Пуштуны

пуштун | |

|---|---|

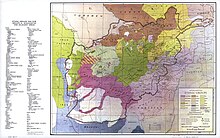

Численность пуштунских племен и религиозных деятелей в Южном Афганистане | |

| Total population | |

| c. 63 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 40,097,131 (2023)[1] | |

| 18,831,361 (2023)[2] | |

| 3,200,000 (2018)[3][4] | |

| 169,000 (2022)[5] | |

| 538,000 (2021)[6] | |

| 100,000 (2009)[7] | |

| 32,400 (2017)[8] | |

| 31,700 (2021)[9] | |

| 19,800 (2015)[10] | |

| 12,662 (2021)[11] | |

| Languages | |

| Pashto in its different dialects: Wanetsi, Central Pashto, Southern Pashto, Northern Pashto[12] | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Sunni Islam Minority: Shia Islam,[13] Hinduism,[14] Sikhism[15] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Iranic peoples | |

Пуштуны ( / ˈ p ʌ ʃ ˌ t ʊ n / , / ˈ p ɑː ʃ ˌ t ʊ n / , / ˈ p æ ʃ ˌ t uː n / ; пушту : пушту , романизированный Pəx̌tānə́ : [16] Пуштунское произношение: [pəxˈtɑːna] ), также известные как пахтуны , [17] или патаны , [а] являются кочевниками , [21] [22] [23] пастораль , [24] [25] Восточноиранская этническая группа [17] в основном проживают на северо-западе Пакистана , а также на юге и востоке Афганистана . [26] [27] Их исторически также называли афганцами. [б] до ратификации Конституции Афганистана 1964 года , в которой говорилось, что любой человек, имеющий гражданство, является афганцем, и 1970-е годы [33] [34] после того, как значение этого термина стало демонимом для представителей всех этнических групп в Афганистане . [33] [35]

Пуштуны говорят на языке пушту , который принадлежит к восточноиранской ветви иранской языковой семьи . Кроме того, дари является вторым языком пуштунов в Афганистане. [36] [37] в то время как жители Пакистана и Индии говорят на хинди-урду и других региональных языках как на втором языке. [38] [39] [40] [41]

There are an estimated 350–400 Pashtun tribes and clans with a variety of origin theories.[42][43][44] The total population of the Pashtun people worldwide is estimated to be around 49 million,[45] although this figure is disputed due to the lack of an official census in Afghanistan since 1979.[46] They are the second-largest ethnic group in Pakistan and one of the largest ethnic groups in Afghanistan,[47] constituting around 18.24% of the total Pakistani population and around 47% of the total Afghan population.[48][49][50] In India, significant and historical communities of the Pashtun diaspora exist in the northern region of Rohilkhand as well as in major Indian cities such as Delhi and Mumbai.[51][52]

Geographic distribution

| Part of a series on |

| Pashtuns |

|---|

| Empires and dynasties |

Pakistan and Afghanistan

Pashtuns are spread over a wide geographic area, south of the Amu river and west of the Indus River. They can be found all over Pakistan and Afghanistan.[26] Big cities with a Pashtun majority include Jalalabad, Kandahar, Bannu, Dera Ismail Khan, Khost, Kohat, Lashkar Gah, Mardan, Mingora, Peshawar, Quetta, among others. Pashtuns also live in Abbottabad, Farah, Ghazni, Herat, Islamabad, Kabul, Karachi, Kunduz, Lahore, Mazar-i-Sharif, Multan, Rawalpindi, Mianwali, and Attock.

The city of Karachi, the financial capital of Pakistan, is home to the world's largest urban community of Pashtuns, larger than Kabul and Peshawar.[53] Likewise, Islamabad, the country's political capital also serves as the major urban center of Pashtuns with more than 20% of the city's population belonging to the Pashto speaking community.

India

Pashtuns in India are often referred to as Pathans (the Hindustani word for Pashtun) both by themselves and other ethnic groups of the subcontinent.[54][55][56][57] Some Indians claim descent from Pashtun soldiers who settled in India by marrying local women during the Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent.[58] Many Pathans chose to live in the Republic of India after the partition of India and Khan Mohammad Atif, a professor at the University of Lucknow, estimates that "The population of Pathans in India is twice their population in Afghanistan".[59]

Historically, Pashtuns have settled in various cities of India before and during the British Raj in colonial India. These include Bombay (now called Mumbai), Farrukhabad, Delhi, Calcutta, Saharanpur, Rohilkhand, Jaipur, and Bangalore.[51][60][52] The settlers are descended from both Pashtuns of present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan (British India before 1947). In some regions in India, they are sometimes referred to as Kabuliwala.[61]

In India significant Pashtun diaspora communities exist.[62][58] While speakers of Pashto in the country only number 21,677 as of 2011, estimates of the ethnic or ancestral Pashtun population in India range from 3,200,000[3][4][63] to 11,482,000[64] to as high as double their population in Afghanistan (approximately 30 million).[65]

The Rohilkhand region of Uttar Pradesh is named after the Rohilla community of Pashtun ancestry; the area came to be governed by the Royal House of Rampur, a Pashtun dynasty.[66] They also live in the states of Maharashtra in central India and West Bengal in eastern India that each have a population of over a million with Pashtun ancestry;[67] both Bombay and Calcutta were primary locations of Pashtun migrants from Afghanistan during the colonial era.[68] There are also populations over 100,000 each in the cities of Jaipur in Rajasthan and Bangalore in Karnataka.[67] Bombay (now called Mumbai) and Calcutta both have a Pashtun population of over 1 million, whilst Jaipur and Bangalore have an estimate of around 100,000. The Pashtuns in Bangalore include the khan siblings Feroz, Sanjay and Akbar Khan, whose father settled in Bangalore from Ghazni.[69]

During the 19th century, when the British were recruiting peasants from British India as indentured servants to work in the Caribbean, South Africa and other places, Rohillas were sent to Trinidad, Surinam, Guyana, and Fiji, to work in the sugarcane fields and perform manual labour.[70] Many stayed and formed communities of their own. Some of them assimilated with the other South Asian Muslim nationalities to form a common Indian Muslim community in tandem with the larger Indian community, losing their distinctive heritage. Some Pashtuns travelled as far as Australia during the same era.[71]

Today, the Pashtuns are a collection of diversely scattered communities present across the length and breadth of India, with the largest populations principally settled in the plains of northern and central India.[72][73][74] Following the partition of India in 1947, many of them migrated to Pakistan.[72] The majority of Indian Pashtuns are Urdu-speaking communities,[75] who have assimilated into the local society over the course of generations.[75] Pashtuns have influenced and contributed to various fields in India, particularly politics, the entertainment industry and sports.[74]

Iran

Pashtuns are also found in smaller numbers in the eastern and northern parts of Iran.[76] Records as early as the mid-1600s report Durrani Pashtuns living in the Khorasan Province of Safavid Iran.[77] After the short reign of the Ghilji Pashtuns in Iran, Nader Shah defeated the last independent Ghilji ruler of Kandahar, Hussain Hotak. In order to secure Durrani control in southern Afghanistan, Nader Shah deported Hussain Hotak and large numbers of the Ghilji Pashtuns to the Mazandaran Province in northern Iran. The remnants of this once sizable exiled community, although assimilated, continue to claim Pashtun descent.[78] During the early 18th century, in the course of a very few years, the number of Durrani Pashtuns in Iranian Khorasan, greatly increased.[79] Later the region became part of the Durrani Empire itself. The second Durrani king of Afghanistan, Timur Shah Durrani was born in Mashhad.[80] Contemporary to Durrani rule in the east, Azad Khan Afghan, an ethnic Ghilji Pashtun, formerly second in charge of Azerbaijan during Afsharid rule, gained power in the western regions of Iran and Azerbaijan for a short period.[81] According to a sample survey in 1988, 75 percent of all Afghan refugees in the southern part of the Iranian Khorasan Province were Durrani Pashtuns.[82]

In other regions

Indian and Pakistani Pashtuns have utilised the British/Commonwealth links of their respective countries, and modern communities have been established starting around the 1960s mainly in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia but also in other commonwealth countries (and the United States). Some Pashtuns have also settled in the Middle East, such as in the Arabian Peninsula. For example, about 300,000 Pashtuns migrated to the Persian Gulf countries between 1976 and 1981, representing 35% of Pakistani immigrants.[83] The Pakistani and Afghan diaspora around the world includes Pashtuns.

Etymology

Ancient historical references: Pashtun

A tribe called Pakthās, one of the tribes that fought against Sudas in the Dasarajna, or "Battle of the Ten Kings", are mentioned in the seventh mandala of the Rigveda, a text of Vedic Sanskrit hymns dated between c. 1500 and 1200 BCE:[84][85]

Together came the Pakthas (पक्थास), the Bhalanas, the Alinas, the Sivas, the Visanins. Yet to the Trtsus came the Ārya's Comrade, through love of spoil and heroes' war, to lead them.

— Rigveda, Book 7, Hymn 18, Verse 7

Heinrich Zimmer connects them with a tribe mentioned by Herodotus (Pactyans) in 430 BCE in the Histories:[86][87][88]

Other Indians dwell near the town of Caspatyrus[Κασπατύρῳ] and the Pactyic [Πακτυϊκῇ] country, north of the rest of India; these live like the Bactrians; they are of all Indians the most warlike, and it is they who are sent for the gold; for in these parts all is desolate because of the sand.

