Ирландская война за независимость

| Ирландская война за независимость | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Часть ирландского революционного периода | |||||||||

Шона Хогана из Летающая колонна ИРА 3-й бригады Типперэри во время войны. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Military commanders:Political leaders: | Military commanders:Political leaders: | ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| c. 15,000 IRA members | Total: c. 42,100

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

491 dead[3]

| 936 dead[3]

| ||||||||

| |||||||||

Ирландская за война Cogadh na Saoirseнезависимость [4] или Англо-ирландская война — партизанская война , которая велась в Ирландии с 1919 по 1921 год между Ирландской республиканской армией (ИРА, армия Ирландской Республики ) и британскими войсками: британской армией вместе с квазивоенной Королевской ирландской полицией (RIC) . ) и его военизированные формирования - Вспомогательные силы и Специальная полиция Ольстера (USC). Это было частью ирландского революционного периода .

In April 1916, Irish republicans launched the Easter Rising against British rule and proclaimed an Irish Republic. Although it was defeated after a week of fighting, the Rising and the British response led to greater popular support for Irish independence. In the December 1918 election, republican party Sinn Féin won a landslide victory in Ireland. On 21 January 1919 they formed a breakaway government (Dáil Éireann) and declared Irish independence. That day, two RIC officers were killed in the Soloheadbeg ambush by IRA volunteers acting on their own initiative. The conflict developed gradually. For most of 1919, IRA activity involved capturing weaponry and freeing republican prisoners, while the Dáil set about building a state. In September, the British government outlawed the Dáil throughout Ireland, Sinn Féin was proclaimed (outlawed) in County Cork and the conflict intensified.[5] The IRA began ambushing RIC and British Army patrols, attacking their barracks and forcing isolated barracks to be abandoned. The British government bolstered the RIC with recruits from Britain—the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries—who became notorious for ill-discipline and reprisal attacks on civilians,[6] some of which were authorised by the British government.[7] Thus the conflict is sometimes called the "Black and Tan War".[8] Конфликт также включал гражданское неповиновение , в частности отказ ирландских железнодорожников перевезти британские войска или военные грузы.

In mid-1920, republicans won control of most county councils, and British authority collapsed in most of the south and west, forcing the British government to introduce emergency powers. About 300 people had been killed by late 1920, but the conflict escalated in November. On Bloody Sunday in Dublin, 21 November 1920, fourteen British intelligence operatives were assassinated; then the RIC fired on the crowd at a Gaelic football match, killing fourteen civilians and wounding sixty-five. A week later, the IRA killed seventeen Auxiliaries in the Kilmichael Ambush in County Cork. In December, the British authorities declared martial law in much of southern Ireland, and the centre of Cork city was burnt out by British forces in reprisal for an ambush. Violence continued to escalate over the next seven months; 1,000 people were killed and 4,500 republicans were interned. Much of the fighting took place in Munster (particularly County Cork), Dublin and Belfast, which together saw over 75 percent of the conflict deaths.[9]

The conflict in north-east Ulster had a sectarian aspect (see The Troubles in Ulster (1920–1922)). While the Catholic minority there mostly backed Irish independence, the Protestant majority were mostly unionist/loyalist. A mainly Protestant special constabulary was formed, and loyalist paramilitaries were active. They attacked Catholics in reprisal for IRA actions, and in Belfast a sectarian conflict raged in which almost 500 were killed, most of them Catholics.[10] In May 1921, Ireland was partitioned under British law by the Government of Ireland Act, which created Northern Ireland.

A ceasefire began on 11 July 1921. The post-ceasefire talks led to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty on 6 December 1921. This ended British rule in most of Ireland and, after a ten-month transitional period overseen by the Provisional Government, the Irish Free State was created as a self-governing Dominion on 6 December 1922. Northern Ireland remained within the United Kingdom. After the ceasefire, violence in Belfast and fighting in border areas of Northern Ireland continued, and the IRA launched the failed Northern Offensive in May 1922. In June 1922, disagreement among republicans over the Anglo-Irish Treaty led to the eleven-month Irish Civil War. The Irish Free State awarded 62,868 medals for service during the War of Independence, of which 15,224 were issued to IRA fighters of the flying columns.[11]

Origins of the conflict

[edit]Home Rule Crisis

[edit]Since the 1870s, Irish nationalists in the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) had been demanding home rule, or self-government, from Britain, while not ruling out eventual complete independence. Fringe organisations, such as Arthur Griffith's Sinn Féin, instead argued for some form of immediate Irish independence, but they were in a small minority.[12]

The demand for home rule was eventually granted by the British government in 1912,[13] immediately prompting a prolonged crisis within the United Kingdom as Ulster unionists formed an armed organisation – the Ulster Volunteers (UVF) – to resist this measure of devolution, at least in territory they could control. In turn, nationalists formed their own paramilitary organisation, the Irish Volunteers.[14]

The British parliament passed the Government of Ireland Act 1914, known as the Home Rule Act, on 18 September 1914 with an amending bill for the partition of Ireland introduced by Ulster Unionist MPs, but the act's implementation was immediately postponed by the Suspensory Act 1914 due to the outbreak of the First World War in the previous month.[15] The majority of nationalists followed their IPP leaders and John Redmond's call to support Britain and the Allied war effort in Irish regiments of the New British Army, the intention being to ensure the commencement of home rule after the war.[16] However, a significant minority of the Irish Volunteers opposed Ireland's involvement in the war. The Volunteer movement split, a majority leaving to form the National Volunteers under Redmond. The remaining Irish Volunteers, under Eoin MacNeill, held that they would maintain their organisation until home rule had been granted. Within this Volunteer movement, another faction, led by the separatist Irish Republican Brotherhood, began to prepare for a revolt against British rule in Ireland.[17]

Easter Rising

[edit]The plan for revolt was realised in the Easter Rising of 1916, in which the Volunteers launched an insurrection whose aim was to end British rule. The insurgents issued the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, proclaiming Ireland's independence as a republic.[18] The Rising, in which over four hundred people died,[19] was almost exclusively confined to Dublin and was put down within a week, but the British response, executing the leaders of the insurrection and arresting thousands of nationalist activists, galvanised support for the separatist Sinn Féin[20] – the party which the republicans first adopted and then took over as well as followers from Countess Markievicz, who was second-in-command of the Irish Citizen Army during the Easter Rising.[21] The British execution of the Rising's leaders also increased support in Ireland for both a violent uprising to achieve independence from British rule and an independent Irish republic. This support was further bolstered by the British government's decision to maintain martial law in Ireland until November 1916, the arrest of Irish critics of government policies and the possibility of conscription being extended to Ireland.[22]

First Dáil

[edit]

In April 1918, the British cabinet, in the face of the crisis caused by the German spring offensive, attempted with a dual policy to simultaneously link the enactment of conscription into Ireland with the implementation of home rule, as outlined in the report of the Irish Convention of 8 April 1918. This further alienated Irish nationalists and produced mass demonstrations during the Conscription Crisis of 1918.[23] In the 1918 general election Irish voters showed their disapproval of British policy by giving Sinn Féin 70% (73 seats out of 105,) of Irish seats, 25 of those being uncontested.[24] Sinn Féin won 91% of the seats outside of Ulster on 46.9% of votes cast but was in a minority in Ulster, where unionists were in a majority. Sinn Féin pledged not to sit in the UK Parliament at Westminster, but rather to set up an Irish parliament.[25] This parliament, known as the First Dáil, and its ministry, called the Aireacht, consisting only of Sinn Féin members, met at the Mansion House on 21 January 1919. The Dáil reaffirmed the 1916 proclamation with the Irish Declaration of Independence,[26] and issued a Message to the Free Nations of the World, which stated that there was an "existing state of war, between Ireland and England". The Irish Volunteers were reconstituted as the "Irish Republican Army" or IRA.[27] The IRA was perceived by some members of Dáil Éireann to have a mandate to wage war on the British Dublin Castle administration.[citation needed]

Forces

[edit]British

[edit]

The heart of British power in Ireland was the Dublin Castle administration, often known to the Irish as "the Castle".[28] The head of the Castle administration was the lord lieutenant, to whom a chief secretary was responsible, leading—in the words of the British historian Peter Cottrell—to an "administration renowned for its incompetence and inefficiency".[28] Ireland was divided into three military districts. During the war, two British Army divisions, the 5th and the 6th divisions, were based in Ireland with their respective headquarters in the Curragh and Cork.[28] By July 1921 there were 50,000 British troops based in Ireland; by contrast there were 14,000 soldiers in metropolitan Britain.[29] While the British Army had historically been heavily dependent on Irish recruitment, concern over divided loyalties led to the redeployment from 1919 of all regular Irish regiments to garrisons outside Ireland itself.[30]

