Концентрационный лагерь Освенцим

| Освенцим Концентрационный лагерь Освенцим ( нем .) | |

|---|---|

| Нацистский концлагерь и лагерь смерти (1940–1945) | |

Top: Gate to Auschwitz I with its Arbeit macht frei sign ("work sets you free")Bottom: Auschwitz II-Birkenau gatehouse. The train track, in operation from May to October 1944, led toward the gas chambers.[1] | |

| Coordinates | 50°02′09″N 19°10′42″E / 50.03583°N 19.17833°E |

| Known for | The Holocaust |

| Location | German-occupied Poland |

| Built by | IG Farben |

| Operated by | Nazi Germany and the Schutzstaffel |

| Commandant | See list |

| Original use | Army barracks |

| Operational | May 1940 – January 1945 |

| Inmates | Mainly Jews, Poles, Romani, Soviet prisoners of war |

| Number of inmates | At least 1.3 million[2] |

| Killed | At least 1.1 million[2] |

| Liberated by | Soviet Union, 27 January 1945 |

| Notable inmates | Auschwitz prisoners: Adolf Burger, Edith Eger, Anne Frank, Viktor Frankl, Imre Kertész, Maximilian Kolbe, Primo Levi, Fritz Löhner-Beda, Irène Némirovsky, Tadeusz Pietrzykowski, Witold Pilecki, Liliana Segre, Edith Stein, Simone Veil, Rudolf Vrba, Alfréd Wetzler, Elie Wiesel, Else Ury, Eddie Jaku, Władysław Bartoszewski |

| Notable books |

|

| Website | auschwitz |

| Official name | Auschwitz Birkenau, German Nazi Concentration and Extermination Camp (1940–1945) |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | vi |

| Designated | 1979 (3rd session) |

| Reference no. | 31 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

Концлагерь Освенцим ( нем . концентрационный лагерь Освенцим , произносится [контсентʁaˈtsi̯oːnsˌlaːɡɐ ˈʔaʊʃvɪts] ; также KL Auschwitz или KZ Auschwitz ) — комплекс из более чем 40 концентрационных лагерей и лагерей смерти, управляемых нацистской Германией в оккупированной Польше (часть которой была аннексирована Германией в 1939 году). [ 3 ] во время Второй мировой войны и Холокоста . Он состоял из Освенцима I , главного лагеря ( Stammlager ) в Освенциме ; Освенцим II-Биркенау , концентрационный лагерь и лагерь смерти с газовыми камерами ; Освенцим III-Моновиц , трудовой лагерь химического конгломерата IG Farben ; и десятки подлагерей . [ 4 ] нацистами Лагеря стали основным местом окончательного решения еврейского вопроса .

После того, как Германия начала Вторую мировую войну, вторгнувшись в Польшу в сентябре 1939 года, Шуцстаффель (СС) превратил Освенцим I, армейские казармы, в лагерь для военнопленных . [ 5 ] Первоначальная транспортировка политических заключенных в Освенцим состояла почти исключительно из поляков (для которых лагерь изначально был создан). В течение первых двух лет большинство заключенных были поляками. [6] В мае 1940 года немецкие преступники, доставленные в лагерь в качестве функционеров, создали репутацию лагеря как места садизма. Заключенных избивали, пытали и казнили по самым банальным причинам. Первые отравления газом советских и польских заключенных произошли в 11-м блоке Освенцима I примерно в августе 1941 года.

Construction of Auschwitz II began the following month, and from 1942 until late 1944 freight trains delivered Jews from all over German-occupied Europe to its gas chambers. Of the 1.3 million people sent to Auschwitz, 1.1 million were murdered. The number of victims includes 960,000 Jews (865,000 of whom were gassed on arrival), 74,000 non-Jewish Poles, 21,000 Romani, 15,000 Soviet prisoners of war, and up to 15,000 others.[7] Those not gassed were murdered via starvation, exhaustion, disease, individual executions, or beatings. Others were killed during medical experiments.

At least 802 prisoners tried to escape, 144 successfully, and on 7 October 1944, two Sonderkommando units, consisting of prisoners who operated the gas chambers, launched an unsuccessful uprising. After the Holocaust ended, only 789 Schutzstaffel personnel (no more than 15 percent) ever stood trial.[8] Several were executed, including camp commandant Rudolf Höss. The Allies' failure to act on early reports of mass murder by bombing the camp or its railways remains controversial.

As the Soviet Red Army approached Auschwitz in January 1945, toward the end of the war, the SS sent most of the camp's population west on a death march to camps inside Germany and Austria. Soviet troops entered the camp on 27 January 1945, a day commemorated since 2005 as International Holocaust Remembrance Day. In the decades after the war, survivors such as Primo Levi, Viktor Frankl, and Elie Wiesel wrote memoirs of their experiences, and the camp became a dominant symbol of the Holocaust. In 1947, Poland founded the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum on the site of Auschwitz I and II, and in 1979 it was named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. Auschwitz is the site of the largest mass murder in a single location in history.[9][10]

Background

The ideology of Nazism combined elements of "racial hygiene", eugenics, antisemitism, pan-Germanism, and territorial expansionism, Richard J. Evans writes.[11] Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party became obsessed by the "Jewish question".[12] Both during and immediately after the Nazi seizure of power in Germany in 1933, acts of violence against German Jews became ubiquitous,[13] and legislation was passed excluding them from certain professions, including the civil service and the law.[a]

Harassment and economic pressure encouraged Jews to leave Germany; their businesses were denied access to markets, forbidden from advertising in newspapers, and deprived of government contracts.[15] On 15 September 1935, the Reichstag passed the Nuremberg Laws. One, the Reich Citizenship Law, defined as citizens those of "German or related blood who demonstrate by their behaviour that they are willing and suitable to serve the German People and Reich faithfully", and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor prohibited marriage and extramarital relations between those with "German or related blood" and Jews.[16]

When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, triggering World War II, Hitler ordered that the Polish leadership and intelligentsia be destroyed.[17] The area around Auschwitz was annexed to the German Reich, as part of first Gau Silesia and from 1941 Gau Upper Silesia.[18] The camp at Auschwitz was established in April 1940, at first as a quarantine camp for Polish political prisoners. On 22 June 1941, in an attempt to obtain new territory, Hitler invaded the Soviet Union.[19] The first gassing at Auschwitz—of a group of Soviet prisoners of war—took place around August 1941.[20] By the end of that year, during what most historians regard as the first phase of the Holocaust, 500,000–800,000 Soviet Jews had been murdered in mass shootings by a combination of German Einsatzgruppen, ordinary German soldiers, and local collaborators.[21] At the Wannsee Conference in Berlin on 20 January 1942, Reinhard Heydrich outlined the Final Solution to the Jewish Question to senior Nazis,[22] and from early 1942 freight trains delivered Jews from all over occupied Europe to German extermination camps in Poland: Auschwitz, Bełżec, Chełmno, Majdanek, Sobibór, and Treblinka. Most prisoners were gassed on arrival.[23]

Camps

Auschwitz I

Growth

A former World War I camp for transient workers and later a Polish army barracks, Auschwitz I was the main camp (Stammlager) and administrative headquarters of the camp complex. Fifty kilometres (31 mi) southwest of Kraków, the site was first suggested in February 1940 as a quarantine camp for Polish prisoners by Arpad Wigand, the inspector of the Sicherheitspolizei (security police) and deputy of Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski, the Higher SS and Police Leader for Silesia. Richard Glücks, head of the Concentration Camps Inspectorate, sent Walter Eisfeld, former commandant of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Oranienburg, Germany, to inspect it.[25] Around 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) long and 400 metres (1,300 ft) wide,[26] Auschwitz consisted at the time of 22 brick buildings, eight of them two-story. A second story was added to the others in 1943 and eight new blocks were built.[27]

Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, approved the site in April 1940 on the recommendation of SS-Obersturmbannführer Rudolf Höss of the camps inspectorate. Höss oversaw the development of the camp and served as its first commandant. The first 30 prisoners arrived on 20 May 1940 from the Sachsenhausen camp. German "career criminals" (Berufsverbrecher), the men were known as "greens" (Grünen) after the green triangles on their prison clothing. Brought to the camp as functionaries, this group did much to establish the sadism of early camp life, which was directed particularly at Polish inmates, until the political prisoners took over their roles.[28] Bruno Brodniewicz, the first prisoner (who was given serial number 1), became Lagerälteste (camp elder). The others were given positions such as kapo and block supervisor.[29]

First mass transport

The first mass transport—of 728 Polish male political prisoners, including Catholic priests and Jews—arrived on 14 June 1940 from Tarnów, Poland. They were given serial numbers 31 to 758.[b] In a letter on 12 July 1940, Höss told Glücks that the local population was "fanatically Polish, ready to undertake any sort of operation against the hated SS men".[31] By the end of 1940, the SS had confiscated land around the camp to create a 40-square-kilometer (15 sq mi) "zone of interest" (Interessengebiet) patrolled by the SS, Gestapo and local police.[32] By March 1941, 10,900 were imprisoned in the camp, most of them Poles.[26]

