Психическое расстройство

| Психическое расстройство | |

|---|---|

| Другие имена | Психическое расстройство, умственная отсталость, психическое заболевание, состояние психического здоровья, психическое заболевание, нервный срыв, психиатрическая инвалидность, психическое расстройство, психологическая инвалидность, психологическое расстройство [1] [2] [3] [4] |

| Специальность | Психиатрия , клиническая психология |

| Симптомы | Возбуждение , тревога , депрессия , мания , паранойя , психоз. |

| Осложнения | Когнитивные нарушения, социальные проблемы, самоубийство. |

| Типы | Тревожные расстройства , расстройства пищевого поведения , расстройства настроения , расстройства личности , психотические расстройства , расстройства, связанные с употреблением психоактивных веществ. |

| Causes | Genetic and environmental factors |

| Treatment | Psychotherapy and medications |

| Medication | Antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, mood stabilizers, stimulants |

| Frequency | 18% per year (United States)[5] |

, Психическое расстройство также называемое психическим заболеванием , [6] состояние психического здоровья , [7] или психиатрическая инвалидность , [2] Поведенческий или психический паттерн, который вызывает значительный дистресс или нарушение личностного функционирования. [8] Психическое расстройство также характеризуется клинически значимым нарушением когнитивных функций, эмоциональной регуляции или поведения человека, часто в социальном контексте . [9] [10] Такие нарушения могут возникать в виде единичных эпизодов, могут быть персистирующими или иметь рецидивно-ремиттирующий характер . Существует множество различных типов психических расстройств, признаки и симптомы которых сильно различаются в зависимости от конкретного расстройства. [10] [11] Психическое расстройство является одним из аспектов психического здоровья .

The causes of mental disorders are often unclear. Theories incorporate findings from a range of fields. Disorders may be associated with particular regions or functions of the brain. Disorders are usually diagnosed or assessed by a mental health professional, such as a clinical psychologist, psychiatrist, psychiatric nurse, or clinical social worker, using various methods such as psychometric tests, but often relying on observation and questioning. Cultural and religious beliefs, as well as social norms, should be taken into account when making a diagnosis.[12]

Services for mental disorders are usually based in psychiatric hospitals, outpatient clinics, or in the community, Treatments are provided by mental health professionals. Common treatment options are psychotherapy or psychiatric medication, while lifestyle changes, social interventions, peer support, and self-help are also options. In a minority of cases, there may be involuntary detention or treatment. Prevention programs have been shown to reduce depression.[10][13]

In 2019, common mental disorders around the globe include: depression, which affects about 264 million people; dementia, which affects about 50 million; bipolar disorder, which affects about 45 million; and schizophrenia and other psychoses, which affect about 20 million people.[10] Neurodevelopmental disorders include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and intellectual disability, of which onset occurs early in the developmental period.[14][10] Stigma and discrimination can add to the suffering and disability associated with mental disorders, leading to various social movements attempting to increase understanding and challenge social exclusion.

Definition

The definition and classification of mental disorders are key issues for researchers as well as service providers and those who may be diagnosed. For a mental state to be classified as a disorder, it generally needs to cause dysfunction.[15] Most international clinical documents use the term mental "disorder", while "illness" is also common. It has been noted that using the term "mental" (i.e., of the mind) is not necessarily meant to imply separateness from the brain or body.

According to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), published in 1994, a mental disorder is a psychological syndrome or pattern that is associated with distress (e.g., via a painful symptom), disability (impairment in one or more important areas of functioning), increased risk of death, or causes a significant loss of autonomy; however, it excludes normal responses such as the grief from loss of a loved one and also excludes deviant behavior for political, religious, or societal reasons not arising from a dysfunction in the individual.[16]

DSM-IV predicates the definition with caveats, stating that, as in the case with many medical terms, mental disorder "lacks a consistent operational definition that covers all situations", noting that different levels of abstraction can be used for medical definitions, including pathology, symptomology, deviance from a normal range, or etiology, and that the same is true for mental disorders, so that sometimes one type of definition is appropriate and sometimes another, depending on the situation.[17]

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) redefined mental disorders in the DSM-5 as "a syndrome characterized by clinically significant disturbance in an individual's cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior that reflects a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or developmental processes underlying mental functioning."[18] The final draft of ICD-11 contains a very similar definition.[19]

The terms "mental breakdown" or "nervous breakdown" may be used by the general population to mean a mental disorder.[20] The terms "nervous breakdown" and "mental breakdown" have not been formally defined through a medical diagnostic system such as the DSM-5 or ICD-10 and are nearly absent from scientific literature regarding mental illness.[21][22] Although "nervous breakdown" is not rigorously defined, surveys of laypersons suggest that the term refers to a specific acute time-limited reactive disorder involving symptoms such as anxiety or depression, usually precipitated by external stressors.[21] Many health experts today refer to a nervous breakdown as a mental health crisis.[23]

Nervous illness

In addition to the concept of mental disorder, some people have argued for a return to the old-fashioned concept of nervous illness. In How Everyone Became Depressed: The Rise and Fall of the Nervous Breakdown (2013), Edward Shorter, a professor of psychiatry and the history of medicine, says:

About half of them are depressed. Or at least that is the diagnosis that they got when they were put on antidepressants. ... They go to work but they are unhappy and uncomfortable; they are somewhat anxious; they are tired; they have various physical pains—and they tend to obsess about the whole business. There is a term for what they have, and it is a good old-fashioned term that has gone out of use. They have nerves or a nervous illness. It is an illness not just of mind or brain, but a disorder of the entire body. ... We have a package here of five symptoms—mild depression, some anxiety, fatigue, somatic pains, and obsessive thinking. ... We have had nervous illness for centuries. When you are too nervous to function ... it is a nervous breakdown. But that term has vanished from medicine, although not from the way we speak.... The nervous patients of yesteryear are the depressives of today. That is the bad news.... There is a deeper illness that drives depression and the symptoms of mood. We can call this deeper illness something else, or invent a neologism, but we need to get the discussion off depression and onto this deeper disorder in the brain and body. That is the point.

— Edward Shorter, Faculty of Medicine, the University of Toronto[24]

In eliminating the nervous breakdown, psychiatry has come close to having its own nervous breakdown.

— David Healy, MD, FRCPsych, Professor of Psychiatry, University of Cardiff, Wales[25]

Nerves stand at the core of common mental illness, no matter how much we try to forget them.

— Peter J. Tyrer, FMedSci, Professor of Community Psychiatry, Imperial College, London[26]

"Nervous breakdown" is a pseudo-medical term to describe a wealth of stress-related feelings and they are often made worse by the belief that there is a real phenomenon called "nervous breakdown".

— Richard E. Vatz, co-author of explication of views of Thomas Szasz in "Thomas Szasz: Primary Values and Major Contentions"[page needed]

Classifications

There are currently two widely established systems that classify mental disorders:

- ICD-11 Chapter 06: Mental, behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorders, part of the International Classification of Diseases produced by the WHO (in effect since 1 January 2022).[27]

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) produced by the APA since 1952.

Both of these list categories of disorder and provide standardized criteria for diagnosis. They have deliberately converged their codes in recent revisions so that the manuals are often broadly comparable, although significant differences remain. Other classification schemes may be used in non-western cultures, for example, the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders, and other manuals may be used by those of alternative theoretical persuasions, such as the Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual. In general, mental disorders are classified separately from neurological disorders, learning disabilities or intellectual disability.

