Сан-Паулу

Сан-Паулу | |

|---|---|

| Муниципалитет Сан-Паулу Муниципалитет Сан-Паулу | |

| Псевдоним(ы): | |

| Девиз(ы): | |

Расположение в штате Сан-Паулу | |

| Координаты: 23 ° 33' ю.ш., 46 ° 38' з.д. / 23,550 ° ю.ш., 46,633 ° з.д. | |

| Страна | Бразилия |

| Состояние | Сан-Паулу |

| Исторические страны | Королевство Португалия Соединенное Королевство Португалии, Бразилии и Алгарви Империя Бразилии |

| Основан | 25 января 1554 г |

| Основан | Мануэль да Нобрега и Жозеф Анчиета |

| Named for | Paul the Apostle |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Body | Municipal Chamber of São Paulo |

| • Mayor | Ricardo Nunes (MDB) |

| • Vice Mayor | Vacant |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 1,521.11 km2 (587.3039 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 11,698 km2 (4,517 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 7,946.96 km2 (3,068.338 sq mi) |

| • Macrometropolis | 53,369.61 km2 (20,606.12 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 760 m (2,500 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Municipality | 11,451,999 |

| • Rank | 1st in South America 1st in Brazil |

| • Density | 8,005.25/km2 (20,733.5/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 22,439,956 |

| • Metro | 22,807,000 (Greater São Paulo) |

| • Metro density | 2,714.45/km2 (7,030.4/sq mi) |

| • Macrometropolis (Extended Metro) | 34,500,000[1] |

| Demonym | Paulistan |

| GDP (nominal) (metro area) | |

| • Year | 2023 |

| • Total | $319.3 billion[5] |

| GDP (PPP, constant 2015 values) (metro area) | |

| • Year | 2023 |

| • Total | $531.3 billion[5] |

| Time zone | UTC−03:00 (BRT) |

| Postal Code (CEP) | 01000-000 |

| Area code | +55 11 |

| HDI (2010) | 0.805 – very high[6] |

| Primary Airport | São Paulo–Guarulhos International Airport |

| Domestic Airports | São Paulo–Congonhas Airport Campo de Marte Airport |

| Interstates | |

| Rapid Transit | São Paulo Metro |

| Commuter Rail | CPTM |

| Website | Capital.sp.gov.br |

Сан- ( / ˌs aʊ ˈ / p aʊ l oʊ ) Паулу [7] — самый густонаселенный город Бразилии и столица штата Сан-Паулу . Внесенный в список » Сети исследований глобализации и мировых городов (GaWC) «альфа-глобального города , он оказывает существенное международное влияние в сфере торговли, финансов, искусства и развлечений. [8] Это крупнейший по численности населения городской район за пределами Азии и самый густонаселенный португалоязычный город в мире. Название города дано в честь апостола Павла , а жителей города называют паулистанос . города Латинский девиз — Non ducor, duco , что переводится как «Меня не ведут, я веду». [9]

Основанный в 1554 году священниками-иезуитами , город был центром поселенцев -бандейрантес во времена колониальной Бразилии , но значимой экономической силой он стал только во время бразильского кофейного цикла в середине 19 века, а позже укрепил свою роль главного национального экономического центра. с индустриализацией Бразилии в 20-м веке, которая превратила город в космополитический плавильный котел , где проживают крупнейшие арабские , итальянские и японские диаспоры в мире, с этническими кварталами, такими как Биксига , Бом-Ретиро и Либердаде , и людьми из более чем 200 других стран. [10] города В столичном районе , Большом Сан-Паулу , проживает 20 миллионов человек, и он считается самым густонаселенным в Бразилии и одним из самых густонаселенных в мире . Процесс агломерации между мегаполисами вокруг Большого Сан-Паулу также создал Макрометрополис Сан-Паулу . [11] первый мегаполис в Южном полушарии с населением более 30 миллионов человек. [12] [13]

Сан-Паулу — крупнейшая городская экономика Латинской Америки . [14] что составляет около 10% ВВП Бразилии [15] и чуть более трети ВВП штата Сан-Паулу. [16] В городе находится штаб-квартира B3 , крупнейшей фондовой биржи Латинской Америки по рыночной капитализации . [17] и имеет несколько финансовых районов , в основном в районах вокруг проспектов Паулиста , Фариа Лима и Беррини . Сан-Паулу является домом для 63% транснациональных корпораций Бразилии. [16] и является источником около трети бразильской научной продукции. [18] Его главный университет, Университет Сан-Паулу , часто считается лучшим в Бразилии и Латинской Америке . [19] [20] Мегаполис также является домом для нескольких самых высоких небоскребов Бразилии , в том числе Миранте-ду-Вале , Эдификио Италия , Банеспа , Северной башни и многих других.

Город является одним из главных культурных центров Латинской Америки и является домом для памятников, парков и музеев, таких как Латиноамериканский мемориал , парк Ибирапуэра , Художественный музей Сан-Паулу , Пинакотека , Синематека , Культурный центр Итау , Музей Ипиранги , Катавенто. Музей , Музей футбола , Музей португальского языка и Музей изображения и звука . В Сан-Паулу также проводятся соответствующие культурные мероприятия, такие как джазовый фестиваль в Сан-Паулу , биеннале искусств в Сан-Паулу , Неделя моды в Сан-Паулу , Lollapalooza , Primavera Sound , Comic Con Experience и гей-парад в Сан-Паулу , второе по величине событие ЛГБТ в мире. [21] [22] Сан-Паулу также был местом проведения многих спортивных мероприятий, таких как 1950 и чемпионаты мира по футболу 2014 годов , Панамериканские игры 1963 года и Сан-Паулу Инди 300, а также ежегодный Гран-при Сан-Паулу Формулы -1 и гонка Святого Сильвестра .

История

[ редактировать ]Доколониальный период

[ редактировать ]

Португальская империя 1554–1815 гг.

Соединенное Королевство Португалии, Бразилии и Алгарви 1815–1822 гг.

Бразильская империя 1822–1889 гг.

Республика Бразилия 1889 – настоящее время

Район современного Сан-Паулу, тогда известный как равнины Пиратининга вокруг реки Тиете , был населен людьми тупи , такими как тупиниким , гуанас и гуарани . Другие племена также жили на территориях, которые сегодня образуют столичный регион. [23]

Во время встречи с европейцами регион был разделен на Caciquedoms (вождества). [24] Самым известным вождем был Тибириса , известный своей поддержкой португальцев и других европейских колонистов. Среди многих местных названий мест, рек, кварталов и т. д., сохранившихся до наших дней, есть Тиете , Ипиранга , Тамандуатеи , Анхангабау , Пиратининга , Итакакесетуба , Котиа , Итапеви , Баруэри , Эмбу-Гуасу и т. д.

Колониальный период

[ редактировать ]

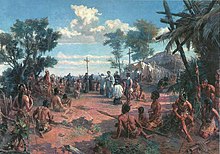

The Portuguese village of São Paulo dos Campos de Piratininga was marked by the founding of the Colégio de São Paulo de Piratininga on 25 January 1554. The Jesuit college of twelve priests included Manuel da Nóbrega and Spanish priest José de Anchieta. They built a mission on top of a steep hill between the Anhangabaú and Tamanduateí rivers.[25]

They first had a small structure built of rammed earth, made by Native Indian workers in their traditional style. The priests wanted to evangelize these Indians who lived in the Plateau region of Piratininga and convert them to Christianity. The site was separated from the coast by the Serra do Mar mountain range, called "Serra Paranapiacaba" by the Indians.

The college was named for a Christian saint and its founding on the feast day of the celebration of the conversion of the Apostle Paul of Tarsus. Father José de Anchieta wrote this account in a letter to the Society of Jesus:

The settlement of the region's Courtyard of the College began in 1560. During the visit of Mem de Sá, Governor-General of Brazil, the Captaincy of São Vicente, he ordered the transfer of the population of the Village of São Bernardo do Campo to the vicinity of the college. It was then named "College of St. Paul of the Piratininga". The new location was on a steep hill adjacent to a large wetland, the Várzea do Carmo. It offered better protection from attacks by local Indian groups. It was renamed Vila de São Paulo, belonging to the Captaincy of São Vicente.

For the next two centuries, São Paulo developed as a poor and isolated village that survived largely through the cultivation of subsistence crops by the labor of natives. For a long time, São Paulo was the only village in Brazil's interior, as travel was too difficult for many to reach the area. Mem de Sá forbade colonists to use the Caminho do Piraquê (Piraquê Path) and today known as Piaçaguera, because of frequent Indian raids along it.

On 22 March 1681, Luís Álvares de Castro, the Second Marquis de Cascais and donee of the Captaincy of São Vicente, moved the capital to the village of São Paulo (see Timeline of São Paulo), designating it the "Head of the captaincy". The new capital was established on 23 April 1683, with public celebrations.

