лютеранство

| Часть серии о |

| лютеранство |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Protestantism |

|---|

|

Лютеранство — основная ветвь протестантизма , отождествляющая себя прежде всего с богословием Мартина Лютера , XVI века немецкого монаха и реформатора , чьи усилия по реформированию богословия и практики католической церкви положили начало протестантской Реформации . [1]

Раскол между лютеранами и католиками был обнародован и очевиден в Вормсском эдикте 1521 года . Указы сейма осудили Лютера и официально запретили гражданам Священной Римской империи защищать или пропагандировать его идеи, подвергая сторонников лютеранства конфискации всей собственности, при этом половина конфискованной собственности должна была быть передана имперскому правительству, а оставшаяся половина - конфискации. стороне, выдвинувшей обвинение. [2]

Разногласия касались в первую очередь двух пунктов: собственно источника власти в церкви , часто называемого формальным принципом Реформации, и доктрины оправдания , часто называемой материальным принципом лютеранской теологии. [а] Lutheranism advocates a doctrine of justification "by Grace alone through faith alone on the basis of Scripture alone," the doctrine that scripture is the final authority on all matters of faith. This is in contrast to the belief of the Roman Catholic Church, defined at the Council of Trent, concerning final authority coming from both the Scriptures and Tradition.[3]

Unlike Calvinism, Lutheranism retains many of the liturgical practices and sacramental teachings of the pre-Reformation Western Church, with a particular emphasis on the Eucharist, or Lord's Supper, though Eastern Lutheranism uses the Byzantine Rite.[4] Lutheran theology differs from Reformed theology in Christology, divine grace, the purpose of God's Law, the concept of perseverance of the saints, and predestination amongst other matters.

Etymology[edit]

The name Lutheran originated as a derogatory term used against Luther by German Scholastic theologian Johann Maier von Eck during the Leipzig Debate in July 1519.[5] Eck and other Roman Catholics followed the traditional practice of naming a heresy after its leader, thus labeling all who identified with the theology of Martin Luther as Lutherans.[2]

Martin Luther always disliked the term Lutheran, preferring the term evangelical, which was derived from εὐαγγέλιον euangelion, a Greek word meaning "good news", i.e. "Gospel".[5] The followers of John Calvin, Huldrych Zwingli, and other theologians linked to the Reformed tradition also used that term. To distinguish the two evangelical groups, others began to refer to the two groups as Evangelical Lutheran and Evangelical Reformed. As time passed by, the word Evangelical was dropped. Lutherans themselves began to use the term Lutheran in the middle of the 16th century, in order to distinguish themselves from other groups such as the Anabaptists and Calvinists.

In 1597, theologians in Wittenberg defined the title Lutheran as referring to the true church.[2]

History[edit]

Lutheranism has its roots in the work of Martin Luther, who sought to reform the Western Church to what he considered a more biblical foundation.[6][7] The reaction of the government and church authorities to the international spread of his writings, beginning with the Ninety-five Theses, divided Western Christianity.[8] During the Reformation, Lutheranism became the state religion of numerous states of northern Europe, especially in northern Germany, Scandinavia and the then-Livonian Order. Lutheran clergy became civil servants and the Lutheran churches became part of the state.[1]

Spread to Northern Europe[edit]

Lutheranism spread through all of Scandinavia during the 16th century as the monarchs of Denmark–Norway and Sweden adopted the faith. Through Baltic-German and Swedish rule, Lutheranism also spread into Estonia and Latvia. It also began spreading into Lithuania Proper with practically all members of the Lithuanian nobility converting to Lutheranism or Calvinism, but at the end of the 17th century Protestantism at large began losing support due to Counter-Reformation and religious persecutions.[9] In German-ruled Lithuania Minor, however, Lutheranism remained to be the dominant branch of Christianity.[10] Lutheranism played a crucial role in preserving the Lithuanian language.[11]

Since 1520, regular[12] Lutheran services have been held in Copenhagen. Under the reign of Frederick I (1523–33), Denmark–Norway remained officially Catholic. Although Frederick initially pledged to persecute Lutherans, he soon adopted a policy of protecting Lutheran preachers and reformers, the most significant of which was Hans Tausen.[13]

During Frederick's reign, Lutheranism made significant inroads in Denmark. At an open meeting in Copenhagen attended by King Christian III in 1536, the people shouted; "We will stand by the holy Gospel, and do not want such bishops anymore".[14] Frederick's son was openly Lutheran, which prevented his election to the throne upon his father's death in 1533. However, following his victory in the civil war that followed, in 1536 he became Christian III and advanced the Reformation in Denmark–Norway.

The constitution upon which the Danish Norwegian Church, according to the Church Ordinance, should rest was "The pure word of God, which is the Law and the Gospel".[15] It does not mention the[12] Augsburg Confession. The priests had to[12] understand the Holy Scripture well enough to preach and explain the Gospel and the Epistles to their congregations.

The youths were taught[16] from Luther's Small Catechism, available in Danish since 1532. They were taught to expect at the end of life:[12] "forgiving of their sins", "to be counted as just", and "the eternal life". Instruction is still similar.[17]

The first complete Bible in Danish was based on Martin Luther's translation into German. It was published in 1550 with 3,000 copies printed in the first edition; a second edition was published in 1589.[18] Unlike Catholicism, Lutheranism does not believe that tradition is a carrier of the "Word of God", or that only the communion of the Bishop of Rome has been entrusted to interpret the "Word of God".[12][19]

The Reformation in Sweden began with Olaus and Laurentius Petri, brothers who took the Reformation to Sweden after studying in Germany. They led Gustav Vasa, elected king in 1523, to Lutheranism. The pope's refusal to allow the replacement of an archbishop who had supported the invading forces opposing Gustav Vasa during the Stockholm Bloodbath led to the severing of any official connection between Sweden and the papacy in 1523.[13]

Four years later, at the Diet of Västerås, the king succeeded in forcing the diet to accept his dominion over the national church. The king was given possession of all church properties, as well as the church appointments and approval of the clergy. While this effectively granted official sanction to Lutheran ideas,[13] Lutheranism did not become official until 1593. At that time the Uppsala Synod declared Holy Scripture the sole guideline for faith, with four documents accepted as faithful and authoritative explanations of it: the Apostles' Creed, the Nicene Creed, the Athanasian Creed, and the unaltered Augsburg Confession of 1530.[20] Mikael Agricola's translation of the first Finnish New Testament was published in 1548.[21]

Counter-Reformation and controversies[edit]

After the death of Martin Luther in 1546, the Schmalkaldic War started out as a conflict between two German Lutheran rulers in 1547. Soon, Holy Roman Imperial forces joined the battle and conquered the members of the Schmalkaldic League, oppressing and exiling many German Lutherans as they enforced the terms of the Augsburg Interim. Religious freedom in some areas was secured for Lutherans through the Peace of Passau in 1552, and under the legal principle of Cuius regio, eius religio (the religion of the ruler was to dictate the religion of those ruled) and the Declaratio Ferdinandei (limited religious tolerance) clauses of the Peace of Augsburg in 1555.[22]

Religious disputes between the Crypto-Calvinists, Philippists, Sacramentarians, Ubiquitarians and Gnesio-Lutherans raged within Lutheranism during the middle of the 16th century. This finally ended with the resolution of the issues in the Formula of Concord. Large numbers of politically and religiously influential leaders met together, debated, and resolved these topics on the basis of Scripture, resulting in the Formula, which over 8,000 leaders signed. The Book of Concord replaced earlier, incomplete collections of doctrine, unifying all German Lutherans with identical doctrine and beginning the period of Lutheran Orthodoxy.

