Македонцы (этническая группа)

Карта македонской диаспоры в мире | |

| Регионы со значительной численностью населения | |

|---|---|

| 111 352 (перепись 2021 г.) –200 000 [2] [3] | |

| 115,210 (2020) [3] [4] | |

| 65,347 (2017) [5] | |

| 61,753–200,000[6][3] | |

| 61,304–63,000[3][7] | |

| 45,000[8] | |

| 43,110 (2016 census)–200,000[9][10] | |

| 31,518 (2001 census)[11] | |

| 30,000[8] | |

| 10,000–30,000[12] | |

| 22,755 (2011 census)[13] | |

| 20,135[3][14] | |

| 10,000–15,000[3] | |

| 9,000 (est.)[3] | |

| 8,963[15] | |

| 7,253[16] | |

| 2,281 (2023 census)[17] | |

| 5,392 (2018)[18] | |

| 4,600[19] | |

| 4,491 (2009)[20] | |

| 4,138 (2011 census)[21] | |

| 3,972 (2002 census)[22] | |

| 3,419 (2002)[23] | |

| 3,045[24] | |

| 2,300–15,000[25] | |

| 2,278 (2005)[26] | |

| 2,011[27] | |

| 2,000–4,500[28][29] | |

| 1,264 (2011 census)[30] | |

| 1,143 (2021 census)[31] | |

| 900 (2011 census)[32] | |

| 807–1,500[33][34] | |

| 310[28][35] | |

| 155[36] | |

| Languages | |

| Macedonian | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Eastern Orthodox Christianity (Macedonian Orthodox Church) Minority Sunni Islam (Torbeši) Catholicism (Roman Catholic and Macedonian Greek Catholic) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other South Slavs, especially Slavic speakers of Greek Macedonia, Bulgarians[a] and Torlak speakers in Serbia | |

Македонцы ( македонский : Македонци , латинизированный : Makedonci ) — нация и южнославянская этническая группа, родом из региона Македонии в Юго-Восточной Европе . Они говорят на македонском языке , южнославянском языке . Подавляющее большинство македонцев идентифицируют себя как восточные православные христиане , которые разделяют культурное и историческое «православное византийско-славянское наследие» со своими соседями. Около двух третей всех этнических македонцев проживают в Северной Македонии , а также существуют общины в ряде других стран .

Концепция македонской этнической принадлежности, отличной от ее ортодоксальных балканских соседей, считается сравнительно новой. [б] Самые ранние проявления зарождающейся македонской идентичности возникли во второй половине XIX века. [46] [47] [48] среди ограниченных кругов славяноязычной интеллигенции, преимущественно за пределами региона Македонии. Они возникли после Первой мировой войны и особенно в 1930-е годы и, таким образом, были закреплены правительственной политикой коммунистической Югославии после Второй мировой войны . [c] The formation of the ethnic Macedonians as a separate community has been shaped by population displacement[54] as well as by language shift,[55][dubious – discuss] оба являются результатом политических событий в регионе Македонии в 20 веке. После распада Османской империи решающим моментом в этногенезе южнославянского этноса стало создание после Второй мировой войны Социалистической Республики Македонии — государства в рамках Социалистической Федеративной Республики Югославии . За этим последовало развитие отдельного македонского языка и национальной литературы, а также основание отдельной Македонской православной церкви и национальной историографии.

History

Ancient and Roman period

In antiquity, much of central-northern Macedonia (the Vardar basin) was inhabited by Paionians who expanded from the lower Strymon basin. The Pelagonian plain was inhabited by the Pelagones and the Lyncestae, ancient Greek tribes of Upper Macedonia; whilst the western region (Ohrid-Prespa) was said to have been inhabited by Illyrian tribes, such as the Enchelae.[56] During the late Classical Period, having already developed several sophisticated polis-type settlements and a thriving economy based on mining,[57] Paeonia became a constituent province of the Argead – Macedonian kingdom.[58] In 310 BC, the Celts attacked deep into the south, subduing various local tribes, such as the Dardanians, the Paeonians and the Triballi. Roman conquest brought with it a significant Romanization of the region. During the Dominate period, 'barbarian' foederati were settled on Macedonian soil at times; such as the Sarmatians settled by Constantine the Great (330s AD)[59] or the (10 year) settlement of Alaric I's Goths.[60] In contrast to 'frontier provinces', Macedonia (north and south) continued to be a flourishing Christian, Roman province in Late Antiquity and into the Early Middle Ages.[60][61]

Medieval period

Linguistically, the South Slavic languages from which Macedonian developed are thought to have expanded in the region during the post-Roman period, although the exact mechanisms of this linguistic expansion remains a matter of scholarly discussion.[62] Traditional historiography has equated these changes with the commencement of raids and 'invasions' of Sclaveni and Antes from Wallachia and western Ukraine during the 6th and 7th centuries.[63] However, recent anthropological and archaeological perspectives have viewed the appearance of Slavs in Macedonia, and throughout the Balkans in general, as part of a broad and complex process of transformation of the cultural, political and ethnolinguistic Balkan landscape before the collapse of Roman authority. The exact details and chronology of population shifts remain to be determined.[64][65] What is beyond dispute is that, in contrast to "barbarian" Bulgaria, northern Macedonia remained Roman in its cultural outlook into the 7th century.[61] Yet at the same time, sources attest numerous Slavic tribes in the environs of Thessaloniki and further afield, including the Berziti in Pelagonia.[66] Apart from Slavs and late Byzantines, Kuver's "Sermesianoi"[67] – a mix of Byzantine Greeks, Bulgars and Pannonian Avars – settled the "Keramissian plain" (Pelagonia) around Bitola in the late 7th century.[68][69][70][71] Later pockets of settlers included "Danubian" Bulgars[72][73] in the 9th century; Magyars (Vardariotai)[74] and Armenians in the 10th–12th centuries,[75] Cumans and Pechenegs in the 11th–13th centuries,[76] and Saxon miners in the 14th and 15th centuries.[77] Vlachs (Aromanians) and Arbanasi (Albanians) also inhabited this area in the Middle ages and mingeled with the local Slavic-speakers.[78][79]

Having previously been Byzantine clients, the Sklaviniae of Macedonia switched their allegiance to the Bulgarians with their incorporation into the Bulgarian Empire in the mid-800s.[80] In the 860s, Byzantine missionaries Cyril and Methodius, created the Glagolitic alphabet and Slavonic liturgy based on the Slavic dialect around Thessaloniki for a mission to Great Moravia.[81][82][83] After the demise of the Great Moravian mission in 886, exiled students of the two apostles brought the Glagolitic alphabet to the Bulgarian Empire, where Khan Boris I of Bulgaria (r. 852–889) welcomed them. As part of his efforts to limit Byzantine influence and assert Bulgarian independence, he adopted Slavic as official ecclesiastical and state language and established the Preslav Literary School and Ohrid Literary School, which taught Slavonic liturgy and the Glagolitic and subsequently the Cyrillic alphabet.[84][85][86] The success of Boris I's efforts was a major factor in making the Slavs in Macedonia—and the other Slavs within the First Bulgarian State—into Bulgarians and transforming the Bulgar state into a Bulgarian state.[87][88] Subsequently, the literary and ecclesiastical centre in Ohrid became a second cultural capital of medieval Bulgaria.[89][90]

Ottoman period

After the final Ottoman conquest of the Balkans by the Ottomans in the 14/15th century, all Eastern Orthodox Christians were included in a specific ethno-religious community under Graeco-Byzantine jurisdiction called Rum Millet. Belonging to this religious commonwealth was so important that most of the common people began to identify themselves as Christians.[91] However ethnonyms never disappeared and some form of primary ethnic identity was available.[92] This is confirmed from a Sultan's Firman from 1680 which describes the ethnic groups in the Balkan territories of the Empire as follows: Greeks, Albanians, Serbs, Vlachs and Bulgarians.[93]

Throughout the Middle Ages and Ottoman rule up until the early 20th century[52][53][94] the Slavic-speaking population majority in the region of Macedonia were more commonly referred to (both by themselves and outsiders) as Bulgarians.[95][96][97] However, in pre-nationalist times, terms such as "Bulgarian" did not possess a strict ethno-nationalistic meaning, rather, they were loose, often interchangeable terms which could simultaneously denote regional habitation, allegiance to a particular empire, religious orientation, membership in certain social groups.[d] Similarly, a "Byzantine" was a Roman subject of Constantinople, and the term bore no strict ethnic connotations, Greek or otherwise.[102] Overall, in the Middle Ages, "a person's origin was distinctly regional",[103] and in Ottoman era, before the 19th-century rise of nationalism, it was based on the corresponding confessional community.

The rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire in the early 19th century brought opposition to this continued situation. At that time, the classical Rum Millet began to degrade. The coordinated actions, carried out by Bulgarian national leaders and supported by the majority of the Slavic-speaking population in today's Republic of North Macedonia (the second anti-Greek revolt was in Skopje) to have a separate "Bulgarian Millet", finally bore fruit in 1870 when a firman for the creation of the Bulgarian Exarchate was issued.[104] In September 1872, the Ecumenical Patriarch Anthimus VI declared the Exarchate schismatic and excommunicated its adherents, accusing them of having “surrendered Orthodoxy to ethnic nationalism”, i.e., "ethnophyletism" (Greek: εθνοφυλετισμός).[105] At the time of its creation, the only Vardar Macedonian bishopric included in the Exarchate was Veles.[106]

However, in 1874, the Christian population of the bishoprics of Skopje and Ohrid were given the chance to participate in a plebiscite, where they voted overwhelmingly in favour of joining the Exarchate (Skopje by 91%, Ohrid by 97%)[107][108] Referring to the results of the plebiscites, and on the basis of statistical and ethnological indications, the 1876 Conference of Constantinople included all of present-day North Macedonia (except for the Debar region) and parts of present-day Greek Macedonia.[109] The borders of new Bulgarian state, drawn by the 1878 Treaty of San Stefano, also included Macedonia, but the treaty was never put into effect and the Treaty of Berlin (1878) "returned" Macedonia to the Ottoman Empire.

For Christian Slav peasants, however, the choice between the Patriarchate and the Exarchate was not tainted with national meaning, but was a choice of Church or millet. Thus adherence to the Bulgarian national cause was attractive as a means of opposing oppressive Christian chiflik owners and urban merchants, who usually identified with the Greek nation, as a way to escape arbitrary taxation by Patriarchate bishops, via shifting allegiance to the Exarchate and on account of the free (and, occasionally, even subsidized) provision of education in Bulgarian schools.[110][111]Alignment of the Slavs of Macedonia with the Bulgarian, the Greek or sometimes the Serbian national camp did not imply adherence to different national ideologies: these camps were not stable, culturally distinct groups, but parties with national affiliations, described by contemporaries as "sides", "wings", "parties" or "political clubs".[112]

Identity

The first expressions of Macedonian nationalism occurred in the second half of the 19th century mainly among intellectuals in Belgrade, Sofia, Thessaloniki and St. Petersburg.[114] Since the 1850s some Slavic intellectuals from the area adopted the Greek designation Macedonian as a regional label, and it began to gain popularity.[115] In the 1860s, according to Petko Slaveykov, some young intellectuals from Macedonia were claiming that they are not Bulgarians, but rather Macedonians, descendants of the Ancient Macedonians.[116] Slaveikov, himself with Macedonian roots,[117] started in 1866 the publication of the newspaper Makedoniya. Its main task was "to educate these misguided [sic] Grecomans there", who he called also Macedonists.[118] In a letter written to the Bulgarian Exarch in February 1874 Petko Slaveykov reports that discontent with the current situation "has given birth among local patriots to the disastrous idea of working independently on the advancement of their own local dialect and what's more, of their own, separate Macedonian church leadership."[119] The activities of these people were also registered by the Serbian politician Stojan Novaković,[120] who promoted the idea to use the Macedonian nationalism in order to oppose the strong pro-Bulgarian sentiments in the area.[121] The nascent Macedonian nationalism, illegal at home in the theocratic Ottoman Empire, and illegitimate internationally, waged a precarious struggle for survival against overwhelming odds: in appearance against the Ottoman Empire, but in fact against the three expansionist Balkan states and their respective patrons among the great powers.[122]

The first known author that overtly speaks of a Macedonian nationality and language was Georgi Pulevski, who in 1875 published in Belgrade a Dictionary of Three languages: Macedonian, Albanian, Turkish, in which he wrote that the Macedonians are a separate nation and the place which is theirs is called Macedonia.[123] In 1880, he published in Sofia a Grammar of the language of the Slavic Macedonian population, a work that is today known as the first attempt at a grammar of Macedonian. However, he alternately described his language as "Serbo-Albanian"[124] and "Slavo-Macedonian"[125] and himself as a "Mijak from Galičnik",[126] a "Serbian patriot"[127] and a "Bulgarian from the village of Galičnik",[128][129] i.e. changing ethnicity multiple times during his lifetime.[130] Therefore, his Macedonian self-identification is considered by historians to be inchoate[131][132] and to resemble a regional phenomenon.[133] In 1885, Theodosius of Skopje, a priest who held a high-ranking position within the Bulgarian Exarchate, was chosen as a bishop of the episcopacy of Skopje. In 1890 he renounced de facto the Bulgarian Exarchate and attempted to restore the Archbishopric of Ohrid as a separate Macedonian Orthodox Church in all eparchies of Macedonia,[134] responsible for the spiritual, cultural and educational life of all Macedonian Orthodox Christians.[122] During this time period Metropolitan Bishop Theodosius of Skopje made a plea to the Greek Patriarchate of Constantinople to allow a separate Macedonian church, and ultimately on 4 December 1891 he sent a letter to the Pope Leo XIII to ask for a recognition and a protection from the Roman Catholic Church, but failed. Soon after, he repented and returned to pro-Bulgarian positions.[135] In the 1880s and 1890s, Isaija Mažovski designated Macedonian Slavs as "Macedonians" and "Old Slavic Macedonian people", and also distinguished them from Bulgarians as follows: "Slavic-Bulgarian" for Mažovski was synonymous with "Macedonian", while only "Bulgarian" was a designation for the Bulgarians in Bulgaria.[136]

In 1890, Austrian researcher of Macedonia Karl Hron reported that the Macedonians constituted a separate ethnic group by history and language. Within the next few years, this concept was also welcomed in Russia by linguists including Leonhard Masing, Pyotr Lavrov, Jan Baudouin de Courtenay, and Pyotr Draganov.[137][138] Draganov, of Bulgarian descent, conducted research in Macedonia and determined that the local language had its own identifying characteristics compared to Bulgarian and Serbian. He wrote in a Saint Petersburg newspaper that the Macedonians should be recognized by Russia in a full national sense.[139]

Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization leader Boris Sarafov in 1901 stated that Macedonians had a unique "national element" and, the following year, he stated "We the Macedonians are neither Serbs nor Bulgarians, but simply Macedonians... Macedonia exists only for the Macedonians." However after the failure of the Ilinden Uprising, Sarafov wanted to keep closer ties with Bulgaria, supporting the Bulgarian aspirations towards the area.[140][141] Gyorche Petrov, another IMRO member, stated Macedonia was a "distinct moral unit" with its own "aspirations",[142] while describing its Slavic population as Bulgarian.[143]

National antagonisms and Macedonian separatism

Macedonian separatism

In 1903, Krste Misirkov published in Sofia his book On Macedonian Matters, wherein he laid down the principles of the modern Macedonian nationhood and language. This book, written in the standardized central dialect of Macedonia, is considered by ethnic Macedonians as a milestone of the process of Macedonian awakening. Misirkov argued that the dialect of central Macedonia (Veles-Prilep-Bitola-Ohrid) should be adopted as a basis for a standard Macedonian literary language, in which Macedonians should write, study, and worship; the autocephalous Archbishopric of Ohrid should be restored; and the Slavic people of Macedonia should be recognized as a separate ethnic community, when the necessary historical circumstances would arise.[144]

However, throughout the book, Misirkov lamented that "no local Macedonian patriotism exists" and stated that the Slavic Macedonian population had always called itself "Bulgarian".[145] He also claimed that it was first the Byzantine Greeks who starting calling the local Slavs "Bulgarians" because of their alliance with the Bulgars, during the incessant Byzantine–Bulgarian conflict which in the eyes of the Byzantine Greeks eventually forged both Slavs and Bulgars into one people with a Bulgarian name and a Slavonic language.[146] Misirkov's primary motivation for a separate Macedonian nationhood and language was Serbia and Bulgaria's conflict over Macedonia, which according to Misirkov would eventually lead to its partition.[147][148] Therefore, he argued, it would be better for both Macedonians and Bulgarians if there was a united Macedonian Macedonia than a partitioned Bulgarian one, where Bulgaria would not be allowed to go any further than the left bank of the Vardar.[149][150] In 1905, he returned to a pro-Bulgarian stance and renounced the positions he espoused in On Macedonian Matters.[151][152] Later in his life, Misirkov oscillated between a pro-Macedonist and Greater Bulgarian stance, including controversially claimed that all Macedonian and Torlakian dialects were, in fact, Bulgarian.[153]

Another major figure of the Macedonian awakening was Dimitrija Čupovski, one of the founders of the Macedonian Literary Society, established in Saint Petersburg in 1902. One of the members was also Krste Misirkov. In 1905 the Society published Vardar, the first scholarly, scientific and literary journal in the central dialects of Macedonia, which later would contribute in the standardization of Macedonian language.[154] In 1913, the Macedonian Literary Society submitted the Memorandum of Independence of Macedonia to the British Foreign Secretary and other European ambassadors, and it was printed in many European newspapers. In the period 1913–1914, Čupovski published the newspaper Македонскi Голосъ (Macedonian Voice) in which he and fellow members of the Saint Petersburg Macedonian Colony propagated the existence of a Macedonian people separate from the Greeks, Bulgarians and Serbs, and sought to popularize the idea for an independent Macedonian state.

