Район залива Сан-Франциско

Район залива Сан-Франциско | |

|---|---|

Расположение района залива в Калифорнии . Район залива девяти округов. из тринадцати округов Дополнительные округа в более крупной объединенной статистической зоне . | |

| Страна | Соединенные Штаты |

| Состояние | Калифорния |

| Субрегионы | |

| Округа | Список |

| Основные города | Окленд San Francisco Сан-Хосе |

| Другие муниципалитеты | Список |

| Область | |

| • Девять округов | 6966 квадратных миль (18040 км²) 2 ) |

| • Сан-Хосе-Сан-Франциско-Окленд (CSA) | 10 191 квадратных миль (26 390 км ) 2 ) |

| Самая высокая точка | 4360 футов (1330 м) |

| Самая низкая высота | −13 футов (−4 м) |

| Население (2020) | |

| • Девять округов | 7,76 миллиона [4] |

| • Сан-Хосе-Сан-Франциско-Окленд (CSA) | 9,71 миллиона [4] |

| ВВП | |

| • Девять округов | 1,132 триллиона долларов (2022 г.) |

| • Сан-Хосе-Сан-Франциско-Окленд (CSA) | 1,383 триллиона долларов (2022 г.) |

| Часовой пояс | UTC−08:00 ( Тихоокеанский регион ) |

| • Лето ( летнее время ) | UTC−07:00 ( тихоокеанское время ) |

| Коды городов | 408 / 669 , 415 / 628 , 510 / 341 , 650 , 707 , 925 [7] |

| Веб-сайт | Байареаметро |

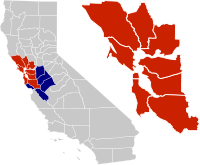

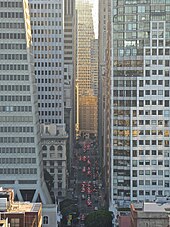

Район залива Сан-Франциско , широко известный как Район залива , представляет собой регион в Калифорнии, и включающий его окружающий залив Сан-Франциско . [8] Ассоциация правительств области залива определяет территорию залива как включающую девять округов, граничащих с устьями заливов Сан-Франциско, Сан-Пабло и Суисун : Аламеда , Контра-Коста , Марин , Напа , Сан-Матео , Санта-Клара , Солано , Сонома. и Сан-Франциско . Другие определения могут быть меньше или больше и могут включать соседние округа, такие как Центрального побережья округа Санта-Крус , Сан-Бенито и Монтерей или Центральной долины округа Сан-Хоакин , Мерсед и Станислав . [9] Район залива известен своей природной красотой, прогрессивной политикой, известными университетами, технологическими компаниями и богатством. В районе залива расположено множество городов, поселков, аэропортов и связанных с ними региональных, государственных и национальных парков, соединенных сложной мультимодальной транспортной сетью.

Самые ранние археологические свидетельства существования человеческих поселений в районе залива датируются 8000–10 000 гг. до н.э. Устные предания народов олоне и мивок предполагают, что они жили в районе залива уже несколько сотен, если не тысяч лет. [10] [11] Испанская империя претендовала на эту территорию в ранний период испанской колонизации Америки . Самое раннее испанское исследование района залива состоялось в 1769 году. Мексиканское правительство контролировало этот район с 1821 года до договора Гваделупе-Идальго 1848 года . Также в 1848 году Джеймс В. Маршалл обнаружил золото в близлежащих горах , что привело к взрывной иммиграции в этот район и резкому сокращению местного населения . Калифорнийская золотая лихорадка привела к быстрому росту Сан-Франциско. [12] Калифорния была признана 31-м штатом в 1850 году. Сильное землетрясение и пожар сравняли с землей большую часть Сан-Франциско в 1906 году. Во время Второй мировой войны район Залива играл важную роль в военных действиях Америки на Азиатско-Тихоокеанском театре военных действий , включая Сан-Франциско. Порт посадки , в котором Форт Мейсон был одним из 14 объектов и местом расположения штаба, выступающего в качестве основного пункта посадки американских войск. С тех пор в районе залива произошло множество политических, культурных и художественных движений, которые развивали уникальные местные жанры в музыке и искусстве и становились очагом прогрессивной политики . В экономическом отношении в послевоенном районе Залива наблюдался значительный рост финансовой и технологической отраслей, в результате чего была создана экономика с валовым внутренним продуктом более 700 миллиардов долларов. В 2018 году здесь находилась третья по величине концентрация компаний из списка Fortune 500 в США. [13] [14]

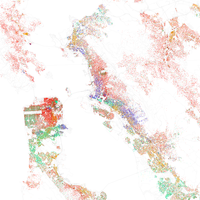

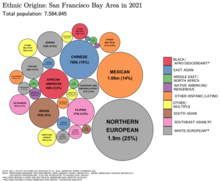

В районе залива проживает около 7,52 миллиона человек. [15] Более крупная федеральная классификация, объединенная статистическая территория региона, включающая 13 округов, [9] является вторым по величине в Калифорнии (после Большого Лос-Анджелеса ) и пятым по величине в Соединенных Штатах с населением более 9 миллионов человек. [16] Население района Залива этнически разнообразно: примерно три пятых жителей региона составляют латиноамериканцы , азиаты , афроамериканцы или жители островов Тихого океана , все из которых имеют значительное присутствие по всему региону. Большую часть оставшихся двух пятых населения составляют белые американцы неиспаноязычного происхождения. Самыми густонаселенными городами района залива являются Окленд , Сан-Франциско и Сан-Хосе , население последнего из которых в 2022 году составляло 971 233 человека, что делает его 12-м по численности населения в Соединенных Штатах . [17] [18]

Несмотря на свой городской характер, залив Сан-Франциско является одним из наиболее экологически чувствительных мест обитания в Калифорнии, обеспечивая важные экосистемные услуги , такие как фильтрация загрязняющих веществ и отложений из рек и поддерживая ряд исчезающих видов . Кроме того, район залива известен своими прибрежными секвойами , многие из которых охраняются в парках штата и округа. Этот регион также известен сложностью форм рельефа, возникшей в результате миллионов лет тектонических движений плит . Поскольку район залива пересекают 6 крупных сейсмических разломов , регион особенно подвержен опасностям, связанным с сильными землетрясениями. Климат умеренный и благоприятствует развлекательным и спортивным мероприятиям на свежем воздухе, таким как пеший туризм, бег и езда на велосипеде. Район залива принимает 6 профессиональных спортивных команд и является культурным центром музыки, театра и искусства. Здесь также расположены многочисленные высшие учебные заведения, в том числе исследовательские университеты, такие как Стэнфордский университет. и Калифорнийский университет в Беркли . В районе залива расположен 101 муниципалитет и 9 округов, а управление в районе залива включает в себя множество местных и региональных юрисдикций, часто с широкими и частично дублирующими обязанностями.

История

[ редактировать ]

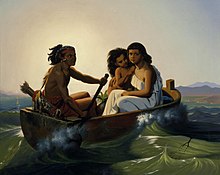

Курган из ракушек Койот-Хиллз, самое раннее известное археологическое свидетельство проживания людей в устьях залива, датируется примерно 10 000 годом до нашей эры, причем данные указывают на еще более раннее поселение в Пойнт-Рейес в округе Марин . [19] Было высказано предположение, что люди, жившие в районе залива во время первого контакта с европейцами, произошли от сибирских племен, которые прибыли около 1000 г. до н.э., переплыв Северный Ледовитый океан и следуя за миграцией лосося. [20] Однако нынешний академический консенсус совместим с устной традицией народов олоне и мивок , которая предполагает, что они жили в районе залива в течение нескольких сотен, если не тысяч лет. [10] [11]

Во время колонизации народы олоне в районе залива в основном жили на полуострове Сан-Франциско, в Южном заливе и в Восточном заливе, а мивок в основном жили в Северном заливе, на севере Восточного залива и в Центральной долине. Деревни Олоне были разбросаны по полуострову, Ист-Бэй, Саут-Бэй, а также дальше на юг, в район залива Монтерей . [21] Существовало восемь основных подразделений народа олоне, четыре из которых базировались в районе залива: каркин пролива Каркинес , чоченьо Восточного залива , рамайтуш полуострова Сан-Франциско и тамиен Южного залива. было У мивок две основные группы в районе залива: залива Контра -Коста и мивок побережья Марина мивок и Сономы .

