Космический мусор

| Part of a series on |

| Pollution |

|---|

|

Космический мусор (также известный как космический мусор , космическое загрязнение , [ 1 ] космические отходы , космический мусор , космический мусор или космический мусор [ 2 ] ) — это несуществующие искусственные объекты в космосе (в основном на околоземной орбите ), которые больше не выполняют полезных функций. К ним относятся заброшенные космические корабли (нефункциональные космические корабли и заброшенные ступени ракет-носителей), мусор, связанный с миссией, и особенно многочисленные на околоземной орбите осколки, образовавшиеся в результате распада заброшенных корпусов ракет и космических кораблей. Помимо заброшенных искусственных объектов, оставленных на орбите, космический мусор включает в себя фрагменты, образовавшиеся в результате распада, эрозии или столкновений ; затвердевшие жидкости, выброшенные из космического корабля; несгоревшие частицы твердотопливных ракетных двигателей; и даже пятна краски. Космический мусор представляет опасность для космических кораблей. [3]

Space debris is typically a negative externality. It creates an external cost on others from the initial action to launch or use a spacecraft in near-Earth orbit, a cost that is typically not taken into account nor fully accounted for[4][5] by the launcher or payload owner.[6][1][7]

Several spacecraft, both crewed and un-crewed, have been damaged or destroyed by space debris. The measurement, mitigation, and potential removal of debris is conducted by some participants in the space industry.[8]

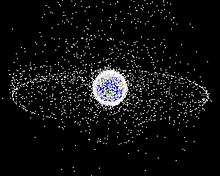

As of November 2022[update], the US Space Surveillance Network reported 25,857 artificial objects in orbit above the Earth,[9] including 5,465 operational satellites.[10] However, these are just the objects large enough to be tracked and in an orbit that makes tracking possible. Satellite debris that is in a Molniya orbit, such as the Kosmos Oko series, might be too high above the Northern Hemisphere to be tracked.[11] As of January 2019[update], more than 128 million pieces of debris smaller than 1 cm (0.4 in), about 900,000 pieces of debris 1–10 cm, and around 34,000 of pieces larger than 10 cm (3.9 in) were estimated to be in orbit around the Earth.[8] When the smallest objects of artificial space debris (paint flecks, solid rocket exhaust particles, etc.) are grouped with micrometeoroids, they are together sometimes referred to by space agencies as MMOD (Micrometeoroid and Orbital Debris).

Collisions with debris have become a hazard to spacecraft. The smallest objects cause damage akin to sandblasting, especially to solar panels and optics like telescopes or star trackers that cannot easily be protected by a ballistic shield.[12]

Below 2,000 km (1,200 mi), pieces of debris are denser than meteoroids. Most are dust from solid rocket motors, surface erosion debris like paint flakes, and frozen coolant from Soviet nuclear-powered satellites.[13][14][15] For comparison, the International Space Station (ISS) orbits in the 300–400 kilometres (190–250 mi) range, while the two most recent large debris events, the 2007 Chinese antisatellite weapon test and the 2009 satellite collision, occurred at 800 to 900 kilometres (500 to 560 mi) altitude.[16] The ISS has Whipple shielding to resist damage from small MMOD. However, known debris with a collision chance over 1/10,000 are avoided by maneuvering the station.

History

[edit]

Space debris began to accumulate in Earth orbit with the launch of the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, into orbit in October, 1957. But even before this event, humans might have produced ejecta that became space debris, as in the August 1957 Pascal B test.[17][18] Going back further, natural ejecta from Earth has entered orbit.

After the launch of Sputnik, the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) began compiling a database (the Space Object Catalog) of all known rocket launches and objects reaching orbit, including satellites, protective shields and upper-stages of launch vehicles. NASA later published modified versions of the database in two-line element sets,[19] and beginning in the early 1980s, they were republished in the CelesTrak bulletin board system.[20]

NORAD trackers who fed the database were aware of other objects in orbit, many of which were the result of in-orbit explosions.[21] Some were deliberately caused during anti-satellite weapon (ASAT) testing in the 1960s, and others were the result of rocket stages blowing up in orbit as leftover propellant expanded and ruptured their tanks. More detailed databases and tracking systems were gradually developed, including Gabbard diagrams, to improve the modeling of orbital evolution and decay.[22][23]

When the NORAD database became publicly available during the 1970s,[clarification needed] techniques developed for the asteroid-belt were applied to the study[by whom?] of known artificial satellite objects.[citation needed]

Time and natural gravitational/atmospheric effects help to clear space debris. A variety of technological approaches have also been proposed, though most have not been implemented. A number of scholars have observed that systemic factors, political, legal, economic, and cultural, are the greatest impediment to the cleanup of near-Earth space. There has been little commercial incentive to reduce space debris since the associated cost does not accrue to the entity producing it. Rather, the cost falls to all users of the space environment who benefit from space technology and knowledge. A number of suggestions for increasing incentives to reduce space debris have been made. These would encourage companies to see the economic benefit of reducing debris more aggressively than existing government mandates require.[24] In 1979, NASA founded the Orbital Debris Program to research mitigation measures for space debris in Earth orbit.[25][26]

Debris growth

[edit]

During the 1980s, NASA and other U.S. groups attempted to limit the growth of debris. One trial solution was implemented by McDonnell Douglas in 1981 for the Delta launch vehicle by having the booster move away from its payload and vent any propellant remaining in its tanks.[27] This eliminated one source for pressure buildup in the tanks which had previously caused them to explode and create additional orbital debris.[28] Other countries were slower to adopt this measure and, due especially to a number of launches by the Soviet Union, the problem grew throughout the decade.[29]

A new battery of studies followed as NASA, NORAD, and others attempted to better understand the orbital environment, with each adjusting the number of pieces of debris in the critical-mass zone upward. Although in 1981 (when Schefter's article was published) the number of objects was estimated at 5,000,[21] new detectors in the Ground-based Electro-Optical Deep Space Surveillance system found new objects. By the late 1990s, it was thought that most of the 28,000 launched objects had already decayed and about 8,500 remained in orbit.[30] By 2005 this was adjusted upward to 13,000 objects,[31] and a 2006 study increased the number to 19,000 as a result of an ASAT and a satellite collision.[32] In 2011, NASA said that 22,000 objects were being tracked.[33]

A 2006 NASA model suggested that if no new launches took place, the environment would retain the then-known population until about 2055, when it would increase on its own.[34][35] Richard Crowther of Britain's Defence Evaluation and Research Agency said in 2002 that he believed the cascade would begin about 2015.[36] The National Academy of Sciences, summarizing the professional view, noted widespread agreement that two bands of LEO space – 900 to 1,000 km (620 mi) and 1,500 km (930 mi) – were already past critical density.[37]

In the 2009 CEAS European Air and Space Conference, University of Southampton researcher Hugh Lewis predicted that the threat from space debris would rise 50 percent in the next decade and quadruple in the next 50 years. As of 2009[update], more than 13,000 close calls were tracked weekly.[38]

A 2011 report by the U.S. National Research Council warned NASA that the amount of orbiting space debris was at a critical level. According to some computer models, the amount of space debris "has reached a tipping point, with enough currently in orbit to continually collide and create even more debris, raising the risk of spacecraft failures." The report called for international regulations limiting debris and research of disposal methods.[39]

Debris history in particular years

[edit]- By mid-1994 there had been 68 breakups or debris "anomalous events" involving satellites launched by the former Soviet Union/Russia and 18 similar events had been discovered involving rocket bodies and other propulsion-related operational debris.[40]

- As of 2009[update], 19,000 debris over 5 cm (2 in) were tracked by the United States Space Surveillance Network.[16]

- As of July 2013[update], estimates of more than 170 million debris smaller than 1 cm (0.4 in), about 670,000 debris 1–10 cm, and approximately 29,000 larger pieces of debris were in orbit.[41]

- As of July 2016[update], nearly 18,000 artificial objects were orbiting above Earth,[42] including 1,419 operational satellites.[43]

- As of October 2019[update], nearly 20,000 artificial objects were in orbit above the Earth,[9] including 2,218 operational satellites.[10]

Characterization

[edit]Size and numbers

[edit]As of January 2019[update] there were estimated to be over 128 million pieces of debris smaller than 1 cm (0.39 in), and approximately 900,000 pieces between 1 and 10 cm. The count of large debris (defined as 10 cm across or larger[44]) was 34,000 in 2019,[8] and at least 37,000 by June 2023.[45] The technical measurement cut-off[clarification needed] is c. 3 mm (0.12 in).[46]

As of 2020[update], there were 8,000 metric tons of debris in orbit, a figure that is expected to increase.[47]

Low Earth orbit

[edit]

In the orbits nearest to Earth – less than 2,000 km (1,200 mi) orbital altitude, referred to as low-Earth orbit (LEO) – there have traditionally been few "universal orbits" that keep a number of spacecraft in particular rings (in contrast to GEO, a single orbit that is widely used by over 500 satellites). There is currently 85% pollution in LEO (Low Earth Orbit). This was beginning to change in 2019, and several companies began to deploy the early phases of satellite internet constellations, which will have many universal orbits in LEO with 30 to 50 satellites per orbital plane and altitude. Traditionally, the most populated LEO orbits have been a number of Sun-synchronous satellites that keep a constant angle between the Sun and the orbital plane, making Earth observation easier with consistent sun angle and lighting. Sun-synchronous orbits are polar, meaning they cross over the polar regions. LEO satellites orbit in many planes, typically up to 15 times a day, causing frequent approaches between objects. The density of satellites – both active and derelict – is much higher in LEO.[48]

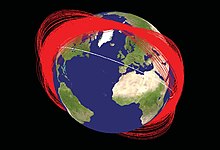

Orbits are affected by gravitational perturbations (which in LEO include unevenness of the Earth's gravitational field due to variations in the density of the planet), and collisions can occur from any direction. The average impact speed of collisions in Low Earth Orbit is 10 km/s with maximums reaching above 14 km/s due to orbital eccentricity.[49] The 2009 satellite collision occurred at a closing speed of 11.7 km/s (26,000 mph),[50] creating over 2,000 large debris fragments.[51] These debris cross many other orbits and increase debris collision risk.