— Herodotus, The Histories, Book III, Chapter 102, Section 1

These Pactyans lived on the eastern frontier of the Achaemenid Arachosia Satrapy as early as the 1st millennium BCE, present-day Afghanistan.[89] Herodotus also mentions a tribe of known as Aparytai (Ἀπαρύται).[90] Thomas Holdich has linked them with the Afridi tribe:[91][92][93]

The Sattagydae, Gandarii, Dadicae, and Aparytae (Ἀπαρύται) paid together a hundred and seventy talents; this was the seventh province

— Herodotus, The Histories, Book III, Chapter 91, Section 4

Joseph Marquart made the connection of the Pashtuns with names such as the Parsiētai (Παρσιῆται), Parsioi (Πάρσιοι) that were cited by Ptolemy 150 CE:[94][95]

"The northern regions of the country are inhabitedby the Bolitai, the western regions by the Aristophyloi below whom live the Parsioi (Πάρσιοι). The southern regions are inhabited by the Parsiētai (Παρσιῆται), the eastern regions by the Ambautai. The towns and villages lying in the country of the Paropanisadai are these: Parsiana Zarzaua/Barzaura Artoarta Baborana Kapisa niphanda"

— Ptolemy, 150 CE, 6.18.3-4

Strabo, the Greek geographer, in the Geographica (written between 43 BC to 23 AD) makes mention of the Scythian tribe Pasiani (Πασιανοί), which has also been identified with Pashtuns given that Pashto is an Eastern-Iranian language, much like the Scythian languages:[96][97][98][99][100]

"Most of the Scythians...each separate tribe has its peculiar name. All, or the greatest part of them, are nomades. The best known tribes are those who deprived the Greeks of Bactriana, the Asii, Pasiani, Tochari, and Sacarauli, who came from the country on the other side of the Iaxartes (Syr Darya)"

— Strabo, The Geography, Book XI, Chapter 8, Section 2

This is considered a different rendering of Ptolemy's Parsioi (Πάρσιοι).[99] Johnny Cheung,[101] reflecting on Ptolemy's Parsioi (Πάρσιοι) and Strabo's Pasiani (Πασιανοί) states: "Both forms show slight phonetic substitutions, viz. of υ for ι, and the loss of r in Pasianoi is due to perseveration from the preceding Asianoi. They are therefore the most likely candidates as the (linguistic) ancestors of modern day Pashtuns."[102]

Middle historical references: Afghan

In the Middle Ages until the advent of modern Afghanistan in the 18th century, the Pashtuns were often referred to as "Afghans".[103]The etymological view supported by numerous noted scholars is that the name Afghan evidently derives from Sanskrit Aśvakan, or the Assakenoi of Arrian, which was the name used for ancient inhabitants of the Hindu Kush.[104] Aśvakan literally means "horsemen", "horse breeders", or "cavalrymen" (from aśva or aspa, the Sanskrit and Avestan words for "horse").[105] This view was propounded by scholars like Christian Lassen,[106] J. W. McCrindle,[107] M. V. de Saint Martin,[108] and É. Reclus,[109][110][111][112][113][114]

The earliest mention of the name Afghan (Abgân) is by Shapur I of the Sassanid Empire during the 3rd century CE,[115] In the 4th century the word "Afghans/Afghana" (αβγανανο) as a reference to a particular people is mentioned in the Bactrian documents found in Northern Afghanistan.[116][117]

"To Ormuzd Bunukan, from Bredag Watanan ... greetings and homage from ... ), the ( sotang ( ? ) of Parpaz ( under ) [ the glorious ) yabghu of Hephthal, the chief of the Afghans, ' the judge of Tukharistan and Gharchistan . Moreover, ' a letter [ has come hither ] from you, so I have heard how [ you have ] written ' ' to me concerning ] my health . I arrived in good health, ( and ) ( afterwards ( ? ) ' ' I heard that a message ] was sent thither to you ( saying ) thus : ... look after the farming but the order was given to you thus. You should hand over the grain and then request it from the citizens store: I will not order, so.....I Myself order And I in Respect of winter sends men thither to you then look after the farming, To Ormuzd Bunukan, Greetings"

— the Bactrian documents, 4th century

"because [you] (pl.), the clan of the Afghans, said thus to me:...And you should not have denied? the men of Rob[118] [that] the Afghans took (away) the horses"

— the Bactrian documents, 4th century, Sims-Williams 2007b, pp. 90-91

"[To ...]-bid the Afghan... Moreover, they are in [War]nu(?) because of the Afghans, so [you should] impose a penalty on Nat Kharagan ... ...lord of Warnu with ... ... ...the Afghan... ... "

— the Bactrian documents, 4th century, Sims-Williams 2007b, pp. 90-91

The name Afghan is later recorded in the 6th century CE in the form of "Avagāṇa" [अवगाण][119] by the Indian astronomer Varāha Mihira in his Brihat-samhita.[120][121]

"It would be unfavourable to the people of Chola, the Afghans (Avagāṇa), the white Huns and the Chinese."[121]

— Varāha Mihira, 6th century CE, chapt. 11, verse 61

The word Afghan also appeared in the 982 Ḥudūd al-ʿĀlam, where a reference is made to a village, Saul, which was probably located near Gardez, Afghanistan.[122]

"Saul, a pleasant village on a mountain. In it live Afghans".[122]

The same book also speaks of a king in Ninhar (Nangarhar), who had Muslim, Afghan and Hindu wives.[123] In the 11th century, Afghans are mentioned in Al-Biruni's Tarikh-ul Hind ("History of the Indus"), which describes groups of rebellious Afghans in the tribal lands west of the Indus River in what is today Pakistan.[122][124]

Al-Utbi, the Ghaznavid chronicler, in his Tarikh-i Yamini recorded that many Afghans and Khiljis (possibly the modern Ghilji) enlisted in the army of Sabuktigin after Jayapala was defeated.[125] Al-Utbi further stated that Afghans and Ghiljis made a part of Mahmud Ghaznavi's army and were sent on his expedition to Tocharistan, while on another occasion Mahmud Ghaznavi attacked and punished a group of opposing Afghans, as also corroborated by Abulfazl Beyhaqi.[126] It is recorded that Afghans were also enrolled in the Ghurid Kingdom (1148–1215).[127] By the beginning of the Khilji dynasty in 1290, Afghans have been well known in northern India.

Ibn Battuta, when visiting Afghanistan following the era of the Khilji dynasty, also wrote about the Afghans.

"We travelled on to Kabul, formerly a vast town, the site of which is now occupied by Afghans. They hold mountains and defiles and possess considerable strength, and are mostly highwaymen. Their principal mountain is called Kuh Sulayman. It is told that the prophet Sulayman [Solomon] ascended this mountain and having looked out over India, which was then covered with darkness, returned without entering it."[128]

— Ibn Battuta, 1333

Ferishta, a 16th-century Muslim historian writing about the history of Muslim rule in the subcontinent, stated:

He [Khalid bin Abdullah son of Khalid bin Walid] retired, therefore, with his family, and a number of Arab retainers, into the Sulaiman Mountains, situated between Multan and Peshawar, where he took up his residence, and gave his daughter in marriage to one of the Afghan chiefs, who had become a proselyte to Mahomedism. From this marriage many children were born, among whom were two sons famous in history. The one Lodhi, the other Sur; who each, subsequently, became head of the tribes which to this day bear their name. I have read in the Mutla-ul-Anwar, a work written by a respectable author, and which I procured at Burhanpur, a town of Khandesh in the Deccan, that the Afghans are Copts of the race of the Pharaohs; and that when the prophet Moses got the better of that infidel who was overwhelmed in the Red Sea, many of the Copts became converts to the Jewish faith; but others, stubborn and self-willed, refusing to embrace the true faith, leaving their country, came to India, and eventually settled in the Sulimany mountains, where they bore the name of Afghans.[31]

History and origins

The ethnogenesis of the Pashtun ethnic group is unclear. There are many conflicting theories amongst historians and the Pashtuns themselves. Modern scholars believe that Pashtuns do not all share the same origin. The early ancestors of modern-day Pashtuns may have belonged to old Iranian tribes that spread throughout the eastern Iranian plateau.[129][130][27] historians have also come across references to various ancient peoples called Pakthas (Pactyans) between the 2nd and the 1st millennium BC,[131][132]

Mohan Lal stated in 1846 that "the origin of the Afghans is so obscure, that no one, even among the oldest and most clever of the tribe, can give satisfactory information on this point."[133] Others have suggested that a single origin of the Pashtuns is unlikely but rather they are a tribal confederation.

