Консервативная партия (Великобритания)

Консервативная и юнионистская партия , обычно Консервативная партия и в просторечии известная как Тори , [18] — одна из двух основных политических партий Соединенного Королевства , наряду с Лейбористской партией . Она является официальной оппозицией с тех пор, как потерпела поражение на всеобщих выборах 2024 года . Партия занимает правое крыло [16] к правоцентристам [12] [13] политического спектра. В его состав входят различные идеологические фракции, в том числе консерваторы единой нации , сторонники Тэтчер и консерваторы-традиционалисты . Было двадцать премьер-министров от консерваторов .

Консервативная партия была основана в 1834 году на базе партии Тори и была одной из двух доминирующих политических партий XIX века наряду с Либеральной партией . При Бенджамине Дизраэли оно играло выдающуюся роль в политике на пике расцвета Британской империи . В 1912 году Либеральная юнионистская партия объединилась с партией и образовала Консервативную и юнионистскую партию. Соперничество с Лейбористской партией формировало современную британскую политику последнего столетия. Дэвид Кэмерон стремился модернизировать консерваторов после своего избрания лидером в 2005 году, и партия управляла с 2010 по 2024 год под руководством пяти премьер-министров, последним из которых был Риши Сунак .

The party has generally adopted liberal economic policies favouring free markets since the 1980s, although historically it advocated for protectionism. The party is British unionist, opposing a united Ireland as well as Scottish and Welsh independence, and has been critical of devolution. Historically, the party supported the continuance and maintenance of the British Empire. The party has taken various approaches towards the European Union (EU), with eurosceptic and, to an increasingly lesser extent, pro-European factions within it. Historically, the party took a socially conservative approach.[27][28] In defence policy, it supports an independent nuclear weapons programme and commitment to NATO membership.

For much of modern British political history, the United Kingdom exhibited a wide urban–rural political divide;[29] the Conservative Party's voting and financial support base has historically consisted primarily of homeowners, business owners, farmers, real estate developers and middle class voters, especially in rural and suburban areas of England.[30][31][32][33][34] However, since the EU referendum in 2016, the Conservatives targeted working class voters from traditional Labour strongholds.[35][36][37][38] The Conservatives' domination of British politics throughout the 20th century made it one of the most successful political parties in the Western world.[39][40][41][42] The most recent period of Conservative government was marked by extraordinary political turmoil.[43]

History

Origins

Some writers trace the party's origins to the Tory Party, which it soon replaced. Other historians point to a faction, rooted in the 18th century Whig Party, that coalesced around William Pitt the Younger in the 1780s. They were known as "Independent Whigs", "Friends of Mr Pitt", or "Pittites" and never used terms such as "Tory" or "Conservative". From about 1812, the name "Tory" was commonly used for a new party that, according to historian Robert Blake, "are the ancestors of Conservatism". Blake adds that Pitt's successors after 1812 "were not in any sense standard-bearers of 'true Toryism'".[44]

The term Tory was an insult that entered English politics during the Exclusion Bill crisis of 1678–1681, which derived from the Middle Irish word tóraidhe (modern Irish: tóraí) meaning outlaw or robber, which in turn derived from the Irish word tóir, meaning pursuit, since outlaws were "pursued men".[45][46]

The term "Conservative" was suggested as a title for the party in an article by J. Wilson Croker published in the Quarterly Review in 1830.[47] The name immediately caught on and was formally adopted under the aegis of Robert Peel around 1834. Peel is acknowledged as the founder of the Conservative Party, which he created with the announcement of the Tamworth Manifesto. The term "Conservative Party" rather than Tory was the dominant usage by 1845.[48][49]

1867–1914: Conservatives and Unionists

The widening of the electoral franchise in the 19th century forced the Conservative Party to popularise its approach under Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby and Benjamin Disraeli, who carried through their own expansion of the franchise with the Reform Act of 1867. The party was initially opposed to further expansion of the electorate but eventually allowed passage of Gladstone's 1884 Reform Act. In 1886, the party formed an alliance with Spencer Cavendish and Joseph Chamberlain's new Liberal Unionist Party and, under the statesmen Robert Gascoyne-Cecil and Arthur Balfour, held power for all but three of the following twenty years before suffering a heavy defeat in 1906 when it split over the issue of free trade.

Young Winston Churchill denounced Chamberlain's attack on free trade, and helped organise the opposition inside the Unionist/Conservative Party. Nevertheless, Balfour, as party leader, introduced protectionist legislation.[50] Churchill crossed the floor and formally joined the Liberal Party (he rejoined the Conservatives in 1925). In December, Balfour lost control of his party, as the defections multiplied. He was replaced by Liberal Prime Minister Henry Campbell-Bannerman who called an election in January 1906, which produced a massive Liberal victory. Liberal Prime Minister H. H. Asquith enacted a great deal of reform legislation, but the Unionists worked hard at grassroots organizing. Two general elections were held in 1910, in January and in December. The two main parties were now almost dead equal in seats, but the Liberals kept control with a coalition with the Irish Parliamentary Party.[51][52]

In 1912, the Liberal Unionists merged with the Conservative Party. In Ireland, the Irish Unionist Alliance had been formed in 1891 which merged Unionists who were opposed to Irish Home Rule into one political movement. Its MPs took the Conservative whip at Westminster, essentially forming the Irish wing of the party until 1922. In Britain, the Conservative party was known as the Unionist Party because of its opposition to home rule.[53][54] Under Bonar Law's leadership in 1911–1914, the Party morale improved, the "radical right" wing was contained, and the party machinery strengthened. It made some progress toward developing constructive social policies.[55]

First World War

While the Liberals were mostly against the war until the invasion of Belgium, Conservative leaders were strongly in favour of aiding France and stopping Germany. The Liberal party was in full control of the government until its mismanagement of the war effort under the Shell Crisis badly hurt its reputation. An all-party coalition government was formed in May 1915. In late 1916 Liberal David Lloyd George became prime minister but the Liberals soon split and the Conservatives dominated the government, especially after their landslide in the 1918 election. The Liberal party never recovered, but Labour gained strength after 1920.[56]

Nigel Keohane finds that the Conservatives were bitterly divided before 1914 but the war pulled the party together, allowing it to emphasise patriotism as it found new leadership and worked out its positions on the Irish question, socialism, electoral reform, and the issue of intervention in the economy. The fresh emphasis on anti-Socialism was its response to the growing strength of the Labour Party. When electoral reform was an issue, it worked to protect their base in rural England.[57] It aggressively sought female voters in the 1920s, often relying on patriotic themes.[58]

1920–1945

In 1922, Bonar Law and Stanley Baldwin led the breakup of the coalition, and the Conservatives governed until 1923, when a minority Labour government led by Ramsay MacDonald came to power. The Conservatives regained power in 1924 but were defeated in 1929 as a minority Labour government took office. In 1931, following the collapse of the Labour minority government, it entered another coalition, which was dominated by the Conservatives with some support from factions of both the Liberal Party and the Labour Party (National Labour and National Liberals).[59] In May 1940, a more balanced coalition was formed[59]—the National Government—which, under the leadership of Winston Churchill, saw the United Kingdom through the Second World War. However, the party lost the 1945 general election in a landslide to the resurgent Labour Party.[60][61]

The concept of the "property-owning democracy" was coined by Noel Skelton in 1923 and became a core principle of the party.[62]

1945–1975: Post-war consensus

Popular dissatisfaction

While serving in Opposition during the late 1940s, the Conservative Party exploited and incited growing public anger at food rationing, scarcity, controls, austerity, and government bureaucracy. It used the dissatisfaction with the socialist and egalitarian policies of the Labour Party to rally middle-class supporters and build a political comeback that won them the 1951 general election.[63]

Modernising the party

In 1947, the party published its Industrial Charter which marked its acceptance of the "post-war consensus" on the mixed economy and labour rights.[64] David Maxwell Fyfe chaired a committee into Conservative Party organisation that resulted in the Maxwell Fyfe Report (1948–49). The report required the party to do more fundraising, by forbidding constituency associations from demanding large donations from candidates, with the intention of broadening the diversity of MPs. In practice, it may have had the effect of lending more power to constituency parties and making candidates more uniform.[65] Winston Churchill, the party leader, brought in a Party chairman to modernise the party: Frederick Marquis, 1st Earl of Woolton rebuilt the local organisations with an emphasis on membership, money, and a unified national propaganda appeal on critical issues.[66]

With a narrow victory at the 1951 general election, despite losing the popular vote, Churchill was back in power. Apart from rationing, which was ended in 1954, most of the welfare state enacted by Labour were accepted by the Conservatives and became part of the "post-war consensus" that was satirised as Butskellism and that lasted until the 1970s.[67][68] The Conservatives were conciliatory towards unions, but they did privatise the steel and road haulage industries in 1953.[69] During the Conservatives' thirteen-year tenure in office, pensions went up by 49% in real terms, sickness and unemployment benefits by 76% in real terms, and supplementary benefits by 46% in real terms. However, family allowances fell by 15% in real terms.[70] "Thirteen Wasted Years" was a popular slogan attacking the Conservative record, primarily from Labour. In addition, there were attacks by the right wing of the Conservative Party itself for its tolerance of socialist policies and reluctance to curb the legal powers of labour unions.