Unlike the DSM and ICD, some approaches are not based on identifying distinct categories of disorder using dichotomous symptom profiles intended to separate the abnormal from the normal. There is significant scientific debate about the relative merits of categorical versus such non-categorical (or hybrid) schemes, also known as continuum or dimensional models. A spectrum approach may incorporate elements of both.

In the scientific and academic literature on the definition or classification of mental disorder, one extreme argues that it is entirely a matter of value judgements (including of what is normal) while another proposes that it is or could be entirely objective and scientific (including by reference to statistical norms).[28] Common hybrid views argue that the concept of mental disorder is objective even if only a "fuzzy prototype" that can never be precisely defined, or conversely that the concept always involves a mixture of scientific facts and subjective value judgments.[29] Although the diagnostic categories are referred to as 'disorders', they are presented as medical diseases, but are not validated in the same way as most medical diagnoses. Some neurologists argue that classification will only be reliable and valid when based on neurobiological features rather than clinical interview, while others suggest that the differing ideological and practical perspectives need to be better integrated.[30][31]

The DSM and ICD approach remains under attack both because of the implied causality model[32] and because some researchers believe it better to aim at underlying brain differences which can precede symptoms by many years.[33]

Dimensional models

The high degree of comorbidity between disorders in categorical models such as the DSM and ICD have led some to propose dimensional models. Studying comorbidity between disorders have demonstrated two latent (unobserved) factors or dimensions in the structure of mental disorders that are thought to possibly reflect etiological processes. These two dimensions reflect a distinction between internalizing disorders, such as mood or anxiety symptoms, and externalizing disorders such as behavioral or substance use symptoms.[34] A single general factor of psychopathology, similar to the g factor for intelligence, has been empirically supported. The p factor model supports the internalizing-externalizing distinction, but also supports the formation of a third dimension of thought disorders such as schizophrenia.[35] Biological evidence also supports the validity of the internalizing-externalizing structure of mental disorders, with twin and adoption studies supporting heritable factors for externalizing and internalizing disorders.[36][37][38] A leading dimensional model is the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology.

Disorders

There are many different categories of mental disorder, and many different facets of human behavior and personality that can become disordered.[39][40][41][42]

Anxiety disorder

An anxiety disorder is anxiety or fear that interferes with normal functioning may be classified as an anxiety disorder.[40] Commonly recognized categories include specific phobias, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, obsessive–compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Mood disorder

Other affective (emotion/mood) processes can also become disordered. Mood disorder involving unusually intense and sustained sadness, melancholia, or despair is known as major depression (also known as unipolar or clinical depression). Milder, but still prolonged depression, can be diagnosed as dysthymia. Bipolar disorder (also known as manic depression) involves abnormally "high" or pressured mood states, known as mania or hypomania, alternating with normal or depressed moods. The extent to which unipolar and bipolar mood phenomena represent distinct categories of disorder, or mix and merge along a dimension or spectrum of mood, is subject to some scientific debate.[43][44]

Psychotic disorder

Patterns of belief, language use and perception of reality can become dysregulated (e.g., delusions, thought disorder, hallucinations). Psychotic disorders in this domain include schizophrenia, and delusional disorder. Schizoaffective disorder is a category used for individuals showing aspects of both schizophrenia and affective disorders. Schizotypy is a category used for individuals showing some of the characteristics associated with schizophrenia, but without meeting cutoff criteria.

Personality disorder

Personality—the fundamental characteristics of a person that influence thoughts and behaviors across situations and time—may be considered disordered if judged to be abnormally rigid and maladaptive. Although treated separately by some, the commonly used categorical schemes include them as mental disorders, albeit on a separate axis II in the case of the DSM-IV. A number of different personality disorders are listed, including those sometimes classed as eccentric, such as paranoid, schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders; types that have described as dramatic or emotional, such as antisocial, borderline, histrionic or narcissistic personality disorders; and those sometimes classed as fear-related, such as anxious-avoidant, dependent, or obsessive–compulsive personality disorders. Personality disorders, in general, are defined as emerging in childhood, or at least by adolescence or early adulthood. The ICD also has a category for enduring personality change after a catastrophic experience or psychiatric illness. If an inability to sufficiently adjust to life circumstances begins within three months of a particular event or situation, and ends within six months after the stressor stops or is eliminated, it may instead be classed as an adjustment disorder. There is an emerging consensus that personality disorders, similar to personality traits in general, incorporate a mixture of acute dysfunctional behaviors that may resolve in short periods, and maladaptive temperamental traits that are more enduring.[45] Furthermore, there are also non-categorical schemes that rate all individuals via a profile of different dimensions of personality without a symptom-based cutoff from normal personality variation, for example through schemes based on dimensional models.[46][non-primary source needed]

Eating disorder

An eating disorder is a serious mental health condition that involves an unhealthy relationship with food and body image. They can cause severe physical and psychological problems.[47] Eating disorders involve disproportionate concern in matters of food and weight.[40] Categories of disorder in this area include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, exercise bulimia or binge eating disorder.[48][49]

Sleep disorder

Sleep disorders are associated with disruption to normal sleep patterns. A common sleep disorder is insomnia, which is described as difficulty falling and/or staying asleep. Other sleep disorders include narcolepsy, sleep apnea, REM sleep behavior disorder, chronic sleep deprivation, and restless leg syndrome.

Narcolepsy is a condition of extreme tendencies to fall asleep whenever and wherever. People with narcolepsy feel refreshed after their random sleep, but eventually get sleepy again. Narcolepsy diagnosis requires an overnight stay at a sleep center for analysis, during which doctors ask for a detailed sleep history and sleep records. Doctors also use actigraphs and polysomnography.[50] Doctors will do a multiple sleep latency test, which measures how long it takes a person to fall asleep.[50]

Sleep apnea, when breathing repeatedly stops and starts during sleep, can be a serious sleep disorder. Three types of sleep apnea include obstructive sleep apnea, central sleep apnea, and complex sleep apnea.[51] Sleep apnea can be diagnosed at home or with polysomnography at a sleep center. An ear, nose, and throat doctor may further help with the sleeping habits.

Sexuality related

Sexual disorders include dyspareunia and various kinds of paraphilia (sexual arousal to objects, situations, or individuals that are considered abnormal or harmful to the person or others).

Other

Impulse control disorder: People who are abnormally unable to resist certain urges or impulses that could be harmful to themselves or others, may be classified as having an impulse control disorder, and disorders such as kleptomania (stealing) or pyromania (fire-setting). Various behavioral addictions, such as gambling addiction, may be classed as a disorder. Obsessive–compulsive disorder can sometimes involve an inability to resist certain acts but is classed separately as being primarily an anxiety disorder.

Substance use disorder: This disorder refers to the use of drugs (legal or illegal, including alcohol) that persists despite significant problems or harm related to its use. Substance dependence and substance abuse fall under this umbrella category in the DSM. Substance use disorder may be due to a pattern of compulsive and repetitive use of a drug that results in tolerance to its effects and withdrawal symptoms when use is reduced or stopped.

Dissociative disorder: People with severe disturbances of their self-identity, memory, and general awareness of themselves and their surroundings may be classified as having these types of disorders, including depersonalization derealization disorder or dissociative identity disorder (which was previously referred to as multiple personality disorder or "split personality").

Cognitive disorder: These affect cognitive abilities, including learning and memory. This category includes delirium and mild and major neurocognitive disorder (previously termed dementia).