It is theorized that a sufficiently large collision of spacecraft could potentially lead to a cascade effect, or even make some particular low Earth orbits effectively unusable for long term use by orbiting satellites, a phenomenon known as the Kessler syndrome.[52] The theoretical effect is projected to be a theoretical runaway chain reaction of collisions that could occur, exponentially increasing the number and density of space debris in low-Earth orbit, and has been hypothesized to ensue beyond some critical density.[53]

Crewed space missions are mostly at 400 km (250 mi) altitude and below, where air drag helps clear zones of fragments. The upper atmosphere is not a fixed density at any particular orbital altitude; it varies as a result of atmospheric tides and expands or contracts over longer time periods as a result of space weather.[54] These longer-term effects can increase drag at lower altitudes; the 1990s expansion was a factor in reduced debris density.[55] Another factor was fewer launches by Russia; the Soviet Union made most of their launches in the 1970s and 1980s.[56]: 7

Higher altitudes

[edit]

At higher altitudes, where air drag is less significant, orbital decay takes longer. Slight atmospheric drag, lunar perturbations, Earth's gravity perturbations, solar wind, and solar radiation pressure can gradually bring debris down to lower altitudes (where it decays), but at very high altitudes this may take centuries.[57] Although high-altitude orbits are less commonly used than LEO and the onset of the problem is slower, the numbers progress toward the critical threshold more quickly.[contradictory][page needed][58]

Many communications satellites are in geostationary orbits (GEO), clustering over specific targets and sharing the same orbital path. Although velocities are low between GEO objects, when a satellite becomes derelict (such as Telstar 401) it assumes a geosynchronous orbit; its orbital inclination increases about 0.8° and its speed increases about 160 km/h (99 mph) per year. Impact velocity peaks at about 1.5 km/s (0.93 mi/s). Orbital perturbations cause longitude drift of the inoperable spacecraft and precession of the orbital plane. Close approaches (within 50 meters) are estimated at one per year.[59] The collision debris pose less short-term risk than from a LEO collision, but the satellite would likely become inoperable. Large objects, such as solar-power satellites, are especially vulnerable to collisions.[60]

Although the ITU now requires proof a satellite can be moved out of its orbital slot at the end of its lifespan, studies suggest this is insufficient.[61] Since GEO orbit is too distant to accurately measure objects under 1 m (3 ft 3 in), the nature of the problem is not well known.[62] Satellites could be moved to empty spots in GEO, requiring less maneuvering and making it easier to predict future motion.[63] Satellites or boosters in other orbits, especially stranded in geostationary transfer orbit, are an additional concern due to their typically high crossing velocity.

Despite efforts to reduce risk, spacecraft collisions have occurred. The European Space Agency telecom satellite Olympus-1 was struck by a meteoroid on 11 August 1993 and eventually moved to a graveyard orbit.[64] On 29 March 2006, the Russian Express-AM11 communications satellite was struck by an unknown object and rendered inoperable;[65] its engineers had enough contact time with the satellite to send it into a graveyard orbit.

Sources

[edit]Dead spacecraft

[edit]

In 1958, the United States of America launched Vanguard I into a medium Earth orbit (MEO). As of October 2009[update], it, the upper stage of Vanguard 1's launch rocket and associated piece of debris, are the oldest surviving artificial space objects still in orbit and are expected to be until after the year 2250.[68][69] As of May 2022[update], the Union of Concerned Scientists listed 5,465 operational satellites from a known population of 27,000 pieces of orbital debris tracked by NORAD.[70][71]

Occasionally satellites are left in orbit when they're no longer useful. Many countries require that satellites go through passivation at the end of their life. The satellites are then either boosted into a higher, "graveyard" orbit or a lower, short-term orbit. Nonetheless, satellites that have been properly moved to a higher orbit have an eight-percent probability of puncture and coolant release over a 50-year period. The coolant freezes into droplets of solid sodium-potassium alloy, creating more debris.[13][72]

Despite the use of passivation, or prior to its standardization, many satellites and rocket bodies have exploded or broken apart on orbit. In February 2015, for example, the USAF Defense Meteorological Satellite Program Flight 13 (DMSP-F13) exploded on orbit, creating at least 149 debris objects, which were expected to remain in orbit for decades.[73] Later that same year, NOAA-16 which had been decommissioned after an anomaly in June 2014, broke apart on orbit into at least 275 pieces.[74] For older programs, such as the Soviet-era Meteor 2 and Kosmos satellites, design flaws resulted in numerous break-ups – at least 68 by 1994 – following decommissioning, resulting in more debris.[40]

In addition to the accidental creation of debris, some has been made intentionally through the deliberate destruction of satellites. This has been done as a test of anti-satellite or anti-ballistic missile technology, or to prevent a sensitive satellite from being examined by a foreign power.[40] The United States has conducted over 30 anti-satellite weapons tests (ASATs), the Soviet Union/Russia has performed at least 27, China has performed 10 and India has performed at least one.[75][76] The most recent ASATs were the Chinese interception of FY-1C, Russian trials of its PL-19 Nudol, the American interception of USA-193 and India's interception of an unstated live satellite.[76]

Lost equipment

[edit]

Space debris includes a glove lost by astronaut Ed White on the first American space-walk (EVA), a camera lost by Michael Collins near Gemini 10, a thermal blanket lost during STS-88, garbage bags jettisoned by Soviet cosmonauts during Mir's 15-year life,[77] a wrench, and a toothbrush.[78] Sunita Williams of STS-116 lost a camera during an EVA. During an STS-120 EVA to reinforce a torn solar panel, a pair of pliers was lost, and in an STS-126 EVA, Heidemarie Stefanyshyn-Piper lost a briefcase-sized tool bag.[79]

Boosters

[edit]

A significant portion of debris is due to rocket upper stages (e.g. the Inertial Upper Stage) breaking up due to decomposition of unvented fuel.[80] The first such instance involved the launch of the Transit-4a satellite in 1961. Two hours after insertion, the Ablestar upper stage exploded. Even boosters that don't break apart can be a problem. A major known impact event involved an (intact) Ariane booster.[56]: 2

Although NASA and the United States Air Force now require upper-stage passivation, other launchers – such as the Chinese and Russian space agencies – do not. Lower stages, like the Space Shuttle's solid rocket boosters or the Apollo program's Saturn IB launch vehicles, do not reach orbit.[81]

Examples:

- Two Japanese H-2A rockets broke up in 2006.[82]

- A Russian Briz-M booster stage exploded in orbit over South Australia on 19 February 2007. Launched on 28 February 2006 carrying an Arabsat-4A communications satellite, it malfunctioned before it could use up its propellant. Although the explosion was captured on film by astronomers, due to the orbit path the debris cloud has been difficult to measure with radar. By 21 February 2007, over 1,000 fragments were identified.[83][84] A 14 February 2007 breakup was recorded by Celestrak.[85]

- Another Briz-M broke up on 16 October 2012 after a failed 6 August Proton-M launch. The amount and size of the debris was unknown.[86]

- The second stage of the Zenit-2, called the SL-16 by western governments, along with the second stages of the Vostok and Kosmos launch vehicles, make up about 20% of the total mass of launch debris in Low Earth Orbit (LEO).[87] An analysis that determined the 50 "statistically most concerning" debris objects in low Earth orbit determined that the top 20 were all Zenit-2 upper stages.[88]

- a Delta II rocket used to launch NASA's 1989 COBE spacecraft exploded on December 3, 2006. This occurred even though its residual fuel had already been vented to space.[82]

- In 2018–2019, three different Atlas V Centaur second stages broke up.[89][90][91]