The Conservatives were re-elected in 1955 and 1959 with larger majorities. Conservative Prime Ministers Churchill, Anthony Eden, Harold Macmillan and Alec Douglas-Home promoted relatively liberal trade regulations and less state involvement throughout the 1950s and early 1960s. The Suez Crisis of 1956 was a humiliating defeat for Prime Minister Eden, but his successor, Macmillan, minimised the damage and focused attention on domestic issues and prosperity. Following controversy over the selections of Harold Macmillan and Alec Douglas-Home via a process of consultation known as the 'Magic Circle',[71][72] a formal election process was created and the first leadership election was held in 1965, won by Edward Heath.[73]

1965–1975: Edward Heath

Edward Heath's 1970–74 government was known for taking the UK into the EEC, although the right-wing of the party objected to his failure to control the trade unions at a time when a declining British industry saw many strikes, as well as the 1973–75 recession. Since accession to the EEC, which developed into the EU, British membership has been a source of heated debate within the party.

Heath had come to power in June 1970 and the last possible date for the next general election was not until mid-1975.[74] However a general election was held in February 1974 in a bid to win public support during a national emergency caused by the miners' strike. Heath's attempt to win a second term at this "snap" election failed, as a deadlock result left no party with an overall majority. Heath resigned within days, after failing to gain Liberal Party support to form a coalition government. Labour won the October 1974 election with an overall majority of three seats.[75]

1975–1990: Margaret Thatcher

Loss of power weakened Heath's control over the party and Margaret Thatcher deposed him in the 1975 leadership election. Thatcher led her party to victory at the 1979 general election with a manifesto which concentrated on the party's philosophy.[76]

As Prime Minister, Thatcher focused on rejecting the mild liberalism of the post-war consensus that tolerated or encouraged nationalisation, strong labour unions, heavy regulation, and high taxes.[77] She did not challenge the National Health Service, and supported the Cold War policies of the consensus, but otherwise tried to dismantle and delegitimise it. She built a right-wing political ideology that became known as Thatcherism, based on social and economic ideas from British and American intellectuals such as Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman. Thatcher believed that too much socially democratic-oriented government policy was leading to a long-term decline in the British economy. As a result, her government pursued a programme of economic liberalism, adopting a free-market approach to public services based on the sale of publicly owned industries and utilities, as well as a reduction in trade union power.

One of Thatcher's largest and most successful policies assisted council house tenants in public housing to purchase their homes at favourable rates. The "Right to Buy" had emerged in the late 1940s but was too great a challenge to the post-war consensus to win Conservative endorsement. Thatcher favoured the idea because it would lead to a "property-owning democracy", an important idea that had emerged in the 1920s.[62] Some local Conservative-run councils enacted profitable local sales schemes during the late 1960s. By the 1970s, many working-class people could afford to buy homes, and eagerly adopted Thatcher's invitation to purchase their homes at a sizable discount. The new owners were more likely to vote Conservative, as Thatcher had hoped.[78][79]

Thatcher led the Conservatives to two further electoral victories in 1983 and 1987. She was deeply unpopular in certain sections of society due to high unemployment and her response to the miners' strike. Unemployment had doubled between 1979 and 1982, largely due to Thatcher's monetarist battle against inflation.[80][81] At the time of the 1979 general election, inflation had been at 9% or under for the previous year, then increased to over 20% in the first two years of the Thatcher ministry, but it had fallen again to 5.8% by the start of 1983.[82]

The period of unpopularity of the Conservatives in the early 1980s coincided with a crisis in the Labour Party, which then formed the main opposition. Victory in the Falklands War in June 1982, along with the recovering British economy, saw the Conservatives returning quickly to the top of the opinion polls and winning the 1983 general election with a landslide majority, due to a split opposition vote.[80] By the time of the general election in June 1987, the economy was stronger, with lower inflation and falling unemployment and Thatcher secured her third successive electoral victory.[83]

The introduction of the Community Charge (known by its opponents as the poll tax) in 1989 is often cited as contributing to her political downfall. Internal party tensions led to a leadership challenge by the Conservative MP Michael Heseltine and she resigned on 28 November 1990.[84]

1990–1997: John Major

John Major won the party leadership election on 27 November 1990, and his appointment led to an almost immediate boost in Conservative Party fortunes.[85] The election was held on 9 April 1992 and the Conservatives won a fourth successive electoral victory, contrary to predictions from opinion polls.[86][87] The Conservatives became the first party to attract 14 million votes in a general election.[88][89]

On 16 September 1992, the Government suspended Britain's membership of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), after the pound fell lower than its minimum level in the ERM, a day thereafter referred to as Black Wednesday.[90] Soon after, approximately one million householders faced repossession of their homes during a recession that saw a sharp rise in unemployment, taking it close to 3 million people.[91] The party subsequently lost much of its reputation for good financial stewardship. The end of the recession was declared in April 1993.[92][91] From 1994 to 1997, Major privatised British Rail.

The party was plagued by internal division and infighting, mainly over the UK's role in the European Union. The party's Eurosceptic wing, represented by MPs such as John Redwood, opposed further EU integration, whilst the party's pro-European wing, represented by those such as Chancellor of the Exchequer Kenneth Clarke, was broadly supportive. The issue of the creation of a single European currency also inflamed tensions.[93] Major survived a leadership challenge in 1995 by Redwood, but Redwood received 89 votes, further undermining Major's influence.[94]

The Conservative government was increasingly accused in the media of "sleaze". Their support reached its lowest ebb in late 1994. Over the next two years the Conservatives gained some credit for the strong economic recovery and fall in unemployment.[95] But an effective opposition campaign by the Labour Party culminated in a landslide defeat for the Conservatives in 1997, their worst defeat since the 1906 general election. The 1997 election left the Conservative Party as an England-only party, with all Scottish and Welsh seats having been lost, and not a single new seat having been gained anywhere.

1997–2010: Political wilderness

Major resigned as party leader and was succeeded by William Hague.[96] The 2001 general election resulted in a net gain of one seat for the Conservative Party and returned a mostly unscathed Labour Party back to government.[97] This all occurred months after the fuel protests of September 2000 had seen the Conservatives briefly take a narrow lead over Labour in the opinion polls.[98]

In 2001, Iain Duncan Smith was elected leader of the party.[96] Although Duncan Smith was a strong Eurosceptic,[99] during his tenure, Europe ceased to be an issue of division in the party as it united behind calls for a referendum on the proposed European Union Constitution.[100] However, before he could lead the party into a general election, Duncan Smith lost the vote on a motion of no confidence by MPs.[101] This was despite the Conservative support equalling that of Labour in the months leading up to his departure from the leadership.[95]

Michael Howard then stood for the leadership unopposed on 6 November 2003.[102] Under Howard's leadership in the 2005 general election, the Conservative Party increased their total vote share and—more significantly—their number of parliamentary seats, reducing Labour's majority.[103] The day following the election, Howard resigned.