The "Macedonian Slavs" in cartography

From 1878 until 1918 most independent European observers viewed the Slavs of Macedonia as Bulgarians or as Macedonian Slavs, while their association with Bulgaria was almost universally accepted.[155] Original manuscript versions of population data mentioned "Macedonian Slavs", though the term was changed to "Bulgarians" in the official printing.[156] Western publications usually presented the Slavs of Macedonia as Bulgarians, as happened, partly for political reasons, in Serbian ones.[157] Prompted by the publication of a Serbian map by Spiridon Gopčević claiming the Slavs of Macedonia as Serbs, a version of a Russian map, published in 1891, in a period of deterioration of Bulgarian-Russian relations, first presented Macedonia inhabited not by Bulgarians, but by Macedonian Slavs.[158] Austrian-Hungarian maps followed suit in an effort to delegitimize the ambitions of Russophile Bulgaria, returning to presenting the Macedonian Slavs as Bulgarians when Austria-Bulgaria relations ameliorated, only to renege and employ the designation "Macedonian Slavs" when Bulgaria changed its foreign policy and Austria turned to envisaging an autonomous Macedonia under Austrian influence within the Murzsteg process.[159]

The term "Macedonian Slavs" was used either as a middle solution between conflicting Serbian and Bulgarian claims, to denote an intermediary grouping of Slavs, associated with the Bulgarians, or to describe a separate Slavic group with no ethnic, national or political affiliation.[160] The differentiation of ethnographic maps representing rival national views produced to satisfy the curiosity of European audience for the inhabitants of Macedonia, after the Ilinden uprising of 1903, indicated the complexity of the issue.[161] Influenced by the conclusions of the research of young Serb Jovan Cvijić, that Macedonia's culture combined Byzantine influence with Serbian traditions, a map of 1903 by Austrian cartographer Karl Peucker depicted Macedonia as a peculiar area, where zones of linguistic influence overlapped.[162] In his first ethnographic map of 1906, Cvijic presented all Slavs of Serbia and Macedonia merely as "Slavs".[163] In a pamphlet translated and circulated in Europe the same year, he elaborated his ostensibly impartial views and described the Slavs living south of the Babuna and Plačkovica mountains as "Macedo-Slavs" arguing that the appellation "Bugari" meant simply "peasant" to them, that they had no national consciousness and could become Serbs or Bulgarians in the future.[164] Cvijić thus transformed the political character of the IMRO's appeals to "Macedonians" into an ethnic one.[165] Bulgarian cartographer Anastas Ishirkov countered Cvijić's views, pointing to the involvement of Macedonian Slavs in Bulgarian nationalist uprisings and the Macedonian origins of Bulgarian nationalists before 1878. Although Cvijic's arguments attracted the attention of Great Powers, they did not endorse at the time his view on the Macedo-Slavs.[166]

- Austrian ethnographic map of the vilayets of Kosovo, Saloniki, Scutari, Janina and Monastir, ca. 1900.

- Ethnographical Map of Central and Southeastern Europe - War Office, London (1916)

- Ethnographic map of the Balkans from the Serbian author Jovan Cvijic (1918)

- Greek map by Georgios Sotiriadis submitted to the Paris Peace Conference (1919)

- Ethnographic map of the Balkans in the New Larned History (1922)

Cvijić further elaborated the idea that had first appeared in Peucker's map and in his map of 1909 he ingeniously mapped the Macedonian Slavs as a third group distinct from Bulgarians and Serbians, and part of them "under Greek influence".[167][168] Envisioning a future agreement with Greece, Cvijic depicted the southern half of the Macedo-Slavs "under Greek unfluence", while leaving the rest to appear as a subset of the Serbo-Croats.[169][170] Cvijić's view was reproduced without acknowledgement by Alfred Stead, with no effect on British opinion,[171][172] but, reflecting the reorientation of Serbian aims towards dividing Macedonia with Greece, Cvijić eliminated the Macedo-Slavs from a subsequent edition of his map.[173] However, in 1913, before the conclusion of the Treaty of Bucharest he published his third ethnographic map distinguishing the Macedo-Slavs between Skopje and Salonica from both Bulgarians and Serbo-Croats, on the basis of the transitional character of their dialect per the linguistic researches of Vatroslav Jagić and Aleksandar Belić, and the Serb features of their customs, such as the zadruga.[174] For Cvijić, the Macedo-Slavs were a transitional population, with any sense of nationality they displayed being weak, superficial, externally imposed and temporary.[175] Despite arguing that they should be considered neutral, he postulated their division into Serbs and Bulgarians based on dialectical and cultural features in anticipation of Serbian demands regarding the delimitation of frontiers.[176]

A Balkan committee of experts rejected Cvijić's concept of the Macedo-Slavs in 1914.[177] However, Bulgaria's entry into World War I on the side of the Central Powers in 1915, after the Allies failed to convince Serbia to hand over the ‘Uncontested Zone’ in Macedonia to Bulgaria, precipitated a complete turnaround in the Allies' opinion of Macedonian ethnography, and several British and French maps echoing Cvijić were released within months.[178] Thus, as the Entente approached victory in the First World War, a number other maps and atlases, including those produced by the Allies replicated Cvijić's ideas, especially its depiction of the Macedo-Slavs.[179][180] The prevalence of the Yugoslav point of view, obliged Georgios Sotiriades, a professor of History at the University of Athens, to map the Macedo-Slavs as a distinct group in his work of 1918, that mirrored Greek views of the time and was used as an official document to advocate for Greece's positions in the Paris peace conference.[181][182] After World War I, Cvijić's map became the point of reference for all Balkan ethnographic maps,[183] while his concept of Macedo-Slavs was reproduced in almost all maps,[184] including German maps, that acknowledged a Macedonian nation.[185]

Macedonian Nationalism and Interwar Communism

After the Balkan Wars (1912–1913) and the World War I (1914–1918), following the division of the region of Macedonia amongst the Kingdom of Greece, the Kingdom of Bulgaria and the Kingdom of Serbia, the idea of belonging to a separate Macedonian nation was further spread among the Slavic-speaking population. The suffering during the wars, the endless struggle of the Balkan monarchies for dominance over the population increased the Macedonians' sentiment that the institutionalization of an independent Macedonian nation would put an end to their suffering. On the question of whether they were Serbs or Bulgarians, the people more often started answering: "Neither Bulgar, nor Serb... I am Macedonian only, and I'm sick of war."[186][187] Stratis Myrivilis noted a specific instance of a Slav-speaking family wanting to be referred to, not as "Bulgar, Srrp, or Grrts", but as "Makedon ortodox".[188] By the 1920s, following a negative reaction to the national proselytization of the previous decades, a majority of Christian Slavs inhabiting Greek and Vardar Macedonia used the collective name "Macedonians" to describe themselves, either as a nation or as a distinct ethnicity.[189] The 1928 Greek census recorded 81,844 Slavo-Macedonian speakers, distinct from 16,755 Bulgarian speakers.[190] In 1924 the Politis–Kalfov Protocol was signed between Greece and Bulgaria, concerning the protection of the Bulgarian minority In Greece. However, it was not ratified by the Greek side, because public opinion stood against the recognition of any “Bulgarian” minority".[191] Prior to the 1930s, "it seems to have been acceptable" for Greeks to refer to Slavophones of Macedonia as Macedonians and their language as Macedonian. Ion Dragoumis had argued this viewpoint.

The consolidation of an international Communist organization (the Comintern) in the 1920s led to some failed attempts by the Communists to use the Macedonian Question as a political weapon. In the 1920 Yugoslav parliamentary elections, 25% of the total Communist vote came from Macedonia, but participation was low (only 55%), mainly because the pro-Bulgarian IMRO organised a boycott against the elections. In the following years, the communists attempted to enlist the pro-IMRO sympathies of the population in their cause. In the context of this attempt, in 1924 the Comintern organized the filed signing of the so-called May Manifesto, in which independence of partitioned Macedonia was required.[192] In 1925 with the help of the Comintern, the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (United) was created, composed of former left-wing Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) members. This organization promoted for the first time in 1932 the existence of a separate ethnic Macedonian nation.[193][194][195] In 1933 the Communist Party of Greece, in a series of articles published in its official newspaper, the Rizospastis, criticizing Greek minority policy towards Slavic-speakers in Greek Macedonia, recognized the Slavs of the entire region of Macedonia as forming a distinct Macedonian ethnicity and their language as Macedonian.[196] The idea of a Macedonian nation was internationalized and backed by the Comintern which issued in 1934 a resolution supporting the development of the entity.[197] This action was attacked by the IMRO, but was supported by the Balkan communists. The Balkan communist parties supported the national consolidation of the ethnic Macedonian people and created Macedonian sections within the parties, headed by prominent IMRO (United) members.