The Bandeirantes

[edit]

In the 17th century, São Paulo was one of the poorest regions of the Portuguese colony. It was also the center of interior colonial development. Because they were extremely poor, the Paulistas could not afford to buy African slaves, as did other Portuguese colonists. The discovery of gold in the region of Minas Gerais, in the 1690s, brought attention and new settlers to São Paulo. The Captaincy of São Paulo and Minas de Ouro (see Captaincies of Brazil) was created on 3 November 1709, when the Portuguese crown purchased the Captaincies of São Paulo and Santo Amaro from the former grantees.[26]

Conveniently located in the country, up the steep Serra do Mar escarpment/mountain range when traveling from Santos, while also not too far from the coastline, São Paulo became a safe place to stay for tired travelers. The town became a center for the bandeirantes, intrepid invaders who marched into unknown lands in search for gold, diamonds, precious stones, and Indians to enslave. The bandeirantes, which could be translated as "flag-bearers" or "flag-followers", organized excursions into the land with the primary purpose of profit and the expansion of territory for the Portuguese crown. Trade grew from the local markets and from providing food and accommodation for explorers. The bandeirantes eventually became politically powerful as a group, and forced the expulsion of the Jesuits from the city of São Paulo in 1640. The two groups had frequently come into conflict because of the Jesuits' opposition to the domestic slave trade in Indians.

On 11 July 1711, the town of São Paulo was elevated to city status. Around the 1720s, gold was found by the pioneers in the regions near what are now Cuiabá and Goiânia. The Portuguese expanded their Brazilian territory beyond the Tordesillas Line to incorporate the gold regions. When the gold ran out in the late 18th century, São Paulo shifted to growing sugar cane. Cultivation of this commodity crop spread through the interior of the Captaincy. The sugar was exported through the Port of Santos. At that time, the first modern highway between São Paulo and the coast was constructed and named the Calçada do Lorena ("Lorena's settway"). Nowadays, the estate that is home to the Governor of the State of São Paulo, in the city of São Paulo, is called the Palácio dos Bandeirantes (Bandeirantes Palace), in the neighborhood of Morumbi.

Imperial period

[edit]

After Brazil became independent from Portugal in 1822, as declared by Emperor Pedro I where the Monument to the Independence of Brazil is located, he named São Paulo as an Imperial City. In 1827, a law school was founded at the Convent of São Francisco, today part of the University of São Paulo. The influx of students and teachers gave a new impetus to the city's growth, thanks to which the city became the Imperial City and Borough of Students of St. Paul of Piratininga.

The expansion of coffee production was a major factor in the growth of São Paulo, as it became the region's chief export crop and yielded good revenue. It was cultivated initially in the Paraíba Valley region in the East of the State of São Paulo, and later on in the regions of Campinas, Rio Claro, São Carlos and Ribeirão Preto.

From 1869 onward, São Paulo was connected to the port of Santos by the Estrada de Ferro Santos-Jundiaí (Santos-Jundiaí Railroad), nicknamed The Lady. In the late 19th century, several other railroads connected the interior to the state capital. São Paulo became the point of convergence of all railroads from the interior of the state. Coffee was the economic engine for major economic and population growth in the State of São Paulo.

In 1888, the "Golden Law" (Lei Áurea) was sanctioned by Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil, abolishing the institution of slavery in Brazil. Slaves were the main source of labor in the coffee plantations until then. As a consequence of this law, and following governmental stimulus towards the increase of immigration, the province began to receive a large number of immigrants, largely Italians, Japanese and Portuguese peasants, many of whom settled in the capital. The region's first industries also began to emerge, providing jobs to the newcomers, especially those who had to learn Portuguese.

Old Republican period

[edit]

By the time Brazil became a republic on 15 November 1889, coffee exports were still an important part of São Paulo's economy. São Paulo grew strong in the national political scene, taking turns with the also rich state of Minas Gerais in electing Brazilian presidents, an alliance that became known as "coffee and milk", given that Minas Gerais was famous for its dairy production. During this period, São Paulo went from regional center to national metropolis, becoming industrialized and reaching its first million inhabitants in 1928. Its greatest growth in this period was relative in the 1890s when it doubled its population. The height of the coffee period is represented by the construction of the second Luz Station (the present building) at the end of the 19th century and by the Paulista Avenue in 1900, where they built many mansions.[27]

Industrialization was the economic cycle that followed the coffee plantation model. By the hands of some industrious families, including many immigrants of Italian and Jewish origin, factories began to arise and São Paulo became known for its smoky, foggy air. The cultural scene followed modernist and naturalist tendencies in fashion at the beginning of the 20th century. Some examples of notable modernist artists are poets Mário de Andrade and Oswald de Andrade, artists Anita Malfatti, Tarsila do Amaral and Lasar Segall, and sculptor Victor Brecheret. The Modern Art Week of 1922 that took place at the Theatro Municipal was an event marked by avant-garde ideas and works of art. In 1929, São Paulo won its first skyscraper, the Martinelli Building.[27]

The modifications made in the city by Antônio da Silva Prado, Baron of Duprat and Washington Luís, who governed from 1899 to 1919, contributed to the climate development of the city; some scholars consider that the entire city was demolished and rebuilt at that time. São Paulo's main economic activities derive from the services industry – factories are since long gone, and in came financial services institutions, law firms, consulting firms. Old factory buildings and warehouses still dot the landscape in neighborhoods such as Barra Funda and Brás. Some cities around São Paulo, such as Diadema, São Bernardo do Campo, Santo André, and Cubatão are still heavily industrialized to the present day, with factories producing from cosmetics to chemicals to automobiles.

In 1924 the city was the stage of the São Paulo Revolt, an armed conflict fought in working-class neighborhoods near the center of São Paulo that lasted 23 days, from 5 to 28 July, leaving hundreds dead and thousands injured. The confrontation between the federal troops of president Artur Bernardes against rebels of the Brazilian Army and the Public Force of São Paulo was classified by the federal government as a conspiracy, a mutiny and a "revolt against the Fatherland, without foundation, headed by disorderly members of the Brazilian Army".[28] To face the rebels, the federal government launched an indiscriminate artillery bombardment against the city, which affected mostly civilian targets; as a result of the bombing, a third of São Paulo's 700,000 inhabitants fled the city. The revolt has been described as "the largest urban conflict in the history of Brazil".[29]

Revolution of 1932 and contemporary era

[edit]

In 1932, São Paulo mobilized in its largest civic movement: the Constitutionalist Revolution, when the entire population engaged in the war against the "Provisional Government" of Getúlio Vargas. In 1934, with the reunion of some faculties created in the 19th century, the University of São Paulo (USP) was founded, today the largest in Brazil.[30][31]

The first major project for industrial installation in the city was the industrial complex of Indústrias Matarazzo in Barra Funda. In the 1930s, the Jafet brothers, operating in the fabric business, Rodolfo Crespi, the Puglisi Carbone brothers and the Klabin family, who would found the first large cellulose industry in Brazil, the Klabin.[32] Another major industrial boom occurred during the Second World War, due to the crisis in coffee farming in the 1930s and restrictions on international trade during the war, which resulted in the city having a very high economic growth rate that remained high in the post-war period.[33]

In 1947, São Paulo gained its first paved highway: the Via Anchieta (built on the old route of José de Anchieta), connecting the capital to the coast of São Paulo. In the 1950s, São Paulo was known as "the city that never stop" and as "the fastest growing city in the world".[33] São Paulo held a large celebration, in 1954, of the "Fourth Centenary" of the city's founding, when the Ibirapuera Park was inaugurated, many historical books are released and the source of the Tietê River in Salesópolis is discovered. With the transfer of part of the city's financial center, which was located in the historic center (in the region called the "Historic Triangle"), to Paulista Avenue, its mansions were, for the most part, replaced by large buildings.[33]

In the period from the 1930s to the 1960s, the great entrepreneurs of São Paulo's development were mayor Francisco Prestes Maia and the governor Ademar de Barros, who was also mayor of São Paulo between 1957 and 1961. Prestes Maia designed and implemented, in the 1930s, the "Avenue Plan for the City of São Paulo", which revolutionized São Paulo's traffic.[34] These two rulers are also responsible for the two biggest urban interventions, after the Avenues Plan, which changed São Paulo: the rectification of the Tietê river with the construction of its banks and the São Paulo Metro: on February 13, 1963, governor Ademar de Barros and mayor Prestes Maia created study commissions (state and municipal) to prepare the basic project for the São Paulo Metro, and allocated their first funds to the Metro.[35] At the beginning of the 1960s, São Paulo already had four million inhabitants. Construction of the metro began in 1968, under the administration of Mayor José Vicente de Faria Lima, and the commercial operation started on September 14, 1974. In 2016 the system had a network 71.5 km long and 64 stations spread across five lines. That year, 1.1 billion passengers were transported by the system.[36]

At the end of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st century, São Paulo became the main financial center in South America and one of the most populous cities in the world. As the most influential Brazilian city on the global stage, São Paulo is currently classified as an alpha global city.[8] The metropolis has one of the largest GDP in the world, representing, alone, 11% of all Brazilian GDP,[15] and is also responsible for one third of the Brazilian scientific production.[37]