David Cameron won the 2005 leadership election.[104] He then announced his intention to reform and realign the Conservatives.[105][106] For most of 2006 and the first half of 2007, polls showed leads over Labour for the Conservatives.[107] Polls became more volatile in summer 2007 with the accession of Gordon Brown as Prime Minister. The Conservatives gained control of the London mayoralty for the first time in 2008 after Boris Johnson defeated the Labour incumbent, Ken Livingstone.[108]

2010–2024: Austerity, Brexit, and the pandemic

In May 2010 the Conservative Party came to government, first under a coalition with the Liberal Democrats and later as a series of majority and minority governments. During this period there were five Conservative Prime Ministers: David Cameron, Theresa May, Boris Johnson, Liz Truss, and Rishi Sunak. The initial period of this time, primarily under the premiership of David Cameron, was marked by the ongoing effects of the late-2000s financial crisis and the implementation of austerity measures in response. From 2015 the predominant political event was the Brexit referendum and the process to implement the decision to leave the trade bloc.

The Conservatives' time in office was marked by several controversies. The presence of Islamophobia in the Conservative Party, including allegations against its policies, fringes, and structure, was often in the public eye. These include allegations against senior politicians such as Boris Johnson, Michael Gove, Theresa May, and Zac Goldsmith.

During the period of the Cameron[109][110][111] and Johnson governments,[112] a number of Conservative MPs have been accused or convicted of sexual misconduct, with cases including the consumption of pornography in parliament, rape, groping, and sexual harassment.[113][114][115] In 2017, a list of 36 sitting Conservative MPs accused of inappropriate sexual behaviour was leaked. The list is believed to have been compiled by party staff.[116] Following accusations of multiple cases of rape against an unnamed Tory MP in 2023[117] and allegations of a cover-up,[118][119] Baroness Warsi, who has served as the party's co-chairman under David Cameron, stated that the Conservative Party has had a problem handling complaints of sexual misconducts against members appropriately.[120]

2010–2016: David Cameron

The 2010 election resulted in a hung parliament with the Conservatives having the most seats but short of an overall majority.[121] Following the resignation of Gordon Brown, Cameron was named Prime Minister, and the Conservatives entered government in a coalition with the Liberal Democrats—the first postwar coalition government.[122][123]

Cameron's premiership was marked by the ongoing effects of the late-2000s financial crisis; these involved a large deficit in government finances that his government sought to reduce through controversial austerity measures.[124][125] In September 2014, the Unionist side, championed by Labour as well as by the Conservative Party and the Liberal Democrats, won in the Scottish Independence referendum by 55% No to 45% Yes on the question "Should Scotland be an independent country".[126][127]

At the 2015 general election, the Conservatives formed a majority government under Cameron.[128] After speculation of a referendum on the UK's EU membership throughout his premiership, a vote was announced for June 2016 in which Cameron campaigned to remain in the EU.[129][130] On 24 June 2016, Cameron announced his intention to resign as Prime Minister, after he failed to convince the British public to stay in the European Union.[131]

2016–2019: Theresa May

On 11 July 2016, Theresa May became the leader of the Conservative Party.[132] May promised social reform and a more centrist political outlook for the Conservative Party and its government.[133] May's early cabinet appointments were interpreted as an effort to reunite the party in the wake of the UK's vote to leave the European Union.[134]

She began the process of withdrawing the UK from the European Union in March 2017.[135] In April 2017, the Cabinet agreed to hold a general election on 8 June.[136] In a shock result, the election resulted in a hung parliament, with the Conservative Party needing a confidence and supply arrangement with the DUP to support a minority government.[137][138]

May's Premiership was dominated by Brexit as she carried out negotiations with the European Union, adhering to the Chequers Plan, which resulted in her draft Brexit withdrawal agreement.[139] May survived two votes of no confidence in December 2018 and January 2019, but after versions of her draft withdrawal agreement were rejected by Parliament three times, May announced her resignation on 24 May 2019.[140]

Subsequent to the EU referendum vote, and through the premierships of May, Boris Johnson, and their successors, the party shifted right on the political spectrum.[16]

2019–2022: Boris Johnson

In July 2019 Boris Johnson became Leader of the party.[141] He became Prime Minister the next day. Johnson had made withdrawal from the EU by 31 October "with no ifs, buts or maybes" a key pledge during his campaign for party leadership.[142]

Johnson lost his working majority in the House of Commons on 3 September 2019.[143] Later that same day, 21 Conservative MPs had the Conservative whip withdrawn after voting with the Opposition to grant the House of Commons control over its order paper.[144] Johnson would later halt the Withdrawal Agreement Bill, calling for a general election.[145]

The 2019 general election resulted in the Conservatives winning a majority, the Party's largest since 1987.[146] The party won several constituencies, particularly in formerly traditional Labour seats.[35][36] On 20 December 2019, MPs passed an agreement for withdrawing from the EU; the United Kingdom formally left on 31 January 2020.[147][148]

Johnson presided over the UK's response to the COVID-19 pandemic.[149] From late 2021 onwards, Johnson received huge public backlash for the Partygate scandal, in which staff and senior members of government were pictured holding gatherings during lockdown contrary to Government guidance.[150] The Metropolitan Police eventually fined Johnson for breaking lockdown rules in April 2022.[151] In July 2022, Johnson admitted to appointing Chris Pincher as deputy chief whip while being aware of allegations of sexual assault against him.[152] This, along with Partygate and increasing criticisms on Johnson's handling of the cost-of-living crisis, provoked a government crisis following a loss in confidence and nearly 60 resignations from government officials, eventually leading to Johnson announcing his resignation on 7 July.[153][154]

2022: Liz Truss

Boris Johnson's successor as leader was confirmed as Liz Truss on 5 September, following a leadership election.[155] In a strategy labelled Trussonomics she introduced policies in response to the cost of living crisis,[156] including price caps on energy bills and government help to pay them.[157] Truss's mini-budget on 23 September faced severe criticism and markets reacted poorly;[158] the pound fell to a record low of 1.03 against the dollar, and UK government gilt yields rose to 4.3 per cent, prompting the Bank of England to trigger an emergency bond-buying programme.[159][160] After condemnation from the public, the Labour Party and her own party, Truss reversed some aspects of the mini-budget, including the abolition of the top rate of income tax.[161][162] Following a government crisis Truss announced her resignation as prime minister on 20 October[163] after 44 days in office, the shortest premiership in British history.[163][164] Truss also oversaw the worst polling the Conservatives had ever received, with Labour polling as high as 36 per cent above the Conservatives amidst the crisis.[165]

2022–2024: Rishi Sunak

On 24 October 2022, Rishi Sunak was declared Leader, the first British Asian Leader of the Conservatives and the first British Asian Prime Minister. On 22 May Sunak announced a general election to be held on 4 July 2024.[166]

During the 2024 general election, public opinion in favour of a change in government was reflected by poor polling from the Conservative Party, with Reform UK making strong polling gains.[167] The Conservative manifesto focused on the economy, taxes, welfare, expanding free childcare, education, healthcare, environment, energy, transport, and crime.[168][169] It pledged to lower taxes, increase education and NHS spending, deliver 92,000 more nurses and 28,000 more doctors, introduce a new model of National Service, and to treble Britain's offshore wind capacity and support solar energy.[170][171] The final result was the lowest seat total at a general election in the history of the Conservative party, with well below the previous record low of 156 seats won at the 1906 general election.[172]

Policies

Economic policy

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

The Conservative Party believes that a free market and individual achievement are the primary factors behind economic prosperity. A leading economic theory advocated by Conservatives is supply-side economics, which holds that reduced income tax rates increase growth and enterprise (although a reduction in the budget deficit has sometimes taken priority over cutting taxes).[173] The party focuses on the social market economy, promoting a free market for competition with social balance to create fairness. This has included education reform, vocational skills reform, expanding free childcare, curbs on the banking sector, enterprise zones to revive regions in Britain, and grand and extensive infrastructure projects, such as high-speed rail.[174][175]

One concrete economic policy of recent years has been opposition to the European single currency, the euro. With the growing Euroscepticism within his party, John Major negotiated a British opt-out in the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, which enabled the UK to stay within the European Union without adopting the single currency. All subsequent Conservative leaders have positioned the party firmly against the adoption of the euro.