World War II and Yugoslav nation-state building

The sense of belonging to a separate Macedonian nation gained credence during World War II when ethnic Macedonian communist partisan detachments were formed. In 1943 the Communist Party of Macedonia was established and the resistance movement grew up.[198][199] On the other hand, due to the different trajectories of Macedonian Slavs in the three nation-states that ruled the region, the designation "Macedonian" acquired different meanings for them by the time of the National Liberation War of Macedonia in the 1940s. According to historian Ivan Katardžiev those who came from the Bulgarian part or were members of the IMRO (United) practically felt themselves as Bulgarians, while those who had experienced Serbian rule and had interacted with the Croatian and Slovenian national movements within Yugoslavia had developed a stronger Macedonian consciousness.[200] After the World War II ethnic Macedonian institutions were created in the three parts of the region of Macedonia, then under communist control,[201] including the establishment of the People's Republic of Macedonia within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRJ).

The available data indicates that despite the policy of assimilation, pro-Bulgarian sentiments among the Macedonian Slavs in Yugoslavia were still sizable during the interwar period.[e] However, if the Yugoslavians would recognize the Slavic inhabitants of Vardar Macedonia as Bulgarians, it would mean that the area should be part of Bulgaria. Practically in post-World War II Macedonia, Yugoslavia's state policy of forced Serbianisation was changed with a new one — of Macedonization. The codification of Macedonian and the recognition of the Macedonian nation had the main goal: finally to ban any Bulgarophilia among the Macedonians and to build a new consciousness, based on identification with Yugoslavia. As a result, Yugoslavia introduced again an abrupt de-Bulgarization of the people in the PR Macedonia, such as it already had conducted in the Vardar Banovina during the Interwar period. Bulgarian sources claim around 100,000 pro-Bulgarian elements were imprisoned for violations of the special Law for the Protection of Macedonian National Honour, and over 1,200 were allegedly killed.[210][211] In this way generations of students grew up educated in a strong anti-Bulgarian sentiment which during the times of Communist Yugoslavia, increased to the level of state policy. Its main agenda was a result from the need to distinguish between the Bulgarians and the new Macedonian nation, because Macedonians could confirm themselves as a separate community with its own history, only through differentiating itself from Bulgaria. This policy has continued in the new Republic of Macedonia after 1990, although with less intensity. Thus, the Bulgarian part of the identity of the Slavic-speaking population in Vardar Macedonia has died out.

Contemporary state of identity and polemics

Following the collapse of Yugoslavia, the issue of Macedonian identity emerged again. Nationalists and governments alike from neighbouring countries, especially Greece and Bulgaria, espouse the view that the Macedonian ethnicity is a modern, artificial creation. Such views have been seen by Macedonian historians to represent irredentist motives on Macedonian territory.[122] Moreover, some historians point out that all modern nations are recent, politically motivated constructs based on creation "myths",[212] that the creation of Macedonian identity is "no more or less artificial than any other identity",[213] and that, contrary to the claims of Romantic nationalists, modern, territorially bound and mutually exclusive nation-states have little in common with their preceding large territorial or dynastic medieval empires, and any connection between them is tenuous at best.[214] In any event, irrespective of shifting political affiliations, the Macedonian Slavs shared in the fortunes of the Byzantine commonwealth and the Rum millet and they can claim them as their heritage.[122] Loring Danforth states similarly, the ancient heritage of modern Balkan countries is not "the mutually exclusive property of one specific nation" but "the shared inheritance of all Balkan peoples".[215]

A more radical and uncompromising strand of Macedonian nationalism has recently emerged called "ancient Macedonism", or "Antiquisation". Proponents of this view see modern Macedonians as direct descendants of the ancient Macedonians. This view faces criticism by academics as it is not supported by archaeology or other historical disciplines and also could marginalize the Macedonian identity.[216][217] Surveys on the effects of the controversial nation-building project Skopje 2014 and on the perceptions of the population of Skopje revealed a high degree of uncertainty regarding the latter's national identity. A supplementary national poll showed that there was a great discrepancy between the population's sentiment and the narrative the state sought to promote.[218]

Additionally, during the last two decades, tens of thousands of citizens of North Macedonia have applied for Bulgarian citizenship.[219] In the period since 2002 some 97,000 acquired it, while ca. 53,000 applied and are still waiting.[220] Bulgaria has a special ethnic dual-citizenship regime which makes a constitutional distinction between ethnic Bulgarians and Bulgarian citizens. In the case of the Macedonians, merely declaring their national identity as Bulgarian is enough to gain a citizenship.[221] By making the procedure simpler, Bulgaria stimulates more Macedonian citizens (of Slavic origin) to apply for a Bulgarian citizenship.[222] However, many Macedonians who apply for Bulgarian citizenship as Bulgarians by origin,[223] have few ties with Bulgaria.[224] Further, those applying for Bulgarian citizenship usually say they do so to gain access to member states of the European Union rather than to assert Bulgarian identity.[225] This phenomenon is called placebo identity.[226] Some Macedonians view the Bulgarian policy as part of a strategy to destabilize the Macedonian national identity.[227] As a nation engaged in a dispute over its distinctiveness from Bulgarians, Macedonians have always perceived themselves as threatened by their neighbor.[228] Bulgaria insists its neighbor admit the common historical roots of their languages and nations, a view Skopje continues to reject.[229] As a result, Bulgaria blocked the official start of EU accession talks with North Macedonia.[230]

Despite sizable number of Macedonians that have acquired Bulgarian citizenship since 2002 (ca. 9.7% of the Slavic population), only 3,504 citizens of North Macedonia declared themselves as ethnic Bulgarians in the 2021 census (roughly 0.31% from the Slavic population).[231] The Bulgarian side does not accept these results as completely objective, citing as an example the census has counted less than 20,000 people with Bulgarian citizenship in the country, while in fact they are over 100,000.[232]

Ethnonym

The national name derives from the Greek term Makedonía, related to the name of the region, named after the ancient Macedonians and their kingdom. It originates from the ancient Greek adjective makednos, meaning "tall",[233] which shares its roots with the adjective makrós, meaning the same.[234] The name is originally believed to have meant either "highlanders" or "the tall ones", possibly descriptive of these ancient people.[235][236][237] In the Late Middle Ages the name of Macedonia had different meanings for Western Europeans and for the Balkan people. For the Westerners it denoted the historical territory of the Ancient Macedonia, but for the Balkan Christians, it covered the territories of the former Byzantine province of Macedonia, situated around modern Turkish Edirne.[238]

With the conquest of the Balkans by the Ottomans in the late 14th century, the name of Macedonia disappeared as a geographical designation for several centuries. The name was revived just during the early 19th century, after the foundation of the modern Greek state with its Western Europe-derived obsession with Ancient Greece.[239][240] As a result of the rise of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire, massive Greek religious and school propaganda occurred, and a process of Hellenization was implemented among Slavic-speaking population of the area.[241][242] In this way, the name Macedonians was applied to the local Slavs, aiming to stimulate the development of close ties between them and the Greeks, linking both sides to the ancient Macedonians, as a counteract against the growing Bulgarian cultural influence into the region.[243][244]

Although the local intellectuals initially rejected the Macedonian designation as Greek,[245] since the 1850s some of them, adopted it as a regional identity, and this name began to gain popularity.[115] Serbian politics then, also encouraged this kind of regionalism to neutralize the Bulgarian influx, thereby promoting Serbian interests there.[246] The local educator Kuzman Shapkarev concluded that since the 1870s this foreign ethnonym began to replace the traditional one Bulgarians.[247] At the dawn of the 20th century the Bulgarian teacher Vasil Kanchov marked that the local Bulgarians and Koutsovlachs call themselves Macedonians, and the surrounding people also call them in the same way.[248] During the interbellum Bulgaria also supported to some extent the Macedonian regional identity, especially in Yugoslavia. Its aim was to prevent the Serbianization of the local Slavic speakers, because the very name Macedonia was prohibited in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.[249][250] Ultimately the designation Macedonian, changed its status in 1944, and went from being predominantly a regional, ethnographic denomination, to a national one.[251]

Population

| Part of a series on |

| Macedonians |

|---|

|

| By region or country |

| Macedonia (region) |

| Diaspora |

|

|

|

|

| Subgroups and related groups |

| Culture |

| Religion |

| Other topics |

The vast majority of Macedonians live along the valley of the river Vardar, the central region of the Republic of North Macedonia. They form about 64.18% of the population of North Macedonia (1,297,981 people according to the 2002 census). Smaller numbers live in eastern Albania, northern Greece, and southern Serbia, mostly abutting the border areas of the Republic of North Macedonia. A large number of Macedonians have immigrated overseas to Australia, the United States, Canada, New Zealand and to many European countries: Germany, Italy, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Austria among others.

