Джакарта

Джакарта | |

|---|---|

| Особый столичный регион Джакарта Особый столичный регион Джакарта | |

| Nicknames: | |

| Motto(s): | |

Interactive map outlining Jakarta (parts of Thousand Islands not visible) | |

Location in Java | |

| Coordinates: 6°10′30″S 106°49′39″E / 6.17500°S 106.82750°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Java |

| Administrative cities and regencies | |

| Originated | 5th CE (first settlement) |

| Founded | 22 June 1527[3] |

| Established as Batavia | 30 May 1619[4] |

| City status | 4 March 1621[3] |

| Province status | 28 August 1961[3] |

| Capital | Central Jakarta (de facto)[b] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Special administrative area |

| • Body | Special Capital Region of Jakarta Provincial Government |

| • Governor | Heru Budi Hartono (Acting) |

| • Vice Governor | Vacant |

| • Legislature | Jakarta Regional People's Representative Council |

| Area | |

| • Special Capital Region | 660.982 km2 (255.207 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 3,546 km2 (547.16 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 7,076.31 km2 (2,732.18 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 38th in Indonesia |

| Elevation | 8 m (26 ft) |

| Population (2023)[5] | |

| • Special Capital Region | 11,350,328 |

| • Rank | 6th in Indonesia |

| • Density | 17,000/km2 (44,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 35,386,000 |

| • Urban density | 10,000/km2 (65,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 32,594,159 |

| • Metro density | 4,600/km2 (12,000/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Jakartan |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic groups | List |

| • Religion (2022)[8] | List |

| GDP | |

| • City | Rp 3,442.98 trillion US$ 225.88 billion Int$ 724.01 billion (PPP) |

| • Per capita | Rp 322.62 million US$ 21,166 Int$ 67,842 (PPP) |

| • Metro | Rp 6,404.70 trillion US$ 420.192 billion Int$ 1.346 trillion (PPP) |

| Time zone | UTC+07:00 (Indonesia Western Time) |

| Postal codes | 10110–14540, 19110–19130 |

| Area code | +62 21 |

| ISO 3166 code | ID-JK |

| Vehicle registration | B |

| HDI (2023) | |

| Website | jakarta |

Джакарта [с] ( / dʒ ə ˈ k ɑːr t ə / ; Индонезийское произношение: [dʒaˈkarta] , Бетави : Джакарта ), официально особый столичный регион Джакарты. [12] ( Индонезийский : Даэра Хусус Ибукота Джакарта , сокращенно DKI Джакарта ) и ранее известный как Батавия до 1949 года, является уходящей столицей и крупнейшим городом Индонезии Явы до 17 августа 2024 года. Расположен на северо-западном побережье , в мире самого густонаселенного острова , Джакарта – крупнейший мегаполис в Юго-Восточной Азии и дипломатическая столица АСЕАН . Особый столичный регион имеет статус, эквивалентный статусу провинции , и граничит с двумя другими провинциями: Западная Ява на юге и востоке; и (с 2000 года, когда он был отделен от Западной Явы) Бантен на западе. Его береговая линия обращена к Яванскому морю на севере и имеет морскую границу с Лампунгом на западе. Агломерация Джакарты является второй по величине экономикой АСЕАН после Сингапура .

Джакарта — экономический, культурный и политический центр Индонезии. Хотя Джакарта простирается всего на 661,23 км. 2 (255.30 sq mi) and thus has the smallest area of any Indonesian province, its metropolitan area covers 7,076.31 km2 (2,732.18 sq mi), which includes the satellite cities of Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, South Tangerang, and Bekasi, and has an estimated population of 32.6 million as of 2022[update], что делает его крупнейшим городским районом в Индонезии и вторым по величине в мире (после Токио ). Джакарта занимает первое место среди индонезийских провинций по индексу человеческого развития . Возможности бизнеса и трудоустройства Джакарты, а также ее способность предложить потенциально более высокий уровень жизни по сравнению с другими частями страны привлекают мигрантов со всего индонезийского архипелага , что делает Джакарту плавильным котлом множества культур.

Jakarta is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Southeast Asia. Established in the fourth century as Sunda Kelapa, the city became an important trading port for the Sunda Kingdom. At one time, it was the de facto capital of the Dutch East Indies, when it was known as Batavia. Jakarta was officially a city within West Java until 1960 when its official status was changed to a province with special capital region distinction. As a province, its government consists of five administrative cities and one administrative regency. Jakarta is an alpha world city and is the seat of the ASEAN secretariat. Financial institutions such as the Bank of Indonesia, Indonesia Stock Exchange, and corporate headquarters of numerous Indonesian companies and multinational corporations are located in the city. In 2021, the city's GRP PPP was estimated at US$602.946 billion.

Jakarta's main challenges include rapid urban growth, ecological breakdown, air pollution, gridlocked traffic, congestion, and flooding due to subsidence (sea level rise is relative, not absolute). Jakarta is sinking up to 17 cm (6.7 inches) annually, which has made the city more prone to flooding and one of the fastest-sinking capitals in the world. In response to these challenges, in August 2019, President Joko Widodo announced plans to move the capital from Jakarta to the planned city of Nusantara, in the province of East Kalimantan on the island of Borneo. The MPR approved the move on 18 January 2022.

Name

[edit]Jakarta has been home to multiple settlements. Below is the list of names used during its existence:

Sunda Kelapa (13th CE–1527)

Jayakarta (1527–1619)Batavia (1619–1949)

Djakarta (1942–1972)

Jakarta (1972–present)

The original name for the city was 'Sunda Kelapa' or 'Coconut of Sunda', growing to be the main harbour for the Sunda Kingdom, due to its desirable location.[13][14]

The name 'Jakarta' is derived from the word Jayakarta (Devanagari: जयकर्त) which is ultimately derived from the Sanskrit जय jaya (victorious),[15] and कृत krta (accomplished, acquired),[16] thus Jayakarta translates as 'victorious deed', 'complete act' or 'complete victory'. It was named for the Muslim troops of Fatahillah which successfully defeated and drove the Portuguese away from the city in 1527, eventually renaming it 'Jayakarta'.[17] Tomé Pires, a Portuguese apothecary, wrote the name of the city in his magnum opus as Jacatra or Jacarta[18] during his journey to the East Indies.

After the Dutch East India Company took over the area in 1619, they renamed it to 'Batavia', after the Batavi, a Germanic tribe who were seen as the ancestors of the Dutch. The city was then also known as Koningin van het Oosten (Queen of the Orient), a name that was given for the urban beauty of downtown Batavia's canals, mansions and ordered city layout.[19] After expanding to the south in the 19th century, this nickname came to be more associated with the suburbs (e.g. Menteng and the area around Merdeka Square), with their wide lanes, green spaces and villas.[20] During the Japanese occupation, the city was renamed as Jakaruta Tokubetsu-shi (ジャカルタ特別市, Jakarta Special City).[13] After the Japanese surrender, the name was changed to 'Jakarta'.[13]

History

[edit]Precolonial era

[edit]

The north coast area of western Java including Jakarta was the location of prehistoric Buni culture that flourished from 400 BC to 100 AD.[21] The area in and around modern Jakarta was part of the 4th-century Sundanese kingdom of Tarumanagara, one of the oldest Hindu kingdoms in Indonesia.[22] The area of North Jakarta around Tugu became a populated settlement in the early 5th century. The Tugu inscription (probably written around 417 AD) discovered in Batutumbuh hamlet, Tugu village, Koja, North Jakarta, mentions that King Purnawarman of Tarumanagara undertook hydraulic projects; the irrigation and water drainage project of the Chandrabhaga river and the Gomati river near his capital.[23] Following the decline of Tarumanagara, its territories, including the Jakarta area, became part of the Hindu Kingdom of Sunda. From the 7th to the early 13th century, the port of Sunda was under the Srivijaya maritime empire. According to the Chinese source, Chu-fan-chi, written circa 1225, Chou Ju-kua reported in the early 13th century that Srivijaya still ruled Sumatra, the Malay peninsula and western Java (Sunda).[24] The source says the port of Sunda is strategic and thriving, mentioning pepper from Sunda as among the best in quality. The people worked in agriculture, and their houses were built on wooden piles.[25] The harbour area became known as Sunda Kelapa, (Sundanese: ᮞᮥᮔ᮪ᮓ ᮊᮨᮜᮕ) and by the 14th century, it was an important trading port for the Sunda Kingdom.

The first European fleet, four Portuguese ships from Malacca, arrived in 1513 while looking for a route to obtain spices.[26] The Sunda Kingdom made an alliance treaty with the Portuguese by allowing them to build a port in 1522 to defend against the rising power of Demak Sultanate from central Java.[17] In 1527, Fatahillah, a Pasai-born military commander of Demak attacked and conquered Sunda Kelapa, driving out the Portuguese. Sunda Kelapa was renamed Jayakarta,[17] and became a fiefdom of the Banten Sultanate, which became a major Southeast Asian trading centre.

