Орегон

Орегон | |

|---|---|

| Прозвище : Бобровый штат | |

| Девиз(ы) : | |

| Гимн: Орегон, мой Орегон | |

Карта Соединенных Штатов с выделенным Орегоном | |

| Страна | Соединенные Штаты |

| До государственности | Территория Орегона |

| Принят в Союз | 14 февраля 1859 г (33-е) |

| Капитал | Салем |

| Крупнейший город | Портленд |

| Самый большой округ или его эквивалент | Малтнома |

| Крупнейшие метро и городские районы | Портленд |

| Правительство | |

| • Губернатор | Тина Котек ( З ) |

| • Государственный секретарь | Лавонн Гриффин-Валад (З) [ а ] |

| Законодательная власть | Законодательное собрание |

| • Верхняя палата | Сенат штата |

| • Нижняя палата | Палата представителей |

| Judiciary | Oregon Supreme Court |

| U.S. senators | Ron Wyden (D) Jeff Merkley (D) |

| U.S. House delegation | 4 Democrats 2 Republicans (list) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 98,381 sq mi (254,806 km2) |

| • Land | 95,997 sq mi (248,849 km2) |

| • Water | 2,384 sq mi (6,177 km2) 2.4% |

| • Rank | 9th |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 360 mi (580 km) |

| • Width | 400 mi (640 km) |

| Elevation | 3,300 ft (1,000 m) |

| Highest elevation | 11,249 ft (3,428.8 m) |

| Lowest elevation (Pacific Ocean[2]) | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population (2023) | |

| • Total | 4,233,358[3] |

| • Rank | 27th |

| • Density | 39.9/sq mi (15.0/km2) |

| • Rank | 39th |

| • Median household income | $71,562[4] |

| • Income rank | 18th |

| Demonym | Oregonian |

| Language | |

| • Official language | De jure: none[5] De facto: English |

| Time zones | |

| most of state | UTC−08:00 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−07:00 (PDT) |

| majority of Malheur County | UTC−07:00 (Mountain) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−06:00 (MDT) |

| USPS abbreviation | OR |

| ISO 3166 code | US-OR |

| Traditional abbreviation | Ore. |

| Latitude | 42° N to 46°18′ N |

| Longitude | 116°28′ W to 124°38′ W |

| Website | oregon |

| ASN | |

| List of state symbols | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Motto | She Flies With Her Own Wings[6] |

| Living insignia | |

| Bird | Western meadowlark (Sturnella neglecta) |

| Butterfly | Oregon swallowtail (Papilio machaon oregonia) |

| Crustacean | Dungeness crab (Metacarcinus magister) |

| Fish | Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) |

| Flower | Oregon grape (Mahonia aquifolium) |

| Grass | Bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata) |

| Insect | Oregon swallowtail (Papilio oregonius) |

| Mammal | American beaver (Castor canadensis) |

| Mushroom | Pacific golden chanterelle (Cantharellus formosus) |

| Tree | Douglas-fir |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Beverage | Milk |

| Dance | Square dance |

| Food | Pear (Pyrus) |

| Fossil | Metasequoia |

| Gemstone | Oregon sunstone |

| Rock | Thunderegg |

| Shell | Oregon hairy triton (Fusitriton oregonensis) |

| Soil | Jory soil |

| Other | Nut: Hazelnut |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

Released in 2005 | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

Орегон ( / ˈ ɒr ɪ ɡ ən , - ɡ ɒ n / ORR -ih-ghən , -gon ) [ 7 ] [ 8 ] — штат в Тихоокеанском северо-западном регионе США. Это часть западной части США , где река Колумбия определяет большую часть северной границы Орегона с Вашингтоном , а река Снейк определяет большую часть его восточной границы с Айдахо . Параллель 42° северной широты определяет южную границу с Калифорнией и Невадой . Западная граница образована Тихим океаном .

Орегон был домом для многих коренных народов на протяжении тысячелетий. Первые европейские торговцы, исследователи и поселенцы начали исследовать территорию, которая сейчас является тихоокеанским побережьем Орегона, в начале-середине 16 века. Еще в 1564 году испанцы начали отправлять суда на северо-восток от Филиппин по течению Куросио по широкому круговому маршруту через северную часть Тихого океана. В 1592 году Хуан де Фука провел детальное картографирование и исследование океанских течений на северо-западе Тихого океана, включая побережье Орегона, а также пролив, носящий теперь его имя. Экспедиция Льюиса и Кларка пересекла Орегон в начале 1800-х годов, и первые постоянные европейские поселения в Орегоне были основаны охотниками за мехом и торговцами. было сформировано автономное правительство В 1843 году в стране Орегон , а в 1848 году была создана территория Орегон . 14 февраля 1859 года Орегон стал 33-м штатом США.

Сегодня, когда проживает 4,2 миллиона человек на территории площадью более 98 000 квадратных миль (250 000 км²), 2 ), Орегон — девятый по величине и 27-й по численности населения штат США. Столица Салем — третий по численности населения город штата Орегон с населением 175 535 человек. [ 9 ] Портленд с населением 652 503 человека занимает 26-е место среди городов США. Агломерация Портленда , в которую входят соседние округа Вашингтона, является 25-й по величине агломерацией в стране с населением 2 512 859 человек. Орегон также является одним из самых географически разнообразных штатов США. [ 10 ] отмечен вулканами, обильными водоемами, густыми вечнозелеными и смешанными лесами, а также высокими пустынями и полузасушливыми кустарниками . высотой 11 249 футов (3429 м) Гора Худ является самой высокой точкой штата. Единственный национальный парк штата Орегон, Национальный парк Кратер-Лейк , включает в себя кальдеру, окружающую Кратер-Лейк , самое глубокое озеро в США. В штате также обитает самый крупный организм в мире, Armillaria ostoyae , гриб, обитающий на территории площадью 2200 акров (8,9 км2). 2) of the Malheur National Forest.[11]

Oregon's economy has historically been powered by various forms of agriculture, fishing, logging, and hydroelectric power. Oregon is the top lumber producer of the contiguous U.S., with the lumber industry dominating the state's economy during the 20th century.[12] Technology is another one of Oregon's major economic forces, beginning in the 1970s with the establishment of the Silicon Forest and the expansion of Tektronix and Intel. Sportswear company Nike, Inc., headquartered in Beaverton, is the state's largest public corporation with an annual revenue of $46.7 billion.[13]

Etymology

[edit]

The origin of the state's name is uncertain. The earliest geographical designation "orejón" (meaning "big ear") comes from the Spanish historical chronicle Relación de la Alta y Baja California (1598),[14] written by Rodrigo Montezuma of New Spain; here it refers to the region of the Columbia River as it was encountered by the first Spanish scouts. The "j" in the Spanish phrase "El Orejón" was eventually corrupted into a "g".[15]

Another possible source is the Spanish word oregano, which refers to a plant that grows in the southern part of the region.

It is also possible that the area around the Columbia River was named after a stream in Spain called "Arroyo del Oregón", located in the province of Ciudad Real.

Another early use of the name, spelled Ouragon, was by Major Robert Rogers in a 1765 petition to the Kingdom of Great Britain. The term referred to the then-mythical River of the West (the Columbia River). By 1778, the spelling had shifted to Oregon.[16] Rogers wrote:

... from the Great Lakes towards the Head of the Mississippi, and from thence to the River called by the Indians Ouragon ...[17]

One suggestion is that this name comes from the French word ouragan ("windstorm" or "hurricane"), which was applied to the River of the West based on Native American tales of powerful Chinook winds on the lower Columbia River, or perhaps from first-hand French experience with the Chinook winds of the Great Plains. At the time, the River of the West was thought to rise in western Minnesota and flow west through the Great Plains.[18]

Another suggestion comes from Joaquin Miller, who wrote in Sunset magazine in 1904:

The name, Oregon, is rounded down phonetically, from Ouve água—Oragua, Or-a-gon, Oregon—given probably by the same Portuguese navigator that named the Farallones after his first officer, and it literally, in a large way, means cascades: "Hear the waters." You should steam up the Columbia and hear and feel the waters falling out of the clouds of Mount Hood to understand entirely the full meaning of the name Ouve a água, Oregon.[19]

Yet another account, endorsed as the "most plausible explanation" in the book Oregon Geographic Names, was advanced by George R. Stewart in a 1944 article in American Speech. According to Stewart, the name came from an engraver's error in a French map published in the early 18th century, on which the Ouisiconsink (Wisconsin) River was spelled "Ouaricon-sint", broken on two lines with the -sint below, so there appeared to be a river flowing to the west named "Ouaricon".

According to the Oregon Tourism Commission, present-day Oregonians /ˌɒrɪˈɡoʊniənz/[20] pronounce the state's name as "or-uh-gun, never or-ee-gone".[21] After being drafted by the Detroit Lions in 2002, former Oregon Ducks quarterback Joey Harrington distributed "Orygun" stickers to members of the media as a reminder of how to pronounce the name of his home state.[22][23] The stickers are sold by the University of Oregon Bookstore.[24]

History

[edit]Earliest inhabitants

[edit]

While there is considerable evidence that Paleo-Indians inhabited the region, the oldest evidence of habitation in Oregon was found at Fort Rock Cave and the Paisley Caves in Lake County. Archaeologist Luther Cressman dated material from Fort Rock to 13,200 years ago,[25] and there is evidence supporting inhabitants in the region at least 15,000 years ago.[26] By 8000 BC, there were settlements throughout the state, with populations concentrated along the lower Columbia River, in the western valleys, and around coastal estuaries.

