani prisoners of war should be held to account and subjected to the due process of law".[167] In 1974, the Third International Criminal Law Conference was held at the Bangladesh Institute of Law and International Affairs; the meeting supported calls for the creation of an international penal court.[168]

Economic policy

Mujib declared socialism as a national policy. His land reforms restricted land ownership to less than 25 bighas of land which effectively ended all traces of the zamindari system. Land owners with more than 25 bighas were subjected to taxes.[158] Farmers had to sell their products at prices set by the government instead of the market. Mujib nationalised all banks, insurance companies, and 580 industrial plants.[158] There was little foreign investment. The stock exchange remained closed. In 1974, the government sought to invite international oil companies to explore the Bay of Bengal for oil and natural gas. Shell sold five gas fields to the Bangladeshi government which set the stage for the creation of Petrobangla.[169] The national airline Biman was set up with planes from British Caledonian, the Indian government and the World Council of Churches. In the industrial sector, the Bangladeshi government built the Ghorashal Fertilizer Factory.[158] Work began on the Ashuganj Power Station. Operations in the Port of Chittagong were restored after the Soviet Navy conducted a clearing operation for naval mines.[170]

Industrial activity was eventually restored to pre-1971 levels.[171] Banking services rapidly expanded in rural areas.[171] Mujib recruited CEOs from the private sector to run state-owned companies.[171] The first Five Year Plan was adopted by the Planning Commission, which was headed by the Harvard-trained economist Nurul Islam.[171] The Planning Commission sought to diversify Bangladesh's exports. In trade with India, the Planning Commission identified fertilizer, iron, cement and natural gas as potential export sectors in Bangladesh. The Planning Commission, with Mujib's approval, wanted to transform Bangladesh into a producer of value added products generated from imported Indian raw materials.[171] In addition to state-owned firms, many private sector companies emerged, including the Bangladesh Export Import Company and Advanced Chemical Industries. These companies later became some of Bangladesh's biggest conglomerates.

The Mujib government faced serious challenges, which included the resettlement of millions of people displaced in 1971, organisation of food supply, health services and other necessities. The effects of the 1970 cyclone had not worn off, and the economy of Bangladesh had immensely deteriorated due to the conflict.[172] In 1973, thousands of Bengalis arrived from Pakistan while many non-Bengali industrialists and capitalists emigrated; poorer non-Bengalis were stranded in refugee camps. Major efforts were launched to help an estimated 10 million former refugees who returned from India. The economy began to recover eventually.[173] The five-year plan released in 1973 focused state investments into agriculture and cottage industries.[174] But a famine occurred in 1974 when the price of rice rose sharply. In that month there was widespread starvation in Rangpur district. Government mismanagement was blamed.[175][176] Many of Mujib's socialist policies were eventually overturned by future governments. The five years of his regime marked the only intensely socialist period in Bangladesh's history. Successive governments de-emphasised socialism and promoted a market economy. By the 1990s, the Awami League returned to being a centre-left party in economics.

Legal reforms

The Constitution of Bangladesh became the first Bengali written constitution in modern history. The Awami League introduced a new bill of rights, which was more broad and expansive than the laws of East and West Pakistan.[177] In addition to freedom of speech and freedom of religion, the new constitution emphasized property rights, the right to privacy, the prohibition of torture, safeguards during detention and trial, the prohibition of forced labor, and freedom of association.[178] The Awami League repealed many controversial laws of the Pakistani period, including the Public Safety Act and Defense of Pakistan Rules. Women's rights received more attention than before. Discrimination on grounds of religion, ethnicity, gender, place of birth or disability was discouraged.[179]

Secularism

While Pakistan adopted progressive reforms to Muslim family law as early as 1961,[180] Bangladesh became the first constitutionally secular state in South Asia in 1972 when its newly adopted constitution included the word "secularism" for the first time in the region.[181] Despite the constitution's proclamation of secularism as a state policy, Mujib banned "anti-Islamic" activities, including gambling, horse racing and alcohol. He established the Islamic Foundation to regulate religious affairs for Muslims, including the collection of zakat and setting dates for religious observances like Eid and Ramadan.[158] Under Mujib, Bangladesh joined the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) in 1974. Bangladesh was not the only Muslim-majority secular republic in the OIC; others included Turkey and Nigeria. Secularism was later removed from the constitution by the military dictatorship in the late 1970s. Secularism was reinstated by the Supreme Court into the constitution in 2010.[182]