- In December 2020, scientists confirmed that a previously detected near-Earth object, 2020 SO, was rocket booster space junk launched in 1966 orbiting Earth and the Sun.[92]

- At least eight Delta rockets have contributed orbital debris in the Sun-synchronous low Earth orbit environment. The variant of the Delta upper stage that was used in the 1970s was found to be prone to in-orbit explosions. Starting in 1981, depletion burns – to get rid of excess propellant – became standard and no Delta Rocket Bodies launched after 1981 experienced severe fragmentations afterward, but some of those launched prior to 1981 continued to explode. In 1991, the Delta 1975-052B fragmented, 16 years after launch, demonstrating the resilience of the propellent.[93]

Weapons

[edit]A former source of debris was anti-satellite weapons (ASATs) testing by the U.S. and Soviet Union during the 1960s and 1970s. North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) only collected data for Soviet tests, and debris from U.S. tests were identified subsequently.[94] By the time the debris problem was understood, widespread ASAT testing had ended. The U.S. Program 437 was shut down in 1975.[95]

The U.S. restarted their ASAT programs in the 1980s with the Vought ASM-135 ASAT. A 1985 test destroyed a 1-tonne (2,200 lb) satellite orbiting at 525 km (326 mi), creating thousands of debris larger than 1 cm (0.39 in). At this altitude, atmospheric drag decayed the orbit of most debris within a decade. A de facto moratorium followed the test.[96]

China's government was condemned for the military implications and the amount of debris from the 2007 anti-satellite missile test,[97] the largest single space debris incident in history (creating over 2,300 pieces golf-ball size or larger, over 35,000 1 cm (0.4 in) or larger, and one million pieces 1 mm (0.04 in) or larger). The target satellite orbited between 850 km (530 mi) and 882 km (548 mi), the portion of near-Earth space most densely populated with satellites.[98] Since atmospheric drag is low at that altitude, the debris is slow to return to Earth, and in June 2007 NASA's Terra environmental spacecraft maneuvered to avoid impact from the debris.[99] Brian Weeden, U.S. Air Force officer and Secure World Foundation staff member, noted that the 2007 Chinese satellite explosion created an orbital debris of more than 3,000 separate objects that then required tracking.[100]

On 20 February 2008, the U.S. launched an SM-3 missile from the USS Lake Erie to destroy a defective U.S. spy satellite thought to be carrying 450 kg (1,000 lb) of toxic hydrazine propellant. The event occurred at about 250 km (155 mi), and the resulting debris has a perigee of 250 km (155 mi) or lower.[101] The missile was aimed to minimize the amount of debris, which (according to Pentagon Strategic Command chief Kevin Chilton) had decayed by early 2009.[102]

On 27 March 2019, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that India shot down one of its own LEO satellites with a ground-based missile. He stated that the operation, part of Mission Shakti, would defend the country's interests in space. Afterwards, US Air Force Space Command announced they were tracking 270 new pieces of debris but expected the number to grow as data collection continues.[103]

On 15 November 2021, the Russian Defense Ministry destroyed Kosmos 1408[104] orbiting at around 450 km, creating "more than 1,500 pieces of trackable debris and hundreds of thousands of pieces of un-trackable debris" according to the US State Department.[105]

The vulnerability of satellites to debris and the possibility of attacking LEO satellites to create debris clouds has triggered speculation that it is possible for countries unable to make a precision attack.[clarification needed] An attack on a satellite of 10 t (22,000 lb) or more would heavily damage the LEO environment.[96]

Hazards

[edit]

To spacecraft

[edit]Space junk can be a hazard to active satellites and spacecraft. It has been suggested that Earth orbit could even become impassable if the risk of collision becomes too great.[106][failed verification]

However, since the risk to spacecraft increases with exposure to high debris densities, it is more accurate to say that LEO would be rendered unusable by orbiting craft. The threat to craft passing through LEO to reach a higher orbit would be much lower owing to the short time span of the crossing.

Uncrewed spacecraft

[edit]

Although spacecraft are typically protected by Whipple shields, solar panels, which are exposed to the Sun, wear from low-mass impacts. Even small impacts can produce a cloud of plasma which is an electrical risk to the panels.[107]

Satellites are believed to have been destroyed by micrometeorites and (small) orbital debris (MMOD). The earliest suspected loss was of Kosmos 1275, which disappeared on 24 July 1981 (a month after launch). Kosmos contained no volatile fuel, therefore, there appeared to be nothing internal to the satellite which could have caused the destructive explosion which took place. However, the case has not been proven and another hypothesis forwarded is that the battery exploded. Tracking showed it broke up, into 300 objects.[108]

Many impacts have been confirmed since. For example, on 24 July 1996, the French microsatellite Cerise was hit by fragments of an Ariane 1 H-10 upper-stage booster which exploded in November 1986.[56]: 2 On 29 March 2006, the Russian Ekspress-AM11 communications satellite was struck by an unknown object and rendered inoperable.[65] On 13 October 2009, Terra suffered a single battery cell failure anomaly and a battery heater control anomaly which were subsequently considered likely the result of an MMOD strike.[109] On 12 March 2010, Aura lost power from one-half of one of its 11 solar panels and this was also attributed to an MMOD strike.[110] On 22 May 2013, GOES 13 was hit by an MMOD which caused it to lose track of the stars that it used to maintain an operational attitude. It took nearly a month for the spacecraft to return to operation.[111]

The first major satellite collision occurred on 10 February 2009. The 950 kg (2,090 lb) derelict satellite Kosmos 2251 and the operational 560 kg (1,230 lb) Iridium 33 collided, 500 mi (800 km)[112] over northern Siberia. The relative speed of impact was about 11.7 km/s (7.3 mi/s), or about 42,120 km/h (26,170 mph).[113] Both satellites were destroyed, creating thousands of pieces of new smaller debris, with legal and political liability issues unresolved even years later.[114][115][116] On 22 January 2013, BLITS (a Russian laser-ranging satellite) was struck by debris suspected to be from the 2007 Chinese anti-satellite missile test, changing both its orbit and rotation rate.[117]

Satellites sometimes[clarification needed] perform Collision Avoidance Maneuvers and satellite operators may monitor space debris as part of maneuver planning. For example, in January 2017, the European Space Agency altered the orbit of one of its three[118] Swarm mission spacecraft, based on data from the US Joint Space Operations Center, to lower the risk of collision from Cosmos-375, a derelict Russian satellite.[119]

Crewed spacecraft

[edit]Crewed flights are particularly vulnerable to space debris conjunctions in the orbital path of the spacecraft. Occasional avoidance maneuvers or longer-term space debris wear have affected the space shuttle, the MIR space station, and the International Space Station.

Space Shuttle missions

[edit]

From the early shuttle missions, NASA used NORAD space monitoring capabilities to assess the shuttle's orbital path for debris. In the 1980s, this consumed a large proportion of NORAD capacity.[28] The first collision-avoidance maneuver occurred during STS-48, in September,1991,[120] a seven-second thruster burn to avoid debris from the derelict satellite Kosmos 955.[121] Similar maneuvers were executed on missions 53, 72 and 82.[120]

One of the earliest events to publicize the debris problem occurred on Space Shuttle Challenger's second flight, STS-7. A fleck of paint struck its front window, creating a pit over 1 mm (0.04 in) wide. On STS-59 in 1994, Endeavour's front window was pitted about half its depth. Minor debris impacts increased from 1998.[122]

Window chipping and minor damage to thermal protection system tiles (TPS) were already common by the 1990s. The Shuttle was later flown tail-first to take a greater proportion of the debris load on the engines and rear cargo bay, which are not used in orbit or during descent, and thus are less critical for post-launch operation. When flying attached to the ISS, a shuttle was flipped around so the better-armoured station shielded the orbiter.[123]

A NASA 2005 study concluded that debris accounted for approximately half of the overall risk to the Shuttle.[123][124] Executive-level decision to proceed was required if the catastrophic impact was more likely than 1 in 200. On a normal (low-orbit) mission to the ISS, the risk was approximately 1 in 300, but the Hubble telescope repair mission was flown at the higher orbital altitude of 560 km (350 mi) where the risk was initially calculated at a 1-in-185 (due in part to the 2009 satellite collision). A re-analysis with better debris numbers reduced the estimated risk to 1 in 221, and the mission went ahead.[125]

Debris incidents continued on later Shuttle missions. During STS-115 in 2006, a fragment of circuit board bored a small hole through the radiator panels in Atlantis's cargo bay.[126] On STS-118 in 2007, debris blew a bullet-like hole through Endeavour's radiator panel.[127]

Mir

[edit]

Impact wear was notable on the Soviet space station Mir, since it remained in space for long periods with its original solar module panels.[128][129]