During the prehistoric period, the Willamette Valley region was flooded after the collapse of glacial dams from then Lake Missoula, located in what would later become Montana. These massive floods occurred during the last glacial period and filled the valley with 300 to 400 feet (91 to 122 m) of water.[27]

By the 16th century, Oregon was home to many Native American groups, including the Chinook, Coquille (Ko-Kwell), Bannock, Kalapuya, Klamath, Klickitat, Molala, Nez Perce, Shasta, Takelma, Umatilla, and Umpqua.[28][29][30][31]

European and pioneer settlement

[edit]

The first Europeans to visit Oregon were Spanish explorers led by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, who sighted southern Oregon off the Pacific coast in 1543.[32] Sailing from Central America on the Golden Hind in 1579 in search of the Strait of Anian during his circumnavigation of the Earth, the English explorer and privateer Sir Francis Drake briefly anchored at South Cove, Cape Arago, just south of Coos Bay, before sailing for what is now California.[33][34] Martín de Aguilar, continuing separately from Sebastián Vizcaíno's scouting of California, reached as far north as Cape Blanco and possibly to Coos Bay in 1603.[35][36] Exploration continued routinely in 1774, starting with the expedition of the frigate Santiago by Juan José Pérez Hernández, and the coast of Oregon became a valuable trade route to Asia. In 1778, British captain James Cook also explored the coast.[37]

French Canadians, Scots, Métis, and other continental natives (e.g. Iroquois) trappers arrived in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, soon to be followed by Catholic clergy. Some traveled as members of the Lewis and Clark and Astor Expeditions. Few stayed permanently such as Étienne Lussier, often referred to as the first "European" farmer in the state of Oregon. Evidence of the French Canadian presence can be found in numerous names of French origin such as Malheur Lake, the Malheur, Grande Ronde, and Deschutes Rivers, and the city of La Grande. Furthermore, many of the early pioneers first came out West with the North West Company and the Hudson's Bay Company before heading South of the Columbia for better farmland as the fur trade declined. French Prairie by the Willamette River and French Settlement by the Umpqua River are known as early mixed ancestry settlements.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled through northern Oregon also in search of the Northwest Passage. They built their winter fort in 1805–1806 at Fort Clatsop, near the mouth of the Columbia River, staying at the encampment from December until March.[38]

British explorer David Thompson also conducted overland exploration. In 1811, while working for the North West Company, Thompson became the first European to navigate the entire Columbia River.[39] Stopping on the way, at the junction of the Snake River, he posted a claim to the region for Great Britain and the North West Company. Upon returning to Montreal, he publicized the abundance of fur-bearing animals in the area.[40]

Also in 1811, New Yorker John Jacob Astor financed the establishment of Fort Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia River as a western outpost to his Pacific Fur Company;[41] this was the first permanent European settlement in Oregon.

In the War of 1812, the British gained control of all Pacific Fur Company posts. The Treaty of 1818 established joint British and American occupancy of the region west of the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. By the 1820s and 1830s, the Hudson's Bay Company dominated the Pacific Northwest from its Columbia District headquarters at Fort Vancouver (built-in 1825 by the district's chief factor, John McLoughlin, across the Columbia from present-day Portland).

In 1841, the expert trapper and entrepreneur Ewing Young died leaving considerable wealth and no apparent heir, and no system to probate his estate. A meeting followed Young's funeral, at which a probate government was proposed.[42] Doctor Ira Babcock of Jason Lee's Methodist Mission was elected supreme judge.[43] Babcock chaired two meetings in 1842 at Champoeg, (halfway between Lee's mission and Oregon City), to discuss wolves and other animals of contemporary concern. These meetings were precursors to an all-citizen meeting in 1843, which instituted a provisional government headed by an executive committee made up of David Hill, Alanson Beers, and Joseph Gale.[44] This government was the first acting public government of the Oregon Country before annexation by the government of the United States. It was succeeded by a Second Executive Committee, made up of Peter G. Stewart, Osborne Russell, and William J. Bailey, and this committee was itself succeeded by George Abernethy, who was the first and only Governor of Oregon under the provisional government.

Also in 1841, Sir George Simpson, governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, reversed the Hudson's Bay Company's long-standing policy of discouraging settlement because it interfered with the lucrative fur trade.[45] He directed that some 200 Red River Colony settlers be relocated to HBC farms near Fort Vancouver, (the James Sinclair expedition), in an attempt to hold Columbia District.

Starting in 1842–1843, the Oregon Trail brought many new American settlers to the Oregon Country. Oregon's boundaries were disputed for a time, contributing to tensions between the U.K. and the U.S., but the border was defined peacefully in the 1846 Oregon Treaty. The border between the U.S. and British North America was set at the 49th parallel.[46] The Oregon Territory was officially organized on August 13, 1848.[47]

Settlement increased with the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 and the forced relocation of the native population to Indian reservations in Oregon.

The first Oregon proposition for a railroad in Oregon was made in 1850 by H. M. Knighton, the original owner of the townsite of St. Helens. Knighton asserted that this would fulfill his township's belief that it should be the supreme metropolitan seaport in that area upon the Columbia River, as opposed to Portland. He suggested building a railroad in 1851 from St. Helens, through the Cornelius pass and across Washington County to the city of Lafayette, which was at the time the big town of the Willamette Valley.[48][49]

Black exclusion laws

[edit]In December 1844, Oregon passed its first black exclusion law, which prohibited African Americans from entering the territory while simultaneously prohibiting slavery. Slave owners who brought their slaves with them were given three years before they were forced to free them. Any African Americans in the region after the law was passed were forced to leave, and those who did not comply were arrested and beaten. They received no less than twenty and no more than thirty-nine stripes across the back if they still did not leave. This process could be repeated every six months.[50]

Statehood

[edit]Slavery played a major part in Oregon's history and even influenced its path to statehood. The territory's request for statehood was delayed several times, as members of Congress argued among themselves whether the territory should be admitted as a "free" or "slave" state. Eventually politicians from the South agreed to allow Oregon to enter as a "free" state, in exchange for opening slavery to the southwest U.S.[51]

Oregon was admitted to the Union on February 14, 1859, though no one in Oregon knew it until March 15.[52] Founded as a refuge from disputes over slavery, Oregon had a "whites only" clause in its original state Constitution.[53][54] At the outbreak of the American Civil War, regular U.S. troops were withdrawn and sent east to aid the Union. Volunteer cavalry recruited in California were sent north to Oregon to keep peace and protect the populace. The First Oregon Cavalry served until June 1865.

Post-Reconstruction

[edit]Beginning in the 1880s, the growth of railroads expanded the state's lumber, wheat, and other agricultural markets, and the rapid growth of its cities.[55] Due to the abundance of timber and waterway access via the Willamette River, Portland became a major force in the lumber industry of the Pacific Northwest, and quickly became the state's largest city. It would earn the nickname "Stumptown",[56] and would later become recognized as one of the most dangerous port cities in the United States due to racketeering and illegal activities at the turn of the 20th century.[57] In 1902, Oregon introduced direct legislation by the state's citizens through initiatives and referendums, known as the Oregon System.[58]

On May 5, 1945, six civilians were killed by a Japanese balloon bomb that exploded on Gearhart Mountain near Bly.[59][60] They remained the only people on American soil whose deaths were attributed to an enemy balloon bomb explosion during World War II. The bombing site is now located in the Mitchell Recreation Area.

Industrial expansion began in earnest following the 1933–1937 construction of the Bonneville Dam on the Columbia River. Hydroelectric power, food, and lumber provided by Oregon helped fuel the development of the West, although the periodic fluctuations in the U.S. building industry have hurt the state's economy on multiple occasions. Portland, in particular, experienced a population boom between 1900 and 1930, tripling in size; the arrival of World War II also provided the northwest region of the state with an industrial boom, where Liberty ships and aircraft carriers were constructed.[61]

During the 1970s, the Pacific Northwest was particularly affected by the 1973 oil crisis, with Oregon suffering a substantial shortage.[62]

In 1972, the Oregon Beverage Container Act of 1971,[63] popularly called the Bottle Bill, became the first law of its kind in the United States. The Bottle Bill system in Oregon was created to control litter. In practice, the system promotes recycling, not reusing, and the collected containers are generally destroyed and made into new containers. Ten states[64] currently have similar laws.