В 1542 году Хуан Родригес Кабрильо исследовал побережье Тихого океана в районе залива, хотя экспедиция не увидела Золотые Ворота или устья рек, вероятно, из-за тумана. Сэр Фрэнсис Дрейк стал первым европейцем, высадившимся в этом районе и заявившим права на него в июне 1579 года, когда он высадился в заливе Дрейкс возле Пойнт-Рейес. Несмотря на то, что он заявил, что регион королевы Елизаветы I называется Новым Альбионом или Новым Альбионом , англичане не предприняли немедленных действий по этому требованию. [22] [23] [24]

В 1595 году король Испании Филипп II поручил Себастьяну Родригешу Сороменью составить карту западного побережья Америки. Сороменью отплыл на манильском галеоне Сан-Агустин 5 июля 1595 года и в начале ноября они достигли суши между мысом Сент-Джордж и Тринидад-Хед , к северу от района залива, на Затерянном побережье . Экспедиция проследовала вдоль побережья на юг, и 7 ноября « Сан-Агустин» бросил якорь в заливе Дрейкс и объявил этот регион Пуэрто-и-Баия-де-Сан-Франциско . [25] [26] [27] В конце ноября шторм затонул « Сан-Агустин» , унеся жизни от 7 до 12 человек. 8 декабря 80 оставшихся членов экипажа отправились в плавание на катере «Сан-Буэнавентура» , частично построенном на пути из Филиппин . В поисках кратчайшего пути на юг экспедиция прошла мимо Золотых Ворот и прибыла в Пуэрто-де-Чакала, Мексика . 17 января 1596 года [28]

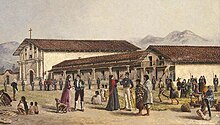

Устья залива оставались неизвестными европейцам до тех пор, пока члены экспедиции Портолы , путешествуя вдоль побережья Калифорнии, не столкнулись с ним в 1769 году, когда Золотые Ворота заблокировали их дальнейшее путешествие на север. [29] несколько миссий В этот период в районе залива было основано . В 1806 году испанская экспедиция под руководством Габриэля Мораги началась в Президио, отправилась к югу от залива, а затем на восток, чтобы исследовать долину Сан-Хоакин . [30]

В 1821 году Мексика получила независимость от Испании, и район залива стал частью мексиканской провинции Альта Калифорния . Этот период характеризовался жизнью на ранчо и посещением американских охотников. [31] Однако контроль Мексики над территорией был недолгим, и в 1846 году группа поселенцев заняла Сонома-Плаза и провозгласила независимость новой Республики Калифорния . [31] В том же году началась мексикано-американская война , и американский капитан Джон Берриен Монтгомери направил военный корабль США « Портсмут » в залив и захватил Сан-Франциско, который тогда был известен как Йерба Буэна , и поднял американский флаг впервые над Портсмутской площадью . [32]

В 1848 году открытие Джеймсом Маршаллом золота в Американской реке спровоцировало Калифорнийскую золотую лихорадку , и в течение полугода 4000 человек мыли золото вдоль реки и находили 50 000 долларов в день. [33] Обещание баснословных богатств быстро привело к тому, что на Саттерс-Милл хлынул поток искателей богатства . Население района залива быстро опустело, поскольку рабочие, клерки, официанты и слуги присоединились к спешке в поисках золота, а первая калифорнийская газета The Californian была вынуждена объявить о временном прекращении выпуска новых номеров из-за нехватки рабочей силы. [33] К концу 1849 года новости распространились по всему миру, и в район залива хлынули вновь прибывшие со скоростью тысяча человек в неделю, направляясь во внутренние районы Калифорнии. [33] включая первый крупный приток китайских иммигрантов в США [34] Ажиотаж был настолько велик, что сотни судов были брошены в портах Сан-Франциско, а экипажи бросились на золотые прииски. [35] Беспрецедентный приток вновь прибывших ослабил зарождающуюся правительственную власть, и военные не смогли предотвратить дезертирство. В результате для обеспечения порядка сформировались многочисленные группы линчевателей, но многие поставили перед собой задачу насильственно переселить или убить местных коренных американцев , и к концу золотой лихорадки две трети коренного населения были убиты. [36]

В это же время было созвано конституционное собрание , чтобы определить заявку Калифорнии на получение статуса штата в Соединенных Штатах. После того, как статус штата был предоставлен, столица переместилась между тремя городами в районе залива: Сан-Хосе (1849–1851), Вальехо (1851–1852) и Бенисией (1852–1853), прежде чем окончательно обосноваться в Сакраменто в 1854 году. [37] Когда золотая лихорадка утихла, богатство, полученное в результате этих усилий, привело к созданию банков Wells Fargo и Bank of California , а рабочие-иммигранты, привлеченные обещаниями богатства, изменили демографический состав региона. Строительство Первой трансконтинентальной железной дороги от Окленд-Лонг-Уорф привлекло так много рабочих из Китая , что к 1870 году восемь процентов населения Сан-Франциско было выходцами из Азии. [38] The completion of the railroad connected the Bay Area with the rest of the United States, established a truly national marketplace for the trade of goods, and accelerated the urbanization of the region.[39]

In the early morning of April 18, 1906, a large earthquake with an epicenter near the city of San Francisco hit the region.[40] Immediate casualty estimates by the U.S. Army's relief operations were 498 deaths in San Francisco, 64 deaths in Santa Rosa, and 102 in or near San Jose, for a total of about 700. More recent studies estimate the total death count to be over 3,000, with over 28,000 buildings destroyed.[41] Rebuilding efforts began immediately. Amadeo Peter Giannini, owner of the Bank of Italy (now known as the Bank of America), had managed to retrieve the money from his bank's vaults before fires broke out through the city and was the only bank with liquid funds readily available and was instrumental in loaning out funds for rebuilding efforts.[42] Congress immediately approved plans for a reservoir in Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park, a plan they had denied a few years earlier, which now provides drinking water for 2.4 million people in the Bay Area. By 1915, the city had been sufficiently rebuilt and advertised itself to the world during the Panama Pacific Exposition that year, although the effects of the quake hastened the loss of the region's dominant status in California to the Los Angeles metropolitan area.[42]

During the 1929 stock market crash and subsequent economic depression, not a single San Francisco-based bank failed,[43] while the region attempted to spur job growth by simultaneously undertaking two large infrastructure projects: construction of the Golden Gate Bridge, which would connect San Francisco with Marin County,[44] and the Bay Bridge, which would connect San Francisco with Oakland and the East Bay.[45] After the United States joined World War II in 1941, the Bay Area became a major domestic military and naval hub, with large shipyards constructed in Sausalito and across the East Bay to build ships for the war effort.[46] The Army's San Francisco Port of Embarkation was the primary origin for Army forces shipping out to the Pacific Theater of Operations.[47][48] That command consisted of fourteen installations including Fort Mason, the Oakland Army Base, Camp Stoneman and Fort McDowell in San Francisco Bay and the sub port of Los Angeles.[49]

After World War II, the United Nations was chartered in San Francisco, and in September 1951, the Treaty of San Francisco to re-establish peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers was signed in San Francisco, entering into force a year later.[50] In the years immediately following the war, the Bay Area saw a huge wave of immigration as populations increased across the region. Between 1950 and 1960, San Francisco welcomed over 100,000 new residents, inland suburbs in the East Bay saw their populations double, Daly City's population quadrupled, and Santa Clara's population quintupled.[46]

By the early 1960s, the Bay Area and the rest of Northern California became the center of the counterculture movement. Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley and the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood in San Francisco were seen as centers of activity,[51] with the hit American pop song San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair) further enticing like-minded individuals to join the movement in the Bay Area and leading to the Summer of Love.[52] In the proceeding decades, the Bay Area would cement itself as a hotbed of New Left activism, student activism, opposition to the Vietnam War and other anti-war movements, the black power movement, and the gay rights movement.[51] At the same time, parts of San Mateo and Santa Clara counties began to rapidly develop from an agrarian economy into a hotbed of the high-tech industry.[53] Fred Terman, the director of a top-secret research project at Harvard University during World War II, joined the faculty at Stanford University in order to reshape the university's engineering department. His students, including David Packard and William Hewlett, would later help usher in the region's high-tech revolution.[46] In 1955, Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory opened for business in Mountain View near Stanford, and although the business venture was a financial failure, it was the first semiconductor company in the Bay Area, and the talent that it attracted to the region eventually led to a high-tech cluster of companies later known as Silicon Valley.[54]

In 1989, in the middle of a World Series game between two Bay Area baseball teams, the Loma Prieta earthquake struck and caused widespread infrastructural damage, including the failure of the Bay Bridge, a major link between San Francisco and Oakland.[55] Even so, the Bay Area's technology industry continued to expand and growth in Silicon Valley accelerated: the United States census confirmed that year that San Jose had overtaken San Francisco in terms of population.[56] The commercialization of the Internet in the middle of the decade rapidly created a speculative bubble in the high-tech economy known as the dot-com bubble. This bubble began collapsing in the early 2000s and the industry continued contracting for the next few years, nearly wiping out the market. Companies like Amazon.com and Google managed to weather the crash however, and following the industry's return to normalcy, their market value increased significantly.[57]