"Looking for the origin of Pashtuns and the Afghans is something like exploring the source of the Amazon. Is there one specific beginning? And are the Pashtuns originally identical with the Afghans? Although the Pashtuns nowadays constitute a clear ethnic group with their own language and culture, there is no evidence whatsoever that all modern Pashtuns share the same ethnic origin. In fact it is highly unlikely."[122]

— Vogelsang, 2002

Linguistic origin

Pashto is generally classified as an Eastern Iranian language.[134][135][136] It shares features with the Munji language, which is the closest existing language to the extinct Bactrian,[137] but also shares features with the Sogdian language, as well as Khwarezmian, Shughni, Sanglechi, and Khotanese Saka.[138]

It is suggested by some that Pashto may have originated in the Badakhshan region and is connected to a Saka language akin to Khotanese.[139] In fact major linguist Georg Morgenstierne has described Pashto as a Saka dialect and many others have observed the similarities between Pashto and other Saka languages as well, suggesting that the original Pashto speakers might have been a Saka group.[140][141] Furthermore, Pashto and Ossetian, another Scythian-descending language, share cognates in their vocabulary which other Eastern Iranian languages lack[142] Cheung suggests a common isogloss between Pashto and Ossetian which he explains by an undocumented Saka dialect being spoken close to reconstructed Old Pashto which was likely spoken north of the Oxus at that time.[143] Others however have suggested a much older Iranic ancestor given the affinity to Old Avestan.[144]

Diverse origin

According to one school of thought, Pashtun are descended from a variety of ethnicities, including Persians, Greeks, Turks, Arabs, Bactrians, Scythians, Tartars, Huns (Hephthalites), Mongols, Moghals (Mughals), and anyone else who has crossed the region where these Pashtun live. Further they are also, and probably most surprisingly, of Israelite descent.[145][146]

Some Pashtun tribes claim descent from Arabs, including some claiming to be Sayyids.[147]

One historical account connects the Pashtuns to a possible Ancient Egyptian past but this lacks supporting evidence.[148]

Henry Walter Bellew, who wrote extensively on Afghan culture, noted that some people claim that the Bangash Pashtuns are connected to Ismail Samani.[149]

Greek origin

According to Firasat et al. 2007, a proportion of Pashtuns may descend from Greeks, but they also suggest that Greek ancestry may also have come from Greek slaves brought by Xerxes I.[150]

The Greek ancestry of the Pashtuns may also be traced on the basis of a homologous group. And Hoplogroup J2 is from the Semitic population, and this Hoplogroup is found in 6.5% of Greeks and Pashtuns and 55.6% of the Israelite population.[151]

A number of genetic studies on Pashtuns have lately been undertaken by academics from various institutions and research institutes. The Greek heritage of Pakistani Pashtuns has been researched in. In this study, the Pashtuns, Kalash, and Burusho to be descended from Alexander's soldiers considered.[152]

Henry Walter Bellew (1834 – 1892) was of the view that the Pashtuns likely have mixed Greek and Indian Rajput roots.[153][154]

Following Alexander's brief occupation, the successor state of the Seleucid Empire expanded influence on the Pashtuns until 305 BCE when they gave up dominating power to the Indian Maurya Empire as part of an alliance treaty.[155]

Some groups from Peshawar and Kandahar believe to be descended from Greeks who arrived with Alexander the Great.[156]

Hephthalite origin

According to some accounts the Ghilji tribe has been connected to the Khalaj people.[157] Following al-Khwarizmi, Josef Markwart claimed the Khalaj to be remnants of the Hephthalite confederacy.[158] The Hephthalites may have been Indo-Iranian,[158] although the view that they were of Turkic Gaoju origin[159] "seems to be most prominent at present".[160] The Khalaj may originally have been Turkic-speaking and only federated with Iranian Pashto-speaking tribes in Medieval times.[161]

However, according to linguist Sims-Williams, archaeological documents do not support the suggestion that the Khalaj were the successors of the Hephthalites,[162] while according to historian V. Minorsky, the Khalaj were "perhaps only politically associated with the Hephthalites."[163]

According to Georg Morgenstierne, the Durrani tribe who were known as the "Abdali" before the formation of the Durrani Empire 1747,[164] might be connected to with the Hephthalites;[165] Aydogdy Kurbanov endorses this view who proposes that after the collapse of the Hephthalite confederacy, Hephthalite likely assimilated into different local populations.[166]

According to The Cambridge History of Iran volume 3, Issue 1, the Ghilji tribe of Afghanistan are the descendants of Hephthalites.[167]

Anthropology and oral traditions

Theory of Pashtun descent from Israelites

Some anthropologists lend credence to the oral traditions of the Pashtun tribes themselves. For example, according to the Encyclopaedia of Islam, the theory of Pashtun descent from Israelites is traced to Nimat Allah al-Harawi, who compiled a history for Khan-e-Jehan Lodhi in the reign of Mughal Emperor Jehangir in the 17th century.[168] The 13th century Tabaqat-i Nasiri discusses the settlement of immigrant Bani Israel at the end of the 8th century CE in the Ghor region of Afghanistan, settlement attested by Jewish inscriptions in Ghor. Historian André Wink suggests that the story "may contain a clue to the remarkable theory of the Jewish origin of some of the Afghan tribes which is persistently advocated in the Persian-Afghan chronicles."[169] These references to Bani Israel agree with the commonly held view by Pashtuns that when the twelve tribes of Israel were dispersed, the tribe of Joseph, among other Hebrew tribes, settled in the Afghanistan region.[170] This oral tradition is widespread among the Pashtun tribes. There have been many legends over the centuries of descent from the Ten Lost Tribes after groups converted to Christianity and Islam. Hence the tribal name Yusufzai in Pashto translates to the "son of Joseph". A similar story is told by many historians, including the 14th century Ibn Battuta and 16th century Ferishta.[31] However, the similarity of names can also be traced to the presence of Arabic through Islam.[171]

This theory of Pashtuns Jewish origin has been largely denied and is said that Its biblical claims are anecdotal, its historical documentation is inconsistent, its geographic claims are incoherent, and its linguistic assertions are implausible.[172]

One conflicting issue in the belief that the Pashtuns descend from the Israelites is that the Ten Lost Tribes were exiled by the ruler of Assyria, while Maghzan-e-Afghani says they were permitted by the ruler to go east to Afghanistan. This inconsistency can be explained by the fact that Persia acquired the lands of the ancient Assyrian Empire when it conquered the Empire of the Medes and Chaldean Babylonia, which had conquered Assyria decades earlier. But no ancient author mentions such a transfer of Israelites further east, or no ancient extra-Biblical texts refer to the Ten Lost Tribes at all.[173]

Some Afghan historians have maintained that Pashtuns are linked to the ancient Israelites. Mohan Lal quoted Mountstuart Elphinstone who wrote:

"The Afghan historians proceed to relate that the children of Israel, both in Ghore and in Arabia, preserved their knowledge of the unity of God and the purity of their religious belief, and that on the appearance of the last and greatest of the prophets (Muhammad) the Afghans of Ghore listened to the invitation of their Arabian brethren, the chief of whom was Khauled...if we consider the easy way with which all rude nations receive accounts favourable to their own antiquity, I fear we much class the descents of the Afghans from the Jews with that of the Romans and the British from the Trojans, and that of the Irish from the Milesians or Brahmins."[174]

— Mountstuart Elphinstone, 1841

This theory has been criticised for not being substantiated by historical evidence.[171] Zaman Stanizai criticises this theory:[171]

"The 'mythified' misconception that the Pashtuns are the descendants of the lost tribes of Israel is a fabrication popularized in 14th-century India. A claim that is full of logical inconsistencies and historical incongruities, and stands in stark contrast to the conclusive evidence of the Indo-Iranian origin of Pashtuns supported by the incontrovertible DNA sequencing that the genome analysis revealed scientifically."

— [171]

According to genetic studies Pashtuns have a greater R1a1a*-M198 modal halogroup than Jews:[175]

"Our study demonstrates genetic similarities between Pathans from Afghanistan and Pakistan, both of which are characterized by the predominance of haplogroup R1a1a*-M198 (>50%) and the sharing of the same modal haplotype...Although Greeks and Jews have been proposed as ancestors to Pathans, their genetic origin remains ambiguous...Overall, Ashkenazi Jews exhibit a frequency of 15.3% for haplogroup R1a1a-M198"

— "Afghanistan from a Y-chromosome perspective", European Journal of Human Genetics

Modern era

Their modern past stretches back to the Delhi Sultanate (Khalji and Lodi dynasty), the Hotak dynasty and the Durrani Empire. The Hotak rulers rebelled against the Safavids and seized control over much of Persia from 1722 to 1729.[176] This was followed by the conquests of Ahmad Shah Durrani who was a former high-ranking military commander under Nader Shah and founder of the Durrani Empire, which covered most of what is now Afghanistan, Pakistan, Kashmir, Indian Punjab, as well as the Kohistan and Khorasan provinces of Iran.[177] After the decline of the Durrani dynasty in the first half of the 19th century under Shuja Shah Durrani, the Barakzai dynasty took control of the empire. Specifically, the Mohamedzais held Afghanistan's monarchy from around 1826 to the end of Zahir Shah's reign in 1973.

During the so-called "Great Game" of the 19th century, rivalry between the British and Russian empires was useful to the Pashtuns of Afghanistan in resisting foreign control and retaining a degree of autonomy (see the Siege of Malakand). However, during the reign of Abdur Rahman Khan (1880–1901), Pashtun regions were politically divided by the Durand Line – areas that would become western Pakistan fell within British India as a result of the border.