Mujib said "secularism doesn't mean irreligiosity. Hindus will practice their religion; Muslims will practice their religion; Christians, Buddhists - everyone will practice their respective religions. No one will interfere in someone else's religion; the people of Bengal do not seek to interfere in matters of religion. Religion will not be used for political purposes. Religion will not be exploited in Bengal for political gain. If anyone does so, I believe the people of Bengal will retaliate against them".[55]

Foreign policy

In the early 1970s, Sheikh Mujib emerged as one of the most charismatic leaders of the third world.[183][184] His foreign policy maxim was "friendship to all, malice to none".[185] Mujib's priorities were to secure aid for reconstruction and relief efforts; normalizing diplomatic relations with the world; and joining major international organizations.

Mujib's major foreign policy achievement was to secure normalisation and diplomatic relations with most countries of the world. Bangladesh joined the Commonwealth, the UN, the OIC, and the Non-Aligned Movement.[186][187][188][189] His allies included Prime Minister Indira Gandhi of India and Marshal Tito of Yugoslavia.[190][191][192]Japan became a major aid provider to the new country. Mujib attended Commonwealth summits in Canada and Jamaica, where he held talks with Queen Elizabeth II, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson, Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and New Zealand Prime Minister Norman Kirk.[193][194] The Soviet Union supplied several squadrons of MiG-21 planes for the Bangladesh Air Force.[195] China initially blocked Bangladesh's entry to the UN in 1972, but withdrew its veto in 1974 which allowed Bangladesh to join the UN.[193] The United States recognized the independence of Bangladesh on 4 April 1972 and pledged US$300 million in aid.[196][197] Britain, Malaysia, Indonesia, West Germany, Denmark, Norway and Sweden were among the several countries which recognized Bangladesh in February 1972.[198][199]

Africa

Mujib was a firm opponent of apartheid. In his first speech to the United Nations General Assembly in 1974, Mujib remarked that "In spite of the acceleration of the process of abolishing colonialism, it hasn't reached its ultimate goal. This is more strongly true of Africa, where the people of Rhodesia and Namibia are still engaged in the final struggle for national independence and absolute freedom. Although racism has been identified as a serious offence in this council, it's still destroying the conscience of the people".[200][201] This was the first speech in the UN General Assembly to be spoken in Bengali.

Bangladesh joined the Non Aligned Movement (NAM) during the 4th Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement in Algiers.[202][203] Mujib told Nigerian leader Yakubu Gowon that "if we had remained in Pakistan, it would be a strong country. Again, if India had not been divided in 1947, it would be an even stronger country. But, then, Mr. President, in life do we always get what we desire?".[204] The comment was in response to Gowon questioning the need for the break up of Pakistan.[205] Mujib met Zambian leader Kenneth Kaunda and Senegalese president Léopold Sédar Senghor.[206] He developed a good rapport with President Anwar Sadat of Egypt, who gifted 30 tanks to the Bangladeshi military in return for Mujib's support to Egypt.[207][208][209] Algerian president Houari Boumédiène brought Mujib to the OIC Summit in Lahore on his plane.[198]

Middle East

While addressing the UN General Assembly in 1974, Mujib said "injustice is still rampant in many parts of the world. Our Arab brothers are still fighting for the complete eviction of the invaders from their land. The equitable national rights of the Palestinian people have not yet been achieved".[200][201] While Israel was one of the first countries to recognize Bangladesh,[210] the Mujib government dispatched an army medical unit to support Arab countries during the Arab-Israeli War of 1973.[211] This was Bangladesh's first dispatch of military aid overseas.[212] Kuwait sent its foreign minister Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah to persuade Mujib to join the OIC Summit in Lahore in 1974.[200][213][214] The Lebanese foreign minister accompanied Sabah during the visit to Dhaka.[215] Bangladesh enjoyed strong relations with the secular Arab government of Iraq.[216][217] Mujib had a warm rapport with Sheikh Zayed of the UAE, with the two men joking about their names.[218]