In 1994, Oregon became the first U.S. state to legalize physician-assisted suicide through the Oregon Death with Dignity Act. A measure to legalize recreational use of marijuana in Oregon was approved on November 4, 2014, making Oregon only the second state at the time to have legalized gay marriage, physician-assisted suicide, and recreational marijuana.[65]

Gasoline pump law

[edit]Self service gasoline was banned in Oregon from 1951 until August 2023.[66][67] Although self-serve is now allowed in Oregon, gas stations are not required to offer it and many currently do not.[68]

New Jersey is the only state remaining where self serve gas stations are not allowed.[69]

Geography

[edit]

Oregon is 295 miles (475 km) north to south at longest distance, and 395 miles (636 km) east to west. With an area of 98,381 square miles (254,810 km2), Oregon is slightly larger than the United Kingdom. It is the ninth largest state in the U.S.[70] Oregon's highest point is the summit of Mount Hood, at 11,249 feet (3,429 m), and its lowest point is the sea level of the Pacific Ocean along the Oregon Coast.[71] Oregon's mean elevation is 3,300 feet (1,006 m). Crater Lake National Park, the state's only national park, is the site of the deepest lake in the U.S. at 1,943 feet (592 m).[72] Oregon claims the D River as the shortest river in the world,[73] though the state of Montana makes the same claim of its Roe River.[74] Oregon is also home to Mill Ends Park (in Portland),[75] the smallest park in the world at 452 square inches (0.29 m2).

Oregon is split into eight geographical regions. In Western Oregon: Oregon Coast (west of the Coast Range), the Willamette Valley, Rogue Valley, Cascade Range and Klamath Mountains; and in Central and Eastern Oregon: the Columbia Plateau, the High Desert, and the Blue Mountains.

Oregon lies in two time zones. Most of Malheur County is in the Mountain Time Zone, while the rest of the state lies in the Pacific Time Zone.

Geology and terrain

[edit]

Western Oregon's mountainous regions, home to three of the most prominent mountain peaks of the U.S. including Mount Hood, were formed by the volcanic activity of the Juan de Fuca Plate, a tectonic plate that poses a continued threat of volcanic activity and earthquakes in the region. The most recent major activity was the 1700 Cascadia earthquake.[76] Washington's Mount St. Helens erupted in 1980, an event visible from northern Oregon and affecting some areas there.[77]

The Columbia River, which forms much of Oregon's northern border, also played a major role in the region's geological evolution, as well as its economic and cultural development. The Columbia is one of North America's largest rivers, and one of two rivers to cut through the Cascades (the Klamath River in southern Oregon is the other). About 15,000 years ago, the Columbia repeatedly flooded much of Oregon during the Missoula Floods; the modern fertility of the Willamette Valley is largely the result. Plentiful salmon made parts of the river, such as Celilo Falls, hubs of economic activity for thousands of years.

Today, Oregon's landscape varies from rain forest in the Coast Range to barren desert in the southeast, which still meets the technical definition of a frontier. Oregon's geographical center is further west than any of the other 48 contiguous states (although the westernmost point of the lower 48 states is in Washington). Central Oregon's geographical features range from high desert and volcanic rock formations resulting from lava beds. The Oregon Badlands Wilderness is in this region of the state.[78]

Flora and fauna

[edit]Typical of a western state, Oregon is home to a unique and diverse array of wildlife. Roughly 60 percent of the state is covered in forest,[79] while the areas west of the Cascades are more densely populated by forest, making up around 80 percent of the landscape. Some 60 percent of Oregon's forests are within federal land.[79] Oregon is the top timber producer of the lower 48 states.[12][80]

- Typical tree species include the Douglas fir (the state tree), as well as redwood, ponderosa pine, western red cedar, and hemlock.[81] Ponderosa pine are more common in the Blue Mountains in the eastern part of the state and firs are more common in the west.

- Many species of mammals live in the state, which include opossums, shrews, moles, little pocket mice, great basin pocket mice, dark kangaroo mouse, California kangaroo rat, chisel-toothed kangaroo rat, ord's kangaroo rat,[82] bats, rabbits, pikas, mountain beavers, chipmunks, squirrels, yellow-bellied marmots, beavers (the state mammal), porcupines, coyotes, wolves, foxes[83] black bears, raccoons, badgers, skunks, antelopes, cougars, bobcats, lynxes, deer, elk, and moose.

- Marine mammals include seals, sea lions, humpback whales, killer whales, gray whales, blue whales, sperm whales, pacific white-sided dolphins, and bottlenose dolphins.[84]

- Notable birds include American widgeons, mallard ducks, great blue herons, bald eagles, golden eagles, western meadowlarks (the state bird), barn owls, great horned owls, rufous hummingbirds, pileated woodpeckers, wrens, towhees, sparrows, and buntings.[85]

Moose have not always inhabited the state but came to Oregon in the 1960s; the Wallowa Valley herd numbered about 60 as of 2013[update].[86] Gray wolves were extirpated from Oregon around 1930 but have since found their way back; most reside in northeast Oregon, with two packs living in the south-central part.[87] Although their existence in Oregon is unconfirmed, reports of grizzly bears still turn up, and it is probable some still move into eastern Oregon from Idaho.[88]

Oregon is home to what is considered the largest single organism in the world, an Armillaria solidipes fungus beneath the Malheur National Forest of eastern Oregon.[11]

Oregon has several National Park System sites, including Crater Lake National Park in the southern part of the Cascades, John Day Fossil Beds National Monument east of the Cascades, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park on the north coast, and Oregon Caves National Monument near the south coast.[citation needed] Other areas that were considered for potential national park status in the 20th century include the southern Oregon Coast, Mount Hood, and Hells Canyon to the east.[89]

Climate

[edit]

Most of Oregon has a generally mild climate, though there is significant variation given the variety of landscapes across the state.[90] The state's western region (west of the Cascade Range) has an oceanic climate, populated by dense evergreen mixed forests. Western Oregon's climate is heavily influenced by the Pacific Ocean; the western third of Oregon is very wet in the winter, moderately to very wet during the spring and fall, and dry during the summer. The relative humidity of Western Oregon is high except during summer days, which are semi-dry to semi-humid; Eastern Oregon typically sees low humidity year-round.[91]

The state's southwestern portion, particularly the Rogue Valley, has a Mediterranean climate with drier and sunnier winters and hotter summers, similar to Northern California.[92]

Oregon's northeastern portion has a steppe climate, and its high terrain regions have a subarctic climate. Like Western Europe, Oregon, and the Pacific Northwest in general, is considered warm for its latitude, and the state has far milder winters at a given elevation than comparable latitudes elsewhere in North America, such as the Upper Midwest, Ontario, Quebec and New England.[91] However, the state ranks fifth for coolest summer temperatures of any state in the country, after Maine, Idaho, Wyoming, and Alaska.[93]

The eastern two thirds of Oregon, which largely comprise high desert, have cold, snowy winters and very dry summers. Much of the east is semiarid to arid like the rest of the Great Basin, though the Blue Mountains are wet enough to support extensive forests. Most of Oregon receives significant snowfall, but the Willamette Valley, where 60 percent of the population lives,[94] has considerably milder winters for its latitude and typically sees only light snowfall.[91]

Oregon's highest recorded temperature is 119 °F (48 °C), which was set at Prineville on July 29, 1898, and tied at Pendleton on August 10, 1898, and Pelton Dam on June 29, 2021.[95] The lowest recorded temperature is −54 °F (−48 °C) at Seneca on February 10, 1933.[96]

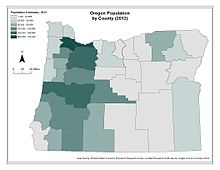

Cities and towns

[edit]Oregon's population is largely concentrated in the Willamette Valley, which stretches from Eugene in the south (home of the University of Oregon) through Corvallis (home of Oregon State University) and Salem (the capital) to Portland (Oregon's largest city).[97]

Astoria, at the mouth of the Columbia River, was the first permanent English-speaking settlement west of the Rockies in what is now the U.S. Oregon City, at the end of the Oregon Trail, was the Oregon Territory's first incorporated city, and was its first capital from 1848 until 1852, when the capital was moved to Salem. Bend, near the geographic center of the state, is one of the ten fastest-growing metropolitan areas in the U.S.[98][better source needed] In southern Oregon, Medford is a rapidly growing metro area and is home to the Rogue Valley International–Medford Airport, the state's third-busiest airport. To the south, near the California border, is the city of Ashland. Eastern Oregon is sparsely populated, but is home to Hermiston, which with a population of 18,000 is the largest and fastest-growing city in the region.[99]

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portland  Eugene |

1 | Portland | Multnomah | 635,067 |  Salem  Gresham | ||||

| 2 | Eugene | Lane | 177,923 | ||||||

| 3 | Salem | Marion | 177,487 | ||||||

| 4 | Gresham | Multnomah | 111,621 | ||||||

| 5 | Hillsboro | Washington | 107,299 | ||||||

| 6 | Bend | Deschutes | 103,254 | ||||||

| 7 | Beaverton | Washington | 97,053 | ||||||

| 8 | Medford | Jackson | 85,556 | ||||||

| 9 | Springfield | Lane | 61,400 | ||||||

| 10 | Corvallis | Benton | 60,956 | ||||||

Demographics

[edit]Population

[edit]