An inmate's first encounter with Auschwitz, if they were registered and not sent straight to the gas chamber, was at the prisoner reception centre near the gate with the Arbeit macht frei sign, where they were tattooed, shaved, disinfected, and given a striped prison uniform. Built between 1942 and 1944, the center contained a bathhouse, laundry, and 19 gas chambers for delousing clothing. The prisoner reception center of Auschwitz I became the visitor reception center of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.[24]

Crematorium I, first gassings

Construction of crematorium I began at Auschwitz I at the end of June or beginning of July 1940.[34] Initially intended not for mass murder but for prisoners who had been executed or had otherwise died in the camp, the crematorium was in operation from August 1940 until July 1943, by which time the crematoria at Auschwitz II had taken over.[35] By May 1942 three ovens had been installed in crematorium I, which together could burn 340 bodies in 24 hours.[36]

The first experimental gassing took place around August 1941, when Lagerführer Karl Fritzsch, at the instruction of Rudolf Höss, murdered a group of Soviet prisoners of war by throwing Zyklon B crystals into their basement cell in block 11 of Auschwitz I. A second group of 600 Soviet prisoners of war and around 250 sick Polish prisoners were gassed on 3–5 September.[37] The morgue was later converted to a gas chamber able to hold at least 700–800 people.[36][c] Zyklon B was dropped into the room through slits in the ceiling.[36]

First mass transport of Jews

Historians have disagreed about the date the all-Jewish transports began arriving in Auschwitz. At the Wannsee Conference in Berlin on 20 January 1942, the Nazi leadership outlined, in euphemistic language, its plans for the Final Solution.[38] According to Franciszek Piper, the Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss offered inconsistent accounts after the war, suggesting the extermination began in December 1941, January 1942, or before the establishment of the women's camp in March 1942.[39] In Kommandant in Auschwitz, he wrote: "In the spring of 1942 the first transports of Jews, all earmarked for extermination, arrived from Upper Silesia."[40] On 15 February 1942, according to Danuta Czech, a transport of Jews from Beuthen, Upper Silesia (Bytom, Poland), arrived at Auschwitz I and was sent straight to the gas chamber.[d][42] In 1998 an eyewitness said the train contained "the women of Beuthen".[e] Saul Friedländer wrote that the Beuthen Jews were from the Organization Schmelt labor camps and had been deemed unfit for work.[44] According to Christopher Browning, transports of Jews unfit for work were sent to the gas chamber at Auschwitz from autumn 1941.[45] The evidence for this and the February 1942 transport was contested in 2015 by Nikolaus Wachsmann.[46]

Around 20 March 1942, according to Danuta Czech, a transport of Polish Jews from Silesia and Zagłębie Dąbrowskie was taken straight from the station to the Auschwitz II gas chamber, which had just come into operation.[47] On 26 and 28 March, two transports of Slovakian Jews were registered as prisoners in the women's camp, where they were kept for slave labour; these were the first transports organized by Adolf Eichmann's department IV B4 (the Jewish office) in the Reich Security Head Office (RSHA).[f] On 30 March the first RHSA transport arrived from France.[48] "Selection", where new arrivals were chosen for work or the gas chamber, began in April 1942 and was conducted regularly from July. Piper writes that this reflected Germany's increasing need for labour. Those selected as unfit for work were gassed without being registered as prisoners.[49]

There is also disagreement about how many were gassed in Auschwitz I. Perry Broad, an SS-Unterscharführer, wrote that "transport after transport vanished in the Auschwitz [I] crematorium."[50] In the view of Filip Müller, one of the Auschwitz I Sonderkommando, tens of thousands of Jews were murdered there from France, Holland, Slovakia, Upper Silesia, and Yugoslavia, and from the Theresienstadt, Ciechanow, and Grodno ghettos.[51] Against this, Jean-Claude Pressac estimated that up to 10,000 people had been murdered in Auschwitz I.[50] The last inmates gassed there, in December 1942, were around 400 members of the Auschwitz II Sonderkommando, who had been forced to dig up and burn the remains of that camp's mass graves, thought to hold over 100,000 corpses.[52]

Auschwitz II-Birkenau

Construction

After visiting Auschwitz I in March 1941, it appears that Himmler ordered that the camp be expanded,[53] although Peter Hayes notes that, on 10 January 1941, the Polish underground told the Polish government-in-exile in London: "the Auschwitz concentration camp ...can accommodate approximately 7,000 prisoners at present, and is to be rebuilt to hold approximately 30,000."[54] Construction of Auschwitz II-Birkenau—called a Kriegsgefangenenlager (prisoner-of-war camp) on blueprints—began in October 1941 in Brzezinka, about three kilometers from Auschwitz I.[55] The initial plan was that Auschwitz II would consist of four sectors (Bauabschnitte I–IV), each consisting of six subcamps (BIIa–BIIf) with their own gates and fences. The first two sectors were completed (sector BI was initially a quarantine camp), but the construction of BIII began in 1943 and stopped in April 1944, and the plan for BIV was abandoned.[56]

SS-Sturmbannführer Karl Bischoff, an architect, was the chief of construction.[53] Based on an initial budget of RM 8.9 million, his plans called for each barracks to hold 550 prisoners, but he later changed this to 744 per barracks, which meant the camp could hold 125,000, rather than 97,000.[57] There were 174 barracks, each measuring 35.4 by 11.0 m (116 by 36 ft), divided into 62 bays of 4 m2 (43 sq ft). The bays were divided into "roosts", initially for three inmates and later for four. With personal space of 1 m2 (11 sq ft) to sleep and place whatever belongings they had, inmates were deprived, Robert-Jan van Pelt wrote, "of the minimum space needed to exist".[58]

The prisoners were forced to live in the barracks as they were building them; in addition to working, they faced long roll calls at night. As a result, most prisoners in BIb (the men's camp) in the early months died of hypothermia, starvation or exhaustion within a few weeks.[59] Some 10,000 Soviet prisoners of war arrived at Auschwitz I between 7 and 25 October 1941,[60] but by 1 March 1942 only 945 were still registered; they were transferred to Auschwitz II,[41] where most of them had died by May.[61]

Crematoria II–V

The first gas chamber at Auschwitz II was operational by March 1942. On or around 20 March, a transport of Polish Jews sent by the Gestapo from Silesia and Zagłębie Dąbrowskie was taken straight from the Oświęcim freight station to the Auschwitz II gas chamber, then buried in a nearby meadow.[47] The gas chamber was located in what prisoners called the "little red house" (known as bunker 1 by the SS), a brick cottage that had been turned into a gassing facility; the windows had been bricked up and its four rooms converted into two insulated rooms, the doors of which said "Zur Desinfektion" ("to disinfection"). A second brick cottage, the "little white house" or bunker 2, was converted and operational by June 1942.[62] When Himmler visited the camp on 17 and 18 July 1942, he was given a demonstration of a selection of Dutch Jews, a mass-murder in a gas chamber in bunker 2, and a tour of the building site of Auschwitz III, the new IG Farben plant being constructed at Monowitz.[63] Use of bunkers I and 2 stopped in spring 1943 when the new crematoria were built, although bunker 2 became operational again in May 1944 for the murder of the Hungarian Jews. Bunker I was demolished in 1943 and bunker 2 in November 1944.[64]

Plans for crematoria II and III show that both had an oven room 30 by 11.24 m (98.4 by 36.9 ft) on the ground floor, and an underground dressing room 49.43 by 7.93 m (162.2 by 26.0 ft) and gas chamber 30 by 7 m (98 by 23 ft). The dressing rooms had wooden benches along the walls and numbered pegs for clothing. Victims would be led from these rooms to a five-yard-long narrow corridor, which in turn led to a space from which the gas chamber door opened. The chambers were white inside, and nozzles were fixed to the ceiling to resemble showerheads.[65] The daily capacity of the crematoria (how many bodies could be burned in a 24-hour period) was 340 corpses in crematorium I; 1,440 each in crematoria II and III; and 768 each in IV and V.[66] By June 1943 all four crematoria were operational, but crematorium I was not used after July 1943. This made the total daily capacity 4,416, although by loading three to five corpses at a time, the Sonderkommando were able to burn some 8,000 bodies a day. This maximum capacity was rarely needed; the average between 1942 and 1944 was 1,000 bodies burned every day.[67]