International Space Station

[edit]The ISS also uses Whipple shielding to protect its interior from minor debris.[130] However, exterior portions (notably its solar panels) cannot be protected easily. In 1989, the ISS panels were predicted to degrade approximately 0.23% in four years due to the "sandblasting" effect of impacts with small orbital debris.[131] An avoidance maneuver is typically performed for the ISS if "there is a greater than one-in-10,000 chance of a debris strike".[132] As of January 2014[update], there have been sixteen maneuvers in the fifteen years the ISS had been in orbit.[132] By 2019, over 1,400 meteoroid and orbital debris (MMOD) impacts had been recorded on the ISS.[133]

As another method to reduce the risk to humans on board, ISS operational management asked the crew to shelter in the Soyuz on three occasions due to late debris-proximity warnings. In addition to the sixteen thruster firings and three Soyuz-capsule shelter orders, one attempted maneuver was not completed due to not having the several days' warning necessary to upload the maneuver timeline to the station's computer.[132][134][135] A March 2009 event involved debris believed to be a 10 cm (3.9 in) piece of the Kosmos 1275 satellite.[136] In 2013, the ISS operations management did not make a maneuver to avoid any debris, after making a record four debris maneuvers the previous year.[132]

Kessler syndrome

[edit]

The Kessler syndrome,[138][139] proposed by NASA scientist Donald J. Kessler in 1978, is a theoretical scenario in which the density of objects in low Earth orbit (LEO) is high enough that collisions between objects could cause a cascade effect where each collision generates space debris that increases the likelihood of further collisions.[140] He further theorized that one implication, if this were to occur, is that the distribution of debris in orbit could render space activities and the use of satellites in specific orbital ranges economically impractical for many generations.[140]

The growth in the number of objects as a result of the late-1990s studies sparked debate in the space community on the nature of the problem and the earlier dire warnings. According to Kessler's 1991 derivation and 2001 updates,[141] the LEO environment in the 1,000 km (620 mi) altitude range should be cascading. However, only one major satellite collision incident occurred: the 2009 satellite collision between Iridium 33 and Cosmos 2251. The lack of obvious short-term cascading has led to speculation that the original estimates overstated the problem.[142] According to Kessler in 2010 however, a cascade may not be obvious until it is well advanced, which might take years.[143]

On Earth

[edit]

Although most debris burns up in the atmosphere, larger debris objects can reach the ground intact. According to NASA, an average of one cataloged piece of debris has fallen back to Earth each day for the past 50 years. Despite their size, there has been no significant property damage from the debris.[144] Burning up in the atmosphere contributes to air pollution.[145] Numerous small cylindrical tanks from space objects have been found, designed to hold fuel or gasses.[146]

Tracking and measurement

[edit]Tracking from the ground

[edit]Radar and optical detectors such as lidar are the main tools for tracking space debris. Although objects under 10 cm (4 in) have reduced orbital stability, debris as small as 1 cm can be tracked,[147][148] however determining orbits to allow re-acquisition is difficult. Most debris remain unobserved. The NASA Orbital Debris Observatory tracked space debris with a 3 m (10 ft) liquid mirror transit telescope.[149] FM Radio waves can detect debris, after reflecting off them onto a receiver.[150] Optical tracking may be a useful early-warning system on spacecraft.[151]

The U.S. Strategic Command keeps a catalog of known orbital objects, using ground-based radar and telescopes, and a space-based telescope (originally to distinguish from hostile missiles). The 2009 edition listed about 19,000 objects.[152] Other data come from the ESA Space Debris Telescope, TIRA,[153] the Goldstone, Haystack,[154] and EISCAT radars and the Cobra Dane phased array radar,[155] to be used in debris-environment models like the ESA Meteoroid and Space Debris Terrestrial Environment Reference (MASTER).

Measurement in space

[edit]

Returned space hardware is a valuable source of information on the directional distribution and composition of the (sub-millimetre) debris flux. The LDEF satellite deployed by mission STS-41-C Challenger and retrieved by STS-32 Columbia spent 68 months in orbit to gather debris data. The EURECA satellite, deployed by STS-46 Atlantis in 1992 and retrieved by STS-57 Endeavour in 1993, was also used for debris study.[156]

The solar arrays of Hubble were returned by missions STS-61 Endeavour and STS-109 Columbia, and the impact craters studied by the ESA to validate its models. Materials returned from Mir were also studied, notably the Mir Environmental Effects Payload (which also tested materials intended for the ISS[157]).[158][159]

Gabbard diagrams

[edit]A debris cloud resulting from a single event is studied with scatter plots known as Gabbard diagrams, where the perigee and apogee of fragments are plotted with respect to their orbital period. Gabbard diagrams of the early debris cloud prior to the effects of perturbations, if the data were available, are reconstructed. They often include data on newly observed, as yet uncatalogued fragments. Gabbard diagrams can provide insights into the features of the fragmentation, the direction and point of impact.[23][160]

Dealing with debris

[edit]

An average of about one tracked object per day has been dropping out of orbit for the past 50 years,[161] averaging almost three objects per day at solar maximum (due to the heating and expansion of the Earth's atmosphere), but one about every three days at solar minimum, usually five and a half years later.[161] In addition to natural atmospheric effects, corporations, academics and government agencies have proposed plans and technology to deal with space debris, but as of November 2014[update], most of these are theoretical, and there is no business plan for debris reduction.[24]

A number of scholars have also observed that institutional factors – political, legal, economic, and cultural "rules of the game" – are the greatest impediment to the cleanup of near-Earth space. There is little commercial incentive to act, since costs are not assigned to polluters, though a number of technological solutions have been suggested.[24] However, effects to date are limited. In the US, governmental bodies have been accused of backsliding on previous commitments to limit debris growth, "let alone tackling the more complex issues of removing orbital debris."[162] The different methods for removal of space debris have been evaluated by the Space Generation Advisory Council, including French astrophysicist Fatoumata Kébé.[163]

In May 2024, a NASA report from the Office of Technology, Policy, and Strategy (OTPS) introduced new methods for addressing orbital debris. The report, titled Cost and Benefit Analysis of Mitigating, Tracking, and Remediating Orbital Debris,[164] provided a comprehensive analysis comparing the cost-effectiveness of over ten different actions, including shielding spacecraft, tracking smaller debris, and removing large debris. By evaluating these measures in economic terms, the study aims to inform cost-effective strategies for debris management, highlighting that methods like rapid deorbiting of defunct spacecraft can significantly reduce risks in space.

National and international regulation

[edit]

There is no international treaty minimizing space debris. However, the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) published voluntary guidelines in 2007,[165] using a variety of earlier national regulatory attempts at developing standards for debris mitigation. As of 2008, the committee was discussing international "rules of the road" to prevent collisions between satellites.[166] By 2013, a number of national legal regimes existed,[167][168][169] typically instantiated in the launch licenses that are required for a launch in all spacefaring nations.[170]

The U.S. issued a set of standard practices for civilian (NASA) and military (DoD and USAF) orbital-debris mitigation in 2001.[171][172][168] The standard envisioned disposal for final mission orbits in one of three ways: 1) atmospheric reentry where even with "conservative projections for solar activity, atmospheric drag will limit the lifetime to no longer than 25 years after completion of mission;" 2) maneuver to a "storage orbit:" move the spacecraft to one of four very broad parking orbit ranges (2,000–19,700 km (1,200–12,200 mi), 20,700–35,300 km (12,900–21,900 mi), above 36,100 km (22,400 mi), or out of Earth orbit completely and into any heliocentric orbit; 3) "Direct retrieval: Retrieve the structure and remove it from orbit as soon as practicable after completion of mission."[167] The standard articulated in option 1, which is the standard applicable to most satellites and derelict upper stages, has come to be known as the "25-year rule".[173] The US updated the Orbital Debris Mitigation Standard Practices (ODMSP) in December 2019, but made no change to the 25-year rule even though "[m]any in the space community believe that the timeframe should be less than 25 years."[174] There is no consensus however on what any new timeframe might be.[174]

In 2002, the European Space Agency (ESA) worked with an international group to promulgate a similar set of standards, also with a "25-year rule" applying to most Earth-orbit satellites and upper stages. Space agencies in Europe began to develop technical guidelines in the mid-1990s, and ASI, UKSA, CNES, DLR and ESA signed a "European Code of Conduct" in 2006,[169] which was a predecessor standard to the ISO international standard work that would begin the following year. In 2008, ESA further developed "its own "Requirements on Space Debris Mitigation for Agency Projects" which "came into force on 1 April 2008."[169]

Germany and France have posted bonds to safeguard property from debris damage.[clarification needed][175] The "direct retrieval" option (option no. 3 in the US "standard practices" above) has rarely been done by any spacefaring nation (exception, USAF X-37) or commercial actor since the earliest days of spaceflight due to the cost and complexity of achieving direct retrieval, but the ESA has scheduled a 2026 demonstration mission (ClearSpace-1) to do this with a single small 94 kg (207 lb) satellite (PROBA-1)[176] at a projected cost of €120 million not including the launch costs.[177]