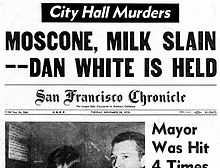

Even as the growth of the technology sector transformed the region's economy, progressive politics continued to guide the region's political environment. By the turn of the millennium, non-Hispanic whites, the largest ethnic group in the United States, were only half of the population in the Bay Area as immigration among minority groups accelerated.[58] During this time, the Bay Area was the center of the LGBT rights movement: in 2004, San Francisco began issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples, a first in the United States,[59] and four years later a majority of voters in the Bay Area rejected California Proposition 8, which sought to constitutionally restrict marriage to opposite-sex couples but ultimately passed statewide.[60]

The Bay Area was also the center of contentious protests concerning racial and economic inequality. In 2009, an African-American man named Oscar Grant was fatally shot by Bay Area Rapid Transit police officers, precipitating widespread protests across the region and even riots in Oakland.[61] His name was symbolically tied to the Occupy Oakland protests two years later that sought to fight against social and economic inequality.[62] By August 2023, San Francisco was in such severe decline that Mayor Matt Mahan of San Jose joked that one day the region might be renamed the "San Jose Bay Area", after its largest and most prosperous city.[63]

Geography

[edit]Boundaries

[edit]

The borders of the San Francisco Bay Area are not officially delineated, and the unique development patterns influenced by the region's topography, as well as unusual commute patterns caused by the presence of three central cities and employment centers located in various suburban locales, has led to considerable disagreement between local and federal definitions of the area.[64] Because of this, professor of geography at the University of California, Berkeley Richard Walker claimed that "no other U.S. city-region is as definitionally challenged [as the Bay Area]."[64]

When the region began to rapidly develop during and immediately after World War II, local planners settled on a nine-county definition for the Bay Area, consisting of the counties that directly border the San Francisco, San Pablo, and Suisun estuaries: Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, Napa, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Solano, and Sonoma counties.[65] Today, this definition is accepted by most local governmental agencies including San Francisco Regional Water Quality Control Board,[66] Bay Area Air Quality Management District,[67] the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority,[68] the Metropolitan Transportation Commission,[69] and the Association of Bay Area Governments,[70] the latter two of which partner to deliver a Bay Area Census using the nine-county definition.[71]

Various U.S. Federal government agencies use definitions that differ from their local counterparts' nine-county definition. For example, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) which regulates broadcast, cable, and satellite transmissions, includes nearby Colusa, Lake and Mendocino counties in their "San Francisco-Oakland-San Jose" media market, but excludes eastern Solano county.[72] On the other hand, the United States Office of Management and Budget, which designates metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) and combined statistical areas (CSA) for populated regions across the country, has five MSAs which include, wholly or partially, areas within the nine-county definition, and one CSA which includes eight Bay Area counties (excluding Sonoma), but including neighboring San Benito, Santa Cruz, San Joaquin, Merced, and Stanislaus counties.[9]

The Association of Bay Area Health Officers (ABAHO), an organization that has fought local outbreaks of HIV/AIDS in 1980s and with COVID-19 pandemic and Deltacron hybrid variant (2020–22), consists of the public health officers of 9 Bay Area counties, in addition to the Central Coast counties of Santa Cruz, San Benito, and Monterey and the city of Berkeley.

| County | 2022 estimate | 2020–22 change | 2020 Population | 2010 Population | 2010–20 change | 2020 Density (per sq mi) | MSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alameda | 1,628,997 | -3.2% | 1,682,353 | 1,510,271 | +11.4% | 2,281.3 | San Francisco–Oakland–Berkeley‡ |

| Contra Costa | 1,156,966 | -0.8% | 1,165,927 | 1,049,025 | +11.1% | 1,626.3 | |

| Marin | 256,018 | -2.4% | 262,321 | 252,409 | +3.9% | 504.1 | |

| San Francisco | 808,437 | -7.5% | 873,965 | 805,235 | +8.5% | 18,629.1 | |

| San Mateo | 729,181 | -4.6% | 764,442 | 718,451 | +6.4% | 1,704.0 | |

| San Benito | 67,579 | +5.3% | 64,209 | 55,269 | +16.2% | 46.2 | San Jose–Sunnyvale–Santa Clara |

| Santa Clara | 1,870,945 | -3.4% | 1,936,259 | 1,781,642 | +8.7% | 1,499.7 | |

| Napa | 134,300 | -2.7% | 138,019 | 136,484 | +1.1% | 184.4 | Napa |

| Solano | 448,747 | -1.0% | 453,491 | 413,344 | +9.7% | 551.8 | Vallejo–Fairfield |

| Sonoma† | 482,650 | -1.3% | 488,863 | 483,878 | +1.0% | 310.3 | Santa Rosa–Petaluma |

| Merced | 290,014 | +3.1% | 281,202 | 255,793 | +9.9% | 145.1 | Merced |

| Santa Cruz | 264,370 | -2.4% | 270,861 | 262,382 | +3.2% | 608.5 | Santa Cruz–Watsonville |

| San Joaquin | 793,229 | +1.3% | 779,233 | 685,306 | +13.7% | 559.6 | Stockton–Lodi |

| Stanislaus | 551,275 | -0.3% | 552,878 | 514,453 | +7.5% | 369.6 | Modesto |

| Bay Area counties colored red †Sonoma County was separated from the CSA in 2023.[9] ‡Renamed to San Francisco–Oakland–Fremont in 2023.[9] | |||||||

Subregions

[edit]Among locals, the nine-county Bay Area is divided into five sub-regions: the East Bay, North Bay, Peninsula, city of San Francisco, and South Bay.

The "East Bay" is the densest region of the Bay Area outside of San Francisco and includes cities and towns in Alameda and Contra Costa counties centered around Oakland. As one of the larger subregions, the East Bay includes a variety of enclaves, including the suburban Tri-Valley area and the highly urban western part of the subregion that runs alongside the bay, including Oakland.[74]

The "North Bay" includes Marin, Sonoma, Napa, and Solano counties, and is the largest and least populated subregion. The western counties of Marin and Sonoma are encased by the Pacific Ocean on the west and the bay on the east and are characterized by their mountainous and woody terrain. Sonoma and Napa counties are known internationally for their grape vineyards and wineries, and Solano County to the east, centered around Vallejo, is the fastest growing region in the Bay Area.[75]

- Regions of the Bay Area

- East Bay

- South Bay

- North Bay

- San Francisco and the Peninsula

The "Peninsula" subregion includes the cities and towns on the San Francisco Peninsula, excluding the titular city of San Francisco. Its eastern half, which runs alongside the Bay, is highly populated, while its less populated western coast traces the coastline of the Pacific Ocean and is known for its open space and hiking trails. Roughly coinciding with the borders of San Mateo County, it also includes the northwestern Santa Clara County cities of Palo Alto, Mountain View, and Los Altos.[76]

Although geographically located on the tip of the San Francisco Peninsula, the city of San Francisco is not considered part of the "Peninsula" subregion, but as a separate entity.[77][78]

The term "South Bay" has different meanings to different groups: Writing in 1959 for the Army Corps of Engineers, the United States Department of Commerce defined the South Bay as comprising five counties, corresponding to their two-way division of the bay into north and south regions.[79] In 1989, the federal Environmental Protection Agency defined the South Bay as the northern part of Santa Clara County and the southeastern part of San Mateo County.[80] This latter definition corresponds to common usage.[81]

Climate

[edit]

The Bay Area is located in the warm-summer Mediterranean climate zone (Köppen Csb) that is a characteristic of California's coast, featuring mild to cool winters with occasional rainfall, and warm to hot, dry summers.[82] It is largely influenced by the cold California Current, which penetrates the natural mountainous barrier along the coast by traveling through various gaps.[83] In terms of precipitation, this means that the Bay Area has pronounced seasons. The winter season, which roughly runs between November and March, is the source of about 82% of annual precipitation in the area. In the South Bay and further inland, while the winter season is cool and mild, the summer season is characterized by warm sunny days,[83] while in San Francisco and areas closer to the Golden Gate strait, the summer season is periodically affected by fog.[84]

Due to the Bay Area's diverse topographic relief (itself the result of the clashing tectonic plates), the region is home to numerous microclimates that lead to pronounced differences in climate and temperature over short distances.[82][85] Within the city of San Francisco, natural and artificial topographical features direct the movement of wind and fog, resulting in startlingly varied climates between city blocks. Along the Golden Gate Strait, oceanic wind and fog from the Pacific Ocean are able to penetrate the mountain barriers inland into the Bay Area.[85]

During the summer, rising hot air in California's interior valleys creates a low pressure area that draws winds from the North Pacific High through the Golden Gate, which creates the city's characteristic cool winds and fog.[84] The microclimate phenomenon is most pronounced during this time, when fog penetration is at its maximum in areas near the Golden Gate strait,[85] while the South Bay and areas further inland are sunny and dry.[83]