Auschwitz III–Monowitz

After examining several sites for a new plant to manufacture Buna-N, a type of synthetic rubber essential to the war effort, the German chemical conglomerate IG Farben chose a site near the towns of Dwory and Monowice (Monowitz in German), about 7 km (4.3 mi) east of Auschwitz I.[68] Tax exemptions were available to corporations prepared to develop industries in the frontier regions under the Eastern Fiscal Assistance Law, passed in December 1940. In addition to its proximity to the concentration camp, a source of cheap labour, the site had good railway connections and access to raw materials.[69] In February 1941, Himmler ordered that the Jewish population of Oświęcim be expelled to make way for skilled laborers; that all Poles able to work remain in the town and work on building the factory; and that Auschwitz prisoners be used in the construction work.[70]

Auschwitz inmates began working at the plant, known as Buna Werke and IG-Auschwitz, in April 1941, demolishing houses in Monowitz to make way for it.[71] By May, because of a shortage of trucks, several hundred of them were rising at 3 am to walk there twice a day from Auschwitz I.[72] Because a long line of exhausted inmates walking through the town of Oświęcim might harm German-Polish relations, the inmates were told to shave daily, make sure they were clean, and sing as they walked. From late July they were taken to the factory by train on freight wagons.[73] Given the difficulty of moving them, including during the winter, IG Farben decided to build a camp at the plant. The first inmates moved there on 30 October 1942.[74] Known as KL Auschwitz III–Aussenlager (Auschwitz III subcamp), and later as the Monowitz concentration camp,[75] it was the first concentration camp to be financed and built by private industry.[76]

Measuring 270 m × 490 m (890 ft × 1,610 ft), the camp was larger than Auschwitz I. By the end of 1944, it housed 60 barracks measuring 17.5 m × 8 m (57 ft × 26 ft), each with a day room and a sleeping room containing 56 three-tiered wooden bunks.[77] IG Farben paid the SS three or four Reichsmark for nine- to eleven-hour shifts from each worker.[78] In 1943–1944, about 35,000 inmates worked at the plant; 23,000 (32 a day on average) were killed through malnutrition, disease, and the workload. Within three to four months at the camp, Peter Hayes writes, the inmates were "reduced to walking skeletons".[79] Deaths and transfers to the gas chambers at Auschwitz II reduced the population by nearly a fifth each month.[80] Site managers constantly threatened inmates with the gas chambers, and the smell from the crematoria at Auschwitz I and II hung heavy over the camp.[81]

Although the factory had been expected to begin production in 1943, shortages of labour and raw materials meant start-up was postponed repeatedly.[82] The Allies bombed the plant in 1944 on 20 August, 13 September, 18 December, and 26 December. On 19 January 1945, the SS ordered that the site be evacuated, sending 9,000 inmates, most of them Jews, on a death march to another Auschwitz subcamp at Gliwice.[83] From Gliwice, prisoners were taken by rail in open freight wagons to the Buchenwald and Mauthausen concentration camps. The 800 inmates who had been left behind in the Monowitz hospital were liberated along with the rest of the camp on 27 January 1945 by the 1st Ukrainian Front of the Red Army.[84]

Subcamps

Several other German industrial enterprises, such as Krupp and Siemens-Schuckert, built factories with their own subcamps.[85] There were around 28 camps near industrial plants, each camp holding hundreds or thousands of prisoners.[86] Designated as Aussenlager (external camp), Nebenlager (extension camp), Arbeitslager (labor camp), or Aussenkommando (external work detail),[87] camps were built at Blechhammer, Jawiszowice, Jaworzno, Lagisze, Mysłowice, Trzebinia, and as far afield as the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in Czechoslovakia.[88] Industries with satellite camps included coal mines, foundries and other metal works, and chemical plants. Prisoners were also made to work in forestry and farming.[89] For example, Wirtschaftshof Budy, in the Polish village of Budy near Brzeszcze, was a farming subcamp where prisoners worked 12-hour days in the fields, tending animals, and making compost by mixing human ashes from the crematoria with sod and manure.[90] Incidents of sabotage to decrease production took place in several subcamps, including Charlottengrube, Gleiwitz II, and Rajsko.[91] Living conditions in some of the camps were so poor that they were regarded as punishment subcamps.[92]

Life in the camps

SS garrison

Rudolf Höss, born in Baden-Baden in 1900,[94] was named the first commandant of Auschwitz when Heinrich Himmler ordered on 27 April 1940 that the camp be established.[95] Living with his wife and children in a two-story stucco house near the commandant's and administration building,[96] he served as commandant until 11 November 1943,[95] with Josef Kramer as his deputy.[26] Succeeded as commandant by Arthur Liebehenschel,[95] Höss joined the SS Business and Administration Head Office in Oranienburg as director of Amt DI,[95] a post that made him deputy of the camps inspectorate.[97]

Richard Baer became commandant of Auschwitz I on 11 May 1944 and Fritz Hartjenstein of Auschwitz II from 22 November 1943, followed by Josef Kramer from 15 May 1944 until the camp's liquidation in January 1945. Heinrich Schwarz was commandant of Auschwitz III from the point at which it became an autonomous camp in November 1943 until its liquidation.[98] Höss returned to Auschwitz between 8 May and 29 July 1944 as the local SS garrison commander (Standortältester) to oversee the arrival of Hungary's Jews, which made him the superior officer of all the commandants of the Auschwitz camps.[95]

According to Aleksander Lasik, about 6,335 people (6,161 of them men) worked for the SS at Auschwitz over the course of the camp's existence;[99] 4.2 percent were officers, 26.1 percent non-commissioned officers, and 69.7 percent rank and file.[100] In March 1941, there were 700 SS guards; in June 1942, 2,000; and in August 1944, 3,342. At its peak in January 1945, 4,480 SS men and 71 SS women worked in Auschwitz; the higher number is probably attributable to the logistics of evacuating the camp.[101] Female guards were known as SS supervisors (SS-Aufseherinnen).[102]

Most of the staff were from Germany or Austria, but as the war progressed, increasing numbers of Volksdeutsche from other countries, including Czechoslovakia, Poland, Yugoslavia, and the Baltic states, joined the SS at Auschwitz. Not all were ethnically German. Guards were also recruited from Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia.[103] Camp guards, around three quarters of the SS personnel, were members of the SS-Totenkopfverbände (death's head units).[104] Other SS staff worked in the medical or political departments, or in the economic administration, which was responsible for clothing and other supplies, including the property of dead prisoners.[105] The SS viewed Auschwitz as a comfortable posting; being there meant they had avoided the front and had access to the victims' property.[106]

Functionaries and Sonderkommando

Certain prisoners, at first non-Jewish Germans but later Jews and non-Jewish Poles,[107] were assigned positions of authority as Funktionshäftlinge (functionaries), which gave them access to better housing and food. The Lagerprominenz (camp elite) included Blockschreiber (barracks clerk), Kapo (overseer), Stubendienst (barracks orderly), and Kommandierte (trusties).[108] Wielding tremendous power over other prisoners, the functionaries developed a reputation as sadists.[107] Very few were prosecuted after the war, because of the difficulty of determining which atrocities had been performed by order of the SS.[109]

Although the SS oversaw the murders at each gas chamber, the forced labor portion of the work was done by prisoners known from 1942 as the Sonderkommando (special squad).[110] These were mostly Jews but they included groups such as Soviet POWs. In 1940–1941 when there was one gas chamber, there were 20 such prisoners, in late 1943 there were 400, and by 1944 during the Holocaust in Hungary the number had risen to 874.[111] The Sonderkommando removed goods and corpses from the incoming trains, guided victims to the dressing rooms and gas chambers, removed their bodies afterwards, and took their jewelry, hair, dental work, and any precious metals from their teeth, all of which was sent to Germany. Once the bodies were stripped of anything valuable, the Sonderkommando burned them in the crematoria.[112]

Because they were witnesses to the mass murder, the Sonderkommando lived separately from the other prisoners, although this rule was not applied to the non-Jews among them.[113] Their quality of life was further improved by their access to the property of new arrivals, which they traded within the camp, including with the SS.[114] Nevertheless, their life expectancy was short; they were regularly murdered and replaced.[115] About 100 survived to the camp's liquidation. They were forced on a death march and by train to the camp at Mauthausen, where three days later they were asked to step forward during roll call. No one did, and because the SS did not have their records, several of them survived.[116]

Tattoos and triangles

Uniquely at Auschwitz, prisoners were tattooed with a serial number, on their left breast for Soviet prisoners of war[117] and on the left arm for civilians.[118][119] Categories of prisoner were distinguishable by triangular pieces of cloth (German: Winkel) sewn onto on their jackets below their prisoner number. Political prisoners (Schutzhäftlinge or Sch), mostly Poles, had a red triangle, while criminals (Berufsverbrecher or BV) were mostly German and wore green. Asocial prisoners (Asoziale or Aso), which included vagrants, prostitutes and the Roma, wore black. Purple was for Jehovah's Witnesses (Internationale Bibelforscher-Vereinigung or IBV)'s and pink for gay men, who were mostly German.[120] An estimated 5,000–15,000 gay men prosecuted under German Penal Code Section 175 (proscribing sexual acts between men) were detained in concentration camps, of whom an unknown number were sent to Auschwitz.[121] Jews wore a yellow badge, the shape of the Star of David, overlaid by a second triangle if they also belonged to a second category. The nationality of the inmate was indicated by a letter stitched onto the cloth. A racial hierarchy existed, with German prisoners at the top. Next were non-Jewish prisoners from other countries. Jewish prisoners were at the bottom.[122]