By 2006, the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) had developed a number of technical means of debris mitigation (upper stage passivation, propellant reserves for movement to graveyard orbits, etc.) for ISRO launch vehicles and satellites, and was actively contributing to inter-agency debris coordination and the efforts of the UN COPUOS committee.[178]

In 2007, the ISO began preparing an international standard for space-debris mitigation.[179] By 2010, ISO had published "a comprehensive set of space system engineering standards aimed at mitigating space debris. [with primary requirements] defined in the top-level standard, ISO 24113." By 2017, the standards were nearly complete. However, these standards are not binding on any party by ISO or any international jurisdiction. They are simply available for use in voluntary ways. They "can be adopted voluntarily by a spacecraft manufacturer or operator, or brought into effect through a commercial contract between a customer and supplier, or used as the basis for establishing a set of national regulations on space debris mitigation."[173]

The voluntary ISO standard also adopted the "25-year rule" for the "LEO protected region" below 2,000 km (1,200 mi) altitude that has been previously (and still is, as of 2019[update]) used by the US, ESA, and UN mitigation standards, and identifies it as "an upper limit for the amount of time that a space system shall remain in orbit after its mission is completed. Ideally, the time to deorbit should be as short as possible (i.e., much shorter than 25 years)".[173]

Holger Krag of the European Space Agency states that as of 2017 there is no binding international regulatory framework with no progress occurring at the respective UN body in Vienna.[106]

Growth mitigation

[edit]

As of the 2010s, several technical approaches to the mitigation of the growth of space debris are typically undertaken, yet no comprehensive legal regime or cost assignment structure is in place to reduce space debris in the way that terrestrial pollution has reduced since the mid-20th century.

To avoid excessive creation of artificial space debris, many – but not all – satellites launched to above-low-Earth-orbit are launched initially into elliptical orbits with perigees inside Earth's atmosphere so the orbit will quickly decay and the satellites then will be destroyed upon reentry into the atmosphere. Other methods are used for spacecraft in higher orbits. These include passivation of the spacecraft at the end of its useful life; as well as the use of upper stages that can reignite to decelerate the stage to intentionally deorbit it, often on the first or second orbit following payload release; satellites that can, if they remain healthy for years, deorbit themselves from the lower orbits around Earth. Other satellites (such as many CubeSats) in low orbits below approximately 400 km (250 mi) orbital altitude depend on the energy-absorbing effects of the upper atmosphere to reliably deorbit a spacecraft within weeks or months.

Increasingly, spent upper stages in higher orbits – orbits for which low-delta-v deorbit is not possible, or not planned for – and architectures that support satellite passivation, are passivated at end of life. This removes any internal energy contained in the vehicle at the end of its mission or useful life. While this does not remove the debris of the now derelict rocket stage or satellite itself, it does substantially reduce the likelihood of the spacecraft destructing and creating many smaller pieces of space debris, a phenomenon that was common in many of the early generations of US and Soviet[72] spacecraft.

Upper stage passivation (e.g. of Delta boosters[28]) achieved by releasing residual propellants reduces debris from orbital explosions; however even as late as 2011, not all upper stages implement this practice.[181] SpaceX used the term "propulsive passivation" for the final maneuver of their six-hour demonstration mission (STP-2) of the Falcon 9 second stage for the US Air Force in 2019, but did not define what all that term encompassed.[182]

With a "one-up, one-down" launch-license policy for Earth orbits, launchers would rendezvous with, capture, and de-orbit a derelict satellite from approximately the same orbital plane.[183] Another possibility is the robotic refueling of satellites. Experiments have been flown by NASA,[184] and SpaceX is developing large-scale on-orbit propellant transfer technology.[185]

Another approach to debris mitigation is to explicitly design the mission architecture to leave the rocket second-stage in an elliptical geocentric orbit with a low-perigee, thus ensuring rapid orbital decay and avoiding long-term orbital debris from spent rocket bodies. Such missions will often complete the payload placement in a final orbit by the use of low-thrust electric propulsion or with the use of a small kick stage to circularize the orbit. The kick stage itself may be designed with the excess-propellant capability to be able to self-deorbit.[186]

Self-removal

[edit]Although the ITU requires geostationary satellites to move to a graveyard orbit at the end of their lives, the selected orbital areas do not sufficiently protect GEO lanes from debris.[61] Rocket stages (or satellites) with enough propellant may make a direct, controlled de-orbit, or if this would require too much propellant, a satellite may be brought to an orbit where atmospheric drag would cause it to eventually de-orbit. This was done with the French Spot-1 satellite, reducing its atmospheric re-entry time from a projected 200 years to about 15 by lowering its altitude from 830 km (516 mi) to about 550 km (342 mi).[187][188]

The Iridium constellation – 95 communication satellites launched during the five-year period between 1997 and 2002 – provides a set of data points on the limits of self-removal. The satellite operator – Iridium Communications – remained operational over the two-decade life of the satellites (albeit with a company name change through a corporate bankruptcy during the period) and, by December 2019, had "completed disposal of the last of its 65 working legacy satellites."[189] However, this process left 30 satellites with a combined mass of (20,400 kg (45,000 lb), or nearly a third of the mass of this constellation) in LEO orbits at approximately 700 km (430 mi) altitude, where self-decay is quite slow. Of these satellites, 29 simply failed during their time in orbit and were thus unable to self-deorbit, while one – Iridium 33 – was involved in the 2009 satellite collision with the derelict Russian military satellite Kosmos-2251.[189] No contingency plan was laid for the removal of satellites that were unable to remove themselves. In 2019, the CEO of Iridium, Matt Desch, said that Iridium would be willing to pay an active-debris-removal company to deorbit its remaining first-generation satellites if it were possible for an unrealistically low cost, say "US$10,000 per deorbit, but [he] acknowledged that price would likely be far below what a debris-removal company could realistically offer. 'You know at what point [it's] a no-brainer, but [I] expect the cost is really in the millions or tens of millions, at which price I know it doesn't make sense.'"[189]

Passive methods of increasing the orbital decay rate of spacecraft debris have been proposed. Instead of rockets, an electrodynamic tether could be attached to a spacecraft at launch; at the end of its lifetime, the tether would be rolled out to slow the spacecraft.[190] Other proposals include a booster stage with a sail-like attachment[191] and a large, thin, inflatable balloon envelope.[192]

In late December 2022, ESA successfully carried out a demonstration of a breaking sail-based satellite deorbiter, ADEO, which could be used by mitigation measures and is part of ESA's Zero Debris Initiative. Around one year earlier, China also tested a drag sail.[193][194]

External removal

[edit]A variety of approaches have been proposed, studied, or had ground subsystems built to use other spacecraft to remove existing space debris.

A consensus of speakers at a meeting in Brussels in October 2012, organized by the Secure World Foundation (a U.S. think tank) and the French International Relations Institute,[195] reported that removal of the largest debris would be required to prevent the risk to spacecraft becoming unacceptable in the foreseeable future (without any addition to the inventory of dead spacecraft in LEO). To date in 2019, removal costs and legal questions about ownership and the authority to remove defunct satellites have stymied national or international action. Current space law retains ownership of all satellites with their original operators, even debris or spacecraft which are defunct or threaten active missions.[citation needed]

Multiple companies made plans in the late 2010s to conduct external removal on their satellites in mid-LEO orbits. For example, OneWeb planned to use onboard self-removal as "plan A" for satellite deorbiting at the end of life, but if a satellite were unable to remove itself within one year of end of life, OneWeb would implement "plan B" and dispatch a reusable (multi-transport mission) space tug to attach to the satellite at an already built-in capture target via a grappling fixture, to be towed to a lower orbit and released for re-entry.[196][197]

Remotely controlled vehicles

[edit]A well-studied solution uses a remotely controlled vehicle to rendezvous with, capture, and return debris to a central station.[198] One such system is Space Infrastructure Servicing, a commercially developed refueling depot and service spacecraft for communications satellites in geosynchronous orbit originally scheduled for a 2015 launch.[199] The SIS would be able to "push dead satellites into graveyard orbits."[200] The Advanced Common Evolved Stage family of upper stages is being designed with a high leftover-propellant margin (for derelict capture and de-orbit) and in-space refueling capability for the high delta-v required to de-orbit heavy objects from geosynchronous orbit.[183] A tug-like satellite to drag debris to a safe altitude for it to burn up in the atmosphere has been researched.[201] When debris is identified the satellite creates a difference in potential between the debris and itself, then using its thrusters to move itself and the debris to a safer orbit.