The 50% top rate of income tax was reduced to 45% by the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition.[176] Alongside a reduction in tax and commitments to keep taxation low, the Conservative Party has significantly reduced government spending, through the austerity programme which commenced in 2010, subsequent to the 2007–2008 financial crisis. In 2019 and during the election campaign that year, Boris Johnson signalled an end to austerity with increased public expenditure, in areas including healthcare, education, transport, welfare, and the police.[177][178]

Social policy

Socially conservative policies such as tax incentives for married couples may have played a role in the party's electoral decline in the 1990s and early 2000s, and so the party has attempted to seek a new direction. As part of their coalition with the Liberal Democrats, the Conservative government did support the introduction of equal marriage rights for LGBT+ individuals in 2010, though 139 Conservative MPs, a majority, voted against the 2013 same-sex marriage act. Thus the extent to which this policy represented a more liberal Conservative party has been challenged.[185]

Since 1997 debate has occurred within the party between 'modernisers' such as Alan Duncan,[186] who believe that the Conservatives should modify their public stances on social issues, and 'traditionalists' such as Liam Fox[187][188] and Owen Paterson,[189] who believe that the party should remain faithful to its traditional conservative platform. In the previous parliament, modernising forces were represented by MPs such as Neil O'Brien, who has argued that the party needs to renew its policies and image, and is said to be inspired by Macron's centrist politics.[190] Ruth Davidson is also seen as a reforming figure. Many of the original 'traditionalists' remain influential, though Duncan Smith's influence in terms of Commons contributions has waned.[191]

The party has strongly criticised what it describes as Labour's "state multiculturalism".[192] Shadow Home Secretary Dominic Grieve said in 2008 that state multiculturalism policies had created a "terrible" legacy of "cultural despair" and dislocation, which has encouraged support for "extremists" on both sides of the debate.[193] David Cameron responded to Grieve's comments by agreeing that policies of "state multiculturalism" that treat social groups as distinct, for example policies that "treat British Muslims as Muslims, rather than as British citizens", are wrong. However, he expressed support for the premise of multiculturalism on the whole.[193]

Official statistics showed that EU and non-EU mass immigration, together with asylum seeker applications, all increased substantially during Cameron's term in office.[194][195][196] However, this was not solely as a result of intentional government policy – during this period, there were significant refugee flows into the UK and an increased level of asylum applications due to conflict and persecution globally.[197][198] In 2019 former Conservative Home Secretary Priti Patel announced that the government would enact stricter immigration reforms, crack down on illegal immigration, and scrap freedom of movement with the European Union following the completion of Brexit.[199] In the four years following this announcement, net migration increased annually, in large part due to the number of health care workers, and their dependents, that were invited into the country because of recruitment problems caused by Brexit and the pandemic.[200][201] The number of asylum seekers dropped as a proportion of total net migrants, whereas the number of people coming to the UK to study increased during that time period.[202]

Foreign policy

For much of the 20th century, the Conservative Party took a broadly Atlanticist stance in relations with the United States, Members of EU and NATO, favouring close ties with the United States and similarly aligned nations such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Japan. The Conservatives have generally favoured a diverse range of international alliances, ranging from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to the Commonwealth of Nations. The Conservatives have proposed a Pan-African Free Trade Area, which it says could help entrepreneurial dynamism of African people.[203] The Conservatives pledged to increase aid spending to 0.7% of national income by 2013.[203] They met this pledge in 2014, when spending on aid reached 0.72% of GDP and the commitment was enshrined in UK law in 2015.[204]

Close Anglo-American Relationship have been an element of Conservative foreign policy since the Second World War. Though the Anglo–American relationship in foreign affairs has often been termed a 'Special Relationship', a term coined by Winston Churchill, this has often been observed most clearly where leaders in each country are of a similar political stripe. David Cameron had sought to distance himself from former US President Bush and his neoconservative foreign policy.[205] Despite traditional links between the UK Conservatives and US Republicans, London Mayor Boris Johnson, a Conservative, endorsed Barack Obama in the 2008 election.[206] However, after becoming Prime Minister, Johnson developed a close relationship with Republican President Donald Trump.[207][208][209] This has also been described as a reestablishing of the Special Relationship with the United States following Britain's withdraw from the European Union, as well as returning to the links between the Conservatives and Republican Party.[210] Beyond relations with the United States, the Commonwealth and the EU, the Conservative Party has generally supported a pro free-trade foreign policy within the mainstream of international affairs.

Although stances have changed with successive leadership, the modern Conservative Party generally supports cooperation and maintaining friendly relations with Israel. Historic Conservative statesmen such as Arthur Balfour and Winston Churchill supported the idea of national home for the Jewish people. Under Margaret Thatcher Conservative support for Israel was seen to crystallise.[211][212] Support for Israel has increased under the leaderships of Theresa May and Boris Johnson, with prominent Conservative figures within the May and Johnson ministries strongly endorsing Israel. In 2016, Theresa May publicly rebutted statements made by US Secretary of State John Kerry over the composition of the Israeli government.[213][214] In 2018, the party pledged to proscribe all wings of the Lebanese-based militant group Hezbollah and this was adopted as a UK-wide policy in 2019.[215][216] In 2019, the Conservative government under Boris Johnson announced plans to stop the influence of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement on local politics which included prohibiting local councils from boycotting Israeli products.[217][218][219]

Defence policy

After the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, the Conservative Party supported the coalition military action in Afghanistan. The Conservative Party believed that success in Afghanistan would be defined in terms of the Afghans achieving the capability to maintain their own internal and external security. They have repeatedly criticised the former Labour Government for failing to equip British Forces adequately in the earlier days on the campaign—especially highlighting the shortage of helicopters for British Forces resulting from Gordon Brown's £1.4bn cut to the helicopter budget in 2004.[220]

The Conservative Party believes that in the 21st century defence and security are interlinked. It has pledged to break away from holding a traditional Strategic Defence Review and committed to carrying out a more comprehensive Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR).[221] As well as an SDSR, the Conservative Party pledged in 2010 to undertake a fundamental and far-reaching review of the procurement process and how defence equipment is provided in Britain, and to increase Britain's share of the global defence market as Government policy.[222]

The Conservative Party upholds the view that NATO remains and should remain the most important security alliance for the United Kingdom.[223] It has advocated for the creation of a fairer funding mechanism for NATO's expeditionary operations and called for all NATO countries to meet their required defence spending 2% of GDP. Some Conservatives believe that there is scope for expanding NATO's Article V to include new threats such as cybersecurity.

The Conservative Party aims to build enhanced bilateral defence relations with key European partners and believes that it is in Britain's national interest to cooperate fully with all its European neighbours. It has pledged to ensure that any EU military capability must supplement and not supplant British national defence and NATO, and that it is not in the British interest to hand over security to any supranational body.[224]

The Conservatives see it as a priority to encourage all members of the European Union to do more in terms of a commitment to European security at home and abroad. Regarding the defence role of the European Union, the Conservatives pledged to re-examine some of Britain's EU Defence commitments to determine their practicality and utility; specifically, to reassess UK participation provisions like Permanent Structured Cooperation, the European Defence Agency and EU Battlegroups to determine if there is any value in Britain's participation.

The Conservatives support the UK's possession of nuclear weapons through the Trident nuclear programme.[224]

Health and drug policy

In 1945 the Conservatives declared support for universal healthcare.[225] They introduced the Health and Social Care Act 2012, constituting the biggest reformation that the NHS has ever undertaken.[226]

The Conservative Party supports drug prohibition.[227] However, views on drugs vary amongst some MPs in the party. Some Conservative politicians take the libertarian approach that individual freedom and economic freedom of industry and trade should be respected over prohibition. Other Conservative politicians, despite being economically liberal, are in favour of full drug prohibition. Legalisation of cannabis for medical uses is favoured by some Conservative politicians.[228] The party has rejected both decriminalising drugs for personal use and the creation of safe consumption sites.[229] In 2024, the Conservatives banned smoking for future generations, with an aim to make England smoke-free by 2030.[230]

Education and research

In education, the Conservatives pledged to review the National Curriculum, introduce the English Baccalaureate, and reform GCSE, A-level, other national qualifications, apprenticeships and training.[231] The restoration of discipline was also highlighted, as they want it to be easier for pupils to be searched for contraband items, the granting of anonymity to teachers accused by pupils, and the banning of expelled pupils being returned to schools via appeal panels.