Developmental disorder: These disorders initially occur in childhood. Some examples include autism spectrum disorder, oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which may continue into adulthood. Conduct disorder, if continuing into adulthood, may be diagnosed as antisocial personality disorder (dissocial personality disorder in the ICD). Popular labels such as psychopath (or sociopath) do not appear in the DSM or ICD but are linked by some to these diagnoses.

Somatoform disorders may be diagnosed when there are problems that appear to originate in the body that are thought to be manifestations of a mental disorder. This includes somatization disorder and conversion disorder. There are also disorders of how a person perceives their body, such as body dysmorphic disorder. Neurasthenia is an old diagnosis involving somatic complaints as well as fatigue and low spirits/depression, which is officially recognized by the ICD-10 but no longer by the DSM-IV.[52][non-primary source needed]

Factitious disorders are diagnosed where symptoms are thought to be reported for personal gain. Symptoms are often deliberately produced or feigned, and may relate to either symptoms in the individual or in someone close to them, particularly people they care for.

There are attempts to introduce a category of relational disorder, where the diagnosis is of a relationship rather than on any one individual in that relationship. The relationship may be between children and their parents, between couples, or others. There already exists, under the category of psychosis, a diagnosis of shared psychotic disorder where two or more individuals share a particular delusion because of their close relationship with each other.

There are a number of uncommon psychiatric syndromes, which are often named after the person who first described them, such as Capgras syndrome, De Clerambault syndrome, Othello syndrome, Ganser syndrome, Cotard delusion, and Ekbom syndrome, and additional disorders such as the Couvade syndrome and Geschwind syndrome.[53]

Signs and symptoms

Course

The onset of psychiatric disorders usually occurs from childhood to early adulthood.[54] Impulse-control disorders and a few anxiety disorders tend to appear in childhood. Some other anxiety disorders, substance disorders, and mood disorders emerge later in the mid-teens.[55] Symptoms of schizophrenia typically manifest from late adolescence to early twenties.[56]

The likely course and outcome of mental disorders vary and are dependent on numerous factors related to the disorder itself, the individual as a whole, and the social environment. Some disorders may last a brief period of time, while others may be long-term in nature.

All disorders can have a varied course. Long-term international studies of schizophrenia have found that over a half of individuals recover in terms of symptoms, and around a fifth to a third in terms of symptoms and functioning, with many requiring no medication. While some have serious difficulties and support needs for many years, "late" recovery is still plausible. The World Health Organization (WHO) concluded that the long-term studies' findings converged with others in "relieving patients, carers and clinicians of the chronicity paradigm which dominated thinking throughout much of the 20th century."[57][non-primary source needed][58]

A follow-up study by Tohen and coworkers revealed that around half of people initially diagnosed with bipolar disorder achieve symptomatic recovery (no longer meeting criteria for the diagnosis) within six weeks, and nearly all achieve it within two years, with nearly half regaining their prior occupational and residential status in that period. Less than half go on to experience a new episode of mania or major depression within the next two years.[59][non-primary source needed]

Disability

| Disorder | Disability-adjusted life years[60] |

|---|---|

| Major depressive disorder | 65.5 million |

| Alcohol-use disorder | 23.7 million |

| Schizophrenia | 16.8 million |

| Bipolar disorder | 14.4 million |

| Other drug-use disorders | 8.4 million |

| Panic disorder | 7.0 million |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder | 5.1 million |

| Primary insomnia | 3.6 million |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 3.5 million |

Some disorders may be very limited in their functional effects, while others may involve substantial disability and support needs. In this context, the terms psychiatric disability and psychological disability are sometimes used instead of mental disorder.[2][3] The degree of ability or disability may vary over time and across different life domains. Furthermore, psychiatric disability has been linked to institutionalization, discrimination and social exclusion as well as to the inherent effects of disorders. Alternatively, functioning may be affected by the stress of having to hide a condition in work or school, etc., by adverse effects of medications or other substances, or by mismatches between illness-related variations and demands for regularity.[61]

It is also the case that, while often being characterized in purely negative terms, some mental traits or states labeled as psychiatric disabilities can also involve above-average creativity, non-conformity, goal-striving, meticulousness, or empathy.[62] In addition, the public perception of the level of disability associated with mental disorders can change.[63]

Nevertheless, internationally, people report equal or greater disability from commonly occurring mental conditions than from commonly occurring physical conditions, particularly in their social roles and personal relationships. The proportion with access to professional help for mental disorders is far lower, however, even among those assessed as having a severe psychiatric disability.[64] Disability in this context may or may not involve such things as:

- Basic activities of daily living. Including looking after the self (health care, grooming, dressing, shopping, cooking etc.) or looking after accommodation (chores, DIY tasks, etc.)

- Interpersonal relationships. Including communication skills, ability to form relationships and sustain them, ability to leave the home or mix in crowds or particular settings

- Occupational functioning. Ability to acquire an employment and hold it, cognitive and social skills required for the job, dealing with workplace culture, or studying as a student.

In terms of total disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), which is an estimate of how many years of life are lost due to premature death or to being in a state of poor health and disability, psychiatric disabilities rank amongst the most disabling conditions. Unipolar (also known as Major) depressive disorder is the third leading cause of disability worldwide, of any condition mental or physical, accounting for 65.5 million years lost. The first systematic description of global disability arising in youth, in 2011, found that among 10- to 24-year-olds nearly half of all disability (current and as estimated to continue) was due to psychiatric disabilities, including substance use disorders and conditions involving self-harm. Second to this were accidental injuries (mainly traffic collisions) accounting for 12 percent of disability, followed by communicable diseases at 10 percent. The psychiatric disabilities associated with most disabilities in high-income countries were unipolar major depression (20%) and alcohol use disorder (11%). In the eastern Mediterranean region, it was unipolar major depression (12%) and schizophrenia (7%), and in Africa it was unipolar major depression (7%) and bipolar disorder (5%).[65]

Suicide, which is often attributed to some underlying mental disorder, is a leading cause of death among teenagers and adults under 35.[66][67] There are an estimated 10 to 20 million non-fatal attempted suicides every year worldwide.[68]

Risk factors

The predominant view as of 2018[update] is that genetic, psychological, and environmental factors all contribute to the development or progression of mental disorders.[69] Different risk factors may be present at different ages, with risk occurring as early as during prenatal period.[70]

Genetics

A number of psychiatric disorders are linked to a family history (including depression, narcissistic personality disorder[71][72] and anxiety).[73] Twin studies have also revealed a very high heritability for many mental disorders (especially autism and schizophrenia).[74] Although researchers have been looking for decades for clear linkages between genetics and mental disorders, that work has not yielded specific genetic biomarkers yet that might lead to better diagnosis and better treatments.[75]

Statistical research looking at eleven disorders found widespread assortative mating between people with mental illness. That means that individuals with one of these disorders were two to three times more likely than the general population to have a partner with a mental disorder. Sometimes people seemed to have preferred partners with the same mental illness. Thus, people with schizophrenia or ADHD are seven times more likely to have affected partners with the same disorder. This is even more pronounced for people with Autism spectrum disorders who are 10 times more likely to have a spouse with the same disorder.[76]

Environment

During the prenatal stage, factors like unwanted pregnancy, lack of adaptation to pregnancy or substance use during pregnancy increases the risk of developing a mental disorder.[70] Maternal stress and birth complications including prematurity and infections have also been implicated in increasing susceptibility for mental illness.[77] Infants neglected or not provided optimal nutrition have a higher risk of developing cognitive impairment.[70]

Social influences have also been found to be important,[78] including abuse, neglect, bullying, social stress, traumatic events, and other negative or overwhelming life experiences. Aspects of the wider community have also been implicated,[79] including employment problems, socioeconomic inequality, lack of social cohesion, problems linked to migration, and features of particular societies and cultures. The specific risks and pathways to particular disorders are less clear, however.