Geography

[edit]

São Paulo is the capital of the most populous state in Brazil, São Paulo, located at latitude 23°33'01'' south and longitude 46°38'02'' west. The total area of the municipality is 1,521.11 square kilometres (587.30 sq mi), according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), being the ninth largest in the state in terms of territorial extension.[39] Of the entire area of the municipality, 949,611 square kilometres (366,647 sq mi) are urban areas (2015), being the largest urban area in the country.[40]

The city is on a plateau placed beyond the Serra do Mar (Portuguese for "Sea Range" or "Coastal Range"), itself a component of the vast region known as the Brazilian Highlands, with an average elevation of around 799 meters (2,621 ft) above sea level, although being at a distance of only about 70 kilometers (43 mi) from the Atlantic Ocean. The distance is covered by two highways, the Anchieta and the Imigrantes, (see "Transportation" below) that roll down the range, leading to the port city of Santos and the beach resort of Guarujá. Rolling terrain prevails within the urbanized areas of São Paulo except in its northern area, where the Serra da Cantareira Range reaches a higher elevation and a sizable remnant of the Atlantic Rain Forest. The region is seismically stable and no significant activity has ever been recorded.[41]

Hydrography

[edit]The Tietê River and its tributary, the Pinheiros River, were once important sources of fresh water and leisure for São Paulo. However, heavy industrial effluents and wastewater discharges in the later 20th century caused the rivers to become heavily polluted. A substantial clean-up program for both rivers is underway.[42][43] Neither river is navigable in the stretch that flows through the city, although water transportation becomes increasingly important on the Tietê river further downstream (near river Paraná), as the river is part of the River Plate basin.[44]

No large natural lakes exist in the region, but the Billings and Guarapiranga reservoirs in the city's southern outskirts are used for power generation, water storage and leisure activities, such as sailing. The original flora consisted mainly of broadleaf evergreens. Non-native species are common, as the mild climate and abundant rainfall permit a multitude of tropical, subtropical and temperate plants to be cultivated, especially the ubiquitous eucalyptus.[45]

The north of the municipality contains part of the 7,917 hectares (19,560 acres) Cantareira State Park, created in 1962, which protects a large part of the metropolitan São Paulo water supply.[46] In 2015, São Paulo experienced a major drought, which led several cities in the state to start a rationing system.[47]

Parks and biodiversity

[edit]São Paulo is located in an ecotone area between 3 biomes: mixed ombrophilous forest, dense ombrophilous forest and cerrado; the latter had some plant species native to the pampas in the city. There were several species typical of both biomes, among them we can mention: araucarias, pitangueiras, cambucís, ipês, jabuticabeiras, queen palms, muricís-do-campo, etc.[48]

In 2010, São Paulo had 62 municipal and state parks,[49] such as the Cantareira State Park, part of the São Paulo Green Belt Biosphere Reserve and home to one of the largest urban forests on the planet with 7,900 hectares (20,000 acres) of extension,[50] the Fontes do Ipiranga State Park, the Ibirapuera Park, the Tietê Ecological Park, the Capivari-Monos Environmental Protection Area, the Serra do Mar State Park, Villa-Lobos State Park, People's Park, and the Jaraguá State Park, listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1994.[51]

In 2009, São Paulo had 2,300 hectares (5,700 acres) of green area, less than 1.5% of the city's area[52] and below the 12 square metres (130 sq ft) per inhabitant recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).[53] About 21% of the municipality's area is covered by green areas, including ecological reserves (2010 data).[54][55]

In the municipality it is possible to observe forest birds that usually appear in the spring, due to the belt of native forest that still surrounds the metropolitan region. Species such as the rufous-bellied thrush, golden-chevroned tanager, great kiskadee and hummingbird are the most common. Despite the intense pollution, the main rivers of the city, the Tietê and the Pinheiros, shelter several species of animals such as capybaras, hawks, southern lapwings, herons and nutrias. Other species found in the municipality are the gray brocket, howler monkey, green-billed toucan and the Amazonian umbrellabird.[56]

Environment

[edit]Air pollution in some districts of the city exceeds local standards, mainly due to car traffic.[57] The World Health Organization (WHO) sets a limit of 20 micrograms of particulate matter per cubic meter of air as a safe annual average. In an assessment carried out by the WHO among over a thousand cities around the world in 2011, the city of São Paulo was ranked 268th among the most polluted, with an average rate of 38 micrograms per cubic meter, a rate well above the limit imposed by the organization, but lower than in other Brazilian cities, such as Rio de Janeiro (64 micrograms per cubic meter).[58] A 2013 study found that air pollution in the city causes more deaths than traffic accidents.[59][60]

The stretch of the Tietê River that runs through the city is the most polluted river in Brazil.[61] In 1992, the Tietê Project began, with the aim to clean up the river by 2005. 8.8 billion reais was spent on the failed project.[62] In 2019, the Novo Rio Pinheiros Project began, under the administration of João Doria, with the aim to reduce sewage discharged into the Tietê's tributary, the Pinheiros River.[63][64]

The problem of balanced water supply for the city - and for the metropolis, in general - is also a worrying issue: São Paulo has few sources of water in its own perimeter, having to seek it in distant hydrographic basins. The problem of water pollution is also aggravated by the irregular occupation of watershed areas, caused by urban expansion, driven by the difficulty of access to land and housing in central areas by the low-income population[65] and associated with real estate speculation and precariousness in new subdivisions. With this, there is also an overvaluation of individual transport over public transport – leading to the current rate of more than one vehicle for every two inhabitants and aggravating the problem of environmental pollution.[66]

Climate

[edit]

According to the Köppen classification, the city has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa, bordering on Cwa).[68][69] In summer (January through March), the mean low temperature is about 19 °C (66 °F) and the mean high temperatures is near 28 °C (82 °F). In winter, temperatures tend to range between 12 and 22 °C (54 and 72 °F). The record high temperature was 37.8 °C (100.0 °F) on 17 October 2014[70] and the lowest −3.2 °C (26.2 °F) on 25 June 1918.[71][72] The Tropic of Capricorn, at about 23°27' S, passes through north of São Paulo and roughly marks the boundary between the tropical and temperate areas of South America. Because of its elevation, however, São Paulo experiences a more temperate climate.[73] The summer is warm and rainy. Autumn and spring are transitional seasons. Winter is mild, but still the coldest season, with cloudiness around town and frequent polar air masses. Frosts occur sporadically in regions further away from the center, in some winters throughout the city.[74]

Rainfall is abundant, annually averaging 1,454 millimeters (57.2 in).[75] It is especially common in the warmer months averaging 219 millimeters (8.6 in) and decreases in winter, averaging 47 millimeters (1.9 in). Neither São Paulo nor the nearby coast has ever been hit by a tropical cyclone and tornadic activity is uncommon. During late winter, especially August, the city experiences the phenomenon known as "veranico" or "verãozinho" ("little summer"), which consists of hot and dry weather, sometimes reaching temperatures well above 28 °C (82 °F). On the other hand, relatively cool days during summer are fairly common when persistent winds blow from the ocean. On such occasions daily high temperatures may not surpass 20 °C (68 °F), accompanied by lows often below 15 °C (59 °F), however, summer can be extremely hot when a heat wave hits the city followed by temperatures around 34 °C (93 °F), but in places with greater skyscraper density and less tree cover, the temperature can feel like 39 °C (102 °F), as on Paulista Avenue for example. In the summer of 2014, São Paulo was affected by a heat wave that lasted for almost 4 weeks with highs above 30 °C (86 °F), peaking on 36 °C (97 °F). Secondary to deforestation, groundwater pollution, and climate change, São Paulo is increasingly susceptible to drought and water shortages.[76]