Through the relationship with Prince Jayawikarta of the Banten Sultanate, Dutch ships arrived in 1596. In 1602, an English East India Company (EIC) voyage led by Sir James Lancaster arrived in Aceh and sailed on to Banten, where they were allowed to build a trading post. This site became the centre of English trade in the Indonesian archipelago until 1682.[27] Jayawikarta is thought to have made trading connections with the English merchants, who were rivals with the Dutch, by allowing them to build houses directly across from the Dutch buildings in 1615.[26]

Colonial era

[edit]

When relations between Prince Jayawikarta and the Dutch deteriorated, his soldiers attacked the Dutch fortress. His army and their EIC allies, however, were defeated by the Dutch, in part owing to the timely arrival of Jan Pieterszoon Coen. The Dutch burned the EIC trading post and forced them to retreat to their ships. The victory consolidated Dutch power, and they renamed the city Batavia in 1619.

Commercial opportunities in the city attracted native and especially Chinese and Arab immigrants. This sudden population increase created burdens on the city. Tensions grew as the colonial government tried to restrict Chinese migration through deportations. Following a revolt, 5,000 Chinese were massacred by the Dutch and natives on 9 October 1740, and the following year, Chinese inhabitants were moved to Glodok outside the city walls.[28] At the beginning of the 19th century, around 400 Arabs and Moors lived in Batavia, a number that changed little during the following decades. Among the commodities traded were fabrics, mainly imported cotton, batik and clothing worn by Arab communities.[29]

The city began to expand further south as epidemics in 1835 and 1870 forced residents to move away from the port. The Koningsplein, now Merdeka Square was completed in 1818, the housing park of Menteng was started in 1913,[30] and Kebayoran Baru was the last Dutch-built residential area.[28] By 1930, Batavia had more than 500,000 inhabitants,[31] including 37,067 Europeans.[32] The city was expanded in 1935 through the annexation of the town of Meester Cornelis, modern Jatinegara.[33]

On 5 March 1942, the Japanese captured Batavia from Dutch control, and the city was named Jakarta (Jakarta Special City (ジャカルタ特別市, Jakaruta tokubetsu-shi), under the special status that was assigned to the city). After the war, the Dutch name Batavia was internationally recognised until full Indonesian independence on 27 December 1949. The city, now renamed Jakarta, was officially proclaimed the national capital of Indonesia.

Independence era

[edit]

After World War II ended, Indonesian nationalists declared independence on 17 August 1945,[34] and the government of Jakarta City was changed into the Jakarta National Administration in the following month. During the Indonesian National Revolution, Indonesian Republicans withdrew from Allied-occupied Jakarta and established their capital in Yogyakarta.

After securing full independence, Jakarta again became the national capital in 1950.[28] With Jakarta selected to host the 1962 Asian Games, Sukarno, envisaging Jakarta as a great international city, instigated large government-funded projects with openly nationalistic and modernist architecture.[35] Projects included a cloverleaf interchange, a major boulevard (Jalan MH Thamrin-Sudirman), monuments such as The National Monument, Hotel Indonesia, a shopping centre, and a new building intended to be the headquarters of CONEFO. In October 1965, Jakarta was the site of an abortive coup attempt in which six top generals were killed, precipitating a violent anti-communist purge which killed at least 500,000 people, including some ethnic Chinese.[36] The event marked the beginning of Suharto's New Order. The first government was led by a mayor until the end of 1960 when the office was changed to that of a governor. The last mayor of Jakarta was Soediro until he was replaced by Soemarno Sosroatmodjo as governor.

In 1966, Jakarta was declared a 'special capital region' (Daerah Khusus Ibukota), with a status equivalent to that of a province.[37] Based on law No. 5 of 1974 relating to regional governments, the Jakarta Special Capital Region was confirmed as the capital of Indonesia and one of the country's then 26 provinces.[38] Lieutenant General Ali Sadikin served as governor from 1966 to 1977; he rehabilitated roads and bridges, encouraged the arts, built hospitals and a large number of schools. He cleared out slum dwellers for new development projects — some for the benefit of the Suharto family,[39]— and attempted to eliminate rickshaws and ban street vendors. He began control of migration to the city to stem overcrowding and poverty.[40] Foreign investment contributed to a real estate boom that transformed the face of Jakarta.[41] The boom ended with the 1997 Asian financial crisis, putting Jakarta at the centre of violence, protest, and political manoeuvring.

After three decades in power, support for President Suharto began to wane. Tensions peaked when four students were shot dead at Trisakti University by security forces. Four days of riots and violence in 1998 ensued that killed an estimated 1,200, and destroyed or damaged 6,000 buildings, forcing Suharto to resign.[42] Much of the rioting targeted Chinese Indonesians.[43] In the post-Suharto era, Jakarta has remained the focal point of democratic change in Indonesia.[44] Jemaah Islamiyah-connected bombings occurred almost annually in the city between 2000 and 2005,[28] with another in 2009.[45] In August 2007, Jakarta held its first-ever election to choose a governor as part of a nationwide decentralisation program that allows direct local elections in several areas. Previously, governors were elected by the city's legislative body.[46]

During the Jokowi presidency, the Government adopted a plan to move Indonesia's capital to Nusantara after 17 August 2024.[47]

Between 2016 and 2017, a series of terrorist attacks rocked Jakarta with scenes of multiple suicide bombings and gunfire. In suspicion to its links, the Islamic State, the perpetrator led by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi claimed responsibility for the attacks.

Geography

[edit]Jakarta covers 661.23 km2 (255.30 sq mi), the smallest among any Indonesian provinces. However, its metropolitan area covers 6,392 km2 (2,468 sq mi), which extends into the two bordering provinces of West Java and Banten.[48] The Greater Jakarta area includes three bordering regencies (Bekasi Regency, Tangerang Regency and Bogor Regency) and five adjacent cities (Bogor, Depok, Bekasi, Tangerang and South Tangerang).

Jakarta is situated on the northwest coast of Java, at the mouth of the Ciliwung River on Jakarta Bay, an inlet of the Java Sea. It is strategically located near the Sunda Strait. The northern part of Jakarta is plain land, some areas of which are below sea level,[49] and subject to frequent flooding. The southern parts of the city are hilly. It is one of only two Asian capital cities located in the southern hemisphere (along with East Timor's Dili). Officially, the area of the Jakarta Special District is 661.23 km2 (255 sq mi) of land area and 6,977 km2 (2,694 sq mi) of sea area.[50] The Thousand Islands, which are administratively a part of Jakarta, are located in Jakarta Bay, north of the city.

Jakarta lies in a low and flat alluvial plain, ranging from −2 to 91 m (−7 to 299 ft) with an average elevation of 8 m (26 ft) above sea level with historically extensive swampy areas. Some parts of the city have been constructed on reclaimed tidal flats that occur around the area.[51] Thirteen rivers flow through Jakarta. They are Ciliwung River, Kalibaru, Pesanggrahan, Cipinang, Angke River, Maja, Mookervart, Krukut, Buaran, West Tarum, Cakung, Petukangan, Sunter River and Grogol River.[52][53] They flow from the Puncak highlands to the south of the city, then across the city northwards towards the Java Sea. The Ciliwung River divides the city into the western and eastern districts.

These rivers, combined with the wet season rains and insufficient drainage due to clogging, make Jakarta prone to flooding.

Moreover, Jakarta is sinking about 5 to 10 cm (2.0 to 3.9 in) each year, and up to 20 cm (7.9 in) in the northern coastal areas. After a feasibility study, a ring dyke known as Giant Sea Wall Jakarta is under construction around Jakarta Bay to help cope with the threat from the sea. The dyke will be equipped with a pumping system and retention areas to defend against seawater and function as a toll road. The project is expected to be completed by 2025.[54] In January 2014, the central government agreed to build two dams in Ciawi, Bogor and a 1.2 km (0.75 mi) tunnel from Ciliwung River to Cisadane River to ease flooding in the city.[55] Nowadays, a 1.2 km (0.75 mi), with capacity 60 m3 (2,100 cu ft) per second, underground water tunnel between Ciliwung River and the East Flood Canal is being worked on to ease the Ciliwung River overflows.[56] In 2023, the New York Times reported that in some places Jakarta is sinking up to 12 inches (30 cm) annually.[57]

Environmental advocates point out that subsidence is driven by the extraction of groundwater, much of it illegal. Furthermore, the government's lack of strict regulation amplifies the issue as many recently built high-rise buildings, corporations, and factories around Jakarta opt for illegally extracting groundwater. In fact, in a recent inspection of 80 buildings in Jalan Thamrin, a busy road lined with skyscrapers and shopping malls, 56 buildings had a groundwater pump, and 33 were pumping groundwater illegally.[58] This could be halted by stopping extraction (as the city of Tokyo has done), increasing efficiency, and finding other sources for water use. Moreover, increasing regulation through higher taxes or limiting groundwater pumping has proven to help cities like Shanghai, Tokyo, and San Jose relieve their subsidence issue.[59] The rivers of Jakarta are highly polluted and currently unsuitable for drinking water.[60]

Jakarta, faces significant air pollution, particularly during the dry season from August to December. Dry air during this period allows pollutants to remain suspended in the atmosphere for extended periods, contributing to poor air quality.[61][62]

Architecture

[edit]

Jakarta has architecturally significant buildings spanning distinct historical and cultural periods. Architectural styles reflect Malay, Sundanese, Javanese, Arabic, Chinese and Dutch influences.[63] External influences inform the architecture of the Betawi house. The houses were built of nangka wood (Artocarpus integrifolia) and comprised three rooms. The shape of the roof is reminiscent of the traditional Javanese joglo.[64] Additionally, the number of registered cultural heritage buildings has increased.[65]

Colonial buildings and structures include those that were constructed during the colonial period. The dominant colonial styles can be divided into three periods: the Dutch Golden Age (17th to late 18th century), the transitional style period (late 18th century – 19th century), and Dutch modernism (20th century). Colonial architecture is apparent in houses and villas, churches, civic buildings and offices, mostly concentrated in the Jakarta Old Town and Central Jakarta. Architects such as J.C. Schultze and Eduard Cuypers designed some of the significant buildings. Schultze's works include Jakarta Art Building, the Indonesia Supreme Court Building and Ministry of Finance Building, while Cuypers designed Bank Indonesia Museum and Mandiri Museum. In the early 20th century, most buildings were built in Neo-Renaissance style. By the 1920s, the architectural taste had begun to shift in favour of rationalism and modernism, particularly art deco architecture. The elite suburb Menteng, developed during the 1910s, was the city's first attempt at creating an ideal and healthy housing for the middle class. The original houses had a longitudinal organisation, with overhanging eaves, large windows and open ventilation, all practical features for a tropical climate.[66] These houses were developed by N.V. de Bouwploeg, and established by P.A.J. Moojen.