Along the San Francisco peninsula, gaps in the Santa Cruz Mountains, one south of San Bruno Mountain and another in Crystal Springs, allow oceanic weather into the interior, causing a cooling effect for cities along the Peninsula and even as far south as San Jose. This weather pattern is also the source for delays at San Francisco International Airport. In Marin county north of the Golden Gate strait, two gaps north of Muir Woods bring cold air across the Marin Headlands, with the cooling effect reaching as far north as Santa Rosa.[85] Further inland, the East Bay receives oceanic weather that travels through the Golden Gate strait, and further diffuses that air through the Berkeley Hills, Niles Canyon and the Hayward Pass into the Livermore Valley and Altamont Pass. Here, the resulting breeze is so strong that it is home to one of the world's largest array of wind turbines. Further north, the Carquinez Strait funnels the ocean weather into the San Joaquin River Delta, causing a cooling effect in Stockton and Sacramento, so that these cities are also cooler than their Central Valley counterparts in the south.[85]

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fairfield[86] | 55 / 39 (13 / 4) | 61 / 42 (16 / 6) | 66 / 45 (19 / 7) | 71 / 47 (22 / 8) | 78 / 52 (26 / 11) | 85 / 56 (29 / 13) | 90 / 58 (32 / 14) | 89 / 57 (32 / 14) | 86 / 56 (30 / 13) | 78 / 51 (26 / 11) | 65 / 44 (18 / 7) | 55 / 39 (13 / 4) |

| Oakland[87] | 58 / 44 (14 / 7) | 67 / 47 (19 / 8) | 64 / 49 (18 / 9) | 66 / 50 (19 / 10) | 69 / 53 (21 / 12) | 72 / 55 (22 / 13) | 72 / 56 (22 / 13) | 73 / 58 (23 / 14) | 74 / 57 (23 / 14) | 72 / 54 (22 / 12) | 65 / 49 (18 / 9) | 58 / 45 (14 / 7) |

| San Francisco[88] | 57 / 46 (14 / 8) | 60 / 48 (16 / 9) | 62 / 49 (17 / 9) | 63 / 49 (17 / 9) | 64 / 51 (18 / 11) | 66 / 53 (19 / 12) | 66 / 54 (19 / 12) | 68 / 55 (20 / 13) | 70 / 55 (21 / 13) | 69 / 54 (21 / 12) | 63 / 50 (17 / 10) | 57 / 46 (14 / 8) |

| San Jose[89] | 58 / 42 (14 / 6) | 62 / 45 (17 / 7) | 66 / 47 (19 / 8) | 69 / 49 (21 / 9) | 74 / 52 (23 / 11) | 79 / 56 (26 / 13) | 82 / 58 (28 / 14) | 82 / 58 (28 / 14) | 80 / 57 (27 / 14) | 74 / 53 (23 / 12) | 64 / 46 (18 / 8) | 58 / 42 (14 / 6) |

| Santa Rosa[90] | 59 / 39 (15 / 4) | 63 / 41 (17 / 5) | 67 / 43 (19 / 6) | 70 / 45 (21 / 7) | 75 / 48 (24 / 9) | 80 / 52 (27 / 11) | 82 / 52 (28 / 11) | 83 / 53 (28 / 12) | 83 / 52 (28 / 11) | 78 / 48 (26 / 9) | 67 / 43 (19 / 6) | 59 / 39 (15 / 4) |

Ecology

[edit]

Marine wildlife

[edit]The Bay Area is home to a diverse array of wildlife and, along with the connected San Joaquin River Delta represents one of California's most important ecological habitats.[91] California's Dungeness crab, Pacific halibut, and the California scorpionfish are all significant components of the bay's fisheries.[92] The bay's salt marshes now represent most of California's remaining salt marsh and support a number of endangered species and provide key ecosystem services such as filtering pollutants and sediments from the rivers.[93] Most famously, the bay is a key link in the Pacific Flyway and with millions of shorebirds annually visiting the bay shallows as a refuge, is the most important component of the flyway south of Alaska.[94] Many endangered species of birds are also found here: the California least tern, the California clapper rail, the snowy egret, and the black crowned night heron.[95]

There is also a significant diversity of salmonids present in the bay. Steelhead populations in California have dramatically declined due to human and natural causes; in the Bay Area, all naturally spawned anadromous steelhead populations below natural and manmade impassable barriers in California streams from the Russian River to Aptos Creek, and the drainages of San Francisco, San Pablo, and Suisun Bays are listed as threatened under the Federal Endangered Species Act.[96] The Central California Coast coho salmon population is the most endangered of the many troubled salmon populations on the west coast of the United States, including populations residing in tributaries to the San Francisco Bay.[97] California Coast Chinook salmon were historically native to the Guadalupe River in San Francisco Bay, and Chinook salmon runs persist today in the Guadalupe River, Coyote Creek, Napa River, and Walnut Creek.[98] Industrial, mining, and other uses of mercury have resulted in a widespread distribution of that poisonous metal in the bay, with uptake in the bay's phytoplankton and contamination of its sportfish.[99]

Aquatic mammals are also present in the bay. Before 1825, Spanish, French, English, Russians and Americans were drawn to the Bay Area to harvest prodigious quantities of beaver, river otter, marten, fisher, mink, fox, weasel, harbor and fur seals and sea otter. This early fur trade, known as the California Fur Rush, was more than any other single factor, responsible for opening up the West and the San Francisco Bay Area, in particular, to world trade.[100] By 1817 sea otter in the area were practically eliminated.[101] Since then, the California golden beaver re-established a presence in Alhambra Creek, followed by the Napa River and Sonoma Creek in the north, and the Guadalupe River and Coyote Creek in the south.[102] The North American river otter which was first reported in Redwood Creek at Muir Beach in 1996,[103] has since been spotted in the North Bay's Corte Madera Creek, the South Bay's Coyote Creek,[104] as well as in 2010 in San Francisco Bay itself at the Richmond Marina. Other mammals include the internationally famous sea lions who began inhabiting San Francisco's Pier 39 after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake[105] and the locally famous Humphrey the Whale, a humpback whale who entered San Francisco Bay twice on errant migrations in the late 1980s and early 1990s.[106] Bottlenose dolphins and harbor porpoises have recently returned to the bay, having been absent for many decades. Historically, this was the northern extent of their warm-water species range.[107]

Birds

[edit]

In addition to the many species of marine birds that can be seen in the Bay Area, many other species of birds make the Bay Area their home, making the region a popular destination for birdwatching.[108] Many birds are listed as endangered species despite once being common in the region.

Western burrowing owls were originally listed as a species of special concern by the California Department of Fish and Game in 1979. California's population declined 60% from the 1980s to the early 1990s, and continues to decline at roughly 8% per year.[109] A 1992–93 survey reported little to no breeding burrowing owls in most of the western counties in the Bay Area, leaving only Alameda, Contra Costa, and Solano counties as remnants of a once large breeding range.[110]

Bald eagles were once common in the Bay Area, but habitat destruction and thinning of eggs from DDT poisoning reduced the California state population to 35 nesting pairs. Bald eagles disappeared from the Bay Area in 1915, and only began returning in recent years.[111] In the 1980s an effort to re-introduce the species to the area began with the Santa Cruz Predatory Bird Research Group and the San Francisco Zoo importing birds and eggs from Vancouver Island and northeastern California,[112] and there are now nineteen nesting couples in eight of the Bay Area's nine counties.[111] Other once absent species that have returned to the Bay Area include Swainson's hawk, white tailed kite, and the osprey.[111]

In 1927, zoologist Joseph Grinnell wrote that osprey were only rare visitors to the San Francisco Bay Area, although he noted records of one or two used nests in the broken tops of redwood trees along the Russian River.[113] In 1989, the southern breeding range of the osprey in the Bay Area was Kent Lake, although osprey were noted to be extending their range further south in the Central Valley and the Sierra Nevada.[114] In 2014, a Bay Area-wide survey found osprey had extended their breeding range southward with nesting sites as far south as Hunters Point in San Francisco on the west side and Hayward on the east side, while further studies have found nesting sites as far south as the Los Gatos Creek watershed, indicating that the nesting range now includes the entire length of San Francisco Bay.[115] Most nests were built on man-made structures close to areas of human disturbance, likely due to lack of mature trees near the Bay.[116] The wild turkey population was introduced in the 1960s by state game officials, and by 2015 have become a common sight in East Bay communities.[117]

Geology and landforms

[edit]