Egyptian president Anwar Sadat visited Bangladesh on 25 February 1974 to thank Mujib for his support during the 1973 war.[219] Sadat became a close friend of Mujib.[220] Algerian president Houari Boumédiène was instrumental in getting Bangladesh into the OIC. Mujib met with Takieddin el-Solh, the Prime Minister of Lebanon.[221] He also met Hafez Al Assad, the President of Syria.[222] Mujib visited Iraq, Egypt, and Algeria. During his trip to Iraq, crowds of several thousand Iraqis welcomed him on the streets of Baghdad, Karbala and Babylon.[223]

South Asia

Mujib and Indira Gandhi signed the 25-year Indo-Bangladeshi Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Peace.[224][225] India and Bangladesh developed extremely cordial relations based on shared political values, a common nonaligned worldview and cultural solidarity. In February 1972, Mujib visited the Indian city of Kolkata in West Bengal to thank the people of India for their support during the liberation war. Mujib was immensely popular in India. Many of India's leading film directors, singers, writers, actors and actresses came to meet with Mujib, including Satyajit Ray, Hemanta Mukherjee and Hema Malini.[226] In Pakistan, a constitutional amendment was passed to establish diplomatic relations with Bangladesh.[227] In the Delhi Agreement of 1974, Bangladesh, India and Pakistan pledged to work for regional stability and peace. The agreement paved the way for the return of interned Bengali officials and their families stranded in Pakistan, as well as the establishment of diplomatic relations between Bangladesh and Pakistan.[228] However, Bangladesh had to concede on the issue of putting 195 Pakistani PoWs on trial for war crimes, after the three countries agreed by consensus to transfer the 195 PoWs to Pakistani custody.[229]

Mujib and Gandhi also signed a Land Boundary Treaty concerning the India-Bangladesh enclaves. The treaty was challenged in court.[230][231] The government attempted to ratify the treaty without consulting parliament. Chief Justice Abu Sadat Mohammad Sayem ruled that parliament had to ratify the treaty in accordance with the constitution, otherwise the government's actions were illegal and unconstitutional. The Chief Justice dissented with the government's actions. The treaty was subsequently ratified by parliament. In his decision, Justice Sayem referred to the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.[232] The land boundary treaty was finally implemented in 2015.[233]

Left-wing insurgency

At the height of Mujib's power, left-wing insurgents from the Gonobahini fought against Mujib's government to establish a Marxist government.[234][235] The government responded by forming an elite paramilitary force called Jatiya Rakkhi Bahini on 8 February 1972. Many within the Bangladeshi military viewed the new paramilitary force with suspicion.[236][237] The new paramilitary force was responsible for human rights abuses against the general populace, including extrajudicial killings,[238][239][240] shootings by death squads,[241] and rape.[240] Members of the Jatiya Rakkhi Bahini were granted immunity from prosecution and other legal proceedings.[242][243] The force swore an oath of loyalty to Mujib.[244]

One-party state

Mujib's political philosophy dramatically changed in 1975. Elections were approaching in 1977 after the end of his five-year term. Mujib sensed growing dissatisfaction with his regime. He changed the constitution, declared himself president, and established a one party state. Ahrar Ahmed, commenting in The Daily Star, noted that "Drastic changes were introduced through the adoption of the 4th amendment on Jan[uary] 25, 1975, which radically shifted the initial focus of the constitution and turned it into a single-party, [p]residential system, which curtailed the powers of the [p]arliament and the [j]udiciary, as well as the space for free speech or public assembly".[245] Censorship was imposed in the press. Civil society groups like the Committee for Civil Liberties and Legal Aid were suppressed. The Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (BAKSAL), meaning the "Bangladesh Farmers Workers Peoples League", became the only legal political party. Bureaucrats and military officers were ordered to join the single party. These actions profoundly impacted Mujib's legacy. Many Bangladeshis opposed to the Awami League cite his creation of BAKSAL as the ultimate hypocrisy. The one party state lasted for 7 months till Mujib's assassination on 15 August 1975.