After independence, the process of nation-building in Indonesia and demolishing the memory of colonialism was as important as the symbolic building of arterial roads, monuments, and government buildings. The National Monument in Jakarta, designed by Sukarno, is Indonesia's beacon of nationalism. In the early 1960s, Jakarta provided highways and super-scale cultural monuments as well as Senayan Sports Stadium. The parliament building features a hyperbolic roof reminiscent of German rationalist and Corbusian design concepts.[67] Built-in 1996, Wisma 46 soars to a height of 262 m (860 ft) and its nib-shaped top celebrates technology and symbolises stereoscopy.

The urban construction boom continued during the 21st century. The Golden Triangle of Jakarta is one of the fastest evolving CBD's in the Asia-Pacific region.[68] According to CTBUH and Emporis, there are 88 skyscrapers that reach or exceed 150 m (490 ft), which puts the city in the top 10 of world rankings.[69] It has more buildings taller than 150 metres than any other Southeast Asian or Southern Hemisphere cities.

Landmarks

[edit]

Most landmarks, monuments and statues in Jakarta were begun in the 1960s during the Sukarno era, then completed in the Suharto era, while some date from the colonial period. Although many of the projects were completed after his presidency, Sukarno, who was an architect, is credited for planning Jakarta's monuments and landmarks, as he desired the city to be the beacon of a powerful new nation. Among the monumental projects that were built, initiated, and planned during his administration are the National Monument, Istiqlal mosque, the Legislature Building, and the Gelora Bung Karno stadium. Sukarno also built many nationalistic monuments and statues in the capital city.[70]

The most famous landmark, which became the symbol of the city, is the 132 m-tall (433 ft) obelisk of the National Monument (Monumen Nasional or Monas) in the centre of Merdeka Square. On its southwest corner stands a Mahabharata-themed Arjuna Wijaya chariot statue and fountain. Further south through Jalan M.H. Thamrin, one of the main avenues, the Selamat Datang monument stands on the fountain in the centre of the Hotel Indonesia roundabout. Other landmarks include the Istiqlal Mosque, Jakarta Cathedral and the Immanuel Church. The former Batavia Stadhuis, Sunda Kelapa port in Jakarta Old Town is another landmark. The Autograph Tower in Central Jakarta, at 382.9 metres is the tallest building in Indonesia. The most recent landmark built is the Jakarta International Stadium.

Some of the statues and monuments are nationalist, such as the West Irian Liberation Monument, the Tugu Tani, the Youth statue and the Dirgantara Monument. Some statues commemorate Indonesian national heroes, such as the Diponegoro and Kartini statues in Merdeka Square. The Sudirman and Thamrin statues are located on the streets bearing their names. There is also a statue of Sukarno and Hatta at the Proclamation Monument as well as at the entrance to Soekarno–Hatta International Airport.

Parks and public spaces

[edit]In June 2011, Jakarta had only 10.5% green open spaces (Ruang Terbuka Hijau), although this grew to 13.94%. Public parks are included in public green open spaces.[71] There are about 300 integrated child-friendly public spaces (RPTRA) in the city in 2019.[72] As of 2014, 183 water reservoirs and lakes supported the greater Jakarta area.[73]

- Merdeka Square (Medan Merdeka) is an almost 1 km2 field housing the symbol of Jakarta, Monas or Monumen Nasional (National Monument). Until 2000, it was the world's largest city square. The square was created by Dutch Governor-General Herman Willem Daendels (1810) and was originally named Koningsplein (King's Square). On 10 January 1993, President Soeharto started the beautification of the square. Features include a deer park and 33 trees that represent the 33 provinces of Indonesia.[74]

- Ancol Dreamland is the largest integrated tourism area in Southeast Asia. It is located along the bay, at Ancol in North Jakarta.

- Lapangan Banteng (Buffalo Field) is located in Central Jakarta near Istiqlal Mosque, Jakarta Cathedral, and Jakarta Central Post Office. It covers about 4.5 hectares. Initially, it was called Waterlooplein and functioned as a ceremonial square during the colonial period. During the Sukarno era, colonial buildings and memorials that were erected in the square during the colonial period were destroyed and the most famous monument in this square was the West Irian Liberation Monument.[75]

- Jakarta History Museum Museum about the history of the city of Jakarta. This museum is located on the south side of Fatahillah Square (former Batavia city square) near Wayang Museum and Fine Art and Ceramic Museum.[76]

- Taman Mini Indonesia Indah (Miniature Park of Indonesia), in East Jakarta, has ten mini-parks.

- National Gallery of Indonesia is an art gallery and museum in Jakarta, Indonesia. This art gallery was established as a cultural institution in the field of fine arts since May 8 1999. The institution plays an important role in expanding public's awareness of artworks through preservation, development and exploitation of the visual arts in Indonesia.[77]

- Suropati Park is located in Menteng, Central Jakarta. The park is surrounded by Dutch colonial buildings. Taman Suropati was known as Burgemeester Bisschopplein during colonial time. The park is circular-shaped with a surface area of 16,322 m2 (175,690 sq ft). Several modern statues were made for the park by artists of ASEAN countries, which contributes to its nickname 'Taman persahabatan seniman ASEAN' ('Park of the ASEAN artists friendship').[78]

- Menteng Park was built on the site of the former Persija football stadium. Situ Lembang Park is also located nearby, which has a lake at the centre.

- Kalijodo Park is the newest park, in Penjaringan subdistrict, with 3.4 ha (8.4 acres) beside the Krendang River. It formally opened on 22 February 2017. The park is open 24 hours as a green open space (RTH) and child-friendly integrated public space (RPTRA) and has international-standard skateboard facilities.[79]

- Muara Angke Wildlife Sanctuary and Angke Kapuk Nature Tourism Park at Penjaringan in North Jakarta.[80]

- Tebet Eco Park, Puring Park, Mataram Park, Langsat Park, Ayodya Park and Martha Christina Tiahahu Literacy Park in South Jakarta.[81][82]

- Ragunan Zoo is located in Pasar Minggu, South Jakarta. It is the world's third-oldest zoo and the second-largest with the most diverse animal and plant populations.[83]

- Glodok is an area known as Pecinan or Chinatown since the Dutch colonial era, and is considered the largest in Indonesia.

- National Museum of Indonesia is an archeology, history, ethnology, and geographical museum whose extensive collections cover the entire territory of Indonesia and almost all of its history. This museum has attempted to preserve Indonesia's heritage for two centuries.[84]

- Setu Babakan is a 32-hectare lake surrounded by Betawi cultural village, located at Jagakarsa, South Jakarta.[85] Dadap Merah Park is also found in this area.

- UI park is the largest Urban forest in Jakarta with 90 ha (222 acre). It located at South Jakarta bordering with Depok, West Java.[86]

- National Library of Indonesia is legitimate deposit of literature, manuscripts and archival books from the state of Indonesia. It is located in Gambir, south side of Merdeka Square, Jakarta. The earliest collection comes from the library of the National Museum, opened in 1868 and previously operated by the Royal Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences.[87][88]

- Taman Waduk Pluit/Pluit Lake park and Putra Putri Park at Pluit, North Jakarta.[89]

- Gelora Bung Karno Sports Complex The Gelora Bung Karno complex is one of the largest sports activity centers in Indonesia and is often used for sporting activities by Jakarta residents [90]

- Taman Literasi Martha Christina Tiahahu Literacy Park Martha Chirstina Tiahahu Is City Park And Literacy Park In Blok M business and shopping quarter located in Blok M Kebayoran Baru, South Jakarta, Indonesia.

- GBK City Park is the city park in Golden Triangle of Jakarta, it located within Gelora Bung Karno Sports Complex.[91]

- Pantai Indah Kapuk (PIK) is often the most sought after residential area for wealthy Chinese Indonesians, featuring large houses in exclusive, gated clusters. This area never floods, even though it is close to a flood-prone district. Although most of Pantai Indah Kapuk is a residential area, there are businesses and tourist attractions on the main roads such as North Beach, South Beach and Marina Indah. Ruko Cordoba and Crown Golf on Jalan Marina Indah are very popular for restaurants and cafes. PIK is one of the nightlife areas in Jakarta. Full of nightclubs, discos, bars and cafes.[92]

- GBK City Park is a Park in Centre of Јаkаrtа, location on Gelora Bung Karno Sports Complex.