The Bay Area is well known for the complexity of its landforms that are the result of the forces of plate tectonics acting over of millions of years, since the region is located in the middle of a meeting point between two plates.[118] Nine out of eleven distinct assemblages have been identified in a single county, Alameda.[119] Diverse assemblages adjoin in complex arrangements due to offsets along the many faults (both active and stable) in the area. As a consequence, many types of rock and soil are found in the region. The oldest rocks are metamorphic rocks that are associated with granite in the Salinian Block west of the San Andreas fault. These were formed from sedimentary rocks of sandstone, limestone, and shale in uplifted seabeds.[120] Volcanic deposits also exist in the Bay Area, left behind by the movement of the San Andreas fault, whose movement sliced a subduction plate and allowed magma to briefly flow to the surface.[121]

The region has considerable vertical relief in its landscapes that are not in the alluvial plains leading to the bay or in inland valleys. The topography, and geologic history, of the Bay Area can largely be attributed to the compressive forces between the Pacific Plate and the North American plate.[122]

The three major ridge structures in the Bay Area, part of the Pacific Coast Range, are all roughly parallel to the major faults. The Santa Cruz Mountains along the San Francisco Peninsula and the Marin Hills in Marin County follow the San Andreas fault, The Berkeley Hills, San Leandro Hills and their southern ridgeline extension through Mission Peak roughly follow the Hayward fault, and the Diablo Range, which includes Mount Diablo and Mount Hamilton and runs along the Calaveras fault.[123]

In total, the Bay Area is traversed by seven major fault systems with hundreds of related faults, all of which are stressed by the relative motion between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate or by compressive stresses between these plates. The fault systems include the Hayward Fault Zone, Concord-Green Valley Fault, Calaveras Fault, Clayton-Marsh Creek-Greenville Fault, Rodgers Creek Fault, and the San Gregorio Fault.[124] Significant blind thrust faults (faults with near vertical motion and no surface ruptures) are associated with portions of the Santa Cruz Mountains and the northern reaches of the Diablo Range and Mount Diablo. These "hidden" faults, which are not as well known, pose a significant earthquake hazard.[125] Among the more well-understood faults, as of 2014, scientists estimate a 72% probability of a magnitude 6.7 earthquake occurring along either the Hayward, Rogers Creek, or San Andreas fault, with an earthquake more likely to occur in the East Bay's Hayward Fault.[126] Two of the largest earthquakes in recent history were the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

Hydrography

[edit]

The Bay Area is home to a complex network of watersheds, marshes, rivers, creeks, reservoirs, and bays that predominantly drain into the San Francisco Bay and Pacific Ocean. The largest bodies of water in the Bay Area are the San Francisco, San Pablo, and Suisun estuaries. Major rivers of the North Bay include the Napa River, the Petaluma River, the Gualala River, and the Russian River; the former two drain into San Pablo Bay, the latter two into the Pacific Ocean. In the South Bay, the Guadalupe River drains into San Francisco Bay near Alviso.[127] There are also several lakes present in the Bay Area, including man-made lakes like Lake Berryessa[128] and natural albeit heavily modified lakes like Lake Merritt.[129]

Prior to the introduction of European agricultural methods, the shores of San Francisco Bay consisted mostly of tidal marshes.[130] Today, the bay has been significantly altered heavily re-engineered to accommodate the needs of water delivery, shipping, agriculture, and urban development, with side effects including the loss of wetlands and the introduction of contaminants and invasive species.[131] Approximately 85% of those marshes have been lost or destroyed, but about 50 marshes and marsh fragments remain.[130] Huge tracts of the marshes were originally destroyed by farmers for agricultural purposes, then repurposed to serve as salt evaporation ponds to produce salt for food and other purposes.[132] Today, regulations limit the destruction of tidal marshes, and large portions are currently being rehabilitated to their natural state.[130]

Over time, droughts and wildfires have increased in frequency and become less seasonal and more year-round, further straining the region's water security.[133][134][135]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 114,074 | — | |

| 1870 | 265,808 | 133.0% | |

| 1880 | 422,128 | 58.8% | |

| 1890 | 547,618 | 29.7% | |

| 1900 | 658,111 | 20.2% | |

| 1910 | 925,708 | 40.7% | |

| 1920 | 1,182,911 | 27.8% | |

| 1930 | 1,578,009 | 33.4% | |

| 1940 | 1,734,308 | 9.9% | |

| 1950 | 2,681,322 | 54.6% | |

| 1960 | 3,638,939 | 35.7% | |

| 1970 | 4,628,199 | 27.2% | |

| 1980 | 5,179,784 | 11.9% | |

| 1990 | 6,023,577 | 16.3% | |

| 2000 | 6,783,760 | 12.6% | |

| 2010 | 7,150,739 | 5.4% | |

| 2020 | 7,765,640 | 8.6% | |

| Note: Nine-County Population Totals[58] | |||

According to the 2010 United States Census, the population of the nine-county Bay Area was 7.15 million, with 49.6% male and 50.4% female.[58] Of these, approximately 2.3 million (32%) are foreign born.[136] In 2010 the racial makeup of the nine-county Bay Area was 52.5% White (42.4% were non-Hispanic and 10.1% were Hispanic), 23.3% Asian, 6.7% non-Hispanic Black or African American, 0.7% Native American or Alaska Native, 0.6% Pacific Islander, 5.4% from two or more races and 10.8% from other races.[137] Hispanic or Latino residents of any race formed 23.5% of the population.

The Bay Area cities of Vallejo, Suisun City, Oakland, San Leandro, Fairfield, and Richmond are among the most ethnically diverse cities in the United States.[138]

Non-Hispanic whites form majorities of the population in Marin, Napa, and Sonoma counties.[58] Whites also make up the majority in the eastern regions of the East Bay centered around the Lamorinda and Tri-Valley areas.[58] San Francisco's North Beach district is considered the Little Italy of the city, and was once home to a significant Italian-American community. San Francisco, Marin County[139] and the Lamorinda area[140] all have substantial Jewish communities. There is a Little Russia community in northwestern San Francisco, and there are Russian communities throughout the Bay Area, especially in San Mateo County and Santa Clara County; there are also Eastern European American groups such as Ukrainians and Poles in dozens of thousands to hundreds of thousands especially in San Francisco and in the Peninsula, including recent immigrants and American-born citizens of Eastern European descent. There are dozens of Russian-, Ukrainian-, and Polish-speaking churches in San Francisco, the South Bay, the East Bay, and on the Peninsula.

Like much of the U.S., the Bay Area has a large Irish population and this is reflected in the Richmond District area of San Francisco. San Jose has a Little Portugal.

The Latino population is spread throughout the Bay Area, but among the nine counties, the greatest number live in Santa Clara County, while Contra Costa County has seen the highest growth rate.[141] The largest Hispanic or Latino groups were those of Mexican (17.9%), Salvadoran (1.3%), Guatemalan (0.6%), Puerto Rican (0.6%) and Nicaraguan (0.5%) ancestry. Mexican Americans make up the largest share of Hispanic residents in Napa county,[142] while Central Americans make up the largest share in San Francisco, many of whom live in the Mission District which is home to many residents of Salvadoran and Guatemalan descent.[143]

The Asian-American population in the Bay Area is one of the largest in North America. Asian-Americans make up the plurality in two major counties in the Bay Area: Santa Clara County and Alameda County.[144] The largest Asian-American groups were those of Chinese (7.9%), Filipino (5.1%), Indian (3.3%), Vietnamese (2.5%), and Japanese (0.9%) heritage. Asian Americans also constitute a majority in Cupertino, Fremont, Milpitas, Union City and significant populations in Dublin, Foster City, Hercules, Millbrae, San Ramon, Saratoga, Sunnyvale and Santa Clara. The cities of San Jose and San Francisco had the third and fourth most Asian-American residents in the United States.[145] In San Francisco, Chinese Americans constitute 21.4% of the population and constitute the single largest ethnic group in the city.[146] The Bay Area is home to over 382,950 Filipino Americans, one of the largest communities of Filipino people outside of the Philippines with the largest proportion of Filipino Americans concentrating themselves within American Canyon, Daly City, Fairfield, Hercules, South San Francisco, Union City and Vallejo.[147] Santa Clara county, and increasingly the East Bay, house a significant Indian American community.[148] There are more than 100,000 people of Vietnamese ancestry residing within San Jose city limits, the largest Vietnamese population of any city in the world outside of Vietnam.[149] In addition, there is a sizable community of Korean Americans in Santa Clara county, where San Jose is located.[150] East Bay cities such as Richmond, San Pablo, and Oakland, and the North Bay city of Santa Rosa, have plentiful populations of Laotian and Cambodians in certain neighborhoods.[151]

Pacific Islanders such as Samoans and Tongans have the largest presence in East Palo Alto, where they constitute over 7% of the population.[152] San Bruno also has a large Tongan population and so does San Mateo and South San Francisco, which also have smaller communities of Samoans. The Visitacion Valley has a designated Pacific Islander district and Samoan and Tongans have a presence in Southeast San Francisco and Daly City's Bayshore neighborhood.