| Climate data for São Paulo (Mirante de Santana, 1991–2020, extremes 1887–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 37.0 (98.6) | 35.9 (96.6) | 34.3 (93.7) | 33.4 (92.1) | 31.7 (89.1) | 28.8 (83.8) | 30.2 (86.4) | 33.0 (91.4) | 35.7 (96.3) | 37.8 (100.0) | 37.7 (99.9) | 35.6 (96.1) | 37.8 (100.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 28.6 (83.5) | 29.0 (84.2) | 28.0 (82.4) | 26.6 (79.9) | 23.4 (74.1) | 22.9 (73.2) | 22.9 (73.2) | 24.5 (76.1) | 25.2 (77.4) | 26.5 (79.7) | 26.9 (80.4) | 28.3 (82.9) | 26.1 (79.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 23.1 (73.6) | 23.5 (74.3) | 22.5 (72.5) | 21.2 (70.2) | 18.4 (65.1) | 17.5 (63.5) | 17.2 (63.0) | 18.1 (64.6) | 19.1 (66.4) | 20.5 (68.9) | 21.2 (70.2) | 22.6 (72.7) | 20.4 (68.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 19.4 (66.9) | 19.6 (67.3) | 18.9 (66.0) | 17.5 (63.5) | 14.7 (58.5) | 13.5 (56.3) | 12.8 (55.0) | 13.3 (55.9) | 14.9 (58.8) | 16.5 (61.7) | 17.3 (63.1) | 18.7 (65.7) | 16.4 (61.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 6.5 (43.7) | 12.4 (54.3) | 12.0 (53.6) | 6.8 (44.2) | 3.7 (38.7) | 1.2 (34.2) | 0.8 (33.4) | 3.4 (38.1) | 3.5 (38.3) | 7.0 (44.6) | 7.0 (44.6) | 10.3 (50.5) | 0.8 (33.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 292.1 (11.50) | 257.7 (10.15) | 229.1 (9.02) | 87.0 (3.43) | 66.3 (2.61) | 59.7 (2.35) | 48.4 (1.91) | 32.3 (1.27) | 83.3 (3.28) | 127.2 (5.01) | 143.9 (5.67) | 231.3 (9.11) | 1,658.3 (65.29) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 17 | 14 | 13 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 110 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76.9 | 75.0 | 76.6 | 74.6 | 75.0 | 73.5 | 70.8 | 68.2 | 71.3 | 73.7 | 73.7 | 73.9 | 73.6 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 18.9 (66.0) | 18.9 (66.0) | 18.5 (65.3) | 16.8 (62.2) | 14.3 (57.7) | 13.1 (55.6) | 12.3 (54.1) | 12.4 (54.3) | 13.9 (57.0) | 15.8 (60.4) | 16.6 (61.9) | 18.0 (64.4) | 15.8 (60.4) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 139.1 | 153.5 | 161.6 | 169.3 | 167.6 | 160.0 | 169.0 | 173.1 | 144.5 | 157.9 | 152.8 | 145.1 | 1,893.5 |

| Source 1: Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia (sun 1981–2010)[77][78][79][80][81][82][83](Dew Point[84]) | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[85][70][86] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for São Paulo (Horto Florestal, 1961–1990) |

|---|

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1872 | 31,385 | — |

| 1890 | 64,934 | +106.9% |

| 1900 | 239,820 | +269.3% |

| 1920 | 579,033 | +141.4% |

| 1940 | 1,326,261 | +129.0% |

| 1950 | 2,198,096 | +65.7% |

| 1960 | 3,781,446 | +72.0% |

| 1970 | 5,924,615 | +56.7% |

| 1980 | 8,493,226 | +43.4% |

| 1991 | 9,646,185 | +13.6% |

| 2000 | 10,434,252 | +8.2% |

| 2010 | 11,253,503 | +7.9% |

| 2022 | 11,451,245 | +1.8% |

| [96] | ||

São Paulo's population has grown rapidly. By 1960 it had surpassed that of Rio de Janeiro, making it Brazil's most populous city. By this time, the urbanized area of São Paulo had extended beyond the boundaries of the municipality proper into neighboring municipalities, making it a metropolitan area with a population of 4.6 million. Population growth has continued since 1960, although the rate of growth has slowed.[97]

In 2013, São Paulo was the most populous city in Brazil and in South America.[98] According to the 2010 IBGE Census, there were 11,244,369 people residing in the city of São Paulo.[99] Portuguese remains the most widely spoken language and São Paulo is the largest city in the Portuguese speaking world.[100]

In 2010, the city had 2,146,077 opposite-sex couples and 7,532 same-sex couples. The population of São Paulo was 52.6% female and 47.4% male.[101] The 2022 census found 6,214,422 White people (54.3%), 3,820,326 Pardo (multiracial) people (33.4%), 1,160,073 Black people (10.1%), 238,603 Asian people (2.1%) and 17,727 Amerindian people (0.2%).[102]

Immigration and migration

[edit]São Paulo is considered the most multicultural city in Brazil. From 1870 to 2010, approximately 2.3 million immigrants arrived in the state, from all parts of the world. The Italian community is one of the strongest, with a presence throughout the city. Of the 12 million inhabitants of São Paulo, 50% (6 million people) have full or partial Italian ancestry. São Paulo has more descendants of Italians than any Italian city (the largest city of Italy is Rome, with 2.8 million inhabitants).[103]

The main groups, considering all the metropolitan area, are: 6 million people of Italian descent,[104] 3 million people of Portuguese descent,[105] 1.7 million people of African descent,[106] 1 million people of Arab descent,[107] 665,000 people of Japanese descent,[107] 400,000 people of German descent,[107] 250,000 people of French descent,[107] 150,000 people of Greek descent,[107] 120,000 people of Chinese descent,[107] 120,000–300,000 Bolivian immigrants,[108] 50,000 people of Korean descent,[109] and 80,000 Jews.[110]

Even today, Italians are grouped in neighborhoods like Bixiga, Brás, and Mooca to promote celebrations and festivals. In the early twentieth century, Italian and its dialects were spoken almost as much as Portuguese in the city, which influenced the formation of the São Paulo dialect of today. Six thousand pizzerias are producing about a million pizzas a day. Brazil has the largest Italian population outside Italy, with São Paulo being the most populous city with Italian ancestry in the world.[111]

The Portuguese community is also large; it is estimated that three million paulistanos have some origin in Portugal. The Jewish colony is more than 80,000 people in São Paulo and is concentrated mainly in Higienópolis and Bom Retiro.[112]

From the nineteenth century through the first half of the twentieth century, São Paulo also received German immigrants (in the current neighborhood of Santo Amaro), Spanish and Lithuanian (in the neighborhood Vila Zelina).[112]

"A French observer, travelling to São Paulo at the time, noted that there was a division of the capitalist class, by nationality (...) Germans, French and Italians shared the dry goods sector with Brazilians. Foodstuffs was generally the province of either Portuguese or Brazilians, except for bakery and pastry which was the domain of the French and Germans. Shoes and tinware were mostly controlled by Italians. However, the larger metallurgical plants were in the hands of the English and the Americans. (...) Italians outnumbered Brazilians two to one in São Paulo."

— [113]

Until 1920, 1,078,437 Italians entered in the State of São Paulo. Of the immigrants who arrived there between 1887 and 1902, 63.5% came from Italy. Between 1888 and 1919, 44.7% of the immigrants were Italians, 19.2% were Spaniards and 15.4% were Portuguese.[114] In 1920, nearly 80% of São Paulo city's population was composed of immigrants and their descendants and Italians made up over half of its male population.[114] At that time, the Governor of São Paulo said that "if the owner of each house in São Paulo display the flag of the country of origin on the roof, from above São Paulo would look like an Italian city". In 1900, a columnist who was absent from São Paulo for 20 years wrote "then São Paulo used to be a genuine Paulista city, today it is an Italian city."[114]

São Paulo also is home of the largest Japanese community outside Japan.[115] In 1958 the census counted 120,000 Japanese in the city and by 1987, there were 326,000 with another 170,000 in the surrounding areas within São Paulo state.[116] As of 2007, the Paulistano Japanese population outnumbered their fellow diaspora in the entirety of Peru, and in all individual American cities.[116]

Research conducted by the University of São Paulo (USP) shows the city's high ethnic diversity: when asked if they are "descendants of foreign immigrants", 81% of the students reported "yes". The main reported ancestries were: Italian (30.5%), Portuguese (23%), Spanish (14%), Japanese (8%), German (6%), Brazilian (4%), African (3%), Arab (2%) and Jewish (1%).[117]

The city once attracted numerous immigrants from all over Brazil and even from foreign countries, due to a strong economy and for being the hub of most Brazilian companies.[118] São Paulo is also receiving waves of immigration from Haiti and from many countries of Africa and the Caribbean. Those immigrants are mainly concentrated in Praça da Sé, Glicério and Vale do Anhangabaú in the Central Zone of São Paulo.

Since the 19th century people began migrating from northeastern Brazil into São Paulo. This migration grew enormously in the 1930s and remained huge in the next decades. The concentration of land, modernization in rural areas, changes in work relationships and cycles of droughts stimulated migration. The largest concentration of northeastern migrants was found in the area of Sé/Brás (districts of Brás, Bom Retiro, Cambuci, Pari and Sé). In this area they composed 41% of the population.[119]

Metropolitan area

[edit]

The nonspecific term "Grande São Paulo" ("Greater São Paulo") covers multiple definitions. The legally defined Região Metropolitana de São Paulo consists of 39 municipalities in total and a population of 21.1 million[120] inhabitants (as of the 2014 National Census[update]).

The Metropolitan Region of São Paulo is known as the financial, economic, and cultural center of Brazil. Among the largest municipalities, Guarulhos, with a population of more than 1 million people is the biggest one. Several others count more than 100,000 inhabitants, such as São Bernardo do Campo (811,000 inh.) and Santo André (707,000 inh.) in the ABC Region. The ABC Region, comprising Santo André, São Bernardo do Campo and São Caetano do Sul in the south of Grande São Paulo, is an important location for industrial corporations, such as Volkswagen and Ford Motors.[121]

Because São Paulo has urban sprawl, it uses a different definition for its metropolitan area alternately called the Expanded Metropolitan Complex of São Paulo and the São Paulo Macrometropolis. Analogous to the BosWash definition, it is one of the largest urban agglomerations in the world, with 32 million inhabitants,[122] behind Tokyo, which includes four contiguous legally defined metropolitan regions and three micro-regions.