Balkans

Greece

The existence of an ethnic Macedonian minority in Greece is rejected by the Greek government. The number of people speaking Slavic dialects has been estimated at somewhere between 10,000 and 250,000.[f] Most of these people however do not have an ethnic Macedonian national consciousness, with most choosing to identify as ethnic Greeks[260] or rejecting both ethnic designations and preferring terms such as "natives" instead.[261] In 1999 the Greek Helsinki Monitor estimated that the number of people identifying as ethnic Macedonians numbered somewhere between 10,000 and 30,000,[12][262] Macedonian sources generally claim the number of ethnic Macedonians living in Greece at somewhere between 200,000 and 350,000.[263] The ethnic Macedonians in Greece have faced difficulties from the Greek government in their ability to self-declare as members of a "Macedonian minority" and to refer to their native language as "Macedonian".[261]

Since the late 1980s there has been an ethnic Macedonian revival in Northern Greece, mostly centering on the region of Florina.[264] Since then ethnic Macedonian organisations including the Rainbow political party have been established.[265] Rainbow first opened its offices in Florina on 6 September 1995. The following day, the offices had been broken into and had been ransacked.[266] Later Members of Rainbow had been charged for "causing and inciting mutual hatred among the citizens" because the party had bilingual signs written in both Greek and Macedonian.[267] On 20 October 2005, the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) ordered the Greek government to pay penalties to the Rainbow Party for violations of 2 ECHR articles.[261] Rainbow has seen limited success at a national level, its best result being achieved in the 1994 European elections, with a total of 7,263 votes. Since 2004 it has participated in European Parliament elections and local elections, but not in national elections. A few of its members have been elected in local administrative posts. Rainbow has recently re-established Nova Zora, a newspaper that was first published for a short period in the mid-1990s, with reportedly 20,000 copies being distributed free of charge.[268][269][270]

Serbia

Within Serbia, Macedonians constitute an officially recognised ethnic minority at both a local and national level. Within Vojvodina, Macedonians are recognised under the Statute of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, along with other ethnic groups. Large Macedonian settlements within Vojvodina can be found in Plandište, Jabuka, Glogonj, Dužine and Kačarevo. These people are mainly the descendants of economic migrants who left the Socialist Republic of Macedonia in the 1950s and 1960s. The Macedonians in Serbia are represented by a national council and in recent years Macedonian has begun to be taught. The most recent census recorded 22,755 Macedonians living in Serbia.[271]

Albania

Macedonians represent the second largest ethnic minority population in Albania. Albania recognises the existence of a Macedonian minority within the Mala Prespa region, most of which is comprised by Pustec Municipality. Macedonians have full minority rights within this region, including the right to education and the provision of other services in Macedonian. There also exist unrecognised Macedonian populations living in the Golo Brdo region, the "Dolno Pole" area near the town of Peshkopi, around Lake Ohrid and Korce as well as in Gora. 4,697 people declared themselves Macedonians in the 1989 census.[272]

Bulgaria

Bulgarians are considered most closely related to the neighboring Macedonians, and it is sometimes claimed that there is no clear ethnic difference between them.[273] A total of 1,143 people officially declared themselves to be ethnic Macedonians in the last Bulgarian census in 2021.[31] During the same year, there were five times as many Bulgarian residents born in North Macedonia, 5,450.[274] Most of them held Bulgarian citizenship, with only 1,576 of them being citizens of the Republic of North Macedonia.[275] According to the 2011 Bulgarian census, there were 561 ethnic Macedonians (0.2%) in the Blagoevgrad Province,[276] the Bulgarian part of the geographical region of Macedonia, out of a total of 1,654 Macedonians in the entire country.[277] Also, a total of 429 citizens of the Republic of North Macedonia resided in the province.[278]

In 1998, Krassimir Kanev, chairman of the non-governmental organization Bulgarian Helsinki Committee, claimed that there were 15,000–25,000 ethnic Macedonians in Bulgaria (see here). In the same report, Macedonian nationalists (Popov et al., 1989) claimed that 200,000 ethnic Macedonians lived in Bulgaria. However, according to the Bulgarian Helsinki Committee, the vast majority of the Slavic-speaking population in Pirin Macedonia had a Bulgarian national self-consciousness and a regional Macedonian identity similar to the Macedonian regional identity in Greek Macedonia. According to ethnic Macedonian political activist, Stoyko Stoykov, the number of Bulgarian citizens with ethnic Macedonian self-consciousness in 2009 was between 5,000 and 10,000.[279] In 2000, the Bulgarian Constitutional Court banned UMO Ilinden-Pirin, a small Macedonian political party, as a separatist organization. Subsequently, activists attempted to re-establish the party but could not gather the required number of signatures.

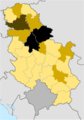

- Macedonians in North Macedonia, according to the 2002 census

- Concentration of Macedonians in Serbia

- Regions where Macedonians live within Albania

- Macedonian Muslims in North Macedonia

Diaspora

Significant Macedonian communities can also be found in the traditional immigrant-receiving nations, as well as in Western European countries. Census data in many European countries (such as Italy and Germany) does not take into account the ethnicity of émigrés from the Republic of North Macedonia.

Argentina

Most Macedonians can be found in Buenos Aires, the Pampas and Córdoba. An estimated 30,000 Macedonians can be found in Argentina.[280]

Australia

The official number of Macedonians in Australia by birthplace or birthplace of parents is 83,893 (2001). The main Macedonian communities are found in Melbourne, Geelong, Sydney, Wollongong, Newcastle, Canberra and Perth. The 2006 census recorded 83,983 people of Macedonian ancestry and the 2011 census recorded 93,570 people of Macedonian ancestry.[281]

Brazil

An estimated 45,000 people in Brazil are of Macedonian ancestry.[282] The Macedonians can be primarily found in Porto Alegre, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and Curitiba.

Canada

The Canadian census in 2001 records 37,705 individuals claimed wholly or partly Macedonian heritage in Canada,[283] although community spokesmen have claimed that there are actually 100,000–150,000 Macedonians in Canada.[284]

United States

A significant Macedonian community can be found in the United States. The official number of Macedonians in the US is 49,455 (2004). The Macedonian community is located mainly in Michigan, New York, Ohio, Indiana and New Jersey[285]

Germany

There are an estimated 61,000 citizens of North Macedonia in Germany (mostly in the Ruhrgebiet) (2001).

Italy

There are 74,162 citizens of North Macedonia in Italy (Foreign Citizens in Italy).

Switzerland

In 2006 the Swiss Government recorded 60,362 Macedonian Citizens living in Switzerland.[286]

Romania

Macedonians are an officially recognised minority group in Romania. They have a special reserved seat in the nation's parliament. In 2002, they numbered 731.

Slovenia

Macedonians began relocating to Slovenia in the 1950s when the two regions formed a part of a single country, Yugoslavia.

Other countries

Other significant Macedonian communities can also be found in the other Western European countries such as Austria, France, Luxembourg, Netherlands, United Kingdom, and the whole European Union. [citation needed] Also in Uruguay, with a significant population in Montevideo.[citation needed]

Culture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2019) |

The culture of the people is characterized with both traditionalist and modernist attributes. It is strongly bound with their native land and the surrounding in which they live. The rich cultural heritage of the Macedonians is accented in the folklore, the picturesque traditional folk costumes, decorations and ornaments in city and village homes, the architecture, the monasteries and churches, iconostasis, wood-carving and so on. The culture of Macedonians can roughly be explained as Balkanic, closely related to that of Bulgarians and Serbs.

Architecture

The typical Macedonian village house is influenced by Ottoman Architecture. Presented as a construction with two floors, with a hard facade composed of large stones and a wide balcony on the second floor. In villages with predominantly agricultural economy, the first floor was often used as a storage for the harvest, while in some villages the first floor was used as a cattle-pen.

The stereotype for a traditional Macedonian city house is a two-floor building with white façade, with a forward extended second floor, and black wooden elements around the windows and on the edges.