In the 20th century, many politically active Pashtun leaders living under British rule of undivided India supported Indian independence, including Ashfaqulla Khan,[178][179] Abdul Samad Khan Achakzai, Ajmal Khattak, Bacha Khan and his son Wali Khan (both members of the Khudai Khidmatgar), and were inspired by Mohandas Gandhi's non-violent method of resistance.[180][181] Many Pashtuns also worked in the Muslim League to fight for an independent Pakistan through non violent resistance, including Yusuf Khattak and Abdur Rab Nishtar who was a close associate of Muhammad Ali Jinnah.[182]The Pashtuns of Afghanistan attained complete independence from British political intervention during the reign of Amanullah Khan, following the Third Anglo-Afghan War. By the 1950s a popular call for Pashtunistan began to be heard in Afghanistan and the new state of Pakistan. This led to bad relations between the two nations. The Afghan monarchy ended when President Daoud Khan seized control of Afghanistan from his cousin Zahir Shah in 1973 on a Pashtun Nationalist agenda, which opened doors for a proxy war by neighbors. In April 1978, Daoud Khan was assassinated along with his family and relatives in a bloody coup orchestrated by Hafizullah Amin. Afghan mujahideen commanders in exile in neighboring Pakistan began recruiting for a guerrilla warfare against the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan - the Marxist government which was also dominated by Pashtun Khalqists who held Nationalist views including Hafizullah Amin, Nur Muhammad Taraki, General Mohammad Aslam Vatanjar, Shahnawaz Tanai, Mohammad Gulabzoy and many more. In 1979, the Soviet Union intervened in its southern neighbor Afghanistan in order to defeat a rising insurgency. The Afghan mujahideen were funded by the United States, Saudi Arabia, China and others, and included some Pashtun commanders such as Abdul Rasul Sayyaf, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, Jalaluddin Haqqani, Mohammad Nabi Mohammadi and Mohammad Yunus Khalis. In the meantime, millions of Pashtuns joined the Afghan diaspora in Pakistan and Iran, and from there tens of thousands proceeded to Europe, North America, Oceania and other parts of the world.[183] The Afghan government and military would remain predominantly Pashtun until the fall of Mohammad Najibullah's Republic of Afghanistan in April 1992.[184]

Many high-ranking government officials in the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan were Pashtuns, including: Abdul Rahim Wardak, Abdul Salam Azimi, Anwar ul-Haq Ahady, Amirzai Sangin, Ghulam Farooq Wardak, Hamid Karzai, Mohammad Ishaq Aloko, Omar Zakhilwal, Sher Mohammad Karimi, Zalmay Rasoul, Yousef Pashtun. The list of current governors of Afghanistan also include large percentage of Pashtuns. Mullah Yaqoob serves as acting Defense Minister, Sirajuddin Haqqani as acting Interior Minister, Amir Khan Muttaqi as acting Foreign Minister, Gul Agha Ishakzai as acting Finance Minister, and Hasan Akhund as acting Prime Minister. A number of other ministers are also Pashtuns.

The Afghan royal family, which was represented by King Zahir Shah, are referred to Mohammadzais. Other prominent Pashtuns include the 17th-century poets Khushal Khan Khattak and Rahman Baba, and in contemporary era Afghan Astronaut Abdul Ahad Mohmand, former U.S. Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad, and Ashraf Ghani among many others.

Many Pashtuns of Pakistan and India have adopted non-Pashtun cultures, mainly by abandoning Pashto and using languages such as Urdu, Punjabi, and Hindko.[185] These include Ghulam Mohammad (first Finance Minister, from 1947 to 1951, and third Governor-General of Pakistan, from 1951 to 1955),[186][187][188][189][190] Ayub Khan, who was the second President of Pakistan, Zakir Husain who was the third President of India and Abdul Qadeer Khan, father of Pakistan's nuclear weapons program.

Many more held high government posts, such as Asfandyar Wali Khan, Mahmood Khan Achakzai, Sirajul Haq, and Aftab Ahmad Sherpao, who are presidents of their respective political parties in Pakistan. Others became famous in sports (e.g., Imran Khan, Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi, Younis Khan, Shahid Afridi, Irfan Pathan, Jahangir Khan, Jansher Khan, Hashim Khan, Rashid Khan, Shaheen Afridi, Naseem Shah, Misbah Ul Haq, Mujeeb Ur Rahman and Mohammad Wasim) and literature (e.g., Ghani Khan, Hamza Shinwari, and Kabir Stori). Malala Yousafzai, who became the youngest Nobel Peace Prize recipient in 2014, is a Pakistani Pashtun.

Many of the Bollywood film stars in India have Pashtun ancestry; some of the most notable ones are Aamir Khan, Shahrukh Khan, Salman Khan, Feroz Khan, Madhubala, Kader Khan, Saif Ali Khan, Soha Ali Khan, Sara Ali Khan, and Zarine Khan.[191][192] In addition, one of India's former presidents, Zakir Husain, belonged to the Afridi tribe.[193][194][195] Mohammad Yunus, India's former ambassador to Algeria and advisor to Indira Gandhi, is of Pashtun origin and related to the legendary Bacha Khan.[196][197][198][199]

In the late 1990s, Pashtuns were the primary ethnic group in the ruling regime i.e. Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (Taliban regime).[200][201][failed verification] The Northern Alliance that was fighting against the Taliban also included a number of Pashtuns. Among them were Abdullah Abdullah, Abdul Qadir and his brother Abdul Haq, Abdul Rasul Sayyaf, Asadullah Khalid, Hamid Karzai and Gul Agha Sherzai. The Taliban regime was ousted in late 2001 during the US-led War in Afghanistan and replaced by the Karzai administration.[202] This was followed by the Ghani administration and the reconquest of Afghanistan by the Taliban (Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan).

The long wars in Afghanistan have led to Pashtuns gaining a reputation for being exceptional fighters.[203] Some activists and intellectuals are trying to rebuild Pashtun intellectualism and its pre-war culture.[204]

Genetics

The majority of Pashtuns from Afghanistan belong to R1a, with a frequncy of 50-65%.[205] Subclade R1a-Z2125 occurs at a frequency of 40%.[206] This subclade is predominantly found in Tajiks, Turkmen, Uzbeks and in some populations in the Caucasus and Iran.[207] Haplogroup G-M201 reaches 9% in Afghan Pashtuns and is the second most frequent haplogroup in Pashtuns from southern Afghanistan.[205][208] Haplogroup L and Haplogroup J2 occurs at an overall frequncy of 6%.[205] According to a Mitochondrial DNA analysis of four ethnic groups of Afghanistan, the majority of mtDNA among Afghan Pashtuns belongs to West Eurasian lineages, and share a greater affinity with West Eurasian and Central Asian populations rather than to populations of South Asia or East Asia. The haplogroup analysis indicates the Pashtuns and Tajiks in Afghanistan share ancestral heritage. Among the studied ethnic groups, the Pashtuns have the greatest mtDNA diversity.[209] The most frequent haplogroup among Pakistani Pashtuns is haplogroup R which is found at a rate of 28-50%. Haplogroup J2 was found in 9% to 24% depending on the study and Haplogroup E has been found at a frequency of 4% to 13%. Haplogroup L occurs at a rate of 8%. Certain Pakistani Pashtun groups exhibit high levels of R1b.[210][211] Overall Pashtun groups are genetically diverse, and the Pashtun ethnic group is not a single genetic population. Different Pashtun groups exhibit different genetic backgrounds, resulting in considerable heterogeneity.[212]

Y haplogroup and mtdna haplogroup samples were taken from Jadoon, Yousafzai, Sayyid, Gujar and Tanoli men living in Swabi District, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in Pakistan. Jadoon men have predominantly East Asian origin paternal ancestry with West Eurasian maternal ancestry and a lesser amount of South Asian maternal ancestry according to a Y and mtdna haplogroup test indicating local females marrying immigrant males during the medieval period. Y Haplogroup O3-M122 makes up the majority of Jadoon men, the same haplogroup carried by the majority (50-60%) of Han Chinese. 82.5% of Jadoon men carrying Q-MEH2 and O3-M122 which are both of East Asian origin. O3-M122 was absent in the Sayyid (Syed) population and appeared in low numbers among Tanolis, Gujars and Yousafzais. There appears to be founder affect in the O3-M122 among the Jadoon.[213][214][215] 76.32% of Jadoon men carry O3-M122 while 0.75% of Tanolis, 0.81% of Gujars and 2.82% of Yousafzais carry O3-M122.[216][217]

56.25% of the Jadoons in another test carried West Eurasian maternal Haplogroup H (mtDNA).[218] Dental morphology of the Swabi Jadoons was also analyzed and compared to other groups in the regions like Yousufzais and Sayyids.[219]

Definitions

The most prominent views amongst Pashtuns as to who exactly qualifies as a Pashtun are:[220]

- Those who are well-versed in Pashto and use it significantly. The Pashto language is "one of the primary markers of ethnic identity" amongst Pashtuns.[221]

- Adherence to the code of Pashtunwali.[220][222] The cultural definition requires Pashtuns to adhere to Pashtunwali codes.[223]

- Belonging to a Pashtun tribe through patrilineal descent, based on an important orthodox law of Pashtunwali which mainly requires that only those who have a Pashtun father are Pashtun. This definition places less emphasis on the language.[224]

Tribes

A prominent institution of the Pashtun people is the intricate system of tribes.[226] The tribal system has several levels of organisation: the tribe they are in is from four 'greater' tribal groups: the Sarbani, the Bettani, the Gharghashti, and the Karlani.[227] The tribe is then divided into kinship groups called khels, which in turn is divided into smaller groups (pllarina or plarganey), each consisting of several extended families called kahols.[228]