A variation of this approach is for the remotely controlled vehicle to rendezvous with debris, capture it temporarily to attach a smaller de-orbit satellite and drag the debris with a tether to the desired location. The "mothership" would then tow the debris-smallsat combination for atmospheric entry or move it to a graveyard orbit. One such system is the proposed Busek ORbital DEbris Remover (ORDER), which would carry over 40 SUL (satellite on umbilical line) de-orbit satellites and propellant sufficient for their removal.[24]

On 7 January 2010 Star, Incorporated reported that it received a contract from the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command for a feasibility study of the ElectroDynamic Debris Eliminator (EDDE) propellantless spacecraft for space-debris removal.[202] In February 2012 the Swiss Space Center at École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne announced the Clean Space One project, a nanosatellite demonstration project for matching orbit with a defunct Swiss nanosatellite, capturing it and de-orbiting together.[203] The mission has seen several evolutions to reach a pac-man inspired capture model.[204] In 2013, Space Sweeper with Sling-Sat (4S), a grappling satellite which captures and ejects debris was studied.[205][needs update] In 2022, a Chinese satellite, SJ-21, grabbed an unused satellite and "threw" it into an orbit with a lower risk for it to collide.[206][207]

In December 2019, the European Space Agency awarded the first contract to clean up space debris. The €120 million mission dubbed ClearSpace-1 (a spinoff from the EPFL project) is slated to launch in 2026. It aims to remove the 94 kg PROBA-1 satellite from orbit.[176] A "chaser" will grab the junk with four robotic arms and drag it down to Earth's atmosphere where both will burn up.[177]

Laser methods

[edit]The laser broom uses a ground-based laser to ablate the front of the debris, producing a rocket-like thrust that slows the object. With continued application, the debris would fall enough to be influenced by atmospheric drag.[208][209] During the late 1990s, the U.S. Air Force's Project Orion was a laser-broom design.[210] Although a test-bed device was scheduled to launch on a Space Shuttle in 2003, international agreements banning powerful laser testing in orbit limited its use to measurements.[211] The 2003 Space Shuttle Columbia disaster postponed the project and according to Nicholas Johnson, chief scientist and program manager for NASA's Orbital Debris Program Office, "There are lots of little gotchas in the Orion final report. There's a reason why it's been sitting on the shelf for more than a decade."[212]

The momentum of the laser-beam photons could directly impart a thrust on the debris sufficient to move small debris into new orbits out of the way of working satellites. NASA research in 2011 indicates that firing a laser beam at a piece of space junk could impart an impulse of 1 mm (0.039 in) per second, and keeping the laser on the debris for a few hours per day could alter its course by 200 m (660 ft) per day.[213] One drawback is the potential for material degradation; the energy may break up the debris, adding to the problem.[214] A similar proposal places the laser on a satellite in Sun-synchronous orbit, using a pulsed beam to push satellites into lower orbits to accelerate their reentry.[24] A proposal to replace the laser with an Ion Beam Shepherd has been made,[215] and other proposals use a foamy ball of aerogel or a spray of water,[216] inflatable balloons,[217] electrodynamic tethers,[218] electroadhesion,[219] and dedicated anti-satellite weapons.[220]

Nets

[edit]On 28 February 2014, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) launched a test "space net" satellite. The launch was an operational test only.[221] In December 2016 the country sent a space junk collector via Kounotori 6 to the ISS by which JAXA scientists experimented to pull junk out of orbit using a tether.[222][223] The system failed to extend a 700-meter tether from a space station resupply vehicle that was returning to Earth.[224][225] On 6 February the mission was declared a failure and leading researcher Koichi Inoue told reporters that they "believe the tether did not get released".[226]

Between 2012 and 2018, the European Space Agency was working on the design of a mission to remove large space debris from orbit using mechanical tentacles or nets. The mission, e.Deorbit, had an objective to remove debris heavier than 4,000 kilograms (8,800 lb) from LEO.[227] Several capture techniques were studied, including a net, a harpoon, and a combination robot arm and clamping mechanism.[228] Funding of the mission was stopped in 2018 in favor of the ClearSpace-1 mission, which is currently under development.

Harpoon

[edit]The RemoveDEBRIS mission plan is to test the efficacy of several ADR technologies on mock targets in low Earth orbit. In order to complete its planned experiments the platform is equipped with a net, a harpoon, a laser ranging instrument, a dragsail, and two CubeSats (miniature research satellites).[229] The mission was launched on 2 April 2018.[citation needed]

Recycling space debris

[edit]Metal processing technologies to melt space debris and transform it into other useful form factors are developed by CisLunar Industries. Their system uses electromagnetic heating to melt metal and shape it into metal wire, sheet metal, and metal fuel.[230]

Reusing space debris

[edit]

A propulsion system dubbed the Neumann Drive has been developed in Adelaide, Australia, and first sent into space in June 2023. Metal space junk is converted into fuel rods, which can be plugged into the Neumann Drive, "basically converting the solid metal propellant into plasma". The Drive will be used by American space companies which already carry nets or robotic arms to capture orbital waste. The thruster enables these satellites to return to Earth with the waste they have collected, allowing it to be melted down to make more fuel.[45]

Barriers to dealing with debris

[edit]With the rapid development of the computer and digitalization industries, more countries and companies have engaged in space activities since the turn of the 20th century. The tragedy of the commons is an economic theory referring to a situation where maximizing self-interest through using a shared resource can lead to the resource degradation shared by all.[231] Based on the theory, individuals' rational action in space will lead to an irrational collective result: orbits crowded with debris. As a common-pool resource, the Earth's orbits, especially LEO and GEO that accommodate most satellites, are nonexcludable and rivalrous.[232]

To address the tragedy and ensure space sustainability, many technical approaches have been developed. In terms of governance mechanisms, a top-down centralized one is less suitable to tackle the complex debris problem due to the increasing number of space actors.[233] Instead, a polycentric form of governance developed by Elinor Ostrom may work in space.[234] In the process of promoting the polycentric network, there are some existing barriers needed to be dealt with.

Incomplete data of space debris

[edit]Поскольку орбитальный мусор является глобальной проблемой, затрагивающей как космические, так и некосмические страны, ее необходимо решать в глобальном контексте. [231] Because of the complexity and dynamics of object movements like spacecraft, debris, meteorites, etc., many countries and regions including the United States, Europe, Russia, and China have developed their space situational awareness (SSA) to avoid potential threats in space or plan actions in advance.[235] To an extent, SSA plays a role in tracking space debris. In order to build a powerful SSA system, there are two prerequisites: international cooperation and exchange of information and data.[235] Однако ограничения существуют, несмотря на улучшение качества данных за последние десятилетия. Некоторые космические державы не желают делиться собранной ими информацией, а те, кто поделился этими данными, например США, держат часть их в секрете. [ 236 ] Вместо скоординированного объединения многие программы ССА и национальные базы данных работают параллельно друг другу с некоторым дублированием, что препятствует формированию совместной системы мониторинга. [ 236 ]

Некоторые частные субъекты также пытаются создать системы SSA. Например, Ассоциация космических данных (SDA), созданная в 2009 году, является неправительственной организацией. В настоящее время в его состав входят 21 глобальный оператор спутниковой связи и 4 исполнительных члена: Eutelsat , Inmarsat , Intelsat и SES . SDA — это некоммерческая платформа, целью которой является предотвращение радиопомех и космических столкновений путем независимого сбора данных от операторов. [ 235 ] Исследователи предполагают, что крайне важно создать международный центр по обмену информацией о космическом мусоре, поскольку сети SSA не полностью эквивалентны системам слежения за мусором — первые больше ориентированы на активные и угрожающие объекты в космосе. [ 237 ] Что касается количества мусора и вышедших из строя спутников, немногие операторы предоставили данные. [ 237 ]

В полицентрической сети управления ресурс, за которым невозможно целостное наблюдение, с меньшей вероятностью будет хорошо управляться. [ 236 ] Недостаточное транснациональное сотрудничество и обмен информацией препятствуют решению проблемы мусора. Предстоит пройти долгий путь к созданию глобальной сети, охватывающей полные данные и обладающей прочной взаимосвязью и функциональной совместимостью.