Assassination

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was assassinated along with most of his family in his personal residence on 15 August 1975 during a military coup by renegade army officers.[246][247] His wife, brother, three sons, two daughters-in-law, and hosts of other relatives, personal staff, police officers, a brigadier general of the Bangladesh Army and many others were killed during the coup.[248][249] More than 40 people got injured.[249] The army chief K. M. Shafiullah was caught unaware and failed to stop the coup.[250] Mujib was shot on the staircase of his house.[250] Radio announcements were made across the country.[251]

Mujib was warned by many including the Indian intelligence about a possible coup.[252][253] Mujib shrugged off these warnings by saying his own people would never hurt him.[254] Moreover, being the president, he did not stay in Bangabhaban but stayed in his unguarded house at 32 Dhanmondi.[255] German politician and federal chancellor Willy Brandt said in emotion, "Bengalis can no longer be trusted after the killing of Sheikh Mujib. Those who killed Mujib can do any heinous act."[256]

Funeral and memorials

On 16 August 1975, Mujib's coffin was taken to his birthplace Tungipara in an army helicopter. He was buried next to his parents after his funeral led by Sheikh Abdul Halim.[257] Others were buried in the Banani graveyard of Dhaka.[257] The national flag was kept at half-mast in several government and non-government institutions mourning Mujib's death.[258] During the time, the Bangladesh national football team was in the Merdeka Tournament in Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia.[258] There the national flag of Bangladesh was kept at half-mast on the day of Bangladesh's match. Prior to match, the players observed a minute's silence for Mujib and his eldest son Sheikh Kamal, who was a keen sportsman and the founder of Abahani Limited Dhaka.[258]

Absentee funeral prayers were held in the Eidgah field of Jessore, Dhanmondi of Dhaka and Baitul Mukarram National Mosque.[259][251] Thousands of people including the students of Dhaka University joined the mass procession and special prayer in Dhaka on 4 November 1975.[251][260] Heads of state, political figures and media of several countries including United States, United Kingdom, India, Iraq and Palestine mourned Mujib's death.[256] Cuban prime minister Fidel Castro stated upon Mujib's death, "The oppressed people of the world have lost a great leader of theirs in the death of Sheikh Mujib. And I have lost a truly large-hearted ally."[256]

Today, Mujib rests beside his parents grave in a white marble tomb in his native Tungipara.[261] His personal residence where he was assassinated along with most of his family members is now a museum called Bangabandhu Memorial Museum.[262]

Aftermath

After the coup, a martial law regime was established. Four allies of Mujib who led the Provisional Government of Bangladesh in 1971 were arrested and eventually executed on 3 November 1975. Mujib's killers included fifteen junior army officers with ranks of colonels, majors, lieutenants and havildars. They were backed up by Awami League politician Khondaker Mostaq Ahmad, who usurped the presidency. On the day of the coup, the junior officers ordered their soldiers to take over the national radio and television stations.[250] They were all later toppled by yet another coup led by Brigadier General Khaled Mosharraf on 3 November 1975.[263]

According to American investigative journalist Lawrence Lifschultz, the army's deputy chief Ziaur Rahman was approached by the coup plotters and expressed interest in the proposed coup plan, but refused to become the public face of the coup.[264][265][266] Zia did not deny meeting with the coup plotters, according to Anthony Mascarenhas. Zia was legally obliged to prevent a mutiny against the country's legally appointed president but did not stop the impending mutiny despite having knowledge of it.[267] Zia eventually emerged as the dictator of Bangladesh after the coup. The only survivors from Mujib's family were his daughters Sheikh Hasina and Sheikh Rehana, who were visiting Hasina's physicist husband in West Germany at the time. After the coup, they were barred from returning to Bangladesh and were granted asylum by India. Sheikh Hasina lived in New Delhi in exile before returning to Bangladesh on 17 May 1981.[268] On 26 September 1975, the martial law regime introduced the Indemnity Ordinance, 1975, which gave legal immunity to all persons involved in the coup of 15 August 1975.