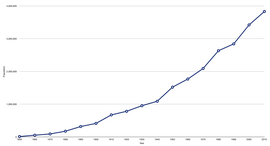

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 12,093 | — | |

| 1860 | 52,465 | 333.8% | |

| 1870 | 90,923 | 73.3% | |

| 1880 | 174,768 | 92.2% | |

| 1890 | 317,704 | 81.8% | |

| 1900 | 413,536 | 30.2% | |

| 1910 | 672,765 | 62.7% | |

| 1920 | 783,389 | 16.4% | |

| 1930 | 953,786 | 21.8% | |

| 1940 | 1,089,684 | 14.2% | |

| 1950 | 1,521,341 | 39.6% | |

| 1960 | 1,768,687 | 16.3% | |

| 1970 | 2,091,385 | 18.2% | |

| 1980 | 2,633,105 | 25.9% | |

| 1990 | 2,842,321 | 7.9% | |

| 2000 | 3,421,399 | 20.4% | |

| 2010 | 3,831,074 | 12.0% | |

| 2020 | 4,237,256 | 10.6% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 4,233,358 | −0.1% | |

| Sources: 1910–2020[102] | |||

The 2020 U.S. census determined that the population of Oregon was 4,237,256 in 2020, a 10.60% increase over the 2010 census.[3]

Oregon was the nation's "Top Moving Destination" in 2014, with two families moving into the state for every one moving out (66.4% to 33.6%).[104] Oregon was also the top moving destination in 2013,[105] and the second-most popular destination in 2010 through 2012.[106][107]

As of the 2020 census, the population of Oregon was 4,237,256. The gender makeup of the state was 49.5% male and 50.5% female. 20.5% of the population were under the age of 18; 60.8% were between the ages of 18 and 64; and 18.8% were 65 years of age or older.[108]

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 17,959 homeless people in Oregon.[109][110]

| Racial composition | 1970[111] | 1990[111] | 2000[112] | 2010[113] | 2020[114] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White including White Hispanics | 97.2% | 92.8% | 86.6% | 83.6% | 74.8% |

| Black or African American | 1.3% | 1.6% | 1.6% | 1.8% | 2% |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 0.6% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 1.5% |

| Asian | 0.7% | 2.4% | 3.0% | 3.7% | 4.6% |

| Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander | – | – | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.5% |

| Other race | 0.2% | 1.8% | 4.2% | 5.3% | 6.3% |

| Two or more races | – | – | 3.1% | 3.8% | 10.5% |

| Non-Hispanic White | 95.8% | - | - | - | 71.7% |

According to the 2020 census, 13.9% of Oregon's population was of Hispanic or Latino origin (of any race) and 71.7% non-Hispanic White, 2.0% African American, 1.5% Native American, 4.6% Asian, 1.5% Pacific Islander, and 10.5% two or more races.[115] According to the 2016 American Community Survey, 12.4% of Oregon's population were of Hispanic or Latino origin (of any race): Mexican (10.4%), Puerto Rican (0.3%), Cuban (0.1%), and other Hispanic or Latino origin (1.5%).[116] The five largest ancestry groups for White Oregonians were: German (19.1%), Irish (11.7%), English (11.3%), American (5.3%), and Norwegian (3.8%).[117]

The state's most populous ethnic group, non-Hispanic Whites, decreased from 95.8% of the total population in 1970 to 71.7% in 2020, though it increased in absolute numbers.[118][119]

As of 2011[update], 38.7% of Oregon's children under one year of age belonged to minority groups, meaning they had at least one parent who was not a non-Hispanic White.[120] Of the state's total population, 22.6% was under the age 18, and 77.4% were 18 or older.

The center of population of Oregon is located in Linn County, in the city of Lyons.[121] Around 60% of Oregon's population resides within the Portland metropolitan area.[122]

As of 2009[update], Oregon's population comprised 361,393 foreign-born residents.[123] Of the foreign-born residents, the three largest groups are originally from countries in: Latin America (47.8%), Asia (27.4%), and Europe (16.5%).[123] Mexico, Vietnam, China, India and the Philippines were the top countries of origin for Oregon's immigrants in 2018.[124]

The Roma first reached Oregon in the 1890s. There is a substantial Roma population in Willamette Valley and around Portland.[125] The majority of Oregon's population predominantly of white (European) ancestry and are American-born. Around one-tenth of Oregon's population is made up of Hispanics. There are also small population of Asians, Native Americans, and African Americans in state.[126]

Languages

[edit]| Rank | Language | Number of Speakers |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spanish | 128,303 |

| 2 | Vietnamese | 16,292 |

| 3 | Chinese | 15,816 |

| 4 | Russian | 8,559 |

| 5 | Korean | 4,903 |

| 6 | Ukrainian | 2,534 |

| 7 | Arabic | 1,480 |

| 8 | Tagalog | 447 |

| 9 | Marshallese | 336 |

| 10 | Japanese | 333 |

| 11 | Thai | 169 |

| 12 | French | 142 |

| 13 | German | 139 |

Religious and secular communities

[edit]Religious self-identification in Oregon, per PRRI American Values Atlas (2022)[c][129]

Oregon has frequently been cited by statistical agencies for having a smaller percentage of religious communities than other U.S. states.[130][131] According to a 2009 Gallup poll, Oregon was paired with Vermont as the two "least religious" states in the U.S.[132]

In the same 2009 Gallup poll, 69% of Oregonians identified themselves as being Christian.[133] The largest Christian denominations in Oregon by number of adherents in 2010 were the Roman Catholic Church with 398,738; The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with 147,965; and the Assemblies of God with 45,492.[134] Oregon also contains the largest community of Russian Old Believers to be found in the U.S.[135] Judaism is the largest non-Christian religion in Oregon with more than 50,000 adherents, 47,000 of whom live in the Portland area.[136][137] Recently, new kosher food and Jewish educational offerings have led to a rapid increase in Portland's Orthodox Jewish population.[138] The Northwest Tibetan Cultural Association is headquartered in Portland. There are an estimated 6,000 to 10,000 Muslims in Oregon, most of whom live in and around Portland.[139]

Most of the remainder of the population had no religious affiliation; the 2008 American Religious Identification Survey placed Oregon as tied with Nevada in fifth place of U.S. states having the highest percentage of residents identifying themselves as "non-religious", at 24 percent.[140][141] Secular organizations include the Center for Inquiry, the Humanists of Greater Portland, and the United States Atheists.

During much of the 1990s, a group of conservative Christians formed the Oregon Citizens Alliance, and unsuccessfully tried to pass legislation to prevent "gay sensitivity training" in public schools and legal benefits for homosexual couples.[142]

| Race | 2013[143] | 2014[144] | 2015[145] | 2016[146] | 2017[147] | 2018[148] | 2019[149] | 2020[150] | 2021[151] | 2022[152] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 40,219 (89.1%) | 40,634 (89.2%) | 40,484 (88.7%) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| > Non-Hispanic White | 31,998 (70.8%) | 32,338 (71.0%) | 32,147 (70.4%) | 31,057 (68.2%) | 29,232 (67.0%) | 28,265 (67.0%) | 27,639 (66.0%) | 26,256 (65.9%) | 26,662 (65.2%) | 23,034 (58.3%) |

| Asian | 2,696 (6.0%) | 2,811 (6.2%) | 2,895 (6.3%) | 2,354 (5.2%) | 2,376 (5.4%) | 2,260 (5.4%) | 2,376 (5.7%) | 2,112 (5.3%) | 2,106 (5.1%) | 2,151 (5.4%) |

| Black | 1,331 (2.9%) | 1,333 (2.9%) | 1,463 (3.2%) | 944 (2.1%) | 994 (2.3%) | 959 (2.3%) | 1,007 (2.4%) | 973 (2.4%) | 1,065 (2.6%) | 1,007 (2.5%) |

| American Indian | 909 (2.0%) | 778 (1.7%) | 813 (1.8%) | 427 (0.9%) | 429 (1.0%) | 388 (0.9%) | 402 (1.0%) | 378 (0.9%) | 378 (0.9%) | 370 (0.9%) |

| Pacific Islander | ... | ... | ... | 315 (0.7%) | 300 (0.7%) | 309 (0.7%) | 341 (0.8%) | 278 (0.7%) | 337 (0.8%) | 374 (0.9%) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 8,448 (18.7%) | 8,524 (18.7%) | 8,518 (18.6%) | 8,467 (18.6%) | 8,275 (19.0%) | 7,993 (18.9%) | 8,180 (19.5%) | 7,923 (19.9%) | 8,334 (20.4%) | 8,510 (21.5%) |

| Total | 45,155 (100%) | 45,556 (100%) | 45,655 (100%) | 45,535 (100%) | 43,631 (100%) | 42,188 (100%) | 41,858 (100%) | 39,820 (100%) | 40,914 (100%) | 39,493 (100%) |

- Since 2016, data for births of White Hispanic origin are not collected, but included in one Hispanic group; persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race.