Durrani and Ghilji Pashtuns

The Durranis and Ghiljis (or Ghilzais) are the two largest groups of Pashtuns, with approximately two-thirds of Afghan Pashtuns belonging to these confederations.[229] The Durrani tribe has been more urban and politically successful, while the Ghiljis are more numerous, more rural, and reputedly tougher. In the 18th century, the groups collaborated at times and at other times fought each other. With a few gaps, Durranis ruled modern Afghanistan continuously until the Saur Revolution of 1978; the new communist rulers were Ghilji.[230]

Tribal allegiances are stronger among the Ghilji, while governance of the Durrani confederation is more to do with cross-tribal structures of land ownership.[229]

Language

Pashto is the mother tongue of most Pashtuns.[231][232][233] It is one of the two national languages of Afghanistan.[234][235] In Pakistan, although being the second-largest language being spoken,[236] it is often neglected officially in the education system.[237][238][239][240][241][242] This has been criticised as adversely impacting the economic advancement of Pashtuns,[243][244] as students do not have the ability to comprehend what is being taught in other languages fully.[245] Robert Nichols remarks:[246]

The politics of writing Pashto language textbooks in a nationalist environment promoting integration through Islam and Urdu had unique effects. There was no lesson on any twentieth century Pakhtun, especially Abdul Ghaffar Khan, the anti-British, pro-Pakhtun nationalist. There was no lesson on the Pashtun state-builders in nineteenth and twentieth century Afghanistan. There was little or no sampling of original Pashto language religious or historical material.

— Language Policy and Language Conflict in Afghanistan and Its Neighbors, Chapter 8, page 278

Pashto is categorised as an Eastern Iranian language,[247] but a remarkably large number of words are unique to Pashto.[248][249] Pashto morphology in relation to verbs is complex compared to other Iranian languages.[250] In this respect MacKenzie states:[251]

If we compare the archaic structure of Pashto with the much simplified morphology of Persian, the leading modern Iranian language, we see that it stands to its 'second cousin' and neighbour in something like the same relationship as Icelandic does to English.

— David Neil MacKenzie

Pashto has a large number of dialects: generally divided into Northern, Southern and Central groups;[252] and also Tarino or Waṇetsi as distinct group.[253][254] As Elfenbein notes: "Dialect differences lie primarily in phonology and lexicon: the morphology and syntax are, again with the exception of Wanetsi, quite remarkably uniform".[255] Ibrahim Khan provides the following classification on the letter ښ: the Northern Western dialect (e.g. spoken by the Ghilzai) having the phonetic value /ç+/, the North Eastern (spoken by the Yusafzais etc.) having the sound /x/, the South Western (spoken by the Abdalis etc.) having /ʂ/ and the South Eastern (spoken by the Kakars etc.) having /ʃ/.[256] He illustrates that the Central dialects, which are spoken by the Karlāṇ tribes, can also be divided on the North /x/ and South /ʃ/ distinction but provides that in addition these Central dialects have had a vowel shift which makes them distinct: for instance /ɑ/ represented by aleph the non-Central dialects becoming /ɔː/ in Banisi dialect.[256]

The first Pashto alphabet was developed by Pir Roshan in the 16th century.[257] In 1958, a meeting of Pashtun scholars and writers from both Afghanistan and Pakistan, held in Kabul, standardised the present Pashto alphabet.[258]

Culture

Pashtun culture is based on Pashtunwali, Islam and the understanding of Pashto language. The Kabul dialect is used to standardize the present Pashto alphabet.[258] Poetry is also an important part of Pashtun culture and it has been for centuries.[259] Pre-Islamic traditions, dating back to Alexander's defeat of the Persian Empire in 330 BC, possibly survived in the form of traditional dances, while literary styles and music reflect influence from the Persian tradition and regional musical instruments fused with localised variants and interpretation. Like other Muslims, Pashtuns celebrate Islamic holidays. Contrary to the Pashtuns living in Pakistan, Nowruz in Afghanistan is celebrated as the Afghan New Year by all Afghan ethnicities.

Jirga

Another prominent Pashtun institution is the lóya jirgá (Pashto: لويه جرګه) or 'grand council' of elected elders.[260] Most decisions in tribal life are made by members of the jirgá (Pashto: جرګه), which has been the main institution of authority that the largely egalitarian Pashtuns willingly acknowledge as a viable governing body.[261]

Religion

Before Islam there were various different beliefs which were practiced by Pashtuns such as Zoroastrianism,[262] Buddhism and Hinduism.[263]

The overwhelming majority of Pashtuns adhere to Sunni Islam and belong to the Hanafi school of thought. Small Shia communities exist in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Paktia. The Shias belong to the Turi tribe while the Bangash tribe is approximately 50% Shia and the rest Sunni, who are mainly found in and around Parachinar, Kurram, Hangu, Kohat and Orakzai.[264]

A legacy of Sufi activity may be found in some Pashtun regions, especially in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, as evident in songs and dances. Many Pashtuns are prominent Ulema, Islamic scholars, such as Maulana Aazam an author of more than five hundred books including Tafasee of the Quran as Naqeeb Ut Tafaseer, Tafseer Ul Aazamain, Tafseer e Naqeebi and Noor Ut Tafaseer etc., as well as Muhammad Muhsin Khan who has helped translate the Noble Quran, Sahih Al-Bukhari and many other books to the English language.[265] Many Pashtuns want to reclaim their identity from being lumped in with the Taliban and international terrorism, which is not directly linked with Pashtun culture and history.[266]

Little information is available on non-Muslim as there is limited data regarding irreligious groups and minorities, especially since many of the Hindu and Sikh Pashtuns migrated from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa after the partition of India and later, after the rise of the Taliban.[267][268]

There are also Hindu Pashtuns, sometimes known as the Sheen Khalai, who have moved predominantly to India.[269][270] A small Pashtun Hindu community, known as the Sheen Khalai meaning 'blue skinned' (referring to the color of Pashtun women's facial tattoos), migrated to Unniara, Rajasthan, India after partition.[271] Prior to 1947, the community resided in the Quetta, Loralai and Maikhter regions of the British Indian province of Baluchistan.[272][271][273] They are mainly members of the Pashtun Kakar tribe. Today, they continue to speak Pashto and celebrate Pashtun culture through the Attan dance.[272][271]

There is also a minority of Pashtun Sikhs in Tirah, Orakzai, Kurram, Malakand, and Swat. Due to the ongoing insurgency in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, some Pashtun Sikhs were internally displaced from their ancestral villages to settle in cities like Peshawar and Nankana Sahib.[274][275][276]

Pashto literature and poetry

The majority of Pashtuns use Pashto as their native tongue, belonging to the Iranian language family,[278] and spoken by up to 60 million people.[279][280] It is written in the Pashto-Arabic script and is divided into two main dialects, the southern "Pashto" and the northern "Pukhto". The language has ancient origins and bears similarities to extinct languages such as Avestan and Bactrian.[281] Its closest modern relatives may include Pamir languages, such as Shughni and Wakhi, and Ossetic.[282] Pashto may have ancient legacy of borrowing vocabulary from neighbouring languages including such as Persian and Vedic Sanskrit. Modern borrowings come primarily from the English language.[283]

The earliest describes Sheikh Mali's conquest of Swat.[284] Pir Roshan is believed to have written a number of Pashto books while fighting with the Mughals. Pashtun scholars such as Abdul Hai Habibi and others believe that the earliest Pashto work dates back to Amir Kror Suri, and they use the writings found in Pata Khazana as proof. Amir Kror Suri, son of Amir Polad Suri, was an 8th-century folk hero and king from the Ghor region in Afghanistan.[285][286] However, this is disputed by several European experts due to lack of strong evidence.

The advent of poetry helped transition Pashto to the modern period. Pashto literature gained significant prominence in the 20th century, with poetry by Ameer Hamza Shinwari who developed Pashto Ghazals.[287] In 1919, during the expanding of mass media, Mahmud Tarzi published Seraj-al-Akhbar, which became the first Pashto newspaper in Afghanistan. In 1977, Khan Roshan Khan wrote Tawarikh-e-Hafiz Rehmatkhani which contains the family trees and Pashtun tribal names. Some notable poets include Abdul Ghani Khan, Afzal Khan Khattak, Ahmad Shah Durrani, Ajmal Khattak, Ghulam Muhammad Tarzi, Hamza Shinwari, Hanif Baktash, Khushal Khan Khattak, Nazo Tokhi, Pareshan Khattak, Rahman Baba, Shuja Shah Durrani, and Timur Shah Durrani.[288][289]

Media and arts

Pashto media has expanded in the last decade, with a number of Pashto TV channels becoming available. Two of the popular ones are the Pakistan-based AVT Khyber and Pashto One. Pashtuns around the world, particularly those in Arab countries, watch these for entertainment purposes and to get latest news about their native areas.[290] Others are Afghanistan-based Shamshad TV, Radio Television Afghanistan, TOLOnews and Lemar TV, which has a special children's show called Baghch-e-Simsim. International news sources that provide Pashto programs include BBC Pashto and Voice of America.

Producers based in Peshawar have created Pashto-language films since the 1970s.