The two main police forces in Ireland were the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and the Dublin Metropolitan Police.[31] Of the 17,000 policemen in Ireland, 513 were killed by the IRA between 1919 and 1921 while 682 were wounded.[31] Of the RIC's senior officers, 60% were Irish Protestants and the rest Catholic, while 70% of the rank and file of the RIC were Irish Catholic with the rest Protestant.[31] The RIC was trained for police work, not war, and was woefully ill-prepared to take on counter-insurgency duties.[32] Until March 1920, London regarded the unrest in Ireland as primarily an issue for the police and did not regard it as a war.[33] The purpose of the Army was to back up the police. In the course of the war, about a quarter of Ireland was put under martial law, mostly in Munster; in the rest of the country British authority was not deemed sufficiently threatened to warrant it.[29] The British created two paramilitary police forces to supplement the work of the RIC, recruited mostly from World War I veterans, namely the Temporary Constables (better known as the "Black and Tans") and the Temporary Cadets or Auxiliary Division (known as the "Auxies").[34]

Irish republican

[edit]

On 25 November 1913, the Irish Volunteers were formed by Eoin MacNeill in response to the paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) that had been founded earlier in the year to fight against home rule.[35] Also in 1913, the Irish Citizen Army was founded by the trade unionists and socialists James Larkin and James Connolly following a series of violent incidents between trade unionists and the Dublin police in the Dublin lock-out.[36] In June 1914, Nationalist leader John Redmond forced the Volunteers to give his nominees a majority on the ruling committee. When, in September 1914, Redmond encouraged the Volunteers to enlist in the British Army, a faction led by Eoin MacNeill broke with the Redmondites, who became known as the National Volunteers, rather than fight for Britain in the war.[36] Many of the National Volunteers did enlist, and the majority of the men in the 16th (Irish) Division of the British Army had formerly served in the National Volunteers.[37] The Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army launched the Easter Rising against British rule in 1916, when an Irish Republic was proclaimed. Thereafter they became known as the Irish Republican Army (IRA). Between 1919 and 1921 the IRA claimed to have a total strength of 70,000, but only about 3,000 were actively engaged in fighting against the Crown.[38] The IRA distrusted those Irishmen who had fought in the British Army during the First World War, but there were exceptions, such as Emmet Dalton, Tom Barry and Martin Doyle.[38] The basic structure of the IRA was the flying column which could number between 20 and 100 men.[38] Finally, Michael Collins created the "Squad"—gunmen responsible to himself who were assigned special duties such as the assassination of policemen and suspected informers within the IRA.[38]

Course of the war

[edit]Pre-war violence

[edit]The years between the Easter Rising of 1916 and the beginning of the War of Independence in 1919 were not bloodless. Thomas Ashe, one of the Volunteer leaders imprisoned for his role in the 1916 rebellion, died on hunger strike, after attempted force-feeding in 1917. In 1918, during disturbances arising out of the anti-conscription campaign, six civilians died in confrontations with the police and British Army and more than 1,000 people were arrested. There were also raids for arms by the Volunteers,[39] at least one shooting of a Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) policeman and the burning of an RIC barracks in Kerry.[40] The attacks brought a British military presence from the summer of 1918, which only briefly quelled the violence, and an increase in police raids.[41] However, there was as yet no co-ordinated armed campaign against British forces or RIC. In County Cork, four rifles were seized from the Eyeries barracks in March 1918 and men from the barracks were beaten that August.[41] In early July 1918, Volunteers ambushed two RIC men who had been stationed to stop a feis being held on the road between Ballingeary and Ballyvourney in the first armed attack on the RIC since the Easter Rising – one was shot in the neck, the other beaten, and police carbines and ammunition were seized.[41][42] Patrols in Bantry and Ballyvourney were badly beaten in September and October. In November 1918, Armistice Day was marked by severe rioting in Dublin that left over 100 British soldiers injured.[43]

Initial hostilities

[edit]

While it was not clear in the beginning of 1919 that the Dáil ever intended to gain independence by military means, and war was not explicitly threatened in Sinn Féin's 1918 manifesto,[44] an incident occurred on 21 January 1919, the same day as the First Dáil convened. The Soloheadbeg Ambush, in County Tipperary, was led by Seán Treacy, Séumas Robinson, Seán Hogan and Dan Breen acting on their own initiative. The IRA attacked and shot two RIC officers, Constables James McDonnell and Patrick O'Connell,[45] who were escorting explosives. Breen later recalled:

...we took the action deliberately, having thought over the matter and talked it over between us. Treacy had stated to me that the only way of starting a war was to kill someone, and we wanted to start a war, so we intended to kill some of the police whom we looked upon as the foremost and most important branch of the enemy forces. The only regret that we had following the ambush was that there were only two policemen in it, instead of the six we had expected.[46]

This is widely regarded as the beginning of the War of Independence.[47] The British government declared South Tipperary a Special Military Area under the Defence of the Realm Act two days later.[48] The war was not formally declared by the Dáil, and it ran its course parallel to the Dáil's political life. On 10 April 1919 the Dáil was told:

As regards the Republican prisoners, we must always remember that this country is at war with England and so we must in a sense regard them as necessary casualties in the great fight.[49]

In January 1921, two years after the war had started, the Dáil debated "whether it was feasible to accept formally a state of war that was being thrust on them, or not", and decided not to declare war.[50] Then on 11 March, Dáil Éireann President Éamon de Valera called for acceptance of a "state of war with England". The Dail voted unanimously to empower him to declare war whenever he saw fit, but he did not formally do so.[51]

Violence spreads

[edit]

Volunteers began to attack British government property, carry out raids for arms and funds and target and kill prominent members of the British administration. The first was Resident Magistrate John C. Milling, who was shot dead in Westport, County Mayo, for having sent Volunteers to prison for unlawful assembly and drilling.[52] They mimicked the successful tactics of the Boers' fast violent raids without uniform. Although some republican leaders, notably Éamon de Valera, favoured classic conventional warfare to legitimise the new republic in the eyes of the world, the more practically experienced Collins and the broader IRA leadership opposed these tactics as they had led to the military débacle of 1916. Others, notably Arthur Griffith, preferred a campaign of civil disobedience rather than armed struggle.[53]

During the early part of the conflict, roughly from 1919 to the middle of 1920, there was a relatively limited amount of violence. Much of the nationalist campaign involved popular mobilisation and the creation of a republican "state within a state" in opposition to British rule. British journalist Robert Lynd wrote in The Daily News in July 1920 that:

So far as the mass of people are concerned, the policy of the day is not active but a passive policy. Their policy is not so much to attack the Government as to ignore it and to build up a new government by its side.[54]

Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) as special target

[edit]

The IRA's main target throughout the conflict was the mainly Irish Catholic Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), the British government's armed police force in Ireland, outside Dublin. Its members and barracks (especially the more isolated ones) were vulnerable, and they were a source of much-needed arms. The RIC numbered 9,700 men stationed in 1,500 barracks throughout Ireland.[55]

A policy of ostracism of RIC men was announced by the Dáil on 11 April 1919.[52] This proved successful in demoralising the force as the war went on, as people turned their faces from a force increasingly compromised by association with British government repression.[56] The rate of resignation went up and recruitment in Ireland dropped off dramatically. Often, the RIC were reduced to buying food at gunpoint, as shops and other businesses refused to deal with them. Some RIC men co-operated with the IRA through fear or sympathy, supplying the organisation with valuable information. By contrast with the effectiveness of the widespread public boycott of the police, the military actions carried out by the IRA against the RIC at this time were relatively limited. In 1919, 11 RIC men and 4 Dublin Metropolitan Police G Division detectives were killed and another 20 RIC wounded.[57]

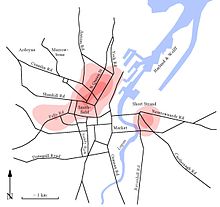

Other aspects of mass participation in the conflict included strikes by organised workers, in opposition to the British presence in Ireland. In Limerick in April 1919, a general strike was called by the Limerick Trades and Labour Council, as a protest against the declaration of a "Special Military Area" under the Defence of the Realm Act, which covered most of Limerick city and a part of the county. Special permits, to be issued by the RIC, would now be required to enter the city. The Trades Council's special Strike Committee controlled the city for fourteen days in an episode that is known as the Limerick Soviet.[58]

Similarly, in May 1920, Dublin dockers refused to handle any war matériel and were soon joined by the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union, who banned railway drivers from carrying members of the British forces. Blackleg train drivers were brought over from England, after drivers refused to carry British troops. The strike badly hampered British troop movements until December 1920, when it was called off.[59] The British government managed to bring the situation to an end, when they threatened to withhold grants from the railway companies, which would have meant that workers would no longer have been paid.[60] Attacks by the IRA also steadily increased, and by early 1920, they were attacking isolated RIC stations in rural areas, causing them to be abandoned as the police retreated to the larger towns.