Religion

[edit]Like the cultural variety verifiable in São Paulo, there are several religious manifestations present in the city. Although it has developed on an eminently Catholic social matrix, both due to colonization and immigration – and even today most of the people of São Paulo declare themselves Roman Catholic – it is possible to find in the city dozens of different Protestant denominations, as well as the practice of Islam, Spiritism, among others. Buddhism and Eastern religions also have relevance among the beliefs most practiced by Paulistanos. It is estimated that there are more than one hundred thousand Buddhist and Hindu followers each. Also considerable are Judaism, Mormonism and Afro-Brazilian religions.[123]

According to data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), in 2010 the population of São Paulo was 6,549,775 Roman Catholics (58.2%), 2,887,810 Protestants (22.1%), 531,822 Spiritists (4.7%), 101,493 Jehovah's Witnesses (0.9%), 75,075 Buddhists (0.7%), 50,794 Umbandists (0.5%), 43,610 Jews (0.4%), 28,673 Catholic Apostolic Brazilians (0.3%), 25,583 eastern religious (0.2%), 18,058 Candomblecists (0.2%), 17,321 Mormons (0.2%), 14,894 Eastern Orthodox (0.1%), 9,119 spiritualists (0.1%), 8,277 Muslims (0.1%), 7,139 esoteric (0.1%), 1,829 practiced Indian traditions (<0.1%) and 1,008 were Hindu (<0.1%). Others 1,056 008 had no religion (9.4%), 149,628 followed other Christian religiosities (1.3%), 55,978 had an undetermined religion or multiple belonging (0.5%), 14,127 did not know (0.1%) And 1,896 reported following other religiosities (<0.1%).[123]

The Catholic Church divides the territory of the municipality of São Paulo into four ecclesiastical circumscriptions: the Archdiocese of São Paulo, and the adjacent Diocese of Santo Amaro, the Diocese of São Miguel Paulista and the Diocese of Campo Limpo, the last three suffragans of the first. The archive of the archdiocese, called the Metropolitan Archival Dom Duarte Leopoldo e Silva, in the Ipiranga neighborhood, holds one of the most important documentary heritage in Brazil. The archiepiscopal is the Metropolitan Cathedral of São Paulo (known as Sé Cathedral), in Praça da Sé, considered one of the five largest Gothic temples in the world. The Catholic Church recognizes as patron saints of the city Saint Paul of Tarsus and Our Lady of Penha of France.[124][125]

The city has the most diverse Protestant or Reformed creeds, such as the Evangelical Community of Our Land, Maranatha Christian Church, Lutheran Church, Presbyterian Church, Methodist Church, Anglican Episcopal Church, Baptist churches, Assemblies of God in Brazil (the largest evangelical church in the country),[126][127] The Seventh-day Adventist Church, the World Church of God's Power, the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, the Christian Congregation in Brazil,[128] among others, as well as Christians of various denominations.[125]

Public security

[edit]

In 2008, the city of São Paulo ranked 493rd on the list of the most violent cities in Brazil. Among the capitals, it was the fourth least violent, registering, in 2006, homicide rates higher only than those of Boa Vista, Palmas and Natal.[129][130] In November 2009, the Ministry of Justice and the Brazilian Public Security Forum released a survey that identified São Paulo as the safest Brazilian capital for young people.[131] Between 2000 and 2010, the city of São Paulo reduced its homicide rate by 78%.[132]

According to the 2011 Global Homicide Study, released by the United Nations (UN), in the period between 2004 and 2009 the homicide rate fell from 20.8 to 10.8 murders per hundred thousand inhabitants. In 2011, the UN pointed to São Paulo as an example of how large cities can reduce crime.[133] In a survey on the Adolescent Homicide Index (AHI) in 2010, the city of São Paulo was considered the least lethal for adolescents, among 283 municipalities surveyed, with more than 100,000 inhabitants.[134] According to data from the "Map of Violence 2011", published by the Sangari Institute and the Ministry of Justice, the city had the lowest homicide rate per hundred thousand inhabitants that year among all the state capitals in Brazil.[135]

Crime indicators, such as homicide, according to data from April 2017, showed a reduction in the capital of São Paulo, compared to 2016. In the same period, there was a 12.64% reduction in homicides, the number of robbery records fell by eleven to seven (34% reduction), and there was an 8.09% reduction in rape cases.[136] The 9th DP in the Carandiru neighborhood was considered, in March 2007, one of the five best police stations in the world and the best in Latin America.[137]

Based on data from IBGE and the Ministry of Health, it is considered the 2nd safest capital[138] and the least lethal capital in the country, according to the 2023 Brazilian Public Security Yearbook.[139]

Social challenges

[edit]

Since the beginning of the 20th century, São Paulo has been a major economic center in Latin America. During two World Wars and the Great Depression, coffee exports (from other regions of the state) were critically affected. This led wealthy coffee farmers to invest in industrial activities that turned São Paulo into Brazil's largest industrial hub.

- Crime rates consistently decreased in the 21st century. The citywide homicide rate was 6.56 in 2019, less than a fourth of the 27.38 national rate.[140]

- Air quality[57] has steadily increased during the modern era.

- The two major rivers crossing the city, Tietê and Pinheiros, are highly polluted. A major project to clean up these rivers is underway.[42][43]

- The Clean City Law or antibillboard, approved in 2007, focused on two main targets: anti-publicity and anti-commerce. Advertisers estimate that they removed 15,000 billboards and that more than 1,600 signs and 1,300 towering metal panels were dismantled by authorities.[141]

- São Paulo metropolitan region, adopted vehicle restrictions from 1996 to 1998 to reduce air pollution during wintertime. Since 1997, a similar project was implemented throughout the year in the central area of São Paulo to improve traffic.[142]

- There were more than 30,000 homeless people in 2021 according to official data. It increased by 31% in two years, and doubled in 20 years.[143]

Languages

[edit]The primary language is Portuguese. The general language from São Paulo General, or Tupi Austral (Southern Tupi), was the Tupi-based trade language of what is now São Vicente, São Paulo, and the upper Tietê River. In the 17th century it was widely spoken in São Paulo and spread to neighboring regions while in Brazil. From 1750 on, following orders from Marquess of Pombal, Portuguese language was introduced through immigration and consequently taught to children in schools. The original Tupi Austral language subsequently lost ground to Portuguese, and eventually became extinct. Due to the large influx of Japanese, German, Spanish, Italian and Arab immigrants etc., the Portuguese idiom spoken in the metropolitan area of São Paulo reflects influences from those languages.

The Italian influence in São Paulo accents is evident in the Italian neighborhoods such as Bela Vista, Mooca, Brás and Lapa. Italian mingled with Portuguese and as an old influence, was assimilated or disappeared into spoken language. The local accent with Italian influences became notorious through the songs of Adoniran Barbosa, a Brazilian samba singer born to Italian parents who used to sing using the local accent.[144]

Other languages spoken in the city are mainly among the Asian community: São Paulo is home to the largest Japanese population outside Japan. Although today most Japanese-Brazilians speak only Portuguese, some of them are still fluent in Japanese. Some people of Chinese and Korean descent are still able to speak their ancestral languages.[145] In some areas it is still possible to find descendants of immigrants who speak German[146] (especially in the area of Brooklin paulista) and Lithuanian or Russian or East European languages (especially in the area of Vila Zelina).[147][148] In the west zone of São Paulo, specially at Vila Anastácio and Lapa region, there is a Hungarian colony, with three churches (Calvinist, Baptist and Catholic), so on Sundays it is possible to see Hungarians talking to each other on sidewalks.