Transports

Deportees were brought to Auschwitz crammed in wretched conditions into goods or cattle wagons, arriving near a railway station or at one of several dedicated trackside ramps, including one next to Auschwitz I. The Altejudenrampe (old Jewish ramp), part of the Oświęcim freight railway station, was used from 1942 to 1944 for Jewish transports.[123][124] Located between Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II, arriving at this ramp meant a 2.5 km journey to Auschwitz II and the gas chambers. Most deportees were forced to walk, accompanied by SS men and a car with a Red Cross symbol that carried the Zyklon B, as well as an SS doctor in case officers were poisoned by mistake. Inmates arriving at night, or who were too weak to walk, were taken by truck.[125] Work on a new railway line and ramp (right) between sectors BI and BII in Auschwitz II, was completed in May 1944 for the arrival of Hungarian Jews[124] between May and early July 1944.[126] The rails led directly to the area around the gas chambers.[123]

Life for the inmates

The day began at 4:30 am for the men (an hour later in winter), and earlier for the women, when the block supervisor sounded a gong and started beating inmates with sticks to make them wash and use the latrines quickly.[127] There were few latrines and there was a lack of clean water. Each washhouse had to service thousands of prisoners. In sectors BIa and BIb in Auschwitz II, two buildings containing latrines and washrooms were installed in 1943. These contained troughs for washing and 90 faucets; the toilet facilities were "sewage channels" covered by concrete with 58 holes for seating. There were three barracks with washing facilities or toilets to serve 16 residential barracks in BIIa, and six washrooms/latrines for 32 barracks in BIIb, BIIc, BIId, and BIIe.[128] Primo Levi described a 1944 Auschwitz III washroom:

It is badly lighted, full of draughts, with the brick floor covered by a layer of mud. The water is not drinkable; it has a revolting smell and often fails for many hours. The walls are covered by curious didactic frescoes: for example, there is the good Häftling [prisoner], portrayed stripped to the waist, about to diligently soap his sheared and rosy cranium, and the bad Häftling, with a strong Semitic nose and a greenish colour, bundled up in his ostentatiously stained clothes with a beret on his head, who cautiously dips a finger into the water of the washbasin. Under the first is written: "So bist du rein" (like this you are clean), and under the second, "So gehst du ein" (like this you come to a bad end); and lower down, in doubtful French but in Gothic script: "La propreté, c'est la santé" [cleanliness is health].[129]

Prisoners received half a litre of coffee substitute or a herbal tea in the morning, but no food.[130] A second gong heralded roll call, when inmates lined up outside in rows of ten to be counted. No matter the weather, they had to wait for the SS to arrive for the count; how long they stood there depended on the officers' mood, and whether there had been escapes or other events attracting punishment.[131] Guards might force the prisoners to squat for an hour with their hands above their heads or hand out beatings or detention for infractions such as having a missing button or an improperly cleaned food bowl. The inmates were counted and re-counted.[132]

After roll call, to the sound of "Arbeitskommandos formieren" ("form work details"), prisoners walked to their place of work, five abreast, to begin a working day that was normally 11 hours long—longer in summer and shorter in winter.[134] A prison orchestra, such as the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz, was forced to play cheerful music as the workers left the camp. Kapos were responsible for the prisoners' behaviour while they worked, as was an SS escort. Much of the work took place outdoors at construction sites, gravel pits, and lumber yards. No rest periods were allowed. One prisoner was assigned to the latrines to measure the time the workers took to empty their bladders and bowels.[135]

Lunch was three-quarters of a litre of watery soup at midday, reportedly foul-tasting, with meat in the soup four times a week and vegetables (mostly potatoes and rutabaga) three times. The evening meal was 300 grams of bread, often moldy, part of which the inmates were expected to keep for breakfast the next day, with a tablespoon of cheese or marmalade, or 25 grams of margarine or sausage. Prisoners engaged in hard labour were given extra rations.[136]

A second roll call took place at seven in the evening, in the course of which prisoners might be hanged or flogged. If a prisoner was missing, the others had to remain standing until the absentee was found or the reason for the absence discovered, even if it took hours. On 6 July 1940, roll call lasted 19 hours because a Polish prisoner, Tadeusz Wiejowski, had escaped; following an escape in 1941, a group of prisoners was picked out from the escapee's barracks and sent to block 11 to be starved to death.[137] After roll call, prisoners retired to their blocks for the night and received their bread rations. Then they had some free time to use the washrooms and receive their mail, unless they were Jews: Jews were not allowed to receive mail. Curfew ("nighttime quiet") was marked by a gong at nine o'clock.[138] Inmates slept in long rows of brick or wooden bunks, or on the floor, lying in and on their clothes and shoes to prevent them from being stolen.[139] The wooden bunks had blankets and paper mattresses filled with wood shavings; in the brick barracks, inmates lay on straw.[140] According to Miklós Nyiszli:

Eight hundred to a thousand people were crammed into the superimposed compartments of each barracks. Unable to stretch out completely, they slept there both lengthwise and crosswise, with one man's feet on another's head, neck, or chest. Stripped of all human dignity, they pushed and shoved and bit and kicked each other in an effort to get a few more inches' space on which to sleep a little more comfortably. For they did not have long to sleep.[141]

Sunday was not a workday, but prisoners had to clean the barracks and take their weekly shower,[142] and were allowed to write (in German) to their families, although the SS censored the mail. Inmates who did not speak German would trade bread for help.[143] Observant Jews tried to keep track of the Hebrew calendar and Jewish holidays, including Shabbat, and the weekly Torah portion. No watches, calendars, or clocks were permitted in the camp. Only two Jewish calendars made in Auschwitz survived to the end of the war. Prisoners kept track of the days in other ways, such as obtaining information from newcomers.[144]

Women's camp

About 30 percent of the registered inmates were female.[145] The first mass transport of women, 999 non-Jewish German women from the Ravensbrück concentration camp, arrived on 26 March 1942. Classified as criminal, asocial and political, they were brought to Auschwitz as founder functionaries of the women's camp.[146] Rudolf Höss wrote of them: "It was easy to predict that these beasts would mistreat the women over whom they exercised power ... Spiritual suffering was completely alien to them."[147] They were given serial numbers 1–999.[48][g] The women's guard from Ravensbrück, Johanna Langefeld, became the first Auschwitz women's camp Lagerführerin.[146] A second mass transport of women, 999 Jews from Poprad, Slovakia, arrived on the same day. According to Danuta Czech, this was the first registered transport sent to Auschwitz by the Reich Security Head Office (RSHA) office IV B4, known as the Jewish Office, led by SS Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann.[48] (Office IV was the Gestapo.)[148] A third transport of 798 Jewish women from Bratislava, Slovakia, followed on 28 March.[48]

Women were at first held in blocks 1–10 of Auschwitz I,[149] but from 6 August 1942,[150] 13,000 inmates were transferred to a new women's camp (Frauenkonzentrationslager or FKL) in Auschwitz II. This consisted at first of 15 brick and 15 wooden barracks in sector (Bauabschnitt) BIa; it was later extended into BIb,[151] and by October 1943 it held 32,066 women.[152] In 1943–1944, about 11,000 women were also housed in the Gypsy family camp, as were several thousand in the Theresienstadt family camp.[153]

Conditions in the women's camp were so poor that when a group of male prisoners arrived to set up an infirmary in October 1942, their first task, according to researchers from the Auschwitz Museum, was to distinguish the corpses from the women who were still alive.[152] Gisella Perl, a Romanian-Jewish gynecologist and inmate of the women's camp, wrote in 1948:

There was one latrine for thirty to thirty-two thousand women and we were permitted to use it only at certain hours of the day. We stood in line to get in to this tiny building, knee-deep in human excrement. As we all suffered from dysentry, we could barely wait until our turn came, and soiled our ragged clothes, which never came off our bodies, thus adding to the horror of our existence by the terrible smell that surrounded us like a cloud. The latrine consisted of a deep ditch with planks thrown across it at certain intervals. We squatted on those planks like birds perched on a telegraph wire, so close together that we could not help soiling one another.[154]

Langefeld was succeeded as Lagerführerin in October 1942 by SS Oberaufseherin Maria Mandl, who developed a reputation for cruelty. Höss hired men to oversee the female supervisors, first SS Obersturmführer Paul Müller, then SS Hauptsturmführer Franz Hössler.[155] Mandl and Hössler were executed after the war. Sterilisation experiments were carried out in barracks 30 by a German gynecologist, Carl Clauberg, and another German doctor, Horst Schumann.[152]