Недостаточное участие частных субъектов

[ редактировать ]С коммерциализацией спутников и космоса частный сектор становится все более заинтересованным в космической деятельности. Например, SpaceX планирует создать сеть из примерно 12 000 небольших спутников, которые смогут передавать высокоскоростной интернет в любую точку мира. [ 238 ] Доля коммерческих космических аппаратов увеличилась с 4,6% в 1980-х годах до 55,6% в 2010-х. [ 239 ] Несмотря на высокий уровень участия коммерческих организаций, КОПУОС ООН однажды намеренно лишил их права голоса в обсуждениях, если только они не были официально приглашены государством-членом. [ 233 ] Остром сказал, что вовлечение всех соответствующих заинтересованных сторон в процесс разработки и внедрения правил является одним из важнейших элементов успешного управления. [ 240 ] Исключение частных игроков в значительной степени снижает эффективность роли комитета в создании механизмов коллективного выбора, отражающих интересы всех пользователей космоса. [ 233 ]

Ограниченное участие частных лиц замедляет процесс решения проблемы космического мусора. [ 241 ] Связи между разными заинтересованными сторонами в сети управления открывают доступ к разнообразным ресурсам. [ 242 ] Различная компетентность заинтересованных сторон может помочь более разумно распределить задачи. В этом случае знания и опыт частных операторов имеют решающее значение для того, чтобы помочь миру достичь космической устойчивости. [ 241 ] Взаимодополняющие сильные стороны различных заинтересованных сторон позволяют сети управления лучше адаптироваться к изменениям и более эффективно достигать общих целей. [ 242 ] В последние годы многие частные компании увидели коммерческие возможности уничтожения космического мусора. Предполагается, что к 2022 году мировой рынок мониторинга и удаления мусора принесет доход около 2,9 миллиарда долларов. [ 243 ] Например, Astroscale заключила контракт с европейскими и японскими космическими агентствами на разработку возможностей по удалению орбитального мусора. [ 244 ] Несмотря на это, их пока мало по сравнению с количеством тех, кто запустил спутники в космос. Privateer Space , гавайская стартап-компания, основанная американским инженером Алексом Филдингом , космическим экологом Морибой Джа и Apple соучредителем Стивом Возняком , объявила о планах в сентябре 2021 года запустить на орбиту сотни спутников для изучения космического мусора. [ 245 ] Однако компания заявила, что находится в «скрытом режиме» и никаких подобных спутников не запускалось. [ 245 ]

К счастью, нынешнее освоение космоса не полностью обусловлено конкуренцией, и все еще существует шанс для диалога и сотрудничества между всеми заинтересованными сторонами как в развитых, так и в развивающихся странах, чтобы достичь соглашения по борьбе с космическим мусором и обеспечить справедливое и упорядоченное исследование. [ 246 ] Помимо частных участников, сетевое управление не обязательно исключает участие государств. Вместо этого различные функции государств могут способствовать процессу управления. [ 247 ] Чтобы улучшить полицентрическую сеть управления космическим мусором, исследователи предлагают: поощрять обмен данными между различными национальными и организационными базами данных на политическом уровне; разработать общие стандарты для систем сбора данных для улучшения совместимости; и расширять участие частных субъектов путем их вовлечения в национальные и международные дискуссии. [ 236 ]

На других небесных телах

[ редактировать ]

Проблема космического мусора была поднята как проблема смягчения последствий миссий вокруг Луны с опасностью увеличения космического мусора вокруг нее. [ 248 ] [ 249 ]

Считается, что 4 марта 2022 года впервые космический мусор человека — скорее всего, отработанный корпус ракеты , третья ступень Long March 3C 2014 года миссии Chang’e 5 T1 — непреднамеренно ударился о поверхность Луны , создав неожиданный двойной эффект. кратер. [ 250 ] [ 251 ]

В 2022 году на Марсе было обнаружено несколько элементов космического мусора: корпус « Персеверанса » был найден на поверхности кратера Джезеро, [ 252 ] и кусок теплового одеяла, который, возможно, остался со спускаемой ступени марсохода. [ 253 ] [ 254 ]

По состоянию на февраль 2024 г. [update]Марс завален примерно семью тоннами искусственного мусора. Большая часть его состоит из разбившихся и бездействующих космических кораблей, а также выброшенных компонентов. [ 255 ] [ 256 ]

В популярной культуре

[ редактировать ]«До конца света» (1991) — французская научно-фантастическая драма, действие которой происходит на фоне вышедшего из-под контроля индийского ядерного спутника, который, по прогнозам, снова войдет в атмосферу, угрожая обширным населенным пунктам Земли. [ 257 ]

«Гравитация» — фильм о выживании 2013 года, снятый Альфонсо Куароном , — о катастрофе во время космической миссии, вызванной синдромом Кесслера. [ 258 ]

В первом сезоне сериала « Любовь, смерть и роботы» (2019) эпизод 11 «Рука помощи» вращается вокруг космонавта, которого ударил винт из космического мусора, который сбил ее со спутника на орбите. [ 259 ]

Манга и аниме Planetes рассказывает историю о команде станции космического мусора, которая собирает и утилизирует космический мусор. [ 260 ]

Помимо космического мусора как проблемы научно-фантастических рассказов, в других рассказах он рассматривается как резервуар для истории, как в рассказах об уборщиках космического мусора, таких как « Космические уборщики» (2021), или как результат или среда повествования.

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Категория:Заброшенные спутники

- Межпланетное загрязнение

- Конвенция об ответственности

- Список крупного возвращающегося космического мусора

- Список событий, связанных с образованием космического мусора

- Объект длительного воздействия

- Околоземный объект

- Координационная рабочая группа по орбитальному мусору

- Проект Вест Форд

- Спутниковая война

- Солнечная максимальная миссия

- Кладбище космических кораблей

- Осведомленность о космической сфере

- Космическая устойчивость

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Jump up to: а б « Мы оставили мусор повсюду»: почему загрязнение космоса может стать следующей большой проблемой человечества» . Хранитель . 26 марта 2016 г. Архивировано из оригинала 8 ноября 2019 г. . Проверено 28 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ Пауэлл, Джонатан (2017). Космический мусор . Вселенная астрономов. Бибкод : 2017cdwi.book.....P . дои : 10.1007/978-3-319-51016-3 . ISBN 978-3-319-51015-6 .

- ^ «Путеводитель по космическому мусору» . spaceacademy.net.au . Архивировано из оригинала 26 августа 2018 года . Проверено 13 августа 2018 г.

- ^ Коуз, Рональд (октябрь 1960 г.). «Проблема социальных издержек» (PDF) . Журнал права и экономики (PDF) . 3 . Издательство Чикагского университета: 1–44. дои : 10.1086/466560 . JSTOR 724810 . S2CID 222331226 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 17 июня 2012 года . Проверено 13 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ Хейн, Пол; Беттке, Питер Дж.; Причитко, Дэвид Л. (2014). Экономический образ мышления (13-е изд.). Пирсон. стр. 227–228. ISBN 978-0-13-299129-2 .

- ^ Муньос-Патчен, Челси (2019). «Регулирование общего пользования космоса: обращение с космическим мусором как с брошенной собственностью в нарушение Договора по космосу» . Чикагский журнал международного права . Юридический факультет Чикагского университета. Архивировано из оригинала 13 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 13 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ Вернер, Дебра (30 марта 2018 г.). «Предотвращение загрязнения космоса» . Аэрокосмическая Америка . Проверено 21 января 2023 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с «Космический мусор в цифрах» . www.esa.int . Проверено 18 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Оценка спутникового ящика» (PDF) . Ежеквартальные новости об орбитальном мусоре . Том. 26, нет. 4. НАСА . Ноябрь 2022. с. 14. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 24 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 24 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «База данных спутников UCS» . Ядерное оружие и глобальная безопасность . Союз неравнодушных ученых . 1 мая 2022 года. Архивировано из оригинала 20 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 24 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ Кларк, Дэвид (2006). Элгарский спутник исследований развития . Издательство Эдварда Элгара. п. 668. ИСБН 978-1-84376-475-5 .

- ^ «Угроза орбитального мусора и защита космических активов НАСА от столкновений спутников» (PDF) . Космический справочник. 2009. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 23 декабря 2015 года . Проверено 18 декабря 2012 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Видеманн, К. (2 апреля 2009 г.). «Распределение капель НаК по размерам для МАСТЕР-2009» . Материалы 5-й Европейской конференции по космическому мусору . 672 : 17. Бибкод : 2009ESASP.672E..17W .

- ^ А. Росси и др., «Влияние капель RORSAT NaK на долгосрочную эволюцию популяции космического мусора» , Пизанский университет, 1997.

- ^ Видеманн, К.; Освальд, М.; Стаброт, С.; Клинкрад, Х.; Вёрсманн, П. (2005). «Распределение размеров капель NaK, выделившихся при выбросе активной зоны реактора RORSAT». Достижения в космических исследованиях . 35 (7): 1290–1295. Бибкод : 2005AdSpR..35.1290W . дои : 10.1016/j.asr.2005.05.056 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Угроза орбитального мусора и защита космических активов НАСА от столкновений спутников (PDF) , Space Reference, 2009 г., заархивировано (PDF) из оригинала 23 декабря 2015 г. , получено 18 декабря 2012 г.

- ^ Харрингтон, Ребекка (5 февраля 2016 г.). «Самым быстрым объектом, когда-либо запущенным, была крышка люка – вот история парня, который запустил его в космос» . Tech Insider – www.businessinsider.com Business Insider . Проверено 11 июня 2021 г.

- ^ Томсон, Иэн (16 июля 2015 г.). «Позволила ли американская крышка люка ускорить полет спутника в космос? Главный ученый беседует с Эль Регом: как крышка ядерного взрыва могла опередить Советы на несколько месяцев» . www.theregister.com . Проверено 11 июня 2021 г.

- ^ Хутс, Шумахер и Гловер 2004 , стр. 174–185.

- ^ «CelesTrak: Исторические наборы двухстрочных элементов NORAD» . celestrak.org . Проверено 18 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Шефтер, с. 48.