Nutrition also plays a role in mental disorders.[10][80]

In schizophrenia and psychosis, risk factors include migration and discrimination, childhood trauma, bereavement or separation in families, recreational use of drugs,[81] and urbanicity.[79]

In anxiety, risk factors may include parenting factors including parental rejection, lack of parental warmth, high hostility, harsh discipline, high maternal negative affect, anxious childrearing, modelling of dysfunctional and drug-abusing behavior, and child abuse (emotional, physical and sexual).[82] Adults with imbalance work to life are at higher risk for developing anxiety.[70]

For bipolar disorder, stress (such as childhood adversity) is not a specific cause, but does place genetically and biologically vulnerable individuals at risk for a more severe course of illness.[83]

Drug use

Mental disorders are associated with drug use including: cannabis,[84] alcohol[85] and caffeine,[86] use of which appears to promote anxiety.[87] For psychosis and schizophrenia, usage of a number of drugs has been associated with development of the disorder, including cannabis, cocaine, and amphetamines.[88][84] There has been debate regarding the relationship between usage of cannabis and bipolar disorder.[89] Cannabis has also been associated with depression.[84] Adolescents are at increased risk for tobacco, alcohol and drug use; Peer pressure is the main reason why adolescents start using substances. At this age, the use of substances could be detrimental to the development of the brain and place them at higher risk of developing a mental disorder.[70]

Chronic disease

People living with chronic conditions like HIV and diabetes are at higher risk of developing a mental disorder. People living with diabetes experience significant stress from the biological impact of the disease, which places them at risk for developing anxiety and depression. Diabetic patients also have to deal with emotional stress trying to manage the disease. Conditions like heart disease, stroke, respiratory conditions, cancer, and arthritis increase the risk of developing a mental disorder when compared to the general population.[90]

Personality traits

Risk factors for mental illness include a propensity for high neuroticism[91][92] or "emotional instability". In anxiety, risk factors may include temperament and attitudes (e.g. pessimism).[73]

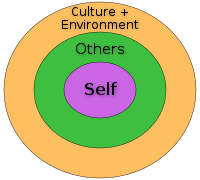

Causal models

Mental disorders can arise from multiple sources, and in many cases there is no single accepted or consistent cause currently established. An eclectic or pluralistic mix of models may be used to explain particular disorders.[92][93] The primary paradigm of contemporary mainstream Western psychiatry is said to be the biopsychosocial model which incorporates biological, psychological and social factors, although this may not always be applied in practice.

Biological psychiatry follows a biomedical model where many mental disorders are conceptualized as disorders of brain circuits likely caused by developmental processes shaped by a complex interplay of genetics and experience. A common assumption is that disorders may have resulted from genetic and developmental vulnerabilities, exposed by stress in life (for example in a diathesis–stress model), although there are various views on what causes differences between individuals. Some types of mental disorders may be viewed as primarily neurodevelopmental disorders.

Evolutionary psychology may be used as an overall explanatory theory, while attachment theory is another kind of evolutionary-psychological approach sometimes applied in the context of mental disorders. Psychoanalytic theories have continued to evolve alongside and cognitive-behavioral and systemic-family approaches. A distinction is sometimes made between a "medical model" or a "social model" of psychiatric disability.

Diagnosis

Psychiatrists seek to provide a medical diagnosis of individuals by an assessment of symptoms, signs and impairment associated with particular types of mental disorder. Other mental health professionals, such as clinical psychologists, may or may not apply the same diagnostic categories to their clinical formulation of a client's difficulties and circumstances.[94] The majority of mental health problems are, at least initially, assessed and treated by family physicians (in the UK general practitioners) during consultations, who may refer a patient on for more specialist diagnosis in acute or chronic cases.

Routine diagnostic practice in mental health services typically involves an interview known as a mental status examination, where evaluations are made of appearance and behavior, self-reported symptoms, mental health history, and current life circumstances. The views of other professionals, relatives, or other third parties may be taken into account. A physical examination to check for ill health or the effects of medications or other drugs may be conducted. Psychological testing is sometimes used via paper-and-pen or computerized questionnaires, which may include algorithms based on ticking off standardized diagnostic criteria, and in rare specialist cases neuroimaging tests may be requested, but such methods are more commonly found in research studies than routine clinical practice.[95][96]

Time and budgetary constraints often limit practicing psychiatrists from conducting more thorough diagnostic evaluations.[97] It has been found that most clinicians evaluate patients using an unstructured, open-ended approach, with limited training in evidence-based assessment methods, and that inaccurate diagnosis may be common in routine practice.[98] In addition, comorbidity is very common in psychiatric diagnosis, where the same person meets the criteria for more than one disorder. On the other hand, a person may have several different difficulties only some of which meet the criteria for being diagnosed. There may be specific problems with accurate diagnosis in developing countries.

More structured approaches are being increasingly used to measure levels of mental illness.

- HoNOS is the most widely used measure in English mental health services, being used by at least 61 trusts.[99] In HoNOS a score of 0–4 is given for each of 12 factors, based on functional living capacity.[100] Research has been supportive of HoNOS,[101] although some questions have been asked about whether it provides adequate coverage of the range and complexity of mental illness problems, and whether the fact that often only 3 of the 12 scales vary over time gives enough subtlety to accurately measure outcomes of treatment.[102]

Criticism

Since the 1980s, Paula Caplan has been concerned about the subjectivity of psychiatric diagnosis, and people being arbitrarily "slapped with a psychiatric label." Caplan says because psychiatric diagnosis is unregulated, doctors are not required to spend much time interviewing patients or to seek a second opinion. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders can lead a psychiatrist to focus on narrow checklists of symptoms, with little consideration of what is actually causing the person's problems. So, according to Caplan, getting a psychiatric diagnosis and label often stands in the way of recovery.[103]

In 2013, psychiatrist Allen Frances wrote a paper entitled "The New Crisis of Confidence in Psychiatric Diagnosis", which said that "psychiatric diagnosis... still relies exclusively on fallible subjective judgments rather than objective biological tests." Frances was also concerned about "unpredictable overdiagnosis."[104] For many years, marginalized psychiatrists (such as Peter Breggin, Thomas Szasz) and outside critics (such as Stuart A. Kirk) have "been accusing psychiatry of engaging in the systematic medicalization of normality." More recently these concerns have come from insiders who have worked for and promoted the American Psychiatric Association (e.g., Robert Spitzer, Allen Frances).[105] A 2002 editorial in the British Medical Journal warned of inappropriate medicalization leading to disease mongering, where the boundaries of the definition of illnesses are expanded to include personal problems as medical problems or risks of diseases are emphasized to broaden the market for medications.[106]

Gary Greenberg, a psychoanalyst, in his book "the Book of Woe", argues that mental illness is really about suffering and how the DSM creates diagnostic labels to categorize people's suffering.[107] Indeed, the psychiatrist Thomas Szasz, in his book "the Medicalization of Everyday Life", also argues that what is psychiatric illness, is not always biological in nature (i.e. social problems, poverty, etc.), and may even be a part of the human condition.[108]

Potential routine use of MRI/fMRI in diagnosis

in 2018 the American Psychological Association commissioned a review to reach a consensus on whether modern clinical MRI/fMRI will be able to be used in the diagnosis of mental health disorders. The criteria presented by the APA stated that the biomarkers used in diagnosis should:

- "have a sensitivity of at least 80% for detecting a particular psychiatric disorder"

- should "have a specificity of at least 80% for distinguishing this disorder from other psychiatric or medical disorders"

- "should be reliable, reproducible, and ideally be noninvasive, simple to perform, and inexpensive"

- proposed biomarkers should be verified by 2 independent studies each by a different investigator and different population samples and published in a peer-reviewed journal.