In lands where Catholicism was the state religion, Lutheranism was officially illegal, although enforcement varied. Until the end of the Counter-Reformation, some Lutherans worshipped secretly, such as at the Hundskirke (which translates as dog church or dog altar), a triangle-shaped Communion rock in a ditch between crosses in Paternion, Austria. The crowned serpent is possibly an allusion to Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor, while the dog possibly refers to Peter Canisius. Another figure interpreted as a snail carrying a church tower is possibly a metaphor for the Protestant church. Also on the rock is the number 1599 and a phrase translating as "thus gets in the world".[23]

Lutheran orthodoxy[edit]

The historical period of Lutheran Orthodoxy is divided into three sections: Early Orthodoxy (1580–1600), High Orthodoxy (1600–1685), and Late Orthodoxy (1685–1730). Lutheran scholasticism developed gradually, especially for the purpose of arguing with the Jesuits, and it was finally established by Johann Gerhard. Abraham Calovius represents the climax of the scholastic paradigm in orthodox Lutheranism. Other orthodox Lutheran theologians include Martin Chemnitz, Aegidius Hunnius, Leonhard Hutter, Nicolaus Hunnius, Jesper Rasmussen Brochmand, Salomo Glassius, Johann Hülsemann, Johann Conrad Dannhauer, Johannes Andreas Quenstedt, Johann Friedrich König, and Johann Wilhelm Baier.

Near the end of the Thirty Years' War, the compromising spirit seen in Philip Melanchthon rose up again in Helmstedt School and especially in theology of Georgius Calixtus, causing the syncretistic controversy. Another theological issue that arose was the Crypto-Kenotic controversy.[24]

Late orthodoxy was torn by influences from rationalism, philosophy based on reason, and Pietism, a revival movement in Lutheranism. After a century of vitality, the Pietist theologians Philipp Jakob Spener and August Hermann Francke warned that orthodoxy had degenerated into meaningless intellectualism and formalism, while orthodox theologians found the emotional and subjective focuses of Pietism to be vulnerable to Rationalist propaganda.[25] In 1688, the Finnish Radical Pietist Lars Ulstadius ran down the main aisle of Turku Cathedral naked while screaming that the disgrace of Finnish clergymen would be revealed like his current disgrace.

The last famous orthodox Lutheran theologian before the rationalist Aufklärung, or Enlightenment, was David Hollatz. Late orthodox theologian Valentin Ernst Löscher took part in the controversy against Pietism. Medieval mystical traditions continued in the works of Martin Moller, Johann Arndt, and Joachim Lütkemann. Pietism became a rival of orthodoxy but adopted some devotional literature by orthodox theologians, including Arndt, Christian Scriver and Stephan Prätorius.

Rationalism[edit]

Rationalist philosophers from France and England had an enormous impact during the 18th century, along with the German Rationalists Christian Wolff, Gottfried Leibniz, and Immanuel Kant. Their work led to an increase in rationalist beliefs, "at the expense of faith in God and agreement with the Bible".[25]

In 1709, Valentin Ernst Löscher warned that this new Rationalist view of the world fundamentally changed society by drawing into question every aspect of theology. Instead of considering the authority of divine revelation, he explained, Rationalists relied solely on their personal understanding when searching for truth.[26]

Johann Melchior Goeze (1717–1786), pastor of St. Catherine's Church, Hamburg, wrote apologetical works against Rationalists, including a theological and historical defence against the historical criticism of the Bible.[27]

Dissenting Lutheran pastors were often reprimanded by the government bureaucracy overseeing them, for example, when they tried to correct Rationalist influences in the parish school.[28] As a result of the impact of a local form of rationalism, termed Neology, by the latter half of the 18th century, genuine piety was found almost solely in small Pietist conventicles.[25] However, some of the laity preserved Lutheran orthodoxy from both Pietism and rationalism through reusing old catechisms, hymnbooks, postils, and devotional writings, including those written by Johann Gerhard, Heinrich Müller and Christian Scriver.[29]

Revivals[edit]

Luther scholar Johann Georg Hamann (1730–1788), a layman, became famous for countering Rationalism and striving to advance a revival known as the Erweckung, or Awakening.[30] In 1806, Napoleon's invasion of Germany promoted Rationalism and angered German Lutherans, stirring up a desire among the people to preserve Luther's theology from the Rationalist threat. Those associated with this Awakening held that reason was insufficient and pointed out the importance of emotional religious experiences.[31][32]

Small groups sprang up, often in universities, which devoted themselves to Bible study, reading devotional writings, and revival meetings. Although the beginning of this Awakening tended heavily toward Romanticism, patriotism, and experience, the emphasis of the Awakening shifted around 1830 to restoring the traditional liturgy, doctrine, and confessions of Lutheranism in the Neo-Lutheran movement.[31][32]

This Awakening swept through all of Scandinavia except Iceland.[33] It developed from both German Neo-Lutheranism and Pietism. Danish pastor and philosopher N. F. S. Grundtvig reshaped church life throughout Denmark through a reform movement beginning in 1830. He also wrote about 1,500 hymns, including God's Word Is Our Great Heritage.[34]

In Norway, Hans Nielsen Hauge, a lay street preacher, emphasized spiritual discipline and sparked the Haugean movement,[35] which was followed by the Johnsonian Awakening within the state-church.[36] The Awakening drove the growth of foreign missions in Norway to non-Christians to a new height, which has never been reached since.[33] In Sweden, Lars Levi Læstadius began the Laestadian movement that emphasized moral reform.[35] In Finland, a farmer, Paavo Ruotsalainen, began the Finnish Awakening when he took to preaching about repentance and prayer.[35]

In 1817, Frederick William III of Prussia ordered the Lutheran and Reformed churches in his territory to unite, forming the Prussian Union of Churches. The unification of the two branches of German Protestantism sparked the Schism of the Old Lutherans. Many Lutherans, called "Old Lutherans", chose to leave the state churches despite imprisonment and military force.[30] Some formed independent church bodies, or "free churches", at home while others left for the United States, Canada and Australia. A similar legislated merger in Silesia prompted thousands to join the Old Lutheran movement. The dispute over ecumenism overshadowed other controversies within German Lutheranism.[37]

Despite political meddling in church life, local and national leaders sought to restore and renew Christianity. Neo-Lutheran Johann Konrad Wilhelm Löhe and Old Lutheran free church leader Friedrich August Brünn[38] both sent young men overseas to serve as pastors to German Americans, while the Inner Mission focused on renewing the situation home.[39] Johann Gottfried Herder, superintendent at Weimar and part of the Inner Mission movement, joined with the Romantic movement with his quest to preserve human emotion and experience from Rationalism.[40]

Ernst Wilhelm Hengstenberg, though raised Reformed, became convinced of the truth of historic Lutheranism as a young man.[41] He led the Neo-Lutheran Repristination School of theology, which advocated a return to the orthodox theologians of the 17th century and opposed modern Bible scholarship.[42][better source needed] As editor of the periodical Evangelische Kirchenzeitung, he developed it into a major support of Neo-Lutheran revival and used it to attack all forms of theological liberalism and rationalism. Although he received a large amount of slander and ridicule during his forty years at the head of revival, he never gave up his positions.[41]

The theological faculty at the University of Erlangen in Bavaria became another force for reform.[41] There, professor Adolf von Harless, though previously an adherent of rationalism and German idealism, made Erlangen a magnet for revival oriented theologians.[43] Termed the Erlangen School of theology, they developed a new version of the Incarnation,[43] which they felt emphasized the humanity of Jesus better than the ecumenical creeds.[44] As theologians, they used both modern historical critical and Hegelian philosophical methods instead of attempting to revive the orthodoxy of the 17th century.[45]

Friedrich Julius Stahl led the High Church Lutherans. Though raised Jewish, he was baptized as a Christian at the age of 19 through the influence of the Lutheran school he attended. As the leader of a neofeudal Prussian political party, he campaigned for the divine right of kings, the power of the nobility, and episcopal polity for the church. Along with Theodor Kliefoth and August Friedrich Christian Vilmar, he promoted agreement with the Roman Catholic Church with regard to the authority of the institutional church, ex opere operato effectiveness of the sacraments, and the divine authority of clergy. Unlike Catholics, however, they also urged complete agreement with the Book of Concord.[44]

The Neo-Lutheran movement managed to slow secularism and counter atheistic Marxism, but it did not fully succeed in Europe.[39] It partly succeeded in continuing the Pietist movement's drive to right social wrongs and focus on individual conversion. The Neo-Lutheran call to renewal failed to achieve widespread popular acceptance because it both began and continued with a lofty, idealistic Romanticism that did not connect with an increasingly industrialized and secularized Europe.[46] The work of local leaders resulted in specific areas of vibrant spiritual renewal, but people in Lutheran areas became increasingly distant from church life.[39] Additionally, the revival movements were divided by philosophical traditions. The Repristination school and Old Lutherans tended towards Kantianism, while the Erlangen school promoted a conservative Hegelian perspective. By 1969, Manfried Kober complained that "unbelief is rampant" even within German Lutheran parishes.[47]

Doctrine[edit]

Bible[edit]

Traditionally, Lutherans hold the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments to be the only divinely inspired books, the only presently available sources of divinely revealed knowledge, and the only infallible source of Christian doctrine.[48] Scripture alone is the formal principle of the faith, the final authority for all matters of faith and morals because of its inspiration, authority, clarity, efficacy, and sufficiency.[49]

The authority of the Scriptures has been challenged during the history of Lutheranism. Martin Luther taught that the Bible was the written Word of God, and the only infallible guide for faith and practice. He held that every passage of Scripture has one straightforward meaning, the literal sense as interpreted by other Scripture.[50] These teachings were accepted during the orthodox Lutheranism of the 17th century.[51] During the 18th century, Rationalism advocated reason rather than the authority of the Bible as the final source of knowledge, but most of the laity did not accept this Rationalist position.[52] In the 19th century, a confessional revival re-emphasized the authority of the Scriptures and agreement with the Lutheran Confessions.