Medical experiments, block 10

German doctors performed a variety of experiments on prisoners at Auschwitz. SS doctors tested the efficacy of X-rays as a sterilization device by administering large doses to female prisoners. Carl Clauberg injected chemicals into women's uteruses in an effort to glue them shut. Prisoners were infected with spotted fever for vaccination research and exposed to toxic substances to study the effects.[156] In one experiment, Bayer—then part of IG Farben—paid RM 150 each for 150 female inmates from Auschwitz (the camp had asked for RM 200 per woman), who were transferred to a Bayer facility to test an anesthetic. A Bayer employee wrote to Rudolf Höss: "The transport of 150 women arrived in good condition. However, we were unable to obtain conclusive results because they died during the experiments. We would kindly request that you send us another group of women to the same number and at the same price." The Bayer research was led at Auschwitz by Helmuth Vetter of Bayer/IG Farben, who was also an Auschwitz physician and SS captain, and by Auschwitz physicians Friedrich Entress and Eduard Wirths.[157]

The most infamous doctor at Auschwitz was Josef Mengele, the "Angel of Death", who worked in Auschwitz II from 30 May 1943, at first in the gypsy family camp.[158] Interested in performing research on identical twins, dwarfs, and those with hereditary disease, Mengele set up a kindergarten in barracks 29 and 31 for children he was experimenting on, and for all Romani children under six, where they were given better food rations.[159] From May 1944, he would select twins and dwarfs from among the new arrivals during "selection",[160] reportedly calling for twins with "Zwillinge heraus!" ("twins step forward!").[161] He and other doctors (the latter prisoners) would measure the twins' body parts, photograph them, and subject them to dental, sight and hearing tests, x-rays, blood tests, surgery, and blood transfusions between them.[162] Then he would have them killed and dissected.[160] Kurt Heissmeyer, another German doctor and SS officer, took 20 Polish Jewish children from Auschwitz to use in pseudoscientific experiments at the Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg, where he injected them with the tuberculosis bacilli to test a cure for tuberculosis. In April 1945, the children were murdered by hanging to conceal the project.[163]

A Jewish skeleton collection was obtained from among a pool of 115 Jewish inmates, chosen for their perceived stereotypical racial characteristics. Rudolf Brandt and Wolfram Sievers, general manager of the Ahnenerbe (a Nazi research institute), delivered the skeletons to the collection of the Anatomy Institute at the Reichsuniversität Straßburg in Alsace-Lorraine. The collection was sanctioned by Heinrich Himmler and under the direction of August Hirt. Ultimately 87 of the inmates were shipped to Natzweiler-Struthof and murdered in August 1943.[164] Brandt and Sievers were executed in 1948 after being convicted during the Doctors' trial, part of the Subsequent Nuremberg trials.[165]

Punishment, block 11

Prisoners could be beaten and killed by guards and kapos for the slightest infraction of the rules. Polish historian Irena Strzelecka writes that kapos were given nicknames that reflected their sadism: "Bloody", "Iron", "The Strangler", "The Boxer".[166] Based on the 275 extant reports of punishment in the Auschwitz archives, Strzelecka lists common infractions: returning a second time for food at mealtimes, removing one's gold teeth to buy bread, breaking into the pigsty to steal the pigs' food, putting one's hands into one's pockets.[167]

Flogging during rollcall was common. A flogging table called "the goat" immobilised prisoners' feet in a box, while they stretched themselves across the table. Prisoners had to count out the lashes—"25 mit besten Dank habe ich erhalten" ("25 received with many thanks")— and if they got the figure wrong, the flogging resumed from the beginning.[167] Punishment by "the post" involved tying prisoners' hands behind their backs with chains attached to hooks, then raising the chains so the prisoners were left dangling by the wrists. If their shoulders were too damaged afterwards to work, they might be sent to the gas chamber. Prisoners were subjected to the post for helping a prisoner who had been beaten, and for picking up a cigarette butt.[168] To extract information from inmates, guards would force their heads onto the stove, and hold them there, burning their faces and eyes.[169]

Known as block 13 until 1941, block 11 of Auschwitz I was the prison within the prison, reserved for inmates suspected of resistance activities.[170] Cell 22 in block 11 was a windowless standing cell (Stehbunker). Split into four sections, each section measured less than 1.0 m2 (11 sq ft) and held four prisoners, who entered it through a hatch near the floor. There was a 5 cm × 5 cm (2 in × 2 in) vent for air, covered by a perforated sheet. Strzelecka writes that prisoners might have to spend several nights in cell 22; Wiesław Kielar spent four weeks in it for breaking a pipe.[171] Several rooms in block 11 were deemed the Polizei-Ersatz-Gefängnis Myslowitz in Auschwitz (Auschwitz branch of the police station at Mysłowice).[172] There were also Sonderbehandlung cases ("special treatment") for Poles and others regarded as dangerous to Nazi Germany.[173]

Death wall

The courtyard between blocks 10 and 11, known as the "death wall", served as an execution area, including for Poles in the General Government area who had been sentenced to death by a criminal court.[173] The first executions, by shooting inmates in the back of the head, took place at the death wall on 11 November 1941, Poland's National Independence Day. The 151 accused were led to the wall one at a time, stripped naked and with their hands tied behind their backs. Danuta Czech noted that a "clandestine Catholic mass" was said the following Sunday on the second floor of Block 4 in Auschwitz I, in a narrow space between bunks.[174]

An estimated 4,500 Polish political prisoners were executed at the death wall, including members of the camp resistance. An additional 10,000 Poles were brought to the camp to be executed without being registered. About 1,000 Soviet prisoners of war died by execution, although this is a rough estimate. A Polish government-in-exile report stated that 11,274 prisoners and 6,314 prisoners of war had been executed.[175] Rudolf Höss wrote that "execution orders arrived in an unbroken stream".[172] According to SS officer Perry Broad, "[s]ome of these walking skeletons had spent months in the stinking cells, where not even animals would be kept, and they could barely manage to stand straight. And yet, at that last moment, many of them shouted 'Long live Poland', or 'Long live freedom'."[176] The dead included Colonel Jan Karcz and Major Edward Gött-Getyński, executed on 25 January 1943 with 51 others suspected of resistance activities. Józef Noji, the Polish long-distance runner, was executed on 15 February that year.[177] In October 1944, 200 Sonderkommando were executed for their part in the Sonderkommando revolt.[178]

Family camps

Gypsy family camp

A separate camp for the Roma, the Zigeunerfamilienlager ("Gypsy family camp"), was set up in the BIIe sector of Auschwitz II-Birkenau in February 1943. For unknown reasons, they were not subject to selection and families were allowed to stay together. The first transport of German Roma arrived on 26 February that year. There had been a small number of Romani inmates before that; two Czech Romani prisoners, Ignatz and Frank Denhel, tried to escape in December 1942, the latter successfully, and a Polish Romani woman, Stefania Ciuron, arrived on 12 February 1943 and escaped in April.[180] Josef Mengele, the Holocaust's most infamous physician, worked in the gypsy family camp from 30 May 1943 when he began his work in Auschwitz.[158]

The Auschwitz registry (Hauptbücher) shows that 20,946 Roma were registered prisoners,[181] and another 3,000 are thought to have entered unregistered.[182] On 22 March 1943, one transport of 1,700 Polish Sinti and Roma was gassed on arrival because of illness, as was a second group of 1,035 on 25 May 1943.[181] The SS tried to liquidate the camp on 16 May 1944, but the Roma fought them, armed with knives and iron pipes, and the SS retreated. Shortly after this, the SS removed nearly 2,908 from the family camp to work, and on 2 August 1944 gassed the other 2,897. Ten thousand remain unaccounted for.[183]

Theresienstadt family camp

The SS deported around 18,000 Jews to Auschwitz from the Theresienstadt ghetto in Terezin, Czechoslovakia,[184] beginning on 8 September 1943 with a transport of 2,293 male and 2,713 female prisoners.[185] Placed in sector BIIb as a "family camp", they were allowed to keep their belongings, wear their own clothes, and write letters to family; they did not have their hair shaved and were not subjected to selection.[184] Correspondence between Adolf Eichmann's office and the International Red Cross suggests that the Germans set up the camp to cast doubt on reports, in time for a planned Red Cross visit to Auschwitz, that mass murder was taking place there.[186] The women and girls were placed in odd-numbered barracks and the men and boys in even-numbered. An infirmary was set up in barracks 30 and 32, and barracks 31 became a school and kindergarten.[184] The somewhat better living conditions were nevertheless inadequate; 1,000 members of the family camp were dead within six months.[187] Two other groups of 2,491 and 2,473 Jews arrived from Theresienstadt in the family camp on 16 and 20 December 1943.[188]