The review concluded that although neuroimaging diagnosis may technically be feasible, very large studies are needed to evaluate specific biomarkers which were not available.[109]

Prevention

The 2004 WHO report "Prevention of Mental Disorders" stated that "Prevention of these disorders is obviously one of the most effective ways to reduce the [disease] burden."[110]The 2011 European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on prevention of mental disorders states "There is considerable evidence that various psychiatric conditions can be prevented through the implementation of effective evidence-based interventions."[111]A 2011 UK Department of Health report on the economic case for mental health promotion and mental illness prevention found that "many interventions are outstandingly good value for money, low in cost and often become self-financing over time, saving public expenditure".[112]In 2016, the National Institute of Mental Health re-affirmed prevention as a research priority area.[113]

Parenting may affect the child's mental health, and evidence suggests that helping parents to be more effective with their children can address mental health needs.[114][115][116]

Universal prevention (aimed at a population that has no increased risk for developing a mental disorder, such as school programs or mass media campaigns) need very high numbers of people to show effect (sometimes known as the "power" problem). Approaches to overcome this are (1) focus on high-incidence groups (e.g. by targeting groups with high risk factors), (2) use multiple interventions to achieve greater, and thus more statistically valid, effects, (3) use cumulative meta-analyses of many trials, and (4) run very large trials.[117][118]

Management

Treatment and support for mental disorders are provided in psychiatric hospitals, clinics or a range of community mental health services. In some countries services are increasingly based on a recovery approach, intended to support individual's personal journey to gain the kind of life they want.

There is a range of different types of treatment and what is most suitable depends on the disorder and the individual. Many things have been found to help at least some people, and a placebo effect may play a role in any intervention or medication. In a minority of cases, individuals may be treated against their will, which can cause particular difficulties depending on how it is carried out and perceived. Compulsory treatment while in the community versus non-compulsory treatment does not appear to make much of a difference except by maybe decreasing victimization.[119]

Lifestyle

Lifestyle strategies, including dietary changes, exercise and quitting smoking may be of benefit.[13][80][120]

Therapy

There is also a wide range of psychotherapists (including family therapy), counselors, and public health professionals. In addition, there are peer support roles where personal experience of similar issues is the primary source of expertise.[121][122][123][124]

A major option for many mental disorders is psychotherapy. There are several main types. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is widely used and is based on modifying the patterns of thought and behavior associated with a particular disorder. Other psychotherapies include dialectic behavioral therapy (DBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT). Psychoanalysis, addressing underlying psychic conflicts and defenses, has been a dominant school of psychotherapy and is still in use. Systemic therapy or family therapy is sometimes used, addressing a network of significant others as well as an individual.

Some psychotherapies are based on a humanistic approach. There are many specific therapies used for particular disorders, which may be offshoots or hybrids of the above types. Mental health professionals often employ an eclectic or integrative approach. Much may depend on the therapeutic relationship, and there may be problems with trust, confidentiality and engagement.

Medication

A major option for many mental disorders is psychiatric medication and there are several main groups. Antidepressants are used for the treatment of clinical depression, as well as often for anxiety and a range of other disorders. Anxiolytics (including sedatives) are used for anxiety disorders and related problems such as insomnia. Mood stabilizers are used primarily in bipolar disorder. Antipsychotics are used for psychotic disorders, notably for positive symptoms in schizophrenia, and also increasingly for a range of other disorders. Stimulants are commonly used, notably for ADHD.[125]

Despite the different conventional names of the drug groups, there may be considerable overlap in the disorders for which they are actually indicated, and there may also be off-label use of medications. There can be problems with adverse effects of medication and adherence to them, and there is also criticism of pharmaceutical marketing and professional conflicts of interest. However, these medications in combination with non-pharmacological methods, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are seen to be most effective in treating mental disorders.

Other

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is sometimes used in severe cases when other interventions for severe intractable depression have failed. ECT is usually indicated for treatment resistant depression, severe vegetative symptoms, psychotic depression, intense suicidal ideation, depression during pregnancy, and catatonia. Psychosurgery is considered experimental but is advocated by some neurologists in certain rare cases.[126][127]

Counseling (professional) and co-counseling (between peers) may be used. Psychoeducation programs may provide people with the information to understand and manage their problems. Creative therapies are sometimes used, including music therapy, art therapy or drama therapy. Lifestyle adjustments and supportive measures are often used, including peer support, self-help groups for mental health and supported housing or supported employment (including social firms). Some advocate dietary supplements.[128]

Reasonable accommodations (adjustments and supports) might be put in place to help an individual cope and succeed in environments despite potential disability related to mental health problems. This could include an emotional support animal or specifically trained psychiatric service dog. As of 2019[update] cannabis is specifically not recommended as a treatment.[129]

Epidemiology

Mental disorders are common. Worldwide, more than one in three people in most countries report sufficient criteria for at least one at some point in their life.[130] In the United States, 46% qualify for a mental illness at some point.[131] An ongoing survey indicates that anxiety disorders are the most common in all but one country, followed by mood disorders in all but two countries, while substance disorders and impulse-control disorders were consistently less prevalent.[132] Rates varied by region.[133]

A review of anxiety disorder surveys in different countries found average lifetime prevalence estimates of 16.6%, with women having higher rates on average.[134] A review of mood disorder surveys in different countries found lifetime rates of 6.7% for major depressive disorder (higher in some studies, and in women) and 0.8% for Bipolar I disorder.[135]

In the United States the frequency of disorder is: anxiety disorder (28.8%), mood disorder (20.8%), impulse-control disorder (24.8%) or substance use disorder (14.6%).[131][136][137]

A 2004 cross-Europe study found that approximately one in four people reported meeting criteria at some point in their life for at least one of the DSM-IV disorders assessed, which included mood disorders (13.9%), anxiety disorders (13.6%), or alcohol disorder (5.2%). Approximately one in ten met the criteria within a 12-month period. Women and younger people of either gender showed more cases of the disorder.[138] A 2005 review of surveys in 16 European countries found that 27% of adult Europeans are affected by at least one mental disorder in a 12-month period.[139]

An international review of studies on the prevalence of schizophrenia found an average (median) figure of 0.4% for lifetime prevalence; it was consistently lower in poorer countries.[140]

Studies of the prevalence of personality disorders (PDs) have been fewer and smaller-scale, but one broad Norwegian survey found a five-year prevalence of almost 1 in 7 (13.4%). Rates for specific disorders ranged from 0.8% to 2.8%, differing across countries, and by gender, educational level and other factors.[141] A US survey that incidentally screened for personality disorder found a rate of 14.79%.[142]

Approximately 7% of a preschool pediatric sample were given a psychiatric diagnosis in one clinical study, and approximately 10% of 1- and 2-year-olds receiving developmental screening have been assessed as having significant emotional/behavioral problems based on parent and pediatrician reports.[143]

While rates of psychological disorders are often the same for men and women, women tend to have a higher rate of depression. Each year 73 million women are affected by major depression, and suicide is ranked 7th as the cause of death for women between the ages of 20–59. Depressive disorders account for close to 41.9% of the psychiatric disabilities among women compared to 29.3% among men.[144]

History

Ancient civilizations

Ancient civilizations described and treated a number of mental disorders. Mental illnesses were well known in ancient Mesopotamia,[145] where diseases and mental disorders were believed to be caused by specific deities.[146] Because hands symbolized control over a person, mental illnesses were known as "hands" of certain deities.[146] One psychological illness was known as Qāt Ištar, meaning "Hand of Ishtar".[146] Others were known as "Hand of Shamash", "Hand of the Ghost", and "Hand of the God".[146] Descriptions of these illnesses, however, are so vague that it is usually impossible to determine which illnesses they correspond to in modern terminology.[146] Mesopotamian doctors kept detailed record of their patients' hallucinations and assigned spiritual meanings to them.[145] The royal family of Elam was notorious for its members often being insane.[145] The Greeks coined terms for melancholy, hysteria and phobia and developed the humorism theory. Mental disorders were described, and treatments developed, in Persia, Arabia and in the medieval Islamic world.