Today, Lutherans disagree about the inspiration and authority of the Bible. Theological conservatives use the historical-grammatical method of Biblical interpretation, while theological liberals use the higher critical method. The 2008 U.S. Religious Landscape Survey conducted by the Pew Research Center surveyed 1,926 adults in the United States that self-identified as Lutheran. The study found that 30% believed that the Bible was the Word of God and was to be taken literally word for word. 40% held that the Bible was the Word of God, but was not literally true word for word or were unsure. 23% said the Bible was written by men and not the Word of God. 7% did not know, were not sure, or had other positions.[53]

Inspiration[edit]

Although many Lutherans today hold less specific views of inspiration, historically, Lutherans affirm that the Bible does not merely contain the Word of God, but every word of it is, because of plenary, verbal inspiration, the direct, immediate word of God.[54] The Apology of the Augsburg Confession identifies Holy Scripture with the Word of God[55] and calls the Holy Spirit the author of the Bible.[56] Because of this, Lutherans confess in the Formula of Concord, "we receive and embrace with our whole heart the prophetic and apostolic Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments as the pure, clear fountain of Israel".[57] The prophetic and apostolic Scriptures are confessed as authentic and written by the prophets and apostles. A correct translation of their writings is seen as God's Word because it has the same meaning as the original Hebrew and Greek.[58] A mistranslation is not God's word, and no human authority can invest it with divine authority.[58]

Clarity[edit]

Historically, Lutherans understand the Bible to present all doctrines and commands of the Christian faith clearly.[59] In addition, Lutherans believe that God's Word is freely accessible to every reader or hearer of ordinary intelligence, without requiring any special education.[60] A Lutheran must understand the language that scriptures are presented in, and should not be so preoccupied by error so as to prevent understanding.[61] As a result of this, Lutherans do not believe there is a need to wait for any clergy, pope, scholar, or ecumenical council to explain the real meaning of any part of the Bible.[62]

Efficacy[edit]

Lutherans confess that Scripture is united with the power of the Holy Spirit and with it, not only demands, but also creates the acceptance of its teaching.[63] This teaching produces faith and obedience. Holy Scripture is not a dead letter, but rather, the power of the Holy Spirit is inherent in it.[64] Scripture does not compel a mere intellectual assent to its doctrine, resting on logical argumentation, but rather it creates the living agreement of faith.[65] As the Smalcald Articles affirm, "in those things which concern the spoken, outward Word, we must firmly hold that God grants His Spirit or grace to no one, except through or with the preceding outward Word".[66]

Sufficiency[edit]

Lutherans are confident that the Bible contains everything that one needs to know in order to obtain salvation and to live a Christian life.[67] There are no deficiencies in Scripture that need to be filled with by tradition, pronouncements of the Pope, new revelations, or present-day development of doctrine.[68]

Law and Gospel[edit]

Lutherans understand the Bible as containing two distinct types of content, termed Law and Gospel (or Law and Promises).[69] Properly distinguishing between Law and Gospel prevents the obscuring of the Gospel teaching of justification by grace through faith alone.[70]

Lutheran confessions[edit]

The Book of Concord, published in 1580, contains 10 documents which some Lutherans believe are faithful and authoritative explanations of Holy Scripture. Besides the three Ecumenical Creeds, which date to Roman times, the Book of Concord contains seven credal documents articulating Lutheran theology in the Reformation era.

The doctrinal positions of Lutheran churches are not uniform because the Book of Concord does not hold the same position in all Lutheran churches. For example, the state churches in Scandinavia consider only the Augsburg Confession as a "summary of the faith" in addition to the three ecumenical creeds.[71] Lutheran pastors, congregations, and church bodies in Germany and the Americas usually agree to teach in harmony with the entire Lutheran confessions. Some Lutheran church bodies require this pledge to be unconditional because they believe the confessions correctly state what the Bible teaches. Others allow their congregations to do so "insofar as" the confessions are in agreement with the Bible. In addition, Lutherans accept the teachings of the first seven ecumenical councils of the Christian Church.[72][73]

The Lutheran Church traditionally sees itself as the "main trunk of the historical Christian Tree" founded by Christ and the Apostles, holding that during the Reformation, the Church of Rome fell away.[74][75] As such, the Augsburg Confession teaches that "the faith as confessed by Luther and his followers is nothing new, but the true catholic faith, and that their churches represent the true catholic or universal church".[76] When the Lutherans presented the Augsburg Confession to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, they explained "that each article of faith and practice was true first of all to Holy Scripture, and then also to the teaching of the church fathers and the councils".[76]

Justification[edit]

The key doctrine, or material principle, of Lutheranism is the doctrine of justification. Lutherans believe that humans are saved from their sins by God's grace alone (Sola Gratia), through faith alone (Sola Fide), on the basis of Scripture alone (Sola Scriptura).[77] Orthodox Lutheran theology holds that God made the world, including humanity, perfect, holy and sinless. However, Adam and Eve chose to disobey God, trusting in their own strength, knowledge, and wisdom.[78][79] Consequently, people are saddled with original sin, born sinful and unable to avoid committing sinful acts.[80] For Lutherans, original sin is the "chief sin, a root and fountainhead of all actual sins".[81]

Lutherans teach that sinners, while capable of doing works that are outwardly "good", are not capable of doing works that satisfy God's justice.[82] Every human thought and deed is infected with sin and sinful motives.[83] Because of this, all humanity deserves eternal damnation in hell.[84] God in eternity has turned His Fatherly heart to this world and planned for its redemption because he loves all people and does not want anyone to be eternally damned.[85]

To this end, "God sent his Son Jesus Christ, our Lord, into the world to redeem and deliver us from the power of the devil, and to bring us to Himself, and to govern us as a King of righteousness, life, and salvation against sin, death, and an evil conscience", as Luther's Large Catechism explains.[86] Because of this, Lutherans teach that salvation is possible only because of the grace of God made manifest in the birth, life, suffering, death, resurrection, and continuing presence by the power of the Holy Spirit, of Jesus Christ.[87] By God's grace, made known and effective in the person and work of Jesus Christ, a person is forgiven, adopted as a child and heir of God, and given eternal salvation.[88] Christ, because he was entirely obedient to the law with respect to both his human and divine natures, "is a perfect satisfaction and reconciliation of the human race", as the Formula of Concord asserts, and proceeds to summarize:[89]

[Christ] submitted to the law for us, bore our sin, and in going to his Father performed complete and perfect obedience for us poor sinners, from his holy birth to his death. Thereby he covered all our disobedience, which is embedded in our nature and in its thoughts, words, and deeds, so that this disobedience is not reckoned to us as condemnation but is pardoned and forgiven by sheer grace, because of Christ alone.

Lutherans believe that individuals receive this gift of salvation through faith alone.[90] Saving faith is the knowledge of,[91] acceptance of,[92] and trust[93] in the promise of the Gospel.[94] Even faith itself is seen as a gift of God, created in the hearts of Christians[95] by the work of the Holy Spirit through the Word[96] and Baptism.[97] Faith receives the gift of salvation rather than causes salvation.[98] Thus, Lutherans reject the "decision theology" which is common among modern evangelicals.