Sexual diversity

[edit]

The Greater São Paulo is home to a prominent self-identifying gay, bisexual and transgender community, with 9.6% of the male population and 7% of the female population declaring themselves to be non-heterosexual.[149] Same-sex civil unions have been legal in the whole country since 5 May 2011, while same-sex marriage in São Paulo was legalized on 18 December 2012. Since 1997, the city has hosted the annual São Paulo Gay Pride Parade, considered the biggest pride parade in the world by the Guinness Book of World Records with over 5 million participants, and typically rivalling the New York City Pride March for the record.[21]

Strongly supported by the State and the City of São Paulo government authorities, in 2010, the city hall of São Paulo invested R$1 million reais in the parade and provided a solid security plan, with approximately 2,000 policemen, two mobile police stations for immediate reporting of occurrences, 30 equipped ambulances, 55 nurses, 46 medical physicians, three hospital camps with 80 beds. The parade, considered the city's second largest event after the Formula One, begins at the São Paulo Museum of Art, crosses Paulista Avenue, and follows Consolação Street to Praça Roosevelt in Downtown São Paulo. According to the LGBT app Grindr, the gay parade of the city was elected the best in the world.[150]

Education

[edit]

São Paulo has public and private primary and secondary schools and vocational-technical schools. More than nine-tenths of the population are literate and roughly the same proportion of those age 7 to 14 are enrolled in school. There are 578 universities in the state of São Paulo.[151]

The city of São Paulo is also home to research and development facilities and attracts companies due to the presence of regionally renowned universities. Science, technology and innovation is leveraged by the allocation of funds from the state government, mainly carried out by means of the Foundation to Research Support in the State of São Paulo (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo – FAPESP), one of the main agencies promoting scientific and technological research.[152]

Health care

[edit]

São Paulo is one of the largest health care hubs in Latin America. Among its hospitals are the Albert Einstein Israelites Hospital, ranked the best hospital in all Latin America[155] and the Hospital das Clínicas, the largest in the region, with a total area of 600,000 square meters and offers 2,400 beds, distributed among its eight specialized institutes and two assisting hospitals.[156]

The main hospitals in the city of São Paulo concentrate in the upper-income areas, the majority of the population of the city has a private health insurance. This can includes hospitals, private practices and pharmacies. The city of São Paulo has the largest number of foreigners comparing with any other Brazilian city and an intense health tourism. In Brazil, the city of São Paulo has the largest number of doctors who can speak more than one language, which in this case is Portuguese, with the secondary languages predominantly are English and Spanish.[157]

The private health care sector is very large and most of Brazil's best hospitals are in the city. As of September 2009, the city of São Paulo had: 32,553 ambulatory clinics, centers and professional offices (physicians, dentists and others); 217 hospitals, with 32,554 beds; 137,745 health care professionals, including 28,316 physicians.[158]

The municipal government operates public health facilities across the city's territory, with 770 primary health care units (UBS), ambulatory and emergency clinics and 17 hospitals. The Municipal Secretary of Health has 59,000 employees, including 8,000 physicians and 12,000 nurses. 6,000,000 citizens uses the facilities, which provide drugs at no cost and manage an extensive family health program (PSF – Programa de Saúde da Família).[159]

The Sistema Integrado de Gestão de Assistência à Saúde de São Paulo – SIGA Saúde (Integrated Health Care Management System in São Paulo) has been operating in the city of São Paulo since 2004. Today there are more than 22 million registered users, including the people of the Greater São Paulo, with a monthly average of 1.3 million appointments.[159]

Government

[edit]

As the capital of the state of São Paulo, the city is home to the Bandeirantes Palace (state government) and the Legislative Assembly. The Executive Branch of the municipality of São Paulo is represented by the mayor and his cabinet of secretaries, following the model proposed by the Federal Constitution.[160] The organic law of the municipality and the Master Plan of the city, however, determine that the public administration must guarantee to the population effective tools of manifestation of participatory democracy, which causes that the city is divided in regional prefectures, each one led by a Regional Mayor appointed by the Mayor.[161]

The legislative power is represented by the Municipal Chamber, composed of 55 aldermen elected to four-year posts (in compliance with the provisions of Article 29 of the Constitution, which dictates a minimum number of 42 and a maximum of 55 for municipalities with more than five million inhabitants). It is up to the house to draft and vote fundamental laws for the administration and the Executive, especially the municipal budget (known as the Law of Budgetary Guidelines).[162] In addition to the legislative process and the work of the secretariats, there are also a number of municipal councils, each dealing with different topics, composed of representatives of the various sectors of organized civil society. The actual performance and representativeness of such councils, however, are sometimes questioned.

The following municipal councils are active: Municipal Council for Children and Adolescents (CMDCA); of Informatics (WCC); of the Physically Disabled (CMDP); of Education (CME); of Housing (CMH); of Environment (CADES); of Health (CMS); of Tourism (COMTUR); of Human Rights (CMDH); of Culture (CMC); and of Social Assistance (COMAS) and Drugs and Alcohol (COMUDA). The Prefecture also owns (or is the majority partner in their social capital) a series of companies responsible for various aspects of public services and the economy of São Paulo:

- São Paulo Turismo S/A (SPTuris): company responsible for organizing large events and promoting the city's tourism.

- Companhia de Engenharia de Tráfego (CET):[163] subordinated to the Municipal Transportation Department, is responsible for traffic supervision, fines (in cooperation with DETRAN) and maintenance of the city's road system.

- Companhia Metropolitana de Habitação de São Paulo (COHAB): subordinate to the Department of Housing, is responsible for the implementation of public housing policies, especially the construction of housing developments.

- Empresa Municipal de Urbanização de São Paulo (EMURB): subordinate to the Planning Department, is responsible for urban works and for the maintenance of public spaces and urban furniture.

- Companhia de Processamento de Dados de São Paulo (PRODAM): responsible for the electronic infrastructure and information technology of the city hall.

- São Paulo Transportes Sociedade Anônima (SPTrans): responsible for the operation of the public transport systems managed by the city hall, such as the municipal bus lines.

Subdivisions

[edit]São Paulo is divided into 32 subprefectures, each with an administration ("subprefeitura") divided into several districts ("distritos").[161] The city also has a radial division into nine zones for purpose of traffic control and bus lines, which do not fit into the administrative divisions. These zones are identified by colors in the street signs. The historical core of São Paulo, which includes the inner city and the area of Paulista Avenue, is in the Subprefecture of Sé. Most other economic and tourist facilities of the city are inside an area officially called Centro Expandido (Portuguese for "Broad Center", or "Broad Downtown"), which includes Sé and several other subprefectures, and areas immediately around it.

| Subprefectures of São Paulo[164] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subprefecture | Area | Population | Subprefecture | Area | Population | |||

| 1 | Aricanduva/Vila Formosa | 21.5 km2 | 266 838 |  | 17 | Mooca | 35.2 km2 | 305 436 |

| 2 | Butantã | 56.1 km2 | 345 943 | 18 | Parelheiros | 353.5 km2 | 110 909 | |

| 3 | Campo Limpo | 36.7 km2 | 508 607 | 19 | Penha | 42.8 km2 | 472 247 | |

| 4 | Capela do Socorro | 134.2 km2 | 561 071 | 20 | Perus | 57.2 km2 | 109 218 | |

| 5 | Casa Verde/Cachoeirinha | 26.7 km2 | 313 176 | 21 | Pinheiros | 31.7 km2 | 270 798 | |

| 6 | Cidade Ademar | 30.7 km2 | 370 759 | 22 | Pirituba/Jaraguá | 54.7 km2 | 390 083 | |

| 7 | Cidade Tiradentes | 15 km2 | 248 762 | 23 | Sé | 26.2 km2 | 373 160 | |

| 8 | Ermelino Matarazzo | 15.1 km2 | 204 315 | 24 | Santana/Tucuruvi | 34.7 km2 | 327 279 | |

| 9 | Freguesia do Ó/Brasilândia | 31.5 km2 | 391 403 | 25 | Jaçanã/Tremembé | 64.1 km2 | 255 435 | |

| 10 | Guaianases | 17.8 km2 | 283 162 | 26 | Santo Amaro | 37.5 km2 | 217 280 | |

| 11 | Ipiranga | 37.5 km2 | 427 585 | 27 | São Mateus | 45.8 km2 | 422 199 | |

| 12 | Itaim Paulista | 21.7 km2 | 358 888 | 28 | São Miguel Paulista | 24.3 km2 | 377 540 | |

| 13 | Itaquera | 54.3 km2 | 488 327 | 29 | Sapopemba | 13.4 km2 | 296 042 | |

| 14 | Jabaquara | 14.1 km2 | 214 200 | 30 | Vila Maria/Vila Guilherme | 26.4 km2 | 302 899 | |

| 15 | Lapa | 40.1 km2 | 270 102 | 31 | Vila Mariana | 26.5 km2 | 311 019 | |

| 16 | M'Boi Mirim | 62.1 km2 | 523 138 | 32 | Vila Prudente | 33.3 km2 | 480 823 | |

International relations

[edit]São Paulo is twinned with:[165]