Cinema and theater

The history of film making in North Macedonia dates back over 110 years. The first film to be produced on the territory of the present-day the country was made in 1895 by Janaki and Milton Manaki in Bitola. In 1995 Before the Rain became the first Macedonian movie to be nominated for an Academy Award.[287]

From 1993 to 1994, 1,596 performances were held in the newly formed republic, and more than 330,000 people attended. The Macedonian National Theater (drama, opera, and ballet companies), the Drama Theater, the Theater of the Nationalities (Albanian and Turkish drama companies) and the other theater companies comprise about 870 professional actors, singers, ballet dancers, directors, playwrights, set and costume designers, etc. There is also a professional theatre for children and three amateur theaters. For the last thirty years a traditional festival of Macedonian professional theaters has been taking place in Prilep in honor of Vojdan Černodrinski, the founder of the modern Macedonian theater. Each year a festival of amateur and experimental Macedonian theater companies is held in Kočani.

Music and art

Macedonian music has many things in common with the music of neighboring Balkan countries, but maintains its own distinctive sound.

The founders of modern Macedonian painting included Lazar Licenovski, Nikola Martinoski, Dimitar Pandilov, and Vangel Kodzoman. They were succeeded by an exceptionally talented and fruitful generation, consisting of Borka Lazeski, Dimitar Kondovski, Petar Mazev who are now deceased, and Rodoljub Anastasov and many others who are still active. Others include: Vasko Taskovski and Vangel Naumovski. In addition to Dimo Todorovski, who is considered to be the founder of modern Macedonian sculpture, the works of Petar Hadzi Boskov, Boro Mitrikeski, Novak Dimitrovski and Tome Serafimovski are also outstanding.

Economy

In the past, the Macedonian population was predominantly involved with agriculture, with a very small portion of the people who were engaged in trade (mainly in the cities). But after the creation of the People's Republic of Macedonia which started a social transformation based on Socialist principles, middle and heavy industries were started.

Language

Macedonian (македонски јазик) is a member of the Eastern group of South Slavic languages. Standard Macedonian was implemented as the official language of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia after being codified in the 1940s, and has accumulated a thriving literary tradition.

The closest relative of Macedonian is Bulgarian,[288] followed by Serbo-Croatian. All the South Slavic languages form a dialect continuum, in which Macedonian and Bulgarian form an Eastern subgroup. The Torlakian dialect group is intermediate between Bulgarian, Macedonian and Serbian, comprising some of the northernmost dialects of Macedonian as well as varieties spoken in southern Serbia and western Bulgaria. Torlakian is often classified as part of the Eastern South Slavic dialects.

The Macedonian alphabet is an adaptation of the Cyrillic script, as well as language-specific conventions of spelling and punctuation. It is rarely Romanized.

Religion

Most Macedonians are members of the Macedonian Orthodox Church. The official name of the church is Macedonian Orthodox Church – Ohrid Archbishopric and is the body of Christians who are united under the Archbishop of Ohrid and North Macedonia, exercising jurisdiction over Macedonian Orthodox Christians in the Republic of North Macedonia and in exarchates in the Macedonian diaspora.

The church gained autonomy from the Serbian Orthodox Church in 1959 and declared the restoration of the historic Archbishopric of Ohrid. On 19 July 1967, the Macedonian Orthodox Church declared autocephaly from the Serbian church. Due to protest from the Serbian Orthodox Church, the move was not recognised by any of the churches of the Eastern Orthodox Communion. Thereafter, Macedonian Orthodox Church was not in communion with any Orthodox Church, until 2022 when it was reintegrated.[289] A small number of Macedonians belong to the Roman Catholic and the Protestant churches.

Between the 15th and the 20th centuries, during Ottoman rule, a number of Orthodox Macedonian Slavs converted to Islam. Today in the Republic of North Macedonia, they are regarded as Macedonian Muslims, who constitute the second largest religious community of the country.

Names

Cuisine

Macedonian cuisine is a representative of the cuisine of the Balkans—reflecting Mediterranean (Greek) and Middle Eastern (Turkish) influences, and to a lesser extent Italian, German and Eastern European (especially Hungarian) ones. The relatively warm climate in North Macedonia provides excellent growth conditions for a variety of vegetables, herbs and fruits. Thus, Macedonian cuisine is particularly diverse.

Shopska salad, a food from Bulgaria, is an appetizer and side dish which accompanies almost every meal.[citation needed] Macedonian cuisine is also noted for the diversity and quality of its dairy products, wines, and local alcoholic beverages, such as rakija. Tavče Gravče and mastika are considered the national dish and drink of North Macedonia, respectively.

Symbols

Symbols used by members of the ethnic group include:

- Lion: The lion first appears in the Fojnica Armorial from the 17th century, where the coat of arms of Macedonia is included among those of other entities. On the coat of arms is a crown; inside a yellow crowned lion is depicted standing rampant, on a red background. On the bottom enclosed in a red and yellow border is written "Macedonia". The use of the lion to represent Macedonia was continued in foreign heraldic collections throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.[290][291] Nevertheless, during the late 19th century the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization arose, which modeled itself after the earlier Bulgarian revolutionary traditions and adopted their symbols as the lion, etc.[292][293] Modern versions of the historical lion has also been added to the emblem of several political parties, organizations and sports clubs. However, this symbol is not totally accepted while the state coat of arms of Bulgaria is somewhat similar.

- Vergina Sun: (official flag, 1992–1995) The Vergina Sun is used unofficially by various associations and cultural groups in the Macedonian diaspora. The Vergina Sun is believed to have been associated with ancient Greek kings such as Alexander the Great and Philip II, although it was used as an ornamental design in ancient Greek art long before the Macedonian period. The symbol was depicted on a golden larnax found in a 4th-century BC royal tomb belonging to either Philip II or Philip III of Macedon in the Greek region of Macedonia. The Greeks regard the use of the symbol by North Macedonia as a misappropriation of a Hellenic symbol, unrelated to Slavic cultures, and a direct claim on the legacy of Philip II. However, archaeological items depicting the symbol have also been excavated in the territory of North Macedonia.[294] Toni Deskoski, Macedonian professor of International Law, argues that the Vergina Sun is not a Macedonian symbol but it's a Greek symbol that is used by Macedonians in the nationalist context of Macedonism and that the Macedonians need to get rid of it.[295] In 1995, Greece lodged a claim for trademark protection of the Vergina Sun as a state symbol under WIPO.[296] In Greece the symbol against a blue field is used vastly in the area of Macedonia and it has official status.The Vergina sun on a red field was the first flag of the independent Republic of Macedonia, until it was removed from the state flag under an agreement reached between the Republic of Macedonia and Greece in September 1995.[297] On 17 June 2018, Greece and the Republic of Macedonia signed the Prespa Agreement, which stipulates the removal of the Vergina Sun's public use across the latter's territory.[298][299] In a session held on early July 2019, the government of North Macedonia announced the complete removal of the Vergina Sun from all public areas, institutions and monuments in the country, with the deadline for its removal being set to 12 August 2019, in line with the Prespa Agreement.[300][301][302]

Genetics

Anthropologically, Macedonians possess genetic lineages postulated to represent Balkan prehistoric and historic demographic processes.[303] Such lineages are also typically found in neighboring South Slavs such as Bulgarians and Serbs, in addition to Greeks, Albanians, Romanians and Gagauzes.[g]

Y-DNA studies suggest that Macedonians along with neighboring South Slavs are distinct from other Slavic-speaking populations in Europe and near half of their Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups are likely to be inherited from inhabitants of the Balkans that predated sixth-century Slavic migrations.[313] A diverse set of Y-DNA haplogroups are found in Macedonians at significant levels, including I2a1b, E-V13, J2a, R1a1, R1b, G2a, encoding a complex pattern of demographic processes.[314] Similar distributions of the same haplogroups are found in neighboring populations.[315][316] I2a1b and R1a1 are typically found in Slavic-speaking populations across Europe[317][318] while haplogroups such as E-V13 and J2 occur at high frequencies in neighboring non-Slavic populations.[315] On the other hand R1b is the most frequently occurring haplogroup in Western Europe and G2a is most frequently found in Caucasus and the adjacent areas. According to a DNA data for 17 Y-chromosomal STR loci in Macedonians, in comparison to other South Slavs and Kosovo Albanians, the Macedonian population had the lowest genetic (Y-STR) distance against the Bulgarian population while having the largest distance against the Croatian population. However, the observed populations did not have significant differentiation in Y-STR population structure, except partially for Kosovo Albanians.[319] Genetic similarity, irrespective of language and ethnicity, has a strong correspondence to geographic proximity in European populations.[310][311][320]