Since the term "grace" has been defined differently by other Christian church bodies.[99] Lutheranism defines grace as entirely limited to God's gifts to us, which is bestowed as pure gift, not something we merit by behavior or acts. To Lutherans, grace is not about our response to God's gifts, but only His gifts.

Trinity[edit]

Lutherans believe in the Trinity, rejecting the idea that the Father and God the Son are merely faces of the same person, stating that both the Old Testament and the New Testament show them to be two distinct persons.[100] Lutherans believe the Holy Spirit proceeds from both the Father and the Son.[101] In the words of the Athanasian Creed: "We worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity; Neither confounding the Persons, nor dividing the Substance. For there is one Person of the Father, another of the Son, and another of the Holy Ghost. But the Godhead of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost is all one: the glory equal, the majesty coeternal."[102]

Two natures of Christ[edit]

Lutherans believe Jesus is the Christ, the savior promised in the Old Testament. They believe he is both by nature God and by nature man in one person, as they confess in Luther's Small Catechism that he is "true God begotten of the Father from eternity and also true man born of the Virgin Mary".[103]

The Augsburg Confession explains:[104]

[T]he Son of God, did assume the human nature in the womb of the blessed Virgin Mary, so that there are two natures, the divine and the human, inseparably enjoined in one Person, one Christ, true God and true man, who was born of the Virgin Mary, truly suffered, was crucified, dead, and buried, that He might reconcile the Father unto us, and be a sacrifice, not only for original guilt, but also for all actual sins of men.

Sacraments[edit]

Lutherans hold that sacraments are sacred acts of divine institution.[106] Whenever they are properly administered by the use of the physical component commanded by God[107] along with the divine words of institution,[108] God is, in a way specific to each sacrament, present with the Word and physical component.[109] He earnestly offers to all who receive the sacrament[110] forgiveness of sins[111] and eternal salvation.[112] He also works in the recipients to get them to accept these blessings and to increase the assurance of their possession.[113]

Lutherans are not dogmatic about the number of the sacraments.[114] In line with Luther's initial statement in his Large Catechism some speak of only two sacraments,[115] Baptism and Holy Communion, although later in the same work he calls Confession and Absolution[116] "the third sacrament".[117]

The definition of sacrament in the Apology of the Augsburg Confession lists Absolution as one of them.[118] Private Confession is expected before receiving the Eucharist for the first time.[119][120] Some churches also allow for individual absolution on Saturdays before the Eucharistic service.[121] A General Confession and Absolution, known as the Penitential Rite, is proclaimed in the Eucharistic liturgy.[122]

Baptism[edit]

Lutherans hold that Baptism is a saving work of God,[123] mandated and instituted by Jesus Christ.[124] Baptism is a "means of grace" through which God creates and strengthens "saving faith" as the "washing of regeneration"[125] in which infants and adults are reborn.[126] Since the creation of faith is exclusively God's work, it does not depend on the actions of the one baptized, whether infant or adult. Even though baptized infants cannot articulate that faith, Lutherans believe that it is present all the same.[127]

It is faith alone that receives these divine gifts, so Lutherans confess that baptism "works forgiveness of sins, delivers from death and the devil, and gives eternal salvation to all who believe this, as the words and promises of God declare".[128] Lutherans hold fast to the Scripture cited in 1 Peter 3:21, "Baptism, which corresponds to this, now saves you, not as a removal of dirt from the body but as an appeal to God for a good conscience, through the resurrection of Jesus Christ."[129] Therefore, Lutherans administer Baptism to both infants[130] and adults.[131] In the special section on infant baptism in his Large Catechism, Luther argues that infant baptism is God-pleasing because persons so baptized were reborn and sanctified by the Holy Spirit.[132][133]

Eucharist[edit]

Lutherans hold that within the Eucharist, also referred to as the Sacrament of the Altar or the Lord's Supper, the true body and blood of Christ are truly present "in, with, and under the forms" of the consecrated bread and wine for all those who eat and drink it,[134] a doctrine that the Formula of Concord calls the sacramental union.[135]

Confession[edit]

Many Lutherans receive the sacrament of penance before receiving the Eucharist.[136][121] Prior to going to Confessing and receiving Absolution, the faithful are expected to examine their lives in light of the Ten Commandments.[120] An order of Confession and Absolution is contained in the Small Catechism, as well as in liturgical books.[120] Lutherans typically kneel at the communion rails to confess their sins, while the confessor listens and then offers absolution while laying their stole on the penitent's head.[120] Clergy are prohibited from revealing anything said during private Confession and Absolution per the Seal of the Confessional, and face excommunication if it is violated. Apart from this, Laestadian Lutherans have a practice of lay confession.[137]

Conversion[edit]

In Lutheranism, conversion or regeneration in the strict sense of the term is the work of divine grace and power by which man, born of the flesh, and void of all power to think, to will, or to do any good thing, and dead in sin is, through the gospel and holy baptism, taken from a state of sin and spiritual death under God's wrath into a state of spiritual life of faith and grace, rendered able to will and to do what is spiritually good and, especially, made to trust in the benefits of the redemption which is in Christ Jesus.[138]

During conversion, one is moved from impenitence to repentance. The Augsburg Confession divides repentance into two parts: "One is contrition, that is, terrors smiting the conscience through the knowledge of sin; the other is faith, which is born of the Gospel, or of absolution, and believes that for Christ's sake, sins are forgiven, comforts the conscience, and delivers it from terrors."[139]

Predestination[edit]

Lutherans adhere to divine monergism, the teaching that salvation is by God's act alone, and therefore reject the idea that humans in their fallen state have a free will concerning spiritual matters.[140] Lutherans believe that although humans have free will concerning civil righteousness, they cannot work spiritual righteousness in the heart without the presence and aid of the Holy Spirit.[141][142] Lutherans believe Christians are "saved";[143] that all who trust in Christ alone and his promises can be certain of their salvation.[144]

According to Lutheranism, the central final hope of the Christian is "the resurrection of the body and the life everlasting" as confessed in the Apostles' Creed rather than predestination. Lutherans disagree with those who make predestination—rather than Christ's suffering, death, and resurrection—the source of salvation. Unlike some Calvinists, Lutherans do not believe in a predestination to damnation,[145] usually referencing "God our Savior, who desires all people to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth"[146] as contrary evidence to such a claim. Instead, Lutherans teach eternal damnation is a result of the unbeliever's sins, rejection of the forgiveness of sins, and unbelief.[147]

Divine providence[edit]

According to Lutherans, God preserves his creation, cooperates with everything that happens, and guides the universe.[148] While God cooperates with both good and evil deeds, with evil deeds he does so only inasmuch as they are deeds, but not with the evil in them. God concurs with an act's effect, but he does not cooperate in the corruption of an act or the evil of its effect.[149] Lutherans believe everything exists for the sake of the Christian Church, and that God guides everything for its welfare and growth.[150]

The explanation of the Apostles' Creed given in the Small Catechism declares that everything good that people have is given and preserved by God, either directly or through other people or things.[151] Of the services others provide us through family, government, and work, "we receive these blessings not from them, but, through them, from God".[152] Since God uses everyone's useful tasks for good, people should not look down upon some useful vocations as being less worthy than others. Instead people should honor others, no matter how lowly, as being the means God uses to work in the world.[152]

Good works[edit]

Lutherans believe that Augsburg Confession's "Article XX: Of Good Works" are the fruit of faith,[154] always and in every instance.[155] Good works have their origin in God,[156] not in the fallen human heart or in human striving;[157] their absence would demonstrate that faith, too, is absent.[158] Lutherans do not believe that good works are a factor in obtaining salvation; they believe that we are saved by the grace of God—based on the merit of Christ in his suffering and death—and faith in the Triune God. Good works are the natural result of faith, not the cause of salvation. Although Christians are no longer compelled to keep God's law, they freely and willingly serve God and their neighbors.[159]

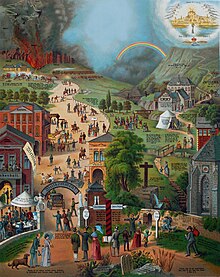

Judgment and eternal life[edit]