Pashtun performers remain avid participants in various physical forms of expression including dance, sword fighting, and other physical feats. Perhaps the most common form of artistic expression can be seen in the various forms of Pashtun dances. One of the most prominent dances is Attan, which has ancient roots. A rigorous exercise, Attan is performed as musicians play various native instruments including the dhol (drums), tablas (percussions), rubab (a bowed string instrument), and toola (wooden flute). With a rapid circular motion, dancers perform until no one is left dancing, similar to Sufi whirling dervishes. Numerous other dances are affiliated with various tribes notably from Pakistan including the Khattak Wal Atanrh (eponymously named after the Khattak tribe), Mahsood Wal Atanrh (which, in modern times, involves the juggling of loaded rifles), and Waziro Atanrh among others. A sub-type of the Khattak Wal Atanrh known as the Braghoni involves the use of up to three swords and requires great skill. Young women and girls often entertain at weddings with the Tumbal (Dayereh) which is an instrument.[291]

Sports

Both the Pakistan national cricket team and the Afghanistan national cricket team have Pashtun players.[292] One of the most popular sports among Pashtuns is cricket, which was introduced to South Asia during the early 18th century with the arrival of the British. Many Pashtuns have become prominent international cricketers, including Imran Khan, Shahid Afridi, Majid Khan, Misbah-ul-Haq, Younis Khan,[293] Umar Gul,[294] Junaid Khan,[295] Fakhar Zaman,[296] Mohammad Rizwan,[297] Usman Shinwari, Naseem Shah, Shaheen Afridi, Iftikhar Ahmed, Mohammad Wasim and Yasir Shah.[298] Australian cricketer Fawad Ahmed is of Pakistani Pashtun origin who has played for the Australian national team.[299]

Makha is a traditional archery sport in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, played with a long arrow (gheshai) having a saucer shaped metallic plate at its distal end, and a long bow.[300] In Afghanistan, some Pashtuns still participate in the ancient sport of buzkashi in which horse riders attempt to place a goat or calf carcass in a goal circle.[301][302][303]

Women

Pashtun women are known to be modest and honorable because of their modest dressing.[304][305] The lives of Pashtun women vary from those who reside in the ultra-conservative rural areas to those found in urban centres.[306] At the village level, the female village leader is called "qaryadar". Her duties may include witnessing women's ceremonies, mobilising women to practice religious festivals, preparing the female dead for burial, and performing services for deceased women. She also arranges marriages for her own family and arbitrates conflicts for men and women.[307] Though many Pashtun women remain tribal and illiterate, some have completed universities and joined the regular employment world.[306]

The decades of war and the rise of the Taliban caused considerable hardship among Pashtun women, as many of their rights have been curtailed by a rigid interpretation of Islamic law. The difficult lives of Afghan female refugees gained considerable notoriety with the iconic image Afghan Girl (Sharbat Gula) depicted on the June 1985 cover of National Geographic magazine.[308]

Modern social reform for Pashtun women began in the early 20th century, when Queen Soraya Tarzi of Afghanistan made rapid reforms to improve women's lives and their position in the family. She was the only woman to appear on the list of rulers in Afghanistan. Credited with having been one of the first and most powerful Afghan and Muslim female activists. Her advocacy of social reforms for women led to a protest and contributed to the ultimate demise of King Amanullah's reign in 1929.[309] Civil rights remained an important issue during the 1970s, as feminist leader Meena Keshwar Kamal campaigned for women's rights and founded the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA) in the 1977.[310]

Pashtun women these days vary from the traditional housewives who live in seclusion to urban workers, some of whom seek or have attained parity with men.[306] But due to numerous social hurdles, the literacy rate remains considerably lower for them than for males.[311] Abuse against women is present and increasingly being challenged by women's rights organisations which find themselves struggling with conservative religious groups as well as government officials in both Pakistan and Afghanistan. According to a 1992 book, "a powerful ethic of forbearance severely limits the ability of traditional Pashtun women to mitigate the suffering they acknowledge in their lives."[312]

Further challenging the status quo, Vida Samadzai was selected as Miss Afghanistan in 2003, a feat that was received with a mixture of support from those who back the individual rights of women and those who view such displays as anti-traditionalist and un-Islamic. Some have attained political office in Afghanistan and Pakistan.[313] A number of Pashtun women are found as TV hosts, journalists and actors.[60] In 1942, Madhubala (Mumtaz Jehan), the Marilyn Monroe of India, entered the Bollywood film industry.[191] Bollywood blockbusters of the 1970s and 1980s starred Parveen Babi, who hailed from the lineage of Gujarat's historical Pathan community: the royal Babi Dynasty.[314] Other Indian actresses and models, such as Zarine Khan, continue to work in the industry.[192] During the 1980s many Pashtun women served in the ranks of the Afghan communist regime's Military. Khatol Mohammadzai served paratrooper during the Afghan Civil War and was later promoted to brigadier general in the Afghan Army.[315] Nigar Johar is a three-star general in the Pakistan Army, another Pashtun female became a fighter pilot in the Pakistan Air Force.[316] Pashtun women often have their legal rights curtailed in favour of their husbands or male relatives. For example, though women are officially allowed to vote in Pakistan, some have been kept away from ballot boxes by males.[317]

Notable people

Explanatory notes

- Note: population statistics for Pashtuns (including those without a notation) in foreign countries were derived from various census counts, the UN, the CIA's The World Factbook and Ethnologue.

References

- ^ "South Asia :: Pakistan – The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". cia.gov. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ "Afghanistan". 11 April 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ali, Arshad (15 February 2018). "Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan's great granddaughter seeks citizenship for 'Phastoons' in India". Daily News and Analysis. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

Interacting with mediapersons on Wednesday, Yasmin, the president of All India Pakhtoon Jirga-e-Hind, said that there were 32 lakh Phastoons in the country who were living and working in India but were yet to get citizenship.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Frontier Gandhi's granddaughter urges Centre to grant citizenship to Pathans". The News International. 16 February 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Ethnologue report for Southern Pashto: Iran (2022)". Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ 42% of 200,000 Afghan-Americans = 84,000 and 15% of 363,699 Pakistani-Americans = 54,554. Total Afghan and Pakistani Pashtuns in USA = 538,554.

- ^ Maclean, William (10 June 2009). "Support for Taliban dives among British Pashtuns". Reuters. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ^ "Ethnologue report for Southern Pashto: Tajikistan (2017)". Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ "Knowledge of languages by age and gender: Canada, provinces and territories, census divisions and census subdivisions". Census Profile, 2021 Census. Statistics Canada Statistique Canada. 7 May 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Perepis.ru". perepis2002.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ "Language used at home". profile.id.com.au. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ Khan, Ibrahim (7 September 2021). "Tarīno and Karlāṇi dialects". Pashto. 50 (661). ISSN 0555-8158.

- ^ U.S. plan to win Afghanistan tribe by tribe is risky, by Thomas L. Day, McClatchy Newspapers Thomas L. Day, Mcclatchy Newspapers. February 4, 2010.

- ^ Haidar, Suhasini (3 February 2018). "Tattooed 'blue-skinned' Hindu Pushtuns look back at their roots". The Hindu. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ "Pakhtun Sikhs keeping their culture alive". Dawn. 7 July 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ David, Anne Boyle (1 January 2014). Descriptive Grammar of Pashto and its Dialects. De Gruyter Mouton. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-61451-231-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Minahan, James B. (30 August 2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598846607 – via Google Books.

- ^ James William Spain (1963). The Pathan Borderland. Mouton. p. 40. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

The most familiar name in the west is Pathan, a Hindi term adopted by the British, which is usually applied only to the people living east of the Durand.

- ^ Pathan. World English Dictionary. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

Pathan (pəˈtɑːn) — n a member of the Pashto-speaking people of Afghanistan, Western Pakistan, and elsewhere, most of whom are Muslim in religion [C17: from Hindi]

- ^ von Fürer-Haimendorf, Christoph (1985). Tribal populations and cultures of the Indian subcontinent. Handbuch der Orientalistik/2,7. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 126. ISBN 90-04-07120-2. OCLC 240120731. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ Lindisfarne, Nancy; Tapper, Nancy (23 May 1991). Bartered Brides: Politics, Gender and Marriage in an Afghan Tribal Society. Cambridge University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-521-38158-1.

As for the Pashtun nomads, passing the length of the region, they maintain a complex chain of transactions involving goods and information. Most important, each nomad household has a series of 'friends' in Uzbek, Aymak and Hazara villages along the route, usually debtors who take cash advances, animals and wool from them, to be redeemed in local produce and fodder over a number of years. Nomads regard these friendships as important interest-bearing investments akin to the lands some of them own in the same villages; recently villagers have sometimes withheld their dues, but relations between the participants are cordial, in spite of latent tensions and backbiting.

- ^ Rubin, Barnett R. (1 January 2002). The Fragmentation of Afghanistan: State Formation and Collapse in the International System. Yale University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-300-09519-7.

In some parts of Afghanistan, Pashtun nomads favored by the state often clashed with non- Pashtun (especially Hazara) peasants. Much of their pasture was granted to them by the state after being expropriated from conquered non-Pashtun communities. The nomads appear to have lost these pastures as the Hazaras gained autonomy in the recent war.___Nomads depend on peasants for their staple food, grain, while peasants rely on nomads for animal products, trade goods, credit, and information...Nomads are also ideally situated for smuggling. For some Baluch and Pashtun nomads, as well as settled tribes in border areas, smuggling has been a source of more income than agriculture or pastoralism. Seasonal migration patterns of nomads have been disrupted by war and state formation throughout history, and the Afghan-Soviet war was no exception.