In higher education, the Conservatives have increased tuition fees to £9,250 per year, however have ensured that this will not be paid by anyone until they are earning over £25,000. The Scottish Conservatives also support the re-introduction of tuition fees in Scotland. In 2016, the Conservative government extended student loan access in England to postgraduate students to help improve access to education.[232]

Within the EU, the UK was one of the largest recipients of research funding in the European Union, receiving £7 billion between 2007 and 2015, which is invested in universities and research-intensive businesses.[233] Following the vote to leave the EU, Prime Minister Theresa May guaranteed that the Conservative government would protect funding for existing research and development projects in the UK.[234] In 2017, the Conservatives introduced the T Level qualification aimed at improving the teaching and administration of technical education.[235]

Family policy

As prime minister, David Cameron wanted to 'support family life in Britain' and put families at the centre of domestic social policymaking.[236] He stated in 2014 that there was 'no better place to start' in the Conservative mission of 'building society from the bottom up' than the family, which was responsible for individual welfare and well-being long before the welfare state came into play.[236] He also argued that 'family and politics are inextricably linked'.[236] Both Cameron and Theresa May aimed at helping families achieve a work-home balance and have previously proposed to offer all parents 12 months parental leave, to be shared by parents as they choose.[237] This policy is now in place, offering 50 weeks total parental leave, of which 37 weeks are paid leave, which can be shared between both parents.[238]

Other policies have included doubling the free hours of childcare for working parents of three and four-year-olds from 15 hours to 30 hours a week during term-time, although parents can reduce the number of hours per week to 22 and spread across 52 weeks of the year. The government also introduced a policy to fund 15 hours a week of free education and childcare for 2-year-olds in England if parents are receiving certain state benefits or the child has a SEN statement or diagnosis, worth £2,500 a year per child.[239][240]

Jobs and welfare policy

One of the Conservatives' key policy goals in 2010 was to reduce the number of people unemployed, and increase the number of people in the workforce, by strengthening apprenticeships, skills and job training.[241] Between 2010 and 2014, all claimants of Incapacity Benefit were moved onto a new benefit scheme, Employment and Support Allowance, which was then subsumed into the Universal Credit system alongside other welfare benefits in 2018.[242][243][244] The Universal Credit system came under immense scrutiny following its introduction. Shortly after her appointment to the Department for Work and Pensions, the then Secretary of State Amber Rudd acknowledged there were real problems with the Universal Credit system, especially the wait times for initial payments and the housing payments aspect of the combined benefits.[245] Rudd pledged specifically to review and address the uneven impact of Universal Credit implementation on economically disadvantaged women, which had been the subject of numerous reports by the Radio 4 You and Yours programme and others.[245]

Until 1999, Conservatives opposed the creation of a national minimum wage, as they believed it would cost jobs, and businesses would be reluctant to start business in the UK from fear of high labour costs.[246] However the party have since pledged support and in the July 2015 budget, Chancellor George Osborne announced a National Living Wage of £9/hour.[247] The National Minimum Wage in 2024 was £11.44 for those over 21.[248] The party support, and have implemented, the restoration of the link between pensions and earnings, and seek to raise retirement age from 65 to 67 by 2028.[249]

Energy and climate change policy

David Cameron brought several 'green' issues to the forefront of his 2010 campaign. These included proposals designed to impose a tax on workplace car parking spaces, a halt to airport growth, a tax on cars with exceptionally poor petrol mileage, and restrictions on car advertising. Many of these policies were implemented in the Coalition—including the 'Green Deal'.[250] A law was passed in 2019, that UK greenhouse gas emissions will be net zero by 2050.[251] The UK was the first major economy to embrace a legal obligation to achieve net zero carbon emissions.[252]

In 2019, the Conservatives became the first national government in the world to officially declare a climate emergency (second in the UK after the SNP).[251] In November 2020, the Conservatives announced a 10-point plan for a 'green industrial revolution', with green enterprises, an end to the sale of petrol and diesel cars, quadruple the amount of offshore wind power capacity within a decade, fund a variety of emissions-cutting proposals, and spurn a proposed green post-COVID-19 recovery.[253] In 2021, the Conservatives announced plans to cut carbon emissions by 78% by 2035.[254]

Justice, crime and security policy

In 2010, the Conservatives campaigned to cut the perceived bureaucracy of the modern police force and pledged greater legal protection to people convicted of defending themselves against intruders.

The party has also campaigned for the creation of a UK Bill of Rights to replace the Human Rights Act 1998, but this was vetoed by their coalition partners the Liberal Democrats.[255] The Conservatives' 2017 manifesto pledged to create a national infrastructure police force, subsuming the existing British Transport Police; Civil Nuclear Constabulary; and Ministry of Defence Police "to improve the protection of critical infrastructure such as nuclear sites, railways and the strategic road network".[256]

Transport and infrastructure policy

The Conservatives have invested in public transport and infrastructure, aimed to promoting economic growth.[257] This has included rail (including high-speed rail), electric vehicles, bus networks, and active transport.[258]

In 2020, new funding for active travel infrastructure was announced by the Conservatives.[259] The party's stated aim was for England to be a "great walking and cycling nation" and for half of all journeys in towns and cities being walked or cycled by 2030. The plan was accompanied by £2 billion in additional funding over the following five years for cycling and walking. The plan also introduced new inspectorate, known as Active Travel England.[260][261]

In 2021, the Conservatives announced a white paper that would transform the operation of the railways. The rail network will be partly renationalised, with infrastructure and operations brought together under the state-owned public body Great British Railways.[262] On 18 November 2021, the government announced the biggest ever public investment in Britain's rail network costing £96 billion and promising quicker and more frequent rail connections in the North and Midlands: the Integrated Rail Plan includes substantially improved connections North-South as well as East-West and includes three new high speed lines.[263][264]

European Union policy

No subject has proved more divisive in the Conservative Party in recent history than the role of the United Kingdom within the European Union. Though the principal architect of the UK's entry into the European Communities (which became the European Union) was Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath, most contemporary Conservative opinion is opposed to closer economic and particularly political union with the EU. This is a noticeable shift in British politics, as in the 1960s and 1970s the Conservatives were more pro-Europe than the Labour Party: for example, in the 1971 House of Commons vote on whether the UK should join the European Economic Community, only 39 of the then 330 Conservative MPs were opposed.[265][266]

The Conservative Party has members with varying opinions of the EU, with pro-European Conservatives joining the affiliate Conservative Group for Europe, while some Eurosceptics left the party to join the United Kingdom Independence Party. Whilst the vast majority of Conservatives in recent decades have been Eurosceptics, views among this group regarding the UK's relationship with the EU have been polarised between moderate, soft Eurosceptics who support continued British membership but oppose further harmonisation of regulations affecting business and accept participation in a multi-speed Europe, and a more radical, economically libertarian faction who oppose policy initiatives from Brussels, support the rolling back of integration measures from the Maastricht Treaty onwards, and have become increasingly supportive of a complete withdrawal.[265]

Constitutional policy

Traditionally the Conservative Party has supported the uncodified constitution of the United Kingdom and its traditional Westminster system of politics. The party opposed many of Tony Blair's reforms, such as the removal of the hereditary peers,[267] the incorporation of the European Convention on Human Rights into British law, and the 2009 creation of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, a function formerly carried out by the House of Lords.

There was also a split on whether to introduce a British Bill of Rights that would replace the Human Rights Act 1998; David Cameron expressed support, but party grandee Ken Clarke described it as "xenophobic and legal nonsense".[268]

In 2019, the Conservatives' manifesto committed to a broad constitutional review in a line which read "after Brexit we also need to look at the broader aspects of our constitution: the relationship between the government, parliament and the courts".[269]

Organisation

Party structure

The Conservative Party comprises the voluntary party, parliamentary party (sometimes called the political party) and the professional party.