Lutherans do not believe in any sort of earthly millennial kingdom of Christ either before or after his second coming on the last day.[160] Lutherans teach that, at death, the souls of Christians are immediately taken into the presence of Jesus,[161] where they await the second coming of Jesus on the last day.[162] On the last day,[163] all the bodies of the dead will be resurrected.[164]

Their souls will then be reunited with the same bodies they had before dying.[165] The bodies will then be changed, those of the wicked to a state of everlasting shame and torment,[166] those of the righteous to an everlasting state of celestial glory.[167] After the resurrection of all the dead,[168] and the change of those still living,[169] all nations shall be gathered before Christ,[170] and he will separate the righteous from the wicked.[171]

Christ will publicly judge[172] all people by the testimony of their deeds,[173] the good works[174] of the righteous in evidence of their faith,[175] and the evil works of the wicked in evidence of their unbelief.[176] He will judge in righteousness[177] in the presence of all people and angels,[178] and his final judgment will be just damnation to everlasting punishment for the wicked and a gracious gift of life everlasting to the righteous.[179]

| Protestant beliefs about salvation | |||

| This table summarizes the classical views of three Protestant beliefs about salvation.[180] | |||

| Topic | Calvinism | Lutheranism | Arminianism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human will | Total depravity:[181] Humanity possesses "free will",[182] but it is in bondage to sin,[183] until it is "transformed".[184] | Total depravity:[181][185][186] Humanity possesses free will in regard to "goods and possessions", but is sinful by nature and unable to contribute to its own salvation.[187][188][189] | Total depravity: Humanity possesses freedom from necessity, but not "freedom from sin" unless enabled by "prevenient grace".[190] |

| Election | Unconditional election. | Unconditional election.[181][191] | Conditional election in view of foreseen faith or unbelief.[192] |

| Justification and atonement | Justification by faith alone. Various views regarding the extent of the atonement.[193] | Justification for all men,[194] completed at Christ's death and effective through faith alone.[195][196][197][198] | Justification made possible for all through Christ's death, but only completed upon choosing faith in Jesus.[199] |

| Conversion | Monergistic,[200] through the means of grace, irresistible. | Monergistic,[201][202] through the means of grace, resistible.[203] | Synergistic, resistible due to the common grace of free will.[204][205] |

| Perseverance and apostasy | Perseverance of the saints: the eternally elect in Christ will certainly persevere in faith.[206] | Falling away is possible,[207] but God gives gospel assurance.[208][209] | Preservation is conditional upon continued faith in Christ; with the possibility of a final apostasy.[210] |

Practices[edit]

Liturgy[edit]

Lutherans place great emphasis on a liturgical approach to worship services;[211] although there are substantial non-liturgical minorities, for example, the Haugean Lutherans from Norway. Martin Luther was a great proponent of music, and this is why music forms a central part of Lutheran services to this day. In particular, Luther admired the composers Josquin des Prez and Ludwig Senfl, and wanted singing in the church to move away from the ars perfecta (Catholic Sacred Music of the late Renaissance) and towards singing as a Gemeinschaft (community).[212] Lutheran hymns are sometimes known as chorales. Lutheran hymnody is well known for its doctrinal, didactic, and musical richness. Most Lutheran churches are active musically with choirs, handbell choirs, children's choirs, and occasionally change ringing groups that ring bells in a bell tower. Johann Sebastian Bach, a devout Lutheran, composed a huge body of sacred music for the Lutheran church.

Lutherans also preserve a liturgical approach to the celebration of the Holy Eucharist/Communion, emphasizing the Sacrament as the central act of Christian worship. Lutherans believe that the actual body and blood of Jesus Christ are present in, with and under the bread and the wine. This belief is called Real Presence or sacramental union and is different from consubstantiation and transubstantiation. Additionally Lutherans reject the idea that communion is a mere symbol or memorial. They confess in the Apology of the Augsburg Confession:

[W]e do not abolish the Mass but religiously keep and defend it. Among us the Mass is celebrated every Lord's Day and on other festivals, when the Sacrament is made available to those who wish to partake of it, after they have been examined and absolved. We also keep traditional liturgical forms, such as the order of readings, prayers, vestments, and other similar things.[213]

In addition to the Holy Communion (Divine Service), congregations frequently also hold offices, which are worship services without communion. They may include Matins, Vespers, Compline, or other observances of the Daily Office. Private or family offices include the Morning and Evening Prayers from Luther's Small Catechism.[214] Meals are blessed with the Common table prayer, Psalm 145:15–16, or other prayers, and after eating the Lord is thanked, for example, with Psalm 136:1. Luther himself encouraged the use of Psalm verses, such as those already mentioned, along with the Lord's Prayer and another short prayer before and after each meal: Blessing and Thanks at Meals from Luther's Small Catechism.[214] In addition, Lutherans use devotional books, from small daily devotionals, for example, Portals of Prayer, to large breviaries, including the Breviarium Lipsiensae and Treasury of Daily Prayer.

The predominant rite used by Lutheran churches is a Western one based on the Formula missae ("Form of the Mass"), although other Lutheran liturgies are also in use, such as those used in the Byzantine Rite Lutheran Churches, such as the Ukrainian Lutheran Church and Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in Slovenia.[215] Although Luther's Deutsche Messe was completely chanted except for the sermon, this is less common today.

In the 1970s, many Lutheran churches began holding contemporary worship services for the purpose of evangelistic outreach. These services were in a variety of styles, depending on the preferences of the congregation. Often they were held alongside a traditional service in order to cater to those who preferred contemporary worship music. Today, a few Lutheran congregations have contemporary worship as their sole form of worship. Outreach is no longer given as the primary motivation; rather this form of worship is seen as more in keeping with the desires of individual congregations.[216] In Finland, Lutherans have experimented with the St Thomas Mass and Metal Mass in which traditional hymns are adapted to heavy metal. Some Laestadians enter a heavily emotional and ecstatic state during worship. The Lutheran World Federation, in its Nairobi Statement on Worship and Culture, recommended every effort be made to bring church services into a more sensitive position with regard to cultural context.[217]

In 2006, both the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) and the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod (LCMS), in cooperation with certain international English speaking church bodies within their respective fellowships, released new hymnals: Evangelical Lutheran Worship (ELCA) and Lutheran Service Book (LCMS). Along with these, the most widely used among English speaking congregations include: Evangelical Lutheran Hymnary (1996, Evangelical Lutheran Synod), The Lutheran Book of Worship (1978, Lutheran Council in the United States of America), Lutheran Worship (1982, LCMS), Christian Worship (1993, Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod), and The Lutheran Hymnal (1941, Evangelical Lutheran Synodical Conference of North America). In the Lutheran Church of Australia, the official hymnal is the Lutheran Hymnal with Supplement of 1986, which includes a supplement to the Lutheran Hymnal of 1973, itself a replacement for the Australian Lutheran Hymn Book of 1921. Prior to this time, the two Lutheran church bodies in Australia (which merged in 1966) used a bewildering variety of hymnals, usually in the German language. Spanish-speaking ELCA churches frequently use Libro de Liturgia y Cántico (1998, Augsburg Fortress) for services and hymns. For a more complete list, see List of English language Lutheran hymnals.

Missions[edit]

Sizable Lutheran missions arose for the first time during the 19th century. Early missionary attempts during the century after the Reformation did not succeed. However, European traders brought Lutheranism to Africa beginning in the 17th century as they settled along the coasts. During the first half of the 19th century, missionary activity in Africa expanded, including preaching by missionaries, translation of the Bible, and education.[218]

Lutheranism came to India beginning with the work of Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg, where a community totaling several thousand developed, complete with their own translation of the Bible, catechism, their own hymnal, and system of Lutheran schools. In the 1840s, this church experienced a revival through the work of the Leipzig Mission, including Karl Graul.[219] After German missionaries were expelled in 1914, Lutherans in India became entirely autonomous, yet preserved their Lutheran character. In recent years India has relaxed its anti-religious conversion laws, allowing a resurgence in missionary work.