Collapse of the British administration

[edit]In early April 1920, 400 abandoned RIC barracks were burned to the ground to prevent them being used again, along with almost one hundred income tax offices. The RIC withdrew from much of the countryside, leaving it in the hands of the IRA.[61] In June–July 1920, assizes failed all across the south and west of Ireland; trials by jury could not be held because jurors would not attend. The collapse of the court system demoralised the RIC and many police resigned or retired. The Irish Republican Police (IRP) was founded between April and June 1920, under the authority of Dáil Éireann and the former IRA Chief of Staff Cathal Brugha to replace the RIC and to enforce the ruling of the Dáil Courts, set up under the Irish Republic. By 1920, the IRP had a presence in 21 of Ireland's 32 counties.[62] The Dáil Courts were generally socially conservative, despite their revolutionary origins, and halted the attempts of some landless farmers at redistribution of land from wealthier landowners to poorer farmers.[63]

The Inland Revenue ceased to operate in most of Ireland. People were instead encouraged to subscribe to Collins' "National Loan", set up to raise funds for the young government and its army.[64] By the end of the year the loan had reached £358,000. It eventually reached £380,000. An even larger amount, totalling over $5 million, was raised in the United States by Irish Americans and sent to Ireland to finance the Republic.[60] Rates were still paid to local councils but nine out of eleven of these were controlled by Sinn Féin, who naturally refused to pass them on to the British government.[63] By mid-1920, the Irish Republic was a reality in the lives of many people, enforcing its own law, maintaining its own armed forces and collecting its own taxes. The British Liberal journal, The Nation, wrote in August 1920 that "the central fact of the present situation in Ireland is that the Irish Republic exists".[54]

The British forces, in trying to re-assert their control over the country, often resorted to arbitrary reprisals against republican activists and the civilian population. An unofficial government policy of reprisals began in 1919 in Fermoy, County Cork, when 200 soldiers of the King's Shropshire Light Infantry looted and burned the main businesses of the town on 8 September, after a member of their regiment- who was the first British Army soldier to die in the war – was killed in an armed raid by local IRA volunteers[65] on a church parade the day before (7 September). The ambushers were members of a unit of the No. 2 Cork Brigade under the command of Liam Lynch, who also wounded four British soldiers and disarmed the rest before fleeing in their cars. The local coroner's inquest refused to return a murder verdict over the soldier and local businessmen who had sat on the jury were targeted in the reprisal.[66]

Arthur Griffith estimated that in the first 18 months of the conflict, British forces carried out 38,720 raids on private homes, arrested 4,982 suspects, committed 1,604 armed assaults, carried out 102 indiscriminate shootings and burnings in towns and villages, and killed 77 people including women and children.[67] In March 1920, Tomás Mac Curtain, the Sinn Féin Lord Mayor of Cork, was shot dead in front of his wife at his home, by men with blackened faces who were seen returning to the local police barracks. The jury at the inquest into his death returned a verdict of wilful murder against David Lloyd George (the British Prime Minister) and District Inspector Swanzy, among others. Swanzy was later tracked down and killed in Lisburn, County Antrim. This pattern of killings and reprisals escalated in the second half of 1920 and in 1921.[68]

IRA organisation and operations

[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

Collins was a driving force behind the independence movement. Nominally the Minister of Finance in the Republic's government and IRA Director of Intelligence, he was involved in providing funds and arms to the IRA units and in the selection of officers. Collins' charisma and organisational capability galvanised many who came in contact with him. He established what proved an effective network of spies among sympathetic members of the Dublin Metropolitan Police's G Division and other important branches of the British administration. The G Division men were a relatively small political division active in subverting the republican movement. They were detested by the IRA as often they were used to identify volunteers, who would have been unknown to British soldiers or the later Black and Tans. Collins set up the "Squad", a group of men whose sole duty was to seek out and kill "G-men" and other British spies and agents. Collins' Squad began killing RIC intelligence officers in July 1919.[69] Many G-men were offered a chance to resign or leave Ireland by the IRA. One spy who escaped with his life was F. Digby Hardy, who was exposed by Arthur Griffith before an "IRA" meeting, which in fact consisted of Irish and foreign journalists, and then advised to take the next boat out of Dublin.[70]

The Chief of Staff of the IRA was Richard Mulcahy, who was responsible for organising and directing IRA units around the country.[71] In theory, both Collins and Mulcahy were responsible to Cathal Brugha, the Dáil's Minister of Defence, but, in practice, Brugha had only a supervisory role, recommending or objecting to specific actions. A great deal also depended on IRA leaders in local areas (such as Liam Lynch, Tom Barry, Seán Moylan, Seán Mac Eoin and Ernie O'Malley) who organised guerrilla activity, largely on their own initiative. For most of the conflict, IRA activity was concentrated in Munster and Dublin, with only isolated active IRA units elsewhere, such as in County Roscommon, north County Longford and western County Mayo.

While the paper membership of the IRA, carried over from the Irish Volunteers, was over 100,000 men, Collins estimated that only 15,000 were active in the IRA during the war, with about 3,000 on active service at any time. There were also support organisations Cumann na mBan (the IRA women's group) and Fianna Éireann (youth movement), who carried weapons and intelligence for IRA men and secured food and lodgings for them. The IRA benefitted from the widespread help given to them by the general Irish population, who generally refused to pass information to the RIC and the British military and who often provided "safe houses" and provisions to IRA units "on the run".

Much of the IRA's popularity arose from the excessive reaction of the British forces to IRA activity. When Éamon de Valera returned from the United States, he demanded in the Dáil that the IRA desist from the ambushes and assassinations, which were allowing the British to portray it as a terrorist group and to take on the British forces with conventional military methods. The proposal was immediately dismissed.

Martial law

[edit]

The British increased the use of force; reluctant to deploy the regular British Army into the country in greater numbers, they set up two auxiliary police units to reinforce the RIC. The first of these, quickly nicknamed as the Black and Tans, were seven thousand strong and mainly ex-British soldiers demobilised after World War I. Deployed to Ireland in March 1920, most came from English and Scottish cities. While officially they were part of the RIC, in reality they were a paramilitary force. After their deployment in March 1920, they rapidly gained a reputation for drunkenness and poor discipline. The wartime experience of most Black and Tans did not suit them for police duties and their violent behavior antagonised many previously neutral civilians.[72]

In response to and retaliation for IRA actions, in the summer of 1920, the Tans burned and sacked numerous small towns throughout Ireland, including Balbriggan,[73] Trim,[74] Templemore[75] and others.

In July 1920, another quasi-military police body, the Auxiliaries, consisting of 2,215 former British army officers, arrived in Ireland. The Auxiliaries had a reputation just as bad as the Tans for their mistreatment of the civilian population but tended to be more effective and more willing to take on the IRA. The policy of reprisals, which involved public denunciation or denial and private approval, was famously satirised by Lord Hugh Cecil when he said: "It seems to be agreed that there is no such thing as reprisals but they are having a good effect."[76]

On 9 August 1920, the British Parliament passed the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act. It replaced the trial by jury by courts-martial by regulation for those areas where IRA activity was prevalent.[77]

On 10 December 1920, martial law was proclaimed in Counties Cork, Kerry, Limerick and Tipperary in Munster; in January 1921 martial law was extended to the rest of Munster in Counties Clare and Waterford, as well as counties Kilkenny and Wexford in Leinster.[78]

It also suspended all coroners' courts because of the large number of warrants served on members of the British forces and replaced them with "military courts of enquiry".[79] The powers of military courts-martial were extended to cover the whole population and were empowered to use the death penalty and internment without trial; Government payments to local governments in Sinn Féin hands were suspended. This act has been interpreted by historians as a choice by Prime Minister David Lloyd George to put down the rebellion in Ireland rather than negotiate with the republican leadership.[80] As a result, violence escalated steadily from that summer and sharply after November 1920 until July 1921. It was in this period that a mutiny broke out among the Connaught Rangers, stationed in India. Two were killed whilst trying to storm an armoury and one was later executed.[81]

Escalation: October–December 1920

[edit]

A number of events dramatically escalated the conflict in late 1920. First the Lord Mayor of Cork, Terence MacSwiney, died on hunger strike in Brixton Prison in London in October, while two other IRA prisoners on hunger strike, Joe Murphy and Michael Fitzgerald, died in Cork Jail.

Sunday, 21 November 1920, was a day of dramatic bloodshed in Dublin that became known as Bloody Sunday. In the early morning, Collins' Squad attempted to wipe out leading British intelligence operatives in the capital, in particular the Cairo Gang, killing 16 men (including two cadets, one alleged informer, and one possible case of mistaken identity) and wounding five others. The attacks took place at different places (hotels and lodgings) in Dublin.[82]

In response, RIC men drove in trucks into Croke Park (Dublin's GAA football and hurling ground) during a football match, shooting into the crowd. Fourteen civilians were killed, including one of the players, Michael Hogan, and a further 65 people were wounded.[83] Later that day two republican prisoners, Dick McKee, Peadar Clancy and an unassociated friend, Conor Clune who had been arrested with them, were killed in Dublin Castle. The official account was that the three men were shot "while trying to escape", which was rejected by Irish nationalists, who were certain the men had been tortured and then murdered.[84]

On 28 November 1920, one week later, the West Cork unit of the IRA, under Tom Barry, ambushed a patrol of Auxiliaries at Kilmichael, County Cork, killing all but one of the 18-man patrol.