- Births in table do not sum to 100% because Hispanics are counted both by their ethnicity and by their race.

| Affiliation | % of Oregon population | |

|---|---|---|

| Christianity | 59 | |

| Protestant | 43 | |

| Evangelical Protestant | 29 | |

| Mainline Protestant | 13 | |

| Black Protestant | 1 | |

| Catholic | 12 | |

| Mormon | 4 | |

| Orthodox | 1 | |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 0.5 | |

| Other Christianity | 1 | |

| Judaism | 2 | |

| Islam | 1 | |

| Buddhism | 0.5 | |

| Hinduism | 0.5 | |

| Other faiths | 3 | |

| No religion | 31 | |

| Agnostic | 1 | |

| Total | 100 | |

Future projections

[edit]Projections from the U.S. Census Bureau show Oregon's population increasing to 4,833,918 by 2030, an increase of 41.3% compared to the state's population of 3,421,399 in 2000.[154] The state's own projections forecast a total population of 5,425,408 in 2040.[155]

Economy

[edit]As of 2015[update], Oregon ranks as the 17th highest in median household income at $60,834.[4] The gross domestic product (GDP) of Oregon in 2013 was $219.6 billion, a 2.7% increase from 2012; Oregon is the 25th wealthiest state by GDP. In 2003, Oregon was 28th in the U.S. by GDP. The state's per capita personal income (PCPI) in 2013 was $39,848, a 1.5% increase from 2012. Oregon ranks 33rd in the U.S. by PCPI, compared to 31st in 2003. The national PCPI in 2013 was $44,765.[156]

Oregon's unemployment rate was 5.5% in September 2016,[157] while the U.S. unemployment rate was 5.0% that month.[158] Oregon has the third largest amount of food stamp users in the nation (21% of the population).[159]

Agriculture

[edit]

Oregon's diverse landscapes provide ideal environments for various types of farming. Land in the Willamette Valley owes its fertility to the Missoula Floods, which deposited lake sediment from Glacial Lake Missoula in western Montana onto the valley floor.[160] In 2016, the Willamette Valley region produced over 100 million pounds (45 kt) of blueberries.[161] The industry is governed and represented by the Oregon Department of Agriculture.[162]

Oregon is also one of four major world hazelnut (Corylus avellana) growing regions, and produces 95% of the domestic hazelnuts in the United States. While the history of the wine production in Oregon can be traced to before Prohibition, it became a significant industry beginning in the 1970s. In 2005, Oregon ranked third among U.S. states with 303 wineries.[163] Due to regional similarities in climate and soil, the grapes planted in Oregon are often the same varieties found in the French regions of Alsace and Burgundy. In 2014, 71 wineries opened in the state. The total is currently 676, which represents growth of 12% over 2013.[164]

In the southern Oregon coast, commercially cultivated cranberries account for about 7 percent of U.S. production, and the cranberry ranks 23rd among Oregon's top 50 agricultural commodities. Cranberry cultivation in Oregon uses about 27,000 acres (110 square kilometers) in southern Coos and northern Curry counties, centered around the coastal city of Bandon. In the northeastern region of the state, particularly around Pendleton, both irrigated and dry land wheat is grown.[165] Oregon farmers and ranchers also produce cattle, sheep, dairy products, eggs and poultry.

Caneberries (Rubus) are farmed here.[166]: 25 Stamen blight (Hapalosphaeria deformans) is significant here and throughout the PNW.[166]: 25 Here it especially hinders commercial dewberries.[166]: 25

Phytophthora ramorum was first discovered in the 1990s on the California Central Coast[167] and was quickly found here as well.[168] P. ramorum is of economic concern due to its infestation of Rubus and Vaccinium spp. (including cranberry and blueberry).[168]

Peaches grown in the Willamette Valley are mostly sold directly and do not enter the more distant markets.[169] OSU Extension recommended several peach and nectarine cultivars for Willamette.[169]

Forestry and fisheries

[edit]

Vast forests have historically made Oregon one of the nation's major timber-producing and logging states, but forest fires (such as the Tillamook Burn), over-harvesting, and lawsuits over the proper management of the extensive federal forest holdings have reduced the timber produced. Between 1989 and 2011, the amount of timber harvested from federal lands in Oregon dropped about 90%, although harvest levels on private land have remained relatively constant.[170]

Even the shift in recent years towards finished goods such as paper and building materials has not slowed the decline of the timber industry in the state. The effects of this decline have included Weyerhaeuser's acquisition of Portland-based Willamette Industries in January 2002, the relocation of Louisiana-Pacific's corporate headquarters from Portland to Nashville, and the decline of former lumber company towns such as Gilchrist. Despite these changes, Oregon still leads the U.S. in softwood lumber production; in 2011, 4,134 million board feet (9,760,000 m3) was produced in Oregon, compared with 3,685 million board feet (8,700,000 m3) in Washington, 1,914 million board feet (4,520,000 m3) in Georgia, and 1,708 million board feet (4,030,000 m3) in Mississippi.[171] The slowing of the timber and lumber industry has caused high unemployment rates in rural areas.[172]

Oregon has one of the largest salmon-fishing industries in the world, although ocean fisheries have reduced the river fisheries in recent years.[173] Because of the abundance of waterways in the state, it is also a major producer of hydroelectric energy.[174]

On June 30, 2022, an emerald ash borer infestation was found in Forest Grove in 2022, the first for Western North America.[175][176][177][178]

Tourism and entertainment

[edit]

Tourism is also a strong industry in the state. Tourism is centered on the state's natural features – mountains, forests, waterfalls, rivers, beaches and lakes, including Crater Lake National Park, Multnomah Falls, the Painted Hills, the Deschutes River, and the Oregon Caves. Mount Hood and Mount Bachelor also draw visitors year-round for skiing and other snow activities.[179]

Portland is home to the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry, the Portland Art Museum, and the Oregon Zoo, which is the oldest zoo west of the Mississippi River.[180] The International Rose Test Garden is another prominent attraction in the city. Portland has also been named the best city in the world for street food by several publications, including the U.S. News & World Report and CNN.[181][182] Oregon is home to many breweries, and Portland has the largest number of breweries of any city in the world.[183]

The state's coastal region produces significant tourism as well.[184] The Oregon Coast Aquarium comprises 23 acres (9.3 ha) along Yaquina Bay in Newport, and was also home to Keiko the orca whale.[185] It has been noted as one of the top ten aquariums in North America.[186] Fort Clatsop in Warrenton features a replica of Lewis and Clark's encampment at the mouth of the Columbia River in 1805. The Sea Lion Caves in Florence are the largest system of sea caverns in the U.S., and also attract many visitors.[187]

In Southern Oregon, the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, held in Ashland, is also a tourist draw, as is the Oregon Vortex and the Wolf Creek Inn State Heritage Site, a historic inn where Jack London wrote his 1913 novel Valley of the Moon.[188]

Oregon has also historically been a popular region for film shoots due to its diverse landscapes, as well as its proximity to Hollywood.[189] Movies filmed in Oregon include: Animal House, Free Willy, The General, The Goonies, Kindergarten Cop, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, and Stand By Me. Oregon native Matt Groening, creator of The Simpsons, has incorporated many references from his hometown of Portland into the TV series.[190] Additionally, several television shows have been filmed throughout the state including Portlandia, Grimm, Bates Motel, and Leverage.[191] The Oregon Film Museum is located in the old Clatsop County Jail in Astoria. Additionally, the last remaining Blockbuster store is located in Bend.[192]

Technology

[edit]High technology industries located in Silicon Forest have been a major employer since the 1970s. Tektronix was the largest private employer in Oregon until the late 1980s. Intel's creation and expansion of several facilities in eastern Washington County continued the growth that Tektronix had started. Intel, the state's largest for-profit private employer,[193][194] operates four large facilities, with Ronler Acres, Jones Farm and Hawthorn Farm all located in Hillsboro.[195]

The spinoffs and startups that were produced by these two companies led to establishment of the so-called Silicon Forest. The recession and dot-com bust of 2001 hit the region hard; many high technology employers reduced the number of their employees or went out of business. Open Source Development Labs made news in 2004 when they hired Linus Torvalds, developer of the Linux kernel. In 2010, biotechnology giant Genentech opened a $400 million facility in Hillsboro to expand its production capabilities.[196] Oregon is home to several large datacenters that take advantage of cheap power and a climate conducive to reducing cooling costs. Google operates a large datacenter in The Dalles, and Facebook built a large datacenter near Prineville in 2010. Amazon opened a datacenter near Boardman in 2011, and a fulfillment center in Troutdale in 2018.[197][198]

Corporate headquarters

[edit]

Oregon is also the home of large corporations in other industries. The world headquarters of Nike is located near Beaverton. Medford is home to Harry and David, which sells gift items under several brands. Medford is also home to the national headquarters of Lithia Motors. Portland is home to one of the West's largest trade book publishing houses, Graphic Arts Center Publishing. Oregon is also home to Mentor Graphics Corporation, a world leader in electronic design automation located in Wilsonville and employs roughly 4,500 people worldwide.