His assassins continued to enjoy immunity from prosecution for 26 years. The Indemnity Ordinance was repealed in 1996 after his daughter Sheikh Hasina was elected as Prime Minister. A murder case was subsequently initiated in the courts of Bangladesh. Several of the fifteen assassins, including coup leader Syed Faruque Rahman, were arrested and put on trial. Others like Khandaker Abdur Rashid became fugitives. The fifteen were given the death penalty by a court in 1998.[269] Five of the convicts were hanged in 2010.[270] A sixth convict was hanged in 2020.[271] Of the remaining fugitives, a few have died or are in hiding. In 2022, the Bangladeshi government reported that five fugitives are still on the run, including coup leader Rashid.[272] One of the convicted assassins is living in Canada.[273] One of the convicts is living in the United States.[274] Bangladesh has requested Canada and the United States to deport the fugitives following the precedent set by the deportation of A.K.M. Mohiuddin Ahmed in 2007.[275]

Principles and ideology

Mujib's statements, letters and life have attracted much political and scholarly analysis of his principles, ideology and beliefs, including what influenced him. These are consists of four fundamental policies:

When the Constitution of Bangladesh was adopted in 1972, the four policies become the four fundamental state policies of Bangladesh.[278]

Legacy

In 2004, listeners of the BBC Bangla radio service ranked Mujib first among the 20 Greatest Bengalis, ahead of Asia's first Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore; Bangladesh's national poet Kazi Nazrul Islam; and other Bengali icons like Subhash Chandra Bose, Amartya Sen, Titumir, Begum Rokeya, Muhammad Yunus, and Ziaur Rahman.[279] The survey was modelled on the BBC's 100 Greatest Britons poll.

Birthday of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is celebrated around the country. National Children's Day is being observed as a public holiday on his birthday.[280] In 2020, the government of Bangladesh celebrated Mujib Year to mark 100 years since the birth of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1920.[281] The commemorations preceded Bangladesh's 50th anniversary of independence in 2021. Mujib continues to be a revered, popular, divisive, and controversial figure in Bangladesh. His party, the Awami League, has built a personality cult around his legacy.[citation needed]

Opponents of the League are fierce critics of Mujib's populism and authoritarianism, including his creation of BAKSAL. League supporters and other Bangladeshis credit Mujib for successfully leading the country to independence in 1971. However, Mujib's socialist and economic policies after 1971 are largely frowned upon except among his most loyal supporters and family members. Many roads, institutions, military bases, bridges and other places in Bangladesh are named in his honour. Under the Awami League's rule, Mujib's picture is printed on the national currency Bangladeshi taka. Bangladeshis across the political divide often refer to him as Bangabandhu out of respect. A satellite is also named after him.

Mujib is remembered in India as an ally. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Road in New Delhi and an avenue in Kolkata in the Indian state of West Bengal are named in his honour. The Palestinian Authority named a street in Hebron in honour of Mujib.[282] Bangabandhu Boulevard in Ankara, Turkey is named after Mujib. There is also a Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Street in Port Louis, Mauritius.[283] Sheikh Mujib Way in Chicago in the United States is named after him.[284]

Followers and international influence

Archer Blood described Mujib as charismatic.[285] Gary J. Bass wrote that "Mujib's very appearance suggested raw power," cabled Blood, "a power drawn from the masses and from his own strong personality." He was tall and sturdy, with rugged features and intense eyes. Blood found him serene and confident amid the turmoil, but eager for power. "On the rostrum he is a fiery orator who can mesmerize hundreds of thousands in a pouring rain," Blood wrote. "Mujib has something of a messianic complex which has been reinforced by the heady experience of mass adulation. He talks of 'my people, my land, my forests, my rivers.' It seems clear that he views himself as the personification of Bengali aspirations." According to Time magazine, "A man of vitality and vehemence, Mujib became the political Gandhi of the Bengalis, symbolizing their hopes and voicing their grievances. Not even Pakistan's founder, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, drew the million-strong throngs that Mujib has attracted in Dacca. Nor, for that matter, has any subcontinent politician since Gandhi's day spent so much time behind bars for his political beliefs".[286]

|  |  |

An Egyptian journalist noted that "Sheikh Mujibur Rahman does not belong to Bangladesh alone. He is the harbinger of freedom for all Bengalis. His Bengali nationalism is the new emergence of Bengali civilization and culture. Mujib is the hero of the Bengalis, in the past and in the times that are".[286] Fidel Castro remarked that "I have not seen the Himalayas. But I have seen Sheikh Mujib. In personality and in courage, this man is the Himalayas. I have thus had the experience of witnessing the Himalayas".[286] Mujib cited Abraham Lincoln, Mao Zedong, Winston Churchill, John F. Kennedy, Sukarno and Kemal Ataturk, Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Suhrawardy, Subhas Chandra Bose, and A. K. Fazlul Huq as the individuals he admires during an interview with David Frost.[287]