These actions marked a significant escalation of the conflict. In response, the counties of Cork, Kerry, Limerick, and Tipperary – all in the province of Munster – were put under martial law on 10 December under the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act; this was followed on 5 January in the rest of Munster and in counties Kilkenny and Wexford in the province of Leinster.[78] Shortly afterwards, in January 1921, "official reprisals" were sanctioned by the British and they began with the burning of seven houses in Midleton, County Cork. Questioned in the House of Commons in June 1921, Attorney-General for Ireland Denis Henry stated that he was informed by Commander-in-Chief Nevil Macready that 191 houses were destroyed in official reprisals in the area under martial law since January of that year.[85] In December 1920 Macready informed the Cabinet of the British Government that Military Governors in the martial law areas had been authorized to conduct reprisals.[86]

On 11 December, the centre of Cork City was burnt out by the Black and Tans, who then shot at firefighters trying to tackle the blaze, in reprisal for an IRA ambush in the city on 11 December 1920 which killed one Auxiliary and wounded eleven.[87] In May of that year, the IRA began a campaign of big house burnings which totaled 26 in Cork alone.[88]

Attempts at a truce in December 1920 were scuppered by Hamar Greenwood, who insisted on a surrender of IRA weapons first.[89]

Peak of violence: December 1920 – July 1921

[edit]During the following eight months until the Truce of July 1921, there was a spiralling of the death toll in the conflict, with 1,000 people including the RIC police, army, IRA volunteers and civilians, being killed in the months between January and July 1921 alone.[90] This represents about 70% of the total casualties for the entire three-year conflict. In addition, 4,500 IRA personnel (or suspected sympathisers) were interned in this time.[91] In the middle of this violence, de Valera (as President of Dáil Éireann) acknowledged the state of war with Britain in March 1921.[92]

Between 1 November 1920 and 7 June 1921 twenty-four men were executed by the British.[93] The first IRA volunteer to be executed was Kevin Barry, one of The Forgotten Ten who were buried in unmarked graves in unconsecrated ground inside Mountjoy Prison until 2001.[94] On 1 February, the first execution under martial law of an IRA man took place: Cornelius Murphy, of Millstreet in County Cork, was shot in Cork City. On 28 February, six more were executed, again in Cork.

On 19 March 1921, Tom Barry's 100-strong West Cork IRA unit fought an action against 1,200 British troops – the Crossbarry Ambush. Barry's men narrowly avoided being trapped by converging British columns and inflicted between ten and thirty killed on the British side. Just two days later, on 21 March, the Kerry IRA attacked a train at the Headford junction near Killarney. Twenty British soldiers were killed or injured, as well as two IRA men and three civilians. Most of the actions in the war were on a smaller scale than this, but the IRA did have other significant victories in ambushes, for example at Millstreet in Cork and at Scramogue in Roscommon, also in March 1921 and at Tourmakeady and Carrowkennedy in Mayo in May and June. Equally common, however, were failed ambushes, the worst of which, for example at Mourneabbey,[95] Upton and Clonmult in Cork in February 1921, saw six, three, and twelve IRA men killed respectively and more captured. The IRA in Mayo suffered a comparable reverse at Kilmeena, while the Leitrim flying column was almost wiped out at Selton Hill. Fears of informers after such failed ambushes often led to a spate of IRA shootings of informers, real and imagined.

The biggest single loss for the IRA, however, came in Dublin. On 25 May 1921, several hundred IRA men from the Dublin Brigade occupied and burned the Custom House (the centre of local government in Ireland) in Dublin city centre. Symbolically, this was intended to show that British rule in Ireland was untenable. However, from a military point of view, it was a heavy defeat in which five IRA men were killed and over eighty captured.[96] This showed the IRA was not well enough equipped or trained to take on British forces in a conventional manner. However, it did not, as is sometimes claimed, cripple the IRA in Dublin. The Dublin Brigade carried out 107 attacks in the city in May and 93 in June, showing a falloff in activity, but not a dramatic one. However, by July 1921, most IRA units were chronically short of both weapons and ammunition, with over 3,000 prisoners interned.[97] Also, for all their effectiveness at guerrilla warfare, they had, as Richard Mulcahy recalled, "as yet not been able to drive the enemy out of anything but a fairly good sized police barracks".[98]

Still, many military historians have concluded that the IRA fought a largely successful and lethal guerrilla war, which forced the British government to conclude that the IRA could not be defeated militarily.[99] The failure of the British efforts to put down the guerrillas was illustrated by the events of "Black Whitsun" on 13–15 May 1921. A general election for the Parliament of Southern Ireland was held on 13 May. Sinn Féin won 124 of the new parliament's 128 seats unopposed, but its elected members refused to take their seats. Under the terms of the Government of Ireland Act 1920, the Parliament of Southern Ireland was therefore dissolved, and executive and legislative authority over Southern Ireland was effectively transferred to the Lord Lieutenant (assisted by Crown appointees). Over the next two days (14–15 May), the IRA killed fifteen policemen. These events marked the complete failure of the British Coalition Government's Irish policy—both the failure to enforce a settlement without negotiating with Sinn Féin and a failure to defeat the IRA.

By the time of the truce, however, many republican leaders, including Collins, were convinced that if the war went on for much longer, there was a chance that the IRA campaign as it was then organised could be brought to a standstill. Because of this, plans were drawn up to "bring the war to England".[citation needed] The IRA did take the campaign to the streets of Glasgow.[100] It was decided that key economic targets, such as the Liverpool docks, would be bombed. The units charged with these missions would more easily evade capture because England was not under, and British public opinion was unlikely to accept, martial law. These plans were abandoned because of the truce.

Truce: July–December 1921

[edit]

The war of independence in Ireland ended with a truce on 11 July 1921. The conflict had reached a stalemate. Talks that had looked promising the previous year had petered out in December when Prime Minister of the United Kingdom David Lloyd George insisted that the IRA first surrender their arms. Fresh talks, after the Prime Minister had come under pressure from H. H. Asquith and the Liberal opposition, the Labour Party and the Trades Union Congress, resumed in the spring and resulted in the truce. From the point of view of the British government, it appeared as if the IRA's guerrilla campaign would continue indefinitely, with spiralling costs in British casualties and in money. More importantly, the British government was facing severe criticism at home and abroad for the actions of British forces in Ireland. On 6 June 1921, the British made their first conciliatory gesture, calling off the policy of house burnings as reprisals. On the other side, IRA leaders, and in particular Collins, felt that the IRA as it was then organised could not continue indefinitely. It had been hard pressed by the deployment of more regular British soldiers to Ireland and by the lack of arms and ammunition.

The initial breakthrough that led to the truce was credited to three people: King George V, Prime Minister of South Africa General Jan Smuts and David Lloyd George. The King, who had made his unhappiness at the behaviour of the Black and Tans in Ireland well known to his government, was dissatisfied with the official speech prepared for him for the opening of the new Parliament of Northern Ireland, created as a result of the partition of Ireland. Smuts, a close friend of the King, suggested to him that the opportunity should be used to make an appeal for conciliation in Ireland. The King asked him to draft his ideas on paper. Smuts prepared this draft and gave copies to the King and to Lloyd George. Lloyd George then invited Smuts to attend a British cabinet meeting consultations on the "interesting" proposals Lloyd George had received, without either man informing the Cabinet that Smuts had been their author. Faced with the endorsement of them by Smuts, the King and Lloyd George, the ministers reluctantly agreed to the King's planned "reconciliation in Ireland" speech.

The speech, when delivered in Belfast on 22 June, was universally well received. It called on "all Irishmen to pause, to stretch out the hand of forbearance and conciliation, to forgive and to forget, and to join in making for the land they love a new era of peace, contentment, and good will".[101]

On 24 June 1921, the British coalition government's cabinet decided to propose talks with the leader of Sinn Féin. Coalition Liberals and Unionists agreed that an offer to negotiate would strengthen the government's position if Sinn Féin refused. Austen Chamberlain, the new leader of the Unionist Party, said that "the King's Speech ought to be followed up as a last attempt at peace before we go the full lengths of martial law".[102] Seizing the momentum, Lloyd George wrote to Éamon de Valera as "the chosen leader of the great majority in Southern Ireland" on 24 June, suggesting a conference.[103] Sinn Féin responded by agreeing to talks. De Valera and Lloyd George ultimately agreed to a truce that was intended to end the fighting and lay the ground for detailed negotiations. Its terms were signed on 9 July and came into effect on 11 July. Negotiations on a settlement, however, were delayed for some months as the British government insisted that the IRA first decommission its weapons, but this demand was eventually dropped. It was agreed that British troops would remain confined to their barracks.