- The iconic golden snail IMAX special-built cinema at Taman Mini Indonesia Indah. It was the only IMAX cinema in Indonesia until the opening of an IMAX screen in Gandaria City in the 2010s

- Martha Chirstina Tiahahu Literacy Park, South Jakarta

- The Contempory Art Gallery at Taman Mini Indonesia Indah. It is an Art Gallery in Jakarta

- Tebet Eco Park is the one of largest parks in Jakarta

Climate

[edit]

Jakarta experiences a tropical monsoon climate (Köppen: Am) as classified by the system. The city’s wet season spans most of the year, from October to May. The dry season lasts from June to September, with each of these months receiving less than 100 millimetres (3.9 in) of rainfall on average. Situated in the western part of Java, Jakarta sees its highest rainfall in January and February, averaging 299.7 millimetres (11.8 in) per month, while the drier season month is August, with an average rainfall of 43.2 millimetres (1.7 in).[93]

Every year faces recurring issues, such as floods and thunderstorms. A cyclonic vortex leads to moisture convergence over a large area, including western Java Island. Additionally, this vortex causes a mainly meridional monsoon flow, where near-surface winds blow almost perfectly from north to south over West Java. The impact of these predominant northerly winds hitting the rugged topography in southern West Java likely contributes to the increased convection that causes floods in Jakarta.[94]

Average temperatures is very high and moderate rainfall. During the day, the temperature usually hovers around 32 °C (89.6 °F) but drops to about 24 °C (75.2 °F) in the evening. These are average temperatures, and some days can be hotter. It's advisable to dress appropriately to handle the heat. January is the rainiest month, with over 300 millimetres (11.8 in) of precipitation, whereas August is the driest, with around 45 millimetres (1.8 in) of rainfall. The average temperature in the coldest month (February) is 27 °C (80.6 °F), and in the warmest month (October), it is 28 °C (82.4 °F). Sea temperatures range from 26.5 °C (79.7 °F) in August to 29.5 °C (85.1 °F) in March, April, November, and December.[95][96] Record low temperatures in Jakarta recorded 18.9 °C (66.0 °F), while the highest record reached 37.9 °C (100.2 °F).[97]

| Climate data for Jakarta (Kemayoran) (1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36.9 (98.4) | 34.8 (94.6) | 36.0 (96.8) | 35.9 (96.6) | 36.1 (97.0) | 36.3 (97.3) | 35.6 (96.1) | 35.6 (96.1) | 37.1 (98.8) | 37.9 (100.2) | 37.1 (98.8) | 36.7 (98.1) | 37.9 (100.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 31.0 (87.8) | 30.8 (87.4) | 32.1 (89.8) | 32.8 (91.0) | 33.2 (91.8) | 32.9 (91.2) | 32.7 (90.9) | 33.0 (91.4) | 33.4 (92.1) | 33.4 (92.1) | 32.8 (91.0) | 32.0 (89.6) | 32.5 (90.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.5 (81.5) | 27.3 (81.1) | 28.0 (82.4) | 28.4 (83.1) | 28.7 (83.7) | 28.4 (83.1) | 28.2 (82.8) | 28.3 (82.9) | 28.6 (83.5) | 28.8 (83.8) | 28.4 (83.1) | 28.0 (82.4) | 28.2 (82.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 25.2 (77.4) | 25.2 (77.4) | 25.5 (77.9) | 25.6 (78.1) | 25.8 (78.4) | 25.5 (77.9) | 25.3 (77.5) | 25.3 (77.5) | 25.5 (77.9) | 25.6 (78.1) | 25.6 (78.1) | 25.5 (77.9) | 25.5 (77.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 20.6 (69.1) | 20.6 (69.1) | 20.6 (69.1) | 20.6 (69.1) | 21.1 (70.0) | 19.4 (66.9) | 19.4 (66.9) | 19.4 (66.9) | 18.9 (66.0) | 20.6 (69.1) | 20.0 (68.0) | 19.4 (66.9) | 18.9 (66.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 373.3 (14.70) | 381.4 (15.02) | 210.4 (8.28) | 164.1 (6.46) | 103.2 (4.06) | 80.4 (3.17) | 77.7 (3.06) | 51.5 (2.03) | 61.0 (2.40) | 112.2 (4.42) | 134.8 (5.31) | 183.3 (7.22) | 1,933.3 (76.11) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 17.5 | 17.9 | 14.1 | 11.5 | 8.2 | 6.2 | 4.8 | 3.3 | 4.0 | 7.4 | 10.4 | 12.8 | 118.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85 | 85 | 83 | 82 | 82 | 81 | 78 | 76 | 75 | 77 | 81 | 82 | 81 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 84.6 | 78.9 | 119.6 | 129.7 | 130.4 | 120.4 | 148.5 | 172.3 | 176.9 | 153.4 | 103.0 | 83.6 | 1,501.3 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization[98] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Sistema de Clasificación Bioclimática Mundial[99]Danish Meteorological Institute (humidity)[100] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Jakarta | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | 28.0 (82.0) | 28.0 (82.0) | 29.0 (84.0) | 30.0 (86.0) | 30.0 (86.0) | 29.0 (84.0) | 29.0 (84.0) | 29.0 (84.0) | 29.0 (84.0) | 29.0 (84.0) | 29.0 (84.0) | 29.0 (84.0) | 29.0 (84.0) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 12 |

| Source: Weather Atlas[101] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 65,000 | — |

| 1875 | 99,100 | +52.5% |

| 1880 | 102,900 | +3.8% |

| 1883 | 97,000 | −5.7% |

| 1886 | 100,500 | +3.6% |

| 1890 | 105,100 | +4.6% |

| 1901 | 115,900 | +10.3% |

| 1905 | 138,600 | +19.6% |

| 1918 | 234,700 | +69.3% |

| 1920 | 253,800 | +8.1% |

| 1925 | 290,400 | +14.4% |

| 1928 | 311,000 | +7.1% |

| 1930 | 435,184 | +39.9% |

| 1940 | 530,000 | +21.8% |

| 1945 | 600,000 | +13.2% |

| 1950 | 1,800,000 | +200.0% |

| 1959 | 2,814,000 | +56.3% |

| 1960 | 2,678,740 | −4.8% |

| 1961 | 2,906,533 | +8.5% |

| 1970 | 3,915,406 | +34.7% |

| 1980 | 6,700,000 | +71.1% |

| 1985 | 7,900,000 | +17.9% |

| 1990 | 8,174,756 | +3.5% |

| 2000 | 8,389,759 | +2.6% |

| 2010 | 9,625,579 | +14.7% |

| 2020 | 10,562,088 | +9.7% |

| 2021 | 10,609,681 | +0.5% |

| 2022 | 10,679,951 | +0.7% |

| 2023 | 10,672,100 | −0.1% |

| Note: Census figures cover the actual and projected populations of the largest Asian urban agglomerations.[102] According to the Indonesia Central Bureau of Statistics, 23 per cent of urban residents live in poverty. With a population of 7.9 million in 1985, Jakarta accounted for 19 per cent of the total Indonesia urban population. [103] Source: [104][105] | ||

Jakarta attracts people from across Indonesia, often in search of employment. The 1961 census showed that 51% of the city's population was born in Jakarta.[106] Inward immigration tended to negate the effect of family planning programs.[38] Ministry of Home Affairs (Kemendagri) tabulates its own data, which has improved since ID card requirements in last decade, lists Jakarta's population at 11,261,595 in yearend 2021.

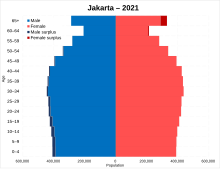

Between 1961 and 1980, the population of Jakarta doubled, and during the period 1980–1990, the city's population grew annually by 3.7%.[107] The 2010 census counted some 9.58 million people, well above government estimates.[108] The population rose from 4.5 million in 1970 to 9.5 million in 2010, counting only legal residents, while the population of Greater Jakarta rose from 8.2 million in 1970 to 28.5 million in 2010. As of 2014, the population of Jakarta stood at 10 million,[109] with a population density of 15,174 people/km2.[110][111] In 2014, the population of Greater Jakarta was 30 million, accounting for 11% of Indonesia's overall population.[112] It is predicted to reach 35.6 million people by 2030 to become the world's biggest megacity.[113] The gender ratio was 102.8 (males per 100 females) in 2010,[114] and 101.3 in 2014.[115]

Ethnicity

[edit]Jakarta is pluralistic and religiously diverse, without a majority ethnic group. As of 2010, 36.17% of the city's population were Javanese, 28.29% Betawi (locally established mixed race, cemented by diverse creole), 14.61% Sundanese, 6.62% Chinese, 3.42% Batak, 2.85% Minangkabau, 0.96% Malays, Indo and others 7.08%.