Europe

Middle Ages

Conceptions of madness in the Middle Ages in Christian Europe were a mixture of the divine, diabolical, magical and humoral, and transcendental.[147] In the early modern period, some people with mental disorders may have been victims of the witch-hunts. While not every witch and sorcerer accused were mentally ill, all mentally ill were considered to be witches or sorcerers.[148] Many terms for mental disorders that found their way into everyday use first became popular in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Eighteenth century

By the end of the 17th century and into the Enlightenment, madness was increasingly seen as an organic physical phenomenon with no connection to the soul or moral responsibility. Asylum care was often harsh and treated people like wild animals, but towards the end of the 18th century a moral treatment movement gradually developed. Clear descriptions of some syndromes may be rare before the 19th century.

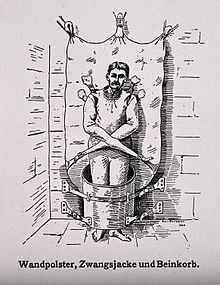

Nineteenth century

Industrialization and population growth led to a massive expansion of the number and size of insane asylums in every Western country in the 19th century. Numerous different classification schemes and diagnostic terms were developed by different authorities, and the term psychiatry was coined (1808), though medical superintendents were still known as alienists.

Twentieth century

The turn of the 20th century saw the development of psychoanalysis, which would later come to the fore, along with Kraepelin's classification scheme. Asylum "inmates" were increasingly referred to as "patients", and asylums were renamed as hospitals.

Europe and the United States

Early in the 20th century in the United States, a mental hygiene movement developed, aiming to prevent mental disorders. Clinical psychology and social work developed as professions. World War I saw a massive increase of conditions that came to be termed "shell shock".

World War II saw the development in the U.S. of a new psychiatric manual for categorizing mental disorders, which along with existing systems for collecting census and hospital statistics led to the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) also developed a section on mental disorders. The term stress, having emerged from endocrinology work in the 1930s, was increasingly applied to mental disorders.

Electroconvulsive therapy, insulin shock therapy, lobotomies and the neuroleptic chlorpromazine came to be used by mid-century.[149] In the 1960s there were many challenges to the concept of mental illness itself. These challenges came from psychiatrists like Thomas Szasz who argued that mental illness was a myth used to disguise moral conflicts; from sociologists such as Erving Goffman who said that mental illness was merely another example of how society labels and controls non-conformists; from behavioral psychologists who challenged psychiatry's fundamental reliance on unobservable phenomena; and from gay rights activists who criticised the APA's listing of homosexuality as a mental disorder. A study published in Science by Rosenhan received much publicity and was viewed as an attack on the efficacy of psychiatric diagnosis.[150]

Deinstitutionalization gradually occurred in the West, with isolated psychiatric hospitals being closed down in favor of community mental health services. A consumer/survivor movement gained momentum. Other kinds of psychiatric medication gradually came into use, such as "psychic energizers" (later antidepressants) and lithium. Benzodiazepines gained widespread use in the 1970s for anxiety and depression, until dependency problems curtailed their popularity.

Advances in neuroscience, genetics, and psychology led to new research agendas. Cognitive behavioral therapy and other psychotherapies developed. The DSM and then ICD adopted new criteria-based classifications, and the number of "official" diagnoses saw a large expansion. Through the 1990s, new SSRI-type antidepressants became some of the most widely prescribed drugs in the world, as later did antipsychotics. Also during the 1990s, a recovery approach developed.

Africa and Nigeria

Most Africans view mental disturbances as external spiritual attack on the person. Those who have a mental illness are thought to be under a spell or bewitched. Often than usual, People view a mentally ill person as possessed of an evil spirit and is seen as more of sociological perspective than a psychological order.[151]

The WHO estimated that fewer than 10% of mentally ill Nigerians have access to a psychiatrist or health worker, because there is a low ratio of mental-health specialists available in a country of 200 million people. WHO estimates that the number of mentally ill Nigerians ranges from 40 million to 60 million. Disorders such as depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, personality disorder, old age-related disorder, and substance-abuse disorder are common in Nigeria, as in other countries in Africa.[152]

Nigeria is still nowhere near being equipped to solve prevailing mental health challenges. With little scientific research carried out, coupled with insufficient mental-health hospitals in the country, traditional healers provide specialized psychotherapy care to those that require their services and pharmacotherapy[153][154]

Society and culture

Different societies or cultures, even different individuals in a subculture, can disagree as to what constitutes optimal versus pathological biological and psychological functioning. Research has demonstrated that cultures vary in the relative importance placed on, for example, happiness, autonomy, or social relationships for pleasure. Likewise, the fact that a behavior pattern is valued, accepted, encouraged, or even statistically normative in a culture does not necessarily mean that it is conducive to optimal psychological functioning.

People in all cultures find some behaviors bizarre or even incomprehensible. But just what they feel is bizarre or incomprehensible is ambiguous and subjective.[155] These differences in determination can become highly contentious. The process by which conditions and difficulties come to be defined and treated as medical conditions and problems, and thus come under the authority of doctors and other health professionals, is known as medicalization or pathologization.

Mental illness in the Latin American community

There is a perception in Latin American communities, especially among older people, that discussing problems with mental health can create embarrassment and shame for the family. This results in fewer people seeking treatment.[156]

Latin Americans from the US are slightly more likely to have a mental health disorder than first-generation Latin American immigrants, although differences between ethnic groups were found to disappear after adjustment for place of birth.[157]

From 2015 to 2018, rates of serious mental illness in young adult Latin Americans increased by 60%, from 4% to 6.4%. The prevalence of major depressive episodes in young and adult Latin Americans increased from 8.4% to 11.3%. More than a third of Latin Americans reported more than one bad mental health day in the last three months.[158] The rate of suicide among Latin Americans was about half the rate of non-Latin American white Americans in 2018, and this was the second-leading cause of death among Latin Americans ages 15 to 34.[159] However, Latin American suicide rates rose steadily after 2020 in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic, even as the national rate declined.[160][161]

Family relations are an integral part of the Latin American community. Some research has shown that Latin Americans are more likely rely on family bonds, or familismo, as a source of therapy while struggling with mental health issues. Because Latin Americans have a high rate of religiosity, and because there is less stigma associated with religion than with psychiatric services,[162] religion may play a more important therapeutic role for the mentally ill in Latin American communities. However, research has also suggested that religion may also play a role in stigmatizing mental illness in Latin American communities, which can discourage community members from seeking professional help.[163]