Most IRA officers on the ground interpreted the truce merely as a temporary respite and continued recruiting and training volunteers. Nor did attacks on the RIC or British Army cease altogether. Between December 1921 and February of the next year, there were 80 recorded attacks by the IRA on the soon-to-be disbanded RIC, leaving 12 dead.[104] On 18 February 1922, Ernie O'Malley's IRA unit raided the RIC barracks at Clonmel, taking 40 policemen prisoner and seizing over 600 weapons and thousands of rounds of ammunition.[105] In April 1922, in the Dunmanway killings, an IRA party in Cork killed 10 local suspected Protestant informers in retaliation for the shooting of one of their men. Those killed were named in captured British files as informers before the truce signed the previous July.[106] Over 100 Protestant families fled the area after the killings.[citation needed]

Treaty

[edit]

Ultimately, the peace talks led to the negotiation of the Anglo-Irish Treaty (6 December 1921), which was then ratified in triplicate: by Dáil Éireann on 7 January 1922 (so giving it legal legitimacy under the governmental system of the Irish Republic), by the House of Commons of Southern Ireland in January 1922 (so giving it constitutional legitimacy according to British theory of who was the legal government in Ireland), and by both Houses of the British parliament.[107][108]

The Treaty allowed Northern Ireland, which had been created by the Government of Ireland Act 1920, to opt out of the Free State if it wished, which it duly did on 8 December 1922 under the procedures laid down. As agreed, an Irish Boundary Commission was then created to decide on the precise location of the border of the Free State and Northern Ireland.[109] The republican negotiators understood that the commission would redraw the border according to local nationalist or unionist majorities. Since the 1920 local elections in Ireland had resulted in outright nationalist majorities in County Fermanagh, County Tyrone, the City of Derry and in many district electoral divisions of County Armagh and County Londonderry (all north and west of the "interim" border), this might well have left Northern Ireland unviable. However, the Commission chose to leave the border unchanged; as a trade-off, the money owed to Britain by the Free State under the Treaty was cancelled (see Partition of Ireland).[110]

A new system of government was created for the new Irish Free State, though for the first year two governments co-existed; an Dáil Ministry headed by President Griffith, and a Provisional Government nominally answerable to the House of Commons of Southern Ireland and appointed by the Lord Lieutenant.[111]

Most of the Irish independence movement's leaders were willing to accept this compromise, at least for the time being, though many militant republicans were not. A majority[citation needed] of the pre-Truce IRA who had fought in the War of Independence, led by Liam Lynch, refused to accept the Treaty and in March 1922 repudiated the authority of the Dáil and the new Free State government, which it accused of betraying the ideal of the Irish Republic. It also broke the Oath of Allegiance to the Irish Republic which the Dáil had instated on 20 August 1919.[112] The anti-Treaty IRA were supported by the former president of the Republic, Éamon de Valera, and ministers Cathal Brugha and Austin Stack.[113]

St. Mary's Pro-Cathedral, Dublin, August 1922

While the violence in the North was still raging, the South of Ireland was preoccupied with the split in the Dáil and in the IRA over the Treaty. In April 1922, an executive of IRA officers repudiated the Treaty and the authority of the Provisional Government which had been set up to administer it. These republicans held that the Dáil did not have the right to disestablish the Irish Republic. A hardline group of anti-Treaty IRA men occupied several public buildings in Dublin in an effort to bring down the Treaty and restart the war with the British. There were a number of armed confrontations between pro and anti-Treaty troops before matters came to a head in late June 1922.[108] Desperate to get the new Irish Free State off the ground and under British pressure, Collins attacked the anti-Treaty militants in Dublin, causing fighting to break out around the country.[108]

The subsequent Irish Civil War lasted until mid-1923 and cost the lives of many of the leaders of the independence movement, notably the head of the Provisional Government Michael Collins, ex-minister Cathal Brugha, and anti-Treaty republicans Harry Boland, Rory O'Connor, Liam Mellows, Liam Lynch and many others: total casualties have never been determined but were perhaps higher than those in the earlier fighting against the British. President Arthur Griffith also died of a cerebral haemorrhage during the conflict.[114]

Following the deaths of Griffith and Collins, W. T. Cosgrave became head of government. On 6 December 1922, following the coming into legal existence of the Irish Free State, W. T. Cosgrave became President of the Executive Council, the first internationally recognised head of an independent Irish government.[citation needed]

The civil war ended in mid-1923 in defeat for the anti-Treaty side.[115]

North-east

[edit]

The conflict in the north-east had a sectarian aspect. While Ireland as a whole had an Irish nationalist and Catholic majority, Unionists and Protestants were a majority in the north-east, largely due to 17th century British colonization. These Ulster Unionists wanted to maintain ties to Britain and did not want to be part of an independent Ireland. They had threatened to oppose Irish home rule with violence. The British government proposed to solve this by partitioning Ireland on roughly political and religious lines, creating two self-governing territories of the UK: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. Irish nationalists opposed this, most of them supporting the all-island Irish Republic.

The IRA carried out attacks on British forces in the north-east, but was less active than in the south. Protestant loyalists attacked the Catholic community in reprisal. There were outbreaks of sectarian violence from June 1920 to June 1922, influenced by political and military events. Most of it was in the city of Belfast, which saw "savage and unprecedented" communal violence between Protestants and Catholics.[116] In the Belfast violence, Hibernians were more involved on the Catholic/nationalist side than the IRA,[117] while groups such as the Ulster Volunteers were involved on the Protestant/loyalist side. There was rioting, gun battles and bombings. Almost 1,000 homes and businesses were destroyed and people were expelled from workplaces and mixed neighbourhoods. More than 500 were killed[118] and more than 10,000 became refugees, most of them Catholics.[119] The British Army was deployed and the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC) was formed to help the regular police. The USC was almost wholly Protestant and some of its members carried out reprisal attacks on Catholics.[120] Conflict continued in Northern Ireland after the July 1921 truce; both communal violence in Belfast and guerrilla conflict in rural border areas.[121]

Irish nationalists argued that the violence around Belfast was a pogrom against Catholics/nationalists, as Catholics were a quarter of the city's population but made up two-thirds of those killed, suffered 80% of the property destruction and made up 80% of refugees.[118] Historian Alan Parkinson says the term 'pogrom' is misleading, as the violence was not all one-sided nor co-ordinated.[122] The Irish government estimated that 50,000 left Northern Ireland permanently due to violence and intimidation.[123]

Лето 1920 г.

[ редактировать ]

Хотя ИРА была менее активна на северо-востоке, чем на юге, юнионисты Ольстера считали себя осажденными ирландскими республиканцами. На местных выборах в январе и июне 1920 года ирландские националисты и республиканцы получили контроль над многими северными городскими советами, а также Тайрон и Фермана советами графств . В Дерри-Сити появился первый мэр-ирландский националист и католик. [124]

Бои в Дерри начались 18 июня 1920 года и продолжались неделю. Католические дома подверглись нападениям в основном протестантском Уотерсайде , и католики бежали на лодках через Фойл, попав под обстрел. В городской части лоялисты открыли огонь из района Фонтан по католическим улицам, в то время как ИРА оккупировала колледж Святого Колумба и открыла ответный огонь. В результате насилия были убиты по меньшей мере четырнадцать католиков и пять протестантов. [125] В конце концов, 1500 британских солдат были размещены в Дерри и ввели комендантский час. [126]

17 июля британский полковник Джеральд Смит был убит боевиками ИРА в Корке. Он якобы приказал полицейским стрелять в мирных жителей, которые не подчинялись приказам немедленно. [127] Смит родился в Банбридже , графство Даун . Лоялисты в ответ напали на многие католические дома и предприятия в Банбридже и изгнали католиков с работы, вынудив многих бежать из города. [128] Подобные нападения произошли и в соседнем Дроморе . [129]

21 июля лоялисты выгнали с работы на верфях Белфаста 8000 «нелояльных» коллег, все они были либо католиками, либо протестантскими профсоюзными активистами . Некоторые подверглись жестоким нападениям. [130] Частично это произошло в ответ на недавние действия ИРА, а частично из-за конкуренции за рабочие места из-за высокого уровня безработицы. Этому способствовала риторика политиков-юнионистов. В своей двенадцатого июля речи Эдвард Карсон призвал лоялистов взять дело в свои руки и связал республиканизм с социализмом и католической церковью. [131] Изгнание вызвало ожесточенные межконфессиональные беспорядки в Белфасте, и британские войска применили пулеметы для разгона бунтовщиков. К концу дня одиннадцать католиков и восемь протестантов были убиты и сотни ранены. [130] Рабочие-католики вскоре были изгнаны со всех крупных заводов Белфаста. В ответ Dáil одобрил « Бойкот Белфаста » предприятий и банков города, принадлежащих юнионистам. Его соблюдение осуществляла ИРА, которая останавливала поезда и грузовики и уничтожала товары. [132]