On 8 March 1944, 3,791 of the prisoners (men, women and children) were sent to the gas chambers; the men were taken to crematorium III and the women later to crematorium II.[189] Some of the groups were reported to have sung Hatikvah and the Czech national anthem on the way.[190] Before they were murdered, they had been asked to write postcards to relatives, postdated to 25–27 March. Several twins were held back for medical experiments.[191] The Czechoslovak government-in-exile initiated diplomatic manoeuvers to save the remaining Czech Jews after its representative in Bern received the Vrba-Wetzler report, written by two escaped prisoners, Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler, which warned that the remaining family-camp inmates would be gassed soon.[192] The BBC also became aware of the report; its German service broadcast news of the family-camp murders during its women's programme on 16 June 1944, warning: "All those responsible for such massacres from top downwards will be called to account."[193] The Red Cross visited Theresienstadt in June 1944 and were persuaded by the SS that no one was being deported from there.[186] The following month, about 2,000 women from the family camp were selected to be moved to other camps and 80 boys were moved to the men's camp; the remaining 7,000 were gassed between 10 and 12 July.[194]

Selection and extermination process

Gas chambers

The first gassings at Auschwitz took place on September 3, 1941, when around 850 inmates—Soviet prisoners of war and sick Polish inmates—were killed with Zyklon B in the basement of block 11 in Auschwitz I. The building proved unsuitable, so gassings were conducted instead in crematorium I, also in Auschwitz I, which operated until December 1942. There, more than 700 victims could be killed at once.[196] Tens of thousands were killed in crematorium I.[51] To keep the victims calm, they were told they were to undergo disinfection and de-lousing; they were ordered to undress outside, then were locked in the building and gassed. After its decommissioning as a gas chamber, the building was converted to a storage facility and later served as an SS air raid shelter.[197] The gas chamber and crematorium were reconstructed after the war. Dwork and van Pelt write that a chimney was recreated; four openings in the roof were installed to show where the Zyklon B had entered; and two of the three furnaces were rebuilt with the original components.[33]

In early 1942, mass exterminations were moved to two provisional gas chambers (the "red house" and "white house", known as bunkers 1 and 2) in Auschwitz II, while the larger crematoria (II, III, IV, and V) were under construction. Bunker 2 was temporarily reactivated from May to November 1944, when large numbers of Hungarian Jews were gassed.[199] In summer 1944 the combined capacity of the crematoria and outdoor incineration pits was 20,000 bodies per day.[200] A planned sixth facility—crematorium VI—was never built.[201]

From 1942, Jews were being transported to Auschwitz from all over German-occupied Europe by rail, arriving in daily convoys.[202] The gas chambers worked to their fullest capacity from May to July 1944, during the Holocaust in Hungary.[203] A rail spur leading to crematoria II and III in Auschwitz II was completed that May, and a new ramp was built between sectors BI and BII to deliver the victims closer to the gas chambers (images top right). On 29 April the first 1,800 Jews from Hungary arrived at the camp.[204] From 14 May until early July 1944, 437,000 Hungarian Jews, half the pre-war population, were deported to Auschwitz, at a rate of 12,000 a day for a considerable part of that period.[126] The crematoria had to be overhauled. Crematoria II and III were given new elevators leading from the stoves to the gas chambers, new grates were fitted, and several of the dressing rooms and gas chambers were painted. Cremation pits were dug behind crematorium V.[204] The incoming volume was so great that the Sonderkommando resorted to burning corpses in open-air pits as well as in the crematoria.[205]

Selection

According to Polish historian Franciszek Piper, of the 1,095,000 Jews deported to Auschwitz, around 205,000 were registered in the camp and given serial numbers; 25,000 were sent to other camps; and 865,000 were murdered soon after arrival.[206] Adding non-Jewish victims gives a figure of 900,000 who were murdered without being registered.[207]

During "selection" on arrival, those deemed able to work were sent to the right and admitted into the camp (registered), and the rest were sent to the left to be gassed. The group selected to die included almost all children, women with small children, the elderly, and others who appeared on brief and superficial inspection by an SS doctor not to be fit for work.[208] Practically any fault—scars, bandages, boils and emaciation—might provide reason enough to be deemed unfit.[209] Children might be made to walk toward a stick held at a certain height; those who could walk under it were selected for the gas.[210] Inmates unable to walk or who arrived at night were taken to the crematoria on trucks; otherwise, the new arrivals were marched there.[211] Their belongings were seized and sorted by inmates in the "Kanada" warehouses, an area of the camp in sector BIIg that housed 30 barracks used as storage facilities for plundered goods; it derived its name from the inmates' view of Canada as a land of plenty.[212]

Inside the crematoria

The crematoria consisted of a dressing room, gas chamber, and furnace room. In crematoria II and III, the dressing room and gas chamber were underground; in IV and V, they were on the ground floor. The dressing room had numbered hooks on the wall to hang clothes. In crematorium II, there was also a dissection room (Sezierraum).[214] SS officers told the victims they had to take a shower and undergo delousing. The victims undressed in the dressing room and walked into the gas chamber; signs said "Bade" (bath) or "Desinfektionsraum" (disinfection room). A former prisoner testified that the language of the signs changed depending on who was being killed.[215] Some inmates were given soap and a towel.[216] A gas chamber could hold up to 2,000; one former prisoner said it was around 3,000.[217]

The Zyklon B was delivered to the crematoria by a special SS bureau known as the Hygiene Institute.[218] After the doors were shut, SS men dumped in the Zyklon B pellets through vents in the roof or holes in the side of the chamber. The victims were usually dead within 10 minutes; Rudolf Höss testified that it took up to 20 minutes.[219] Leib Langfus, a member of the Sonderkommando, buried his diary (written in Yiddish) near crematorium III in Auschwitz II. It was found in 1952, signed "A.Y.R.A":[220]

It would be difficult to even imagine that so many people would fit in such a small [room]. Anyone who did not want to go inside was shot [...] or torn apart by the dogs. They would have suffocated from the lack of air within several hours. Then all the doors were sealed tight and the gas thrown in by way of a small hole in the ceiling. There was nothing more that the people inside could do. And so they only screamed in bitter, lamentable voices. Others complained in voices full of despair, and others still sobbed spasmodically and sent up a dire, heart-rending weeping. ... And in the meantime, their voices grew weaker and weaker ... Because of the great crowding, people fell one atop another as they died, until a heap arose consisting of five or six layers atop the other, reaching a height of one meter. Mothers froze in a seated position on the ground embracing their children in their arms, and husbands and wives died hugging each other. Some of the people made up a formless mass. Others stood in a leaning position, while the upper parts, from the stomach up, were in a lying position. Some of the people had turned completely blue under the influence of the gas, while others looks entirely fresh, as if they were asleep.[221]

Use of corpses

Sonderkommando wearing gas masks dragged the bodies from the chamber. They removed glasses and artificial limbs and shaved off the women's hair;[219] women's hair was removed before they entered the gas chamber at Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka, but at Auschwitz it was done after death.[222] By 6 February 1943, the Reich Economic Ministry had received 3,000 kg of women's hair from Auschwitz and Majdanek.[222] The hair was first cleaned in a solution of sal ammoniac, dried on the brick floor of the crematoria, combed, and placed in paper bags.[223] The hair was shipped to various companies, including one manufacturing plant in Bremen-Bluementhal, where workers found tiny coins with Greek letters on some of the braids, possibly from some of the 50,000 Greek Jews deported to Auschwitz in 1943.[224] When they liberated the camp in January 1945, the Red Army found 7,000 kg of human hair in bags ready to ship.[223]

Just before cremation, jewelry was removed, along with dental work and teeth containing precious metals.[225] Gold was removed from the teeth of dead prisoners from 23 September 1940 onwards by order of Heinrich Himmler.[226] The work was carried out by members of the Sonderkommando who were dentists; anyone overlooking dental work might themselves be cremated alive.[225] The gold was sent to the SS Health Service and used by dentists to treat the SS and their families; 50 kg had been collected by 8 October 1942.[226] By early 1944, 10–12 kg of gold was being extracted monthly from victims' teeth.[227]

The corpses were burned in the nearby incinerators, and the ashes were buried, thrown in the Vistula river, or used as fertilizer. Any bits of bone that had not burned properly were ground down in wooden mortars.[228]

Death toll

At least 1.3 million people were sent to Auschwitz between 1940 and 1945, and at least 1.1 million died.[7] Overall 400,207 prisoners were registered in the camp: 268,657 male and 131,560 female.[145] A study in the late 1980s by Polish historian Franciszek Piper, published by Yad Vashem in 1991,[229] used timetables of train arrivals combined with deportation records to calculate that, of the 1.3 million sent to the camp, 1,082,000 had died there, a figure (rounded up to 1.1 million) that Piper regarded as a minimum.[7] That figure came to be widely accepted.[h]