In Latin America, missions began to serve European immigrants of Lutheran background, both those who spoke German and those who no longer did. These churches in turn began to evangelize those in their areas who were not of European background, including indigenous peoples.[220]

In 1892, the first Lutheran missionaries reached Japan. Although work began slowly and a major setback occurred during the hardships of WWII.[221] Lutheranism there has survived and become self-sustaining.[222] After missionaries to China, including those of the Lutheran Church of China, were expelled, they began ministry in Taiwan and Hong Kong, the latter which became a center of Lutheranism in Asia.[222]

The Lutheran Mission in New Guinea, though founded only in 1953, became the largest Lutheran mission in the world in only several decades. Through the work of native lay evangelists, many tribes of diverse languages were reached with the Gospel.[222]

Today the Lutheran World Federation operates Lutheran World Relief, a relief and development agency active in more than 50 countries.

Education[edit]

Catechism instruction is considered foundational in most Lutheran churches. Almost all maintain Sunday Schools, and some host or maintain Lutheran schools, at the preschool, elementary, middle, high school, folk high school, or university level. Lifelong study of the catechism is intended for all ages so that the abuses of the pre-Reformation Church will not recur.[224] Lutheran schools have always been a core aspect of Lutheran mission work, starting with Bartholomew Ziegenbalg and Heinrich Putschasu, who began work in India in year 1706.[225] During the Counter-Reformation era in German speaking areas, backstreet Lutheran schools were the main Lutheran institution among crypto-Lutherans.[226]

Pastors almost always have substantial theological educations, including Koine Greek and Biblical Hebrew so that they can refer to the Christian scriptures in the original language. Pastors usually teach in the common language of the local congregation. In the U.S., some congregations and synods historically taught in German, Danish, Finnish, Norwegian, or Swedish, but retention of immigrant languages has been in significant decline since the early and middle 20th century.

Church fellowship[edit]

Lutherans were divided about the issue of church fellowship for the first 30 years after Luther's death. Philipp Melanchthon and his Philippist party felt that Christians of different beliefs should join in union with each other without completely agreeing on doctrine. Against them stood the Gnesio-Lutherans, led by Matthias Flacius and the faculty at the University of Jena. They condemned the Philippist position for indifferentism, describing it as a "unionistic compromise" of precious Reformation theology. Instead, they held that genuine unity between Christians and real theological peace was only possible with an honest agreement about every subject of doctrinal controversy.[227]

Complete agreement finally came about in 1577, after the death of both Melanchthon and Flacius, when a new generation of theologians resolved the doctrinal controversies on the basis of Scripture in the Formula of Concord of 1577.[228] Although they decried the visible division of Christians on earth, orthodox Lutherans avoided ecumenical fellowship with other churches, believing that Christians should not, for example, join for the Lord's Supper or exchange pastors if they do not completely agree about what the Bible teaches. In the 17th century, Georgius Calixtus began a rebellion against this practice, sparking the Syncretistic Controversy with Abraham Calovius as his main opponent.[229]

In the 18th century, there was some ecumenical interest between the Church of Sweden and the Church of England. John Robinson, Bishop of London, planned for a union of the English and Swedish churches in 1718. The plan failed because most Swedish bishops rejected the Calvinism of the Church of England, although Jesper Swedberg and Johannes Gezelius the younger, bishops of Skara, Sweden and Turku, Finland, were in favor.[230] With the encouragement of Swedberg, church fellowship was established between Swedish Lutherans and Anglicans in the Middle Colonies. Over the course of the 1700s and the early 1800s, Swedish Lutherans were absorbed into Anglican churches, with the last original Swedish congregation completing merger into the Episcopal Church in 1846.[231]

In the 19th century, Samuel Simon Schmucker attempted to lead the Evangelical Lutheran General Synod of the United States toward unification with other American Protestants. His attempt to get the synod to reject the Augsburg Confession in favor of his compromising Definite Platform failed. Instead, it sparked a Neo-Lutheran revival, prompting many to form the General Council, including Charles Porterfield Krauth. Their alternative approach was "Lutheran pulpits for Lutheran ministers only and Lutheran altars...for Lutheran communicants only."[232]

Beginning in 1867, confessional and liberal minded Lutherans in Germany joined to form the Common Evangelical Lutheran Conference against the ever looming prospect of a state-mandated union with the Reformed.[233] However, they failed to reach consensus on the degree of shared doctrine necessary for church union.[39] Eventually, the fascist German Christians movement pushed the final national merger of Lutheran, Union, and Reformed church bodies into a single Reich Church in 1933, doing away with the previous umbrella German Evangelical Church Confederation (DEK). As part of denazification the Reich Church was formally done away with in 1945, and certain clergy were removed from their positions. However, the merger between the Lutheran, United, and Reformed state churches was retained under the name Protestant Church in Germany (Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland, EKD). In 1948 the Lutheran church bodies within the EKD founded the United Evangelical Lutheran Church of Germany (VELKD), but it has since been reduced from being an independent legal entity to an administrative unit within the EKD.

Lutherans are currently divided over how to interact with other Christian denominations. Some Lutherans assert that everyone must share the "whole counsel of God" (Acts 20:27) in complete unity (1 Cor. 1:10)[234] before pastors can share each other's pulpits, and before communicants commune at each other's altars, a practice termed closed (or close) communion. On the other hand, other Lutherans practice varying degrees of open communion and allow preachers from other Christian denominations in their pulpits.

While not an issue in the majority of Lutheran church bodies, some of them forbid membership in Freemasonry. Partly, this is because the lodge is viewed as spreading Unitarianism, as the Brief Statement of the LCMS reads, "Hence we warn against Unitarianism, which in our country has to a great extent impenetrated the sects and is being spread particularly also through the influence of the lodges."[235] A 1958 report from the publishing house of the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod states that, "Masonry is guilty of idolatry. Its worship and prayers are idol worship. The Masons may not with their hands have made an idol out of gold, silver, wood or stone, but they created one with their own mind and reason out of purely human thoughts and ideas. The latter is an idol no less than the former."[236]

The largest organization of Lutheran churches around the world are the Lutheran World Federation (LWF), the Global Confessional and Missional Lutheran Forum, the International Lutheran Council (ILC), and the Confessional Evangelical Lutheran Conference (CELC). These organizations together account for the great majority of Lutheran denominations. The LCMS and the Lutheran Church–Canada are members of the ILC. The WELS and ELS are members of the CELC. Many Lutheran churches are not affiliated with the LWF, the ILC or the CELC: The congregations of the Church of the Lutheran Confession (CLC) are affiliated with their mission organizations in Canada, India, Nepal, Myanmar, and many African nations; and those affiliated with the Church of the Lutheran Brethren are especially active doing mission work in Africa and East Asia.

The Lutheran World Federation-aligned churches do not believe that one church is singularly true in its teachings. According to this belief, Lutheranism is a reform movement rather than a movement into doctrinal correctness. As part of this, in 1999 the LWF and the Roman Catholic Church jointly issued a statement, the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification, that stated that the LWF and the Catholics both agreed about certain basics of Justification and lifted certain Catholic anathemas formerly applying to the LWF member churches.The LCMS has participated in most of the official dialogues with the Roman Catholic Church since shortly after the Second Vatican Council, though not the one which produced the Joint Declaration and to which they were not invited. While some Lutheran theologians saw the Joint Declaration as a sign that the Catholics were essentially adopting the Lutheran position, other Lutheran theologians disagreed, claiming that, considering the public documentation of the Catholic position, this assertion does not hold up.[citation needed]

Besides their intra-Lutheran arrangements, some member churches of the LWF have also declared full communion with non-Lutheran Protestant churches. The Porvoo Communion is a communion of episcopally led Lutheran and Anglican churches in Europe. Beside its membership in the Porvoo Communion, Church of Sweden also has declared full communion with the Philippine Independent Church and the United Methodist Church.[citation needed] The state Protestant churches in Germany many other European countries have signed the Leuenberg Agreement to form the Community of Protestant Churches in Europe. The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America has been involved in ecumenical dialogues with several denominations. The ELCA has declared full communion with multiple American Protestant churches.[237]

Although on paper the LWF churches have all declared have full communion with each other, in practice some churches within the LWF have renounced ties with specific other churches.[238] One development in this ongoing schism is the Global Confessional and Missional Lutheran Forum, which consists of churches and church related organizations tracing their heritage back to mainline American Lutheranism in North America, European state churches, as well as certain African churches. As of 2019, the Forum is not a full communion organization. Similar in this structure is the International Lutheran Council, where issues of communion are left to the individual denominations. Not all ILC churches have declared church-fellowship with each other. In contrast, mutual church-fellowship is part of the CELC member churches, and unlike in the LWF, this is not contradicted by individual statements from any particular member church body.