In regard to population genetics, not all regions of Southeastern Europe had the same ratio of native Byzantine and invading Slavic population, with the territory of the Eastern Balkans (Macedonia, Thrace and Moesia) having a significant percentage of locals compared to Slavs. Considering that the majority of Balkan Slavs came via the Eastern Carpathian route, lower percentage in the east does not imply that the number of the Slavs there was lesser than among the Western South Slavs. Most probably on the territory of Western South Slavs was a state of desolation which produced there a founder effect.[321][322] The region of Macedonia suffered less disruption than frontier provinces closer to the Danube, with towns and forts close to Ohrid, Bitola and along the Via Egnatia. Re-settlements and the cultural links of the Byzantine Era further shaped the demographic processes which the Macedonian ancestry is linked to.[323] Nevertheless, even present-day Peloponnesian Greeks carry a small, but significant amount of Slavic ancestry; the admixture ranged from 0.2% to 14.4%.[324]

See also

- Demographic history of North Macedonia

- List of Macedonians

- Demographics of the Republic of North Macedonia

- Macedonian language

- Ethnogenesis

- South Slavs

- Macedonians (Greeks)

- Macedonians (Bulgarians)

References

- ^ State Statistical Office

- ^ "Cultural diversity: Census". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Republic of Macedonia MFA estimate Archived 26 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ 2006 figures Archived 19 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Foreign Citizens in Italy, 2017 Archived 6 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ 2020 Community Survey

- ^ 2005 Figures Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nasevski, Boško; Angelova, Dora; Gerovska, Dragica (1995). Македонски Иселенички Алманах '95. Skopje: Матица на Иселениците на Македонија. pp. 52–53.

- ^ "My Info Agent". Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ 2006 census Archived 25 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ 2001 census Archived 15 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Report about Compliance with the Principles of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (Greece) – GREEK HELSINKI MONITOR (GHM) Archived 23 May 2003 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Попис у Србији 2011". Archived from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Tabelle 13: Ausländer nach Staatsangehörigkeit (ausgewählte Staaten), Altersgruppen und Geschlecht — p. 74.

- ^ "United Nations Population Division | Department of Economic and Social Affairs". un.org. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ^ 1996 estimate Archived 5 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Population and Housing Census 2023" (PDF). Instituti i Statistikës (INSTAT).

- ^ Population by country of origin

- ^ OECD Statistics.

- ^ Population by country of birth 2009.

- ^ "Population by Ethnicity, by Towns/Municipalities, 2011 Census". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012.

- ^ 2002 census (stat.si).

- ^ "Belgium population statistics". dofi.fgov.be. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

- ^ 2008 figures Archived 12 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ 2003 census Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine,Population Estimate from the MFA Archived 26 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ 2005 census Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ czso.cz

- ^ Jump up to: a b Makedonci vo Svetot Archived 26 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Polands Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918–1947, p. 260.

- ^ "Rezultatele finale ale Recensământului din 2011 – Tab8. Populaţia stabilă după etnie – judeţe, municipii, oraşe, comune" (in Romanian). National Institute of Statistics (Romania). 5 July 2013. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ива Капкова, Етноанализът на НСИ: 8,4% в България се определят към турския етнос, 4,4% казват, че са роми; 24.11.2022, Dir.bg

- ^ Montenegro 2011 census.

- ^ "2006 census". Archived from the original on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ Population Estimate from the MFA Archived 30 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "República de Macedonia - Emigrantes totales".

- ^ {{https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Frosstat.gov.ru%2Fstorage%2Fmediabank%2FTom5_tab1_VPN-2020.xlsx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK}}

- ^ "Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States", p. 517 The Macedonians are a Southern Slav people, closely related to Bulgarians.

- ^ "Ethnic groups worldwide: a ready reference handbook", p. 54 Macedonians are a Slavic people closely related to the neighboring Bulgarians.

- ^ Day, Alan John; East, Roger; Thomas, Richard (2002). Political and economic dictionary of Eastern Europe. Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 9780203403747.

- ^ Krste Misirkov, On the Macedonian Matters (Za Makedonckite Raboti), Sofia, 1903: "And, anyway, what sort of new Macedonian nation can this be when we and our fathers and grandfathers and great-grandfathers have always been called Bulgarians?"

- ^ Sperling, James; Kay, Sean; Papacosma, S. Victor (2003). Limiting institutions?: the challenge of Eurasian security governance. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7190-6605-4.

Macedonian nationalism Is a new phenomenon. In the early twentieth century, there was no separate Slavic Macedonian identity

- ^ Titchener, Frances B.; Moorton, Richard F. (1999). The eye expanded: life and the arts in Greco-Roman antiquity. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-520-21029-5.

On the other hand, the Macedonians are a newly emergent people in search of a past to help legitimize their precarious present as they attempt to establish their singular identity in a Slavic world dominated historically by Serbs and Bulgarians. ... The twentieth-century development of a Macedonian ethnicity, and its recent evolution into independent statehood following the collapse of the Yugoslav state in 1991, has followed a rocky road. In order to survive the vicissitudes of Balkan history and politics, the Macedonians, who have had no history, need one.

- ^ Kaufman, Stuart J. (2001). Modern hatreds: the symbolic politics of ethnic war. New York: Cornell University Press. p. 193. ISBN 0-8014-8736-6.

The key fact about Macedonian nationalism is that it is new: in the early twentieth century, Macedonian villagers defined their identity religiously—they were either "Bulgarian," "Serbian," or "Greek" depending on the affiliation of the village priest. ... According to the new Macedonian mythology, modern Macedonians are the direct descendants of Alexander the Great's subjects. They trace their cultural identity to the ninth-century Saints Cyril and Methodius, who converted the Slavs to Christianity and invented the first Slavic alphabet, and whose disciples maintained a centre of Christian learning in western Macedonia. A more modern national hero is Gotse Delchev, leader of the turn-of-the-century Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), which was actually a largely pro-Bulgarian organization but is claimed as the founding Macedonian national movement.

- ^ Rae, Heather (2002). State identities and the homogenisation of peoples. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 278. ISBN 0-521-79708-X.

Despite the recent development of Macedonian identity, as Loring Danforth notes, it is no more or less artificial than any other identity. It merely has a more recent ethnogenesis – one that can therefore more easily be traced through the recent historical record.

- ^ Zielonka, Jan; Pravda, Alex (2001). Democratic consolidation in Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-19-924409-6.

Unlike the Slovene and Croatian identities, which existed independently for a long period before the emergence of SFRY Macedonian identity and language were themselves a product federal Yugoslavia, and took shape only after 1944. Again unlike Slovenia and Croatia, the very existence of a separate Macedonian identity was questioned—albeit to a different degree—by both the governments and the public of all the neighboring nations (Greece being the most intransigent)

- ^ Bonner, Raymond (14 May 1995). "The World; The Land That Can't Be Named". The New York Times. New York. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

Macedonian nationalism did not arise until the end of the last century.

- ^ Rossos, Andrew (2008). Macedonia and the Macedonians: A History (PDF). Hoover Institution Press. p. 269. ISBN 978-0817948832. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

They were also insisting that the Macedonians sacrifice their national name, under which, as we have seen throughout this work, their national identity and their nation formed in the nineteenth century.

- ^ Rossos, Andrew (2008). Macedonia and the Macedonians: A History (PDF). Hoover Institution Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-0817948832. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

Under very trying circumstances, most ethnic Macedonians chose a Macedonian identity. That identity began to form with the Slav awakening in Macedonia in the first half of the nineteenth century.

- ^ Loring M. Danforth, The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World, 1995, Princeton University Press, p.65, ISBN 0-691-04356-6

- ^ Stephen Palmer, Robert King, Yugoslav Communism and the Macedonian question, Hamden, Connecticut Archon Books, 1971, p.p.199-200

- ^ Livanios, Dimitris (17 April 2008). The Macedonian Question: Britain and the Southern Balkans 1939–1949. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191528729. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Woodhouse, Christopher M. (2002). The Struggle for Greece, 1941–1949. Hurst. ISBN 9781850654926. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Poulton, Hugh (1995). Who are the Macedonians?. Hurst. ISBN 9781850652380. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ James Horncastle, The Macedonian Slavs in the Greek Civil War, 1944–1949; Rowman & Littlefield, 2019, ISBN 1498585051, p. 130.

- ^ Stern, Dieter and Christian Voss (eds). 2006. "Towards the peculiarities of language shift in Northern Greece". In: "Marginal Linguistic Identities: Studies in Slavic Contact and Borderland Varieties." Eurolinguistische Arbeiten. Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz Verlag; ISBN 9783447053549, pp. 87–101.

- ^ A J Toynbee. Some Problems of Greek History, Pp 80; 99–103

- ^ The Problem of the Discontinuity in Classical and Hellenistic Eastern Macedonia, Marjan Jovanonv. УДК 904:711.424(497.73)

- ^ A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Wiley -Blackwell, 2011. Map 2

- ^ Peter Heather, Goths and Romans 332–489. p. 129

- ^ Jump up to: a b Macedonia in Late Antiquity p. 551. In A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Wiley -Blackwell, 2011

- ^ Jump up to: a b Curta, Florin (2012). "Were there any Slavs in seventh-century Macedonia?". Journal of History. 47: 73.