22 августа ИРА убила инспектора RIC Освальда Суонзи, когда он выходил из церкви в Лисберне. Суонзи был замешан в убийстве мэра Корка Томаса Мак Кертейна. В отместку лоялисты сожгли и разграбили сотни католических предприятий и домов в Лисберне, вынудив многих католиков бежать (см. « Поджоги в Лисберне» ). В результате Лисберн стал первым городом, нанявшим на работу специальных констеблей . После того, как некоторым из них были предъявлены обвинения в массовых беспорядках, их коллеги пригрозили уйти в отставку, и они не были привлечены к ответственности. [133]

В сентябре лидер юнионистов Джеймс Крейг написал британскому правительству письмо с требованием набрать специальную полицию из рядов добровольцев Ольстера. Он предупредил: «Лидеры лоялистов сейчас чувствуют, что ситуация настолько отчаянная, что, если правительство не предпримет немедленных действий, им, возможно, будет целесообразно посмотреть, какие шаги можно предпринять в направлении системы организованных репрессий против повстанцев». [134] USC был сформирован в октябре и, по словам историка Майкла Хопкинсона, «представлял собой официально утвержденную UVF». [134]

Весна – лето 1921 г.

[ редактировать ]

После затишья в насилии на Севере конфликт снова обострился весной 1921 года. В феврале в отместку за расстрел специального констебля бойцы ОСК и УФФ сожгли десять католических домов и дом священника в Россли , графство Фермана. [135] В следующем месяце ИРА атаковала дома шестнадцати специальных констеблей в районе Россли, убив троих и ранив других. [136]

Акт о разделе вступил в силу 3 мая 1921 года. [137] В том же месяце Джеймс Крейг тайно встретился с Имоном де Валерой в Дублине. Они обсуждали возможность перемирия в Ольстере и амнистию пленным. Крейг предложил компромисс: ограниченная независимость Юга и автономия Севера внутри Великобритании. Переговоры ни к чему не привели, и насилие на Севере продолжалось. [138] выборы в Северный парламент 24 мая состоялись , на которых большинство мест получили юнионисты. Ее парламент впервые собрался 7 июня и сформировал автономное правительство во главе с Крейгом. Члены республиканцев и националистов отказались присутствовать. Король Георг V выступил на торжественном открытии Северного парламента 22 июня. [137] На следующий день поезд, перевозивший вооруженный эскорт короля, 10-й Королевский гусарский полк , сошел с рельсов в результате взрыва бомбы ИРА в Адавойле , графство Арма. Погибли пять солдат и охрана поезда, а также пятьдесят лошадей. Британские солдаты также застрелили гражданского прохожего. [139]

Лоялисты осудили перемирие как «предательство» республиканцам. [140] 10 июля, за день до начала прекращения огня, полиция начала рейд против республиканцев на западе Белфаста. ИРА устроила им засаду на улице Рэглан, убив офицера. Это спровоцировало день насилия, известный как « Кровавое воскресенье Белфаста» . Протестантские лоялисты атаковали католические анклавы на западе Белфаста, сжигая дома и предприятия. Это привело к религиозным столкновениям между протестантами и католиками, а также перестрелкам между полицией и националистами. ОСК якобы проезжал через католические анклавы и вел беспорядочный огонь. [141] Двадцать человек были убиты или смертельно ранены (в том числе двенадцать католиков и шесть протестантов) до начала перемирия в полдень 11 июля. [142] После вступления в силу перемирия 11 июля ОСК была демобилизована (июль — ноябрь 1921 г.). Пустота, оставленная демобилизованным ОСК, была заполнена лоялистскими группами линчевателей и возрожденными УФФ. [143]

После перемирия в Белфасте произошли новые вспышки насилия. Двадцать человек погибли в уличных боях и убийствах с 29 августа по 1 сентября 1921 года и еще тридцать человек были убиты с 21 по 25 ноября. К этому времени лоялисты начали беспорядочно бросать бомбы на католические улицы, а ИРА ответила взрывами трамваев, перевозивших протестантских рабочих. [144]

Начало 1922 года

[ редактировать ]Несмотря на принятие Даилом англо-ирландского договора в январе 1922 года, который подтвердил будущее существование Северной Ирландии, с начала 1922 года вдоль новой границы происходили столкновения между ИРА и британскими войсками. Частично это отражало точку зрения Коллинза. что Договор был «ступенькой», а не окончательным урегулированием. В том же месяце Коллинз стал главой нового Временного правительства Ирландии и была основана Ирландская национальная армия , хотя ИРА продолжала существовать. [145]

В январе 1922 года члены гэльской футбольной команды Монагана были арестованы северной полицией по дороге на матч в Дерри. Среди них были добровольцы ИРА, планировавшие освободить заключенных ИРА из тюрьмы Дерри. В ответ в ночь с 7 на 8 февраля подразделения ИРА пересекли границу и захватили почти пятьдесят специальных констеблей и видных лоялистов в Фермана и Тайроне. Их должны были держать в качестве заложников для пленников Монагана. В ходе рейдов также были схвачены несколько добровольцев ИРА. [146] Эту операцию одобрили Майкл Коллинз, Ричард Малкахи, Фрэнк Эйкен и Эоин О'Даффи . [147] Власти Северной Ирландии отреагировали перекрытием многих трансграничных дорог. [148]

В феврале и марте 1922 года насилие на Севере достигло невиданного ранее уровня. С 11 февраля по 31 марта 51 католик был убит, 115 ранены, 32 протестанта убиты и 86 ранены. [149] 11 февраля добровольцы ИРА остановили группу вооруженных специальных констеблей на Клонс железнодорожной станции в графстве Монаган. Подразделение ОСК ехало поездом из Белфаста в Эннискиллен (оба в Северной Ирландии), но Временное правительство не знало, что британские войска будут пересекать его территорию. ИРА призвала спецназовцев сдаться для допроса, но один из них застрелил сержанта ИРА. Это спровоцировало перестрелку, в которой четыре спецназовца были убиты и несколько ранены. Еще пятеро были схвачены. [150] Инцидент грозил спровоцировать крупную конфронтацию между Севером и Югом, и британское правительство временно приостановило вывод британских войск с Юга. Пограничная комиссия была создана для урегулирования любых будущих пограничных споров, но добилась очень малого. [151]

Эти инциденты спровоцировали ответные нападения лоялистов на католиков в Белфасте, что спровоцировало дальнейшие межконфессиональные столкновения. За три дня после инцидента с клонами в городе было убито более 30 человек, в том числе четверо детей-католиков и две женщины, убитые лоялистской гранатой на Уивер-стрит. [151]

18 марта северная полиция совершила рейд на штаб-квартиру ИРА в Белфасте, конфисковав оружие и списки добровольцев ИРА. Временное правительство осудило это как нарушение перемирия. [152] В течение следующих двух недель ИРА совершила рейд на несколько полицейских казарм на севере, убила нескольких офицеров и захватила пятнадцать. [152] [153]

24 марта шесть католиков были застрелены специальными констеблями, ворвавшимися в дом семьи МакМахонов . Это было местью за убийство ИРА двух полицейских. [154] Неделю спустя еще шесть католиков были убиты спецназовцами в ходе еще одного нападения из мести, известного как резня на Арнон-стрит . [155]

Уинстон Черчилль организовал встречу Коллинза и Джеймса Крейга 21 января, и бойкот товаров из Белфаста на юге был отменен, но затем вновь введен через несколько недель. Два лидера провели дальнейшие встречи, но, несмотря на совместное заявление о том, что «мир объявлен» 30 марта, насилие продолжалось. [156]

Лето 1922 года: Северное наступление

[ редактировать ]В мае 1922 года ИРА начала Северное наступление , тайно поддержанное Коллинзом, главой Временного правительства Ирландии. К этому времени ИРА раскололась из-за англо-ирландского договора, но в нем участвовали как сторонники, так и противники договора. Некоторое оружие, отправленное британцами для вооружения Национальной армии, на самом деле было передано подразделениям ИРА, а их оружие было отправлено на Север. [157] Однако наступление провалилось. В отчете Белфастской бригады ИРА в конце мая был сделан вывод, что продолжение наступления «бесполезно и глупо» и «поставит католическое население во власть спецназа». [158]