Adidas Corporations American Headquarters is located in Portland and employs roughly 900 full-time workers at its Portland campus.[199] Nike, located in Beaverton, employs roughly 5,000 full-time employees at its 200-acre (81 ha) campus. Nike's Beaverton campus is continuously ranked as a top employer in the Portland area-along with competitor Adidas.[200] Intel Corporation employs 22,000 in Oregon[194] with the majority of these employees located at the company's Hillsboro campus located about 30 minutes west of Portland. Intel has been a top employer in Oregon since 1974.[201]

| # | Corporation | Headquarters | Market cap (billions US$) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Nike | Beaverton | 91.35 |

| 2. | FLIR Systems | Wilsonville | 4.77 |

| 3. | Portland General Electric | Portland | 4.05 |

| 4. | Columbia Sportswear | Beaverton | 4.03 |

| 5. | Umpqua Holdings Corporation | Portland | 3.68 |

| 6. | Lithia Motors | Medford | 2.06 |

| 7. | Northwest Natural Gas | Portland | 1.7 |

| 8. | The Greenbrier Companies | Lake Oswego | 1.25 |

The U.S. Federal Government and Providence Health systems are respective contenders for top employers in Oregon with roughly 12,000 federal workers and 14,000 Providence Health workers.

In 2015, a total of seven companies headquartered in Oregon landed in the Fortune 1000: Nike, at 106; Precision Castparts Corp. at 302; Lithia Motors at 482; StanCorp Financial Group at 804; Schnitzer Steel Industries at 853; The Greenbrier Companies at 948; and Columbia Sportswear at 982.[203]

Taxes and budgets

[edit]Oregon's biennial state budget, $2.6 billion in 2017, comprises General Funds, Federal Funds, Lottery Funds, and Other Funds.[204]

Oregon is one of only five states that have no sales tax.[205] Oregon voters have been resolute in their opposition to a sales tax, voting proposals down each of the nine times they have been presented.[206] The last vote, for 1993's Measure 1, was defeated by a 75–25% margin.[207]

The state also has a minimum corporate tax of only $150 a year,[208] amounting to 5.6% of the General Fund in the 2005–07 biennium; data about which businesses pay the minimum is not available to the public.[209][better source needed] As a result, the state relies on property and income taxes for its revenue. Oregon has the fifth highest personal income tax in the nation. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Oregon ranked 41st out of the 50 states in taxes per capita in 2005 with an average amount paid of 1,791.45.[210]

A few local governments levy sales taxes on services: the city of Ashland, for example, collects a 5% sales tax on prepared food.[211]

The City of Portland imposes an Arts Education and Access Income Tax on residents over 18—a flat tax of $35 collected from individuals earning $1,000 or more per year and residing in a household with an annual income exceeding the federal poverty level. The tax funds Portland school teachers, and art focused non-profit organizations in Portland.[212]

The State of Oregon also allows transit district to levy an income tax on employers and the self-employed. The State currently collects the tax for TriMet and the Lane Transit District.[213][214]

Oregon is one of six states with a revenue limit.[215] The "kicker law" stipulates that when income tax collections exceed state economists' estimates by two percent or more, any excess must be returned to taxpayers.[216] Since the enactment of the law in 1979, refunds have been issued for seven of the eleven biennia.[217] In 2000, Ballot Measure 86 converted the "kicker" law from statute to the Oregon Constitution, and changed some of its provisions.

Federal payments to county governments that were granted to replace timber revenue when logging in National Forests was restricted in the 1990s, have been under threat of suspension for several years. This issue dominates the future revenue of rural counties, which have come to rely on the payments in providing essential services.[218]

55% of state revenues are spent on public education, 23% on human services (child protective services, Medicaid, and senior services), 17% on public safety, and 5% on other services.[219]

Oregon has had a $15 bicycle tax for each new bicycles over $200 since 2018. Oregon is the only state in the nation with a bicycle excise tax.[220][221]

Healthcare

[edit]For health insurance, as of 2018 Cambia Health Solutions has the highest market share at 21%, followed by Providence Health.[222] In the Portland region, Kaiser Permanente leads.[222] Providence and Kaiser are vertically integrated delivery systems which operate hospitals and offer insurance plans.[223] Aside from Providence and Kaiser, hospital systems which are primarily Oregon-based include Legacy Health mostly covering Portland, Samaritan Health Services with five hospitals in various areas across the state, and Tuality Healthcare in the western Portland metropolitan area. In Southern Oregon, Asante runs several hospitals, including Rogue Regional Medical Center. Some hospitals are operated by multi-state organizations such as PeaceHealth and CommonSpirit Health. Some hospitals such Salem Hospital operate independently of larger systems.

Oregon Health & Science University is a Portland-based medical school that operates two hospitals and clinics.

The Oregon Health Plan is the state's Medicaid managed care plan, and it is known for innovations.[224] The Portland area is a mature managed care and two-thirds of Medicare enrollees are in Medicare Advantage plans.[224]

Education

[edit]Elementary, middle, and high school

[edit]In the 2013–2014 school year, the state had 567,000 students in public schools.[225] There were 197 public school districts, served by 19 education service districts.[225]

In 2016, the largest school districts in the state were:[226] Portland Public Schools, comprising 47,323 students; Salem-Keizer School District, comprising 40,565 students; Beaverton School District, comprising 39,625 students; Hillsboro School District, comprising 21,118 students; and North Clackamas School District, comprising 17,053 students.

Approximately 90.5% of Oregon high school students graduate, improving on the national average of 88.3% as measured from the 2010 U.S. census.[227]

On May 8, 2019, educators across the state protested to demand smaller class sizes, hiring more support staff, such as school counselors, librarians, and nurses, and the restoration of art, music, and physical education classes. The protests caused two dozen school districts to close, which equals to about 600 schools across the state.[228]

Colleges and universities

[edit]

Especially since the 1990 passage of Measure 5, which set limits on property tax levels, Oregon has struggled to fund higher education. Since then, Oregon has cut its higher education budget and now ranks 46th in the country in state spending per student. However, 2007 legislation funded the university system far beyond the governor's requested budget though still capping tuition increases at 3% per year.[229] Oregon supports a total of seven public universities and one affiliate. It is home to three public research universities: The University of Oregon (UO) in Eugene and Oregon State University (OSU) in Corvallis, both classified as research universities with very high research activity, and Portland State University which is classified as a research university with high research activity.[230]

UO is the state's highest nationally ranked and most selective[231] public university by U.S. News & World Report and Forbes.[232] OSU is the state's only land-grant university, has the state's largest enrollment for fall 2014,[233] and is the state's highest ranking university according to Academic Ranking of World Universities, Washington Monthly, and QS World University Rankings.[234] OSU receives more annual funding for research than all other public higher education institutions in Oregon combined.[235] The state's urban Portland State University has Oregon's second largest enrollment.

The state has three regional universities: Western Oregon University in Monmouth, Southern Oregon University in Ashland, and Eastern Oregon University in La Grande. The Oregon Institute of Technology has its campus in Klamath Falls. The quasi-public Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) includes medical, dental, and nursing schools, and graduate programs in biomedical sciences in Portland and a science and engineering school in Hillsboro. The state also supports 17 community colleges.

Oregon is home to a wide variety of private colleges, the majority of which are located in the Portland area. The University of Portland, a Catholic university, is affiliated with the Congregation of Holy Cross. Reed College, a rigorous liberal arts college in Portland, was ranked by Forbes as the 52nd best college in the country in 2015.[236]

Other private institutions in Portland include Lewis & Clark College; Multnomah University; Portland Bible College; Warner Pacific College; Cascade College; the National University of Natural Medicine; and Western Seminary, a theological graduate school. Pacific University is in the Portland suburb of Forest Grove. There are also private colleges further south in the Willamette Valley. McMinnville is home to Linfield College, while nearby Newberg is home to George Fox University. Salem is home to two private schools: Willamette University (the state's oldest, established during the provisional period) and Corban University. Also located near Salem is Mount Angel Seminary, one of America's largest Roman Catholic seminaries. The state's second medical school, the College of Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific, Northwest, is located in Lebanon. Eugene is home to three private colleges: Bushnell University, New Hope Christian College, and Gutenberg College.

Law and government

[edit]

A writer in the Oregon Country book A Pacific Republic, written in 1839, predicted the territory was to become an independent republic. Four years later, in 1843, settlers of the Willamette Valley voted in majority for a republican form of government.[237] The Oregon Country functioned in this way until August 13, 1848, when Oregon was annexed by the U.S. and a territorial government was established. Oregon maintained a territorial government until February 14, 1859, when it was granted statehood.[238]

Structure

[edit]Oregon state government has a separation of powers similar to the federal government, with three branches:

- a legislative branch (the bicameral Oregon Legislative Assembly),

- an executive branch which includes an "administrative department" and Oregon's governor as chief executive, and

- a judicial branch, headed by the Chief Justice of the Oregon Supreme Court.

Governors in Oregon serve four-year terms and are limited to two consecutive terms, but an unlimited number of total terms. Oregon has no lieutenant governor; in case the office of governor is vacated, Article V, Section 8a of the Oregon Constitution specifies that the Secretary of State is first in line for succession.[239] The other statewide officers are Treasurer, Attorney General, and Labor Commissioner.