Members of the public join the party by becoming part of a local constituency Conservative Association.[270] The country is also divided into regions, with each region containing a number of areas, both having a similar structure to constituency associations. The National Conservative Convention sets the voluntary party's direction. It is composed of all association chairs, officers from areas and regions, and 42 representatives and the Conservative Women's Organisation.[271] The Convention meets twice a year. Its Annual General Meeting is usually held at Spring Forum, with another meeting usually held at the Conservative Party Conference. In the organisation of the Conservative Party, constituency associations dominate selection of local candidates, and some associations have organised open parliamentary primaries.

The 1922 Committee consists of backbench MPs, meeting weekly while parliament is sitting. Frontbench MPs have an open invitation to attend. The 1922 Committee plays a crucial role in the selection of party leaders. All Conservative MPs are members of the 1922 Committee by default. There are 20 executive members of the committee, agreed by consensus among backbench MPs.

The Conservative Campaign Headquarters (CCHQ) is effectively head of the Professional Party and leads financing, organisation of elections and drafting of policy.

The Conservative Party Board is the party's ultimate decision-making body, responsible for all operational matters (including fundraising, membership and candidates) and is made up of representatives from each (voluntary, political and professional) section of the Party.[271] The Party Board meets about once a month and works closely with CCHQ, elected representatives and the voluntary membership mainly through a number of management sub-committees (such as membership, candidates and conferences).

Membership

Membership peaked in the mid-1950s at approximately 3 million, before declining steadily through the second half of the 20th century.[274] Despite an initial boost shortly after David Cameron's election as leader in December 2005, membership resumed its decline in 2006 to a lower level than when he was elected. In 2010, the Conservative Party had about 177,000 members according to activist Tim Montgomerie,[275] and in 2013 membership was estimated by the party itself at 134,000.[276] The Conservative Party had a membership of 124,000 in March 2018.[277] In May 2019, its membership was thought to be around 160,000, with over half of its members being over 55.[278][279] Its membership rose to 200,000 in March 2021.[280] In July 2022 it had 172,437 members.[4]

The membership fee for the Conservative Party is £25, or £5 if the member is under the age of 23.

Prospective parliamentary candidates

Associations select their constituency's candidates.[270][281] Some associations have organised open parliamentary primaries. A constituency Association must choose a candidate using the rules approved by, and (in England, Wales and Northern Ireland) from a list established by, the Committee on Candidates of the Board of the Conservative Party.[282] Prospective candidates apply to the Conservative Central Office to be included on the approved list of candidates, some candidates will be given the option of applying for any seat they choose, while others may be restricted to certain constituencies.[283][284] A Conservative MP can only be deselected at a special general meeting of the local Conservative association, which can only be organised if backed by a petition of more than fifty members.[283]

Young Conservatives

Young Conservatives is the youth wing of the Conservative Party for members aged 25 and under. The organisation aims to increase youth ownership and engagement in local associations.[285] From 1998 to 2015, the youth wing was called Conservative Future, and had branches at universities and at parliamentary constituency level. It was shut down in 2015 after allegations that bullying by Mark Clarke had caused the suicide of Elliot Johnson, a 21-year-old party activist.[286][287][288] The current incarnation was launched in March 2018.

Conferences

The major annual party events are the Spring Forum and the Conservative Party Conference, which takes place in Autumn in alternately Manchester or Birmingham. This is when the National Conservative Convention holds meetings.

Funding

In the first decade of the 21st century, half the party's funding came from a cluster of fifty "donor groups", and a third of it from only fifteen.[289] In the year after the 2010 general election, half the Conservatives' funding came from the financial sector.[290]

For 2013, the Conservative Party had an income of £25.4 million, of which £749,000 came from membership subscriptions.[291] In 2015, according to accounts filed with the Electoral Commission, the party had an income of about £41.8 million and expenditures of about £41 million.[292]

Construction businesses, including the Wates Group and JCB, have also been significant donors to the party, contributing £430,000 and £8.1m respectively between 2007 and 2017.[293]

The Advisory Board of the party represents donors who have given significant sums to the party, typically in excess of £250,000.[294]

In December 2022 The Guardian reported 10% of Conservative peers were large party donors and gave nearly £50m in total. 27 out of the party's 274 peers had given over £100,000 to the Conservatives. At least 6 large donor peers got government jobs in the 10 years to 2022.[295]

Financial ties to Russian oligarchs

The Conservative Party has received funding from Russian oligarchs, beginning in the early 2000s, for which it has been criticised.[296][297] Scrutiny became more prominent after alleged interference in the 2016 Brexit referendum by the Kremlin to support the Vote Leave campaign, and increased after the Intelligence and Security Committee Russia report into Russian interference in British politics was published in July 2020. Concerns over Conservative Party funds have become increasingly controversial due to Vladimir Putin's human rights abuses and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[298]

One of the first was Lubov Chernukhin, wife of former deputy finance minister and investment company VEB.RF founder Vladmir Chernukhin, who had donated north of £2.2 million as of the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[299][300] Donations to British political parties is only legal for citizens; the individuals who donated to the party had dual UK-Russian citizenship, and the donations were legal and properly declared.[301] However, an investigation conducted by The New York Times shortly after the invasion of Ukraine determined that a £399,810 donation made by British-Israeli businessman Ehud Sheleg in 2018 was in fact given directly to him by his father-in-law, Russian oligarch Sergei Kopytov. Kopytov, a former minister in Russian-occupied Crimea, has strong ties to Vladimir Putin's government.[296] Barclays Bank reported that in January 2021, they "[traced] a clear line back from this donation to its ultimate source", and reported it accordingly to the National Crime Agency.[296]

An investigation by the Good Law Project found that in spite of Johnson's claims that donations from those with links to the Russian government was to stop,[298] since the start of the war, the Conservatives have accepted at least £243,000 from Russia and Kremlin-associated donors.[302] In February 2022, the Labour Party used Electoral Commission information to calculate that donors who had made money from Russia or Russians had given £1.93m to either the Conservative party or constituency associations since Boris Johnson's premiership began.[303] Then-party leader Liz Truss said that the donations would not be returned, stating that they had been "properly declared".[304]

International organisations

The Conservative Party is a member of a number of international organisations, most notably the International Democracy Union which unites right-wing parties including the United States Republican Party, the Liberal Party of Australia, the Conservative Party of Canada and the South Korean People Power Party.

At a European level, the Conservatives are members of the European Conservatives and Reformists Party (ECR Party), which unites conservative parties in opposition to a federal European Union, through which the Conservatives have ties to the Ulster Unionist Party and the governing parties of Israel and Turkey, Likud and the Justice and Development Party respectively. In the European Parliament, the Conservative Party's MEPs sat in the European Conservatives and Reformists Group (ECR Group), which is affiliated to the ACRE. Party leader David Cameron pushed the foundation of the ECR, which was launched in 2009, along with the Czech Civic Democratic Party and the Polish Law and Justice, before which the Conservative Party's MEPs sat in the European Democrats, which had become a subgroup of the European People's Party in the 1990s. Since the 2014 European election, the ECR Group has been the third-largest group, with the largest members being the Conservatives (nineteen MEPs), Law and Justice (eighteen MEPs), the Liberal Conservative Reformers (five MEPs), and the Danish People's Party and New Flemish Alliance (four MEPs each). In June 2009, The Conservatives required a further four partners apart from the Polish and Czech supports to qualify for official fraction status in the parliament; the rules state that a European parliamentary caucus requires at least 25 MEPs from at least seven of the 27 EU member states.[305] In forming the caucus, the party broke with two decades of co-operation by the UK's Conservative Party with the mainstream European Christian Democrats and conservatives in the European parliament, the European People's Party (EPP). It did so on the grounds that it is dominated by European federalists and supporters of the Lisbon treaty, which the Conservatives were generally highly critical of.[305]

Logo

When Sir Christopher Lawson was appointed as a marketing director at Conservative Central Office in 1981, he developed a logo design based on the Olympic flame in the colours of the Union Jack,[306] which was intended to represent leadership, striving to win, dedication, and a sense of community.[307] The emblem was adopted for the 1983 general election.[306] In 1989, the party's director of communications, Brendan Bruce, found through market research that recognition of the symbol was low and that people found it old fashioned and uninspiring. Using a design company headed by Michael Peters, an image of a hand carrying a torch was developed, which referenced the Statue of Liberty.[308]