- ^ Curta (2004, p. 148)

- ^ Fine (1991, p. 29)

- ^ T E Gregory, A History of Byzantium. Wiley- Blackwell, 2010. p. 169

- ^ Curta (2001, pp. 335–345)

- ^ Florin Curta. Were there any Slavs in seventh-century Macedonia? 2013

- ^ The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Denis Sinor, Cambridge University Press, 1990, ISBN 0521243041, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Fine 1991, pp. 71.

- ^ Во некрополата "Млака" пред тврдината во Дебреште, Прилеп, откопани се гробови со наоди од доцниот 7. и 8. век. Тие се делумно или целосно кремирани и не се ниту ромеjски, ниту словенски. Станува збор наjвероjатно, за Кутригурите. Ова протобугарско племе, под водство на Кубер, а како потчинето на аварскиот каган во Панониjа, околу 680 г. се одметнало од Аварите и тргнало кон Солун. Кубер ги повел со себе и Сермесиjаните, (околу 70.000 на број), во нивната стара татковина. Сермесиjаните биле Ромеи, жители на балканските провинции што Аварите ги заробиле еден век порано и ги населиле во Западна Панониjа, да работат за нив. На Кубер му била доверена управата врз нив. In English: In the necropolis 'Malaka' in the fortress of Debreshte, near Prilep, graves were dug with findings from the late 7th and early 8th century. They are partially or completely cremated and neither Roman nor Slavic. The graves are probably remains from the Kutrigurs. This Bulgar tribe was led by Kuber... Средновековни градови и тврдини во Македонија. Иван Микулчиќ (Скопје, Македонска цивилизација, 1996) стр. 32–33.

- ^ "The" Other Europe in the Middle Ages: Avars, Bulgars, Khazars and Cumans, East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450 – 1450, Florin Curta, Roman Kovalev, BRILL, 2008, ISBN 9004163891, p. 460.

- ^ W Pohl. The Avars (History) in Regna and Gentes. The Relationship Between Late Antique and Early Medieval Peoples and Kingdoms in the Transformation of the Roman World. pp. 581, 587

- ^ They spread from the original heartland in north-east Bulgaria to the Drina in the west, and to Macedonia in the south-west.; На целиот тој простор, во маса метални производи (делови од воената опрема, облека и накит), меѓу стандардните форми користени од словенското население, одвреме-навреме се појавуваат специфични предмети врзани за бугарско болјарство како носители на новата државна управа. See: Средновековни градови и тврдини во Македонија. Иван Микулчиќ (Скопје, Македонска цивилизација, 1996) стр. 35; 364–365.

- ^ Деян Булич, Укрепления поздней античности и ранневизантийского периода на позднейшей территории южнославянских княжеств и их повторная оккупация в Тиборе Живковиче и др., Мир славян: исследования Востока, Запада и южные славяне: Чивитас, Оппидас, виллы и археологические свидетельства (7-11 века нашей эры) под ред. Срджана Рудича. Исторический институт, 2013, Белград; ISBN 8677431047 , стр. 186–187.

- ^ Флорин Курта. «Эдинбургская история греков, ок. 500–1050 гг.: Раннее средневековье». стр. 259, 281

- ^ Исследования внутренней диаспоры Византийской империи под редакцией Элен Арвайлер , Анжелики Э. Лайу , стр. 58. Многие из них, очевидно, базировались в Битоле, Стумнице и Моглене.

- ^ Половцы и татары: Восточные военные на доосманских Балканах, 1185–1365. Иштван Варсари. п. 67

- ^ Стоянович, Траян (сентябрь 1994 г.). Балканские миры . Я Шарп. ISBN 9780765638519 . Проверено 18 марта 2015 г.

- ^ Чаманска, Илона. (2016). Валахи и славяне в средние века и новое время. Рес Историка. 41. 11. 10.17951/р.2016.0.11.

- ^ Гузелев, Боян. Албанцы на Восточных Балканах, София, 2004 г., редактор: Василька Танкова, IMIR (Международный центр изучения меньшинств и культурных взаимодействий), ISBN 9789548872454 , стр. 10-22.

- ^ Fine 1991 , стр. 110–111.

- ^ Fine 1991 , стр. 113, 196 Два брата... Константин и Мефодий свободно владели диалектом славянского языка в окрестностях Салоник. Они разработали алфавит для передачи славянской фонетики.

- ^ Francis Dvornik. The Slavs p. 167

- ^ Острогорский, История Византийского государства с. 310

- ^ Прайс, Гланвилл (18 мая 2000 г.). Энциклопедия языков Европы . Уайли. ISBN 978-0-63122039-8 .

- ^ Парри, Кен (10 мая 2010 г.). Блэквеллский компаньон восточного христианства . Джон Уайли и сыновья. ISBN 978-1-44433361-9 .

- ^ Розенквист, Ян Олоф (2004). Взаимодействие и изоляция в поздневизантийской культуре . Академик Блумсбери. ISBN 978-1-85043944-8 .

- ^ Fine 1991 , стр. 127 [Славянская миссия должна была стать основным средством превращения этих славян в Македонии, а также других славян внутри Болгарского государства, в болгар.].

- ^ Хапчик, Деннис (2002). Балканы: от Константинополя к коммунизму . Нью-Йорк: Пэлгрейв Макмиллан. п. 44. ИСБН 978-1-4039-6417-5 .

Борис I приветствовал беженцев с распростертыми объятиями, предложил им свое покровительство и помог им организовать миссионерскую операцию с центром в Охриде в Булгарской Македонии, где они готовили молодежь для духовенства и переводили всю православную литургию на славянский язык. Новообученных славяноязычных священников затем отправили к славянским подданным государства. По мере распространения их влияния и увеличения числа новообращенных среди населения возникло новое чувство общности и государства. Отдельные этнические идентичности постепенно сливались в общую болгарскую, а региональная или племенная лояльность заметно смещалась к государству, олицетворяемому его теперь уже христианским правителем. Возникло государство Булгария, в отличие от Булгарского государства.

- ^ Александр Шенкер. Рассвет славянства . стр. 188–190. Шенкер утверждает, что Охрид был «новаторским» и «исконно славянским», в то время как Преслав во многом полагался на греческое моделирование.

- ^ Согласно Курте, Преслав был центром, из которого письменность, связанная с введением кириллицы, распространилась на другие регионы Болгарии. Флорин Курта (2006) Юго-Восточная Европа в средние века, 500–1250, издательство Кембриджского университета, стр. 221, ISBN 9780521894524 .

- ^ Детрез, Раймонд; Сегерт, Барбара (2008). Европа и историческое наследие на Балканах . Питер Лэнг. ISBN 9789052013749 . Проверено 18 марта 2015 г.

- ^ Балканская культурная общность и этническое разнообразие. Раймонд Детрез (Гентский университет, Бельгия).

- ^ История болгар. Позднее Средневековье и Возрождение, том 2, Георгий Бакалов, Издательство ТРУД, 2004, ISBN 9545284676 , стр. 23. (Bg.)

- ^ Центр документации и информации о меньшинствах в Европе, Юго-Восточной Европе (CEDIME-SE) – «Македонцы Болгарии», с. 14. Архивировано 23 июля 2006 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ Поултон, Хью (2000). Кто такие македонцы? . Херст. ISBN 9781850655343 . Проверено 18 марта 2015 г.

- ^ «Средневековые города и крепости Македонии, Иван Микульчич, Македонская академия наук и искусств - Скопье, 1996, стр. 72» . Проверено 18 марта 2015 г.

- ^ Академик Димитр Симеонов Ангелов (1978). «Формирование болгарской нации (краткое содержание)» . София-Пресс. стр. 413–415 . Проверено 18 марта 2015 г.

- ^ Когда этническая принадлежность не имела значения на Балканах. JVA Хорошо. стр. 3–5.

- ^ Гипотеза релексификации на румынском языке. Пол Векслер. п. 170

- ^ Половцы и татары: Восточные военные на доосманских Балканах. Иштван Васари. п. 18

- ^ Балканская граница Византии. Пол Стивенсон. п. 78–79

- ^ Эдинбургская история греков; 500–1250: Средние века. Флорин Курта. 2013. с. 294 (вторя Энтони Д. Смиту и Энтони Калделлису) «не существует четкого представления о том, что греческая нация дожила до византийских времен… этническую идентичность тех, кто жил в Греции в средние века, лучше всего описать как римскую».

- ^ Матс Рослунд. Гости в доме: культурная передача между славянами и скандинавами ; 2008. с. 79