22 мая, после убийства депутата-юниониста Западного Белфаста Уильяма Твадделла , правительство Севера ввело интернирование, и 350 членов ИРА были арестованы в Белфасте, что нанесло ущерб ее организации там. [159] Самым крупным столкновением в наступлении ИРА стала битва при Петтиго и Беллик , которая закончилась тем, что британские войска с помощью артиллерии выбили около 100 добровольцев ИРА из приграничных деревень Петтиго и Беллик , убив трех добровольцев. Это было последнее крупное противостояние между ИРА и британскими войсками в революционный период. [160] Цикл межконфессионального насилия в Белфасте продолжился. В мае в Белфасте было убито 75 человек, а в июне — еще 30. Несколько тысяч католиков бежали от насилия и нашли убежище в Глазго и Дублине . [161] 17 июня в отместку за убийство двух католиков спецназовцами подразделение ИРА Фрэнка Эйкена застрелило шесть мирных протестантов в Альтнави, на юге Армы. Трое спецназовцев также попали в засаду и были убиты. [162]

Коллинз считал фельдмаршала сэра Генри Уилсона , члена парламента от Норт-Дауна, ответственным за нападения на католиков на Севере и, возможно, стоял за его убийством в июне 1922 года, хотя кто заказал стрельбу, не доказано. [163] Это событие помогло спровоцировать гражданскую войну в Ирландии. Уинстон Черчилль после убийства настоял на том, чтобы Коллинз принял меры против ИРА, выступающей против договора , которую он считал ответственной. [164] Начало гражданской войны на юге положило конец насилию на севере, поскольку война деморализовала северную ИРА и отвлекла организацию от вопроса о разделе. Ирландское Свободное Государство незаметно положило конец политике тайных вооруженных действий Коллинза в Северной Ирландии.

Насилие на Севере закончилось к концу 1922 года. [165]

Задержание

[ редактировать ]Лагерь для интернированных Балликинлар был первым лагерем для массовых интернированных в Ирландии во время ирландской войны за независимость, в котором содержалось почти 2000 человек. [166] Баллыкинлар заслужил репутацию жестокого человека: трое заключенных были застрелены, а пятеро умерли от жестокого обращения. [167] В тюрьме Ее Величества Крамлин Роуд в Белфасте, тюрьме округа Корк (см . голодовку в Корке 1920 года ) и тюрьме Маунтджой в Дублине некоторые политические заключенные объявили голодовку. В 1920 году в результате голодовки погибли два ирландских республиканца — Майкл Фицджеральд (ум. 17 октября 1920 г. и Джо Мерфи ум. 25 октября 1920 г. [168]

Условия во время интернирования не всегда были хорошими - в 1920-х годах судно HMS Argenta было пришвартовано в Белфаст-Лох и использовалось британским правительством в качестве тюремного корабля для содержания ирландских республиканцев после Кровавого воскресенья. Запертые под палубой в клетках, вмещавших 50 интернированных , заключенные были вынуждены пользоваться сломанными туалетами, которые часто переполнялись в их общую зону. Лишенные столов, и без того ослабленные мужчины ели с пола, в результате часто погибая от болезней и недомоганий. На Ардженте было несколько голодовок, в том числе крупная забастовка, в которой приняли участие более 150 человек зимой 1923 года. [169]

Убийство предполагаемых шпионов

[ редактировать ]В последние десятилетия внимание было привлечено к убийствам ИРА мирных жителей на юге, которые, как они утверждали, были информаторами. Некоторые историки, в частности Питер Харт, утверждали, что убитых таким образом часто просто считали «врагами», а не доказанными информаторами. Утверждается, что особенно уязвимыми были протестанты, бывшие солдаты и бродяги. «Это был не просто (или даже главным образом) вопрос шпионажа, шпионов и охотников за шпионами, это была гражданская война между сообществами и внутри них». [170] Представление о том, что сектантство было фактором большинства убийств, подвергалось критике, при этом историки-противники утверждали, что жертвы-протестанты были убиты за сопротивление республиканским целям, а не за свои религиозные убеждения. [171] [88]

Тела жертв часто были изуродованы и оставлены с записками, в которых говорилось о шпионаже, брало на себя ответственность и/или препятствовало подобному обману. [171] Им насильно удаляли волосы, женщин чаще изуродовали, чем убивали, а вместо этого отмечали как предполагаемых предателей. [171]

Пропагандистская война

[ редактировать ]

Ирландский триколор, возникший во времена Молодой Ирландии восстания 1848 года.

Штандарт лорда-лейтенанта с использованием флага Союза , созданного в соответствии с Законом о Союзе 1800 года.

Еще одной особенностью войны было использование пропаганды обеими сторонами. [172]

Британское правительство также собрало материалы о связи между Шинн Фейн и Советской Россией в безуспешной попытке изобразить Шинн Фейн как криптокоммунистическое движение. [173]

Иерархия католической церкви критиковала насилие с обеих сторон, но особенно со стороны ИРА, продолжая давнюю традицию осуждения воинствующего республиканизма. Епископ Килмора Патрик Финеган сказал: « Любая война… чтобы быть справедливой и законной , должна быть подкреплена хорошо обоснованной надеждой на успех. Какая у вас надежда на успех против могущественных сил Британской империи ? Никакой… .ничего, и если это незаконно, то каждая жизнь, отнятая в результате этого, является убийством». [174] Томас Гилмартин , архиепископ Туама , опубликовал письмо, в котором говорилось, что бойцы ИРА, принимавшие участие в засадах, «нарушили Божье перемирие, они понесли вину за убийство». [175] Однако в мае 1921 года Папа Бенедикт XV встревожил британское правительство, опубликовав письмо, в котором призывал «англичан, а также ирландцев спокойно рассмотреть... некоторые средства взаимного согласия», поскольку они настаивали на осуждении бунт. [176] Они заявили, что его комментарии «поставили HMG (правительство Его Величества) и ирландскую банду убийц на основу равенства». [176]

Десмонд Фитцджеральд и Эрскин Чайлдерс принимали активное участие в выпуске « Ирландского бюллетеня» , в котором подробно описывались зверства правительства, которые ирландские и британские газеты не хотели или не могли освещать. Он был тайно напечатан и распространен по всей Ирландии, а также среди международных агентств печати, а также среди американских, европейских и симпатизирующих британским политикам.

Хотя военная война с начала 1920 года сделала большую часть Ирландии неуправляемой, она фактически не удалила британские войска ни из одной части страны. Но успех пропагандистской кампании Шинн Фейн лишил британское правительство возможности углубить конфликт; его особенно беспокоило влияние на отношения Британии с США, где такие группы, как Американский комитет помощи Ирландии, имели так много видных членов. Британский кабинет не стремился к войне, которая развивалась с 1919 года. К 1921 году один из его членов, Уинстон Черчилль , размышлял:

Какая была альтернатива? Целью было погрузить один маленький уголок империи в железные репрессии, которые не могли быть осуществлены без примеси убийств и контрубийств... Только национальное самосохранение могло оправдать такую политику, и ни один разумный человек не мог бы оправдать такую политику. мог утверждать, что здесь имело место самосохранение. [177]

Потери

[ редактировать ]

По данным The Dead of the Irish Revolution , в результате конфликта погибли или погибли 2346 человек. Это небольшое количество смертей до и после войны, с 1917 года до подписания Договора в конце 1921 года. Из убитых 919 были гражданскими лицами, 523 - полицейскими, 413 - британскими военными и 491 - ИРА. волонтеры [3] (хотя другой источник сообщает о 550 погибших ИРА). [57] Около 44% этих смертей британских военных произошли в результате несчастных случаев (например, в результате случайной стрельбы) и самоубийств во время нахождения на действительной службе, как и 10% потерь полиции и 14% потерь ИРА. [178] Около 36% погибших полицейских родились за пределами Ирландии. [178]

По меньшей мере 557 человек были убиты в результате политического насилия на территории, которая стала Северной Ирландией в период с июля 1920 по июль 1922 года. Многие из этих смертей произошли после перемирия, положившего конец боевым действиям на остальной территории Ирландии. Из этих погибших от 303 до 340 были гражданскими католиками, от 172 до 196 - гражданскими протестантами, 82 - сотрудниками полиции (38 RIC и 44 USC) и 35 - добровольцами ИРА. Большая часть насилия произошла в Белфасте: там были убиты по меньшей мере 452 человека – 267 католиков и 185 протестантов. [179]

Послевоенная эвакуация британских войск

[ редактировать ]

К октябрю 1921 года британская армия в Ирландии насчитывала 57 000 человек, а также 14 200 полицейских RIC и около 2600 вспомогательных сил и черно-коричневых. Давно запланированная эвакуация из десятков казарм в том, что армия называла «Южной Ирландией», началась 12 января 1922 года, после ратификации Договора, и заняла почти год и была организована генералом Невилом Макреди . Это была огромная логистическая операция, но в течение месяца Дублинский замок и казармы Нищих Буша были переданы Временному правительству. Последний раз РИК проводил парад 4 апреля и был официально расформирован 31 августа. К концу мая оставшиеся силы были сосредоточены в Дублине, Корке и Килдэре . К тому времени напряженность, которая привела к гражданской войне в Ирландии, стала очевидной, и эвакуация была приостановлена. К ноябрю около 6600 солдат оставались в Дублине в 17 местах. Наконец, 17 декабря 1922 года Королевские казармы (ныне в которых размещаются коллекции Национального музея Ирландии ) были переданы генералу Ричарду Малкахи, и в тот же вечер гарнизон погрузился в порт Дублина. [180]