In 2006, there was a rebranding exercise to emphasise the Conservatives' commitment to environmentalism; a project costing £40,000 resulted in a sketched silhouette of an oak tree, a national symbol, which was said to represent "strength, endurance, renewal and growth".[309] A change from green to the traditional Conservative blue colour appeared in 2007,[310] followed by a version with the Union Jack superimposed in 2010.[311] An alternative version featuring the colours of the Rainbow flag was unveiled for an LGBT event at the 2009 conference in Manchester.[312]

Party factions

The Conservative Party has a variety of internal factions or ideologies, including one-nation conservatism,[313][314] Christian democracy,[315] social conservatism, Thatcherism, traditional conservatism, neoconservatism,[316][317] Euroscepticism,[318] and, since 2016, right-wing populism.[20][319]

One-nation Conservatives

| Part of the Conservatism series |

| One-nation conservatism |

|---|

One-nation conservatism was the party's dominant ideology in the 20th century until the rise of Thatcherism in the 1970s. It has included in its ranks Conservative Prime Ministers such as Stanley Baldwin, Harold Macmillan and Edward Heath.[320] One-nation Conservatives in the contemporary party include former First Secretary of State Damian Green, the current chair of the One Nation Conservatives caucus.

The name itself comes from a famous phrase of Disraeli. Ideologically, one-nation conservatism identifies itself with a broad paternalistic conservative stance. One-nation Conservatives are often associated with the Tory Reform Group and the Bow Group. Adherents believe in social cohesion and support social institutions that maintain harmony between different interest groups, classes, and—more recently—different races or religions. These institutions have typically included the welfare state, the BBC, and local government.

One-nation Conservatives often invoke Edmund Burke and his emphasis on civil society ("little platoons") as the foundations of society, as well as his opposition to radical politics of all types. The Red Tory theory of Phillip Blond is a strand of the one-nation school of thought; prominent Red Tories include former Cabinet Ministers Iain Duncan Smith and Eric Pickles and Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State Jesse Norman.[321] There is a difference of opinion among supporters regarding the European Union. Some support it perhaps stemming from an extension of the cohesion principle to the international level, though others are strongly against the EU (such as Peter Tapsell).

Free-market Conservatives

The "free-market wing" of economic liberals achieved dominance after the election of Margaret Thatcher as party leader in 1975. Their goal was to reduce the role of the government in the economy and to this end, they supported cuts in direct taxation, the privatisation of nationalised industries and a reduction in the size and scope of the welfare state. Supporters of the "free-market wing" have been labelled as "Thatcherites". The group has disparate views of social policy: Thatcher herself was socially conservative and a practising Anglican but the free-market wing in the Conservative Party harbour a range of social opinions from the civil libertarian views of Michael Portillo, Daniel Hannan, and David Davis to the traditional conservatism of former party leaders William Hague and Iain Duncan Smith. The Thatcherite wing is also associated with the concept of a "classless society".[322]

Whilst a number of party members are pro-European, some free-marketeers are Eurosceptic, perceiving most EU regulations as interference in the free market and/or a threat to British sovereignty. EU centralisation also conflicts with the localist ideals that have grown in prominence within the party in recent years. Rare Thatcherite Europhiles included Leon Brittan. Many take inspiration from Thatcher's Bruges speech in 1988, in which she declared that "we have not successfully rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain only to see them reimposed at a European level". A number of free-market Conservatives have signed the Better Off Out pledge to leave the EU.[323] Thatcherites and economic liberals in the party tend to support Atlanticism, something exhibited between Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan.

Thatcher herself claimed philosophical inspiration from the works of Burke and Friedrich Hayek for her defence of liberal economics. Groups associated with this tradition include the No Turning Back Group and Conservative Way Forward, whilst Enoch Powell and Keith Joseph are usually cited as early influences in the movement.[324] Some free-market supporters and Christian Democrats within the party tend to advocate the Social Market Economy, which supports free markets alongside social and environmental responsibility, as well a welfare state. Joseph was the first to introduce the model idea into British politics, writing the publication: Why Britain needs a Social Market Economy.

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Toryism |

|---|

|

Traditionalist Conservatives

This socially conservative right-wing grouping is currently associated with the Cornerstone Group (or Faith, Flag and Family), and is the oldest tradition within the Conservative Party, closely associated with High Toryism. The name stems from its support for three social institutions: the Church of England, the unitary British state and the family. To this end, it emphasises the country's Anglican heritage, oppose any transfer of power away from the United Kingdom—either downwards to the nations and regions or upwards to the European Union—and seek to place greater emphasis on traditional family structures to repair what it sees as a broken society in the UK. It is a strong advocate of marriage and believes the Conservative Party should back the institution with tax breaks and have opposed the alleged assaults on both traditional family structures and fatherhood.[325]

Prominent MPs from this wing of the party include Andrew Rosindell, Edward Leigh and Jacob Rees-Mogg—the latter two being prominent Roman Catholics, notable in a faction marked out by its support for the established Church of England.

Relationships between the factions

Sometimes two groupings have united to oppose the third. Both Thatcherite and traditionalist Conservatives rebelled over Europe (and in particular Maastricht) during John Major's premiership; and traditionalist and One Nation MPs united to inflict Margaret Thatcher's only major defeat in Parliament, over Sunday trading.

Not all Conservative MPs can be easily placed within one of the above groupings. For example, John Major was the ostensibly "Thatcherite" candidate during the 1990 leadership election, but he consistently promoted One-Nation Conservatives to the higher reaches of his cabinet during his time as Prime Minister. These included Kenneth Clarke as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Michael Heseltine as Deputy Prime Minister.[326]

Electoral performance and campaigns

National campaigning within the Conservative Party is fundamentally managed by the CCHQ campaigning team, which is part of its central office[327]However, it also delegates local responsibility to Conservative associations in the area, usually to a team of Conservative activists and volunteers[327] in that area, but campaigns are still deployed from and thus managed by CCHQNational campaigning sometimes occurs in-house by volunteers and staff at CCHQ in Westminster.[328]

The Voter Communications Department is line-managed by the Conservative Director of Communications who upholds overall responsibility, though she has many staff supporting her, and the whole of CCHQ at election time, her department being one of the most predominant at this time, including project managers, executive assistants, politicians, and volunteers.[329] The Conservative Party also has regional call centres and VoteSource do-it-from-home accounts.

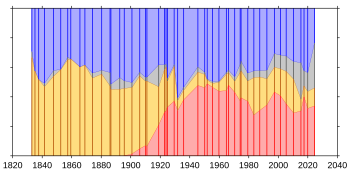

UK general election results

This chart shows the electoral performance of the Conservative Party in each general election since 1835.[330][331]

For all election results, including: devolved elections, London elections, Police and Crime Commissioner elections, combined authority elections and European Parliament elections see: Electoral history of the Conservative Party (UK)

For results of the Tories, the party's predecessor, see here.