The African-American population of San Francisco was formerly substantial, had a thriving jazz scene and was known as "Harlem of the West." While black residents formed one-seventh of the city's population in 1970, today they have mostly moved to parts of the East Bay and North Bay, including Antioch,[153] Fairfield and out of the Bay Area entirely.[154] The South Park neighborhood of Santa Rosa was once home to a primarily black community until the 1980s, when many Latino immigrants settled in the area.[155] Other cities with large numbers of African Americans include Vallejo (28%),[156] Richmond (26%),[157] East Palo Alto (17%)[152] and the CDP of Marin City (38%).[158] Suisun City and Vacaville both have African American populations that have accelerated in population since the 2000s. There are also Eritrean, Ethiopian and Nigerian communities.

There is also a significant Middle Eastern and Balkan population. There are 4,000 Armenians in San Francisco, and some in the San Jose area. The San Jose area, especially the Campbell area and some areas off of San Jose's Stevens Creek Blvd contain a Bosnian community. There are several thousand Turks in San Francisco, and a Palestinian population is concenrated in Daly City and San Francisco.

Since the economy of the Bay Area heavily relies on innovation and high-tech skills, a relatively educated population exists in the region. Roughly 87.4% of Bay Area residents have attained a high school degree or higher,[159] while 46% of adults in the Bay Area have earned a post-secondary degree or higher.[160]

| Counties by population and ethnicity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County | Type | Population | White | Other | Asian | African | Native | Hispanic |

| Counties by population and income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County | Type | Population | Per capita income | Median household income | Median family income |

Affluence

[edit]The Bay Area is the wealthiest region per capita in the United States, due, primarily, to the economic power engines of San Jose, San Francisco, and Oakland. The Bay Area city of Pleasanton has the second-highest household income in the country after New Canaan, Connecticut. However, discretionary income is very comparable with the rest of the country, primarily because the higher cost of living offsets the increased income.[161]

There are 285,000 millionaires living in the region, the third-highest amongst the world's metropolitan areas after New York City and Tokyo as of 2022.[162]The amount of wealth held by Bay Area residents is about $2.6 trillion, the second-highest in the world after New York City, and just ahead of Tokyo as of 2021.[163]

By 2014, the Bay Area's wealth gap was considerable: the top ten percent of income-earners took home over eleven times as much as the bottom ten percent,[164] and a Brookings Institution study found the San Francisco metro area, which excludes four Bay Area counties, to be the third most unequal urban area in the country.[165] Among the wealthy, forty-seven Bay Area residents made Forbes magazine's 400 richest Americans list, published in 2007.

Crime

[edit]Statistics regarding crime rates in the Bay Area generally fall into two categories: violent crime and property crime. Historically, violent crime has been concentrated in a few cities in the East Bay, namely Oakland, Richmond, and Antioch, but also East Palo Alto in the Peninsula, Vallejo in the North Bay, and San Francisco.[166] Nationally, Oakland's murder rate ranked 18th among cities with over 100,000 residents, and third for violent crimes per capita.[167] According to a 2015 Federal Bureau of Investigation report, Oakland was also the source of the most violent crime in the Bay Area, with 16.9 reported incidents per thousand people. Vallejo came in second, at 8.7 incidents per thousand people, while San Pablo, Antioch, and San Francisco rounded out the top five. East Palo Alto, which used to have the Bay Area's highest murder rate, saw violent crime incidents drop 65% between 2013 and 2014, while Oakland saw violent crime incidents drop 15%.[166] Meanwhile, San Jose, which was one of the safest large cities in the United States in the early 2000s, has seen its violent crime rates trend upwards.[168] Cities with the lowest rate of violent crime include the Peninsula cities of Los Altos and Foster City, East Bay cities of San Ramon and Danville, and southern foothill cities of Saratoga and Cupertino. In 2015, 45 Bay Area cities counted zero homicides, the largest of which was Daly City.[166]

In 2015, Oakland also saw the highest rates of property crime in the Bay Area, at 59.4 incidents per thousand residents, with San Francisco following close behind at 53 incidents per thousand residents. The East Bay cities Pleasant Hill, Berkeley, and San Leandro rounded out the top five. Saratoga and Windsor saw the least rates of property crime.[166] Additionally, San Francisco saw the most reports of arson.[167]

Several street gangs operate in the Bay Area, including the Sureños and Norteños in San Francisco's Mission District.[169] African-American street gangs familiar in other cities, including the Crips, have struggled to establish footholds in the city,[170] although gangs with shotcallers in China, including Triad groups such as the Wo Hop To, have been reported active.[171] In 1977, an ongoing rivalry between two Chinese gangs led to a shooting attack at the Golden Dragon restaurant in Chinatown, which left five people dead and eleven wounded. Five members of the Joe Boys gang were arrested and convicted of the crime.[172] Oakland, which also sees organized gang violence, implemented Operation Ceasefire in 2012 in an effort to reduce the violence.[173]

Economy

[edit]

The three principal cities of the Bay Area represent separate employment clusters and are dominated by different but commingled industries. San Francisco is home to the region's tourism, financial industry, and is host to numerous conventions. The East Bay, centered around Oakland, is home to heavy industry, metalworking, oil, and shipping, while San Jose is the heart of Silicon Valley where a major pole of economic activity around the technology industry resides. Furthermore, the North Bay is a major player in the country's agriculture and wine industry.[64] In all, the Bay Area is home to the second highest concentration of Fortune 500 companies, second only to the New York metropolitan area, with thirty such companies based throughout the region.[174]

In 2019, the greater fourteen-county statistical area had a GDP of $1.086 trillion, the third-highest among combined statistical areas.[176] The smaller nine-county Bay Area had a GDP of $995 billion in the same year, which nonetheless would rank it fifth among U.S. states and 17th among countries.[176]

The COVID-19 pandemic caused an exodus of businesses from the downtown cores of San Francisco, San Jose and Oakland, as remote work became more widespread, especially in the tech industry.[177][178] Some observers have warned that this could lead to an economic doom loop for Bay Area cities, particularly San Francisco,[179] while others have argued that these concerns are restricted to the downtown core.[180] Many retailers in Downtown San Francisco and Downtown Oakland have closed since 2020,[181] with some citing complex challenges with visible homelessness and crime in the area.[182] Additionally noted is the Bay Area's steadily decreasing lead in the geographically dispersing high technology field, and its relative geographical isolation from most North American commercial markets.[183][184]

Despite this exodus, Bay Area is still the home to four of the world's ten largest companies by market capitalization; and several major corporations are still headquartered in the Bay Area, including Google, Facebook, Apple Inc., Clorox, Hewlett-Packard, Intel, Adobe Inc., Applied Materials, eBay, Cisco Systems, Symantec, Netflix, Sony Interactive Entertainment, Electronic Arts, and Salesforce; energy company PG&E; financial service company Visa Inc.; apparel retailers Gap Inc., Levi Strauss & Co., and Ross Stores; aerospace and defense contractor Lockheed Martin; local grocer Safeway; and biotechnology companies Genentech and Gilead Sciences.[182][185] The largest manufacturers include Tesla Inc., Lam Research, Bayer, and Coca-Cola.[186] The Port of Oakland is the fifth-largest container shipping port in the United States, and Oakland is also a major rail terminus.[187] In research, NASA's Ames Research Center and the federal research facility Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory are based in Mountain View and Livermore respectively. In the North Bay, Napa and Sonoma counties are well known for their wineries, including Fantesca Estate & Winery, Domaine Chandon California, and D'Agostini Winery.[188]

In spite of the San Francisco Bay Area's industries contributing to the aforementioned economic growth, there is a significant level of poverty in the region. Rising housing prices and gentrification in the San Francisco Bay Area are often framed as symptomatic of high-income tech workers moving in to previously low-income, underserved neighborhoods.[189] Two notable policy strategies to prevent eviction due to rising rents include rent control and subsidies such as Section 8 and Shelter Plus Care.[190] Moreover, in 2002, then San Francisco Supervisor Gavin Newsom introduced the "Care Not Cash" initiative, diverting funds away from cash handouts (which he argued encouraged drug use) to housing. This proved controversial, with some suggesting his rhetoric criminalized poverty, while others supporting the prioritizing of housing as a solution.[191]

Contrary to historical patterns of low incomes within the inner city, poverty rates in the Bay Area are shifting such that they are increasing more rapidly in suburban areas than in urban areas.[192] It is not yet clear whether the suburbanization of poverty is due to the relocation of poor populations or shifting income levels in the respective regions. However, the mid-2000s housing boom encouraged city dwellers to move into the newly cheap houses in suburbs outside of the city, and these suburban housing developments were then most affected by the 2008 housing bubble burst. As such, people in poverty experience decreased access to transportation due to underdeveloped public transport infrastructure in suburban areas. Suburban poverty is most prevalent among Hispanics and Blacks, and affects native-born people more significantly than foreign-born.[192][193]