The 'Betawi' (Orang Betawi, or 'people of Batavia') are immigrant descendants of the old city who became widely recognised as an ethnic group by the mid-19th century. They mostly descend from an eclectic mix of Southeast Asians brought or attracted to meet labour needs.[116] They are thus a creole ethnic group who came from much of Indonesia. Over generations, most have intermarried with one or more ethnicities, especially people of Chinese, Arab and European descent.[117] Most Betawis lived in the fringe zones with few Betawi-majority zones of central Jakarta.[118] It is thus a conundrum for some Javanese people, especially multi-generational Jakarta residents, to identify as either Javanese or Betawi since living in a Betawi-majority district and speaking more of that creole and adapting is a matter of preference for such families.

A significant Chinese community has lived in Jakarta for many centuries. They traditionally reside around old urban areas, such as Pinangsia, PIK, Pluit and Glodok (Jakarta's Chinatown) areas. They also can be found in the old Chinatowns of Senen and Jatinegara. As of 2001 they self-identified as being 5.5%, which was thought of as under-reported;[119] this explains the 6.6% figure ten years later.

The Sumatran residents are diverse. According to the 2020 census, roughly 361,000 Batak; 300,960 Minangkabau and 101,370 Malays lived in the city. The number of Batak people has grown in ranking, from eighth in 1930 to fifth in 2000. Toba Batak is the largest subset in Jakarta.[120] Working Minangkabau in the 1980s in high proportions were well-embedded merchants, artisans, doctors, teachers or journalists.[121][122] Minang merchants are found in traditional markets, such as Tanah Abang and Senen.[123]

Language

[edit]Indonesian is the official and dominant language of Jakarta, while many elderly people speak Dutch or Chinese, depending on their upbringing. English is used for communication, especially in Central and South Jakarta.[124] Each of the ethnic groups uses their mother tongue at home, such as Betawi, Javanese, and Sundanese. The Betawi language is distinct from those of the Sundanese or Javanese, forming itself as a language island in the surrounding area. It is mostly based on the East Malay dialect and enriched by loan words from Dutch, Portuguese, Sundanese, Javanese, Chinese, and Arabic. Over time, many Betawi words and phrases became integrated into Indonesian as Jakartan slang, and is used by most people regardless of their ethnic background.

The Chinese in Jakarta mainly speak Indonesian and English due to a strict language ban during Soeharto's New Order era; older people may be fluent in Hokkien dialect and Mandarin, meanwhile the youngsters are only fluent in Indonesian and English, some educated in Mandarin. With the recent urbanization of Chinese communities from several rural areas in Indonesia, other Chinese dialects have been brought into the Chinese community in Jakarta, such as Hakka, Teochew and Cantonese. Hokkien, which is mainly from Sumatra (Medan, Bagansiapiapi, Batam) is mostly spoken in Northern Jakarta, such as in Pantai Indah Kapuk, Pluit, and Kelapa Gading, meanwhile Hakka and Teochew, which are derived from the Chinese communities in Pontianak and Singkawang, are mainly spoken in West Jakarta, like in Tambora and Grogol Petamburan.

The Batak in Jakarta mostly speak Indonesian, while the older generation tends to speak their native languages, such as Batak Toba, Mandailing, and Karo, depending on which ancestral towns and places in North Sumatra they come from. The Minangkabau mainly speak Minangkabau together with Indonesian.

Education

[edit]

Jakarta is home to numerous educational institutions. The University of Indonesia (UI) is the largest and oldest tertiary-level educational institution in Indonesia. It is a public institution with campuses in Salemba (Central Jakarta) and in Depok.[125] The three other public universities in Jakarta are Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University Jakarta, the State University of Jakarta (UNJ),[126] University of Pembangunan Nasional 'Veteran' Jakarta (UPN "Veteran" Jakarta),[127] and Universitas Terbuka or Indonesia Open University.[128] There is a vocational higher education, Jakarta State Polytechnic. Some major private universities in Jakarta are Trisakti University, The Christian University of Indonesia, Mercu Buana University, Tarumanagara University, Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia, Pelita Harapan University, Pertamina University,[129] Bina Nusantara University,[130] Jayabaya University,[131] Persada Indonesia "YAI" University,[132] and Pancasila University.[133]

STOVIA (School tot Opleiding van Indische Artsen, now Universitas Indonesia) was the first high school in Jakarta, established in 1851.[134] Jakarta houses many students from around Indonesia, many of whom reside in dormitories or home-stay residences. For basic education, a variety of primary and secondary schools are available, tagged with the public (national), private (national and bi-lingual national plus) and international labels. Four of the major international schools are the British School Jakarta, Gandhi Memorial Intercontinental School, IPEKA Integrated Christian School,[135] and the Jakarta Intercultural School. Other international schools in Jakarta metropolitan area include the ACG School Jakarta, Australian Independent School,[136] Bina Bangsa School, Deutsche Schule Jakarta, Global Jaya School, Jakarta Indonesia Korean School, Jakarta Japanese School,[137] Jakarta Multicultural School,[138] Jakarta Taipei School, Lycée français de Jakarta, New Zealand School Jakarta,[139] North Jakarta Intercultural School, Sekolah Pelita Harapan,[140] and Singapore Intercultural School.

Religion

[edit]Religion in Jakarta (2022)[141]

In 2022, Jakarta's religious composition was distributed over Islam (83.87%), Protestantism (8.57%), Catholicism (3.89%), Buddhism (3.48%), Hinduism (0.18%), Confucianism (0.016%), and about 0.004% of population claimed to follow folk religions.[141]

Most pesantren (Islamic boarding schools) in Jakarta are affiliated with the traditionalist Nahdlatul Ulama,[142] modernist organisations mostly catering to a socioeconomic class of educated urban elites and merchant traders. They give priority to education, social welfare programs and religious propagation.[143] Many Islamic organisations have headquarters in Jakarta, including Nahdlatul Ulama, Indonesian Ulema Council, Muhammadiyah, Indonesia Institute of Islamic Dawah, and Jaringan Islam Liberal.

The Roman Catholic community has a Metropolis, the Archdiocese of Jakarta that includes West Java and Banten provinces as part of the ecclesiastical province. Jakarta also hosts the largest Buddhist adherents in Java Island, where most of the followers are the Chinese. Schools of Buddhism practiced in Indonesia vary, including Theravāda, Mahāyāna, Vajrayana, and Tridharma. The city also has Hindu community, which mainly are from Balinese and Indian people. There is also a Sikh and Baháʼí Faith community presence in Jakarta.[144]

- Istiqlal Mosque is the largest mosque in Southeast Asia

- Immanuel's Church is a Protestant church in Jakarta, It is considered one of the oldest churches in Indonesia

- The Jakarta Cathedral, one of the oldest Catholic churches in Jakarta

- Aditya Jaya Hindu temple with Balinese architecture, East Jakarta

Economy

[edit]

Jakarta GDP share by sector (2022)[145]

Indonesia is the largest economy of ASEAN, and Jakarta is the economic nerve centre of the Indonesian archipelago. Jakarta's nominal GDP was US$203.702 billion and PPP GDP was US$602.946 billion in 2021, which is about 17% of Indonesia's.[146] Jakarta ranked at 21 in the list of Cities Of Economic Influence Index in 2020 by CEOWORLD magazine.[147] According to the Japan Center for Economic Research, GRP per capita of Jakarta will rank 28th among the 77 cities in 2030 from 41st in 2015, the largest in Southeast Asia.[148] Savills Resilient Cities Index has predicted Jakarta to be within the top 20 cities in the world by 2028.[149][150]Jakarta's economy depends highly on manufacturing and service sectors such as banking, trading and financial. Industries include electronics, automotive, chemicals, mechanical engineering and biomedical sciences. The head office of Bank Indonesia and Indonesia Stock Exchange are located in the city. Most of the SOEs include Pertamina, PLN, Angkasa Pura, and Telkomsel operate head offices in the city, as do major Indonesian conglomerates, such as Salim Group, Sinar Mas Group, Astra International, Gudang Garam, Kompas-Gramedia, CT Corp, Emtek, and MNC Group. The headquarters of the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry and Indonesian Employers Association are also located in the city. As of 2017, the city is home to six Forbes Global 2000, two Fortune 500 and seven Unicorn companies.[151][152][153]

Google and Alibaba have regional cloud centers in Jakarta.[154] In 2017, the economic growth was 6.22%.[155] Throughout the same year, the total value of the investment was Rp 108.6 trillion (US$8 billion), an increase of 84.7% from the previous year.[156] In 2021, nominal GDP per capita was estimated at Rp 274.710 million (US$19,199).[146] The most significant contributions to GRDP were by finance, ownership and business services (29%); trade, hotel and restaurant sector (20%), and manufacturing industry sector (16%).[38]

The Wealth Report 2015 by Knight Frank reported that 24 individuals in Indonesia in 2014 had wealth of at least US$1 billion and 18 live in Jakarta.[157] The cost of living continues to rise. Both land prices and rents have become expensive. Mercer's 2017 Cost of Living Survey ranked Jakarta as 88th costliest city in the world for expatriates.[158] Industrial development and the construction of new housing thrive on the outskirts, while commerce and banking remain concentrated in the city centre.[159] Jakarta has a bustling luxury property market. Knight Frank, a global real estate consultancy based in London, reported in 2014 that Jakarta offered the highest return on high-end property investment in the world in 2013, citing a supply shortage and a sharply depreciated currency as reasons.[160]

Shopping

[edit]

As of 2015, with a total of 550 hectares, Jakarta had the largest shopping mall floor area within a single city.[161][162] Malls include Plaza Indonesia, Grand Indonesia, Sarinah, Plaza Senayan, Senayan City, Pacific Place, Gandaria City, ÆON Mall Jakarta Garden City and Tanjung Barat, Mall Taman Anggrek, Central Park Mall, as well as Pondok Indah Mall.[163] Fashion retail brands in Jakarta include Debenhams at Senayan City and Lippo Mall Kemang Village,[164] Japanese Sogo,[165] Seibu at Grand Indonesia Shopping Town, and French brand, Galeries Lafayette, at Pacific Place. The Satrio-Casablanca shopping belt includes Kuningan City, Mal Ambassador, Kota Kasablanka, and Lotte Shopping Avenue.[166] Shopping malls are also located at Grogol and Puri Indah in West Jakarta.