The Germans tried to conceal how many they had murdered. In July 1942, according to Rudolf Höss's post-war memoir, Höss received an order from Heinrich Himmler, via Adolf Eichmann's office and SS commander Paul Blobel, that "[a]ll mass graves were to be opened and the corpses burned. In addition, the ashes were to be disposed of in such a way that it would be impossible at some future time to calculate the number of corpses burned."[233]

Earlier estimates of the death toll were higher than Piper's. Following the camp's liberation, the Soviet government issued a statement, on 8 May 1945, that four million people had been murdered on the site, a figure based on the capacity of the crematoria.[234] Höss told prosecutors at Nuremberg that at least 2,500,000 people had been gassed there, and that another 500,000 had died of starvation and disease.[235] He testified that the figure of over two million had come from Eichmann.[236] In his memoirs, written in custody, Höss wrote that Eichmann had given the figure of 2.5 million to Höss's superior officer Richard Glücks, based on records that had been destroyed.[237] Höss regarded this figure as "far too high. Even Auschwitz had limits to its destructive possibilities," he wrote.[238]

| Nationality/ethnicity (Source: Franciszek Piper)[2] |

Registered deaths (Auschwitz) |

Unregistered deaths (Auschwitz) |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jews | 95,000 | 865,000 | 960,000 |

| Ethnic Poles | 64,000 | 10,000 | 74,000 (70,000–75,000) |

| Roma and Sinti | 19,000 | 2,000 | 21,000 |

| Soviet prisoners of war | 12,000 | 3,000 | 15,000 |

| Other Europeans: Soviet citizens (Byelorussians, Russians, Ukrainians), Czechs, Yugoslavs, French, Germans, Austrians |

10,000–15,000 | n/a | 10,000–15,000 |

| Total deaths in Auschwitz, 1940–1945 | 200,000–205,000 | 880,000 | 1,080,000–1,085,000 |

Around one in six Jews murdered in the Holocaust died in Auschwitz.[239] By nation, the greatest number of Auschwitz's Jewish victims originated from Hungary, accounting for 430,000 deaths, followed by Poland (300,000), France (69,000), Netherlands (60,000), Greece (55,000), Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (46,000), Slovakia (27,000), Belgium (25,000), Germany and Austria (23,000), Yugoslavia (10,000), Italy (7,500), Norway (690), and others (34,000).[240] Timothy Snyder writes that fewer than one percent of the million Soviet Jews murdered in the Holocaust were murdered in Auschwitz.[241] Of the at least 387 Jehovah's Witnesses who were imprisoned at Auschwitz, 132 died in the camp.[242]

Resistance, escapes, and liberation

Camp resistance, flow of information

-

Camp of Death pamphlet (1942) by Natalia Zarembina[243]

-

Halina Krahelska report from Auschwitz Oświęcim, pamiętnik więźnia ("Auschwitz: Diary of a prisoner"), 1942.[244]

-

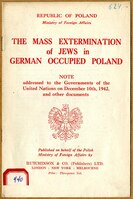

"The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland", a paper issued by the Polish government-in-exile addressed to the United Nations, 1942

Information about Auschwitz became available to the Allies as a result of reports by Captain Witold Pilecki of the Polish Home Army[245] who, as "Tomasz Serafiński" (serial number 4859),[246] allowed himself to be arrested in Warsaw and taken to Auschwitz.[245] He was imprisoned there from 22 September 1940[247] until his escape on 27 April 1943.[246] Michael Fleming writes that Pilecki was instructed to sustain morale, organize food, clothing and resistance, prepare to take over the camp if possible, and smuggle information out to the Polish military.[245] Pilecki called his resistance movement Związek Organizacji Wojskowej (ZOW, "Union of Military Organization").[247]

The resistance sent out the first oral message about Auschwitz with Aleksander Wielkopolski, a Polish engineer who was released in October 1940.[248] The following month the Polish underground in Warsaw prepared a report on the basis of that information, The camp in Auschwitz, part of which was published in London in May 1941 in a booklet, The German Occupation of Poland, by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The report said of the Jews in the camp that "scarcely any of them came out alive". According to Fleming, the booklet was "widely circulated amongst British officials". The Polish Fortnightly Review based a story on it, writing that "three crematorium furnaces were insufficient to cope with the bodies being cremated", as did The Scotsman on 8 January 1942, the only British news organization to do so.[249]

On 24 December 1941, the resistance groups representing the various prisoner factions met in block 45 and agreed to cooperate. Fleming writes that it has not been possible to track Pilecki's early intelligence from the camp. Pilecki compiled two reports after he escaped in April 1943; the second, Raport W, detailed his life in Auschwitz I and estimated that 1.5 million people, mostly Jews, had been murdered.[250] On 1 July 1942, the Polish Fortnightly Review published a report describing Birkenau, writing that "prisoners call this supplementary camp 'Paradisal', presumably because there is only one road, leading to Paradise". Reporting that inmates were being killed "through excessive work, torture and medical means", it noted the gassing of the Soviet prisoners of war and Polish inmates in Auschwitz I in September 1941, the first gassing in the camp. It said: "It is estimated that the Oswiecim camp can accommodate fifteen thousand prisoners, but as they die on a mass scale there is always room for new arrivals."[251]

The Polish government-in-exile in London first reported the gassing of prisoners in Auschwitz on 21 July 1942,[252] and reported the gassing of Soviet POWs and Jews on 4 September 1942.[253] In 1943, the Kampfgruppe Auschwitz (Combat Group Auschwitz) was organized within the camp with the aim of sending out information about what was happening.[254] The Sonderkommando buried notes in the ground, hoping they would be found by the camp's liberators.[255] The group also smuggled out photographs; the Sonderkommando photographs, of events around the gas chambers in Auschwitz II, were smuggled out of the camp in September 1944 in a toothpaste tube.[256]

According to Fleming, the British press responded, in 1943 and the first half of 1944, either by not publishing reports about Auschwitz or by burying them on the inside pages. The exception was the Polish Jewish Observer, a City and East London Observer supplement edited by Joel Cang, a former Warsaw correspondent for the Manchester Guardian. The British reticence stemmed from a Foreign Office concern that the public might pressure the government to respond or provide refuge for the Jews, and that British actions on behalf of the Jews might affect its relationships in the Middle East. There was similar reticence in the United States, and indeed within the Polish government-in-exile and the Polish resistance. According to Fleming, the scholarship suggests that the Polish resistance distributed information about the Holocaust in Auschwitz without challenging the Allies' reluctance to highlight it.[257]

Escapes, Auschwitz Protocols

From the first escape on 6 July 1940 of Tadeusz Wiejowski, at least 802 prisoners (757 men and 45 women) tried to escape from the camp, according to Polish historian Henryk Świebocki.[258][i] He writes that most escapes were attempted from work sites outside the camp's perimeter fence.[260] Of the 802 escapes, 144 were successful, 327 were caught, and the fate of 331 is unknown.[259]

Four Polish prisoners—Eugeniusz Bendera (serial number 8502), Kazimierz Piechowski (no. 918), Stanisław Gustaw Jaster (no. 6438), and Józef Lempart (no. 3419)—escaped successfully on 20 June 1942. After breaking into a warehouse, three of them dressed as SS officers and stole rifles and an SS staff car, which they drove out of the camp with the fourth handcuffed as a prisoner. They wrote later to Rudolf Höss apologizing for the loss of the vehicle.[261] On 21 July 1944, Polish inmate Jerzy Bielecki dressed in an SS uniform and, using a faked pass, managed to cross the camp's gate with his Jewish girlfriend, Cyla Cybulska, pretending that she was wanted for questioning. Both survived the war. For having saved her, Bielecki was recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations.[262]

Jerzy Tabeau (no. 27273, registered as Jerzy Wesołowski) and Roman Cieliczko (no. 27089), both Polish prisoners, escaped on 19 November 1943; Tabeau made contact with the Polish underground and, between December 1943 and early 1944, wrote what became known as the Polish Major's report about the situation in the camp.[263] On 27 April 1944, Rudolf Vrba (no. 44070) and Alfréd Wetzler (no. 29162) escaped to Slovakia, carrying detailed information to the Slovak Jewish Council about the gas chambers. The distribution of the Vrba-Wetzler report, and publication of parts of it in June 1944, helped to halt the deportation of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz. On 27 May 1944, Arnost Rosin (no. 29858) and Czesław Mordowicz (no. 84216) also escaped to Slovakia; the Rosin-Mordowicz report was added to the Vrba-Wetzler and Tabeau reports to become what is known as the Auschwitz Protocols.[264] The reports were first published in their entirety in November 1944 by the United States War Refugee Board as The Extermination Camps of Auschwitz (Oświęcim) and Birkenau in Upper Silesia.[265]