Religion

Religious, spiritual, or transpersonal experiences and beliefs meet many criteria of delusional or psychotic disorders.[164][165] A belief or experience can sometimes be shown to produce distress or disability—the ordinary standard for judging mental disorders.[166] There is a link between religion and schizophrenia,[167] a complex mental disorder characterized by a difficulty in recognizing reality, regulating emotional responses, and thinking in a clear and logical manner. Those with schizophrenia commonly report some type of religious delusion,[167][168][169] and religion itself may be a trigger for schizophrenia.[170]

Movements

Controversy has often surrounded psychiatry, and the term anti-psychiatry was coined by the psychiatrist David Cooper in 1967. The anti-psychiatry message is that psychiatric treatments are ultimately more damaging than helpful to patients, and psychiatry's history involves what may now be seen as dangerous treatments.[171] Electroconvulsive therapy was one of these, which was used widely between the 1930s and 1960s. Lobotomy was another practice that was ultimately seen as too invasive and brutal. Diazepam and other sedatives were sometimes over-prescribed, which led to an epidemic of dependence. There was also concern about the large increase in prescribing psychiatric drugs for children. Some charismatic psychiatrists came to personify the movement against psychiatry. The most influential of these was R.D. Laing who wrote a series of best-selling books, including The Divided Self. Thomas Szasz wrote The Myth of Mental Illness. Some ex-patient groups have become militantly anti-psychiatric, often referring to themselves as survivors.[171] Giorgio Antonucci has questioned the basis of psychiatry through his work on the dismantling of two psychiatric hospitals (in the city of Imola), carried out from 1973 to 1996.

The consumer/survivor movement (also known as user/survivor movement) is made up of individuals (and organizations representing them) who are clients of mental health services or who consider themselves survivors of psychiatric interventions. Activists campaign for improved mental health services and for more involvement and empowerment within mental health services, policies and wider society.[172][173][174] Patient advocacy organizations have expanded with increasing deinstitutionalization in developed countries, working to challenge the stereotypes, stigma and exclusion associated with psychiatric conditions. There is also a carers rights movement of people who help and support people with mental health conditions, who may be relatives, and who often work in difficult and time-consuming circumstances with little acknowledgement and without pay. An anti-psychiatry movement fundamentally challenges mainstream psychiatric theory and practice, including in some cases asserting that psychiatric concepts and diagnoses of 'mental illness' are neither real nor useful.[175][unreliable source?][176][177]

Alternatively, a movement for global mental health has emerged, defined as 'the area of study, research and practice that places a priority on improving mental health and achieving equity in mental health for all people worldwide'.[178]

Cultural bias

Diagnostic guidelines of the 2000s, namely the DSM and to some extent the ICD, have been criticized as having a fundamentally Euro-American outlook. Opponents argue that even when diagnostic criteria are used across different cultures, it does not mean that the underlying constructs have validity within those cultures, as even reliable application can prove only consistency, not legitimacy.[179] Advocating a more culturally sensitive approach, critics such as Carl Bell and Marcello Maviglia contend that the cultural and ethnic diversity of individuals is often discounted by researchers and service providers.[180]

Cross-cultural psychiatrist Arthur Kleinman contends that the Western bias is ironically illustrated in the introduction of cultural factors to the DSM-IV. Disorders or concepts from non-Western or non-mainstream cultures are described as "culture-bound", whereas standard psychiatric diagnoses are given no cultural qualification whatsoever, revealing to Kleinman an underlying assumption that Western cultural phenomena are universal.[181] Kleinman's negative view towards the culture-bound syndrome is largely shared by other cross-cultural critics. Common responses included both disappointment over the large number of documented non-Western mental disorders still left out and frustration that even those included are often misinterpreted or misrepresented.[182]

Many mainstream psychiatrists are dissatisfied with the new culture-bound diagnoses, although for partly different reasons. Robert Spitzer, a lead architect of the DSM-III, has argued that adding cultural formulations was an attempt to appease cultural critics, and has stated that they lack any scientific rationale or support. Spitzer also posits that the new culture-bound diagnoses are rarely used, maintaining that the standard diagnoses apply regardless of the culture involved. In general, mainstream psychiatric opinion remains that if a diagnostic category is valid, cross-cultural factors are either irrelevant or are significant only to specific symptom presentations.[179]

Clinical conceptions of mental illness also overlap with personal and cultural values in the domain of morality, so much so that it is sometimes argued that separating the two is impossible without fundamentally redefining the essence of being a particular person in a society.[183] In clinical psychiatry, persistent distress and disability indicate an internal disorder requiring treatment; but in another context, that same distress and disability can be seen as an indicator of emotional struggle and the need to address social and structural problems.[184][185] This dichotomy has led some academics and clinicians to advocate a postmodernist conceptualization of mental distress and well-being.[186][187]

Such approaches, along with cross-cultural and "heretical" psychologies centered on alternative cultural and ethnic and race-based identities and experiences, stand in contrast to the mainstream psychiatric community's alleged avoidance of any explicit involvement with either morality or culture.[188] In many countries there are attempts to challenge perceived prejudice against minority groups, including alleged institutional racism within psychiatric services.[189] There are also ongoing attempts to improve professional cross cultural sensitivity.[190]

Laws and policies

Three-quarters of countries around the world have mental health legislation. Compulsory admission to mental health facilities (also known as involuntary commitment) is a controversial topic. It can impinge on personal liberty and the right to choose, and carry the risk of abuse for political, social, and other reasons; yet it can potentially prevent harm to self and others, and assist some people in attaining their right to healthcare when they may be unable to decide in their own interests.[191] Because of this it is a concern of medical ethics.

All human rights oriented mental health laws require proof of the presence of a mental disorder as defined by internationally accepted standards, but the type and severity of disorder that counts can vary in different jurisdictions. The two most often used grounds for involuntary admission are said to be serious likelihood of immediate or imminent danger to self or others, and the need for treatment. Applications for someone to be involuntarily admitted usually come from a mental health practitioner, a family member, a close relative, or a guardian. Human-rights-oriented laws usually stipulate that independent medical practitioners or other accredited mental health practitioners must examine the patient separately and that there should be regular, time-bound review by an independent review body.[191] The individual should also have personal access to independent advocacy.

For involuntary treatment to be administered (by force if necessary), it should be shown that an individual lacks the mental capacity for informed consent (i.e. to understand treatment information and its implications, and therefore be able to make an informed choice to either accept or refuse). Legal challenges in some areas have resulted in supreme court decisions that a person does not have to agree with a psychiatrist's characterization of the issues as constituting an "illness", nor agree with a psychiatrist's conviction in medication, but only recognize the issues and the information about treatment options.[192]

Proxy consent (also known as surrogate or substituted decision-making) may be transferred to a personal representative, a family member, or a legally appointed guardian. Moreover, patients may be able to make, when they are considered well, an advance directive stipulating how they wish to be treated should they be deemed to lack mental capacity in the future.[191] The right to supported decision-making, where a person is helped to understand and choose treatment options before they can be declared to lack capacity, may also be included in the legislation.[193] There should at the very least be shared decision-making as far as possible. Involuntary treatment laws are increasingly extended to those living in the community, for example outpatient commitment laws (known by different names) are used in New Zealand, Australia, the United Kingdom, and most of the United States.

The World Health Organization reports that in many instances national mental health legislation takes away the rights of persons with mental disorders rather than protecting rights, and is often outdated.[191] In 1991, the United Nations adopted the Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illness and the Improvement of Mental Health Care, which established minimum human rights standards of practice in the mental health field. In 2006, the UN formally agreed the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities to protect and enhance the rights and opportunities of disabled people, including those with psychiatric disabilities.[194]

The term insanity, sometimes used colloquially as a synonym for mental illness, is often used technically as a legal term. The insanity defense may be used in a legal trial (known as the mental disorder defence in some countries).