Laestadians within certain European state churches maintain close ties to other Laestadians, often called Apostolic Lutherans. Altogether, Laestadians are found in 23 countries across five continents, but there is no single organization which represents them. Laestadians operate Peace Associations to coordinate their churchly efforts. Nearly all are located in Europe, although they there are 15 combined in North America, Ecuador, Togo, and Kenya.

By contrast, the Confessional Evangelical Lutheran Conference and International Lutheran Council as well as some unaffiliated denominations such as the Church of the Lutheran Confession and North American Laestadians maintain that the orthodox confessional Lutheran churches are the only churches with completely correct doctrine. They teach that while other Christian churches teach partially orthodox doctrine and have true Christians as members, the doctrines of those churches contain significant errors. More conservative Lutherans strive to maintain historical distinctiveness while emphasizing doctrinal purity alongside Gospel-motivated outreach. They claim that LWF Lutherans are practicing "fake ecumenism" by desiring church fellowship outside of actual unity of teaching.[239]

Although not an "ecumenical" movement in the formal sense, in the 1990s influences from the megachurches of American evangelicalism have become somewhat common. Many of the largest Lutheran congregations in the United States have been heavily influenced by these "progressive Evangelicals". These influences are sharply criticized by some Lutherans as being foreign to orthodox Lutheran beliefs.[240]

Polity[edit]

Lutheran polity varies depending on influences. Although Article XIV of the Augsburg Confession mandates that one must be "properly called" to preach or administer the Sacraments, some Lutherans have a broad view of on what constitutes this and thus allow lay preaching or students still studying to be pastors someday to consecrate the Lord's Supper.[241] Despite considerable diversity, Lutheran polity trends in a geographically predictable manner in Europe, with episcopal governance to the north and east but blended and consistorial-presbyterian type synodical governance in Germany.

[edit]

To the north in Scandinavia, the population was more insulated from the influence and politics of the Reformation and thus the Church of Sweden (which at the time included Finland) retained the Apostolic succession,[242] although they did not consider it essential for valid sacraments as the Donatists did in the fourth and fifth centuries and the Roman Catholics do today. Recently, the Swedish succession was introduced into all of the Porvoo Communion churches, all of which have an episcopal polity. Although the Lutheran churches did not require this or change their doctrine, this was important in order for more strictly high church Anglican individuals to feel comfortable recognizing their sacraments as valid. The occasional ordination of a bishop by a priest was not necessarily considered an invalid ordination in the Middle Ages, so the alleged break in the line of succession in the other Nordic Churches would have been considered a violation of canon law rather than an invalid ordination at the time. Moreover, there are no consistent records detailing pre-Reformation ordinations prior to the 12th century.[243]

In the far north of the Scandinavian peninsula are the Sámi people, some of which practice a form of Lutheranism called Apostolic Lutheranism, or Laestadianism due to the efforts of Lars Levi Laestadius. However, others are Orthodox in religion. Some Apostolic Lutherans consider their movement as part of an unbroken line down from the Apostles. In areas where Apostolic Lutherans have their own bishops apart from other Lutheran church organizations, the bishops wield more practical authority than Lutheran clergy typically do. In Russia, Laestadians of Lutheran background cooperate with the Ingrian church, but since Laestadianism is an interdenominational movement, some are Eastern Orthodox. Eastern Orthodox Laestadians are known as Ushkovayzet (article is in Russian).[244]

Eastern Europe and Asian Russia[edit]

Although historically Pietism had a significant influence on the understanding of the ministry among Lutherans in the Russian Empire,[b] today nearly all Russian and Ukrainian Lutherans are influenced by Eastern Orthodox polity. In their culture, giving a high degree of respect and authority to their bishops is necessary for their faith to be seen as legitimate and not sectarian.[245] In Russia, lines of succession between bishops and the canonical authority between their present-day hierarchy is also carefully maintained in order to legitimize the existing Lutheran churches as present day successors of the former Lutheran Church of the Russian Empire originally authorized by Catherine the Great. This allows for the post-Soviet repatriation of Lutheran church buildings to local congregations on the basis of this historical connection.[246]

Germany[edit]

In Germany, several dynamics encouraged Lutherans to maintain a different form of polity. First, due to de facto practice during the Nuremberg Religious Peace the subsequent legal principal of Cuius regio, eius religio in the 1555 Peace of Augsburg, German states were officially either Catholic or "Evangelical" (that is, Lutheran under the Augsburg Confession). In some areas both Catholic and Lutheran churches were permitted to co-exist. Because German-speaking Catholic areas were nearby, Catholic-leaning Christians were able to emigrate and there was less of an issue with Catholics choosing to live as "crypto-papists" in Lutheran areas. Although Reformed-leaning Christians were not allowed to have churches, Melancthon wrote Augsburg Confession Variata which some used to claim legal protection as "Evangelical" churches. Many chose to live as crypto-Calvinists either with or without the protection offered by the Variata, but this did not make their influence go away, and as a result the Protestant church in Germany as of 2017 was only about ≈40% Lutheran, with most of the rest being United Protestant, a combination of Lutheran and Reformed beliefs and practices.[247]

In terms of polity, over the 17th and 18th centuries the carefully negotiated and highly prescriptive church orders of the Reformation era gave way to a joint cooperation between state control and a Reformed-style blend of consistorial and presbyterian type synodical governance. Just as negotiations over the details in the church orders involved the laity, so did the new synodical governance. Synodical governance had already been practiced in the Reformed Netherlands prior to its adoption by Lutherans. During the formation of the modern German state, ideas about the nature of authority and the best design for governments and organizations came from the philosophies of Kant and Hegel, further modifying the polity. When the monarchy and the sovereign governance of the church were ended in 1918, the synods took over the governance of the state churches.

Western Hemisphere and Australia[edit]

During the period of the emigration, Lutherans took their existing ideas about polity with them across the ocean,[249][250] though with the exception of the early Swedish Lutherans immigrants of the New Sweden colony who accepted the rule of the Anglican bishops and became part of the established church, they now had to fund churches on their own. This increased the congregationalist dynamic in the blended consistorial and presbyterian type synodical governance. The first organized church body of Lutherans in America was the Pennsylvania Ministerium, which used Reformed style synodical governance over the 18th and 19th centuries. Their contribution to the development of polity was that smaller synods could in turn form a larger body, also with synodical governance, but without losing their lower level of governance. As a result, the smaller synods gained unprecedented flexibility to join, leave, merge, or stay separate, all without the hand of the state as had been the case in Europe.

During their 19th-century persecution, Old Lutheran, defined as scholastic and orthodox believers, were left in a conundrum. Resistance to authority was traditionally considered disobedience, but, under the circumstances, upholding orthodox doctrine and historical practice was considered by the government disobedience. However, the doctrine of the lesser magistrate allowed clergy to legitimately resist the state and even leave. Illegal free churches were set up in Germany and mass emigration occurred. For decades the new churches were mostly dependent on the free churches to send them new ministerial candidates for ordination. These new church bodies also employed synodical governance, but tended to exclude Hegelianism in their constitutions, due to its incompatibility with the doctrine of the lesser magistrates. In contrast to Hegelianism where authority flows in from all levels, Kantianism presents authority proceeding only from the top down, hence the need for a lesser magistrate to become the new top magistrate.

Over the 20th and 21st centuries, some Lutheran bodies have adopted a more congregationalist approach, such as the Protes'tant Conference and the Lutheran Congregations in Mission for Christ, or LCMC. The LCMC formed due to a church split after the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America signed an agreement with the Episcopal Church to start ordaining all of their new bishops into the Episcopalian apostolic succession. In other words, this meant that new ELCA bishops, at least at first, would be jointly ordained by Anglican bishops as well as Lutheran bishops so that the more strict Episcopalians (i.e., Anglo-Catholics) would recognize their sacraments as valid. This was offensive to some in the ELCA at the time because of the implications this practice would have on the teachings of the priesthood of all believers and the nature of ordination.