| Election | Leader | Votes | Seats | Position | Government | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Share | No. | ± | Share | ||||

| 1835 | Robert Peel | 261,269 | 40.8% | 273 / 658 | 41.5% | Whig | ||

| 1837 | 379,694 | 48.3% | 314 / 658 | 47.7% | Whig | |||

| 1841 | 379,694 | 56.9% | 367 / 658 | 55.8% | Conservative | |||

| 1847 | Earl of Derby | 205,481 | 42.7% | 325 / 656 [a] | 49.5% | Whig | ||

| 1852 | 311,481 | 41.9% | 330 / 654 [a] | 50.5% | Conservative | |||

| 1857 | 239,712 | 34.0% | 264 / 654 | 40.4% | Whig | |||

| 1859 | 193,232 | 34.3% | 298 / 654 | 45.6% | Whig | |||

| 1865 | 346,035 | 40.5% | 289 / 658 | 43.9% | Liberal | |||

| 1868[fn 1] | Benjamin Disraeli | 903,318 | 38.4% | 271 / 658 | 41.2% | Liberal | ||

| 1874 | 1,091,708 | 44.3% | 350 / 652 | 53.7% | Conservative | |||

| 1880 | 1,462,351 | 42.5% | 237 / 652 | 36.3% | Liberal | |||

| 1885[fn 2] | Marquess of Salisbury | 1,869,560 | 43.4% | 247 / 670 | 36.9% | Liberal minority | ||

| 1886 | 1,417,627 | 51.4% | 393 / 670 | 58.7% | Conservative–Liberal Unionist | |||

| 1892 | 2,028,586 | 47.0% | 314 / 670 | 46.9% | Liberal | |||

| 1895 | 1,759,484 | 49.3% | 411 / 670 | 61.3% | Conservative–Liberal Unionist | |||

| 1900 | 1,637,683 | 50.2% | 402 / 670 | 60.0% | Conservative–Liberal Unionist | |||

| 1906 | Arthur Balfour | 2,278,076 | 43.4% | 156 / 670 | 23.3% | Liberal | ||

| January 1910 | 2,919,236 | 46.8% | 272 / 670 | 40.6% | Liberal minority | |||

| December 1910 | 2,270,753 | 46.6% | 271 / 670 | 40.5% | Liberal minority | |||

| Merged with Liberal Unionist Party in 1912 to become the Conservative and Unionist Party | ||||||||

| 1918[fn 3] | Bonar Law | 4,003,848 | 38.4% | 379 / 707 332 elected with Coupon | 53.6% | Coalition Liberal–Conservative | ||

| 1922 | 5,294,465 | 38.5% | 344 / 615 | 55.9% | Conservative | |||

| 1923 | Stanley Baldwin | 5,286,159 | 38.0% | 258 / 625 | 41.3% | Labour minority | ||

| 1924 | 7,418,983 | 46.8% | 412 / 615 | 67.0% | Conservative | |||

| 1929[fn 4] | 8,252,527 | 38.1% | 260 / 615 | 42.3% | Labour minority | |||

| 1931 | 11,377,022 | 55.0% | 470 / 615 | 76.4% | Conservative–Liberal–National Labour | |||

| 1935 | 10,025,083 | 47.8% | 386 / 615 | 62.8% | Conservative–Liberal National–National Labour | |||

| 1945 | Winston Churchill | 8,716,211 | 36.2% | 197 / 640 | 30.8% | Labour | ||

| 1950 | 11,507,061 | 40.0% | 282 / 625 | 45.1% | Labour | |||

| 1951 | 13,724,418 | 48.0% | 302 / 625 | 48.3% | Conservative–National Liberal | |||

| 1955 | Anthony Eden | 13,310,891 | 49.7% | 324 / 630 | 51.4% | Conservative–National Liberal | ||

| 1959 | Harold Macmillan | 13,750,875 | 49.4% | 345 / 630 | 54.8% | Conservative–National Liberal | ||

| 1964 | Alec Douglas-Home | 12,002,642 | 43.4% | 298 / 630 | 47.3% | Labour | ||

| 1966 | Edward Heath | 11,418,455 | 41.9% | 250 / 630 | 39.7% | Labour | ||

| 1970[fn 5] | 13,145,123 | 46.4% | 330 / 630 | 52.4% | Conservative | |||

| February 1974 | 11,872,180 | 37.9% | 297 / 635 | 46.8% | Labour minority | |||

| October 1974 | 10,462,565 | 35.8% | 277 / 635 | 43.6% | Labour | |||

| 1979 | Margaret Thatcher | 13,697,923 | 43.9% | 339 / 635 | 53.4% | Conservative | ||

| 1983 | 13,012,316 | 42.4% | 397 / 650 | 61.1% | Conservative | |||

| 1987 | 13,760,935 | 42.2% | 376 / 650 | 57.8% | Conservative | |||

| 1992 | John Major | 14,093,007 | 41.9% | 336 / 651 | 51.6% | Conservative | ||

| 1997 | 9,600,943 | 30.7% | 165 / 659 | 25.0% | Labour | |||

| 2001 | William Hague | 8,357,615 | 31.7% | 166 / 659 | 25.2% | Labour | ||

| 2005 | Michael Howard | 8,785,941 | 32.4% | 198 / 646 | 30.7% | Labour | ||

| 2010 | David Cameron | 10,704,647 | 36.1% | 306 / 650 | 47.1% | Conservative–Liberal Democrats | ||

| 2015 | 11,334,920 | 36.9% | 330 / 650 | 50.8% | Conservative | |||

| 2017 | Theresa May | 13,632,914 | 42.3% | 317 / 650 | 48.8% | Conservative minority with DUP confidence and supply | ||

| 2019 | Boris Johnson | 13,966,451 | 43.6% | 365 / 650 | 56.2% | Conservative | ||

| 2024 | Rishi Sunak | 6,814,650 | 23.7% | 121 / 650 | 18.6% | Labour | ||

- Note

- ^ The first election held under the Reform Act 1867.

- ^ The first election held under the Representation of the People Act 1884 and the Redistribution of Seats Act 1885.

- ^ The first election held under the Representation of the People Act 1918 in which all men over 21, and most women over the age of 30 could vote, and therefore a much larger electorate.

- ^ The first election held under the Representation of the People Act 1928 which gave all women aged over 21 the vote.

- ^ Franchise extended to all 18- to 20-year-olds under the Representation of the People Act 1969.

Associated groups

Ideological groups

Interest groups

Think tanks

Alliances

Party structures

See also

- History of the Conservative Party (UK)

- Electoral history of the Conservative Party (UK)

- List of conservative parties by country

- List of Conservative Party MPs (UK)

- List of Conservative Party (UK) general election manifestos

- List of political parties in the United Kingdom

- Politics of the United Kingdom

Notes

- ^ Jump up to: a b Includes Peelites

References

- ^ "Conservative Party Leadership Election 2024". conservatives.com. 24 July 2024. Retrieved 3 August 2024.

- ^ Croft, Ethan (11 November 2022). "Rishi Sunak donor gets top job with the Tories". Evening Standard. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ^ Wilkins, Jessica (17 March 2018). "Conservatives re-launch youth wing in a bid to take on Labour". PoliticsHome.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wheeler, Brian (5 September 2022). "Tory membership figure revealed". BBC News. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ "Capping welfare and working to control immigration". Conservative and Unionist Party. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ [5]

- ^ Bale, Tim (2011). The Conservative Party: From Thatcher to Cameron. p. 145.

- ^ [7]

- ^ David Dutton, "Unionist Politics and the aftermath of the General Election of 1906: A Reassessment." Historical Journal 22#4 (1979): 861–76.

- ^ McConnel, James (17 February 2011). "Irish Home Rule: An imagined future". BBC. Archived from the original on 4 August 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ [9][10]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Falkenbach, Michelle; Greer, Scott (7 September 2021). The Populist Radical Right and Health

National Policies and Global Trends. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. p. 143. ISBN 9783030707095. - ^ Jump up to: a b James, William (1 October 2019). "Never mind the politics, get a Brexit deal done, says UK business". Reuters. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- ^ Vries, Catherine; Hobolt, Sara; Proksch, Sven-Oliver; Slapin, Jonathan (2021). Foundations of European Politics A Comparative Approach. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780198831303.

- ^ [12][13][14]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c [19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26]

- ^ "Open Council Data UK". opencouncildata.co.uk.

- ^ Buchan, Lizzy (12 November 2018). "What does Tory mean and where does this term come from?". The Independent. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ^ Saini, Rima; Bankole, Michael; Begum, Neema (April 2023). "The 2022 Conservative Leadership Campaign and Post-racial Gatekeeping". Race & Class: 1–20. doi:10.1177/03063968231164599. ISSN 0306-3968.

...the Conservative Party's history in incorporating ethnic minorities, and the recent post-racial turn within the party whereby increasing party diversity has coincided with an increasing turn to the Right

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bale, Tim (March 2023). The Conservative Party After Brexit: Turmoil and Transformation. Cambridge: Polity. pp. 3–8, 291, et passim. ISBN 9781509546015. Retrieved 12 September 2023.