Bombing proposal

In January 1941, the Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Army and prime minister-in-exile, Władysław Sikorski, arranged for a report to be forwarded to Air Marshal Richard Pierse, head of RAF Bomber Command.[266] Written by Auschwitz prisoners in or around December 1940, the report described the camp's atrocious living conditions and asked the Polish government-in-exile to bomb it:

The prisoners implore the Polish Government to have the camp bombed. The destruction of the electrified barbed wire, the ensuing panic and darkness prevailing, the chances of escape would be great. The local population will hide them and help them to leave the neighbourhood. The prisoners are confidently awaiting the day when Polish planes from Great Britain will enable their escape. This is the prisoners unanimous demand to the Polish Government in London.[267]

Pierse replied that it was not technically feasible to bomb the camp without harming the prisoners.[266] In May 1944 Slovak rabbi Michael Dov Weissmandl suggested that the Allies bomb the rails leading to the camp.[268] Historian David Wyman published an essay in Commentary in 1978 entitled "Why Auschwitz Was Never Bombed", arguing that the United States Army Air Forces could and should have attacked Auschwitz. In his book The Abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust 1941–1945 (1984), Wyman argued that, since the IG Farben plant at Auschwitz III had been bombed three times between August and December 1944 by the US Fifteenth Air Force in Italy, it would have been feasible for the other camps or railway lines to be bombed too. Bernard Wasserstein's Britain and the Jews of Europe (1979) and Martin Gilbert's Auschwitz and the Allies (1981) raised similar questions about British inaction.[269] Since the 1990s, other historians have argued that Allied bombing accuracy was not sufficient for Wyman's proposed attack, and that counterfactual history is an inherently problematic endeavor.[270]

Sonderkommando revolt

The Sonderkommando who worked in the crematoria were witnesses to the mass murder and were therefore regularly murdered themselves.[272] On 7 October 1944, following an announcement that 300 of them were to be sent to a nearby town to clear away rubble—"transfers" were a common ruse for the murder of prisoners—the group, mostly Jews from Greece and Hungary, staged an uprising.[273] They attacked the SS with stones and hammers, killing three of them, and set crematorium IV on fire with rags soaked in oil that they had hidden.[274] Hearing the commotion, the Sonderkommando at crematorium II believed that a camp uprising had begun and threw their Oberkapo into a furnace. After escaping through a fence using wirecutters, they managed to reach Rajsko, where they hid in the granary of an Auschwitz satellite camp, but the SS pursued and killed them by setting the granary on fire.[275]

By the time the rebellion at crematorium IV had been suppressed, 212 members of the Sonderkommando were still alive and 451 had been killed.[276] The dead included Zalmen Gradowski, who kept notes of his time in Auschwitz and buried them near crematorium III; after the war, another Sonderkommando member showed the prosecutors where to dig.[277] The notes were published in several formats, including in 2017 as From the Heart of Hell.[278]

Evacuation and death marches

The last mass transports to arrive in Auschwitz were 60,000–70,000 Jews from the Łódź Ghetto, some 2,000 from Theresienstadt, and 8,000 from Slovakia.[279] The last selection took place on 30 October 1944.[200] On 1 or 2 November 1944, Heinrich Himmler ordered the SS to halt the mass murder by gas.[280] On 25 November, he ordered Auschwitz's gas chambers and crematoria be destroyed. The Sonderkommando and other prisoners began the job of dismantling the buildings and cleaning up the site.[281] On 18 January 1945, Engelbert Marketsch, a German criminal transferred from Mauthausen, became the last prisoner to be assigned a serial number in Auschwitz, number 202499.[282]

According to Polish historian Andrzej Strzelecki, the evacuation of the camp was one of its "most tragic chapters".[283] Himmler ordered the evacuation of all camps in January 1945, telling camp commanders: "The Führer holds you personally responsible for ... making sure that not a single prisoner from the concentration camps falls alive into the hands of the enemy."[284] The plundered goods from the "Kanada" barracks, together with building supplies, were transported to the German interior. Between 1 December 1944 and 15 January 1945, over one million items of clothing were packed to be shipped out of Auschwitz; 95,000 such parcels were sent to concentration camps in Germany.[285]

Beginning on 17 January, some 58,000 Auschwitz detainees (about two-thirds Jews)—over 20,000 from Auschwitz I and II and over 30,000 from the subcamps—were evacuated under guard, at first heading west on foot, then by open-topped freight trains, to concentration camps in Germany and Austria: Bergen-Belsen, Buchenwald, Dachau, Flossenburg, Gross-Rosen, Mauthausen, Dora-Mittelbau, Ravensbruck, and Sachsenhausen.[286] Fewer than 9,000 remained in the camps, deemed too sick to move.[287] During the marches, the SS shot or otherwise dispatched anyone unable to continue; "execution details" followed the marchers, killing prisoners who lagged behind.[283] Peter Longerich estimated that a quarter of the detainees were thus killed.[288] By December 1944 some 15,000 Jewish prisoners had made it from Auschwitz to Bergen-Belsen, where they were liberated by the British on 15 April 1945.[289]

On 20 January, crematoria II and III were blown up, and on 23 January the "Kanada" warehouses were set on fire; they apparently burned for five days. Crematorium IV had been partly demolished after the Sonderkommando revolt in October, and the rest of it was destroyed later. On 26 January, one day ahead of the Red Army's arrival, crematorium V was blown up.[290]

Liberation

The first in the camp complex to be liberated was Auschwitz III, the IG Farben camp at Monowitz; a soldier from the 100th Infantry Division of the Red Army entered the camp around 9 am on Saturday, 27 January 1945.[291] The 60th Army of the 1st Ukrainian Front (also part of the Red Army) arrived in Auschwitz I and II around 3 pm. They found 7,000 prisoners alive in the three main camps, 500 in the other subcamps, and over 600 corpses.[292] Items found included 837,000 women's garments, 370,000 men's suits, 44,000 pairs of shoes,[293] and 7,000 kg of human hair, estimated by the Soviet war crimes commission to have come from 140,000 people.[223] Some of the hair was examined by the Forensic Science Institute in Kraków, where it was found to contain traces of hydrogen cyanide, the main ingredient of Zyklon B.[294] Primo Levi described seeing the first four soldiers on horseback approach Auschwitz III, where he had been in the sick bay. They threw "strangely embarrassed glances at the sprawling bodies, at the battered huts and at us few still alive ...":[295]

They did not greet us, nor did they smile; they seemed oppressed not only by compassion but by a confused restraint, which sealed their lips and bound their eyes to the funereal scene. It was that shame we knew so well, the shame that drowned us after the selections, and every time we had to watch, or submit to, some outrage: the shame the Germans did not know, that the just man experiences at another man's crime; the feeling of guilt that such a crime should exist, that it should have been introduced irrevocably into the world of things that exist, and that his will for good should have proved too weak or null, and should not have availed in defence.[296]

Georgii Elisavetskii, a Soviet soldier who entered one of the barracks, said in 1980 that he could hear other soldiers telling the inmates: "You are free, comrades!" But they did not respond, so he tried in Russian, Polish, German, Ukrainian. Then he used some Yiddish: "They think that I am provoking them. They begin to hide. And only when I said to them: 'Do not be afraid, I am a colonel of Soviet Army and a Jew. We have come to liberate you' ... Finally, as if the barrier collapsed ... they rushed toward us shouting, fell on their knees, kissed the flaps of our overcoats, and threw their arms around our legs."[293]

The Soviet military medical service and Polish Red Cross (PCK) set up field hospitals that looked after 4,500 prisoners suffering from the effects of starvation (mostly diarrhea) and tuberculosis. Local volunteers helped until the Red Cross team arrived from Kraków in early February.[297] In Auschwitz II, the layers of excrement on the barracks floors had to be scraped off with shovels. Water was obtained from snow and from fire-fighting wells. Before more help arrived, 2,200 patients there were looked after by a few doctors and 12 PCK nurses. All the patients were later moved to the brick buildings in Auschwitz I, where several blocks became a hospital, with medical personnel working 18-hour shifts.[298]

The liberation of Auschwitz received little press attention at the time; the Red Army was focusing on its advance toward Germany and liberating the camp had not been one of its key aims. Boris Polevoi reported on the liberation in Pravda on 2 February 1945 but made no mention of Jews;[299] inmates were described collectively as "victims of Fascism".[300] It was when the Western Allies arrived in Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen, and Dachau in April 1945 that the liberation of the camps received extensive coverage.[301]

After the war

Trials of war criminals

Only 789 Auschwitz staff, up to 15 percent, ever stood trial;[8] most of the cases were pursued in Poland and the Federal Republic of Germany.[302] According to Aleksander Lasik, female SS officers were treated more harshly than male; of the 17 women sentenced, four received the death penalty and the others longer prison terms than the men. He writes that this may have been because there were only 200 women overseers, and therefore they were more visible and memorable to the inmates.[303]