- ^ Baiza, Yahia (21 August 2013). Education in Afghanistan: Developments, Influences and Legacies Since 1901. Routledge. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-134-12082-6.

A typical issue that continues to disturb social order in Afghanistan even at the present time (2012) concerns the Pashtun nomads and grazing lands. Throughout the period 1929 78, governments supported the desire of the Pashtun nomads to take their cattle to graze in Hazara regions. Kishtmand writes that when Daoud visited Hazaristan in the 1950s. where the majority of the population are Hazaras, the local people com- plained about Pashtun nomads bringing their cattle to their grazing lands and destroying their harvest and land. Daoud responded that it was the right of the Pashtuns to do so and that the land belonged to them (Kishtmand 2002: 106).

- ^ Clunan, Anne; Trinkunas, Harold A. (10 May 2010). Ungoverned Spaces: Alternatives to State Authority in an Era of Softened Sovereignty. Stanford University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-8047-7012-5.

In 1846, the British sought to segregate settled areas on the frontier from the pastoral Pashtun communities found in the surrounding hills." British au- thorities made no attempt "to advance into the highlands, or even to secure the main passages through the mountains such as the Khyber Pass."2" In addition, the Close Border Policy tried to contract services from more resistant hill tribes in an attempt to co-opt them. In exchange for their cooperation, the tribes would receive a stipend for their services.

- ^ Banuazizi, Ali; Weiner, Myron (1 August 1988). The State, Religion, and Ethnic Politics: Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan. Syracuse University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-8156-2448-6.

The Hazaras, who rebelled and fought an extended war against the Afghan government, were stripped of their control over the Hindu Kush pastures and the pastures were given to the Pashtun pastoralists. This had a devastating impact on the Hazara's society and economy. These pastures had been held in common by the vari- ous regional Hazara groups and so had provided important bases for large "tribal" affiliations to be maintained. With the loss of their sum- mer pastures the units of practical Hazara affiliation declined. Also, Hazara leaders were killed or deported, and their lands were confis- cated. These activities of the Afghan government, carried on as a deliberate policy, sometimes exacerbated by other outrages effected by the Pashtun pastoralists, emasculated the Hazaras.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dan Caldwell (17 February 2011). Vortex of Conflict: U.S. Policy Toward Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iraq. Stanford University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8047-7666-0.

A majority of Pashtuns live south of the Hindu Kush (the 500-mile mountain range that covers northwestern Pakistan to central and eastern Pakistan) and with some Persian speaking ethnic groups.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Pashtun". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ Sims-Williams, Nicholas. "Bactrian Documents from Northern Afghanistan. Vol II: Letters and Buddhist". Khalili Collections: 19.

- ^ "Afghan and Afghanistan". Abdul Hai Habibi. alamahabibi.com. 1969. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ "History of Afghanistan". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Muhammad Qasim Hindu Shah (Firishta). "History of the Mohamedan Power in India". Persian Literature in Translation. Packard Humanities Institute. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Glossary". British Library. Archived from the original on 2 July 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Huang, Guiyou (30 December 2008). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Asian American Literature [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-56720-736-1.

In Afghanistan, up until the 1970s, the common reference to Afghan meant Pashtun. . . . The term Afghan as an inclusive term for all ethnic groups was an effort begun by the "modernizing" King Amanullah (1909-1921). . . .

- ^ "Constitution of the Kingdom of Afghanistan - Wikisource, the free online library". en.wikisource.org. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ Tyler, John A. (10 October 2021). Afghanistan Graveyard of Empires: Why the Most Powerful Armies of Their Time Found Only Defeat or Shame in This Land Of Endless Wars. Aries Consolidated LLC. ISBN 978-1-387-68356-7.

The largest ethnic group in Afghanistan is that of Pashtuns, who were historically known as the Afghans. The term Afghan is now intended to indicate people of other ethnic groups as well.

- ^ Bodetti, Austin (11 July 2019). "What will happen to Afghanistan's national languages?". The New Arab.

- ^ Chiovenda, Andrea (12 November 2019). Crafting Masculine Selves: Culture, War, and Psychodynamics in Afghanistan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-007355-8.

Niamatullah knew Persian very well, as all the educated Pashtuns generally do in Afghanistan

- ^ "Hindu Society and English Rule". The Westminster Review. 108 (213–214). The Leonard Scott Publishing Company: 154. 1877.

Hindustani had arisen as a lingua franca from the intercourse of the Persian-speaking Pathans with the Hindi-speaking Hindus.

- ^ Hakala, Walter N. (2012). "Languages as a Key to Understanding Afghanistan's Cultures" (PDF). National Geographic. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

In the 1980s and '90s, at least three million Afghans--mostly Pashtun--fled to Pakistan, where a substantial number spent several years being exposed to Hindi- and Urdu-language media, especially Bollywood films and songs, and being educated in Urdu-language schools, both of which contributed to the decline of Dari, even among urban Pashtuns.

- ^ Krishnamurthy, Rajeshwari (28 June 2013). "Kabul Diary: Discovering the Indian connection". Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

Most Afghans in Kabul understand and/or speak Hindi, thanks to the popularity of Indian cinema in the country.

- ^ Green, Nile (2017). Afghanistan's Islam: From Conversion to the Taliban. University of California Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-520-29413-4.

Many of the communities of ethnic Pashtuns (known as Pathans in India) that had emerged in India over the previous centuries lived peaceably among their Hindu neighbors. Most of these Indo-Afghans lost the ability to speak Pashto and instead spoke Hindi and Punjabi.

- ^ Romano, Amy (2003). A Historical Atlas of Afghanistan. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 28. ISBN 0-8239-3863-8. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ Syed Saleem Shahzad (20 October 2006). "Profiles of Pakistan's Seven Tribal Agencies". Jamestown. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ^ "Who Are the Pashtun People of Afghanistan and Pakistan?". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Lewis, Paul M. (2009). "Pashto, Northern". SIL International. Dallas, TX: Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

Ethnic population: 49,529,000 possibly total Pashto in all countries.

- ^ "Hybrid Census to Generate Spatially-disaggregated Population Estimate". United Nations world data form. Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ "Pakistan - The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ "Afghanistan". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 24 September 2022. (Archived 2022 edition.)

- ^ "South Asia :: Pakistan — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". cia.gov. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ "What Languages Are Spoken In Pakistan?". World atlas. 30 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Canfield, Robert L.; Rasuly-Paleczek, Gabriele (4 October 2010). Ethnicity, Authority and Power in Central Asia: New Games Great and Small. Routledge. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-136-92750-8.

By the late-eighteenth century perhaps 100,000 "Afghan" or "Puthan" migrants had established several generations of political control and economic consolidation within numerous Rohilkhand communities

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Pakhtoons in Kashmir". The Hindu. 20 July 1954. Archived from the original on 9 December 2004. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

Over a lakh Pakhtoons living in Jammu and Kashmir as nomad tribesmen without any nationality became Indian subjects on July 17. Batches of them received certificates to this effect from the Kashmir Prime Minister, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed, at village Gutligabh, 17 miles from Srinagar.

- ^ Siddiqui, Niloufer A. (2022). Under the Gun. Cambridge University Press. p. 186. ISBN 9781009242523.

- ^ "Pashtun". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

Pashtun, also spelled Pushtun or Pakhtun, Hindustani Pathan, Persian Afghan, Pashto-speaking people residing primarily in the region that lies between the Hindu Kush in northeastern Afghanistan and the northern stretch of the Indus River in Pakistan.

- ^ George Morton-Jack (24 February 2015). The Indian Army on the Western Front South Asia Edition. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-1-107-11765-5.

'Pathan', an Urdu and a Hindi term, was usually used by the British when speaking in English. They preferred it to 'Pashtun', 'Pashtoon', 'Pakhtun' or 'Pukhtun', all Pashtu versions of the same word, which the frontier tribesmen would have used when speaking of themselves in their own Pashtu dialects.

- ^ "Memons, Khojas, Cheliyas, Moplahs ... How Well Do You Know Them?". Islamic Voice. Archived from the original on 17 October 2006. Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- ^ "Pathan". Houghton Mifflin Company. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Study of the Pathan Communities in Four States of India". Khyber.org. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 30 January 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Alavi, Shams Ur Rehman (11 December 2008). "Indian Pathans to broker peace in Afghanistan". Hindustan Times.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Haleem, Safia (24 July 2007). "Study of the Pathan Communities in Four States of India". Khyber.org. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "The 'Kabuliwala' Afghans of Kolkata". BBC News. 23 May 2015.

- ^ «Сводка о силе носителей языков и родных языков – 2001» . Перепись Индии. 2001. Архивировано из оригинала 1 февраля 2008 года . Проверено 17 марта 2008 г.

- ^ Бхаттачарья, Равик (15 февраля 2018 г.). «Внучка Фронтир Ганди призывает Центр предоставить гражданство патанам» . Индийский экспресс . Проверено 28 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Пуштун в Индии» . Проект Джошуа .

- ^ Алави, Шамс Ур Рехман (11 декабря 2008 г.). «Индийские патаны будут посредниками в установлении мира в Афганистане» . Индостан Таймс.