Traditional markets include Blok M, Mayestik, Tanah Abang, Senen, Pasar Baru, Glodok, Mangga Dua, Cempaka Mas, and Jatinegara. Special markets sell antique goods at Jalan Surabaya and gemstones in Rawabening Market.[167]

Tourism

[edit]

Though Jakarta has been named the most popular location as per tag stories,[168] and ranked eighth most-posted among the cities in the world in 2017 on image-sharing site Instagram,[169] it is not a top international tourist destination. The city, however, is ranked as the fifth fastest-growing tourist destination among 132 cities according to MasterCard Global Destination Cities Index.[170]The World Travel and Tourism Council also listed Jakarta as among the top ten fastest-growing tourism cities in the world in 2017[171] and categorised it as an emerging performer, which will see a significant increase in tourist arrivals in less than ten years.[172]According to Euromonitor International's latest Top 100 City Destinations Ranking of 2019, Jakarta ranked at 57th among 100 most visited cities of the world.[173]Most of the visitors attracted to Jakarta are domestic tourists. As the gateway of Indonesia, Jakarta often serves as a stop-over for foreign visitors on their way to other Indonesian tourist destinations such as Bali, Lombok, Komodo Island and Yogyakarta. In 2023 about 1.97 million foreign tourist visited the city.[174]

Jakarta is trying to attract more international tourist by MICE tourism, by arranging increasing numbers of conventions.[175][176] In 2012, the tourism sector contributed Rp. 2.6 trillion (US$268.5 million) to the city's total direct income of Rp. 17.83 trillion (US$1.45 billion), a 17.9% increase from the previous year 2011.

Culture

[edit]As the capital of Indonesia, Jakarta is a melting pot of cultures from all ethnic groups in the country. Although Betawi people are Jakarta's indigenous community, the city's culture represents many languages and ethnic groups, favoring differences in religion, tradition and linguistics, rather than a single, dominant culture. Jakarta is dominated by Javanese people, followed by Sundanese people and Betawi people which is the third largest and also the original tribe of this city

Arts and festivals

[edit]

The Betawi culture is distinct from those of the Sundanese or Javanese, forming a language island in the surrounding area. Betawi arts have a "low profile" in Jakarta, and most Betawi people have moved to the suburbs. The cultures of the Javanese and other Indonesian ethnic groups have a "higher profile" than that of the Betawi. There is a significant Chinese influence in Betawi culture, reflected in the popularity of Chinese cakes and sweets, firecrackers and Betawi wedding attire that demonstrates Chinese and Arab influences.

Some festivals such as the Jalan Jaksa Festival, Kemang Festival, Festival Condet and Lebaran Betawi include efforts to preserve Betawi arts by inviting artists to display performances.[177][178][179] Jakarta has several performing art centres, such as the classical concert hall Aula Simfonia Jakarta in Kemayoran, Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM) art centre in Cikini, Gedung Kesenian Jakarta near Pasar Baru, Balai Sarbini in the Plaza Semanggi area, Bentara Budaya Jakarta in the Palmerah area, Pasar Seni (Art Market) in Ancol, and traditional Indonesian art performances at the pavilions of some provinces in Taman Mini Indonesia Indah. Traditional music is often found at high-class hotels, including Wayang and Gamelan performances. Javanese Wayang Orang performances can be found at Wayang Orang Bharata theatre.

Arts and culture festivals and exhibitions include the annual ARKIPEL – Jakarta International Documentary and Experimental Film Festival, Jakarta International Film Festival (JiFFest), Djakarta Warehouse Project, Jakarta Fashion Week, Jakarta Muslim Fashion Week, Jakarta Fashion & Food Festival (JFFF), Jakarnaval, Jakarta Night Festival, Kota Tua Creative Festival, Indonesia International Book Fair (IIBF), Indonesia Comic Con, Indonesia Creative Products and Jakarta Arts and Crafts exhibition. Art Jakarta is a contemporary art fair, which is held annually. Flona Jakarta is a flora-and-fauna exhibition, held annually in August at Lapangan Banteng Park, featuring flowers, plant nurseries, and pets. Jakarta Fair is held annually from mid-June to mid-July to celebrate the anniversary of the city and is mostly centred around a trade fair. However, this month-long fair also features entertainment, including arts and music performances by local musicians. Jakarta International Java Jazz Festival (JJF) is one of the largest jazz festivals in the world, the biggest in the Southern hemisphere, and is held annually in March.

Several foreign art and culture centres in Jakarta promote culture and language through learning centres, libraries and art galleries. These include the Chinese Confucius Institute, the Dutch Erasmus Huis, the British Council, the French Alliance Française, the German Goethe-Institut, the Japan Foundation, and the Jawaharlal Nehru Indian Cultural Center.

Cuisine

[edit]

All varieties of Indonesian cuisine have a presence in Jakarta. The local cuisine is Betawi cuisine, which reflects various foreign culinary traditions. Betawi cuisine is heavily influenced by Malay-Chinese Peranakan cuisine, Sundanese and Javanese cuisine, which is also influenced by Indian, Arabic and European cuisines. One of the most popular local dishes of Betawi cuisine is Soto Betawi which is prepared from chunks of beef and offal in rich and spicy cow's milk or coconut milk broth. Other popular Betawi dishes include soto kaki, nasi uduk (mixed rice), kerak telor (spicy omelette), nasi ulam, asinan, ketoprak, rujak and gado-gado Betawi (salad in peanut sauce).

Jakarta cuisine can be found in modest street-side warung food stalls and Hawkers travelling vendors to high-end fine dining restaurants.[180] Live music venues and exclusive restaurants are abundant.[181] Many traditional foods from far-flung regions in Indonesia can be found in Jakarta. For example, traditional Padang restaurants and low-budget Warteg (Warung Tegal) food stalls are ubiquitous in the capital. Other popular street foods include nasi goreng (fried rice), sate (skewered meats), pecel lele (fried catfish), bakso (meatballs), bakpau (Chinese bun) and siomay (fish dumplings).

Jalan Sabang,[182][183] Jalan Sidoarjo, Jalan Kendal at Menteng area, Kota Tua, Blok S, Blok M,[184] Jalan Tebet,[185] are all popular destinations for street-food lovers. Minangkabau street-food who sell Nasi Kapau, Sate Padang, and Soto Padang can be found at Jalan Kramat Raya and Jalan Bendungan Hilir in Central Jakarta.[186] Chinese street-food is plentiful at Jalan Pangeran, Manga Besar and Petak Sembilan in the old Jakarta area, while the Little Tokyo area of Blok M has many Japanese style restaurants and bars.[187]

Trendy restaurants, cafe and bars can be found at Menteng, Kemang,[188] Jalan Senopati,[189] Kuningan, Senayan, Pantai Indah Kapuk,[190] and Kelapa Gading. Lenggang Jakarta is a food court, accommodating small traders and street vendors,[191] where Indonesian foods are available within a single compound. At present, there are two such food courts, located at Monas and Kemayoran.[192] Thamrin 10 is a food and creative park located at Menteng, where varieties of food stall are available.[193]

Global fast-food chains are present, and usually found in Shopping malls, along with local brands like Sederhana, J'CO, Es Teler 77, Kebab Turki, CFC, and Japanese HokBen and Yoshinoya.[194] Foreign cuisines such as Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Thai, Singaporean, Indian, American, Australian, Malaysian, French, Mediterranean cuisines like Maghrebi, Turkish, Italian, Middle Eastern cuisine, and modern fusion food restaurants can all be found in Jakarta.

Sports

[edit]Jakarta hosted the 1962 Asian Games,[195] and the 2018 Asian Games, co-hosted by Palembang.[196] Jakarta also hosted the Southeast Asian Games in 1979, 1987, 1997 and 2011 (supporting Palembang). Gelora Bung Karno Stadium[197] hosted the group stage, quarterfinal and final of the 2007 AFC Asian Cup along with Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam.[198][199] The largest capacity retractable roof stadium in Asia, Jakarta International Stadium, is located at Tanjung Priok district, completed in 2022.