As greater proportions of their incomes are spent on rent, many impoverished populations in the San Francisco Bay Area also face food insecurity and health setbacks.[194][195]

Housing

[edit]

The Bay Area is the most expensive location to live in the United States outside of Manhattan.[196] Strong economic growth has created hundreds of thousands of new jobs, but coupled with severe zoning restrictions on building new housing units,[197] has resulted in an extreme housing shortage. For example, from 2012 to 2017, the San Francisco metropolitan area added 400,000 new jobs, but only 60,000 new housing units.[198] As of 2016, the entire Bay Area had 3.6 M jobs, and 2.6 M housing units, for a ratio of 1.4 jobs per housing unit,[199] significantly above the ratio for the US as a whole, which stands at 1.1 jobs per housing unit. (152M jobs, 136M housing units[200][201])

As of 2017, the average income needed in order to purchase a house in the region was $179,390, while the median price for a house was $895,000 and the average cost of a home in the Bay Area being $440,000 - more than twice the national average, while the average monthly rent is $1,240 - 50 percent more than the national average.[202][203] In 2018, a Bay Area household income of $117,000 was classified as "low income" by the Department of Housing and Urban Development.[204]

With high costs of living, many Bay Area residents allocate large amounts of their income towards housing. 20 percent of Bay Area homeowners spend more than half their income on housing, while roughly 25 percent of renters in the Bay Area spend more than half of their incomes on rent.[205] Expending an average of more than $28,000 per year on housing in addition to roughly $13,400 on transportation, Bay Area residents spend around $41,420 per year to live in the region. This combined total of housing and transportation signifies 59 percent of the Bay Area's median household income, conveying the extreme costs of living.[205]

The high rate of homelessness in the Bay Area can be attributed to the high cost of living.[206] No approximate number of homeless people living in the Bay Area can be determined due to the difficulty of tracking homeless residents.[206] However, according to San Francisco's Department of Public Health, the number of homeless people in San Francisco alone is 9,975.[207] Additionally, San Francisco was revealed to have the most unsheltered homeless people in the country.[207]

Because of the high cost of housing, many workers in the Bay Area live far from their place of employment, contributing to one of the highest percentages of extreme commuters in the United States, or commutes that take over ninety minutes in one direction. For example, about 50,000 people commute from neighboring San Joaquin County into the nine-county Bay Area daily,[208] and more extremely, some workers commute semimonthly by flying.[209]

Education

[edit]Colleges and universities

[edit]

The Bay Area is home to a large number of colleges and universities. The first institution of higher education in the Bay Area, Santa Clara University, was founded by Jesuits in 1851,[210] who also founded the University of San Francisco in 1855.[211] San Jose State University was founded in 1857 and is the oldest public college on the West Coast of the United States.[212] According to the Brookings Institution, 45% of residents of the two-county San Jose metro area have a college degree and 43% of residents in the five-county San Francisco metro area have a college degree, the second and fourth-highest ranked metro areas in the country for higher educational attainment.[213]

As of 2024[update], Stanford University is the highest ranked university in the Bay Area by U.S. News & World Report,[214] and its business school is ranked #1 in the US, Canada, Europe and Asia by Bloomberg Businessweek.[215] The University of California, Berkeley has been the highest-ranked public university in the country for the past nineteen years.[citation needed] Additionally, San Jose State University and Sonoma State University were ranked 3rd and 12th, respectively, among public colleges in the West Coast by U.S. News & World Report in 2024.[216]

The city of San Francisco is host to two additional University of California schools, neither of which confer undergraduate degrees. The University of California, San Francisco is entirely dedicated to graduate education in health and biomedical sciences. It is ranked among the top five medical schools in the United States[217] and operates the UCSF Medical Center, which is the highest-ranked hospital in California.[218] The University of California, College of the Law, founded in Civic Center in 1878, is the oldest law school in California and claims more judges on the state bench than any other institution.[219] The city is also host to a California State University school, San Francisco State University.[220] Additional campuses of the California State University system in the Bay Area are Cal State East Bay in Hayward and Cal Maritime in Vallejo.

California Community Colleges System also operates a number of community colleges in the Bay Area. According to CNNMoney, the Bay Area community college with the highest "success" rate is De Anza College in Cupertino, which is also the tenth-highest ranked in the nation. Other relatively well-ranked Bay Area community colleges include Foothill College, City College of San Francisco, West Valley College, Diablo Valley College, and Las Positas College.[221]

Many scholars have pointed out the overlap of education and the economy within the Bay Area. According to multiple reports, research universities such as Stanford University, University of California - Santa Cruz and University of California - Berkeley, are essential to the culture and economy in the area.[160] These universities also provide public programs for people to learn and enhance skills relevant to the local economies. These opportunities not only provide educational services to the community, but also generate significant amounts of revenue.[160]

Primary and secondary schools

[edit]

Public primary and secondary education in the Bay Area is provided through school districts organized through three structures (elementary school districts, high school districts, or unified school districts) and are governed by an elected board. In addition, many Bay Area counties and the city of San Francisco operate "special service schools" that are geared towards providing education to students with handicaps or special needs.[222]

An alternative public educational setting is offered by charter schools, which may be established with a renewable charter of up to five years by third parties. The mechanism for charter schools in the Bay Area is governed by the California Charter Schools Act of 1992.[223]

According to rankings compiled by U.S. News & World Report, the highest-ranked high school in California is the Pacific Collegiate School, located in Santa Cruz and part of the greater Bay Area. Within the traditional nine-county boundaries, the highest ranked high school is KIPP San Jose Collegiate in San Jose. Among the top twenty high schools in California include Lowell High School in San Francisco, Monta Vista High School in Cupertino, Lynbrook High School in San Jose, the University Preparatory Academy in San Jose, Mission San Jose High School in Fremont, Oakland Charter High School in Oakland, Henry M. Gunn High School in Palo Alto, Gilroy Early College Academy in Gilroy, and Saratoga High School in Saratoga.[224]

Transportation

[edit]

Transportation in the San Francisco Bay Area is reliant on a complex multimodal infrastructure consisting of roads, bridges, highways, rail, tunnels, airports, ferries, and bike and pedestrian paths. The development, maintenance, and operation of these different modes of transportation are overseen by various agencies, including the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission.[225] These and other organizations collectively manage several interstate highways and state routes, two subway networks, three commuter rail agencies, eight trans-bay bridges, transbay ferry service, local bus service,[226] three international airports (San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland),[227] and an extensive network of roads, tunnels, and paths such as the San Francisco Bay Trail.[228]

The Bay Area hosts an extensive freeway and highway system that is particularly prone to traffic congestion, with one study by Inrix concluding that the Bay Area's traffic was the fourth worst in the world.[229] There are some city streets in San Francisco where gaps occur in the freeway system, partly the result of the Freeway Revolt, which prevented a freeway-only thoroughfare through San Francisco between the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge, the western terminus of Interstate 80, and the southern terminus of the Golden Gate Bridge (U.S. Route 101).[230] Additional damage that occurred in the wake of the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake resulted in freeway segments being removed instead of being reinforced or rebuilt, leading to the revitalization of neighborhoods such as San Francisco's Embarcadero and Hayes Valley.[231] The greater Bay Area contains the three principal north–south highways in California: Interstate 5, U.S. Route 101, and California State Route 1. U.S. 101 and State Route 1 directly serve the traditional nine-county region, while Interstate 5 bypasses to the east in San Joaquin County to provide a more direct Los Angeles–Sacramento route. Additional local highways connect the various subregions of the Bay Area together.[232]

There are over two dozen public transit agencies in the Bay Area with overlapping service areas that utilize different modes, with designated connection points between the various operators. Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART), a heavy rail/metro system, operates in five counties and connects San Francisco and Oakland via the Transbay Tube. Other commuter rail systems link San Francisco with the Peninsula and San Jose (Caltrain), San Jose with the Tri-Valley Area and San Joaquin County (ACE), and Sonoma with Marin County (SMART).[226]

In addition, Amtrak provides frequent commuter service between San Jose and the East Bay with Sacramento, and long-distance service to other parts of the United States.[233] Muni Metro operates a hybrid streetcar/subway system within the city of San Francisco, and VTA operates a light rail system in Santa Clara County. These rail systems are supplemented by numerous bus agencies and transbay ferries such as Golden Gate Ferry and the San Francisco Bay Ferry. Most of these agencies accept the Clipper Card, a reloadable contactless smart card, as a universal electronic payment system.[226]

Government and politics

[edit]