Amman, Jordan

Amman, Jordan Asunción, Paraguay

Asunción, Paraguay Beijing, China

Beijing, China Belmonte, Portugal

Belmonte, Portugal Bucharest, Romania

Bucharest, Romania Chicago, United States

Chicago, United States Cluj-Napoca, Romania

Cluj-Napoca, Romania Coimbra, Portugal

Coimbra, Portugal Córdoba, Spain

Córdoba, Spain Damascus, Syria

Damascus, Syria Funchal, Portugal

Funchal, Portugal Góis, Portugal

Góis, Portugal Hamburg, Germany

Hamburg, Germany Havana, Cuba

Havana, Cuba Huaibei, China

Huaibei, China İzmir, Turkey

İzmir, Turkey Lima, Peru

Lima, Peru Leiria, Portugal

Leiria, Portugal Luanda, Angola

Luanda, Angola Macau, China

Macau, China Mendoza, Argentina

Mendoza, Argentina Milan, Italy

Milan, Italy Naha, Japan

Naha, Japan Ningbo, China

Ningbo, China Osaka, Japan

Osaka, Japan La Paz, Bolivia

La Paz, Bolivia Santiago, Chile

Santiago, Chile Santiago de Compostela, Spain

Santiago de Compostela, Spain Seoul, South Korea

Seoul, South Korea Shanghai, China

Shanghai, China Tel Aviv, Israel

Tel Aviv, Israel Toronto, Canada

Toronto, Canada Yerevan, Armenia

Yerevan, Armenia

Economy

[edit]São Paulo is Brazil's highest GDP city and one of the largest in the world.[168][169] According to data from the IBGE, its gross domestic product (GDP) in 2010 was R$450 billion,[170] approximately US$220 billion, 12.26% of Brazilian GDP and 36% of the São Paulo state's GDP.[171] The per capita income for the city was R$32,493 in 2008.[172]

São Paulo is considered the financial capital of Brazil, as it is the location for the headquarters of major corporations and of banks and financial institutions. The city is the headquarters of B3, the largest stock exchange of Latin America by market capitalization,[17] and has several financial districts, mainly in the areas around Paulista, Faria Lima and Berrini avenues. 63% of all the international companies with business in Brazil have their head offices in São Paulo. São Paulo has one of the largest concentrations of German businesses worldwide[173] and is the largest Swedish industrial hub alongside Gothenburg.[174]

As of 2014[update], São Paulo is the third largest exporting municipality in Brazil after Parauapebas, PA and Rio de Janeiro, RJ. In that year São Paulo's exported goods totaled $7.32B (USD) or 3.02% of Brazil's total exports. The top five commodities exported by São Paulo are soybean (21%), raw sugar (19%), coffee (6.5%), sulfate chemical wood pulp (5.6%), and corn (4.4%).[175]

São Paulo's economy is going through a deep transformation. Once a city with a strong industrial character, São Paulo's economy has followed the global trend of shifting to the tertiary sector of the economy, focusing on services. São Paulo also has a large "informal" economy.[176] According to PricewaterhouseCoopers average annual economic growth of the city is 4.2%.[177] In 2005, the city of São Paulo collected R$90 billion in taxes and the city budget was R$15 billion. The city has 1,500 bank branches and 70 shopping malls.[178]

The city is unique among Brazilian cities for its large number of foreign corporations.[179] São Paulo ranked second after New York in FDi magazine's bi-annual ranking of Cities of the Future 2013–14 in the Americas, and was named the Latin American City of the Future 2013–14.[180] According to Mercer's 2011 city rankings of cost of living for expatriate employees, São Paulo is among the ten most expensive cities in the world.[181][182]

Luxury brands tend to concentrate their business in São Paulo. Because of the lack of department stores and multi-brand boutiques, shopping malls as well as the Jardins district attract most of the world's luxurious brands. Most of the international luxury brands can be found in the Iguatemi, Cidade Jardim or JK shopping malls or on the streets of Oscar Freire, Lorena or Haddock Lobo in the Jardins district. They are home of brands such as Cartier, Chanel, Dior, Giorgio Armani, Gucci, Louis Vuitton, Marc Jacobs, Tiffany & Co. Cidade Jardim was opened in São Paulo in 2008, it is a 45,000-square-meter (484,376-square-foot) mall, landscaped with trees and greenery scenario, with a focus on Brazilian brands but also home to international luxury brands such as Hermès, Jimmy Choo, Pucci and Carolina Herrera. Opened in 2012, JK shopping mall has brought to Brazil brands that were not present in the country before such as Goyard, Tory Burch, Llc., Prada, and Miu Miu.[183]

The Iguatemi Faria Lima, in Faria Lima Avenue, is Brazil's oldest mall, opened in 1966.[184] The Jardins neighborhood is regarded among the most sophisticated places in town, with upscale restaurants and hotels. The New York Times once compared Oscar Freire Street to Rodeo Drive.[185] In Jardins there are luxury car dealers. One of the world's best restaurants as elected by The World's 50 Best Restaurants Award, D.O.M.,[186] is there.

Tourism

[edit]Large hotel chains whose target audience is the corporate traveler are in the city. São Paulo is home to 75% of the country's leading business fairs. The city also promotes one of the most important fashion weeks in the world, São Paulo Fashion Week, established in 1996 under the name Morumbi Fashion Brasil, is the largest and most important fashion event in Latin America.[189] Besides, the São Paulo Gay Pride Parade, held since 1997 on Paulista Avenue is the event that attracts more tourists to the city.[190]

The annual March For Jesus is a large gathering of Christians from Protestant churches throughout Brazil, with São Paulo police reporting participation in the range of 350,000 in 2015.[191] In addition, São Paulo hosts the annual São Paulo Pancake Cook-Off in which chefs from across Brazil and the world participate in competitions based on the cooking of pancakes.[192]

Cultural tourism also has relevance to the city, especially when considering the international events in the metropolis, such as the São Paulo Art Biennial, that attracted almost 1 million people in 2004.

The city has a nightlife that is considered one of the best in the country, and is an international hub of highly active and diverse nightlife with bars, dance bars and nightclubs staying open well past midnight.[193] There are cinemas, theaters, museums, and cultural centers. The Rua Oscar Freire was named one of the eight most luxurious streets in the world, according to the Mystery Shopping International,[194] and São Paulo the 25th "most expensive city" of the planet.[195]

According to the International Congress & Convention Association, São Paulo ranks first among the cities that host international events in Americas and the 12th in the world, after Vienna, Paris, Barcelona, Singapore, Berlin, Budapest, Amsterdam, Stockholm, Seoul, Lisbon, and Copenhagen.[196] According to a study by MasterCard in 130 cities around the world, São Paulo was the third most visited destination in Latin America (behind Mexico City and Buenos Aires) with 2.4 million foreign travelers, who spent US$2.9 billion in 2013 (the highest among the cities in the region). In 2014, CNN ranked nightlife São Paulo as the fourth best in the world, behind New York City, Berlin and Ibiza, in Spain.[197]

The cuisine of the region is a tourist attraction. The city has 62 cuisines across 12,000 restaurants.[198] During the 10th International Congress of Gastronomy, Hospitality and Tourism (Cihat) conducted in 1997, the city received the title of "World Gastronomy Capital" from a commission formed by 43 nations' representatives.[199]

Urban infrastructure

[edit]

Since the beginning of the 20th century, São Paulo has been one of the main economic centers of Latin America. With the First and Second World Wars and the Great Depression, coffee exports to the United States and Europe were heavily affected, forcing the rich coffee growers to invest in the industrial activities that would make São Paulo the largest industrial center in Brazil. The new job vacancies contributed to attract a significant number of immigrants (mainly from Italy)[200] and migrants, especially from the Northeastern states.[201] From a population of only 32.000 people in 1880, São Paulo now had 8.5 million inhabitants in 1980. The rapid population growth has brought many problems for the city.

São Paulo is practically all served by the water supply network. The city consumes an average of 221 liters of water/inhabitant/day while the UN recommends the consumption of 110 liters/day. The water loss is 30.8%. However, between 11 and 12.8% of households do not have a sewage system, depositing waste in pits and ditches. Sixty percent of the sewage collected is treated. According to data from IBGE and Eletropaulo, the electricity grid serves almost 100% of households. The fixed telephony network is still precarious, with coverage of 67.2%. Household garbage collection covers all regions of the municipality but is still insufficient, reaching around 94% of the demand in districts such as Parelheiros and Perus. About 80% of the garbage produced daily by Paulistas is exported to other cities, such as Caieiras and Guarulhos.[202] Recycling accounts for about 1% of the 15,000 metric tons of waste produced daily.[202]

Urban planning

[edit]

São Paulo has a myriad of urban fabrics. The original nuclei of the city are vertical, characterized by the presence of commercial buildings and services; And the peripheries are generally developed with two to four-story buildings – although such generalization certainly meets with exceptions in the fabric of the metropolis. Compared to other global cities (such as the island cities of New York City and Hong Kong), however, São Paulo is considered a "low-rise building" city. Its tallest buildings rarely reach forty stories, and the average residential building is twenty. Nevertheless, it is the fourth city in the world in quantity of buildings, according to the page specialized in research of data on buildings Emporis Buildings,[203] besides possessing what was considered until 2014 the tallest skyscraper of the country, the Mirante do Vale, also known as Palácio Zarzur Kogan, with 170 meters of height and 51 floors.[204]

Such tissue heterogeneity, however, is not as predictable as the generic model can make us imagine. Some central regions of the city began to concentrate indigents, drug trafficking, street vending and prostitution, which encouraged the creation of new socio-economic centralities. The characterization of each region of the city also underwent several changes throughout the 20th century. With the relocation of industries to other cities or states, several areas that once housed factory sheds have become commercial or even residential areas.[205]