Honours

| Prize Name | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Joliot-Curie Medal of Peace | 1973 | [288] |

| Independence Award | 2003 | |

| Gandhi Peace Prize | 2020 | [289] |

| SAARC Literary Award | 2023 | [290] |

Father of the Nation

Бангладешцы широко называют Муджиба отцом нации . [291][292][293] Origin of this title is traced back to a meeting (during Non-cooperation movement) on 3 March 1971 by A. S. M. Abdur Rab where Rab referred Mujib as "The Father of the Nation".[294] Однако позже утверждалось, что Таджуддин Ахмад , первый премьер-министр Бангладеш , был первым, кто назвал Муджиба «Отцом нации». [295] 1972 года Конституция Бангладеш провозгласила Муджиба «Отцом нации». [296] 8 марта 1975 года Маулана Абдул Хамид Хан Бхашани на церемонии закладки фундамента колледжа также назвал Муджиба «Отцом нации». [297] В 2011 году парламент Бангладеш принял 15-ю поправку к конституции страны, в которой Муджиб назван «Отцом нации» в прилагаемых пятом, шестом и седьмом приложениях, охватывающих его речь 7 марта, провозглашение независимости 26 марта 1971 года. и Прокламация независимости, изданная Временным правительством 10 апреля 1971 года. [298]

Изображения

Песня

- « Shono Ekti Mujiburer Theke », песня о нем 1971 года, вдохновила борцов за свободу во время освободительной войны Бангладеш .

- О нем была написана в 1990 году и записана в 1991 году песня под названием « Jodi Raat Pohale Shona Jeto », ставшая популярной во время выборов.

- В 2020 году «Туми Банглар Друботара» («Ты - звезда Бенгалии») песня , написанная поэтом Камалем Чоудхури по случаю Года Муджиба . была выпущена

Литература

- Хумаюн Ахмед включил шейха Муджиба в два своих исторических романа: «Джочона о Джононир Голпо» 2012 года 2004 года и «Дейал» .

- Неамата Имама В романе «Черное пальто» Муджиб изображен как диктатор. [299]

- В 2015 году отдел Центра исследований и информации (CRI) Бангладешской Авами Лиги опубликовал детский комикс из четырех частей под названием «Муджиб», основанный на двух автобиографиях шейха Муджиба.

- В марте 2022 года Муктидата Шейх Муджиб» («Освободитель Шейх Муджиб»). были опубликованы мемуары Муджибура Рахмана « [300]

Документальные фильмы

- В 1972 году «Программа Дэвида Фроста в Бангладеш» вышел документальный фильм , основанный на интервью с шейхом Муджибуром Рахманом. Британский журналист Дэвид Фрост сделал это на основе политической жизни шейха Муджибура Рахмана. [301]

- В японском документальном фильме 1973 года «Бенгару но чичи: Раман» («Рахман, Отец Бенгалии») , снятом японским режиссером Нагаси Осимой, изображена личная жизнь, повседневная деятельность и последующие планы шейха Муджибура Рахмана.

- В 1973 году Добро пожаловать в Бангабандху» , основанный на государственном визите шейха Муджибура Рахмана в Японию. японская компания Mainichi Productions выпустила документальный фильм « [302]

- В 1996 году был снят документальный фильм «Чиронджиб Бангабандху» («Бессмертный Бангабандху») о жизни и творчестве шейха Муджибура Рахмана.

- В документальном фильме 2018 года «Хасина: История дочери » дочь шейха Муджиба Шейх Хасина рассказала об убийстве своего отца. [303]

- В 2021 году документальный фильм «Бангабандхур Раджнойтик Джибон О Бангладешер Оббхудой» («Политическая жизнь Бангабандху и подъем Бангладеш») , документальный фильм о жизни шейха Муджибура Рахмана и независимости Бангладеш, выиграл 45-ю Национальную кинопремию Бангладеш в категории «Лучший документальный фильм». . [304]

- 17 ноября 2023 года » « Убийца по соседству эпизод канадского документального сериала « Пятая власть был выпущен » о Нуре Чоудхури , убийце шейха Муджибура Рахмана. [305]

Фильмы

- В бангладешском фильме 1974 года « Санграм » шейх Муджибур Рахман сыграл самого себя.