Патаны теперь разбросаны по всей стране и имеют очаги влияния в некоторых частях УП, Бихара и других штатов. Они также проявили себя в нескольких областях, особенно в Болливуде и спорте. Известные индийские патаны включают Дилипа Кумара, Шах Рукх Кхана и Ирфана Патана. «Население патанов в Индии вдвое превышает население Афганистана, и хотя у нас больше нет связей (с этой страной), у нас общее происхождение, и мы считаем своим долгом помочь положить конец этой угрозе», - добавил Атиф. В инициативе участвуют академики, общественные деятели, писатели и религиозные учёные. Всеиндийский мусульманский меджлис, Всеиндийская федерация меньшинств и ряд других организаций присоединились к призыву к миру и готовятся к джирге.

- ^ Фрей, Джеймс (16 сентября 2020 г.). Индийское восстание, 1857–1859: краткая история с документами . Издательство Хакетт. п. 141. ИСБН 978-1-62466-905-7 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Пуштун, патан в Индии» . Проект Джошуа .

- ^ Финниган, Кристофер (29 октября 2018 г.). « Кабуливала представляет собой дилемму между государством и миграционной историей мира» – Шах Махмуд Ханифи» . Лондонская школа экономики.

- ^ «Болливудский актер Фироз Хан умер в возрасте 70 лет» . Рассвет . 27 апреля 2009 года . Проверено 6 июня 2020 г.

- ^ «Афганцы Гайаны» . Вахид Моманд . Афганистан.com. Архивировано из оригинала 5 ноября 2006 года . Проверено 18 января 2007 г.

- ^ «Северные пуштуны в Австралии» . Проект Джошуа .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Джасим Хан (27 декабря 2015 г.). Быть Салманом . Пингвин Букс Лимитед. С. 34, 35, 37, 38–. ISBN 978-81-8475-094-2 .

Суперзвезда Салман Хан – пуштун из клана Акузай... Чтобы добраться до невзрачного городка Малаканд, нужно проехать примерно сорок пять километров от Мингоры в сторону Пешавара. Это место, где когда-то жили предки Салман Кхана. Они принадлежали клану Акузай пуштунского племени...

- ^ Сваруп, Шубханги (27 января 2011 г.). «Царство Хана» . Открыть . Архивировано из оригинала 4 июня 2020 года . Проверено 6 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Алави, Шамс Ур Рехман (11 декабря 2008 г.). «Индийские патаны будут посредниками в установлении мира в Афганистане» . Индостан Таймс.

Патаны теперь разбросаны по всей стране и имеют очаги влияния в некоторых частях УП, Бихара и других штатов. Они также проявили себя в нескольких областях, особенно в Болливуде и спорте. Три самых известных индийских патана — Дилип Кумар, Шах Рукх Кхан и Ирфан Патан. «Население патанов в Индии вдвое превышает население Афганистана, и хотя у нас больше нет связей (с этой страной), у нас общее происхождение, и мы считаем своим долгом помочь положить конец этой угрозе», - добавил Атиф. В инициативе участвуют академики, общественные деятели, писатели и религиозные учёные. Всеиндийский мусульманский меджлис, Всеиндийская федерация меньшинств и ряд других организаций присоединились к призыву к миру и готовятся к джирге.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Нил Грин (2017). Ислам Афганистана: от обращения к Талибану . Университет Калифорнии Пресс. стр. 18–. ISBN 978-0-520-29413-4 .

- ^ Виндфур, Гернот (13 мая 2013 г.). Иранские языки . Рутледж. стр. 703–731. ISBN 978-1-135-79704-1 .

- ^ «ДОРРАНИ – Иранская энциклопедия» . iranicaonline.org . Проверено 4 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ «ḠILZĪ – Иранская энциклопедия» . www.iranicaonline.org . Проверено 4 апреля 2021 г.

Надир-шах также победил последнего независимого хальзайского правителя Кандагара, шаха Хосейна Хотака, брата шаха Махмуда, в 1150/1738 году. Шах Хосайн и большое количество хальзи были депортированы в Мазандаран (Марви, стр. 543–52; Локхарт, 1938, стр. 115–20). Остатки этой некогда значительной общины изгнанников, хотя и ассимилировались, продолжают заявлять о своем пуштунском происхождении Хальзи.

- ^ «ДОРРАНИ – Иранская энциклопедия» . iranicaonline.org . Проверено 4 апреля 2021 г.

совершили набег на Хорасан и «за несколько лет значительно увеличились в численности».

- ^ Далримпл, Уильям; Ананд, Анита (2017). Кох-и-Нур: история самого позорного алмаза в мире . Издательство Блумсбери. ISBN 978-1-4088-8885-8 .

- ^ «АЗАД ХАН АФХАН» . iranicaonline.org . Проверено 4 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ «ДОРРАНИ – Иранская энциклопедия» . iranicaonline.org . Проверено 4 апреля 2021 г.

По данным выборочного обследования 1988 года, почти 75 процентов всех афганских беженцев в южной части персидского Хорасана составляли доррани, то есть около 280 тысяч человек (Паполи-Язди, стр. 62).

- ^ Жафрело, Кристоф (2002). Пакистан: национализм без нации? . Книги Зеда. п. 27. ISBN 1-84277-117-5 . Проверено 22 августа 2010 г.

- ^ с. 2 «Некоторые аспекты древнеиндийской культуры», Д. Р. Бхандаркар

- ^ «Ригведа: Риг-Веда, Книга 7: ГИМН XVIII. Индра» . www.sacred-texts.com . Проверено 2 ноября 2020 г. .

- ^ Макдонелл, А.А. и Кейт, AB, 1912. Ведический указатель имен и предметов.

- ^ Карта Мидийской империи , показывающая территорию Пактии на территории нынешнего Афганистана и Пакистана... Ссылка

- ^ «Геродот, «История», книга 3, глава 102, раздел 1» . www.perseus.tufts.edu . Проверено 2 ноября 2020 г. .

- ^ «История Геродота, глава 7, написанная в 440 г. до н.э., перевод Джорджа Роулинсона» . Пайни.com. Архивировано из оригинала 5 февраля 2012 года . Проверено 21 сентября 2012 г.

- ^ «История Геродота, книга 3, глава 91, стих 4; написано в 440 г. до н. э., перевод Г. К. Маколея» . Sacred-texts.com . Проверено 21 февраля 2015 г.

- ^ «Геродот, «История», книга 3, глава 91, раздел 4» . www.perseus.tufts.edu . Проверено 3 ноября 2020 г. .

- ^ Дэни, Ахмад Хасан (2007). История Пакистана: Пакистан на протяжении веков . Публикации Санг-э Мил. п. 77. ИСБН 978-969-35-2020-0 .

- ^ Холдич, Томас (12 марта 2019 г.). Ворота Индии как исторический рассказ . Креативные Медиа Партнеры, ООО. стр. 28, 31. ISBN. 978-0-530-94119-6 .

- ^ Птолемей; Хумбах, Гельмут; Зиглер, Сюзанна (1998). География, книга 6: Ближний Восток, Центральная и Северная Азия, Китай. Часть 1. Текст и переводы на английский/немецкий язык (на греческом языке). Райхерт. п. 224. ИСБН 978-3-89500-061-4 .

- ^ Маркварт, Джозеф. Исследования по истории Эрана II (1905 г.) (на немецком языке). п. 177.

- ^ «Страбон, География, КНИГА XI., ГЛАВА VIII., раздел 2» . www.perseus.tufts.edu . Проверено 7 ноября 2020 г.

- ^ Сагар, Кришна Чандра (1 января 1992 г.). Иностранное влияние на Древнюю Индию . Северный книжный центр. п. 91. ИСБН 9788172110284 .

Согласно Страбону (ок. 54 г. до н. э., 24 г. н. э.), который ссылается на авторитет Аполлодора Артемийского [ sic ], греки Бактрии стали хозяевами Арианы, расплывчатого термина, грубо обозначающего восточные районы Персидской империи, и Индия.

- ^ Синор, Денис, изд. (1990). Кембриджская история ранней Внутренней Азии . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 117. дои : 10.1017/CHOL9780521243049 . ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9 .

Все современные историки, археологи и лингвисты сходятся во мнении, что поскольку скифские и сарматские племена принадлежали к иранской языковой группе...

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хумбах, Гельмут; Фейсс, Клаус (2012). Скифы Геродота и Средняя Азия Птолемея: семасиологические и ономасиологические исследования . Райхерт Верлаг. п. 21. ISBN 978-3-89500-887-0 .

- ^ Аликузай, Хамид Вахед (октябрь 2013 г.). Краткая история Афганистана в 25 томах . Траффорд Паблишинг. п. 142. ИСБН 978-1-4907-1441-7 .

- ^ Чунг, Джонни. «Cheung2017-О происхождении терминов «афганский» и «пуштун» (снова) - Том Мемориала Гноли.pdf» . п. 39.

- ^ Морано, Энрико; Попробуй, Элио; Росси, Адриано Валерио (2017). «О происхождении терминов афганский и пуштунский» . Studia Philologica Iranica: Том Мемориала Герардо Ньоли . Науки и письма. п. 39. ИСБН 978-88-6687-115-6 .

- ^ «Пуштун | народ» . Британская энциклопедия . Проверено 3 ноября 2020 г. .

Пуштун ... носил исключительное имя «Афган» до того, как это имя стало обозначать любого уроженца нынешней территории Афганистана.