The biennial Oregon Legislative Assembly consists of a thirty-member Senate and a sixty-member House. A debate over whether to move to annual sessions is a long-standing battle in Oregon politics, but the voters have resisted the move from citizen legislators to professional lawmakers. Because Oregon's state budget is written in two-year increments and, there being no sales tax, state revenue is based largely on income taxes, it is often significantly over or under budget. Recent legislatures have had to be called into special sessions repeatedly to address revenue shortfalls resulting from economic downturns, bringing to a head the need for more frequent legislative sessions. Oregon Initiative 71, passed in 2010, mandates the legislature to begin meeting every year, for 160 days in odd-numbered years, and 35 days in even-numbered years.

The state supreme court has seven elected justices, currently including the only two openly gay state supreme court justices in the nation. They choose one of their own to serve a six-year term as Chief Justice.

Ballot measures

[edit]Oregon's constitution provides for ballot initiatives voted upon by the electorate in general. In the 2002 general election, Oregon voters approved a ballot measure to increase the state minimum wage automatically each year according to inflationary changes, which are measured by the consumer price index (CPI).[240] In the 2004 general election, Oregon voters passed ballot measures banning same-sex marriage[241] and restricting land use regulation.[242] In the 2006 general election, voters restricted the use of eminent domain and extended the state's discount prescription drug coverage.[243]

In the 2020 general election, Oregon voters approved a ballot measure decriminalizing the possession of small quantities of street drugs such as cocaine and heroin, becoming the first state in the country to do so after the drugs were originally made illegal.[244] The initiative has been described as a mixed success after three years of implementation, and calls for change arose.[245][246] Drug overdose deaths continued to rise, in line with other states. Funds allocated to treatment and other services have apparently not increased the success of these alternate outcomes.[247][248] In 2024, Governor Kotek signed a bill reversing the decriminalization component of the ballot measure while also expanding funding for drug treatment.[249]

In 2020 the state also approved a ballot measure to create a legal means of administering psilocybin for medicinal use, making it the first state in the country to legalize the drug.[250]

Federal representation

[edit]Like all U.S. states, Oregon is represented by two senators. Following the 1980 census, Oregon had five congressional districts. After Oregon was admitted to the Union, it began with a single member in the House of Representatives (La Fayette Grover, who served in the 35th U.S. Congress for less than a month). Congressional apportionment increased the size of the delegation following the censuses of 1890, 1910, 1940, and 1980. Following the 2020 census, Oregon gained a sixth congressional seat. It was filled in the 2022 Congressional Elections.[251] A detailed list of the past and present Congressional delegations from Oregon is available.

The U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon hears federal cases in the state. The court has courthouses in Portland, Eugene, Medford, and Pendleton. Also in Portland is the federal bankruptcy court, with a second branch in Eugene.[252] Oregon (among other western states and territories) is in the 9th Court of Appeals. One of the court's meeting places is at the Pioneer Courthouse in downtown Portland, a National Historic Landmark built in 1869.

Politics

[edit]

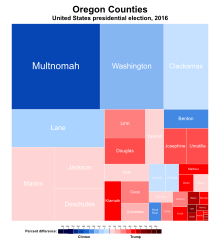

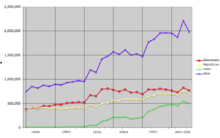

- Total

- Democratic Party

- Republican Party

- Non-affiliated or other

- Democrat ≥ 30%

- Democrat ≥ 40%

- Democrat ≥ 50%

- Republican ≥ 30%

- Republican ≥ 40%

- Republican ≥ 50%

- Unaffiliated ≥ 30%

- Unaffiliated ≥ 40%

Political opinions in Oregon are geographically split by the Cascade Range, with Western Oregon being more liberal and Eastern Oregon being conservative.[253] In a 2008 analysis of the 2004 presidential election, a political analyst found that according to the application of a Likert scale, Oregon boasted both the most liberal Kerry voters and the most conservative Bush voters, making it the most politically polarized state in the country.[254] The base of Democratic support is largely concentrated in the urban centers of the Willamette Valley. The eastern two-thirds of the state beyond the Cascade Mountains typically votes Republican; in 2000 and 2004, George W. Bush carried every county east of the Cascades. However, the region's sparse population means the more populous counties in the Willamette Valley usually outweigh the eastern counties in statewide elections. In 2008, for instance, Republican Senate incumbent Gordon H. Smith lost his bid for a third term, even though he carried all but eight counties. His Democratic challenger, Jeff Merkley, won Multnomah County by 142,000 votes, more than double the overall margin of victory. Oregonians have voted for the Democratic presidential candidate in every election since 1988. In 2004 and 2006, Democrats won control of the State Senate, and then the House. Since 2023, Oregon has been represented by four Democrats and two Republicans in the U.S. House of Representatives. Since 2009, the state has had two Democratic U.S. senators, Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley. Oregon voters have elected Democratic governors in every election since 1986, most recently electing Tina Kotek over Republican Christine Drazan and Independent Betsy Johnson in the 2022 gubernatorial election.

During Oregon's history, it has adopted many electoral reforms proposed during the Progressive Era, through the efforts of William S. U'Ren and his Direct Legislation League. Under his leadership, the state overwhelmingly approved a ballot measure in 1902 that created the initiative and referendum for citizens to introduce or approve proposed laws or amendments to the state constitution directly, making Oregon the first state to adopt such a system. Today, roughly half of U.S. states do so.[255]

In following years, the primary election to select party candidates was adopted in 1904, and in 1908 the Oregon Constitution was amended to include recall of public officials. More recent amendments include the nation's first doctor-assisted suicide law,[256] called the Death with Dignity Act (which was challenged, unsuccessfully, in 2005 by the Bush administration in a case heard by the U.S. Supreme Court), legalization of medical cannabis, and among the nation's strongest anti-urban sprawl and pro-environment laws.[citation needed] More recently, 2004's Measure 37 reflects a backlash against such land-use laws. However, a further ballot measure in 2007, Measure 49, curtailed many of the provisions of 37.

Of the measures placed on the ballot since 1902, the people have passed 99 of the 288 initiatives and 25 of the 61 referendums on the ballot, though not all of them survived challenges in courts (see Pierce v. Society of Sisters, for an example). During the same period, the legislature has referred 363 measures to the people, of which 206 have passed.

Oregon pioneered the American use of postal voting, beginning with experimentation approved by the Oregon Legislative Assembly in 1981 and culminating with a 1998 ballot measure mandating that all counties conduct elections by mail. It remains one of just two states, the other being Washington, where voting by mail is the only method of voting.

In 1994, Oregon adopted the Oregon Health Plan, which made health care available to most of its citizens without private health insurance.[257]

Oregon is the only state that does not have a mechanism to impeach executive officeholders, including the governor.[258] Removing an executive office holder would require a recall election. It is one of four states that requires two-thirds of members of the House and Senate be present to establish a quorum.[259] It is one of a minority of states that does not have a lieutenant governor.[260] The Secretary of State is the first in line of succession to replace the governor in event of a vacancy. This last occurred in 2015, when Gov. John Kitzhaber resigned amid allegation of influence peddling and Secretary of State Kate Brown became governor. Brown won a special election in 2016 to retain the position, and won a full four-year term in 2018.

In the U.S. Electoral College, Oregon cast seven votes through the 2020 presidential election. Under apportionment of Congress under the 2020 U.S. census, Oregon added a sixth congressional seat. Under the Electoral College formula of votes equaling the number of U.S. House seats plus the two U.S. Senators, Oregon will cast eight votes in the 2024 election. Oregon has supported Democratic candidates in the last nine elections. Democratic incumbent Barack Obama won the state by a margin of twelve percentage points, with over 54% of the popular vote in 2012. In the 2016 election, Hillary Clinton won Oregon by 11 percentage points.[261] In the 2020 election, Joe Biden won Oregon by 16 percentage points over his opponent, Donald Trump.[262]

In a 2020 study, Oregon was ranked as the easiest state for citizens to vote in.[263]

В Орегоне сохраняется смертная казнь . В настоящее время губернаторский запрет на казни. [ 264 ]

Спорт

[ редактировать ]

Орегон является домом для трех основных профессиональных спортивных команд: « Портленд Трэйл Блэйзерс» из НБА , « Портленд Торнс» из NWSL и « Портленд Тимберс» из MLS . [ 265 ]

До 2011 года единственной крупной профессиональной спортивной командой в Орегоне была «Портленд Трэйл Блэйзерс» Национальной баскетбольной ассоциации. С 1970-х по 1990-е годы «Блэйзерс» были одной из самых успешных команд НБА как по количеству побед-поражений, так и по посещаемости. [ 266 ] В начале 21 века популярность команды снизилась из-за кадровых и финансовых проблем, но возродилась после ухода спорных игроков и приобретения новых игроков, таких как Брэндон Рой и Ламаркус Олдридж , а еще позже Дэмиан Лиллард . [ 267 ] [ 268 ] «Блэйзерс» играют в «Мода Центре» в портлендском районе Ллойд, который также является домом для команды «Портленд Винтерхокс» Западной юношеской хоккейной лиги . [ 269 ]

«Портленд Тимберс» играют в Провиденс-парке , к западу от центра Портленда. У Тимберс много поклонников: команда регулярно распродает свои игры. [ 270 ] Осенью 2010 года компания Timbers перепрофилировала бывший многофункциональный стадион в футбольный стадион , увеличив при этом количество сидячих мест. [ 271 ] «Тимберс» управляют «Портленд Торнс», женской футбольной командой, которая играет в Национальной женской футбольной лиге с первого сезона лиги в 2013 году. «Торнс», которые также играют в Провиденс Парк, выиграли два чемпионата лиги: в первом сезоне 2013 года и также в 2017 году и с большим отрывом были лидером посещаемости NWSL в каждом сезоне лиги.