The Senayan sports complex has several sports venues, including the Bung Karno football stadium, Madya Stadium, Istora Senayan, an aquatic arena, a baseball field, a basketball hall, a shooting range, several indoor and outdoor tennis courts. The Senayan complex was built in 1960 to accommodate the 1962 Asian Games. For basketball, the Kelapa Gading Sport Mall in Kelapa Gading, North Jakarta, with a capacity of 7,000 seats, is the home arena of the Indonesian national basketball team. The BritAma Arena serves as a playground for Satria Muda Pertamina Jakarta, the 2017 runner-up of the Indonesian Basketball League. Jakarta International Velodrome is a sporting facility located at Rawamangun, which was used as a venue for the 2018 Asian Games. It has a seating capacity of 3,500 for track cycling, and up to 8,500 for shows and concerts,[200] which can also be used for various sports activities such as volleyball, badminton and futsal. Jakarta International Equestrian Park is an equestrian sports venue located at Pulomas, which was also used as a venue for 2018 Asian Games.[201]

The Jakarta Car-Free Days are held weekly on Sunday on the main avenues of the city, Jalan Sudirman, and Jalan Thamrin, from 6 am to 11 am. The briefer Car-Free Day, which lasts from 6 am to 9 am, is held on every other Sunday. The event invites local pedestrians to do sports and exercise and have their activities on the streets that are usually full of traffic. Along the road from the Senayan traffic circle on Jalan Sudirman, South Jakarta, to the "Selamat Datang" Monument at the Hotel Indonesia traffic circle on Jalan Thamrin, north to the National Monument in Central Jakarta, cars are blocked from entering. During the event, morning gymnastics, callisthenics and aerobic exercises, futsal games, jogging, bicycling, skateboarding, badminton, karate, on-street library and musical performances take over the roads and the main parks.[202]

Jakarta's most popular home football club is Persija, which plays in Liga 1. Another football team in Jakarta is Persitara which competes in Liga 3 and plays in Tugu Stadium.

Jakarta Marathon each November is recognised by AIMS and IAAF. It was established in 2013. It brings sports tourism. In 2015, more than 15,000 runners from 53 countries participated.[203][204][205][206][207]

Jakarta successfully hosted the first Jakarta ePrix race of the Formula E championship in June 2022 at Ancol Circuit, North Jakarta.[208]

Media and entertainment

[edit]

Jakarta is home to most of the Indonesian national newspapers, besides some local-based newspapers. Daily local newspapers in Jakarta are Pos Kota and Warta Kota, as well as the now-defunct Indopos. National newspapers based in Jakarta include Kompas and Media Indonesia, most of them have a news segment covering the city. A number of business newspapers (Bisnis Indonesia, Investor Daily and Kontan) and sports newspaper (Super Ball) are also published.

Newspapers other than in Indonesian, mainly for a national and global audience, are also published daily. Examples are English-language newspapers The Jakarta Post and online-only The Jakarta Globe. Chinese language newspapers also circulate, such as Indonesia Shang Bao (印尼商报), Harian Indonesia (印尼星洲日报), and Guo Ji Ri Bao (国际日报). The only Japanese language newspaper is The Daily Jakarta Shimbun (じゃかるた新聞).

Around 75 radio stations broadcast in Jakarta, 52 on the FM band, and 23 on the AM band. Radio entities are based in Jakarta, for example, national radio networks MNC Trijaya FM, Prambors FM, Trax FM, I-Radio, Hard Rock FM, Delta FM, Global FM and the public radio RRI; as well as local stations Gen FM, Radio Elshinta and PM2FAS.

Jakarta is the headquarters for Indonesia's public television TVRI as well as private national television networks, such as Metro TV, tvOne, Kompas TV, RCTI and NET. Jakarta has local television channels such as TVRI Jakarta, JakTV, Elshinta TV and KTV. Many TV stations are analogue PAL, but some are now converting to digital signals using DVB-T2 following a government plan to digital television migration.[209]

Government and politics

[edit]

Jakarta is administratively equal to a province with special status. The executive branch is headed by an elected governor and a vice governor, while the Jakarta Regional People's Representative Council (Indonesian: Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah Provinsi Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta, DPRD DKI Jakarta) is the legislative branch with 106 directly elected members. The Jakarta City Hall at the south of Merdeka Square houses the office of the governor and the vice governor, and serves as the main administrative office.

Executive governance consists of five administrative cities (Indonesian: Kota Administrasi), each headed by a mayor (walikota) and one administrative regency (Indonesian: Kabupaten Administrasi) headed by a regent (bupati). Unlike other cities and regencies in Indonesia where the mayor or regent is directly elected, Jakarta's mayors and regents are chosen by the governor. Each city and regency is divided into administrative districts.

Aside from representatives to the provincial parliament, Jakarta sends 21 delegates to the national lower house parliament. The representatives are elected from Jakarta's three national electoral districts, which also include overseas voters.[210] It also sends 4 delegates, just like other provinces, to the national upper house parliament.

The Jakarta Smart City (JSC) program was launched on 14 December 2014 with the goal for smart governance, smart people, smart mobility, smart economy, smart living and a smart environment in the city using the web and various smartphone-based apps.[211]

Public safety

[edit]The Greater Jakarta Metropolitan Regional Police (Indonesian: Polda Metro Jaya) is the police force that is responsible to maintain law, security, and order for the Jakarta metropolitan area. It is led by a two-star police general (Inspector General of Police) with the title of "Greater Jakarta Regional Police Chief" (Indonesian: Kepala Kepolisian Daerah Metro Jaya, abbreviated Kapolda Metro Jaya). Its office is located at Jl. Jenderal Sudirman Kav. 55, Senayan, Kebayoran Baru, South Jakarta and their hotline emergency number is 110.

The Jayakarta Military Regional Command (Indonesian: Komando Daerah Militer Jayakarta, abbreviated Kodam Jaya) is the territorial army of the Indonesian Army, which serves as a defence component for Jakarta and its surrounding areas (Greater Jakarta). It is led by an army Major General with the title of "Jakarta Military Regional Commander" (Indonesian: Panglima Daerah Militer Kodam Jaya, abbreviated Pangdam Jaya). The Jakarta Military Command is located at East Jakarta and oversees several military battalions ready for defending the capital city and its vital installations. It also assists the Jakarta Metropolitan Police during certain tasks, such as supporting security during state visits, VVIP security, and riot control.

Municipal finances

[edit]The Jakarta provincial government relies on transfers from the central government for the bulk of its income. Local (non-central government) sources of revenue are incomes from various taxes such as vehicle ownership and vehicle transfer fees, among others.[212] The ability of the regional government to respond to Jakarta's many problems is constrained by limited finances.

The provincial government consistently runs a surplus of between 15 and 20% of planned spending, primarily because of delays in procurement and other inefficiencies.[213] Regular under-spending is a matter of public comment.[214] In 2013, the budget was around Rp 50 trillion ($US5.2 billion), equivalent to around $US380 per citizen. Spending priorities were on education, transport, flood control, environment and social spending (such as health and housing).[215] Jakarta's regional budget (APBD) was Rp 77.1 trillion ($US5.92 billion), Rp 83.2 trillion ($US6.2 billion), and Rp 89 trillion ($US6.35 billion) for the year of 2017, 2018 and 2019 respectively.[216][217][218]

Administrative divisions

[edit]

Jakarta consists of five Kota Administratif (Administrative cities/municipalities), each headed by a mayor, and one Kabupaten Administratif (Administrative regency). Each city and regency is divided into districts (kecamatan). The administrative cities/municipalities of Jakarta are:

- Central Jakarta (Jakarta Pusat) is Jakarta's smallest city and administrative and political centre. It is divided into eight districts. It is characterised by large parks and Dutch colonial buildings. Landmarks include the National Monument (Monas), Istiqlal Mosque, Jakarta Cathedral and museums.[219]

- West Jakarta (Jakarta Barat) has the city's highest concentration of small-scale industries. It has eight districts. The area includes Jakarta's Chinatown and Dutch colonial landmarks such as the Chinese Langgam building and Toko Merah. It contains part of Jakarta Old Town.[220]

- South Jakarta (Jakarta Selatan), originally planned as a satellite city, is now the location of upscale shopping centres and affluent residential areas. It has ten districts and functions as Jakarta's groundwater buffer,[221] but recently the green belt areas are threatened by new developments. Much of the central business district is concentrated all area in Kebayoran Baru, Setiabudi, a small part in Tebet, Pancoran, Mampang Prapatan, and bordering the Tanah Abang/Sudirman area of Central Jakarta. The area is known as the Jakarta Golden Triangle.

- East Jakarta (Jakarta Timur) territory is characterised by several industrial sectors.[222] Also located in East Jakarta are Taman Mini Indonesia Indah and Halim Perdanakusuma International Airport. This city has ten districts.

- North Jakarta (Jakarta Utara) is bounded by the Java Sea. It is the location of Port of Tanjung Priok. Large- and medium-scale industries are concentrated there. It contains part of Jakarta Old Town, which was the centre of VOC trade activity during the colonial era. Also located in North Jakarta is Ancol Dreamland (Taman Impian Jaya Ancol), the largest integrated tourism area in Southeast Asia.[223] North Jakarta is divided into six districts.