- ^ Каушал, Сураб; Арора, Нишант (август 2010 г.). «Космический мусор и борьба с ним» . Конференция ISEC по космическим лифтам . Проверено 11 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Дэвид Портри и Джозеф Лофтус. «Орбитальный мусор: хронология». Архивировано 1 сентября 2000 г. в Wayback Machine , НАСА, 1999, стр. 13.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Фауст, Джефф (15 ноября 2014 г.). «У компаний есть технологии, но нет бизнес-планов по очистке орбитального мусора» . Космические новости . Архивировано из оригинала 6 декабря 2014 года . Проверено 28 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ «Программа НАСА по орбитальному мусору» . Архивировано из оригинала 3 ноября 2016 года . Проверено 10 октября 2016 г.

- ^ «Космический мусор» . НАСА. 1 июля 2019 года . Проверено 4 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Джессика (21 июля 2017 г.). «Клапаны SMA для предотвращения взрывов на орбите» (публикация в блоге). Европейское космическое агентство . Проверено 21 января 2023 г.

Верхняя ступень «Дельта»: на вторых ступенях «Дельта» произошло несколько событий из-за остатков топлива, пока в 1981 году не было введено сжигание на истощение.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Шефтер 1982 , с. 50.

- ^ См. диаграммы, Хоффман, стр. 7.

- ^ См. диаграмму, Хоффман, с. 4.

- ^ За время между написанием Главы 1 Клинкрада (2006 г.) (ранее) и Пролога (позже) Космического мусора Клинкрад изменил число с 8 500 до 13 000 – сравните стр. 6 и ix.

- ^ Майкл Хоффман, «Там становится людно». Космические новости , 3 апреля 2009 г.

- ^ «Угроза космического мусора будет расти для астронавтов и спутников». Архивировано 9 апреля 2011 года в Wayback Machine , Fox News, 6 апреля 2011 года.

- ^ Стефан Ловгрен, «Необходима очистка космического мусора, предупреждают эксперты НАСА». Архивировано 7 сентября 2009 года в Wayback Machine National Geographic News , 19 января 2006 года.

- ^ Ж.-К. Лиу и Н.Л. Джонсон, «Риски в космосе, связанные с орбитальным мусором». Архивировано 1 июня 2008 г. в Wayback Machine , Science , Volume 311, номер 5759 (20 января 2006 г.), стр. 340–341.

- ^ Энтони Милн, Статика неба: кризис космического мусора , Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, ISBN 0-275-97749-8 , с. 86.

- ^ Глегхорн 1995 , с. 7.

- ^ Маркс, Пол (27 октября 2009 г.). «Угроза космического мусора будущим запускам» . Новый учёный . Проверено 18 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ «Космический мусор находится на переломном этапе, — говорится в отчете» . Новости Би-би-си . 2 сентября 2011 года . Проверено 18 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Кларк, Филипп. «Инциденты с космическим мусором, связанные с советскими и российскими запусками» . Архивировано из оригинала 25 октября 2021 года . Проверено 7 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ «Сколько объектов космического мусора сейчас находится на орбите?» Архивировано 18 мая 2016 года в Wayback Machine ESA , июль 2013 года. Проверено 6 февраля 2016 года.

- ^ «Оценки спутникового ящика» (PDF) . Ежеквартальные новости об орбитальном мусоре . Том. 20, нет. 3. НАСА . Июль 2016. с. 8. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 11 октября 2016 г. Проверено 10 октября 2016 г.

- ^ «База данных спутников UCS» . Ядерное оружие и глобальная безопасность . Союз неравнодушных ученых . 11 августа 2016 года. Архивировано из оригинала 3 июня 2010 года . Проверено 10 октября 2016 г.

- ^ Технический отчет по космическому мусору (PDF) . Объединенные Нации. 1999. ISBN 978-92-1-100813-5 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 24 июля 2009 г. - через НАСА .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Олдерсон, Бетани (13 июня 2023 г.). «Космический мусор создает беспорядок вокруг Земли, но небольшой куб может помочь сократить количество мусора» . ABC News (Австралия) . Проверено 11 июля 2023 г.

- ^ «Часто задаваемые вопросы об орбитальном мусоре: сколько орбитального мусора в настоящее время находится на околоземной орбите?» Архивировано 25 августа 2009 года в Wayback Machine NASA , март 2012 года. Проверено 31 января 2016 года.

- ^ Лю 2020 .

- ^ Форд, Мэтт (27 февраля 2009 г.). «Выведение космического мусора на орбиту повышает риск спутниковых катастроф» . Арс Техника . Проверено 18 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Вертц, Джеймс; Эверетт, Дэвид; Пушелл, Джеффри (2011). Инженерия космических полетов: новый SMAD . Хоторн, Калифорния: Microcosm Press. п. 139. ИСБН 978-1881883159 .

- ^ «Европейское космическое агентство» . www.esa.int . 19 февраля 2009 года . Проверено 18 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ «Ежеквартальные новости об орбитальном мусоре, июль 2011 г.» (PDF) . Офис программы НАСА по орбитальному мусору. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 20 октября 2011 года . Проверено 1 января 2012 г.

- ^ Кесслер, Дональд Дж. (8 марта 2009 г.). «Синдром Кесслера» . Архивировано из оригинала 27 мая 2010 года . Проверено 22 сентября 2009 г.

- ^ Лиза Гроссман, «НАСА рассматривает возможность стрельбы по космическому мусору с помощью лазеров». Архивировано 22 февраля 2014 г. в Wayback Machine , телеграфно , 15 марта 2011 г.

- ^ Нванкво, Виктор У. Дж.; Дениг, Уильям; Чакрабарти, Сандип К.; Аджакайе, Муйива П.; Фатокун1, Джонсон; Аканни, Адении В.; Рален, Жан-Пьер; Коррейя, Эмилия; Энох, Джон Э. (15 сентября 2020 г.). «Влияние атмосферного сопротивления на смоделированные спутники LEO во время Дня взятия Бастилии в июле 2000 года в отличие от периода геомагнитно-спокойных условий» . Анналы геофизики . дои : 10.5194/angeo-2020-33-rc2 .

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: числовые имена: список авторов ( ссылка ) - ^ Кесслер 1991 , с. 65.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Клинкрад, Хайнер (2006). Космический мусор: модели и анализ рисков . Практика Спрингера. ISBN 3-540-25448-Х . Архивировано из оригинала 12 мая 2011 года . Проверено 20 декабря 2009 г.

- ^ Браун, Гэри; Харрис, Уильям (19 мая 2000 г.). «Как работают спутники» . HowStuffWorks.com . Проверено 21 января 2023 г.

- ^ Шильдкнехт, Т.; Мусси, Р.; Флюри, В.; Куусела, Дж.; Де Леон, Дж.; Домингес Палмеро, Л. Де Фатима (2005). «Оптическое наблюдение космического мусора на высотных орбитах». Материалы 4-й Европейской конференции по космическому мусору (ESA SP-587). 18–20 апреля 2005 г. 587 : 113. Бибкод : 2005ESASP.587..113S .

- ^ «Стратегия колокации и предотвращение столкновений геостационарных спутников на 19 градусах западной долготы». Симпозиум CNES по космической динамике , 6–10 ноября 1989 г.

- ^ ван дер Ха, JC; Гехлер, М. (1981). «Вероятность столкновения геостационарных спутников». 32-й Международный астронавтический конгресс . 1981 : 23. Бибкод : 1981rome.iafcR....V .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Ансельмо, Л.; Пардини, К. (2000). «Снижение риска столкновений на геостационарной орбите». Космический мусор . 2 (2): 67–82. Бибкод : 2000СпДеб...2...67А . дои : 10.1023/А:1021255523174 . S2CID 118902351 .

- ^ Глегхорн 1995 , с. 86.

- ^ Глегхорн 1995 , с. 152.

- ^ «Провал Олимпа» Пресс-релиз ЕКА , 26 августа 1993 г. Архивировано 11 сентября 2007 г. в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Извещение для пользователей спутника «Экспресс-АМ11» в связи с аварией космического корабля» Российская компания спутниковой связи , 19 апреля 2006 г.

- ^ «Авангард 1» . Архивировано из оригинала 15 августа 2019 года . Проверено 4 октября 2019 г.

- ^ «Авангард I отмечает 50-летие пребывания в космосе» . Eurekalert.org. Архивировано из оригинала 5 июня 2013 года . Проверено 4 октября 2013 г.

- ^ Джонсон 1998 , с. 62.

- ^ «Авангарду 50 лет» . Архивировано из оригинала 5 июня 2013 года . Проверено 4 октября 2013 г.

- ^ «База данных спутников UCS» . Проверено 17 января 2023 г.

- ^ «Космический мусор и пилотируемые космические корабли» . НАСА.gov . 13 апреля 2015 года . Проверено 17 января 2023 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б А. Росси и др., «Влияние капель RORSAT NaK на долгосрочную эволюцию популяции космического мусора» , Пизанский университет, 1997.