Компенсация

[ редактировать ]В мае 1922 года британское правительство с согласия Временного правительства Ирландии учредило комиссию под председательством лорда Шоу Данфермлинского для рассмотрения требований о компенсации за материальный ущерб, причиненный в период с 21 января 1919 года по 11 июля 1921 года. [181] Закон Ирландского Свободного государства о возмещении ущерба собственности (компенсации) 1923 года предусматривал, что для требования компенсации можно использовать только Комиссию Шоу, а не Законы об уголовных травмах. [182] Первоначально британское правительство оплатило претензии профсоюзов, а ирландское правительство — националистов; претензии «нейтральных» сторон разделились. [183] После распада Ирландской пограничной комиссии в 1925 году правительства Великобритании, Свободного государства и Северной Ирландии провели переговоры о внесении изменений в Договор 1921 года; Свободное государство прекратило вносить вклад в обслуживание государственного долга Великобритании, но взяло на себя полную ответственность за компенсацию военного ущерба, при этом в 1926 году фонд увеличился на 10%. [184] Компенсационная (Ирландия) комиссия работала до марта 1926 года, обрабатывая тысячи исков. [183]

Роль женщин в войне

[ редактировать ]

Хотя большую часть боевых действий вели мужчины, женщины сыграли существенную вспомогательную роль в ирландской войне за независимость. Перед Пасхальным восстанием 1916 года многие ирландские женщины-националистки объединились через организации, борющиеся за избирательное право женщин , такие как Ирландская женская лига франчайзинга . [185] Республиканская социалистическая Ирландская гражданская армия пропагандировала гендерное равенство, и многие из этих женщин, в том числе Констанс Маркевич , Мадлен Френч-Маллен и Кэтлин Линн , присоединились к группе. [186] В 1914 году в качестве вспомогательного подразделения ирландских добровольцев была создана женская военизированная группа «Куманн на мБан». Во время Пасхального восстания некоторые женщины участвовали в боях и разносили послания между постами ирландских добровольцев, находясь под огнем британских войск. [187] После поражения повстанцев Эамон де Валера выступил против участия женщин в боевых действиях, и они ограничились второстепенными ролями. [188]

Во время конфликта женщины укрывали добровольцев ИРА, которых разыскивали британцы, ухаживали за ранеными добровольцами и собирали деньги, чтобы помочь заключенным-республиканцам и их семьям. Куманн на мБан занимался секретной работой, чтобы помешать британским военным усилиям. Они переправляли ИРА оружие, боеприпасы и деньги; Кэтлин Кларк переправила контрабандой золото стоимостью 2000 фунтов стерлингов из Лимерика в Дублин для Коллинза. [189] Поскольку они укрывали разыскиваемых мужчин, многие женщины подвергались обыскам со стороны британских сил в их домах, причем актах сексуального насилия , но они не подтверждались. иногда сообщалось об [188] К женщинам чаще применялось запугивание, чем физическое насилие. [190] По оценкам, во время войны в Куманн на мБан насчитывалось от 3000 до 9000 членов, а в 1921 году по всему острову было 800 отделений. По оценкам, во время войны британцы заключили в тюрьму менее 50 женщин. [189]

Мемориал

[ редактировать ]Мемориал под названием « Сад памяти» был установлен в Дублине в 1966 году, к пятидесятой годовщине Пасхального восстания. Дата подписания перемирия отмечается как Национальный день памяти , когда все те ирландские мужчины и женщины, которые участвовали в войнах в составе определенных армий (например, ирландские подразделения, сражавшиеся в британской армии в 1916 году в битве при Сомма) отмечаются.

Последний выживший в конфликте Дэн Китинг (член ИРА) умер в октябре 2007 года в возрасте 105 лет. [191]

Культурные изображения

[ редактировать ]Литература

[ редактировать ]- 1923 — «Тень стрелка» по пьесе Шона О’Кейси.

- 1929 — «Последний сентябрь» , роман Элизабет Боуэн.

- 1931 — «Гости нации» , рассказ Фрэнка О’Коннора.

- 1970 — «Проблемы» , роман Дж. Дж. Фаррелла

- 1979 — «Старая шутка» , роман Дженнифер Джонстон , лауреата премии Whitbread Award.

- 1991 — «Среди женщин», роман Джона МакГахерна.

- 2010 — «Солдатская песня» , роман Алана Монагана.

Телевидение и кино

[ редактировать ]- 1926 — «Ирландская судьба» , немой фильм.

- 1929 — «Информатор» , частично звуковой фильм.

- 1934 — «Ключ» — американский «Pre-Code» . фильм

- 1935 — «Информатор» , фильм Джона Форда.

- 1936 — «Рассвет» , ирландский фильм (также называемый «Рассвет над Ирландией »)

- 1936 — «Одни себя» , британский фильм.

- 1936 — «Любимый враг» , американский драматический фильм.

- 1937 — «Плуг и звезды» , фильм Джона Форда.

- 1959 — «Рукопожатие с дьяволом» , художественный фильм

- 1975 – Дни надежды , 1916: Присоединение

- 1988 — «Рассвет» , фильм по роману Дженнифер Джонстон « Старая шутка».

- 1989 - Тень Белнаблата (1989), документальный фильм RTÉ TV Колма Коннолли о жизни и смерти Майкла Коллинза.

- 1991 – «Договор»

- 1996 — Майкл Коллинз , художественный фильм.

- 1999 – «Последний сентябрь»

- 2001 — «Сердце бунтовщика» , мини-сериал BBC. музыкальную тему Одноименную написала Шэрон Корр .

- 2002 - забытых, Десять TG4 телевизионный документальный фильм

- 2006 — «Ветер, который качает ячмень» , художественный фильм

- 2014 — «Падение соловья» , фильм

- 2019 — Сопротивление , мини-сериал RTÉ из пяти частей

См. также

[ редактировать ]Ирландия

[ редактировать ]- Ирландский национализм

- Ирландский республиканизм

- Проблемы

- Список конфликтов в Ирландии

- Военная история Ирландии

- Кризис самоуправления

- Объединенная Ирландия

Другой

[ редактировать ]- Валлийские восстания против английского правления

- Войны за независимость Шотландии

- независимость Шотландии

- независимость Уэльса

- Последствия Первой мировой войны

- Революции 1917–1923 гг.

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Каутт, Уильям Х. (1999). Англо-ирландская война 1916–1921 годов: Народная война . Издательство Прагер . п. 101. ИСБН 978-0-275-96311-8 . ; Хойт, Тимоти Д. (2009). «Почему Ирландия победила: Война с ирландской стороны» . Звездный час . 143 . Международное общество Черчилля : 55. Архивировано из оригинала 13 мая 2021 года . Проверено 1 июня 2021 г.

- ^ Костелло, Фрэнсис Дж. (январь 1989 г.). «Роль пропаганды в англо-ирландской войне 1919–1921 гг.» . Канадский журнал ирландских исследований . 14 (2): 5–24. JSTOR 25512739 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 сентября 2021 года . Проверено 11 мая 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Юнан О'Халпин и Дайти О Коррен. Мертвецы ирландской революции . Издательство Йельского университета , 2020. стр.544.

- ^ Хизерли, Кристофер Дж. (2012). Когад На Сирша: Операции британской разведки во время англо-ирландской войны, 1916–1921 (переиздание). БиблиоБазар. ISBN 9781249919506 . Архивировано из оригинала 29 декабря 2020 года . Проверено 22 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Тауншенд 1975 , с. 31.

- ^ Динан, Брайан (1987). Клэр и ее люди . Дублин: Мерсье Пресс. п. 105. ИСБН 085342-828-Х .

- ^ Коулман, Мари (2013). Ирландская революция, 1916–1923 гг . Рутледж. стр. 86–87.

- ^ «Черно-коричневая война – девять увлекательных фактов о кровавой борьбе за независимость Ирландии» . Militaryhistorynow.com . 9 ноября 2015 г. Архивировано из оригинала 28 марта 2019 г. . Проверено 15 января 2018 г. ; «Irishmedals.org» . Сайт Irishmedals.org . Архивировано из оригинала 12 июня 2018 года . Проверено 15 января 2018 г. ; «Майкл Коллинз: Человек против Империи» . ИсторияНет . 12 июня 2006 г. Архивировано из оригинала 17 ноября 2017 г. . Проверено 15 января 2018 г.