The only administrative regency (kabupaten) of Jakarta is the Thousand Islands (Kepulauan Seribu), formerly a district within North Jakarta. It is a collection of 105 small islands located on the Java Sea. It is of high conservation value because of its unique ecosystems. Marine tourism, such as diving, water bicycling, and windsurfing, are the primary tourist activities in this territory. The main mode of transportation between the islands is speed boats or small ferries.[224]

| Name of City or Regency | Area in km2 | Pop'n 2010 census[225] | Pop'n 2020 census[226] | Pop'n mid 2023 estimate[227] | Pop'n density (per km2) in mid 2023 | HDI [228] 2021 estimates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Jakarta | 144.942 | 2,062,232 | 2,226,812 | 2,235,606 | 15,424 | 0.849 (Very High) |

| East Jakarta | 185.538 | 2,693,896 | 3,037,139 | 3,079,618 | 16,598 | 0.829 (Very High) |

| Central Jakarta | 47.565 | 902,973 | 1,056,896 | 1,049,314 | 22,061 | 0.815 (Very High) |

| West Jakarta | 124.970 | 2,281,945 | 2,434,511 | 2,470,054 | 19,765 | 0.817 (Very High) |

| North Jakarta | 147.212 | 1,645,659 | 1,778,981 | 1,808,985 | 12,288 | 0.805 (Very High) |

| Thousand Islands | 10.725 | 21,082 | 27,749 | 28,523 | 2,659 | 0.721 (High) |

The province comprises three of Indonesia's 84 national electoral districts to elect members to the People's Representative Council. The Jakarta I Electoral District consists of the administrative city of East Jakarta, and elects 6 members to the People's Representative Council. The Jakarta II Electoral District consists of the administrative cities of Central Jakarta and South Jskarta, together with all overseas voters, and elects 7 members to the People's Representative Council. The Jakarta III Electoral District consists of the administrative cities of North Jakarta and West Jakarta, together with the Thousand Islands Regency, and elects 8 members to the People's Representative Council.[229]

Infrastructure

[edit]To transform the city into a more livable one, a ten-year urban regeneration project was undertaken, for Rp 571 trillion ($40.5 billion). The project aimed to develop infrastructure, including the creation of a better integrated public transit system and the improvement of the city's clean water and wastewater systems, housing and flood control systems.[230]

Transportation

[edit]

As a metropolitan area of about 30 million people, Jakarta has a variety of transport systems.[231] Jakarta was awarded 2021 global Sustainable Transport Award (STA) for integrated public transportation system.[232]

The city prioritized development of road networks, which were mostly designed to accommodate private vehicles.[233] A notable feature of Jakarta's present road system is the toll road network. Composed of an inner and outer ring road and five toll roads radiating outwards, the network provides inner as well as outer city connections. An 'odd-even' policy limits road use to cars with either odd or even-numbered registration plates on a particular day as a transitional measure to alleviate traffic congestion until the future introduction of electronic road pricing.

There are many bus terminals in the city, from where buses operate on numerous routes to connect neighborhoods within the city limit, to other areas of Greater Jakarta and to cities across the island of Java. The biggest of the bus terminal is Pulo Gebang Bus Terminal, which is arguably the largest of its kind in Southeast Asia.[234] Main terminus for long distance train services are Gambir and Pasar Senen. Whoosh High-speed railways is connecting Jakarta to Bandung and another one is at the planning stage from Jakarta to Surabaya.

As of September 2023, Jakarta's public transport service coverage has reached 86 percent, which is targeted to Increase to 95 percent. Rapid transit in Greater Jakarta consists of TransJakarta bus rapid transit, Jakarta LRT, Jakarta MRT, KRL Commuterline, Jabodebek LRT, and Soekarno-Hatta Airport Rail Link. The city administration is building transit oriented development like Dukuh Atas TOD and CSW-ASEAN TOD in several area across Jakarta to facilitate commuters to transfer between different mode of public transportation.

Privately owned bus systems like Kopaja, MetroMini, Mayasari Bakti and PPD also provide important services for Jakarta commuters with numerous routes throughout the city, many routes are/will replaced/replaced by Minitrans and Metrotrans buses.[235] Pedicabs are banned from the city for causing traffic congestion. Bajaj auto rickshaw provide local transportation in the back streets of some parts of the city. Angkot microbuses also play a major role in road transport of Jakarta. Taxicabs and ojeks (motorcycle taxis) are available in the city. As of January 2023, about 2.6 million people use public transportation daily in Jakarta.[236]

The city administration has undertaken a project to build about 500 kilometers of bicycle lanes. As of June 2021, Jakarta already has 63 kilometers of bicycle lanes, and another 101 kilometers will be added by the end of the year 2021.[237][238]

Soekarno–Hatta International Airport (CGK) is the main airport serving the Greater Jakarta area, while Halim Perdanakusuma Airport (HLP) accommodates private and low-cost domestic flights. Other airports in the Jakarta metropolitan area include Pondok Cabe Airport and an airfield on Pulau Panjang, part of the Thousand Island archipelago.

Indonesia's busiest and Jakarta's main seaport Tanjung Priok serves many ferry connections to different parts of Indonesia. The old port Sunda Kelapa only accommodate pinisi, a traditional two-masted wooden sailing ship serving inter-island freight service in the archipelago. Muara Angke is used as a public port to Thousand Islands (Indonesia), while Marina Ancol is used as a tourist port.[239]

For payment method in public transportation (for KAI Commuter line, TransJakarta, LRT Jakarta, LRT Jabodebek, MRT Jakarta) already using cashless. Travelers can use Electronic money banking cards. The electronic money cards include those issued, namely:

- BRIZZI (issued by Bank BRI)

- TapCash (issued by Bank BNI)

- e-Money (issued by Bank Mandiri)

- Flazz (issued by Bank BCA)

- Jakcard (issued by Bank DKI)

The electronic banking cards is integrated cad can be accepted in KAI Commuter line, TransJakarta, LRT Jakarta, LRT Jabodebek, MRT Jakarta, eToll payment and parking payment. The electronic bank card can be bought in Bank Branch office or in e-commerce.

For the electronic banking card Top Up can be done at:

- Indomaret Outlet (convenient store).

- Alfamart Outlet (convenient store).

- Alfamidi Outlet (convenient store).

- e-Money Card Vending Machine.

Jakarta is part of the Maritime Silk Road that runs from the Chinese coast via the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean and there to the Upper Adriatic region.[240][241][242]

Healthcare

[edit]страны В Джакарте имеется множество наиболее оснащенных частных и государственных медицинских учреждений . В 2012 году губернатор Джакарты Джоко Видодо представил программу всеобщего здравоохранения «Карта здоровой Джакарты» ( Kartu Jakarta Sehat , KJS). [243] In January 2014, the Indonesian government launched a universal health care system called the Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional (JKN), which is run by BPJS Kesehatan.[244] KJS is being integrated into JKN,[245] and KJS cards are still valid as of 2018.[246] По состоянию на 2021 год 85,55% жителей Джакарты охвачены JKN. [247]

Государственные больницы соответствуют высоким стандартам, но часто переполнены. Государственные специализированные больницы включают больницу доктора Сипто Мангункусумо , армейский госпиталь Гатот Соэброто , а также общественные больницы и пускесмас . Другие варианты медицинских услуг включают частные больницы и клиники. В частном секторе здравоохранения произошли значительные изменения с тех пор, как в 2010 году правительство начало разрешать иностранные инвестиции в частный сектор. Хотя некоторыми частными учреждениями управляют некоммерческие или религиозные организации, большинство из них являются коммерческими. такие сети больниц, как Siloam , Pondok Indah Hospital Group, Mayapada, Mitra Keluarga, Medika, Medistra, Ciputra, Radjak Hospital Group, RS Bunda Group и Hermina. В городе работают [248] [249] [250]

Водоснабжение

[ редактировать ]Две частные компании, PALYJA и Aetra, обеспечивают водопроводной водой западную и восточную половину Джакарты соответственно в соответствии с 25-летними концессионными контрактами, подписанными в 1998 году. Инфраструктурой владеет государственная холдинговая компания PAM Jaya. Восемьдесят процентов воды, распределяемой в Джакарте, поступает через систему каналов Западный Тарум из водохранилища Джатилухур на реке Читарум , в 70 км (43 мили) к юго-востоку от города. Водоснабжение было приватизировано президентом Сухарто в 1998 году французской компании Suez Environnement и британской компании Thames Water International. Обе компании впоследствии продали свои концессии индонезийским компаниям. Рост числа клиентов в первые семь лет действия концессий был ниже, чем раньше, возможно, из-за существенного повышения тарифов с поправкой на инфляцию в этот период. В 2005 году тарифы были заморожены, что побудило частные компании водоснабжения сократить инвестиции.

По данным PALYJA, коэффициент покрытия услугами существенно увеличился с 34% (1998 г.) до 65% (2010 г.) в западной половине концессии. [251] По данным Управления по регулированию водоснабжения Джакарты, доступ в восточной половине города, обслуживаемой PTJ, увеличился с примерно 57% в 1998 году до примерно 67% в 2004 году, но впоследствии остался на прежнем уровне. [252] Однако другие источники приводят гораздо более низкие показатели доступа к водопроводному водоснабжению в домах, исключая доступ через общественные гидранты: в одном исследовании в 2005 году доступ оценивался всего в 25%, [253] в то время как другой оценил его в 18,5% в 2011 году. [254] Те, у кого нет доступа к водопроводной воде, получают воду в основном из колодцев, которые часто бывают солеными и антисанитарными. По данным Министерства энергетики и минеральных ресурсов , по состоянию на 2017 год в Джакарте наблюдался кризис чистой воды. [255]

Международные отношения

[ редактировать ]Международные организации