São Paulo has a history of actions, projects and plans related to urban planning that can be traced to the governments of Antonio da Silva Prado, Baron Duprat, Washington and Luis Francisco Prestes Maia. However, in general, the city was formed during the 20th century, growing from village to metropolis through a series of informal processes and irregular urban sprawl.[206]

Urban growth in São Paulo has followed three patterns since the beginning of the 20th century, according to urban historians: since the late 19th century and until the 1940s, São Paulo was a condensed city in which different social groups lived in a small urban zone separated by type of housing; from the 1940s to the 1980s, São Paulo followed a model of center-periphery social segregation, in which the upper and middle-classes occupied central and modern areas while the poor moved towards precarious, self-built housing in the periphery; and from the 1980s onward, new transformations have brought the social classes closer together in spatial terms, but separated by walls and security technologies that seek to isolate the richer classes in the name of security.[207] Thus, São Paulo differs considerably from other Brazilian cities such as Belo Horizonte and Goiânia, whose initial expansion followed determinations by a plan, or a city like Brasília, whose master plan had been fully developed prior to construction.[208]

The effectiveness of these plans has been seen by some planners and historians as questionable. Some of these scholars argue that such plans were produced exclusively for the benefit of the wealthier strata of the population while the working classes would be relegated to the traditional informal processes. In São Paulo until the mid-1950s, the plans were based on the idea of "demolish and rebuild", including former Mayor Francisco Prestes Maia's road plan for São Paulo (known as the Avenues Plan) or Saturnino de Brito's plan for the Tietê River. The Plan of the Avenues was implemented during the 1920s and sought to build large avenues connecting the city center with the outskirts. This plan included renewing the commercial city center, leading to real estate speculation and gentrification of several downtown neighborhoods. The plan also led to the expansion of bus services, which would soon replace the trolley as the preliminary transportation system.[209] This contributed to the outwards expansion of São Paulo and the peripherization of poorer residents. Peripheral neighborhoods were usually unregulated and consisted mainly of self-built single-family houses.[207]

In 1968 the Urban Development Plan proposed the Basic Plan for Integrated Development of São Paulo, under the administration of Figueiredo Ferraz. The main result was zoning laws. It lasted until 2004 when the Basic Plan was replaced by the current Master Plan.[210] That zoning, adopted in 1972, designated "Z1" areas (residential areas designed for elites) and "Z3" (a "mixed zone" lacking clear definitions about their characteristics). Zoning encouraged the growth of suburbs with minimal control and major speculation.[211] After the 1970s peripheral lot regulation increased and infrastructure in the periphery improved, driving land prices up. The poorest and the newcomers now could not purchase their lot and build their house, and were forced to look for a housing alternative. As a result, favelas and precarious tenements (cortiços) appeared.[212] These housing types were often closer to the city's center: favelas could sprawl in any unused terrain (often dangerous or unsanitary) and decaying or abandoned buildings for tenements were abundant inside the city. Favelas went back into the urban perimeter, occupying the small lots not yet occupied by urbanization – alongside polluted rivers, railways, or between bridges.[213] By 1993, 19.8% of São Paulo's population lived in favelas, compared to 5.2% in 1980.[214] Today, it is estimated that 2.1 million Paulistas live in favelas, which represents about 11% of the metropolitan area's population.[215]

Transport

[edit]Air

[edit]São Paulo has two main airports, São Paulo/Guarulhos International Airport for international flights and national hub, and São Paulo–Congonhas Airport for domestic and regional flights. Another airport, the Campo de Marte Airport, serves private jets and light aircraft. The three airports together moved more than 58.000.000 passengers in 2015, making São Paulo one of the top 15 busiest in the world, by number of air passenger movements. The region of Greater São Paulo is also served by Viracopos International Airport, São José dos Campos Airport and Jundiaí Airport.

Congonhas Airport operates flights mainly to Rio de Janeiro, Porto Alegre, Belo Horizonte and Brasília. Built in the 1930s, it was designed to handle the increasing demand for flights, in the fastest growing city in the world. Located in Campo Belo District, Congonhas Airport is close to the three main city's financial districts: Paulista Avenue, Brigadeiro Faria Lima Avenue and Engenheiro Luís Carlos Berrini Avenue.

The São Paulo–Guarulhos International, also known as "Cumbica", is 25 km (16 mi) north-east of the city center, in the neighboring city of Guarulhos. Every day nearly 110.000 people pass through the airport, which connects Brazil to 36 countries around the world. 370 companies operate there, generating more than 53.000 jobs. The international airport is connected to the metropolitan rail system, with Line 13 (CPTM).

Campo de Marte is in Santana district, the northern zone of São Paulo. The airport handles private flights and air shuttles, including air taxi firms. Opened in 1935, Campo de Marte is the base for the largest helicopter fleet in Brazil and the world's, ahead of New York and Tokyo.[216] This airport is the home base of the State Civil Police Air Tactical Unit, the State Military Police Radio Patrol Unit and the São Paulo Flying Club.[217]From this airport, passengers can take advantage of some 350 remote helipads and heliports to bypass heavy road traffic.[218]

Roads

[edit]Automobiles are the main means to get into the city. In March 2011, more than 7 million vehicles were registered.[219] Heavy traffic is common on the city's main avenues and traffic jams are relatively common on its highways.

The city is crossed by 10 major motorways: President Dutra Highway/BR-116 (connects São Paulo to the east and north-east of the country); Régis Bittencourt Highway/BR-116 (connects São Paulo to the south of the country); Fernão Dias Highway/BR-381 (connects São Paulo to the north of the country); Anchieta Highway/SP-150 (connects São Paulo to the ocean coast); Immigrants Highway/SP-150 (connects São Paulo to the ocean coast); President Castelo Branco Highway/SP-280 (connects São Paulo to the west and north-west of the country); Raposo Tavares Highway/SP-270 (connects São Paulo to the west of the country); Anhanguera Highway/SP-330 (connects São Paulo to the north-west of the country, including its capital city); Bandeirantes Highway/SP-348 (connects São Paulo to the north-west of the country); Ayrton Senna Highway/SP-70 (named after Brazilian legendary Formula One driver Ayrton Senna, the motorway connects São Paulo to east locations of the state, as well as the north coast of the state).

The Rodoanel Mário Covas (official designation SP-021) is the beltway of the Greater São Paulo. Upon its completion, it will have a length of 177 km (110 mi), with a radius of approximately 23 km (14 mi) from the geographical center of the city. It was named after Mário Covas, who was mayor of the city of São Paulo (1983–1985) and a state governor (1994-1998/1998-2001) until his death from cancer. It is a controlled access highway with a speed limit of 100 km/h (62 mph) under normal weather and traffic circumstances. The west, south and east parts are completed, and the north part, which will close the beltway, is due in 2022 and is being built by DERSA.[220]

Buses

[edit]Bus transport (government and private) is composed of 17,000 buses (including about 290 trolley buses).[223] The traditional system of informal transport (dab vans) was later reorganized and legalized. The trolleybus systems provide a portion of the public transport service in Greater São Paulo with two independent networks.[224][221] The SPTrans (São Paulo Transportes) system opened in 1949 and serves the city of São Paulo, while the Empresa Metropolitana de Transportes Urbanos de São Paulo (EMTU) system opened in 1988 and serves suburban areas to the southeast of the city proper. Worldwide, São Paulo is one of only two metropolitan areas possessing two independent trolleybus systems, the other being Naples, Italy.[221]

São Paulo Tietê Bus Terminal is the second largest bus terminal in the world, after PABT in New York.[222] It serves localities across the nation, with the exception of the states of Amazonas, Roraima and Amapá. Routes to 1,010 cities in five countries (Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Uruguay and Paraguay) are available. It connects to all regional airports and a ride sharing automobile service to Santos.[222]

The Palmeiras-Barra Funda Intermodal Terminal is much smaller and is connected to the Palmeiras-Barra Funda metro and Palmeiras-Barra Funda CPTM stations. It serves the southwestern cities of Sorocaba, Itapetininga, Itu, Botucatu, Bauru, Marília, Jaú, Avaré, Piraju, Santa Cruz do Rio Pardo, Ipaussu, Chavantes and Ourinhos (on the border with Paraná State). It also serves São José do Rio Preto, Araçatuba and other small towns on the northwest of São Paulo State.

Urban rail

[edit]São Paulo has an urban rail transit system (São Paulo Metro and São Paulo Metropolitan Trains) that serves 184 stations and has 377 km (234 mi) of track,[225] forming the largest metropolitan rail transport network of Latin America.[226] The underground and urban railway lines together carry some 7 million people on an average weekday.[227]

The São Paulo Metro operates 104 kilometers (65 mi) of rapid transit system, with six lines in operation, serving 91 stations.[228] In 2015, the metro reached the mark of 11.5 million passengers per mile of line, 15% higher than in 2008, when 10 million users were taken per mile. It is the largest concentration of people in a single transport system in the world, according to the company. In 2014, the São Paulo Metro was elected the best metro system in the Americas.[229]