Perception and discrimination

Stigma

The social stigma associated with mental disorders is a widespread problem. The US Surgeon General stated in 1999 that: "Powerful and pervasive, stigma prevents people from acknowledging their own mental health problems, much less disclosing them to others."[195] Additionally, researcher Wulf Rössler in 2016, in his article, "The Stigma of Mental Disorders" stated

"For millennia, society did not treat persons suffering from depression, autism, schizophrenia and other mental illnesses much better than slaves or criminals: they were imprisoned, tortured or killed".[196]

In the United States, racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to experience mental health disorders often due to low socioeconomic status, and discrimination.[197][198][199] In Taiwan, those with mental disorders are subject to general public's misperception that the root causes of the mental disorders are "over-thinking", "having a lot of time and nothing better to do", "stagnant", "not serious in life", "not paying enough attention to the real life affairs", "mentally weak", "refusing to be resilient", "turning back to perfectionistic strivings", "not bravery" and so forth.[200]

Employment discrimination is reported to play a significant part in the high rate of unemployment among those with a diagnosis of mental illness.[201] An Australian study found that having a psychiatric disability is a bigger barrier to employment than a physical disability.[202][better source needed] The mentally ill are stigmatized in Chinese society and can not legally marry.[203]

Efforts are being undertaken worldwide to eliminate the stigma of mental illness,[204] although the methods and outcomes used have sometimes been criticized.[205]

Media and general public

Media coverage of mental illness comprises predominantly negative and pejorative depictions, for example, of incompetence, violence or criminality, with far less coverage of positive issues such as accomplishments or human rights issues.[206][207][208] Such negative depictions, including in children's cartoons, are thought to contribute to stigma and negative attitudes in the public and in those with mental health problems themselves, although more sensitive or serious cinematic portrayals have increased in prevalence.[209][210]

In the United States, the Carter Center has created fellowships for journalists in South Africa, the U.S., and Romania, to enable reporters to research and write stories on mental health topics.[211] Former US First Lady Rosalynn Carter began the fellowships not only to train reporters in how to sensitively and accurately discuss mental health and mental illness, but also to increase the number of stories on these topics in the news media.[212][213] There is also a World Mental Health Day, which in the United States and Canada falls within a Mental Illness Awareness Week.

The general public have been found to hold a strong stereotype of dangerousness and desire for social distance from individuals described as mentally ill.[214] A US national survey found that a higher percentage of people rate individuals described as displaying the characteristics of a mental disorder as "likely to do something violent to others", compared to the percentage of people who are rating individuals described as being troubled.[215] In the article, "Discrimination Against People with a Mental Health Diagnosis: Qualitative Analysis of Reported Experiences," an individual who has a mental disorder, revealed that, "If people don't know me and don't know about the problems, they'll talk to me quite happily. Once they've seen the problems or someone's told them about me, they tend to be a bit more wary."[216] In addition, in the article,"Stigma and its Impact on Help-Seeking for Mental Disorders: What Do We Know?" by George Schomerus and Matthias Angermeyer, it is affirmed that "Family doctors and psychiatrists have more pessimistic views about the outcomes for mental illnesses than the general public (Jorm et al., 1999), and mental health professionals hold more negative stereotypes about mentally ill patients, but, reassuringly, they are less accepting of restrictions towards them."[217]

Recent depictions in media have included leading characters successfully living with and managing a mental illness, including in bipolar disorder in Homeland (2011) and post-traumatic stress disorder in Iron Man 3 (2013).[218][219][original research?]

Violence

Despite public or media opinion, national studies have indicated that severe mental illness does not independently predict future violent behavior, on average, and is not a leading cause of violence in society. There is a statistical association with various factors that do relate to violence (in anyone), such as substance use and various personal, social, and economic factors.[220] A 2015 review found that in the United States, about 4% of violence is attributable to people diagnosed with mental illness,[221] and a 2014 study found that 7.5% of crimes committed by mentally ill people were directly related to the symptoms of their mental illness.[222] The majority of people with serious mental illness are never violent.[223]

In fact, findings consistently indicate that it is many times more likely that people diagnosed with a serious mental illness living in the community will be the victims rather than the perpetrators of violence.[224][225] In a study of individuals diagnosed with "severe mental illness" living in a US inner-city area, a quarter were found to have been victims of at least one violent crime over the course of a year, a proportion eleven times higher than the inner-city average, and higher in every category of crime including violent assaults and theft.[226] People with a diagnosis may find it more difficult to secure prosecutions, however, due in part to prejudice and being seen as less credible.[227]

However, there are some specific diagnoses, such as childhood conduct disorder or adult antisocial personality disorder or psychopathy, which are defined by, or are inherently associated with, conduct problems and violence. There are conflicting findings about the extent to which certain specific symptoms, notably some kinds of psychosis (hallucinations or delusions) that can occur in disorders such as schizophrenia, delusional disorder or mood disorder, are linked to an increased risk of serious violence on average. The mediating factors of violent acts, however, are most consistently found to be mainly socio-demographic and socio-economic factors such as being young, male, of lower socioeconomic status and, in particular, substance use (including alcohol use) to which some people may be particularly vulnerable.[62][224][228][229]

High-profile cases have led to fears that serious crimes, such as homicide, have increased due to deinstitutionalization, but the evidence does not support this conclusion.[229][230] Violence that does occur in relation to mental disorder (against the mentally ill or by the mentally ill) typically occurs in the context of complex social interactions, often in a family setting rather than between strangers.[231] It is also an issue in health care settings[232] and the wider community.[233]

Mental health

The recognition and understanding of mental health conditions have changed over time and across cultures and there are still variations in definition, assessment, and classification, although standard guideline criteria are widely used. In many cases, there appears to be a continuum between mental health and mental illness, making diagnosis complex.[41]: 39 According to the World Health Organization, over a third of people in most countries report problems at some time in their life which meet the criteria for diagnosis of one or more of the common types of mental disorder.[130] Corey M Keyes has created a two continua model of mental illness and health which holds that both are related, but distinct dimensions: one continuum indicates the presence or absence of mental health, the other the presence or absence of mental illness.[234] For example, people with optimal mental health can also have a mental illness, and people who have no mental illness can also have poor mental health.[235]

Other animals

Psychopathology in non-human primates has been studied since the mid-20th century. Over 20 behavioral patterns in captive chimpanzees have been documented as (statistically) abnormal for frequency, severity or oddness—some of which have also been observed in the wild. Captive great apes show gross behavioral abnormalities such as stereotypy of movements, self-mutilation, disturbed emotional reactions (mainly fear or aggression) towards companions, lack of species-typical communications, and generalized learned helplessness. In some cases such behaviors are hypothesized to be equivalent to symptoms associated with psychiatric disorders in humans such as depression, anxiety disorders, eating disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder. Concepts of antisocial, borderline and schizoid personality disorders have also been applied to non-human great apes.[236][237]

The risk of anthropomorphism is often raised concerning such comparisons, and assessment of non-human animals cannot incorporate evidence from linguistic communication. However, available evidence may range from nonverbal behaviors—including physiological responses and homologous facial displays and acoustic utterances—to neurochemical studies. It is pointed out that human psychiatric classification is often based on statistical description and judgment of behaviors (especially when speech or language is impaired) and that the use of verbal self-report is itself problematic and unreliable.[236][238]