Some Lutheran churches permit dual-rostering.[251] Situations like this one where a church or church body belongs to multiple larger organizations that do not have ties are termed "triangular fellowship". Another variant is independent Lutheran churches, although for some independent churches the clergy are members of a larger denomination. In other cases, a congregation may belong to a synod, but the pastor may be unaffiliated. In the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, the Lutheran Church of Australia,[252] the Wisconsin Synod, the Evangelical Lutheran Synod, the Church of the Lutheran Confession, and the Missouri Synod, teachers at parochial schools are considered to be ministers of religion, with the latter defending this before the Supreme Court in 2012. However, differences remain in the precise status of their teachers.[253]

Throughout the world[edit]

Lutheran churches currently have millions of members, and are present on all populated continents.[254] The Lutheran World Federation estimates the total membership of its churches over 77 million.[255] This figure miscounts Lutherans worldwide as not all Lutheran churches belong to this organization, and many members of merged LWF church bodies do not self-identify as Lutheran or attend congregations that self-identify as Lutheran.[256] Lutheran churches in North America, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean regions are experiencing decreases and no growth in membership, while those in Africa and Asia continue to grow. Lutheranism is the largest religious group in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Latvia, Namibia, Norway, Sweden, and North Dakota and South Dakota in the United States.

Lutheranism is also the dominant form of Christianity in the White Mountain and San Carlos Apache nations. In addition, Lutheranism is a main Protestant denomination in Germany (behind United Protestant (Lutheran & Reformed) churches; EKD Protestants form about 24.3% of the country's total population),[257] Estonia, Poland, Austria, Slovakia, Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Papua New Guinea, and Tanzania.[258] Although some convents and monasteries voluntarily closed during the Reformation, and many of the remaining damenstift were shuttered by communist authorities following World War II, the Lüne abbeys are still open. Nearly all active Lutheran orders are located in Europe.

Although Namibia is the only country outside Europe to have a Lutheran majority, there are sizable Lutheran bodies in other African countries. In the following African countries, the total number of Lutherans exceeds 100,000: Nigeria, Central African Republic, Chad, Kenya, Malawi, Congo, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Madagascar. In addition, the following nations also have sizable Lutheran populations: Canada, France, the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Malaysia, India, Indonesia, the Netherlands (as a synod within the PKN and two strictly Lutheran denominations), South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States, especially in the heavily German and Scandinavian Upper Midwest.[259][260]

Lutheranism is also a state religion in Denmark and Iceland. Lutheranism was also the state church in Finland, Norway and Sweden, but its status in Norway and Sweden was changed to that of a national church in 2017 and 2000 respectively.[261][262]

Brazil[edit]

The Evangelical Church of the Lutheran Confession in Brazil (Igreja Evangélica de Confissão Luterana no Brasil) is the largest Lutheran denomination in Brazil. It is a member of the Lutheran World Federation, which it joined in 1952. It is a member of the Latin American Council of Churches, the National Council of Christian Churches and the World Council of Churches. The denomination has 1.02 million adherents and 643,693 registered members. The church ordains women as ministers. In 2011, the denomination released a pastoral letter supporting and accepting the Supreme Court's decision to allow same-sex marriage.

The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Brazil (Portuguese: Igreja Evangélica Luterana do Brasil, IELB) is a Lutheran church founded in 1904 in Rio Grande do Sul, a southern state in Brazil. The IELB is a conservative, confessional Lutheran synod which holds to the Book of Concord. It started as a mission of the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod and operated as the Brazilian District of that body. The IELB became an independent church body in 1980. It has about 243,093 members. The IELB is a member of the International Lutheran Council.

The Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod (WELS) started a Brazilian mission, the first for WELS in the Portuguese language, in the early 1980s. Its first work was done in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, in the south of Brazil, alongside some small independent Lutheran churches which had asked for help from WELS. Today, the Brazilian WELS Lutheran Churches are self-supporting and an independent mission partner of the Latin America WELS missions team.

Distribution[edit]

This map shows where countries with over 25,000 members of the Lutheran World Federation were located in 2019.[263][c]

This map shows where members of the Confessional Evangelical Lutheran Conference were located in 2013:

See also[edit]

- List of Lutheran churches

- List of Lutheran clergy

- List of Lutheran colleges and universities

- List of Lutheran denominations

- List of Lutheran denominations in North America

- List of Lutheran dioceses and archdioceses

- List of Lutheran schools in Australia

- Lutheran orders (both loose social organizations and physical communities such as convents)

Notes[edit]

- ^ Cf. material and formal principles in theology

- ^ See Edward Wust [ru] and Wustism [ru] in the Russian Wikipedia for more on this.

- ^ This map undercounts several countries, notably the United States. The LWF does not include the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod and several other Lutheran bodies which together have over 2.5 million members

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Markkola, P (2015). "The Long History of Lutheranism in Scandinavia. From State Religion to the People's Church". Perichoresis. 13 (2): 3–15. doi:10.1515/perc-2015-0007.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c Fahlbusch, Erwin, and Bromiley, Geoffrey William, The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 3. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 2003. p. 362.

- ^ Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent, Fourth Session, Decree on Sacred Scripture (Denzinger 783 [1501]; Schaff 2:79–81). For a history of the discussion of various interpretations of the Tridentine decree, see Selby, Matthew L., The Relationship Between Scripture and Tradition according to the Council of Trent, unpublished Master's thesis, University of St Thomas, July 2013.

- ^ Уэббер, Дэвид Джей (1992). «Почему лютеранская церковь является литургической церковью?» . Бетани Лютеранский колледж . Проверено 18 сентября 2018 г.

Однако в византийском мире этот образец богослужения основывался не на литургической истории латинской церкви, как в случае с церковными орденами эпохи Реформации, а на литургической истории византийской церкви. (На самом деле именно это произошло с Украинской евангелической церковью Аугсбургского исповедания, которая опубликовала в своем Украинском евангелическом богослужебном справочнике 1933 года первый в истории лютеранский литургический порядок, основанный на историческом восточном обряде.)

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Эспин, Орландо О. и Николофф, Джеймс Б. Вводный словарь теологии и религиоведения . Колледжвилл, Миннесота: Liturgical Press, стр. 796.

- ^ «Лютеранское служение Бетани - Дом» . Бетани Лютеранское служение . Архивировано из оригинала 18 января 2012 года . Проверено 5 марта 2015 г.

- ^ Лютеране , Biblehistory.com

- ^ MSN Encarta, sv « Лютеранство. Архивировано 31 января 2009 года в Wayback Machine », Джордж Вольфганг Форелл ; Христианская циклопедия , св. « Реформация, лютеранство » Люкера, Э. и др. Архивировано 31 октября 2009 г. Лютеране верят, что Римско-католическая церковь — это не то же самое, что первоначальная христианская церковь .

- ^ Культурные и религиозные связи в XVI веке (на литовском языке). Istorijai.lt Оригинал архивирован 5 августа 2018 года. Проверено 4 апреля 2023 года.

- ^ Лютеранство в Малой Литве (на литовском языке). 500 за Реформацию.

- ^ Вишняускене, М. (31 октября 2015 г.) Миндаугас Сабутис. Если бы не лютеране, мы, вероятно, не говорили бы сегодня по-литовски [Если бы не лютеране, мы, вероятно, не говорили бы сегодня по-литовски] (по-литовски). Бернардинай.lt .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и Романн, Дж. Л. (1836). Историческое представление о введении Реформации в Дании . Проверено 5 марта 2015 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Глава 12: Реформация в Германии и Скандинавии , Возрождение и Реформация Уильяма Гилберта.

- ^ Романн, Дж. Л. (1836). Историческое представление о введении Реформации в Дании . Копенгаген. стр. 195 . Проверено 5 марта 2015 г.

- ^ Дж. Л. Романн (1836 г.). Историческое представление о введении Реформации в Дании . Копенгаген. стр. 202 . Проверено 5 марта 2015 г.

- ^ Романн, Дж. Л. (1836). Историческое представление о введении Реформации в Дании . Проверено 5 марта 2015 г.

- ^ «Церковный ритуал Дании и Норвегии (Церковный ритуал)» . ретсинформация.дк 25 июля 1685 года . Проверено 5 марта 2015 г.

- ^ Гастингс, Джеймс (октябрь 2004 г.). Библейский словарь . Группа Минерва. ISBN 9781410217301 . Проверено 5 марта 2015 г.