В Юджине и Хиллсборо есть бейсбольные команды низшей лиги: « Юджин Эмеральдс» и «Хиллсборо Хопс» играют в High-A High-A West . [ 272 ] В прошлом в Портленде были бейсбольные команды низшей лиги, в том числе « Портленд Биверс» и «Портленд Рокиз» , которые совсем недавно играли в Провиденс-парке, когда он был известен как PGE Park. В Салеме также ранее была команда короткого сезона Северо-Западной лиги класса А , « Вулканы Салем-Кейзер» , которая не была включена в реорганизацию Малой бейсбольной лиги 2021 года . Владельцы Volcanoes позже сформировали любительскую независимую бейсбольную лигу Mavericks , которая полностью базируется в Салеме. [ 273 ]

Футбольные команды « Бобры штата Орегон» и «Утки университета Орегона», участвовавшие в конференции Pac-12, ежегодно встречаются в футбольном соперничестве между штатами Орегон и штатом Орегон . Обе школы в последнее время добились успехов и в других видах спорта: штат Орегон выиграл подряд чемпионаты колледжей по бейсболу в 2006 и 2007 годах, [ 274 ] выигрыш третьего в 2018 году; [ 275 ] а Университет Орегона выиграл подряд мужские чемпионаты NCAA по кроссу в 2007 и 2008 годах. [ 276 ]

Побратимские регионы

[ редактировать ]- Фуцзянь , Провинция

Китайская Народная Республика [ 277 ]

Китайская Народная Республика [ 277 ] - Провинция Тайвань ,

Китайская Республика (Тайвань) [ 277 ]

Китайская Республика (Тайвань) [ 277 ] - Префектура Тояма ,

Япония [ 277 ] [ 278 ]

Япония [ 277 ] [ 278 ] - Провинция Чолланамдо ,

Республика Корея (Южная Корея) [ 277 ] [ 278 ]

Республика Корея (Южная Корея) [ 277 ] [ 278 ] - Иракский Курдистан ,

Ирак [ 279 ]

Ирак [ 279 ]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Очерк Орегона (организованный список тем об Орегоне)

- Указатель статей, связанных с Орегоном

- Библиография истории Орегона

Портал Тихоокеанского Северо-Запада

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ↑ Поскольку Гриффин-Валад не был избран, казначей штата Орегон Тобиас Рид будет первым в линии преемственности до окончания всеобщих выборов 2024 года.

- ^ Высота приведена к североамериканской вертикальной системе отсчета 1988 года .

- ^ Расовые субдемографические группы религиозных традиций суммируются. произошел сбой Примечание. При отображении данных о религиозных традициях штата Орегон в Public Religion Research Institute . Нажмите кнопку «Список», если результаты показывают «Н/Д». Не удаляйте круговую диаграмму.

Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ «Высшая точка горы Худ» . Технический паспорт НГС . Национальная геодезическая служба , Национальное управление океанических и атмосферных исследований , Министерство торговли США . Проверено 24 октября 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Высоты и расстояния в США» . Геологическая служба США . 2001. Архивировано из оригинала 15 октября 2011 года . Проверено 24 октября 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Результаты распределения переписи 2020 года, Таблица 2 Постоянное население 50 штатов, округа Колумбия и Пуэрто-Рико: перепись 2020 года» . Бюро переписи населения США . 30 апреля 2021 года. Архивировано из оригинала 26 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 26 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Средний годовой доход семьи» . Фонд Генри Дж. Кайзера . 17 ноября 2022 года. Архивировано из оригинала 9 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 9 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Холл, Кальвин (30 января 2007 г.). «Английский как официальный язык Орегона? Такое может случиться» . Орегон Дейли Изумруд . Архивировано из оригинала 17 января 2013 года . Проверено 8 мая 2007 г.

- ^ «Символы штата Орегон: девиз гидроэнергетики» . Государственный секретарь штата Орегон. Архивировано из оригинала 23 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 10 мая 2021 г.

- ^ «Орегон» . Словарь Merriam-Webster.com . Мерриам-Вебстер.

- ^ Уэллс, Джон К. (2008). Словарь произношения Лонгмана (3-е изд.). Лонгман. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0 .

- ^ Бюро переписи населения США (1 июля 2022 г.). «Краткая информация о переписи населения: Салем, Орегон, США» . Краткие сведения Бюро переписи населения США: город Салем, штат Орегон; Соединенные Штаты . Архивировано из оригинала 6 июня 2023 года . Проверено 1 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Джуэлл и Макрей 2014 , с. 4.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бил, Боб (10 апреля 2003 г.). «Огромный гриб: самый большой организм в мире?» . Новости окружающей среды и природы. Азбука. Архивировано из оригинала 31 декабря 2006 года . Проверено 9 декабря 2016 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Программа защиты лесных земель» . Департамент рыбы и дикой природы штата Орегон. Архивировано из оригинала 8 июля 2018 года . Проверено 7 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ «Письмо акционерам Nike, Inc., 2022 г.» (PDF) . Nike, Inc. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 9 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 13 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Министерство связи и транспорта, 1988 г. , с. 149.

- ^ Джонсон 1904 , с. 51.

- ^ «Синяя книга штата Орегон: Альманах штата Орегон: от гор до национальных заповедников дикой природы» . Архивировано из оригинала 24 октября 2018 года . Проверено 23 октября 2018 г.

- ^ Откуда произошло название «Орегон»? Архивировано 24 октября 2018 года в Wayback Machine из онлайн-издания Oregon Blue Book .

- ^ Эллиотт, TC (июнь 1921 г.). «Происхождение названия Орегон» . Исторический ежеквартальный журнал Орегона . XXIII (2): 99–100. ISSN 0030-4727 . ОСЛК 1714620 . Архивировано из оригинала 5 сентября 2015 года . Проверено 27 июня 2015 г. - через Google Книги.

- ^ Миллер, Хоакин (сентябрь 1904 г.). «Море тишины» . Закат . XIII (5): 395–396 - через Интернет-архив.

- ^ «Орегон» . Интернет-словарь Мерриам-Вебстера. Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2008 года . Проверено 14 сентября 2006 г.

- ^ «Краткие факты об Орегоне» . Путешествие по Орегону. Архивировано из оригинала 23 марта 2012 года.

- ↑ Бэнкс, Дон (21 апреля 2002 г.). «Харрингтон уверен в успехе Детройта QB» . Архивировано 7 сентября 2008 года в Wayback Machine Sports Illustrated .

- ^ Беллами, Рон (6 октября 2003 г.). «Не вижу зла, не слышу зла» . Регистр-охрана . Архивировано из оригинала 20 февраля 2021 года . Проверено 1 июня 2011 г.

- ^ «Желто-зеленая внешняя наклейка с печатной буквой ORYGUN» . УО Утиный магазин. Архивировано из оригинала 8 декабря 2010 года . Проверено 3 августа 2011 г.

- ^ Роббинс 2005 .

- ^ Мо II, Томас Х. (12 июля 2012 г.). «Кто был первым? Новая информация о первых жителях Северной Америки» . Лос-Анджелес Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 21 декабря 2014 года . Проверено 8 ноября 2016 г.

- ^ Аллен, Бернс и Сарджент 2009 , стр. 175–189.

- ^ «История Орегона: Большой бассейн» . Синяя книга штата Орегон . Государственный архив штата Орегон. Архивировано из оригинала 24 октября 2018 года . Проверено 2 сентября 2007 г.

- ^ «История Орегона: Северо-Западное побережье» . Синяя книга штата Орегон . Государственный архив штата Орегон. Архивировано из оригинала 24 октября 2018 года . Проверено 2 сентября 2007 г.

- ^ «История Орегона: плато Колумбия» . Синяя книга штата Орегон . Государственный архив штата Орегон. Архивировано из оригинала 24 октября 2018 года . Проверено 2 сентября 2007 г.

- ^ Кэри 1922 , с. 47.

- ^ Хемминг 2008 , стр. 140–141.

- ^ Фон дер Портен, Эдвард (январь 1975 г.). «Первый выход Дрейка на берег». Pacific Discovery, Калифорнийская академия наук . 28 (1): 28–30.

- ^ Джонсон 1904 , с. 39.

- ^ Когсвелл, Филип младший (1977). Имена Капитолия: личности, вплетенные в историю Орегона . Портленд, Орегон: Историческое общество Орегона . стр. 9–10.