Government in the San Francisco Bay Area consists of multiple actors, including 101 city and nine county governments, a dozen regional agencies, and a large number of single-purpose special districts such as municipal utility districts and transit districts.[234] Incorporated cities are responsible for providing police service, zoning, issuing building permits, and maintaining public streets among other duties.[235] County governments are responsible for elections and voter registration, vital records, property assessment and records, tax collection, public health, agricultural regulations, and building inspections, among other duties.[236][237] Public education is provided by independent school districts, which may be organized as elementary districts, high school districts, unified school districts combining elementary and high school grades, or community college districts, and are managed by an elected school board.[222] A variety of special districts also exist and provide a single purpose, such as delivering public transit in the case of the Bay Area Rapid Transit District,[238] or monitoring air quality levels in the case of the Bay Area Air Quality Management District.[67]

Politics in the Bay Area is widely regarded as one of the most liberal in California and in the United States.[239][240] Since the late 1960s, the Bay Area has cemented its role as the most liberal region in California politics, giving greater support for the center-left Democratic Party's candidates than any other region of the state, even as California trended towards the Democratic Party over time.[241] According to research by the Public Policy Institute of California, the Bay Area and the North Coast counties of Humboldt and Mendocino were the most consistently and strongly liberal areas in California.[241]

According to the California Secretary of State, the Democratic Party holds a voter registration advantage in every congressional district, State Senate district, State Assembly district, State Board of Equalization district, all nine counties, and all of the 101 incorporated municipalities in the Bay Area. On the other hand, the center-right Republican Party holds a voter registration advantage in only one State Assembly sub-district (the portion of the 4th in Solano County).[242] According to the Cook Partisan Voting Index (CPVI), the Bay Area's districts tend to favor Democratic candidates by roughly 40 to 50 percentage points, considerably above the mean for California and the nation overall.[243]

In U.S. Presidential elections since 1960, the nine-county Bay Area voted for Republican candidates only two times, in both cases voting for a Californian: in 1972 for Richard Nixon and again in 1980 for Ronald Reagan. The last county to vote for a Republican presidential candidate was Napa county in 1988 for George H. W. Bush. Since then, all nine Bay Area counties have voted consistently for the Democratic candidate.[246] Currently, both of California's U.S. Senators are Democrats, and all twelve U.S. congressional districts located wholly or partially in the Bay Area are represented by a Democratic representative. Additionally, every Bay Area member of the California State Senate and the California State Assembly is a registered Democrat.

The Bay Area's association with progressive politics has led to the term "San Francisco values" being used by conservative commentators in a pejorative sense to describe the secular progressive culture in the area.[247]

Regional governance

[edit]The Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG) is the principal metropolitan planning organization for the Bay Area. The Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) is the region's transportation planning agency, which has functionally merged with ABAG through staff consolidation. ABAG and MTC developed Plan Bay Area, which is the area's regional transportation plan, in 2013 and with its goal date for 2040.

Other regional governance agencies include the Bay Area Air Quality Management District, Bay Area Toll Authority, Bay Restoration Authority, and the Bay Conservation & Development Commission.

Culture

[edit]Arts

[edit]

The Bay Area was a hub of the Abstract Expressionism movement of painting. It is associated with the works of Clyfford Still, who began teaching at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute) in 1946, leaving a lasting influence on the artistic styles of Bay Area painters up to the present day.[248] A few years later, Abstract Expressionist painter David Park painted Kids on Bikes in 1950, which retained many aspects of abstract expressionism but with original distinguishing features that would later lead to the Bay Area Figurative Movement.[249]

While both the Figurative Movement and the Abstract Expressionism movement arose from art schools, Funk art would later rise out of the region's underground and was characterized by informal sharing of technique among groups of friends and art showcases in "cooperative" galleries instead of formal museums. Later, the Bay Area art movement would be heavily influenced by the counterculture movement in the 1960s, and art produced during this time reflected the political environment.[250]

The San Francisco Renaissance was an era of poetic activity centered on San Francisco and poets such as Gary Snyder, Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, which brought it to prominence as a hub of the American poetry avant-garde in the 1950s. The movement, which often included visual and performing arts, was heavily influenced by cross-cultural interests, particularly Buddhism, Taoism, and a general interest in East Asian cultures.[251]

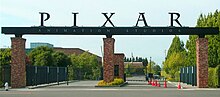

The Bay Area is presently home to a thriving computer animation industry[252] led by Pixar Animation Studios and Industrial Light & Magic. Pixar, based in Emeryville, produced the first fully computer animated feature film, Toy Story, with software it designed in-house and whose computer animation films have since garnered 26 Academy Awards and critical acclaim.[253] Industrial Light & Magic, which is based in the Presidio in San Francisco, was created in 1975 to help create visual effects for the Star Wars series has since been involved with creating visual effects for over three hundred Hollywood films.[254]

Music

[edit]

Throughout its recent history, the Bay Area has been home to several musical movements that left lasting influences on the genres they affected. San Francisco, in particular, was the center of the counterculture movement in the 1960s, which directly led to the rise of several notable musical acts: The Grateful Dead, which formed in 1965, and Jefferson Airplane and Janis Joplin; all three would be closely associated with the 1967 Summer of Love.[255] Jimi Hendrix also had strong connections to the movement and the Bay Area, as he lived in Berkeley for a brief time as a child and played in many local venues in that decade.[256][255] By the 1970s, San Francisco had developed a vibrant jazz scene, earning the moniker, "Harlem of the West".[153] The Vietnam War was being fought at the time, and Bay Area bands such as Creedence Clearwater Revival of El Cerrito became known for their political and socially-conscious lyrics against the conflict.[257] Carlos Santana rose to fame in the early 1970s with his Santana band and would later be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[258] Two former members of Santana, Neal Schon and Gregg Rolie would later lead the formation of the band Journey.[259]

During the 1980s and early 1990s, the Bay Area became home to heavy metal and hard rock bands, including Ludicra,[260] and also to one of the largest and most influential thrash metal scenes in the world, with contributions from Exodus, Testament, Death Angel, Forbidden, Vio-lence, Lȧȧz Rockit, Possessed and Blind Illusion, in addition to three of the "Big Four" (Metallica, Slayer and Megadeth); although Metallica, Slayer and Megadeth were all technically from Los Angeles, those bands are often credited for popularizing and contributing to the Bay Area thrash metal scene during the 1980s by frequently playing shows there, especially early in their careers and/or before they were signed to a record label.[261][262]

The post-grunge era in the 1990s featured prominent Bay Area bands Third Eye Blind of San Francisco, Counting Crows of Berkeley, and Smash Mouth of San Jose, and later pop punk rock bands like Green Day.[256]

The 1990s also saw the emergence of the influential hyphy movement in hip hop, derived from the Oakland slang for "hyperactive", and pioneered by Bay Area rappers Andre "Mac Dre" Hicks, Mistah Fab, and E-40.[263] Other notable rappers from the Bay Area include Lil B,[264] Tupac Shakur, MC Hammer, Too $hort, and G-Eazy.[265] Today, much of the rap coming out of Oakland and the East Bay is "conscious rap", which concerns itself with social issues and awareness.[265]

The Bay Area is also home to hundreds of classical music ensembles, from community choirs to professional orchestras, such as the San Francisco Symphony, California Symphony, Fremont Symphony Orchestra, Oakland Symphony and the San Francisco Chamber Orchestra.[266]

Theater

[edit]

According to the regional theater service organization Theatre Bay Area, the San Francisco Bay Area is the third largest center of activity for theater companies and actors in the United States, after the New York City and Chicago metropolitan areas, with 400 companies spread throughout the region.[267] The organization was founded in 1976 by the Magic Theatre and American Conservatory Theater (ACT) in San Francisco and the Berkeley Repertory Theatre in Berkeley.[268] The latter two, along with the San Francisco Mime Troupe and Palo Alto-based Theatreworks, have since gone on to win one Regional Theatre Tony Award each.[269][270]

Several famous actors have arisen from the Bay Area's theatre community, including Daveed Diggs from Hamilton and Darren Criss from Hedwig, A Very Potter Musical, and Glee.[271] Locally, well-regarded actors include James Carpenter, a stage actor who has performed at the ACT, Berkeley Repertory, and San Jose Repertory Theatre among others, Rod Gnapp of the Magic Theatre Company, Sean San Jose, one of the founders of the Campo Santo theater, and Campo Santo member Margo Hall.[272]

The Bay Area also has an active youth theater scene. ACT and the Berkeley Repertory both run classes and camps for young actors, as do the Peninsula Youth Theater and Willow Glen Children's Theatre in the Peninsula and South Bay, Bay Area Children's Theater and Danville Children's Musical Theater in the East Bay, and Marin Shakespeare in the North Bay, among many others.[273][274]

Media

[edit]